Twist & Shout

A conversation with illustrator Philip Burke (Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair, The New York Observer, more). Interview by Anne Quito

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT COMMERCIAL TYPE AND FREEPORT PRESS.

A Burke self portrait

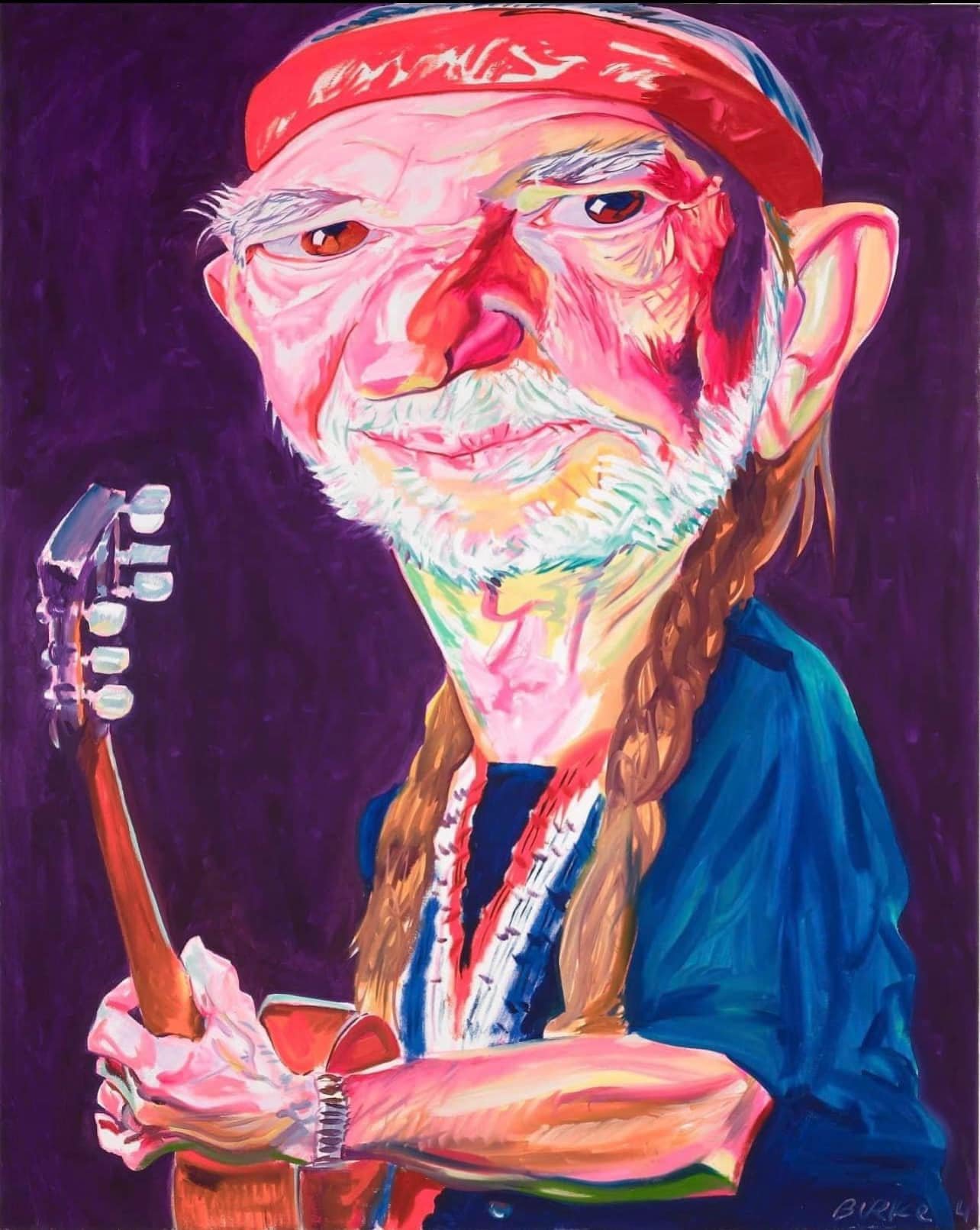

Philip Burke’s portraits don’t just look like the people he paints—they actually vibrate. Just look at them. With wild color, skewed proportions, and emotional clarity, his illustrations have lit up the pages of Rolling Stone, The New Yorker, Time, and Vanity Fair, capturing cultural icons in a way that feels both chaotic and essential.

But behind that explosive style is a steady, spiritual core.

Burke begins each day by chanting. It sounds like this: “Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō. Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō. Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō.” It means “devotion to the mystic law of cause and effect through sound,” he says. The chant grounds Burke and opens a space where true connection—on the canvas and in life—can happen.

This daily practice is more than a ritual—it’s a source of creative clarity.

Burke’s rise was rapid and raw. Emerging from Buffalo, New York, he made his name in the punk-charged art scene of the 1980s with a fearless, high-voltage style. But it was through his spiritual journey that the work began to transform—less about distortion for shock, and more about essence, empathy, and insight. Less funhouse mirror, more human.

Our Anne Quito spoke to Burke about how Buddhism reshaped his approach to portraiture, what it means to truly see a subject, and why staying present—both on the page and in life—is his greatest creative discipline.

“I would just go to a magazine shop, open a magazine, look at the masthead, and then call up the art director and get an appointment to see him with my portfolio the next day.”

