The System Works

A conversation with designer Debra Bishop (The New York Times Kids, More, Rolling Stone, more). Interview by George Gendron

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT COMMERCIAL TYPE AND FREEPORT PRESS.

When I decided to launch this podcast back in 2019, it didn’t take me long to realize that I didn’t want to do it alone. The first person I called? Today’s guest, Debra Bishop.

I’ve known Deb a little bit for a long time, but well enough to know her insight, humor, and world view would elevate every conversation we’d have. But also, and more importantly, she is without question one of the most consequential editorial designers working today.

Deb has helped define the visual and structural DNA of some of the most iconic media brands of the last few decades, from Martha Stewart’s Blueprint, to More Magazine, and now to The New York Times for Kids.

What sets Deb apart is not just her eye, but her mind. She’s a master of creating editorial systems—cohesive, flexible frameworks that hold entire magazines together, giving them both structure and soul. Her designs guide readers effortlessly, creating rhythm, clarity, and a sense of trust.

Deb never overdesigns or distracts—she amplifies. Her layouts are confident, elegant, quietly powerful, and often these days, lots of fun. And as a leader and mentor, she’s shaped not just magazines but careers. She’s helped raise the standard for what editorial design can be, and what a creative partnership should look like.

Deb makes everything better: the work, the process, the people around her. Her influence is everywhere—including on this podcast—and I feel incredibly lucky to call her a friend and colleague.

—Patrick Mitchell

“It’s about the making, but it’s about it coming to you, to your desk, at the end. And there it is. It’s the thing that you have created. And I don’t think you have the same experience online.”

George Gendron: I want to start, Deb, by welcoming you. It’s thrilling for me to have you here both because I’m a huge fan of yours, and also because you’re part of the crew. Sometimes people will find you on the other side of the microphone. So welcome. It just struck me earlier today that you’re another Canadian export. We’ll come back to Canada in a little while.

Debra Bishop: It’s in the news.

George Gendron: It’s in the news. You happened to arrive in New York City from Canada almost exactly four decades ago.

Debra Bishop: That’s true. And I’ve lived here longer than I lived in Canada.

George Gendron: There you go. So now you’re not, as some members of the administration might say, you’re not a ‘foreigner’ anymore. You’re actually an American. Congratulations.

Debra Bishop: Thank you. And thanks for asking me to do this.

George Gendron: Oh, it’s our pleasure. You arrived in New York City from Canada back in 1984, and you told me you came with a friend and a boyfriend. Do you have any idea at all where that boyfriend is today?

Debra Bishop: Yes. He’s downstairs in his studio two floors down, as we speak.

George Gendron: So you kept him?

Debra Bishop: I did keep him.

George Gendron: Wow.

Debra Bishop: We came here together and we both went to the School of Visual Arts and he took his Master’s in Illustration with Marshall Arisman and Jim McMullan.

George Gendron: Wow.

Debra Bishop: The first day I went to SVA, I went up to Richard Wilde’s office and I was just, you know, this young Canadian and I was just so in awe of the whole experience. And I walked into his office and he had all these advertising awards up on the wall. He was basically the head dude in the design department. And he was so lovely, and he just said, “Oh, you’ve got to go to Paula Scher’s class.” And that’s what I did. And—

George Gendron: —The rest is history.

