A Style All Her Own

A conversation with editor and designer Stella Bugbee (New York Times Style Section, The Cut, Domino, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS A SPECIAL COLLABORATION WITH OUR FRIENDS AT THE SPREAD

EDITOR’S NOTE:

This summer, our first collaboration with The Spread—the Episode 21 interview with former Cosmopolitan Editor-in-Chief Joanna Coles—became our most-listened-to episode ever. Now Rachel Baker and Maggie Bullock are back, and this time they’re speaking with another game-changing woman in media: Stella Bugbee, the editor of The New York Times Style section.

For our new listeners, Rachel and Maggie are a pair of former Elle magazine editors and “work wives.” In 2021, like many of you, they found themselves wishing for a great women’s magazine—and watching the old-school women’s mags drop like icebergs from a glacier. They decided to be the change they wanted to see—and The Spread was born.

Now, more than two years into publishing their dream weekly on Substack, rounding up juicy gossip, big ideas, and deeply personal examinations of women’s lives—from The New York Times and The Atlantic to Vogue and Elle to NplusOne and The Drift—The Spread is a cult favorite of media mavens and the media-curious.

Rachel & Maggie call Bugbee “a magazine-making unicorn”—we’re excited to be able to share their conversation with you.

—

Maggie Bullock: Last month, the big, bad headline in the world of women’s media was the shuttering of the groundbreaking feminist website Jezebel. We’ve since learned that Jezebel could be revived, but who even knows what that means? Regardless, the “closure” unleashed a wave of mourning, even among magazine fanatics like us who’ve become a little bit inured to the decimation of the legacy magazines that Jezebel was invented to skewer. Rachel, Jezebel was supposed to be the radical “antidote to the establishment”—and it didn’t have to contend with the print and circulation costs that sink bigger ships. When that topples, you have to ask yourself: What era of women’s media are we in now?

