A Mag Man with a Plan

A conversation with designer Walter Bernard (New York, Fortune, Time, The Atlantic, WBMG, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH THE SUPPORT OF STACK MAGAZINES

When your business partner is Milton Glaser, the most celebrated designer in the world, what does that mean for you? If you’re Walter Bernard, today’s guest, you accept it as the gift it is, and then you go out and make yourself an extraordinary career.

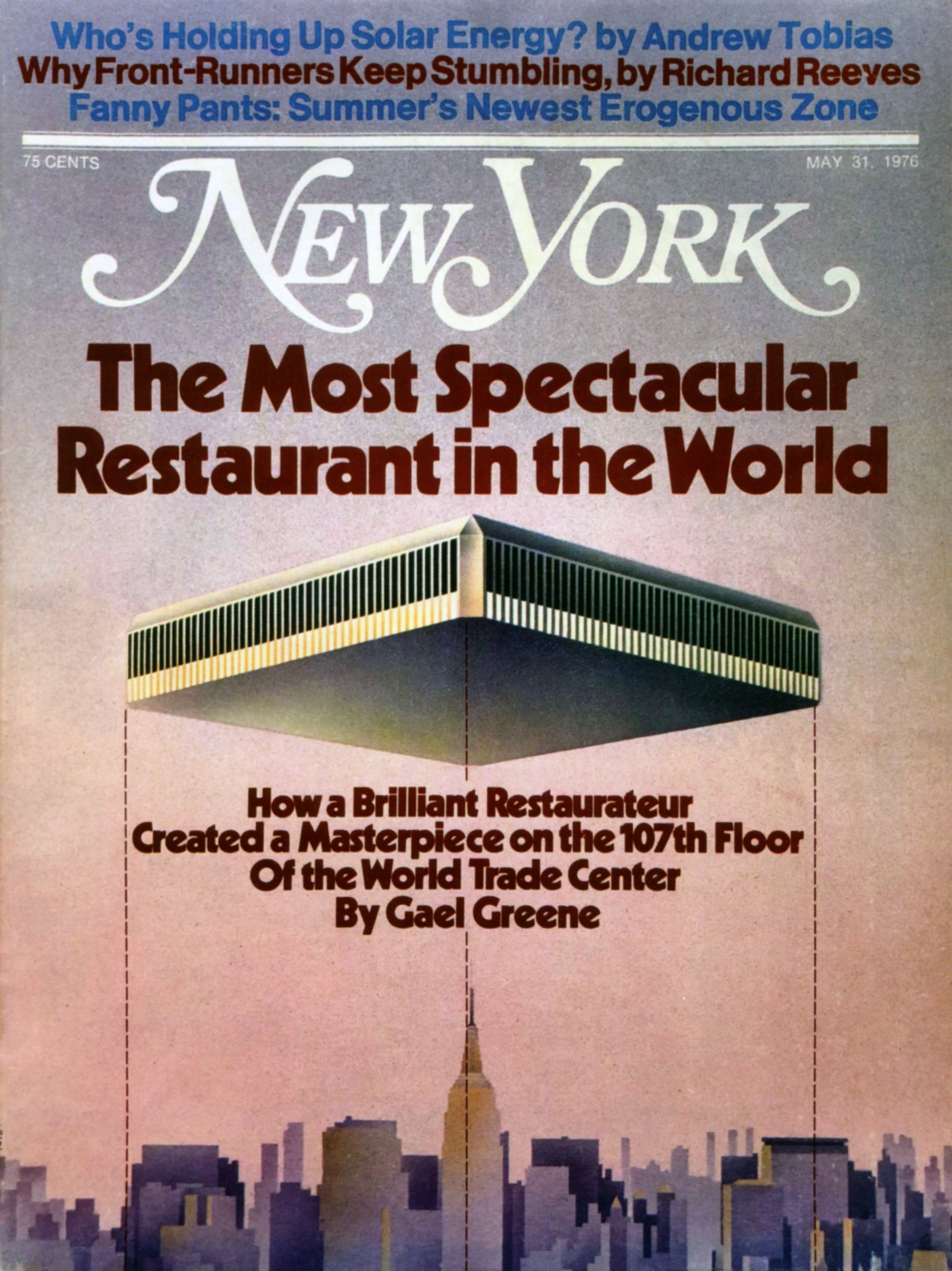

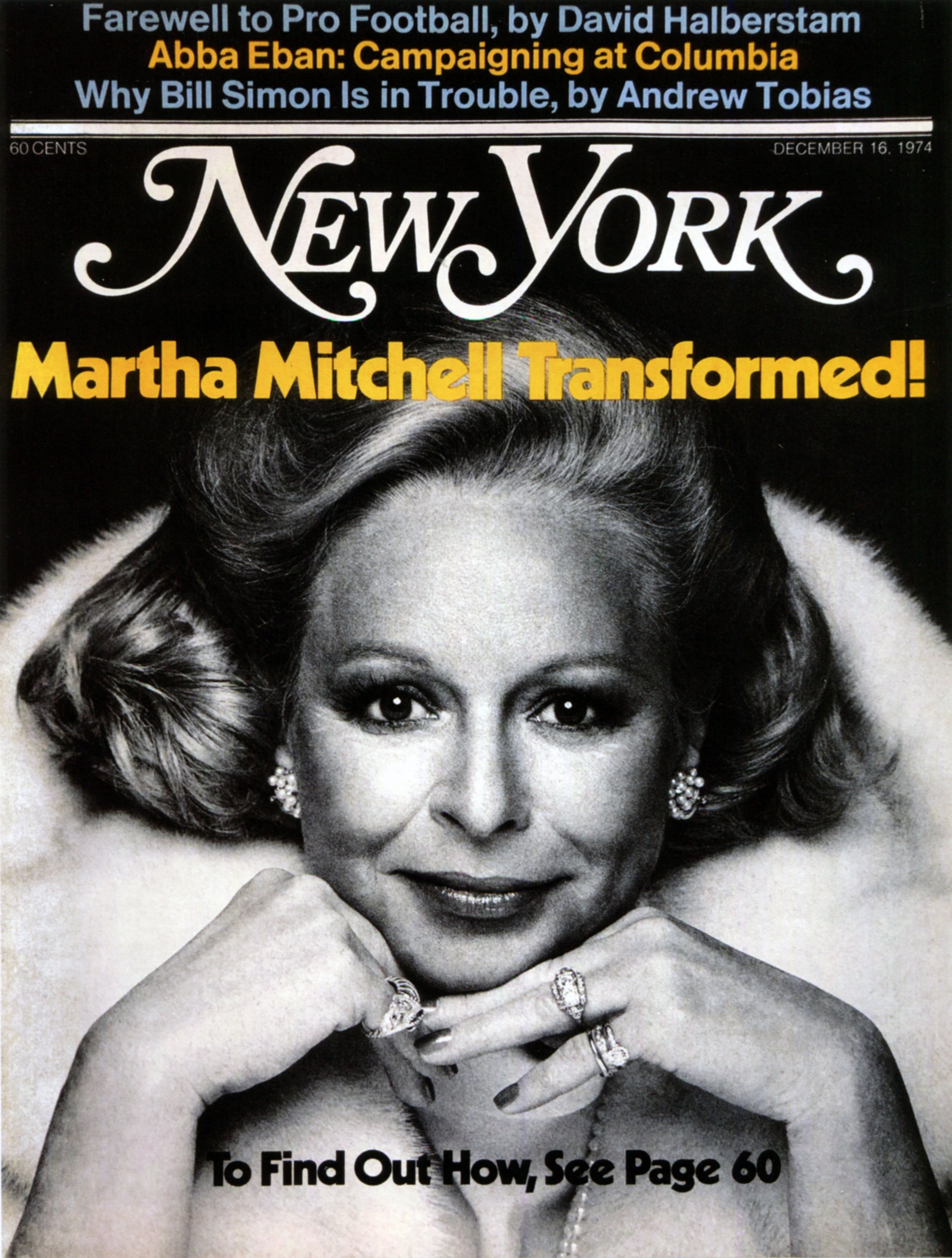

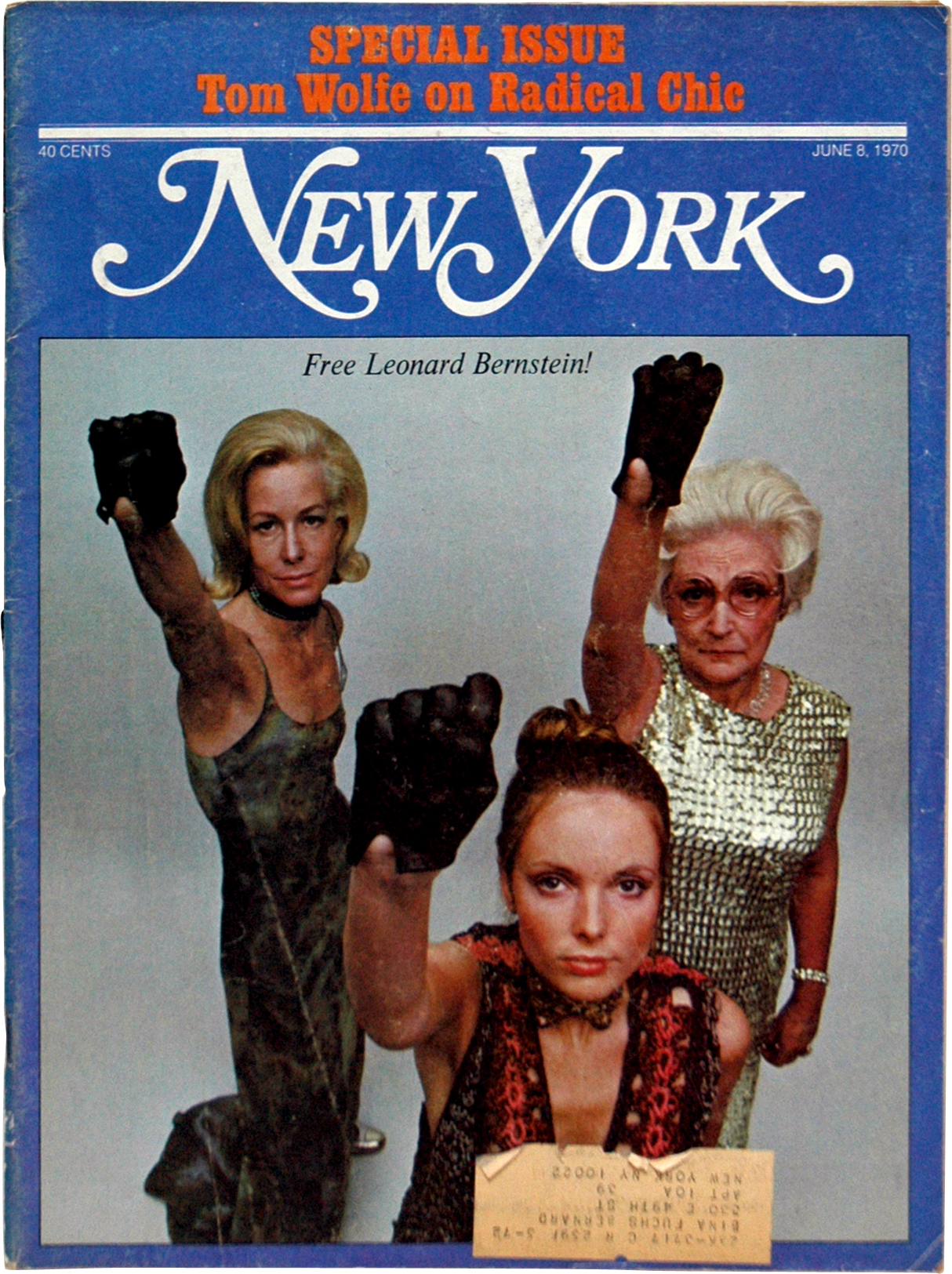

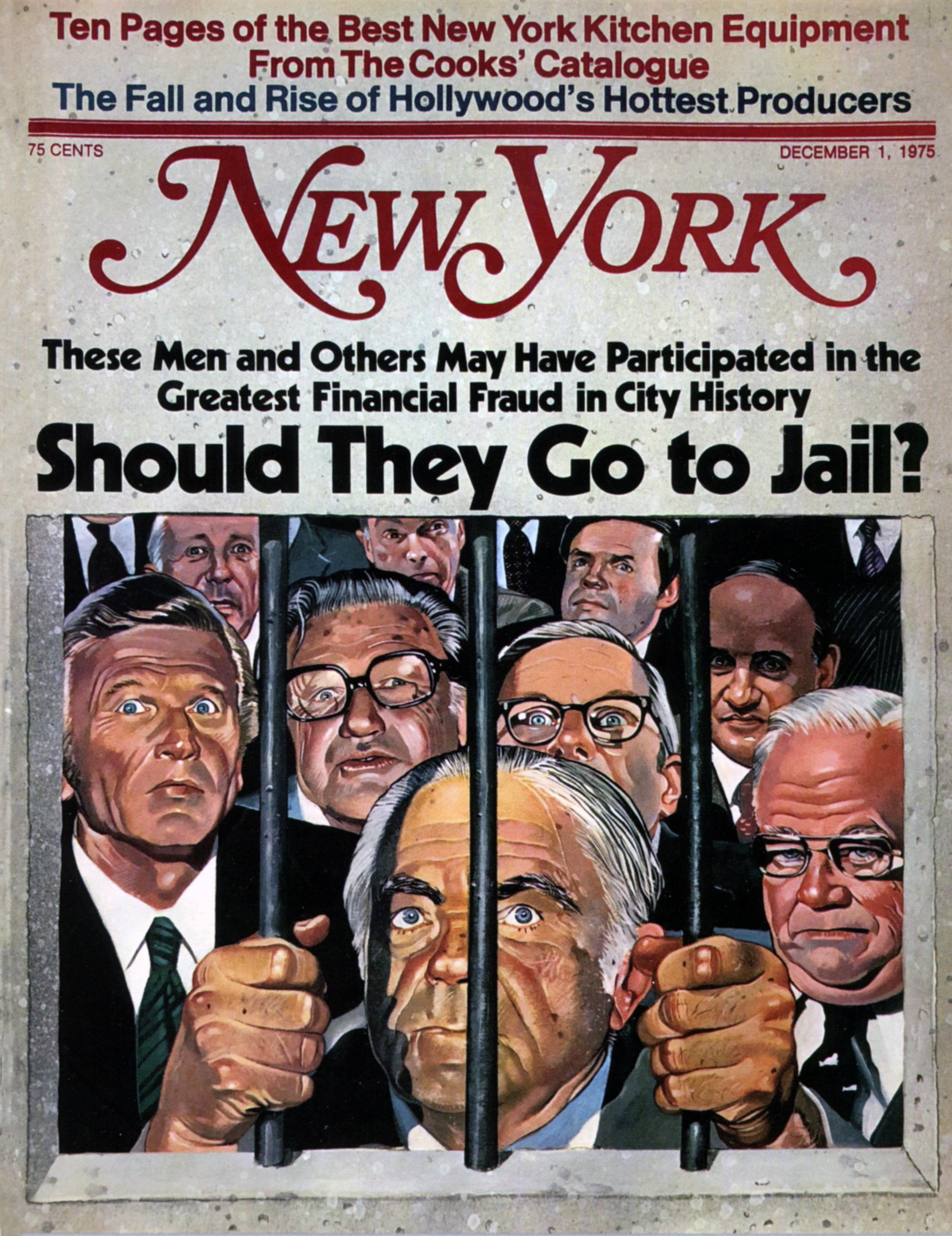

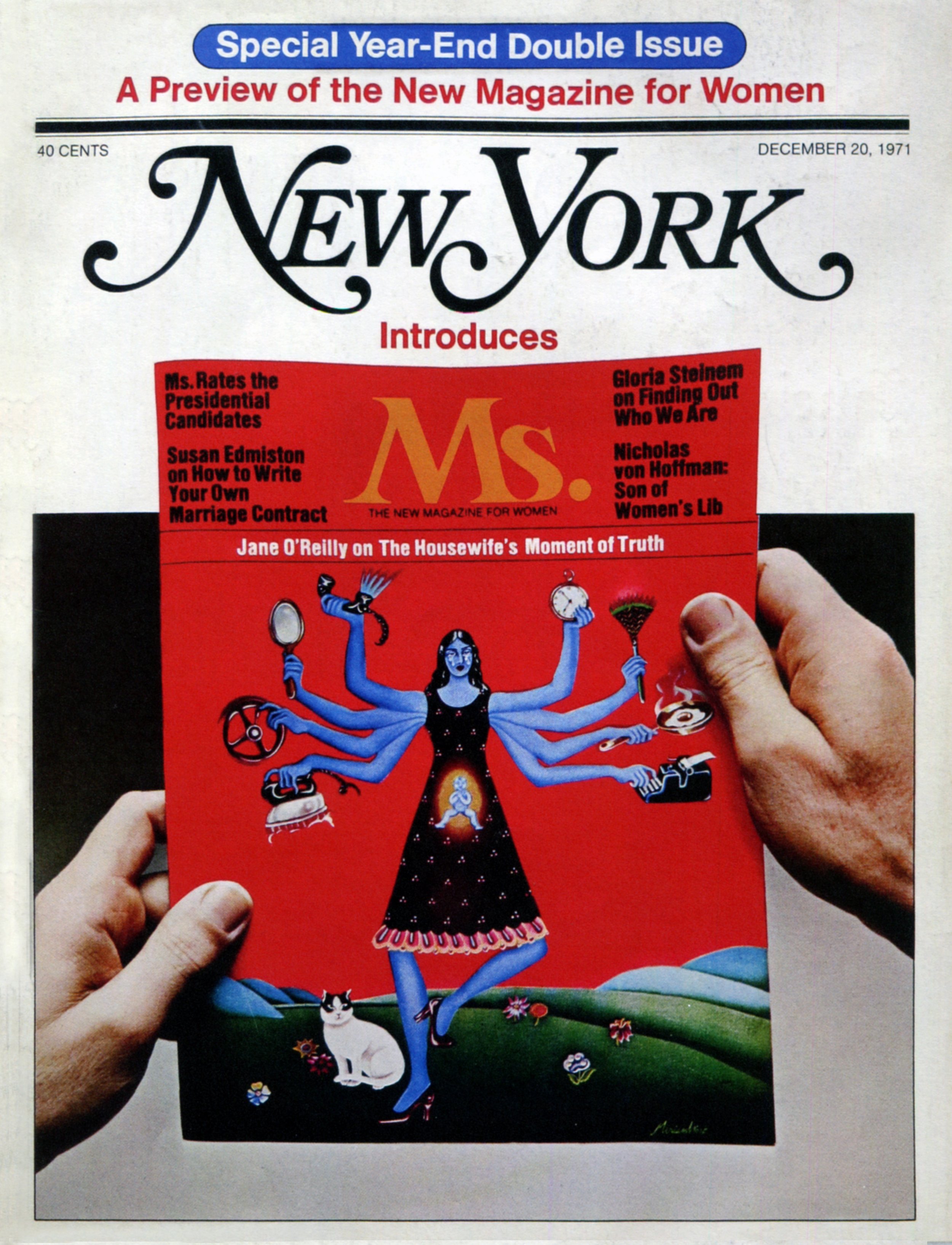

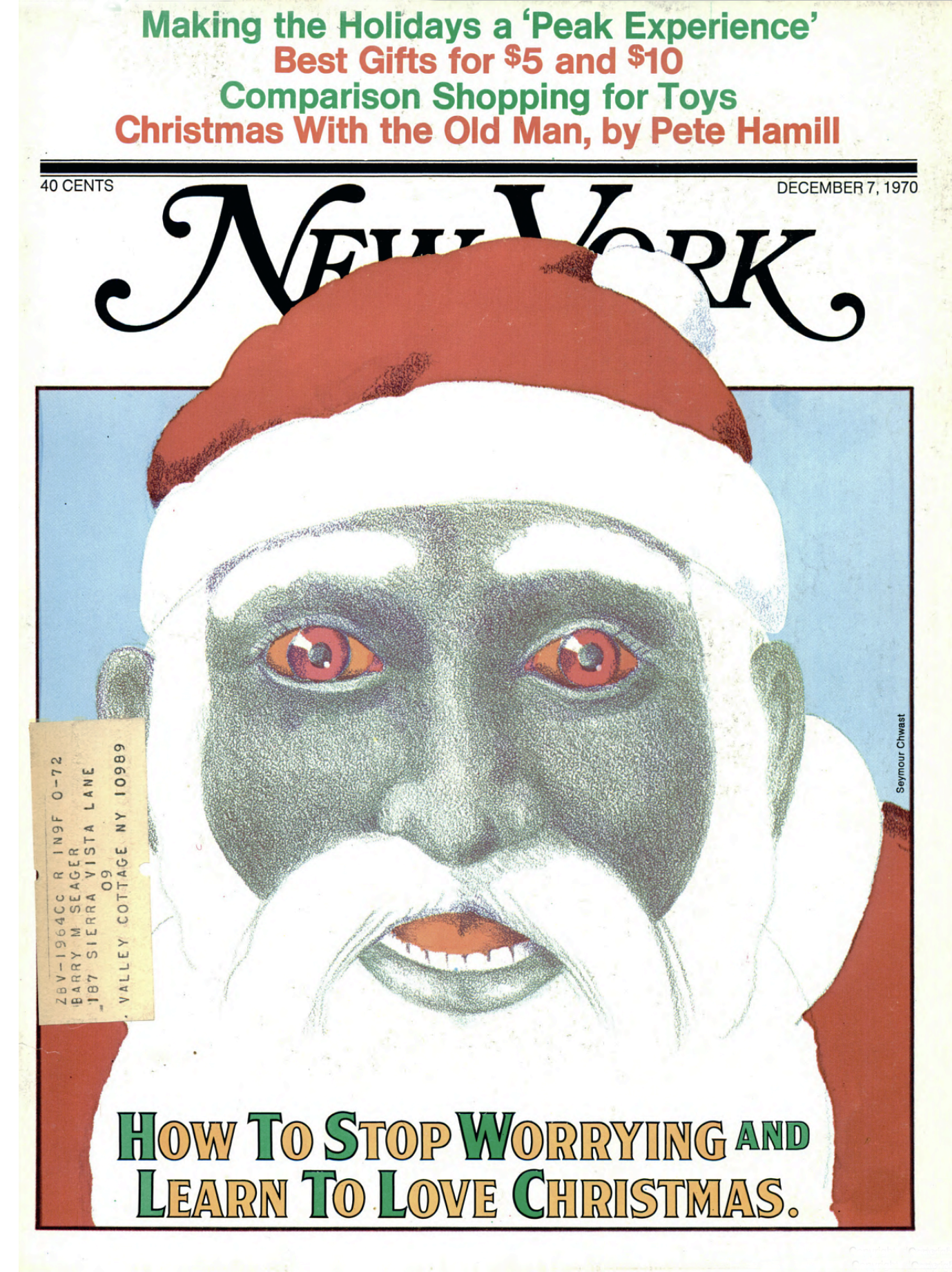

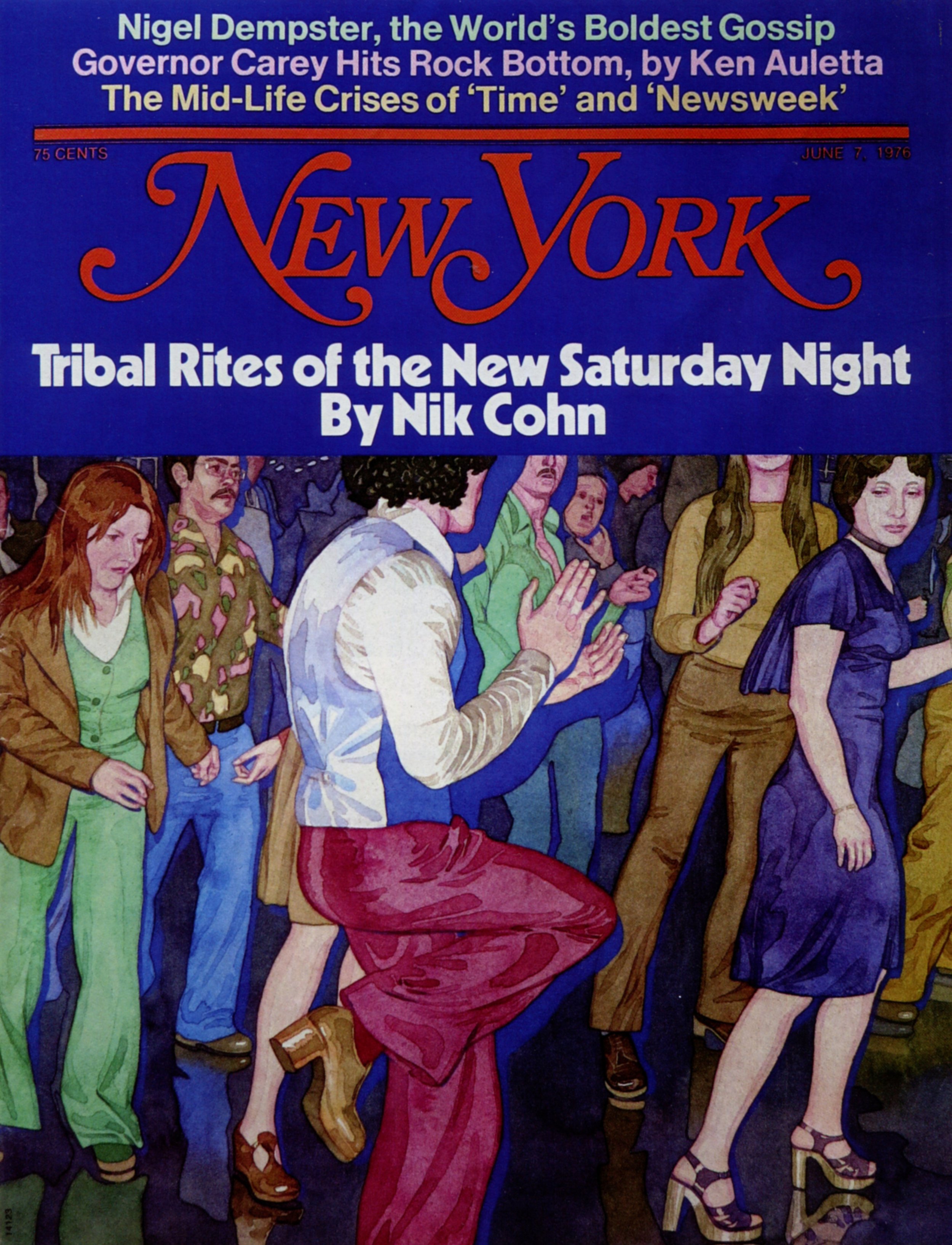

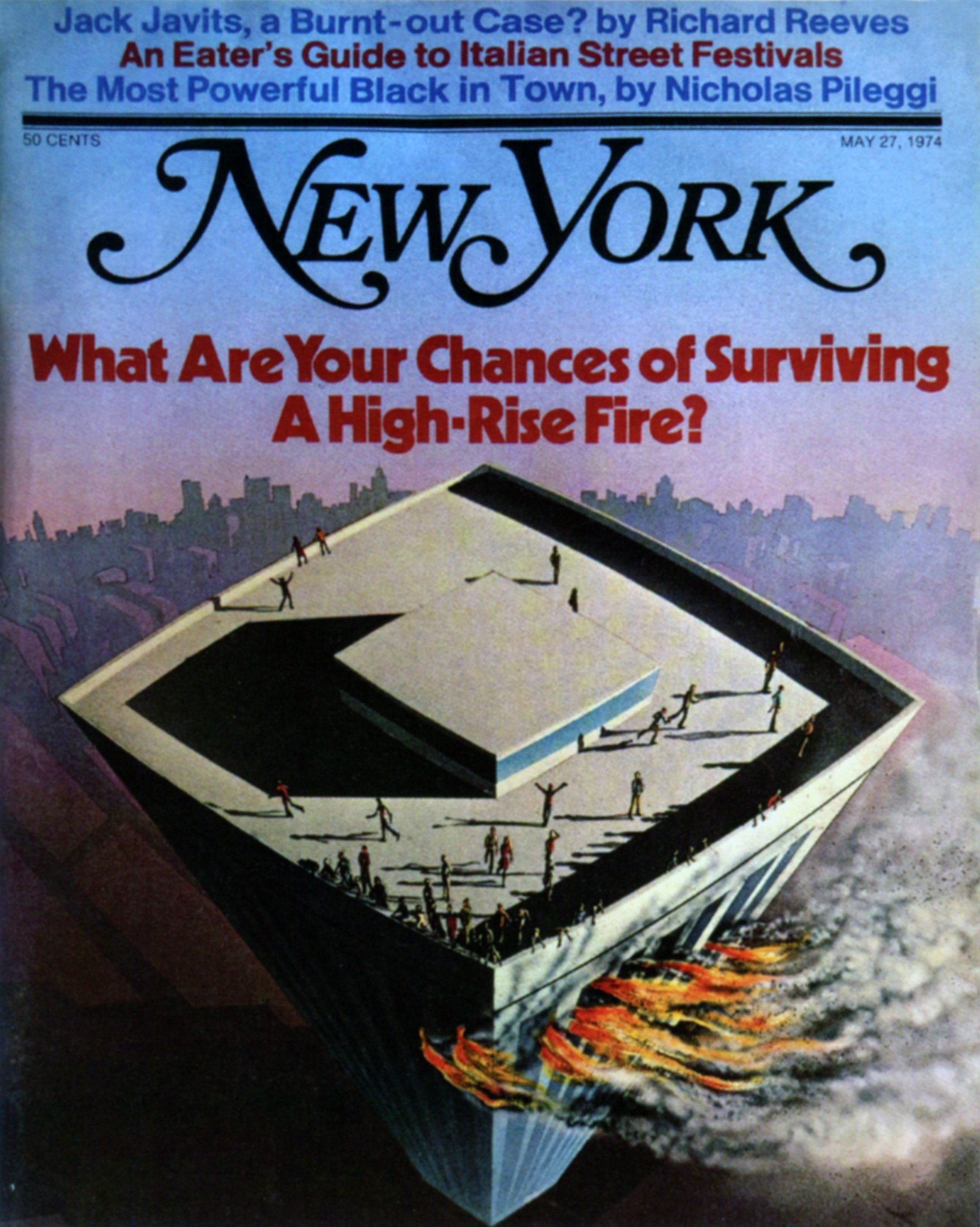

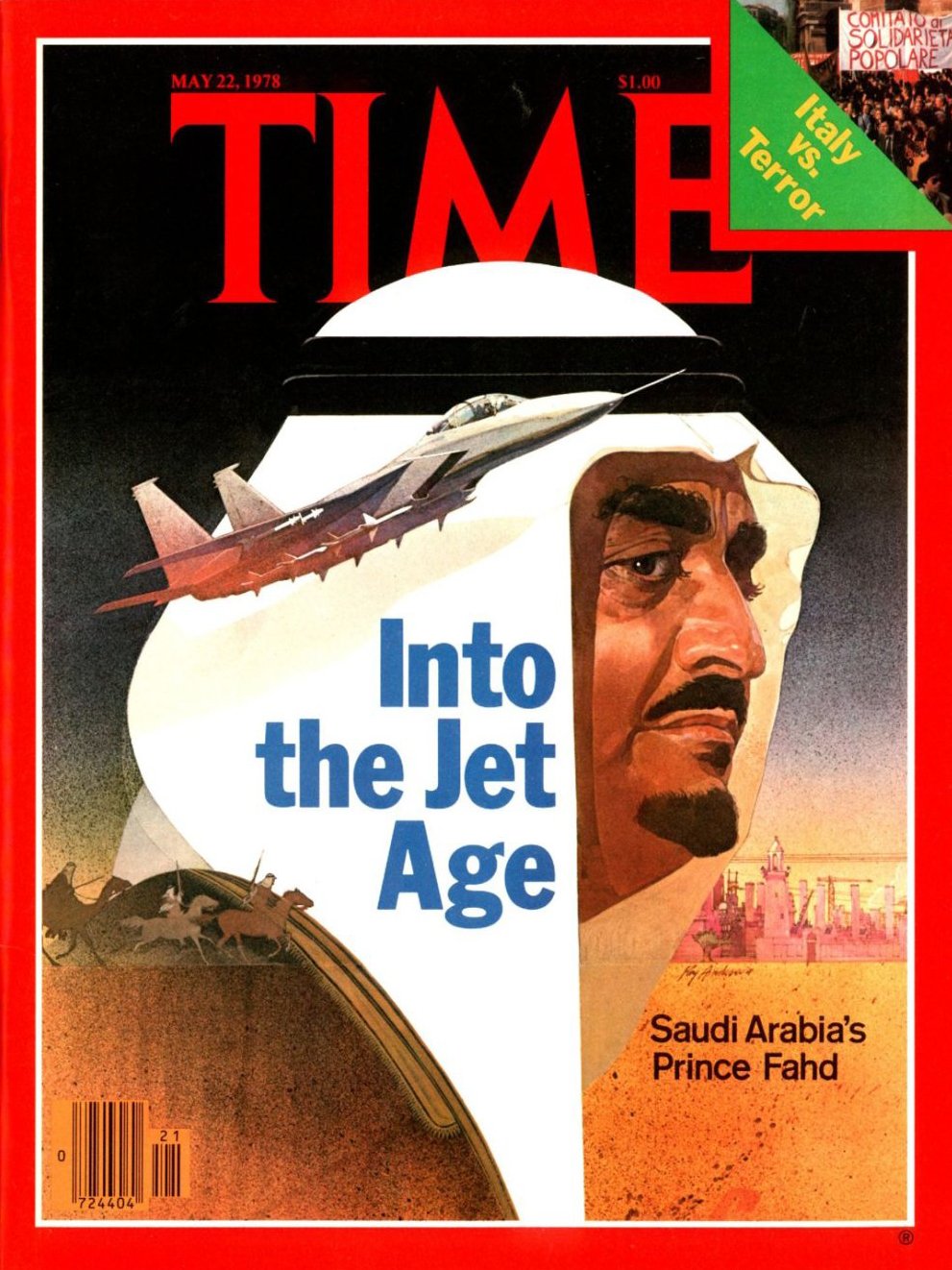

Here’s three things you need to know about Walter Bernard: 1) He was the founding art director of New York magazine, 2) he once produced a top-secret overhaul of Time magazine, and later became its art director, and 3), along with Glaser, he’s designed or redesigned over 100 publications around the world.

And Bernard is happy to talk about working in Glaser’s shadow:

“Milton was extraordinary in his capacity to work, and work quickly, and work brilliantly. And, there was no competition there. I was just kind of a student. And even though we worked together at New York, and I was the art director and he was design director, there was no question that he was the mentor and also the lead.”

But as we all know, magazine making is among the most collaborative pursuits in the world. As Gloria Steinem wrote in the foreword of Mag Men, Bernard’s and Glaser’s career retrospective monograph, “There is something about word and visual people sitting together in a room, riffing off each other’s ideas like jazz musicians, arguing and coming up with a result that no one of us would have imagined on our own. It’s as much a proof of freedom as laughter, which is also a mark of editorial meetings.”

As Bernard says, “On its most fundamental level, a magazine is a collection of energy and information.” That’s his wheelhouse. Collaboration is where Walter lives.

His secret weapon is his calming and confident presence, along with a Rolodex of the greatest photographers and illustrators around—priceless skills for a usually frenzied and chaotic line of work.

We talked to Walter about working with George Lois at the height of his powers, the time he and Glaser were redesigning competing newsweeklies just a few feet away from each other, and about the thrilling late-night knocks on his door every Sunday in the late 70s.

Patrick Mitchell: You know, this seems like a recurring theme on our podcast, and it’s true for just about every guy I know in this business. You even opened your book with a quote from Henry Wolf about it. So I want to ask you, what was it about Esquire that made everybody, including you, want to work there so badly?

Walter Bernard: I think you have to remember the late ’50s, early ’60s—especially starting in about ’62, when, first of all, I was just a late teenager and aware of Esquire—George Lois started doing covers. And it drew you into looking at every issue, reading it. Before that, I had seen Esquire occasionally and loved the covers as well. They were much different than what George Lois was doing, but they were signed with a little signature that said “Henry Wolf.”

And I had remembered that. They were charming, whimsical covers. And then George started later. But, you know, Playboy had started, but it was hard to get access. Esquire was beautifully designed. It was big. It had provocative stories. It was really terrific. I used to buy it on the newsstand. And when I finally got out of school and started thinking about working in magazines, my dream would’ve been to work at Esquire.

The women’s magazines were well done, but there weren’t those kinds of magazines that you would aspire to work on, unless you wanted to work on a special-interest like Holiday magazine, or something like that. And nobody wanted to work at the news magazines, in terms of design. So Esquire was an ambition.

Debra Bishop: Were there other magazines you particularly loved when you were growing up?

The Hudson Tubes, ca. 1909

Walter Bernard: Oh, sure. My father read the Saturday Evening Post, and I was obviously aware of that, and all of their illustrated covers were really interesting. I occasionally got Time magazine and I guess it was their portraits and it also seemed like an important magazine. I was aware of Look and Collier’s, magazines like that. Some of them came into our house. Some of them you had to see at dentist offices.

