In the Realm of the Senses

A conversation with Hillary Brenhouse, founder and editor-in-chief of Elastic.

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT FREEPORT PRESS.

Psychedelia has an image problem. At least that’s what editor and journalist Hillary Brenhouse realized after she saw through the haze.

Both in art and literature, psychedelia was way more than tie-dye t-shirts and magic mushrooms. Instead of letting that idea fade into the mist, she kept thinking about it. And the more she looked, the more she realized maybe she should create a magazine to address this. And so she did.

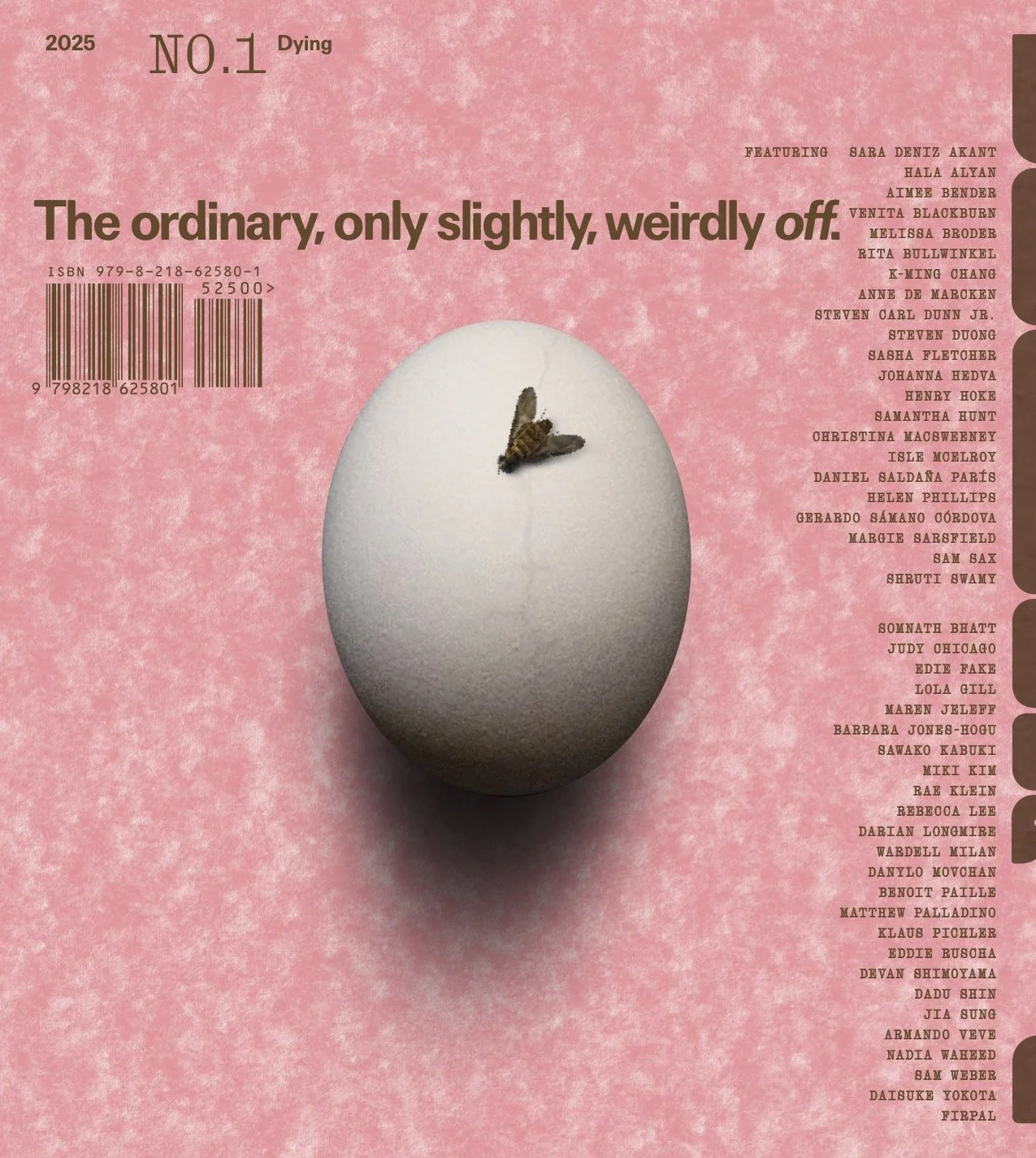

Elastic is a magazine of psychedelic art and literature. It says so right there on the cover of the beautiful first issue that just launched. So this is not your standard issue lit or art mag. After all, this is one backed by … Harvard, and UC Berkeley, and a couple of major foundations.