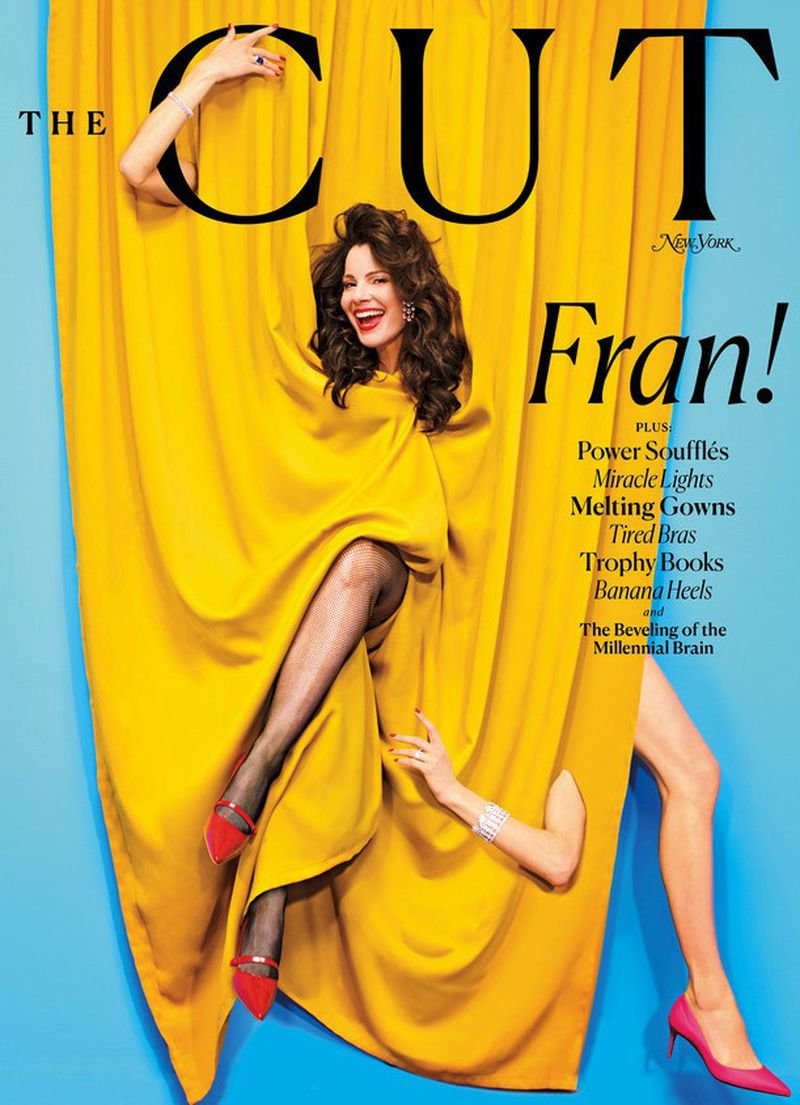

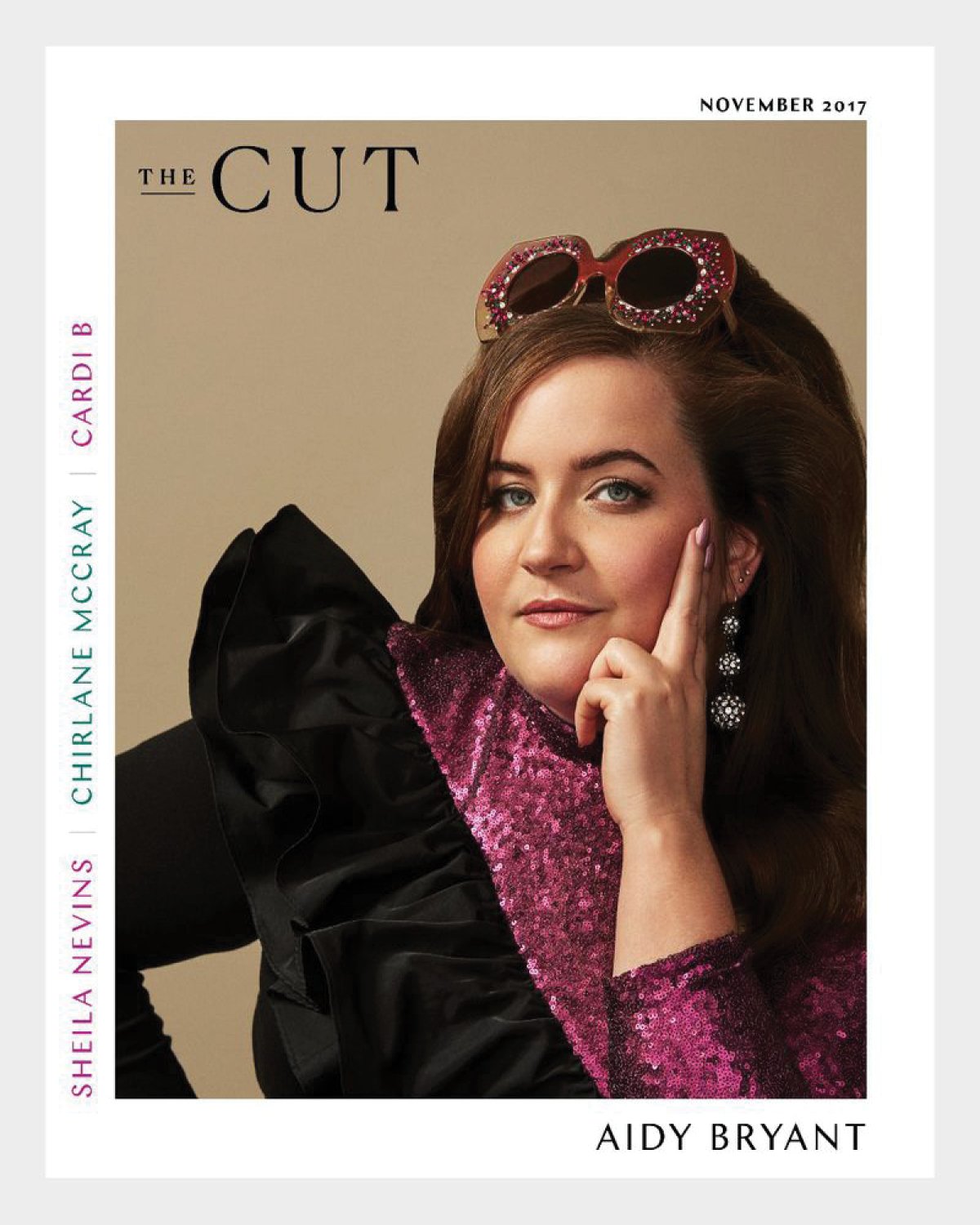

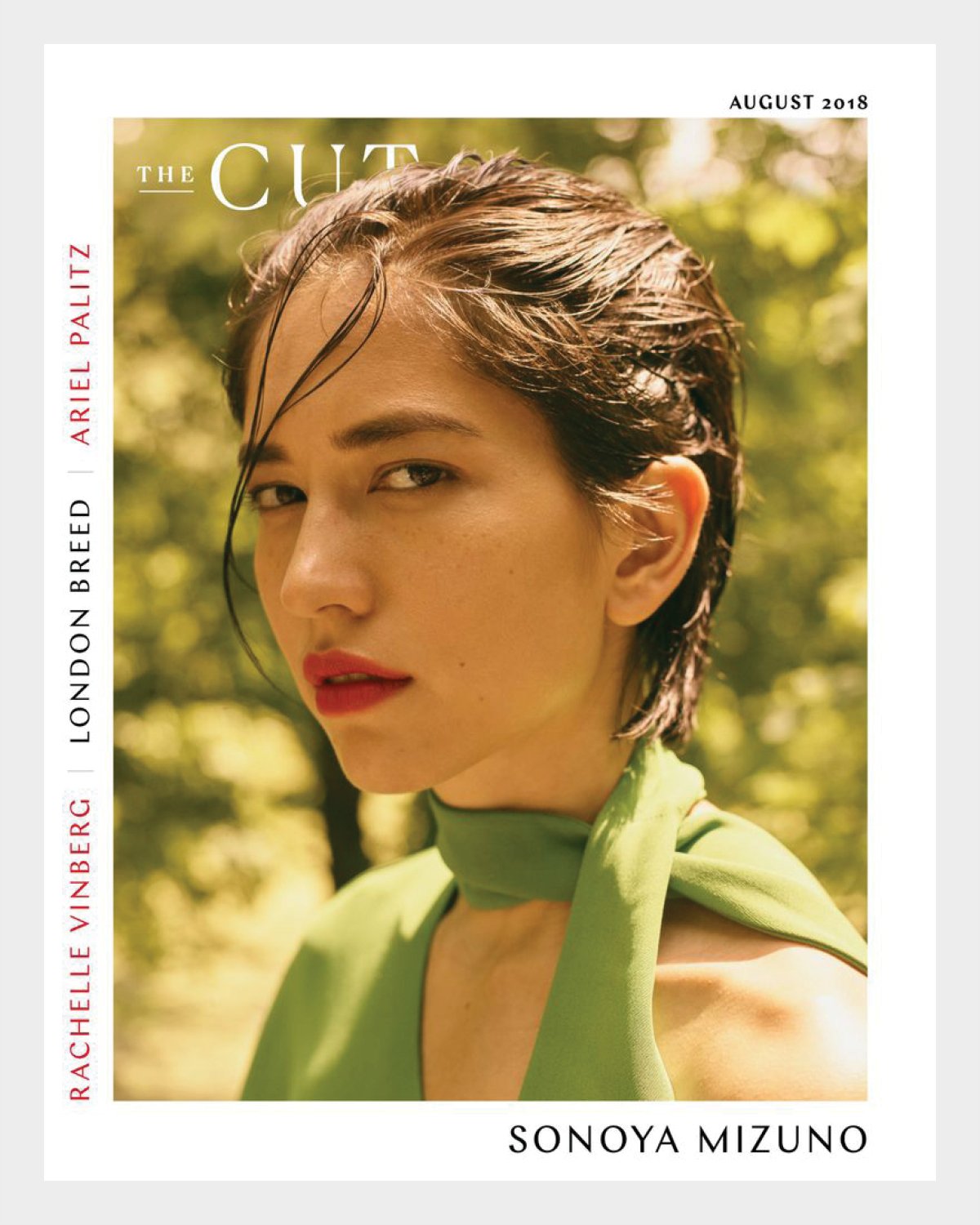

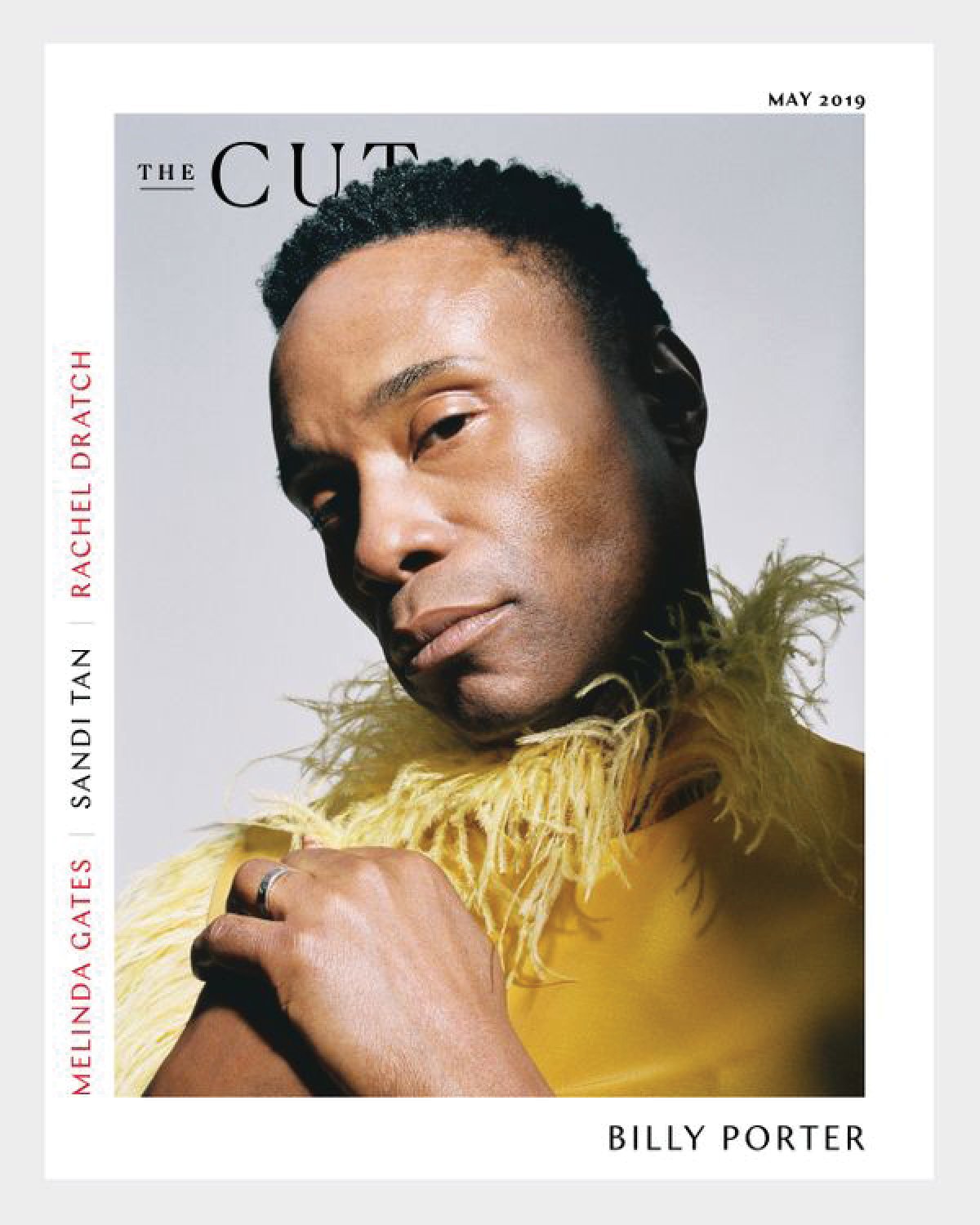

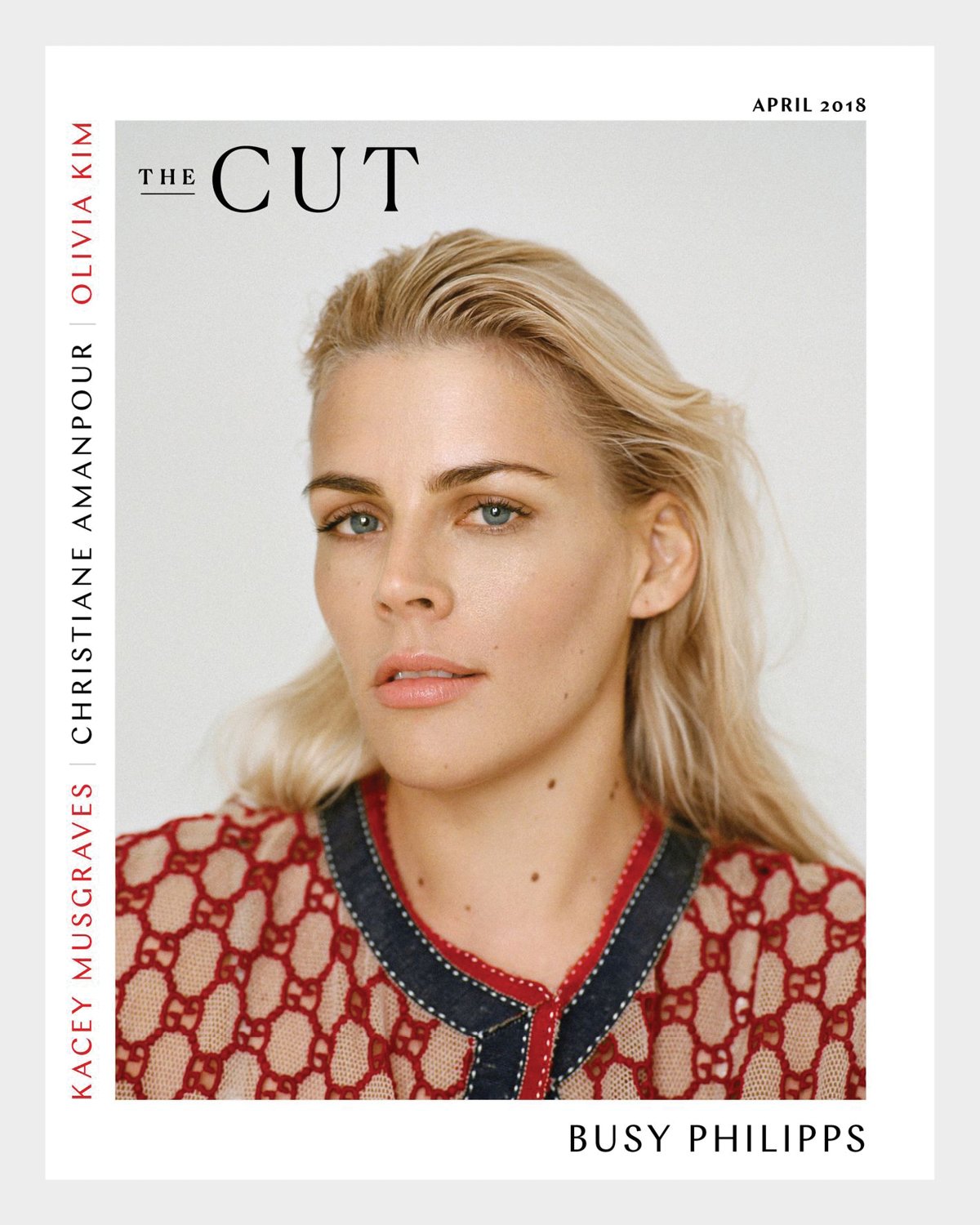

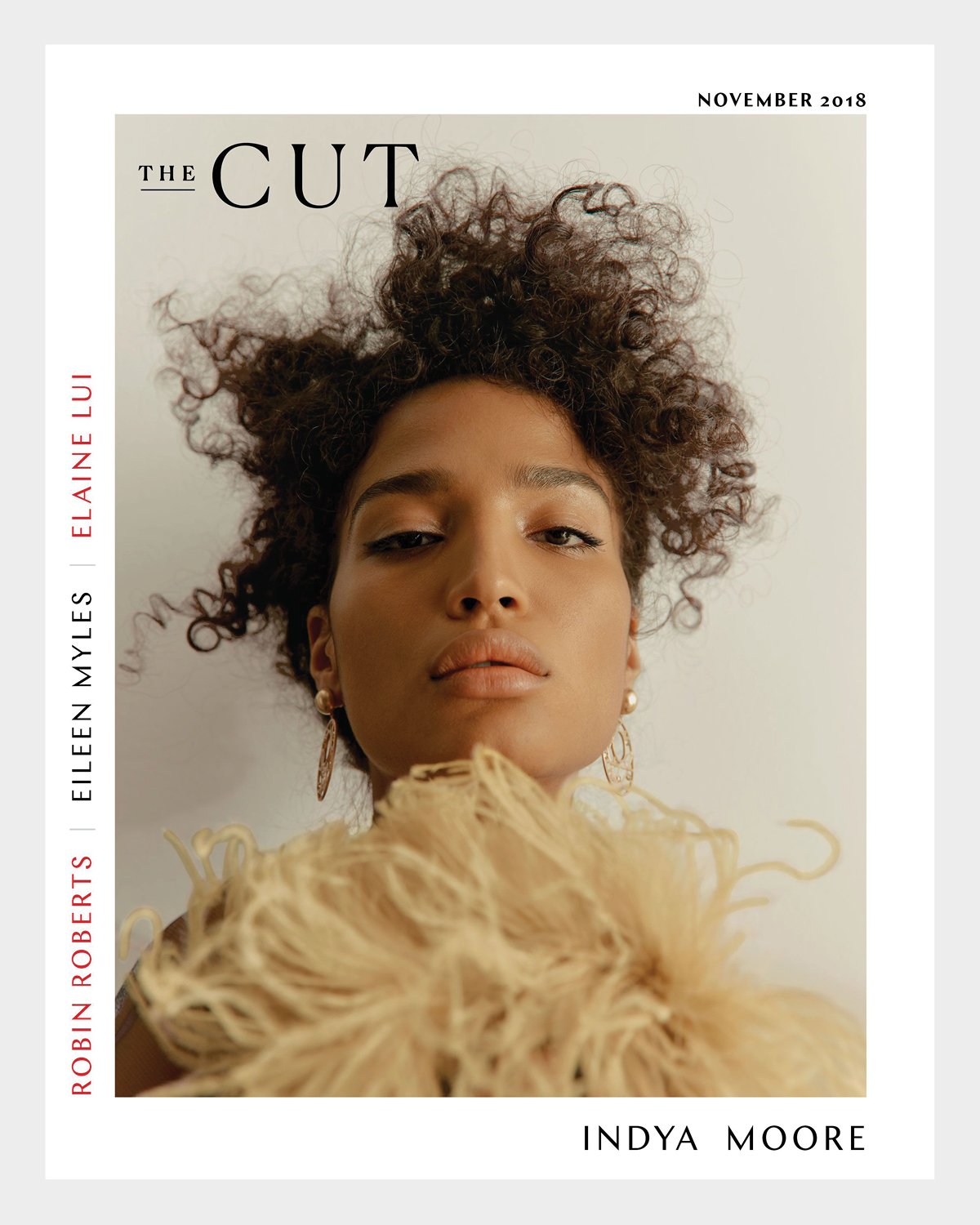

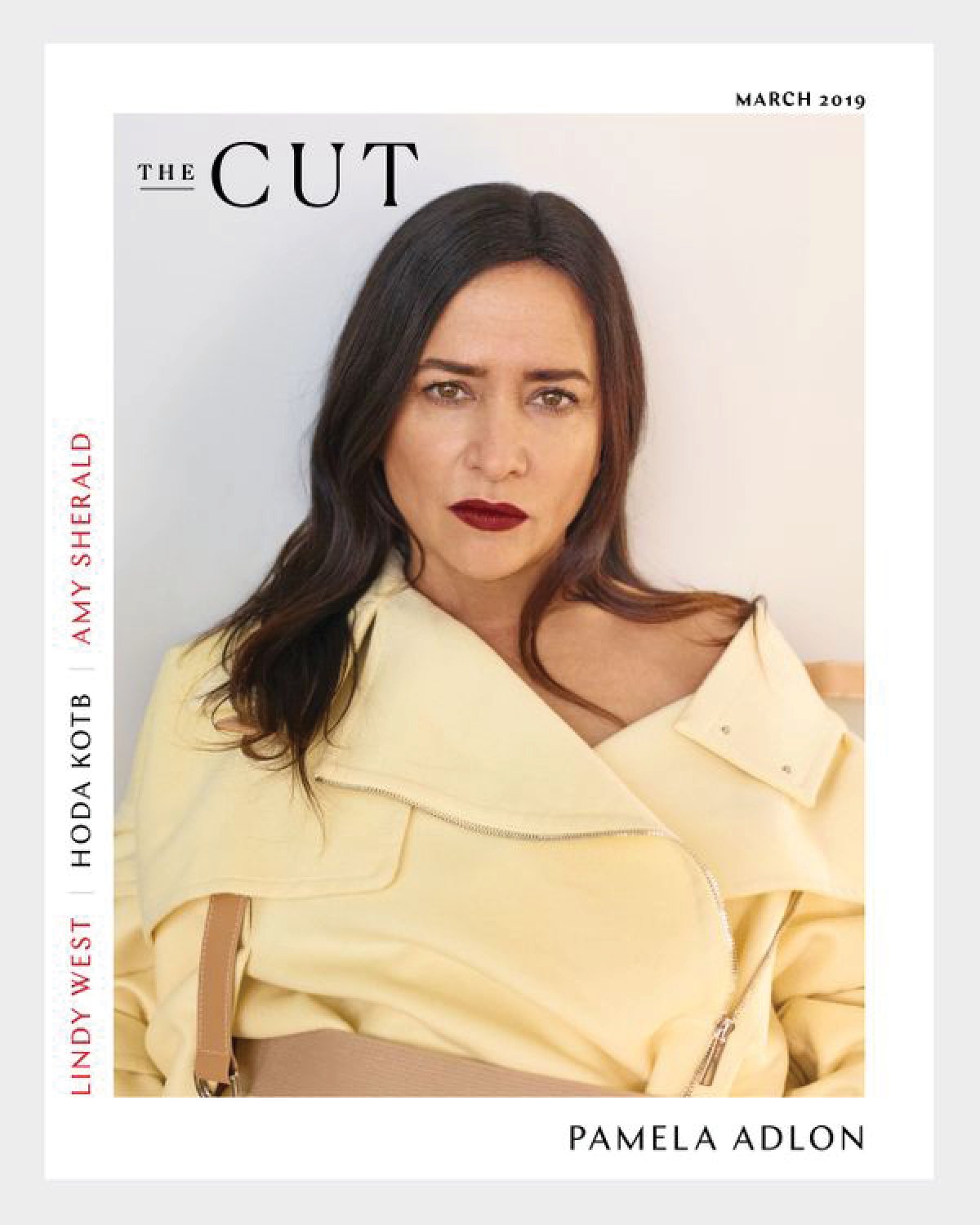

Rachel Baker: That’s what makes it such an interesting time to talk to Stella Bugbee. Ask any 30- or 40-something today about the one women’s media brand that is absolutely a daily must-read, and she will say New York magazine’s The Cut—the site that, starting in 2012, Stella built. The Cut was not just a women’s magazine re-sized for the internet, but a whole-cloth reinvention of the form. Jezebel (which was founded in 2007) was as much its forebear as the Elles and Vogues of the world: The Cut had the irreverence and voice-yness and political savvy of new media and the high-caliber production value of old media. And it was built to last: While we may have lost Jezebel, The Cut is still operating, more or less, on the blueprint that Stella created—and going strong.

Maggie Bullock: What we’ve always found fascinating about Bugbee is that she started out as a designer—she worked at a creative agency and on the visual side of a ton of cool indie magazines (like Interview and Topic) and had a stint at The New York Times before becoming the design director of the original Domino. But then when that magazine folded, she somehow totally switched teams, becoming an editor and a really great writer. I can’t think of anybody else who did that, can you? It's no surprise that The New York Times tried for years to get Stella to come to run the Styles desk. Somehow, the middle of the pandemic—when most of the Times was still working remotely, when she was unable to meet her team in person—felt like the right time for her?

Rachel Baker: Now I think you can really see the Stella touch in the way they package their stories. Like, a couple weeks ago, when the section ran a cover story titled, “Ozempic vs. Thanksgiving.” The idea sounds almost obvious, but I’d argue that it’s a masterclass in headline writing—it demonstrates a specific Bugbee-an ability to survey the culture and zero in on the thing everyone is thinking about—like when Styles spotlighted the “girl dinner” over the summer. My group texts are still full of photos of “cheese plates for one,” how about yours?

Maggie Bullock: Totally. So should we stop yammering so folks can listen to what Stella has to say?

Rachel Baker: Let’s do it.

Maggie Bullock: Okay, so now we shall ask some questions. So Stella, thank you for joining us here. We’re super excited to have you and we are taping this on a Monday afternoon, it is 1:02 p.m., and we were wondering what’s going on at the Times at 1:02 p.m. on a Monday. What are you guys doing right now?

