Guardian at the Gatefold

A conversation with author, educator, and designer Steven Heller (The NY Times Book Review, Screw, The New York Review of Sex, more). Interview by George Gendron

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT COMMERCIAL TYPE AND FREEPORT PRESS.

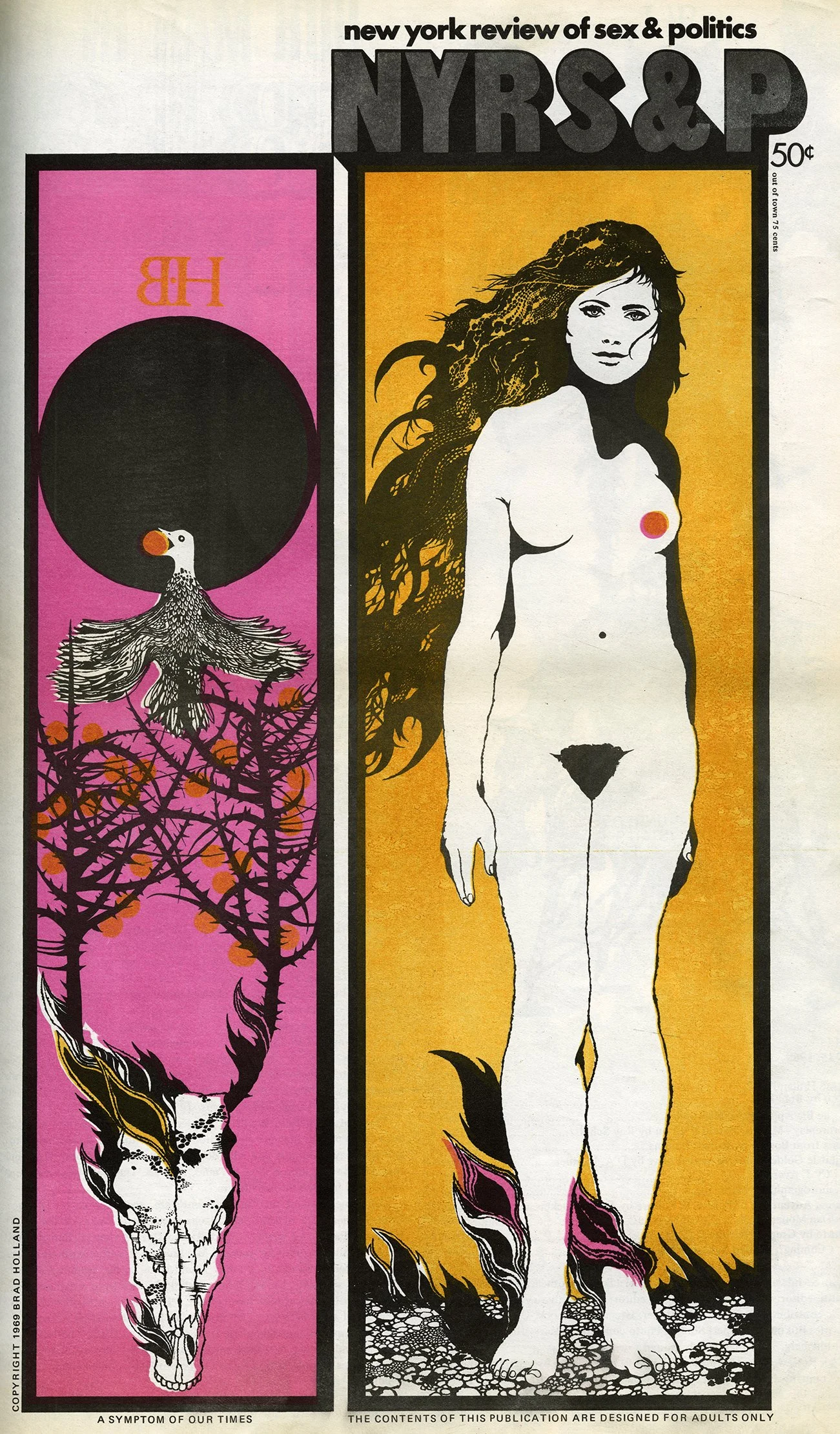

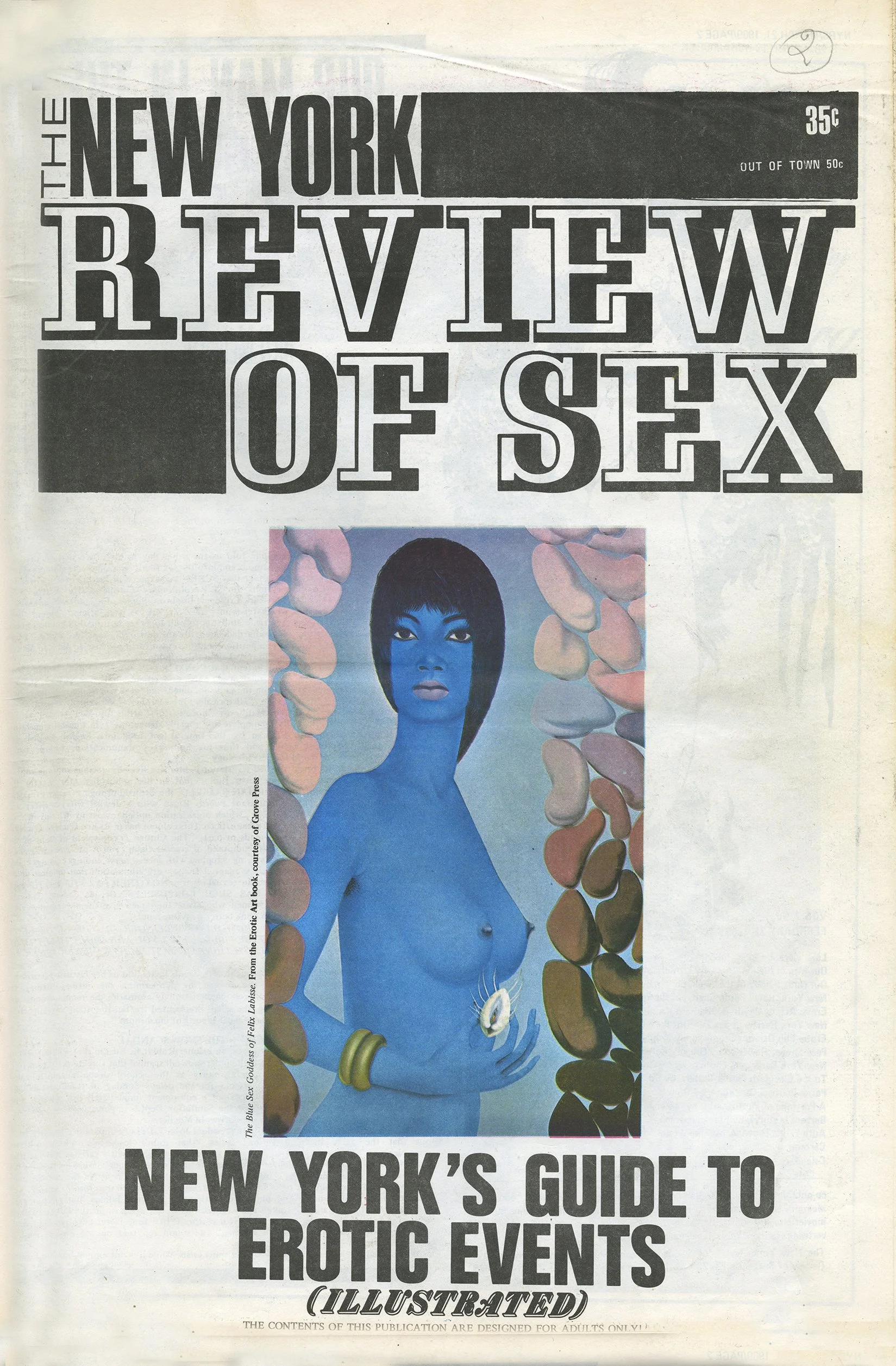

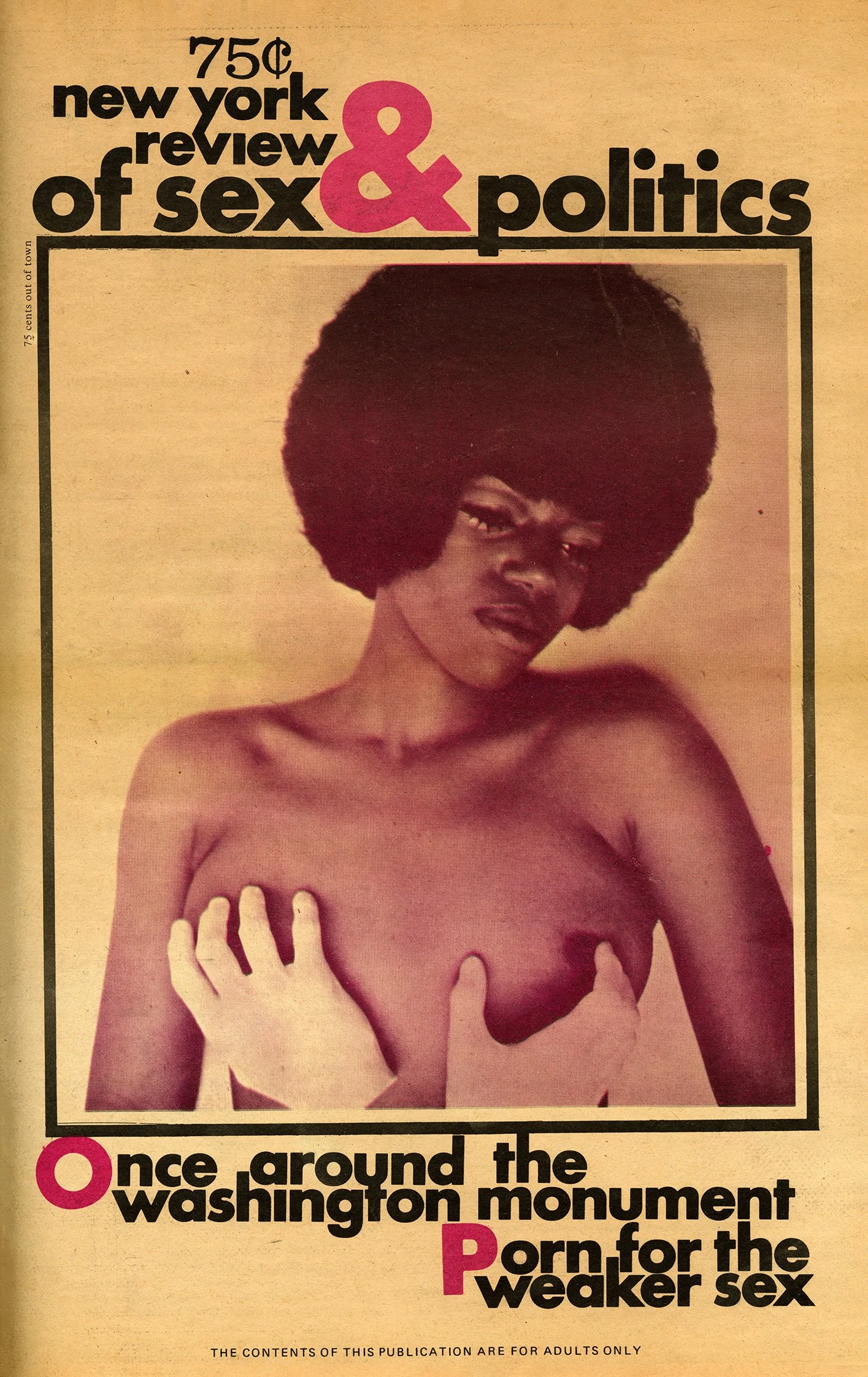

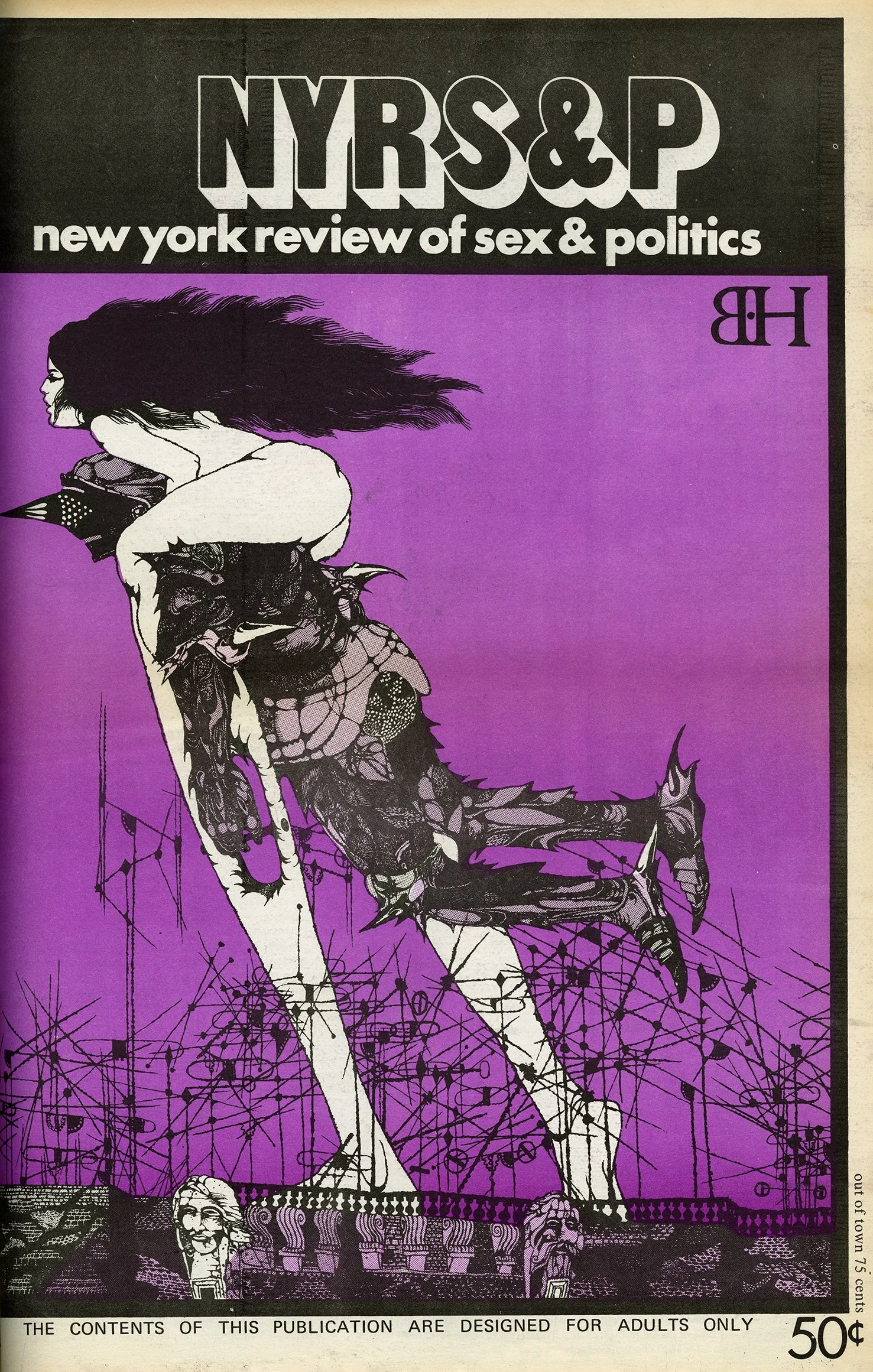

Today’s guest has become almost synonymous with graphic design and magazine publishing. His career began in the defiant New York “sex press” of the late 1960s, where, astonishingly, as a teenager he was already art-directing magazines like Screw and The New York Review of Sex. That unlikely starting point gave him a rare education in the power of design to command attention and shape meaning.

We're talking about designer, author, editor, educator, and true legend Steven Heller.

Heller went on to spend more than three decades at The New York Times most memorably as the art director of The New York Times Book Review. There, he transformed the visual life of the section, commissioning bold, original illustration, and making the case—over and over again—that design is not ornamental, it’s integral to editorial voice. Through his advocacy, he’s helped elevate the status of designers in newsrooms, giving visual thinkers a seat at the table alongside their editorial partners.

Beyond the newsroom, Heller has been prolific, almost to the point of obsession. He has written, edited, or co-authored more than 200 books on design, creating an extraordinary record of the field’s history, ideas and influences.

And most recently, he turned that critical eye inward with his memoir, Growing Up Underground, a candid account of his early years in New York’s counterculture publishing scene. Steve is a practitioner, a chronicler, and an advocate for design, and he’s also part of the team here at Magazeum.

We are thrilled to turn the mic on him for this special conversation. Welcome to Season 7 of Print is Dead (Long Live Print!).

“Not much strategy. A lot of tits and ass.”

