The Brand Called Us

A conversation with Fast Company founders Alan Webber and Bill Taylor

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT COMMERCIAL TYPE, MOUNTAIN GAZETTE, AND FREEPORT PRESS.

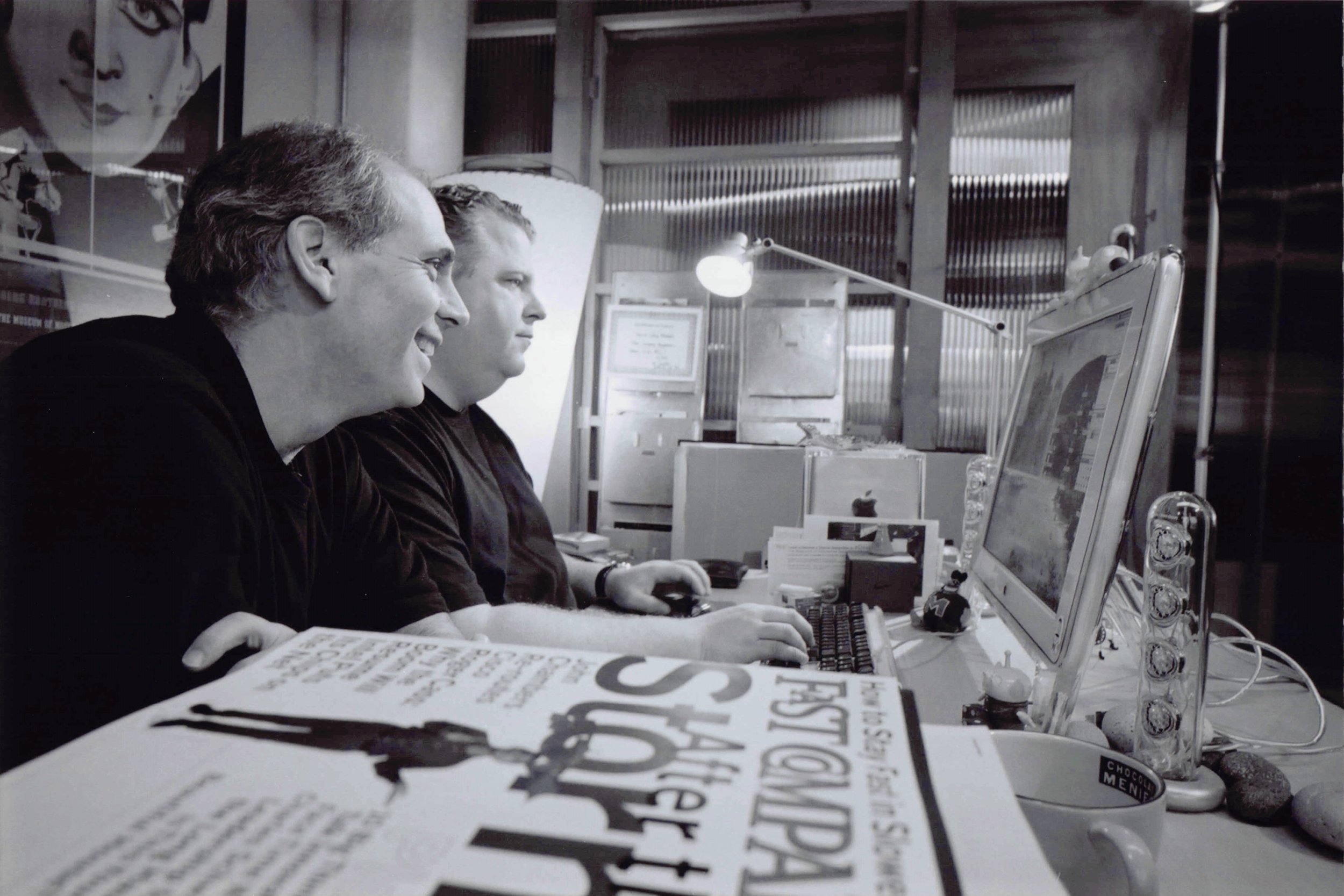

Alan Webber (left) and Bill Taylor

In the summer of 1995, I got an offer I couldn’t refuse. It came from my guests today, Alan Webber and Bill Taylor, the founding editors of Fast Company, widely acknowledged as one of the magazine industry’s great success stories.

Their vision for the magazine was an exercise in thinking different. Nothing we did hewed to the conventional wisdom of magazine-making. Our founders came from politics and activism born in the ivy halls of Harvard. Our HQ was far from the center of the magazine world, in Boston’s North End—“leave the pages, take the cannolis.” And Fast Company was not a part of the five families of magazine publishing. It wouldn’t have worked if it was.

I was one of the first people Alan and Bill hired, and as the magazine’s founding art director, I could tell Fast Company was going to be big. And it was big. Huge, in fact. Shortly after its launch, a typical issue of the magazine routinely topped out at almost 400 pages. We had to get up to speed, and fast.

Its mission was big, too. Bill and Alan’s plan sounded simple: to offer rules for radicals that would be inspiring and instructive; to encourage their audience to think bigger about what they might achieve for their companies and themselves, and to provide tools to help us all succeed in work … and in life. Their mantra: Work is personal.

The effect, however, was even bigger. The magazine was a blockbuster hit, winning ASME awards for General Excellence and Design. It was Ad Age’s 1995 Launch of the Year. Bill and Alan were named Adweek’s editors of the year in 1999. It even spawned its own reader-generated social network, the Company of Friends, that counted over 40,000 members worldwide. And it brought together an extraordinary team of creatives who, to this day, carry on the mission in their own way—including the founders.

Nearly thirty years after the launch of the magazine, Alan is currently serving his second term as the mayor of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Bill is the best-selling author of Mavericks at Work, among other books, and continues to lead the conversation on transforming business.

We often said that Fast Company was the one that would ruin us for all future jobs. It was a moment in time that I and my colleagues will treasure forever. I am thrilled to be able to share that story with you today.

A prototype (left) was created as a pre-launch test in 1993. Right, the 1995 premiere issue.

“What we unleashed was a point of view about the future that took the form of a magazine. The magazine was the vessel, but the magazine wasn’t the point. The message was the point.”

