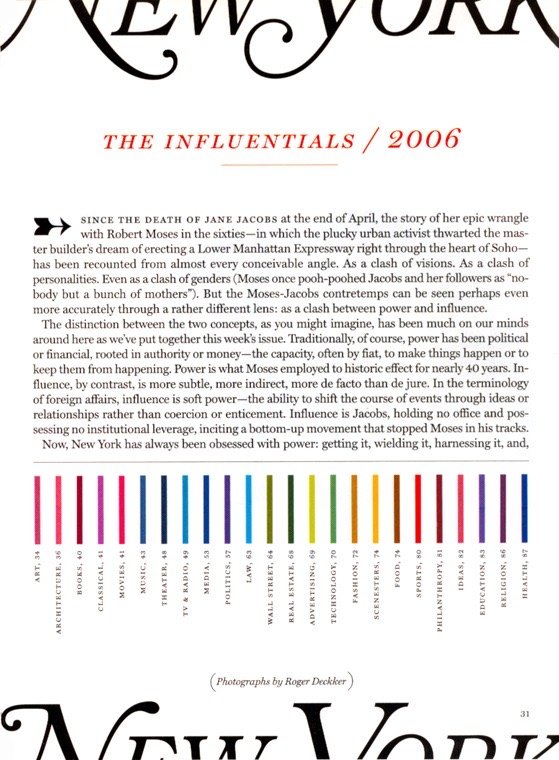

Highbrow, Brilliant: The Adam Moss Approval Matrix

A conversation with editor Adam Moss (New York, The New York Times Magazine, 7 Days, more)

Adam Moss is probably painting today. He’s not ready to share it. He may never be ready to share it. You see, this ASME Hall of Famer unabashedly labels himself as “tenth rate” with the brush. And he’s okay with that.

As Moss explains, it’s not about the painting. After decades of creating some of the world’s great magazines, he is throttling down. He’s working with canvas, paint, and brush — and reveling in the thrill of making something, finally, for an audience of one.

It hasn’t always been this way for Moss. Like most accomplished editors — like most serious creatives — Moss spent the better part of his career obsessed. Obsession is essential, he says, to the making of something great.

Growing up on Long Island, Moss became obsessed with Esquire and New York magazines. “My parents were subscribers,” he says. “I was in the suburbs. I’d open them and it was my invitation to New York City. And to cosmopolitan life. And to sophistication.” And knowing that it was all happening just a short subway ride away made it irresistible.

Moss’s publishing portfolio is rotten with blue-blood brands: Rolling Stone, Esquire, The New York Times, and New York magazine. He’s collaborated with editorial legends.

In 1987 Moss decided to create something of his own. Invited to pitch an idea for a new magazine to the owners of The Village Voice, Moss did his song and dance. The folks in the boardroom were … unmoved. Afterwards, Moss retreated to the men’s room to ponder his humiliation. Minutes later, Leonard Stern, the Voice’s owner, took a spot at the next urinal, where he turned to Moss and said, “Okay, we’ll do your magazine.”

What Moss pitched was a city magazine called 7 Days. It only lasted two years. But two weeks after ceasing publication, 7 Days was presented the National Magazine Award for general excellence.

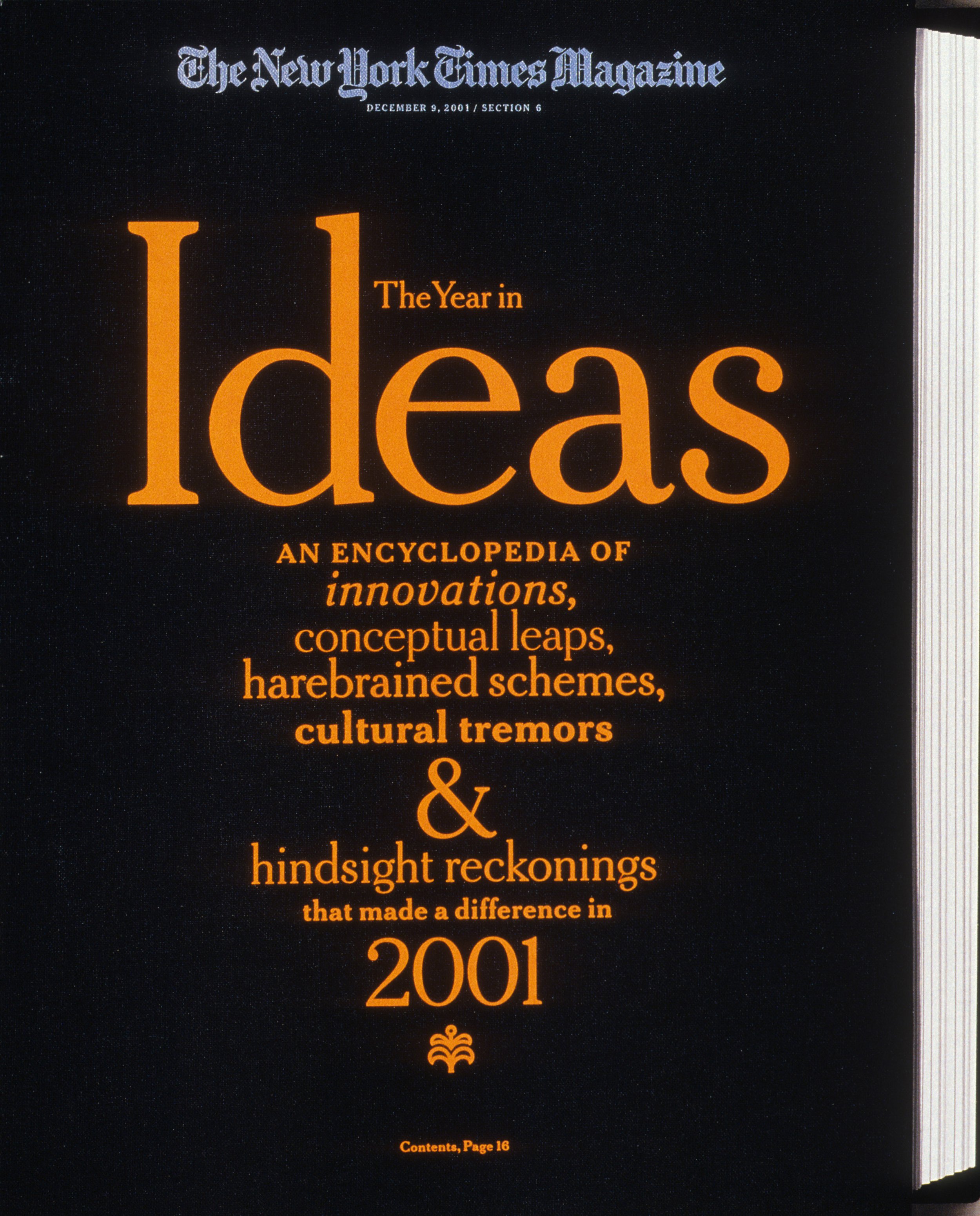

The splash it created propelled Moss to The New York Times, where, in a few short years, he transformed the paper’s Sunday supplement into an editorial juggernaut for creative talent — the Esquire or New York magazine of the 1990s.

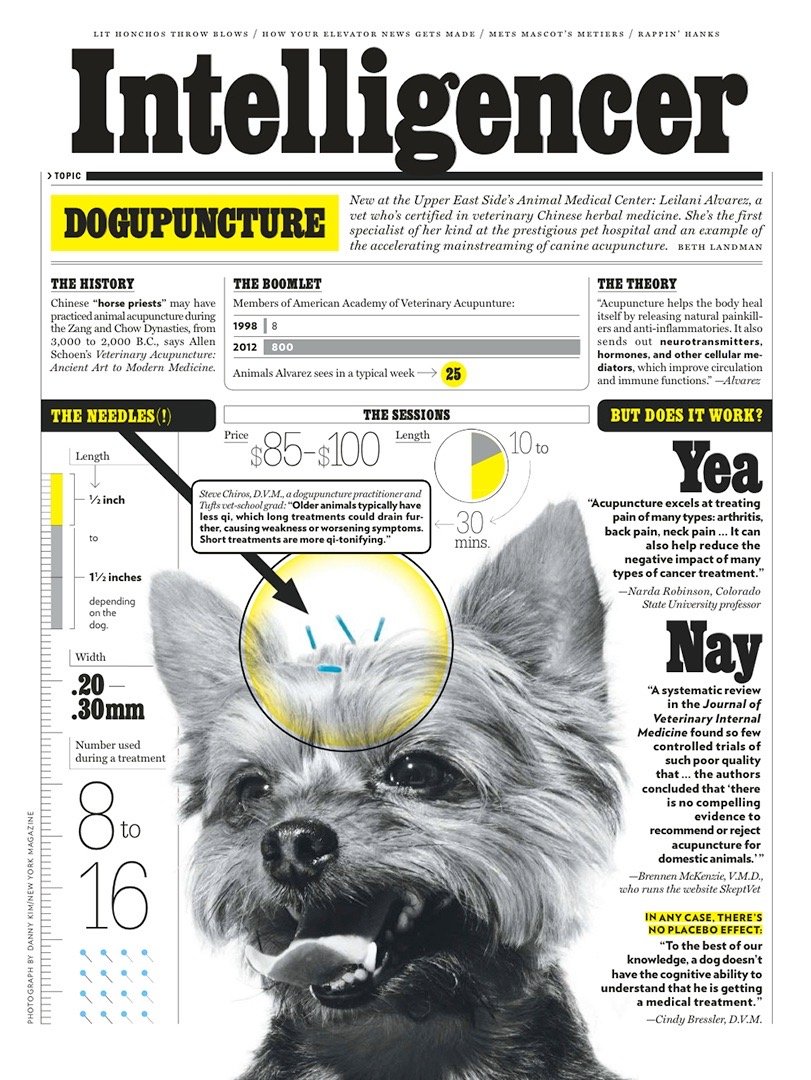

In 2004 Moss joined another venerable brand, New York magazine, where he not only completely reimagined the print magazine, he bear-hugged the encroaching internet menace, creating more than 20 new digital-only brands, five of which — Vulture, The Cut, Intelligencer, The Strategist, and Grub Street — remain heavyweights of modern online editorial.

In 2019, Adam Moss ended his 15-year run at New York, saying, “I want to see what else I can do.” So … painting. But, once obsessed, always obsessed. Moss is currently at work on a book about creation and creativity. The book will decode how creative geniuses transform an idea into something real. A song by Stephen Sondheim. A sculpture by Kara Walker. A film by Sofia Coppola.

Asked to describe what he’s making, Moss calls it a “big, overgrown magazine.” Of course he does.

Moss launched 7 Days in 1987.

“Most of the time I’m just working by myself. And that has its own pleasures, but it’s not the same thing at all as that kind of group hug that is magazine making.”

George Gendron: So I want to start by asking: Do you miss all the attention, all the accolades, all the awards — even a little?

Adam Moss: No, actually, I don’t miss that at all. I always felt a little mystified by the attention and always ran away from it while also, of course, loving it. But feeling kind of embarrassed about the kind of attention an editor-in-chief gets, which is so, in my view, disproportionate to the amount of work that that person does.

The staff itself does all the work. So, I was always proud of the accolades on behalf of the staff and embarrassed about them on behalf of myself. But what I miss is not any of that at all. What I miss is the actual work. Which is to say, the work with other people. I miss the camaraderie of the magazine. That was the best part of it.

George Gendron: And given what you’re doing right now, you don’t have much of that, do you? Or any of it?

Adam Moss: No. I try to create little versions of it here and there in my life. I’m working on a book and the book involves design, so I’m fairly happily working with some folks at Pentagram.

The lead person is Luke Hayman, who was art director of New York. I hired him when I got there. Wonderful. And his wonderful team. And I have these consulting gigs which are somewhat social, I suppose. They involve working with other people. And those are very, very satisfying.

But no, most of the time I’m just working by myself. And that has its own pleasures, but it’s not the same thing at all as that kind of group hug that is magazine making.

George Gendron: Let’s go back to the book. What can you tell us about it?

Adam Moss: Well, I don’t want to say a whole lot at this point, but it’s a book about how artists think or, I guess, more loosely “creative process,” a phrase I don’t like, but I’m stuck with. And it traces the evolution of certain works through conversations with the artists and artifacts of the process of making the thing.

You know, there’s a chapter on Stephen Sondheim — I talked to him before he died — on the making of one of his songs. There’s a chapter on Louise Glück, the Nobel Prize winning poet, on a poem. A chapter on George Saunders and the writing of Lincoln in the Bardo book that I love. Kara Walker and the making of her sculpture called A Subtlety, that big, sort of “mammy sphinx” that she had in Brooklyn. You know, Sophia Coppola on Lost in Translation and Marie Antoinette.

Anyway, it’s kind of case studies on making creative things, and then trying to come up with some theories about why it works when it does. The book is, it’s a little bit of like a, it’s like a big, overgrown magazine is really what it is.

George Gendron: In terms of the form factor? The size?

Adam Moss: Yeah, the physicalness of it. I mean, you read it, you look at images, you cross back and forth between the images and the words. It’s not like there’s imagery segregated in one part of the book and then words in another. It’s all very much tumbled together. And what I hope feels a little bit different in book form.

George Gendron: You and I talked a couple days ago about this and you said it might include photographs, artifacts…

Adam Moss: Yep.

George Gendron: …And it left me with the impression that what you are really trying to do is kind of decode the process that an artist goes through from an initial idea to the finished product, and you might get to see the evolution of that idea.

Adam Moss: Yeah. That’s exactly right. That’s, I mean, that’s the aim. And, you know, these documents, or the artifacts or specimens, or — I call them all sorts of things, exhibits — they’re amazing, for the most part. And especially those that are kind of "notes to self."

George Gendron: Yeah.

Adam Moss: These, sort of, journal entries that the artists are writing, or are sketching, as they’re making the thing. You can actually just feel teleported into the artist’s brain. Which I personally find enormously satisfying and interesting. Much more than my own words about it. These artifacts are kind of rich archeological finds.

George Gendron: So it sounds as if we’re going to get to see the Adam Moss editing sensibility at work, in this case, in a book.

Adam Moss: I guess.

George Gendron: Oh, come on.

Adam Moss: Sure. Yes. That’s right!

George Gendron: Drop that humility, man.

Adam Moss: It’s an editor’s book.

George Gendron: That’s what I was getting at. Yeah.

Adam Moss: Yes, I think it is. But, as mentioned before, it’s very much a book in which I’m playing all the parts. I feel like it’s a Marx Brothers movie where I just keep running in one door and out the other door. I’m the writer, I’m writing the captions. I’m dictating the way I think it ought to look. And I’m just doing it. I did the interviewing, I’m the writer, I’m the... I’m everything. And it’s kind of hilarious. But it’s quite different from the “groupness,” just getting back to how you make a magazine.