George Gendron: I was going over some of my notes this morning and I was thinking about Tom Wolfe and his cover story for the 1980s, “The Me Decade.” And I was thinking about what Tom would’ve written if he had covered the sixties and seventies—“The We Decade.” The emergence of sex in every single aspect of the culture. If people weren’t living in New York at the time, or familiar with the city, I don’t think they’d have any idea what was going on. And so what I want you to do, if you would for those people who were not in New York, or people who weren’t even alive then, could you set the scene for the sex mag scene? You have a phrase for it.

Steven Heller: I do.

George Gendron: Yeah. You do. What was it? The “Sex Press.” Who were the individuals and the publications that were driving this, at least on the media side?

Steven Heller: Screw was driving it. And Screw came out of the New York Free Press, which was an Upper West Side community newspaper that tried to become something larger—more like the LA Free Press or the Berkeley Barb. And we found that when we put nude pictures on the front page—and we often got those nude pictures from Yayoi Kusama, the artist—we sold more copies—in fact, we sold copies because I don’t think it sold much at all. Al Goldstein was the progenitor of the sex press and he was working at the time for the blood-and-guts, sensationalist rags that would talk about a mother eating a child’s foot or something.

George Gendron: Was he writing for them?

Steven Heller: He was writing for them.

George Gendron: Because you describe him as a really terrific writer. I think at one point you said he could “write his way out of a paper bag.”

Steven Heller: If he was writing seriously, he needed editing. And that’s how he got together with his partner, Jim Buckley, and together they formulated this idea to start Screw right outside my office at the New York Free Press on 72nd and Broadway. And they started it at our IBM MT/ST typesetting machine.

George Gendron: So you were privy to those conversations?

Steven Heller: I could hear those conversations.

George Gendron: Wow. A lot of strategy being discussed, I suspect.

Steven Heller: Yeah. Not much strategy. A lot of tits and ass.

George Gendron: Yeah.

Steven Heller: And Goldstein had come to the Free Press with his first investigative report story, in which he had become a spy for the Bendix Corporation. He was an industrial spy. And he was writing a confessional. And that’s how the Free Press and he got together and how Jim Buckley and he got together. And I was brought in because I happened to be the art director that was there.