Patrick Mitchell: My first real big Fast Company moment, you had brought in a bunch of people to interview for the design—this was before the prototype, even. You brought in Hans Teensma and he dragged me along to the meeting, where I got to meet you guys. You ended up going with Roger Black, but then I would say about a year later, totally coincidentally, I ran into Alan on a plane. And I think you were sitting in the good seats—boy, life had turned for you in that year. So I came up and said, hello. And then when we got off the plane, you handed me a copy of the prototype with the Mutant baby on the cover. And you said, "Hey, maybe you should come in for a conversation because we’re launching." And that’s how my career at Fast Company began. But I would love to hear you guys talking about really, how you met, go back to how you met and how—

Bill Taylor: —you don’t want to go down that road. It’s an ugly tale of betrayal and intention, and horrible stuff.

Patrick Mitchell: How did this little idea get started?

Bill Taylor: Alright. I’m going to give my version and then Alan can deny it. But my version is the truth. And then, rather than starting too much with the history, I’d like to suggest we start at the end and work back.

Patrick Mitchell: You’re way better at this than I am.

Bill Taylor: So I was a business school student at the MIT Sloan School of Management. I had just written a book with Ralph Nader. It had come out and one of the deals at Sloan school at that time was that the Sloan Management Review was edited by three students who were chosen by the administration.

And if you were chosen you didn’t pay tuition for the two years. So I figured, among the sort of spreadsheet jockeys and propellerheads, I had a pretty decent chance of being chosen as the editor of the Sloan Management Review. So I applied to Sloan. And that happened.

So I was editing Sloan Management Review, and at the time, Ted Levitt, the brilliant marketing professor at Harvard Business Review was reinventing HBR with Alan—unbeknownst to me at that time—and I was watching from the other side of the Charles River.

So as I was about to graduate, or what have you, I paddled my kayak across the Charles and went over to the HBR headquarters, and it was there I met Alan.

But I did my research beforehand and realized he had written an absolutely scurrilous review of the book I had written with Ralph Nader and published it in HBR. ‘Scurrilous’ isn’t the right word. It was more ‘contemptuous,’ I think. And very dismissive.

Alan Webber: I would say ‘scathing.’

Bill Taylor: So we didn’t exactly get off on the right foot, but I am nothing if not a man of grace and of second chances to one and all. So anyway, I wind up signing up over at HBR. And then that began a multi-year conversation with Alan.

Alan Webber: It’s much worse than that. Bill’s being very kind. What happened was if you roll back the time machine even further, I’d worked in Washington DC for Neil Goldschmidt when he was Secretary of Transportation, and he was under constant attack from Ralph Nader and Joan Claybrook. And so when I saw this book by Ralph Nader and some obscure MIT guy, I did write a scathing review.

And then Bill came over for an interview and his first question was, “Did you actually read the book?”

And I said, “No. Why would I read a terrible book like that? It’s a waste of time.”

And then we had this conversation and I went back to see Ted Levitt. And Ted said, “We’ve got to hire this guy. He is absolutely brilliant.” And he said, “I will create a position for him. We don’t have any positions, but we can’t pass this guy up. He’s amazing.”

And so, bygones be bygones—no hard feelings on either part since Bill and I are very much non-judgmental individuals and we always suspend our worst misgivings about anybody—we met up at HBR under the very, very kind and brilliant leadership of Professor Theodore Levitt.

And Ted was right. I was trying to recraft HBR, but we were a little thin in the ranks at the time. And we needed people who could actually think and be idea entrepreneurs, and that was Bill’s trademark. He was not only the smartest guy on the staff, he was the most entrepreneurial in terms of seeing ideas that were coming out, but had not yet really reached their peak of being adopted by the business community.

And he also worked well with other people. He and Bernie Avishai, who also came over from MIT at the time, really were collaborators in coming up with great ideas that took HBR in a very brand new direction in a way that was thought leadership and in many ways, an academic version of what Fast Company would become, with at least one of the strands of DNA that fed into the early days of Fast Company.

