The Jazz of the Newsroom

A conversation with editor George Gendron (Inc., New York, Boston Magazine, more).

In this episode, we talk to George Gendron, the long-time editor [Inc. Magazine] and educator who created one of the first liberal arts-based entrepreneurship programs in America. We talk about his first job working under legendary editor Clay Felker in the early days of New York magazine, how a third-grade book report set him up for a life in publishing, the near-fatal car accident that changed everything, why we should look to TV for the future of magazines, and how to build an economically-sustainable life around doing the work that you love.

—

George Gendron has spent his professional life at the intersection of media, innovation, business, and education. For over 20 years, he documented the burgeoning world of startups and entrepreneurship as the editor of Inc. magazine. But nothing has done more to influence his career than his time working for the legendary founder and editor of New York magazine, Clay Felker. We’ll circle back to Felker and New York magazine in a bit. But first, where does a 50-year career as an editor begin?

In New Jersey, of course. In the third grade…

George Gendron: The first vivid memory I have of this kind of compulsion to make stuff was when I was around eight. We were given a book report to do. You had to read a book and do a two-page summary—just write it up. And the book was Treasure Island, and I fell in love with the book and I decided it sounded really boring to do a two page summary.

So I made a book and I drew illustrations. There was a whole full-page illustration of, you know, the black mark that signifies that you’re about to die. I did a beautiful illustration, or I thought at the time, of a pirate eye patch. I made a cover for it and I wrote more than two pages. And then I bound it with needle and thread—I think I still have a copy of this—and I didn’t realize this at the time, but looking back on it, I began to realize later in life that what fed this was this kind of almost allergic reaction I had to being bored.

And so to me, the idea of reading a book and then doing a two-page summary was really boring, but making a book about the experience was really cool. And all of these activities from the book report to building a tree house and then tearing it down and building it again, had to do with making every day as interesting as I possibly could. And that became a huge driver in my life.

He definitely kept things interesting. Gendron had only ever attended Catholic schools, which accounts for his fondness for discipline, but maybe not quite explaining what came next…

George Gendron: By the time I’m a junior in high school, figuring out what do I, where do I want to go to school, I had never been in anything other than the Catholic school. And so the Air Force Academy seemed appealing to me for two reasons. It was almost kind of like a continuation of the kind of discipline that I had grown up in, in Catholic schools. And secondly, I’d get to fly. Or so I thought.

Patrick Mitchell: Isn’t it really hard to get into the Air Force?

George Gendron: Yeah. Very, very competitive. You had to get a senator or a congressman to nominate you.

Patrick Mitchell: So who nominated you?

George Gendron: Who’s the guy in New Jersey who not only ended up being convicted of crimes and being sent to jail, but they made a movie about it? Was it Case or Williams? [Ed: It was Harrison A. Williams, who was convicted in the Abscam scandal].

Patrick Mitchell: How did you get to a senator to do that for you?

George Gendron: My dad did okay professionally, but we weren’t “connected” to anybody.

But my best friend, Mike Feely, at the time, at one point I was saying to him, “You wanna go to this party this coming weekend?” This was junior year.

He says “I can’t. I’m going up to Stewart Air Force Base [in Newburg, NY]. I’m taking the tests, both physical and athletic, and academic, for Annapolis.”

And I said, “Well, I’m not doing anything. I’ll go with you.”

“Well, you can’t just come with me. You gotta …”

I thought, “Well, no, I think that’d be really cool. I’d like to see how I do.”

So I went, and I put down on the application “I want to go to the Air Force Academy.” And I’m not sure I even knew where it was!

And next thing I know, one day I’m in the backyard, playing ball with my brothers, and my mother comes out in the back porch and she says, “Look, I don’t know if this is one of your friends or not, but there’s a ‘senator’ on the phone who wants to talk to you.”

And it turned out that Senator Williams had an opening, and they had gone through the nominations, and he gave me his nomination. And suddenly I thought—I remember thinking to myself after I hung up the phone—”I think I gotta go now!”

“I remember at one point my girlfriend at the time saying to me, ‘You know, if you’re not careful, instead of being a participant in events like this, you’re gonna be an observer. You’re going to end up going through life as an observer.’ And I didn’t take it as an insult. I thought, ‘Yeah, that’s what I want to be. I want to be an observer. I’d love to write about this. I’d love to write stuff that’s true about all of this.’”

And he did go. But after completing basic training and beginning classes at the Academy, Gendron determined the Air Force was a bad fit and decided to leave and head back east, where he enrolled at yet another Catholic school, Manhattan College, in The Bronx.

It was 1968. The country was in turmoil. There was social unrest everywhere. And though he had left the military, Gendron found the ubiquitous anti-war protests troubling, especially when they were directed at soldiers. That fall, he restarted college with a sharper focus on a career in journalism, though, it could have, probably, gotten off to a better start.

George Gendron: I eventually got into Columbia and Manhattan College, but Columbia wouldn’t accept any of my credits. So I went to Manhattan. And at the end of my first semester, I got a call from the president of the college, and I thought, “Wow, he wants to welcome me officially.”

So I went in, and he had, I guess, what you would call my progress report. And I, I don't know, I hadn’t really seen my grades, but he said to me, “This is—coming from where you’ve come from—this is a really distinguished record.”

And he pushed it across. And I was failing everything. And incompletes. And I had never showed up for classes. And he said, “I’m going to recommend that you take a sabbatical.” He said, “Here’s the deal: We’re not really kicking you out, but we sort of are. But if you get to a point where decide you really want to be here, let me know. But no sooner than six months.”

So I went back to work in construction. Making a lot of money. Hanging out with my girlfriend and all of her wild friends. And it was just—it was music, it was fast cars, it was a ton of money, beautiful girls, a ton of drugs (because they worked in the hospital).

I started to develop this very detached sensibility. And I guess I remember at one point my girlfriend at the time saying to me, “You know, if you’re not careful, instead of being a participant in events like this, you’re gonna be an observer. You’re going to end up going through life as an observer.”

And I didn’t take it as an insult. I thought, “Yeah, that’s what I want to be. I want to be an observer. I’d love to write about this. I'd love to write stuff that’s true about all of this.”

I had been very disenchanted by my experience at Manhattan. And for the first time, I acted out. This was a way of me kind of shedding all that Roman Catholic discipline, the discipline from the Air Force Academy, trying to figure out as we all were, right? This was well, you know, “searching for who I am, baby…”

Patrick Mitchell: That’s what people did in 1968.

George Gendron: They did that in 1968, but I had to do it with a sense of urgency, Pat, because at the Academy, they had done a pretty good job, through basic training, of kind of stripping you of your former identity. But it takes four years to build you back up as a soldier. So I was kind of almost like creating an identity from scratch and I was completely out of control.

I eventually did go back to school. I went to Manhattan. I went to other schools at night taking courses. When it came time for me to eventually get out of school, I didn’t really have enough credits to graduate because I didn’t had never fulfilled any of the requirements. And so I ended up negotiating for a diploma.

—

After a somewhat meandering path to graduation that included alternating stints of college courses and construction gigs, Gendron found himself at a tragic, and life-changing inflection point.

George Gendron: But the big catastrophic event, if you will, for me, was when I was on a job at Newark Airport. They were building the new terminal and it was in January, and it was freezing, and they were closing the job down because it was unsafe conditions. And so the super asked me if I would ride around with him in his truck to make sure everything was closed down and protected. And we skidded off of a runway that we were building into an irrigation pond. The truck went under water. We were fine. We got out, but we were freezing our asses off and his truck was his only transportation. So he said to me, “Can you give me a ride home?” So I said, “Fine, I’m going to pick up my girlfriend down….” She was coming into Penn Station. So I dropped him off at his apartment in The Bronx, which was above a bar.

And we were really a lot more shaken up than we thought we were. And so we sat there and I had a lot to drink and I got in my car to go pick up my girlfriend. And I remember Joe, the super, saying to me, “Man, you can’t drive.” And I said, “I’ll be fine.”

And I got out and ended up veering off of the Cross Bronx Expressway at 100 mph or so, and totaled my car, and hit a bus, a bunch of cars, and a light pole. And I was in really bad shape for a while. I had a blood clot. Had brain surgery. And that was my kind of proverbial wake up call and my graduation.

And I went from one extreme to the other thinking, man, “I gotta settle down.” I ended my relationship with Colleen because the two of us together, we were both wild and out of control, and I felt like “I gotta settle down.” And so it was a turbulent … I didn’t have a regular, normal four years of college.