Anne Quito: Thank you for making time for this. I thought we could begin with a little time travel to the theme of this podcast about print magazines. I wonder if you could take us back to 1977. I think you were 21 years old. You first moved to New York and maybe found yourself in the thick of perhaps the golden age of print. Can you take us there? Where did you come from? What did you look like? What are you wearing? Where did you sleep? Who did you meet? All that.

Philip Burke: Okay. All right. Well, I was 21 and I grew up in Buffalo. So I always had a feeling I would end up going to New York to try to get started as a caricaturist. I don’t know how to describe if that was the golden age. I suppose it is.

When I went there, I had a portfolio of very vicious political black-and-white pen-and-ink drawings. I went there with a hundred dollars in my pocket and just a lot of ambition, a lot of drive. But at that time I would just go to a magazine shop, open a magazine, look at the masthead, and then call up the art director and get an appointment to see him with my portfolio the next day.

So that was a really wonderful time in terms of access to art directors directly and working with art directors directly. At first I was getting a lot of work from magazines like New Times and Politics Today, The Village Voice, left-leaning publications. The timing was great for me because this was like the moment of punk and that for me was like a musical awakening to me.

I had, just like the rest of the world, I suffered through the late seventies and the desert of any exciting music. And this just woke me right up. It coincided with the anger I was feeling. I really came to New York fueled primarily by anger against my father. And then, by extension, anyone in authority. And that anger really carried me to New York and gave me the drive to get work. And I got work very quickly.

Anne Quito: Who are the art directors you met with?

Philip Burke: Well, let’s see. I got work immediately, though not regularly, from Time magazine, The New York Times, and Fortune. There was some excitement to my work because I had the feel of David Levine but something more, something newer. Or an energy that hadn’t been felt. So I was getting work pretty quickly from big publications. And then I met Steven Heller at The New York Times and he really gave me a push.

He published a couple of things in the Book Review, but in general turned me on to Gerald Scarfe’s work that I wasn’t familiar with and also to the work of the artists in Simplicissimus from Germany. And that really helped me move beyond my influences when I left Buffalo for New York—David Levine and Ralph Steadman. And then George Gross.

But anyway, in terms of the art directors, there was an art director named Peter Morantz at Politics Today. And there was an art director, George Del Mirico, at The Village Voice. We became friends, too. He lived down the block from me.

There was also New York magazine. JC Suares was there and was giving me work. New Times was actually Patricia Bradbury, but the editor was Peter Kaplan who ended up being a major client for me at The New York Observer. In the air in New York, there was excitement with the music—I’m not so sure about the art—but definitely I felt like I had landed there at the perfect time.

Anne Quito: I want to go back to the music. The moment that you fell in love with punk. Can you describe this punk scene? I read that you love to dance—

Philip Burke: Yes.

Anne Quito: —in clubs more.

Philip Burke: Probably my second passion was dancing. I’ve always been very particular about music. I was living on very little. Not long after I got there, I met a man named Rudi Stern, who had brought the revival back of neon, the new neon. I think he had started out doing light shows for The Velvet Underground.

When I met him, he had this gallery and he let me sleep on the gallery floor for a month while I took my portfolio around to get work. But at that time, I think it started with The Clash, London Calling. And then I just started to become immediately engrossed in all the different punk music.

I didn’t have a lot of money to go to clubs, but I saw a few really exciting shows at CBGB’s, but I would go to the other clubs where you can just dance all night. It was recorded, but I could just dance all night. But that has always been a part of my work—music in the studio has always been really key for me.

If I felt like I could dance to the music then I could draw to the music. There was definitely, there was an energy and an excitement in Manhattan. I moved into a small, one-bedroom apartment on Christopher Street, and I think I was paying $275. By the time I left five years later, it was still only maybe $425. So you could survive as a starving artist, so to speak.

Anne Quito: And how much would an illustration get during that time?

Philip Burke: Oh, good question. So for the pen and ink drawings my guess is a few hundred.

Anne Quito: How many would you have to make rent?

Philip Burke: That’s a good question. This business has always been, from the very start, like a rollercoaster—like very busy, and then slow, and busy, and slow. I remember one summer my twin brother who was studying to be a lawyer shared the apartment with me. And another friend once shared the apartment with me. But man, I can’t remember those numbers.

Anne Quito: But you made it work in New York City.

Philip Burke: Yeah. It was basically do or die, that kind of feeling.

Anne Quito: I have heard you complain about your knees now, about too much dancing. What kind of dancing are we talking about?

Philip Burke: Well, it was not what you really consider ... it was freeform, it was going inside my head letting the music move me. But a lot of times I would drop to my knees on the floor—don’t ask me why, that’s what I would do—and it was all different kinds. I mean it was not anything that I practiced or anything, it was just letting the music move me and letting my imagination go. I was no good at dancing with a partner. I was fine, and I loved and had no problem being very creative in my dancing—maybe scaring some people. But I was not good at dancing with a partner.

Anne Quito: I want to go back to what you said about music being very important to your process. I want to thank you because I think I told you I’ve been listening to Miles Davis all week preparing for this interview. And today you said you were listening to Ska and New African. I started doing that as well. You say you’re very particular about music when you work. I wonder how that all plays out in how you choose music. Is it by the theme, by the season?

Philip Burke: For the past 10 or 15 years, I’ve really been relying on my son, Jeffrey, to hear new music. I always had my radar out. For decades, I had my radar out for music. It started with punk music, then in the nineties there was a big explosion of African music, starting with Youssou N’Dour and then Peter Gabriel had his label. So the African music really inspired me at that time. And also Nirvana.

