Imagine Friendsgiving as a Magazine

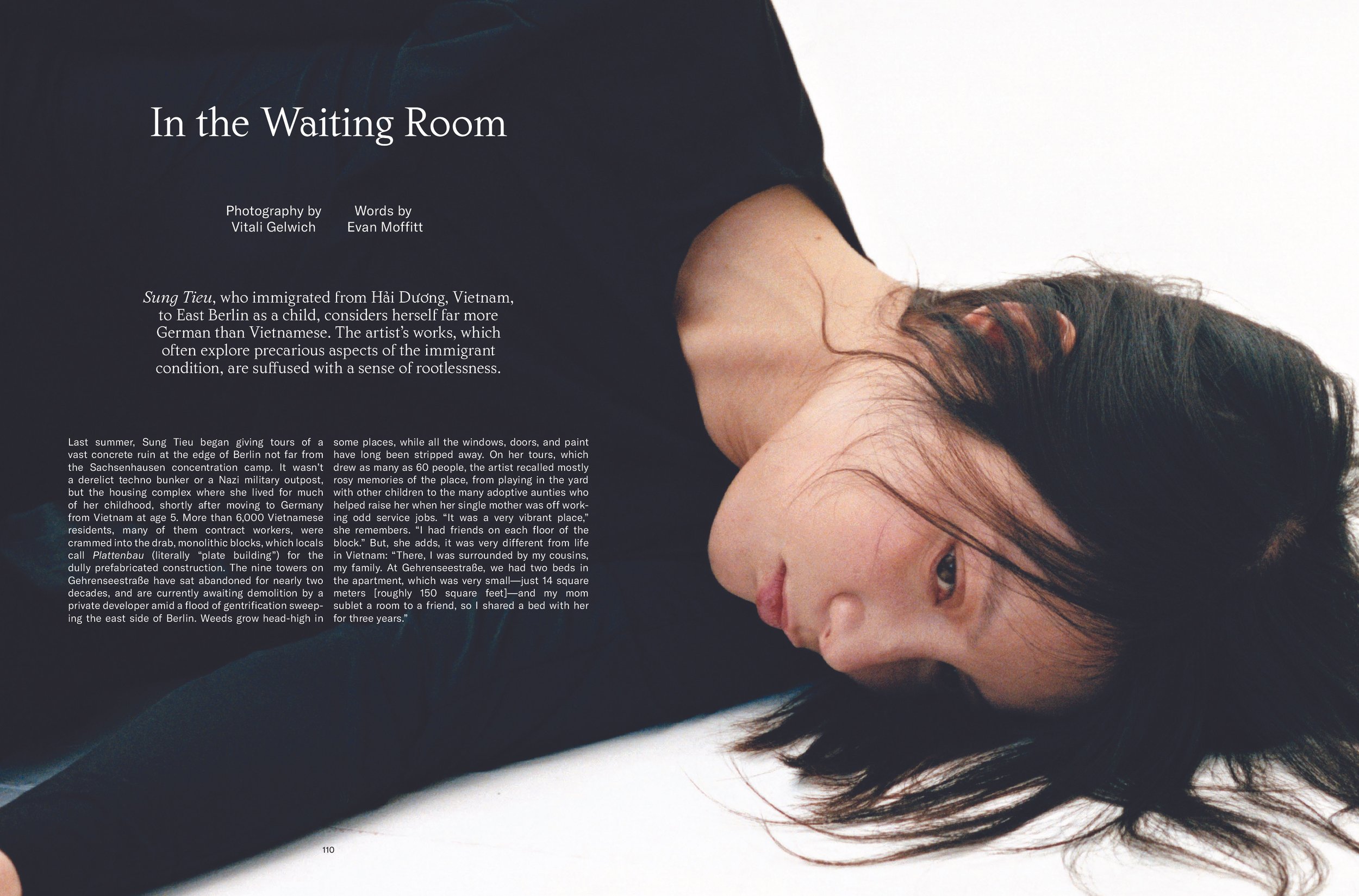

A conversation with Family Style founder, Joshua Glass

The pandemic hit New York first and harder and longer than most places. And as a New Yorker, Joshua Glass was appalled by the eerily quiet and empty city that resulted. He wanted to connect with people, any people, but he wanted quality gatherings, as opposed to quantity.

