The Magazine Evangelist

A conversation with magCulture creator/curator Jeremy Leslie

Jeremy Leslie is a magazine person. A lifer. He has had his hands in a diverse group of publications and media, including Time Out, The Guardian, Blitz, and many others.

Since 2006, he has led magCulture, which started out as a research project, became a well-respected blog, but now includes a retail outlet in London, a consultancy, events and conferences, and really, anything magazine.

He has written books about editorial design and magazines, and his talents are sought after by clients the world over. magCulture, however, is more than a mere destination for magazine lovers. It is a resource, and perhaps more than anything, an evangelist for all things magazine. Its existence has been a boon to indie mags everywhere.

magCulture continues to produce a vast array of content on all sorts of platforms and channels, and all of them are worth your while. magCulture's battle cry—something they shout from the rooftops—is a simple one, and one that we at Magazeum share: WE LOVE MAGAZINES!

Jeremy is arguably the best person to speak to about the state of the magazine today, and what the future of the magazine might be.

The magCulture shop, in the Clerkenwell section of London

Arjun Basu: If there wasn’t someone in the United States called Mr. Magazine, I would call you Mr. Magazine. Why don’t you tell everyone about your journey to this point?

Jeremy Leslie: How far do you want me to go back?

Arjun Basu: There’s a lot there, right? Just a brief abridged version of your journey to magCulture.

Jeremy Leslie: I’ve been working in publishing now for 40 years, I think. Or maybe 38, 39. But looking back, I’m amazed to calculate it’s around about 40 years of working in magazines so far. My first interest in magazines was simply through reading a music magazine called the New Musical Express (NME) back in the late seventies/eighties. That’s where I first got the magazine bug. Albeit without realizing I was getting the bug. I was just a teenager into the music and that was the first magazine that really engaged me.

But then if I zoom forward from there I went on to study graphic design at the London College of Printing which is now the London College of Communication. And even as I was studying design there, I hadn’t really figured that magazines and design had a huge crossover.

I was still obsessed with music and reading the NME and then I was doing this design thing. But of course the two kind of came together.

Arjun Basu: Did you get into design thinking you were going into music and do album covers, or were you not even thinking that far yet? Those were two separate interests.

Jeremy Leslie: No, it wasn’t even it, you can look back and in all these situations and patch together a really convincing kind of plan strategy of a story, but it wasn’t that organized at all. I hadn’t done very well academically at school. My art teacher was a hero and he sensed that I was quite good at typography and structure. So he said, “Graphic design.” He pushed me in that direction and I went off obligingly. And then found this world that was my people.

But there was no big plan to it. It fell into place thanks to the good thoughts of some decent people around me and the support of my parents. So there wasn’t a goal at the end of that, but I didn’t immediately click with it all. But as it transpired, you know, studying and I got very into design.

I had some conflict with my tutors and the people teaching me there, but I found a way out by moving out of typography and into a moving image. Which took me actually naturally away from print and the potential for magazine design. But actually stood me in good stead later on in, in other respects of what I do.

But then it was when I left university and I covered for somebody in a magazine design studio over the summer for two or three weeks. And I just got the bug there. And then that was City Limits magazine, which was a listings magazine in London that it’s set up as a kind of competitor as an alternative to TimeOut, which is probably a better known brand.

And the craft of making, putting together pages on a magazine, listings, nothing special. It wasn’t about design. It was about getting stuff done, and keeping it straight, and making it work. But I loved the immediacy of it, the rushing on print day to get it all out. And then the following morning you come into the office and there was the printed item.

While working at John Brown, Leslie served as creative director of Virgin Atlantic’s Upper Class inflight magazine, Carlos

Arjun Basu: Yeah, there was, and continues to be, just this magical part of that process where you go from screen to page and you touch it.

Jeremy Leslie: Yeah I think that’s an underlying almost Anything I can say about magazines that is the key thing Is that the fact that something is in your hands at the end of it?

Arjun Basu: Yeah, the sensual nature of the medium.

Jeremy Leslie: You’re right. It’s the sensual side. We’re so used to our screens in every sense whether it’s the screen we are recording this on, or our phone that we take for granted, that there’s really only one sense being engaged when we’re reading and that environment. And that is your eyes, your visual. But with the magazine, you get sound and touch and smell. It’s a much more all around engaging prospect.

Arjun Basu: So then you did a lot. We don’t have to go through every step of your journey. But you landed with magCulture, which started as a blog. And what were you missing that made you decide that, I’d like to share my joy with the medium.

Jeremy Leslie: Well, as you say, I worked through various different businesses from the early style magazine Blitz. I was art director at Time Out. And then I was at John Brown producing contract or customer magazines, custom publishing for the 10 years of the noughties.