I can’t say I got into a lot of grunge, but Nirvana—I think I started more paintings to that one album than anything else at that time. Nirvana particularly creates the perfect mind space to leap into a painting, fearlessly. It’s really intense but at the same time, even though it’s really energetic, there’s a certain kind of calmness mentally where I felt like I could just have the freedom and the confidence—I don’t know how to describe it. It’s the one album that’s affected me like that.

In terms of Miles, there was a period, I think, in the aughts, where I discovered, so to speak—even though I had heard his music before, but it was the right time for me. But I was looking for something where I could put on an album and forget about it, because for me an important thing is to not have to change the music because that cuts the concentration or the flow. But with Miles, I never knew where I was at in the album. It just kept going and going.

Anne Quito: It’s so fitting that music is part of your process because a lot of listeners will remember your work from Rolling Stone. You were doing the table of contents for a whole year, I believe.

Philip Burke: Seven years—

Anne Quito: Seven years! Incredible.

Philip Burke: —which was unheard of. When I first got to New York, I started approaching Rolling Stone and for 10 years, every art director came along and I brought my portfolio. But nothing happened until Fred Woodward.

And I had seen his work in some of the annuals or some articles about his work when he was in Texas and he was using New York artists. And I always felt okay, this is an art director that I can work with. I always felt since I was in high school that Rolling Stone is where I should work because I used to buy Rolling Stone to get the Ralph Steadman drawings. And I always felt like that was the perfect place for me.

But it took 10 years of knocking on their door every time there was a new art director. I had already moved back to Buffalo at that time when Fred arrived in New York. So I flew to New York and went into his office and just said, “We’ve got to do something. We’ve got to do something. This is a perfect match.” So he came up with this idea to have me do the contents page. It was incredible because there was no real art direction. It was complete freedom.

He said that he had loved what he saw that I was doing for Bea Feitler. Vanity Fair started publishing and that’s when I was first starting to paint and he was very excited to work with me ever since he saw that. So he came up with this idea and there was never any talk about how long it would last.

When I was in New York during those 10 years, different artists would be chosen to do the record review page, for maybe a year or two, but never me. So I didn’t have any great expectations. I just kept doing paintings as long as Fred was happy. I worked with Gail. Gail Anderson was phenomenal. Even one time she traveled to Niagara and watched me do a painting. She was doing a talk there and she came into my studio and watched me paint.

But anyway as long as I kept Fred happy, Gail kept calling. And it ended up being seven years. The only thing that really stopped it was Jann Wenner. Fred had seen the writing on the wall. I remember we did a seminar with Anita Kunz and Henrik Drescher at the LA Art Center. And at that time Jann was starting to be overly concerned about demographics and that he knew that the freedom that he had to hire me and other artists and give them freedom was coming to an end.

“I really came to New York fueled by anger against my father. And then, by extension, anyone in authority. That carried me to New York and gave me the drive to get work.”

Anne Quito: I want to talk about that freedom and zoom to today. So I imagine that time, that period must have been incredibly busy for you. Everyone was calling.

Philip Burke: Extremely busy. That contents page spot was really like a stage. And I think I mentioned this to you before, but Fred was excited by the idea that he didn’t know what he was going to get. He’d just know what he told me to do. There was no approval of sketches or anything, he liked that. So because there was a wildness, every magazine wanted a piece of it.

At one point, I even had to turn some work down, which was hard after the early years—hard anytime to turn work down. But anyway, yeah, I got so much work during the nineties. It was ridiculous.

Anne Quito: And this element of surprise or this pressure to surprise and delight and keep Fred happy—was that a challenge you enjoyed or was it tormenting ?

Philip Burke: No, No. I loved it. To have that kind of freedom, and also I was still experimenting. There was a lot of experimentation. That was also a period in my life where I was going through a lot of, I don’t know, opening up a lot of freedom in my life and in my heart. And it was perfect timing. So yeah, that was just a joy.

Anne Quito: I have a technical question. I know that you make these spot drawings as paintings, as very big canvases. And they get printed on a page. Are you thinking of how it translates to print whenever you’re making these big portraits or caricatures?

Philip Burke: Yes, I’ve always had it in my mind that it’s going to appear small. So it’s designed to appear small. But it wasn’t so much analyzed as much as just that’s in my mind. Yeah, I found that when I started painting, actually, a lot of it had to do with my wife pushing me to go large, don’t be afraid to go large.

When I first started painting, I was in New York and I was just going to 23rd Street and buying tempered masonite and gessoing it because I didn’t have the money. And then she really pushed me. She said, “Stop thinking so much about that. Just get the supplies you need and just go for it.”

The energy that I felt when I was dancing in clubs, it was very much the energy that moved me in the studio. So it would always be a big canvas and I would be standing. And the physical movement would have a lot to do with the flow in the painting, which could never happen at a small scale.

Anne Quito: I read that you once wanted to be a rock star. Was this kind of your way of doing it? Drawing as a kind of performance?

Philip Burke: I guess so. Yeah. I think I probably shared a dream of most teenage young men and women, to be a rock star. But I had no patience to learn any music. I was no good at that. Even when I was in high school in my notebooks—I couldn’t really draw—but I was doing these cartoons of bands. So somewhere it was always in there. It all came out with the Rolling Stone gig. In terms of performing, that happened later, starting maybe in the aughts, but I started doing some live paintings.

And then, for four years—I think it was just before the pandemic—I was doing live paintings at concerts at a place called Art Park in Lewiston near Niagara Falls. So that was great.

