The Return of the Prodigal Son

A conversation with Spin founder and editor Bob Guccione Jr. Interview by Sean Plottner

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT COMMERCIAL TYPE, MOUNTAIN GAZETTE, AND FREEPORT PRESS.

Nearly 40 years after its launch, Spin magazine has returned to print—and at the helm, once again, is its founding editor and today’s guest, Bob Guccione Jr.

Launched in 1985 as a scrappy, rebellious alternative to Rolling Stone, Spin became a defining voice in music journalism, championing emerging artists and underground movements that mainstream media often overlooked.

Now, as it relaunches its print edition, Spin will attempt to find its place in a media landscape that looks completely different. But Spin’s origin story—and Guccione Jr.’s career—has been shaped by a complicated legacy. His father, Bob Guccione Sr., was the founder of Penthouse magazine, a publishing mogul who built an empire on provocation and controversy.

Launched in 1965 as a scrappy, rebellious alternative to Playboy, Penthouse was more than just an explicit adult magazine. It was a cultural lightning rod, sparking debates on censorship, free expression, and morality.

Though Penthouse funded Spin’s launch, the father/son dynamic was soon fraught with conflict over Spin’s editorial direction combined with Penthouse’s declining appeal. That tension led to a deep rift—the two were estranged for years. But Spin survived, thriving under Guccione Jr.’s leadership as it defined a new era of music journalism.

We talked to Guccione upon his return to the magazine he built, and offers a spin-free take on dad, the launch, and the comeback.

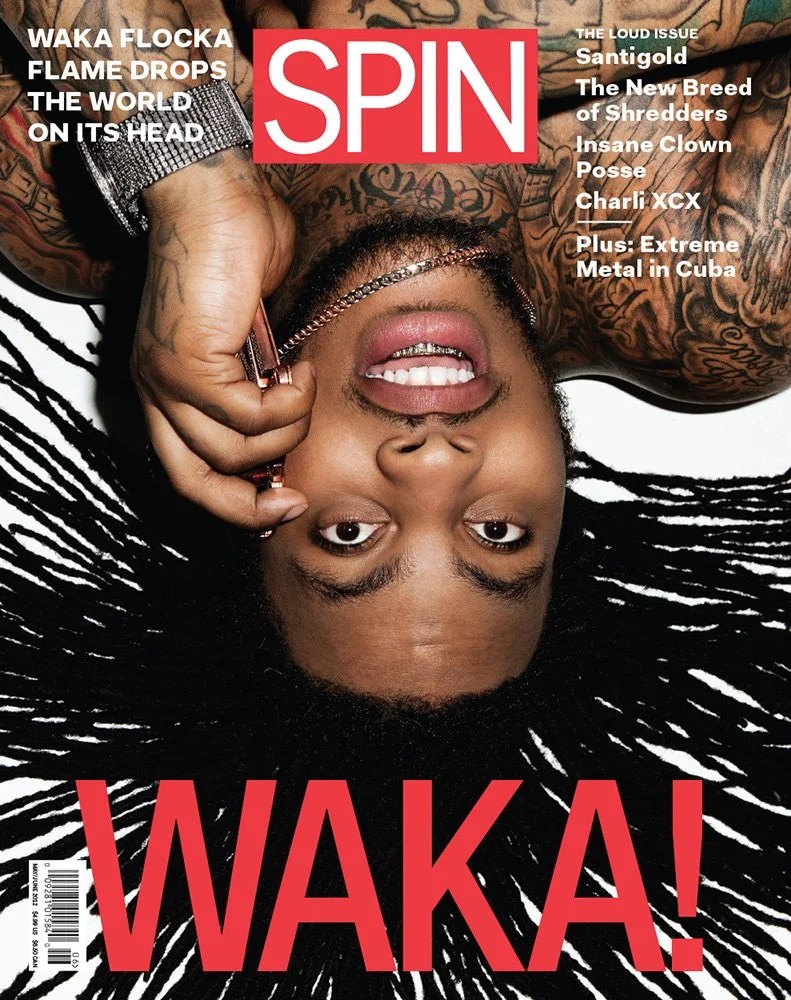

The latest edition of Spin, ca. 2025

“Magazines now are a bit of a fashion accessory.”

Sean Plottner: Okay, Bob, obviously the big news coming out of the print magazine world is that Spin magazine, which never really went away, is back in print. And it’s Bob Goo-CHONE-ee. Am I saying that correctly?

Bob Guccione Jr: You are, indeed. Perfect.

Sean Plottner: Bob Guccione Jr., the founding editor of Spin, who is back at Spin and in print—what important Spin duties are we taking you away from today?

Bob Guccione Jr: Nothing today because I’m not working today. Although having said that, I’ve got a number of things I have to do, which I probably will do today. I sold the magazine in 1997. It’s had a succession of owners since then, some more successful than others. And in the latter years, it just went fallow.

