A Revolution from Within

A conversation with editor and author Gloria Steinem (Ms., New York, Esquire, Show, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY COMMERCIAL TYPE.

This episode is about a girl from East Toledo, Ohio.

A girl who taught herself to read by devouring comic books, horse stories, and Louisa May Alcott. A girl who didn’t set foot in a school until she was 14.

A young woman who went to India for two years to avoid getting married—to anyone. A young woman who was described by one Esquire editor as the only writer he knew who could make sex boring.

A woman who has never, ever, worked for a paycheck—who made up and launched her own idea for a column in New York magazine. (It kind of still exists.)

A woman who, while on assignment, was kicked out of the lobby of the Plaza Hotel because “she must have been a hooker.” Because all unescorted women who hung out in hotel lobbies in the 1960s must be sex workers, right?

A woman who describes herself as a “hope-aholic.”

This episode is about Gloria Steinem, the woman who created Ms. magazine—and started a revolution.

—

Our editor-at-large George Gendron caught up with Steinem on the occasion of the magazine’s 50th anniversary.

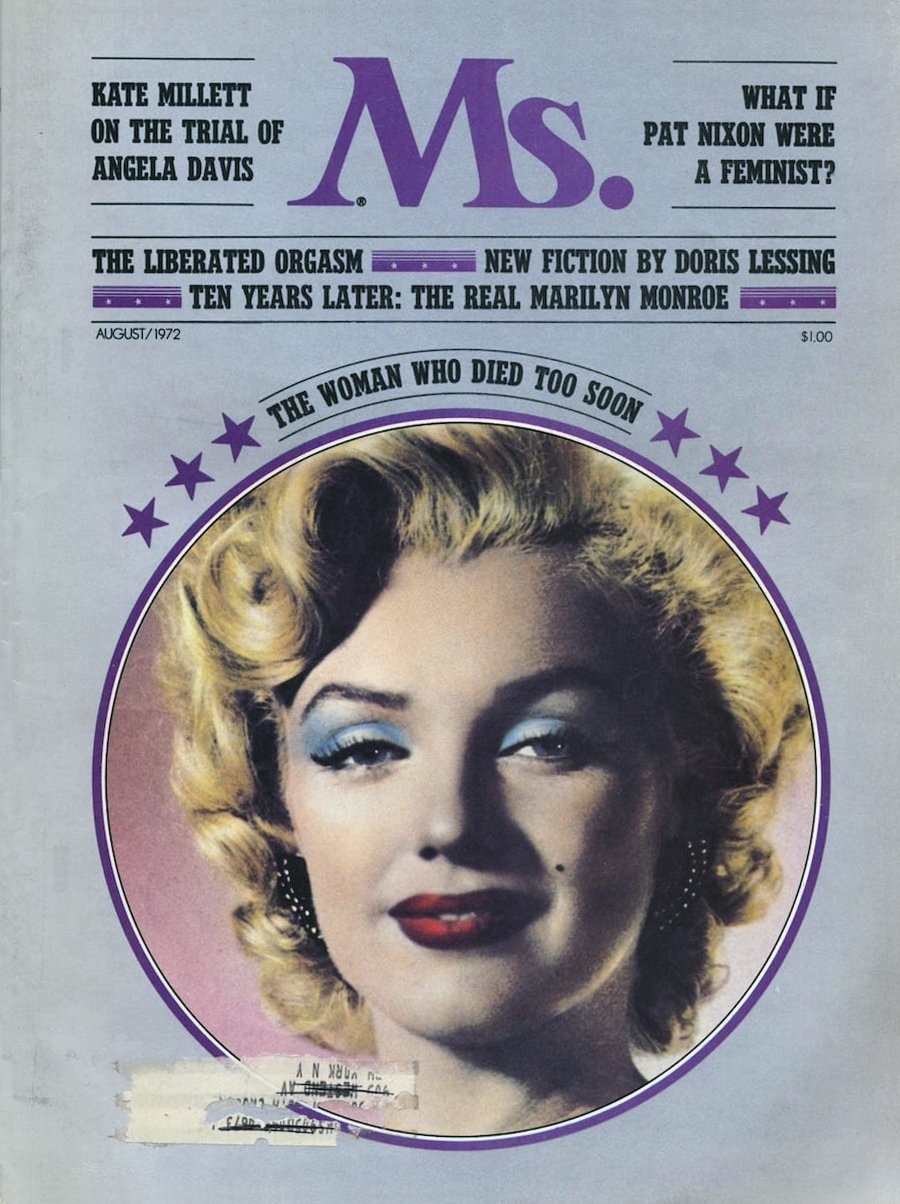

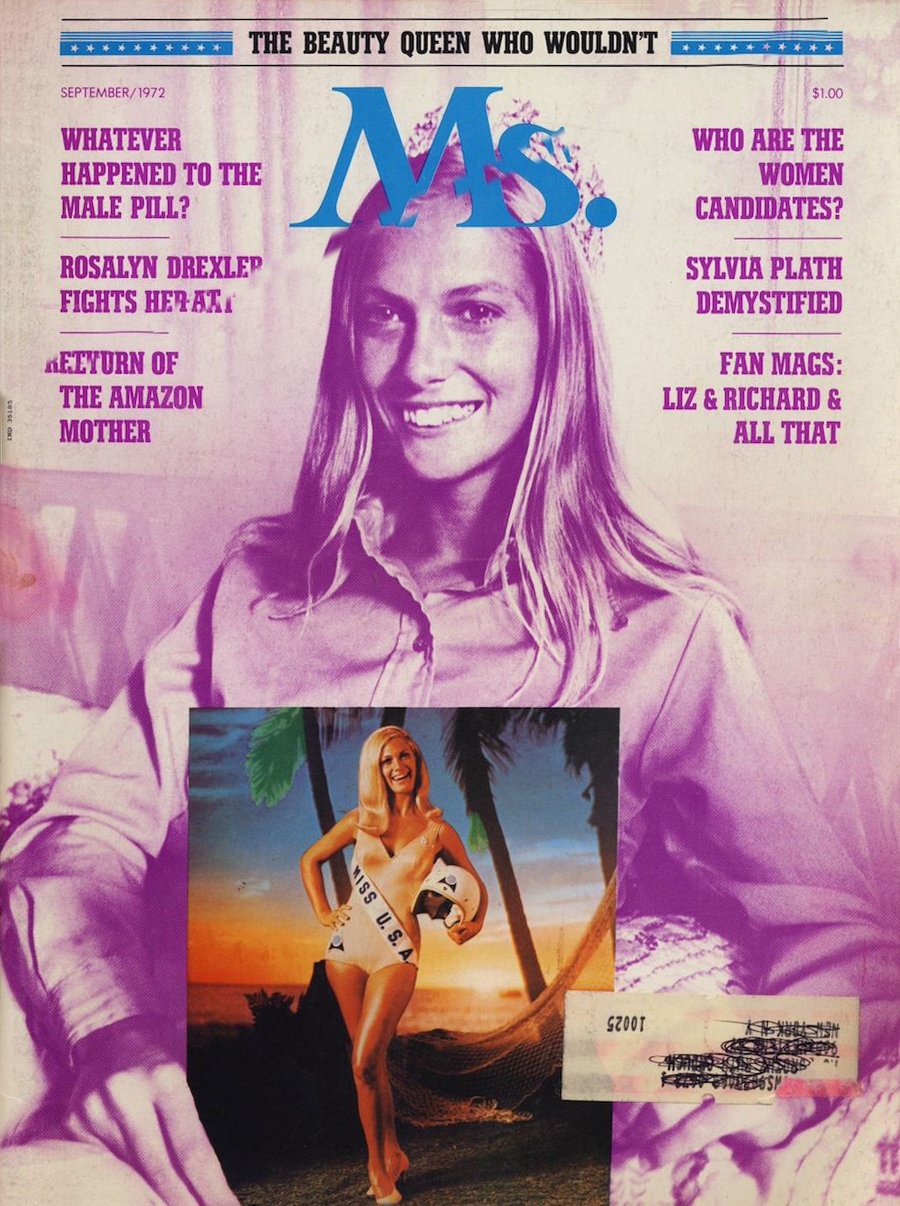

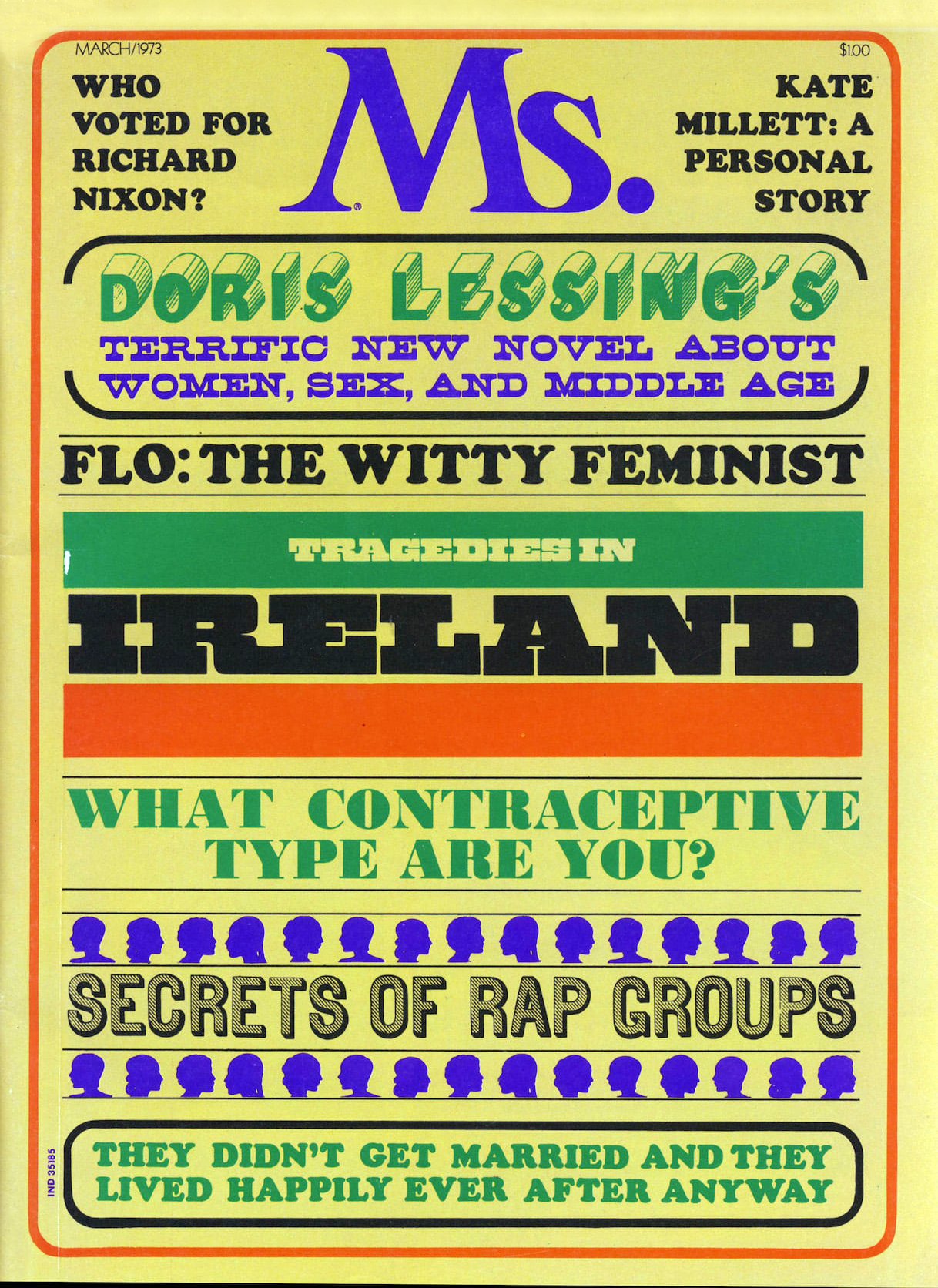

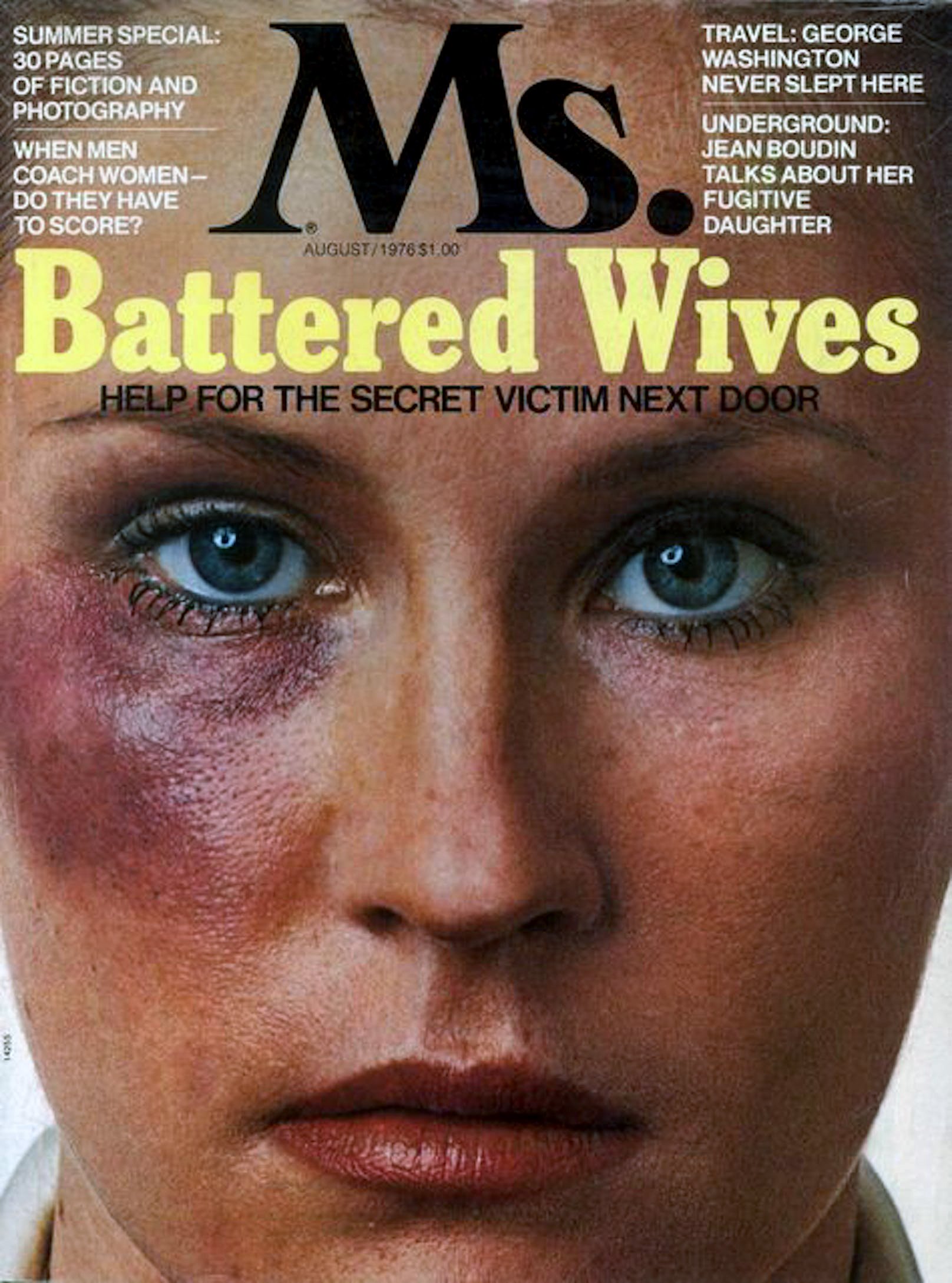

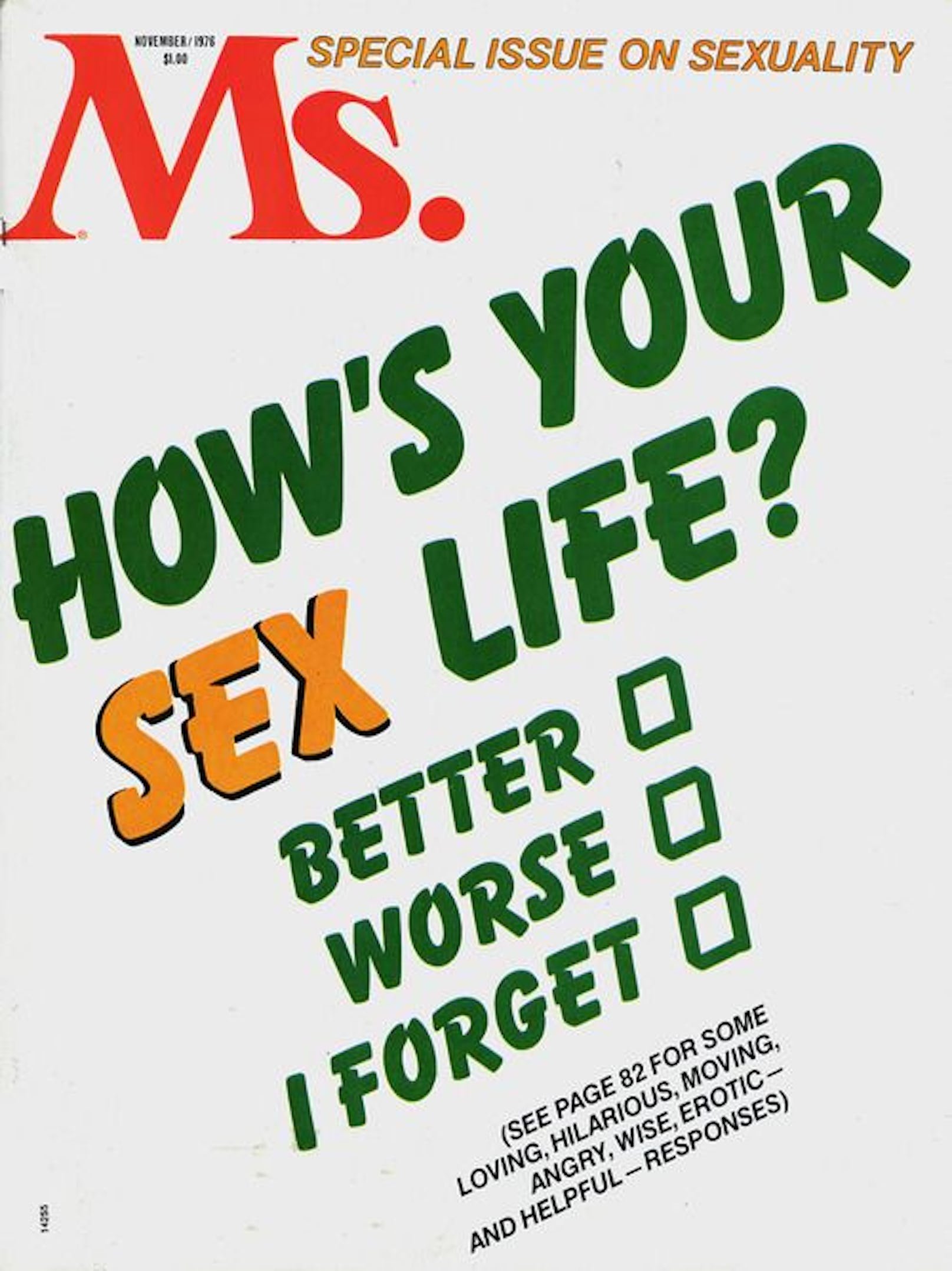

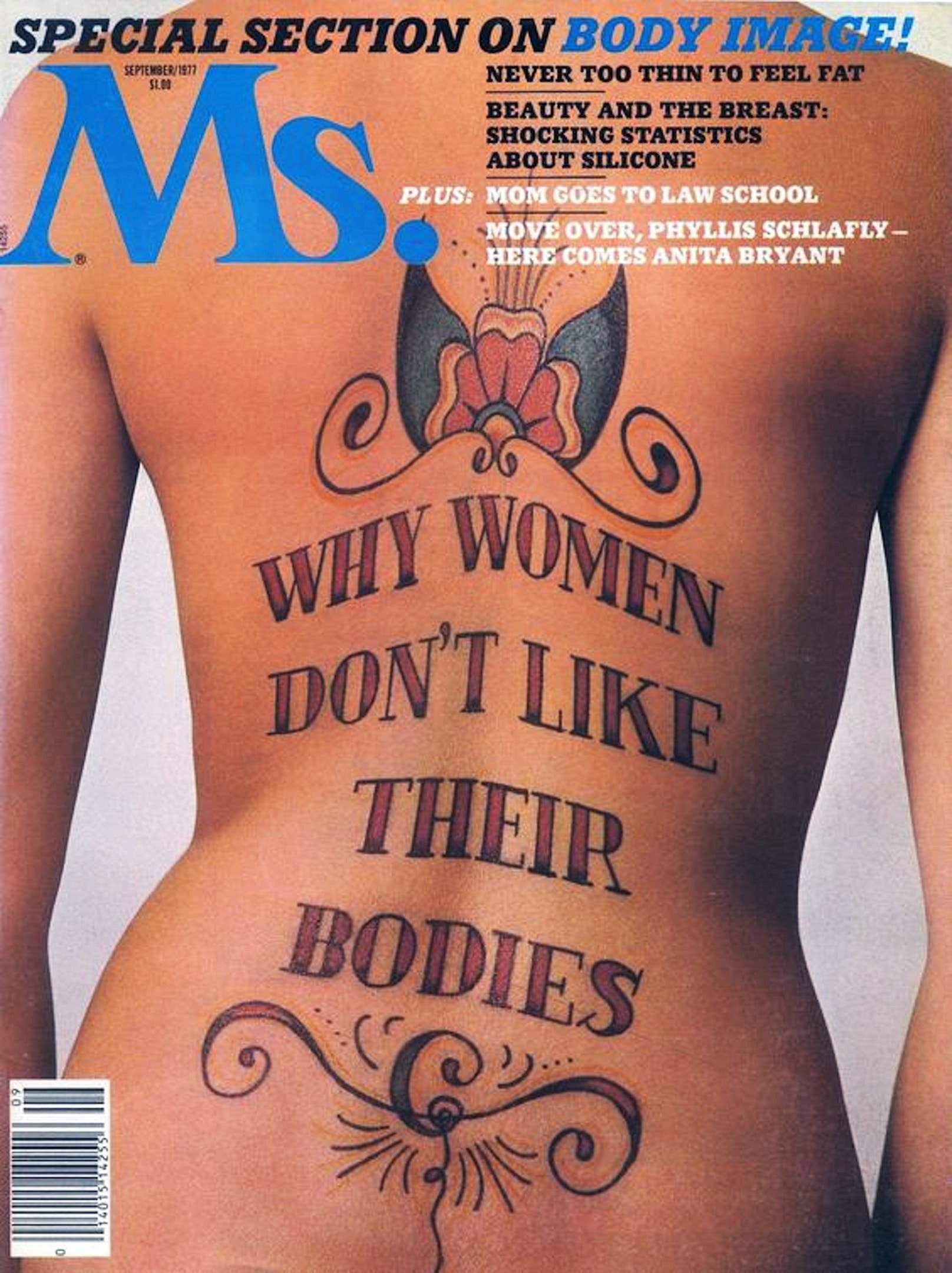

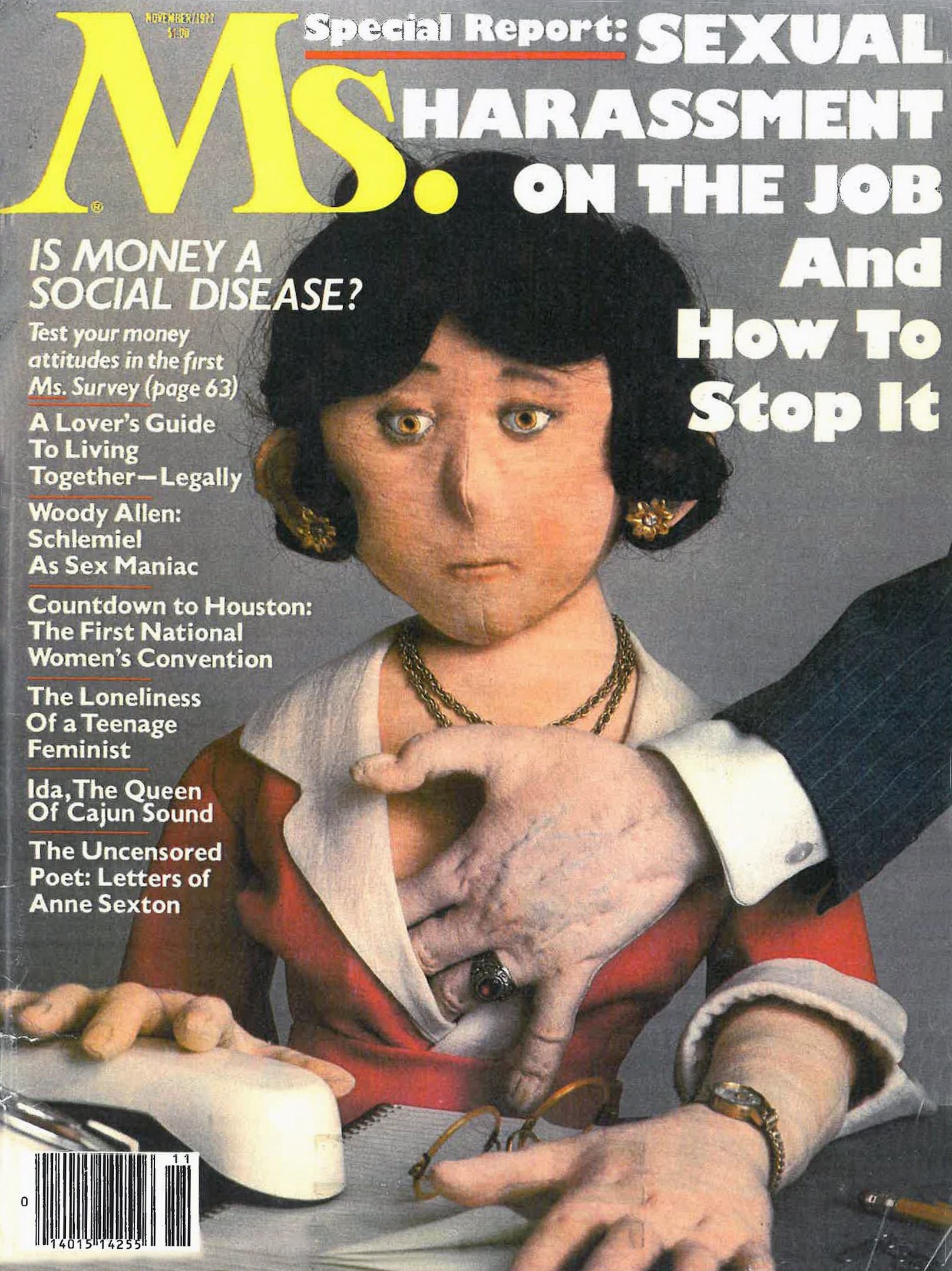

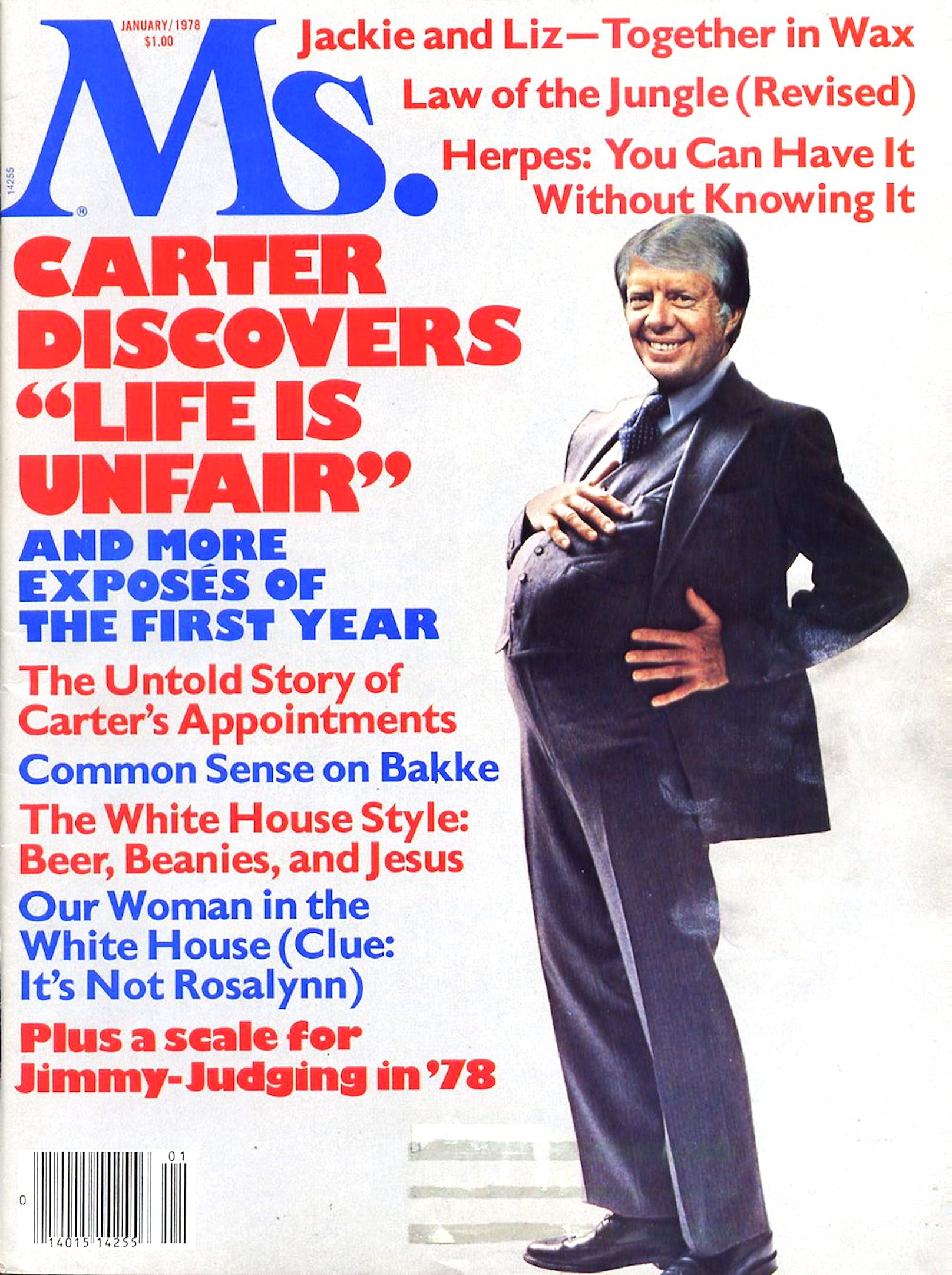

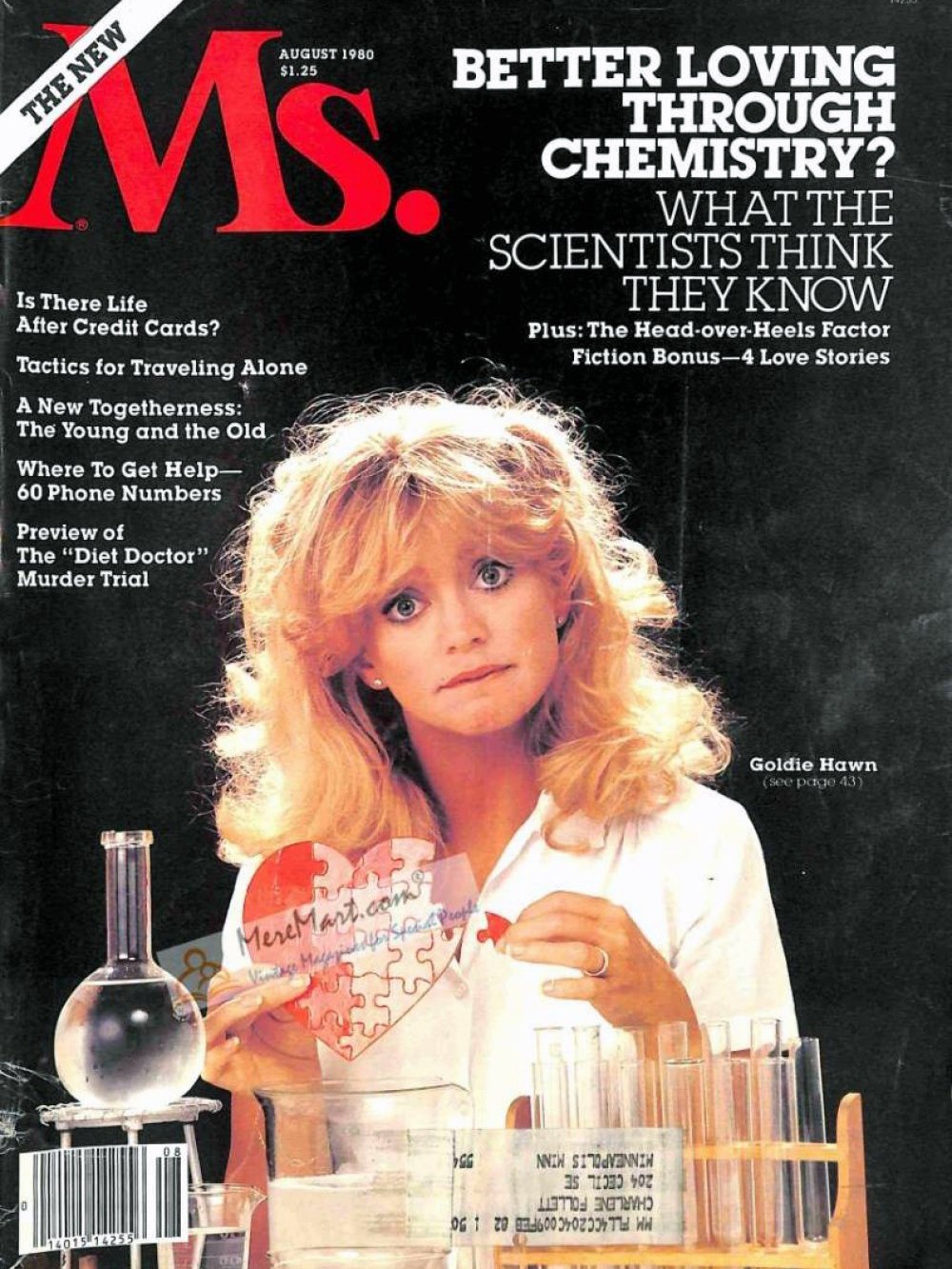

