When ‘House’ Is Not a Home

A conversation with editor Dominique Browning (House & Garden, Esquire, Texas Monthly, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT COMMERCIAL TYPE, MOUNTAIN GAZETTE, AND FREEPORT PRESS.

Dominique Browning jokes that after the interview for this episode, she might end up having PTSD. After more than 30 years writing and editing at some of the top magazines in the world, Browning has blocked a lot of it out.

And after listening today, you’ll understand why.

At Esquire, where she worked early in her career, Browning says she cried nearly every day. There were men yelling and people quitting. Apartment keys being dropped off with mistresses. A flash, even, of a loaded gun in a desk drawer.

At House & Garden, where she ended her magazine career in 2007 after 12 years as the editor-in-chief, the chaos was less Mad Men and more Devil Wears Prada. It was glitzy Manhattan lunches mixed with fierce competition and coworkers who complained that her wardrobe wasn’t “designer” enough. The day she took the job, she says she felt like she had walked into Grimm’s Fairy Tales. (Her friends had warned her that it was going to be a snake pit.)

When the magazine unexpectedly folded on a Monday, she and her staff were told they had until Friday to clear out their offices. “Without warning,” she says, “our world collapsed.”

In this episode, Browning talks with Lory Hough, editor of Harvard Ed. magazine, about those chaotic years, which, she admits, could also be fun. (Spoiler: The fun had nothing to do with the loaded gun.) You’ll also hear why in her editor’s columns she often wrote about her kids, why she still thinks of herself as an editor, and why a certain bit of advice from a golfer friend helped her during the stressful parts of her life when she worried too much about what others were thinking: Keep your eye on the ball and just swing through.

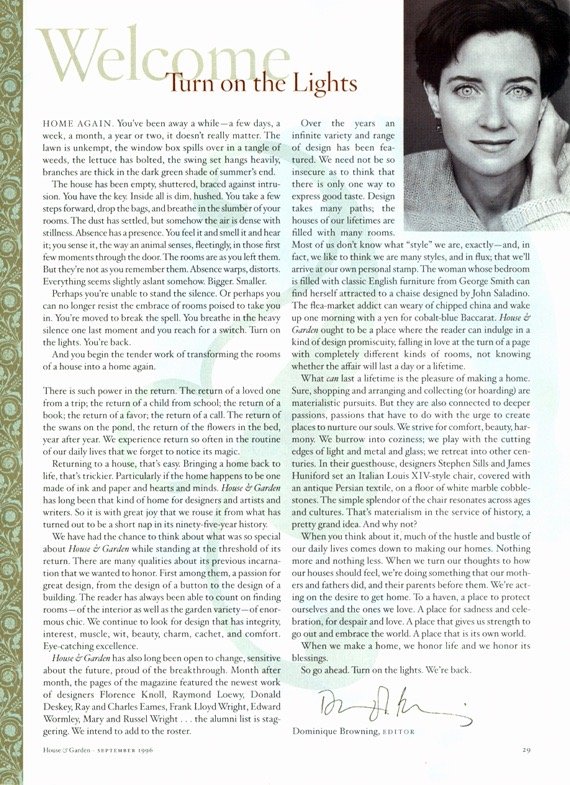

Browning’s relaunch issue of House & Garden

Lory Hough: I have so many questions for you but let’s start with your first day at House & Garden in 1996. The magazine had closed a couple of years earlier, and you were hired to bring it back to life. And let me read something you wrote in your book, Slow Love: How I Lost My Job, Put on My Pajamas, and Found Happiness, about that day. You wrote, “The day I started, the editor of Architectural Digest announced to the press, ‘I killed that magazine once and I’ll kill it again.’” And then you wrote, “I felt as if I had walked into Grimm’s Fairy Tales.” That’s a tough start for the first day or first week. So how did you motivate yourself to move forward with a start like that?

Dominique Browning: I would not say that Condé Nast was a welcoming place right? But that’s the kind of comment that reverse-motivates me. I just get really angry when people do things like that. And my attitude was, We’re just going to show you that we can make a great magazine.