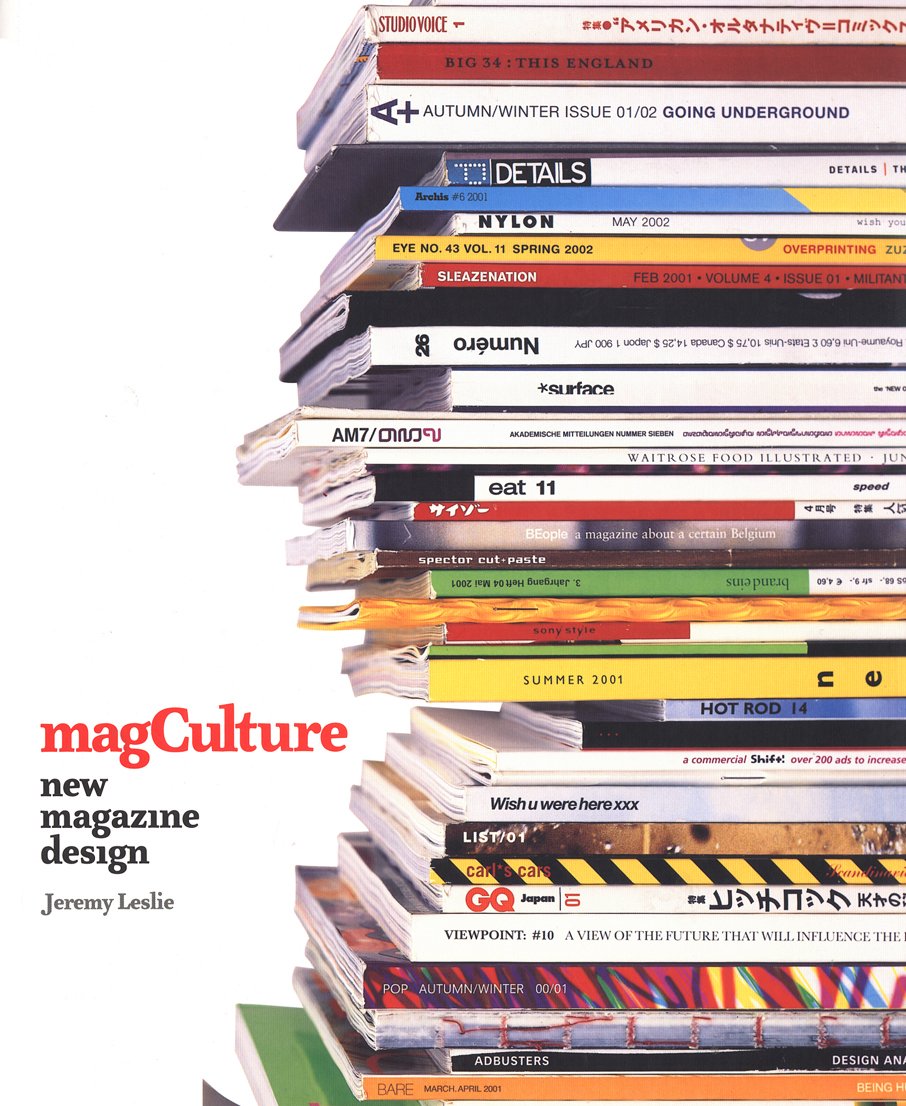

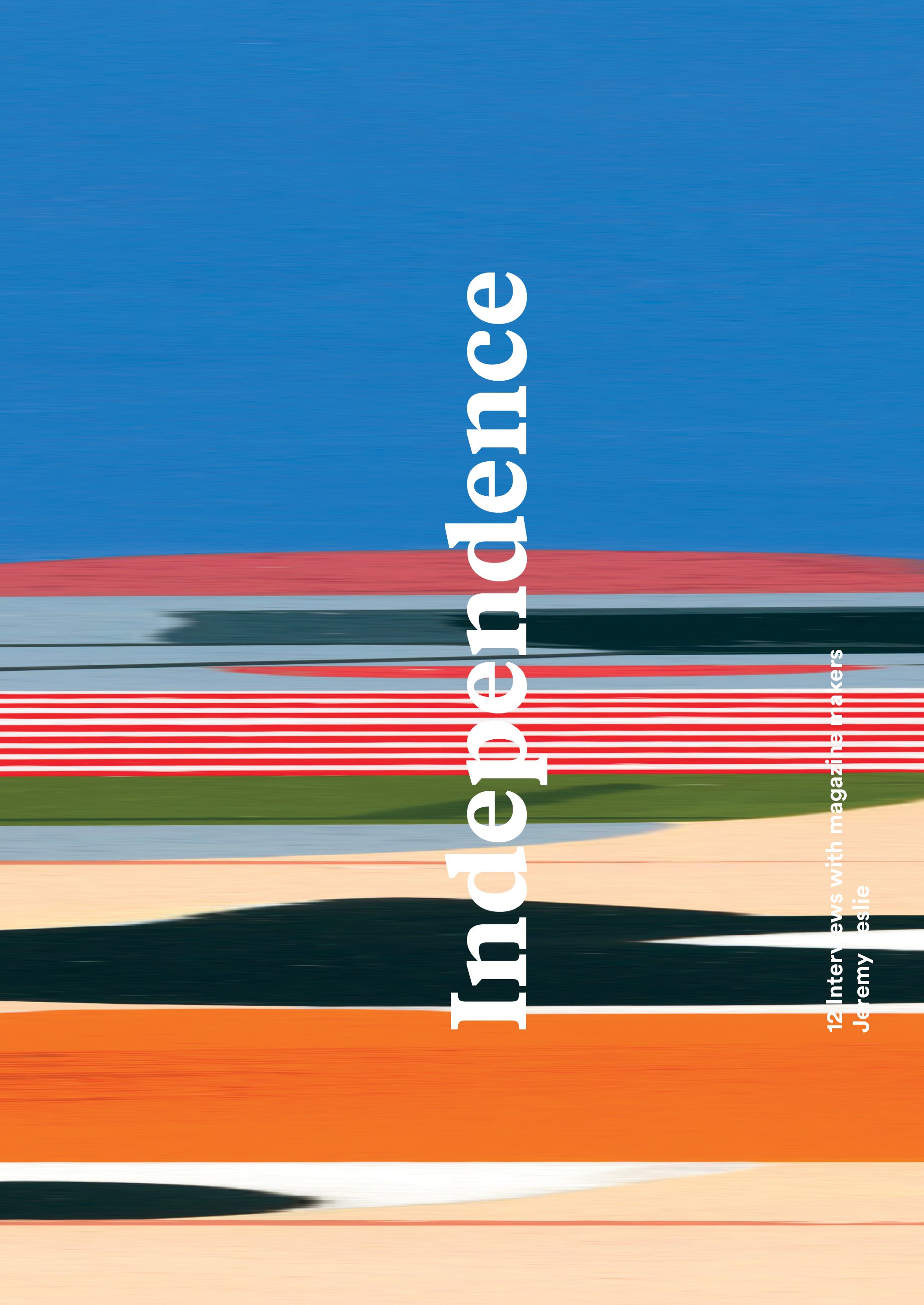

It was while I was at John Brown I really began to develop bigger ideas about what magazines could be. And at the turn of the century, you know around about 2001 or 2003, I published a couple of books about magazine design, which were sort of key to the later developments. And the second of those books was called magCulture and that did well enough that the publishers were interested in doing a second volume or second edition or a follow-up book.

And I’ve always been interested in new technology and experimenting with things. And I was interested in the idea of blogging and I just registered magCulture.com and pondered the idea of having a website which could be the research tool for the next book. And that’s what it was.

It was a very simple WordPress template. A free one. There was no money behind it. I was still working full time at John Brown. But I just set it up as a little experiment on the side and it just blew up. There was nothing else out there writing about magazines really at all, let alone from the design aspect or primarily the design aspect.

So it just caught a moment and, looking back, I realized it was the same time big publishing businesses were investing in proper broadband access for their staff in the office. Suddenly, the internet was a legitimate business tool.

And the people who might be my audience, the people working in publishing, from a creative standpoint, suddenly had the internet on their desk and they wanted something to read and my little blog turned up and it was a very timely kind of coincidence.

Arjun Basu: It’s the right blog at the right time.

