The Shop Around the Corner

Introducing our newest show, The Next Page Pod, featuring a conversation with former designer—books at Knopf, magazines and more at Martha Stewart Living, apps at The New York Times—and now bookstore proprietress, Barbara deWilde.

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT COMMERCIAL TYPE, MOUNTAIN GAZETTE, AND FREEPORT PRESS.

I was a publication designer for 20 years, making book covers at Knopf with Sonny Mehta, Carol Carson, and Chip Kidd. Later, in the early aughts, I made stories and books—and other things—at Martha Stewart Living. Then I took a brief adventure to graduate school—to learn a new trade. And finally I moved to The New York Times, where I helped create several of its legendary digital products, like NYT Cooking.

In December 2020, I bought a building on the Delaware River—and opened the Frenchtown Bookshop.

My name is Barbara deWilde—and this is The Next Page.

There’s a lot of talk these days about the new arc of a career replacing the long-standing one—at least in our business—of “work until you drop.” And given our focus here at Magazeum, we’re painfully aware that, for many, sudden change comes earlier than expected.

But magazine people are built different. And these days, with an industry in turmoil, more of us are resetting intentionally—creating a “second act” that’s often more purposeful than our prior work, doing something we’re good at with people we trust and admire. Over and over, we’re meeting more and more experienced magazine makers who tell us they want that for themselves.

We believe that creative magazine work—call it “magazine thinking” and its related skillset—can be a powerful driver of individual professional change.

The Next Page is our new podcast series featuring conversations with magazine creators who’ve left high-profile positions to see what comes next. We’re glad you're here.

Above, a selection of deWilde’s work at Knopf

“When Barnes & Noble became a major presence in retail, it was suddenly like having gallery space for graphic design.”

George Gendron: I’d like to start off with you giving us a brief overview of your media career. Think of it as the equivalent of a “verbal” LinkedIn. Although I don’t even think you have a LinkedIn page, do you?

Barbara deWilde: I do have a LinkedIn page. My media career, I started at Knopf as a freelancer designing book covers. Actually, I started making mechanicals for other people’s book covers. Mechanicals were those handmade, separated layers of film that printers used to print. I had a desk, not a full time job, and I signed a contract every time I did a book cover. Slowly over time, they just couldn’t get rid of me. I just stayed.

And I worked there very happily for um, 12 years. From there, I jumped away and worked at Martha Stewart Living. I started really just to help out. There was a new magazine coming out called Baby that Deb Bishop was working on. She needed a hand. She was having a baby herself. I finished that project then moved over to the main magazine.

That was just at the time when MSLO (Martha Stewart Living OmniMedia) was going public. So they were in a period of enormous growth. I ran the magazine division. Magazines and books. From there, I left after about four years and worked out of my home in a very small capacity, just exploring smaller projects. That MSLO job was big and I needed a bit of a breather.

And I got recruited back into the magazine world. I worked only for about a year at Hearst then I went back to Knopf. And I went back to Knopf and I thought, what do I really want to do? And those are hard questions that you ask yourself, what do you really want to do?

George Gendron: People often don’t realize how difficult it is to do that for yourself. Some of us are very good at helping others.

Barbara deWilde: So much easier! And I had a wonderful weekend back at my alma mater Penn State. And I thought, Oh, I know what I want to do. I want to be a teacher. And so I looked at all the job postings for graphic design professorships and realized that I wasn’t qualified after all this time and all this experience. The main attribute that a college wanted was expertise in interactive design. And I didn’t even know what that meant.

So I had to go on something—I’m in exploration mode, asking everyone I knew who was in a digital role, what it meant to be an interaction designer. And ultimately, I found that this was a world that I couldn’t learn on the fly. I couldn’t learn while I was doing a job. I needed to stop. I needed to go back to school.

It was a pretty difficult jump, but I spoke with Liz Danzico at the School of Visual Arts, and she had just started an MFA program in interaction design. And I applied and I got in. And I spent the next two years in learning mode just dropping my expertise and starting over. I graduated. Um, I got a job.

George Gendron: How old were you—if you don’t mind my asking—when you graduated?

