She Looks Forward to Your Prompt Reply

A conversation with photography director Jody Quon (New York, The New York Times Magazine, W, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT COMMERCIAL TYPE, MOUNTAIN GAZETTE, AND FREEPORT PRESS.

Jody Quon’s desk is immaculate. There’s a lot there, but she knows exactly where everything is. It’s like an image out of Things Organized Neatly.

She rarely swears. Or loses her temper. In fact she’s one of the most temperate people in the office. Maybe the most. She’s often been referred to as a “rock.”

She remembers every shoot and how much it cost to produce. She knows who needs work and who owes her favors.

She’s got the magazine schedule memorized and expects you to as well. She’s probably got your schedule memorized, too. She’s stylish, graceful, and charming. And she doesn’t take ‘no’ for an answer.

She’s usually one of the first in the office and last to leave. In fact, on the day she was scheduled to give birth to her first child, she came to work and put in a full day. When her water broke at around 6pm, she called her husband to say, “It’s time.”

I don’t know if any of this is true. Except the baby thing. That is true. Kathy Ryan told me so.

I had a teacher in high school, Ms. Trice. She was tough. I didn’t much like her. She would often call me out for this or that. Forty years later, she’s the only one I remember, and I remember her very fondly. In my career, I’ve often thought that the best managing editors, production directors, and photography directors were just like Ms. Trice. These positions, more than any others, are what make magazines work. They’re hard on you because they expect you to be as professional as you can be. They make you better. (I see you, Claire, Jenn, Nate, Carol, and Sally.)

I suspect that a slew of Jody Quon’s coworkers and collaborators feel that same way about her. Actually, I don’t suspect. I know. I’ve heard it from all corners of the magazine business. I heard it again yesterday from her mentor and good friend, Kathy Ryan.

“She just has that work ethic,” Ryan says. “It’s just incredible when you think about it. The ambition of some of the things that they’ve done. And that has been happening right from the beginning. Ambition in the best sense. Thinking big. And she’s cool, always cool under pressure. We had a grand time working together. I still miss her.”

Jody Quon is one of those people who makes everybody around her better. That’s what I believe. And after this conversation, you probably will, too.

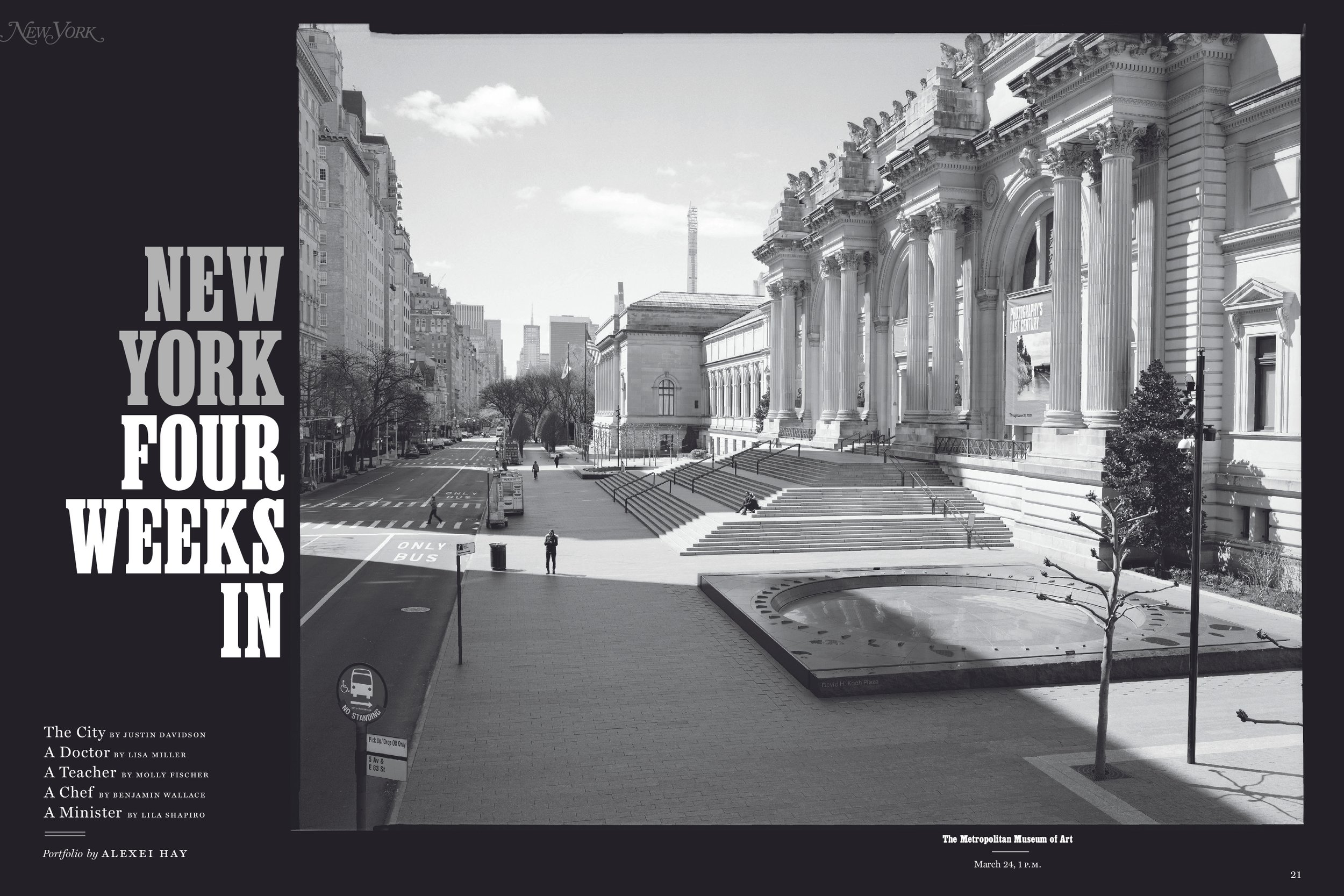

The New York editorial team (above) at work on the Hurricane Sandy issue (top)

“We have to get a helicopter up in the air right away.”

Karen Frank: Jody, it is great to have you with us today. And I want to start with something very interesting that we learned about you when we spoke last week. Of all the amazing things in your life, and there are a lot that we learned from our conversation, we were really surprised to find out that you have not one, not two, but three Rolodexes on your desk. I can see them now behind you. And you told us that you use them, still, you never throw out any cards. and that you continue to add to them. So what we took away from that and what we know about you is you feel really strongly about the importance of making a call versus sending an email or texting. That’s really a lost art and I would love to have you talk a little bit about that.

Jody Quon: Sure. I feel that voice to voice is so much more powerful and so much more nuanced than what can be expressed in an email, or certainly a text. And my typical method, and it’s really the way I’ve been taught, is sending an initial message by email, or just going straight to the phone.

And I think that so often there’s so much room for things to get lost in translation when you express something through the written word. But if you can pick up the phone and they can hear your voice it can be very calming. It can be very reassuring. It can also be very convincing.

And part of my job consistently for the last 30-odd years has been to convince people to do things that they generally don’t want to do. Or to be able to convince people to do things on our timeline, or to convince people to do three things as opposed to one thing, or turning a ‘no’ into a ‘yes’—the art of the appeal. Which is what we do all the time. And I think you have a greater shot at doing that if you can get them on the phone than if you’re just reliant upon an email.

Patrick Mitchell: Easy to ignore, those emails and texts.

Jody Quon: Very easy to ignore. Even when I was in college, I would send a letter requesting the chance to be considered for an internship. And I would immediately build into the letter, “I will call you within a week’s time if I don’t hear back from you.”

