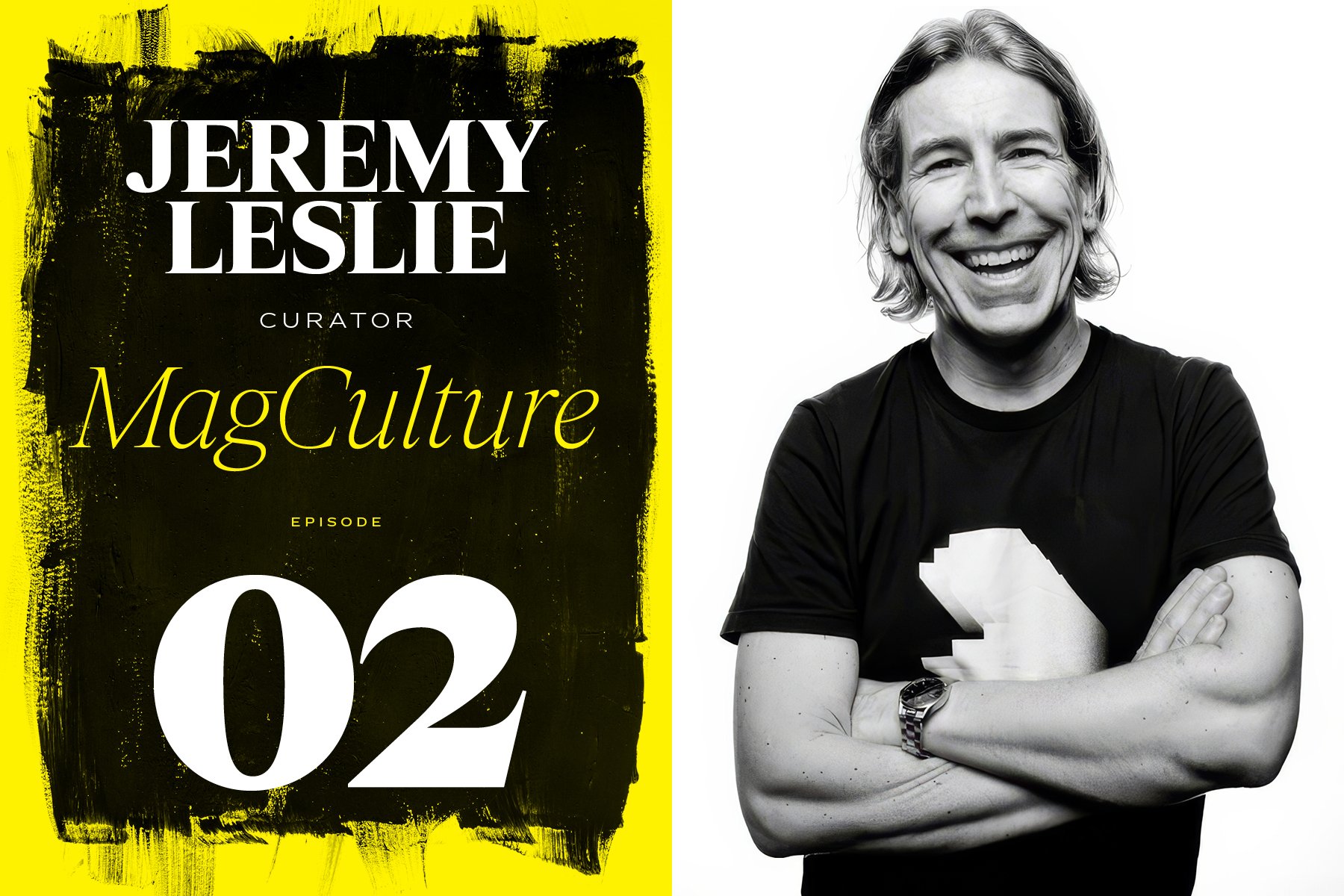

My Effing Career

A conversation with designer John Korpics (ESPN, Esquire, HBR, more. Lots more)

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT MOUNTAIN GAZETTE AND COMMERCIAL TYPE

When you’re born in a town called Media, your career path is pretty much preordained. It has to be, right?

And when you end up leading the design teams at blue-chip magazine brands at Condé Nast, Hearst, and Time Inc., the prophecy is then fully realized. (Yes, I just watched Dune). But the journey in between is not as cushy as you might imagine.

Since the age of 10, with his mother’s admonition—“you need to have a job”—ringing in his ears, designer John Korpics has found work doing all of the following: he’s bent sheetwork into duct metal, cleaned windows at factories, he was a fitness instructor, he had a paper route. He worked his way through college in food service—cleaning chicken, wiping counters, serving meals.

When you hear the title creative director, you’d be forgiven if your mind painted a picture. You know the type—the thoroughbred who studied at Parsons or SVA, apprenticed under Tibor Kalman or Roger Black, who gets included on some “30 Under 30” list. That’s not John Korpics. He’s worked hard to get where he’s gotten. Korpics will tell you that. He told me that:

“I always felt like I was the Pete Rose of magazine designers. I hustle, I work hard, I crank stuff out. Occasionally I get one and I hit one out of the park, but there are people in this industry that I think are truly giants. And I’ve never quite thought of the work I did in that league, but I am always inspired by them.”

And then, one day, he was 24 and hired to art direct his first magazine. And then another. And another. And like many of us, some of his jobs haven’t worked out. And when that happens, what does Korpics do? He gets himself another job. Like the time he became a Manhattan bike messenger after one particularly messy ending.

“I delivered mops to the 79th Street Boat Basin. I delivered products to Late Night with Jimmy Fallon. I delivered clothes from a studio to Vogue. I delivered a lot of lunches. And I actually really enjoyed it. Although I will say it’s not possible to make a living doing that. On my best day ever, I think I made about $90.”

It takes a special person to survive in the magazine business. Forty years in, Korpics is still at it. He’s focused on the big picture now—brands, systems, pixels—at Harvard Business Review, the 102-year-old publishing wing of the 116-year-old Harvard Business School.

Yes, mom, he’s still got a job. Let’s meet John.

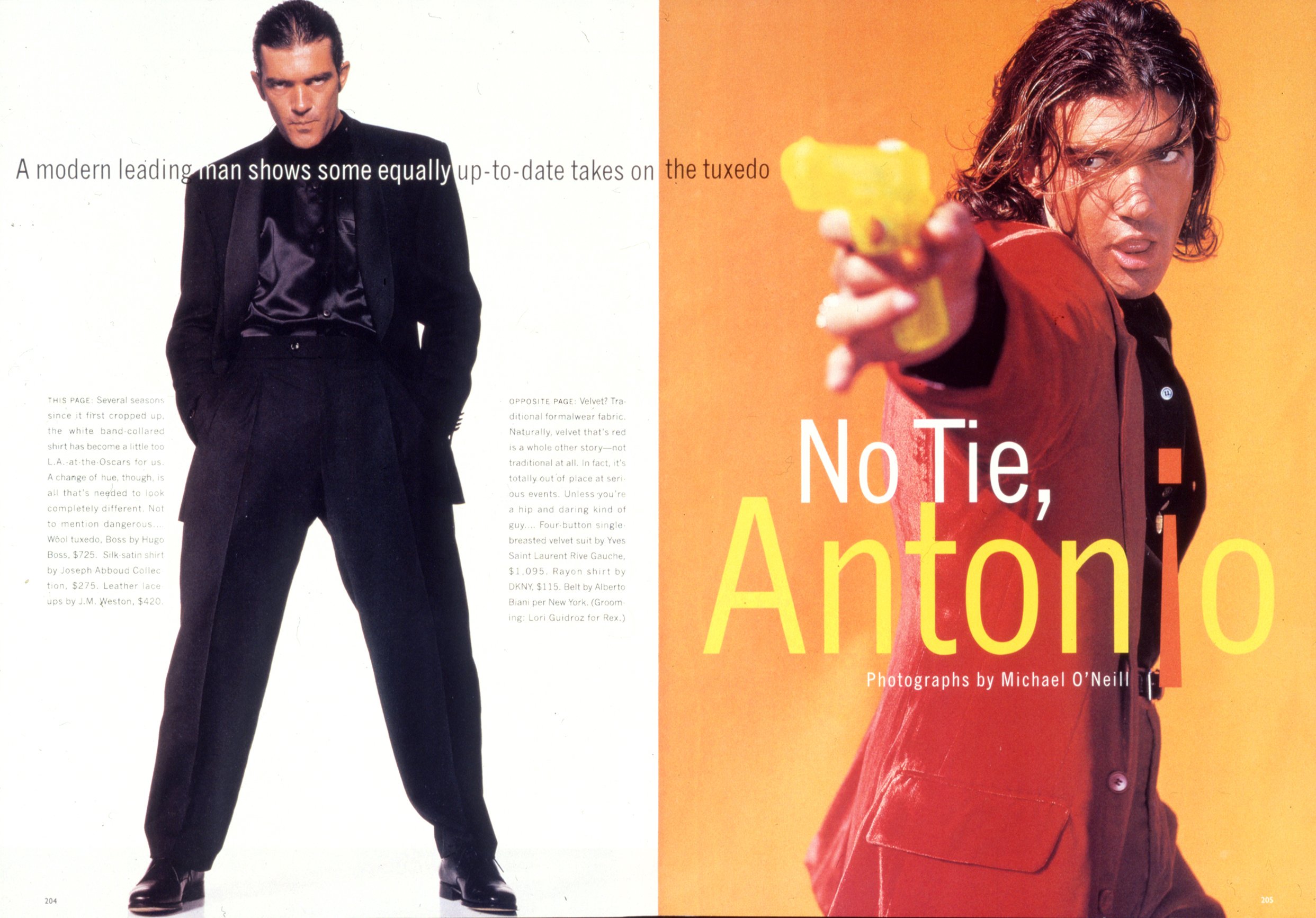

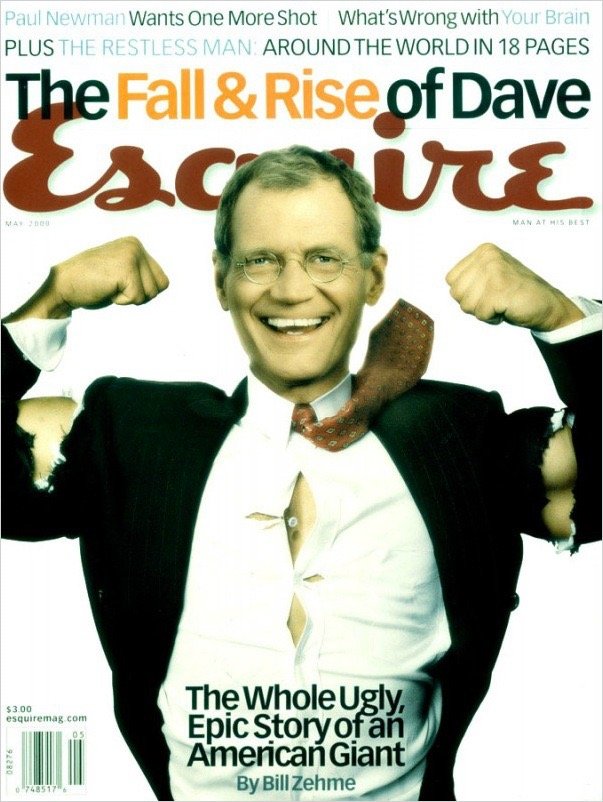

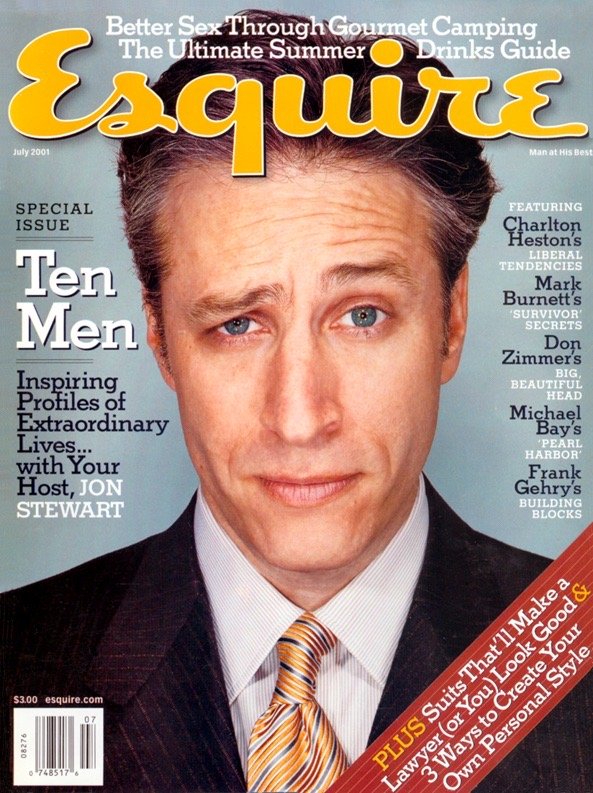

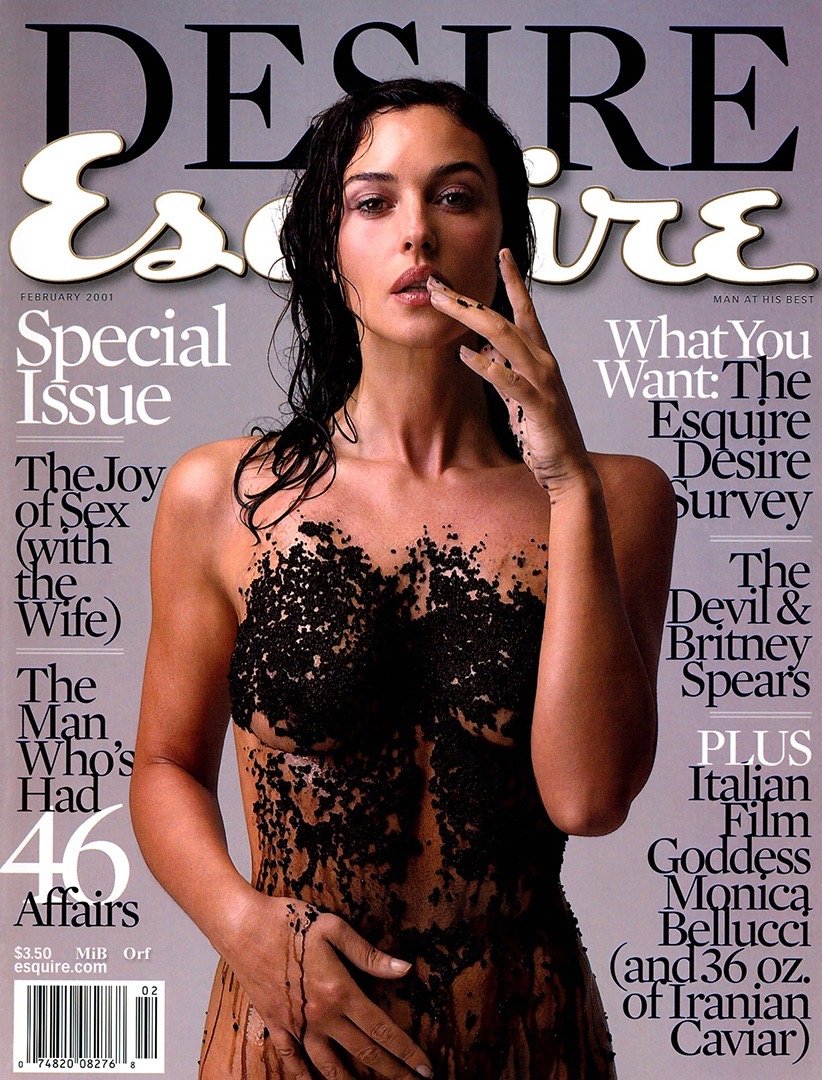

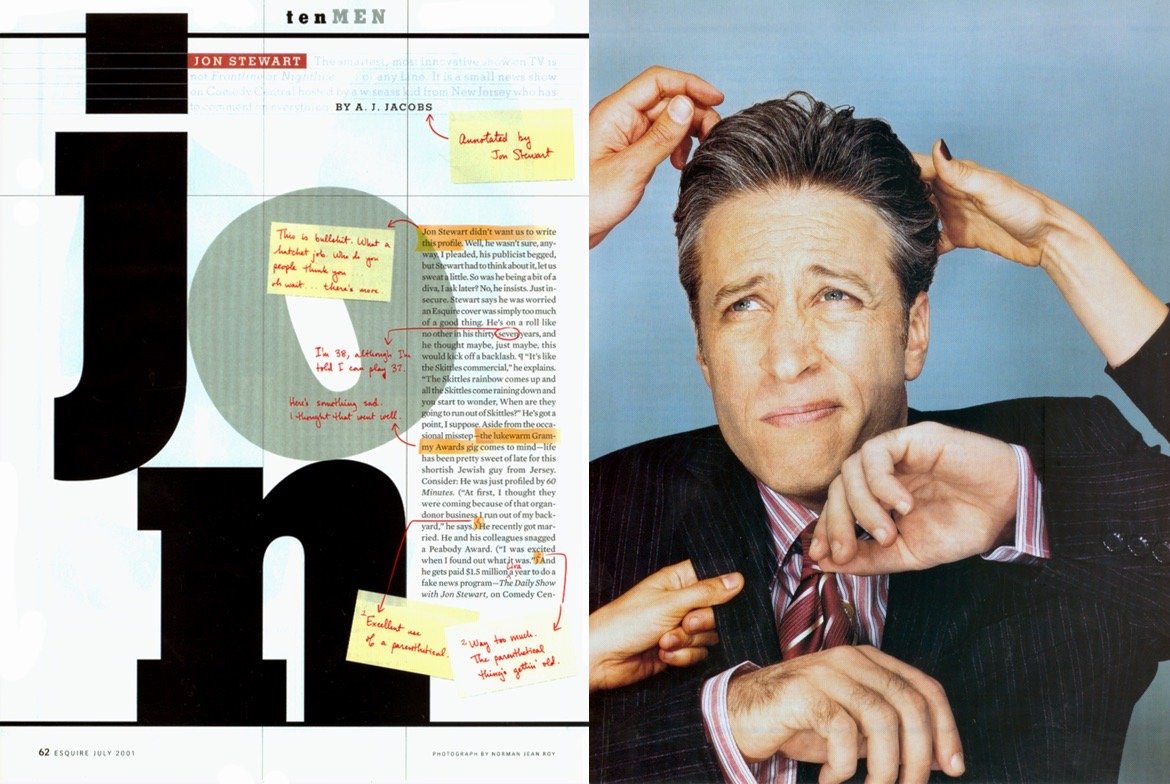

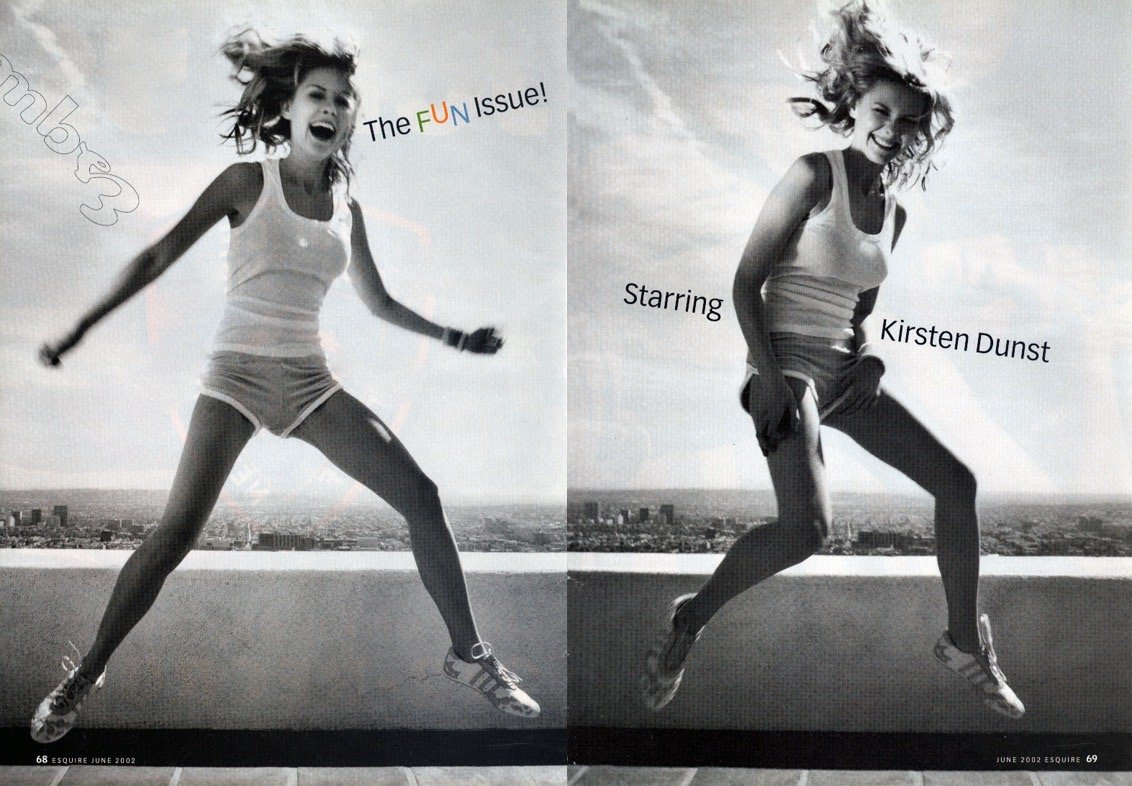

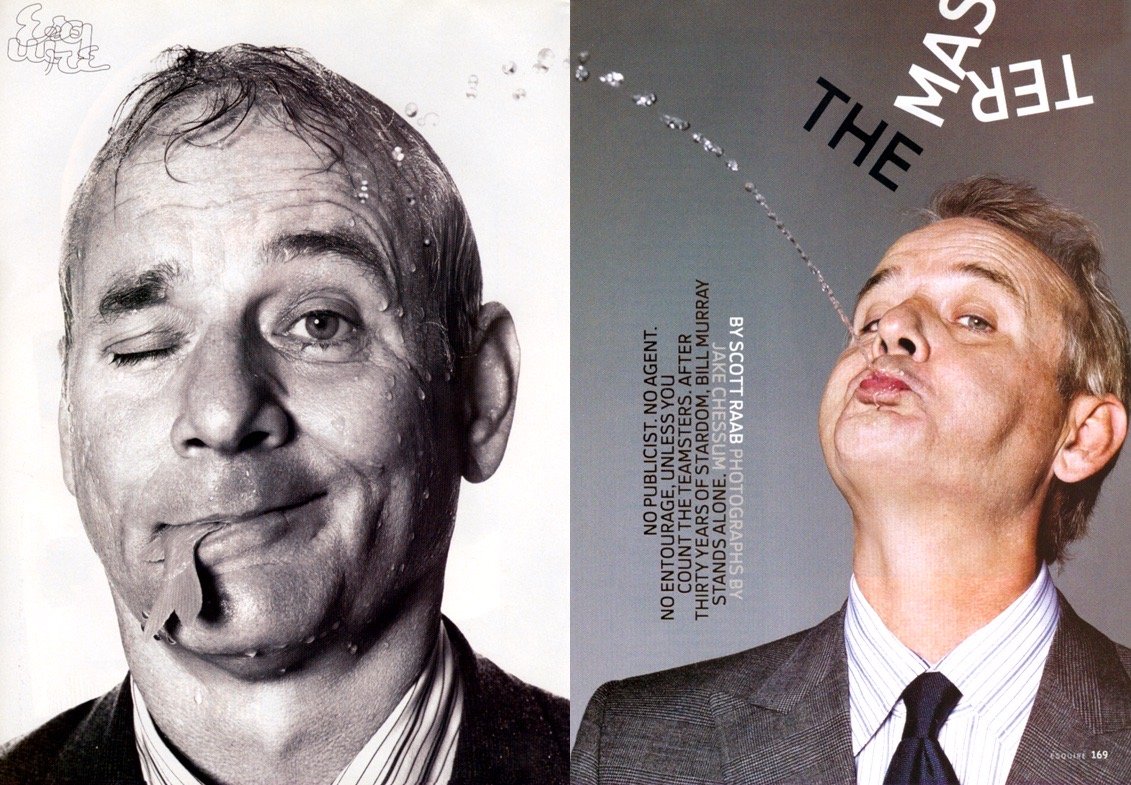

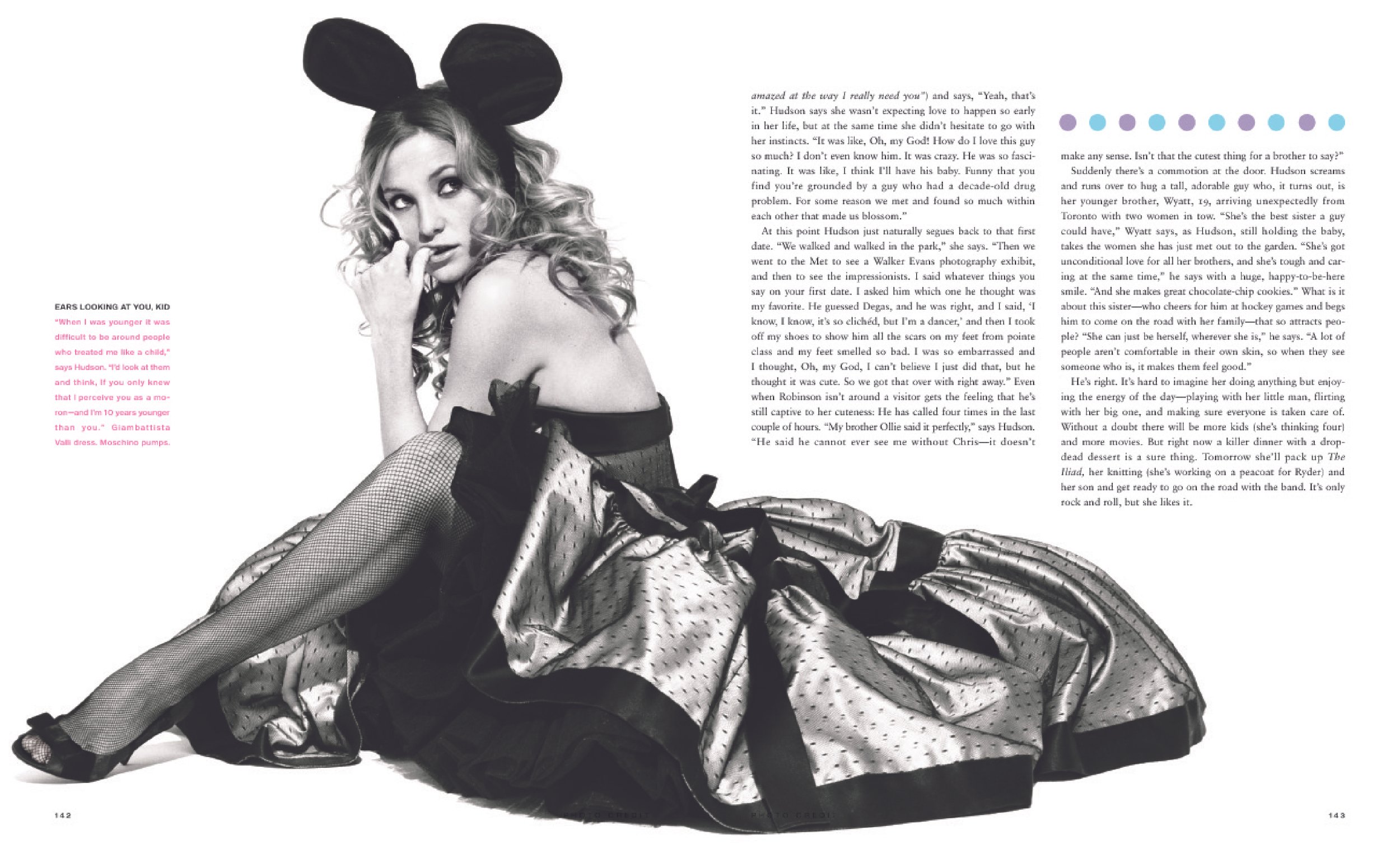

Monica Bellucci, and caviar, for Esquire, February 2001

“It was the first time I felt like I was truly the partner of the editor at any of the magazines I’d worked for.”

Korpics career is jammed with blue-chip magazine brands, all of his stops (sans his first job at Philadelphia magazine) shown here in chronological order.

Patrick Mitchell: Before we get into who exactly you are, I want to start by talking about your limited-run blog from back in the late aughts, called My Effing Commute, which I thought, and still think, was pretty brilliant. And, sure, it was funny, but I think part of the reason I loved it so much was that you were actually showing the world the range of skills that one can develop working in this business. Did it start just because you wanted to dabble in writing? Why’d you start the blog?

John Korpics: At the time I had a hellish commute. I was commuting from northern Westchester, New York into the city. The train ride alone was an hour and 10 minutes. And I started to feel like I wanted to be productive in that time. And the only thing I was doing was working. So I was doing layouts for magazines or I was doing emails, things like that, and I didn’t want to give that time over to my job.

And so I decided that I was going to try to write a blog. I wasn’t sure how often. I tried to do it every week. I Was going to try and write it in the time it took to ride the train. And I was going to post it at the end of the train ride, which didn’t always happen, but I was giving myself that guideline to say, “This is not something I want to work on all day or all week. I just want to knock it out and do it.”

And so it became an exercise in observation. It became an exercise in writing. And packaging. And you’re right—all of the things that we bring to the job that we do, all the storytelling skills—it was a microcosm for that. And it also started to become an examination of my life and the lives of the people around me, and my shortcomings, and my successes, and my failures. And I leaned into that. I liked that piece of it. It was fun to do that.

Patrick Mitchell: So it’s interesting that you had a very demanding high pressure job, you had a long commute, you had a wife and two little kids at home, and yet you just decided to pile more on by giving yourself a daily deadline, doing something outside your comfort zone.

John Korpics: Yes. It became kind of a Jekyll and Hyde thing. It was almost an alter ego. It was a place where I was allowed to be sarcastic, and snarky, and self-deprecating, and unforgiving—a, you know, a curmudgeon to some extent.

And then when it was over, I had to go into an office and be polite and cooperative and try to work across teams. So it became a nice outlet. I liked having that. Like the “evil“ John for an hour a day.

Patrick Mitchell: It was a form of therapy, it sounds like.

John Korpics: It was. Yeah, to some extent, it was.

Patrick Mitchell: Alright. Well, another odd job—maybe even a weird job—that you had that needs to be talked about—this was post-ESPN—you were a bike messenger in Manhattan. What’s the story there?

John Korpics: Well, I’ve been riding bikes since I was five years old. I was part of a big layoff at ESPN, so I was out of work for about a year and a half. And there were times when I would ride my bike around Manhattan to take my mind off of things. And I, weirdly, enjoy riding my bike through traffic and through congested cities and navigating unpredictable moments of car doors opening and people jumping out at you.

So I was doing that a couple of times a week, just to clear my head. And my older daughter, Daisy said, “You know, you should just be a bike messenger. You can get paid for this.”

And I thought about it and I said, “That’s not a bad idea.”

So I went and I took the 30-minute training session to be an Uber bike messenger, which essentially was, “Don’t break the law, and here’s your bag, and on ahead and start working.” And I would do it, like, once a week. I wasn’t a day-to-day bike messenger, but I did it every week.

Patrick Mitchell: Oh, you made your own hours. Okay, well…

John Korpics: Yeah, I mean, that is the gig economy. It’s the way Uber drivers work. And it was again, it was very humbling at times. Some people are very nice to you. Some people treat you pretty rudely. You have a purpose to your riding, you go all over the city.

And I delivered mops to the 79th Street Boat Basin. I delivered products to Late Night with Jimmy Fallon. I delivered a lot of lunches. And I actually really enjoyed it. Although I will say it’s not possible to make a living doing that. On my best day ever, I think I made about $90.

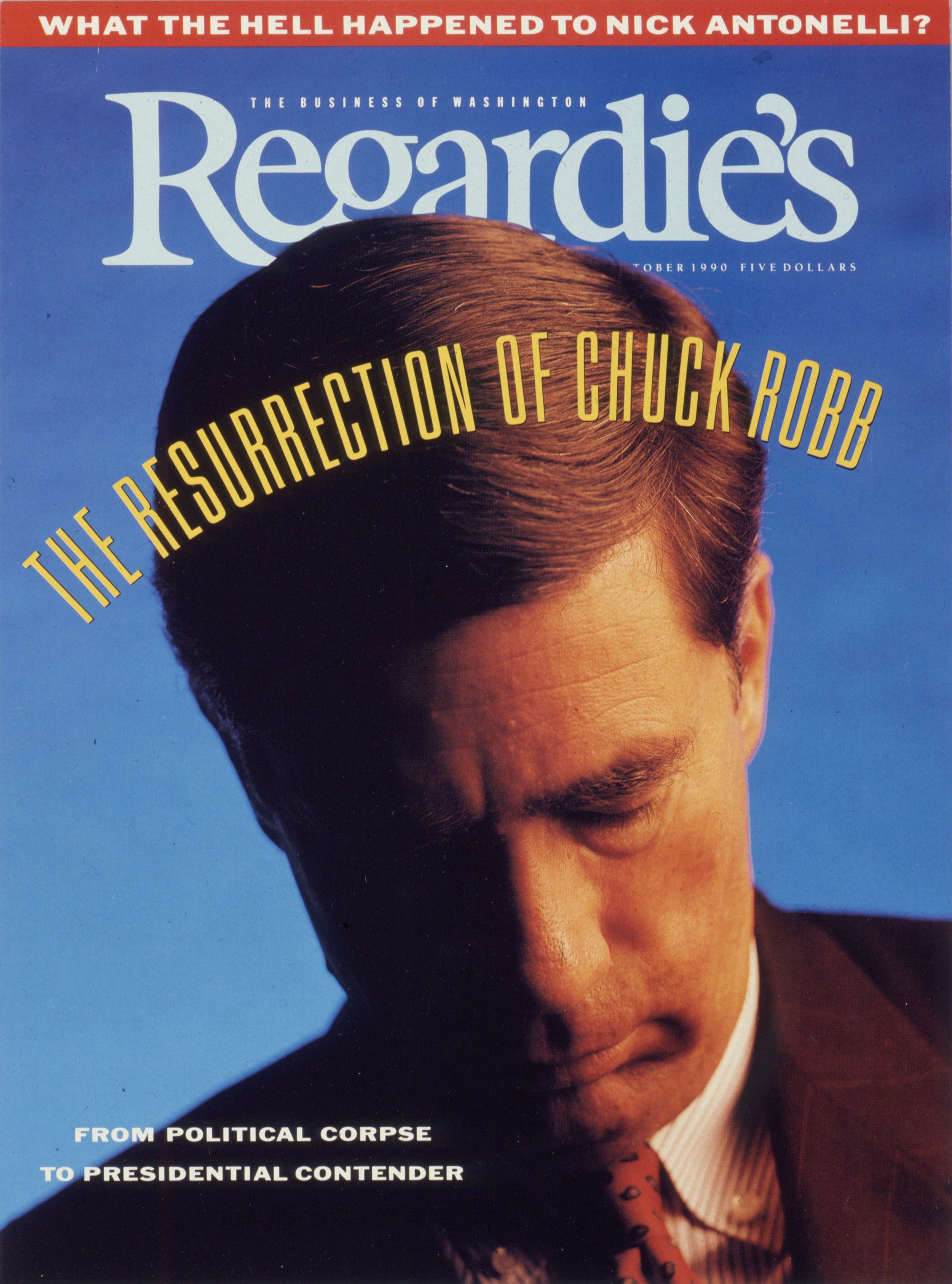

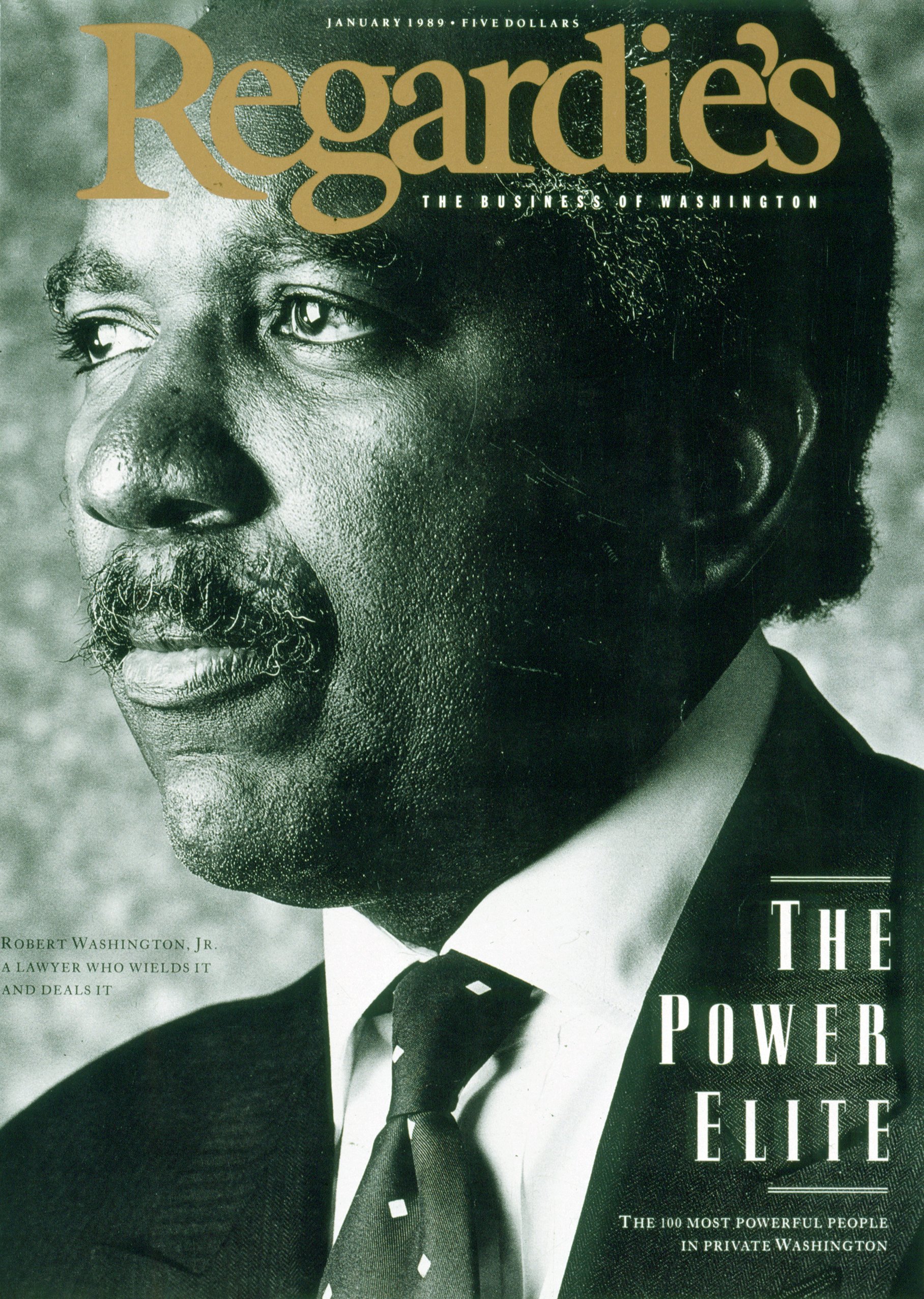

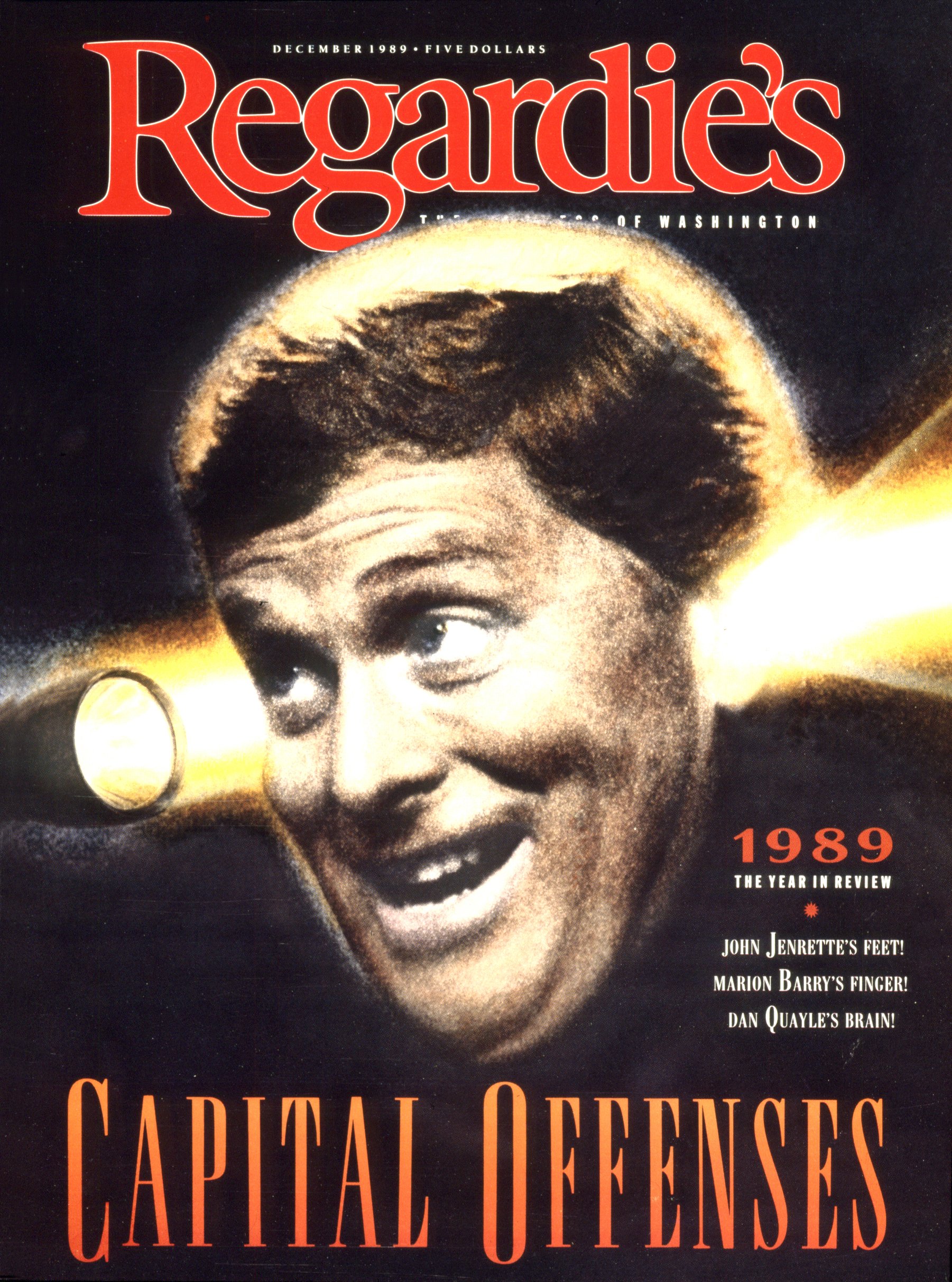

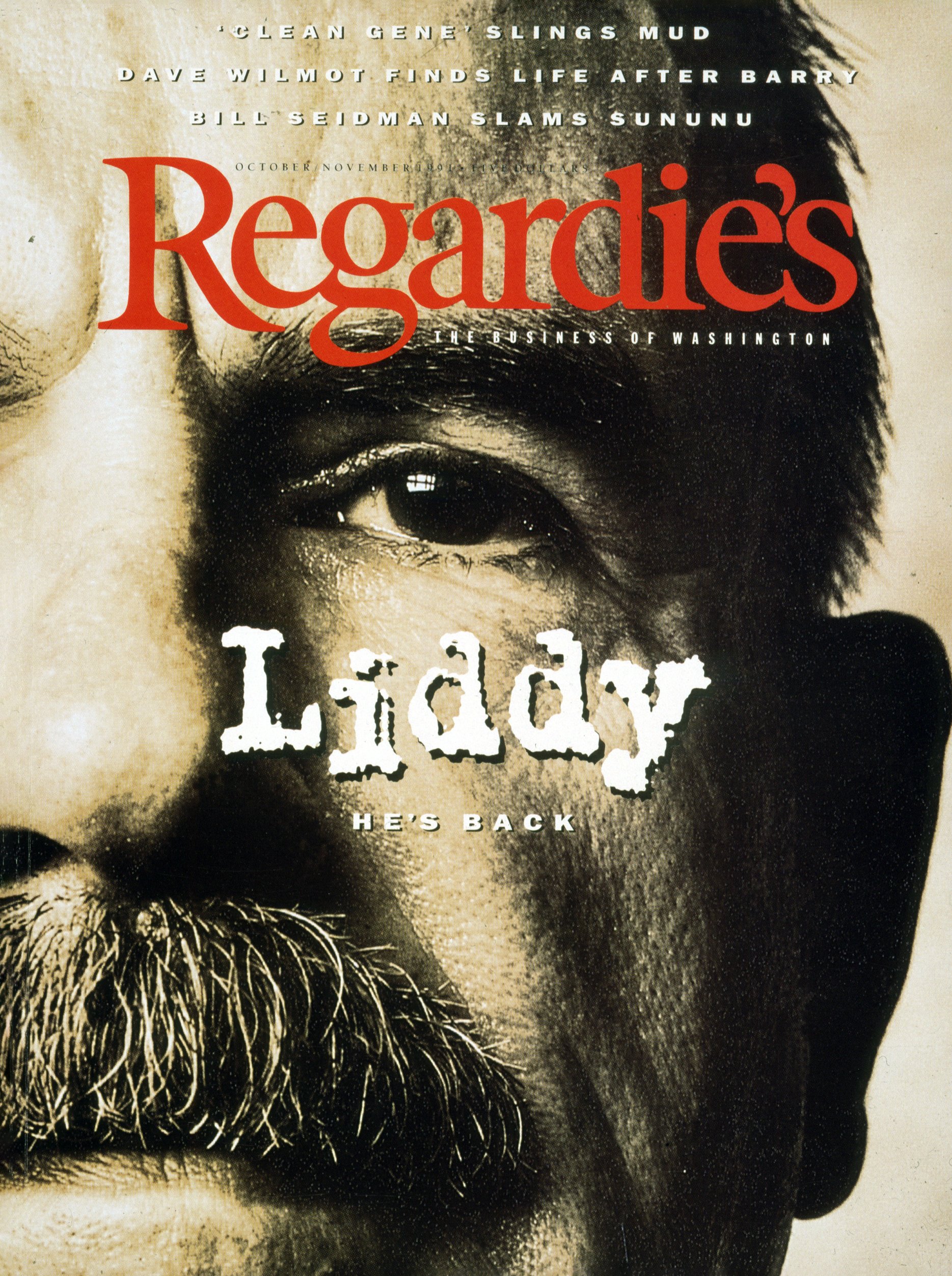

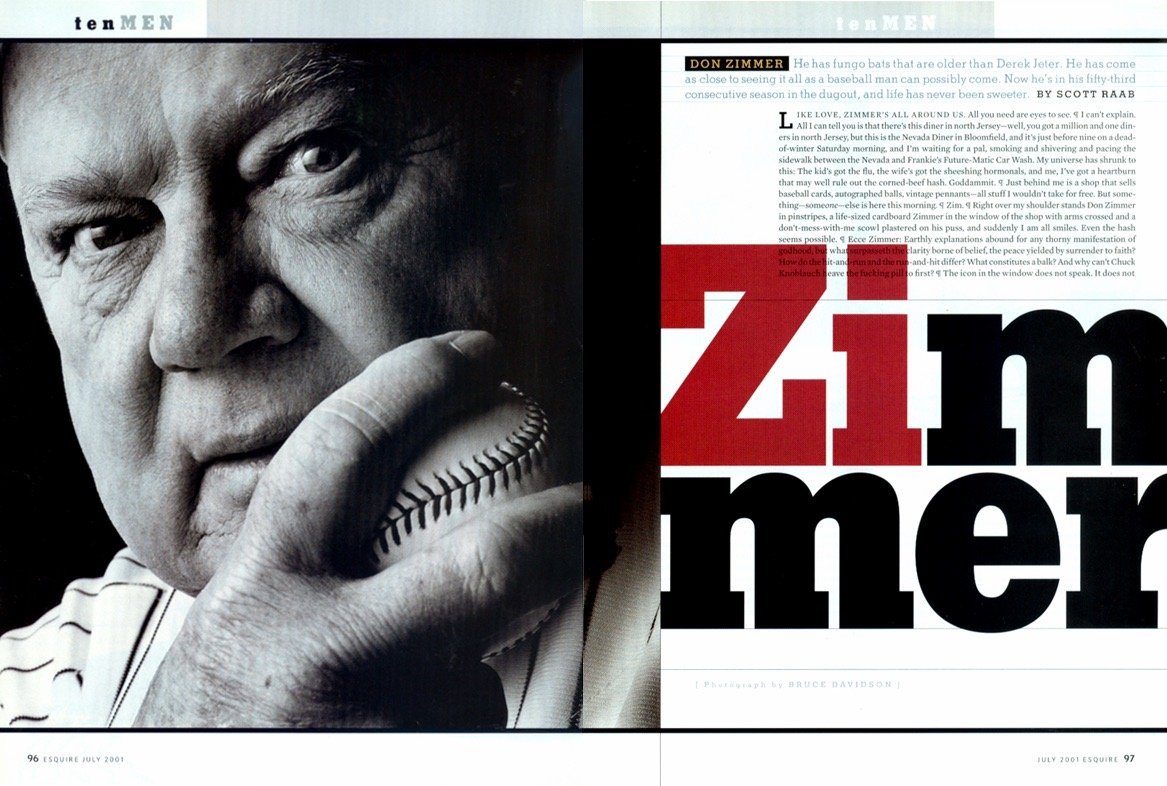

Regardie’s was a Washington, DC business magazine published from 1980–1992

“The magazine went to 6x/year, and they started doing black and white forms—the writing was on the wall.”

