The Greatest Startup in the History of Magazine Startups

A conversation with editor and author Kurt Andersen (Spy, New York, Time, more)

We’ve always had a thing for magazine launches. They’re filled with drama and melodrama, people behaving with passion and conviction, and people ... misbehaving. Anything to get that first issue onto the stands and into the hands of readers.

Some new ventures seem to sneak in the back door. Who saw Wired or Fast Company coming?

Others are to the manner born, and from the most elite print parents. But, even with that pedigree they never gain traction, never display the scrappiness and experimentation that we’ve come to expect from anything new. (You know who you are).

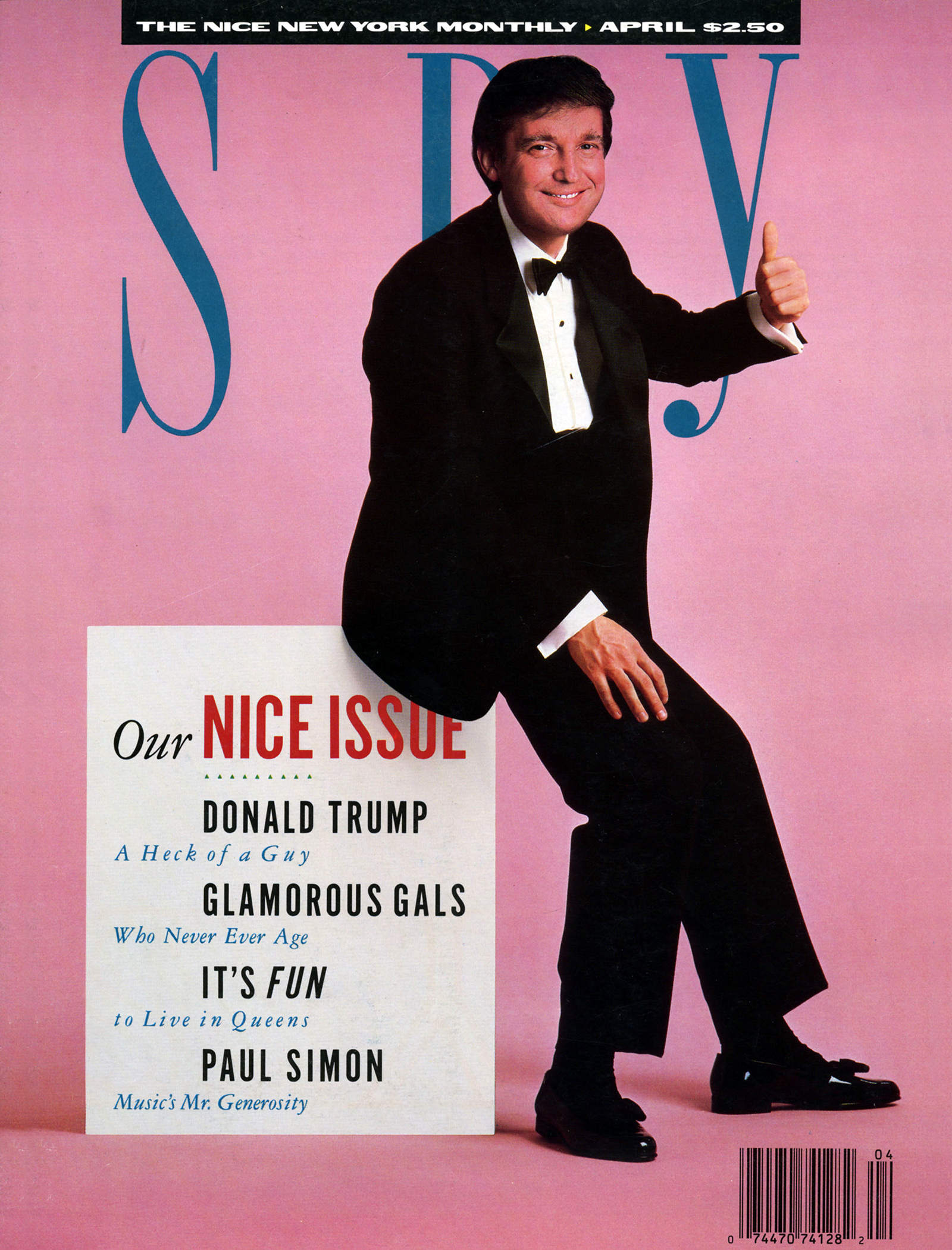

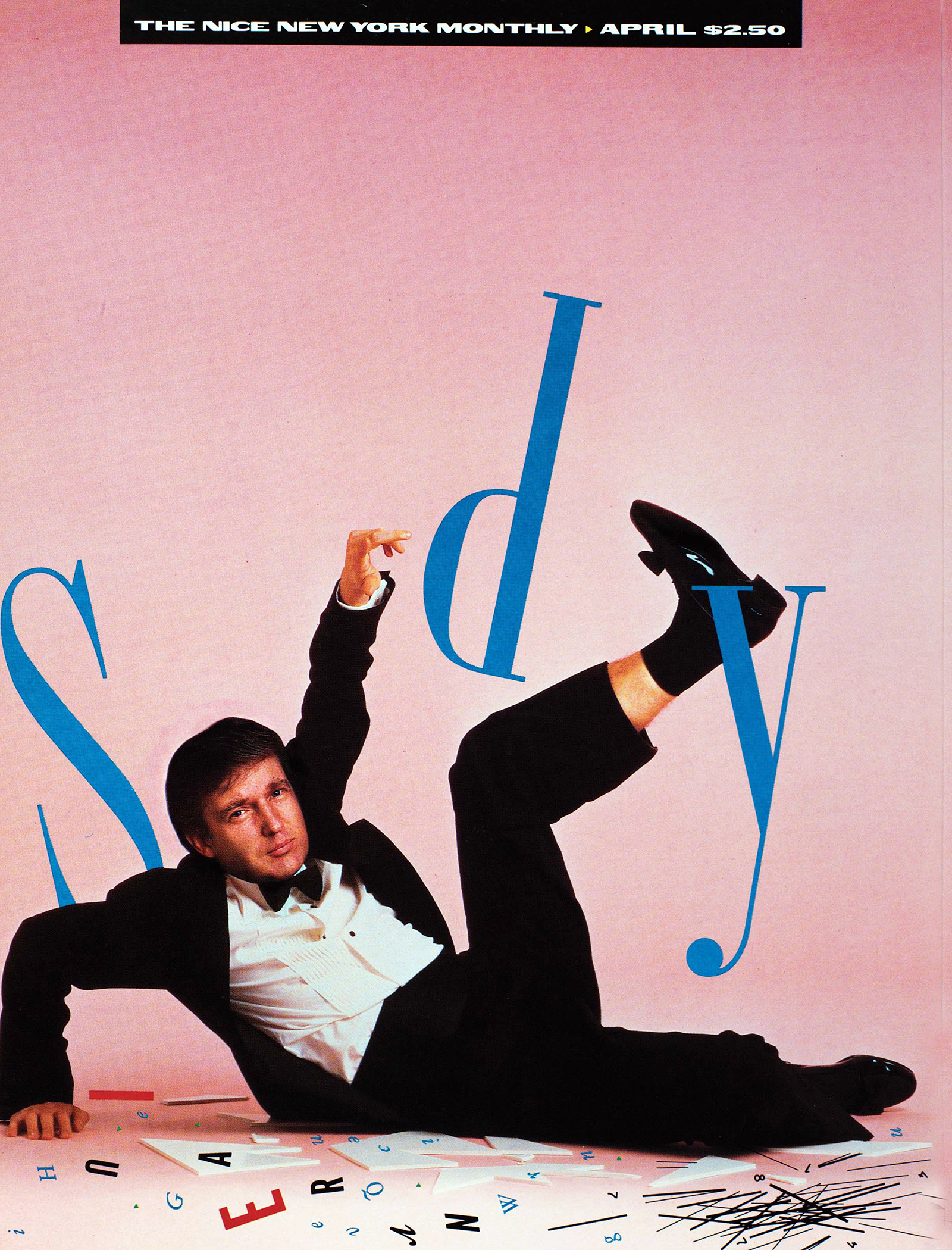

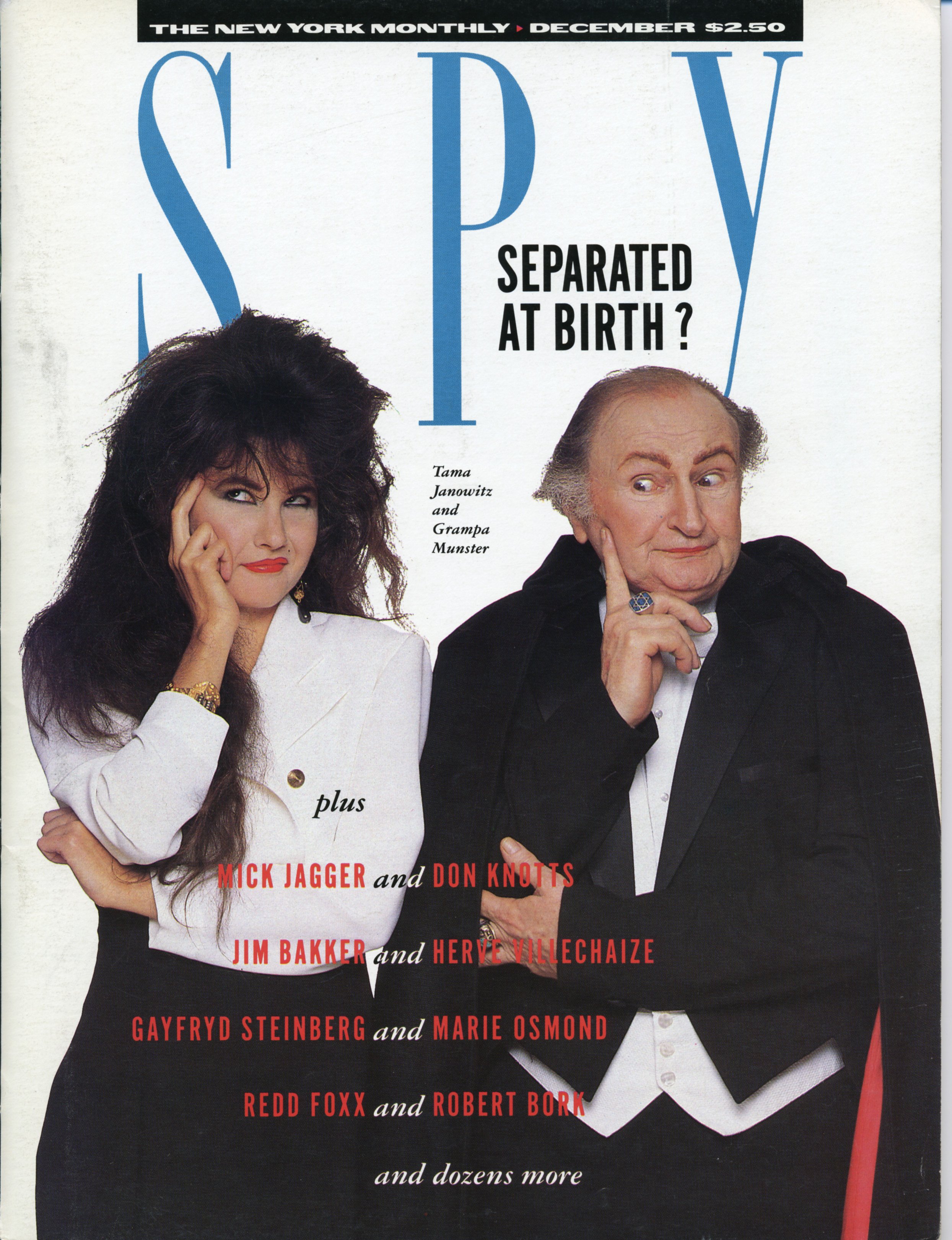

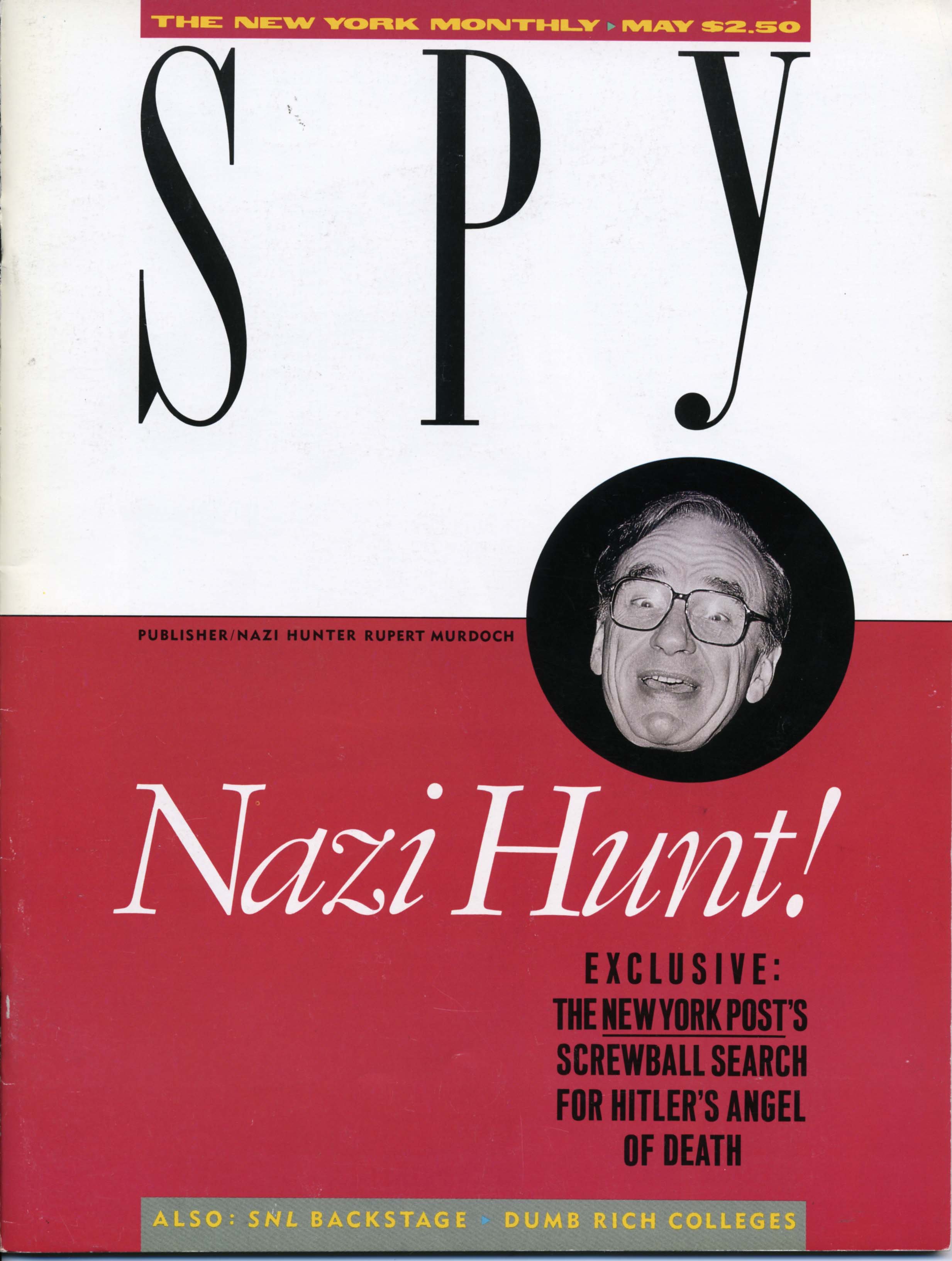

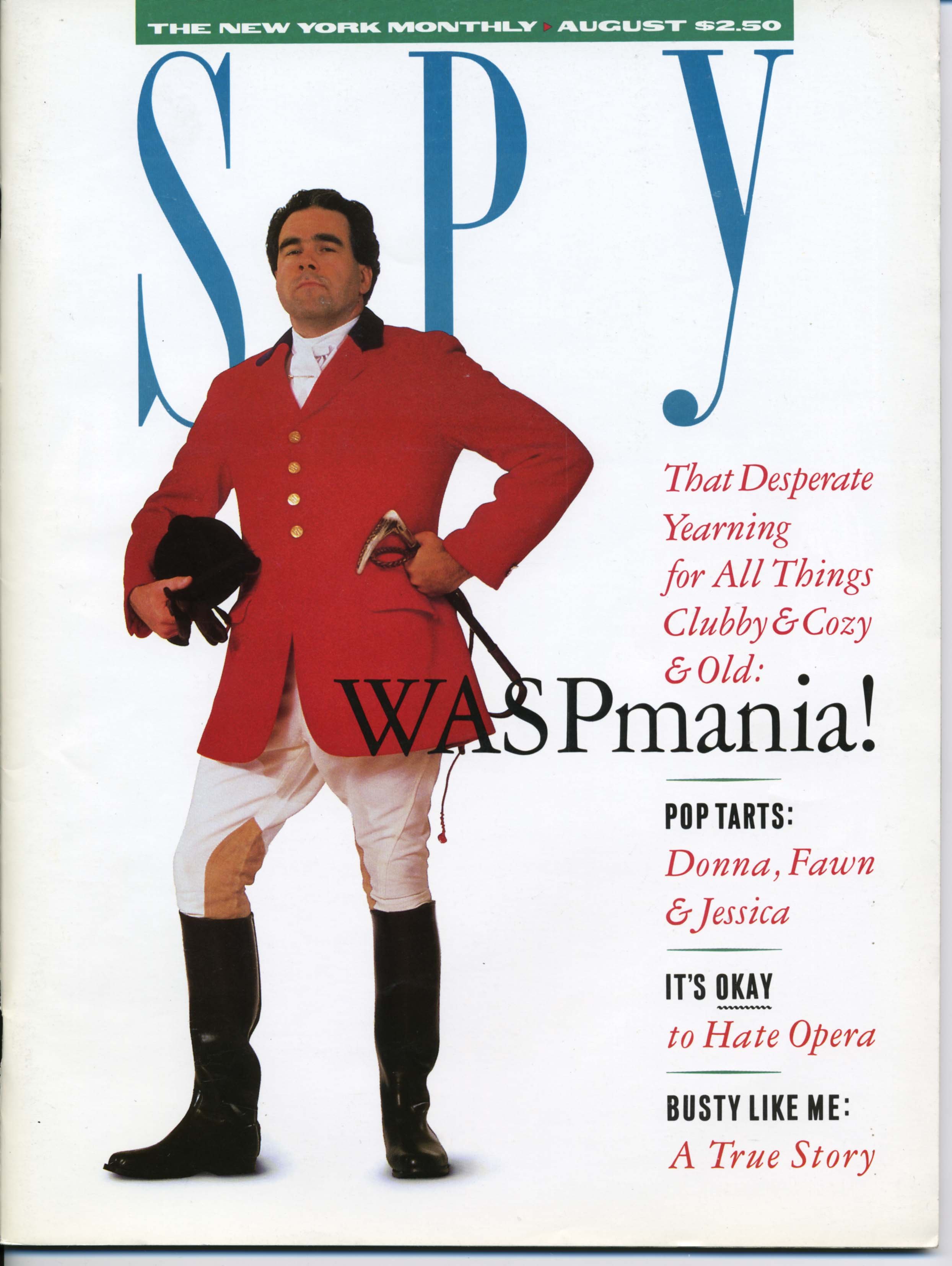

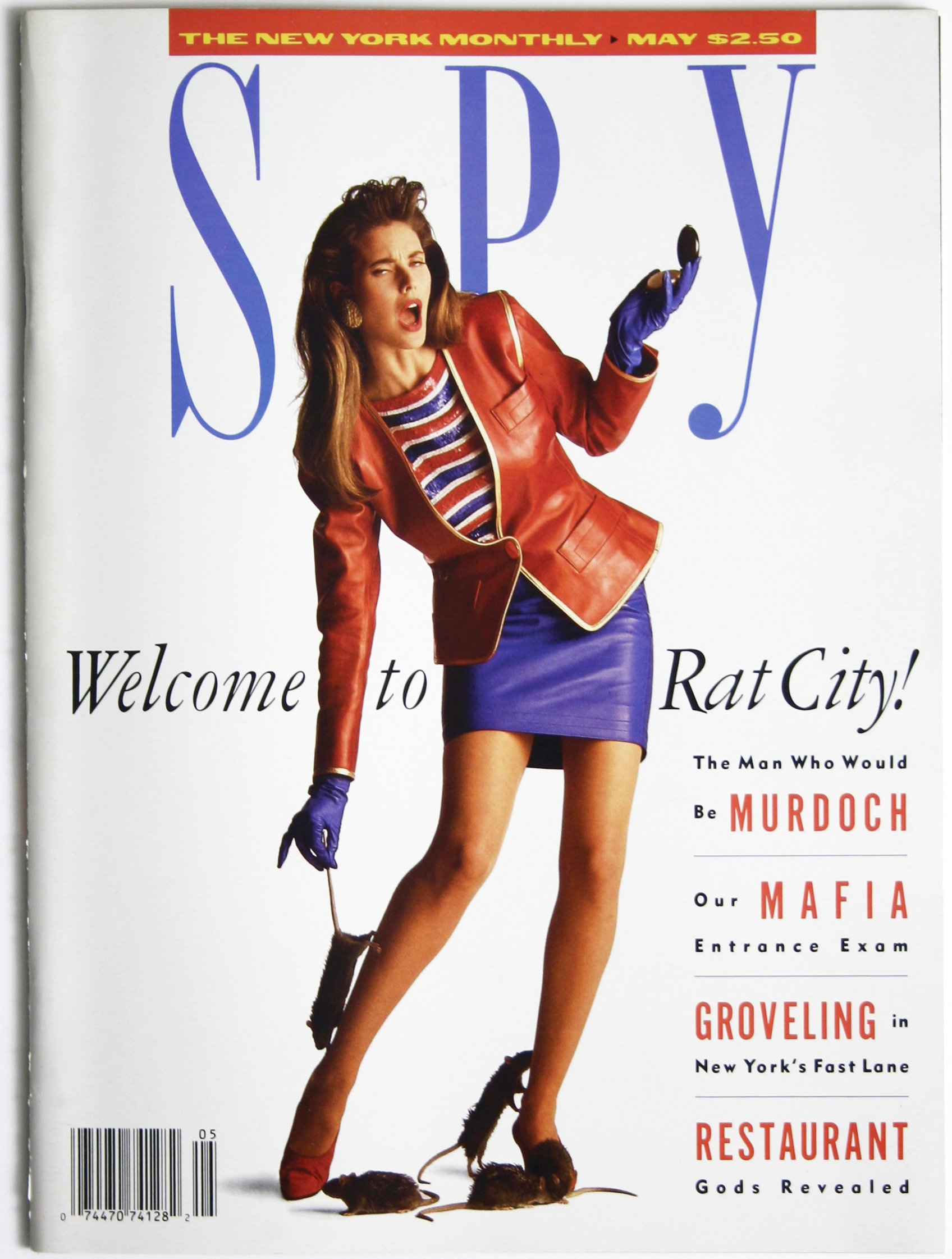

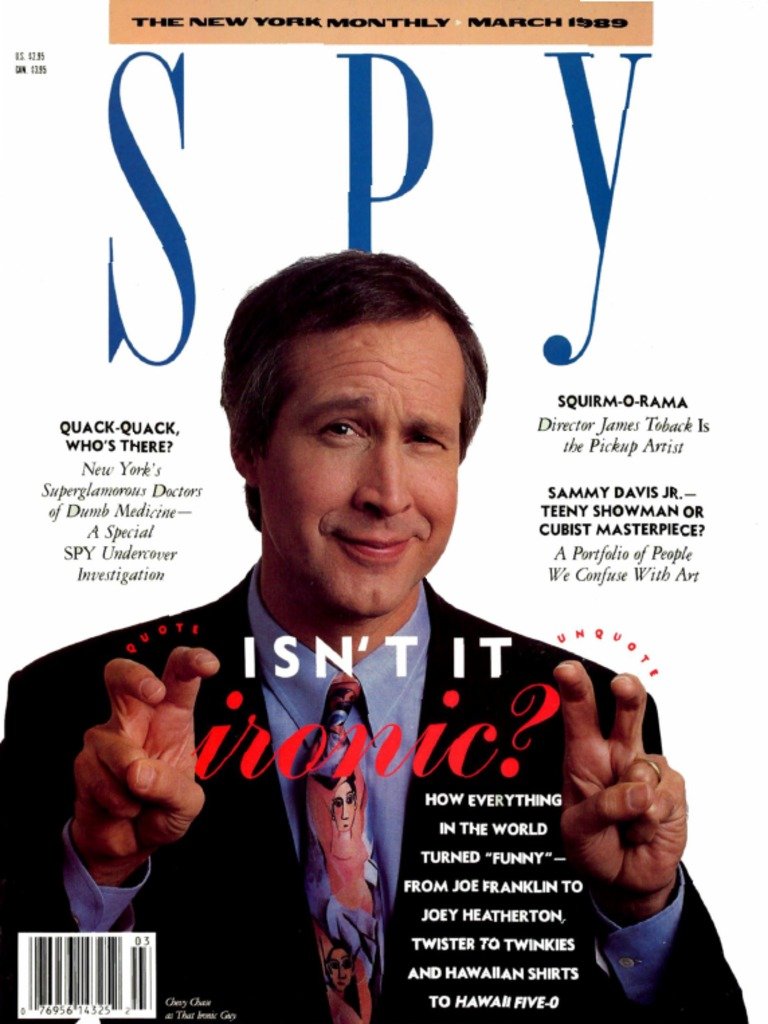

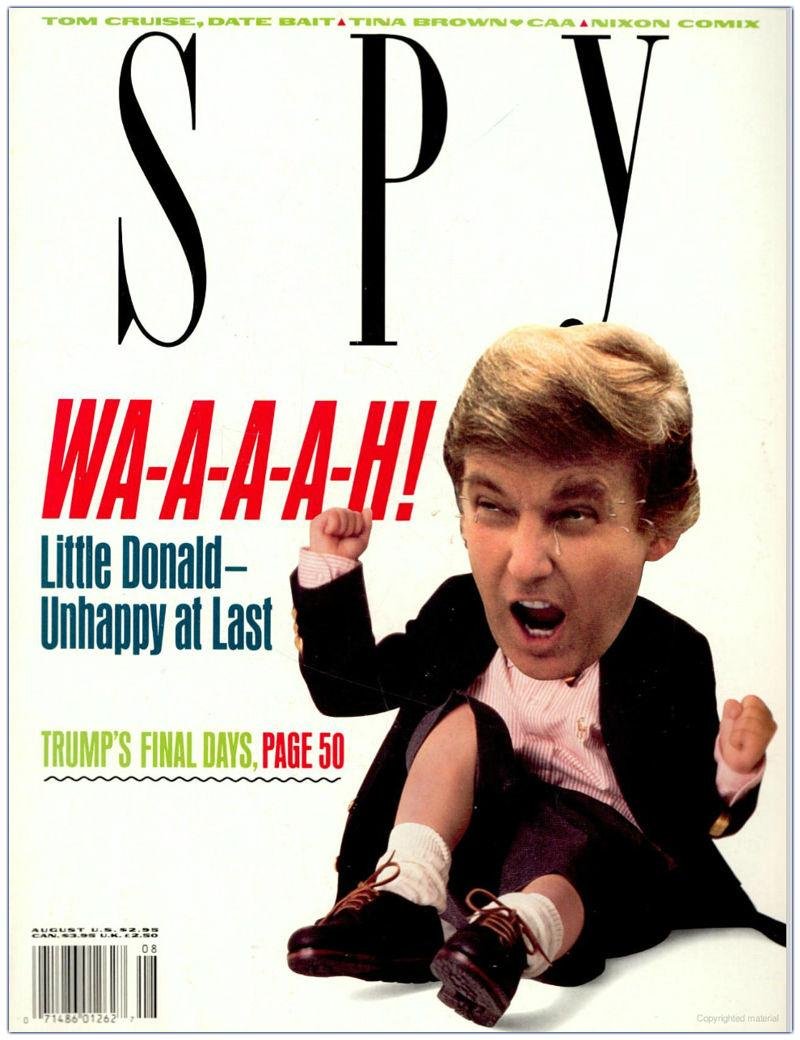

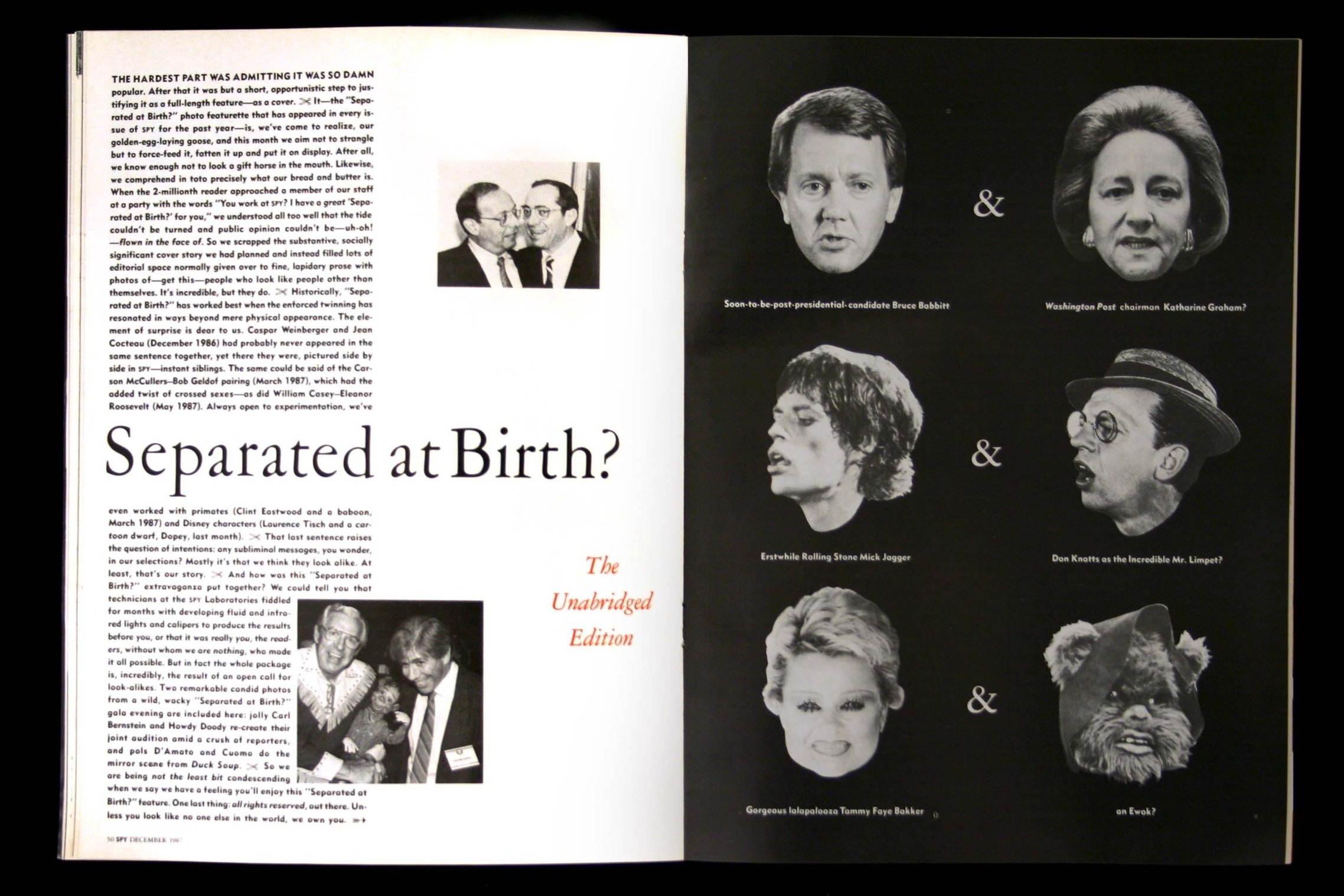

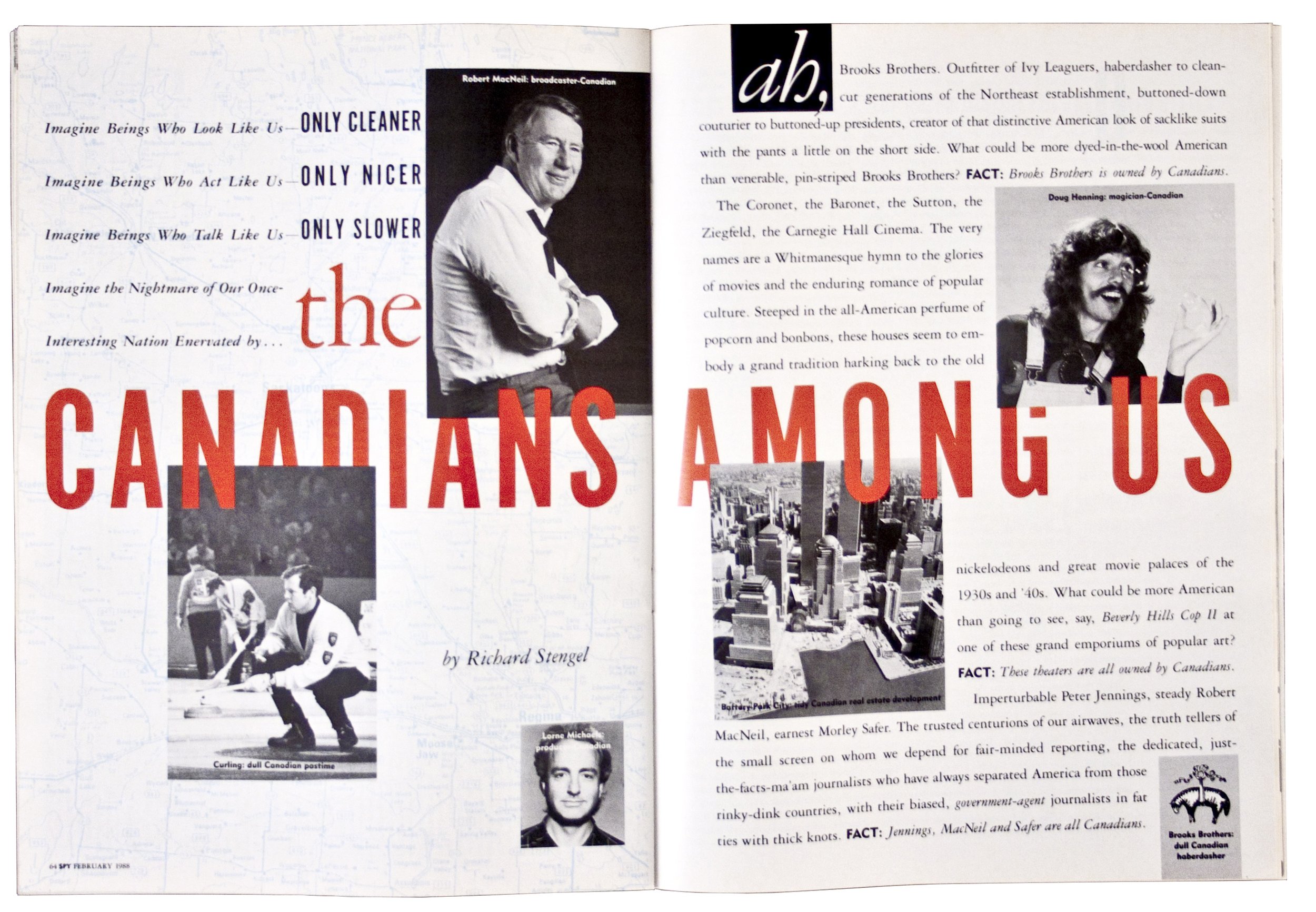

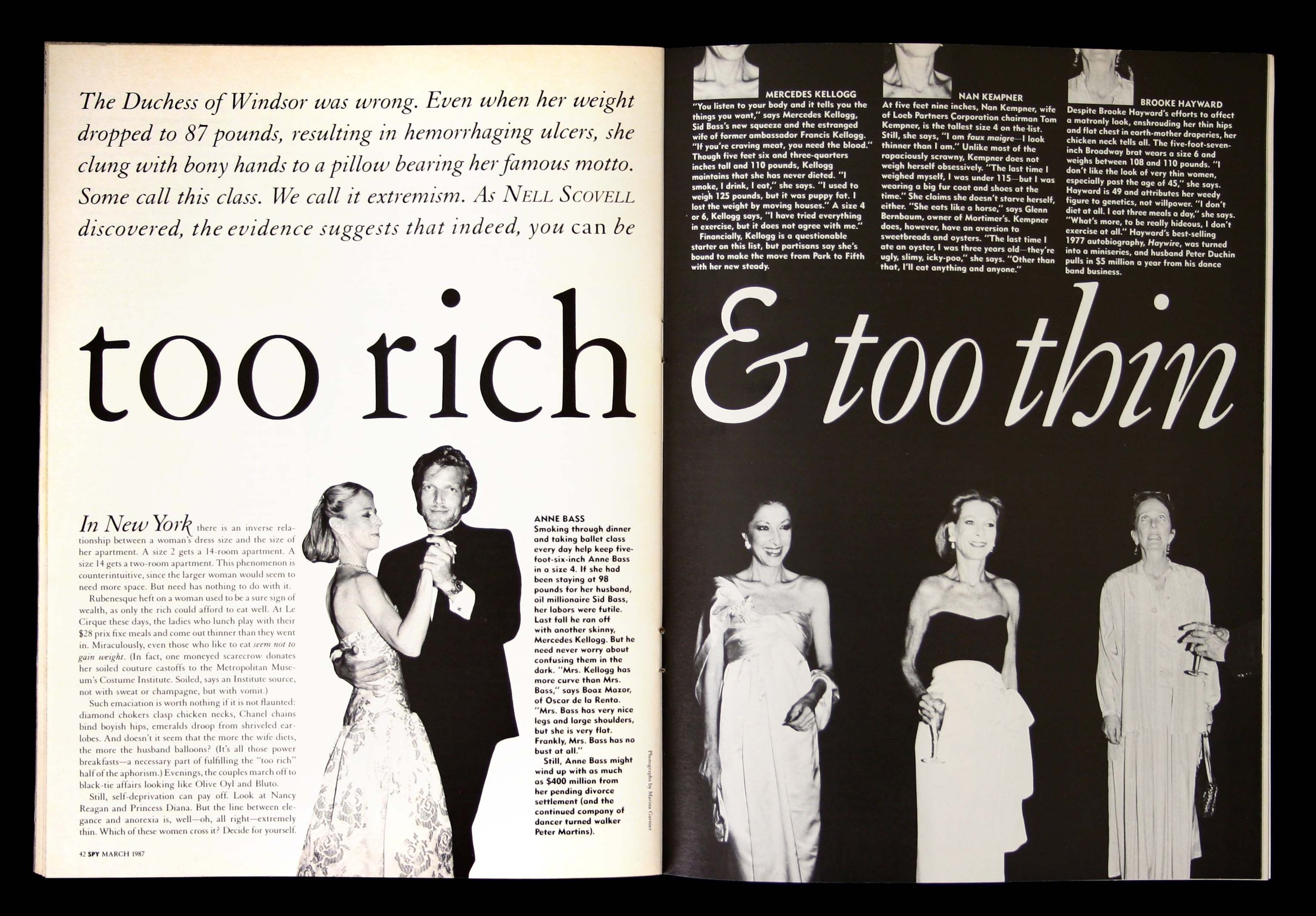

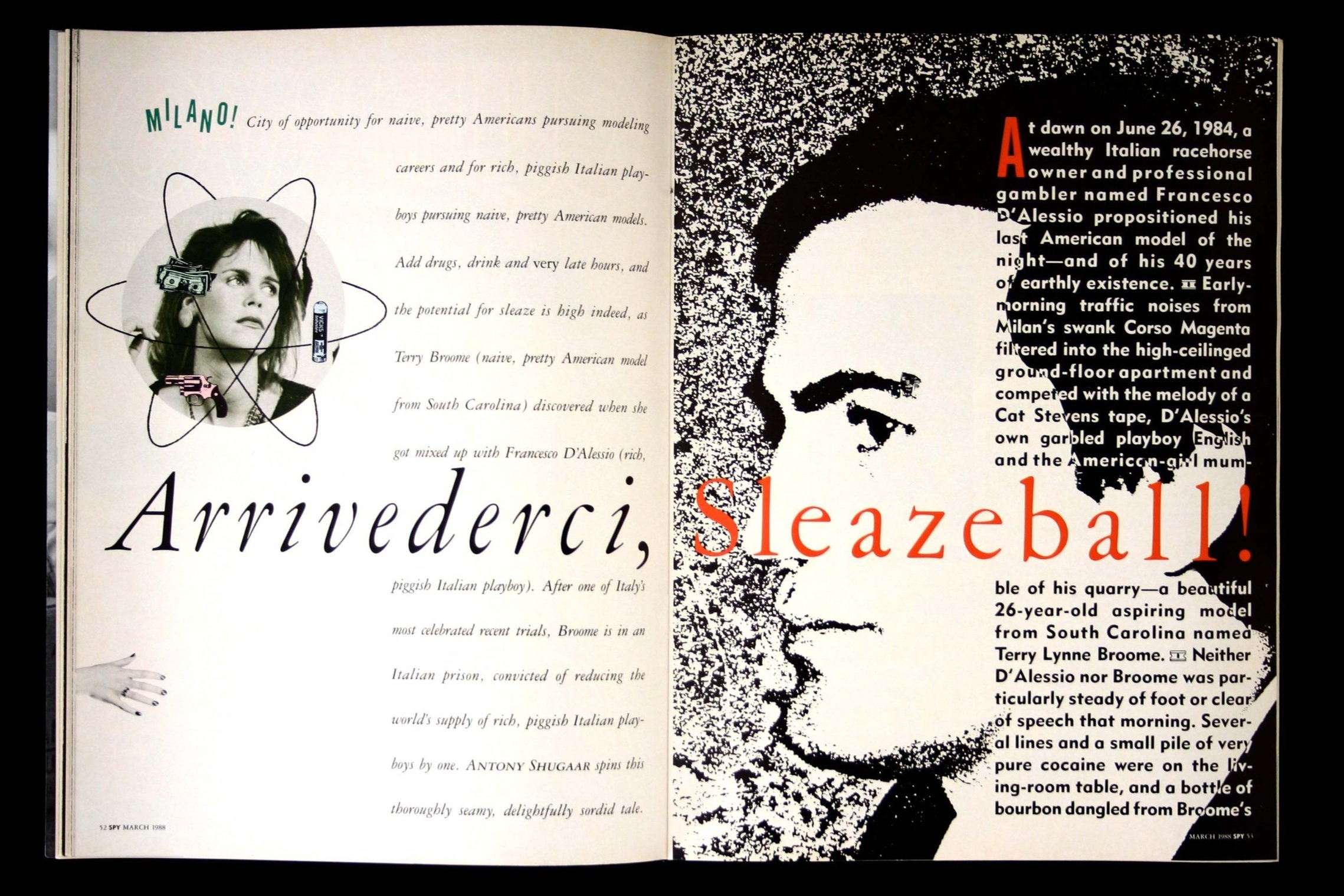

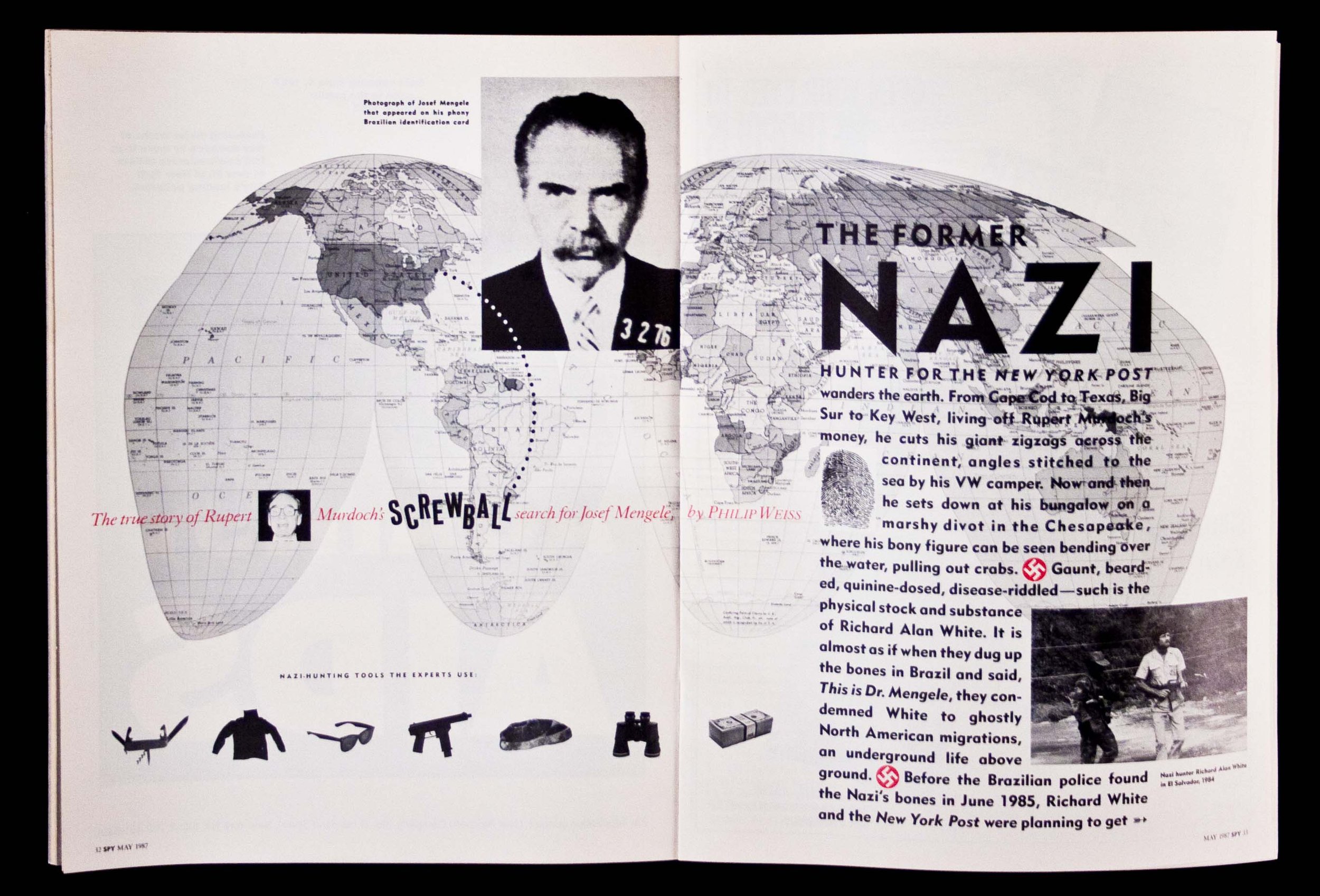

But then, one day, along comes The Greatest Startup in the History of Magazine Startups. A magazine that dares to mercilessly, and humorously, vilify high society. The one that big time journalists pretend to ignore but were first to the newsstand each month to grab their copy. The one that created packaging conceits: Separated at Birth, Private Lives of Public Enemies, Blurb-o-mat, and Naked City. Plus, the adorable nicknames—“Short-fingered vulgarian”—that persist to this day.

That’s right, we’re talking about Spy.

