It’s the Journey, Not the Destination

A conversation with photographer Albert Watson (Vogue, Rolling Stone, Harper’s Bazaar, more).

—

THIS EPISODE WAS MADE POSSIBLE WITH THE SUPPORT OF MAGCULTURE

Today’s guest, the celebrated photographer Albert Watson, OBE, is a man on the move.

This is not a recent development. Watson’s professional journey began in Scotland in 1959, where he studied mathematics at night. His day job? Working for the Ministry of Defense plotting courses—speed, altitude, distance, payload—for British missiles pointed towards Cold War Russia.

Watson’s affinity for the mathematical gave way to his interest in the arts when, in school, he dove head-first into all of them: drawing, painting, textiles, pottery, silversmithing, and graphic design.

Later, on his 21st birthday his wife bought him a small camera. He became obsessed:

“All I know is that I clicked the shutter, and suddenly, magically, I got negatives back, that I could learn to process myself. And then, even better, I got into a dark room with a piece of white paper under an enlarger, and you put it in some chemistry, and lo and behold, up comes an image. Magic! Black magic! I called it. Amazing, insane, beautiful.”

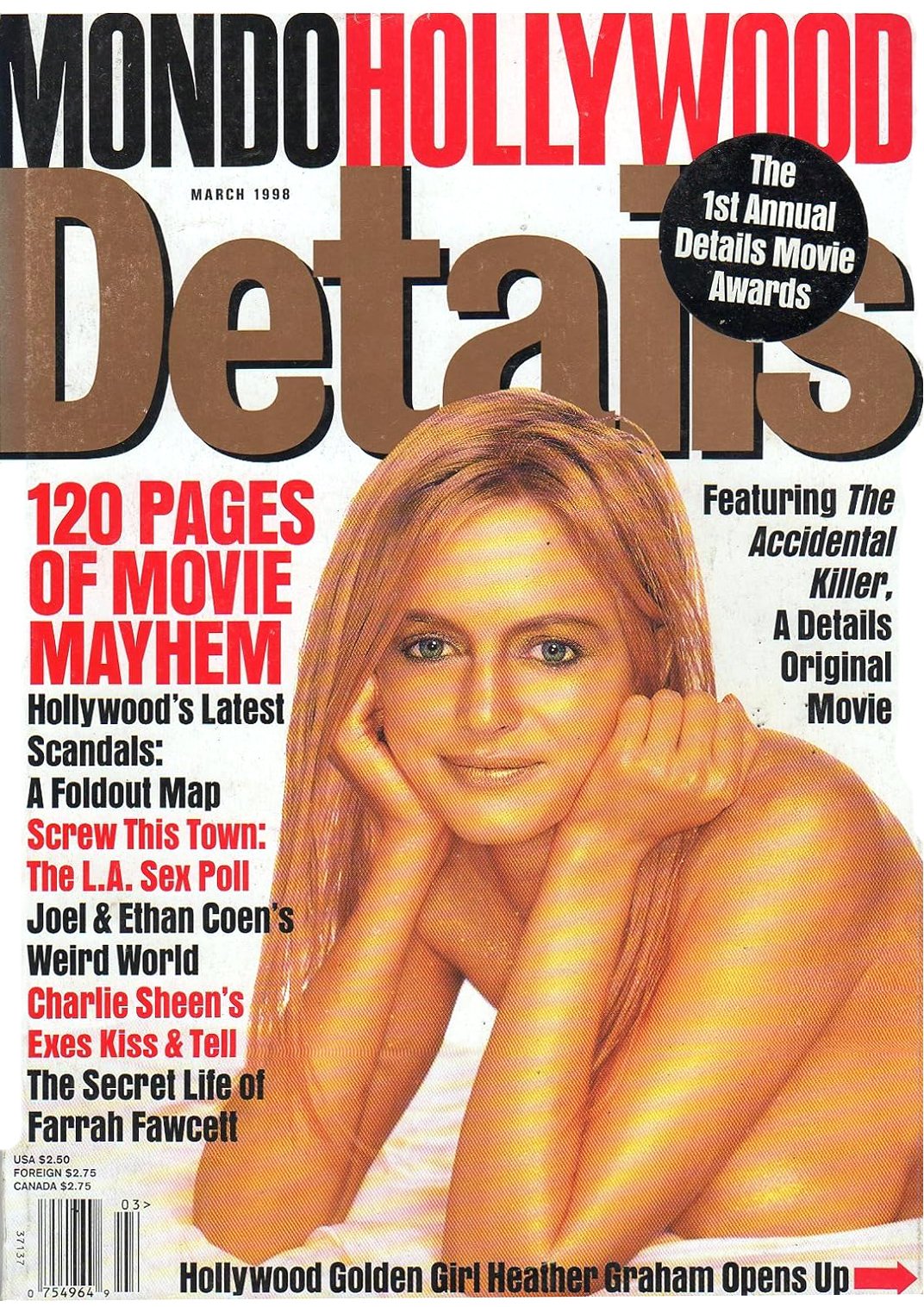

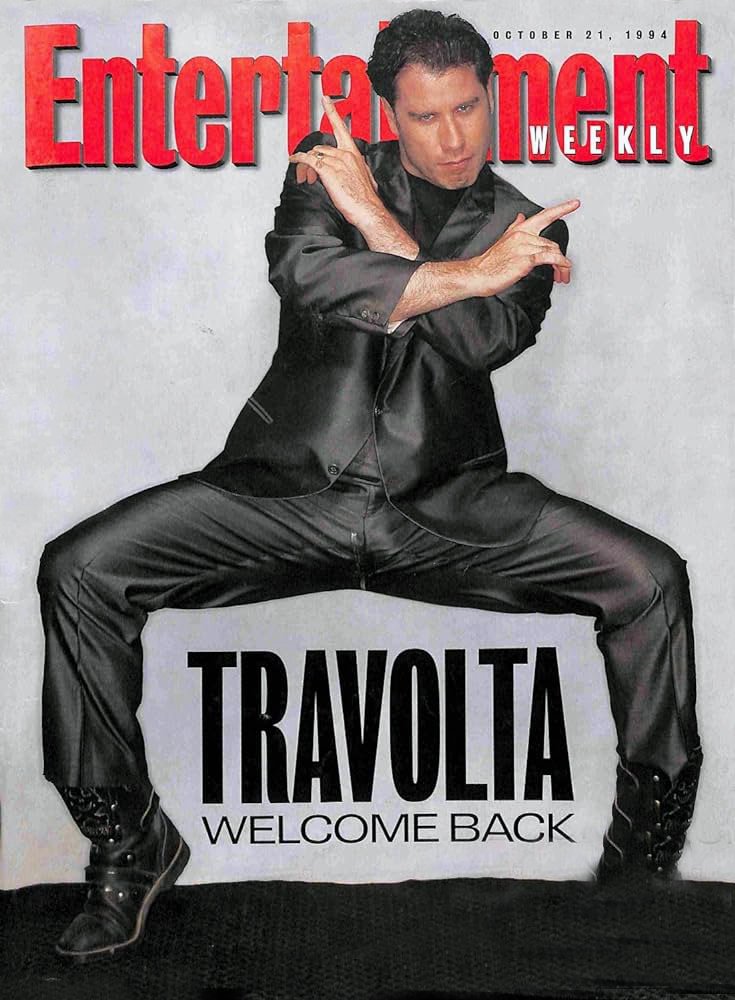

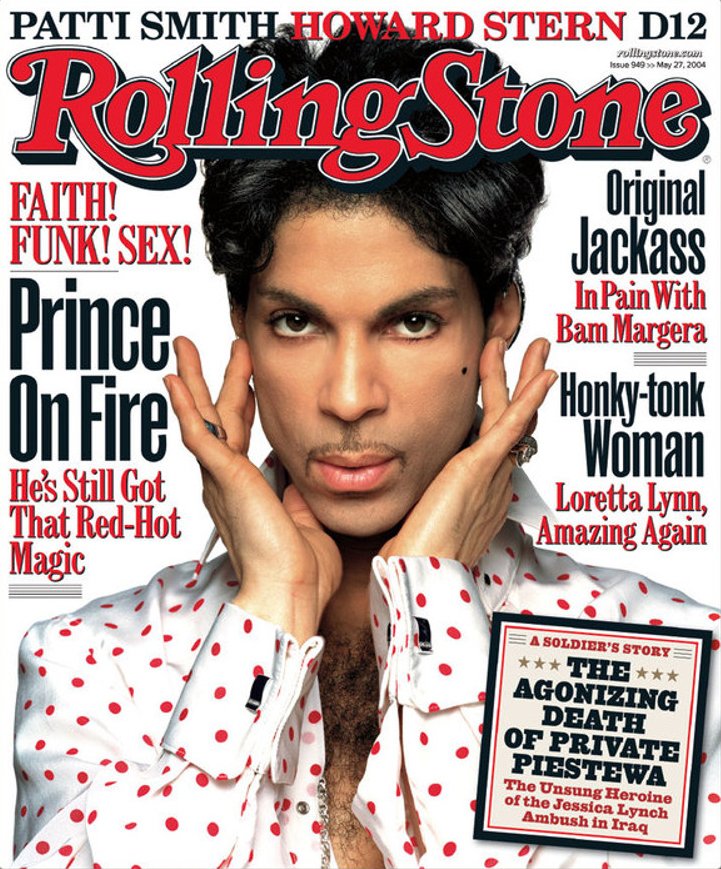

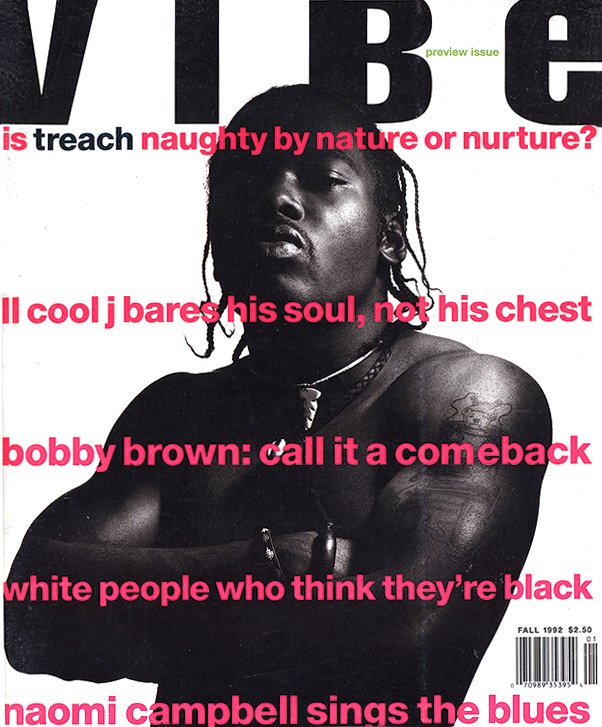

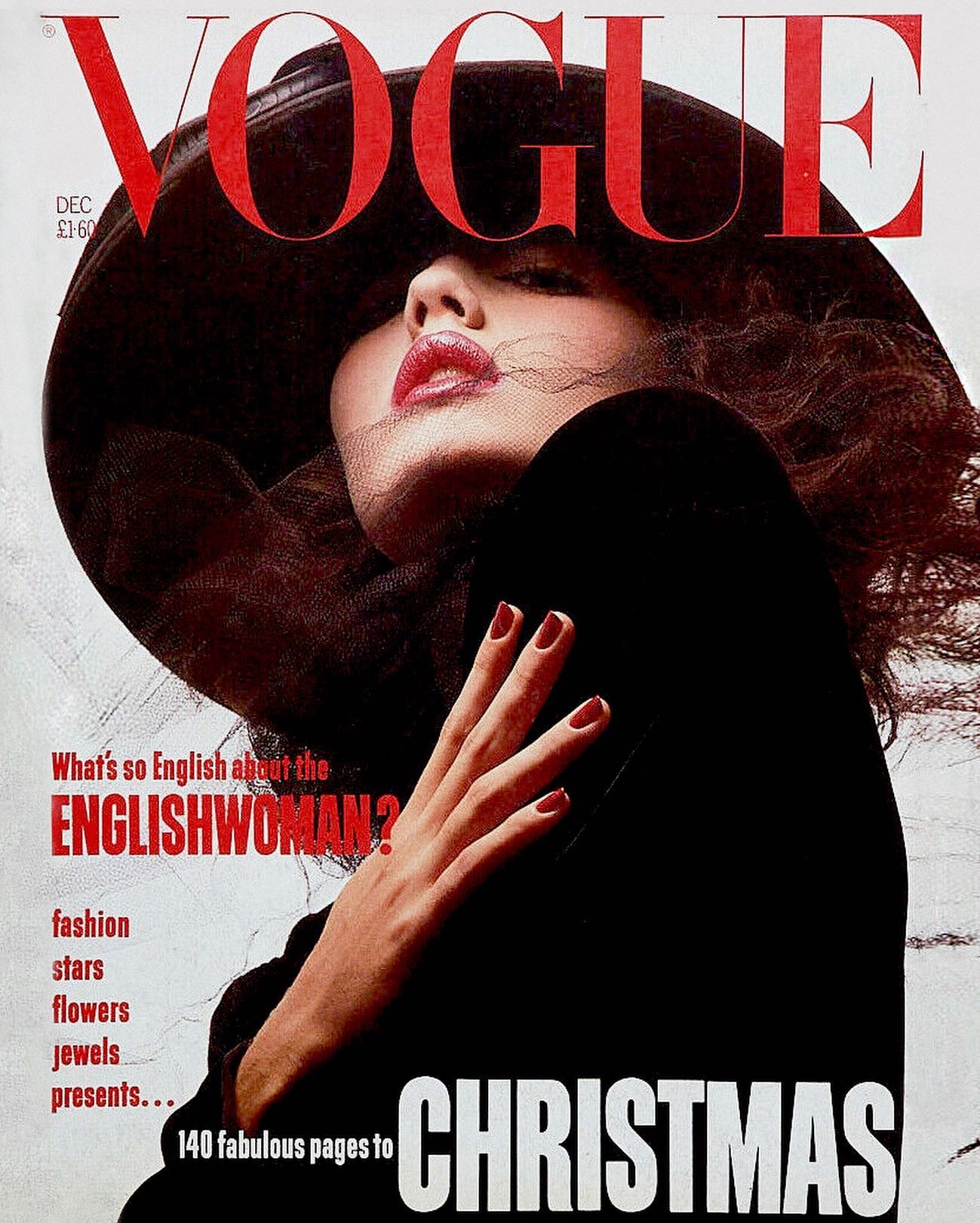

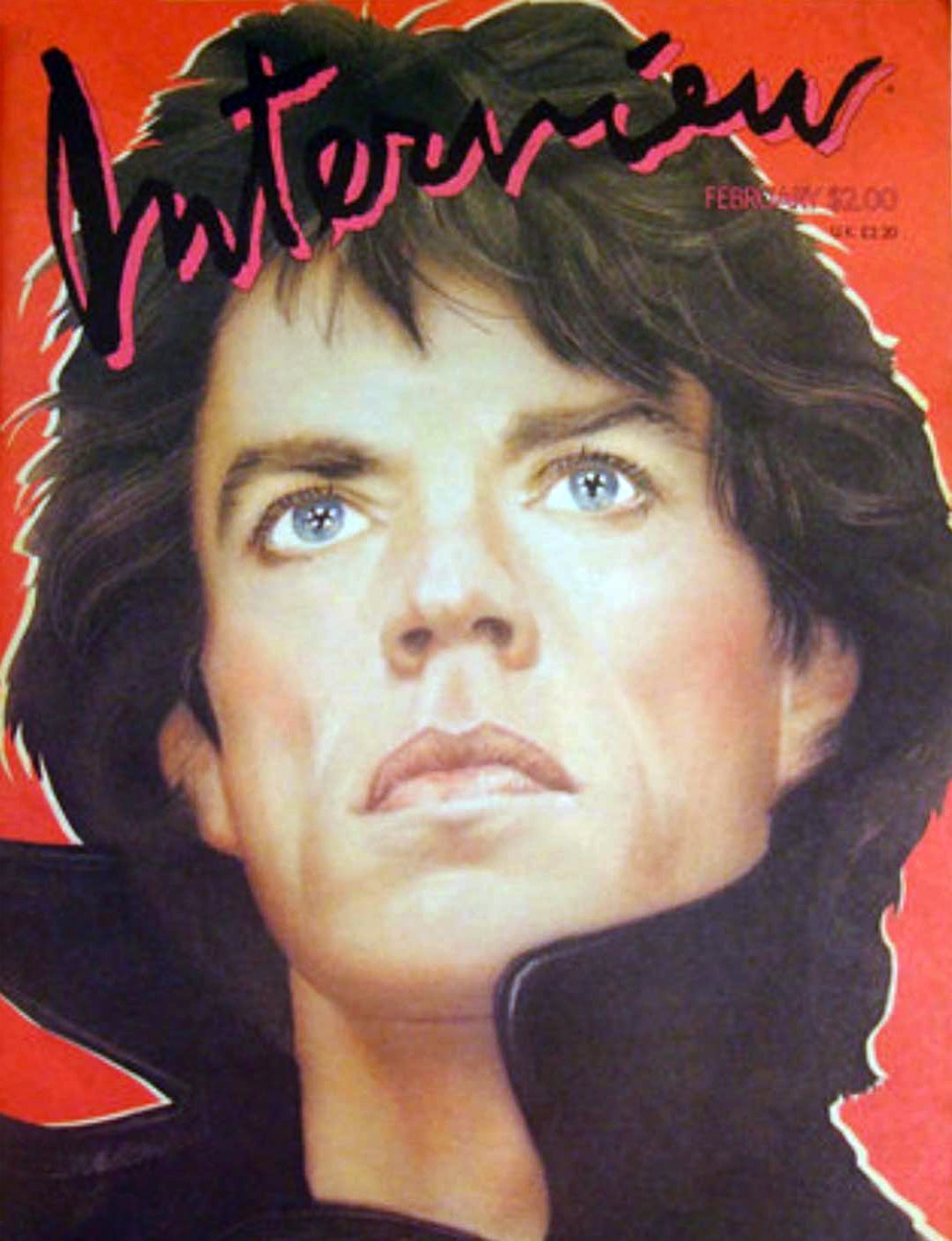

Then came the magazines: Harper’s Bazaar, Rolling Stone, GQ, Mademoiselle, Entertainment Weekly, Details, and Vogue. All of the Vogues. And the ad campaigns: Prada, Chanel, Revlon, and Levis.

And yet, after all that, talk to the man about his work, any facet of his career, and the conversation invariably comes back to the print—the math, the chemistry, the graphic design involved—and about the journey the print takes, from camera to magazine, from magazine to gallery and, sometimes, from gallery to museum, as so many of his have.

Our editor-at-large George Gendron talks to Watson about all of it—day rates, social media, and that stunning apartment in TriBeCa.

George Gendron: I want to go back to a conversation you and I were having just yesterday. And I said to you I think there are a lot of people, even veterans of the magazine industry, who look around and think that if you had to sum up the effects of the internet and technological change on the magazine industry, you’d say, “Oh, well, magazines, the ones that are still around, have fewer ad pages, and therefore their budgets are smaller.” But you were telling me about the fashion magazines, and you did a great job of comparing a shoot that you might have done for a fashion magazine, let’s say back in 2000, and what the economics of that might have been, compared to how that works today. Could you do that for us here?

Albert Watson: Sure. Basically, I would get a call—different times of the year—and of course, it related to collections. And we are speaking about fashion magazines. I would get a call from a magazine and they would say, “Where do you want to go this winter?” Now, what they mean by that is, “Where do you want to go where there’s some sun?” And that you can get up in the morning at 7:30–8:00, and then work until, you know, 4:30 in the afternoon. And you do summer clothes, and it’s somewhere where you can work outside. So they end up with outside pictures, you know? And sometimes we’d go to the desert Southwest. You might go to New Mexico or Arizona. You go to White Sands or to Death Valley. You go to Palm Springs, perhaps.

And you would go to these locations, and, basically, what would happen is a model would be flown in from Paris, maybe New York, could be London. Makeup artists could come from Paris or New York. Once in a while there’d be somebody in LA, and you fly them all into, let’s say, Death Valley. And we arrived there on a Sunday. And then on Monday we’d do try-ons. And in the olden days we did Polaroids—or nowadays you do a digital file—and you try on all the clothes to see where you’re going, what you’re doing. You would have a heads up about that.

So now, going to the economics of that, of course, there’s a hotel, there’s food, there’s road transportation, there’s the hiring of a vehicle that we would be in. Sometimes it was better for us to be in a van, not, you know, a Winnebago-type, large vehicle but more flexible. But there was a large budget and in the end, I’m sure it cost the magazine thousands of dollars to do that.

George Gendron: What was your day rate back then, Albert?

Albert Watson: The day rate for a magazine could vary gigantically. Back then you would probably be looking at, maybe $750/page, and then maybe $1,500 for a cover or something like that. And you might do 18–20 pages. So in the end, of course, it was nothing like an advertising rate.

The important thing was it didn’t cost me anything. Nobody ever said, “Oh, by the way, you have to pay for this shoot.” And, although we’re now laughing, that, unfortunately, is where we are now. Magazines don’t have any money at all. Because the advertising is down. Magazine numbers are down. Things are at a critical state right now where magazines have a very hard time.

And there are small groups that do independent magazines, that do art magazines. And they might do them with quite nice printing. And sometimes they do four magazines a year, sometimes two a year. They’re underground magazines. And you have a lot of freedom. But, of course, for them also, you have to pay for the shooting. And that’s one thing that’s changed. So sometimes a young photographer has to save up, and he has to beg favors, and ask assistants to work for nothing, and models to work for nothing, and hairdressers to work for nothing. And you’re certainly not flying to Palm Springs and staying in a hotel. So, that’s changed.

Now, another side issue of all of this, we’re discussing Print Is Dead, and magazines, and so on—magazines are failing now all the time. And their numbers are catastrophically low. But another slight issue is that the fashion business in general is on life support. There’s a problem right now because a lot of the fashion business is dying and a lot of it is dying because young people in general are not so interested in fashion. They’re a little bit more interested in styling.

And I think I mentioned to you that I photographed in a high school 20 years ago, and there’s a high school near me right now. And when you look at what the kids were wearing 20 years ago—I still have the pictures—and you see what they’re wearing now, guess what? It’s pretty much the same thing. And now, the vast majority of the girls in the school, of course, wear jeans. And they wear hoodies. Or an anorak, because it’s obviously warmer than a hoodie.

Basically, fashion is slowly but surely grinding to a halt. And what you’re seeing right now in fashion is recycling is going on a lot, but the overall mass change of fashion doesn’t happen anymore. So if you start looking at the way kids dressed in 1952, and look at the way they dressed in 1963, and then 1968, and ’69, there is a vast difference between the overall style of young kids and what they’re into and what happened with the change in music and so on.

So, going back to everything, print is dying for different reasons, you know? And the internet is sometimes amazing and doing amazing things. Other times it’s very strange to me—and sometimes things like Instagram. Someone that I’ve worked with quite a few times, like Gigi Hadid, is very famous. She has, whatever it is, 80 million followers. And when she posts what I would consider not a great shot of herself trying on a new pair of sneakers, you get 3.8 million people saying, “Fabulous! Amazing! Incredible! You’re a goddess! You’re amazing! Incredible! Wow!”

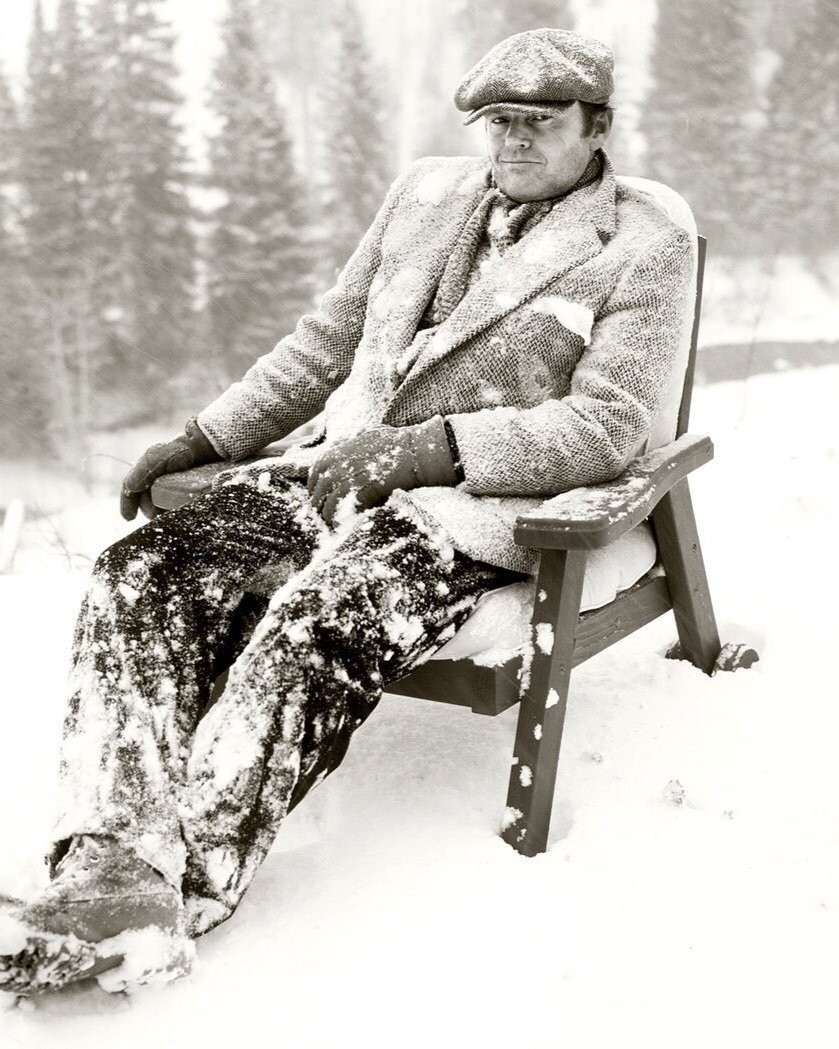

Watson in Manhattan Beach, Calif., c. 1971

George Gendron: Well, the point’s well-taken. To go back to what you were saying about the fashion industry, which is, it’s not just the fashion magazines being impacted by magazine trends. The whole industry is changing. And, of course, the same thing is true in music.

Albert Watson: It’s stuck in a weird kind of rap, hip hop, disco-influenced dance kind of thing. You look back at my generation right now, which looks old-fashioned, of course, you look at a performance by Led Zeppelin, or the Rolling Stones, basically they came out on stage and they sang and that’s what they did. They played their guitars and sang.

Now, if you get Rihanna at a Super Bowl, there are not 20 dancers—my God!—but 260 dancers, all dancing the same routine. And all of this, of course, is fluff, and adding, and so on. And, of course, people realize that. If you just stick Rihanna out there on top of a platform, nowadays that isn’t going to cut it. Especially since she was five months pregnant. That’s not going to cut it at all. She’s not going to be able to dance much. And, therefore, there’s a lot of stuff right now that’s covered up with fluff and decoration, a bit like a Christmas tree, you know?

George Gendron: So, when you step back and think about this, from your point of view as a photographer—as I would dare say a fine artist—what impact does this have on you creatively?

Albert Watson: Well, many photographers are different—there are different types of photographer. And the fashion business very often attracts two types. It attracted people who really wanted to be fashion photographers. I mean, they loved fashion. They loved the fashion business. They love the buzz of fashion, the glamor of fashion.

Where it all began: Alfred Hitchcock for Harper’s Bazaar, 1973 (above); the world-famous Cheryl Tiegs poster, 1978

“Sometimes a young photographer has to save up, to beg favors, ask assistants to work for nothing, models to work for nothing, and hairdressers to work for nothing.”

George Gendron: What photographer comes to mind that really symbolizes this kind of photographer for you?

Albert Watson: I would say someone who loves fashion, and loves the fashion business, and could easily be a fashion editor, and who is a brilliant fashion photographer, is Stephen Meisel. Because he understands the difference between a bronze eyeliner and a charcoal eyeliner. He would research things very carefully from the fashion perspective.

Now, another type of photographer that worked in the fashion business, a good example of it, would be Richard Avedon. Richard Avedon, strangely enough to me, was not a fashion photographer. But he was a photographer that enjoyed photographing fashion.

What am I saying? Is it not the same thing? It’s actually different. Because in the end, Steven might’ve had a hard job doing the In the American West project that Avedon did. Or Steven might’ve had a hard time photographing New Guinea warriors that Irving Penn did. Irving Penn was another photographer that enjoyed working in the fashion business.

George Gendron: Let’s put you in this category. He would have had a hard time doing Vegas, the Strip.

Albert Watson: I was somebody who enjoyed photographing women and the fashion business was an obvious entree to that. And I did a lot of homework with fashion to understand fabrics, the light on fabrics, and the obvious difference between, you know, a silk chiffon and a polyester nylon chiffon and so on. I did do the homework on that.