Debra Bishop: What was your first memory of design? When did you start thinking it was something you might like to pursue?

Walter Bernard: When I started there was no such thing as a design school that I heard of. All I’d heard of was “commercial art.” You were a commercial artist. And even art schools didn’t have the word “design” in them. So I went to a Catholic prep school and I wanted to go to art school. I had no idea—I used to draw a lot, that’s about it—had no idea what commercial art was except from advertising and the idea of illustration.

But I wanted to go to an art school, and the only school I heard of was Cooper Union. I heard it was a free school, somebody told me. I lived in New Jersey, so I took the PATH train, which was called the Hudson Tubes at that time, to 6th Street, and signed up to take a test at Cooper Union. Which, of course, I failed completely because I didn’t know anything.

And I realized I couldn’t go to Cooper Union, so I got a phone book outside of Cooper Union in a phone booth and looked up the line of the Hudson Tubes. And on 23rd Street there was an art school called the Art Career School, and it was in the Flatiron Building. So I knew how to get there because it was the same train.

I had never been to New York City. And I went there and it turned out that I, not only could apply, but get in, because I was coming in after the GI Bill, in which they were able to give veterans good breaks on education. But they were kind of running out, so they needed students. And they took me.

Debra Bishop: And that was the first time that you were in New York City?

Walter Bernard: Yes.

Debra Bishop: Wow! And where were you from in New Jersey? What town?

Walter Bernard: North Bergen. It’s right near Hoboken in Jersey City.

Debra Bishop: And what did your parents do? Were they a huge influence on you?

Walter Bernard: My father was a master carpenter, and he had his own business. He was a great craftsman. He built houses for people. He also was always invited to work on churches because he did fine woodwork. And so, while he wasn’t educated—he never even went to high school—somehow he knew math to a degree. But he was a great carpenter. And my mother worked at home, obviously. My parents had no clue about art school or anything, but it was not very expensive.

After I graduated from St. Peter’s they were happy that I was going to go somewhere. My brother was going to an engineering school and he did very well. But I wasn’t interested.

Bernard, left, with his parter and New York’s cofounder, Milton Glaser in 1972.

Patrick Mitchell: What were the prospects for a young kid in the ’60s going into what they called commercial art back then?

Walter Bernard: Well, I had no idea. I was very lucky. The school was not very good. By the way it was in the penthouse of the Flatiron Building. It was a great place. And I could get there easily. I took the bus to Journal Square and got on the Hudson Tubes, and it took me to 23rd Street and Sixth Avenue, and I just had to walk a block to the Flatiron Building.

I was very lucky because the city dumped three scholarship students into that school. One was from the High School of Music and Art, and the other guys were from Brooklyn. They got dumped in that school. And the great thing about that for me was they knew how to work. They had already been in art classes. They knew what a tissue pad was. They knew how to make sketches. They knew how to prepare. They were my education. And even though the school wasn’t very good, and mostly concerned with advertising and doing posters, et cetera. Commercial art at that time was in transition.

I was educated by these three guys who became my friends, of course. And they all went into advertising. They were gung ho for advertising. And especially when George Lois, and Herb Lubalin, and all those guys from Sudler & Hennessey became well known. Advertising was the big thing. They all wanted to work for Doyle Dane Bernbach, or something like that.

I wanted to go into magazines. So when we graduated, I had to go to Florida for a year with my parents, who were not well and moved there for a year. Then I came back and found out that on 23rd Street, which I knew how to get to, was a new school called the School of Visual Arts, which had been [for] cartoonists and illustrators.