And a very smart young guy called Jimmy Hutcheson [Spin’sCEO] bought it about five years ago now. Almost five, not quite five. And he had a vision to just bring back its importance and its vitality and its attitude, which I think is the key to any successful publication is to have courage and attitude.

And at some point he, within that first year, asked me if I’d help him, consult him. So I said, “Yeah.” I said, “You’re the first guy smart enough to ask me!” Because he wanted to bring back some of that old pop we had, that old vigor. And I said, “It’s about taking a stand about caring for things, showing you care. It’s not about being worried about being wrong and it’s not about being worried about being unpopular because if you do your job right, you will be.”

And he signed on for that, accepted that. He said, “That’s exactly what I want.” So I consulted him for a couple of years and then sort of took over the site for a bit. But then the idea for the print magazine came up and that’s what I’m doing now pretty much exclusively.

I still consult him and advise him. And we were working on some new projects. But the operational part of this is the print magazine, which he wanted to revive and which we revived in September.

Sean Plottner: And so it’s back in print quarterly?

Bob Guccione Jr: Yep.

Sean Plottner: I believe you’ve already produced two issues? Or three?

Bob Guccione Jr: Yeah, we’re working on the third. I’m the editor—for my sins and for everybody else’s.

Sean Plottner: So why bother? Why bother to go back to Spin and back to print?

Bob Guccione Jr: That’s two questions. One of which I can answer very completely. It’s a personal one. And the second one I’ll answer in my knowledge of what Jimmy is thinking. The first one, why I bother, is that I’m eternally curious. I’m interested in creating, working, editing, and writing. I sometimes wish I wasn’t as interested. And I would lead a quieter and simpler life.

I live in a quiet and simple place in rural Pennsylvania, but I really work as if I’m still in Manhattan. I am driven. It’s certainly a curse, but I’m not sure it’s also a virtue. And so when Jimmy asked, it was an interesting set of problems to try and contrive a solution for.

Spin had gone fallow. I used the analogy with him that it was like a great old vineyard in Napa Valley that no one had made wine in in 20 years. And it was going to take a while to nurse it back to health. So that’s the reason. I’ve done some consultancies in the past several years and enjoyed some of them and not enjoyed others.

Some have been very creative and very exciting. And Spin is certainly the most of those. So that’s why it was a no brainer. I loved it. And why go back and print? Jimmy felt—and he felt this before the recent spate of print [relaunches]. And we looked into doing it last March and just couldn’t get it together in time.

So we decided that September is a good month to launch a magazine, but he just felt that it added dimensionality to the company. In many ways online, which is so ubiquitous is also so therefore flat and a magazine is not flat. But I impressed upon him right from the beginning that online is about immediacy. It’s about addressing something when it happens, or as it’s happening.

But a magazine can’t do that. It is by definition, the second you put ink on the paper, it’s out of date. So you have to make it something that is more pensive, more of a read, that you spend more time with that you lose yourself with. And that is in itself a physical and tactile pleasurable experience.

So that’s why I wanted to bring it back and I think it’s great. The newsstand infrastructure for magazines—you didn’t ask, but I’ll tell you—is so bad that it’s impossible actually to produce a magazine that will work on newsstands.

It is dilapidated. It is corrupted in the sense that it is rusted rather than it is illegally corrupted. It’s monopolistic, which may or may not be legal. And so you cannot do much with the newsstand. So really, it’s there for presence. It’s there in places we know it will sell. We’re selling about 40%, which is actually double the average magazines, maybe more, and we’re going to build a subscription business so people get it in their homes.

But we’re about delivering a great product. And the first thing we said about, and I spoke to the editors who were working on it was, "let’s make this a great product, not just go through the motions." I feel a lot of what’s out there in print, whether it’s just come back or it’s been there for a while. It’s just going through the motions.

I said, “Let’s be bold. Let’s take stands. Let’s have opinions, popular or not. And let’s go back to what made Spin great—that it was its own entity. It wasn’t owned by anybody. The record companies didn’t own us. The politicians didn’t own us. Only the readers we answered to,” I said. “We’ve got to go back to that."

Sean Plottner: It sounds like, to continue the vineyard analogy, it sounds like you’re going to stomp on some grapes a little bit.

Bob Guccione Jr: Yes, that’s beautifully put. And that will now become part of my new analogy.

Sean Plottner: Well, And I see Spin is available at Barnes & Noble. It is hard to find a newsstand anywhere and it’s nice to know that they have some. I got the copy with Oasis on the cover. And I had two magazines sitting on my table here the other day and my 20-something boys were here with their friends and I mentioned the magazine and I said, “Hey, your father has an article in this magazine. You might want to just take note.” And they immediately went to the Spin magazine—not the one I’d written for—and they found Sabrina Carpenter and were all over it. So it was interesting to see 20-somethings interacting with the print magazine.

