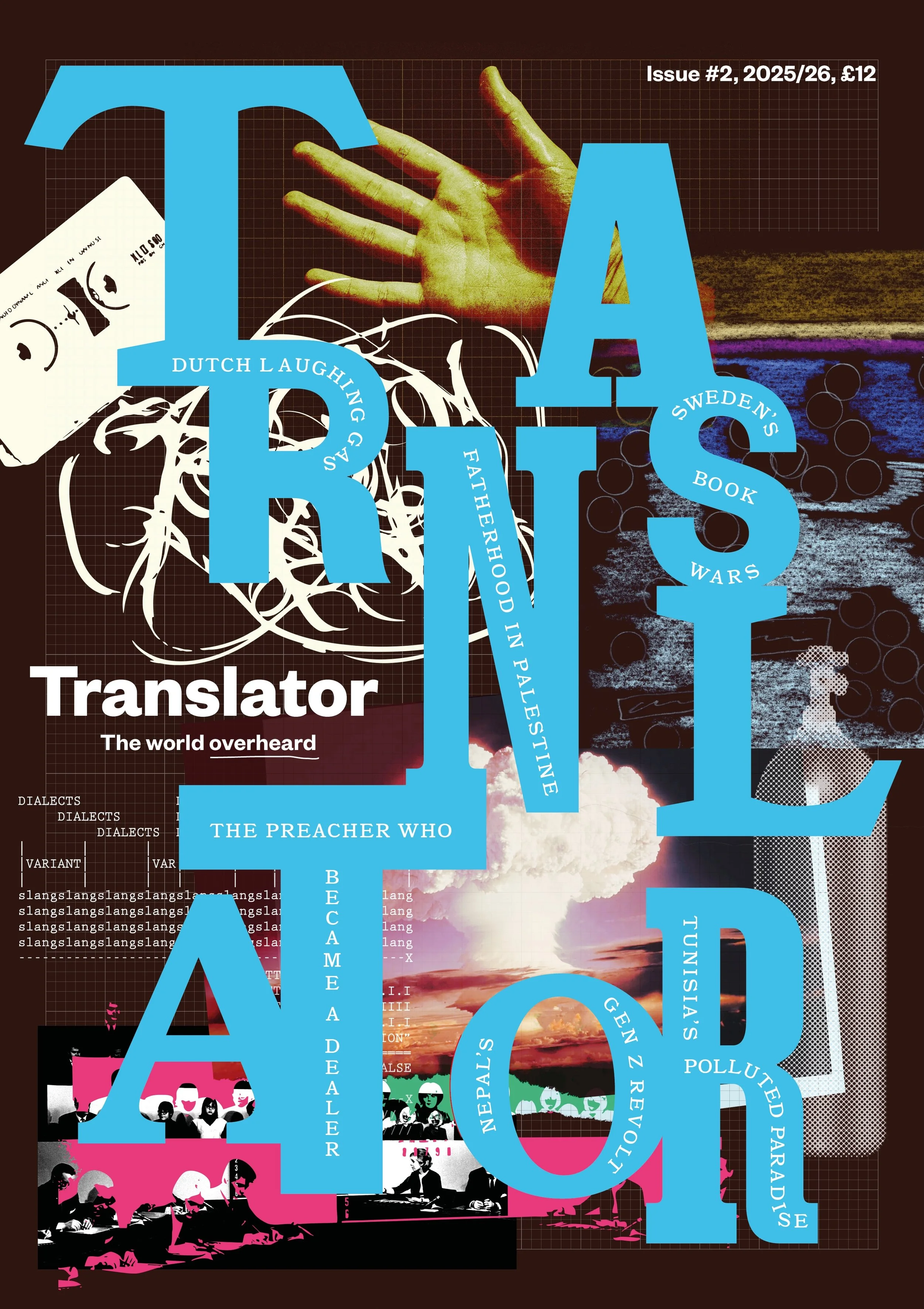

Lost in Translator

A conversation with Translator founder Charles Emmerson. Interview by Arjun Basu

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT FREEPORT PRESS.

There are more than 7,000 languages in the world and there’s a good chance that you don’t speak or read most of them. Being an English-language speaker is, among other things, a huge privilege in this multilingual world because while it may not be the most widely spoken first language, English is the language that is most widely spoken.