I went to the School of Visual Arts one day, got a brochure, and sure enough to my surprise was an announcement that Henry Wolf and Milton Glaser were teaching a class together, which I applied for and got in. So that was my beginning. It was, I believe it was 1960 or ’61. And Henry and Milton jointly taught a class called “Designing for the Written Word,” which was really spectacular. And that got me excited about magazines. I had not known Milton except for his bylines. That’s when I first met him.

Patrick Mitchell: You mentioned that Henry Wolf, his signature was on the covers of Esquire. Was he actually creating, like illustrating or collaging the covers himself?

Walter Bernard: He was the art director.

Patrick Mitchell: Right. But did he actually produce the artwork for the cover?

Walter Bernard: No. I think he worked with photographers. Sometimes he did—they were kind of collages. But I think he worked with photography and other things. He did an awful lot by hand as well, but they weren’t illustrations per se. But you would have, for instance, a model—I remember one cover of a model sitting in a chair. Her back is toward you, and you see the back of the chair. It’s a wire chair, but the wire forms a heart, and it's a very beautiful photograph. By the way, the photographer probably got credit, but Henry created all of these covers.

Patrick Mitchell: He was getting credit for the concept.

Walter Bernard: Exactly. And later he did, of course, Show magazine with brilliant covers.

Debra Bishop: Your first job was as a designer at Ingenue magazine. “The magazine for sophisticated teens.” That was in the early ’60s. How did that come to be, Walter? And what was the 1960 version of a sophisticated teen?

Bernard launched his career at Ingenue in 1961.

Walter Bernard: I had no idea. But you’d get those jobs through want ads at the time. In those days you either went to an employment agency or you looked in The New York Times. And I believe Ingenue was owned by Dell Publishing. And I believe they probably put an ad in the Times. And I just went up there and they needed an assistant. And I was lucky I got the job.

At the time, I guess the most sophisticated magazine in that category was Seventeen. And they were trying to be a rival to Seventeen. Which, of course, they were not. They didn’t have the budget or staff.

Patrick Mitchell: So a few years later, you circled back and Milton gave you a job. Can you talk about how that came to pass?

Walter Bernard: Well, I didn’t want to stay at Ingenue because there was no place to go. So I decided that every two years on the anniversary, I would quit my job. So in 1962, I quit and went out on the street again to employment agencies and found a job at American Heritage, which was terrific.

American Heritage did Horizon and American Heritage magazine, and they also did huge books like The Civil War, et cetera. And the great thing about American Heritage was, I didn’t get paid very much and I was just an assistant in the art department. Irwin Glusker, who just died, was the art director.

At night I continued going to SVA, and studying with Henry and Milton, so that two years later, when I was ready to quit on the same day in July that I had quit in ’62, I had known Henry and Milton by then. I had done well in their class. And it turned out that Henry’s former assistant, Sam Antupit, was going to be hired as art director of Esquire. And Sam needed an assistant.

They were just wiping out the art department. And Henry and Milton both recommended me to Sam. So, I met him, and he said, “Fine, come on.” And we started on the same day: July 1st, or 2nd, of 1964.

Patrick Mitchell: So you were there while George Lois was producing these covers?

Walter Bernard: Absolutely. Yes.

Patrick Mitchell: God, what a great start to a career.

Walter Bernard: Yeah, well, we met George of course, and I got to know him, but he was rarely in the office. He would just deal with Harold Hayes. And the great thing about Esquire is that it was really a collaboration. It really taught me about magazines. Harold Hayes was a terrific editor. He would ask everybody to submit five ideas or more a week. And it was a small enough staff so that everybody knew what was going on, even though it was not an open office, you know, people had individual offices. The art department was sort of the kitchen. I met great editors and writers there: Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Byron Dobell, et cetera.

Patrick Mitchell: But, my God, as a young guy, starting your career to be working at a magazine that’s going through such a revolution—in the way magazines thought about themselves and how to sell themselves—and to have a rebel like George Lois making covers that just weren’t seen anywhere else, must have been foundational into the way you went forward in your career.