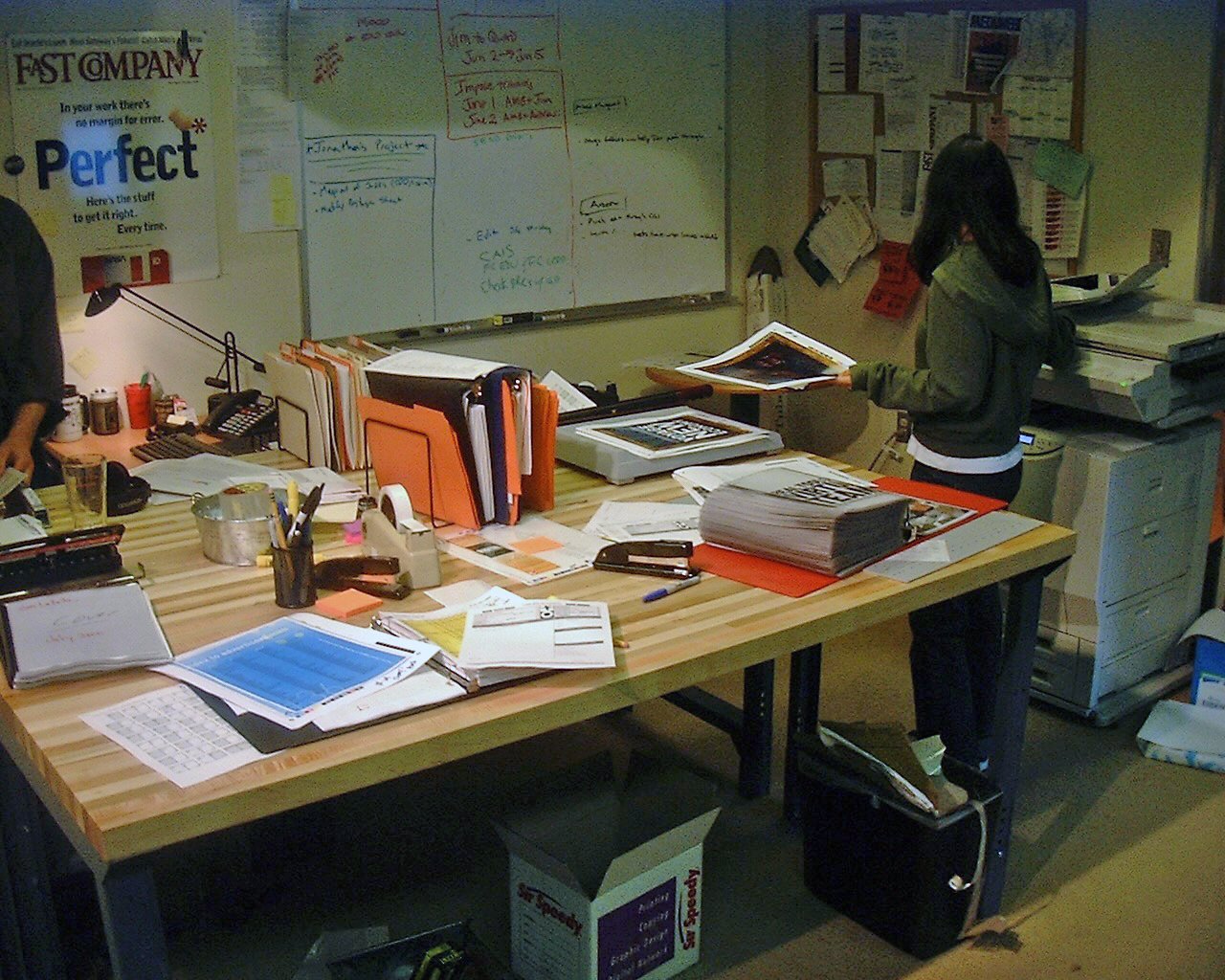

Scenes from the turn of the century at Fast Company’s Boston office

“We were the lunatics amidst these very serious people. They’re smoking pipes and have bow ties and we’re complete barbarians, maniacs.”

Bill Taylor: It’s interesting listening to Alan now, in a way, some of what we did at HBR, and not just the thought leadership part, really did prefigure Fast Company. I’m thinking really about the rather eccentric cast of characters that Alan and Ted assembled—in the sense that there were so many folks who really were great thinkers and great storytellers who really didn’t have any traditional connection to the world of business, per se, and even in some sense, to the world of magazining.

And it was the power of this collective group of people, the power of our ideas and our capacity for storytelling, in that case in a more academic setting, really is what—the reinvention of HBR really wasn’t about design, it really wasn’t that much about, new elements of the magazine, the art and craft of magazining. It was really about a new point of view, a new voice, a new sense of what success meant and impact for the publication we’re going to be.

And as I think about Fast Company, it really is to some degree the same story in the sense that ultimately, I think what we unleashed was a point of view about the future and a different way of finding characters and telling stories that then took the form of a magazine.

The magazine was the vessel, but the magazine wasn’t the point. The message was the point. The point of view was the reason for all this happening. And then we situated it in the format of a magazine, which is why I think when it appeared it felt different and fresh and offbeat and original, if you will. And all that kind of stuff.

Alan Webber: Bill’s right. What we started at HBR was revamping the performance of the publication. And also rethinking how a magazine that was not a magazine—HBR was a journal, an academic journal. And we tried to drag it kicking and screaming toward a different kind of performance.

So we created a spreadsheet about the different ways you could bring ideas between the covers of a journal. You could do it with an interview, you could do it with an essay, you could do it with the back of the book that we reinvented into something called “The Gray Area,” where we actually let HBR have humor, and fun, and a little bit of performance creativity.

And then when we went to start Fast Company, that same design mindset prevailed. And we used all kinds of fun metaphors: How is a magazine like a rock and roll album? You need a slow song, you need a number one hit, you need something that people can dance to. It really was trying to reframe performance of ideas: How do you bring ideas into a different performance setting and call it a magazine. Bill is laughing at “The Gray Area.”

Bill Taylor: Geez, I forgot about “The Gray Area”! Alan will probably remember this—really, that was truly a departure for the format of the magazine. But one issue we did five posters of movies we wish had more of a business twist. We took the Fellini film 8 1/2 and we retitled it 8 1/2, Up a Quarter as if it were a hilarious movie poster. That was genuinely funny.

Alan Webber: Remember when Ted was absolutely insistent that we had to have a poster of the “gazellephant.”

Bill Taylor: The gazellephant!

Alan Webber: “What is a great company? It’s as agile as a gazelle and as stalwart as an elephant.” And he would not let it go. So we printed this poster—I don’t know how many copies of it—of a fantasy gazellephant. I don’t think anybody except Ted really loved it. But it didn’t matter because you could try stuff. And that was also the spirit of Fast Company: “Let’s try stuff and see what happens.”

A Collection of Manifestos

“If you looked at the covers of business magazines at the time, they were always white men facing right, because that exuded power. We wanted to portray a world that was being born, not the one that was gradually dying off.”

Patrick Mitchell: We interviewed Kurt Andersen a while back and it was interesting to hear how he and Graydon Carter actually started putting together the idea for Spy. And they said they were both working at Time Inc. and they would go to lunch in Times Square and they would go to these video arcades and play Pac-Man and throw out ideas for how to launch a magazine. So Fast Company launches in the fall of ’95, talk about the time when this idea first came up. What were the practical, scary scenes of building this thing? Did you get office space? Also, talk about looking for money.

Bill Taylor: So I left HBR before Alan. And Fast Company was—first of all there was no name to it yet, it was just a glimmer. And so I went off and got my own little office in Harvard Square and wrote a book with a brash CEO from Silicon Valley by the name of TJ Rogers.

And there were two offices together and my office neighbor was David Mamet, the playwright. And he had a piano in his office and he would often come in and play the piano as a way of getting himself ready to work on whatever play he was writing at the time.

And obviously—he was Glengarry Glen Ross—he’s like the most, totally, the dark side of business and human nature and “always be closing,” and all that kind of stuff. And so we would have coffee in his office and he would be tickling the piano and we’d be talking about business and I would give him this utopian, kind of optimism for the future about how business can reinvent society. And it’s becoming small-d democratic.

And he would look at me like I was a fucking lunatic. He was like, “I write about aluminum siding salesmen. What are you possibly talking about?” So that was a fun part of the Fast Company prehistory for me.

But then when Alan left, we started—interestingly we’re writing about the future of business and friends of ours at a consulting firm called the Winthrop Group, which did these very serious and sober histories of corporations, they allowed us to borrow office space with them. And we were the lunatics amidst these very serious people in the same way as when we started Fast Company with the premier issue. When we got into business with Mort Zuckerman, he let us use office space nestled inside the offices of The Atlantic. And, they're smoking pipes and have bow ties, and we’re, like, complete barbarians, acting like maniacs.

Patrick Mitchell: I remember there was a critic who got very upset with us throwing the football in the hallway.

Bill Taylor: Corby Kummer did not like football while he was analyzing the fine points of the new espresso bean from Italy … or Kenya, or whatever.

But it was, but to me, one of the sort of lessons, I think, of Fast Company is even though the magazine was called Fast Company, we moved rather deliberately—maybe of necessity—but there was a certain reflection and restraint. We didn’t really want to rush into anything, and so we raised enough money from some high net worth individuals to do basically one issue—if this were software it would’ve been the beta version of the software—printed 30,000 copies of it, cobbled together a database of who we felt we were trying to reach, sent it to them for free, put in a response card, gave them an email address.