Barbara deWilde: Aren’t you charming. I was 51 years old.

George Gendron: In a class where the average age was, what would you guess?

Barbara deWilde: Oh, 28.

George Gendron: Did that make you feel young or did it make you feel ancient or both?

Barbara deWilde: Everything! It made me feel weird. It made me feel old. It made me feel terrified. But when I think about that class of peers, there were about 15 of us. And there were students who came from China. They came from Denmark. They came from the UK and the Philippines, Korea, and they all came to the United States. They were all from different countries coming and studying with English as their second language. And here I am worried about my age. These folks were brave.

So I realized I really had to get over myself and just put my massive ego aside and just get down to work. I decided I was definitely going to—with my newly minted degree I’d go out and do something completely different. So I started working at The New York Times.

It was a great place to go because I loved the Times as a media company. And they had a really robust digital product group led by Ian Adelman. And I was going to be in a different part. I wasn’t going to be in the part of the company that produced the paper, quote unquote paper for the daily report. I was going to be in a new products group.

And I stayed in that new products group for eight years. I worked on projects like NYT Cooking, which is an app and a cooking database. And an opinion product and I worked on newsletters. I worked on a couple different, big endeavors. I left in 2020 and opened a bookstore.

George Gendron: I want to go back—I think of this as three blocks: book covers, Martha Stewart Living and The New York Times. And of course in between going back to school. But you were part of a group of three other people beside yourself that were—you were it. And at least from my perspective, this was the golden age of book cover design.

Barbara deWilde: Yeah. Carol Carson, Chip Kidd, Archie Ferguson, and myself.

George Gendron: And I guess my first question is what was going on in the world at large where suddenly book covers became and still are just these unbelievably attractive artifacts. I don’t know how else to put it. there are books I’ve bought, they’re on my shelf. I paid decent money for them. I never read them, and I will never read them, but I bought them for the book cover.

Barbara deWilde: There are many great ages of book cover design. And before this Knopf group, the four of us, there was a group of women, Louise Fili, Judy Lesser, Carin Goldberg, Lorraine Louie, that were creating incredibly beautiful postmodern designs. And they were objects in and of themselves.

I think that there was a good foundation that had started to happen. And then, a few other things happened in addition. One, there was a new editor in chief at Knopf, where I was working. Sonny Mehta came from the UK. He had a background in paperback publishing.

He was a great enthusiast for design. He wanted to come to this imprint, Knopf, and really expand the list. So publish more books and publish them in a way that really celebrates an individual design approach. So he was a champion. And you need a champion. And things often change when everyone’s new at the same time. We were all new.

Carol Carson had recently been hired. Chip had recently been hired. Sonny was the new leader of this group. Then Barnes & Noble became a presence in the retail scene, and suddenly it was like having gallery space for graphic design. Those stores were so large, they were able to put books face out, prominently displayed, and they were building those stores pretty rapidly. In Manhattan, in the suburbs.

It used to be that we would go and feel like a million dollars if our covers were face out on a table at Rizzoli. Now, there was so much space. So I think there are a lot of factors. Then you get the four of us together and we just felt inspired by each other.

George Gendron: I remember riding the subway or being on a plane and becoming conscious of the fact that book covers were also becoming fashion statements. People would hold them up as they were coming down the aisle. They would always travel with their book outside their briefcase as if to say, “Everything you need to know about me is broadcast right here on this book cover.”

Barbara deWilde: It is a proxy, whether you’re carrying it or whether you have it on a shelf in your living room. Now, people have their Zoom backgrounds that tell a story about their reading life and their cultural life.

It is competitive. You want someone to be holding your book cover. You want someone to be holding the book that you worked on. And I mean that for the authors but the designers too. It was also an exciting time within publishing where there were a whole new generation of writers. So with that, people don’t want to look like their predecessors, they want to look like themselves.

George Gendron: Two of your book covers come to mind immediately that are iconic, in a lot of different ways, including illustrating what you just said. One is Donna Tartt, The Secret History, and the other is Jennifer Egan. This is from the Goon Squad. Okay. So you decide at a certain point, you make the move—this is going to be a broad generalization—from the book world, where every single book you had a contract for that book cover. Talk about the project economy! You go from that to a magazine, which is completely different, a completely different process. At one point you said to me, and maybe this is an overstatement, like, I had no idea what I was doing.