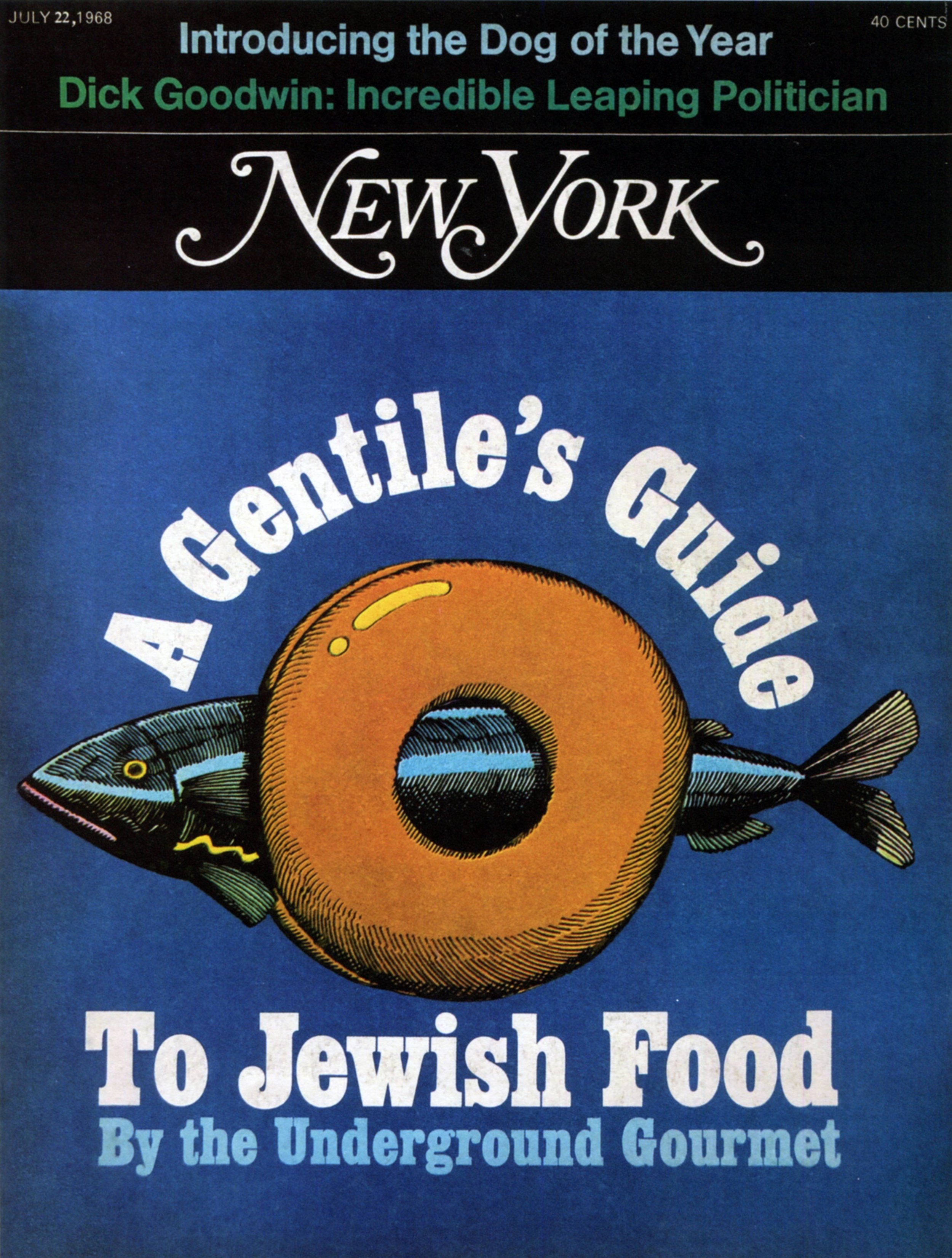

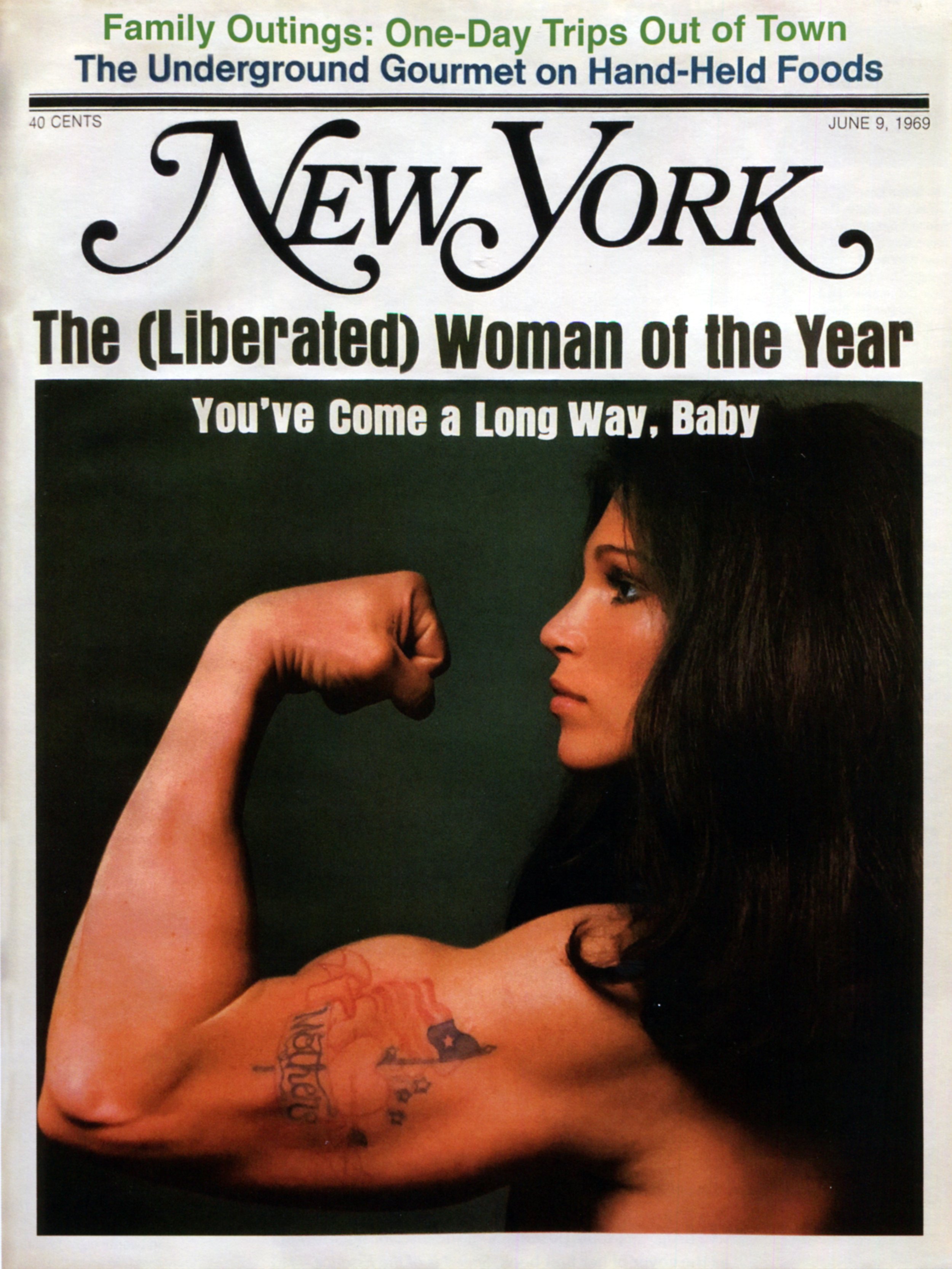

Walter Bernard: Well, it was a great time. I stayed there for four years instead of two. And I really had a great time there. The change was that in June or July of ’68, Milton called and said, “It’s time for you to come work with me.” Now, New York magazine had started in April of ’68, so it was already six weeks old. And he realized that there was a little more work to a weekly than he thought.

Patrick Mitchell: I bet.

Walter Bernard: And so I decided to take a chance because everybody, all the designers were saying, “Oh my God, this is terrible. This magazine’s never going to make it.” But it was really thrilling because it was in that brownstone, at 207 East 32nd Street, on the top floor. And just one big open room that everybody worked in. And I learned how to put out a weekly.

Patrick Mitchell: For obvious reasons, New York magazine, and its early days, has come up quite a bit on this podcast, so we’re not going to rehash the entire history, but I know you have a specific perspective on it. But in your book, there’s a two page photo that I wanted to ask you about with you and Milton at New York with your feet up on the desks. And I really want that to be a long stogie in your mouth, but maybe it’s a non-repro blue marker. What are we looking at there? What does that picture say?

Walter Bernard: Let me just give you the background. Milton was really brilliant and fast, but he was also, with Seymour [Chwast], running Push Pin Studios on the second floor. It’s not like he was there all the time. So we had to meet. We met on the stairway, we met at my desk, we met at his desk. Whenever something came up, a new story came in, I’d call him and we’d say, “Look, if you have time to read this,” or, “Here’s what it’s about.”

So that was my desk. That was where I sat. And Milton and I would meet and sit there. And we were obviously in a cover discussion. We never had these, kind of, sit-down long meetings about a story so much. They went faster. But the covers we would really be going back and forth on.

Glaser and Bernard assessing a cover.

So we were obviously sitting talking about a cover. Milton looks like he’s sketching. And it happened to be one of the days that Cosmos Sarchiapone was around the office and photographing. But that was typical. We met daily. Sometimes down at his office. Sometimes just in the stairway. And we would talk about either an upcoming cover or a story. But Milton was actually an editor there. He had many good story ideas. And he often came upstairs, not only to see me, but to meet with Clay [Felker] because there were all sorts of—since he was co-owner—there were all sorts of other things going on, business, staffing, et cetera.

But Milton and I met on-the-fly constantly. We probably had lunch three or four times a week. Only because he did the “Underground Gourmet” as well, as you know. So I’d often join him and several others, with Jerome Snyder, checking out cheap restaurants. But you asked about whether we were buddies or friends and socialized.

Fact is we saw each other every day. Probably had lunch three or four times a week. But on the weekends, I came out to Bridgehampton and he went to Woodstock. So we didn’t socialize. Milton loved working, but he wasn’t someone to go to movies or theater either. So we didn’t see each other, except at certain occasions at night.

I mean, I had many dinners with him, but basically we did not socialize that way because we had seen each other five days a week.

Patrick Mitchell: There’ve been a lot of retrospectives, you know, with Clay passing and then Milton passing, and then Adam Moss leaving. A lot of documentation of the early days of New York magazine. And from all those, you know, people looking back through rose colored glasses, you’d get the impression that it was sort of a “love fest” back then. But those were the days of editors and designers not exactly being equals. What did people think of you, and Milton, and Clay inside of the office? I’m thinking about the people who worked for you. What was your sense of how they felt about the leadership of the magazine?

Walter Bernard: Well, I would say everybody, despite their, perhaps, difficulties with him, all loved Clay. He was so eccentric and so creative and again, we were all, we could hear every one of his phone conversations. I mean, everybody was in this big room.

Clay and Milton were the most powerful people at New York, just by hierarchy. Clay being the editor and part owner and Milton co-founder and owner. So they ruled the roost. Even though there were many good editors like Jack Nessel, Shelley Zalaznik, Byron Dobell, et cetera, and even publishers.

But Milton and Clay ran the day-to-day in that sense, in terms of authority. I think most people loved them. Milton got along with almost everybody. Obviously there would be differences as the staff grew. But everybody had to chip in because, you know, it was so unlike magazines now. I mean, if you had to assign a photograph, you’d get it back and have to go through contacts and then order a picture. And then in order to get it reproduced to your size, you’d go to a LucyGraph and trace it.

The steps of writing, editing, designing, and production were just enormous. Enormously complicated. We’d be there late at night with Exacto knives putting in commas, re-fixing edits because they couldn’t go back to the typesetter, who was in Philadelphia. You had to go through galleys and reproductions. And then at the end of the week as you were about to send it out, somebody would find 10 errors of punctuation or words or something they’d want changed. And you do it by hand.

So everybody worked together. I don’t think there were a lot of major differences on that side. There were some major differences on the publishing side.

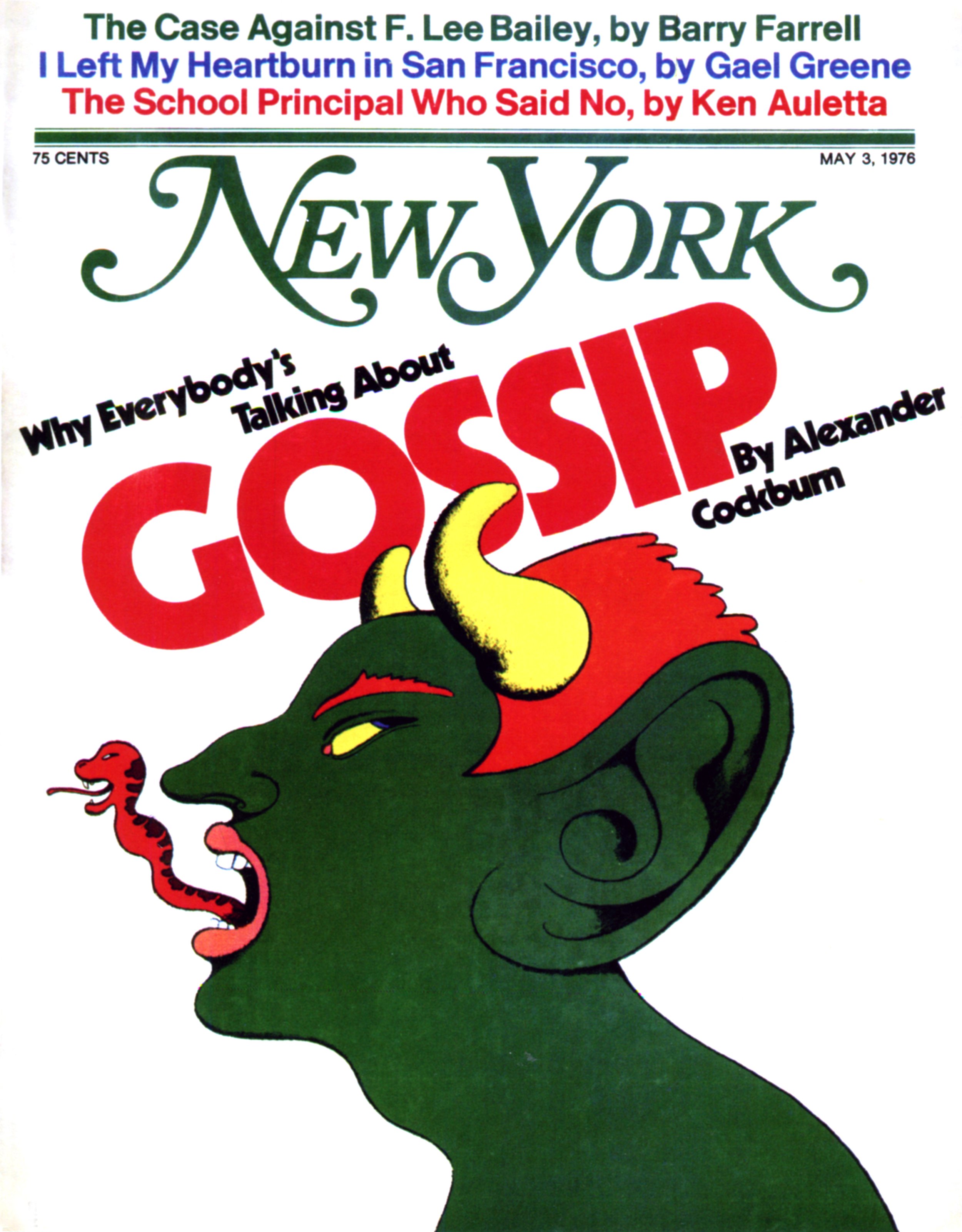

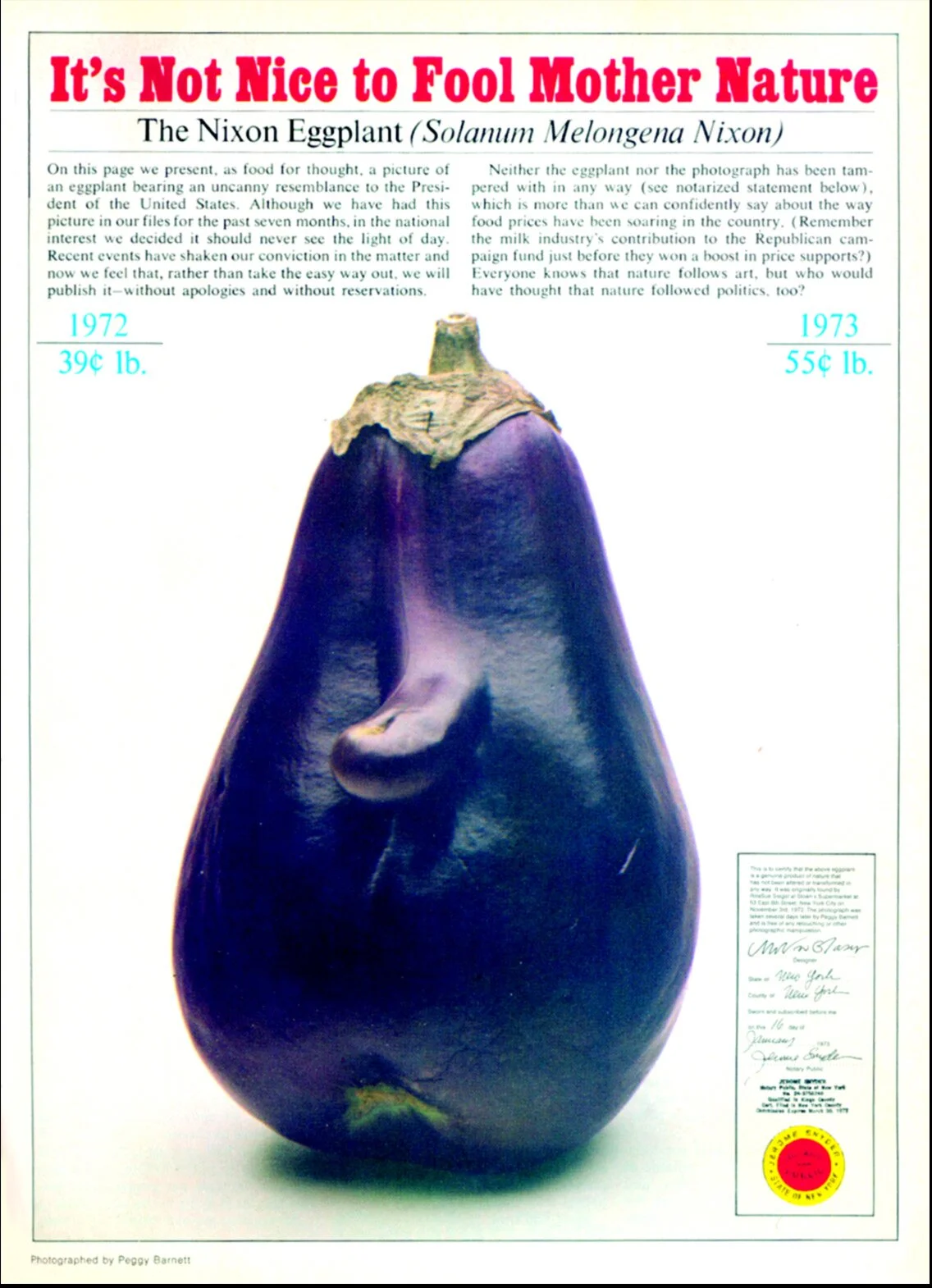

The legendary Nixon eggplant

Debra Bishop: Walter, when it came to visuals New York featured a ton of illustration in the early days. How did you think about illustration versus photography?

