The Extraordinary Life of Things

A conversation with MacGuffin founders Kirsten Algera and Ernst van der Hoeven

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT LANE PRESS

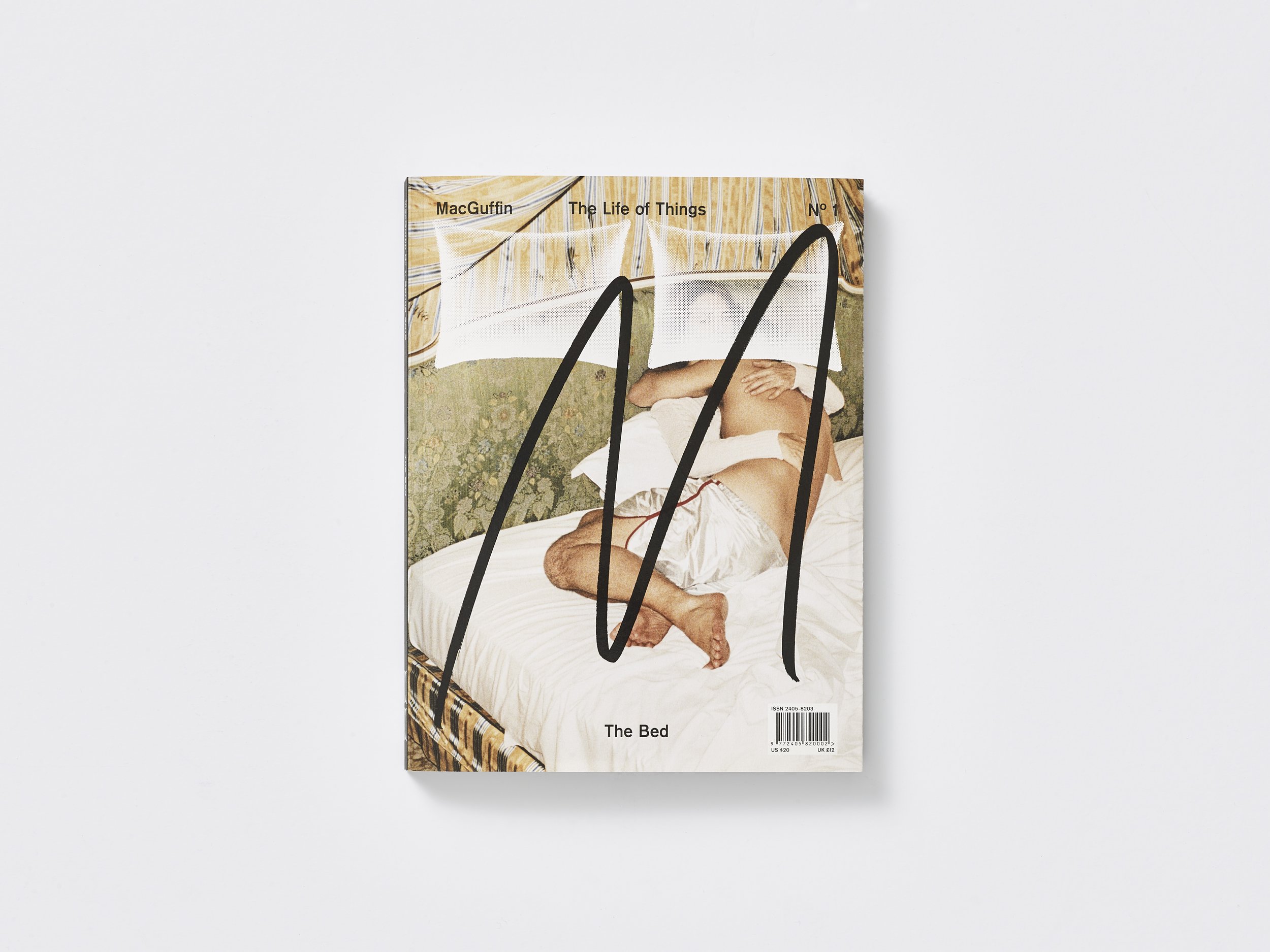

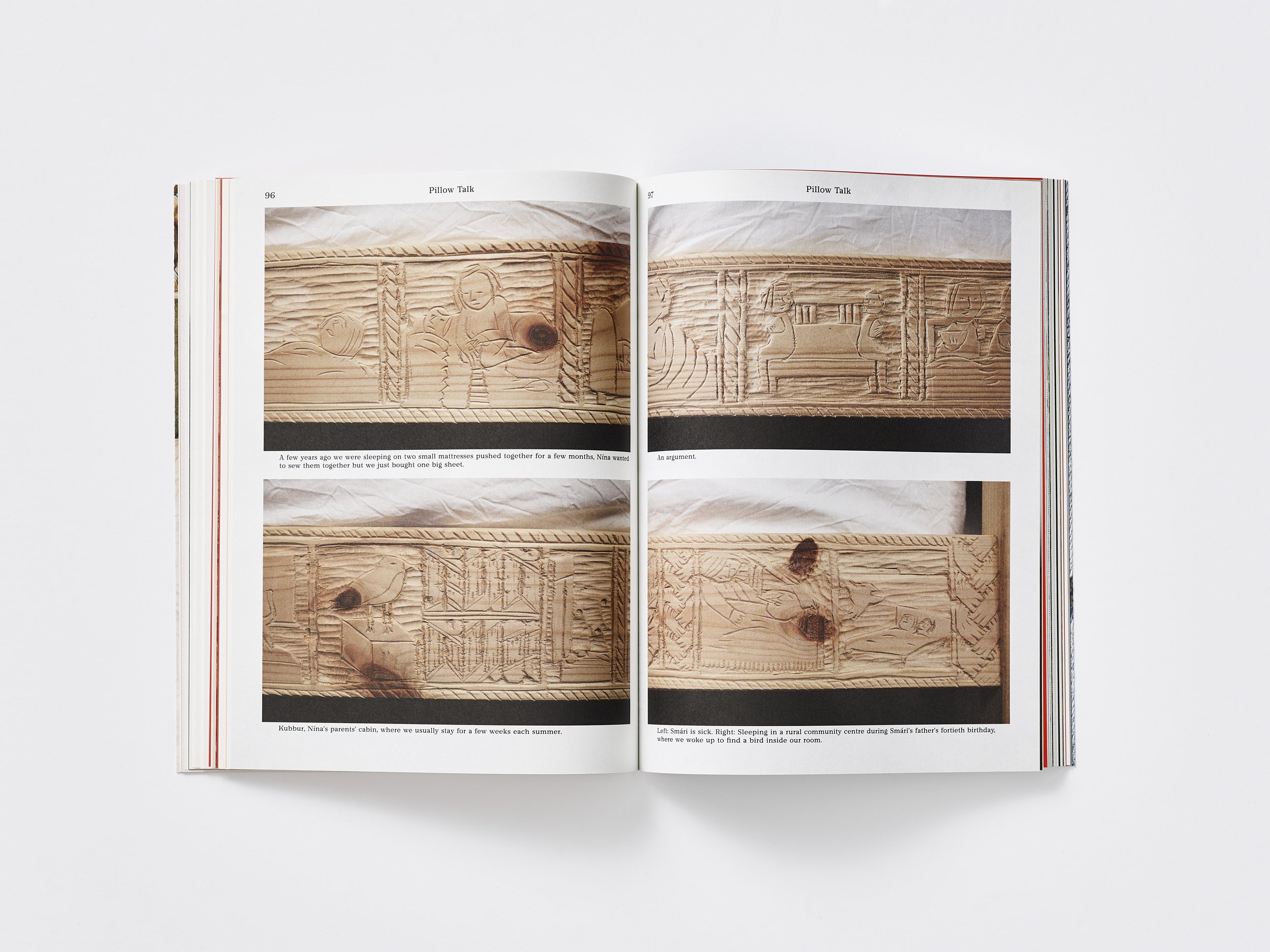

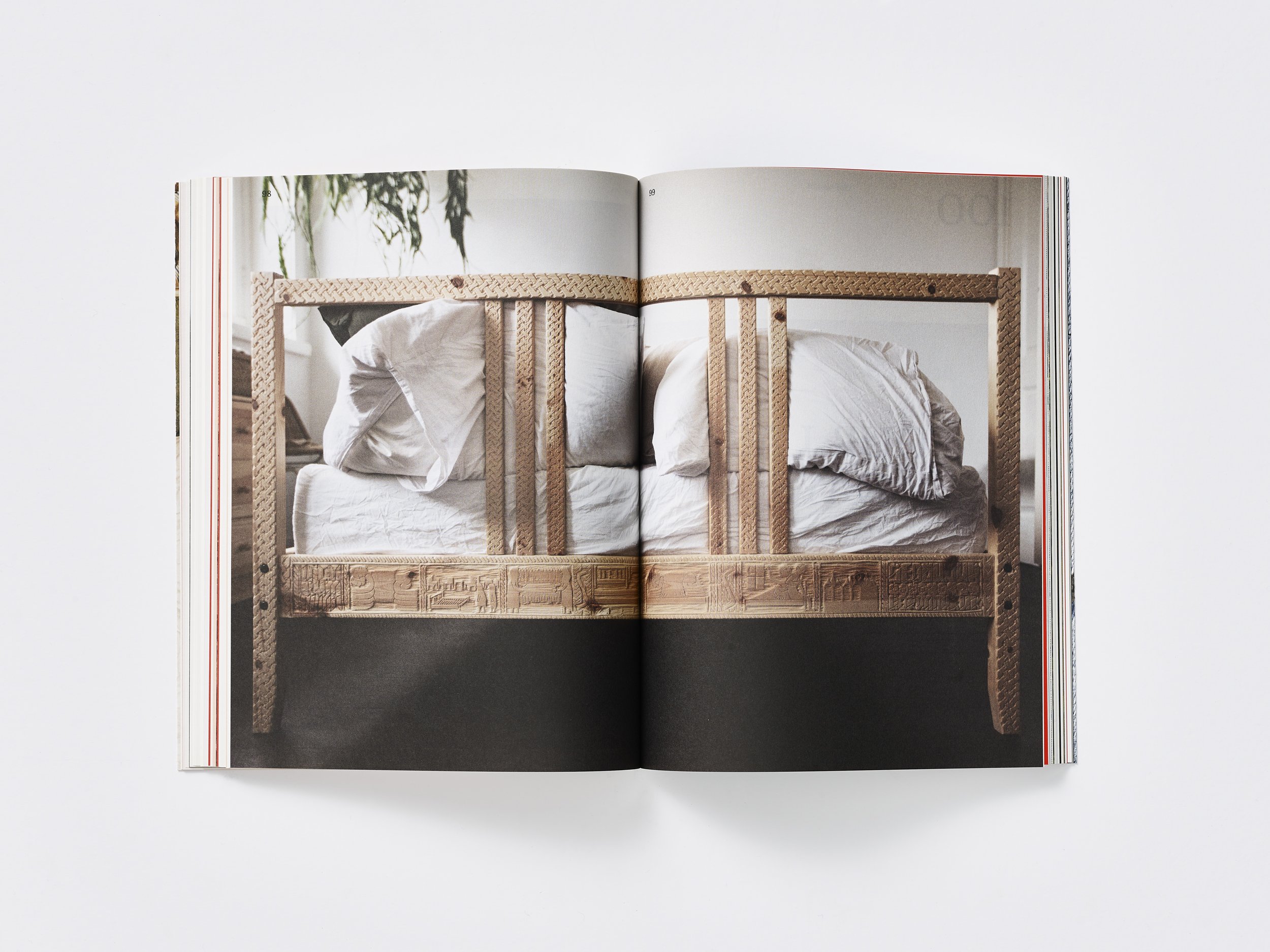

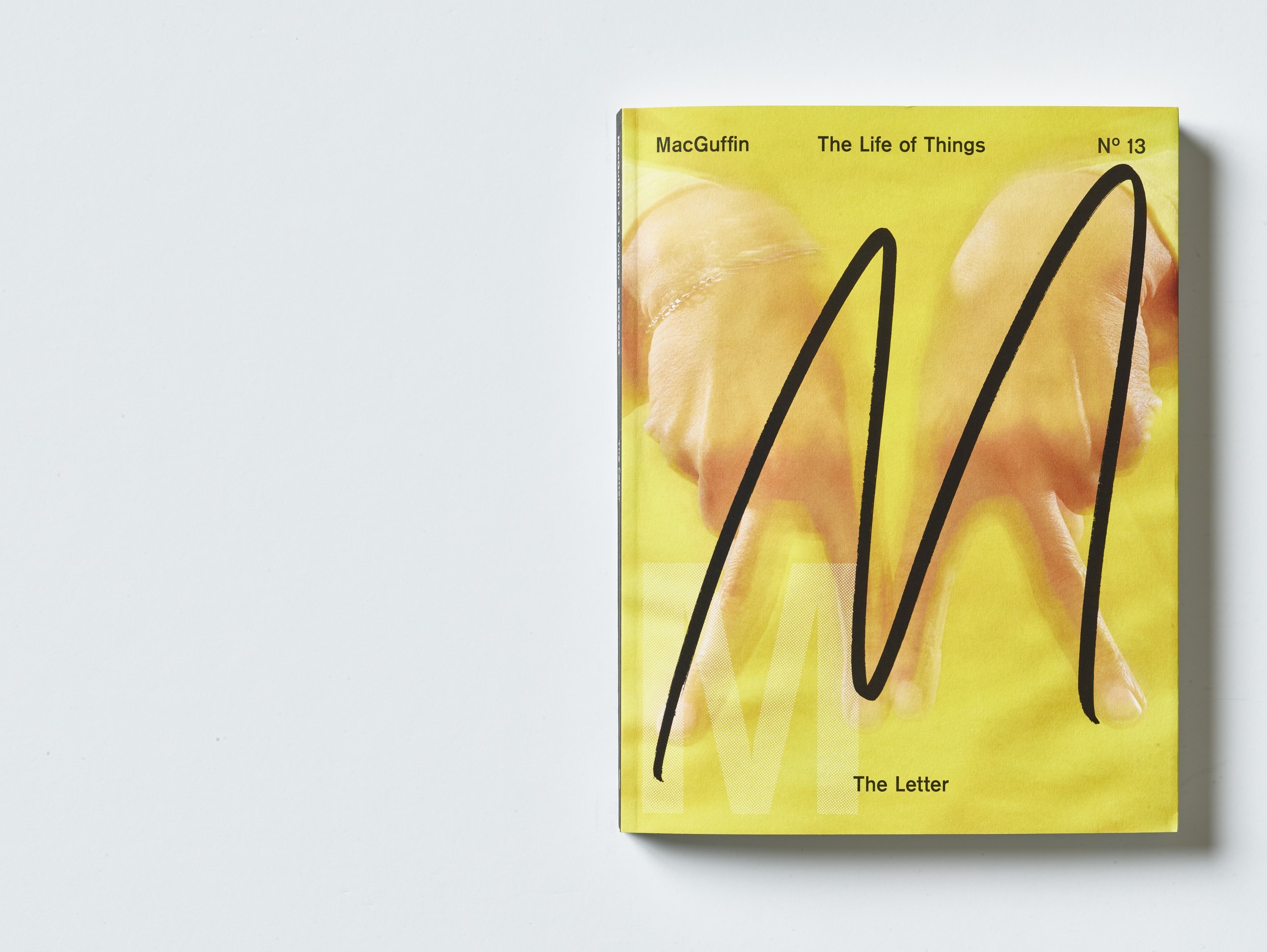

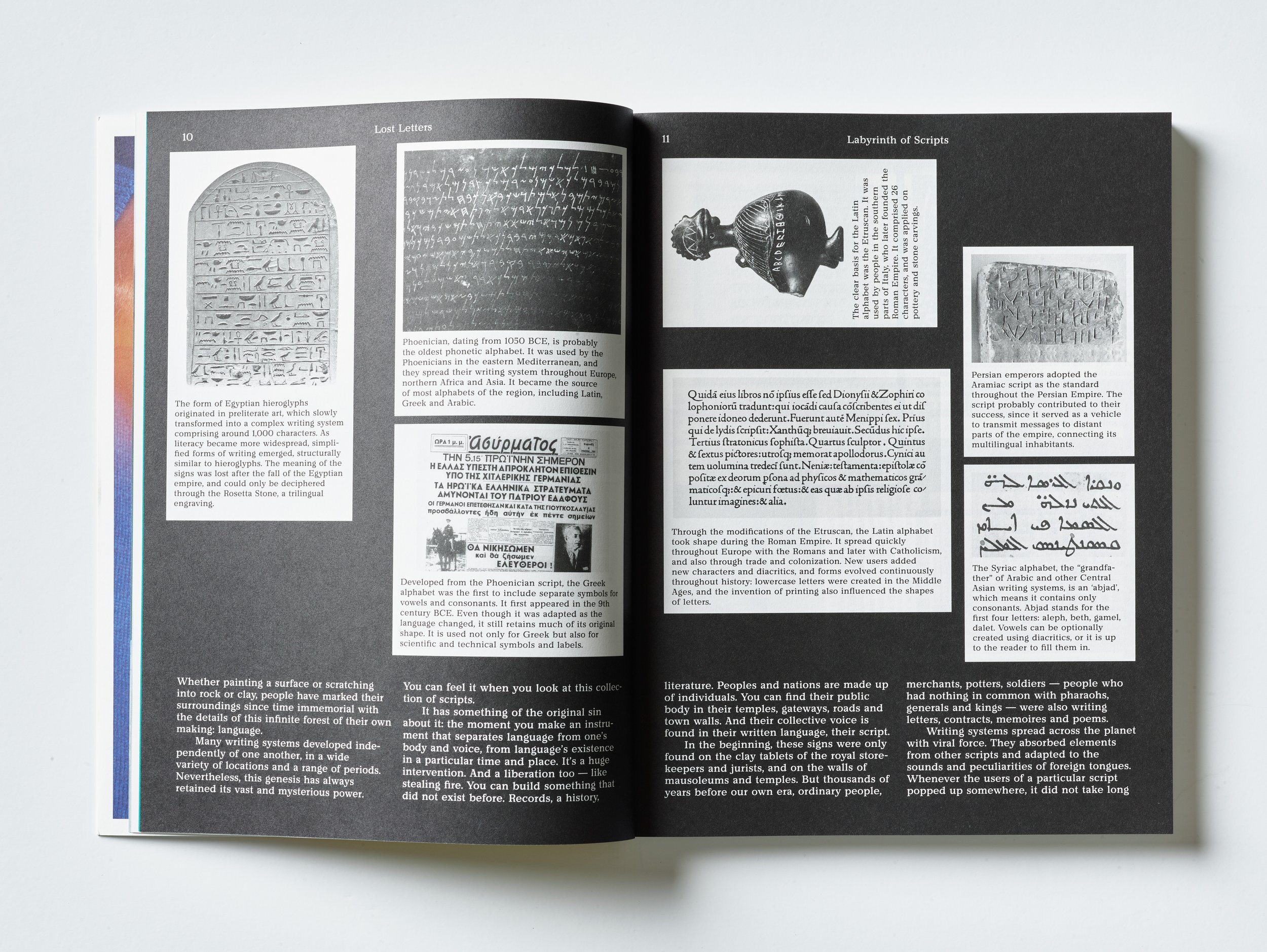

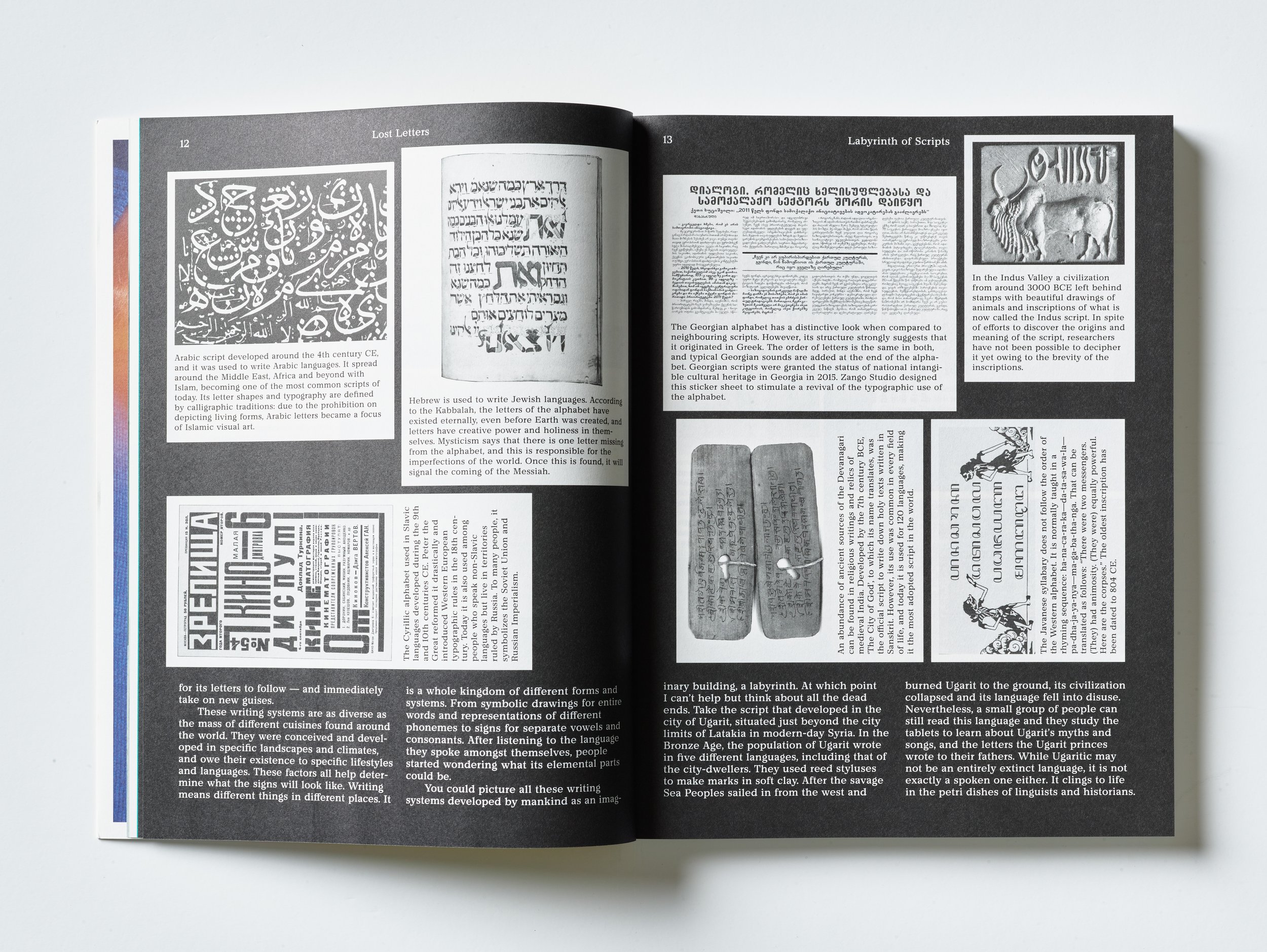

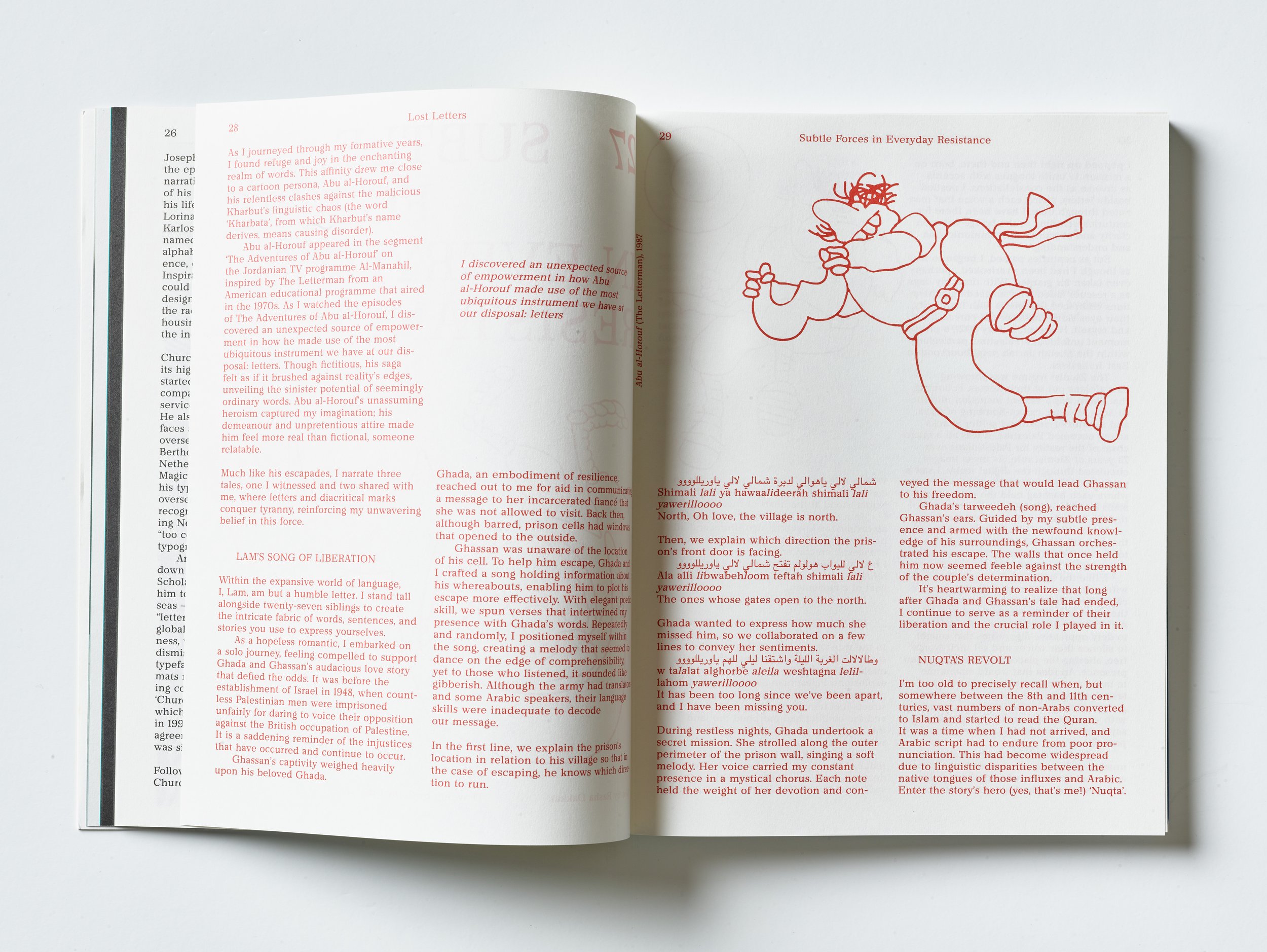

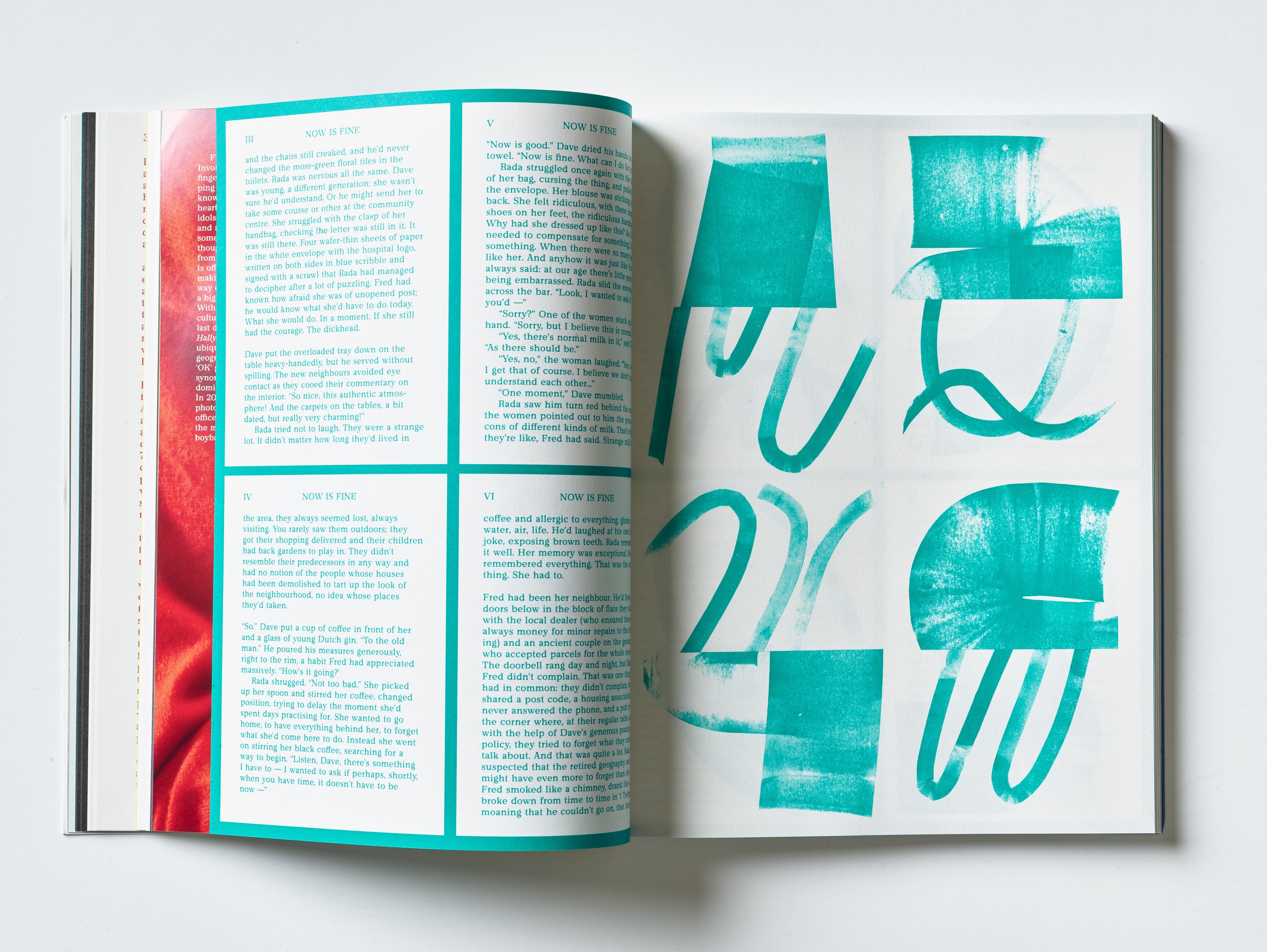

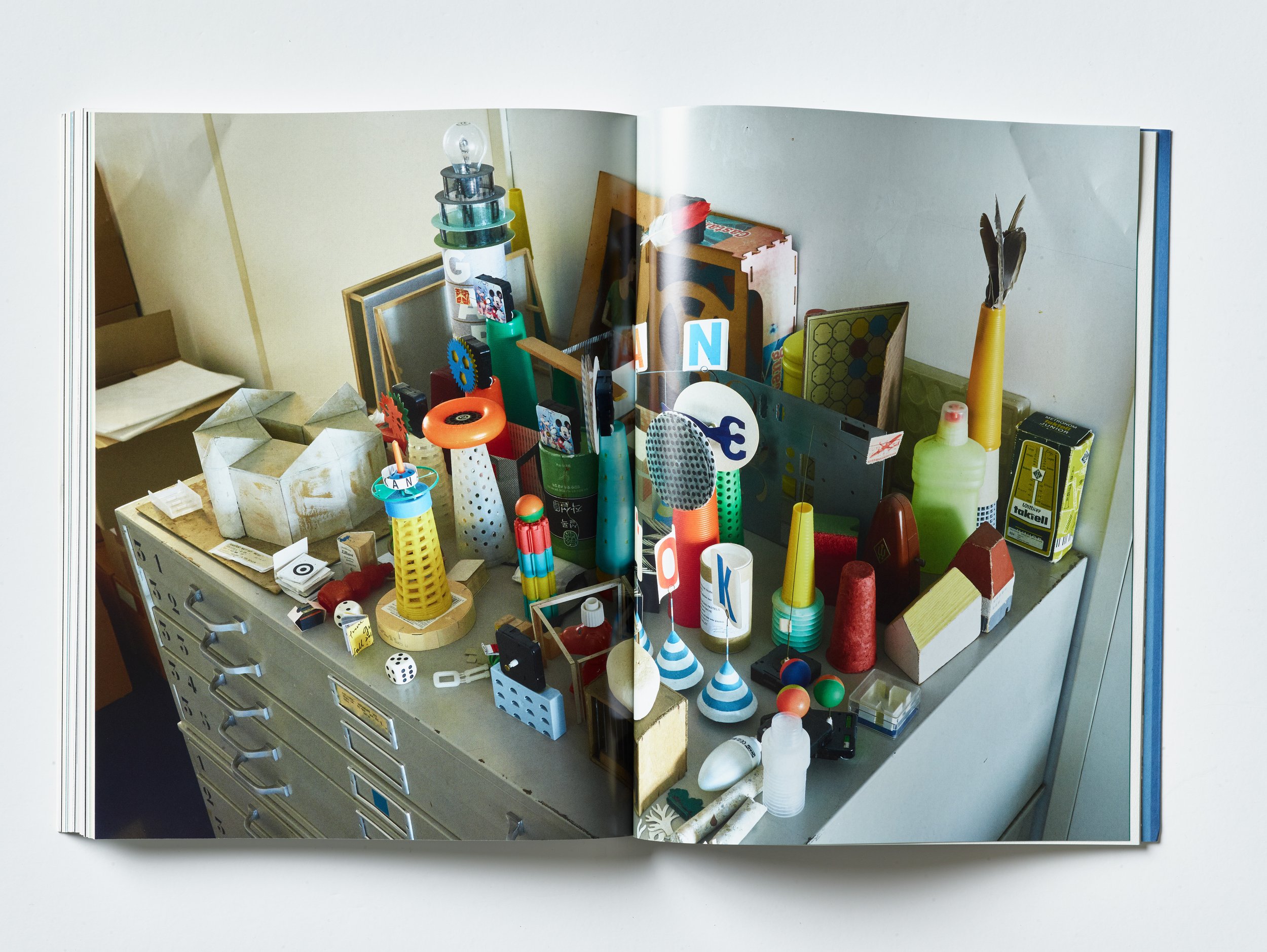

The Bed. The Window. The Rope. The Sink. The Cabinet. The Ball. The Trousers. The Desk. The Rug. The Bottle. The Chain. The Log. The Letter. These aren’t random words thrown together. Nor am I reading a list of things I need to buy—though stop for a moment and admire the poetry and cadence of the list. No, those words are the themes of every issue of MacGuffin.

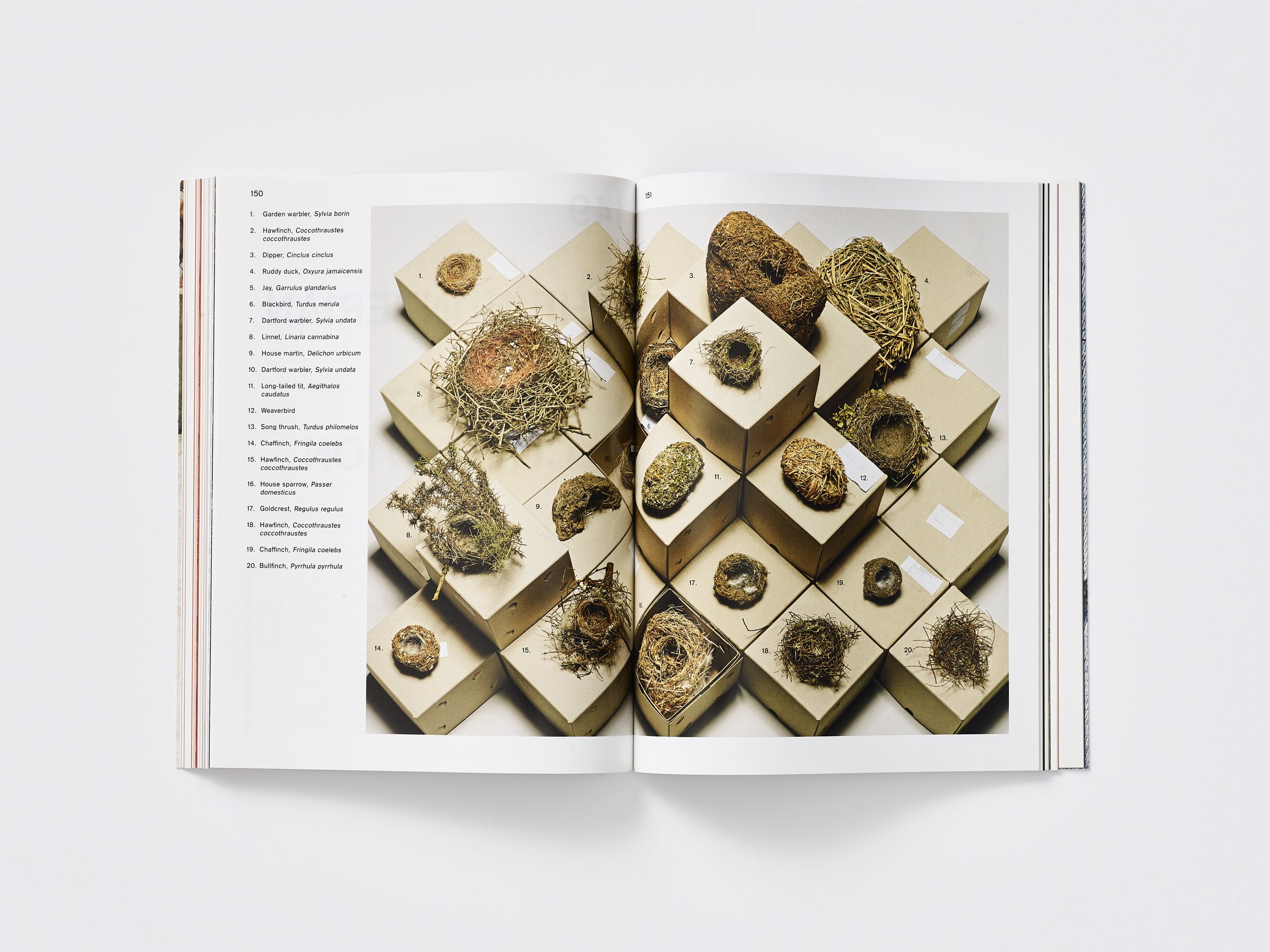

MacGuffin bills itself as a design and crafts magazine about the life of ordinary things. And in that simple descriptor, you can discover an entire world. Founded in 2015 by Kirsten Algera and Ernst van der Hoeven, two Dutch art historians and designers, each biannual issue of MacGuffin is based around a single object or word, and then explores that thing in its entirety in quite surprising, and inspiring, ways.

MacGuffin doesn’t ask much of its global audience but reading it and experiencing it, might change the way you look at the world. The magazine came about because Ernst and Kirsten both felt that the discourse around design had become disconnected from the concerns of most of the world’s people.