Patrick Mitchell: Did you ever deliver anything to any of the big publishing companies?

John Korpics: I did. I delivered clothes from a studio to Vogue. But the funniest one was I had a pickup at Pentagram. And they came down and like, I remember I’m there on my bike hoping that none of the people who I’m friends with at Pentagram recognize me.

They come downstairs and they hand me this tube that has something in it. And they said, “Okay, this is going up to this studio in New Rochelle.”

And I’m like, “I’m a bike messenger. I can’t ride my bike to New Rochelle. It’s, like, 30 miles away. I think you meant to call car service.” They had to cancel. And nobody ever saw me, so I got away with it.

Patrick Mitchell: So this one is not quite the same as the others. Actually it might’ve been a real job, but it was a little outside of your core skills, in terms of—I think this was again, post-ESPN—you were the head of marketing for a school or schools called the Harlem Village Academies. What was that about?

John Korpics: Yes. I had done a lot of pro bono work for them for going on, like, 10 years. And I was looking around for something to do for work, honestly. And I called my friend, Deborah Kenny, who was the president of the school. And I said, “If you’ve got anything, let me know.”

And she asked me to do a couple of back-to-school videos for the kids, and then a couple of videos for teacher recruiting, and then one or two other things. And then she just said, “Hey, I think we might be able to use you full time. Do you want to come in and try this?”

And I said, “Sure. Love to.”

And it was great. I loved it. I was working with students and teachers who are pretty remarkable, in a really wonderful environment, a very supportive environment, inspirational in many ways. And doing everything from helping to do all of the media planning for the annual fundraising event, to doing student recruiting forms in multiple languages, to doing bus ads and videos. And I rebuilt the website, did all the social media. So I was a one-man show and I had a blast. It was a real fun place to be.

Patrick Mitchell: So I’m sure you had kind of a bitter taste in your mouth after a rough ending at ESPN, but did you, at any point while you were doing this work—it was also a terrible time to be in the magazine business—did it cross your mind to just end your time in the magazine business and stick with this or pursue more of this kind of work?

John Korpics: Oh, yeah. I thought my media career was done, honestly. And I didn’t have a horrible ending at ESPN. I think that when you work in an environment like that, there’s always an expectation that change is inevitable. And they treated me very well when I was “released from the company” as they say.

I came away fine. It was a shock for a while, but honestly, it wasn’t so bad. And then I had leaned into this job as the marketing director of the charter school and I started to embrace it. I started to look around at what other schools were doing and I was reaching out to peers to learn more about best practices and things like that. And then I got a call from a recruiter about this job at HBR.

But we don’t get to pick and choose when our career ends. Some of us do, which is pretty rare, but you’re just told one day that, “Yeah, we’re going in a different direction.” And it’s possible that might be the last one you get.

So I do think that there was a point there where I was facing that and saying, “It’s not so bad. I really actually enjoy this job. The people are great. I’m still able to use a lot of the skill sets that I’ve developed over the years.” And I was ready to move forward with it.

But, this thing came up, HBR came up and the only caveat was I had to move. The job sounded great. The people were great. And I think that it was mutually understood that this would work out, but I had to make a decision to move from New York to Boston.

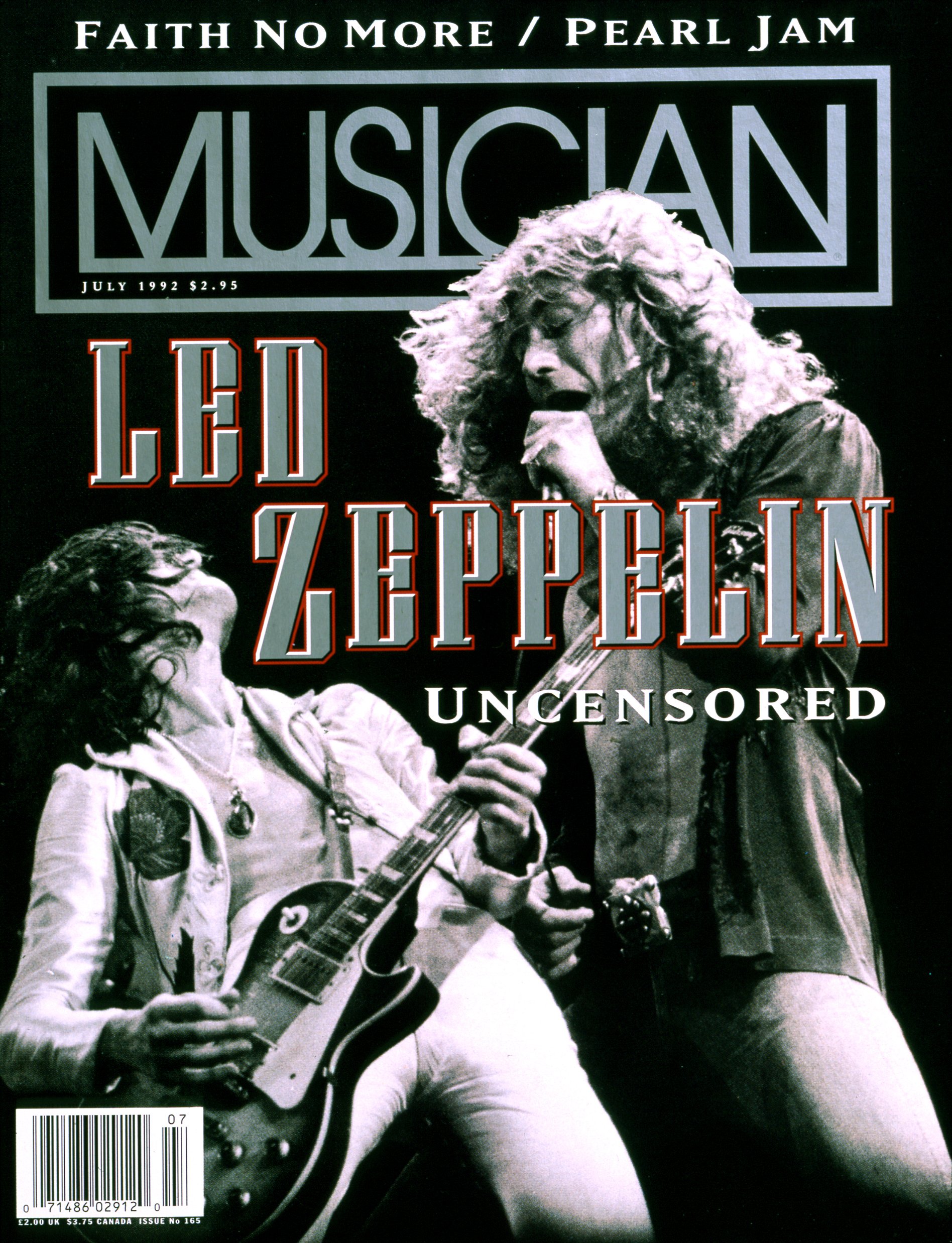

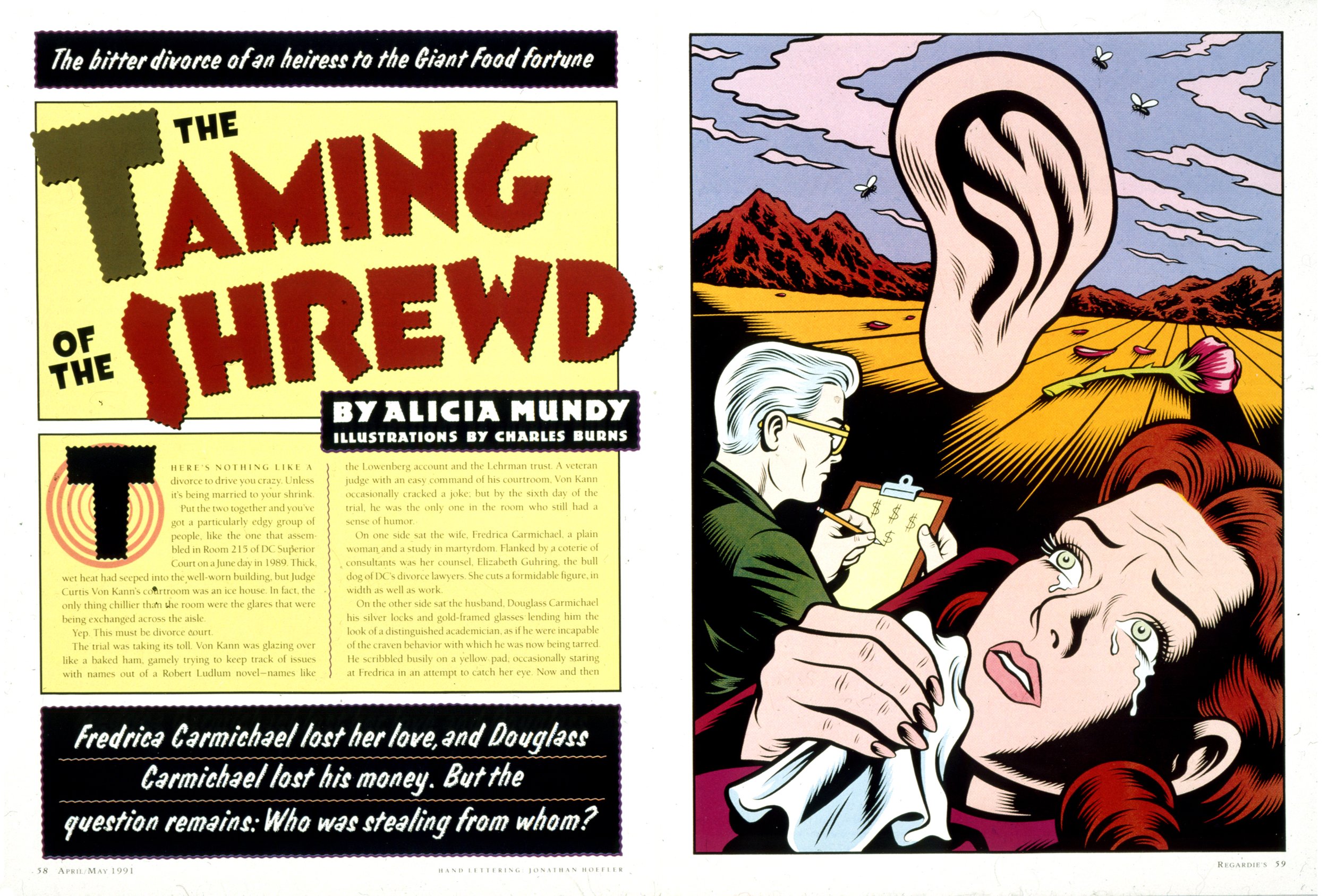

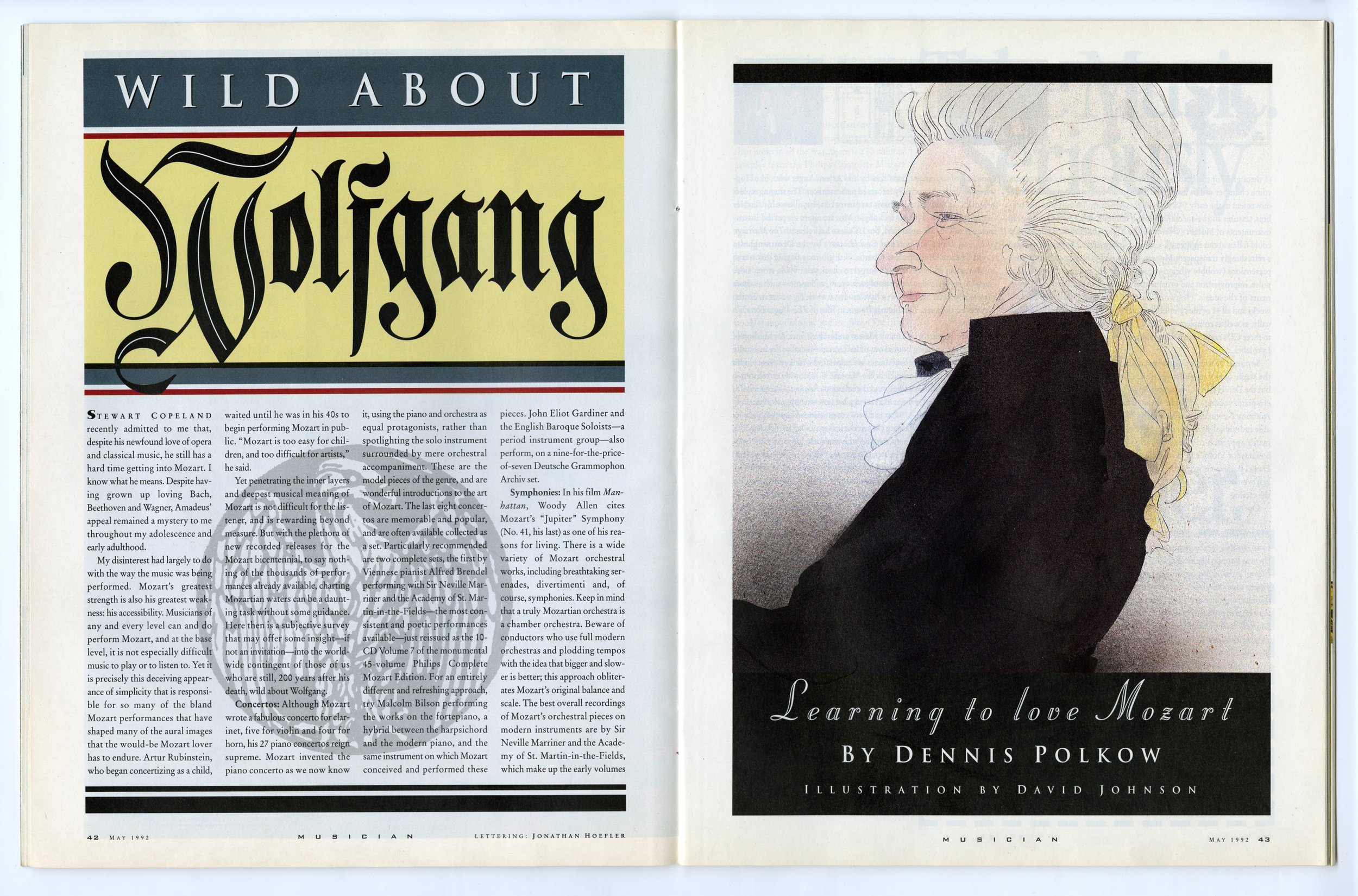

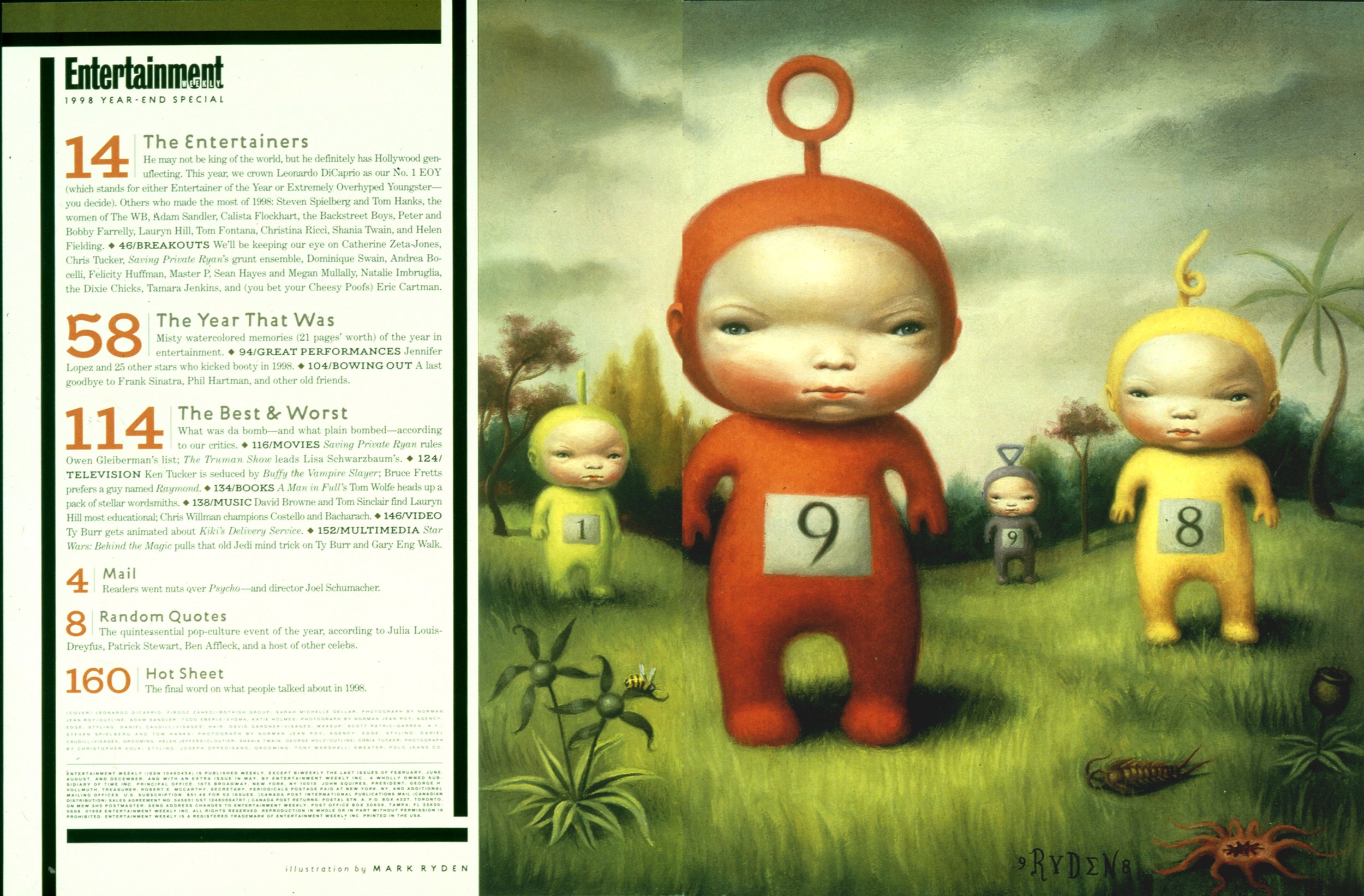

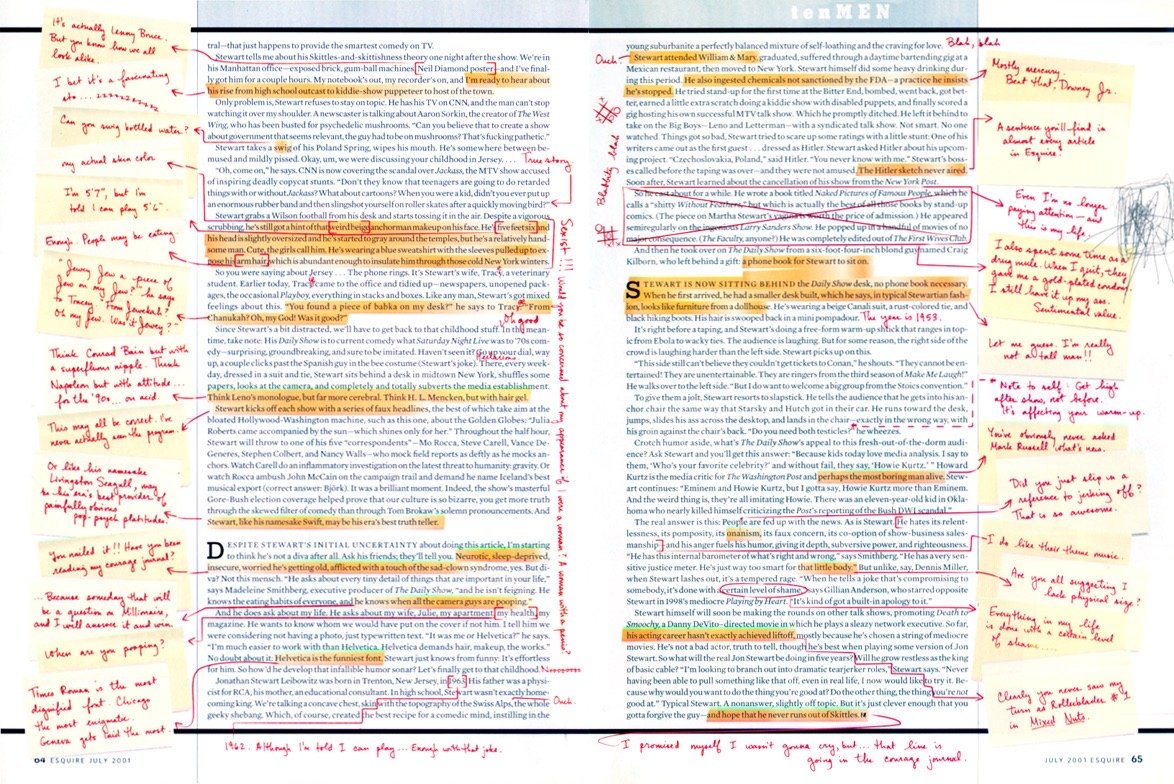

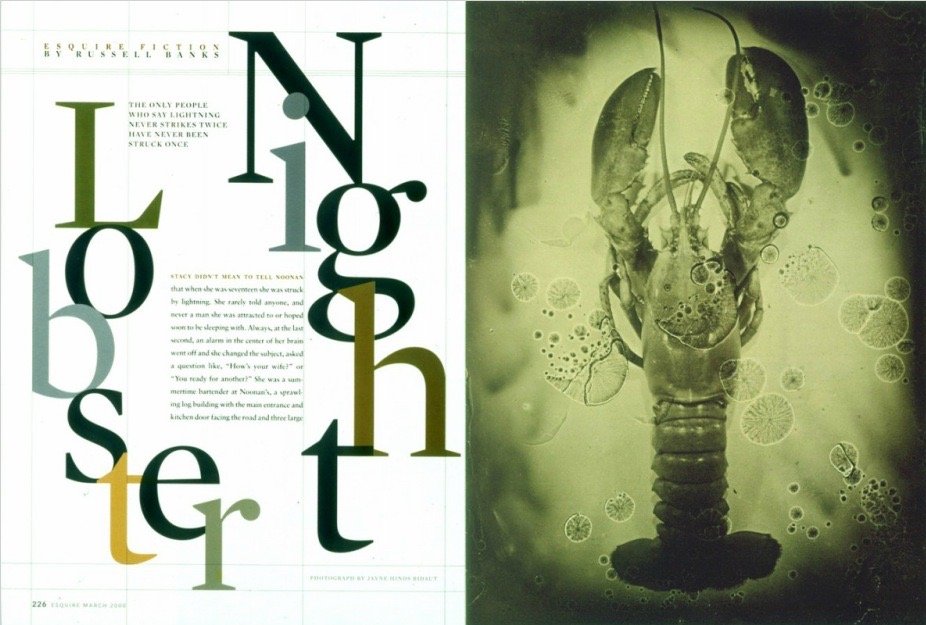

Spreads from Musician magazine

Patrick Mitchell: You took the safe option.

John Korpics: What does that mean? I don’t even know what that means.

Patrick Mitchell: You were landing back in the profession that you had a ton of experience in.

John Korpics: Yes. It was almost like, “Holy cow! I get to go back and do this thing that I’ve been doing my whole life that I think I’ve learned a lot about, and that I think I’m pretty good at, and now somebody actually still needs that.”

So yeah, that’s a good feeling for sure. I don’t know if it’s ‘safe,’ but it just felt really comfortable and I felt very privileged to be able to come back and do it.

Patrick Mitchell: We’ll circle back to HBR in a minute, but now I want to wind back to Media, Pennsylvania, where you were born and raised. Talk a little bit about your childhood. What did your parents do?

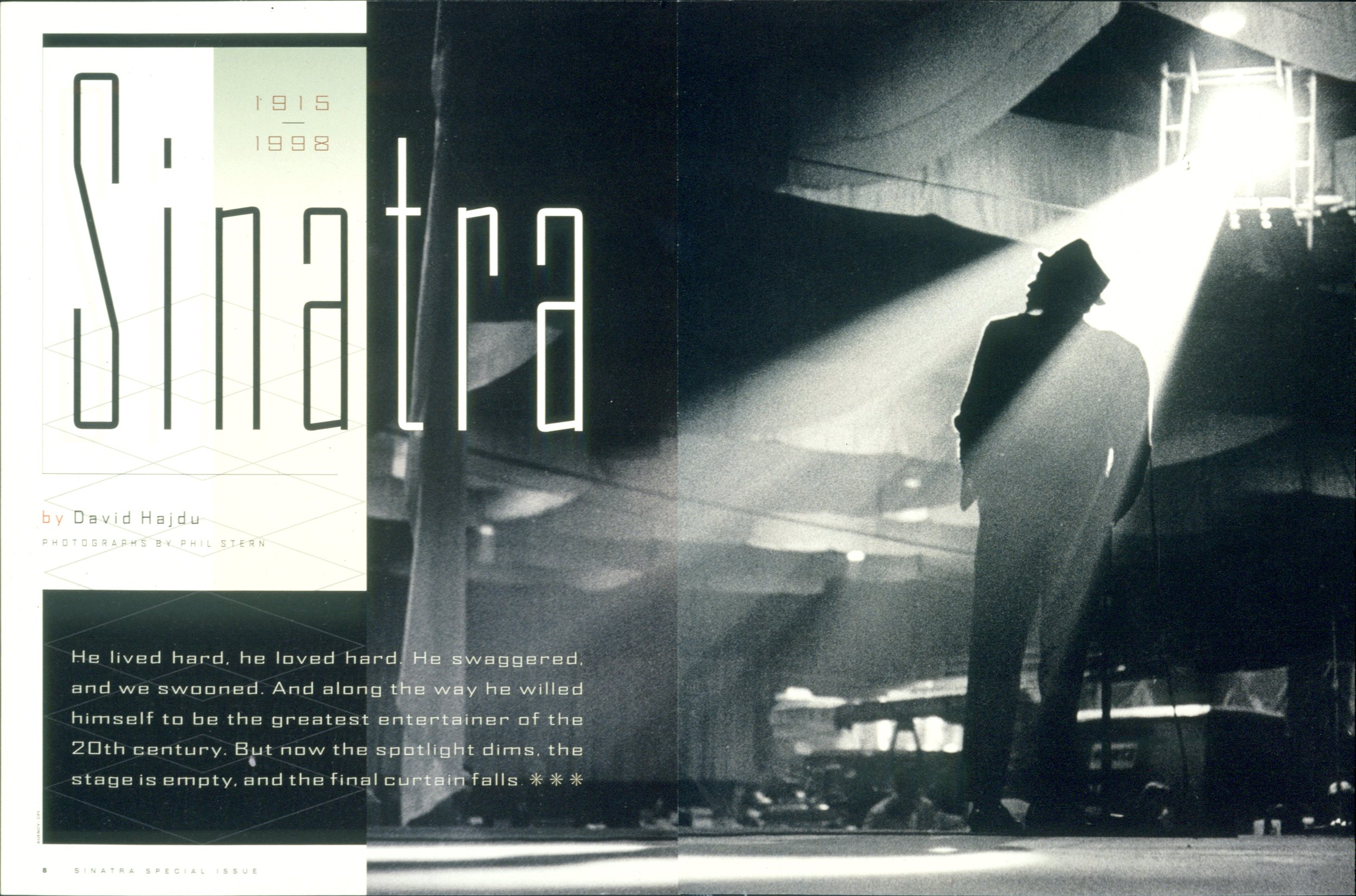

John Korpics: My father was a musician. I guess, like, a professional musician. Like a dinner club/lounge musician. In the old days you would go to dinner at a place, and they would have live music. And for the first two sets they’d play quiet, nice jazz. And then for the next three sets, they’d do more like dance music so people could get up.

So my dad did that most of my life growing up. He was a guitar player. And my mom, she raised us essentially, and was our north star. Set the boundaries for us, gave us a purpose, and showed us what was proper and what was right. Always had vegetables in the house and made us watch PBS a lot.

Mom and Dad Korpics

Patrick Mitchell: Did she work?

John Korpics: Oh, yeah, she worked as well. She had a lot of different jobs growing up. She worked at a bookstore for a while. She worked at the local fuel oil company for a while. And eventually she landed at a local community college as an administrator. Both my parents are still alive, hopefully listening, and happily retired.

Patrick Mitchell: That’s great. Do you remember your first, sort of, recognition of magazines and taking notice of them?

John Korpics: I had a subscription to Ranger Rick when I was a kid. I don’t know if anybody even knows what that is anymore.

Patrick Mitchell: I remember. I had one too.

John Korpics: And I grew up with Time magazine. My mom always had a subscription to Time. My grandparents had Life magazine. The classics, nothing special. I think we may have had National Geographic for a while. My grandparents had the Life magazine photograph book. I don’t know if you remember it, but it was this amazing collection of all the great photographs of Life magazine.

And whenever I’d visit my grandparents, I’d just pour through that book and it was pictures of Louis Armstrong crying and playing at JFK’s funeral, and the amazing tragic photo of the woman who had jumped off the empire state building. And I would just stare at that book for hours at my grandparents house. It was pretty amazing.

Patrick Mitchell: We’ve got to get somebody from Ranger Rick on the podcast. I think everybody subscribed to that. Alright, so you decide to go to Carnegie Mellon—how did that come about? Carnegie Mellon is $60,000 a year now tuition. And it’s very highly-ranked to this day. So talk about your process of discovering Carnegie Mellon and deciding to go there.

John Korpics: In high school I was all in on my art major class, most of my other classes were not working out so well. I got a D in chemistry and I had to drop out of calculus because I had no interest. And, I was sort of like, well, I guess it’s art. That seems to be the thing.

And my teacher said, “Your art is very controlled. It has a lot of structure to it. It was always very planned.” I wasn’t doing a lot of abstract painting or anything like that. I was thinking things through and planning them out. And he said, “You might want to consider going into graphic design.”

So I applied to Carnegie Mellon. I applied to Tyler School of Art, which was in Philadelphia. And the University of Delaware. And that was it. I got into Carnegie Mellon, and that’s where I went.

Patrick Mitchell: Did you work during school?

John Korpics: Yes, I worked. Yeah, I didn’t pay the full tuition. I worked 20 hours a week in food service, mostly. Cleaned a lot of chicken. Did a lot of the grunt work, worked behind the counters, and did all that kind of stuff. Yeah, 20 hours a week, all four years.

I got a lot of grants. I took out student loans. The maximum you could take out in those days was $2,500 a year. So I graduated with $10,000 in debt, which seems almost laughable nowadays. And I think my mom paid, I think my mom had to pay, like, $2,000 a year for me to go to school there.

Patrick Mitchell: It explains the previous conversation about how you’re just born to do multiple things at once under pressure.

John Korpics: I’ve always had a work ethic. My mom always used to say to me, “You need to have a job” like, from the age of 10. And she would say, “If you don’t get into college, that’s fine. You’ll have four choices: Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marines.” So when you have that kind of hanging over you it’s definitely a motivating factor.

So I had jobs. I bent sheetwork into duct metal. And I cleaned windows at factories. And I was a fitness instructor. And I had a paper route. You name it—every cliche job you can imagine from the age of 10 on, I had it. So working in college was just one more thing. I was like, “Yeah, sure. No problem. Whatever.”

Patrick Mitchell: Alright, we’re going to skip a little bit. We’re going to go to New York City now. And I think maybe this was around when we first met. You were hired as the art director—were you replacing me or somebody else?

John Korpics: Yeah, I replaced you. You left. I didn’t replace you. You can’t be replaced, Pat. I Came in after you, how’s that?

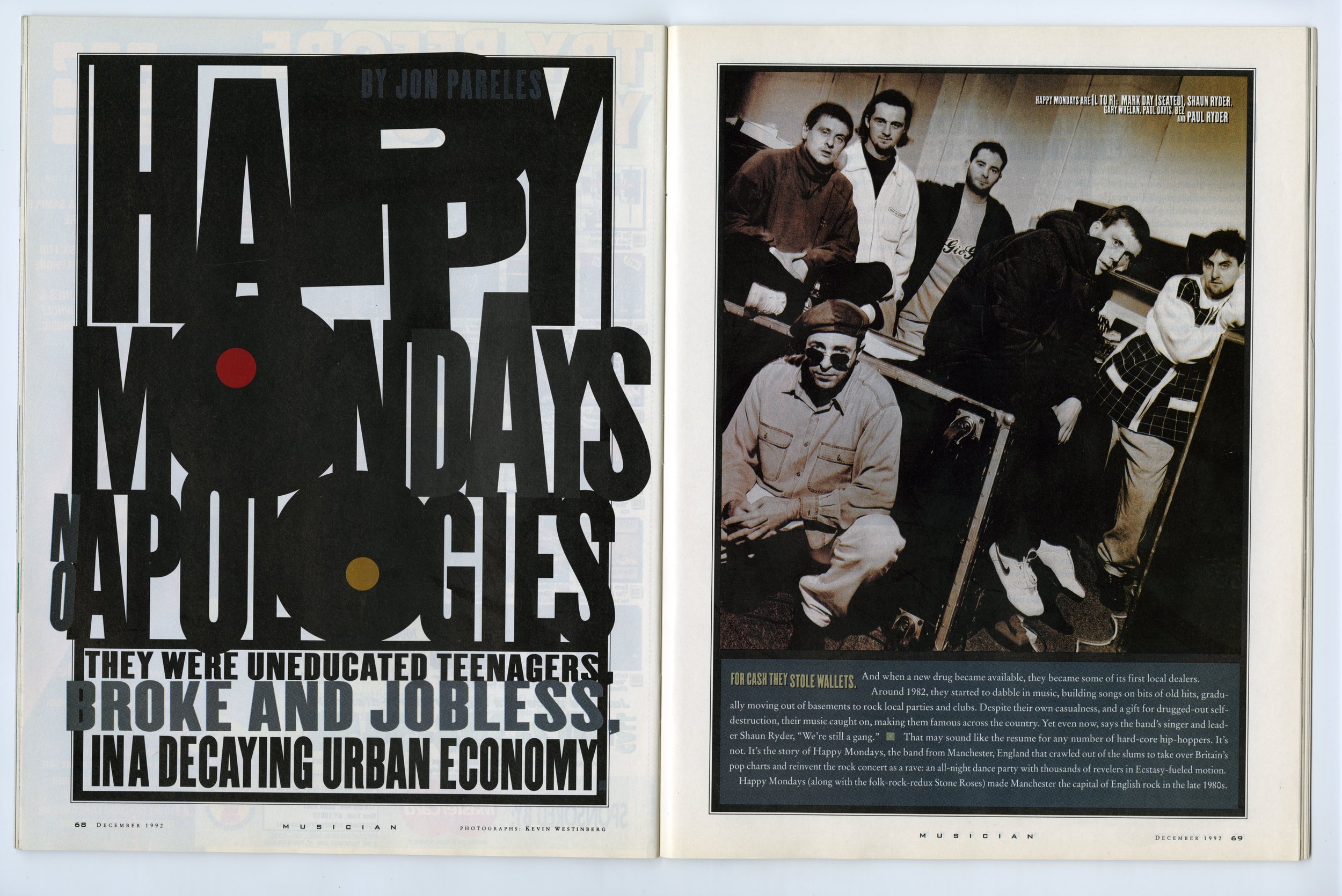

Patrick Mitchell: Alright, well, so Musician magazine was a nice little music magazine that was based here where I am on Cape Ann in Massachusetts, strangely. It was owned by Billboard, and the entire time I was there, the pressure to move to New York was increasing because the whole editorial staff was in Manhattan. The holdout was the owner, who had a very nice house here on the water. And me leaving and you coming in was the straw that broke the camel’s back. And great for you because I think you’d been wanting to get to New York—as all magazine designers do. And so your first stop was Musician magazine. Now, you had worked in Philadelphia and DC before that, but, is it safe to assume that New York was the goal all along?

John Korpics: Not specifically. I was at Regardie’s magazine in Washington. I was having a lot of fun. And I was really enjoying it.

Patrick Mitchell: Where you replaced Fred Woodward?

John Korpics: Indirectly. I came in after Rip Georges, actually. But I would have stayed. I was having a lot of fun. It was a great community. Richard Baker was down there at the time. And Deb Needleman and Tom Wolff. There was a really fun group of people down there.

And then all the advertising dried up. The magazine went to six times a year, and they started doing black and white forms—the writing was on the wall. And I just needed a job.

And I think you had left. You had announced that you were leaving for some reason. So I took the job and I moved up to Cape Ann for two weeks, did the last issue in Gloucester, and then I moved it down to New York after that.

But I do remember being in that office in Gloucester at, like, 11 o’clock at night, working on a Mac for maybe the second time in my life, and having to figure out which of the 7,000 fonts that you had loaded onto that computer I was supposed to be using in the layout.

And I called you and I said, “Pat, what are all these fonts on here?”

And you were like, “Have you ever even worked on a Mac before?” You were just annoyed that I was bothering you.

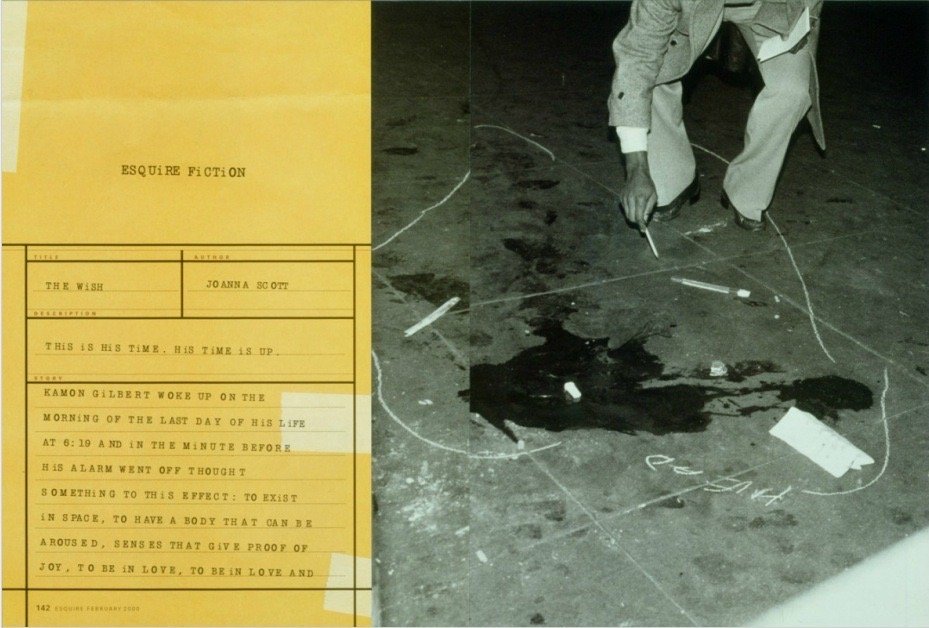

Patrick Mitchell: We’re going to talk about addiction later, but we all have one.

John Korpics: The one thing I’ll say about Musician is I was alone, so I did everything. And I learned a ton because I was doing all the layout. I was doing all the photo assignments. I was doing all the illustration assignments. I was mailing back artwork to artists with tear sheets. But, you know, to be able to assign and work with a lot of photographers for the first time—I’d done that at Regardie’s, but it was different now because I was assigning pictures of Elvis Costello, and Bono, and sort of significant pop-culture people. And I was working with photographers in New York a lot.

So that actually opened my eyes to how to work with photographers, for the first time, in a way that I hadn’t really done in DC. But it’s true. It was a tough job. I was only there for about a year. And then I got pulled in by Roger Black to come over to Premiere.