Walter Bernard: Well, two reasons. One, we had very bad reproduction. We had a terrible engraver in Queens. And when I first got there I did a cover in which I took the photograph. It was only because I had this idea that they agreed on and I did it on top of a building, et cetera.

And when it came out, it was horrible. The engraver process, which had to be fast, was not very good. And we had trouble at the beginning reproducing photographs. On the other hand, illustrations reproduced very well. And even when they were a little off, nobody could tell. It wasn’t like it was blurry or if that red wasn’t as bright. And artists like Robert Weaver and Robert Grossman and others were able to be reproduced pretty accurately.

“I decided that every two years I would quit my job.”

Now. We then did use more photography. We started to use more photography on the cover. I used Carl Fisher, whom I met at Esquire and had done a lot of work for George Lois, and he worked with us very quickly and did a lot of covers. But that was probably a year and a half in when we were finally able to get better reproduction.

We didn’t have any photo editors. I did all the assigning, whether it was illustration or photography. Even at Esquire, there was no photo editor. I think there was a photo department at Time and Newsweek, but most magazines just had art directors at that time.

Patrick Mitchell: Editors also did a lot of assigning.

Walter Bernard: Yes. And in our case, Clay, who once worked at Life, knew a lot of photographers and introduced us to Burt Glinn and other photographers.

And I met a lot of photographers from Esquire, because at Esquire, Sam and I did the assigning along with some editors. Byron Dobell was a very good editor of photography. He knew a lot of photography and loved photographs. But I didn’t run into a photo editor until I got the Time.

Debra Bishop: And speaking of illustration again, how would you describe the power of illustration? And why was it so right for New York magazine?

Walter Bernard: I think the power was based on the stories. But, we did nurture a group of illustrators who were not only quick, but smart. People like Ed Sorel, Jim McMullan, Robert Grossman, many others would come to us with good ideas and if we gave them work fairly frequently, they responded quickly. It wasn’t like, “Oh no, I can’t do this. I’m doing something else.”

And don’t forget, we were paying, for a spot illustration, a hundred bucks and for a cover $250 or something. It was not a lot of money. But there were enthusiastic illustrators. Now illustration did become fairly powerful, I think. Do you remember the name Julian Allen? Julian was a wonderful illustrator that Milton and Clay found in England and brought to the US under contract exclusively to New York magazine. And he began to do all of these wonderful recreations, like Watergate or the Mafia or something else.

And they got a lot of good response. We couldn’t do what George Lois did—first of all because he did really great covers—but we’d get the cover story on Wednesday and it had to close on Thursday. So we, kind of, acted faster and sometimes not as well. But weekly had one saving grace and that is, there was always another one next week. No matter how bad this week was, it passed pretty quickly.

Patrick Mitchell: But also, you had a full-service illustration studio one floor down in Push Pin, which Milton was a founder of. Were there advantages or disadvantages of having them so convenient?

Walter Bernard: Absolutely. Yes. First of all, in a pinch, Milton, Seymour, or Barry Zaid, or Jim McMullan, or Tim Lewis, could do little drawings and spots or things we needed very quickly. And it was great having them there.

Patrick Mitchell: Maybe you can tell our younger listeners what Push Pin was.

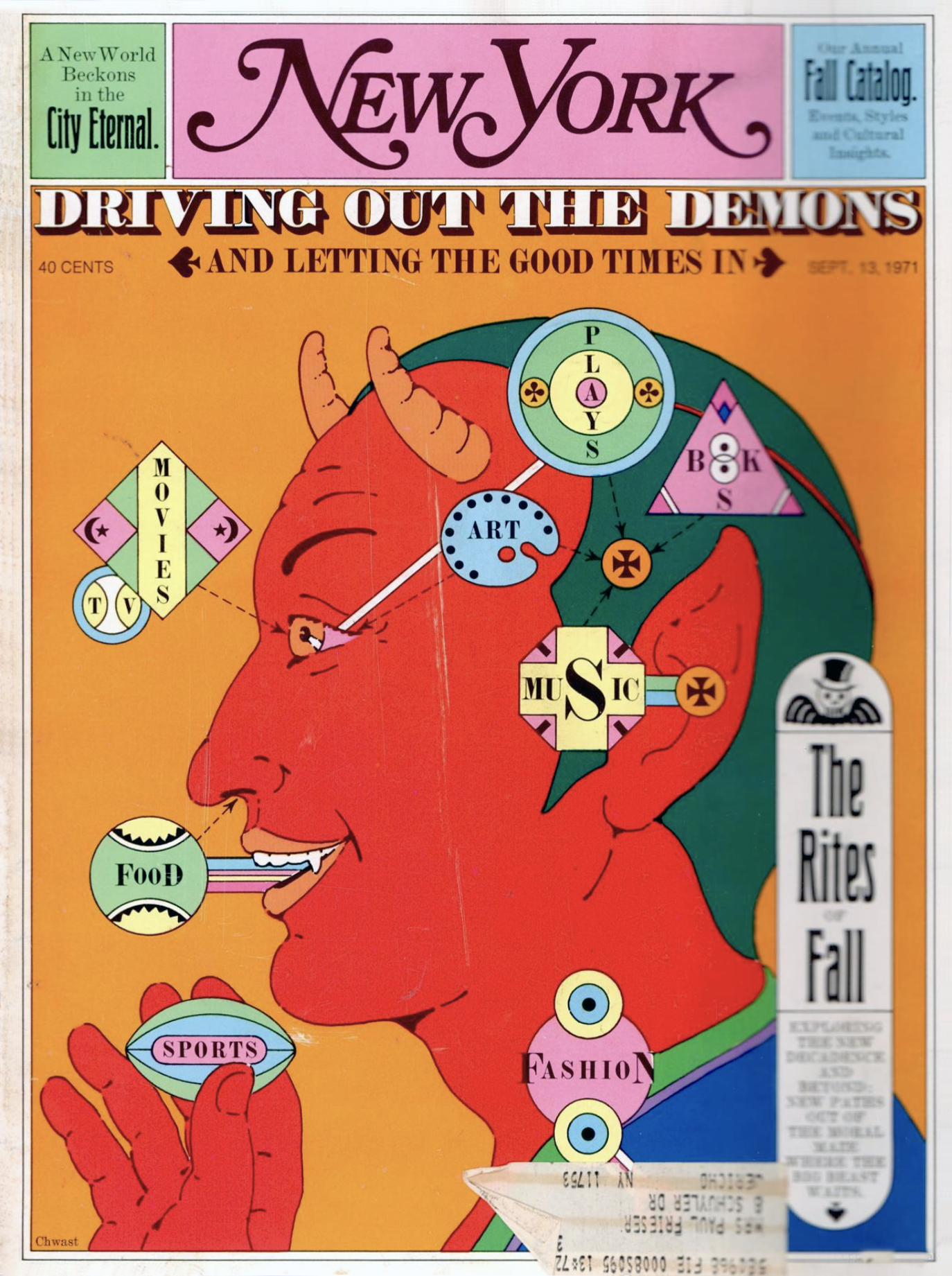

Walter Bernard: Push Pin was a great design studio founded by Milton, Seymour Chwast, Ed Sorel, and Reynold Ruffins. And by about 1968, it had developed into not only a great illustration studio, but a great design studio. And they had, at the time I got there, Paul Davis, James McMullan, Barry’s Zaid, Jerry Joyner—several young, energetic illustrators who all worked under Milton and Seymour.

And Milton had a great capacity for doing illustration on the weekend. He didn’t do anything except go to Woodstock on the weekend and do his illustration, which he couldn’t do in the studio. He worked all the time and was able to do big projects. Seymour, likewise. He did some wonderful fall catalog covers for us. But Push Pin was a great resource for us. If we were stuck on a Friday night and we needed something, there was somebody downstairs who could give it a shot.

Patrick Mitchell: And Seymour still has it running.

Walter Bernard: Yeah. Well, as you know, when New York magazine moved out of that building, Milton decided to stay with the magazine because he was an owner. So he left Push Pin and started Milton Glaser, Inc. And I don’t know what the business side of it was, but Seymour got Push Pin and Milton got his independence and I think in that case he bought the building as well.

Patrick Mitchell: All right. So moving on here, in your book you talk about the time gap between leaving New York and starting WBMG—you’re right, it does just kind of flow right off the lips: W-B-M-G—with Milton. So why was that time in between important to you? And what was your plan after leaving New York?

Walter Bernard: Well, one of your questions was about feeling overshadowed by Milton. Milton was extraordinary in his capacity to work, and work quickly, and work brilliantly. And, there was no competition there. I was just, uh, kind of a student. And even though we worked together at New York, and I was the art director and he was design director, there was no question that he was the mentor and also the lead. And so, when we all left New York in ’77, I got the opportunity to do something without my mentor.

And when Time magazine called, and I think they called me because there were not that many art directors who had done weeklies. A lot had done monthlies. So I got the opportunity to do that, and also the opportunity to work without Milton’s guiding hand.

“Time had a big budget. It took me a while to realize the information and the resources I had at my fingertips. I was totally amazed. ”

Patrick Mitchell: And so it was kind of like figuring out who you were on your own two feet.

Walter Bernard: Yeah. To see if I could do it. And I mean, I had learned a lot, but you know, there is something about the fact that if I couldn’t come up with something, or there was a problem about something, I could say, “Milton, what do you think?” Or, “What should we do?” And we would collaborate. Or he’d have an answer. Whatever.