Stella Bugbee: Should I tell you the truth?

Maggie Bullock: Preferably.

Stella Bugbee: Normally at 1:02 on a Monday I’m catching up. Usually I’m probably eating lunch at 1:02, actually, because at noon there is this meeting called the enterprise meeting where a lot of desk heads come together with the masthead and we talk about the developing big story of the day or of the week.

And people kind of think about how their section might get in on telling that story or what they could contribute. Mostly, I listen in those meetings. But every once in a while, there’s a way that Styles could get into the story, and it’s really helpful to be at those. And then after those end, I usually go upstairs and eat a salad.

Maggie Bullock: Perfect. So you’re fueled. That’s important. And like, what’s the stressful part of the week in terms of your deadlines and Styles?

Stella Bugbee: Styles closes two issues a week. We have a Thursday edition and a Sunday edition. So we are closing Thursday on Wednesday afternoon, and we were closing Sunday on Friday morning.

But, we’re really digital-first as they love to say, but it’s true. So we’re really meeting every, we meet a couple times a week. One of those moments is Monday mornings and we look at the whole week and we sort of publish divorced from the print product. And then we look at what’s going to fill Thursday and what’s going to fill Sunday, but we publish way in advance, often, online.

So we’re looking at this big Airtable—I don’t know if anybody uses Airtable, but that has our whole calendar. And I try to have at least three or four things publishing every day, regardless of the print product. But we’re sort of in a real rhythm with publishing Thursdays and Sundays.

And mostly what we’re thinking about is like, what’s the cover of Thursday and what’s the cover of Sunday. And how are we going to spread out the stories that we’ve published all week into either one of those places.

Maggie Bullock: So we’re going to get more into the nitty gritty of that, but for now we’re going to back up a little bit. So you grew up in Park Slope, Brooklyn, correct?

Stella Bugbee: Where I still live.

Maggie Bullock: Where you still live. You went to the smarty-pants high school, Stuyvesant.

Stella Bugbee: Wow. You did your research. Yes, I did.

Maggie Bullock: And then you went to Parsons, right? And you majored there in communication design.

Stella Bugbee: Yes. Magazines, basically.

Maggie Bullock: In magazines? So it seems safe to say you’re a total dyed-in-the-wool New Yorker. Is that safe to say?