Barbara deWilde: I had never designed a magazine before.

George Gendron: How did you get hired there then?

Barbara deWilde: Well, you’re going to have to ask Gael Towey, but I think it was a time when they were looking to bring in new voices. This inflection point where they had gone public and there was going to be explosive growth.

Their business model was fascinating, magazine design was one aspect of it, but they were also producing product for K-mart. They were producing product of their own for their own catalog. They were doing television. So they wanted to grow across multiple axes and they needed more voices.

George Gendron: And there you were.

Barbara deWilde: And there I was.

“Working at a place like Martha Stewart was almost like turning my entire understanding of the world of graphic design upside down.”

George Gendron: What was the learning curve like going from book project to magazine flow?

Barbara deWilde: They were so large and they were such a well oiled machine that they had their systems in place. They weren’t looking for someone to come in and how they were doing it. So for me, I think the biggest difference was when I would start on a book jacket project, I started with a manuscript. I would read the manuscript and then I would pitch a few directions for designs for the cover. But it was all based on that manuscript and that author.

With magazine design though, especially at Martha Stewart, all the stories were homegrown. So you worked in a team with a content editor and a photographer and stylist and art director and writer and you all came together and created the story.

So you didn’t have a starting place that existed. You became the sort of the content source in this team format. So the thing that you learn by working at a place like Martha Stewart is how to think editorially. We would often have the story sketched out, the photographs would be taken, and then the text was flowed in after the fact. That’s almost like turning my entire understanding of the world of graphic design upside down.

George Gendron: And that was going to happen again, but we’ll get there in a second. Someone once asked me ages ago when I was talking to a journalism class up here at Boston University what was it like when you, a young kid, became a very junior arts and entertainment editor at New York magazine, a weekly. And I said, “If you’ve ever surfed or body surfed and you get caught in a rip current, you just go with the flow. You have no choice and you adapt really quickly.” It’s exactly what you were saying about systems being in place and they just drag you along, man.

Barbara deWilde: Exactly. I brought my own special “weird” to the process. They were a remarkable institution of design.

George Gendron: What’s it like working with Martha?

Barbara deWilde: Oh, Martha's funny. She’s really funny and she’s so smart and she’s quite intimidating because she suffers no fools. But I think that as long as you were on time and honest and creative, she’d be in your corner. So I enjoyed working with her very much and she’s very mischievous.

We had this project that we were doing which was a special Halloween issue and I had done a story on makeup and she was going to become this spider woman witch. The lesson was how to put white face on someone and apply prosthetic spiders to the hair—everything’s a lesson at Martha Stewart.

And she came with these magnificent three inch fingernails and her manicurist. And so while the makeup lesson is going on, she’s getting these fabulous nails added to her fingers. And when we took the photos, she used the nails in these gestures and peered through them. She made that shoot fantastic. It was absolutely dynamite. But that was Martha.

George Gendron: Okay, you made the decision to take a sabbatical from magazines or from print or from graphic design around 2011. You make the decision to go back to school. That was when people in the industry, but particularly designers, were at this crossroads, right? You realized that your training in graphic design was in less and less demand, and so you could stick it out, do the best you possibly could, ride it as long as you possibly could, or you had to figure out how to adapt. And as you pointed out earlier in this conversation, that was not a seamless evolution. That was a completely, dramatically, different way of thinking about design and the design process. You go back to school. You go back to get your graduate degree at the School of Visual Arts at SVA.

Barbara deWilde: Yes, I couldn’t have made a better decision at the time. It seemed like a pretty good idea, but there also seemed to be a risk and I felt exposed, showing that I didn’t really know what interaction design was. And yet I felt like I was an expert in some ways, but in other ways I was not even a novice.

But I felt privileged to be able to stop working. I taught during that time as a means of making a little bit of income. But I relied on my family to keep us going. And what I found was I really needed to change the way my brain worked. It took two years and not taking on any design projects that were in that traditional graphic design field was very important because I really wanted to remake the way I was thinking.