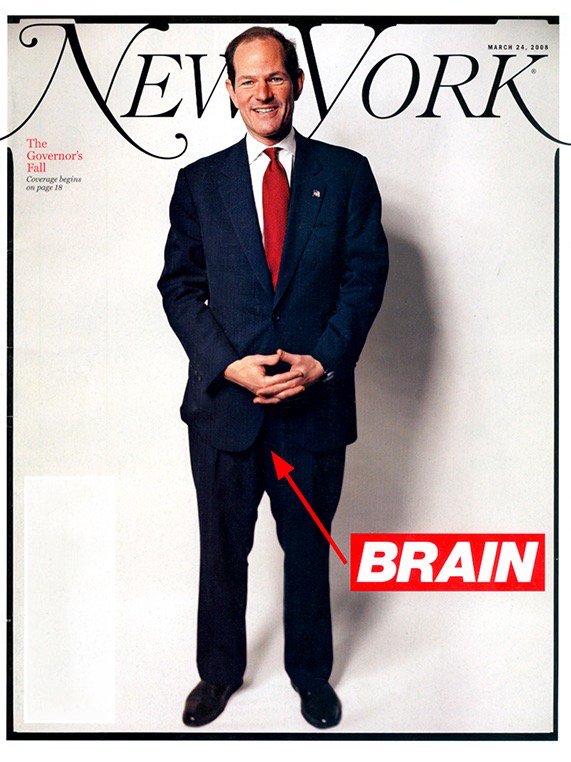

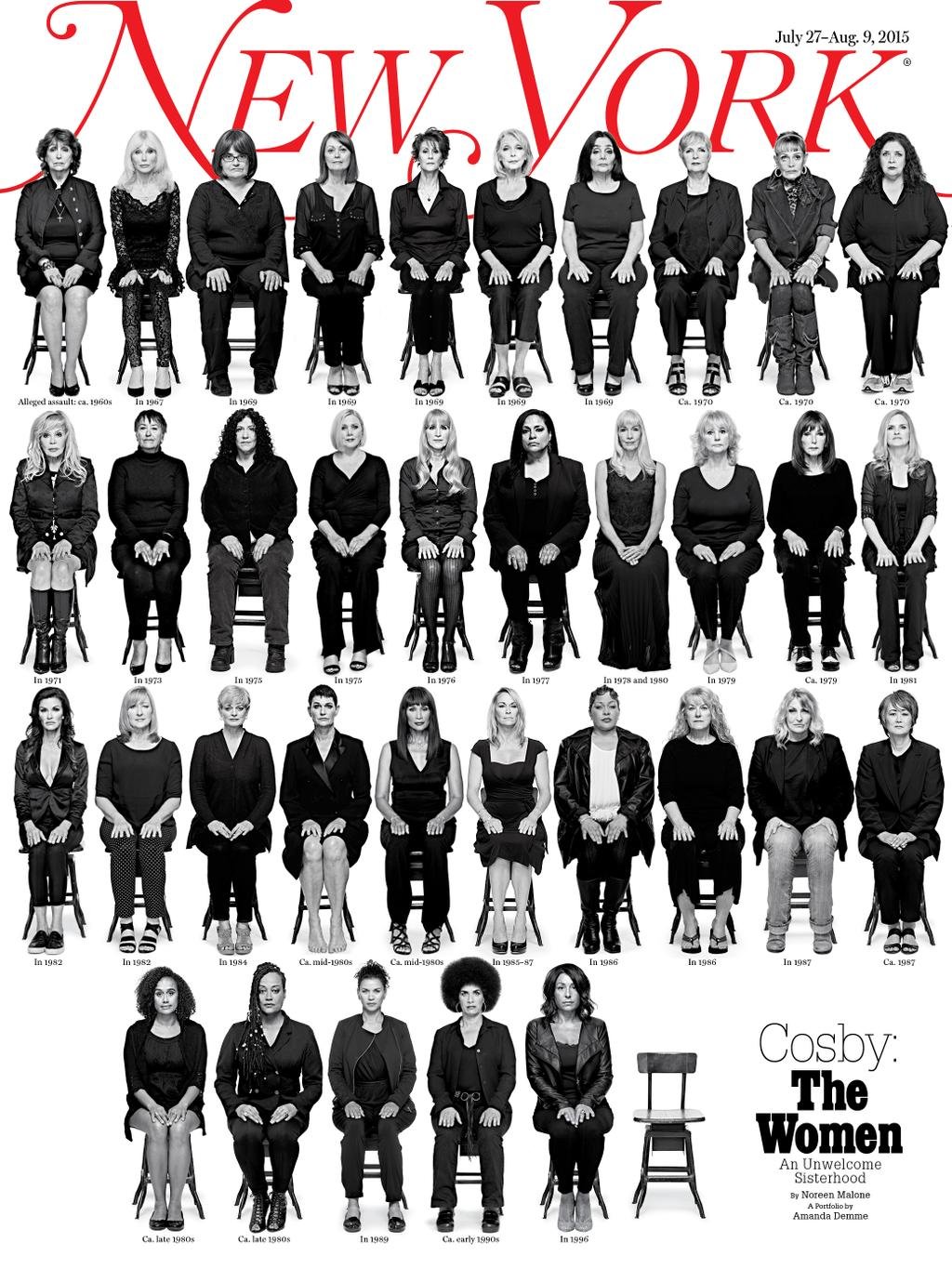

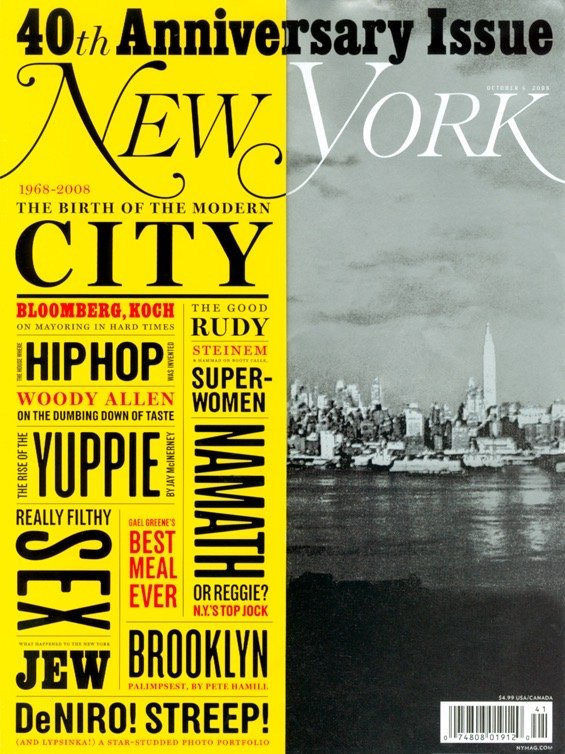

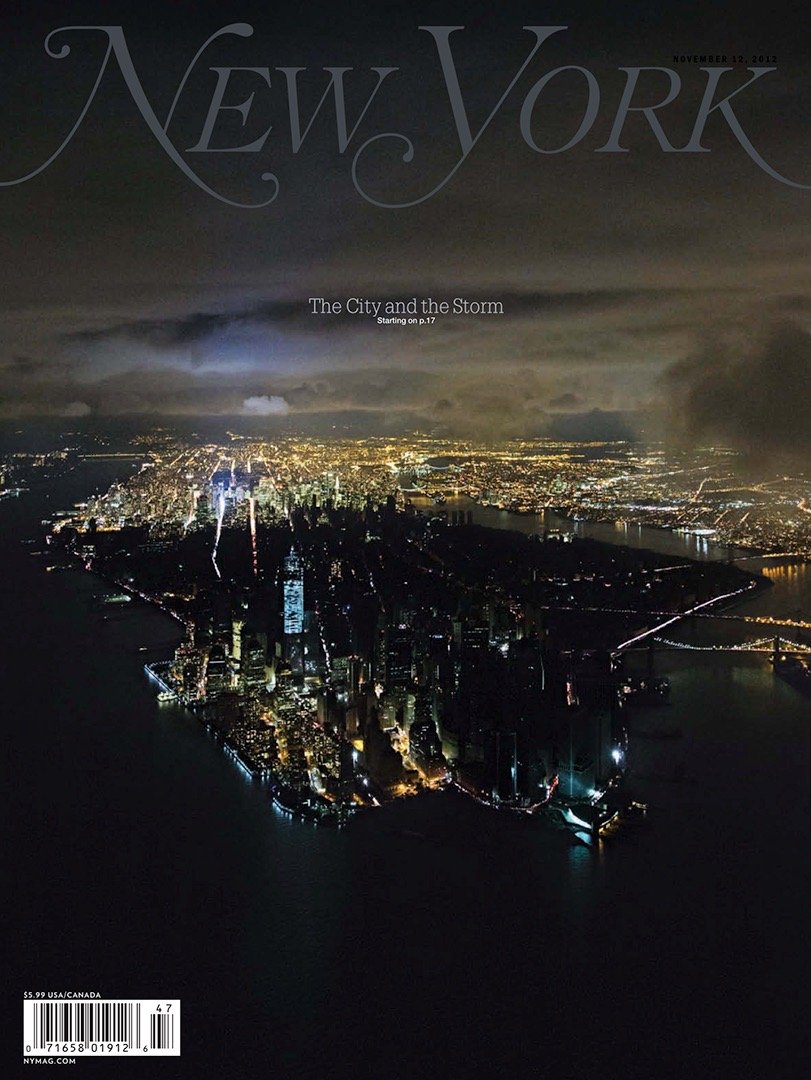

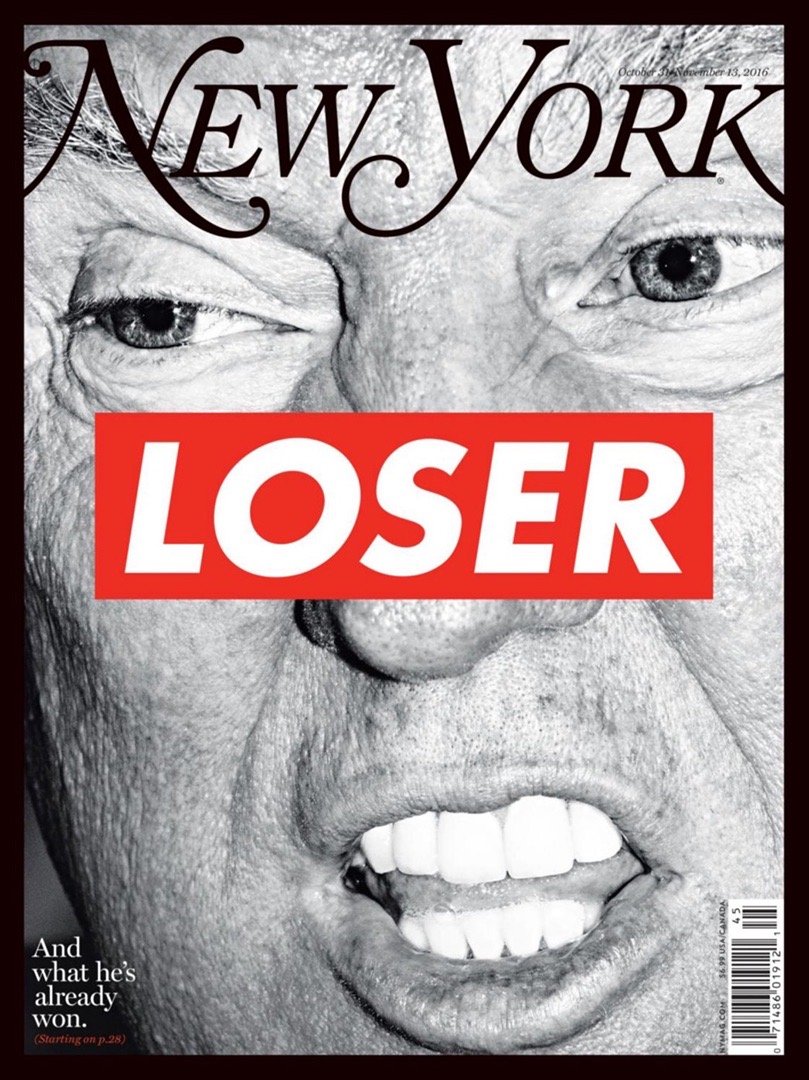

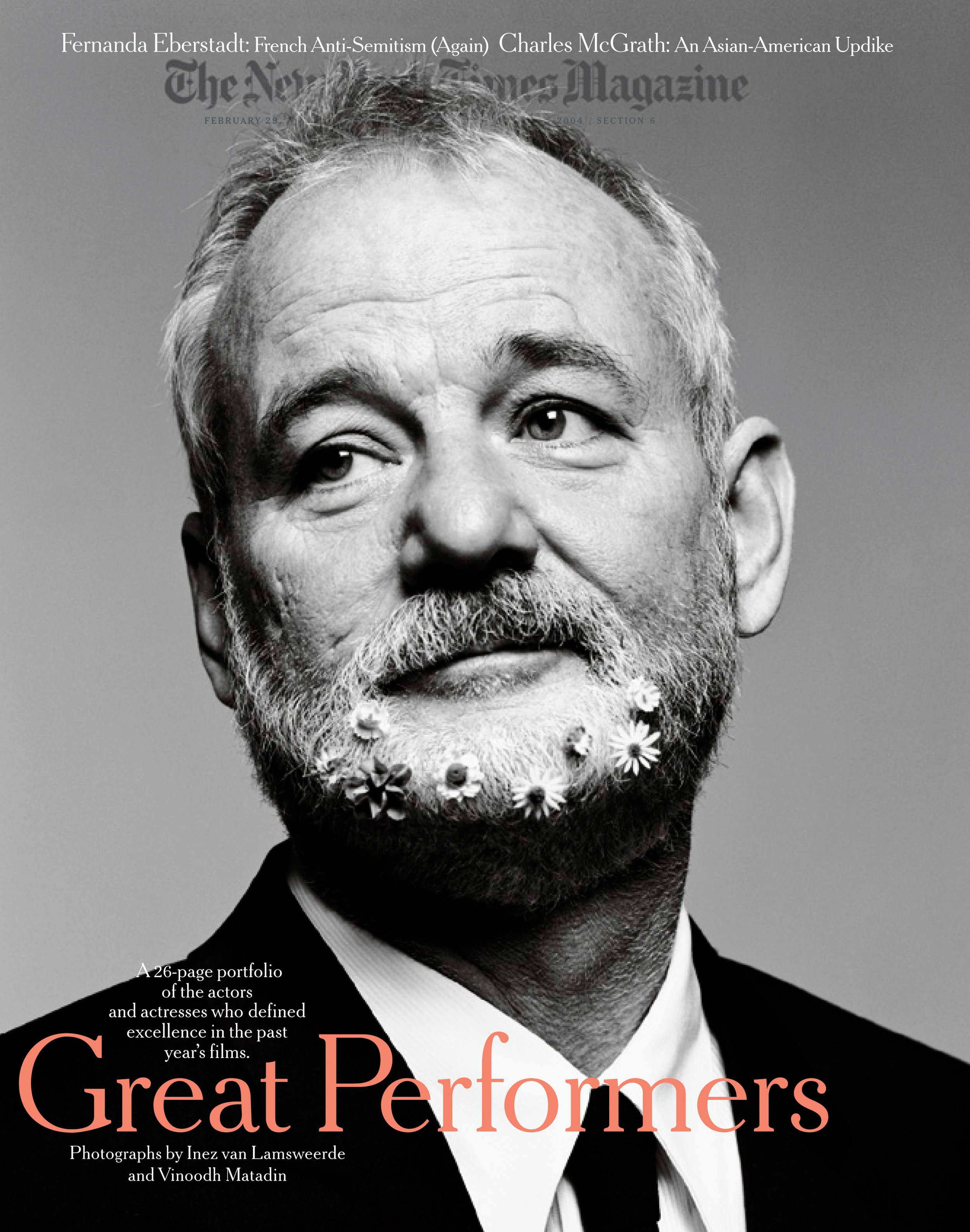

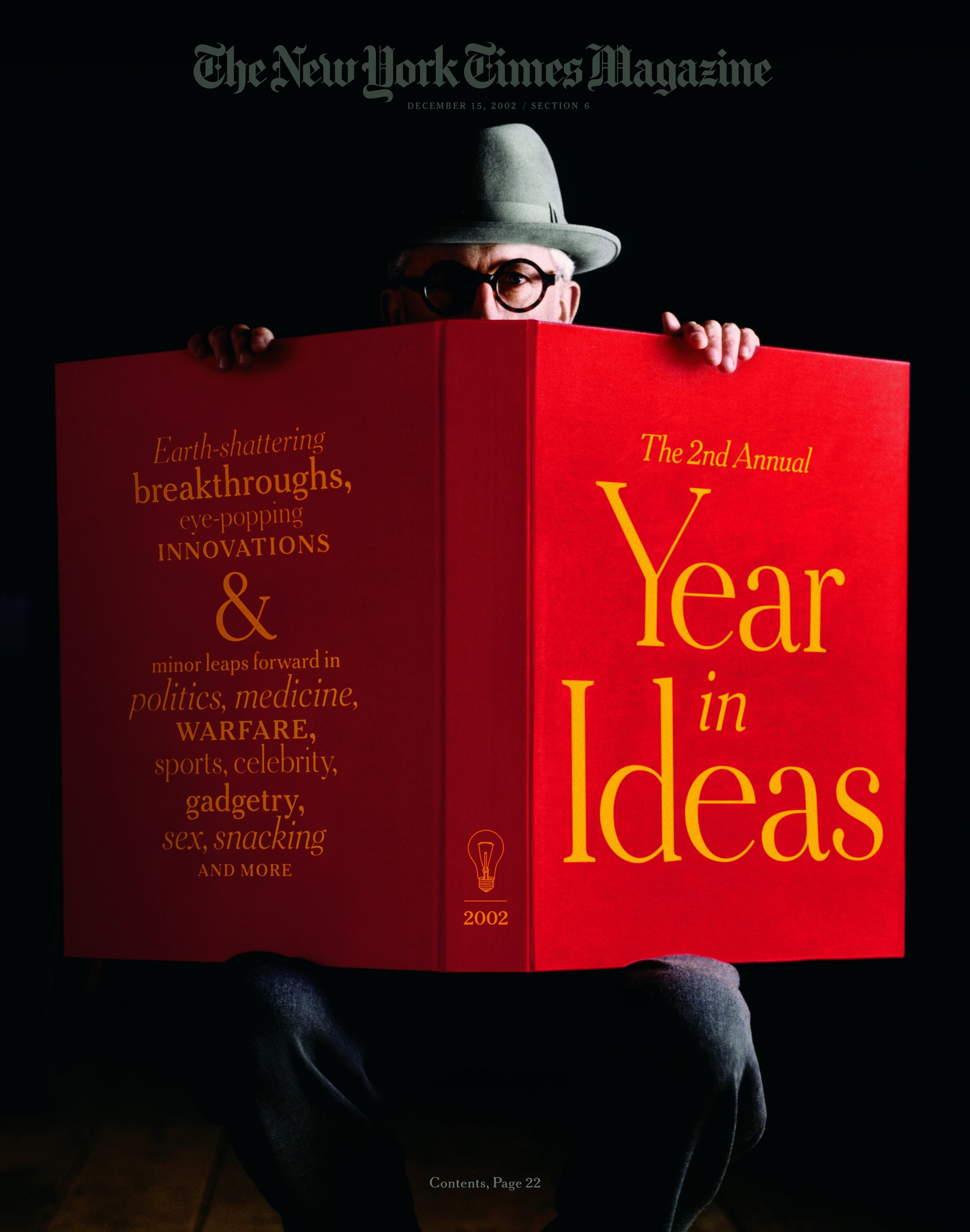

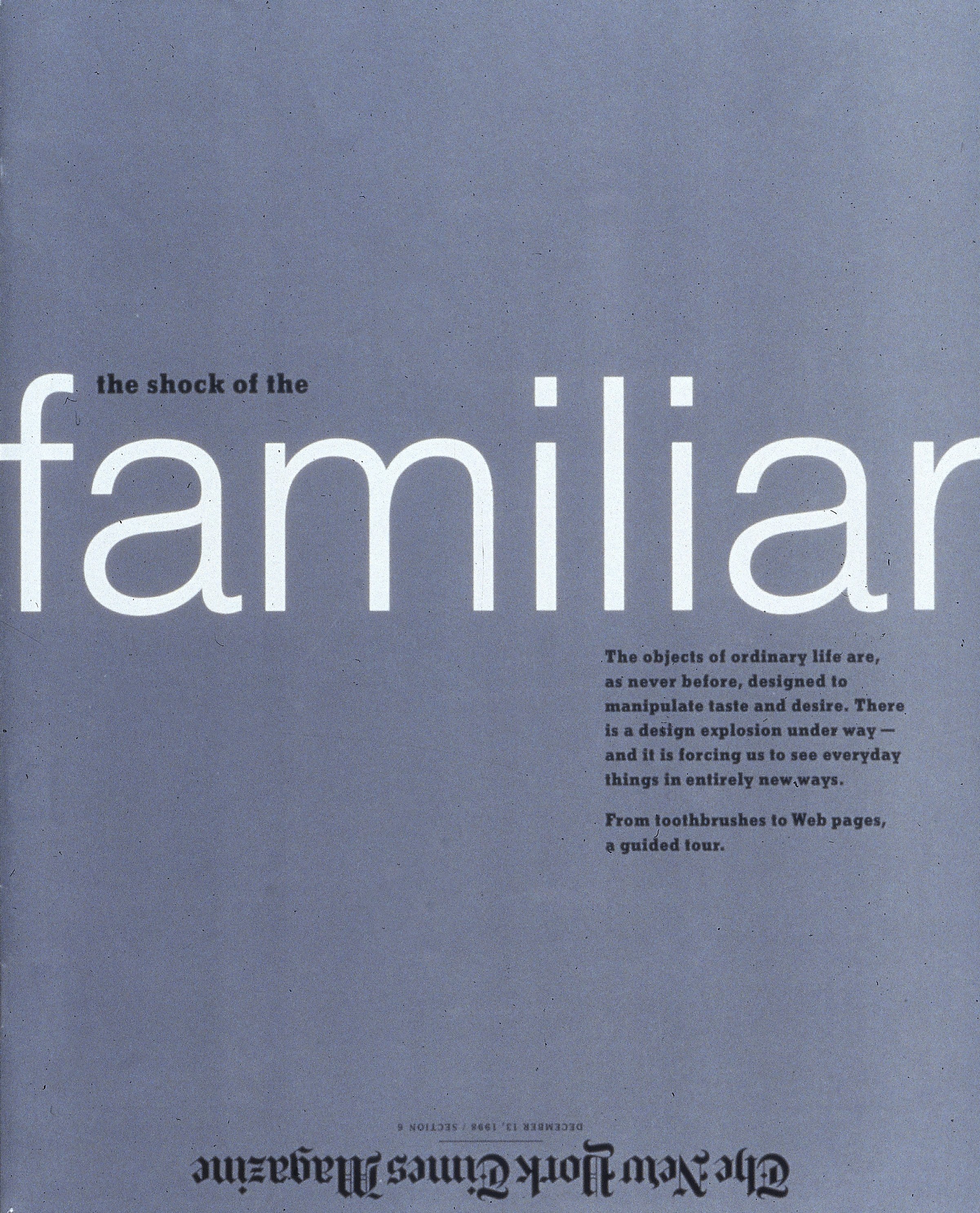

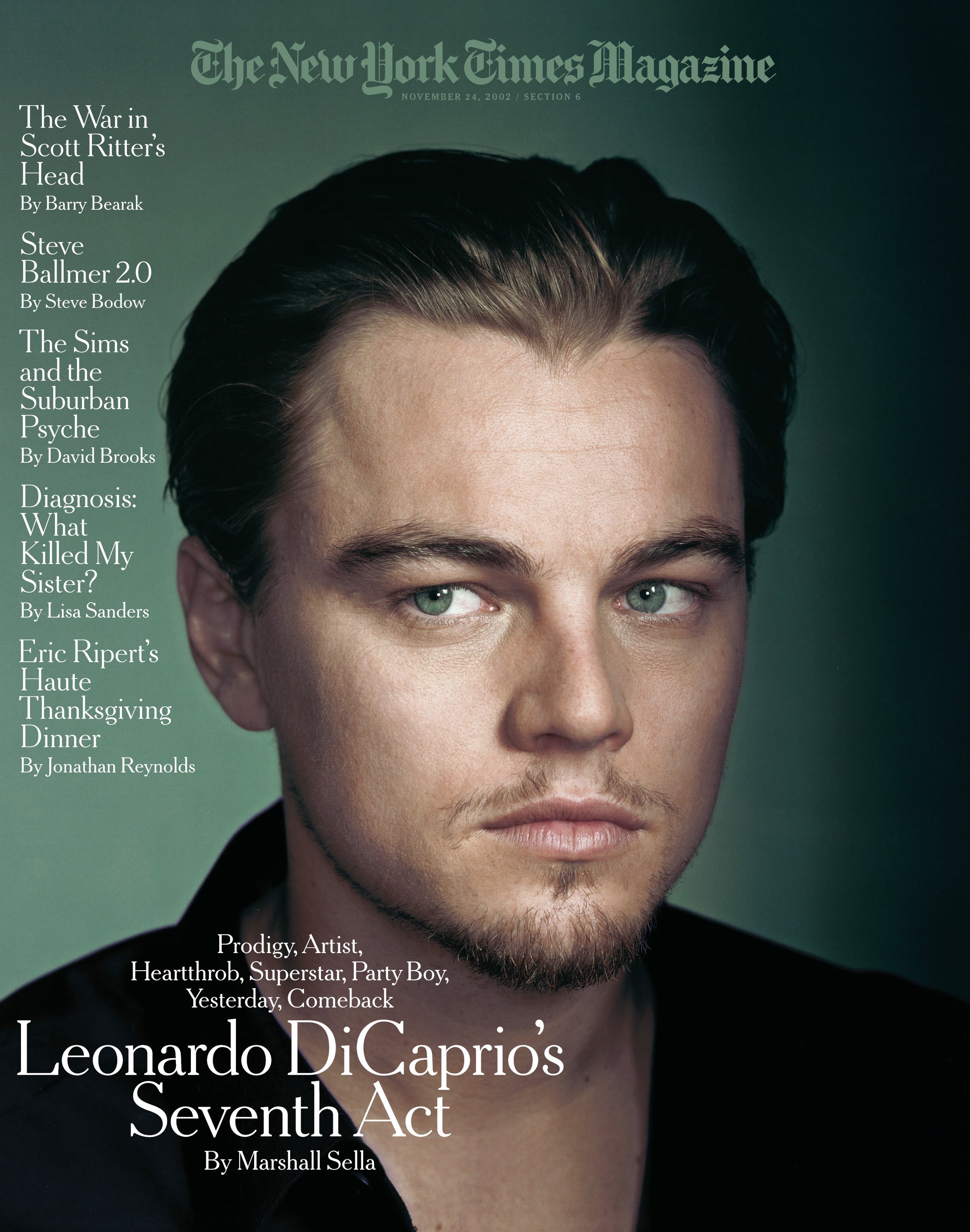

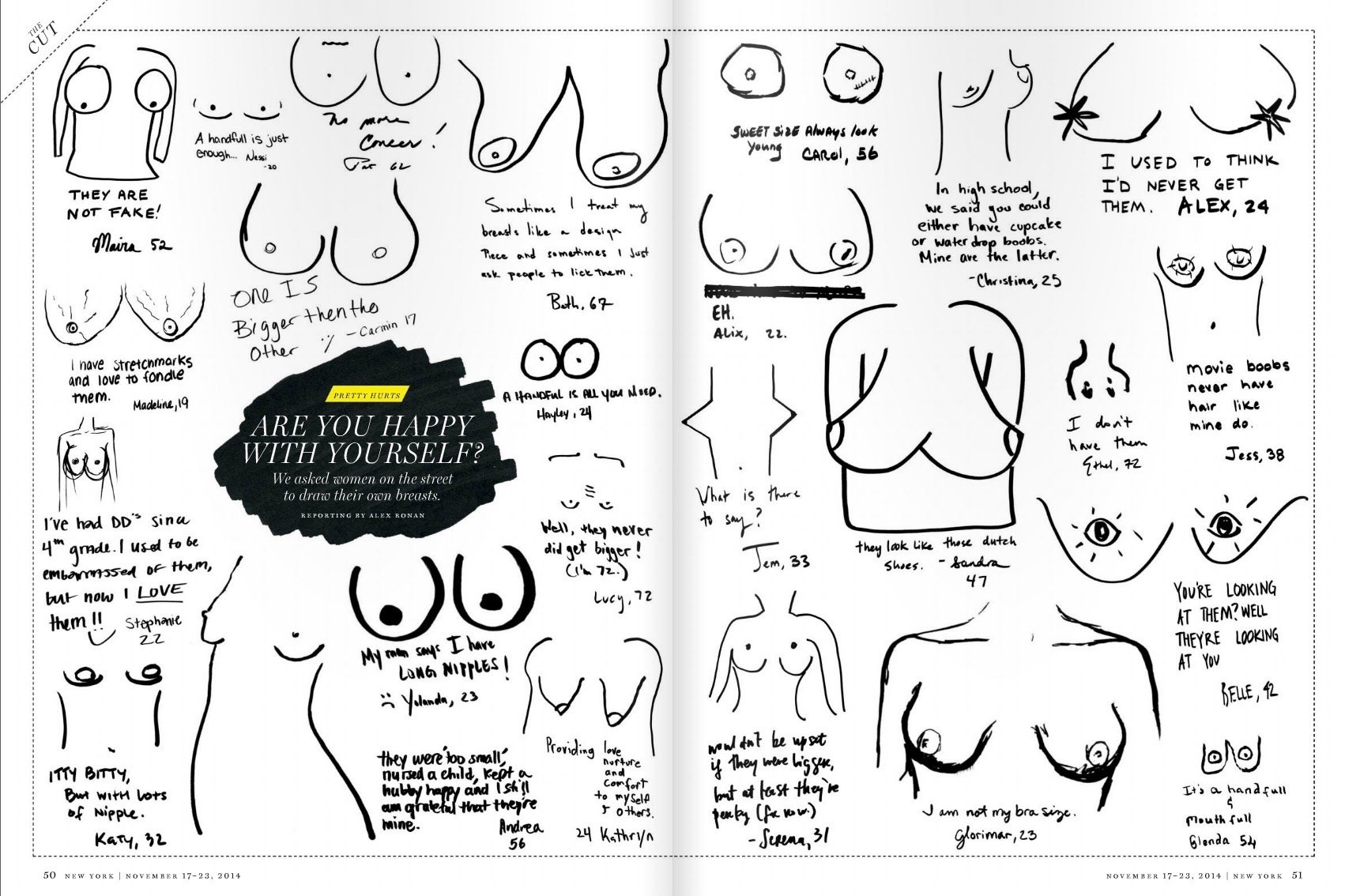

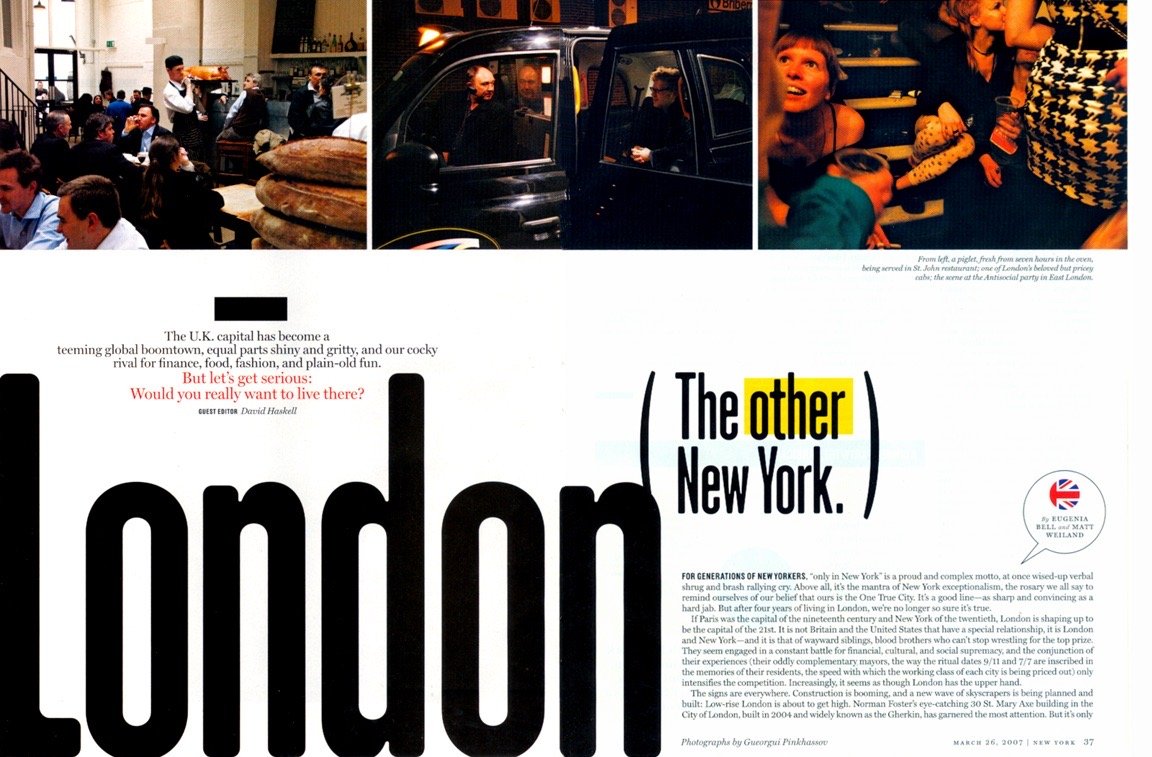

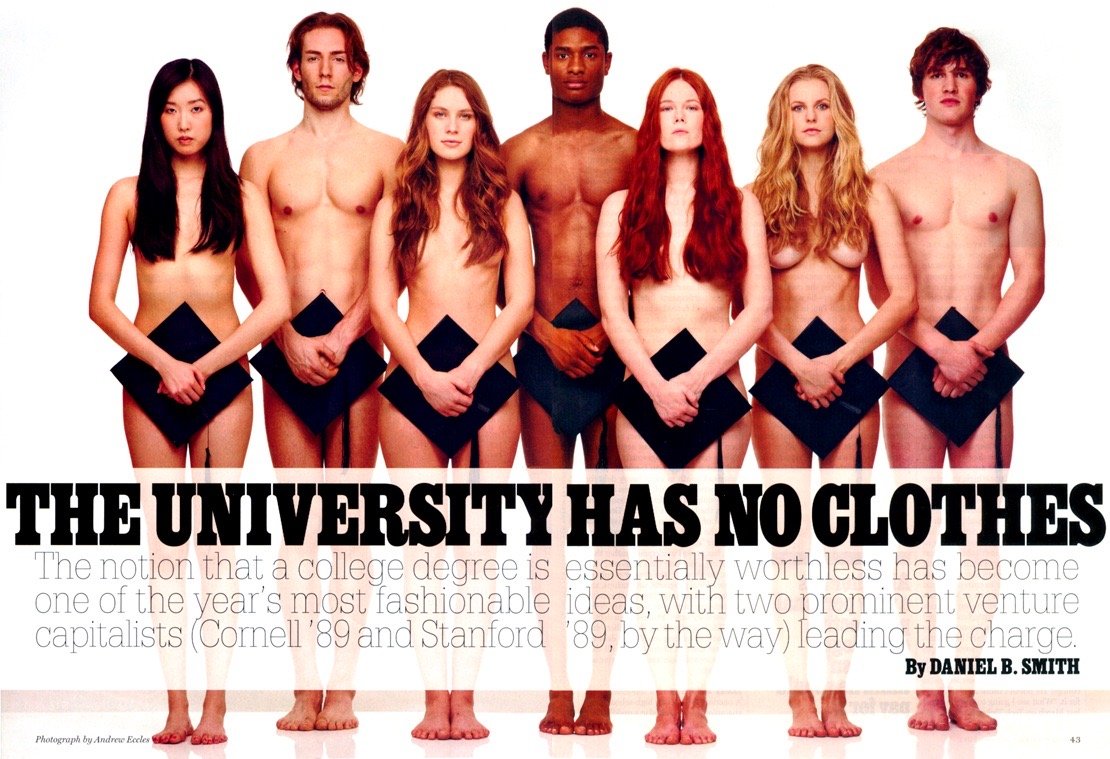

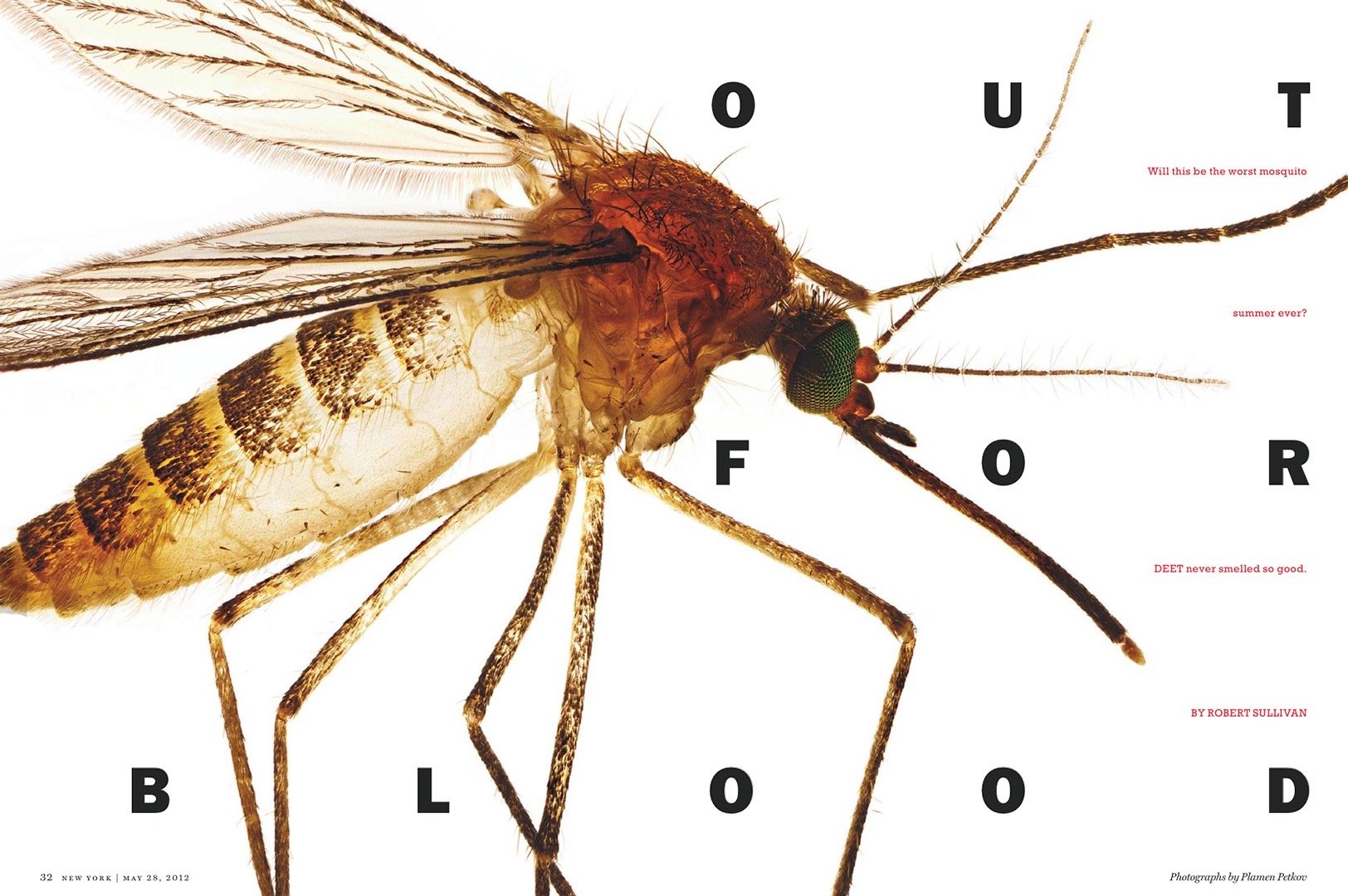

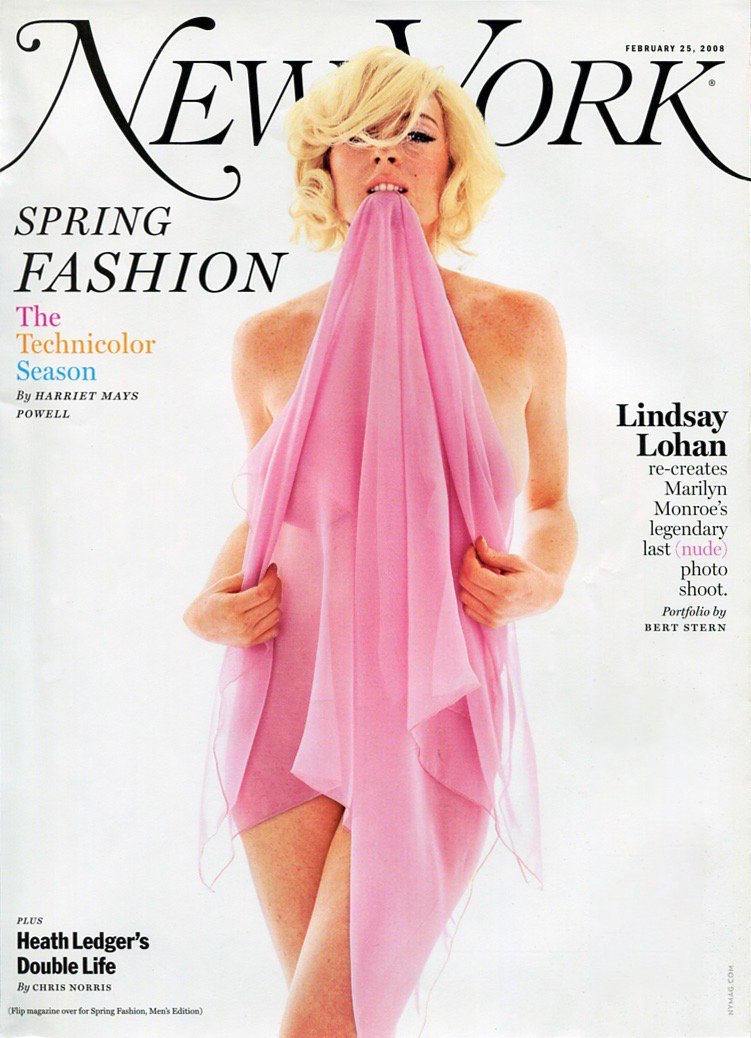

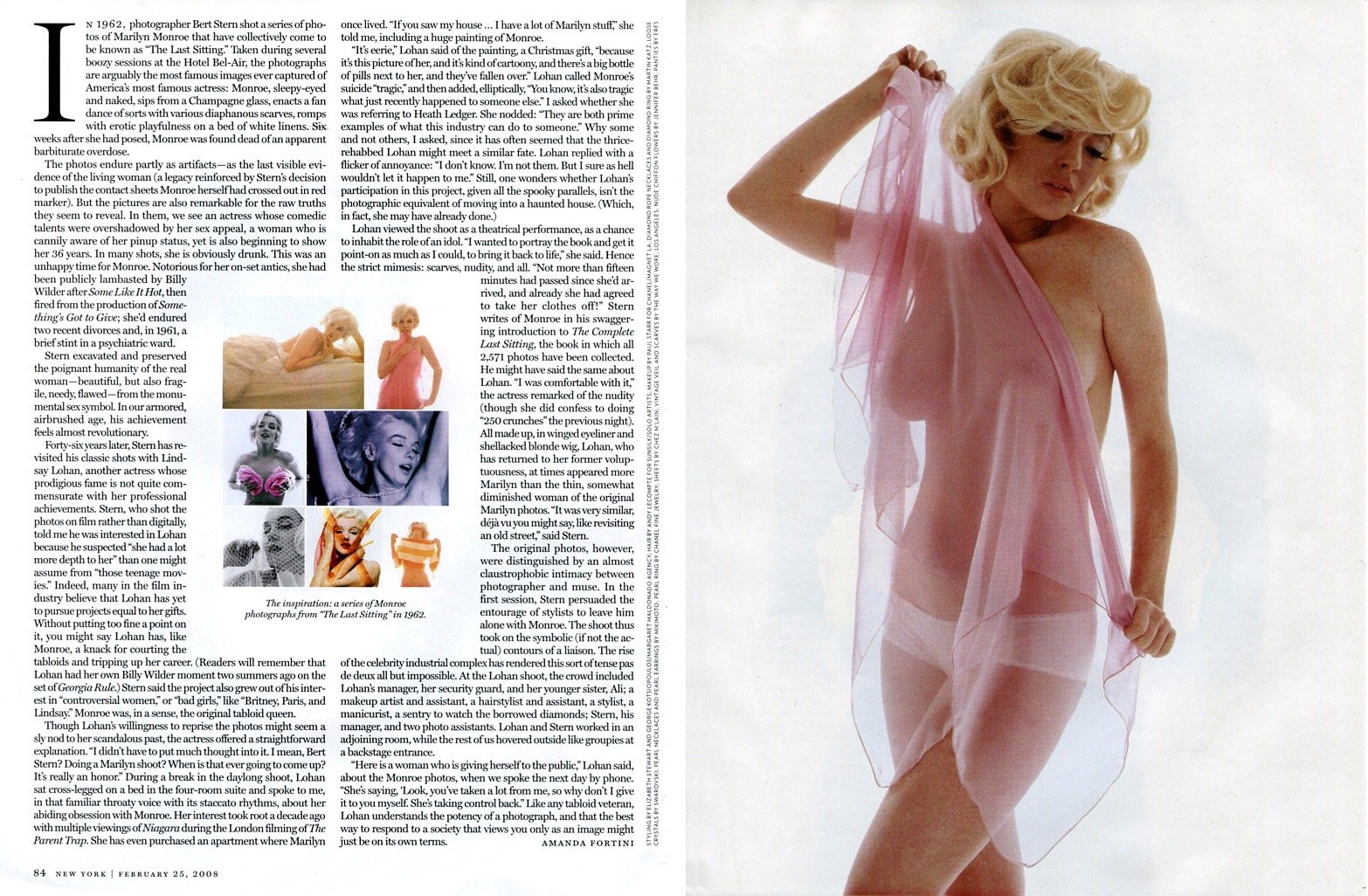

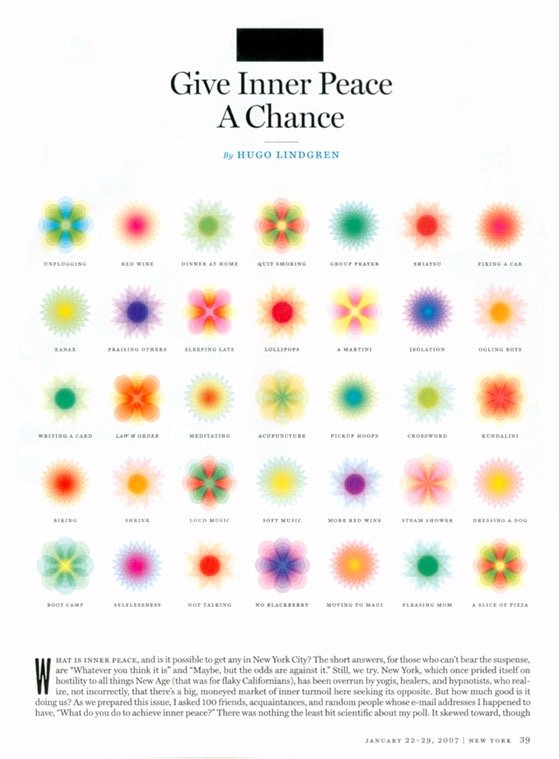

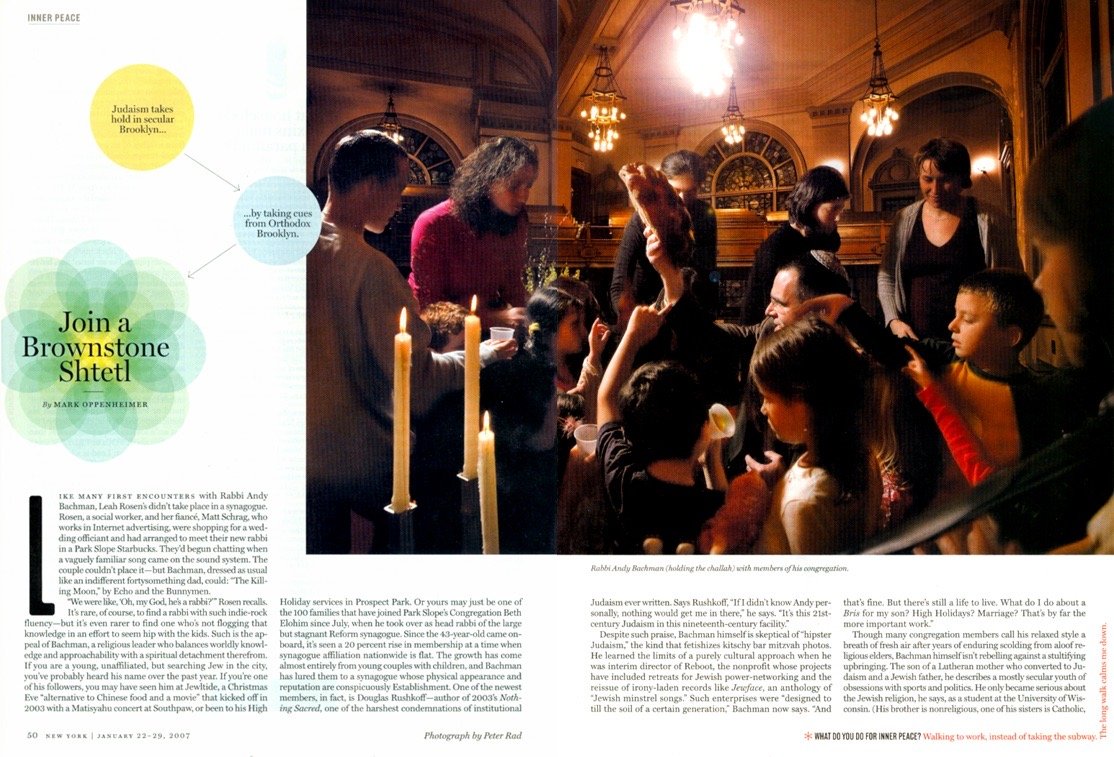

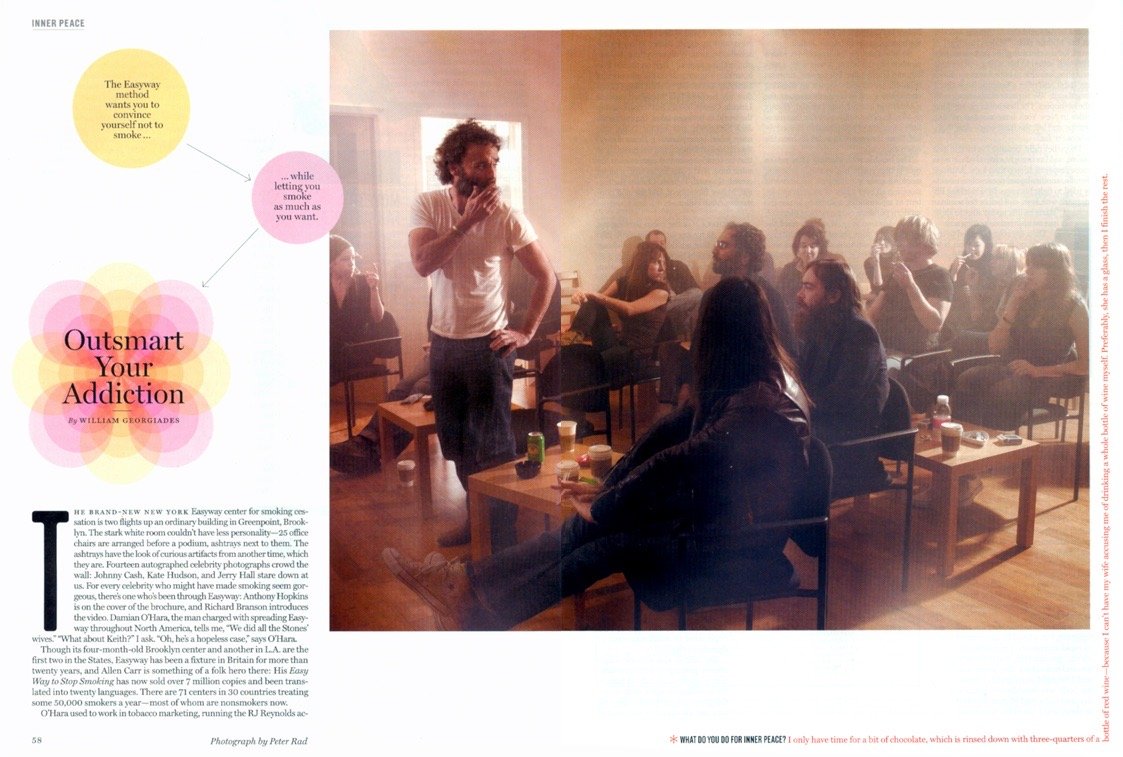

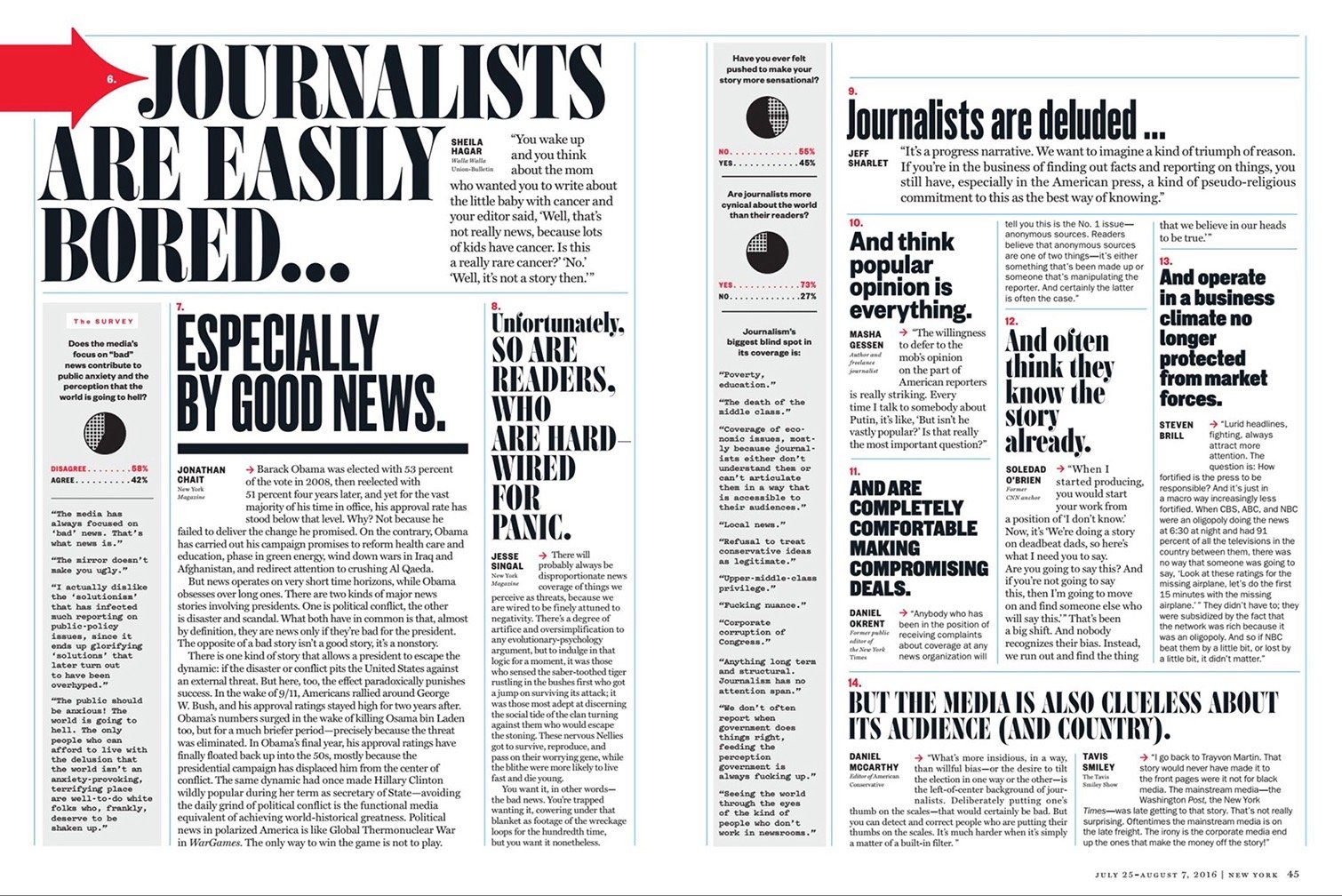

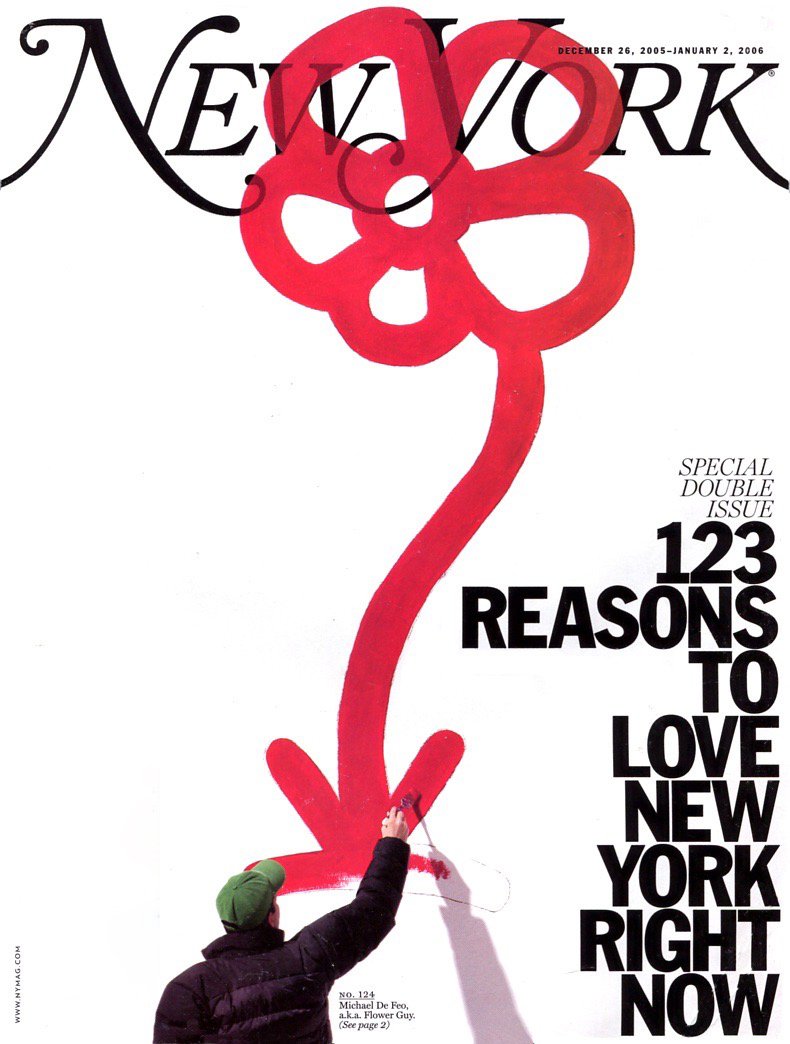

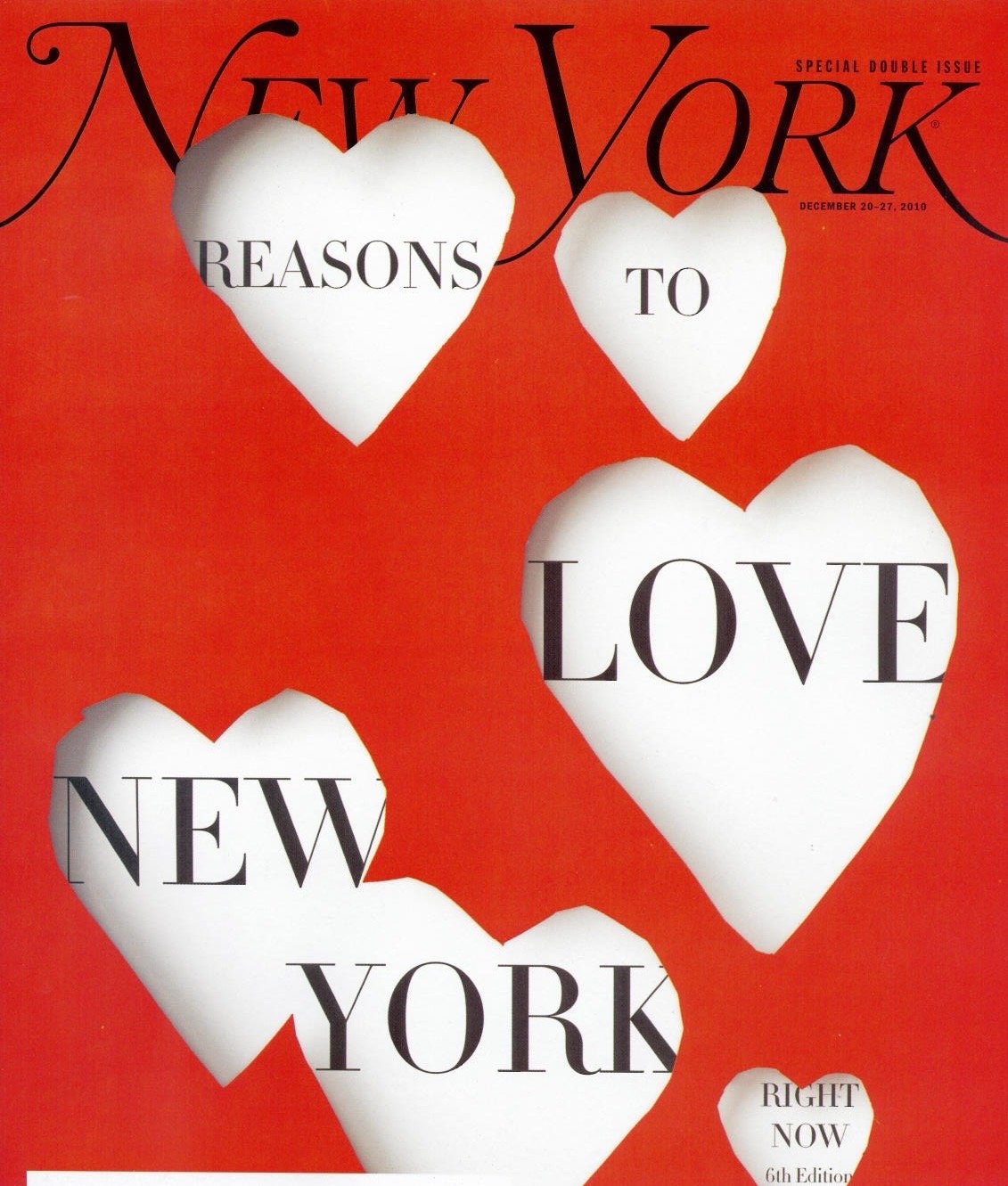

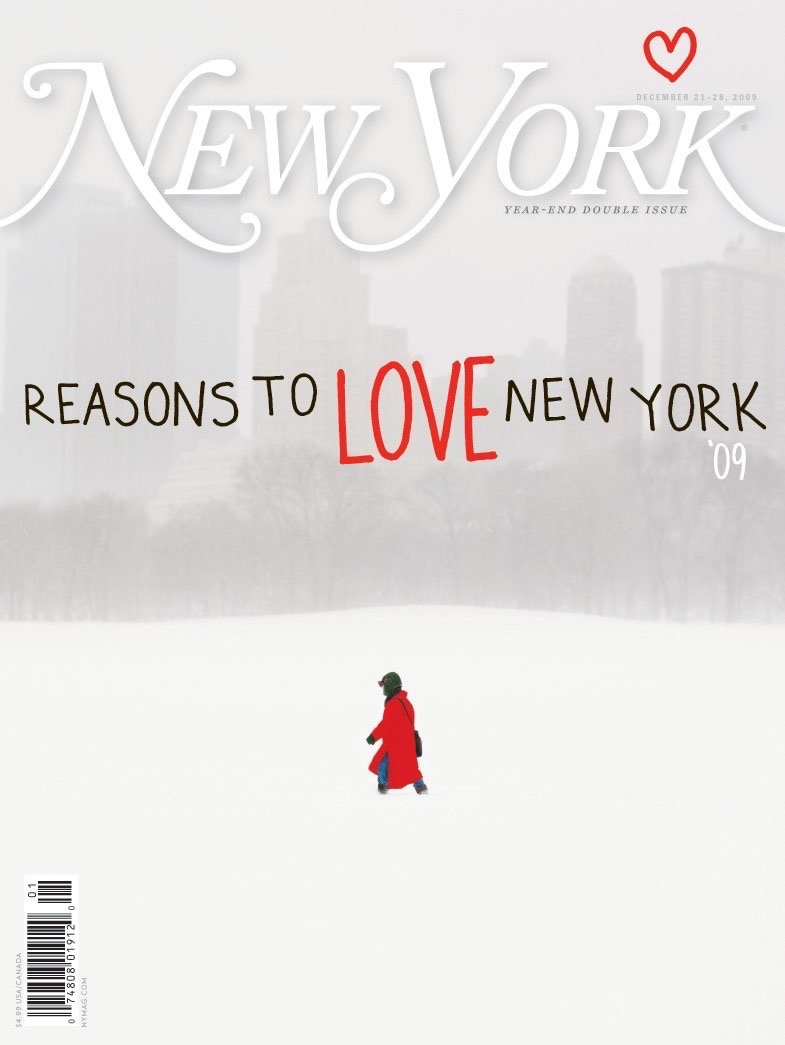

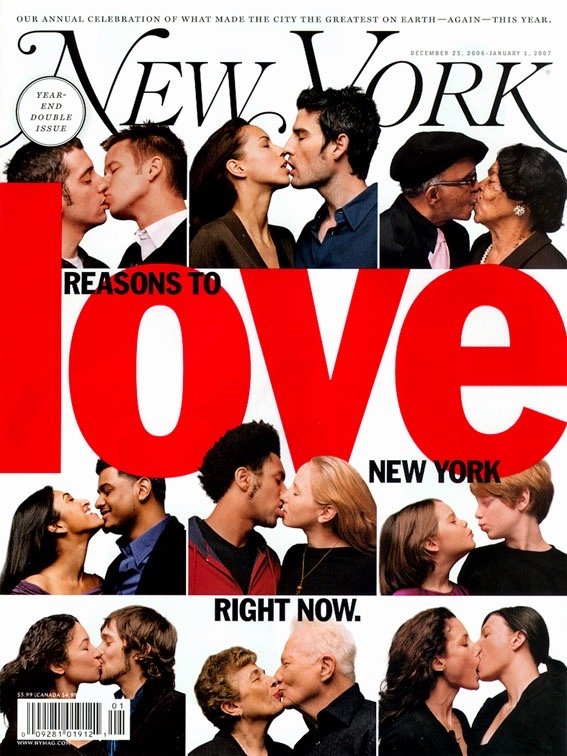

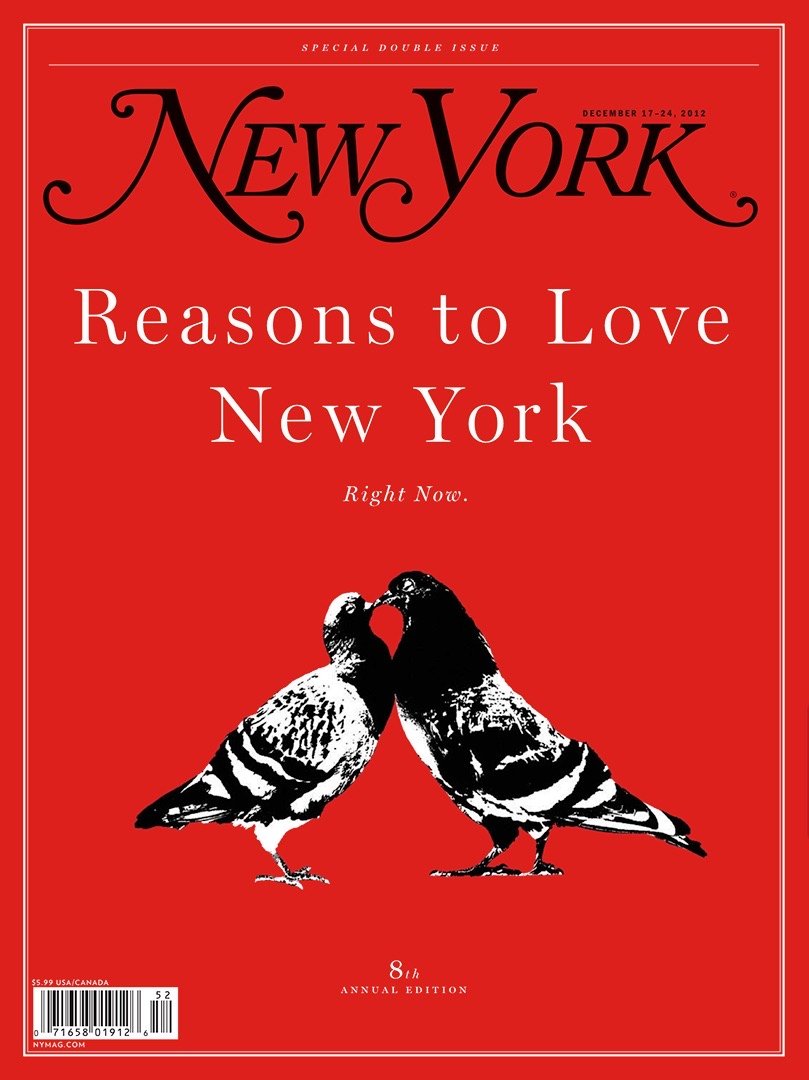

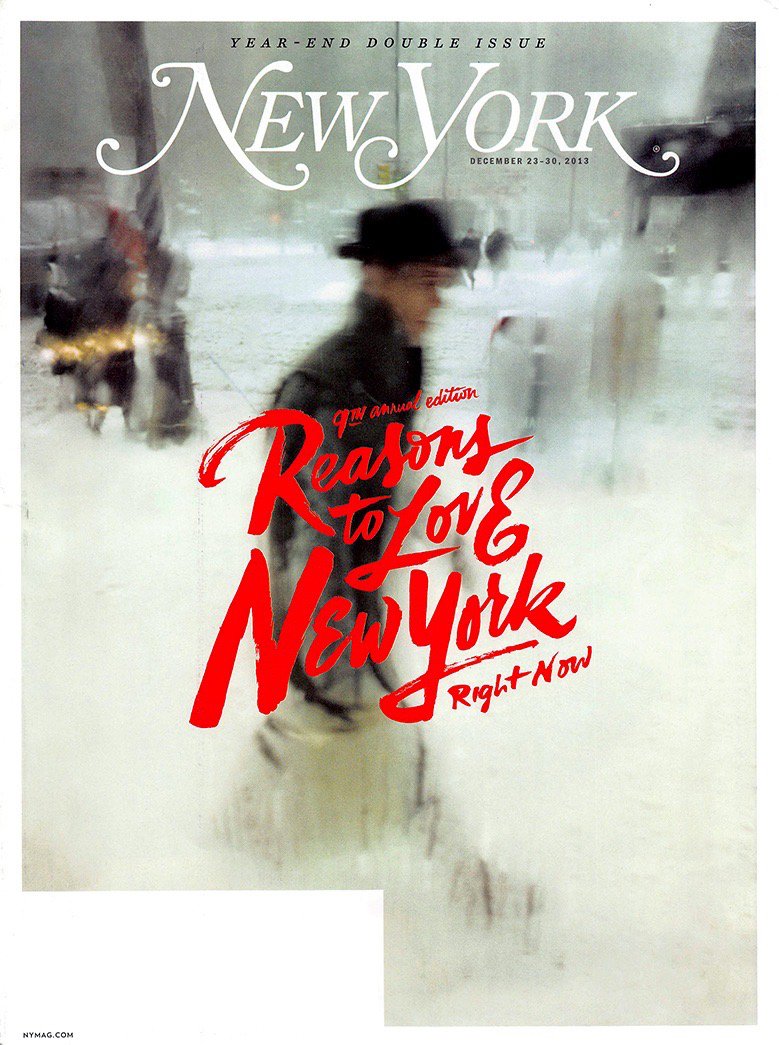

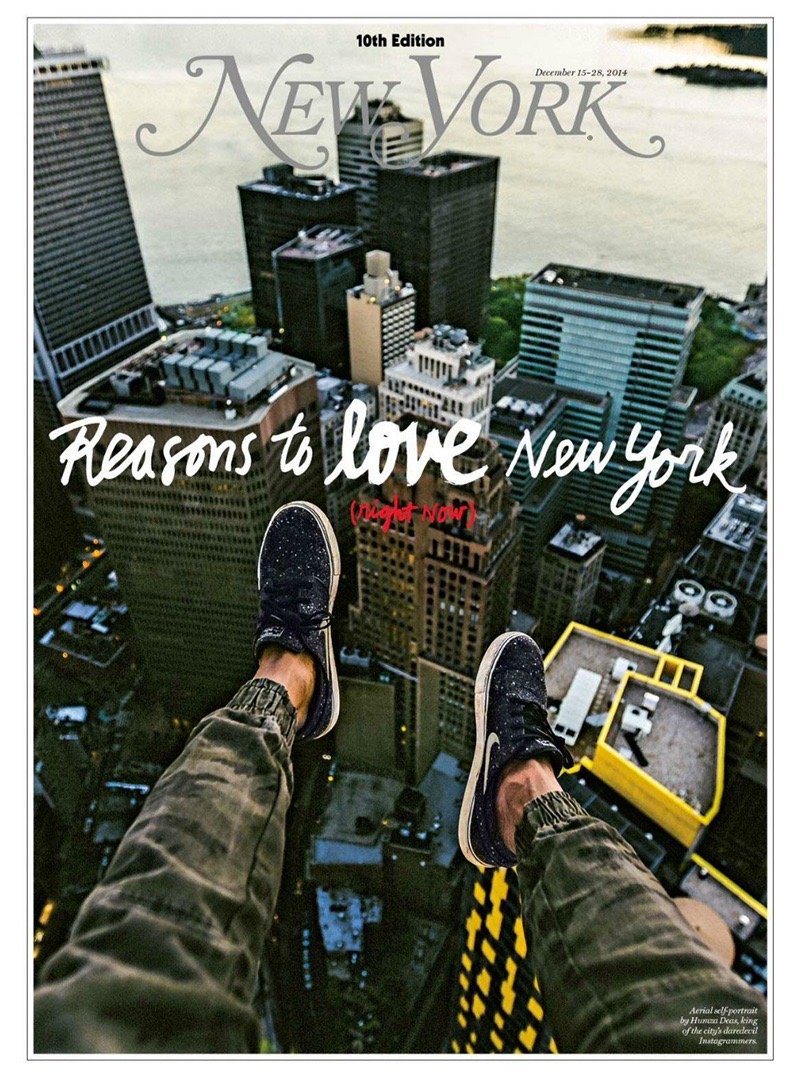

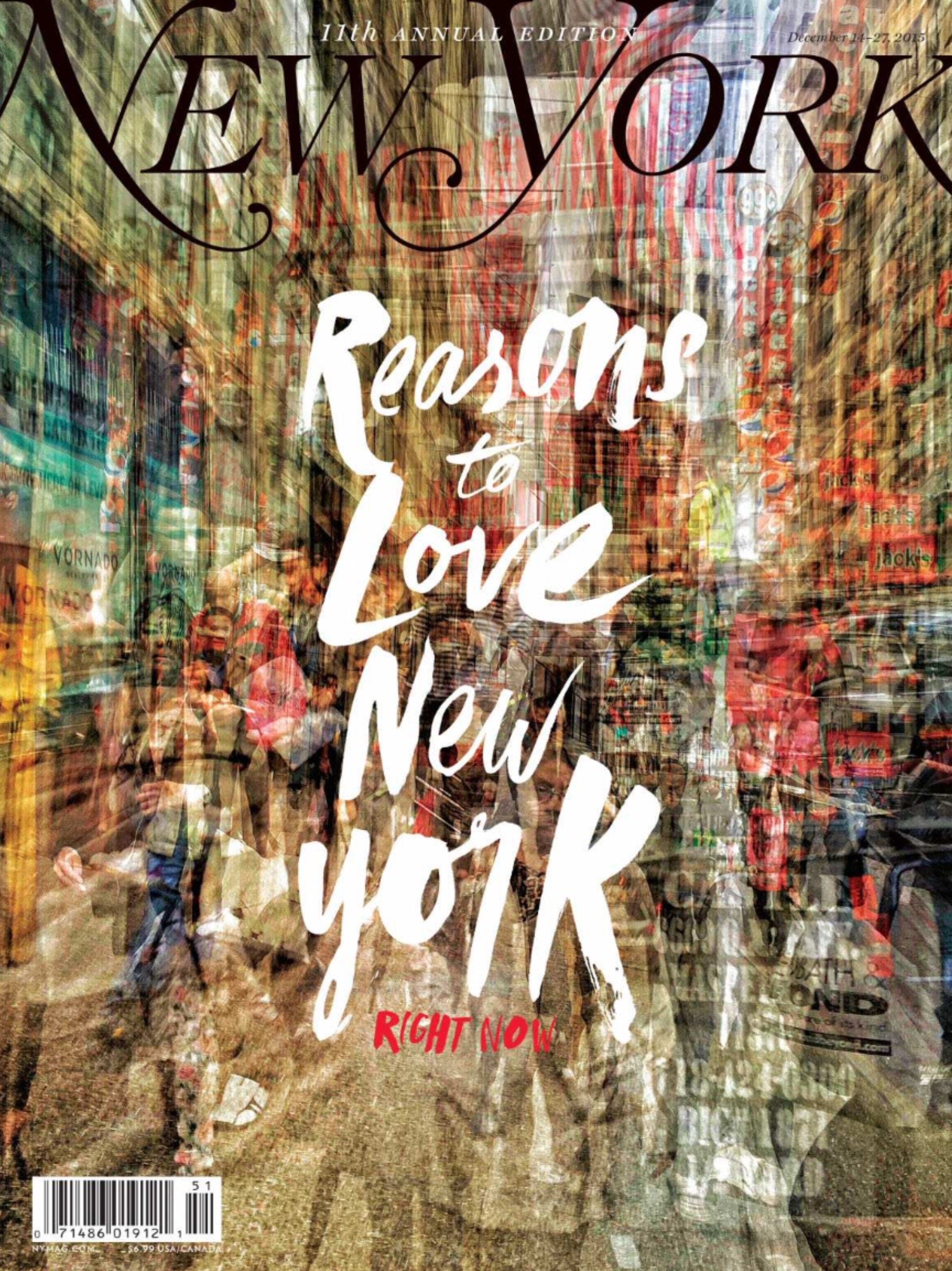

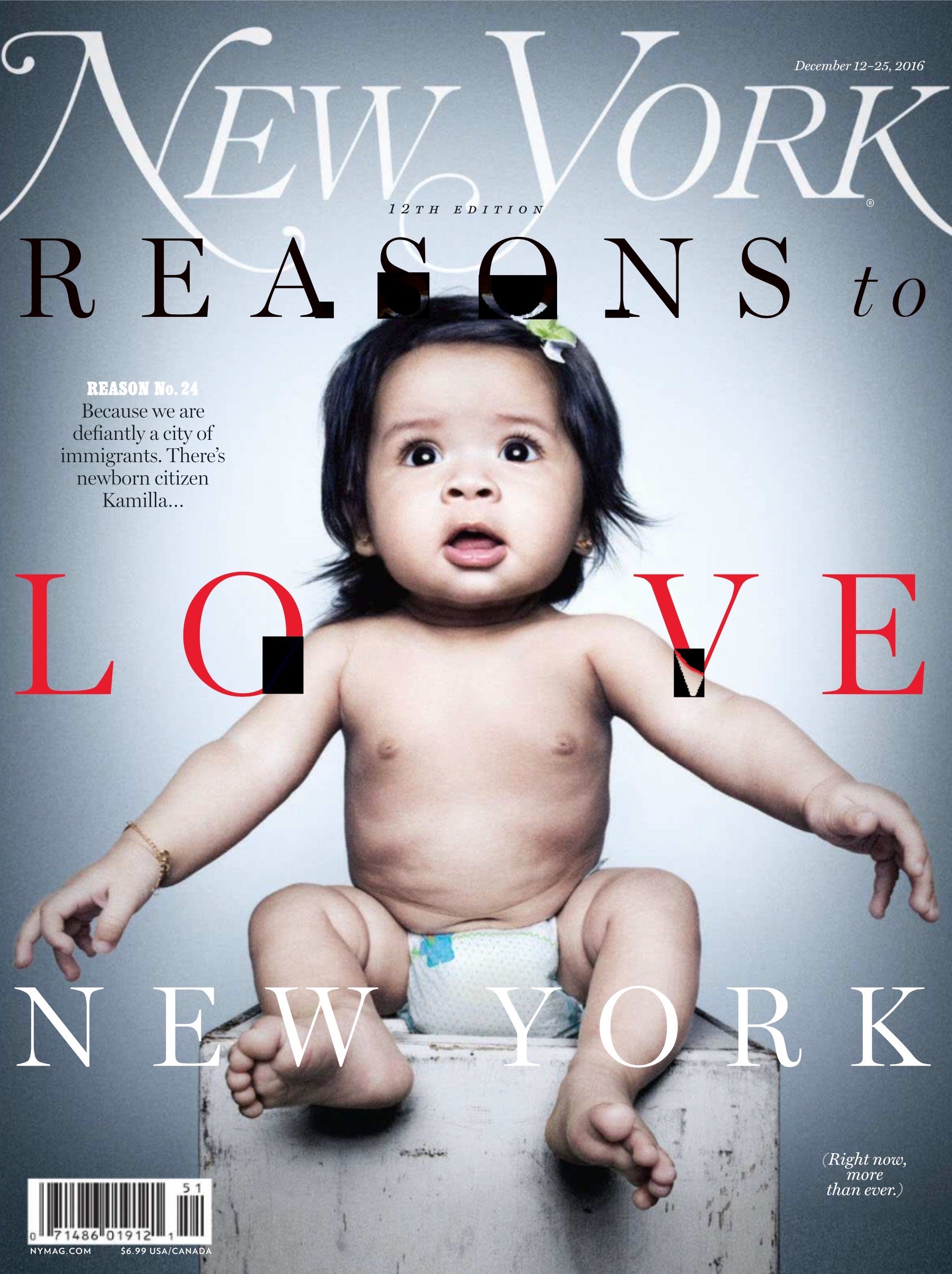

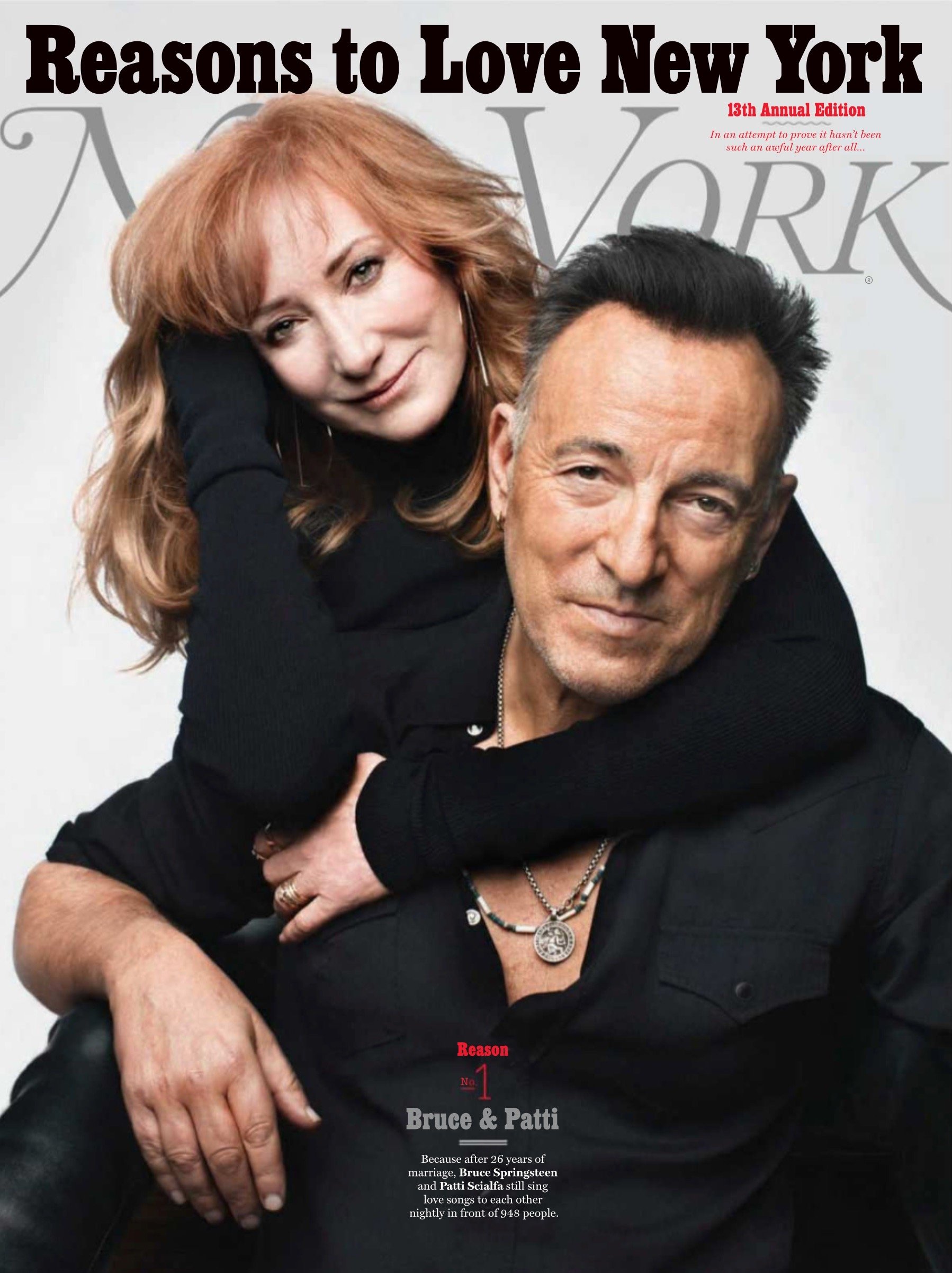

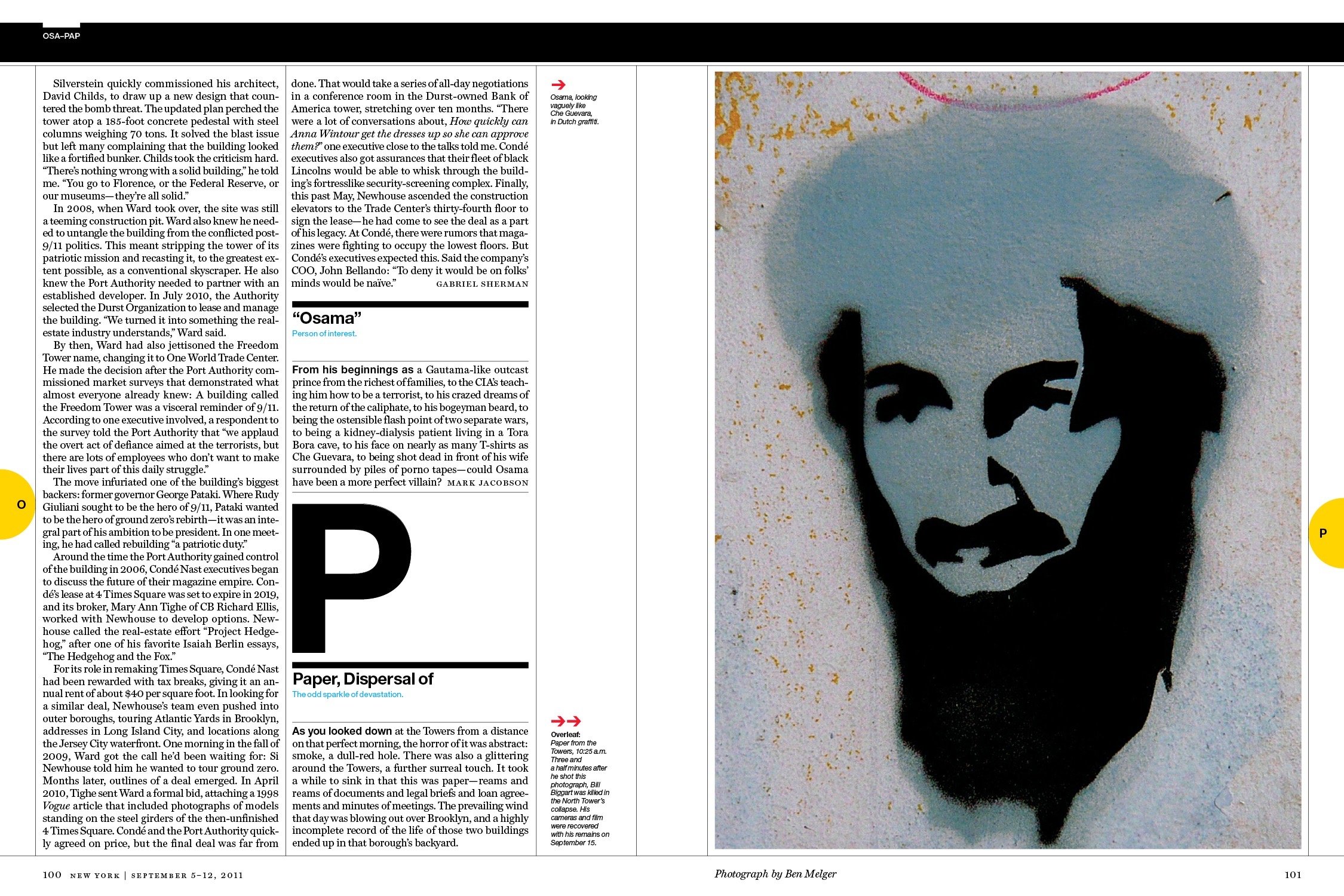

A few of Moss’ favorite New York covers

“The ownership of the magazine before I got there wanted a magazine in the mold of the imitators of New York magazine rather than New York magazine itself. So it had lost, in my opinion, an essential part of its DNA.”

George Gendron: A lot of people have said to me in a different context, “When are you going to write a book, or “the book” about entrepreneurship or innovation and creativity?” And man, I have just no desire to write a book. I just know too much about how hard it is. And then my partner, Patrick [Mitchell], who’s producing this, at one point said to me something really interesting. He said to me, “Don’t think about it as writing a book. Think about it as making a book.”

Adam Moss: Well, that’s exactly the verb I use to do this. I created this book deliberately in a way that it would be “writer proof.” I mean, I myself, hate writing so much that it would be a book that, really, the writing would be the least important part.

George Gendron: Boy, do I identify with that! So great, you’re going to be an inspiration to a lot of editors to write. When does the book come out?

Adam Moss: It’s not clear. It’s due kind of soon. But the way book publishing works is that that’s just the beginning of a long, long process. My guess is spring of 2024.

George Gendron: Are you going to meet your deadline?

Adam Moss: Yeah. You know, I’m a good, good student. I try to please the teacher.