In some ways, they have created a magazine that rejects the modern to appreciate what already exists. But don’t mistake the magazine or their ambition for nostalgia: MacGuffin is a thoroughly modern project and an ambitious one: oversized, heavy and thick.

Both Ernst and Kirsten acknowledge they are creating an object about objects. A collectible. A collection. They do this with an openness to the world and a thoughtfulness that is admirable. Because the world of MacGuffin is the world all of us live in.

Arjun Basu: A lot of people that I’ve spoken to have already mentioned MacGuffin. There’s two magazines that they bring up—and we’ll get back to why they mention both of these—but it’s either you or Apartamento, and it really is across the board. If I kept a running tab of who got mentioned more, right now maybe Apartamento’s in the lead, but MacGuffin is a close second. So I’ll start with you, Kirsten. Tell us about your journey to this point, to the creation of the magazine.

Kirsten Algera: Okay. That’s a long story. I’ll try to keep it short. I think it started when we met, Ernst and I, because we both worked for a department that was called the Dienst Aesthetische Vormgeving, which is the Department of Aesthetic Design.

And it was a government institution for post and telephone companies. So lots of different things, stamps and telephone cards and post offices and all sorts of other design that this department guided in a way.

And it was a very special department because it not only it guarantees quality in, in the design of things, but also it was a nursery you could say for graphic design and for spatial design and for product design. So it was a special place. And I came there and Ernst, I think you were already gone by then.

So it was very, very short that we met each other, but we kept in contact. And after I think like 10 years or 12 years, I had a very bad accident. I fell out of a window in my home here in Amsterdam and I was in hospital for a long time and did a lot of revalidation. And it was a sort of point in my life where I was confronted with what I could and could not do and had to decide what to do.

So I started doing freelance jobs and doing a PhD in graphic design. And then I met Ernst again, and he asked me to work for him on the research of a project that he did. It was a project, it was an art installation in a park in The Netherlands and it consisted of a sort of cascade of textiles of cloth, indigo, hemp. Woven cloth.

And Ernst wanted to make it in the north of Vietnam, where there was this sort of refugee community of women that needed a job because they were abducted to China in their youth. And they came back and they were expelled from their communities.

And the only way that you could go there was by motorcycle. So we had long rides and then, afterwards, long evenings to discuss all kinds of things. And one of the things that we discussed was design because we both worked in the design world and we were very much uninspired by it, you could say, because it was about commercial success and innovation and star designers. And we were not really into that.

And when we talked to the women there in the north of Vietnam. We realized that the design world that we were working in was so one-dimensional. And in the talks with the women that we encountered there it was really, for us, it was surprising to hear: A completely different view on what design and crafts are in a human life. And Ernst, maybe you remember that you told me once that one of these women came to you after the textile was made, no?

Ernst van der Hoeven: Yeah, there was a whole fuss about how this woven cloth would have been sewn together. Of course I had the idea it would be beautiful, because it was 88 different grades of indigo. And I thought it would be nice if it would be gradient, but they could not understand why that was so important. Because for them, it was just a big cloth, like for maybe a fan or whatever. The whole concept of art, and the whole concept of a park, they could not understand that. I had, of course, brought with me some sketches, but they looked at me very bluntly and said, “We do it our way.”

We could not communicate because I don’t speak Vietnamese. But in the end what I did, I just went with them on the field and there we assembled the cloth together with the women, and that helped—by just doing. The good thing is that Kirsten and I both realized that the whole idea of art or design was not in their minds, but 88 percent of the whole project was done by them, anonymously.