And in this episode we’ll meet Kurt Andersen who, along with Graydon Carter and Tom Phillips, founded what became an instantaneous cultural phenomenon: Spy magazine. The axis of the publishing world tilted when it hit the stands.

“Spy was the most influential magazine of the 1980s,” the author Dave Eggers wrote. “It definitely changed the whole tone of magazine journalism. It was cruel, brilliant, beautifully-written and perfectly-designed—and feared by all.”

There had never been anything like Spy before. Nothing since has come close.

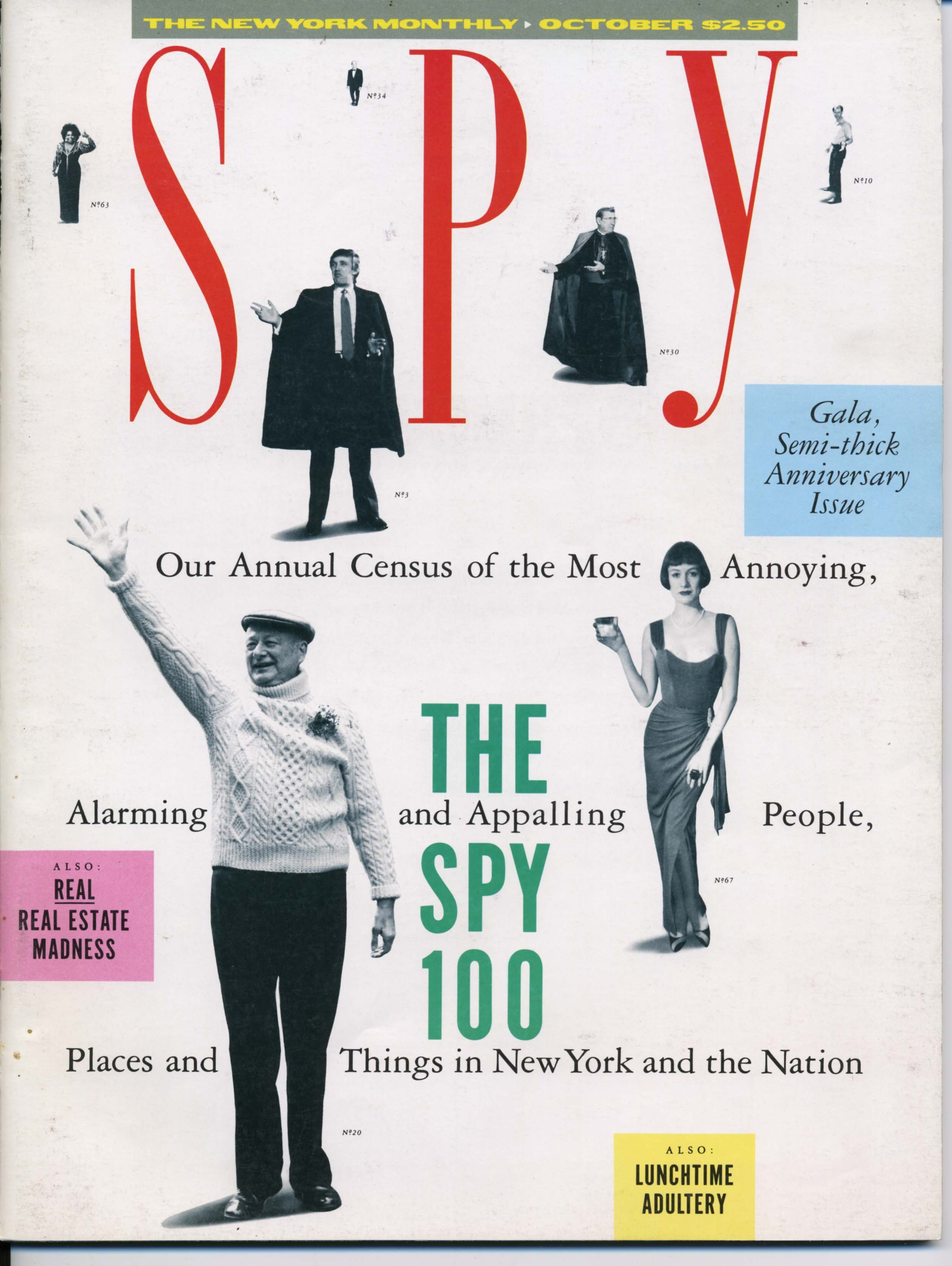

Spy’s premiere issue (October 1986) featured comedian Chris Elliott.

George Gendron: What was the very first conversation you had with Graydon Carter about a new magazine? When was that?

Kurt Andersen: It was probably 1984. It’s my best guess. You know we’d become friends. I’d arrived at Time magazine three years earlier and we’d become very good friends. And it may have been earlier than that, but I distinctly remember some lunches in 1984 where we were talking about this unnamed new magazine that we would love to have. It didn’t begin as a conversation of “Oh let’s start a magazine.” It began as “Wow, we loved magazines when we were young. What do we miss? What isn’t there now that could be?”

George Gendron: Say more about that. What was—from your point of view and Graydon’s—what was the state of the magazine industry at that point?

Kurt Andersen: Well, we were, you know, still young enough to be, like, dissatisfied and want to cause trouble but old enough to have been around enough—at that point you know I was 30, and he was old. He was 35 [laughs], and you know I guess we felt everything was safe and kind of fat and happy and unambitious, and you know basically what I remember in our prospectus, once it became like “yeah, let’s see if we can do this” and started writing it up, one of the terms we used was “literate sensationalism.”