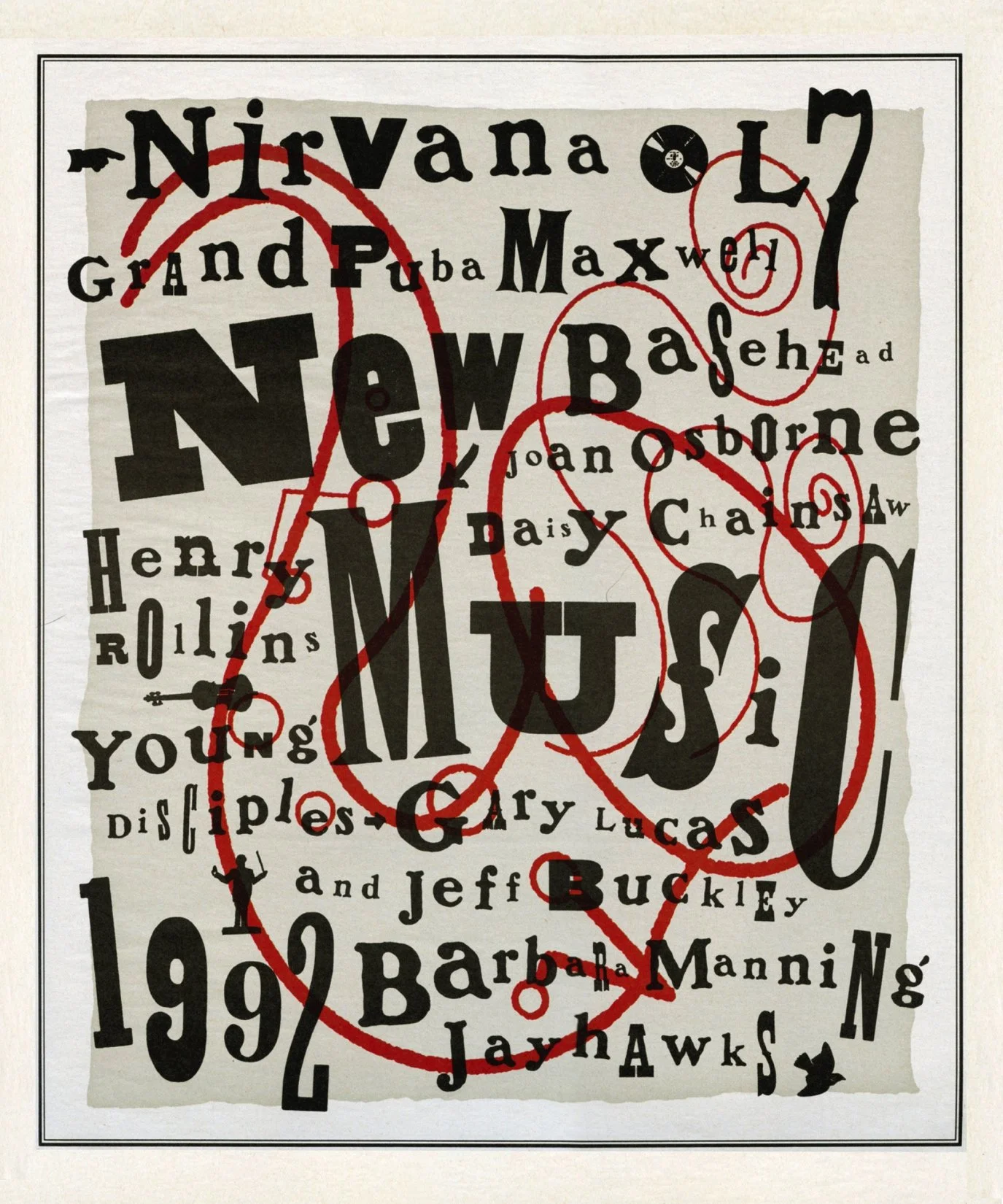

Debra Bishop: The rest is history. But the teachers at SVA during the eighties were hugely influential. There was Paula Scher, there was Louise Fili, and there was Henrietta Condak, and there was Carin Goldberg.

George Gendron: Oh my God.

Debra Bishop: And Carin and Paula and Henrietta had worked at CBS records in the record industry. And they were just so cool because they designed record covers. What’s cooler than that?

George Gendron: They were rock stars.

Debra Bishop: Exactly. And they were doing these incredible book covers that sort of revolutionized design at that time.

George Gendron: Were you intimidated by this?

Debra Bishop: Of course! The first class that I went to was Paula’s. It was a portfolio class. And I remember I walked into the room and it was just a scruffy classroom with desks spread out all over. Very un-Canadian. And there were two kids at the back. One who I still know to this day is a talented designer, Archie Ferguson and another designer, obviously a student, who was at the back. And they had a boombox on and they were dancing and they’re all dressed in black. There I was with my little le Château crop jeans and an argyle sweater.

George Gendron: Could have been worse.

Debra Bishop: And my short hair. I didn’t fit the part, but anyway.

George Gendron: When you get a bunch of magazine people together for a drink, inevitably, especially if they don’t know each other well, people start asking, “Did you have a big break? Did you have that moment when something happened, and when you look back, it changed the trajectory of your professional career, even if you didn’t know it at the moment?” And you’ve already answered that question. It was when somebody said, “Oh, you’ve got to take Paula’s class.”

Debra Bishop: Exactly. And I was so lucky that she hired me out of her class, you know, maybe about six months—I wasn’t there, you know, to get a degree. I had already been through four years of art school, I was there just for the experience and to improve my portfolio. Anyway, Paula, we somehow connected in her class and she hired me to work in her studio, Koppel & Scher.

George Gendron: So that leads to an approach you and I might take since you’ve got such a long and storied bio when it comes to where you’ve been. If we might just go from one to the next, starting with Paula, and just tell us quickly at each juncture, what were you doing and what do you feel was the one thing that you learned on what you describe as a journey? Because you talked about how you feel as if to this day you’re still learning.

Debra Bishop: Almost every job that I’ve had, I was on the learning curve. The first one, obviously I was completely in awe of Paula Scher. I mean, what a break, this little girl from Portneuf, Quebec getting to work at Paula Scher’s studio!

George Gendron: And you realized that at the time?

Debra Bishop: Oh, yes.

George Gendron: So Paula was already “Paula.”

Debra Bishop: It was a huge break. But, you know, I was quite naive and just learning but I learned the basics, initially. So, you know, I spent a lot of time in the stat room, which a lot of designers my age will tell you, “Oh no, The dreaded stat room.”