When restrictions on gatherings began to ease up, he started curating a series of dinner parties around town. And these get-togethers led to the creation of Family Style, a media brand that brought all his interests under a single, and perhaps singular, cultural umbrella.

The result is, finally, what the people at those highly-curated, and probably well-dressed, dinner parties talked about—and the magazine is the core of a growing brand that encompasses production, events, digital, and social.

Family Style is a magazine at the intersection of food and culture—an interesting magazine about interesting people interested in interesting things, all united by a kind of global glossy aesthetic.

So is Family Style a fashion magazine, a culture magazine, a food magazine, or an arts journal? The answer is “yes.”

Arjun Basu: So Josh, the pandemic and supper clubs. Tell the story.

Joshua Glass: Yeah. So like everyone, the pandemic changed my life completely. I remember I was in Milan when we first started hearing about what was happening. And at the time I worked for a different fashion magazine. And my colleague and I had this moment where we looked at each other right after the Prada show and we thought, is this going to be anything?

And I try to be an optimist, even though I think I’m a realist. And I was like, no, it’s not, like we’re here for 15 days we got to do it. We got to make the most of our budget. We have to do our jobs. We have to go to shows.

So we went to Paris. And one by one, all of our colleagues started going back, but we stayed to the end of Paris fashion week. I viscerally remember being at the Louis Vuitton show, which is the last show of Paris fashion week, and looking around the show set up and half the typical showgoers were there and I was like, okay, something is really happening. When we got back to New York, that’s when the city started shutting down, the world started shutting down.

And at the time I lived in a very tiny studio apartment in the Lower East Side in an area now infamously known as Dime Square. When I moved there it was very hip, it was very cool, people were outside all the time, smoking weed, eating food, hanging out, getting drunk. And throughout the pandemic it was silent. The whole city was silent. Everyone had to stay inside.

I remember going on mental health walks for an hour at a time and I couldn’t even vocalize the sadness and the awkwardness of being in a city that was shut down, in a city like New York that’s constantly congested. So being alone—I lived alone—being alone in a very small space, I started rethinking what food meant to me, what a lot of things meant to me. I started rethinking my relationship with fashion, with fitness, with health, with my family. But food, because when you live alone, everything you do In terms of upkeep has to be efficient. I can’t make a meal for 10 people if I live alone because then you waste nine people’s food.

And I started cooking very differently. I started experimenting with what I was making, but also questioning what my relationship was with food. Growing up—I’m from Houston, Texas—both my parents are immigrants. I was raised with my mom. My mom is a refugee from Vietnam.

She came over to the States sponsored by the Catholic church from Vietnam. And then she moved. That’s where she studied. She’s a translator, a linguist. So she has a very interesting relationship with food because Vietnamese food is what we grew up with—she represented her homeland. And then the small little changes or evolutions she would make to her dishes, be they French, be they German, represent the places that she lived in almost like an edible scrapbook of her life.

And so for me, as a multiracial son of a single mother who had never been to Vietnam, and I don’t look Vietnamese, the food that I grew up with, Vietnamese food, was always a sort of taste of something far away that I never really understood, but also knew really well. And so when I came to New York, I had that around me. I was a student. I came here for college. I went to NYU. I was truly—I was the definition of broke. I think I had $300 when I moved to New York and I spent $200 at Ikea buying like a blanket, literally, and like one pot. And so I learned the city by eating dollar pizzas and $2 falafel.

That’s how I literally survived. And when I finally had enough money, I go to Trader Joe’s, which is the cheapest grocery store to buy frozen food that I would make. Eventually, as I left college, started working, and grew in my professional career, food became a very different access point to culture for me. Going to Michelin star-rated restaurants, going to private dinners, understanding that food can also be a gate to high culture. So all of this was brewing.