Lory Hough: I heard you say in a podcast interview that when you took that job, a lot of your friends were appalled. Was that the reason why—because of comments like that? Or was there another reason?

Dominique Browning: I think my friends were really worried about me walking into Condé Nast—a place I had never been—and I think they were shocked that I would go there. And also I had done many different kinds of magazines. That was my seventh magazine, and “shelter”—as the category was called, maybe still is called—was a category of magazines that I loved reading. People used to refer to it as “girl porn.”

Not something I had ever thought, Well, I want to edit one of these magazines. I knew only what I had read in these magazines for 20 or 30 years. And never had a background as a decorator and gardener. So I think I was royally unprepared for what was going to happen. But people warned me it was going to be a snake pit.

Lory Hough: So speaking of getting into that world, that was not the kind of magazine you had been working on. Why don’t you tell us a little bit about that path? But before you do that, I wanted to ask first about getting into the magazine world in general. I read that you graduated from Wesleyan with degrees in philosophy, literature, history—not journalism, not anything like that. But you didn’t want to go into academia. And then your sister, who was in college at the time, overheard someone at the gym talking about the Radcliffe Publishing Course. So tell us about how that led into this world of magazines.

Dominique Browning: So I thought the Radcliffe Publishing Course sounded like a very good crash-course way to think about the book publishing business, which is, I thought, I love books. Maybe I’ll go into book publishing. That’s what I thought I was going to do.

And the book publishing section of it came and went, and it was interesting, but like book publishing, it was slow. And then Mike Levy appeared, and he, at the time, was the publisher of Texas Monthly. And he is a larger-than-life character. And he is like Texas, brash and bold—willing to say and do whatever crossed his mind. He’s very hyperactive, as am I. And I immediately felt a kinship.

And I thought, Wow, magazines! That’s interesting. The only magazine I ever read was Ms. magazine, which was my Bible when I was a teenager. But I didn’t really read magazines. But as Mike was talking about it, and as other magazine editors came through, I thought, I could get into this. This is really fun, and lively, and interesting, and touches all parts of life. So I moved to New York and got a job.

Lory Hough: And was American Photographer your first?

Dominique Browning: American Photographer was actually my second. My first was Savvy magazine, “the magazine for executive women,” run by the wonderful Judith Daniels, who had been at New York magazine for a long time working for Clay Felker.

And she had gotten seed money, so even though I thought I was getting an editorial job, I ended up doing a lot of circulation work, and copywriting, and things like that to start to generate subscriptions. And we were housed in the same office as American Photographer. And the idea was that the publisher who was doing that magazine might then be interested in doing American Photographer.

So I ended up working for American Photographer too, also on the circulation side, about which I knew only something because of the publishing course. And that lasted maybe a year, I’m not even sure. But I was really going off the path of editorial work. And then Binky—Amanda Urban, who was at that time Clay Felker’s executive assistant—Binky called Judith and said, “I’ve just fired a bunch of receptionists and some people here and I need help. Do you know anybody?”

Lory Hough: This was at Esquire?

Dominique Browning: Yes. Clay had just taken over or at Esquire. And so I was sent over there for an interview and got a job.

Lory Hough: But I read that it also was a tough intro into the magazine world. You write in your book, and I know you’ve talked about this before, I think you said you cried every day when you worked there. And that at one point you had asked an older staff member, another woman, how she put up with that culture—men yelling, all of that—and she opened her desk drawer and there was the loaded gun and a bottle of bourbon. How did this not send you back into a different career, back into maybe becoming a philosopher or something like that? You stayed with it.

Dominique Browning: Yes, the loaded gun! Esquire was like the spawn of “Mad Men” at that time. It was crazy! But it was also incredibly fun—a mess. The magazine was in transition. And that is a great environment for a young person to walk into because people are quitting, they’re getting fired, there’s nobody to write captions or book reviews.