Bob Guccione Jr: It’s interesting that they have become a real market for print. In much the same way that vinyl made a comeback. As—this is not meant to be pejorative when I say this—but as a fashion accessory. So magazines now are a bit of a fashion accessory.

Magazines once had a real, defined purpose of delivering information you weren’t going to get somewhere else. A magazine like Spin or Rolling Stone or Esquire at its best took it further and gave you really, deep information you weren’t going to find, went places that most people didn’t have the guts to go, told stories most people wouldn’t put out. That’s magazines at its very best.

But even average magazines gave you information you weren’t otherwise able to access. But today that’s an anachronistic concept. You can access any information anytime simultaneously. Magazines had to change. And part of that change is to become something shiny and tactile and take you to deep places where you think and read and get lost in.

Escapist journalism rather than informative journalism, we have a record review section as much for nostalgia as anything else because who hasn’t already heard all the records we’re talking about. But I think the opinions of our writers are interesting, therefore that justifies it.

But people have to accept and realize that today magazines are not the same, never will be the same, as they were in the heyday up until the end of the nineties.

Sean Plottner: Yes. Fashion accessory, luxury item. I noticed in the spread house ad you have to ask readers to subscribe, it just sounds so charming: “Four quarterly issues delivered to your door.” And then you say, “Start your collection today.” Something I don’t think I’ve ever seen in an advertisement about subscribing to a magazine. But that speaks to what you’re talking about.

Bob Guccione Jr: Yeah, it does. Yeah. And I didn’t write that copy. It was written by somebody in-house who really got it. And I really appreciated that. It is like having a collection. A magazine today is almost like a coffee table book was say 20-30 years ago. And that’s great. Let it be what it is.

Talking about subscriptions, I’m old enough to remember when the advertising pitch for subscriptions was, “Get it before it’s available on the newsstand.” And a magazine will be delivered to you a week before it went on sale. That was the real pitch for that. And I’ve just betrayed how incredibly old I am.