Ms., “The New Magazine for Women,” premiered as bound-in supplement in a 1972 issue of New York magazine

George Gendron: I want to start by asking you, Gloria, before there was Ms. magazine, there was Gloria Steinem, the journalist. And I think lots more people are familiar with the Ms. legacy than they are with your days as a journalist. Could you go back and tell us a little bit about those early days for you as a journalist and what the environment was like, particularly for young women, trying to break into journalism then?

Gloria Steinem: Speaking personally, I think I always wanted to be a journalist—ever since I was a child. Louisa May Alcott, the author of Little Women and many books for young people, but also a lot of serious, depressed novels was a journalist. And in addition, my mother had been a journalist. She worked for the Toledo Blade and always regretted having given up her way of making a living for reasons of my father’s because he moved us all to southern Michigan where he had a dance hall.

I mean there were familial reasons, but altogether, from my mother to Louisa May Alcott and back, being a journalist seemed the most attractive, magnetic, full of learning, diverse profession, I could imagine. And on top of that I hated talking in public in any way. And I was only kind of forced to do so much later.

But the idea of being a writer and not having to talk was very seductive.

George Gendron: At a certain point, I, too, hated talking in public. And when I took over Boston magazine, I had to start doing it. And I read a survey, a poll, asking Americans what were their most primal fears. And number two was death by drowning. And number one was speaking before a group.

