The Last Emperor

A conversation with editor John Huey (Fortune, Time Inc., The Wall Street Journal, more)

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT MOUNTAIN GAZETTE

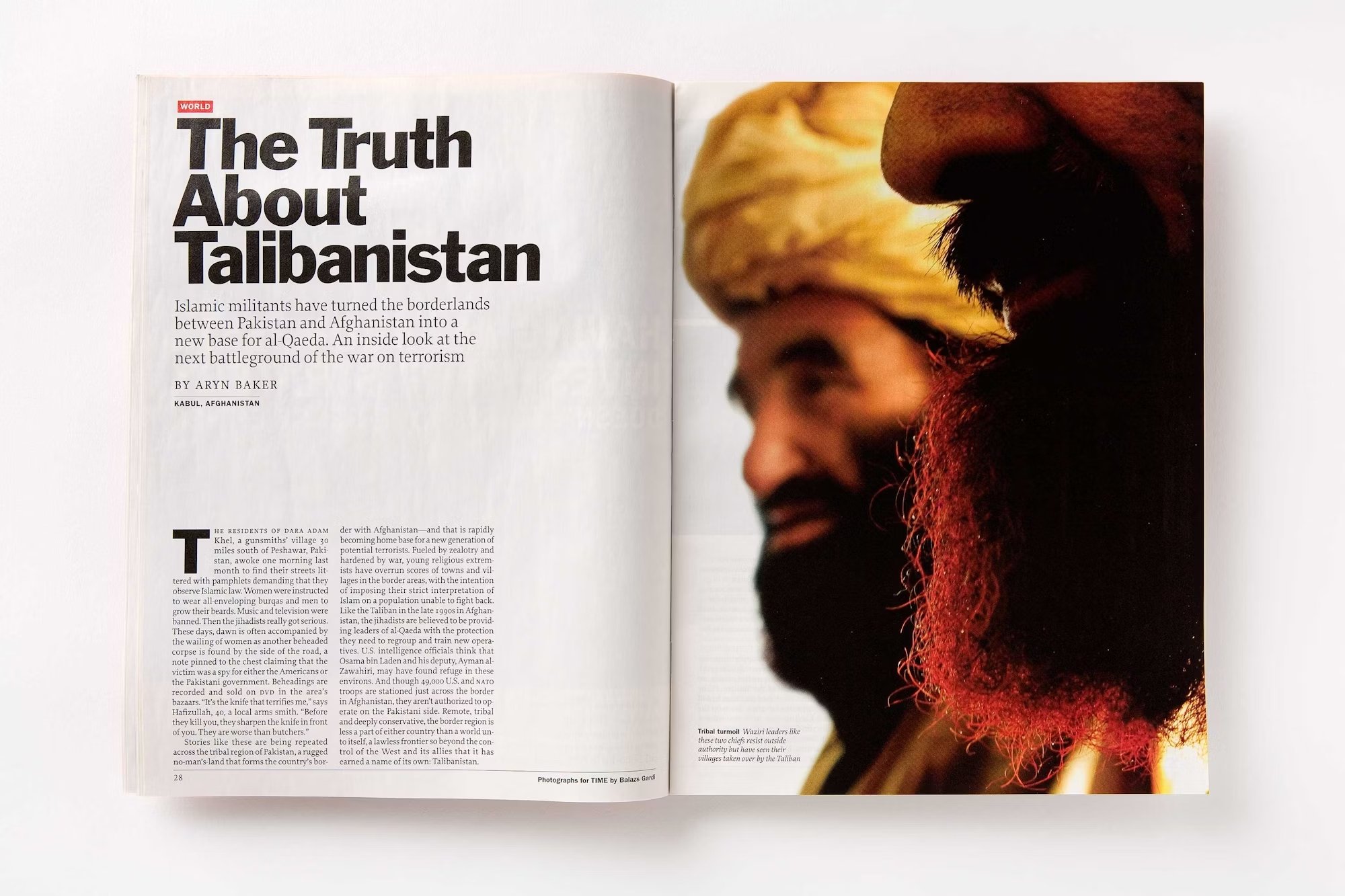

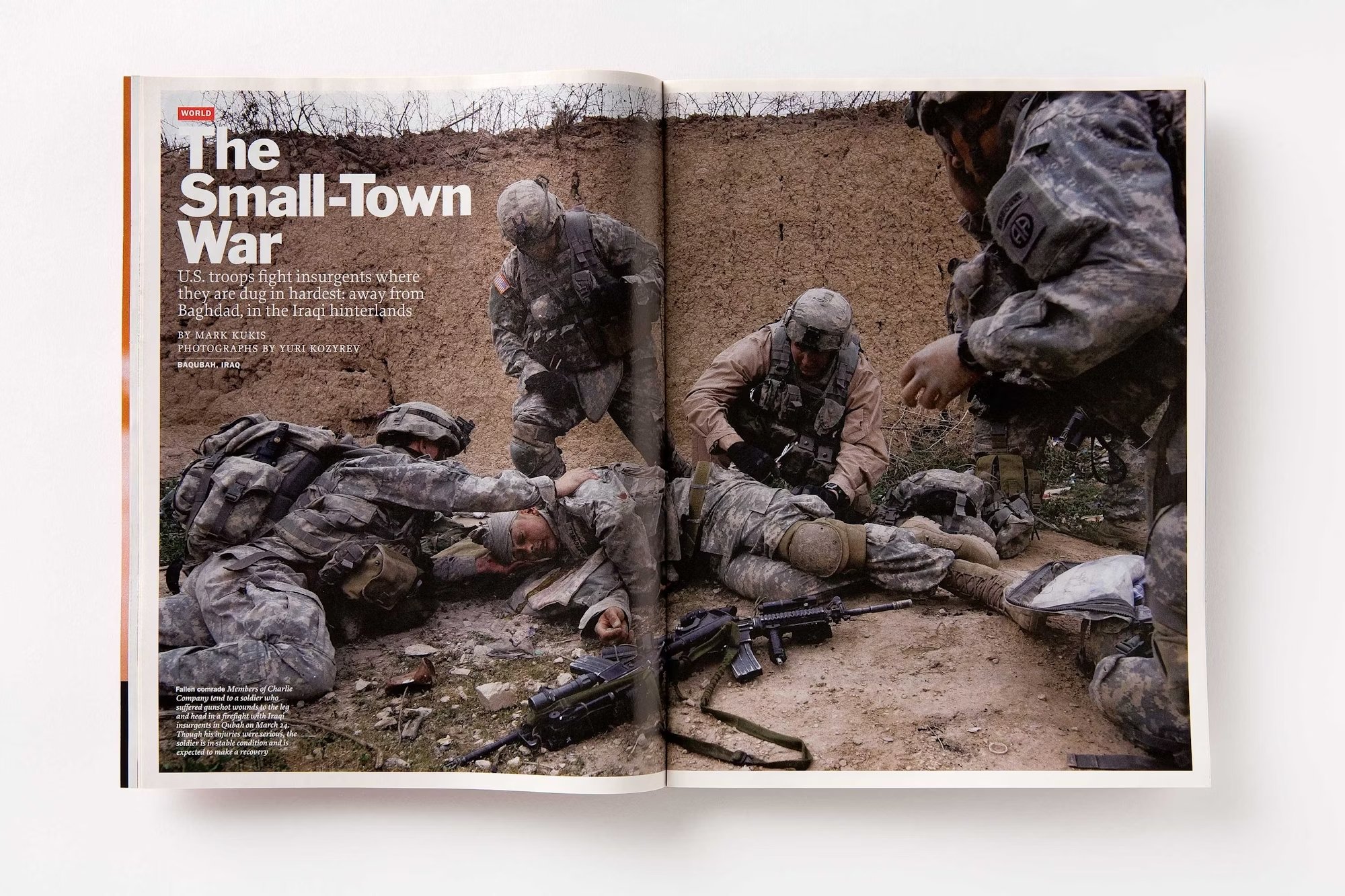

It might be difficult to remember, at least for our younger listeners, how vast the Time-Life empire was. At its height, during the John Huey dynasty of the late 1990s/early 2000s, the company published over 100 magazines.

Quite a rise from its humble beginning in 1922, when Henry Luce launched Time as the country’s first newsweekly. It was followed shortly by Fortune in 1930, Life in 1936, Sports Illustrated in 1954, and, finally, People in 1974. It was the largest and most prestigious magazine publisher in the world—and those five titles were the bedrock.

In 2006, Huey became the sixth editor-in-chief of Time Inc., overseeing more than 3,000 journalists.

In an interview with New York magazine, Huey described Time Inc. as having a “public trust” and perhaps “an importance beyond profitability.” But not even a giant as powerful as Time Inc. was immune to the financial havoc brought about by the new digital age.

Huey retired in 2012, the last emperor of a vastly downsized and damaged empire. “Google sort of sucked all the honey out of our business,” he lamented then. In 2017, after Time was sold to its bitter rival Meredith Corporation, Huey tweeted “RIP, Time Inc. The 95-year run is over.”

