The Accidental Editor-in-Chief

A conversation with editor and author Terry McDonell (Rolling Stone, Esquire, Sports Illustrated, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY AIGANY.

Today’s guest, Terry McDonell, is the kind of editor you fear based on reputation, but would probably run through a wall for at 3am on deadline day.

As for that reputation, we’ve never worked with McDonell, but a simple Google search fills the screen with an undeviating set of impressions like these:

“he helped define American masculinity”

“one of the last of the larger-than-life magazine editors”

“the manliest of literary men”

And indeed, his corps of collaborators includes a rogue’s gallery of literary tough guys: Jim Harrison, Edward Abbey, Tom McGuane, George Plimpton, and Hunter Thompson.

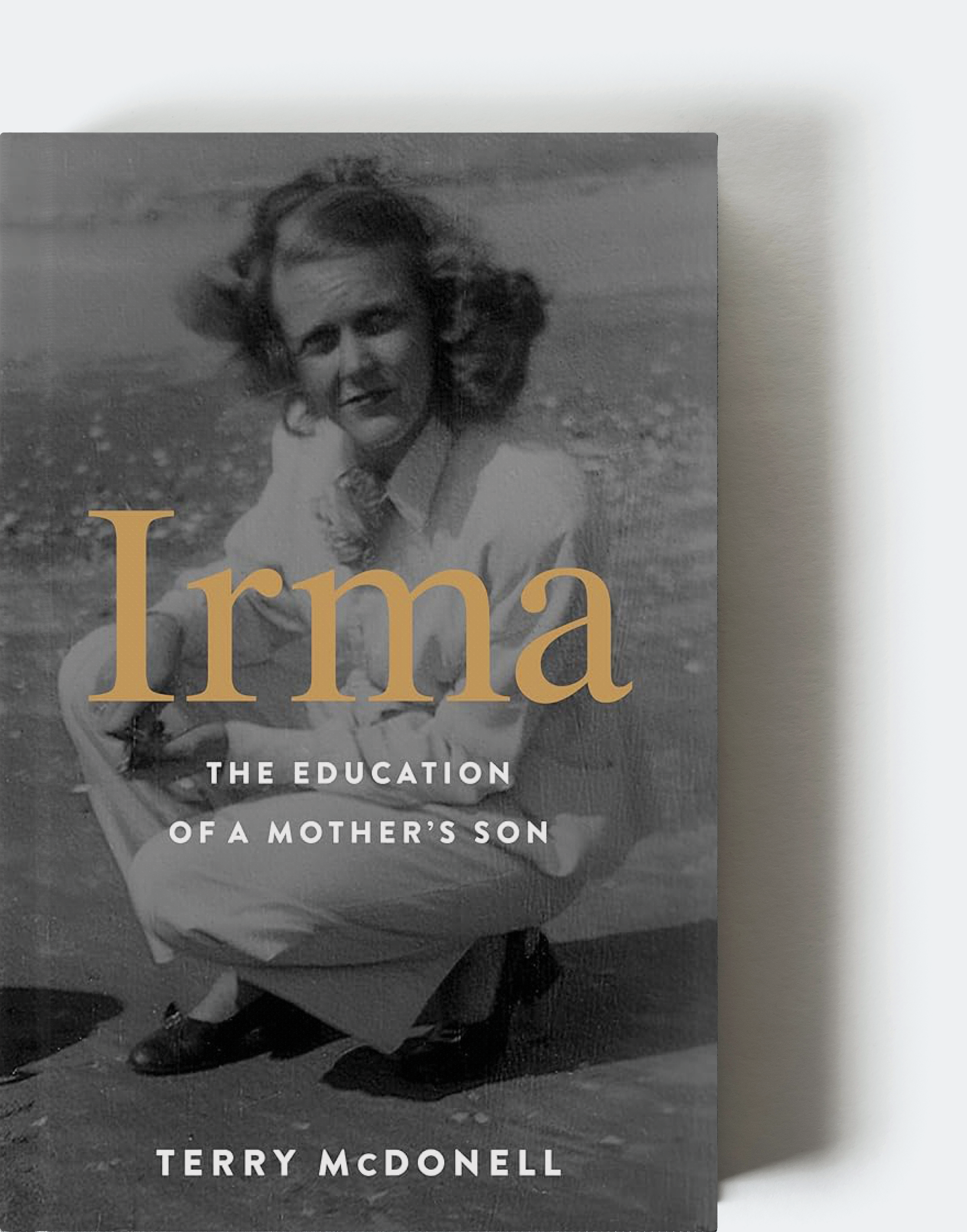

But missing from all that testosterone, until now, has been the true hero of McDonell’s life and career, and the subject of his beautifully-crafted new memoir: Irma: The Education of a Mother’s Son.

But read his other book, The Accidental Life, and you’ll discover a true editorial savant—an engaged partner to his colleagues, whose adventurousness knows no limits.

And apparently, neither does his resume. McDonell, an ASME Editor’s Hall of Famer, has topped the masthead at more magazines than anybody we know.

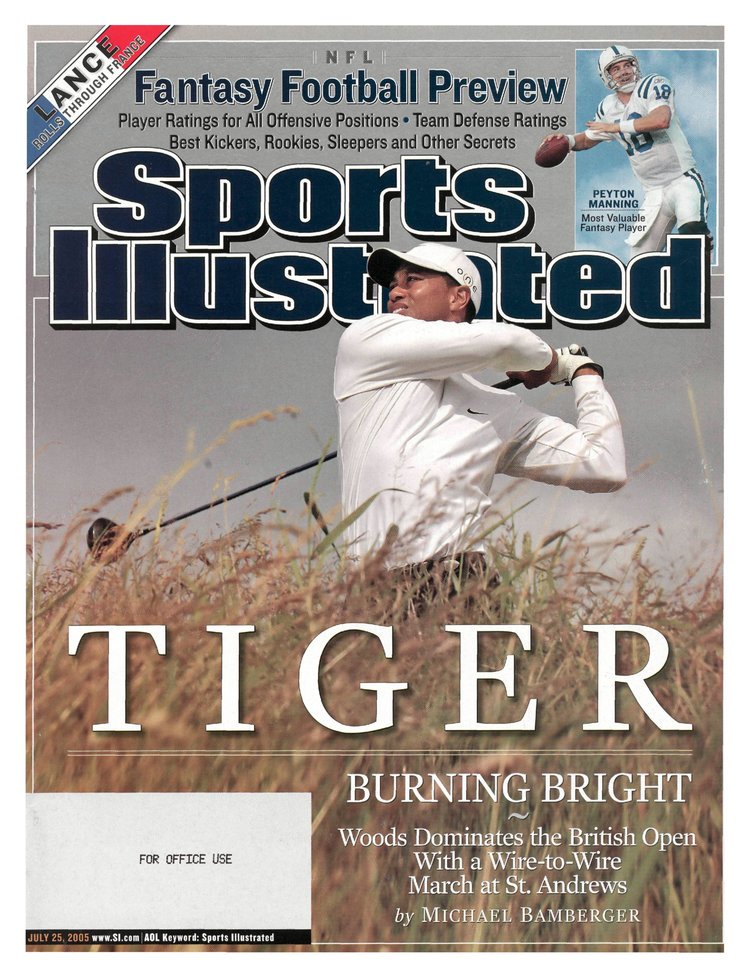

And those magazines have been nominated for 29 National Magazine Awards, winning in 2003, 2005 and 2010.

“Terry is one of the legends of our craft,” says ASME’s executive director Sid Holt. “He’s a supremely talented editor whose legacy to magazines will include not only unforgettable stories and images but also an inspiring vision of what magazines can be both in print and on digital platforms.”