There’s a chance that you can get by in English almost everywhere. And so English speakers tend not to learn other languages. To their detriment. (And to the resentment of others. But that’s another story.)

Not all of the world’s 7,000 languages are robust enough to support their own media. But guess what—there’s a lot of media in this world that isn’t created in English. Enter Translator, a magazine of translated journalism and reportage from around the world for, “the open-minded and the language-curious.”

And in a world where much of our media is controlled by fewer and fewer people, this kind of wider view of what others are saying and thinking is, perhaps, more necessary than ever.

Maybe the only surprising thing about Translator is that it wasn’t created … sooner.

Arjun Basu: Charles, thanks for being here.

Charles Emmerson: Thank you very much.

Arjun Basu: How did this project come about? I can imagine how it did, but I want to see if I’m assuming things right properly.

Charles Emmerson: I’ve essentially always been working in writing of different sorts and generally writing and researching. Because I’ve also worked in think tanks about the world. Not just the Anglosphere. But what I’ve noticed, and I’m not the only person, is that over the last few years there’s been a kind of linguistic flattening, or flattening in general, of what is available easily to an English language audience in terms of reporting about the world beyond the Anglosphere.

And I find this a really interesting phenomenon. It’s, I think, also a very destructive phenomenon, but it’s also an understandable phenomenon, right? Because there are a lot of people in the English speaking world who imagine that the world takes place in English because so much of it does; that the world is just in English.

And actually what’s happening is that people in the Anglosphere are getting a narrower view of the richness and diversity of the world. And that’s a problem for all kinds of reasons. And so we wanted to do something a bit different; looking at the very rich media landscapes beyond the Anglosphere and translating pieces from these very rich and diverse media landscapes into English.

Arjun Basu: So you answered part of my next question. You answered maybe a few of them, and I’m going to come back to it, but you’re a historian. You’ve written three books. I’ve had 1913 on my read to read list for. Longer than it should be, but if you read a lot, that those lists tend to become very large and then long—

Charles Emmerson: Aspirational.

Arjun Basu: Aspirational is good. They’re, they are aspirational. Yes. And, and then your other books, I looked them up and after this conversation I might actually just order them just to get that over with. So you talked about going out into the world and you needing sources, obviously other than English language sources. So at what point did you just say wait a second we need to do something about this. There’s like a tipping point or something in your research that bleeds into this.

Charles Emmerson: I agree that there’s always a tipping point, and the honest answer is that for the longest time I imagined that because it simply made sense to me to try and translate pieces from languages other than English into English that someone else would do it.

And I kept on thinking it’s going to happen. It must happen. And then it didn’t happen, and then it didn’t happen some more and eventually came to the conclusion that if it isn’t happening, maybe we should do it. I think there were some good reasons, perhaps why journalism translated into English was considered not to be a viable proposition because a couple of big newspapers, like for example El Pais in Spain ran an English language version of that newspaper and various other large mostly European languages, newspapers have tried out English language versions, and they haven’t been, as I understand it, not a huge success.

But I think that’s really because if, for example, you’re somebody who wants to read an entire newspaper about Spain, you probably speak Spanish. So it’s not the fact that it doesn’t necessarily work out doesn’t mean that it is not an argument against translated journalism. It’s an argument in favor of putting together a product which actually brings different pieces of translators to journalism from different media landscapes. And the tipping point for me really was when I just realized that this, this Protean dream, which was forming in my mind, and then in the minds of my co-conspirators at various times, wasn’t happening.

And so we had to do it. And there’s a sort of, I think, there’s an urgency to this now, which probably didn’t even exist five years ago. Because I see model linguistic media bubbles becoming more and more entrenched. And the flattening of the media landscape, risking entrenching political and other inequalities and we’ve moved beyond, I think, a world where it would be acceptable to imagine really that the world does take place in English. So I think it’s also for anglophones to realize that the world's gone and and in a sense good rinse to it and therefore it’s incumbent to try and do things differently.

Arjun Basu: I live in Montréal, so I have understood that reality for a long time, and it is one of the complaints for the francophones here, that they just know more of what’s going on on the other side than vice versa. And, to the point where they’re starting to become almost, a certain segment, are almost becoming anglophone in their disdain, or just we’re going to ignore the other side. And that’s too bad. And I know the local papers, some of them try really hard to, I. Bring in other voices from the other linguistic groups to write in the other language. But it really is like one of those ground zeros of everything you’re talking about because of the situation here. Okay, so you’ve decided all that. And the next step of course is I’m going to do a magazine. So what is that process? That’s not the most normal thing to think, but how did you come to that?

