The Hollywood Reporter

A conversation with editor Janice Min (The Hollywood Reporter, Us Weekly, Ankler Media, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT MOUNTAIN GAZETTE, COMMERCIAL TYPE, AND LANE PRESS

A good editor can, theoretically, edit any magazine, regardless of genre. But in some cases, you need an outsider to make things right. To see the forest for the trees.

To that end, Janice Min has planted acres of forests—one tree at a time—on both coasts, where the Colorado-born editor considers herself an outsider.

“I cared about almost none of this. I don’t care about celebrities or reality stars. It was my job to just think about how to interpret what they were saying and turn that passion into stories. I don’t think that the editors always have to be their audience, but I also think, as an editor I was able to be removed from it and glean like, ‘That pops. That’s the most important story.’”

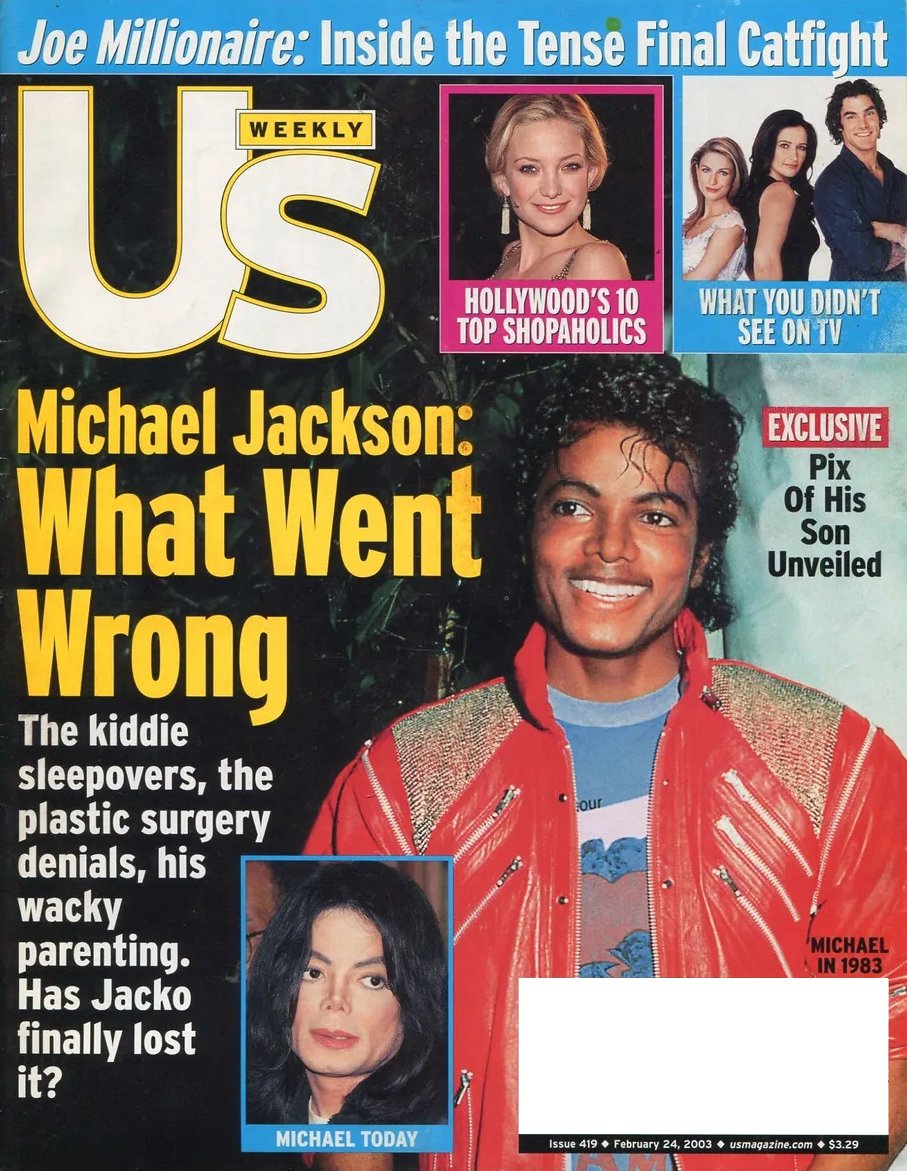

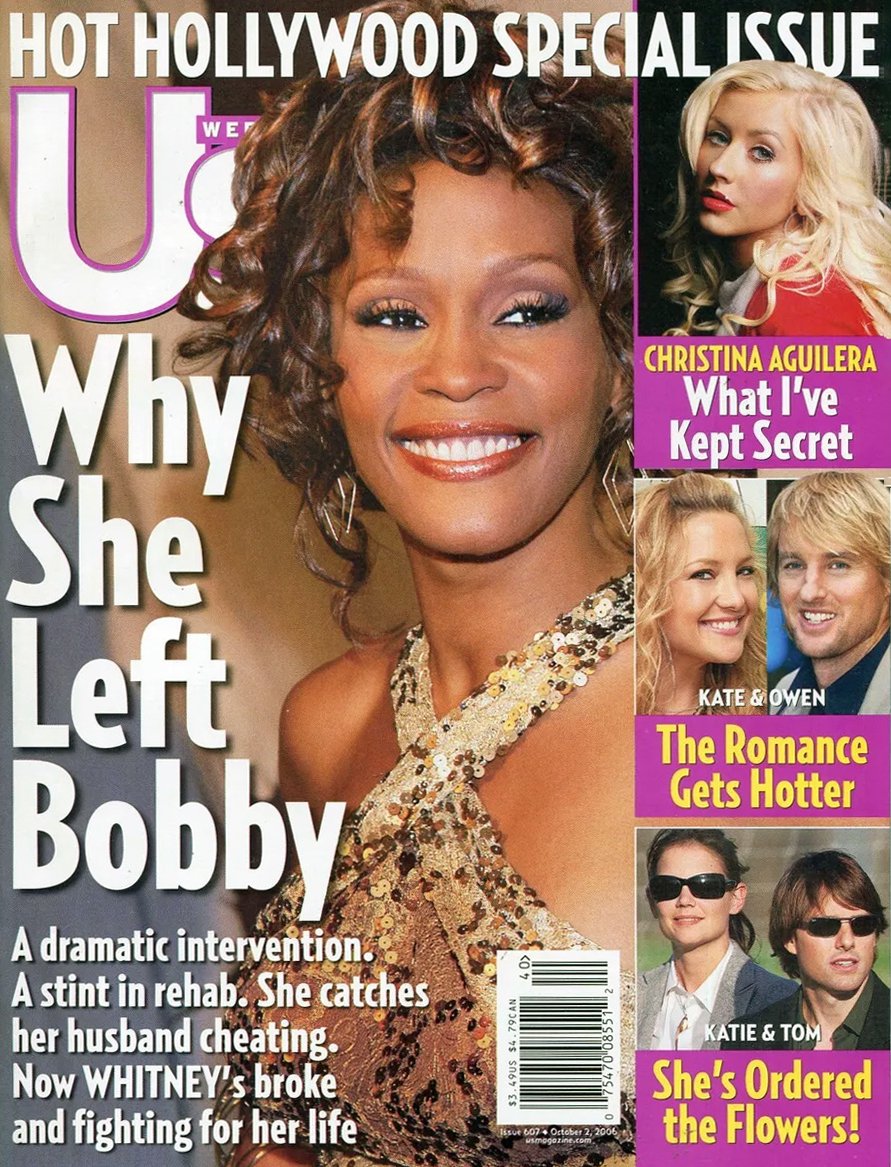

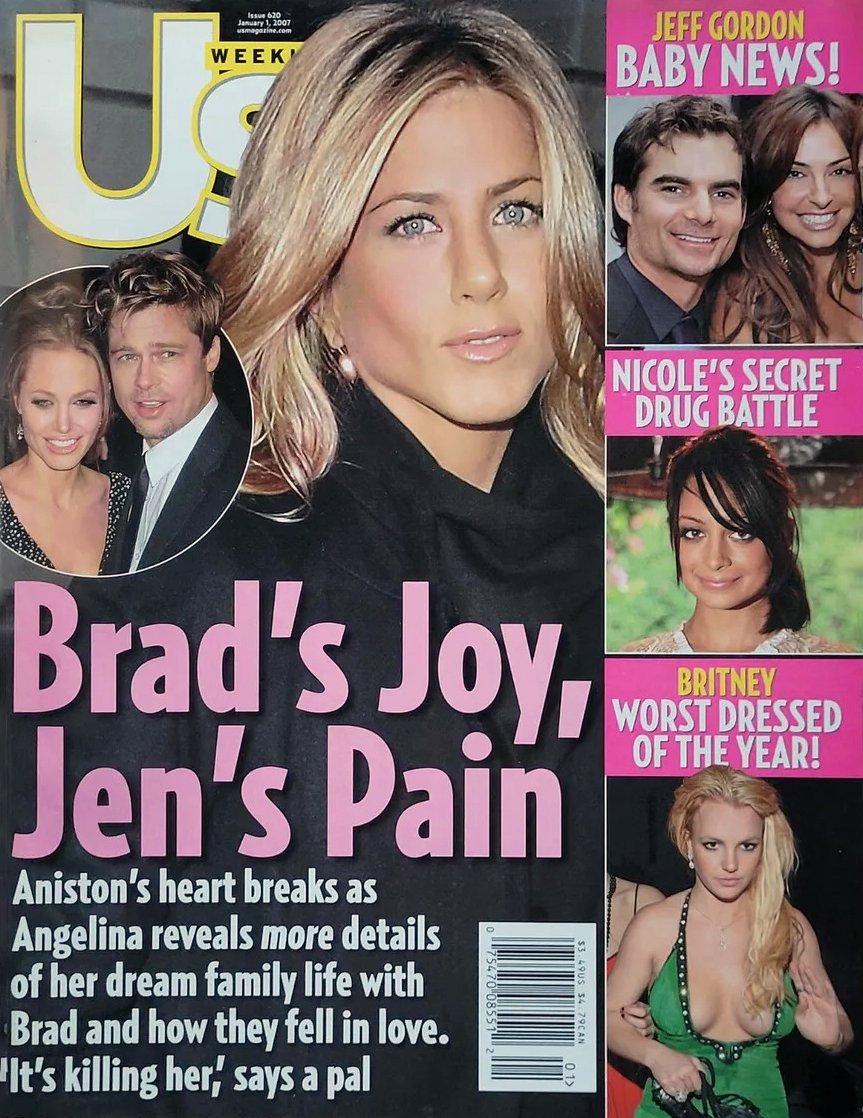

From Us Weekly, where her instincts led to a massive increase in readership that saved a floundering publication—and likely all of Wenner Media—to The Hollywood Reporter, which was in a death spiral but is now, once again, a widely-respected and well-read industry bible, Min has played a major role in creating what we now call the celebrity-industrial complex, as well as the rise of what became social media and the influencer economy. That’s all.