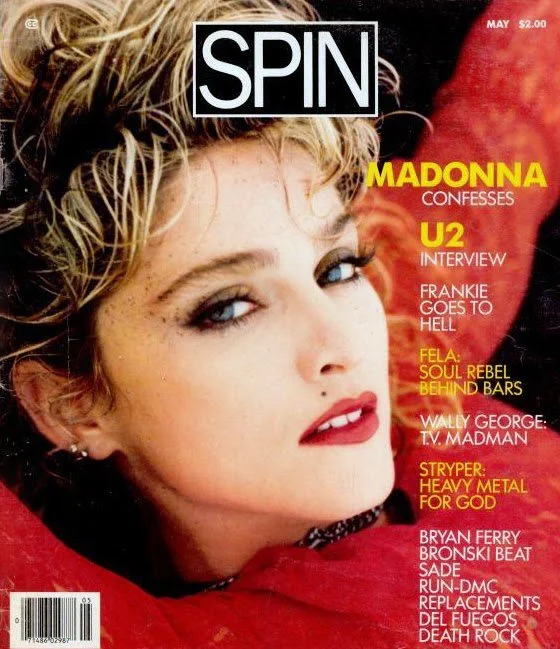

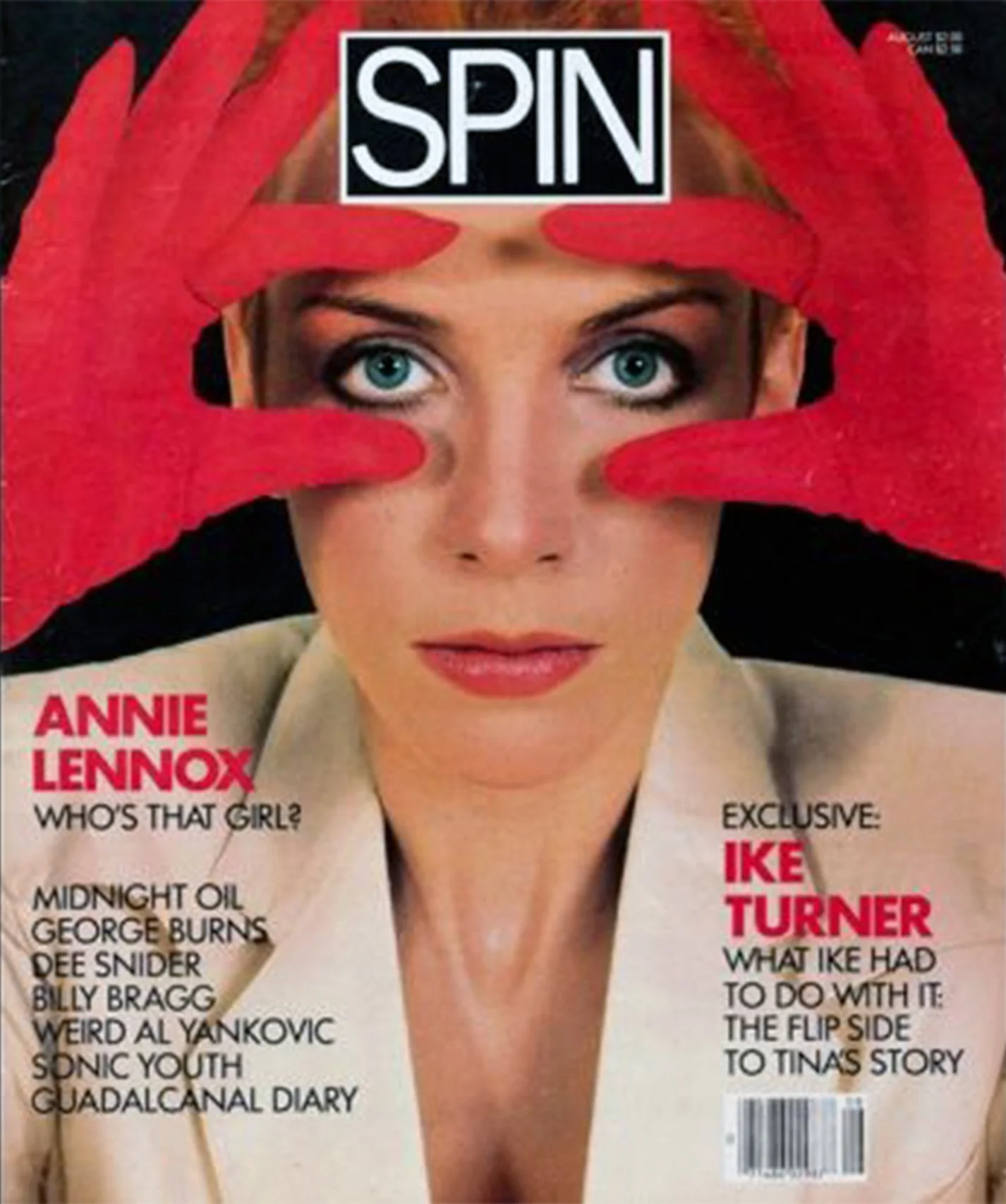