My photographs in fashion were always based on pure photography. And sometimes I had difficulty with fashion editors. Grace Coddington once said to me, “Be careful with your pictures. They’re becoming, sometimes, too strong.” I’m a big fan of Grace Coddington. She was a brilliant fashion editor. And she was really in touch with fashion and I knew what she meant because there is a certain point where there is a key ingredient that should really be in a fashion picture. Where it should have a sense of “fashionability.” In other words, the photography should have a sense of fashionability.

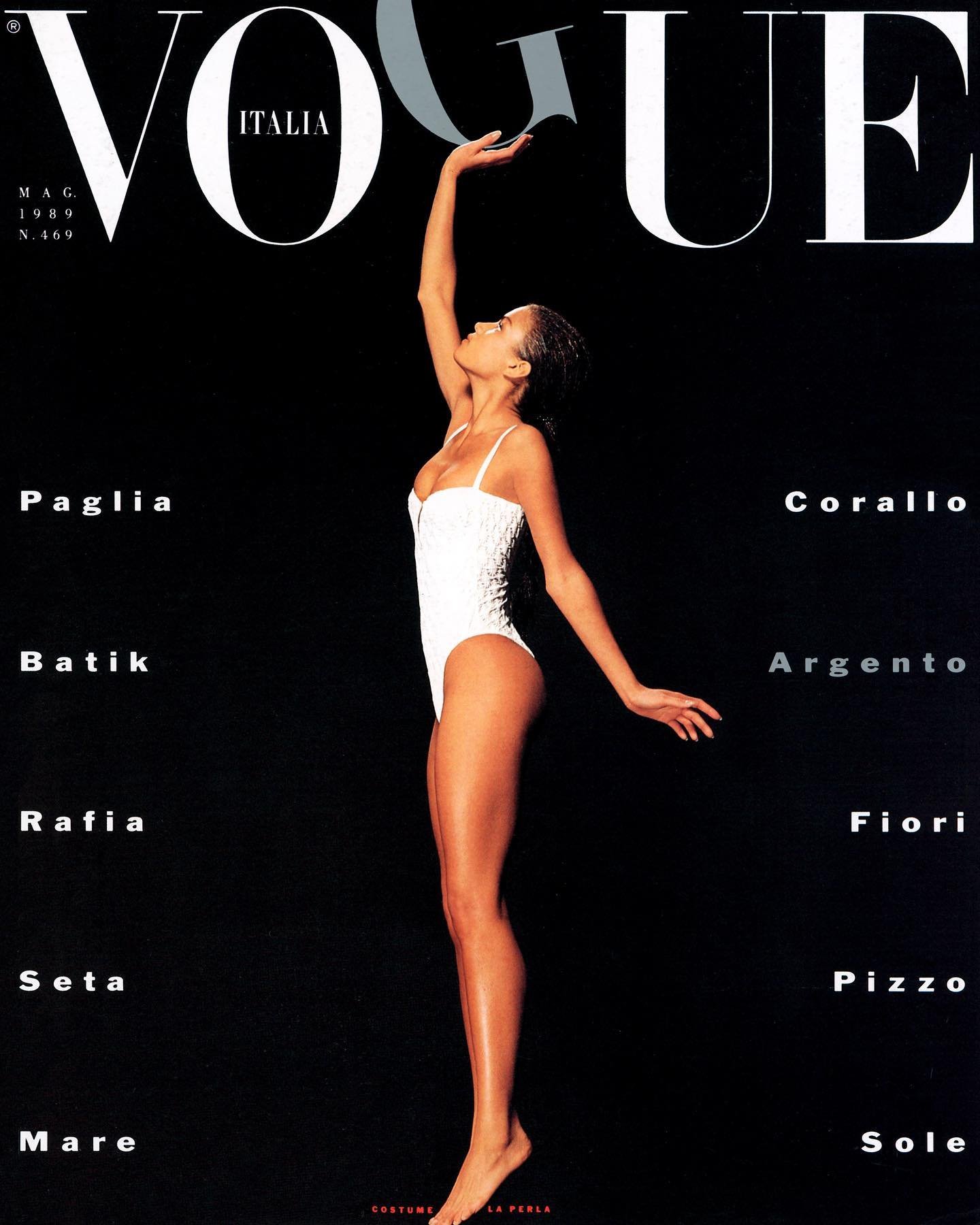

And maybe the best compliment I ever got, from Franca Sozzani, who was a great editor of Italian Vogue, when I had an exhibition in Milan. I had done so many pictures for her. And she was never a big fan of the pictures—she would always prefer a Steven Meisel picture—but the biggest compliment I ever got from her, she said, “When you did the pictures for me, I was never that crazy about the pictures. But now that I see them in the Museum of Modern Art, I think they look better!” This is a funny thing because at that point, you say, “What is the difference?”

The difference is there’s a journey that a photograph takes from the camera to a print that’s printed in a magazine. You can do a picture for a fashion magazine and it can be totally successful. Everybody loves it. Hairdressers love it. Makeup artists love it. Fashion editors love it. Everybody loves it and it’s successful. And I had done a lot of that work. The work was, at that time, very successful. And it wasn’t so photographic, it was more driven by what a magazine liked. I found out what they liked, and I would do that.

The problem was the journey a photograph takes from the camera to a magazine. And then there’s a big quantum leap. Something can look fabulous in a magazine. And then you say, “Okay, now I’m going to put it in a coffee table book.” Right? What I suddenly realized was that lots of the pictures—when I came to doing my first book, Cyclops, I looked at all these fashion pictures that were so successful, and I suddenly realized that when I put it into a book format, it didn’t look so good.

And I was like, “Why is that?” I did a good job on it, I think. Everybody loved it. But it doesn’t look fabulous. It doesn’t look amazing. Quite honestly, it’s not good enough for a book. And the journey that photograph takes—it then takes another quantum leap and ends up in a frame on a wall in a gallery. That’s another leap it takes. And then it suddenly looks different there.

And then it takes the final leap, you might say, onto a museum wall. And a museum buys it, you know, whether it’s The Getty or the National Portrait Gallery or something like that, that it makes it all the way. So there could be a point that you might say to a fashion photographer that he may not have that interest in a coffee table book, the gallery, and museum.

And if it does make the final journey that way, then he might say, “Well, yeah, that’s pretty good. I’m happy with that.” That it made the journey. Whereas there are other photographers, that was their goal right from the beginning. Every time they picked up a camera to work for a fashion magazine, that was their goal. They were hoping that every damn picture ended up on a museum wall. And so you were always looking for that.

And I made the transition into that in the eighties. So my handheld, snappy “Girl Eating a Banana”-type of picture, that everybody loved, suddenly developed into stronger pictures. Hence the comment by Grace Coddington. And in other words, “Your pictures are looking a bit heavy.”

So the good news is your pictures are getting heavy. The bad news is, your pictures are getting heavy.

George Gendron: So, several times, you talked about “the journey” of a photograph which was really interesting. I’ve never heard it put quite that way before. But now I want to talk about your journey. And I want to start in Scotland. In your book, Creating Photographs, the book opens with a wonderful statement. You said, “I was born in Scotland, and I went to school outside of Edinburgh, and I had a very ordinary childhood, and my mom was a hairdresser…”

Albert Watson: “…my father started as a professional boxer, but then he became a physical education teacher.”

George Gendron: Yeah, well, in the book it just says, “My mom was a hairdresser and my dad was a boxer.” And I thought, “Well, where I come from, that’s not an ordinary upbringing—having a father who was a boxer.”

Albert Watson: Yeah. But then, a little bit later of course, he became a physical education teacher. So that was a little bit more normal.

George Gendron: So you have, if you move on to your education, a very interesting and unusual education, in terms of your background, that you can see manifest in your photographs even today. And so could you talk a little bit about graphic design and filmmaking—your education—and the impact that it has on your photographs?

Albert Watson: Sure. I’ll do this very quickly in less than 60 seconds. The first job I had in leaving school, I worked for what was called the Air Ministry, which is the Ministry of Defense. And I was very good, when I was younger, at mathematics. and I worked with a slide rule and a very primitive computer and I was plotting missile courses between the east coast of England aimed at Russia.

This was 1959. My first job was to plot altitude, distance, speed, time allotments, and the weight of the payload, the war load, the bomb load, and things like that for something called the Blue Streak missile. I had two scientific officers above me and I worked with them doing lengthy complications, equations, and things like that.

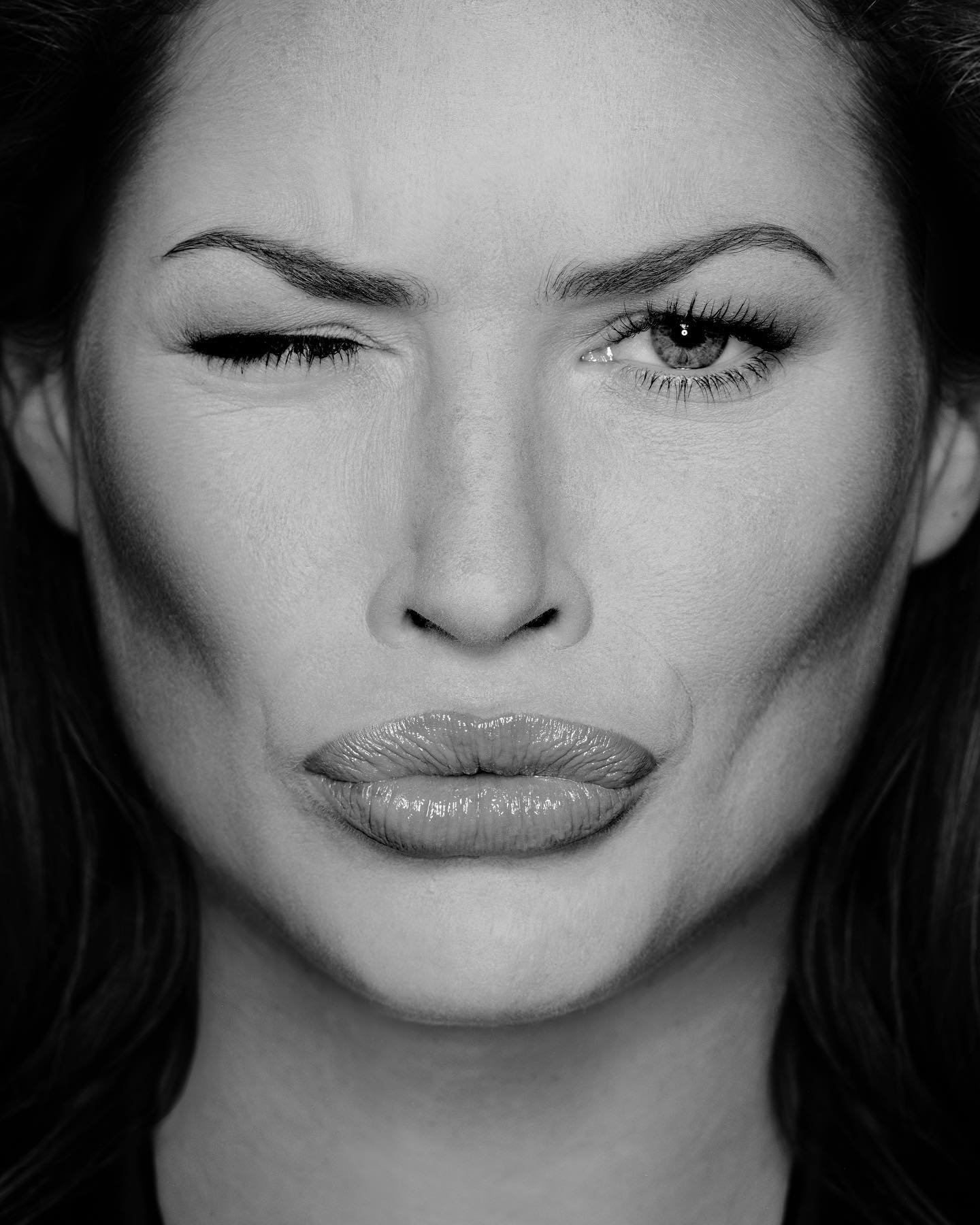

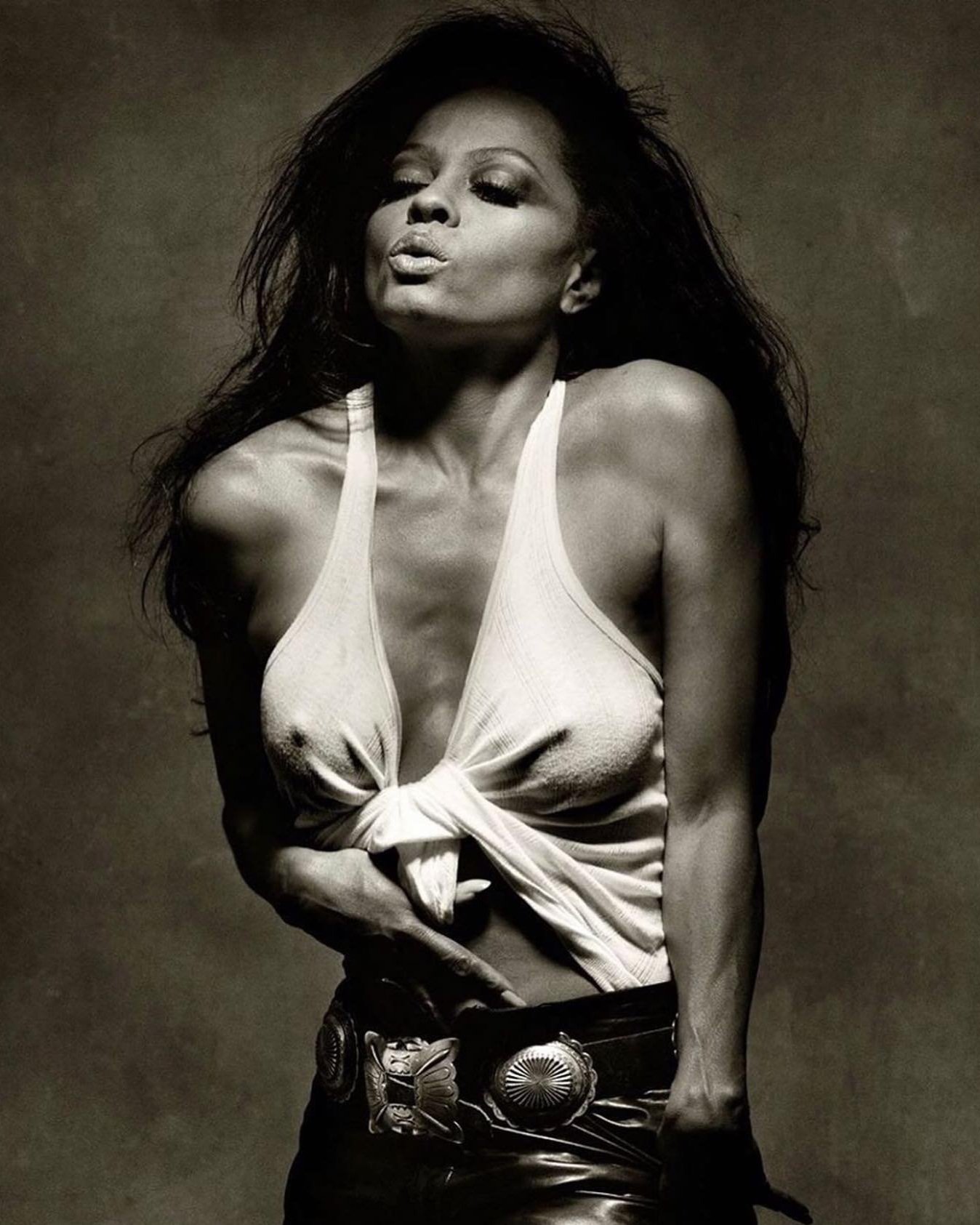

Albert Watson x Supermodels

George Gendron: Is that where all great photographers get their start?

Albert Watson: Yeah! I think so. And I did that for a year and then decided to go back—I got married when I was 18—I decided to go back to Scotland. And I got a job working in a laboratory in a chocolate factory, doing chemical analysis of chocolates. And I did that for a year.

But during that year, I went and I took three night classes, two night classes were in mathematics. And I qualified then to have the opportunity to go to Edinburgh University and do math. I spent one night a week for some obscure reason, I can’t even remember why, to do painting classes and drawing classes at the Edinburgh Art College in the evening, for students that were outside of the normal curriculum.

And I got into Dundee College of Art, it was part of St. Andrews University. And I went up there to begin a four year course with my wife, and by that time I had a child. I started there in 1962 and I had a very disciplined education in different aspects of art, which involved drawing, painting, textile design, graphic design, and pottery and silversmithing. And at the end of two years, you had an opportunity to specialize. I loved graphic design and I chose graphic design.

That was my third year. And at the same time, for the first time ever, they had a class in photography that was available to you as your craft subject. So here, I had a disciplined beginning. I then continued the studies with graphic design, specializing. And as a craft subject, one day a week, I had photography.

That was my first real connection with photography. And my wife bought me for my 21st birthday a small camera, and the minute I got that camera, I became really obsessed with photography.

George Gendron: What was it about that camera, Albert? Can you try to go back?

Albert Watson: I’ve got no idea. All I know is that I clicked the shutter and suddenly, magically, I got negatives back that I could learn to process myself. And then, even better, I got into a dark room with a piece of white paper under an enlarger, and you put it in some chemistry, and lo and behold, up comes an image. Magic! “Black magic,” I called it. Amazing, insane, beautiful. The control that you had over it—you give it too much exposure, it went black. Too little, it was white.

And I was heavily involved with graphic design. I was still getting a heavy education in that. I did that for two years, and then I got into the Royal College of Art to do a master’s degree, and they put me in the film school. So now I’d had three years’ education in film…

George Gendron: …So you didn’t select film school?

Albert Watson: I selected graphic design school and the head of the school requested that I consider film school because he felt that, due to the photographic nature of my graphic design, that I would enjoy film school more and that I could make a very interesting filmmaker.

And during that period of time, between 1966 and 1969, I studied film and television. And to this day, if you look at all of the work that I’ve done, you can see those seven years stamped on everything. There’s art (we hope) and there’s photography, there’s graphics, and there’s film. And that should be a connecting factor because that was my education, what I loved, and what I held on to.

George Gendron: Now, shortly after this, you, Elizabeth, and your first son, you pick up and you go to LA.

Albert Watson: She got a teaching job in LA, and I went in as her dependent.

George Gendron: So that answers my question. I was going to say, “Why LA? Why not Paris or London or New York?”

Albert Watson: Because that was what was offered. And one thing I didn’t mention, that was an important part of my life, in 1966, between finishing at the Art College and going to the Royal College of Art, I won a traveling scholarship to come to America.

That was by IBM. And I flew into New York for the first time in my life, of course. And I met a lot of interesting people in New York: Push Pin Studios, Milton Glaser, a lot of graphic design people. Interesting people. I flew from there to the design conference in Aspen.

And then I went from Aspen to LA, and met people like Charles Eames. I met John Cage. And I met a lot of industrial designers, famous ones—Henry Dreyfus, the industrial designer. So it was very informative.

Then I went to San Francisco, then to Chicago, then to Washington DC, then back to Scotland. And then I packed up my bags and went down to the Royal College of Art.