Now, as cofounder of Ankler Media, Min is once again rethinking publishing—and celebrity. The company is centered around its newsletter, The Ankler, which bills itself as “the newsletter Hollywood loves to hate—and hates to love” and is currently one of the top three business publications on Substack.

“We had three months to do the first one—which nearly killed us. And then we had to do the next one in a week—another week!”

Sean Plottner: I’m going to start out with a really simple, basic question. Given your success, your wild success as the editor of Us Weekly and The Hollywood Reporter for really a good chunk of the 21st century so far, how responsible are you for the celebrity-industrial complex as we now know it?

Janice Min: Well, it depends. If you think it’s a good thing, I will say I was responsible. If you think it destroyed civilization, I will accept no responsibility. I guess I will say that I cannot claim responsibility for it, but I met a moment through a publication [Us Weekly] that capitalized on it. And I think that someone was going to do that regardless. And I happened to be running a publication that did it first and best at that moment in time during the aughts.

Sean Plottner: And spawned a thousand imitators, too.

Janice Min: Spawned a thousand imitators. And I think you can see its lineage through social media and everything that came after that—for better or worse. And then I think, I’d like to think it also played a role in what I did next, doing The Hollywood Reporter, where people became consumed by this idea of Los Angeles and the entertainment industry in itself. Where the interest in the business expanded beyond just the stars and into the machinery behind the scenes. And so I think, in some ways, working at both those publications had a lot of connective tissue.

Sean Plottner: Yes, indeed. And I look forward to talking to you some more here, as we get into this, about those two publications and what you did. But let’s back up to 16-year-old Janice—you’d been accepted to Columbia University.

Janice Min: I’m from this town called Littleton, Colorado. And whenever I say that people are like, “Oh, I’ve heard of that.” And then it’s, “Oh, it’s the town where Columbine High School—the first mass school shooting in the United States—where that occurred.” That happened shortly after I left Colorado.

But to give you some color during that time, Colorado, definitely when I was growing up there, did not have this glossy sheen that it has now as a place where Californians move to and Aspen, Vail, and Deion Sanders. It definitely had a sort of fly-over quality to it. Certainly in relation to New York at the time.

And, from the time I was a child, I felt like, I need to live in New York. And I would like to do this journalism thing. And I think if you’re going to do that, you have to move to New York City. I had never been there but it just felt like the place I belonged.

And so I did my applications. I went to a large, average public high school, and I have to say probably I assume now having one child who went through the college admissions process, that part of the appeal was that I came from a school where no one had ever gone to Columbia before.

And they got their geographic diversity in me. So I got in. And then, in August of that year, I got on a plane and went to New York for the first time in my life and started at Columbia.

Sean Plottner: Well, you must’ve had some confidence. Maybe you were a little afraid. How did you feel when I think you arrived in New York at 17 and it was your first time in New York?

Janice Min: First time in New York. And, for people who live in New York, I’m sure they’ll understand this feeling. It certainly wasn’t the New York of television and movies at first glance. I got in a cab at LaGuardia, and you’re driving from LaGuardia across the 125th Street bridge, and it’s sweaty and dirty and, like, honking.

And you get dropped off at Columbia and, if I recall correctly, the elevator in my dorm was broken and my room was on the 10th floor. And no one wants your cab to linger there for more than 20 seconds. So it was definitely trial-by-fire to enter New York my first time.

Sean Plottner: And so you must have settled in somewhat at some point.

Janice Min: Yeah. I think I was born with this. There’s like a slightly—I don’t mean to say I’m stupid—but there’s a thick, there’s like a stupidity to me where you’re just like, “No, I’m going to just do it. And it’s going to work out. And it’s going to be good.” And I don’t think I’m arrogant, but I always have felt pretty sure about what I’m doing.

Sean Plottner: How did you originally get interested in journalism as a kid?

Janice Min: I have no idea. And I think it’s interesting because I see it certainly with kids—I have three kids—and there’s so much cultivation of kids. It’s, “Let’s get you in this class, and do this and do that.” And it’s ridiculous—going back to Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hours where everyone lost their minds—I do think that people find their passions organically, and that’s the best way to do it.

And luckily I was of Generation X, and I think people say we were the least parented people in history. And so like just tons of freedom to do what I wanted. I think I had very atypical Asian-American parents in that they were not putting me on some crazy path or like hovering over me with homework.

And in junior high, I had the option to do a newspaper class and I just felt like, “I’ll try that.” And I just loved it. It was so much fun. And it was the days when you would go to the printer—let’s say it was a Friday night. You would stay and you would cut out the column inches, and put glue, and lay it out. And I liked the kinds of people who did it. I still do. I like these kinds of people. I liked what it represented.

I imagine some of it is—and I think a lot of your audience might share similar feelings—there was a certain power with interviewing people and being a journalist because you could just go talk to anyone. And it was a way to fulfill what you were curious about—fulfill your interests and pursue those.

Sean Plottner: What was your earliest exposure to print media, to magazines? Did your parents subscribe to anything?

Janice Min: Yes. So I loved newspapers. I loved The Denver Post. And I was obsessed with the op-ed pages. And I loved reading about politics. And that was my first exposure. We weren’t really a magazine family. My parents subscribed to Time magazine—they, and probably, 20 million other American households. And so I looked through that. I liked Newsweek. And I loved watching television news. I loved the Nightly News on NBC. I just loved the news.

And I was always, I’m sure annoyingly so, the over-informed kid in the current events class or in history, and the person who was always raising their hand—no one else would. And then the teacher would have to be, like, “Okay, Janice.” Because no one else was going to answer the question. But I just loved reading about all of that.

Sean Plottner: And you liked to know what was going on. Great. Were you a big reader of books growing up?

Janice Min: Yeah. I read books for class, for school. It wasn’t until much later in my adult life that I became an avid, almost fanatical, reader of books. I don’t think I was different from a lot of kids. You’re reading the books you need to read for school.

“Hollywood is a land of bullies.”

Sean Plottner: You got an undergraduate degree in history. Why not get a degree in journalism right away?

Janice Min: Because you couldn’t get one at Columbia. And I always loved history and never considered being an English major. I think studying history is definitely parallel to journalism because it’s storytelling. And one of the most impactful classes in my life was in high school. I did AP European History, and it was an amazing teacher—Mr. Roberts was his name—and he just brought this whole world alive of European history.

And today we would say that’s incredibly limited in its scope because we tell history in a different way than we did when I was growing up. But he was fantastic. And it’s interesting—I don’t know why I think about this—he said in class once, he was talking about existentialism, and he just said, “It’s that feeling when things are going well, and it’s always in the back of your mind, How is this going to go wrong?” I guess maybe because I’ve worked in publishing!

Sean Plottner: Eyes in the back of your head—they come in handy. So you got your master’s and then you I think fairly quickly you rolled into a newspaper job. Is that right?

Janice Min: Yeah. So I think there’s some romantic notion that once it was really easy to get jobs in journalism. It’s never been easy to get jobs in journalism! It was always a little bit of a lousy profession. And so I was finishing my master’s at Columbia. I lived in a dorm called Fernald. And right next to Fernald was the Columbia Journalism School. And my senior year, I just went right over there and started doing that in the fall.

So then I did my master’s. And when I graduated, it was a recession and trying to find a job was like—I just wanted a job. And I got this job in northern Westchester County, working Tuesday through Saturday, 2 to 10pm, covering North Salem and Lewisboro, which are two towns which, of course, have stories, but not a lot of stories. And you had to make stone soup every day. And so I became very familiar with sitting in at planning board meetings, town board meetings, school board meetings.

And there was a lot of bickering among locals. But it was a good experience. I have nothing negative to say about it. It was owned by Gannett, and at that time, Gannett was a powerful newspaper company. It was called the Reporter-Dispatch. And I didn’t even work in the main Reporter-Dispatch. I worked in the Reporter-Dispatch, Northern Westchester edition.

“I don’t think editors have to be their audience, but I think it certainly helped to be a 33-year-old editor writing about topics that interested that same group of people. ”

Sean Plottner: Oh, well. All news is local.

Janice Min: Exactly.

Sean Plottner: So I don’t want to spend a whole lot of time on this, but you ended up going to Time Inc. And you were on staff at People magazine. How did you land that?