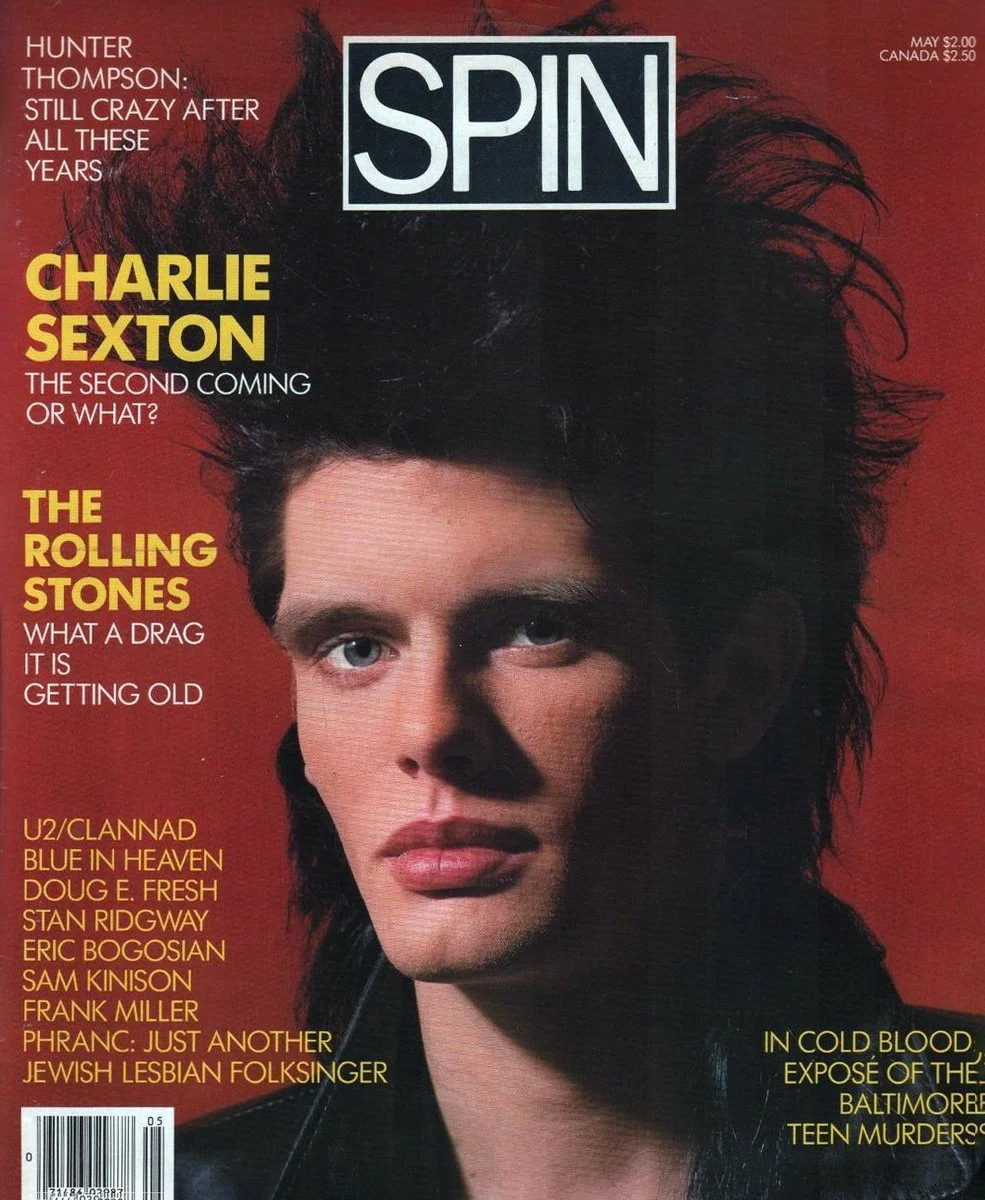

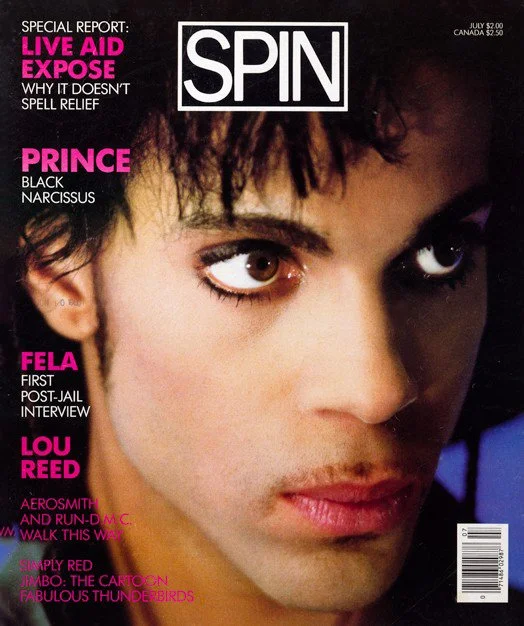