Gloria Steinem: I’m more surprised by the drowning than the speaking before a group.

“Being a journalist seemed the most attractive, magnetic, full of learning, diverse profession I could imagine.”

George Gendron: I am too, but that kind of establishes a certain context for both of our fears of public speaking.

Gloria Steinem: No, I only began to do it after New York magazine had created invitations to do it first in New York and then in other places, and I absolutely couldn’t do it by myself. So I recruited Flo Kennedy. Do you remember Florynce Kennedy? She was fearless. And so, yeah, we traveled together. And then Dorothy Pitman Hughes. And I never really did it by myself.

George Gendron: So what kind of journalism—were you freelancing initially?

Gloria Steinem: Yes. No, I’ve never been on salary. I’ve always been freelance.

George Gendron: I think many people, probably when they think of you as a journalist, think back to that article that you wrote for Show magazine about being a Playboy Bunny, but I’m more interested in your work for New York magazine. Did you actually create the “City Politic” column?

Gloria Steinem: Yes, I did. Yeah. Because we were starting the magazine, all of us together, working out departments and the balance between articles and columns and so on. And in the process I gave myself a column.

George Gendron: You gave yourself a column. Well, that’s one of the virtues of being there at a startup, right?

Gloria Steinem: Right. It was Clay [Felker], and Tom Wolfe, and Jimmy Breslin and all the people.