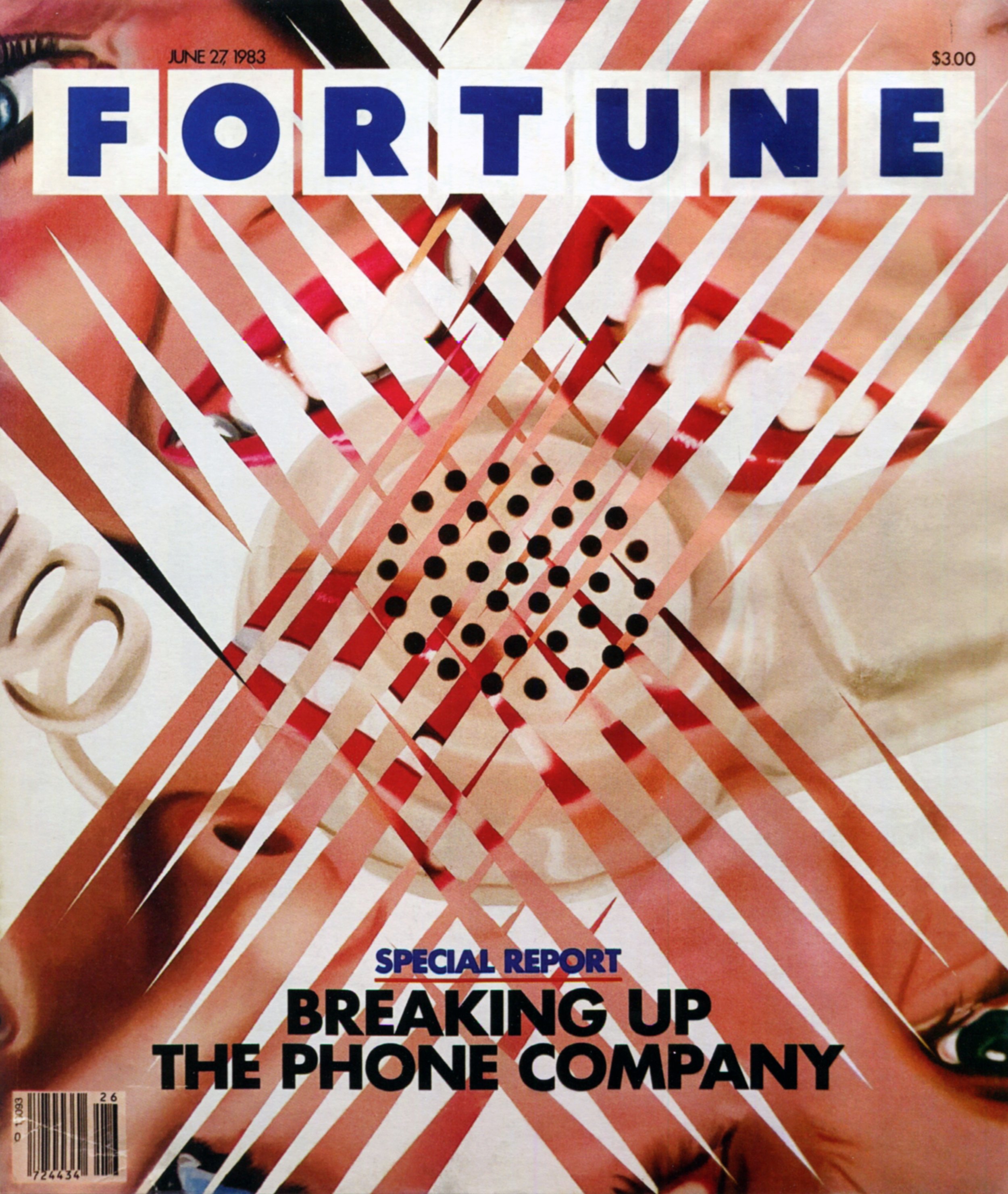

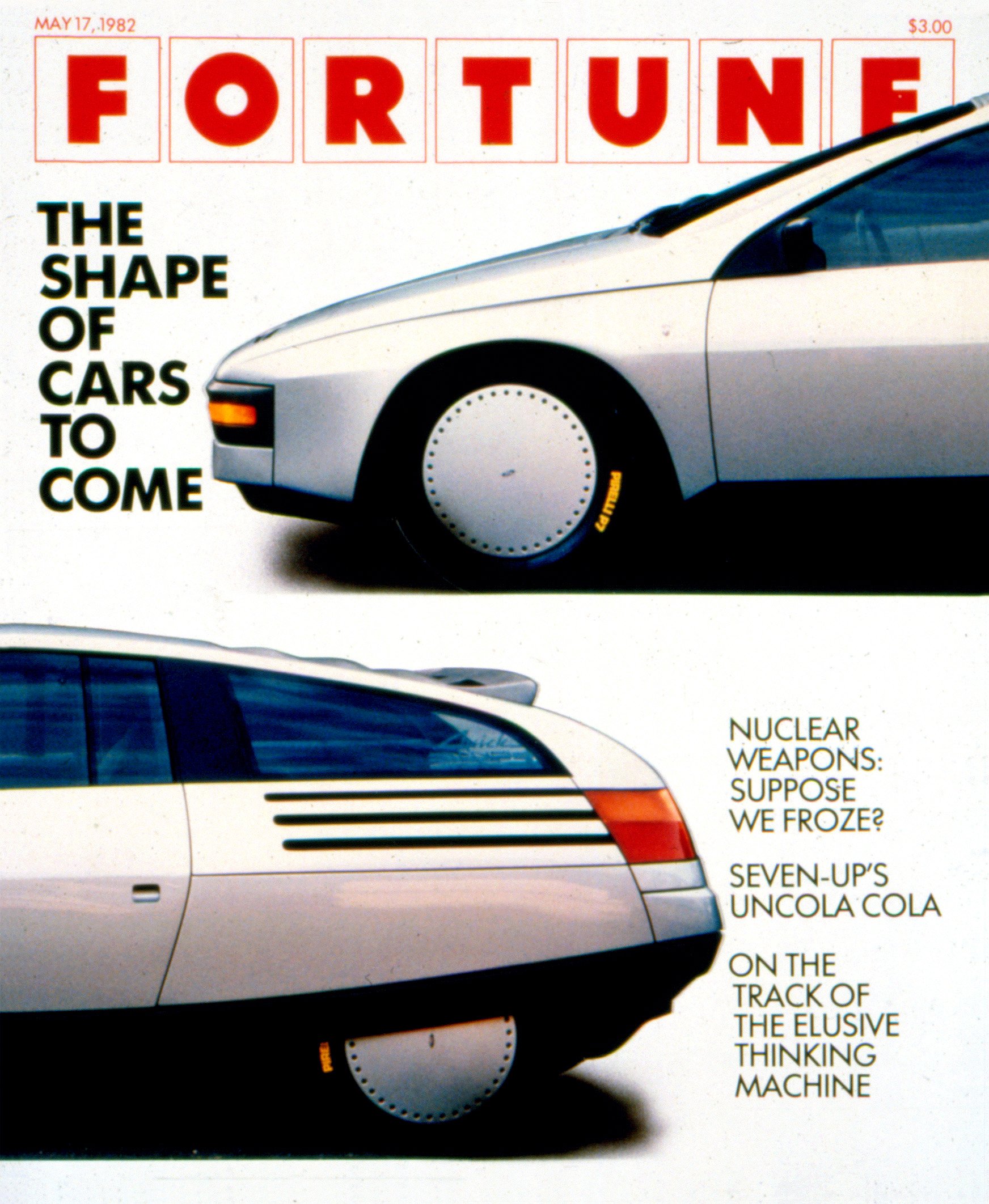

And those five years between our starting, my leaving Time, and working on my own with Adweek, and Fortune, and The Atlantic Monthly, and The Sophisticated Traveler, and a couple of other things, were really important. And also, I think, encouraged Milton—we missed working together and I think he began to feel that we could be partners in a new venture.

But, as art director yourselves, aside from your staff, et cetera, you’ve got to make the decision. And you don’t have somebody on your shoulder. So I wanted to work and see what I could do on my own. And Time gave me the opportunity.

Patrick Mitchell: So, when you just started thinking about life after New York, were you thinking you’d start your own thing? Or that you’d get a job at a magazine?

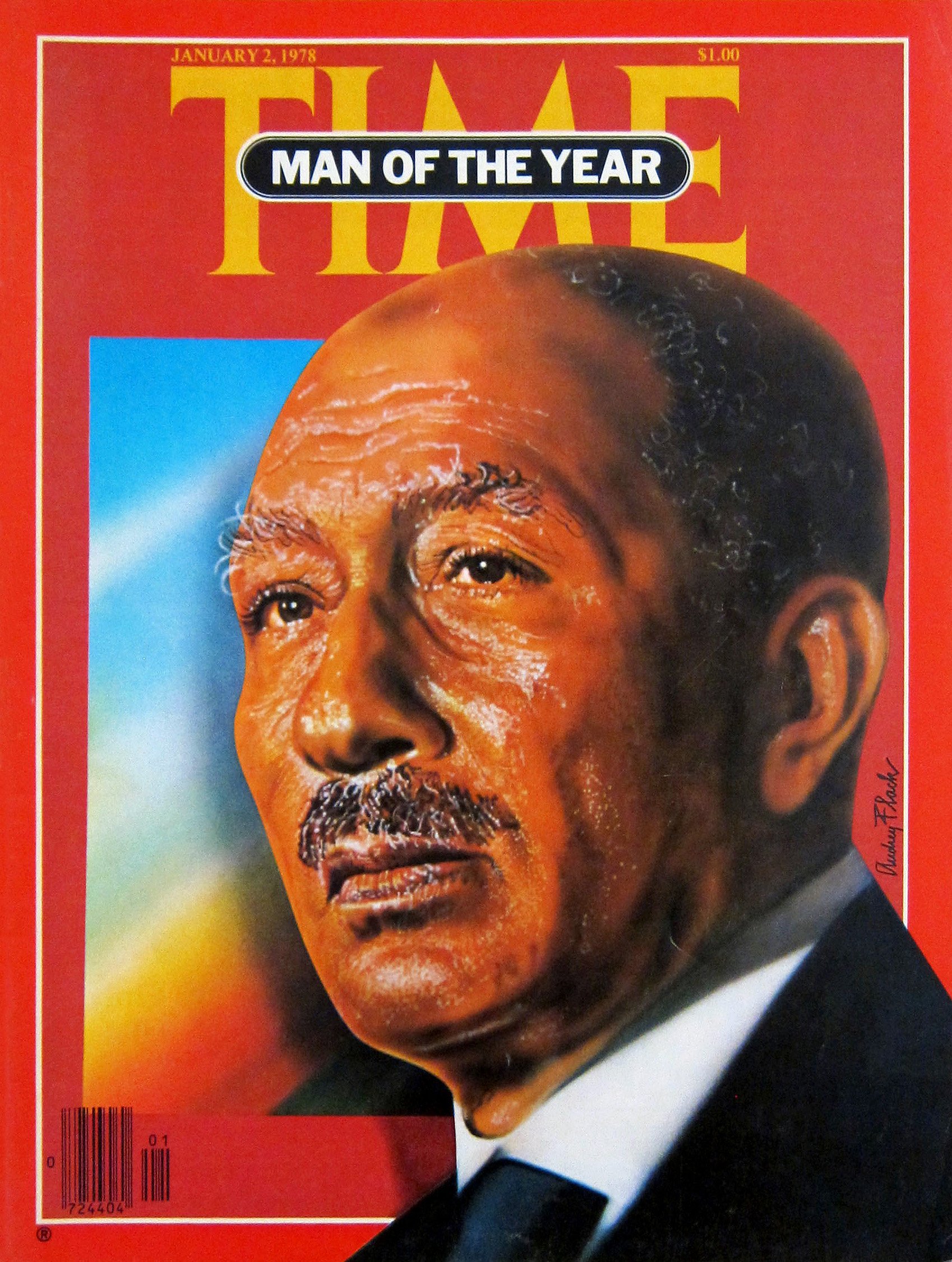

Walter Bernard: No, I needed a job. And luckily, in February of ’77, I got a call from someone at Time asking if I would talk to them. What was interesting to me was that I made a deal with Time because—by the way, we all thought Time looked terrible and Newsweek looked terrible and most of the news magazines didn’t look good either—and so I made a deal that said I would become the art director, and guarantee that I would stay for a year, if I could redesign it. And we agreed that I would redesign it secretly, so that if they didn’t like it, nothing would happen, and Newsweek wouldn’t know about it. And also it wouldn’t upset the staff or anything like that.

So I called Milton and said, “I’m going to redesign Time. I need a space.” Well, Milton was still up at 42nd Street at the New York magazine offices, and Seymour had not yet moved into the building, so there was an empty floor and he said, “You can have it as long as you want.” So I hired my friend Rudy Hoglund, and we started designing Time on the first floor.

And a month later, Milton ends up leaving 42nd Street and coming back to the building. So I had to move out into a little room. And as soon as Milton got there, he came to me and said, “You won’t believe this, but I just got a call from Newsweek. I’m redesigning Newsweek.” So it turned out that I was designing Time in one room and upstairs Milton was designing Newsweek.

We didn’t show each other anything, and nobody knew that we were both doing this. I was lucky because I had agreed to be the art director if they liked the design. And Milton was not going to be the art director of Newsweek. And I realized he had no chance. No matter what his design was like, that was not the whole problem. You had to make Newsweek work with illustration, photography, design, and you had to manage a staff, otherwise it would all blow up. And when Time accepted my design and I agreed to go there for a year, Newsweek just put Milton’s design in their bottom drawer and never did anything.

So that’s the only time we actually competed. And it was kind of fun knowing that we were both working on competing magazines and not talking to each other about it.

Patrick Mitchell: And while you were there, you introduced the world to Nigel Holmes, essentially the godfather of modern infographics (with the apologies to Fritz Kahn and Edward Tufte). Let’s say “magazine infographics.”

Walter Bernard: Yeah, well, Nigel was a real gift. What happened is that, shortly after I got to Time, I got a call from Nigel Holmes saying that he had tried to find me at New York magazine and couldn’t, and could he show me his portfolio. I knew nothing about him, but I was open to looking at portfolios.

In those days, you didn’t have to go through any hierarchy or even many secretaries. You could just call up. And when I saw his work, I realized that it was really very clever and very smart. And I decided to go to the editors and say that we have to hire a new chart and graph person because the charts and the information graphics in Time were really bad. And not only that, they were ignored. They were used as fillers.

So I convinced Henry Grunwald to let me move Nigel and his family to New York. Hire him, pay for the move, fly his family over. And it was one of the best decisions that I could have made at Time because he really revitalized not only the Time’s graphics, but as you said,influenced other things. He’s a good friend to this day, and he did a marvelous job for Time. I was very lucky that he called me.

Yes, there was once a weekly magazine about magazines.

Patrick Mitchell: How difficult was the selling process? Because it had to be a jarring change for the existing editors.

Walter Bernard: Well, actually, at Time they were delighted. You know, we suddenly did a chart and made it the main illustration of a story, because it was not only graphically good, but it did some explaining that they had only done with bar charts before. The editors of each individual section really were enthusiastic about it. Everybody loved Nigel’s work pretty quickly. All the editors were very delighted to use him. That’s the least problems I ever had.

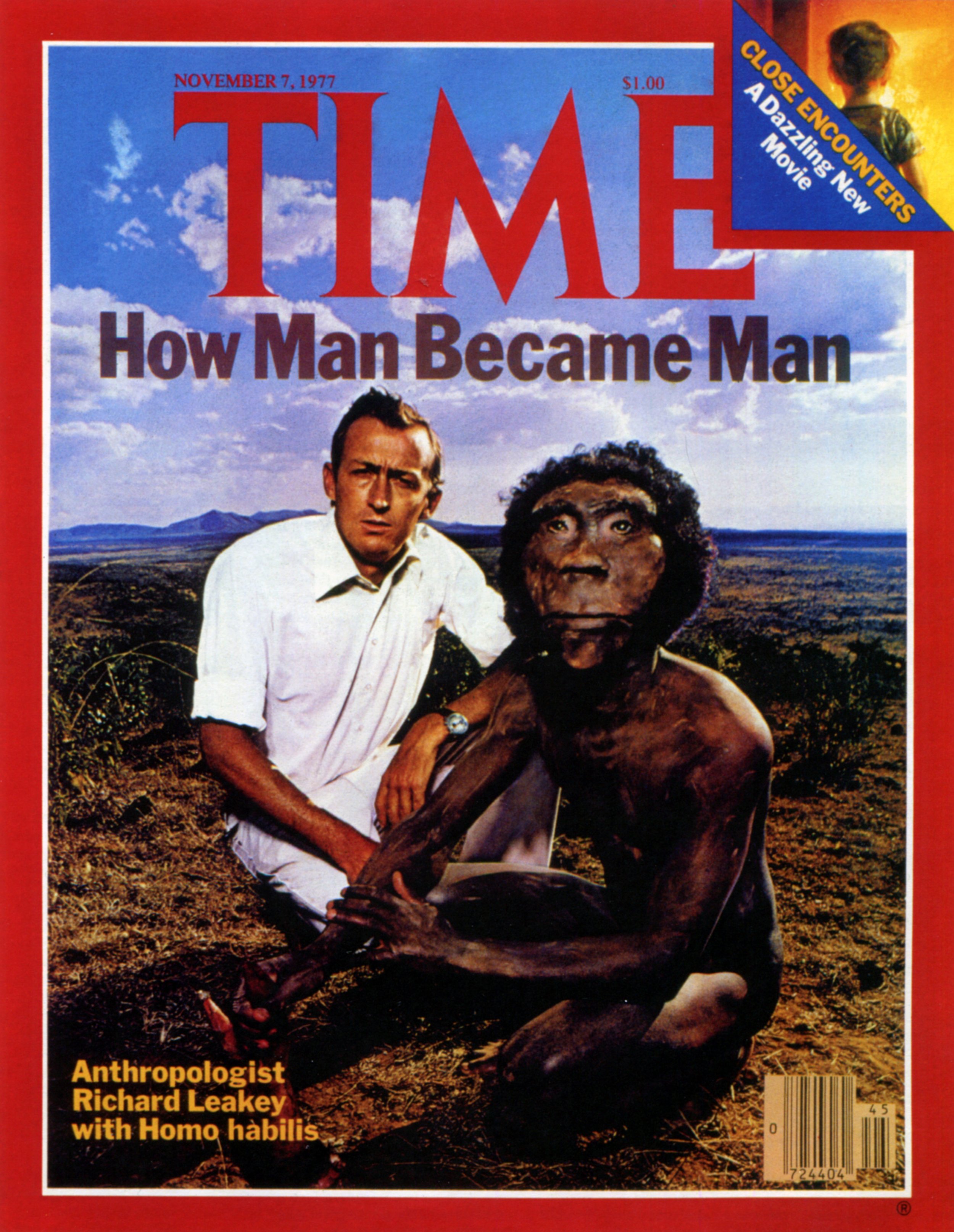

Patrick Mitchell: I think my favorite story in your book is about a Time cover that went wrong at the last minute. And I think the story says a lot about how dramatically the magazine business has changed—and maybe even why this podcast exists. Can you share the story of your Richard Leakey cover?

Walter Bernard: Yes, yes. Richard Leakey, well-known anthropologist, was going to be the subject of a cover story. And he was also lecturing in the United States at a certain point. And I had arranged for Carl Fisher to photograph him in his studio, which Leakey agreed to.

In fact, I had sent him a sketch in which I’d kind of copied, or referred to, one of Irving Penn’s photographs of when he photographed, I think, some people in the Amazon. But what I wanted to do was have a model of the discovery that Leakey made, of Early Man, and have him pose with his arm around this model in Carl Fisher’s studio.

And they had agreed. And Carl hired a model maker and began working on it. And a couple of days before we were to do the shoot, we got a call from Leakey’s people saying his lecture was canceled and he’s not coming to the US. Now this is early in my career at Time and I had just come from New York magazine where we had absolutely no budget, so it didn’t occur to me to do anything else.

And I went into Henry Grunwald and I said, “Leakey’s not coming. We’re going to have to think of something else because Carl can’t photograph him. He won’t be here in time.”

And Grunwald said, “Well, where is he?”

I said, “Well, he’s staying in Africa.”

And he looked at me and said, “So go to Africa!”

And it had never occurred to me that we could do that! Now, I knew photographers flew all over and, you know, we were getting film from Europe, et cetera, but didn’t occur to me, because of my previous training at New York, that I could get on a plane, put Carl on a plane, the model on a plane, his assistants on a plane, and just go over there in a couple of days and shoot the cover.

So we rescued it because Carl was very good about working with people and Leakey was very happy to work with him, as you could see from those photographs. And we photographed Leakey and the homo habilis right on the spot that Leakey had made his discovery. And it became the best-selling Time cover since Nixon’s resignation.

