Once Upon a Time in the West

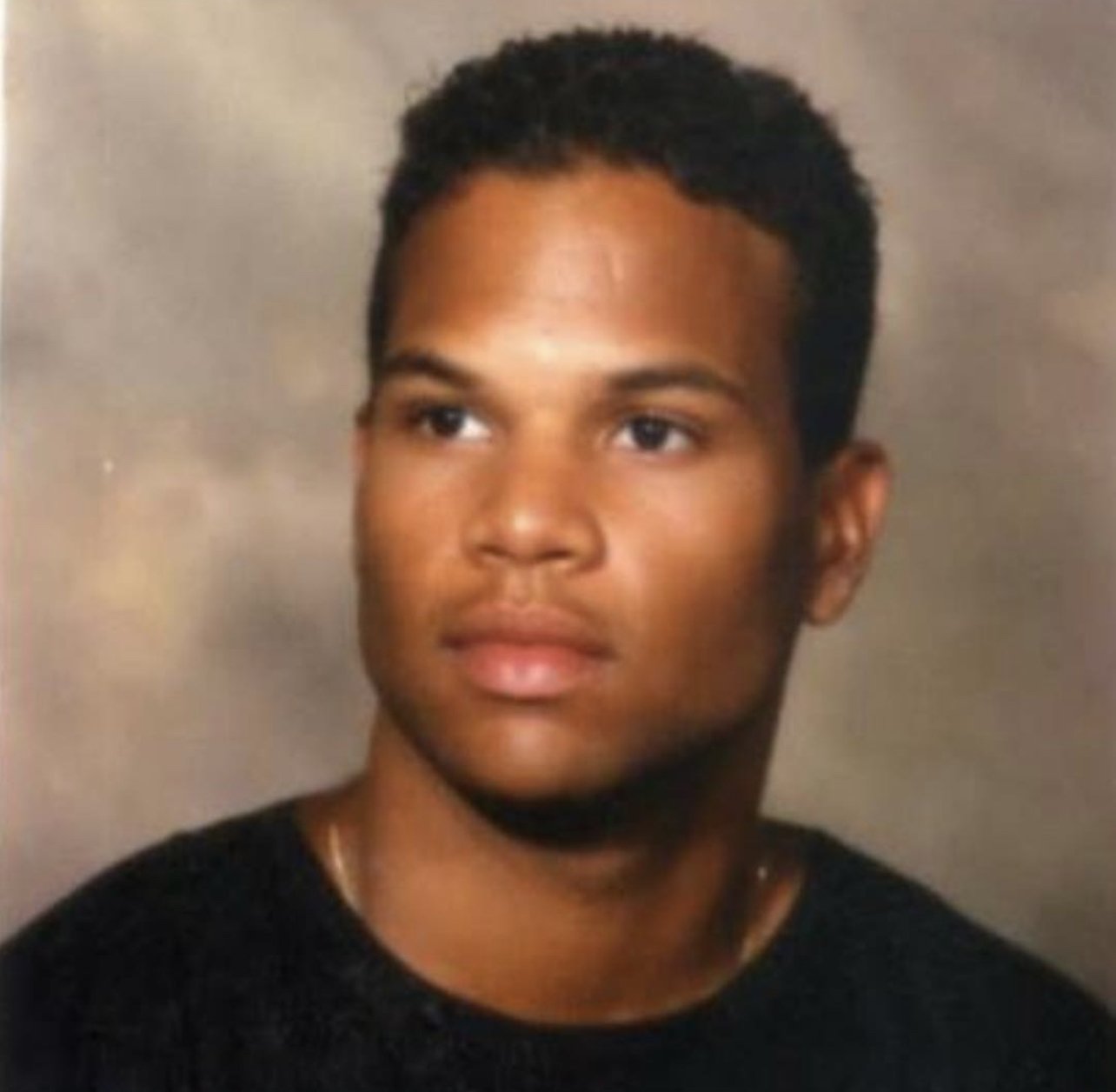

A conversation with designer Arem Duplessis (Apple, The New York Times Magazine, GQ, more).

Where do magazine designers go after all the magazines are gone? That’s a question we’ve often pondered in recent years.

Well, if you’ve been paying close attention, you’d probably guess, as it turns out, a lot of them go to Cupertino. And much of this migration can be traced to 2014, when today’s guest, AIGA Medalist and Emmy Award-winning creative director Arem Duplessis, left his storied job at The New York Times Magazine to go to work at Apple.

You might be asking yourself, Why would one of America’s most high-profile magazine designers leave a coveted job at an iconic publication—one that brought him global recognition, countless awards, and deep creative satisfaction—for a famously secretive company known, well, for locking away its talent in a vault of non-disclosure agreements?

But the better question might be, Why wouldn’t he?