Anne Quito: How does that feel?

Philip Burke: Oh, it feels great. What was wonderful was a couple things. When you’re painting, everybody’s behind you, so there’s no interference, but you feel everybody’s energy. And I always felt when I was painting live that everybody’s energy threw me into the painting.

Anne Quito: Incredible.

Philip Burke: So it’s a little daunting. Particularly in the beginning, it was a little daunting, but once I get going, then everything just flows.

Anne Quito: We talked a little bit about your shyness—you say you’re a little shy. And sometimes I look at your work and there’s the kind of exuberance and almost extroversion. Is that something you play with?

Philip Burke: When I was younger, I was not shy at all. I was the opposite way just in terms of survival. And also when I got started the early success for me was not good for my ego. I was really ego driven and I was not shy at all. I was always giving my opinion, all the time. I was criticizing everybody. I had gotten this success as a caricaturist and I was judging everybody. Literally. I was judging everybody all the time, and it had a really bad effect on me.

After about five years, I started actually developing an ulcer because of all the anger inside. It created, like, a wall around me. I had friends, a lot of friends, but I was not really letting anyone in. People would probably not know it, but I was really not letting anyone in. And after about five years of being in New York like that, I started to feel really desperate.

A couple of things happened. Vanity Fair magazine had just republished, and brought me on as their “young find,” and it was like a jump. All of a sudden I was getting work that artists a generation before me were getting. Right at the same time that my magazine career was just starting to explode and take off, I was starting to feel really desperate that, “Okay, is this it? Is this what life’s all about?”

Anne Quito: You were in your 20s and this crisis has already struck you.

Philip Burke: Twenty-five. Yeah, 25.

Anne Quito: So successful at 25. Feels like a rock star’s dilemma, no?

Philip Burke: Yeah, I was feeling quite desperate and I took a trip back to Buffalo, just to try to get a break from New York. And then I met a woman who introduced me to Nichiren Shōshū Buddhism, chanting “Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō.”

I had grown up Catholic—ultra Catholic—in a big Irish Catholic family in Buffalo, but lost any faith when I was seven. And really was just moving on my own ego, really. I had this idea of myself that I was such a compassionate, loving, caring person.

When I met this woman who introduced me to Buddhism, what attracted me was the way she behaved—toward me and toward the people around her—made me immediately aware that, No. This is how I think I am, but it’s very obvious being around this person that I’m not that way at all.

And so I remember saying to her, “Whatever you’re doing, I’m going to do it.” And from the very first time I chanted “Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō” with a group of people, I just felt like this wall around me dissolved. And I felt my heart just come out, and I could feel the life around me, I could feel the people, I could feel the trees, I could feel everything.

Anne Quito: Can you teach us this chant? What does it mean?

Philip Burke: “Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō” is actually the law. So “Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō” is the law that governs life. And it’s the essence of all Buddhism. It was the purpose, or the intent, of the Buddha who appeared 3,000 years ago in India, but the actual practice in its purest form appeared 700 years ago in Japan.

When I first started practicing in the early eighties it was still new in America, but “Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō” is the nature of enlightenment that exists in all life. And Nichiren Daishonin, the true Buddha, from time without beginning, revealed it in Japan, when we’re chanting “Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō,” we’re actually fusing our life with the enlightenment of the true Buddha.

So we’re living our life from the deepest consciousness. “Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō” is difficult to translate word for word because it’s so deep and profound. “Nam” comes from Sanskrit, and it means to fuse with something, or to become one with something, or to worship something.

Then, “Myōhō Renge Kyō” comes from Chinese. And “Myōhō” means mystic law, or “Myō” means like mystic or unfathomable aspect of our life. “Hō” is the phenomenal part of our life—mystic law. We are fusing with the mystic law. And “Renge” means the lotus flower. And the lotus flower is the perfect representation in nature, of simultaneous cause and effect. The lotus is the only flower that seeds and blooms at the same time, bears fruit and seeds at the same time.

It’s a perfect representation of karma, the law of karma, or the simultaneous cause and effect, meaning everything we think, say, and do from moment to moment is a cause. Each cause, each mini, micro cause, each big cause, each cause we make, the effect of that is existing deep in our life, the moment we make the cause. And in the future, we’ll experience that effect.

So that’s simultaneous cause and effect. So on the one hand, there’s the reality that we created all the suffering through past causes, through uncountable past lifetimes. We’re experiencing the effects of all those causes. But the flip side is that in the moment that we chant “Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō” and fuse with the enlightenment of the Buddha, in that moment, we experience the life condition of enlightenment.

And then, for the rest of the day, we’re coming from the highest possible, compassionate wisdom, joy, freedom, like all the qualities of the Buddha we have woken in our life for that day. And then finally, “Kyō” means vibration, or teaching of the Buddha, ultimately. So it’s re-fusing our life with the mystic, wonderful law of the simultaneity of cause and effect by chanting.

That’s still really simplified. Over the years my artwork reflected the changes in my life based on becoming—it’s not like becoming enlightened and then you stay enlightened, but rather as I develop more compassion, as I develop more ability and desire to connect with and care about people, it came out in my work. And particularly I think it really started to come out when I was doing the Rolling Stone paintings.

And I think that beyond the color, beyond the distortion and the excitement, I think what people felt was a recognition of something in that painting that resonated with themself. So I think as the years went by, without necessarily analyzing it or specifically saying to myself, “This is what I’m going to do.” I think that my work started to reflect the deeper part of my life that everybody shares.