And we actually learned quite a bit from all that feedback. But we also had to then figure out how to get this business off the ground. But I do think we figured out fairly early on we weren’t going to go to individual venture capitalists. We were going to go into partnership with an existing publishing company. And that eventually led us to Mort Zuckerman and Fred Drasner.

But as I reflect on this stuff, it’s amazing how slowly and methodically we went. It’s the opposite of “act fast and break things.” And I think that wound up working to our credit because we finally did get the chance to launch, we had thought it through clearly. Even though we’re newbies to the world of true commercial magazining, I think we had learned a lot and had a lot in our foundation about what we were really trying to do.

Patrick Mitchell: What was the timeframe?

Bill Taylor: The “Mutant Baby” issue came out in, let’s say, the fall of 1993. And then the premier issue came out in fall of 1995. But obviously we were working on it for a long time and staffing up and so on. But it was probably 18 months of, really, wandering in the wilderness, getting feedback, trying to figure out how we’re going to launch this goddamn thing.

Alan Webber: Bill’s right about the business-like approach that we took to this. And in some ways I’m pretty proud of that. I just mentioned that we thought that magazines were like rock and roll albums. We were like The Beatles practicing in The Cavern Club or Bruce Springsteen over at The Stone Pony. Nobody knew what we were doing, but we were spending a couple of years honing our chops.

A little bit of the story from my side of the aisle or my part of the partnership—because it really had to be a partnership. There was no doubt in my mind that this had to be a team sport. And I was very lucky to have the best teammate available anywhere when Bill and I joined forces.

I had gone to Japan on a fellowship courtesy of the Japan Society of New York. And I spent three months away from the United States, away from HBR, on a mini-sabbatical and I had the Harvard Business Review and the Japan Society of New York on my business card, which got me in to see anybody I wanted to see for a three-month period.

And when I got done with that sabbatical I thought I had seen the future of rock and roll. I’d seen the future of business and it involved globalization. It involved digital technology that was just coming to the fore. I had demonstrations in Japanese companies of the CEO of a large Japanese company taking a picture of me with his digital camera, putting it on a digital copy machine, and faxing it to a digital printer. All of this at a time when laptops weighed about 25 pounds and nobody knew what to do with them.

“We were trying to promote change that would be beneficial to the business community, but also to people individually and collectively.”

So there was change in technology. There was change in global competition. There was change in generational power. The World War II generation, which I thought was reflected in Fortune, Forbes, and Businessweek at that time—and in the White House actually—the World War II generation was gradually shuffling off the stage to be replaced by a bunch of baby boomers who felt that we needed to shake things up, we needed to change things.

We were the generation that took nothing for granted. And there was more diversity. Women, people of color were in the world of work, and the business magazines at the time were predominantly white men. Bill and I had a standing joke that if you looked at the covers of those business magazines at the time, they were always white men facing right, because that exuded power. And we wanted to portray a world that was being born, not the one that was gradually dying off.

Patrick Mitchell: There was something in your first editor’s note—a really great line in light of this week’s debate—you guys had said part of the inspiration was that you grew up at a time when the most brilliant, inspiring people went into politics. And that was no longer happening. You were finding those people going into business.

Alan Webber: Yeah, Bill and I had a lot of time on our hands and we philosophized quite a bit about how we made sense of the changes that were going on in the world. And one of the subtexts of Fast Company, always, was change. We were tracking change. We were trying to promote certain kinds of change that we thought would be beneficial to the business community, but also to people individually and collectively.

And there was a big shift going on in the United States at the time. Politics was taking a back seat to business as the driving force that would create change in the world. The first line of that letter from Bill and me was, “the world is changing and business is changing the world.” And that was a major shift from what we’d grown up with when Bill was working with Ralph Nader and I was working in the [Jimmy] Carter administration.

So I came back from Japan with this burning idea. And I think Bill came out of the experience in his career as a journalist before he became a business student, that writing and thinking and publishing was a really important way to have an impact on the world. And I had always wanted to have a magazine.

We didn’t want to do a restaurant and we didn’t want to do a rock and roll band. We wanted to do a magazine and that was going to take us down a certain path. So we had an idea. We had a business case from the Harvard Business School and we pretty much used that as a template. And we did, both of us, have great rolodexes. People listening may not know what a rolodex is. A rolodex is a card file of everybody you ever met on the planet.

And between Bill’s experiences as an author with Ralph Nader, and I, as the top editor at HBR, who could go out and talk to people in the world of finance and in Silicon Valley, between the two of us, we made a list of who we would like to have as our first-round investors. And we were very methodical about it.

Not all money is created equal. So we wanted the first-round investors to reflect the kind of magazine we wanted to be. We collected as our first round of investors, people who themselves not only gave us money, they gave us credibility, they gave us links into the different subsets of business activists.

And so when we put out that pilot issue and put it on the shuttle between Boston, New York, and Washington, DC, all of a sudden we were able to get feedback on what worked, what didn’t work, and how to make it better by the time we launched. And we really built our sense of place and performance and confidence that we knew what we were doing. We didn’t really know what we were doing, but we had a theory of how to go about doing it.

Bill Taylor: I’m big into takeaways, and I think Alan and I, and you probably as well, given that Fast Company was reasonably successful, people who want to do something similar in the world of publishing will come and ask for your advice and all that kind of stuff, we did the same thing.

And you realize how limited that advice really is. You take it with a grain of salt. But one thing I always say is that the partnership was just so absolutely essential. And it’s not, I think, primarily because you have complimentary skills or anything like that. It’s because so much of, I think, any entrepreneurial feat but certainly magazining, the way we did it, is an emotional rollercoaster.

And there were so many times I was ready to just throw in the towel and say, “Jesus, it’s been a year since the beta issue came out. What the hell are we doing?” And I didn’t really—the money wasn’t an issue, I could write for money—it’s more like you go to a party and they’re like, “Hey, how’s that magazine coming? It’s been a year, hasn’t it? What the hell’s going on?”

And you just need the kind of emotional wherewithal to stick with it. When I was ready to throw in the towel, Alan had just had a good meeting and he was all excited. When he was ready to throw in the towel, I’d had a good meeting and I was all excited.

And I think being together created a kind of joint resilience and stick-to-itiveness, that I’m not sure either of us—I certainly wouldn’t have had it. I would have thrown in the towel much earlier. And so I think that was a really key thing. I also do think the fact that it took us a lot of time meant we were ready—the moment we got the investment from Mort and Fred we were ready to go.