Charles Emmerson: The wonderful thing is is that the world of independent magazines is a space full of very friendly and supportive people. And when you tell people what you wish to do, certainly when I tell people what I wanted to do, the response generally within this community of people who work in independent magazines was gosh, that sounds a bit crazy. How can I help? And I think the fact that it struck a chord and that people did want to help – they thought it was a good idea and did want to help – encouraged me with the notion that it was possible to do. But of course that involves building a team. It involves figuring out all the messiness of actually creating a physical product where you have physical constraints on the page.

Because of course, we do have a Substack, and a weekly set of summaries that we put on Substack. But of course the core is this physical paper magazine and that has all kinds of constraints. So we started talking to people. We started talking to a wonderful design team in London based out of MagCulture, Jeremy Leslie and Osman Bari.

And we also started assembling our team, our very small team, in London. And a little bit further down the line, we can come onto that, we started thinking about contributing editors and how we would actually be able to find the really wonderful articles that we wish to summarize or to translate.

So that’s a sort of telescoping of the process. Something that took actually about six months maybe. Before we got into the real, real nitty gritty of actually getting in touch with those publications saying, would you be willing for us to translate an article? finding the right translators for those articles, editing the translations, putting them out on the page, all that difficult, fun, exciting process, which goes into making a magazine.

You’re not someone who created a magazine before. You’re a writer. So the whole thing was new to you in terms of the core team you assembled. I’m imagining that their background is more relevant in terms of magazine making, or maybe I’m wrong.

Charles Emmerson: I have in fact worked as a journalist to some degree. I have worked in media organizations so I had some sense of that. I have a lot of friends who are journalists also. I mean they, journalists, tend to be friendly and fun, I have to say.

So that helps. I was certainly very helped at the outset with a colleague, Sally Davies who has been the editor of a great publication called Aeon. And then with the core team that we now have. Nazrene, Trà, Zanta Nkumane, actually, we wanted to achieve a balance between people who’d worked in independent publications before.

So that’s the case with, for example, Zanta, and then with people who had worked also in organizations relating to translation, because obviously the translation community is a really key part of what it is that we’re trying to do here. And then through our contributing editors, we’re also trying to reach people who have worked in newsrooms as well and who can help us with the more journalistic end of things. So it’s really about assembling a team with a very wide set of skills and knowledge and backgrounds, and then seeing how that works.

Arjun Basu: Assembling a team is difficult enough, but then you found people all over the world in terms of being contributing editors. Your translators are also all over. They’re not necessarily sitting in London. So how did that happen? How did you assemble those people? How do you find them?

Charles Emmerson: A lot of it’s just asking people who do you know? Who would you recommend? We’re still very much in that process. This is not a one time thing. We’re doing it all the time. We’re always looking for new contributing editors. We’re always looking for people who might recommend articles to us in languages beyond our media landscapes, beyond the Anglosphere that we can then translate into English or summarize.

So it really is a never ending process. And the really great thing about that is you get an ever greater sense of the sheer richness and diversity of global journalism. You get a sense of the different ways in which stories are written also in different parts of the world. So there's not a single journalistic way of putting together a story.

There are different traditions of writing. There are different story structures. There are many places, of course, around the world where journalism is in crisis for political reasons. In some places or in other cases because the business model of journalism is broken.

And yet through all of this, the really inspiring thing, which I’m sure you come across all the time, is wonderful, very often mission-driven publications, which do understand the fundamental role of journalism in holding power to account and providing a space where ideas and discussion can really flourish. And it’s wonderful to be on the fringes of, or trying to bring a tiny fraction of, that wonderful diversity into the anglophone arena.

Arjun Basu: So how did the story come to the attention of the editors? Are you being pitched or are people saying you should look into this? I was just reading the Substack yesterday and, you put up the story about what’s going on in Morocco in terms of the protests. So how does it get onto your radar before you say let’s go through the process?

Charles Emmerson: We’re still asking people to recommend pieces to us. That is the fundamental thing. If you see something which is of interest, in a language other than English, just write us an email. We actually have on our website, we have a WhatsApp number. You can text a picture of the article, you can text the link to the article. We call it a hot tip line. So just send things in.

