All the News that Fit

A conversation with editor and founder Jann Wenner (Rolling Stone, Outside, Men’s Journal, Us Weekly, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT COMMERCIAL TYPE

Imagine there’s no sixties.

In 1967, today’s guest was a college dropout whose Plan B was to start a rock ’n’ roll magazine. Plan A? “Kicking back, having a good time, delivering letters, and smoking dope all day” as a San Francisco postal worker. But thanks to a nudge from his mentor, Ralph Gleason, and a cash infusion from his soon-to-be-wife, Jane Schindelheim, Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner dove head first into Plan B. And the rest is magazine history.

Imagine there’s no Gonzo.

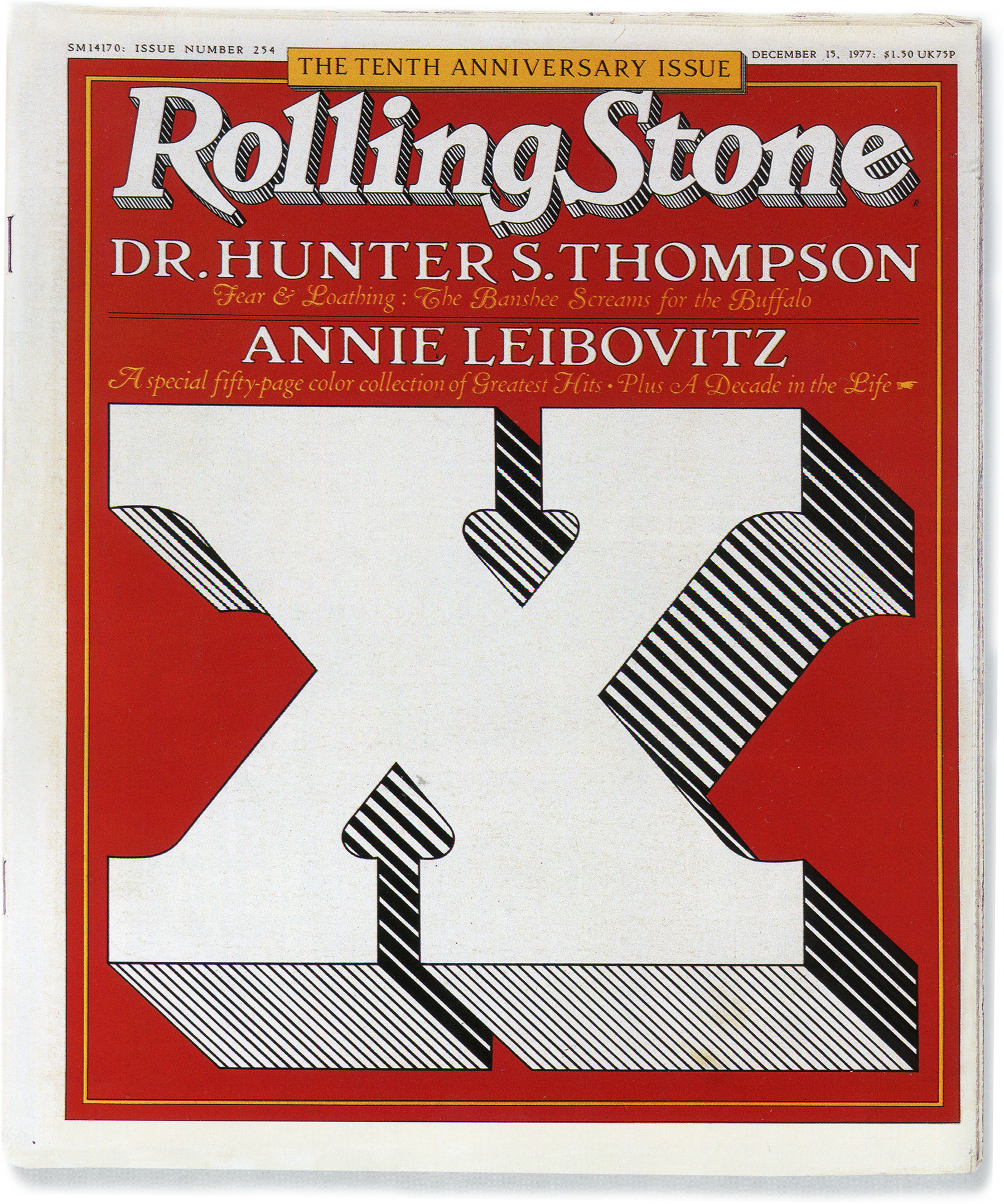

Rolling Stone was an instant hit. But it wasn’t until Wenner met the now legendary journalist, Hunter S. Thompson, and later published his “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” that Wenner found the editorial promised land. Thompson’s explosive, unhinged prose created space at Rolling Stone for a legion of iconic writers—Tom Wolfe, Lester Bangs, Joe Eszterhas, PJ O’Rourke, Matt Taibbi, and others—and allowed the magazine to expand its reach from music to something much bigger. “If it feels good, man, just do it.”

Imagine there’s no Annie.

In 1970, a 21-year-old newcomer was given her first paid assignment for Rolling Stone: a cover shoot with recent ex-Beatle John Lennon. In short time, Annie Leibovitz was named the magazine’s chief photographer. But it was a nude portrait of teen idol David Cassidy for a 1972 cover that signaled another watershed moment for Wenner. The allure of celebrity fueled the young editor’s personal obsession to join the cultural elite, and the cover of Rolling Stone became his ticket in. The combination of Thompson’s wild-eyed, uninhibited ramblings and Leibovitz’s intimate, provocative imagery was the magic that set Wenner free.

Imagine all the memories. It’s easy if you try.