The minute the flag went down, the race began, we didn’t have one good album in us, we had a whole bunch of good albums. We had mocked out so many issues and headlines and so on and so forth. So we were ready to come out with a ferocity that I think only came from the fact that we had so much time to reflect on what we wanted to do.

And this is so different from so much of magazining today, and I don’t want to overdo the thinking like we’re making albums, but we actually did talk about that. We were going to go into the studio and say, “Okay, what’s our next album? Is it going to be Born in the USA or is it going to be Nebraska? Is it going to be a hard rocker or is it going to be something more quiet and thoughtful?”

“We were in the business of discovering people who deserved a lot more attention than they were getting, because what they were doing had so much to teach the people who are going to come to Fast Company for ideas, insights, and information.”

And the assumption behind that was that people would come to the magazine as a complete issue and they would literally read it cover-to-cover and kind of sense that there was a screaming, loud, highly-agitated, provocative piece, and then there was a more sober, thoughtful, caring sort of piece. And obviously that’s not how most people consume media today.

And there are probably a few exceptions—even Fast Company itself. I do a lot of speeches and people come up to me afterwards and say, “I love Fast Company.” They don’t even know it’s a print magazine for goodness sake. Fast Company is such a big presence on the web that many people just subscribe to one channel—Co.Create, or Co.Design, or whatever. We’ve gone from albums to Spotify and singles that are streaming.

Patrick Mitchell: So talk about just quickly—you brought Roger Black in to create the prototype. And I believe the brief was “Rolling Stone meets Fortune”? “Rolling Stone meets HBR?”

Alan Webber: Rolling Stone meets HBR. We wanted to have the thinking, the quality of mind, the business mind, and the actual managerial experience of HBR, but the energy, the sensibility, the design chops of Rolling Stone. And that’s what we got. We filled the bill with things that really did correspond to those two design components.

Let me back up one minute, Pat. There was a part of your question we didn’t address which was how long did we wander around in the wilderness and what did we do? And one of the things we came up with that was both a way of making a living but also a way of practicing putting out a magazine was the very famous Fast Company Knowledge Exchange (FCKE). The Fast Company Knowledge Exchange—

Bill Taylor: Say it. Say it! Better known as FCKE. F-C-K-E. FCKE. “Here comes your issue of FCKE.”

Alan Webber: —the lovingly abbreviated FCKE. And we had to make a living. We were off the payroll from HBR. Bill, you know, had written a book. I didn’t have any income. And we had bills to pay. But also, again, we over-thought it. We said, “What can we do to keep our hands in the game?” So we practiced putting out the magazine we would put out if it were a magazine.

We went to some of the people who had been our friends during the HBR days. People at the Boston Consulting Group stepped up, and other folks paid us a stipend to basically go out into the world. And Bill would attend a conference and come back and write up a three-page report from the conference. Or we would put a book review that wasn’t about business, but was fascinating to a business person who wanted to have peripheral vision.

What do we learn from The Glass Bead Game that informs business? I don’t know, but we’ll make something up and it’ll be a new way of thinking. So we put out FCKE. It paid us enough money to make a living. It also gave us an excuse to go out into the world and be journalists.

Bill Taylor: When I talked about how we were ready to go once we launched a magazine, a lot of the language, and even some of the characters we discovered for FCKE wound up appearing in the early issues of the magazine, because it gave us an excuse to go out in the world and basically say, “We’re in the process of launching this magazine. We can show you the prototype, so it’s not complete vaporware. At the same time we’re, you know, negotiating with world-class publishing companies that get it off the ground, but we want to come and visit your organization, tease out lessons, share those with members of our coalition of change agents that were assembling to be part of this thing.”

The other thing we did in terms of entrepreneurial advice is we wrote regular, very entertaining I thought, newsletters to the 15 individual investors who funded the first round of the magazine. And we kept them apprised, entertained, and in the loop in this two-year journey between the appearance of the beta issue and the appearance of the launch issue. Many of them saying, “Where the hell did my money go? I didn’t expect to make a billion dollars on this thing, but what happened to everything?”

Another lesson for aspiring entrepreneurs I’d like to share is that you really need to treat your financial partners exceptionally well. And that’s not just returning their phone calls and being polite, it’s giving them a sense of an ongoing engagement in the enterprise, even when, or maybe especially when, things are moving a little bit more slowly than they may have wanted.

One of our internal taglines was, “Ideas before they’re safe, characters before they’re famous.” We were in the business of discovering people who deserved a lot more attention than they were getting, not because of the immediate scale of what they were doing, but because what they were doing had so much to teach the people who are going to come to Fast Company for ideas, insights, information, and so on.

I think it really made us feel so different. People would read the magazine and say, “I’ve never read this kind of story before. I’ve never heard of these people before.” We were trying to help usher in the world we wanted to see exist. In that sense, we were an advocacy magazine. We did advocacy journalism. Advocating for a set of values, a kind of sense of possibility about business that we really deeply believed in. And it’s not seeing is believing. It’s believing is seeing. If you believe it, you actually will see it out there.

Now, 30-some years later, looking back, I don’t take any of it back. It was truly a magic moment. I find myself deeply disillusioned by how the world has taken these ideas and disfigured them, and corrupted them, and turned the world of, kind of, technology-meets-new-organizational-forms into something—ultimately the love of money is the root of all evil.

We can have all the wonderful ideas we want about participation, and innovation, and change, but when so much money washes into any kind of area, it can’t help but corrupt those who are part of it. I’ve done guest lectures with a bunch of college classes and I’ve got a thing I do called “Reflections of a Disillusioned Disruptor.”

We were so eager to disrupt everything, and overthrow everything, and change everything. And 35 years later, I still believe in all the ideas, but one can’t help but be chastened by so much of what has been wrought under the banner of those ideas. But I feel it because you really can’t divorce Fast Company, the magazine, from the worldview and set of ideas that were the foundation of everything we did, basically.

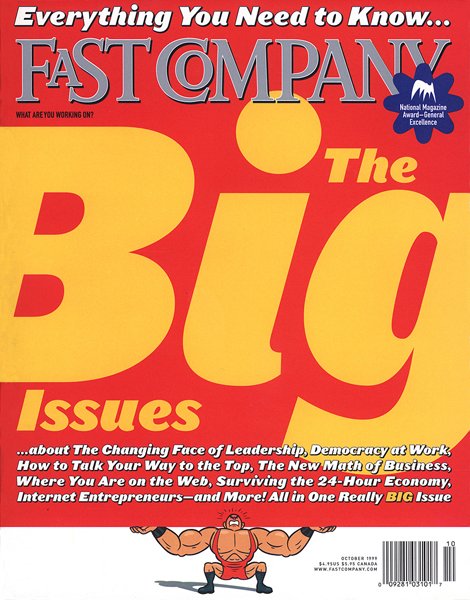

Alan Webber: And Pat, you designed that first cover, which probably is the most iconic cover of a business magazine ever. And it wasn’t a cover. It was a statement of core beliefs, right?