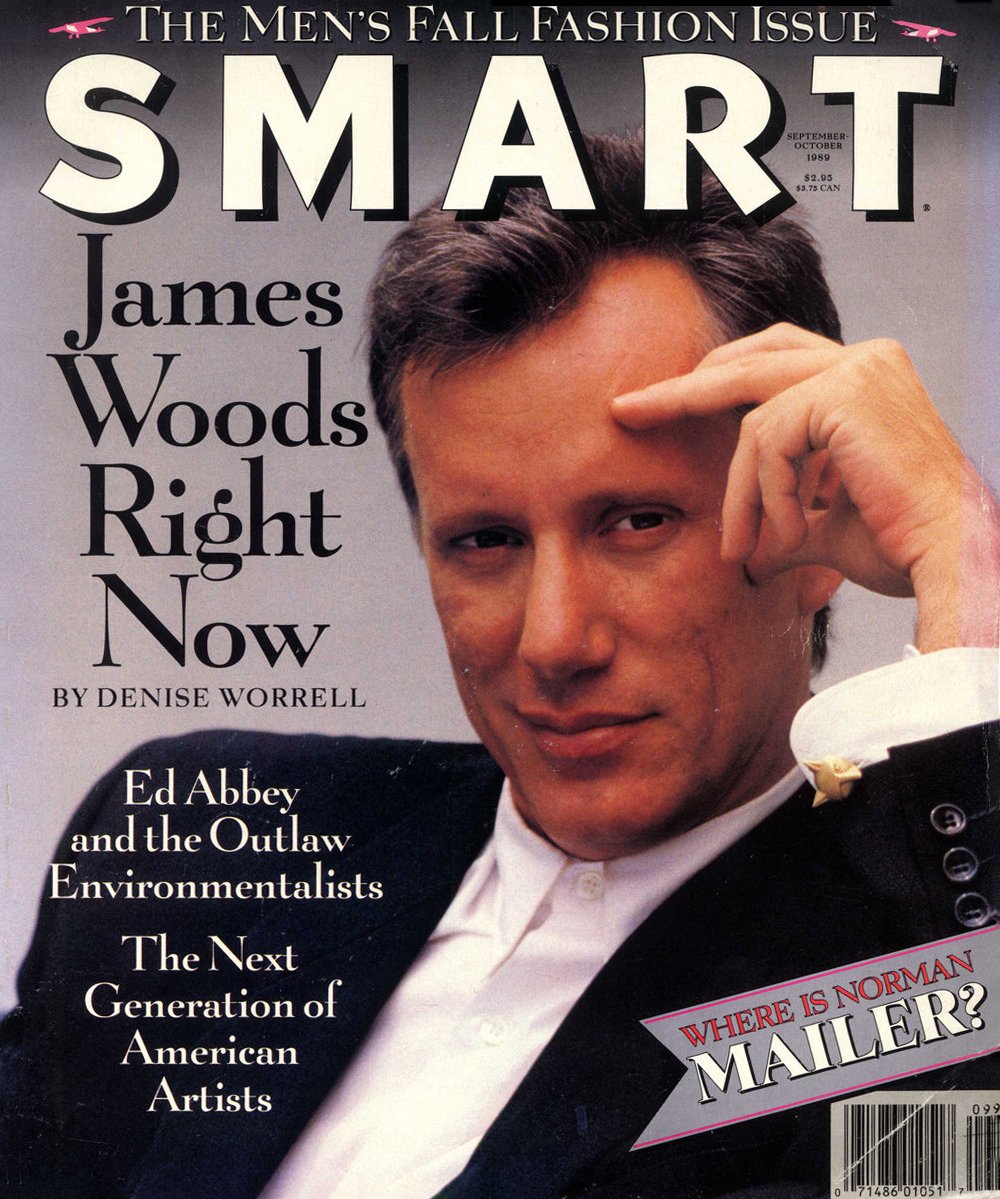

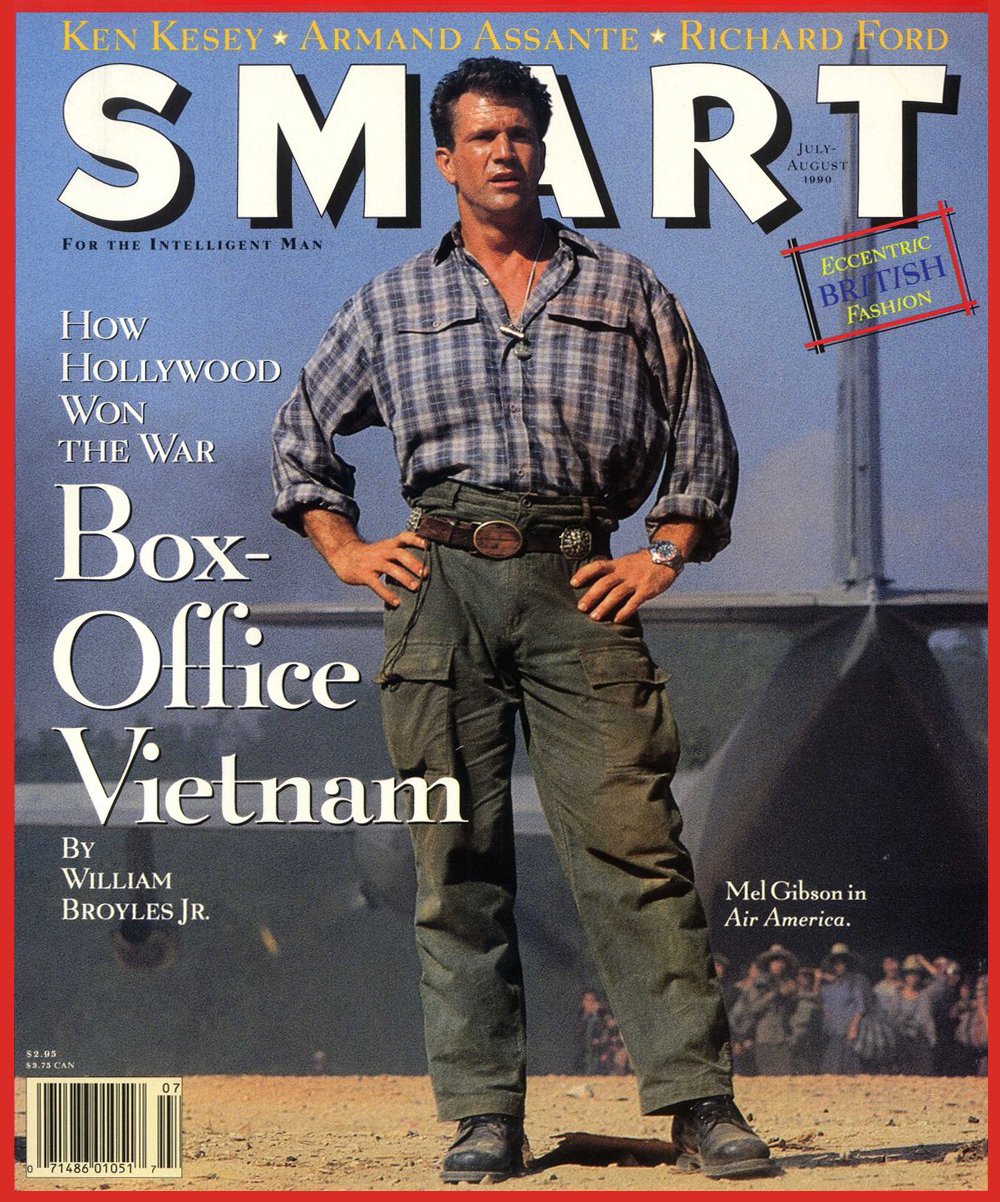

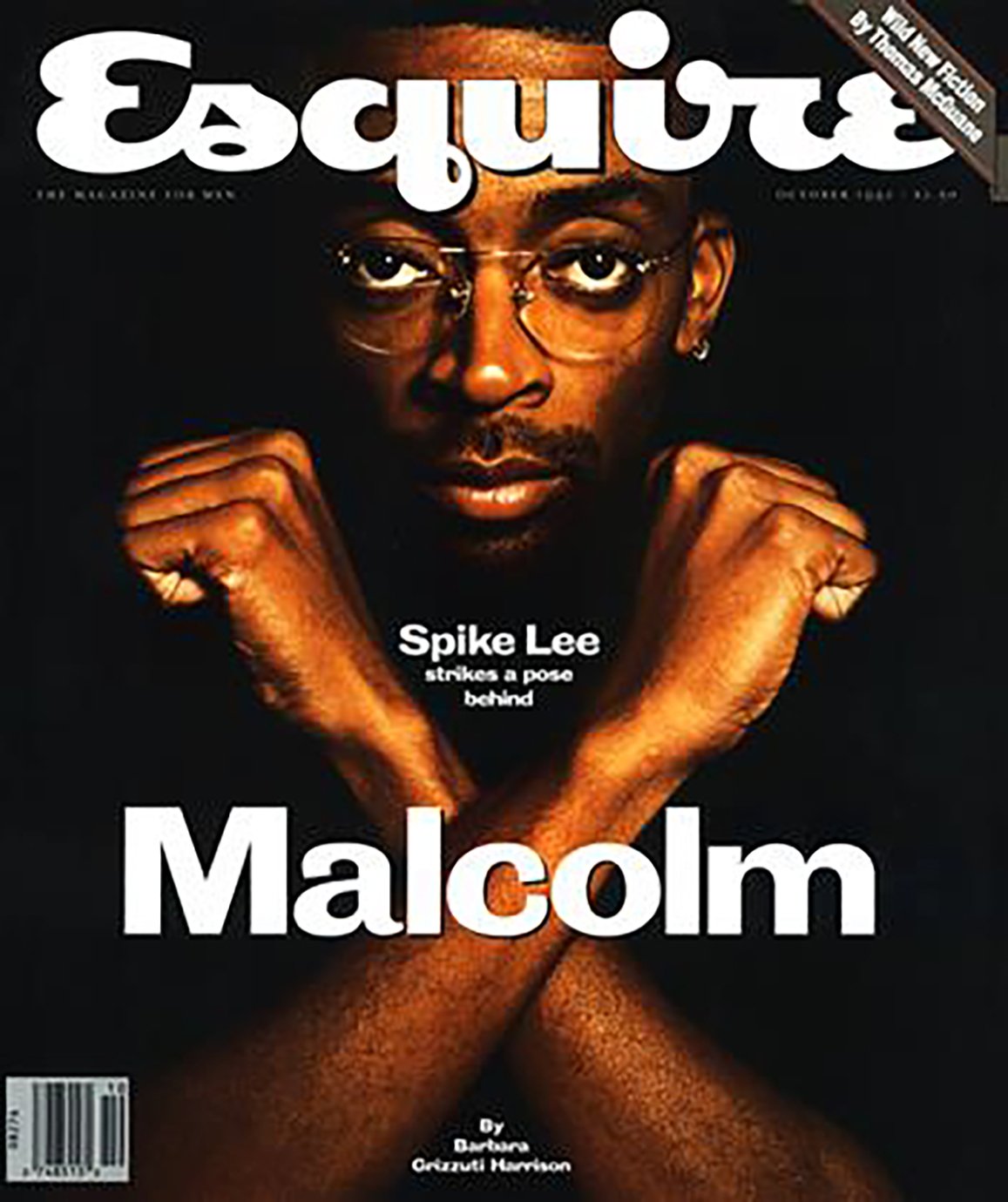

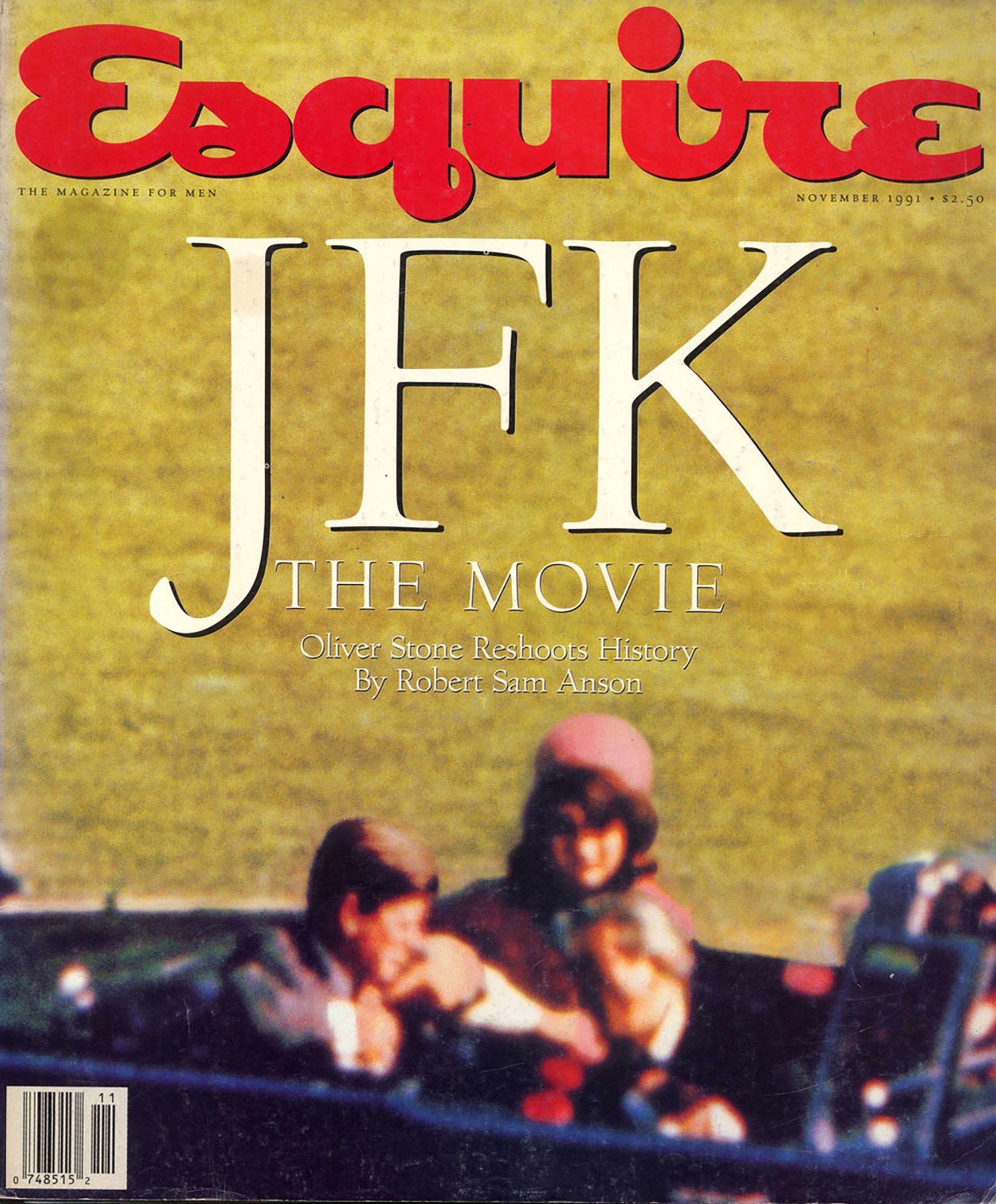

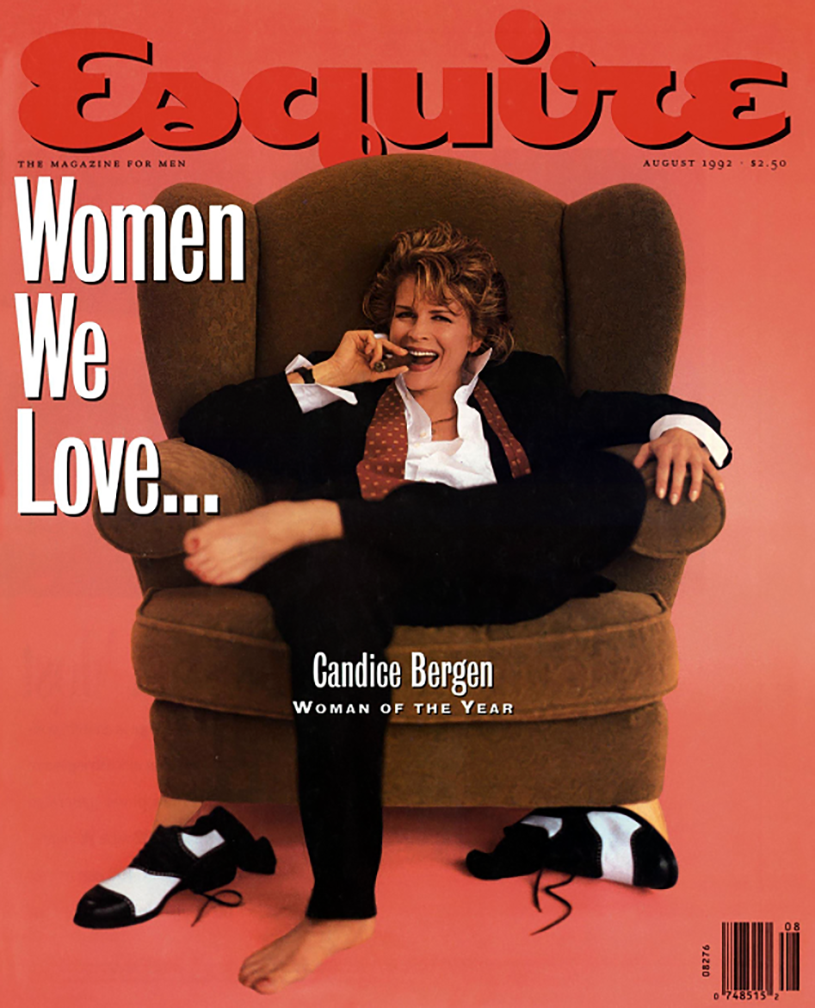

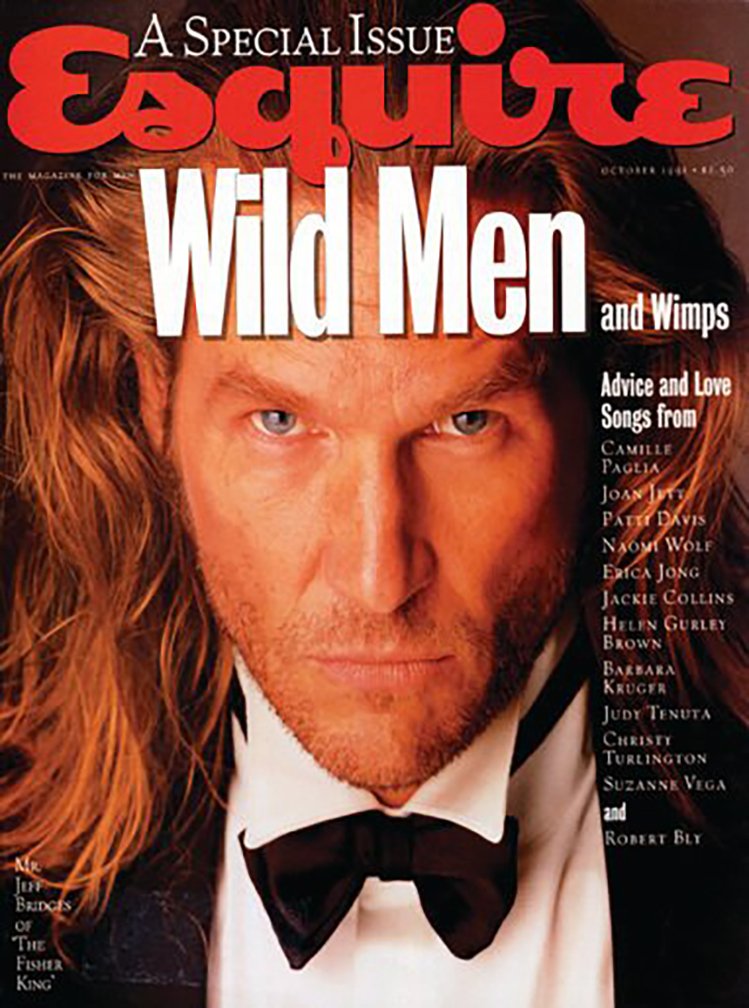

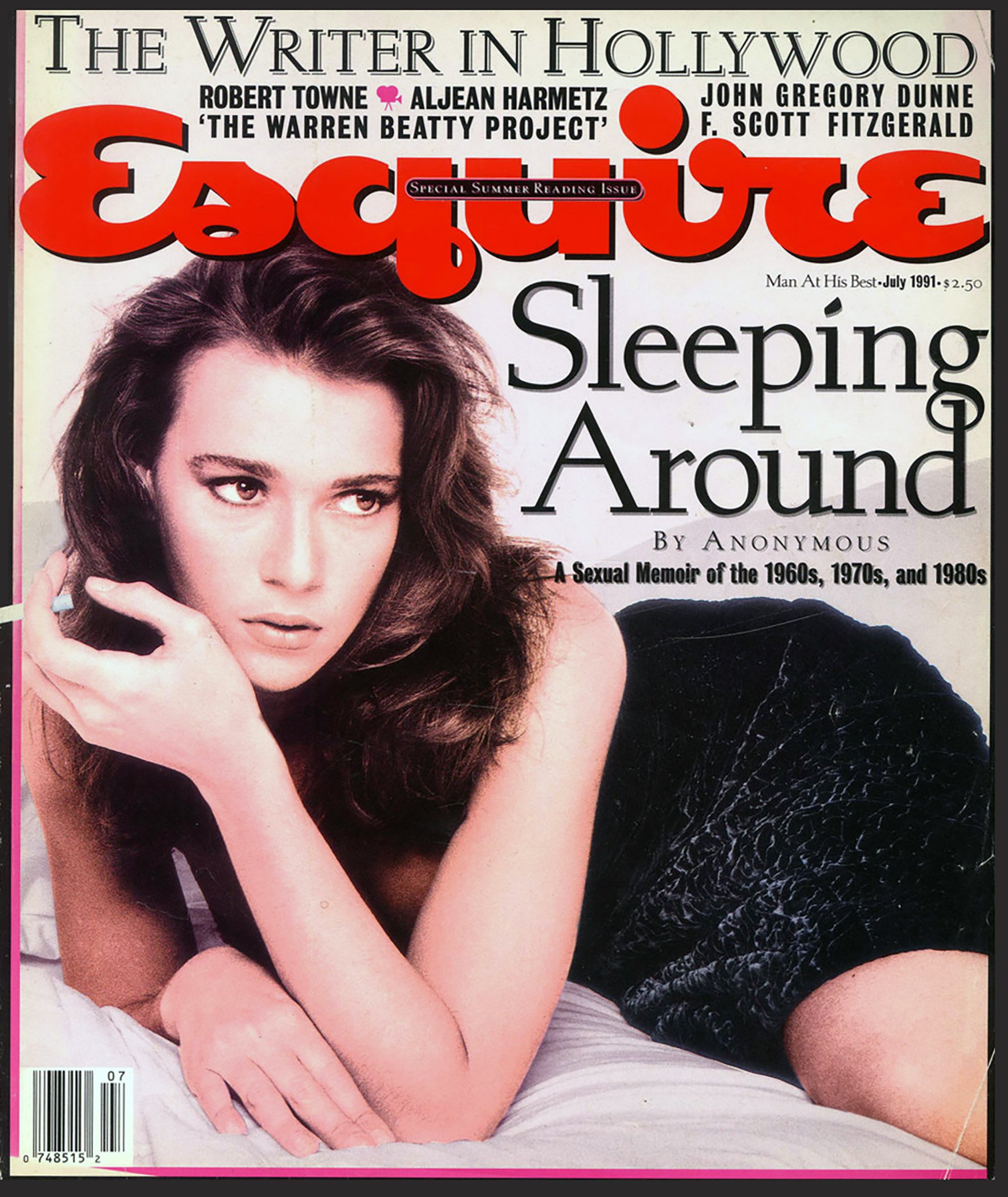

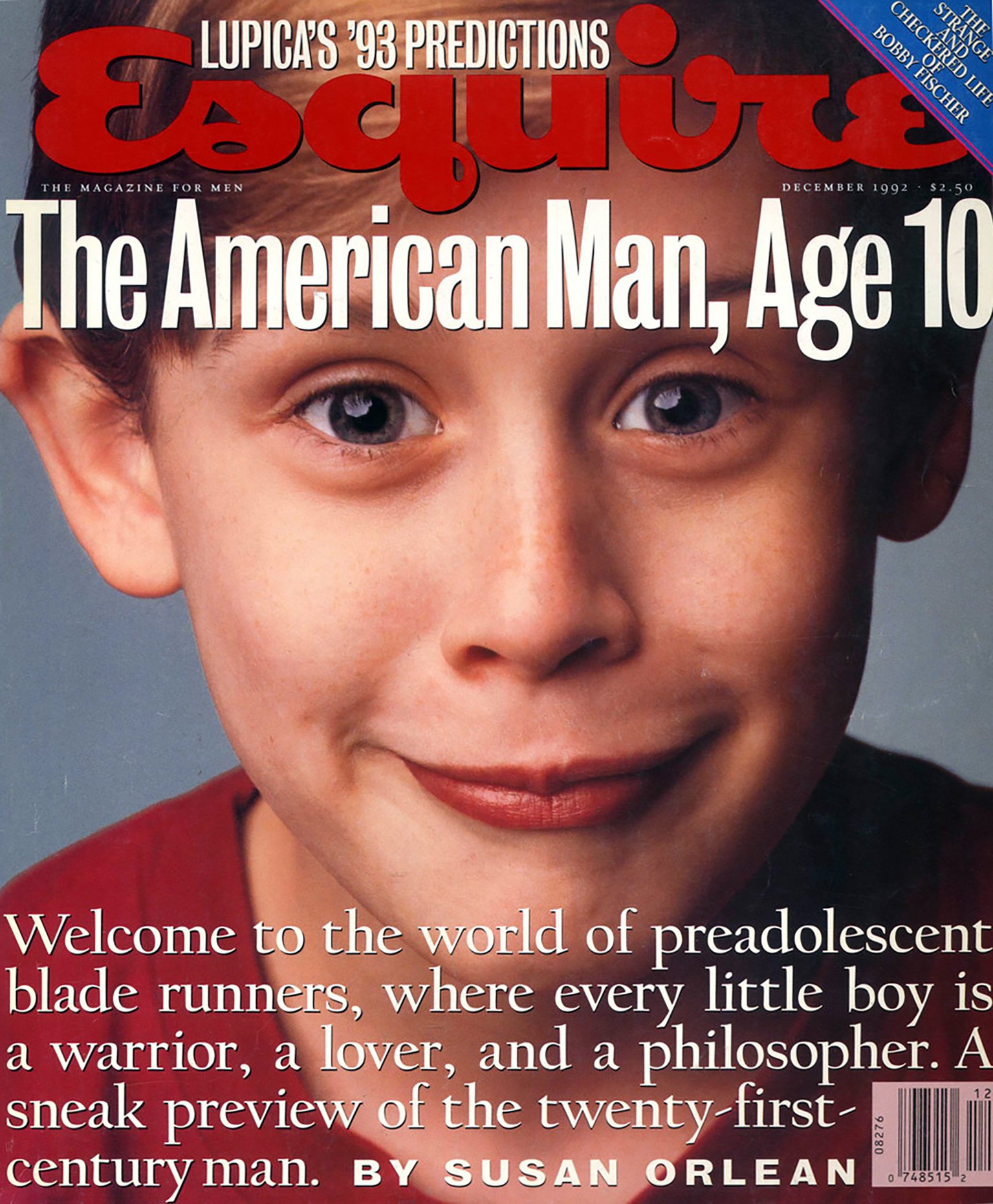

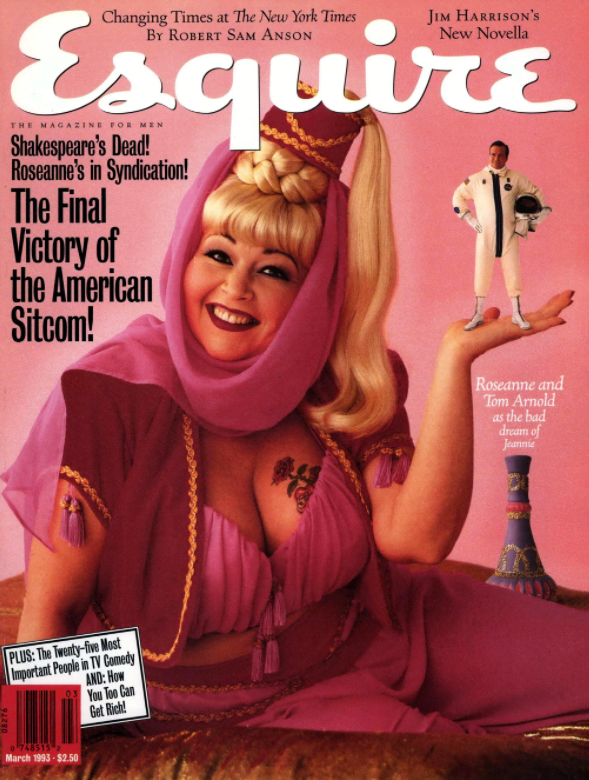

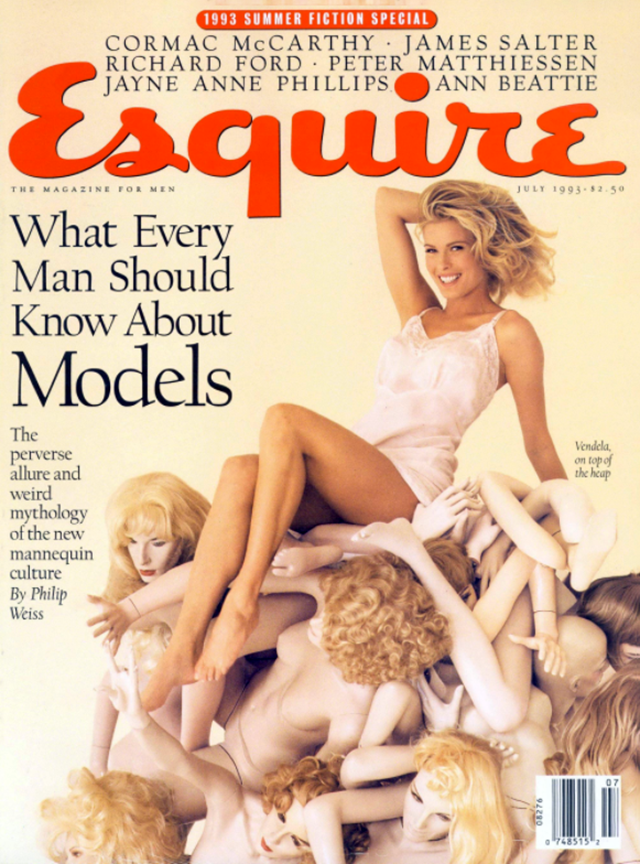

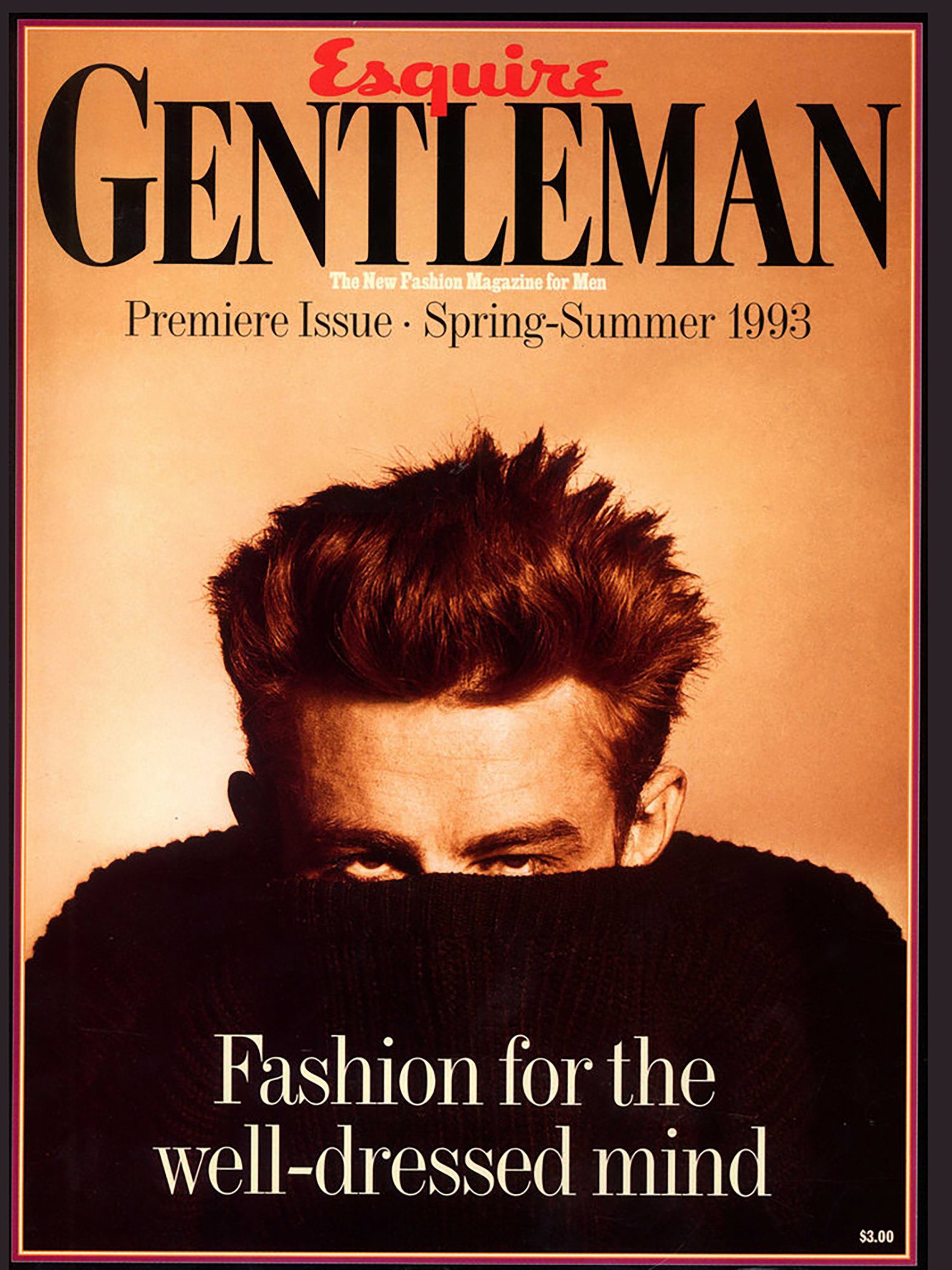

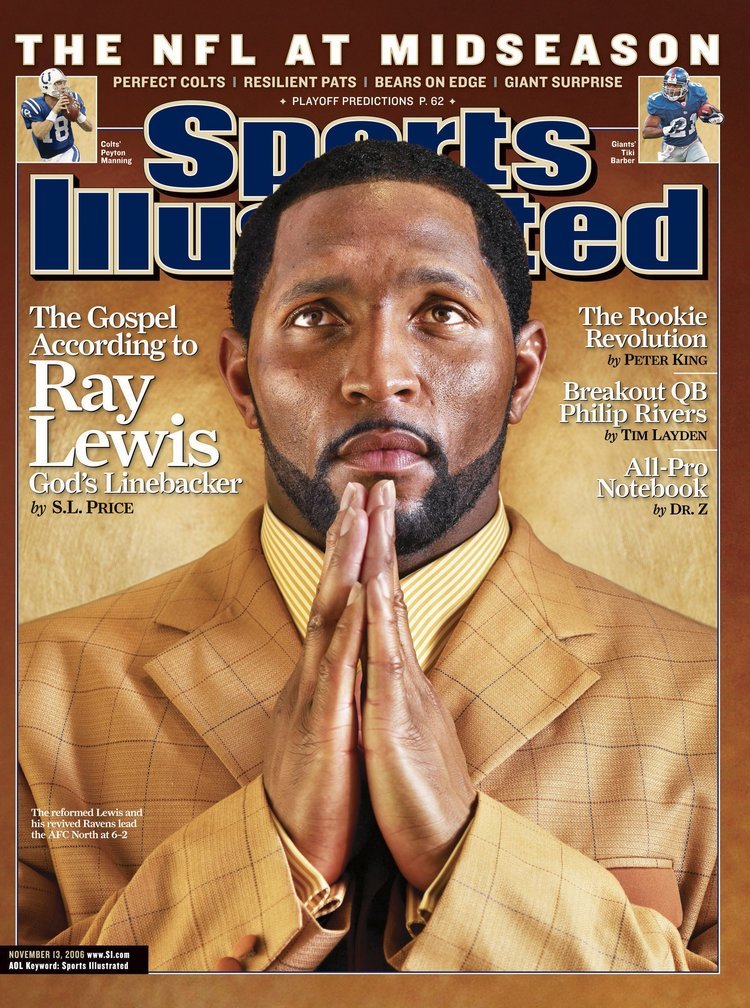

McDonell attributes his firing from Esquire to this controversial 1992 cover (above), and this Spike Lee feature (below).

Sean Plottner: Well, Terry, I thought we could start before we go way back to the very, very beginning, just take a look back at 11 years ago when you were inducted into the Editors’ Hall of Fame during the annual National Magazine Award ceremony (see video, above). It’s not long ago, although in the context of media evolution, it may seem like an eon.

Anyway, it’s May 2012. You’re standing before the magazine industry’s best and brightest giving your induction speech. Here’s what you said:

“It is the most interesting time to be an editor because of all the possibilities that are coming. I think it’s absolutely going to rip. And, in that sense, change is going to be very good, especially when the challenge is ‘Change or go home.’ My response to that is ‘No fear. Bring it.’ There’s just so much interesting stuff to do.”

Do you still feel the same way?

Terry McDonell: Sure.

Sean Plottner: Has the last decade changed anything? Does it make you feel at all different?

McDonell in his AP days.

Terry McDonell: Yes. There’s been all kinds of change. People have learned a lot. I think, though, that what still remains problematic is enough confidence in the content of media to actually charge enough for it to sustain it. What I mean is, way back in the, when we were first starting all this stuff, we should have built commerce into the original browsers.

So when the “bros” in Silicon Valley convinced various traditional media executives that they should put it up for free. And, basically came up with an advertising model. It was almost all over right there. No one understood that if you could not charge for what you were making, if you did not have enough confidence in your editorial, you might as well not even be in the game.

And that was an argument that was had all across all traditional media companies. It was very frustrating, if you were on the side that I was on, saying that we’ve got to charge for this.

Sean Plottner: Yeah. Interesting. Because it’s certainly hard to start charging once you’ve been giving it away for free.

Terry McDonell: Well, now that’s the biggest cliche that there was at the time, too, as we went through all those years. And now look what The New York Times is doing, they were in a deep hole when they were giving it away for free. They had the confidence, and the firepower, and the strategic wisdom to stand by what they were really about.

Sean Plottner: That speech was really interesting, and to me, knowing what you’ve done, it’s certainly not just a bunch of macho bluster. Your career proves that you’ve embraced change heartily, you’ve done it all working in the era of pasteup, an early adopter of computers, desktop publishing, creating the first magazine for the iPad, you helped launch a digital hub for lovers of books and literature recently. And I don’t think you’ve stopped working. Terry McDonell is far from being a print “dinosaur.”

Terry McDonell: Ha-ha! Thank you, Sean!

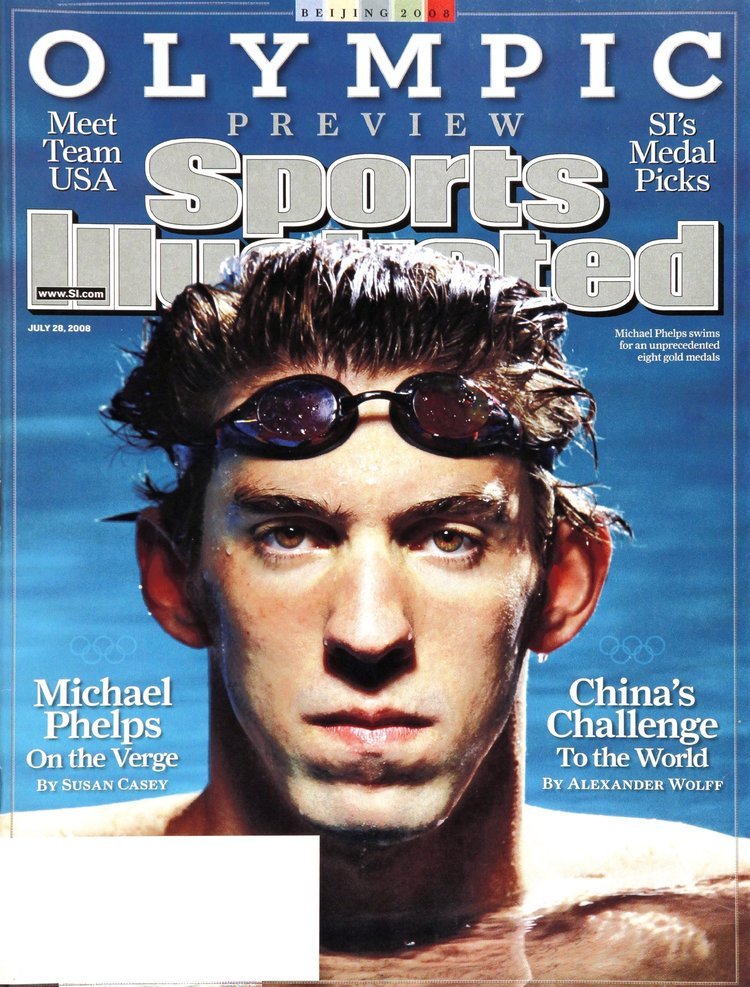

Sean Plottner: But just to give listeners a sense of where you’ve been and what you’ve done—journalism, and writing, and magazine editing has taken you to quite a few places. And I’m just going to list them here real quickly and forgive me if I forget a few, but the Associated Press, San Francisco, City Magazine, Outside, Rocky Mountain Magazine, Rolling Stone, Newsweek, Smart, Esquire, Sports Afield, Men’s Journal, US Weekly, Sports Illustrated, and Time, Inc. We got startups and launches, new platforms, new appliances. Not to mention your books and your poetry and your various other projects, to which I just say, “Wow.” You really have done quite a bit and you’re keeping at it. But let’s go way back to the beginning. What was your first exposure to magazines as a child?

Terry McDonell: I remember magazines being around. I remember Life magazine being around and liking to look at it, but I remember my mother bringing home a copy of Life magazine that had Ernest Hemingway on the cover, and it had “The Old Man and the Sea” inside. And she told me that I would like it before she read it to me, and I did.

And it turned me on to a kind of reading where I, as a little boy, I imagined that if I could read something, maybe I could do that stuff. Maybe I could go see the lions playing on the beach. It opened me up. It made me wide open to whatever I saw in magazines.

And after that, I was constantly going through them, looking at the pictures, at first, and then I began to be more interested, like I had been with The Old Man and the Sea, that there was really something wonderful in these packages. And I wanted to make them. I remember wanting to do that when I was in high school.

“When the ‘bros’ in Silicon Valley convinced traditional media executives that they should put it up for free, it was all over right there.”

McDonell got his start at LA, the “Village Voice for LA.” There he met designer Roger Black, with whom he would collaborate for the rest of his career.

Sean Plottner: In your lovely new memoir about your mother, Irma, you described where you’ve got books stashed in the car.

Terry McDonell: Yeah. I had a problematic stepfather. They used to go out and go to bars, and they would leave me in the car. So when I’m in the car, if I had a book, I was much happier than without. But he didn’t want me to keep books in the car, so I would hide them under the seat.

Sean Plottner: Do you remember any titles that you had there? Any favorites?

Terry McDonell: I remember all of those. Like Custer’s Last Stand, The Alamo, The Lewis & Clark Expedition. There was a whole series of Random House books. I loved those, especially.

Sean Plottner: In the book, you describe what comes across as a pretty tough, rugged childhood. Fatherless, hardscrabble. Before you’re 10, your mom’s boyfriend puts out a cigar on your forehead. Another one calls you a “panty waist” and grabs you by the nuts. There’s a cowboy kid who sucker punches you right in the gut. It’s tough stuff. And finally you get out, there’s a little incident with a bench that you used against your stepfather and move on. But it sounds pretty tough.

Terry McDonell: Well, yeah, maybe from a distance. But I had my mother. And everything that we went through together—and I thought about it that way—was something that affected me and taught me something. When I got to Time Inc., Or when I started moving up, like, the corporate ladder or whatever, I would remember her telling me, “You don’t have to talk all the time to get people to listen to you.” Stuff like that.

“Never raise your voice if you want people to listen to you.” And, “Always be thinking what it is you are really trying to accomplish, because sometimes it will not be what you’re thinking about in the moment. You have to constantly refresh yourself about what you’re doing.” And I would never have been who I turned out to be if I had not learned things like that from her.

Sean Plottner: Where, primarily, did you grow up?

Terry McDonell: The Santa Clara Valley, now Silicon Valley. I was just becoming suburban and then it became mass suburban and Silicon Valley all at the same time. But when I was there, it was orchards, fruit trees, and a lot of vacant lots.

I could ride my bike from where I was, like three or four miles up the valley towards San Francisco, to Cupertino, where Steve Jobs was from—20 years behind me—but they were just starting to build houses. It was just cherry orchards, and open fields, walnuts, apricots. It was wild, nature. It was a really a wondrous, beautiful place.

Jann Wenner, when he read the book—he’s from Northern California too, from Mill Valley—he said that he had learned a lot about me, because I was down in those “lonely, gray suburbs.”

That was the way they viewed it if you were a sophisticated kid from San Francisco or Marin County. But down there, I didn’t even know about Marin County. But it was a beautiful place to grow up.

Sean Plottner: And you ended up with a football scholarship to [University of California] Berkeley, correct?