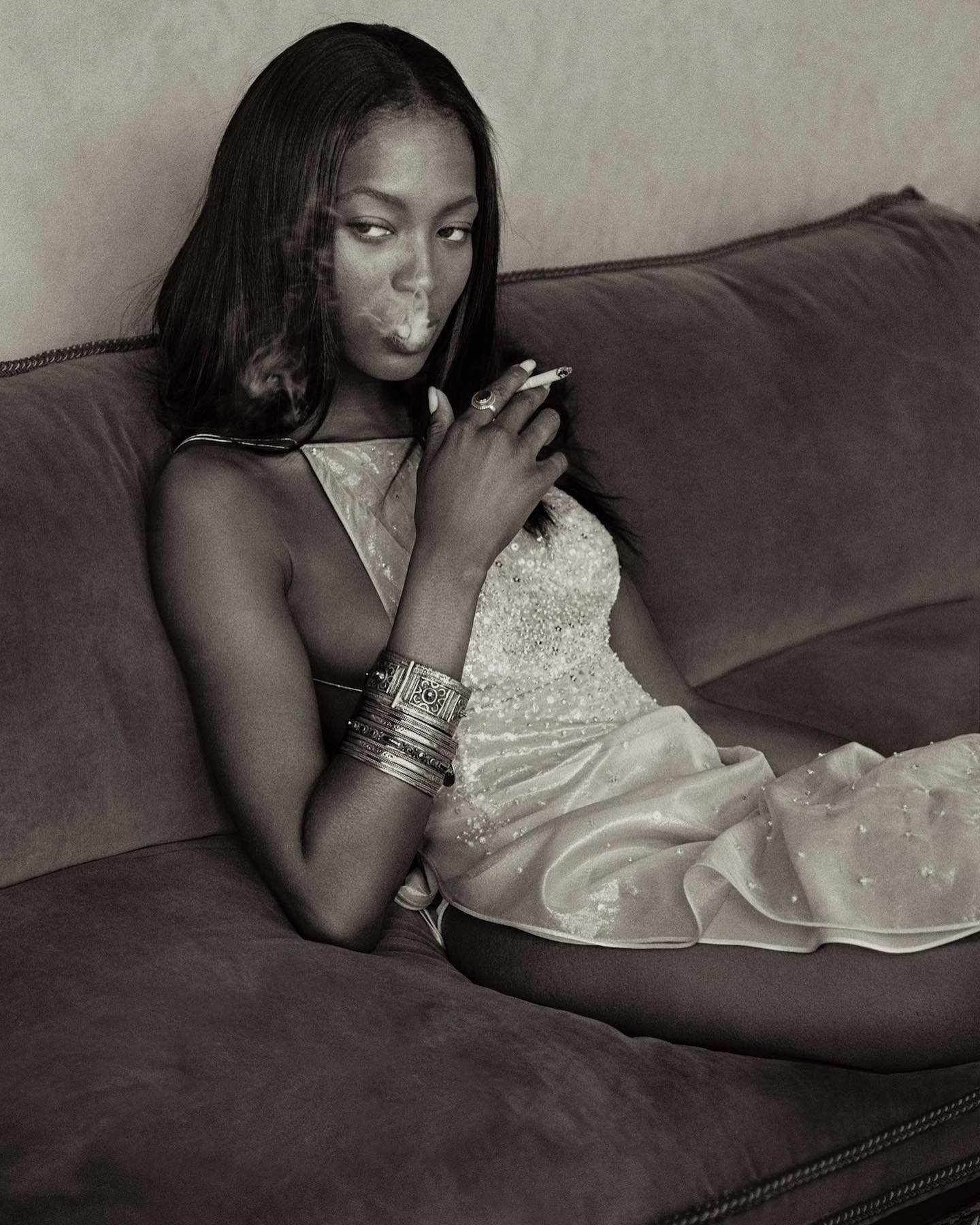

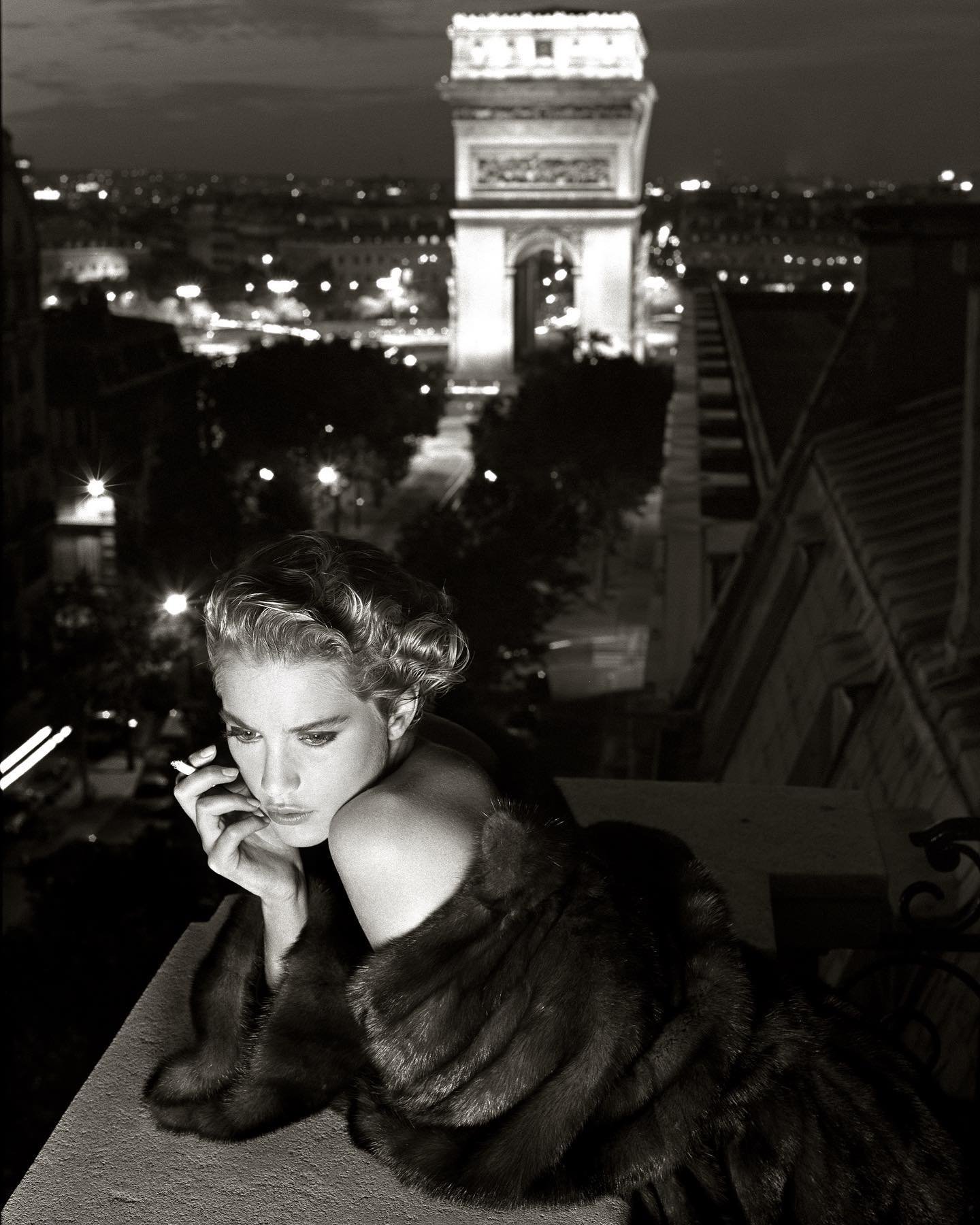

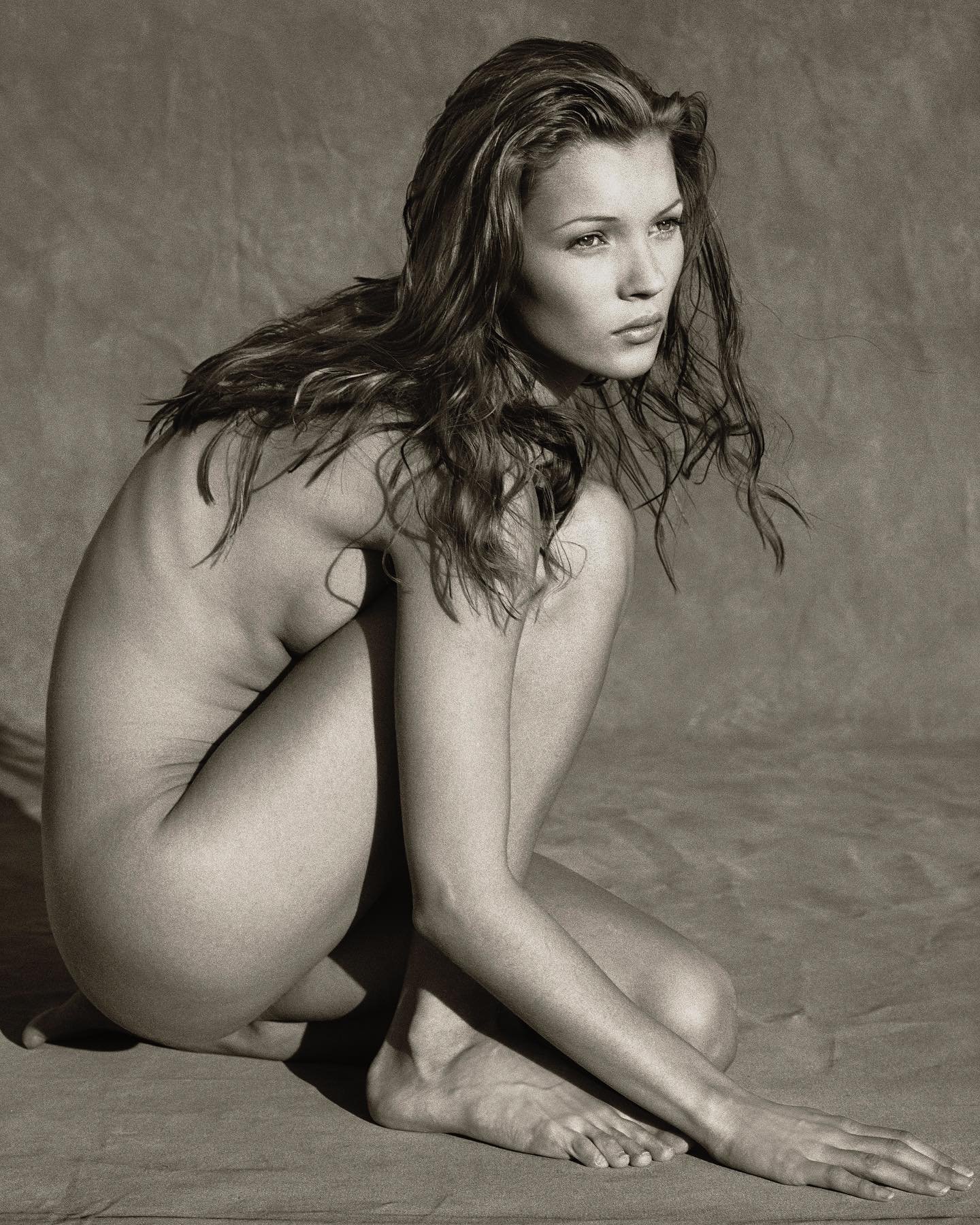

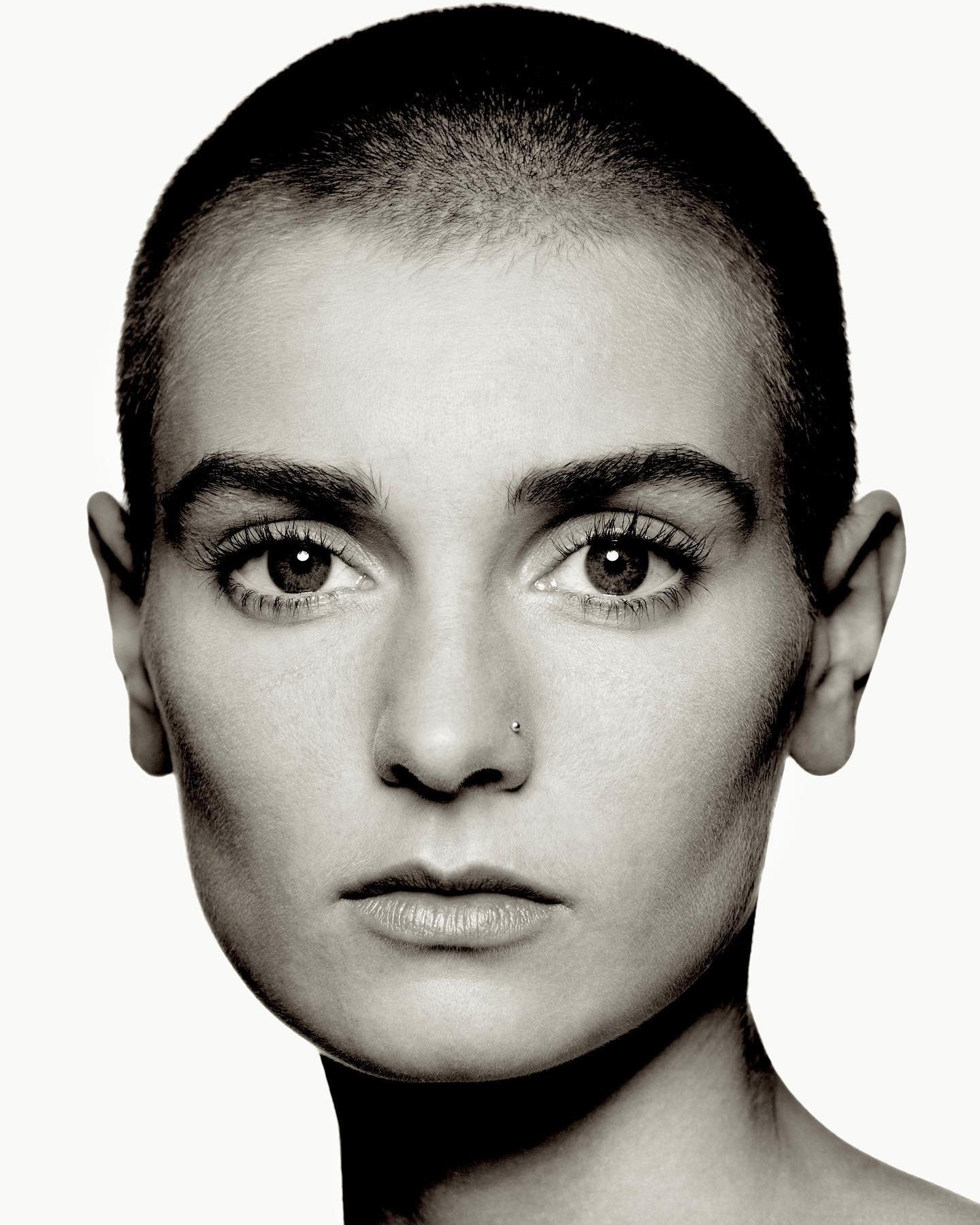

Model Kate Moss, photographed in Marrakech, Morocco (c. 1993) for German Vogue. Prints from this session can found at auction for upwards of $35,000 US.

George Gendron: What’s interesting about what you just said is that every time I’ve seen you talking to a group of designers, and presumably, it seems as if you’re really addressing in particular young designers, you emphasize the importance of go to galleries, go to museums, go to the opera, listen to music, listen to jazz go to the movies all the time. The importance of having kind of a liberal education, if you will, when it comes to culture.

Albert Watson: Yeah, I’m actually shocked these days, that I meet a lot of hip people that are sadly lacking, unfortunately, in a historical education. They don’t have a great knowledge of painting. They don’t have a great knowledge of music from the past. They know famous things from the past like the Beatles, of course.

Going back further than that, they have no idea, really. You can mention to a young person now Tchaikovsky and they have no idea who Tchaikovsky is. They have no idea who that is. They’ve never heard the name. Nobody’s said to them the word Tchaikovsky.

And people listening to this podcast would say, “Well, that’s ridiculous.” I can tell you it’s true. That’s a true story. And then they can say things like, “I’ve never heard of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.” And then they say to me, “Ah, well, that was before my time.” Well, I can say, I’ve got a shock for you. It was before my damn time. Yeah. It was way before my time.

“I was kind of astonished that every year Peter Lindbergh took six weeks off. Six weeks! That’s 42 days!”

George Gendron: Kids look at you and I and think there was nothing before our time.

Albert Watson: So, you know, everything is available to you. Everything. If you don’t know what impressionism is, you can hit a button and you can get 2.8 million pieces of information on Impressionism. At seven o’clock in the evening, you can switch on your computer, and if you want to study for five hours, you can cram quite a lot of information on Impressionism, and that can help you in your own work.

George Gendron: Now let’s go back to you, Elizabeth, your son. You moved to LA. You moved because she has a teaching job there. It sounds as if, from the way you describe it, you had one significant introduction when you got to LA, and that was to somebody at Max Factor.

Albert Watson: I had a connection at an advertising agency and that person knew the head of the international division of Max Factor. And he gave me that introduction.

George Gendron: Okay. Now you’re with this guy, and tell the story about what led, basically, to the first work you had ever done and gotten a US dollar for.

Albert Watson: I went in and I had a little portfolio of slides and things. And he said, “I love these pictures, but there’s one problem.”

I said, “What’s that?”

He said, “You don’t really have any beauty shots here, and this is Max Factor and we sell cosmetics. But I like your pictures.” And he said, “I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’ll pay for a model for you for an hour. And there’s a lot of dresses in the closet there. You can take a dozen dresses if you want. And book a model for an hour. And let’s see what you can do.”

So he said, “Go to the advertising agency.”

And I picked a model, a blonde, and I said, “I’d like to meet her.” So the following day I went back and I met her and I said to her, “Is there any chance we could work a whole day and I’ll give you some pictures for your portfolio?”

So she said, “What time do you want to start?”

I said, “Eight o’clock.”

So I was there with my camera—no assistant, no lights, nothing, except a model who did her own makeup. So I had dresses, a model and my camera and invested all of the money that we had available, which bought 60 rolls of film. And I had a car. And I had done a little bit of location driving around because I’d only been there for a couple of months, and I came across a beautiful field of yellow grass. And I started off there.

And I did close up shots. I did wide shots. And I went down to the beach and I did these shots with her in a dress in the ocean. I shot all 60 rolls of film in about 10 hours. And two days later, I went into Max Factor with the 60 rolls. And of course the obvious silly question was, “How did you manage to do 60 rolls of film in an hour?”

And I said, “Why, to be honest, I didn’t. She’s just charging you for an hour, no more. And I talked her into [shooting for] the whole day.”

And he looked at the pictures, and he said, “Just sit down now, I’ll be right back.” And he left for a long time. And all I was concerned about was if he was going to pay for the 60 rolls of film and the processing, which was all the money we had.

And he came back, he said, “I have good news for you, we will buy three and the national division is buying two of these shots because we have a new product coming out called “California Blonde.” And we can use these pictures. Then he said, “I’ll give you a PO for the pictures and your expenses. And any gas receipts that you have, we’ll pay for.”

But he didn’t tell me how much, and I left there with a piece of paper, and I opened it up, and when I looked at it quickly, I saw that it was expenses, plus $150 per shot, times five—$750. Which I was very happy with. I thought that was great. I was very excited.

I got home and I asked Liz, my wife, if she could borrow a typewriter and type the bill out. And when she was typing the bill out, she said, “Wait a minute. It’s not $150, it’s $1,500! And at this point, her salary a year was about $3,500 a year. So therefore, doing the math on that, you’ll see it was $7,500. And that was a fortune.

And at that point, we said, “Well, we can’t charge him that. It’s obviously a mistake. Nobody would pay that much money.” And I said, “We don’t want to be deported. So I’ll go in and speak to him.”

So I went the next day and asked for an appointment, and I waited for him for half an hour. I saw him and I said, “I just want to talk to you about the money that you paid me.” And then he said to me, “$1,500 a shot is all I have at the moment. But next time I can pay you more.”

George Gendron: Welcome to advertising, Albert!

Albert Watson: So in other words, that was the beginning of my financial career. And that was shocking, of course. When I got back to tell my wife, and by that time we had two kids, we went out and went to McDonald’s as a celebration.

George Gendron: So you go on to become a pretty big deal. You have, I think, one of the largest studios in LA. But no sooner have you done that, then you, Elizabeth, and your two sons, you pick up and you move to New York.

Albert Watson: Yeah, but the story I just told you is approximately 1971. And in 1973, I did the shot that’s quite well known of Alfred Hitchcock holding the plucked goose. That began to change my direction and fortune. And we were running this huge studio in Los Angeles, and in 1974, I got an agent in New York. And I had a small studio in New York and a large studio in LA. And I would say 5 percent of my work in 1974 was New York, the rest was LA. By the time it got to 1976, about 85 percent of my work was New York, and only 15 percent was LA.

George Gendron: Was that intentional on your part?

Albert Watson: Yes. And then what happened was we decided to sell the LA studio and we moved to New York. And then we bought a townhouse on the Upper East Side and converted the townhouse into a two-floor studio and a two-floor apartment. And by the end of 1977, we were 100 percent in New York.

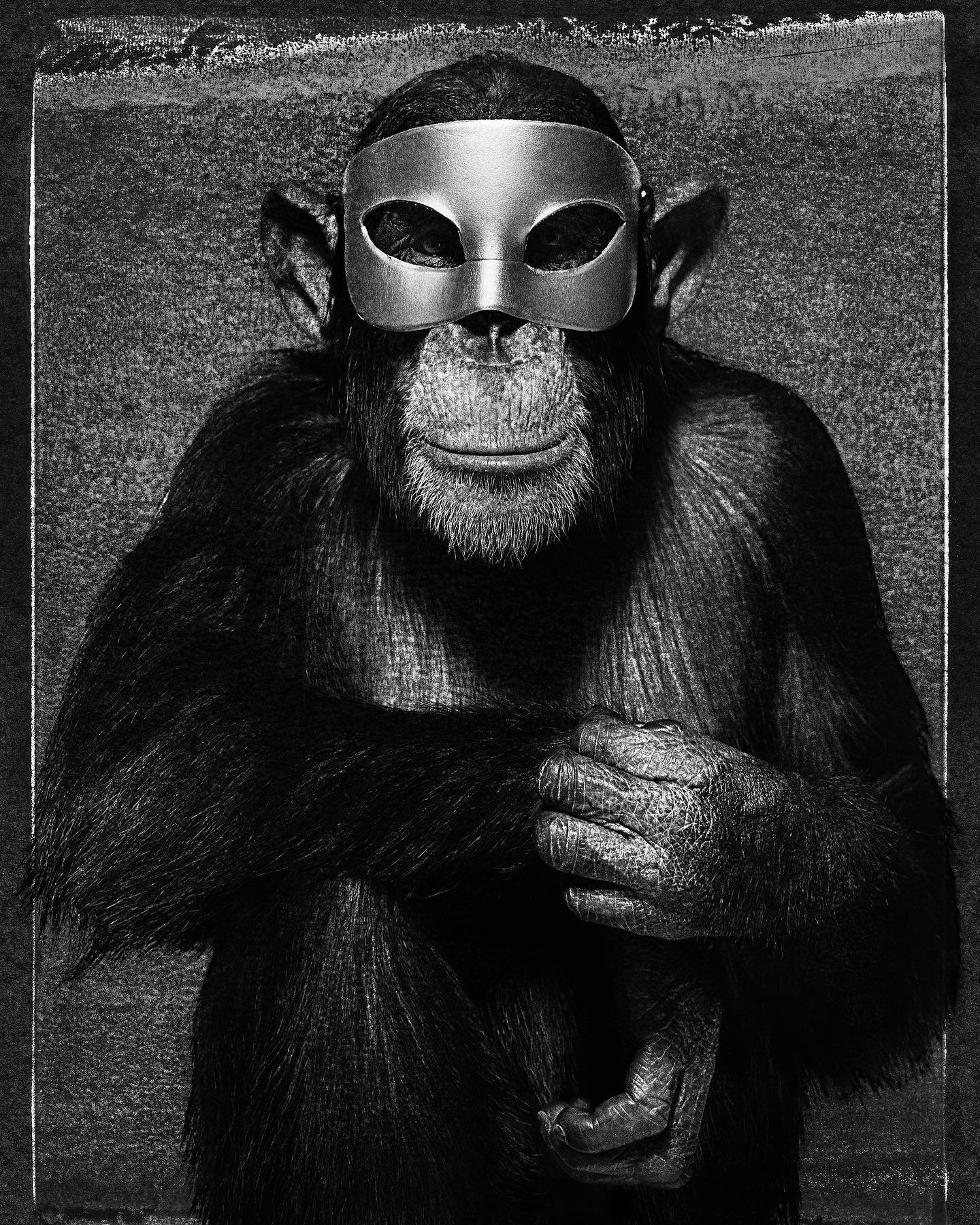

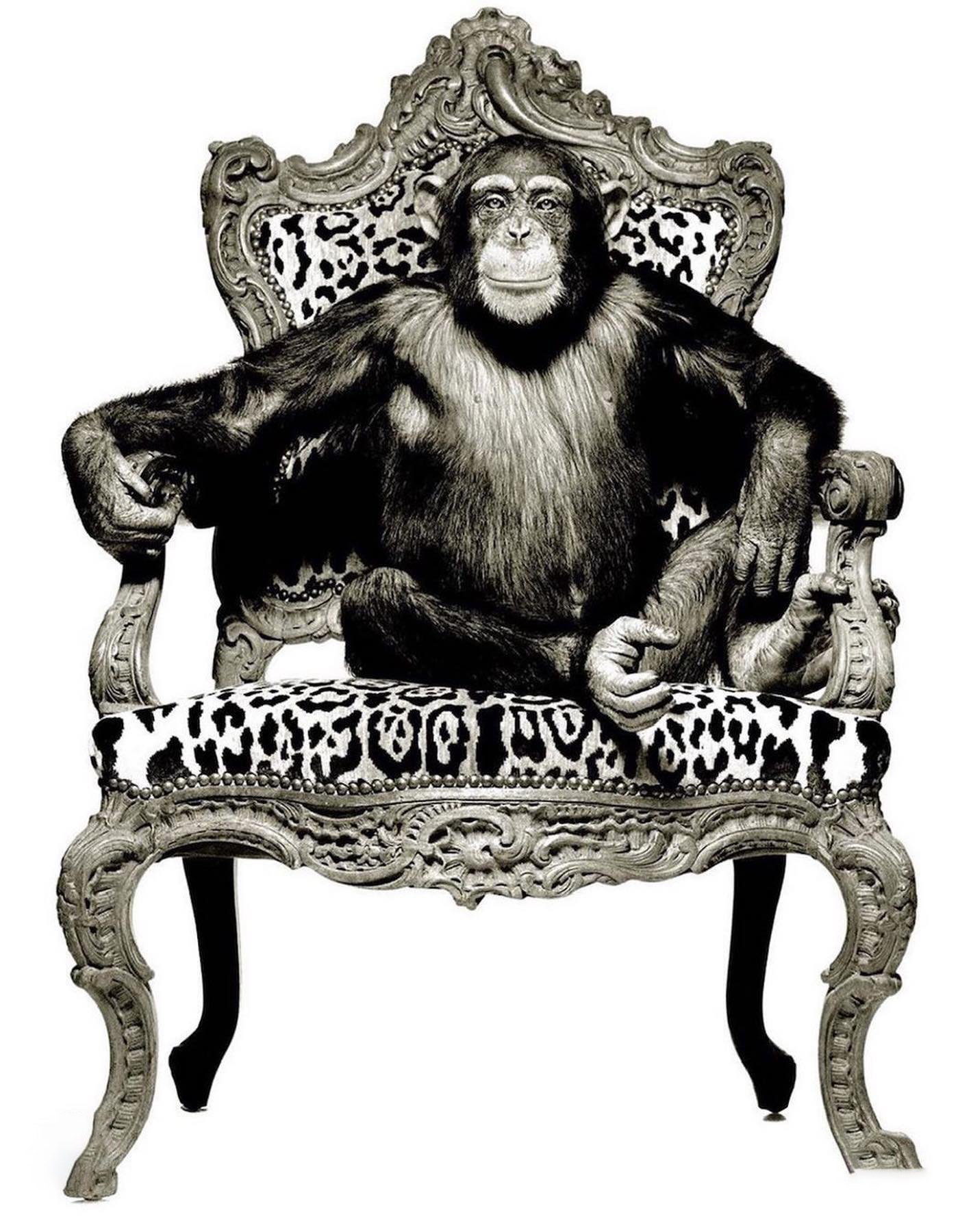

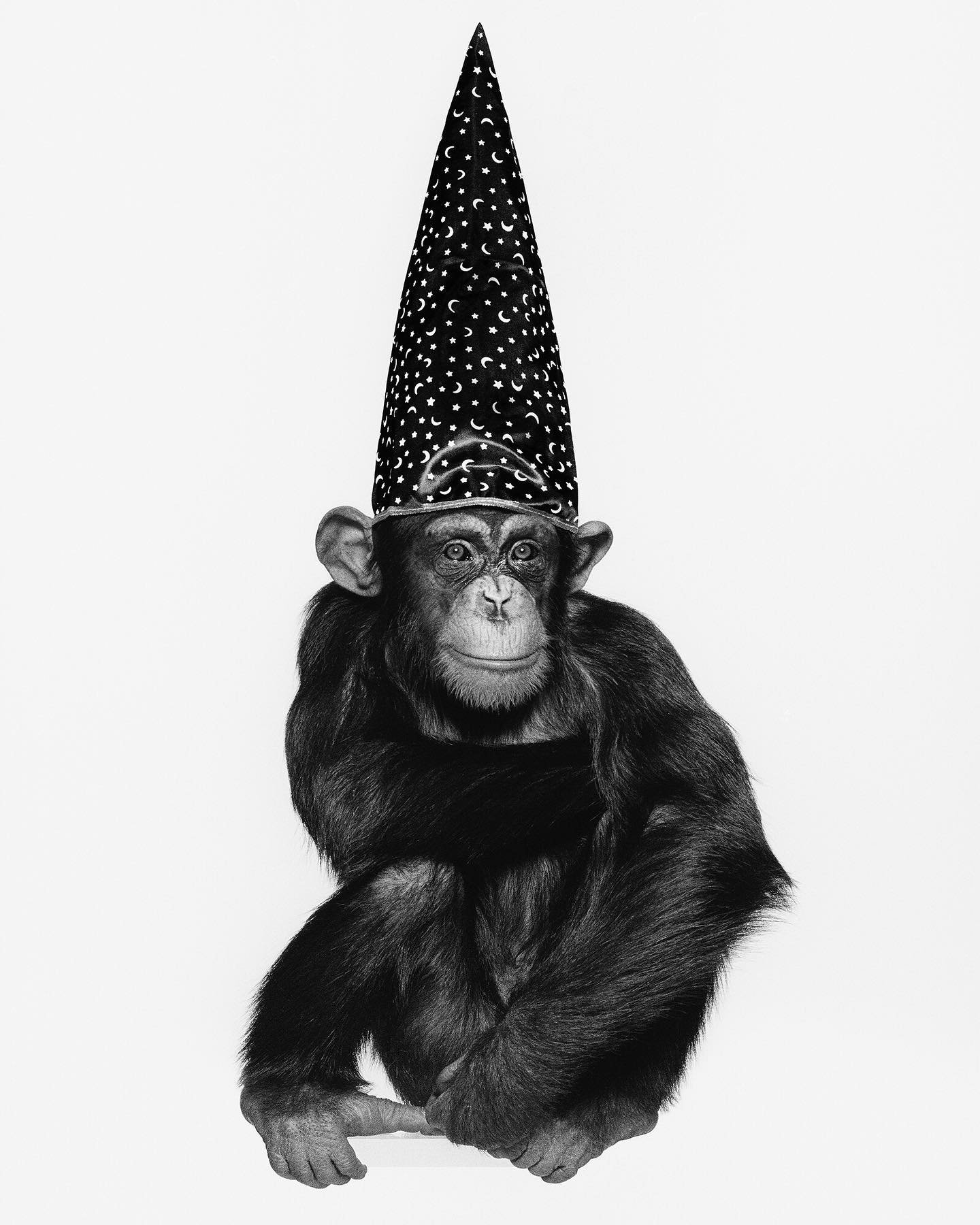

Casey the chimp, photographed in New York, c. 1992

George Gendron: Now, given the theme of this podcast, Print is Dead, we have to go back and point out that in the mid-seventies, you’re in the middle of one of the real heydays, if not the heyday, of magazine publishing in the United States.

Albert Watson: Well, there was money everywhere.

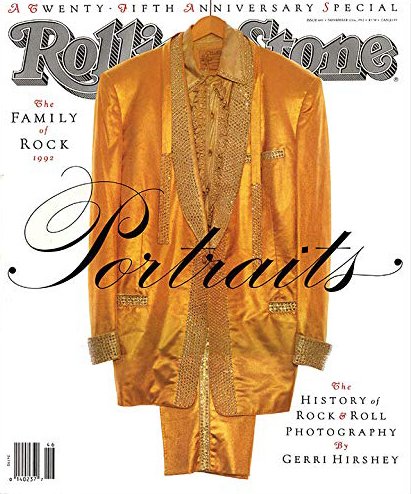

George Gendron: There was money everywhere. People were starting new ventures constantly. I’d love to hear you talk a little bit about the work you did, for not so much the fashion magazines, but the mainstream magazines, general interest magazines, the Rolling Stones of the world, for example, and some of the art directors and photo editors that you worked with.

Albert Watson: There was—starting with Alfred Hitchcock—I’d always held on to portraiture. I was interested in portraiture. At that time I was doing about 80 percent fashion. I was doing lots of different things. I was doing still lifes for Clinique, photographing perfume bottles. I was photographing a drop of water exploding on top of a lipstick, which was not easy in those days. Now it would be a piece of cake. But in those days you were putting it on one piece of film. Nowadays you just shoot a water explosion and stick it on top. They were different times.