George Gendron: That’s good to hear. But we’ll look forward to the book. So what, if anything, can you tell us about the consulting projects? Or are you all NDA’d up?

Adam Moss: Well, I’m not technically NDA’d up. But I think these relationships are best when they’re private. I’ll just tell you that they’re, basically, working with various journalistic outfits that seek me out for whatever reason.

And you know, I perform all sorts of different kinds of roles: a sounding board, a shrink sometimes, sometimes evaluating ideas and giving feedback on them, evaluating manuscripts and giving feedback on them. But basically just someone to talk to in a kind of discreet way.

And it’s very satisfying to me because it allows me to function as a journalist without a lot of the things that I had come to not like about journalism, mainly management. Which becomes, as you get more positions of responsibility, that also means that you’re spending a lot of time worrying about management, a lot of time worrying about business strategy, and all these other things.

Especially when, toward the end of my tenure as an editor, when things got very complicated, in terms of the economics of magazines. It sort of distills the pure journalism of it. So I like all that. Even though, basically no one has to listen to me. That’s a little frustrating. You know, you give your thoughts and then that’s it. You’re finished. Somebody else decides whether they’re worth anything or not.

George Gendron: It’s interesting. A university did a case study about the culture that we created at Inc. And it turned out that there was something that I mentioned very casually to them that became a big deal. And I actually felt that I learned a lot from the case study. Which is often the case, right? We do things intuitively, but we don’t really think about the intentionality behind it. And at one point I had said, “You know, I really don’t like to manage and I think I’m really bad at it.” And as a result of that, I tend to hire people who don’t need a lot of management and don’t want a lot of management. So, boy I can identify with that.

Adam Moss: I actually think I was a good manager. But there came a point when I just couldn’t do it anymore. When it had so crowded out the other reasons why I had gone into journalism in the first place, that I just want to figure out a way to get back to that.

George Gendron: Well, unlike you, I can say unequivocally, I was not a good manager. And I have lots of people who will attest to that. So I hired a managing editor who was. And then I ended up marrying her.

Adam Moss: Oh, well that’s nice. What a lovely story.