Jeremy Leslie: Nice, nice phraseology. I like that. Yes. The right blog at the right time. Indeed. And so it was really a research tool that sort of became something else. And I really enjoyed working with it and developing it, and writing, and I found a voice, and began to get a lot of feedback from people who were reading it back in the day when you could have comments safely. And it’s, yeah, it just went from there. That was the beginning of magCulture.

Arjun Basu: When did you realize it was something actually more than a research project?

Jeremy Leslie: It started in 2006 and it took a couple of years. But I found I was getting invited to speak at more conferences and that just drove me on because I found myself getting invited to speak at conferences as, frankly, the odd one out. All these publishing conferences at that stage, were obsessed with digital and were obsessed with moving everything onto the phone, even though it’s pre-Apple.

But then, the future was digital and so you’d have what were once quite creatively orientated conferences about publishing going on. And every other speaker’s talking about the death of print and talking about print was over and the future is digital and holding up their Nokia.

And I just didn’t buy that and so I then stand up and I deliver my talk reminding people that there’s this fantastic new generation of magazines that I was collecting, and observing, and noting. And I just found myself developing a kind of almost evangelistic role, just reminding people not that print was going to beat digital or it wasn’t an either/or. Print wasn’t going anywhere, not yet and I don’t see now that print is ever going to disappear completely. It’s completely central to the idea of content.