Janice Min: I had gotten a big promotion at the Reporter-Dispatch to the Southern Westchester newsroom that was based in White Plains. And so that was like, I had made it to the big time. And so I was nearing my two years doing this. And I was like, I want to go work back in the city. And so I sent out clips to a bunch of people and places and I got called and I was a features writer at that point for the newspaper.

And so I got called by a recruiter from Time Inc. I got called in for two interviews. The first one was at People and the second one was at Entertainment Weekly. And this is ridiculous given what I ended up doing with my life, but I had never read People magazine.

I knew what it was, of course. It was just a massive magazine. And I went to the store and bought a People and read through it. I’m like, Okay, I get it. I get what this is. And then I went in and did the interview and got offered a job as a staff writer.

Sean Plottner: Was Carol Wallace the editor then?

Janice Min: No, it was Landon Jones. He was Carol Wallace’s predecessor. And the thing with Time Inc. at that time, People magazine, the genius in it was like professionalizing ridiculous content and making it very packageable and digestible to a wide audience. And that was the Time Inc. formula.

But everyone there was, like, a Princeton grad. Some of the most educated people in the world were editing stories about … Princess Diana! And I had some of these ridiculous beats. I became the editor of Hero Animals. My job was to edit stories about heroic animals, like the pig who warns their owner about a fire.

So I did Hero Animals. And I did the Oscars. And one of my beats was JFK Jr. And so you have these highly-educated, very good writers and editors putting this out for mass consumption in America.

Sean Plottner: You were at Time Inc., and I think you—bounced around might not be the right term—but I know you were at Life when it was a monthly, briefly. And InStyle, correct?

Janice Min: Yeah. So I was at People for five years and I had been promoted from staff writer to senior editor. And I was 28 years old and I had been getting recruited by The Wall Street Journal to come there and be a Page One editor.

Sean Plottner: Oh really?

Janice Min: Yeah, back in the day, it was a big deal. Because they always had these very clever, like very stylish—they would call them the A1 Head, I think. They’re like these very fun features. They were absolutely the best—right down the middle. I think they still might do them, but they’re buried somewhere.

And I loved that idea. And there was someone who was the “king” of the page one editors named John Brecher. And John asked me to have lunch with him. So I’m way away from the Time Inc. building—you know 35 blocks away from the Time Inc. building—having lunch.

And so we’re sitting there having lunch and then in comes Norm Pearlstein, who was then the editor-in-chief of Time Inc., and he sits down at the table next to us. And for anyone who remembers earlier eras, Norm had previously been the editor of The Wall Street Journal. And I believe he had hired John Brecher, so he looks at both of us, we say, “Hi.”

And then that afternoon, he called me into his office on the 34th floor at Time Inc., and he said, “What was that about?” And then it became the whole, “We’d love you to stay. What can we do? What would you like to do?” It was, you know, one of those Sliding Doors moments. I would have loved to have worked at the Journal, but Time Inc. paid a lot more.

It’s one of the few times I made a decision about money. Actually Time Inc. paid a lot better. And Norm said, “Well, how about if we send you to go try to save Life magazine [for the hundredth time]?” It was the rescue mission at Life magazine. And I said, “Sure.” And I decided to stay and I did it. And obviously, you know how that ended. Life magazine was very much not saved.

“One of the Glamour coverlines was, ‘Is my vagina too big?’ I just looked at that and I’m like, ‘This is not going to be my thing.’”

Sean Plottner: So let’s move on to Us. How did you end up at Us? I believe Bonnie Fuller was the editor and you...

Janice Min: …Yeah. So there was a step after Life where that ended up not becoming a thing, as we all know now, and then they moved me over to InStyle and I launched these publications. Imagine—they had so much ad revenue coming in that they needed to find new places for their ad revenue!

So they wanted to launch these spinoffs and these standalone issues that could capitalize on different sectors of the ad market. One of them was weddings. One of them was makeovers. One of them was an entertaining publication. One of them was a fashion-only publication as opposed to InStyle, which was fashion and beauty.

So I worked on those. And I truly hated working at InStyle. I hated it. I really liked a lot of people there but I was just not a fashion and beauty editor. I didn’t care. I just really didn’t care very much. And so I decided to just—this is what I was saying earlier—I’m sure of my decisions even though they might sound crazy. I just decided to quit. And I just quit. And I was like, Okay, I’m going to figure something out, but I don’t want to do this and it makes me miserable to do this.

And it was a little bit of a boom time for magazines still, or maybe a lot of a boom time for magazines still then. It was right after 9/11. And so I just wrote to some people. Bonnie Fuller had tried to hire me before when she was running Glamour.

Some of you recall, she was the It girl of magazines. And her comings and goings were a staple of Keith Kelly’s column in the New York Post. Like, Was she going go to Cosmo? And this and that. And she had tried to hire me at Glamour. And I remember when I interviewed with her at Glamour, and she has this very talented creative director named Donald Robertson, who I’m still very friendly with. But so they had mockups of pages and a cover.

And one of the cover lines on Glamour—and remember, this was a time when there was a lot of controversy around overhyped sexual content on the covers of women’s magazines. In addition to the men’s magazines, the laddie books—and one of the cover lines was, “Is my vagina too big?” I just looked at that and I’m like, “This is not going to be my thing.” Like, there’s an audience for this, but I can’t imagine doing an “Is my vagina too big?” coverline.

So Bonnie and I parted. And then at Us Weekly, she had just been brought on by Jann Wenner. And Jann owned Us monthly, and was turning it into a weekly because if you hit that right, it becomes like a cash cow, like an ATM machine at a company.

And if you hit it wrong, it becomes, as people described it at the time in the press, “Jann’s Vietnam.” Where you’re just constantly trying to fight a war that you’re not going to win. But he had this idea to bring on Bonnie Fuller. And so I met with Bonnie right when she was starting, thought like, Okay, this could be interesting. The idea of remaking something sounded interesting to me. And I started. And that was how I ended up there.

Sean Plottner: And Bonnie didn’t last much longer.

Janice Min: I don’t think there was enough air in the room for Bonnie and Jann to coexist. It was just wild. She was there, I think, for 14 months. And I think anyone who ever stayed late for a close when a print magazine was closing, I can best you in any story.

I’ll just never forget my despair walking out and like the bread trucks were coming to restaurants and the sun was out, so it had to have been like 6:30 in the morning. And just like crawling home to bed and then showing back up around one or two the next day. It was crazy because it was a reinvention in addition to probably not the most efficient management or scheduling of how to get this done.

Sean Plottner: Was that on Bonnie? Or was it Bonnie and Jann tussling over things at closing?

Janice Min: Bonnie’s a perfectionist. Bonnie wanted things exactly how she wanted them done. And I think the staff was willing to make that sacrifice because they wanted to be part of something that might take off. And there were early signs that it could change and it could take off.

And if you recall, Terry McDonell had been the editor before. And so you had a middle-aged man trying to do a magazine that would largely be bought by women. And it just wasn’t—no fault of Terry’s—it just didn’t click.

And so I think one of the things that Bonnie had was—Bonnie is all id. She’s just all instinct. And I think she’s been smart about having deputies who help shape that into something. And I think Donald Robertson was that for her at the various publications where they worked together.

And I think I took on that role in the 14 months she and I worked together. “Do you have an idea? Okay, I’ll help make it happen. I’m going to work with the staff and get this done and hire these people.” And so that was the role.