Stella Bugbee: I like to think so, yes.

Maggie Bullock: And how do you think that informs your editorial point of view—certainly your job now? Like, how key to your makeup is the fact that you grew up the way that you did?

Stella Bugbee: I sometimes think about, going back to Stuyvesant, like If you had said to people who knew me back then, “Someday she’s going to be editing the Style section of The New York Times,” I think people would have said like, “Oh yeah, that makes sense.” Because it was a huge interest of mine. Fashion was like a huge part of how I identified within my friend group and I was always super-interested in it, always had subscriptions to Vogue and Interview and a lot of interest in that stuff. And also in writing.

I think I took a lot of detours. I didn’t necessarily think I would end up here. But then I think if I told my high school self, “Oh that’s what you’ll be doing in 30 years,” I think I’d be like, “Oh yeah, I guess so.” It makes sense in retrospect. So I think growing up in New York, you’re just exposed to fashion all the time by just leaving the house.

You can’t help but see all the stuff around you. And I just naturally found it so interesting. I just loved the way people looked and I couldn’t stop watching them. And I think being on the subway every day, walking through Manhattan, it’s unavoidable.

“I don’t think a career in fashion was necessarily something that I thought was a valid career. Which is a shame because it truly is.”

Maggie Bullock: And did you grow up—I mean, every New Yorker really grows up reading the Style section.

Stella Bugbee: Yeah, I guess so. We had a subscription to the Times. I feel like I read the Book Review a lot. (I was a little pretentious). And I apologize to the people who knew me then. Yeah, I mean, it was around. It was, like, in the world. I don’t think a career in fashion was necessarily something that I thought was a valid career then. Which is a shame because it truly is. There’s so much you can do in fashion. I just didn’t have that awareness. My family didn’t work in fashion. I didn’t really have any examples of people who had careers in fashion. My parents were teachers.

Like it just didn’t seem like a valid direction. And then at Parsons, it’s obviously a huge part of the school, although I wasn’t in that program. So again, I saw magazines as this bridge between what I enjoyed about fashion, which is image making and culture creation and analysis, and writing. Like a magazine back then—this is, whatever, mid- to late-nineties—was this place where you could catalog culture in this way that was really permanent and relevant.

And I was looking to the magazines to give me the information about these communities that I really wanted to be part of or that I really admired. And so it just sort of felt like, well, that’s where I want to be working. I want to be doing that. And the communication design program was really about—you could pick a lot of different things within that. But for me, magazines were the natural crossover of my many interests: writing, and visuals, and culture. It wasn’t just fashion.

Maggie Bullock: But that said, when you got out of Parsons, you didn’t follow what we think of as the traditional path to magazine success, exactly. You went into advertising, right? Was that the first leap?

Stella Bugbee: Yeah. There were a couple of people that I really admired in the late ’90s. Some of them were my teachers and some of them were just people in the design community that were bridging this gap between designer and editor. Like, Tibor Kalman was a person that had been incredibly influential in New York City and he had employed most of my teachers.

So I’m, let’s just say, like, third-generation—maybe I’m second-generation? So all of my teachers at Parsons were working designers, that’s the way it worked. And they had all worked for Tibor. So he was, kind of, this grandfather figure in the city. And he had done Colors magazine. It was this very groundbreaking project where a designer could tell stories as an art director and it was super powerful and this huge commentary, but it kind of crossed this line between advertising/advertorial/content. But it really was independent of, I guess it was Benetton who was the company that put out Colors.

And so Tibor was this figure for me that I kind of wanted to emulate. And then in college, I worked for Roger Black, who is this seminal magazine designer. And at that point he had a firm where he redesigned magazines. And I loved it. I worked on Reader’s Digest, I worked on Men’s Health, I worked on all these magazines.

But what didn’t appeal to me about that was the sort of rigorous work your way up as an art director and have like no say in the content part of it. And there was just a little bit of fluidity between advertising and design in the people that I most admired, like [Stefan] Sagmeister or Tibor Kalman. And I ended up just taking a job that I got, which happened to be in advertising at the end.

And it was advertising for theater, so it felt kind of editorial in a weird way. Like I had to come up with art direction in the same way you might for a story. Because you’re reading a play, and you’re trying to come up with how to advertise that play. The other day I was in my basement and I found the Playbill for one of the plays that I designed right out of college, which was this play called W;t.

Maggie Bullock: Oh wow, I remember that.

Rachel Baker: Yeah.

Stella Bugbee: Yeah. And it had a semicolon instead of the “i.” It was advertising, but it was extremely creative, that part of it.

Rachel Baker: But you’re responsible for the semicolon?

Stella Bugbee: I’m responsible for that logo, yeah. It’s in the play. Like, I read the play and I was like, “Let’s make the “i” a semicolon.”

Rachel Baker: Right.

Stella Bugbee: The semicolon is like a character in this play. Anyway, it was a way not to have to commit to a linear work-my-way-up-to-being-a-creative-director type of move out of college. And when you’re out of college, if somebody offers you a job, you’re just like, “Yeah, I’ll take it.” And I loved that job. I loved my boss and it was a fantastic job. But I only did that for about a year.

Maggie Bullock: So, I want to talk about all of these things, but we also want to cover a lot of ground. So I’m going to leap forward to 2006. Is that the year that you got hired at Domino?

Stella Bugbee: Yeah. I had a brief detour working here at The New York Times for the summer. I was obsessed with Adam Moss and The New York Times Magazine. And there was an opening—somebody went on maternity leave in the art department. So I was like, “I’ve just got to go and try it out and see what it’s like.”

So I got to do that. I got to cover her mat leave. So I was here for like this minor tiny moment and I got to see just like, “Oh, that’s what it’s like to work at a magazine.” And then I took a couple more detours before going back to magazines. But it was cool.

“All of us were obsessed with Adam [Moss], and just dying to get to Adam.”

Maggie Bullock: So that’s where you met Adam then, and where that started?

Stella Bugbee: No, that’s where I met Rob Giampietro, who is another graphic designer who knew David Haskell. And he said, “This guy I know from college is starting a magazine and I think he could use some help on it.”

And so I was like, “Oh, I’ll do that. That sounds fun.” And we just kind of took it over from, not from David, but for David, like in terms of just trying to reimagine what it could look like.

And at that point, working on that, I was like, “I want to be the editor.” That was where I got this, like, “Well, I have more ideas for the stories than I actually have for the art and design of this.” And I got this bug.

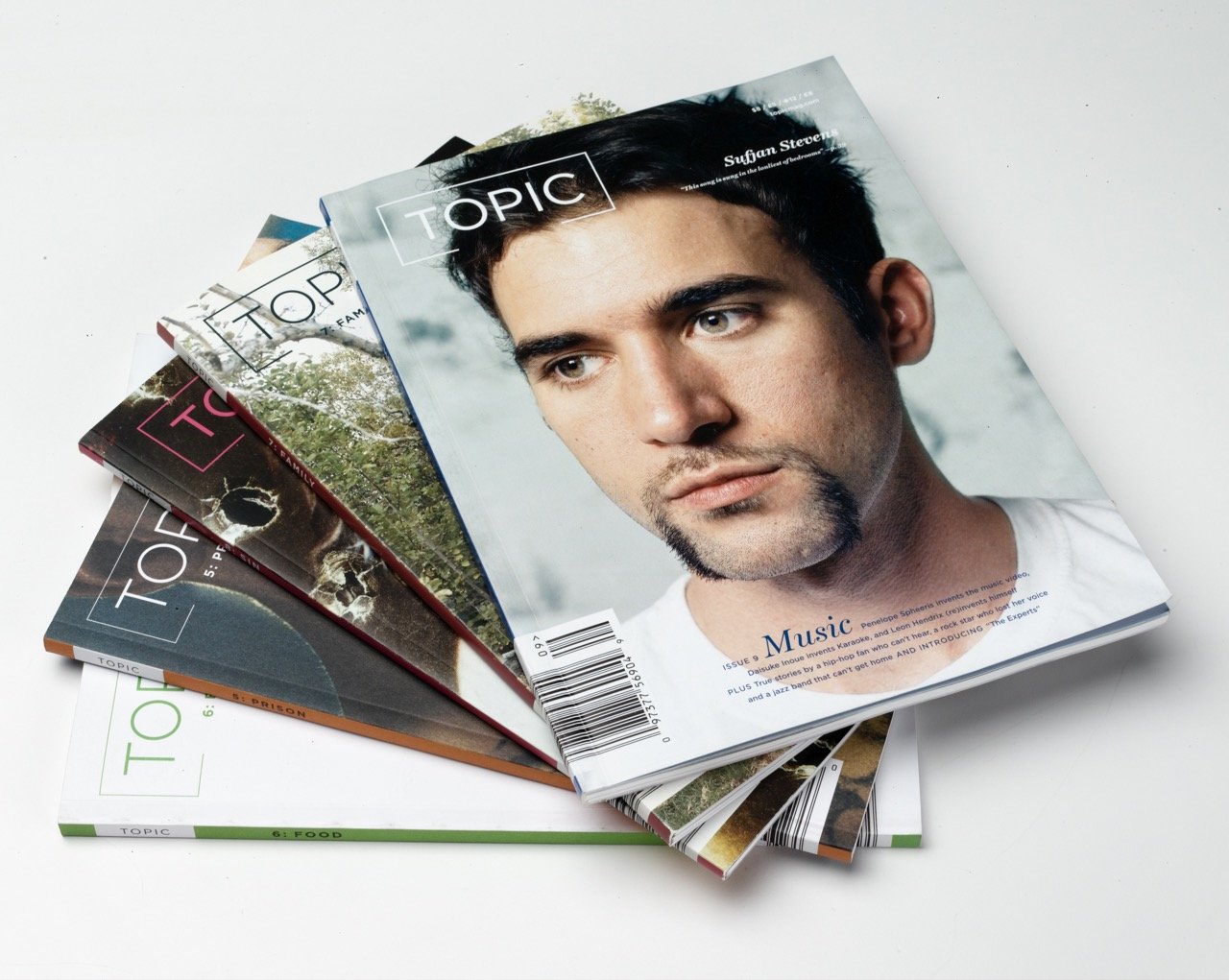

Maggie Bullock: Is that Topic?

Stella Bugbee: That was Topic magazine.

Maggie Bullock: Can we just tell our listeners, briefly, what was Topic?

Stella Bugbee: So Topic was David Haskell’s literary magazine that he started when he was, I think, I should fact check this, but I think he was at Cambridge when he started it. And when he moved back to America, he talked to Rob. And Rob talked to me.