Terry McDonell: I did. But I didn’t stay there. I “joined the revolution,” I guess is the way to put that, you know. A columnist for the San Francisco Examiner named Charles McCabe, after the spring game, called me "the fastest of the slow." I was okay, but I was not going to be a football star, that’s for sure. I was just pretty lucky in high school.

Sean Plottner: So you must have played and played fairly well in high school.

Terry McDonell: Yeah. That was a good part of my identity in high school. That’s what I did.

Sean Plottner: When you play at the local club, the club championship in golf, if you’re in the last flight, and you win it, you can say you’re “the best of the worst.”

Terry McDonell: That’s good.

Sean Plottner: So you ended up doing some work abroad. Can you quickly tell us what you did?

Terry McDonell: I wanted to be in journalism, and I’d gone to art school, and I had learned about some cameras, and so I thought, “I’ve got to get out of here.” I was working construction and said, “How do I get to become a journalist?”

So my mother loaned me enough money to buy a good camera—an H16 Bolex, used, for $700, and a ticket. And I left. And I wound up in Beirut during what was then called Black September. This is the way back in 1970. Yasser Arafat was organizing the PLO. And that’s where they first hijacked an airplane and blew it up on the runway. And that’s what I did.

But I was, like a lot of freelancers at the time, anyway, I was faking it. I was acting like I was some real correspondent and I was just sort of bouncing around.

But I was good enough, because I sold some pictures that got picked up by the Associated Press, and I got to work in New York in news features, making film strips, if you remember what those were. They were like single-frame things that would click through and there’d be a narration with a little bell that would tell you to move to the next slide.

[You] shot the pictures, you wrote the script, you recorded it. Stuff like, “Alienation and Mass Society,” was [one of the] titles.

Sean Plottner: So you dove right into it and then you’re back in the US and tell us about how you got your first job in magazines. I think someone you knew at LA Magazine moved to San Francisco?

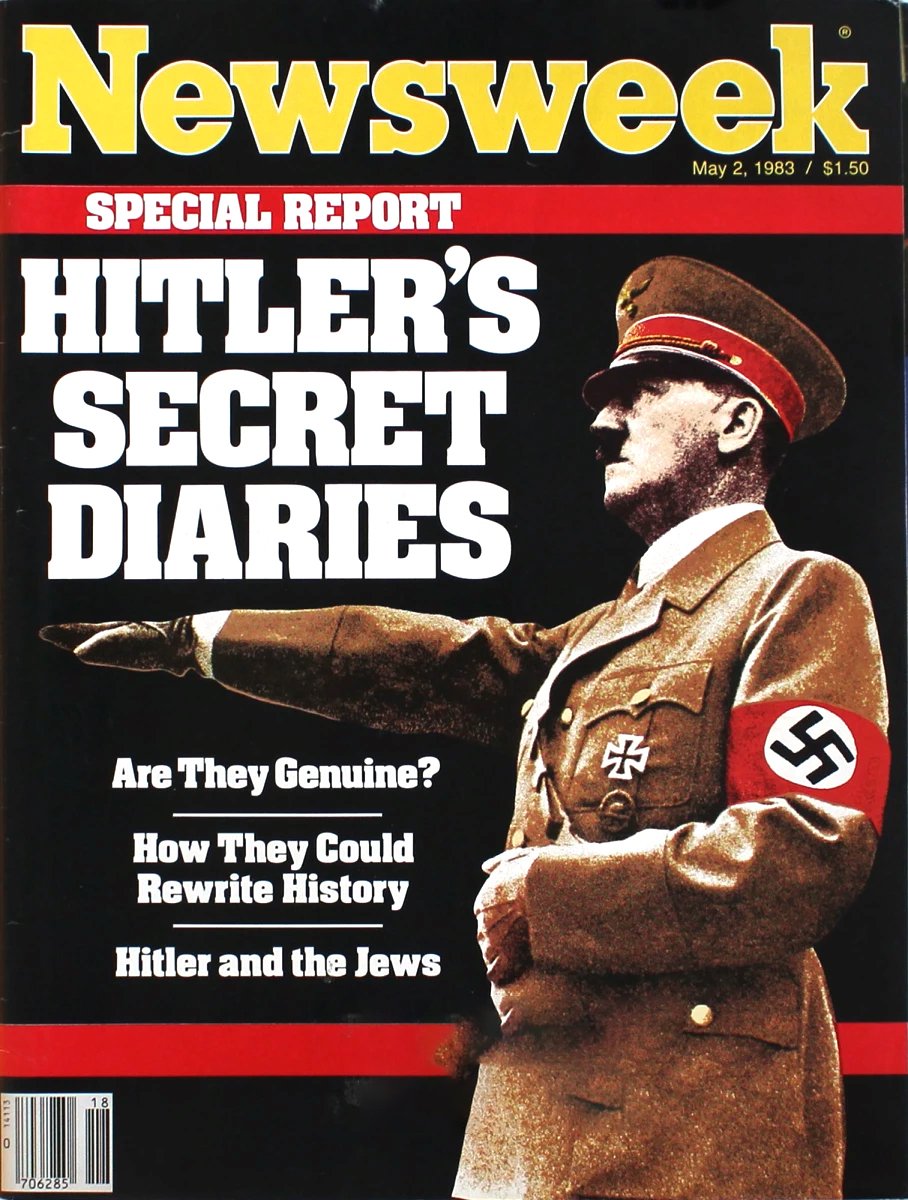

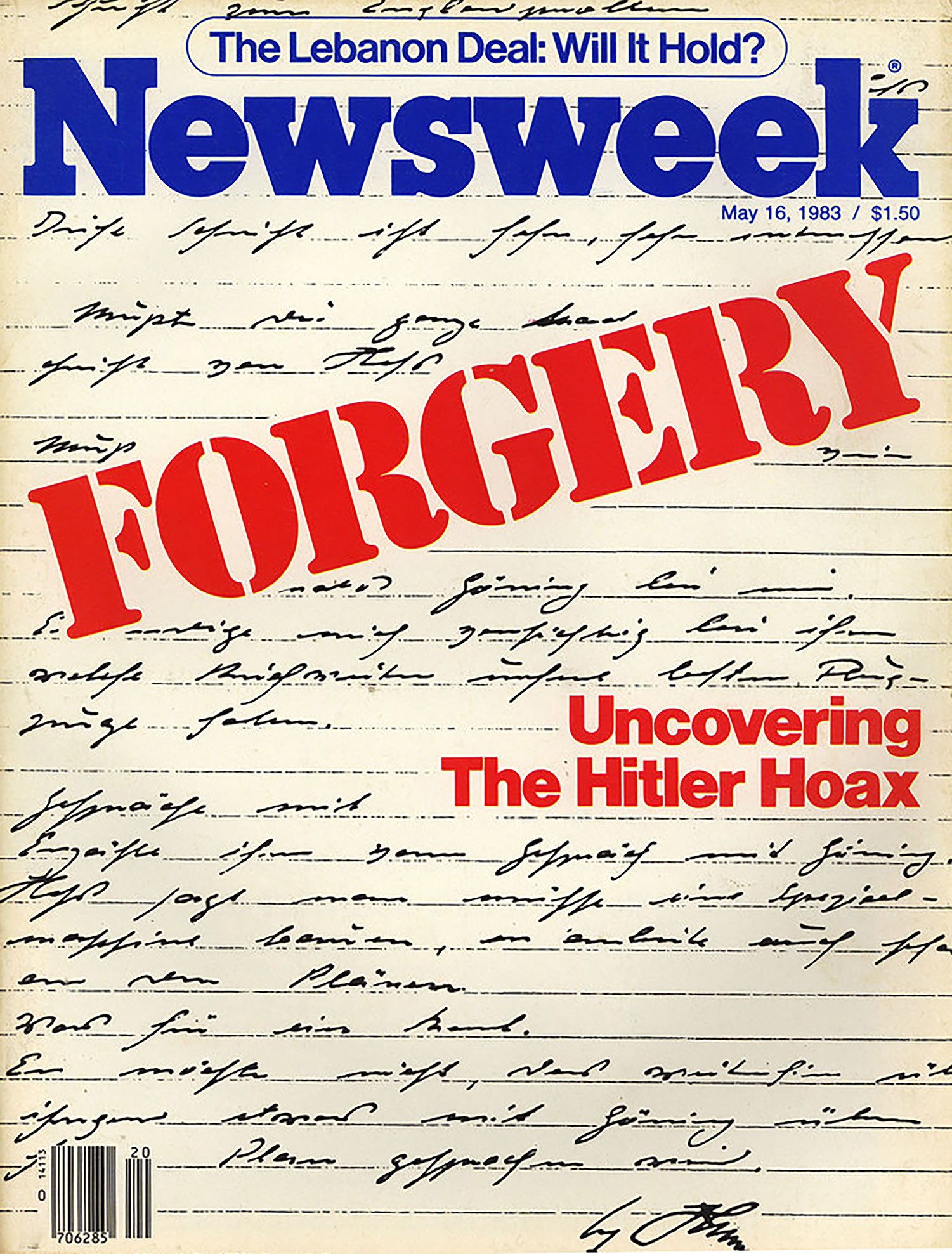

Terry McDonell: No, I just, I heard about this thing in LA that a guy named Karl Fleming had started. He had been the bureau chief for Newsweek and he wanted to do his own idea of what a magazine would be like for Los Angeles. He loved Los Angeles.

And he hired a guy named Bob Sherrill, who was a friend from the South where Karl was from. Bob had been at Esquire for a number of years. And so I wrote to them and they said, “Okay, come on out. You’re hired.”

Because I was working at the Associated Press, I think they thought they were getting a hardcore, AP, on-the-nose journalist. And they weren’t, they were getting me. But it worked out.

And it was from them that I learned that I might want to be an editor, because it was all about ideas and it was wide open, and it was just fun to ride around LA with Bob Sherrill and talk about this story or that story or whatever came to our minds.

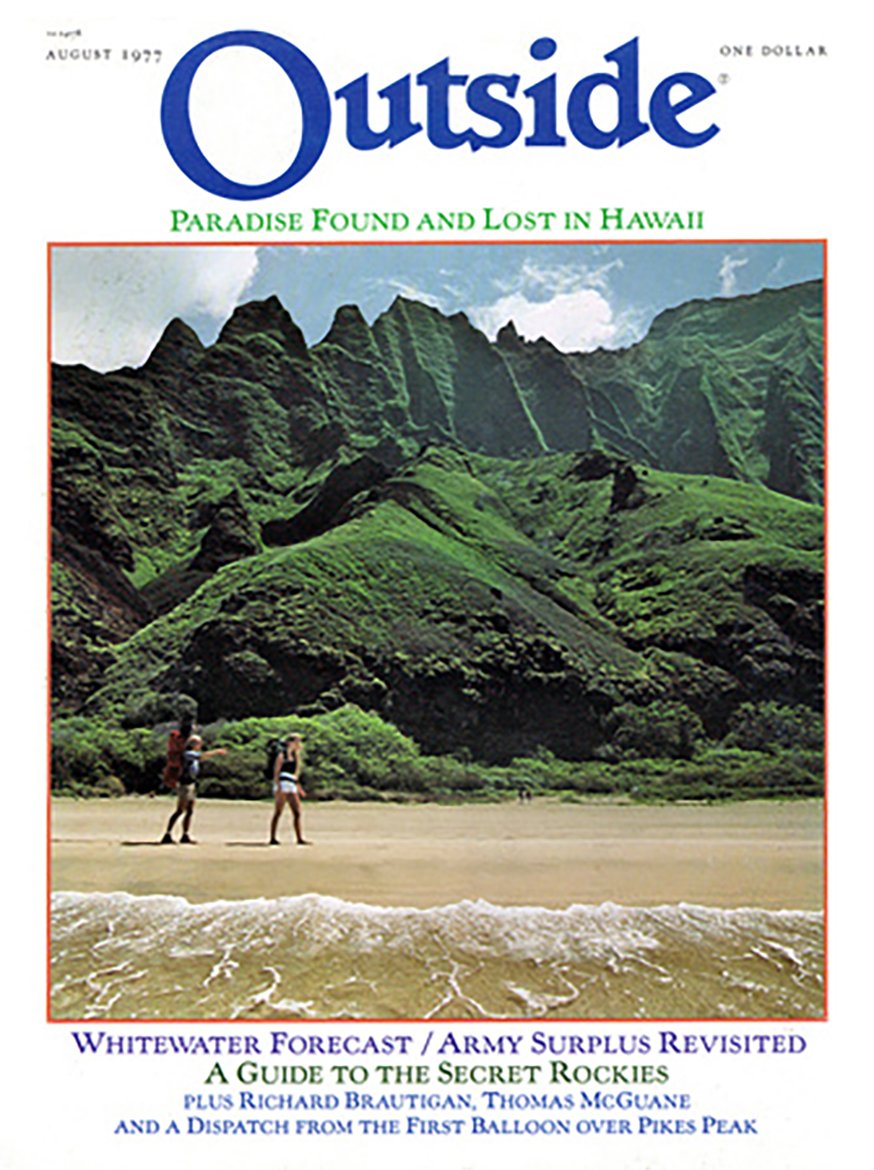

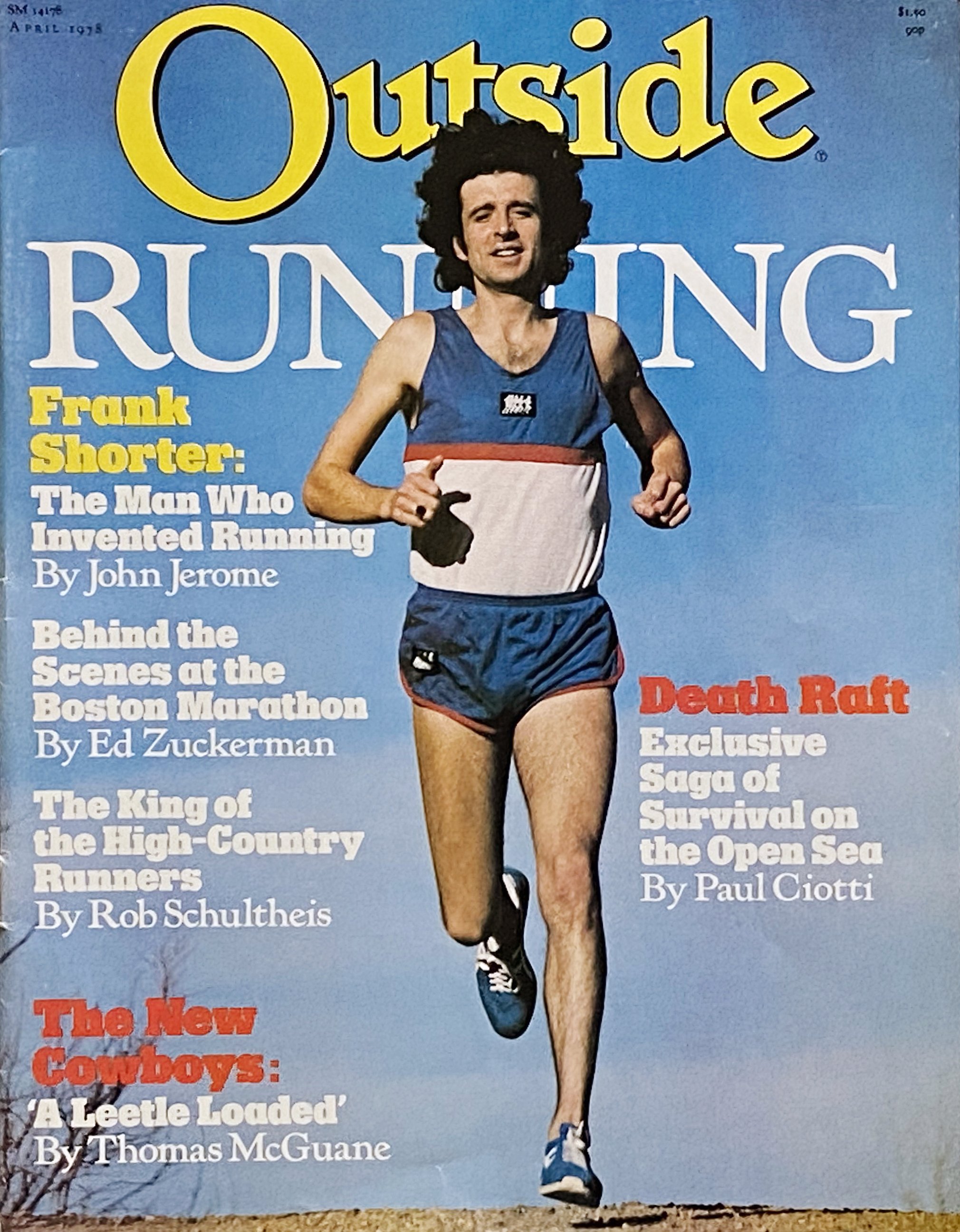

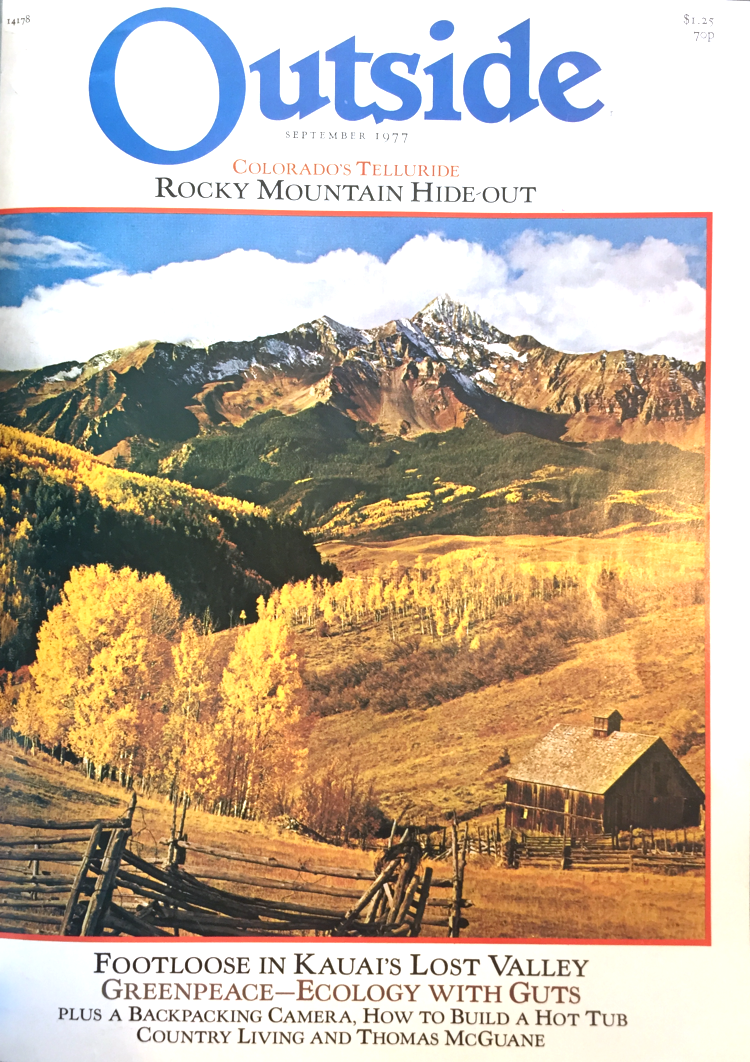

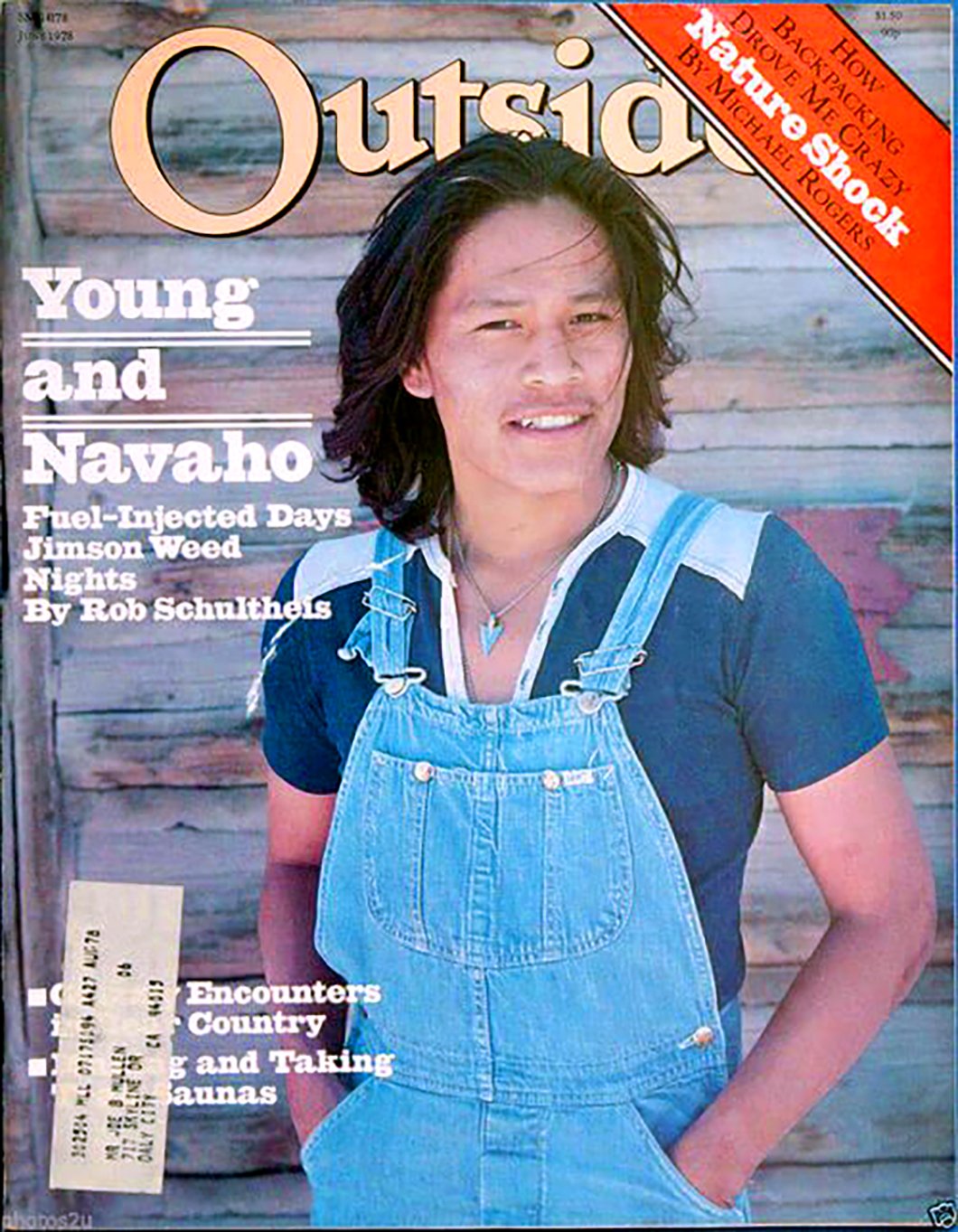

Sean Plottner: I know we’re cutting through a lot of things here quickly, but you then end up in New York City at Outside magazine, at its founding. And that’s, of course, a Jann Wenner-owned publication. This is 1977. How did you end up there?

Terry McDonell: Well, actually, what happened was Jann could not wait to get Rolling Stone to New York, but we launched Outside out of San Francisco, right as Rolling Stone moved to New York. So Outside remained in San Francisco. And that’s what happened. But I’d been in San Francisco, and I was out of work and I had written a novel and I couldn’t get anybody to buy it.

And there was Outside magazine, and I went in there and talked my way into a job. And then I knew that was what I was going to do. It was about the work. [I was] more serious than I had been before.

Sean Plottner: And that was when you first met Jann?

Terry McDonell: Yeah. Yeah.

Sean Plottner: And he’s the one you talked into hiring you?

Terry McDonell: No, it was William Randolph Hearst III. Will Hearst, who now sits on top of the Hearst Corporation. He’s the chairman of the board.

Sean Plottner: And how was it at Outside?

Terry McDonell: It was great! The idea was that the outdoors were about a lot more than, like, the Sierra Club. But what we really did was invent the adventure travel genre.