Arjun Basu: There was a panic, I think, within the industry overall. A lot of it had to do with the advertising industry looking at the new shiny thing and going, “Oh my gosh!” But that panic led a lot of print people to sort of adapt to digital. And I kept saying, print needs to actually get printy-er now. It’s such a tactile thing. It needs to be more tactile and it needs to highlight its strengths and that wasn’t what was happening. It was just a general panic in the industry.

Jeremy Leslie: I think that there were several stages of panic and I think the solutions brought to try and mitigate that situation that was causing the panic were completely upside down. Things needed to be printy-er, or more magazine-y, as I say.

And actually, the big publishers opted for the opposite. They opted to cut corners and reduce quality and drop the level of the paper and generally just try to keep their profit margins up when a little bit of investment in print, albeit alongside digital, might have stood them a lot better for the future.

But you can’t point your finger at one event or one thing or one reason. But there was a whole kind of series of situations and panics and things that just played into the hands of people that wanted to do digital.

Arjun Basu: What is your definition of a magazine? Has it changed over time?

Jeremy Leslie: I’m very clear what a magazine is. A magazine is any cultural item, or object, or event, which is part of a series.

Leslie has authored a slew of books on independent magazines

“I found myself getting invited to speak at all these publishing conferences that were obsessed with digital and with moving everything onto the phone—even though it’s pre-Apple.”

Arjun Basu: So that’s interesting. Because I always called conferences and events, experiential, whatever you want to call it, content farms, because you could just do so much with those. And they could go onto any format, print, they could be reported on, they could be video, they could be audio. So that’s an interesting idea you just threw in there that it’s this series of connected things. No matter how they originated.

Jeremy Leslie: Absolutely. Specifically, the event reference I'm thinking of is Pop-Up Magazine. It was a magazine conceived as an event. It’s not taking an event and saying it’s a magazine. It’s a publication that comes off the page and into a live environment. But it’s definitely positioned as a magazine, as the spring issue and the fall issue.

But the point is it’s a series of issues and that one comes out as a series of events. Of course, most magazines come out as more familiar formats in print. And this isn’t a new thing. You go back to the sixties and something like Aspen magazine, which was a kind of box full of bits of various things created by different artists and contributors.

And you go back to the meaning of the word magazine. It relates to, in various languages, ‘storehouse,’ ‘shop,’ and ‘collection.’ You have a magazine of bullets that you put in a gun. The name ‘magazine’ only got applied to what we know as a magazine today in, I think it was 1873, with the Gentleman’s Magazine here in the UK.

But before that they existed without having the name magazine. And a magazine is just another word like ‘review’ or ‘journal’ or whatever. But the word magazine frees you up, I think. And if you look at the meaning and the etymology and origins of that word, it can really help open up what you think a magazine is.

Arjun Basu: I read two things in preparation for this. One was a story in GQ and one was a Substack by Joe Berger, who writes about magazines, and both of them were asking the same question: Are magazines—are print magazines—a luxury item now, or an elite pursuit? I understand why it’s being framed that way. I don’t really agree, obviously. I wonder what you thought of that.

Jeremy Leslie: I’ve read one of those pieces and I understand the argument, but I think it’s a sort of irrelevant argument. I think there are definitely magazines that are being created from the point of view of wanting to be a luxury item and wanting to be in that market in terms of rarity and value and et cetera.

But I think that’s always been the case. I think there’s always been magazines of that ilk. But equally, I think there’s magazines which are much more down and dirty and much more kind of, wanting to attract a very different audience. And I think that’s one of the joys of it is the variety.

And I think you know something I read recently was Jeff Jarvis’s book about his experience in magazines. I’m sure you’ve seen that. And that was a really interesting tale of the high life of the seventies and eighties, the New York publishing industry and retelling the stories of the drinks truck that went around the Time building every day at five o’clock or whatever. And the expenditure and your expectation and getting into trouble for not spending enough money on your expenses and all this kind of overblown stuff which all sounds fantastic.

And you can get into conversations with people, “Oh. Those were the days.” My feeling about the kind of those big days of magazines was, I’ve spent a lot of time in New York and when I was working at John Brown, we used to have an office in Manhattan and I’d be out there quite a bit.

And I’d come through the airport and look at Hudson News and see all these really glossy covers shining—not just the ones that remain now, but all the other ones. You know, all the Condé Nast and Hearst titles, rows and rows of them, all brightly lit and colorful and vivid and very exciting. And I remember judging the SPD Awards in New York and being amazed by this extraordinary typographics and such. Very impressive.

And there was that era of Scott Dadich and Brandon Kavulla and great designers who’ve all now moved on to the West Coast and are working in tech. And that was a great time. It was a great time creatively and we in London looked across there with great envy at that, the resources and the time that people had to spend on these projects.

But I wonder, in retrospect, I mean in a way it was all very much the same. And in a way I think we’re in danger of allowing nostalgia to overawe us. And I think at any time you can go back through different eras, there’s always something interesting going on in the world of publishing and that’s the case now.