Hillary Brenhouse has learned a lot about the craft and the business of making and selling magazines this past year. Lucky for us, she and her team are quick studies. You can see it on every page of Elastic. And she also may have redefined the literary magazine. Without a single tie-dyed t-shirt or magic mushroom in the lot, man.

“It’s such a crazy—quite psychedelic actually—feeling to, like, finally hold something that you’ve been thinking about for two years.”

Arjun Basu: Okay, so you are still in the high and the buzz of this new creation. Every magazine in the world starts out with a single idea and there’s a larger origin story. So let’s talk about the idea and then how you went around making this happen.

Hillary Brenhouse: Sure. First, thanks so much for having me. I’m completely thrilled to be here. It’s launch week, so it’s crazy in Elastic headquarters.

So I’ll tell you a little bit about how this came to be. Essentially I had been going to a lot of conferences, electronic music festivals, and various spaces in which “psychedelic art” was being featured.

And most of that psychedelic art really looked the same to me. It was, as you’d imagine, psychedelic. Fluorescent mandalas, contorted mushrooms like Rick and Morty, running through space, scapes, all that jazz. And I thought to myself, this must be like a more, a vast or more expansive category then psychedelia as it’s been portrayed and as it lives in the popular imagination. As an editor, I am really drawn to, so I’ve been in books and magazines for a long time and I’ve always been really drawn to work that plays with time and space that is genre defying. And I was like, so much of what I’m reading as an editor and just as a reader for pleasure seems to conjure the psychedelic experience to me more than what I was seeing on the walls. And so I really just wanted to make a space for that kind of work to live and started to talk to people about, what psychedelic culture might be, what it might look like in 2025.

Arjun Basu: So you were reclaiming the brand. “Psychedelic” has really bad branding. I think you say the word and there’s an image in the head, and so when I first saw this, and you and I met you and you mentioned psychedelic art, that image came to my head right away. And it’s an unfortunate one because, you’re like two-steps ahead of tie dye and a room that smells like weed and is foggy.

Hillary Brenhouse: Yeah. And it’s also full of white people. It’s like historians haven’t taken psychedelic art seriously at all. And when they have, they’ve cited, like, the same three white male artists over and over again.

And meanwhile, when you really get into it, like the first psychedelic era in the sixties and seventies was rich, like it was very much a period of radical artistic innovation, and it was led by artists and thinkers of color. I think that some people have posited, and I think that they’re right, that the arrival of the psychedelic era had a huge impact on modern art. It exploded the boundaries between high and low art. It exploded boundaries between painting and sculpture. It encouraged a ton of experimentation and so you look at the art from that era, so much of which can be considered psychedelic and so much of which has just been grossly overlooked, and you think like, why now, are we in 2025? There are no art historians who specialize in that period, and there’s nobody talking now in this, like we can call it the second psychedelic era, like it’s a time when psychedelics are ubiquitous, when tons of money is being poured into the various industries linked to psychedelics.

All of your friends are going to Ketamine clinics and it’s like nobody is talking about what psychedelic art and design might look like right now.

Arjun Basu: Yeah. I’m going to upset some people by saying this—but as a brown person I think I can say it—but I find Hinduism in general is like the psychedelic religion. That’s there’s nothing not psychedelic about it. But before we get too much into the magazine, let’s talk about your past.

Hillary Brenhouse: So I started out as a journalist, I guess I’m still a journalist. You never really stop being a journalist.

Arjun Basu: That’s a tattoo.