George Gendron: You make it seem so logical and yet that was brave.

Barbara deWilde: Thank you. I shake my head a little bit because when I do any of these things now, if I had only known, maybe I would have thought better of it, but I really thought I need to do this.

George Gendron: Do you have an allergy to being comfortable?

Barbara deWilde: Yes.

George Gendron: Okay, we got that on the record.

Barbara deWilde: No, my family roll their eyes. They’re so tired of my inability to sit still. They know I talk a good game when I say I’m going to take some time and relax and they know it’s not true.

George Gendron: So you get your graduate degree in interaction design at SVA. And then is it right after that, that you land this cozy little job working in the digital project group in The New York Times?

Barbara deWilde: Yes. It was almost a week after graduating. So once again, I thought, Oh I’ll take some time and I’ll really think about this and I saw a job posting on Twitter and I thought, no, that’s for me. That’s what I want.

George Gendron: Wait, you saw a job posting on Twitter?

Barbara deWilde: Yes, there was a job posting. It wasn’t ultimately the job that I got but that’s how I knew that they were hiring. And so I thought, I’ll give this a try.

George Gendron: Way to leverage your reputation and network.

Barbara deWilde: You have to get rid of your network. If you get rid of your expertise, you get rid of your network. By going to school, I remade my network. It was a whole new group of people. So yes, you see design postings on Twitter and you jump at them.

George Gendron: As you were saying that last sentence, it looked as if you were breathing very deeply. Just occurring to you the magnitude of the change.

Barbara deWilde: Exactly. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could stay with our friends forever?

George Gendron: And you also happen to arrive at The New York Times at a point when probably the world’s greatest newspaper is starting to experiment really aggressively to figure out a more sustainable newspaper model. Were you aware of the larger context about this experiment that was going on? The stakes couldn’t have been higher.

Barbara deWilde: Well, and there’s a generational change. I think it coincided with—the Sulzberger family owns The New York Times—there was the next generation of family members who were becoming involved in leadership roles. With that generational change came a change of technology as well as business model and journalism.

So all these things, once again, seem to be starting at the same time. And they had already done some pretty remarkable work. That’s David Purpich putting up a paywall around the website then the app, because there was a time when we chased clicks, we were looking for engagement through numbers and numbers drove revenue and, like ad imprints and they were looking for another way of monetizing.

Even with the doomsday predictions that a paywall would kill the newspaper—and I say newspaper, I mean the Times. But they found that it didn’t and that was really the most significant work. And that happened before I got there and they were looking to build on this success.

They had a subscription model for digital, but then the question is, how can we grow that subscription model? And that’s at the point where I stepped in and these ideas of new products and other subscriptions that were different slices of The New York Times became the goal.

“It’s all in the language of ‘habit.’ That is the entrepreneurial understanding of interaction design.”