That’s the first thing. The great thing is also, of course, that once you’ve produced a first issue, because our first issue came out in June and now we’re working on issue two, which will come out in November, is that people start understanding who you are. They understand the kind of thing that might work for you.

And so they approach you. And that’s a wonderful thing that happens more and more is people say, “Oh, I read this piece. It was really interesting. I wonder if you’d be interested in something about this.” That’s actually how to read between the lines, which is a new format for us. Same for the Moroccan article that you are, that you were referring to. So that essentially what we’re doing with this read between the lines is we’re speaking to an expert in a media landscape beyond the Anglosphere and asking them to decode for an anglophone audience an article about something that is happening where they are.

And in this case, it was an article about these recent protests in Morocco, which have not been widely covered in the anglophone media, but which are hugely significant in Morocco. And that came to us through a journalist approaching us and saying, actually, this is a very important story. Would you be interested in us writing something about that?

Arjun Basu: So let’s talk about the first issue and how it did. Were you satisfied with it? Or are you already thinking this can be better?

Charles Emmerson: We always think things can be better. I think both things are true. One can be satisfied. Yes. I think it’s a really good issue, which I believe it to be. But then you also think, of course, how can we tweak it? How can we make it better? The second issue will be better. The second issue, apart from anything else, will be actually bigger.

So we’re increasing the number of pages. In the second issue, we’re increasing the number of articles in the second issue. We’re increasing the number of particular pieces of translated reportage in the second issue. In the first issue, we had some commissioned articles, mostly about language politics, one by a journalist called Theo Mertz about minority languages in Russia and the way in which the Putin regime is putting pressure on those minority language groups.

And then we actually had one about Sophia Smith Galer, who’s a fantastic British journalist and has a wonderful book coming out next year. President Trump’s declaration in the United States, that English be the sole official federal language in the United States and the kind of chilling effect, what this represented, what it signaled, about that government and then the chilling effect that it might have on linguistic diversity in the US.

I, basically I’m very pleased with that first issue. I hope you’ve seen a copy. It’s, you got one. There we go. Okay, good. It’s also beautiful, right? And it’s fun. And I think this was another thing which is very important to us translators, is that – although many of the issues in the magazine are incredibly serious issue – we also have an article in there called “The Hunter” which is translated from a Cuban author and that’s serious, but also it has fun elements too: It's a fun piece essentially about how sex became a currency in Cuba after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the sort of the economic fallout from all of that.

And it’s a very serious article, but also written in a very fun and entertaining way. And as you’ve seen from the visuals of the magazine, there’s a lot of bright colors. There’s a lot of fantastic illustrators who did the illustrations for the different articles who were all from beyond the Anglosphere.

And we wanted this to be a magazine that one could pick up and have fun with. And yes, there would be some very serious things in it. But that it would be a pleasurable reading experience. That’s the key for us also.

Arjun Basu: But I also note, the size it’s almost … it’s oversized. It almost has a newspaper feel. It’d be interesting to talk to Jeremy about it, but was some intent in terms of even just the shape of it?

Charles Emmerson: We wanted it to stand out. You’re right that we were somewhat inspired by traditional magazine sizes. We also actually, of course, on the back page have a crossword, which is a feature which we’re keeping for the second issue as well. We’re working together. I learned this wonderful word, cruciverbalist, which is the name of somebody who puts together a crossword.

And we thought a crossword on the back was really a sort of a statement of intent. And it’s funny, I’ve spoken to lots of people about the crossword and many people say, I love the crossword. And I say, have you done it? And they say, no, but we love it. And the reason they love it is because they haven’t finished it. It’s quite hard to finish, to be honest.

Or one person has, and he’s got a prize of getting a subscription to Translator Magazine. But what it signals, I think, is our desire that this leans into. The sort of traditional idea of newspapers as things which have got lots of diversity in them. And you can read them at different times. You can pick them up, you can put them down, you can read them in bed, you can read them on your way to work, you can read them wherever and that's all. There’s also something which is very important to me, which is that you can roll up this publication. It’s not too precious.

Because very often I find magazines – there is a certain kind of magazine – which is really an object magazine. These really heavy things, which you always want to put gloves on to hold them. I don’t want people to put on gloves to handle Translator. I want them to be looking at them in the kitchen while they’re cooking. Maybe that’s not safe, I don’t know. But if they’re a very good cook, don’t do this at home.