And if you’re willing to put in the hours—when you’re not crying—you can do a lot. You can just take things on. And that’s what I did in between also organizing to get the proper key to an apartment dropped off with a proper mistress with whom so-and-so was having an affair and all the other crazy stuff that was going on.

Lory Hough: Will any of that end up in your next book?

Dominique Browning: No. It will not. No.

Browning worked with designer Robert Priest to create the look for House & Garden

“I felt very proud of making ‘House & Garden’ a smart magazine. Beautiful and smart.”

Lory Hough: After the podcast interviews. So this is getting away from that a little bit. I want to go back to House & Garden in a minute, but I noticed that a lot of your writing is in the first person. Your editor’s, letters, of course. But other things that you’ve written, like there was a piece that you wrote for The New York Times Book Review that you began, “I love food.…” I just noticed that’s your style and I don’t know if that’s intentional or not. It’s something I’m always interested in with other writers.

Dominique Browning: I love to write about life—my experiences of it. I write what I think of as interlinked essays, often. I am very deliberately writing from my point of view and not claiming universality. And I don’t generally feel a need to say, “Climate anxiety depresses me,” and then quote 10 other people who say the same thing, because I think I can say what I need to say in a much more authentic and genuine way.

So I do write from that first person point of view, unless I’m doing a reporting piece, of course, which I did mostly for Texas Monthly. And that was not first person.

Lory Hough: How often did your kids end up, when you’re writing first person, in your editor’s letters or other pieces? And did they mind?

Dominique Browning: My children didn’t mind when they were young. I was writing about them and they were often in my columns.

The point—first of all, nobody ever told me that an editor’s letter would be written by somebody else and all I had to do was sign my name and it was just the table of contents. I thought, Oh, okay, I have to write a note. So I started doing it and I found I really loved it. And one of the reasons I loved it was to show the messy side of houses and gardens and where things were not perfect or done up for company or a photographer.

Kids are great for mess, and putting a certain slant on things like sofas in the kitchen. And so they were wonderful to write about. And once I got old enough to understand what I was doing, I wrote much less about them.

Lory Hough: Let’s go back to House & Garden, speaking of messes. The good and the messes, right? I was never in that world—the Condé Nast world—or any sort of professional magazine like that. I was more on the academic side of magazines. But when I started reading about your experience, it really sounded like the best and the worst, right? Kind of what you talked about at Esquire it was a tough environment, but you also got a lot of opportunity. So maybe talk about that a little bit with House & Garden. There was a piece that I read on NPR’s site, where they described your job as, “fabulously high powered in a Devil Wears Prada kind of world filled with business meetings in Paris and glitzy benefit dinners in Manhattan.” I know that the restaurant 44 in Manhattan was kind of a power lunch spot for the publishing set. So that’s kind of the best-of world. But then the stressful part that you write about in Slow Love and other places that there was no such thing as corporate camaraderie. Every editor was on her own.

In a TV interview on One to One, you said that there are so few top editor positions at magazines like this that there’s a lot of politicking. And your quote was, “You’re watching forward. You’re watching your back. You’re watching all around you. While also trying to create this bubble environment for your team so that they can stay focused.” That sounds exhausting! And that’s the bad stuff. But then there’s that glitzy stuff, that Devil Wears Prada-sort of world. How could you be in a job that is so both sides?

Dominique Browning: It was a great lesson. I might have PTSD after this conversation because I’ve blocked a lot of it. But the life lesson, in a way, was to learn how to put a bubble around yourself and around your team, which I think I did learn. I used to get very upset. And people I knew, people who were my friends were publicly saying terrible things about the magazine, the first issue, my art director, what we were doing—to say nothing of people I’d never met before.

I didn’t come from the decorating world, so I certainly didn’t have champions there. And I had been completely unaware that Condé Nast was looking to bring House & Garden back. So I didn’t realize that a lot of editors had talked to management there and wanted the job. So I wandered into it a little bit innocently, or rather naively. But it’s a good lesson in life to learn how to just keep your eye on the ball.