And then it grew. Then the East Village Other, they realized their personal ads brought in most of the income. And the same with Rat, which was an SDS newspaper to begin with. And then through a twist of fate, and the fact that I was still underage, Al and I got into a fight over a logo.

George Gendron: Milton Glaser’s logo?

Steven Heller: No, that came later. No, it was just a logo I was trying to draw. Because he had brought in this awful psychedelic piece of shit. He yelled at me. He had a temper. I’d rarely gotten the brunt of his temper, but this time I did. And I was just in tears and I said, “I’m quitting.”

And the next day I went into the Free Press office and suggested to the publisher that we start a sex paper to compete with Screw.

George Gendron: And did you?

Steven Heller: We did: The New York Review of Sex. We became one of the four sex papers in the city.

George Gendron: How’d it do?

Steven Heller: It did terribly. I said in my last interview with Patrick that I was called the only person in New York that could make a sex paper fail.

George Gendron: That reminds me of a piece that Gloria Steinem did for Esquire when Clay was there. And Clay was her editor, not Harold Hayes. And she handed it in and the next day she came back and said, “What do you think?”

And he said, “You’re the only person I know who can make sex boring.”

Here’s something that really surprised me, which is that at some point you said you loved Al Goldstein, and I have to read you something from the obituary that appeared in The New York Times. Now, keep in mind, this is the normally unbelievably staid New York Times back then. And here’s one of the things that they said about him, “a bundle of insatiable neuroses and appetites—he once weighed around 350 pounds—Mr. Goldstein used and abused the bully pulpit of his magazine and later his flesh parading public access cable show to curse his countless enemies, among them the Nixon administration, an Italian restaurant that omitted garlic from its spaghetti sauce, and most troubling to his defenders, his own family.” And it only got worse from there. But what was it about Al Goldstein that you loved?

Steven Heller: He was a friend. He was a good friend. He saw that I was shy and I didn’t have too many girlfriends. He introduced me to my first wife. And then he threw the wedding party for us at Ratner’s. He—

George Gendron: —how long did that one last? Not the party, the marriage.

Steven Heller: The marriage lasted about six months. But we were legally married for two years. Al used to let me use his limousine all the time. He would loan me his car that had a telephone in it. In those days they were party lines.

George Gendron: I didn’t know that. A party line in your car?

Steven Heller: It wasn’t cellular at that point.

George Gendron: So when you think about things like that New York Times obit, do you think he was misunderstood?

Steven Heller: He wanted so desperately to be in the Times that he would do anything he could to get in a news story—including die. And I wrote a large piece about Al and his book that came out around the same time as the Milos Foreman film on Larry Flynt. And Larry Flynt I met at Screw when he came to try to get Al to be the editor of Hustler.

And we had worked out a deal where I would be the art director and it fell through. I don’t know why, but I’m glad it did. And he hired our managing editor to run the thing, Bruce David. Eventually he hired Paul Krasner.

George Gendron: Now, during this period of time, is this when you met Brad Holland?

Steven Heller: I met him when I was working at the Free Press before Screw. I put a call out through the Village Voice for possible contributors to this magazine that I wanted to publish, which I did publish and paid my own money for it—Bar Mitzvah money—and it was printed by a right wing antisemitic printer who happened to be my best friend’s stepfather.

George Gendron: What a world back then, man.

Steven Heller: He censored one thing in the magazine. He told me before he took it on that he would not do anything politically liberal or radical. And I had an ad for the New York Free Press that was illustrated by JC Suares and it showed the Sistine Chapel ceiling painting, except God was touching President Thiệu of Vietnam.

George Gendron: And what happened?

Steven Heller: He made me take out the copy.

George Gendron: So he really scrutinized what was going in?

Steven Heller: He saw it and he got worried because I think he had some government contracts.

George Gendron: Oh, okay. So you and Brad met back then and he became not just a lifelong friend, but he became your mentor, your teacher, your rabbi.

Steven Heller: Yeah. I think I was the first Jew he ever met, so I wouldn’t call him a rabbi. But he became very important in my life. And that he passed away recently still troubles me.

George Gendron: What a force of nature of that man was.

Steven Heller: He was.

George Gendron: I think at one point you described him when he arrived in New York as “getting off the boat.”

Steven Heller: It was a bus, but it was his “boat” across the river.

George Gendron: Was he coming directly from Hallmark?

Steven Heller: He might have been coming directly from Hallmark. He had a stayover in Chicago for a while and worked for John Dioszegi for a few years. And there was always this Oklahoma connection where his family lived.

George Gendron: The idea of Brad Holland working for Hallmark is something I just can’t get my arms around.

Steven Heller: Can you get your arms around R. Crumb working for American Greetings? Because that was his first job in Cleveland.

George Gendron: This period, the Sex Press and the alternative weeklies, they were a great place for young journalists and illustrators and designers to get a job, get a paycheck, cut their teeth and launch their careers. Although at the time, it probably didn’t feel like a great first step on a career path. But nonetheless, and you have to wonder, I moved up here from New York magazine and the city in 1975, and I was blown away by the collection of journalistic and design talent up here because of The Real Paper and the Boston Phoenix. Ten years later you were sitting and looking in publications like The New York Times and New York magazine, and it seemed that everybody had moved from Boston down to New York and they were flourishing. Where do young people—just talk about designers—where do young designers, illustrators, people in the visual arts, where are they these days? What’s the equivalent? Is there one?

Steven Heller: Well, there’s no real equivalent, but there is a substitution. Print is dead to many, so they go into branding, they go into strategy. They get whatever jobs they can get and try to get into the better studios who have decent paying clients that allow them a certain—I wouldn’t call it freedom, but they allow them a certain kind of prestige.

A lot is made about the industry, which I hate calling graphic design, but the field condensing and at the same time expanding the media that is used and comes under the umbrella—podcasts are something that graphic designers do, so it’s kind of part of their toolkit now. Animation is something that they do, so it’s part of their toolkit. Graphic novels are something that designers do, so it’s part of the toolkit.

There’s a lot of integration and many of the people who go into it have considerable skill at going from one medium to another. It doesn’t mean that they’re innovative and it doesn’t mean that they come up with great solutions, but it does mean that they can cross-pollinate.

“I was called ‘the only person in New York that could make a sex paper fail.’”

George Gendron: That’s very interesting, listening to you talk, I hadn’t quite thought about it that way. Part of what made environments like New York, for sure, Boston, San Francisco to some extent, LA, so rich was the social networks that formed as well. And the relationships, the professional relationships, that formed like yours with Brad, and that lasted a lifetime. I know that’s true for me. I wonder, is that still true, do you think, to some extent?

Steven Heller: Oh yeah. The school—for example at SVA—the grad programs are a hotbed for familial relationships. The students live with each other, basically, for two years. And you can’t help but develop the closest of friendships and the most distant of acquaintanceships.

George Gendron: Let’s say students applying to SVA, RISD, whatever it happens to be, is that part of the recommendation is the social networks and the relationships that you’ll form?

Steven Heller: Yeah, the community.

George Gendron: The community, yeah.

Steven Heller: We don’t call it “social networks” because Facebook took that.

George Gendron: That’s a good point. You do have to watch your vocabulary these days. You mentioned earlier that you’re working in the Sex Press and you’re still underage. So you were very precocious here. But I do want to ask you about one thing. You and I were talking about our teen years. You were in Manhattan. I was across the river in Jersey, and you started talking about how important it was—and if I’m misquoting you, then tell me because I really don’t want to invite any kind of backlash—but I think the phrase you used was “attracting chicks.”

Steven Heller: I probably said that.

George Gendron: And we got into a conversation about that and I said, the euphemism that we used, although we didn’t think of it as a euphemism, but in Jersey where I grew up, man, it was all about being cool—being perceived as cool—and not just by women or girls, but by your peers. And we had a really interesting conversation about that. And then you pointed to a file drawer behind you and you said, “I still have letters from my high school girlfriends.”

Steven Heller: Yeah. It’s not in that drawer, but I have them at home.

George Gendron: Okay. But the gist of it was accurate.

Steven Heller: The gist of it was accurate, and I only realized that I had those letters last week when I needed to go through what I call “the cave” to find something for somebody. I can’t remember what, but I found these letters and one of them, I remember when I got it, it was written on a vomit bag from an airplane.

George Gendron: How romantic!

Steven Heller: Well, I was trying to figure out who sent it to me. There were lots of kissy sounds coming out of it. And she was very articulate about what was going on. And then I read the name and I had a vivid picture of her in my mind. And then I started reading other pieces of mail and with DM and email, you put in the least amount of effort in writing those things to people.

And these letters that I received from girlfriends who had gone away for the summer, gone away for a winter vacation with their parents and would rather have preferred being with me were lengthy letters that will not go down in history as Edith Wharton’s letters or somebody else’s.

George Gendron: Never say never, Steve. Might end up in your museum which we’ll talk about later.

Steven Heller: But they were long and caring. And it made me wistful for the old days.

George Gendron: You and I are one year apart. I think I’m your senior. So as we go through this conversation, show some respect.

Steven Heller: You have to be three years apart to get respect.

George Gendron: You guys did things really differently across the river. I don’t think I ever got a letter from a high school girlfriend. I don’t think I ever got a letter from a girlfriend. I don’t think I ever got a letter from a girl until I went to the Air Force Academy. And then you would do anything, you would plead for anybody you knew to write to you so you could get something when the mail was delivered. But you guys, your girlfriends were actually writing you letters.