And for younger people, they wouldn’t know what that was, but it was like going into a closet and it was about 120 degrees. And then you turn on the lights, because you had to photograph—it’s such a complicated process, what we used to have to do—you’d take a picture of something and then you’d put two sheets of paper together and you had to put it through this machine with all these stinky chemicals. So not only were you in a room that was about 500 degrees, especially in the summer, you were also inhaling all of these photo chemicals.

George Gendron: Kind of like a home dark room?

Debra Bishop: Exactly. So I did a lot of that and I learned how to make mechanicals—in those days, everything had to be reduced to black and white. I used to make chromatech book comps that were, again, using ink. Basically I was Paula’s hands. But I learned a lot doing that because I would see how she designed things through creating these beautiful book comps.

George Gendron: Yeah.

Debra Bishop: And Paula was incredibly generous. I learned for the first time how to design for a client. Oftentimes when she was, for example, doing a brochure for Bloomingdale’s, she would let me do one option as well and pitch it to the client.

George Gendron: Oh, that’s phenomenal.

Debra Bishop: For a young designer, for me anyway, that kind of competition and inclusion and competitiveness was an incredible experience.

“It was not a conventional magazine environment. We were not reacting to manuscripts at all. We worked in teams and images came before the words.”

George Gendron: And so you stayed there just for people who might not have a clear sense of time here, especially when you’re talking about a stat room, you’re talking about 1984 through 1989?

Debra Bishop: I was there for about four years.

George Gendron: Four years, yeah. What a start! And then you go from the sublime to the ridiculous—you end up at Rolling Stone.

Debra Bishop: That’s right. And Paula used to say to me, “Oh, you’re really good at editorial design.”

I’m like, “No!” I wanted to design record covers. But in those days, that whole thing was starting to wind down and shrink. So the idea of going to Rolling Stone seemed just as exciting in a way.

George Gendron: How’d that come about?

Debra Bishop: I had heard that Fred [Woodward] was looking for a freelancer to work on a book. So when I went to Rolling Stone, the first thing I did was work on a book called Rolling Stone: The Photographs with Fred doing mechanicals. He’d lay it all out, but I would put it all together. And, again, I was thrilled to be there and working on that.

And then later I was lucky enough that he hired me. I don’t think he even had a position, but he wanted to keep me, so that was really wonderful. And so he hired me to work on the magazine. I learned so much there, you know. What was really fun was that he would give everybody a feature to do and it was yours.

And that was the first time that I had my very own sort of project that was pretty much mine, as long as he approved it, to work on. It was very much about craftsmanship, which, having worked, you know, on all of these comps, and also because of my schooling in Canada, I had some pretty good hand skills.

George Gendron: Yeah.

Debra Bishop: It was a biweekly, so we had three days to come up with an idea and three days to execute it pretty much. And we would work with Xeroxes and use overlays and everybody had their own system, but I would wax down my designs with Xeroxes and I would hand draw You know, with layers of tracing paper. And everything had to be inked in black so that you had reduced everything to black and white.

So I would get everything as tight as I possibly could, and then I would give it to this amazing artist—her name was Anita Karl—and she would ink it with French curves and a rapidograph. What a process for one feature! And my designs were actually pretty, elaborate so to have her to help me was pretty great.

George Gendron: This might sound strange, but for a lot of non-designers in the magazine business—and here I’m thinking both of editors and writers—Rolling Stone was a wake-up call because you couldn’t pick it up without noticing the design. Designers admired what Milton Glaser had done at New York magazine, but at the end of the day, the truth is New York was really a monthly features magazine designed to come out once a week. And so it was very functional. Rolling Stone—I can remember going into a newsroom in places and people having coffee and they were dissecting page-by-page, spread-by-spread Rolling Stone. They didn’t have the vocabulary because they were not designers, but they were blown away by it. They were just blown away by it.

Debra Bishop: Well, beside the fact that I loved working with Fred and he had such incredible charisma and you wanted to do something great for him. He was a little bit like a sports coach. And he was a great motivator, even though he didn’t really say a lot. But just to get a smile—when you would show him your design and he would smile at you, you’d be like, in heaven. It was a very eclectically-designed magazine—except for the front and the back—within the well, and a lot of people tried to emulate that.

But one thing that we did that you absolutely needed, I felt, to do such an eclectic project was the borders that we created. We had an Oxford rule that was very Rolling Stone. And that rule, no matter what you did within that border, it still felt like Rolling Stone. The importance of that design system has really stayed with me.

And just if I’m going to really think about what I really learned there, we were always doing special issues. Everybody would get to do one or two a year. And that experience was really pivotal because you had to basically create a magazine within a magazine. You learned how to package, as I call it. There was always a theme and you had to package those consecutive pages to feel like they belong together.

George Gendron: I want to come back to that because of course it’s very relevant to what you’re doing now. And I also want to come back to the word “packaging,” about which I have very strong feelings. But anyway, when you think of the thematic spectrum of magazines, you go from Rolling Stone to House & Garden.