Our George Gendron talked to Huey about Fortune’s battles with Forbes—and their pet names for each other, about giving Graydon Carter and Kurt Andersen at Spy a taste of their own medicine, about not hiring Tina Brown, and about what his mother really thought he should’ve done with his life.

George Gendron: As you and I were discussing, your career spans stints at the Atlanta Constitution, Wall Street Journal, Fortune magazine, as editor in chief of Time Inc., and its 155 magazines in the first decade of the 2000s. And one of my personal favorites, as host of a podcast called Whole Hog, from Garden & Gun, about all things southern. And so today what we’d like to do is explore, frankly, what it took to turn around Fortune magazine in the 1990s. Now I’ve asked a lot of people who have worked directly with you, who know you, have known you, what did they think was the defining characteristic that allowed you to accomplish what you accomplished at Fortune, prior to Fortune, after Fortune, but particularly at Fortune magazine. And Dan Okrent said, “Look, I’ll put it politely. John just doesn’t really give a damn what other people think.” Would you agree with that?

John Huey: Up to a point, I would agree with that. I wouldn’t want everyone to think that I was an utter failure, or an idiot, or a total prick. I would care about that. But during those years at Time Inc., I was not feeling the strictures of tradition or popular opinion. And if that’s what is meant by that, that would be true. I was following my own light during that era.

I thought of it as a great adventure and a period of discovery because I knew that I didn’t know that much about magazines. I had been a newspaper man most of my career. And a very formatted, strictured newspaper for most of that time. The Wall Street Journal, in those days, had three features on the front page and that’s mostly what I did. And I did some news as well.

So, I’m at Fortune, and Fortune was a very formatted magazine at that time. Very formatted. And you recall, it wasn’t a weekly, it wasn’t a monthly. It was a ‘fortnightly,’ which meant it came out every two weeks, which is an interesting pace.

George Gendron: I remember that.

John Huey: So I talked to everybody I knew, who I liked and trusted, who knew anything about magazines, including Dick Stolley, who had been the editor of Life and the founder of People, who was very kind to me and very generous to me.

And I would say one of the reasons I may have appeared to not care what other people thought at Time Inc., is because a lot of people were pretty clear in not really wishing me success. It wasn’t personal, nor was it paranoia, it was just, “Look, I’ve been here 25 years. This is the way we’ve always done it. This place is a church. One doesn’t come in and mess with the church. And we always read the catechism before we sing this hymn.” And I’m like, “What?”

George Gendron: That reminds me of a quote, and I’m pretty sure this is a direct quote, from an interview that you did ages ago, and boy, is it relevant to what you just said. You said, “People think of journalists being radicals, and revolutionaries, and liberals, and whatnot, but they’re actually personally and institutionally among the most conservative people in the world. They just don’t want to change anything.”

John Huey: Yeah, I’m sure I said that and I believe it. After doing it for more than 40 years, I think it’s mostly true. You know I can look back and I can remember just a few moments when various people did something that was different.

I was covering the legislature at the Atlanta Constitution. And in the press gallery somebody sent around a copy of the front of the book “Random Notes” from Rolling Stone. And everybody was passing around and I looked at it and I thought, “Now this is different. Everybody should be doing this. This is great.”

But of course we weren’t doing that. And that was during the period when everybody was trying to be either Woodward and Bernstein. Or Jann Wenner. Or both.

George Gendron: Let’s go back. You took over Fortune in 1995?

John Huey: It was not a very sharp-edged succession. It was Valentine’s Day 1995 when I was officially given the reins of Fortune.