Steven Heller: I remember when I was at Valley Forge Military Academy there was a pen pal that I had. I forget how we became pals. I certainly had more in mind than just pals. But I would anticipate letters from her and they would come every four or five days. And it was like a scene out of a movie. You’d see the mail call and the guy would get his mail and run off to a corner and read it like it was a Bible.

George Gendron: Oh, yeah. And then reread it. Now, switching gears slightly, you never graduated from college. You’re very open about that. You have now, I think, many or multiple honorary degrees, but you never graduated from college. You never got a degree. You did graduate from high school, right?

Steven Heller: I think so.

George Gendron: Yeah. But you have to check?

Steven Heller: I was looking for some validation that I got some kind of diploma and I couldn’t find that. I found my draft notices that indicated I was 1A, and had 30 days to appeal. And I found all my draft cards, 2S cards, 1Y cards, 1A cards. But there was no diploma to be found. It may have ended up in my parents’ things and when they died, I basically threw everything out.

George Gendron: So is it fair for me to call you ‘rebellious’?

Steven Heller: I wouldn’t say I was rebellious. I’d say I was bored. I had aspirations. I was a smart alec.

George Gendron: You were very single-minded.

Steven Heller: I was single-minded, I guess.

George Gendron: Without a college degree. We fast forward and there you are the art director for the op-ed pages of The New York Times.

Steven Heller: Yeah. That amazed me.

George Gendron: Yes. And amazes me to this day. How did that happen?

Steven Heller: It goes back to what you were talking about, networking, and it goes back to Brad Holland. He lived in the same loft for over 40 years, and at one point he had a girlfriend who lived in the same building. It was very convenient. And they were going to throw a party one night. I forget what the occasion was, but they had decided that I should meet the art director of the Times magazine section, who they invited and who came, Ruth Ansel.

I had no idea that she was a hot art director for Harper’s Bazaar, and had worked for Marvin Israel and before that Alexey Brodovitch. They made sure that we had a chance to talk to one another. And one-on-one I was really charming. If I was one-on-fifty, I was a wallflower.

We talked for a long time and she expressed an interest in seeing my work. And I expressed an interest in wanting to show it to her. And at the same time, I was very reluctant because a lot of the work in my portfolio was pornography. But it was good pornography. The typography was pretty good for a self-taught person. I look at it now—I put some of it in my memoir—and she was very impressed with it. And I felt that I could work on a magazine in the same way I worked for undergrad newspapers.

And we had lunch together and she told me she was going to take the portfolio up to Lou Silverstein, who was the chief art director and a brilliant journalist at the Times. And I got a call from him saying, “We’d like to see you and discuss your helping out at the Times.” Lou was very careful in his language.

JC Suares, who preceded me at the Times op-ed page was going to be fired and they wanted a replacement tout de suite. And he saw in me something that he must have seen in JC. And just coincidentally, JC gave me my first job at the New York Free Press. He made me the art director within three weeks because he left to start a magazine called Caricature, which never happened.

And so I got a call from Silverstein and he basically gave me a job, but I didn’t know what it was. And I didn’t know that he had given me the job. I just knew I had to show up at a certain time the following week. And in fact, I didn’t really have the job because the op-ed department at that time, which had been run by Harrison Salisbury, had changed hands and was now in the hands of Charlotte Curtis, who was not anywhere near as good an editor as Harrison.

The place was being run essentially by David Schneiderman, who later went on to be publisher and editor in chief and media guru of The Village Voice and some other publications. And he died this year—which all gives me the creeps that so many people have died that I know.

They said to Lou Silverstein that they’re not hiring anybody for that job until they feel that person’s right. So there was a war going on and I was stuck in the middle of it. But fortunately, JC, who I learned to dislike, stood up for me and said I was the perfect choice. So it worked out that I got the job.

George Gendron: Growing up my parents subscribed intermittently to The New York Times and the Herald Tribune before it folded in the late sixties. And I remember even just looking over my shoulder at either one of them reading the paper and thinking that the op-ed pages were probably the most uninviting thing I had ever seen in print. It looked as if they were, I wouldn’t even call them designed, but I’ll use the phrase here, designed to not be inviting. Maybe it was considered to be a badge of honor that you read them anyway in spite of the design. That’s how passionate you were about ideas.

Steven Heller: It was not supposed to be a designed page. It was supposed to contain visual content. And one of the things that Brad was very obsessed over was having pictures run on their own, with their own headline or caption. And that was something that the Times had not done—except with Raymond Lowey—and was not about to do.

And that was one of the envelopes that I pushed with David Schneiderman—who was mixed in his feelings about it—but we did it from time to time. And we did one where Brad was the visual columnist and it was called “Observatory.”

And the first image he did was in his semi-Goya style of Roland Topor’s surrealism, where there’s a head of a man and around the head is an observation deck like the Statue of Liberty, and it was just a brilliant image. What it meant was something else again.

There was an article in New York Magazine in which Ed Sorel was quoted as saying that op-ed art was a cop out because it never directly dealt with issues. It always used metaphor or allegory to get around the prohibition of having an independent critic.

George Gendron: Do you think that was fair?

Steven Heller: I think it was a fair criticism, yes.

George Gendron: But if you think about what I’ll call “before and after,” which is the image I grew up with of op-ed pages, and then let’s say what the op-ed pages looked like a decade or two into your tenure there, they’d been transformed. And yet when you and I were talking, you talked about how important it was that you did that in very incrementally.

“He wanted so desperately to be in the ‘Times‘ that he would do anything he could to get in a news story—including die.”

Steven Heller: It was important to make the changes. And now they’re radically changed. They don’t even have an op-ed anymore. They just have the Opinion section. I think it was important to do—if you were to press me on why it was so important—I’m not sure I could answer the question. But being a design person and being an illustration maven, I felt it was important just for those reasons: that in-and-of itself was its importance.

George Gendron: Yeah, I understand that. But they’re more accessible, they’re more inviting. There were times when bigger illustrations would stop you in your tracks in a way that op-ed pages before that wouldn’t have.

Steven Heller: One of my favorite pages that I did there—we always had to contend with an ad. Usually it was Mobil. And Mobil would write these op-ed advertisements especially for that page. And therefore you always had a “dogleg” when you had the quarter-page ad. And sometimes the ad wouldn’t appear and we’d have fun. And most of the time the ad would appear and everything was stuck together, shoehorned in.

And we did a piece on the anniversary of Kent State. Must have been the 10th anniversary. Part of it was that I didn’t have any budget for illustration after a while. I was allotted so much money and I used illustration almost exclusively for seven or eight months. And then I ran out of budget. So I had to come up with stuff on my own. And I had to ask some people to do things for nothing, which I hated doing. But it was necessary.

So for this Kent State article, what I did was I looked at the famous photograph of the girl screaming that her friend had died. I cut the dead body out of the photograph and just put it at the very end of the story and put a little black border around it. And that was the only art on the page. And it just drew the eye right into the story, and it was the most poignant thing I could have done.

Similarly, I did something on the anniversary of the Kennedy assassination. And I didn’t want to do a drawing because what are you going to say? We know the famous picture. And we knew the famous picture of one of the police officers holding up the men like their rifle that Oswald supposedly used.

And I had space on the page to do something big. And the only way to deal with that was to take that photograph that was so familiar. And I cropped out the rifle and airbrushed out the hands and I put the rifle on an angle and put a border around the piece. The columnists were on either side of the page and I had just the rifle leaning against the right hand border, and that was it. And that was something I really loved. David Schneiderman was away that day and when he came back on Monday, he said, “If I were here, that would never have happened.”

George Gendron: Why?

Steven Heller: He just didn’t like it. He must have heard from friends of his that they didn’t like it. A lot of decisions were made by whose friend said what.

George Gendron: Or who they talked to last.

Steven Heller: Yeah.

George Gendron: I hate that. I was just about to say something absolutely contrary, which is that sometimes the most memorable things we make are a response to resource scarcity—you don’t have money, and so you’ve got to invent, you’ve got to be resourceful.

Steven Heller: And you don’t want to be embarrassed.

George Gendron: Yeah. Now I have to ask you one more question about your tenure at the op-ed page. You were at the book review for a long time—

Steven Heller: —Thirty years.

George Gendron: Okay. So one of the most memorable things, maybe the most memorable thing, was a fan letter you wrote to someone who was the art director at Pantheon and had produced more than I think 2,000 book covers and was legendary for her book covers. And whatever happened as a result of that fan letter?

Steven Heller: We’ve been married 41 years. And we had one son, who just got married himself.

George Gendron: That must have been some fan letter, Steve.

Steven Heller: I used to write to people all the time when I liked their work. She thought it was a “mash” letter, but it was just what I used to do. I tried to create community and I sent this letter and I was doing some exhibitions at the time. I was working on a series of exhibitions of satirical magazines of the late 19th century—Europe and the United States—and I was doing an exhibition at L’Assiette au Beurre at the French Institute. L’Assiette au Beurre was the publication I was doing, which means the “butter dish.”

And I did it at the French Institute, which was then called L’Alliance Français. And on opening night the art director who I sent the note to was escorted into my exhibition by Ed Koren. And I realized, She’s beautiful. I want to somehow connect.

And the next thing I knew, I invited her to another book party I was having for a book on cartooning called Man Bites Man. And another friend, Marshall Arisman, figured, “I’ll help him get hooked up with her.” So he invited us to both judge a show together. And that’s what started the romance.

George Gendron: I don’t know whether you said this or someone told me. And I’m assuming that this is public knowledge, so it’s not as if I’m giving away a family secret, but growing up your first name was not Steve.

Steven Heller: No. It was Harmon.