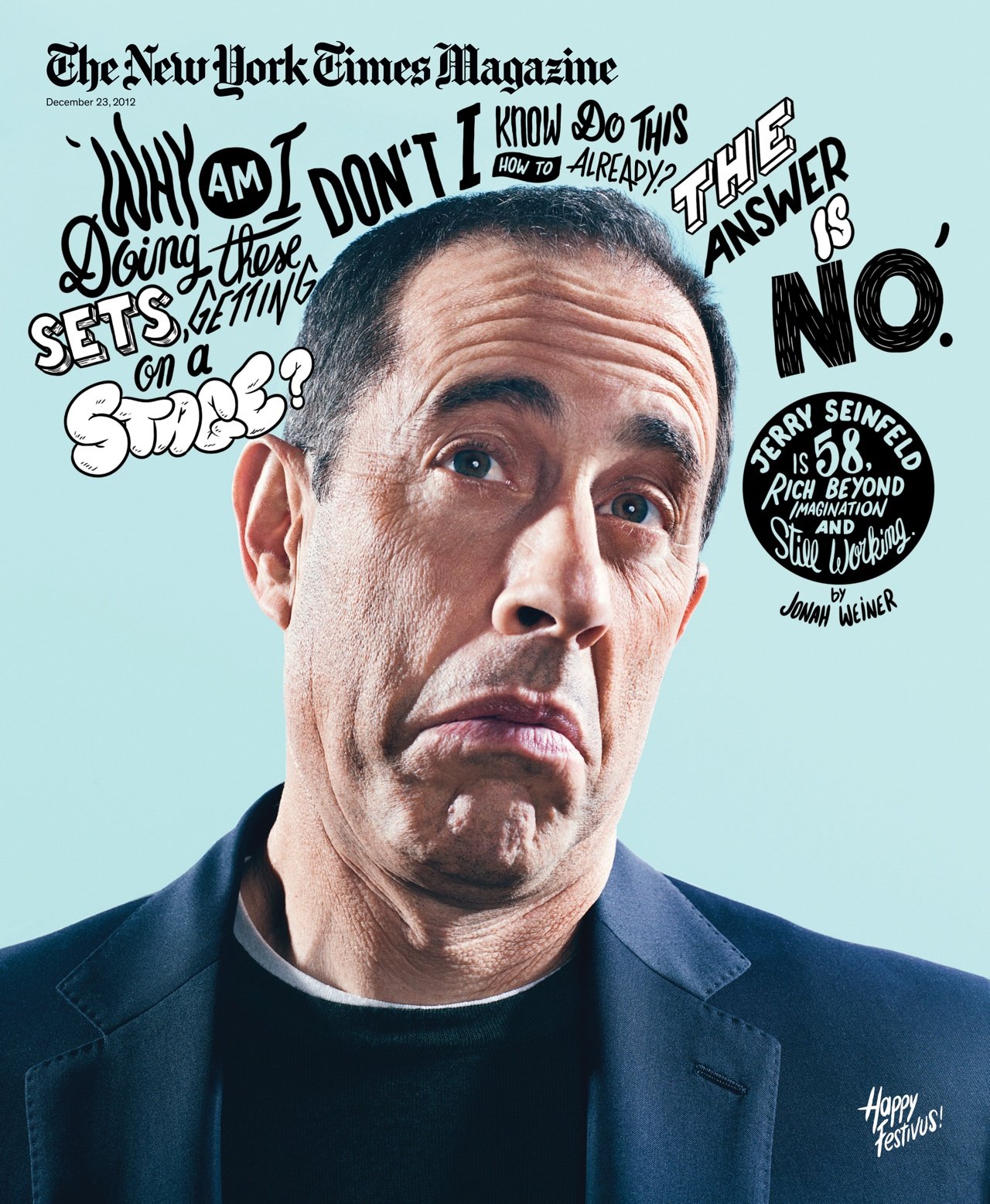

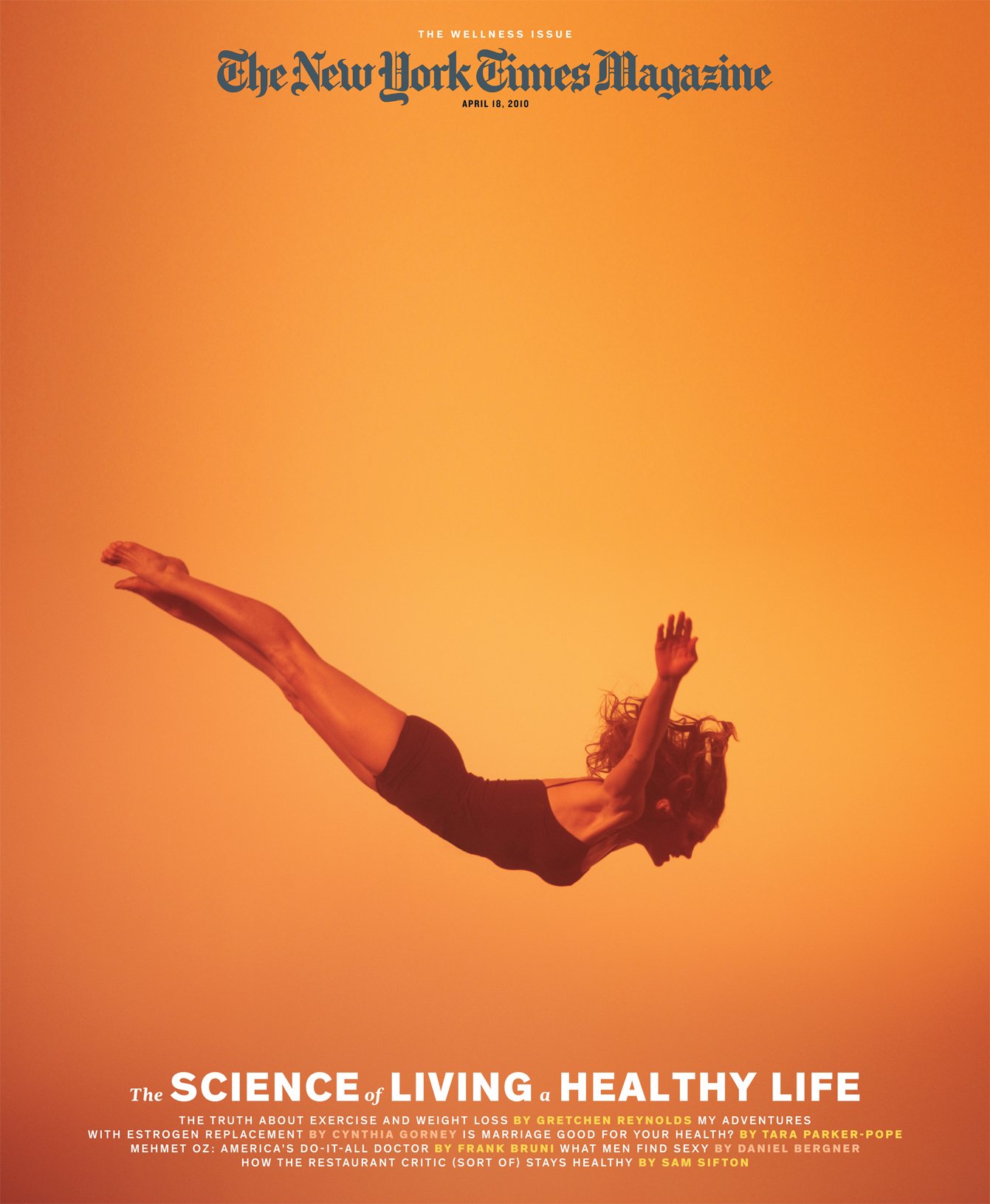

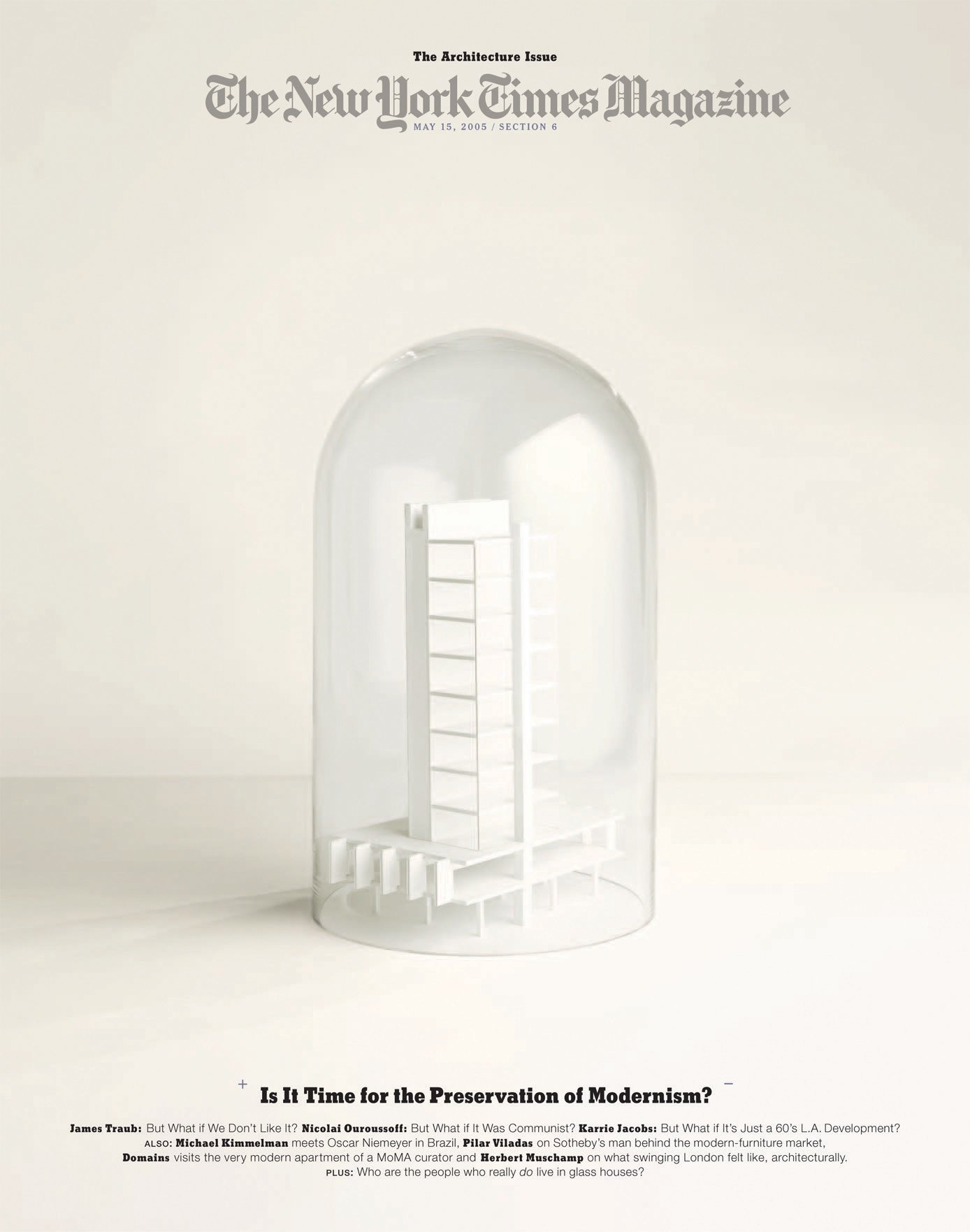

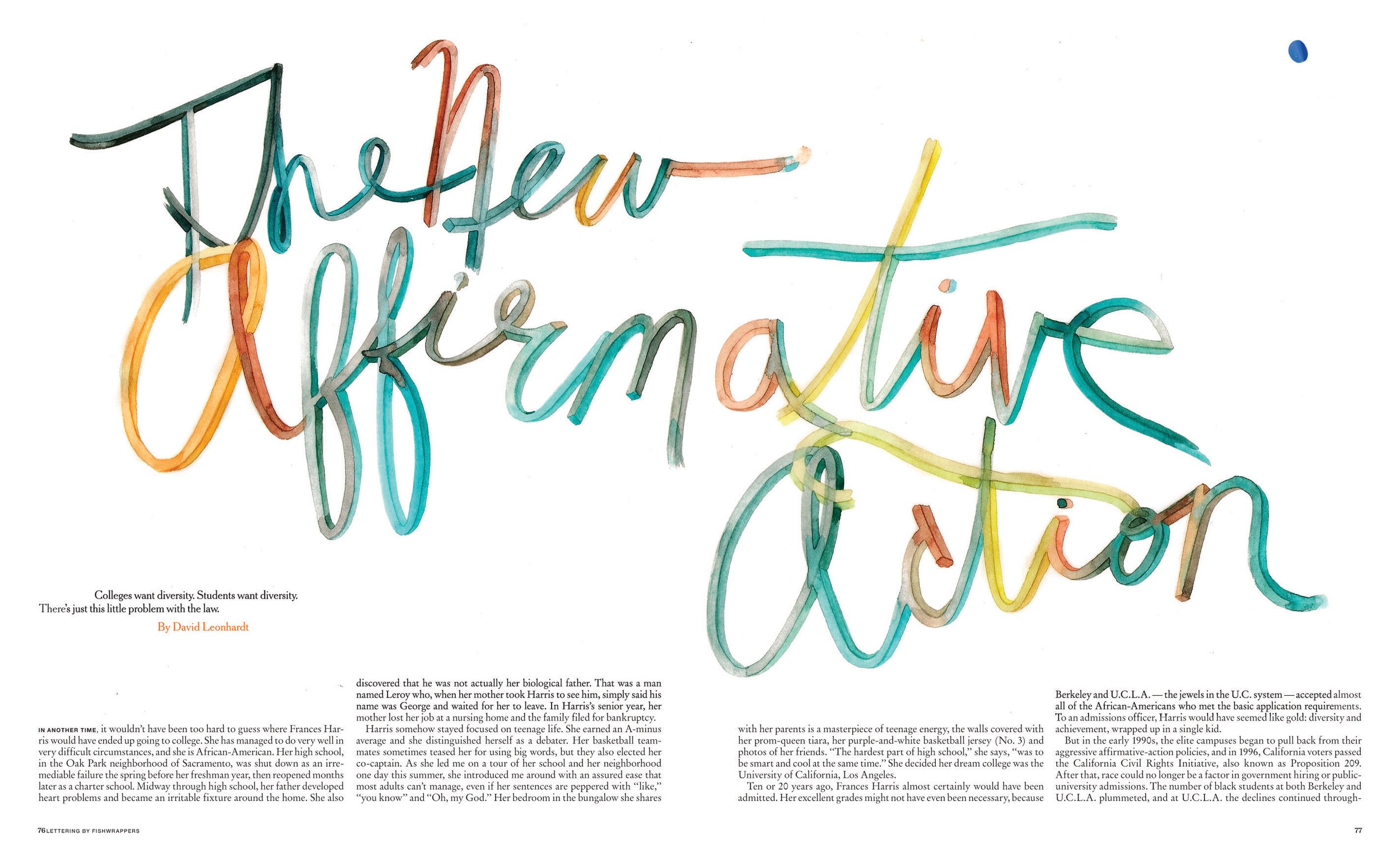

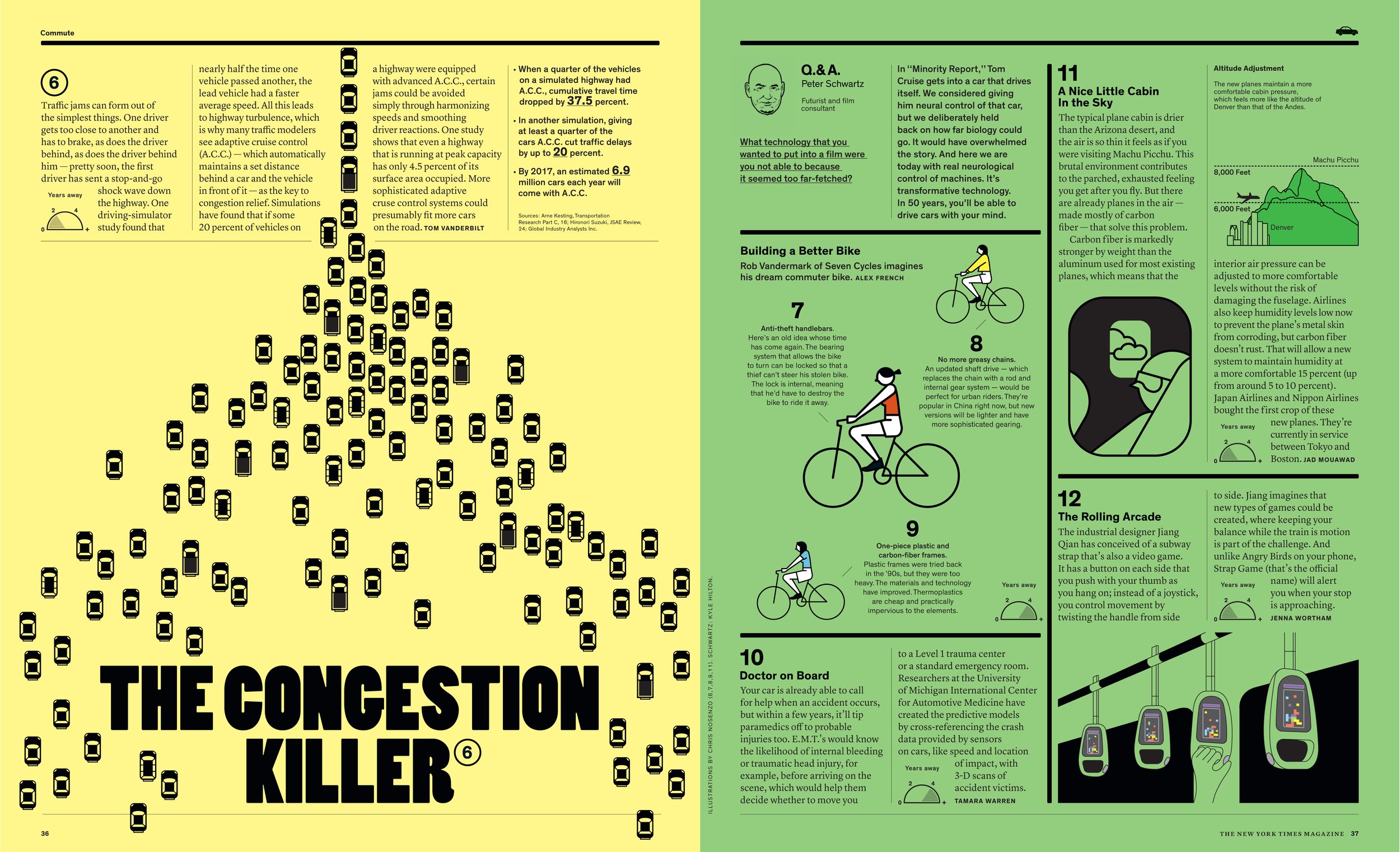

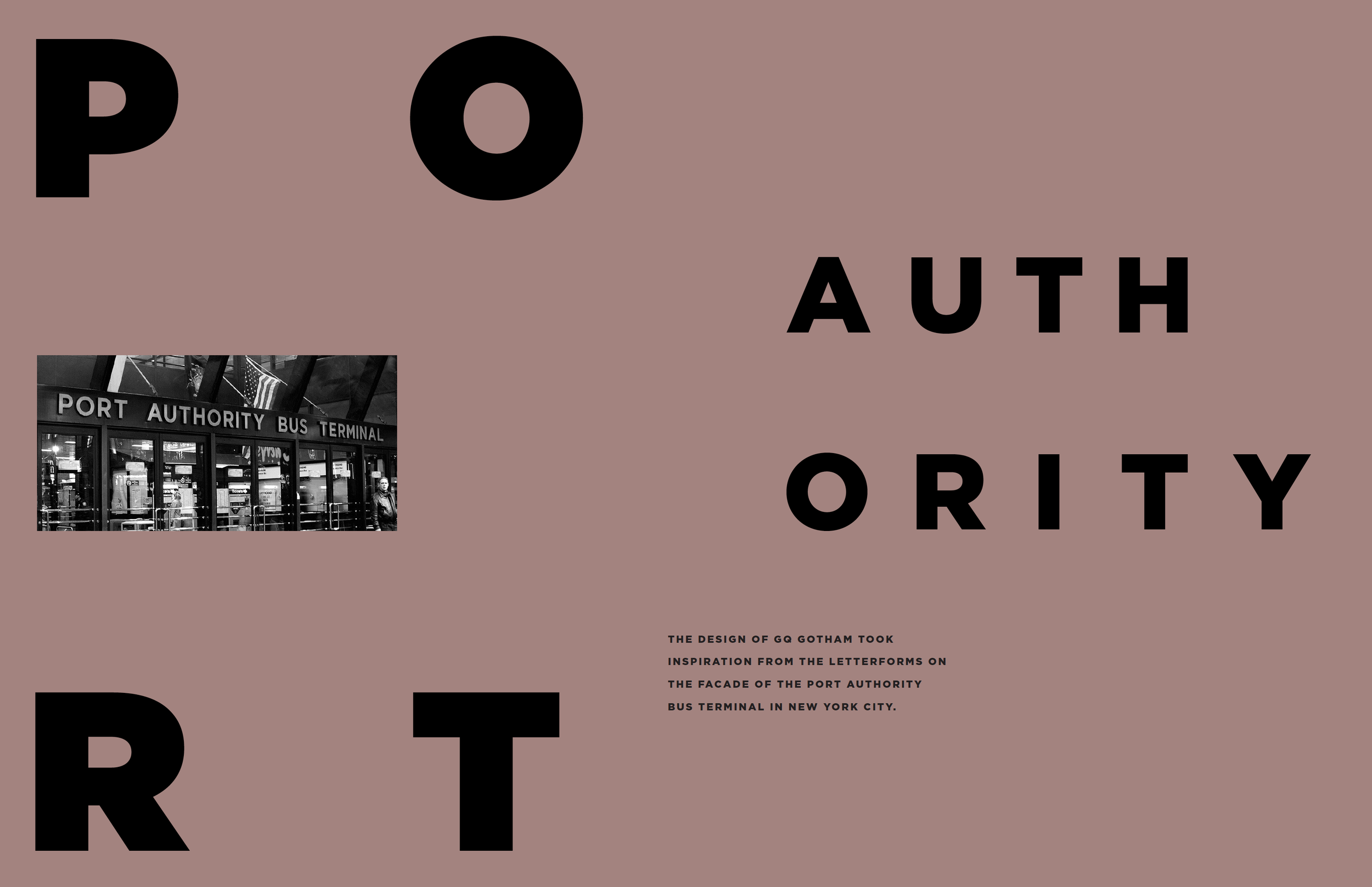

Duplessis is arguably one of the most influential creative directors of his time. His ten years of covers for The New York Times Magazine shaped its vision and identity. As design director at GQ, he helped create the now-ubiquitous Gotham family of fonts. And now he’s blazed the trail for print designers in search of digital futures.

While the departure of big-name magazine designers like Duplessis to Silicon Valley may strike fear in some, it reaffirms what many of us have long known: Despite years of slumping newsstand sales and magazine closures, the all-purpose skills of elite creative directors are still very much in demand.

As former ESPN creative director Neil Jamieson says, “Why wouldn’t Apple be hiring magazine designers? No other category of designer is more multifaceted. Beyond the fundamentals, they do branding, packaging, identity, storytelling. They have experience on set, with video, social, and short-form storytelling.”

There’s no question there’s a dire need in the corporate world for these kinds of skills. The question that remains unanswered, so far, is: Can that kind of digital work ever deliver the same creative fulfillment that magazines do?

We talked to Duplessis about learning to scuba dive in his Dad’s Virginia quarry, the modeling career that wasn’t, cutting his teeth at the controversial hip-hop magazine, Blaze, adapting to life on the West Coast, and what he’s planning for life after work.