Hillary Brenhouse: Yeah, that’s it. And I guess, my first job was at Time Magazine. I did a lot of writing. I’m interested in, and I’ve, I’m still interested in, inequitable systems and how we can overcome them and, reporting about paths toward a better future.

And so I started out doing that in a straightforward way. I was mostly reporting on reproductive health. I still do some reporting on reproductive health. But then I quickly learned that I was really attracted to very literary writing and like ways of challenging power and those inequitable systems through extraordinary uses of language and form, like just writers who are exploding form.

And after that I began to edit Guernica, the online lit mag of art and politics. And I was at Guernica for 10 years. I did all of the jobs there. And I left after editor-in-chiefing for a little while, and then I moved into books. So I was the editorial director of Bold Type Books, which is an imprint of Hachette and publishes work that challenges power through narrative.

I’ve always wanted to start a magazine and I’ve always wanted to start a print magazine, so this is truly a dream come true in every sense. People were like, wow, you had been so interested in the intersection of the personal and the political, literary writing that is quite political, and now you’re interested in psychedelic art, like what happened to you?

And I’ve always said that this work to me anyway, is extremely political and fits so well into my interests and my career path because these are writers and artists who don’t give a shit. They are like resisting the shapes that the literary world and the art world are constantly trying to push creators into.

They’re experimenting with time and space often to resist colonial story structures, linear story structures to embrace like alternate histories. And some of the time they’re just, like, I’m not going to plumb my identity; I’m just going to make work that is elusive and disorienting and I don’t have to give you a reason for it. And I think that’s, like, incredibly subversive. So that’s my past.

Arjun Basu: Okay. So then we get to Elastic and you have this idea and magazines aren’t—they’re not easy at the best of times. And you, if you look at the masthead and everything, you see these two funders from these two schools Harvard and Berkeley. How did that come about?

Hillary Brenhouse: So as I was working on the idea for the magazine and thinking about, drawing up like a visual mockup and thinking about how to find investors for this thing. Harvard and UC Berkeley came out with this initiative called Psychedelics in Society and Culture, which is funded by the Gracias Family Foundation and Flourish Trust.

And they essentially were inviting proposals for projects that are interested in psychedelic culture. I think because psychedelic research was shut down so swiftly and intensely the first time around, and I think. There is this feeling right now that if we want to do research related to psychedelics, it has to be legitimate. Like we have to keep it, we’re trying to heal people from PTSD and X, Y, Z. It’s just like this is a medical endeavor.

And Harvard and UC Berkeley are like, “What happens to the humanities in all of this? Why aren’t we talking about the impact that psychedelics can have on artwork?” And I was just so thrilled to see that. And at the same time had been in the middle of building a body of contributing editors and artists. And some of them were from those schools, like the wonderful Laura Van Den Berg, who is like a very prolific novelist playing with time and space who’s at Harvard.

And so I just recruited this band and was like, let’s go for this funding. And thankfully we’re, I think, the only project that applied to both schools and received the funding from both schools. We’ve just applied again, so cross your fingers. But yeah, they’ve been like just a massive help.

People are always asking me what I mean by psychedelic art and literature, and I have an answer for that. But like I never set out to be a gatekeeper, and I really feel like this is the goal. The primary goal here is to start a conversation that is not being had, or is only just beginning. And Harvard and UC Berkeley were like the first major institutions to be, like, let’s start having this talk. What about psychedelics and art? What about psychedelics and music?

Arjun Basu: So you answered me. There’s a chicken/egg question I’ve been having, again, back to the making of this. Every editor starts with a blank page and you literally started with a blank page, a blank canvas, and then you started filling it in and I always wondered if you had the idea and then sold it to Harvard and Berkeley first. But it seems like you were already creating this magazine

Hillary Brenhouse: Oh, yeah.

“I wrote in my editor’s note that nobody gave me what I asked for—or even what they said they would. And that is a hundred percent true.”

Arjun Basu: Without anything. Had you found an art director yet? How do you start filling in the lineup and what do you pitch? Because like you say, some of the names that you have here, all of the names are very impressive, very accomplished writers and artists. So I just keep thinking like that. You must be really good at pitching.