A friend of mine who was a golfer would say to me, “Keep your eye on the ball and swing through.” And I’ve never played golf, but that made a lot of sense to me. Stop worrying about what everybody’s thinking. Just think about what you want to do. And what I wanted to do was bring back what had been a gorgeous, intelligent American institution to which people turned for generations for advice on how to live. And how to design their homes, how to make gardens, all of it.

Lory Hough: And you were successful. You won numerous design awards. Your circulation was almost a million. So on the editorial side, it seemed like you were very successful. But on the business side, you went through a lot of publishers, and there was a lot of turnover, and there was a lot of competition with all of these other magazines—including Condé Nast starting magazines that were direct competitors. So in some ways, what could you have done?

Dominique Browning: I think they got greedy perhaps, or perhaps thought, Oh, we can slice this up different ways. And of course a magazine editor who creates a healthy circulation—which we did, readers loved the magazine—and our renewal rates were up there with the legendary New Yorker renewal rate. They were very high. The more readers you have, the more you charge per page of advertising. And the more you charge per page of advertising, the harder it is to sell those ad pages.

So there were two tiers of ad pages, one for the entire home industry that was much less expensive than the ones for the big luxury companies. So the economics of that world were tricky to begin with. And it was inevitable that advertising going into House & Garden would cut into advertising that was going into Architectural Digest, for example.

And while that was happening, the economy began to change significantly. But we were at the very beginning edge of that. It was interesting—people felt things tighten at home first, right? People stopped shopping for furniture, and stopped redecorating. Things slowed down, and there was starting to be a retrenchment of the whole economy in the housing market, nevermind the magazine business, which came a little later.

Lory Hough: Thinking about the closing, I don’t want to bring the PTSD any sharper here, but I thought this was really interesting. You wrote that as you were packing up your office, after you found out the magazine was closing you were overwhelmed with an urge to hoard and begin stuffing, “every House & Garden paper bag, pencil, and notepad I could get my hand on into the box.” You called it a “twisted sort of recycling.” I can totally relate to that sort of thing. I would do the same thing. So tell me about the urge and also what was the best thing that you took? And was there something you didn’t take that you wish you had taken?

Dominique Browning: Oh, that is really funny to remember. I still have pencils that say Esquire on them, and I still wear my Newsweek t-shirt, and I just uncovered in a closet recently, a paper bag full of paper bags that say House & Garden on them that were gift bags for people when we would make a new issue. And they’re really gorgeous paper bags with very heavy paper, so I use them only for special occasions. So therefore my children will probably inherit these paper bags.

Lory Hough: Was there anything you didn’t take that you wish you had taken?

Dominique Browning: Early on, we did a show celebrating House & Garden’s history called “The Well-Lived Life.” And we had a lot of the old photographs reprinted, and mounted, and framed in and put in on display, and it was a beautiful show.

And those pictures then hung all over the office walls. I wish I had taken more of those because they weren’t worth anything, but they were the history of House & Garden, with amazing designers, amazing photographers, world-renowned photographers over the decades. It was quite rich and quite astonishing.

And I wish I had more mementos of that. And at the time, Condé Nast’s photo archives were just in disarray. The stuff was in cardboard boxes all over the place.

Lory Hough: What was it actually like your last day? Were there security guards? Was it that sort of walking people out to their cars to make sure you weren’t taking computers? Or was that more the stuff of television fiction?

Dominique Browning: I don’t remember security guards, but there could have been. It was more a lot of wailing, and gnashing of teeth, and tearing of hair. I immediately hit the phones to start calling people to get people jobs. I felt very deeply responsible, and perhaps loyal to a fault, but I felt very responsible for everybody’s welfare and wellbeing.

There were people we had hired pretty recently, because nobody saw this coming. So it didn’t hit me full force until after a while. So yeah, people started packing and people were on the phone and there was a lot of emoting. But I don’t remember feeling this threat of security guards. Maybe they were there or maybe they came in later and there was, I don’t remember. I have a bit of a blur.