Patrick Mitchell: The “manifesto.”

“We were trying to help usher in the world we wanted to see exist.”

Alan Webber: Yeah. “Work is personal.” It is a manifesto. And I don’t think most magazines have a manifesto. When we actually hired real journalists to work with us, they were often frustrated because, as Bill said, journalists are used to going out into the world and bringing back a story. And our model was, We’ve already got the story, we’ve got to go out in the world and find it. A very different mindset. And a very different mindset to say a magazine has a set of core beliefs, a manifesto: work is personal, knowledge is power. This is a core set of beliefs and we want to launch them out into the world and then find the people who embody them, who enact them.

I remember early on when we were trying to get support for the magazine and we’d explain these cross-cutting themes to people and one of the many negative pieces of feedback—because the world wants to tell you that if an idea you had was a good one it would already exist, and sometimes that’s true, but we didn’t believe it.

We thought, No, this idea deserves to exist because it’s important. But we would say, “We’re going to go out and find examples of these unbelievably cool disruptors, these cool new ways of doing business, being an entrepreneur of your own life, of your own world.”

And people would say, “You’ll run out of stories after about three issues.”

And we’d say, “No, no, no, no, no. It’s all out there. It’s already there. We just have to go find it.”

And that was part of the two years of the Fast Company Knowledge Exchange, the book project, the sitting around imagining—we sat and worked our way through I don’t know how many different tables of contents. We created tables of contents for a magazine that didn’t exist yet. And then, of course, the design part was absolutely essential.

Patrick Mitchell: Why was that?

Alan Webber: Look and feel had to embody the energy, the spirit, the vitality, the optimism, the sense of experimentation that the ideas that were presented in the articles really were bringing forward. And when we finally hired this very rambunctious art director named Patrick Mitchell, we told him, “You’re not the art director. You’re the Vice President of Look and Feel.” Because look and feel is everything.

In our design specs, we said, “The paper has to feel like it’s still got chunks of wood in it. We don’t want slick, thin, cheap paper. We want thick, tangible paper that when you feel it you think, This is a substantial magazine.” And I remember we looked at other magazines, but we also looked at how Nike approached design.

What is the best design in the world that communicates the underlying spirit, and values, and ideas, and energy of the performance that you’re bringing out into the world? And that was the heart and soul of the design specs for the magazine.

Patrick Mitchell: I remember you actually went to a product design firm when you were wandering in the wilderness and said, “If we didn’t launch this in print what would a magazine be?”

Alan Webber: Yeah. I mean, we had a lot of time on our hands. That really was a big piece of it. Lateral thinking about, “Help us imagine something that doesn’t exist. And use metaphor and comparables to get us out of the same old world.” And some things we finally concluded, and Bill was a very good pair of gravity boots saying, “No, you actually do need a table of contents. You can’t do away with the table of contents. You do need a front of the book. People are used to having a front of the book. You do need a back of the book.”

So while you want to try and experiment with some things, you don’t change because people will never understand. You’ll be so out of the norm that it doesn’t look or feel like something they can relate to. But within that, how do you change things and shake things up? And I think it was a design principle that if you read the magazine cover-to-cover, when you’re done, you should have more energy as a reader than when you started. And if we achieved that, it was a good issue.

Bill Taylor: Yeah. We’re using the language of design, which is, of course, essential, but I think the spirit behind the design was that of performance and entertainment. We really did have a lot of fun with even many of the traditional conventions of magazining. Alan mentioned the front of the book, which was “Report from the Future,” or RFTF—we were big on acronyms. The back of the book was “The User’s Guide to the New Economy,” or UGNE. And we did so many things, both in terms of the words, but also in terms of the design to signal as strongly as we could that these are unlike any fronts of the book or backs of the book you’ve encountered before.

And for the first year or so, the front of the book had borders around each page where we would put random quotes or factoids—our version of Ripley’s Believe It or Not!—and you literally would have to turn the magazine 360 degrees to read them. And magazine folks looked at this and said, “That’s the most insane thing I’ve ever seen in my life. What are you possibly doing?”

And I don’t know how many people read them, turned the magazine, but it was just such an explosion of energy. And if you actually did read them, they were so goddamn hilarious that not reading them you really miss something.

We recently lost Bill Breen, one of our first and dearest colleagues whose early portfolio was the back of the book. And I went back recently and just reread that. Oh my God! Some of it was corny, but it was such relentlessly useful, helpful, hands-on stuff. But it was delivered with such a degree of hilarity, at least our friends thought so.

But I was laughing out loud reading some of the stuff he and we were doing back then. There was really such a sense that, “If I can’t dance, I don’t want your revolution.” If we’re going to have a business revolution, we’ve got to make it fun.

And the design was how that came to be. But the design wasn’t meant to be slick, or avant garde, or different for the sake of being different. It was to enact this sense of performance art and entertainment that, again, people, I just think when they picked it up, felt it intuitively. “What are these folks—what game are these people playing?”

This was not like any business magazine. Or really any magazine period, I think, that we had encountered. We used to call it “serious fun.” We did take the mission of the magazine very seriously. We tried not to take ourselves too seriously. Quite the opposite, have a lot of fun and let the readers therefore have fun reading it.

Patrick Mitchell: It was a real reflection of its founders. Alright. In the scope of where Fast Company fits in, in publishing—so you ended up going into business with Mort Zuckerman who owned The Atlantic Monthly at the time, and US News & World Report, and the Daily News. But I’m trying to picture you both, briefcases in hand, walking around New York City, pitching to Hearst, Condé, Time Inc. ...

Bill Taylor: Early on, we thought that having meetings with important companies was a sign that we’re doing something right. And so, as you say, we had meetings with Hearst, and Condé, and The Economist. And then I think it dawned on us that these big companies are so overstaffed, there are a lot of people who do nothing but have meetings all day. And it was not a sign that our idea was great or that we’re making progress, it was a sign that somebody said, “Oh, good! I can expense another lunch and take these guys out.”

And I think by-and-large folks were impressed with what we were thinking about. But to me, the key point is for most of these organizations, we did not solve a problem that they had. By investing in Fast Company, or more importantly, by partnering with Fast Company and taking on a lot of the business-side responsibilities, we were not—as an idea and as a young company—we were not addressing holes in their portfolio or the need to refresh the overall persona of the holding company or what have you.