So I already built in the fact that they can expect a phone call from me. And that’s what I try to impart to my team is, “Let’s not wait for them to just get back to us. Let’s stay on top of them.” I think you have to realize that people have very busy schedules and you just have to insert yourself if you want to get it done.

Karen Frank: I’ve heard from Roxanne Behr, specifically, that you would take a card out of your Rolodex and just place it on her desk. And she was expected to follow up on that. And it would just be a landline that’s on the card, nothing else.

Patrick Mitchell: That’s great. All right. So we’re going to stay old school. We’re going to talk about growing up in Montréal.

Jody Quon: I grew up in a suburb just outside of Montréal. Montréal is one of those cities that the suburb is not like living in Westchester vis-a-vis New York. My parents thought nothing of letting us go downtown. It was like a very easy thing.

We had tons of magazine subscriptions and we had two newspaper subscriptions. There was the Montréal Gazette that arrived every morning. And then there was the Montréal Star that arrived every evening.

And so between those two newspapers, and then Time magazine, Newsweek, Golf World, Sports Illustrated, probably a couple of others in there, we also had a television on at all times. The news was playing during breakfast. We ate dinner with the six o’clock news on. I grew up with CBS Sunday Morning and 60 Minutes. That was an event in our family.

So I feel like I was exposed to a lot of news, through different portals, from a very young age. And I think that my parents always instilled in both of my brothers and I that it was important to be up on the news, that it was important to be aware of current affairs. And also I was seeing fashion through the news. Like I was seeing fashion in The New York Times, the Sunday papers, Styles, Bill Cunningham.

Patrick Mitchell: Were you a stylish kid?

Jody Quon: I liked to consider myself one. I certainly admired great style. When I turned 13, my godparents got me a subscription to French Marie Claire magazine, which was a really elegant magazine. And it was a big deal to get a Parisian subscription in my town. And so I’d be flipping the pages and that’s where I had exposure to European designers, and occasionally I would get my parents to help me pay for Harper’s Bazaar magazine at the time.

Another relative of mine got me a subscription to Mademoiselle magazine, which as a teenager, was a really influential magazine for me because the readership was a little bit younger. It wasn’t quite as sophisticated as the Harper’s Bazaar reader. It just felt a little bit more attainable.

And I would just rip out pages. I’d write down names of designers and I would write down names of stores. So I was, like, just obsessed with that. And one of the things I wanted to do was to intern for Giorgio Armani. I wrote a letter to Giorgio Armani. I sent it to Milan. I figured out where the corporate office was and I was like, “Oh, if you could ever consider me one day for a job, I would work so hard for you.”

Patrick Mitchell: How old are you at this point?

Jody Quon: I’m probably 12 or 13. And, my parents were always very encouraging. They felt that you couldn’t know unless you tried and that to try to do something is a very good thing because even if you don’t reach that destination, you are one step closer than if you didn’t try.

“I learned that organization, that level of detail and organization, is the baseline foundation to prepare you for the chaos that ultimately comes with big projects.”

Patrick Mitchell: You went on to study, no surprise, fashion design at RISD. And after that you moved to Paris, you found yourself a place to live, you found work—all that at a tender young age of what, 21, 22? So let’s talk about Paris.

Jody Quon: The first phase of Paris started when, in the fall of my junior year of college, during that winter session at RISD, you got a 6-week break. I decided that I would much prefer to see if I could get an internship in Paris, as opposed to doing something in the garment district on 7th Avenue in New York.

So in Montreal, Marithé + François Girbaud had just opened a new store there. And it was the first time that Montréal would have this store imported from Paris. I happened to meet the manager of that store. And that manager expressed interest in me possibly going to Paris for six weeks. I would work for free. Is there any way that they could stitch together an internship for me?

And they were delighted at the possibility of that. And they basically got it done. So my mother said, “Okay, but then you need a place to live.” So they made living arrangements for me. The Montréal manager’s apartment that he still had in Paris, that’s where I would live. So I did that. It was a fantastic experience. It was my first time—it was my dream to go to Paris. I had six weeks of pure bliss.

So when it came time for me to go to Paris after I graduated, I had that connection with Marithé + François Girbaud. So I went back and worked for them basically as an intern again. An extension of my initial internship. And I found a place to live through friends of friends. We had two older roommates, two older gentlemen who were essentially like big brothers to me. So they really protected me.

They were probably in their early thirties and I was this young 22-year-old and they were really loving towards me in the best possible way. It was really a year of self discovery for me, because I thought that I would arrive in Paris and that I would take Paris by storm. I was top of my class in apparel design and I was just going to conquer Paris.

But the exact opposite happened. The job that I had with Marithé + François Girbaud dried up after a few months. They didn’t have any more need for me. They didn’t have a full time position to offer me. So I had to find another job. None of the design houses that I wanted to work with had anything available for me, none of the big labels.

And so I found a job working for a much smaller designer. And while I respected her very much, I didn’t love the work that she was doing and I found myself not wanting to work as hard as I should and I just wasn’t inspired. So I quit after a couple of months. I had no energy. And frankly, I was not a very responsible young adult.

I just quit. I didn’t tell my parents. I stopped calling my parents back. My parents were livid with me. And I went through a little bit of a depression. I didn’t know what to do with myself. I didn’t want to call my parents because I didn’t want to have to lie to them that I quit my job and that I wasn’t working.

I didn’t want to tell them the truth and I didn’t want to lie to them. So I thought, Oh, I’ll just avoid them altogether. That was the wrong decision. It was a long winter for me and I was just thinking through, What do I do? How do I figure this out? My brother came from Montréal to visit me. I told him what was happening. He said, “You’ve got to call mom and dad. You have to.”

And eventually I did. One day I was riding my bicycle in the Marais near the Palais and I saw a sign. And it said, “Barneys New York.” And I said, “Oh, I know Barneys. I can work for Barneys! Let me knock on their door.”

So I get off my bike, I knock on their door, I’m like, “Do you need any help? I speak French and English, I could do whatever you need me to do.” Because at that point, I realized that it’s possible that I was not the designer that I thought I was going to be. It was the first realization that maybe I need to do something adjacent to fashion design. Still in fashion, but not design, proper.

And Barney’s was the first moment where I thought, Oh, maybe there’s room for me there. It’s a small office. It’s a buying office and it’s where all the New York buyers go to place their orders when they’re on their overseas buying trips. And essentially it’s a beautiful office with a fax machine with the view of the Palais-Royale.

So I did it for a few months. Three months later, they said, “Okay, thank you very much. But we actually found the experienced person we were looking for. And, we don’t need you anymore.” And that’s when I decided, “Okay, I gave Paris my best shot. It’s time for me to move back home.”

Karen Frank: So Jody, I believe you met someone in Paris that shaped who you are today, Marion Greenberg. You told us that she really changed your life and she really taught you how to work. Can you talk a little bit about your relationship with her?

Jody Quon: Marion met me at a time in my life when I was so confused about who I was. I had lost a job, I had no confidence in myself as a professional. School doesn’t really teach you how to do that. She was actually the person that was running the Barneys’ Paris office. She was running it remotely from New York.

And aside from running that office she also represented very avant-garde designers. One of them being one of the designers that I respected very much. The same designer whose clothes I was wearing when she finally met me in the Paris office one week before I moved back to Montreal.

She saw what I was wearing and she said, “Oh, is that Comme des Garçons?”

And I said, “Yes.”

She said, “Oh! You like Comme des Garçons?”

I said, “Yes, I love it. I’ve been wearing whatever I could afford of their clothes for years. And it would be my dream to work for them.”