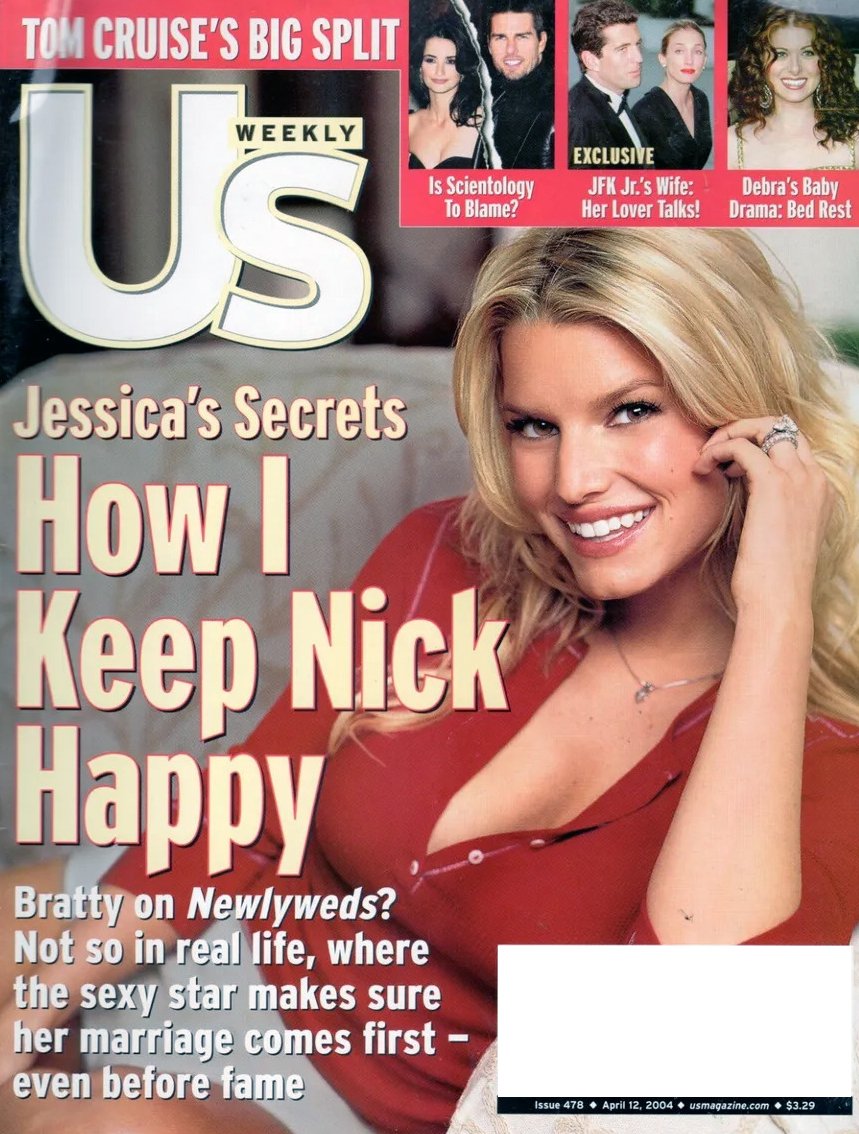

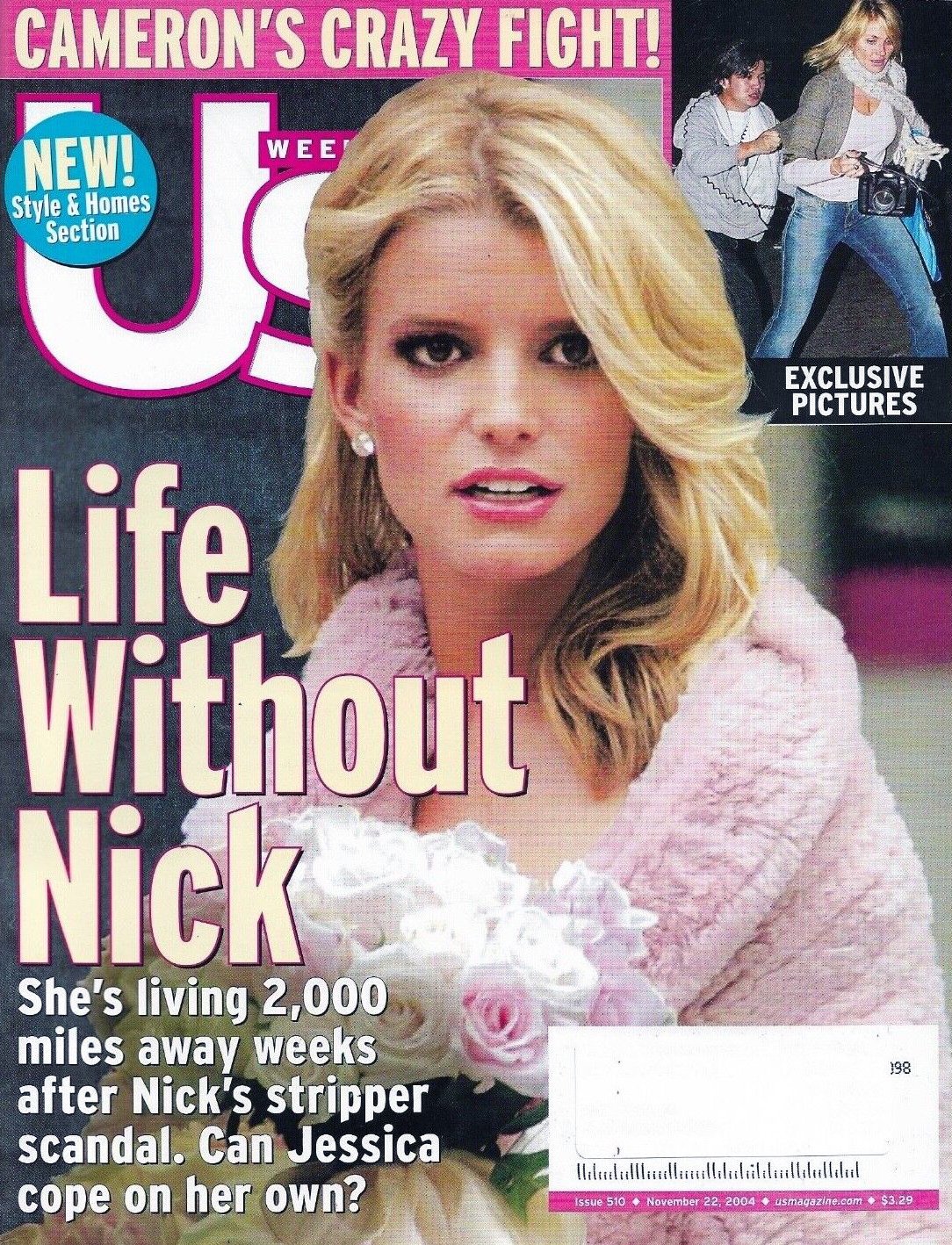

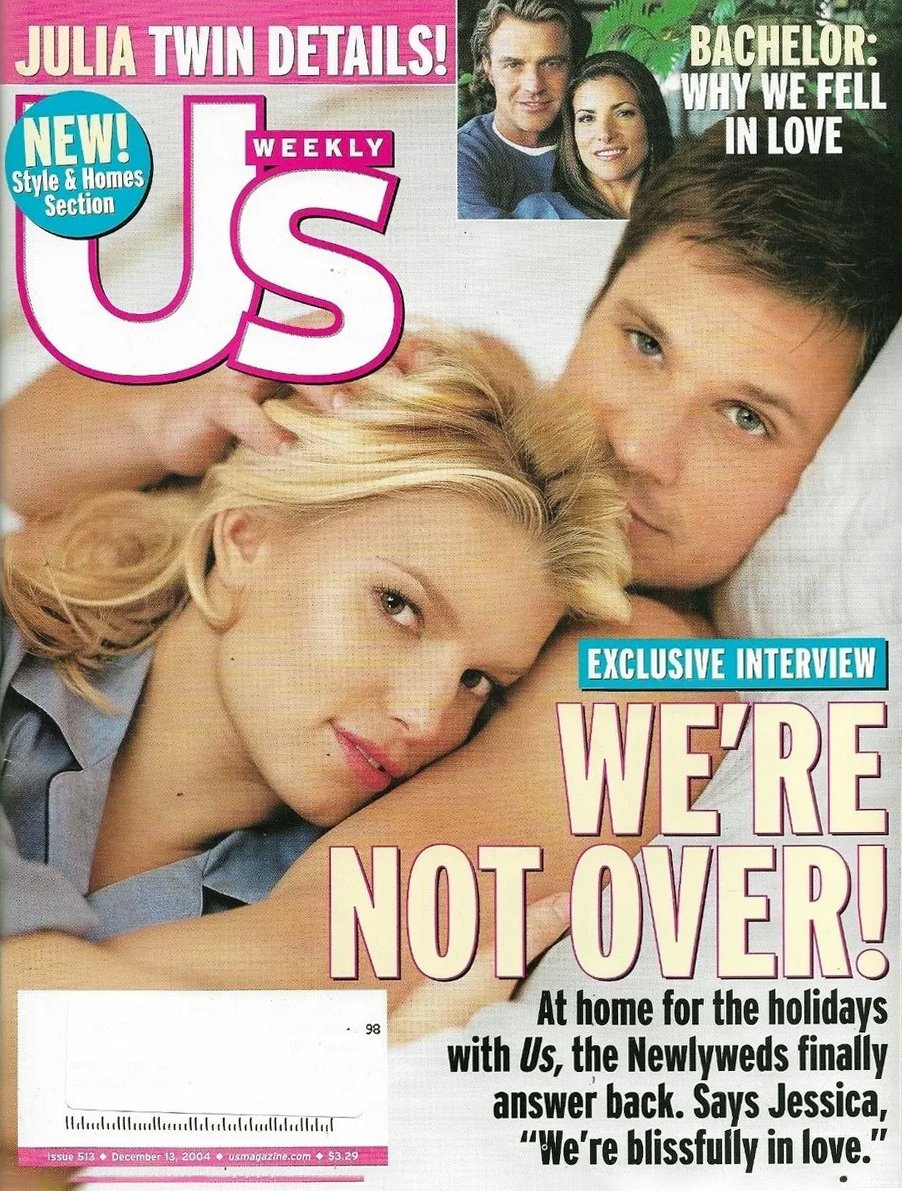

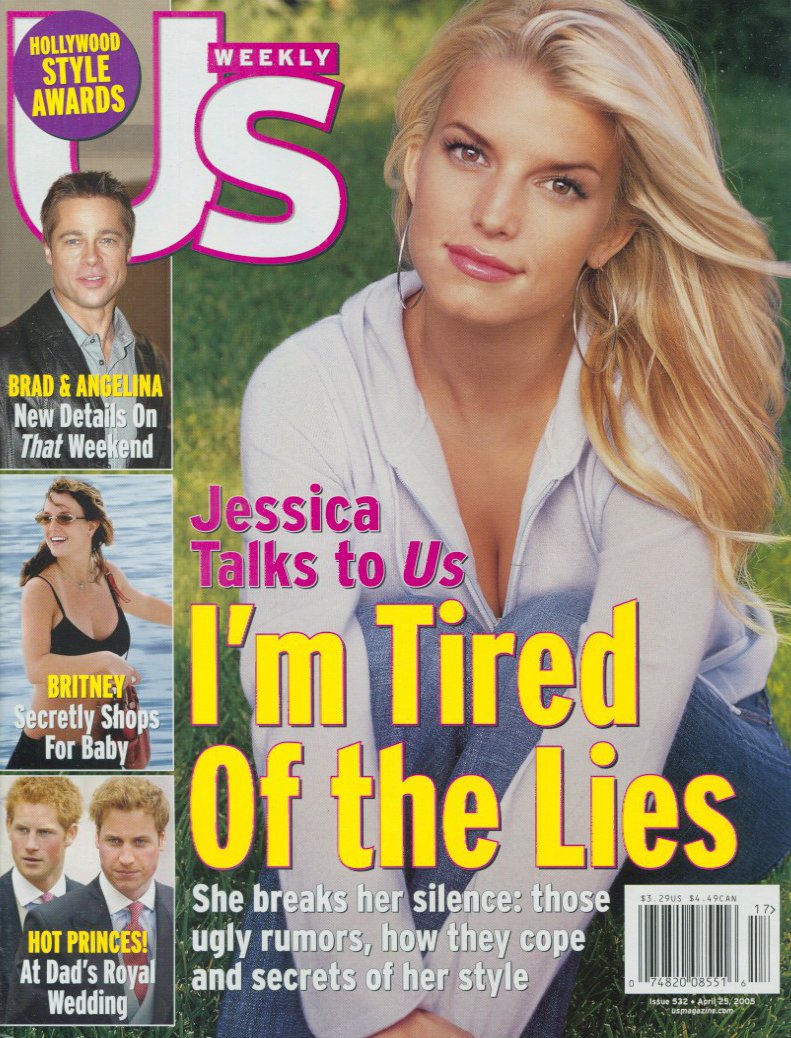

Jessica Simpson was cover gold for Us Weekly in the 2000s.