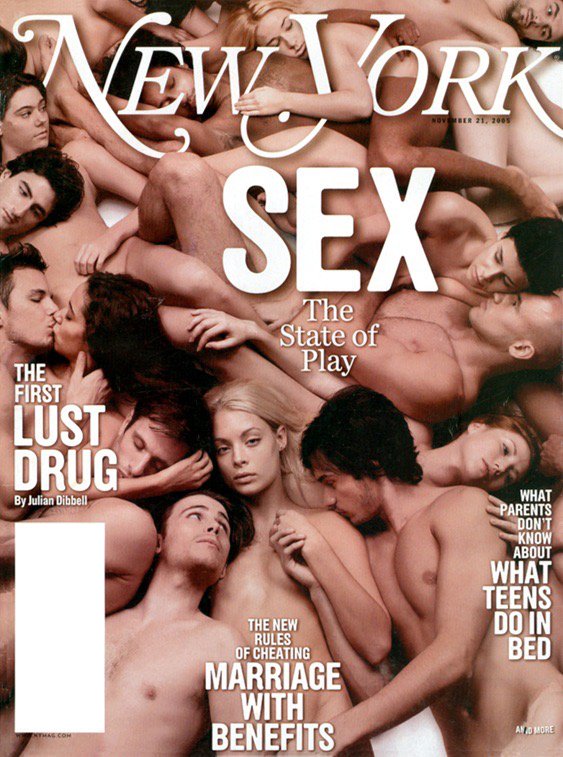

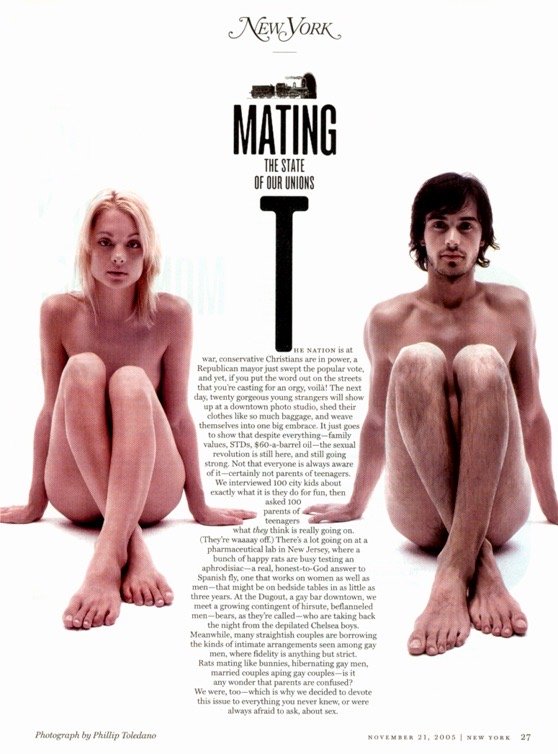

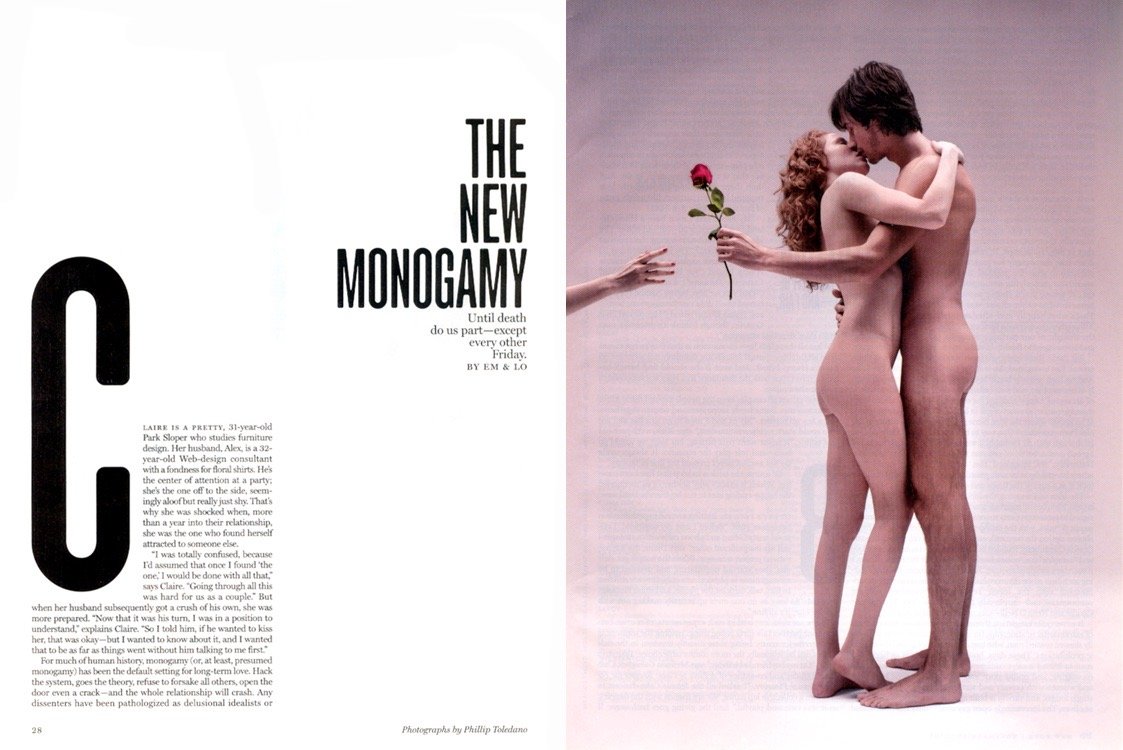

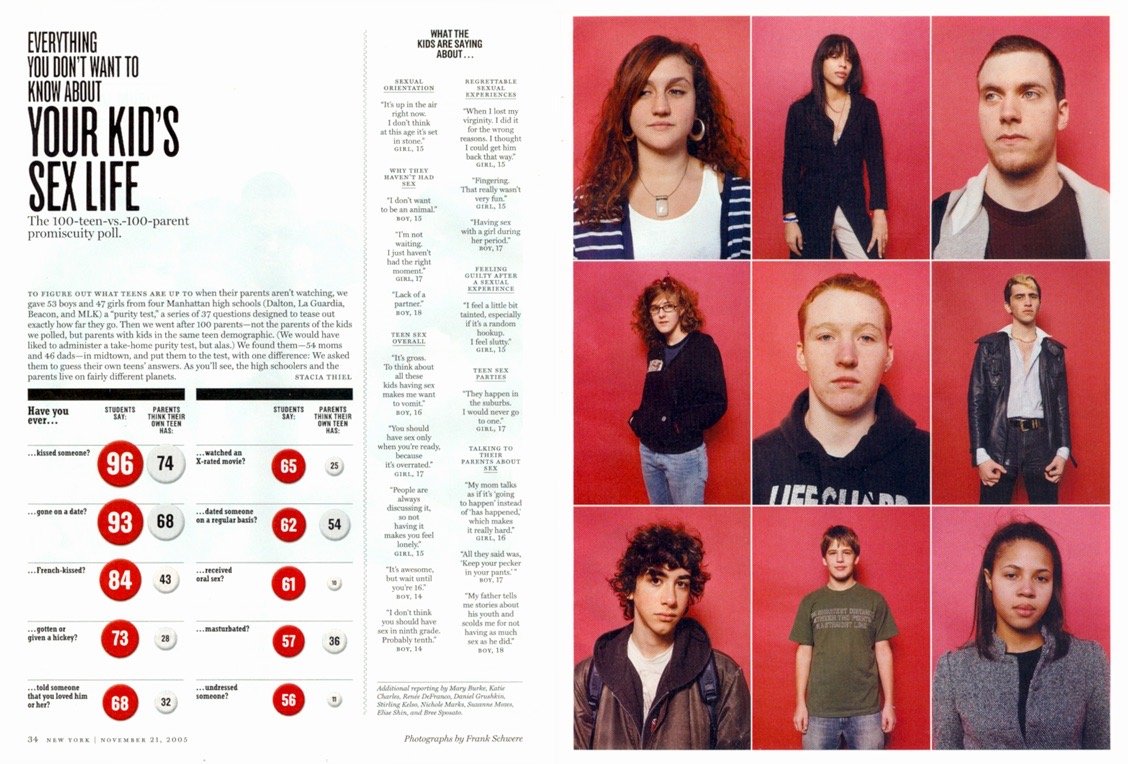

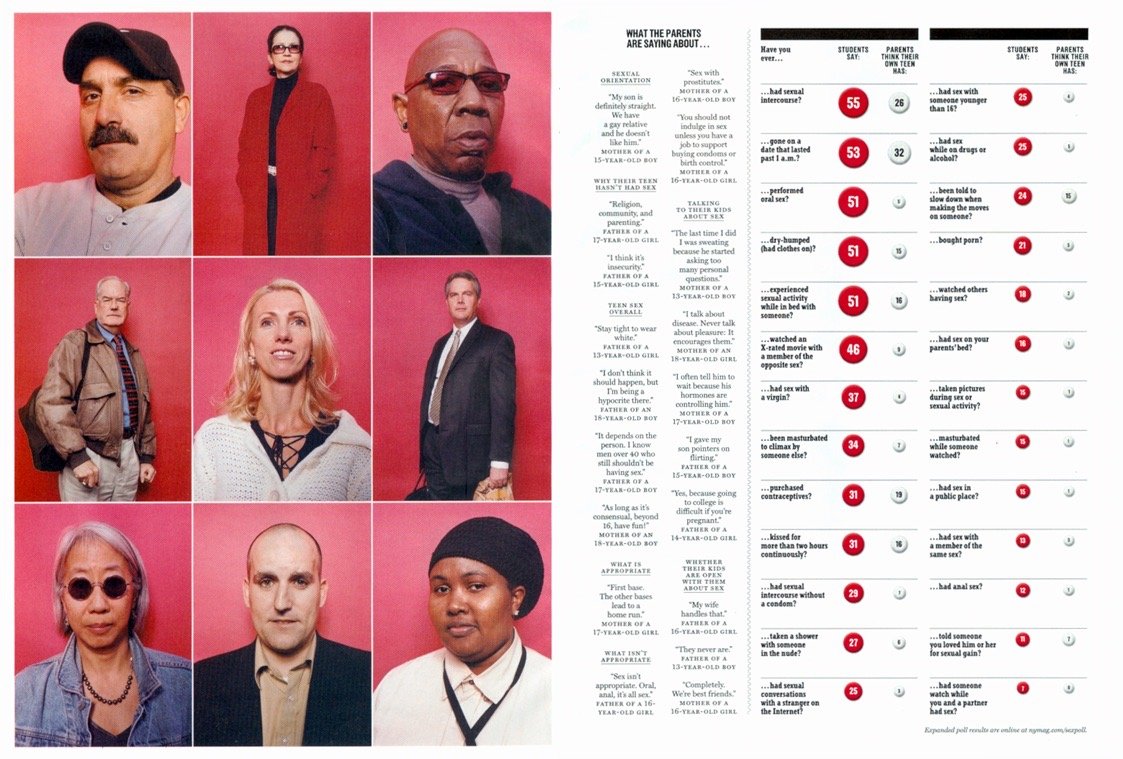

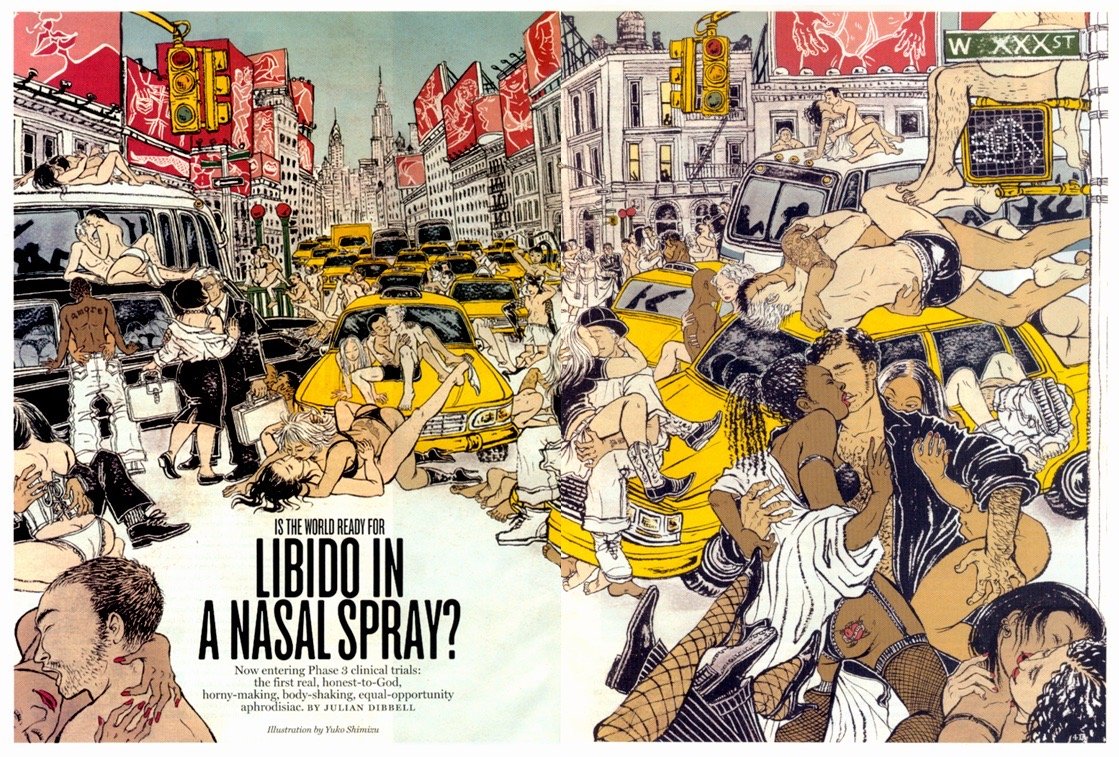

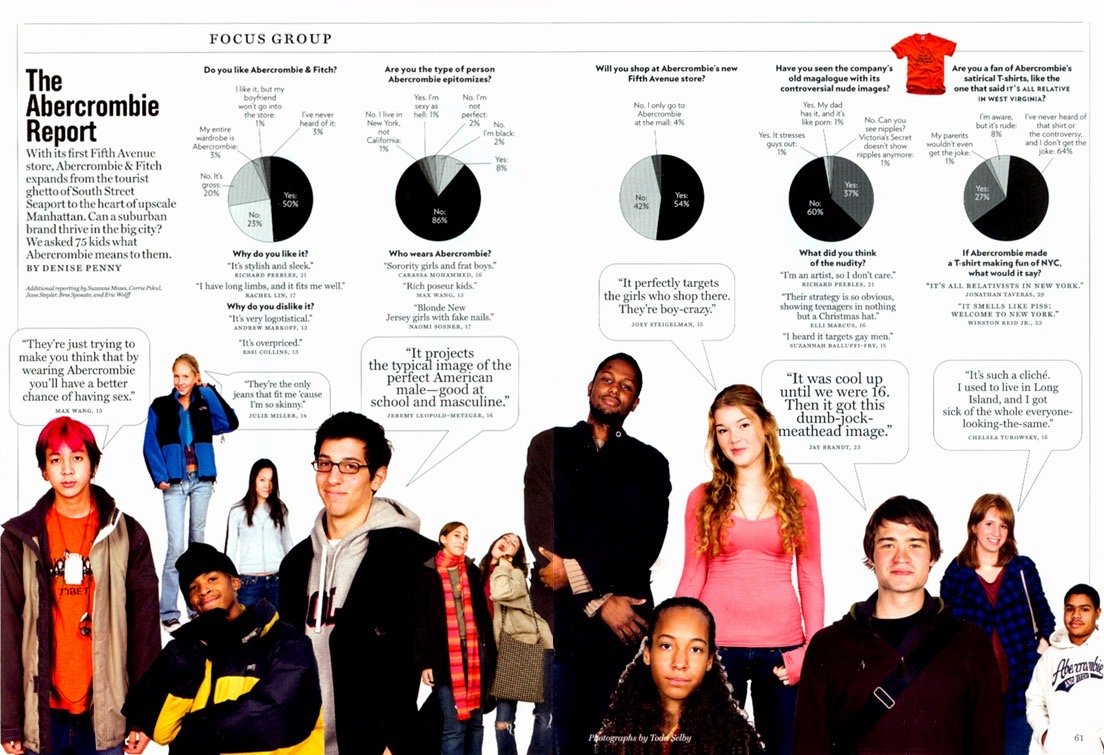

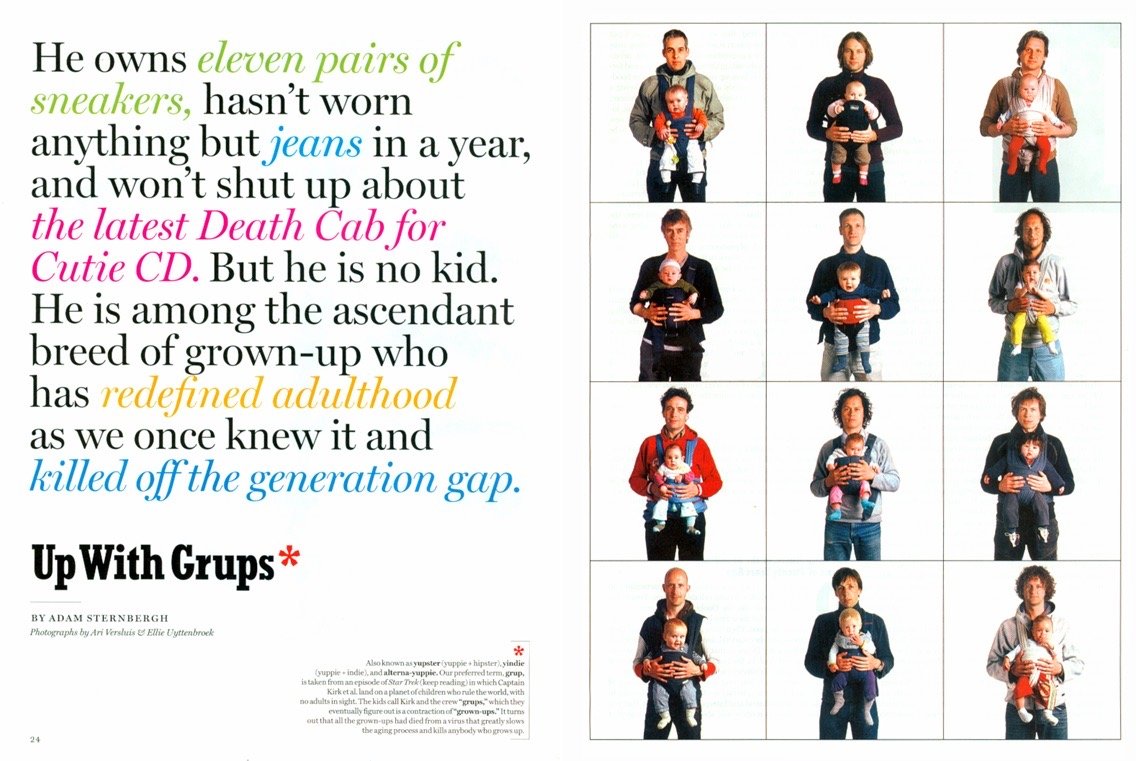

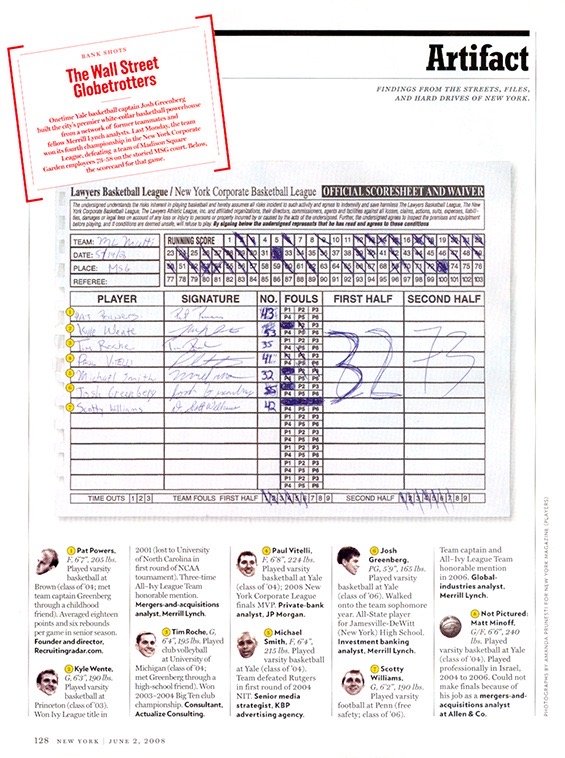

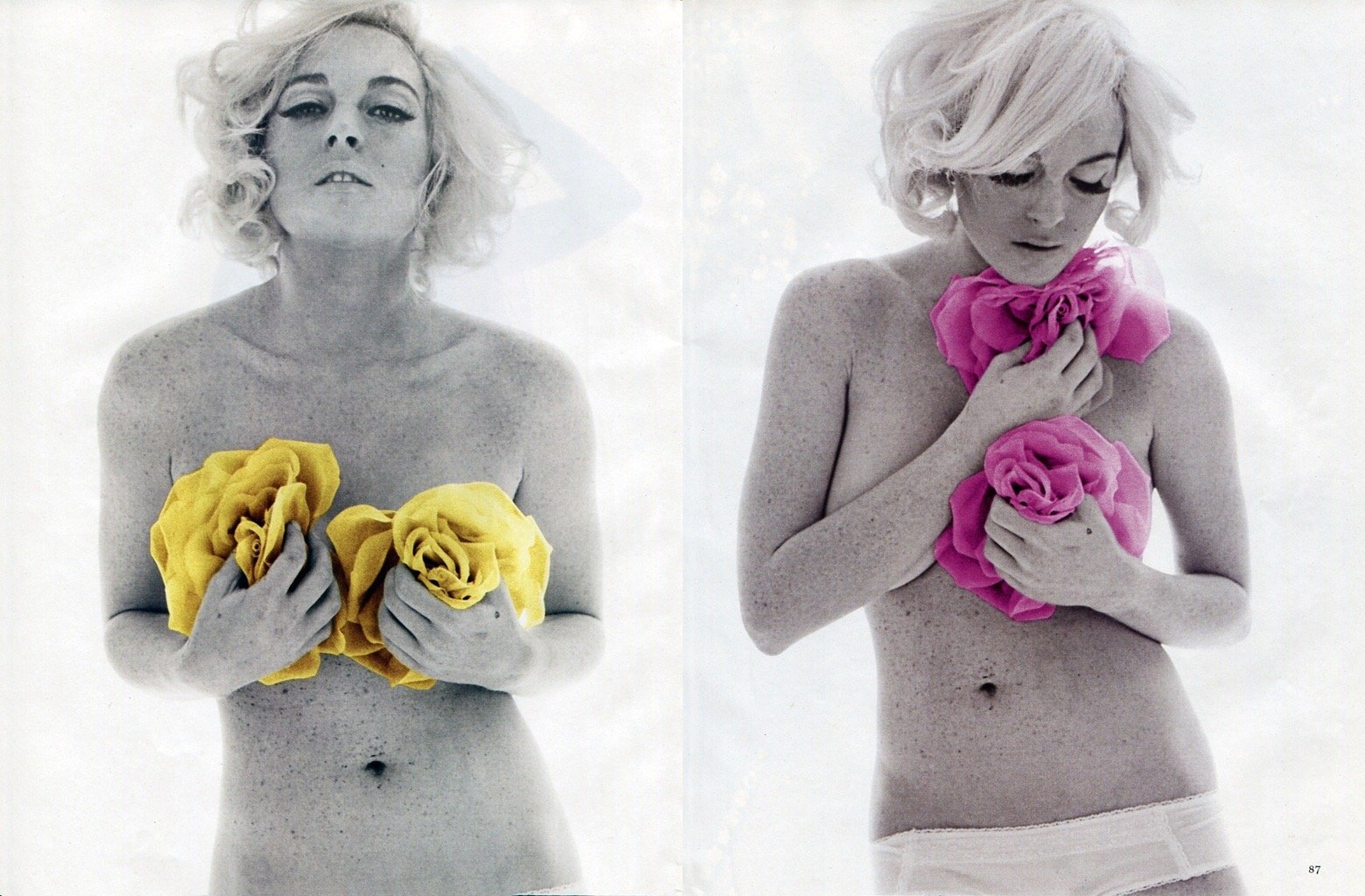

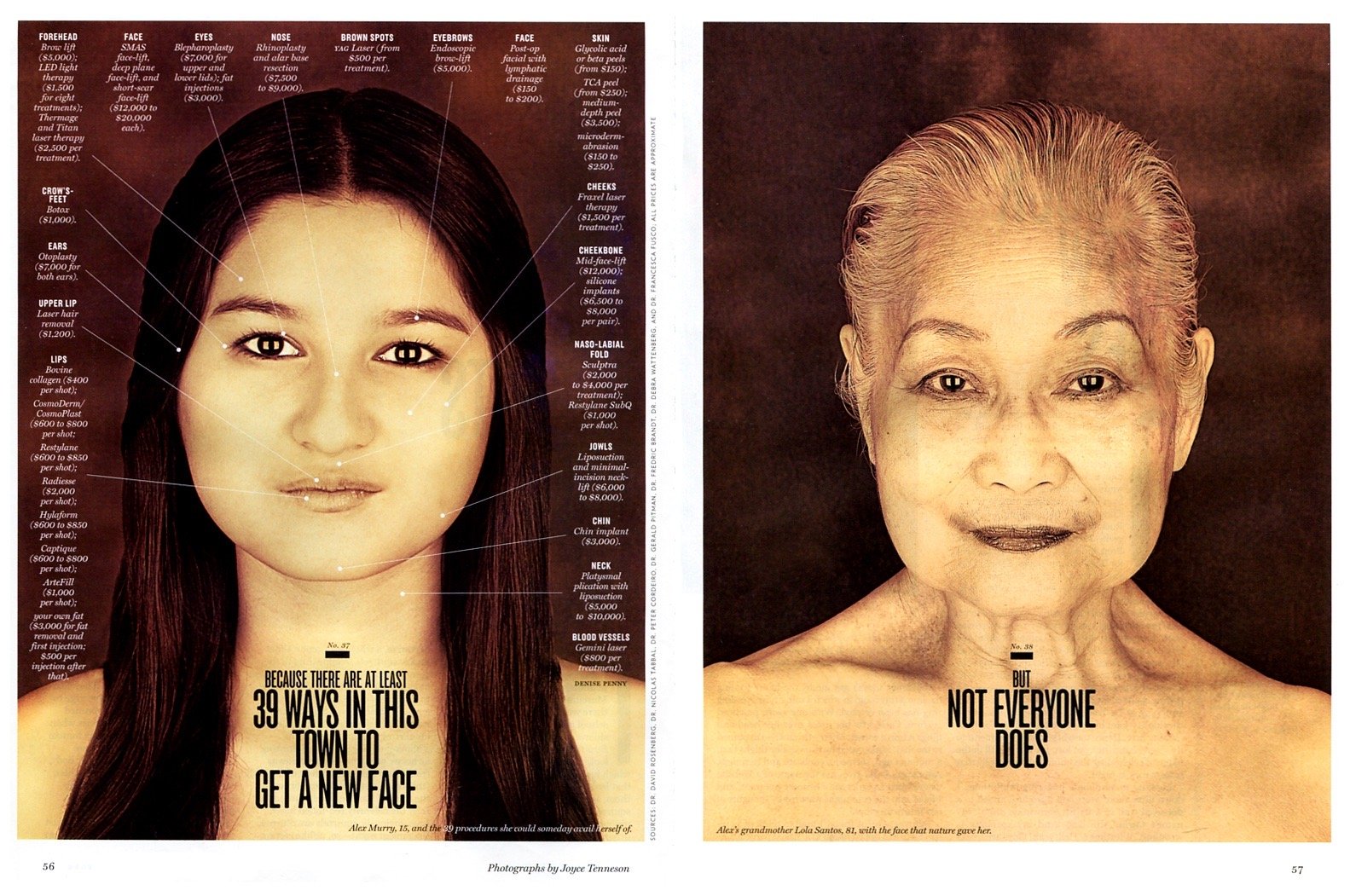

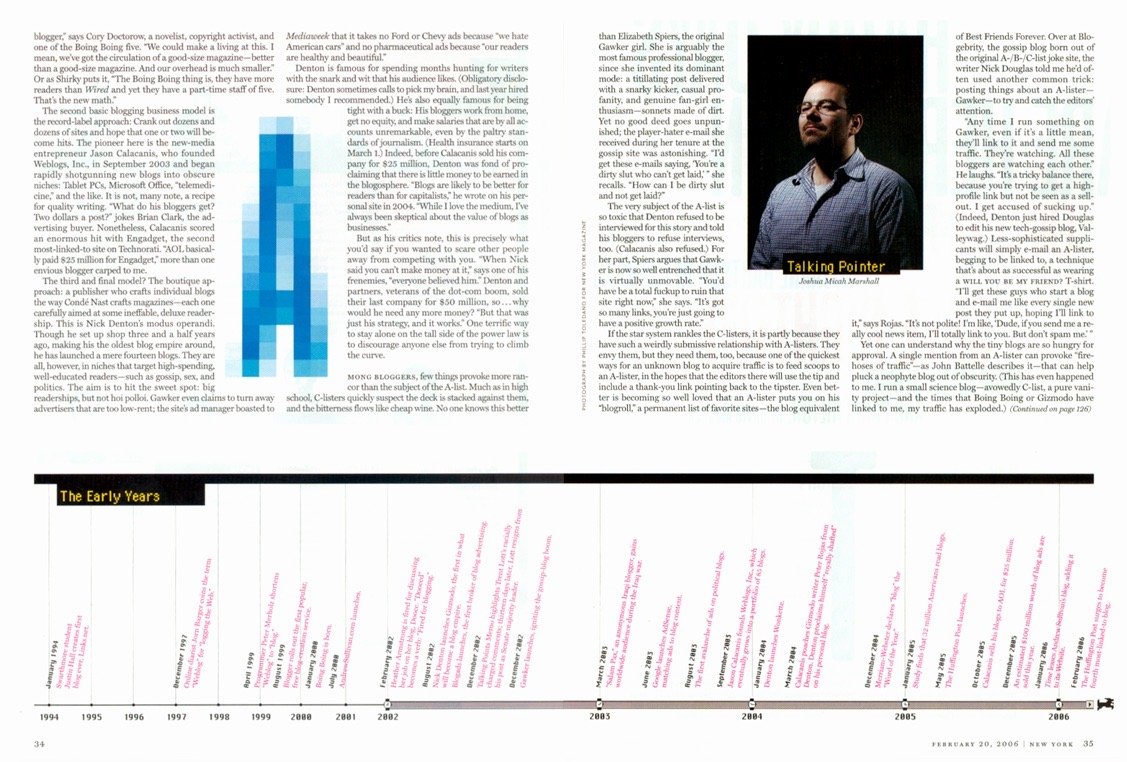

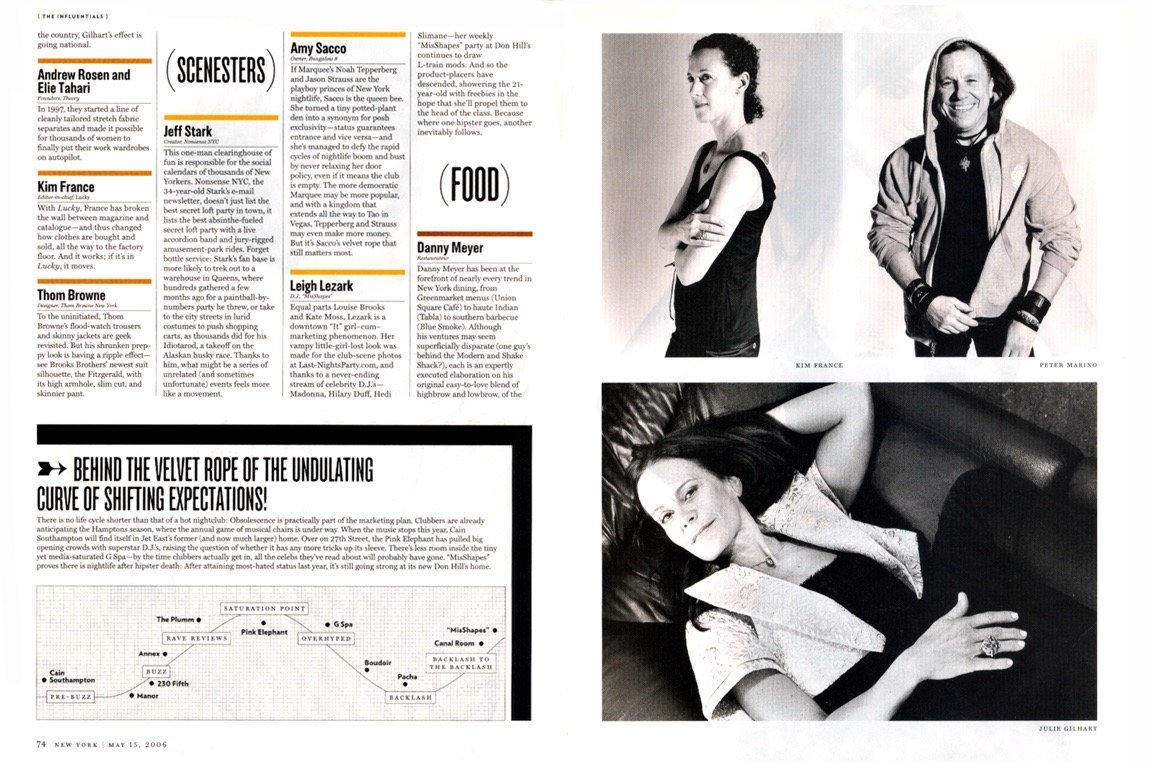

Moss and his team created several recurring packages like this 2005 one (above) on sex. In 2006 (below), Moss introduced the world to “Grups.”

“In journalism in general, the thing that I always liked the most was the inventing part.”

George Gendron: That was, yeah. So it’s interesting listening to you talk because we sold Inc. to Bertlesman in 2001. Boy were we lucky, because Bertlesman wasn’t publicly traded, it was an all cash deal. People talked about the deal and said, “Man, you guys were so smart strategically about when to sell.” No, we weren’t. We were just lucky. A year later, BusinessWeek was sold for a buck. But since then, I’ve never had a job. I’ve just worked on projects.

Adam Moss: Right.

George Gendron: And, on the one hand I love that. On the other hand, the one thing that I find challenging about it is often not having what I call an “anchor deal.” Does that make any sense to you?

Adam Moss: Sure. I’m going to be finished with this book soon, and I will lack an anchor. And we’ll see how that goes. When I left New York I did spend six months trying to figure out what I wanted to do. And then I very much needed something to do. I thought at first maybe I wouldn’t. Maybe I could just paint, which is what I do sometimes. But it turned out not to be enough. So, yeah, I missed that.

George Gendron: I got some really good advice after we sold Inc.: “Whatever you do, don’t do anything at all. Don’t do anything major for a year.” And on the one hand it was good advice. Don’t jump into things just to keep busy. On the other hand, six months through that year, one of my daughters came to me and said, “Would you do me a favor and go get a project, a big project?”

Adam Moss: Get out of my hair!

George Gendron: Yeah. It was kind of like that, and kind of moping around.

Adam Moss: I understand.

George Gendron: There’s a lot to parse there. So, you just said you painted.

I was having a conversation recently with Janet Froelich, your former colleague, and she said, “Yeah. I’ve heard that Adam’s painting.”

Adam Moss: I really enjoy it, most of the time, when I’m not actually putting pressure on myself to paint well. Which is like a trick you have to play. It’s very hard to let go of the idea that you have to actually be good at it.

George Gendron: That is, isn’t it?

Adam Moss: Yeah.

George Gendron: Anyway, she said, “The trick I’ve learned is to do pottery. Because it’s unbelievably difficult. So difficult that I don’t have any illusions about ever being good at it.”

Adam Moss: Yeah.

George Gendron: “...But I love it. It’s like therapy. It’s like meditation for me.”

Adam Moss: Well, I think the meditation thing is really relevant to my love of painting. I’m sure pottery’s even more difficult, but I find painting very hard and very consuming. The amount of focus you need to paint well. I mainly paint figures. Sort of abstracted figures. And you just have to be all there.

And what that does is it completely takes me out of my head and puts me in this place where all I’m thinking about is the next decision I make on this painting. And I spend a lot of time in my head generally, and sometimes I want to get out of it. And painting is such an effective way of transporting me into a place that doesn’t feel like me. Or at least where my conscious self is somehow not part of the equation. And you go in and out of that. But when you’re there, when you’ve eradicated the thinking self, it’s very satisfying.

And then you know, you just have to separate yourself from the outcome. Because sometimes you look at these paintings afterwards and you think, “Oh God! This is so terrible!” But the process of making it was so pleasurable. And how do you square part of that with the other part?

And then you start, if you do it long enough, you start to really get happy about little things that happen in the painting. And the whole painting doesn’t have to work. But yeah, this part was actually kind of interesting. And I liked this accident that happened. And I liked this part of the painting or this way I solved this problem. You just become enamored of the process and not of the end result.

George Gendron: Yeah. When you left New York, you were quoted, I think, many times as saying, “I’m doing it because I worked full throttle for 40 years.” How are you doing at backing off “full throttle?” It sounds as if painting is one of the mechanisms.

Adam Moss: Yeah. It does a pretty good job. I need to do things but I don’t need to do them with the intensity that I used to do them. Or with the worry. So I’m probably as full throttle in terms of my day-to-day working metabolism. But it doesn’t come with the anxiety that used to, it doesn’t come with the worry.

So in that sense, I did, I think, succeed at not being full throttle. I don’t want to be idle. Idleness just to me is not pleasant at all. Some people really like it. For me it’s not, but I do want to be less anxious, and I think I’ve mostly succeeded at that.

George Gendron: I’ve heard several times you talk about your love for Provincetown. What role does Provincetown play in not being full throttle? And I say that because my wife and I love it as well and it performs a very specific role in our lives for 40 years now. And that is that it’s one of the few places we can go, spend a lot of time there, and we get in the car heading back to Boston, and we look at each other and we always ask the same question, which is, “Did anybody ask you what you did the entire time we were out here?” It was like, “Nope.”

Adam Moss: Yeah. Well I have a wonderful life there. And I spend, in the warmer months, because, like, this time of year, in my view it’s just bleak. But In the warmer months, I go and I park there. And we bought this old art school. It used to be something called the Hawthorne School of Art, started by Charles Webster Hawthorne at the turn of the last century. And it’s a beautiful place. It is this giant barn, which used to be the painting studio of it. There’s ghosts everywhere, which are friendly ghosts. One of the reasons I started painting was because it’s like you had all this painting history in this place and it seemed a shame not to try it myself.

But, basically, I have a bunch of very close, loving friends up there, and it’s gorgeous. And I love the ocean, and get there as much as possible. And it’s an amazing place to bike. I could say all sorts of wonderful things about Provincetown. But it’s true that you’re there and you’re not elsewhere. You are just in this place at the end of the world. My friend, Michael Cunningham, talked about it as the “end of the world.” And it’s a great place to be.

George Gendron: Yeah. Yeah. I agree completely. I want to go back to the book for a second because one of the things you and I talked about a couple of days ago was, I guess what I would call a kind of thread that seems to have run through your adult life. And it has to do with the thrill of invention — both in the magazine world, where you’re working with other people, and also with the book, which is, I know you’re working with other people, but it’s much more solitary.

Adam Moss: Yeah.