Arjun Basu: Maybe if you add recipes, if you add recipes from the rest of the world.

Charles Emmerson: You know what? That’s not a bad idea.

Arjun Basu: So how does that, how did that conversation happen? You’re starting a magazine you go to, MagCulture and say, “You want to design this for us?” How does that conversation happen? What is talked about?

Charles Emmerson: I should say that actually the way in which we came across MagCulture was initially, of course, as a shop. And then later actually they run an event called the Flatplan, which we attended online. And there was actually this one particular person Osman Bari, who was talking about his magazine, Chutney. And Osman is just the nicest guy. I dunno whether you’ve had him on your program, but he is the nicest guy. And Sally and I said to each other,

“We need to work with Osman.”

So we asked Jeremy: how could we get in touch with Osman? And then he said, actually, maybe we can work all together. And so that was how that came about. And I feel that in the independent magazine space, as I said, because it’s generally a very friendly space, people want to collaborate. People want to work on things they find interesting. It’s a mission and passion driven world. But it still needs to be made, it still needs to make sense financially and economically of course, and be sustainable both on a personal level and on a financial level. But a lot of where it comes from is that desire and that interest and that curiosity. So that’s how that relationship started.

Arjun Basu: So then how long did it? You’re dealing with a blank canvas.

Charles Emmerson: You see you’re dealing with a blank canvas, but soon you’re dealing with not quite a blank canvas, but a blank canvas with some squares on it.

And those squares are pages. And let me tell you, you already know this, but if there’s one thing more terrifying than one blank page, it’s 40 blank pages. Because you think, oh my God, how am I going to fill 40 pages worth of material?

By the time you got to the end of the magazine, of course, the end of putting the magazine together, you realize there’s so much more you’d like to go in. And that provides the momentum for issue two and issue three and going forward. But that first encounter with the notion of multiple empty pages and how you feel that’s obviously a big issue in terms of things like paper quality. Again, we were very much driven by this idea that we wanted it to be not too glossy, not too heavy, but at the same time to be very legible. Because this is ultimately about—although there’s fantastic illustrations in the magazine—about the words.

And so it has to be very clear to read. We can’t let design or aesthetics take us in the direction of something which is illegible, unreadable, unapproachable. Because these are quite long articles. I think the longest article in this magazine is actually as long as six and a half thousand words.

So it’s a serious commitment of time that we’re expecting from the reader and we want to respect that by ensuring that it’s easy to read, that it’s clear. So balancing those different factors was how we made our decisions about design. Of course, we also have in the middle of the magazine a photo essay. And that requires a different kind of paper. But most of the magazine is, it’s, it’s definitely not translucent in any sense, but it’s not particularly heavy either.

Arjun Basu: No, it’s not. You can roll it up in swat flies if you need to. It’s not really that hard to do. How does the website and the Substack and the magazine, like, how does that ecosystem work?

Charles Emmerson: Bear in mind we’re not coming from 20 years of working in magazines. So a lot of this is experimentation. And it’s driven by the desire to see more articles from beyond the Anglosphere in English and to really act as a portal to those worlds. So actually how we started this off was by putting together a Substack.

We thought where do we begin? Let’s begin by getting recommendations and reading a lot. And if we read a lot, then we might as well also try and summarize and try and also refine our own sense of what we think would make a good piece that might ultimately fit in Translator Magazine. So we set up a Substack where basically every week we summarize three or four pieces from beyond the Anglosphere in English. And that was partly a kind of training for us in terms of allowing us to, or putting parameters around us, spending time reading journalism from beyond the sphere. With others. And then that’s become a regular feature.

We do that every week. We’re broadening it now somewhat because we’re introducing this format of Read Between the Lines, as I mentioned, where we ask a journalist or an expert in a media landscape beyond the Anglosphere to decode an article. We recently asked one of our contributing editors, Sanam Maher, who’s based in Karachi: she wrote a piece from BBC Urdu about the recent floods in Pakistan and what that sparked in her, what the context was in Pakistan’ how it touched on other discussions and debates. And that’s a format which we’ve started on Substack, but then we’ll actually have a Read Between the Lines piece also in the magazine.