And then I brought on a photo editor that was a friend of mine. And it was just this small, quarterly, sometimes only twice-a-year, self-funded literary magazine. And it covered a different topic each time. So we did games, we did prison, we did money—kind of like a little prototype of what a special issue of New York magazine might look like.

And all of us were obsessed with Adam, and just dying to get to Adam. And then David actually did get to Adam first. And David started working at New York magazine. That must’ve been, maybe 2007, 2006, something like that. And at that point I had gone to Domino.

Maggie Bullock: So somewhere along the line, you also had a few babies in there.

Stella Bugbee: Yes, right around Topic. I bounced around between advertising, just working and learning how to be an art director and stuff. I got pregnant and was sort of like kicking around, not sure what to do.

I also did this project with Joanna Goddard. She did this magazine that was all about Italy. It’s called Bene. I took the same photo editor from Topic and we went over to help her do this. It was really kind of a fun dream project all about Italy, but for Americans. They don’t do projects like this anymore. It’s like one of those things that you hear about, you’re like, “People don’t do that!”

Rachel Baker: Yeah. Who was funding that? Where is it? Can we get a copy?

Stella Bugbee: I might still have some copies like in my basement. I think we only did four or three, I can only remember the three covers. But I did that for a little while. And I was out of work, technically. I was at home with my babies. And I remember saying like, “I got to get to Condé. I got to get, I just got to get—I just need to be, like, a design director somewhere.”

Maggie Bullock: Because you needed, like, stability, insurance? Or you had bigger ambitions? What was, "I gotta get to Condé?"

Stella Bugbee: Well, I was like, “Okay, it’s time. It’s time to go do that thing I’ve been avoiding doing and just actually do it. If I’m going to do it.” And a guy that I had gone to college with had designed the original prototype for Domino. And he just put my name up for the job and I went and got the job.

Rachel Baker: And you were 30.

Stella Bugbee: I was 30. Yeah. It’s crazy to think about, yes.

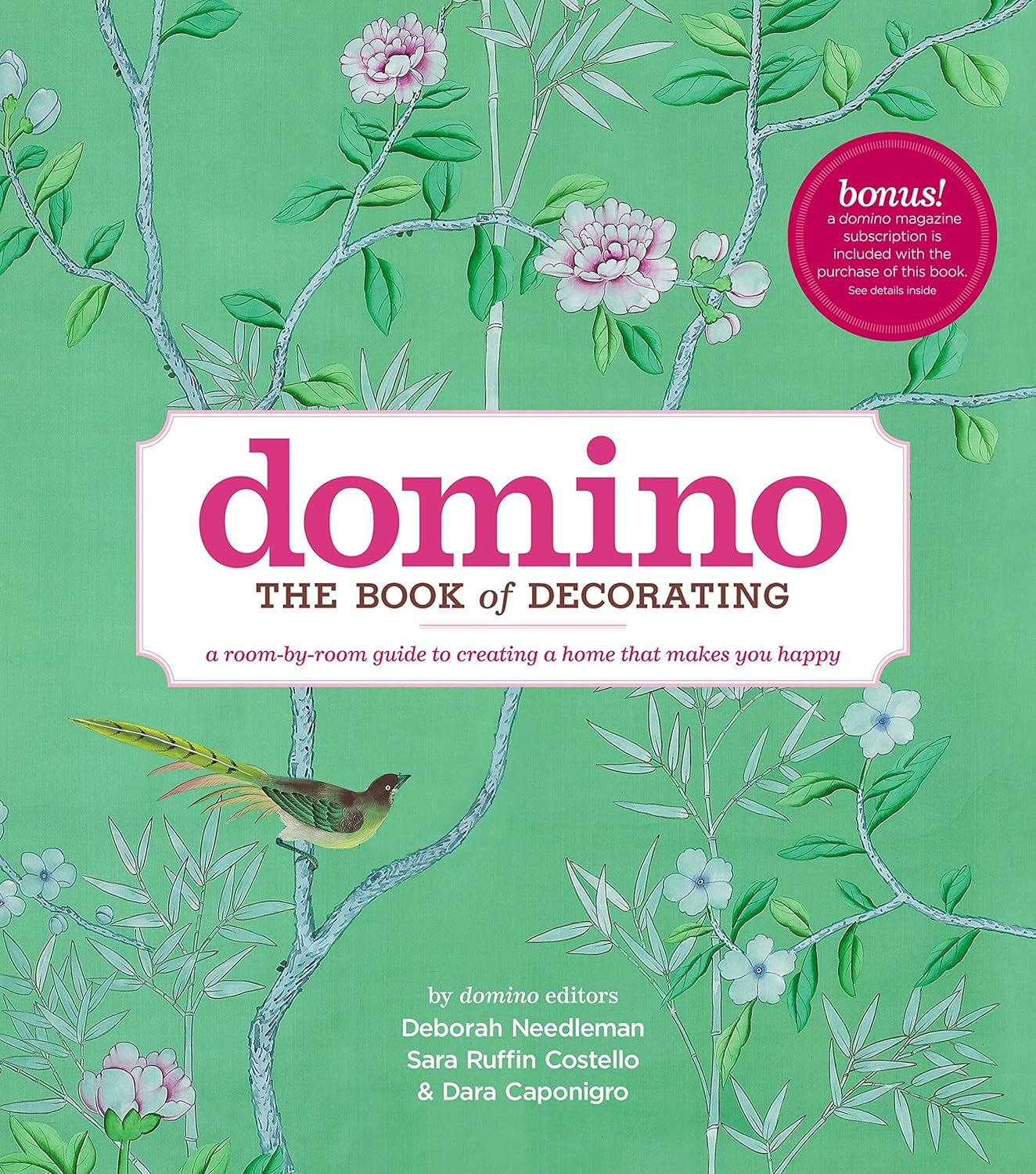

Maggie Bullock: So we love Domino. Rachel and I both loved Domino. And to me it really made interiors, which had been this, sort of, off limits, rich person’s hobby into, like, a shoppable, fun, younger—I thought it was really innovative. It was so fun to consume. But looking back on Domino what do you think was the brilliance of that publication?

Stella Bugbee: Well, I think Deborah [Needleman] was brilliant. I think Deborah, who also comes kind of from a visual background—she was a photo editor before she became an editor— understood how to tell the story about how a regular person could decorate their house.

And the genius of it is that I didn’t realize just quite how expensive everything was until I actually went to work there and got a deep education in interior design from all these brilliant, amazing women that I worked with. And you never felt that as a reader, which, I thought, was a really nice sleight-of-hand that she was able to pull off. Because actually designing a house is so expensive.

And somehow, as a reader, you’re like, “I could do this.” And I think that feeling of being invited in to participate was super-key to the success of that magazine. And it’s something that I feel is very important, especially for fashion, right? So it’s an ethos that I, like, took a big note from with Deborah.

And Deborah was obsessive about captions, which I think was also a great lesson for me. Like, she cared more about the captions than she cared about the actual long copy, because she understood that readers have all these different entry points into a story. And as a designer, like, who really was a reader first I think the way that I thought about design, and still think about editing, is like as a reader first.

So you’re sort of saying like, “I know that as a reader first, I’m going to go to the caption. I’m going to go to the headline, caption, and then I’m going to read the story.” Because it’s all these different entry points. And she really taught me the value of being obsessive about that small copy And that kind of what it contributes to the overall experience of a magazine.

Maggie Bullock: That is a hundred percent. Two, two hundred percent! Okay, but so this is a podcast called Print is Dead. So people are going to want to hear—tell the people about your experience just a few years later of watching that OG Domino be shuttered. What was that like from your vantage point and what did you learn from that?

Stella Bugbee: It was devastating, frankly, to have this project that everybody worked so hard on—I mean we were just finishing the book, The Domino Book of Decorating, which we had killed ourselves on. And we were doing that on top of the magazine, and I had this incredible design team of seven people, and they were just the loveliest, best people. And there was no warning. And they fired us all—like a hundred and some people—within 10 minutes.

I was out that day. I was sick at home. And I just got a whole bunch of phone calls. And they called everybody into a conference room, and when they got back to their desks, there were, like, “you’re fired” notices on their chairs. Then I pulled myself out of bed, andI went to work. And everybody was inconsolable.

It was really quite upsetting and disorienting for everyone because everywhere you went, people said like, “I love Domino. I love that magazine. It’s so great.” And you felt like you were working on something that people really were relating to. And then you get shut down in a mass firing.

So I was pretty discouraged. I’d finally committed to being in magazines, and I gave up on them almost immediately—well, that’s not true. I had a brief stint at Interview while Glenn [O’Brien] was there. And then he got fired. And I quit and went back to advertising. But this time in fashion, which was again, like kind of an incredible education. So every job that I had, I tried to use it as a way to just get a deeper understanding of how to do a skill.

And so when I went to work in fashion, it was really this, sort of, deep plunge into visual storytelling and brand building. And it happened to be working for Raul Martinez, who was a legendary Vogue art director forever with Anna [Wintour], and his husband Alex Gonzalez, who was also an art director at many Hearst publications.

And they had, in the Tibor model, also made their own magazines. One was called Influence. This was like long before the term “influencers” was broadly used. And II just kind of put myself at their feet and just learned everything there was to learn from them about how to tell a story.

And one of the most amazing things about working there is they had every issue of Vogue ever made. I mean, they had every issue of every fashion magazine. And there’s huge stacks of library magazine racks. And you basically spent all day looking through old Vogues. So, it was not only an incredible experience to work for these two great men who I loved, it was this immersion in the history of fashion photography.

So I really learned a lot of the cliches, a lot of the popular tropes, a lot of who the models were. It was kind of like a graduate thesis program, but instead I was also working. But it was great. And I’m so, so grateful for that time of just being able to like, literally spend hours looking through every Vogue ever made from the beginning to now.

“I saw magazines as this bridge between what I enjoyed about fashion, which is image making and culture creation and analysis, and writing.”

Rachel Baker: Wow. I mean, I’ve been sitting here this whole time being like, “I’ve got to get into Stella’s basement. I bet there are Dominos and Topics in there too.” And now I’m like, “Oh, I’ve got to call Alex and Raul and see their collection.”

Stella Bugbee: Yeah. Well, there used to be this place, I don’t know if you guys ever went there, called Gallagher’s. And they dealt in vintage magazine collections. And so when somebody would die—or I don’t even know actually how they came about these massive collections—you could get every magazine. Of any kind. And I discovered it in college.

And you would just go down there—and you have to imagine this is before Google image search, so you were kind of hoarding imagery, if this was your trade, because having access to historical imagery meant that you had references that nobody could find. So you were always building on this history of photography, and always building on this history of fashion and references, because no one else could find those things. It was cool.