She said, “I do all their PR. Why don’t you come to work for me in New York?”

So that’s what happened. That is what brought me to New York. And the minute I got to Marion’s office—I didn’t even know what PR meant, but I soon found out. And I also found out that I knew nothing about what it meant to be a professional. And Marion taught me all of that.

She taught me how to answer the phone, how to greet people professionally. We were communicating with Japan. We were the American press office for the headquarters in Japan. There’s a 12-hour time change. So it meant that at the end of every business day, we were to send a very detailed, very formulated fax to Tokyo to give them all of the updates of the day. So it had to be clear. It had to be concise. It had to be clean and elegant.

Everything had to look good and had to be very clear. We had to clean off our desks every night. There was a correct way to staple correspondence. There was a correct way to label something. There was a correct way to put a paperclip on something.

Presentation was everything, which taught me so much because I learned through Marion that organization, that level of detail and organization, is the baseline foundation to prepare you for the chaos that ultimately comes with big projects. And if you know where everything is at every moment, then you can do your job that much better. And that’s what she taught me.

One of my jobs was finding artists in America that would be interesting for this designer to collaborate with. So I would be doing all this research and updating Tokyo every single day. And preparing these packages that I would ship once a week. And it was all about presentation.

How do you make this make sense to a company in Japan that seeing it for the first time, they have no time. So every time you unfold something or unwrap something, you have to put it in a certain order, so it blossoms in just the right way, so that everything starts to be cohesive to them. That’s the kind of thing that school doesn’t teach you.

And I loved it. I loved my job working for them. I went to Paris twice-a-year—the city that I loved—and it was a great city to visit. Obviously it wasn’t the right place for me to live four years earlier, but it was still a dream to go visit. But ultimately I felt that I had done what I needed to do there and I wanted to actually work at the Costume Institute at The Met.

A pair of Quon’s collabs with artist Barbara Kruger

“I think that’s really the first great cover we ever did because it was meeting a news moment. It gets better with age.”

Patrick Mitchell: You were a kid who was really aware of fashion and you’ve said that you worshiped Carrie Donovan, who was the iconic fashion editor at the Times when you were around this age. People remember her from those crazy Old Navy commercials. A wild old lady with the giant glasses.

Jody Quon: Yes, that was her chapter after The New York Times, after she retired. The New York Times Magazine had a fashion supplement. It was called Fashions of the Times. It was basically what T is now, but twice-a-year as opposed to nine times or whatever the frequency of T is at the moment. And Carrie Donovan was the fashion editor. Also Carrie, before that, had worked under Diana Vreeland. She was part of that older, really legendary school of fashion editors.

Harold Koda and Richard Martin, who were then the curators of the Costume Institute at The Met, put me in touch with her because they were doing a 50th anniversary issue of the Fashions of the Times. And Carrie met Harold and she needed a really hardworking photo researcher that could dig up the archives and get in touch with old photographers to get rights to pictures for this issue that they were going to be going to press with in six months.

And Harold and Richard thought of me and they called me and they said, “Listen, we know you want to work at The Met. We can’t hire you here, but we think you would be perfect working for Carrie. What do you think?”

And I said, “I would love to. That would be my dream.” So Carrie and I met. I got the job.

Patrick Mitchell: Was she fun as she appears?

Jody Quon: So fun. Every time I spoke with her she had some crazy anecdote to share with me. And I was just like a sponge. I couldn’t believe that I was face-to-face with this woman whose pages I had been oohing and aahing over for so many years.

It was thrilling for me, but the thing that Carrie Donovan said to me on the first day of my job there, which was in May of 1993, she said, “Okay, you’re going to be doing research on this and you’re going to be exploring this. I’m going to be giving you pages and you’re going to be trying to find all those pictures. I want you to find books. I want you to go through tons of magazines and then you’re eventually going to meet with Kathy Ryan, who is the photo editor for the magazine. And she’s the best photo editor in the world. And you should only be so lucky to be having this one hour meeting with her every week. So you’re going to meet with her every Friday at three. And you better be organized for that meeting.”

Quon took a brief 6-month sortie from New York to work for W (and with Kruger again) before returning.

I was like, “No problem.” So I put my Marion Greenberg hat on and I’m like, “Okay, I’m going to do all my work.” And I knew that Kathy was so busy closing the weekly magazines on Fridays at 3pm. I knew that I definitely needed to be organized so that she could easily dip in and out of the photo research I was doing for an issue that was not going to be published for another six months.

I just knew that her head was not going to be in that headspace. So how could I make it easy for her to dip in and out of that material? Long story short, the meetings were wonderful. I so looked forward to every Friday at three. And I think Kathy did too. I think in the end it was a nice break for her from the regular magazine.

And we developed this lovely relationship over the course of the six months. And at the end of that six-month period, Kathy realized that she had an opening in her department for a full-time photo editor. She asked me if I would be interested in joining her team.

Patrick Mitchell: So you took a job at The New York Times Magazine and you were there with—was Adam Moss already there at that point?

Jody Quon: Yes.

Patrick Mitchell: Okay. So you’re with Adam and Janet Froelich, the great designer— Episode Eight for our listeners. And Adam, Episode 11.

Karen Frank: And Kathy!

Patrick Mitchell: And Kathy Ryan, Episode 14. But I have to say now, we’re all of the same age, and we were well aware of those days when the four of you were at the Times magazine, and Karen, I think I can speak for you and just say that Times magazine was sort of the center of the magazine universe. And a lot of people thought it was unfair because you had the whole New York Times at your disposal. And the reputation of the New York Times. And you could get anybody to work for you. But it was really the center of the magazine universe on all levels. Talk about being in the middle of all that.

Jody Quon: It was thrilling for me. I will tell you one thing that I realized very early on, like in my Paris days right after graduating from college, was that it was important for me, moving forward, to work for companies that I admired. I knew that I would only be energized and do my best if I was working for people that I looked up to.

If I didn’t respect something wholly then I was going to be bored. I wasn’t going to do my very best work. So that’s why I did what I did with Marion Greenberg. And that’s why when I went to The New York Times Magazine to work with Carrie Donovan, it would be for Carrie Donovan. Little did I know that I would also be working with the “best photo editor in the world,” as Carrie said.

When Kathy offered me the job, I didn’t really even think that I was qualified to work for her. And I said to her, “I don’t know that you really know who I am. I was great for the fashion project for Fashions of the Times, that worked out, but I know nothing about photojournalism. I know nothing about everything else that you do at the magazine. I really just like the fashion and art part of it. But I am not as intelligent as you might think I am.”

And Kathy said, “No, I like the way you work and I appreciate that you’re not immersed in the world of photojournalism. That’s okay. You can leave that to me. I like the way you work. And the way you work will find a good home in this department.”

I said, “If you feel that way, that’s fine. I just want to make sure you know who you’re getting. And if it doesn’t work out in six months, we can walk away.”

She said, “No problem. I’d love to have you.”

And that was right when Adam started, the same time I started as well, coincidentally, except for those first six months I was working on this fashion special. And what was happening there at that moment was that they were redesigning the magazine. Paula Scher had come in, she was working on the redesign.

And Adam was such a left-of-center thinker—a very experimental magazine thinker—and injecting a kind of energy into the magazine that I think the magazine had not seen before. And I know Kathy has talked a lot about that kind of new energy that Adam was bringing in. And the kinds of questions and the kinds of prompts he was giving her as she was even thinking about the photography assignments.

So when I started six months later the architecture of the magazine was changing. There was “The Way We Live Now” section in the front. And then there was a profile. And then there were a couple of features in the feature well, and then the Style pages, “The Back of the Book,” we called it.