So Substack and online has been really a testing ground for us in many ways. But it’s also allowed us to reach a large number of publications and journalists and to get a sense for ourselves of the richness of those media landscapes. And it’s free.

Arjun Basu: And it’s free. I know, I was just about to say that. And you also have a great game on the website. I love the word thing. More games! Especially with words and, you’re dealing with languages. It’s such an easy way to get people involved in the thing.

Charles Emmerson: We would love to have Word games. Everyone knows these days that, no one actually buys the New York Times for the articles, but people buy the New York Times for the crossword and for they buy…

Arjun Basu: for the games and for the recipes. Those are the two things they buy.

Charles Emmerson: So yes the game which we have on the website, it’s just a little bit of fun. I’m glad you appreciate it. I certainly have had a lot of fun. It’s essentially a translation tool: you type in one word and then you get four versions of that word in four other languages.

It’s a fun game, I think also because you can sometimes see connections, the connections, the etymological connections between the words of course, people who are fascinated in language are often fascinating loan words from one language to another. There can be all kinds of surprises thrown up there, and that’s something we’re also leaning into in the magazine, the politics of language, which is very important.

And also the fun that one can have with language and the slipperiness also of language. As we know, translation is not simply: there’s the word cat, and then it becomes cat. It’s not one for one. Translation involves choices. It’s a craft. This is one reason why AI can do it pretty well. But not perfectly.

Arjun Basu: And there’s also a cultural context of translation. If you have something in another language where they keep referencing a local talk show host, let’s just say, that means nothing to the English reader. Do you include that name and then have, do something parenthetically? Or do you change it? I used to be the editor of a bilingual magazine, English, French. And often we did make the cultural change. So that it would be understood, without having to stop. Because that’s when you realize, oh yeah, this is translated.

Charles Emmerson: Well, it’s interesting. It’s a big discussion in literary translation, of course, is how you translate, for example, jokes. Do you try and translate jokes? Literally a joke. I, Have you ever tried explaining a joke? When you explain a joke, it’s no longer funny. If you translate a joke, it’s the same as explaining a joke. It loses all humor immediately, and there are so many layers to it.

So what many literary translators these days will do is they will not translate a joke. For one language, another, they will substitute it for a language which has the same kind of vibe. So it’s very much not a direct translation.

Now we don’t have jokes in Translator Magazine. Maybe we should. But what we do is we have margins along the pages of the magazine so that we wouldn’t put in, for example, footnotes, but where there’s a word which is particularly interesting from a translation perspective or part particular weight, then we’ll highlight that and if there’s some additional contextual factor which needs to be highlighted, then we will also try and explain that. So the article could be read on these multiple levels.

Arjun Basu: I just thought you could do a piece where you have a joke that’s really well known in English. Have someone translate it and then have someone translate it back.

Charles Emmerson: Huh. I like that. I’m writing that down. That’s a great idea!

Arjun Basu: When you’re putting the magazine together, do you have a map of the world in front of you and say we’re really not covering this place? Do you try, and are you trying to be, to spread the wealth in that sense we should cover the world? Or do you worry sometimes that you’re only covering one place or is it just the story that run that?

Charles Emmerson: No, we absolutely want to spread the wealth, as you put it. I don’t have a map of the world i my study or in my kitchen. But we do definitely have a mental map of the world and we’re trying to ensure that we translate articles from a range of different parts of the world. And there is, of course, a vast inequality in what is currently translated. There is a vast inequality of accessibility of different types of articles from around the world.

You can’t just sit back and see what comes in. We try to be active in ensuring that we translate articles from a range of different places and recognizing that the journalistic traditions of writing in general, and the conditions of writing, may be very different in different places.

Arjun Basu: Yeah. The conditions is really, I think, what I’m getting at because, Germany, for example, is a place that isn’t in the Anglosphere that has a lot of media and that you would have no trouble finding the story from. Whereas, I don’t know, Afghanistan or parts of Africa, would be, or even, I don’t know, indigenous languages in Australia. Those would all be different difficult places in terms of source material. So it’s not equal in that sense.

Charles Emmerson: No, it’s absolutely not equal. And we still have a lot of work to do in this area which is one reason why we always want recommendations from any language we’re not only interested in French and Spanish and Italian and German, for example. Although it should be said, there is an incredibly rich ecosystem of Italian journalistic writing, which is a lot of fun. And of course there is a very rich ecosystem of journalism in Spanish, which is not just Spain, of course, but all of Latin America apart from Brazil.