Anne Quito: And in terms of your process, I understand you chant before you work.

Philip Burke: Yes I started pretty quickly—because I could see immediately the effect that it had on my whole being.

Anne Quito: Before approaching a piece of work or a canvas, how long do you say these words?

Philip Burke: I would chant for an hour before painting. But there was a period 20 years ago where I chanted for three hours a day before painting. And that lasted for about a year or two. But then it dawned on me that, Okay, I can chant for hours and hours. But the ultimate purpose of the Buddha was enlightenment for yourself and others.

So I’m doing the practice for myself intensely, but am I spending enough time trying to share it with other people? So that’s the difference between Buddhism in its purest form and Buddhism that most people know in terms of, say, meditation. Meditation is all about your own enlightenment, but the intent of the Buddha always has been, always will be that we practice to attain our own enlightenment in this lifetime, but also to help other people in our life.

“I could just dance all night. But that has always been a part of my work—music in the studio has always been really key for me.”

Anne Quito: After three hours of chanting, you begin to paint or sketch?

Philip Burke: Actually, what I was doing was before I did anything in the studio, I would do that.

Anne Quito: It’s a kind of preparation. Preparing the ground.

Philip Burke: So now it’s just, it’s an hour, but I try not to go into the studio until I’ve chanted for an hour.

Anne Quito: How does that compare to when you were not doing that? How do you feel after an hour of chanting and you approach a blank page?

Philip Burke: Less hesitant.

Anne Quito: Okay.

Philip Burke: Much less hesitant. This is relative, but much less doubting myself as I go. When it comes to the painting, the freedom that happens in the painting is the result of days of pencil studies. Very detailed, straight—straight as possible—drawings of my subject’s face from both profiles, then three quarters and straight on, a couple straight on, and then different expressions. Then start to stretch it this way and that way.

Anne Quito: So you have an embodied knowledge of the face. Is that right?

Philip Burke: Yes.

Anne Quito: There is a 2016 video from Vanity Fair circulating again, called “How To Draw Donald Trump.” You’re in it, and you say your only job is to be true to how you feel about a subject. Using this incoming president, how do you draw a face? Can you go through these steps in a more detailed way about this preparation?

Philip Burke: First I try to see whatever I can on YouTube. And then I go to Getty, and—used to be Google but now it’s Yahoo—and get pictures, as clear as I can of both profiles, of three quarter angles. I usually end up printing out anywhere from 30–50 pictures.

Anne Quito: Wow.

Philip Burke: And then draw—usually at the least 5 and at the most usually 10—really intense studies. So these studies are not easy, not fun, but without them, I could never do the dance or the free thing that I do in the painting.

Anne Quito: And you do this for every face. Every commission. Incredible.

Philip Burke: The only times I don’t do it is when I’m painting from life.

Anne Quito: We’ll get into that in a bit. So your portfolio really is about the face, about the portrait. What is it about the topography of the human face, or the mystery of the human figure, that continues to fascinate you? There’s no landscape phase—you don’t just paint objects. It’s always the human and you’ve never seemed to lose your interest.

Philip Burke: It’s hard to understand where it came from, but it’s been something that I just could not do since I was very young—I think I was about 15 when I saw the work of David Levine and I felt, “Okay, this is what I have to do. This is what I must do.” And I think at first it was just the excitement of being able to create an image that would start to have some 3D and also have a feeling in it. But I think over time why it stays so exciting for me and fresh for me is because it’s all about connecting with people.

So I think the hardest thing to draw is a human face. I’ve done landscapes. I had a client about 20 years ago who had me do some landscapes for a pharmaceutical company that was selling asthma medicine. They wanted to have landscapes that show wind.

I think if you can draw a face and get a likeness, you can draw anything. It’s not necessarily why I’ve been drawn to it my whole life, but as time goes on, I find more and more I want to not just do the face, but do the body language as much as possible.

You can never get tired of meeting people, you can never get tired of the variety of humanity. I can’t think of a person I wouldn’t want to paint. That’s not true. There are a few people I wouldn’t want to paint. But I will do Trump. And I’ve done Trump, I need to say.

Anne Quito: I’m looking at you through this interface. Our video is on, for those who are listening. And I’m looking at a painting of your son behind you. Jeffrey, is that right?

Philip Burke: Yes.

Anne Quito: Can you—for our audio listeners—can you describe what we’re seeing and how you came up with this composition?

Philip Burke: So composition for me is something that—how can I put this—it’s like breathing. It just happens. So it’s not really analyzed. To answer your question, over the years—I think I mentioned this to you before—but since I started, I would rarely pick up a pencil or anything if I wasn’t getting paid.

I spent so much time drawing—and then later painting—that if I was doing my own kind of work, I wouldn’t have time, but also I wouldn’t be able to survive. Different artists approach art in different ways, but I’ve always been mercenary that way. It’s really important.

This is partly because it creates the freedom to be able to do the work. So trying to work and not knowing how you’re going to eat doesn’t work well for me. But anyway, over the years I have had, oh, I don’t know, 20, 40, 50—I don’t know how many times—where I would have some time and I would paint someone close to me or paint myself. And the great thing about when I paint Jeffrey, which I’ve done a few times, is this complete freedom.

And actually that’s also when I paint myself, of course. I can do anything I want because I don’t have to be worried about the reaction of this model. But the same with Jeffrey, first of all, that I know him so well, but also that he is such a creative person and I feel completely uninhibited.