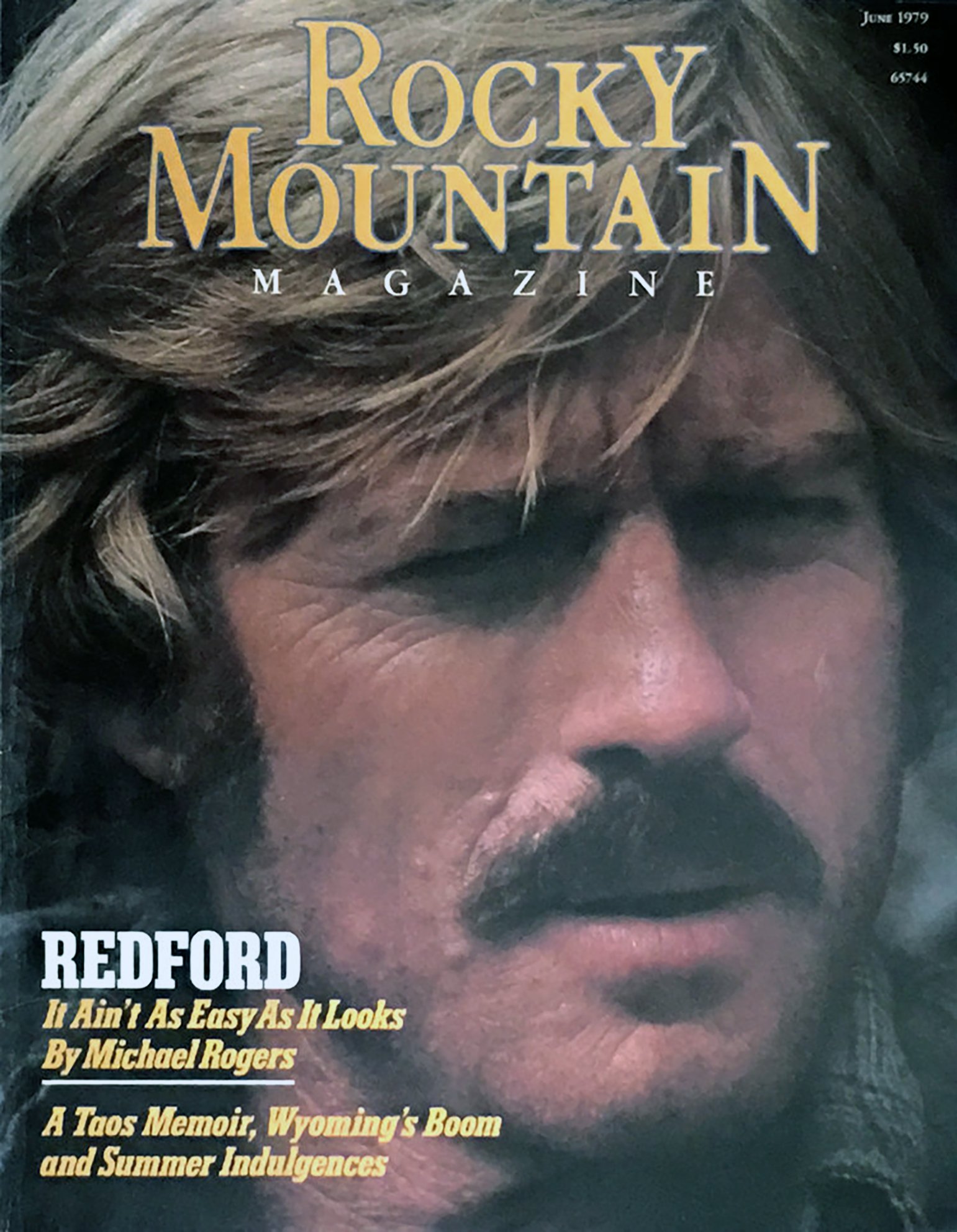

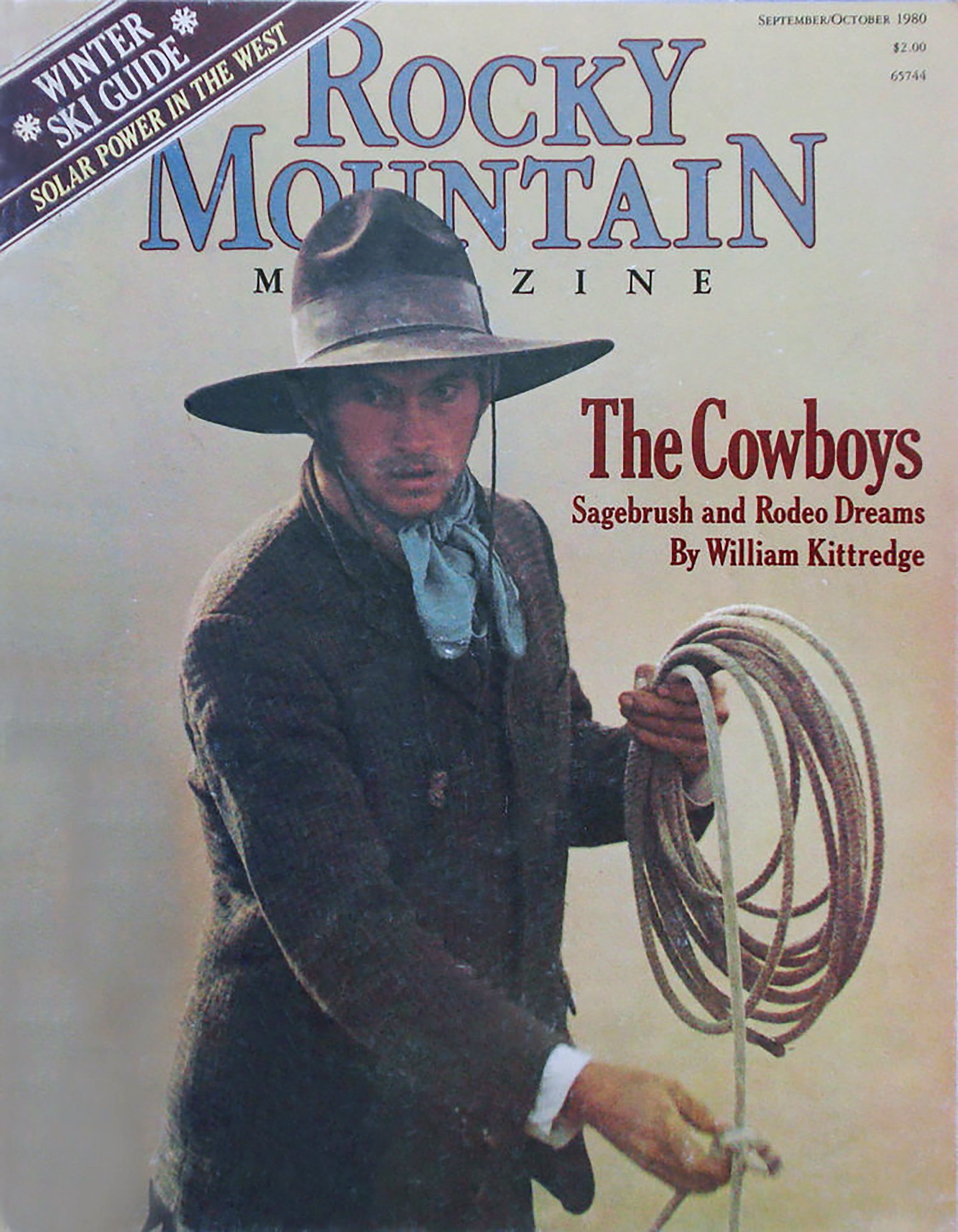

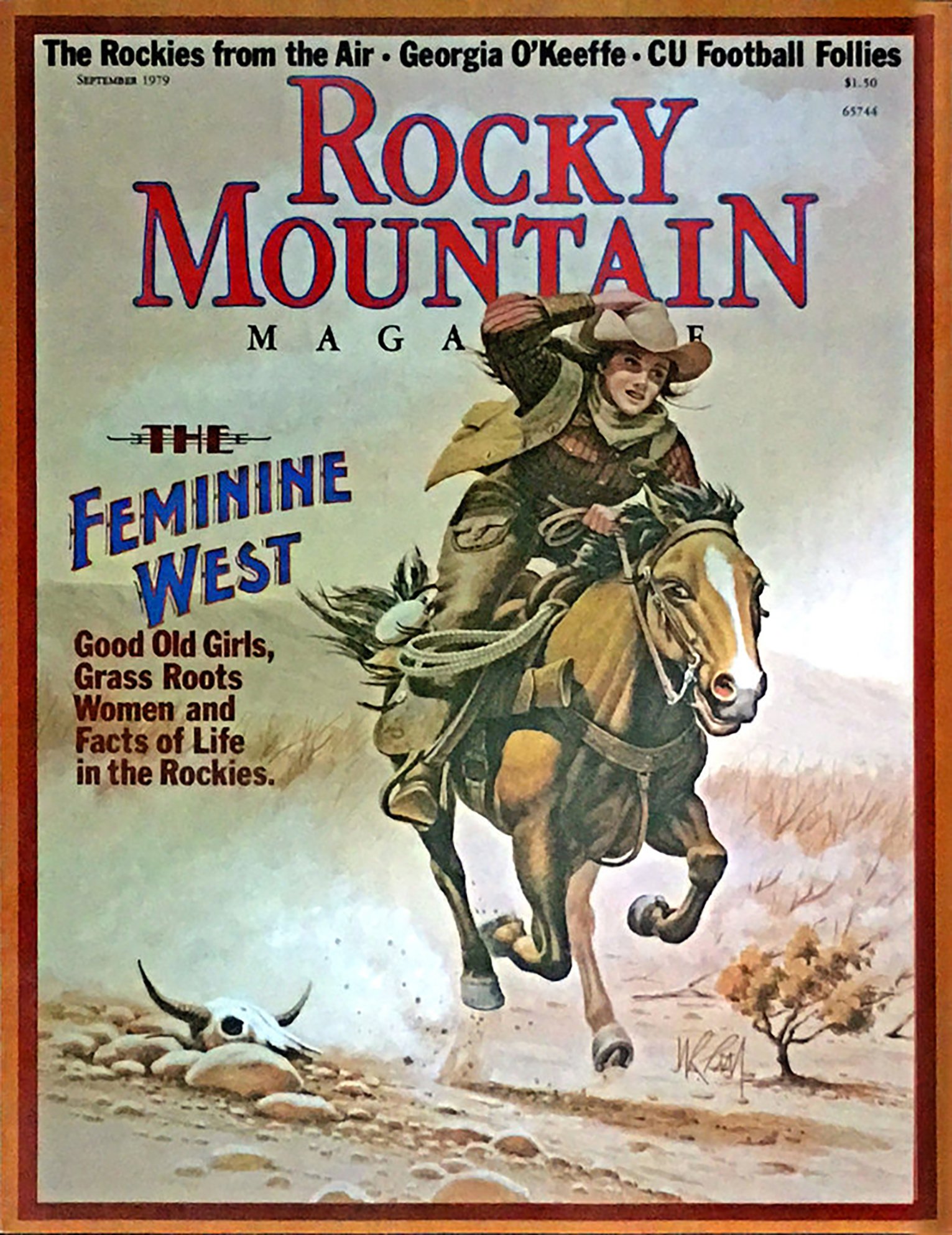

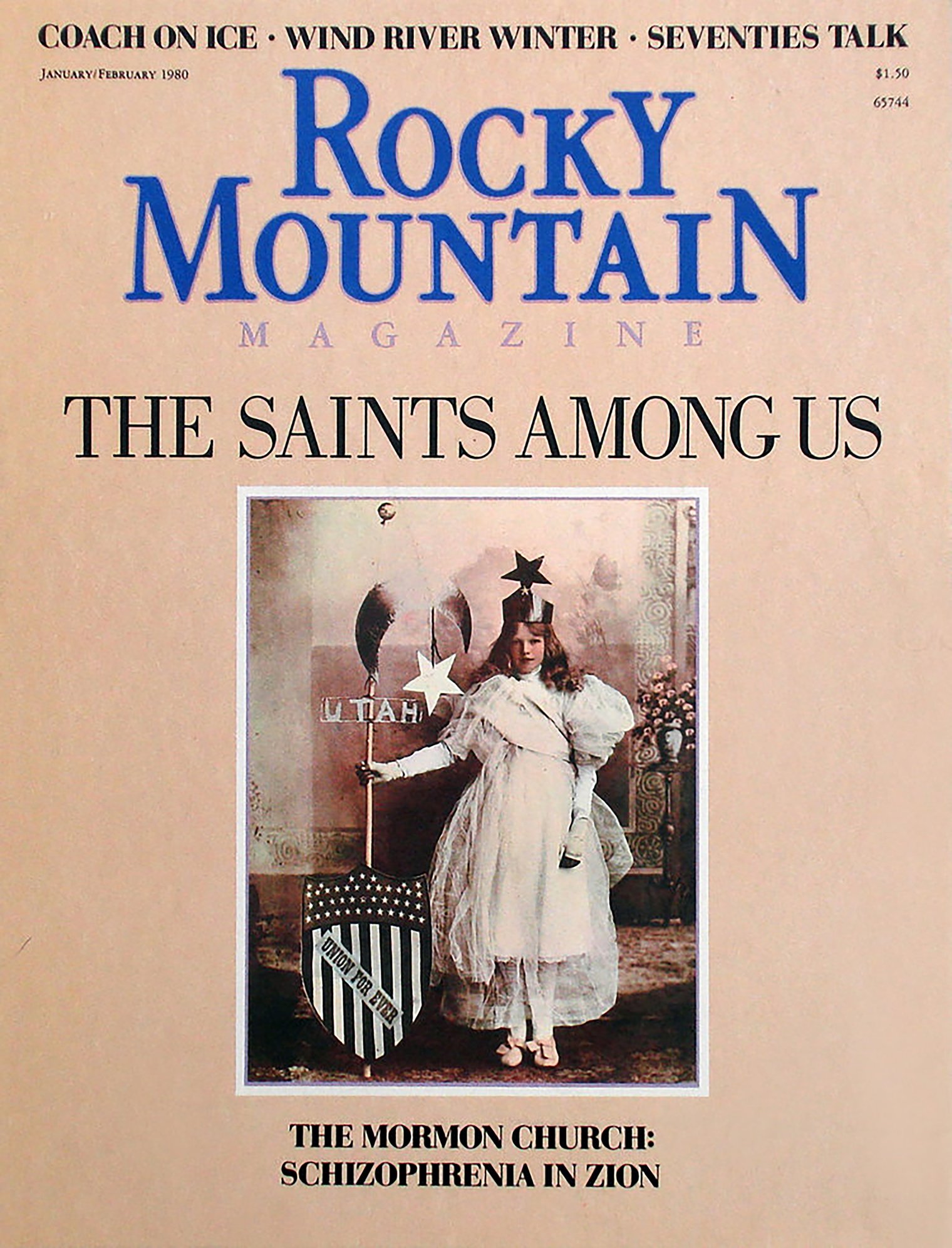

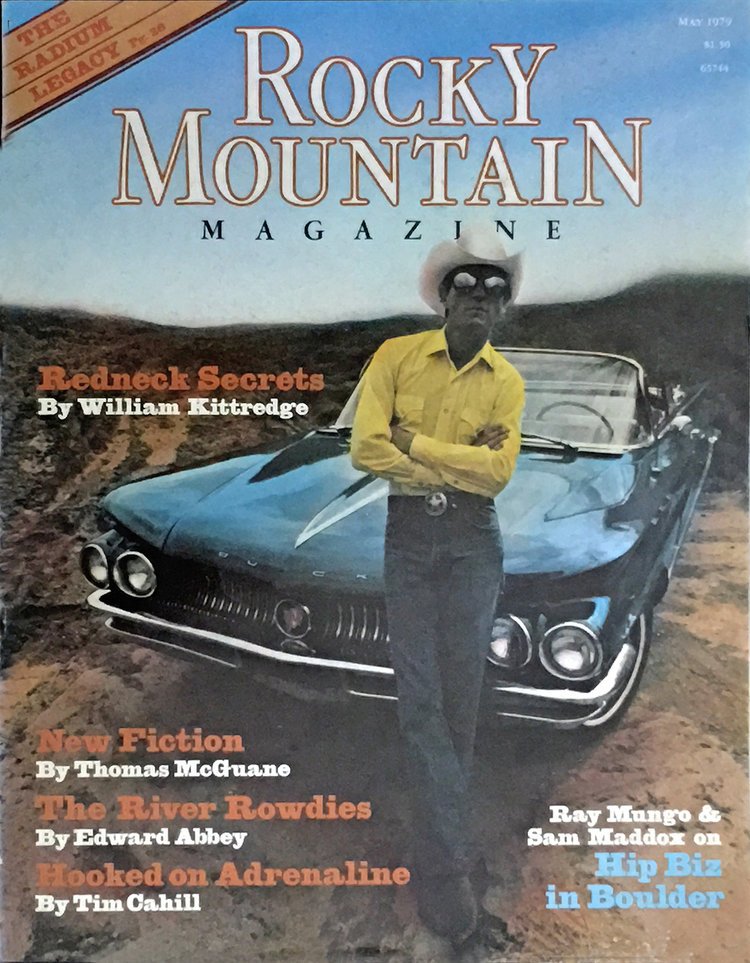

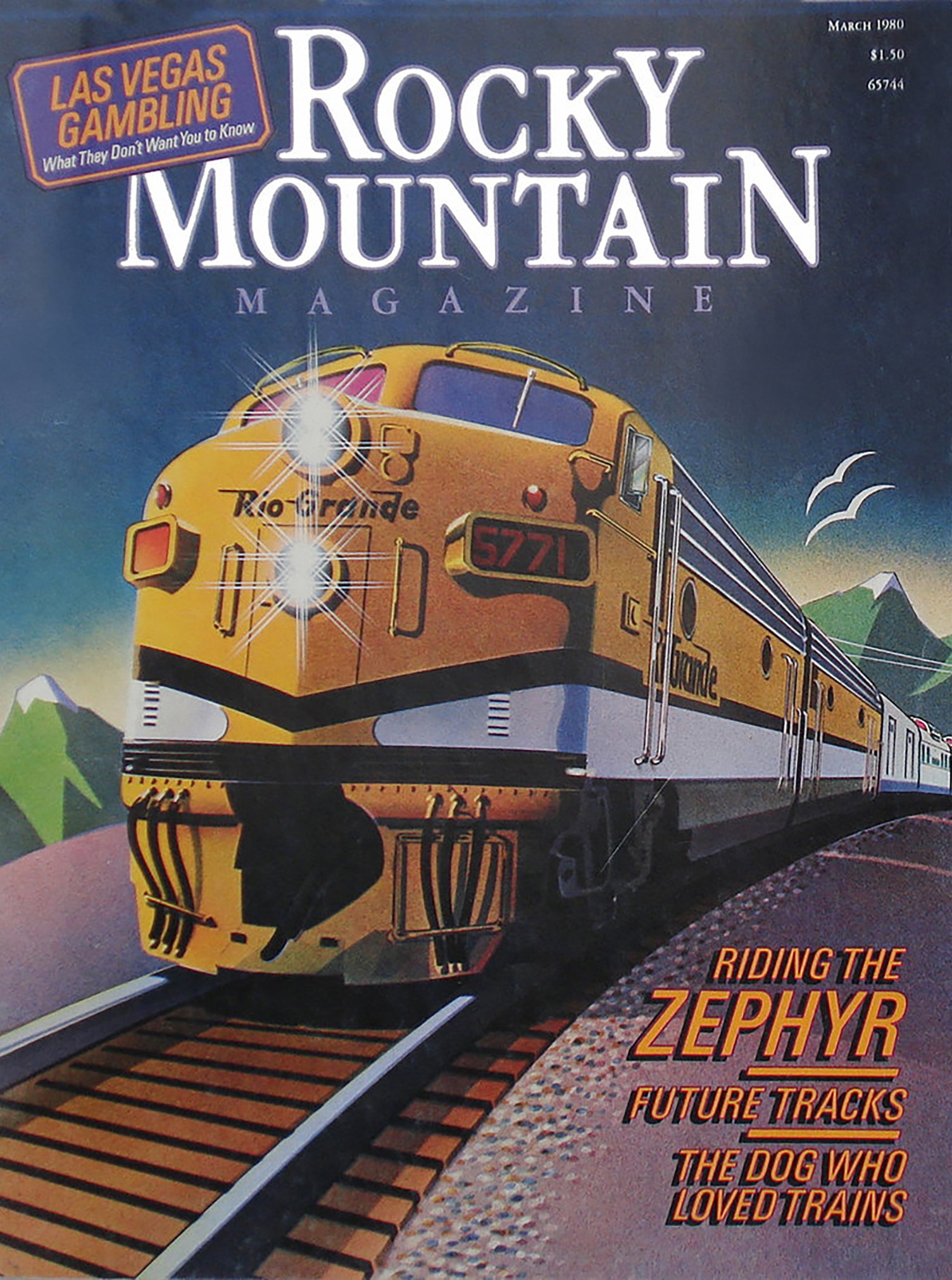

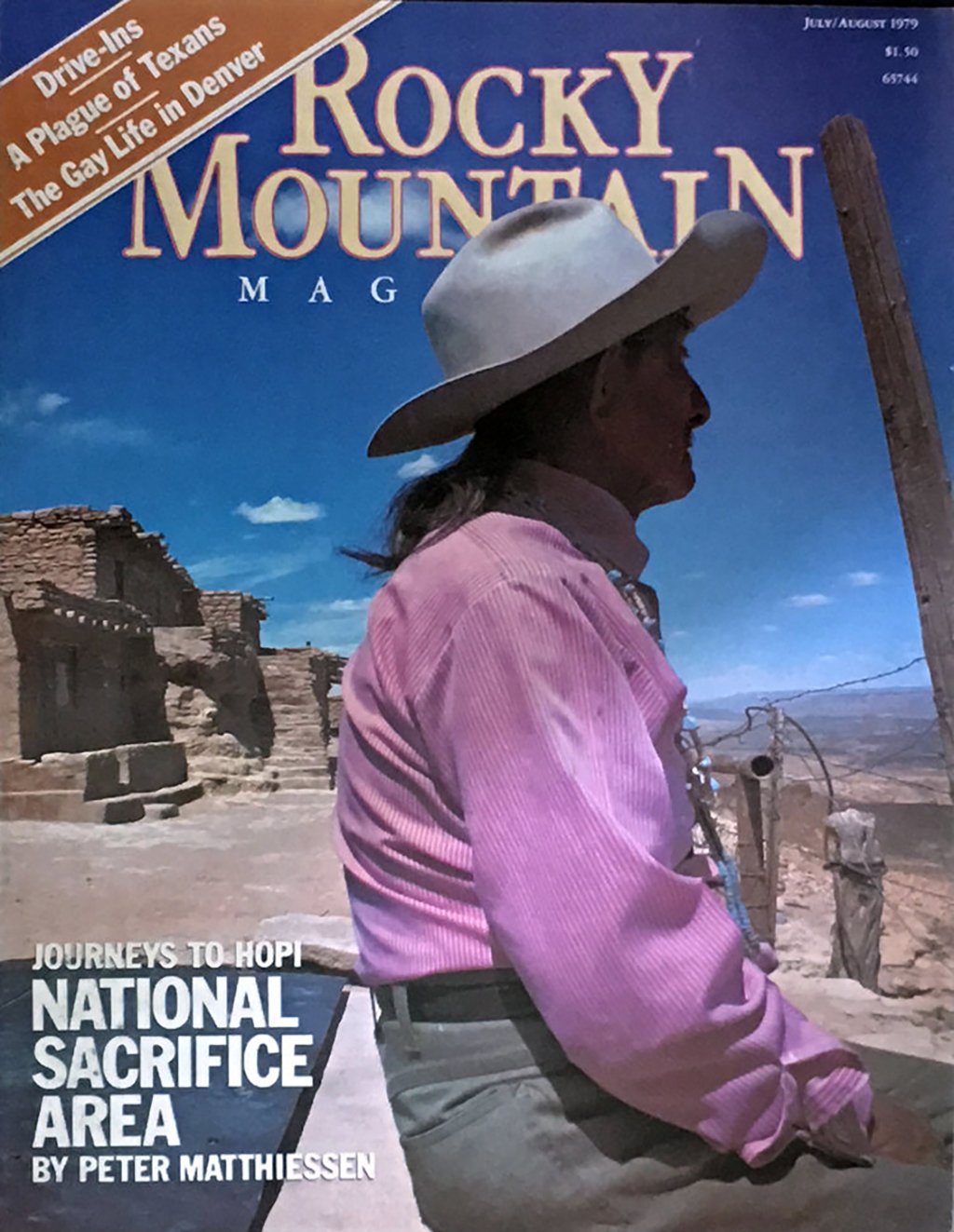

Sean Plottner: Okay, so Wenner sells it just two years after launch. And apparently you hadn’t had enough of that genre and you dive into Rocky Mountain Magazine.

Terry McDonell: That wasn’t about the outdoors and adventure travel that was a regional magazine for what we call “the deep west.”

I was a big fan of Texas Monthly and Bill Broyles. They had done that. And when I was in New York, I was in awe of Clay Felker. I didn’t know him until later, but I had watched him. And what he had done was put two things in the same magazine that, at the time, were very surprising: shopping and politics. And suddenly, it was a big “click” in the minds of New Yorkers.

That was exactly what they were interested in. Shopping—including real estate. That was the quintessential city magazine for me. And I thought, “Well, this is a new thing.”

Sean Plottner: And where were you based?

Terry McDonell: Denver. Cherry Creek. But I traveled all over the west. All over New Mexico, Wyoming, Colorado, many times, Montana—where I wound up living—Idaho, Utah. Wonderful places.

Sean Plottner: Well, it’s really sad there’s no digital footprint for the publication. I was hunting around and I kept finding Rocky Mountain Bride, which I don’t think has anything to do with it. Your art director, Hans Teensma, who appeared on this podcast in Season One, says you guys went out there and drove all over the place and said you were freaking out because there really wasn’t much out there. And he said one of you took a photo of dead rabbits—I’m not sure which one of you—and that you fell in love with it and turned it into a full spread/full bleed image in the magazine. Do you remember that?

Terry McDonell: Well, there was no more symbolic image of a particular part of Wyoming than that. And that was sophisticated. And ironic. And Hans was brilliant at that. He gave that magazine a look that translated beyond the visual that gave you an attitude about how you loved where you lived, and you embraced all of the ironies that went along with that. Including roadkill.

Inspired by Clay Felker’s New York magazine and the recently-launched Texas Monthly, McDonell moved to Denver as the founding editor of Rocky Mountain Magazine.

Sean Plottner: And that magazine won a National Magazine Award in the General Excellence category. Pretty impressive. So you ended up, again, with all these Jann Wenner connections, I think next you went on to Rolling Stone?

Terry McDonell: Yeah. And then I was in New York.

Sean Plottner: And how did you evolve what Rolling Stone was at the time?

Terry McDonell: Well, three things happened. The bottom fell out of the music business. The Cars were the biggest hit—they were the band. And The Police were not even on the scene yet. So I talked Jann into putting the music reviews in the back and putting something we called Art & Politics in the front, and then the features.

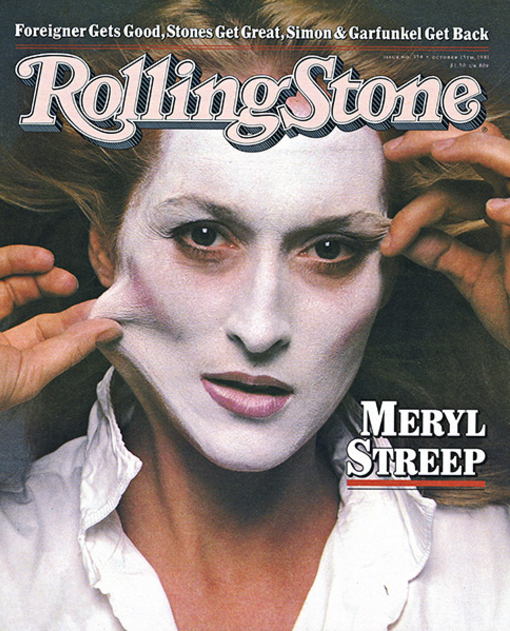

And we started putting movie stars on the cover: Jack Nicholson, Goldie Hawn, Meryl Streep. And that all really worked. So Rolling Stone kind of took off again. And Jann spent part of that time in the movie business. So I had probably more autonomy for a while than most of his editors had, but we got along really well and it really worked out.

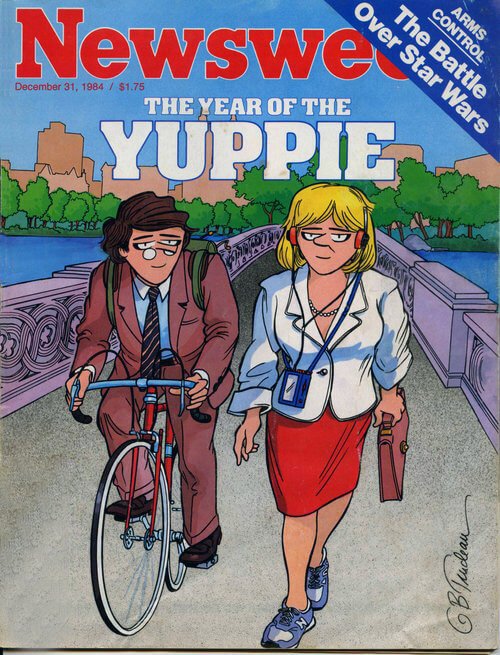

And then right when I was leaving to go to Newsweek, MTV came. And the music business was back. It was all new. All interesting—all kinds of great new acts, bands, whatever.