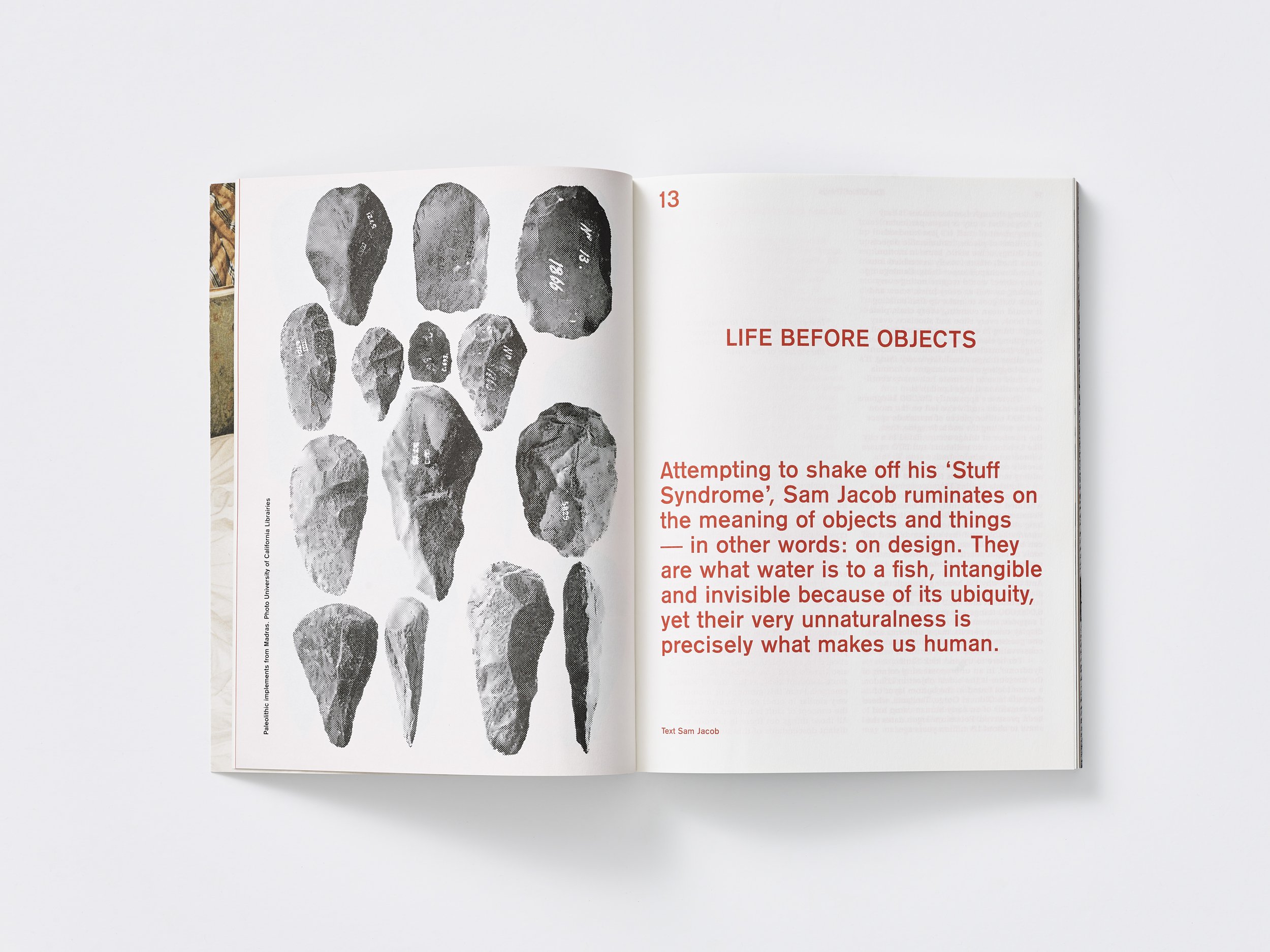

So we thought, Why isn’t there a platform that is there for all the people that make beautiful things and are not heard? Or all the things that are already there and have a second life? Or other things that are having a history because of their use?

Arjun Basu: So was that the impetus for the thing? That there was just this basic thing missing in the world, which was that celebration—as opposed to the celebration of the new, and the shiny, and avant garde stuff, or just “high design,” and that the world was missing a celebration of what these women celebrated?

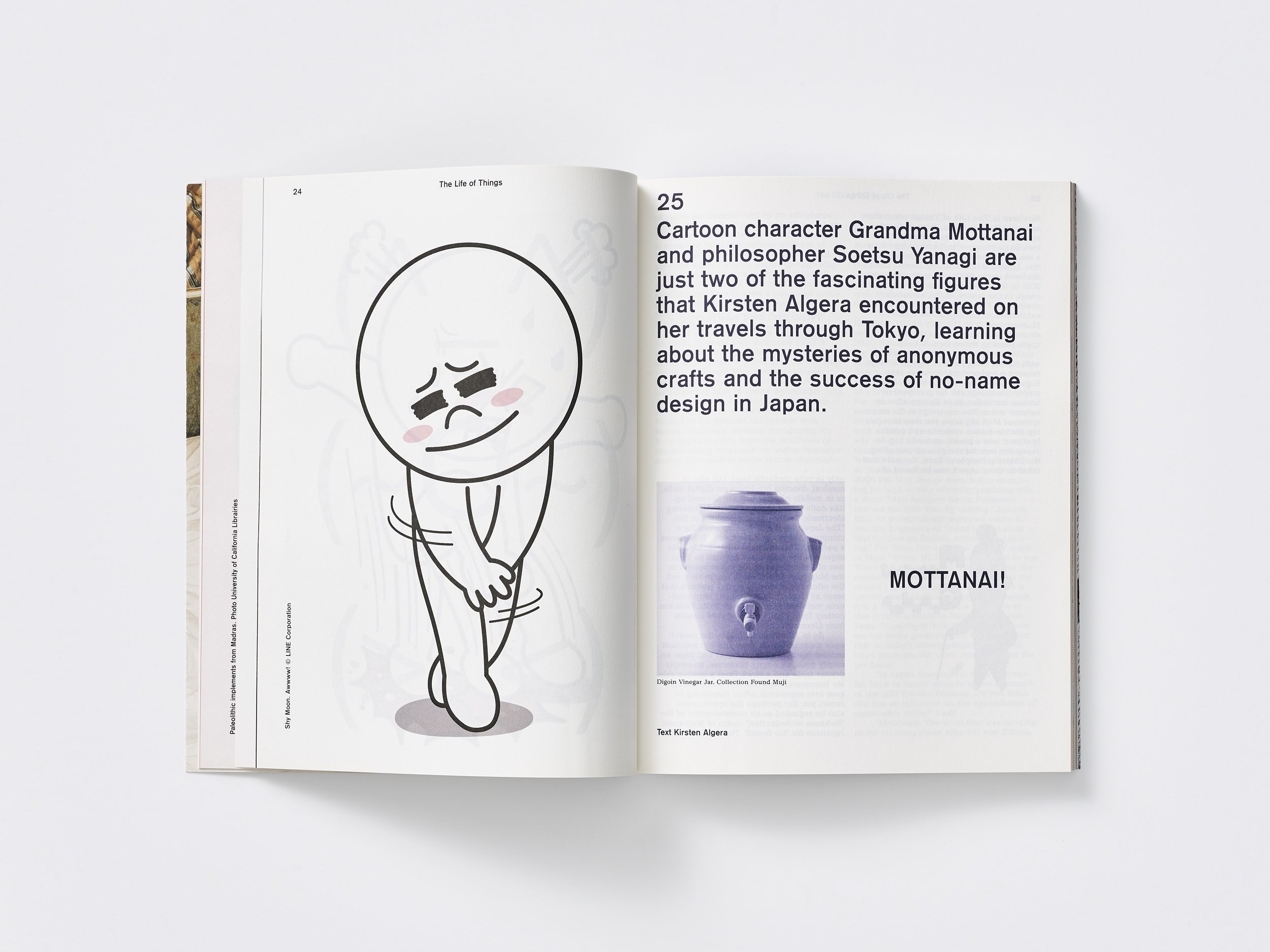

Kirsten Algera: Yeah, I think so. I think that we really felt the need to stretch the whole definition of design to make it a lot more broader than all these iconic and these new things. So it’s beyond the new that what we wanted. And also I think we wanted to tell the stories that these objects set in motion.

So one of the first things that we had, actually, was the title of the magazine, MacGuffin. Because we saw that an object has a life—it’s not just something that is made, or just something that is sold. It tells us a story, and you can look at the world through the eyes of this object. And that was our starting point.

Arjun Basu: You’re both art historians. How much of that influences the way MacGuffin actually turned out?

Ernst van der Hoeven: We both started maybe as art historians, but we’ve done a lot of things. And after my study of art history, I went into city development and urbanism. And after that I did a master’s in landscaping. And in between I did a lot of art-related projects. So I always had the problem that I was a generalist and then, at a certain moment I was designing gardens and parks and then curating exhibitions.

So people always ask me, “What are you doing? What is your discipline?” I always had difficulties deciding in which discipline I wanted to be. And the moment we started the magazine, this all fell together. Because you use all the knowledge that you have on the different fields. And I think that is something that I really enjoy now that I can say, “I’m an editor of a magazine.” And all the disciplines that I’ve worked in feel like something that I can use.

Arjun Basu: There’s two words that are parallel to each other, but that really do mean different things, except I think you guys just destroy it. And that’s, ‘editor’ as you just said, but ‘curator’ as well. And I think in an odd way, you have really just combined those two words in a way that is, I think, amazingly unique. You said you’re an editor, but do you consider yourself, what you’re doing, curation?