Patrick Mitchell: So what age are we talking about here?

George Gendron: By this time I was maybe 22. I had caught up by doing classes at night and all that stuff. So I had lived this very compressed life since coming back from the Air Force Academy, because I had failed out of school, worked in construction, gone back to school, raced around taking classes wherever I could. Took extra credits, wanting to get out of school now after my car accident. And so I graduated, maybe, I don’t know, maybe a year behind my class, maybe 1972.

—

He did settle down. He got married and started looking for work in the magazine business. And, while working at a job procured by his father-in-law, Gendron unexpectedly received, well, an offer he couldn’t refuse.

George Gendron: So I’ll set the scene: It’s January of 1973. Not a good period in New York at all.

Patrick Mitchell: This was the oil crisis.

George Gendron: This was also—the city of New York is not in great shape. Oil crisis, big recession. I’m talking to my father-in-law. And I said, “You know, I need to make some money, but I really do need flexibility.” Naïve as I was, “because I’m gonna have all these job interviews.” So he said, “Well, I’ll give you a job.” I said, “Doing what?” He says, “Just show up. In fact, I’ll drive you the first day.”

So he picks me up and we go to Byron, Connecticut. And he was the president of a company that made virtually all of the Weight Watchers food for the United States. It’s a food processing plant.

And he gave me a job working on the food line, making Weight Watchers food. It was me and, like, 150 illegal Colombians, all women. And one day I’m sitting on the curb during my lunch hour, and this guy comes up to me and he introduces himself—and he is right out of The Sopranos.

Nice guy, very gruff, shirt open to his waist, a lot of gold chains. And he said, “I’ve been talking to your father-in-law and I hear you wanna be in publishing?”

I said, “Yeah.”

He says, “Here.” And he hands me his card.

“What is it?”

“My son. Tomorrow. Nine o’clock. Be there.”

And he walks away. And the guy’s name was Tony Carvette. And he was the chief financial officer for New York magazine. So I go home that night to my wife, Holly, and say, “You’re not gonna believe this, but I got a job in publishing. Man, your father, he is connected!”

So I show up, probably earlier than nine o’clock. 32nd between Second and Third. It’s the Push Pin Building. Milton Glaser’s building. New York magazine is there. I go in, Tony’s there. We make some small talk. “Yeah. He met my dad, blah, blah, blah.”

He says, “Come on, I’ll take you to your office.” And I had a jacket and tie on, and he brings me to my office, which is the mail room [laughs]. And so I was the mail boy for New York magazine.

And you know what? I didn’t give a shit. I was ecstatic.

And you were asking earlier about kind of the environment at large. This is 1973 and New York is hot in a way that I’m not sure any magazine had ever been before or after. It was kind of … the closest thing would’ve been Esquire in the sixties.

Patrick Mitchell: When did New York magazine launch?

George Gendron: They spun out … the Trib folded in ’67 I wanna say? Clay Felker and Milton Glaser got together enough capital to launch in, maybe ’69.

Patrick Mitchell: And it was originally the Sunday magazine?

George Gendron: It was originally the Sunday supplement in the old New York Herald-Tribune. Yeah. And they had a good staff, some cool editors. They had a lot of interesting contributors. And the pitch back then, when it was the Trib’s Sunday magazine was, you know, “Come here and you can do some, you can do some shit, frankly, that nobody else will let you do.”

And you could argue that this was really where a lot of the roots of the new journalism were nourished. If you can’t afford to pay writers, let ‘em do some crazy stuff and experiment. Right?

“New York was a magazine where design was so fully-baked into the culture of the place that it almost didn’t occur to me as a young kid that it was like a separate discipline. There were no boundaries.”

Patrick Mitchell: Writers like?

George Gendron: Tom Wolfe, Jimmy Breslin, Norman Mailer. I think Gail Sheehy was there at the time. Nora Ephron was writing there. Gay Talese, Nick Pileggi was doing, I think, stuff about organized crime.

And it was just a Who’s Who of American journalism. It was just astonishing. And so, on the one hand, you could argue the magazine … it was really three years old at that point, but it was still a startup, and by startup, I mean, you know, it was still kind of trying to figure out what it was going to be when it grew up. It was losing money. There was more work than there were people.

So I go around delivering mail. And when, after about two weeks and I got confident enough to introduce myself, I would go around and, I swear to God, Pat, I would go up and say to people, “Hi. I’m, I’m George Gendron. And, you know, I mean I’m delivering mail, but I’m really not a mail boy. I’m a, I’m a [laughs] college graduate.”

And most of the people there were so nice. They were like, “That’s good to know. I’ll keep that in mind.”

I got to know a lot of the people up in the newsroom and there was a young woman there, Wendy Thomas, and she was on an exchange program with the BBC. And she said to me, “Look, I know you’re really into the arts.” And she was kind of like the junior editor for the arts and entertainment stuff. “I’m heading back early to the BBC. So I”, she said, “I’ll tip you off once it’s underway. And I said, “That’s great!”

About a week later, Judy Daniels, a managing editor and the woman who launched Savvy magazine comes to me and says, “I heard you’re a college graduate [laughs]. Would you like to be my assistant?” So we went out and we had some coffee. We talked about it. It sounded like a lot of typing. So I said, “Look, I really appreciate the offer, but now I think I’ll pass.”

And she was like stunned. The managing editor of New York magazine has offered the mail boy a job in the newsroom. And he said, “No.”

And a week later, Wendy says to me, “I’m leaving. Go up and make your pitch.” So I did. And I became the junior editor for the arts and entertainment section. It was called the Lively Arts and it was Judith Crist writing about movies, John Simon, legendary drama critic on theater, Tom Hess, and Barbara Rose on art.

I mean, it was just … and my boss was Alan Rich, the music critic, who didn’t want to be a boss. Didn’t want to be an editor. And so very quickly, I developed enough of relationship with columnists and the contributors and the people in the art department that I was kind of, you could think of me as an assistant managing editor for the back of the book. And then here I was. I was in the fucking newsroom of New York magazine!

And so, instead of delivering mail to Nora Ephron, who didn’t have an office, but she would come in. And it was four-square desks. And three of them were occupied by the arts people. And there was a vacant one for writers. Nora would come in and she’d do her reporting and stuff and I’d be sitting there and I had to kind of, you know, slap myself to think, That’s Nora Ephron and that’s Tom Wolf over there. It was amazing! It was just amazing.

And so I ended up editing the back of the book, and then I started to write for the Intelligencer, which was alive and well then, and still is today. Same thing. I mean, Jack Nessel, the editor, needed a ton of stuff. And so I started contributing about the arts and entertainment scene, Broadway, a lot of gossip stuff, movies. And that magazine shaped my professional life in ways that I still am discovering to this day.

I’ll just give you an example. It’s very relevant to your livelihood. And that was that New York was a magazine where design was so fully-baked into the culture of the place that it almost didn’t occur to me as a young kid that it was like a separate discipline. Because when we were on 32nd Street, at Push Pin Studios, Milton’s studio was on the third floor. But he was upstairs in the newsroom all the time. And you could argue, it was classic case of, you know, was Milton a designer who happens to be a really brilliant editor, or is he a brilliant editor who happens to be a designer? There were no boundaries.

Patrick Mitchell: And Clay was the editor …

George Gendron: Clay Felker was the founder, and CEO, and editor.

Patrick Mitchell: What was their relationship like, Milton and Clay?

George Gendron: It was passionate and sometimes really turbulent.

Patrick Mitchell: Was there a turf war in any way?

George Gendron: No.

Patrick Mitchell: Who was in the art department when you were there?

George Gendron: Milton was technically, I guess back then you would’ve called Milton the art director. But the number two was Walter Bernard. Number three was Tom Bentkowski.

Patrick Mitchell: Was there a photo editor?

George Gendron: No, I don’t think there really was a photo editor. I got that impression because when we moved from 32nd Street to 41st, it was still a newsroom environment. But instead of Push Pin being on a separate floor, now the art department was part of the newsroom. And my four-square desk was right next to, I mean, literally 30 feet, from the art department. And so I could hear, and see, and watch as each magazine was being put together. It was very different than you would imagine, because the way in which Clay and Milton had conceived New York, it was a monthly feature magazine that happened to come out weekly.