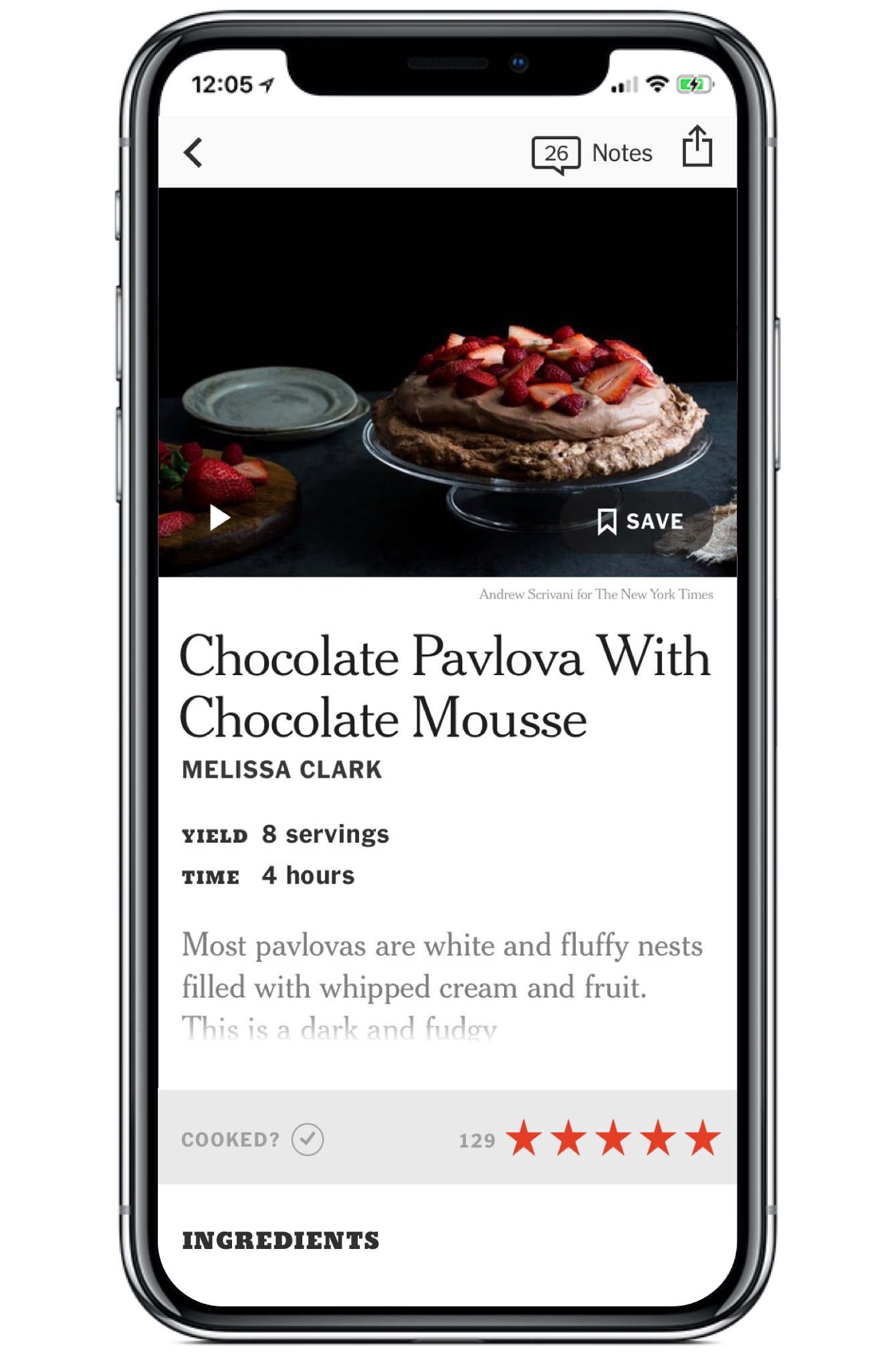

George Gendron: And some of these are now such a part of the day to day culture. Among my friends and I and my wife—real amateur chefs—we are so dependent on The Times Cooking. It’s unbelievable. There was a great recipe today, by the way.

Barbara deWilde: See?

George Gendron: And I can’t tell you how many times you’re at dinner and people start talking about when you start the day, do you, do you go to The New York Times Games first?

Barbara deWilde: It’s all in the, in the language of habit. And that is part of an entrepreneurial understanding of interaction design.

George Gendron: Yeah, that’s interesting. One of the people I had a conversation with for this podcast made a comment that I really didn’t appreciate until after the conversation was over and that was that for all their talk about change, and writing about change and documenting change, people who run journalistic enterprises can be among the most conservative people on the face of the earth.

And it’s true. It really is true. When you start to think about what The Times was doing, I wouldn’t call it brave because I think they did it in a way that was really shrewd and minimized risk in a way that was really smart. And as a result, you now have a really sustainable 21st century business model. I don’t know how replicable it is for other newspapers. We’ll see. But anyway, it must have been thrilling to be a part of that. Of course, being a part of that for a couple of years. You quit.

Barbara deWilde: I was there eight years. I think that’s a very reputable amount of time to stay, with a company and a job. But with digital products, you spin them up and it takes anywhere from a year to four years—I worked on cooking for four years before we launched the paywall around that recipe product.