And then during the pandemic, which was your original question, I was exploring all of this. Food is a gateway to a lot of things. When you’re home with nothing, what does food mean to you? And on one hand, I started making the recipes of the Vietnamese food I grew up with. On one hand, I started experimenting. I made stupid banana bread. I made those silly little cookies, the almond cookies that everyone loves. I loved it.

And I gained a lot of weight and I was like, “I’ve got to stop doing this.” But the whole point was I was looking at what food meant to me. And I was also watching how everyone else around the world was doing the exact same thing. My entire life pre-COVID, I always thought TikTok was a silly app for dancing. And it very much is that, but it also is a portal to creation, to creators, to ideas, and, I know it’s been a hugely important vehicle for a lot of non-professional chefs to understand that you can still be a chef and not work in a professional setting.

And I was watching stay-at-home moms. I was watching young culinary students. I was watching bankers, right, like cooking on Tik Tok, understanding that. Whatever you are doesn’t define who you are. While I was seeing all these things, I was also missing my friends. I primarily have used dinner as a way to get together with people.

I live in New York City. It’s constantly chaotic. My schedule is crazy, let’s say nauseous. And food is, dinner specifically, is really the time that you can see people, meet new people, catch up with old friends, talk about work, talk about love, talk about everything in between. And when the pandemic finally ended, or I guess halfway through the pandemic, when we were finally able to eat outside again, and we had our restrictions lifted, I would have these pseudo dinner parties. Just our restaurants are in the park and dinners are always a really lovely way to entertain, but it’s also a great way to see how we are as humans.

And then when the pandemic was finally over, I doubled-down on food and I think I have gone out to dinner every night since the pandemic. But the whole experience really changed the way I looked at the idea of community, of coming together, of communion, and of food’s ability to foster all of that.

And so I have, personally, professionally, everything in between, used these dinners as a way to meet people, as a way to talk about bigger concepts, bigger issues, female reproductive rights, racial issues, philosophy, et cetera, but also small things like, “Oh my God, did you watch Succession? Or what music are you listening to?” That’s the really lovely thing about a dinner party. You can talk about deep philosophical debates and then you can pivot and talk about something silly like flatware. But the sort of spectrum of conversation is what I love about these sort of moments. And when I was starting to conceive my own publication, having worked at some of the best magazines, I realized that creating a dinner, fostering a dinner, hosting a dinner is a very similar sort of mental space as curating and editing and publishing a magazine.

You have to think about it. Of course, like it’s not a one to one parallel, but you have to think about a lot of different factors. How do people and ideas and concepts sit next to each other? What if it’s literally at a dinner table or conceptually in pages, right? How can you make surprise feel authentic and organic and not for shock value? What is the theme that you’re exploring?

There are, of course, logistical questions and challenges like timing and conflict and ego. All of these come into play when you think about this idea of communion. And that is a thing that keeps me interested, but also activated and constantly trying to create something that feels fresh and new.

“When I was starting to conceive my own publication—having worked at the best magazines—I realized that hosting a dinner is a very similar to curating and editing and publishing a magazine.”

Arjun Basu: So let’s talk about you a little in terms of your past magazine work. Professionally, how did you get to this point?

Joshua Glass: My first full-time job in New York City, I worked for an amazing publicist who has a reputation for being incredibly tough. And we’re still very good friends. Her name is Kelly Cutrone. She told me—she was like, “Josh, you’re a terrible assistant, but you’re a great writer.” And she was really one of the first people that really unlocked the idea that you can work at a magazine.

I remember fantasizing over magazines when I grew up in the suburbs, but she was the one that showed me, working at a PR agency, I understood what working at a magazine actually meant and she was one that really pushed me to do that. My first magazine job was at a magazine called BlackBook magazine, which no longer exists today. But BlackBook was like the quintessential cool New York magazine for a long time.

I covered a mix of everything. I was an assistant. I mostly did like front-of-book stuff and some online newsletter stuff. But it was a really great way to understand the politics of a very amorphous industry, but also understand the business side.