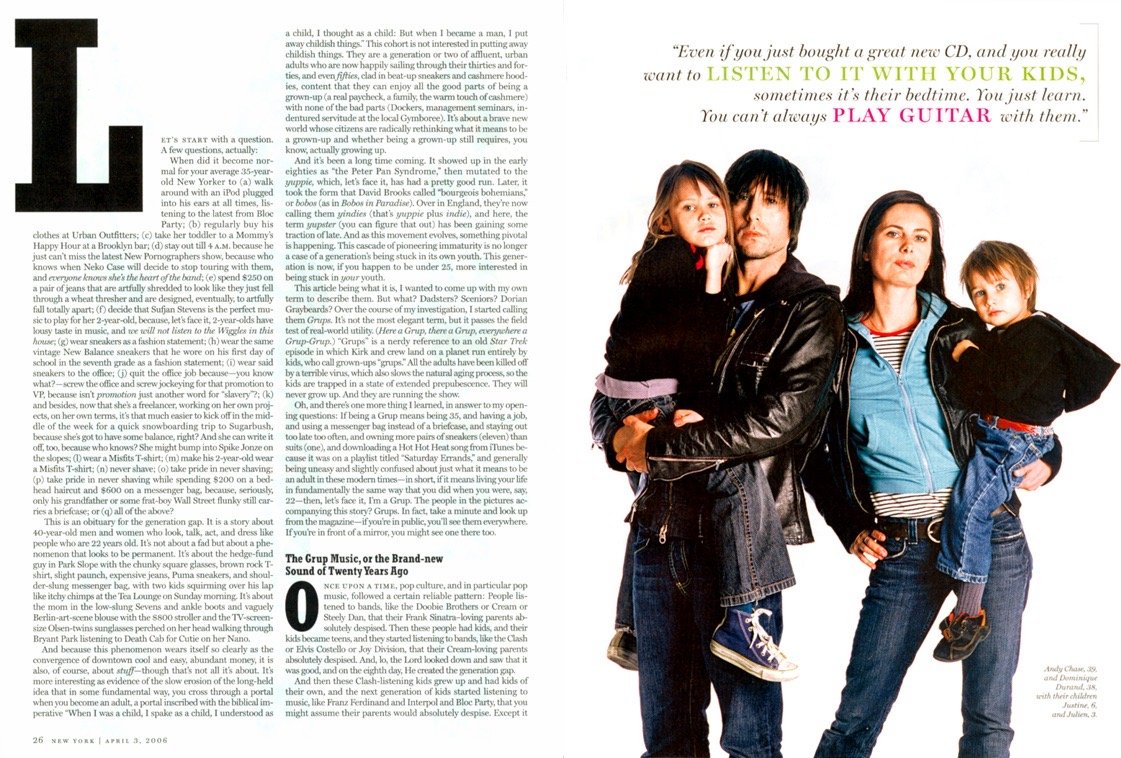

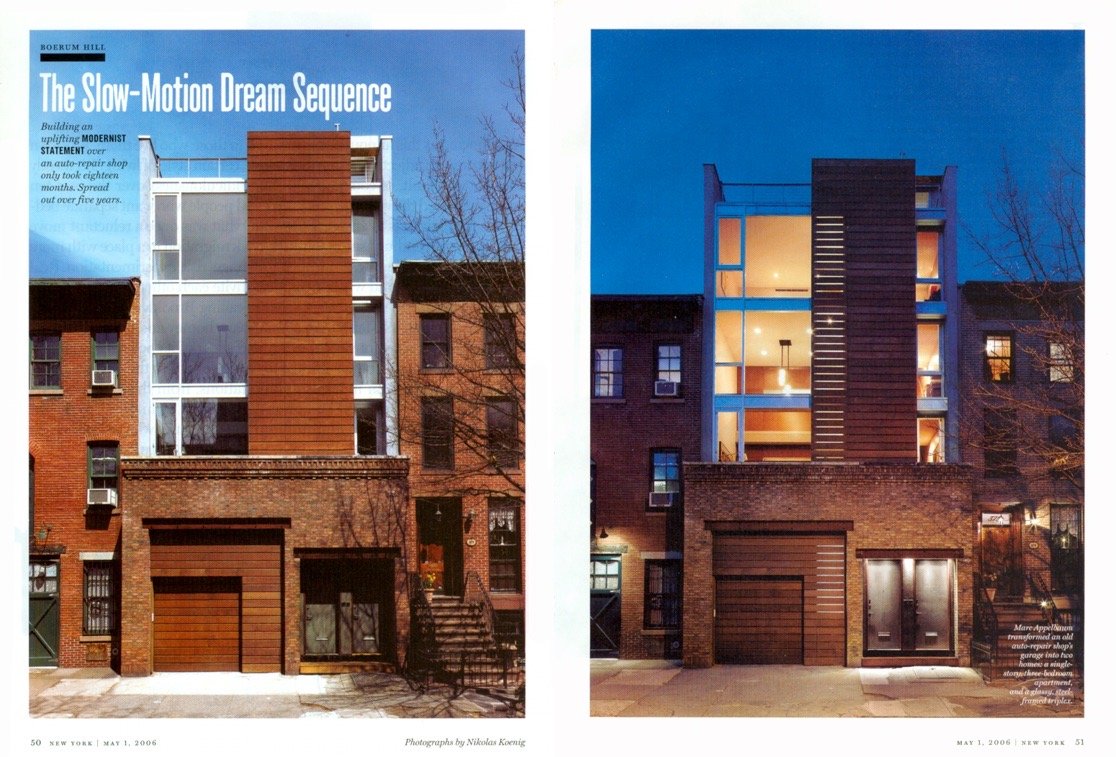

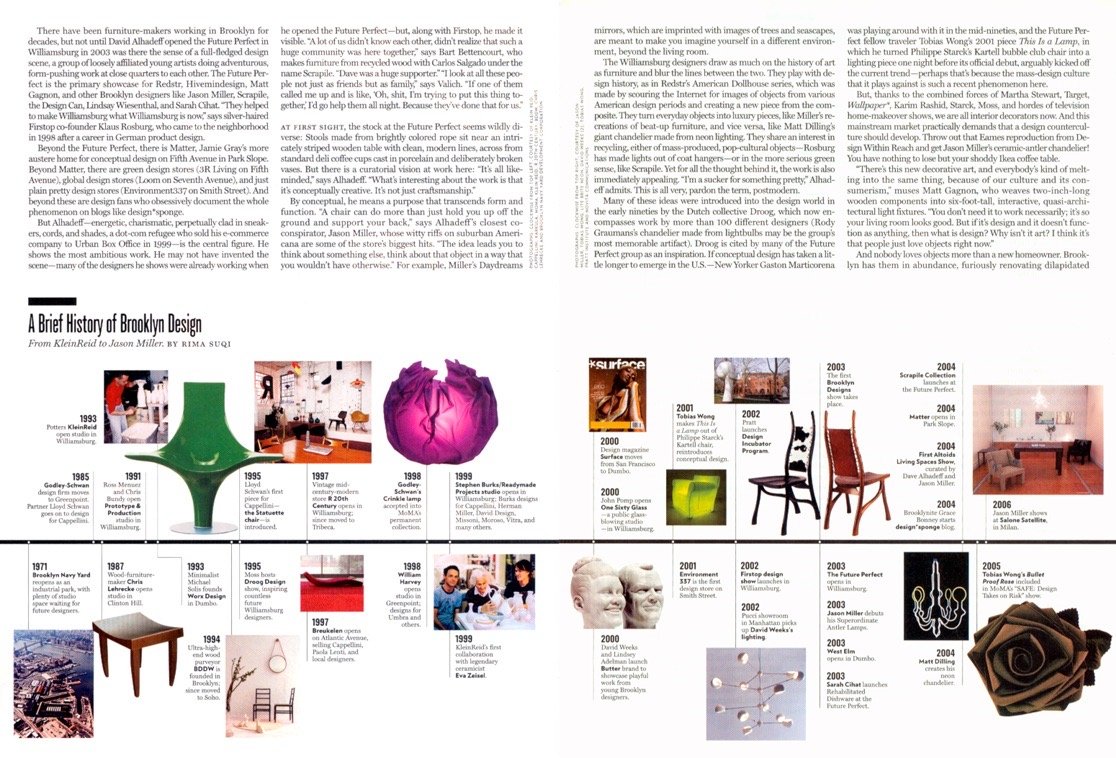

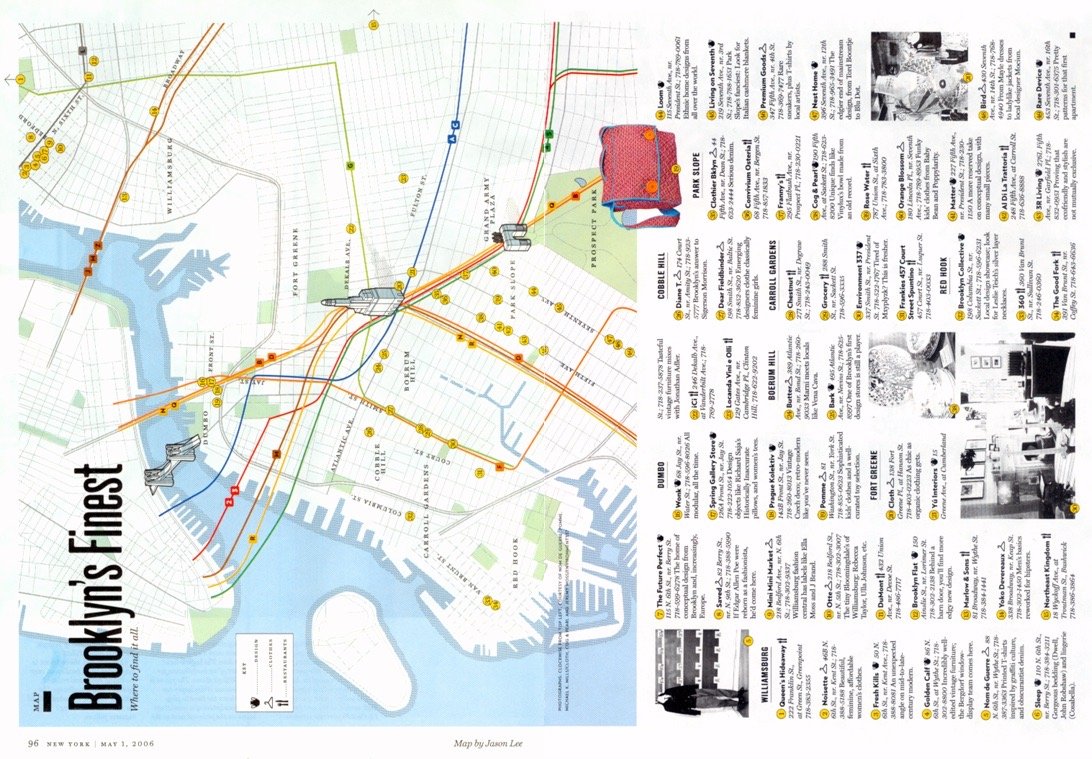

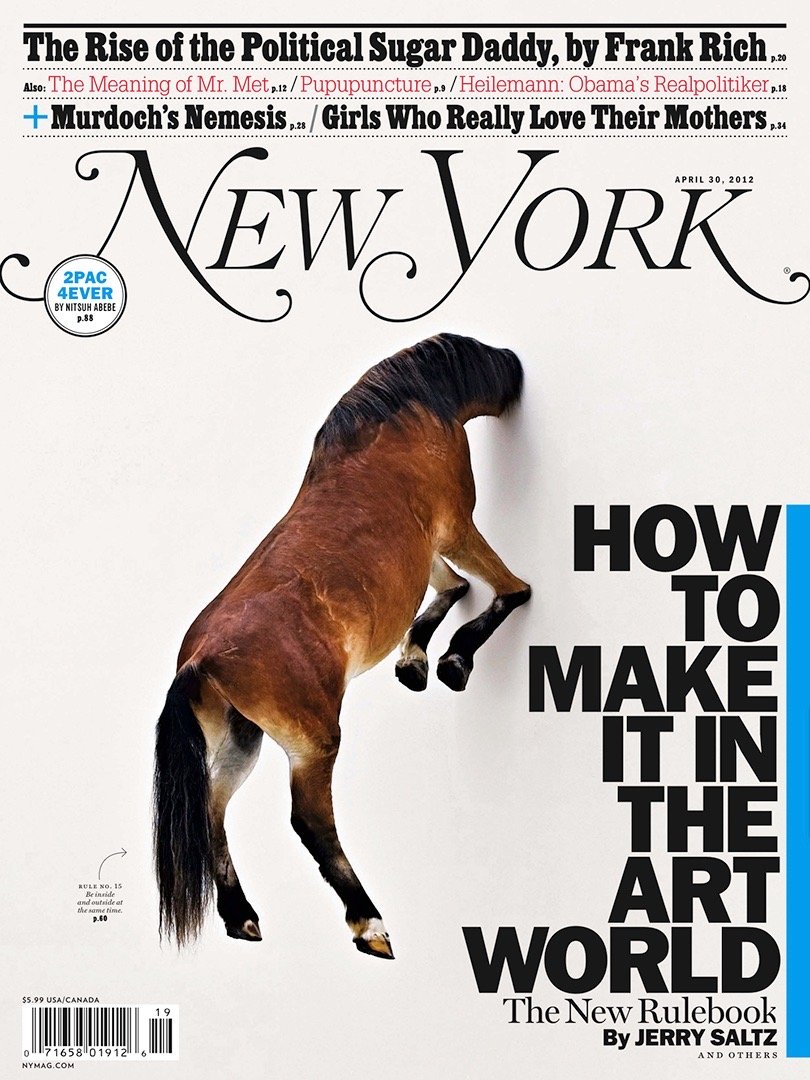

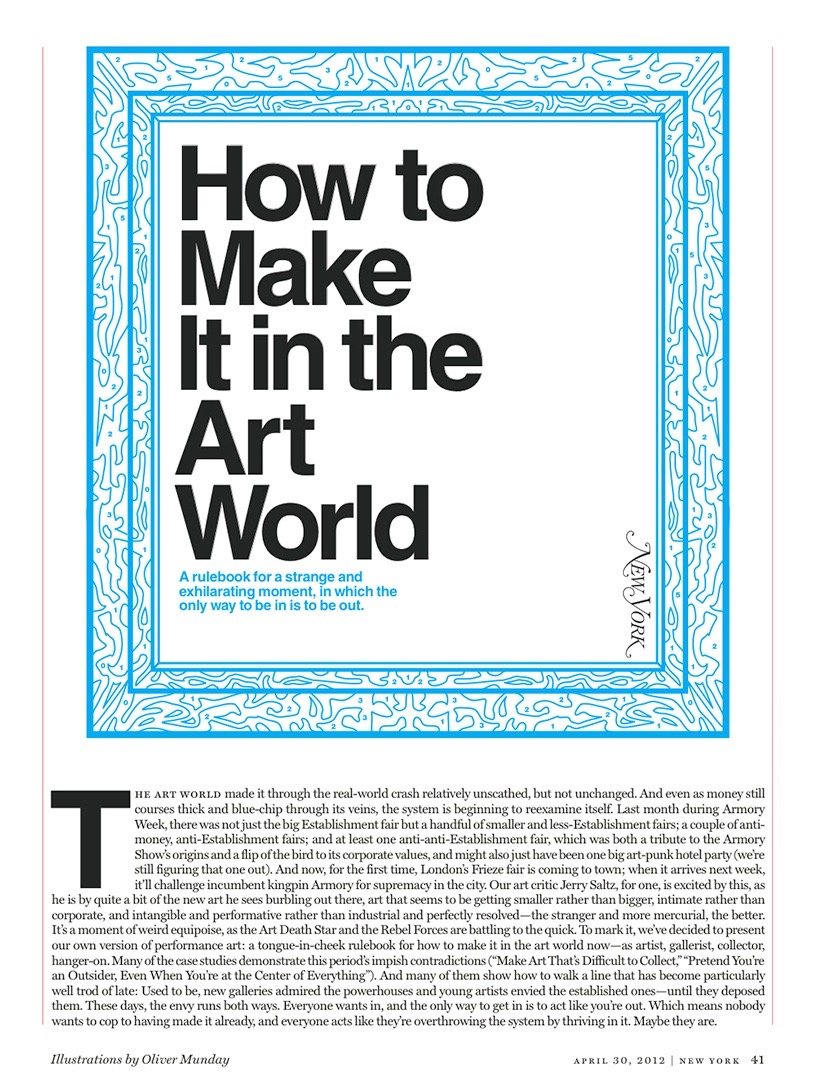

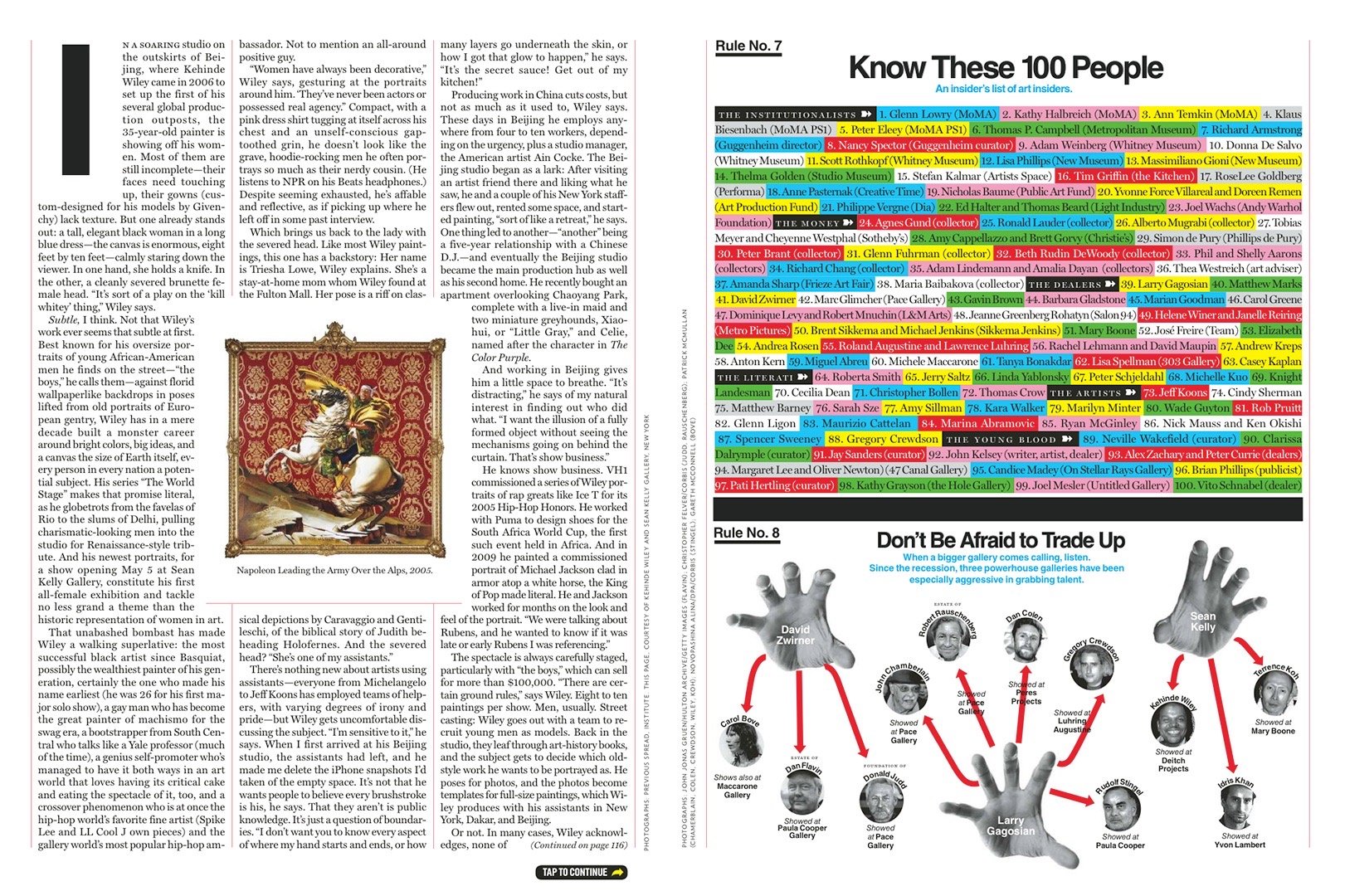

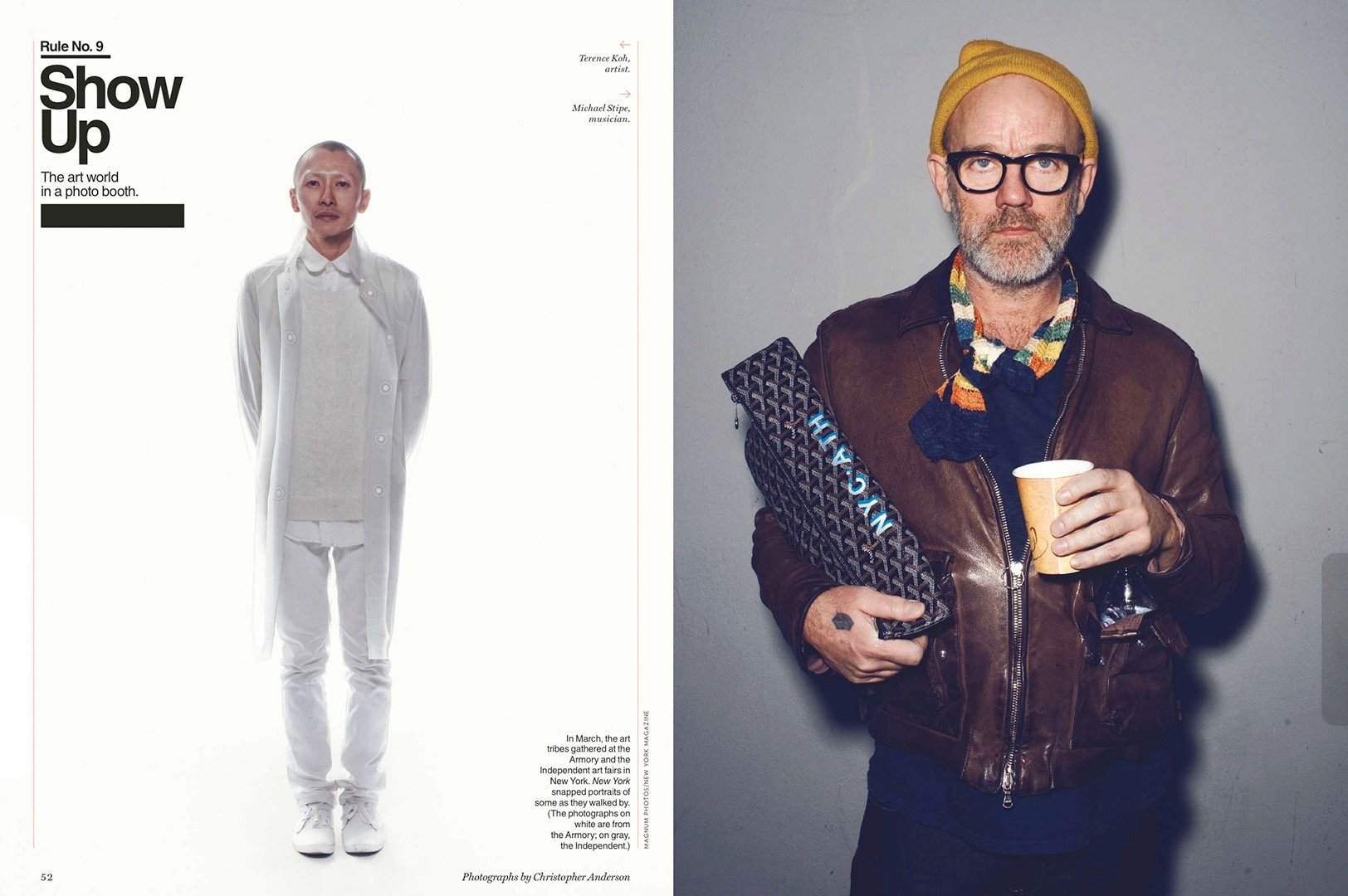

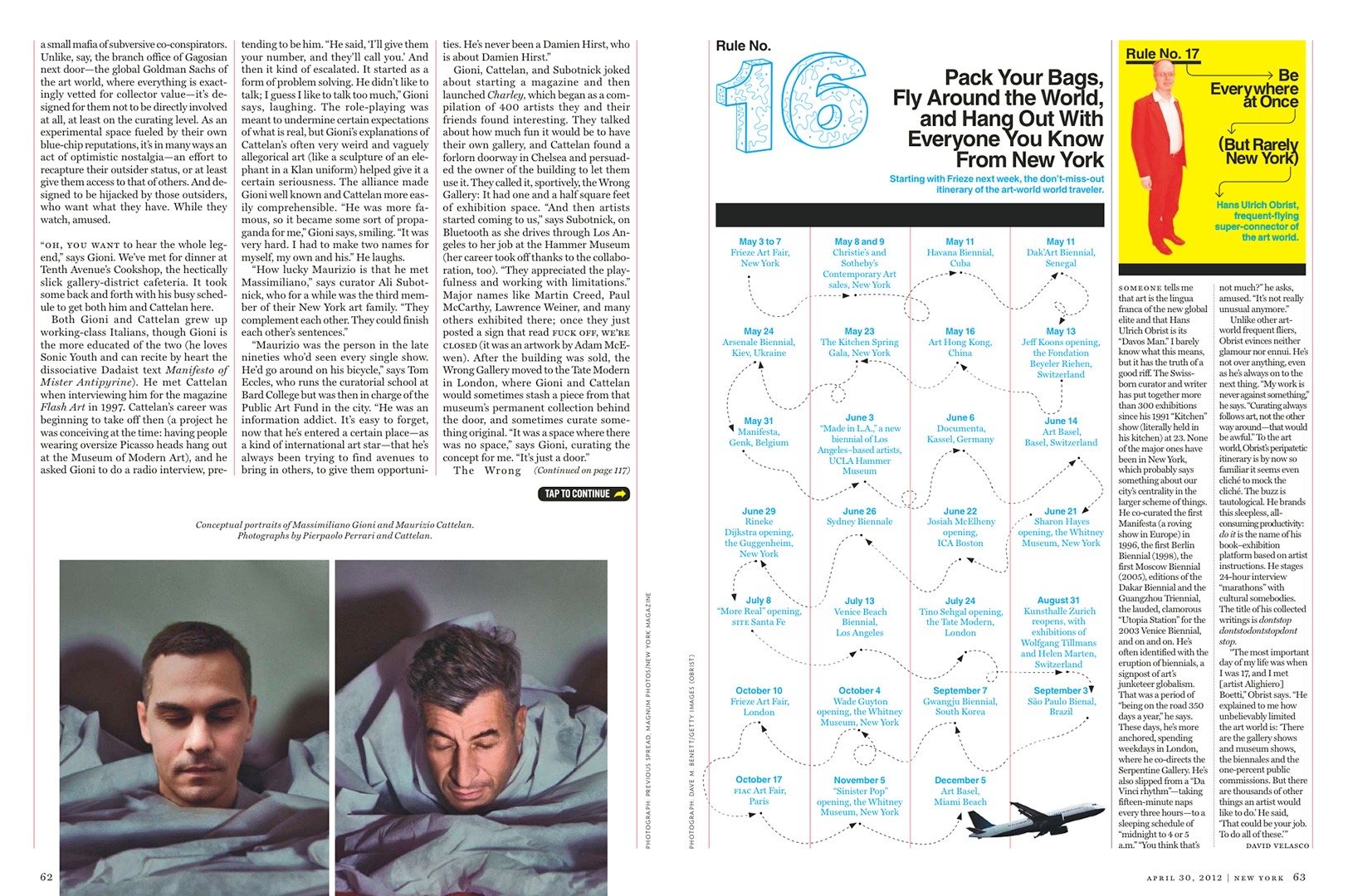

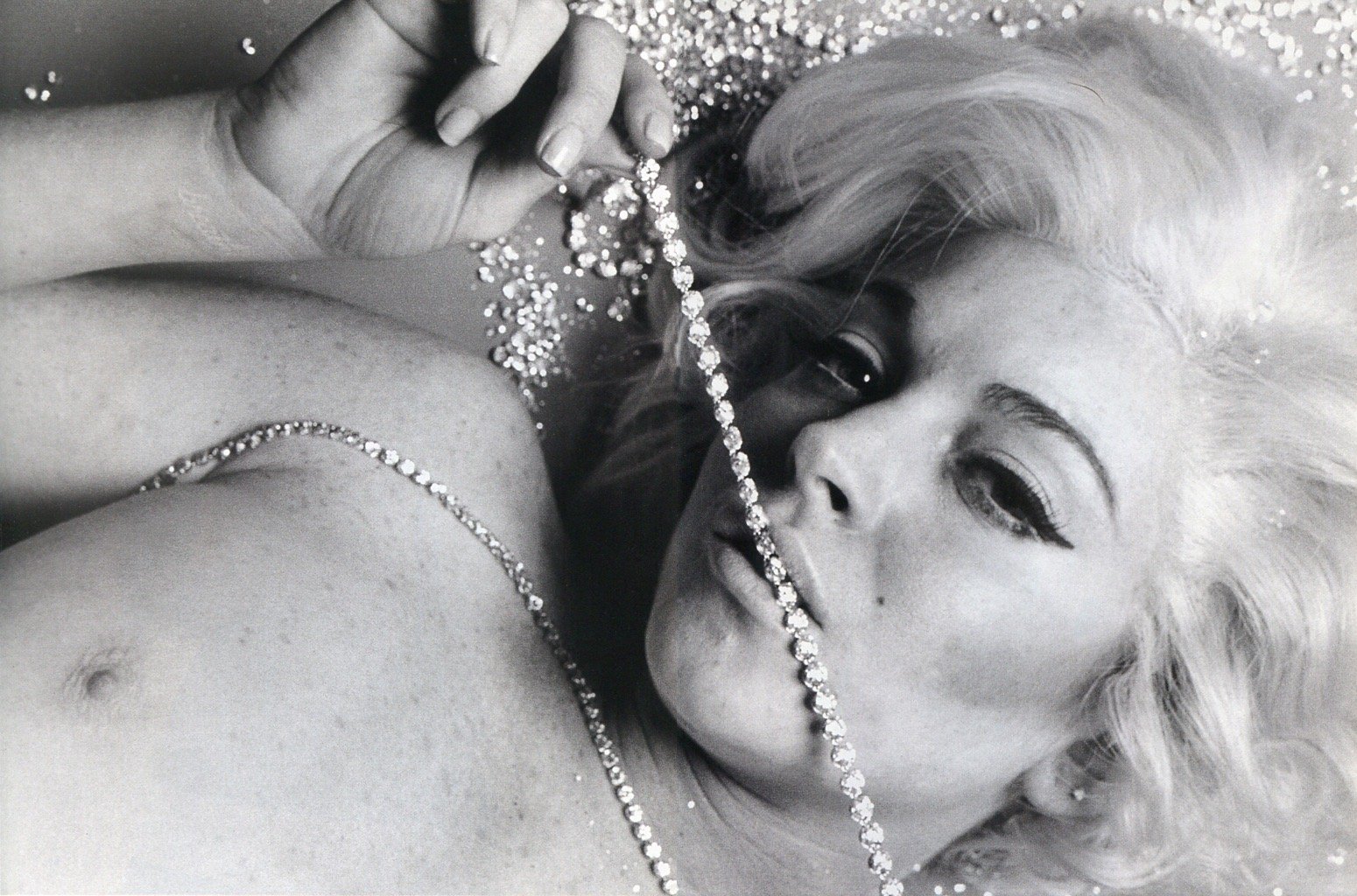

Above, the rise of Brooklyn inspired this 2006 special issue. Below, a 2012 issue titled, “How to Make It in the Art World.”

George Gendron: I think we share something that my partner and I talk about all the time, which is the thrill of the making of things. The sheer process of making things. I just want to hear you talk about that and what it means to you.

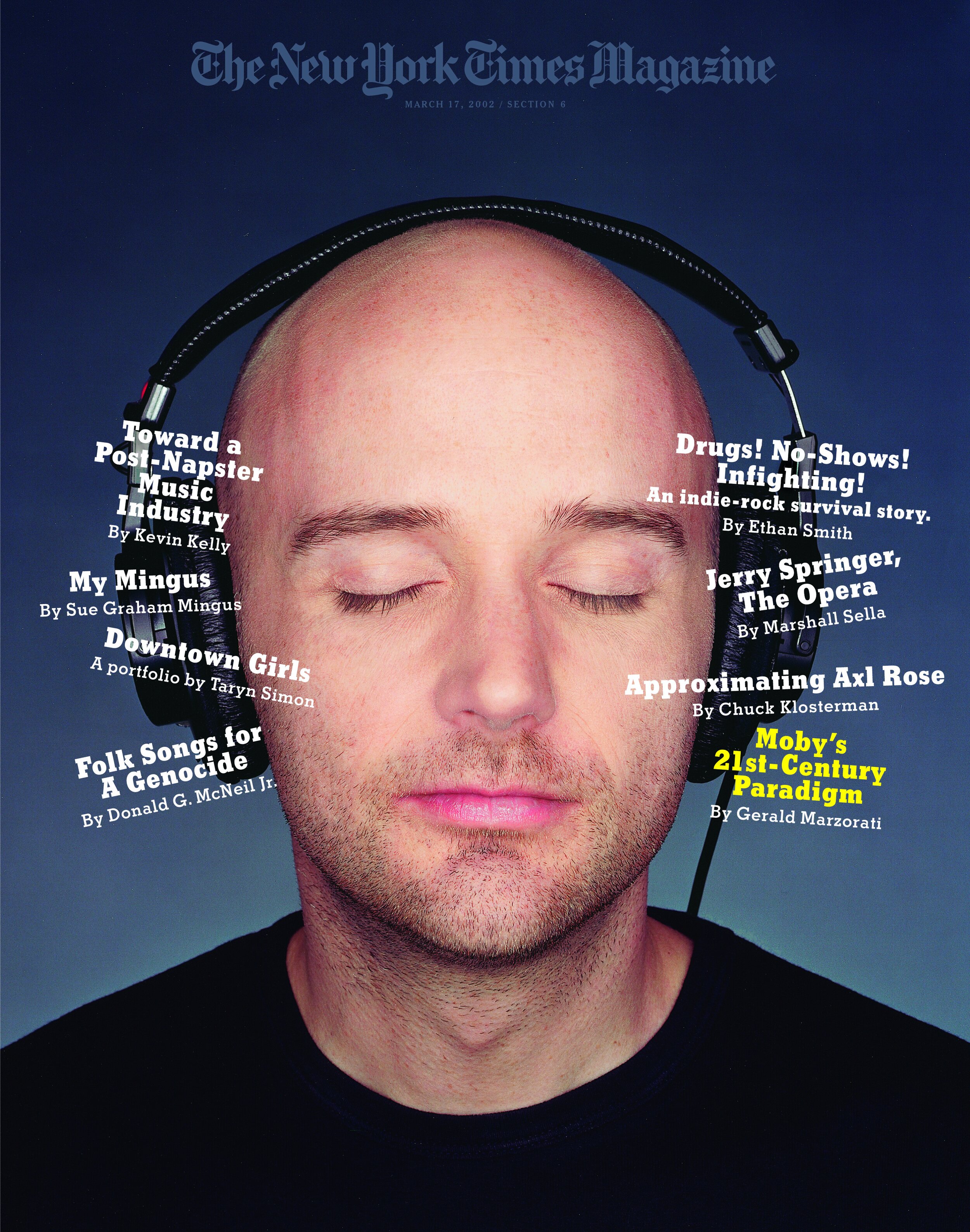

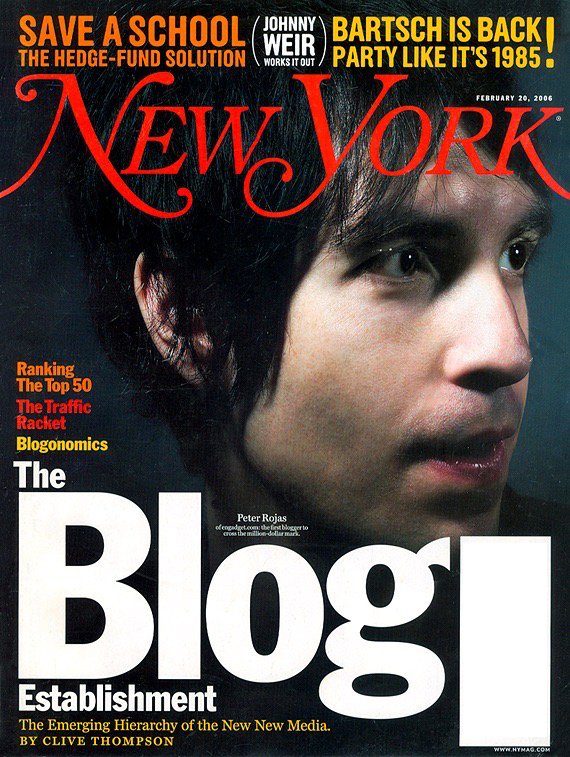

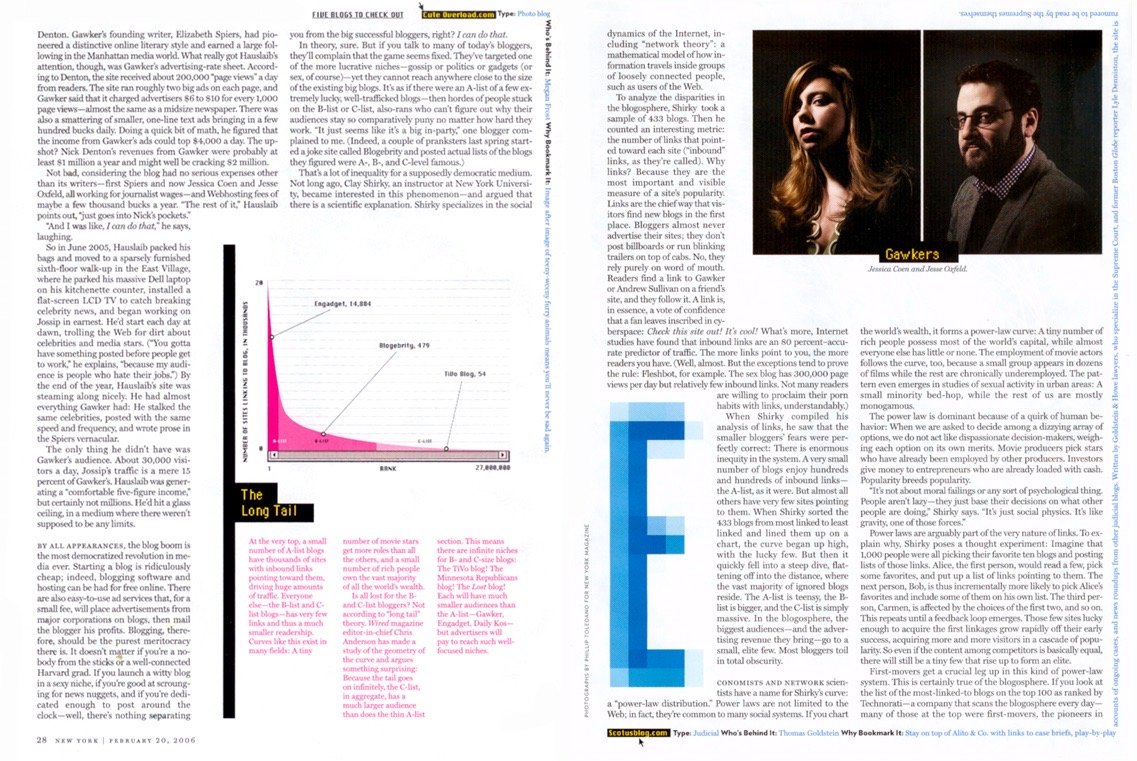

Adam Moss: Well, I’ll talk about it not in the context of the book, although we can get back to it in the context of the book. But in journalism in general, the thing that I always liked the most was the inventing part. And I was fortunate to have come of an age in journalism when new technologies were galloping ahead. And there was a need to figure out ways to make journalism work in them. I’m thinking, obviously, of digital publishing in particular. But what did it mean to make a magazine, a digital magazine from a physical magazine?

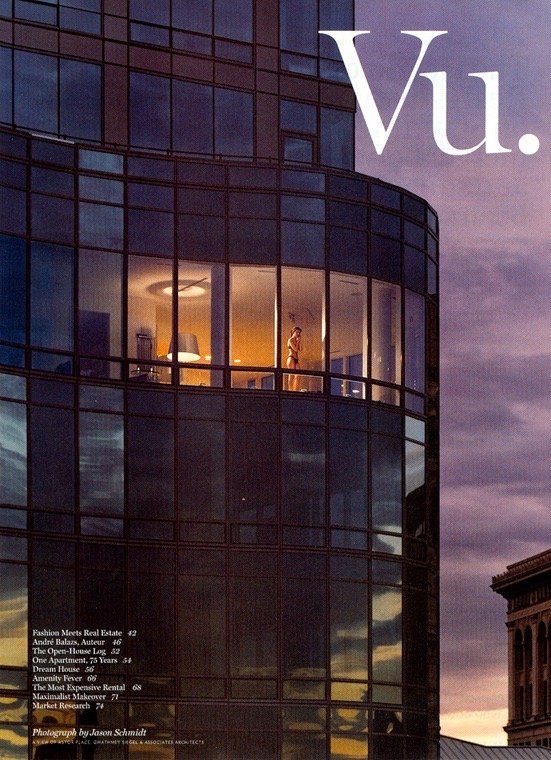

That was an amazing question that we had to solve over and over and over again at New York. when we made, we probably ultimately made, like, 12 or 15 magazines. Some of them stuck and some of them didn’t. When I left, there were five. This thing called Vulture, The Cut, Intelligencer, Grub Street, The Strategist.

These were all different magazines, with their own identity and own way of looking at the world, and way of covering, obsessively, its subject: politics, culture, the whole world of sort of women’s stuff. Which was both the politics of it and the style of it and the sort of more intimate social aspect of it. Food. And The Strategist was about shopping. But super smart and funny.

And you know, inventing all of those was among the more interesting parts of my career. At the same time, when I got to New York magazine, the whole thing had to be, kind of, reinvented itself. Or, at least that’s what I chose to do. And then it had to be reinvented again when it went biweekly.

At the Times magazine, when I got there, we were given license to imagine it in a way that was quite different from the way that the magazine had been thought about for the hundred years before that. Which was really as a magazine, as opposed to a newspaper supplement. And there were various reasons why that came to be, but that was crucial and fascinating because we looked at the Times magazine as a startup.

And then, of course, there was the actual startup that I did earlier, which was this thing called 7 Days, which was a kind of preposterous invention of my youth. And the youth of all of the amazingly talented people who worked on it. It was just kind of real blundered into it. But we did something that was a little weird and maybe, in retrospect, interesting. Also in retrospect, slightly embarrassing. But also interesting.

And so, even at Esquire, there was a kind of moment when I was asked to figure out a culture magazine that could be in the magazine. And so several of us made this thing called The Esquire Review, which was essentially about the business of entertainment, which was kind of a new way to look at culture.

So that was interesting too. Anyway, throughout my career, the point is, I’ve been kind of infatuated with the dynamic in magazines of starting something. I love publishing important, great stories. I love the continuity of a publication. But nothing is as satisfying as the figuring out of something new.

George Gendron: Let’s stick with New York magazine for just a moment. And then let’s work our way back through some of the publications and maybe from a slightly different point of view, that might be fun.

First of all, for some of our younger listeners, can you remind us, when did you get to New York? And why did you feel that it had to be reinvented?

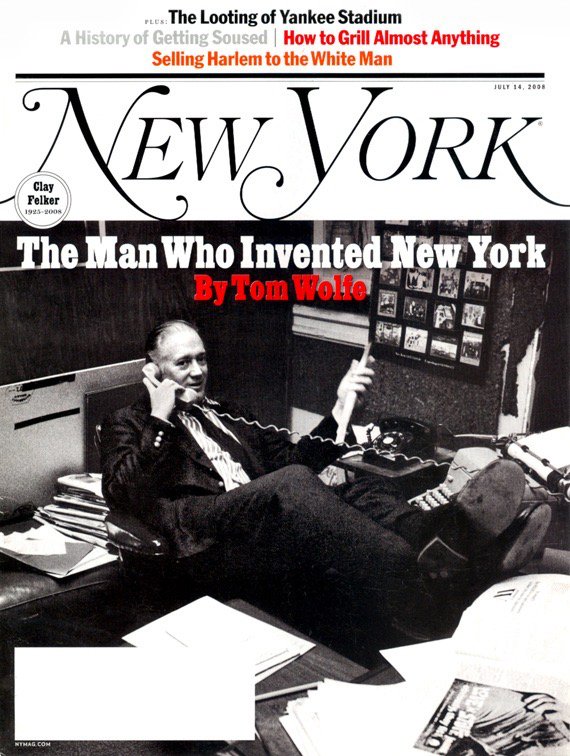

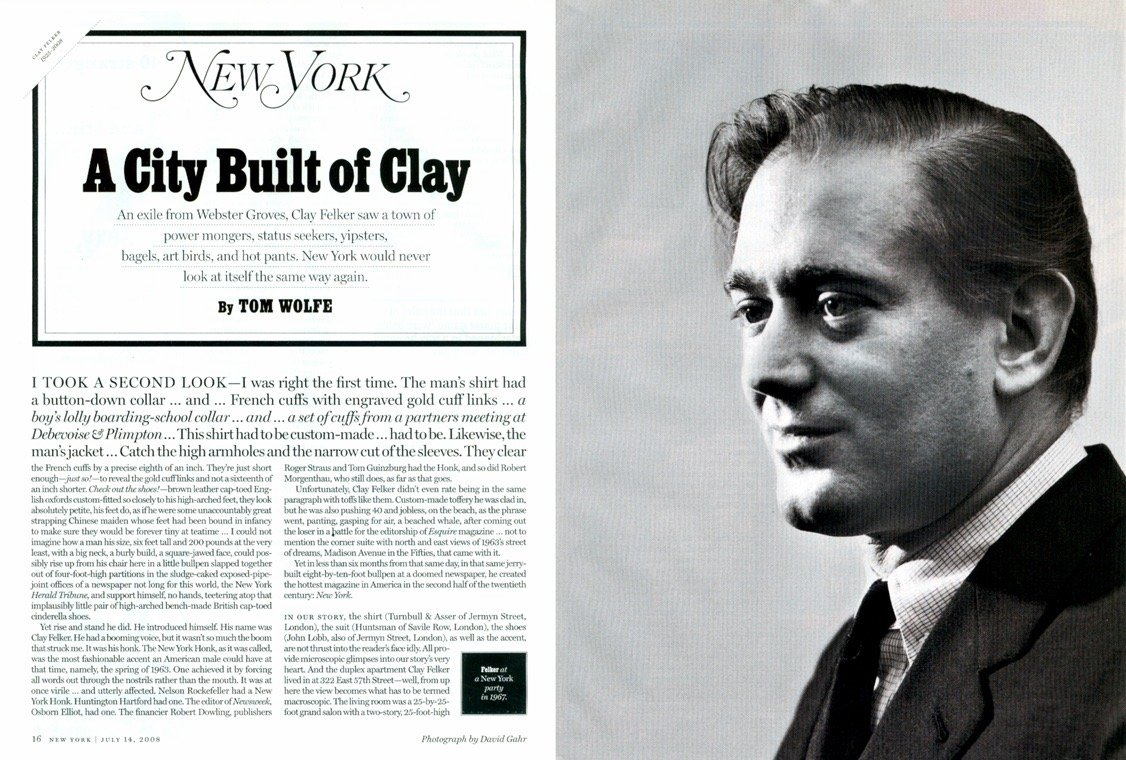

Adam Moss: I got there in 2004, and I felt it had to be reinvented because it had drifted too far away from the Clay Felker proposition. (Clay Felker being the one of the two founders of the magazine, along with Milton Glaser, the fantastic creative director of it.)

And Clay’s idea was kind of fabulous. And it was the first of the city magazines, but it had a very expansive view of what that meant for a magazine. Whereas it started a movement of magazines that became, I think, less interesting in the city mold.

And eventually New York passed through many different ownerships. And the ownership of the magazine before I got there wanted a magazine in the mold of the imitators of New York magazine rather than New York magazine itself. So it had lost, in my opinion, an essential part of its DNA. Through no fault of the people who were making the magazine, who were hugely talented. But having to do with the sort of corporate idea of what the magazine wants to be.

New York magazine had meant a great deal to me as a kid. My parents were charter subscribers. I was in the suburbs. It was the magazine that — I’d open it and it was my invitation to New York City and to cosmopolitan life and to sophistication.

And it was very powerful in the way that magazines can be very powerful, or at least it used to be. And I just felt that it had lost something essential about it. So when Bruce Wasserstein bought the magazine and hired me, I got permission to remake it and that was why I went there.

“Inventing all of those [spin-offs] was among the more interesting parts of my career,” says Moss about New York’s many brand extensions.

George Gendron: You described the process of remaking in an interesting way. Keeping the print product out — make sure it kept publishing — your day job. And then at night working on what became these other magazines-slash-channels.

Adam Moss: Yeah, so we had, you know, it’s a weekly, or it was a weekly then, and we had to publish the damn thing. So we were working in two, sort of, “time zones.” The “now” time zone, which we published the magazine, making the magazine, and then a kind of “future” time zone, which we worked on, as you say, at night. And what we were doing there was not yet doing the digital channels because that kind of was not in our sights yet.

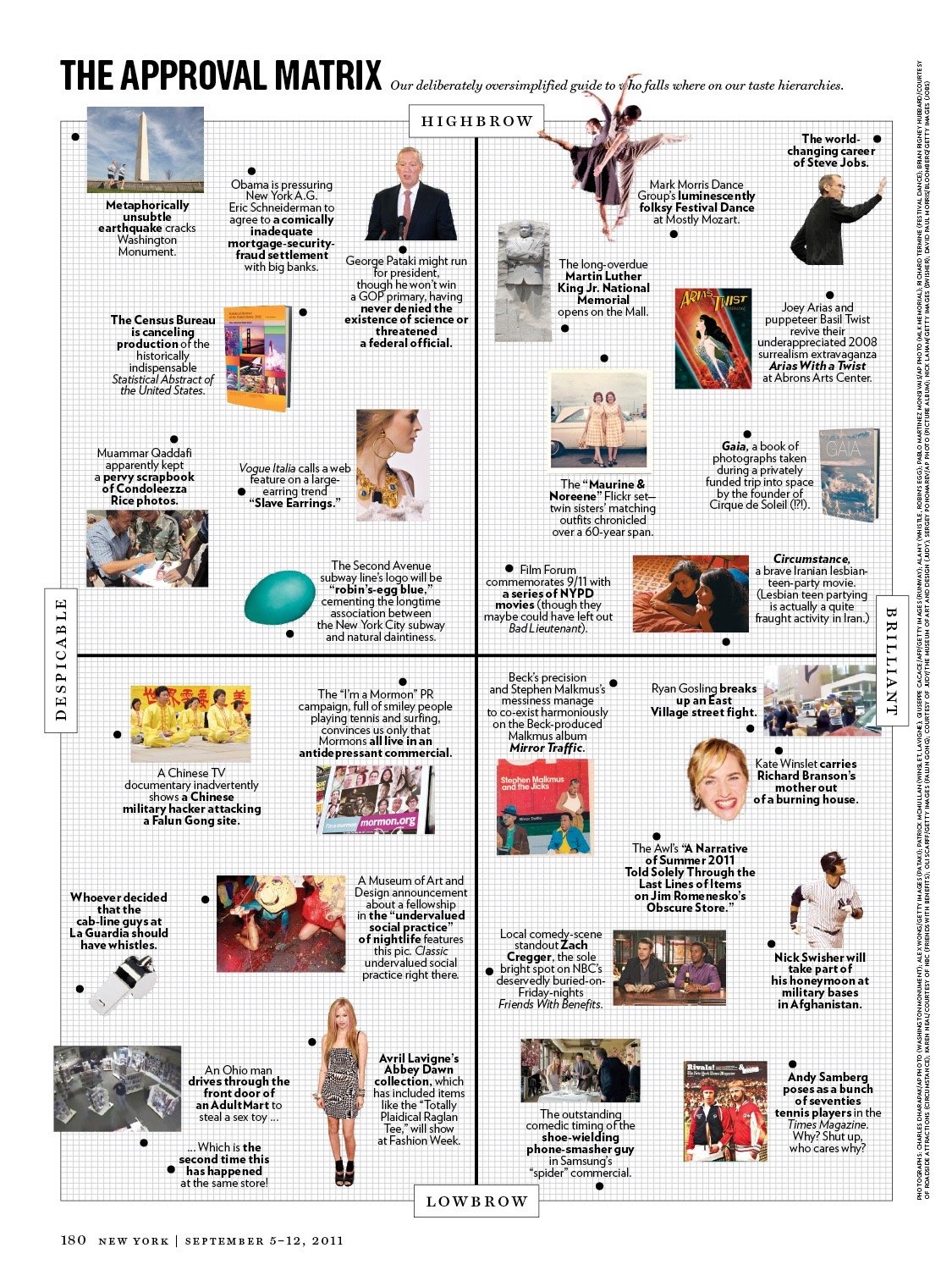

We were remaking the physical magazine. So we would have these teams — it’s very much a group process — and have these teams like, “Well, how should we cover culture in a way that feels different and true to certain principles that we’ve set out about the whole place.” “What is a cover?”