And I remember it was forcing us to think about photography for portraiture. It was a really magical time. It was a time when Kathy started thinking about cross pollinating. Looking beyond the traditional boundaries of editorial photography, reaching out to fine artists. That’s when she’s calling Nan Golden. Lyle Ashton Harris makes his debut at the Whitney Biennial. And then all of a sudden Lyle Ashton Harris’s portraiture is making it into the magazine. In the Times Square issue, Chuck Close is making these incredible 20x24 Polaroids in the magazine.

We were breaking all the traditional magazine rules. And I think what was interesting about it is that especially for me. I didn’t come from the magazine world at all, but I did come from, like, art-meets-fashion. So that to me felt very natural to be thinking about contributors in this way.

Also, Janet came from a fine art background—both Janet and Kathy thought like artists, which not a lot of photography directors and art directors do. That was a unique situation. And I’m so glad that I was raised in that situation, because that’s also how I think as well.

I couldn’t have survived. I couldn’t have been as happy, I don’t think, in a more traditional commercial magazine. Because it was The New York Times Magazine, we were allowed to—it just fell out of the paper—we could break rules. We could do whatever we wanted. And Adam was like, the more you broke them, the more you reinvented, the better. He wanted innovation.

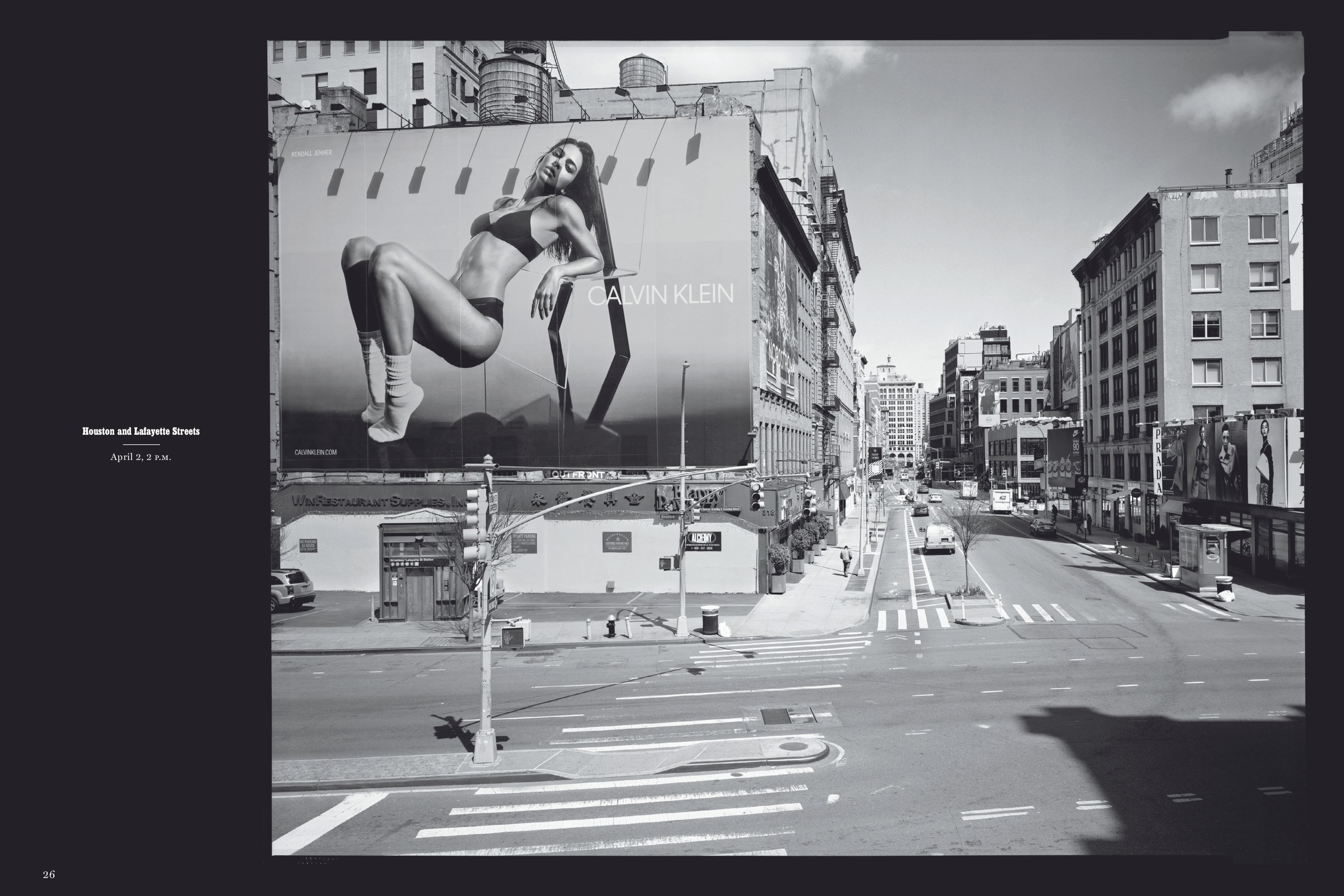

New York collaborated with photographer Bert Stern and actor Lindsay Lohan to reimagine his legendary 1968 session with Marilyn Monroe for their 40th anniversary issue.

“We’d have to do it exactly like ‘The Last Sitting.’ She’d have to take her clothes off.”

Patrick Mitchell: You’ve just described that moment where The New York Times just elevated beyond where a lot of magazines have ever been.

Karen Frank: If I could just add to that, you arrived there at that magical moment, which is amazing, but it also coincided with a little bit of a redirect in your life. Because up until that point, you had pretty much been on a fashion-adjacent road. And you said that you really found yourself at the Times that it was really where you discovered what your life was going to be. And then came a time when Adam left and he went to New York Magazine and he offered you an opportunity there. How did you reckon with the idea of leaving this incredible place that you had found?

Jody Quon: It was very hard. I was at The New York Times Magazine for 11 years, and every moment of those 11 years was extraordinary. We did so much together. I felt so blessed to be walking through those doors of The New York Times, going up to the 8th floor and walking into this sea of 50, or so, brilliant editors, writers, thinkers. I never wanted to be found out. There was so much extra homework that I would have to do so that I was in the know.

I remember my first evaluation with Kathy and Adam, they were like, “Oh we love what you’re doing. You work too hard.”

I was like, “No, I don’t work too hard. I just have a little bit more catch up than most people do. But it was really magical. I didn’t want to leave. I could have worked for Kathy forever.

Patrick Mitchell: You said, and I think you’re getting to this, I just think it was really interesting the way you said it: “Kathy gets a rush from this that I don’t.”

Jody Quon: Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: So that’s all part of this picture of you identifying your own path.

Jody Quon: Exactly. I loved every moment, but there was one thing that I noticed. And I would talk to my husband about it. I would say, “I love my job. I love my job. I talk about it all the time. I tell you about every single assignment. But I look at Kathy every day. I sit right outside her office. And as much as I love my job, I do not have that same rush that I can see Kathy has every time she edits a story or gets a story thrown onto her plate. She lives and breathes it in a way that I almost do but not quite. What’s wrong with me? Why don’t I love it as much as she does?

And that really bothered me because I’d been there for 10 years. I was Kathy’s deputy at that point, and I loved it. But why did I not feel as passionate as she did? Why was I not shrieking as loudly as she was when something amazing was happening in the layout?

And I realized what it was, and I’ll get to that. Adam goes to New York magazine. Shockingly, he calls me and says he wants me to be his photography director at New York, and I couldn’t believe that he had asked me—of all people. I didn’t even think Adam knew me. I think he knew me, but he didn’t know me. Like, I never talked about photography in front of him.