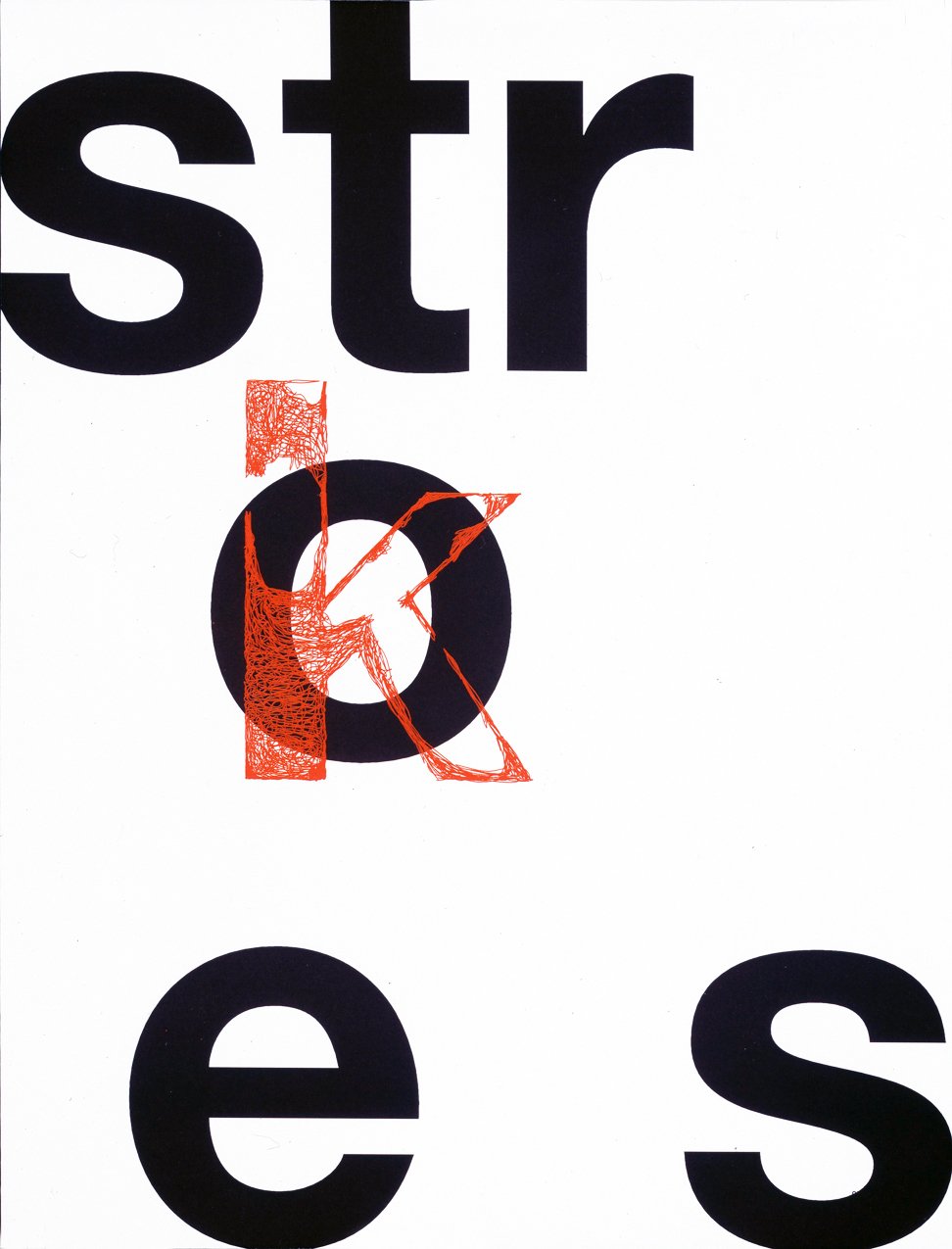

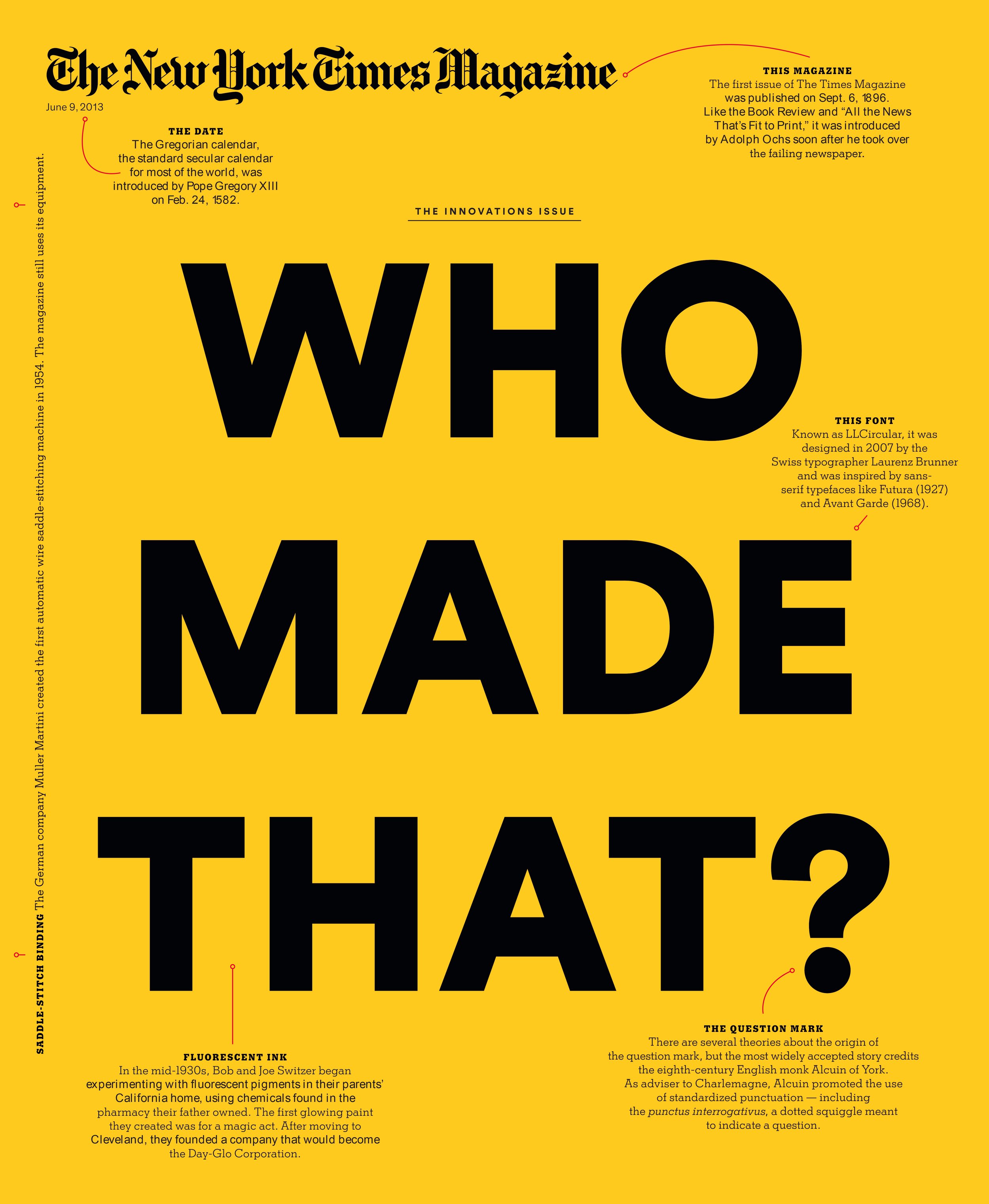

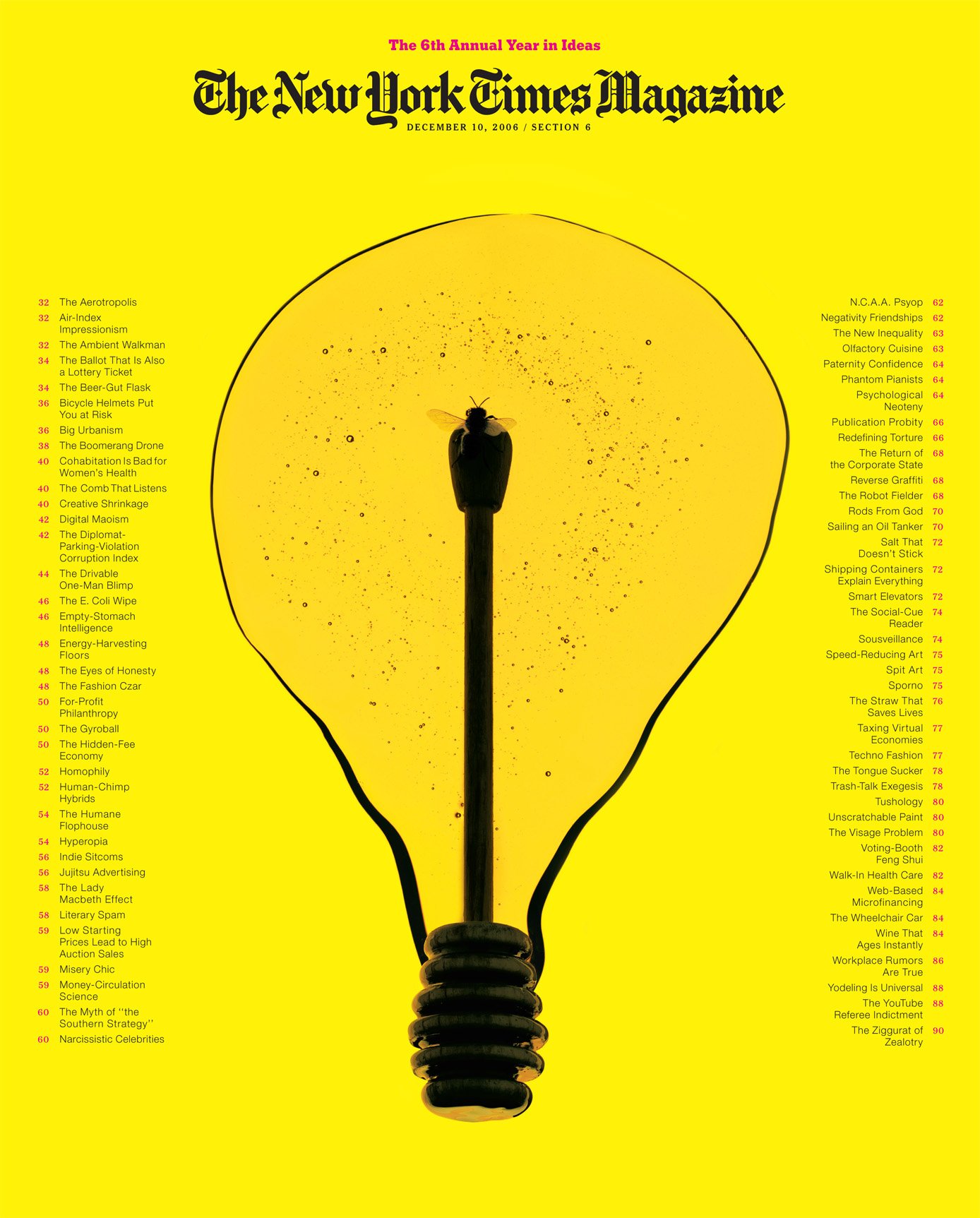

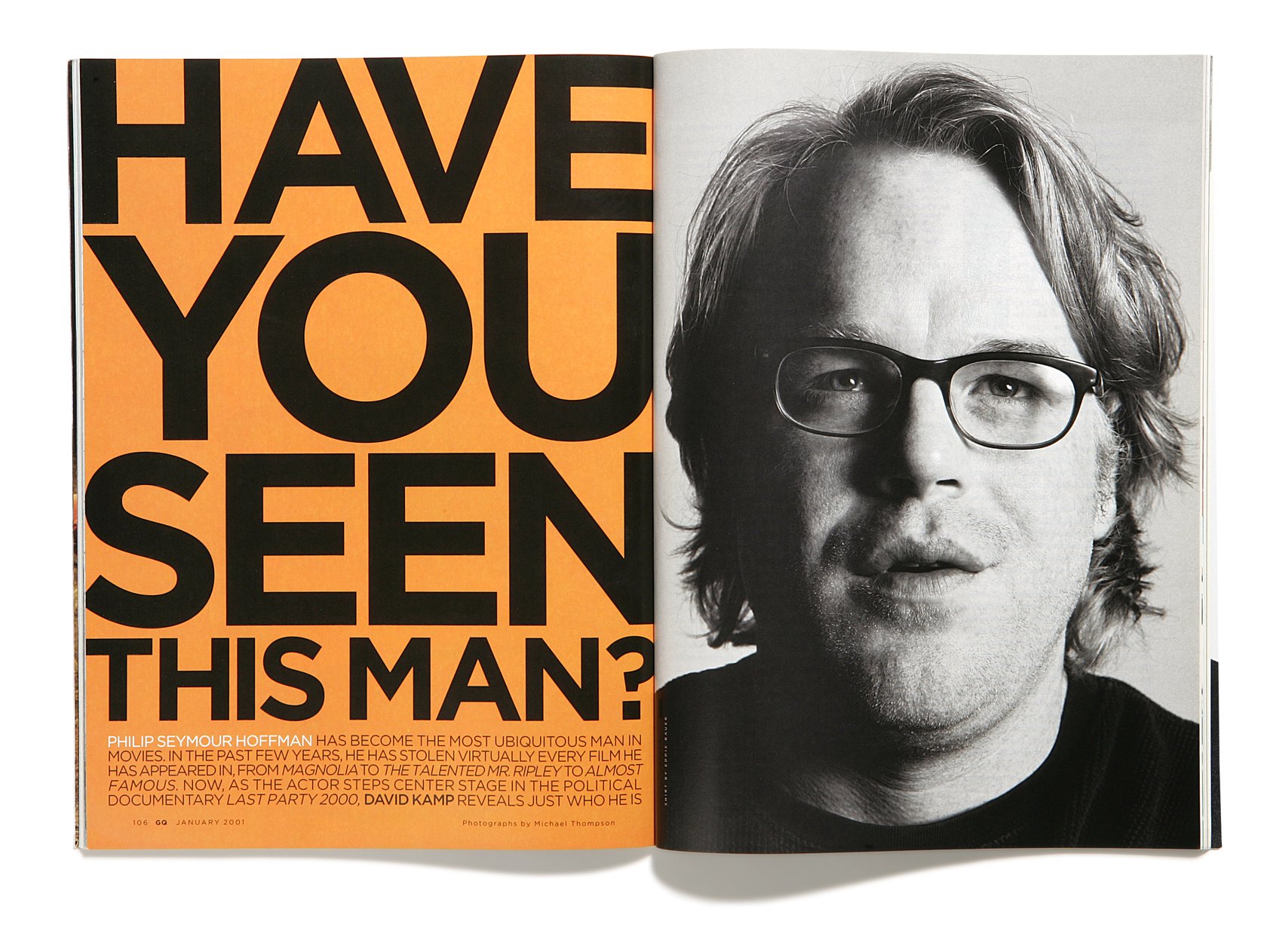

Quite possibly one of the most imitated magazine covers of all time.

Patrick Mitchell: Let me start by saying that I predate you by a bit. And by that I mean, I worked on magazines before computers came along. So, given that Steve Jobs and Apple are almost god-like in the effect that they’ve had on our business. And because of that, most art directors I know are total Apple nerds. We watch every keynote. We buy all the products. We cried when Steve died. So, in the eyes of many of us in 2014, you basically moved to heaven. Or the Garden of Eden. However you want to think about it.

Arem Duplessis: [Laughs].

Patrick Mitchell: But I’m wondering, did you have a similar sort of “spiritual relationship” with Apple? And, if so, did that play any kind of role in the decision-making process that led you there? Was it purely about creativity and career or was the Apple ‘mystique’ part of it too?

Arem Duplessis: Well, like you mentioned, and like for so many others, it was a part of my, you know, it’s equivalent to a foreman and his hammer. Those were the tools of the trade. When I got into the business, I did start out on a Mac. And it was a big part of what I did. And I quickly became a fan of Apple. And an Apple nerd, for sure. And I needed every product—wanted every product—as it was announced. And that excitement continues to this day. I’m still a huge fan.

And deciding to come to Apple was definitely centered around Steve’s messaging about Apple being a design company. And design being at the forefront. And design being so important to the company’s mission. It just seemed like that the “north star” of Apple from the beginning was design. And good design. So for me, that was extremely appealing. And it made sense, once I decided to transition out of the magazine world.

Patrick Mitchell: I saw this quote from an unnamed magazine editor, “I think some designers are enamored with the notion of working for Apple. But once you get there, you become anonymous.” The magazine business is really the only place where designers get credited publicly. Do you miss seeing your name out there? Getting credit for all that amazing work?

Arem Duplessis: No. I think that the thing about magazines in general, and it’s not just Apple, it’s really magazines. There’s a masthead. I mean, there’s literally a place where you can go and see who the creative director is, who the director of photography is, the editor and contributing writers. It’s all right there in front of you. There’s no other platform that does that. But I don’t miss it. I don’t miss getting any credit for the work that I do because it was definitely always a team effort. I hired some really good people. That was the magazine business. That was very much a part of the magazine business, but also it was a unique thing about the magazine business to have that kind of baby that you literally have your name on, and your team’s name on, and you get all this credit for it—or blame when it’s not so good too [laughs].

But, no. I don’t miss that. I got into this business because I had a love and fondness for design. And I’ve always felt blessed. And I’m not bullshitting. I’m serious. I’ve always felt blessed that I’ve been able to work in this field.

And when I first started out, I went to a school that had a really small design department. I think there were, like, four of us in my class. But for me, I just wanted a job in design. That was my goal. It wasn’t to win awards and have my name on a magazine. Nothing close to that.

Nicole Dyer: Do you miss those collaborations? Are you able to maintain that or is it mostly internal collaborations at this point?

Arem Duplessis: No. I’m still able to collaborate with creators, not only internally, but externally, too. So I still have that, which is great. I definitely enjoy that part of the job.

Patrick Mitchell: Apple has come up in several of our previous interviews. Everyone’s talking about how Apple keeps hiring all these magazine people.

Arem Duplessis: Mm-hmm.

Patrick Mitchell: And I know you can’t divulge anything about what goes on in there, but what is it about magazine thinking that makes magazine makers so appealing? Not just to Apple, but to other sorts of non-magazine companies.

Arem Duplessis: Looking back on it—and, and I didn’t have this perspective while I was in magazines—it got to a point where I felt, in many ways, that I was becoming obsolete toward the end, you know, or magazines were becoming obsolete. At least in the way that I kind of came of age with them. So for me, it was, I was nervous about being able to tell my story as a magazine creative to these other brands. You know, I was in magazines my whole career.

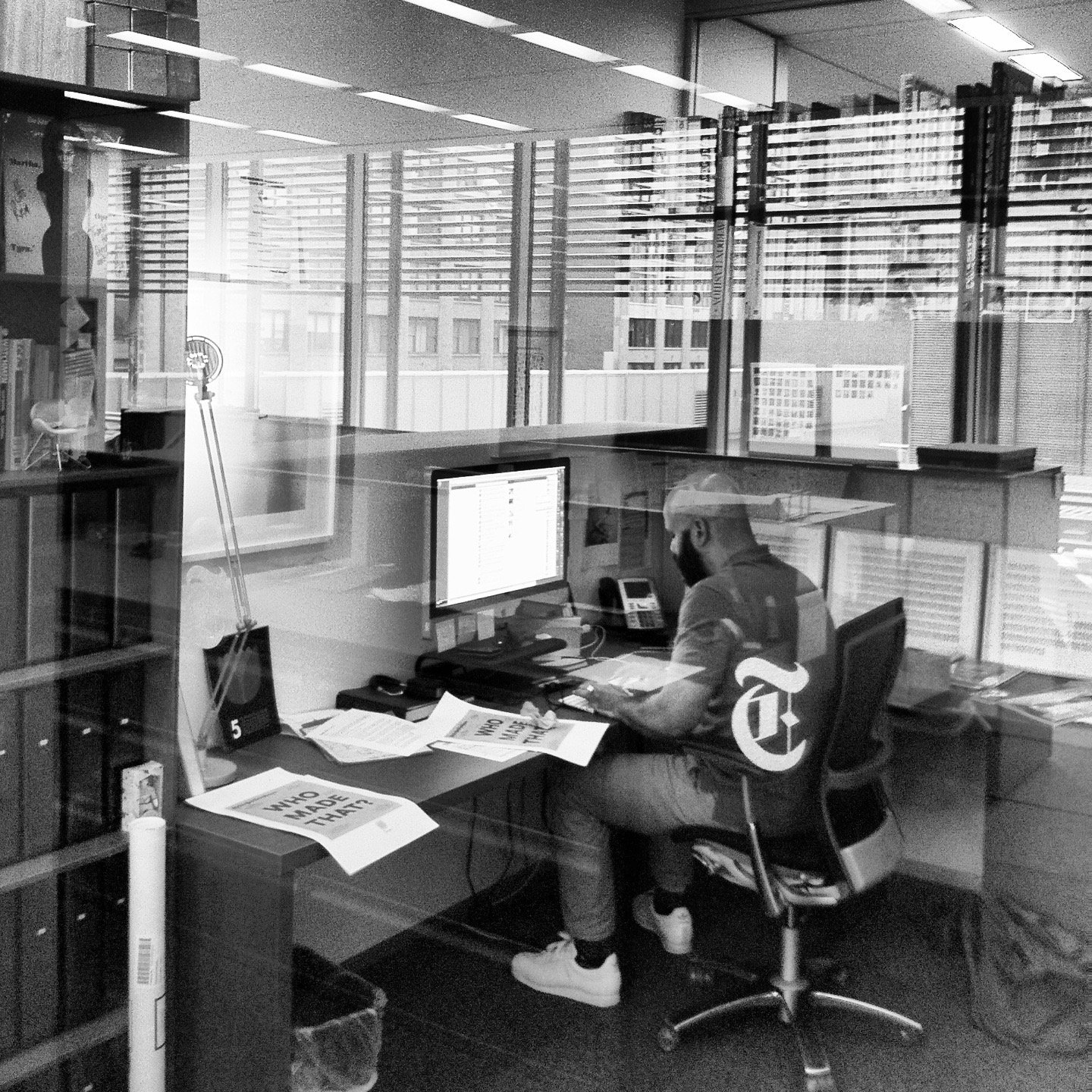

So I quickly learned that what I perceived as a weakness was actually a real strength. Because if you look at the creation of a magazine—when you work for an agency or even a design firm to a certain degree, you’re not assigning illustration, you’re not working with photographers, you’re not working with fine artists. You’re not working with writers on projects in the way you do at a magazine. At The New York Times, that happened for me 52 times a year. It was weekly. So I was able to collaborate with some of the most amazing people. I was able to get in and refine type and be a design nerd in that way. I was able to articulate art direction and go on sets and lead shoots. It’s very rare that you have all of that in one place and still get your hands dirty and design. I was able to do all of that. I still designed magazine covers and feature spreads, even as the lead.

“In reality, coming from the magazine world was a big deal. You know, people wanted to know about it. That was exciting. ”

Patrick Mitchell: That’s interesting because I think you’re right. I think a lot of us feel like, maybe it’s changing now, but I think we probably felt like we would’ve had to apologize for our background, and try to convince people we can do jobs outside of the magazine business. But I think what has happened is the outside world has realized what kind of thinking goes into magazines and realized the affection people have, the relationship they have, to these storytelling objects.

Arem Duplessis: Exactly. To be able to tell narratives. Well, I mean, honestly, what I learned was that it’s not like that happened in 2014 when I started at Apple, where all of a sudden there was this kind of epiphany of, “Hey magazine people actually do have something to offer.” Those were just my insecurities. But in reality, coming from the magazine world was a big deal. You know, people wanted to know about it. That was exciting. Most of the people that I work with are from design firms or from agencies. So, at the time when I started, there weren’t any, there weren’t too many magazine people coming into Apple. So people were intrigued by it. And they were fascinated by it. And they were very respectful of it.

What I quickly learned is the amount of work that we put into a magazine and the collaborations that we have, it really allowed us to be able to tell a really strong narrative. And being able to tell a really strong narrative in what we do—our job is to communicate. That applies to anything that any brand that you work for outside of the magazine world. If you can tell a strong narrative, if you’re really good at telling a story visually, and directing that mission, there’s a lot of value there.

Nicole Dyer: At The New York Times Magazine, you must have been thinking about digital outputs. So at what point do you stop thinking of yourself as a magazine designer, when you’re thinking about all of these digital strategies and ways to extend the content beyond the printed page. You must have been doing that already.

Arem Duplessis: Yeah, I was. And I loved it. I mean, I loved being at The New York Times, and I loved being a part of the magazine world. But I was still relatively young at the time. And I just felt like, “What does my career look like”—I guess at that point, maybe halfway through my career—“Do I want to continue doing this and transition into someone who’s leading digital work?” Because I love the smell of print. I mean, opening up that box of fresh magazines and you smell that. I still love that. But if that’s going away, then does it make sense for me, in my career, to stay in that world versus trying out something new. And then having an opportunity to try out something new at a brand like Apple, it just made perfect sense.

Nicole Dyer: I’ve been thinking a lot about the way in which young designers now think about design, given the dramatic shifts to digital platforms and the decline of magazines and wondering what jobs they actually aspire to. What would be the pinnacle for a young designer? Would they aspire to work at Rolling Stone or The New York Times Magazine? And does it matter if your design never materializes on paper?

Arem Duplessis: I don’t know if that matters to them because they really didn’t have that option coming out of school now, in 2022. Not too many people are saying, “Hey, you should go work for Rolling Stone.” It’s just a different world.

But I think there are more opportunities for designers than ever before. There are way more jobs now for designers than there were when I was coming out of school. I mean, I went to Pratt Institute. I finished graduate school there in 1996. And you had choices. You had a design firm, you had an ad agency, or you had magazines. For the most part. Of course, there are other things you could do within brands, but that’s where most of my contemporaries wanted to work. For the big design firms. For the most part, that was the big thing. Working for Pentagram or a big design firm like that. And then, if you were in the magazine world, you wanted to go work for Fred [Woodward] and Rolling Stone.