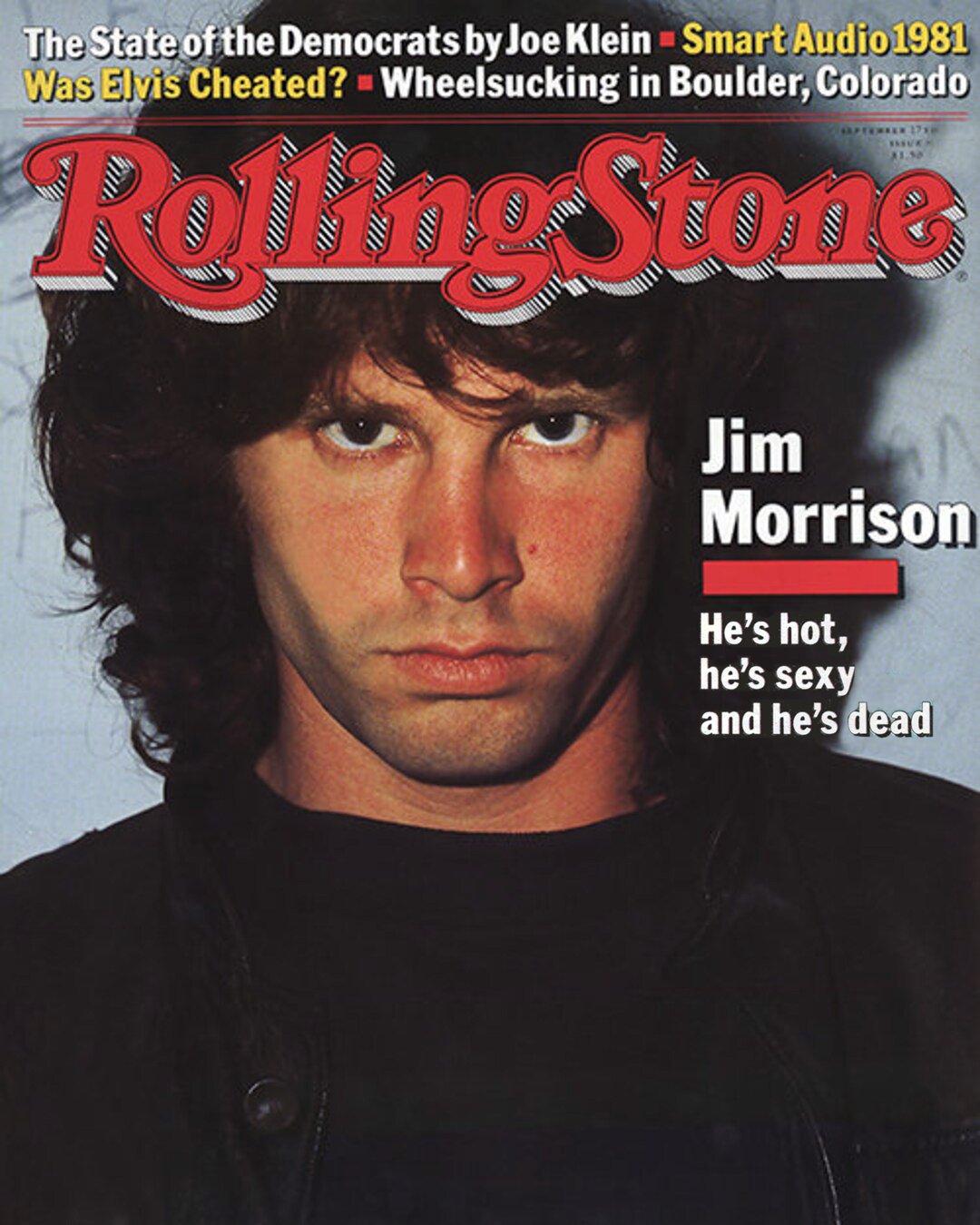

Sean Plottner: Interesting time. I’ve long been a big reader of Rolling Stone, and I remember in 1980 I was a freshman in college and had a big poster of L.A. Woman, The Doors album cover in my room. And I was part of that massive amount of people who were completely reengaged with The Doors, long after Jim Morrison’s death. And they were selling like crazy. And you picked up on that and did a cover story in which Jim Morrison was on the cover with what I think is a Hall of Fame headline: “Jim Morrison, He’s Hot, He’s Sexy, and He’s Dead.” Can you tell us a little bit about how that headline came to be?

Terry McDonell: There’s been a lot of discussion of that headline because, as I recall, it came out of a room, and in the room were Jann Wenner, David Rosenthal, who was my deputy at the time, and who replaced me as the editor when I went to Newsweek, and me. And somehow out of that room came that headline.

David claims that it’s his, that he wrote it. Jann says that’s absurd, he wrote it. It sounds just like him. And then of course, I thought that I had done it. And this has been, like, a rolling fake feud for a long time. And in the end, I don’t think it really matters, because what it does is it underlines the kind of collaboration that makes magazines really fun when they’re clicking.

Sean Plottner: Yeah, that’s great. I’ve had that experience myself. Where, well after the fact, there’s that great cover or great cover line and multiple people are taking responsibility for it. And at the end of the day it doesn’t really matter. And I guess, ultimately, the editor atop the masthead deserves credit for making it happen. It does say something about collaboration, memory, and ego.

Terry McDonell: Yeah, good point.

Sean Plottner: You’ve said that headlines can ruin a good story and they can also be the most fun part of editing. Talk a little more about writing headlines.

Terry McDonell: Well, I think that, in those moments, you had to assume, or at least I assumed, that some people were going to go through your magazine and only read the headlines and the display copy.

So that was the place where you had to throw your attitude, and your identity, and your humor, and everything about yourself as a magazine—or as a brand, as it was soon beginning to be called. “Brand” became like a monstrous word almost all of a sudden. It used to be applied to Corn Flakes, and then it was suddenly used for magazines.

But the thing about it was that that language—if it was powerful, and funny, and not arrogant, and never mean—would serve you well. And the people would understand who you were and what it was about. And if you could convince them to read a story, fine. But sometimes people would just read the headlines and really like the magazine.

I had a really terrible experience. I made a terrible mistake. Spike Lee had just directed X, his great film about Malcolm X. And we had a funny story that was also serious in a way that Spike always was—always is—in spite of the way he would front off. He’s a complicated, good man, right?

And so we shot the picture of him with his hands crossed across his chest, making an X. And it was beautiful, rich, deep, dark. And him looking really good.

Sean Plottner: And this is for Esquire?

Terry McDonell: Yeah. I’ve slowed down because I hate to think about what I did. I had this idea, because I knew him a little bit, that would be funny would be in the headline inside we said, “Spike Lee Hates Your Cracker Ass.” Which was going right at Esquire’s demo, right? But, we thought it was pretty funny.

And he called me up and he said, “What’s wrong with you?”

And I knew as soon as I saw it in print that I had made this huge mistake. But only one word was wrong. If I had said, “Spike Lee Loves Your Cracker Ass,” it would’ve been a completely different story.

Sean Plottner: Does Spike Lee hate your cracker ass? That’s what I want to know.

Terry McDonell: No! That was the whole point. He’s making these movies as an anti-racist. He’s a righteous guy. He’s not kidding. He wasn’t even really angry at me on the phone. He just said, “What’s wrong with you? I thought you were not stupid.”

Sean Plottner: Yeah, I think I’ve heard you say before that a headline is better if it is not mean-spirited. I think you put that in the mean-spirited bank, but thanks for sharing that.

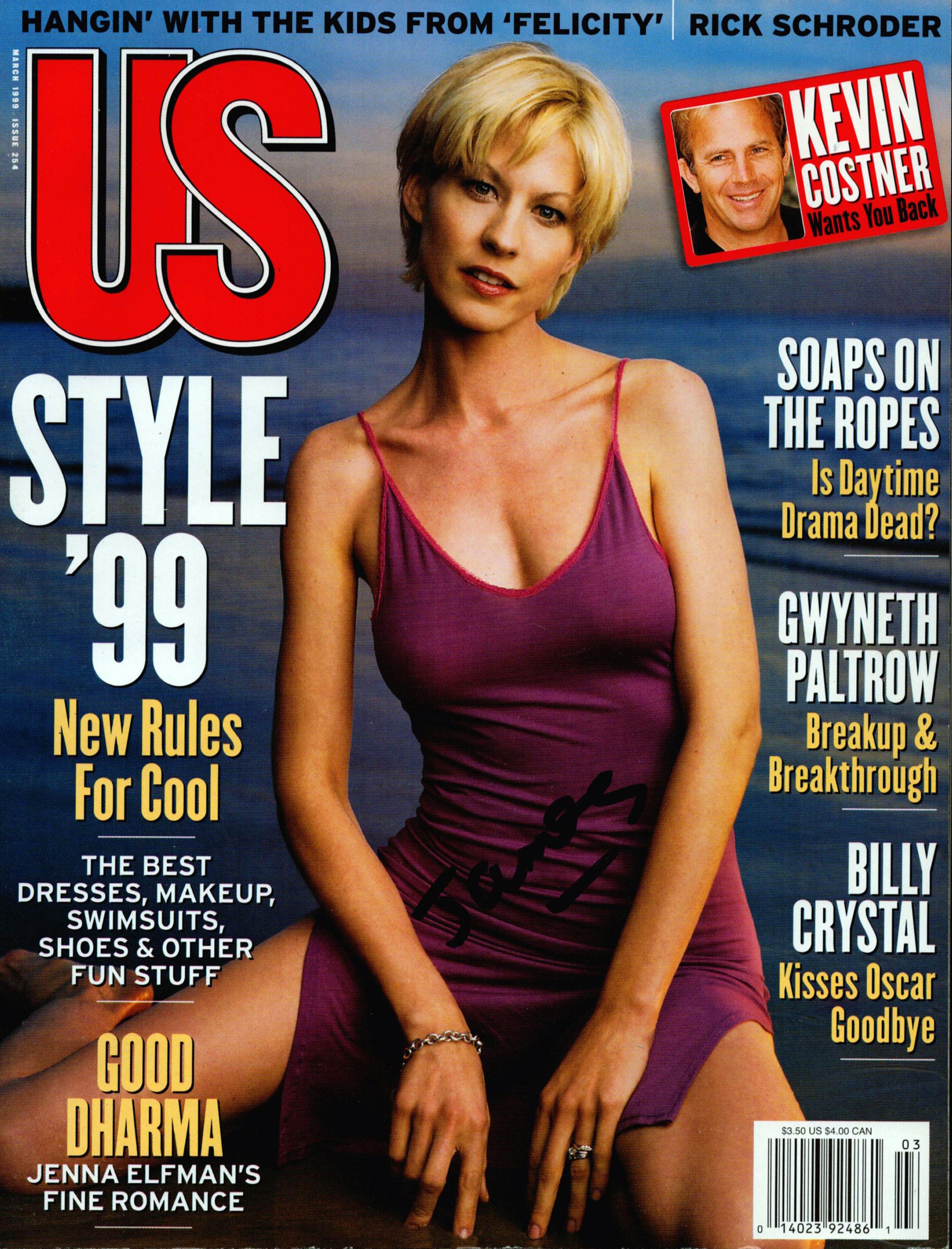

Terry McDonell: That was the whole trick to why Us Weekly worked, too. We wanted to create an American tabloid, but not mean. So, like, the Fashion Police that was supposed to make fun of what people were wearing, wasn’t mean at all. It was either funny, or complimentary, or whatever. And we didn’t do those hard-ass stories. Only once in a while. It was fluffy-ass journalism. But it was not mean-spirited and people really liked that. Not my favorite job, however.