I never thought that I showed him who I was as a professional. I knew he knew Kathy, and I knew he knew Janet, but I didn’t think he knew me. I didn’t think he knew who he was asking. So I was like, “Are you sure you know who I am?”

And he was like, “Yes.”

And I was like, “But you’re asking me to come with you to New York. I’m very honored. But I don’t know that what I do is what you need for New York magazine. New York is not The New York Times Magazine. And I’m artier, I’m a left-of-center thinker. I’m not as commercial as what New York is. I don’t know that I have the right DNA to deliver what you’re going to need for New York.”

He’s like, “No, that’s what I want. I want art. I want a different New York. Don’t think of the New York now as the New York we’re going to make together.”

So I decided to take the job and it was the hardest thing I had ever done. I remember telling Kathy and we cried together. It was really hard to leave each other. We really worked so well together as a team. But I think ultimately Kathy was happy for me. I think she realized that it was an opportunity that I should exercise. And, the person that she is, she accepted my resignation with grace.

Patrick Mitchell: So did something that Adam said make you feel like this was an opportunity where you would get this rush that Kathy gets?

Jody Quon: It wasn’t so much that I mean, I was very nervous. I was like, “Okay, I’m going to try this.” And I wasn’t even thinking about the rush factor at that point. I was like, “Can I deliver what Adam wants? I know I’m going to learn from him. Will I be able to perform at that level.” And I remember Jerry Marzorati, who was at that time, the editor of The New York Times Magazine, he said to me, “Jody, you’re going to be great. But promise me that you will voice your opinion. Make sure you do that on day one.”

And I looked at him and I said, “Okay, I promise I will.”

So then when I got to New York magazine and it was the first issue and Adam said, “Okay, we just decided what the cover is going to be. And you need to go shoot this person. They haven’t signed on yet. So you need to call them and hopefully you can convince them to sit for the picture. And we go to press on Thursday.”

I couldn’t believe the new timeline. Because at the Times magazine, it wasn’t quite that fast, even though it’s a weekly. And I said, “Okay.” And I managed to get the shoot done. Adam blessed the photographer, assigned it, made the pictures, happy with the pictures, I go to Adam’s office with the pictures and Adam says, “Okay, so what do you think? Which one should we go with?” So that’s the first moment. I’m like—

Patrick Mitchell: “Let me call Kathy!”

Jody Quon: I wanted to call Kathy. No. I said, “Okay, I think this, and this, it just all depends on what the headline is.”

He’s like, “Good answer. Let’s go down to Luke Hayman,” who just started as the design director. And Adam says, “Hey Luke, Jody just got the pictures in and she thinks it should be this or this to try. I think she’s right. Let’s look at them. Can you throw them into the layout? Let’s see how they look under the cover matte.”

And that was the moment where I was like, that’s my opinion that’s being considered right now. And that was a really big deal. As the weeks progressed, and as I was like making experiments with assigning, and with Adam’s encouragement, he was just so excited for the visual voice of that magazine to change.

And so the more I could experiment, the bolder the difference, the better. So I was on fire and I was like, “Oh, let’s do food like this. Let’s do architecture like this.” And let’s just break the mold everywhere. And it was thrilling. And that’s when the rush started to happen. The pictures would come in and the photo editors would come to me with their assignments. I’d be like, "Oh my God, look at these pictures!"

Patrick Mitchell: Alright, so here you are, you do go to New York and you join Adam Moss and Luke Hayman. And for the second time in your career you’re at the center of the magazine universe—again. At the best-designed, best-edited, best-vibing magazine around. The most interesting magazine in the world at its time. Are you aware of that when you’re at the moment?

Jody Quon: No. I will tell you, this is funny, but Adam would say to me and to either Luke, at the time, or Chris Dixon who succeeded Luke, “We just don’t know how to make a cover.”

Patrick Mitchell: I’ve heard that before.

Jody Quon: “We do not know how to make a cover.” I remember there was a George Lois exhibition at MoMA and Adam’s like, “We’re going. We’re going to make a field trip. We’re going to go look at those covers.” The Esquire covers. And we went. And listen, I love those covers as much as everybody else does. But you realize not every cover was great. And that’s what you realize when you’re at a weekly, it’s impossible to do a stellar cover every single time.

Patrick Mitchell: Not every cover story inspires a great cover.

Jody Quon: Not every cover story inspires a great cover. And I will say that those years—I’d say 2004 to 2007—was a very experimental period in which we were trying to figure out what our cover voice was. I’m going to say that the first great cover that we did was the Elliott Spitzer/Barbara Kruger cover. I think that was truly the first one. We hit some decent ones before. Decent ones. But that was, I think, the first real solid, memorable cover that people could actually talk about.

Patrick Mitchell: It’s funny. You mentioned Esquire because we had David Granger on and I remember him saying, “Covers suck. They suck, and they suck, and they suck until they don’t suck anymore.” That’s a universal issue in the magazine business.

Jody Quon: Covers don’t have to suck. I’m so happy that at a place like New York we don’t have, like, credit obligations. We don’t have celebrity obligations. We can do whatever we want on the cover. We can be as nimble as we want. Some of us have learned with experience that we can be free to lean into a moment and take cover liberties. And we’ve done that and that is something really special.

New York’s 2024 “Reasons to Love New York” issue coincided with SNL’s 50th anniversary season

Karen Frank: Jody, there have been so many memorable covers in your time at New York magazine. Adam told us that we would have to get you to talk about the Hurricane Sandy cover. So let’s start with that one.

Jody Quon: 2012. Okay. We knew that the hurricane was coming. The day after the hurricane, the offices were closed. We were flooded downtown—we were at Varick Street. And we had an emergency meeting at the Wasserstein offices in Midtown. Bruce Wasserstein’s company graciously allowed us to set up shop at their offices for the duration of the week because our offices were not functioning. Everything was transported to Midtown.

Some of us went for an emergency meeting the day after the hurricane to decide what to do. Adam decided to rip up the contents of the feature well and devote it to coverage of the aftermath of the hurricane, and looked at me and said, “Let’s assign original photography wherever you think best and cover it every which way.”

I was like, “Absolutely.”

My husband came to pick me up at the office that evening. We were driving along Seventh Avenue. Midtown was not affected at all. Lights were on, business as usual. The minute you got to 34th street, everything went black. And I couldn’t believe it. The contrast was so stark from lights on to lights off.

So I went into the office the next morning in Midtown and I was like, “We have to get a helicopter up in the air right away.” The only way to get the lights on/lights off is from an aerial photographer. I didn’t even talk to Adam. I didn’t want to even get into the budget with him. I was like, “We just have to do it.”

The first photographer I called was in South America on assignment. He’s like, “I could do it on Friday.”

I’m like, “No, I need to do it tonight, because I don’t know when the lights are going to get turned back on.” So I call Iwan Baan. He’s this architectural photographer that does work from a helicopter—and he’s a vagabond. He’s everywhere all of the time. He was in town because he was taking pictures of the parish art museum, which was about to be unveiled. He had taken them from a helicopter.

So he was like, “Yeah, I can do the assignment.”

My only marching orders to him were, “Iwan, the only thing you need to do is make sure you get the tip of the island in the picture. You’ve got to get the tip of the island.”

He’s like, “No problem.”

The next morning, Iwan delivers the pictures. He’s like, “It was a little hard.”

I’m like, “Wait, what do you mean?” We’re looking at them on the computer and Adam’s looking over our shoulder. And it’s crazy. We were like, “Oh my God, thank God this worked!” The minute I saw the picture with the tip, I’m like, “It worked!”