“I deeply believe that magazines are about love. I really do. I don’t think you could be a good magazine editor if you didn’t get a charge out of the subject.”

Lory Hough: Understandably. So what was your proudest moment, though, being the editor for 12 years?

Dominique Browning: Yeah. I am still incredibly proud of what we did. A lot of my career has been fighting the “airhead” attitude. People think, when I was at Newsweek, I eventually was running what they call the “back of the book.” And they referred to that as the “soft stuff.”

And we were enormously successful with cover sales, for example, of stories we did. So Newsweek, under my direction, was the first magazine to do a cover story on depression. And at that time, we had bags of mail pouring into the office from people saying, “Thank you. Nobody’s ever talked about this.”

So things like psychology, and design, and all these issues that people think of as “women's issues,” I think, are deeply important and deeply fascinating to people. And I felt very proud of making House & Garden a smart magazine. Beautiful and smart.

In those days, magazines would have these studies that would look at how many seconds-per-page, or how many minutes-per-page somebody would linger in a magazine. And when I started the magazine, I looked at those numbers, and they had declined at House & Garden, and in the shelter world, significantly to the point where people were literally just flipping through the pages and tossing it.

And that’s not a good thing for an advertiser who’s spending $150,000 a page. But it’s not a good thing for a reader, either, because you don’t linger. My goal was to get people to stay in the magazine much longer to linger over the pages and to remember things. And we had wonderful writers and great photographers. So that’s what I’m really proud of.

Lory Hough: I also remember reading somewhere that you were one of the first editors at the magazine to embrace bloggers and create content specifically for the web, which was probably fairly new at that time.

Dominique Browning: Yes. Yeah. That was an uphill battle too. And sadly for Condé Nast they were very slow getting online, getting into any kind of blogging at that time. It’s hard to believe that blogging was new not that long ago. But it wasn’t that long ago. So I hired Grace Bonney, who went on to have a very successful site called Design*Sponge. And I hired Sam Joaquin, who’s in San Francisco, who is a fabulous talent and wrote about green design and shopping for toxic chemical-free things. We were able to do moments. But I was never able to convince Si [Newhouse] that we needed an entire site that was House & Garden and that it could be a commerce site.

I loved being online. And that was one of the first things I did after I wrote the book was to start my own blog. Blogs, which are now called Substack.

Lory Hough: Do you think their hesitation was a control thing or not knowing how they could make money from it? You’re giving content away for free—was that their concern?

Dominique Browning: Si said to me, “This whole thing could be a flash in the pan. Why don’t we let other people do it and let’s see how it goes? And if it’s good, then we can jump into it.” And it turned out to take too long to jump in and to catch up.

Lory Hough: Let me ask you some questions about gardening—we’ll move to something happy. What did gardening do for you after the magazine closed? You said you’d been reading these, sort of, shelter magazines for years. Could you have led a magazine focused on house and garden if you weren’t interested in those things? If you weren’t a good gardener? If you didn’t like doing things to make your house look nicer?

Dominique Browning: Oh, what a, what a good question. I deeply believe that magazines are about love. I really do. I don’t think you could be a good magazine editor about food, or wine, or the news, or politics if you didn’t love politics, or the news breaking, or if you didn’t get a charge out of the subject. You could mechanically make things happen. And maybe you could hire people who loved the subject, but you would be a step removed from that creative spark of obsession. And I still love to garden. And gardens do for me now—in my work on climate change and toxic chemicals—they do for me now what they did for me during heartbreak, which is they give me a place to regenerate and to focus on a tiny little thing and to slow way down.

Lory Hough: Your interest in gardening, does that have an impact on your direction that you’re in now with the Moms Clean Air Force? Or was that something that you’d always been thinking about, the environment? Is it because you have kids and you think about their future?