And when we first connected with Mort Zuckerman—and really Fred Drasner, Mort Zuckerman’s partner—it was so obvious that this was, in a way, business partnership-wise, a marriage made in heaven. They had US News who, back then, was super-successful—literally the “News You Can Use” stuff. But also dull, kind of targeted to the older demographic. You had The Atlantic with the 150-year-old, genteel, Henry David Thoreau sensibility. And then in came razzle-dazzle Fast Company, the voice of a new generation appealing to a new demographic.

“And our model was, ‘We’ve already got the story, we’ve got to go out in the world and find it.’ A very different mindset.”

However, in terms of an advertising base, appealing to, in many ways, the same group of advertisers. IBM, but a different side of IBM, it’s not going to be the IBM with the giant servers, it’s going to be the IBM that wants to tell the world, “We’re open for 20-somethings to come work for us, that we’ve embraced the PC revolution.”

Xerox was a huge client early on. And again, not the Xerox of the gigantic backroom copiers, but the Xerox of, “We’re entering the digital world. We want to tell you what a modern company was.” And the reason, ultimately, the partnership with Mort and Fred worked in ways that we didn’t get much traction with others is they had a problem we could solve.

And that’s a lesson I’ve taken away on a lot of sides of life—when you’re trying to, sort of, get somebody else to help you with something—is being interesting, being reasonably intelligent. It doesn’t mean anything if you’re not speaking to the needs of the folks on the other side of the table. And in this partnership, we spoke to the needs of the folks on the other side of the table.

Alan Webber: Bill’s spot on with that. And I also think, I’ve got to say, there was an element of secretly, it’s a cool project. They had to choose between Senior Tennis and Fast Company. They were going to invest in one of two new magazines. And if you were a New York business person and feeling pretty hip and cool would you rather publish Senior Tennis, or take a risk with these crazy guys looking at the world through a whole different set of lenses in business, and in technology, and in work?

Yeah, I think Fred Drasner’s famous words were—I can’t imitate Fred’s voice, but if I could it would sound like Joe Pesci: “Alright, we’ll give you one shot at it. And if it sucks, we’ll bury it so deep, nobody will ever know it existed.” But it didn’t suck.

Patrick Mitchell: Did cement shoes come up at any point?

Bill Taylor: No, no, no, no, no.

Patrick Mitchell: I want to talk about the juggernaut that Fast Company became, but I want to close with you guys looking at what it’s become now, 30 years later. So we started in the Fall of ’95—we were going to do a one-off. That was the plan. And it was way more successful than people thought it was going to be. So we quickly went quarterly or biannual, maybe. Or, before we even went biannual, we were quarterly. I don’t even know if we did four quarterly issues because, boom, we went bimonthly because the ads were taking off. And then before anybody expected, we were monthly. People often refer to Fast Company as one of the most successful startups in magazine history. So talk a little bit about how this thing just hit like a ton of bricks. And, before we knew it, we were doing 400-page issues.

Bill Taylor: First of all, the moral of this is it’s better to be lucky than smart. And if you read—I’m sitting here with the original business plan of the magazine or the revised business plan of the magazine between the mutant baby issue and the launch issue. And I don’t think anywhere in that plan, will you find the word ‘internet.’ Truly nowhere.

And yet we launched in, let’s call it October/November of 1995. And of course the shot heard around the world was August 7th, 1995, when Netscape did its IPO. And the first popularizer of the web browser became this massive entrepreneurial success.

And when we came out, I think the world looked at us as the business/work culture magazine of the internet era. Which is honestly nothing we planned on. Part of our worldview was the role of technology as a small-d democratizing force. But that Netscape IPO and everything that followed it unleashed the animal spirits, as John Maynard Keynes used to write about, of so much excitement, so much energy.

Suddenly everybody wanted to either be a digital entrepreneur or be a young change agent inside a big company. And so many consulting firms and so many ad agencies felt, “Wow, we really need to get with the program here. This tiger has been freed from a cage and we don’t know what to make of it.”

And the world saw us, both the rank-and-file participants in this revolution—which is who we really cared about—but then the idea merchants, the ad agencies, the big established companies, the venture capitalists, they all realized, “Ooh! If we take this Fast Company brand seriously, they’re going to translate for us what’s really going on in the world.” And that was totally in the spirit of what we were doing. But the explosion of the internet economy is nothing we predicted or saw coming. So there’s that.

Second thing is, none of this success was on a continuum. We had several Big Bang moments. We did the premier issue. It was great. I think everybody recognized it as great, but it wasn’t a massive, popular success. There’s really the Fast Company history before the Tom Peters cover story—and Pat, you had as big a hand as anybody in this—“The Brand Called You,” with the famous cover that evoked the spirit of the Tide box.

Before that issue came out, we were a cult band and we were playing in The Stone Pony and The Cavern Club. After that issue, we were playing at football stadiums. That moment took us to a whole new level of visibility. And it was the substance of the article and the argument, but honestly, I think more than anything, it was the cover. And everybody paid attention. It was our—I’m a big Bruce fan, as many people know—that was our Born in the USA. And it was just, it was—overnight, I feel like—we could sense, sort of, the tectonic plates. And we’re playing at a much bigger stage here. And we had a few other articles like that. Dan Pink’s “Free Agent Nation.”

Now, why? Because it introduced into the conversation a new way of making sense of the world. You don’t have to be an employee—even in a startup. You could be a free agent. You could be your own boss. You could make your own way through the world. In a way it was a kind of a personal strategy version of “The Brand Called You,” which is you have to think of yourself as an individual, as a brand capable of telling your story. And it was disfigured by a lot of people, like the song “Born in the USA.”

Tom Peters was saying if you want to act that way, it imposes upon you certain standards of behavior and you have to live into and work into the brand you want to create for yourself and so on. “Built to Flip,” by the great Jim Collins became a major contribution because it was cutting against the grain of what had rapidly become a startup frenzy. The national pastime in America isn’t baseball. It’s the tendency to take a good idea and wildly overdo it.

And so that was what was happening. There were four or five, whatever it might be, very special moments that took us to new levels of popularity and announced our seriousness of purpose as, like, the ’conscience,’ in a way, of “The New Economy.” Or the conscience of the digital revolution. And so looking at Fast Company’s growth as this straight line up-and-to-the-right isn’t really how it worked. It was a series of big bangs or mini-explosions that kept taking us to new levels of popularity.

Alan Webber: Yeah, I think that’s really true. And some of those pieces, as well as just the cumulative effect of the sense that something important was happening here. And you’ve got to go back in time—this is a long time ago—the conference world was important. There were a lot of gatherings going on. People loved getting together, whether at TED or other technology gatherings, where people were beginning to talk about there’s a whole different world of work out there.