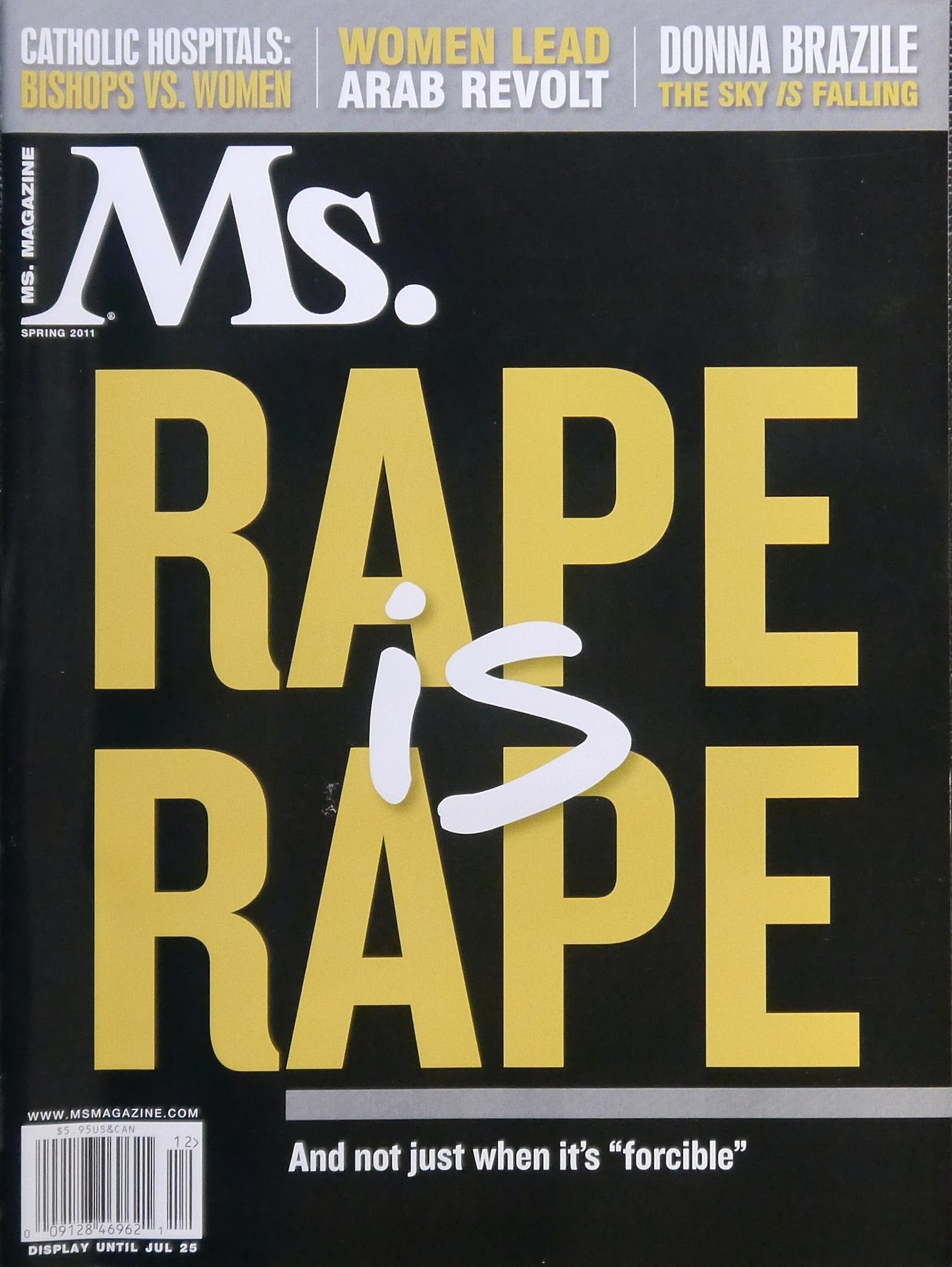

The premiere issue of Ms. hit newsstands in June 1972.

George Gendron: Yeah, you had all left by the time I got there, but I was still delivering mail to you somehow. So what was the “City Politic” back then? What were you covering?

Gloria Steinem: It was literally events in the city because, I mean, we were the first of the city magazines. But many of the substantive, bigger articles were about issues that stretched beyond New York City. And I loved New York in the way that only somebody from Toledo, Ohio, can love New York.

So, it felt natural to focus on the city. And also I had gone to cover an early women’s liberation meeting and realized that this was a movement that was not getting covered and I could help to cover it.

George Gendron: So, when you get a bunch of journalists together, very often the conversation turns to what I refer to as The Big Break. You’re going along and sometimes you don’t even realize it’s the big break at the time. Looking back, what was your big break as a journalist?

Gloria Steinem: I suppose from an external point of view, writing about being a Playboy Bunny was the big break. But certainly not from my point of view. Because the kinds of assignments I got because of it were not assignments I wanted to have.

George Gendron: So what was it? Was it your relationship with Clay and New York magazine that ended up in retrospect being The Big Break?

Gloria Steinem: I don’t even know how it happened because it felt kind of organic. I knew Robert Benton, who was the art director of Esquire at the time. And Esquire was, I believe, looking for someone to write an article about the contraceptive pill, which was then new. And so I wrote that article, and that was the beginning, even though I am not sure I knew it was the beginning.

George Gendron: For that article, Clay Felker was your editor, wasn’t he?

Gloria Steinem: Yes.

George Gendron: And rumor had it in the New York magazine newsroom that he made you do a major revision of that article? Or is that just urban legend?

Gloria Steinem: No, no. I think it’s true because I remember him saying to me that I had performed “the miracle of making sex boring.”

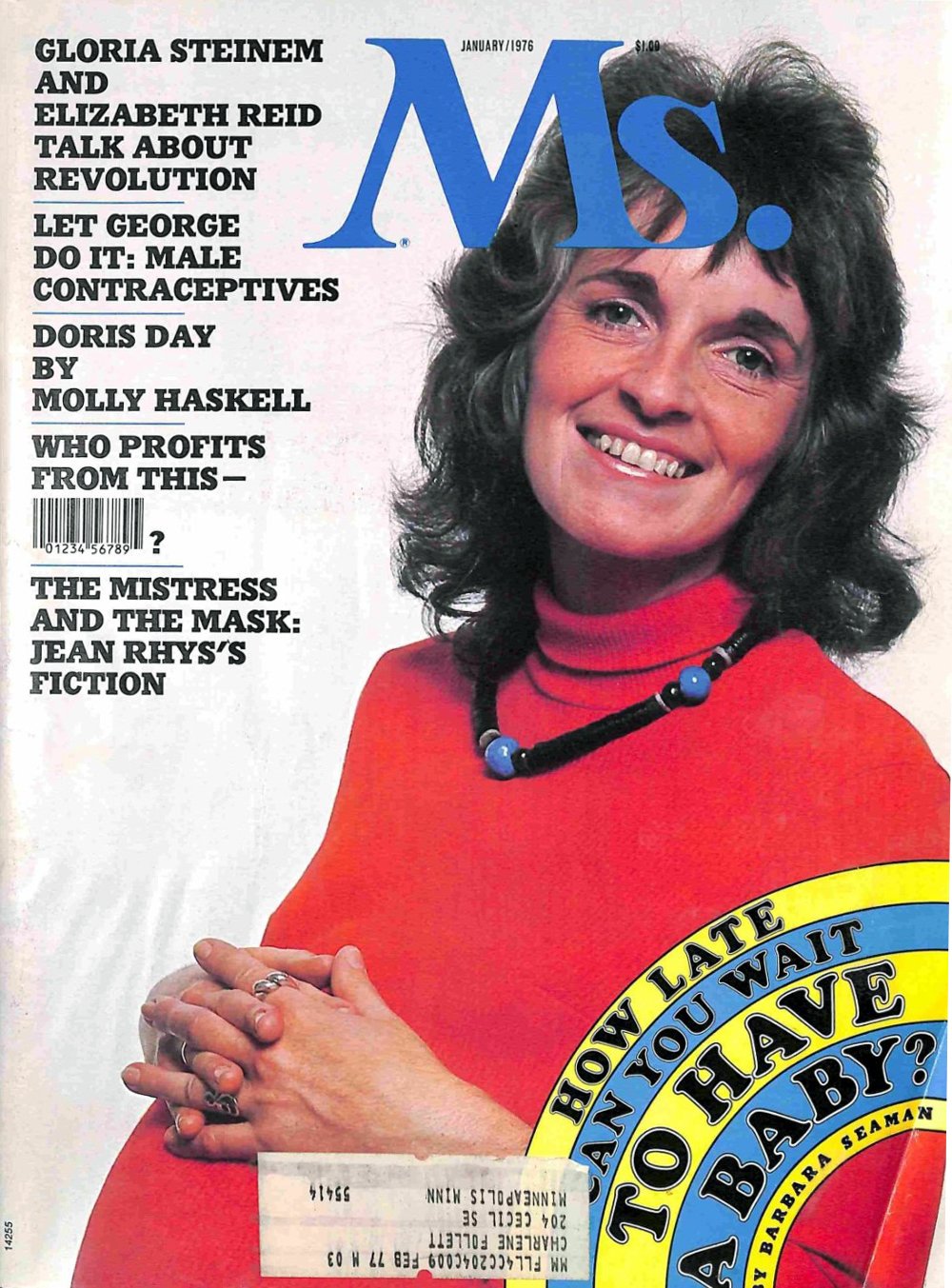

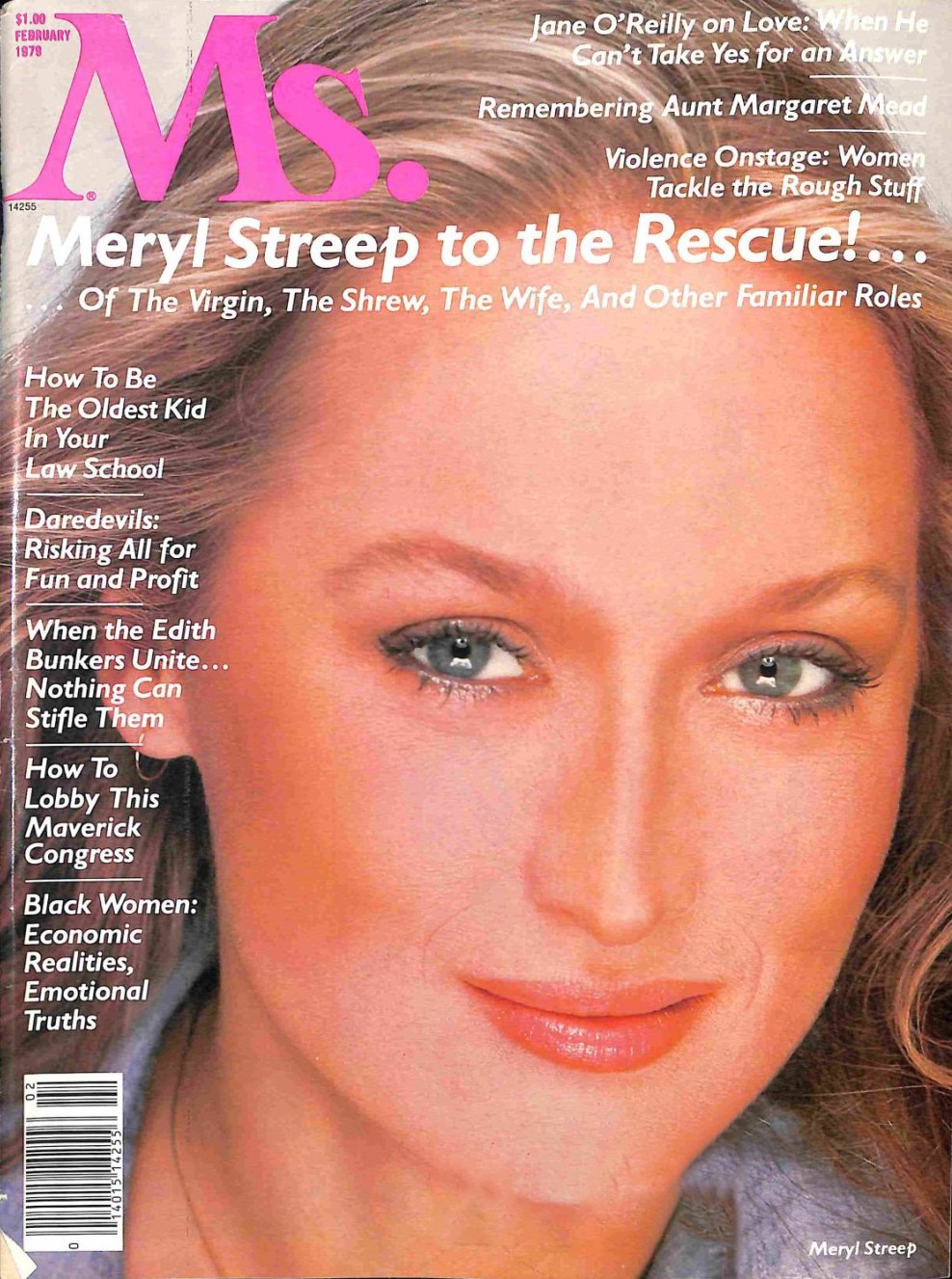

Steinem with Ms. publisher Patricia Carbine.

“I’ve never been on salary. I’ve always been freelance.”