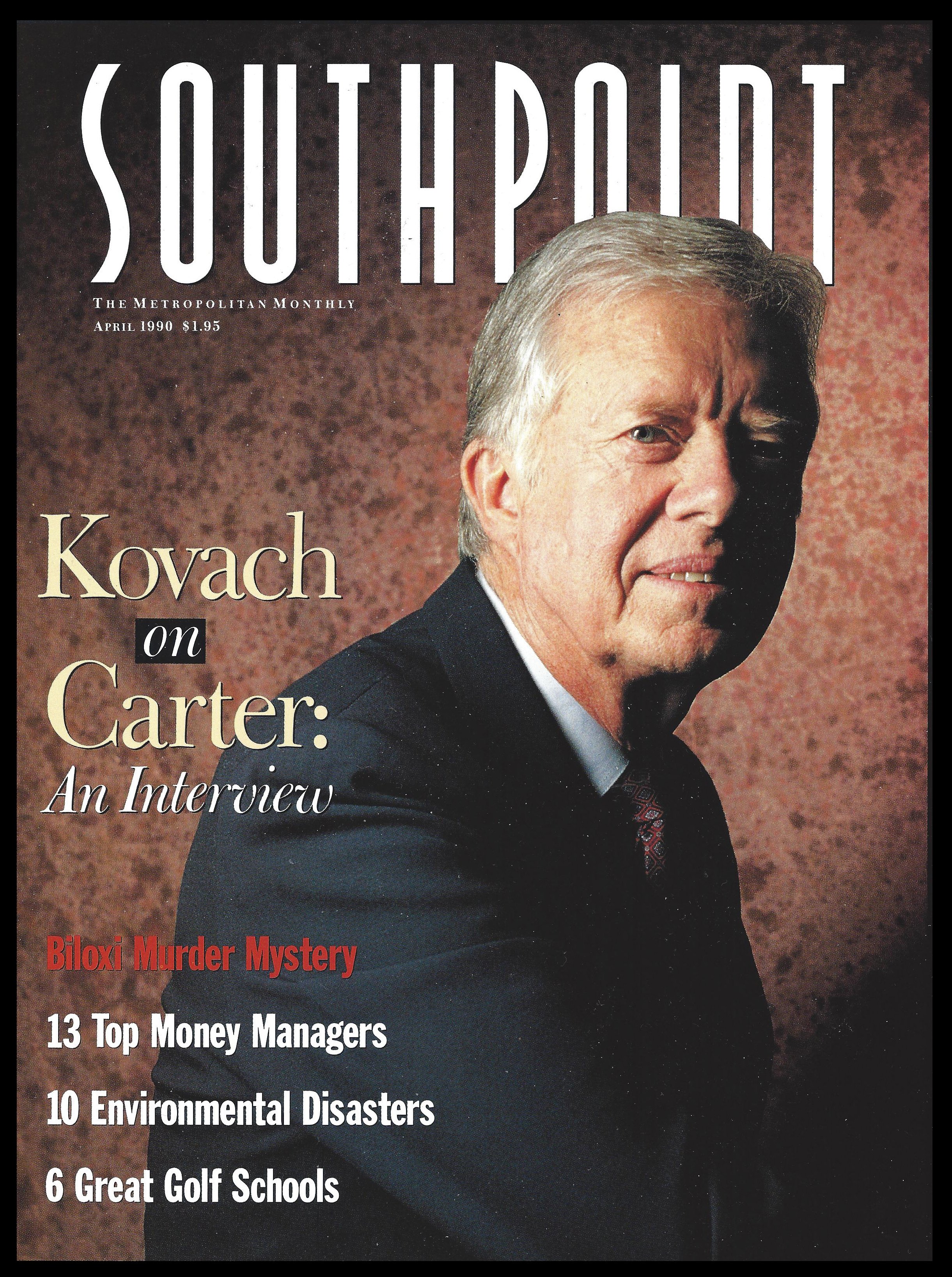

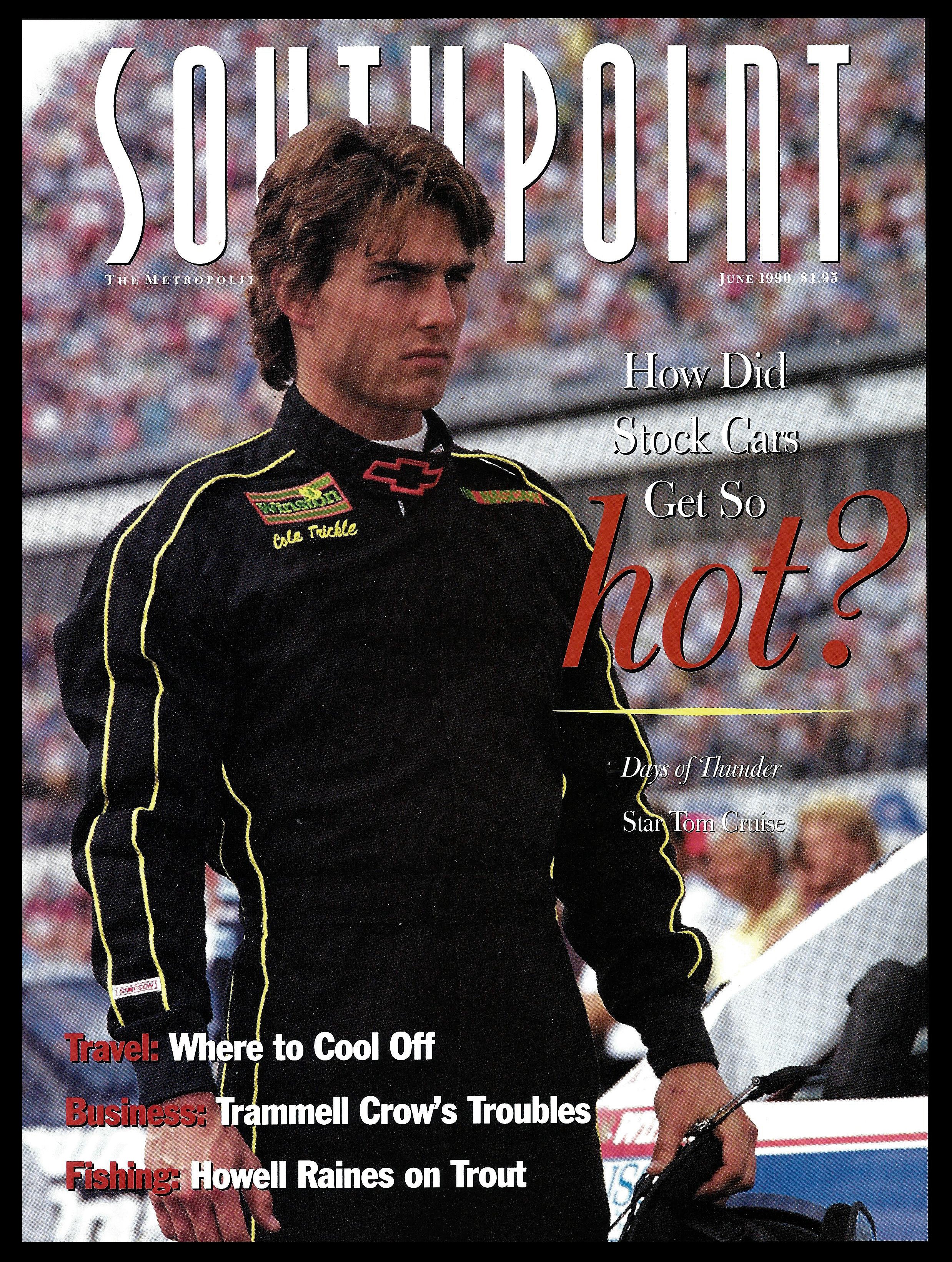

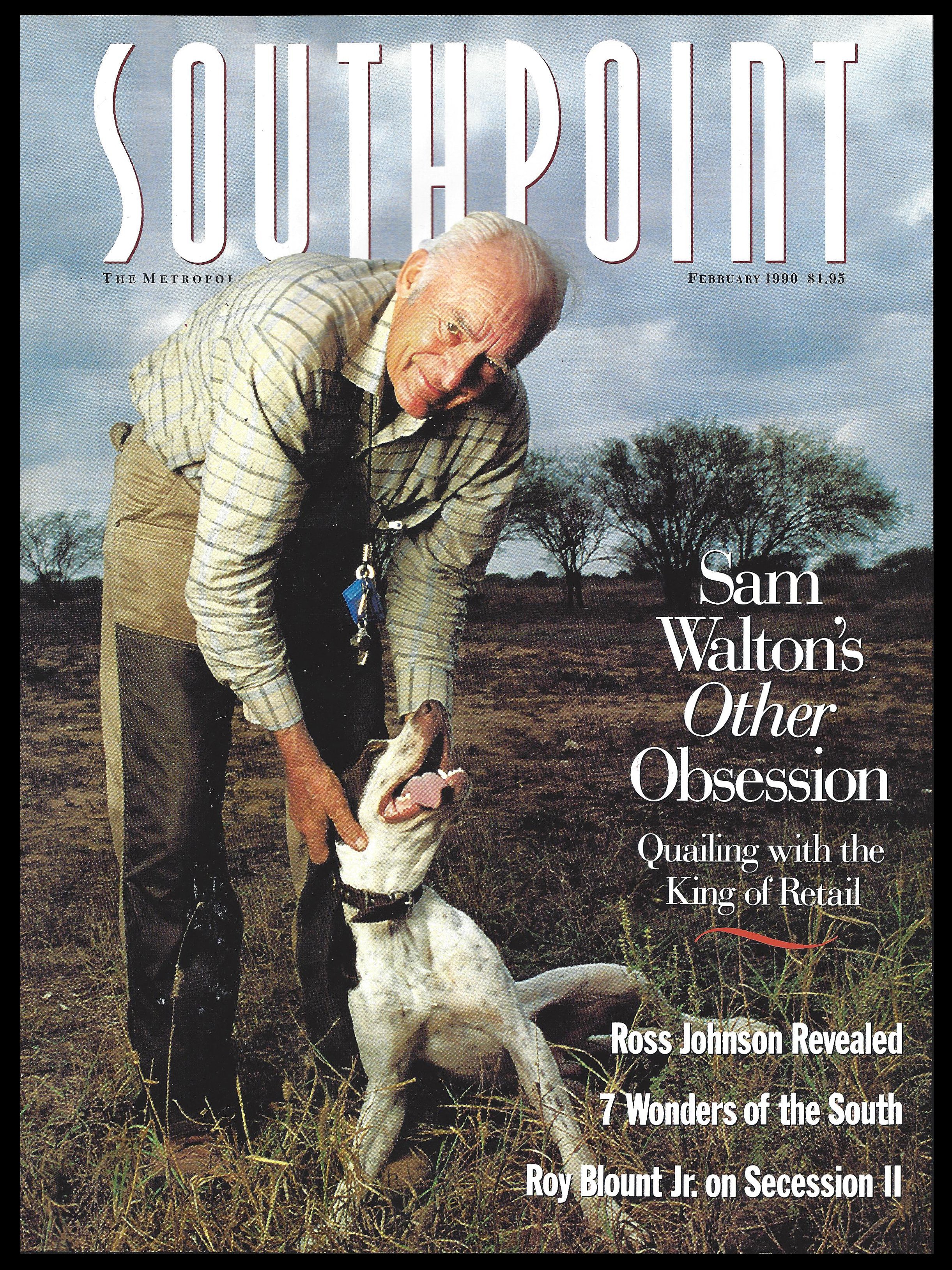

In 1988, with the backing of Fortune and Time Inc.’s Southern Progress subsidiary, Huey launched Southpoint, a “Texas Monthly-style” business magazine for the Southeast.

George Gendron: A lot of people—certainly this was the take among those of us who were outsiders—were stunned. Not so much that they were replacing Walter Kiechel after such a short period of time. I don’t think Walter had been in that job for more than a year, but that you seem like a newcomer to the stable.

John Huey: Yeah. Imagine how the internal people felt about it.

George Gendron: Tell me what the internal people felt.

John Huey: Well, I think they were just shocked, honestly. The way it went down, no one came down from the 34th floor. No one made the announcement. There was no memo. Walter and I just stood up in this room, and called everybody in.

And Walter and I, we had both been Navy officers and we weren’t hostile to each other. We weren’t great friends, but we weren’t enemies. And I think he’d been struggling on a number of levels. And he decided we were going to replicate the changing of the con on a naval ship, where you stand there and say, “You have the con. I stand relieved.”

“I stand ready to relieve you.”

And I’m like, “Really?”

We did that. And there was this conference room full of the whole staff and we did that. And they were just standing there looking at us like, “Is this a joke?”

George Gendron: And isn’t the tradition that the commander who’s being relieved just leaves, right?

John Huey: He was gone. And I think some people thought either that it was a joke or that I had a gun on him or something. I don’t know what they thought. I had a couple of days’ notice that it may be coming. And I had lined up a couple of people to support me in the beginning and they knew it was real. I don’t know what happened then. I think I told everybody to go back to their office and think about it and we’d talk about it in the morning or something.

But they were shocked. And some people were pleasantly surprised. Some people were horrified. And then, as Stanley Bing once wrote, “The only really important thing about a corporate succession is what does this mean for me?”

George Gendron: Of course. What was the very first significant thing you did as the new managing editor of Fortune?

John Huey: I don’t really know, but...

George Gendron: I heard a rumor that it was that you fired somebody.

John Huey: Yeah. That might have happened.

George Gendron: Wait, it “might have happened?” You were there!

John Huey: Yeah, but I’m an old guy and this was a long time ago. I think the first thing that I consciously did was—without conducting a major redesign—I got rid of the formatted headlines. Up until then all Fortune headlines had to fit a particular space. And I never thought in magazines that was a great idea. Some headlines ought to be playful and able to run on. But every headline cannot fit into the same space with the same size subhead throughout the magazine. I thought that had a numbing effect.

And so I couldn’t really redesign the magazine like, immediately or on the fly. So I worked with Margery Peters—we were together the whole time I was there—and she immediately knew what I was talking about. And we were able to write what I thought were more enticing headlines and that more reflected what was going on.

So that’s probably the first thing I did that sent an attitude change. And the second thing I did was thinking about cover stories in a different way. And I was looking to be more provocative. Fortune was a very solid, serious business magazine with a lot of talent and a pretty good readership. It wasn’t like a derelict property. I just thought it needed more than a refresh.