Arjun Basu: You know, no matter what the magazine is, if it’s a down and dirty, mimeographed zine right up to something, obviously very expensive, I’ve always thought magazines are aspirational more than anything else.

Jeremy Leslie: Absolutely. I think people frown upon the idea of aspiration. But I think that’s what we want. People are naturally ambitious and wanting to find out about the next thing. But you’re right: Ambition and aspiration are a part of it. I think that’s a key kind of human quality, isn’t it, to aspire and to want to know more and to find out more. And I think magazines are great ways of doing that. Of course, it can go a bit sour if you’re kind of flicking through pages, aspiring to have things that you can’t afford to have. And, there’s that side to it. There’s also the healthier kind of side to aspiration in terms of bettering yourself and learning more and developing yourself.

Arjun Basu: 100%. But, coming from the custom world, the brands that understood the tactile and sensual nature of magazines were tactile and sensual themselves. And that was fashion and luxury. They understood that and that’s why they still advertise so much in traditional magazines.

Jeremy Leslie: Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely.

Arjun Basu: You are, for want of a better word, you’re the curator of the new magazines. How does something get on your radar? How do you discover them?

Jeremy Leslie: As I said, the magCulture blog, as it was, started in 2006. So I’ve been at this now—and before that in 2001, my first book came out—so I’ve been in this in one way or the other for 23 years. People come to me. People come to us, people come to magCulture now.

Arjun Basu: Are you like a ‘stamp of approval’ now, in a way? That might make you uncomfortable, but ...

Jeremy Leslie: I feel that there’s a bit more of the story to explain to flesh this out. I was running this little side project, the magCulture blog, and that was beginning to grow an audience and get people interested in me for other reasons than my design career. And I had this kind of parallel thing going on. I was designing at John Brown and I was writing and contributing to conferences, writing for other publications about editorial design, et cetera, beginning to teach a bit.

And my time at John Brown came to an end in 2009. And I just decided to migrate myself into the name magCulture. And the magCulture studio started up and I began to work with clients of my own in that respect. Various things here in Europe and the States and then alongside that we opened the shop. And my studio was situated behind the shop. So it was an all in one kind of site with the retail shop selling the magazines that we’re a hero-ing, and the business running the consultancy and design behind it.

And so, you know, across the years, my voice in terms of, talking about and highlighting certain magazines and what’s happening in the scene has developed. And we get, you know, there’s a big lightning conductor above the building that says, “Send us your magazines!” So we get sent stuff all the time. We reach out and see stuff, we’ll find stuff on Instagram. People wander in off the street to show us their magazines. All sorts of ways.

I look back now and realize there’ve been two enormous catalysts for magCulture as an entity. And that was the website back in 2006, which sort of created the digital space. But I didn’t realize how much more the physical space of having a shop would add. And that’s been extraordinary, not just because it’s a shop, but because it attracts attention and people come in and they want to know about what’s going on.

People are either already on board and want to just know more or else they come in and they look around and they’re just like, “What is this place?” “This is a magazine shop?” “Are you crazy?” And so it’s a fantastic vehicle for explaining what’s going on.

Arjun Basu: And then they touch the magazines. You can’t do that online, right?

Jeremy Leslie: Yeah, exactly. Which is an entirely different experience. And the reality is that any business, mine included, all the magazines we sell rely on the internet. Of course they’re primarily print projects, but they wouldn’t exist otherwise. And there’s a sort of paradox built into this in the sense that so many magazines, for instance, the New Musical Express, that I started off this conversation as a kind of a touchstone for what first got me involved in magazines, the internet brought it down. It was a weekly news and listings magazine.

And that – kind of semi-professional kind of functioning, you know, making money out of all the advertising – that kind of project is long dead because of the internet. But meanwhile what the internet has done positively has empowered smaller magazines to launch and then within months they’re selling copies across the world because of the internet.

Arjun Basu: Yeah. Do you find, you know, as a Londoner—and London’s always been a magazine center, or printed word center, let’s just say—and then going to New York and seeing what they have. Do you find that the geography of magazines, like where the creative output is coming from changes and shifts over time? Because I feel that’s true. I don’t know if that’s my own impression or if that’s actually true.

Jeremy Leslie: No it, it does change. In terms of the English language, I’m very clear that the traditional centers of excellence are London and New York. Maybe one or two other cities might argue the toss. But I would say London and New York are the heart of the English speaking magazine publishing world.

But it’s interesting to see what happens elsewhere and how different cities, the sort of slightly smaller cities are more creatively orientated than the bigger full on cities. So for instance in the UK, Manchester and Bristol have contributed a lot to all sorts of creativity, not just magazine publishing. But they have, and Bristol was a center for some stage. And then suddenly that sort of fades away somehow.