I remember when I started working at BlackBook, within the first week, it was acquired by another company, and then that company acquired three other magazines. So we went from being an office with one magazine to being an office with four magazines. And each magazine, each team was incredibly different.

And my role changed—me being the lowest of the low on the masthead changed—my scope and my role changed several times from working just on BlackBook to working on all of them in different capacities. And, at this time I was 21, maybe, understanding how, as someone in the media industry, in a time when media was being rethought, you have to become a chameleon.

Because BlackBook was a very specific kind of brand. It was a very specific audience. But then our sister brand was a magazine called Vibe magazine, which is a historically black magazine. It’s historically about hip hop, right? I started as a fashion/entertainment writer and now I’m doing hip hop coverage.

So understanding the difference in my relationship with their editors and understanding the difference in the audience and understanding the difference in tone. That was a really formative experience. And when I eventually got laid off, I also understood the realities of the industry. You can be the coolest magazine, you can have the coolest cover, but if you’re not succeeding at whatever financial means—whether it’s print revenue or experiential, or just as a business, as a commercial business, then your magazine won’t last.

And was 15 years ago. And I think about that every minute of every day. I’m happy with making a really successful and creative project, but we also have to be a viable business. And those are the two most important things for us: thoughtfulness and longevity.

Arjun Basu: So you have talked about the mag, the business you’ve created around Family Style, which encompasses events and social content and event production and the magazine, but you’ve called the magazine “the purest expression of the brand.” So it’s the brand-as-aspirational thing. And it also becomes a calling card for the company.

Joshua Glass: Yeah, a hundred percent. I say, especially when we’re talking to non-media people or to—I had to raise money to start the brand. I talked to a lot of my friends who don't work in this industry. I try to explain it. The magazine is our brand expression. It represents the brand fully in the intention, the thoughtfulness, the pillars of the brand a hundred percent. And we have almost laborious conversations about everything we do for the magazine, because everything needs to be the best that it can be. Because again, it’s permanent.

We’re not a monthly magazine. You don’t flip through it, throw it away. We’re not based on the TV schedule or award shows where we have the benefit of being ephemeral or temporary. Everything we do is meant to be collectible in terms of the print magazine, and I want the brand to be for more than just a season for more than just a year.

And I’ve worked in past roles between print, digital, and a mix, and, I’m lucky to understand both landscapes, and so I would never say that I’m only a print person, I’m only a digital person, but what I understand and what I value the most about creating a print product is this idea of endurance and of longevity. And so we do take our time and we do consider everything incredibly, almost laboriously long, as I was saying before, because it really is us at our heart, if that makes sense.

Arjun Basu: Yeah. No, it does. It does. And I agree with you that a magazine in a multimedia environment, the magazine is the purest expression because it’s, like I said, it lasts the longest. It’s not a throwaway product. So as I was researching you, one idea kept popping up and that was you saying that you have this deep love for magazines. Where does that come from?

Joshua Glass: If I’m being honest, and I actually wrote about this in our next issue’s edit letter, it’s always this idea of escapism. Listen, I didn’t have a terrible adolescence. I didn’t have the best adolescence. I think I had a fine adolescence growing up with a single mom.

We were lower middle class. I was the only person that I knew in my suburban town that lived in an apartment. But having watched my mom struggle, and for a lot of years we weren’t able to turn the AC on because it was too expensive. So having seen her go through that, having watched her not just stretch a penny, but more fit into the longest linear shape a penny could be, I think I always crave this idea of another world, the world that we saw on TV or in movies or read about in glossy magazines.

And back to your point about print. The storytelling that a magazine allows you to do—and I’m not just talking about a luxury story about a beautiful car and a beautiful hotel, I’m just talking about this idea of permanence—it always spoke to me. It always was like, “Wow. One day in one place, I could have this.”

And I also love this idea of consideration and of time. I went to film school in college and I realized I hated making movies because it was almost too considered. You would spend, minimum, two years, sometimes five, six years, making this product that was overanalyzed and dissected like a surgeon’s, like a surgery, to a point that it ruined all sense of creativity.