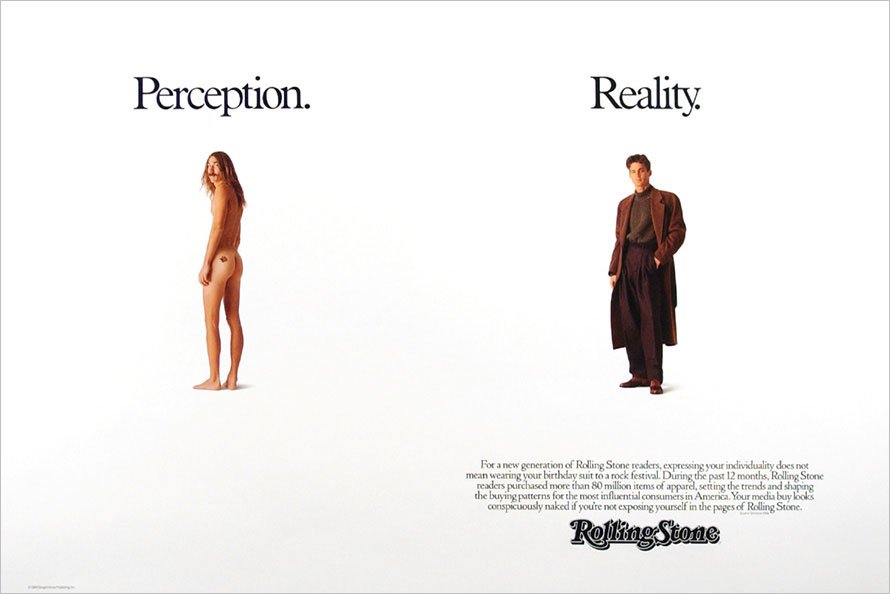

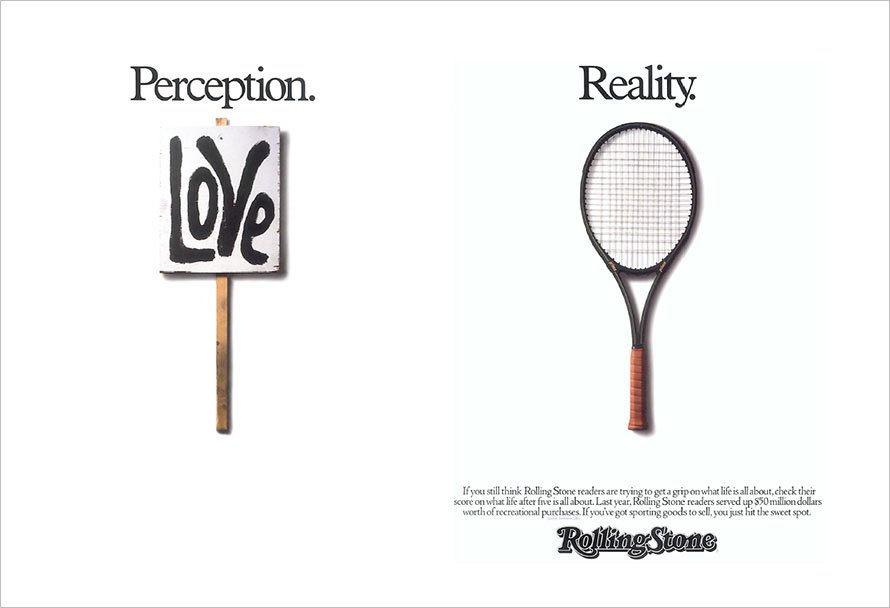

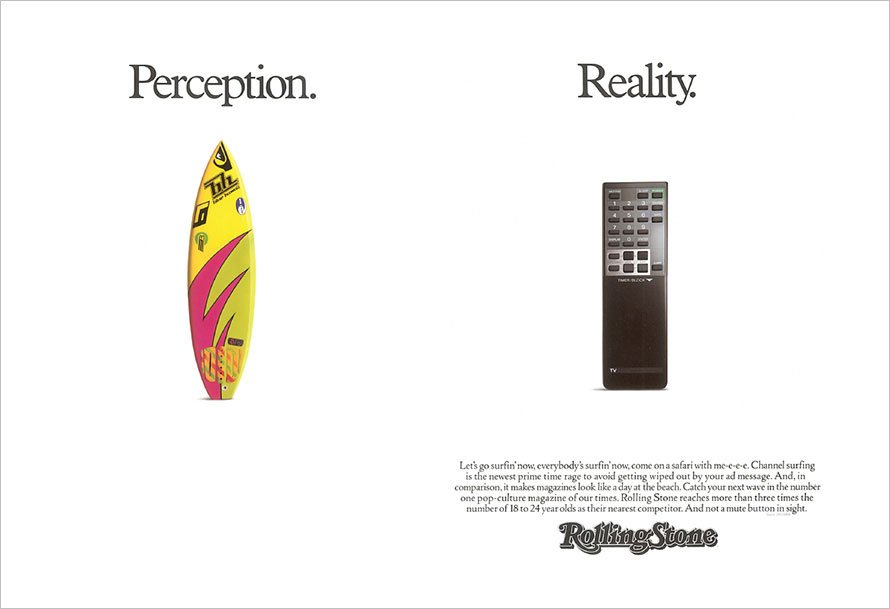

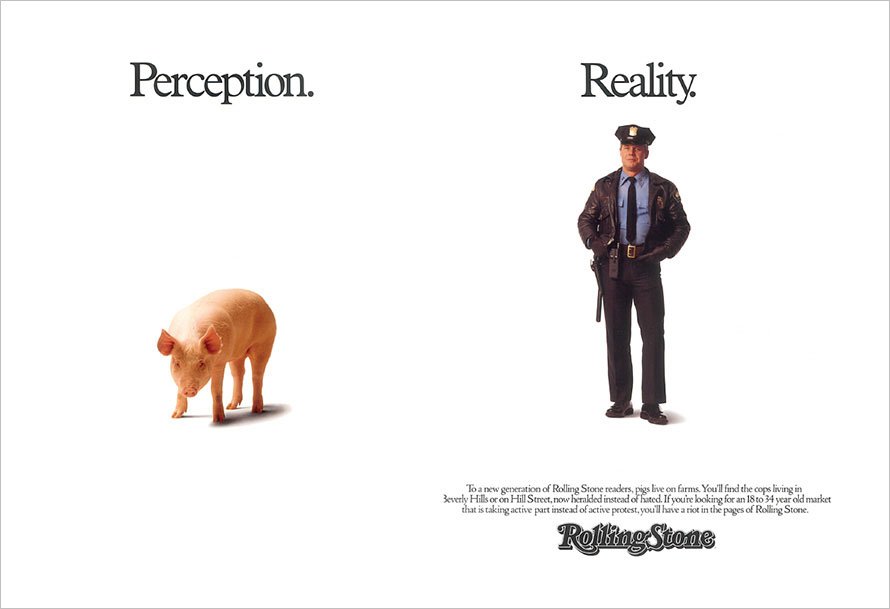

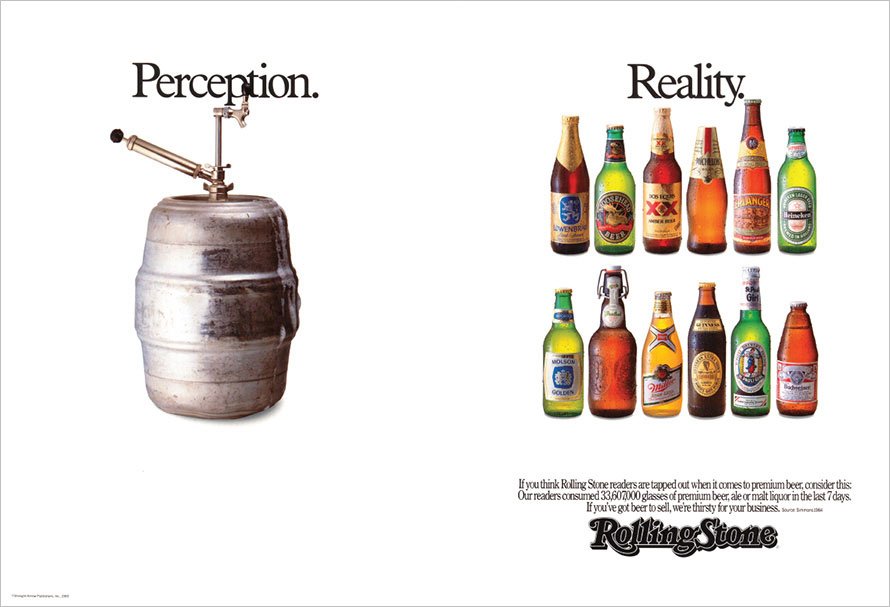

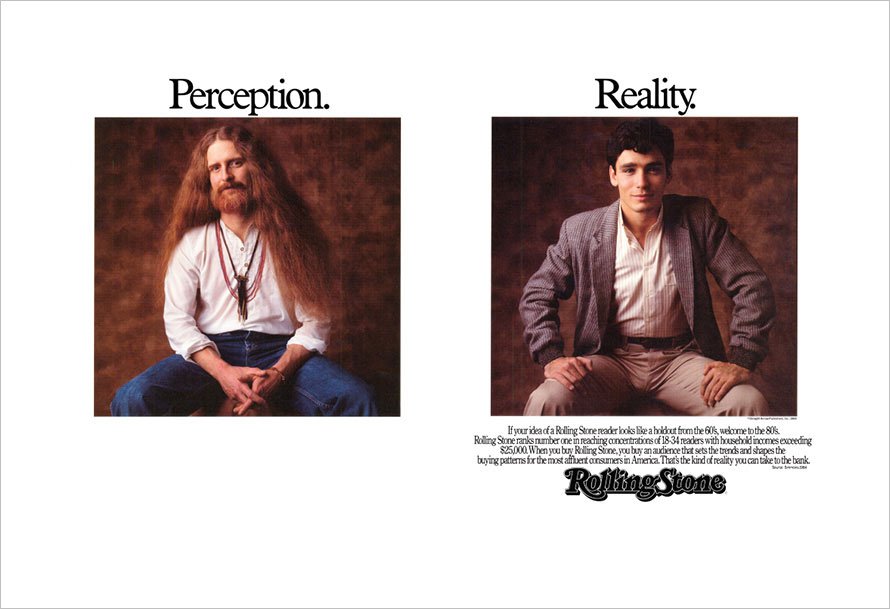

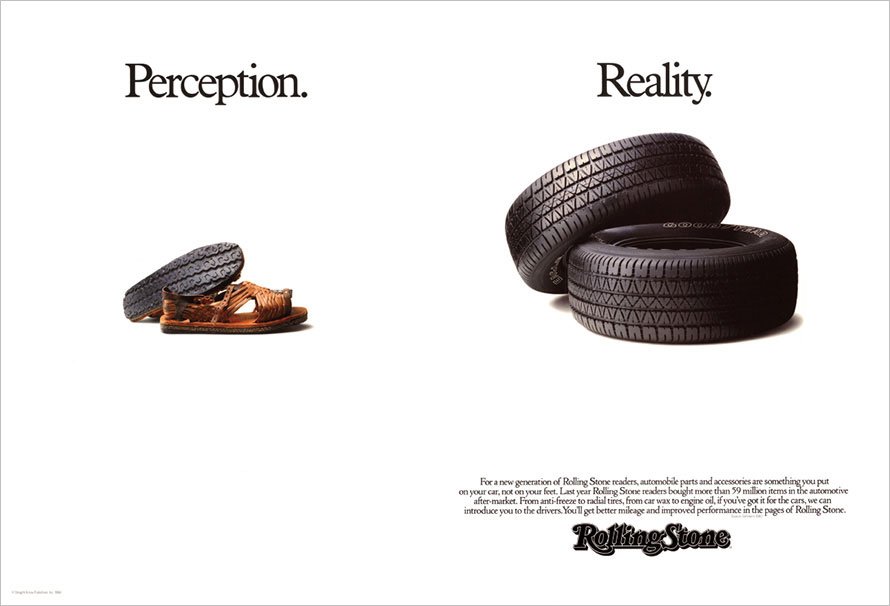

Five decades on, Rolling Stone is a boomer autobiography—its pages filled with Random Notes and “All the News that Fits,” epic stories documenting massive successes, abject failures, and the lives and deaths of the culturally relevant, all accompanied by unforgettable photographs and game-changing design. The magazine has survived near-bankruptcies, editorial scandals, cross-country moves, and yes, even that Reagan-era “Perception vs Reality” ad campaign.

In the end, though, Wenner’s story is a somber one. Any time a parent outlives a child, there’s immeasurable sadness. Of course Rolling Stone lives on—“digital-first” as they say—with new owners. And with Wenner’s son Gus taking the reins in 2017. But it’s not the same Rolling Stone. How could it be?

As for the man himself, that legacy is “complicated.” But in this episode, you’ll get glimpses, as Rich Cohen describes in The Atlantic, of Wenner’s “infectious charm, his gleeful, let’s-hope-we-don’t-get-shot zeal for adventure, how contagious his enthusiasm was, and how important his loyalty could be.

“Wenner’s pen and language weren’t what defined him as an editor. It was his vision and energy that attracted the best talent and inspired such memorable work.”