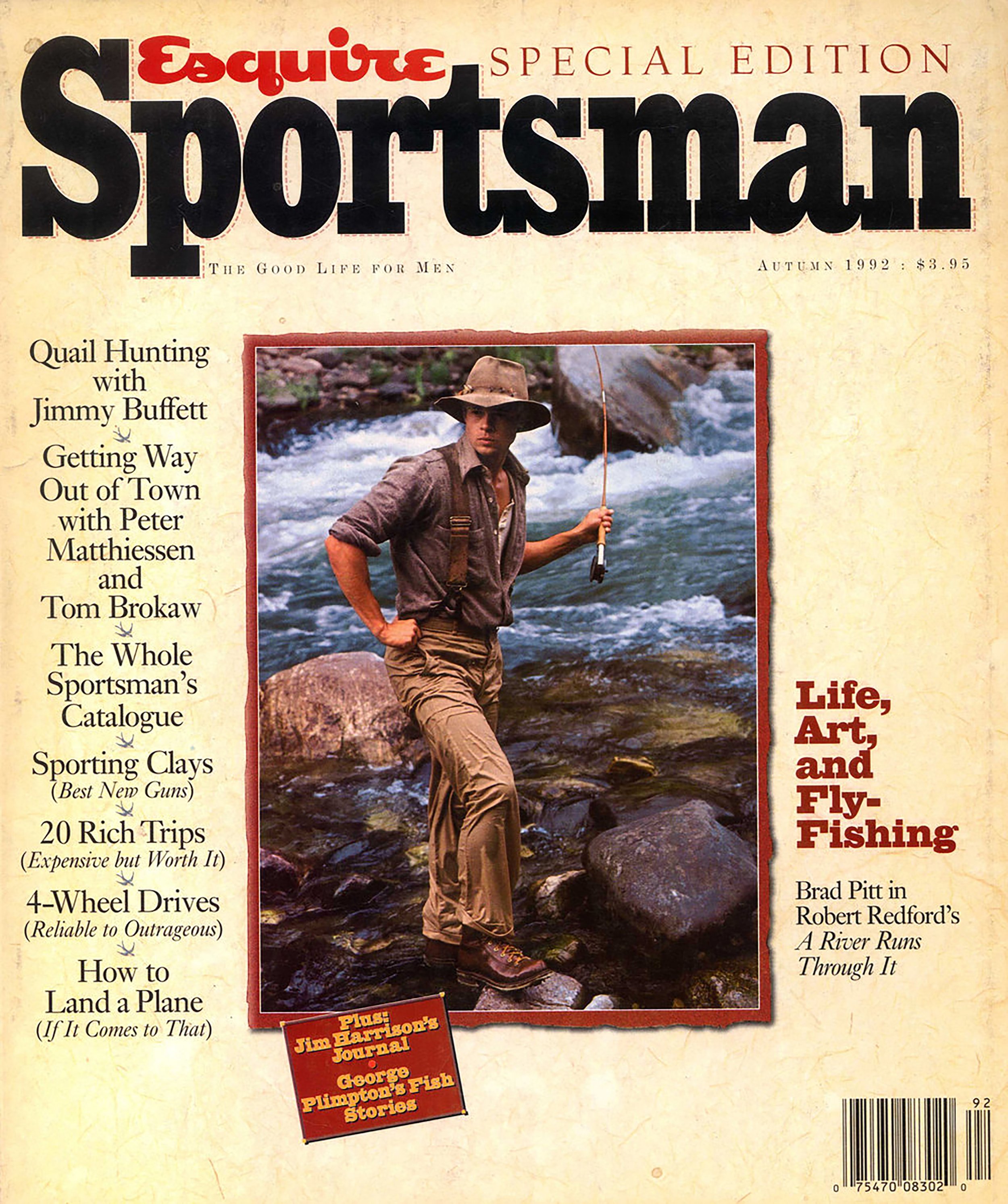

McDonell on the hunt with musician Jimmy Buffet

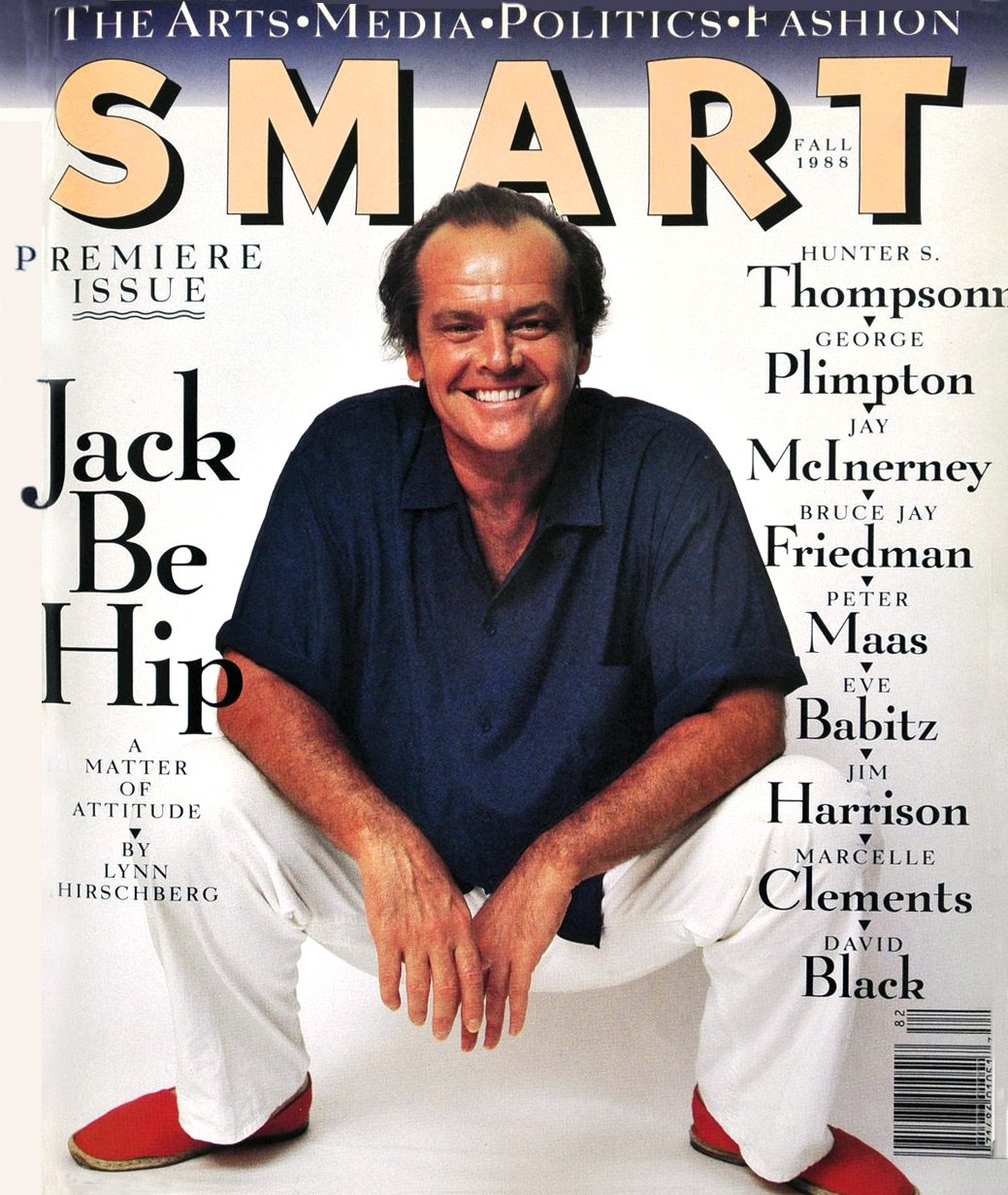

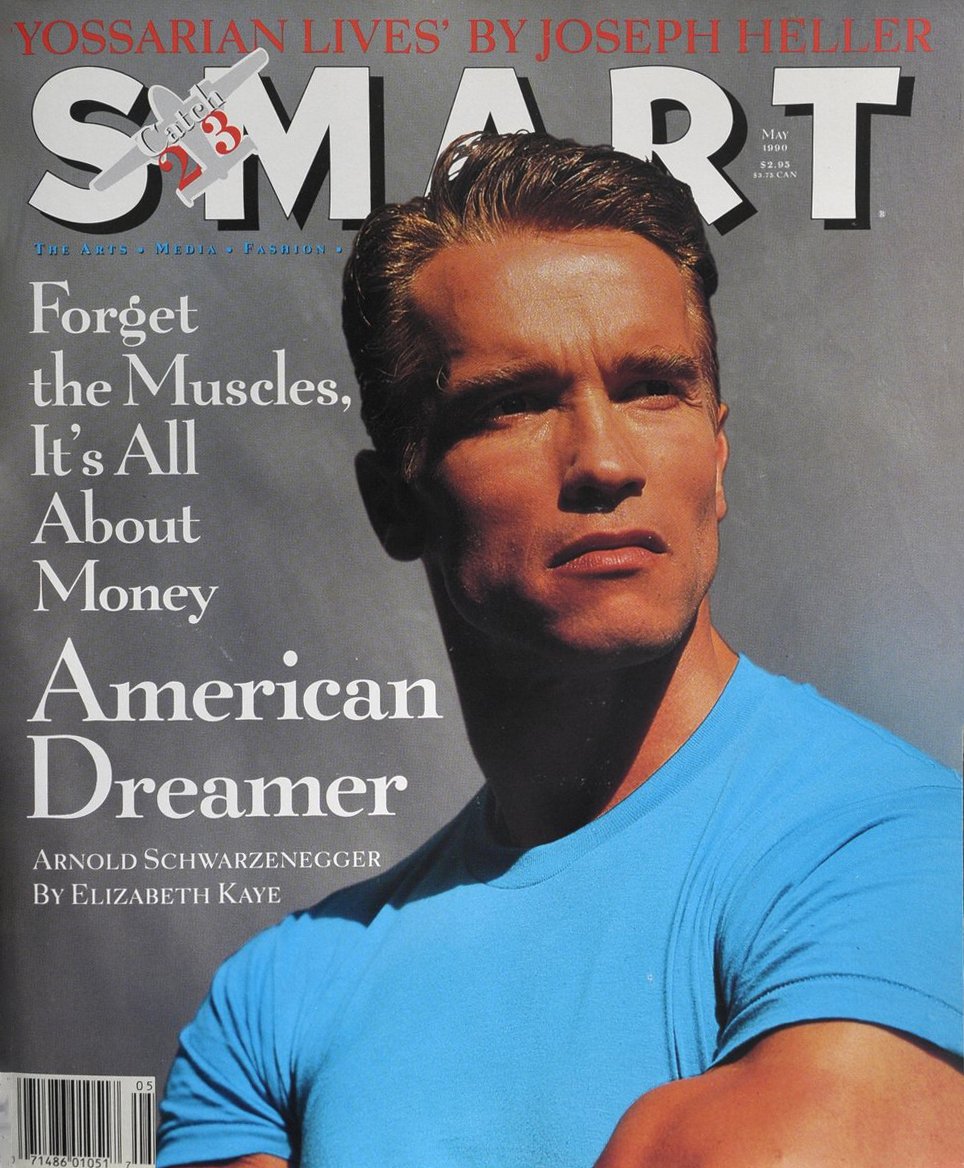

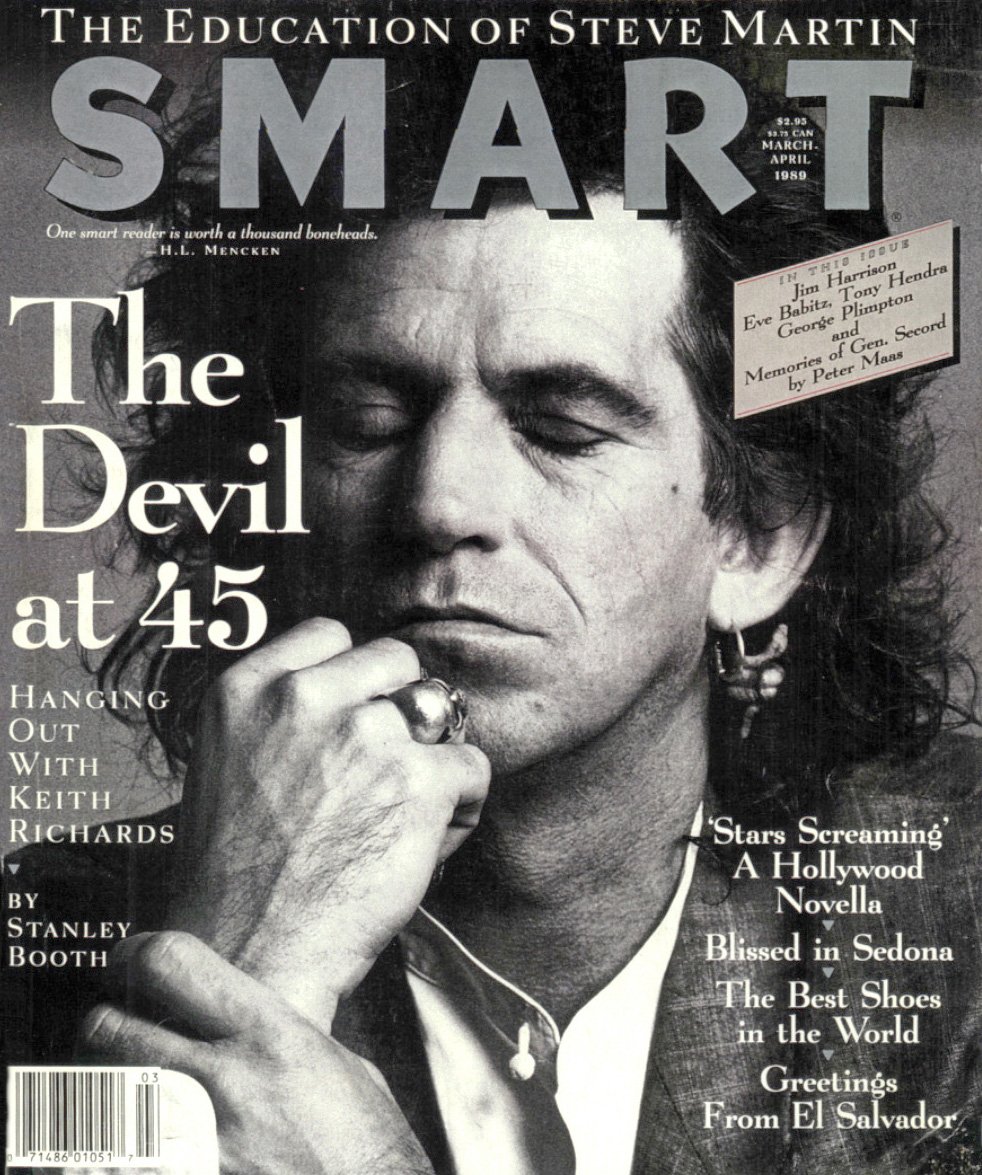

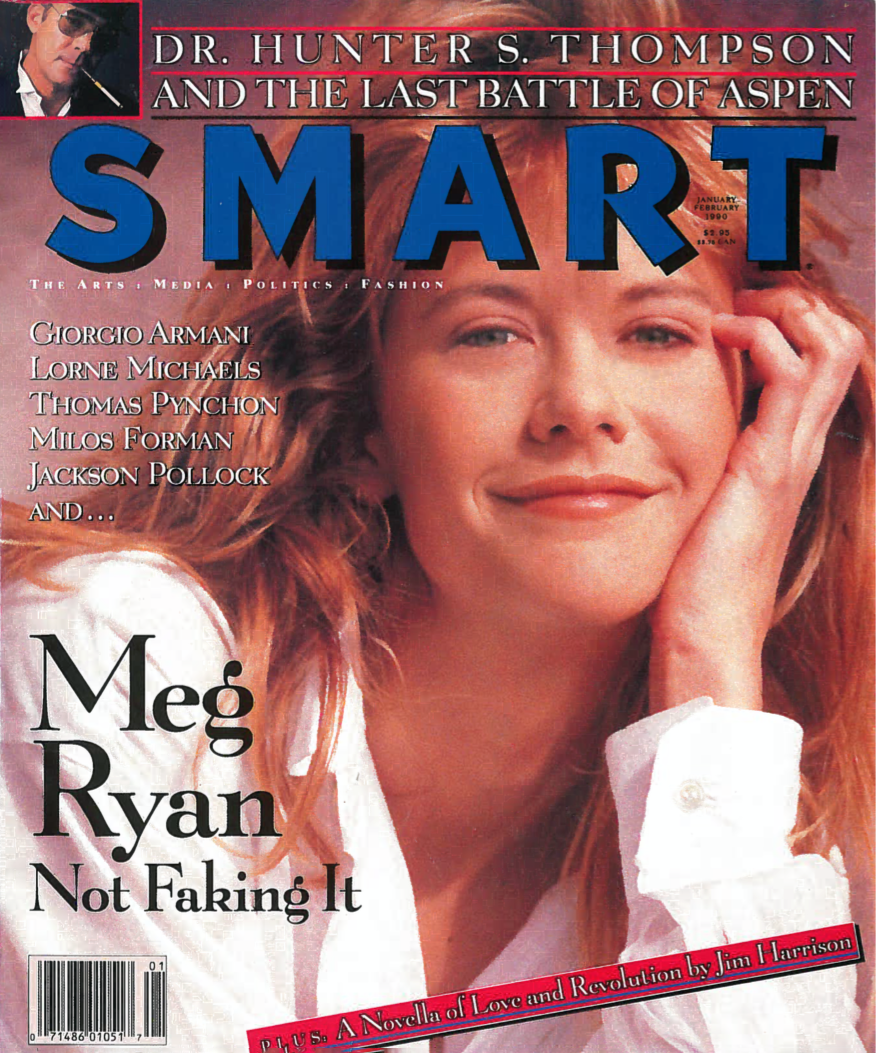

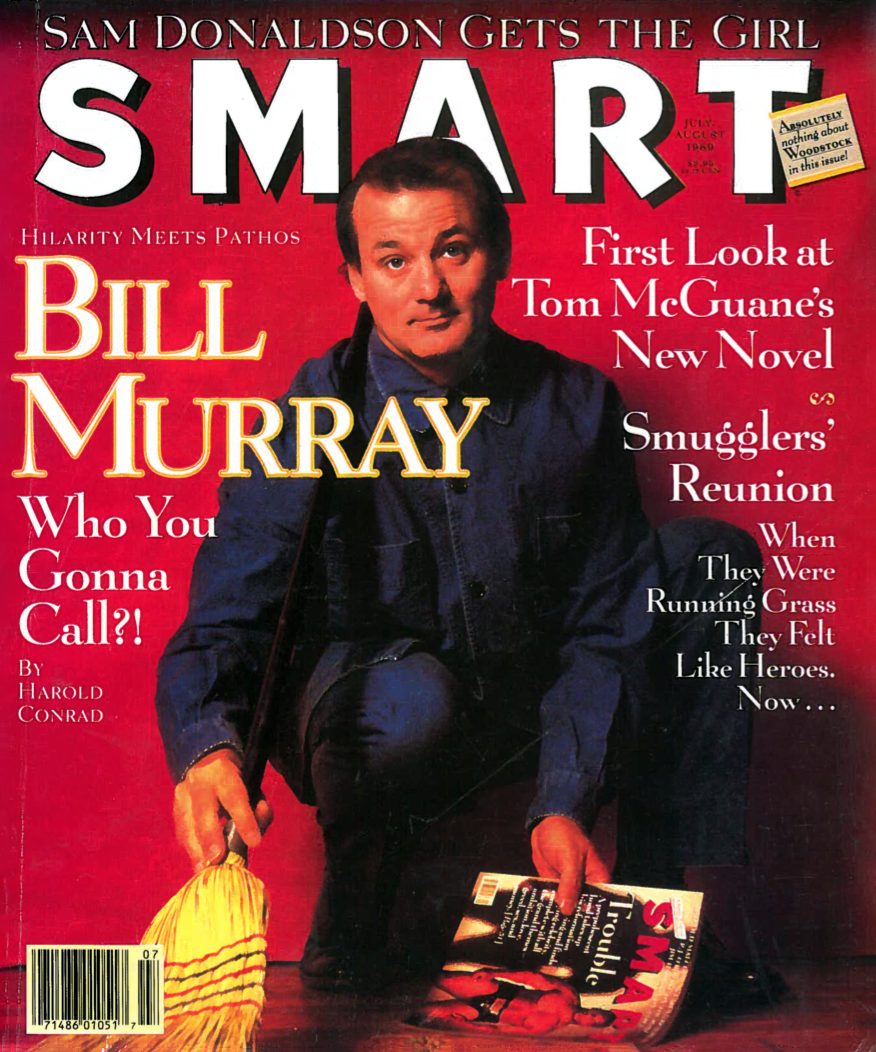

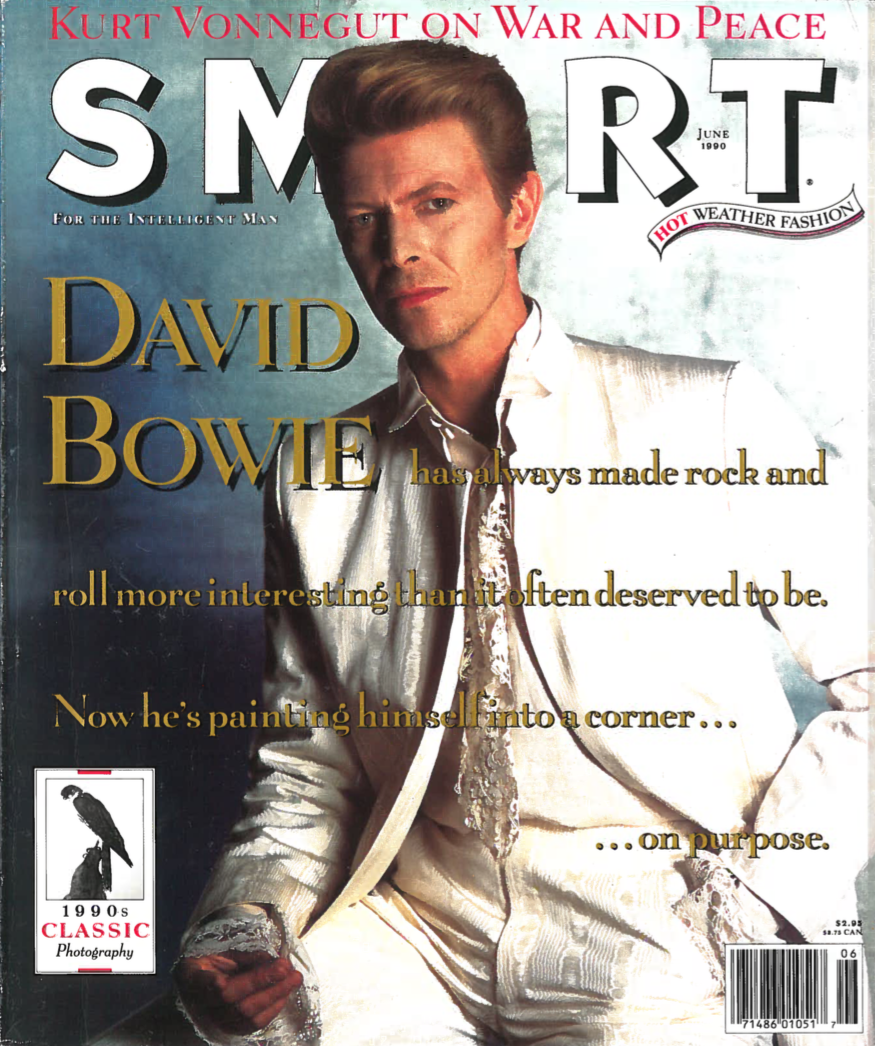

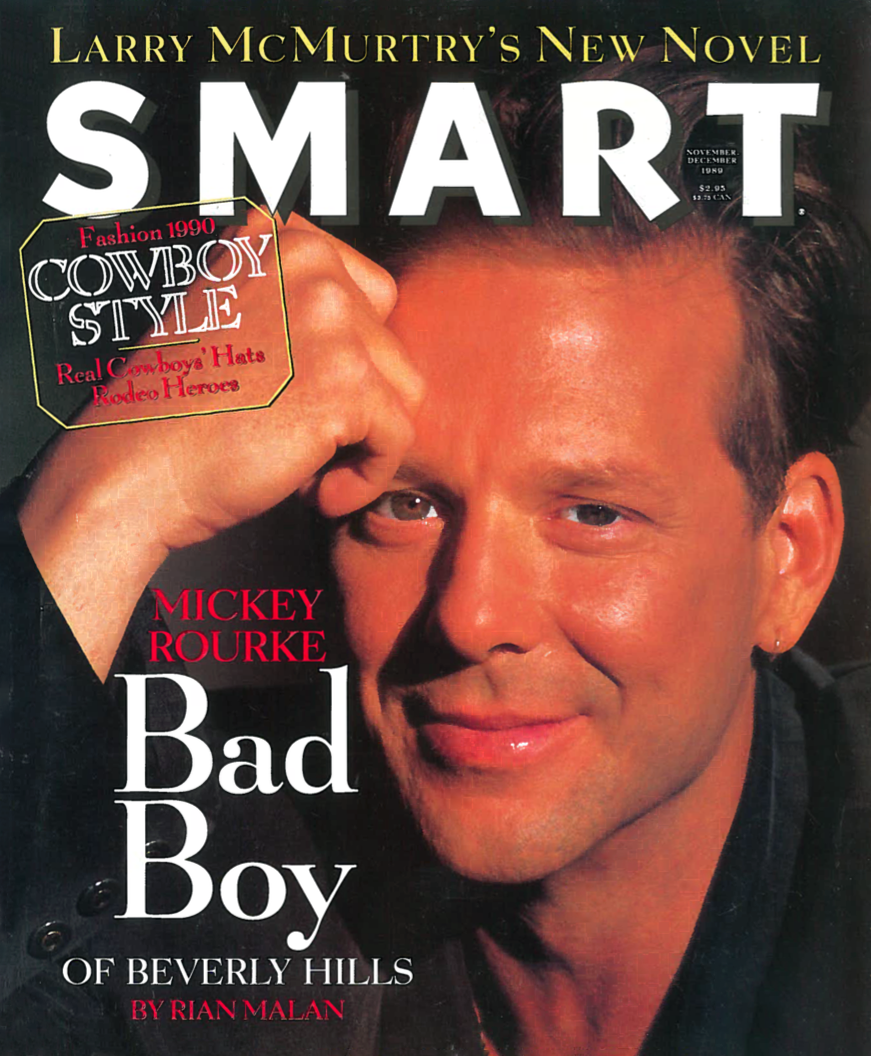

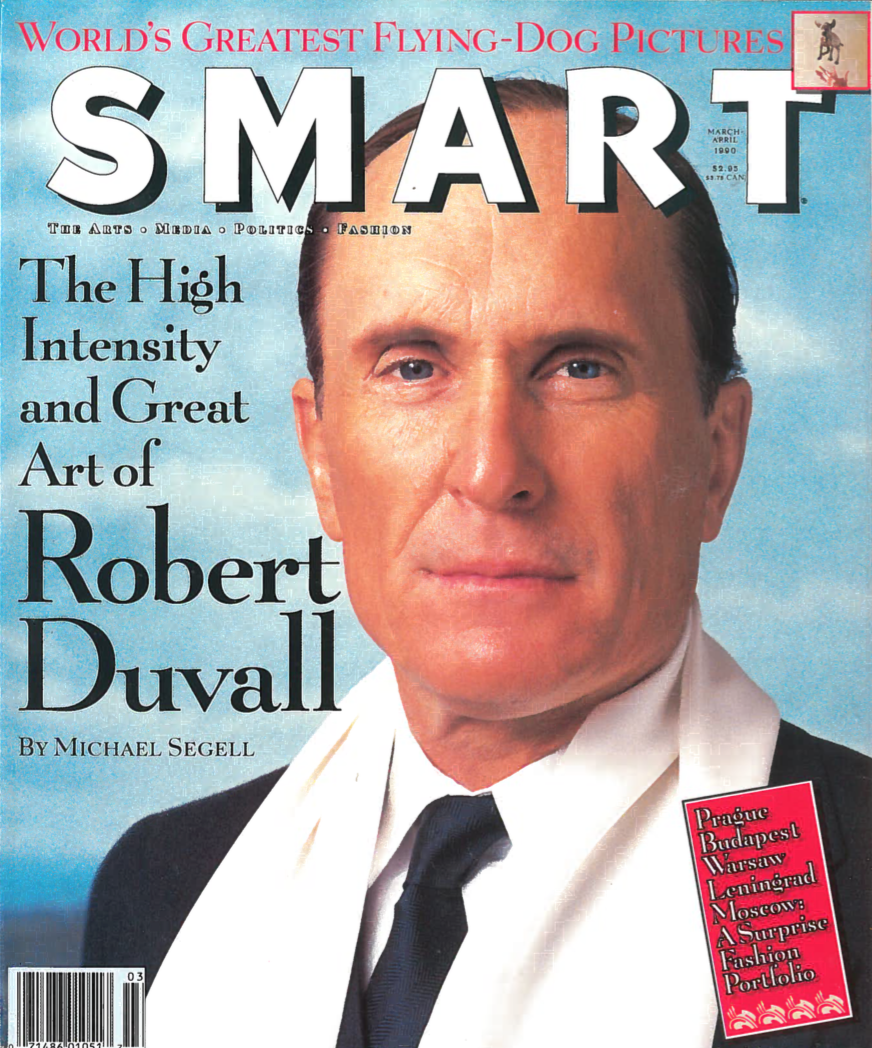

Sean Plottner: Well, yeah, and I’m going to ask you a question or two about Us in a couple of minutes here. I’m wondering now if you could tell us about the conception and launch of Smart magazine. This was primarily you doing the driving and the fundraising. Tell us what you were trying to do and how it came together.

Terry McDonell: I wanted to start my own magazine because I had been around these launches and I liked doing that. It was fun, creative, energizing—all of those wonderful words.

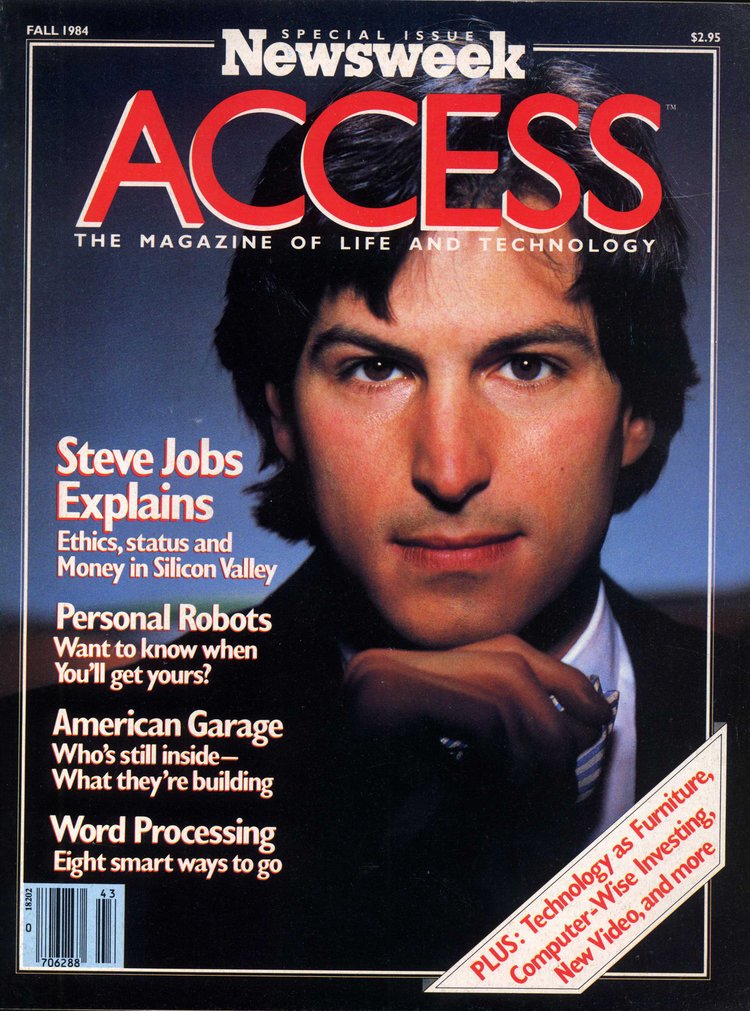

And I was at Newsweek and it occurred to me that I could maybe raise a little money. And I had just met Steve Jobs and he had given me, to play with, one of the first Macs. Those ones that stood up, like, you put disks in them.

And I realized that you could probably do a whole magazine on that. Adobe was just getting started. We were a beta site for them when we got rolling. Roger Black came—he was the one who said, “type is the sushi of the nineties”—and we were just playing with all this digital stuff. And we were able to create a magazine and shipped it directly to the printer with no paste up. None. All that was gone. It was just so much cheaper.

So we launched Smart for, like, $300–400,000, when most startups would’ve taken $3–4 million. And I wanted to create my own sort of version of Esquire or New York magazine, other stuff that I had envied. I wanted it to be a writer’s magazine. And I gave some of the writers stock for being part of it.

Sean Plottner: And all those writers got filthy rich off that, right?

Terry McDonell: Yeah. Every time they’re basking in their pool, they’re thanking me for that. Hunter Thompson thought that was great, but then thought we should sell it all to Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, who we all knew. And they were big supporters of it. And so we, for a minute it looked like that might actually happen.

And then I was broke. We didn’t have enough money to sustain it. And we got an offer from a Japanese company. And that was right when I got the offer from Hearst to go to Esquire, which wouldn’t have happened if I had not started Smart.

Sean Plottner: Interesting how that happens.

Terry McDonell: I was told that I can either take that job and just not care about Smart or the job is going to go away. You got like 20 seconds to make that decision.

Sean Plottner: Did the buyer of Smart keep it alive?

Terry McDonell: It went for a couple more issues and then it went away because his company in Tokyo started having a lot of problems.

“Jann [Wenner] spent part of that time in the movie business, so I had probably more autonomy than most of his editors had.”

Sean Plottner: And how, from your perspective, how was Smart received by advertisers and readers?

Terry McDonell: Well, everybody told me they liked it. And we had some serious, good advertisers who got the program. But it wasn’t mass enough. And we didn’t have the circulation we might have had, although we were critically well-received.

But it was how I got to know Tina Brown and Graydon Carter. They had both told me, “this is great.” And they were very complimentary about it within the small world of magazines. And there was a lot of satisfaction in that. And that went a long way. Graydon was starting Spy at the same time.

Sean Plottner: Well, I remember it and I remember it had a really sharp look. And again, no digital footprint for that publication, which is quite sad, although you can find some of the covers online. I also noticed, just in case you have a bunch of bound volumes down in the basement, that somebody is selling a complete set of Smart magazines for $450 online if you are so inclined to sell or buy.

Terry McDonell: Well, all those covers are on my website.

Sean Plottner: How did you connect with the great art director, Roger Black, to work on that publication?

Terry McDonell: When I left the AP to go to New York to work on this little counterculture startup in Los Angeles for Karl Fleming, they hired me. I was 25. And they hired Roger to be the art director, and he was 24. And we were immediately drawn to each other, and we have been friends ever since then. Many years.

Sean Plottner: And I get the sense you were pretty active in partnering with art directors. Can you describe what your relationship was with art directors over the years?

Terry McDonell: Well, the joke among them was that I wanted to be an art director, which was fair enough. But I used to sit right next to them, especially Roger, and we would create. We would blow through the whole magazine. I would write headlines and he would slap them in there and we’d look at it. We’d play with the pictures. And so instead of having to send things back and forth and taking what sometimes seemed like forever on deadlines, we would just sit at that computer with the big screen and knock it out.

When he was starting Out magazine, I even sat next to him when he was doing that and wrote these headlines. Although some of the people that were also helping us didn’t think it was right for a guy who wasn’t gay to be writing the first big gay magazine’s coverlines. But that was maybe a window into the future.

Sean Plottner: Back to Hans Teensma, whom you hired at Outside, he says, “You never forget your first editor.” And he has very nice things to say about you. And one of them is that you mentored him and taught him how to go out drinking and stay up all night.

Terry McDonell: Well, he’s not bad at that himself.

Sean Plottner: Well, those Europeans, I think they do have a hand up on that. Have you ever had to fire an art director?

Terry McDonell: Not exactly. But some people had moved around a little bit. That was the hardest thing about any of those jobs—when the cost-cutting started. I never worked with an art director that I didn’t like. Ever.

Sean Plottner: I believe you wrote in your 2016 book, The Accidental Life, I think you’ve said there that despite all the jobs you had, you only got fired from one. Where was that? Esquire?

Terry McDonell: That was Esquire.

Sean Plottner: And can you share with us how you got the news? How did you learn you were out?

Terry McDonell: My agent called me and said, “You’ve been fired.”

And I said, “How do you know?”

And she said, “Because they just announced over at New York magazine that Ed Kosner”—who was the editor there at the time—“was the new editor of Esquire.”

I said, “No. That cannot be.”

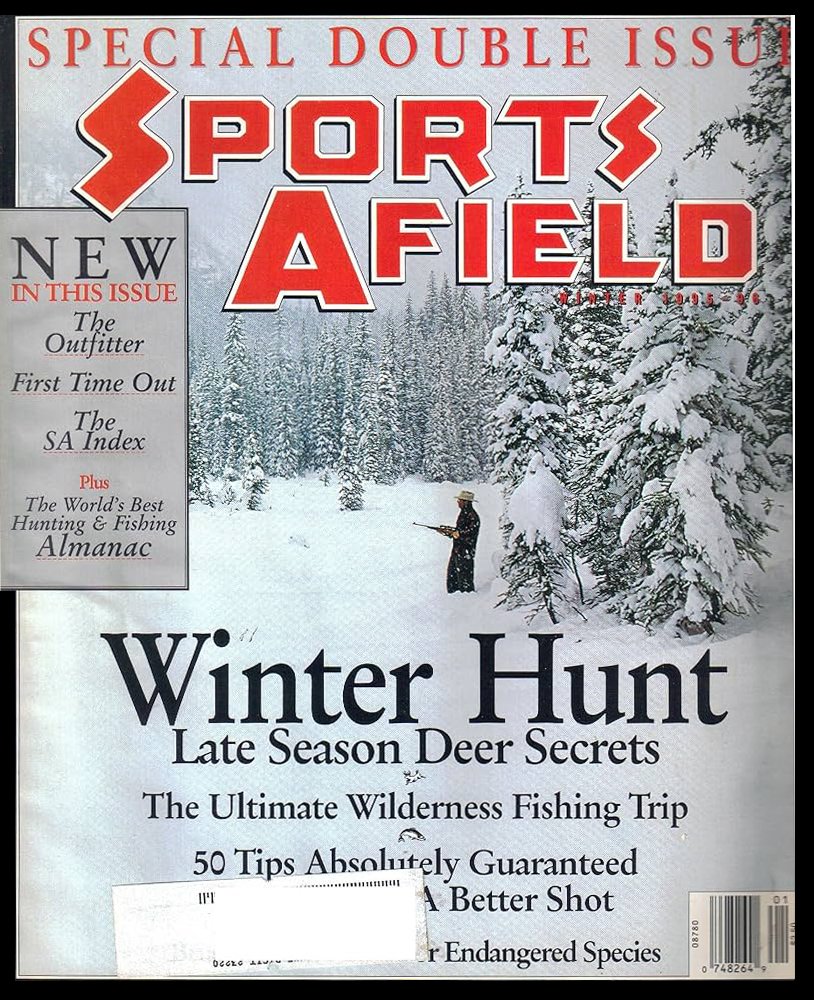

And then I got a call to go talk to Claeys Bahrenberg, who ran the Hearst magazine division then, and he said, “Well, there’s two things you can do here. You can either go away—sue me, get your contract, get a bunch of money, and leave. Or you can go over and edit Sports Afield, make it a different kind of magazine.” So I did the latter.