I was looking back at a couple of things just before I came here, just thumbing through some issues. And I saw one headline that I really liked that said, “From Gutenberg to Katzenberg: A Selective History of the Media Business.”

A headline like that would not have run. First of all, they wouldn’t have been running a “selective history of media business” and “From Gutenberg to Katzenberg” would not have fit. And they didn’t use stickers. All the dropout type, all the pull quotes were very formatted and there was a uniformity of the whole thing.

So that’s probably the first thing. And the second thing I did was I brought in a few people who I knew could deliver a few stories that I knew I was going to need.

George Gendron: People we know?

John Huey: Yeah, probably. I brought in Joe Nocera.

George Gendron: Everybody knows Joe.

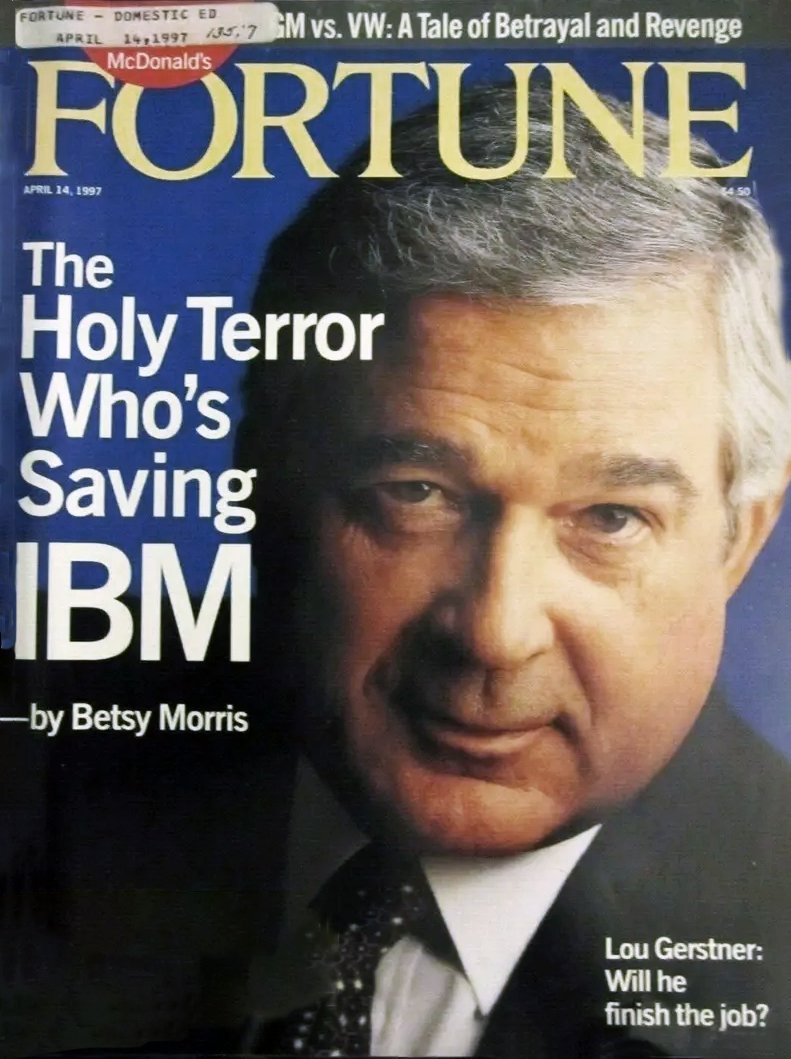

John Huey: Everybody knows Joe. I brought him in. I brought in some people from the Journal who were looking to spread their wings. Betsy Morris. Tim Smith, as an editor. He didn’t write a lot of bylined stories, but he had been working with me off and on for years. He was one of those editors who could just fix anything. You can hand him a shoebox full of a wire copy and say, "Give me three stories out of this.” And he just knew how to do it. So I brought him in because he was just a great prose artist.

George Gendron: So John, correct me if I’m wrong, but it sounds as if you did not have a detailed three year editorial map when you took over that job.

John Huey: I didn’t have a clue. I just had an instinct. I just had a feeling. I’ll give credit to Norm Pearlstein, whose only mandate to me was, “Just make it the best magazine in the world that happens to be about business.”

George Gendron: “Oh, that’s all.”

John Huey: Yeah, that’s it. So I thought that was pretty good. I had two things in mind when I was editing it. Three things. I had a whole bunch of great magazines that I had read growing up. All the ones that all the people on your podcast talk about: Harold Hayes’ Esquire, and Clay Felker’s New York, and Jann’s Rolling Stone. I wasn’t a big fan of The New Yorker at that time. I’m a big fan of [David] Remnick’s New Yorker, but that wasn’t much of an influence on me at that time.

“I didn’t have a clue. I just had an instinct, a feeling. My mandate was, ‘Just make it the best magazine in the world that happens to be about business.’”

George Gendron: I don’t think that was a big influence on most of us growing up, frankly.

John Huey: No, because there wasn’t a lot of magazine-making going on there. It was a lot of ruminating and some great journalism. But it wasn’t really magazine-making. So I had that in mind. I had “the best magazine in the world that happens to be about business.” And I had, I was a 45-year-old guy. I guess you’d say mid-career. I was pretty ambitious. I had some thwarted ambitions along the way. And some problems. I had not had a very linear life or career. And I thought, I’m gonna put out a magazine that I want to read.

And I have to say I wasn’t immune to the Spy influence either. I loved what those guys did. And I knew that I couldn’t do Spy. Although—hardly anyone remembers this—Tim Carvell, who is now the head writer for John Oliver, we had him do a thing in the front of Fortune that was a story about Graydon [Carter] and Kurt [Andersen]. Graydon was at Vanity Fair, and Kurt was at New York. And we did a whole thing about how Spy would have covered Graydon and Kurt. I don’t know why the hell we did that. I probably paid a price for it, but it was very funny, and our readers probably had no idea what we were doing.

By the way, that’s another good thing about a biweekly—you can do monthly quality, but if you really screw up, it’s only out there for two weeks. If you have a real stinko cover and it’s not going anywhere, at least pretty quickly you’re deep into the next one. Whereas a monthly, or— my friends at Garden & Gun, they only put out six issues a year! That’s intense. Because if you get a bad one of those—and they don’t get many bad ones, they have an incredible sell through and whatnot—but they have a lot of time to think about it too, six issues a year.

George Gendron: So on the one hand, you’re a newsman, as you say, when you look at your career prior to Fortune. And yet clearly you were influenced by magazines, and magazine sensibility, magazine-making—the whole craft—given the magazines you talk about.

John Huey: Yeah, I had a newspaper man’s body but inside I was a magazine man wanting to get out.

George Gendron: Well, you did get out, man.

John Huey: I got out. And I never looked back.

George Gendron: One of the things that interests me was that I remember hearing about the fact that you not only didn’t mind, but you seem to really enjoy being on the road and talking and sharing your passion and your vision for Fortune with advertisers. And I’m not being critical here, I’m just stating a fact—most of the prior editors of Fortune, editors of Forbes, Businessweek, Harvard Business Review, they were reluctant to do that. Some of them just flatly refused to do it. “Church and State” and stuff.

John Huey: I was an unabashed promoter of the magazine. And when I could, I was a willing partner with the advertising side. But there were limits. I never allowed the advertising people to tell me what to do or what to run. And by the way, there were some other editors at Time Inc. who shared this attribute with me who are pretty famous and more successful than anybody.

At Time Inc. in that era, if you weren’t trying to help the business be healthy, you were just committing suicide, because you didn’t have to advertise in these magazines. And on the side of getting the readers, that was a pretty pure play. But there was so much business advertising back then. At the same time, there were some pretty well-known stories about advertising that I ran off.

I cost the magazine a lot of money by doing a big profile of Lou Gerstner, who was the head of IBM at the time. And he not only pulled all of his advertising from the magazine, he refused to talk to us for as long as he remained there. And as long as I remained there, he wouldn’t talk to us.

And I remember Don Logan, who was the president of the company, took me out to lunch and I said, “So are you going to fire me for losing all this money?” Because it was millions of dollars.

And he said, “No. I’m not going to do anything to you unless you let this thing spill over into something and it costs Time all their IBM advertising. If that happens, then I’m gonna fire you.”

And I’m like, “Okay, we won’t let that happen.” I said, “Don’t let Lou know that. Or he’ll pull the ads from Time.”

So yes, I’m guilty of what you said, but I don’t think anyone ever accused me of or suspected me of selling out the franchise. I just was a promoter. Look, for all of the journalistic integrity and everything of Fortune when I got there, and as much as I liked Marshall Loeb and admired what he’d done in his career in the break he gave me, we were last. We were in last place. We were in third place. We were not mentioned in magazine chatter.

“In that era, if you weren’t trying to help the business be healthy, you were just committing suicide, because you didn’t have to advertise in these magazines.”