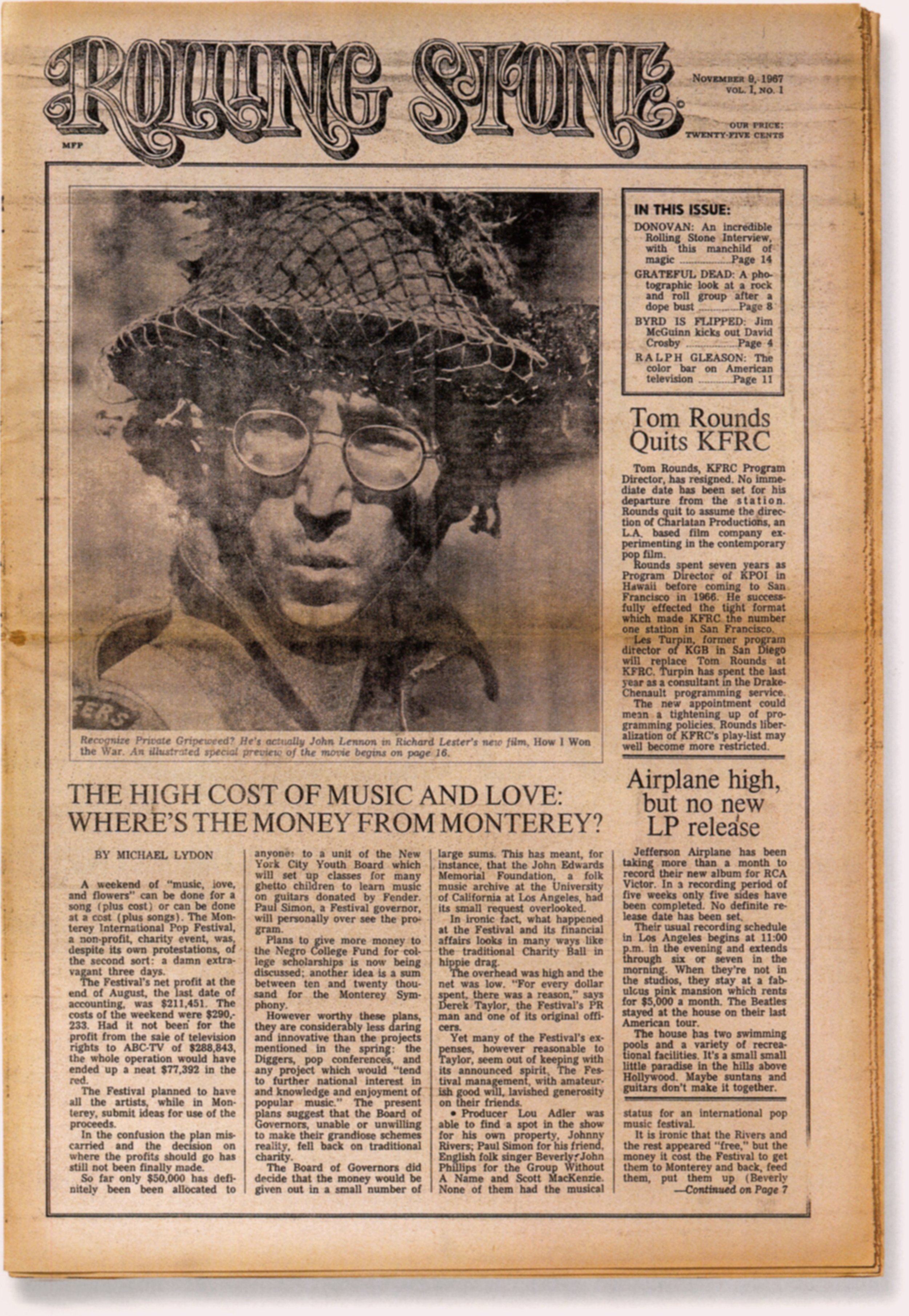

Rolling Stone debuted on November 9, 1967 as an 11x17-inch newsprint magazine, folded in half.

George Gendron: Given the name of this podcast, we really do have to start by asking you, if you don’t mind, to recount for our listeners the emotional story of your last day in the Rolling Stone offices, right from the prologue of your book.

I mean it was really, really emotional and so relatable to so many people in our business. It’s almost like a eulogy to a child you’ve lost.

Jann Wenner: Well, it is. I do compare it to a death and, as you say, it goes through the various stages of trying to accept it. And it’s not until, really, the body is in the ground you actually believe it. Even as sick as the patient is, you’ve still got the patient, the loved one around. And you hang on. You hang on and you cling and try and keep it alive. But even when dead, the body’s still there.

It’s that moment of burial. That moment when I left the office, though it was empty by that time. And the chairs and the computers had been thrown in trash bins and, you know, just nothing was left.

I was sitting there writing and I got a call from a friend of mine, Patty Scialfa, who’s Bruce Springsteen’s wife, and I was telling her what I was doing, and she says, “Well, why don’t you just drop what you’re writing and write this scene?” And I did write it, sitting there as it was happening. And it turned out to be the opening scene of the book.

George Gendron: Man, it’s really powerful.

Jann Wenner: Well, thank you.

George Gendron: It does make me wonder, though, why did you subject yourself to that? Why did you actually go into the office when the physical symbols, if you will, of what you had created were being torn down and carted out?

Jann Wenner: Well, I was using it as a place to write my book and I was set up there in my office with my writing desk and computer and research and all that stuff. So it was a convenient place to go to work. That was the primary reason. I suppose there’s an underlying psychological reason of wanting to just cling on to something I was familiar with for so long. I mean, I was still in my office. My office for some 30 years. Where, as I say in the book, I had risen to fame and fortune and ruled an empire.

George Gendron: Founders often talk about a moment in a startup where suddenly something happens. They’re sitting there one day and they go. This is going to work. They know it. It’s not about the confidence that you bring when you launch. It’s about, kind of, the response. The response in terms of revenue. It’s like, “Okay, this thing is sustainable.” But also people tend to feel that way when they know something is over. Was there a moment when you just knew that for you personally, this was over?

Jann Wenner: I guess it was kind of a creeping dawning of reality. I mean, going back some years to 2008-2009 when the ad recession started and the internet was starting to come on substantially, we were in a position where we kind of bucked it for the first year or two because our demographics were so good and were so desirable. That’s because we were a quality magazine, which goes last.

And then it just started to shrink year after year, after year, after year. The first couple of years of decline, you could say, “Oh well. We’ll turn around the advertising, sell something.” But then it just became inexorable. And I suppose the moment when my son [Gus Wenner] and Tim Walsh, my CFO, came and said, “We have to sell Rolling Stone.” And I always knew that if I sold Rolling Stone, you know, I was not going with it. It’s too late.

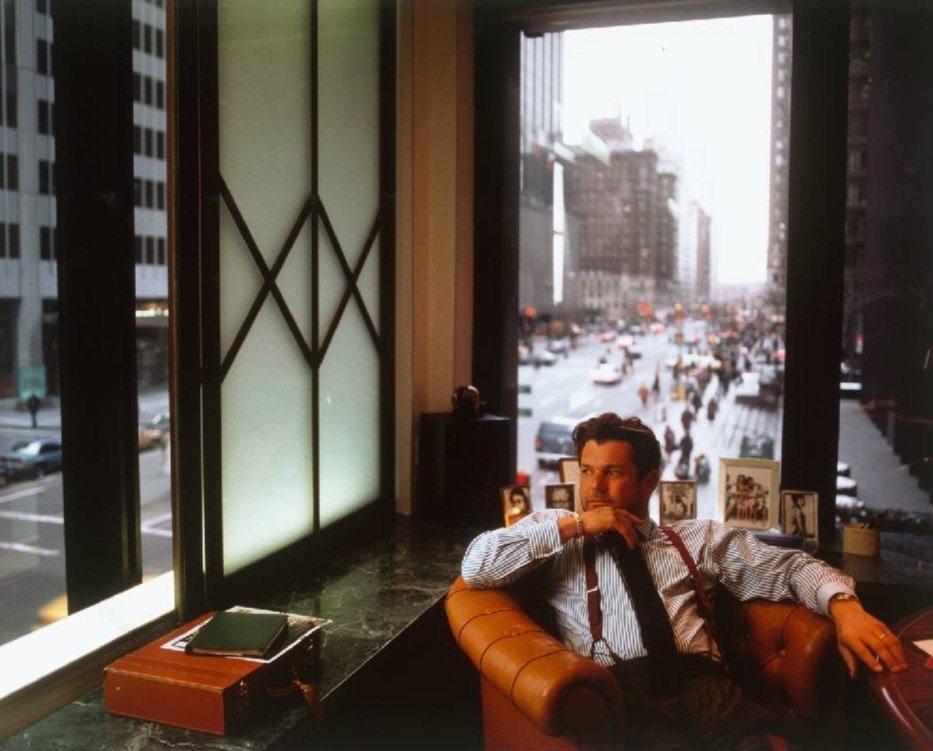

Wenner with his wife and co-founder, Jane, in San Francisco.

George Gendron: When would that have been roughly?

Jann Wenner: Gosh. The years! I don’t even know what this year is. Like the end of 2017, 2018? I’m not sure. Maybe 2016, 2017. [Ed: It was 2017].

George Gendron: I think a lot of people experienced those same feelings around that same time. I want to go back now. The story about the launch of Rolling Stone, of course, is legendary. But I do want to touch on just a few quick things. The first is just a personal response I have every time I’m reminded that just before you launched Rolling Stone, you had taken the civil service exam, wanting to be a postal worker. Could you explain to young kids listening to this, what was so attractive about being a postal worker in San Francisco back then?

Jann Wenner: Let me take you back to San Francisco then. It was a small town, still. It was beautiful weather outside, generally. Always pretty pleasant weather. And it was just, if you came out of the hippie scene, I mean, the thing was you didn’t really want to work.

A career was, you know, no good. There was no big sense of ambition. “I’ve got to go into marketing” or “It’s time to go to business school or Wall Street” for me. There was none of that.The ideal thing was to sort of kick back and have a good time.

So if you worked for the postal service, you could go out and deliver letters or whatever and smoke dope all day. And you know what? What’s wrong with that? That’s cool.

“I always knew that if I sold Rolling Stone, you know, I was not going with it. It’s too late.”