George Gendron: Harmon. And was it you who said, or Louise said, that things might’ve turned out differently in terms of your relationship with her if she knew?

Steven Heller: Louise said that as a joke. It was a good joke and I believed it because I believe that name was a big hindrance to me, particularly in terms of my early tween years.

George Gendron: I bet. With all due respect, it does sound like, I don’t know, a family business that makes mayonnaise or something, I don’t know, how old were you when you changed it to Steve?

Steven Heller: I changed it when I was 14 or 15.

George Gendron: Good move. How’d your parents react?

Steven Heller: They accepted it. My grandmother on my mother’s side had trouble remembering to call me Steve and I’d always correct her. But it was my middle name. The problem is I never changed it legally. So 50-60 years later, I’m getting jury notices for both Steve Heller and Harmon Heller.

Formally I was at NYU studying English—actually not studying much at all—but working for the Free Press and after a certain amount of time I was working for Screw as well, and NYU got a whiff of Screw somehow.

And I had done a comic strip where I put my philosophy professor in the strip and it was a pretty disgusting strip. And I was requested to see the school shrink. And after five mandatory sessions with him, he advised me to get psychoanalysis—either with him or with somebody else. And I refused and they let me go.

George Gendron: In other words, you were a student and you were kicked out.

Steven Heller: That’s the gist of it. And so I had to maintain my 2S, my student deferment. My father, who was a great guy, and I didn’t really realize it at the time, got me into the School of Visual Arts in the middle of a year. And because I was working, I spent more time at work than I did at school.

So I went to SVA for about a year, maybe a little more, and was called into Marshall Arisman’s office. He was chair of illustration and he looked at my portfolio and said, “You’ve got professional work here. I’ll promote you to the senior class from the freshmen if you just attend some classes.”

And I hemmed and hawed and said, “Okay.” But I never attended those classes, so he was forced to let me go.

George Gendron: God, you didn’t make it easy for people.

Steven Heller: No. And then a year later I suggested a newspaper design class, which Marshall or Richard Wilde, one of the two, hired me for. And it was going to be the school newspaper. I named it AIR (Artists in Residence). And I designed a logo, which I must say was pretty damn good.

And I got the class together and I would use my own experiences in what was called teaching. And there was a feminist woman in the class who took great exception to my being at Screw and showing copies of Screw and using that as our standard for newspaper design.

And I eventually won her over somehow. But by that time it was the second semester and I had just gotten the job at the Times. So I left. And then a few years later, Marshall and I became friends, good friends. And he invited me to join his faculty for the first Master’s program in illustration at SVA, which I did and I taught for 14 years.

George Gendron: When you think about the arc of your career, the thread for most people is a relationship with institutions: “I went to NYU for four years, got my degree. I went to Columbia, got my master’s, blah, blah, blah. Then I went to work for CBS.” And for you, it’s exactly the opposite. It’s all about personal relationships. Or professional relationships. Or both.

Steven Heller: It was a course that I realized could pose problems in the future. And I’ve always suffered from imposter syndrome. I did this commencement address for SVA this year—

George Gendron: —It was magnificent.

Steven Heller: I admitted to the imposter syndrome in the talk—that I had no business, really, being up on stage like that. But things happen in strange ways. I am not a religious person, but I believe in God. And I figured God had something in store for me if I followed a few rules.

George Gendron: And you also said to me during that same conversation that having given that commencement address, you felt that somehow the end of a chapter in your life had occurred. And I said, “What was the chapter?” And you said to me, “Oh, it was everything I’ve ever done before that.”

Steven Heller: Yeah, it was the beginning of the epilogue.

George Gendron: So now what?

Steven Heller: I thought about that after our conversation. Now what? And now what is still a big question mark for me. I still have a number of books in mind that I’d like to do, but not sure whether I have the energy to do them.

George Gendron: Oh. Come on. You’ve already written what, 201?

Steven Heller: Yeah.

George Gendron: What’s a few more?

Steven Heller: I have Parkinson’s and that depletes my energy at the end of the day.

George Gendron: Yeah. I shouldn’t joke like that.

Steven Heller: No, joking is perfect for the disease—everybody’s got to have something. We all have our flaws. Like, you know I have a BMW car and I got it because it was all computerized and I figured it would never have a problem. And I’m just anticipating the problem coming.

George Gendron: How many miles you got?

Steven Heller: Well, I’ve had it since 2018, and I’ve only got about 32,000 on it.

George Gendron: Oh, that’s nothing.

Steven Heller: Yeah, it’s nothing.

Steven Heller’s Favorite Magazines of All Time

“These magazines—most of them don’t exist anymore—are great monuments to what could be done in print if you’re allowed the time and the effort and the space.”

George Gendron: I had a 2000 Audi S6. It was the one 10-cylinder engine that they dropped in from their Lamborghini. And I had bought it used. And God I loved it. I was commuting back and forth to Worcester, Massachusetts, which was a long commute—it was like 75 miles each way—where I was building out an entrepreneurship center. And I brought it in to be serviced by the Audi dealer. And it had 99,000 miles on it. And the head of the service department took me aside and he said to me, “You know what you have?”

I said, “What? I love this car.”

He said to me, “You’re driving a time bomb. It goes off usually for this engine at around 100,000 miles. And an engine rebuild costs more than you paid for this car.”

And so it’s the same thing, that sense of impending doom.

Steven Heller: Yeah. Well, life is a sense of impending doom.

George Gendron: It can be. You do get to a point—you commented on this earlier in the conversation about, “Oh my God, so many people I know are dying.” Boy, that’s the truth. You were sharing with me what sounded like a real fascination with the George Lucas Museum of Narrative Art and he has been working on it for, I don’t know, five years or more, but it’s still not open.

Steven Heller: No, it’s supposed to open this year.

George Gendron: Do you ever think about the Steve Heller Museum?

Steven Heller: No. In fact, I’ve begun de-assessing. If you look online, there’s Under The Cave by Nicholas Heller, my son. Years before he came to be well known in his field (as “New York Nico”), he did a documentary about the apartment that I had was the sole receptacle for all of my collections and materials that I used for my books.

I had to dismantle that and get rid of a lot of things when we moved from 16th Street to 30th Street. And right now I have stuff in too many places and I’m just finding outlets for them to go to. Like I have a large collection of maybe over 700 or more pieces in the SVA archive. And they run the gamut from my own work to other people’s posters and illustrations and magazines. And I love the fact that it’s here and it’s in physical form. They put some things up online, but primarily it’s for those students who want to come and look and feel and touch printed material.

George Gendron: That sounds like the beginnings of the kernel of an idea for a museum, but we’ll talk about that offline at some point. So recently you said to me in response to a question that we have to ask everybody: So what do you think of the future of print? And you said to me, “Print is here to stay.” What exactly did you mean by that? And do you see examples of things, tangible things in print that provide for you even a glimmer of what the longer-term future of print might look like?

Steven Heller: Well, I see that print is coveted. There’s the Poster House Museum in New York City. And I’ve done collaborations with Poster House. And it’s all about the tactile material. We did a podcast for a couple of months before COVID, which was basically an interview that I would do with a curator of a particular exhibition. And you still had to go see the material. You couldn’t look online and get a sense of what the material was like—the size, the way the ink was applied to the paper.

Still one of the most popular courses here in MFA design at SVA is a course given by Warren Lehr on the history and the making the practice of book design of creating literary design works. People like getting their hands dirty. But I was thinking this morning, as I was throwing out the daily newspaper collection—every morning we get the New York Times, and every week we get New York Magazine and The New Yorker. And they just build up like fungus.

The disposal room is only five feet away, and I take great pleasure in taking those read or unread artifacts and throwing them out. So I have mixed feelings about print. I love the sensation of it. Certainly, as an author, I’d much rather have my work in print than online, where it’s subject to the vicissitudes of technology.

George Gendron: I have that same ambivalence. How can you not? But any rate that was more future looking. But now looking back to the past, magazines in particular, what were your five all-time favorite magazines?

Steven Heller: I was thinking about that as well. And I was thinking about that when I should have been asleep.

George Gendron: But you never sleep.

Steven Heller: I know. I’m always thinking about something. And I came up with a list of more than five.

George Gendron: How many?

Steven Heller: Ten or 11 that I can point to having done no research. But I’ll tell you what they are.