And so the back of the book was highly formatted. I did all the type spec’ing, and as Milton would go on to say later on, people raved about the look of the magazine, but it was designed for efficiency. And so you had a system here where all of the regular columnists in the back of the magazine had regular illustrators and they were all illustrated. And so I was the liaison with them and I would send them the copy. They’d send in a sketch or an illustration and I’d give it to Tom Bentkowski—I don’t think we had a separate photo editor. I think that Walter and Tom did a lot of the assigning to photographers and to illustrators. And if you remember back then, there was a lot of illustration in the magazine. A lot. And some brilliant work, including by Milton himself.

—

The mail boy was hooked. Spending his days, surrounded by the A-list of the New York publishing world was a dream come true. He knew what he wanted to do for the rest of his life.

George Gendron: I couldn’t wait to get into that newsroom every day where you had editors, and writers, and illustrators would come in, and photographers would hang around, and designers, and I was a kid. I was not an important part of this mix, but just to like sit there and watch it? Pat, it was, it was magic. And I fell in love with publishing. I fell in love with magazines. I fell in love with the jazz of the newsroom. Of what work could be like when you had this kind of collaborating together where there were no boundaries. No one would ever say, “Look, I'm the editor of this piece.” It was, you know, it was like … best ideas win. It was about influence, not title.

Coming up, George Gendron talks about his mentor, Clay Felker. But first, here’s Felker in an interview on the Charlie Rose Show back in 1995, where he described the environment that had soured him on the magazine business:

Rose: Why isn’t Clay Felker, heralded by all these writers, who adore what you did, who thought you had vision, and passion—and you still do, to the Nth degree—why aren’t you editing a magazine today? Because that’s what you love the most.

Felker: Well, the last two magazines I edited were victims of the recession and we had endless budget cuts, sometimes every two weeks, as we were losing advertising and so on. And as somebody pointed out, I’m really not made for big corporate organizations, and only big corporate organizations can start magazines now. And I think that maybe I’m just not…. People don’t find me easy, in the corporate structure. Because, perhaps my entrepreneurial zest, journalistic, entrepreneurial zest, may not fit in somebody else’s corporate culture. I don’t really know the answer to this, but I’ve thought about it. That’s the best answer I can come up with.

Little did he, or anybody, know that a few short years later, the dotcom bubble would burst and change magazine publishing forever.

Most of us are lucky if our first boss teaches us a thing or two. Gendron’s first boss, Clay Felker, played a pivotal role for a whole generation of magazine makers. A visionary editor who was widely credited with inventing the formula for modern magazines, Felker is best known for creating the glossy weekly named for, and devoted to, the city that fascinated him: New York.

It was at New York magazine that Felker left his biggest imprint on American journalism. He had edited the magazine when it was launched as a Sunday supplement to the New York Herald-Tribune in 1964. Four years later, after the newspaper folded, Felker and the legendary graphic designer, Milton Glaser, joined forces to launch New York as a glossy, standalone magazine. The look and attitude captured the attention of the city and influenced editors and designers for years to come.

Dozens of city magazines, modeling themselves after New York, sprang up around the country. “I know why Clay is such a good editor,” said a close friend. “He works until eight o’clock. He goes somewhere every night. He’s out with people. He talks to people. He listens to people. And he doesn’t drink.”

Adam Moss, the recently-retired and universally-celebrated editor of New York magazine said, “American journalism would not be what it is today without Clay Felker.”

As mentors go, Gendron and had found a pretty good one.

George Gendron: He was, from my point of view—and this is just my point of view—he could be unbelievably socially awkward. I think his worst moment, when we moved to 41st Street, and you had to take an elevator to get upstairs to the newsroom, would be to be caught in the elevator with a low-level employee like me [laughs].

He was so awkward. He didn’t know how to make small talk or anything. I think he, and yet this is the same guy who basically said, you know, ”Every story idea I ever got, every writer I ever recruited, came at a dinner party.” So he kind of was this bundle of contradictions in a way.

Patrick Mitchell: And wasn’t his wife kind of a powerhouse, too?

George Gendron: Well, his first wife was an actress. But the love of his life was Gail Sheehy.

And I have no idea—I don’t know Clay, I didn’t know Clay personally—I have no idea about his personal relationships with women, but he was the most promiscuous talent scout I have ever seen in my life. And I mean that as a compliment. Gloria Steinem adored him.

Patrick Mitchell: Meaning he wasn’t a hung up on ‘pedigree’?

George Gendron: No. Not pedigree. Not gender. It was just like, he just had this incredibly keen instinct for who and what at the right time. And so he launched Ms. magazine.

Steinem couldn’t figure out … “I’ve got the idea for the product the right time. I’ve got all this editorial talent, but I have no distribution deal.”

So she’s sitting there talking to Clay, and he says, “Well, we’ll just insert it in New York magazine, you’ll have our distribution for issue one.”

You know, Gail Sheehy had become really interested in this notion of ‘female psychological and personality development.’ All the emphasis had been on males. And so she wanted to do this book that eventually came out, and I don’t think people were really enamored of the idea at all, called Passages. And it was about women and how women developed. And we published a lot of Gail’s stuff in the magazine that eventually led to the book.

He was a huge fan of Nora Ephron. I mean, it was just the woman who really invented “Best Bets,” which I think is still part of New York magazine. There was this woman, Ellen Stern. She wasn’t a journalist. He met her at a party and he was really taken by what he called … she had, I remember overhearing him say, “she’s like this ‘urban scavenger.’ She knows where all the really cool shit is. So she’ll learn how to write.” And he brought her in. And I became very good friends with an architect, Peter Blake, who eventually ended up becoming the architecture critic because Clay was at dinner with him one night and heard him talking and said, “Oh, you should write that.” It’s like, “I don’t really write. I run architecture schools.” “No, no, we’ll help you write it.” You know?

Patrick Mitchell: Do you feel like he influenced the way you evaluate talent?

George Gendron: Yeah, absolutely. And I think he influenced me in a way that, again, might have been a misreading, but I don’t think so, because I have talked to a lot of people about him and, and it’s not like I didn't know him, but I didn’t know him as a peer.

He was unbelievably selfish in a really healthy way. He wanted to produce a magazine that reflected what he thought made New York, New York. And I remember pitching a story to him at one point. I wanted to get a bunch of jazz musicians to start writing about kind of the renaissance of jazz. And I said to him, “You did this at Esquire.” And he was like, “No, the timing isn’t right.” End of story. Couldn’t debate it.

It was just like, “nope.” You have this filter that he just trusted. Absolutely. There was a kind of like simplicity about all of this. Everything was clear and yet there were no HR meetings. There were no discussions about culture. You know what I mean?

It just kind of evolved and what I loved about New York, and then I’ll shut up because I could keep going, was that the discipline. Nobody cared like, you know, “Was Gay Talese really writing?” You know, “Is he in the office today?” It was like, you gotta be kidding me. The discipline came from—we were publishing once a week. That was not negotiable. There’d be a messenger coming for your part of the magazine. And you wouldn’t even entertain the idea that it wouldn’t be ready. You just did whatever had to be done.

It’s it wasn’t, for me, a prescription for burnout. But it was two things.

One, was that it was that nobody at New York had any interest in management or leadership. It was all about the stuff they were making. It’s all anybody ever talked about. Ever.

The other thing to keep in mind, what made Esquire in the sixties so heretical on so many levels—and Clay, of course, was there with Harold Hayes—was magazines weren’t designed. They were like pasted up. So this idea of, you know, people talk about Milton Glaser as kind of the father of graphic design. Most people are too old to remember that …

Patrick Mitchell: … He was a magazine guy.

George Gendron: People didn’t even know what graphic design was! It was like, “Oh, you get galleys, and then you go to repro,” and everything was fine. And you give them to guys in the the production department. And they paste that shit up on boards. And all you had to do was make sure that all the columns were even at the bottom. So this was crazy stuff, man.