Hillary Brenhouse: I think I am. Thank you. Yeah, this is the lineup of my literal dreams. We were at AWP, the huge literary conference this past weekend, and we had this big sign with some of the writer’s names on it, and people kept walking by and being like, holy shit.

And I was like, yeah, all the illustrious weirdos are in this issue. Like all the people doing wacky, strange work are here. And they’re brilliant. Yeah. At the time that I pitched to Harvard and Berkeley, we were pretty well set up. I’d been thinking about the idea for a long time. I knew, one of the most important parts here is the creative direction, obviously.

And I knew that I wanted Chloe Scheffe and Natalie Shields to be the art directors to be the creative directors and the designers. Their work is just so incredible. They’ve done a lot of magazines together but one of the magazines they’ve done is called Here, the travel magazine, which sadly no longer exists.

And going through issues of Here, I was just like, If somebody’s going to imagine what contemporary psychedelic design means it should be these two. It’s just like things are upside down. They’re doing, like, hand lettering, their experimentation with color. It’s just they think completely out of the box. I pursued them for a year before they signed on. So actually—

Arjun Basu: —so they’re, like, a team? They have a design studio?

Hillary Brenhouse: Yeah. They call themselves Scheffe Shields, their last names. And I’m good at pitching—actually what it is that I’m so determined, I don’t leave people alone. I will chase them for days, weeks, months. So I think I pursued Chloe and Natalie for a year until finally I …

Arjun Basu: When I was an editor I said, “Persistence pays off always, and either I will tell you to stop persisting, but if I don’t, that means, keep going.” And, people got jobs that way with me.

Hillary Brenhouse: That’s like the way that I operate. It’s like after a year I told them like, this is real now, we have funding, we’ve picked a theme: It’s dying. I think it’s the dying issue that like, did it for Natalie. She was like, I’m a goth. I’m really into it. Let’s just do it.

Arjun Basu: I love the idea. I love the idea of a magazine launching with the theme of dying.

Hillary Brenhouse: Me too. Me too. Truly. I just, like, really wanted to find something that I knew would speak to people who are interested in the psychedelic experience, are often thinking about dying, but so are writers and artists, obviously, and we’ve interpreted the theme so broadly to include like any process by which the self is transformed or shattered or transcended.

So you have weird short stories about childbirth or about transition or about chronic pain or loss in grief. There’s a whole bunch of stuff in here. And then, with the writers and the artists, it’s like I just started reaching out to people and saying, I’m looking for work that uses strange means, like plays with time and space, blurs, waking and dreaming life as a way to get at states that are impossible to describe straightforwardly or linearly. So you want to get at the center as a writer or an artist of grief and loss, you want to get at what it’s like to give birth. You want to get to what it’s like to lose the self during sex. How are you going to describe that on the page through art or writing?

I just feel as a reader, like, the people who have gotten closest to grief on the page are the ones who are experimenting heavily. And I think that prompt just spoke to people and when it didn’t, I just chased them.

Arjun Basu: The most psychedelic idea I had while reading the magazine was like, Wow, entropy. It does not happen in a straight line. And I’d never thought of it that way. And then I love the Garth Greenwell quote that you use in your editorial: Sometimes I think all art is repeating again and again the same message. I’m dying. Love me. That’s such a great quote. But another thing from the editorial: “The idea behind this magazine is simple enough: it exists to bring together psychedelic art and writing,” and then you go on to write about the cramped corridor that the word finds itself in. I called it a bad brand. Yeah. This is liberating everyone’s idea or notion. Did you know all these great writers and artists, did they think about it in those terms or was it just oh, that’s a cool idea, let me run with it? Did the result happen or was there a plan?

Hillary Brenhouse: So I’ll say first that just in terms of the word psychedelic, it’s if you’re a visual artist and your work has even like a tinge of the psychedelic, you’ve probably associated the term with your work before or you’re not surprised to hear it called that.

But obviously nobody’s talking about psychedelic writing, so none of the writers had heard that term associated with their work, and I was, like, afraid. I wondered if the project would be legible to these writers, some of whom I’ve worked with before at Guernica or in other places.