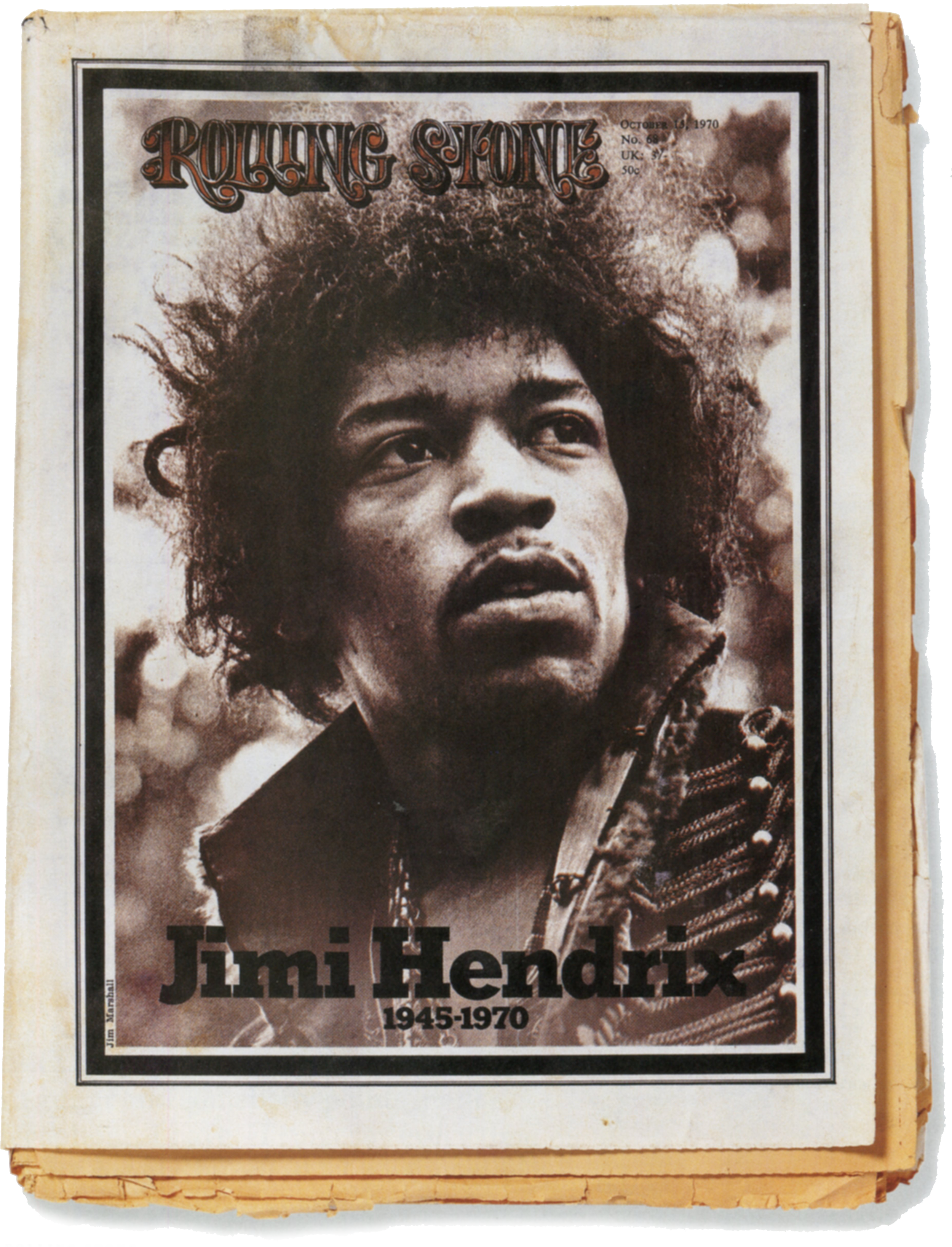

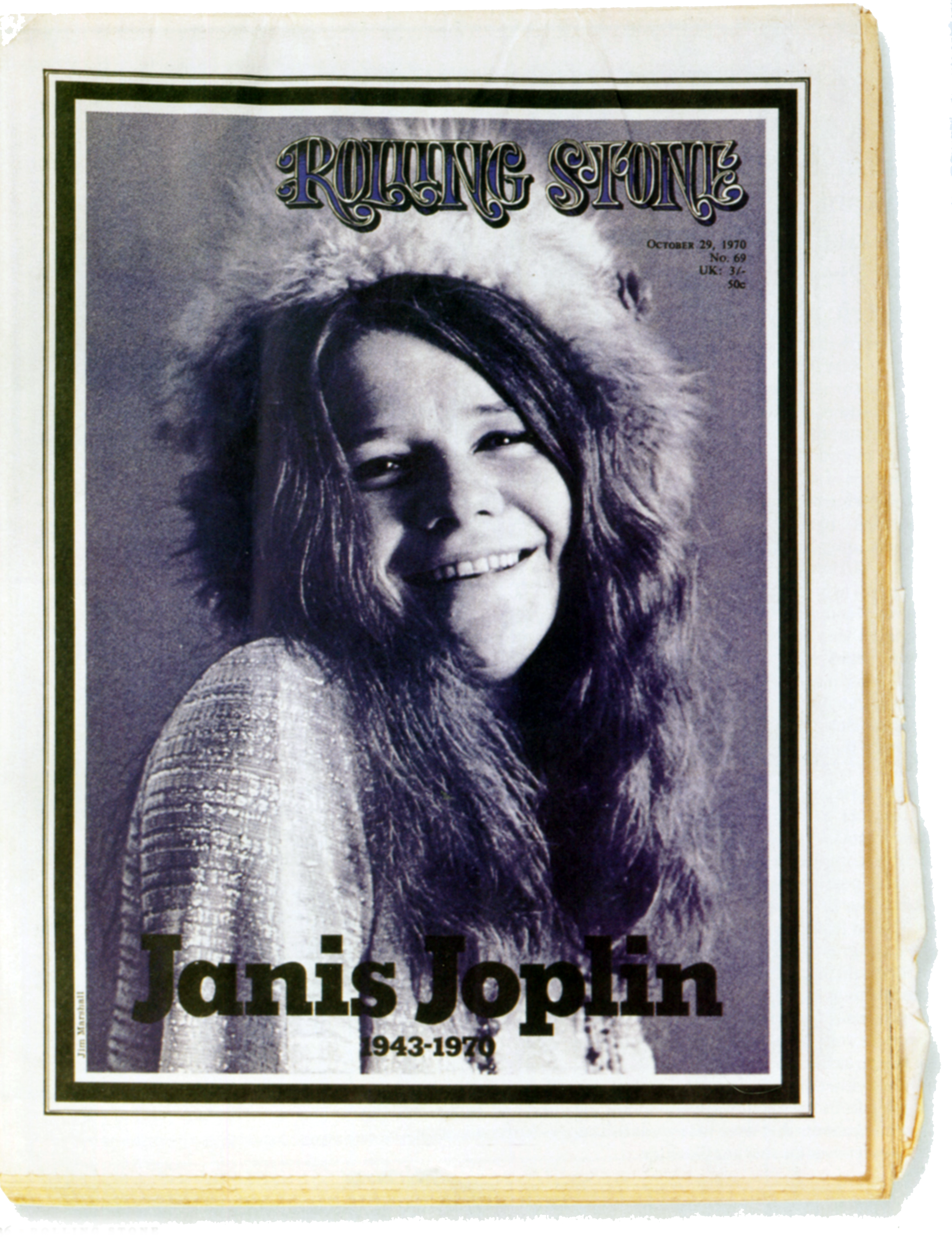

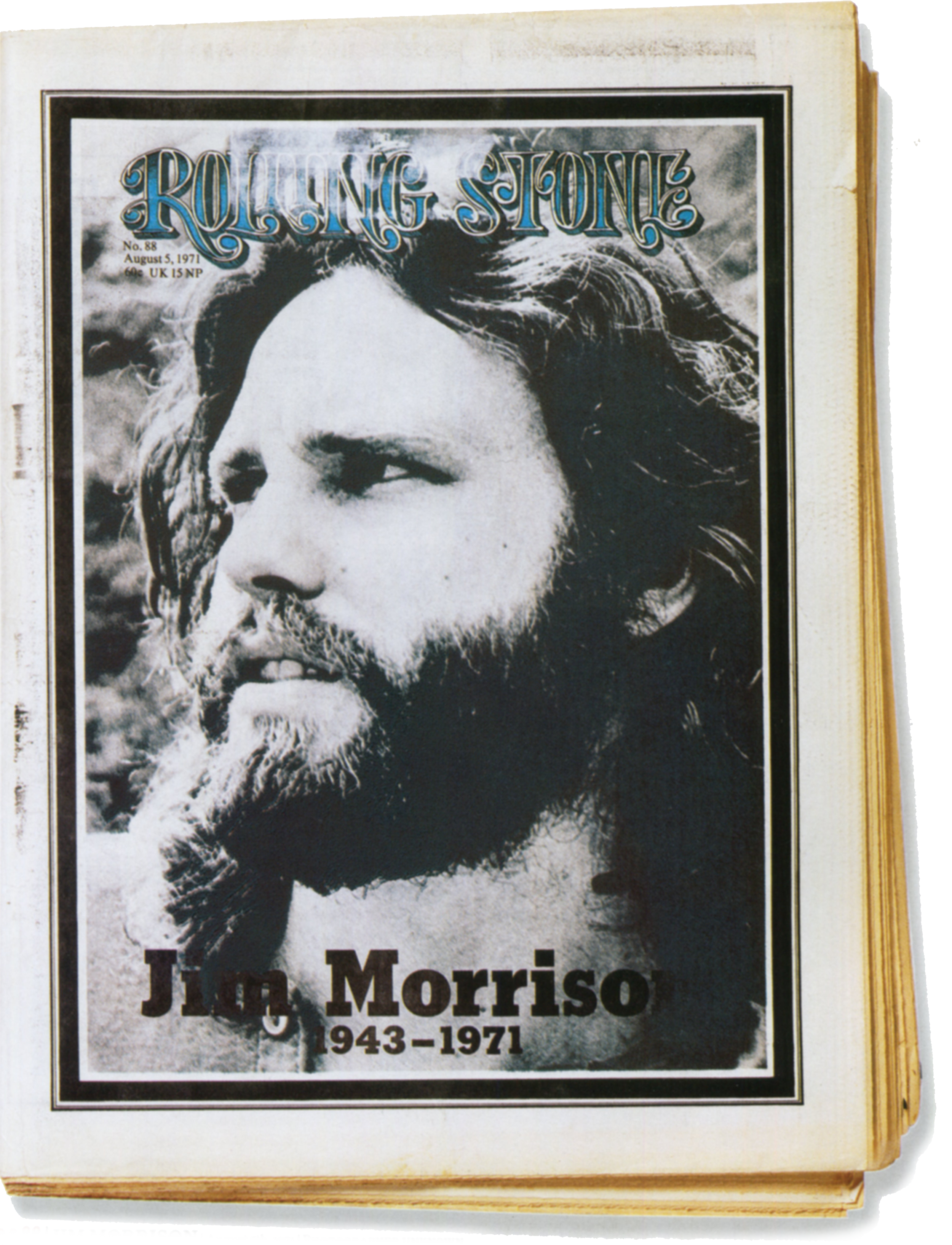

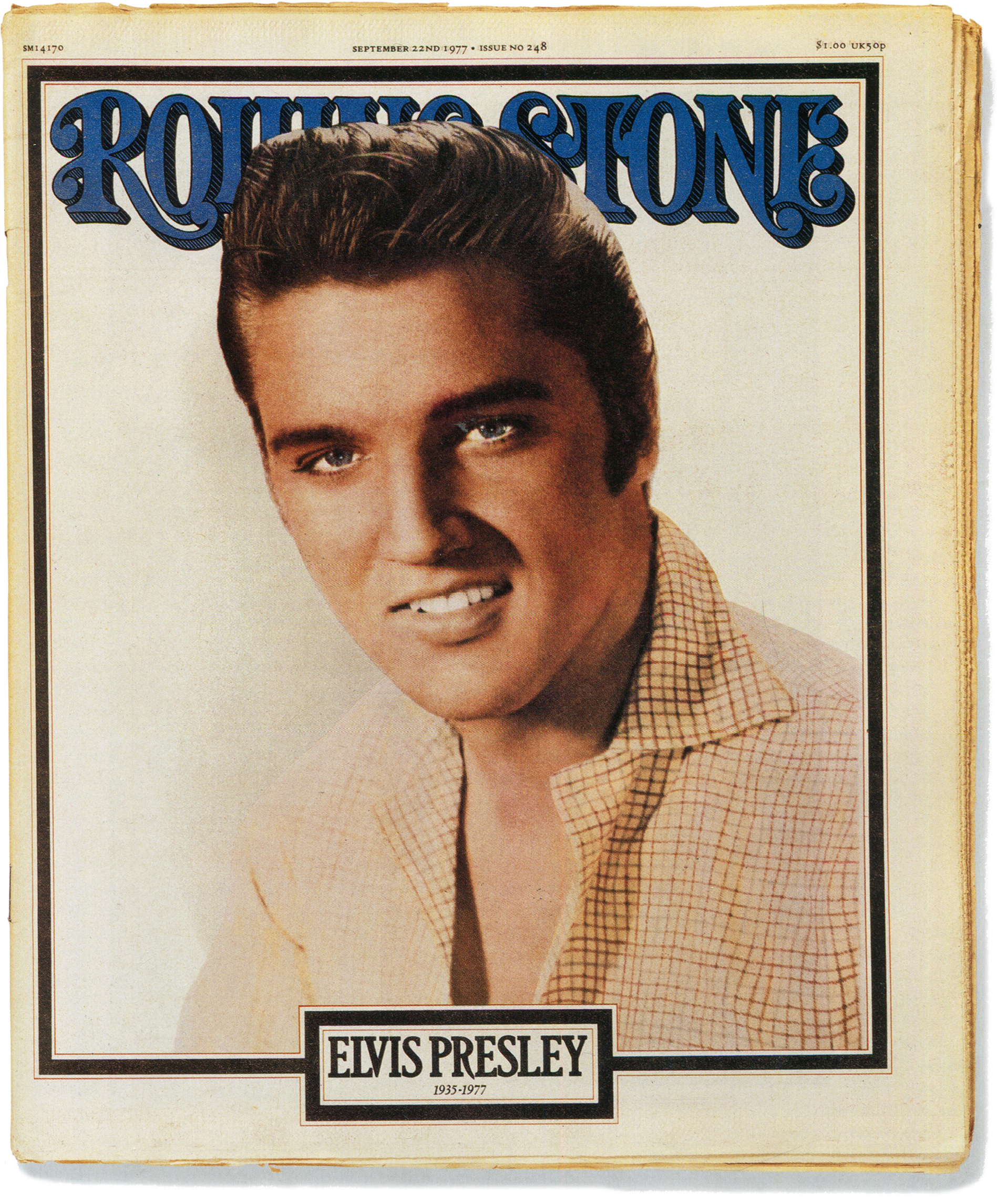

Nobody did death like Rolling Stone.

George Gendron: So in a way it was perfect training for the launch of Rolling Stone.

Jann Wenner: Well, no. No. It was like a laissez faire time. It was a kick back era. People didn’t need money that badly. There was plenty of money around.

George Gendron: That was also starting to surface, believe it or not, even here on the east coast, although not with that same intensity.

Jann Wenner: The East Coast was never as laid back.

George Gendron: No. But I can remember with my college buddies talking about the fact that nobody wanted to go into a profession. Everybody was trying to figure out, well, what are the alternatives?

Jann Wenner: That was the cool thing. I mean, really, the fifties was a very prosperous era. Everybody was raised with some level of money. Let me just say it was comfortable, really, for everybody. You were lower middle class, you went to a good public school. You know, there were jobs aplenty. The country was so small then. Less than half the size it is now. Less than half the size it is now.

George Gendron: It’s amazing, isn’t it?

Jann Wenner: Think about that. Think about New York City with half the number of people in it, for example. Anyway, and so there was no real struggle or need to survive. Your education was free. Benefits were everywhere. Your parents had money. People had a second car in the garages. It was not like today. So the need to support yourself, let alone the need to do something highly ambitious, was not there.

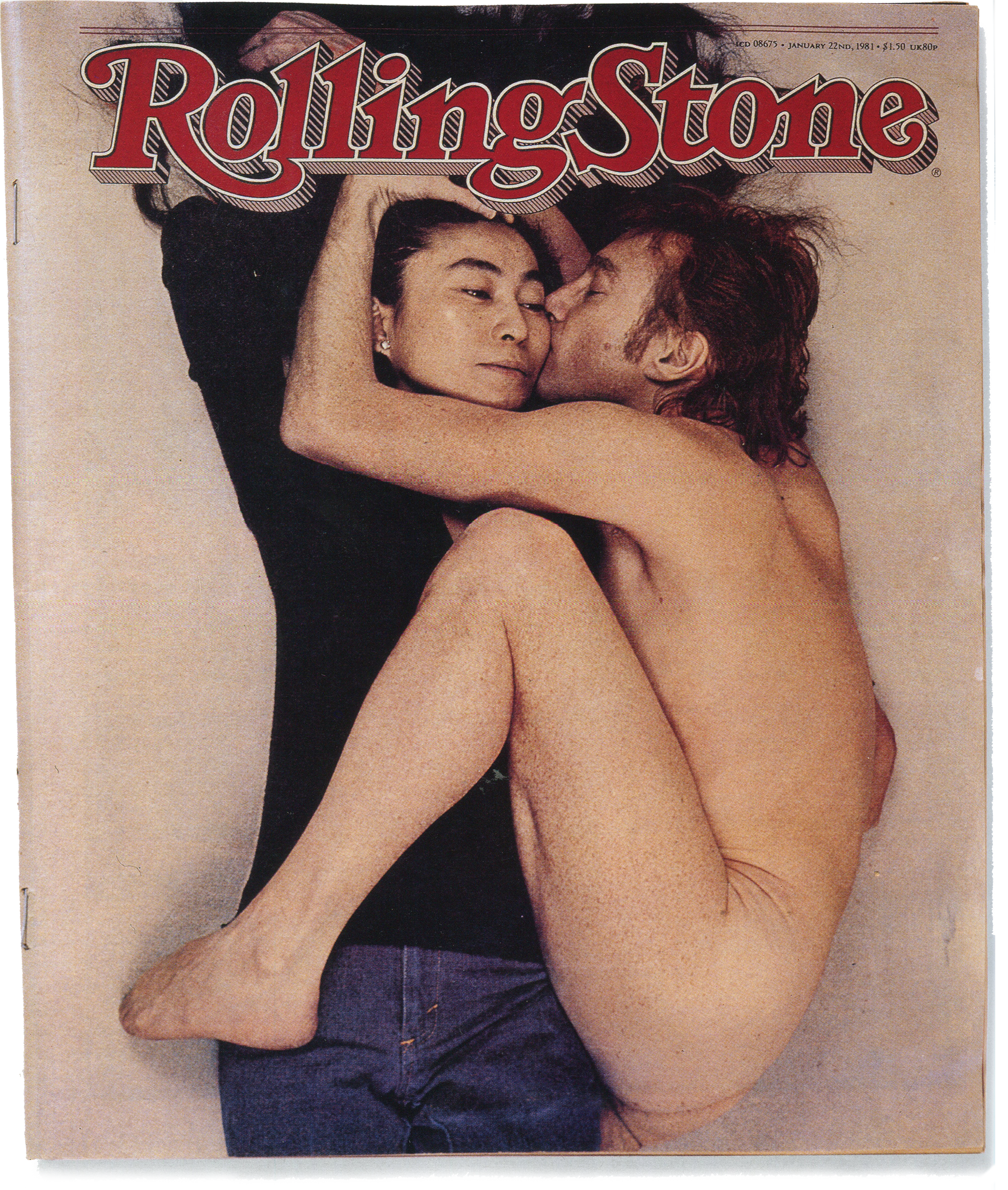

An Issue of firsts: Lennon’s first post-Beatles interview and Annie Leibovitz’s first cover assignment.

George Gendron: Now I want to touch on something else that I think you touch on in the prologue. And that is the mission. But you write about it in a very interesting way. I can’t recreate the actual sentence, but you’re talking about the mission of the magazine Rolling Stone. But you also talk about your personal mission. And I wonder, can you describe the two of those as you were thinking about them back then?

Jann Wenner: Well, I think they’re kind of one and the same really. I mean, the general idea is, I had developed this deep belief and love of rock and roll. I really wanted to be part of it. It was the magic that could set you free. And I wanted to be part of it, know more about it, and just have it infuse my life.