“I cared about almost none of this. I don’t care about celebrities or reality stars”

Sean Plottner: When she left, was that a relief for you? You you promoted?

Janice Min: I don’t know what I thought. I was just so wiped. It was so exhausting. It was fun, but it was so exhausting. And things were going badly between Jann and Bonnie. Things were going badly. But also the magazine had plateaued. It still wasn’t making money.

And there are these crazy statistics when you published a weekly magazine back in the day that you had to sell 550,000 copies on the newsstand to begin making money. And after you sold your 550,000th copy, you would start raking it in.

And it was, I believe, $1.89 an issue that would just be pure profit in Jann’s pocket. So you needed to reach that magic threshold. And it was not reaching that magic threshold. There are times it would get close, but most weeks it was still losing a lot of money. So the future of the publication was uncertain.

I think if you talk to Kent Brownridge, who was Jann’s legendary number two for lots of years—I just had dinner with him actually last week—Kent would say the publication was weeks from closing when the company and Bonnie broke up. And I was totally spent. Clueless.

I think I’m like 31 at the time—an idiot. And I hadn’t been on vacation the whole time. And so I go on vacation to Italy. And Bonnie had disappeared. No one really knew where she was. And then she ends up, while I’m on vacation in Italy, she calls Jann and resigns.

And Jann calls me and offers me the job. And I don’t really know how I felt about it. It wasn’t one of those things where it was like elation, Oh my God, I get to be the editor and try to save this publication that no one else has ever saved and be publicly humiliated. And it wasn’t like I won the lottery. It was like. “Okay.”

I thought about it a while and decided to do it. Part of the thought process was I felt like I had been doing it. I had been making the decisions and keeping the trains running and felt like the staff, I think largely liked me. And so some of it was just like, Okay. Give it a whirl.

And the other part of me that was really concerned was that I felt so nervous about the way editors were covered in the press—that media publishing was like the center of so much other media. And talking about the foibles of different editors, and who was about to get fired, and where they were sitting at the Condé Nast holiday lunch. And Bonnie had been fairly crucified in the media at various times. So that kind of made me cringe. But I did it.

Sean Plottner: And did you do anything to have a calming effect on the staff as you took over and try to minimize some of the chaos?

Janice Min: I think so. I do think observing other leaders gives you a lot of insight into what you do and don’t do yourself, right? And what you can see, like the pitfalls and traps that can create chaos. And I would say I am very decisive. I would say I put in the same amount of work and hours as anyone else would. I was not someone who is going to go off and disappear for five hours and leave everyone hanging on a July 3rd.

Sean Plottner: Well, and you mentioned decisiveness and I think that’s an important attribute. I think staff appreciate that whether they agree or disagree they like a decision being made and certainly don’t want to be lingering and wondering about all the waffling that might be taking place.

Janice Min: Agree. And I think what was so fun about Us Weekly is that it was a really young staff and it became this—like I was definitely like a dictator—but it became a very collaborative environment as well. I cared about almost none of this. I don’t care about celebrities or reality stars. But I could tell, like, the fervor they brought to it. They really loved this stuff and cared about it. And so it was my job to just think about how to interpret what they were saying and turn that passion into stories.

And so the meetings were really fun. People would sit around and pitch ideas. I would learn things, like Jessica Simpson and Nick Lachey from The Newlyweds on MTV. So I think when you listen to your staff—I’ve never watched an episode of The Bachelor. I’ve never watched an episode of The Newlyweds, Real Housewives—none of these shows that we were covering extensively. And I give tons of credit to the staff for educating me about what those things were.

But I also think, as an editor I was able to be removed from it and glean like, “That pops. That’s the story, this is what we’re doing.” And be able to package it so it could have the widest appeal to an audience that would include me at the time.

I don’t think that the editors always have to be their audience, but I think it certainly helped at that time to be a 33-year-old editor-in-chief writing about topics that interested that same group of people.

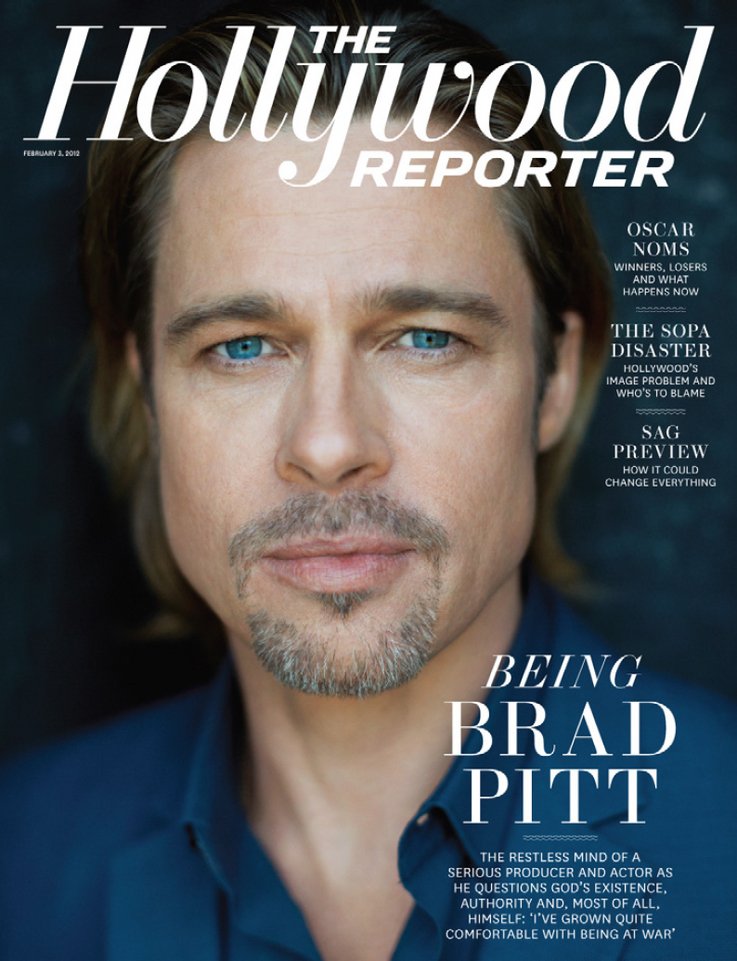

Sean Plottner: I know you told Bill Simmons that you guys would get the paparazzi shots and the exclusives and I think that it was Brangelina—Brad Pitt and Angelina—that you would have to go to Jann to get him to sign off on big expensive photos or stories. And he signed off on that one, I think to the tune of a half-million, quarter-million dollars?

Janice Min: I think it was $75,000 actually, which was an extraordinary sum then. And Jann, in his—not the book with the unfortunate name of The Masters—his memoir, right before this book came out, he talks about that incident. And he says that Angelina Jolie was the one who originally had tipped off the photographers themselves.

And he’s trying to underscore the way that celebrities interplayed with an Us Weekly. But yeah, it’s funny when you look back at it all. What were we thinking? Who cares about any of this? But everybody was consumed by these stories during that decade.

Sean Plottner: Well, and I just said earlier, it was certainly of the moment. Did you ever go to him and want to run something or spend some money and he said “no”?

Janice Min: I’m sure, I can’t think of any instances, but the whole place was very mom and pop. Like I would just walk down the hall, go see Jann. He had an assistant named Mary Mac. You would ask if Jann’s free, you would go in, you would have a quick talk and then you would leave. There were no layers of hierarchy. If I needed other answers, I would call Kent. It was about as streamlined as you could possibly get.

Sean Plottner: Well, I know a lot of money was being made and you’re probably familiar with Sticky Fingers, the Hagen book, that I think came out in 2017. Sticky Fingers: The History of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone. And he writes that, “every Monday morning Wenner would arrive at the office and immediately calculate his cut of the sales. He would tabulate the advertising, $95,000 a page. At its peak Us Weekly was clearing almost $90 million a year in pure profit. It was raining money, and Wenner reveled. Once, when the sales figures dipped a few thousand copies, he wrote a memo reminding Min how much she had lost him.”

Janice Min: These are true facts. And that’s where I don’t care how successful you are, unless you have your own company you still are working for somebody. And I think Jann and I probably had—maybe he would agree—probably the best working relationship he ever had with an editor. I would say because I did something for him he could not do. He could not have been the editor of Us Weekly, and he knew that.