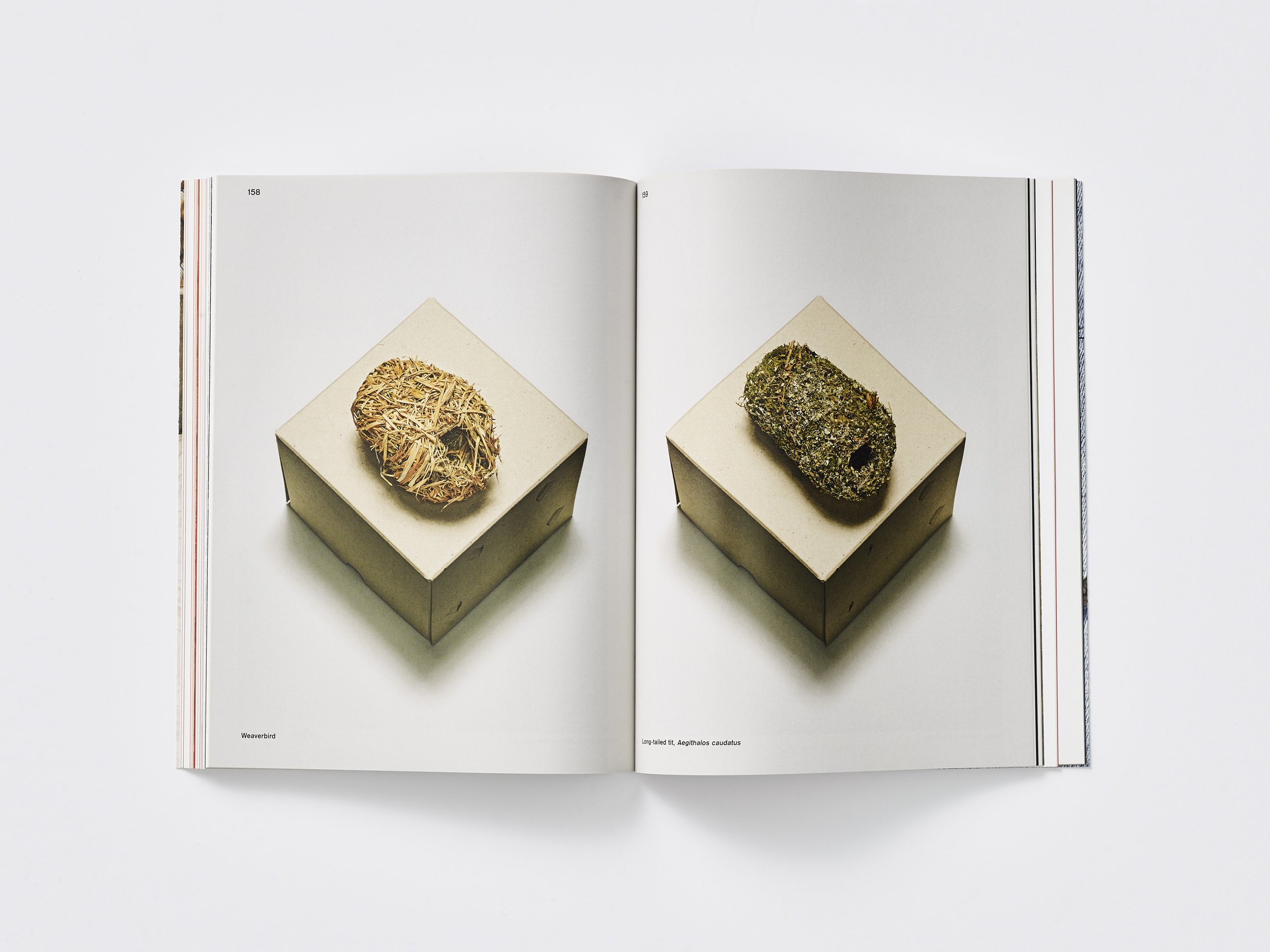

Ernst van der Hoeven: I’m very happy with this question, because it’s exactly what we do: We curate a magazine. And for us, it’s as we make this magazine, it could easily also be an exhibition. So we work on it as curators. And that’s also the reason why we’ve been asked to make various exhibitions for design museums or institutions, or together with students for their presentations.

Arjun Basu: Kirsten, how do you feel about those words?

Kirsten Algera: I think it’s very good that you mention it because we always try to make a portable exhibition, in a way. That’s what we say. So for the magazine, it’s really important that there’s a mix of visual essays, and text, and all these layers that form the magazine together. And I think, yeah, we’re curators, maybe even more curators than we are editors.

But I also think that in a lot of places, because everything in the design and art world has become so hybrid, a lot of people are curating these days. I’m teaching graphic designers and I always tell them. “You’re curators too—curating your portfolio, curating the work that you make.”

Arjun Basu: That, I think, goes into the decision process for the selection of the word for each issue. The way each word is—they’re all objects, sure—but the words themselves feel stretched, and the definitions are very elastic and almost poetic. The way you tackled The Sink, for example, and it led you to the underground. It’s very elastic, very open. Every issue functions as a kind of metaphor. So how do you come up with the word?

Kirsten Algera: Actually it’s quite easy for us to find the new theme. People always ask us, “Do you have a bucket list? How long is it? Is it difficult? How do you decide?” And most of the time it’s quite spontaneous. And of course it’s also in a dialogue between us two, but there are also some things that we take into account, for example: What did we do before?

So the first one was a piece of furniture, The Bed. Then came a building element, The Window. Then we did The Rope, a material. And then we did The Sink—sort of a world in between. So there’s a rhythm in that, I think. And then it, of course, has to be an interesting theme and also a theme that allows us to go in different disciplines and different fields.

And also, an object that we are motivated to describe because it’s interesting. And because if you look through its eyes, you can see lots of interesting things. That’s really important to us. And most of the time it starts with a quite concrete start. For The Sink, we read the novel by Italo Calvino.

Arjun Basu: Invisible Cities.

Kirsten Algera: Yeah. It was about Armilla, a city of pipes, and sewers, and hoses. And that got us thinking about the sink, like this world in between the sewer and the kitchen. So, many times there’s some sort of starting point. And it can be a novel, but it also can be a work that we saw, or a situation, or whatever. So the next issue will be The Wall, which is not a coincidence since we’re living in a world where walls are the talk of the day, of course. And also very important. It’s urgent.

Arjun Basu: So the MacGuffin experience includes your Projects, which you mentioned. The curations you do, the art exhibits, and then you have a podcast about the pawn shop in Amsterdam, which is fascinating in-and-of-itself. It just seems so perfect for what MacGuffin is that you would do a podcast based on a pawn shop in Amsterdam. It just feels right. What else do you think might be coming to enhance the MacGuffin world?

Kirsten Algera: I think the podcasts will be a series of podcasts. So we’re working right now on one that is based on The Log. It will be about trees, of course. And the next one will be about The Letter. So we’re working on that.

And, like you say, I think it’s the perfect medium for things we want to do because it gives us the chance to also incorporate sound, and sound design, and telling stories in a different way. So that’s really interesting to us.

The other thing we were thinking of, but we’re a super small team so we don’t know yet if we can manage that, is to make a website that shows our research. Because before we produce the magazine, we do months and months of research, so do the contributors, and you never see anything of that. And sometimes objects or subjects just don’t make it into the magazine.

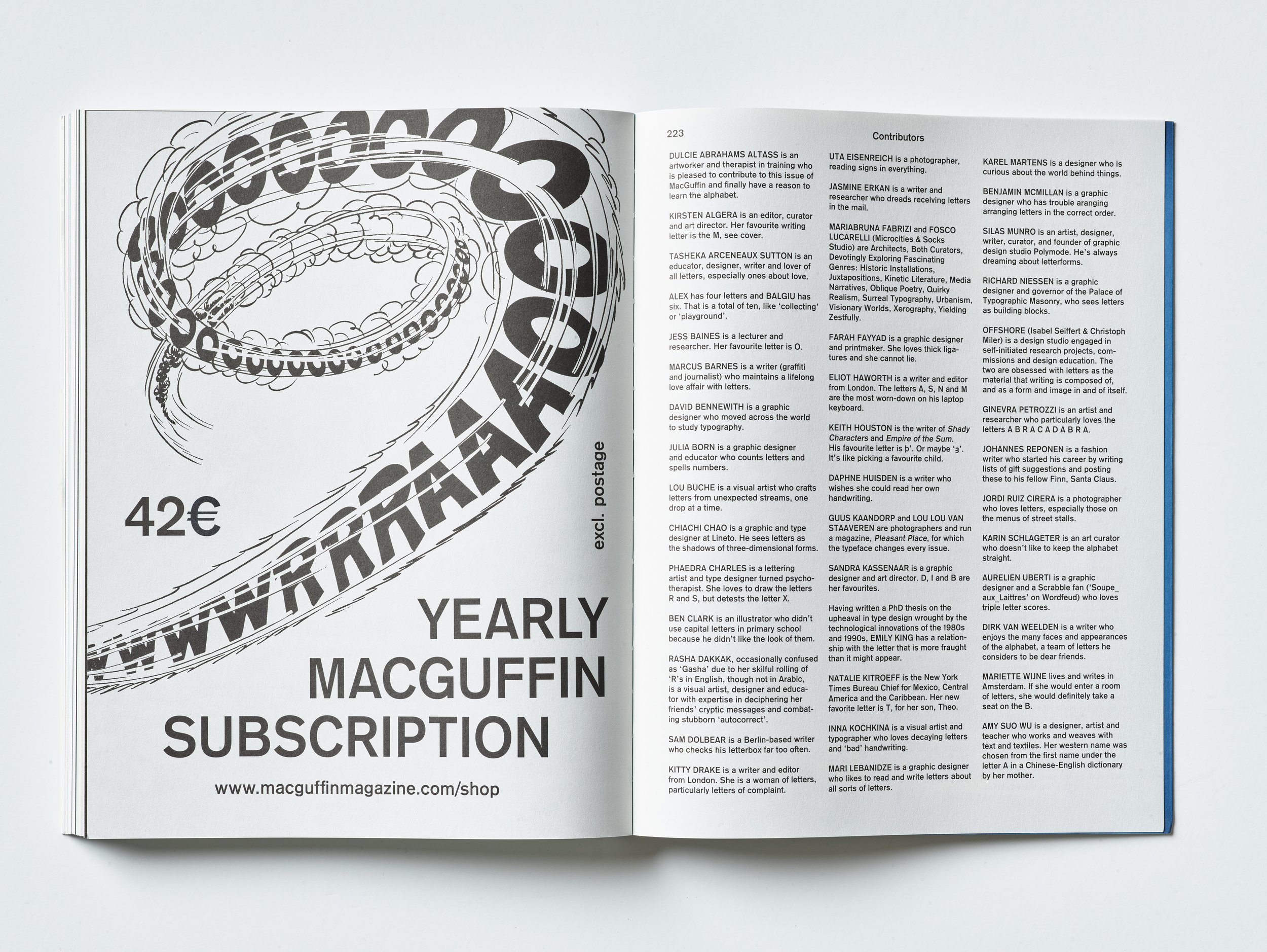

So that’s something that we want to show on a website, all this research. And also we think that it can be interesting for other people to use it, and annotate it in a way, or do something with it. And the other thing that we would love to do is make a sort of digital newsletter that gives a more actual relation to what is in the magazine.

So all the interesting events, and movies, and websites, and stuff that is related to what we discussed in the magazine, but we can’t show because when it’s printed, it’s finished, of course. But those two things, I think we can only do that if our team grows a little bit. And we’re not sure if that’s going to happen.