Then you have a decision: do you want to take it to the next level, or do you want the next team to come in, have fresh eyes and fresh talent, and take over? And I think it’s really a good idea not to stay with a product too long. It is cyclical.

There is smaller, incremental work that is done to slowly move it forward and the exciting parts are at the beginning. I really didn’t want to keep talking about recipes for eight more years. Four years of recipes is plenty of recipes for me. And I love everybody there. But I was ready to talk about something else.

George Gendron: Did you have a specific game plan in mind when you left, or were you just thinking once again that you were going to take some time?

Barbara deWilde: Take some time. Really think about it. I was at a point and, and, you know, I think overlaid on everyone’s professional life is a personal life. I had just sold my home in Montclair, New Jersey. I had helped my sister fix up her house and sell it. And then my mom passed away and I fixed up her house and sold it.

And that was all in the course of two years. I thought, I think I have the hang of this thing now. I’m used to working with contractors. I know how to look at the foundation and see if it’s going to be fixable or not. And I thought, I think I probably have one more building in me.

We had just moved out from Montclair and bought a small house in Pennsylvania as a place to go on the weekends. It’s a beautiful part of the country. I grew up around here. It’s the Lehigh Valley area, the river towns. We were renting in New York city and it’s so lovely here. And I was starting to think, could I live in the country full time? It didn’t even seem possible.

I’d never wanted that, but I like being in the country on the weekends. And I like getting away. And really what started to lure me was the idea of buying another building. And I was wondering if the building could indicate what the next thing I was going to do would be.

My friend texted me, I was at The Times, and he texted me that this beautiful building in Frenchtown, New Jersey, that had been built in 1883 had come up for sale and it had the bookstore in it. I was the first appointment that Saturday morning. I didn’t even let anyone else look at it. I just said, “Let’s do this. Let’s buy this.”

George Gendron: So this does really sound like an improbable fairy tale of a startup, right? You start a bookstore, an independent bookstore, in a small town in New Jersey. I have it right here: population, 1,370. Which happened to be three fewer people than 10 years before. The town was shrinking, and being market timers, you and your husband Scott decided, “I know, we’ll launch it right now during the pandemic.” Bam!

Barbara deWilde: Genius move! There’s a few more steps that have happened.

George Gendron: I know. But that’s the arc of the narrative.

Barbara deWilde: It's just so crazy it might work!

George Gendron: What was your dream? What was your vision when you were just starting out? What’d you want to accomplish?

Barbara deWilde: I have a very tired old personal anecdote that really did inform this next project. When I was 16, I worked at a place called Kenny’s News Agency in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. And it was the place where all the newspapers came in and all the paper boys picked up their stacks. They sold books, paperbacks, magazines, and lottery tickets. I stood behind the counter and that was my job.

I remember one winter day, it snowed easily three feet. This was before everybody had an SUV. We had to jump in this jeep kind of car, my boss and I, and dig out the store to make sure that everybody got their newspapers. It was ridiculous because even if we could get you your newspapers, you wouldn’t find it under all that snow.

Somebody had to make sure that this happened. And at the end of the day, no one came into the store all day. At the end of the day, my boss took me out to dinner at the diner and the diner owners were there. They were in their forties, I think forties and fifties. And they said, “Barbara, whatever you do, never open your own business. Never get a break.”

I thought, This is the coolest day I’ve ever had. This is so much fun. All I want to do is open my own business.

Scenes from the Frenchtown Bookshop

“You can get a book anywhere else at a lower price. That’s true and we don’t dispute it or try to fight it. What we do is try to make a place that is of value.”

George Gendron: Give us a sense today of the Frenchtown Bookstore and its activities.

Barbara deWilde: We are open six days a week. We’re family run. So it’s my husband, my daughter, myself. We have two part time employees. During the week we do the part of book selling that’s called receiving. We receive and buy books. So the UPS guy who used to have a pretty easy route now curses the day we ever opened because we get 15–16 boxes a day and all the CrossFit in the world did not prepare him for this kind of volume. We unpack and shelf the books and that is a constant cycle.