And yeah, I said to them, “This is what I mean by psychedelic. I see your work as like fitting into this. What do you think?” And nobody bristled at that. Nobody said, “Oh, I don’t want to associate my work with psychedelia.” They were just, like, “It’s true. I do play with time and space. I do aim to, like, take a completely different perspective. I am blurring, waking and dreaming life. I can see that my work is pretty psychedelic.” So that didn’t end up being problematic, which is wonderful in terms of what I received.

I write in my editor’s note that nobody gave me what I asked for—or even what they said they would. And that is a hundred percent true. It’s just like I came into this with all kinds of ideas. I used to commission special issues for Guernica. I love themed issues, and I used to go about it in a pretty straightforward way and say, “Okay, like here’s the theme. What are all the various ways in which it can be interpreted? Let’s, like, fill this up with as much diverse work as possible.”

And I’m working with a wonderful senior editor, Meara Sharma, who used to work with me at Guernica. And we tried to do the same thing. We were just, like “What should go in here? Who could do it?” And we approached people and they were, like, “Yeah, I’m in, but I think I’m going to give you something else.”

Or they’d say, “Yeah, sure, I’ll give you 500 words about that.” And then they submit something completely different because this is a psychedelic art magazine. It’s like they just let themselves go and we just followed them and it was incredible. At the beginning when I started receiving work, I was like, “This is not what I thought. This magazine is going to be very strange and differently-shaped from what I’d envisioned.”

But that ended up being wonderful. And the resonances between the pieces, it’s crazy. I’ll talk about one, which is that two totally different writers who don’t know each other at all, Aimee Bender and Gerardo Sámano Córdòva, both mention “tooth plants” in their piece, like a plant that has teeth that grows teeth instead of flowers.

And I was like, What are the chances of that? It felt so wildly psychedelic. Like when you take a psychedelic substance and you see something weird and then an hour later you see it again. It’s like that’s what this issue feels like. And so I approached this artist, Matthew Palladino, this painter who’s amazing, who doesn’t really take commissions. And I was like, “You make incredible trippy plants. I want a tooth plant for the cover. I know you probably don’t usually take commissions, but this is what’s going on here.”

And he was like, “Aimee Bender was my language arts teacher in elementary school, 30 years. So yeah, I’ll do a tooth plant for you.”

I was like, “There’s nothing more psychedelic than this.” And in the end, the magazine feels like the trip to me. If you read it from cover to cover, as I have a thousand times, it’s wild.

Arjun Basu: So you talked about Harvard and Berkeley and the foundations: I have to ask about the second issue and you’re still on the high of the launch. For our listeners, this is early April and Elastic has just launched and still has some launch events coming up. So you’re in the high of this period and look, congratulations, you’ve birthed a media and that’s, that’s just hard. But at a certain point—and you’ve probably already started thinking about the future—so is the magazine contingent on that funding?Do you have to fulfill anything? Is the funding contingent on anything? So what’s the deal there?

Hillary Brenhouse: Yeah, I’m hopeful that we’ll have a second round of funding. But we’ve also just met so many people, very gratefully over the past few months who are interested in donating who have encouraged us to apply for grants.

And so I don’t think it’s going to be an easy road, but we’ve started putting the second one together. It’ll be the theme—I think I can just reveal now for the first time—it will be on, like, interspecies exchange. So many people in this first one wanted to write about, like, plants and animals and humans and the various interactions that can happen there.

So we’re going to have a lush second issue full of plants and animals and humans and other species. I hope that these two universities stay involved. It’s been, like, an incredibly fruitful, generative relationship. But thankfully a lot of other funding sources have presented themselves.

I think we’re just very lucky to be in the right place at the right time. This is a very rich field in every sense of the word. And it just so happens that we’re in the center at the front of a conversation around psychedelic culture that’s only just getting off of the ground.

So I was pitching a panel to Psychedelic Science, which is probably the largest psychedelics conference in the world that takes place in Denver in June. And I myself was looking desperately for an art historian who specializes in psychedelic artwork and couldn’t really find anyone who fit the bill.