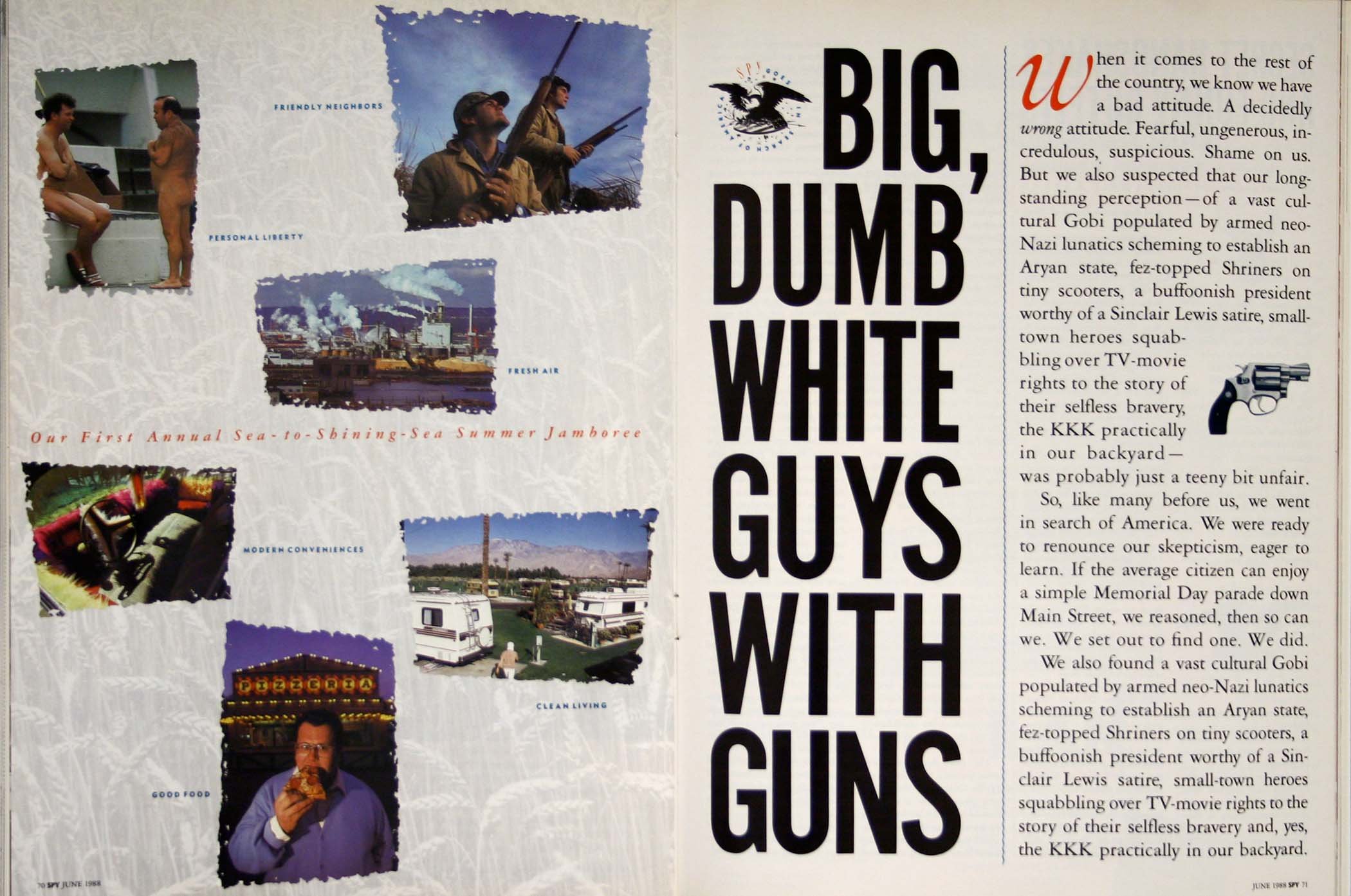

We thought that it was possible to be, you know, well the motto we came up with was “Smart. Funny. Fearless.” We thought it was possible to be smart and thoughtful but no-holds-barred and shocking in a non-ideological way. We’d been around long enough and hanging around with reporters and journalists long enough that we realized you hear all the great stories at the bar, and never see them in print, effectively, and we thought, “why can’t we do that? Why can’t we put them in print?” This was also when there was afoot a kind of humorous ironic comedic zeitgeist change. The Late Show with David Letterman was part of that. Maureen Dowd as a reporter was part of that, and there are other things happening and we were part of that wave I suppose in imagining this magazine that would be both satirical but not in any sense a humor magazine.

Different than Private Eye in Britain, which was a kind of predecessor but very different than what we ended up doing. The old Esquire had been very important to both of us. The National Lampoon back in the day—again, a pure humor magazine and not journalistic at all—that had shaped us and certainly MAD magazine when we were children. Bits of Harper’s and these magazines of the ’60s and ’70s when we were young had sort of made us fall in love with magazines and there didn’t seem to be being done very much. I mean Esquire had its annual dubious achievements awards you know which was creditable and okay, but once a year, a big piece once a year. So we felt there was room to move.

George Gendron: What’s your theory looking back on why magazines were—I’ll use the word ‘bland.’ In the book about Spy one of you was quoted as saying something about the fact that they had lost their edge. They didn’t really have a personality. Was that a response to or a reflection of the culture at large, or was that more to do with the life cycle of individual magazines?