But also I think a lot of a painting, when you’re painting from life, has to do with the life of the person. And there’s just no effort or struggle—we shared our life for his whole lifetime. So that becomes a thing.

But when you’re working from life, it’s uncountable moments. And it’s so challenging because every time you look back at the model, even if the person is trying their best to stay still, it’s different every single time. So it creates the necessity. You really have to have freedom. You really have to have a fearlessness to work from life. My real passion is painting from life.

Anne Quito: I understand you had a famous sitter one time. Andy Warhol sat for you.

Philip Burke: Yes. That was an incredible experience, actually.

Anne Quito: Can you tell us how that went?

Philip Burke: He was like a sphinx, but very generous. Very generous. It’s funny because I had an interaction at a distance with him maybe a year or two before. I had a crazy thing that happened with The Clash. I was so into their music. And somehow, when they were coming to play a big concert at Bonds in New York, I found out where their manager was staying.

I don’t know how I did it, but I found out where the manager was staying—this was before the internet or anything. And then knocked on the door. And I had done these beautiful drawings of the band. And the manager said, “Oh, come on in. Nobody ever wants to give us anything.” And he was really sweet and wonderful, and then he invited me to come to the show and meet the band after.

That followed up with being invited to a big show they did with The Who at Yankee Stadium. And they had what they called artists backstage. Which was a big joke, actually. It was a huge show and we didn’t get to see the show. We were backstage and then the band ran through at the end.

But Andy Warhol was one of the artists. And I remember just looking at him across the way. We met eyes and I just felt really strongly, like, There’s something. There’s some destiny. There’s some connection.

So anyway, after I moved out of New York—so this was probably ’83, could have been ’84—one of my brothers had taken over my apartment and I was back visiting. This was a small building in the West Village. And I looked down from the third story and I saw that hair and I ran down to the street and I ran up to him. I said, “My name’s Philip Burke, and I’d like to paint you.”

And I didn’t know what to expect, because these years of living in New York the image I had of him was that he was like a space cadet, that he was just out there. But not at all. He immediately said, “Oh, I love what Bea is doing with you over at Vanity Fair, so come over any time.”

It took me a lot of courage—it took me a year actually—to take up this invitation. I think I felt like I had to have Vanity Fair say they would publish it if I did it, which they never did. So finally, I packed up, and I rented a station wagon. Geri and I drove to New York, went up to The Factory, and I was like, “Can you sit for a couple hours?”

He said, “Sure.”

And after a couple hours—I was still new to painting. I was doing work for Vanity Fair, but it was early paintings, I was very new to it—after a couple hours, I started to feel like I was stuck in quicksand because the way I work, I’m always dipping my brushes into oil and turp to mix it with the paint. I was so nervous I kept forgetting to do that.

All of a sudden I felt like I was just stuck. And I was trying not to freak out. And then I said to him, “Do you think you could give me a little more time?” And then he seemed more relaxed and I was more relaxed. And I think he sat for about four hours. Luckily, Geri was keeping him in conversation, that helped a lot.

Anne Quito: Geri [Minicucci] is your wife, yes?

Philip Burke: Yes, Geri’s my wife. When it was done, I showed it to him and he said, I showed it to him and he said, “Oh, looks just like me.” He was hard to figure out. He was really hard to figure out, but with his spirit he was very generous.

At the time, I think he wanted to try to get me to come and join this group of young artists that he was, I don’t know, nurturing. But I didn’t like the vibe at all. I went once and whatever I experienced turned me off. But I was so nervous about this painting that I asked him if I could take some pictures of him so that I could go back to Buffalo and do a really good painting. I didn’t say that to him.

And so I went, took pictures of him and then did this painting that took days where it was perfectly detailed and everything. And then I brought it and gave it to him to thank him for sitting for me. And then years later, I realized the real portrait, the real gutsy—what really captured him—was the one I did on the spot.

Anne Quito: I’ve seen the formal one. It doesn’t look like a caricature. It looks like a more formal portrait. Do you still have the raw one from the city?

Philip Burke: Yes. Yeah, I do.

Anne Quito: Oh my gosh.

Philip Burke: It’s small too. It’s just a little canvas. Maybe three by four at the most, maybe less.

“I had a sense that when I was doing a piece, I was on a stage. And that’s something that’s very exciting. It can be nerve wracking, but it’s very exciting.”

Anne Quito: I once wrote this profile about Everett Kinsler, the presidential portraitist. I spent some time with him and he said having a sitter and the painter, there is embodied energy in that whole encounter, no? It’s like a charge, in a way. I wonder if you feel that way, whenever you have a live sitter versus a commission—versus a self portrait or a portrait of someone you have affection for. How did those scenarios differ for you?

Philip Burke: Yes, actually the only paintings that I can live with in my home are paintings that I’ve done from life. Otherwise, no matter how much I like the painting that I’ve done, within a month, I’m tired of looking at it.

And I think it’s because when I’m working from—even if I have 15 photos that I’m looking at—still the energy that goes into the canvas, the canvas, the actual energy that it holds is my energy. When I do something from life, the energy of both lives is in the painting.

So beyond the fact that there’s something that I can’t even describe that’s different between working from life and working from photos in terms of why the work from life keeps its ability to keep me interested for decades. I think that it’s the life that’s in the canvas. It’s the life that’s in the image on the canvas. It’s like the combination of the energy of the sitter and the painter.