Rachel Baker: In 2011, you came to New York magazine to work on relaunching The Cut. I was working at New York at the time, and I was so intrigued when you walked in the door—I’m still intrigued—but I just remember being like, “Who is this woman?” Because you were a designer, but you were also an editor, with all these amazing ideas. And I think your title was creative director. And then, Boom!—you were the editor of The Cut. How did all that happen?

Stella Bugbee: Well, I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Adam Moss, who was the editor of New York magazine, who I think did one of these podcasts, right? I love him. I don’t know that many people might’ve said, “Oh, you can do this.” It’s hard, in our industry, to break out of whatever role you’ve been assigned early on. Which is maybe one of the reasons I didn’t want to take an early path that just “put me on a path” because I didn’t really want to be pigeonholed in that way.

But it was actually David Haskell who suggested that I come and talk to them about The Cut. I’d had another baby, and I was out of work. And he said, “We can’t quite find anybody that Adam feels really excited about to help with this project.” And I was really unsure about it.

But I thought the internet seemed really interesting, given what had happened at Domino. And I decided to come on as a consultant. I wasn’t sure and I didn’t have enough confidence frankly to just say, “I can do this.” And then I just loved it so much. And I got along with Adam. And, you know, I just like I just started to have so many ideas. And then I started to have a real vision for what it could be. And it was slow. It didn’t happen right away.

And even when I came on to be the editor in 2012, I would say for the first two years we were just trying a ton of stuff. I feel like we found our rhythm in 2014. And then from 2014 on, it built in ambition and in relevance. It was a very slow process. Seems like it wasn’t, but it really actually took a long time from when I came to when I felt like we were starting to really get going.

An anonymous note delivered with a box of donuts during the height of the #MeToo movement.

Rachel Baker: But when you showed up at The Cut, the ambition was so grand. The ambition was to reinvent the women’s magazine. How did you set out to do that? And what was the mandate from Adam? You mentioned your relationship with fashion magazines. What about traditional women’s magazine content? Did you read and like that stuff?

Stella Bugbee: I definitely read all that stuff. My whole life. So it was steeped in that. The internet allowed us to be voicey-er, and to be more immediate, and to reflect what the writers wanted to say, and how they wanted to speak in a different way than a magazine may have constrained the voices of some of the people working on it.

And there was just a feeling of like, “Well, you just put it up.” And you see, and then you react. It didn’t feel precious. I will say that. And we didn’t have any budget. It wasn’t like we had a huge media budget and we had all this stuff that a Condé Nast magazine had.

So with that came a lot of freedom. And I think right away I thought, there’s a way to talk about fashion that I’ve never encountered before, which is sort of “it’s a big party and you’re invited, if you want to come in.” It’s here for you. Anybody can participate. Anyone can, in theory, be stylish. But I think that the top-down message from a lot of fashion magazines, a lot of women’s magazines was, like, “Nope, you’re on the outside.”

And you didn’t really know what you had to do to get past that barrier. What, as a woman, did you have to do to be able to wear the clothes or be invited to wear the clothes? And I just thought that was all garbage. So right away, we just had a different way of talking about fashion, and about beauty, and about what was happening on the internet.

So It wasn’t that hard to “remake a women’s magazine” because women’s magazines had gotten a little bit stale. At the same time as we were doing that, there were other publications popping up that I think were addressing this, as well. Like The Gentlewoman, for example, which, right out of the gate, Penny Martin had this very crystal clear idea about how she wanted to talk about fashion and women.

And it was kind of simpatico to what we were doing, but in a very different tone. But it had a similar kind of motivation behind it, which is like, “I don’t really like what I’ve been seeing. I don’t really relate to that. But I still love this subject matter. And I think there’s probably a lot of other women who feel that way.”

One of the beautiful things about the internet is that you get feedback right away. So, if you feel like you’re on to something, you can hear right away whether people are also on board with it.

Rachel Baker: Yeah, one of the things about The Cut that felt so singular was that not only did you comment on the culture, you were really creating the culture, like normcore, millennial pink, BDE (“Big Dick Energy” for our listeners who don’t know what BDE is), Dad Bod. These were coinages and cultural touchstones made by The Cut. What was the secret sauce there and how were you able to establish such authority just to be, like, “We’re creating the culture”?

Stella Bugbee: I think New York magazine has a certain place in the culture where that’s their role. And we benefited from being part of the history of that place. It’s a provocative place. Its whole identity is to be on the cutting edge of culture and be lobbing provocations out into the world.

And we were, I think actually, just operating in that tradition. It’s a bold, scrappy place. All of it. Every single person who works there had that same—I mean, you worked there, so you know—you would take these big swings quite confidently. But those story ideas, and all of the things that we did, came out of conversations that were happening on the staff.

And it was very important to me to create a place where what we wanted to say was okay to say. And sometimes that was at odds with what was happening outside of our little pod. But I stuck very strongly to that feeling. I would say that the continuity between what I was doing at The Cut and now is [exactly] that. They get to say what they want to say in the way that they want to say it.

I think that’s the most important thing about that part of New York magazine. We just got to do it the way we wanted to do it. And I hope that continues. And I see Lindsay [Peoples] doing that beautifully. But I also felt like no one’s ever going to give me this chance again—or what if no one ever gives me this chance again? So you saying, like, right away “there was this ambition”—it was more that I felt insecure.

After going through Domino, I was like, “Well, you could have a really limited time to get to do everything you feel like doing. You’ve got to just, you’ve gotta do it. Because nothing in life is guaranteed.” And I just saw this bright, shiny thing and I was like, “I’ve got to just throw every single thing at this because you never know. You just never know what could happen.”

And I really didn’t want to miss a single second of it. And I hoped to communicate that to the whole team. It’s just like, “We’ve got this opportunity. We have to just go for it.” So that’s why I probably felt that way, too, coming in.

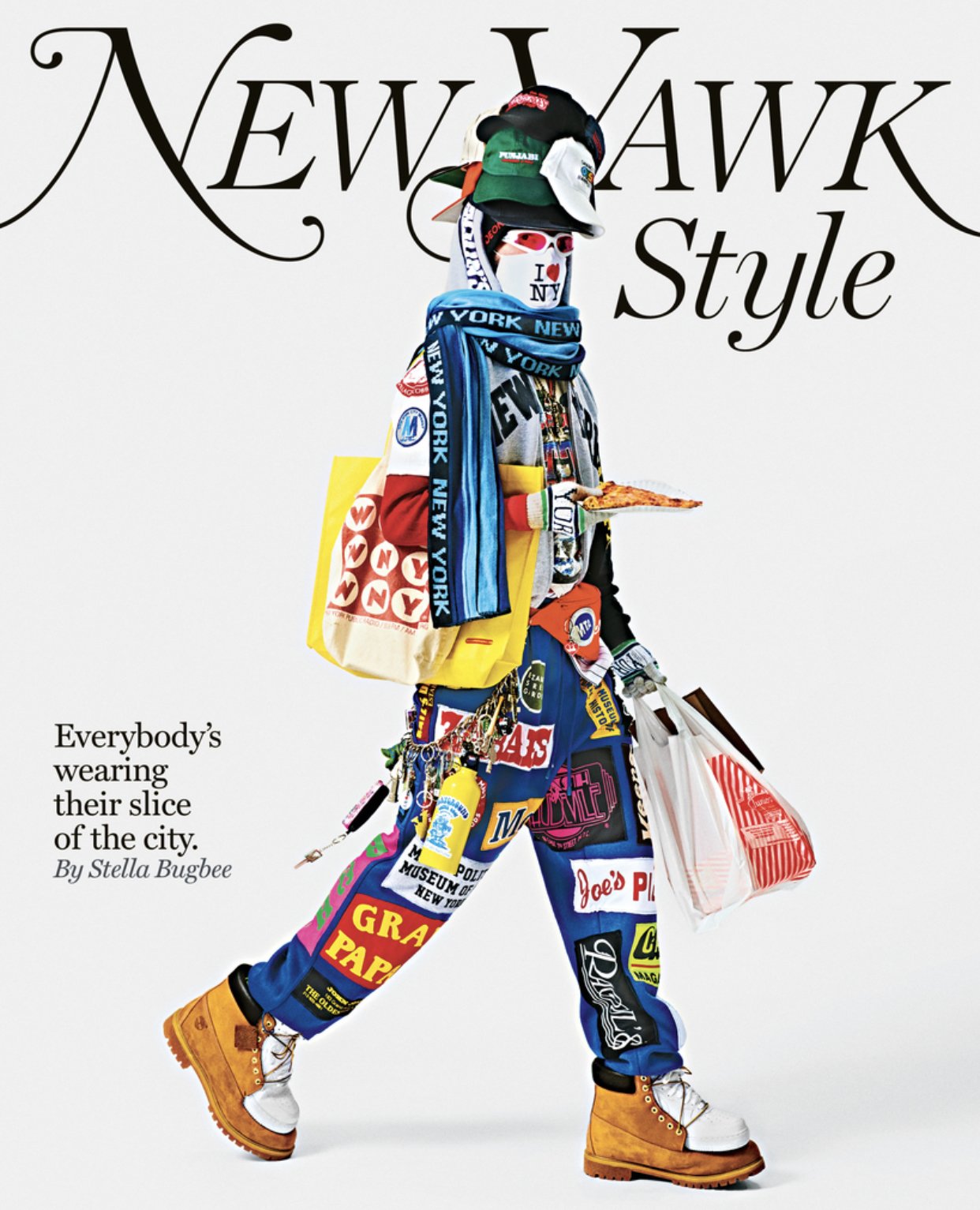

New York magazine’s bi-annual fashion issue featured Bugbee’s cover story about regional pride as a fashion statement.

Rachel Baker: Meanwhile, you guys were really finding your wings amid the wider cultural reckoning with gender, and race, and class, and #metoo, and Trump. And you wrote these brilliant and blazingly confident editor’s letters every step of the way. Maggie and I are still obsessed with the one about “skinny privilege”—by the way, we like, quote it. So what’s the best and the worst thing about helming a magazine that had become the voice of the generation during that upheaval—what was that like?

Stella Bugbee: So many of the things that you’re mentioning were just circumstantial things that were happening. I feel lucky to have been at a place like that, at a moment where those issues were what people wanted to talk about. Women’s issues were suddenly what everybody wanted to talk about. I don’t think that is the case anymore.

It’s like we’re in this total #metoo backlash moment. That wouldn’t be the place for—that would be harder for me, I think, as an editor. But the fact that everything that I wanted to do coincided with this cultural moment was just luck, honestly. And it was a lot of pressure to get it right.