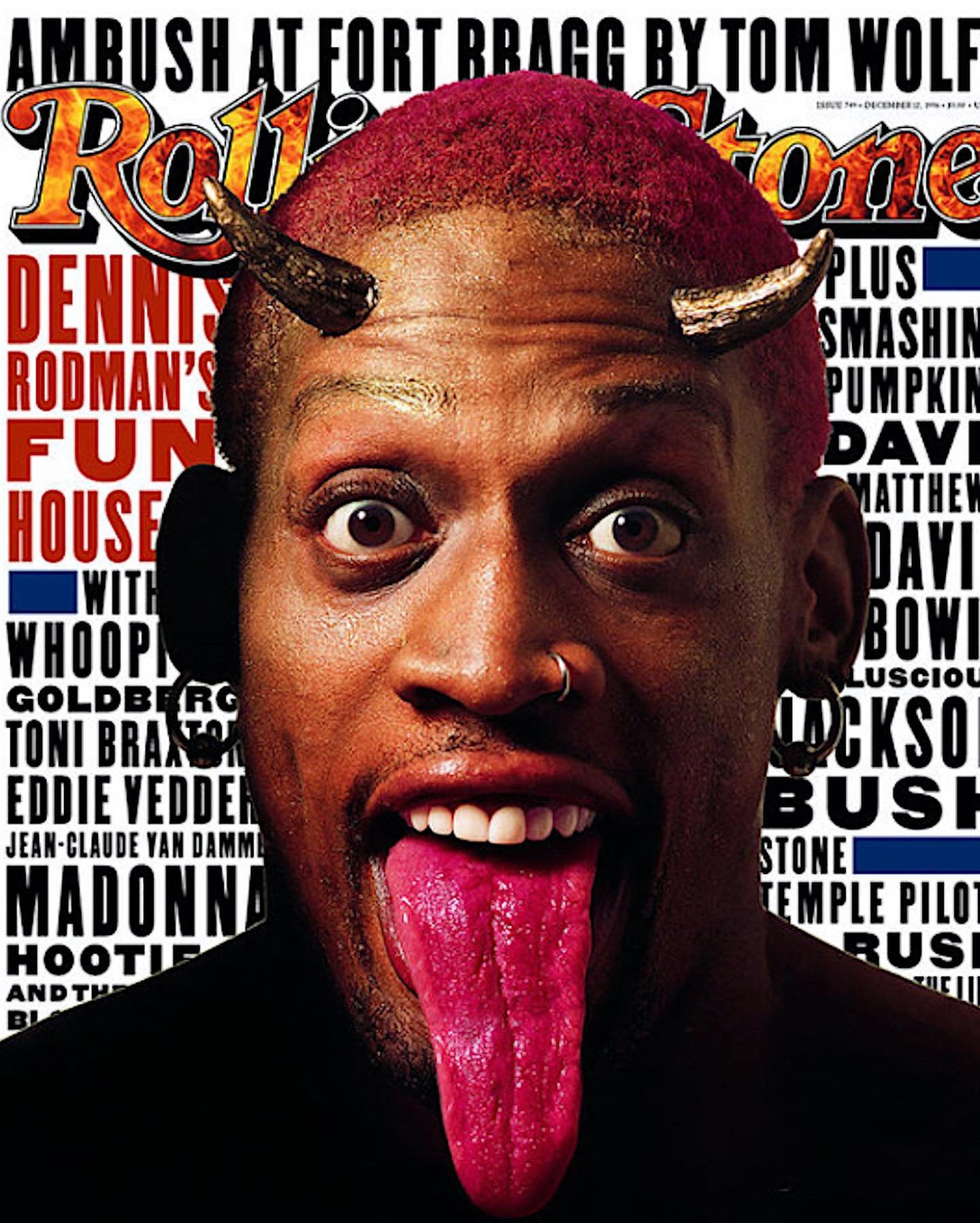

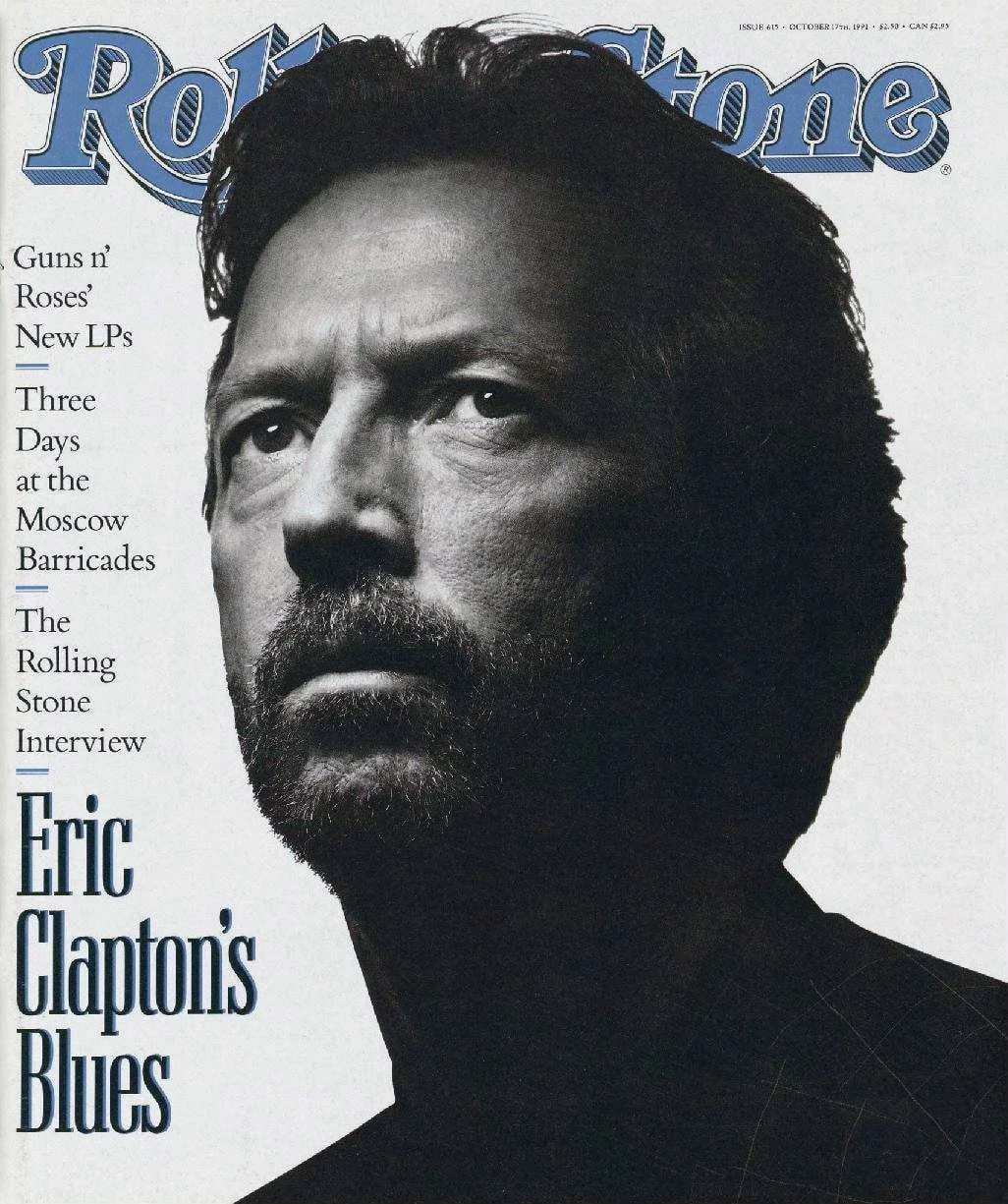

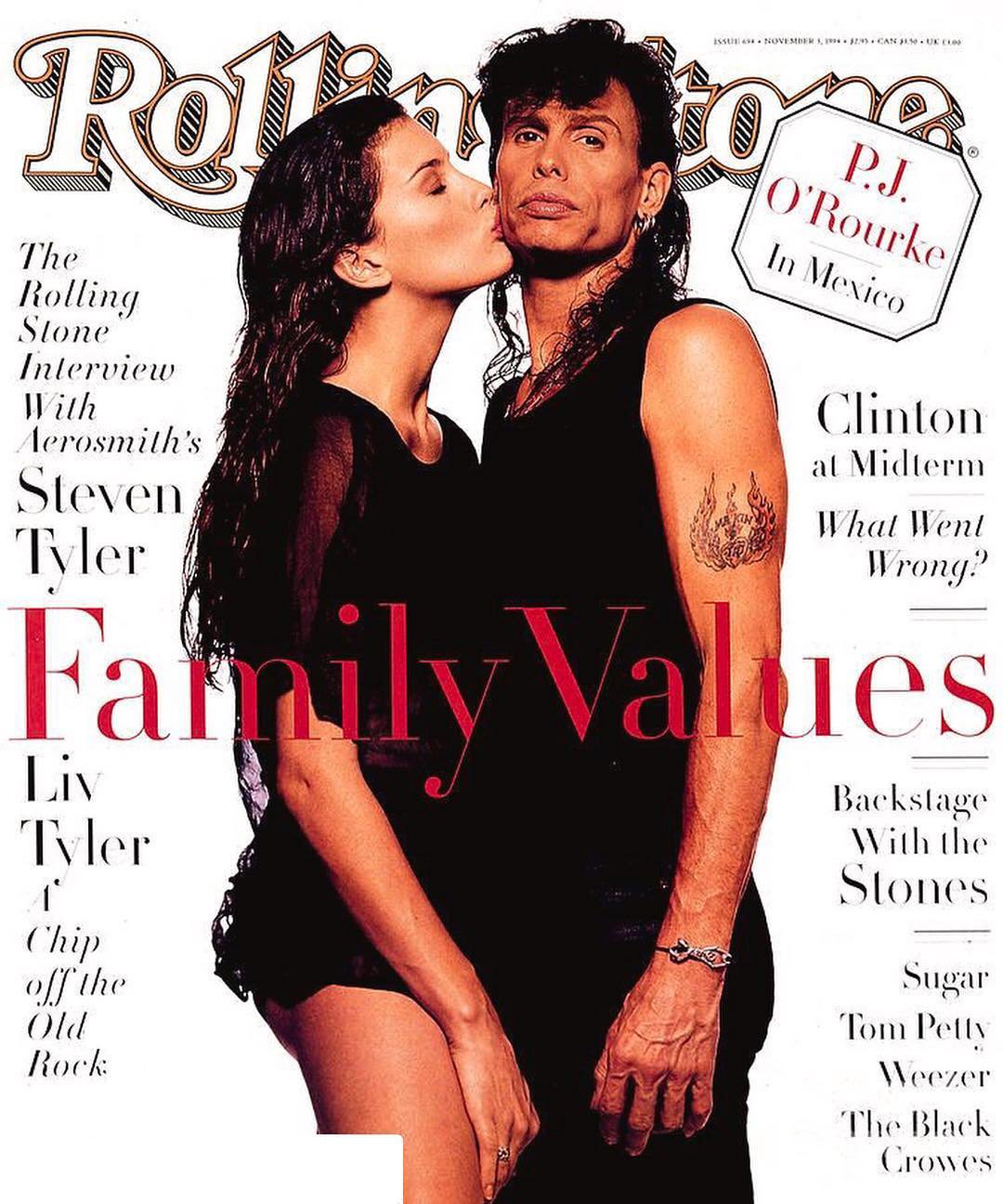

So I was doing that, plus I was doing lots of portraiture, and the portraiture led to Rolling Stone magazine. And I began working heavily with them and doing a lot of covers for them. I was working with Laurie Kratochvil, who was the photo editor there, and Fred Woodward was the art director. He was a brilliant art director and typographer. Very smart guy. He won award after award for the design of the magazine.

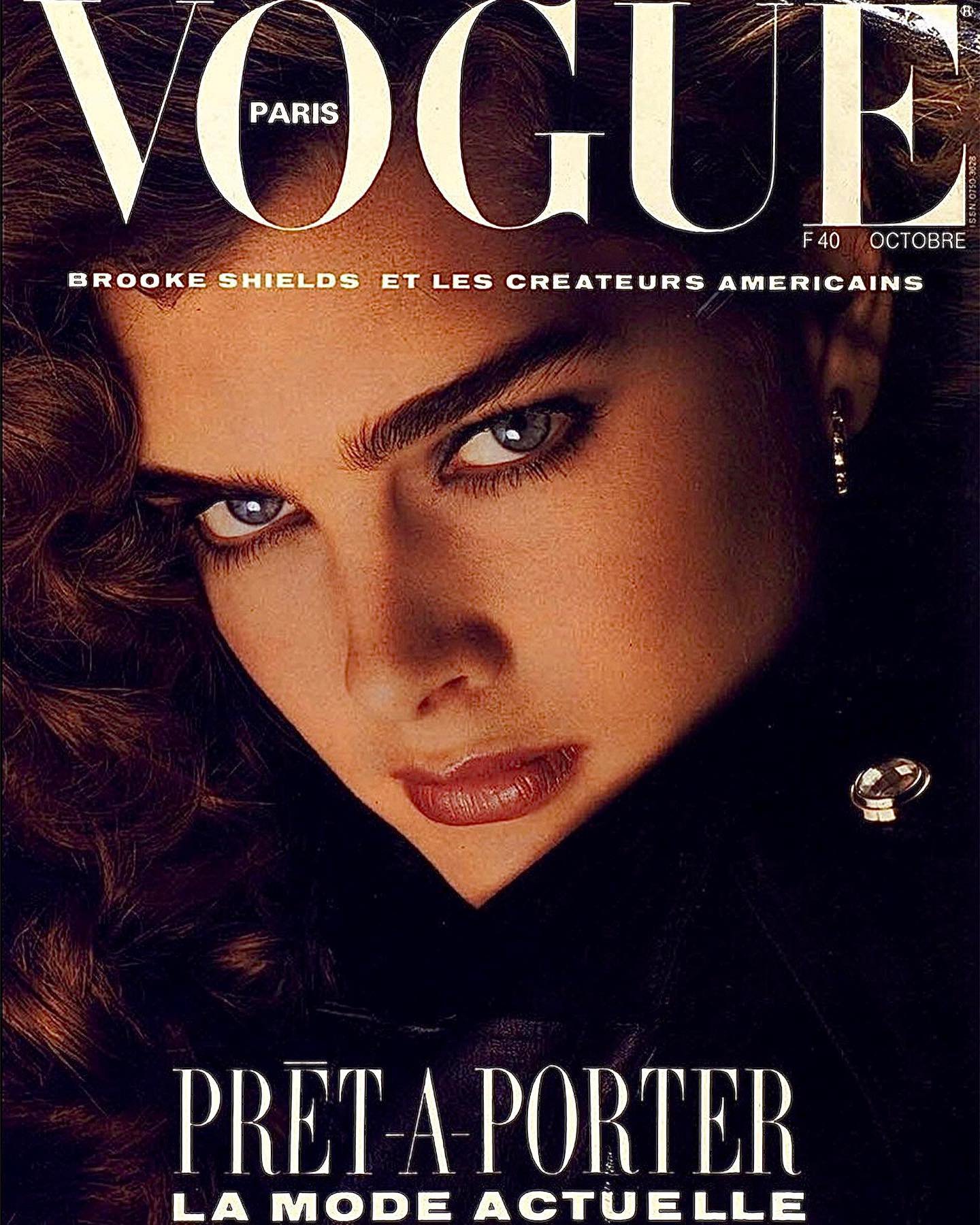

And in parallel, I was working for Vogues all over Europe. And then I got a contract for three years to shoot every single cover of French Vogue. To do every one. I was the only one that was shooting cover after cover for them. And I was working in Paris and the kind of people I was working right alongside were Helmut Newton, Guy Bourdin, and guest photographers like Cecil Beaton.

George Gendron: Let’s go back for one second to Rolling Stone and Fred Woodward. I’m curious, what was your ideal relationship when you were out doing an editorial assignment—which is very different from working commercially?

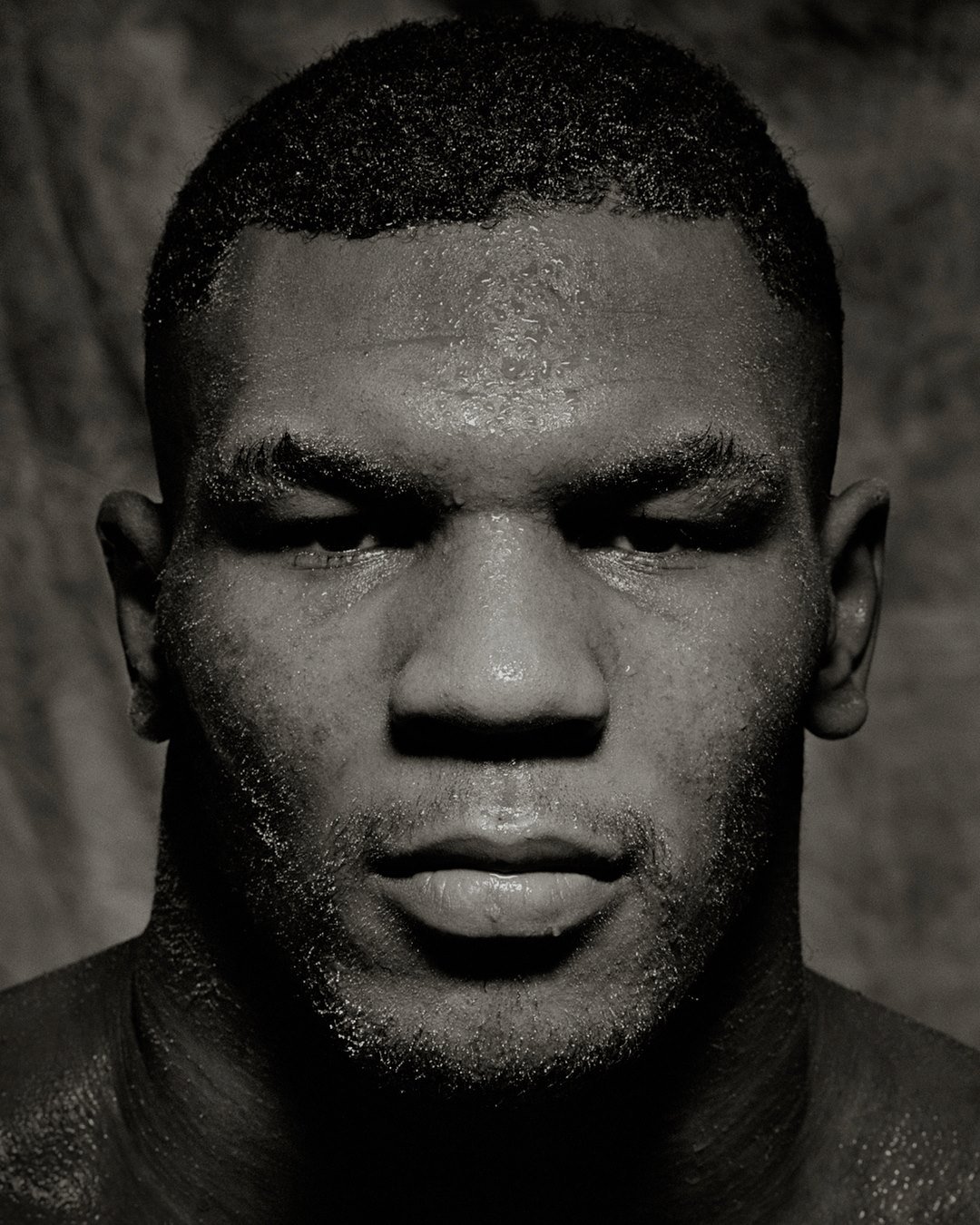

Albert Watson: The editorial assignment: “We’d like you to photograph Mike Tyson, up and coming boxer. He’s 18, but he’s slated to become a big name in boxing. And we’d like you to photograph him, and he’s in the Catskills. You have to drive up there and photograph him.”

George Gendron: Who is this for?

Albert Watson: Rolling Stone.

George Gendron: Rolling Stone, okay.

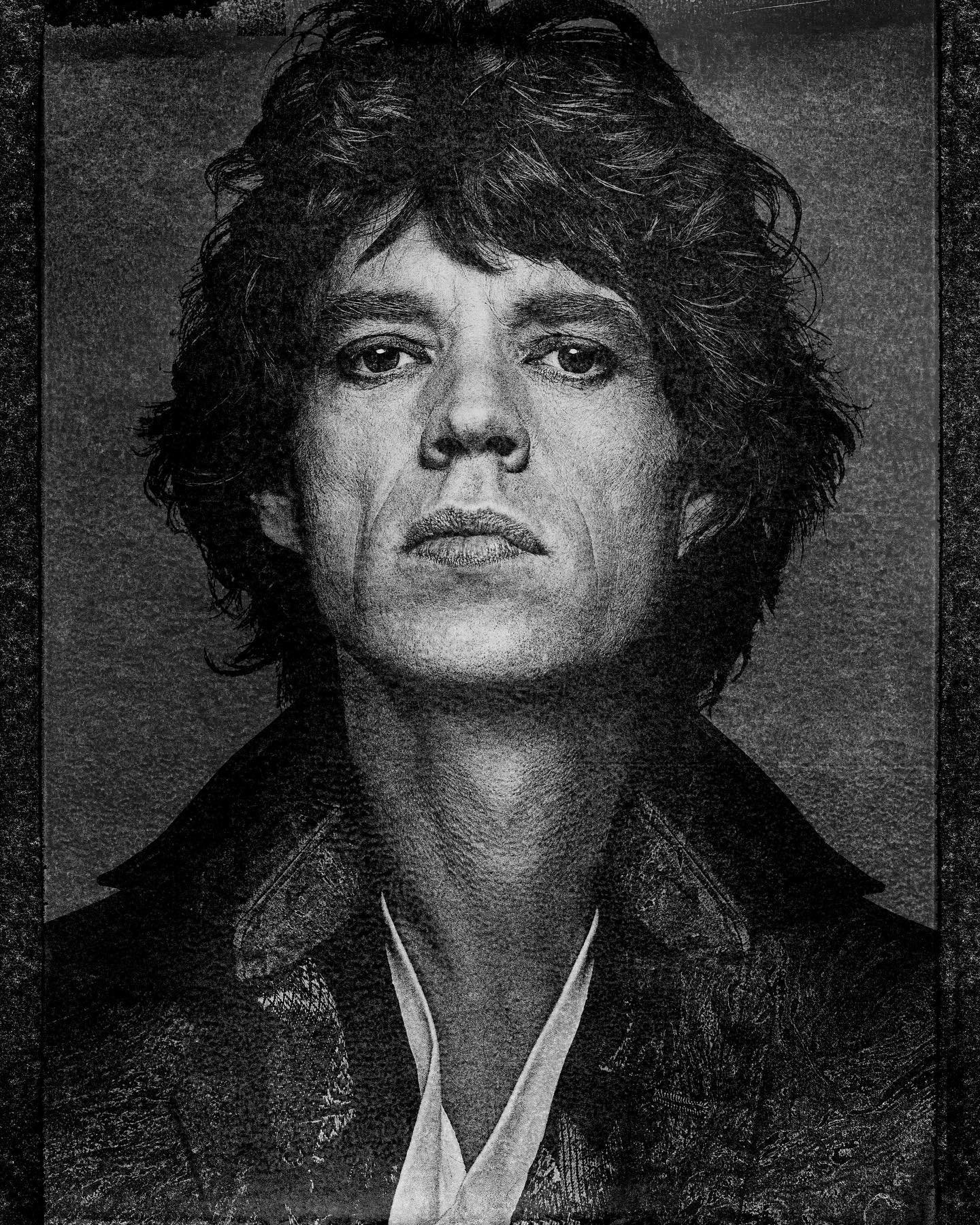

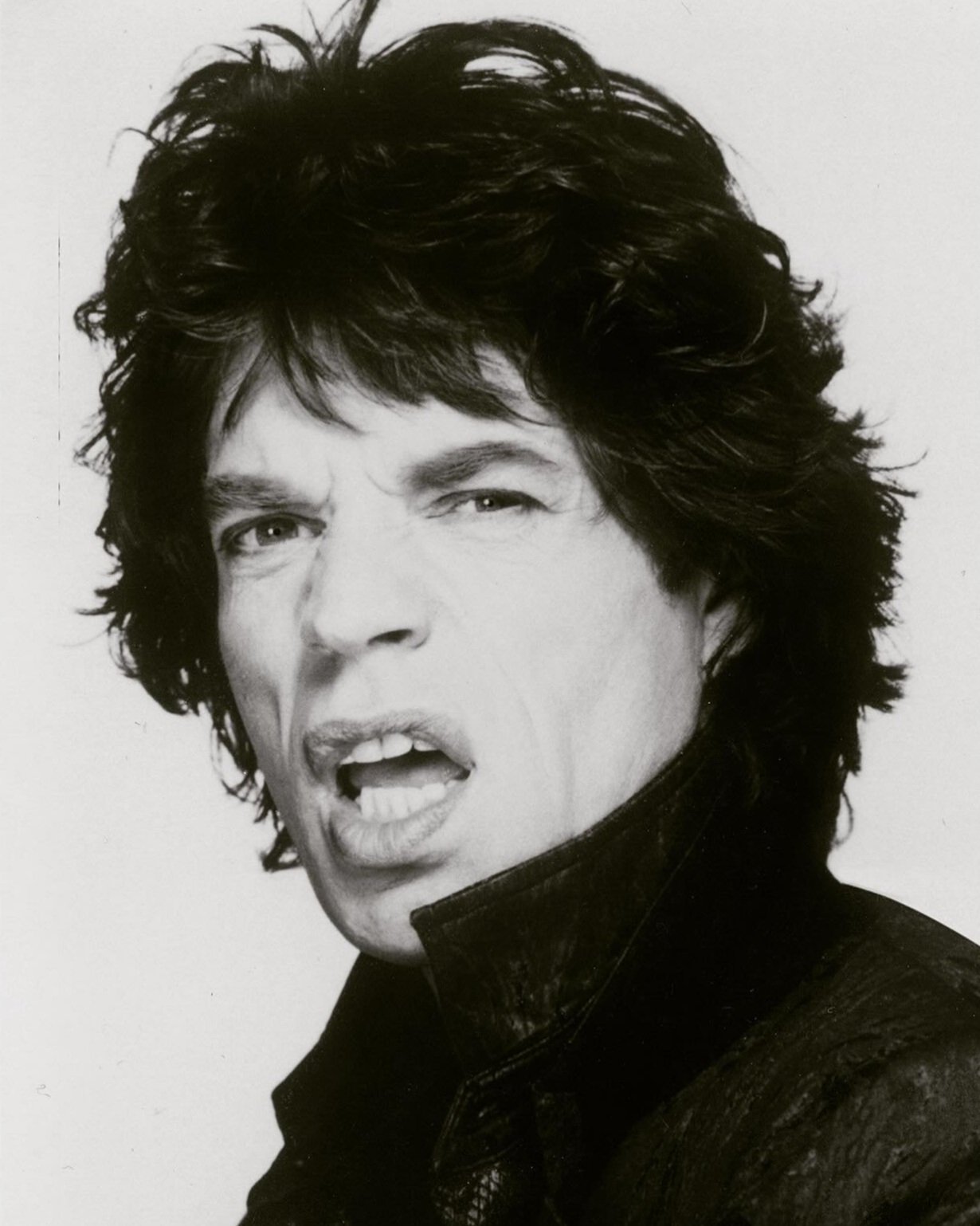

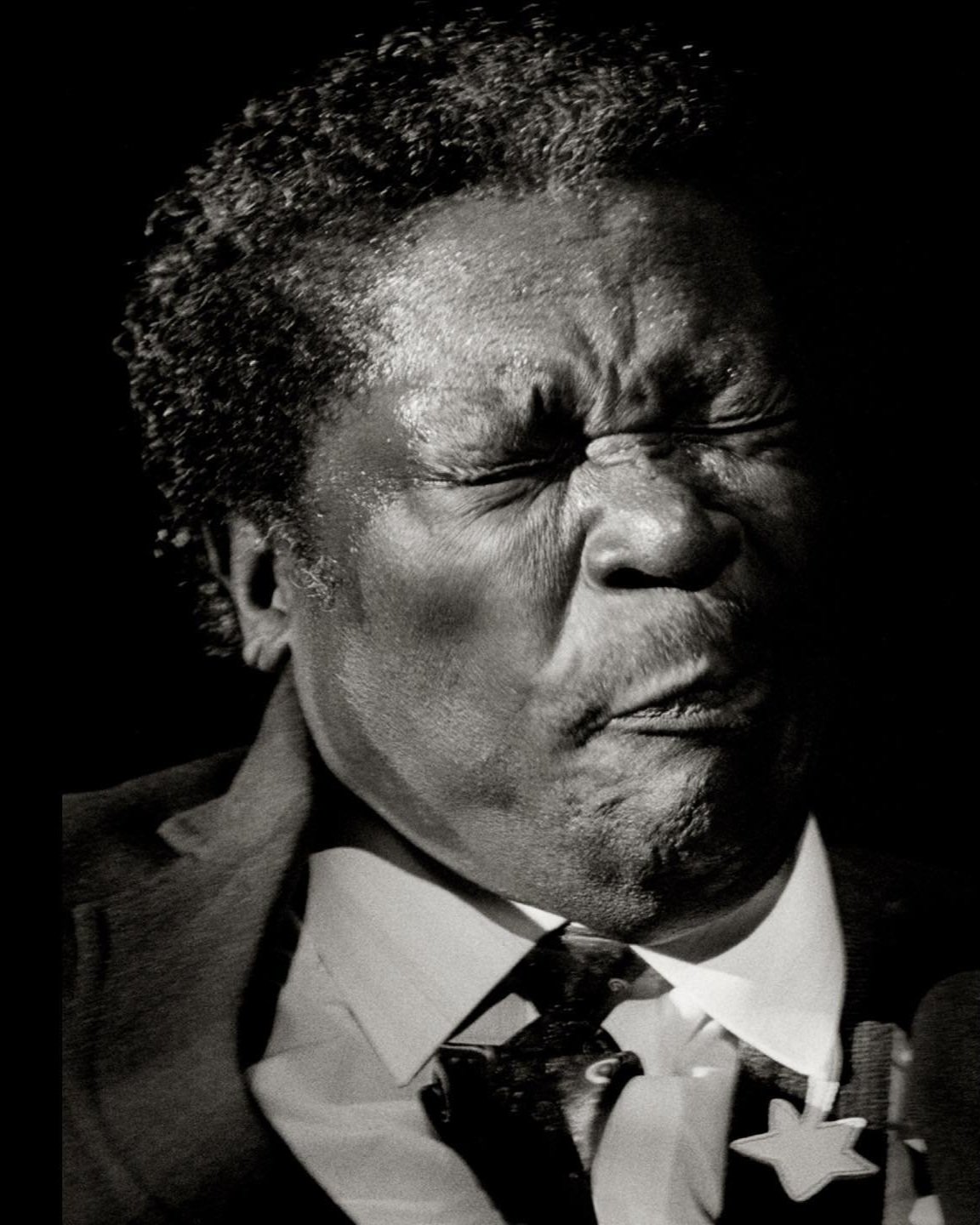

Albert Watson: So, that’s how the commissions are done. I shot for that issue, which was the 25th anniversary issue, which we did the cover for called the “Heroes of Rock and Roll.” And every photographer was allocated a certain number of people to photograph. I got Mick Jagger, Chuck Berry, and BB King. They asked me to photograph Graceland. And I photographed Elvis Presley’s gold lamé suit, which is the one they put on the cover.

And a lot of these things were different kinds of commissions. You had great freedom. They just expected a great shot of Mick Jagger, or something interesting of Mike Tyson, or BB King. And I suggested to them that I photograph him in concert. So I went up to Connecticut where he was playing and I did concert footage.

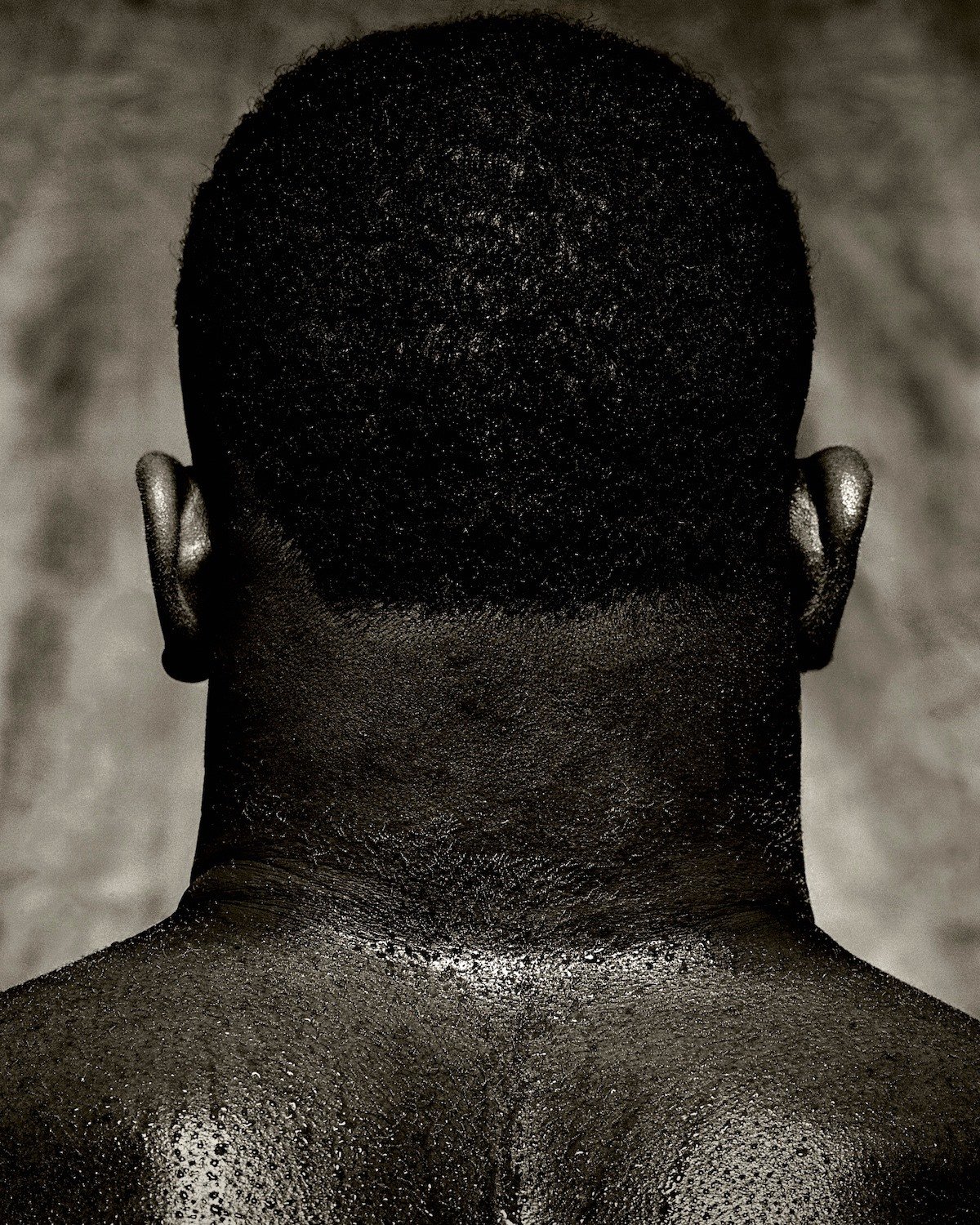

George Gendron: Albert, for younger listeners who never saw the Mike Tyson cover, explain that shoot, because that was brilliant.