Whereas the pace of a magazine still allows that wonderful consideration and the conversations and the thought process, but there is a hard cut off, there’s a hard deadline that you have to respect. Yes, you can push the deadline by a week. (Don’t tell our advertisers that!) You can fudge that a little bit by days, but if we’re going to print in December, we’re going to print in December. We’re not printing in January because that will ruin literally everything.

And so I think having grown up with this sort of fantasy of it, and then working and understanding that it represented or fostered creativity, but with disciplines, or with roadblocks that fostered more creativity and more creative challenges, I think I really just, the more and more I worked on it, the more and more I’m beginning to love it.

I love the feeling of going to a printer and smelling the paper when it goes to press. I love the weirdness of touching the cardboard box. I don’t know if you have that. Certain people have this sort of affectation where like the touch of cardboard, like it gives them the shivers.

And I have that and I hate it, but I also love it because inside that cardboard box is a magazine that we spent six, seven months working on and pouring over and sweating over and crying. I love the chaotic emails about distribution and, “Sit, we didn’t make the boat. So the magazine is going to be a week late.”

And what is that going to mean for everything? It is—don’t get me wrong, it’s a total nightmare, but it’s almost a fantasy inside that nightmare, because what we’re doing is something I fully believe in. I’ve worked at places where I didn’t believe in the product and that situation—no matter what industry—I don’t think it’s a healthy thing because you’re not in it. Right now I have the benefit of truly living in it. Breathing, being Family Style, but also enjoying it. So it is a win-win for me, even though it is very stressful.

Arjun Basu: There are people who love the assembly of it, but it’s also a massive pain in the ass. So someone who admits that they love making a magazine is maybe saying more about them than they care to admit.

Joshua Glass: Yeah even this morning—I grew up competitively swimming and this morning I went swimming at 5am—and our Livings editor Beverly texted me. She goes, “You love punishing yourself. Why are you swimming at 5am the day after Halloween? We just closed an issue. What are you doing?”

And I’m like, “Yeah, I do.”

I think there is a certain sadomasochist element to it. I don’t like suffering, but I do love the gratification of spending so much time and energy and effort into something, and then it comes out and you’re so happy with it.

I think it’d be another conversation, like I was saying before, if I didn’t like what I was doing, but I think to make it through the fire and you’re there and you’re at this sort of Garden of Eden—whatever the metaphor is—you can enjoy it. It makes the oasis even better, sweeter, brighter, whatever metaphor you want to use.

“I’m happy with making a really successful and creative project, but we also have to be a viable business. Those are the most important things: thoughtfulness and longevity.”

Arjun Basu: I kept this quote from, I think it’s your first editorial, and it’s about your mother’s fridge. You say, “I grew up Vietnamese, but the concept of her country” (meaning your mother’s country) “of being there and of leaving it is something I could not, nor will ever comprehend. Our home was her home, but hers was not mine. How strange it is to know something so well, yet also feel completely alien to it.” I think just based on everything you’ve said, that’s the start, that image.

Joshua Glass: A hundred percent.

Arjun Basu: And it’s in your first editorial and the picture, there was a picture of the fridge, which is not something you would expect in a magazine that is relatively glossy.

Joshua Glass: Yeah. It confused a lot of our advertisers. They were like, “What are we doing?” It goes back to what I was saying before about Vietnamese food, but it also I think speaks to my experience as a capital “B” broke 17 year old in New York City, to everyone’s experience, even going to a fashion show. Now I’ve been to a thousand fashion shows. Everyone has this imposter syndrome, for whatever reason. I had it being raised in a Vietnamese household, being surrounded by Vietnamese culture, but not feeling Vietnamese, and not looking Vietnamese, not understanding where I fit in.

And I think we have this sort of imposter syndrome. Everyone wants to fit in in some kind of way. I’m not saying everyone wants to be popular and cool, but everyone wants to feel like they know where they’re a part of. And I have struggled with that in different ways, whether it’s through racial and ancestry culture. Whether it’s through navigating the art world—the art world is historically dominated by familial wealth.