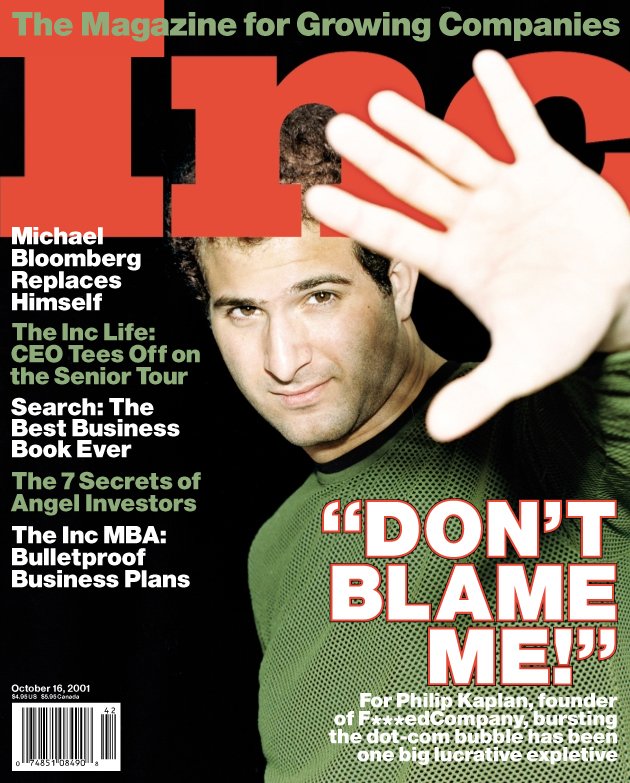

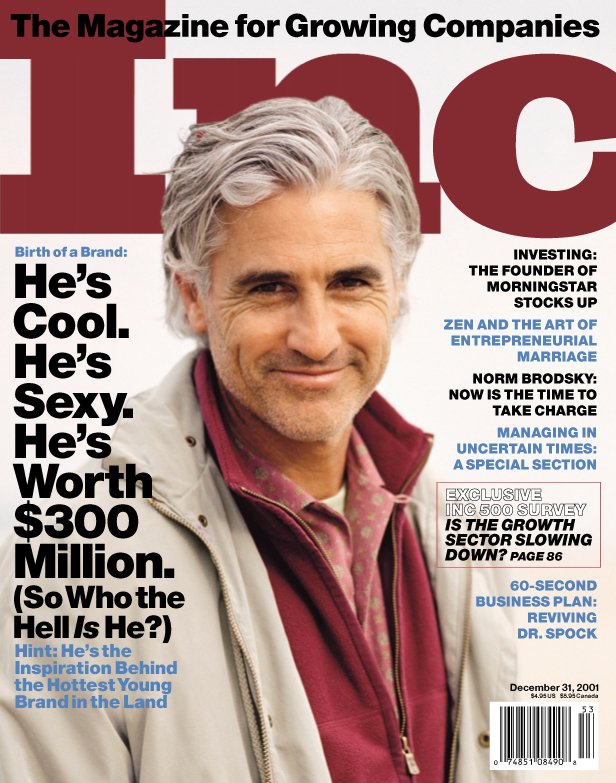

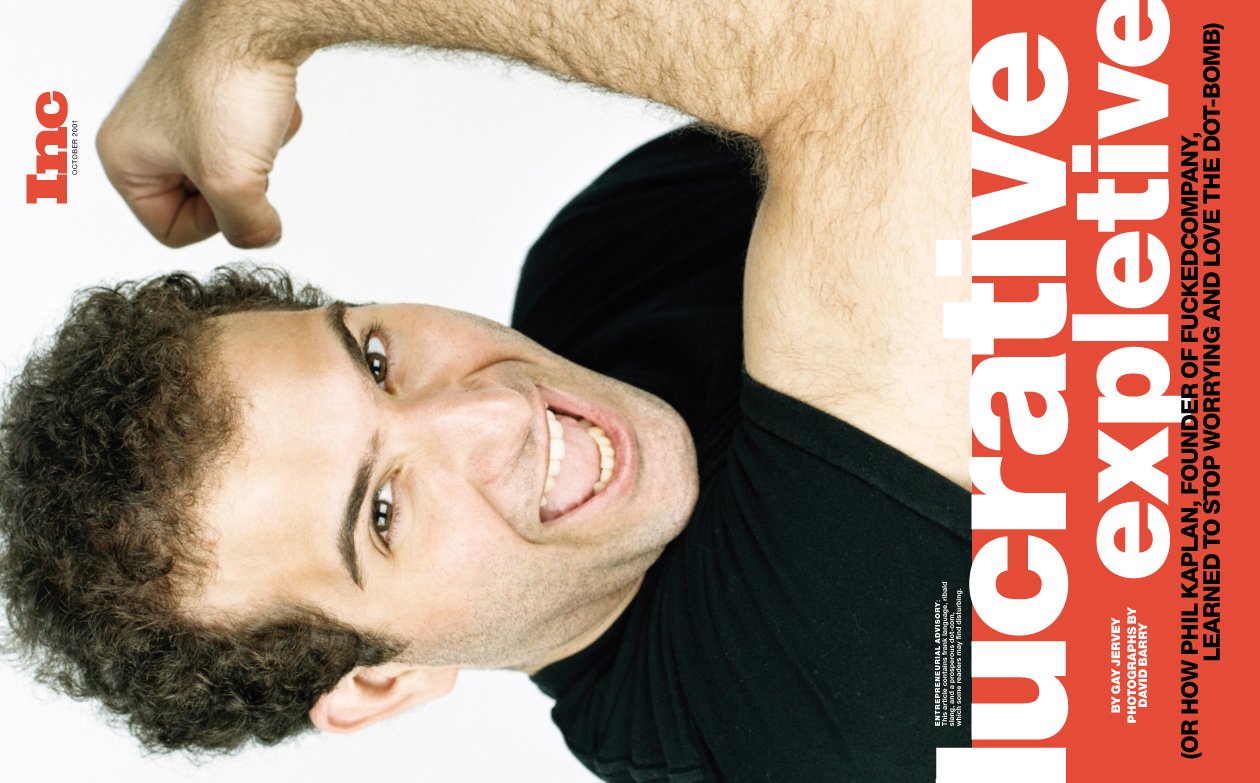

Gendron’s Inc. Magazine introduced the world to Steve Jobs.

It is common practice in the magazine business for publishers to poach talent from the big guys. It was bound to happen to a rising star like Gendron. And in 1975 it did.

Patrick Mitchell: So you outgrew your job at New York?

George Gendron: No, I didn’t. I loved my job, but I had gotten a feeler from The New York Times from the Arts & Leisure section. And if there was one place in New York that I thought would be kind of like a step up for me personally, that would’ve been it.

But then I brought in this young, I thought, brilliant movie critic who had been mentored by Pauline Kael. His name was Michael Sragow. And Michael, was writing movie criticism for Boston magazine. And so he evidently mentioned to the owner of Boston magazine, Herb Lipson, that there was this really brilliant young editor at New York. He was thinking of leaving. So I get a call from Herb and he says to me, “Come down to Philly. I’d like to meet you.” So I went down and after two hours of meeting, he said to me, “You wanna take over Boston magazine?”

I was 25. So I summed up the courage to say, “Let me think about that, Herb. I’m flattered.” So I flew back, talked to Holly about whether she was willing to leave New York and go up to Boston.

And the next day I go into Clay’s office and I tell him about my meeting with Herb, and that Herb basically has offered me the job to run Boston magazine. To be the editor-in-chief of Boston magazine. And Clay says to me, “I got two things to say. The first is that, you know, look, Herb Lipson is an a**hole. And he will wanted to be an investor in New York. And I checked them out and I said, ‘No.’ And for me to say no to a guy who wants to invest in my magazine back then, that was a big deal. The second thing is: take the job. How many times do you think anybody’s going to offer a 25-year-old a job as an editor in chief? If it doesn’t work out, come back. We’ll give you a job.”

So I took it.

Patrick Mitchell: So you came to Boston.

George Gendron: Came to Boston, ended up being introduced to one of the most villainous publishers in American magazines. Should I repeat that?

Patrick Mitchell: “The opinions expressed in this podcast … .” Hey, he fired me, too.

George Gendron: Somebody—and it might even have been his son, David—once said to me, “Anybody with any talent will be fired by my dad within three years.” It’s a control mechanism.

Patrick Mitchell: There’s a whole community of really talented people who’ve been fired by Herb.

George Gendron: Yeah. I went to a party once and they gave out badges that said “I Survived Herb Lipson.” So I came up to Boston and what’s memorable about that was, for a young guy, I, if I had a regret about leaving New York, it wasn’t leaving New York magazine. It was leaving New York City. I mean, that’s where all magazine publishing was. But I convinced my wife, Holly. “We’ll go up to Boston for a couple years and then we’ll go back to New York.”