And when we didn’t get it right, which happens, there’s a great amount of disappointment in our audience. And again, they let you know right away. And it felt like every mess up was so colossal for me. I felt personally on the line for every mistake, every wrong idea. And it didn’t just coincide with all these political moments. It coincided with this incredible social media moment where mistakes felt very permanent. They felt very colossal.

So if you did a story that people hated—I know this is still the case—you just felt like, “Oh my God, I can’t get up. I can’t keep going.” And it was a lot of pressure. It was very dramatic. Very dramatic. There were a lot of things that happened, like the [Shitty] Media Men List and publishing E. Jean Carroll’s accusation.

We really benefited from the broader New York magazine brain. I don’t think I could have done it without all those incredible editors that were also working on the magazine, in the room talking these things through. I could never have done it without a big group of people. It was a very big group effort.

Rachel Baker: So then in 2017, there were rumblings that The New York Times had offered you the Style section job, but you stayed at The Cut where you were promoted from editorial director to editor in chief and president and the to SVP. You must be a master negotiator, Stella! I need you to teach me how to negotiate. I’m curious about where you learned to negotiate like that, and also to what degree money has driven your decision making throughout your career?

Stella Bugbee: Well, If money had driven my decision making throughout my career, I probably wouldn’t be in this career, to be honest. And I have always chosen the opportunities that I think are going to get the best work and be around the people that will enable that. And the relationship I had with Adam at New York magazine really pushed me in a way that I never had been pushed before.

And it was whatever I needed at that time. And I just needed it and it unlocked some kind of feeling of possibility. So I would say I was much more motivated by opportunity than salary. And as far as staying at New York magazine. Again, I just saw the opportunity and it was, we were going to relaunch again.

And that relaunch was really exciting to me. I’d already put a ton of work into that relaunch. Strategic thinking, not just editorial thinking, but business thinking and strategy. And it was an acknowledgement that the job that I had been doing had grown into something that was more than just an editor, because I was really involved in a lot of the business decisions. I don’t know if I “negotiated” it that much. It was an acknowledgement, I think, more than a negotiation.

“I remember saying, ‘I gotta get to Condé. I just need to be, like, a design director somewhere.’”

Maggie Bullock: But in 2021, you did make the leap to Style. And you’re a person who’s on the record saying “print is dead.”

Stella Bugbee: Did I say that? I probably did.

Maggie Bullock: You have said it, yeah. Which works very well for this podcast.

Rachel Baker: We listen to every podcast.

Stella Bugbee: I disavow everything I’ve ever said. What did I say? Where did I say it?

Rachel Baker: Refinery29. But times change.

Maggie Bullock: You are a person who, perhaps at one time, thought that print was dead, and now you are a person sitting at the Grey Lady as we speak. So what made you decide to make the change when you did, and what was the opportunity in your mind that you couldn’t turn down at that time?

Stella Bugbee: Well, at that time I had already stepped down from The Cut, so I was at New York magazine as, I think, the title was Editor at Large. And I was debating, “Should I be more of a writer?” I think editor-at-large is kind of a funny title, and you’re like, “What am I doing?” And then the Styles job opened up and it was like, “Oh. I had missed that opportunity back when and maybe I should try it.”

And it’s so funny because I don’t think of this as a “print job” primarily at all. I love the print product and it’s very fun to think about how these things translate, but I don’t think about this as a print job. This is a journalism job. It’s like journalism happens online. It happens like what you guys are doing here. It happens on Tik Tok. It happens in print.

And Styles just seem like a natural place to get to do some of the things that I was still really interested in doing. And one of the things that’s super appealing about it is that it’s not just print and it’s not just women.

And that felt like this opportunity to do a lot of stories that I hadn’t gotten to do before. I don’t know. I mean, it’s kind of cool to work at The New York Times. It just feels really interesting to take this leap, journalistically. To be at a news organization primarily, as opposed to a magazine, feels really interesting and kind of suits my pace, that I actually prefer.

And it’s just something that I’ve realized over time is I really love that online cadence. I know that it burns a lot of people out, but I love being able to do things quickly. This is somewhere in between—you can do things really quickly, you can take a lot of time. We’re not a magazine, so we don’t have to come out in this sort of weekly cadence quite the same way. Like we do have these print products, but it has a very different energy than a magazine.

Maggie Bullock: So when you started there, I think, are we right that things were still pretty pandemic-y? Like, were people even coming to the office? What was that like for you to start that kind of job under those circumstances?

Stella Bugbee: That was very challenging. That was one of the most challenging experiences I’ve ever had at a job, where I didn’t even meet some of these people that I worked with for seven or eight months. Some of them I never even saw their faces, they didn’t turn their cameras on.

I think every one of us had been going through a lot for like over a year by the time I joined. Emotions were high, people were stressed out, people were burned out. Just everybody, the whole world, was feeling that way.

So it’s hard to have a sense of how to direct anything from afar. And at that point, not even as a team, you couldn’t meet your team. It was challenging. It was really challenging. And I think all of us were also highly emotional to begin with. I wouldn’t wish that on anybody.

Maggie Bullock: How long did you actually have to run it before people started coming back into the office again?

Stella Bugbee: We’re really just starting to come back. I mean, by this point obviously, I’ve met my whole team. It’s been over two years since I started. And I made a lot of hires and you know, there was one person I didn’t meet for like seven or eight months.

Maggie Bullock: That’s so crazy.

Stella Bugbee: Yeah. And she’s like one of the most important editors on my team. We just communicated remotely. I do think that it was helpful that we’d all been doing this for over a year by the time I joined. Some people were in the habit. We all knew how to do it. It just wasn’t that much fun to do that with a new team. It was very hard to build consensus, to just get people excited. It was really hard.

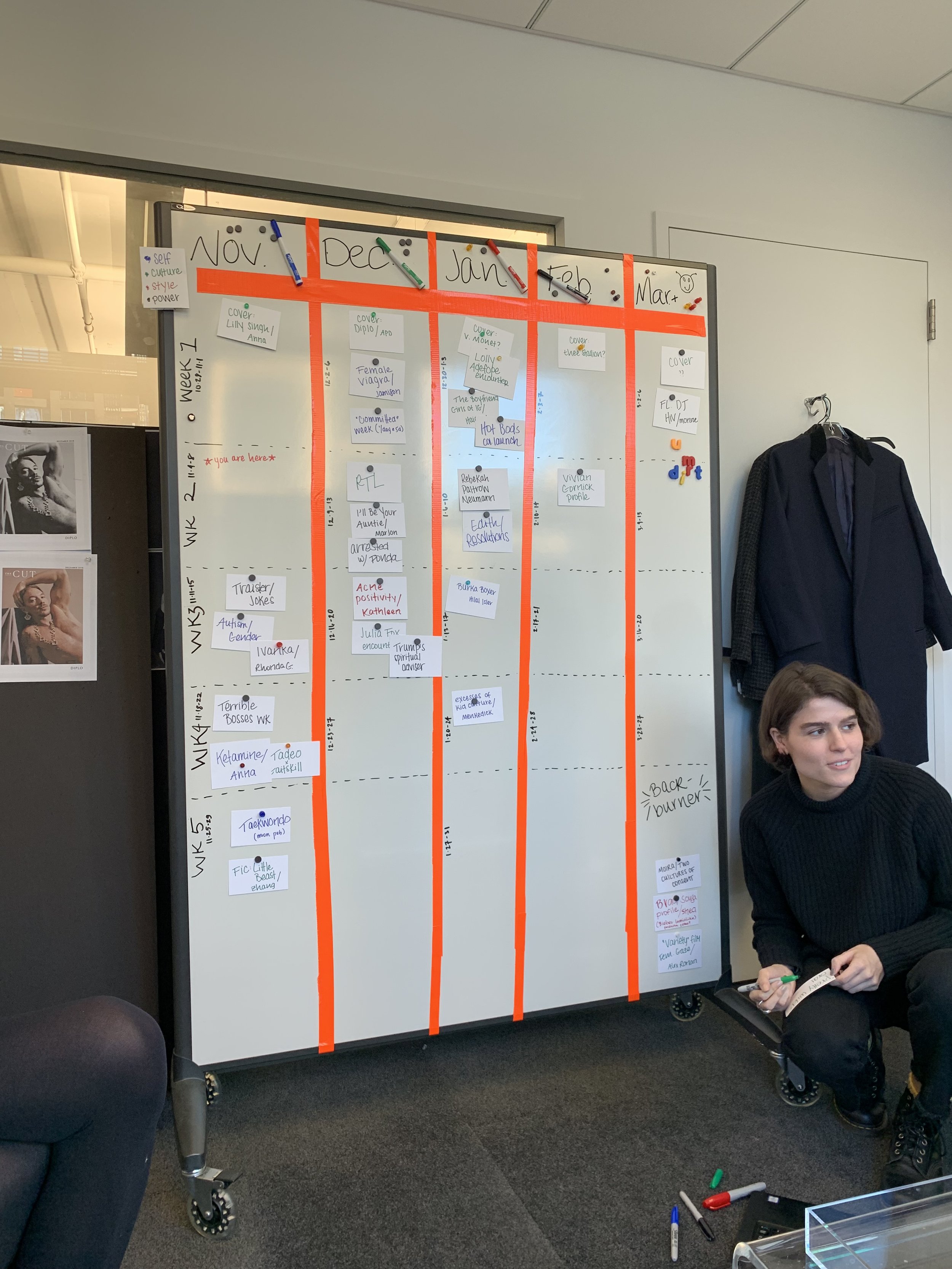

How The Cut gets it done

Maggie Bullock: So in addition to that, you were also in a very different environment. And a wildly different type of publication. At The Cut, as I understand it, it was really very much a blank slate to reinvent the women’s magazine, as we’ve said, for a new era. But the Times is so different from that. How is running a section there different from pretty much anything you’ve done before?

Stella Bugbee: It can’t be overstated how totally different it is. It’s like night and day. New York magazine, The Cut, were these fairly new, very open, undefined—well, New York magazine has more of a legacy. But The Cut really didn’t. So it’s building something versus fitting yourself into a legacy publication with a lot of expectations around it internally and externally.

I met with somebody when I first came here, and she runs another desk and she’s been here for a while and she said, “Well, I’m new.”

And I said, “Really? How long have you been here?”

And she was like, “About six years.”

And I was just like, “Oh my goodness.” And it started to dawn on me that a big part of the job is learning about this institution and learning how to make work inside of it so that you are getting to the reader again. I always think about the reader.

But the reader of The New York Times is very hard to figure out. And the reader of the Style section is many, many people—different kinds and for different reasons. And so, whereas I had this really hardcore understanding of the reader at The Cut, I had to relearn what that was here at the Times. And I had to try to understand how to work with the newsroom a lot more.