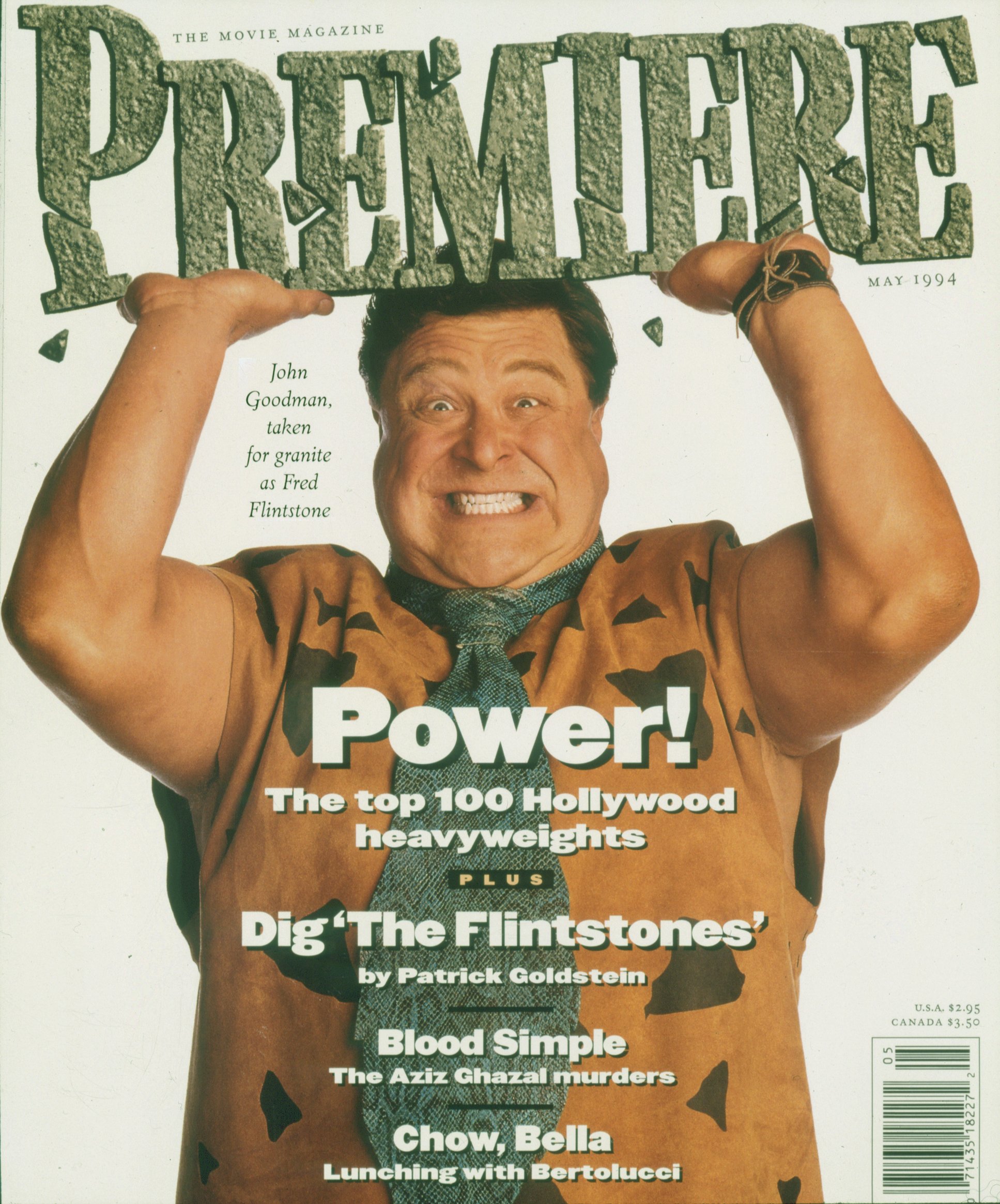

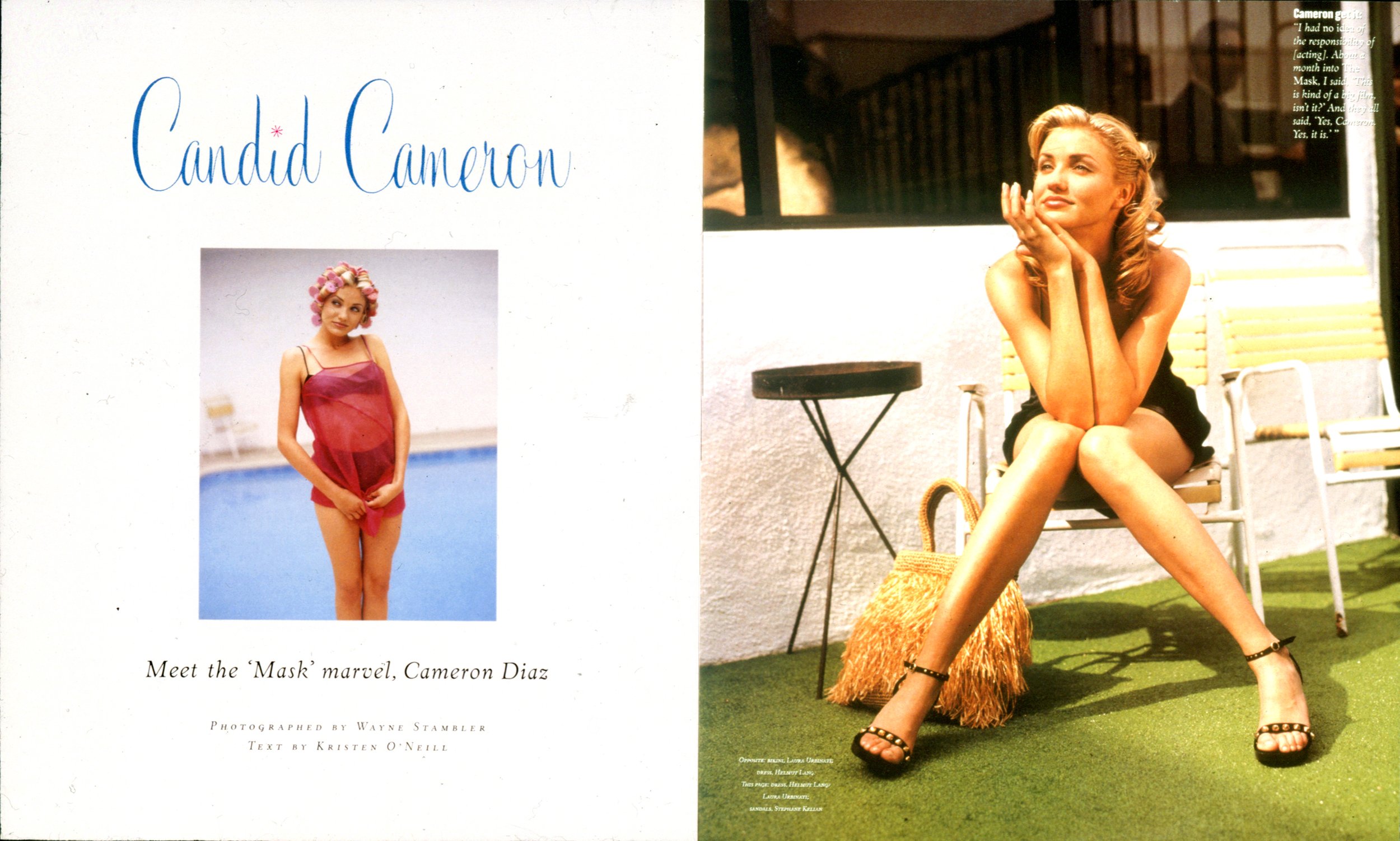

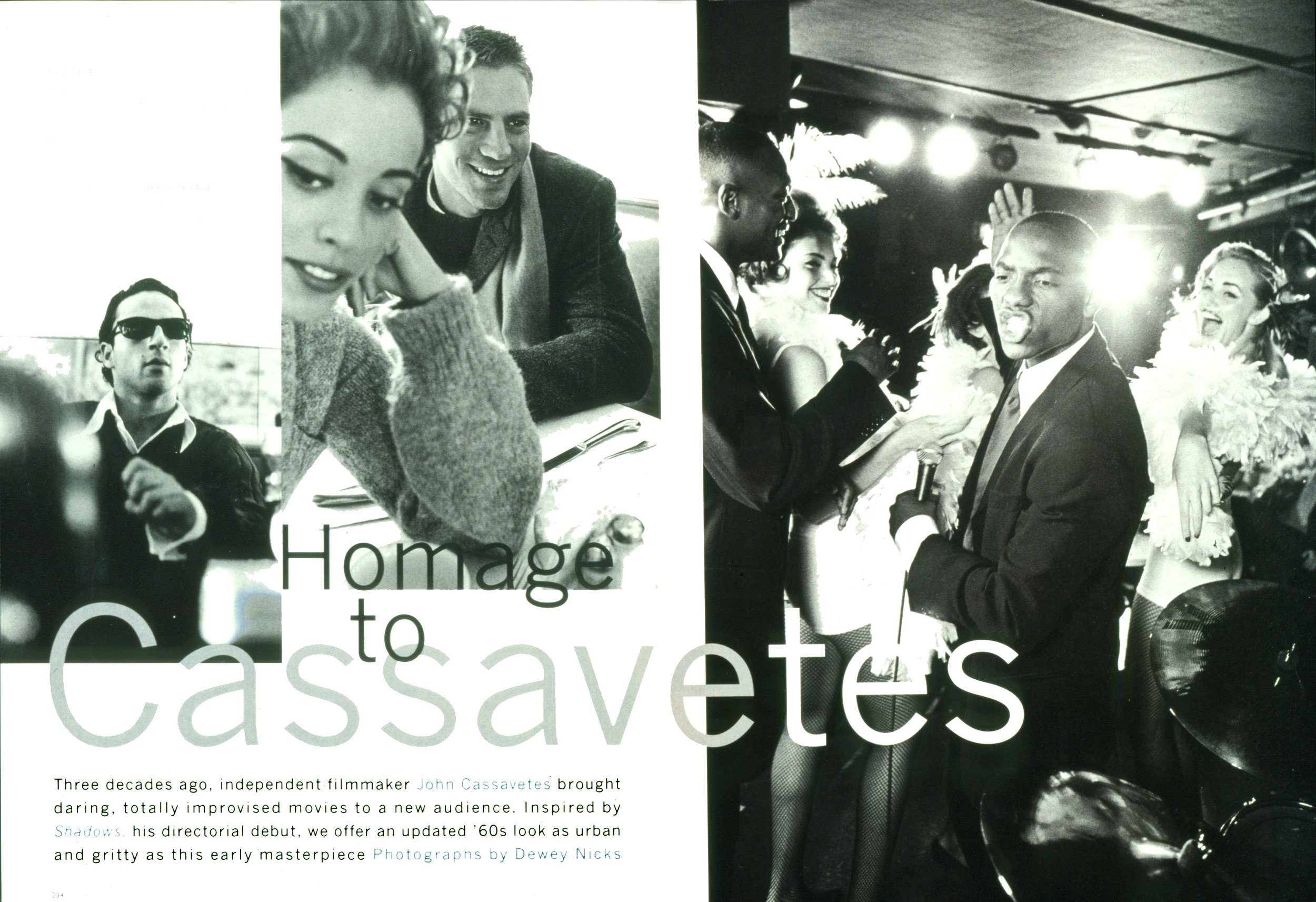

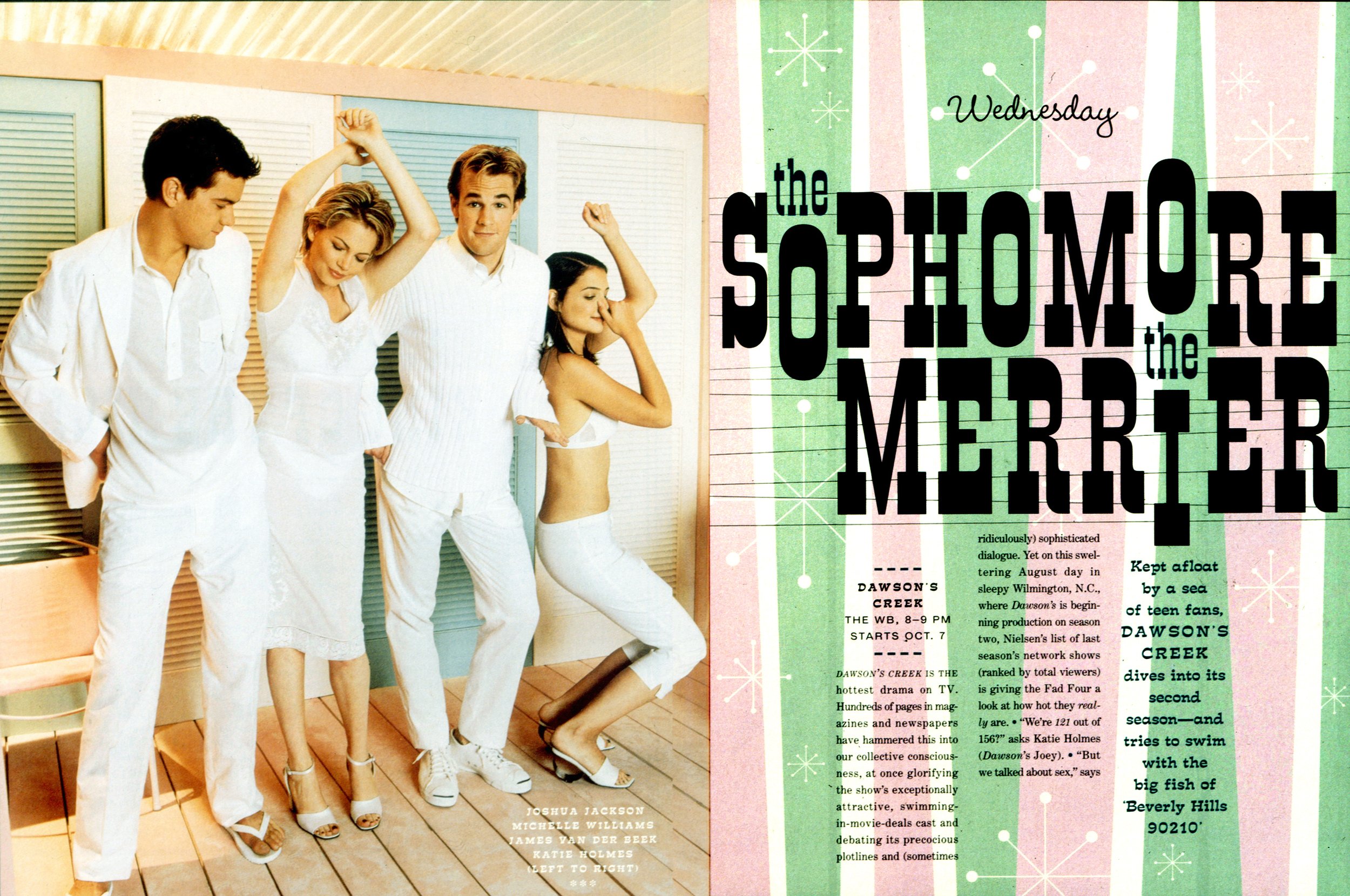

Patrick Mitchell: And just for the record, I took Musician over from David Carson who was there before me, and he took it over from Gary Koepke. And I know Bob Newman was a big fan of Musician, he did a thing on the SPD website about all the people who’ve worked there, at a magazine nobody’s really ever heard of and no longer exists, which is interesting. You’ve mentioned to me that Susan Lyne at Premiere was one of your favorite editors to work with. And I have thoughts about Premiere. Sometimes we ask people to answer the question: what were the five best-executed magazines that they can remember. And if somebody asked me that, Premiere would be on that list, because I think, in its heyday, and I think this was probably when you were there, that it was one of the smartest magazines going. Just really clicking on all cylinders: great headlines, great voice in general, great photography and illustration, of course, design. One of the best- executed of its era. Can you talk a little bit about your life at Premiere?

John Korpics: Yeah. So...

“I spent like $3,500 in the first month on car services and lunches. It was like, ‘This is great! I’m at Condé Nast. This is fantastic!’”

Patrick Mitchell: It was fairly new at the time, right?

John Korpics: Bob Best was the art director of New York magazine, and when Premiere started, they asked him to design it. And I think he designed it, like, on his lunch hour. So he’s doing a weekly city magazine—a high profile weekly city magazine—and then he’s doing Premiere. He’s zipping over to a different office because they were in a different building and he was just cranking out this movie magazine in his spare time.

So if you want to get a workhorse designer on the show, I think he should be your call. But it was a blast. There were so many good people there when I was there—people I’m still friends with today, like Chris Connelly, John Richardson, Holly Millea, and Cindy Stivers. And they had really interesting stories about Hollywood and celebrities.

Charlie Holland was my photo editor and she was fantastic. She was only there briefly, but I learned a ton from Charlie. And I was just a kid. I was just like, “This is a blast. Let me see what I can learn. Let me see how much fun I can have.”

Roger Black had just done a redesign. And the thing I loved about Susan was, like, once Roger was done, they handed the redesign over and Susan said, “You can do what you want. If you don’t like pieces of the redesign, don’t worry about it. Just have fun and make it good.” I was a kid in a candy shop. I was going to shoots in LA every month, shooting Sharon Stone and Arnold Schwarzenegger and just having a blast.

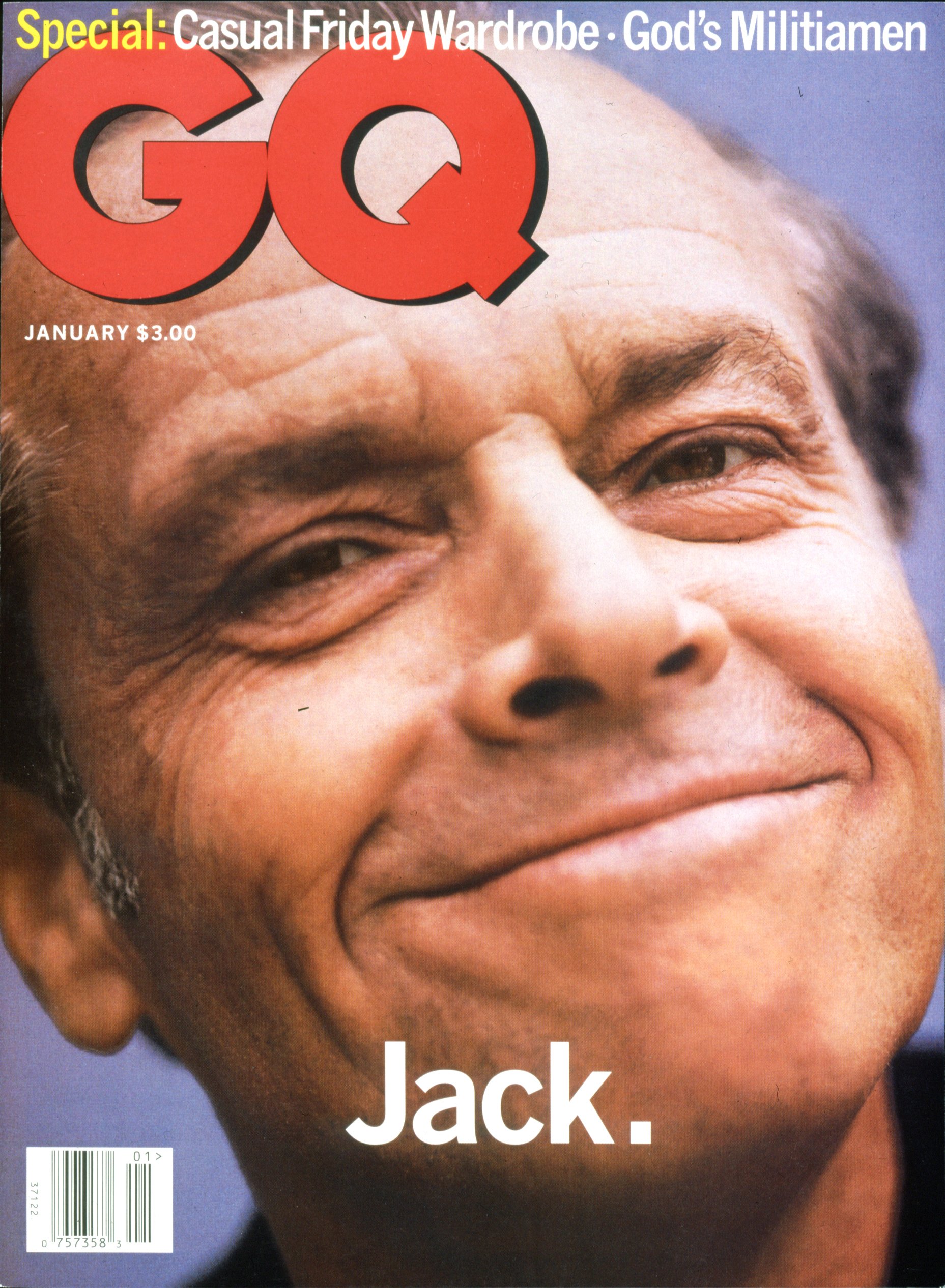

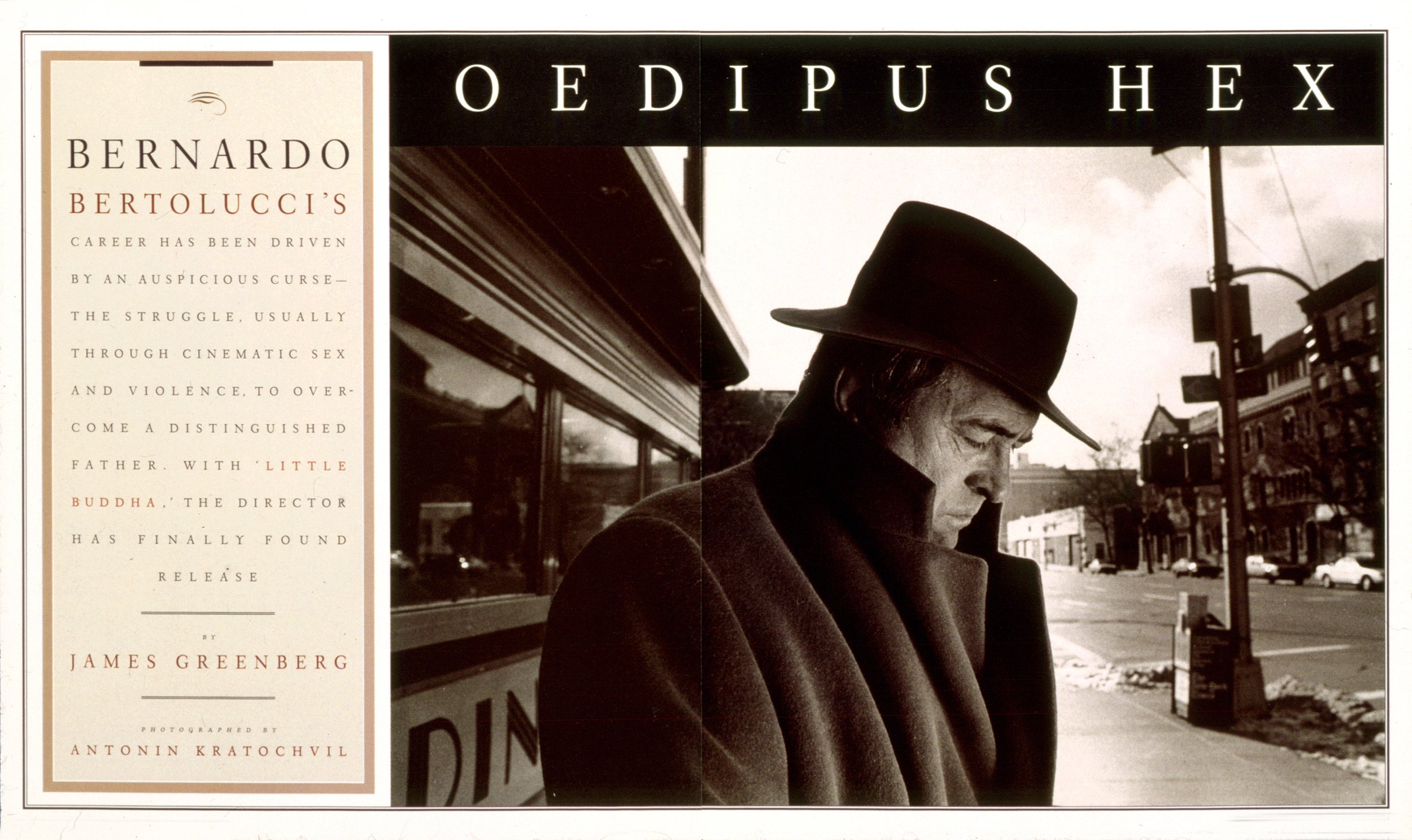

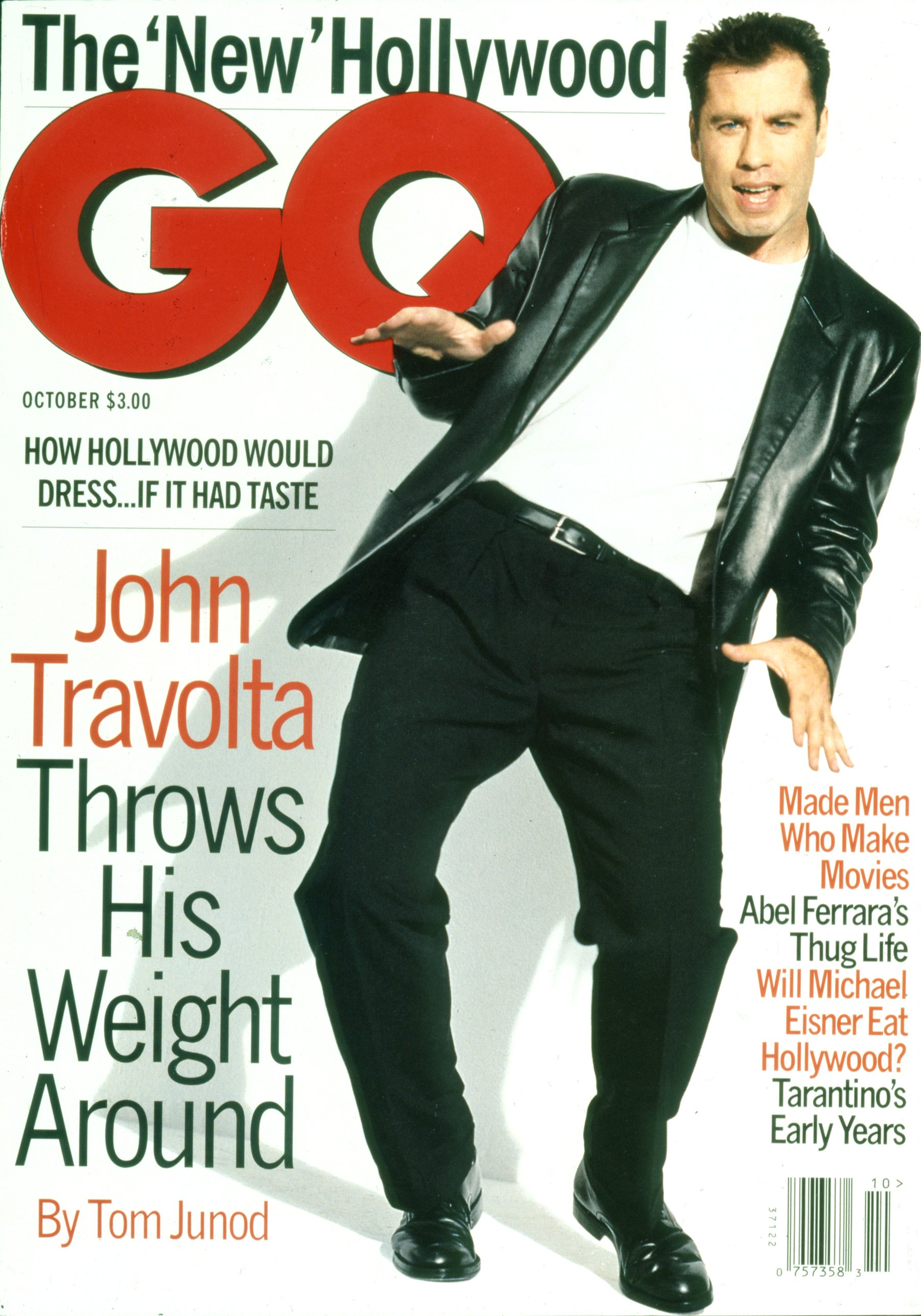

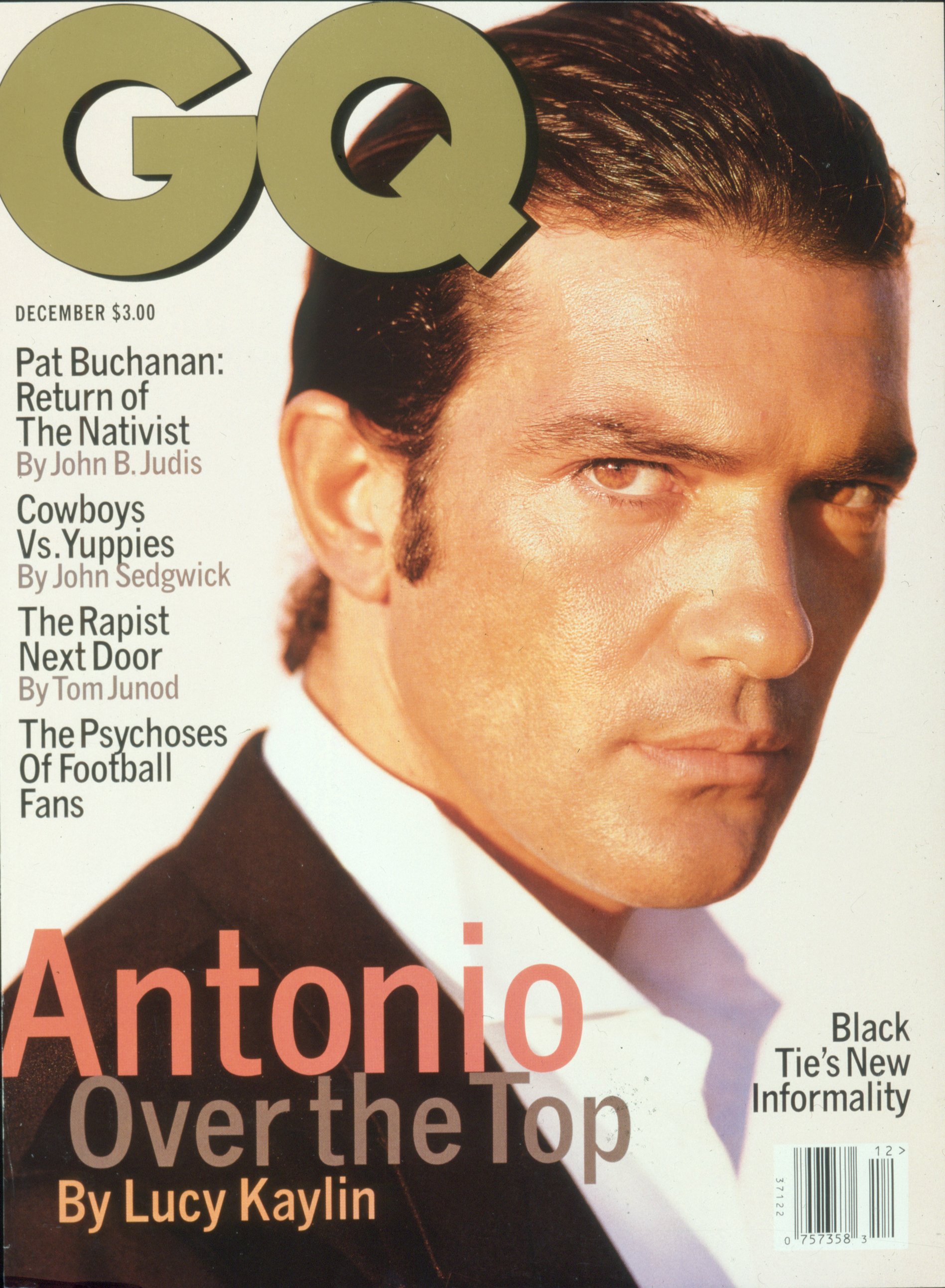

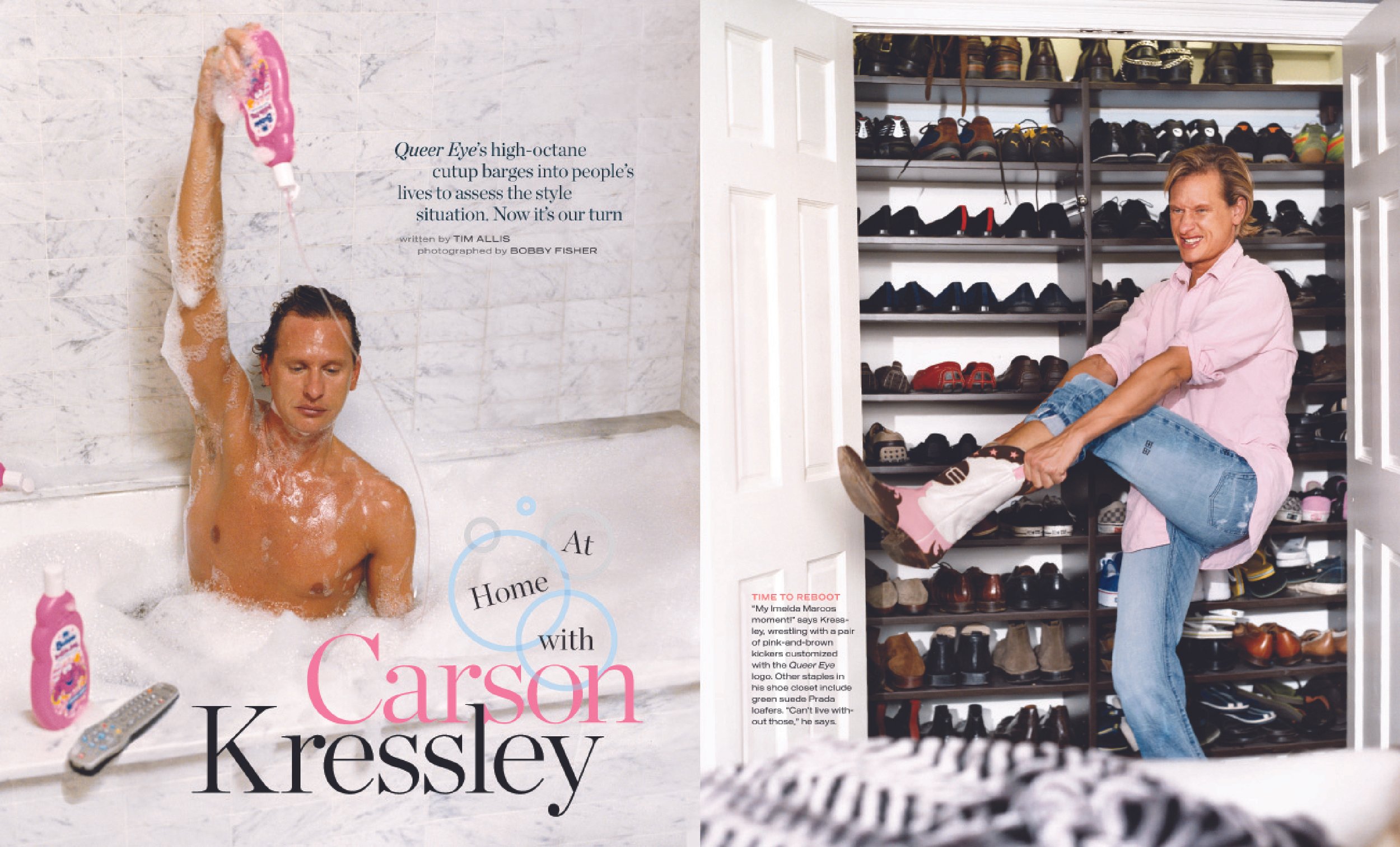

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. Dream job. Another one that bit the dust prematurely. But you go from there to GQ. Everybody’s got an Art Cooper story—and yours may be one of the best—about your interview for the job at GQ. But before you tell that, were you ready to leave Premiere at the time or did this just fall into your lap?

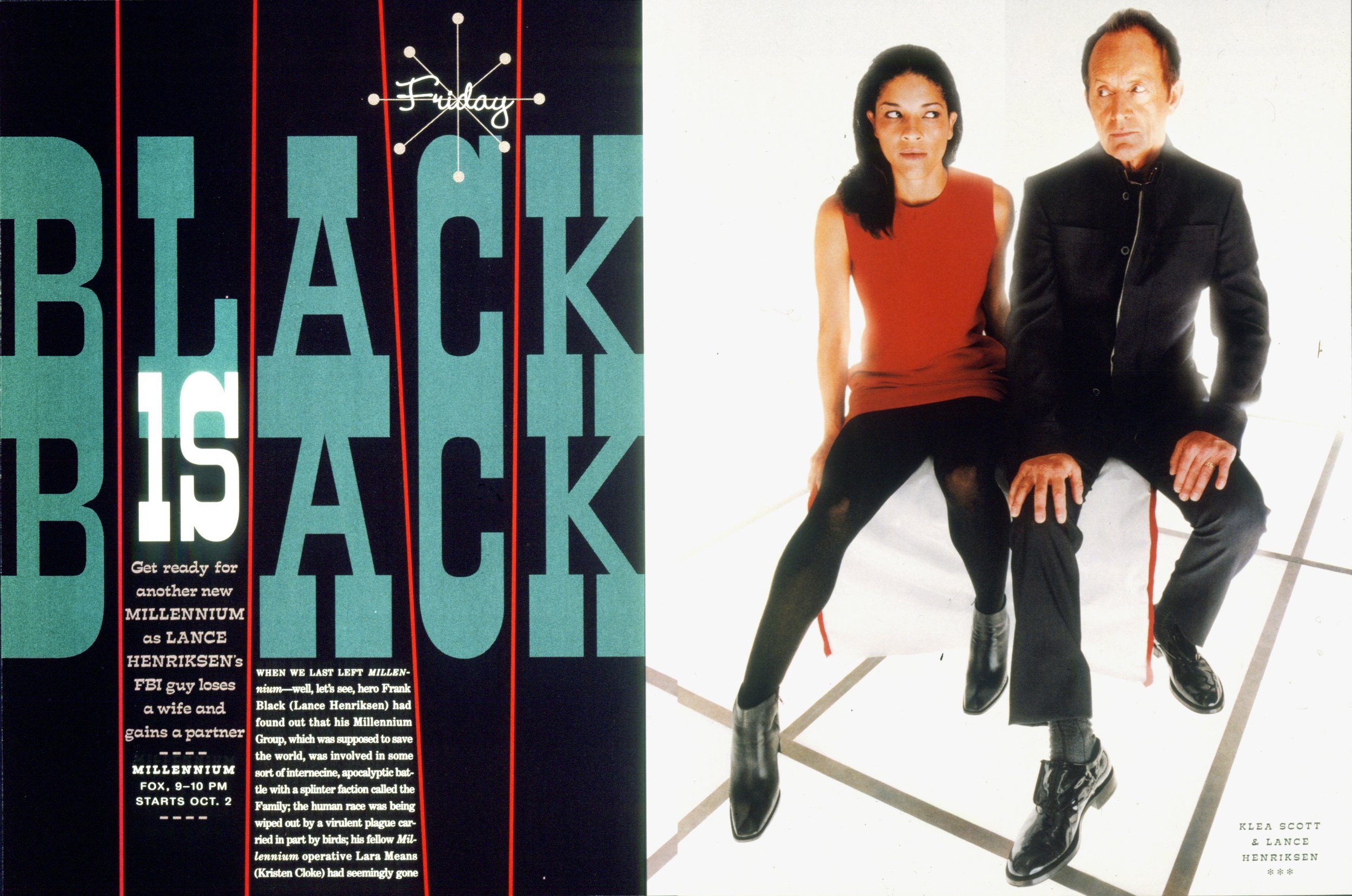

John Korpics: Premiere got bought out by a group of people that was led by David Pecker, who is the guy who is, I guess he still runs The National Enquirer or something. That guy. And we could all tell that the culture was about to change dramatically.

And Susan announced that she was going to leave. And a few other people announced that they were going to leave. And so I just decided that this was the time for me to start looking. And it just so happened that Robert Priest had just left GQ and so that job was open. And I threw my hat in the ring for that.

Patrick Mitchell: And then you got called for an interview.

John Korpics: Yeah. So I had an interview with Art. Art’s a very intimidating person. He was. He’s passed away, but he was a very intimidating person. And I had an interview with him at the Four Seasons restaurant, which is a very intimidating place to go as well.

I had a black suit. It was a 97 degree July day. And I went to the Four Seasons Hotel and said, “I’m here to have lunch with Art Cooper.”

And they said, “I’m sorry, there’s nobody with that name in the reservations.” And then they said, “Maybe you mean the restaurant, which is eight blocks south of here.”

And I was like, “Oh shit!”

And so I’m sprinting down Park Avenue in my black suit on a 97 degree day. I arrive at the Four Seasons restaurant, 15 minutes late, covered in sweat. And I walk up and there’s Art sitting at a table in the middle of the restaurant. The very dead center of the restaurant, not saying anything, with his hands folded, sitting straight up, just staring into space.

I sit down and I was like, “I’m so sorry I’m late. It won’t happen again.”

And he just looks at me and he says, “It better not.”

I was like, “Oh, this is going to be fun.”

Futher evidence that Korpics is everywhere.

Patrick Mitchell: How long was the gap between that interview and you getting the job? Did it happen that day?

John Korpics: I think he gave it to me pretty quickly, yeah. I think Art saw me as a project. I think he said, “This is a young guy. I’m going to guide him in what a GQ design should be and what the model of GQ should be.” And he saw me as this, sort of, untested person that he was going to take a chance on.

And, to some extent, I guess there were things that I could still learn about creating magazines, but I also felt like there were times when it was just—he had a very set-in-his-way idea of what a magazine should be.

He gave me a list of rules. He gave me a list that said, “Headlines should always be at the top. There should always be rules around the pages. The subhead should always be smaller than the headline. I prefer black instead of color. Bylines should be big.”

I was like, “Oh, this is a blast.” I didn’t last very long there. I was there for about 11 months. But I did meet some good people and made a lot of friends.

Patrick Mitchell: Why didn’t you last?

John Korpics: Because of that culture. I felt like I wasn’t really able to define what I thought the magazine should be. It was handed to me in an instruction manual. You need to be able to have a piece of it that you feel like you own, that you’re actually bringing something to. And I don’t think it ever got to that point.

Patrick Mitchell: What was it like? I mean, nobody in New York is really from there, but I’m picturing this kid from Media, Pennsylvania, walking past all those limos and into the Condé Nast building every morning. Was it intimidating in any way to you?

John Korpics: No. I embraced it. When I first started, David Granger, who I wound up working for at Esquire told me, “In your first month here, you should spend as much as you can on your expense account, because once that threshold is set, people will think that’s normal.” And so I literally spent, like $3,500 in the first month on car services and lunches and things like that. Like, “This is great! I’m at Condé Nast. This is fantastic!”

But when the expense sheets came in, I heard this scream from down the hall. It’s Art Cooper. He’s like, “Korpics, get the fuck in here! What the hell are you doing?” And he said, “Your limit is 800 bucks a month. Deal with it.” And that was it. I had to figure that out. But I think, literally, the first year I was there, I took so many car services that Apple Car Service gave me like a little crystal award.

I liked it. I had fun. It was like I was trying to make the job fun. And we did good work. I don’t want to downplay the work we did. I think we did some really nice stuff there. But ultimately at the end of it, it wasn’t fun to work under the thumb of somebody who felt like they knew what the magazine should look like.

The culture was very different for me. I’ve worked at all three of the big publishing houses: Condé Nast, Hearst, and Time Inc. And Condé Nast is absolutely the—I don’t know how to say it, but there’s just like a level of expectation there that I haven’t really experienced at the other places.

Patrick Mitchell: Did you find it helpful or not?

John Korpics: No, it can be intimidating. I had a person on my team whose job it was—this was their only job—to put together what they called “the book” for Si [Newhouse]. As the magazine’s coming together, this person is taking the pages and putting them into a binder, so whenever Si calls for the book, that person can get it to him.

And then, when the magazine’s ready, the editor would take the binder up to Si, and walk them through the whole book. And I think there’s a scene in The Devil Wears Prada where they take the binder over to...

Patrick Mitchell: …Amanda Priestley.

John Korpics: Yeah. And that’s real. Like, that happened. And I thought it was crazy. To have somebody whose job it was to do this felt a little nuts. But that was just the way that things worked over there. They also had the newsstand on the ground floor that was run by Helmut and his wife. I can’t remember her name.

You could go down there whenever you wanted and buy four or five hundred dollars worth of magazines and bring them up as “research” because you wanted to see what everybody else was doing. And you were, “I’m working at GQ. It is the premier men’s magazine. I should know exactly what’s going on out there.”

That was the culture. Art used to take a black car to a restaurant called 44, which was around the corner. Literally four blocks. The car would pick him up in front of the building, take him to 44. The car would wait for him outside of 44 for an hour and a half while he had lunch, and then the car would bring him back. And I don’t think that was unusual. There were a lot of people living like that at Condé Nast.

Patrick Mitchell: Alright. So you met Granger at GQ?

John Korpics: Yes.

Patrick Mitchell: And did he leave before you?