But I discovered that Boston was this unbelievably vibrant print world with The Boston Globe, The Real Paper, the Phoenix, Boston magazine, The Atlantic. And a lot of journalists. I’m talking about, kind of, more of a youth journalism movement. A lot of the people who were up here went on to became big names down in New York eventually. I mean, it’s like a Who’s Who of newspaper and magazine journalism.

But the most memorable thing that happened for me at Boston was that I became really enamored of The Real Paper. Particularly the design. It turned out that there were these two designers over there, Ronn Campisi and Lynn Staley, who were doing this really extraordinary stuff. Typographically, stuff that just wasn’t being done elsewhere.

And to try to kind of mitigate against the size of the paper itself, which was a tabloid, they were doing these columns that weren’t justified at the bottom of the page, with a lot of white space and really interesting illustration and photography, and taking chances. And so I lured Ronn over to the magazine and we did some really crazy stuff together. And we put together a redesign package and Herb Lipson, the owner, came up to Boston for a review session and we presented it to him. And he didn’t say a word.

Then we went across the street to the Ritz. Ronn, and Herb, and I. And Herb ordered his usual order of pancakes. And he said, “Yeah, I really like it. Don’t get me wrong, but I think it might be shocking for our readers.” And he kept looking at his watch. “I have to catch a plane. I’m heading to the Cannes Film Festival. So here’s what I’d like you to do: Let’s introduce the redesign one page at a time. So you can start with contents and we’ll see what the reaction is...” and then Herb left.

And Ronn and I sat there at the table in the Ritz dining room and we looked at each other, and, I think, at the same time we said, “Fuck him.” And we did the redesign. And we put an advanced copy together, and we sent it by messenger—which was very expensive—down to Herb in Philly.

And I got a call from Herb saying, “Be in my office tomorrow morning.”

So Ronn and I flew down to Philly and we walked in and Herb closed the door, and he walked over and he said, “So, when can you redesign Philadelphia magazine?”

And that was, for me, this experience. It wasn’t a wake-up call because I’d come from New York—where again, design was everything—into a magazine where there was no design. It wasn’t designed. But this is what I wanted to do. I wanted to make things that were beautiful and engaging, but not beautiful for their own sake. They had this kind of energy—and I didn’t even have a vocabulary to describe it.

—

All good things come to an end and, with Herb Lipson, the end usually comes before you expect it. In 1978, after three years at Boston magazine, Gendron and found himself in search of a new opportunity. What he found was how he’d be spending the next two decades.

Patrick Mitchell: So how did this lead you to Inc.?

George Gendron: So I get fired. And …

Patrick Mitchell: … as one does …

George Gendron: … [laughs] As one does. I lasted a full three years. I think it was actually almost exactly on my third year anniversary that I got fired. And by that time I already knew what I wanted to do next. And I met this very unusual man, Bernie Goldhirsh, who had started a magazine called Sail. And he had sold it—I think for $12 million. And everybody said, “Oh, you know, you gotta go over and talk to Bernie.”

So I did it. After one meeting, I realized this was the least design-conscious man I had ever met in my life. And all he talked about was this business magazine that he was starting. And it was a small business magazine. And I was completely uninterested in business. And he was completely uninterested in design. But after the third meeting, he had launched the magazine and it was a commercial success already. It was doing pretty well and it was just horrendous. It was like a bad trade magazine.

And so at the end of the conversation, he said to me, “Look, you guys in the consumer magazine business, you can make shopping for pizza, this great life drama. Imagine what you could do for people who are building companies. These aren’t jobs. This is a life!”

And I needed money really bad. So I said, “Here’s what I’ll do. I’ll do a deal. I’ll come over for three years and I’ll help you build a really engaging business magazine. And then I’m going to go back to consumer magazines.” And he said, “Yeah, fine.” So I came over, and 20 years later, I was still there!

—

At around this time, the Silicon Valley was booming. The young companies that defined the era—Apple, Microsoft, Netscape, Yahoo, AOL—were reinventing the way work got done. It was an evolution of the culture at his beloved New York magazine. Gendron saw a way to create the newsroom of his dreams for his team at Inc.—without the foosball tables.

George Gendron: There were these young companies—Apple Computer, Lotus, Oracle, Microsoft—that were building this new portable technology that started to capture, not just the attention of the business community, but of the world at large, because they weren’t started by “business” guys. It was started by people who were college dropouts, with long hair, and, you know, they didn’t wear suits to the office and they never talk. Ever. They didn’t ever talk about business stuff. They never talked about “market share” and “scaling” and “profitability.” They talked about—well, invoke the cliche: “making insanely great products.” And so we, although we didn’t realize it at the time, it was this inflection point.

So you had this magazine that was making money and that was positioned in a way that was really cool, but the product was really dismal. And so the question is: How do you turn the product around without screwing up the commercial agenda?

And that’s what got me excited. And so I was there for three years, and I was out on the West Coast spending a lot of time with the tech community out there. And I was flying back on a red eye and I suddenly realized, “Oh my God! My three years are up!”

And I started thinking, “I don’t know, this is kind of cool.” Talking to these people and hanging out with these tech guys reminds me of being at New York magazine. It’s like, it’s all about creating really cool stuff. And this was not just talk. And it was about possibility, on so many levels.

The word that keeps coming to mind is democratization, right? And what the personal computer industry did was, they put this incredibly powerful tool into the hands of the masses, but also at the same time, entrepreneurship was being discovered by a whole generation of Baby Boomers—going back to 1968—who had grown up arguing, “Death to the corporation!” and it was like, “Look, ma: No hands!”

I don’t know. “I started this thing. It was like a hobby,” says Yvon Chouinard. “I was creating these climbing tools called Black Damond. And, and, and the next thing I know I have this company called Patagonia and now, so now what?” And we tapped into that.

“And I started to think, ‘Well, how do I create a place that I want to work at?’ And I don’t want to manage. I don’t want to have to do administration or organization. And so what if I were to hire a bunch of editors and writers like me, that are driven by this kind of relentless curiosity about how shit works—‘How does it really work?’”

Whether it takes 10,000 hours, as Malcolm Gladwell says, or just four as Tim Ferris seems to believe, the good ones at some point will achieve mastery over their craft. Over the span of working at three magazines, Gendron began to see with the clarity he ascribed to his mentor, Clay Felker, and charted a path for success at Inc.

Patrick Mitchell: So what comes next?

George Gendron: That’s a great question. And it’s a question that, you know, people who know me and have interviewed me always gloss over, but it’s the pivotal question.

I was immersed in the world of entrepreneurship and what motivated me to wanna stay at the magazine was this, what I didn’t talk about at New York, that wasn’t just about the magazine business, because as I was in the arts and entertainment field, was that I got to, either secondhand or in some cases firsthand, I got exposed to the process that creative people, mostly artists, went through to turn an idea into something tangible. And, in some cases, they were … I spent a long interview with Claes Oldenburg, the monumental sculptor—it could be a painting, but it could also be an idea for script for a movie, or a Broadway play—and I became obsessed with that. I became obsessed with, Where do ideas come from? Where do new ideas come from? How do you keep them coming? What is it?

And in a way, this is very connected to what you and I were talking about earlier about Broadway productions, or about high school productions, is, as consumers, we get to see the show. But what we don’t know is: How do you get from that first glimmer to that production that night when the curtains part?

Flying back from San Francisco after three years in Inc., I was struck by how the conversations that I was having with these tech entrepreneurs was the same thing. It was really about … it was about creation.

And I found it as stimulating and exciting and provocative as the conversations with artists. In fact, I actually thought of it back then almost as an art form, but the ‘palette’ was business. And by business, I mean business in the best sense of the word. It wasn’t business like about a spreadsheet or a balance sheet. It was about making really cool shit. And all of this stuff, the Broadway theater, the jazz of the newsroom, the jazz of being at Oracle when it was a $4 million company and people were just thrilled with what they were doing, all came together.

I began to think that, completely selfishly, á la Clay Felker: “This could be really interesting for me in a bunch of different ways.”

And the first is, that we can pull together a magazine that’s really focused on what I would call ‘early stage entrepreneurship.’ And it’s, it’s the stuff that just thrills me: “How do you take an idea and turn it into something tangible?” So it’s not a business magazine. It’s not a management magazine. People will call it an entrepreneurship magazine. That’s fine. I’d call it a magazine about economic creation.