I think now designers have a lot more choices. But in terms of doing the interesting, fun kind of design, I don’t know if they're leaning toward many companies in tech. I mean, I think Apple still offers a lot of variety for sure, but other companies, they pretty much are traditionally digital. So designers still probably lean toward, “Hey, I’m going to go work for this design firm.”

A lot of younger people now I’m seeing have the entrepreneurial spirit, so they’re starting their own agencies right away. I think it just depends on what kind of person you are. I do think—and I do see still a lot of respect and value and aspirations around print for young designers, too. They want to do ’zines. They want to do anything in print. They still think it’s cool. They think it's fun, but they just view it in a different way than I did. Print was pretty much all we had, for the most part, versus now it’s kind of like vinyl. They think of it as a cool, vintage kind of project.

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. It was a “career” and now it’s a “project."

Arem Duplessis: Yeah. Now it’s a cool little side project. But you know, if you go work for an ad agency, and they have a variety of clients, you’re still doing some cool work. If you work for a good agency, they may be doing movie posters, they may be doing things that still involve print. But it’s a broader world now for design.

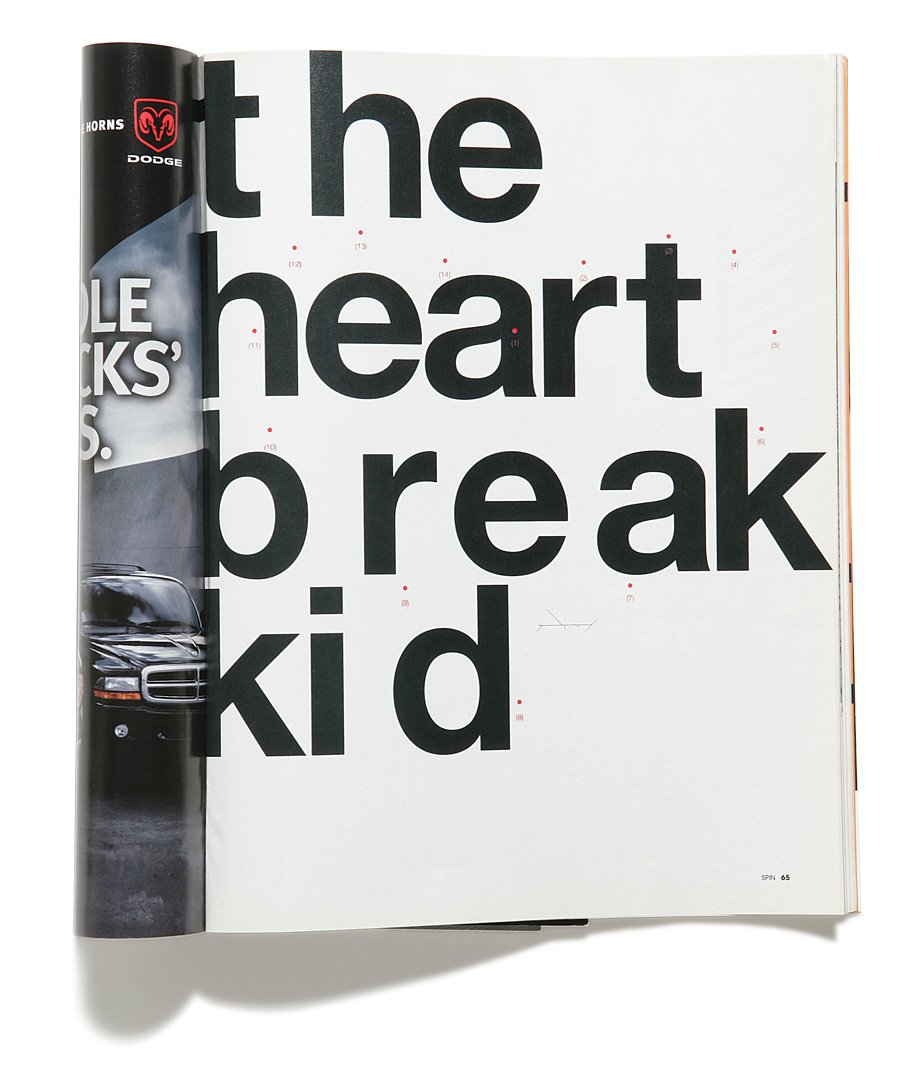

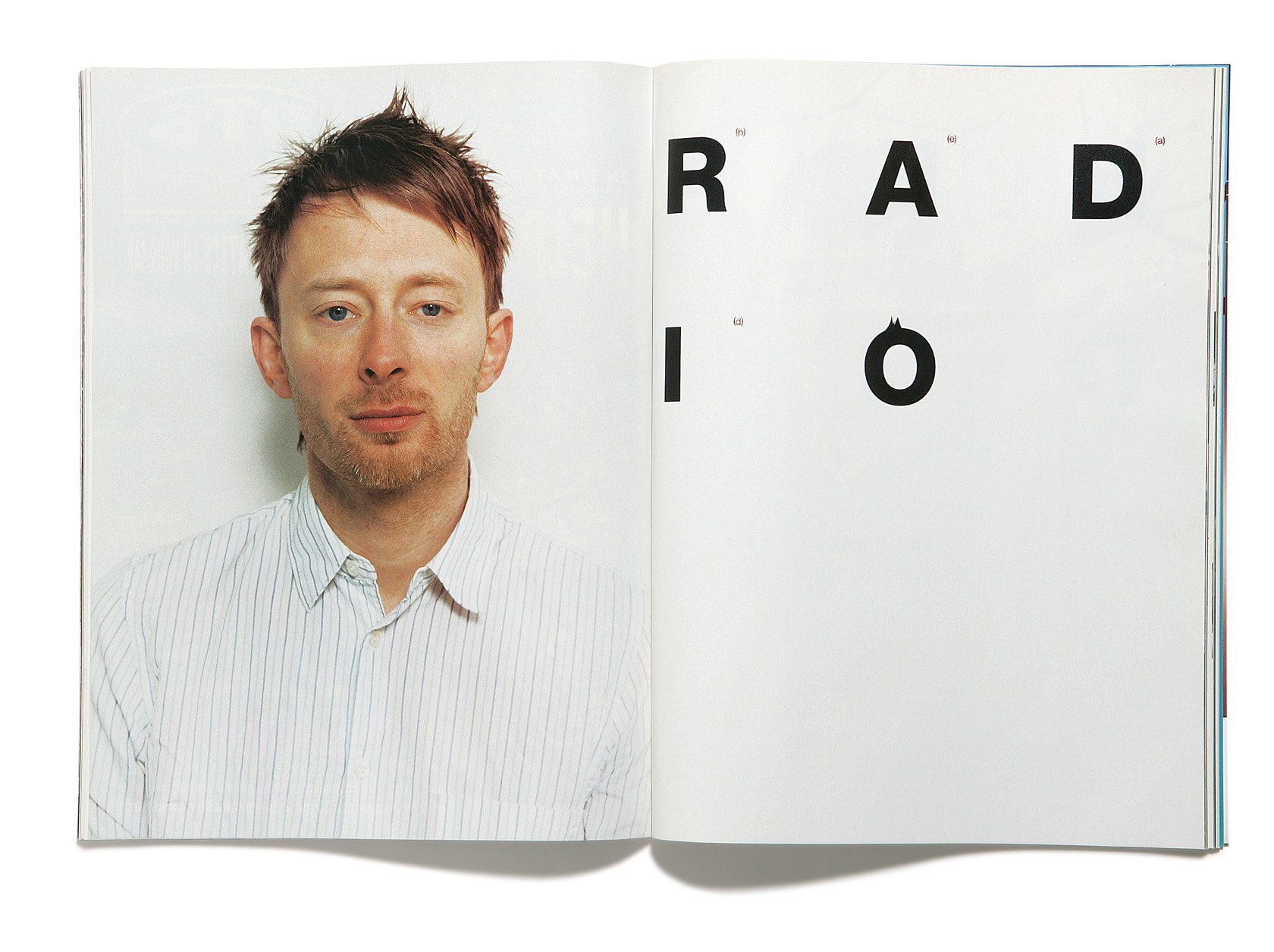

“Going to Spin after GQ was intentional. I took a salary cut, but it was the best career move I ever made because Sia [Michel] gave me freedom and autonomy. And that’s what got me to The New York Times.”

Patrick Mitchell: The magazine business is super tough with deadlines and, on a weekly, even deadlier. Has moving to the corporate world had a positive effect on your lifestyle? What has the Cali lifestyle meant for you personally?

Arem Duplessis: Well, coming from a weekly—you know, 52 times a year—that was pretty brutal. I loved it, but the hours were completely insane. At least they were predictable. Because you know what the schedule is. And, unless the editor changes the cover story at the last minute, which happens, you pretty much know your schedule.

Moving to California, I had to change my New York attitude. I never really had a New York attitude—at least I didn’t think I did—until I moved to California. And all of a sudden—you know, in New York people considered me pretty chill—but I move out here and people are like, “You need to relax, man. You’re being a little aggressive.”

So I think California’s been good for my patience level. I no longer sit at the grocery store. Like, you know, “Come on, hurry up! Why are those fucking tomatoes taking so long to be put into the bag?”

I don’t have that anxiety anymore that I did in New York. But in terms of my hours, it depends on what project I’m on. You know how it is in the creative world. I mean, I think that a lot of times we put those hours on ourselves because we want to reach a certain level of work. So when I’m working late, generally, it’s because I’m trying to push the envelope, me and my team. We want to make something great and we’re all in on it. But I don’t believe in the creative space that there’s such thing as a nine-to-five because we love what we do, you know? Or, I feel like you should love what you do if you’re in this space. Because most of my friends that are attorneys or are in finance hate what they do. So if you have a job that you hate and you’re a creative, I don't think that’s a that’s good combination. I think we should all strive to do better because, for most people, this is a passion, you know. What we do is our passion.

Patrick Mitchell: I imagine, as you’re saying that about weekly, you must have deadlines that are now half-years, years—like real long-term.

Arem Duplessis: No, that’s not true. No, not at all.

Patrick Mitchell: Turnaround is pretty quick?

Arem Duplessis: Yeah. I mean, it depends on what you’re working on, but it’s pretty quick. It’s just different because sometimes there’s just different components to it. The schedule isn’t always as predictable as magazines.

Patrick Mitchell: I remember being at a cocktail party with a guy who was a civil engineer and he said his projects are typically 15 to 20 years. And I was thinking, “Imagine working on two projects your entire life.”

Arem Duplessis: Yeah. That’s crazy. But I mean, it all comes down to what you’re used to and what foundation you started with.

Nicole Dyer: You gotta miss the energy of New York City though.

Arem Duplessis: Oh, of course. Yeah. Without question. I definitely miss it. I miss it all the time. Oddly enough, when I first moved away from New York, I think I had had enough, because I was commuting and I was taking my kids to school. It was a lot. It was a lot because I lived in Brooklyn. My son went to school on the Upper East Side. We didn’t have the train running up the East Side, so it was a pain in the ass. And I remember just being squeezed on the subway every day. I just felt like a rat. I really felt like a part of the rat race. So when I first moved to California, I didn’t miss that at all. I still don’t miss the cold. But recently, and I think Covid did this because I was forced to stay away from New York, once I was able to travel again I went back to New York City for the first time in, I think, 2020, or maybe late ’20 or early ’21, I can’t remember. But all of the sudden the nostalgia was there. Like I missed it tremendously. It was just, “Oh, New York!”

New York will always be there, but for now it’s California for me. And what I love about California is I can jump in my car and in 20 minutes, I’m on the beach or I’m hiking somewhere—and hiking somewhere where it’s a destination for people from around the world! You know, that kind of thing. The level of nature is amazing. And there’s some really good restaurants here too. For me, the hard part about the Bay Area is the lack of diversity. I can walk down the street and not see a black person for, like, the whole day, which is little odd. That’s hard. That really is. But I love the weather. It’s pretty consistent and it doesn’t get too hot here. It doesn’t get too cold.

Nicole Dyer: In New York City, the street art is amazing. And, as a creative person, you draw so much energy just from the environment, because there’s art everywhere. And that’s special about New York City. But I hear you on the lifestyle pain points. They’re real [laughs].

Arem Duplessis: Yeah, for sure. But I love New York and I always will. That won’t change. I was there for 21 years. I became an adult there.

Patrick Mitchell: So in the world of My Dad Is Cooler Than Your Dad, you win. Your dad, Erol Duplessis owned a quarry where he trained scuba divers. Was that his full-time job? What’s the story there?

Arem Duplessis: My mother was a fine artist and she did what she loved. And, when I was young, she was doing fine art. And my father was working for the government and hated it. They would get into arguments about it because he just felt like it wasn’t fair for her to be able to pursue her dreams and he had to have this government job.

So one day he just quit. He couldn’t do it anymore. And he became a swim coach at a high school in Boston. I don’t know if it’s still around. It was called Umana High School. And from there he was able to begin his career in aquatics. So he did that for a few years. And then he became the assistant aquatics director at UMass (the University of Massachusetts, Amherst). And he did that for several years. Became certified as a scuba diver, then as an instructor.

So he started instructing people on how to become divers. And then he just ended up getting all these certifications to the point where he could certify instructors to become instructors. You know, that kind of thing.

From there, he became a university professor, the director of aquatics at Hampton University. He worked there for 20 years. And during that time, I think near the end of his tenure at Hampton, a buddy of his said, “Hey, you want to come diving with me? There’s this quarry [Lake Rawlings] and it’s pretty cool.” And he was like, “Sure.” And at that point the quarry was longer in use. Originally, they were digging for limestone and they hit an underwater spring. It filled up and this quarry just sat there. No one used it. But the water was so clear that sometimes divers would sneak in there and go diving.

And my father went and right away, he said, “You know, this could be a business. This is amazing.” He didn’t have a background in business and I’m not going to say that he was the best businessman, but his journey was to turn the quarry into a dive destination. And he did just that. He had government contracts, they filmed a few movies there. They trained divers at Lake Rawlings and also people would bring their families. It was a swimming destination and a recreational diving spot. So he did that for, god, you know, another 20 years he had Lake Rawlings and he loved every minute of it.

But during his time at Hampton, he certified—I don’t have the statistics on this, but I can’t find anyone that could argue the fact—my father certified more black divers than anyone in the United States. Just because, being a university professor, every semester he’s certifying 20, 30 divers.

Patrick Mitchell: Have you dived there?

Arem Duplessis: Yeah. Yeah, yeah. I did. It was really fucking cold. The water, it had a thermocline. So after 15 feet, it got really cold, man.

Patrick Mitchell: How deep was it?

Arem Duplessis: Sixty feet at the deepest. And they sunk a few boats, they made some artificial reefs. They sunk a car, a school bus. So, you know, divers could go there and kind of play around with the things that were at the bottom of the lake. So it was pretty cool. All of his grandchildren, their first foray into diving was at Lake Rawlings. He’d put a tank on them and teach them the basics. It was pretty awesome.

Patrick Mitchell: There, that sounds incredible.

Arem Duplessis: Yeah. Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: You give credit to your mom for guiding you into this career. She was an artist herself. Can you talk a little bit about Laurel?

Arem Duplessis: My mother was a fine artist. And in high school, I’ll be honest, I was a—I don’t want to say “fuck up”—you know, but I just, like, what is the term if you don’t give a shit? You know, I wasn’t getting in trouble, really, but school wasn’t my thing at all. I just didn’t have a lot of confidence in what I was doing. And years later I got diagnosed with ADD. Probably like half the creatives out there in the world. But it’s not a joke. I mean, I really did. And there was really no term for that. Schools didn’t know how to deal with kids that had Attention Deficit Disorder. So they would always say, you know, the report was always, “Rem needs to focus.” You know? And the only time I didn’t get that feedback was in art class.

And I think that, because in elementary school in my early education years, not knowing that I had ADD, it did fuck with my confidence in terms of school. And I didn’t try as hard, you know, I just stopped trying. Which is unfortunate, but it’s the truth. And so when my mother came to me and said, “Hey, what do you want to do with your life?” I said, “I have no idea.” I told her I wanted to go to New York and model [laughs] or join the Marines. And the reason why I said modeling was because I was in class my junior year in this government class, and this woman came in to visit. She was on Broadway, some New York/Broadway woman. I think she was a director or producer. And she was good friends with my government teacher. And she was like, “Hey you in the back. Back there. The quiet one,” and she was talking to me and she said, “You should come to New York and model.” And I was like, “Whoa. Yeah, that’s my plan. That’s what I’m going to do.”

So I told my mother, she was like, “What do you want to do with your life?” And I said, “I think I’m going to go to New York and model.” And she said, “Well, the hell you are.” And then I said, “Okay, well I’ll probably join the Marines then.” And she said, “No, you’re not doing that either.” So then we started going through choices. “Choices” meaning you have no choice but to go to college, but then choices around what are you going to major in? And she threw out fine art. And I said, “I don’t want to do that.” Just because I saw the struggles that she went through as a fine artist. And we talked about architecture and we had a friend of the family that was an architect. And he told me about the projects he worked on. And it wasn’t anything that I thought it would be. You know, he was like, “When you first start out, you’re an apprentice and you’re designing a bathroom for the first five years.” So I definitely didn’t want to do that. And then she said, “Well, what about commercial art?” And I said, “What’s that?” And, of course, she was referring to graphic design.

And the minute she started talking about that, “You can design magazines. You can work for an ad agency. You can do movie titling.” I was blown away. I was like, “Really? People do that for their—there’s actually a job for that?” So immediately I was like, “Yeah, that’s what I want to study. I want to do that.” It was almost like that day, when she described it, it’s like the skies opened up. The sun started beaming. It really did because for the first time in my life, I felt like I had a real direction.

Nicole Dyer: Did you have any favorite magazines at that time?

Arem Duplessis: No, not really, because I didn’t really understand design. I didn’t really look at magazines in that way. I paid attention to the photography a little more, but in terms of the design of magazines, I guess if I saw something cool, I would appreciate it. But I didn’t aspire in high school to become a magazine designer. It was more around just studying graphic design and then figuring it out. I really didn’t develop a love for magazines until, well, indirectly I probably did early on, because my parents had probably way too many magazine subscriptions. More than they needed. So I did grow up with a lot of magazines laying around. But in terms of an appreciation around the design of magazines, it wasn’t until graduate school, when Vibe magazine was launched, I think in 1993, with Richard Baker and Gary Koepke. And they did some beautiful work. And George Pitts. It was just, like, this amazing stuff.