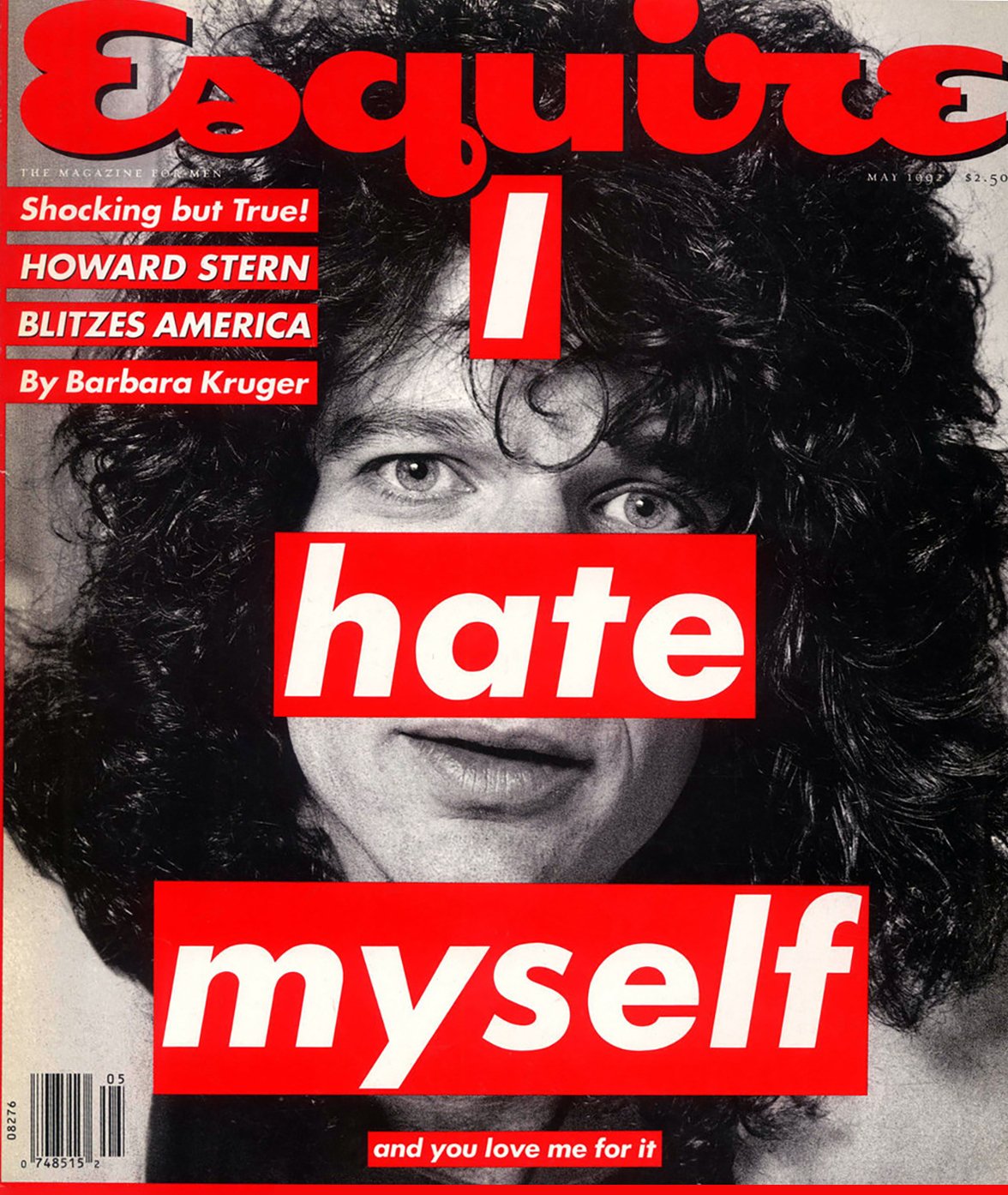

The reason I was fired was discussed at some length in the media. The cover that everyone seems to think got me there was—I did a cover that was white on white and it said, “White People…” And very small at the bottom, in black, it said, “The Trouble with America.” And then inside we set out to prove that in sort of a literary, ironic, sometimes bad-ass way. That proved both popular, and something that I’m quite proud of in most ways, but also problematic for me.

Sean Plottner: So you got a call from your agent. That's interesting. That’s almost the precursor of firing by Tweet in a way.

Terry McDonell: No, but they didn’t tell her. She was just better connected than I was.

Sean Plottner: Yeah, I understand.

Terry McDonell: And someone in another magazine office told her. I always thought I was her pet, but she has many pets. She’s still my agent, Binky Urban.

Sean Plottner: Well, let me let me do something here—I’ve got a list of 10 things here. They’re names, titles, phrases. I’m just going to say them one at a time and ask you to just quickly tell me the first thing that comes to mind and we’ll try to be brief, but there could be some storytelling here. And god knows, I might even bait you a little bit.

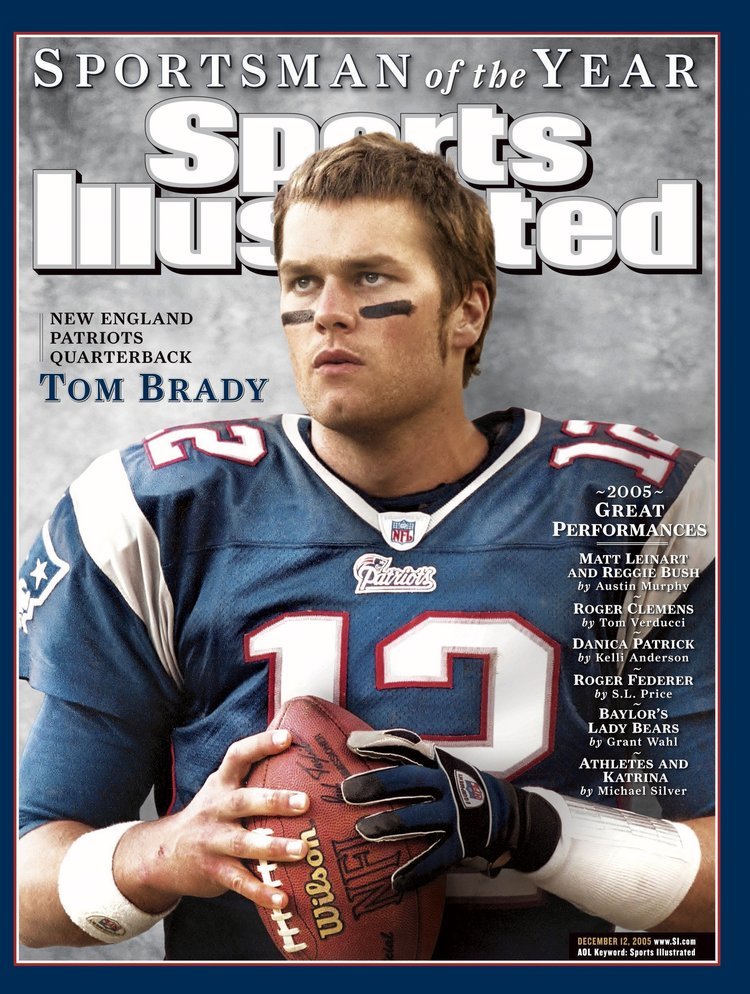

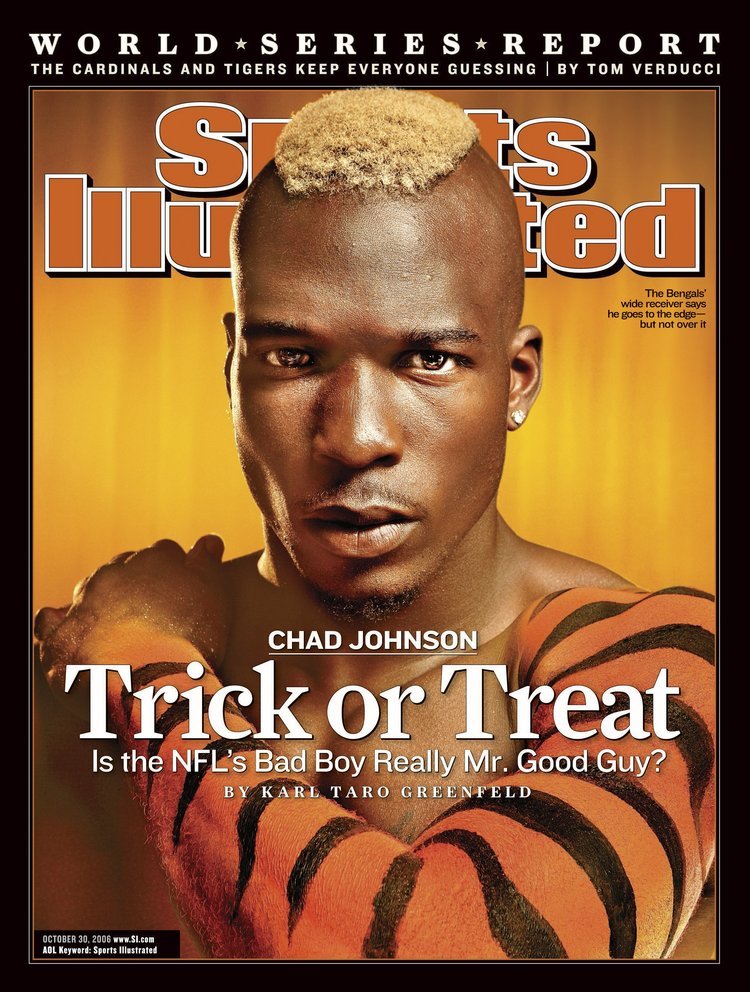

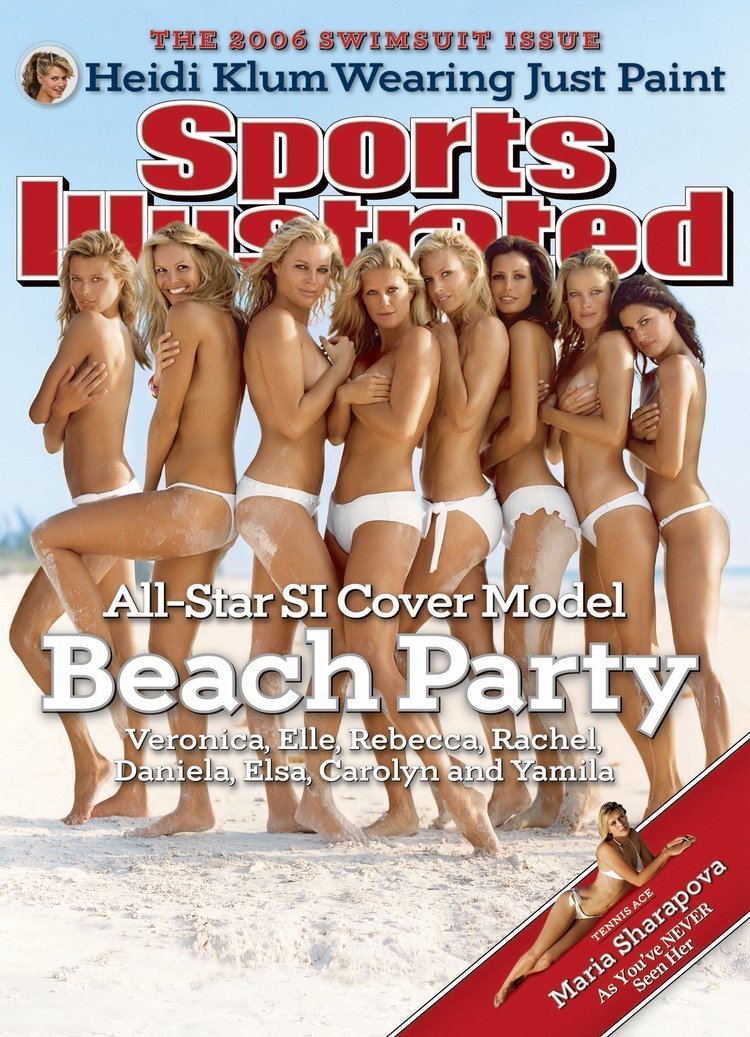

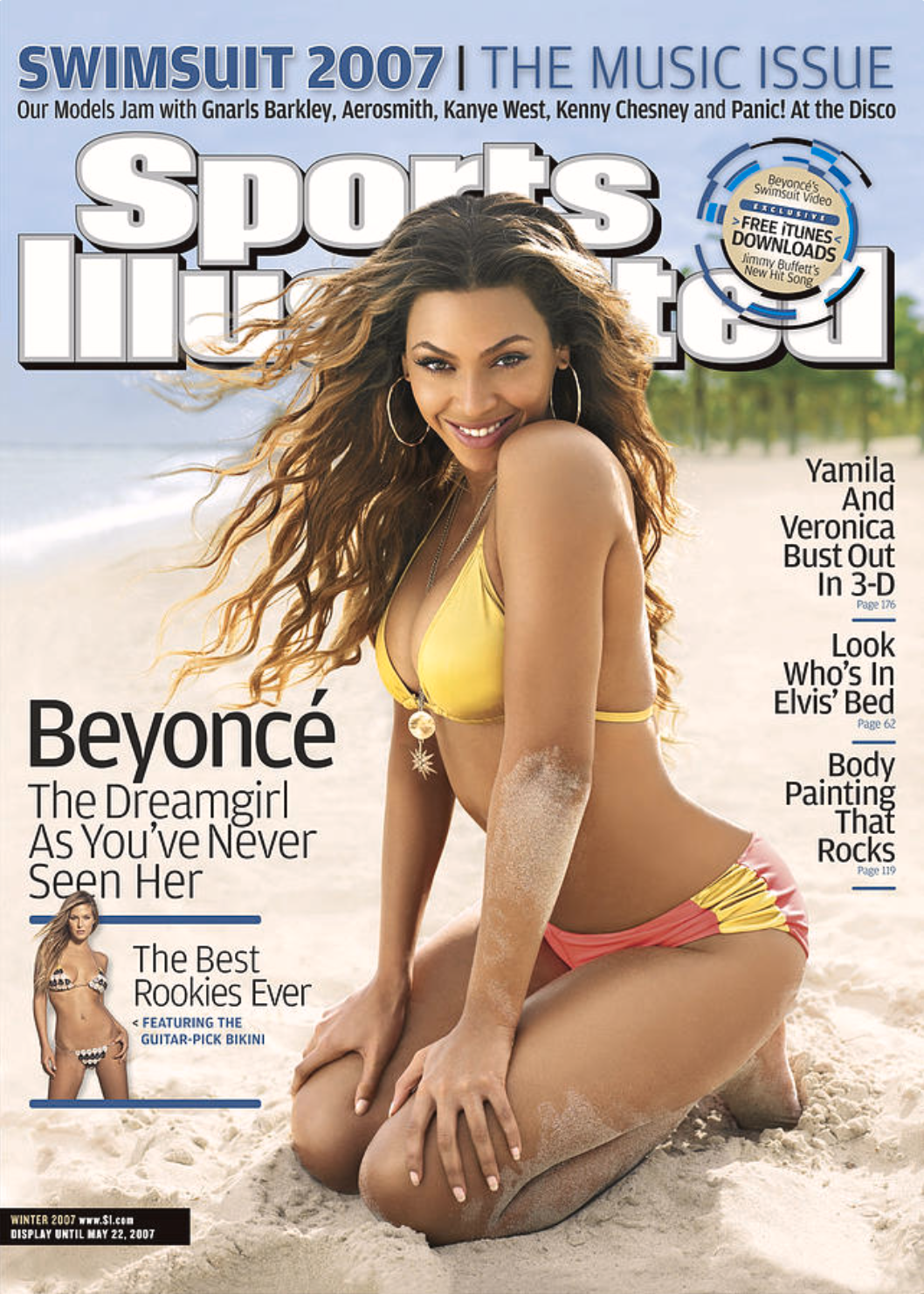

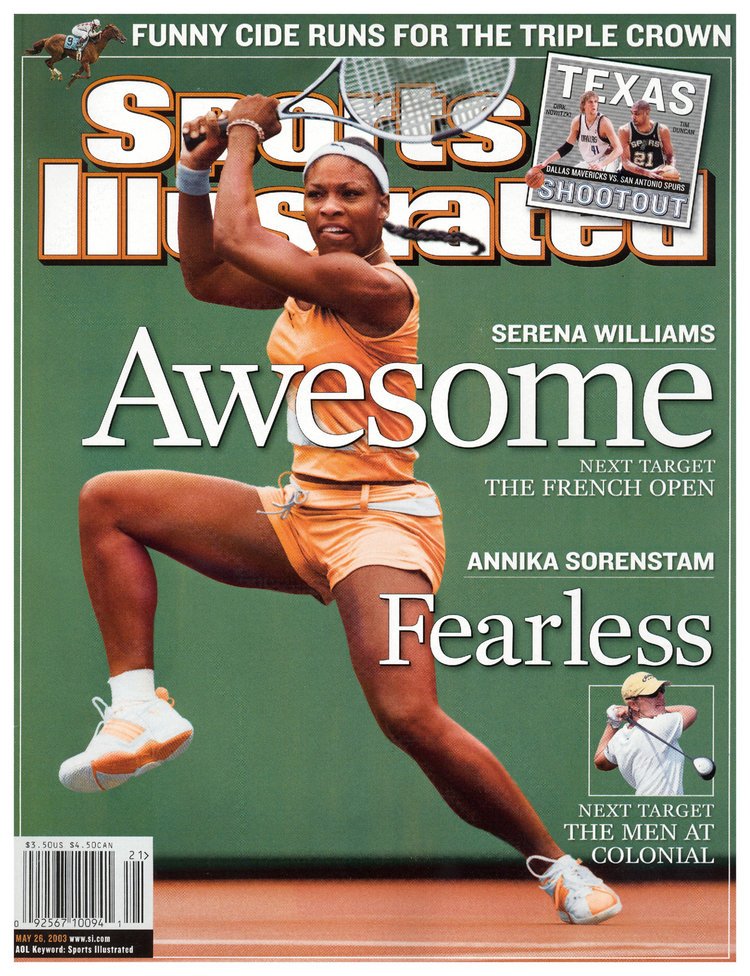

Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue.

Terry McDonell: Complicated. Stupid. Pain in the ass. Moneymaker.

Sean Plottner: Jann Wenner.

Terry McDonell: Brilliant editor. Misunderstood.

Sean Plottner: Liz Tilberis.

Terry McDonell: My best friend while she was here. Brilliant editor.

Sean Plottner: She, of course, was from British Vogue, came to America and edited Harper’s Bazaar at Hearst. How did you meet her?

Terry McDonell: Claeys Bahrenberg, who had hired her, called me into the office and said, “I’ve hired Tilberis. Would you please introduce her around?” So I met her right away. And she came out to stay with us in Sagaponack the next weekend. And it was Easter and there was a party. And we went and she met a whole bunch of people.

And from then on she was staying with me. And she always credited me, incorrectly of course, with showing her the way in New York. Because if there was ever anyone whose instincts were perfect for negotiating media minefields, and using creative firepower, talent, whatever, to create really unique things, that would’ve been her. And she’s also an extremely funny woman.

“What I will always like is something that I can feel is really touched by an editor.”

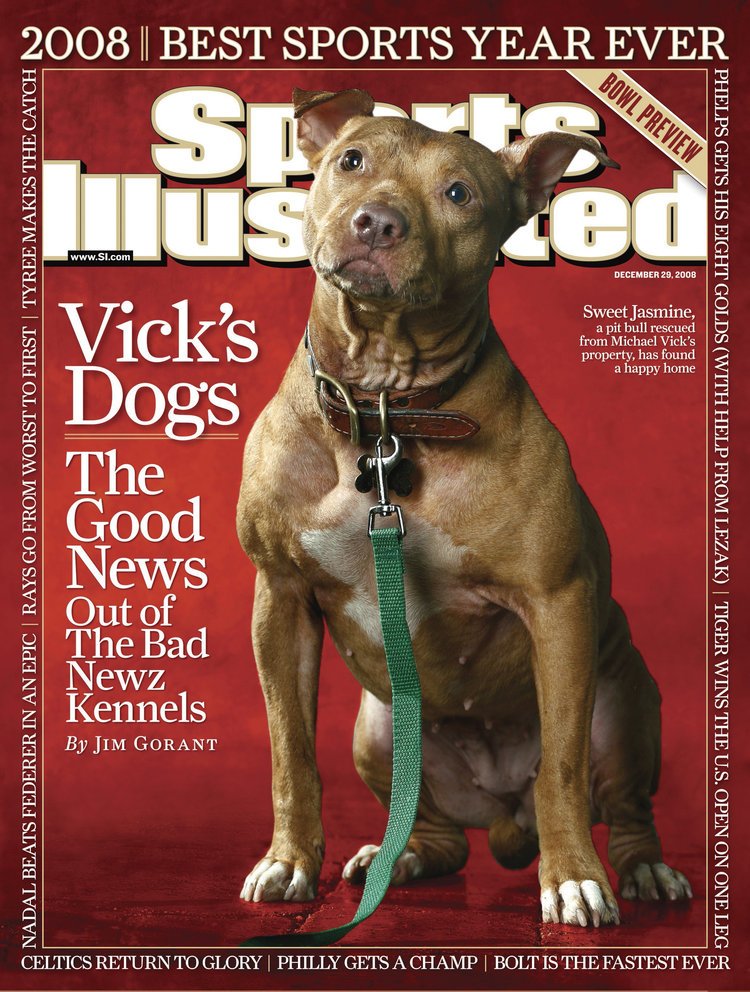

Sean Plottner: Okay. The fourth one here is: “A dog on every page.”

Terry McDonell: Ah! That was wonderful. I was vaguely bitter. No, not vaguely. I was not in the perfect mental health when I went from Esquire to the—well, no. I mean, think about it. At Esquire I would go to Fashion Week in Milan.

And then I’m suddenly at Sports Afield, and I go to the Shot Show in Las Vegas. If you don’t know what the Shot Show is, it speaks for itself. It’s the biggest gun show in the world.

So just to prove that I could do some things—and of course everyone who liked Sports Afield liked dogs. So I thought, “This is a challenge. How do we do this?” But we did it.

Sean Plottner: So you had a picture or an illustration or some form of a dog on every page?

Terry McDonell: Every editorial page.

Sean Plottner: And it was basically to say that you did it?

Terry McDonell: It was very popular. It was like the kind of a thing you do as an instinct. Or as a joke. And then somebody says, “Hey, I really like that with a dog on every page.”

So they like you. Even if they’re not saying, “Boy, that Terry McDonell, what genius! He put a dog on every page.” There’s something about it. They don’t know who I am, but there’s something about it that makes them say, “This Sports Afield is pretty cool. A dog on every page.”

Sean Plottner: And that was just a one-time deal?

Terry McDonell: Yes. You can’t necessarily do that again, I thought then. But now I’m thinking, maybe it’s time?

Sean Plottner: Well, I’m glad to hear you didn’t follow up with a cat on every page. That might’ve affected the readers somewhat differently.

Terry McDonell: Well, think about that. I mean, there are more cat magazines than dog magazines.

Sean Plottner: Okay. Your favorite poem or poet, having written some poetry yourself.

Terry McDonell: The Waste Land just lit my hair on fire when I first read it. But it would be Jim Harrison. When I was writing this recent book—after he died, there was a huge collection of all of his poetry that came out. It’s a beautiful book and they’re all there. And when I was writing that book, I would read one of his poems every day before I started work, and note the weather or something.

And that gave me some sort of inspiration sometimes. And sometimes when I was stuck, I would go and read the next poem. And maybe that’s not the way you decide who your favorite poet is, but I love that poetry.

Sean Plottner: You’ve worked with so many incredible writers. And I highly recommend your book for those who want to know more about your dealings with these writers. I’m going to pick one out here and just see what you have to say. And the reason I’ve chosen this one is because I feel like he’s being slowly forgotten. Edward Abbey.

Terry McDonell: Oh, God. Ed was just this wonderful, gracious outlaw who you just did not want to fuck with. But if you understood him and got what he was saying, which was, “What’s wrong with you people? This is the earth. This is all we have. The beauty of it changes everything in your life. And accept that.” And he was just a magnificent guy.

The way we started was—he didn’t have a phone, but he was living in Moab, Utah. And I tracked him down. He was at a certain bar in Moab, usually at this time of day for a drink. So I called the bar and I asked for him and he came on. And I introduced myself and I said, “This is Outside magazine, and would [you] like to write something maybe for me?”

And he said, “Well, the last thing I need is another editor, but I guess I could use the money.”

And so he started writing for Outside. And he would send stuff by mail and then I would do something with it. And he would be on the payphone at that bar in Moab and we would work it out. And he wrote a lot of stuff. And every place I went after that he wrote for me.

Sean Plottner: Golf. Specifically with George Plimpton and Hunter Thompson.

Terry McDonell: Well, the first thing that came to mind was Trump cheats at golf.

Sean Plottner: Oh, yes.

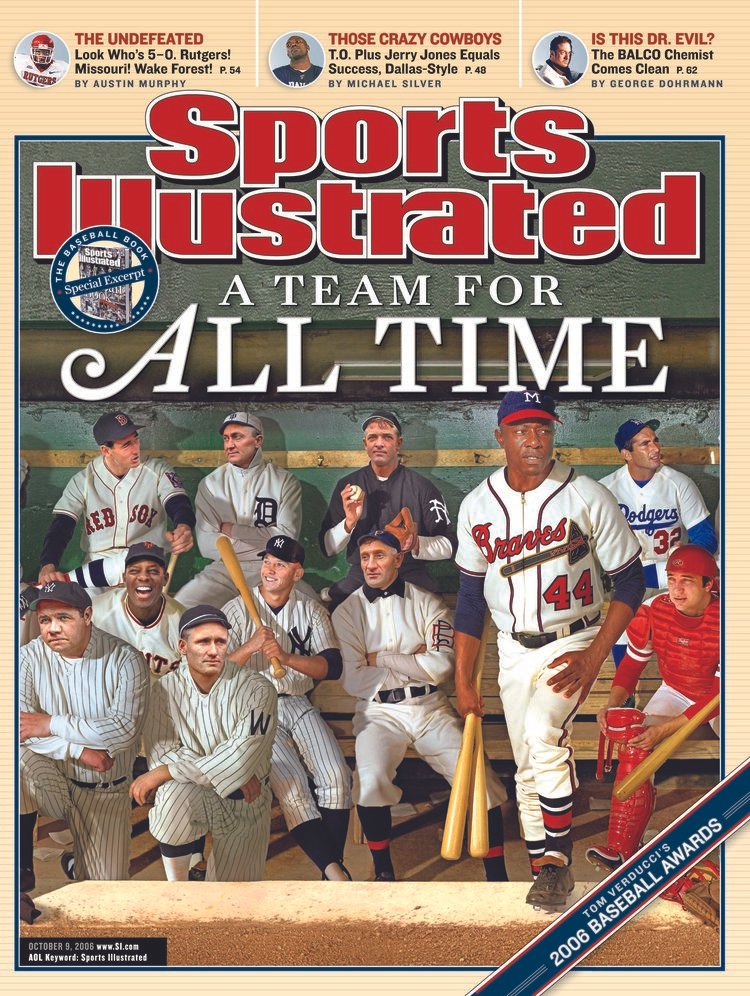

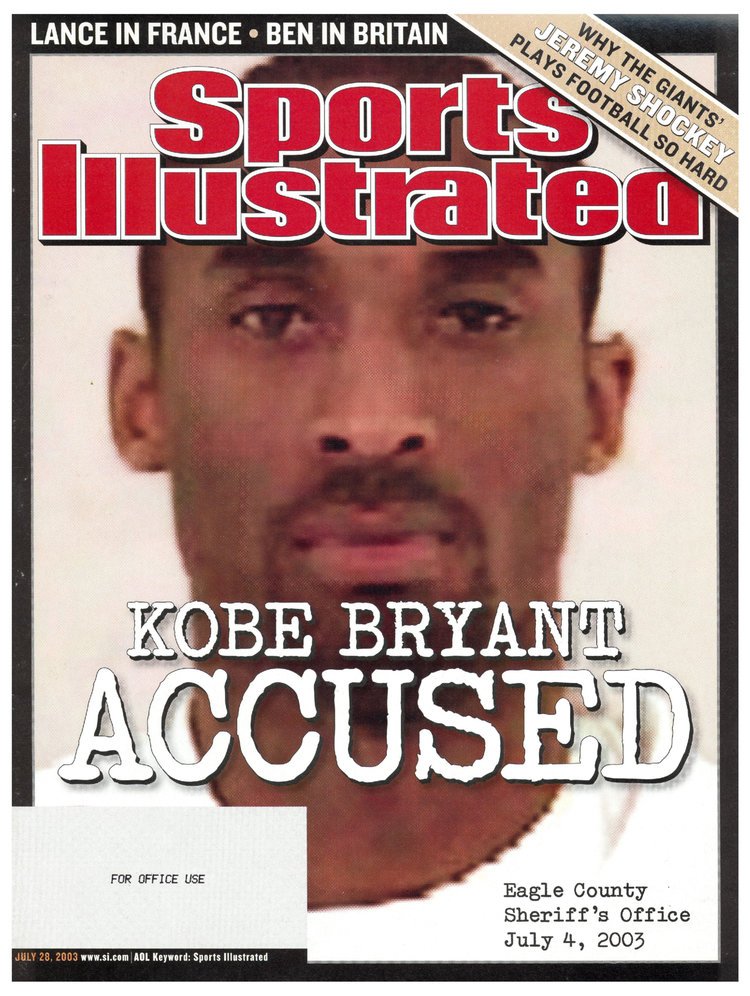

Terry McDonell: Well, when I was at Sports Illustrated, underneath the Sports Illustrated umbrella were all these golf magazines. And Donald always wanted to have his golf courses at the top of the list of best golf courses, best new golf course.