It also gave Leon Jaroff, who wrote the cover story, the ability to sell Time Inc. on a new magazine called Discover. They finally were convinced that he could start that magazine because of the success of the Leakey cover.

Debra Bishop: So “Go to Africa” maybe should become a meme about how the magazine business killed itself.

Walter Bernard: Oh, yeah.

Debra Bishop: But seriously, can you talk a little bit about the contrast of working at New York, essentially a startup and a startup mentality, and then Time Inc. where, at least in those days, money was no object?

Walter Bernard: First of all, New York had an art staff of four or five people. At Time, I had 25 people working for me. And that’s because, a) It was a weekly, b) It really had to be put together in the old-fashioned way in quite a hurry. So we had a big layout department, the people who just did pasteups and corrections.

In fact, they only worked from Wednesday to Friday or Wednesday to Saturday. It was totally different. Time had a big budget. Photographers flew all over the world. Film had to be transported all over the world. Correspondents were all over the world. It took me a while to realize the information and the resources I had at my fingertips. I was totally amazed. And I don’t think that that happens now even in any of the big magazines.

The only other magazine I remember people loving to work for was Holiday magazine, which would send these photographers on wonderful trips to photograph exotic places and had, really, no expense spared. But Time and Newsweek had big budgets.

Don’t forget, we printed 6 million copies a week. And got a lot of reactions. We got real letters from people. By Tuesday, you knew the reaction of the public.

But that era is gone. Both in circulation and budget, and payment. And the fact that they could take a chance on doing a kind of story that didn’t work out and they had to bag.

Patrick Mitchell: It’s funny. You said you get immediate feedback from the readers. In your book, I saw that you had lots of fun notes from unhappy readers about the changes you’d made.

Walter Bernard: Yeah. My end papers. Right.

“At Time the managing editor was revered. The staff treated him like the White House treats the president. When he walks in, everybody stands up.”

Patrick Mitchell: There’s a couple other details from the book I just want to quickly bring up, from the minutiae department. I loved your brilliant example of “form follows function” with your design for Adweek, with regard to the subscriber mailing labels. How did you arrive at that solution?

Walter Bernard: Adweek was founded by two people who worked at New York magazine, Ken Fadner and Jack Thomas, who worked on the business side. And they bought three advertising magazines for Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago. They bought these three magazines and wanted me to redesign—I was at Time, but I was able to do some freelance—to design those magazines.

And I said, “Well, what are your plans?” And they said, “We’re going to start one in Atlanta, and one in Dallas, et cetera.” And I said, “You’re going to have to think of acronyms for all of those cities. Why don’t you just brand it as one magazine?” And they said, “Well, let’s think about it.” So I did a little cover in which I used the name Adweek and they loved the name.

So then the question was then to do a design for them. And these magazines, these little magazines were not run with any kind of art department. They were just put together by editors and paste-up people in typography companies.

So I tried to design a format that would self-design itself. They just had to follow it. And they sent me a whole bunch of these magazines and in some cases, the headlines or part of the lead story was obscured by this big address label. And I thought, “Wow, can that be put somewhere else?”

And I asked them and they said, “No, I can’t go on the back because an advertiser will be unhappy. It’s got to go on the front, it’s got to go near the upper right because the post office wants this.” So then I thought if I made the Adweek logo really big—they need the promotion, they need to shout anyway—they could put the label right on it, and you’d still understand it was Adweek. Jack Thomas was always amused because he asked me what typeface it was, and I said it was Anzeigen Grotesk. And he never forgot that name.

Patrick Mitchell: And also, apropos of nothing, there was a spread in your book—pages 238 and 239 for those following along at home—that almost made me fall out of my chair. Once upon a time, there was a magazine called Magazine Week. That’s it. I don’t really have a question, and, of course, I do remember it. But it’s just stunning, in January 2023, to fathom a weekly magazine about the magazine business.

Walter Bernard: It was started by the people who started Adweek. And, I must say that we didn’t last too long, as you know that as the 2000s came in and the magazine crisis began, there were not enough advertisers anymore to sustain it. But it was a fun thing to do.

Debra Bishop: WBMG just celebrated its 40th anniversary. So congratulations, Walter. I just wanted to ask if there’s any particular job that you remember more fondly than the others? Do you have a favorite?

Walter Bernard: Well, we really did have some wonderful jobs. Fun for us was uh, working on some foreign magazines when we did Lire, and L’Espresso, and L’Express. We got to stay in Paris for a while, stay in Barcelona and Madrid, et cetera. So those were really fun jobs because we got to meet new people and we got to learn a little about the other cultures.

Milton, who liked traveling, became very good friends with Jimmy Goldsmith, for whom we did our first magazine, called Lire, a magazine about books. He became very good friends with Jimmy. And he also bought L’Express and several other French magazines, which we did.

And we also did newspapers in Barcelona and Madrid, a magazine and Tokyo, et cetera. So those were especially fun because we both got to travel and have a good time while we were doing it. We also did some things that were not magazines, even though we were an editorial design and development company.

We ended up doing several movie titles for Nora Ephron, which were fun.

Patrick Mitchell: Sleepless in Seattle was a big one.

Walter Bernard: Well my favorite was You’ve Got Mail (below), because that was the most difficult. And we did a few American Express annual reports. But mostly we did magazines and met a lot of different people. Our longest client was The Nation—the client that paid the least. But we worked for Victor [Navasky] and Katrina [vanden Heuvel] for quite a long time helping The Nation, which was one of our favorite magazines.

Bernard and Glaser, along with their frequent collaborator Mirko Ilić, worked with their former New York magazine colleague, Nora Ephron, designing title sequences for two of her most popular films, Sleepless in Seattle and You’ve Got Mail (above).

Patrick Mitchell: And in that process, you’ve worked with hundreds of editors. Can you say who—I’m going to exclude Clay Felker, because that’s not fair. Who was your best partner? Who helped you do your best work as an editor?

Walter Bernard: Well, possibly Ray Cave at Time. Time was a big hierarchy and the managing editor of Time was revered. The position was revered. And literally the staff would treat him almost as the White House must treat the president. You know, when he walks in, everybody stands up. They all want to agree with him, et cetera. Ray and I had a good working relationship. He encouraged me to disagree with him. To give him ideas about covers and stories. And he was very inventive. He brought in—who’s now a friend of mine—Neil Leifer, one of the great photographers. And he took him from Sports Illustrated and made him a staff photographer at Time who did really great work.

Anyway, I think Ray is one of those who I would consider the best. The most impressive to me was Harold Hayes, when I came to Esquire, because that was a whole new world of an accessible editor who was doing a great magazine, encouraging writers, encouraging the art department to give ideas. It really opened my eyes to what a magazine should be like. Even though I had very little experience before I got there. I mean, it was just really fun to work at Esquire.

Patrick Mitchell: And on the opposite side of that, what kind of partner did you aspire to be for your editors?

Walter Bernard: Well, I did learn—partially from Sam, but definitely from Milton—that you should not, as they say, stay in your lane. You should have editorial ideas, you should criticize stories, you should rewrite headlines, you should accept ideas from the other editors. I mean, somebody might have a great idea for not only a story, but a cover, or a photograph. And at New York, because literally we were all within shouting distance of one another, you could hear somebody with an idea and go over and say, “You know, you could do that instead of that.” And they could do the same to you. So, I found that that was a big education, to not feel like there’s the art department, and there’s the photo department, and there’s the production department, and then there’s, you know, the back of the book.

We all contributed everywhere. And Clay encouraged that. Certainly Milton did. They did not encourage that at Time. I think I broke a lot of rules there, because they were very straight about, you know, what department you were in. You were doing Nation, you were doing World, you were doing back of the book, you were this, you were that.

And my only difficulty at Time was that by taking over the covers—Time, before I got there, they had what was called a “cover editor.” A very smart woman who knew all the artists, illustrators, and artists—I mean fine artists—and she would assign not photography, but illustration covers, painting covers, and she was quite good at it.

But they did about three covers for everything and they’d have several stories, et cetera, and she’d assigned those covers. So when I got there, I said that I had to do the covers, and I also didn’t know whether a particular cover would be photography or illustration or painting. So occasionally I would design a cover that called for photography, but I would assign a photographer.

That would upset the photo editor because they ruled the photographers. And I had to explain that we started to have—George Lois influenced it—but, Time used to do the face of a person on the cover 90% of the time, whether it was a photograph or an illustration.

It was a great idea. The idea was you told the story through a person, but by the time I got there, the stories became more conceptual—about the missiles or about the economy. And it wasn’t concentrated on the Secretary of the Treasury. Or the general. And so we had to design some covers. And in those cases, Rudy and I would make sketches and bring them to Ray Cave and say, “Here’s what we think we should do.”

Occasionally that would be a photograph and I would use photographers I knew. Some that were staff photographers. And certainly, we, obviously, took over the cover design and the only time that was difficult was that the photo department was so used to just reacting.

When they heard what a cover story was, they’d send a photographer somewhere and they would be disappointed to learn that I had assigned a photographer to do a specific, certain kind of design. Like the Richard Leakey cover, for instance.

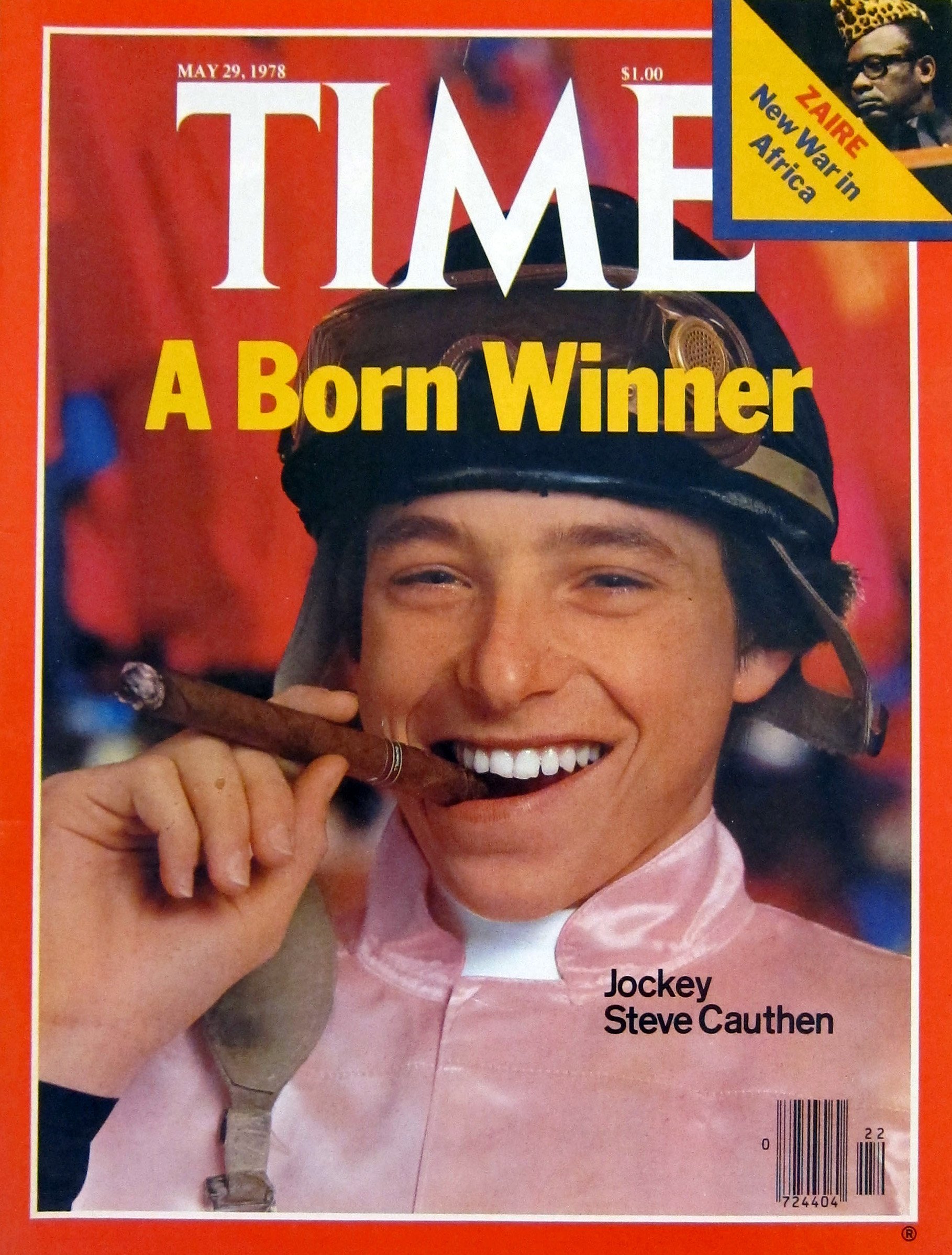

I will tell you one story, though, that is my favorite that involves Time and photography, and that is, I think it was 1978, Stevie Cauthen, who was only 18 years old, was a jockey who, if he won the last race, would be a Triple Crown winner on the same horse. And that was going to be a cover story if he won. The thing about those races is they’re on Saturday. And they start about four or five o’clock in the afternoon—well past a weekly’s deadline.

So, the idea is write the cover story, with just having to put a lead paragraph about winning, and engrave the cover ahead of time, so that if he won, you go to press. If the race is over at 4:30, you go to press at five o’clock. So I hired James McMullan to do a portrait of Steve Cauthen, which was not only really well done and beautiful, but approved by the editors, and we had it all set up and ready for engraving.

Meanwhile, my friend Neil Leifer, who was a real pest but a great photographer, kept saying, “I could do this cover. I could do this cover. I should photograph Cauthen.” And he had that assignment from the photo editor anyway. So I told him that I would look at all the photographs, but I already had a painting.

Two days before the race, he went out to Belmont, and photographed Cauthen with a cigar in his hand. I had told him that I’d only used a photograph if it looked like Cauthen had won something. And he brought me this photograph two days before we were about to go with this wonderful photograph of Cauthen holding a cigar that he had taken from his agent.

He had about six photos left on his camera. And it was great. I had to change the cover at the last minute. And, unfortunately, tell Jim McMullan that his wonderful cover that’s already engraved is not going to be a cover.

Patrick Mitchell: Jim McMullan didn’t lack for Time magazine covers, though.

Walter Bernard: No. And he didn’t lack for wonderful Lincoln Center posters.

Debra Bishop: What is the thing that you love the most about magazine making, Walter? What’s your favorite part of it?

Walter Bernard: Oh, my favorite part was always getting the issue. I mean, the idea that every week, you know, it was so different. Esquire worked three months in advance, practically. At New York we’d close that magazine Friday night and Monday morning, it’s on the newsstand.

And at Time, they printed really fast. The protocol at Time was that the White House, and members of Congress or the Senate, and important people would get a special hand-delivery every Sunday night when it came off press.

And that was the great thing for me. Sunday night, I got a knock on the door, “Here’s your Time magazine.” And it was so thrilling to realize that just a day and a half before we were killing ourselves to put this out, and here it is—6 million copies!

Debra Bishop: It’s so wonderful to have the final result in your hands.

Walter Bernard: Now sometimes you looked at it and said, “Oh my God. This was not a good cover.” Or, “This didn’t work out so well.” But there was always next week to redeem yourself. But the favorite thing was to actually see something in print on a weekly basis. I think everybody at the magazine was always thrilled by that.

Debra Bishop: I love that too. What was your least favorite part of magazine making?

Walter Bernard: Obviously, on the weeklies, we’d spend some really long nights. Things would go right or wrong, or even just the news would change and you’d be there till four or five in the morning, or not even go home. Those were not my favorite times.

I remember that I had been there just a week and I went in to say good night to Henry Grunwald, the editor, and it was a Friday night, and I said, “Good night, I’m going home.” And he said, “Wait a minute.” And he had the television on in his office, and it turned out that the guy who had shot Martin Luther King escaped prison.