Where I grew up, I think the only thing we had on the walls of my mom’s apartment was, like, my report card. We didn’t collect art. And so going to galleries and wearing let’s say maybe a two-year-old Uniqlo shirt as a 19-year-old, I’m like, “How do I fit into this world? Can I even get into this world?” And so years later, to be working with these galleries I used to be terrified of even stepping foot into, not even knowing you could even look into a gallery.

I still have imposter syndrome. I still often feel like Tom Ripley. Where it’s like, “Do I belong here?” I think everyone feels that way. I think you could ask the most important stylist, the biggest who’s-who, and we all have that self doubt. I think it’s how, it’s what we do with that, how we treat other people, how we move in those rooms, knowing that we all have this insecurity and this question dictates the future.

I try to recognize when there’s conflict, when there’s disagreements, when there’s egos, a lot of it comes from that. And that’s how we approach a lot of our stories with this sense of innate humanity. We all know people have all these things brewing—insecurities, questions, doubts.

Arjun Basu: What would you say, Family Style is as a brand? What’s your elevator pitch on the brand?

Joshua Glass: Our elevator pitch is we are an art and fashion brand at the intersection of food and culture. So, the bottom line is, we use food as a metaphor to explore contemporary art, fashion, design.

We’re not an epicurean brand. We do have one recipe in the magazine every issue, but we’re not about how to make a lasagna. We’re just never going to be that. It’s not a home magazine. We explore, What does home mean, but we’re not about cooking, or home, or decorating.

And that’s a big misconception, I think, when people hear that you’re a food magazine. The other misconception is that people think we’re a parenting magazine, because of the name Family Style. A lot of Europeans, specifically, don’t understand the colloquial phrase. So I always explain, why food is something, as we were discussing food, is something that everyone understands, food is something that touches everyone. Everyone has to eat food. Most people, not everyone, but most people like eating food. There is a minority of people that have no taste that just eat food for efficiency purposes for function. Or a lot of athletes that are either like bulking—it’s just for function. But for the most part people like food.

But it’s also personal. It’s the food you make for your family, the food I make for my family. It’s all very different. The food that I stress eat when I get home is different than the food that you eat for dessert. So to have that really beautiful dichotomy of universality, but also ubiquity, that’s a really important thing.

And that exists throughout the creative industries and it allows us to explore it. Art being this sort of high concept unapproachable concept thing that I talked about with its pearly white gates, through the lens of food it becomes more accessible, it becomes more democratic. Same with fashion, same with design. It’s the sort of device that allows us to broach these hard-to-access, hard-to-reach, hard-to-navigate topics. And do so with a little warmth and a little tongue in cheek.

“We use food as a metaphor to explore contemporary art, fashion, design.”

Arjun Basu: Yeah, as you were saying that I was thinking of that, Kate Moss didn’t say it first, but she did say it, that “nothing tastes as good as skinny feels.” I just hated that quote so much. On the cover of the issue I have in front of me, it says: “arts and culture with a taste for more,” which you have been saying. In the magazine you described Family Style as “a fantasy dinner party in the form of a quarterly arts and culture journal.” The section heads in the magazine are food-related or dinner party-related. And they lead up to a recipe, and sometimes the recipe is actually quite simple. I think in the one I have, it’s a cookie.

Joshua Glass: Exactly. Chase Sui Wonders is a cookie.

Arjun Basu: It’s an oat cookie, which is a funny way to end it. It is dessert, but it’s also, you’ve gone through quite a lot of very expensive, very lavish, lovely fashion spreads and shoots. And then you end up with a cookie. So that curation—editing is curation—but you can sense, if you look at the magazine carefully, you can get the idea of this sort of a chaotic, really swish dinner party.