Ernst van der Hoeven: Something we are experimenting with a little bit is how we could develop also as a publishing house. During the period when we were working we found a very interesting lecture of an Italian professor working in Milano. And he had published it in Italian, and we translated that in English into a small booklet called The Poetics of the Oriental Rug. And that became quite successful because by translating it, it opened a whole new audience.

The professor is long dead, but the words he pronounced are still very valuable, and still accessible, by the booklets that we made. So in every issue there’s so much new content that, in our opinion, needs a bigger audience. If we had more time, if we were a bigger team, we would really like to establish a small publishing house and I’m working a little bit more on books as well.

The premiere issue of MacGuffin

Arjun Basu: So many magazines, when they talk about how they expand their ecosystem of media, it seems obvious. But they all follow the same path. Just given the very nature of MacGuffin and “the life of things” as a tagline, it feels infinite what you could actually do with that brand.

Kirsten Algera: That’s true. You could say that it is a way of looking at the world. And you can do that in many places, in all the media that you want. Right now we’re already doing a lot of workshops, so I think it’s working well as a sort of education model in a lot of art schools, at least in design schools.

But we also make exhibitions. And for us, it’s interesting to work in other media because we try, for example, in exhibitions to look at them as if it were a magazine. So, What is an exhibition that has the magazine as a model? And How can a magazine be an exhibition? Or How can an education model be a magazine? So we’re experimenting with that as well. And it’s interesting to us.

Ernst van der Hoeven: Yeah, I’m just thinking about the counter-cultural aspect of the magazine that we make. And that’s something that we also like to focus on when we make exhibitions: the untold stories and maybe the forgotten things that, in the beginning, might not be so interesting, but when we dig deeper, we find very intriguing material. We always like to feature the untold, and the not-so-obvious part of the story. I think there we also see a similarity in how we work.

Arjun Basu: MacGuffin feels very international, but in a very Dutch way. I love Holland, I have many friends from there. And one of my favorite things in the world is vla, which always makes Dutch people laugh.

Ernst van der Hoeven: We never eat vla.

Arjun Basu: Yeah. They always that about poutine where I come from. But from the beginning, it’s felt like a very international project. That the audience is the world, and not people in Amsterdam. How intentional is that—and who is the audience?

Ernst van der Hoeven: That’s not intentional. Not at all. When we started the magazine, this is a question that we have been asked by many people, with whom we’ve pitched the whole idea of making a magazine where we take one object as a departure. And a lot of people thought we were insane. This is not going to work! And Who is going to read this? And we were not so obsessed with our readership. We thought, We have a story to tell.

And we also thought the time was right for an antidote for ‘design’ as a word with a huge ‘D.’ That was something that we were very aware of, and also very confident about. That’s nothing that we were insecure about. So the whole audience was not something that we weren’t worried about too much.

Later on, when we started to monitor Instagram, who was actually reading us, we were amazed by the fact that a lot of young people, from 23–31, are the main readers of our magazine. So we were happily surprised that we make a magazine for a younger generation than the generation we belong to ourselves.

Arjun Basu: That speaks to the design of it too, because it really is an object in and of itself. It’s a big, heavy thing. It’s very tactile. I’ve always said, “Print needs to be printy-er.” It needs to exploit that idea that it’s a sensual object, it’s not a screen. And you guys really do that. It’s this thing that you want to hold.

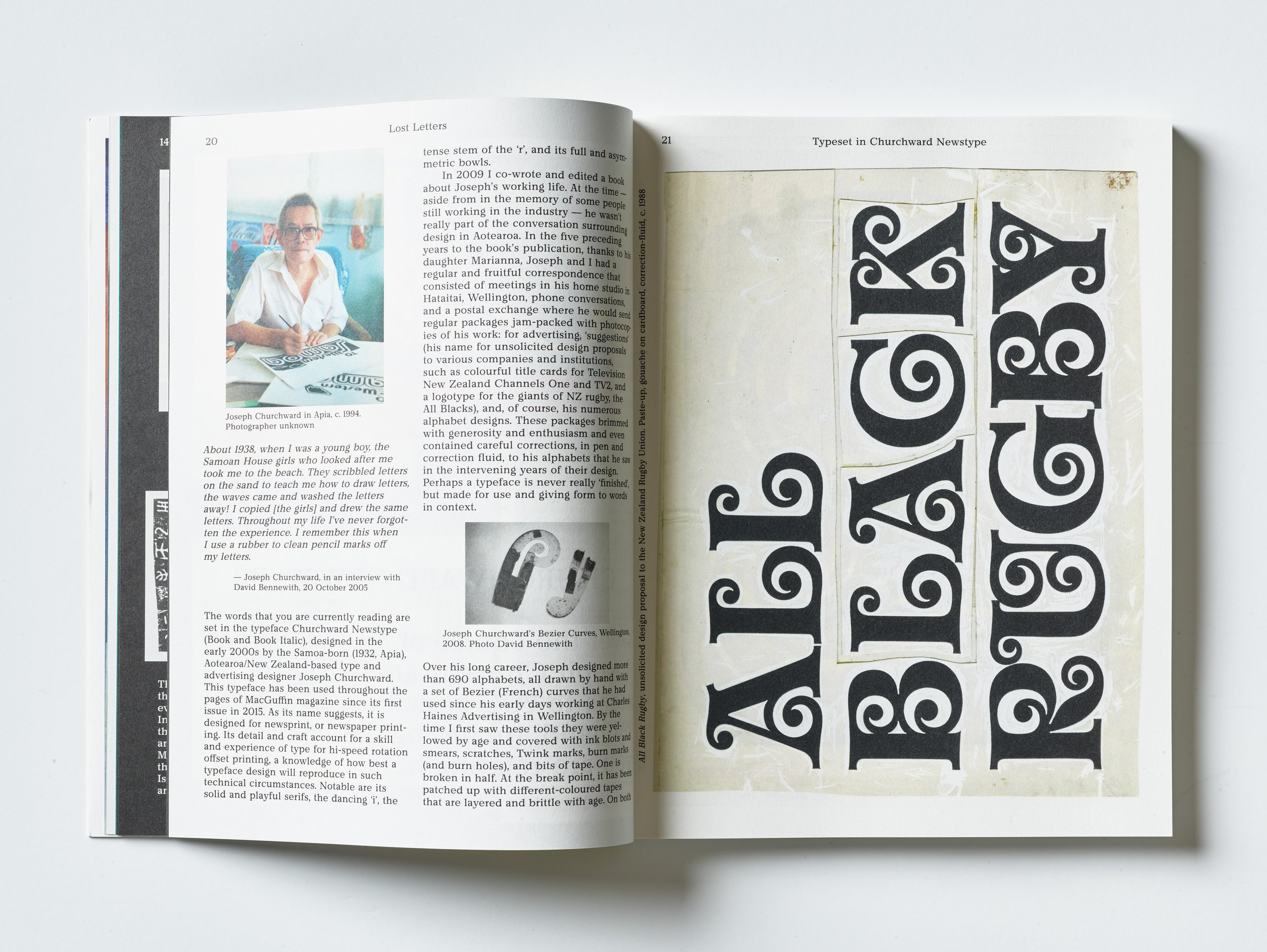

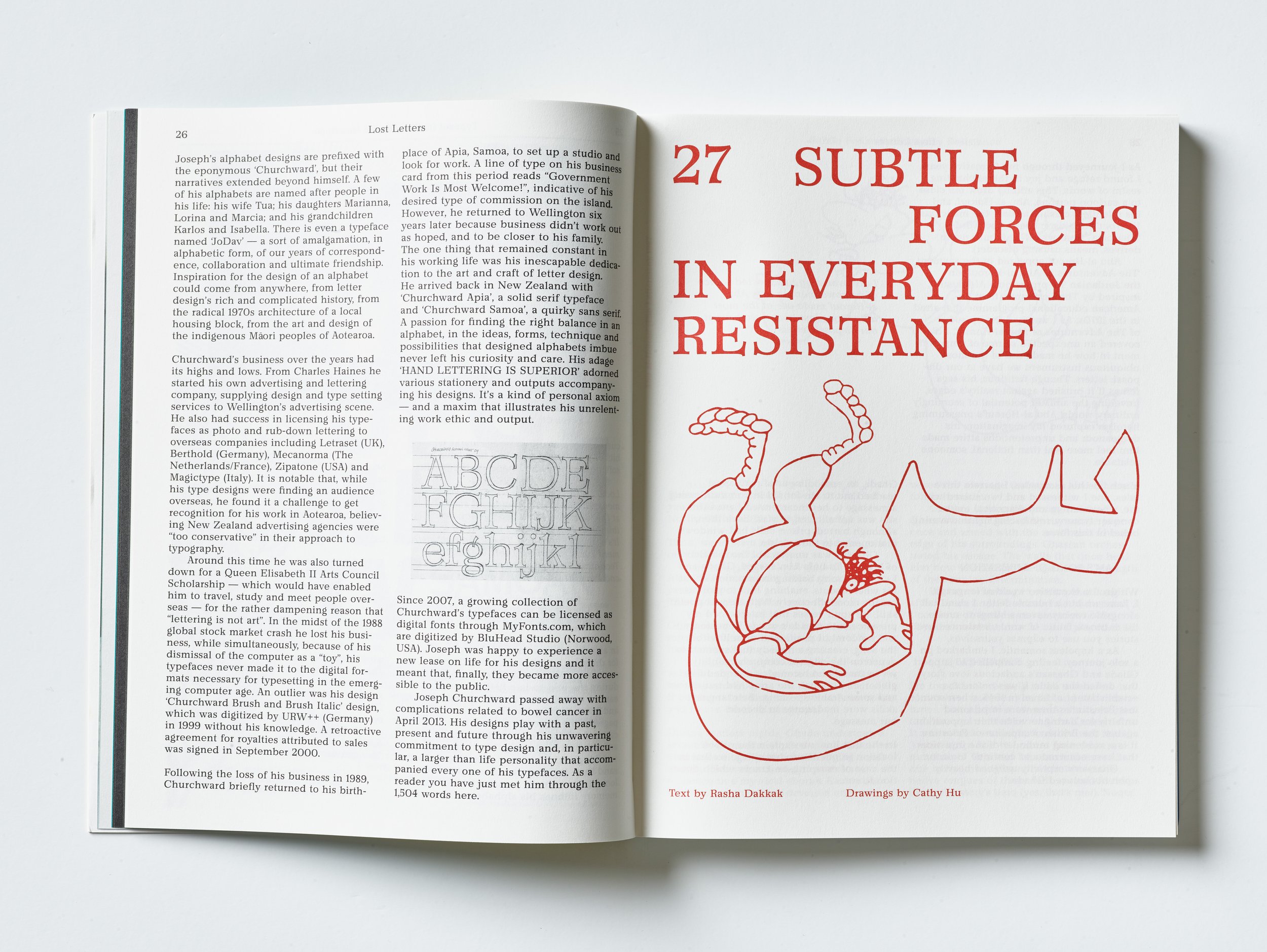

Ernst van der Hoeven: That’s so good that you mentioned that because we really hope that people understand that we see MacGuffin also as an object itself. And the way we make it’s also very crafty and the choices of the paper, the font, everything plays a part in that.