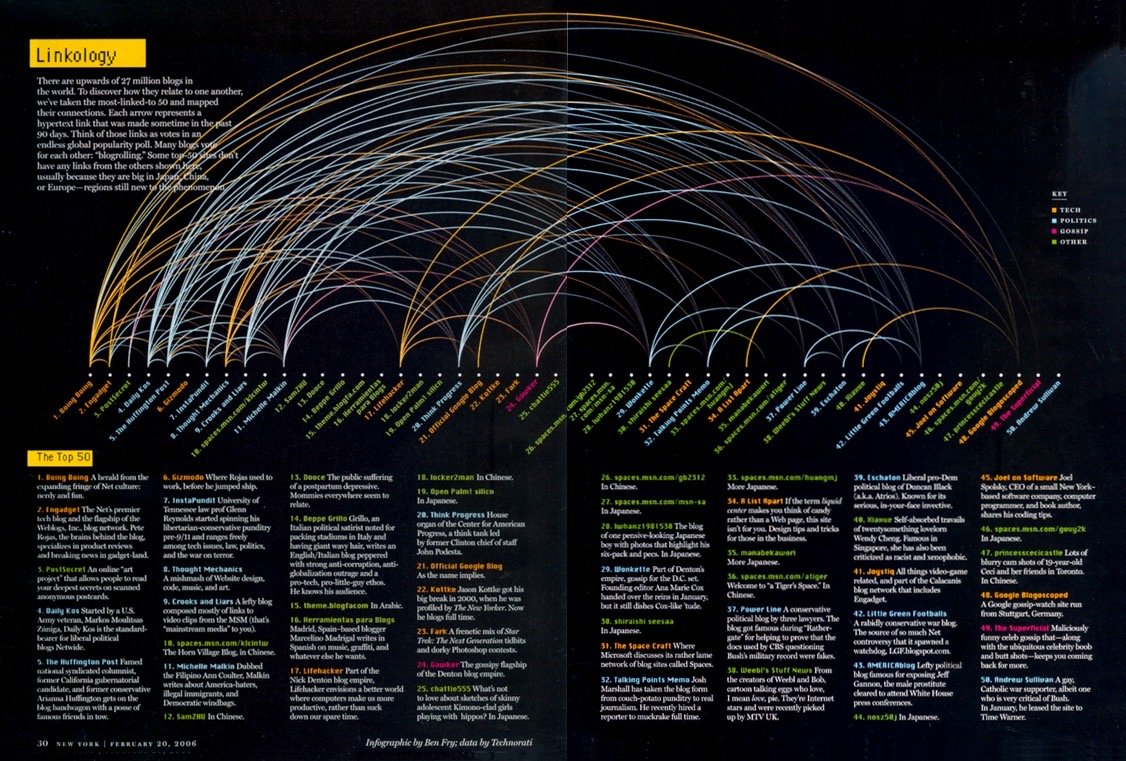

That’s the process that created The Approval Matrix. And all these little forms — some of which worked and some of which didn’t — that animated the new magazine. And there was also, of course, a physical redesign of the magazine being done then. But it was bigger than that.

There was a kind of idea reconceptualization that happened at night. And then gradually we integrated that back into the “day” magazine, the weekly magazine we were publishing, so that by the end of the first year, the magazine had been effectively remade. That was great fun. I mean, it was constant. You just woke up in the morning, did one whole job, then had dinner, came back, did a whole other job. And I think it was probably the most satisfying magazine experience I’ve ever had. I mean, except for individual days or stories.

George Gendron: Yeah. I can tell just from the way you’re talking about it. It’s like you’re back there. There is something about, I don’t know, it’s something about the making of things with a great team that gives you a kind of psychic pleasure that I’m not sure that people can get any other way, or at least I can’t.

Adam Moss: Yeah, because you’re built like I am I’m sure. And this is where you get your kicks. I’ve been talking to artists who work by themselves, for the most part, and for them, the solo activity of that is incredibly rewarding. Otherwise they wouldn’t do it. But for me, the activity of being with other talented people, and experimenting on the way to creating, in real time, making stuff — some of it works, some of it’s terrible, you know, “move on, do this, do that” — that’s great. To me that’s the most fun.

I often say that it’s a little bit like a kindergarten project that you get to do as a grownup. And I’m with you. I don’t know anything more satisfying. And I feel fortunate that I got to do it over, and over, and over again in my career.

George Gendron: Adam, you mentioned earlier, I forget how many channels or magazines you talked about making. Some of them made it into publication. Some of them didn’t. What are some of the ones that didn’t? And why didn’t they?

Adam Moss: God, so many. Physically, there was a magazine that I tried to — I listened to your [episode] with Kurt the other day. Kurt Anderson. Very good conversation. And when he was out there selling Spy, I had this other magazine that I was trying to sell called The Industry. And that was a magazine about the sort mix of entertainment and information industries.

So, it was like the movie industry, the book industry, music. You know, by the time we were finished peddling this thing, it was also the nascent computer industry. But it was basically about how ideas happen. It was a business magazine, but it was also an ideas magazine about what gets traction and what doesn’t. And it was...

George Gendron: Can I stop you there for one second?

Adam Moss: Yeah, sure.

George Gendron: When did you stop peddling The Industry?

Adam Moss: I would say it was right before it was right before I started at The New York Times. So when would that have been? It would’ve been about 1992.

George Gendron: Had you hired Doyle and Drenttel?

Adam Moss: Yes. Yes, yes, yes. Steven Doyle was the designer. You know of this project?

George Gendron: Oh yeah, I know it well. I was very close with Bill Drenttel. And I had a long, sordid history of poor design at Inc. Magazine as a result of the founder constantly meddling with the visual appearance of the magazine. And one day I’m having lunch with Bill, and he says to me, “Why don’t you bring Steven and myself in and we’ll do a redesign?” And I said, “That’s fine. But I have this fear that Steven, he’s looking for a place to park some of his ideas from The Industry.

Adam Moss: May have been!

George Gendron: And he did. And some of them were just, they were brilliant. This was yet another — I had had Milton Glaser take a stab at it. Ronn Campisi. Who else had done this? Oh, there were other great designers. Anyway, all of these redesigns were killed. But I felt that part of what I was witnessing when I got some pages from Doyle and Drenttel was what The Industry might have been, visually. And it was fabulous!

Adam Moss: Oh, well, thanks. It’s a magazine that I’m actually really delighted never happened.

George Gendron: Why?

Adam Moss: Because it was actually a compromised idea. Its financial wellbeing required it to be supported by the various industries that it was theoretically reporting on. And that just became, in prospect, a kind of doomed operation. And also there’s a lot of creepy people that work in those industries, and I actually didn’t want to surround myself with them.

But it was a really fun fantasy project. I love these fantasy projects. And that was, like, a physical magazine that I tried to sell, but then there were like, all the doomed magazines. My god, there’s so many. They were, like, in the incubation of the digital magazines that we did at New York.

There was something called Beta Male, which was a concept for a new kind of men’s magazine. That was kind of interesting. We did a few issues of that. It wasn’t “issues.” But we did some months of that. We did a pretty good technology magazine that I can’t remember the name of. We did many, many.

One of the fantastic things about digital publications is that it doesn’t cost anything to start these things up. So some would have an idea and we would develop it, and then we would let it rip for a while, see if it made any sense. And if it didn’t, we’d shelve it and do something else. And we did that over, and over, and over again.

George Gendron: Man, that sounds thrilling.

Adam Moss: Yeah, it’s great. It’s great. The opportunities of digital publication were just rich. I know that a lot of people you talked to for this podcast, I guess they all came around to it. But at the beginning, most editors were very frightened of digital. Whereas for me, for various reasons that coincided with how digital affected my editorship of the Times Magazine. I just saw it as just nothing but opportunity and fun and adventure. And it was all that.

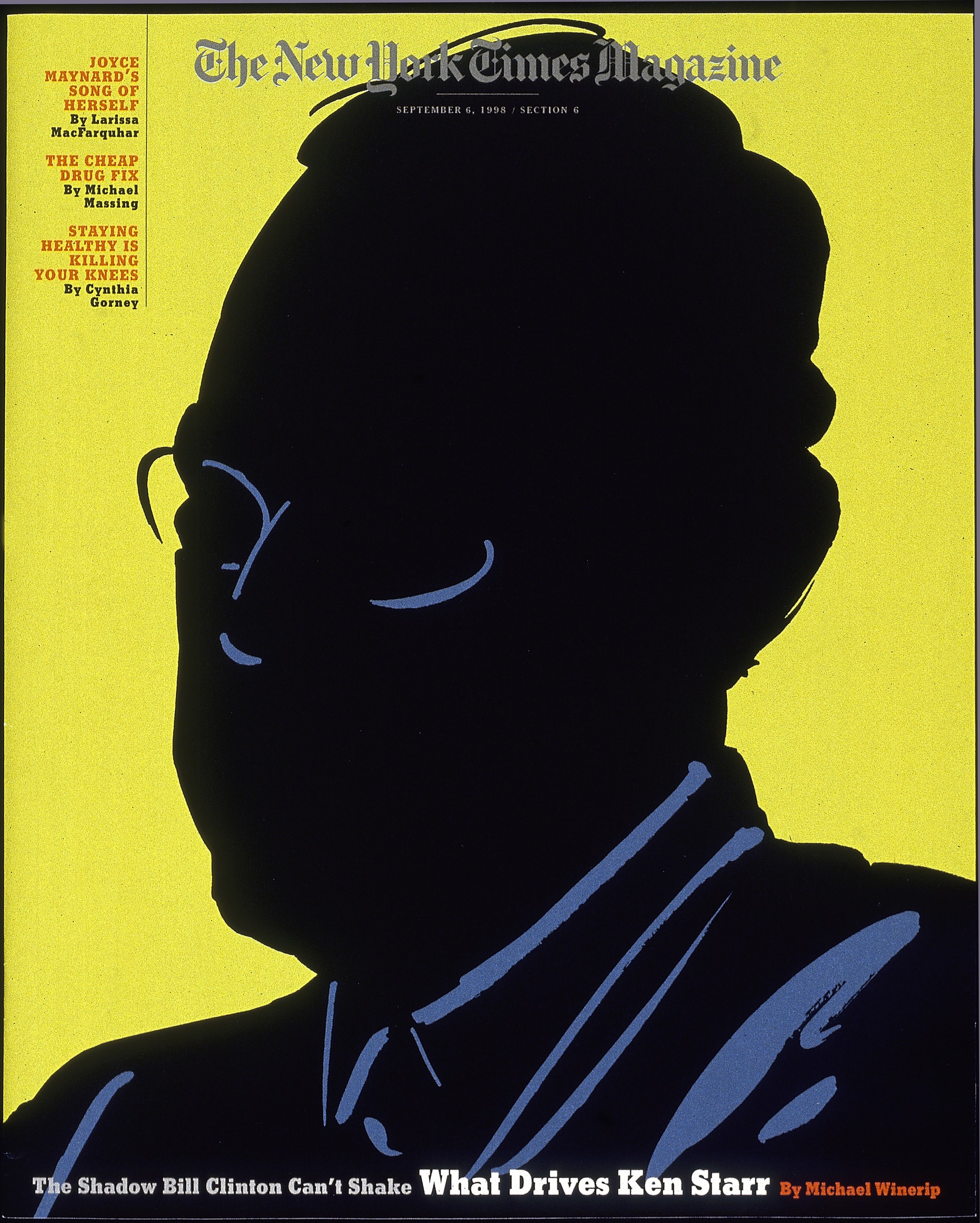

Moss was editor-in-chief of The New York Times Magazine from 1998-2004

“Attitude, used correctly, is a great, great tool of a magazine. Attitude used incorrectly can be very dangerous.”

George Gendron: You just mentioned the Times magazine. Let’s transition to that for a minute. There’s something about the perception of magazine people from our counterparts and our peers in newspapers and vice versa.

And so here you are, you find yourself probably the only real hardcore magazine person at the most newspaper-ish newspaper in the world, right?

Adam Moss: Well, let me give you a little background about how I got there. So 7 Days folds, this magazine that I did for two years in the late ’80s.

And it was a financial, almost, a disaster. It was certainly not successful. And yet, along the way, it had some fans. And some of those fans were at The New York Times. And I was invited in by Joe Lelyveld, who was the managing editor at the Times. The number two position on the news side, who was a real Times traditionalist, but also with a strong rascal streak. And he was a troublemaker. And he felt the whole place had gotten too calcified.

I met him through a mutual friend, Frank Rich, who I had known for years since I edited him at Esquire. And Frank set up the introduction with Joe. And Joe said, “Come on in and, kind of, I’m going to let you loose here” — which was a kind of dangerous invitation — “And see whether you can decalcify this place.” Which was an insane brief.

And I was just 30 at the time. And, you know, I got a lot of grief. Spy, for instance, was just merciless on me. But basically, I understood my job was to help out anyone who wanted my help and otherwise to lay low.

And did a lot of interesting projects, again, some of which happened, some of which didn’t. But the one thing that I wanted to do was to get my hands on the magazine, which I thought had potential that was not fully realized just in its self-concept. And that was the one place that I wasn’t really allowed.

And finally, this man named Jack Rosenthal, who’s a great New York Times editor, had been the editor of the editorial page, Pulitzer winner, all that. He becomes the editor of the magazine and he invites me in. And he says, “Come do your consulting thing” — that I was doing elsewhere — “come do it on the magazine.”

So I did that with him for about six months. And then he said — and all this I should say is when I was trying to sell The Industry, this magazine we were talking about before. And finally, The Industry was basically, I just had to give it up. And he said, “Come on in. But you really have to do it as a job, full-time job.” I said, “Argh! I don’t want a full-time job. And I certainly didn’t want to work at The New York Times, which is where I started my career as a copy boy. And yet, you know, there was a kind of business imperative that said, “We think this magazine can be magazine-like.” For one thing it could be full color, which was like ridiculously, even at that period, it wasn’t. It could have more pages. It could be liberated in certain ways from the newspaper. And that that might have a kind of financial — it might pay for itself or might even make some money.

And so there was a little pressure from the business side to do this. And so I saw this journalistic opportunity in it, or the invention opportunity in it. And I was this stranger in a strange land and I was this person who had not really grown up at The New York Times, even though that’s where I started.

So I wasn’t saturated in “Times-ness,” which can be a wonderful thing, but also can be very inhibiting. And I didn’t have that. And I sought my rewards outside The New York Times rather than inside The New York Times. And that turned out to be exactly a good place to be.

And so with Jack, who was a real institutionalist, and with my kind of outsider point of view, and with Janet, and then with Kathy Ryan, who was the legendary photo editor of the thing, we set about trying to think about how to do this in a completely different way. And then, eventually, I became the editor.

And we put out quite a different magazine than had ever been put out by the Times beforehand. For better and worse. We had a lot of people in the institution who were not happy with what we were doing. But, ultimately it’s some version of the magazine you see now.

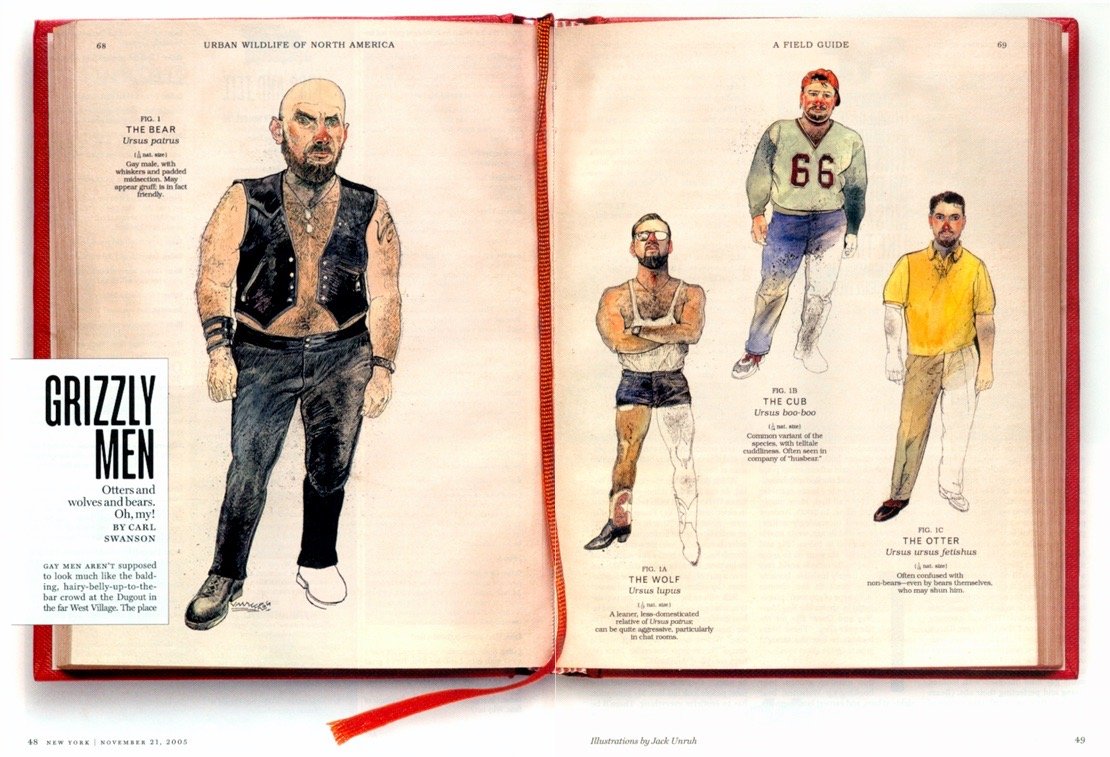

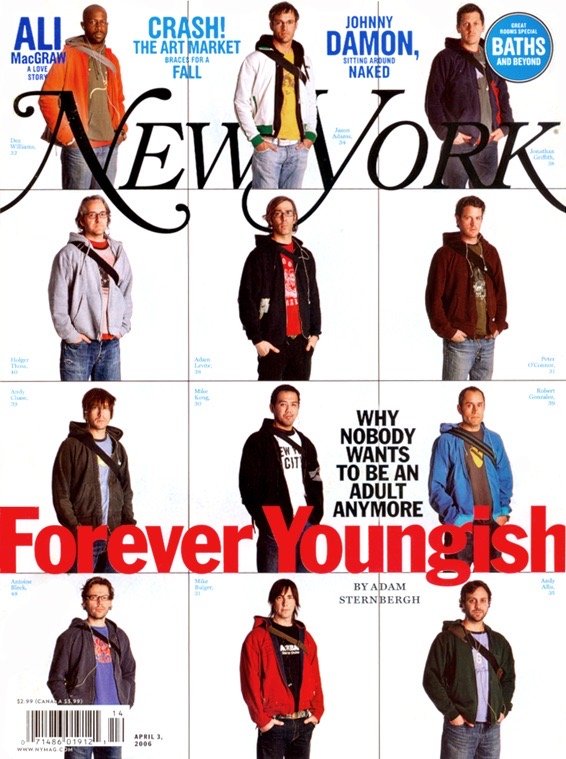

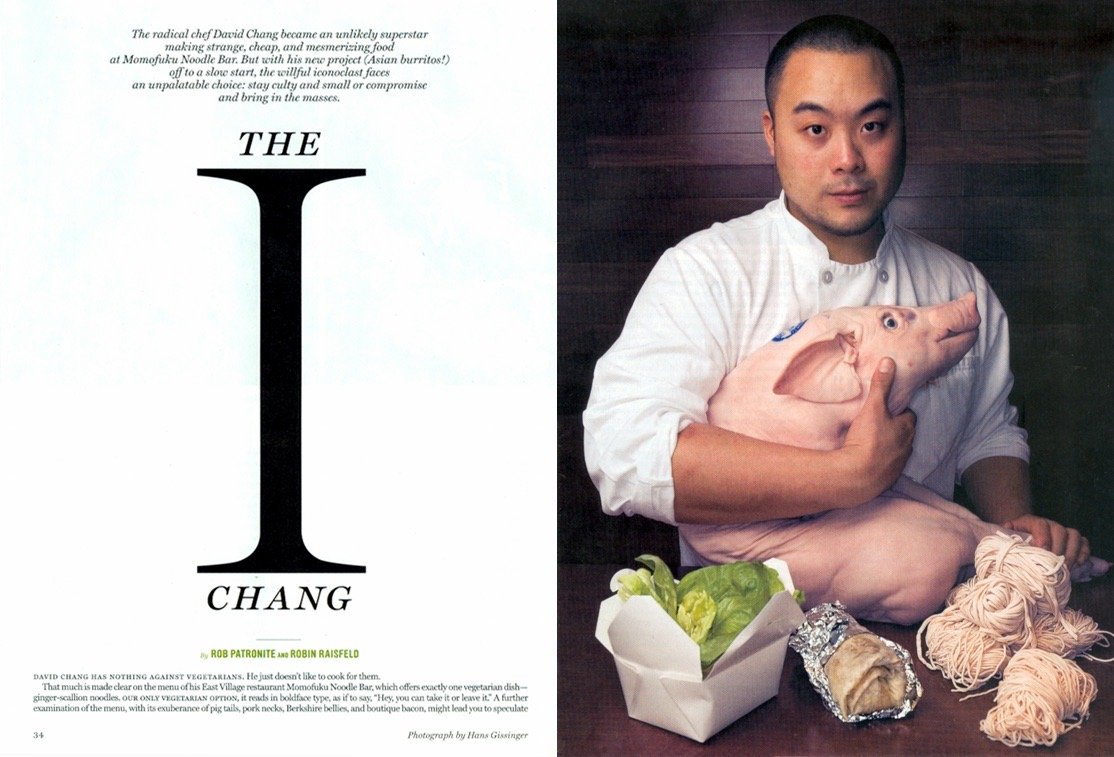

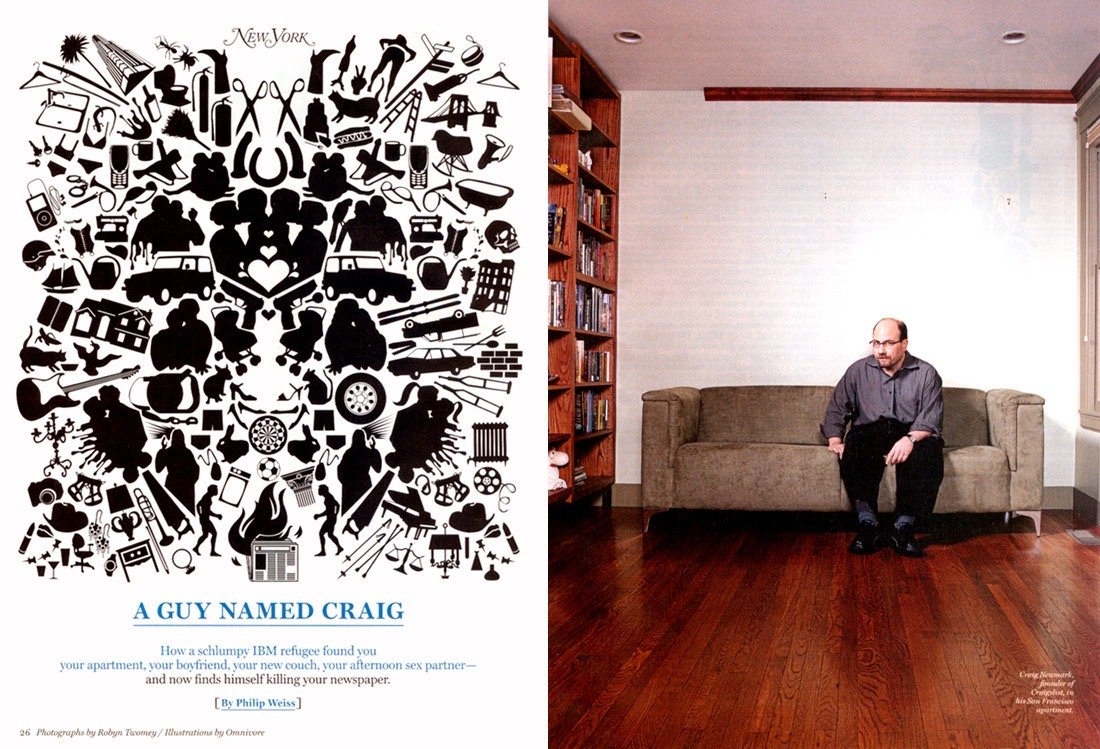

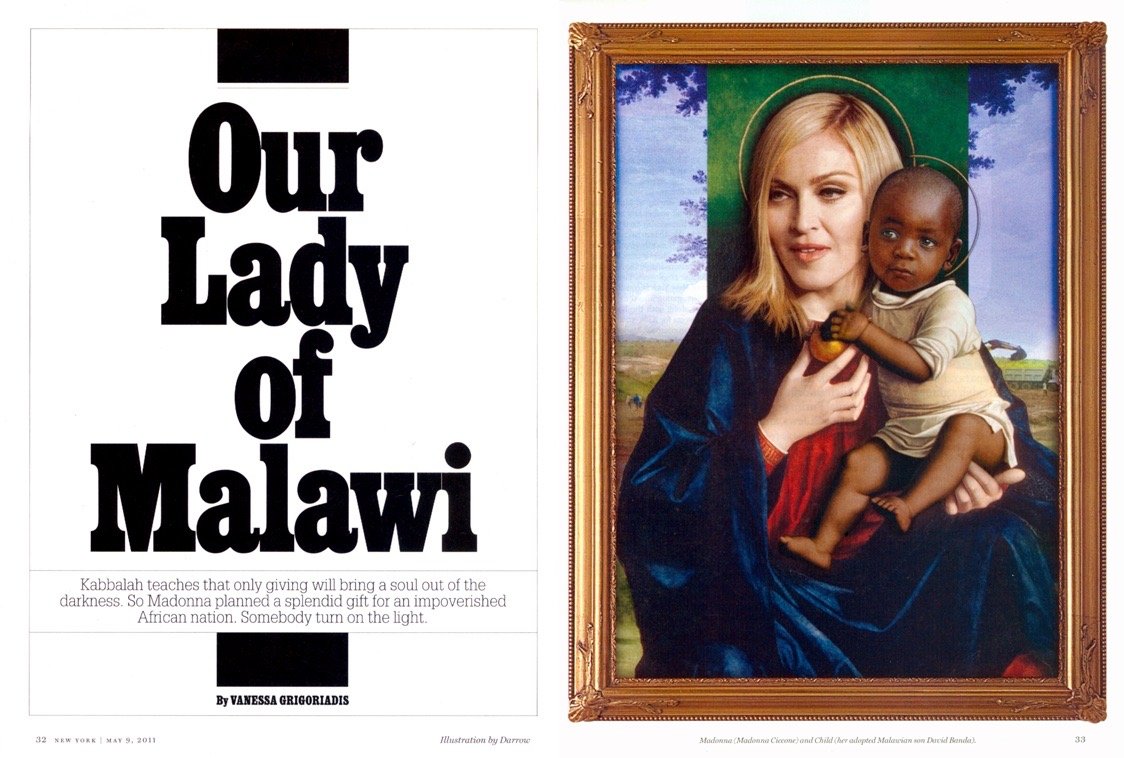

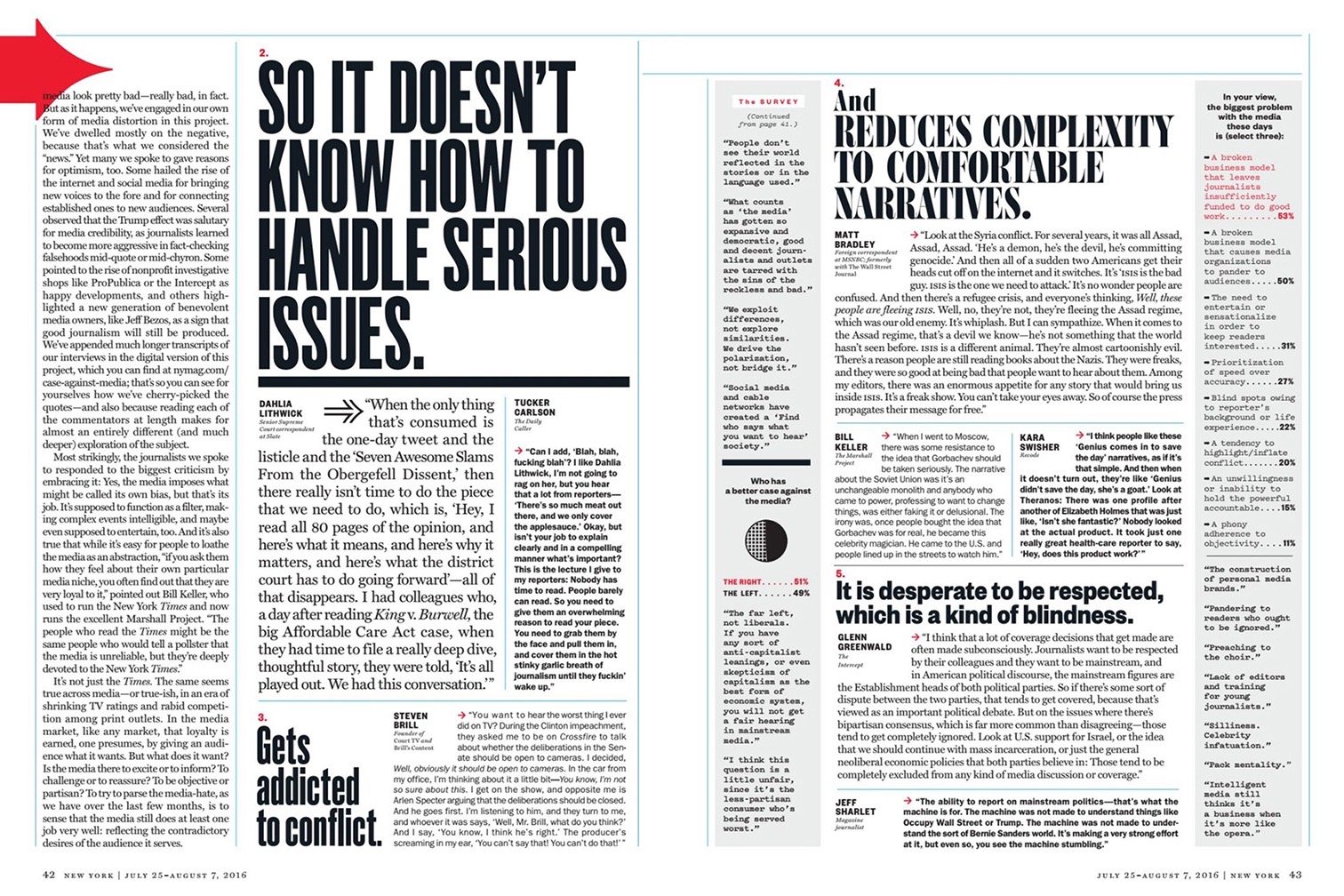

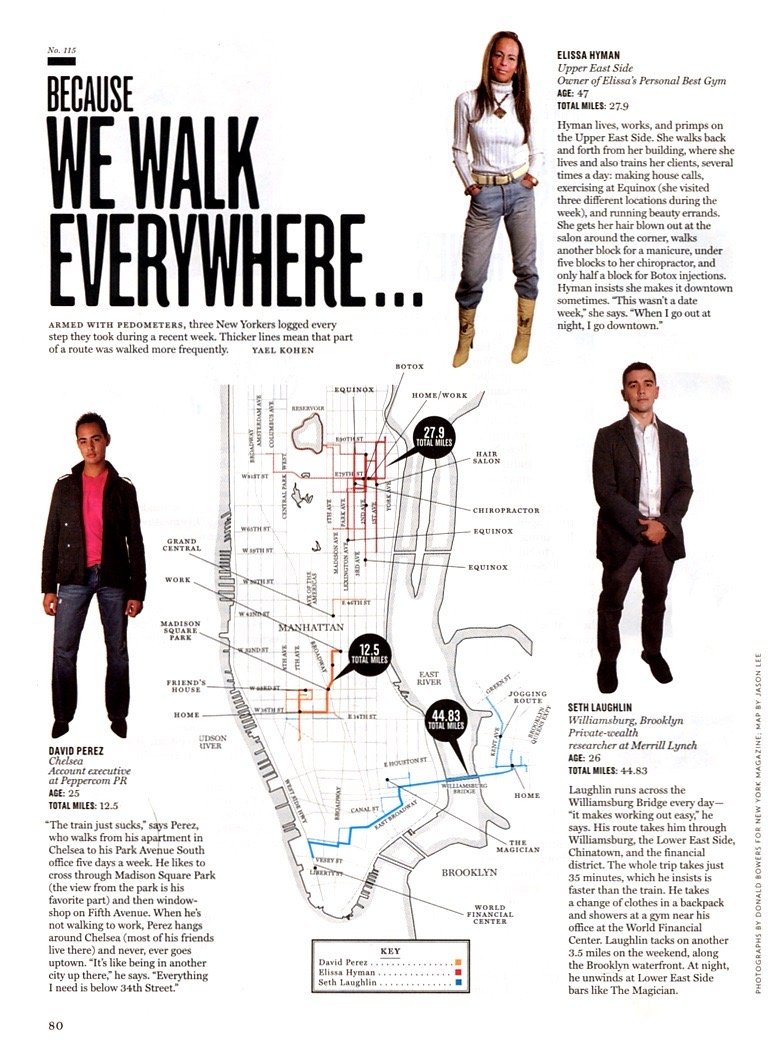

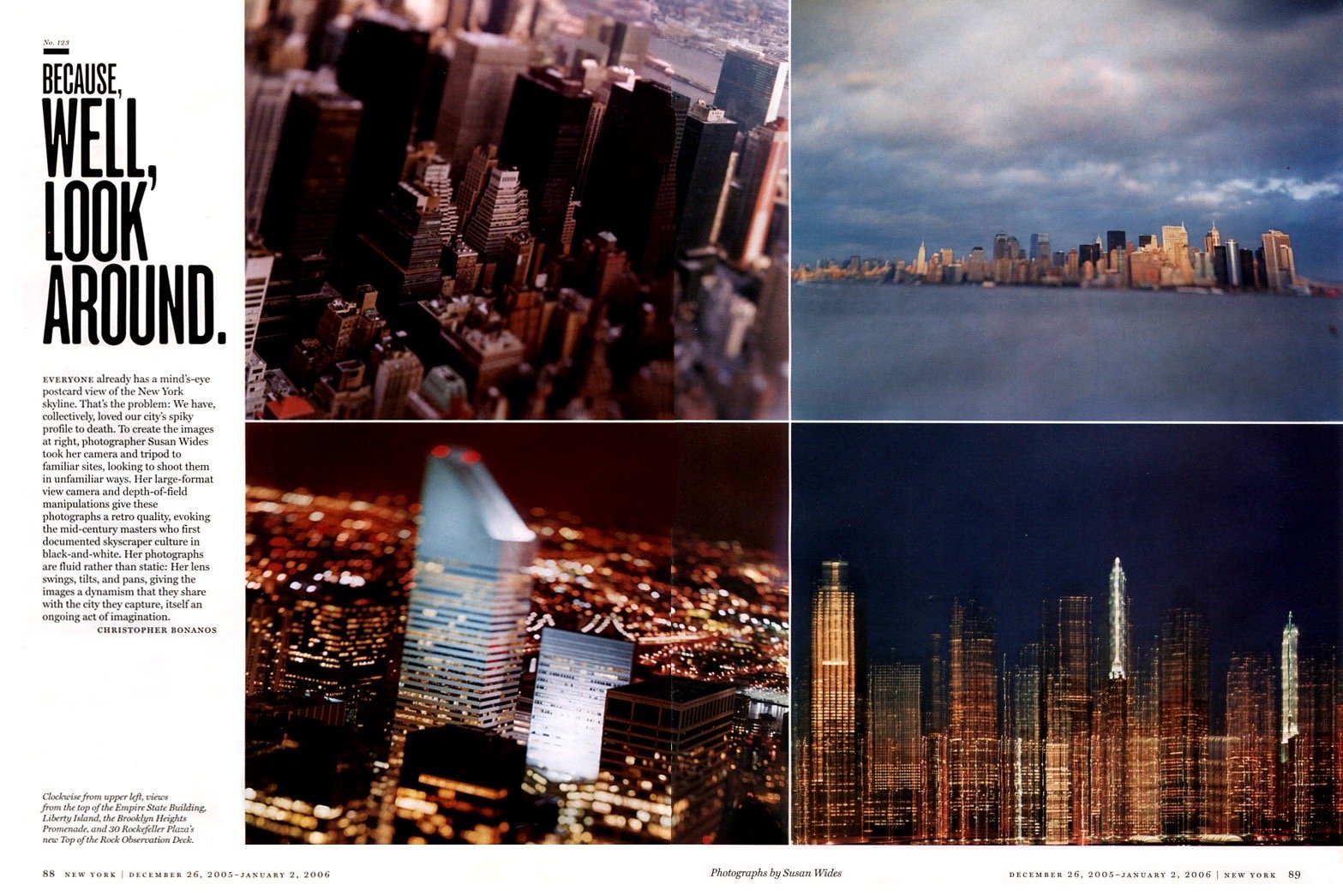

A selection of feature spreads from New York.

George Gendron: Can I stop you there for one minute, Adam?

Adam Moss: Sure.

George Gendron: I have to go back to what a lot of people might view as an inconsequential comment you made about how the endless grief that Spy magazine gave you when you went to the Times. Could you kind of explain that for us?

Adam Moss: Spy magazine used to have this really scurrilous column written by “nobody,” which is to say, written by a pseudonym, so you didn’t have any idea where it came from. It was just a reported bunch of gossip inside the paper and spooled through somebody’s typewriter, probably Graydon Carter.

And it was funny and fun. And it was a forum where you could air all the gossip that never made it into print. And they just decided to make it. And they made characters, they created characters. They did this also for CAA. And Hollywood. And I think there were a couple of other institutions that decided to cover this way. And I just became a character. A running character of their narrative. And, they kind of knew me. So, they saw this as fair game. Some of it was based in truth and some of it was just really completely made up through the eyes of some other people who were tattling stuff to them. I was not terribly upset about it.

George Gendron: Were you honored?

Adam Moss: You become disassociated. It’s like this character that’s not you, but has your name, that they’re talking about.

George Gendron: But you survived. So let’s get back to the magazine itself. You talked about remaking it. Describe, in a paragraph or less, what was the magazine before and what was the magazine after?

Adam Moss: Well, for one thing, the magazine before was written almost entirely, or not almost entirely, but substantially, by New York Times correspondents. All of whom were actually pretty great at their jobs, but they weren’t necessarily what came to be called “long form” writers. Or at least many of them weren’t. They were uncomfortable in a medium that was subjective. And magazine writing is mostly subjective, and uses some of the tools of — even with New Journalism basically devalued over time — many of the conventions of New Journalism lasted through Post-New Journalism. That’s not a thing, but I just called it that.

George Gendron: Oh, it is now.

Adam Moss: So there was a certain kind of storytelling narrative that Times reporters, not always, but often, had trouble with. And one thing we were allowed to do was to go out and look for writers who were natural magazine writers. And the Times was an incredible lure because of the institutional halo of it and its reach. And so Michael Lewis, and Michael Pollan, and Jenny Egan, and Lynn Hirshberg, and Jeffrey Goldberg, and Andrew Sullivan, and Paul Tough. We had, probably, 30 of the best magazine writers in America writing for it. And that changed the magazine utterly. It just was populated by an incredibly talented magazine writing staff.

George Gendron: I remember some of my former New York magazine colleagues making the comment, at the time that you’re describing, that this reminded them of New York.

Adam Moss: It was a kind of paradise of writing talent, the likes of which other magazines have experienced, but not often. And it made my job very easy. I just had to defend it against a sort of institutional bias, which said that this prime real estate ought to go to New York Times reporters, some of which I should really say did a wonderful job.