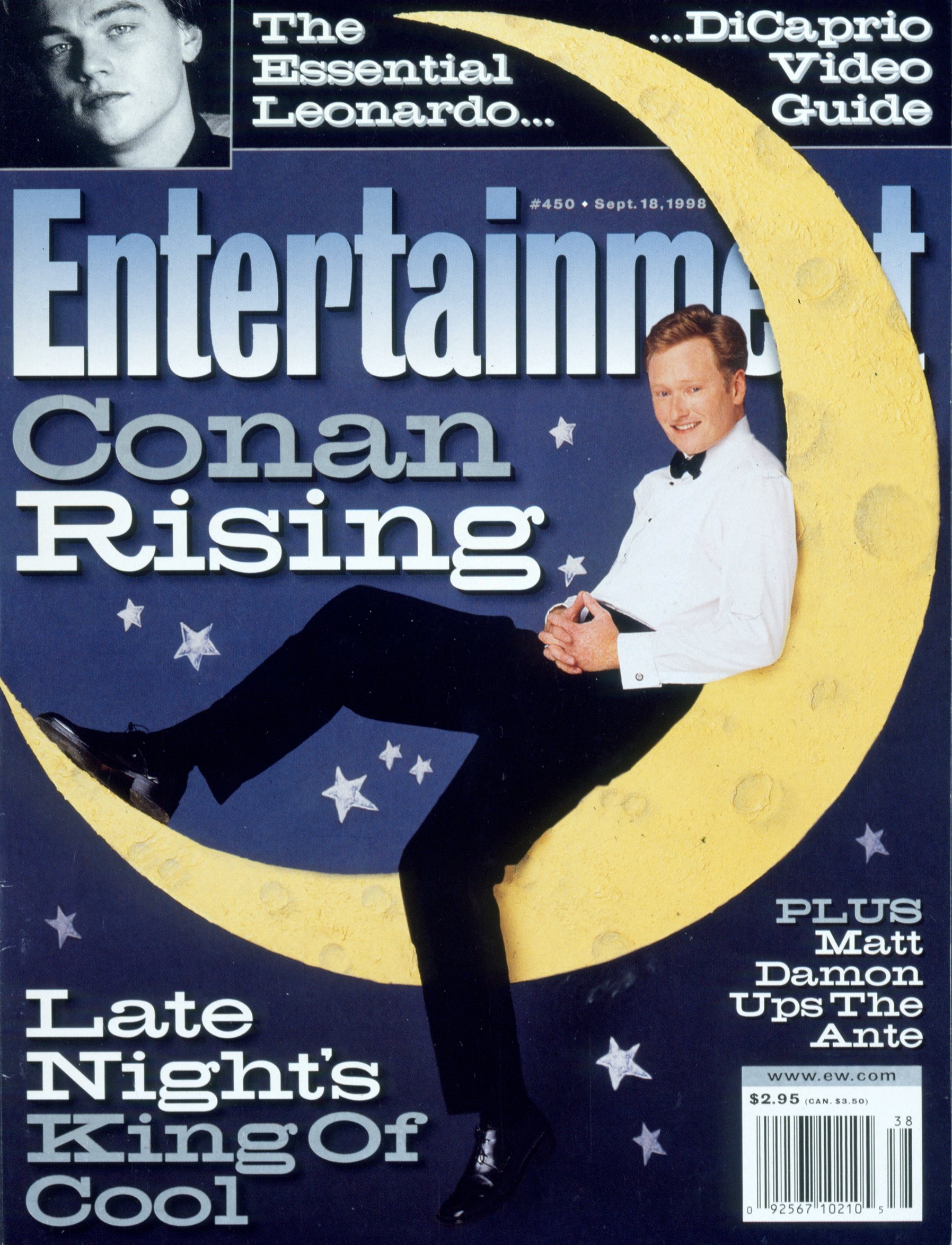

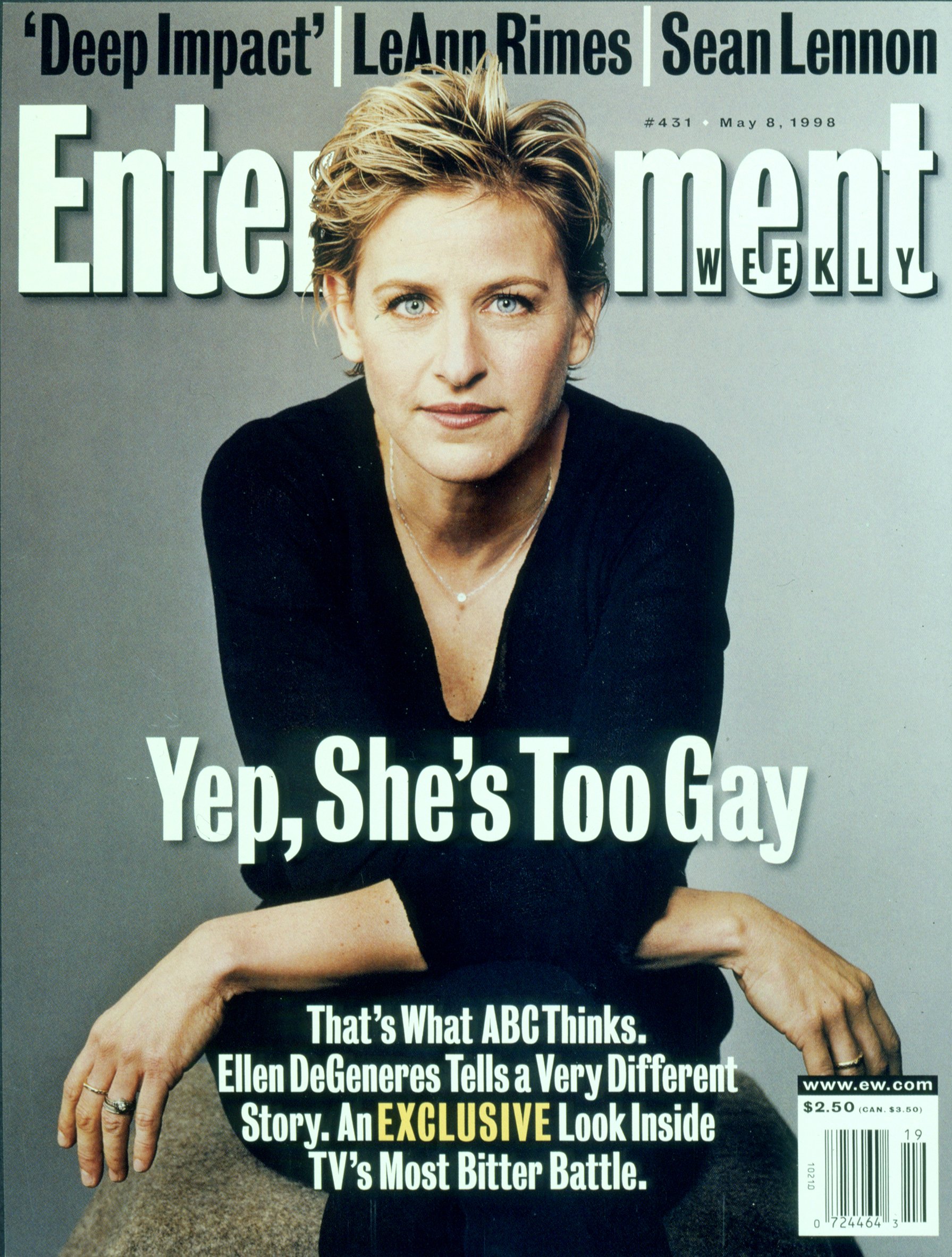

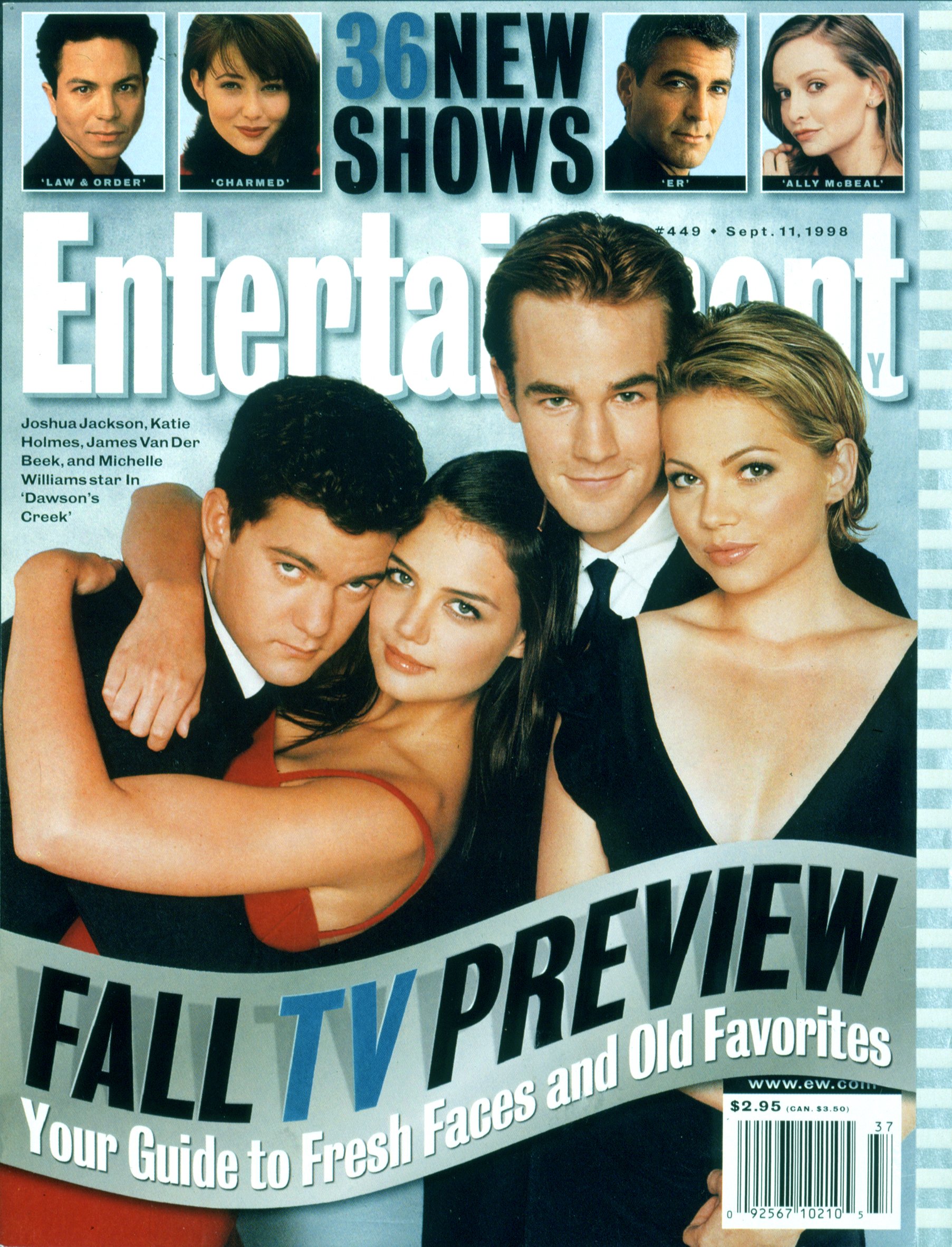

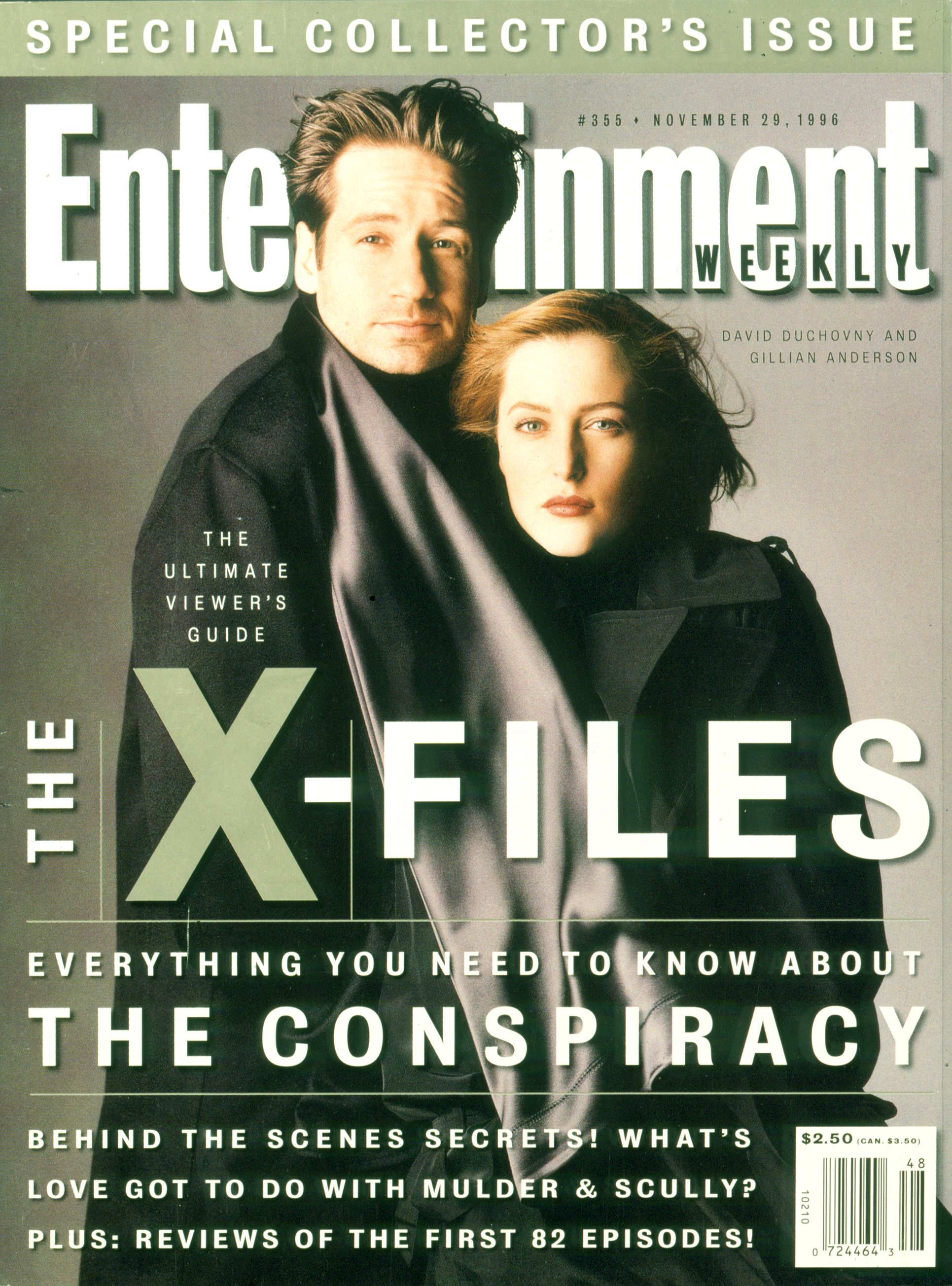

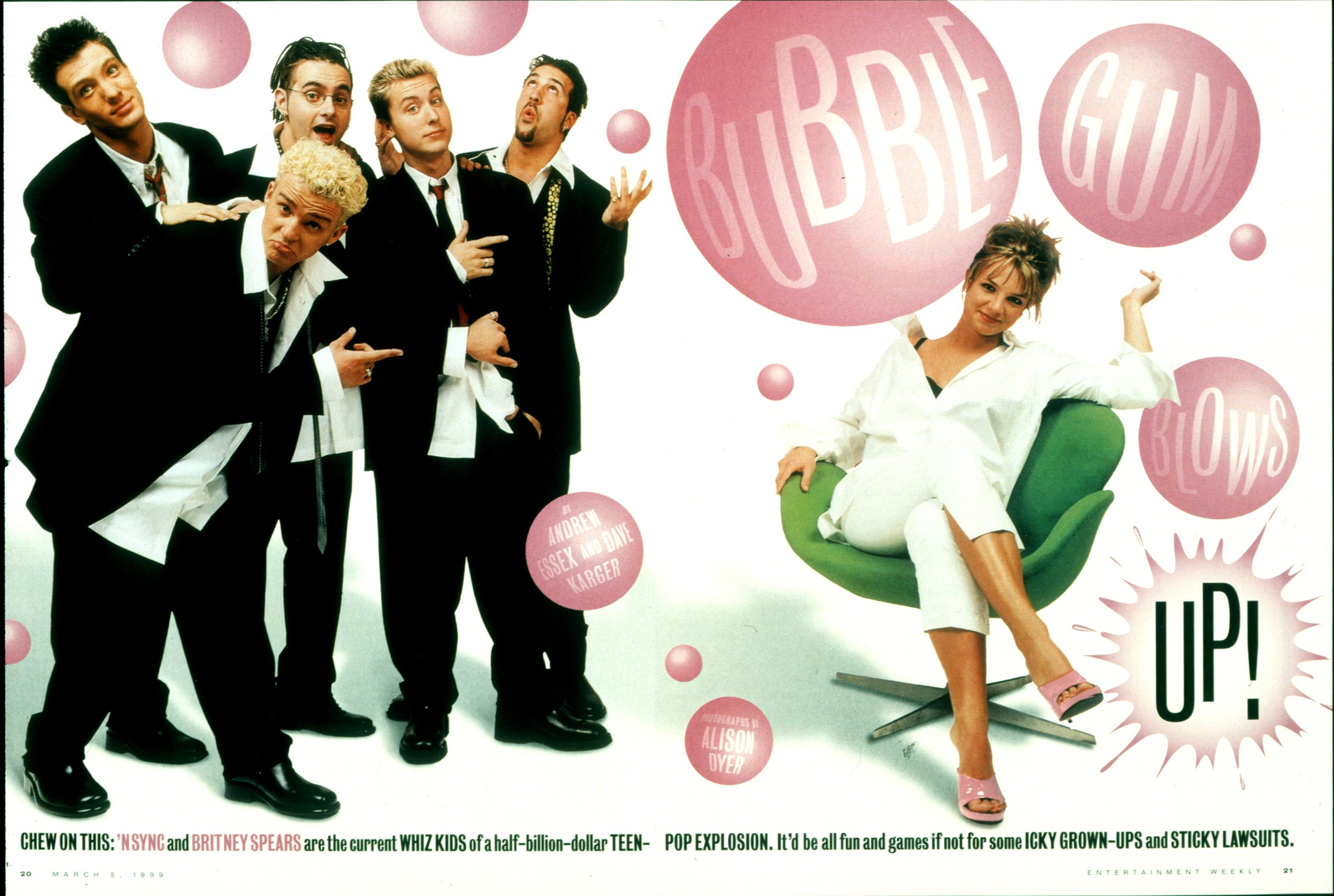

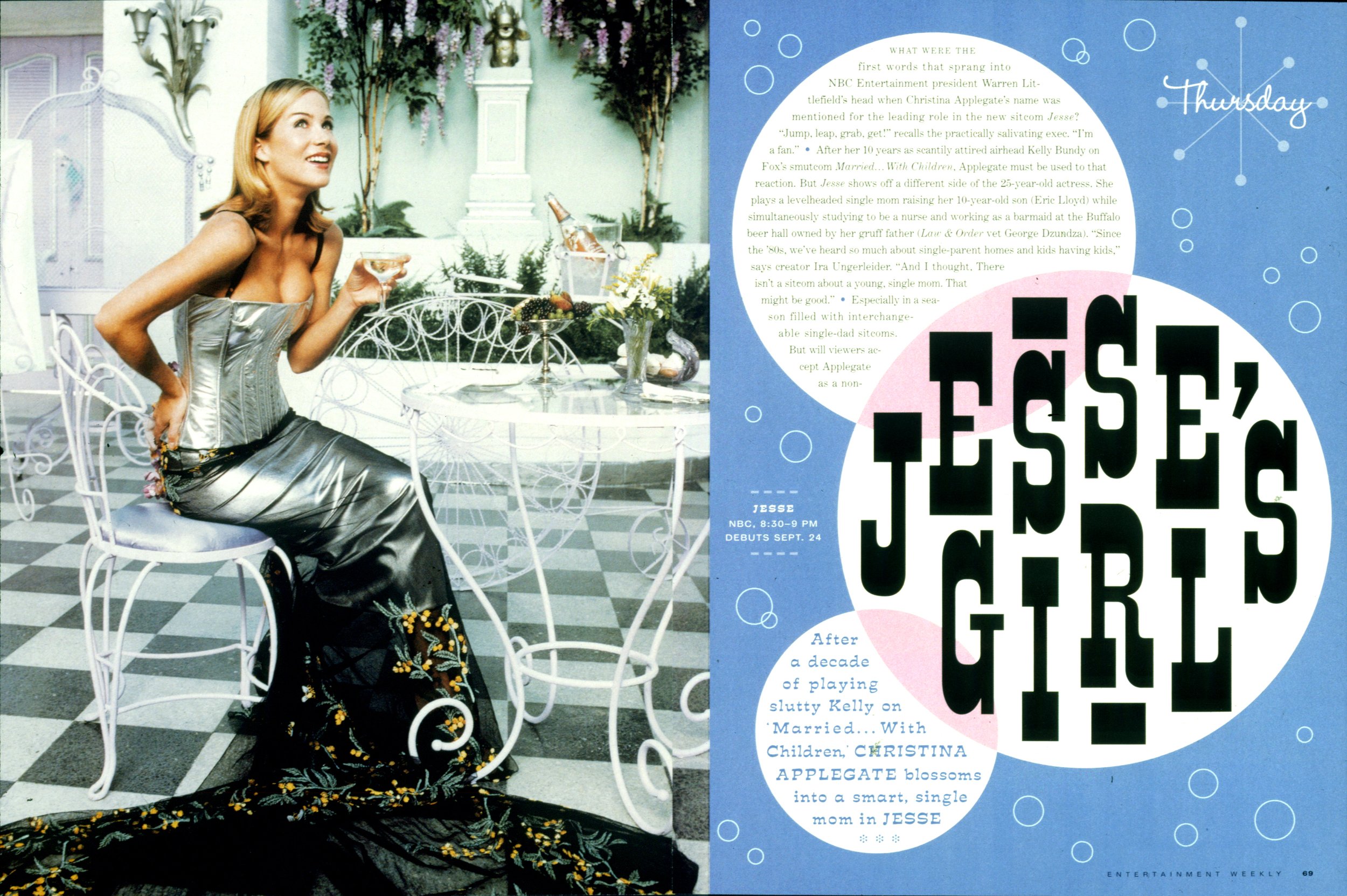

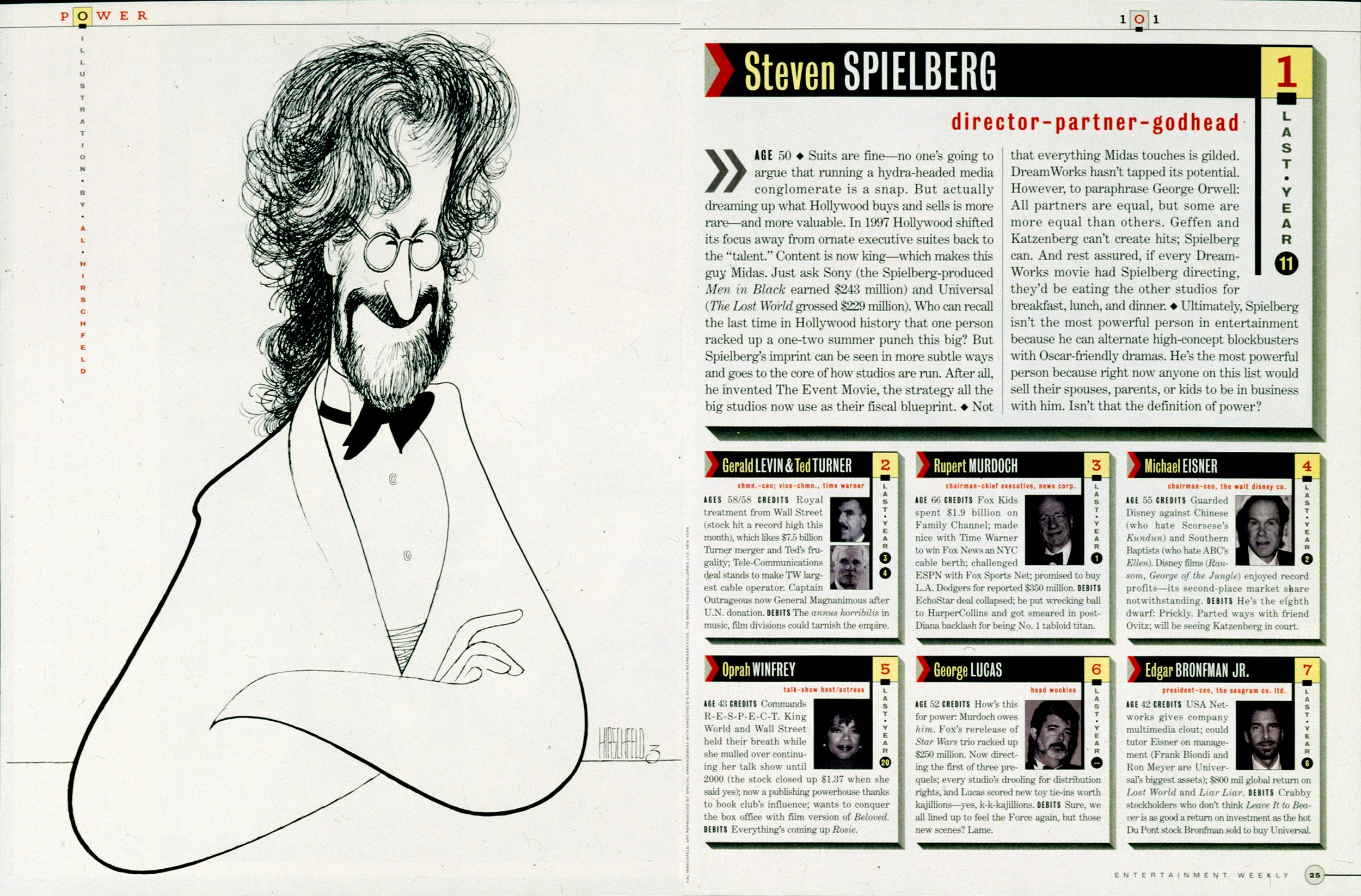

John Korpics: No. I left to go to Entertainment Weekly. I was at Entertainment Weekly for four years. And then, in that time, Granger went to Esquire. And then at some point Granger asked me to come to Esquire.