George Gendron: Businessweek, Forbes, and Fortune.

John Huey: Yeah. We were a third. A distant third. And we were sleepy. And we also weren’t particularly hot at all in just the whole world of magazines. And I thought that we had to do something about that. And that included promoting it, both commercially and editorially. And it also included, I can say, getting in some fights with some people.

And one of them was Jim Michaels of Forbes. He and I got in this real pissing match, and it was great. He was putting things up on the bulletin board down there. And I was saying things about them. And I ran into him at some event, like an ASME event or something, and I was a little nervous. He came over to me and hugged me. He said, “Isn’t this great?”

George Gendron: That’s Michaels alright.

John Huey: I said, “Yes, better than playing ping pong with nobody on the other side of the table.” He’s like, “Yeah. Keep it up.” And then he trashed me the next day. As soon as we started showing a little sign of life. He started attacking us. He said we were “the People magazine of business.” And we started saying Forbes was “a magazine for shut-ins” and whatever.

That may actually have been a Walter Kiechel line, to be honest. But in my era it went public. Jim and I were always slamming each other, but it turned out that we didn’t have any personal hostility.

George Gendron: I would be willing to bet if it were possible to quantify the PR value of that in the magazine community, you guys probably ended up breaking even. It started to get you talked about in a way that you hadn’t been before. It’s not just being number three in terms of the metrics. It’s that people weren’t talking about you. And now they started to.

John Huey: Yeah. I had some business-side colleagues who at first were very agitated by what was going on. But I had a couple who early on—the Fortune business manager was a woman named Eileen Naughton, who ended up becoming a big executive at Google and I think she owns upstate New York now—but for some reason she was very tolerant of what I was trying to do. And she was like, “Let him do it. Let him spend a little money trying to do it. Give him a little rein.”

George Gendron: What’s interesting listening to you talk, John, is you take over, maybe you think this is hyperbole, but a “hidebound” magazine—it really was ultra conservative and very predictable—at a time when you step back and look at the environment at large and all hell was breaking loose. The economy was undergoing this incredible transformation from an industrial economy to an entrepreneurial one. The emergence of the internet. We were all beginning to realize this was not insignificant. I’m not sure we really understood completely what the implications were, but all hell was breaking loose. You had magazines like Wired that launched in 1993, Fast Company in 1995, that changed how people thought about the visual identity of a business magazine. In a way, the timing couldn’t have been better.

John Huey: I had great luck. Having been the wrong guy, on the wrong sea, in the wrong weather before, I was the right guy, in the right weather, on the right water in this thing. The wind was so at my back because I want to do stories about Andy Grove. There’s a cover I just saw a minute ago, it says “Andy Grove wants to make your computer as important to you as your TV.” Wow! What a controversial idea in 1995. And it has a bubble coming out of his head that says, “Intel inside.”

And this was just something that Fortune would not have done. They would have covered Intel as a giant microprocessor company in Silicon Valley and looked at all its fundamentals and all. And this was just like, “Bill Gates, you better get ready, Andy Grove wants to do this” or whatnot.

So we cut it wide open on covering infotech and telecom. And you have to remember back then the advertising was so massive because—I don’t know how many people made PCs and how many people made laptops, the Toshibas, the Hitachis, the Okus. All these people were advertising in there. And there was Microsoft, there was Lotus, there were all these software companies, and there were a bunch of different telephone companies. Plus the old industrial companies were still advertising B2B.

And so what happened was we became the hot book by being on these topics. And I’m not saying that Businessweek didn’t do a great job of covering technology. They did. They always did. That’s where they came from and they understood it and they were probably more authoritative than we were.

But we were a lot more entertaining, and we were a lot more daring, and we got a lot of attention for it, and thus, we got a lot of support. And it got to the point where we had so many ad pages that we had to start inventing editorial. We were doing photo essays—which Fortune had done back in the thirties. But they were doing it because they didn’t have any advertising. We were doing it because we had to fill the pages.

George Gendron: So John, one of the—maybe the principal—characteristics of this period as we were moving through the ninety s, particularly toward the end of that decade, was just the extraordinary hype about the implications of the internet. But you never really bought into that hype at its extreme. And it was really tempting to do that. And it was very difficult to resist the temptation.

John Huey: We did some of it. But you’re right, we did not buy into the magical theory of thinking that you can make money forever. But we still had quite a few very smart—I’d say business intellectuals and fundamentalists who really believed in fundamentals of journalism and of Fortune magazine. To name one in particular: Carol Loomis.

George Gendron: I knew you were going to say that, of course.

John Huey: And everything we ran—if it bordered on being weird financially—it went through Carol’s filter. And she would say, “Yeah let me give you the counter argument for that.” Andy Serwer and I started calling her ‘Mom.’ We’d have a story, we’d look at it and he’d say, “Yeah. But what’s Mom gonna think?” And I said, “We’d better show it to Mom.” And then Mom would tell us what she thought.

I do think, if you wanted to accuse us of something, and if you wanted a mea culpa, it would not be an overhyping of the internet. But I do think that we helped enable—we both enabled and profited off of a little too much of the whole ‘shareholder value’/CEO-as-god phenomenon.

We probably had Jack Welch, Roberto Goizueta, and a few others on our cover more times than we should have. And we bought into the thing called EVA (Economic Value Added). We had some of that. I don’t know of anybody who didn’t, but we became very adept at it. And if I had to amend some editorial stance I’ve had in my life, I would say we could probably have been a little more skeptical than we were.

Not that they didn’t make their shareholders money and all, but I think we were a little too flip about the breaking of the social compact between corporate America and their other stakeholders. And that’s really come home to roost now. That’s a big issue today. And it’s not like I think I did it. But I wasn’t on the right side of history on that one, maybe.

George Gendron: I felt the same thing about idolizing entrepreneurs, which I think led to this obsession in the venture world. Not only that. Idolizing entrepreneurs, romanticizing them and their exploits, which I think led to this incredible imbalance in the venture world of allowing some entrepreneurs to just run roughshod over their companies, their shareholders, their employees—the “WeWork phenomenon” if you will. And I’m not arguing that we caused it. I don’t mean to sound arrogant about that, but I do wonder about that.

John Huey: It was just a different era. Today doing something that featured a bunch of CEOs and how heroic they are, you’d be put on a spit and roasted.

George Gendron: Yes, you would. Now, in thinking back to this conversation and listening to you talk, I have to ask the question, to what extent was your southern drawl a source of competitive advantage at Fortune and at Time Inc.?

John Huey: That’s a good question. You want me to answer that honestly?

George Gendron: Yeah. I do. I have my theory.

John Huey: I avoided New York for a long time. I worked for New York for most of my career. I went to work for the Wall Street Journal in 1975, and I worked for somebody from New York for the rest of the time. But I never lived there until really two years into I was editor of Fortune, and I still only lived there two years.

So even though I spent a lot of time in New York, I was not a New Yorker. And I didn’t have anything against New Yorkers, but I used to say in meetings, I’d ask questions like, “How many people in this room have ever been in a Walmart?” And the answer was usually, like, nobody. Or one guy. “Yeah, you sent me on that story.”

I said, “I’m not pushing Walmart here, but they are a pretty major factor in American business, and they are the largest employer in the country, and maybe you should just drop in sometime and see what the deal is.”

“They said Fortune was ‘the People magazine of business.’ So we started saying Forbes was ‘a magazine for shut-ins.’”

George Gendron: The only people I knew, including myself, who went to Walmart were people who were taking their kids to college. And you would take them shopping for their dorm room there.

John Huey: Exactly. Or you go on vacation and you go to Sam’s Club. But first of all, I was never particularly self conscious about the way I talk. It’s just the way I’ve always talked. I don’t talk like I’m from Illinois when I go to Illinois. I don’t talk like I’m from California. It’s just the way I’ve always talked.

But anyway, in terms of what you’re asking, I think what you’re really asking is at Time Inc.—which still had a little bit of the clenched-teeth, New England-WASP thing about when I arrived—was I underestimated because of it?

George Gendron: Yeah. I guess that’s what I’m getting at, to be frank.

John Huey: And I would say almost certainly. I think there’s a certain percentage of people who just assume you’re stupid if you have a Southern accent. And It’s pretty easy to figure out who they are. And so it just makes it easier.

But on the other hand, the most potent guy in all of Time Inc. at the time was Walter Isaacson. But he has that charming New Orleans accent, and everybody knew he wasn’t stupid. And I don’t think he thought I was stupid. Nor, certainly, did I think he was stupid. But there were people who just thought, “This guy shouldn’t be here.” And also Don Logan was the CEO and he had a Southern accent and they knew how smart he was.

But I know there were people who thought I talked funny. And I know they used to have contests imitating me. I know Andy Serwer was regarded as the best imitator of me. And I never heard it, but I did make him editor.

George Gendron: I think of it more metaphorically. From everything I’ve ever heard, including from some writers who left Inc. and went over and worked at Fortune, you always seemed to have the persona of an outsider.