And when we started the magazine we thought, If you have to sacrifice so many trees, make something that stays, that keeps its value as a compendium or as a series of books, even. Because you can call it a magazine, but a lot of people also collect it as a series of, maybe, books. And that makes sense.

Kirsten Algera: Yeah. And I think the surprising and interesting thing, as well, is that when we started, we thought we would make a magazine for the design world, for people who are interested in design or in art. But I think the audience and the readership is much broader now. And that also started with interest from the magazine world, which is a world in itself, you could say.

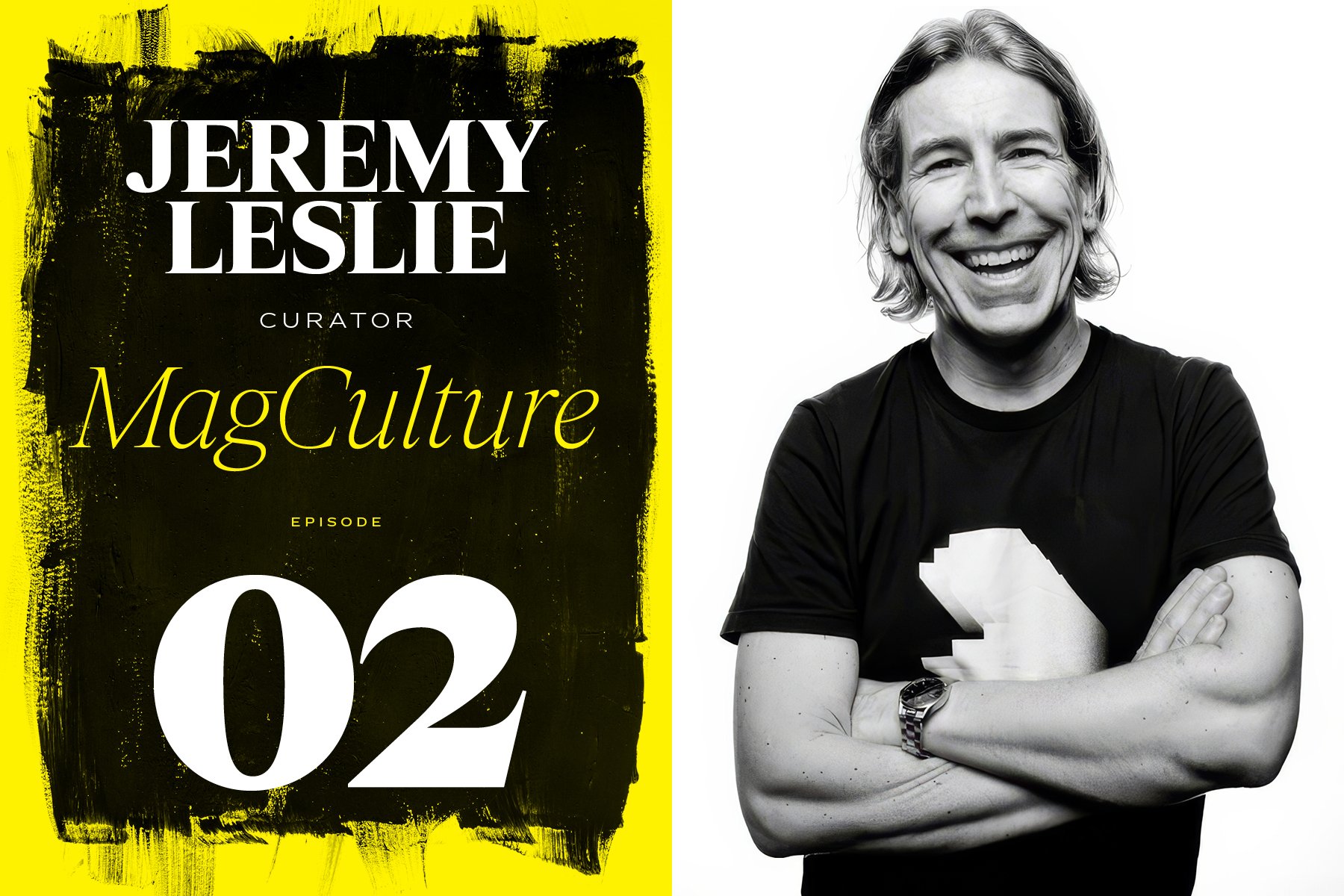

So you talked to Jeremy Leslie last time, and he’s one of those people who are part of this very intense, and very connected, and interesting magazine world. And we didn’t realize that when we started, that that would be part of the readership, as well.

But to come back to your question, from the start we thought We have to be as international as possible. Not only as a business model, but because this is interesting for everybody. And also because we want design to come out of that Euro-centric or Western-oriented bubble and also look at other places and other objects.

Ernst van der Hoeven: I’m just curious to hear from you what you find so typically Dutch about it. Because a lot of people think that we are made in London. They don’t even recognize that we are Dutch. And we’re not against being Dutch.

The most recent issue of MacGuffin on “The Letter”

Arjun Basu: No, you shouldn’t be against being Dutch. But I think there's a curiosity that Dutch people have about the world. And the way they look at it. They are very international. I find Dutch people are very curious about things. And Dutch design, on top of that, the world lost some great looking money when you adopted the euro. Dutch money was the most beautiful money in Europe. Any money that has a Piet Mondrian painting on one of its sides is okay by me. It’s fantastic. And just the design sensibility that happens in Holland. It definitely felt more European. I think an American MacGuffin would obviously be a very different publication. But when you start to think about it, you go, No, this is Dutch. That’s just me. But I just find it a very Dutch thing.

Kirsten Algera: Yeah, I can imagine that. There used to be a very strong Dutch graphic design. And design tradition, of course. That’s the reason that we worked for this Department of Aesthetic Design, that was called, by the way, in the corridors of the organization, the Department of Aesthetic Delay, because they delayed everything by looking carefully at the design.

But that was over in the beginning of this century. And a lot of the subsidies that were very common 10 years ago are gone. So, in that sense, The Netherlands is no longer a country that really pumps a lot of money into design or graphic design. It’s more like the rest of the countries, probably.

Arjun Basu: That’s a shame. I’ll ask each of you this question—I ask this to everyone. Kirsten, what are three magazines or media that you’re consuming right now that really impact you and are meaningful?

Kirsten Algera: That’s a really difficult question because there’s a lot, of course. Maybe the first I can mention is the book I’m reading right now, because we’re researching The Wall, as I said, and I’m reading a book that is called The Wall by Marlen Haushofer. She’s an Austrian writer. She wrote it in 1963.

And it’s a beautiful book, a very strange science fiction book, about a middle-aged woman who wakes up in the morning and finds that everyone has vanished. So it’s very post-apocalyptic in a way, but it’s also really beautifully written. And it took years and years before it got known, this book, because there wasn’t a lot of attention for Austrian female writers. But now there is. So that’s the sort of inspiration, in quite a dystopian way, I have to say.

As for magazines, I really like magazines with a very clean, and maybe not too huge of an editorial concept. Revue Faire is a French magazine that I like very much. It’s about graphic design and it always has one theme that can be one essay or one photo series.

They also started a magazine right now that’s called 12 Photos. It consists of 12 photos, like it says, that can be folded out into posters. And they are the graphic designers that I like most. So they’re very special. The third one…has to be three?

Arjun Basu: That’s what I ask, so yes. It has to be three.

Kirsten Algera: Maybe not so much a current magazine, but more of an inspiration is Nest. Do you know this magazine: a “quarterly of materials”? I think it was really important to us when we started because it showed this other design world that we were interested in—not the iconic design world, but everyday life. It was anti-materialistic, in a way, interiors—so prison cells, and igloos, and strange collectors.

And it was beautifully made, as well. For us that was something that we looked at from the start, although I think we’re a completely different magazine. But the attention to everyday life environments, and how people relate to that, was pretty important to us.

Arjun Basu: Ernst, your turn.

Ernst van der Hoeven: I would start with The Whole Earth Catalog, a counterculture magazine and product catalog at the same time, made by Stuart Brand between 1968–1972, and also occasionally thereafter. It appeared several times a year, so not really regular. And why I like it so much, I think, is mostly because of this editorial focus on self-sufficiency, ecology, alternative education, do-it-yourself, holism, and especially I liked the slogan they featured: “Access to tools.” Something we within MacGuffin also, in a way, do.

And what was very inspirational for us is that you make something that gives access to a lot of people, almost like a paperback Google version. And it was also beautifully-made. And very generous in the sense that it gave all the product information that you could get with very nice tutorials without the possibility to buy it there.

They gave all the information to the vendors, so you could buy it if you wanted to. But this was not a sales document or device. I found that a very beautiful and generous magazine. And you could always scroll through it and find new things—information about machines, and seeds, and tools, and all kinds of stuff. Very rich.

A totally different magazine that I like because it’s very cheerful and gay is Butt magazine, made by Jop van Bennekom and Gert Jonkers. Very Dutch. It was a small, very quite intimate magazine that existed from 2012–2021, and then they took a break, I think, for 10 years.

And quite recently they are back, basically because the Italian brand, Bottega Veneta likes to help re-entering these niche magazines. And they do it with a very clever way that also their advertisement is themed in a way that everybody understands. It’s a very sweet magazine and it was a beautiful platform for queer people and their friends to speak straightforward about their lives, ideas, work, and sex life. So it’s just quite open, and I really loved that.

A third one … well, yeah, there’s a quite young magazine that is made by Lou-Lou van Staaveren. She’s one of the editors who also works for us as a photographer. That’s a nice thing—if you work with young people you really see their development and you can follow that and we could foster that a little bit.

They are making a magazine about gardening. And being an avid gardener myself, I really love that idea. And what they’re doing are very nice, themed, small editions on compost making, or a certain flower, or a certain phenomenon in nature. It’s a quarterly and it is made with a lot of love, and it is something that I really love to get. And I really read it because there’s a lot of knowledge that you’d like to know as a gardener.

Kirsten Algera: Yeah, and it’s also very special, I think, that it joins art, design, and gardening, so it shows all these relationships that are really interesting, I think. Pleasant Place.

Arjun Basu: “Pleasant place” is a way that I think we could describe the world you’ve created with MacGuffin. Thank you both for taking the time to talk to us.

Kirsten Algera: Thank you very much.

Ernst van der Hoeven: Three Things

Kirsten Algera: Three Things

For more information, visit MacGuffin’s website.

More from Magazeum