We prepare the entire week for the weekend because it’s a tourist town and things start cooking at around noon on Friday. And we are nonstop busy all the way through Sunday evening. My husband, who’s quite the impresario, is a great event planner. He has created an event calendar with author readings, poetry readings, music, on and on. I can’t even, I can’t even list them all.

So we often have evening events because the point of the bookstore is really to be a community hub. Bookstores don’t succeed without events. The idea that you can get a book anywhere else at a lower price is really true and we don’t dispute it and we don’t try to fight it.

What we do is we try to make a place that is of value so that you don’t mind spending full price for a book because you’re going to be able to then come next week and hear this lecture and meet friends for a book club and be part of this very small community, but it’s a wonderful community. And I see people waiting in line to buy books and they’re meeting each other, and then they’re exchanging phone numbers, and then the next thing I know I see them having coffee. It really is important for towns to have bookstores.

George Gendron: There’s all this conversation which keeps getting more and more voluminous and intense about loneliness and people aren’t writing much these days about third places, maybe because there are fewer of them, but that’s what you’re describing. It’s a place where people can come together, like minded people around, a passion for something, in this case, for books, for reading, for the making of books. Your newsletter is absolutely phenomenal. That’s Scott.

Barbara deWilde: That is Scott. And that was a big lesson from my time at The New York Times, this idea of building relationships through the written word. I worked on several newsletter teams, first at Cooking and then the larger team for the newsroom. Delivering content that you ask for, to the audience, is incredibly powerful as opposed to creating a website or something that you have to go visit.

This gets delivered to you, and with a little bit of a personal point of view and not too long, just a little bit of an anecdote and then recommendations and then information about upcoming events— you’ve got a newsletter. And we know that nobody else does a newsletter the way we do but that is a direct outcome of working at The Times.

George Gendron: I pride myself on getting through these podcasts without ever using the word brand but what’s remarkable about the newsletter is that you have a feeling that the newsletter prepares you for what you’ll find if you come to the bookstore. It’s got a personality. It projects certain values. It’s better than it has to be. We often used this language when we were judging national magazine awards and these smaller publications that didn’t really have a lot of resources would often end up being discussed as, “Man, they are better than they have to be. They’re a little trade magazine, but they are excellent. They pay attention to detail.” It’s really extraordinary. I really admire that.

So anyway, now I know you guys are a private company. But as the former editor-in-chief of Inc. Magazine, there are a few business questions I have to ask you. How much did you guys spend to get this thing off the ground? And by that I mean, to the point where it was cash flow positive.

Barbara deWilde: Our business model includes our building. We are able to do this because we are landlords. We have an apartment, a one-unit apartment above the store. So we have two LLCs. We charge ourselves rent. That rent covers insurance and maintenance and taxes, the not fun stuff. The bookstore needed a very large renovation. All the wiring needed to be redone, walls needed to be removed, a staircase needed to be removed.

It was still in the architectural configuration of a house, which is what it was, and it needed to be changed into a retail store. So the space needed to be larger and open, especially during COVID when no one wanted to go into a small little room with another person. It needed to have bay windows so that you could look in and see books. It only had gable end windows that looked like a house.

We, I think, budgeted about $200,000 for that renovation. And then in terms of fixtures, we spent about $25,000 on fixtures and about $60,000 on books. The biggest investment that we made was actually the smallest cost—we invested in a point of sale system that’s developed by this brilliant company in British Columbia called Book Manager. It runs not only our inventory, but also our website.

Going to interaction design school made it possible for me to start a spreadsheet and look at all the bookstore point of sale systems and write down all the functionality and pick the one. And this is the one.

George Gendron: That’s great.

Barbara deWilde: And it’s very powerful. It’s designed by a bookstore owner. So they know their stuff.

George Gendron: Are you guys making money now?

Barbara deWilde: So in terms of capital outlay, we’re not looking to build that money back. The building itself became valuable the minute we opened. It wasn’t that valuable before, but now it is. So real estate alone and then post pandemic real estate bumps for all values across all buildings have helped enormously.