And Adam’s like, “That’s a great picture.” But, it wasn’t yet the obvious cover. And I got Iwan on the phone and I’m like, “So Iwan, what happened? Tell me how you got this picture.” I just thought he got the helicopter, he took the picture and that was it. It didn’t work like that. First of all, everything was flooded. So where we would normally charter a helicopter, which would be the 34th Street heliport that was down because of the flooding.

So because Ewan had been photographing the parish art museum in the Hamptons, he had chartered a helicopter from East Hampton. So he called that heliport. Luckily he knew about it. Secondly, when Ewan was anticipating the hurricane, he decided he might need to rent a car. So he reserved a car at LaGuardia, so he already had a car reserved. Thirdly, he anticipated that he might need cash. So he took out like $4,000 in cash.

So what happened? The heliport here in Midtown was closed. He had to get to the heliport in East Hampton, needed a car to get to the heliport in East Hampton. He had the car. He needed cash to pay for the helicopter because their credit card machines were down.

The last thing is, which is unbelievable—it’s like God wanted this picture to happen—the last thing is, remember I said, “You need the tip of the island.” Well, in order for Iwan to get the tip of the island, he has to be at a certain altitude in order to get the tip of the island up through the George Washington Bridge.

That altitude is not normally allowed when there’s regular air traffic. But that day, all commercial air traffic was down because airports were closed. The helicopter was given clearance to fly higher than they normally do in order for him to be able to get that perspective with the tip of the island.

The icing on the cake is that when you’re at that altitude in a moving helicopter with the wind—because it gets windy, the higher you go—there’s no camera that can get a picture in focus at that altitude, except for this Canon camera that he was one of, I think, seven photographers in the world that had in his possession that was like new technology and he was able to get a half a dozen frames in focus because he had this crazy camera. And that’s how we got that picture.

Karen Frank: That is an amazing story!

Jody Quon: My best decision was to not bother Adam with the idea that we were doing this because he might have asked me how much it cost and I might have had to tell him because I probably didn’t want to lie. And he might have said ‘no.’ So I’m glad I didn’t ask.

Patrick Mitchell: You mentioned Barbara Kruger earlier. You’ve collaborated with her several times. Can you talk about what it’s like working with her?

Jody Quon: I’ve always been rooted in contemporary art—contemporary art and fashion. So I’ve been following Barbara’s work for a long time. And it was when Eliot Spitzer was outed when he was—

Patrick Mitchell: He was governor at this point, wasn’t he?

Jody Quon: Yeah, he was governor. And it was so shocking. We had another cover story in the works. And again, Adam was like, “Let’s lean into this moment. Who can we get to report on X, Y, and Z and what do we do for a cover?”

So I thought of Barbara. I was like, this might be a moment—she’s engaged in politics, and I thought that this would be something that she’d want to comment on. So I said, “Adam, if you don’t mind, I’m going to call Barbara. If you think it’s a good idea, I’d like to call Barbara and see what kind of art piece she could make out of this news moment.”

And he’s like, “Great. Yeah, I love that. Do you think she can work quickly?”

I called her right away. She responded immediately. And part of the thing I like to do in general, and this is something I learned early on is, rip the band aid off. Don’t labor over how you are going to ask the question? How are you going to make the pitch? The most important thing is make sure it’s tight, make sure it’s concise, just get the question out there. And be as gracious as you can and make sure that you say, "I look forward to your prompt reply. and if you don’t reply, I’m going to call you." Same thing.

So Barbara teaches in LA. And so she’s like, “I love this. I can do this. What’s your deadline?”

I was like, “It’d be great to see a rough tomorrow. And then we’re going to go to press the day after.”

She’s like, “What? Let me think about it.”

And she calls me back an hour later. She’s like, “I have this idea.” And then she sends it through to me. And what we had done was we decided we would give her three portraits of Eliot Spitzer to respond to and see what she thought. And within an hour, she sent through this email and she took this photograph that I had given her by Henry Leutwyler, and she put “Brain” next to it. And it was brilliant. I ran it down to Adam’s office and I was like, “Look!”

And he was like, “Oh my god, we have a cover.”

Patrick Mitchell: Well, she didn’t just put “Brain” on it. You have to talk about the placement.

Jody Quon: Right. She put the word ‘Brain’ and then the arrow pointing to his crotch which was perfect. And it was the perfect image-meets-language. Perfect commentary. What was especially great was that the cover was going to be coming out on the following Monday. And the Eliot Spitzer story was dominating the news for the better part of that whole week.

You were seeing his picture everywhere. So we barely even needed to put his name on the cover. The only language really was, “The Governor and His Fall.” Tiny. Like, little. And then the logo and “Brain.” And that was like, “Oh!” I think that’s really the first great cover we ever did because it was meeting a news moment. It gets better with age. It just so succinctly gets this message across in this inventive and visceral way. And it reaches a very wide audience. You don’t need to explain that cover.

Patrick Mitchell: And it gives you permission to go down that path.

Jody Quon: It gives us permission to go down that path, which I love.

Patrick Mitchell: You’ve worked with her a few other times including with the current former president, right? That was Barbara Kruger, wasn’t it?

Jody Quon: Yes.

Patrick Mitchell: How did that come around?

Jody Quon: So that was in 2016 and this was a few weeks before the election or maybe it was two weeks out from the election and we thought we were going to be publishing what would be our final piece on Trump and his bid for the presidency.

Patrick Mitchell: I think it was the one on the newsstand when he won.

Jody Quon: It was. And we had done several Trump covers before. It was like, “What do we do now?” And again, Adam gave me permission to call Barbara. I was like, “Barbara, what would you do? What do you think? This is what the piece will be.”

And she said, “I know what it is, Jody.”

I’m like, “What?”

She said, “Loser.”

I said, “What? We can’t call the election.”

She said, “No, loser. Don’t you get it, Jody? It’s everything that he cannot be. It speaks to how infantile he is.”

and I’m like, “Oh my god, Barbara, you’re brilliant!”

So I run down to Adam’s office and he’s like, “Okay, so what’s the good word?”

I’m like “I just got off the phone with Barbara and I think she has a brilliant idea.”

And he’s like, “What’s the idea?”

And I write it down because I don’t want to say it. And he’s, “Absolutely not. That’s going to be read like we’re calling the election.”

I was like “No. Let me explain.” And he’s “No, Jody, we just can’t do that.” This is Friday before the Friday that we’re closing the magazine, so one week out.

And he’s like, “I don’t think so. I love Barbara, but I’m not sure she’s right in this case. I don’t think that we could put out a magazine like that.”

And then I go back to Barbara. I don’t tell her what Adam said. And I’m like, “Can you just mock it up? Let’s just look at it.” So I gave her this great picture by Mark Peterson and she mocks it up over the weekend. I’m looking at it on Monday. And I think on Tuesday it looks really good. And I walk it down to Adam’s office and I’m like, “Look at this. Doesn’t this look good? Might you want to reconsider this?”

And he’s like, “Maybe. I’m not gonna say ‘no’ to it altogether. I’ll reconsider it.” Then by Thursday, he’s, “I think we can consider this.” And I had gone to a few other artists for other commissions as well, but they weren’t quite as strong.

Patrick Mitchell: I was wondering—you weren’t putting all your eggs in that one basket. You can’t.

Jody Quon: No, I put 85 eggs in that basket. 85 out of a hundred. And then I had another contribution from another great artist, actually, Jonathan Horowitz. And that was the backup. And it became one of his famous pieces, actually. It’s Trump swinging a golf club into hell, essentially.