And since I began that search, there are a whole bunch of other people who are also on the same hunt, and they found me. So they’re coming to me like I’m the art historian who specializes in psychedelic artwork, which is so funny. At this point I have plenty to say about psychedelic art—but I obviously don’t have the training of an art historian or a scholar—but I’ve been asked to write, like, museum exhibition catalog introductions and all kinds of things just because this is like an empty space and I’m in it.

“At the beginning, I was like, ‘This is not what I thought. This magazine is going to be very strange and differently shaped from what I’d envisioned.’ But that ended up being wonderful. ”

Arjun Basu: Once you put a tooth plant on your cover you are an expert in the tooth plant. Just sounds like it should have been on the cover of issue number two.

Hillary Brenhouse: It could. I think that there’s there’s so many things that could live. I think that these issues, if you collect them all, will just seem like one big fluid thing, which is also the nature of psychedelic artwork.

There’s so much here that is about dying, but that also has to do with plants and animals. There’s, like, the wonderful Henry Hoke who came by our AWP booth who wrote a novel, one of my favorites, called Open Throat from the perspective of a queer mountain lion roaming the hills in LA.

And it’s such a cool book, and it’s like Henry wrote something about all his dead pets for this issue that also could have lived in an issue about people in animals. But yeah, I think that in the end it’ll be interesting to see. I suspect that all of the issues together will feel like one big fluid project.

Arjun Basu: Yeah, you talk about people and animals and, then I start thinking about anthropomorphized cartoon characters. I just saw a Nightbitch a few weeks ago and I’m thinking about that.

Hillary Brenhouse: That’s a pretty psychedelic book.

Arjun Basu: Oh, completely. And the movie was actually really good, I thought. I didn’t think it would be. Amy Adams did a great job. What have you learned about magazines, especially print? Guernica has been around a long time, but you were on the digital. What have you learned about magazines while doing this?

Hillary Brenhouse: Just that it’s so difficult to put one together. Everybody told me: beware of distribution. Like distribution is such a bitch, it’s going to be terrible. There’s so many things that I put off until I could no longer put them off because I didn’t want to do them. Like I wish I had a machine behind me and that I could have just been editor-in-chief.

Our files were due to the printer on March 3rd, and a lot of people knew that and they texted me, like, “Congratulations, it’s done now! Want to go party?”

And I was like, “Are you kidding?” This is where it starts, actually.

You see this issue? It has 176 pages and 50 contributors. That’s just because I never wanted to stop commissioning. I was just, like, “This is what I know how to do. I edit and commission and I’m just going to keep going until somebody makes me stop.” After that, first I had to deal with the printer, and then I had to deal with distribution and shipping, and I’m still dealing with that now.

Finish getting the website built, get templates for social media, like deal with the launch events. Everything that’s happening now is stuff that I’ve never done before, essentially, or have never done in this form. And it’s just … wow. It is such a crazy, busy universe if you’re going to put a magazine together and you’re going to do it independently, and even though we have this funding, it’s very much like an independent nonprofit magazine.

You have to be ready to, like, get your fingers into all of it. And I never expected that I’d be, like, simultaneously importing contacts into MailChimp while booking a band, while, like, running to FedEx to see how much it is to send an issue to Japan, like all at the same time.

Arjun Basu: So what do you think you’ve learned that you didn’t think you’d ever have to learn—besides knowing shipping rates now and everything—because I think I told you once when we met, everyone talks with distribution. On this show, it is an issue that is universal. What have you learned that you didn’t think you would have to learn?

Hillary Brenhouse: Yeah, I’ve learned about design actually quite a lot. That’s one thing. That’s one of the things that I learned the most about. I love design and I knew that design would be such a huge part of this magazine. I knew that we would be wanting to gesture it, like psychedelic design from the first psychedelic era is so recognizable. Everybody knows this, like, art nouveau-inspired flowing lines, vibrating color type posters. I knew that a big part of this would be, like, what is contemporary psychedelic design? Is there such a thing? Can we gesture here what that might be? And my relationship with these designers, I think, was the most collaborative working relationship I’ve ever had in my life, where it’s like they have a completely different knowledge set and specialty than I do, but I can’t really make any decisions without them. And they can’t really make decisions without me. Like we have to inform each other constantly, and I learn things about design. I’d be, like, “Can we just make this bigger? Or can we just make this smaller?”