Joshua Glass: Yeah, exactly, because isn’t that life, right? I think even, like, when I’m in a room that’s mostly fashion people, sure we’re talking about who’s going to Chanel, what’s happening at Celine, I guess now we know it’s Michael Rider at Celine, what’s happening. Gossip, rumors, “Oh my god Heidi Klum wearing the E.T. costume.” Which was amazing, but we’re also talking about where’d you go to dinner last night, what are you watching right now, did you see the new Luca Guadagnino movie. I think every niche audience or subset wants to be cross-categorical because that’s what life is.

If you think about it from a business sense, which is a lot of my thinking now, and when I talk to brands, the fashion consumer, the VIP Louis Vuitton shopper, the Fendi woman who is being flown from New York to Milan to go to the Fendi showroom, they’re also decorating their houses—plural—with B&B Italia and Flos Lighting. They’re also staying at the Mark Hotel in New York City and Il Pelicano in Tuscany. They’re also eating at the best restaurants and maybe the most unknown restaurants. So we live in this hyper-blurred culture where fashion is lifestyle and everyone wants the best of it. We want to be wearing the best things, we want to be eating at the best places, and we want to be interested and interesting.

And so the magazine is intentionally assembled. Wdo have a structure where there’s three different sections. That follows a sort of imaginary menu. Aperitivo is our traditional front-of-book. And that is meant to evoke the feeling of when you go to a cocktail party. And you’re like, “Oh Arjun, did you hear about Alexander Fury’s amazing fashion collection.”

It’s a light bite. It’s a small little thing. We’re not going to get into it. You don’t need to sit down. It’s a light conversation. We try to cover our different interests being fashion, art, design, culture. The second course is when you’re at the table. It’s called Dinner Service. It’s when you’re really talking. It’s, “Oh my God, did you see this amazing movie? I can’t believe they talked about….” And then you really go into it. And when you look at the way Dinner Service is assembled, we don’t follow the conventional interview fashion, fashion, fashion, because that to me is boring.

The OCD part of me, which my designers will tell you, is I love having the rubric of the three courses, but inside that we have the chaos of life because that’s how conversations happen. You go from talking about Gwyneth Paltrow to Macaroni to Severance coming up next season to, “Oh my God, what are you doing for Christmas?” We bounce back and forth. We interrupt each other. We’re chaotic. We’re silly. And that’s how I want the magazine to be. I want to see an amazing fashion special. And then I want to talk about important topics. And I want levity, but also substance. And that’s why we have that sort of unbalanced back-to-back lineup.

And then the end is called Something Sweet. And that’s meant to be a relief at the end of a long, lovely night. We always start with some kind of really beautiful community story. I think the issue you have is an exquisite property called Casa Dinosauro, which is a never-before-seen iconic house in Tuscany that is shaped like a dinosaur. And the story that Laura Rysman writes is talking about how this really radical house that was untouched and left to waste has become a pillar of unaccepted radical design, which is lovely.

And then we have 16 artist commissions, where it’s like going to a group show and seeing a mix of different arts in the gallery. Everything in the magazine is original to us, so we invite artists to create a work in response to the issue theme. And then the last page is a recipe, because we’re not a food magazine, but ultimately we are a little bit.

So I thought it was a nice way to end this sort of dinner with a takeaway. Be it an oat cookie, be it something more complicated. And it’s also a great way to relate to a kind of talent that you might not otherwise relate to. Chase Sui Wonders an amazing young actress. A lot of people don’t know her. My mom doesn’t know her. So to understand her favorite recipe it’s a nice way to open the door and then get to know her more.

Arjun Basu: So you mentioned the business a few times. Are the advertisers in your magazine, are they doing anything else with you? Are they present in the experiential aspect or the events? How does that work?

Joshua Glass: Yeah, exactly. That’s the whole goal and the whole opportunity of the business. We are a niche company, everything we do is incredibly considered. So we do things strategically. We don’t do 360 programming with everyone. We do it with select partners. But the goal of the company, and what we’ve been able to do really successfully throughout this calendar year, is to create 360 partnerships that either start or culminate with a magazine.