Second thing that strikes me, is that this is a pretty good time to be doing that. The world is changing really rapidly. And that this could be, kind of, the business magazine of this decade. That would document this shift from an industrial economy to an entrepreneurial one.

And the last thing is, that I start to think, selfishly, about, “Okay, so what would it be like to work here?” And I started to think, “Well, how do I create a place that I want to work at?” And I don’t want to manage. I don’t want to have to do administration or organization. And so what if I were to hire a bunch of editors and writers like me, that are driven by this kind of relentless curiosity about how shit works—”How does it really work?“

And I do think, often as a touchstone, “How do you stage a Broadway play?” That’s not a job. That’s not boring, like picking up Fortune or Forbes or The Wall Street Journal or BusinessWeek. This is like—this is amazing stuff.

And so I decide, well, “What if I were to hire editors and writers and designers and who don’t need to be managed, because I don’t wanna manage?” So they’re very independent. They have this incredibly insatiable curiosity. They don’t need to know anything about business. It’s not that complicated, really. It’s not even about business. And create the newsroom that I felt like I had missed since New York magazine. I had some of that at Boston, but not a lot of it. And so I thought, Okay, that’s worth another three years.

—

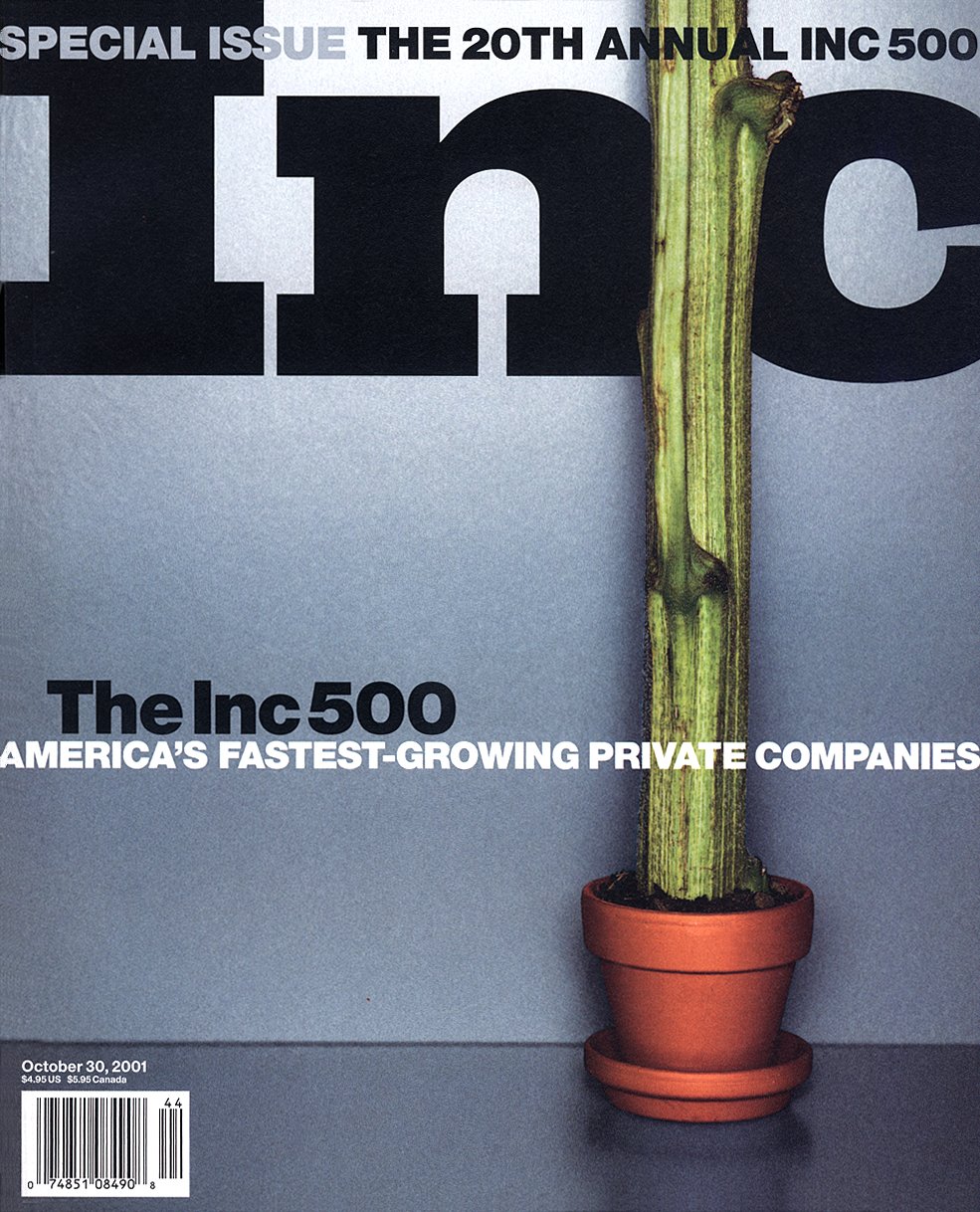

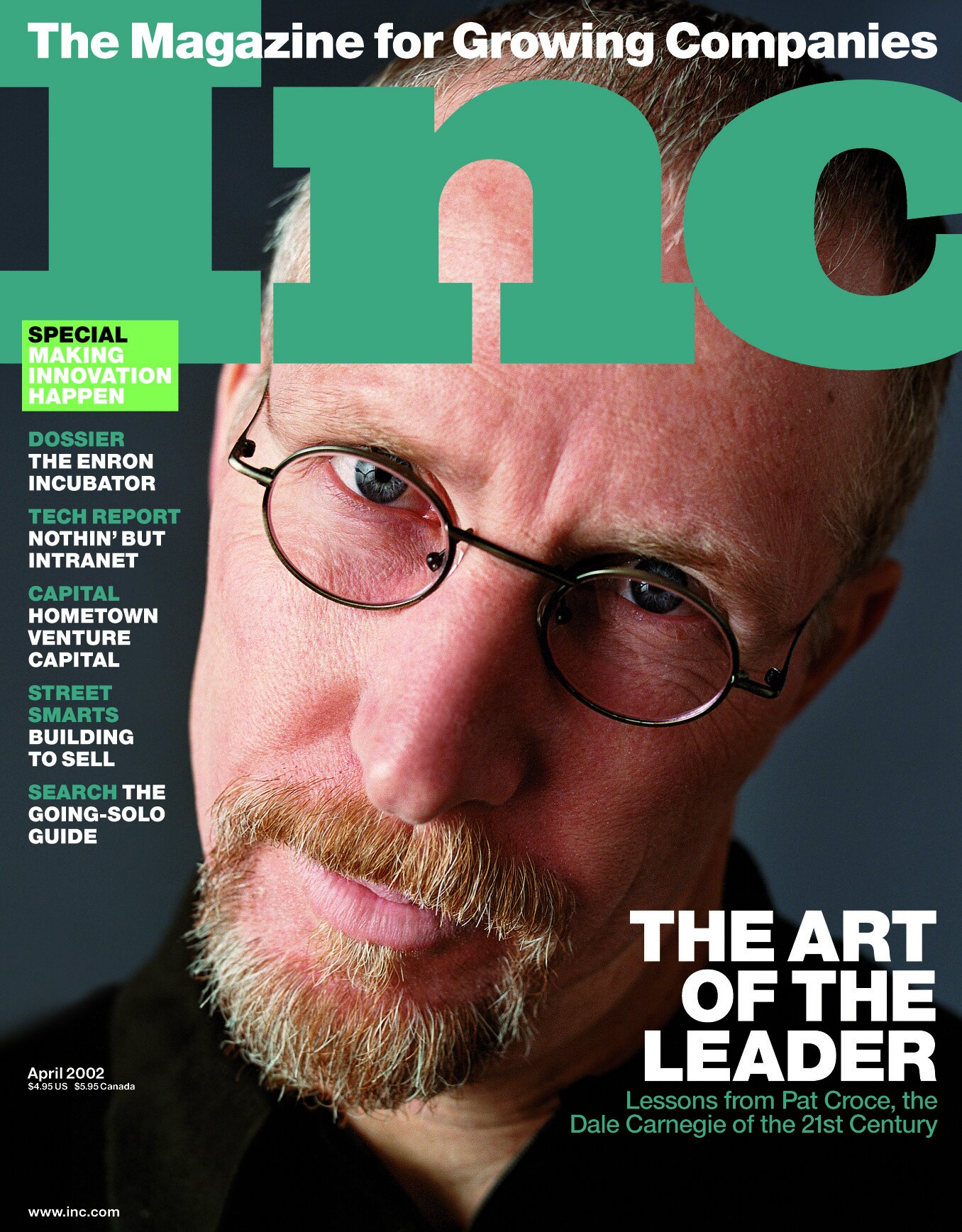

Three years became 15. And that’s when I first met George. In 2000, Fast Company, where I was the creative director, and Inc., where George was the editor-in-chief, were both purchased by the European publishing giant Gruner+Jahr. They merged our Boston-based operations and hired David Carey, who had made his name at Condé Nast for his turnaround at The New Yorker, to become the CEO of what G+J called its Innovation Group. He made me creative director of the group, and my first assignment was to work with Gendron on a redesign of Inc.