Right now, I’m seeing a lot. There’s a lot in Paris, which has always been culturally interesting as a city and a lot going on, but has always been rather closed from a publishing perspective because of the kind of the French approach and indeed legal approach to publishing in their own language. And things are set up to protect themselves against the Anglification of everything they do.

But now there's a new generation of really interesting independent magazines coming from mainly Paris that are in English and are developing international readership. Amsterdam’s big. So yeah, I think it’s a sort of strange kind of cross fertilization.

Leslie’s work for M-Real.

“There was this fantastic new generation of magazines that I was collecting, and observing, and noting. And I just found myself developing a kind of almost evangelistic role.”

Arjun Basu: It happens in every medium. It happens in music. It’s interesting because we’re talking about English magazines and it does move around. Amsterdam for sure. Paris, there was a time, a short time when it was Belgium and fashion magazines. I keep thinking of Australia and their impact on food magazines from the nineties and the aughts. And we’re still feeling that impact in terms of the design of a food magazine and blogs. Researching the show, not the show in particular, but the series, I’m starting to see all these bilingual magazines coming out of China, out of Shanghai in particular, which are really interesting. And I know your store carries some of them, and those centers of excellence just move around in the English language. In Canada where I am, the most interesting magazines in this country are French and they come from Montréal and they’re beautiful and they’re interesting. They’re fearless in a weird way that the rest of the country isn’t managing. So there just seems to be these periods of creative churn, that are geographic.

Jeremy Leslie: I think that’s right. But I also think you have to understand it as a very international market today. And I think you can observe bright spots at various times. The reality is now everyone’s looking at what different cities are doing and everyone’s very conscious of what’s happening elsewhere. The new independent scene, the current independent scene—it has hotspots all across the world, but those hotspots are all networked together.

And magCulture is part of that network. And in your country you have Issues in Toronto, and in Germany there’s Do You Read Me?, and there’s the Athenaeum in Amsterdam, and all these shops. We all know each other and we’re supportive of each other and we know how difficult it is to make these magazines and to make them work. So we’re all trying to push them along and encourage them to keep going.

Arjun Basu: What would you advise someone who is in that position, who’s being encouraged but wants to start something interesting? From an obviously creative point of view, from a content point of view, from a business point of view. If someone came to you, walked into the store and found you and said, “What should I do?” What would you say?

Jeremy Leslie: I have said in the past, “Don’t.” But not because I don’t think they should, but because I think it’s going to be really hard. And you need to be quite clear that it’s not going to be simple. It’s not going to be easy. It’s more than just, “Oh, that looks fun, let’s do it.”

Arjun Basu: That was always true.

Jeremy Leslie: Yeah, exactly. Making a magazine—even making a not very good magazine—is really hard work. So what I would say to them is, “Make the magazine you really want to make. Talk to people, take on advice, listen. But be true to what your idea is and do something that is yours. Do something that you can 100 percent stand behind and say, success or failure, ‘This was great. I believed in this. And I really thought it could go.’”

And if it doesn’t go, it doesn’t go. But the alternative is you listen to too many people and you look at too many other magazines and you think, “Maybe we could do a little bit of this, and a little bit of that, and that could just find a little slot in a market, and then blah blah.” Forget all that.

Just make the best thing that you can do that aligns with what you want to be doing. Because that’s what it’s about. Make something you’re proud of. If you believe in it, it’s then your job to get out there and get other people to believe in it.

Arjun Basu: Do you have any idea about the future of the form, or the medium, or even where the magazine will sit in the larger landscape? It feels like a diminished product, but a product that endures. And it’s only a diminished product because other things seem to have rushed in and reduced its space in many ways.

Jeremy Leslie: I look at it the other way around, I see the failure of the mainstream publishers as leaving a wide open space for these independents, for magazines, and that’s what’s happening. A lot of people have an ambition to make a magazine, and there’s all sorts of reasons why. But definitely one of them is they might have trained as a designer or journalist or whatever, and they want to work in publishing, but there are no entry level jobs anymore. So they’ll start their own thing.

There were several magazines that launched at the turn of the century, which kind of started me thinking about what is happening in this new generation of magazines. I’m thinking of things like Fantastic Man, 032c, Apartamento, all of which now are really strong established businesses. They’re not vanity projects. They are passion projects, but they are actual businesses with members of staff that are on full time salary, producing something that’s very strong—still strong and true to its original self, but big. Big, challenging, scratching at the bottom of where the mainstreams were at one stage.

But I saw these magazines happening and I’ve been following them. And there’s an endless supply of young people wanting to make these new magazines and a lot of them will go on to succeed. It’s brilliant. It’s a really exciting time.

But I also think there’s a lot of focus on this idea that there’s a new generation of independent magazines. And I’ve been talking about that and using that phrase and I stand by that phrase. But I’m also aware that historically there’s always been an interesting kind of counter-alternative world of publishing alongside.