But Jann—it was his personal piggy bank, the company. A lot of people on staff would always joke that Jann is a millionaire who lives like a billionaire. He loved being wealthy and that included a chauffeured Mercedes down to the office every day. I mean, things that were not unusual for the time in publishing, by the way, like even among editors.

I didn’t do that. I rode the subway. But he had his lunch chauffeured from his townhouse, and he had the gorgeous office, and he flew a Gulfstream. He didn’t have a single friend who wasn’t a boldface name, many of whom are featured in The Masters. And yeah, I think he viewed it as a deposit into his bank every Monday morning.

“There aren’t that many people who own media who truly love quality. It’s all about scale. It’s not very often about quality.”

Sean Plottner: You obviously had a unique relationship with him. You’re one of the few editors he did not fire.

Janice Min: It’s stunning to me. And it’s funny. I mean Jann hired someone who was completely unknown. And he really took a chance—you could say I had already proven myself—but he still took a chance. For someone who is so enamored of stars and big names, he definitely hired a complete unknown at the time. And I got paid incredibly well there. He changed the trajectory of my life, all of it. So I owe him a debt of gratitude.

And I think when you see his comments he made recently, you just realize the sort of dichotomy or contradictions in everyone. He clearly said not great things about women, not great things about people of color. But here I am, a female person of color who was probably—I mean, I’m just going to say, I think, Jan Wenner’s most-successful editor he ever had—outside of himself is probably what he would say. So yeah, I read all of that about Jann with ambivalence, and I read all of his interviews and wasn’t surprised by one single word.

Sean Plottner: Sure. Are you in touch with him at all these days?

Janice Min: No. After I moved to LA, we had this very poignant goodbye. And I think he was stunned when I told him I wasn’t going to renew my contract. And he got tears in his eyes. And with great affection, we parted ways. Yeah, I think I made Jann Wenner cry.

Sean Plottner: Did you have a tissue handy for him?

Janice Min: I never thought I needed to bring a box of kleenex in for Jann. Let’s just say that. But the whole thing went by in a blur. It was seven years of insanity. I think people who have worked at a weekly publication or a monthly publication, they know part of why these things succeed is the consistency.

Like someone once said, “Working at a weekly magazine, it’s like being on a professional sports team that has no off season.” It’s just this complete, rigid, brutal closing schedule. I never took a three-day weekend, never had those Monday holidays off. I was always up till 2 am—like once a week.

Just building that relationship with the audience time and time again, to keep it a thing. And it became not just a thing, it became like a huge thing. And so in some ways, like when you have that level of success, you’re also crippled—going to the existential part—you’re crippled by this fear of, Oh my god, what if I can’t do this again? What if it all falls apart? What if I lose my so-called magic touch? And all those things that get into your head.

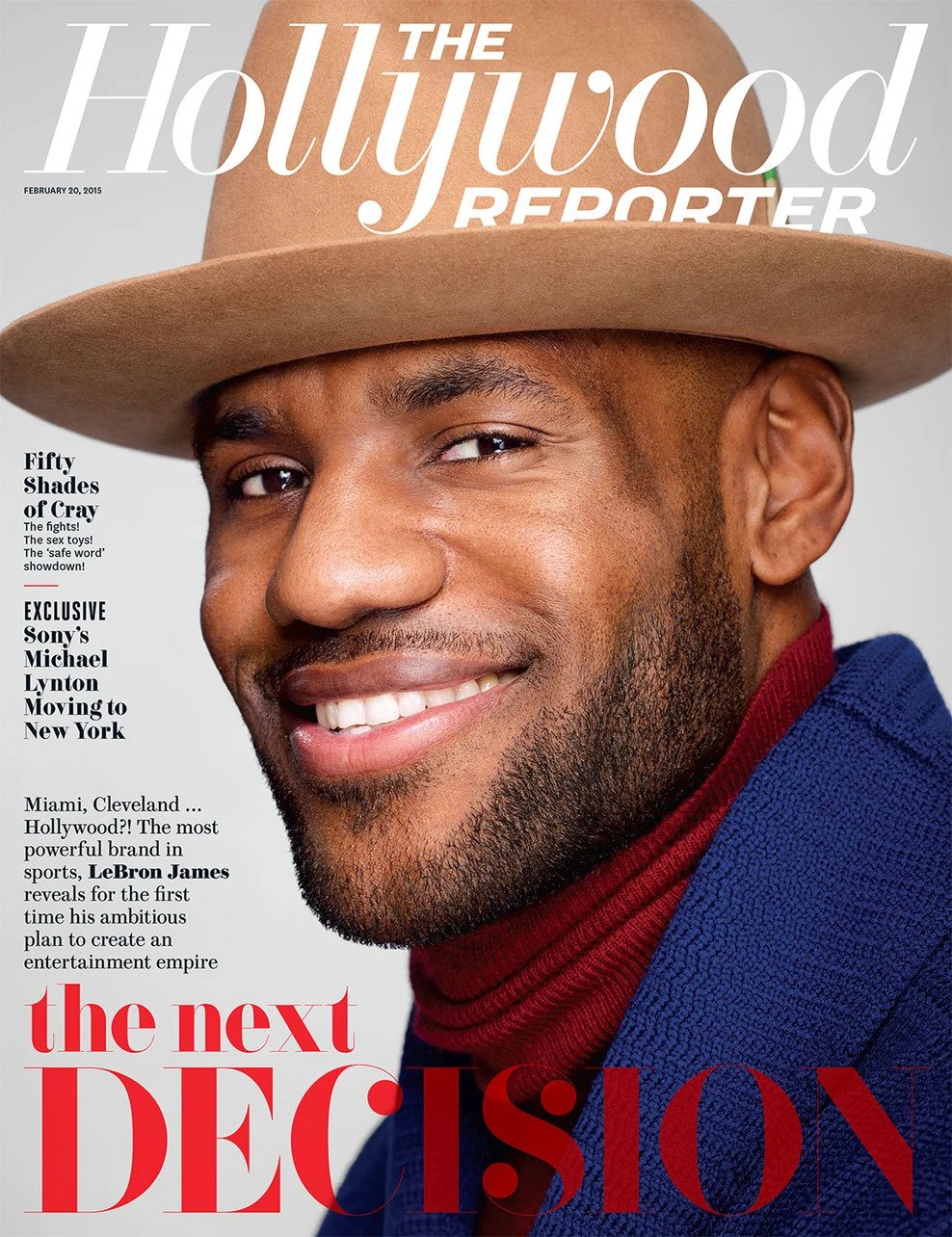

Sean Plottner: Well, clearly there was much of the magic touch left. I want to get to the point where you have accepted the job at The Hollywood Reporter, which I think some would say that it wasn’t even a magazine at the time. And I know that you completely transformed it, but you get the job, you’re told you can do whatever you want, editorially. What were the first things you did in order to start that makeover? I talked to David Granger when he went for the job at Esquire, he had to produce three tables of contents over a weekend. Which is an interesting exercise. What did you do to start that process—where do you begin?

Janice Min: Yeah. Moving to Los Angeles and doing The Hollywood Reporter, that was just again, one of those leaps of faith, “Okay, let’s do it. That’s going to be fun.” And [it took] some convincing for my husband. But we had wanted to go to California anyway. And what I loved about that moment was that you could see not-positive signs starting to happen in publishing.

And the new owners of The Hollywood Reporter had bought this suite of publications out of Nielsen, including Billboard, The Hollywood Reporter, Adweek. And they truly believed something could change in The Hollywood Reporter. And they gave me carte blanche. And that was largely off the success that I’d had at Us Weekly. I don’t think they would have given that to maybe anyone.

But they believed that I could do something with it. And so I am grateful for that. That was a huge opportunity. And one of the few opportunities left in publishing where you could do something like that. Anyway, I had never read The Hollywood Reporter. It was a little bit like going back to People magazine.

I had never read The Hollywood Reporter, and didn't care about the trades in LA. It didn’t matter to me at all. And so I looked at a few “trade” Hollywood Reporters—at that point it was a daily little leaflet that went out to people. Ugly. Hideous. And I was just like, “Nope. No, thank you.”

And so they’d had this idea of turning it into a weekly publication and having a website. So I moved to LA in July of 2010 and it was just like, BOOM! Like a gun went off. And it was, Design a publication! Create a prototype!

And one of the things that was most important to me was that Los Angeles just didn’t have a whole publishing community in the way that New York did. It had largely been trade press and the Los Angeles Times. And one of the things I thought that was going to make this work was if I hired people with New York publishing experience to bring that sort of aesthetic and style into a publication in Los Angeles.

And the thing that struck me about Los Angeles was that it was rising in profile. It was yet to become the place where everyone from New York was moving. It was rising in profile and had highly-educated people, but didn’t have what I called any commensurate press around it. The trade press was pretty … ugh. And insular.

And I thought that the trade press didn’t really recognize how big entertainment had become to the outside world. So it was doing all those things at once. But it was really just this sort of silly thing I did where I just made a fake magazine with blank papers. And I took Post-Its and I put what I thought I would want on every single page.

I put a Post-It on each page—I still have it—of the sections and what the content would be. And that became the prototype. My God, I’m not a drinker but I probably had to drink every night during that whole time. And, It was crazy.

And so then from that built a prototype. And I give full credit also to—there were two key hires from the beginning. One was one of the art directors at Us Weekly named Shanti Marlar, who I convinced to move out to LA with me. And she had been—the legendary Liz Betts, who was the creative director of Us Weekly, who recently passed away, one of my favorite people in the whole world—Shanti had been one of her deputies during that time.