Kurt Andersen: Both, I would say, and also generational. There was something about the Baby Boom generation when they were still young and not yet old. You know, coming of age: I was 30, Graydon was 35. The kind of anti-establishment, fuck-you-ness of our generational sensibility had not really made its way into magazines. In Great Britain I mean there’s lots of things wrong with British journalism and always has been, but there was an ability to kick people in the shins that was lacking in the United States. I mean on the one hand you could say magazines were long in the tooth and old but on the other hand in retrospect I often think that among other things, Spy was representative of or embodied a kind of late “magazine age” thing. Now we didn’t know it was late in the “magazine age” in 1986 because we didn’t know what was about to happen, but in a certain way it was this kind of flourishing of magazines late in the magazine century, if you will.

There was suddenly, starting in 1982, when New York was back and booming and there was money sloshing around because of the bull market, there was a lot of money for angel investors to throw around to enterprises like ours. That, I think, permitted these uppity young people to try to do it in a different way than it was being done by the big Time Inc., Condé Nast entities. Yes, these big dominant magazine companies like Time Inc. and Condé Nast, by their corporate nature, weren’t going to do a lot of risky things.

“The motto we came up with was ‘Smart. Funny. Fearless.’ We thought it was possible to be smart and thoughtful but no-holds-barred and shocking in a non-ideological way.”

George Gendron: What were you and Graydon both doing at the time—were you both at TIME magazine?