And they’d be like, “Okay, sure.”

And then I’d get the magazine back and there would be 15 things that were now smaller. And I’d say, “I just asked for that one thing to be smaller.”

And they’d say, “This is a system, it’s a language. We can’t make one thing smaller. We can’t eliminate or change the color pink here to a darker pink and not change it across the board.”

“We’re just very lucky to be in the right place at the right time. This is a very rich field in every sense of the word.”

Arjun Basu: So Chloe and Natalie must have played a really big role because they’ve done this before. And you haven’t. And did they have to rein you in besides explaining to you what design is? How did you play off each other? Did you drive them crazy?

Hillary Brenhouse: Probably a little. We probably drove each other nuts sometimes, but I think it was like, wow such a deeply fruitful relationship. Like they taught me so much. I think that they deeply respected, like, the work that we put in here. Yeah, I think that we learned a lot from each other, and it’s just without them, this wouldn’t exist. Aesthetically, this is really their vision.

It’s something that we refine together over several passes, but it’s, like they, they really took a stab at what psychedelic design might be. They also acted as art directors, and so they made a list of like artists who they thought could be here. I made my own list. We compared them. We made a short list together.

And we communicated and commissioned art together. They also taught me so much about materials, about paper, like another thing I didn’t know anything about. At one point the printer was, like, “I think we have this paper made by the same company in-house, and so we won’t even have to order it. It’s just the satin version, but the difference between the two is negligible.”

And so I said to Chloe and Natalie, “Okay, so maybe we’ll just go for this slightly more satiny paper.”

“Boy, the difference is negligible—Are you kidding me?”

Arjun Basu: I can only imagine what that conversation was like.

Hillary Brenhouse: They were like, “This feels like plastic.” I had no idea anyone could have such strong feelings about paper.

Arjun Basu: I know enough about the thing, Hillary, to know that was a disastrous thought process.

Hillary Brenhouse: Totally. But now I feel so strongly about paper. The things I know about paper now. Like just communicating with the printer and talking about color profiles. It’s, yeah, it’s insane what you have to cram into your brain.

Arjun Basu: So you talked about distribution. What is the plan? Are the schools, the foundations or anything, are they involved in distribution at all or or are you doing this on your own?

Hillary Brenhouse: I’m doing it on my own. They’re not involved. They’ve placed orders for their students, for their colleagues. But I am, yeah, I’m doing distribution.

It’s like I had to find a fulfillment center. I had to experiment with packaging. Anja from Broccoli Mag, who you recently had on here, told me over a call these things look like paper objects, but they’re like glass. They are so fragile. You can’t imagine how fragile a magazine can be. And she suggested that I get like a bunch of different envelopes and then slam the thing, you know, at the wall pretty much. And that’s what I did. And it’s crazy to see. It’s like you touch it and the corners are messed up. So there’s so many moving parts obviously to figure out. But it’s like people are mostly buying them online also in person.

Like we just had this conference. It was really something to launch. It was such a rush to get ready in time for AWP and toward the end everyone was, like, just don’t go, like, why are you killing yourself to make this self-imposed deadline?

But to launch and be able to sell in person? Like to get that automatic feedback where people come by the table and they’re, like, “What the hell is this? It looks so different. It’s so beautiful. I want it immediately!” So I’d love to, given how lush and immersive this thing is, I’d love to sell in person as much as possible.

Otherwise we’re just shipping them out to Canada and the US and praying that we’ll be able to open up to the rest of the world soon because the number of messages in my inbox that are like, get one to Australia, get one to Belgium. I’m like, “Okay, I am working on it.”

Arjun Basu: So it’s a, this is a weird question to ask, but did it meet your expectations?

Hillary Brenhouse: It did meet my expectations. Truly. It’s such a crazy—quite psychedelic, actually—feeling to, like, finally hold something that you’ve been thinking about for two years, and we did this unboxing video on Wednesday, like I arrived at the LA Convention Center for this literary conference.