And then a photo editor who had only been a freelancer at Us Weekly for part of the time—and this just goes to show you how you can never judge someone by what they’ve most recently done—Jennifer Laski had been editing—OMG—a Twilight bookazine to sell at the grocery store with Robert Pattinson photos. I thought she had incredible taste.

And so I convinced these two people to accept jobs, move to LA, pack up their families—they both had two kids. Shanti would be driving across the country with her family, dogs in the back, stop at McDonald’s to get wifi, and send me layouts and fonts.

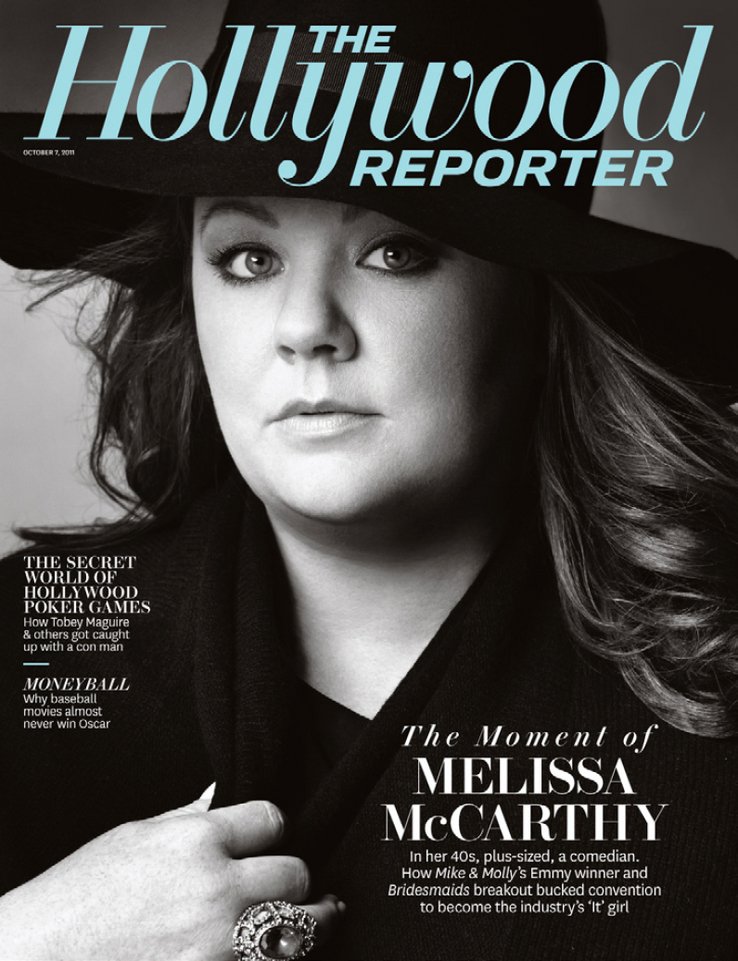

And so we ended up cobbling together like a whole visual look of The Hollywood Reporter. And yes, the content was vastly going to change, but the visual style was one of the things that really enraptured Hollywood. It looked lush, and beautiful, and important, and all these things that just were a total revelation in the trade world.

Sean Plottner: Well, I’m glad you mentioned photo editor because I was going to ask you about that. That’s a pretty key position for both of those publications, Us and THR. And I’m glad you brought that up as one of the most important people that you brought on.

Janice Min: It’s funny because I don’t think people can really articulate the difference between a good photo and a bad photo, but you know it when you see it. And the visual style that Jennifer Laski was able to bring—and remember people wrote horrible things about what was going to happen to The Hollywood Reporter. That it was going to fail. It has a history of failing. It will only continue to fail.

The other trade press here was merciless to us. And once we debuted that conversation stopped. But Jen Laski had to be out there convincing people to do photo shoots with us, “Trust me, it’s going to look amazing.” And within days of us launching, people were dying to have that treatment. They were dying to be photographed looking the way that Jen could get photographers to take photos.

Sean Plottner: Did you, Jen, and Shanti all click?

Janice Min: Oh my God. There’re always just these teams that are like, it’s like kismet. You just cannot make up that chemistry. And the three of us, we remain tight. It all just clicked and the working style was the same. And I think that they are like I am, like, you will do anything to make something work.

Sean Plottner: Who determined that big trim size ?

Janice Min: Richard Beckman was the CEO of the company. I don’t even think he lasted as long as Bonnie Fuller did when I was working for Bonnie, but I’m grateful to Richard. He sought me out and was the one who introduced me to the money people behind The Hollywood Reporter, but he was the champion, he was a spark that lit the fire for me to come on.

And if any of your audience knows Richard Beckman—I’m sure many of them do—he loves luxury and luxurious things and fabulous things. And he was just enamored of that book size. And this was the era when I think Rolling Stone was trimming down and everyone was trimming their book size to save on paper costs.

Sean Plottner: Yeah, it made quite a mark. I had awareness of The Hollywood Reporter before you were there. And I was blown away by the “after” and immediately subscribed. And totally enjoyed it as a non-Hollywood guy. But the greatest thing and the simplest thing I think I can say about it is that you turned it into a “real” magazine. You really did inject a lot of life into it. And of course the visuals were great. How hands on were you with the copy?

Janice Min: Oh my god. I think anyone who’s worked for me knows I read every single word, I rewrite things somewhat mercilessly, if necessary. I would read every single thing. And edit every single thing. My sleep during those years of The Hollywood Reporter was staggered. It was such a terrible sleep schedule.

It was like every day you would wake up and get buried under a new avalanche of stuff to do. And edit, edit, edit all day long. Edit on a plane—I think our managing editor at the time, Sudie Redmond, always marveled, she’s like, “I would never know if you’re in New York or on a plane, because you’re always still turning in your notes.”

But part of these publications is like to make them not just content farms, it's just the voice. And the thing you want to do is you want to like, if the label weren’t on it, would you recognize a story? Would you recognize the tone? What does it say about you? And what does it say about your company and your publication? And that was one of the obsessive things I do. I can’t turn that off.

Sean Plottner: It’s a more reader-driven approach for The Hollywood Reporter than it is an industry-driven thing.

Janice Min: Well, I think that was always in my mind was like, how do you make this something people want-to-read and not have-to-read? And trades typically fall in the have-to-read space. And so when you try to input the want-to-read into it, it changes the entire equation.

“Publishing has always had this consuming idea of The Great Man. And there’s always been these great male editors. And women have gotten very little of the same.”

Sean Plottner: Yeah, well, and then the relationship that the magazine had with Hollywood changed, too, where you guys were not just rewriting press releases. Did that lead to any friction? Were there demands for Janice’s head or to kill stories by studio folks?

Janice Min: It’s funny. In the beginning, there were some people who tried like funny business, and to Richard Beckman’s credit, like people who would go over my head and be like, you know what she’s trying to do. And he was always like, “Sorry. Go talk to Janice.”

He was very church and state. I loved that about him. He was not weak in any way. You have to have partners like that on the business side. But also with Hollywood. Hollywood is a land of bullies. If they think you’re movable at all, like they will try to move you forever. And if you’re not movable they all fall in line.

Sean Plottner: I also recall a lot of polybagged issues, advertising wrapped around the cover, and some inserts that were very attractive and well designed about upcoming movies or whatever. That, to me, was a sign that the magazine was making some money, too.

Janice Min: Yeah. There’s this whole world of New York publishing that’s based on CPMs or circulation and Hollywood’s like the inverse of that, because it’s based on the selectivity of the audience. A small audience is great, because all they want to do is reach the influential people in Hollywood.

They don’t need to have a thousand subscriptions in Peoria. They only want the “right” people in Hollywood to receive those materials and to be—if you’re an advertiser—for you to reach those people. Both because they want those people to vote for them in an award season or they want to flex in front of those people about new projects and all those things.

I went from doing a publication at Us Weekly that sold, like, 1.3 million copies on the newsstand and had a 14 million circulation to one that had a 72,000 circulation in print, but was vastly bigger online than Us Weekly ever was.

Sean Plottner: So when you sent the files to the printer of the first issue that you helmed, you felt pretty good? Were you nervous?

Janice Min: I felt great about it. I look at it like I literally almost died doing it. It was so horrible. We were there forever doing it. And I remember we had a little party for the staff before it came out. And I said to them, “This works. And it’s going to work. I know it. I see it. I feel it. It works.”

And it was just like this classic Hollywood moment. Everyone’s waiting for it to debut in town and it comes out and just like the calls start coming in. Oh my God! Congratulations! Congratulations! Congratulations!

And then, going back to the existential thread, after that, after a short victory lap, it’s like, “Oh my God. We have to do it again.” We had three months to do the first one—which nearly killed us. And then we had to do it in a week—another week!

Sean Plottner: That was literally a big magazine to produce every week. And always a kind of pleasant surprise when it would arrive every week. It’s “Oh yeah, this again. Wow. Okay. Let’s dig in.”

Janice Min: Yeah. I’d like to think we produced a monthly-quality publication every week.

Sean Plottner: Oof. Yeah. Okay. Can you tell me what you’re doing now? The Ankler. Yeah. What is The Ankler? And I’m also curious as to what’s the origin of the name.

Janice Min: So my partner in The Ankler is someone named Richard Rushfield, who is this longtime journalist in LA. And it’s funny, I feel like my career tells a story of media and publishing. Richard had worked at every “scale-media” place or attempting-to-scale, like BuzzFeed and the Los Angeles Times when they were trying to become more digital and HitFix before it flamed out. He was a contributing editor at Vanity Fair.

Richard was not great working in other people’s newsrooms, so he started to do a Substack, as Substack came onto the scene. And someone very influential in town sent it to me, and just said “Oh my god, have you seen this? This is unbelievable.”