Kurt Andersen: I was still at TIME magazine. He by that time had gone to become an editor of a startup called TV Cable Week, which didn’t last very….

George Gendron: Oh my God! [Laughter].

Kurt Andersen: It was a Time Inc. magazine and meant to be a kind of TV Guide of the new cable era, and it was, you know, a big failure—I mean he did his job but was really focused on—once we were really underway trying to start this thing, and we as we've talked about from the beginning we used the infrastructure of Time Inc. The library as it used to be called back then in the nineteenth century, WATS lines for free long distance. We used the means at our disposal to do our little startup in our offices at Time Inc.

George Gendron: So at some point this transforms from a conversation about the magazine you’d both love to read to one that, well, maybe you guys were going to launch this. I’ve been told that you started swapping notes about the magazine.

Kurt Andersen: What made us starting to do that and take it more seriously than just you know, the sixth lunch where we were talking about this larkish thing that we would want, my wife—who was then working at Sesame Street or maybe had just gone to CBS—anyway, one of her friends from college was this guy Tom Phillips, whom she said, you guys need a third person, you guys need a business partner. Let me introduce you to Tom. Maybe you’ll like him. Maybe he’ll be into it. And he was, and he became our third partner and had his business chops—he worked on Wall Street and had an MBA. Having an outsider pushing us to get serious, write some right ideas, start memorializing this and figuring it out: that's really what started making it real.

George Gendron: You know what’s interesting about that: In the industry when you hear the title “publisher” it connotes, “Well he’s the ad sales guy.” And yet, almost every single startup needs somebody who has this kind of infinite capacity to get shit done.

Kurt Andersen: Yes.

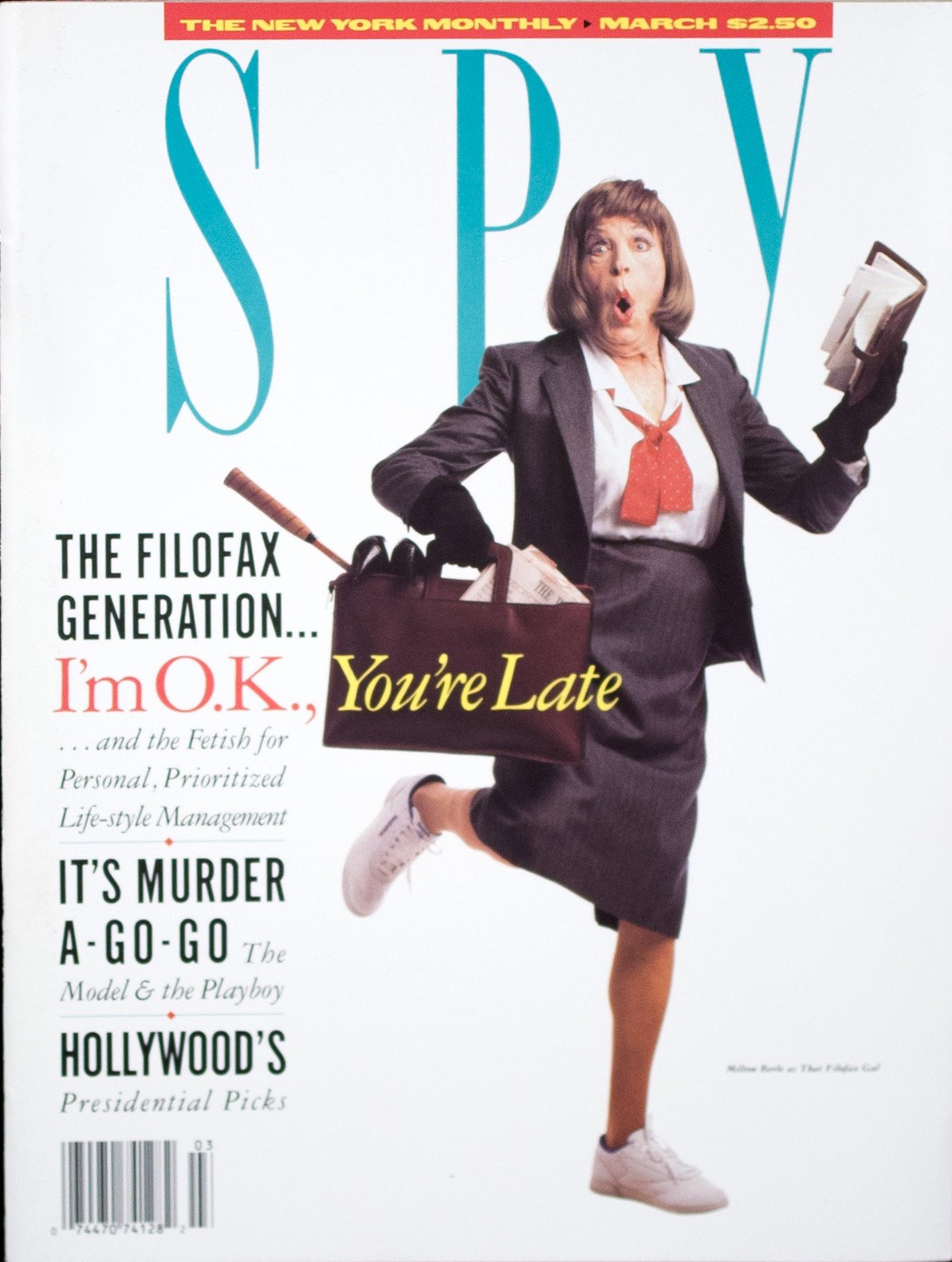

One of Spy’s favorite targets.

George Gendron: And to get other people to get stuff done. It seems as if that was the key role he played for you guys.

Kurt Andersen: It was a very key role. It made for a complementarity, of yes, we were two buddies and pals and the creative whatevers. To have this other person who could do the stuff and set up the meetings and raise the money and all that, and who loved, who liked us and completely shared the mission of the thing. He wasn't at it because it was a job or you know, he was in it. We created a little cult, right? Well it was. It was a mission-oriented operation and he wasn't really the guy who sold ads that much. He was everything else. As we were starting we realized, well we need somebody to sell ads. He/we hired my wife, Anne Kreamer, to be the ad director/marketing director and she in that sense along with our early editors became a kind of co-founder.

George Gendron: What when it comes to selling where are you on the spectrum? A lot of creatives just don't like to sell. They don’t mind going into an environment with a client or an agency where they’re going to talk about the market or the culture at large, but…

Kurt Andersen: Yeah.

George Gendron: Man, we don’t like asking for the business. We don’t like closing a deal, God forbid.

Kurt Andersen: No. Again, my wife was the person, so we were able to work it out pretty well. I remember once actually we’d gone on to St. Louis to sell Anheuser-Busch and we didn’t announce that we were married. We have different names, and at the end somebody said, “Wow, I have never seen an editor and an ad director get along so well, and be in such synch.” At that point we admitted it.

But you know I didn’t go out and sell. I was happy to show up and be interested in this business or whatever at the appropriate time, a kind of pre-closing appearance. I was totally happy to be used that way, and so was Graydon for that matter. And of course raising money was the first important series of selling the thing.

George Gendron: Where’d the name come from?

Kurt Andersen: It was Graydon’s idea and it was from the play and film The Philadelphia Story, in which Cary Grant, no, Jimmy Stewart, works for Spy magazine. You know Graydon always wanted to live in the 1930s and ’40s, and that was another way we could do it. That’s where it came from, and you know it worked out great and, among other things allowed us to have it be a gigantic logo on the cover. That was entirely his idea.

George Gendron: It broadcasts a certain kind of attitude that the title TV Cable Week just doesn’t.

Kurt Andersen: [Laughter] Although unfortunately may you know there were always people who thought it's about espionage or it's about intelligence. No, but occasionally it was.

George Gendron: That’s absolutely true. It’s interesting that in The Funny Years, the book about Spy, reading the excerpts that I think are all Graydon’s and the notes he was sending to you. You guys got to a certain point where it seemed as if the conversation about this new magazine was all about style, attitude, intelligence, sensibility.

Kurt Andersen: Sure—on top of a commitment to rigorous reporting and research.

George Gendron: Well, that was my next question. Where did that come from—this unbelievable, almost maniacal focus on reporting? The reason I ask, here’s why it’s of interest to me in particular: I was at New York in the early seventies and I was really struck as I moved through my career how influential the new journalism was among young journalists who somehow misinterpreted it and didn't understand that the foundation of this was a kind of relentless reporting and attention to observational detail. I mean it was just extraordinary. And when I think about that, the other magazine that I think about was Spy.

Kurt Andersen: That’s nice. Well, the new journalists, I mean Norah Ephron, Joan Didion for that matter, Tom Wolf, Gay Talese, all of them, obviously, were reporters first who also had these amazing sensibilities and prose styles.

George Gendron: In both of your magazines you began to realize quickly those details matter, that they broadcast something about the characters of the stories.

Kurt Andersen: Yes, and because it was satirical, right? We were making fun of people. We wanted it to stick. We didn’t want it to be, “Oh yeah, that was a funny joke about this person.” “Oh that was a funny nickname for this person,” or whatever. We wanted to have an impact, you know, and you only do that by giving new information. Yes, in a new way, and yes stylishly, and God knows I think our art direction was a key to the whole operation in a big way. But yeah, it was reporting driven, and again that was what was new. I mean people were familiar with humor and satire, The National Lampoon, but that combination was rarer. Although one of our predecessors that nobody realized certainly back then, but we had, because we’d look back at old magazines: The New Yorker back in its beginnings, not right at the beginning but like Walcott Gibbs in the ’30s. Those were Spy stories, essentially, that they were doing.

“We were making fun of people. We wanted it to stick. We didn’t want it to be, ‘Oh yeah, that was a funny joke about this person.’ ‘Oh that was a funny nickname for this person,’ or whatever. We wanted to have an impact and you only do that by giving new information.”

Spy’s founders (from left): Tom Phillips, Andersen, and Graydon Carter

George Gendron: That’s a good point. You talked about the zeitgeist earlier but I want to come back to it in a particular way, which is you guys managed to go out and raise, I don’t know, roughly $3 million dollars in angel money.

Kurt Andersen: Yes, ultimately I think that’s right. We raised a million and a half to begin with. I don’t know what that is today, maybe three.

George Gendron: What interests me about the angel money is that it came from very conservative sources. The heirs of Merrill Lynch, Coca-Cola, ConAgra. I mean one of the big Wall Street firms….

Kurt Andersen: … You’ve done your research.

George Gendron: I have done my research [Laughs]

Kurt Andersen: Conservative, not in that they are political conservatives.

George Gendron: No, I didn’t mean it that way.

Kurt Andersen: It was yeah, you know, rich people we happened to know, for whom $50,000 was not a huge deal, especially four years into this new bull market. They were mostly friends of ours. Especially Tom's and mine, and a little bit from my parents as well, but again a little bit, I mean they’re not rich people at all. So yes, conservative in the sense of one’s parents in Nebraska? Yes indeed.

George Gendron: It also says something about the last days of magazines having that kind of cachet for people.

Kurt Andersen: Oh for sure, it and I think in a way we again, by sheer, fortuitous chance, we locked into doing this at a moment of maximum glammyness of magazines as a thing, right?

George Gendron: Yes.

Kurt Andersen: Vanity Fair had been revived-slash-started in 1982 I think and yes, magazines were a glamour… in some ways the most glamorous part of the glamorous New York media industry at that moment.

George Gendron: Having run Inc. Magazine for decades, I have to ask what did you guys take around with you when you were pitching investors? Did you have a prospectus, a business plan, a prototype?

Kurt Andersen: We had all those things. I mean the prototype was six boards of, “here’s how it will look, here’s what the covers will look like,” but yes, a prospectus and somewhere in some archive I still have that. We had a business plan as well, and like all business plans, it was fiction. But plausible fiction. [laughter]

George Gendron: Do you still have a copy of it?

Kurt Andersen: I don’t think so. Tom Phillips probably does, but I do not.

George Gendron: I’d love to take a look at that. I love looking at old business plans.

Kurt Andersen: Again it wasn't crazy and the business as conceived and in the business plan was modest. Our initial subtitle was “Spy, the New York monthly.” We weren’t trying to be a national magazine. We really saw in our direct mail—we sent out direct mail, I guess maybe there’s still direct mail—we sent direct mail, junk mail and tried to make it funny and compare ourselves on this little card to The New Yorker and The New York Times. We thought of ourselves as the little scruffy commandos in New York, my real point is that we wouldn't be a national magazine and sell a million copies. We thought no, we’ll be a New York magazine. I don’t know what we projected as circulation but I’m sure we exceeded it. I’m sure we didn’t say, “and we’ll have 300,000 circulation in three years”—and we did.

George Gendron: Yeah, that was extraordinary. So you guys raised some money and then you go out and you rent an office in, appropriately-enough, the Puck Building.

Kurt Andersen: It’s funny: Even when we were just still talking about it and dreaming about it and Graydon and I were having lunch—we would have lunch in Times Square and play the video game Asteroids in one of those Playlands after lunch—and then we’d walk back to Time Inc. and I literally remember looking up, we were looking up at buildings and we looked up at one old building and one of us, probably Graydon, said “you know that’s the kind of place. We could have these offices for this magazine and it will be like our clubhouse.” I’m not even sure we knew about the Puck Building at that point. But as soon as we discovered it—it had recently been renovated and there weren’t many tenants yet and of course it was the home of this famous satirical magazine a century earlier—but as soon as we saw that building, and it was in Soho, but a kind of grungy edge of Soho, and it was a beautiful little building, and it was just kismet. We had to be there, and it was cheap. It was super cheap.

George Gendron: Not anymore.

Kurt Andersen: Not now that Jared Kushner owns it. Although recently I discovered—I didn’t realize it then—that Jared Kushner’s father was already an investor in it when we were there, which adds something to my retroactive amazement of my various connections with Donald Trump and his family.

George Gendron: Boy that’s ironic, isn’t it? I thought the Kushners were a relatively recent ownership group.

Kurt Andersen: Me too. They weren’t the owners then, but they were part of a group, right around that time we occupied the Puck Building when the future inmate, Mr. Kushner, was part of the investor group who owned it.

George Gendron: Boy you just can’t kick the habit, can you Kurt? It might interest you and your wife to know there’s a nice, tidy little penthouse for sale on one of the top floors of the Puck Building for a mere $42 million dollars if you’re feeling nostalgic.

Kurt Andersen: It’s funny when they opened that and Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump were the doyens of that whole operation. I don’t know if it’s their apartment, but you know Spy was I believe on the eighth floor, and it was nine floors. So I always wonder: are they living in my office now? Yes, indeed I’m aware of that availability.

George Gendron: Did you guys go into the office every day?

Kurt Andersen: No, we worked remotely. Yes, of course we went to the office every day!

George Gendron: I was just curious about work habits back then, especially for our younger listeners.