Debra Bishop: Well, House & Garden is a tough thing for me to talk about, really, in terms of what I learned although I did learn a lot. It was a really tough time for me, both professionally and personally. I just had my first child, and I was trying to balance my career and having a baby.

And so it was just, it feels like a blur, honestly. And I was only there for a year, but one thing that I learned about myself was that it was Condé Nast and Robert [Priest] has such style and such vision, and he loves to take his time to design a magazine. But for me, a year to design the magazine was just too much iterating. I get bored really quickly.

George Gendron: They were doing a redesign?

Debra Bishop: They were bringing the magazine back after many years. And it was just all of those things combined. So yeah, that was tough.

George Gendron: What’s also interesting about that, when you were talking about Rolling Stone, one of the things that’s really interesting to me is frequency. And one of the things that I learned at New York was the value of making decisions when time is scarce. You learn to make those decisions and trust your instincts. Once in a while, they don’t work out. But I had a very difficult time going from New York, a weekly, to Boston magazine where I was the editor-in-chief, and we had a month. It was insane! You had so much time.

Debra Bishop: Yeah. I feel like for a designer, having that repetition and that speed, if you’re talking about learning, you’re going to learn so much faster and you’re going to improve. And you’re going to create much better work. Less interference, faster decisions. Some are going to bomb, but every once in a while you’re going to just nail it. Because there was less interference, because you had to come up with it quickly, you learned how to work faster. I don’t envy, for instance, what Gail Bichler has to do with The New York Times Magazine. I think that’s really very difficult to do every week.

George Gendron: Yeah.

Debra Bishop: It’s hard to sustain.

George Gendron: Yeah, it is hard to sustain.

Debra Bishop: But on the other hand, I did like the pace when I worked there. I kind of liked it. It’s just hard to sustain.

“Fred [Woodward] had such incredible charisma ... you wanted to do something great for him.”

George Gendron: When I got kicked out of Boston magazine, at my going away party somebody pointed out that at New York I had put out 150 issues. And at Boston magazine I had only done 36 issues. And I had never thought of that.

Debra Bishop: It’s trying to run in water when you have a month. I have a month to do the Kids broadsheet, though it’s not really a month because everything’s always late.

George Gendron: We won’t get into that today.

Debra Bishop: Let’s not. We’re not going to talk about that.

George Gendron: No. You went to Martha Stewart. You were there from 1996 to 2008.

Debra Bishop: 12 years!

George Gendron: Yeah.

Debra Bishop: What didn’t I learn there! Because that was really like starting over. And I know Barbara deWilde has talked a little bit about this, but that was not a conventional magazine environment. We were not reacting to manuscripts at all, the art directors and designers. We worked in teams and the image came before the words, basically.

George Gendron: Give me an example.

Debra Bishop: Okay. The story that made me really want to work there was an entertaining story on—don’t forget, Martha Stewart has a mission of showing people how to do something. It’s a how-to. Anyway, there was an entertaining story that I saw, and I was a big fan of the magazine. And a big fan of Martha Stewart.

So on the table were these chocolate cabbages. I loved those chocolate cabbages. I was like, “Oh my God, I want to work there.” Now that kind of story would’ve been done by you know, probably a foodie. Possibly with a stylist. and they would create the cabbages—the ideas could come from anywhere at Martha Stewart, really.

George Gendron: But wait a second, just so we understand this, because I have to say, if you had given me 10,000 guesses about the object you were going to pick, a chocolate cabbage would not have been one of those things.

Debra Bishop: Well imagine, George, a whole table. It’s an Easter table. You walk in and everyone has a full chocolate cabbage on their place setting.

George Gendron: So it wasn’t a cabbage that was covered in chocolate.

Debra Bishop: No, no, no. It was all chocolate.

George Gendron: Of course it was.

Debra Bishop: It was so beautiful. Anyway the whole thing is that we would work in teams. That was probably one part of the Easter dinner, and all the testing and all of the creating would’ve been done in the kitchen, the style department would come up with how to decorate the table, we would photograph it and then the writer would probably come to the party.

We’d probably have a real party—no, I’m not joking! We would have a real party and the writer would come to the party and there would be how-tos where you’d have to show people how to make the chocolate cabbages.

So it wasn’t like somebody sent you this lovely, beautifully-written manuscript that then we would go shoot to. It was the opposite. But it made sense because we were trying to show people how to make things.

George Gendron: One of the things I remember most vividly from maybe the very first conversation you and I had, and you were talking about Martha, and I said, you know, “What was really memorable?” And you said to me, “Twelve Months of Cupcakes.”

Debra Bishop: Oh, that’s right. I forgot. Oh, can we start over? I’ll use that as an example.

George Gendron: Oh, man! Who were the guests?

Debra Bishop: Well, that was one of the most fun moments at Martha Stewart Kids. Our audience was parents for the most part, and the best selling stories in the magazine was what kind of treats parents could bring to school or for a birthday party.