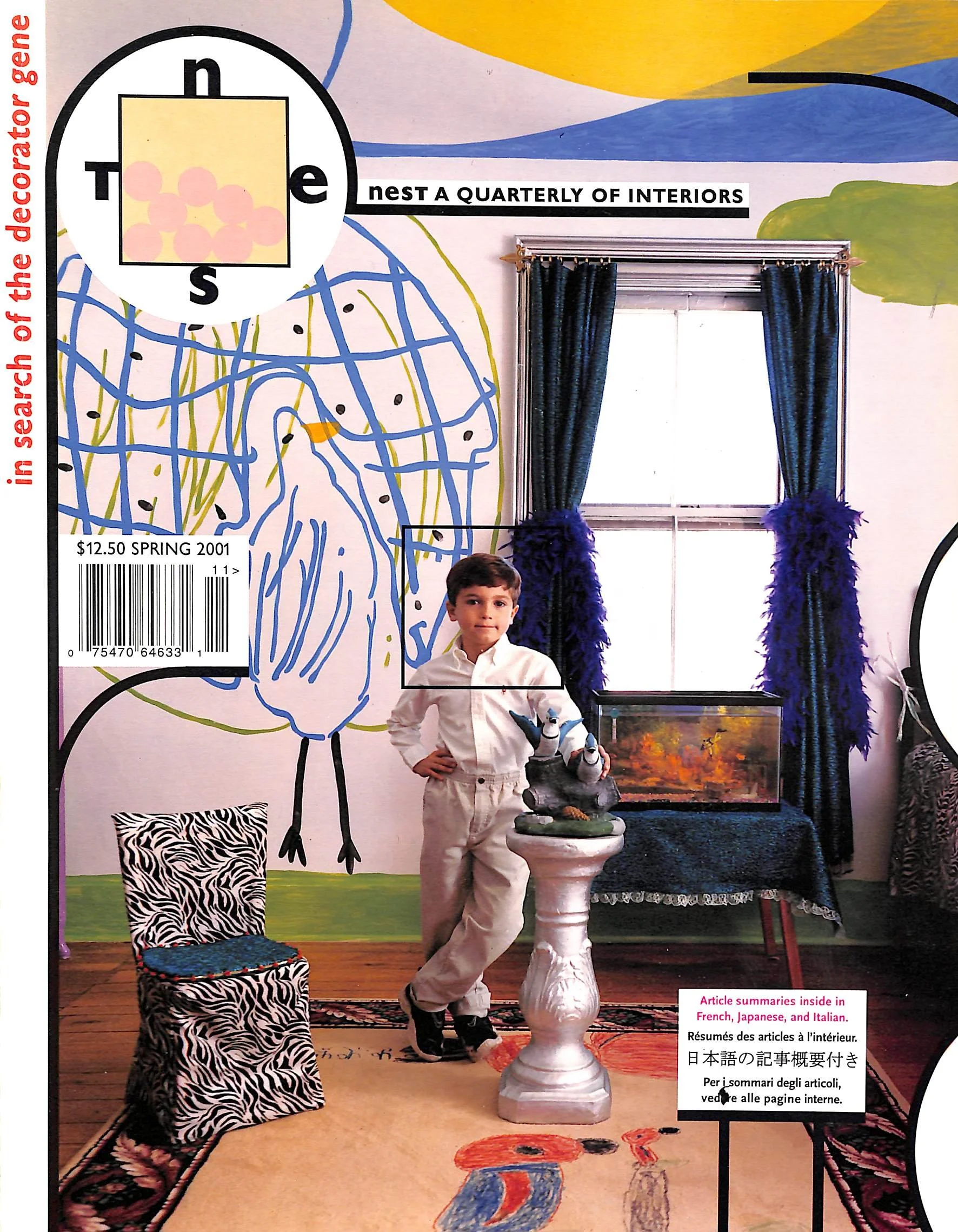

Portfolio Magazine, art directed and designed by Alexey Brodovitch. There were three issues of that edited by Frank Zachary, who was a friend of mine, and somebody who was greatly influential on my life before I ever knew him. Nest by Joseph Holtzman, who was not a graphic designer but he was an interior designer.

And Nest was, at first in my appreciation, a piece of junk. And then I started collecting the issues and I eventually interviewed him and I just came to love the magazine and the way it looked and the fact that he didn’t know all the nuances of typography, that he did it by the seat of his pants.

George Gendron: So what you fell in love with was the evolution of the magazine?

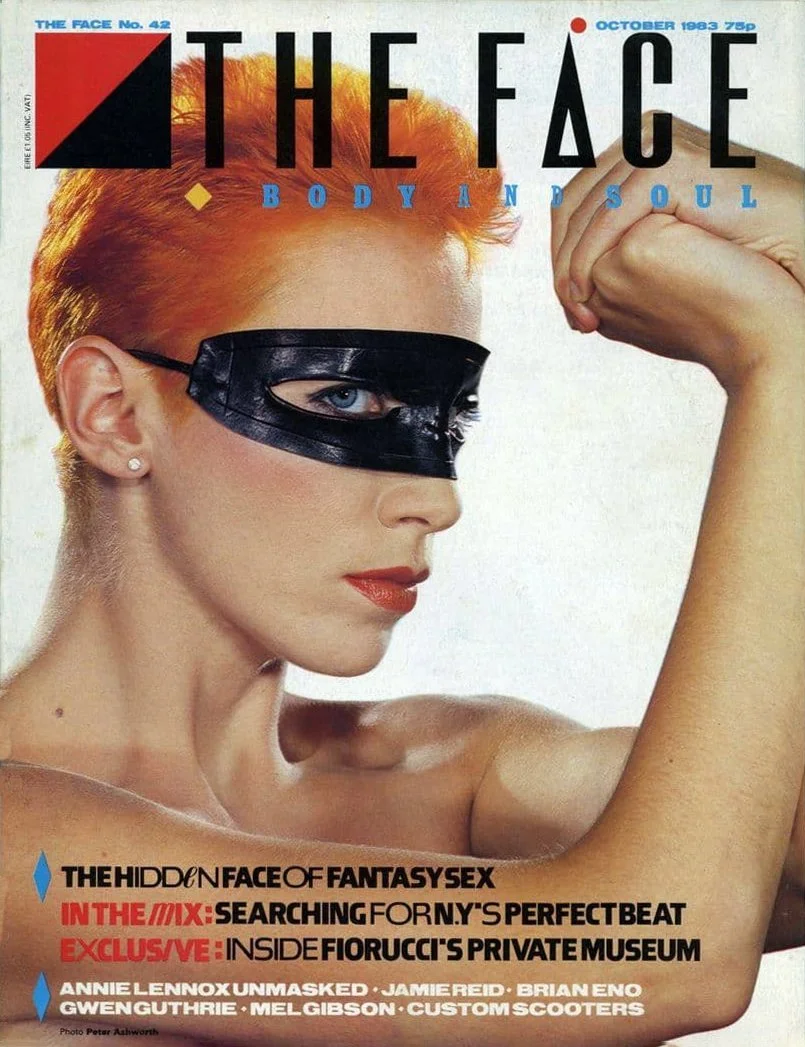

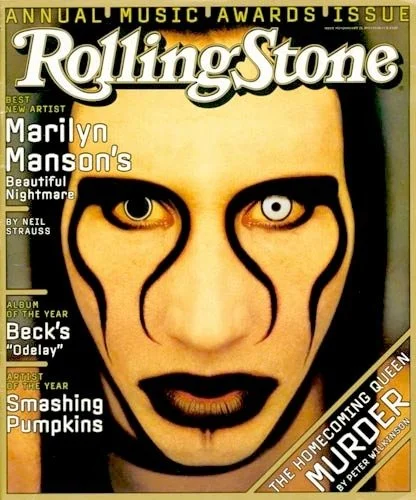

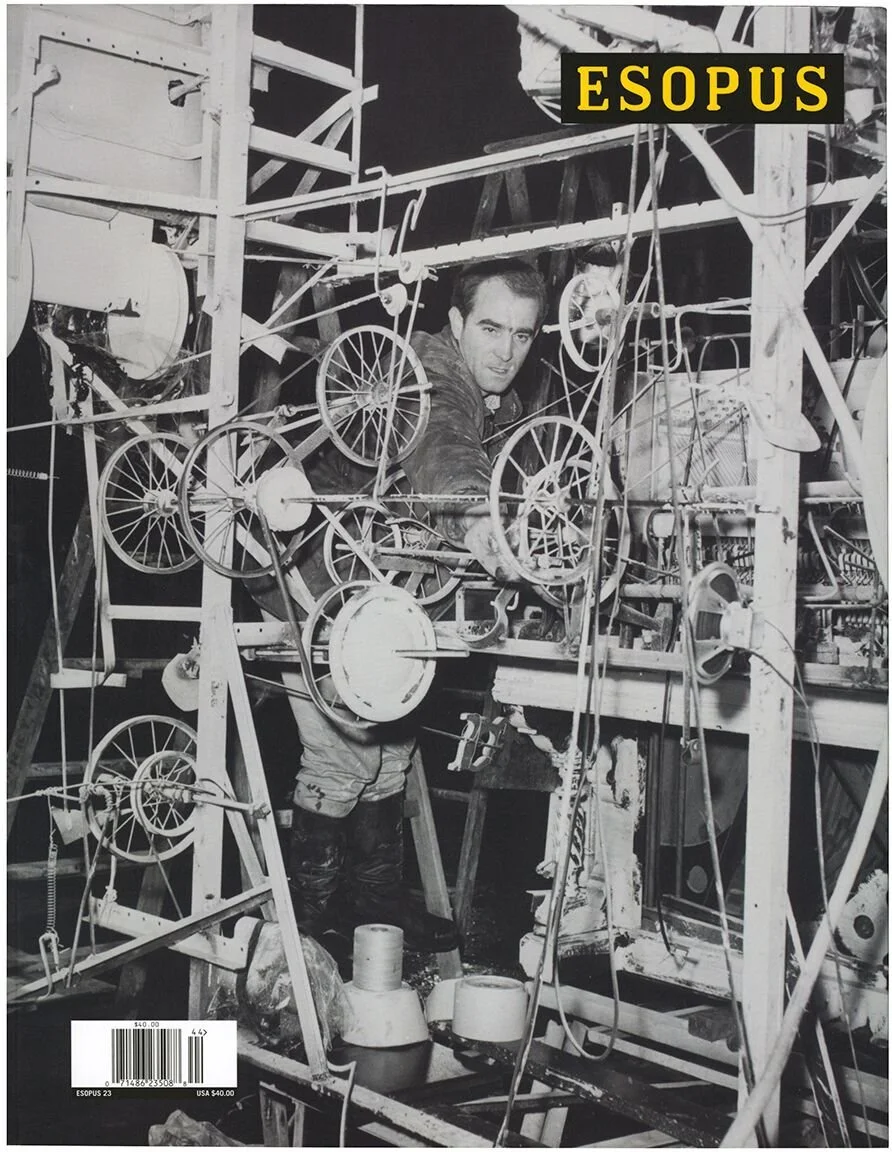

Steven Heller: No, I fell in love with what the magazine was. It evolved interestingly as well, but I started loving it from issue one. The Face, Neville Brody, for obvious reasons. His typography was stellar and it was a hip publication that still holds its own. Rolling Stone when Fred Woodward was doing it with Gail Anderson. Esopus, which was done by Tod Lippy, who was an editor at Print. We met at Print magazine.