And they had a manhunt out for him. So Grunwald said, “You’re not going anywhere. We’re changing the issue.” And I called up Harvey Dinnerstein, a wonderful illustrator who could draw anything. And I asked him if he would work on this story. And he said, “Sure.”

Harvey didn’t do a lot of illustration. He was mostly a painter. But I said, “Here’s our problem. We want to recount the escape and hopefully the capture, but we don’t know when it’s going to happen. So I need you to come into Time, and get the news with me, get the reference with me, and work here.”

And he came in on Friday and stayed all the way through Sunday until we got the news of his capture, and did these drawings. We obviously closed later and it was a special late addition. I think James Earl Ray was his name.

And so, those weren’t fun days. Simply because it wasn’t even necessarily doing a good job, it was just getting something out based on the news. Similar happened when Jimmy Carter’s attempt to go into Iran and rescue the hostages failed and the helicopter crashed in the desert. That was also the end of the week, and we had to completely change and everybody stayed. And you’d have the whole office there all the time because you need every proofreader, every copy editor, et cetera, staying. So nobody got to go home.

Two of Bernards worst-selling covers. (He blames the design).

Patrick Mitchell: Everybody makes mistakes. Do you have any colossal blunders that you want to share from your long and storied career?

Walter Bernard: I could tell you the two worst-selling covers that I remember at New York, which were the fault of the art department.

Debra Bishop: I doubt it!

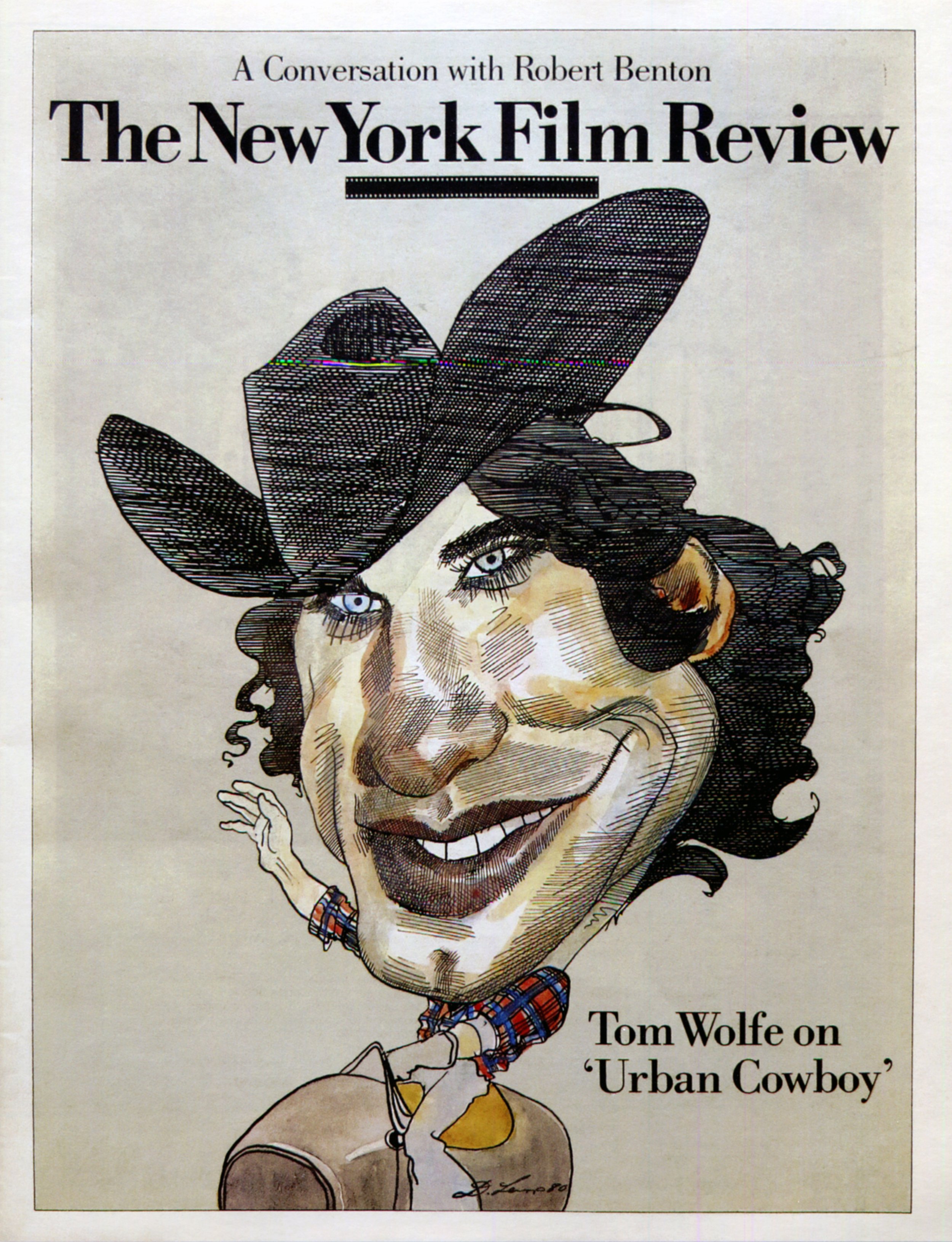

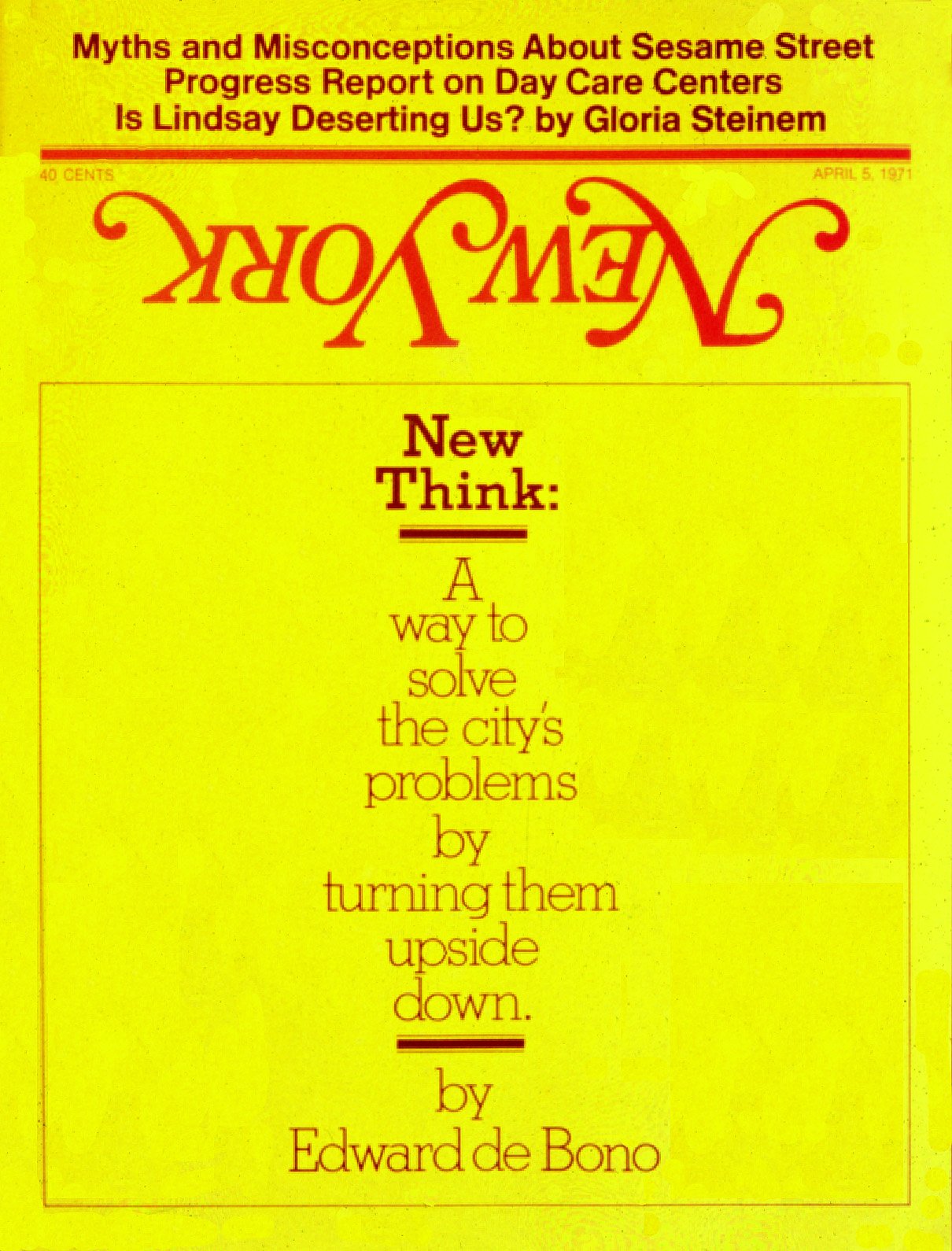

Walter Bernard: Yeah. No. There was a story—a story we couldn’t figure out—by somebody named [Edward] de Bono. And his idea was, in shorthand, you could solve any problem by turning it upside down. Some kind of inversion and a long theory. And God knows why it became a cover story.

Milton and I couldn’t figure out what the hell to do. So we decided to explain it on the cover and turn the logo upside down. So New York’s logo was upside down. And we printed this yellow cover, the red logo upside down. And then it said, “Solving Problems by Turning Them Upside Down.” I don’t remember the exact wording.

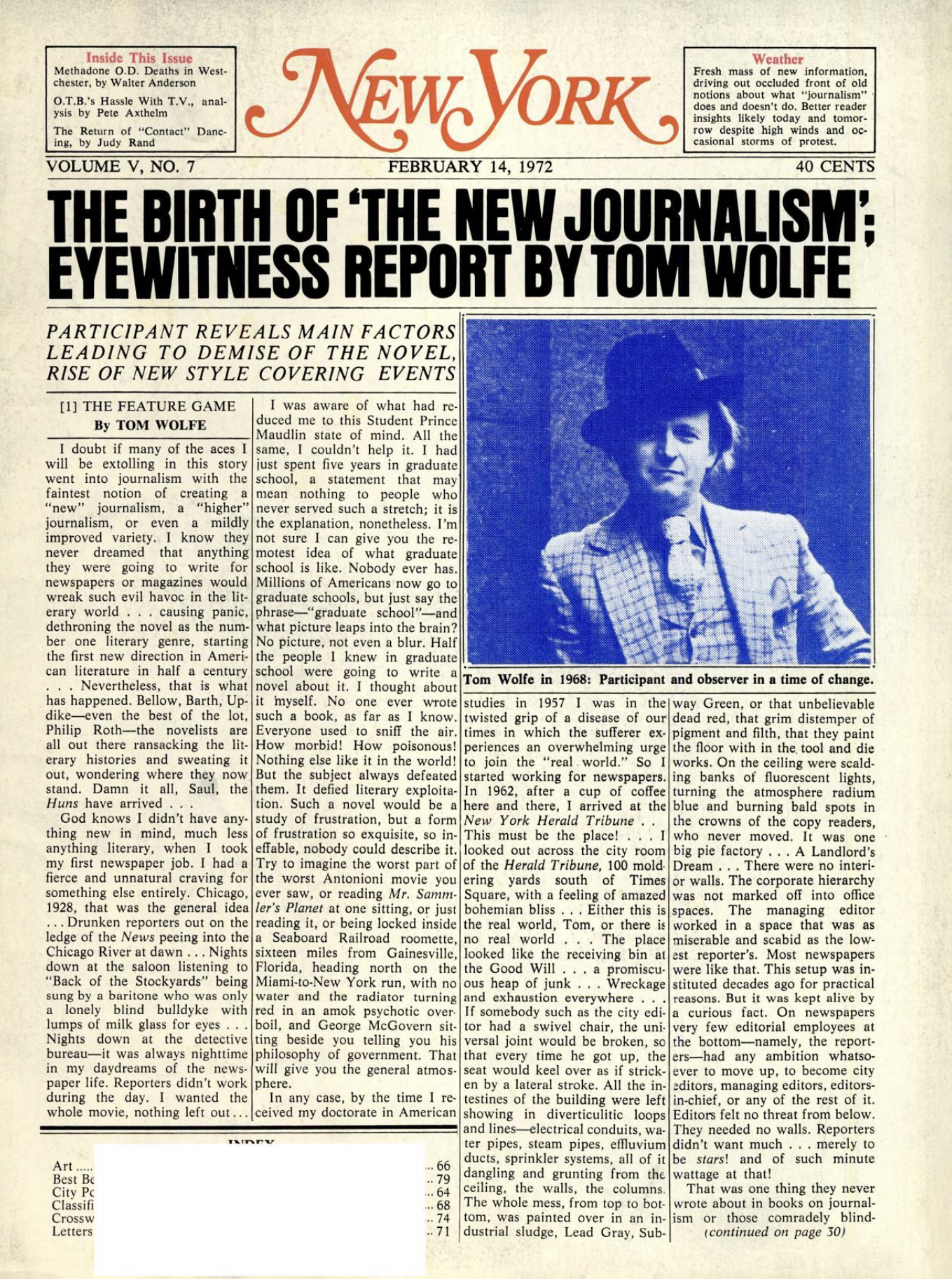

Readers would call saying, “Where the Hell is New York magazine?” Not subscribers, but it didn’t sell, it did nothing on the newsstand. It was horrible. And then we did it again when Tom Wolfe wrote about The New Journalism. I convinced Milton and the editors, because they were talking about how it started with newspapers to kind of write the beginning of the story as a newspaper front page, almost like The New York Times, on the cover.

So it was full of type, like columns of type on the cover, and New York magazine’s logo, again, was small, sort of like The New York Times logo would be on the Times. And this cover was a big bomb. Usually a Tom Wolfe story does very well, but this was really terrible.

Debra Bishop: Well, one last question from me. Do you consider yourself an artist, Walter?

Walter Bernard: Only when I do my watercolors.

Debra Bishop: So you do make art yourself?

Walter Bernard: But I, you know, I think art directing is a kind of a craft, but I’ve even known good editors who could be art directors. They didn’t know anything about type or anything like that, but they really knew how to shape a magazine and could call on the right kind of talent.

And you know, when you do a magazine, especially weekly, I mean, you don’t do it. You’ve got, you couldn’t possibly lay out every page. Luckily Time was formatted. But you had to just direct the talented staff and suggest things to talented people or hire them to execute. And I knew a couple of editors who could do that just as well as I could.

Byron Dobell was a great visual editor. He had great ideas. And he was smart enough. Some editors didn’t know anybody and didn’t care. He knew every illustrator and photographer as well. He really knew everybody and had great suggestions about art and photography. He could have art directed a magazine very easily.

Patrick Mitchell: But could he do watercolors?

Walter Bernard: Actually he did. He and I went on many painting trips together. What he couldn’t do, and neither could I probably, is design a page like The New York Times does these days or that Fred Woodward did in Rolling Stone, you know, in which the typography was king in terms of the visual.

Debra Bishop: And considered art. Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: Your wonderful book ends with the quote, “We had fun indeed.” Which sounds like an amazing epitaph. How would you like to be remembered? Not that you’re going anywhere!

Walter Bernard: Well, you know, there used to be a bad word—you’re not old enough, Deb, and probably you, Patrick—but in the McCarthy era when they were looking for communists you would be either a “communist” or a “collaborator.” And “collaborator” was the wrong word. But I think that to work in a magazine, you’ve got to be a great collaborator.

And that’s one of the things that they taught me at Esquire and at some of the other magazines we later worked with, that, you know, the exchange of ideas, the listening to other people, trying to contribute and collaborate with them was great.

And I think that’s what I would like to be known for, because I think that’s what made me able to survive in magazines, is to work with others.

Above: Mag Men, a retrospective of the work produced by Bernard and his partner, Milton Glaser, who died in 2020 (pictured below).