When I saw that magazine with Dan Winters’ Wesley Snipes cover, where he’s covered in mud—like the mud is cracking on his face. That issue really introduced me to magazines. Then, all of a sudden, I was like, “Okay, how do I learn more?” I found out about SPD and started buying those books and quickly fell in love with it.

But also, when I was in grad school, I needed to get a job. I started running out of money and teaching swim lessons at the Y was no longer cutting it. So I found a job listing for a magazine art director. I had put my book out there to a lot of design firms and got a lot of, “Oh yeah, this is great, but you don’t have enough experience.” Finally, I interviewed for a job at a magazine, a small magazine. It was a trade magazine called Market Watch. That was my first design job, and just happened to be a magazine.

Patrick Mitchell: Backing up. So you went to Hampton for undergrad, an HBCU on the Chesapeake Bay.

Arem Duplessis: Right.

Patrick Mitchell: … And you said you were one of four graduates. I went to a much bigger university, but I was one of three or four graduates in design myself. What was it like studying design there?

Arem Duplessis: Looking back on it. There were not a lot of resources, but when I first started at Hampton, my freshman year, we were learning paste-ups, and I was just starting to get the hang of that. And then all of a sudden this Mac showed up and I was like, “Oh my God, what is this Apple thing?” But I quickly became fond of it and realized, “Wow, this is a huge shortcut to all the things I learned last semester.”

We had one computer. That was our computer lab. And I would always sign up for the last time slot, which was usually around 10 o’clock at night, because then no one would come and disturb me. There were like four or five design majors. And I remember a lot of people, friends, saying to me, “Hey, you know, what the hell are you going to do when you graduate?”

Because they just looked at me as an art major. And to them, it was that basic kind of thinking of ‘starving artists.’ “What are you doing? Why would you ever major in this thing?” And can’t say that didn’t help my confidence, but at least I was in college studying something that I loved. But it was just because it was a small town. There weren’t a lot of designers around. It wasn’t until my junior year where this woman came—she was this black woman from DC who was an art director at Time Life Books. And she gave a presentation on her work and what she did—she was literally the first graphic designer I ever met in my life. And she really got me excited because now, all of a sudden, this thing became real. Here’s a woman talking about the project she’s working on, explaining what she does day-to-day. And it was pretty amazing.

But also, on the fine art side, Hampton University has a really rich history in African American art. And while I was there, John Biggers—he’s no longer with us—but he’s a very well-respected black artist. He was painting the murals in the library at Hampton University. They built a new library and he was the artist that was commissioned to paint these huge panels. So he did three murals within the library and you could see them from the outside because the architecture in the front of the library was all glass. So I spent a lot of time with him just learning about his level of thinking, how he thought and how he approached painting. He taught me about Aaron Douglas, the Harlem Renaissance artist who was also a trained graphic designer as well.

The education didn’t always come in the classroom, but it was there. And it certainly built my foundation and love for design. And the chair of the department, Sharon Beacham, did everything she could with the limited resources that she had. It was pretty great.

Nicole Dyer: What’d you learn from your mom? Did you learn some technical skills from her? Did you arrive at art school knowing how to paint or draw?

Arem Duplessis: My mother also designed a few logos as well. I learned later that she actually studied design at Pratt for a semester or two. So she would design logos for friends and asked me my opinion on them and that kind of stuff. And usually it was all hand-done. I just think, indirectly, she gave me this gift of creativity and creative thinking and decision-making, just by watching her. But in terms of the technical aspects of design, she was terrified of computers. That was all on me. She didn’t really ask too much about the technical part of my job. It was always just, “My son works for GQ magazine.” That kind of thing [laughs].

Patrick Mitchell: You just found out that your son is going to follow in your footsteps and go to Hampton. How does that feel?

Arem Duplessis: It feels great. He doesn’t want to study design. He couldn’t study design at Hampton, actually, because they got rid of the program, unfortunately. But he’s really into music. He composes music. They do have a good music program at Hampton. He ultimately wants to score films. That’s his goal.

I didn’t put pressure on him. I mean he was accepted to some other schools. He had choices. He even had an opportunity to go to a school here in California. But going back to what I said about the lack of diversity here, he loved the idea of having an experience where he’s not the only one.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, congratulations. That’s awesome.

Arem Duplessis: Thank you.

Patrick Mitchell: By my calculation, in your 10 years working at The New York Times Magazine, at 52 issues per year, times 10 years, you produced more than 500 issues, which is the equivalent of 43 years at a monthly magazine…

Arem Duplessis: …Yes [laughs]…

Patrick Mitchell: … And that’s not counting T and other projects from that time. That’s a lot of fucking magazines.

Arem Duplessis: That’s a lot. Yep.

Patrick Mitchell: How do you look back on your 43 years at the Times? [Laughs]. I can imagine a lot of pride and joy, but was there a personal cost. Anything you’d do over? Talk a little about your tenure at the Times. You had a lot of accomplishments. You really made a name for yourself there.

Arem Duplessis: Thank you. I loved every second of it. It was amazing, looking back on things, the only thing that I would change is, and you don’t learn this until you mature and you become—I guess the ‘maturity’ is really the best way to put it—I didn’t realize then what I realize now, in terms of the platform that I have as a creative and as a black creative, I wish that I had had the confidence with my platform to advocate more for a diversity in storytelling. The kind of stories that we were publishing, not just at the Times, but just in general. And then also pushing for more representation on the editorial side, you know, more black editors. More black editors in senior positions.

The New York Times was definitely the most diverse staff I was ever a part of. But at GQ there were no black editors at all. Any senior editors. And you know, I did argue for it because I would say, “Hey, look, we know our team does not represent the readership at all.” There were a lot of women readers at GQ and all the editors knew that, but we didn’t have a lot of female editors. Of course, black folks liked to, you know, we liked to put it on fashion-wise. Black men are fashionable. Let’s just say it. And to not have one black fashion editor at GQ magazine? I wish I had questioned that more. But I was 27 at the time and I was busy. But that’s the only thing that I would go back and do.

Nicole Dyer: So you were 27 then, but when you were 25, you worked at Blaze magazine for, I’m not sure how long…

Arem Duplessis: I was there for like 10 months. Eleven months.

Nicole Dyer: What was that like? That title had such a famous launch and it flamed out pretty quickly. But it was an exciting magazine. What was that like working there for 10 months?

Arem Duplessis: “Flamed out pretty quickly.” No pun intended with Blaze [laughs]. When I got there—I was hired as the design director—it was the first job I ever had as the design lead. Before that I was at Men’s Journal. I was young. I really was. But I just felt, like, at the time I wasn’t getting the jobs at the magazines I wanted to work for. And I just felt like I wasn’t producing the work that I knew I could produce. Let’s put it that way.

So in my opinion, my thinking back then, “If I want to put out the work that I believe in, then I have to be the one leading it.” So I was really excited to take that job at Blaze. I loved it. It was a lot of fun. I would’ve stayed longer than 10 months, but I got a call from Condé Nest and Anne Haggerty. She worked in human resources when she met me and she saw my portfolio. She promised me, “Hey, I’m going to call you one day for one of these magazines, you better be ready.” Two years later, she called me and said, “Hey, GQ needs an art director.” Because there was a design director there at the time. And I said, “Yeah, I’d love to.”