Yes. There are languages which are, in a sense, big languages, journalistically speaking, but we’re also very keen not to ignore the many languages that are less prevalent. And they may be less prevalent. For example, they may be less prevalent online for various reasons.

That’s one big issue, which is one reason why we’re keen also for people to send us photographs of articles that they’re interested in. If it’s not online, it doesn’t need to be a link. It can be a photograph. Because we do want to ultimately translate articles from as many countries and as many languages., I’m not quite sure what our running total is in terms of languages from which we’ve summarized; I think maybe 30 languages. So it’s not bad. And in the upcoming magazine, we have translations from Spanish, from Arabic, from Japanese, a wide range.

But we always want more. And I personally have a great interest in also linguicide and in disappearing languages. And I think often there are very strong communities around journalism and languages that are under pressure, under the strain, under stress. And that’s also something that we wish to highlight.

Arjun Basu: So what’s the reception been to this? You say the magazine is for, I think it’s in the editorial or maybe it’s on the website, for the “open-minded and the language-curious.” I would say it’s for the internationally curious. I think we’re saying the same thing: people who want to better understand the world. It’s a window into the world for sure. So what’s the reception been?

Charles Emmerson: It’s very interesting you use the word window because actually window was one of the words, one of the names that we thought of for the magazine before translator.

The only thing was we were worried that people might think we were somehow owned by Microsoft. Yeah. If you actually look up, if you want to buy www dot window, dot co, It’s incredibly expensive I’m sure. So for various reasons, we decided that we’d go with translator, which is better also because we do exactly what we say we’re going to do: we translate. But translation is not only translation from one language to another. It can also be translating across cultures. And indeed journalists very often are translators of that sort as well. But in terms of the reception, I mean we’ve had a very warm reception from the translation community, which is obviously a very important community for us.

And a very highly networked community. Translators tend to know each other. The world of translation is really a world in itself, so it means a lot to us.

Arjun Basu: And where are most of your readers?

Charles Emmerson: That’s a really good question. I’d say that most of our readers, initially it was very much the United Kingdom and the US. But increasingly it’s really broadened out. A quite a large number in Germany actually. And I don’t have the figures in front of me, but it’s definitely broadening out. So this is another interesting point, I think, which is that although we’re interested in journalism from beyond the Anglosphere, of course people do speak English all around the world.

And people who speak English don’t have to be in the UK or the US or Australia, or even Canada for that matter. And I think it, it often when you see publications that are exclusively based in the UK or the US or Canada, they have in their minds, or the editors may be have in their minds: what would a Canadian reader want? What would an American reader want? What would a British reader want? It tends to be quite reductive because actually there are all kinds of readers. There are lots and lots of readers. There are also lots of Anglophone readers, and they aren’t all in these countries. And so I think we need to get beyond the notion that.

If you speak this language, then you are going to be in this place and you want to think about the world in this way, and you’re only going to be interested in reading about another place in this particular way that other people have written about or read about before. So we need to get beyond that and offer something which is richer, and that’s what we’re trying to do, but to get back to the point about the reception, it’s been…

Arjun Basu: Enough that, you’re obviously, you’re putting the second issue to bed. So what is the hope for this? What is the future of Translator as a media?

Charles Emmerson: Look, we have all kinds of ideas. We certainly want to increase the frequency of the magazine. So I said issue two in November, and then we’re already looking at issues three, four, five, and six. We’d like to make it as frequent as once every two months, but probably quarterly is going to be the right cadence, at least for next year. While we build up our muscle memory, we really do have an ambition to provide a portal for anglophone readers into the very rich and diverse media landscapes of different languages from around the world.

And we think this is a way to do it. We’re thinking about how we might do that also in terms of audio. It turns out, of course, that on Substack you can, I think, listen to the summaries in some kind of computer generated voice. Some people say that’s really good.

I guess that’s another way of accessing the work that we do, at least on Substack, is to listen to those voices. But I think what we would like to also create is a community of readers and writers and translators. Allow for discussions to take place between those individuals, which would then have as a podcast.