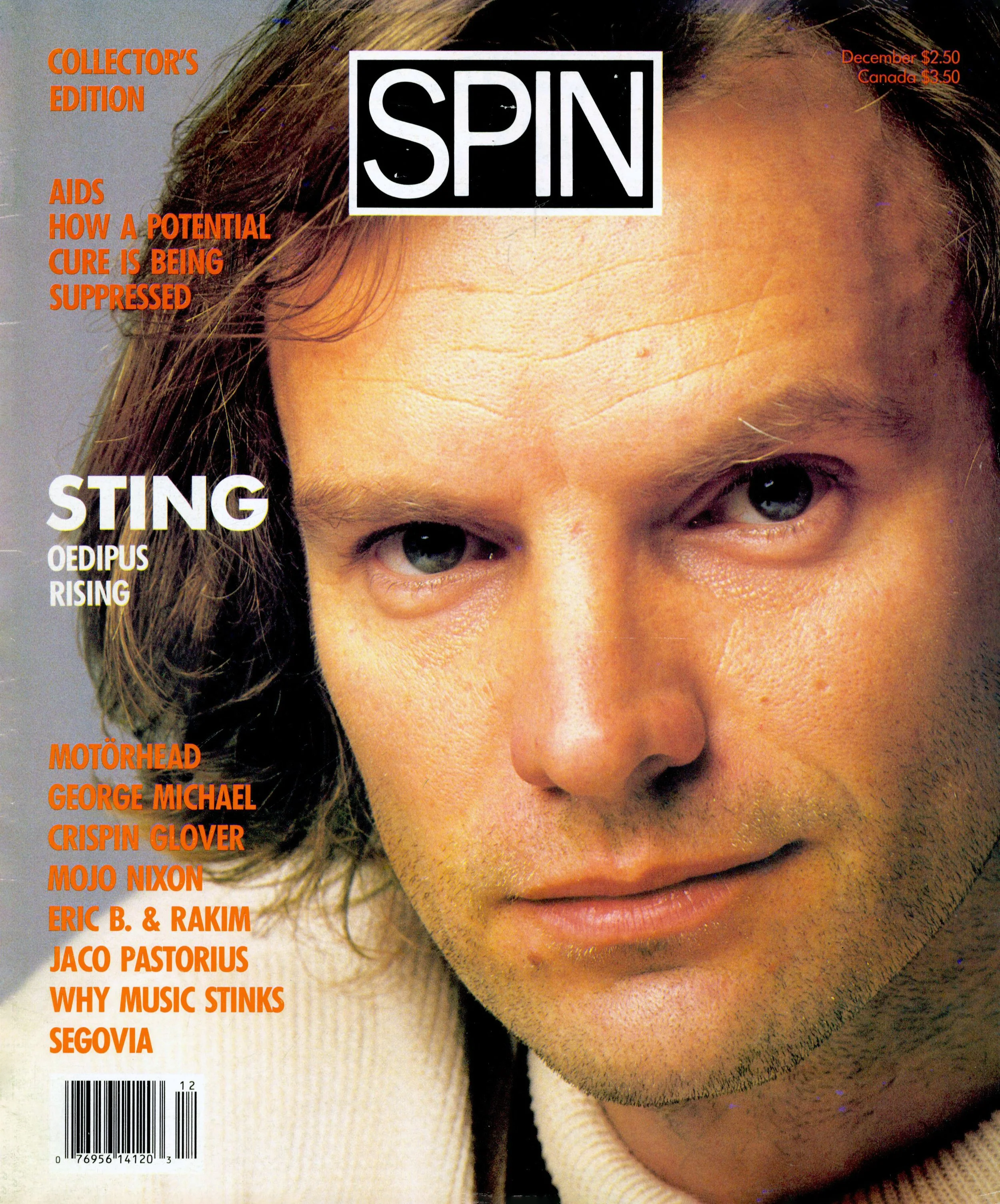