George Gendron: What’s the name of that magazine?

Steven Heller: Esopus. It is named after the town and river in upstate New York. It was a total arts magazine. I made one contribution for it, which was handled so beautifully. It was a series of letters that I had found by a woman who had gone to college trade school to become a hospitality person in the heat of the depression.

And she saved in this box 13 or 14 letters that she received rejecting her, and a list of names of places she tried. And the letters were so compassionate: “We just don’t have any space.” “This is the depression.” Blah, blah, blah. And I showed it to Tod Lippy—who was not a designer, but became a designer—and he printed them on different stocks of paper and ran them in a file in the middle of the magazine.

George Gendron: Oh, wow.

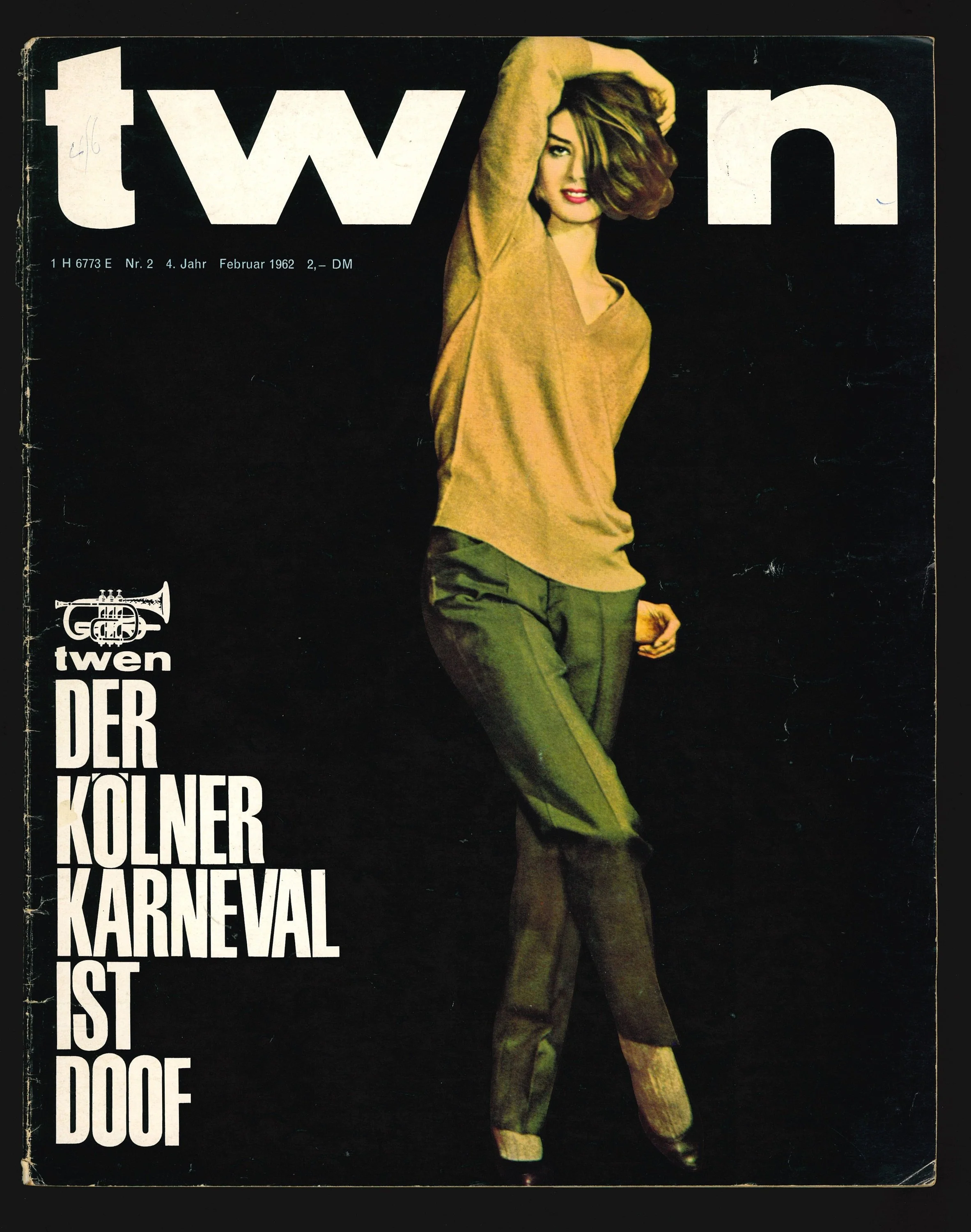

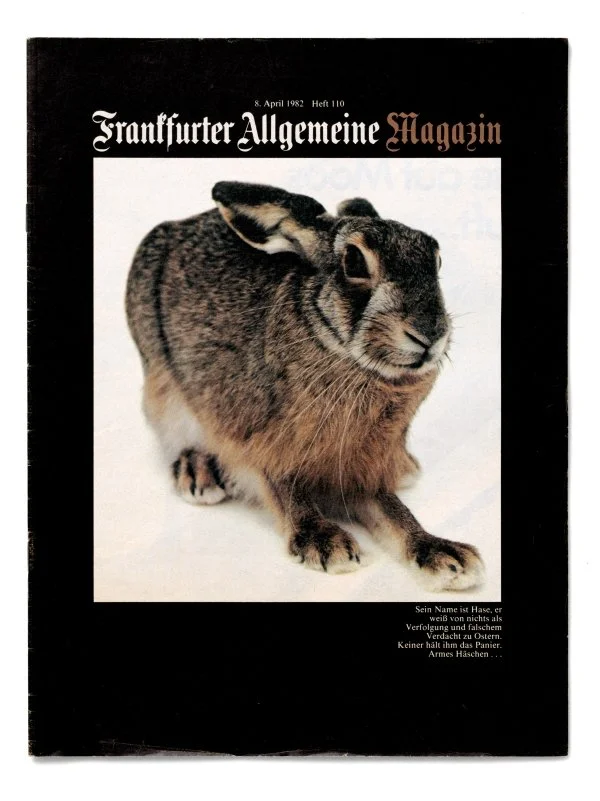

Steven Heller: So the magazine was very much like Portfolio, insofar as there were all these surprises that awaited you. And every issue included a CD on the inside cover with music that he either curated or composed himself. And then there was Twen, which was designed by Willy Fleckhaus, the great German designer. And he also designed the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung magazine, which was beautiful. And Hans-Georg Pospischil took over after Willy Fleckhaus died. And I still save those magazines. They were the best Sunday magazines ever.

George Gendron: It was almost as if we did a podcast about Twen when we were doing, Will Hopkins, the designer of American Photographer.

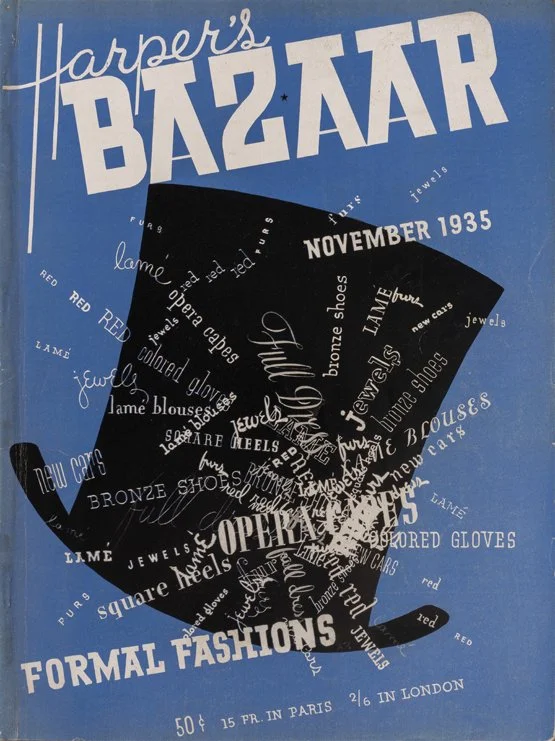

Steven Heller: Will Hopkins did a really great bunch of issues for Look magazine. Harper’s Bazaar Is on my list—the Brodovitch version. But also the Henry Wolf version and the Marvin Israel version. And, of course, the Bea Feitler/Ruth Ansel versions.