“We’ve got a golf course, the best, most classiest golf course.” And they weren’t. Clearly. But he would call up and rail at me about that. “It’s fake news,” he said. “Nah. No. It’s all fake. Mine are the best. Mine are the best. Mine are the best.”

And then Rick Reilly, who was the great columnist there, did a book called Who’s Your Caddy? And he played with everyone. He played with almost every major sports, politics, celebrity you could think about: Michael Jordan, the best golfers. And only two people out of 45 that he played with cheated: Trump and Clinton.

“I wanted it to be a writer’s magazine. And I gave some of the writers stock for being part of it.”

Sean Plottner: Of course, Rick Reilly was your highly paid, highly compensated back page columnist there at Sports Illustrated for a while. Let’s do Golf 2.0. Golf with George Plimpton and Hunter.

Terry McDonell: George Plimpton wanted to do the first Paris Review interviews—“A Journalist at Work” is what they were calling it. So he and I went out to Woody Creek to interview Hunter, and when we arrived, Hunter said, “Well, yeah. Good. But first we’ve got to play golf.” But it was late in the afternoon. It never gets completely dark out there in the summer, but it was dusky.

So we go to the Aspen Golf course. And the guy who runs it waves to Hunter as we go in and he’s driving out, and it’s our course. And in his golf bag, Hunter has a shotgun and all kinds of crazy clubs. And then he’s got a big cooler with all kinds of liquor, and ice, and just got everything. And so we’re going to play this game where you, it’s basically three holes, best-ball kind of thing.

And George is a great athlete and he, of course, can play golf. But before we start, Hunter says, “Again!” And he takes out these three tabs that have this little strange logo on them and says, “Eat this.” And it’s acid. So I do. George sniffs it and says, “I don’t know.” So Hunter grabbed it and ate that one too.

So then we are at the second hole, there’s a lake and geese. And Hunter drives and misses the green and is infuriated, because of the noise that the geese started making. He took the shotgun out of the bag and fired over the head of the geese. They all lifted off—it was this white “thing.”

And Hunter and I are on acid. It was, like, the end of the world, or heaven, or something. And George just looked at us. And then I could hear the tinkle of him making another Dewars and water. Crazy stuff.

Sean Plottner: Well, in, in your book you talk about, you were of an era, the drug culture was part of it. I think you mentioned snorting coke with Jann Wenner, which doesn’t necessarily put you in limited company.

Terry McDonell: Yeah. New York in the eighties.

Sean Plottner: Did drugs affect your work? Any influence on your creativity or your work, directly?

Terry McDonell: No. I mean, I don’t like the way it turned out, because all of that “fun stuff” ultimately killed a bunch of my best friends. Addiction was the worst thing. Alcoholism was everywhere.

We had a joke that there was an organization that Pete Axthelm made up called S.O.F.A., which stood for the Society of Functioning Alcoholics. And this was like a big joke. But when Hunter killed himself, it was because he had such terrible addiction. It didn’t end well. Ever.

Sean Plottner: Although it is tragic that he never got to write for your golf publication.

Terry McDonell: What is really tragic is he never got to cover Trump!

McDonell and George Plimpton enjoyed a memorable round of golf with Hunter Thompson.

Sean Plottner: Yeah. Wow. Okay. Just two more. Miami Vice.

Terry McDonell: Just fun and a huge change for me. Michael Mann.

Sean Plottner: You wrote an episode? Or two? Or three?

Terry McDonell: Yeah. It was really how I learned to write TV movies. I was at Newsweek and it was the anniversary of the fall of Saigon and I found this story about some people who were smuggling heroin out of Vietnam in body bags.

And I thought, “God. This is just … wow.”

And I knew a guy at Fox named David Fields, and he always was saying, “If you come across any stories that might be a movie or whatever, just let me know.”

So I told him about that. The next day, Michael Mann called me and said, “I’ve got this new show I want to talk to you about. Let’s have breakfast.”

And I said, “Yeah.” And I told him what I knew. I gave him the research.

He said, “Why don’t you write it?”

And I said, “I’ve never done anything like this. I don’t know how to do that.”

He said, “I’ll teach you.”

And it was wonderful. And there’s no better writer than him. It was fun.

Sean Plottner: Crockett and Tubbs. I had to look that up to remember, but I just want to be able to say it.

Terry McDonell: My first episode—Don [Johnson] had just emerged, “Crockett” had emerged as a huge star. Like sudden stardom. Although he had been a working actor for a long time already. And for his directorial debut, he was going to do this Miami Vice episode called “Back in the World.”

And Miami Vice then was rolling at about six days, $500,000–$600,000 per episode, a day off, do another one, whatever. This one went $1,500,000 and ran 13 days to get it done. And it was because Don was directing it and could do whatever he wanted. He got all The Doors music. Just that alone was a huge piece of cash. And it’s good. It’s a good episode.

Sean Plottner: It’s probably available somewhere on YouTube.

Terry McDonell: It’s all over YouTube. You can’t get away from it.

Sean Plottner: Okay, finally, Us Weekly. Particularly the Weekly part. I believe you took it weekly?

Terry McDonell: Yeah. That came out of business strategizing and looking at the numbers. The idea was People was, without question, the most successful magazine in the world. And it seemed to be alone in its genre. And US Weekly seemed to be more like Entertainment Weekly or something.

So the idea was if you do, like I said before, a tabloid, that is not mean-spirited. That is not about cats who walk from Seattle to Nome and go home again headlines and stuff like that. It was a friendly, happy weekly about celebrities aimed at young people in their twenties. People’s demo was much older than that. And it was, if you do this right, you can make a lot of money.

Sean Plottner: I believe Carol Wallace was then at People magazine.

Terry McDonell: Yeah. And they were just raking it in.

Sean Plottner: Yeah. And I had worked for her 10 years before at Us Magazine, when it was a biweekly. And I thought the pace was enough there. That was enough for me.

Terry McDonell: Well, you didn’t have any money, right? You didn’t have enough people. Well when we did Us, we staffed up.

Sean Plottner: Everyone always says, “Oh my god, Terry McDonell. He seems like a fish out of water at Us Magazine.” But it’s particularly, in changing the frequency, it just reminds me of something you’ve said that I just relate to so much, and that’s, “Magazines—I love putting them together.” And that’s so subject agnostic. It doesn’t matter what the content is. Talk about that—magazine making is, to be really gushy about it, it’s really cool. It’s really fun.

Terry McDonell: There’s so much to it. There’s the mix, the pacing, the visuals, the design, typography, display copy, does the package work, the cover, great writing, or great news, or great service, or whatever you happen to be doing. It’s a puzzle and it’s collaborative, and it comes together very fast at the end. And that was very attractive to me. And I think a lot of people. Like Graydon Carter says, “You have to be able to see around corners.”

Sean Plottner: You’ve also written about the importance of five key members of any magazine staff, beside the editor in chief, and of course, the art director. The four other ones, when they do their jobs really well, they’re very often unsung heroes. If they don’t do their jobs well, everybody’s fucked. They are: managing editor, copy chief, research editor, and photo editor. Could you just comment on those positions?

Terry McDonell: Yeah. When I wrote about that, it was in the context of women in the magazine business. Because many of the places where I was the editor-in-chief, all of those positions were filled by women.

And the uncomfortable—not secret at all—but the uncomfortable reality of all that was, it was very difficult for women to rise to the top of the masthead, even though they did all of those other jobs, often underneath someone not as good as they were. And a whole bunch of people knew that. And so that was going to change, but it for sure it took too long.

Sean Plottner: But it is hard to imagine getting a magazine out without those people, male or female.

Terry McDonell: I don’t mean to jump into the politics of that. But yeah, you needed all those people. Now you do not. Now you can do it yourself. I mean, look at you guys.

Sean Plottner: Yeah, there’s a lot of do-it yourself out there. And I would say that even with this podcast, in the short time it’s been around, the do-it-yourself tech behind it has evolved greatly, and I don’t even know what I’m talking about. Patrick’s the one who does it all.

Okay. Let’s go down memory lane just a little bit here. How do you look back on the “Go-Go Nineties” and how much freaking money everybody had to spend?

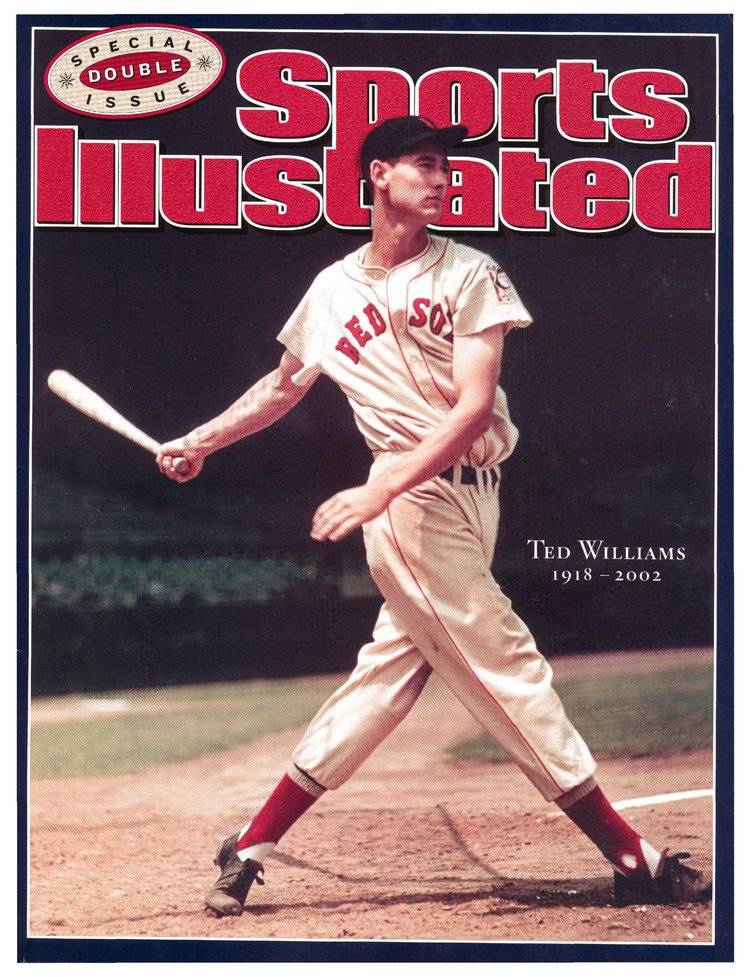

Terry McDonell: That was not really my nineties. Because it was the high point of—magazine editors made more than at any other time. But I was getting more and more excited about technology, up to the time that I got to Sports Illustrated in 2002. It was like—it’s like there was too much money. But there’s still so much money and so much inequity. It’s tragic that we are not able to smooth that out a little bit.

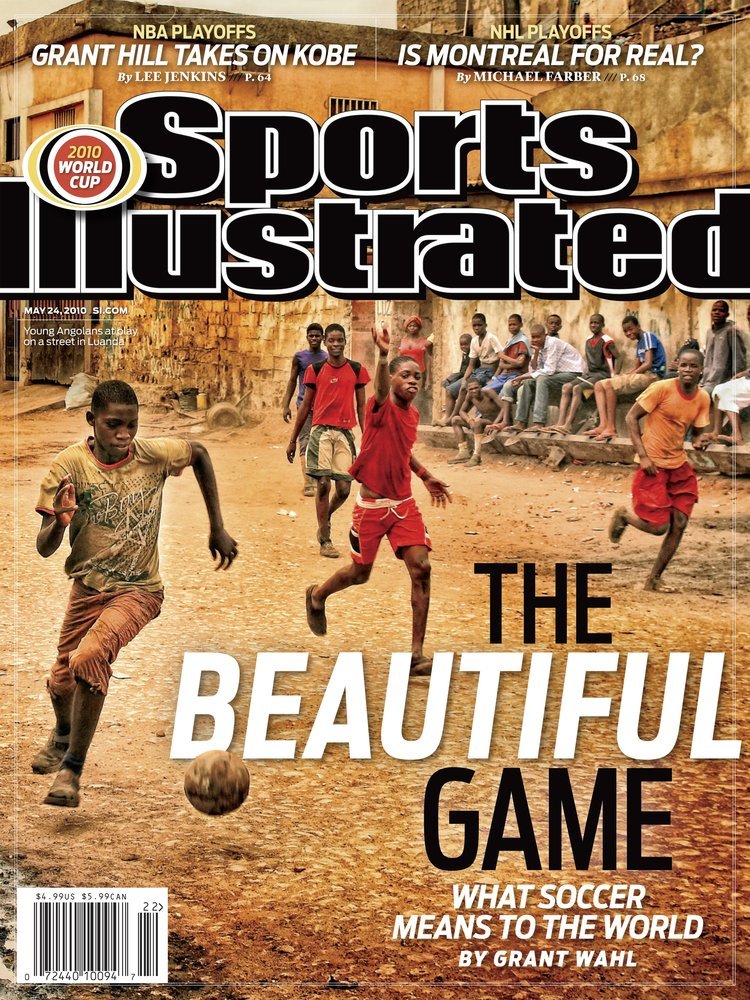

Sean Plottner: Well, in 2010 at Sports Illustrated you—and I remember it so well. It was so exciting, you developing their iPad version.

Terry McDonell: Yeah, that was actually earlier. It was 2006 or eight. The thing about Time Inc. is that it’s a great company with these great brands. And here’s—now it’s 2000—and something’s happening and it’s sort of making everybody a little uncomfortable.

But there were three very distinct cultures at Time Inc. that I saw when I got there. There was an executive culture, which was risk averse and desperate at the same time. Their P&Ls were falling and they were running—it was like trying to catch knives. Some things were falling so fast. This technology is just breaking open.

The edit culture was arrogant, defensive, clueless about what was coming, and generally thought that the people in IT could fix the air conditioning after they fixed your email.

And the people in the IT culture were ironic and more than vaguely bitter about being completely underestimated.

So it was a hard place to really get anything done. But, because of the desperation I spoke about earlier, and because I had this experience and we were doing well digitally with what we did with Swimsuit and the website, I started recruiting people from these different cultures.

And what I would do is I would invite them to join the Machiavelli Club. And then I would send them an email that would say:

“There is no more delicate matter to take in hand, nor more dangerous to conduct, nor more doubtful in its success, than to be a leader in the introduction of change. For he who innovates will have for enemies all those who are well off under the old order of things. And only lukewarm supporters in those who might be better off under the new.”

So we’re the Machiavelli Club. And it was maybe the best six months I’d ever had, when we were developing all that stuff.

“The trick to why US Weekly worked [was that] we wanted to create an American tabloid, but not mean. It was either funny or complimentary. It was fluffy-ass journalism, but it was not mean-spirited and people really liked that.”

Has McDonell edited every magazine? We just don’t know, but here are several more of his projects

Sean Plottner: What a great name.

Terry McDonell: That quote is from The Prince.

Sean Plottner: And listeners can go to your website and see the actual little demos that were put together when the iPad version of SI was being born. And they are wonderfully archaic. They really are.

Terry McDonell: Yeah. Zombie hands.

Sean Plottner: The zombie hands. And the expression that I love is, “combines the best of the magazine with the best of the web.”

Terry McDonell: But there again was that horrible dilemma—that shouldn’t have been a dilemma: Do you charge for it? Maybe it should be free? Maybe it’s an advertisement? Which just muddled the whole thing about the magazine, which was by then reduced to you get, like, a football phone, and a bad windbreaker, and the magazine 50 times a year for like 11 cents. Because it was just all out of whack—we should have been charging for Sports Illustrated what it cost. But it would become this advertising and newsstand juggernaut, which was about to tank.

Sean Plottner: I was always immensely disappointed that renewing my subscription did not get me a football phone. I never got a football phone. And damn it, I wanted a football phone.

A few years ago I discovered a website. I fell in love with it. I go to it at least a couple times a week. And in preparing for this episode, I had no idea you were one of the people behind it. Lit Hub. Literary Hub. LitHub.com. What a great site for anyone who loves books or, if we want to be fancy, who loves literature. Can you talk about what your role is with that?

Terry McDonell: Morgan Entrekin and I—he’s Grove Atlantic—are co-founders. For some years when I was at Sports Illustrated, I would take his books that were about sports and excerpt them online.

And the idea was, Well, why don’t all the publishers do that? Well, they had no connection. And so the books weren’t getting any traction or any attention and they would’ve been great across all these new websites, but it wasn’t happening. So then when I left Time Inc., we started thinking about, was that a business and would it be interesting editorially? And then all of a sudden it was.

So he pulled together all of the big five publishing houses and we got them to all become members and buy subscriptions. And for that we would put their stuff on the website, they would get advertising, and it would grow. And then we would assign some of our own.

And I drew the original wire frames, and I did that thing with Joan Didion, Read to Live, that all that took off. And then we got these really smart people—Andy Hunter and Johnny Diamond and Emily Firetog—and they just took it to the next level. Morgan is still very involved. I’m like the crazy uncle now.

Sean Plottner: Is it doing well?

Terry McDonell: Oh yeah. We’re over 5 million—the traffic is huge. And we’re assigning more and more stories. Crime Reads was spun off of it for people who are into mysteries, crime, whodunnits, thrillers, all that stuff.

That’s a whole, very vital part of the literary community now. And completely and deeply connected to television and movies and, so you get all that’s there for, to help you. And there’s also a place where the book reviews are that summarizes all the different reviews for any particular title that you can see.

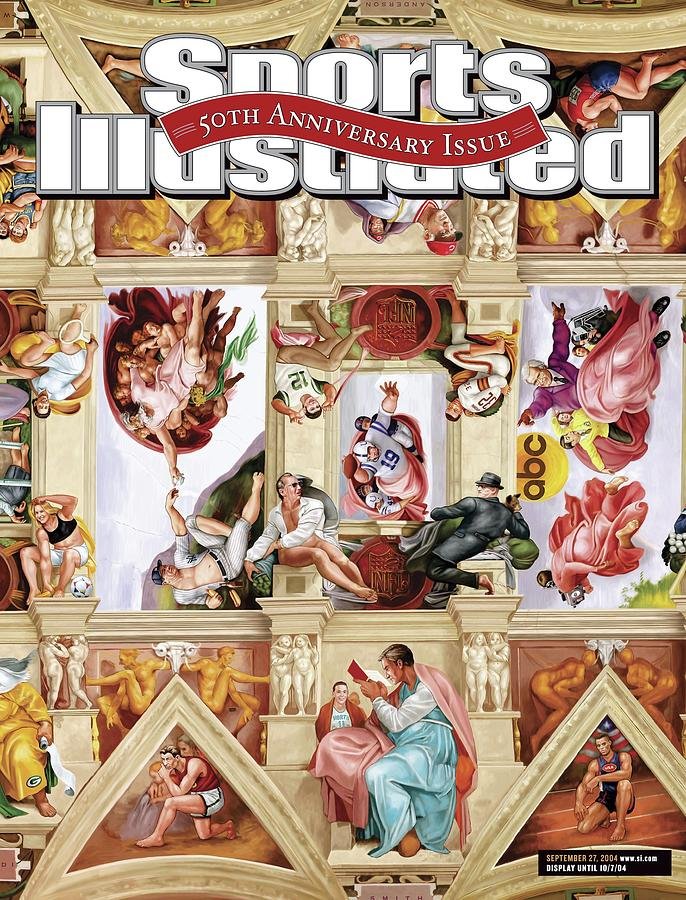

As editor of Sports Illustrated, McDonell created one of the first digital magazines for the iPad.

Sean Plottner: Oh that, to me, is brilliant. The site is dense, there’s so much stuff there. Often I’m finding new things. But, the idea of aggregating book reviews—it’s like, “God, why didn’t I think of that?” I mean, of course. And your aggregator is great. It is sophisticated, but accessible: “Here’s 10 cool new book jackets.” It just comes at the business from so many different angles. I really like that site and it’s great to hear how involved you were with starting it.

Terry McDonell: We’re trying to do a “Not The New York Times Bestseller” list.

Sean Plottner: That’s great, too.

Terry McDonell: We’re working on it.

Sean Plottner: What else are you doing these days?

Terry McDonell: Well, I have the book [Irma: The Education of a Mother’s Son], which is what got us together here, about my mother and how everything ever happened to me revolves around lessons from her. But a bunch of it’s about the media. Some of it’s about why I left Time Inc.—I once asked the senior HR executive what it was about the truth that made it impossible for her to speak it. Which was something I’m very proud of. But I did it in a meeting, and it was not good that I did that. But some of that stuff’s in the book.

Sean Plottner: Yeah, the book’s great. What about the future of media? Are we still in “let it rip” mode? How’s artificial intelligence influencing your thinking as to where things might be going?

Terry McDonell: Well, in a way it goes back to the people making the content that was valuable giving it away for free. Barry Diller was just talking about how you’ve got to find a way to work together out of business, in business, whatever. Because all those AI things are really based on other content, other places. What I think the future is about is, like, niche things that can get bigger and bigger.

You don’t start a general interest mag. You’ve got to find something—LitHub is a good example of what will work on the web. You could probably do that for bicycles. You could probably do it for toys. Maybe they’re all stores, maybe they’re whatever. But what I will always like is something that I can feel is really touched by an editor.

Like, Air Mail feels like that to me now. It may not be everybody’s taste, but for a certain [audience], there it is.

Sean Plottner: Graydon Carter’s website.

Terry McDonell: Yeah. And Jim Kelly. There’s a bunch of really good editors there.

Sean Plottner: Yeah. I get you what you’re saying. Go vertical, go deep.

Terry McDonell: And that’s a model for local, too.

Sean Plottner: I’ve noticed that Air Mail has gotten back into, comically, the magazine business somewhat with this MAGA-zine. Have you seen what they’re doing?

Terry McDonell: Yeah. It’s classic. Yes. It’s Spy.

Sean Plottner: Yeah. Oh, absolutely. It’s Spy Illustrated. And why not?

Terry McDonell: That’s where “short-fingered vulgarian” came from. That’s what they used to call Trump in Spy. Made him crazy. If you go to Graydon’s Restaurant, The Waverly Inn, on the menu across the top it says, “Worst food in New York. –Donald Trump.” They’re just blasting about that stuff.

Sean Plottner: What would your advice be to a 25-year-old who is interested in, I don’t know, journalism? Is that even a thing anymore? A 25-year-old who’s interested in journalism or media. You got any advice?

Terry McDonell: Yeah. Start stuff! Startups are where you learn the most. Try doing your own stuff. I think it’s really hard to get the kind of jobs that ultimately play to our nostalgia about what it’s like to be a reporter, a foreign correspondent, that kind of stuff. But to get there, you’ve got to go out and do stuff. At least my friends, the people that I know, that’s how they got into it. It’s never too early to try to write a novel.

Sean Plottner: Okay. We usually wrap things up with our big-money question. And this time I’m going to ask you if you were given a big boatload of money—let’s say it’s Laurene Powell Jobs. Let’s say, perhaps, she just feels guilty over the fact that her husband and his inventions helped in the demise of the magazine industry. You’ve got an unlimited amount of money. You are the editor. It’s got to be a print magazine. (It can be other things too.) You’re not worried about making money or distribution. What would you do?

Terry McDonell: I think I’m the kind of editor who doesn’t want to do something that doesn’t have a business plan that makes sense. I want what I make to be valued by the people I make it for. So that influences everything that I think about.

And I have one, actually. It’s called Passing Lane. And it’s about “move fast, catch up, learn things, speed up.” That focuses on all of the things that I’m interested in—which is maybe close to what you’re interested in, if it’s journalism, and literature, and design, and whatever. So you get stuff from all over the web—the best of the web—plus, sort of focused on these interests that I have, maybe some other people have, too.

And then I’d do a big-ass quarterly or a big-ass yearly—some big, thumping thing that pulls all that together somehow, that resonates with the old values of graphic design, and big pictures, and ironic headlines.

I have a complicated history with Steve, by the way.

Sean Plottner: Yeah! Let’s go there.

Terry McDonell: You want that story?

Sean Plottner: Of course we do!

Terry McDonell: Well, I knew him from way back. Right when he was launching the first Mac. We had dinner with a journalist from The Washington Post named Tom Zito at the time. And this is in the time when [Jobs] was doing, “it’s like a bicycle for your mind”—he had all this wonderful language. And he’s so charming and so smart. He’s great.

And over the years, I wrote a Miami Vice script on one of those early Macs, and Steve paid attention when I put him on the cover of Newsweek, and we once did a swimsuit shoot and all the model was wearing was an iPod.

But then I did that demo for the Sports Illustrated iPad [app]. So Steve comes to Time Inc. to show us the iPad for the first time. He’s making the rounds—The New York Times, everybody. And at that meeting, in one of the big boardrooms, is the editor of Time, and Fortune, and People, and EW—we’re all there.

And he comes in and he’s got these iPads and he passes them around. And the first thing that Ann Moore, who’s running the company then, does is she goes and she hits it and she happens to hit my voice saying, “Hi, I’m Terry McDonell, and here’s your new issue.” And Andy Serwer said, “So Steve, what do you think of that?”

He said, “I think that’s really stupid.”

And I didn’t say anything. And he looked over and he recognized that we knew each other, and he said, “You make that?”

I said, “Yeah.”

He said, “Huh. That’s too bad.”

And the meeting went on. And then the meeting is over and we’re all going away, and I walked by and I said, “It’s really a great thing that you’ve built.”

And he says, “No hard feelings. I was just negotiating.”

For more information on McDonell, visit his website. We highly recommend grabbing both of his recent books, Irma: The Education of a Mother’s Son and The Accidental Life: An Editor’s Notes on Writing and Writers, available everywhere.

More Like This…