And through that a lot of feelings were expanded, explained, developed about personal freedom, about public duty, about what society should be like, what we should stand for in our lives, having fun. What I boiled it down to, finally, is a passion for, and a belief in, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Which defined, I think, The American Dream. Or if you define it as something other than getting very rich or something.

And let’s call it the foundational principles of the country. And I believed in those. And they were expressed for me through rock and roll. I found them in part through rock and roll. And they were what we were taught when we were growing up. And to grow up, and go to college, and discover that these things were not true created this giant rebellion and this desire to make them become true, despite what we had all embarked on. That my generation embarked on. And that rock and roll was devoted to.

George Gendron: Yeah. It’s funny, almost everybody I knew who was my age, I’m 73 now, growing up then they either wanted to be a rock musician or they wanted to play third base for the Yankees.

Jann Wenner: Well, yeah. It was the land of choices. What can I tell you?

“We didn’t pay salaries. We didn’t pay rent. Our only expense was food for me and my girlfriend and printing the paper itself”

Like father/like son: Wenner passed the torch to his son, Gus, in 2017.

George Gendron: So you rustle up about $7,500 in startup capital. That’s about, I don’t know, $65,000 in 2023 dollars.

Jann Wenner: But that’s not even, it’s not even—is it even comparable? If you were to start a magazine today, you’d need several million dollars.

George Gendron: Yeah, that’s what I was going to ask you.

Jann Wenner: I mean, then maybe, I don’t know. You could do it for a million. You’d need a lot. Who knows? Anyway, yes.

George Gendron: How long did that initial 7,000 bucks last?

Jann Wenner: To today! We just spent money as we could afford it, as we had it. And spent it and it just, you know, just kept it alive. We didn’t pay salaries, so we just paid increasing expenses out of the money that would be coming in. And we didn’t pay salaries. We didn’t pay rent. Our only expense was food for me and my girlfriend and printing the paper itself.

George Gendron: Right. You know, for 20 years I ran the creative team at Inc. Magazine, and chronicled the rise of the entrepreneurial economy. And Rolling Stone is kind of the classic startup story in terms of scrappy, fiercely mission-driven, unbelievably resourceful—because you’ve got to be. And it strikes me that when you and Mick Jagger launched the UK version, it had none of those qualities. Maybe it had too much money. Didn’t seem to have much passion.

Jann Wenner: Yeah. Right. I mean, Mick, represented unlimited financing to an extent.