So by Thursday night, Adam’s like, “We’re going to do this cover.” And then the Hillary email crisis hits. And all of a sudden, Friday at noon it’s, “Oh my God, what’s going to happen?” So Adam’s like, “We can’t do this cover. We can’t do the ‘Loser’ cover.”

And I’m like, “Adam, but it’s not calling the election.” At that point, he’s frustrated with me. He doesn’t want to hear me say this one more time.

He’s like, “Let’s see how the news plays out this afternoon.” And it turned out that we didn’t really think that much was going to come of it. Adam felt pretty confident and by six o’clock he made the decision to put that on the cover.

We put it on the cover. It hits newsstands on Monday. It was thrilling actually because I don’t think another magazine would have ever had the nerve to do that cover. And I felt so proud that I worked at a magazine that had the chutzpah to do this bold, reductive—just courageous—cover in every sense of the word. And had the nerve to apply that language to him.

And I remember on my Instagram, I wrote, “The only magazine in the world that would do this. I’m so proud to work here.” And then the election happens and he wins.

Patrick Mitchell: I’m sure you got pushback from readers who said, “Why are you calling the election?”

Jody Quon: We did. But we also got encouragement from readers who were clapping for us at the same time. Ultimately the best covers are the ones that are the most controversial. I think it’s good to have discourse on both sides. And fervor. I think that’s important. It means the cover is doing something. If the cover is doing nothing, who cares?

Karen Frank: There are just so many incredible covers and we are going to show as many as we can on our site. But another thing that Adam said to us is that you never, ever take no for an answer and that you make the impossible happen. So in that spirit, I wonder if you can talk briefly about the Burt Stern/Marilyn Monroe reshoot with Lindsay Lohan.

Jody Quon: That’s something that we couldn’t have predicted. In 2008, which was the year that New York would be celebrating their 40th anniversary, we had planned that every section of the magazine would pay tribute to 40 and do something that referred back to 1968 over the course of the year, in honor of the 40 years.

I was really calling Bert Stern because I was thinking of the “Strategist” section and “The Look Book” that we do there. We were thinking of turning the clock back on that section and making the whole thing feel like 1968, which is what we ended up doing. And I thought, “Oh, let me call a photographer from that era to make pictures for The Look Book.”

So I called Bert Stern and I said, “We’ve never worked together before, but I had this idea. Would you mind shooting a ‘Look Book’ with your specific lens harkening back to the 60s?”

He’s “No, I’m not interested in that. But what I am interested in is if you could get Lindsay Lohan for me, I would recreate Marilyn Monroe’s last sitting with her. If she would ever say yes.”

I was like, “That’s a great idea.” So I asked Adam, “What do you think of this?””

He’s like, “Yeah, let’s take it if she’ll do it.”

So I called her publicist and this is the only time this has ever happened, I said, “We have this idea. Bert Stern, who famously did Marilyn Monroe’s last sitting, he would love to do it with Lindsay Lohan. Do you think she’d be interested?”

I said, “We’d have to do it exactly like ‘The Last Sitting.’ She’d have to take her clothes off.”

She’s like, “Let me call you back.”

She calls me back in three minutes. I’ve never gotten a call back this fast: “Lindsay would love to do it. When can we do it? She’s available.”

I was like, “What?” I call Bert back. I’m like, “Lindsay would love to do it. She loves you. She would be so honored.”

He’s like, “Will she take her clothes off?”

I said, “Yes. She told me she would take her clothes off.”

A week-and-a-half later, two weeks later, I’m on a plane to LA. We figure out all the details. And this is Lindsay Lohan at the height of her fame. Paparazzi is following her all the time. Everything had to be so top secret. Adam knew about this project, the fashion editor knew about it, and maybe one other person knew, but nobody else in the magazine knew about it.

We had to have labs sign NDAs. I flew to LA. We went to the original hotel room at the Bel Air where the shoot was originally done. We secured that room. I met Bert there. I’m very nervous because I’m just like, “Will she take her clothes off?” I just don’t know.

We get to the day of the shoot, Lindsay arrives on time. She arrives proudly. She’s like, “I’m here. I’m so excited. So nice to meet you.” Kiss-kiss. And then she’s like, “I’ve been doing crunches. I feel ready to take my clothes off.” And then Bert says to me, he’s like, “Okay, Jody, Lindsay and I are going to go off into that room together.” We had adjoining rooms. “And I can’t have other people in the room. I need her focused on me and I need to make sure she feels comfortable.”

I said, “Absolutely.”

So after like 10 minutes of the shoot, he comes out. He’s like, “Jody. She just took her top off.”

I’m like, “Okay, great.”

So I text Adam, “She took her top off!”

Then Bert goes back into the room. He’s shooting more pictures. Half an hour later, he comes over to me. He’s like, “She took her panties off!”

I’m texting Adam, “She took her underwear off. She’s naked!”

And Adam’s in these manuscript meetings in his office. He’s like, “Okay, the report, guys—not to leave this room—but Lindsay Lohan is officially nude and the pictures are really happening.” And, he shot most of the shoot on film, some of it on digital. Bert came to the office with tons of pictures.

And he’s 90-years-old at this point. And he just threw them on the table. And he’s “There’s lots of great stuff in here. You’ll have fun editing. Let me know what you get and call me and just make sure I sign off on all of it.”

I’m like, “Absolutely.”

Karen Frank: Amazing. I’m going to pivot to something that’s of interest, you know, being a fellow photo editor. This is something that I’ve always found remarkable about your work at New York magazine, because in addition to working with all the big-name freelancers, you’ve had an incredible roster of in-house photographers during your tenure there: Hannah Whitaker, Danny Kim, Victor Prado, Bobby Doherty, Hugo Yu, and of course, Christopher Anderson. And we’ll have links to all of them on our website as well. But their work has defined the look of the magazine as much as the freelancers. And I guess I have a couple of questions about that. I’m curious—was that your idea to have someone on staff? How does it work? Are they on salary, are they on contract? Can you talk about the kind of energy that they bring to the mix of what you do with freelance work?

Jody Quon: Yeah. Hannah Whitaker was the first one. That was born out of necessity, actually. We realized that there was a certain amount of life photography that was built into the magazine in every single issue. And it seemed silly to be assigning it out to different photographers every time.

And I went to Adam with this proposal—I did the math and if we hired a staff photographer that was working with us five days a week, if we could find a studio in the office that photographer can work out of, the benefit of me or another photo editor going in and out of that studio, collaborating with the photographer to get this voice right, it would be great.

We could be doing still life together. We could be doing portraiture together and there was no real need to be spending money on messengers, shipping product back and forth and all of that stuff, and that we could do the whole thing in house. And I thought very hard about what kind of a photographer we would want. And what’s been consistent all the way through is I wanted photographers that were artists first and kind of commercial photographers second.

So Hannah Whitaker was the first one. And that’s exactly what she was. Like she did some editorial photography, but she was really like a fine artist. And I really wanted somebody that thought like an artist and wasn’t thinking about commercials and credits. That’s the thing that I abhor so much.

You can give that photographer a creative license, liberties, and rethink how you shoot an apple, because you don’t have to shoot the apple with the watch and the necklace and the, this, and no labels need to be showing you, we could just see the apple. Let’s do the apple. What is the way to shoot an apple in a way that you’ve never seen an apple before?

We now call that page the “Best in Class,” but it was called the “Best Bets”—that first page that opens into “The Strategist.” and that page in terms of magazine making is meant to be this elegant, like visual relief after you’ve been through like a feature well with like heavier stories. It’s supposed to be really reductive and simple.