So whether it is an amazing fashion editorial or a really cool feature or something in between that and having a really interesting presence in the print magazine. Digital and social are our most powerful tools. We’re still a niche audience. I think our Instagram is like 55,000. We’re not Rihanna, we’re not Kendall Jenner, but those 55,000 people are some of the most important people in culture. Artists, designers, photographers—really influential people that I’m super proud of that we’re creating content for on our Instagram, on our website, in our newsletters. And then bringing it to life through experiential events that use the magazine, the social, that use food as a core medium.

So we’ve been able to do this with our fashion partners and with our wine and spirits partners. We’re not exclusive to one category. I actually love the diversity of partners that we work with from Moët Hennessy to a Richemont, a fine jeweler. I love the diversity of it. The whole goal with everything from the events to the editorial is that everything feels very different.

So, the very first dinner we had was with Banana Republic Home to launch their new home category, which is incredibly chic furniture. We did it at Eleven Madison Park, which is a three-star Michelin restaurant—the only plant-based restaurant to have three Michelin stars. It was amazing. I won’t lie to you. It was very fancy. Capital “F” fancy: white tablecloths, multi tens-of-thousands of dollars of florals. Very nice dinner. Lots of famous people, lots of photos. The second dinner we had was a barbecue in the streets of Savannah, Georgia.

I love having that dichotomy of, “We’re not elitists. We like nice things but we like simple things too.” It’s all about people ultimately. We also try to have everything spaced-out throughout the year and around the world. So from New York to Savannah, to Napa Valley, to Milan, to California. I love that idea of we’re not always where you think we are. Not everything we do is the exact same.

The through line is a sense of community. The through line is a luxury experience. I say luxury, but I don’t mean elitist. So this dinner that we did in Savannah, Georgia, it was amazingly produced, but it was not fancy. We were eating cornbread, drinking whiskey. It wasn’t something black tie by any means—I wore jeans and sneakers. But it was just expertly produced and had the coolest people, and to be able to do both, to be able to be at the capitals and in the unexpected is a real win for us because I never want to be the place, the people that are only going to the black-tie places. That’s so against the core of our brand and of me as a person. I love the diversity. I love the spectrum. I love a surprise.

Arjun Basu: Advertising and partnerships are just two brands leveraging each other. So exactly.

Joshua Glass: Exactly.

Arjun Basu: Yeah. We always end with your three favorite magazines. So what are you most excited about right now?

Joshua Glass: My favorite magazine in the world and everyone at this magazine knows that. So if anyone’s listening to it, it will not be a surprise. I love T Magazine. I think Hanya, who’s the editor-in-chief, is a genius. I think Patrick Li, the creative director, is one of the most talented creative directors and also one of the nicest people alive. I think the entire fashion team from Kate to Angela, to all the stylists they work with are just top tier. Nick Haramis, who is the feature editor-at-large, as is Kurt Soller, they’re just the smartest, wittiest, nicest guys. I have nothing but praises to say to T Magazine. And I really love what they’re doing.

I think—not to pick another magazine related to a newspaper—but I think M. de le Monde is fabulous in Paris. I think it’s been around for a bit, but I think the last five years have been so exciting and fresh and just really beautiful.

And I think my third favorite magazine is System magazine which is in London. It’s a very fashion-y magazine. I do know all three founders have recently left the magazine, so I am curious to see how that changes. When System started, it was shockingly amazing. And when I worked at Document Journal, I was like, “Wow, they’re like a lap ahead of us”—to use a swimming term—”we have to catch up. They’re lapping us. They’re just doing it.”

And it’s so chic. And I think what I respect the most about System, which I try to do in our way of Family Style, is that System has it: a very elevated minimalism to it. It’s not overtly designed. It’s not overtly fussy. It’s very straight to its core. And I love that. And it’s so confident in that minimalism. And it’s something I really respect.

Arjun Basu: I always appreciate talking to someone who admits that the magazine is the center of their universe. I’ve used the solar system or universe metaphor with other editors on this program, and they’re really leery of putting it there because they’re thinking of everything else that they do. And I’m like, “No, it’s still the core.” And you say it. So thanks for that.

Joshua Glass: Three Things

Click images to see more.

More from The Full-Bleed Podcast