George Gendron: Well, that sounds like Clay doesn’t it? He doesn’t mince words. So I want to go back, you mentioned your growing up, and your dad, and you grew up—a lot of people, a surprising number of people, based on my informal survey, don’t know about your background. And when I asked them, “Well, speculate. Where do you think Gloria Steinem came from?” They say, “Well, Manhattan, of course. Upper West Side. Her parents were professors at NYU or Barnard…

Gloria Steinem: That’s interesting.

George Gendron: …Or Hunter [College]. And then you say, “Well, actually, no. East Toledo.” And they look at you like, “No way!”

Gloria Steinem: We're so used to thinking of our real background that we don’t understand what the impression may be. I didn’t realize it.

George Gendron: That's true. So talk briefly about your life in a trailer with your mom and dad, and your sister, and the passion that seemed to kindle in you, lifelong, for travel.

Gloria Steinem: First it kindled a life without going to school. So I was just constantly reading in the car as we were going to and from Florida or California, since my father [Leo Steinem] hated the cold weather. And when the dance pavilion in Michigan at Ocean Beach Pier, as he called it—“Dancing over the water and under the stars,” that was his slogan—when that was no longer a way to make a living, then he would go to country auctions and buy small antiques and sell them to the shops along the road to Florida or California.

So it was just pretty much all that I knew. I might go to school for the first month, but as soon as it got cold, my father wanted to put us all in the house trailer and leave.

George Gendron: So we know what homeschooling is. This was mobile homeschooling?

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. And it wasn’t, I mean, I just read all the time. In fact, my mother was more worried about my eyesight reading in the car than she was about my lack of schooling.

George Gendron: So you were self-taught, basically.

Gloria Steinem: You might say so. Or book-taught.

George Gendron: Okay. So I’m curious in reading your memoir about your life on the road, I’m not sure whether you’re, you say this explicitly or whether it’s implicit, that there’s something about the kind of traveling that you did that maybe informed and enhanced you as a reporter in terms of your ability to listen in a really profound way. Am I reading too much into this?

Gloria Steinem: No. I think listening was my preferred form of communication, because, one, I didn’t want to speak in public. And only much later, and with a speaking partner, did I even attempt that. And also I was following in the track of the adult Louisa May Alcott who had done that during the Civil War.

George Gendron: So in addition to Louisa, who else were your role models?

Gloria Steinem: That’s interesting. There were not full-time women writers out there that I was aware of. It wasn’t necessarily women writers. My father, among his purchases for his antique and other business in the wintertime, used to buy entire libraries in order to get one first edition.

So he would leave the rest of the entire library in the garage, just scattered on the floor. And I would go out there and randomly pick books to read. So I think I read the history of part of the Civil War. I mean, I was an “unguided” reader.

George Gendron: I think a lot of us were, frankly, even when we were supposed to be disciplined by, in my case, a Catholic education. But I can’t tell you the number of journalists who describe themselves as lifelong “promiscuous” readers.

Gloria Steinem: Really? No, I think that’s true. And I didn’t really experience learning a different way until I was in high school. And of course, college.

George Gendron: So let’s go back now, after college you’re in New York. I’m back now in your life as a journalist. Do you remember the first time an idea for a publication, a magazine for women first struck you?

Gloria Steinem: Well, in between my arrival in New York and the first magazine, I lived in India for two years. And that was partly because my mother and both grandmothers, even though one family was Jewish and one was Christian, they were all theosophists.

So I had grown up on books like Lotus Leaves for the Young, and so I’d grown up an interest in India. And because I was engaged in trying not to get married, I fled to India and fell in love with it and ended up living there for two years, and also writing for Indian newspapers. So that was the beginning for me, writing columns.

George Gendron: That was beautifully put: “engaged in trying hard not to be married.” Was it that you were trying hard not to be married to a particular individual or was this just in general?

Gloria Steinem: Also remember it was the 1950s, and even in my college classes, the number of engagement rings that showed up in junior and senior year was massive. And I was in love with a very interesting guy, so all of it seemed headed toward marriage. And in those days, marriage was more the end than the beginning for women.

George Gendron: Right, right. So you took the modest step of going to India for two years to get away from it.

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. First I sat in the—remember Pan Am, the airlines—I sat in the office of Pan Am so long that they finally gave me a free ticket.

George Gendron: Is that true?

Gloria Steinem: I told them I would write brochures for them or something, but they finally, I think just to get me outta the office, they gave me a free ticket.

George Gendron: So you’re now back from India. Where and when did the idea for Ms. as a magazine come from?

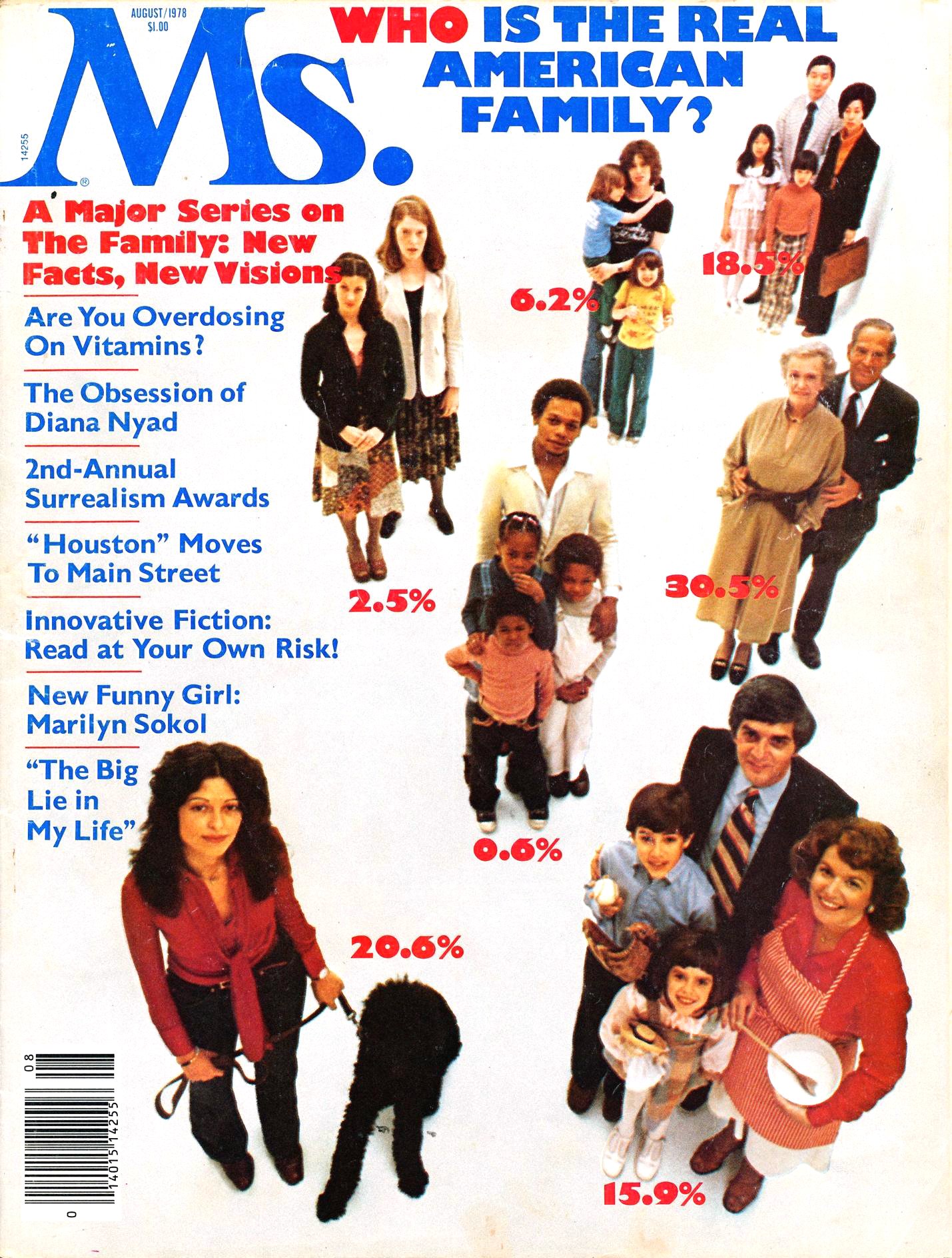

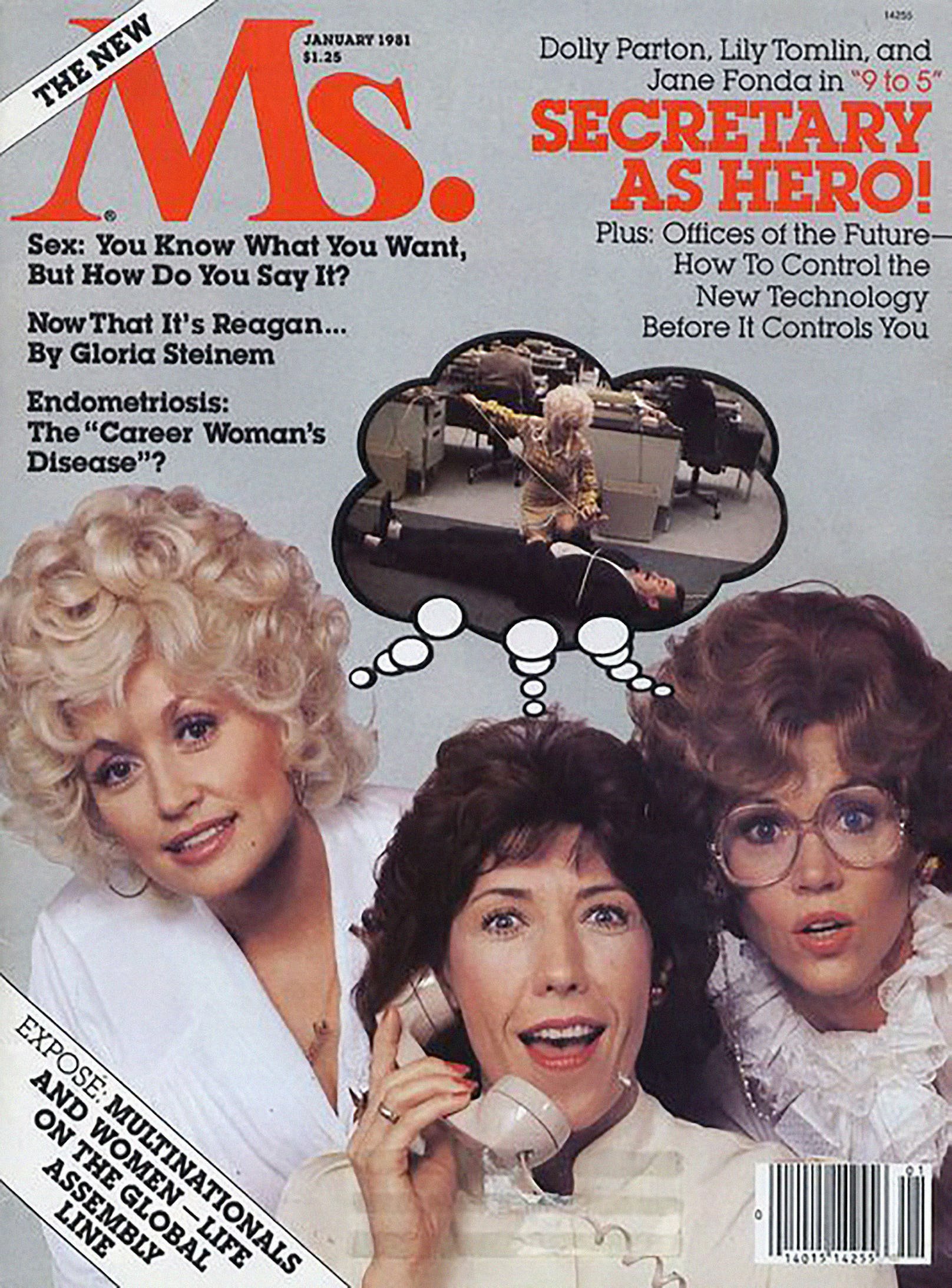

Gloria Steinem: Well, Suzanne Braun Levine, who was our managing editor, Patricia Carbine, who was our publisher, she had been the editor of Look magazine. And indeed, I had written as a freelancer for Pat there. So most of us had been involved in the magazine business in some way and were hyper aware that the magazines for women were catalogs. You were just supposed to write complimentary pieces about makeup and all kinds of subjects that were covered editorially. And, it was literally complimentary copy for the ads.

So they had wanted to be working on a women’s magazine that was different, and I also did. And on top of that, I had seen a magazine get started at New York. So I had faith that it was possible.

George Gendron: For the few people who have never heard the story of how that first issue got launched, can you recreate that? When was the first time you sat down with Clay and discussed the idea of Ms. as an insert in an issue of New York, which gave you, at least for one issue, instant circulation and distribution?