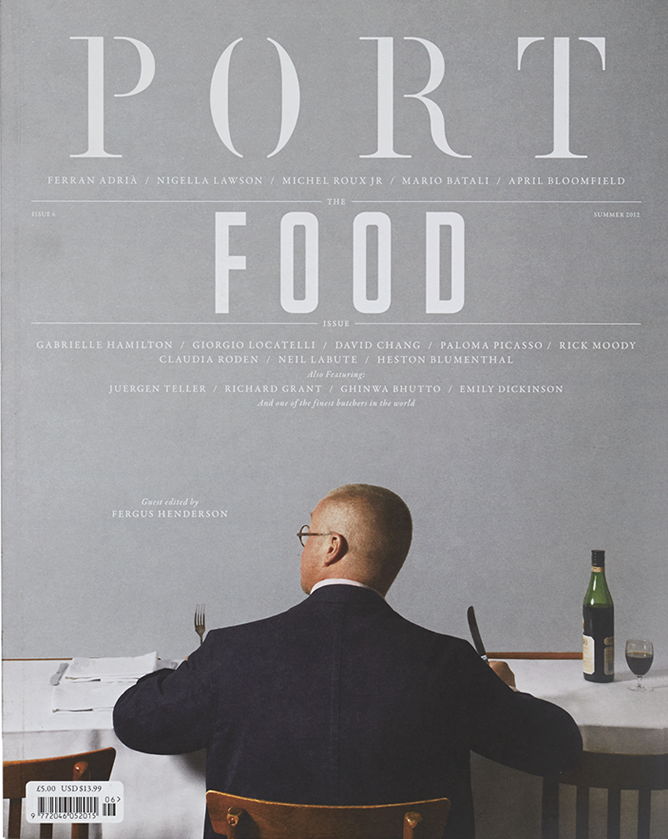

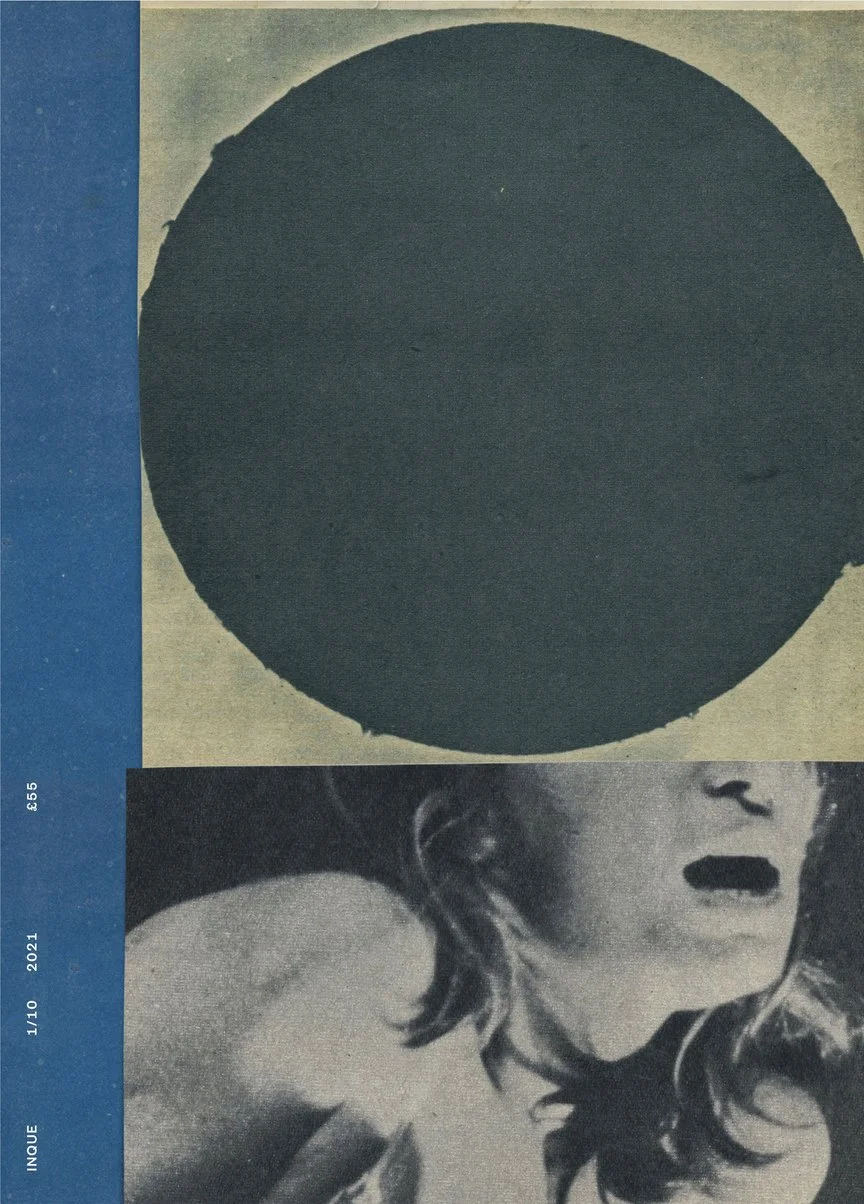

Port magazine, which Matt Willey, who’s now a partner at Pentagram, designed for quite a while. And his magazine, which has only come out two issues, with one promised this year, Inque. I-N-Q-U-E. Which I think is one of the most beautiful magazines ever.

And my favorite issue of The New York Times Magazine history—and I knew many of the art directors there, and I worked on it when I first went into the Times—but my favorite was also by Matt Willey, and it was June 5, 2016, and the theme in that one was, “Life Above 800 Feet.” And the typography was just so perfect for the theme. It was tall, thin, but bold woodtype approximation. And it just went up the page as though it was a bar chart. It was just so extraordinarily beautiful.

George Gendron: I’m going to have to look that up.

Steven Heller: And you know, when you ask, Is print dead? You look at those things and you realize that it shouldn’t be dead. And if it is dead, it’s like your favorite restaurant—and one of my favorite restaurants for my wife and I was Periyali on West 20th Street. And it closed unexpectedly and I just rued the day it left us.

George Gendron: People describe it as losing a family member.

Steven Heller: Yeah. And so these magazines, which—most of them don’t exist anymore—are great monuments to what could be done in print if you’re allowed the time and the effort and the space.

George Gendron: I’m going to see if I can collect as many of these as possible, so thank you for that list. Now we have to move on to one of two final questions and we call it “The Print Is Dead Billion-Dollar Question.” And it is: If somebody cut you a check for a billion dollars with only one provision—you had to use it to create a magazine in print— what would it be?

Steven Heller: Well, the magazine I would create is called Democracy. And it would be a magazine that cautioned people about the threats to democracy using all mediums. And it would be a celebration of democracy, like the four freedoms. And it would be a cautionary tale about what could happen when those freedoms are abridged.

George Gendron: Do you see anything even remotely like that out there now, or aspects of it?

Steven Heller: No, I just see partisan magazines.

George Gendron: The closest thing I can think of is The Atlantic.

Steven Heller: That’s a good response. And The Atlantic is—its design is very handsome.

George Gendron: It really is. Their covers are stunning.

Steven Heller: Yeah. But that’s what I think is the closest magazine to this idea.

George Gendron: Now this question is directed at Steve, the teacher. Although before I ask it, I have to, I don’t know how I could have missed this. I was talking to Jessica Helfand who just adores you and I think you guys met when she was doing a Sunday magazine for The Philadelphia Inquirer—we’re going back a ways. And she said, “The one thing you have to say to Steve, on my behalf, is that I don’t know anybody who has been more generous and has helped more people involved in the visual arts than him.” So I thought I would pass that along.

Steven Heller: I’m touched.

George Gendron: Now our final question is for Steve the longtime teacher. Let’s imagine that we, and by we, I mean anybody who’s interested in the world of print, we’re taking a class with you and we’re getting to the end of the class, and you’re giving us a final assignment. What would that assignment be?

Steven Heller: I would want to see passion for print. I would like to see somebody find a theme that means something to them and create what you might call an entrepreneurial project in print. The MFA design program has always had the subtitle, “the designer as author and entrepreneur.” And then it became, “the designer as entrepreneur.” And I think that print in any of its forms would be the medium.

And the content would be an expression of personal passion. I give a version of this exercise to my students in this class I do on propaganda, which is the umbrella for the Branding Democracy project that I do. And for the first assignment, I tell them to create a propaganda campaign for something they feel very strongly about and convince me that it’s important.

George Gendron: What effect do these projects have on you?

Steven Heller: It makes me feel hopeful that there are people who still care about basic freedoms. But it also is encouraging because I see students like our Chinese students, who did not grow up in a democratic world, coming to grips with this ethos. And so when I hear that President Orangehead and Secretary of State, Marco Asshole will revoke or deny visas it just infuriates me. And I can’t find a way of turning it into a joke.

George Gendron: I agree. I agree. But I agree with you about the impact that has. On a related note, when I talk to journalism students what I find really interesting is that, number one is the level of student journalism activism that exists on campuses right now. By activism I’m not just talking about political activism, I’m talking about students who are actually starting stuff about the extent to which in some places, student journalism is beginning to fill a void, as local newspapers start to either disappear or diminish in their impact. But the other thing that I find really encouraging about the future that I think is related in some way to what you’re saying is a lot of these students, when you talk to them about, Okay, what comes, what happens after you get out of school? There’s just this assumption that they take for granted that, “Oh, I’m going to make something.” Not, “I’m going to go get a job.” “I’m going to make something.” And part of that is just this very practical sense—that pragmatic sense—that I’m going to have to make a job for myself.

Steven Heller: I think the word “making” has become almost a buzzword. But it’s a good buzzword.

George Gendron: It’s a good buzzword. You’re right.

Steven Heller: I think garnering most of these skills are necessary to making a print publication or any publication. I don’t know. I wrote in a piece about my own incompetence when I left the Times that I left my competence behind.

And I can’t do anything—you know I can do some hacks, I can make a page out of Keynote, which is a really absurd hack. But I can’t use InDesign anymore. And I can’t use Figma. I don’t even know what it is. It sounds like a fruit. So there are these people out there that we are now calling designers who know how to make things happen and make things happen that the old fogies around have no idea what to do.

Patrick Mitchell: Including your son.

Steven Heller: Including my son.

More from Print Is Dead (Long Live Print!)