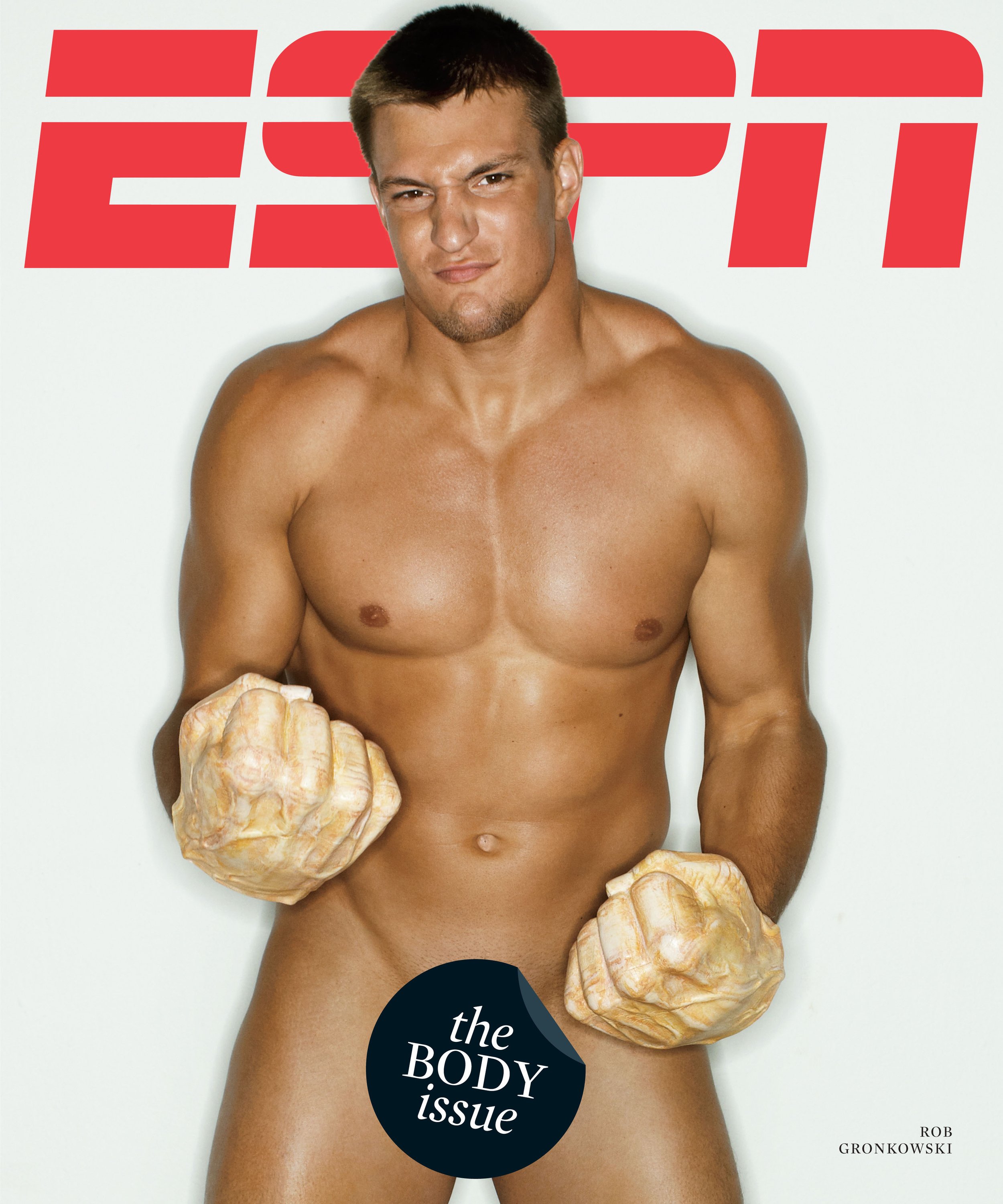

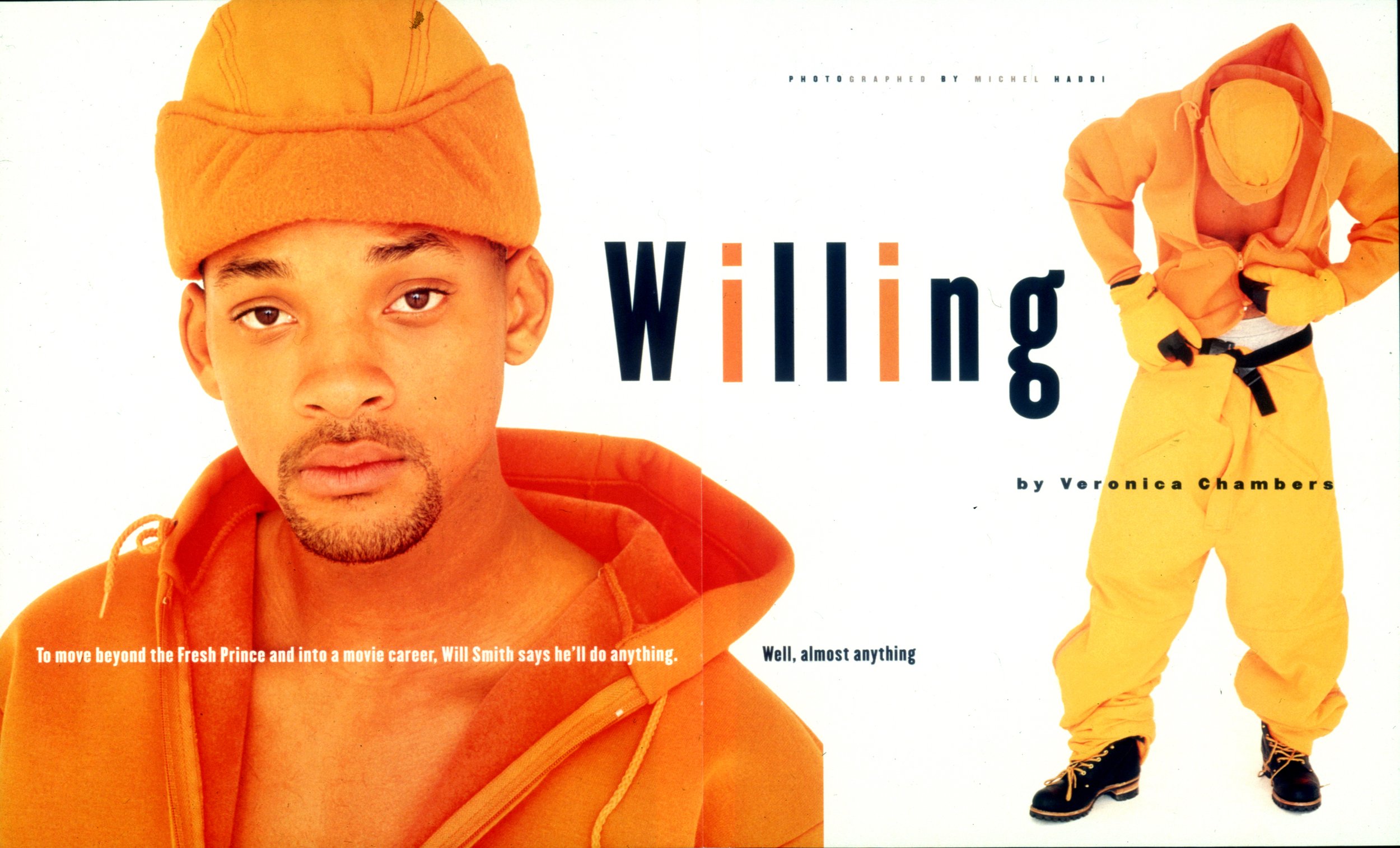

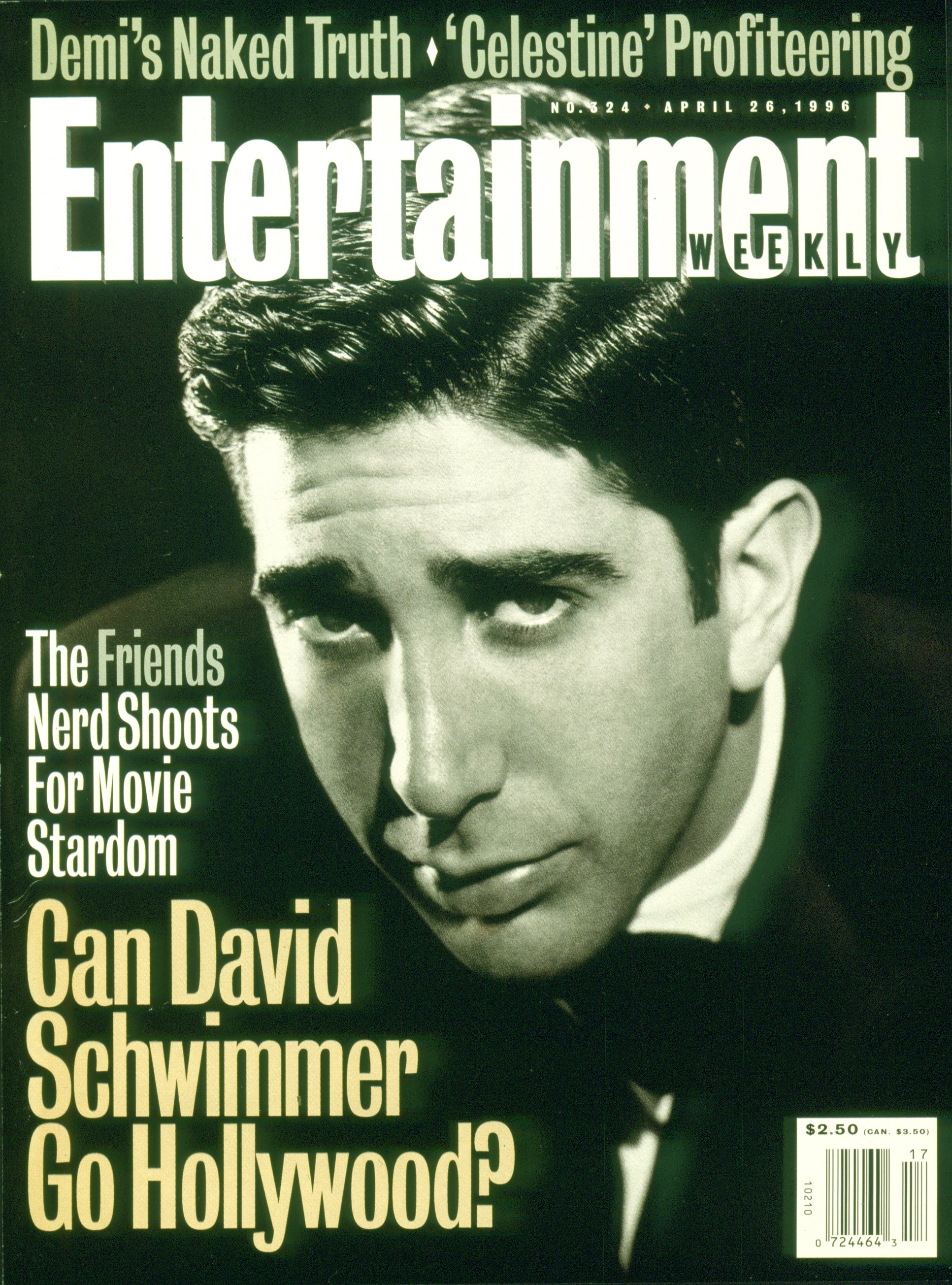

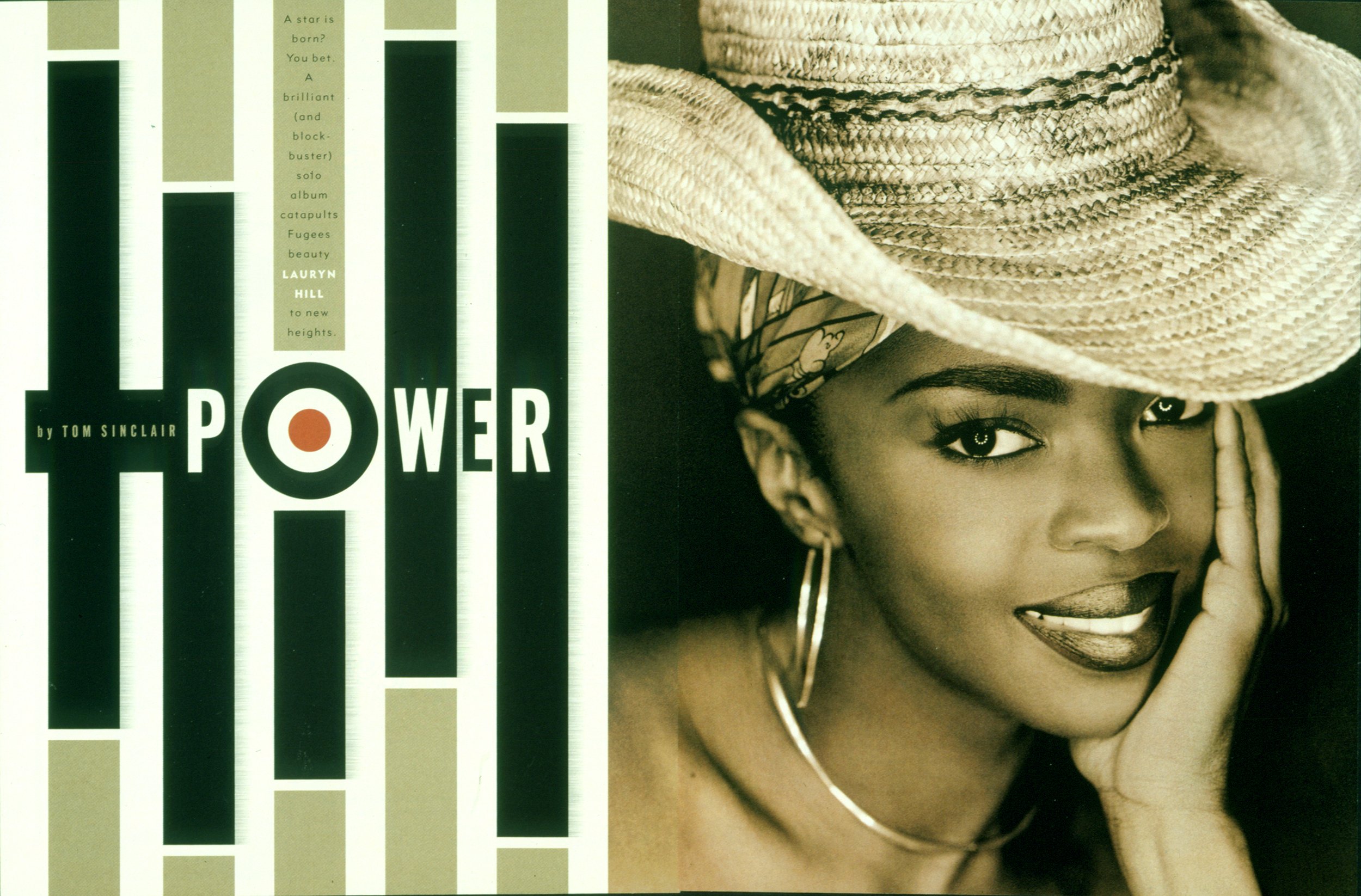

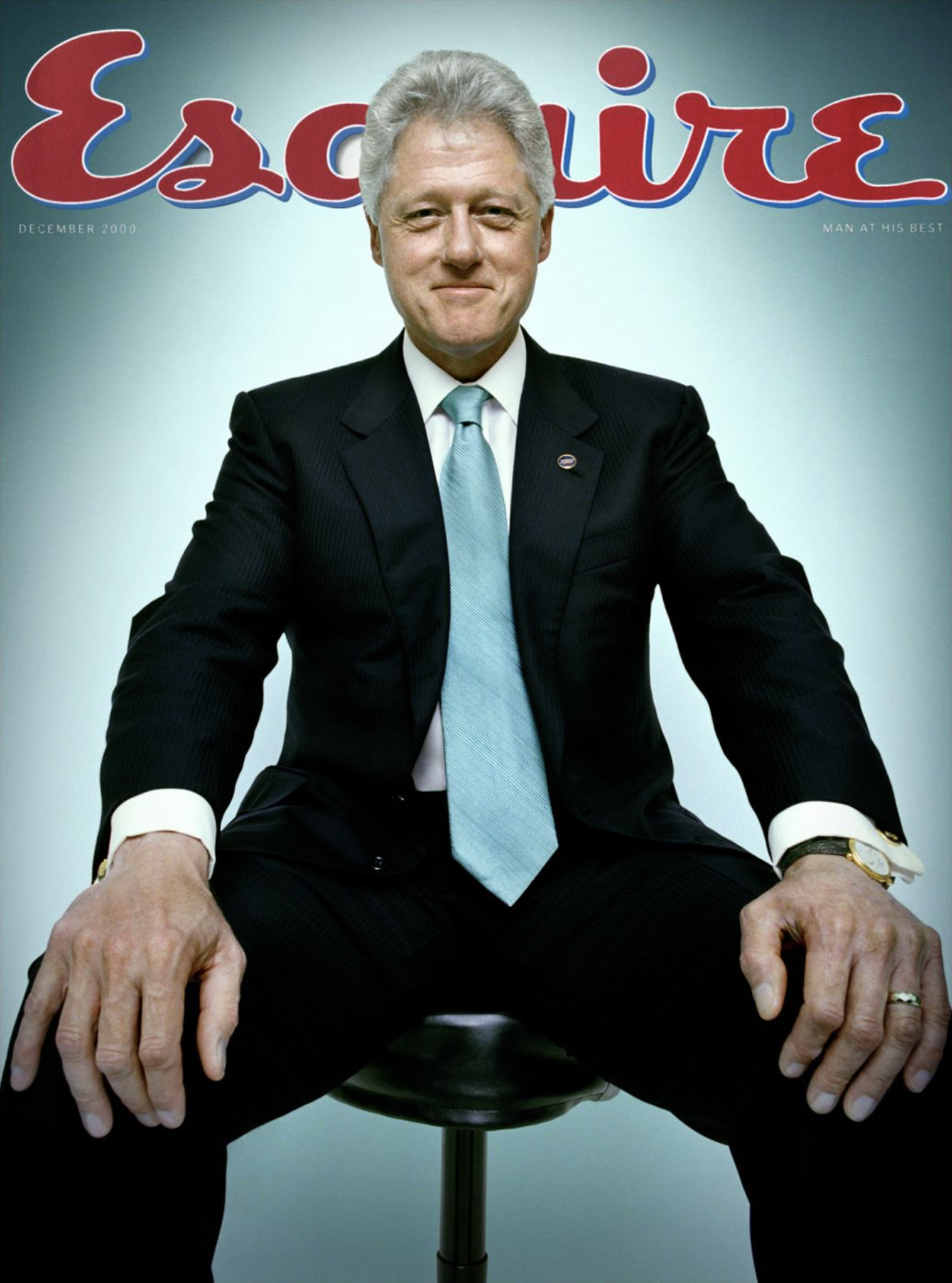

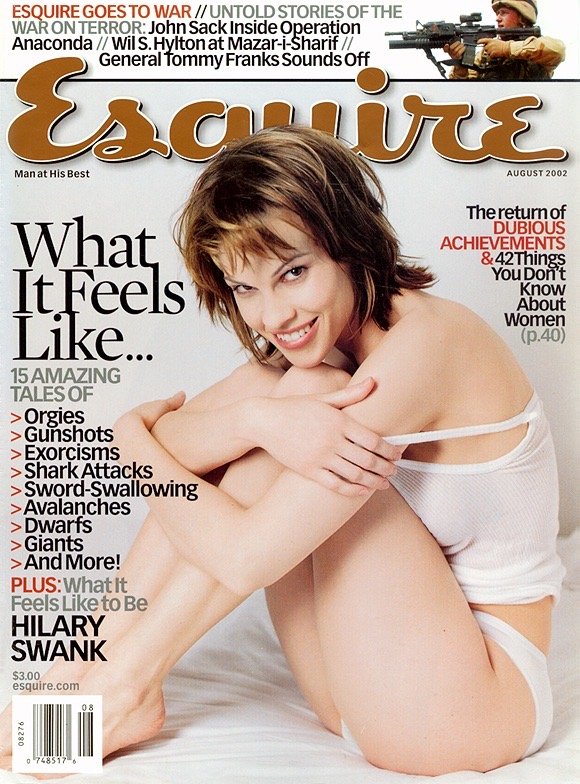

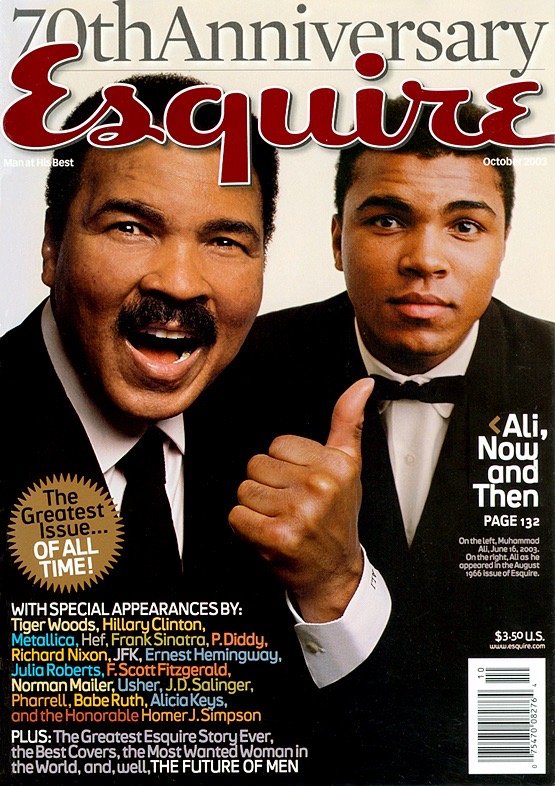

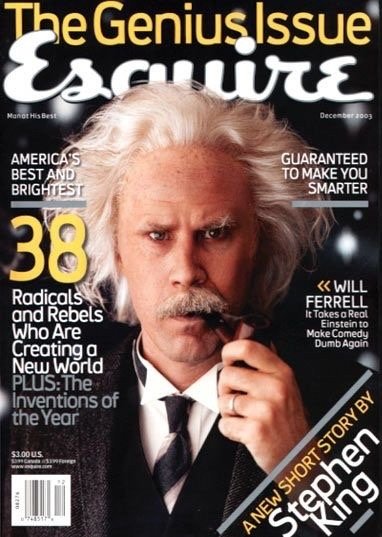

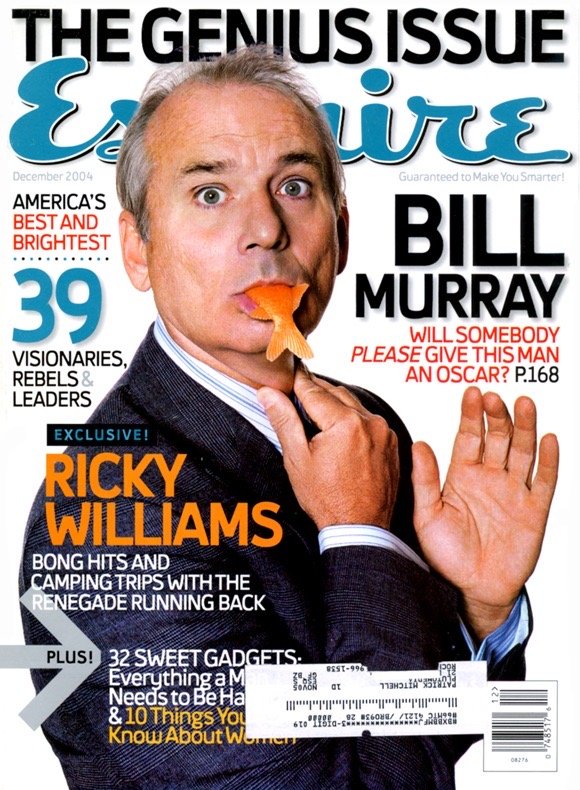

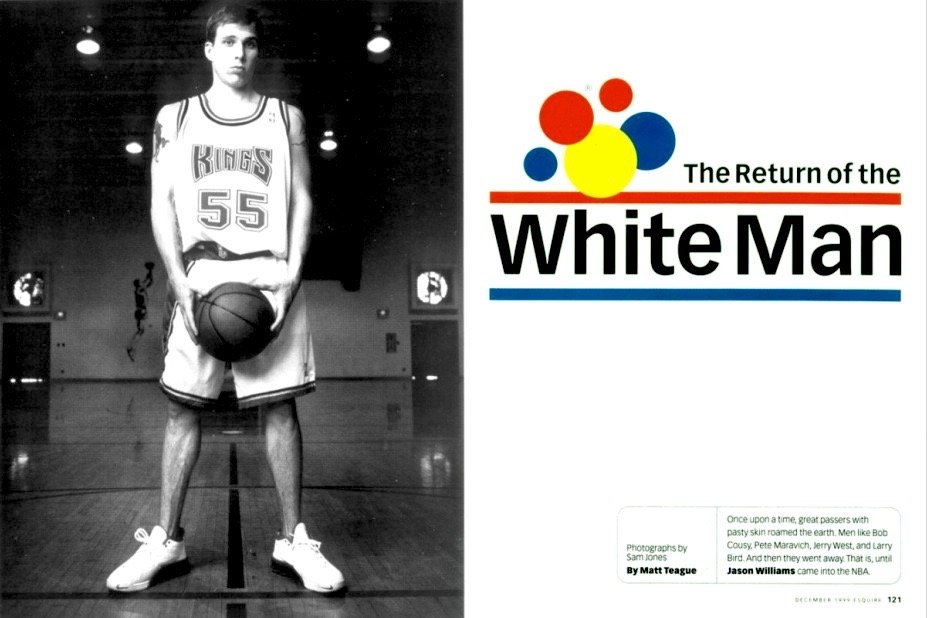

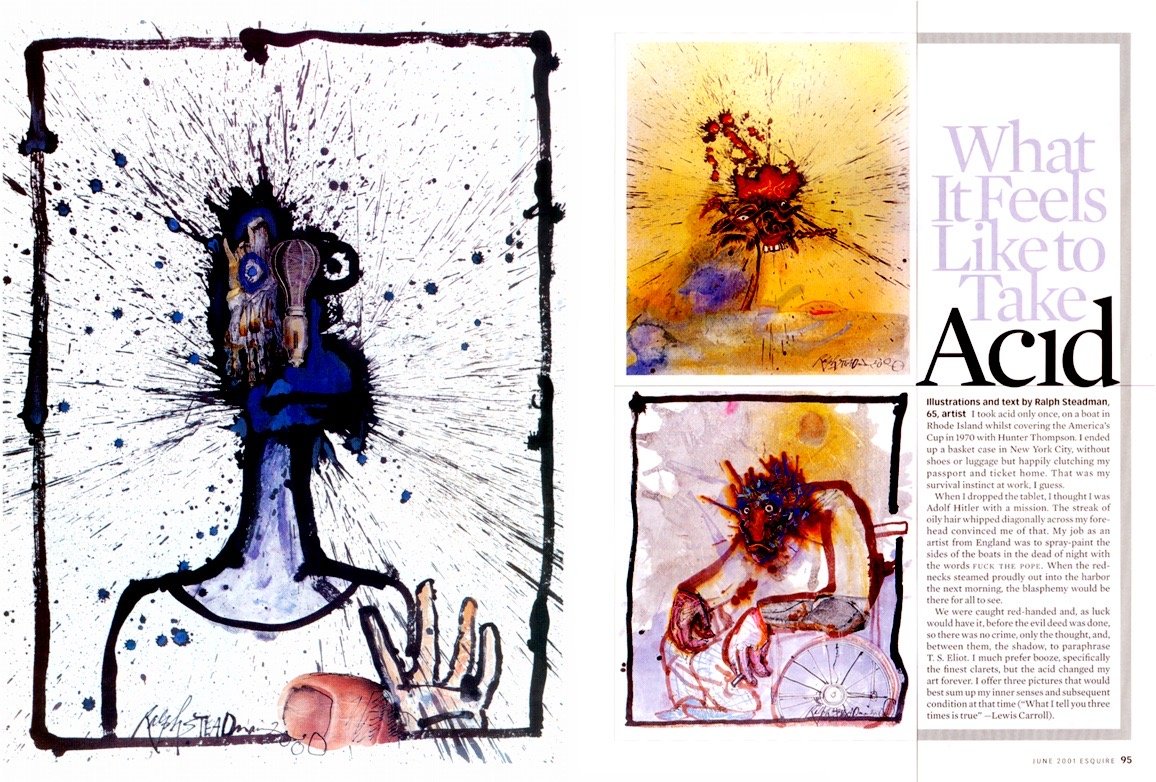

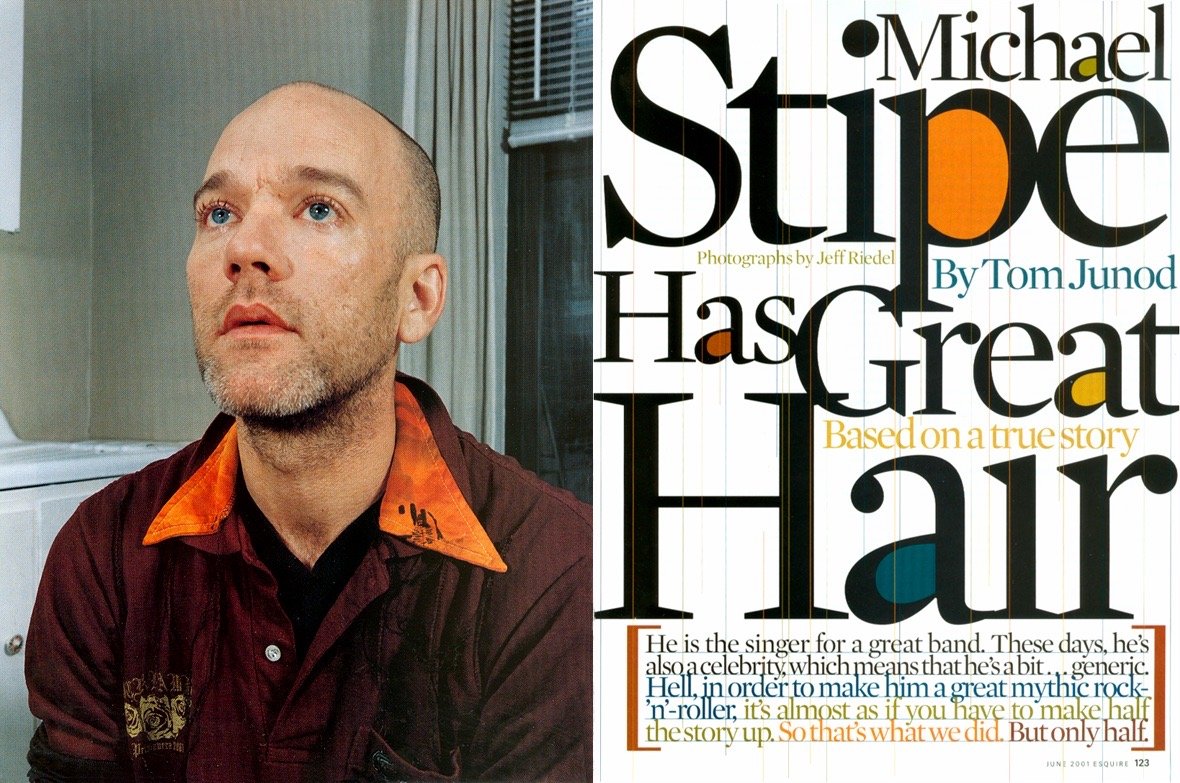

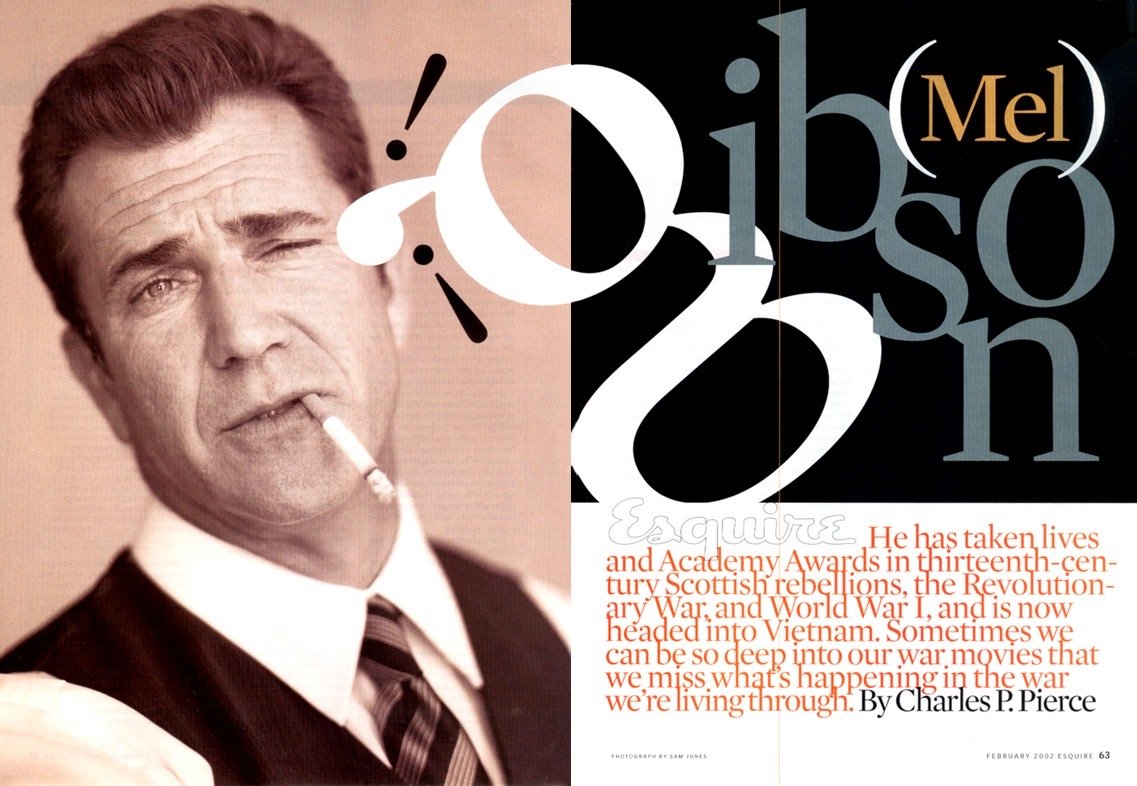

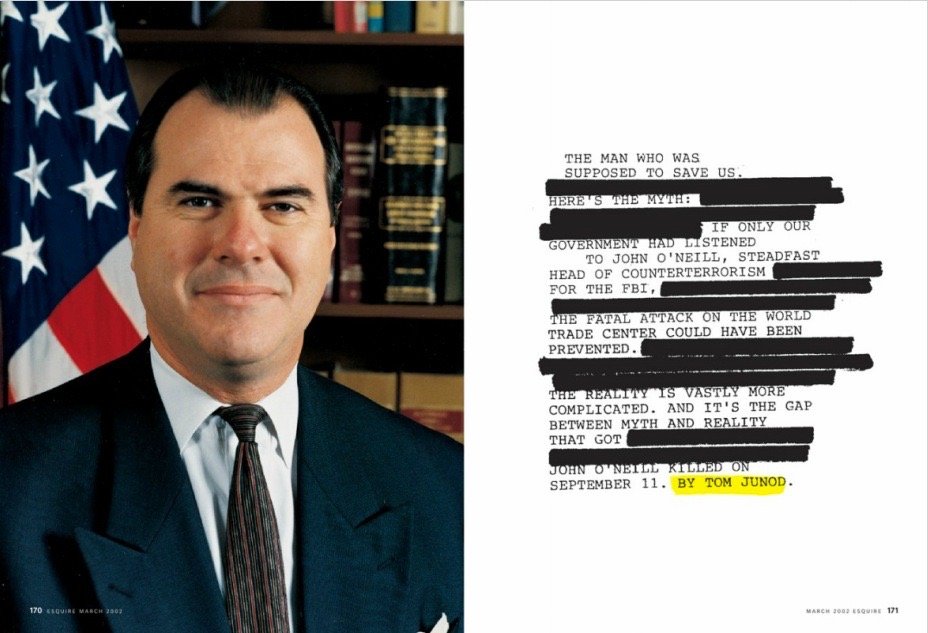

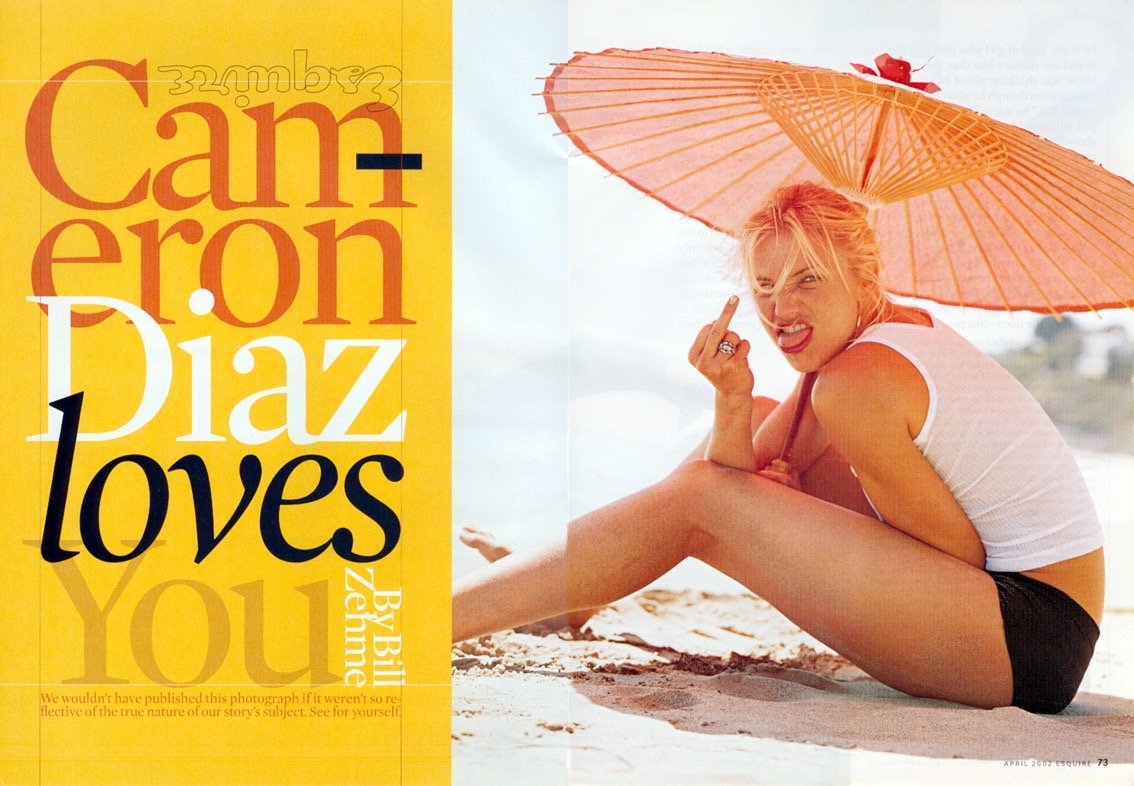

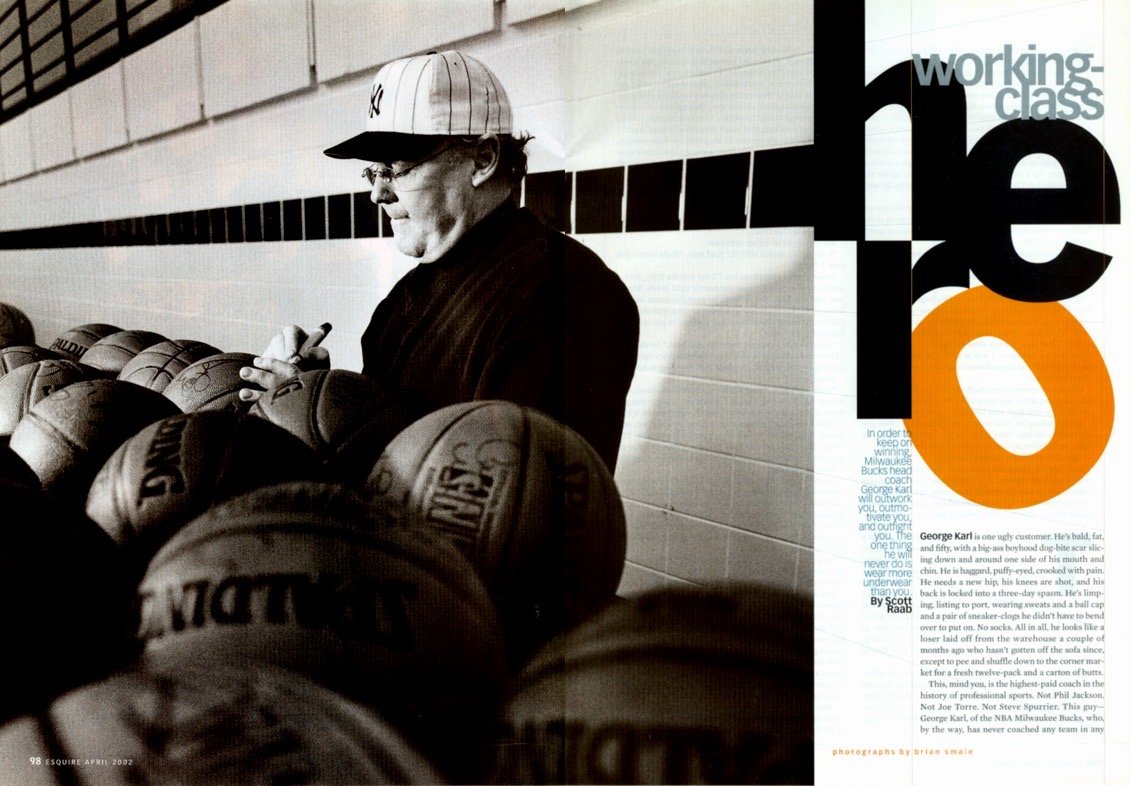

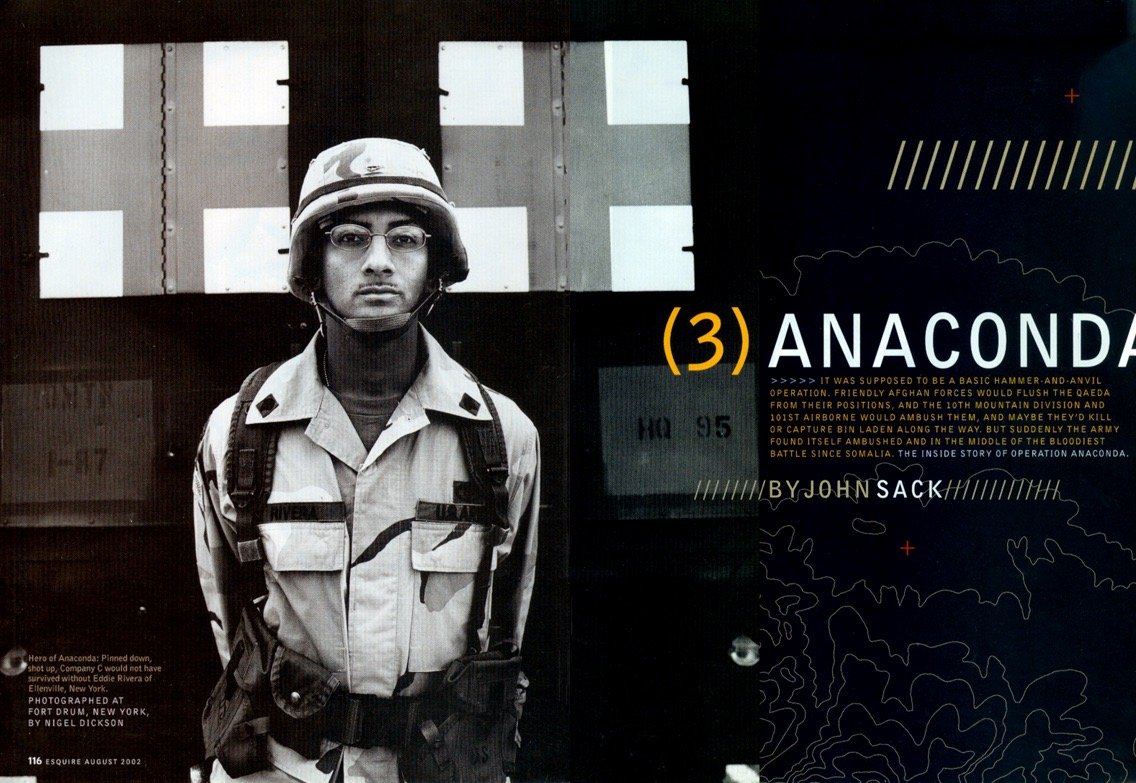

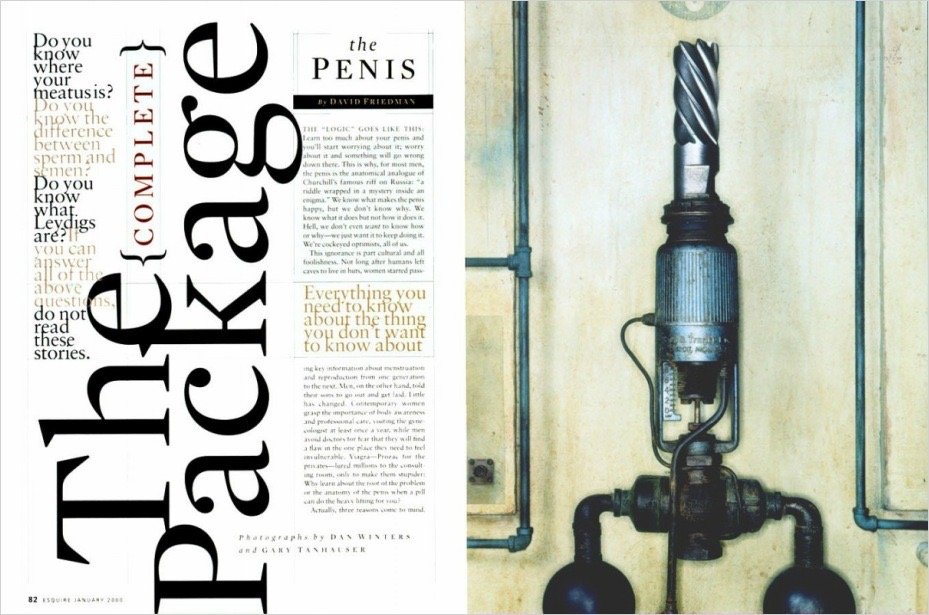

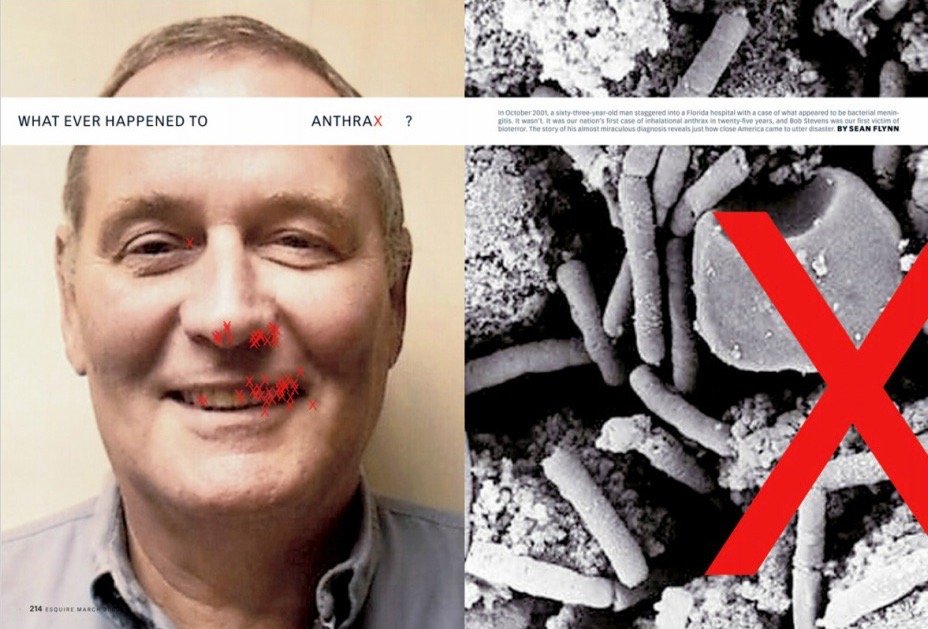

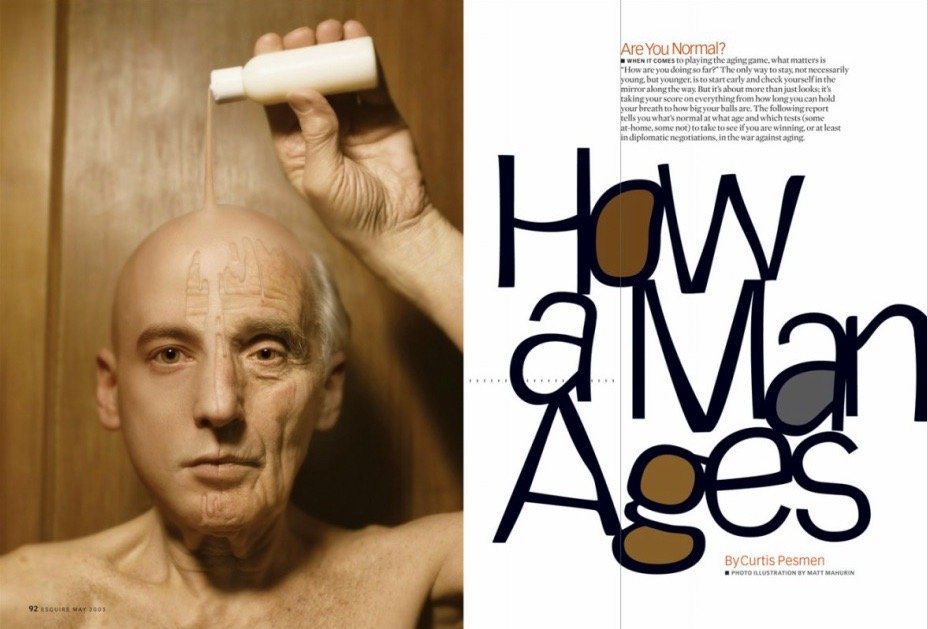

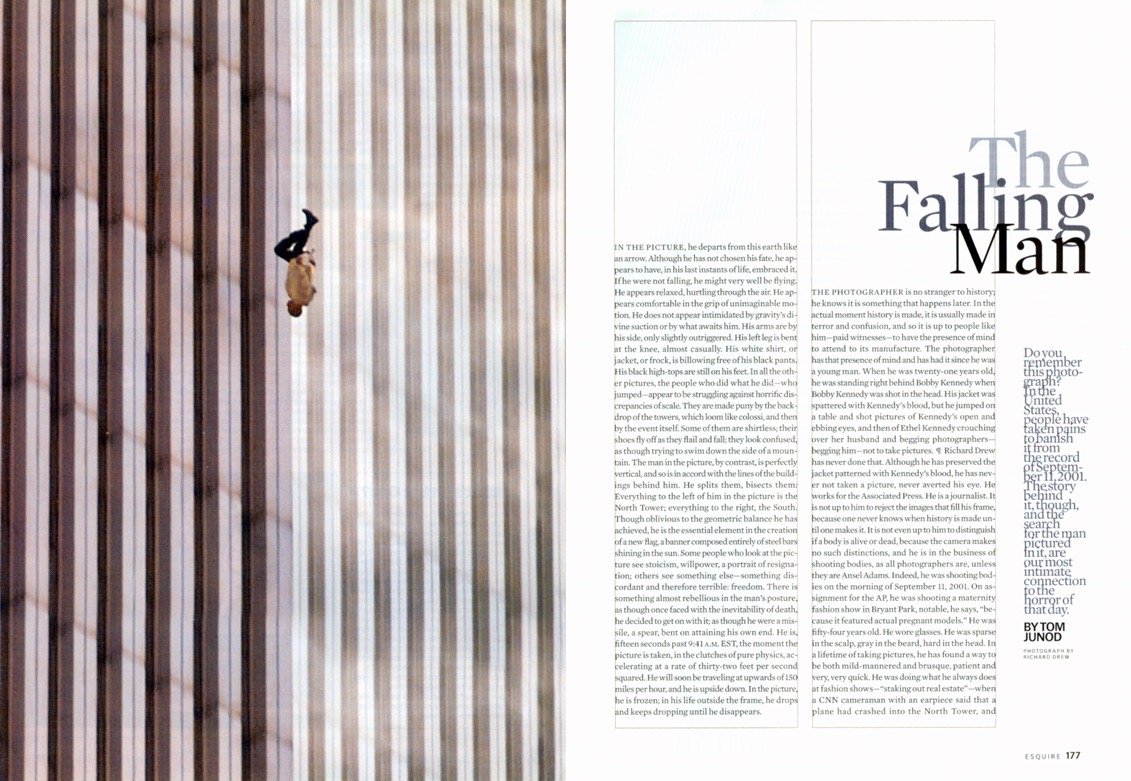

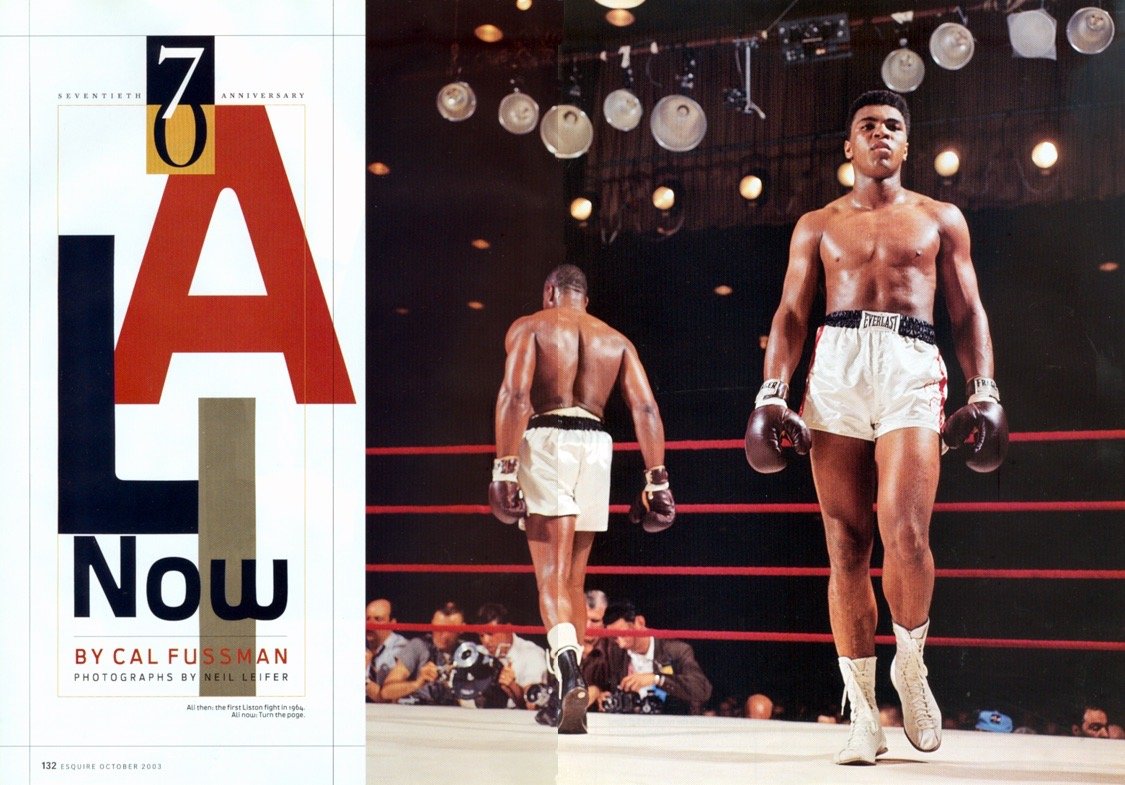

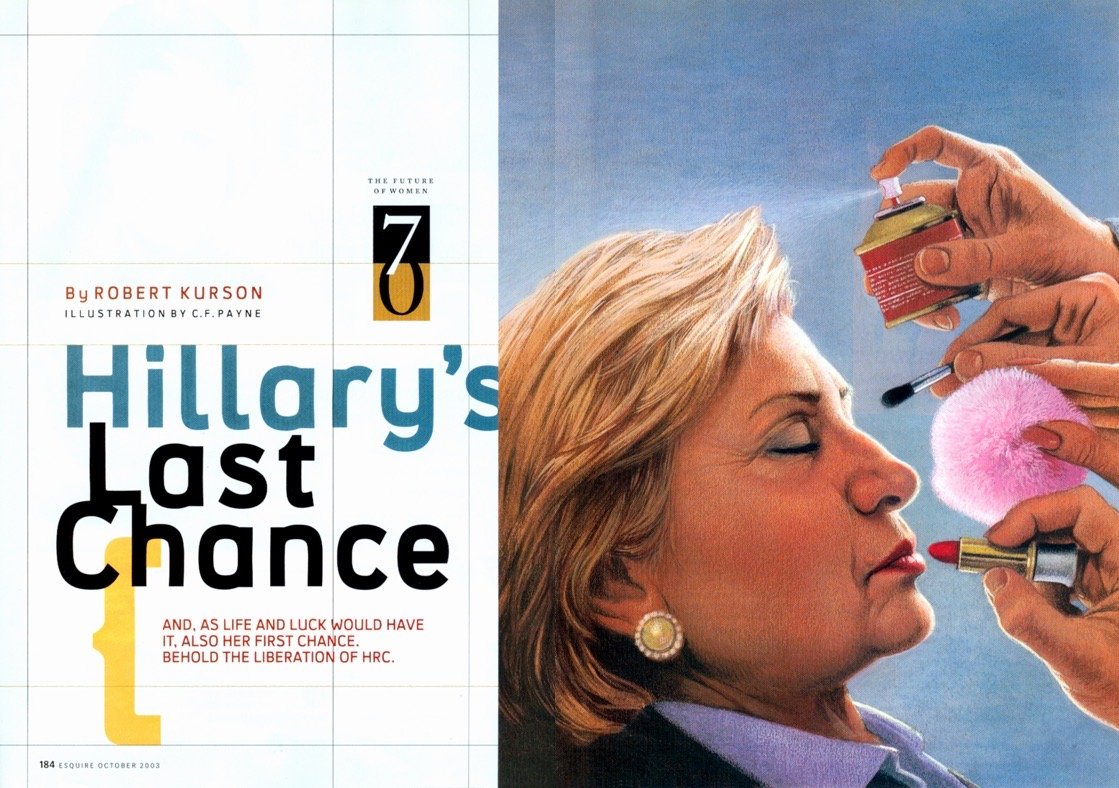

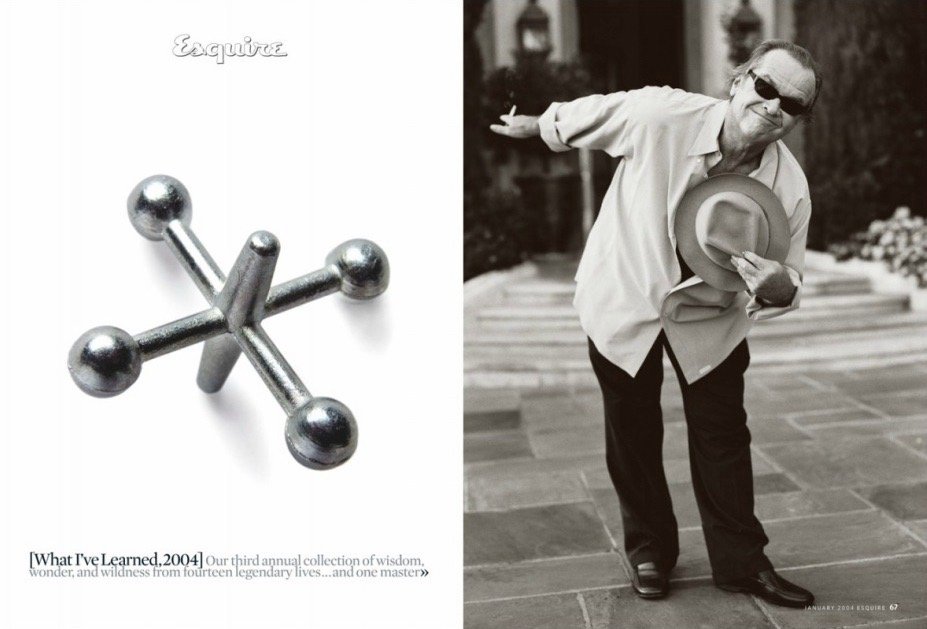

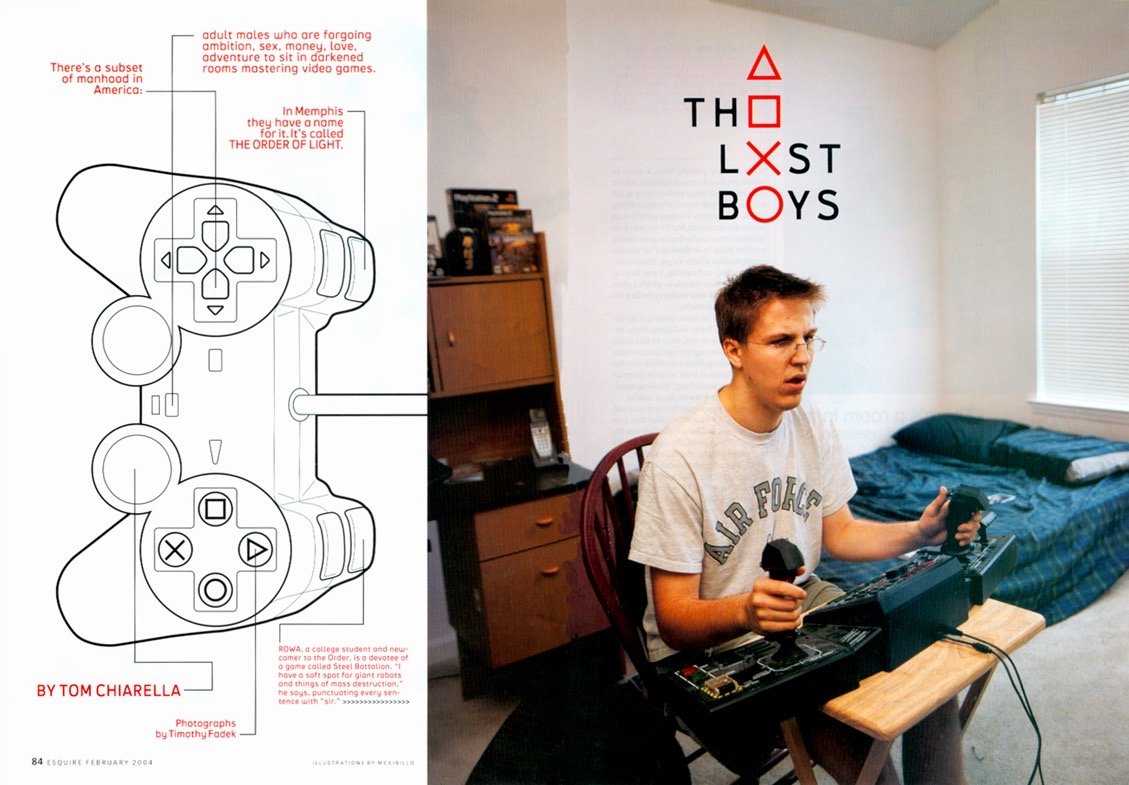

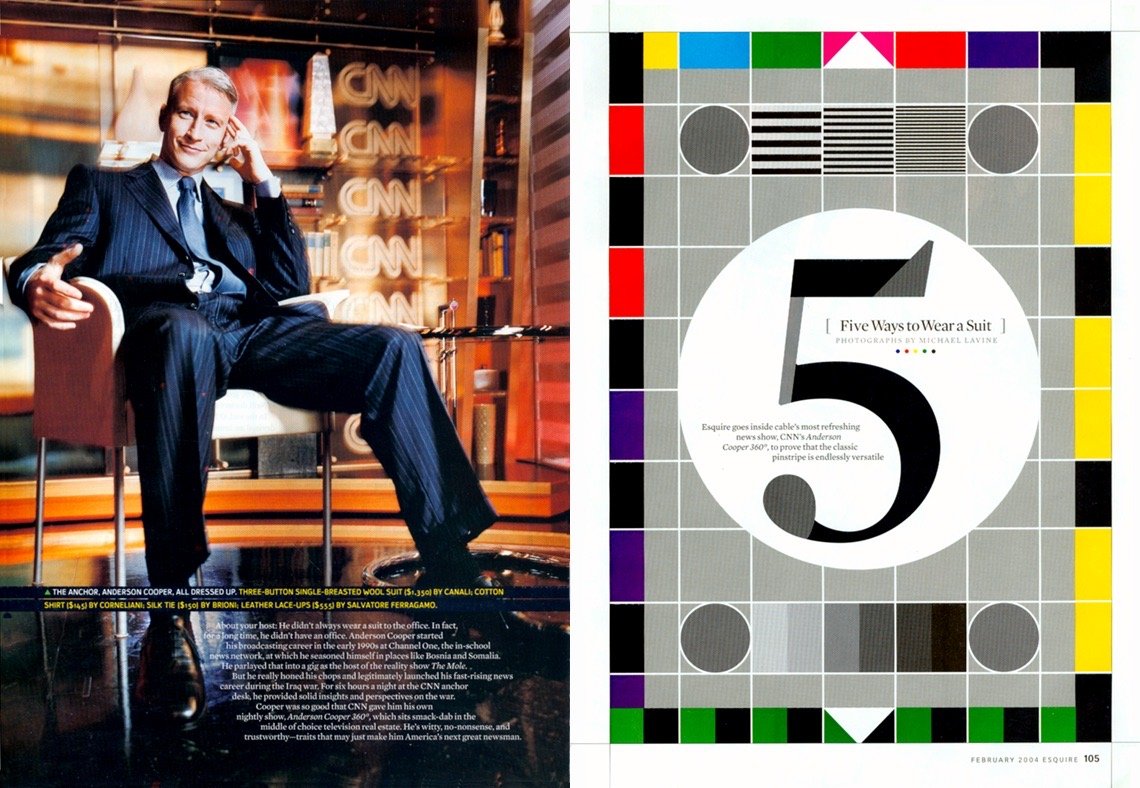

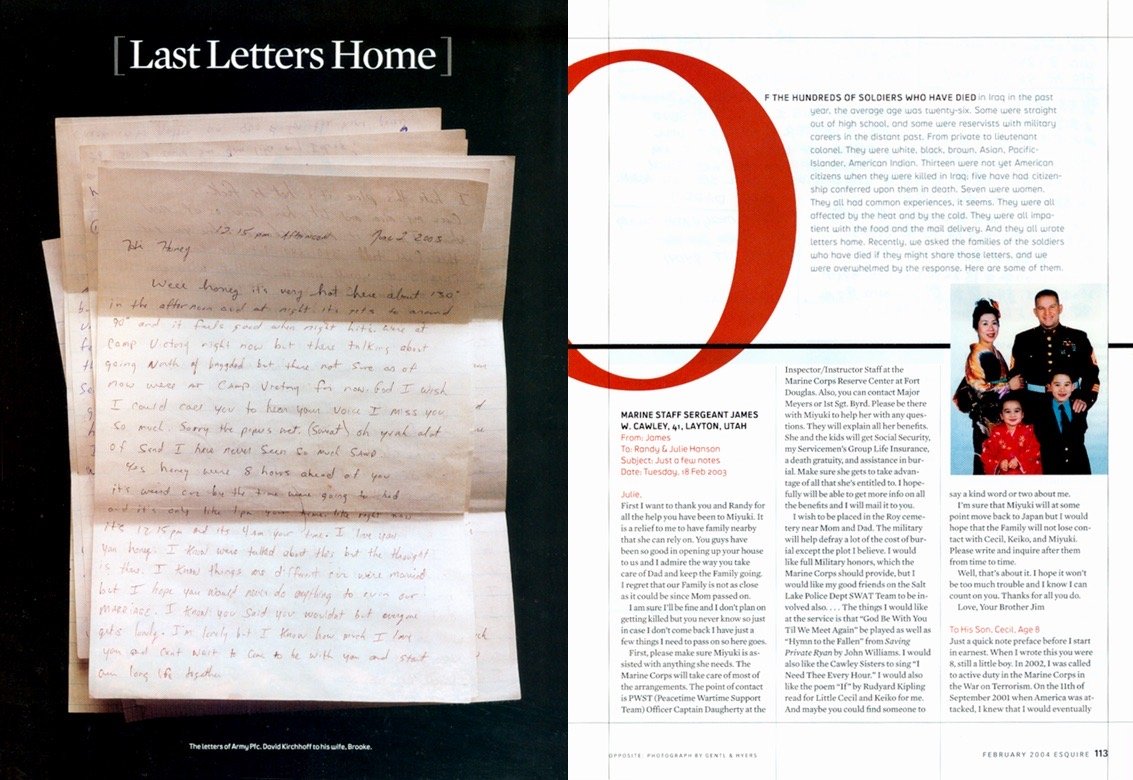

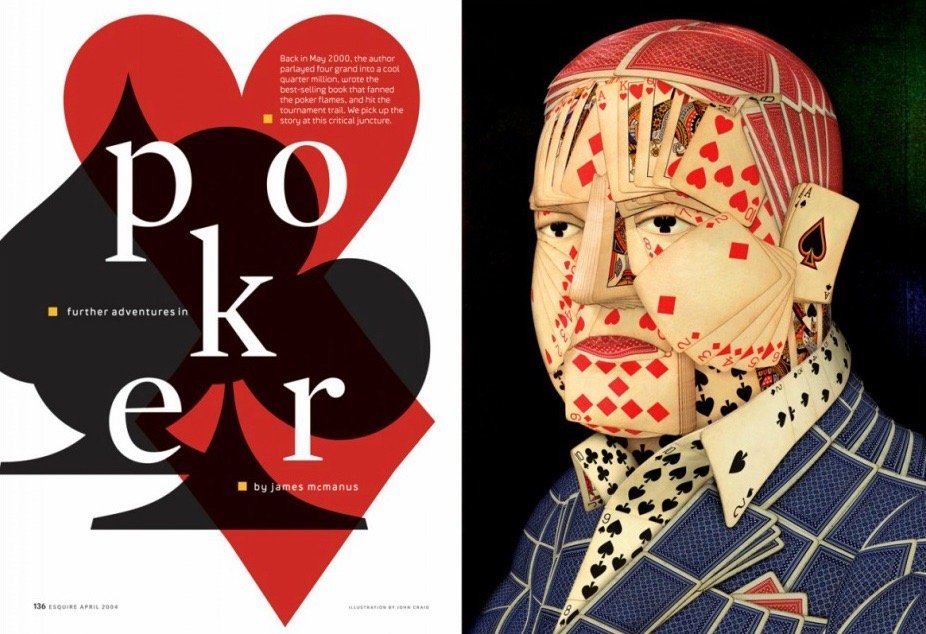

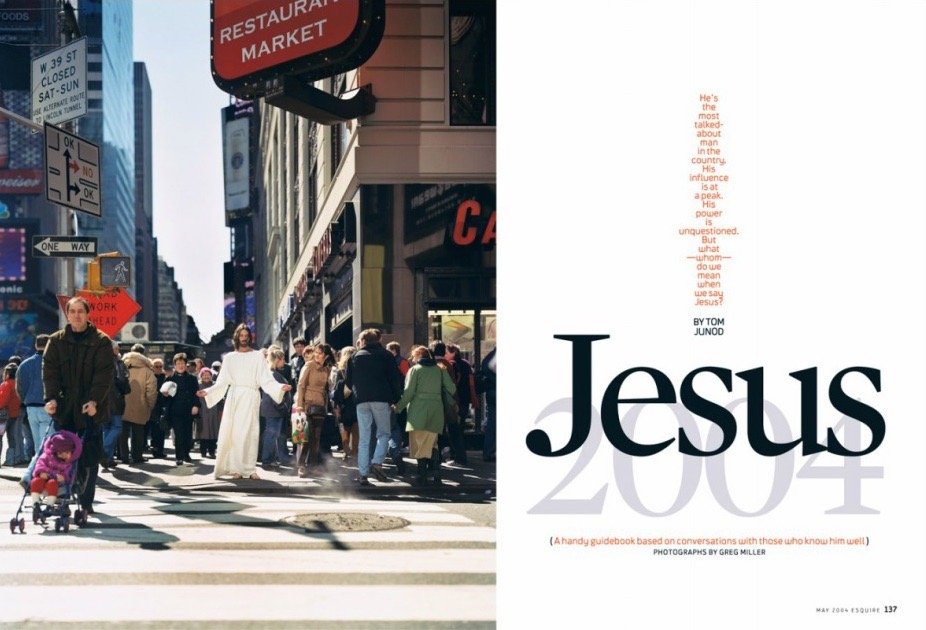

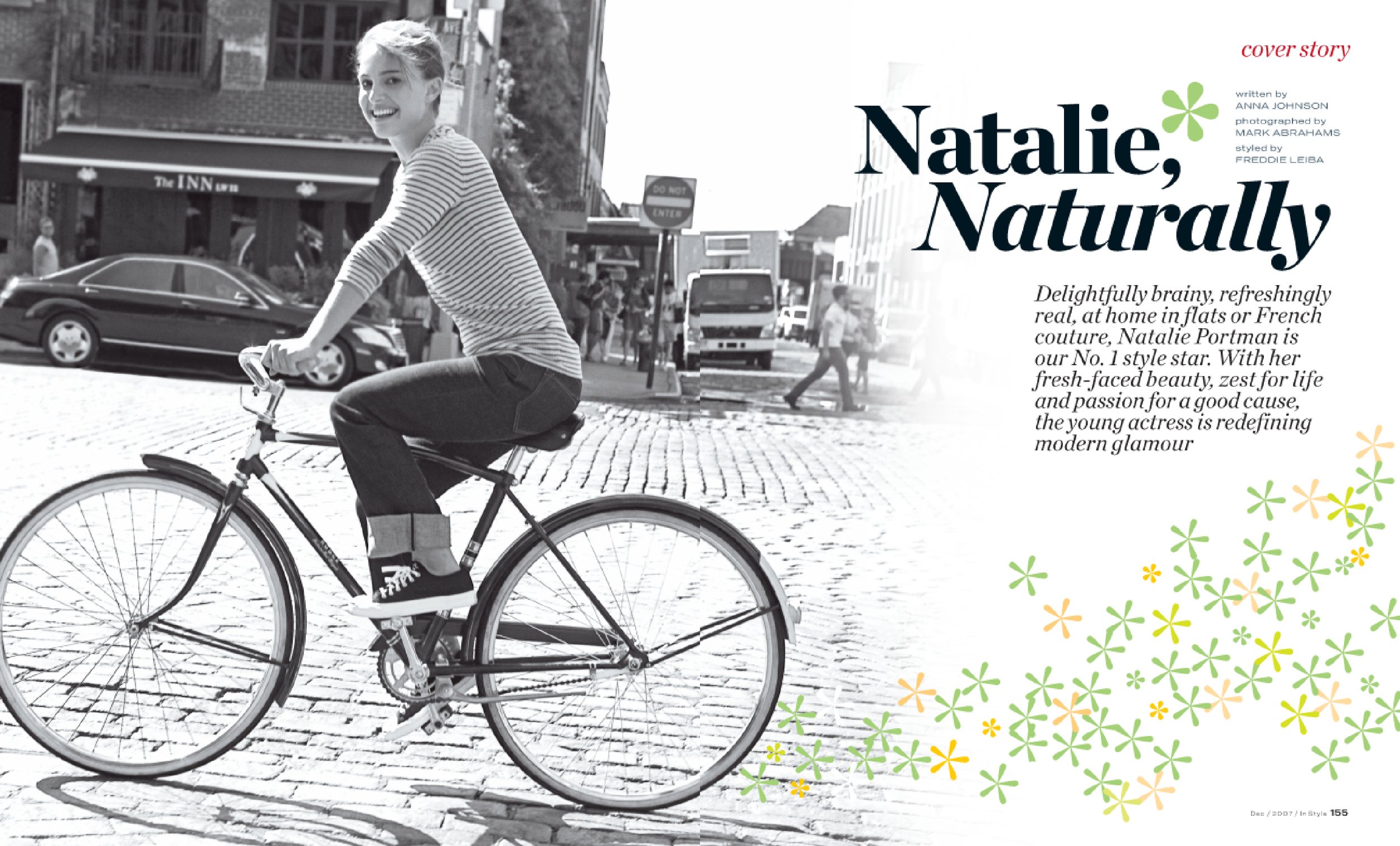

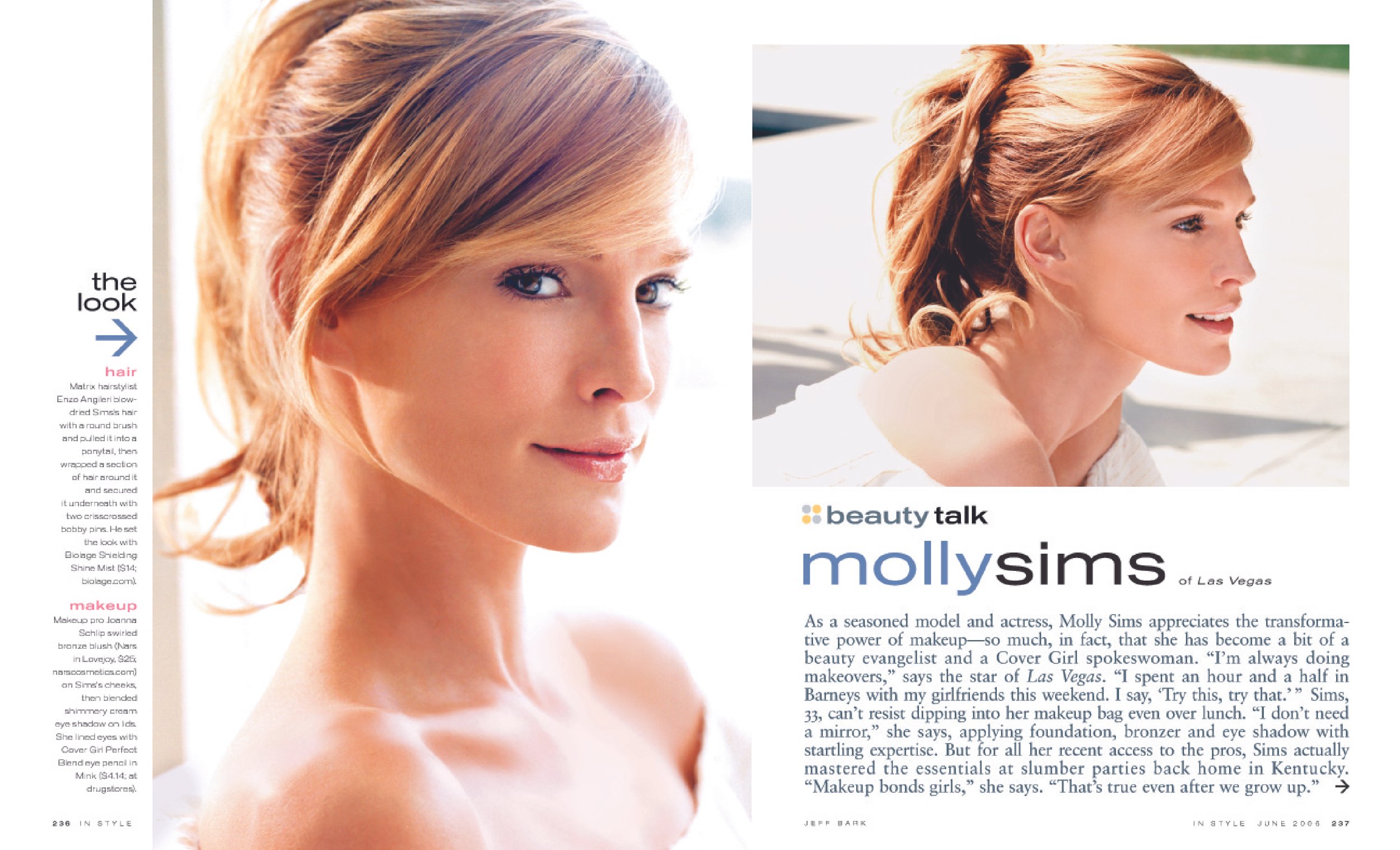

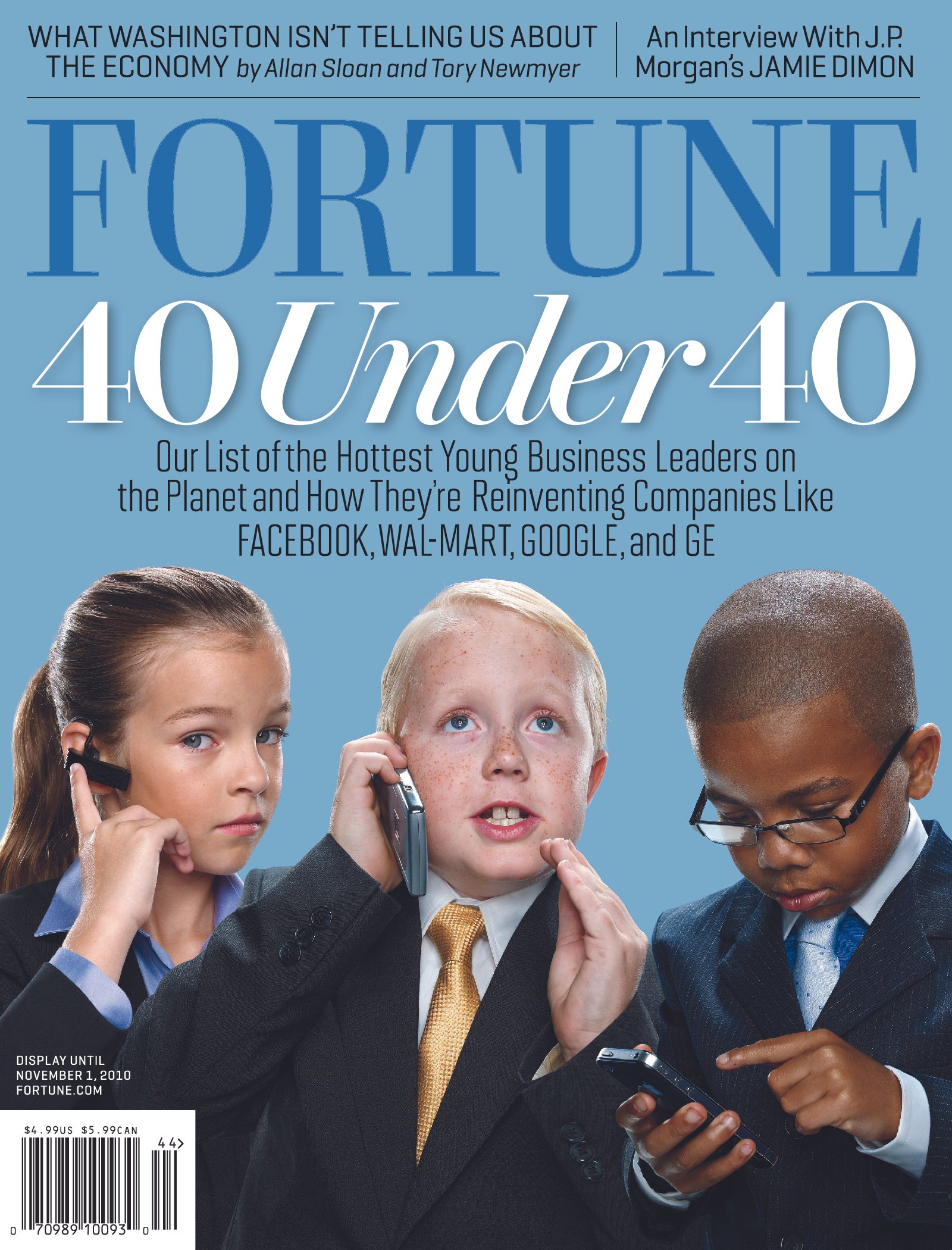

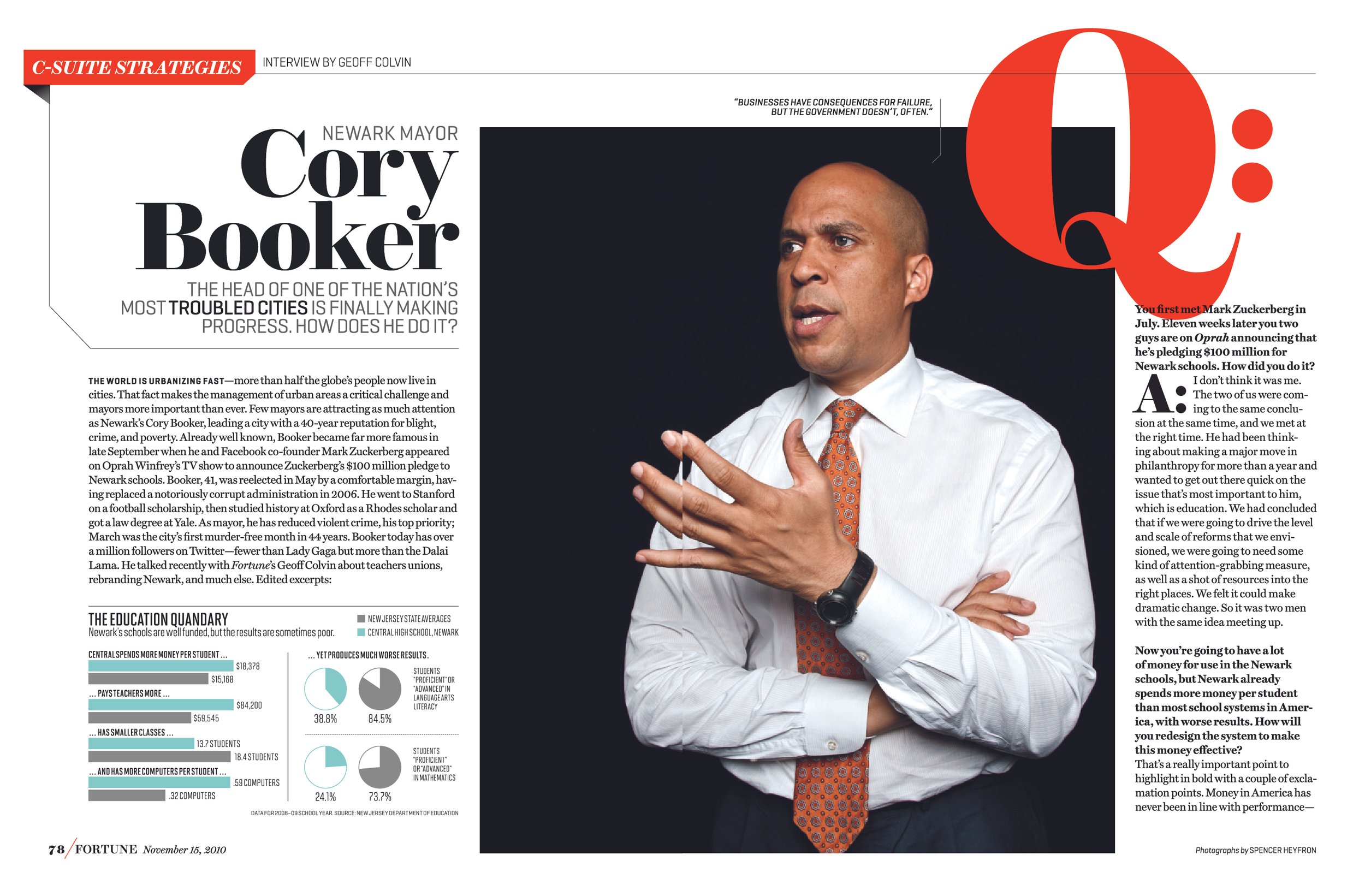

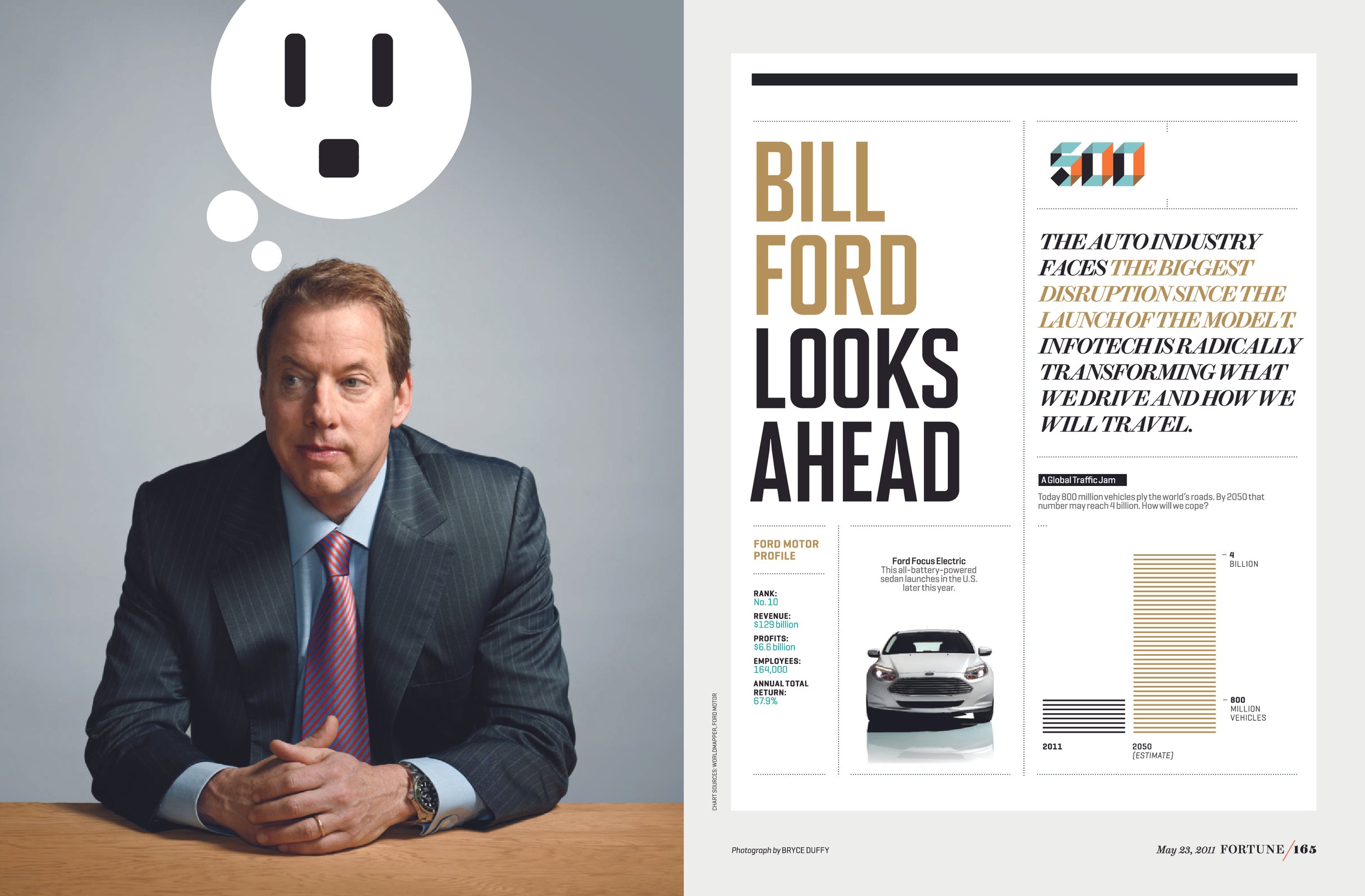

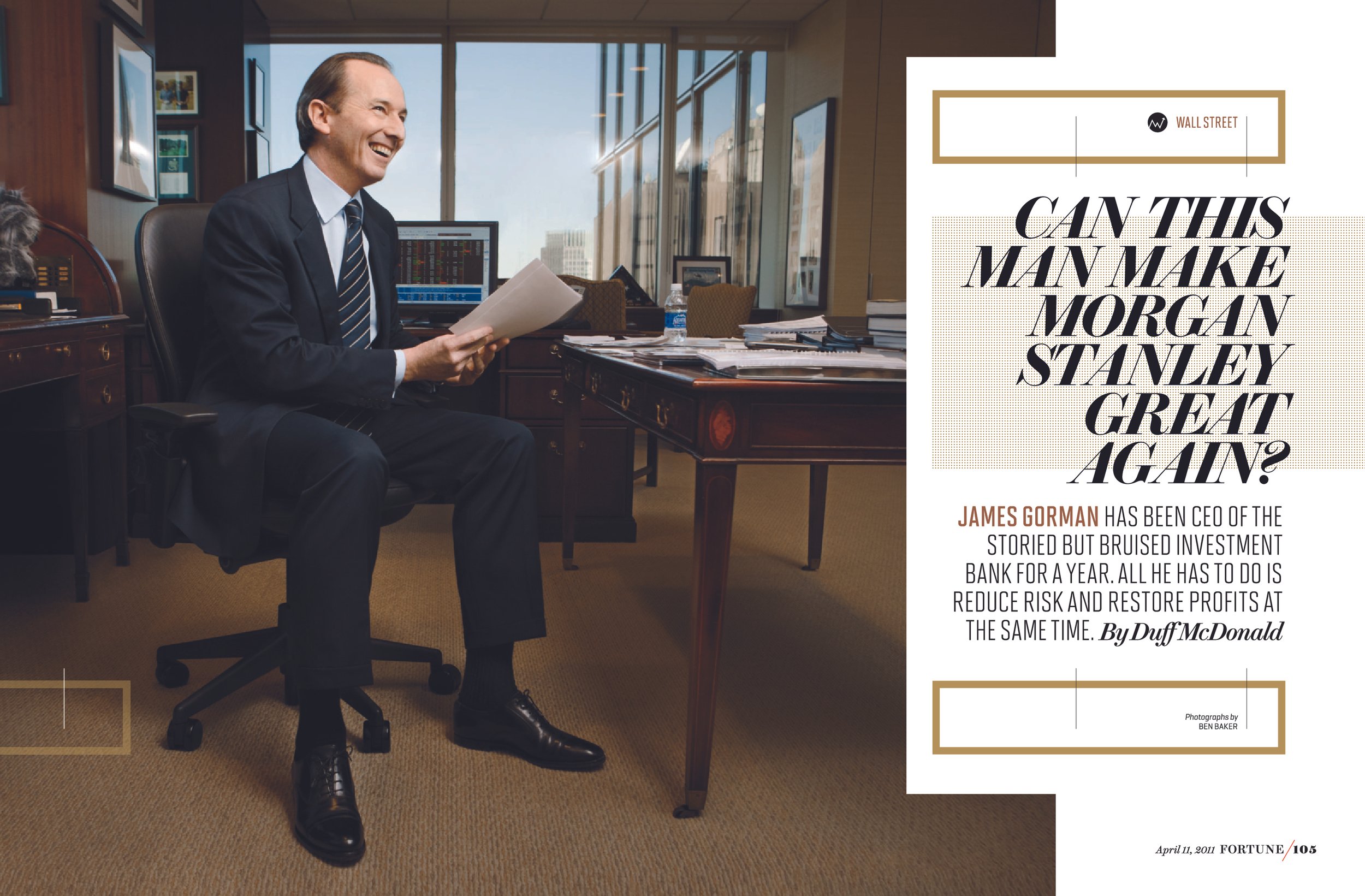

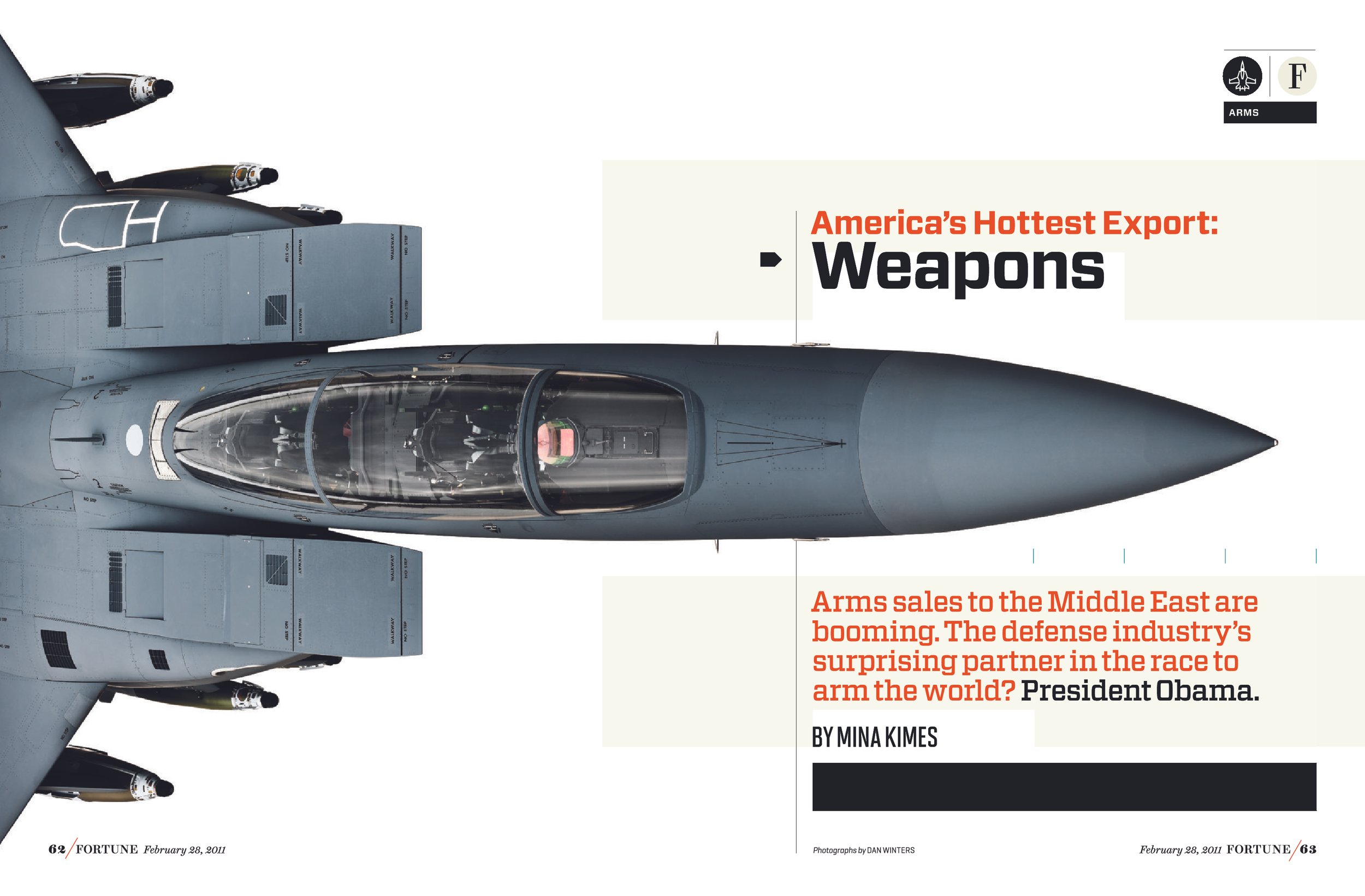

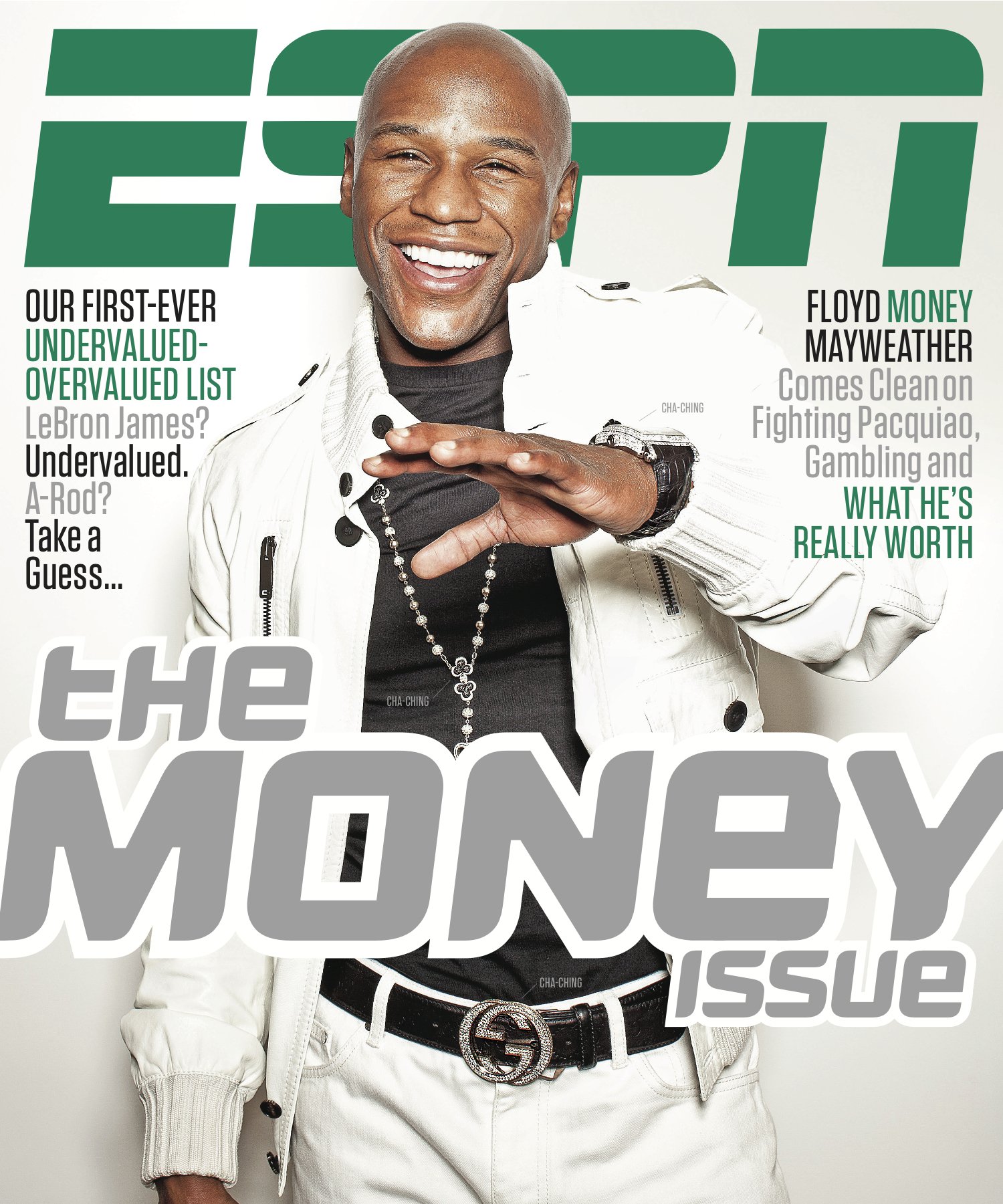

Patrick Mitchell: So in your long and storied career, and let’s just recount all the stops here: Philadelphia magazine, Regardie’s, Musician, Premiere, GQ, Entertainment Weekly, Esquire, InStyle, freelance period, Fortune, ESPN, and HBR. Of those, your longest stay was at Esquire. You were there for six years, 1999–2005. And, you know, from the outside looking in, I would say that might be the magazine you’re best known for. You could argue ESPN too, but it was certainly copied a lot at the time—by me and by many others. I know a guy who designed a city magazine as almost a mirror image of your Esquire. But let’s talk about your time there. It was, boy, it also would be on my list of the five best-executed magazines. Just talk a little bit about your time at Esquire.

John Korpics: It was a great place to work, a very special place to work. I loved my time at Entertainment Weekly, but it was quite a bureaucracy. There were a lot of layers there and, you know, it was Time Inc. It’s a publicly-traded company. There’s sort of a culture around that. So to go to Esquire and to come in as—when I worked with Granger, it was the first time I felt like I was truly the partner of the editor at any of the magazines I’d worked for.

And it was really, like, the first time in my career that I had been able to really stretch a lot of these muscles that I think I knew I had, but had never really been able to show. And I think, frankly, we just went wherever it took us.

So every issue felt different. Every issue felt like you were starting from a clean slate and thinking about what a magazine could be from a new perspective. And I loved doing it. I did it for, like you said, for six years. And I think after six years I was exhausted. I was mentally and physically exhausted from that.

Patrick Mitchell: I can see why. So, I remember a story you told me. In the old days we had these, what they called newsstand consultants who would come and tell you all of the rules of what sells on the cover: use fluorescent colors, put big numbers on the cover, et cetera, et cetera. And I always dismissed it by saying, “If we all do that, then nothing stands out.” But I remember you telling me specifically that you and David decided to do exactly what they asked for. But you designed it really well. Like, I remember you added the little corner flip with the secondary story folded down.

John Korpics: Yes.

Patrick Mitchell: You remember this?

John Korpics: I’ve never pushed back on things that might help sell something. I think it’s part of my job. Part of my job is to build something, to create something that people want to buy. So if somebody’s telling me like—we did this at EW, too. They always wanted to have pictures of people above the logo.

They called them the “teeth.” So you put, like, five pictures of TV stars above the logo and you have a story, something about the five big shows right now. And they were obsessed with it. They were addicted to it. Got to have the teeth on every cover.

At the end of the day, the cover is the hardest thing in the magazine to make look good, because there’s so much pressure on it to perform. There’s a lot of politics around it. Sometimes I will push hard if I see an opportunity, like, “Hey, this one could be really great. Can we just get rid of some of this crap?” But often I’ll say, “Yeah, why not? Let’s take that and design it so it actually looks good. Instead of making it a crappy little banner, let’s make it a nice looking banner. Let’s give it some dimension or something.”

When you have all these things at your disposal—so I’ve got great editorial partners, I have a budget, I have time to work on things, I have flexibility and freedom to create things. You have this enormous responsibility to make it as good as you can.

You can’t just slough it off. You really have to say, first of all, “I don’t know how long this is going to last. This may not last forever.” So you need to really bust your ass to make it as good as you can in those moments that you have, because they’re few and far between.

Patrick Mitchell: Alright, I want to talk about one of your more improbable positions and what it taught you. You learned an interesting lesson when you were at InStyle. I’m sure you learned more than one. But you’ve talked about how that job, as short as it was, really changed the way you thought about your career. The way you thought about what your job was at a magazine.

John Korpics: Yeah. When I left Esquire, I really was looking for a brand. I wanted to get out of this mindset that every layout was its own special thing and every issue was its own special thing. I was looking for something that I could really approach from a brand design perspective.

And so I saw InStyle and I saw a ton of pages. Tons of space to do big photography and simple, elegant typography. And some of those issues were four or 500 pages long. You can’t get in and design every page. You have to come up with systems. And you have to come up with ideas that scale because you just don’t have the bandwidth or the resources to get in and design it the way I was designing Esquire.

So I actually wanted that. I was looking for that. And it forced me to think about things like, we used to have 20 or 30 illustrations in an issue. And in the old days, a lot of designers would try to assign a different artist for every single illustration because they’re trying to develop talent, they’re trying to expand their repertoire.

But I felt like I just wanted to do the opposite. So I thought, I really love Kirsten Ulve’s work. She’s a great illustrator. She gets fashion. She’s also got a really fun personality and energy in her work. We’re just going to use her for every single illustration in the magazine.

So we just co-opted her style as part of the brand and scaled it. And I really love that. I was like, “This is great.” Every time I see it, I like it. It holds together well. And so I started to think about magazine design from that perspective.