John Huey: Yeah, that’s because I was. I never called it the outsider. I used to tell people I had an “American” point of view. I was like, “I live in America. And that’s not always a great thing, but I can tell you what they’re thinking out there. It’s not what you’re thinking.”

Personally, I probably think more like people in New York and New England. But I’m around these people. And I have friends. So yeah, I was an outsider at Time Inc. I guess you could say that’s a little disingenuous, like how outside can you be if you’re the editor-in-chief? But still, I always felt a little...

George Gendron: No, you can still be the outsider. Think about what you said about the fact that you go to take over Fortune and you really don’t know anything about business. I show up at Inc. Magazine and I’m in a story meeting—I was the number two guy there, not the editor in chief yet—and they’re talking about a company, I forget who it was, maybe it was Apple preparing for their IPO. And so I said to the guy sitting next to me, Bob Mamus, a brilliant writer about Wall Street, “What’s an IPO?” And he said to me, “If you want a future here, lower your voice.”

John Huey: Yeah, I had a little bit of that. By the time I got to Fortune, I knew something about business because I’d been at the Wall Street Journal. But I was never a specialist at the Wall Street Journal. I didn’t follow the markets or anything like that.

“Today, doing something that featured a bunch of CEOs and how heroic they are, you’d be put on a spit and roasted.”

George Gendron: We have to talk about, going back to Fortune for a second, we have to go back and talk about the fact that in the thirties, I think many magazine people would agree, Fortune may well have been the best magazine ever, period. I’m not just talking about business magazines, I’m talking about everything from their covers to the writers they brought in, the way they covered business, eventually the photographers they brought in. And so I’m curious, how much time did you spend looking back at that, and what effect did it have on you? And in particular, you bring Walter Bernard in after you’ve been the managing editor of Fortune for about a year to do a redesign. Did you and Walter go back and revisit that magazine and the incredible visual legacy that it had?

John Huey: Yeah, they were all there and I could just pull them off the shelf and look at them. And I had covers of them hanging all over the place all the time because they’re great art. I mean you got Legere doing a cover. And I was aware of them, and I knew that they had Archibald MacLeish, and James Agee, and John McDonald. I knew all that and I went back and read some of it. And I read [Henry] Luce’s prospectus. Time Inc. had all those great files. You could read every memo that Luce ever sent anybody.

George Gendron: That must have been amazing.

John Huey: Including expense account questioning, which I didn’t think anybody ever did at Time Inc. But they did, apparently. I was aware of it, but I was also aware that you couldn’t recreate that. And you couldn’t really mimic it. But I thought what it did argue for was a really high level of photography.

And we had Michelle McNally, who went on to be the picture editor at The New York Times for years and knew everybody and everything. We pulled into the archive and we’d do one old picture per issue as the end paper. We’d find some great Margaret Bourke White or Walker Evans. And we would sometimes sponsor an exhibit at the ICP of Walker Evans. We’d loan out some of the pictures that we owned.

And I became very interested in all that. And I tried to do little homages to it here and there. But I just thought it meant we had to be a handsome magazine, and we had to be not afraid of having some heavyweights weigh in and write. We had some unusual things—Andy Grove got prostate cancer and it was a secret. Nobody knew it. And he came to me and said, “I want to tell my story about how I’ve managed my own care and what I learned and the science. And I want to do a big story for Fortune about my prostate cancer. And I don’t want anybody to know.” So we would do that. And it was a great story.

George Gendron: Yeah, it was a great story.

John Huey: And we got Stanley Bing writing his “While You Were Out” column, which the old Fortune never would have done. And Paul Krugman was our economics columnist, or one of our economics columnists. And there are a lot of people who went on to do a lot of things who came through there.

If you wanted to sit down with a little index card and talk about all the great writers and thinkers that the Fortune of our era had, you could do it. It’s just that people don’t do that anymore, nor should they.

George Gendron: No, but I guess what I was getting at was—I was thinking if I had been in your shoes, what effect would it have had to go back and look at those magazines, those issues from the thirties, and certainly visually, but also editorially, I think what it might’ve done is given me permission.

John Huey: Yeah. Yeah. That and Carol Loomis staring down over me all the time kept me in the right place. It gave me permission and respect. Let’s don’t turn this magazine into something tatty. This magazine has history. Oh! I got this letter one day from John Kenneth Galbraith and he says, “Fifty years ago,” or whatever, “I was hired as a contributor of Fortune magazine by Hedley Donovan. And I wrote there for a number of years. And as a result, he gave me a free subscription to Fortune. And I have read it ever since. Recently, the magazines quit arriving. I’m wondering if you intend to honor Mr. Donovan’s pledge to me.”

George Gendron: Are you serious? I hope you have that framed and hanging on your wall, man.

John Huey: I don’t, but I hope I have it. But I was like, “Yes, we’ll do that. Sure.” And I think he was in his 90s at the time, but I remember thinking at the time, “Okay. There are people who used to read the old Fortune who are still reading this, but there are even people who used to write for it who are still reading! This is a little scary!

George Gendron: And they want to know, “Why’d you drop me from the comp list?”

John Huey: Yeah. Is it something I said? No, we’ll get you back on there.

George Gendron: John, look, here you are, you’re the editor in chief of Time Inc. You’ve got 155 titles. It is a decade of the most serious challenges that magazines had faced. But one of them is more than a magazine title. It’s an American institution. We grew up with it in our homes. It actually framed how we thought about what was happening both in this country and internationally. And, of course, I’m talking about Time magazine. And I want to know a little bit about how you dealt with the weight of that responsibility.

John Huey: As you noted, my tenure as editor in chief of Time Inc., did not coincide with the heyday of the magazine business—either economically or in terms of attention in the media. It was a tumultuous period. Weekly magazines were struggling to remain relevant. We were all trying to transition to digital properties that mattered.

And we had a lot of businesses and a lot of magazines, but one of them always stood out in terms of the gravity of it to the company and to its history. Time’s name was on the building. It had been around since 1923. It had a legacy, an international reach, it had a worldwide appeal, it had access, it had everything. Except it needed to constantly reinvent itself to stay in the game.

And I had not come from weekly magazines, but I had been an editorial director, the number two editorial executive of the company for five years before, and I had worked with Time, so I was very familiar with it. And the editor of Time had done a terrific job of navigating through all this up until then.

Jim Kelly had been at the top, or second to the top, for over a decade. And at some point I decided that the whole thing really needed more than a refresh. It just needed a rethink. And I thought that he and his team had been at it twice as long as I was at the helm of Fortune. And I let it be known and not in any kind of rushed way that I was looking to make a change.

Time was a very leaky place, to say the least. Within like, I don’t know, hours, everyone in the media business knew. And I was not leaking this. I really wanted to do this stealthily, which was like, looking back on it, a joke.

But everyone became aware that I was looking for an editor of Time. And I thought this was probably going to be one of the biggest decisions that I had to make. And I took it very seriously. And so I just started going around talking to everyone who had an opinion or who had a thought about it. And there were quite a few.

And it had some amusing sidelines to it. I had one casual conversation with an editor at Newsweek who is now a good friend of mine, and very famous Pulitzer Prize-winning historian, and within a couple of days of that conversation, he suddenly became editor of Newsweek.

So I realized this is, like, radioactive looking for an editor of Time. And then I got a call from Rich Plepler, the renowned and fabulous head of HBO, who everybody loved. And Richard wanted to see me in my office. And I thought, “Oh my God, this is ‘Jesus would like to see you in the choir room.’” I never thought that I would see Rich Plepler in my office.

So he came over, and it turned out that he was lobbying for his candidate for Time—one Tina Brown. Now, this is the beginning of what I call my “Cinderella Period.” I certainly knew who Tina Brown was. Tina Brown didn’t know who I was, I’m sure, or she didn’t care. But I became, for a brief moment, one of her best friends. I was invited to a glam dinner at her Sutton Place apartment with her and Harry [Evans]. Various people would call me, I can’t even remember. It was a serious lobbying effort.

And, of course, I really admired what she did bringing Vanity Fair back from nowhere, and her brilliant run at The New Yorker. I pretty quickly decided I did not see her as someone who was going to want to hear my suggestions or the suggestions of the people who I worked for. And then she wrote a long treatise on what would be her Time, which I still have today.

I guess I could put it out on eBay, maybe, but I’m not going to. Anyway, it was grandiose and glamorous. And then, of course, when it became clear that I had not picked her, I ceased to be in her contacts. And I’m sure that every time I’ve seen her since then, she has no idea who I am. And if she did, wouldn’t speak to me.

George Gendron: So no more invitations to Sutton Place, I take it?

John Huey: No more. I never went back. Although, Harry sometimes needed to get in the archives, so I would hear from him. But, look, they were brilliant people, but they weren’t right for Time at the moment. So I spent a lot of time talking to people inside and outside, and I became very interested in one candidate who was a guy—I did manage to actually do this stealthily—I wanted somebody who understood the institution but wasn’t at the institution.