George Gendron: You know, that among designers, at least a small group of designers, Inc. was legendary for having killed redesigns by Milton Glaser, Walter Bernard, Lynn Staley, Ronn Campisi, and Steven Doyle and Bill Drenttel (Drenttel Doyle Partners).

And that was Bernie Goldhirsh, the founder’s way of trying to hold onto a magazine he had lost control of a long time ago. But I’d be lying if I didn’t say that, with impossible exception of Lynn, who I really liked working with, I’m not sure that I was willing to go to the mat for any of those designs. I’m not sure that any of the designers had ever kind of really worked their way back to what you were just describing. “So, what’s the DNA of this?”

And I keep thinking, to the extent that you could argue: What’s the one most important lesson I learned in 20 years running the world’s leading entrepreneurship magazine? It’s that organizations in the early stages are inverse pyramids. And they rest on simple proposition, which is “So how’re you different? What makes you special?”

It’s not ‘better, faster.’ It’s “What makes you different?”

And what made Inc. different is exactly what you’re describing, which is that you had this incredible population of people who had gone out and created things. This revolutionary act of starting something new, and here’s why it’s revolutionary.

So you’re sitting there in the midst of the world’s most advanced freaking economic society and culture on the face of the earth, ever. Everything that’s ever been thought of has been done. And yet, these people come along and they go, “No, not really.” “Wait a second. I’ve got an idea.” And it might be something that’s small and not scalable, but it’s sustainable. It might be something that’s small and eventually scalable. And I did find something heroic about that. It wasn’t that I admired all the people who were doing it—don’t get me wrong—but there was something about that.

It reminded me of what I admired about the artists at New York magazine, which was that they had, what I eventually ended up calling, when I went on the road and gave speeches, this freaking rage to control the world. That’s what artists have. It’s how they look at the word world. They think. “This is really fucked up. But I can create a painting, or a play, or a movie, or a script…” that is just kind of, I don’t know, it’s either a reaction to how screwed up the world is, or it’s the way the world should be. And that’s what entrepreneurs were doing, which is that no, “I can create a better product.” In many cases, it was “No, I can create a better organization.” And man, I love that. What’s not heroic about that?

And Bernie Goldhirsh, for all of his foibles, was right: It’s not about a job. That was not a job. That was a life that was big. That was dramatic. And you got that.

—

After 25 years in print, it was time for a new challenge. Enter Peter Drucker. Drucker was one of the world’s best-known and most influential thinkers and writers on the subject of business leadership and strategy. He was an early fan of Inc. magazine and reached out to its young editor. He confessed to Gendron that, like Inc., he had always viewed himself as an outsider and that Gendron should embrace that status. It would be an enormous advantage. He and Gendron bonded immediately.

George Gendron: I was really blessed that probably the most influential mentor I ever had, had nothing to do with publishing. It was Peter Drucker. And I was further blessed because Peter reached out to me rather than the other way around. And I say that in all humility, because I think what prevented me from having more formal mentoring relationships was insecurity. It was Well who am I to go and ask that legendary person to invest their time and energy in me? But Peter called me out of the blue one day and he said to me, “My daring young friend …” in his Viennese accent, “I just love what you’re doing. Why don’t we get together?” And so we did. And he sort of adopted me. And he really, as my mentor, taught what mentorship was really all about in a way and helped me overcome the imposter syndrome phenomenon that we talked about earlier.

And when we sold the magazine, Peter called me and he left me a wonderful, wonderful message about our legacy. I still have it on tape. And he said, “I have one bit of advice that I know you will follow.” And you have to hear Peter say it with his accent. He said, which means “you vill follow this.” And it was, “Don’t do anything full time for at least a year, and preferably, two.” And he said, “People have this image of you as the editor-in-chief of Inc., and so there are all these opportunities out there that might have been available to you that you’ll never know about because people would never talk to you. It’s like you have this dream job.”

—

Gendron took Drucker’s advice, and the phone started ringing. After considering a wide range of opportunities, Gendron accepted an offer from nearby Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, to teach a class he would call “The Art of the New.”

The course got rave reviews, and the administration at Clark made him another ‘offer he couldn’t refuse’: To create an Entrepreneurship and Innovation Center, not for business majors, but for liberal arts students. The first of its kind.

George Gendron: Then the trustees came to me and said, “What if you were to create an entrepreneurship and innovation center based on those principles embedded in your class, the art of the new.” And so I said, “Well, I don’t wanna … I’m not a higher ed guy, but I, I could design it.” And so I did and I gave them the design and then they called and said, “No, you designed it. You gotta run it.”

And so I did for three years, but man, was I a fish out of water. And you know, they didn’t really like me and I didn’t really like them. And I mean, you know, some of them, John Bassett, the president who recruited me, was a great guy, but he could never understand. He kept saying, “Wait, why don’t we do a management contract?” And I was like, “Nah, why don’t we just … we’ll keep doing this as long as I want you and you want me.” It reminded me of high school dating.

So that’s what I did. And I never thought of it as being an ‘indie’ or a ‘soloist,’ but I never had another job.

Patrick Mitchell: So you followed Drucker’s instructions …

George Gendron: … and really cool stuff came to me.

“All the stuff that we loved about design and editorial, creativity, and entrepreneurship. Now we’re being forced to be both entrepreneurs and creators, and that wasn’t the case in the past. And now it’s, you know, the old cliché. It’s well, ‘No, you have to go create a job for yourself.’”

Patrick Mitchell: Which brings us to the burning question: Is print dead?

George Gendron: Print isn’t dead. Bad print is dead. That’s been appropriated by others.

I think print isn’t dead. Mass-market print is dead. And by that I mean, I think that we are on the verge of seeing a whole generation of startups that combined the absolute best creative impulses of designers, and editors, and photographers, and illustrators, and carving out a mark. You’ve got to have both.

And that tension, that’s what New York taught me. People would often say, “God, why did Clay decide to do a weekly?” You know, “If he’d done a monthly, everything could have been better. There’d be more time.” And it was like, he just said, “No, the world’s moving too fast.”

This was back when, you know …

Patrick Mitchell: … Coming out weekly was actually part of the package.

George Gendron: Part of the package. It was essential. It might actually have been kind of the one thing they started with. And maybe that was not up for debate, right? We come out of a weekly, we know what you can do in a weekly. We know it’s habit forming if you come out weekly. People begin to build their Sunday mornings around that.

If you grew up in New York, God almighty, you would go to a coffee shop. And the big deal on a Saturday night was people would get their Sunday New York Times early. It was like, that was really cool. Or, you know, we were a Herald-Tribune family, and so it was like, yeah, that’s an essential part of the DNA. And I remember him occasionally saying things that again, I would overhear, because he didn’t give me these lectures, but he would say, “You know, things are moving so fast now. You come out once a month, people are gonna sit around and go, ‘Oh it’s the first of the month, where’s my New York magazine?’”

Is that prescient, or what?

So, in a way, you know your question that started this podcast, that’s a good question.

We’ve talked about how do you, over time, parse it and redefine it and restate it? You know, Is print dead? It’s a little bit like asking a question that nobody in their right mind would ask today, which is, Is television dead? Well, kind of. Network television seems to be dead. And yet, television, it’s never been more robust, and creative, and innovative, and finally attracting money.

Again, we brush up against the issue of scalability. So, I’m not being naïve, but nonetheless, you read these TV critics and they can’t keep up with stuff anymore. There’s a lot of good stuff out there. And when I say good stuff, here’s what I would love to see about print: What I love a about what’s going on on television right now is originality.