I think the one thing about InStyle where I failed was I wasn’t passionate about the content. And I don’t know that every designer has to be. I’ve worked at a lot of different magazines—I don’t know that there’s a rule that says, “I have to love sports” or “I have to love men’s fashion” or “I have to love business.” But there are times when it really helps you be better at your job.

People would come to me, “We’re going to shoot a still life with cork-wedge heels, and we have 12 to choose from, and we only can do six, which six should we do?”

And I would say, “I don’t care.” Like, “I want to control how the picture’s shot, but I don’t care what’s in it.”

And I think eventually, it’s a disservice. They want to have a creative partner who actually is invested in the content to some extent. And I don’t know that I ever was at InStyle. I think I really loved making a lot of those images. I did love the celebrity stuff. I had a lot of fun with that. I loved coming up with the design systems. But eventually I think it just was obvious to them and to me that this isn’t a great fit.

“It started to become an examination of my life and the lives of the people around me, and my shortcomings, and my successes, and my failures. And I leaned into that.”

Patrick Mitchell: You and I have talked a little bit about your battle with addiction. And I bring it up because issues like this have come up in podcasts we’ve done and podcasts I listen to. And when people are open to talking about it, I feel like it can really help. And I think it’s something that a lot of people in our business have had to deal with. So if you’re game, we could dive in here. Do you want to tell the story—your come-to-Jesus moment?

John Korpics: Let me talk first a little bit about addiction in general. So I’m very OCD. I’m highly-productive, highly-focused, very compulsive in my behavior and I always have been. And I like to say that I have an addictive personality. And at times that manifests itself in playing video games. At times it manifests itself in eating and other things.

And then there definitely were times in my life when I was using drugs and drinking too much. They were not easy things to overcome. There were two moments when I was able to push them back, one was before my first daughter was born and I had been “smoking pot” as the old generation says, since high school.

So I was smoking pot a lot. And I had tried to quit in the past and couldn’t. And I was always aware that was not a good thing. I was like, “I just, I don’t seem to be able to stop this.” And about six months before my first daughter was born, I said, “You know what? This is it. I can’t be that guy who smokes pot every day and is raising a kid.”

And having that out there in front of me helped me say, “I’m done.” And for whatever reason, it stuck. The first couple of months were hard. But then eventually I was able to say, “Alright, I think I can do this.”

What I did, though, was I transferred that addiction to alcohol. And so I started drinking more. I felt really good about stopping the pot smoking, but slowly-but-surely the alcohol use started to increase. To this day, I still wrestle with it at times. It’s always in the back of my head. It is a part of who I am.

This drive that I have, this need to be compulsive, this endless energy that I sometimes can’t let go of, it actually also manifests itself in work that I’m proud of. It helps me achieve certain things in my job that I’ve been able to enjoy or that I feel good about. So it’s kind of a double-edged sword.

Patrick Mitchell: Do you associate the need to drink, etc.—does the work have anything to do with it?

John Korpics: No.

Patrick Mitchell: You’ve had some seriously high-pressure jobs?

John Korpics: No, it’s not really about that. It’s more just about—it gives you an outlet. Like, for the time that you’re going to use whatever it is you’re going to use at the time, if you’re going to smoke a joint or have a few drinks, then you’re giving yourself a chance to turn your brain off. You’re retreating a little bit from reality.

And that’s fine. There’s nothing wrong with that. The problem is that if you do it every day, if it starts to become a way of dealing with everyday life, then you actually stop progressing socially, professionally, emotionally. You basically stagnate.

And if you do that for years on end it can be pretty damaging. It can be pretty alienating. It’s a very selfish way of living your life. And I just think that for anybody who can figure out how to get past it—there’s no rule book. There’s no path that works for everybody.

I happened to have certain things happen in my life that helped me make decisions that I think were healthy. Other people have gone to meetings, have sponsors, and they talk to people. And it’s helpful to them. Whatever you need to do, whatever works for you, that’s the way to do it.

Patrick Mitchell: You watch the old movies and stuff and there was always a connection between drugs and drinking and creativity. All the great masters have these massive drug problems.

John Korpics: Yeah. I have had creative moments but I’ve also had moments where I’ve been staring at and designing a pull quote for three hours cause I’m obsessing over it, which is not healthy.

My dad led bands his whole life. He always had musicians and he was always the leader of the band. And he would always say to me, “These assholes who smoke weed, they think they’re playing better, but they’re not. They think they’re playing like Carlos Santana but they’re actually playing like shit.”

And so I think there’s truth in both of those. There are times when I’ve had interesting ideas and I’m like, “Hey, I’m going to write that down, that might actually work.” But there are definitely times when it's just a bunch of crap.

“It’s part of my job. My job is to create something that people want to buy. ”

Patrick Mitchell: Well, I appreciate you talking about it. I think it’s important for people to hear this. So we’re going to move on to—I’m just going to say some things and you may have quick reactions, one-word reactions. You may have stories to tell. So I’ll just rattle them off. And the first one is the iPad as the “savior” of the magazine business.

John Korpics: Now you’re just teeing me up. So I was at Time Inc. when the iPad came out and I think that most people at the time saw it as, “Oh, if you turn this thing sideways, it’s the shape of a magazine. This is the future of magazines. That’s why this thing was invented so that you could have a magazine on it.”

And most of the magazines that were put onto the iPad were incredibly designed. Like, way over-designed. And many of them were, I guess, what old product designers would call ‘skeuomorphic.’ So they looked like pages, and they turned like pages, and you swiped them, and they were like pages.

Clearly this is not why the iPad was invented. And I was at the meeting at Time Inc. When Steve Jobs came in and presented the iPad to the room. And Terry McDonell famously had produced this really elaborate video of what Sports Illustrated could look like on an iPad.

And I think Terry asked Steve in the meeting, like, “Hey, did you see my video? What did you think of it?” And Steve just said, “It’s ridiculous. That has nothing to do with what this is going to be.” And then there were people in the room saying, “Why should we put our magazine on your device? You’re going to take 30 percent of our revenue. You’re not going to share subscriber information.”

And he’s like, “I don’t care if you put your magazine on my device. I’m not here to get you to put your magazine on my device. I’m here so that you will write a story about my device. That’s the whole point of me being here.” And it’s true. Everybody got really excited because, at the time, people were anxious, print was teetering.