And I became enamored of it. And I’d known Richard. I’d met him at the Golden Globes many years ago, and I asked Richard, “Do you want to do something more with this?” And Richard, who is not a business person, and he’s like, “Okay.”

And I just felt like there was a moment where the entertainment industry was shifting. This was the summer of 2021, when we began to think about what we would do with it. And there were a lot of interested parties. It’s been reported that The Information wanted to do the investment to get us off the ground. Some other places did too.

And so we were like, “Okay.” And it was like this crash course in fundraising. And so Y Combinator, which is the most important investor in Silicon Valley—they invested in The Athletic before us, the only other true media brand they ever did. They were the first money behind Substack, Airbnb, Instacart. Lots of stuff that you know.

So we took money from Y Combinator, Substack gave us an advance, and we got up and running. And when I say Richard knows every CEO in town—if The Hollywood Reporter had captured the mindshare of everyone in town, Richard owned the top of the pyramid. And this was at a time when the entertainment industry was starting to show signs of distress that we have now seen come to fruition this year.

I said to Richard, “We can own that lane. And we can own the transformation.” And it took off. We’ve grown our subscriber base 6x over in 18 months. We’ve grown our revenue 8x. It’s become a big thing out here for the entertainment industry. Of course we’d like it to be bigger elsewhere, but we feel like we have a really good lock on this space right now.

Sean Plottner: That’s very interesting what you say about scale. Does that mean that we may never again see publications with more than a million circulation, or the magazine business as we knew it, or even newsletters? Could newsletters reach that kind of scale?

Janice Min: Well, I think you’ve seen some newsletters do that, like Morning Brew, right? More than a million subscribers. They’re not behind a paywall, but they managed to convert that into an ad-supported model. Axios, obviously. I think a lot of people in media talk about this. But I think that scaled media play has proven itself not to be great for the consumer. That’s for sure. And not necessarily for revenue either. If you read Ben Smith’s book, Traffic, about chasing traffic online, you just have to spend so much to try to even achieve that scale.

Sean Plottner: Okay. Vanity Fair, when the job came open in, I think, 2017 when Graydon Carter left, your name was bandied about as a possible editor of the magazine. Did you go for it? Were you in the running?

Janice Min: Anna Wintour had been talking to me for probably almost 18 months before that happened. And seemed to have interest in me doing it. When I met with them they seemed to have some inkling that relationship would be ending with Graydon.

And when that happened, I met with the CEO at the time, Bob Sauerberg. And I told him, “I can only do this if it’s in California, because I’m not going to move.” And then we never talked about it again. That was sort of it. And I probably had talked to Anna or had lunch with her probably four or five times before that.

And it’s one of these things, once we moved out here, as much as I, at times, would like to go back to New York, no one else in my family wanted to do that. And doing what I do, the main industry for publishing here is entertainment. That’s what you end up doing largely when you live in Los Angeles.

“Done correctly, people just love seeing the evidence of human curation.”

Sean Plottner: We can all wonder what might’ve been. You have done a fair bit of negotiating for salary, for jobs, or for photographs. What’s your advice to those who need to negotiate?

Janice Min: God. By the way, I will say and I think a lot of people in publishing of my era, back in the day when there was a publishing business in New York, like you feel a lot of gratitude that you were there when there was some getting to be had. I see some of these salaries that people are paid now in publishing and, God, it's just incredible. I think Forbes was forced to post its salary structure and top people are making less than I was making at People magazine in the mid-90s. And I hate to see that.

But with negotiations, Jimmy Finkelstein always said something that I think about: he said, “Don’t play so hard-to-get that you can’t get caught.” I think that you advocate for yourself and if you’re lucky enough to be in a position where you have a lawyer at doing that negotiation for you make sure you have a really good lawyer who’s a lovely person also. I think that the yelling and screaming part, that era is gone.

And I find it sad—I don’t think there are that many people who own media who truly love quality media. I think it’s all about scale and the opportunity to plug in this or that or whatever. But it’s not very often about the quality of content.

Sean Plottner: You are certainly not known as a yeller and a screamer. And that has gotten you to where you are.

Janice Min: Yes. I don’t think I’ve ever raised my voice in the office. Ever. I remember Carol Wallace once said—I’m sure she would never remember this—but she once said about me that I have ice running through my veins. Just meaning unflappable. And I like that.

Sean Plottner: Coming from Carol it’s quite a compliment. She could be pretty brusque. She scared me a little bit, but I also learned a lot from her. I remember the day I went to her and said I had an offer to go to The National Sports Daily, it was with some trepidation, but she stopped me mid sentence. She said, “Oh … go!” Because she only had a few more weeks left and I think she knew it.

Janice Min: Wow. Wow. Wow. Carol was my editor for most of the time I was at People magazine. And again I think you never know where your champions are going to come from when you’re starting out in your career. And I think she saw in me like a sort of ambition that she had once had also when she was my age. And she rewarded it.

I remember when I became a senior editor of people and I said to her, “I don’t want to be put on the baby stories. I need to be put on the real stories.” And her face lit up. And I think when you’re running a publication you want someone who wants to keep going, wants to achieve more. So of lucky circumstances in my life, working for Carol Wallace was one of them.

Sean Plottner: What do you really love to do in your off time, if you have any?

Janice Min: I love to read. I just read All the Light We Cannot See. So good. And I work out, because I’m in LA, and that sounds like a really lame thing to do. But dinners out with friends. I don’t know, I would probably say reading is my number one thing.

Sean Plottner: You had mentioned to me recently that you had been to a big book party in New York City, and the hoi polloi were there. You were there. Who else was there? What’s it like out there these days?

Janice Min: It was fun. It was a book party for Michael Wolff, who is one of my old friends. I’ve known Michael since I was running Us Weekly and he just wanted to meet. And we met. And Michael has this big, bad reputation. And we just hit it off.

He was the media columnist for New York magazine at that time. And Michael, as I think much of your audience knows, became this massive bestselling author. And so I had brought him on as a columnist at The Hollywood Reporter to cover the media and he was hilarious, and vicious, and all these things you want. But smart, accurate. He said things that needed to be said.

And I have this forever affinity to Michael. I had mentioned I had interviewed Donald Trump before and so there was going to be the California primary right up to the 2016 election. I had emailed Hope Hicks and I said, “Listen, can we get Donald Trump for another cover? I would love to have Michael Wolff do it.”

So I reached out to Michael. I’m like, “Do you want to do this?” And I think Michael got on a plane before we even had the “yes.” And Michael flew in from New York. He went to go meet Trump at Jimmy Kimmel, where Trump was taping an appearance. They spent a whole evening together at Trump’s house, which Michael Wolff memorably described as “three-star-hotel decor.”

And from that relationship that Michael was able to develop around Trump’s team is how he ended up sitting on the sofa in the White House and got the details to eventually write Fire and Fury, which also changed the trajectory of Michael’s life.

And so Michael had his book party. Lots of media people there, past and present. Really fun. There’s always like this lingering nostalgia around recapturing what media was, but it was also just fun to see people. Like I said earlier, I like these people, these are people that have always been my people. I would like to hang out with them more than probably anyone else. It was fun in that way.

The Ankler’s homepage on Substack

Sean Plottner: How has being an Asian-American woman affected your career—good or bad or not at all?

Janice Min: I don’t think anyone could look at my career and say, “Wow, she was held back by that.” I have no idea. I think that whole discussion around discrimination and bias just wasn’t part of the run up in my career. So, in my oblivious way, I go about in the world like it didn’t really cross my mind. And so like I think there are moments now in hindsight where I think about, Well, would that have been different? Was that happening because of that?

I just will never know those answers. But I think that publishing has always had this consuming idea of The Great Man. And there’s always been these great male editors. And I think women have gotten very little of the same. One of the most irritating things to me when my contracts would come up at Us Weekly, it would always get written about. And there was always this phrase that I was the “overpaid editor of Us Weekly.”

And I’m like, “What makes someone overpaid?” And I just felt like, inherent in that statement that you are undeserving of what you’re getting. And I’ve seen it all over. I’ve seen it from people who I’ve worked with. There is like a pulsating desire or uncontrollable need by some men to diminish a female. Or there’s always this qualification around describing a female’s accomplishments.

I’m sure if I sat down and really did a full analysis of my career, I could come up with a grievance list 20 miles long. But I’ve also had a really great career. And one thing I will say is that I think if you are a female—certainly if you’re a female who is not white—there is no room for error in what you do. You can’t screw up, you can’t be awful, you can’t do all these things that I think male editors probably get away with.

Sean Plottner: Okay. Steve Jobs. We just found out that you’re in his will. Janice Min has to produce a print magazine. Oh, there can be whistles and bells, but you’ve got to do a print magazine. What would you do? Tell Steve to shove it?

Janice Min: Oh, God. This is why I think print is not dead, despite the name of your podcast. I think that if it’s done correctly, people just love seeing the evidence of human curation. And if any of you still look through print magazines, or even look through the print New York Times, you’re like, “Oh, my God, this is how they thought about it. Thank you. You’re telling me what you think is the most important story today.”

And you can see this sort of brilliant packaging. I think New York magazine is one of the few places that still does this where they’re not just putting stories on paper that they were going to put online. That whole packaging element—it makes me sad—I think that is a lost art. It’s going to disappear because people don’t do it anymore.

But I’m avoiding your question because I don’t know the answer. I think the best publications are the ones that take you to another place, like an escape. Not because they’re frivolous or escapism, in a bad sense of the word, but it’s like world-building into a place someone else took you who has great taste and judgment.

For more on Janice Min, check out The Ankler on Substack or follow her on X and Instagram.

More from Print Is Dead (Long Live Print!)