So we all sat down at this huge table. Jodi Levine, who has been my creative partner for many years, was the head of the Kids magazine. And we created this whole table full of candy and the food editor brought the cupcakes and we all sat down and created these different cupcake toppers.

George Gendron: I’m going to make sure that we send an invitation to listen to this podcast to RFK, Jr., given his fondness for sugar.

Debra Bishop: Oh dear.

George Gendron: So you did Martha Stewart Kids, but you also did something that I, frankly, I have to say, I’m a huge Martha Stewart fan. I’m a decent baker now all because of Martha Stewart and her book about pies and tarts. And we could devote the rest of this podcast to just—

Debra Bishop: —I could talk tarts as well.

George Gendron: Okay. That’s going to be on our spinoff, right?

Debra Bishop: Okay, good. Yeah. We may need another couple of hours.

George Gendron: Yeah. “When Designers Redesign a Tart.” You were also doing Blueprint, which I really loved and I thought it was a really clever concept, but it only lasted for, what, six issues or something like that?

Debra Bishop: Yeah. Blueprint was a magazine—I didn’t have the title special projects art director, but I was doing a lot of special projects. And you could say that Martha Stewart Baby, Martha Stewart Kids, the Martha by Mail catalog, those were all special projects.

I never worked on the big magazine [Martha Stewart Living]. For Blueprint, they wanted to lure in a younger audience. And that’s what we did. It was targeted at a 30-year-old who was beginning to “nest,” as they say. And those kinds of magazines were in the air. There were a few other ones. I think Condé Nast had started Domino around the same time.

I loved working on it. In terms of design, I think that what we wanted to do was combine a tomboy-ish something that said Blueprint with something more feminine. And so we ended up with this kind of garage font and that became the logo.

And a lot of people really liked that logo. It has a following of sorts. It was a very difficult font to work with. And I had to tell all the designers, you can only use one word with that—I can’t even remember what it was called. But anyway it was a difficult time at the company.

“[More] was literally the hardest project that I’ve ever worked on. But you don’t get points in the design world for difficulty.”

George Gendron: I was going to ask about that because Martha had just been released from prison. I think she might have still been in home confinement for six months.

Debra Bishop: Yeah. It was difficult. And I think that, financially, Blueprint just became cumbersome.

George Gendron: Yeah.

Debra Bishop: It was a very expensive venture as well, because whenever you do entertaining stories, decorating, all of that kind of thing, it gets very expensive.

George Gendron: So in 2008 you moved over, after a long stint with Martha, to More magazine. And to me at a very interesting time because in 2010 they did what I thought was an extraordinary redesign and that was yours. And I thought that was an extraordinary magazine. And I thought somehow the impact of More and Domino, maybe Domino a little bit earlier, almost ushered in a kind of new category?

Debra Bishop: After Blueprint folded, I obviously was looking for something else. I didn’t really want to leave Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia because I loved it there. But Lesley Jane Seymour came along and said, “I’m looking for somebody to do More magazine with me.” And I remember not really wanting to do it.

Truthfully two very different kinds of projects—like anything at Martha Stewart is not something like that. It was a more conventionally-run magazine again. So I’d be, you know, back into reacting to manuscripts, et cetera, et cetera, and trying to brand it. But I thought, If I can go there and then turn this around, I’ll be golden. That’s what I thought.

George Gendron: And I’m sure you shared that with Lesley.

Debra Bishop: Yeah, absolutely.

George Gendron: Oh, you did?

Debra Bishop: Yeah, sure. I mean that’s what we wanted to do. We wanted to redesign it. I went there to redesign it.

George Gendron: Oh, I didn’t realize that. I thought maybe Lesley thought things were fine.

Debra Bishop: No, we both felt the same way. It needed to be redesigned. Anyway, I worked there for seven years and I redesigned the magazine three times during that time. I think that by the time of the last one—I’m very proud of the last redesign that we did—but by that time it was kind of—

George Gendron: —Is that when you changed the trim size and everything?

Debra Bishop: Yes. And by that time it was a bit of a Hail Mary, you know. We only did about, I don’t know, nine issues. And then it was gone.

George Gendron: I was always a little bit surprised that they didn’t want to at least experiment with it digitally.

Debra Bishop: I don’t think Meredith was there yet in terms of digital.

George Gendron: Yeah, you might be right.

Debra Bishop: That was a hard company for me to work for after having worked at such a creative company at Martha Stewart. Going to Meredith was so much more of a sort of a marketing enterprise. But they really did support More because it had been started there.

But you know, when you’re just talking about design, what I learned there, it’s very hard to walk into a magazine that you’re not all that familiar with and change it. And so the first redesign was very wobbly. And then the second time I felt like we had the wrong idea. Maybe I had the wrong idea.

George Gendron: What was the first one?

Debra Bishop: The first one was when I walked in the door and we didn’t do that much. We tweaked it. It was a very complicated magazine to work on. And it had a lot of contradictions. In the beginning Lesley wanted the celebrity to have her hand on her hip, and she had to be wearing an evening gown. I mean, it was impossible.