Anne Quito: Has anyone ever contested a portrait? Your portraits are of a particular kind, I think. And I love sometimes seeing you describe your work. Sometimes I feel like, “Oh, I love this accident.” Or like you’re almost in awe of the result. I wonder if anyone has ever, any subject has ever said anything negative.

Philip Burke: Yes. Twice. Twice that I remember.

Anne Quito: Twice!

Philip Burke: No, three times actually. The first time was Bill Gates, but not to me directly.

Anne Quito: What did he say?

Philip Burke: He wrote to the magazine, to the editor saying, “I don’t know how you expect to sell magazines using this kind of stuff.”

Anne Quito: How did you draw him?

Philip Burke: I don’t know how to describe it. He was pretty distorted. He was really distorted. Yeah, I don’t know how to put that into words. But it was not a nice portrait. It was a pretty strong caricature. That got me excited to be able to get a rise out of him. It was great.

And then I once did a pen and ink—I think it was for GQ—of Joan Rivers. And I really went out of my way to be extreme with the caricature pen and ink. And she sued the magazine and she sued the writer, but she didn’t come after me. But obviously she was not happy about it.

And then more recently, when I did Stephen Miller and his wife for Vanity Fair just a few years ago. He got really upset and contacted the magazine and said that my painting of them was “like the drawings that Nazis did of the Jews.” Something like that. Made no sense to me at all. But so yeah, there have been a few times.

Anne Quito: How does that land with you, whenever you get that kind of feedback?

Philip Burke: I like getting feedback.

Anne Quito: You like getting feedback of any kind?

Philip Burke: Yeah, but if somebody said, “Oh, your caricature didn’t catch that person at all. Or didn’t catch me at all.” That wouldn’t make me happy. But if I get somebody stirred up? I like that. The best reaction I like—it just happened several times over the years is when someone wants to buy the original. Then I know they want to live with it.

Anne Quito: And I know you publish your paintings, sometimes your sketches, on Facebook.

Philip Burke: Yes.

Anne Quito: And is that sort of to share with the public a work in progress?

Philip Burke: It started when the pandemic started. I felt like I wanted to try to do something entertaining. It was like a gradual retrospective of all the work that I’ve done that I really love. And I just haven’t stopped doing it. It’s getting a little repetitive.

Anne Quito: How does it feel seeing stuff from the past?

Philip Burke: People are enjoying it, which is great, but the great thing—to answer your question—is seeing this work from the past, like music will take you back to a certain place. This work seeing the work from years earlier and there’s been so much work over the years that I otherwise wouldn’t look at. It opens dusty rooms in my mind, I feel.

Like there’s rooms of creativity in my mind that I’m reopening. I can look at a painting, say, of Kurt Cobain or Frank Zappa or something, I can look at it and I can go to that time. But I can also feel the sense of confidence or creativity or the combination of that.

Something happened in this field over the last 20 years that’s sad, which is that publishers still kept hiring, but wanted to be more controlling. Particularly in a place like The New Yorker. They gave me a lot of work, but there was always a lot of control. And this is pretty much across the board, not so much with Rolling Stone.

And also, fortunately, I had this client, New York Observer, where Peter Kaplan, the editor, just gave me complete freedom to do anything. But in general, the editors and therefore art directors became much more controlling. And the wildness, they didn’t want that.

I mean, I know there are still art directors who from time to time do give me the freedom. But for the most part, my work inevitably tightened up. And also I started to create habits that worked for the editor or art director, and then relied on them too much. It’s very easy to feel bored by that.

So what I’m saying is that seeing all this early work, and looking at it all, and then particularly showing other people, has allowed me to go to those places in my mind that I feel like were locked up.

Anne Quito: I hope it inspires any art director listening to this to unshackle you. To embrace this element of surprise. I think I saw an early sketch by you, maybe during the Ralph Steadman, David Levine days. Is it Prince? Just a sketch of Prince in his series. It’s maybe for The Village Voice, I think.

Philip Burke: Yeah, for The Village Voice.

Anne Quito: Stunning.

Philip Burke: Yeah, I did a lot of Princes. I did a lot, a lot of Princes.

Anne Quito: You did a lot of Princes. How many do you think?

Philip Burke: Between drawings and paintings, it has to be at least 30.

Anne Quito: That’s incredible. And how do you approach drawing the same subject over and over again? I know you’ve also done a lot of Arnold Schwarzenegger over the years. How do you approach that over and over again?

Philip Burke: There’s an advantage. How can I put this? I think one person that I probably drew more than anybody else was Reagan.

Anne Quito: Ah, okay.

Philip Burke: This was even before I was painting. I did paintings of him too. I was getting a lot of work to do Reagan, Bush, Clinton. So the advantage of doing someone over and over again is that each time I would take it to a new place, to the point where my latest Clinton for GQ or my latest Reagan for The Village Voice, the caricature was extreme and the likeness was really extreme. And that only happens by doing someone over and over. I’m doing a private commission right now of, I can show you— [Holds up painting]

Anne Quito: Yes. Wow! Look at that!

Philip Burke: So this is a private commission of Trey Anastasio of Phish. There’s a lot of distortion there and caricature, but no matter how hard I try, I’m never going to take it where I’ve been able to take some of these presidents. Or Hillary, for example. I did Hillary so many times.

And Prince is somebody like that. Or Mick Jagger. So many times. I’m able to take it farther and farther out, and yet more and more capture their essence. But to me, I love the challenge. I love the challenge of doing somebody in a completely new way.

“You really have to have freedom. You have to have a fearlessness to work from life. My real passion is painting from life.”