And one of our little cutlines was taken from Bill and me going out to the conference world and listening, and people would ask each other, “What are you working on?” That became a Fast Company slogan. We were listening carefully to people. We held our own conferences, which turned out to be a great way to promote and grow the magazine.

The metaphor was that the magazine was a satellite out in space or a satellite dish that could gather information and then we would repurpose it into big conferences, small conferences. We wrote up a treatment for a TV show. We didn’t ever launch it, but we knew we were capturing ideas and spirit of change that people were very eager to get aligned with.

“We did take the mission of the magazine very seriously. We tried not to take ourselves too seriously.”

And then I would go out—Bill was actually running the magazine, I was wandering around the landscape like a minstrel—but I would go meet with ad agencies to get feedback. And first of all, they were amazed that an editor not from the business side would meet with them. We wanted to hear what they had to say. It wasn’t a wall where editorial couldn’t talk to business. It was a unified effort.

So I’d go meet with ad agencies and the message kept coming back, “I don’t know your magazine, but my clients want to be in it.” And I think that was an important component that people wanted to be affiliated with or associated with what Fast Company was portraying, not just what we were selling. Because we, really we were idea merchants, but we were portraying a different world of work, a different way for people to show up in the office.

And we were on our own learning curve. Early on I don’t think Bill and I took a vacation for, I don’t know how many years, so we were all about, highly-caffeinated, right? What was the cutline for the photos, Pat, that you were dropping in every photo before we actually had to attribute it? “Caff Ratchet.”

Bill Taylor: “Caff Ratchet!” Right, right! “Ratchet up the caffeination!” Exactly.

Alan Webber: “Caff Ratchet” was the character. Why did we go that way? Because people were sleeping in their offices and there were little cubicles where you’d grab a 20-minute nap. Then we got the feedback from people, “I don’t want to live that way. I want a magazine that tells me how to have a more balanced life. I’m losing my sense of personal life.” So we pivoted the magazine and we had a collection of articles on how to find balance in your work life.

One of the things we heard in the early days of Fast Company was, “I thought I was the only one who was thinking like this. And now I know there’s a whole community of people who think like this.” We were students of other magazines before we got started and we looked at what successful magazines do. Successful magazines create a community that already existed, but didn’t know it was a community.

So if you look at The New Yorker. Or you look at Wired, which launched six months before we did. There was a community of people who didn’t have a vehicle through which to connect with each other. And magazines, successful magazines, in every generation, create the space for a community to come together.

And we actually had what we called the “Company of Friends.” There’s another offshoot from a magazine where all of a sudden, thanks to “Mr. Airport,” Heath Row, we’ve got clubs all over the world where people would read an issue and then have a Company of Friends meeting. I went to one in Paris. They started in what, Ohio, Bill? Wasn’t it Columbus that was the first place that said, “Hey, I know all these ideas in this magazine are really great. Are there people I can talk to who share this sensibility?”

And they created the Company of Friends for us, and then Heath Row became the coordinator. We had people in charge of different chapters, different places where people were coming together. We actually held a summit of the Company of Friends coordinators, where they came together to talk about how they could take the magazine and make it even more useful. It was beyond a magazine. It’s a cliche to say it now, but it became a movement.

Bill Taylor: Yeah, “We’re not a magazine, we’re a movement.” That was one of our internal rallying cries. And by the way, it’s amazing, I’m still in touch with a number of the Company of Friends leaders from more than 30 years ago now. It’s just incredible how so many elements of this movement have hung together.

And I know we’re coming to the end of our time. The one thing we haven’t talked nearly enough about is our colleagues, and the incredible set of people—obviously first and foremost, you Pat—but the incredible set of people who were willing to join us in this adventure, many of whom had no experience in the world of magazines at all.

They were super bright. They were terrific writers. They were risk takers. And Alan and I felt like we could teach them the basics of how to do a good interview, how to write a good lead, or we could write it for them if need be or whatever. But you had to have that spirit, that set of commitment to the ideas we were trying to build the magazine around.

And it’s probably true of any startup, but for all three of us, these people have become lifelong friends, lifelong colleagues, and compatriots—people we care deeply about, people who care deeply about the legacy of the magazine. And there was no way to have done—for our readers and that sense of passion and commitment—there’s no way to have done that without having been lucky enough to assemble just an amazing array of talented, devoted, hilarious, amazing people who stuck with us through thick and thin and helped us do all of this.

So it might make sense to close on that. But there’s no way to think about—creating a magazine is such a fundamentally creative process, particularly the way we did it, where everything had to come out from inside us. And then as we would say, we find the stories that made all that come true.

And it was impossible to do that without the incredible commitment of so many people in so many different parts of the magazine. And when we lost our wonderful colleague, Bill Breen, the sense of loss that everybody felt—we recently did a kind of tribute service for him, and the stories people were telling and that sense of camaraderie came back just in an instant as if we were back in the North End of Boston in 1996.

“Successful magazines create a community that already existed, but didn’t know it was a community.

And magazines create the space for a community to come together.”

But to me that’s one of the great gifts of the magazine, this sense of connection with all these people who have gone on to do absolutely amazing stuff. Some in the world of publishing, some not. But we were all forged in the fire of creating this thing. And you have to have just as much passion inside the organization as you can unleash outside the organization for this sort of thing to work.

Alan Webber: I’ll go back to where you started, Pat, which was the job interview with you. And I remember it vividly. I did see you on that airplane ride. I think I was coming back from a speech in Texas. And yes, I was in first class and yes, you were in coach and they let you, because of your force of personality, come up and hobnob with the grandees in the front of the bus.

But when we finally sat down, I asked you why you wanted to be the art director and you said you didn’t want to be an art director of any magazine, you only wanted to be the art director of Fast Company. And that resonated so strongly with me, that if you’re in the magazine business, you could work for any magazine. But you came to me and Bill and you said, “No, I want to be the art director of this magazine.” And every single person who came to work in Boston at Fast Company, they didn’t want to work for a magazine. They wanted to work for this magazine. They wanted to invent this magazine as it was being created.

And that sense of connection, commitment is really what I carry with me from those days. We weren’t putting out a magazine, we were putting out this very special magazine that was about the people who devoted themselves to making it happen and the people who formed the community to embrace it.

And I salute you for that job interview because you carried the day. It was, “I’m not interested in a job. I want to help create something special.” And that carried through with everybody we brought on to the team over time.

More from Print Is Dead (Long Live Print!)