George Gendron: Oh God. Some editors, there’s such control freaks.

Debra Bishop: I think she felt that this was what the company wanted. And so then the second incarnation, I feel like we moved towards it being like an Esquire for women. And that was difficult to do. It didn’t really quite work.

And then by the time Lesley and I had both been there a certain amount of time, I think we were much clearer on what it needed to be. And I’m very proud of that. It was literally the hardest project that I’ve ever worked on. But you don’t get points in the design world for difficulty.

George Gendron: Yeah. Don’t I know.

Debra Bishop: It was difficult.

George Gendron: There should be points for difficulty.

Debra Bishop: Yes.

George Gendron: You’re reminding me of the redesign that we finally did at Inc. Our owner was so difficult when it came to the visual identity of the magazine, which was until Patrick Mitchell came over.

Debra Bishop: Who? Was he there?

George Gendron: Yeah!

Debra Bishop: Yeah.

Projects for The New York Times Mag Lab, which led to the creation of The New York Times for Kids.

George Gendron: He came over and did just something that was extraordinary. And I’ll never forget, I was leaving at that time, and at my going away party, Bernie Goldhirsch got up and said, “You guys are artists. I don’t know how you do this. This is like a miracle.” And I thought, Where were you for 20 fucking years—after having killed designs by Milton Glaser, Walter Bernard, Stephen Doyle? It was unbelievable, but yeah Pat did a brilliant job and I know how difficult it can be. But I want to stop here for a minute, because we’ve been speaking of Kids on and off, and I want to move over to what you’re doing now, which I think is just spectacular. And that’s The New York Times for Kids. And I can’t begin to tell you how brilliant it is. Maybe you hear this all the time, but I have never heard more excitement and anticipation from people who are not media people about The New York Times for Kids. It’s just extraordinary.

Debra Bishop: That’s so wonderful.

George Gendron: It just stops people in their tracks.

Debra Bishop: Wow. I had no idea. But I know that people like it. It started as just an experiment at The New York Times. I was hired to work at the magazine and then Gail Bichler asked me if I would be interested in doing these broadsheets. And Kids was one of them. So it was just an experiment. We did one issue in 2017 and people really liked it.

So then we ended up doing more, clearly. And now it’s monthly. It comes out the third week of every month. I started it with my editorial partner, Caitlin Roper. And it’s, you know, having worked on several kids projects—or at least three at this point—what we wanted to do was create a project that we liked. We’re both parents. Something that wasn’t out there.

We didn’t want it to talk down. We could have made something like the tiny Times, in other words, like something that was just a replica of The New York Times. Those kinds of projects usually end up being stepchildren and why bother? We wanted to create something that didn’t talk down to kids, that we would like ourselves, and that gave kids a seat at the table.

George Gendron: I think you just said something that is so important for anybody who’s involved in anything where you have to create a sense of audience. And that is you start with something that you want to make, that you want to read. It’s not some kind of strategic process, where you’re going to use a little design thinking and bring some kids in. It’s—you’re parents.

Debra Bishop: Absolutely.

George Gendron: What do we want to make? What do we want our kids to have?

Debra Bishop: But let’s not forget that making something for kids, at least most projects, have to get past parents first.

George Gendron: Sure.

Debra Bishop: And a lot of times parents are buying it. And so the smart thing to do is make something that adults like as well.

George Gendron: Yeah.

Debra Bishop: That works great for me because I want to do something rock n’ roll. I want to do something cool. When I was little growing up, I wanted the coolest, latest thing that I could find. Whether that was a comic book, or a deck of cool bubblegum cards, or the latest, coolest outfit, or even a TV show.

And so it needed to be the same. It needed to be able to be a destination that people would go to. Not just, “Oh, here’s the dumbed-down version of the news.” It’s news-based, but it’s its own destination. How do we do that? We do it with great branding.

The idea that we took the New York Times logo and blew it up initially, the idea there was, “Oh, maybe they could color it, maybe they could…” make it as interactive as possible because of course you’re competing with digital products. The idea of playing with it actually emphasizes the strength of The New York Times logo. The fact that you can cover it up, blow it up, have a dinosaur run through it, and it’s still The New York Times logo gives it power.

George Gendron: You could do a case study just on that, right?

Debra Bishop: Yeah. And I love the idea that, of course, each issue is bespoke. And I love to package, so of course that was really fun.

George Gendron: How big is your team? If you did an org chart, you have The New York Times—

Debra Bishop: Yeah.

George Gendron: —under that you have The New York Times Magazine. If my parents were still alive they’d call it “The New York Times Sunday Magazine.”

Debra Bishop: Right. Yes.

George Gendron: And then under that, you have, what is it, a lab? What do they call you guys?

Debra Bishop: Well, Initially we were The New York Times Magazine Lab. And Caitlin was involved in that, and myself, and we had an editor and designer. And then when they decided they didn’t want to do that anymore, then we became New York Times Kids. I also do Puzzle Mania, which is another section that we do bi-annually.