That’s been the fun challenge. That’s why I go to that enterprise meeting—to listen and to hear what their priorities are every day. And like, “Well, I’m here. I run this desk. What do I contribute to that larger story of the day, if possible?” Or just like, “How does what we’re doing on the Style desk fit into the larger mission of The New York Times? And that, again, can’t be overstated how totally different that project feels than The Cut.

Maggie Bullock: So when we were talking about doing this episode, Rachel and I both agreed that 2023 for us feels like a very stressful time to edit a legacy section, a legacy desk like Styles which still has the last vestiges of being like society pages—somewhere back in its DNA it’s still that—and where people are still coming to you for, like Vows. Plus it’s always been sport for people to go bonkers on any Style story for being out of touch in one way or the other. That’s a New York tradition. It just feels like the stakes are incredibly high. I guess the first question there is did Style need reinventing when you came in?

Stella Bugbee: Well, I think Styles always needs reinventing, right? That’s the nature of Styles. And I think I’m reinventing it week to week, which is good. That’s sort of the point. But no, total reinventing? No.

I think Choire Sicha, who had the job before me, did a lot of reinventing and loosened up a lot of the expectations. And there was this big project underway, that started before I came, to reinvent Vows. And there’s a new editor on Vows, Charanna Alexander. And, if you pay close attention, you’ll see that the type of people that are featured are totally different. They started Mini Vows. It's a very different energy than it had maybe 10 or 15 years ago. That predated me.

And in terms of parties, it’s probably not totally evident unless you’re a super close reader of these things, but we really have talked a lot about what kind of parties we cover, what we’re trying to get out of party coverage—there’s this crazy, amazing legacy with Bill Cunningham and what he was doing and why he was doing it. How do we build on that? What do we preserve from what he wanted to be doing?

I don’t think it’s like a crazy, terrible time to be doing any of this stuff. I think it’s really a fun section where we get to play with what’s happening in the culture. And, of course, some people are going to hate it.

I think you have to have a rock solid sense of just, “It’s okay if people hate things.” And maybe, to go back to your earlier question about The Cut, people hated what we did at The Cut too. I got a lot of criticism all the time. I mean, people loved it, but people hated it. And when you work on the internet, you become a little bit numb to the ebb and flow of people hating things.

So that’s a good place to be when you get to a place like Styles where people love to hate on the Style section. And that’s part of it, I guess.

Maggie Bullock: Do you have what you consider to be like a formula, a mix—like we’re x percentage of this and y percentage of that? Or if you were bringing in a new editor, how would you describe to them the way that you want the section to feel and what you want it to embody?

Stella Bugbee: That’s a great question. So Styles is funny because it’s like, don’t quote me on this exact ratio, but it’s like 30 percent fashion beat reporting, maybe 30 percent love, marriage, relationships, advice, and, like, 40 percent this other stuff that’s totally up to whomever is editing it—the group of us—to fill. Like, “Well, what words are people using? Are people smoking cigarettes? How are people treating their children? Who’s interesting? What did Shannon Abloh have to say once she became independent? Who’s the hot designer? Which book is everybody sharing around town?”

It’s much more about the way we live and what’s fun to talk about. That is a kind of amorphous sensibility thing. And the challenge I’ve found is like when to time those things. Because for a Times reader, they may not have heard of something that maybe The Cut reader had definitely heard about three years ago. So you’re always kind of trying to say like, “Well, for the broader Times reader, this will be new.”

And that’s when you get into maybe being annoying to some of the people who are a little bit more ahead of the curve because they’re like, “Oh, how come the Times is just getting to this thing?” At the same time when you’re covering online culture, we will be early to things all the time.

‘Girl Dinner’ for example, was a recent thing that was happening on TikTok that we wrote about. When the Times turns its lens on a thing, it has a bigger reach. Like, broader than TikTok, in some ways. Obviously, I don’t mean like it’s going to get as many views as TikTok, but it’s going to get people who aren’t on TikTok to talk about Girl Dinner.

“It was upsetting and disorienting because everywhere you went, people said like, ‘I love Domino. It’s so great.’ You felt like you were working on something that people really were relating to. And then you get shut down in a mass firing.”

Maggie Bullock: But also broader than The Cut. I mean, I don’t know what the eyeball comparison is, but it’s a much wider swath of the population. And also, Boom! None of us can eat crackers and cheese anymore without thinking it’s a political act.

Stella Bugbee: Exactly.

Maggie Bullock: It’s very complicated now.

Stella Bugbee: I’ve hired a bunch of people that I’ve worked with from the New York mag era, and they bring a certain amount of that hunger for that cultural moment stuff. We just did, “What are men thinking about? The Roman Empire.”

But what’s fun is we can also do an investigation into CoolSculpting and expose the fact that they knew that they were harming people—long before they admitted that they were harming people—in partnership with the actual Investigations desk. And we can do a deep profile of Cheryl Hines, and she doesn’t know she’s about to get this treatment because she thinks she’s in the Style section.

So there’s a real kind of eclecticism. And how I think about Sunday covers is like each week should be really different. Each week should be like, “What is all this? What are they doing?” And if I’m creating that feeling in a reader, either when they open the app or when they look at the paper, then I feel like I’m doing my job.

Maggie Bullock: So, what should Thursday be then?

Stella Bugbee: Traditionally, Thursday has been more fashion news focused. It’s the more hardcore fashion audience. That’s the way we had been doing it for years. I’m actually trying to sort of break that up a little bit, and just say we should just do more of a mix in both. For me it’s all about the mix. You want every day, and every print product, to be a really weird mix of stuff. So you’re getting some advice, you’re getting maybe a little bit of celebrity stuff, you’re getting a little bit of something serious. It should feel like a Girl Dinner of editorial [laughs].

Maggie Bullock: Nicely done. Well played. So, we want to know how many nights a week you have to go out in order to have this job. Like, in order to be the person in charge of Styles. How visible does that make you? How—I don’t know. Rachel and I never leave the house, so this sounds very taxing to us.

Rachel Baker: Because you have this busy life, you have three kids and a long-running marriage, and—I don’t think we said earlier—you live in the same Brownstone in Park Slope that you grew up in.

Stella Bugbee: I do.

Rachel Baker: So, so amazing. It’s the best detail. But you’ve got this rich and complicated life. What is required of you socially and how do you get it done?

Stella Bugbee: I go out less for this job than I did before because we have incredible reporters and they go out. And I have an incredible party editor—that’s Katie Van Syckle, who actually was a New York magazine party reporter herself. She came to the Times before I did. And when I came, I really wanted to reinvent how we cover parties. And we’ve been working on that for like a year.

So, no, we have reporters. That’s the superpower of The New York Times, right? It’s not the editors, it’s the reporters. And the editors are amazing, and they’re super fun, and they all have ideas. But the reporters come back with the information. And they tell you what’s relevant, and they tell you what’s good.

So I go out, but I actually had to go out more, I think, at The Cut, to be honest. It’s a manageable life. It’s good. It’s a good job. It’s a good life. I’m not complaining.

Rachel Baker: Sounds great. So 11 years ago, you were charged with reinventing the women’s magazine, as we’ve said several times throughout this conversation. You did it! You reinvented it. Check! But here we are in 2023, and it’s a totally different media landscape. What do you think is ripe for reinvention now?

Stella Bugbee: I would just love to see somebody reimagine a celebrity profile because I cannot read another one. They’re just deadly. And I think we should just stop doing them. I would like to never read one ever again.

I think, with the invention of social media, they are the most passé form. Because the minute that the celebrity could control their own narrative, and create their own content, and have their own direct relationship with an audience, the form of a celebrity profile, just feels mannerist. And so boring to me. So I’d love it to be reinvented, or maybe to go away, or just to—I don’t know.

I mean, even with all the fantastic celebrity podcasts that there are out there, I just don’t think we need them anymore. One publication that I think is still able to do that really well is The New Yorker because for some reason, people still let The New Yorker follow them for a year and a half, or whatever it is. They still have that.

But other than that, most of us should just stop. I say that and I’m sure we’re going to do like 20 more this year. So take what I said with a grain of salt. But what, yeah, what else? I mean, what needs to be re imagined? Probably social media.

Rachel Baker: Yeah, reinvent that, Stella! Speaking of, we know from Instagram that you love to cook, and that you do so beautifully. So, for The Spread Lightning Round, if you could make dinner for three magazine greats, dead or alive, who would they be?

Stella Bugbee: Are they all together at the same dinner, or is it like one-on-one?

The Cut staff, circa 2014

“If money had driven my decision making throughout my career I probably wouldn’t be in this career, to be honest.”

Rachel Baker: Yeah, they’re together at the same dinner.

Stella Bugbee: I think Diana Vreeland would be really fun as a guest. I would love to just see her up close. Legend. I’m a big Martha Stewart fan. I wouldn’t mind having her over. We could have some potatoes or whatever. One of my favorite magazines of all time was Nest magazine. A brief magazine from the ’90s. And so maybe Joseph Holtzman, who was the editor and founder of Nest. That might be a weird group.

Maggie Bullock: What would you serve?

Stella Bugbee: Oh, Jesus. Actually, maybe serving food to Martha would be pretty—I don’t know. I’ve been really into making pasta, like hand-making pasta lately. So maybe that.

Maggie Bullock: That would find favor even with Martha.

Stella Bugbee: I don’t know. I’m sure she’d be critical. I feel like no matter what I served Martha, I would want, like, the honest—oh, you know, who would be really fun, speaking of food, is Ruth Reichl. I love her.

Rachel Baker: Stella, thank you so much. We really appreciate it.

Stella Bugbee: Oh, it was so fun. Thanks for making me think about magazines again.

Maggie Bullock: It is really hard doing this because all I want to do is interrupt—the amount of energy I’ve spent muzzling myself! You were talking about being at The Cut and how much freedom there was to say what you thought. And I am somebody who started just, like, one generation earlier than that at Vogue, and I had my voice really hammered into that Vogue voice.

And it was such a shock to my system. And I was threatened and confused by all these people—at The Cut specifically—writing so beautifully in their voice, with their point of view. And I can kind of do that now. But I just remember that being in my brain, like, “Why are you allowed to do that now?” And I was told—literally told—that I had to learn the Vogue voice.

Stella Bugbee: But yeah, New York magazine, that’s what they prize. Voice, right? That’s the tradition of that place. And every vertical had that. Vulture had it. And Grub Street had it. That was the name of the game: develop your voice. Spend some time doing that, and then go out into the world.

The Times’ Style section covers a little bit of everything.

See Stella Bugbee's work every Thursday and Sunday in the print edition of The New York Times or online every day at nytimes.com.

More Like This…