I wanted someone who had the kind of gravitas that Time expects. And there was a guy heading up something called the Constitution Center in Philadelphia, named Rick Stengel. A Rhodes Scholar, the former Nation editor of Time, former digital editor of Time, or maybe he was back of the book editor. But he had several positions, and he’d left Time a couple of times.

“One of the reasons I may have appeared to not care what other people thought at Time Inc. is because a lot of people were pretty clear in not really wishing me success.”

George Gendron: I think he was the editor of Time.com.

John Huey: Yes, he edited Time.com for a while, you’re right. And then he edited whatever they call the Culture section. But he had left a couple of times and he was gone. And I approached him—he didn’t approach me—and asked him if he would be interested in it. And Rick and I met several times, usually in Washington in a hotel suite, and he wrote the most compelling, comprehensive pitch for what he would do with Time. And it really just won me over immediately. And then I had to figure out if I could work with him and I felt good about it.

So when I announced him, I think everyone was shocked because they all knew him. They were not expecting him. It was hard to question his credentials. But he really did, I thought, an extraordinary job of re-framing Time.

The design—I think you and I have talked about this—Luke Hayman worked very hard on the redesign. I thought it was a brilliant redesign. They kept the tradition of the photography. I thought Jim had done a great job with excellent photography.

But Time just took on a new life to me. And the whole Person of the Year, and all the franchises, Rick understood how to use them. He had a political sensibility. And I was very comfortable. There were a lot of people who weren’t comfortable. There are people there who I’d known my whole career who haven’t spoken to me since. It was not something that made me popular.

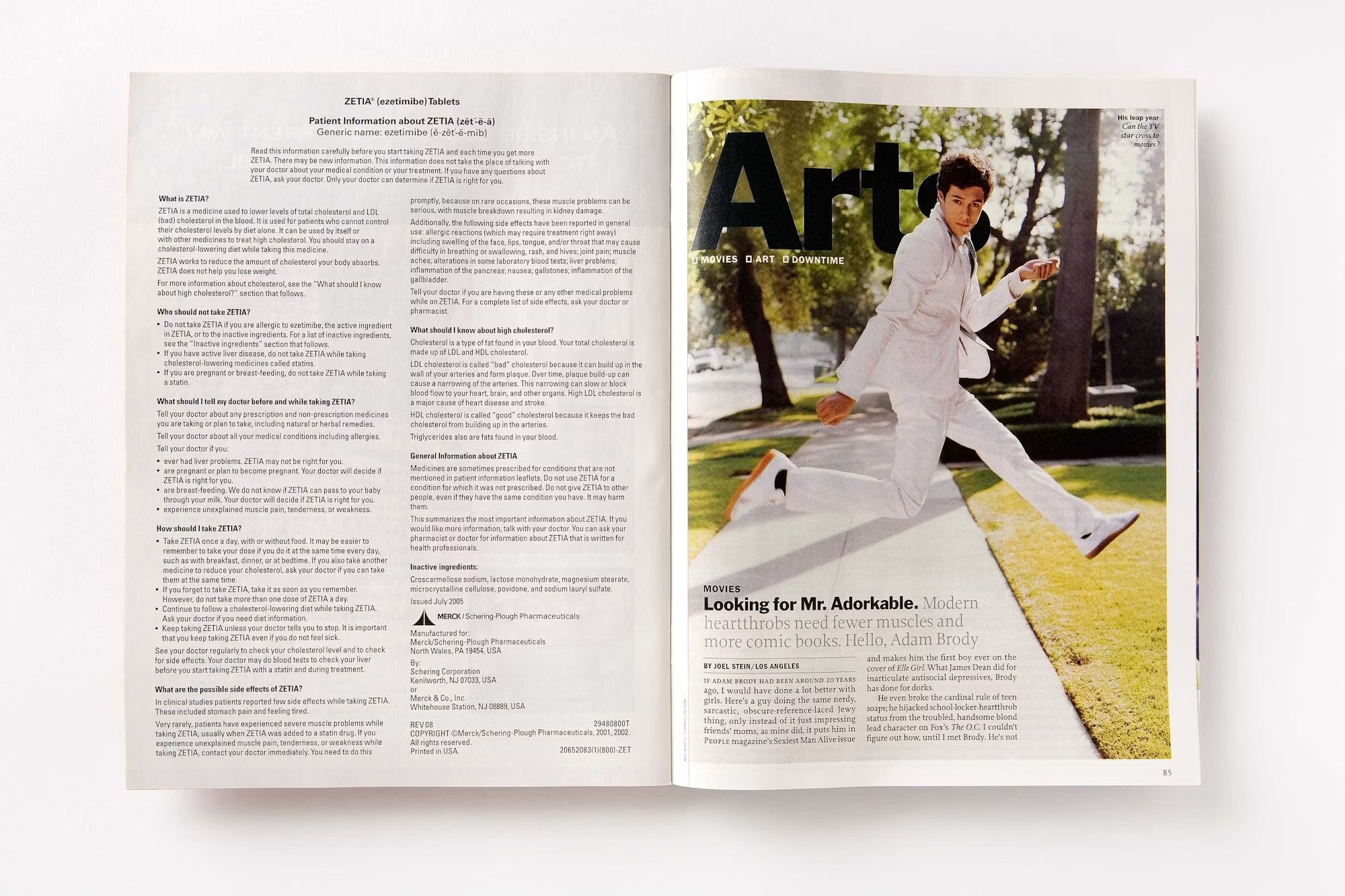

George Gendron: I think we said earlier, I love that redesign. I just thought Luke and Paula Scher, who I think was also involved in it—man, talk about two of the great graphic designers around. They just did a brilliant job. That was the first thing. The second thing was that I thought that Stengel did, and I’m sure that he did it in consultation with you, something that was really smart, which is that you couldn’t afford any longer to have these unbelievably labor-intensive, very staff-intensive news magazines. And so instead, I think what you guys started to do is showcase these columnists that provided a kind of interesting, idiosyncratic voice on the news. And you had a real significant roster of those people, and you played them up. Typographically, you played them up. They became such an incredibly important part of the signature of Time at that point.

John Huey: Yeah, I think you’re right about that. And I think that one of Rick’s skills was that he was a ringmaster. He was very good at keeping the conversation going—and making it a public conversation. We had Joe Klein, Nancy Gibbs, Fareed Zakaria, Michael Kinsley, Bill Kristol. Rick would hire somebody—I’d be on the Acela with him to Washington and he’d see somebody on the train and hire them as a contributor!

George Gendron: You’ve got a captive audience there, man.

John Huey: There they are. But I remember this one story about Time. First of all, the access. We went to Moscow and we interviewed Putin. But I remember there was a particular moment, and I don’t remember the year, but it was right after Jay Carney, who went on to become [Barack] Obama’s press secretary, had just been made Washington Bureau Chief.

And it hit at a time when we did not have a lot of money. And we were not doing our usual party mode unless it had something to do with revenue, like the Time 100 dinner. The Time 100 dinner was an extraordinary event. We would have people as entertainment like Britney Spears, or Sting, or Prince. And we’d have guests that included everybody from Sarah Palin, to Carlos Slim, to...

In 2007, Huey hired Pentagram’s Luke Hayman to give Time its first major redesign since Walter Bernard’s tune up in the seventies.

George Gendron: Yeah, didn’t we all, John? Come on.

John Huey: Yeah. It was a very glam thing. But the truth is we didn’t have a lot of money for internal events, so Jay Carney gets made Washington Bureau Chief, which is a big deal, but we can’t really afford a party. So we had a party at Jay Carney’s house, which is a nice house. Usually in the past, a Time party would have been on a rooftop or whatever.

And at this party—I’ll never forget—it was the most elephant-bump party in somebody’s house—Hillary [Clinton] came in with her briefcase, and Karl Rove was standing there in the hall. John Kerry comes by and says, “Hello, Karl.” And Karl says, “Hello, Senator.” It was like Seinfeld.

And then Obama comes in reeking of cigarettes. All the anchor people—we’re all crowded in this not grand, but respectable house. And I thought, Man, Time still has the draw. And nothing I saw of Time impressed me more than that. Everybody who was anybody in Washington was there.

And Time was one of the titles where the editor-in-chief really did have to put on the pads and the face mask and fight off the banshees, because people wanted to influence Time in a lot of ways.

I remember one time I got a call from Wayne LaPierre, the head of the NRA. And my assistant says, “Wayne LaPierre is on the line.” I thought, Oh great. And Wayne gets on the line and says, “You ran this cover on Time with George Bush as a little bitty person under a cowboy hat. If you ever run anything like that again, we’re gonna pull all our gun ads from Field & Stream and Outdoor Life.”

And I said, “Wayne, I had always been led to believe you were a really sophisticated guy. You really think that’s how the world works? Honestly, I don’t care if you pull all your gun ads from Field & Stream and Outdoor Life. The money they make you could put in a sock. And where else are you going to advertise anyway, by the way? And nobody’s going to call us up and tell us what we can and can’t do with Time magazine.”

George Gendron: We’ll move our gun ads right over to Condé Nast!

John Huey: Yeah. They’ll love it.