Albert Watson: I don’t think they used it on the cover because at that point, Mike Tyson was a big-ish name—he was an up and coming name. So the Mike Tyson shot, basically, he had an amazing physique, and he was easy to photograph. I did a portrait of him, and just towards the end, I got the idea—because my father, who was a boxer, had once said, “A really good boxer has a really good, strong neck. And if you have a good strong neck, there’s less chance that you’ll get knocked out.”

So I asked Mike to turn around and I photographed the back of his head with his neck. And he’d been working out, there were water droplets in his hair and sweat on his neck, and I did it as a silhouette from behind. And it went on to become a well-known shot because, strangely enough, you recognized it as Mike Tyson from the back.

George Gendron: Yes, I remember that.

Albert Watson: And as time went on, European magazines picked up that shot and began to run it. And they ran it as a cover. So at that point the shot became very famous.

George Gendron: That comes back to your emphasis on the concept.

Albert Watson: Yes, sure. An idea. In the same way that Harper’s Bazaar, when they asked me to photograph Alfred Hitchcock, they asked me to photograph a goose. Because he was giving a recipe for a goose for the Christmas issue of Harper’s Bazaar to the magazine because he was a gourmet chef.

And they asked me to photograph him holding a plate with a roast goose on it. And that’s when I said to them, “Isn’t it better that we take a plucked goose and he’s holding it by the neck like he strangled it himself? It seems more Hitchcock. And I can also put some Christmas decorations around the neck of the goose to make that a little bit more interesting because it’s a Christmas issue.”

And the magazine loved that idea. But that’s “concept.” Also, for a young photographer you’re just happy to get a damn job. So in the case of Alfred Hitchcock holding the plate, in the end I would have tried to get it together to have the plucked goose with the head and all of that, as well as the plate, if they’d insisted on it.

But luckily enough, they said, “We just love the plucked goose! Forget the plate.” So I was able to concentrate on that. Graphic design training was part of what that was. In other words, it’s concept training. And I’m not saying that every single damn thing has to have a brilliant concept behind it. It comes in handy once in a while.

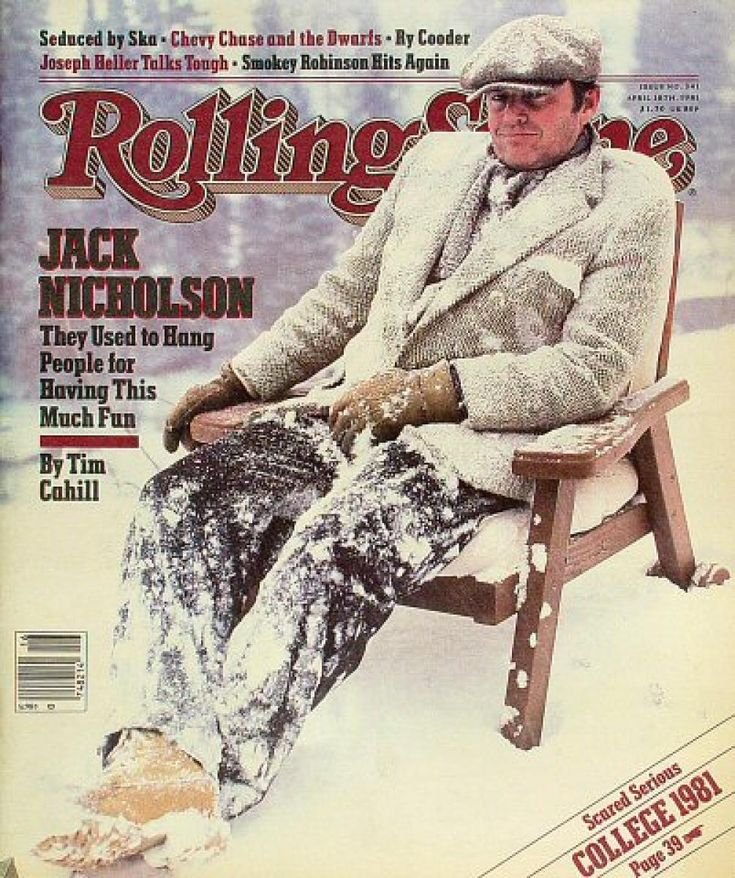

George Gendron: But a lot of your shots—one of the most-photographed actors in Hollywood is Jack Nicholson. And I think my favorite photograph of Nicholson ever taken was a Rolling Stone cover you did—it might have been your first Rolling Stone cover—and you photographed him up in Aspen. It’s snowing. He’s sitting outside covered with snow. And you captured that Jack Nicholson shit-eating-grin that he gets, that little boy grin.

Albert Watson: It was taken in the garden of his house in Aspen. I turned up in the morning at the time that we were given and he answered the door and he was like in kind of a rumpled t shirt with shorts with his hair all over the place.

And he said, “Who the hell are you?”

And I was there with my assistant and I said, “Well, we’re here from Rolling Stone.”

And he said, “What for?”

I said, “To photograph you.”

And then he was like, “Really?” And he said, “God, that’s right. That’s today?”

I said, “Yeah, it’s today. We came from New York.”

And then he said, “Oh, you’d better come in. Do you want a coffee?”

So it was nice. And then just as we came in, we arrived, he looked out the window and he said, “Oh my God, thank God.”

And it started to snow. Aspen had a problem because they didn’t have enough snow. And Aspen without snow was not good. And it just started to snow heavily and he was just jumping up and down. He was like a kid with the snow. And we then went out in the garden, he put on a jacket and a scarf, and his hat, and he went out in the garden and he was sitting there.

And I said, “I need a little bit more snow to make sense of it.”

He said, “Sure.”

Then he went into the house, and his housekeeper had arrived. And he said to the housekeeper, “Cook these two boys some bacon and eggs and give them some coffee”—which they’d already given me—“and I’ll go out and sit in the snow.”

So I actually sat in his kitchen, having breakfast, while he’s outside sitting in that chair, just quite still. And I went out a couple of times and said, “I’m almost finished!”

He said, “Don’t worry about it. It’s fine.”

And then I went out. And of course, by that time he had quite a lot of snow on him and the snow was lying in the ground a lot and so on. And I did that shot. That was the scenario behind it.

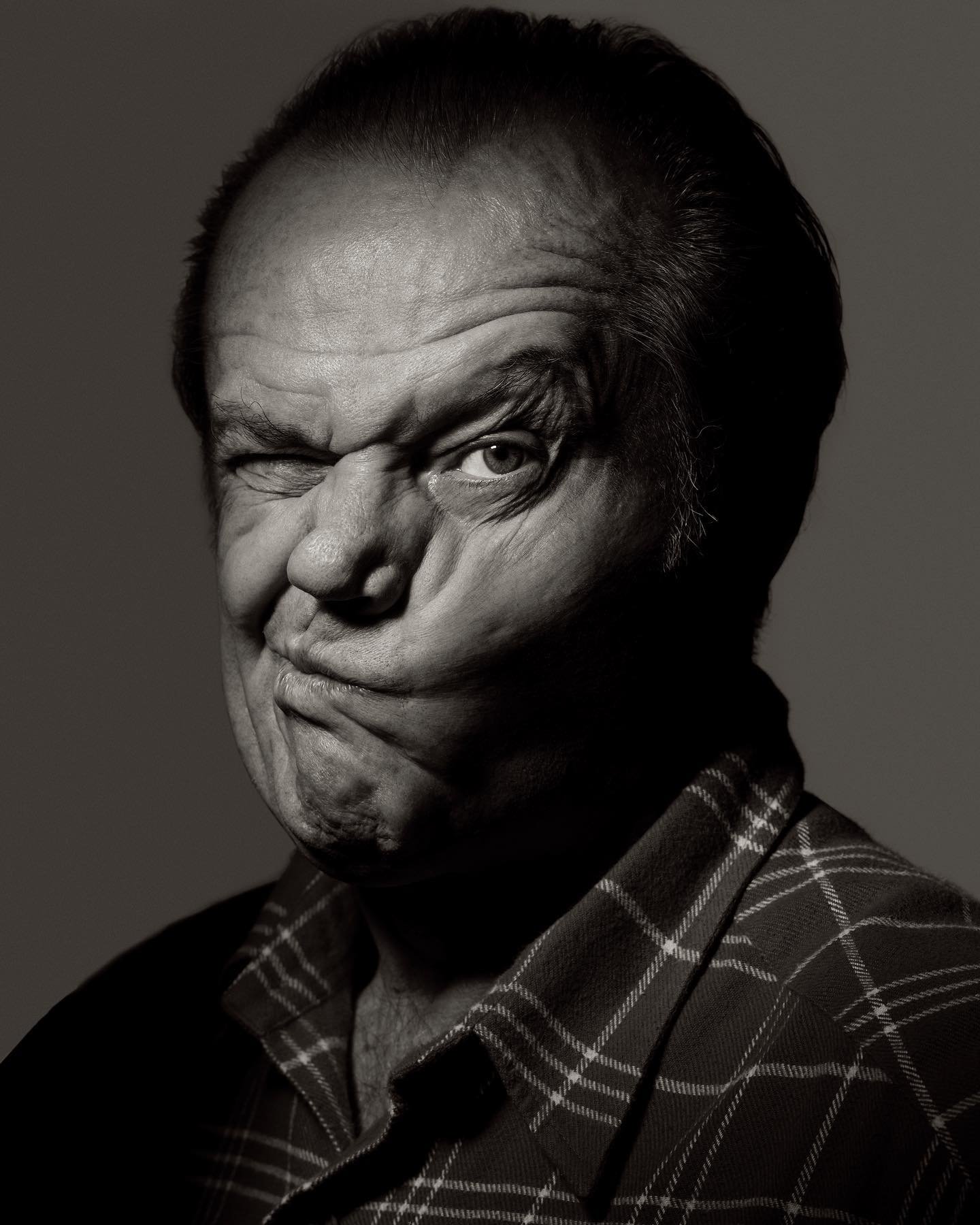

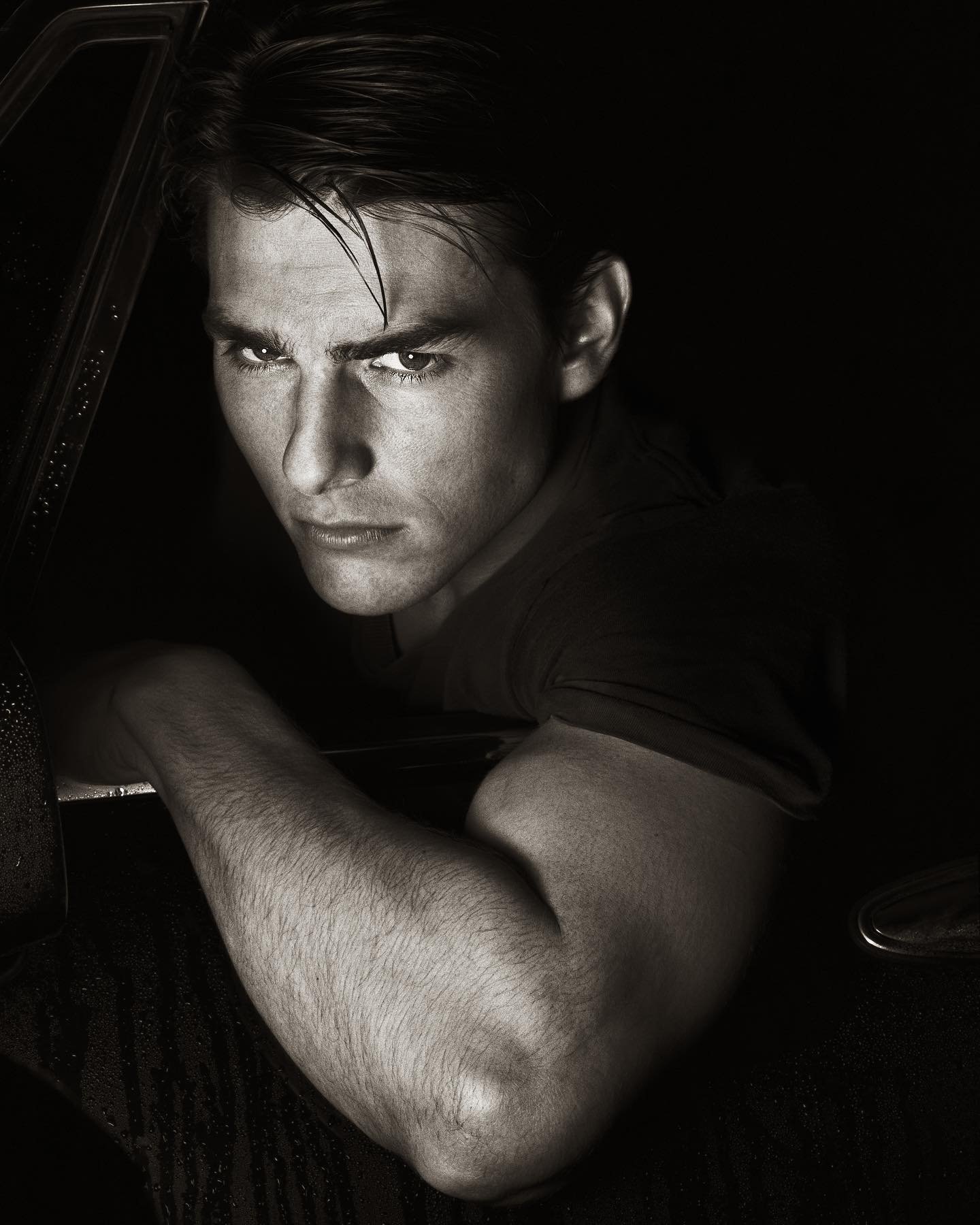

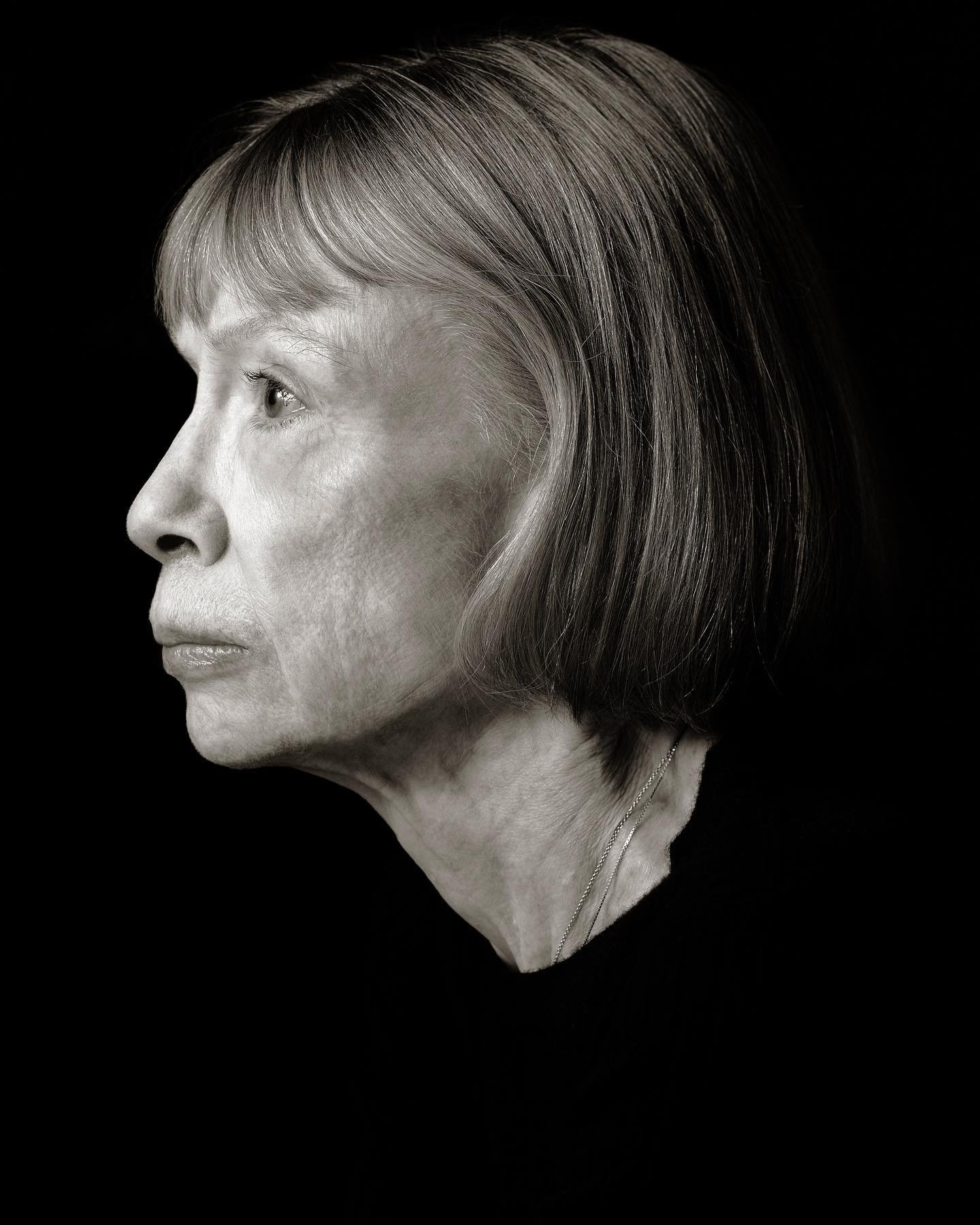

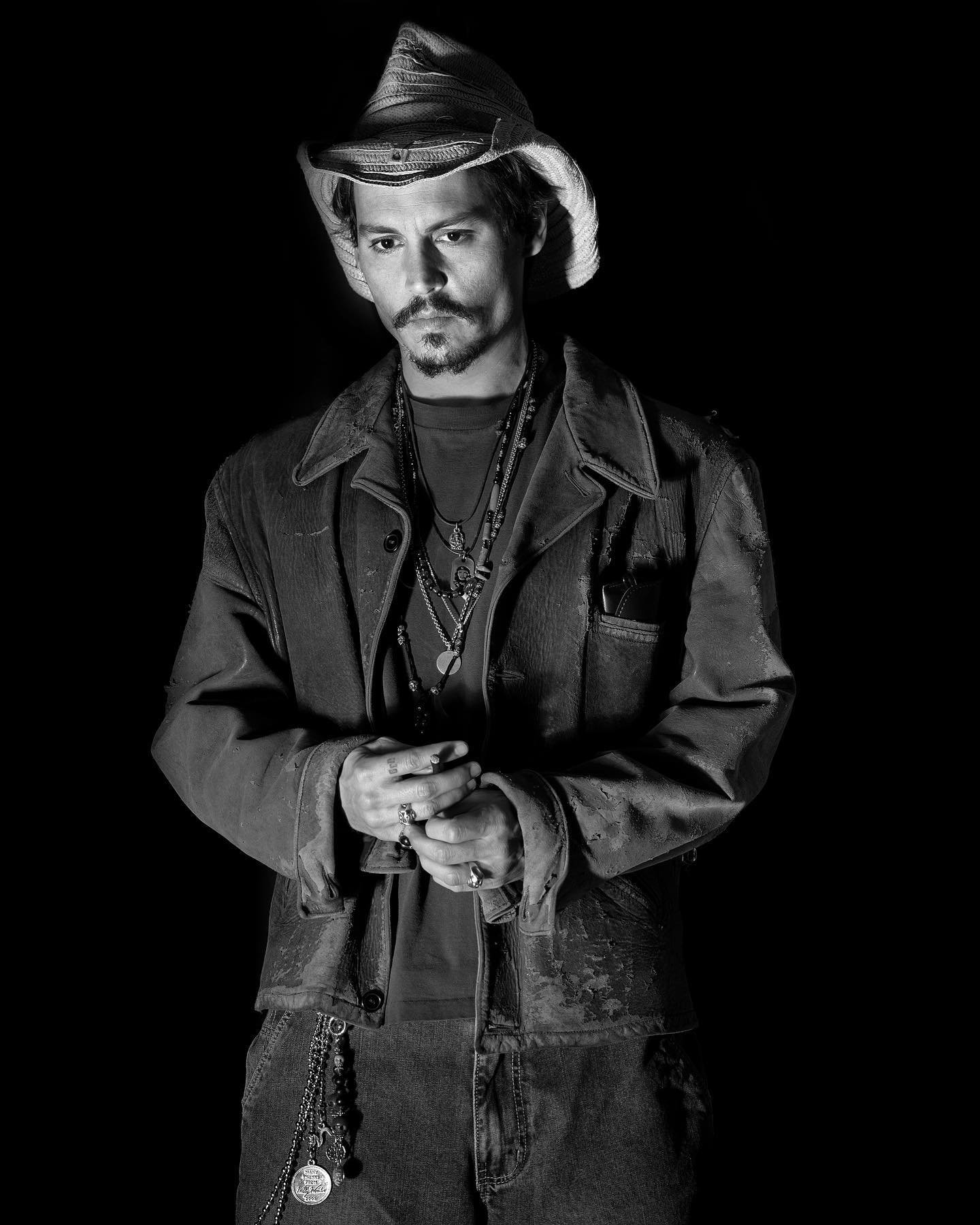

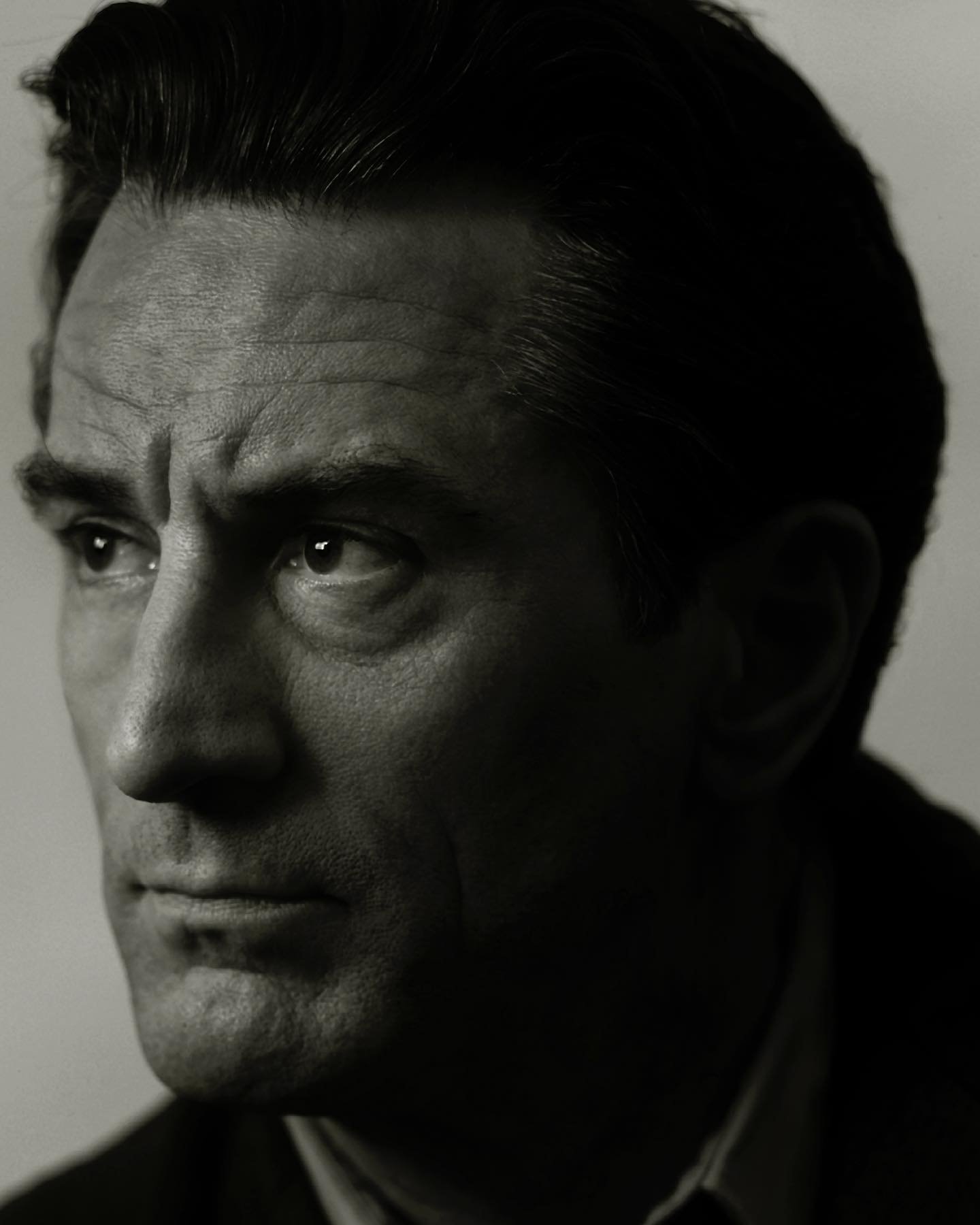

Albert Watson x Hollywood

George Gendron: That was a great photograph.

Albert Watson: I’ve photographed him several times. And I did the multiple-mirror shot—which is, I think, equally well-known—where you see him blowing a smoke ring. And that was a “concept” shot.

When you set up eight mirrors like that, and Jack Nicholson’s face suddenly appears on eight mirrors in your camera at the one time—the concept—you can do that shot and he can come in and you can get them out of there in five minutes, and you have the shot. In other words, when you have a concept like that, then. It helps you create a powerful image that’s original.

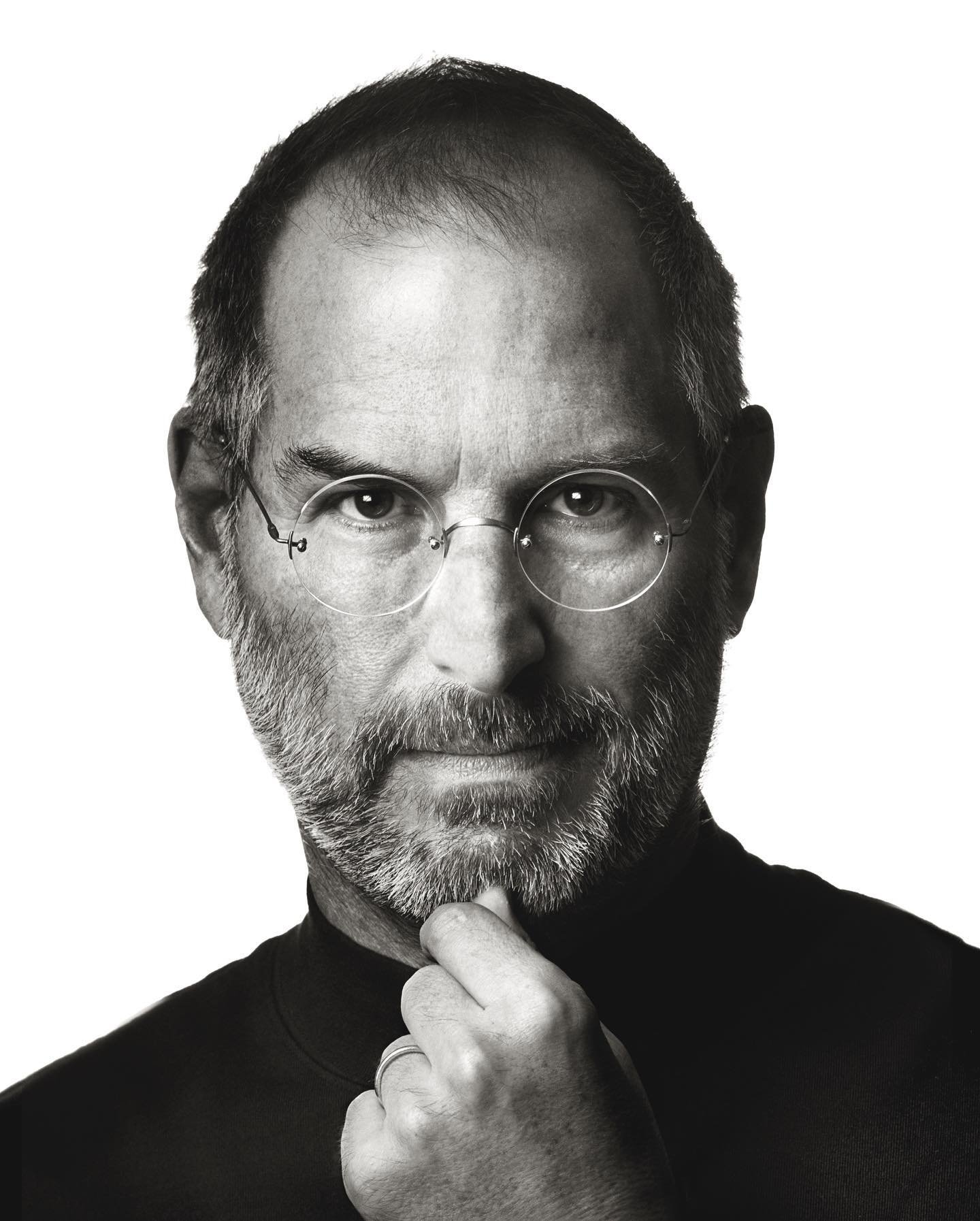

George Gendron: That came in very handy with somebody that we were very close to at Inc. Magazine, Steve Jobs, who notoriously hated seeing images of himself and hated being photographed. He detested it. And you ended up with an iconic image of him that was everywhere when it was announced that Steve had died.