George Gendron: Not a good thing for a startup.

Jann Wenner: Yeah. And the people starting out, we were kind of more laissez faire and their attitudes for things, they weren’t really professional journalists or professional magazine people. They didn’t tend to have that hunger or the drive for it. And the kind of passion that makes you, you know, go further on less resources.

George Gendron: I also think there’s a quality that Rolling Stone had that felt like you were discovering and exploring with your audience rather than kind of you already had all the answers and you were simply imparting it to them, if you know what I mean. Kind of mutual self-discovery.

Jann Wenner: Meaning me and my readers?

George Gendron: Yeah.

Jann Wenner: Yeah. Yeah. Yes. Probably. Yeah.

Determined to change Rolling Stone’s image—and rake in more upscale advertising—Wenner hired Minneapolis-based ad agency Fallon McElligott to appeal to yuppies and their dollars.

George Gendron: I think there’s nothing like that in terms of a bond.

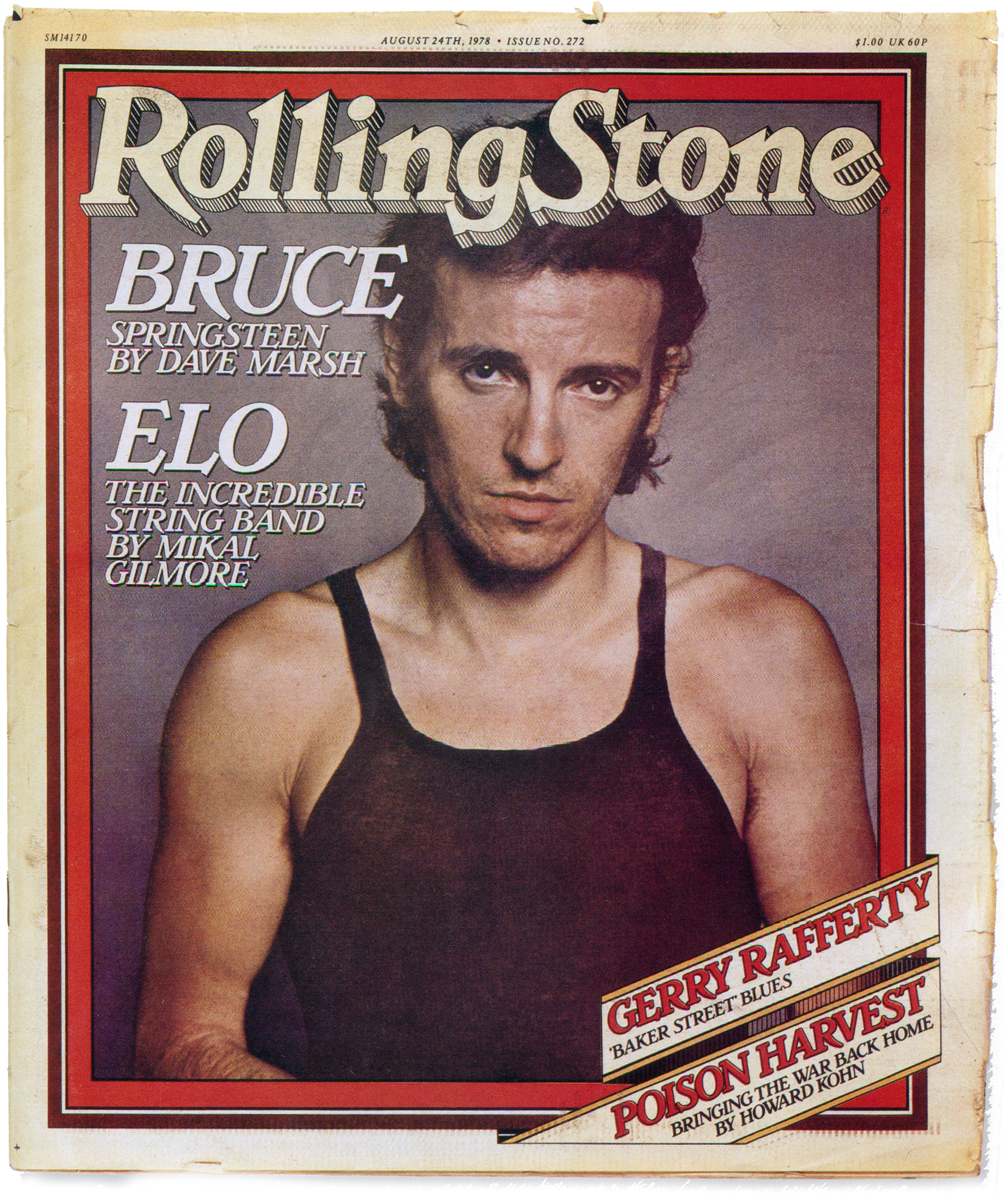

Jann Wenner: That’s the thing. The bond that developed between our readers and ourselves was so incredibly strong. People believed in Rolling Stone, loved Rolling Stone. It just meant the world to so many people at so many levels. Whether it was just an average reader there in Paducah, Kentucky, or whether you were Mick, or Bruce, who’s spoken about it at length. He said, “We were out there in New Jersey in nowhere land hoping there was somebody out there like us. And Rolling Stone would come and it was like a vision of another country.”

They were waiting for it every two weeks, you know. It told them of all the possibilities. What they could be. And the fans who just listened to this music loved it and went, “God, there’s another person who feels the same as I do about this. Wow!”

George Gendron: I live in this little compound on the South shore of Boston, and my neighbor here, Jay, has what he calls the “1968 Museum,” which is basically about five or six rooms devoted to two things: Rolling Stone and Andy Warhol.

Jann Wenner: Awesome.

George Gendron: And he was a young kid. He was growing up in Mississippi. Or Texas, I think it was. And that was his lifeline to, kind of, a different world.

Jann Wenner: That’s great.

George Gendron: So you grow up in San Francisco—the magazine really couldn’t have been launched anywhere but San Francisco—have you thought about the relationship between a magazine’s identity and place? Where that magazine has its roots? And I’m curious if you felt that Rolling Stone’s identity and culture changed when you left San Francisco and moved to New York?

Jann Wenner: Well, all of the above. The more, in a way, kind of spiritual home of it, even more than San Francisco, was Berkeley, when I went to college there. And that’s where all this stuff first started happening. This education in rock and roll, and the local politics, and drugs, and all those things really coalesced there. It started to crystallize.

And it was in San Francisco the year later when I was working for Ramparts that we started Rolling Stone. But once it was so much reflective of that time and place: the drug scene, the rock and roll scene, this hippie thing that was going on, the kind of values and ethos that was trying to be developed there, and what the Grateful Dead and the Airplane were doing. And we were totally of that time and place.

We, obviously, were trying to think internationally because the same kind of thing was happening in London with the Beatles, you know, the same kind of rock and roll scene, all that. So we’re trying to think nationally and internationally but we were such a product of that time and place.

And only over the years did we start to shed some of that local stuff, and started to see it in a broader sense. And we started to put people and writers in LA, in San Francisco, and London and New York, which gave us a broader look at things.

Before we moved to New York we had already kind of outgrown San Francisco, and our fame and reputation and reach had become very national, very international. Hunter [Thompson] had covered the elections, the presidential elections of ’72. We had, by that time, done the Silkwood case, the Patty Hearst case, we had interviewed John Lennon and all that. So we had a national focus already. But when we moved to New York, by that time we’d already kind of, really, left behind the hippie ethos of San Francisco. That had already dissolved several years earlier.

And the San Francisco rock scene had become much less intense. And of course drugs are everywhere now, so you didn’t have to be in San Francisco. But when we moved to York, two things happened. One is my staff for the first 10 years—because it was primarily ex-newspaper guys, hard-hitting reporters, young people looking for stories, you know, really crusaders—stayed behind or dispersed, really.

And when we went to New York, we picked up a lot of people who were more professional magazine writers, and profile writers, and softer in a way. Good writers, good people. Also, we started covering more entertainment, more popular entertainment. But are those also reflective of the change in music itself.

This 1972 cover, featuring Annie Leibovitz’s photograph of teen heartthrob David Cassidy, signaled Rolling Stone’s slow shift away from musicians and towards celebrities.

And then of course you get to New York and your concerns become much more cosmopolitan, maybe a bit more sophisticated, more worldly. And you’ve gone there, really, for purposes of ambition, for purposes of career success. And so we were very busy pursuing that as well. And we wanted to be influential in an entirely different world. Kind of the literary/media capital of the world.

George Gendron: Was there a downside to that from your point of view looking back?

Jann Wenner: Well, I think. Yeah. It’s a little glittery. You get distracted. There’s a lot of dinner parties and there’s a lot of entertainment and, you know, your values are much more about career and success.

It’s always distracting for a while. You have to quickly get your head on or you can lose yourself in all that. And people have. Some people struggle with it, a little back and forth. I struggled with it a little. And end up doing what I always do.