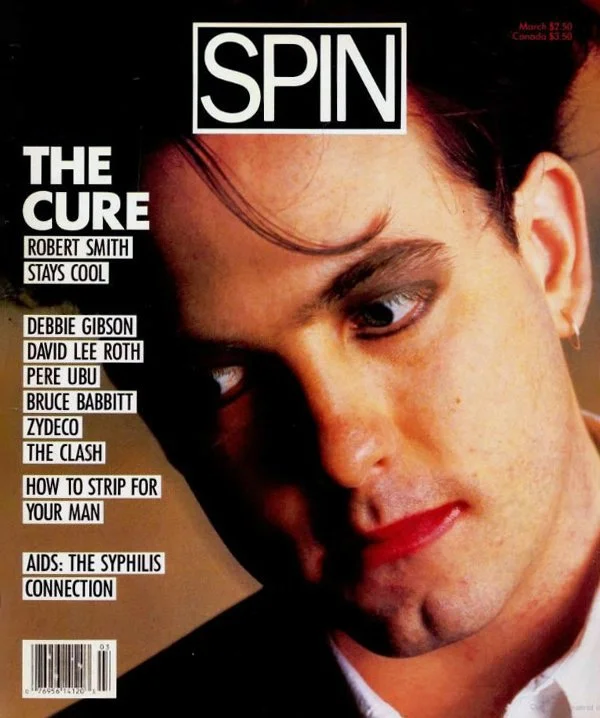

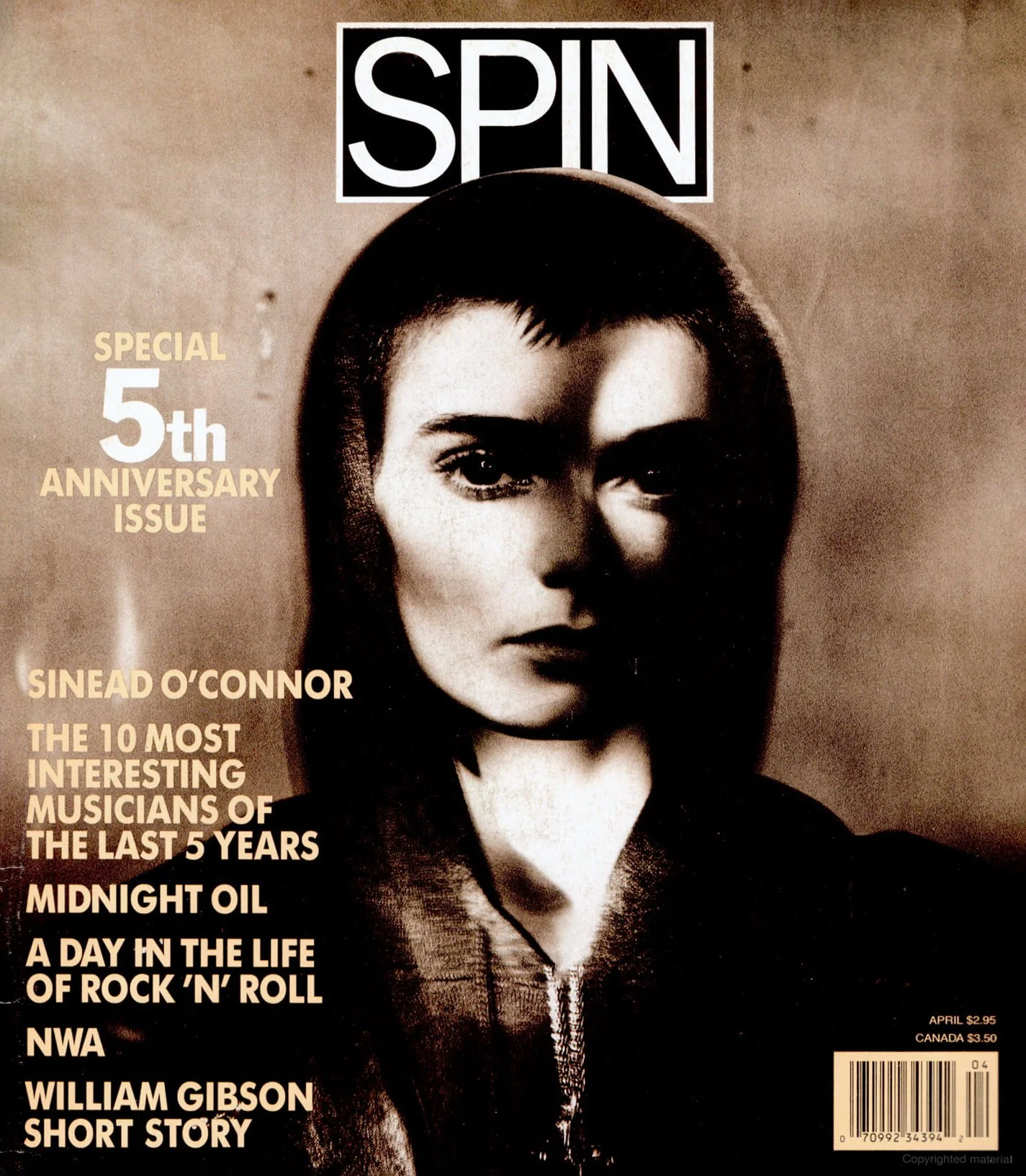