So we will get that money back when the building is sold. We don’t plan to sell it, but that little arc happened. So that was excellent. We were profitable in our first year.

George Gendron: On a cashflow basis.

Barbara deWilde: Yes. And again, not the fixtures, all of that I put into building capital expenses and all that would come back out again, I don’t make a high salary. I didn’t take a salary the first year, but I did pay my health insurance out of the profit from the bookstore. And my daughter takes a salary and her health insurance is paid through the bookstore.

George Gendron: So you got a little family business there. Let’s talk equity. There’s your husband and your daughter. Do they have equity in this business?

Barbara deWilde: They do. They do.

George Gendron: That’s really cool.

Barbara deWilde: It’s cool. It’s nice to make something for yourself for a change.

George Gendron: Boy, isn’t it?

Barbara deWilde: Nice feeling.

George Gendron: Yeah, it really is. Are you bored yet?

Barbara deWilde: Not yet. It’s really fun. It’s actually—it’s fun to plan what each season looks like, where we want to grow. We don’t want to have a big growth mentality around this bookstore. We want a sustainable business model. So we’re thinking more in terms of loops instead of charts that go up, up.

What that means is we want to have an engaged customer base that feels connected to the bookstore. It should feel like it’s their bookstore, not my bookstore. And that they understand that the more they put into the bookstore in terms of their involvement in events and the occasional book that they buy, read, talk about with other friends— the better their experience— the more they’ll get out of us being there.

We’re going to make product. We have very small, unambitious goals around product, but it’s awfully fun. And that means, yes, book bags, t-shirts, and hats. But that’s just fun. And we cook it up in the back room. And we’ve got a couple other ideas too.

George Gendron: To wrap this up, I want to go back to maybe this is the third conversation you and I have had, and, um, you use a phrase, you used it frequently in the first phone conversation you and I had, where you talked about making things, and in a way that was almost like a substitute for designing things. That seems to be a theme for you. And it really resonates—we’re almost obsessed with the making of things. We believe everybody has this desire, maybe even a fundamental need to make things. That it gives you a psychic payoff that it’s hard to get any other way. And that seems to really resonate with you throughout your career.

Barbara deWilde: Yeah, I love, I really love making things. I think there are some people who are happiest when their hands are moving. I can’t watch television unless I’m knitting. I find that most ideas are just so big and so exciting that you have to actually be creating. And design is an aspect of it. Design is one of my favorite things in the world but it’s not necessarily two dimensional design. It is the design of a space and experience of a place, an idea.

I’ll give you an example of how it might be seen in the bookstore when we had opened and the tenants had access to the backyard. They had put rocking chairs and they had landscaped the backyard. And one Saturday, I looked out the back door and saw that one of the bookstore customers had taken his book and was sitting in their chairs. And it made me really nervous. I thought, Oh no! If they see this person, they’re going to get really upset. And then I thought, But wait, that’s a really good idea.

And so when they moved out, we took that space back and we hired a landscape designer and turned it into a reading garden. And it is a place where you can just go and quietly sit with a book. And it’s where the book clubs meet. It’s where we have music. It’s a beautiful space and might not be tied to revenue. I don’t really care. It was just about making that place the most beautiful place where you could spend time.

—

For more, visit Frenchtown Bookshop online, or drop into the brick and mortar (and clapboard) store: Frenchtown Bookshop, 28 Bridge Street, Frenchtown, New Jersey.

Listening to this conversation, it strikes me that, basically, there are two types of startups. In the first—very traditional—a founder sees an opportunity that already exists, spends lots of time analyzing and measuring it, and then launches.

This is not what Barbara deWilde did.

The second approach requires more imagination. It envisions something that nobody is really asking for. It actually creates the need for a product or service before it actually exists.

Enter the Frenchtown Bookshop. With it, deWilde did what so many magazine lifers dream about. In her case, creating a place where people come to buy a book but end up finding a community.

If you get excited by stories like this as much as we do, we want to hear from you. Shoot us an email at hello@magazeum.co. We’d love to hear from you.

Thanks very much for listening. —George Gendron

More from Print Is Dead (Long Live Print!)