Kurt Andersen: It was the hardest job. I mean you know TIME had had its hardness, two nights a week, but man no, we worked. We worked long, hard hours, absolutely, and it’s interesting I felt like I was working every waking hour, but we didn't go into the office much on weekends. But yes, we worked hard. We went to the office you know, showed up whenever we showed up at 8 or 9 and were there till after dark.

George Gendron: Was it what we would call a newsroom-ish environment? Open?

Kurt Andersen: Yes, it was an “open plan,” which we never called it, but it was just a big loft with some cool partitions that our architect friends had put up. It was three-thousand square feet with an increasing number of people just running around screaming at each other in sight of each other all the time. It was great.

George Gendron: Yeah, now we’re getting to something that really interests me, which is the relationship between spaces and how people end up working. I got so hooked on the newsroom at New York, particularly in the old 32nd Street building, which eventually became the Pushpin building. There was just something about that kind of energy and buzz, when you could have all these conversations. I had been the mail boy there, and when I moved up to the newsroom I felt like, man, I could just sit and listen every day.

Kurt Andersen: A hundred percent.

“[Spy was] a scary, fun thing that pretty soon was getting a lot of attention and enthusiasm among readers. We had invented this thing that took a lot of work to do, and we wanted to do it, and so did the art directors and the fact checkers and everybody. It was a labor-intensive labor of love.”

George Gendron: What a way to Iearn.

Kurt Andersen: It’s funny that you mentioned New York because when I went on to New York after Spy, at a different location on 41st Street.

George Gendron: Yes, by the Daily News.

Kurt Andersen: Exactly. There was the editor’s office, which I occupied. It was this big, closed-off, wood-panel thing. I kind of hated that. At one point I proposed, “Can’t we just tear down this wall down here?” But I totally agree. I don’t want to be the old fogey, but it was great back then because nobody wore headphones or earphones and they actually talked. It wasn’t all these Dilberts in their cubicles just typing away alone. There was a communality by the nature of not having…. I mean we had computers, and that was avant garde in 1986.

George Gendron: Boy was it ever.

Kurt Andersen: But it was a lively office culture. As you say, “newsroomy,” in which everybody experienced together all the time. It was great.

George Gendron: One of the other things I loved about it was at least the illusion—and it might have been an illusion for a young kid—that, man, it was hard to keep a secret in a newsroom. Everybody knew everything.

Kurt Andersen: Yes, it was hard to keep a secret. It just occurred to me not only did we have a serious work ethic, for a magazine that was mean. I remember when The Wall Street Journal of all places accused us of being too mean. It was the opposite, mostly, in the office. It was a very collegial, happy band of sisters and brothers, which was an important part of this scary operation we were doing.

George Gendron: I’m really curious: Where did story ideas come from?

Kurt Andersen: All the usual places, which is everywhere. We had regular—I don’t even know how often—frequent editorial meetings, often with lunch, and we would just gather around and bring in sandwiches. The 15-person editorial staff would gather around a table and say, “I have this idea,” or “I have this.” They were such magnificent, wonderful, exciting meetings, and Graydon and I were in charge but it was a pretty democratic, jazz-like, improvisational thing. It was wonderful. And having had a subsequent life of going to meetings that weren't so fun or exciting or jazz-like, it’s one of those things that in retrospect I certainly realize man, I didn’t know quite how good I had it.

The editorial meetings were how people understood what it was we were doing, which they didn’t at first. One of the reasons—I’m sorry I’m digressing—we did so much editing, from the beginning it was a highly edited magazine, was not because we wanted to piss on everything or get our hands on everything but because what we were doing was a new thing that we couldn't point to something and say “It’s like this. Do it like this.” We had to be around for six months or so before writers, let alone everybody else, could say, “Oh I get it. I get what you're trying to do.”

When you said it was about sensibility and style and all that—we certainly had a house style or a set of house styles for sure—but it didn’t begin with that. We had a vision and then it took a while for the rest of the world and our staff and outside writers to sort of come along.

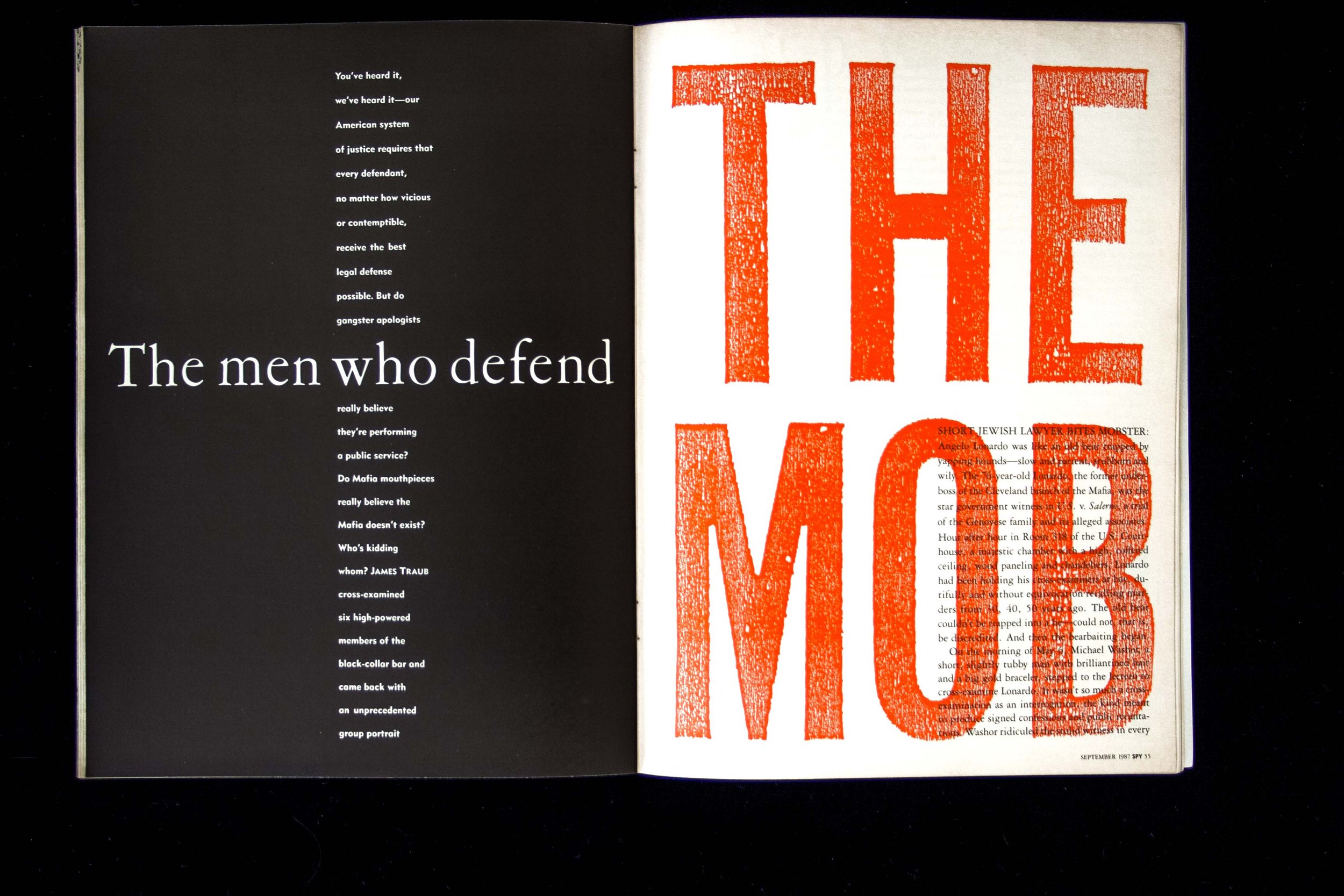

George Gendron: One thing that was absolutely remarkable for me as a reader was that there was more going on per square inch on a page of Spy than anything I had ever seen before. It was literally a conceptual miracle. On the other hand I kept thinking how in God’s name do you guys do this without just burning out?

Kurt Andersen: Well I take that as a great compliment, and many of my friends at magazines at the time were also struck by it. Especially if you do that for a living, you are aware of how much person-hours per square inch that went into this, and I mean we didn’t have any bosses, right? We were working for ourselves doing this. A scary, fun thing that pretty soon was getting a lot of attention and enthusiasm among readers. We had invented this thing that took a lot of work to do, and we wanted to do it, and so did the art directors and the fact checkers and everybody. It was a labor-intensive labor of love.

George Gendron: I was reminded of that when recently I re-read The Funny Years, because that book captured that same sense of layer-after-layer-after-layer kind of editorial conception.

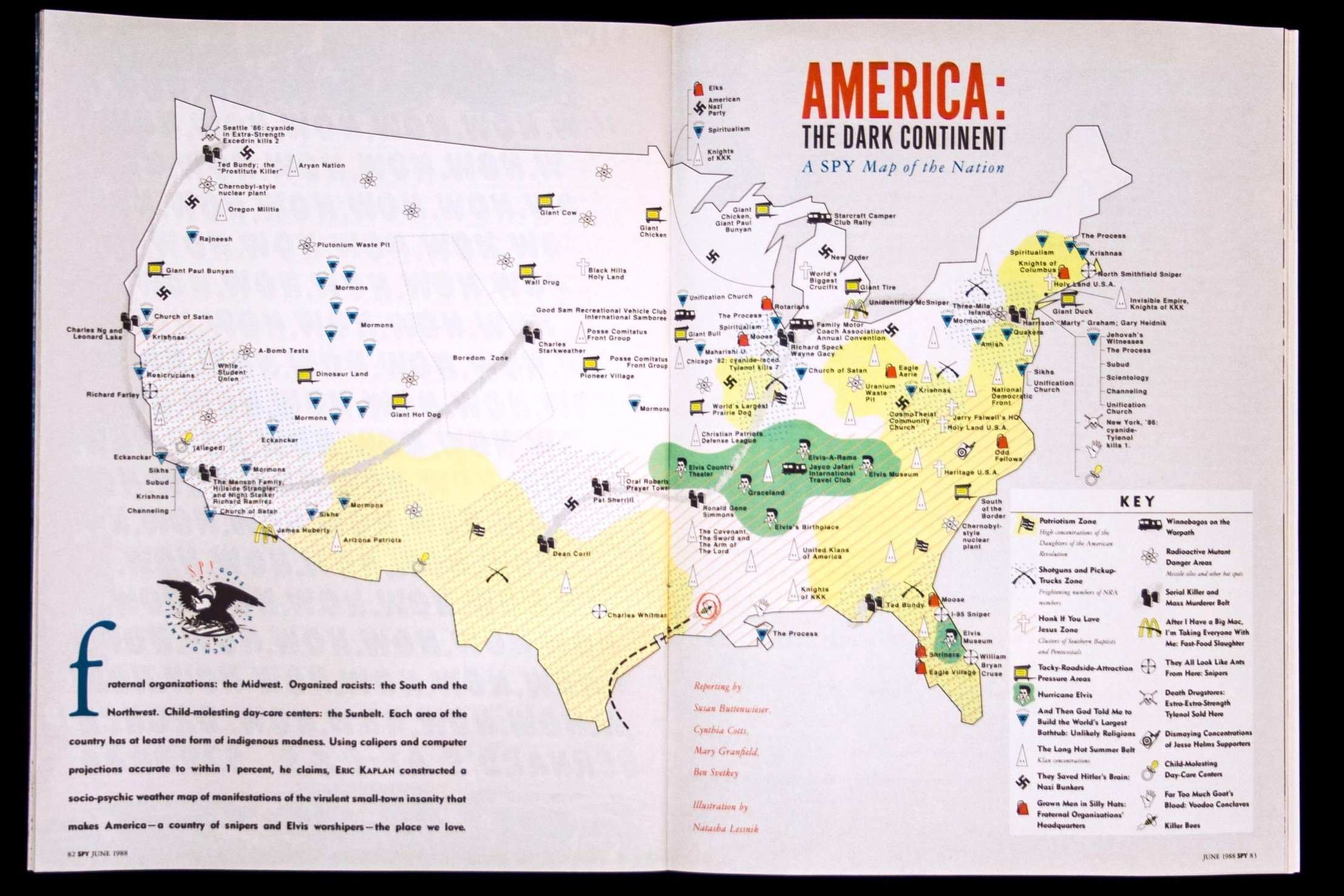

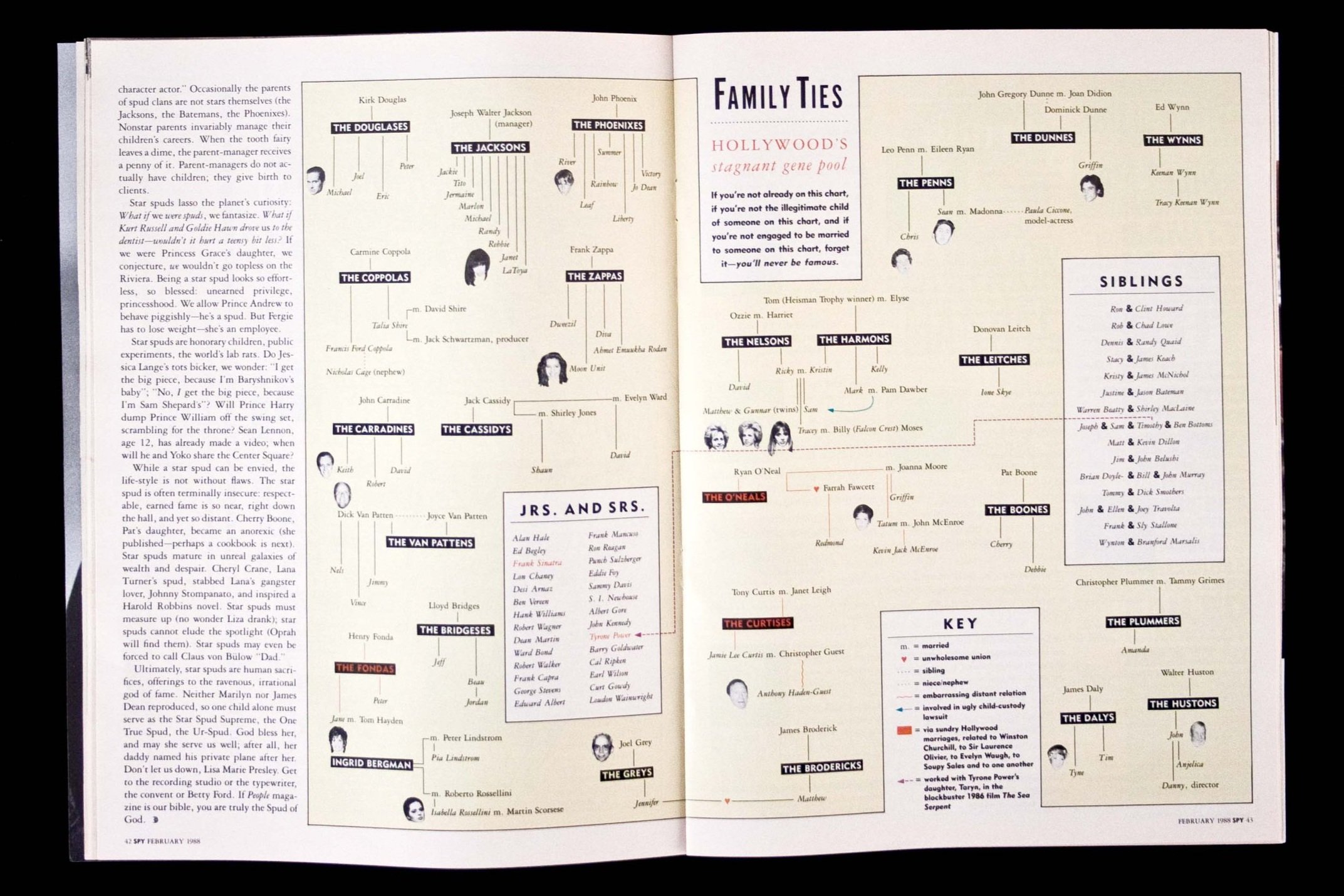

Kurt Andersen: That kind of highly-layered, fussed-over, even Mannerist version of a magazine that we did owed something to our childhoods as MAD Magazine readers. There was all those little marginalia. Together with coming of age to some degree at TIME magazine and all the infographics and charts and stuff and sort of doing that, but subverting it—and doing it without a staff of 500.