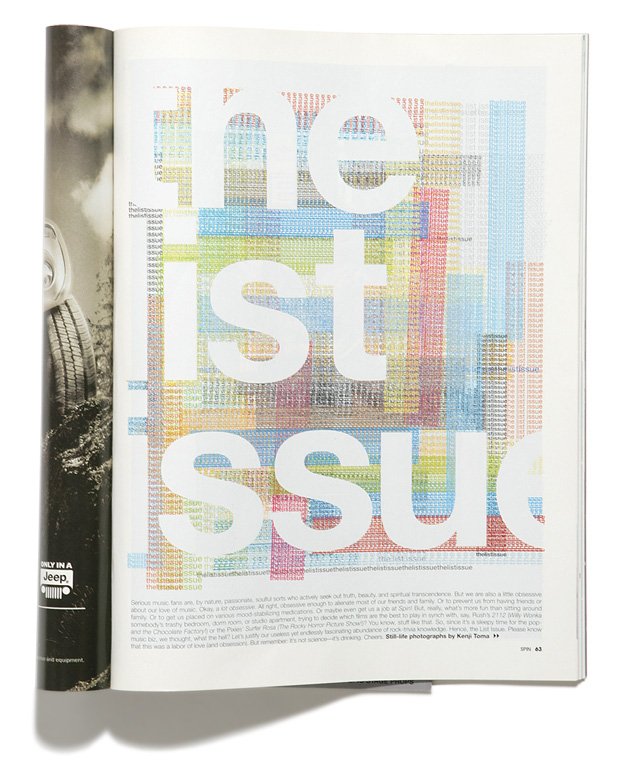

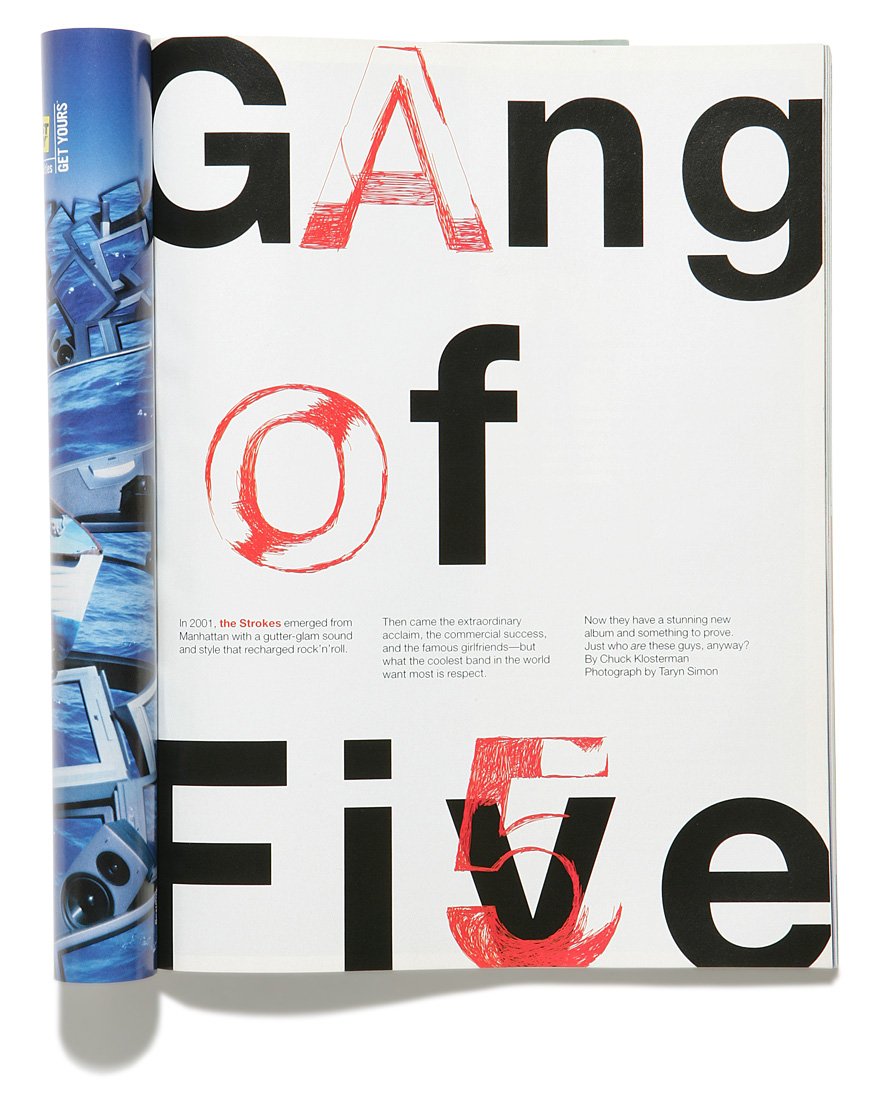

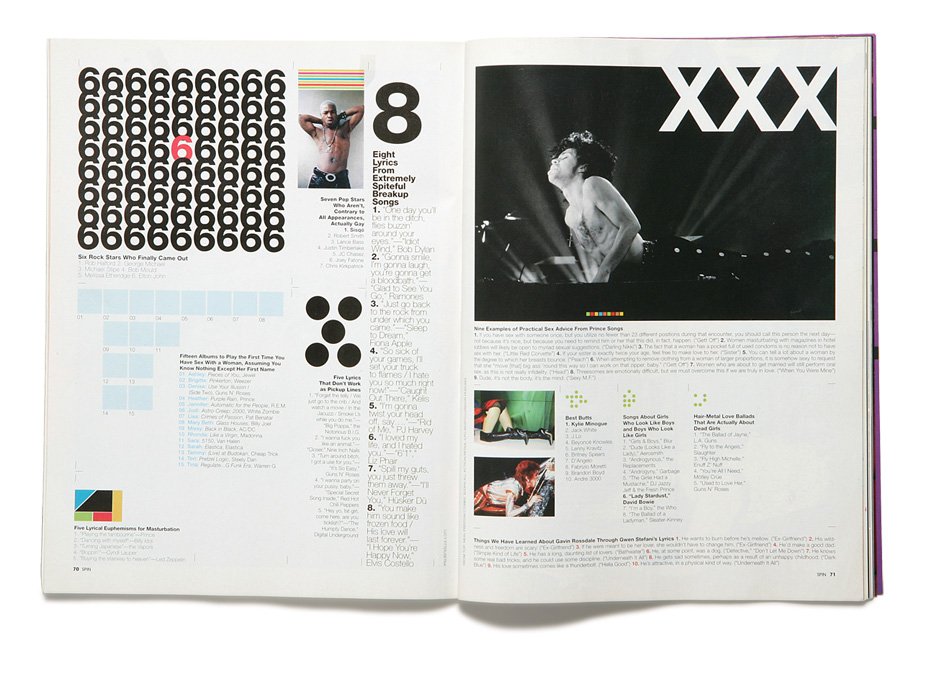

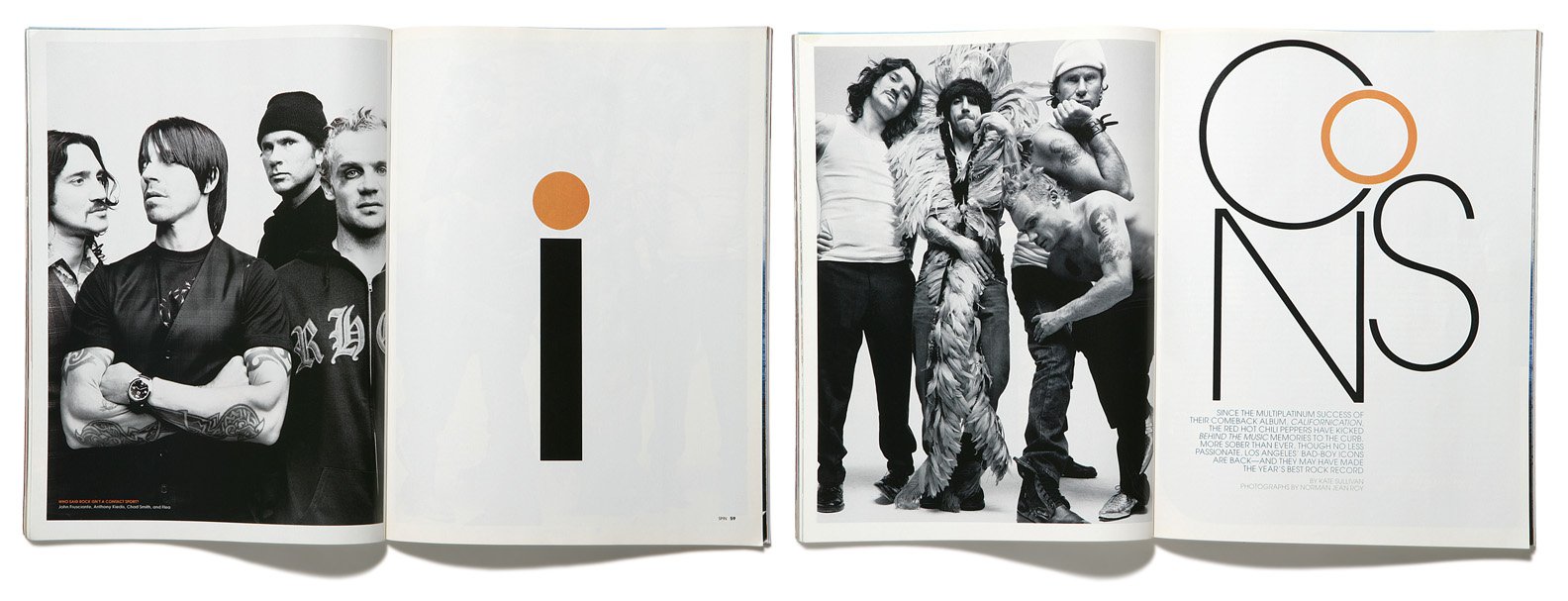

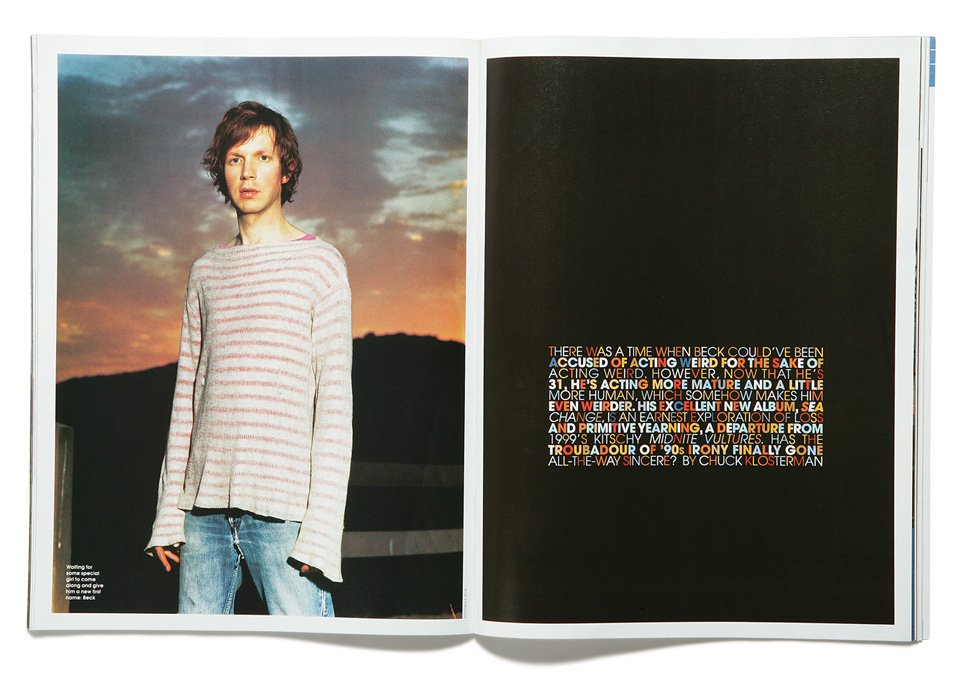

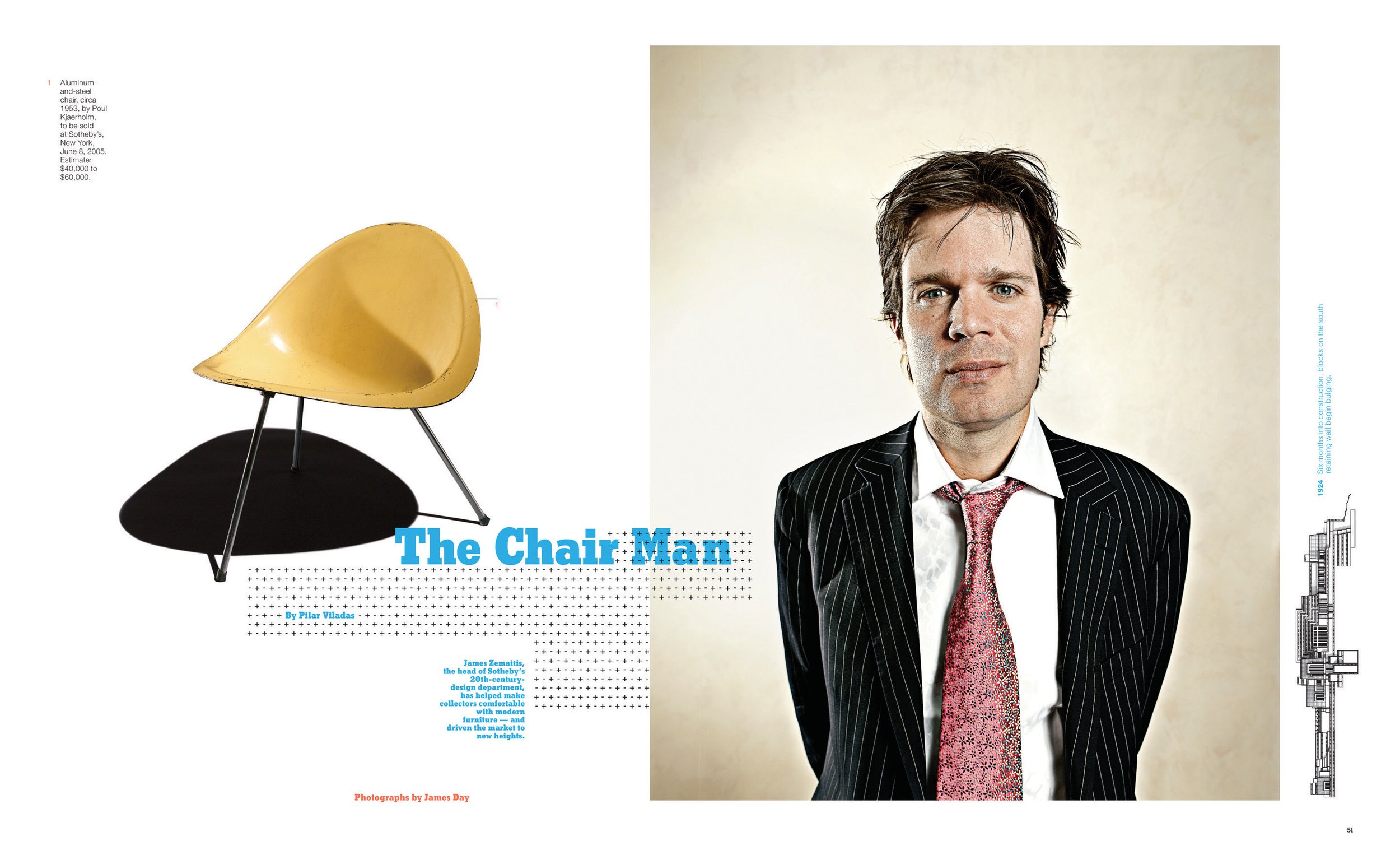

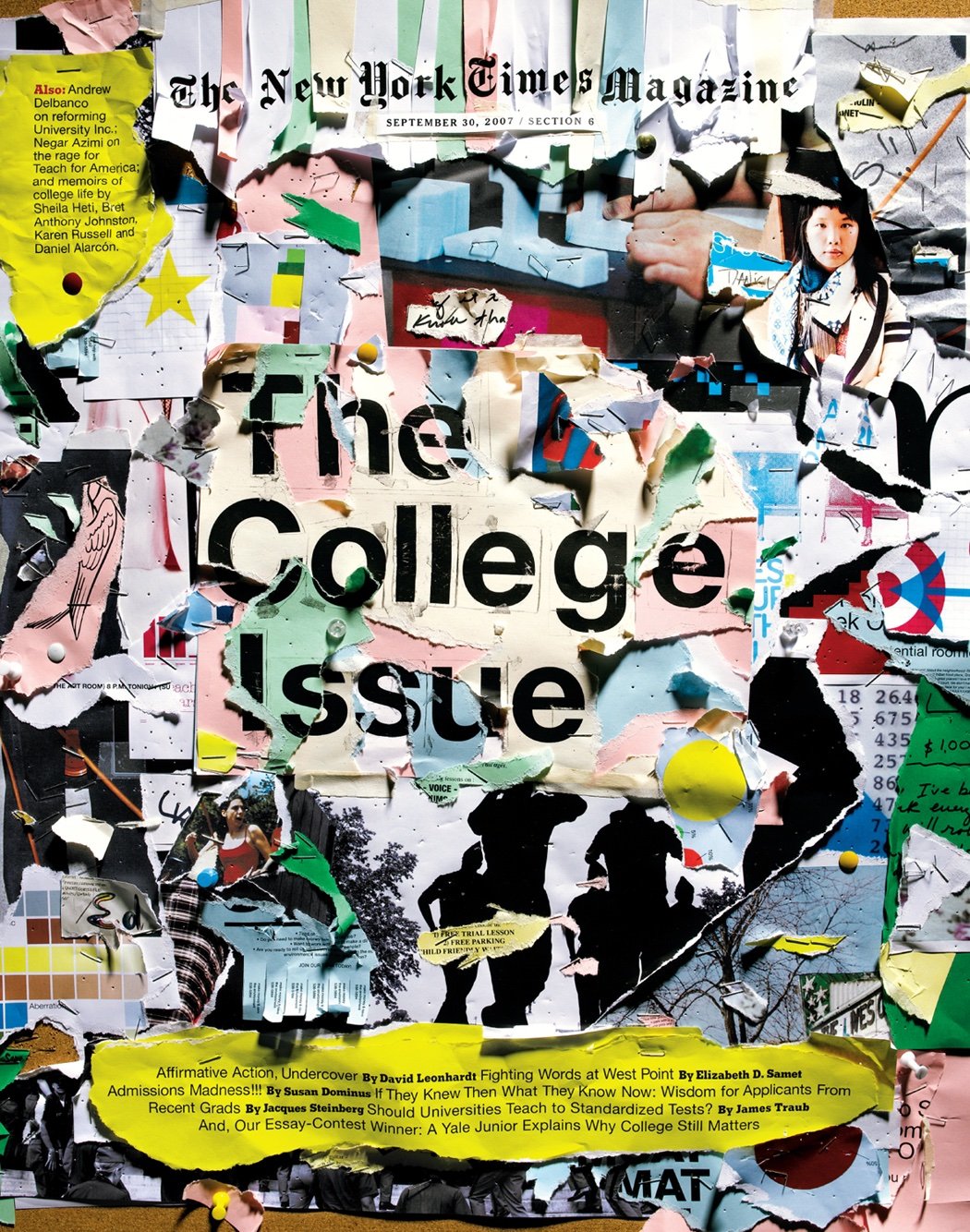

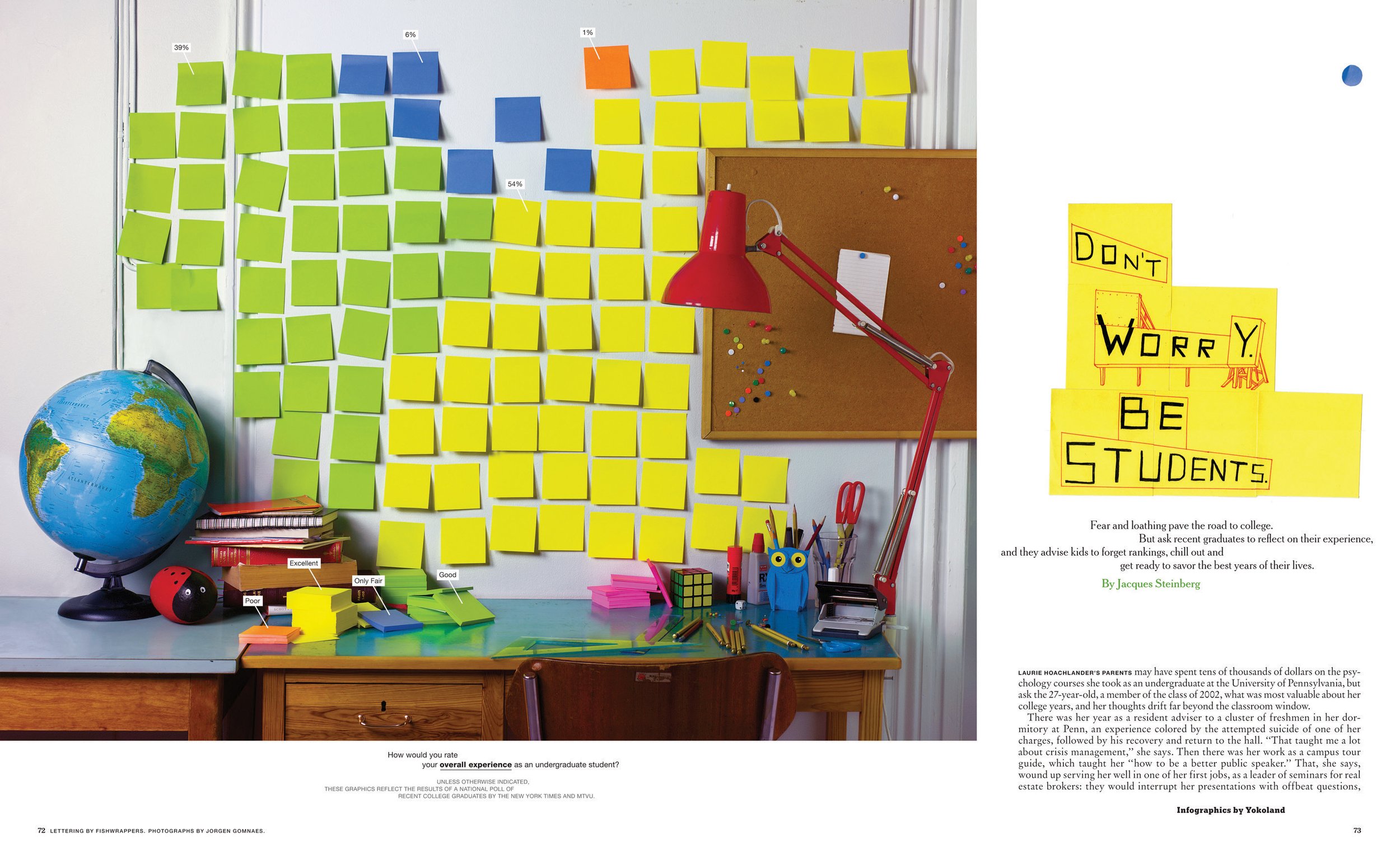

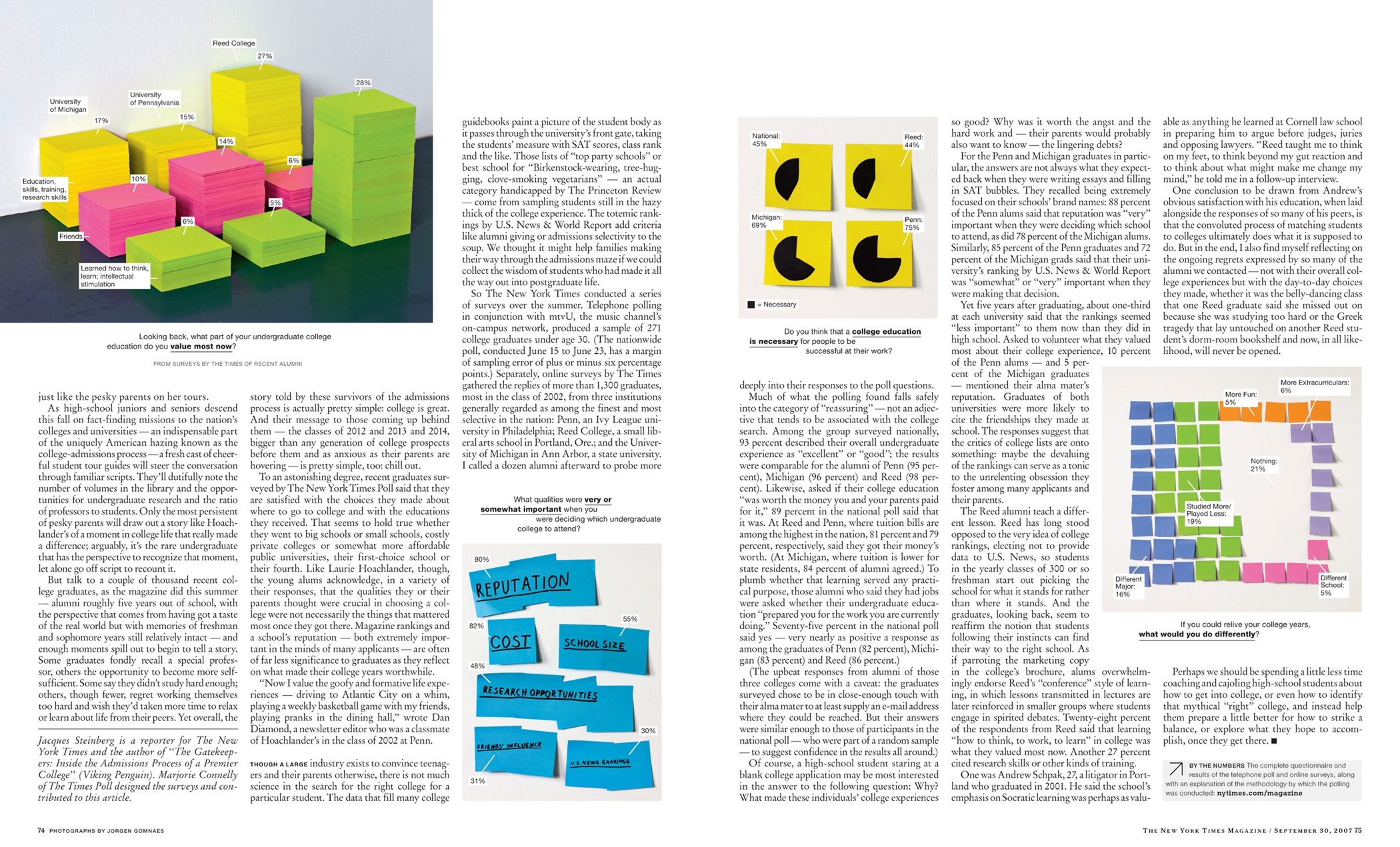

Samples from Duplessis’ work at SPIN

Patrick Mitchell: Who was that?

Arem Duplessis: It was George Moscahlades. George was there for maybe four or five years. He hired me through Anne’s recommendation and then George, he maybe stayed maybe nine months while I was there. And then he wanted to move on to something else. And Art Cooper—the late, great Art Cooper—said, “Hey, look. Do you feel like you’re ready to lead this magazine?” And I said, “Absolutely.” I wouldn’t have told him otherwise. I was pretty young, but I just believed that this opportunity may never come again, so you better be ready.

And the frustrating thing at GQ was it was a huge title. My mother was very proud of it—she called it “Gentleman’s Quarterly.” But the reality was Art Cooper—as we know now—was under tremendous pressure at GQ. He was holding on for dear life. He had been there for 20 years. And I just wasn’t able to do the work that I really strived to do. You know, I knew it could be so much more and I didn’t have the full trust of Art at the time. And to be honest, I was still developing as a magazine designer as well, trying to find my voice.

But going to Spin after GQ was intentional, because Sia Michel was hired as the editor in chief—the first female editor of a music magazine, a rock magazine. I thought that was pretty cool. And after meeting her, I knew she would allow me to kind of explore my goals in design and do work that allowed me and my team to push the envelope. And I feel like at Spin, it was just that. I took a salary cut—a pretty big one. And in terms of prestige, my mother was like, “What the fuck is Spin magazine?” But it was the best career move I ever made because everything that I wanted to do creatively Sia gave me the freedom and the autonomy to do that. And that’s what got me to The New York Times. Janet Froelich liked what we were doing at Spin and called me and said, “Hey, do you want to interview for a gig at The New York Times?”

Patrick Mitchell: Your mom would not have wanted to know that Spin was launched by the Guccione family. (The Guccione family owned Penthouse, a soft-core porn magazine).