Albert Watson: They used that as the obituary picture, Apple did. And he loved that picture. He told me he loved it. And of course, I thought he was just being nice, you know, like, “Oh, I’m glad you like it.”

But then, apparently, he kept that Polaroid on his desk and he said, “When I go, use that picture.” And then they called us the day he died for the picture and then later that night it popped up in my phone that he had died.

George Gendron: When I mentioned to people that I was going to be having a conversation with you for the podcast, everybody said, “Man, if you have never been to his studio, when you go, you have to ask him to see his diaries. You will not believe them. You’ll think they’re fiction.” And I said, “Why?” And they said, “Because nobody alive can get that amount of work done.” And when you and I were talking, you said, “Well, this is not a typical day, but let me tell you about one day that started in Paris and ended in LA.” You started with a shoot with Catherine Deneuve. Can you tell that story?

Albert Watson: It started in Paris, ended in LA, but by the way, there was an advertising job in New York in between.

George Gendron: So how do you pull that off?

Albert Watson: I think if I did it now, that might be the last job of my life. I wouldn’t be able to do it now. And how did I pull it off? I slept on the plane. That’s how I pulled it off. Because the flight from Paris into New York was a Concorde flight. Three hours I slept on the plane. And then there was a flight, six-and-a-half hours from New York to LA. And I slept on that flight. So I did it by sleeping. That was the secret behind it.

No, but it was a lot of stress. And to do an advertising job after, you know, getting up in Paris at six o’clock in the morning to set up the studio for Catherine Deneuve, and then do an advertising job in New York, and then get to LA and so on to do that is not...

George Gendron: So you go from Catherine Deneuve to, I believe, your LA shoot was with Frank Zappa and Beefheart?

Albert Watson: Yes. Captain Beefheart.

George Gendron: Captain Beafheart. Yes.

Albert Watson: Who I photographed a couple of times.

George Gendron: You and I were talking about your studio and you use that as a vehicle to talk about how your business—the business of being Albert Watson—has really changed, thanks to your son. Thanks to your photography and your son. But that’s an astonishing story. Can you tell the story about your son coming to you, after he comes to work for you, and hiring you for two days?

Albert Watson: Well, I think the idea was that people, over the years, were asking, “Can we buy a shot from you?”

And I would say, “Sure.”

And then they’d call me three months later and say, “What happened to the shot?” Sometimes a month later, sometimes six weeks, and sometimes three months.

And they said, “I never got that shot. I’m happy to pay you for it.”

And basically, I was shooting all the time. I love printing in the dark room, but just to get to that print in an evening to print a series of orders for prints, it took me forever. And I did do it. It wasn’t well organized, particularly. And my son came on board. He was already a very successful journalist. He was the head editor at Associated Press for sports. And I offered him a job and I was so happy he took it. And he realized early on that there had to be an idea of booking me to get into the dark room and say, “Right, you have a job. Here’s the money. Get into the dark room and print.”

George Gendron: So he was paying you to print your own images.

Albert Watson: He wanted me to allocate the time to make a transition from working commercially and editorially. To make a transition that I was happy about. I was not forced. I wanted it. That’s why I brought him in.

And to make that transition into getting into the darkroom to print, making prints, and selling prints. So, at that point I would say that was 5 percent of our business, because everything was geared towards shootings and making money from shootings.

George Gendron: And you had a huge studio back then, right?

Albert Watson: Huge studio. We had 14 people working for us. It was a big operation. I loved it. We were shooting all the time. We had a really beautiful studio. We had a building that was 26,000 square feet. The apartment was 13,000 square feet and the studio was 13,000 square feet. So I could work until 10 o’clock at night. I just had to go up the stairs and I was in my apartment. It was a workhorse of a place.

George Gendron: So, fast forward to today, you downsize your studio, and what percentage of your revenue today comes from prints?

Albert Watson: It’s probably closer to what I said the other way around. I think now it’s about 70/30 now. I don’t have exact figures on that. But, obviously, from time to time we still do some big jobs. Big jobs come in—it can be a big project with the city of Rome, or it can be a Pirelli calendar—a big job comes in so, therefore, the income is still very good from photography.

“You say you don’t want to put all your eggs in one basket. To do what I did, all the eggs were in one basket. And that was the photography basket.”

George Gendron: You’re also legendary for personal projects. Las Vegas, which becomes the book, Strip Search. Morocco, an astonishing story, if you want to tell that.

Albert Watson: They wanted to do a book on Morocco. They wanted to call it Morocco. I talked them into calling it Maroc, which is the French name for Morocco. It just made it a little bit more interesting than just putting Morocco on it.

And it’s a very tricky thing—let’s say you were asked to do a book in Paris. Then you’ve got to photograph the Eiffel Tower. If you do a book in London, then you’ve got to do Big Ben. If you do a book on Rome, you’ve got to do the Colosseum, and so on. So you’ve got to do Morocco, then you’ve got to do camels or something. So to do an intellectual book on something like that, you have to be very careful. You have to have a plan. You have to do a lot of research.

That was the last big job I did on film. You know, a big job. I did lots of jobs on film after that, but this was a bigger job. And it was sponsored by the then-Prince, who was shortly to become the king of Morocco. And he was involved in the project and very supportive. And it was great fun to do. He said, “I have two jets. If you need one, why don’t you just fly all over Morocco in my jet? It’s much quicker for you to do that.” So the project was well-financed and well put-together. We organized it well, and we had very good support. So it was kind of a dream project.

And the interesting thing that happened at the end of it, they had done a book the previous year, a photographer had done Cuba and this was meant to be part of the series. And when I was working on the post production, the Cuba book came out and I thought it was terrible. Not the photographs, but I thought the production on it was horrendous. It was a kind of a cheap paperback, and it was not good quality. The printing was not good quality. I was shocked.

And fees had already been allocated for me to do the project, so the only way that we could get out of it was we took our fee and put it into the book itself. So we turned it around. And instead of this being printed on a cheap lithographic system, it went on a 10-color press. It went on a press that had a 4-color black and white, it had the four colors, and it also had two plates of varnish.

So we put the money back into the project, didn’t make any money from the project at all, but we ended up with a very well done project. Even the cover was what they call a French-fold cover, which is folded back on itself so that it doesn’t tear at all. It was actually a beautifully printed book, beautifully put-together. I did a lot of the design, but I didn’t do the typography. I had a very good typographer come in and do that.

George Gendron: Given the span of the kind of work that you’ve done, in almost every category of photography, you look at your career and how can you not ask the question, what advice do you have for a young person today who has discovered that “black magic” that you talked about the first time he or she picked up a camera, and wants to pursue a career in photography. Editorial. Commercial. What advice do you have for them?

Albert Watson: Well, that’s quite a difficult question, really, because are you prepared to give up just about everything? You say, you know, you don’t want to put all your eggs in one basket. To do what I did, all the eggs were in one basket. And that was the photography basket. So there’s a basket there labeled “photography” and all the eggs went in that basket.

I remember speaking with Peter Lindbergh once and he said, “What are you doing this summer?”

I said, “Oh, I’m doing this job, that job. And then I have to go to LA and do a movie poster.”

And he said, “But what are you doing for your holidays?”

And I said, “Oh, I don’t do holidays very much. I take a week off at Christmas. And sometimes if I’m lucky the first week in January.”

And he said, “You don’t take six weeks off in August? September? July?”

“Six weeks?” I said, “I’ve never done that in my life.”

And he said, “Oh, I can’t do without that. I need those six weeks to do no photography.”

And of course, I’d never done that in my life. I was kind of astonished that every year he took six weeks off. Six weeks! And you say six weeks—six times seven, that’s 42 days!