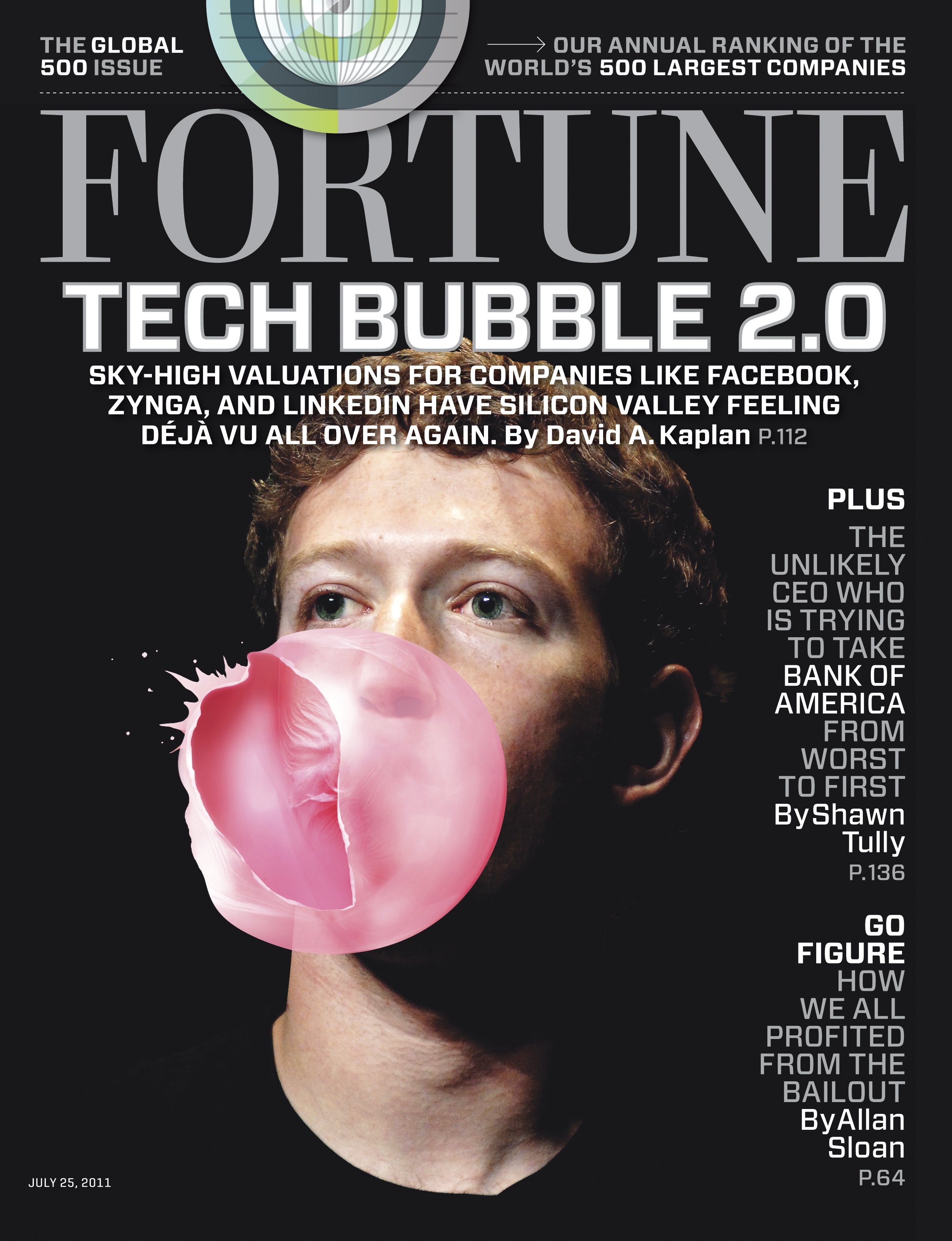

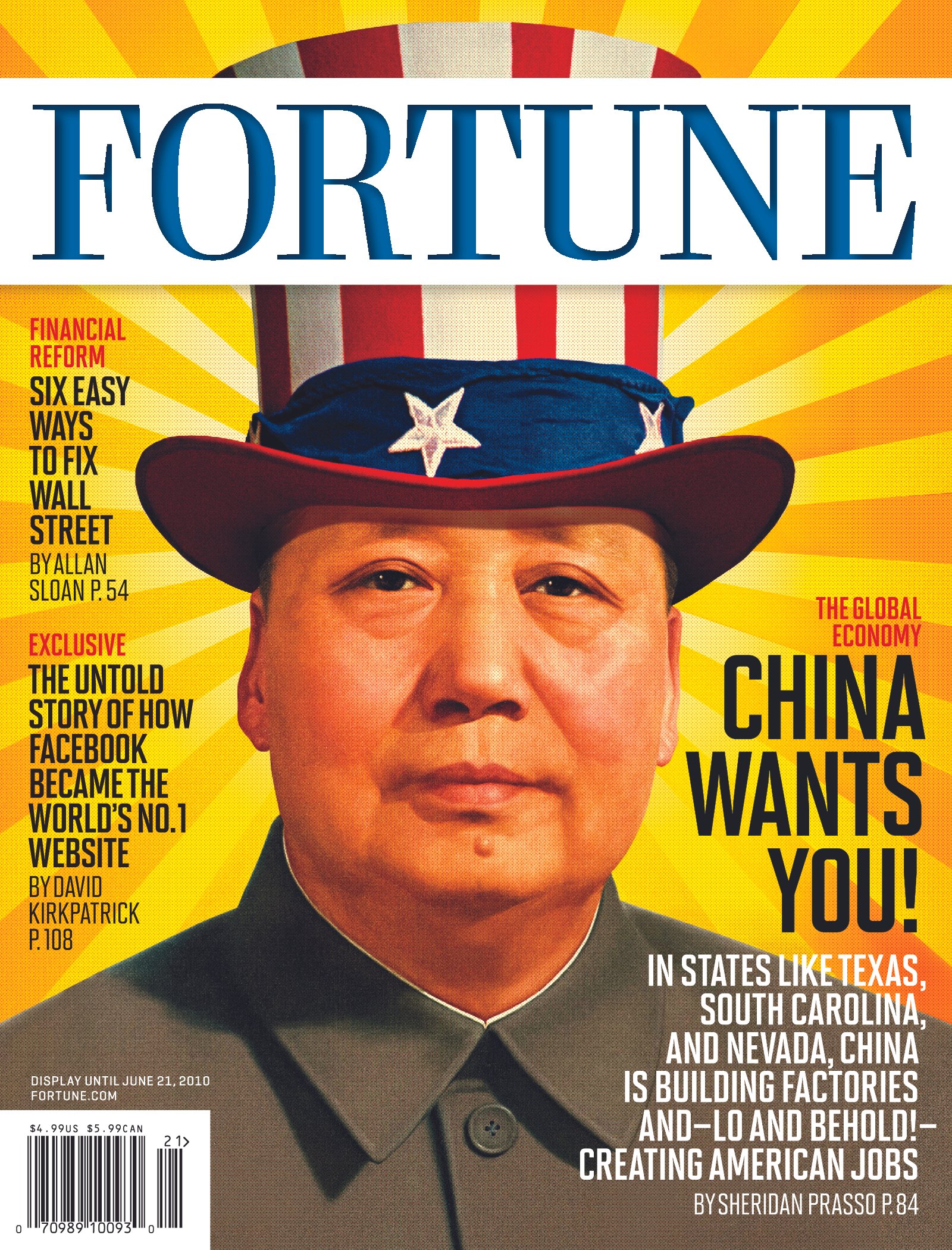

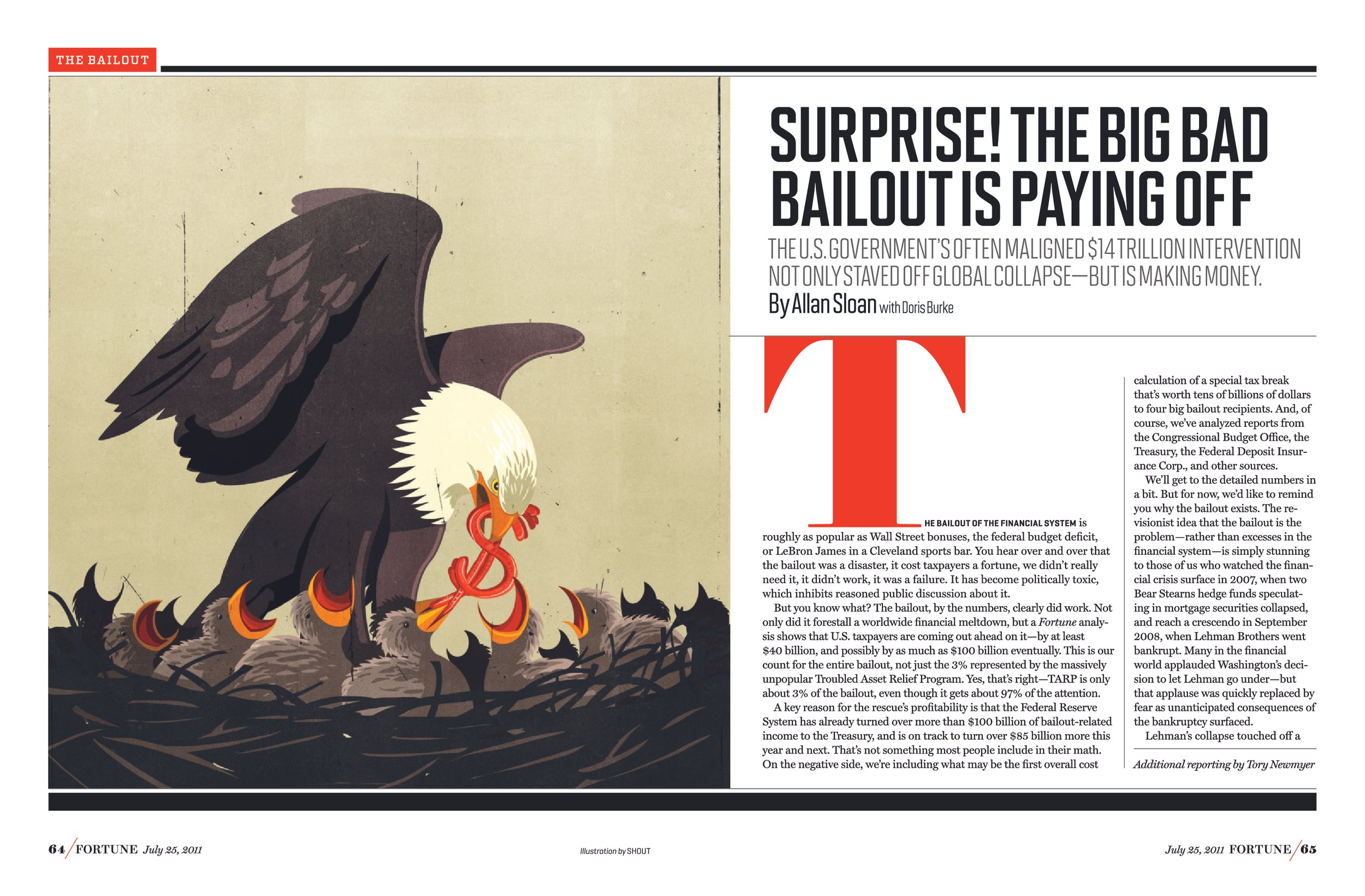

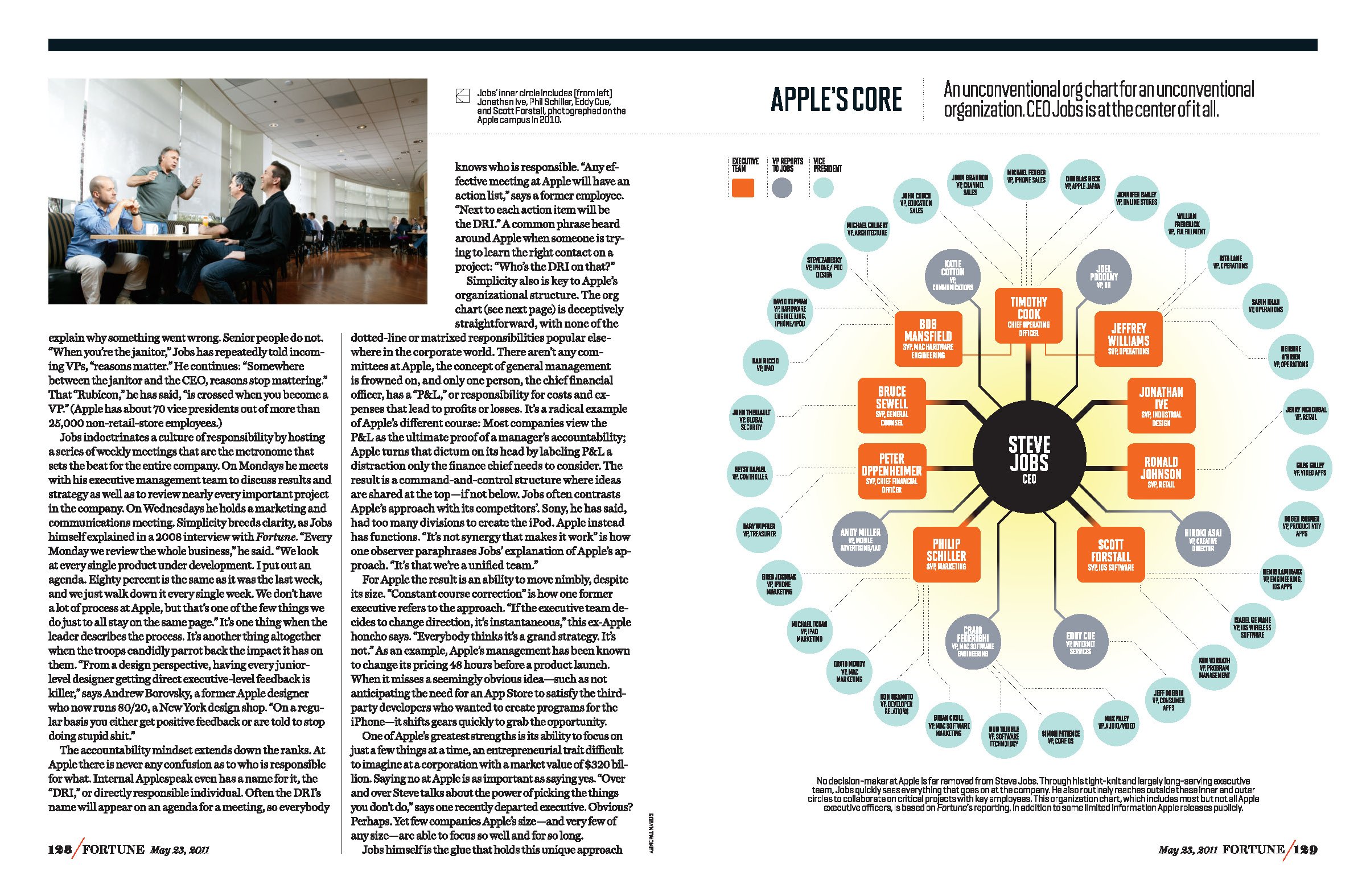

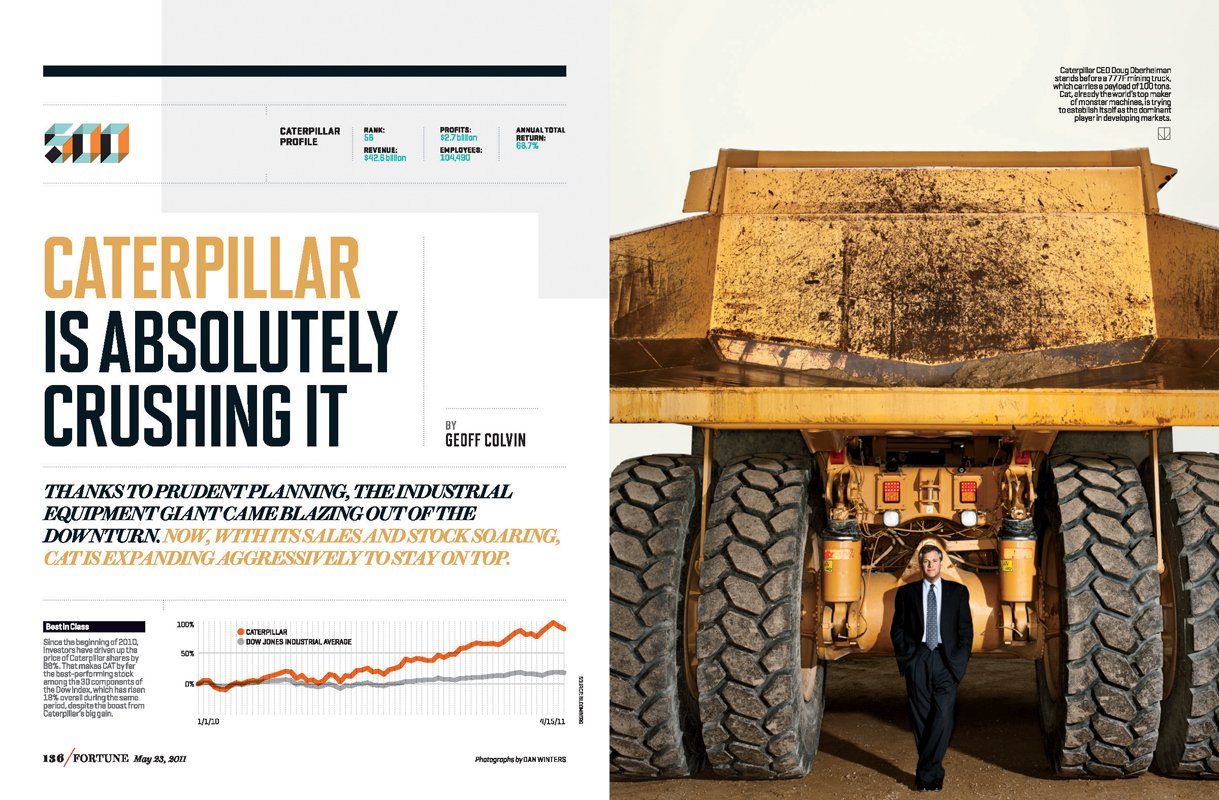

Nobody was quite sure what the future of print was going to be. And so this thing comes out and it looks like it might hold a magazine really well. And I had to dedicate resources to putting Fortune on the iPad. And we tried to minimize the impact that it had on our other jobs, but it still took a lot.

Like we had to dedicate people to it every month. Emily Kehe was working for me at the time running the iPad for me. And she’s a talented, useful person. I don’t want her spending more time on an iPad. I want her to work on the magazine.

I think at some point after that, I realized that I needed to go work for a company that actually had a serious digital product approach, understood what the future of browser-based content was going to be and understood native application design and all that stuff.

And so that was when I realized I should probably be going to work for a place like ESPN.

Korpics as a high school senior, c. 1980

Patrick Mitchell: Good segue. The next thing is Dock Ellis.

John Korpics: Yeah, so at ESPN I had a moment of hubris. That big interactive story called “Snow Fall” that The New York Times had done had come out a year or two earlier and it was still this amazing darling of internet content. We were all blown away by it.

And I’m like, “Okay, I’m at ESPN. I have these resources now. I have engineers, and I have designers, and I have a budget. I’m going to do “Snow Fall.” And so the story about Dock Ellis came up and it wasn’t just the famous story where he throws the no-hitter on acid. It was like his life, his whole life.

And so I was like, “This is it. This is—I’m going to do it here.” And we create this very layered, very dense, very gigantic desktop browser-based story about Dock Ellis that has video and it has parallax scrolling, and it has all the baseball cards he was ever in. And it has audio tracks and everything I could throw at it. I’m like, “This is going to be my—I’m going to be famous. I’m going to do this and I’m going to set the world on fire.”

And I think we were using Flash at the time, which was a huge mistake. So this thing comes out and it took us like two or three months to build it. And they put it on the homepage of ESPN for a couple of days and it got, I don’t know, maybe 50,000 people saw it—as opposed to the average NFL 30-second highlight video, which might get 10 million views.

And nobody could see it on a phone. It didn’t work on a phone. And it was just insane. I was very humbled by that. I walked away from that with a whole new appreciation for, If I’m going to come into this world. And I’m going to be useful—right?—How do I apply the things that I think I’m good at, but also have enough humility to know that this is not my territory yet. I don’t necessarily understand everything I need to know about how this world works.

Patrick Mitchell: To this day, nobody really does.

John Korpics: Yeah, but I come from a content background. So I would be in a meeting where we would be redesigning the play button on a video. And I would say, “Oh, I think it would be great to have the play button on the lower left with the caption, because it explains the video.” And often, on a sports video, if your play button is in the center, it’ll cover the player’s head. And nowadays—I don’t even think this matters anymore because most video is auto-playing—you don’t really necessarily have these play buttons everywhere, but I was like, “I think this will be better.”

And they said, “Okay, why don’t we test it?”

I was like, “Great.”

And so we tested the play button lower left, and play button center. Play button center did two percent better in the test. And I said, “Is two percent really a big enough deal that we shouldn’t consider the editorial value of moving it to the lower left?”

And they said, “Well, two percent difference in a year of ESPN video translates to about 30 or 40 million in revenue.”

And I was like, “Okay, I get it. I’m going to shut up now.”

Patrick Mitchell: Alright. Design awards.

John Korpics: I think it’s good to recognize achievement. Absolutely. It’s good to build community. I think that, at their best, they bring people together to celebrate the work that’s getting done in our industry and to take a break from the year of drudgery that we all go through to crank these things out and say, “Nice job.” Pat you on the back.

I do think though that—and I was guilty of this—as a designer, if your focus is on winning an award, you are doing a disservice to the brand and you’re doing a disservice to your audience, usually, because you’re not necessarily designing with the right end goal in mind.

Patrick Mitchell: Bake-offs.

John Korpics: Bake-offs.

Patrick Mitchell: You have a great story about a bake-off. Is that strictly a Time Inc. process, or have you heard of that happening elsewhere?

John Korpics: Time Inc. is the only place I ever was involved in bake-offs. I never saw it happen anywhere else. It’s kind of a bullshit process, frankly. Because it basically gives whoever’s making the decision cover to say, “Well, you know, we hired these great people to do this…”

Patrick Mitchell: Just quickly explain what a bake-off is.

John Korpics: There’s a couple of different forms. The ones I’ve done—I did one at Fortune, which was they decided they wanted a refresh for the magazine, a design refresh. There is an existing art director in place. And that person is usually not in the best position, unfortunately. And then they bring in all this hired-gun talent from the outside to do new versions of the magazine.

Patrick Mitchell: And the staff art director is aware of this happening?

John Korpics: And usually the staff art director can participate if they want. But it’s clear at that point that the writing’s on the wall. It’s a sort of shitty process to put someone through. It’s like a tap-dance-for-your-job kind of thing. I’ve never really liked that. I’ve seen it happen a few different ways. I’ve also seen it where you have two editors at a magazine and they’re both given a chance to show what they can do with issues and then one gets picked.

But ultimately, if you’re any good at your job, if you’re in a leadership position, you shouldn’t need the bake-off. You should be able to say, “I’ve seen what this person can do. I think I know where this person might take our product and I’m just going to make the call.” I think having the bake off process has always struck me as just lazy. Like, just make a decision.

Patrick Mitchell: And this bake-off—this was at Fortune, right?

John Korpics: Yeah. I was asked to do one of the Bake-off versions for Fortune along with Robert Priest and Neil Jamieson. And it was exactly as I described it. We came in from the outside, we’re able to do whatever we wanted and then we present everything. I think at the time I felt like mine was okay. I thought Neil’s and Robert’s were great.

But I think I also knew, I knew the DNA of Time Inc., and I knew John Huey, the guy who was making the decision. And they are a very populist magazine company. They want something that isn’t going to be too ‘out there.’ They want something that’s going to appeal to a mass audience. That’s going to be friendly. And I think I gave them a well-organized, friendly, not too controversial, but also clean, elegant, modern kind of a thing. And I think that’s ultimately what they wanted.

Patrick Mitchell: And you got the job.

John Korpics: I did get the job. I actually loved that job. We had a real philosophy around how to do that magazine, which was I wanted it to be as if an annual report had really great photography and interesting data viz and, a clean, elegant, systematized design.

So underneath everything we were doing, there was this north star of, We would want this to be a really beautiful annual report, somehow.

Patrick Mitchell: Biggest fuck up?

John Korpics: When I was at ESPN, I used to use the photo credentials to go to big sports events. I went to a couple of Super Bowls as a sideline photographer, like a George Plimpton moment where I’m gonna, I’m gonna see if I can do this.

And I would do it with my friend Rob Tringali, who’s actually a real sports photographer. One of the best in the business. And so we went to a couple of Super Bowls and then we decided we were going to go to the US Open golf tournament, which was in Merion, Pennsylvania. It was near my mother’s house.

So we went down, and we had dinner with my mom. And we worked ‘inside the ropes’ at the US Open for two days. And on Sunday, the final day of the US Open, one of the four major tournaments of the year, I was using Rob’s super-fancy Canon camera and lens. And it had, like, a hair-trigger shutter-release on it. Like you breathe on it and the shutter would go off.

And so I’m on the 11th tee. I’m standing behind the final pairing, which is Hunter Mahan, and Phil Mickelson. They’re both competing to win one of golf’s four major tournaments. And as Hunter Mahan is about to tee off, in his backswing, the camera shutter goes off.

So not only am I not supposed to be there, because I’m not really a photographer, but I’m standing, literally, like I was probably closer to him than any other photographer there. I’m like, “Why am I here?” The shutter goes off. I panic. His caddy immediately comes at me after he hits the shot and I run into the woods to try and hide. And they call the marshall. The marshall finds me, the marshall pulls my credential, and kicks me off the course.

Patrick Mitchell: Oh my god. You might as well have yelled, “BaBa Booey!”

John Korpics: I’m like, “I’m going to get fired. I know I’m going to get fired.” But nothing happened.

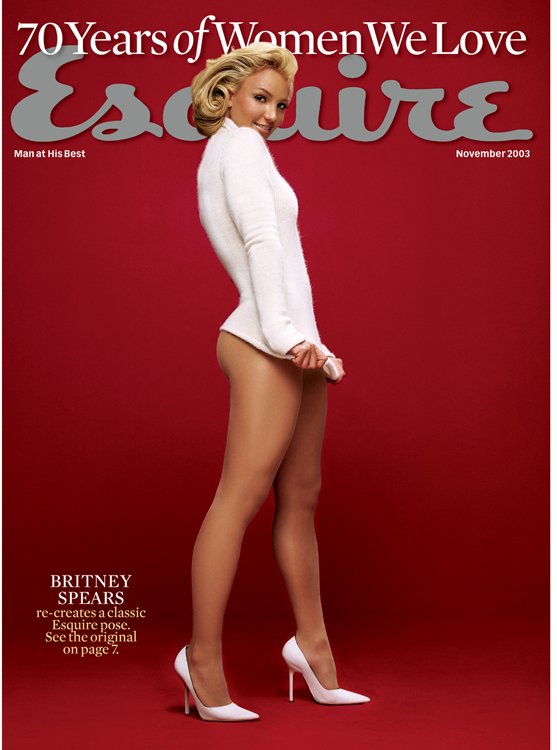

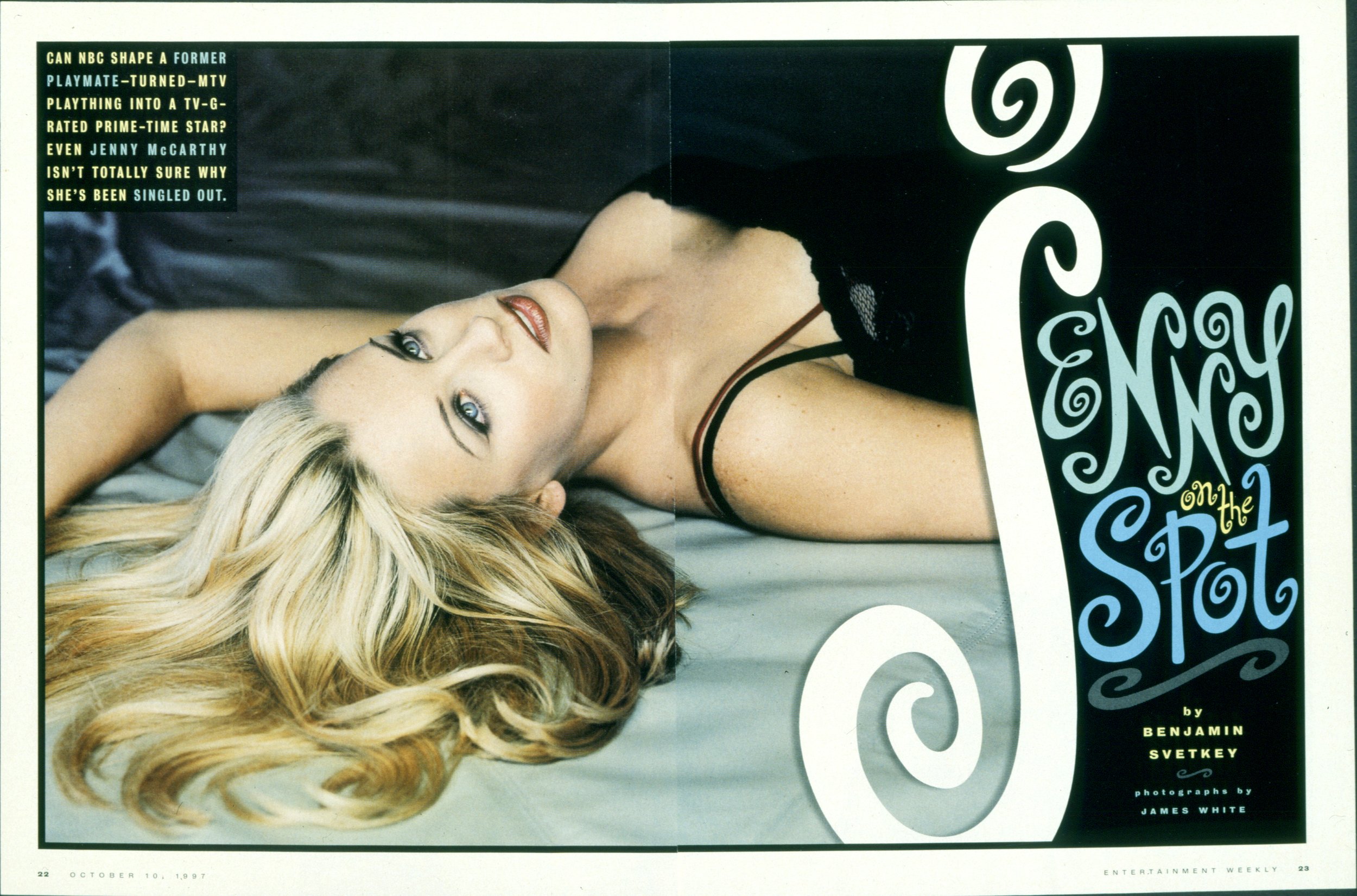

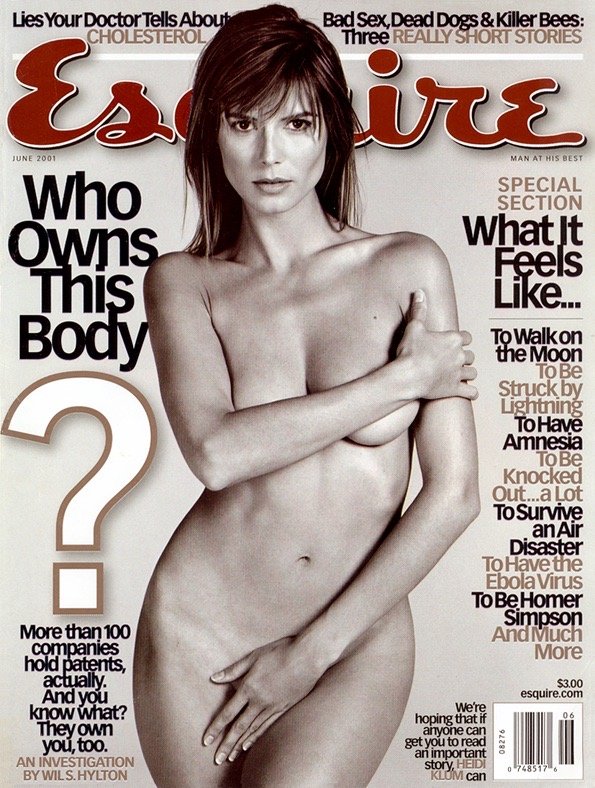

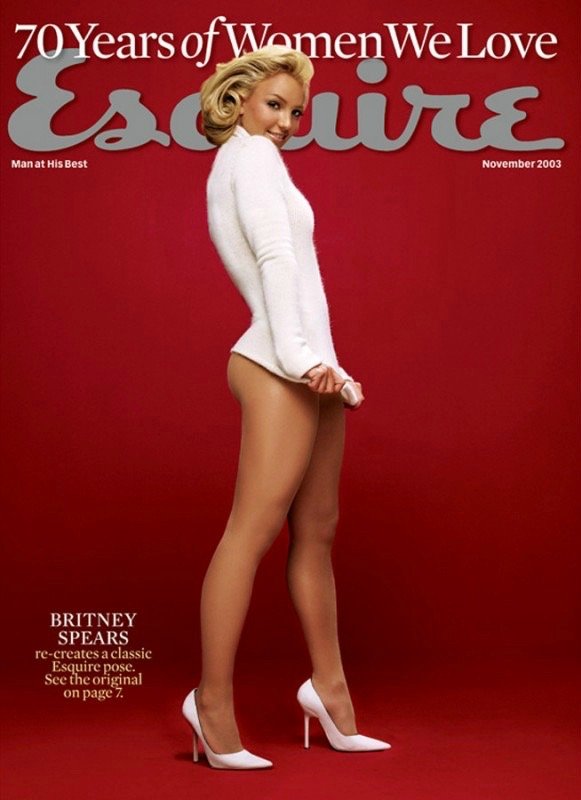

Patrick Mitchell: I thought you were going to talk about the Britney story.

John Korpics: No. That wasn’t a fuck up. That was just—so we shot Britney Spears for the cover of Esquire. We recreated this iconic Esquire cover of Angie Dickinson in this very, you know, tight white sweater and heels. It was our 50th anniversary or something like that. And Britney recreated the picture for us. And it was a great cover.

And on the inside we had shot these mostly nude photos of her with large necklaces around her to cover up the things you’re not supposed to show in a magazine. And they were fun, and they were sexy, and whatever. And it was clearly something she had participated in, like she was styled for those pictures. She had put on all these necklaces and it was something she was a willing participant in.

And Granger had lunch with her and for some reason invited her back into the office to see the cover. And so he’s like, “Hey!”—I didn’t know what was happening—he shows up and he’s like, “Hey, I have Britney with me. Can you show her the cover?”

That time Britney Spears yelled, “Stop the presses!”

And I was like, “Yeah, sure. We’ll show her the cover.”

And she says, “Oh, that’s great. I love it. The cover’s fantastic.”

And I’m like, “Oh, and by the way, here’s the inside spread.” And so I showed her the inside spread.

And she’s like, “What do you mean? You can’t use these pictures.”

And I said, “Well, why did you pose for them? What do you mean I can’t use them?”

And she’s like, “I never agreed for those pictures to be used. I thought we were just shooting those for fun.”

And I was like, “No, I’m pretty sure that everybody was clear on the set that this was part of the shoot.”

And she got really pissed off. She asked me if we could ‘stop the presses.’ And I said, “No. This isn’t a Ron Howard movie. We don’t do that.”

And she stormed out and that was the end of it.

Patrick Mitchell: Time, Hearst, Condé: Which company would you rather walk into every morning?

John Korpics: I liked my time at Time Inc. Hearst—Esquire’s at Hearst, but the DNA of Hearst is a women’s magazine company. I think Esquire was an anomaly. They always thought of Esquire as kind of this odd little thing off to the side that they weren’t quite sure what to do with. Condé was just—I’m not that guy. I’m not a $3,000 suit-and-tie-wearing guy. And so I think I’m a Time Inc. guy at heart.

Patrick Mitchell: Who was the person you worked with who most influenced your life?

John Korpics: My life or my professional life?

Patrick Mitchell: Either.

John Korpics: I don’t know. I’ve never had—I’ve always been the boss. It’s weird. Like, at 24 I was given the job as the art director of Regardie’s. I never really had a mentor. Like I never had a creative—like Fred. I used to look at Fred’s work a lot and I would emulate Fred and I thought Fred was amazing.

And I think, without having a person to talk to and bounce ideas off of, I did that by proxy. I would just watch what he did every week or every month. And I would say, “Okay, how do I do that? How did they do that? And what can I do that’s like that without ripping it off completely and learning from that.”

There were a lot of people in the business like that, who I never worked with, but that I found inspiring. A lot of really talented art directors—Deb Bishop is one of my favorite designers in the business. Robert Priest, super talented. Fred Woodward.

I always felt like I was the Pete Rose of magazine designers. I hustle, I work hard, I crank stuff out. Occasionally I get one and I hit one out of the park, but there are people in this industry that I think are truly giants. And I’ve never quite thought of the work I did in that league, but I am always inspired by them.

Patrick Mitchell: I would say Fred is a proxy mentor to a ton of people. Moving on, is there a job you interviewed for that you didn’t get that you really wish you did?

John Korpics: I don’t know. I don’t think of it that way. I think I’m more of a fatalist. It’s just like, If it was meant to be it’s meant to be. There was a time after ESPN when I tried to sell myself as someone who could lead a product design team, because I’d done that at ESPN.

And when I first started at ESPN, I was definitely learning on the job. And I’m sure my ESPN friends are laughing when they hear that. But by the time I finished, I think I actually knew what I was doing. And so I interviewed at Netflix, at Twitch, at Roku, at Yahoo. And I don’t think any of them ever saw past the magazine designer.

And I get that. I understand that. I wasn’t necessarily “pushing pixel.” I wasn’t actually writing code, but I think I knew enough to lead the teams who were building these things, but I never quite broke through in the Silicon Valley world. I never quite was able to make that leap.

I actually interviewed at Riot Games and I had to learn how to play League of Legends to do it. I’m like in my apartment, a 50-year-old man, trying to figure out how to shoot a bow and arrow across the field on a team of five people. And I actually started to get good at it. I had fun and I got pretty far in the interview process, but that didn’t work out either.

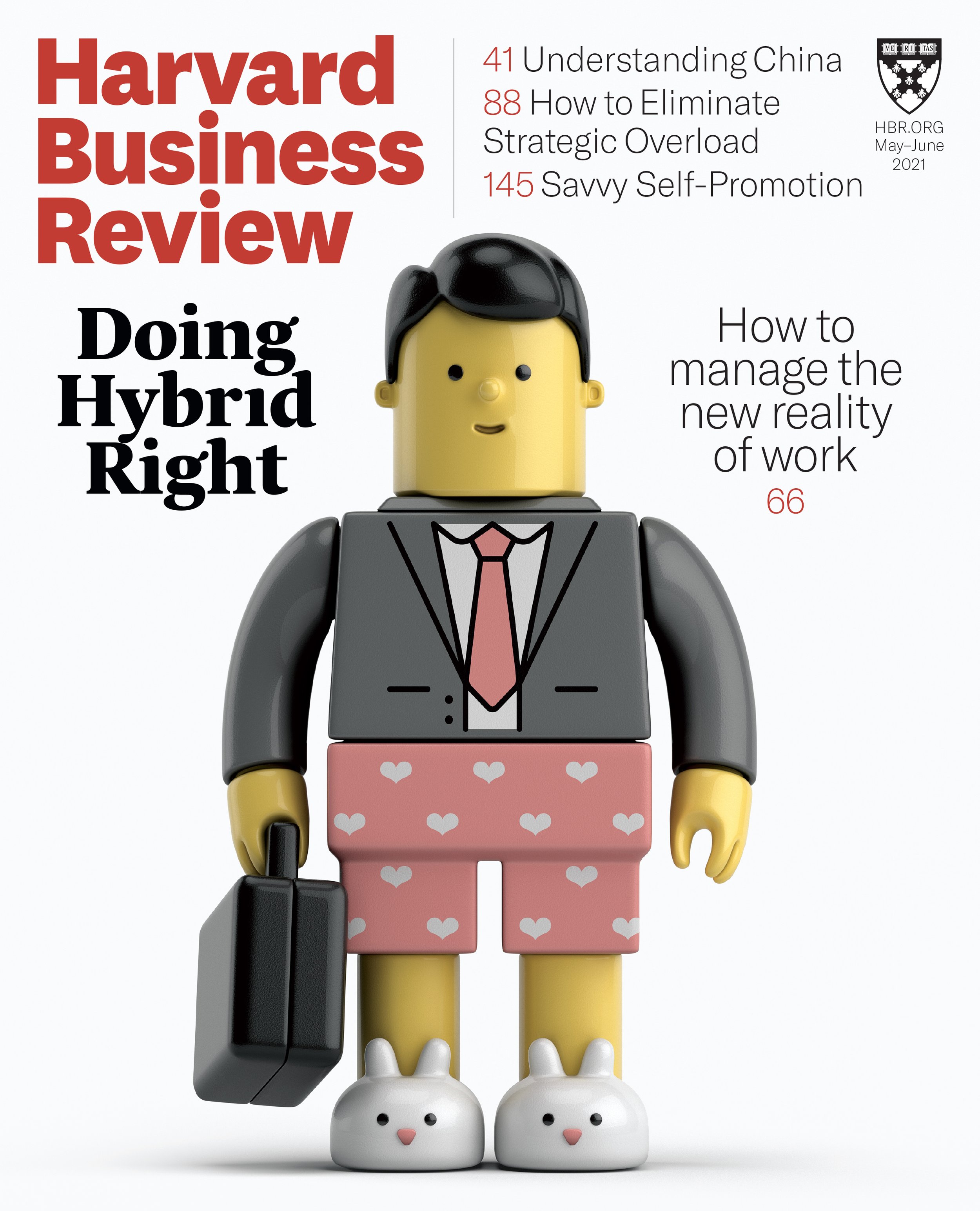

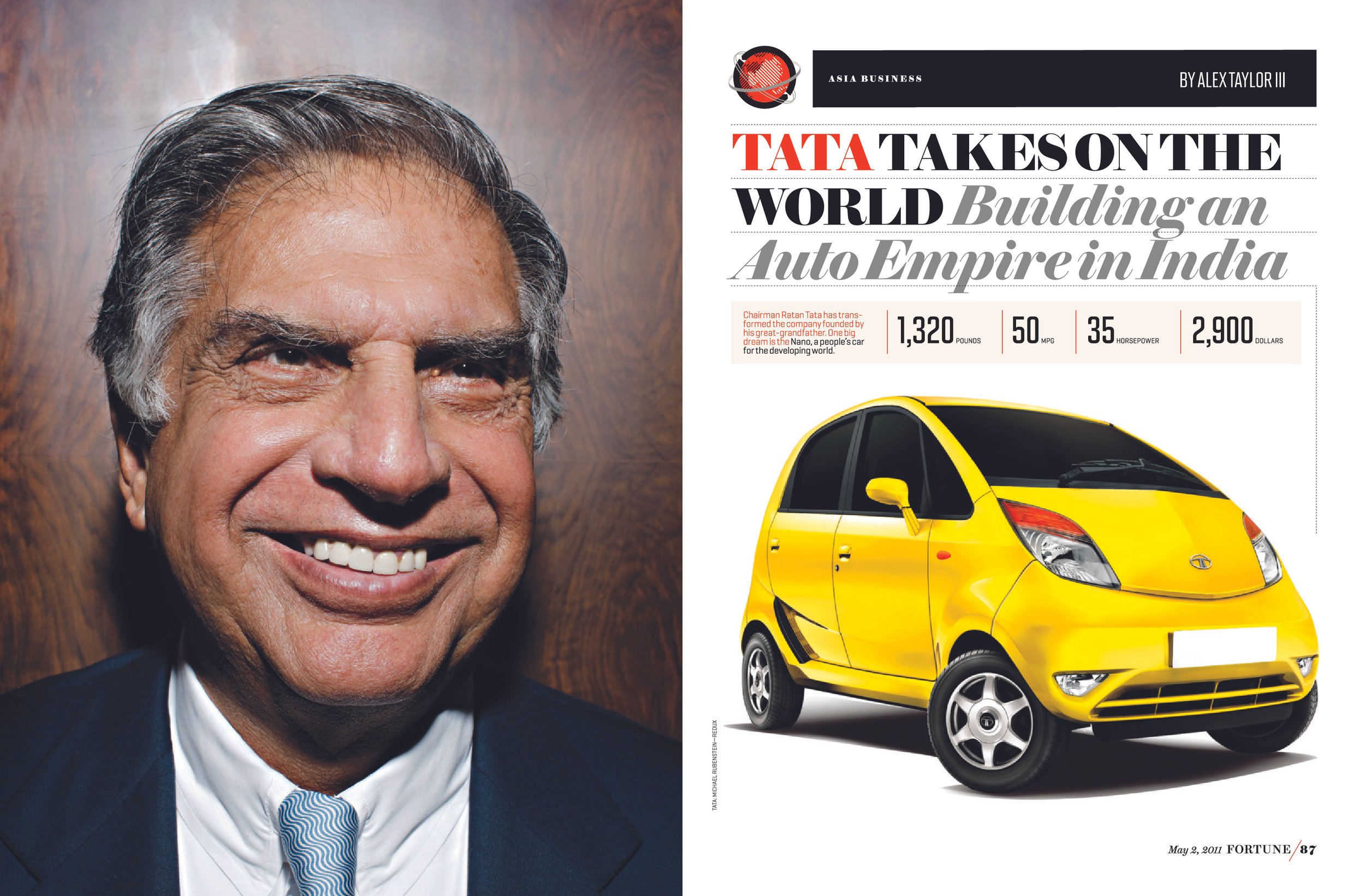

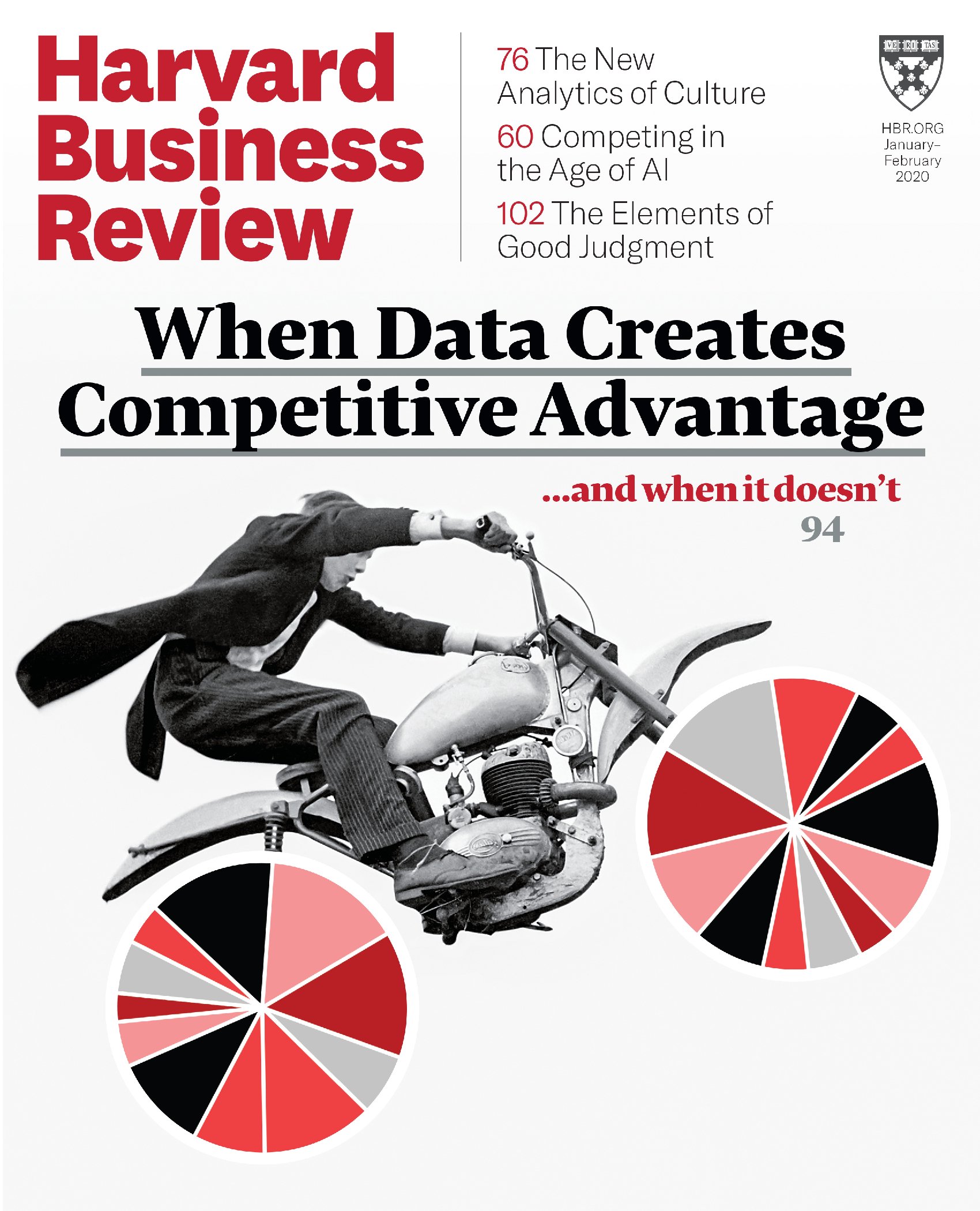

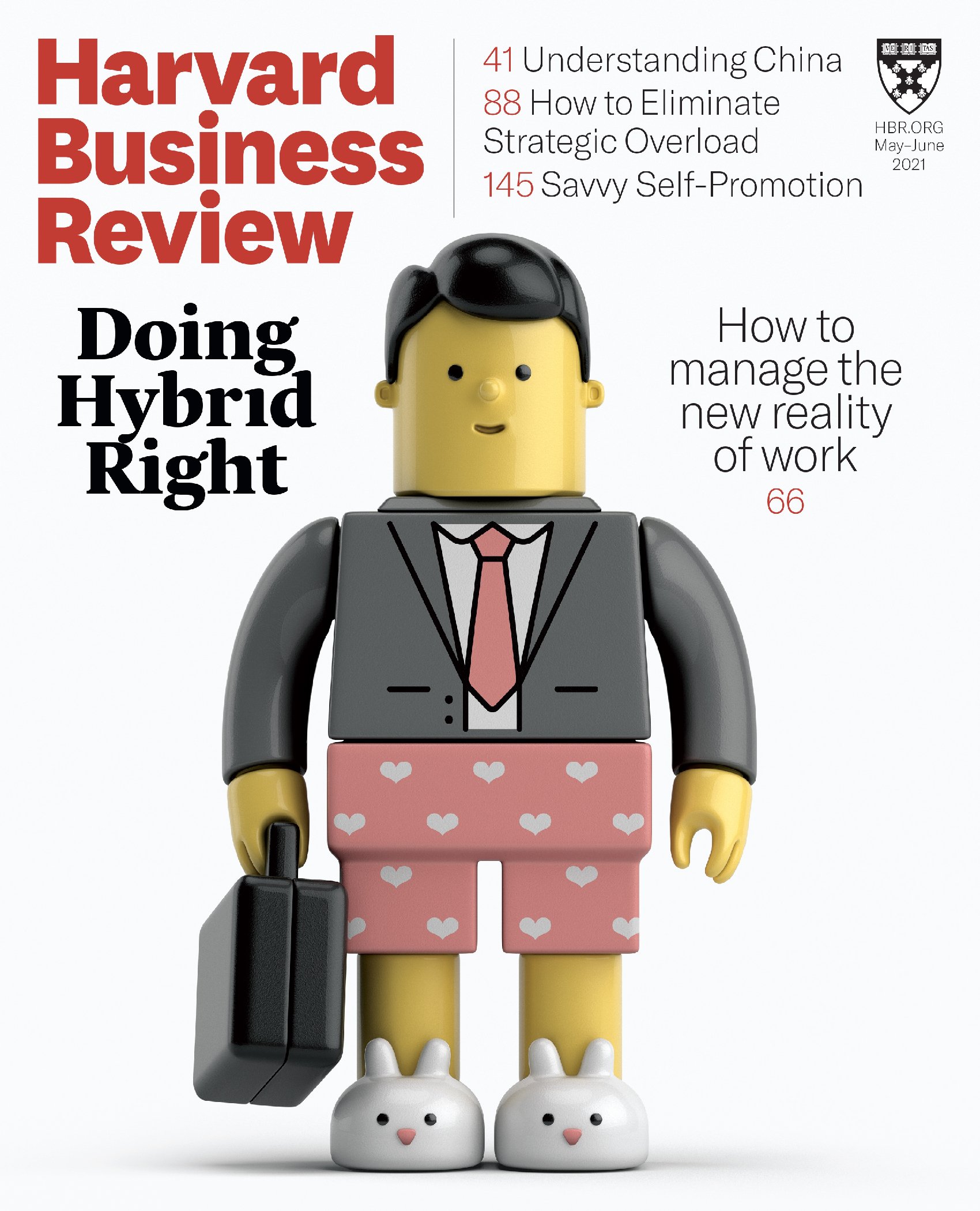

Patrick Mitchell: Alright, we’re near the end now, so I want to talk a little bit about Harvard Business Review where you are now, which is here in the Boston area and actually this question comes from George Gendron. We were all competing with HBR when I was at Fast Company and he was at Inc. And he was curious, like for a magazine like HBR, which is, you could really say, ‘undesigned’ for most of its life. Or design was not a particularly important part of what they were producing. With your background—an amazing design background—how do you conceptualize the look and feel for a brand that’s really never been designed before, that, however, is super-successful and probably the most expensive magazine in the world?