Arem Duplessis: No, no. When I went to Blaze magazine, she was like, “Why would you do that? Why would you leave Men’s Journal?” My father, when I went to Spin, the only thing he said was, “Well, you know, just that music world, there’s a lot of coke in that world. And you just don’t start sniffing coke.” And I’m like, “Yeah, dad, all right. Well, at this point in my life, I’m good. I’m not going to throw it all away by all of a sudden becoming a cokehead.”

And then of course, when I went to The New York Times, my mother was proud of me again, because that title meant a lot to her for many reasons. But also her dad, my grandfather, was a train conductor. But he read the Times every day. That was his thing in the morning. He would read it from front to back. And so when I got the gig there, she was really proud of that.

“I was pretty young, but I just believed that this opportunity may never come again, so [I’d] better be ready.”

Patrick Mitchell: Who were your influences and mentors from your magazine career?

Arem Duplessis: I would say, influences definitely Richard [Baker] and Gary [Koepke] from those days at Vibe. George Pitts was a mentor to me. I would say, obviously, Fred Woodward did some amazing work. You, Patrick. I loved the work that you did at Fast Company. That that was awesome. I would pick that up every single time. I was excited about getting that in the mail. I mean the usual suspects. And then outside of the magazine world, I would just look at a lot of what designers were doing. And I loved and Robert Brownjohn and his philosophy. Paula Scher was a huge influence on me, for multiple reasons. Michael Beirut. The unfortunate thing is at the time there weren’t a lot of black heroes in design. But there were a few. So Michele Washington and Lance Pettiford. I loved the work that he was doing at BET Weekend. There were a few. I loved what David Armario did at Men’s Journal. Him and Tom Brown before I got there. The reason why I went to Men’s Journal was because of the work they were doing, but that quickly changed. They rebranded the magazine. So I had a lot and I had a lot of people that I really looked up to. I looked up to Janet Froelich, obviously, and Kathy Ryan. So it was unreal when I actually got to work with them. It was kind of a dream fulfilled.

Patrick Mitchell: You mentioned Pentagram. You seem like a natural fit for Pentagram. Did they ever approach you?

Arem Duplessis: No. No, they didn’t. I’m friends with Paula [Scher] and Luke [Hayman]. There were times where I kind of felt like they were waiting for me to show interest in doing that. And Paula would certainly recommend me for some really great jobs. But I’m glad they didn’t because I just feel like I’d be a terrible entrepreneur. And the reason why I say that is because I don’t like to be removed from the work, and in a way that sometimes when you’re running your business, you have to go out and get new business. You’re not always able to still get your hands dirty in the workspace.

Patrick Mitchell: That is one thing I’ve heard from some Pentagram partners is just that part of having to churn new work in there—there’s so much pressure.

Arem Duplessis: Yeah, that’s a lot. That’s a lot of pressure. You know, they do great work. I mean, they succeed at it. But being an entrepreneur is not for me. And if it was, I don’t know if they would’ve hired me to be a partner, but it certainly would’ve, if I had that spirit of doing that, it would’ve been a dream gig. It really would’ve. But I maybe they sensed that in me. I don’t know. Or maybe I was never even considered. I can’t answer that, but I love the work that they do. And as much pressure as those folks are under, they still churn out great work—for years.

Patrick Mitchell: Who’s the most famous person you’ve met in your magazine career?

Arem Duplessis: Oh man, that’s subjective because I’ve met a lot of famous people.

Patrick Mitchell: Any heroes?

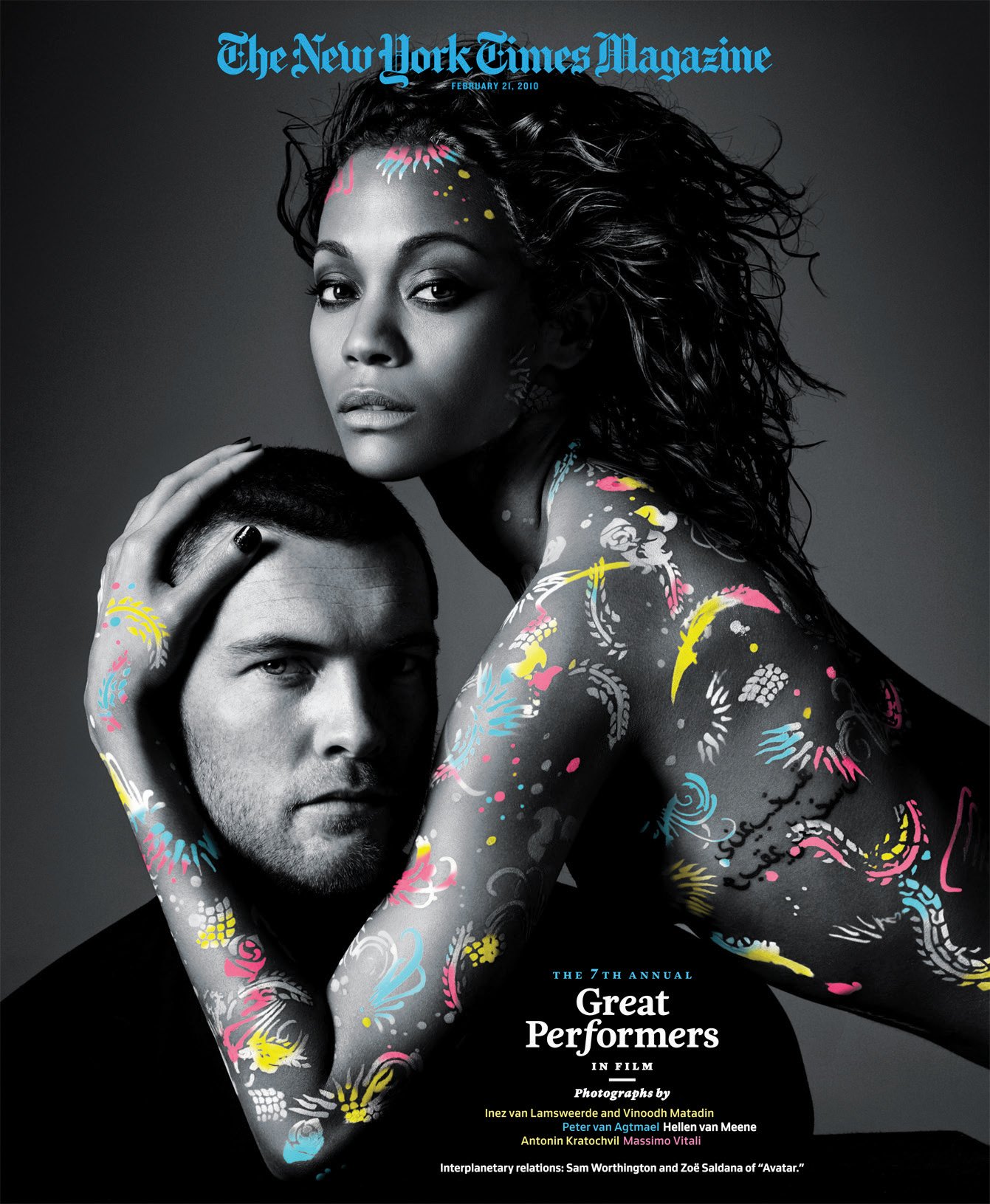

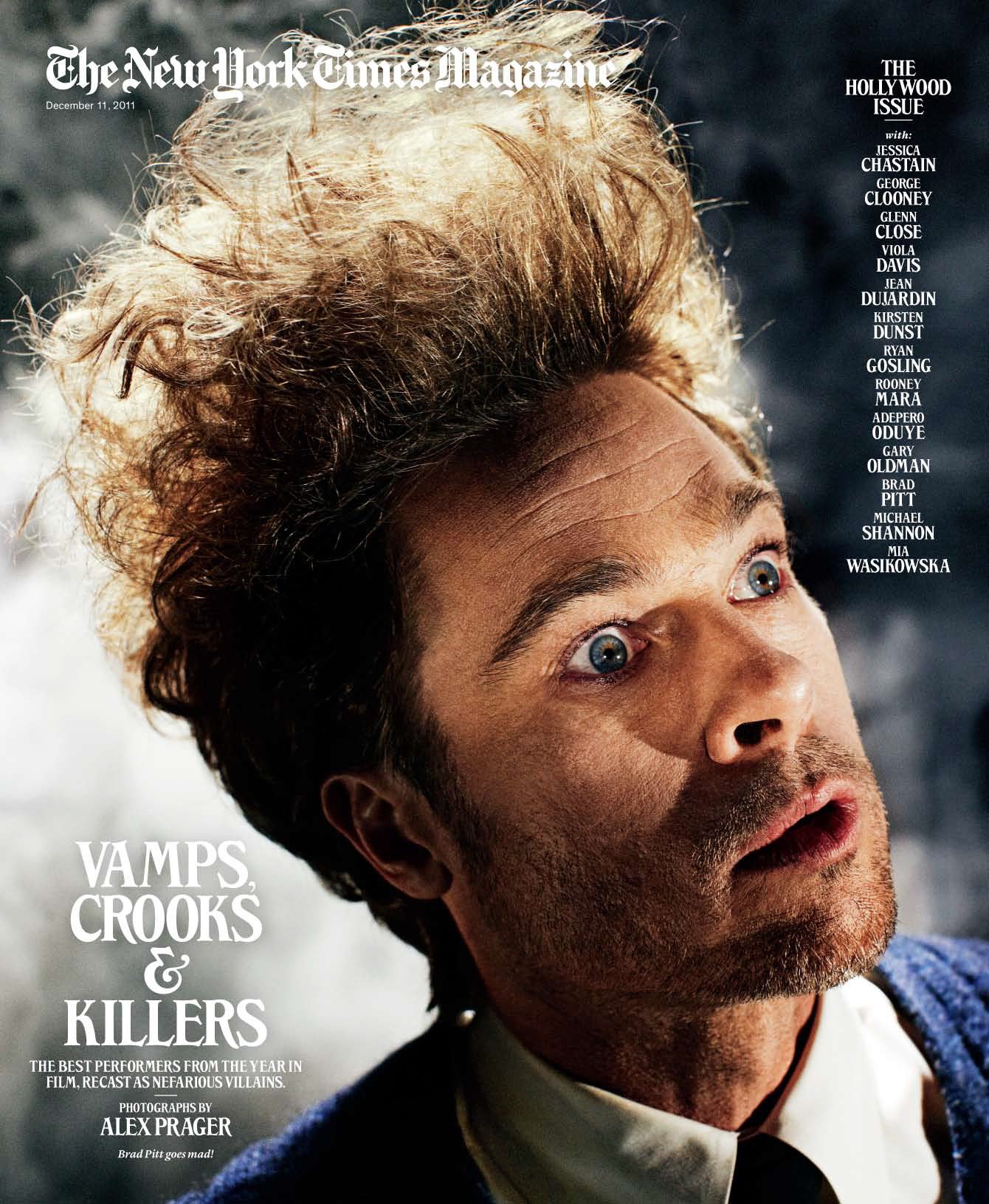

Arem Duplessis: Man, I worked with Kobe Bryant two times. Met Barack Obama, which was amazing. Oprah Winfrey. George Clooney. We worked with George Clooney at The New York Times so much that he knew my name because he was always one of the “Great Performers,” because he’s such a brilliant actor. Brad Pitt was a big name. Pitt and Clooney and Obama were some of the most down-to-earth, nicest people I’ve ever met. When Brad Pitt walked into the studio, literally after five minutes, you forgot that it’s Brad Pitt because he’s just such a cool guy. He just felt very surprisingly normal. And Clooney as well. You can sense the bullshit when someone’s just trying to fit in. And when someone’s truly genuine. Those guys were really cool to work with.

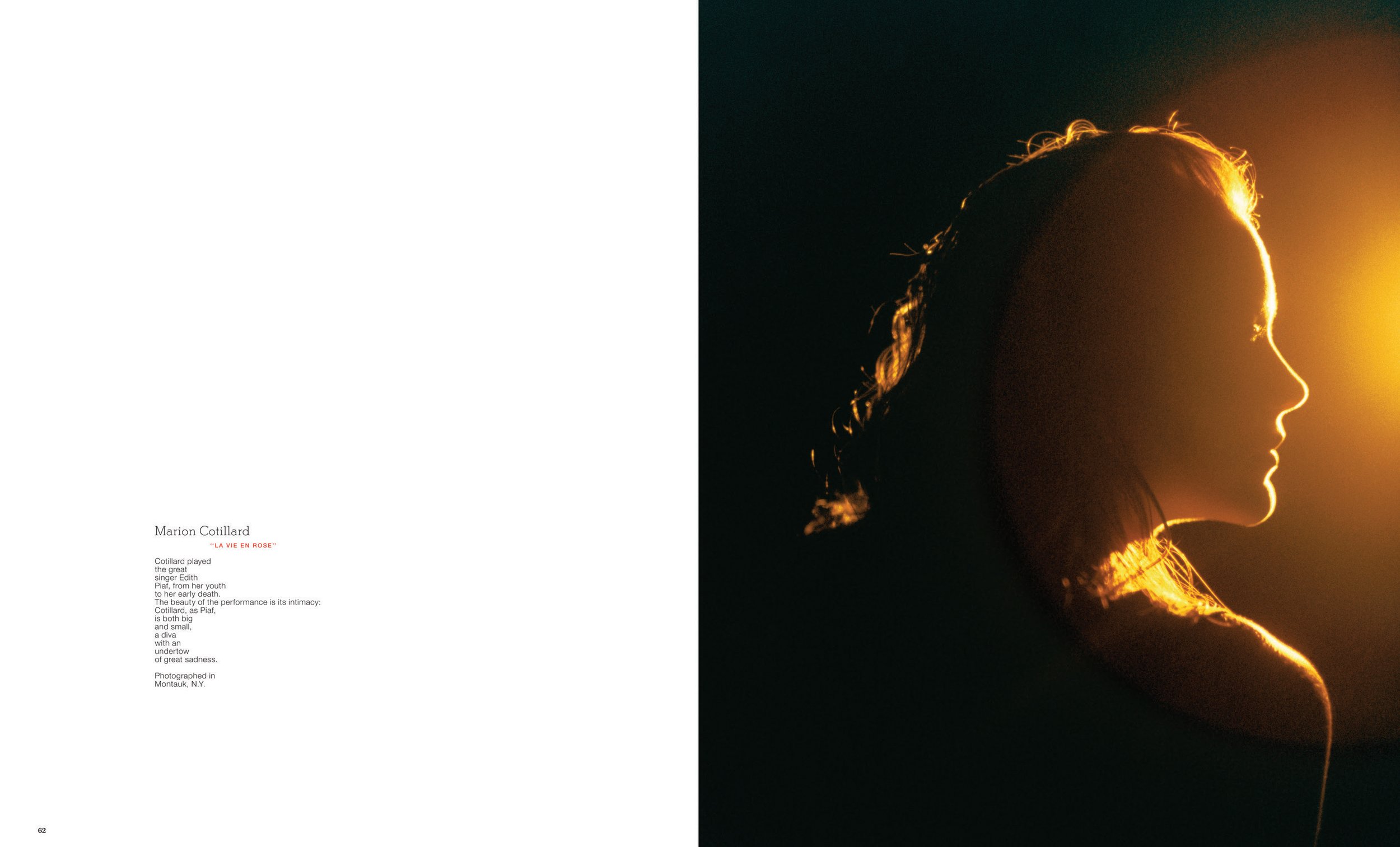

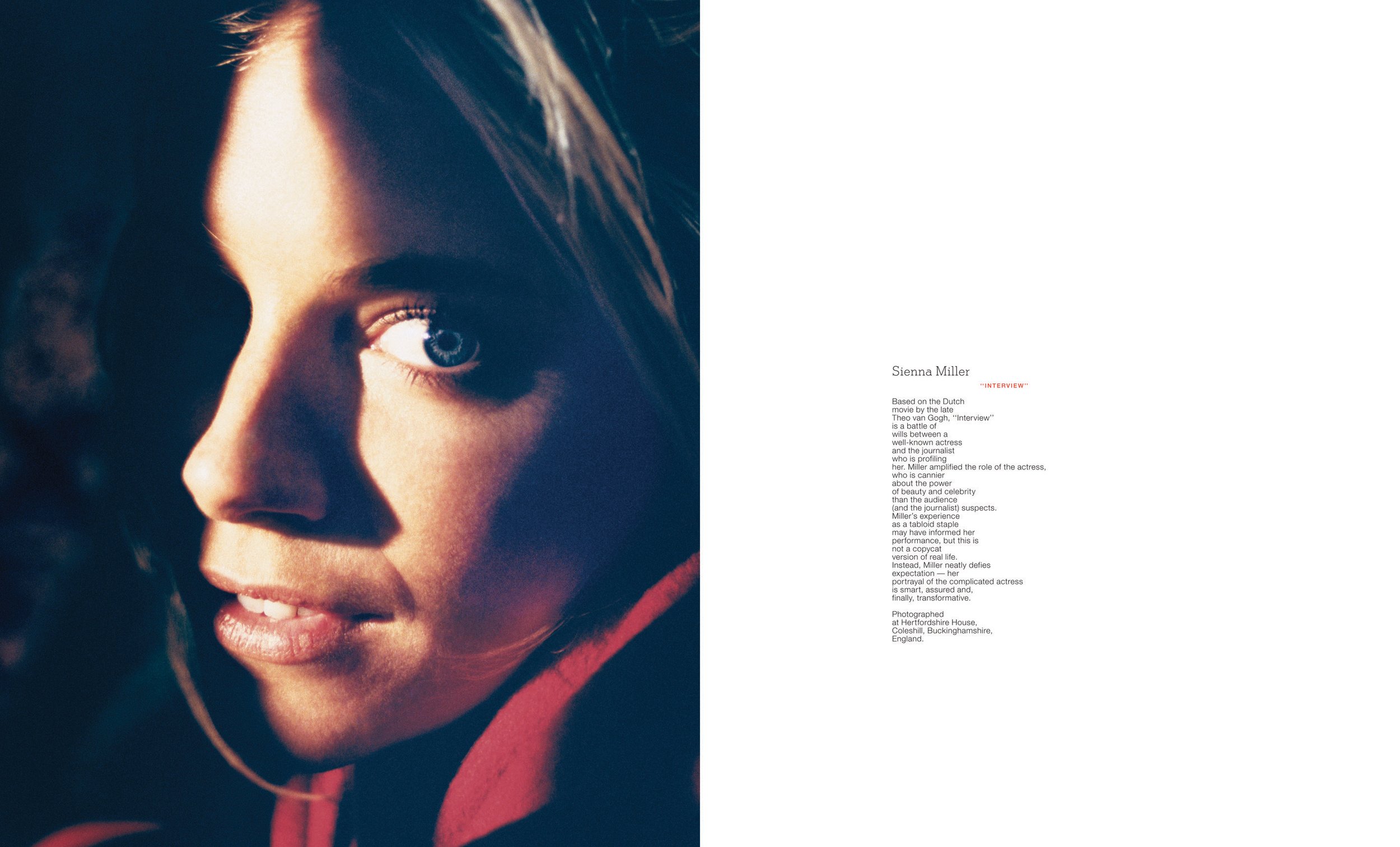

But there were a lot. There were a lot Great Performers. We would usually have about 10 actors and actresses. And we would do that every year. So 10 times 10, that’s like a hundred of some of the biggest names in Hollywood right there. It was pretty incredible.