Not everybody would agree with me, but I’m a subscriber to AppleTV+, and I was really addicted to Dickinson. And, I know it was a show for millennials, but I’m a big Emily Dickinson fan. And what a great show! It was, “What would go on in Emily Dickinson’s mind if she were alive today?” It was brilliant in its originality. And that’s what we’re waiting for in print: The next print generation of people who are going to conceive of Dickinson.

A recent video featuring Gendron on the future of work.

Patrick Mitchell: So what do we do now?

George Gendron: That’s a great question. And the reason I’m hesitating is, I don’t have anything other than a very personal answer, which, I think, is my answer. Which is that, as different we are chronologically, you being younger than me, what we have in common is that we both were catapulted into a world where there were unbelievably interesting and exciting opportunities that already existed out there.

Somebody else had created them. It didn’t make any difference if it was Chris Whittle or Clay Felker or Bernie Goldhirsh. But they existed. And that’s not true anymore.

And so back then, you know, you go to a magazine like New York or Fast Company or Inc. and your opportunity and your challenge was How do I do my best creative work in an environment that already exists? Today, it’s How do I use my creativity to create that environment in the first place? And then I get to actually be creative in doing the work.

And none of us are really prepared for that. So it’s like this intersection of all the stuff that we loved about design and editorial, creativity, and entrepreneurship. It’s like now we’re being forced to be both entrepreneurs and creators, and that wasn’t the case in the past. But what made Clay Felker so unique was that it was very rare that an editor would start a publication. Usually it was a publisher.

And so now we’re put in this position where, I’ve said this before, in the past, you know, a lot of the opportunity that existed was manufactured by the system up until about 2000. And most of it existed in the form of jobs. And some of it existed in the form of projects. Hence, the mandate that we grew up with was go get a job. Meaning, the job exists. You go find it, you go get it.

And now it’s, you know, the old cliché. It’s well, “No, you have to go create a job for yourself.”

Well, I wrote a lot about that, always thinking it applied to somebody else, and now it’s like, “Oh no, no, no. That applies to us.” Which is go create a project that allows us to do our best work.

And that’s what intrigued me about getting together with you and Michael Hopkins for The Solo Project. That’s what it’s about at its heart: It’s about “How do you make your creative way in an economy where the work hasn’t been pre-manufactured?” You’ve got design opportunities. You’ve got to then go create, find funders, sponsors, clients, supporters. And when all that’s done, then you get to do what you really love. Man, that’s a different world. And I think we’re just in the earliest stages of that.

—

Gendron, a very young 72, is still hungry. His reputation and connections continue to open doors to opportunities for him, but that entrepreneurial itch continues to need scratching. So what is he focused on now?

George Gendron: I can tell you what I’ve tried and what hasn’t worked. I’ve tried to just create what some people might refer to as a “portfolio of work.” Doesn’t work for me.

I did a project for MIT and I really liked it, but there’s no newsroom. I started to throw myself into my photography. And what I love about photography is, a camera is what I call a ‘single focus object.’ And so there are no distractions, right? And for me as an editor, it’s non-verbal, and one of the problems you have as an editor is that there’s an endless stream that editors and writers can communicate to each other that ends up disguising more than it reveals. And then for photography, I don’t know about you, but I look at my photographs and once in a while, there’s one and I go, “That’s good.” It's like, no explanation, no debate. I don’t need a third party, but that’s not it.

And so I’ve been consumed lately with some personal stuff: buying a house. And that’s interesting. But I’m not done yet. And that’s why I feel like you, and I, and Michael talking about Solo is so important to me. And I’d be lying if I said, “Oh, it’s all about having this effect on these people. It’s all about this, or it’s all about that …

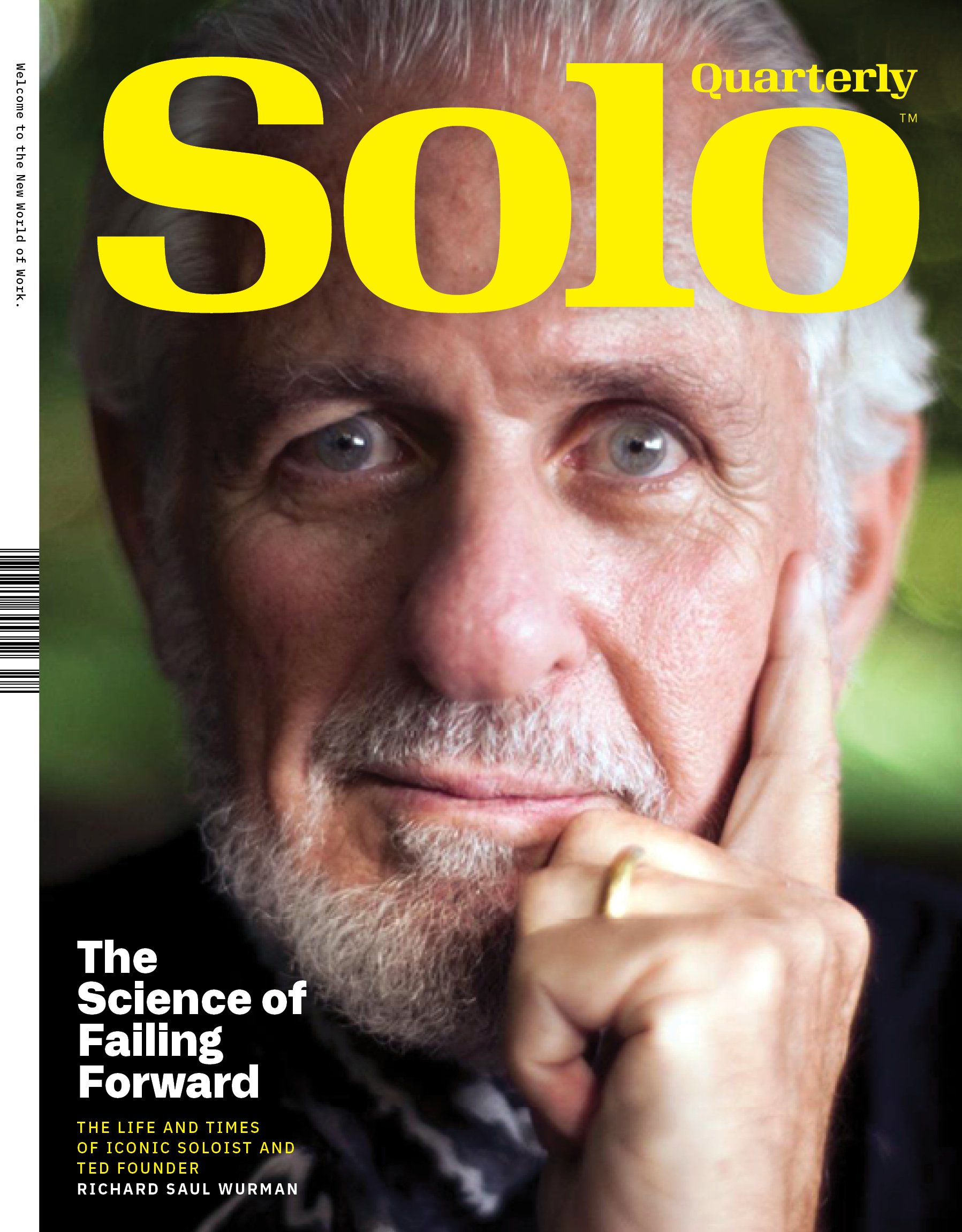

Patrick Mitchell: Give me the elevator pitch. What is The Solo Project?

George Gendron: If Inc. was a resource for entrepreneurs, people building companies, if Fast Company was a resource for thought leaders and change agents within established companies, Solo is going to be a resource for people who want to go off on their own, in what I consider to be the most elemental form of entrepreneurship, which is often a one-person company, two- or three-person company. ‘Human-scale capitalism.’ Where the motivation is to actually do the work yourself. Is to, you know … because the rewards of doing a good job in big companies are more direct reports, more responsibility, more administration, more organization. All that does is take you away from the work that you love in the first place.

Solo is about, “How do you get reacquainted with and build an economically-sustainable life around the work that you love in the first place?” And for me, I want to recreate the newsroom, which to start with, is you and Michael.

Together with a third partner, Michael Hopkins, a former editor at Inc. and MIT Sloan Management Review. Gendron and I have launched The Solo Project, a media and research brand focused on providing inspiration, ideas, tools, and community for the country’s most ambitious indie workers. For more information, visit TheSoloProject.com.