John Korpics: Well, I have to say, I don’t think it was never designed. I think James DeVries before me did a nice job and established the idea of design for the first time at HBR. So he gets credit for that. I think that it’s like anything you have to spend a little time with it. I can’t just walk in off the street and throw a design in and say, “This is what it is.”

I really needed to understand the DNA of it, which was strange because we are publishing research from authors. And it’s a partnership, really. We’re not assigning these pieces, necessarily. We are a very high-profile place for them to publish their research. So there’s a respectful relationship that goes back and forth.

And so there were times when I would assign artwork that played off of a brand or something. So we would create opening art that messed around with the Apple logo and the people who had written the story worked at Apple and they were like, “You can’t mess around with our logo. We have to work here and we don’t think our internal teams will appreciate that.”

You have to understand how the place works and the DNA of it. And then you have to look for, how do you inject yourself into this? I’ve been doing this work for 40 years now. There must be something about what I know how to do that I can start to bring into this and pull it together cohesively as a brand. To elevate it visually. Think about how it spans to digital platforms. Think about how the branding applies to every aspect of it: newsletters, and podcasts, and anything else that comes up.

And then also, understand how our press works. We have a very big press business that works directly with authors. And those authors have a lot to say about how their covers are designed. And that was also new to me. I’d never worked in an environment like that.

And I actually talked to Chip Kidd about this. Like, “How do you do this? How do you work with an author who looks at probably one of the best designs I’ve ever seen and tells you that they just want it to be ‘blue with a big red drop cap’?”

And he’s just like, “Sometimes that’s just how it works. Sometimes that’s the business. It’s hard to work around that.” But you know, you take all that into account and then you just find your way through it. You just figure out, “Okay. I see how I can make this work.”

And it’s not so much about design, necessarily. We’re not trying to reinvent the wheel with design. But it is a lot about creative thinking.

“I was like, ‘Holy cow. I get to go back and do this thing that I’ve been doing my whole life that I think I’ve learned a lot about, and that I think I’m pretty good at, and now somebody actually still needs that.’”

Patrick Mitchell: Can you describe—just so the listeners know the scope of the job—all of the layers of responsibilities you have there?

John Korpics: Of what I do?

Patrick Mitchell: What you’re producing.

John Korpics: So we do a magazine six times a year, we do special issues four times a year. There’s a press. We have a very talented press designer named Stephani Finks and she manages the press design. There are digital products, we have a website and we’re about to launch a new native application on iOS and Android for all you shoppers out there.

And I oversee the creative center, which does all of our marketing and promotional work. I’ve done a lot of work with our learning design team. We have learning products that we licensed to corporations for leadership training. I’ve worked very closely with that team.

And then just in general, the overarching HBP, HBR brand. Stuff like that. A lot of video animation. It’s just whatever comes up. Whatever needs to happen, I try to figure out how to get it done.

Patrick Mitchell: So you’ve moved along and up in your career and part of what happens is you move farther and farther away from making pages. And so this is a podcast about making magazines. Do you miss it? Do you miss picking a font, designing a drop cap, calling an illustrator?

John Korpics: Well I designed—with the magazine design director, Susannah Haesche—I designed the system that the magazine is based on. We came up with the basic typographic foundation. We came up with the structure of the pages. We came up with the initial design, and we’ve enhanced it as we go along. So when I see the magazine, I see a lot of the initial work that I started when I got here five-and-a-half years ago. Susannah has obviously taken it to new places and she’s done amazing things with it. But I still feel connected to it.

We were recently trying to design a new interface for one of our learning products. And I did the design in InDesign, whereas everybody’s like, “Somebody has to translate this to Figma.” And I’m like, “I don’t know what to tell you. I can’t do Figma. But I can do it in InDesign and it should work.” I still like to mess around like that.

Patrick Mitchell: I think you told me you have dabbled in your free time—you have a political candidate you’ve worked for. So you’re known to crack open the InDesign on the weekends every now and again.

John Korpics: I like, sort of, ‘personal’ design. I’ll design t-shirts for friends and family. I did work on a friend’s political campaign. I did all her signage and mailers and things like that. I do like keeping my hands in it. It’s just fun. I don’t think I’ll ever stop designing.

Patrick Mitchell: So in closing, a big, deep philosophical question. Take as much time as you need to think of the answer. If you could change one thing about your career, what would it be?

John Korpics: I don’t know what I would change. I think that my career has been very—like I was never able to stay put. I was always very restless. And to some extent I look back now and I think I learned a lot because of that. And I had a lot of great experiences because of that. But also, it can be very fraught. It’s like riding a roller coaster. You’re up and down a lot. You’re never at the same place for more than three, four, or five years.

I think it might’ve made more sense to do what I do through an agency. Through a place that is bringing clients in that you work with on a temporary basis. So you work with a client for a year or six months, and then you move on to the next client and you’re doing something else.

Because I structured my career that way. I just did it with full time jobs that I had to come in and out of. And sometimes in ways that weren’t ideal. But I look back and I’m very, I’m fond of just about everything I was able to do. And it’s not over yet.

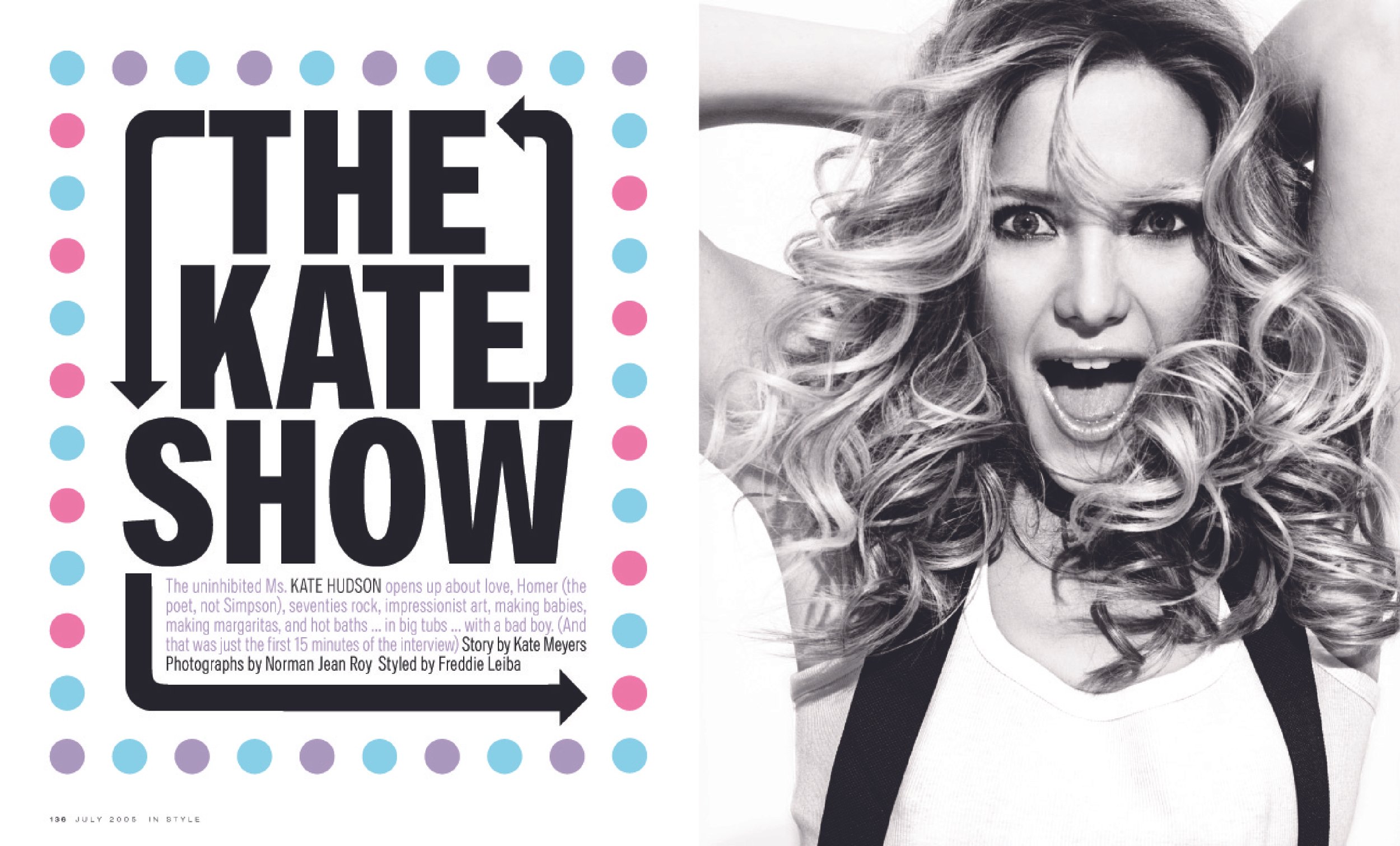

Patrick Mitchell: Alright. It’s time for the Print Is Dead Billion-Dollar Question. And that is: a billionaire of your choice offers you, really, a blank check with the caveat that you have to use this money to create and launch a print magazine. What would you do?

John Korpics: I’ll tell you what I would do, but first I want to be a little philosophical here. I think that print, in order to survive, has to be reinvented. So you can’t keep doing magazines with this structure that has been around for 75–100 years: You’ve got a front of book, a feature well, a back book, a cover. Everything’s designed as if it’s going to be on a newsstand, even though it’s never on a newsstand anymore. Everything’s designed as if people read them linearly.

So somebody has to just say, “We need to figure out what people are interested in and then we need to stick it into print in a way that actually speaks to them.” I don’t think that’s been done yet. I think that there are a lot of magazines that are personal projects and passion projects, but I don’t know that they have reached a wide audience.

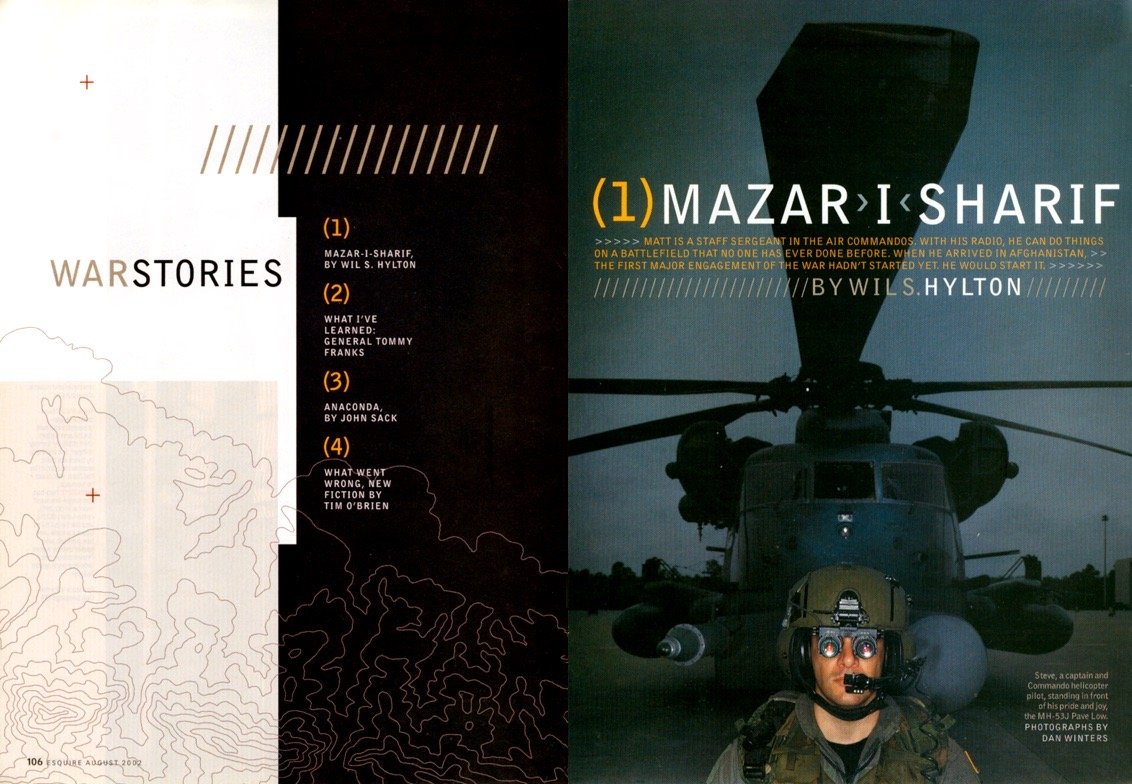

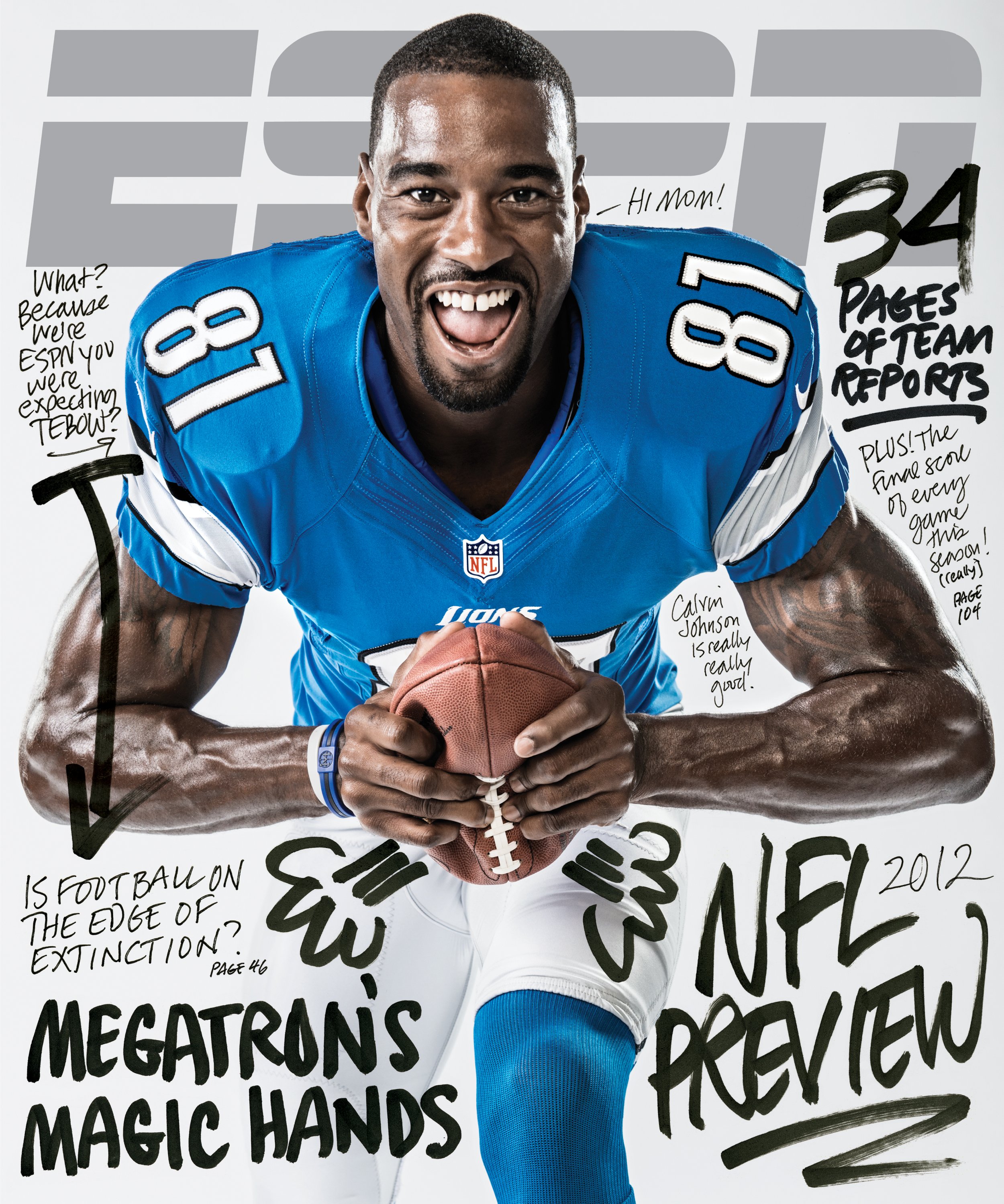

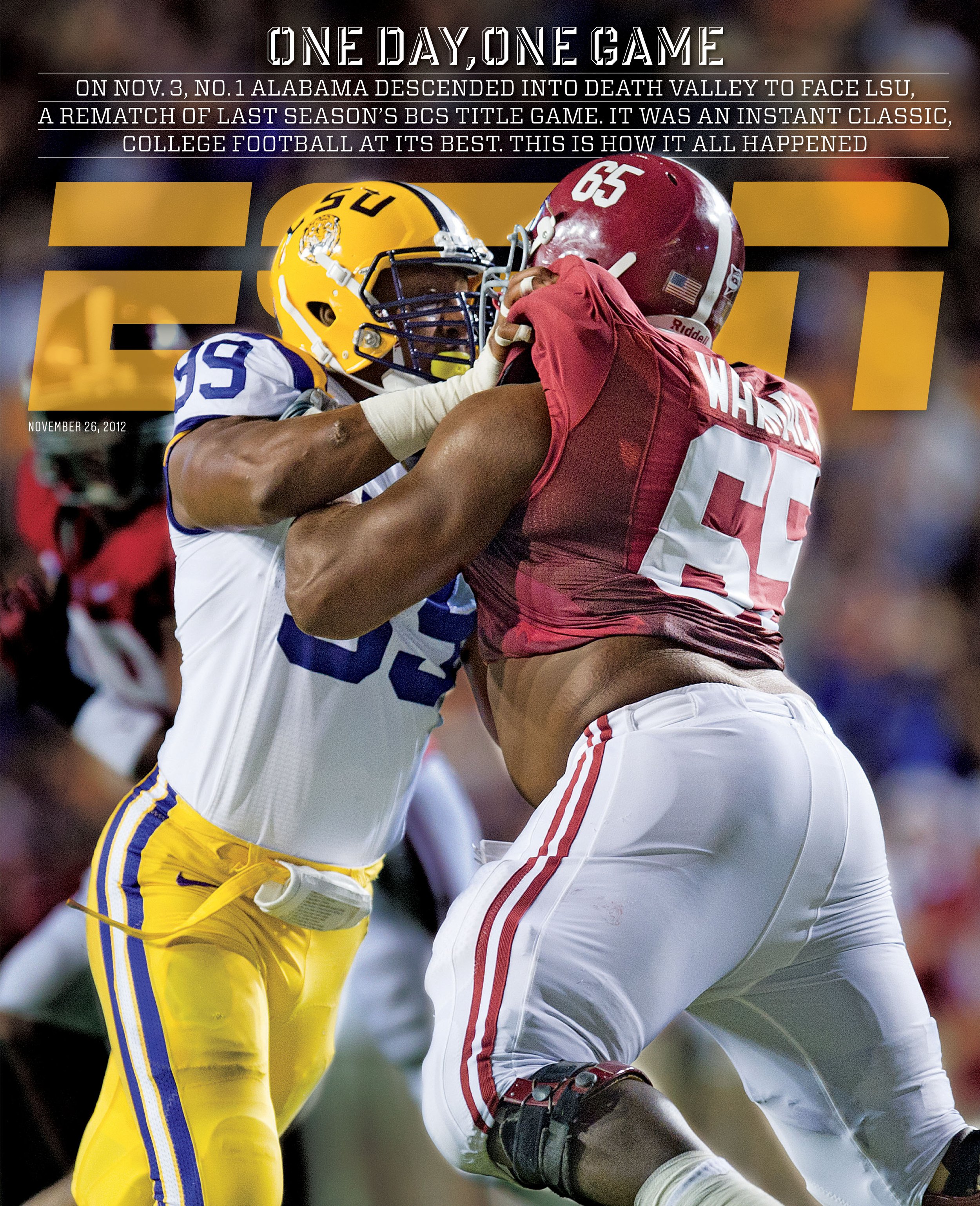

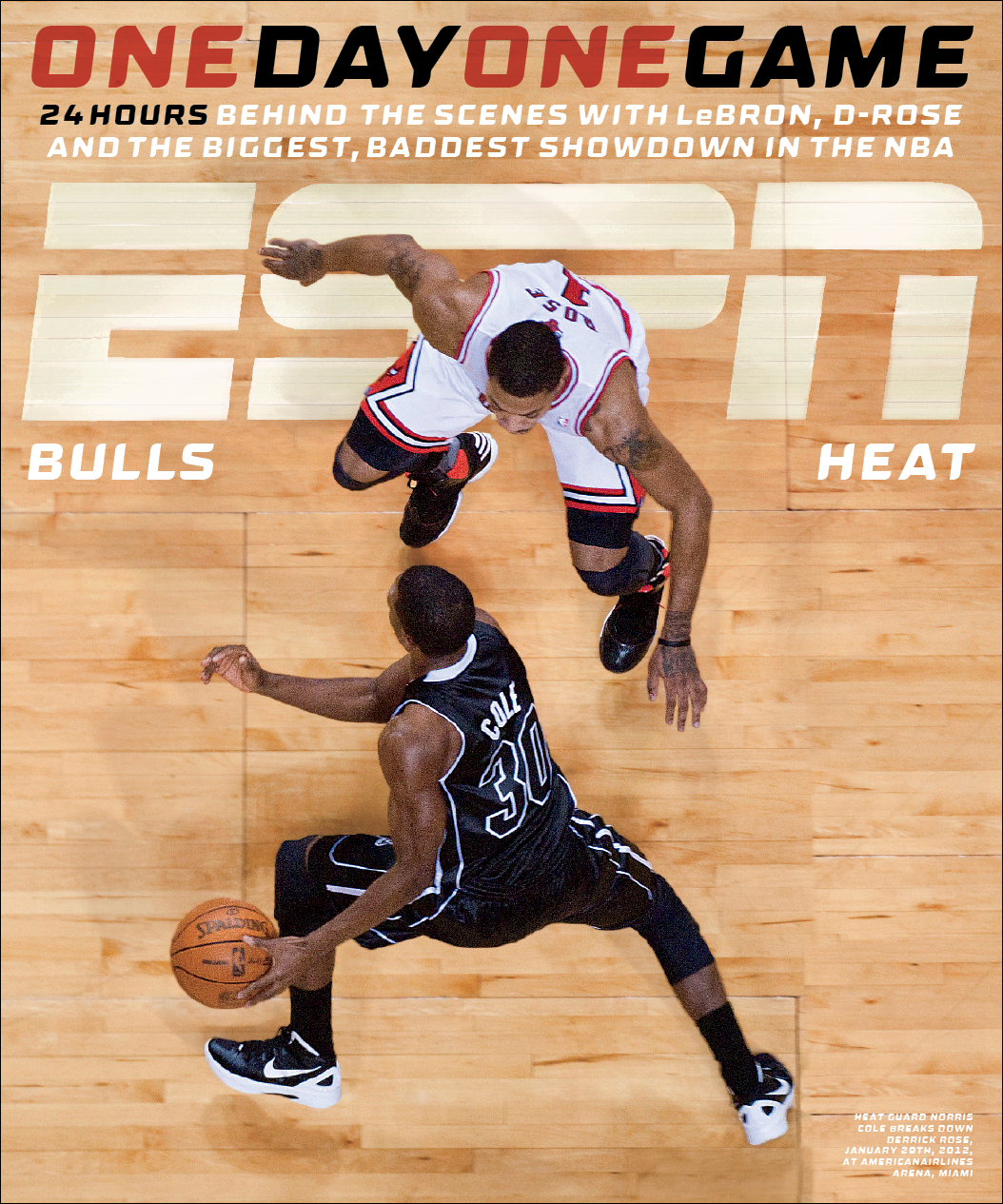

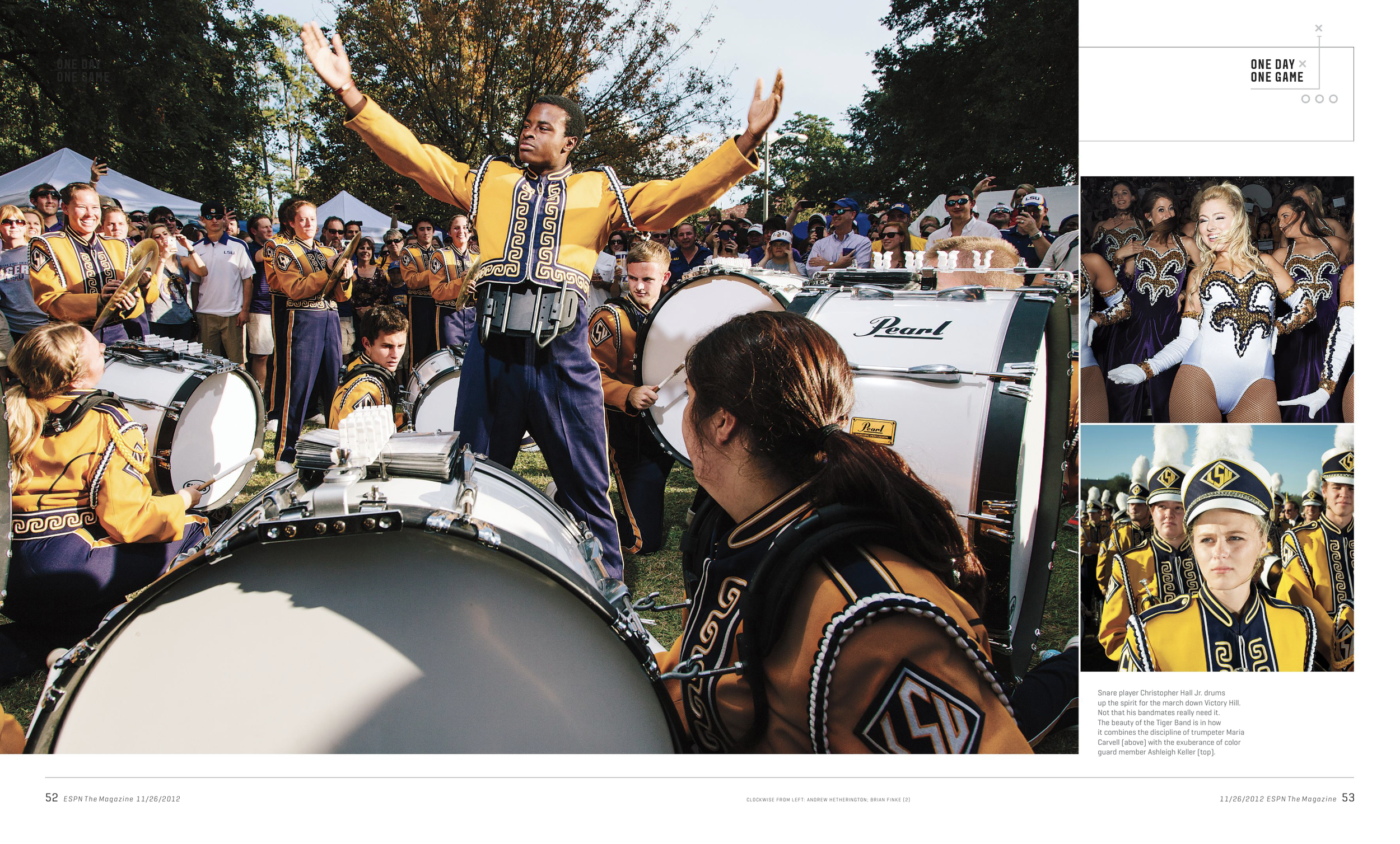

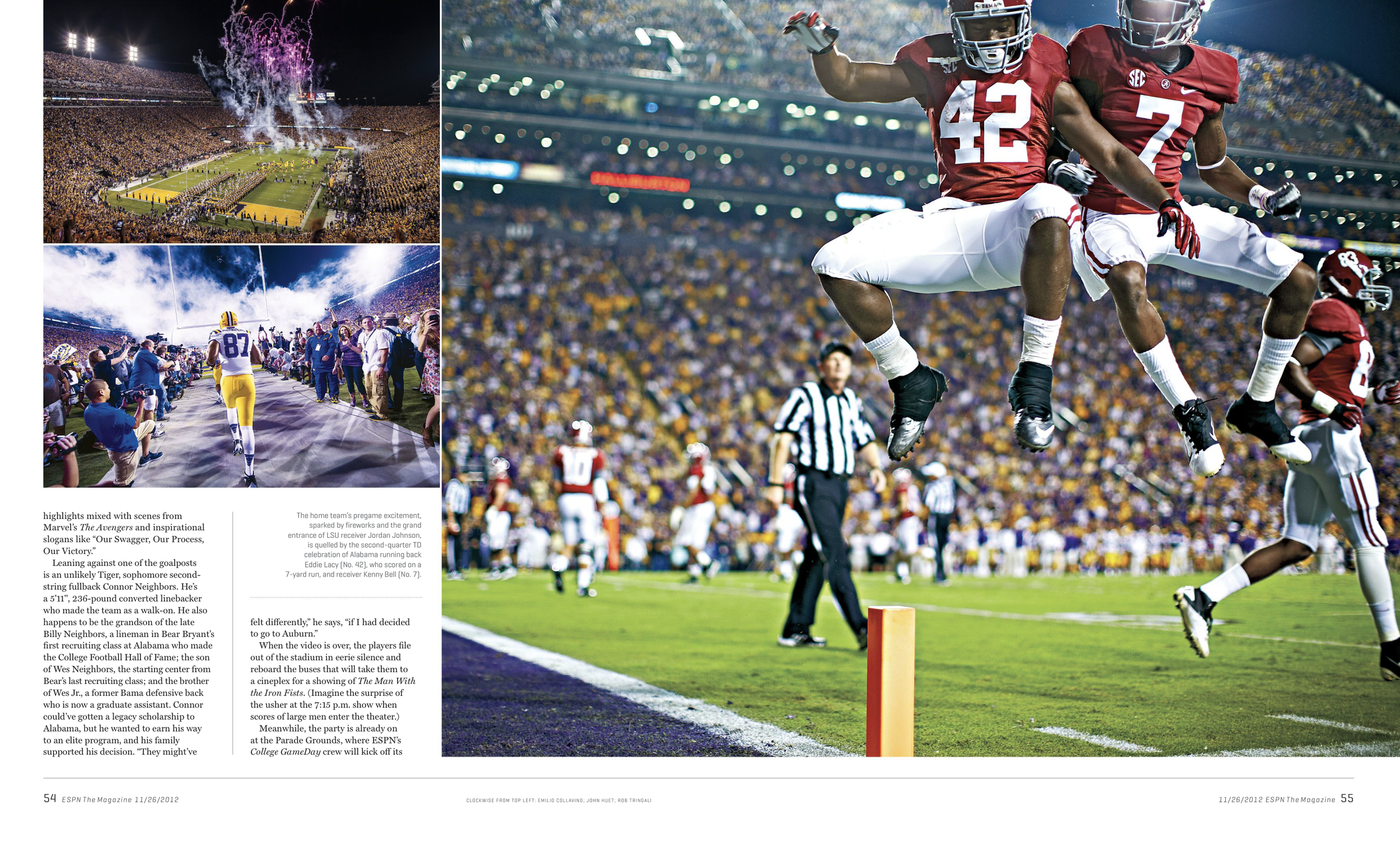

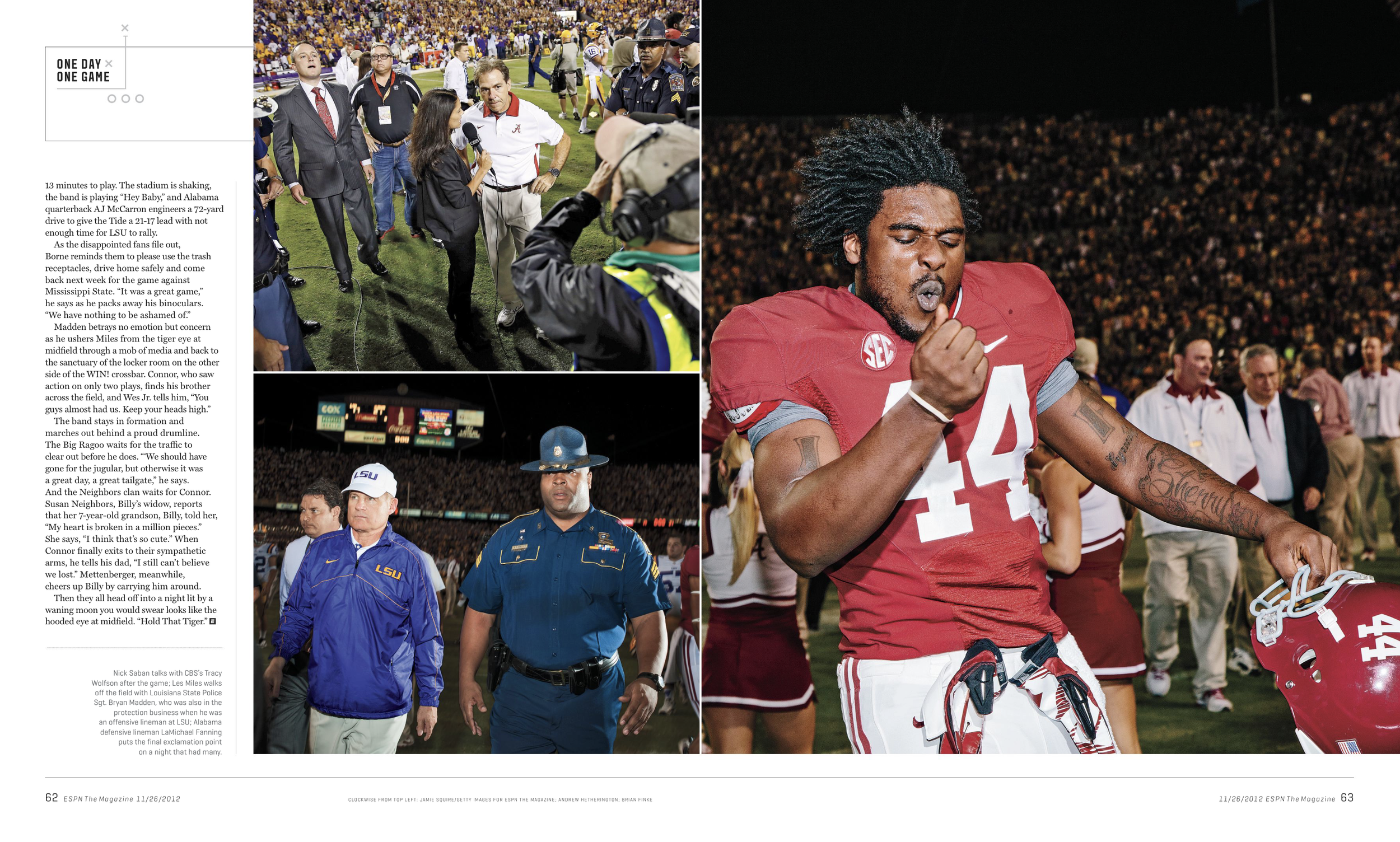

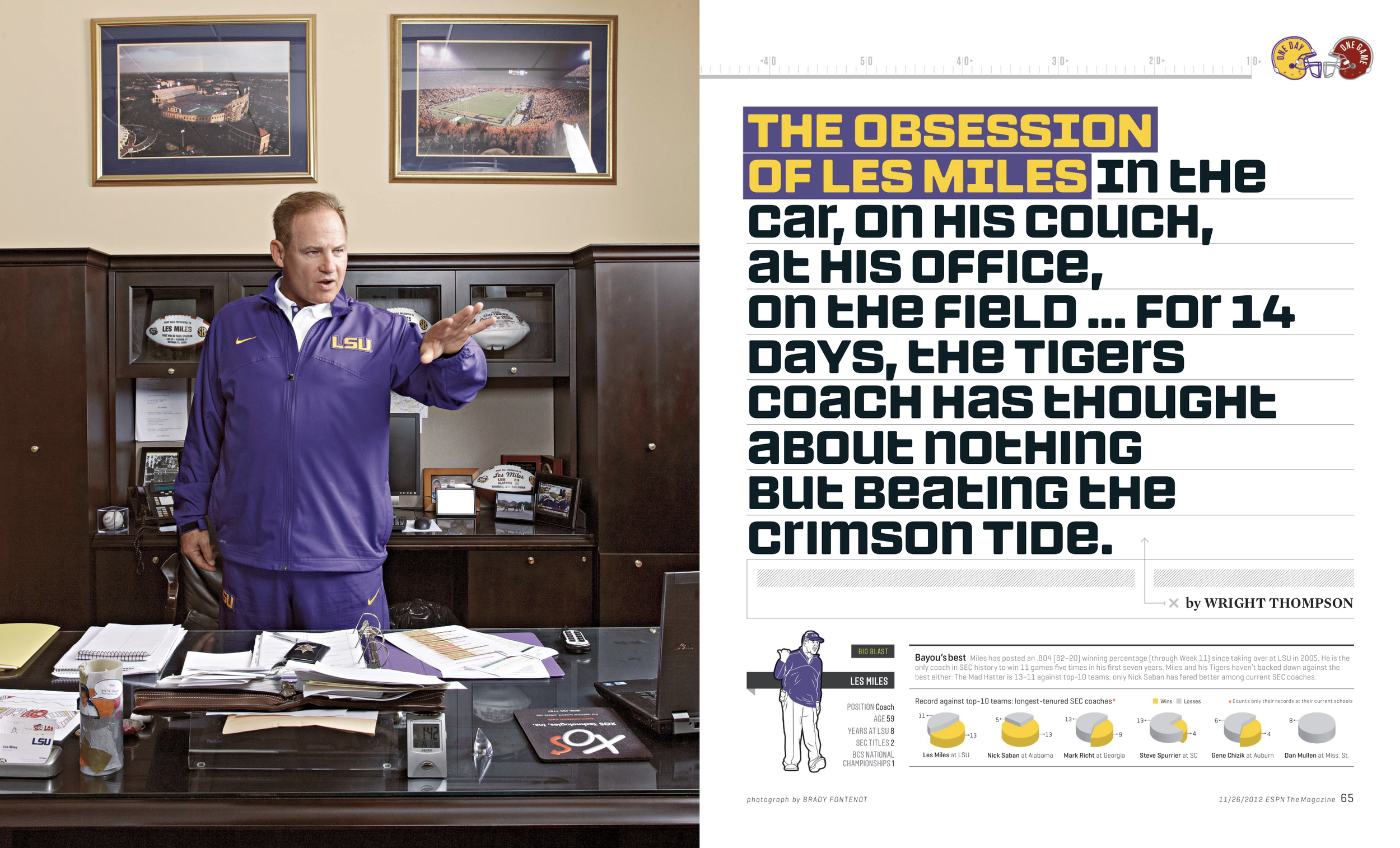

I think that has to happen. I don’t know if I can do that. Somebody else has to do that. But I think my mag—when we were at ESPN, I loved these issues we did called “One Day, One Game” where we would take a single event and we would just dive in and throw everything we could at it and cover it top to bottom.

So we did the LSU/Alabama game and we covered everything from tailgating out front to people making gumbo, and when they bring the tiger out onto the field, to the game itself, to the preparation in the locker room. And I do think there’s an audience for that.

I would love to see an issue that just tells me what it’s like for Costco to run for a day. What goes into running Costco for a day? Or what goes into figuring out how to run the New York City subway system for a day? I could see that that might be really fascinating.

I don’t know if it’s a print publication or not, but I think print is uniquely set up to allow you to browse and relax into that. So you can pick it up and come back to it as often as you want. And I think that there could be an audience for that. So maybe that’s what I would pitch. I’d pitch a day in the life of this—whatever this thing is.

Patrick Mitchell: That’s a great idea. And because, frankly, when I think about what is the one thing that still makes value out of print? That’s photography. Artwork. You can never get big artwork online.

John Korpics: I totally agree with you. But I also think that artwork without words is meaningless.

Korpics’ “Billion-Dollar” magazine would be based on ESPN’s noted “One Day/One Game” special issues.

For more on John Korpics, check out his website. You can also find “My Effing Commute” right here in our Entry/Points blog.

Related Stories