George Gendron: Exactly. So eventually you guys hire Stephen Doyle to design the magazine. Had you and Graydon, or you or Graydon, highly visualized the magazine before Stephen came along?

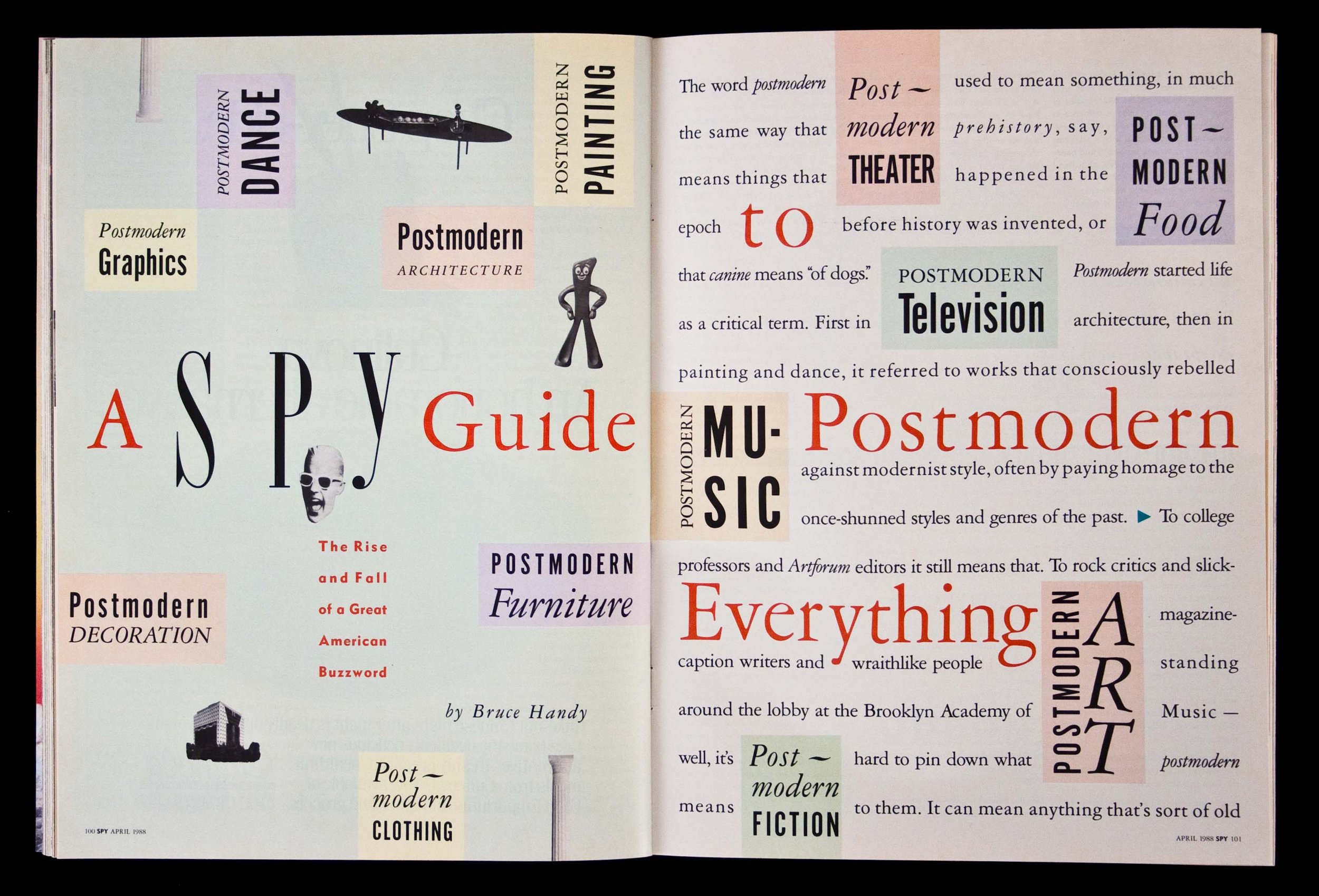

Kurt Andersen: In very basic ways. We had a notion—well, no, Graydon certainly had a notion—that it should have a classical and traditional look because again it was: How did magazines look in 1940? The logo in a certain way bears that out. It wasn’t as though Stephen Doyle just showed us, “No, it’s this.” As one does when you’re an editor working with a very skilled and talented art director, you iteratively go back and have conversations about what there should be and we realized that we wanted it to be, dense and a little strange and a little singular.

But because it was this weird, satirical, edgy thing, we didn’t want it necessarily to be—we liked the idea of it having a certain amount of traditionalism and rigor in various ways. In the end, the art direction was not traditional by any means, although there were these drop cap flourishes and there are bits of traditionalism within this sweet, generous madhouse of possibilities that Steven and his successor Alex Isley invented.

George Gendron: I still find it hard to explain when I’m talking to a journalism class about the impact that you guys had on the look of magazines. In the late ’90s. I hired Drenttel Doyle to redesign Inc. Magazine, and when I went down to their studio and saw the first round of roughs I swore—and Stephen can attest to this—that I could still see vestiges of Spy, and they looked as fresh then as they had a decade earlier.

Kurt Andersen: Well it did have an impact, which was no credit to us except that we made it a good magazine. Yes, ten, twenty years later—even today—when I see these funny charts with silhouetted heads decorating them, I go, “Well, we invented that.”

George Gendron: Yes, that looks familiar…

Kurt Andersen: And in a weird way I jokingly say we invented the internet or anticipated the internet. There’s some anticipation in some of the things we did like these massive connect-the-dot charts and infographics. Because the internet came along while we were doing it or right after we stopped doing it, there was a certain amount of “Wow we want some way to connect all these disparate things and deliver it with this you know satiric sensibility: I mean, the internet.”

George Gendron: Yes

Kurt Andersen: So as it turned out there was there was some kind of proto-internetty quality to much of the of the graphic design, but also just using old photos because they’re dated and the models look funny because they’re from the sixties—again that was just brilliant art direction that Stephen and Alex and others put in there. That helped a lot, too. If it just looked like The Atlantic or Harper’s or The New Yorker but was the same thing, we wouldn’t have had near the impact.

George Gendron: I agree with that completely. Speaking of Stephen and Alex, they both happen to be alums of M&Co., Tibor Kalman’s firm, and I’m curious was that part of what attracted you to those guys I mean it’s hard for people, who forget just how sexy M&Co. was back then. I don’t think there’s anything comparable right now.

Kurt Andersen: Well, there’s Stefan Sagmeister, you know? But Tibor and M&Co. were an amazing thing during his time of efflorescence. It was extraordinary. Frankly, we were not that deep into the graphic design world yet, so we didn’t know Tibor, we were not part of the M&Co. cult yet. But as soon as we hired Stephen and Drenttel Doyle, and then here’s a guy—in the case of Tibor, independently of us. We were working in adjacent lanes in the use of vernacular bits and pieces and the combination of the extreme freshness and mischievousness of it. Yeah, definitely. Fortunately before he died in the ’90s he became one of my best friends.

George Gendron: It’s interesting that when you think about all the talk about human-centered design these days, it puts how far ahead of his time Tibor was—not just in terms of his design style and his antics but his values.

Kurt Andersen: Yes, totally. He could be serious and he could be earnest and all that but, in doing it in a kind of fun way. Misbehaving in a serious way. He wasn’t a yippie—he wasn't just trying to tear it down for no good reason. He combined virtuous intent with a sense of fun and glee.

George Gendron: Not unlike Spy.

Which is why, once we finally met and got along, we talked about starting magazines actually in the late ’90s. We had a couple of different ideas for magazines we wanted to start.

George Gendron: And you guys were both eventually associated with Colors, Benetton’s magazine.

Kurt Andersen: Well, he created it, and I came in near the end to do it for a year and a half.

George Gendron: I’ve spent most of my professional life exploring and documenting entrepreneurship and creativity, and it’s always struck me that many of the most original, edgy, fresh ideas emerge from environments characterized by resource scarcity. When you don’t have capital, you have to invent, you have to be resourceful. You have to substitute ingenuity for financial capital. Was that true at Spy?

Kurt Andersen: Yes. Absolutely. I agree with you both in theory and in my experience. But we didn’t have nothing. We weren’t a zine. We had a million and a half dollars, and then at a crucial time once we were successful but didn’t have enough money to go on, we got another million and a half. That’s a lot of money, that we husbanded a lot. But yes, what I think is not that the less money the better, depending on what you're trying to do, but there is some optimal amount. It wasn’t Portfolio, which was a fine magazine, but not a magazine where having all the money in the world necessarily helped it.

George Gendron: Well at a certain point too much money becomes kind of toxic.

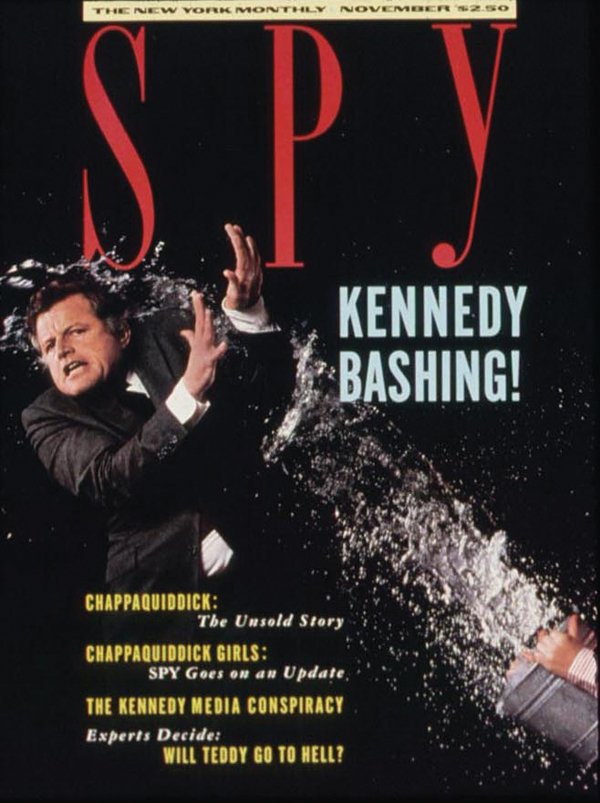

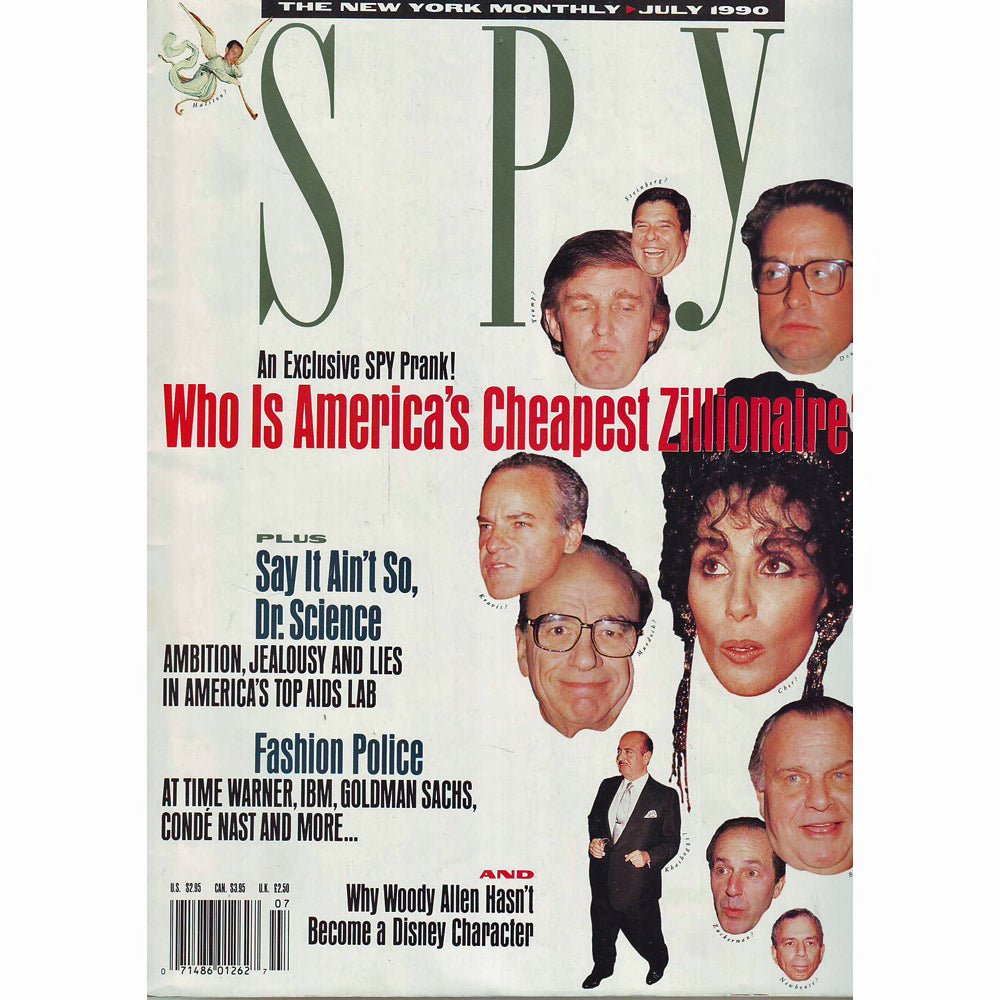

Kurt Andersen: Yes indeed. At a certain point—1988 or 1989—we were able to spend. I would like to go back and look how much we spent on this incredibly expensive, mind- blowing computer—essentially what you can now do in Photoshop—I can’t—but little kids can—we spent thousands of dollars to have a cover of Ted Kennedy having water thrown on him, or whatever it was. So we picked our places to spend a lot of money. We didn’t pay writers very much and we didn't pay ourselves and our staff that much. But whoa, if we can do this amazingly realistic-looking fake—obviously fake—photo cover, then yeah, let’s spend a couple or three thousand dollars or whatever it took. But it was like, literally, like a mainframe computer that was required to do these things.