So we’re keen to create a space where we can learn, for example, about the story behind the story. So if there’s an article in our publication, then how did it come to be? How did it come about? How did it come to us? That’s one thing, but really much more interesting than that is: how did it come to the person who originally wrote the article? How does it fit into the media landscape in which they’re working? And then also a dialogue with a translator. I think would be a fun way of getting to some of those more granular sort of crunchy things, which can make an article fun. And of course, as a journalist, journalists always when they research an article, a long article, they probably have enough material for about, five or 10 other articles. And the thing which ends up being written may not even be their favorite story.

Arjun Basu: I have to say any success that Translator has would make me feel better about the world.

Charles Emmerson: We’d like to make you feel better about the world.

Arjun Basu: Because it just means that you’re finding those open-minded people who are interested in the world and want better information. And I think information is always good, right?

Charles Emmerson: And I really come back to this point that although there are lots – so I hate the word legacy media but it’s a useful shorthand – there are lots of quote unquote legacy media publications that are in crisis. There is a crisis, of course, in journalism across the world for all kinds of reasons: business models, funding, ai, censorship, politics, authoritarianism, all these things are big issues, which are bearing down on journalism all around the world. But there are also people who are trying to do things differently. And I think the human urge to be understood, to be respected too, have ways to show one’s curiosity, to tell you, no, this is what’s happening to me and you need to understand this. And it, this can’t just be something which is reserved to my own personal experience, but it something that should be shared. It touches us more broadly. I think that is driving a lot of independent journalism, sorry, independent magazines. And I think it will continue to drive – often in very difficult circumstances – journalists around the world to keep on writing. And I think there are models that can work to support that.

And you know what? I think there’s a huge number of readers who also recognize the need for that. That they’re not just going to tune out. They want to be informed. I think that appetite is really there, and maybe it’s even particularly there on paper.

Arjun Basu: Yeah, I almost touched on it at the beginning when we talked about, why now. And I think that, what you just said is a big part of it in terms of why now in terms of what has happened to journalism in general and to the legacy media in particular and all these forces that are aligned. So that’s why I think your success would give me optimism.

Charles Emmerson: The great thing is for you and for listeners out there, they can be part of that success. By just buying a copy of the magazine or even subscribing to the Substack for free.

This is not a massively commercial project. We don’t think it’s ever going to be a massively commercial project. What we do hope it is going to be, is a valuable project, and that’s a very different thing.

And we do want to be a community. We think that the way it survives is by people, by readers recommending also, ultimately, that we create this positive ecosystem of recommendation, translation, curation.

Arjun Basu: All the links are up on our website @magazine.co. All the links that we mentioned here. Okay. Charles, three magazines that you want to recommend to everyone right now?

Charles Emmerson: I went to this great event in New York a couple of weeks ago, and there were multiple publications there. One, which I have not had yet had a chance to read, but I really want to read, which is called Racquet. And it’s about tennis, and it just sounded a whole lot of fun. I’m not even a big tennis fan, but I think there’s a whole bunch of magazines which focus on the culture of certain sports. There’s one, I think about skiing called Hard Pack, which is a great name. But Racquet just sounded absolutely great. And I if anyone’s listening who might give me a present for Christmas, then maybe a subscription to Racquet would be one thing that I’d be interested in.

Arjun Basu: I know the editor of Racquet listens to this show because she was on it a few seasons ago. I’m sure it’ll happen if she listens to this episode.

Charles Emmerson: It’s not a magazine, but it’s another media venture, which is going to be starting at the end of this month, which is called Equator. And I’m very excited to see what comes out of that. And that’s very similar to Translator in the sense that it comes from a place of wanting to change the dynamic, if you like, to give more space for voices from the global south in particular. So that’s a publication which hasn’t yet come out, but I’m very excited to see. As I said, it’s going to be online initially at least.

And then I’d love to give a shout out to a publication in Brussels, except that I don’t know how to pronounce the name.I think it’s called, I, it’s called mnemotope and it’s a publication set up by two people I know. And they just have the most open call of open calls for literary writing. And honestly, I think the work they do is just absolutely brilliant because they’re creating space for people to have fun or be serious or direct their emotions or their energies onto the page. And it was also very beautiful. It’s black and white, so it’s completely the opposite of Translator in terms of aesthetics.

Arjun Basu: Great. Charles Emerson, thank you very much.

Charles Emmerson: Thank you very much, Arjun. It’s been a pleasure.

Charles Emmerson: Three Things

Click images to see more.

More from The Full-Bleed Podcast