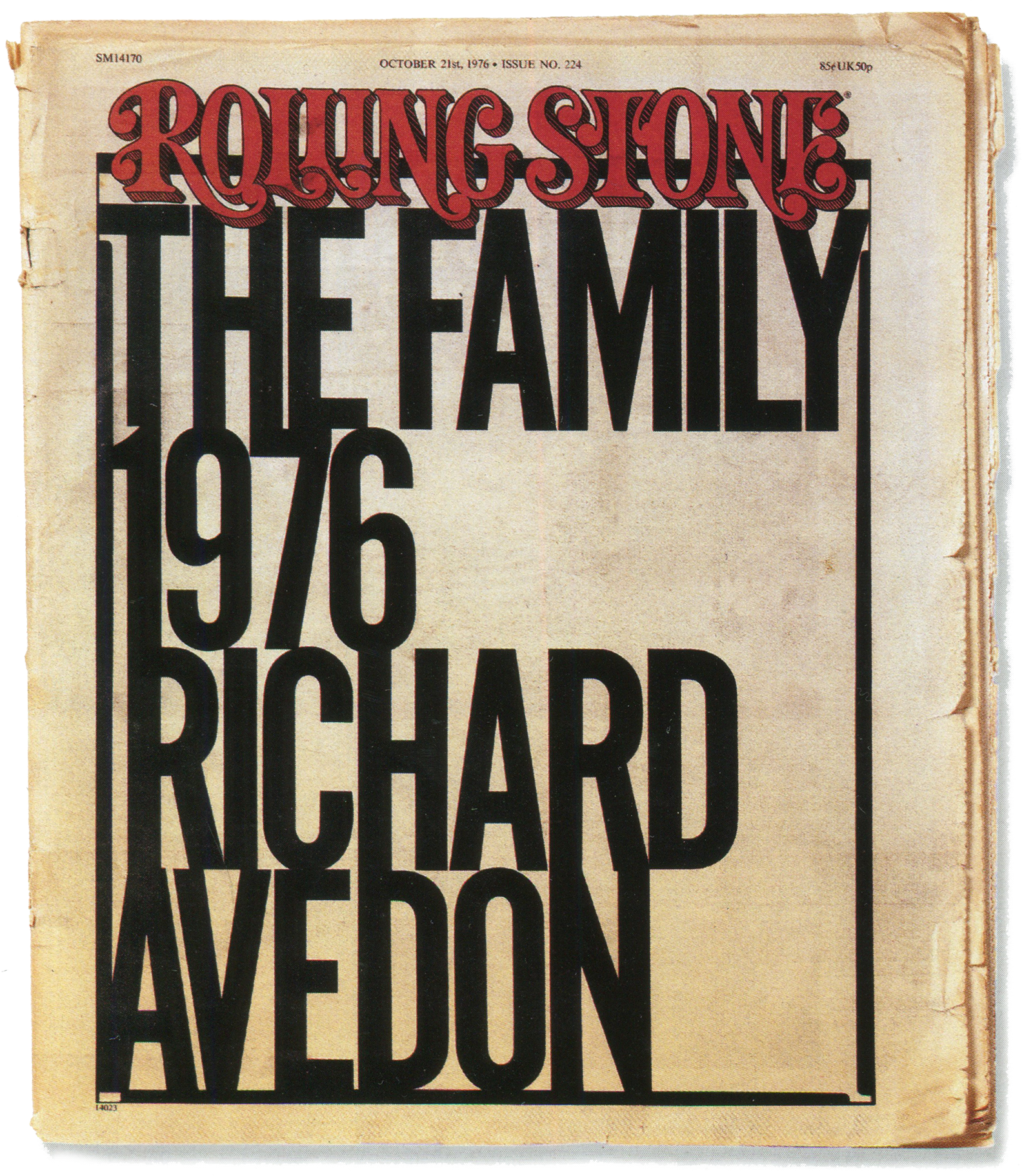

George Gendron: Let me switch gears, Jann, for just one second and talk about the incredible, outsized role that design played in the success of Rolling Stone. It was extraordinary. As I was reading your book and rereading parts of it, I was making a list of your designers and I can’t name them all, but Roger Black, Fred Woodward, Gail Anderson, Nancy Butkus, Deb Bishop. It goes on and on and on. And then of course you have Annie Leibovitz, Richard Avedon, David LaChapelle, Herb Ritts, I mean, God, Albert Watson….

And so I guess my question is did you back then have any idea the outsized role that design would play in Rolling Stone’s success?

Jann Wenner: Well, not really. But coming from Ramparts—Sunday Ramparts—they had a really strong sense of design there because they had a very influential art director there named Dugald Stermer, who copied the London Times for a lot of its tricks, techniques, and Oxford rules. The typeface was, of course, Times Roman.

And so I was raised on that, and the idea of elegance. I was an early reader of The New Yorker and Playboy, both of which were really excellently-designed products. And I wanted to distinguish ourselves so much, from the beginning, from the underground press. So I wanted the type set properly, justified columns, and so forth.

And so I don’t know where I developed that design sense, but I realized early on that the look of the magazine, as much as what you’re saying, defines to the readers who you are—who you think you are and the message you’re trying to give. So my message right away was: this is a straightforward, serious, sober publication with formal rules of design, formal rules of journalism, and reporting.

And then, our first real designer was my brother-in-law, Bob Kingsbury, who gave it a very fine, folksy-looking design where it felt very—it was very personal. It was a very idiosyncratic design. And it evolved over the years saying different things to different people. Ultimately, we started winning a lot of awards.

I always viewed the art director as my essential partner. As well as the managing editor. And I think that if you want people to read your magazine, you have to make it look good, and look attractive, and look inviting to have, to want to buy, to want to own. It should be something you’d be happy to set on your coffee table. You want it in your house you like to look at. And it had to have that look.

I was early on a fan of Twen magazine, a great art director, Willy Fleckhaus, who ran that. And, you know, all those things influenced me. My wife [Jane Wenner] was an art student and had a great sense of taste and style. So I was very lucky.

I liked art directors. To me it was critical. It was really secondary at most other places. To me it was of major importance. The photography as well. To me, what we are covering, rock and roll, is an extremely visual thing as well as a musical thing. The thing that you write about. The looks counted. Their costumes counted. All that counted a lot, and that we had to show. And so that meant you had a visual magazine.

Lennon was murdered just hours after Leibovitz’s legendary shoot.

George Gendron: What was your favorite story and Rolling Stone cover of all time?

Jann Wenner: The all time favorite cover’s gotta be Annie Liebovitz’s portrait of John and Yoko, the naked John curled up and holding onto Yoko, which was taken three or four days before he was killed.

And it’s won every award there is for covers. The best cover of all time. Cover of the Year. And it’s partially because the picture itself shows such vulnerability and love. And a friend of mine, a writer actually Scott Spencer, called it the Pietà of our times, which indeed that’s great it is.

And then given that it has, comes out of that moment in time, that moment in history of the death of John Lennon has taken on us even more rich and extraordinary meaning. So it’s certainly gotta be the most powerful. It’s one of the most beautifully designed and executed as well. So, it’s fantastic.

My favorite story is much harder. I mean you’re talking about—the body of work with Hunter was amazing and so fun for me. And working with Tom Wolfe and doing The Bonfire of the Vanities was just a riot, and laughing all the time. And I’ve just been reading over some of the interviews I did with Bob Dylan and John Lennon and Mick and they were remarkable documents of people in their creative heights and their thinking.

And you were asking me before about my friendships with these people, but friendships had enabled these really direct, open conversations where they’re startlingly frank about what they do and looking to explain themselves.

George Gendron: Just a footnote to what you were just saying is, were you influenced by the rise of the album cover, which was kind of a design frontier and an art form in and of itself?

Jann Wenner: Yes and no. We were always aware of it, but we weren’t trying to design like album covers. Obviously that’s a piece of design we saw all the time. I guess we were influenced by certain lettering things or…. It was in the air. It was in the air.

We were more influenced by the poster artists of San Francisco, in a way. Like Rick Griffin, and Stanley Mouse, and Wes Wilson, than by album covers.

George Gendron: That’s interesting, yeah. But now I want to fast forward and I want to talk to you about something you touched on in the book, but I would’ve loved to have heard more, and that’s about making money. So you, at one point, you start to think about, “Well, how much is enough? How much is too much?” And in fact, I think you go and have a conversation with Jerry Garcia.

Jann Wenner: Right.

George Gendron: And Garcia says something that a lot of very, very smart and wise entrepreneurs have said, which is, “Maybe you’re too big when you don’t know the names of everybody you work with.”

Jann Wenner: Right.

The Beatles, collectively or individually, have been on the cover of Rolling Stone more than thirty times.

George Gendron: But you know, you get to a point at your peak where you’ve got Look Magazine, Family Life, Record Magazine, US Weekly, Men’s Journal, Glixel—kind of the early Wenner Media. I think at one point you guys were thinking about doing restaurants.

Jann Wenner: Uh, yeah. There’s… Yeah.

George Gendron: I know. Okay. That was an outlier, but I just thought ...

Jann Wenner: ...those are people that approached us and wanted to license our name. We never really thought of getting into it.

George Gendron: So, in your mind, what was your ambition? People sometimes referred to you wanting to be kind of a 21st-century Henry Luce. Maybe wanting to build the next generation Condé Nast.

Jann Wenner: I never was that ambitious. Ten years after coming to New York—or even before coming to New York, when we started Outside, a magazine which still thrives—simultaneously, two things came to mind: One is I wanted to turn over being a day-to-day editor to somebody else. I wanted to be less involved. And I felt I’d learned a lot about magazines and I wanted to put that knowledge, and the kind of staff and structure we had developed, and expertise, to leverage that into other magazines.

And I thought I knew how to do that. And I had a couple ideas for magazines I wanted to try out. And so I really wanted to use Rolling Stone to go into the magazine business, as well as the Rolling Stone business. And I pursued that for a number of years and I more or less knew what I was talking about. I still had some big, expensive lessons to learn.

And I enjoyed being a magazine publisher. And I titled that section of the book, “Building the Empire.” And we were lucky in having a couple of good magazines and one wildly successful magazine. So at the end of the day, I could look back on their career and say, “Well, you know, I started five or six magazines, four of them still exist, and two of them were huge hits.”

Hunter Thompson’s presence in any given issue was cause to celebrate. Below, from left, William Greider, PJ O’Rourke, Wenner, and Thompson interviewing presidential hopeful Bill Clinton for in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1992.

George Gendron: Was that enough for you?

Jann Wenner: Yeah! Then, by the time I had the second huge hit, by that time, the internet was coming to destroy the magazine business.

George Gendron: You mentioned in this context that at one point you had an offer to sell at the top of the market.

Jann Wenner: Right.

George Gendron: But you don’t provide any details at all. Can you share more about that?

Jann Wenner: Well, I provide the details of my thinking about whether you take the offer or not, in which I really go through the analysis that I made at the time, which is, “What would I do with this money, and what happiness might that bring me?” versus the happiness that I was getting—the satisfaction from doing this job, which is so incredibly unique.

And you know, was the happiness of buying a small yacht or owning five Picassos going to be as great as the life I’d made for myself and the people I’d met through the magazine? And my sense of self and ability to contribute to the dialogue about national policy? And my joy? And just being deep in the rock and roll thing—was that close to what I have?

So, instead of selling it then and making a fortune, I said, “Just stay around.” And I was there for another 10 years. And what would I have done? I’d have been bored. I couldn’t start another Rolling Stone. You know, I might start other magazines. I might do this, I might do that, but nothing was going to bring the satisfaction that I had with Rolling Stone.

George Gendron: I’m curious, there was, obviously, a period and a pretty extensive one at Rolling Stone, where you really were immersed in the issue-by-issue creation. And then, of course, as time goes on, your energies start to focus on a much broader array of projects and other stuff. Do you ever look back and think, “Man, my best moments were X”?

Jann Wenner: Not in that context. I do remember feeling a special thrill and the adrenaline of working on an issue, of approving layouts, and copyediting. And then, of course, all the fun of the deadline, which everybody hates at the time but realizes it was just too much fun. It was like being with the gang and playing, you know? Whether it was all-nighters or not. But the actual creative moments were great.