It’s been great to work with all of these photographers and rethink, like, how do we shoot this and how do we shoot that? And, how do we look at this shoe? How do we look at this roll of paper towels? Sometimes it’s such a banal object.

This week, for example, we have a picture of Neutrogena face cream. Tell me how to shoot that. We did it. You’ll see it in Monday’s issue. The big joy of my job is working very hands-on with these photographers to make these pictures.

Patrick Mitchell: You’re working in fashion. The way you described how integrated your relationships have been with your editors and your art directors. You’ve worked with Janet Froelich, since you’ve been at New York you’ve worked with Luke Hayman, Chris Dixon, and now Tom Alberty. How do you think about your relationship with art directors?

Jody Quon: The relationships are very close—they need to be. And everybody brings something different to the table. So Adam’s genius, I think, is that he knew from the beginning that art directors, design directors excel at X, photo directors excel at Y. Let each do their best at their best potential, and then let that come together.

So what’s really great is that when I work with Tom, for instance, he’s very involved in the conception of the photography, at least with covers and, bigger, more conceptual stories. We work very well together. And we talk about the stories that are coming down the pipeline, and we conceptualize these things together. Nothing is done in a vacuum. We talk about what’s the right tone for X story and Y story and what’s the message we’re trying to deliver?

David Haskell is very involved in that, as was Adam at the time. And what do we think the headline is going to be? And Tom in that sense is going to be thinking about, “Oh, I think the feeling can be X and design can be Y.”

And I’m thinking about photography and I’m saying, “Oh, what do you guys think of this photographer? That photographer, what about this kind of voice?”

And Tom will weigh in, or if it was Luke, he would weigh in. So it’s very collaborative and that’s great. Tom trusts that I can come to the table with a deeper, more connected knowledge of the photographic quotient of this, and I can trust that he’ll come to the equation with more of a design sensibility, like the layout and how that is going to work.

Or, vis-a-vis the cover, like, how is a picture going to translate with a headline? It’s very collaborative. Making a magazine is very much like baking a cake and you need all the ingredients to be working at their right proportions in order for this cake to rise and for it to work. And that’s what happens here with the magazine. It’s like everybody contributes what they know and what they do best and together we can make this great product.

Patrick Mitchell: In a given week, how many covers are in the mix until you get to the final cover?

Jody Quon: It really depends. We focus group every cover.

Patrick Mitchell: With the general public?

Jody Quon: A mix of staff. We like having members of the staff that have no link to the cover story. We like to get a fresh perspective. So for instance, we might have one photo shoot and four different pictures, four different headlines. And so out of that, you get 20 different combinations, or it might be four different, very different ideas. And then we focus group those.

But by that point, I feel like David, myself, Tom, we each have a pretty good idea of what is probably not working, but we are often taken by surprise. Like sometimes we think, “Oh, we have a slam dunk here.” And then we’ll focus group it and there’s just a reaction to an image or language that perhaps we were too close to the story that we couldn’t have necessarily predicted this reaction. So we’ll eliminate it. So those focus group meetings are very important.

The 2022 “Reasons to Love New York” cover (above), and how it was made (below).

Patrick Mitchell: A few years ago New York was taken over by Vox, which is a big digital media company. Typically you end up hearing nightmares about those kinds of relationships, when old media meets new media. What is your sense of Vox’s strategy for print?

Jody Quon: What I sense and what I’ve been told is that they are fully committed to print. And my everyday sense as I work here and the projects that we work on and the resources that have been made available to us as we work on these projects on our print products is that they’re fully committed.

It’s been a fantastic merger. I couldn’t have predicted such. I came from The New York Times Magazine and that was a different sort of animal. And then going to New York, we had resources, of course, but we’ve always been very prudent and very cost efficient.

But I also think cost efficiency, being prudent makes you better, makes you stronger, and makes you more creative. You think of alternative ways to solve things, which I think often makes for a better product. So I’m grateful for that. I do think that if you have too much money, you get lazy and you get fat. And that’s not a good way to be.

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. And so they reduced your frequency. It certainly may have been a cost-cutting move, but also is just an awareness of people’s habits.

Jody Quon: Yes. Yeah. I think we did that in 2015, around there, and it was terrifying at first, going from a weekly to a biweekly. But I think we made a better magazine. It’s just a more robust product. And I think that was the right call to make at that time. You didn’t need the weekly magazine. People don’t read magazines that way anymore. They just don’t. And I think that was really smart at the time.

Patrick Mitchell: And it seems like the current design was driven by the same sort of reasons of people's patience, the amount of time they have, the way people read print versus the internet. It all seems like a lesson for print magazines that haven’t made it, and how to survive. None of it seems desperate. It all seems thought out and strategic.

Jody Quon: Yes. It’s not as thought out as it probably seems, but I think there was a lot of thinking that went into it. And it was very strategic. And I think that we realized that it’s a different readership. The web readership and print readership don’t necessarily overlap. And now we’re making many more enterprise stories, long-form journalism. The web is not just breaking news here and snippets there. We do feature stories on the web.

A lot of stories that would go in the print magazine, but the print magazine can’t necessarily print all of them because we only have so many pages. But the level of the piece is up to standards with classic magazine pieces.

You can be a reader on the web and you can still experience all these great thought-through, well-edited pieces and then that piece that may have been up online for a week and a half may show up in the print magazine 10 days later and the reader won’t necessarily overlap and it’s fine. So we can put up a piece online and also publish it in print. It doesn’t matter.

Quon (center) and team.

“Making a magazine is very much like baking a cake and you need all the ingredients to be working at their right proportions in order for this cake to rise and for it to work.”

Karen Frank: Jody, you’ve been at New York magazine for 20 years now. I’m just curious how you’ve managed to keep it so cutting edge and fresh, especially those big franchise issues that you do, like “Reasons to Love New York” and others, year after year. How do you manage to do that?

Jody Quon: It’s not me, per se, at all. It’s me and the whole magazine. I have to say that I think that what you’re referring to ... it’s like moving with the news. So many of the projects that I think are so memorable are projects that are a result of a reaction to what’s happening in our life at the time. Like the “Reasons to Love New York” cover that we did two years ago where we had 72 famous New Yorkers crossing the intersection all at the same time.

That was really an experiment that was a result of thinking, “Oh we’ve been isolated from each other for so long. Wouldn’t it be fun to do a cover where everybody’s together on the street again?” And then David Haskell, he’ll one up me and he’ll say, “Okay, but let’s make it so that everybody’s famous in that picture.”

So it’s like one idea feeds another idea, which feeds another idea. And that’s the beauty of working together. And then all of a sudden we are embarking on this project where we’re trying to get as many New Yorkers as we can to all gather on the Monday after the Thanksgiving break to walk on the corner of Little West 12th Street and Washington. And I got this photographer who was going to shoot it and put it all together.

It’s like Hurricane Sandy. That cover would have never happened if the hurricane never happened. The Cosby issue wouldn’t have happened if these women weren’t coming forward and trying to tell their story. It’s just leaning into the news around you and seeing where your opportunity is to make a magazine piece out of that.

And that’s what I’m grateful for. And that’s really how it all comes together. I’m not particularly edgy. It’s just more like, how do you translate what’s happening into something really meaningful that you care about? And those are the pieces that make you excited to keep doing what you do.

I often worry, Am I dried up? Am I too old? Why don’t I know who this singer is? And I’m about to do a cover with this person. But then you lean into it and you realize why, and then you’re like, “Oh, then let’s try it like this.” And thank God I have a team of much younger photo editors around me because they also help to keep me fresh. I constantly worry, like, When are they going to replace me? I worry about that all the time.

More from Print Is Dead (Long Live Print!)