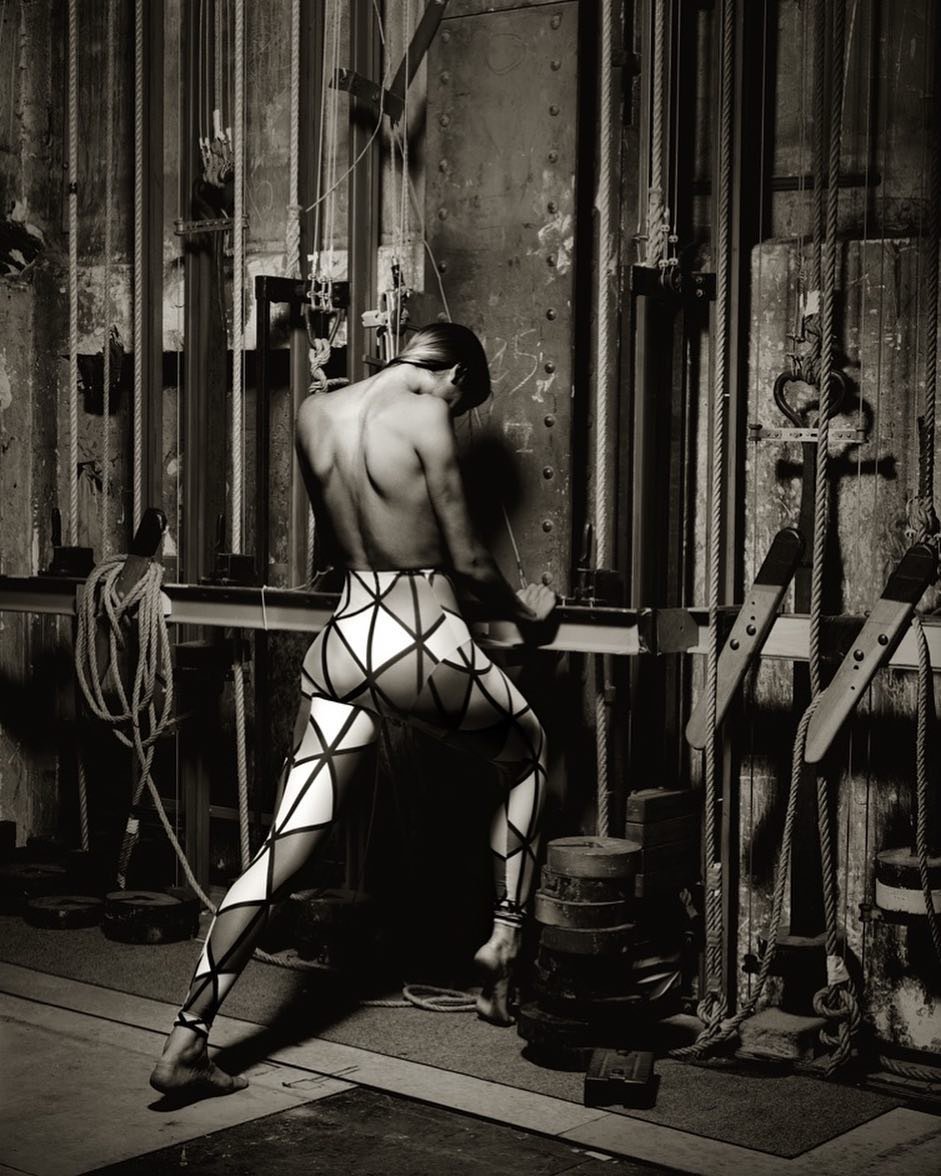

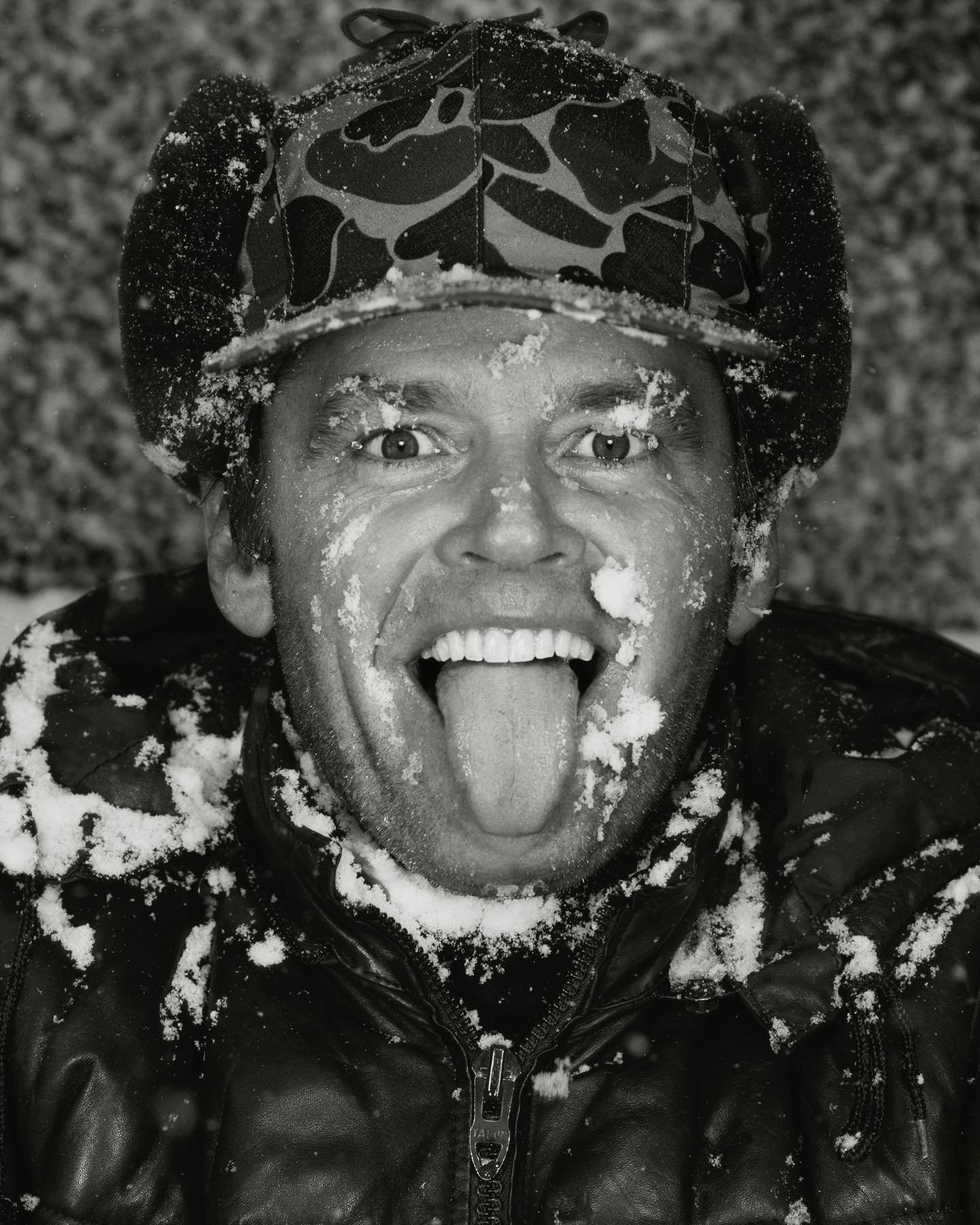

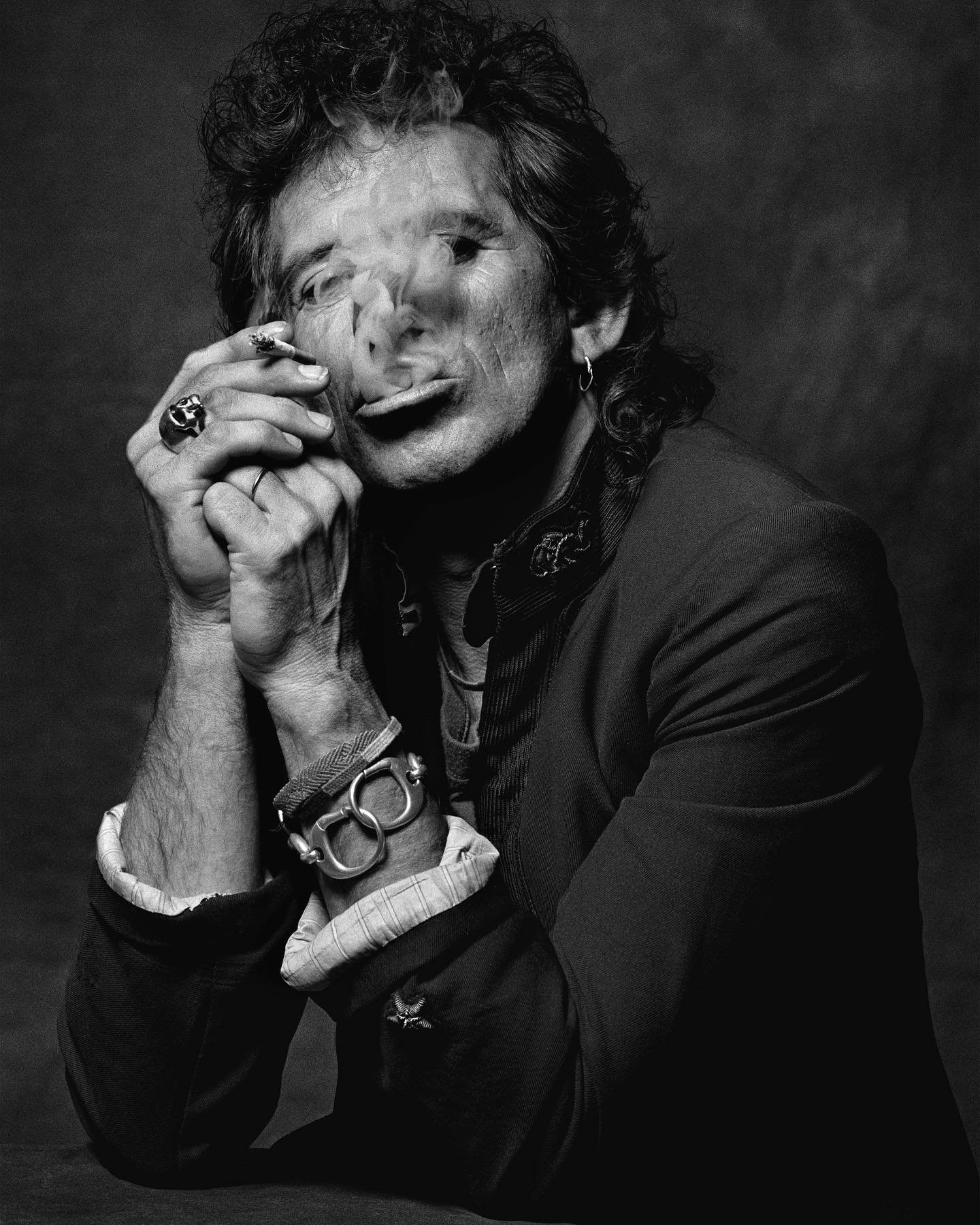

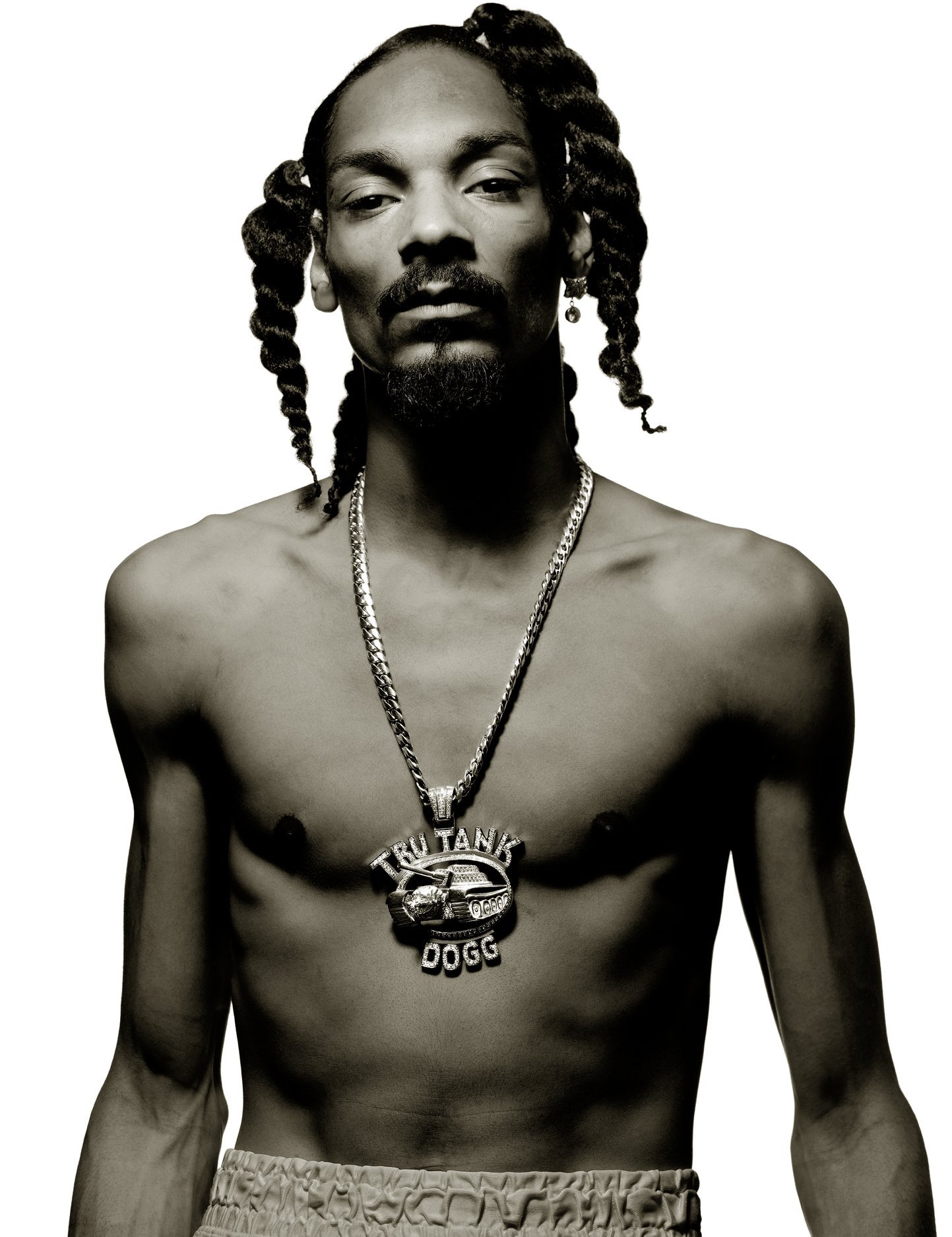

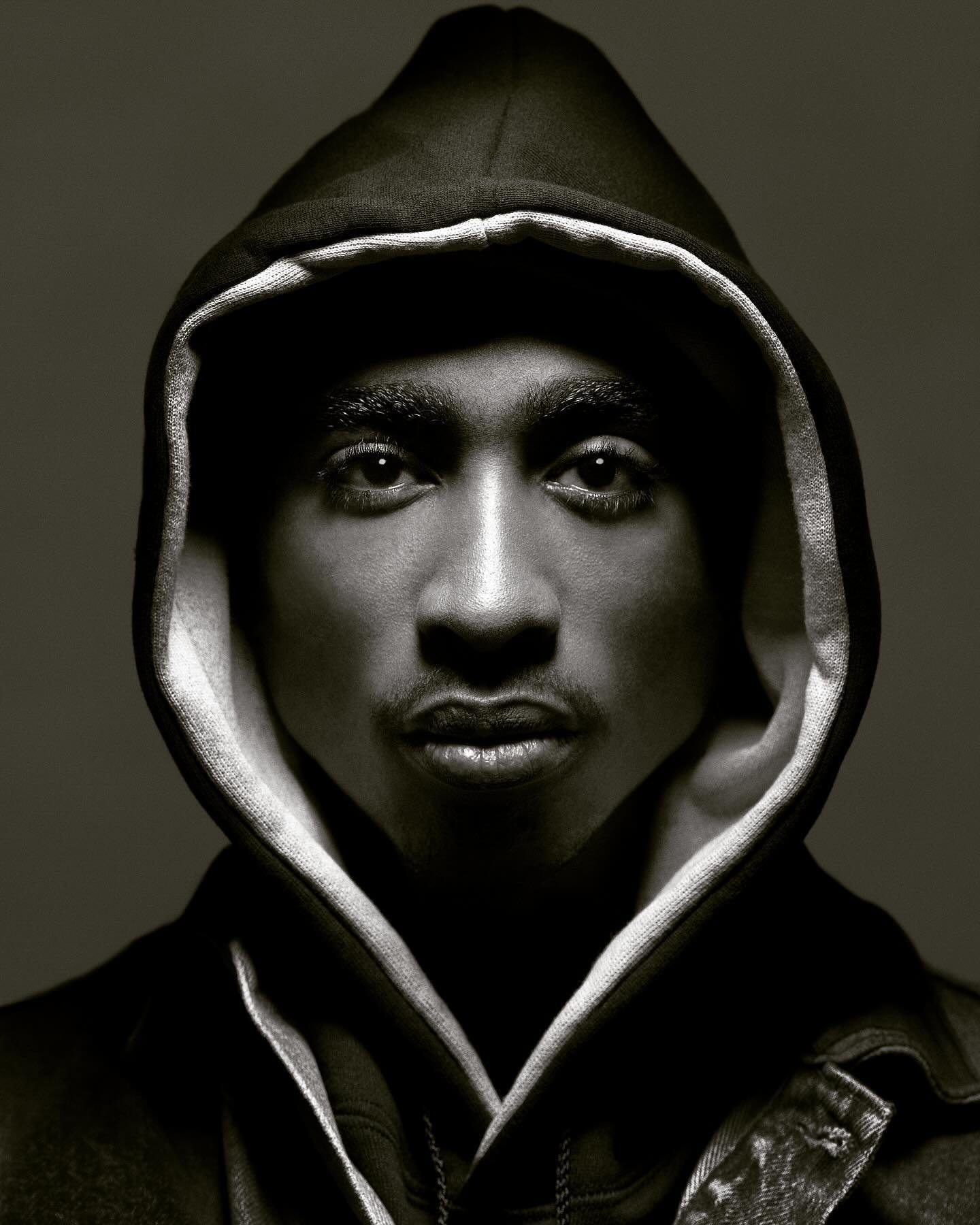

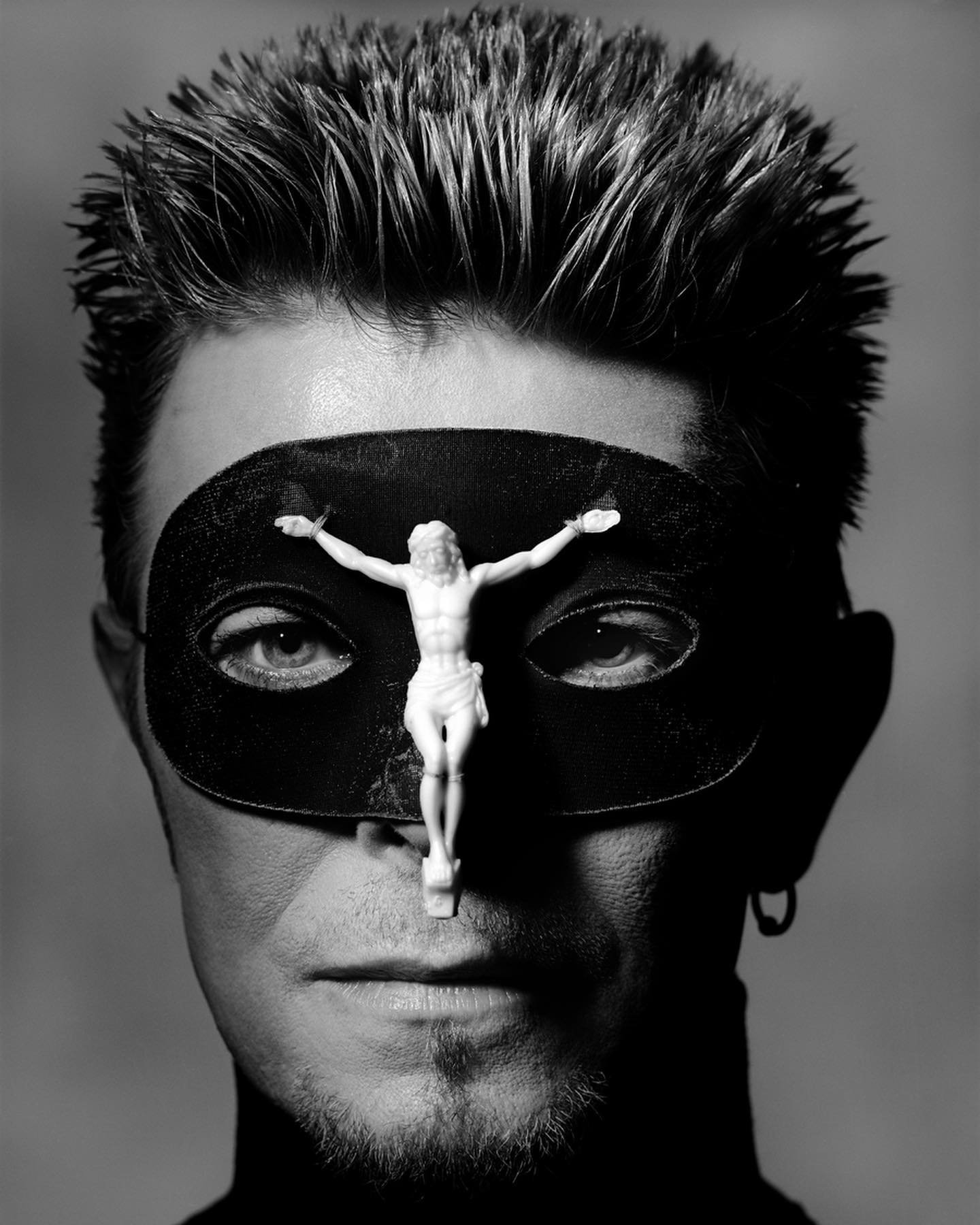

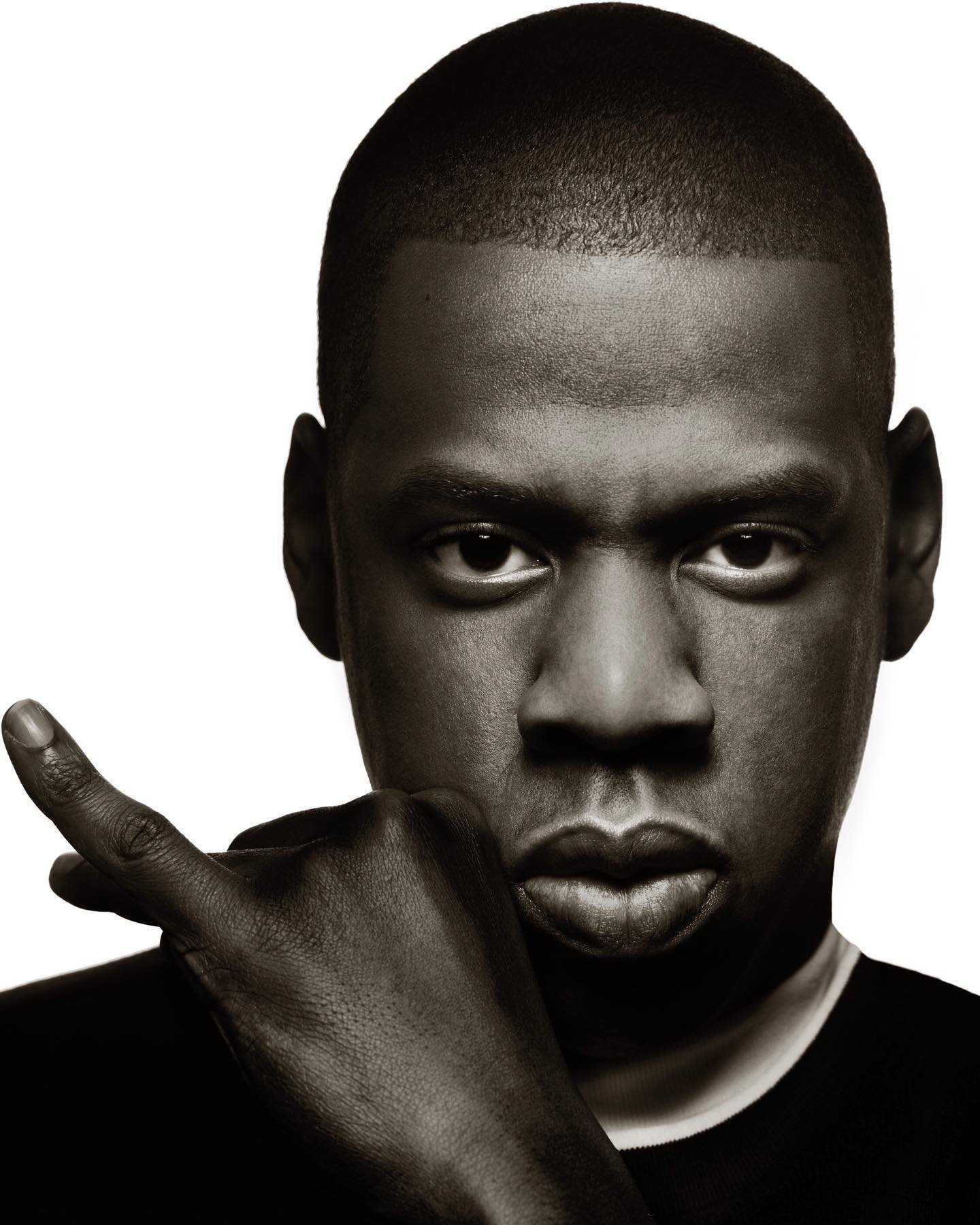

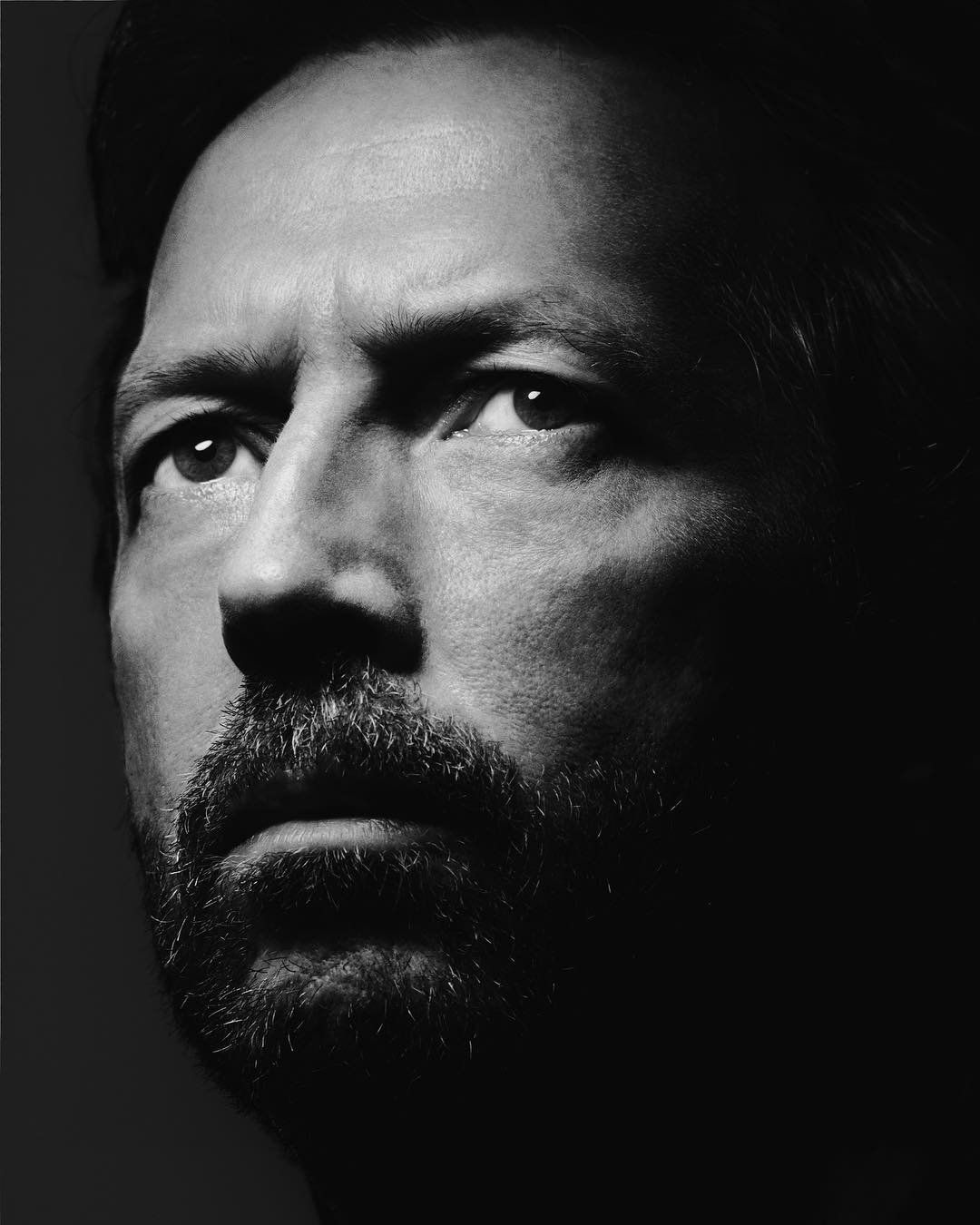

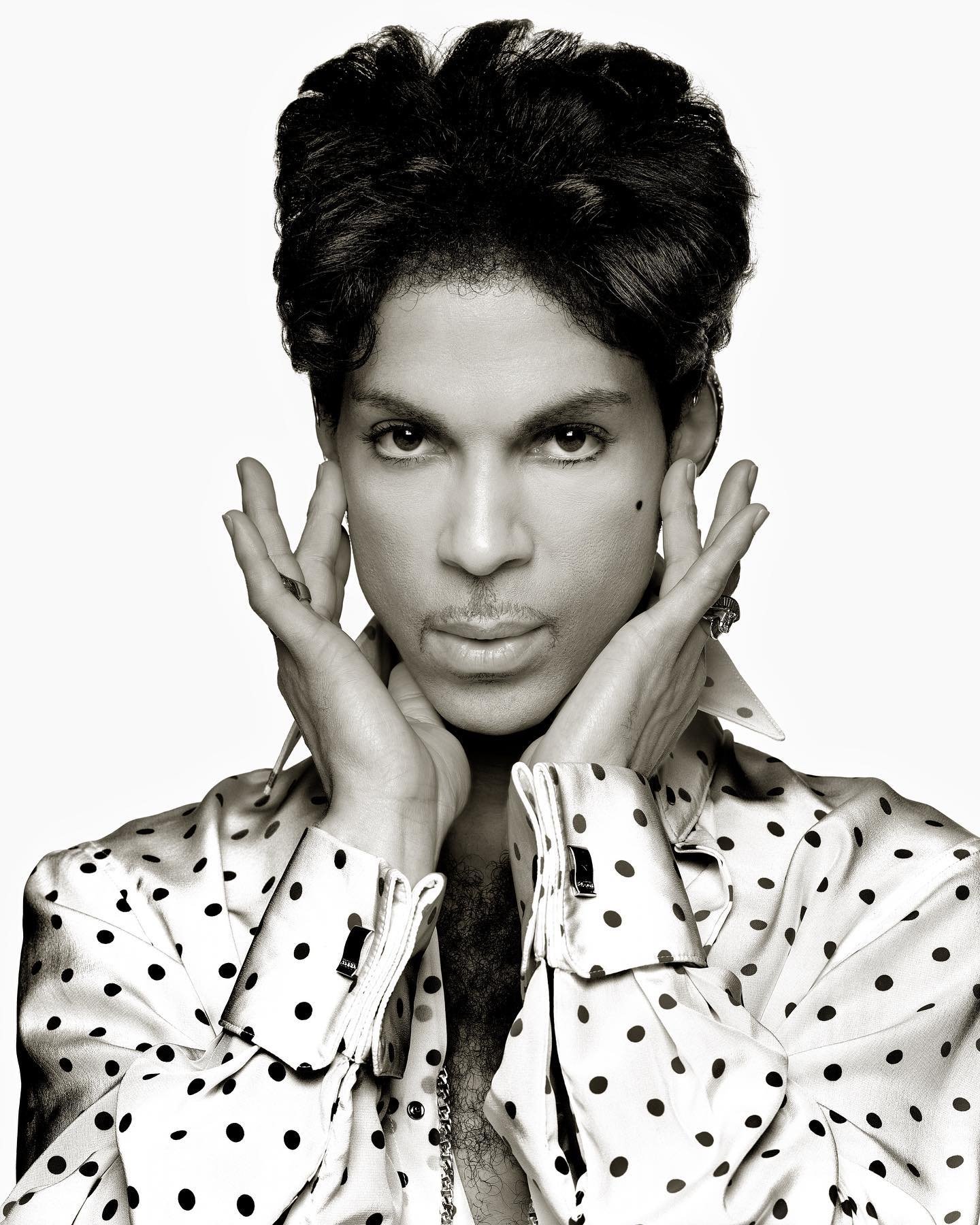

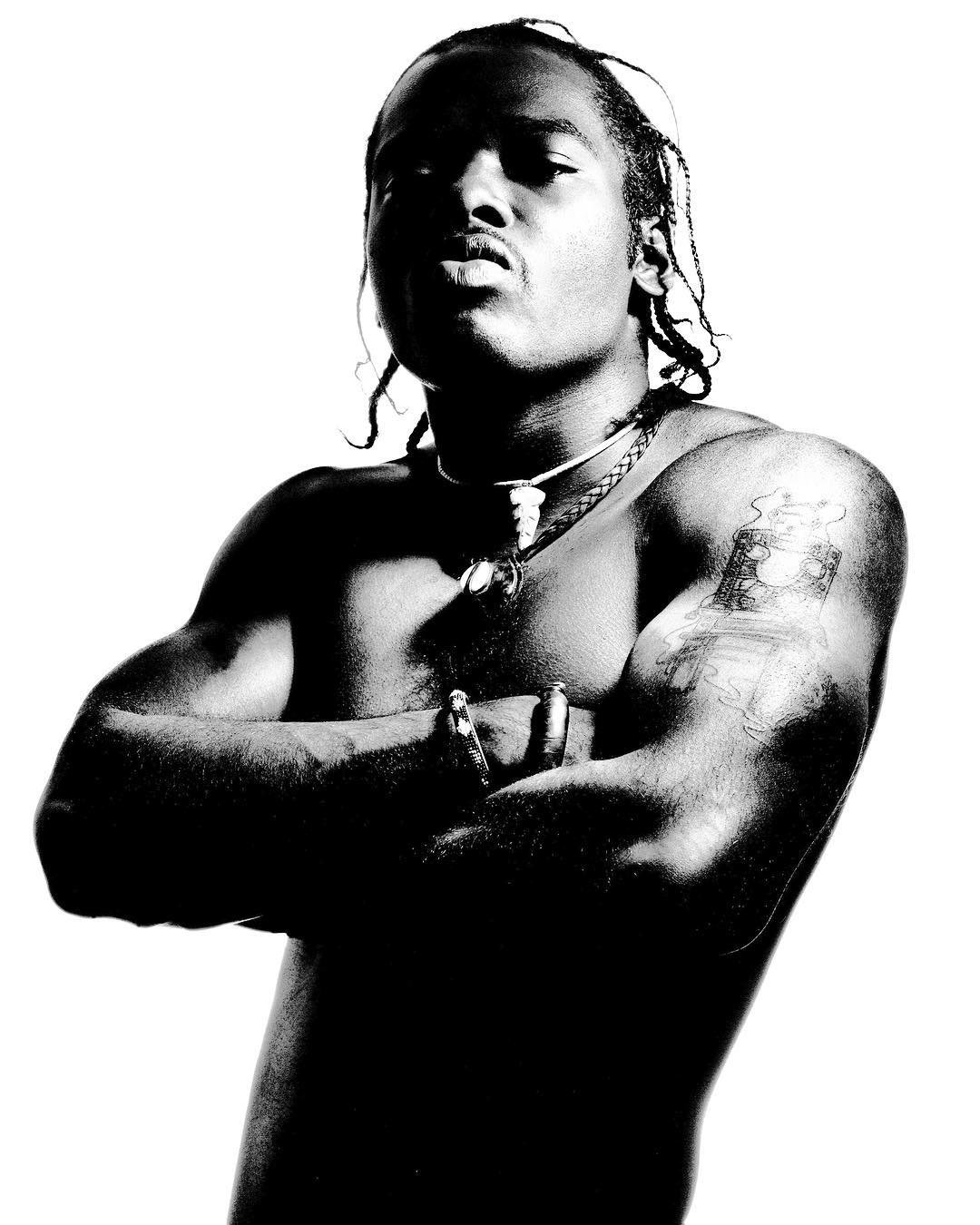

Albert Watson x Music

George Gendron: Where did this come from? You hardwired this way?

Albert Watson: I think part of your life, you’re pretty destitute and poor and worried about food for the family. When you’re destitute and worried about money year in, year out, year in, year out. And that goes on for 11 years. 365 times 11 equals a lot of stress.

So therefore, I almost never turned down a job. And someone would say, “Well, your son graduates from university tomorrow, are you going?”

And I said, “Well, I’d like to, but I’m busy.” You know?

As far as my kids were concerned, the bad news is your father’s not going to be there. But the good news is you won’t have a student loan program. You know? That’s the good news.

George Gendron: How did Elizabeth handle all this?

Albert Watson: I could never have done it without her. And I could never have done it out with the support of the whole family. But especially Elizabeth. She was the one that was always encouraging, and working, and loved it when I was busy, and helped me, and did the casting, and she was the agent, and booked in jobs, took care of all of the difficult stuff. And without Liz it would never have happened. It would never have happened. I might have been an art teacher back in Scotland or something without my wife.

George Gendron: Now, speaking of you and Elizabeth, I mentioned yesterday that I was absolutely enamored of your home on Warren Street, which I’ve never been to—I’ll just repeat one more time, Albert, you’ve never invited me—but I saw it in the pages of The New York Times real estate section when you put it up for sale in, I don’t know, 2016 or something like that. And what I loved about it was not—you know, there are a lot of lavish places in places like New York—but it looked as if every square inch of that home you and Elizabeth intentionally designed. And then I was ecstatic to hear yesterday when we were talking, you said, “Oh, we didn’t sell it. We took it off the market.”

Albert Watson: Yeah, well we didn’t because, you know, it’s 650 feet off the ground, and from it I can see the Hudson. I can see the East River, the Empire State Building, and the new Freedom Tower. I can see the Brooklyn Bridge and there’s a huge, 2000-square-foot terrace. And the problem was we couldn’t find anything that was as fabulous as that, really. That was the problem.

And, eventually, you come to the point where you say, “Why are you moving at all?”

And you say, “Well, I want to move to a bigger place, a better place.”

But it was already a big place. It was already 4,000 square feet, you know? With a terrace that was 2,000 square feet on top of that. It was enough. Enough was enough. We just didn’t sell it. We’re very happy we didn’t sell it. And right now, I’m just redoing it, actually. It’s going to be redone for the first time since we did it the first time. So it’s now going to be done again.

George Gendron: I can’t wait to see it in person [laughs].

Albert Watson: It’ll be spectacular. Very beautiful. A little bit more zen and Japanese looking.

George Gendron: What images of yours hang on the wall in your place?

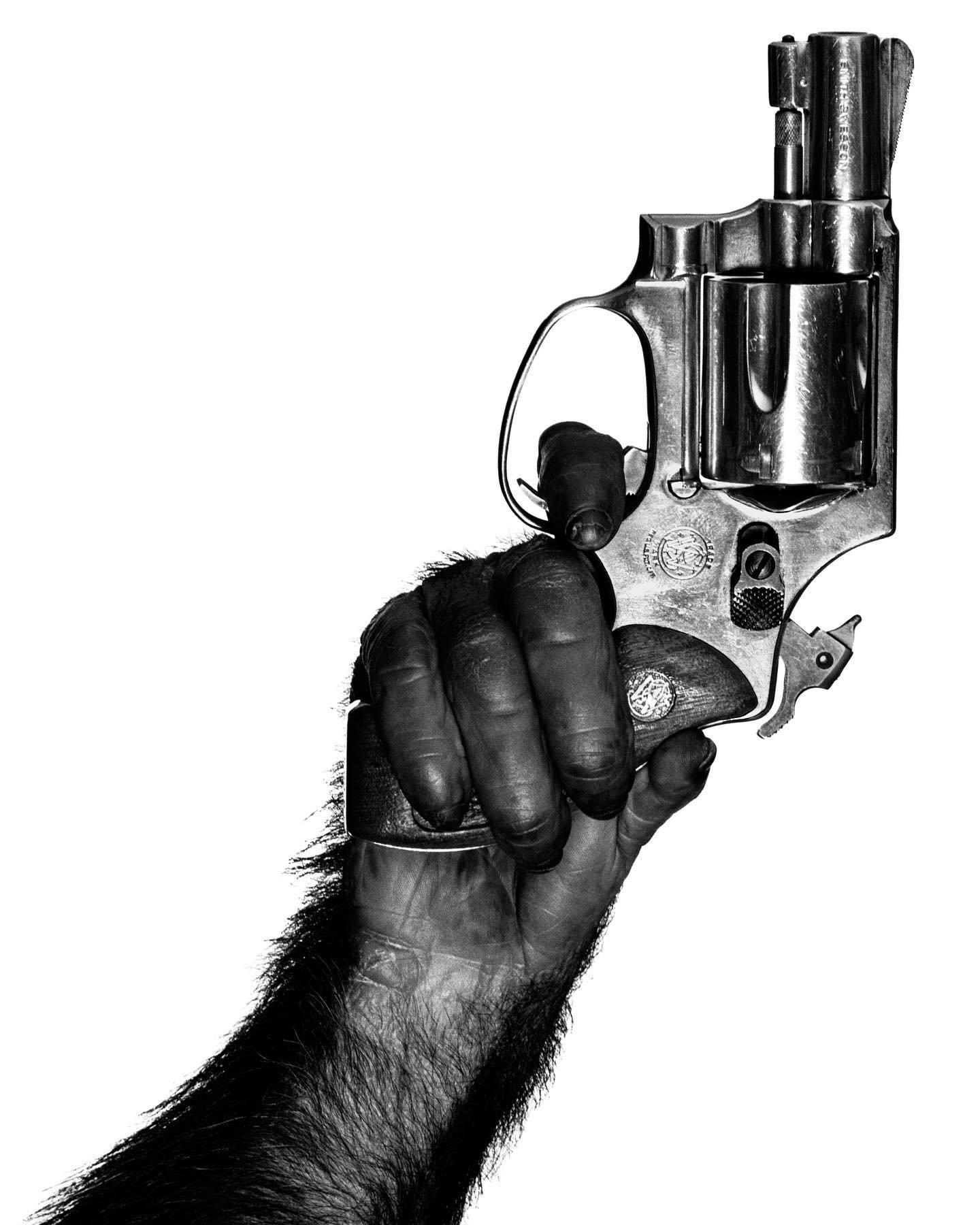

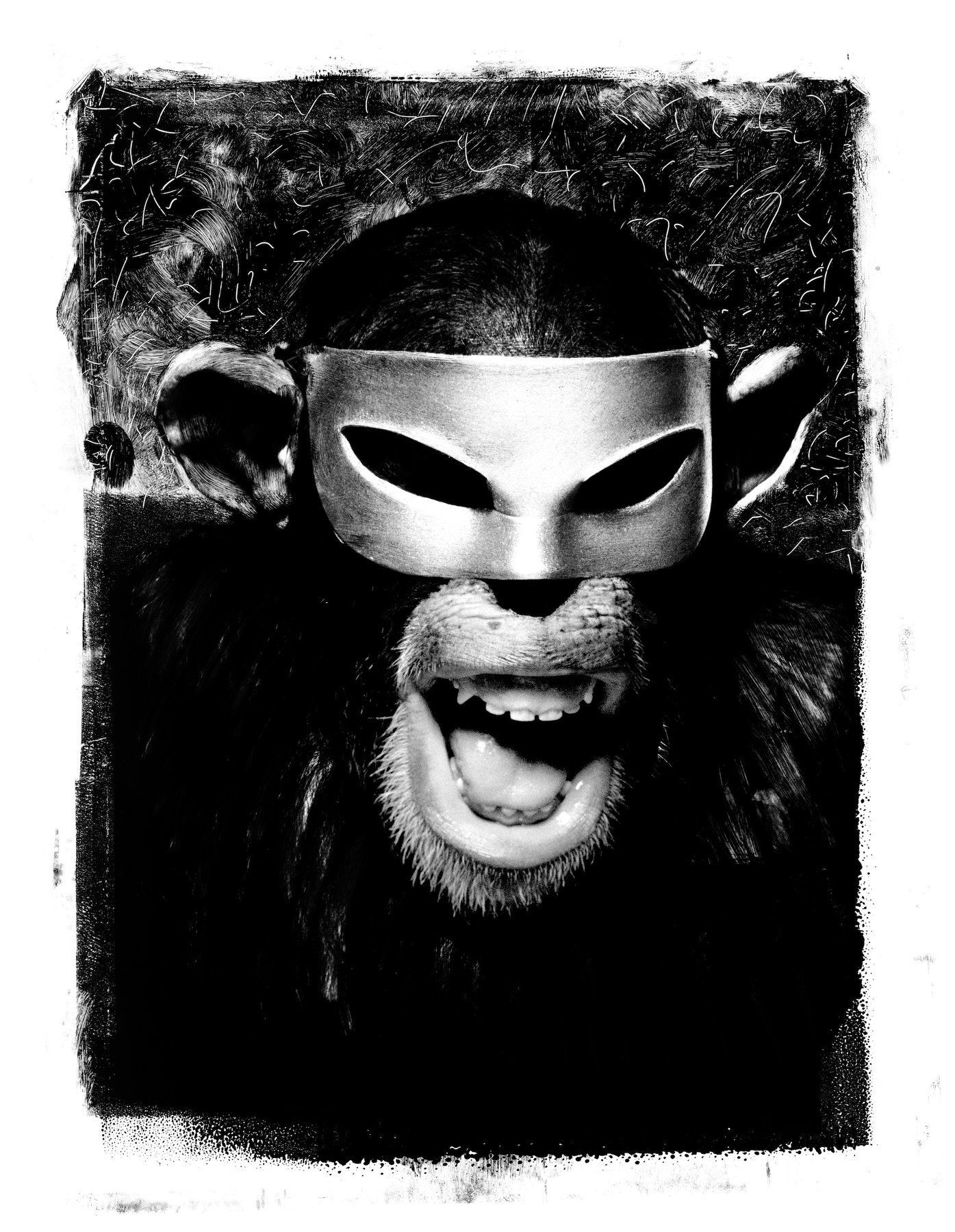

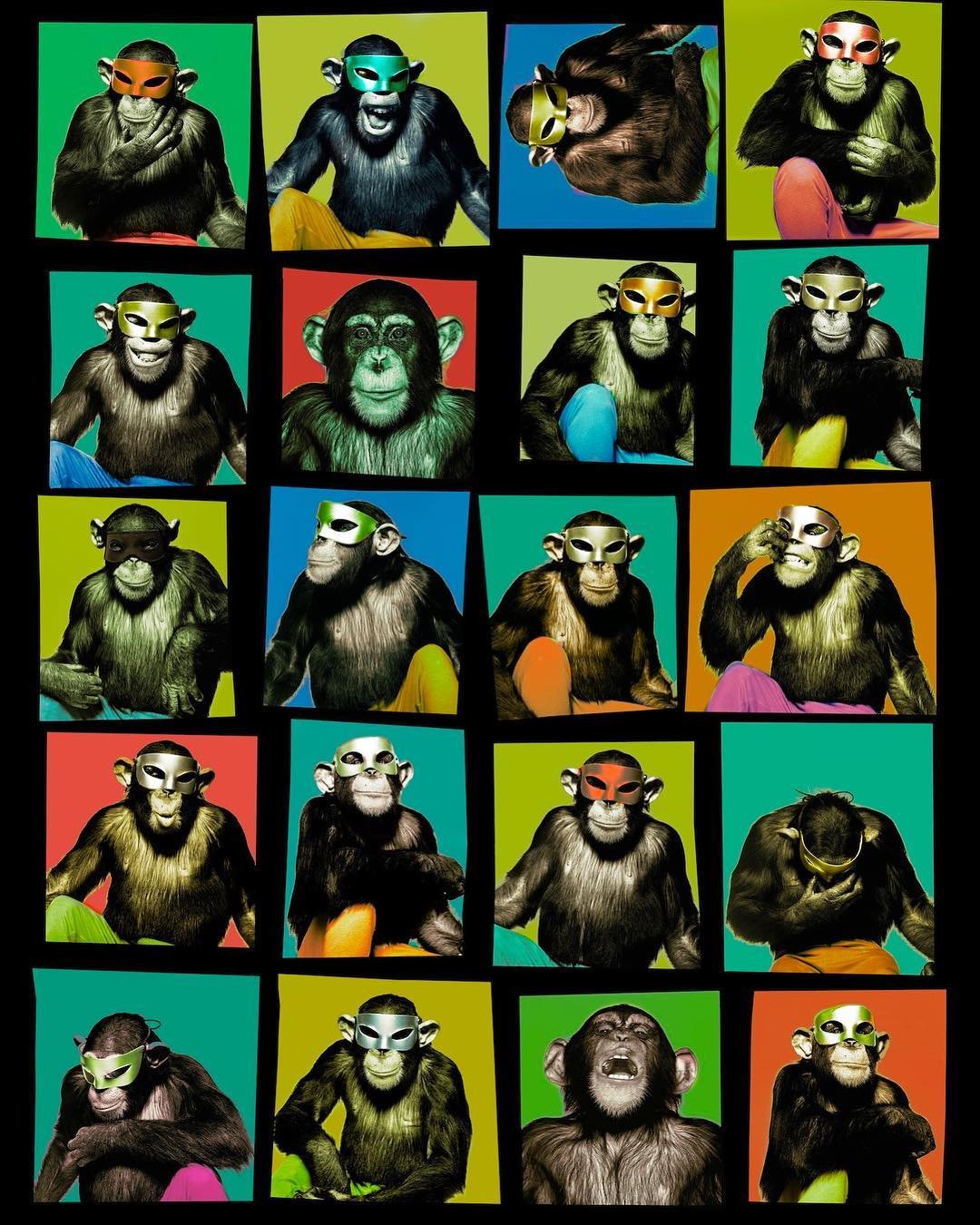

Albert Watson: There’s only actually three shots. I never pushed to put anything up on the wall. But there were three that my wife liked, which is a comic-strip series that I did of monkeys. And it looks like a comic strip of monkeys. And there’s a big print of that. There’s another monkey in a mask. Where I persuaded the monkey to shout at me, you know, to scream at me.