Gloria Steinem: It wasn’t as direct as that. It was first that Clay, who had a great news sense, could see that, along with the peace movement, along with the civil rights movement, there was coming to be a women’s movement, since women had not been able to participate fully in the other movements. He could see that it was happening and that it was news.

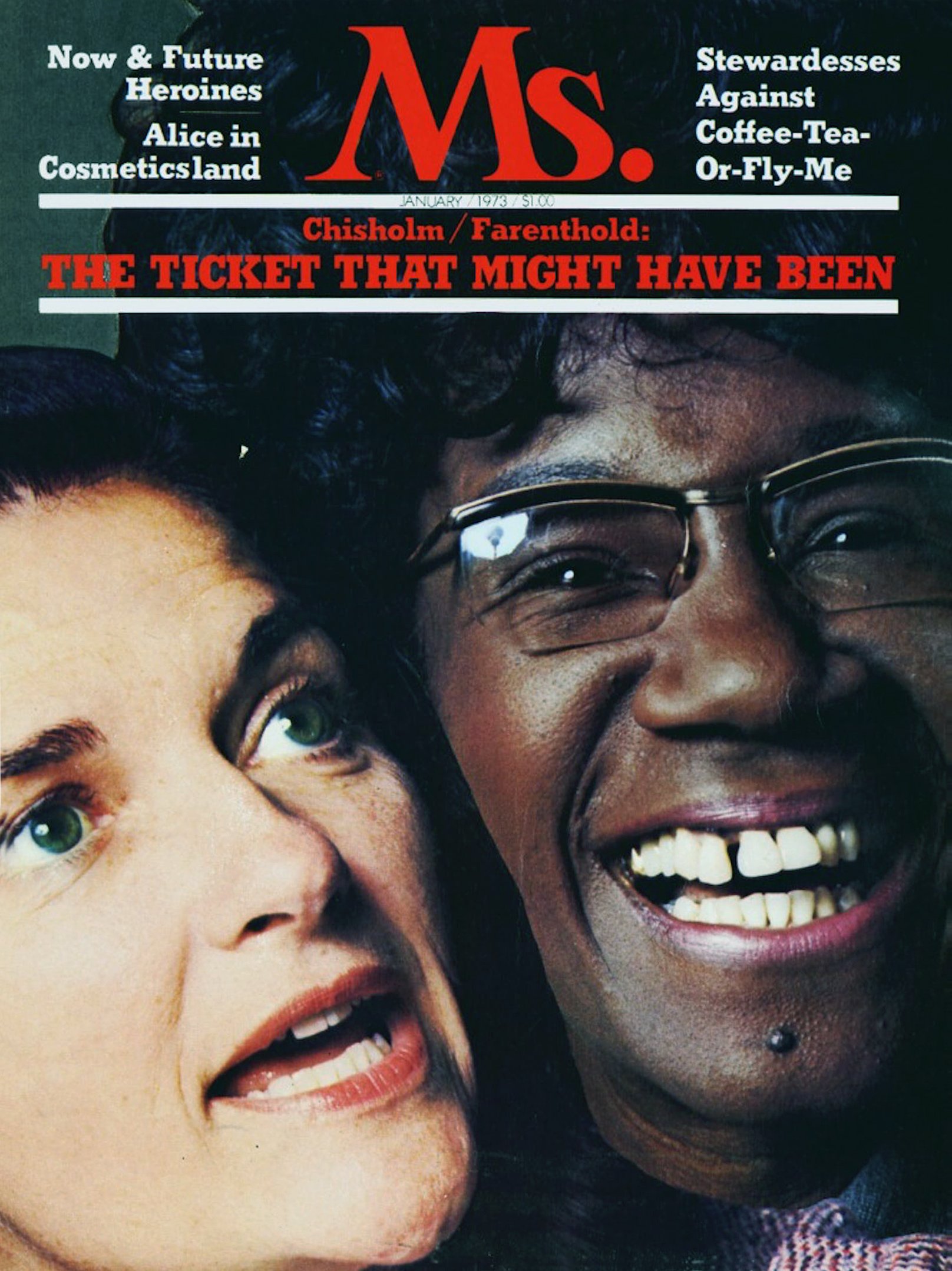

So he suggested that I write about that, and sent me off on a tour to California and back, and a few other places, to promote the issue that we did. And I had written the column that I mentioned, which was called “After Black Power, Women’s Liberation?” I think with a question mark. I’m not sure I was secure enough to say it without a question mark.

George Gendron: When we’re young, we always carry a few question marks around with us.

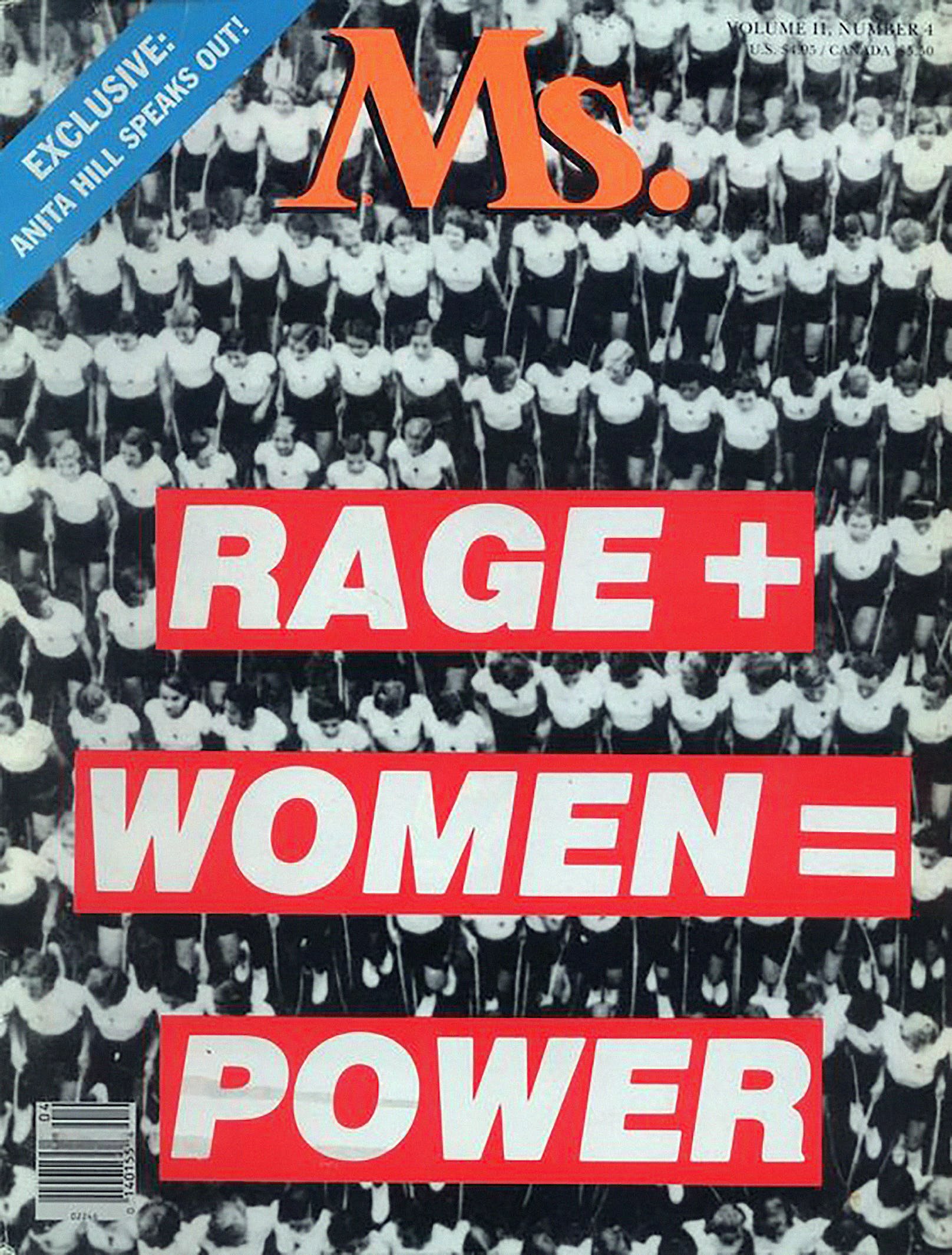

Gloria Steinem: So it was all blossoming. And there were women doing public speak outs against the anti-abortion laws because women were literally dying from and being injured from illegal abortions.

George Gendron: So when you were starting to actually develop the idea for that very first issue that would be inserted in New York, who was your team? Who were the people you turned to for advice? Who were your writers? I’m curious. Give us a sense of how that first issue came together.

Gloria Steinem: Well, they were writers that I knew—either personally or from New York magazine—Jane O’Reilly, for instance, who wrote “The Housewife’s Moment of Truth.”

George Gendron: That was a great story.

Gloria Steinem: So it was like spontaneous combustion, because there were women who had been writing for women’s magazines or for New York.

George Gendron: So the issue gets out. This is, again, the premier issue in New York. Share what happened. What was the response?

Gloria Steinem: It was an insert, part of it was an insert in New York magazine, and then other articles were added and it became a kind of one shot on the newsstand. I was sent by Clay to go to various cities, including Los Angeles, to get on radio talk shows—any way of publicizing it because we both had a fear that this issue was going to “lie like a lox.”

And it was when I was in California that I was on some talk radio show and people called in, women called in and said, “We can’t find it on the newsstands.” I called Clay in a panic and said it never got here, somehow. And he called the distributor and discovered it had sold out. That it was sold out in eight days, even though it was cover-dated spring because we thought it was going to lie on the newsstands for so long.

George Gendron: Is that one of those moments, Gloria, where you think to yourself, Damn, maybe this is going to really work?

Gloria Steinem: Well, I didn’t know what the “it” was. I certainly didn’t see myself as—I’d never had a job, I’d always been a freelancer. And it was only because Pat Carbine, who had been the publisher of Look magazine as I said, who really understood the magazine business, and Suzanne Levine, who also had been the editor of another magazine, that it was possible.

“Our secret weapon with advertising agencies was the women who worked there. Because for the first time they would want to come to the meeting, too.

But at the same time, we got resistance and hostility from the men in the agencies.”

George Gendron: So when you were doing that very first issue, you weren’t necessarily thinking about this as the launch of a monthly magazine?

Gloria Steinem: No. No. The one that was internal to New York magazine I was thinking of as a one shot, as they say.

George Gendron: When did it occur to you and your colleagues that maybe this is more than a one shot?

Gloria Steinem: When, in our little office where we had produced this one shot, we got bales, and bales, and bales of letters. Every day, hundreds, even thousands, of letters arrived with women saying, “At last, here’s a magazine that isn’t just about cooking and raising children. That treats me like an adult.” And, “I loved this article and didn’t like that one.” Just mailbags full of letters. It was stunning. And we saved them all. I think they still exist someplace.

George Gendron: Yeah, you’ve given a lot of your papers to Smith College, haven’t you?

Gloria Steinem: Yes. Archives, yes. Right.

George Gendron: For anybody interested, if you’re in the neighborhood, I think Smith has those letters, if I’m not mistaken.

Gloria Steinem: It may have been earlier. So it may be one of the other women’s colleges who have the first letters.

George Gendron: Okay. So, you guys get together and decide, “Well, maybe we’ve got an idea for a sustainable magazine here.” You do a business plan, go out and look for money. What do you do?

Gloria Steinem: Yes. I’m trying to remember the sequence of events right now, but Warner Communications was, at the time, a company that made all or most of its money from parking lots. And ...

George Gendron: …Of course they did—and they may again in the future!

Gloria Steinem: Right. And we’re wanting to be known as a name in print and magazines, not just parking lots. So they gave us enough money for the first issues. Like $8,000. It wasn’t a lot but it made all the difference.

George Gendron: And they had done Wonder Woman, right?

Gloria Steinem: Yes, and we put Wonder Woman on the cover because Wonder Woman, who was a figure of my and many other women’s childhoods had suddenly, lost all her magical powers and become like a car hop. No more magic lasso. Because the company that owned her [DC Comics] had transformed her. [Ed Note: In 1968, DC Comics’ decided to have Wonder Woman voluntarily surrender her Amazon powers and status to remain in “Man’s World” rather than accompany her fellow Amazons to another dimension where they could “restore their magic” ].

So we put the original Wonder Woman on the cover, striding across the city as a colossus, giving out food with one hand and rescuing people with the other. And after it was very successful, the creators of Wonder Woman called up and said, “Okay. All right. She’s got her magic lasso back. She’s got her invisible ring back. Now will you leave us alone?”

George Gendron: So you were partially responsible for revitalizing Wonder Woman.

Gloria Steinem: Yeah, well I mean, it was Wonder Woman herself in her original form, and then because we put her on the cover, yes.