George Gendron: On a more mundane level, I’ve always wondered how much cost you guys to put together the chart that documented every CAA client in Hollywood?

Kurt Andersen: That wasn’t so much money as sheer sweat and blood and tears. They were this incredibly powerful, all-powerful Hollywood agency that was suddenly the force in Hollywood, but there was no list of who they represented, so we thought people would like to see that. So that was a matter of like a gazillion hours of very poorly paid researchers digging up in every way possible who were the actors and writers and directors they represented, and then we just published the names. That’s all it was. It was just publishing the names on two or three pages.

That single thing as much or more than any of the regular monthly coverage, news or columns or exposes we did on CAA—they were a real focus of ours—that completely freaked Mike Ovitz, who ran it, and them out: “This is the secret we’ve been able to keep, and this little pipsqueak magazine exposed it?” That really set them off, and what a pleasure that was for us to get such a rise out of these big powerful grownups.

George Gendron: With a chart. A list.

Kurt Andersen: Of course. I loved maps as a little kid and I loved charts and I still do.

George Gendron: But it also displays a certain kind of editorial restraint. I could imagine other publications building an entire special issue around that—the Hollywood issue.

Kurt Andersen: Well thank you. It’s true. In that sense, the person-hours per square inch may have been at the maximum. I don't think of it as expensive but of course in some sense it was expensive.

“[Graydon and I] were extremely, in every respect, very complimentary. We were pals, but we were very different people. We all have blind spots and we pretty successfully covered for each other’s blind spots, and we made each other laugh. We intrigued each other. We interested each other. It was a fun, buddy-comedy partnership.”

George Gendron: We’ve got to talk for a second about you and Graydon, because in a way you defied all the odds about the conventional wisdom which is you can’t have co-editors. You can’t have co-CEOs. You can’t have co-directors. It never ever works. I know venture guys who basically say for them that’s a deal breaker. Two guys come in and they can’t answer the question who’s accountable, who’s in charge here. And you did it. I love the quote, I think it was Graydon’s, who said, “Between the two of us we make one great editor.”

Kurt Andersen: In retrospect it is amazing because as you say everybody says, “No you don’t do that,” and there was no precedent… “Oh, we could be like them.”

At that point there weren’t even these brother director teams who made movies successfully. We were extremely, in every respect, very complimentary. To Graydon’s point, we were pals, but we were very different people. We all have blind spots and we pretty successfully covered for each other's blind spots, and we made each other laugh. We intrigued each other. We interested each other. It was a fun, buddy comedy partnership.

George Gendron: How’d you handle it if and when the two of you had what might appear to be an irreconcilable difference?

Kurt Andersen: While we were doing the magazine, I literally can’t remember any such thing. In the startup period there were some moments when there were harsh words. I don’t even remember what the arguments were about but there were some moments, tough moments, and then when we were, you know, selling it. There were some inevitable differences of opinion about how that should go or whatnot. But for the five years we were doing it together, I don’t know, through our fondness for each other and for what we were doing we just got along almost without exception.

George Gendron: That’s really extraordinary. Are you guys still close?

Kurt Andersen: We’re still pals. We don’t go into the office together every day, but yes I still talk to him and communicate with him regularly.

George Gendron: One of the things I find really interesting and remarkable about your career is not just the quality of what you produce but that you’ve produced creative work along a spectrum—from books, which have got to be one of the most solo-intensive creative projects imaginable—to a radio show, which is sort of in the middle of the spectrum, to magazines, which we’ve been talking about. I’m curious to hear where your passions lie when it comes to actually doing the work for these different kinds of projects.

Kurt Andersen: You’re right. Magazines, and everything but books in a certain way, are highly collaborative enterprises. Doing Spy was intense and scary and I felt like I was attached to some giant generator all the time. Not that it aged me but it was just intense, and having this team of people to do it with was such a delight. Frankly because I've never been a natural reporter—I have done it, I can do it, but it isn’t really my happy place—but having ideas for some outrageous story that I can just then ask somebody else or order somebody else to do, that was my ideal. That was fantastic.

And I liked that at New York. I think being a magazine editor—I had not been a magazine editor before I started Spy and then I did New York and then that was the end of that. I think 10 years of doing it—and it was a completely pleasurable 10 years of doing it—was about as much as …. I lucked out. Another of the many ways that I’ve lucked out.

It was like, “Yeah. I didn’t have to, you know, work my way up. I got to run two magazines, and then I was done.” And that was fantastic. And I don’t think I’m a great boss. I think I was an okay boss. I don’t think I was a bad boss. But managing people is not my favorite thing in the world to do.

George Gendron: Oh my God, tell me about it.

Kurt Andersen: You know hiring and firing all that. If you like the thing you’re doing, as in my case, you put up with the managing of people. Once I said now, the rest of my life—didn’t say the rest of my life—now I’m going to write books and novels—and maybe that was a function of being you know 44, when I started being a book writer I was completely, temperamentally highly suited to sitting alone in a room all day. Maybe because I had gotten the ten years of incredibly intense collegial teamwork out of my system.

George Gendron: Yeah, that makes sense. I'm curious. Indulge the print romantic in me for just a minute. What is it about the effect that magazines seem to have on people that makes them so distinctive?

Kurt Andersen: It’s funny, you use the present tense, I guess that’s still true. A bunch of things. Certainly now, in the digital age, the artifactual nature of them is lovely, but it was even before, when it wasn't that big of a deal because everything was physical … a well-made and in in some cases creatively ambitious object of magazines, and we did try to be physically, creatively ambitious with fold outs and maps and bind-in tattoos, and all kinds of stuff. I think that is appealing but I think what is lost pretty much entirely in the digital format is this sense of here is an authored thing, of this week or this month or this quarter or whatever, that is all put together for some set of reasons, and the mix is chosen, and it’s all made. It’s a thing. It’s not an ocean.

It’s not a bit of stuff floating in a sea of the internet. It’s this thing that the editors, for better or worse, successfully or not, have chosen to put together in this way right now. That sounds like “Well yeah,” but that doesn’t exist anymore.

George Gendron: Yes.

Kurt Andersen: And it can’t exist in newspapers, physical or not. I mean the newspaper has never been that because it's this daily thing. A magazine—weekly, fortnightly, monthly, whatever—was “what should we put together this week or this month to do this thing and give it this cool poster,” as I always thought of covers. I think from a reader’s point of view, a consumer's point of view, it’s something more like reading a book.

A book is a relationship—if it’s a good book—it’s this intimate relationship with you and the author and every word she or he chooses or every sentence and how they do it. Magazines have that in a way—individual pieces can be as brilliant as ever online, as they were in magazines. But it’s the collection of them to some larger purpose or expression of sensibility or whatever a given magazine is trying to do.

George Gendron: I think that’s true, and I think that’s also related to so many people that I’ve grown up with, obviously magazine people, often look at their experience, particularly creating a magazine, and say, “That was the best job I ever had.” There’s something about that level of intense collaboration…

Kurt Andersen: Yes.

George Gendron: …with an actual artifact, at the end of the day, something tangible. You can hold it in your hand.

Kurt Andersen: Totally. And I also think that I and other editors and writers tend to have different metabolisms. You can do a daily thing. You can do a quarterly thing. Or you can do a weekly, you can do a monthly. But I knew from early on, after my one day as an employee of the New York Daily News, that daily was not going to be my metabolism. It just wasn’t. Weeklies are exciting, but a monthly, back in the day, when you didn't have the twenty-four/seven gush of news on the internet and cable television, a monthly was possible. But in the digital age monthlies weren’t the first to go necessarily but they were the first to be rendered like: What? Why do we? A monthly magazine? There are still ways to do it, and there are still good monthlies and they figure out ways to do it.

But before the internet, a monthly was an opportunity to do a certain kind of thing that just can’t be done now. I mean yes, The Atlantic does a brilliant job of being a monthly magazine, but it’s all about, you know, the stuff they do every day.

George Gendron: Yes

Kurt Andersen: Not to say, “Well those times are gone forever,” but they are. In addition to this more fundamental thing, as we talked about, this “authored object” that the internet really just cannot provide.

George Gendron: I remember from the time I was relatively young when monthly magazines would arrive in my house and later when I was on my own in my apartment. When my favorite magazines arrived it was an event.

Kurt Andersen: Completely.

George Gendron: You know you have a glass of wine. You go to your favorite chair, you sit down….

Kurt Andersen: You’ll light up the cigarette if you’re me.

George Gendron: We won’t even go there now. You just sit there and think, “I’m going to spend time with my friends.”

Kurt Andersen: Exactly. And if you’re like me growing up in Omaha, Nebraska, you know it’s even true of reading DC comics. In Omaha it was a connection to New York City, which is why as soon as I could I moved there. That loops back to this feeling that I think both Graydon and I had when we decided to do this: we want that, we want that. How do we create that again for ourselves and for people who share our, whatever, taste?

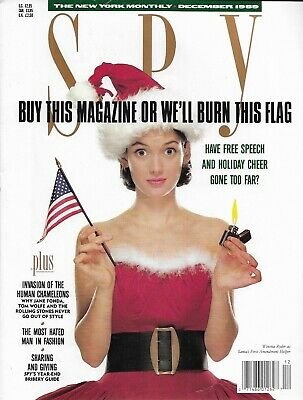

Benetton’s Colors, one of Andersen’s post-Spy projects.

George Gendron: You guys started out kind of skewering the glitterati in New York and then you became kind of celebrities yourselves in a way via Spy. Were there times when the two of you, together at an event or something, you looked at each other and said, “Not bad for kids from Canada and Nebraska?”

Kurt Andersen: In the biopic, yes, we did that. I don’t know if we ever literally did that. We certainly had a sense of how fortunate we were and how great this was as it was going on. I know I did. We thoroughly indulged our ability to be excited at the time. Yes, and you know we knew at the time I mean Graydon used to say to you know these poor youngsters that we paid so little to, “Yeah, you're not paid very much, but this I guarantee—this is going to be the best job you ever had.” And many of them have subsequently said—now middle-aged people, of course—“You know, you’re right? That was the best job I ever had.” So we felt like we had grabbed a brass ring.

George Gendron: Did you ever think to yourself that the fact you were outsiders in a way was a competitive advantage?

Kurt Andersen: Yes. I would never call it a competitive advantage, but absolutely yes. We were aware of that. Being from Ottawa and Omaha, and in the big city we’d seen movies about and TV shows about and dreamed of. And also being able to see all the weird outsized stuff about life in the big city, and the big cities, that we could see with the fresh, yokel, skeptical eye. It was this combination of loving it and seeing the absurdities of it. Pressing our noses against the glass—and breaking the glass occasionally. Something like that.

I think the outsider-ism is a big part of it. I remember reading biographies of Harold Ross, founder of The New Yorker and of course he was from the middle of nowhere as well [Aspen, Colorado]. So I think there is something to that.

George Gendron: A lot of people who enjoy even a modest level of celebrity find that it’s really toxic. There’s a lot of talk in the culture these days about celebrity culture being toxic, but I’m talking about it from a different point of view. I’m talking about it in terms of the effect on the celebrities themselves. And I’ve always wondered as I’ve watched your career evolve and Graydon’s, whether at least for you, the way you kept your feet on the ground was through the pursuit of interesting work.

Kurt Andersen: Each of us has had a certain amount of notoriety if not fame. We haven’t turned it down. But look at what we’ve done and how we’ve lived our lives—that hasn’t been the driver. We haven’t amped it up. We didn’t fall for the modern American sin of fame is everything and that’s really all you want.

I can only speak for myself in saying yes to what you just said, which is you try to be interested and stay interested and do good work, and if you get paid well or if you get praise, great. All that's good. And in my case I know if it allows you, as it has allowed me, to do all these things that I had no natural credential or standing to do like, “Oh, you’ve been a magazine editor. You want to host a radio show?” WHAT? Yeah, sure.

At that point I was writing books and one of my thoughts was, well I got this radio show, everybody who listens to public radio buys books. That's a good thing for an author to do. So I did have some consciousness of how to use having some degree of public profile for my own benefit. Maybe because of how we were raised or where we were raised, I don’t know, we have not spent our time, either of us, being seekers of the limelight. Graydon especially. And God knows as editor of Vanity Fair he could have. He was if anything the opposite of not seeking, trying to get interviews, trying to get photographs, all that stuff. Never at all.

George Gendron: This is going to sound like an offbeat question, but there’s a serious purpose behind it. I want you to imagine that you’re sitting and having lunch with Laurene Powell Jobs…

Kurt Andersen: Okay.

George Gendron: …and she passes across the table a check. A very, very, very large check, and says, “You can use this, but you can use this only to create a print magazine.” What would you do?

Kurt Andersen: I don’t know. It’s a great question and we’ll have to go away for a day and come back if you want me to answer it with any seriousness. It’s a great question, and I’ve never entertained that kind of fantasy because my days editing magazines and the day of the print magazine is done, unless you know you some tiny little niche, fine boatbuilding or whatever.

If you had a gazillion dollars to create a print magazine I have a feeling I could come up with something. I can’t say here’s what I’d do, because if I had that then I’d go to Laurene Jobs and say, “Hey, give me a hundred million dollars.”

The last serious idea that I had, or we had—Tibor Kalman and I back in ’98 or something like that—was we wanted to buy LIFE magazine, which existed, but barely, at that time, and turn it into a modern turn-of-the-century, twenty-first century pictorial weekly like LIFE magazine as it could be today.

Could that be done in 2022? I don’t know, but I can imagine—even though I have said to myself, to my wife, to everybody, “I’m done with jobs,” I can imagine that offer being appealing enough. If those were the only constraints—here’s a gazillion dollars and it has to be a print magazine—I would spend a lot of time thinking about that.

George Gendron: Well, we’d be interested in having you spend a little bit of time thinking about that. I think is an interesting way of exploring a question, which is: What is it that we as readers, as consumers, as a culture, are missing as a result of obsolete magazine business models? Sustainable business models?

Kurt Andersen: It’s a great question. I got to the answer of what we’re missing before in describing why people liked and perhaps like print magazines. They are like a fine boat or like a beautiful house—there is nothing else like them. They are not quite a book and they are certainly not an internet magazine. They’re something else, and it is that sense of craftsmanship and a kind of coherence that can’t be done any other way that I’ve seen. If you could do it just to prove that it could be done and have beauty, usefulness, impact? All that would be fun to figure out.

Andersen’s two most recent books, Evil Geniuses and Fantasyland, both New York Times bestsellers, remain relevant and even timely. Find them at your favorite bookseller.

And if you want a little bit more Spy, grab a copy of the beautifully-designed (by our friend Alexander Isley) and richly-detailed Spy: The Funny Years, which contains over 300 pages of Spy’s funniest and most creative work, along with the ultimate insiders account of how it all came to be.

Follow Kurt on Twitter @KBAndersen, or visit his website, kurtandersen.com for more information.