The magazine—if I was involved in an issue, it was generally much better. I could sharpen the layouts. I could do other stuff. Every time I could bring my touch to it, you know, there’d always be improvements. The headlines would be funnier or whatever it was. And when I stepped away, it was extremely good, but probably not as good as it could have gotten. That was always the dilemma. But I had other things I wanted to do.

George Gendron: What was it like when you were—your offices were I forget they were in the early days in the typesetters?

Jann Wenner: We were in the printer’s loft. We had a, there was a ...

George Gendron: Printer’s loft. That’s right.

Jann Wenner: ...small building, and upstairs above the Goss Community Press that they had downstairs. They had a type shop with about a dozen Linotype machines, big lofts where they stored all these rolls of paper—I mean, huge, heavy things. And an ink melting smelter or something where they would melt all the lead type down and burn all of the ink that was left on the lead, which was the smell we lived with for a long time.

George Gendron: Brings back memories. There was nothing like actually closing a story when you were down at the typesetter side by side with the typesetter himself, man. But the question I wanted to ask was what was it like for you when you grabbed that first issue of Volume One, Number One of Rolling Stone as it came off the press?

Jann Wenner: Well, it was, I don’t know, sometime in the evening and our first staff photographer, Baron Wolman, was there, another great photographer who should have been mentioned. And they came off, you know, it was on cheap paper. It was folded in half and if you picked it up, you smudged the ink on your fingers. You’re just coming out the press. But it smudged anyway.

And I just looked at it. I was paging through it and I thought, “Geez, this is, you know, we’re never going to do as good again. We’ve already peaked, you know, this is as good as it can ever get.” I really thought the dilemma was: How could it get better?

George Gendron: And lo and behold...

Jann Wenner: Blind self-confidence.

George Gendron: Yeah. But I think what you’re getting at is, again, something that Adam Moss and I were talking about. A lot of people bring it up in our podcast and that is kind of this sense of actually making something real, something tangible that you hold in your hands. Man, there’s this kind of psychic thrill that you get that maybe you don’t get from almost any other process.

Jann Wenner: I don’t know. I mean, when the book came about a year ago, whenever I first got the first copies of it, all bound. You look at it, you hold it, you smell it, really. I went to sleep with it. I put it in my bed. And the physical, you know, manifestation of something that came from your, it’s wholly from your mind, wholly a work of imagination is very, very powerful. I mean it. It’s like, in a sense really, dreams that have transmogrified into being true. It trans-substantiated your brain into an actual object. That is a miracle.

George Gendron: That is a miracle.

Jann Wenner: The turning of something into flesh.

“I’m proud of my generation.”

George Gendron: People ask me, how could you possibly stay at Inc. for 20 years? And of course part of the answer is that the world and the market was changing so radically that the magazine was changing year over year, so it wasn’t the same job. But the other was—I agree with you, it’s a great word—it was like chronicling a miracle. The magazine really was about documenting the process that people go through when they transform an idea into something tangible. It’s thrilling.

Another question that comes to mind that I think a lot of journalists cope with to this day. And that is managing the tension between a relationship that forms between you and the subject—let’s call it a friendship—and journalism itself. And you were really close friends with many of the people that you ended up writing about. How did you manage that? What kinds of conflicts did it create for you? Springsteen is the godfather of one of your kids, for God’s sake.

Jann Wenner: Well, I mean, let’s divide this into two things: What are these people like as subjects and what are they like as friends? Let's talk about the very famous stars I was very friendly with or even the record company executives who were not so famous, who I had relationships with professionally and personally.

First off, the business that we were covering, the record business, unlike traditional American businesses, is about making art. About making people feel good. About the creative process. About good people and their imaginations.

And particularly in this one, there’s a lot of soul and spirit and beliefs underlying, more so, say, than other creative businesses like the movies or television, which are really substantially commercial and somewhat cynical enterprises—particularly television. But this was about doing good.

And the people in the record business were nice people. Nobody was making faulty cars or bad washing machines or selling cigarettes—anything. So the idea of having to do investigative reporting on them and harsh stuff was not unknown, but it was not really the business. It was not what was meant to be, what our mission was, what was called for.

Occasionally there’d be things like the prices of CDs, the attempt to shut down home taping—there’d be a few business issues where you had to stand up. That wasn’t difficult. But, so you couldn’t go to an artist and say, “Well, I need to investigate Bruce Springsteen. Or Mick Jagger.” It just didn’t call for it.

What we were there for—and what I was interested in—was we wanted to explore them artistically and thoughtfully, what their intellectual thinking is, what the creative process is, what they stood for, and their belief systems.

The one time, the only real time, it got in the way of a friendship was when we had to cover Altamont in 1969 and lay the blame in part to the Rolling Stones for why that happened. This is after Mick and I had been publishing Rolling Stone together, so, you know, we were close associates at the time and friends and all that stuff and I knew it would put this at risk, but I just really had no choice but to go ahead with this and report the story. It’s a major piece of journalism.

There was a murder, a killing, a bunch of issues that were not necessarily part of the creative, but in any case, then let’s look at the people themselves: Bruce, Mick, these are wonderful people. They are people so smart, so good in their own things, that they understand my process, and my needs, and my creative needs, and principles I live with and have to honor, and what journalists are.

There is a natural guardedness that one starts out with, but over a period of years, you know each other really well and you don’t doubt the friendships going either way. I mean, I understand and love creative people and I know how that works, what the creative process is like, and it’s different for everybody. And how it affects the ego, and how you think and how you perceive things, what you’re looking for, and how talent works. And so I’m very sympathetic and I like it. And so we get to talk.

There’s so much, mutually, that we have together, as well as family. You just develop friendships. I mean, I like the people. I never felt compromised. Nobody ever said, “Give me a good review or a bad review.” The respect goes both ways and nobody would expect me who knew me well to do anything like that.

So I never felt, in any way, compromised to do something or not do something. There was never that. There was always an implicit understanding that I looked after their interests as a friend, you know, but it is a two-way street of respect.

Anita Kunz’ portrait of Michael Jackson was commissioned by Rolling Stone’s great(est?) art director, Fred Woodward.

George Gendron: I want to wrap this up by quoting something that you wrote in the book and it’s, “The battles about the legacy of the sixties continue, known today as ‘culture wars.’ From my first day at college, it seemed we were on trial for intergenerational crimes.” Then later, but very closely related, you go on to say, “this book is a report on today’s world and how we got here.” So Jann, as someone who has chronicled the journey from the sixties to where we are today, where are we now?

Jann Wenner: The period that is called the sixties, or the Baby Boom, or the postwar generation has really significantly reshaped the country. Its values, its morals, and what the country stands for. I mean, the progress on human rights issues, whether it’s racism, sex, women’s equality, all these things. They’re so far advanced at this point—so far more advanced you could have ever imagined they would get from 20 years ago. Or 30 years ago. Or even 10 years ago. Remember, Barack Obama was afraid to come out for gay rights. For gay marriage. And it wasn’t until Joe Biden forced him. And now, of course, it’s a right!

And the generation took on—now the biggest crisis—the climate crisis, the environmental situation. And these are not resolved issues by any means. And there’s still things we’re fighting about and for, but I think most of this is just embedded in American society now.

There’s no going back on abortion no matter what the fights are now. There’s a right to, it still exists. Maybe it’s limited in some places. Maybe you have to go to other places for it. Maybe it’s being overturned. I don’t know. They’re not going to go back on gay marriage, you know? That’s set. If they do, big things are going wrong.

The big issue today is climate. And there, we, as a generation, as a society in whole, our generation has fought hard on this issue. But we are up against the most powerful forces in the world. This is not just being up against the legislature or people you can vote out of office in your state, or being influenced by public opinion and where we can go out in the streets and protest.

We’re fighting the biggest, best financed, greediest, most powerful forces on earth. Not just the United States, but in collaboration with the people in Moscow, and people in Saudi Arabia, and other places where they control the vast carbon resources, where people are regularly killed. Slaughtered. Killed for these things.

So whether it’s control of the rainforest or control of those Middle Eastern governments. So we’re in the biggest fight ever. Now that’s what we’re in. Everything else is on its way to being finally won, I think. But if we can’t win the climate fight, not only do we face short-term peril of disease, we share mid-term peril of vast population changes and migrations and refugees, which will destroy democracy and self-government and all kinds of freedoms that we now enjoy. And long-term extinction. Or, at least, maybe there’ll be a hundred million of us left living on the North Pole.

So, where are we? In an extremely hopeful place because we’re moving fast in a lot of directions, but also in an extremely desperate situation, because we’ve met a huge enemy and we don’t quite have the tools.

George Gendron: It’s interesting listening to you talk. My wife and I were watching Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis last night, and we paused it halfway through, and whatever else you think about the movie, I think Austin Butler’s performance was breathtaking. But my wife turned to me and said, “It is astonishing when you think about how far the culture has come...

Jann Wenner: Really!

George Gendron: ...in such a short time.” And we forget that. We forget that. And I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve been hanging out with my buddies, and my colleagues, and friends and they start to talk about, “Oh my God, as a generation, we have really screwed everything up.” And I think ”No!”

Jann Wenner: That is not true at all!

George Gendron: It’s not true. No!

Wenner published his memoir in 2022

Jann Wenner: In part, my purpose in writing the book was to tell people, “No, we haven’t [screwed everything up].” We’ve got a lot to be proud of. We made a huge, huge difference. Enormous difference.

Think about the fifties. They threw people in jail who were gay. They castrated them. They could do that. Blacks? Jim Crow was still going on! I mean, they couldn’t vote, couldn’t use the same drinking fountain! On, and on, and on. I mean, women, you know, could cook—and that was all!

It’s come so far in such a short period of time. In my lifetime. And I think younger people today are passionate about the environment and they see this as critical. It’s their future. The same way we were against the war because we were going to get drafted and killed.

If they don’t solve the climate problem, these are the people—our children—are the people who are going to get killed, die of asphyxiation. So I’m proud of my generation.

George Gendron: I’m glad to hear that.

Jann Wenner: I’m proud of what I did. And I’m proud of the magazine I put out. I think all these things were historical, important, groundbreaking, and meant a lot to everybody and to the people in their lives, and to the country.

Wenner in his San Francisco office.

Jann Wenner’s autobiography, Like a Rolling Stone: A Memoir, which The New York Times called “entertaining in spades,” is available wherever books are sold.