George Gendron: So there must have been an enormous number of people, mostly men, who when they heard the idea that you were going to take this first issue and now create a monthly magazine around it, thought you were absolutely crazy. And I’m curious, what was the most colorful, negative feedback you got? Because I know, man, you got everybody in every aspect of the culture telling you you’re out of your mind.

Gloria Steinem: Yeah, well, we had a collection of women editors who believed in this, so that made a huge difference. But, aside from Clay, who was at least inadvertently encouraging by inserting a first issue in the magazine, I don’t remember anybody else who was encouraging.

Bea Feitler (right) was the first art director of Ms.

George Gendron: I remember one rainy afternoon at New York magazine, a bunch of people didn’t want to go out in the rain to have lunch, and so we had somebody bring it in. And I was talking to Jane Maxwell, Clay’s assistant, and Jane said that Clay’s response after the first issue when he heard that you were going to do a monthly magazine, was, “Well, now what are they going to write about?” As if you had covered everything that needed to be covered.

Gloria Steinem: That’s true. Clay felt that one issue was it. True.

George Gendron: Did he ever formally acknowledge that he was wrong? I know a lot of well-known people did, including Harry Reasoner on the air, right?

Gloria Steinem: Oh, yes. Oh, that’s very smart of you to remember that. I’d forgotten that. Yes.

George Gendron: It wasn’t frequent that those guys ever acknowledged changing their mind.

Gloria Steinem: I don’t think Clay formally apologized, but he acknowledged that.

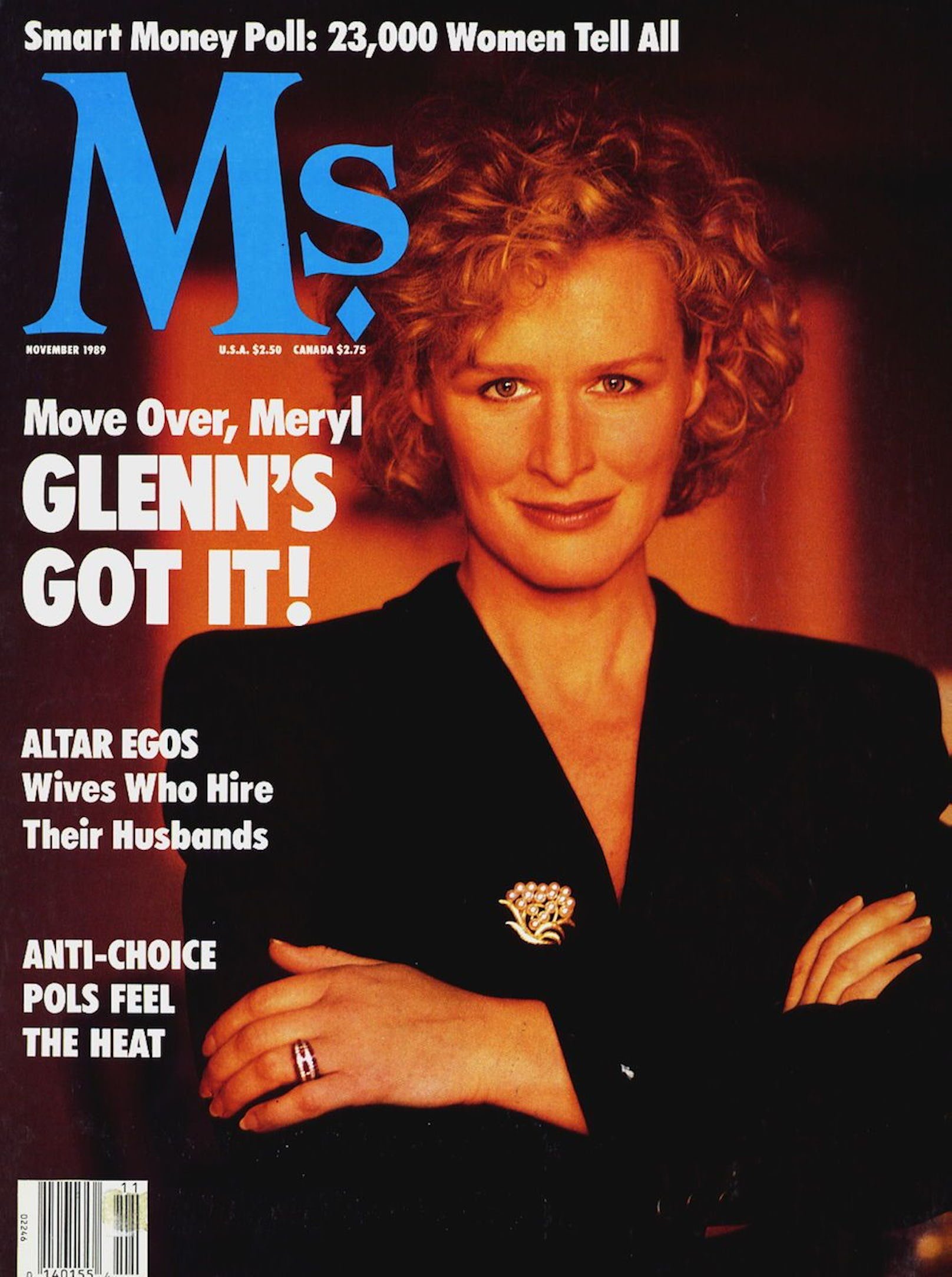

George Gendron: So I’m curious, whenever you read anything about the early days of Ms.—I actually have the first 12 issues of the magazine sitting right here—your masthead is really interesting because there’s no hierarchy.

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. It was by function and then alphabetical.

George Gendron: Yeah, but I’m curious, what was your role? Because people will often say, “Oh, so and so was really kind of acting as the functional editor.” And people always refer to you as a co-founder.

Gloria Steinem: That’s as I was saying. Pat Carbine was the only person who really understood the magazine business because of Look magazine.

George Gendron: So was she kind of the publisher?

Gloria Steinem: Yeah, she was the publisher. Suzanne Levine was really the editor. She was the one who had all the assigned articles on her wall and when they were supposed to come in. And she was the one who was truly a managing editor. But other than that we had meetings of, not only everybody in the magazine, but women who happened to be passing through New York from New Delhi or Paris or something, who would come to our editorial meetings and make suggestions.

George Gendron: At some point you were quoted as saying something about how sitting around in an editorial meeting with a group of people where you can say anything you want, you don’t have to worry, but that’s not about right or wrong, it’s more brainstorming, you’ve got diverse points of view, was just absolutely thrilling for you.

Gloria Steinem: Yes, it was. It was. And it was different because unlike New York magazine, much as I loved it, when we were sitting in a meeting there, we were all trying to interest and intrigue Clay. But in this meeting, there was not that kind of all-powerful individual. It was just all of us sitting in a circle or around a conference table together trying to figure out what was exciting, what we wanted to do, what writer would be good for what subject.

George Gendron: But at some point, somebody has to make decisions, right? And we’re going to do that article, and at least for now, we’re not going to do the other one.

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. And that was really Suzanne Levine, who was the managing editor.

George Gendron: And you were willing, egotistically, you were willing to accept that despite the fact that you were Ms. magazine in the public imagination.

Gloria Steinem: No. I was somebody who was “the traveler.” I was out there bringing back little bits of paper, and information, and article ideas, and here’s a writer. So I was the wanderer and coming back to editorial meetings. But Suzanne was really the editor.

George Gendron: When I was talking to Corey, one of your assistants, when we were setting this up, I said to her, “If I had to guess at what title Gloria might have bestowed on herself, was editor at large.” Because you always talk about coming back from the road with tons of story ideas, and scraps of paper, and notes, and it sounded like, once again, you were “the traveler.”

Gloria Steinem: That’s true. But we listed ourselves alphabetically. So, except, the art director—I mean, some people had distinctive functions, but the rest of us were listed alphabetically.

George Gendron: What kind of resistance did you get from the ad community? I mean, they’re notoriously risk averse when it comes to anything new and suddenly you have people knocking on their door, even someone as well known and highly regarded as Pat Carbine saying, “Well, we’ve got this great new idea for a magazine.” What was the response on Madison Avenue?

Gloria Steinem: It was very negative, especially in the universe of women’s magazines where the editorial is dictated by ads. That is, you know, you have home decorating and all kinds of cooking articles, and articles about family, and so on. And it’s really mostly about the ads.

So our secret weapon in going around to advertising agencies was the women who worked in those agencies. Because for the first time, in many cases, they would want to come to the meeting too. And they had not—whatever their job was, didn't call for that, didn’t demand that—but they wanted to come too.

But we also, at the same time, got resistance and hostility from a few of the men in the agencies.

George Gendron: How could you not, right? That was still kind of the tail end of the Mad Men era.

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. People would even throw the magazine down on their desks or on the floor or demonstrate that this was just a fad, or “We’re not interested,” or “It’s hostile to what normal women want.” There was a fair amount of hostility.

But what made the difference was that we would be at J. Walter Thompson, or some agency, where the men in power did not see that this was a good option, but the women in the office wanted to come to the meeting, for the first time. So that helped.

George Gendron: Yeah. I think, from time to time I teach undergraduates, and I’m struck sometimes by how, to them, the sixties and the seventies are ancient history in some ways. And there’d be times when I would say something really simple, I don’t know, in response to a question about something in a newsroom. And I’d say, “Well, we didn’t have computers. We didn’t have word processors. We had typewriters.” Or at one point somebody was asking, “Well, how did you get the magazine to your printer?” I said, “By messenger.” And they’re like, “By what?”

Gloria Steinem: No. I agree with you. We could use a kind of chronological set of translators, right?

George Gendron: Yeah. But I sometimes think, when reading your memoirs in particular, even for me, I mean, here’s an example: So my mom, a Brooklyn girl, loved the Oak Room at The Plaza. And it used to infuriate her that she could never meet her friends there for lunch. And when I tell my daughters that story, they look at me like, “Well, that’s just fiction.” That there was a time—that must’ve been like in the Victorian era. And I’m like, “That wasn’t that long ago.”

Gloria Steinem: No. Not only could you not go into The Oak Room, but you also couldn’t wait by yourself for some—if I was interviewing somebody who was staying at The Plaza, I couldn’t wait by myself in the lobby. I had to get them to meet me outside the door. Because they were so sure that women waiting by themselves would look like prostitutes or hookers.

George Gendron: I know you probably have told us a million times, but I’m going to ask you to tell it one more time. Tell us your famous Plaza Hotel lobby story.

Gloria Steinem: Well, because I was interviewing someone? Or because—there are various stories. I mean one, one is—it wasn’t me—I’m trying to think who it was. Somebody famous, like Greta Garbo? No, couldn’t have been Greta Garbo. Anyway, some famous actress was told that she could not enter the dining room because she was wearing a pantsuit, and so she stood in the door, took off her pants and her jacket.

George Gendron: That one I haven’t heard. Thank you very much. But there’s one in which you are the protagonist and you were escorted out of the lobby while you were on assignment.

Gloria Steinem: Yes. Because literally, they thought we would look like, or could look like, call girls. Single women were not allowed—or single women of a certain age, anyway—you’re not allowed to sit in the lobby.

George Gendron: But you went back and confronted that person.

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. And not just we in the magazine, but other women’s groups too, confronted that and demonstrated against it.

George Gendron: In fact, I think somewhere there’s a video of you doing some kind of a reenactment on PBS. Do you remember that?

Gloria Steinem: It’s possible. I don’t know.

George Gendron: You actually reenact being escorted out of the lobby, but then coming back later. And in your memoir, it’s interesting because you talk about the process of building self-confidence and self-esteem in situations like that, which is crucial for reporters, but they’re essential for everybody in life.

Gloria Steinem: Yes, of course. It’s essential for everybody. And the problem of the era was that even the word “self-esteem” was thought to be some squishy, unworthy, unserious, “California” concern.

“If I was interviewing somebody who was staying at The Plaza, I couldn’t wait by myself in the lobby, because they were so sure that women waiting by themselves would look like prostitutes or hookers.”

George Gendron: You discovered that with your book, right?

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. there was some resistance to even discussing it in those terms.

George Gendron: I want to talk a bit about young journalists today. And this is not just true for young journalists, it’s true for young men and women in general, of course. Activists, I’m sure, are dealing with this. But what advice do you give to a young woman who comes to you and wants to do something in the media at a time when, you could argue, that the whole industry, across the spectrum, is in a state of complete disarray. But somebody who wants to do what you did with Ms. Something comparable. What advice do you give them? How do you help them make sense of this incredible fragmentation that’s taken place in the media?

Gloria Steinem: Well, I think I’d first ask them what do they love to do? What do they love to do so much they forget what time it is when they’re doing it? Where and how do they feel understood? Are there websites, or countries, or professions, or ways of contacting other like-minded people. If so, start there, expand that. Because the path is not the same, of course, for everybody. But there’s usually, in the story that you hear, a beginning of the path that’s right for that person.

George Gendron: How do you feel personally about social media?