And we did also publish New York Times correspondents, who were amazing. But I would say that the balance of the magazine was written by people who were native to the magazine form. So that was one big thing. Physically it was completely remade. It had certain structural conventions that are shared with magazines, which is to say it had, I mean, this is a magazine podcast, so talk this lingo, but it had a front of the book. It had a back of the book. It had a feature well. It had special issues, single-topic issues. It had many of the forms that we associate with magazines, but that had never really been associated with the Times magazine. I mean when one would be derisive about the old New York Times Magazine, it was that it was a place where reporters dumped their notebook. That is to say all the stuff that they couldn’t get into stories. So it’d be these, meandering notebook stories. Some of which were really good, but it didn’t work as a form. And so the magazine was always underperforming its potential.

It’s a very interesting thing though, what’s happened over time, because a lot of the conventions of magazine-dom have now worked their way back into the newspaper. So the newspaper itself, The New York Times, is very magazine-like in a lot of the ways it tells stories.

So I think it’s actually a harder magazine to edit now than it was when I got there. Because when I got there, it was an all opportunity.

A package for you! And a package for you! And a package for you!

George Gendron: So Adam, we talked about before and after for the Times magazine, and I think, for a lot of us, when we think back to what you did at the Times magazine, you and your colleagues, two things stand out, and one was this “writer’s paradise” that you were describing. And the second was the phrase, “the way we live now.”

Adam Moss: Yeah.

George Gendron: Talk about that a little bit.

Adam Moss: So the one very big brief of The New York Times Magazine, the way I saw it, was to do what the newspaper itself didn’t do. There was no reason to replicate it. And at that point I thought there was huge unexplored territory in what came to be called The Way We Live Now, which was actually a phrase that came from [Anthony] Trollope.

But it was a phrase that was brought into the magazine by Gerry Marzorati, who was my deputy for much of the time, one of the two deputies. And basically it was to try to reclaim the space of private life as the stuff of journalism. There was plenty that was public. Washington, foreign news, Hollywood even. But there was a kind of interior territory that the magazine hadn’t much mined and that we came to think of as having enormous potential. You know, having to do with family, and sex, and the way people dressed, and the way people ate. Not just service journalism on those things, but actually kind of a sociological journalism.

Yeah. And so we created a front of the book that would deal with that explicitly, and we called it The Way We Live Now. That was kind of the mission statement of the magazine. And then we would do deliberately, we would do special issues and run many stories that tried to find a way to talk about the interior of people’s lives with the same journalistic rigor that we brought to a story on George Bush or something.

And I think that, because we had this incredible writing staff, we succeeded for the most part. And we created little devices, just more invention, to find ways to tell this story. We had this thing called What They Were Thinking, which was essentially, because we had such a strong photo staff, it was essentially a photograph that was not of anything that would be familiar to anyone from a — you know, wasn’t like a war picture or something like that. It was a picture of a couple with a baby or something like that.

Pictures of ordinary life. And then we would go to the subjects of the photograph and ask them to describe what they were thinking at the moment of this photograph. And it produced an interesting way to tell stories.

George Gendron: People talked about that all the time.

Adam Moss: It was pretty great. At one point we just stopped doing it.

George Gendron: I’ll tell you how a lot of people read it, which was that they looked at the photo and they imagined what people were thinking in the photo and then they compared what they imagined too.

Adam Moss: Sort of like a New Yorker cartoon where you make...

George Gendron: Make a caption. Yes! Yes, exactly!

Adam Moss: Anyway, that became a big mission of the magazine, to figure out a way to seize this territory that the paper had otherwise not really explored. Which also, by the way, is, the paper does now explore it all sorts of ways. A lot of these things became threaded back into The New York Times as a whole.

“I learned a great, great deal about what made good, credible journalism from being there. I can’t even imagine my career without the education I got at The New York Times.”

George Gendron: When I look back on it — this is just my personal reaction to it — for the first time in a long time, as a really religious New York Times reader, I felt that it was a magazine. Not a Sunday magazine, but a magazine.

Adam Moss: Well, I’m really glad to hear you say that because that was certainly the object. We were trying very hard to to leave you with that impression that, you know, she,

George Gendron: I thought you could have spun it off.

Adam Moss: Well, that’s very nice. As New York magazine actually was spun off, of course. New York, which was, technically, the Sunday magazine of the New York Herald Tribune.

But then, because the New York Herald-Tribune collapsed at a certain point, Clay and Milton were able to raise money to spin it off as its own thing. And the thing about The New York Times Magazine was that it very much was a product of The New York Times. It was general interest at a time when general interest magazines were difficult to publish.

And it benefited very much from the seriousness, from the gravity of The New York Times itself. And The New York Times created standards that, that, were very important for us to meet. Very important for it to be the magazine of The New York Times. Maybe not the Sunday magazine or magazine supplement, but the magazine worthy of The New York Times, which is an institution I revere and always have.

And working there all those years only made me revere it more. And I learned a great, great deal about what made good, credible journalism from being there. I can’t even imagine my career without the education I got at The New York Times.

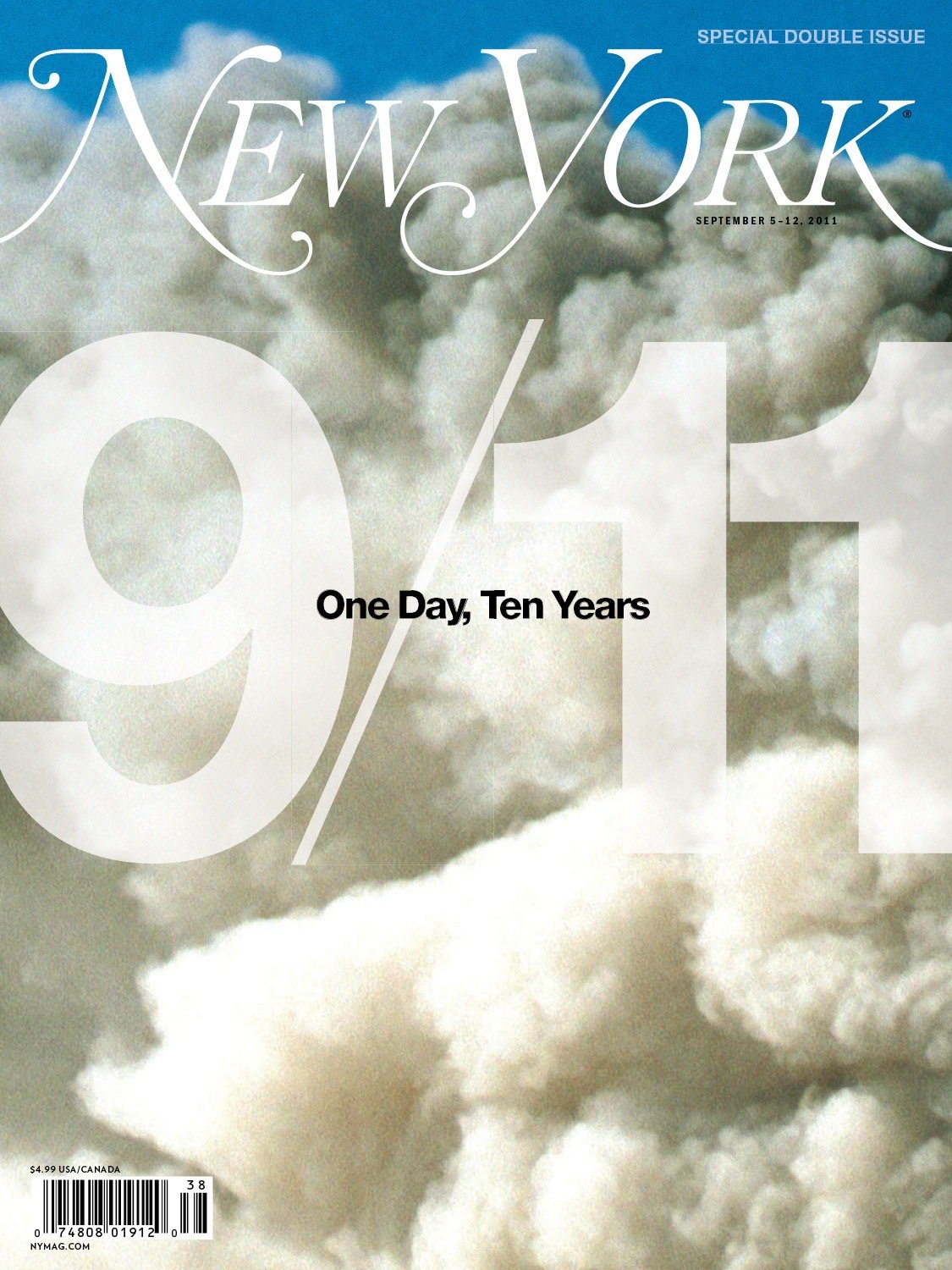

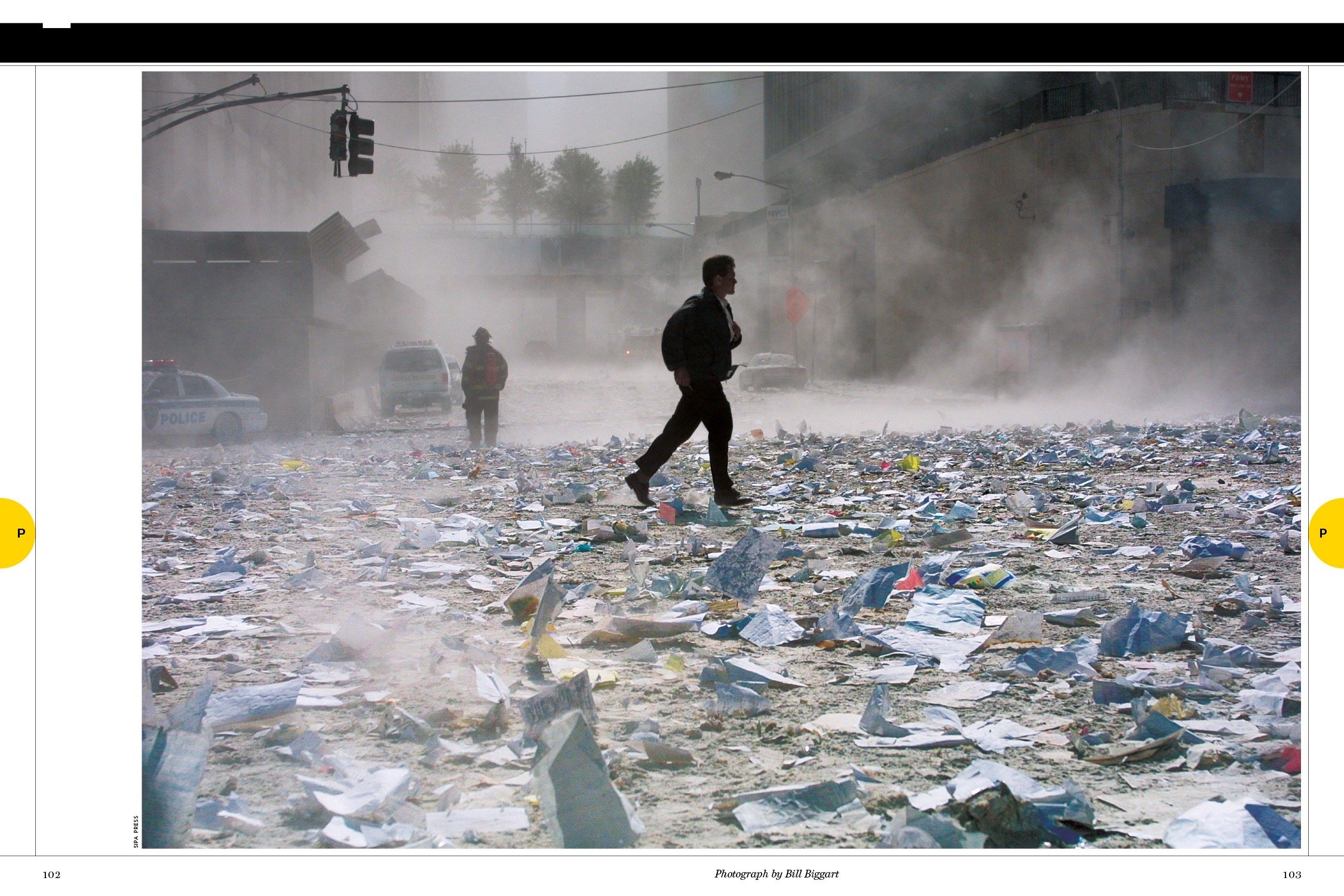

George Gendron: We’ll return to that when we talk about your days at Esquire. And I do want to move on to Esquire and 7 Days, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask you something. Which is, could you recreate what you guys managed to pull off — which a lot of people called a miracle — in response to 9/11? At a time when, just to recreate that scene for younger listeners, everybody was paralyzed.

Adam Moss: Yeah. It was, in every way, an extraordinary day. And my own personal story of it was that I was at the gym, and somebody ran into the gym and said, “Look! The towers are burning.” And the gym is downtown New York. You could see the towers burning from outside.

Everyone in the gym ran outside to see this. And then, really unthinkingly, I just got my stuff and got into the subway, which was still working, probably the last subway that operated that day, and came into the office. Still not really grokking the extraordinariness of this event. And then, there were a whole bunch of editors, and design people, and photo people who were just watching it on television.

And then when the second plane struck, it suddenly dawned on me, and others, that there was no way that we could put out the magazine we were well on our way to publishing. And we did something that I’d never done before, which is we just threw it all out. Like, within 15 minutes, we just said, “Okay, this is impossible.”

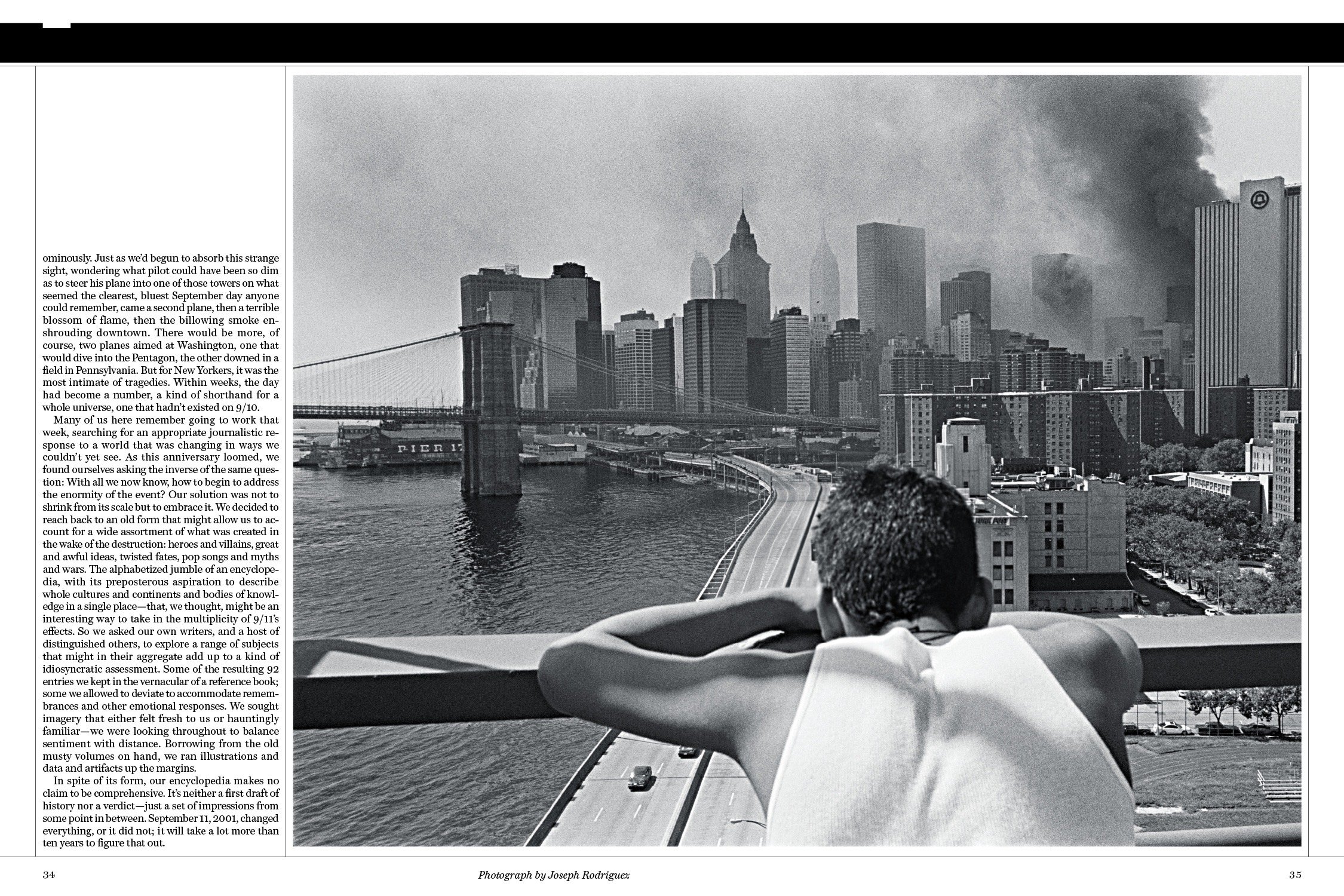

And got everyone together. And then it was like, “Okay, what kind of magazine could we make in three days that would be a contribution to the journalism that was going to be written about 9/11?” And it really had a lot to do with this incredible staff that I keep talking about. Both the editing and visual staff, but also the writing staff.

And we just spun in a thousand different directions and said, “Okay, let’s, kind of, [think about] meditations on the day.” The day being, that very day, 9/11, 2001. And and then, at the same time, have Kathy’s extraordinary staff start shooting that day and then have Janet and her staff start designing it.

But also, I charged Janet with the idea of, like, “Somebody must be, right now, thinking of a memorial to this event. And can you find that person? Can we publish that memorial?” And she went out and she eventually, within 24 hours, found these two guys who were doing these twin towers of light, which came to pass. And that was the cover of the magazine.

But over the next three days, these stories by all of the people I just described earlier came pouring in, beautifully written. I mean, under the urgency, emergency, and huge stakes of 9/11, people wrote incredible things. And it was just a sort of difficulty trying to figure out what to publish and what not to publish. And extraordinary photography.

And then what happened? So, in three days we had this issue called “Remains of the Day,” that was really among the most satisfying things I’ve ever done in journalism. But it was going to sit there for 10 days because that was the lead time of The New York Times magazine. And, I earlier said why I was never afraid of digital was that it occurred to me and to another person there that we actually had a way to publish this thing tomorrow.

It’s just that the magazine had never thought to do that. There was a whole digital operation that meant that we could, in effect, scoop ourselves and make, in a way, the physical magazine moot. But get it out now. And we converted the whole magazine instantly into a digital publication and published it on that Friday.

And we scooped ourselves by about 10 days. And that had never been done before. And it was amazing. So, you know, there wasn’t any sort of purity of idea to that issue. It was just that it had such an extraordinary contribution. And, basically, the focus on the day, rather than its larger meaning, was probably the important — I mean, you always need a limitation. And it was the important focus of the issue. It was an extraordinary magazine and not, I think, an extraordinary magazine the way some are, which are sort of editors’ inventions. It was really about the sum total of the contributions, which were brilliant.

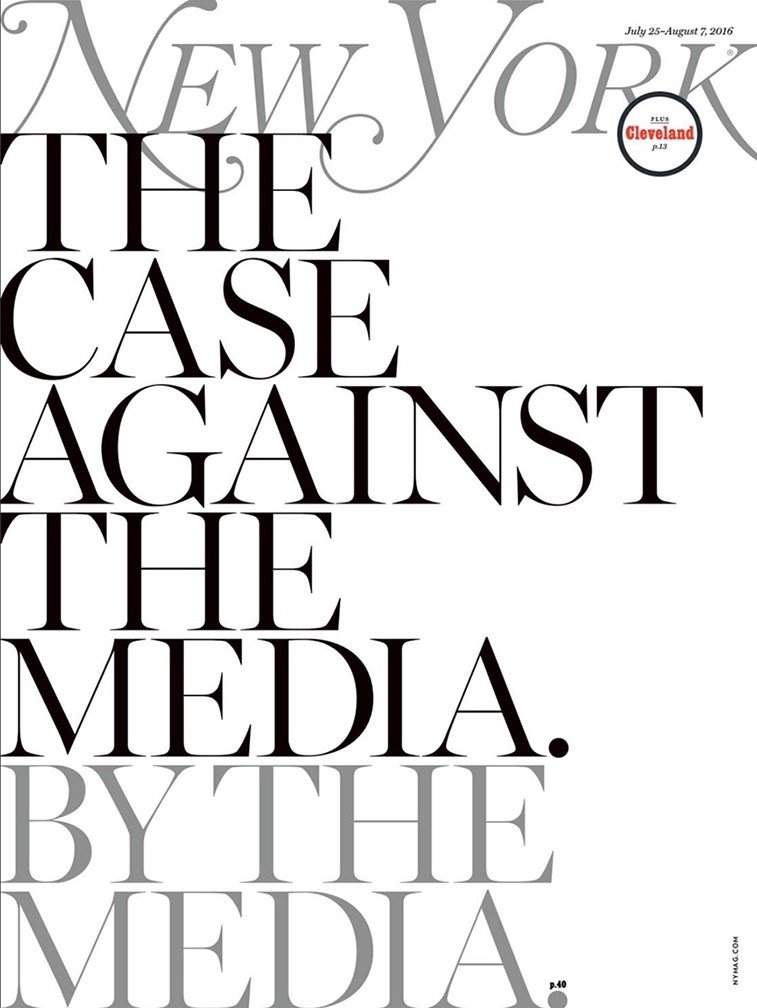

Moss went deep on the media during the 2016 election.

George Gendron: When you were a young guy at Esquire, and Esquire had been purchased by Phillip Moffitt and Chris Whittle. And Moffitt, I guess, feeling maybe he needed a little bit of an education as an editor in chief of a major national magazine, started to invite in legendary editors for their counsel and advice, and it turned out to be an extraordinary experience for you. And could you talk about that?

Adam Moss: Yeah, you know, I didn’t really have any magazine experience when I went to Esquire. Earlier I had talked about my love for New York magazine as a young kid. The other magazine I loved in the same way was Esquire. And read Harold Hayes’ Esquire with a kind of crazy devotion.

George Gendron: By the way, you said you read these as a young kid in the suburbs. Which suburbs were those?

Adam Moss: It was a town called Hewlett, near Kennedy Airport on Long Island. And I was born in Brooklyn, but my folks moved there when I was a toddler.

Well, I don’t know about you, but my experience of the suburbs was — I just couldn’t bear it. And I wanted out, which I did as soon as I could physically get out. But before I could physically get out, I got out through my fantasies of city living, urban living, cosmopolitan living. All that stuff.

And the main vehicles for that imagining were magazines. New York. And Esquire. Anyway, Esquire was where I most wanted to work, if I could ever work in a magazine. And, without belaboring my early history, I had had an internship at The Village Voice when I was in college, met this woman, Kate Wenner, who was Jann Wenner’s sister.

Jann and Kate were starting a magazine called Rolling Stone College Papers. They wanted college-age editors. Because of my time at The Village Voice, I connected up with Kate — wonderful editor, Kate — and did this college magazine, you know, until it died. The way most magazines do. And then I went over to Esquire after it died in order to work on their once-a-year college magazine. They used to do a magazine every September, which was about college. For years and years and years they did that. And they wanted someone with that kind of experience. And I got there and they killed that issue the day I got there.

But I was there. I had the job. And not really a whole lot of experience or a lot of knowledge. I was assistant editor. But I looked around and what was amazing was that all these editors who had created the magazines of my dreams when I was growing up, were sitting right there. Byron Dobell, and Jerry Goodman/Adam Smith. And Lee Eisenberg, who was like a pipsqueak in the old Esquire, and still pretty young, he was there too.

And then there were other great editors. Betsy Carter. Priscilla Flood. Lots of people. But it was this old gang that was such an amazing opportunity. And many of them weren’t doing a whole lot. They were just there for counsel, and moral support, and fun and games and, you know, I suspect that some of them thought it was just this fabulous sinecure where they could come in and, kind of, just jack off and get paid for it. And get paid for it.

And for a young magazine nerd like myself, it was just an unbelievable education. And to the extent that they did work, they didn’t really want to do the work. So they were very happy to have youngsters do their work for them. Which is something that young people these days could complain about: having to do the older people’s job. They don’t understand what a great opportunity it is.

George Gendron: Oh, unbelievable.

Adam Moss: To be able to do grown-up work when you’re still a child. So that was my time at Esquire. And over time I had many different jobs there. And then Lee Eisenberg became the editor — and an incredibly good one. And he gave me lots of opportunities. So that’s my Esquire of time.

George Gendron: Yeah. It reminds me very much of my time at New York magazine. You mentioned Byron Dobell. He was about 10 feet from me. Shelly Zalasnick, who had come from Sports Illustrated. Jack Nessel. Writers like Andy Tobias. I could go on and on. Nora Ephron used to come in and occasionally use a desk. at my foursquare thing So I could sit and listen to her do her reporting.

And so every week I was in touch with John Simon, Judy Christ, Barbara Rosen, Tom Hess. Talk about an education! And I was adjacent to the art department where you had Milton Glaser, Walter Bernard, Tom Bentkowski. Oh my God. It was extraordinary.

Adam Moss: It’s such a small world. So many of those people, I would later meet up with in my own magazine life. Yeah.

George Gendron: You and I talked the other day about how there were periods where there were these massive concentrations of talent. And you do wonder where they are right now.

And you and I talked about that, and I think you said something that certainly resonated with me. I said to you, “Where are those concentrations now?” And you said, “I don’t know. I feel kind of out of it.” And the same for me, but I see these stats about young people going to journalism school, and I wonder, “Where are they going?”

“For the most part, the existence of a publication, per se, does not exist anymore. For the most part magazine material is read in fragments. So what you have lost is that sense of a coherent whole. Magazines do try, but it’s just not the way readers behave, digitally. So it doesn’t exist anymore.”

Adam Moss: Well, there are a lot of publications right now, they’re just not publications that we recognize in the old ways. They’re mostly digital. And there’s amazing work. I mean, if you just think about the coverage of Covid for its first six months, the amount of incredible journalism that came out of — I mean, crisis creates opportunity. So I’m not one of these people who ever feels too nostalgic. You know, there are always concentrations of talent. And I’m not the kind of reader I used to be, so it’s not on my radar exactly, but it pokes through.

George Gendron: The reason I’m interested in this question of fragmentation rather than concentration is just, I personally, and a lot of my colleagues benefited enormously from what you just described. Having these networks of people that you would work with and work on projects with in the future. And I just wonder if it’s the same or if the dynamics are somewhat different right now. Or the networks are just different.

Adam Moss: Well, one thing that’s definitely different is the lack of physical contact. Coming out of Covid, the extent to which magazines and journalism, you know, journalism in general is now remote work for the most part. Even as people are coming back into the offices, it’s less true, I’ve noticed, for journalism. Because a lot of that work can, in a sense, be done remotely. But, what’s missed in all of that is that shoulder to shoulder friction. Which I mean in the very best way that happens in magazines. So I think that’s definitely different.

I hope that that’s temporary and people go back to being together. And I realize there’s a lot of advantages to remote work and all that stuff too, but I think that something is missed when people are not on top of each other.

George Gendron: Pat and I did a project for Inc. and Fast Company, and our team was remote, but we would travel down to 7 World Trade to their offices whenever possible. And I often wonder what effect this has on startups in particular, where that day-to-day, minute-by-minute, infield chatter is just so crucial when you’re creating something, which you described really eloquently when you were talking about your time at New York magazine.

But now let’s talk about 7 Days.

Adam Moss: Okay.

George Gendron: So set the scene for us, first of all, because you launched 7 Days at a time when the magazine industry was, God, there were startups all over the place!

Adam Moss: Right and left. Yeah.

George Gendron: Yeah. It seemed like everybody was starting something. People wouldn’t say, “Where do you work?” They’re like, “What are you starting?”

Adam Moss: Yeah. Those were the days.

Moss in his 7 Days era

George Gendron: Yeah. Tell us, tell us about those days and you know, you were still a kid, right? I mean, 27 is still pretty young in publishing years. And it takes a certain amount of — I don’t know, balls — to launch that kind of a magazine. But isn’t there a certain stage in your career where naïvete is an incredible source of competitive advantage?

Adam Moss: Definitely. I completely agree. And I think that the entire history of 7 Days is the history of people who didn’t know any better doing all the things that their elders had dismissed because, most of the time, it doesn’t work. And a lot of times, even at 7 Days, it didn’t work.

And basically the story of 7 Days is, really briefly, when I was at Esquire, you know, just as you describe, everyone’s starting magazines. And I did have this idea for a magazine which I worked on with these two other guys, who had found me somehow, who were in the ad business.

And we brought this idea to a consultant named Jack Berkowitz. And he kind of liked the idea, but also thought it was just a financial loser. So he definitely recommended that we just shelve it. And then, about six months later, he knew that Leonard Stern, who owned The Village Voice, was looking to start another magazine, but he didn’t really know what kind of magazine he wanted to start. He just wanted to start a magazine that was less “pinko” than The Village Voice. And that might have some shot of getting like Macy’s advertising.

And I think they got Macy’s. Maybe Bloomingdale’s. So they had a bake off. Like, you could go and present a magazine idea to Leonard and to this guy David Schneiderman, who became the publisher of 7 Days and had been the editor of The Village Voice and probably also the publisher of The Village Voice. Great guy. And people just went up and presented their magazines in this boardroom in midtown Manhattan. This was 1987.

George Gendron: Adam, tell us, for younger listeners, what was it? Give us some detail. What was it you were presenting? What was the magazine?

Adam Moss: We were presenting... I don’t even know what we presented! It was a city magazine. It was definitely a city magazine. And I don’t know what they saw in it. I know what the magazine we published was. But I can’t remember the magazine I presented. But the magazine I presented, somehow they liked.

And, I tell this story, but basically, I presented this magazine. It was midnight. It was that late. And Allison Stern, Leonard’s wife, came in and she heard the end of the presentation and she clearly liked it. But there was silence after I presented it. And I went to the bathroom in horror — the way I had humiliated myself — and I was peeing and Leonard Stern came in, this billionaire, and he was peeing next to me and just turned to me very casually and said, “Okay, we’ll do your magazine.”

And then I assembled a small group of people in the same fancy Midtown digs. And, probably three weeks into the development of the magazine, the stock market crashed.

George Gendron: So where are we here? What? Give us the date.

Adam Moss: Well, I don’t remember when the crash was either ’87 or early ’88. I think it was October ’87. Right? So really we didn’t know it, but the moment the stock market crashed, the magazine was dead. It just took two years to die. But thank God for those two years because then we went into some kind of warehouse downtown in Cooper Square and it was a tiny-budgeted thing.

And so I can only hire people who would be willing to work for nothing and who are really ambitious and basically really young and didn’t know any better. And we just got into a room and set about creating a magazine. And we broke every possible rule. But not on purpose. We just didn’t know.

The magazine was basically sidebars. There was no, I mean this is a magazine podcast, so I can say there was like, there was no feature material in it. It was just all, sort of, side conversations. And then JC Suares, the legendary designer, designed this great contraption for this all to be in. And without knowing it, we bumbled into what became the voice of the internet.

Which is to say it was all colloquial, and casual, and intimate, somewhat confessional. And it was all New York City refracted through the subjective experiences of its writers. That’s basically what it was. It was divided into three sections. One was called City, one was called Life, one was called Arts, or something like that. The culture section.

Had amazing writers in it too. All of whom were more or less inexperienced. I mean, Peter Schjeldahl was the art critic. He had experience. But most of the people didn’t. Even Louis Menand, who was the movie critic, had never written about movies before.

Peter Cameron, the novelist, wrote a weekly serial, on deadline, of a novel which eventually became the novel Leap Year. Jesse Green started there. Jonathan Van Meter. Lots of people. And it was huge fun. And we did all these things that we could only really do because we didn’t know the right way to do them.

And the magazine did eventually die. But it won some readers along the way. Quite a few, I think, who kind of liked its freshness. Kind of liked its amateur-ness. Because, in retrospect, it’s quite an amateurish magazine. It doesn’t have any of the, the sort of professional apparatus that magazines do. It had confidence, but it had youthful confidence as opposed to sophisticated confidence. And you know, it was great.

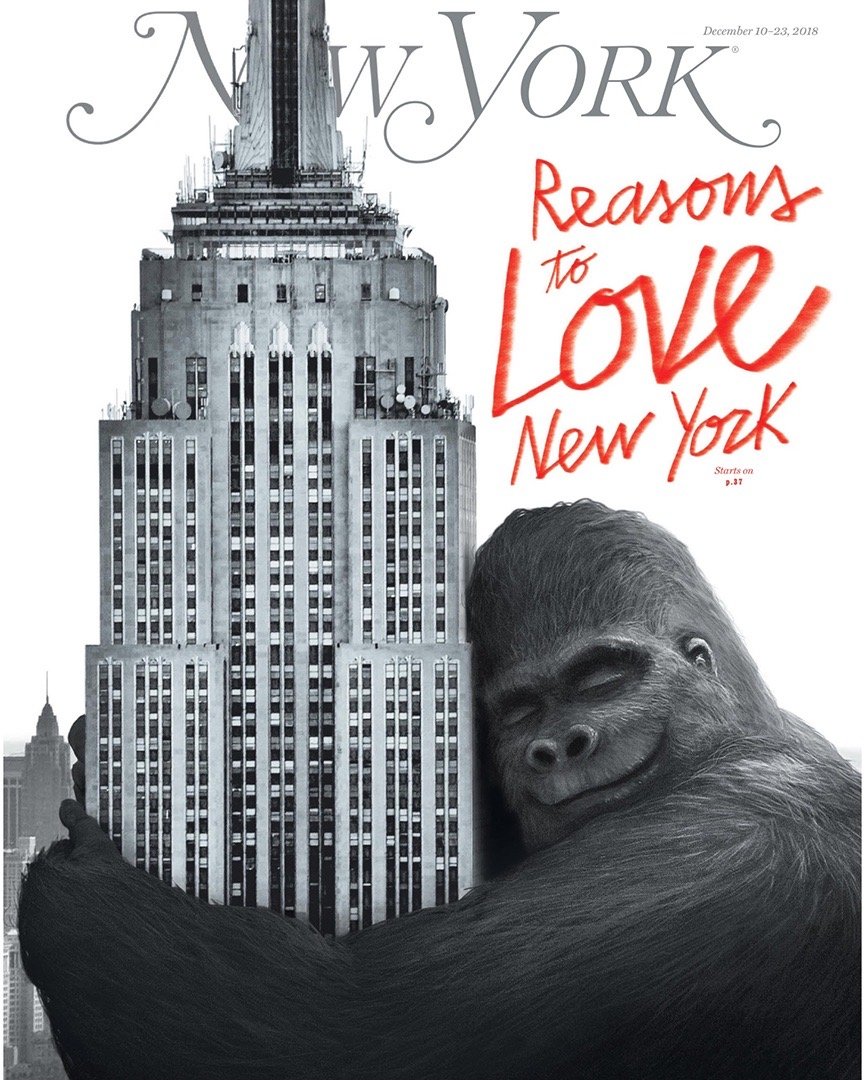

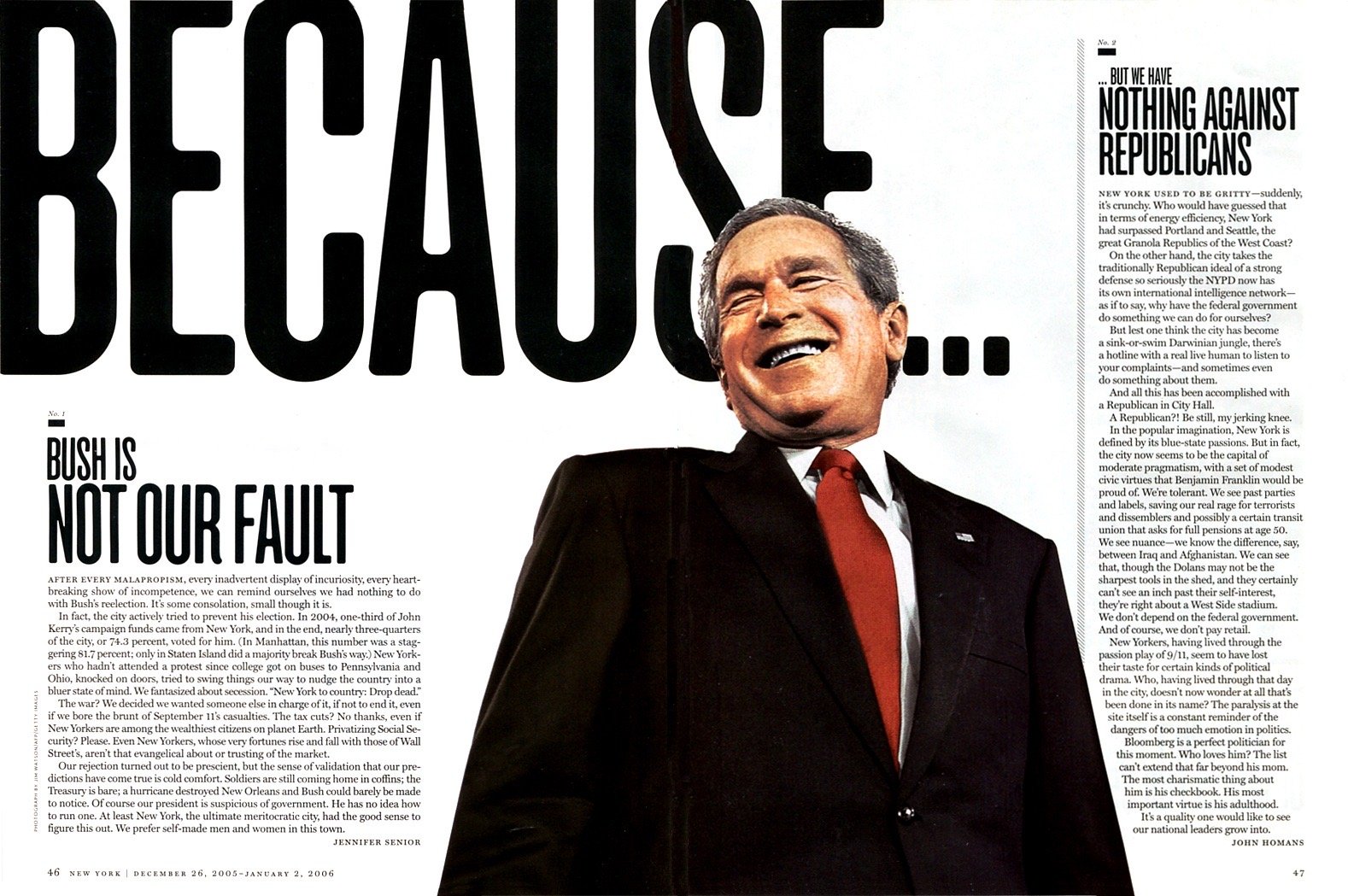

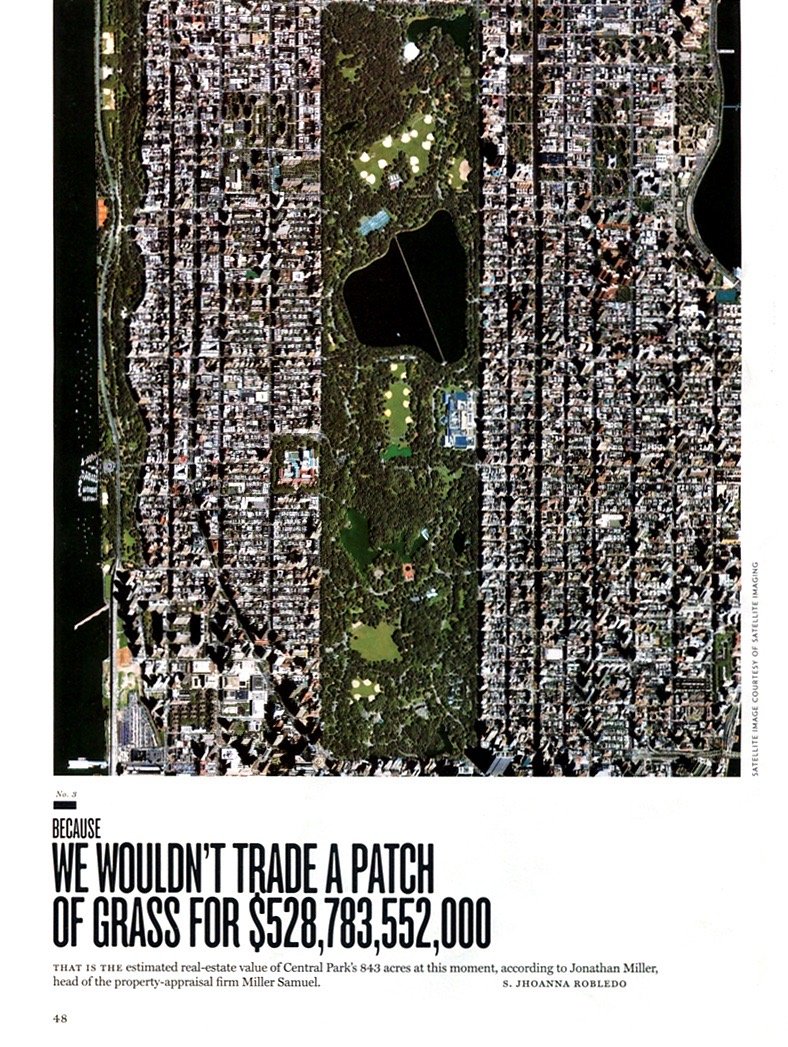

“Reasons to Love New York Right Now,” another Moss franchise, first appeared in 2004 amid a post-9/11 malaise and became an annual special issue.