If you look at the sixties, the very brief kind of précis of what happened in the sixties, you could highlight two big things. One was the realization of the post-Second World War consumer boom, men’s magazines, women’s magazines, the fabulous Esquire covers that George Lois did.

But you can also look at the extraordinary counterculture of Friends, Rolling Stone, IT, Oz, these magazines, which were in effect the independent magazines, as we call them, of their day. And if you go back to the fifties and rock and roll fanzines, you come forward to the seventies and punk zines, the eighties with the star magazines, which I was a part of at Blitz.

There’s always been these magazines. And they’re the young upstarts trying to turn over the cart. And we’re just seeing that again with this generation of magazines. And in terms of what the future is, I can only see a healthy future when I look around me. And I think it’s easy to observe that these are all very, these are more expensive as publications.

They are sometimes self defined as ‘luxury.’ There’s a number of lifestyle magazines. They can veer towards the bland sometimes, some of them. But there’s also, alongside that, there’s all sorts of other really exciting projects. And we’ve seen great big swathes of new magazines about climate change, about LGBTQ, about technology, AI.

There’s a thing happening here in the UK at the moment about the new interest in folk and folklore. So there’s a bunch of magazines like Roam and Weird Walk. The printed ’zine, the printed magazine, still has a fantastic role to enter into a discussion or an interest in a particular area, however small initially, or minority the interest in that area is, and help grow it.

And that’s what we see again and again. It’s important for me to get across that there are magazines about sport and fashion and the traditional tropes of publishing. But there’s also magazines taking on the big issues of the day, and they’re doing it really well.

Arjun Basu: So what are three magazines now that are really making you tick, that are really exciting you?

Jeremy Leslie: You could ask me this last week, you could ask me this next week, and I’d probably come up with something different. But rather than just give you my latest favorite—we always publish a magazine of the month in the magCulture Journal, so there’s always something.

But I think ones which have already begun to establish and last—have got an absolutely foreseeable future—I would recommend MacGuffin, which is a magazine from the Netherlands, from Amsterdam, which is published in English.

And MacGuffin subtitles itself, “The life of things,” which—I think there’s a fine art to the baselines underneath your logo, and I think this is one of the most fabulous baselines I’ve ever come across: “the life of things.” It contains a kind of paradox in four words.

But it takes a single object for each issue, or thing, and uses that as a starting point for a research into all aspects of that object and seeing what fact they find out. So they’ve done, I think issue 13 is out at the moment, and it is about the letter, as in the alphabet. And so it’s not a straightforward history of the alphabet by any means.

But the alphabet the letter is just used—it’s not straightforward. It uses the letter as a starting point so we hear about all forms of media communication, the game Scrabble, some of the history, in terms of different scripts and such. But what you get is a bit of design, a bit of communication, a bit of media, a bit of games, a bit of history, you get all these different aspects.

So on the one hand it’s consistently about one thing, each issue. And previously they’ve done the bed, they’ve done the bottle, they’ve done rope, they’ve done the window. But each one is just squeezing you through this little tiny keyhole, which is really narrow.

But actually you come through that keyhole and you see this whole world, which might involve history, sociology, archaeology, some stuff very modern, some stuff very historic. And it’s a familiar template but every issue is a complete surprise. And I think it’s brilliant. And it’s not just a great idea, but the execution of the thing is always fantastic.

The best writers, great photography, beautifully art directed, et cetera. So I recommend MacGuffin. That also highlights the very powerful difference between print and digital. I think it would be a great blog, and I think I’d probably bookmark it and I’d probably forget about it.

One of Leslie’s early jobs was designing the British style magazine, Blitz, in the eighties.

“Make the magazine you really want to make. Talk to people, take on advice, listen. But be true to what your idea is and do something that is yours.”

Arjun Basu: A blog or a podcast, it could be that. Yeah.

Jeremy Leslie: So, MacGuffin.

Arjun Basu: MacGuffin, one. Two?

Jeremy Leslie: Then I would propose less of a magazine, more of a series of magazines made by one person, and that is Richard Turley, New York-based British art director who has been responsible for a number of things.

He made his name doing Bloomberg Businessweek when it was still a weekly. He did some extraordinary work there, but subsequently moved out of publishing for a period into TV, music, and advertising. But like all the best publishing obsessed art directors, he’s found himself back in publishing again.

He puts together Interview magazine, which I think is going through one of its—it’s not many magazines that managed to have several lives. Another magazine would just be happy with one of those lives. But Interview, Andy Warhol’s late-sixities vehicle for celebrity, is going through one of its purple patches right now courtesy of Richard, and the way he and Mel Ottenberg, the stylist and fashion director, have developed that.