George Gendron: They got a lot of our kind of titles.

John Huey: GQ has a lot of holsters. People would assume that I could do things as editor-in-chief that they wanted done that I would never have done or had any intention of doing because I was not a micromanager of these magazines.

I picked these editors for better or worse. I pretty much stepped back. We collaborated, I shared my opinions, but I can only remember one time when I ordered up a cover of People. I got in an argument with somebody who was standing in for the editor and they wanted to put something on the cover and Steve Irwin, the crocodile guy, got killed by a stingray—stabbed him in the heart while he was underwater.

And I said, “I’m sorry, but this has to go on the cover.” And it was, except for the Sexiest Man Alive and other franchises, it was the best-selling cover of the year. So that was my one trophy from People magazine. Otherwise I was an idiot about People magazine because I didn’t know who half the celebrities were. And my wife would say, “I can’t believe you’re in charge of this magazine. You don’t know who that is?”

George Gendron: John, I got to ask you a question talking about hands-off. So here you are, you’re the editor-in-chief. On the other hand, you’re really not the editor of any magazine the way you were when you were running Fortune. What did you miss the most?

John Huey: I didn’t like that. I didn’t like anything about it. When I look back on it all, for sure, the best part of my career—I was at Time Inc. for 24 years—and for sure the best part of it was the five or six years that I spent editing Fortune.

George Gendron: What did you like the best about it?

John Huey: About editing Fortune?

George Gendron: Yeah, in terms of the day to day.

John Huey: Oh, because it’s like what you would like about being the director of a film or the director of a play. You were in charge of the production. And it was always moving and you had to always be thinking about it. And you never looked back. By the time we got a cover on the newsstand, I never knew what it was. I was so engrossed in the next one. And putting the teams together, putting the people together and having things work out in unexpected ways. I just thought it was exciting, and fun, and intense, and full of adrenaline. It was great.

After that it became—you do a lot of standing with your hands on your hips watching other people have fun. And you do a lot of getting called into unpleasant meetings with lawyers, and CFOs, and all that. And then, of course, toward the end we ran through a few CEOs and that was a bizarre period. So none of that adds up to anything like, “Hey, leave me alone. I’ve got to put this magazine out.”

“I had a newspaper man’s body but inside I was a magazine man wanting to get out.”

George Gendron: What did you refuse to delegate when it came to the editorial operations of Fortune?

John Huey: I generally either wrote, or oversaw the writing of, or edited all the cover language. I sat through all the major picture selection. I personally assigned most of the bigger stories. I would delegate some of that, but when I had one magazine, I had to pretty much read everything before it went to press. After I had so many magazines, I couldn’t do that. And I had people like Dan Okrent, and at one point Jim Kelly as well, reading things and flagging me on, “I think you want to read this one.” Or “I think you better read that.” Or whatever.

But with Fortune, I didn’t want any surprises because I always felt like you’re just one big mistake away from sinking yourself. And I’ve been surprised at some of the journalism scandals of the last few years where major editors of major publications have said, “Oh I didn’t read that before it was printed.”

And I’m like, “What were you doing? What were you reading?”

So I didn’t delegate any of that. And I was not one to delegate a whole lot of hiring and firing. There probably were some people who were let go who I didn’t let go personally, but mostly I did it myself. I didn’t enjoy it. We didn’t do it by email or anything.

George Gendron: I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve been talking to people who ended up with a promotion where they went from running a magazine to running a group. And they all said the exact same thing, “I come in often on days and think, All I did was I got to watch the people who are having all the fun now.”

John Huey: My mother lived to be 101. And when she was about 96, she called me up in New York one day and said, “Johnny, I’ve been thinking about it. What exactly does…”— she prefaces by saying the economy seems to be in trouble and blah, blah, blah—“I’ve been thinking about it. What exactly does an editor in chief do?”

I said, “I don’t know, Mom. Not much, really.”

And then she said, “Don’t you think it’s about time you thought about maybe looking into getting a government job?”

George Gendron: What was it like to preside over the two magazines that were the national magazines of their kind for decades—Time and Life—during a period when the magazine industry was just under siege?

John Huey: You should include Sports Illustrated in that because by then Life was in its third incarnation. So it wasn’t a big issue. Sports Illustrated still made a lot of money and was very popular and emblematic and was a huge thing. And, of course, Time was as well. And Walter [Isaacson] had put Time on tremendous footing.

Time and Fortune both made a lot of money in the early 2000s. They both were very profitable. It would shock people to know how profitable they were. However, what you have to realize about that company at the time, People magazine made eight, nine times more than the two of them put together. People was the engine for the company. And when I took over the job, I asked Don Logan if he had any words of wisdom or advice for me, and he said, “Yes. Don’t fuck up People.”

And to answer your question, that job struck me as a whole different job. And I had this little mantra that I would deliver over and over to the point where I’m sure anyone who worked there was sick of hearing it, but I viewed the job as having three components. And one of them was to make sure that these magazines, all of them, were the best editorial product that they could be in their class—given their economic realities and what was going on—that they would be as good a product, as well-written, as well-edited as they could be. That was Job One.

Job Two was to protect the magazine’s editorial staffs from outside interference. And there was plenty of outside interference. There was the government, there were advertisers—that company was not an uncomplicated company. When I started, it was Time. And then it became Time Warner, and then it became Time Warner with Turner, and then it became AOL Time Warner, and then it became Time Warner again.

But anyway, Job Three, which also kept me up at nights—and this might surprise you—was when you have 2,500 journalists working for you, you’ve got to figure that not every one of them is necessarily pure as the driven snow. So I had to protect the franchises from outside interference, and also from any possible internal treachery. So there was a lot to keep your eye on.

George Gendron: What do you mean by internal treachery?

John Huey: Just think of the various journalism scandals that you can remember over your career.

George Gendron: So you’re talking about plagiarism.

John Huey: Yeah, plagiarism. People making up sources. People being in bed with special interests. People short-selling. Whatever. People are people. And most of the people at Time Inc. were really stand-up, straight-up folks. But we had a lot of people. So there was that. There were some close calls. I didn’t have any disasters that you or anybody else would know about, but there were some things that came pretty close.

George Gendron: I know exactly what you’re talking about. So in closing, we have to honor a tradition here, which we call the Billion-Dollar Question. And that is that Laurene Powell Jobs calls you with an offer. You just can’t refuse. Money is no object. She says, “Look, I followed your magazine career and I would love to see another John Huey magazine. And so I’m going to give you a blank check. Money is no object, but you have to use the money, as much as you want, to create and launch a print magazine.” What would you start?

John Huey: Do I have to eventually turn it into a profitable enterprise or can I just run through a billion dollars?

George Gendron: You can run through a billion dollars because, for someone with that kind of net worth, in order for this to even be worth her time having the conversation, you’ve got to really rack up some serious losses here. That’s why we call it the Billion-Dollar Question.

John Huey: Yeah. Okay. The Billion-Dollar Question. I love the way she spent her money there, so I would be comfortable spending her money. That would be good. I think I would go, not for a niche magazine, a genre magazine, because I became a captive of that at Time Inc. It’s like everything has to be—“This is for a young woman,” “This is for middle-aged men,” “This is for guys who have guns.” Whatever. I wouldn’t go that way.

I’d go back to one of the most successful magazines in history and I would relaunch, for the fourth time, Life magazine. I don’t know how I would distribute it. I don’t know how it would get income, but it would be large-format. It would have lush photography—a lot of Life in the early days was black and white, I probably wouldn’t do that.

But it would be something that could sit around the house, and your whole family could look at it. And it would be just sexy enough to where if you’re me and you’re, like, a 12-year-old kid and Life is on the coffee table, you’re interested in some of the covers. Elizabeth Taylor, Marilyn Monroe, or whatnot.

But it also had really good writing that covered the big issues of the day. It had Ernest Hemingway writing The Old Man and the Sea. It had Winston Churchill’s draft of his memoirs. And it wouldn’t have anything really long in it. And it would be timely. And then it would feed people off into their social media or into their Substack, or whatever, where you could read more.

But it would just be a thing that landed in your house and was beautiful and you could thumb through it. It wouldn’t be about business, it wouldn’t be about politics, it wouldn’t be about sex, it wouldn’t be about the movies, it wouldn’t be Hollywood. It would be about all of that. It would be about life. How is that for a counterintuitive idea for spending a billion dollars? And Patrick has to design it.

Patrick Mitchell: I think, to answer the question about distribution, it would be in bathrooms worldwide.

John Huey: Yeah. There you go. That’s what Jeff Goldblum said about People magazine in The Big Chill, that every article was written to have the length of a good stay in the bathroom. And so that would be just right. And People came out of the loins of Life. Life died and Dick Stolley started People. But a billion dollars, let’s go for it!

George Gendron: “People came out of the loins of Life.” What a way to end a podcast, John!

John Huey: There you go. You gotta have a kicker.

Follow John Huey on Twitter @johnwhuey. Special thanks to Carol Farrah Norton.

More from Magazeum