George Gendron: Oh, I know that image.

Albert Watson: The combination of the monkey screaming at me with a gold mask on, I did a graphic treatment on that, an ink treatment. I’ve done a lot of work with inks and paint and so on, and combined the two. And that’s up at the end of a corridor as a big print.

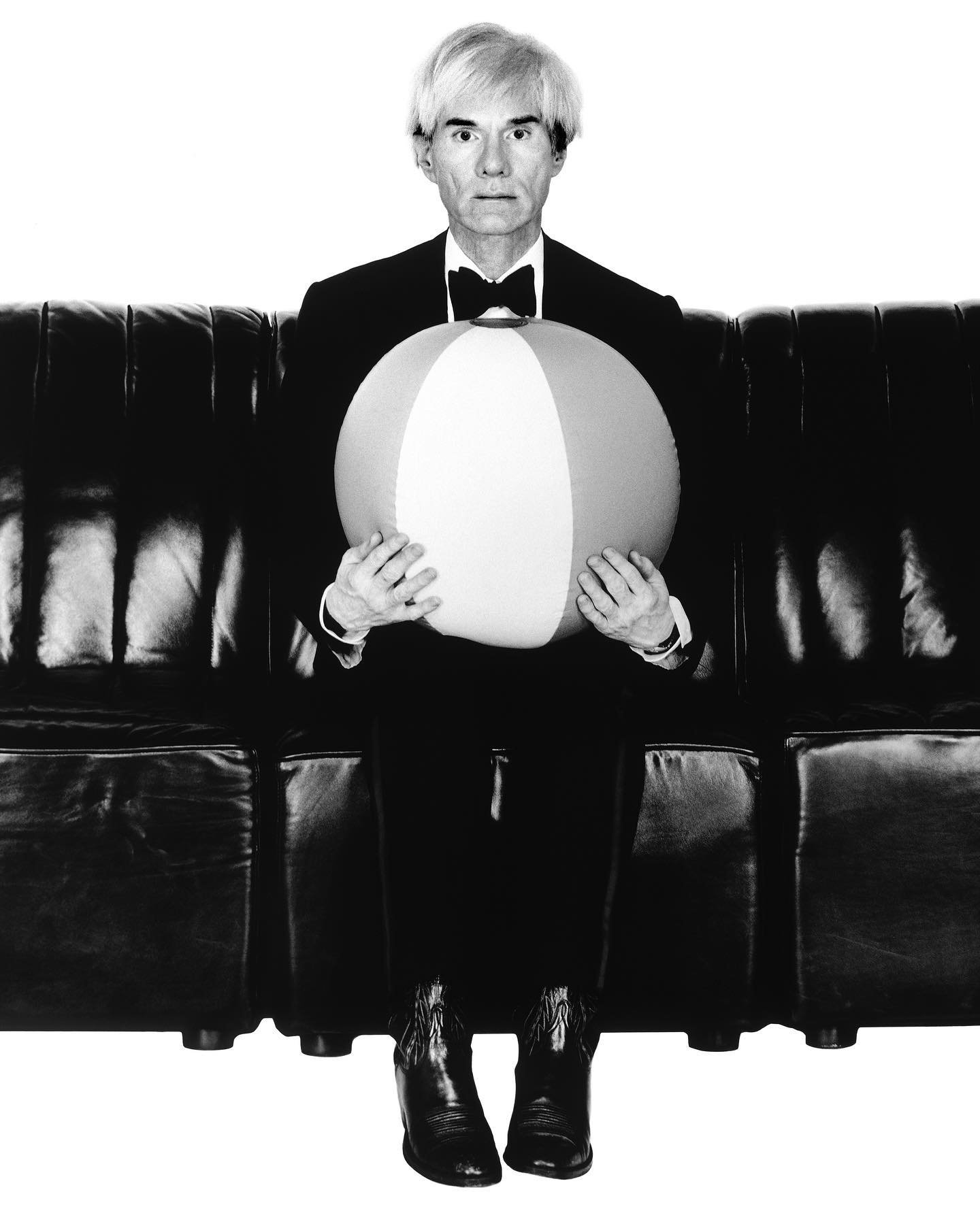

And then in our bedroom, which is next to the Warhols that I have, there's a large print of something called the Tod Motel in Las Vegas. In color at night. And that’s large in the bedroom. And if you remember the pictures below it is a Bugatti couch.

George Gendron: At one point, if I recall The New York Times article, you also had another photo from your book, Strip Search, which was the car in the junkyard. Remember that one? Oh, yes.

Albert Watson: Yeah. I think that at one point it was kind of pinned in the wall. We never had it there permanently like the other ones. And there’s a beautiful Chinese painting, which I just adore, of a street scene in China at nighttime. An oil painting. And I love that, it’s beautiful. And then I have a couple by Cortez on the wall. Beautiful. There’s the tulip in Mondrian’s apartment. That’s beautiful. I have that. And I also have a Eugene Smith. So I have some photography, but not a lot.

George Gendron: So here’s my final question: When I was getting ready for the podcast. I revisited The New York Times piece about your co-op and there was that photo from the junkyard, kind of a beautiful, dark maroon color, and it reminded me a little bit—don’t be offended by this—of a Hockney. And it made me wonder, what photographers do you love? What photographers have you been influenced by?

Albert Watson: I was always fascinated and impressed by Richard Avedon and Irving Penn, like most photographers. I was very impressed by them. But after that, there’s about 320 photographers that are my favorites. There’s so many photographers, historically, when you go back, you know? I mean, I always liked Guy Bourdin, because he was so unique. I always liked him in Paris, and some of these guys became the victim when there was that transition.

Irving Penn was the only one that they held on to. But if you remember, there was a period there where Vogue didn’t use Richard Avedon and Guy Bourdin’s contract with French Vogue was not renewed. And that, of course, that instruction came from New York and they said, “We don’t want these kinds of pictures in there anymore.”

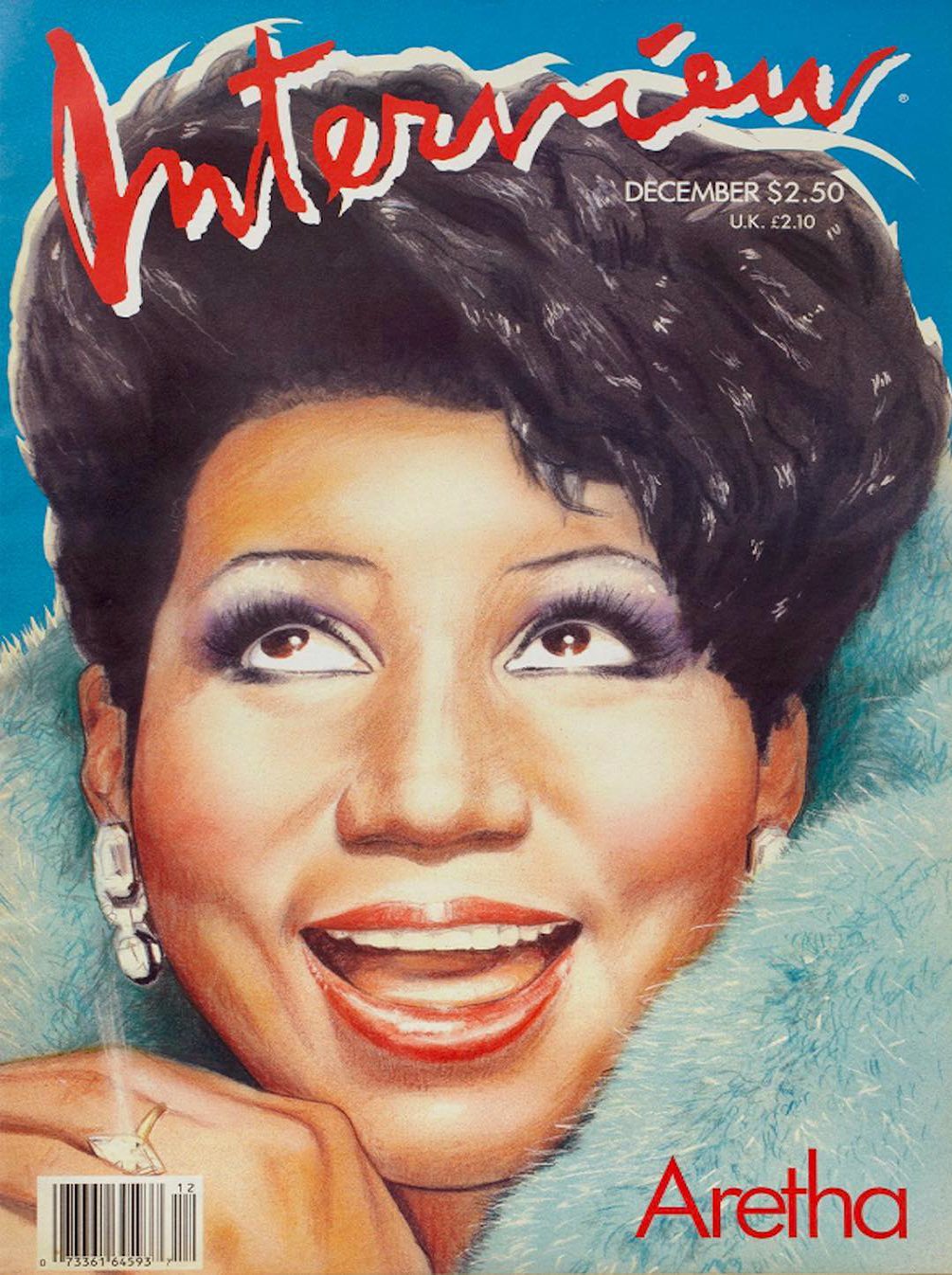

And the big thing that was beginning to happen was the cult of the celebrity. And that’s something that we didn’t speak about, but then you understand, you look back at Vogue covers, from the seventies and a lot of them were models. You know, it would be this model, that model, and so on.

But bit by bit, the cult of the celebrity began to creep in there more and more until celebrities began taking over. That might be a supermodel, but it was never an up-and-coming model that nobody had ever heard of. It would have to be Beyonce or something like that.

And it began as I was doing the contract I had with French Vogue. It began to come into that. And then it began to be me photographing Isabelle Adjani, or photographing Catherine Deneuve, and so on. The cult of the celebrity began to creep in everywhere. To every magazine.

And, as a piece of trivia for you, Alexander Liberman was so excited he told me about Vanity Fair, and he said, “Vanity Fair is going to be “The Bible of the Arts.” It’s going to be stories of every museum in America and every important gallery. And it’s going to be about artists and the life of artists.” And he said, “Of course we’ll also do musicians and opera singers and things like that.”

And they brought the magazine out, it was a reissue, of course, but when they brought it out, it was thick, and then next month it was thinner, and then next month it was thinner still, and it was going nowhere. And of course they realized at that point that People magazine was selling, whatever it was, four million a week.

And so they decided to turn Vanity Fair into a celebrity, sophisticated gossip—with good writers—but there had to be something gossipy. And it ceased to be “The Bible of the Arts.” It became “The Bible of Gossip.”

George Gendron: Yeah, that’s pervasive. The last vestiges were business magazines. You had to have a “business celebrity.” You know? It’s everywhere now.

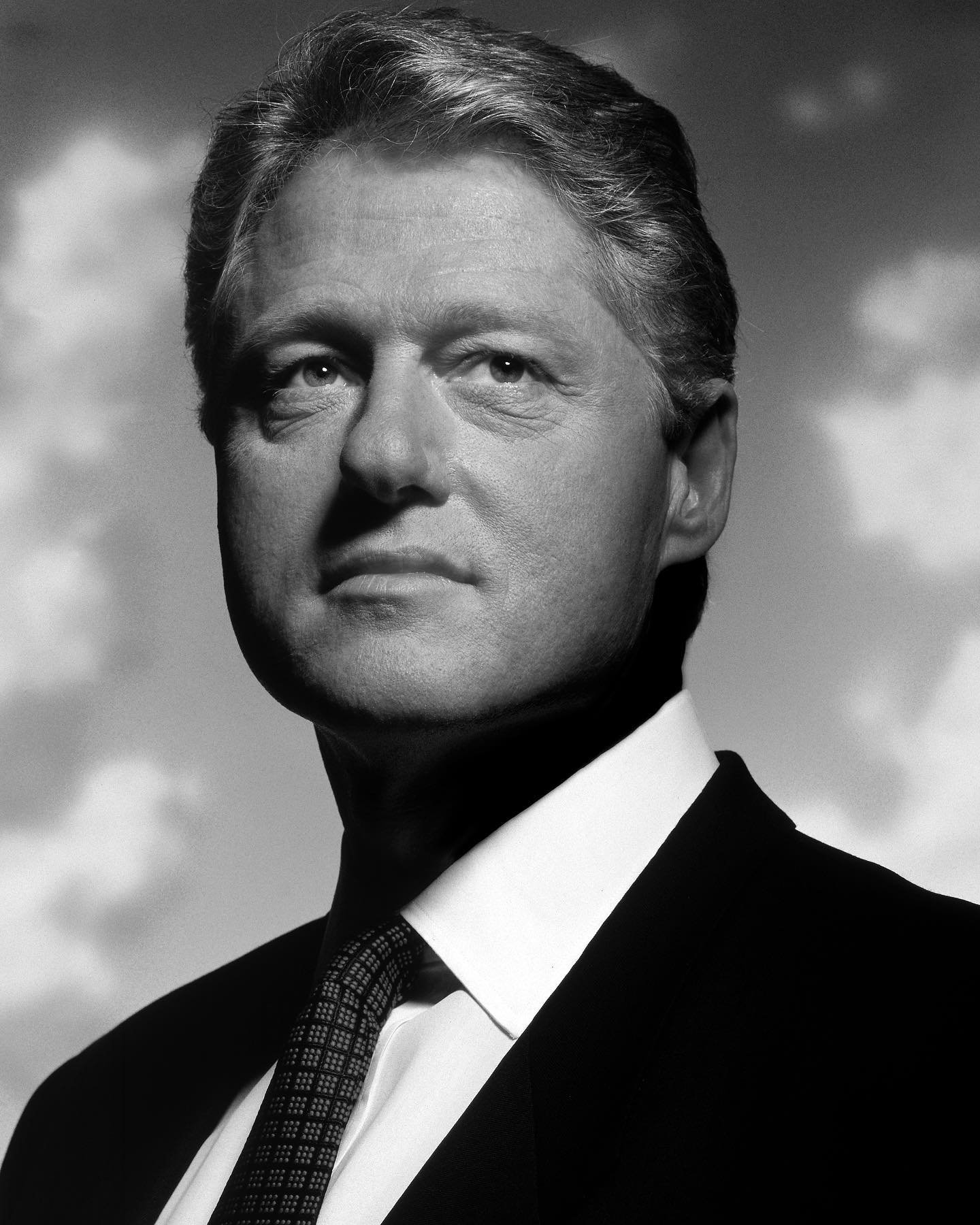

Albert Watson: Yeah. It had to be Musk or Steve jobs. Listen, I did a project for Fortune, it was fascinating, where I did the most powerful people in America. And Steve Jobs was one of those people. I did Bill Gates, and Warren Buffet, and Bernanke at Treasury, Condoleezza Rice. I did portraits of them. It was The Power Issue. So yeah, it was all about celebrity.

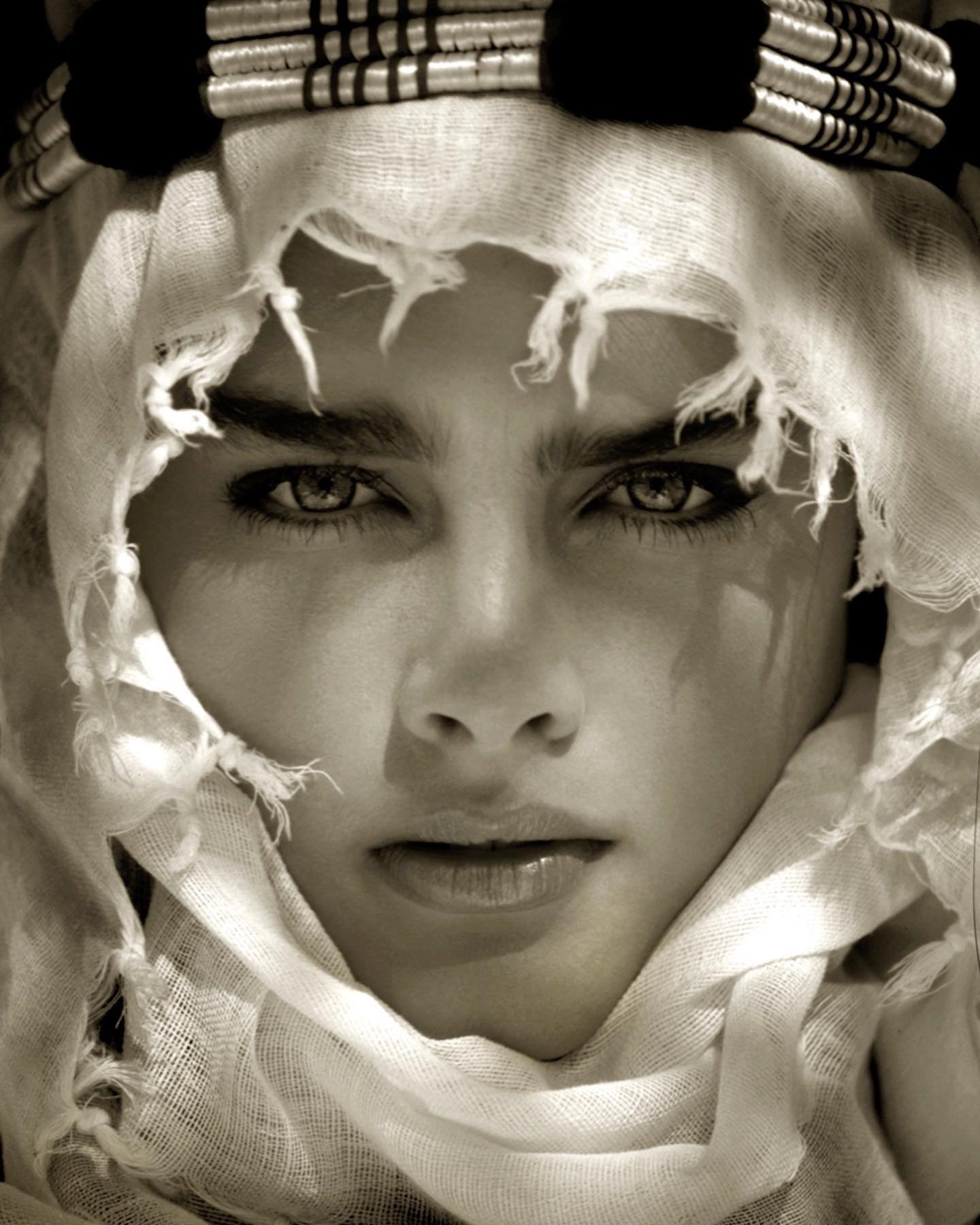

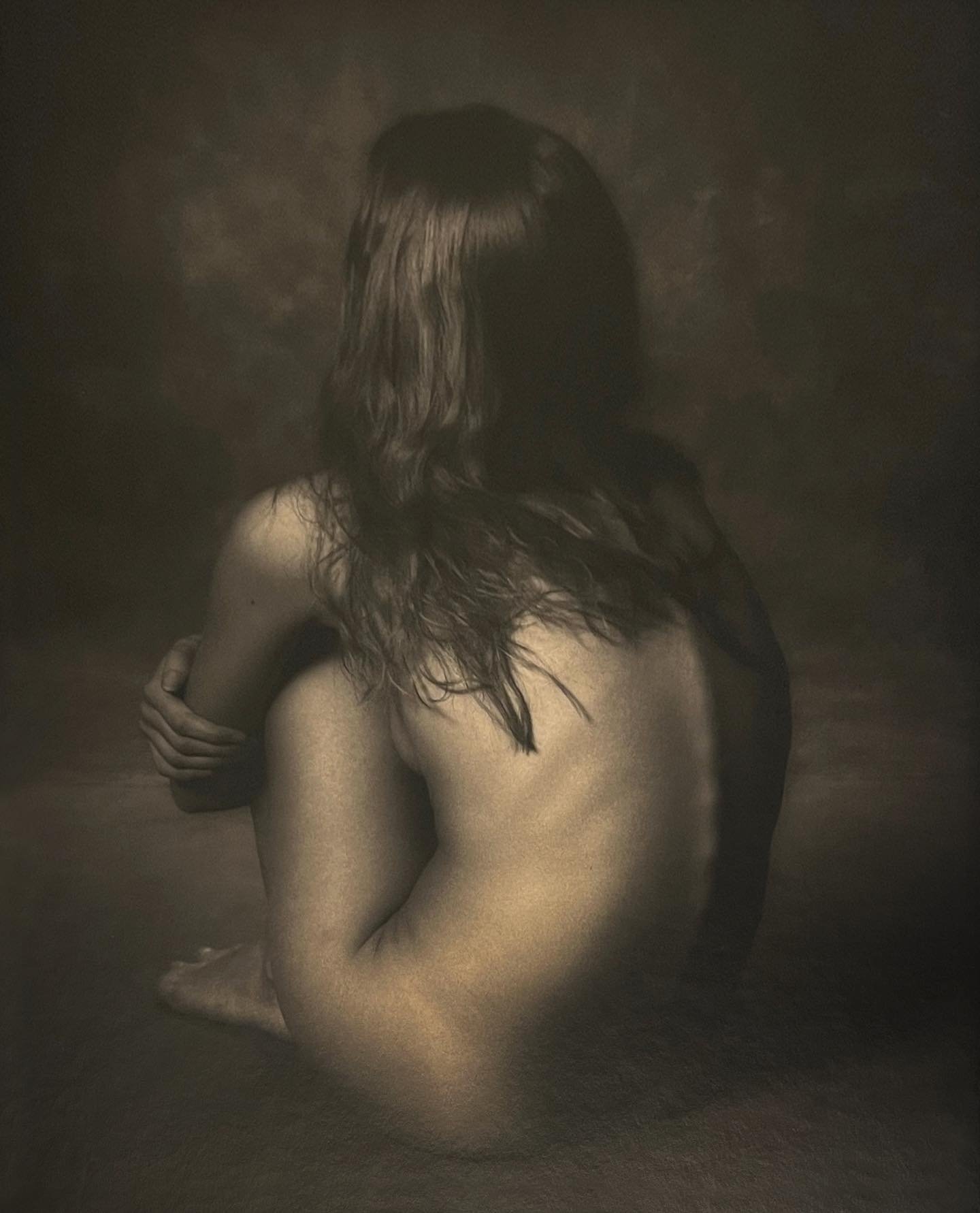

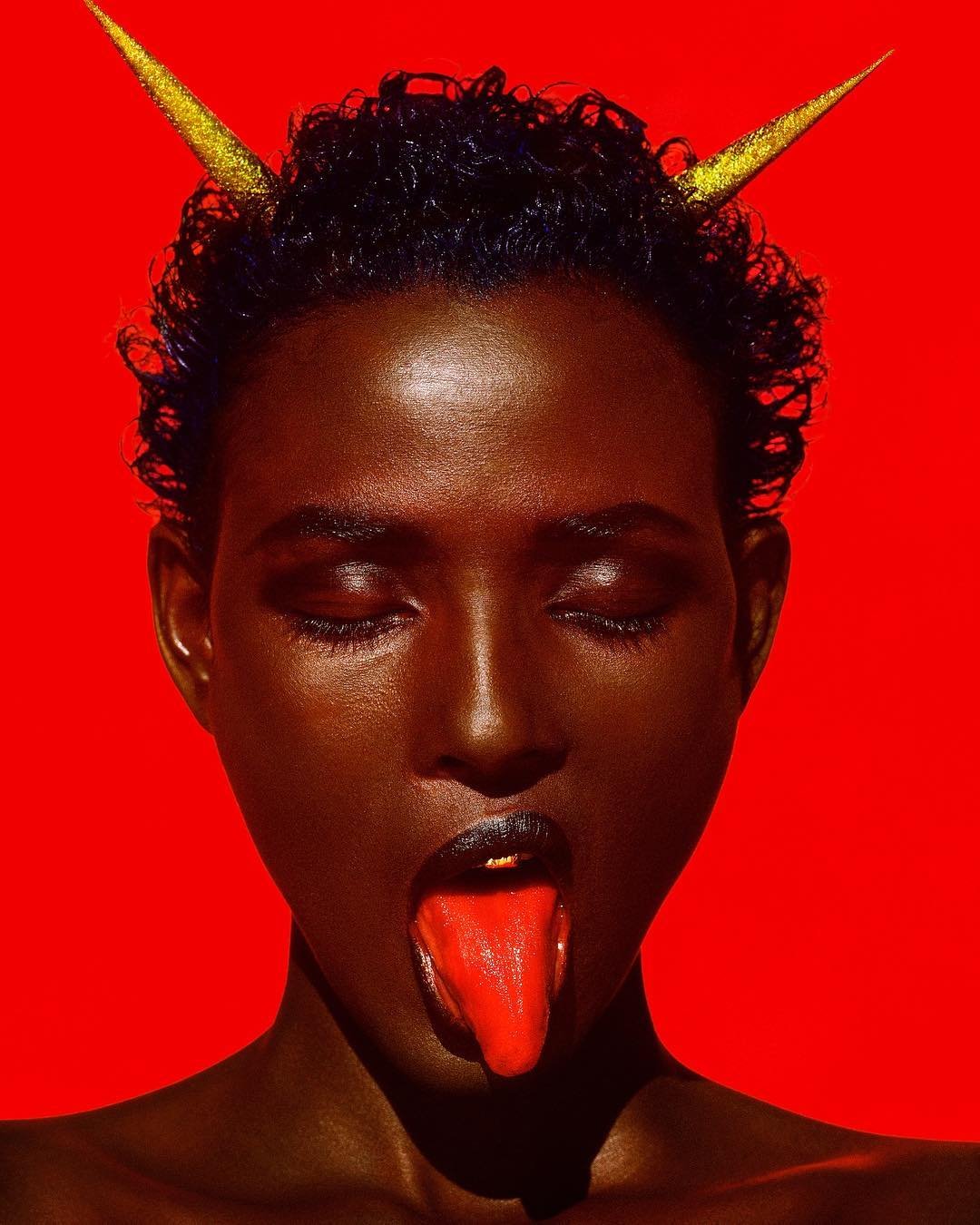

South Sudanese model Ajak Deng for Paper Magazine, (white background) 2017; Somali model Waris Dirie in Morocco, 1993

For more information visit Albert Watson’s website, or follow @albertwatsonphotography on Instagram.

More Like This…