Dominique Browning: Yeah. I have been interested in climate change for a very long time. Even at House & Garden, Bill McKibben wrote a column for us about what it was like to live green. And Sam Joaquin did the work she did at Newsweek. I commissioned articles about it. So it was not an unusual thing for me to be thinking about.

It was after I decided that I was breaking up with the magazine industry completely that I thought, I really care about climate change. Maybe I can do something. I have a lot of skills in communication, and writing, and marketing, and translating tricky language into accessible copy. I think I can help.

And so I went around to talk to headhunters in the nonprofit world and they all looked at me and said, “What the hell do you think you’re doing? You can’t help us. You don’t know anything about this.” I ended up having to make up something.

Lory Hough: You start your own thing, exactly.

Dominique Browning: Exactly.

Lory Hough: That’s a great transition into some of my last questions that have to do with leaving the magazine world full time. You continued to write and freelance, but you did leave that world on a full-time, kind of, career basis. How did that affect your identity? Because for years and years you were a full-time magazine editor.

Dominique Browning: I felt like I had molted. And I also feel like I’m still an editor, in the best sense, having to make decisions all the time about what we’re going to focus on. I loved the magazine world. I used to talk about how the entire magazine industry could fit into a Greyhound bus.

I think that’s pretty accurate—at least from the eighties or nineties. It was like a village, right? A quaint village. And we all knew each other. People had love affairs. People hated each other. You just saw everybody from the time you were 20 till whenever. I worked with amazing, great people.

I feel like I hold that vision of creative teamwork in my mind. I think a lot of what I learned in the magazine business can be applied, and should be applied, to the great issues of the day, to politics.

Browning’s editor’s note in the premiere issue.

“I love to write about life—my experiences of it.”

Lory Hough: Do you think if the magazine hadn’t folded, you would have stayed longer? Or was there a point where you think, I probably only had a couple more years here anyway?

Dominique Browning: That’s a good question. And I don’t know the answer, really. I don’t think I would have stayed. I was pretty fed up with the publisher’s churn and I was feeling like it was time to do something else. I was very drawn to newspapers, and I did some consulting for the Wall Street Journal for a while. They were reinventing their Saturday section and that was really fun.

But I also felt—and as with so many things—when I was in the magazine business, my children were growing up. They were home. I needed a stable income. I was raising them—they were with me and then they were with their father. So I didn’t really want to jump around all over the place or go somewhere where I didn’t know that I would have a salary.

The situation changed when they were away from home. I was no longer mothering them. And I did begin to think a lot about, What can I do to help solve this what seems like a deeply intractable and terribly dangerous situation? Which is a simple pollution problem when you get right down to it.

Lory Hough: So here’s a question—the last question I have for you—this is a question that’s often asked on this podcast. It’s the Billion-Dollar Question: A billionaire wants to give you a blank check, but in order to use it, you have to start a print magazine. Would you do it? And what would it be about?

Dominique Browning: Wow, that is such a good question. It has to be a print magazine? Okay, I can’t squander a billion dollars. Let’s just talk about who’s doing that right now. Look at the Atlantic, right? What a wonderful way to use money for a print magazine and to do great reporting.

But I’ll tell you what, I really miss Life magazine and Look magazine, and those big visual splashes of stories, which we see online, but it’s a firehose.

Maybe I would go to ProPublica and say, “Let’s do a print version that will reach people who aren’t necessarily reading tens of thousands of words online.” I don’t know. It’s such a good question, and I feel like I’m blowing my chance to get a billion dollars.

Lory Hough: There was something else I had wanted to ask you about leaving the magazine: Did you keep a copy of every issue that you were involved in? I know that you downsized and moved from your home in New York that you raised your kids in, and you moved to your smaller house in Rhode Island. So did the magazines come with you?

Dominique Browning: I turned to the dumpster. I did not keep every issue. Up to a certain point, the company had been giving me bound volumes. And that stopped. I kept the bound volumes. But, wow, no. I just threw it all away.

MORE FROM PRINT IS DEAD (LONG LIVE PRINT!)