George Gendron: Pat and I have had conversations where we often comment that we think 7 Days, as you published it back then, might make a great digital brand today.

Adam Moss: I’m not sure you’re right because I think the whole internet talks that way. It was all about voice. A hundred percent. That was its product. And now you see voice just everywhere. But maybe you’re right. If someone wants to give us some money, we’ll start it.

George Gendron: I tend to think of it in the same category as Spy, which is two magazines that aren’t around, that had disproportionate influence on other magazine makers — both editors and designers — about magazine approach, about packaging, and about something that I think your work displays: kind of this compulsion to make use of every square inch of a page. I love that.

Adam Moss: Yeah. I was a huge admirer of Spy, which existed at the same time as 7 Days. In a lot of ways Spy was just a much more complete magazine. Spy was really a work of genius. And we stumbled along in our way, and did some great things. And I’m hugely proud of it. But what both magazines had in common was a kind of, like, “neurosis” that expressed itself on the page. And its physical manifestation was like an ambition of column space. It just crawled. And had so much it wanted to say. And, even if some of it wasn’t really worth saying.

George Gendron: But ultimately people are reacting to a magazine the way they react to an individual. A personality. Those are major contributors to a personality. The throwaways, the small things, the asides. It’s part of what you think of as a great conversation when you have really good friends over for dinner. It feels unrehearsed and spontaneous. Full of conversational cul-de-sacs. And then you back out.

Adam Moss: Well, I think you’ve just defined 7 Days precisely. It was all that. It spoke the way people speak, which is to say it started a sentence and then veered off into something else and then went back to wherever it was talking and, you know, it had the rawness of real conversation.

George Gendron: Okay. I’ve got to ask you this question because the people that I’ve mentioned that I’m doing this podcast with you have all said, “ He’s got to have magazine rules in his head. He’s got to have, like, you know, ’here are the four things you got to do when you are an editor in chief or a creative director thinking about making a great magazine.’”

I’ll give you an example: I said this to Janet Froelich and she said, “Yeah, I think that’s true. One of them is, it’s got to be simple. He’s all about simplicity.”

And I said, “Why?” And she said, “Because he believes that simplicity and clarity is what creates edge.

Adam Moss: She’s better at this than I am. I think that’s true. But I’m not sure I would have expressed it that way, yeah. Great.

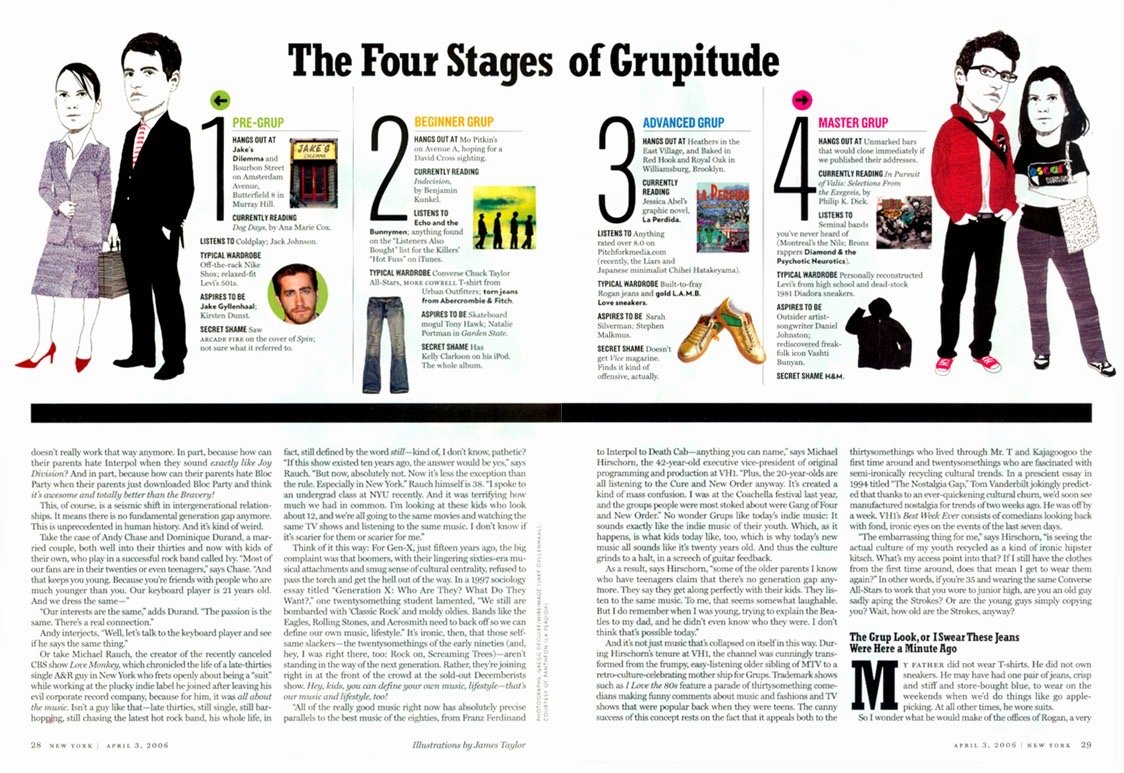

One of New York’s specialties is creating packages around contemporary trends. Above, the rise of digital media, and below, New York power brokers.

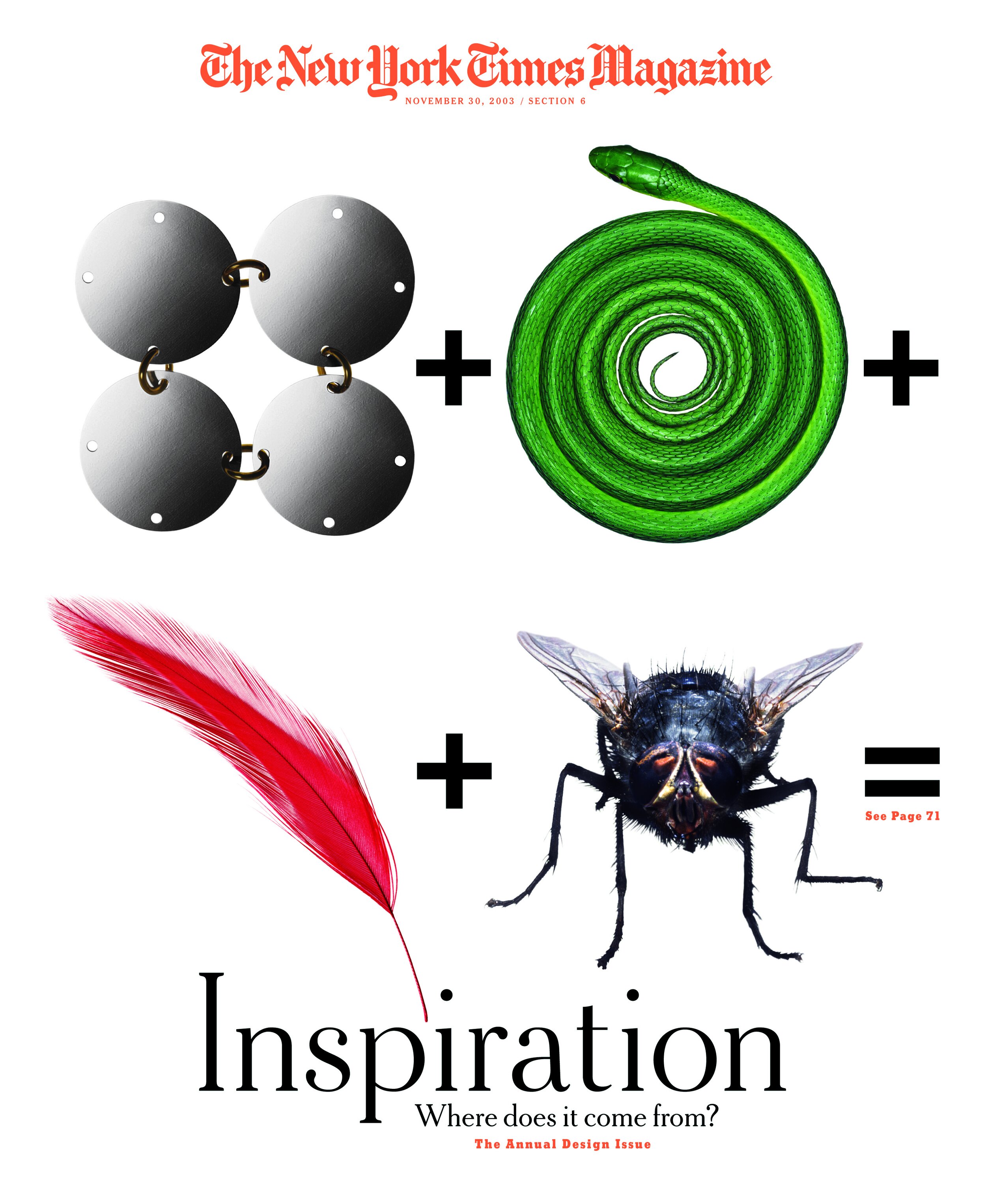

George Gendron: Oh, here’s another one. This is me: you loved photographs over illustration.

Adam Moss: That is true. I felt that photographs had an immediacy that illustrations didn’t. Though later in my career I began to love painting. Painting and figure drawing. I hated “whimsy.” And I felt that magazine illustration was too often in love with whimsy.

Yeah. I mean, you know, yes, clarity. Yes, edge. Absolutely. Voice has to be distinctive and confident. You had to have confidence, otherwise you’d lose your reader. The magazine didn’t pretend it knew what it was doing.

George Gendron: You brought that back to New York. New York, when I was there, was kind of suffused with this sense that it’s a magazine less about New York, per se, and more about a kind of a New York attitude about the world. And I think you reinstilled that sense in New York when you were there.

Adam Moss: Yeah, I tried to. I’m glad you said that. But that’s true. Attitude, used correctly, is a great, great tool of a magazine. Attitude used incorrectly can be very dangerous. One of the things I felt about New York magazine when I got there, for instance, was that it was too in love with the sort of Page Six-ness of New York.

Which is to say it was too invested in Donald Trump, really, is the truth. And all of the things it represented. And so, I tried to also bring a kind of different value set to what the magazine was about and try to instill more generosity without being bland or without being sanctimonious, you know, et cetera.

Look, the magazine is a person. And a successful version of a magazine is also the successful version of a person. It’s someone you want to hang out with. And what kind of person you want to hang out with varies by person. But what you’re doing is trying to create an organism that resembles a living one.

George Gendron: A magazine is the person, yes. And yet I think a lot of the public would think immediately of Graydon Carter and Vanity Fair, where you have this larger than life character. And you, whenever you talk about, not only during these conversations, but interviews that you’ve done in the past, it’s always we, it’s always about the team.

Adam Moss: Well, I never felt that the “magazine is a person” means that the magazine is about me. I just meant that somehow the bunch of people, the collective — and the collective is really what magazines are all about. You know, at the very, very beginning of this conversation, I started by saying that it was always embarrassing to me that the amount of attention that an editor-in-chief got. When, in fact, the entire point of a magazine is that it’s collective. And I mean that sincerely. It’s not an act. And that’s the very best thing about a magazine.

What I mean though is that somehow the group — it’s a little bit like K-Pop. The group has to have a kind of unison. It has to, together, operate as one. Without grounding out its idiosyncrasies, and individual quirks, and individual pieces of expression. But it also has to function as a whole, as a single thing. That’s what I believe.

George Gendron: When you think about what you just described, do you find that online anywhere these days? And if so, where?

Adam Moss: Well, I mean, here’s the thing about the way publications work these days. For the most part, the existence of a publication, per se, does not exist anymore. Because it really is just a whole bunch of individual atomized parts that you come to through social media or you come to through links or you come to the parts, you don’t come to the whole. There are very few things that are read digitally through a homepage. I mean, yes, certainly The New York Times, the Washington Post — newspapers. And maybe The New Yorker, maybe The Atlantic. I don’t know, maybe New York also.

But for the most part magazine material is read in fragments. So what you have lost is that sense of a coherent whole. Which is not for lack of trying. Magazines do try it, but it’s just not the way readers behave, digitally. So it doesn’t exist anymore.

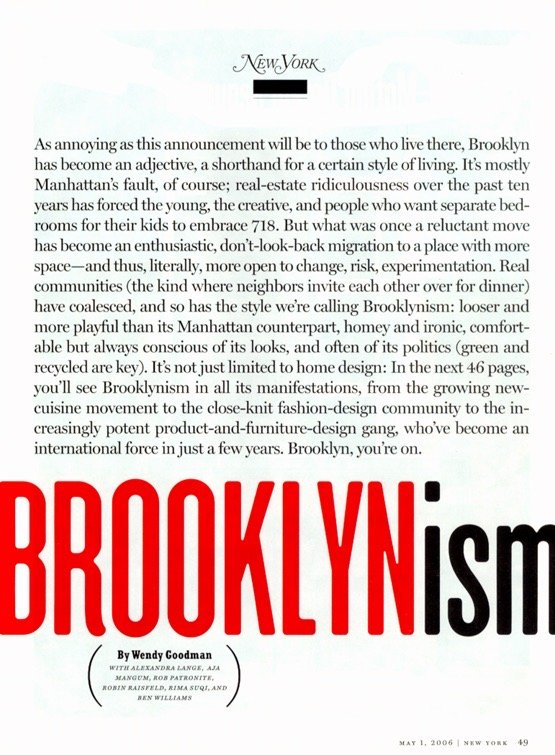

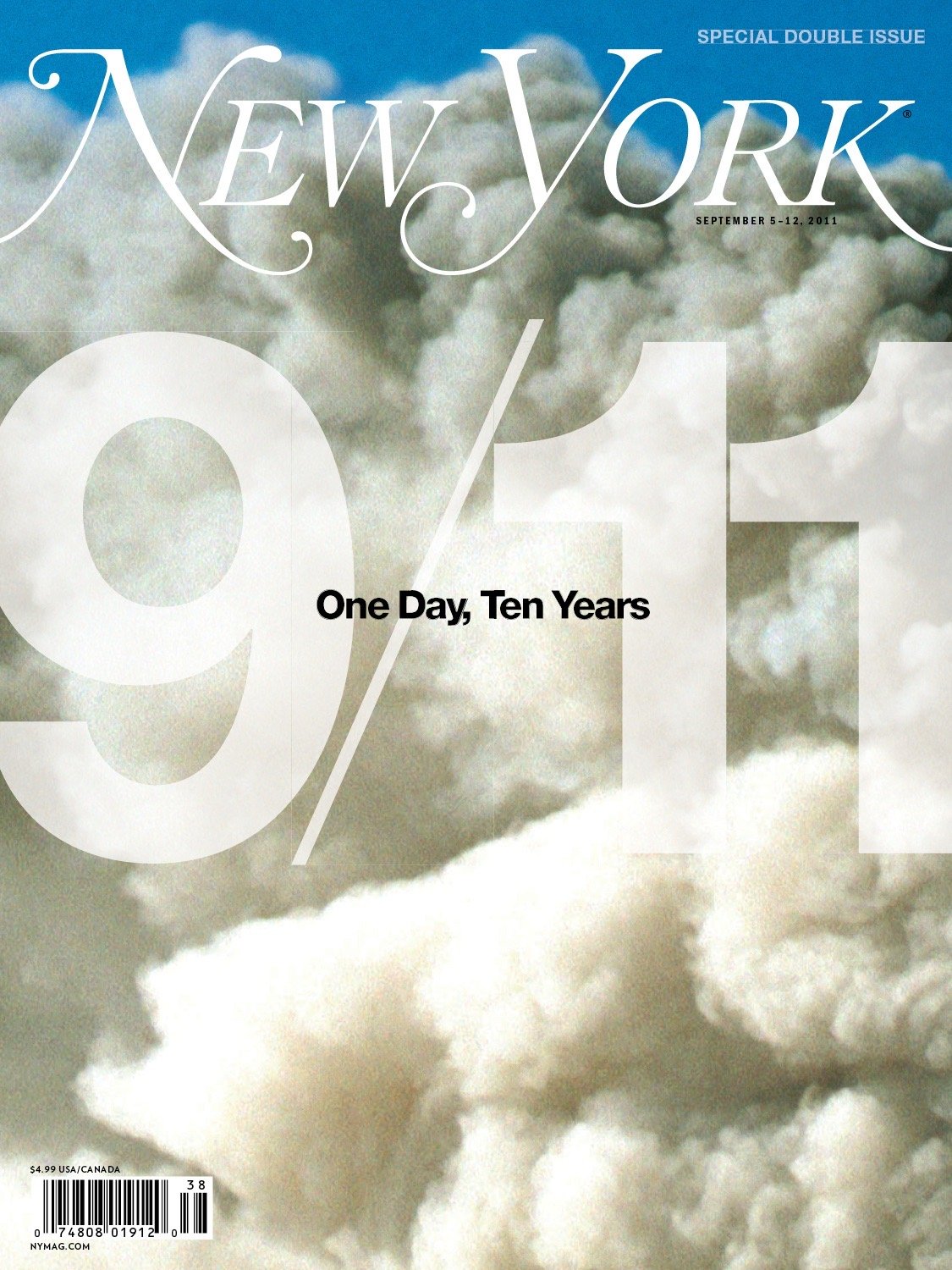

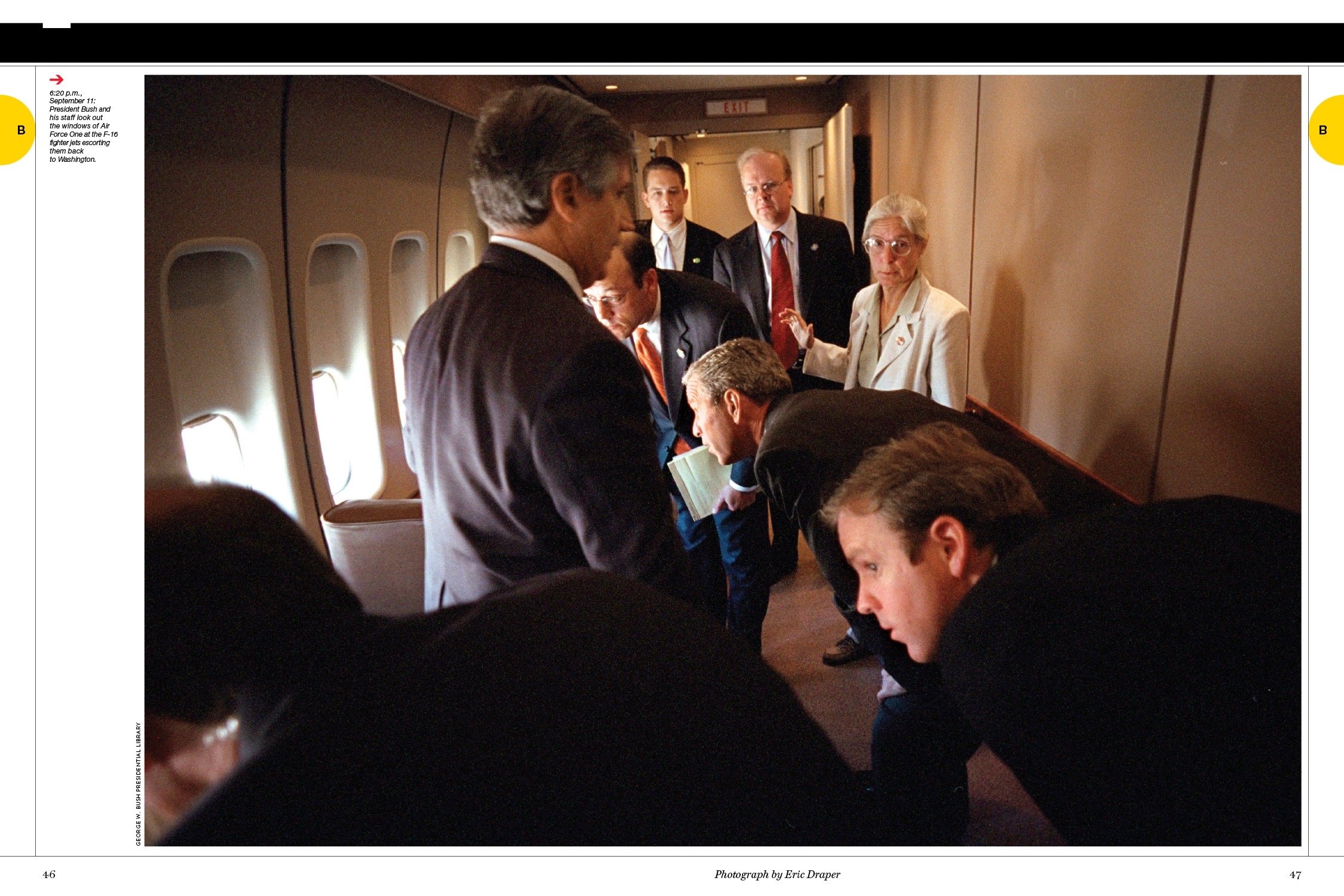

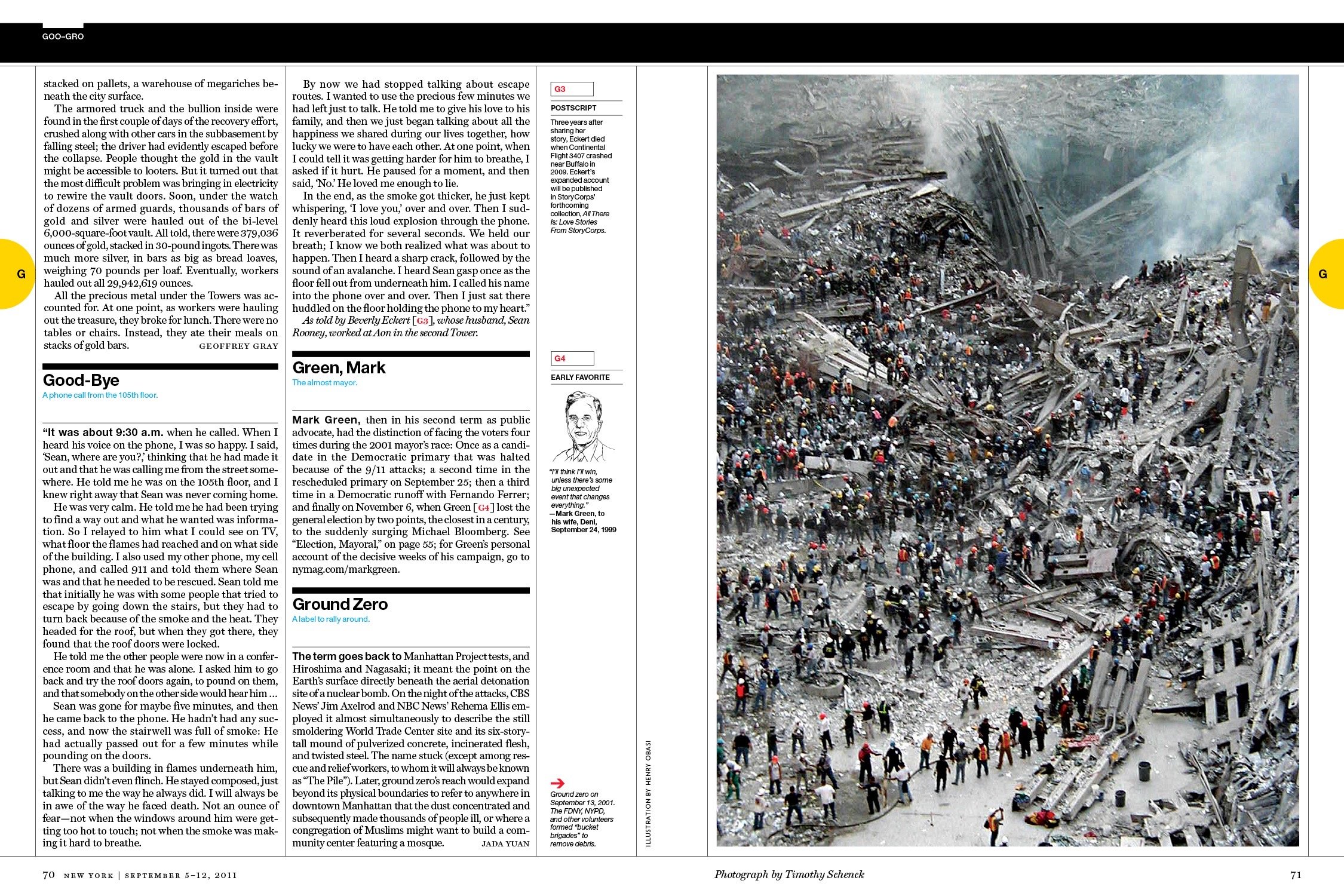

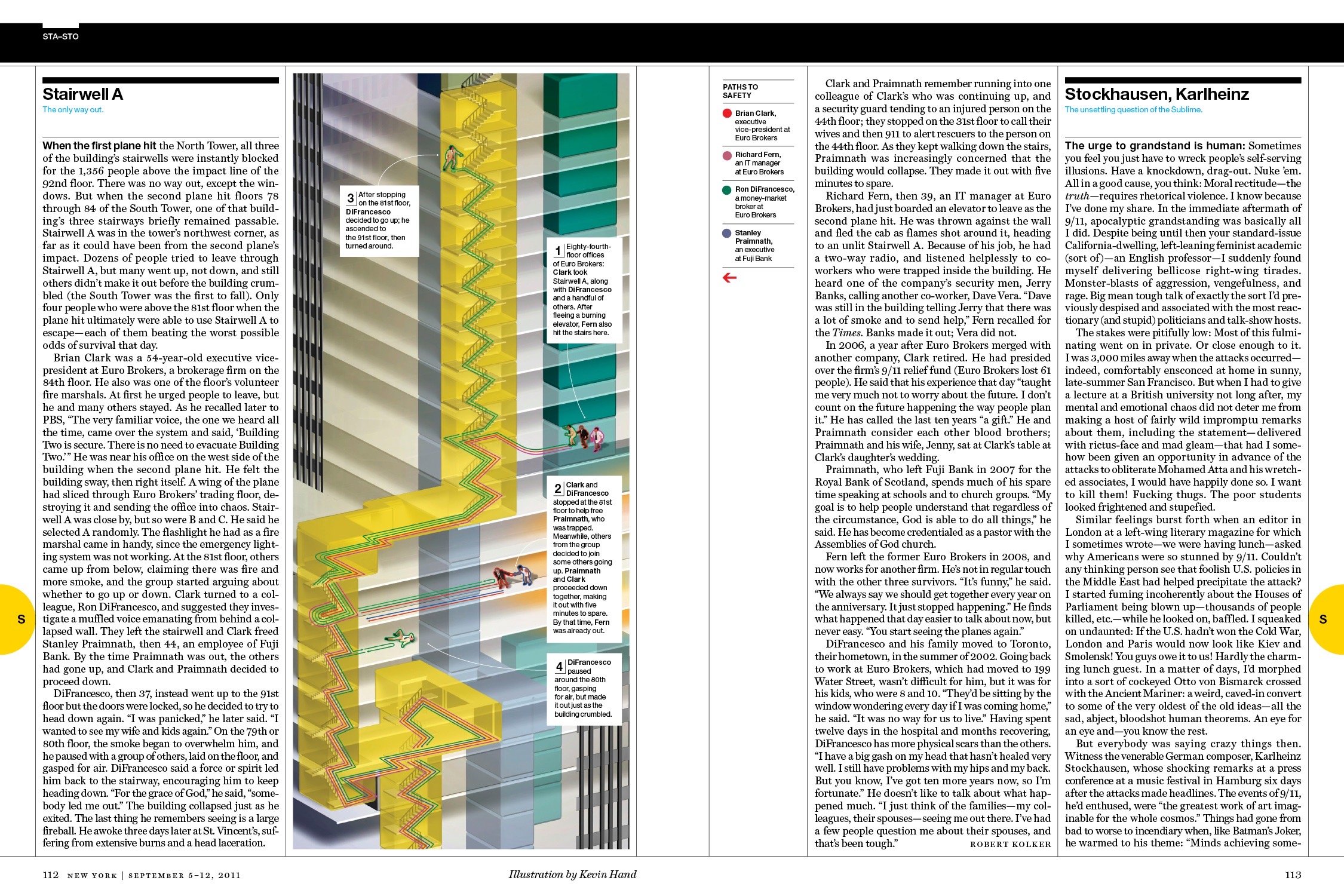

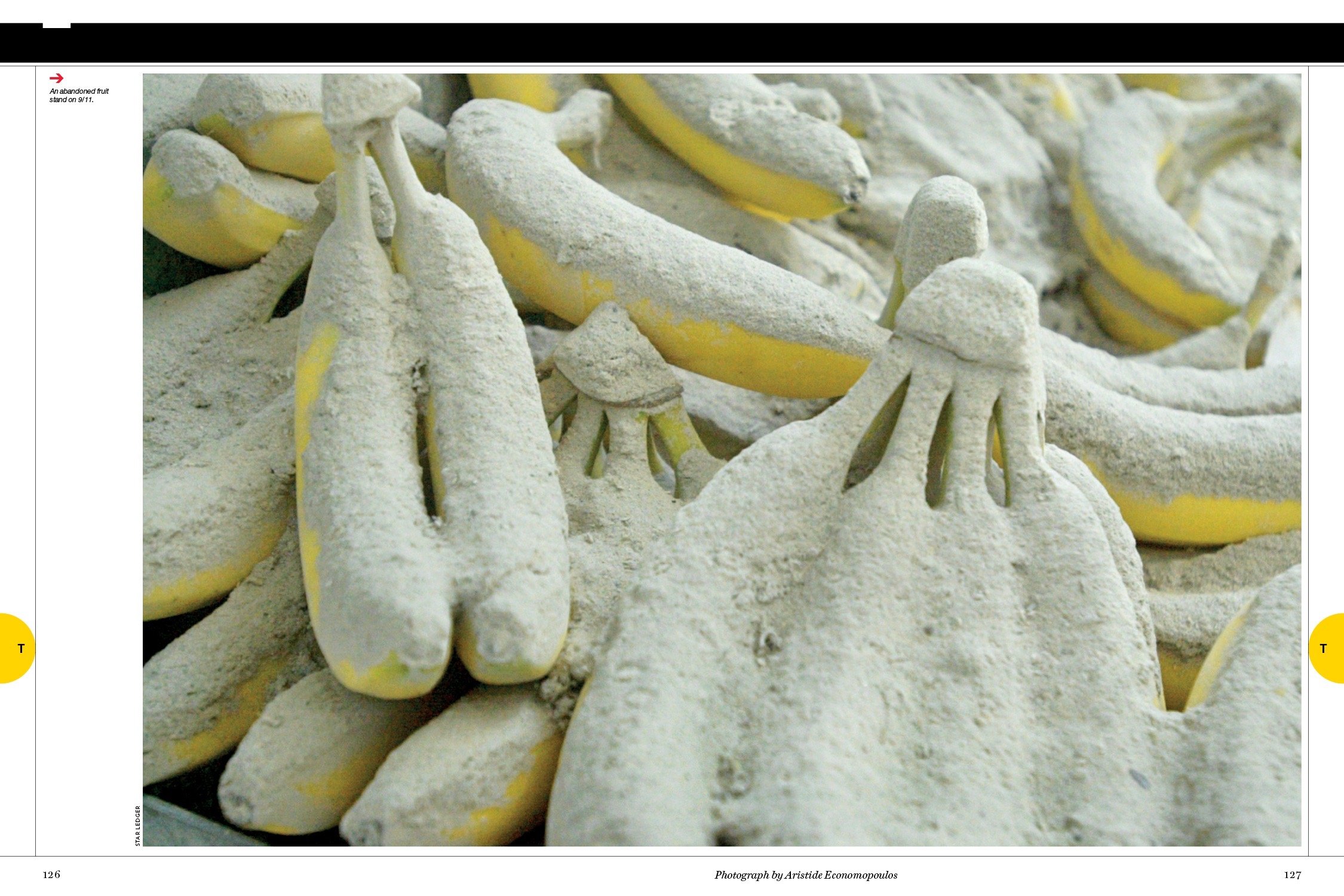

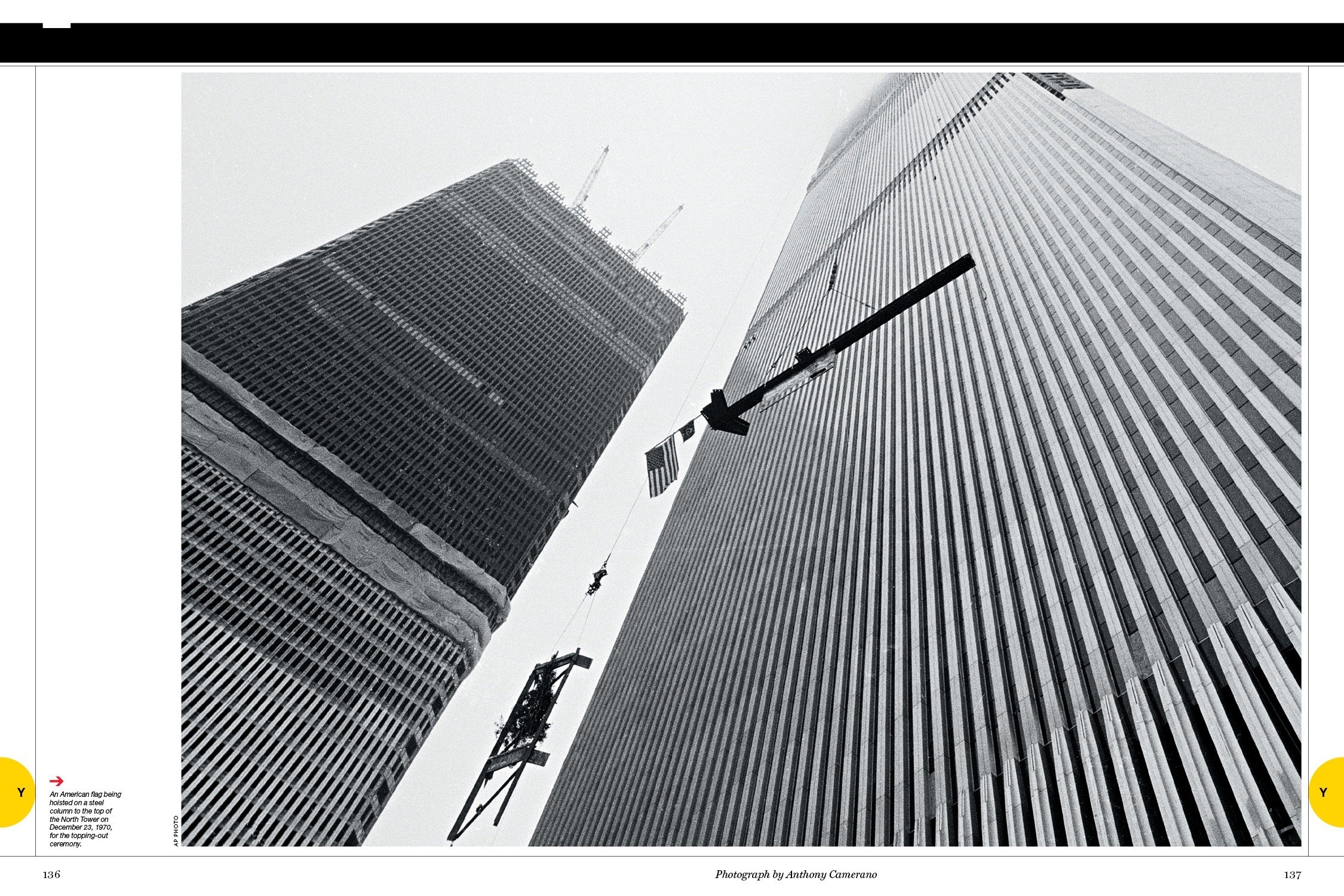

One of Moss’ all-time favorite issues of New York, a 9/11 retrospective in the tenth anniversary of the disaster.

George Gendron: I know you’re not nostalgic, but what are we missing as a result of that?

Adam Moss: We’re missing the strong hand of the magazine staff or the editorial staff. But we’re getting a lot of great material. What I’ve just described, we’re missing the coherent wholeness of it, but we’re, what we’re getting instead is incredible reach. Every piece of material that’s published online can reach gazillion multiples that we ever could reach back in the old days of print. That’s a great thing. It can be interacted with. You can comment on it. It’s animated. It can move. It’s pictures. It’s sound. It’s just a different beast.

And it has lots of attributes that the old days of print didn’t have. Old days of print, however, had certain attributes that don’t really exist today. And that’s the way things have always moved. You gain some, you lose some along the way.

George Gendron: On that note, I’m going to ask you the Print Is Dead Million-Dollar Question, and that is you’re having lunch with Laurene Powell Jobs, who confesses, privately, that she’s always had a soft spot for print. And she’s followed every single step of your career. And she’s willing to provide unlimited finance for you to create or recreate the magazine of your choice. So what will it be Adam Moss, editor-in-chief?

Adam Moss: Here’s what I would say. Given that opportunity, you’d be crazy not to say, “Look, if you’re really willing to do this, let’s do something that will lose you a lot of money.” And so let’s start with that proposition, and then let’s say that if you’re going to do — and look, it’s called Print is Dead, Long Live Print!, right — let’s conceive of a print magazine that has all the best aspects of print.

Which is to say that it would be tactile and it would have — there used to be a magazine called Flair, that existed way long ago, it was a fashion magazine. But, literally, things popped up out of its pages. It was a kind of playhouse, a physical playhouse, within the covers of a magazine. It was a great thing. It lasted a minute-and-a-half.

And so I would say that: let’s do a magazine that’s nothing but, but it just revels in its physical self. And therefore loses a ton of money. And then it’s like, “Well, what would you do? What kind of magazine would you make with that, that you could only do in print that really wouldn’t work the same way online?” And I didn’t come up with anything particularly interesting.

I’m a great fan of cities. And these days I think that the case needs to be made for the values of human interaction and some of the old values of urban life. And I’m wondering whether each issue is devoted to a certain city and then explores it in various very physical ways.

We had talked earlier about Provincetown. And I had this idea always of doing a, kind of, real-life serial of Provincetown in magazine pages. And then I’ve just been spending all this time on process, you know, with this book I’m doing. And, you know, a magazine of, like, of pure process — how things are made, how things begin, the evolution of things, expressed physically, visually inside the pages of a magazine of this, kind of, lavish, and extravagant, and wasteful magazine I’m describing might be kind of fantastic.

So if she wants to fund that, she should give me a call.

Moss is currently at work on a book, tentatively titled The Work of Art, which is due from Penguin Press in 2024.