Gloria Steinem: Well, I’m probably not the best judge because I’m not in it in the same way that younger generations are in it. But, most of all, it worries me that there’s no fact checking. That you can say anything and it assumes a life online, even if it’s completely false, or negative, or libelous or—can anybody sue for libel on social media? I haven’t heard of anybody doing that.

George Gendron: Is your ego also an issue here? And here’s what I mean by that: I rarely like memoirs and yet, I love your book about being on the road. I’ve recommended it to everybody. And one of the things that I find really striking about it, and I’m not saying this to flatter you now—my wife can attest to the fact that I felt this way and said this long before I knew I was going to be doing a podcast with you—is that you don’t have the kind of ego that today we associate with people who have accomplished and achieved what you’ve achieved.

We live in an era of monumental egos. And it seems like so much of social media is clamoring for attention. It’s “pay attention to me! Pay attention to me!” And I wonder, do you have just a personal aversion to that?

Gloria Steinem: I don’t know if it’s an aversion. But I’m just communicating in a way that’s natural for me. And that isn’t it. And then sometimes the online pattern of communication sounds to me like what—when I was in the sixth grade or whatever—we used to call personality books, did you have those? They were, you know, like secretarial handbooks and people would put the name of an individual student on the top of the page and then people would anonymously write what they thought about that person on the page.

So it would say things like, “Cute, but knows it.”

George Gendron: Well, that was a precursor to social media, wasn’t it?

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. No, it was. It was. So at a big, basic level, what troubles me is no fact checking. At another basic level, what troubles me is that huge swaths of the world have no electricity. So the internet is dividing us in very crucial ways because it’s very limited in the people who have access to it.

George Gendron: I’m going to switch gears, slightly here for a second, and go back to a comment you made earlier, which is an obvious characterization of the sixties and seventies when we were experiencing the feminist revolution, anti-war revolution, civil rights revolution, to an extraordinary extent. And there is and was something absolutely exhilarating about that. And yet you could argue maybe that it was a precursor to the complete lack of trust we have these days in institutions. Complete lack of trust. In government, education, business, and capitalism. On, and on, and on. And so it seems to me that, those institutions up until the sixties, they were the ways in which we, for better or worse, made meaning in our lives. That provided meaning for us. Now we're pretty much on our own and alone trying to figure out how you do that. Do you agree with that or disagree with that? And if you agree with that, what advice do you have for people?

Gloria Steinem: I’m trying to think of real examples. I mean, there are obviously individual people who we trust as sources. There are media that we trust, more or less, as sources. I think we are striving or looking toward our own system of reliability, fact checking, trustworthiness—whether from an individual human being or a particular newspaper. Yes, I trust The New York Times and the Boston Globe, but I’m not so sure about—I mean, I think we figure it out on a daily basis and through friends we trust.

George Gendron: So when you see a poll that talks about the low esteem that media in general is held in, or Congress. Your response would be, but within that, there are individuals and individual organizations that we do trust.

Gloria Steinem: Yes. I think it’s too amorphous and general to say Congress, because that includes completely disparate people from Trump to … right? Specificity is very helpful.

George Gendron: Okay. Here’s another kind of non-sequitur, but I think these are related. There’s been a lot written lately—in fact, lately I’d describe it as almost an avalanche of articles—about men, but also about boys, being in peril. And I’m not sure why that surfaced so much recently, but as the father of three daughters and a son—this is something my wife and I have been watching for decades now—I can still remember the first time we had a conversation about this when my oldest daughter in eighth grade was, being inducted into honor society, or something like that, and there were 24 students from her school. And there were 22 girls and two boys. And afterwards, we went up and talked to the teacher about what was going on. She said, “We don’t really know. It’s probably just an aberration.” But we saw this start to repeat itself over, and over, and over again, and a lot of iterations of it.

Gloria Steinem: That’s interesting because you’re in a better position than I am to experience that. What’s your instinct about the ‘why’?

George Gendron: I think that there’s been a process that has supported girls in a way that produces girls—not young women, but girls—first and foremost, who are more centered. They have a greater level of self-esteem. They still experience a lot of the craziness that accompanies young girls as they’re growing up that I discovered—I grew up in a family of four brothers, and so this was a shock to me that you guys are a handful. But I think as girls and then young women started to flourish—as a result of a lot of the changes that we’ve been talking about and more—I think it was threatening to boys. And I think it began to raise really serious questions for them—of which they weren’t aware, of course, at that age of development—about where they belonged. How do they fit into this? I’m not being very articulate about it because, of course, it’s a monumental issue.

Gloria Steinem: I see what you mean. And there is no masculine or feminine, there’s human. But we are still in a time when we have, a lot of us anyway, have been trained to think in terms of masculine or feminine.

And there’s probably a racial parallel to this because the idea of white supremacy was, and I’m afraid still is sometimes, part of our national culture. So there’s an anxiety about the fact that we are now a majority people-of-color country. I mean, the first generation of babies who are majority babies-of-color has already been born.

And on the outside you get racist rebellions against that fact. And insecurity. So it's a discomfort with the unfamiliar. But I still think it’s progress. Because every one of us is a unique individual regardless of gender, or race, or other collective judgements. And hopefully we will get there.

“The problem of the era was that even the word ‘self-esteem’ was thought to be some squishy, unworthy, unserious, ‘California’ concern.”

George Gendron: You have often spoken about the fact that one of the effects that travel has on you is it gives you hope. You’re traveling less these days, I take it. Are you still hopeful?

Gloria Steinem: Yes. No, I am. I’m, I’m a hope-aholic probably, but...

George Gendron: …but just hardwired that way?

Gloria Steinem: Well, hope is a form of planning. If you don’t have hope, you’ve already closed off possibilities by being pessimistic. So I don't mean that we should be insane about it beyond all probability, but I do think that hope is crucial. Absolutely crucial.

George Gendron: That’s nice to hear. It’s encouraging for those of us who are Gloria Steinem fans to hear. This is a question that really interests me because—having spent a big part of my professional life at the intersection of kind of media, and entrepreneurship, and innovation—I’m really stunned, frankly, by the extent to which we are now at a point in our cultural life where we have this mindless love affair with scale.

And you can see it of course, in a lot of the venture-backed companies that we’ve thrown literally billions of dollars at without, necessarily, the hope of ever getting any money back. But one of the things I was really struck by thinking about your life and the extraordinary impact you’ve had is that, as you said earlier, you’ve never had a job.

So, here we are, we live in a world where, frankly, I think there’s a common assumption that underlies our obsession with scale, which is: If you want to get anything done, you have to be big. You have to have access to unlimited resources. And here you are, never having had a job, and it seems as if you’ve been able to do what you’ve done through building relationships, trusting relationships, and groups of relationships that have formed personal networks around shared values.

Can you talk about that a little bit?

Gloria Steinem: Well, I, I think that what you’ve described is any movement, social justice movement—whether it was against Vietnam, or for civil rights, or for gay and lesbian and transgender rights—it’s the contagion of common sense ideas that are in the end really about mutual respect. And we need to communicate with each other and meet in each other’s living rooms, as well as online, in order to perpetuate that.

But it’s the basis of a lot of our actions. I mean, if you get an email or a factoid, you look at the source and consider the person or group that this came from and that dictates, or influences at least, its credibility and what your action will be. It’s always going on.

George Gendron: So, we have a tradition here at Print Is Dead of asking what we call the billion dollar question. So I’m going to put this to you coming on the heels of a question about scale.

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. No, no, no, no stress here. Just a billion-dollar-question.

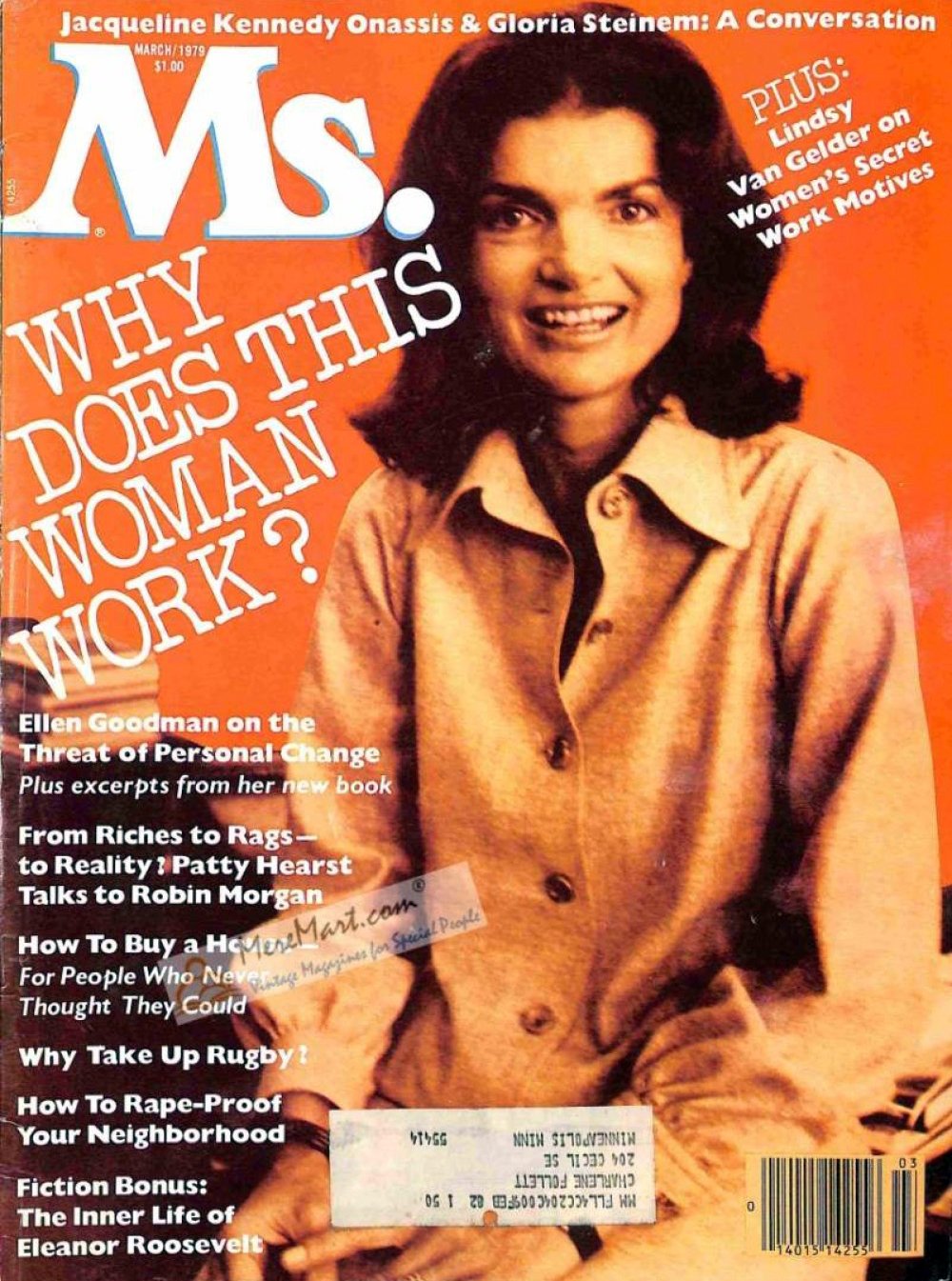

To celebrate its 50th anniversary, Ms. published a new anthology.

George Gendron: It’s just a billion-dollar-question. Exactly. So, Laurene Powell Jobs wants to give Gloria Steinem a blank check with one caveat. Well, two. One is you’ve got to spend a lot of money because otherwise it’s not a substantial enough tax deduction to even make it worthwhile to have a conversation. But the other is she requires that you spend the money on creating a 21st century equivalent of Ms.—could be a magazine, could be a site, could be an association. What would you do with it? What would you do with this billion-dollar blank check?

Gloria Steinem: Ah, very tempting. Well, I’m not enough of a technology person to say this properly, but I think I would create a satellite in the sky that allows people in Central Africa and parts of Asia, and parts of this country, to communicate, at least the way we are now, who now can’t afford to.

Because, I remember going to Google in California, and they had a giant map on the wall with lines going from Google to individual places on the globe. And there were parts of the globe that were completely dark.

And that’s dangerous, I think. That’s divisive and dangerous. So I would do my best, via satellite in the sky or whatever other available technology, to democratize the communication that we already have.

George Gendron: Now I realize Print is Dead has a very, very passionate following, but not a huge one. And yet, I’ll warn you that I expect you’re going to get a call from Laurene wanting to talk to you about your satellite idea.

Gloria Steinem: I would love to talk to her. She’s such a good person.

Steinem in Brooklyn.

For more information on Gloria Steinem, visit her website. Get a copy of 50 Years of Ms.: The Best of the Pathfinding Magazine That Ignited a Revolution wherever books are sold.

More Like This…