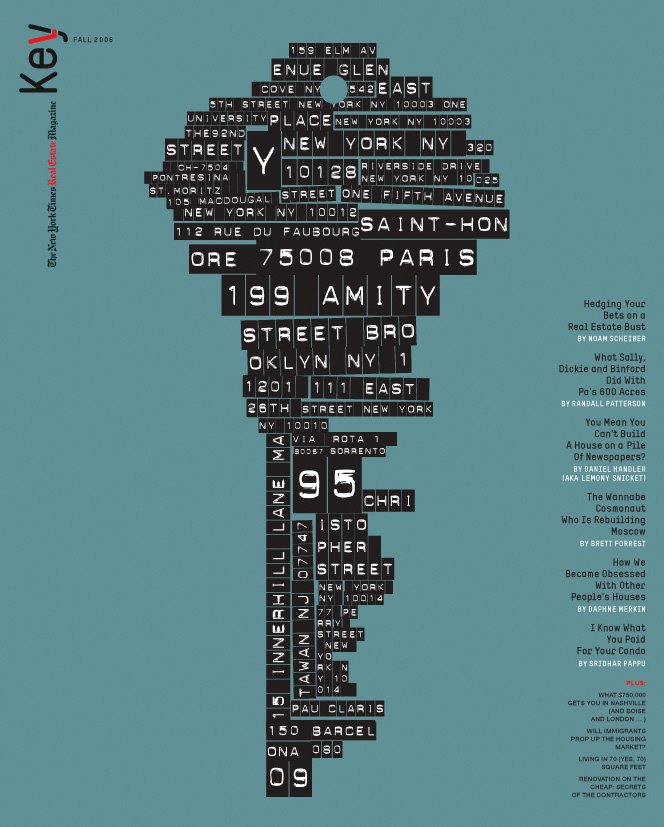

Duplessis worked with font designer Tobias Frere-Jones and Hoefler & Co. to create the wildly popular Gotham family of fonts.

Nicole Dyer: When you start with a print piece, are you already thinking about the digital outputs? You have to have some digital life to the print piece. Are you thinking about that at the beginning and are those digital outputs, whatever they might be? Is that an extension design-wise from the print piece or is it an entirely independent creative concept—and I’m talking more about back at The New York Times Magazine?

Arem Duplessis: Well, it was frustrating, to be honest with you. Because, not that I’m a control freak—I mean, I guess we all are to a certain degree if we want to put out good work—but I had so much control over the printed part of the magazine that was under my domain and my team's domain. And then you had the interactive part, which was not really my domain. It was almost like, and look, they, I mean some of the best interactive people in the world that work at The New York Times, we all know that, but they didn’t always have the bandwidth to do what I wanted them to do. Or sometimes I would want them to do something that they didn’t do, but then they would turn around, do something much better than I thought, whatever my idea was. So it was a good relationship, but it didn’t always—the look of an article didn't always replicate online just because, back then a lack of understanding from my part, to be honest. But also the interactive team at The New York Times, they do a lot of work and myself and my team’s ambitions around what the article should look like digitally, they weren’t always able to take it on.

Nicole Dyer: You have to pass the torch because you want to bring the same vibrancy that lives in print, that we all know and love, and you want to execute that digitally. And at a certain point, it sounds like you do have to pass the torch and leave those creative decisions to another team.

Arem Duplessis: Yeah. And then, as things started to develop because I left in 2014. So, you know, you have to remember these conversations I’m having are 2010 through 2012 with the interactive team. We just didn’t have the same capabilities that they have now. So I can’t speak for Gail [Bichler]. She’s doing amazing work both on the print side and the digital side. But I would imagine that the collaboration looks a lot different now than it did back then. Back then I think both sides of the table were trying to figure out how to do complicated things. And you just didn’t have the same platform.

“My aspirations after Apple are more around going back and teaching. I want to bring a lot more black creatives into the world of design.”

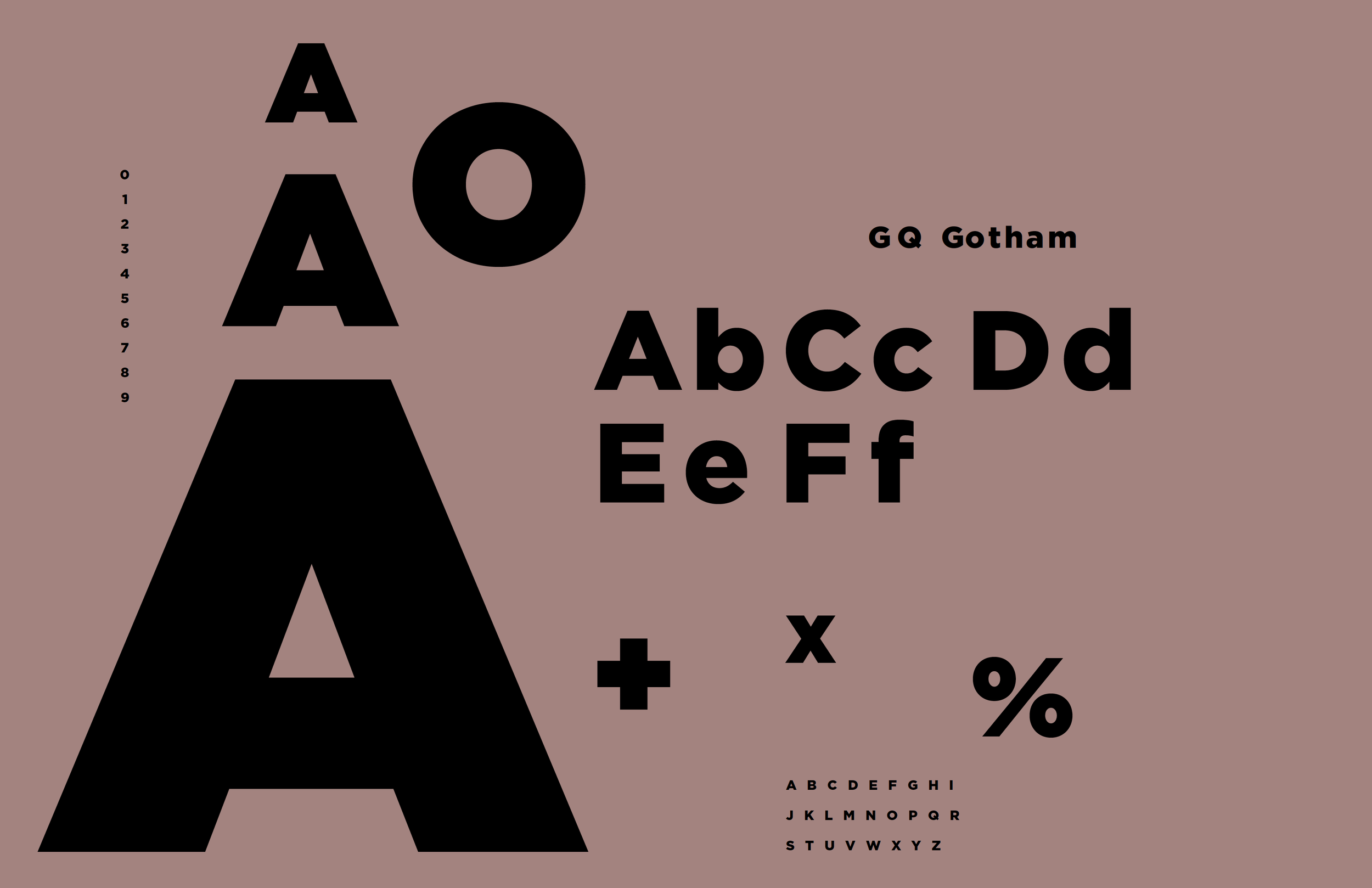

Patrick Mitchell: Back at The New York Times, you co-produced an Emmy Award-winning video series with George Clooney, Viola Davis, Brad Pitt. Do you see doing more of that type of work in your future?

Arem Duplessis: You know, it’s tricky because I’m listed as a producer, but it was really, from me, a creative contribution, but they have all of these rules. So I can’t remember why I couldn’t be listed as a creative, but listed as a producer. At Apple, I do get to work on a lot of different projects that are really varied. So my creative cup is full there in terms of going off in producing my own version of that. No, I mean, I think Scott [Dadich] did a great job with [Abstract], but my aspirations after Apple are more around going back and teaching. I want to bring a lot more black creatives into the world of design. Like my mother did for me. I just want to educate, at a young age, the possibilities of what a design career looks like. And all of the opportunities. That’s my goal after corporate America. For sure.

Patrick Mitchell: If Apple disappeared tomorrow, what would you want to do for work? What would fulfill you?

Arem Duplessis: Definitely being a fine artist. I’ve started doing some side work on the weekends, drawing and doing some collages and I love doing it. It’s very therapeutic. So if money wasn’t an issue, I’d be on my yacht doing artwork [laughs].

Nicole Dyer: I vote for the teaching! I think a lot of people still don’t know that there are design opportunities—that it’s even a job, you know?

Arem Duplessis: Yeah. No, that would certainly be factored into it. The students would be on my yacht with me and we would all just have a great time [laughs]. But, that will always be a goal. And obviously it has nothing to do with money. It’s just more around education.

Patrick Mitchell: What career advice would you give young Rem coming out of college today?

Arem Duplessis: The career advice I would give young Rem coming out of college is: Definitely go to graduate school to learn more and feel like what it means to be a creative in New York. So you’re doing the right thing there. And the other piece of advice I would give is: Stop worrying. You know, everything’s going to work out. You’re on the right path. You got accepted into graduate school. Certainly you have enough talent in this business to get a job and just relax a little bit. Everything’s going to be fine.

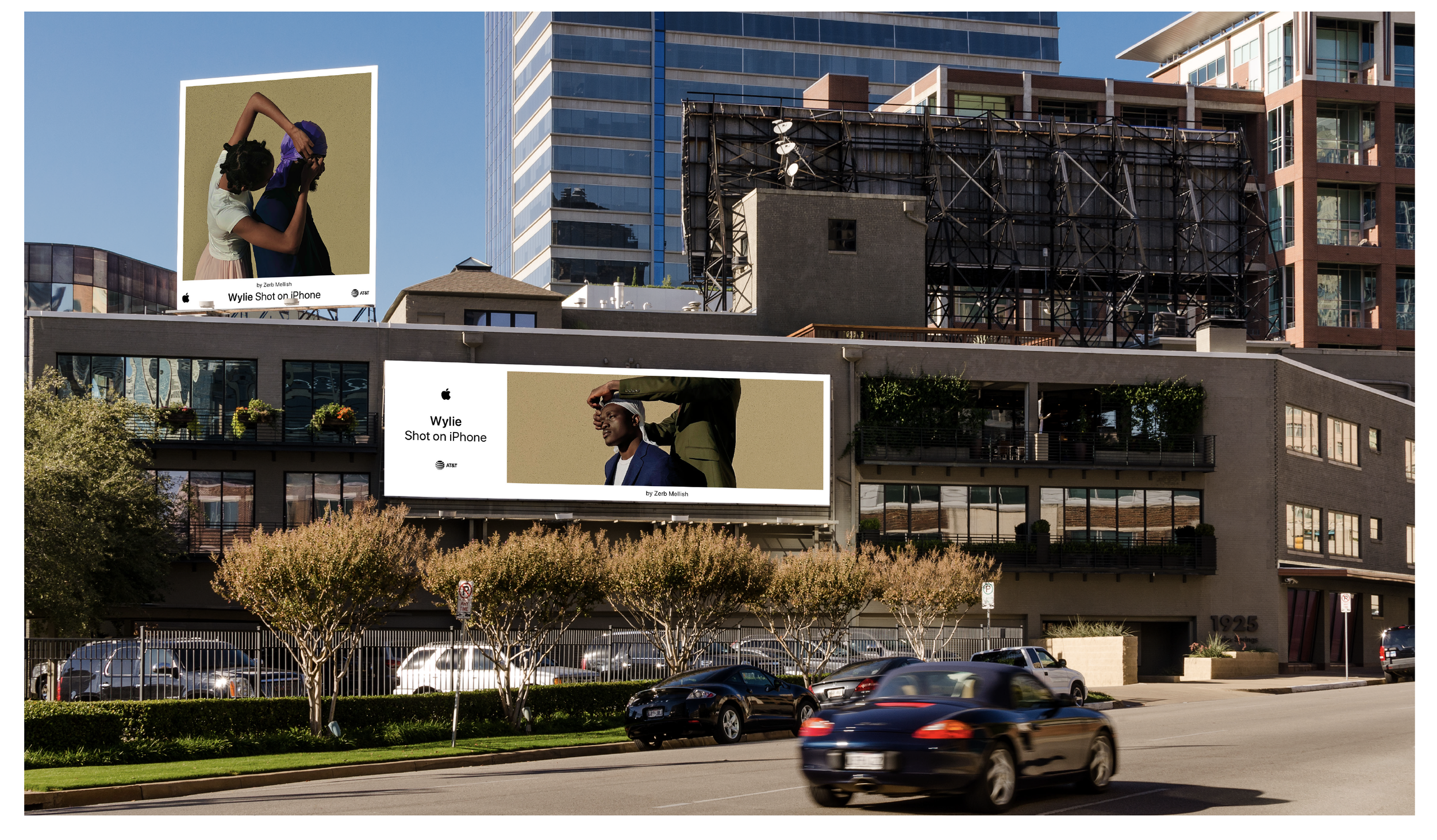

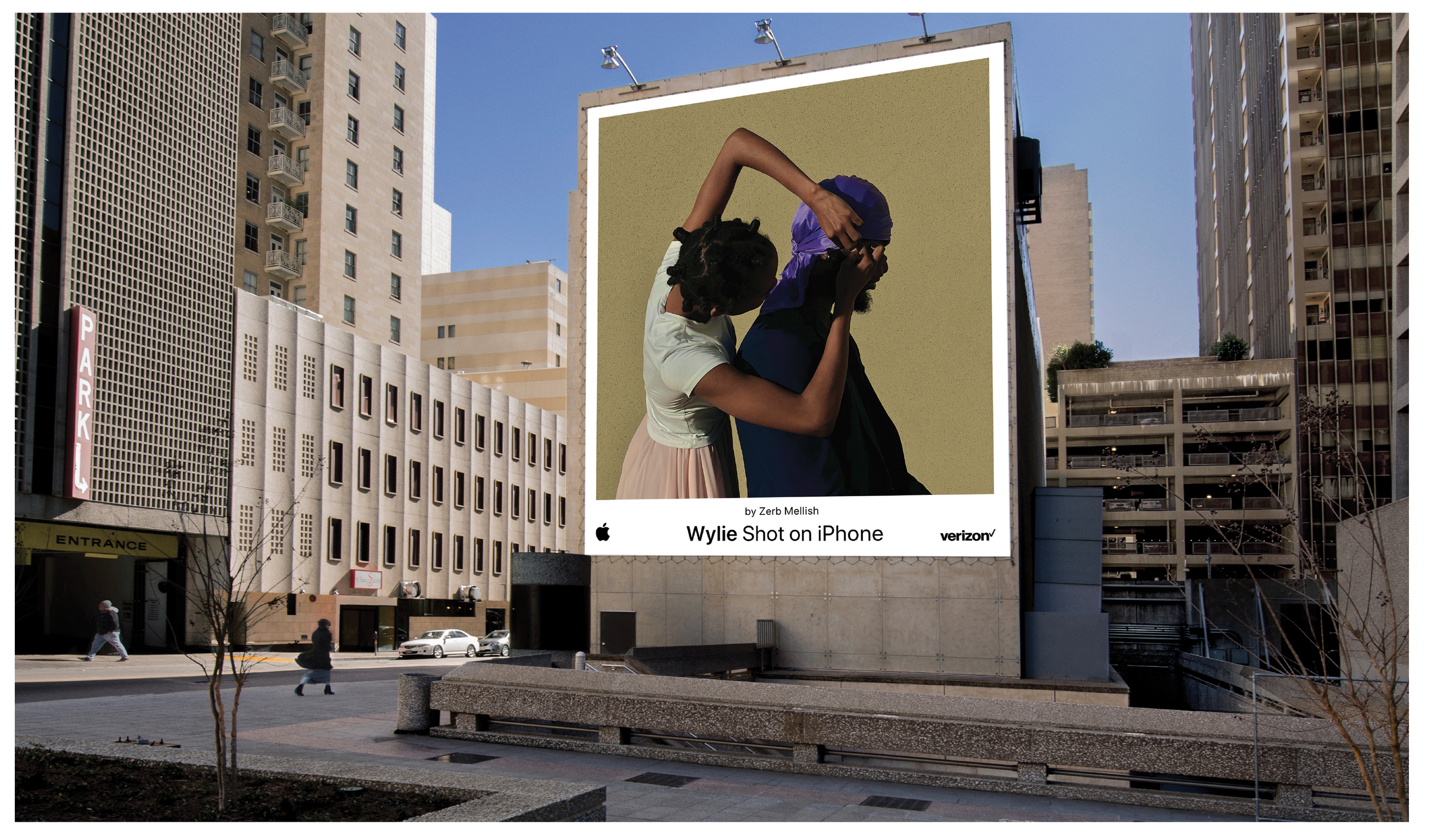

Apple’s “Shot on iPhone” campaign, directed by Duplessis

You can keep up with Rem via his Instagram @aremduplessis.