And my husband came and Meara, our senior editor, and I opened a box for the first time. Also a crazy thing, like to hold the thing and then immediately have to put it on the table and sell it. It’s like you don’t have time to go cry in a closet with it. There’s no, like, processing period. And he started filming me and it was meant to be like, this very joyous unboxing video.

And I just couldn’t. I was in such a state of—I don’t even know how to put words to it, really. I was shocked and I was in love with it. And then obviously there were things that weren’t exactly as I’d envisioned. Like, it’s just suddenly, it’s not on the screen anymore, it’s in your hands. Which is where it was always meant to be. And I just felt completely turned inside out. And I had to say please turn the camera off now. But …

Arjun Basu: Did you smell it?

Hillary Brenhouse: I smelled it. What was nuts is that people were coming by the booth and smelling them and I was like, this is amazing. They were just like, “Wow, this smells like ink. This smells—”

Arjun Basu: Yeah. It’s a great smell. And my favorite thing, when I got a new magazine when I was editing, I would just, it come out of the box and I just put it in my, on my face and take a deep whiff.

Hillary Brenhouse: I didn’t even know that was a thing until people started coming by and sniffing them. I was like, this is amazing, because we decided not to reproduce our content online. It’s like we have a great website, but it’s just there so that you can buy the magazine. Nothing will appear in digital form, and one of the reasons for that is that it’s a psychedelic magazine. It’s meant to be a sensory experience. You’re meant to sit there in person with it and to touch it. And so to have people smelling them felt very apt.

Arjun Basu: Okay, so we always end the show by asking our guests their three favorite magazines or media right now. And what are yours?

Hillary Brenhouse: So this is a very hard question. I think I’m going to cite three magazines that deal with it just a coincidence ’cause they are my three sort of faves right now. But they all deal with either religion, or spirituality, or like transcendence of some kind, which feels like, very akin to what we’re doing in some ways.

One of them is Acacia Mag, which is a new print magazine for and of the Muslim Left. It is amazing. I think that it’s akin in some ways to Jewish Currents. It’s this leftist magazine aiming to bring the community together for political and creative purposes. But it is so beautifully designed by Arsh Razziudin who is a book designer and a magazine designer too, who I’ve admired for a really long time. And it’s edited by Hira Ahmed.

The second thing is Emergence Mag, which I think calls itself a magazine of, like, ecology, spirituality, and culture or something like that.

And it’s such a big object. I think now they’ve gone hardcover, which is awesome. And the last issue was about time, which again feels like, just adjacent to Elastic in a lot of ways.

That magazine is amazing. I spoke to those designers at one point about their practice, and they were like, we go to the printer, like, once a week to talk about glue. And make sure that when you open the magazine, it, like, opens in a very particular way and doesn’t make a sound. I was just like, oh my God.

There are people thinking so hard about glue. It makes my heart sing. But that magazine also is just like a feast and both of those magazines and I’ll say the third one first, so the third one is called amulet. [Note: amulet is now called Kismet] And it launched at the beginning of March and it’s online only. But it’s a literary mag for, like, religion and spirituality for seekers and skeptics, I think that’s how they put it. And so it’s about—there’s all kinds of things in there. Poetry and short fiction and essays, also deeply literary in the way that elastic is. I think that we share some contributors.

I feel like the lit mag is redefining itself right now. And it’s very fun to see a project like Emergence that is in Europe and has this ecological bent and is running these, like, giant amazing photographs. I am interested in the same poet I would publish in Elastic. I think it’s very fun for all of these literary writers. Not to just have to appear on a white page in, in black type.

Somebody came by our table this weekend and said, you know what? I think lit mags at this point should either be this, like an art object that you want to display on your coffee table, or like a zine that you staple together in your basement. And let’s get rid of everything in between.

Arjun Basu: That would be a very interesting conversation to have actually. Go big or go small and if you’re in the middle, too bad. Nothing lives in the middle anymore. Totally. Hillary, thank you. Good luck. I look forward to issue number two.

Hillary Brenhouse: Thank you so much for having me. This was awesome.

Hillary Brenhouse: Three Things

Click images to see more.

More from The Full-Bleed Podcast