George Gendron: Yeah. You should do that more frequently.

Debra Bishop: But it’s just me and it’s Fernanda Didini and Mia Meredith—that’s it for the art department. And then Molly Bennet is our editor and she works with two other editors. So it’s six of us all together.

George Gendron: Small team.

Debra Bishop: Yeah.

George Gendron: Very labor intensive, the Kids issues.

Debra Bishop: They are a lot of work. And I think people can see that it’s special. We put a lot of love and passion into every issue. We only do four special issues and then we do eight regular issues. So a regular issue would be using our format—the cover and the center spread are linked but we have a format that we use, a design system. But when we do the special issues, we shake everything up. And we will create a whole new design template for those issues.

George Gendron: Yeah. Why not make it even harder and more labor intensive?

Debra Bishop: Exactly! Well, you know, a lot of these things I did learn at Martha Stewart. We do a lot of comping so that we can actually see what a cover might look like or what a certain illustrator might do well.

We are very careful about trying to package the issue, even if it’s a regular issue. So we’ll pick maybe five illustrators to hold the issue together. We’ll use a color palette, which is something that I learned at Martha Stewart. Color is huge when you’re trying to package.

Then at the end we kind of circle back and do these little, what we call sprinkles. So all of these things help hold it together. How we keep it on brand, New York Times-wise, is obviously that the logo plays a big part. Black is our favorite color. We use a lot of black, which is not typical for a kids’ product.

George Gendron: Very dramatic though.

Debra Bishop: We anthropomorphize, which is we’ll take—and this is much more kid-centric than adults, but it makes adults laugh—the idea that you’ll turn a plant into a little human or give animals human characteristics. That’s an old book trick. We can definitely take our cue from Pixar or Disney in terms of great stories, beautifully illustrated. But they’re for parents and kids.

George Gendron: At one point I heard you saying that you guys try to sketch out themes as far as a year in advance?

Debra Bishop: What we’ll do is we all work together on what the year might be in special issues. So we come up with four special issues as a team. Molly will decide what special issues that we’re going to be doing. We just did one called “The Huge Issue.”

So we do plan those in advance, but we can’t work in advance until we get the manuscripts because this is a much more conventional way of working. And also because it really has to do with the news.

George Gendron: You at one point said in terms of methodology that your center spreads are very important to the overall theme of the issue and often, I think you actually used the word “dictate,” our covers.

Debra Bishop: Yeah.

George Gendron: Can you explain what you mean by that?

Debra Bishop: What I mean is the center spread is the big “ta-da!” moment. It’s like the big feature. What we do is not necessarily a broadsheet. It’s a mixture of magazine and newspaper. When I first started the project—that was Jake Silverstein’s directive. He said, “The magazine’s over here on one side, the newspaper’s over here on that side. You’re somewhere in the middle.”

And I really took that to heart. And I think that’s really what we do. And so that middle—it’s big, that center spread. That’s like our big feature. We want to make sure that whatever’s featured in there—the scale—is worth that much space. It’s not going to probably be a write-through of 5,000 words because that’s not right for our audience. We’re much more visually-centric.

Sometimes we’ll do a cover that’s more of an eclectic mix, that’s almost like a visual contents page, if we decide to go that route and not connect it to the center spread. So those two things are linked. On a special issue it’s more all-encompassing. Every page relates to the other, whereas in a newspaper, if you think about it, it’s a very eclectic mix of stories. You might have three or four stories on a page.

“We wanted to create something that didn’t talk down to kids, that we would like ourselves, and that gave kids a seat at the table.”

George Gendron: Other than Jake and Gail at the magazine, do you guys get feedback in any systematic way from the Times overall about what’s working, what’s not working, what do people like, what do they not like? Or is it just anecdotal?

Debra Bishop: It’s just anecdotal. We often will get compliments, especially if we’re really hitting the mark. Like with our election issue. It was wonderful to have something like that for kids that sort of ran together with the newspaper. We’re just a small group—I think that they love having us. We’re really there to enhance the Sunday newspaper. We’re there to gain subscribers and a younger audience.

George Gendron: Does somebody measure that in some way?

Debra Bishop: I never get numbers.

George Gendron: Do you want numbers? Would you like to see numbers?

Debra Bishop: No, I actually, I don’t want numbers [laughs].

George Gendron: Welcome to the club.

Debra Bishop: I’m just so happy that I’m still working on it. And it’s still going.

George Gendron: I’m curious—you’ve had such a storied career. Have you ever really screwed up?

Debra Bishop: Oh, always. Of course. Everybody’s screwed up.

George Gendron: But have you screwed up in a way that was actually public?

Debra Bishop: I think I screw up more when I’m doing things like this. That’s why I don’t like doing it.

George Gendron: Oh. Not so far, but we have a little time left.

Debra Bishop: I asked my husband Garnet, “When did I screw up the worst?” And he said it was when we were asked to talk at our school and I spoke for two whole hours. And he missed his slot because he was up after me. And he’s telling me to shut up, like in sign language, from the audience. And I just went on and on and on.