Anne Quito: Have you ever sat for another artist? Who would you entrust to capture your likeness? I’m curious.

Philip Burke: The only person I’ve sat for is Jeffrey.

Anne Quito: Jeffrey.

Philip Burke: Yeah.

Anne Quito: Is that in your studio?

Philip Burke: It’s somewhere here. It’s mostly abstract, but let’s see. I know people have done me, but I don’t, can’t think of anybody else that I sat for.

Anne Quito: You describe a time when you were turning down work. You were getting a lot of calls, getting a lot of commissions. How has it changed now? Are you still working to the bone, like burning the midnight oil, doing commissions?

Philip Burke: I’m burning the midnight oil, but not in editorial. It’s rare for me to get editorial work. I think most of it is because so many publications have died. The ones that are still using illustration, I think it’s a combination of maybe they don’t want to pay the fees that I need or that they really don’t want work that’s going to turn off any possible reader. That’s the bottom line.

I’ll still get some work from Vanity Fair, and I’ve been getting some work from a couple publications. One in California, Alta Journal and one called JAZZIZ. But it’s rare. It just gradually went down to almost nothing. But in the meantime—and I think a lot of it is a result or reaction to the work that I’ve put on Facebook—I’ve been getting one private commission portrait to the next, and it’s keeping me really busy.

Anne Quito: Is it a similar kind of pleasure doing private commissions?

Philip Burke: No, no. I enjoy drawing anyone, but there’s something about knowing that you have an audience. For at least 20 years, I was having regular work from three or four publications at a time. So there was a sense that when I was doing a piece, I was on a stage. And that’s something that’s very exciting in the studio. It can be nerve wracking, but it’s very exciting.

So with the private commission work, it’s different. The part I like about it is the connection to the person and really trying to create an image that person is going to be happy to live with for years. And by that I mean trying to make a painting that I believe reflects how that person sees themself.

As opposed to the caricature where it’s completely my viewpoint. I’m trying to create an image that’s not boring, but at the same time, I’m really trying to bring out what I imagine a lot of them are local and I get to meet the people. Some I don’t get to meet them, but still, I’m trying to read how they feel about themselves, if that makes sense.

Anne Quito: Last question. I want to talk about the self portrait. I love this one. The self portrait of you. I see a little influence of Picasso, maybe. Oh, there it is behind you. Could you talk to us a little bit, how this came about and all the stuff in your mind while you were doing it?

Philip Burke: I’ve done a lot of self portraits, but I think this is my favorite. I believe it was maybe a paper company asking me to do myself for some project. I can’t say that I had Picasso in mind particularly, although Picasso is so embedded in my consciousness from the days that I just started painting. It was a big explosion for me when I discovered Picasso in my twenties.

But for this one, I spent hours and hours close up to a mirror trying to get exact, exact likeness of my face. Absolutely exact. Unfortunately, I’ve lost that drawing and I wish I hadn’t and I don’t know how I did. But then once I had done that, I went overboard in the study part. It’s one straight-on drawing. Then I just dove in and had no doubt at all about anything I was doing. It was just complete freedom.

Anne Quito: If you say a portrait conveys the truth about the sitter or the subject. What does this portrait say of you?

Philip Burke: Okay, so there’s a couple of things—it’s goofy, but when I look at this painting, as you’re looking at it, my left eye or the right eye or the lower eye as you’re looking at it, is on the canvas and the eye right above it is looking back just almost expecting someone to open the door, knock on the door, interrupt me.

So that’s what I see when I look at it still, in terms of representation, I think that to me, it captures the total immersion into the creative extended moment. For so many of my caricatures, after understanding exactly how someone’s eyes line up in the studies, I’ll push it one way or another to bring out their character more.

And I think I always had a desire to take that as far as I could take it. I’m sure if I really thought about it, I could have a better answer, but I think that overall, it captures my art more than anything I’ve done of myself, even to the point of having cartoon hearts all over it.

Anne Quito: So is this a good representation of you as a person you think, fully?

Philip Burke: Let’s put it this way. As I see myself, yes. It feels comfortable. Everything that I’m comfortable about in myself is in that painting.

Anne Quito: Philip, this has been an honor. Thank you so much.

Philip Burke: Oh, thank you. This has been very enjoyable. I feel like maybe I went on too long with certain things.

Anne Quito: No! P.S., give us some things to listen to. I know you curate Spotify playlists. What should we be listening to?

Philip Burke: I don’t know. It keeps changing for me. There’ll be periods where I’ll start with a certain song. Most recently, the song that’s pulling me in is by Elyanna. I think she’s from Palestine. And it’s called “Sokkar”—S-O-K-K-A-R. I have a whole playlist of her. The other one that’s really getting me going is Kneecap from Ireland. As I’m drawing, if the song is moving me, I’ll add it. So I have these different playlists.

Anne Quito: Megan Thee Stallion!

Philip Burke: I never thought that would get me going, but it did. I saw it at Kamala’s big Atlanta rally and then I started listening. I never know really what’s going to get me moving, but if it gets me moving, then I go for it.

Anne Quito: Moving, as in dancing?

Philip Burke: Yeah, and also with, like, with Elyanna, it’s my emotions. She shares her emotions. She really shares her emotions. Plus the music is really exotic. I still always go back to the nineties African music. I get lost in that. Then if I’m feeling lethargic, then I’ll put on my punk mix. And still sometimes, when I’m really in a hard spot, I’ll go back to Nirvana’s Nevermind.

More from Print Is Dead (Long Live Print!)