But in addition to that, he’s still publishing his own stuff. And I think Civilization was a superb project that he did. It was a small, not physically small, but it was small in the sense there were only 2,000 copies and they did six editions to date. Randomly, when they can. But it’s a huge broadsheet piece of newspaper publishing, which is just the absolute kind of iteration of the information overload that we suffer today through digital.

These huge broadsheet pages are absolutely packed with information that is banal. But it’s the sort of thing I could never design. It’s the sort of thing that it’s a very personal project. It has something to say.

It’s almost a sort of a piece of art provocation. It’s dada-esque. It’s fantastically contrary, and I love it for the fact that it is just completely different to anything else that’s out there. It’s a ’zine that has been reborn into a broadsheet newspaper. You could pull out the pages and frame them as artwork. I’m really excited by that project.

But then even more exciting, I think, now is his new magazine, Nuts, which is a stunning piece of publishing as a physical object. And I think it’s notable that, with both Civilization and Nuts, it’s all about the physical nature of it.

The broadsheet format is absurd, and contrary, and a brilliant choice. Not even a newspaper—a newspaper is not going to launch into print today anyway, but if they did they wouldn’t be launching into broadsheets. And Nuts is really well researched in terms of the paper. It’s this really thick, bulky, but extraordinarily light paper stock, which is quite matte.

It’s all printed in black and white, and it’s like the ghost of a fashion magazine. It’s full bleed imagery with big headlines, which are esoteric to the point of poetry. And you flick through it and you think this is a fashion magazine. But it’s not a fashion magazine. It’s just pictures of people in fashion-y type settings. There’s professional photography.

Jeremy Leslie: Three Things

Arjun Basu: It’s almost like a simulacrum.

Jeremy Leslie: Yeah. It might almost be what, if you prompted an AI to create a fashion magazine, and put the right prompt in, it might be that this is what came out the other end. It’s fascinating and I think it’s brilliant. And what I like about both those two particular projects is they’re really challenging of what a magazine can be. And I love projects that question the point and the form and make you wonder, is this a magazine or not?

Arjun Basu: That’s a question we ask a lot.

Jeremy Leslie: Yeah. But the fact that stuff like this is being made, and made to such a level of quality is another argument that there’s a future in this format. People are investigating it and experimenting with it and they’re pushing at the edges to see what happened if? What if? And I love that idea of balancing working on a big project like Interview with doing these smaller, self-financed, self-developed projects.

Arjun Basu: And three?

Jeremy Leslie: The third one is something which is much more parochial in a way and that is The Fence, which is a London-based magazine, and it’s in the spirit of early Private Eye, our very British, very English satirical magazine. But it’s also completely different from Private Eye. And it’s very slight. It’s very different from the other two magazines I’ve mentioned, which are very conscious of their physical entity, their physical being.

This is a magazine which is just 40-odd pages, it’s quite thin, there’s nothing special to its production. Although it is well-done. It’s well-done within what it is. It’s well-printed, but it’s just black and red. It only has illustrations. And the pages are not working hard to make you read it. It’s not over-embellished with design. There’s a lot of illustration.

But content is fascinating because it’s one of the few places where a lot of the young journalists in London and further afield, who are generally perhaps tied to working in lifestyle environments or working online for fashion projects, etc. The Fence lets them go out and do longer research, long-form writing projects about what’s happening in the country.

So you get reports about how London’s becoming a cash free city, and what does that mean, and talking to people about the actual effect of that, and is it a good thing? Things like that, as well as more stories about sex abuse in public schools and things like this. So they do serious reporting. They also have a wicked sense of humor. They carry fiction. And there’s nothing quite like it at the moment. It feels like it’s going back to another era of publishing, but they’ve made it very modern. And I have a lot of time for that project.

As to the future, I'm excited by a lot of what's happening in the digital storytelling space. Particularly from more, sort of, print orientated directions. For instance, I think The New York Times Magazine and the creative team there, led by Jake Silverstein and Gail Bichler, are going to be moving the magazine project into some very interesting spaces online in the following months, years.

But more down and dirty, Byline is another New York project which is run by a young journalist, Michelle “Gutes” Guterman, late of Drunken Canal. It’s a very print-orientated project, but it’s purely online, and I find that an interesting experiment. They’ve yet to find their voice fully, and I’m not sure what the business model is, but for now, it’s an exciting development.

As is Airmail, I think everybody's been, well, certainly I’ve been a bit blindsided by Graydon Carter’s success of making something out of his newsletter project. It’s, you know, it’s carrying on where he left off really in terms of Vanity Fair, but it’s his own baby and I can’t help feeling that such a print-orientated background is going to lead him to make a print product sooner than later.

And then in print, I’m eternally optimistic. I just think there is this difference between print and digital and the key thing is the difference between reader and consumer, and I think people need a space away from their screens. I think people want a space where they are presented with a curated set of stories that will sometimes be familiar, sometimes surprising.

For more information, visit magCulture online or in person, at its London shop.

Related Stories