George Gendron: I am shocked to hear that.

Debra Bishop: Give me a stage and I might really screw up.

George Gendron: If that’s the worst someone can say about you, you’re fine.

Debra Bishop: Well, I mean, we all make mistakes and, you know. I think I probably made more mistakes when I was younger.

George Gendron: I just have a couple of quick things that I wanted to talk about. One is that you use a word, “packaging” that is near and dear to my heart, I know Pat’s heart. And we think of it as the ultimate process when you’re making a magazine. It’s like synthesis, right? You’re taking all of the elements and pulling them together to achieve a certain effect. And for some reason that I can’t understand, people almost object to the word now.

Debra Bishop: Oh, they do? Because I use it all the time. That’s what I love to do.

George Gendron: Yeah.

Debra Bishop: Maybe there’s a new word for it, but I love to work around a theme. I love to have an idea or a sense of what an issue is about. For instance, Kids, “The Huge Issue,” and then, package it.

One thing at Martha Stewart that I learned when I did Martha Stewart Kids was—Jodi Levine, who I worked with for many years, was the editor of Martha Stewart Kids. And we would work on the lineups together, side by side. And it was just like being in art school. So I’m used to that. You really can’t package unless you can collaborate on that level—the visual with the editorial.

George Gendron: For almost everybody that I’ve had conversations with for this podcast that’s the thrill. It’s that process of collaboration.

Debra Bishop: That’s very magazine-like, right? It’s not like that at newspapers because that has to be very much a system. The stories all just get poured into those spaces and the photographs or the illustrations, everything gets poured into that system. I do like creating a system, but in magazines, it can be one complete thought.

You have the ability to package because you can affect the cover. You can treat it as a sort of evolving—you can see the pages turning and one story can fold into the next. Whereas newspapers, every story is very separate.

George Gendron: This leads to something else you and I have talked about, which is at one point we were talking about the difference between designing for print where there’s a tangible object involved and digital design. And you were saying you weren’t being judgmental about it, but you said, “Look, it’s a completely different job, digital versus print.” And then you went on to say, “I actually often don’t think of myself as designing when I’m thinking about what is the thrill, I think of the making of things.” And Pat and I have talked about this for as long as we’ve known each other. That’s what it’s about. It’s the making of something. And what’s interesting about that phrase is it gets back to collaboration. It’s not about the thing, it’s about the making of things.

Debra Bishop: Right. And it’s about the making, but it’s about it coming to you, to your desk, at the end. And there it is. It’s the thing that you have created. And I don’t think you have the same experience online. Everything is more fleeting. Not only are you packaging—but you get a package at the end. It’s tactile. It’s something that you can save and say, “This is something that I’m very proud of.” It’s like making art. It’s the same thing as creating a renovation or making a beautiful clay pot. In magazines we got to do that.

George Gendron: Yeah. In fact, Tina Brown was very explicit toward the end when she said, “People just don’t understand that magazine making is an art form.” So anyway, I want to wrap this up with what we call The Billion-Dollar Question. You probably have heard it asked by us. And that is that if somebody heard this podcast and thought, Oh my God, this is the woman who creates that thing that I love. In fact, I love it so much. I never even bother passing it to my kids. And they call you and they say, “Look, I’d like to give you a check for a billion dollars. And you can do anything you want with it, as long as you make something in print.” What would you make?

Debra Bishop: I have heard this question before. And I should know how to answer it. I am so lucky that at the end of my career—not the total end, but near the end—I’m doing exactly what I like to do. And I have to thank The New York Times for that. I’m very grateful for it. I love to package. So if I was going to create a magazine, it would be theme-based, but it would be very eclectic.

What I’m doing now, but you’d have a theme like—okay, this sounds really banal—but like “The Sea.” But you might have fashion, you might have a wonderful essay, you might have an entertaining story. And I’ve always loved that. I’ve always loved very eclectic content. But held together with a theme.

George Gendron: Well, I like that idea a lot, because one of the things that’s happened in our culture, understandably—and it’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it has very serious consequences—is the specialization of everything. So if I’m very interested in the sea on a lot of levels then I subscribe. I even subscribe to academic journals and stuff. But I love the idea of a general interest magazine.

Debra Bishop: Oh yeah. So many different angles. You could do an article on deep sea fish— which is fascinating to me—or you could do a great article about how Coco Chanel started the striped boat neck shirt that was from French sailors.

Or you could just have a glossary of the different colors of the sea. It’s a paint chart because blue, the color blue for your wall is incredibly hard to get—trust me. I painted my dining room blue—I’m in the middle of a reno—and I hate it. So now I’m going to have to repaint it, but I have to wait.

George Gendron: Where do you go to look for your palette? Do you go to Farrow & Ball?

Debra Bishop: I did go to Farrow & Ball. And I even got their expert to come help me. But blue is tough. Blue’s a tough color.

More from Print Is Dead (Long Live Print!)