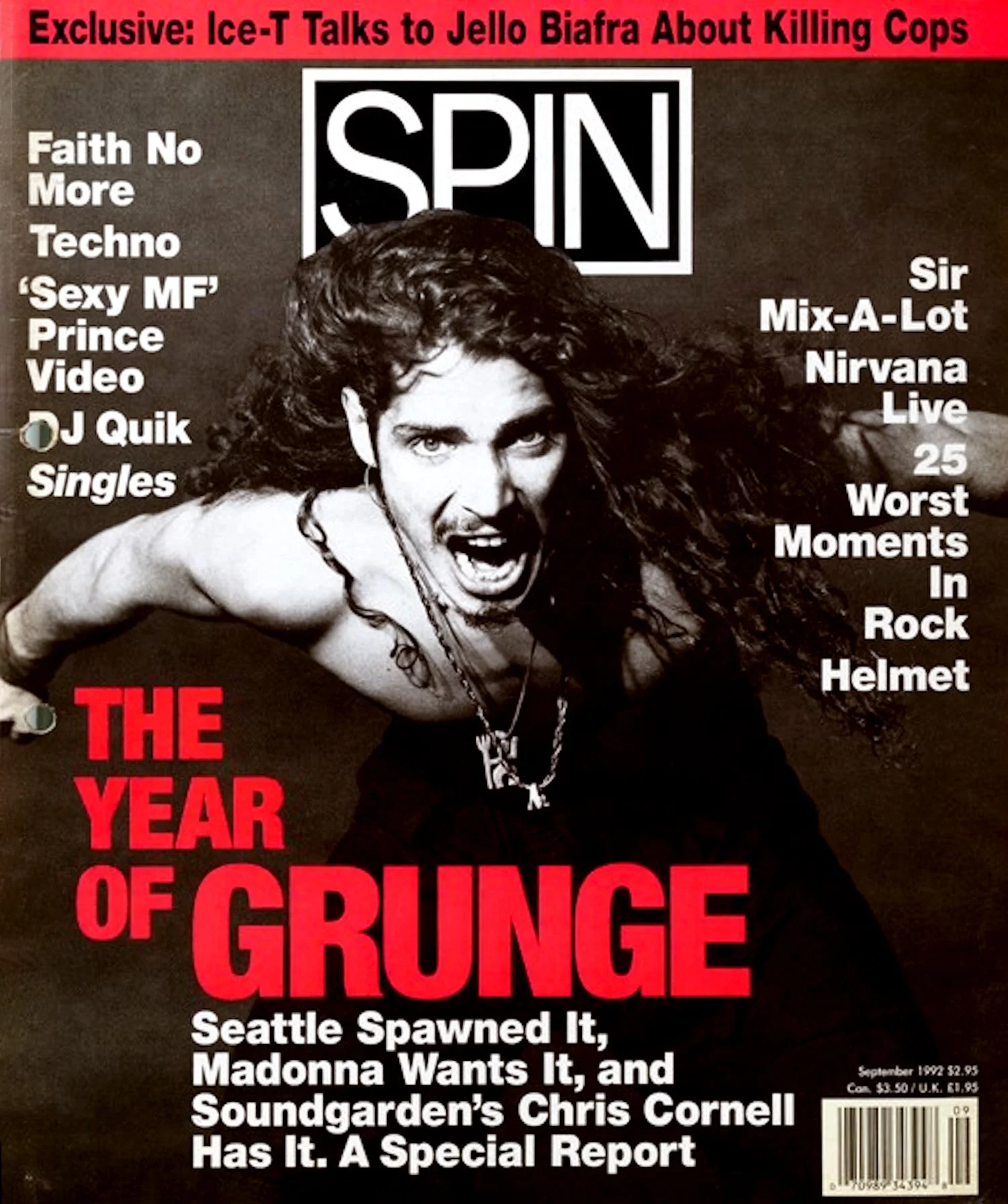

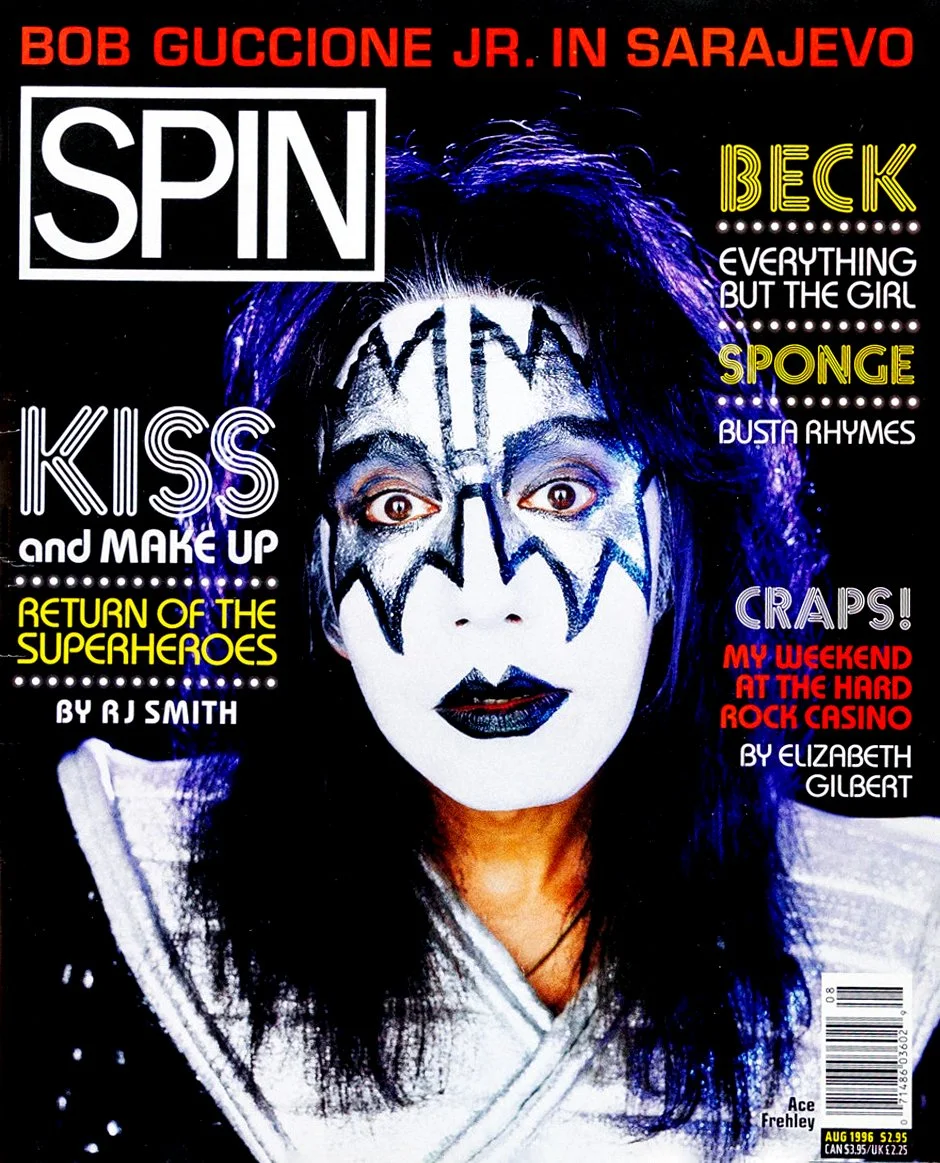

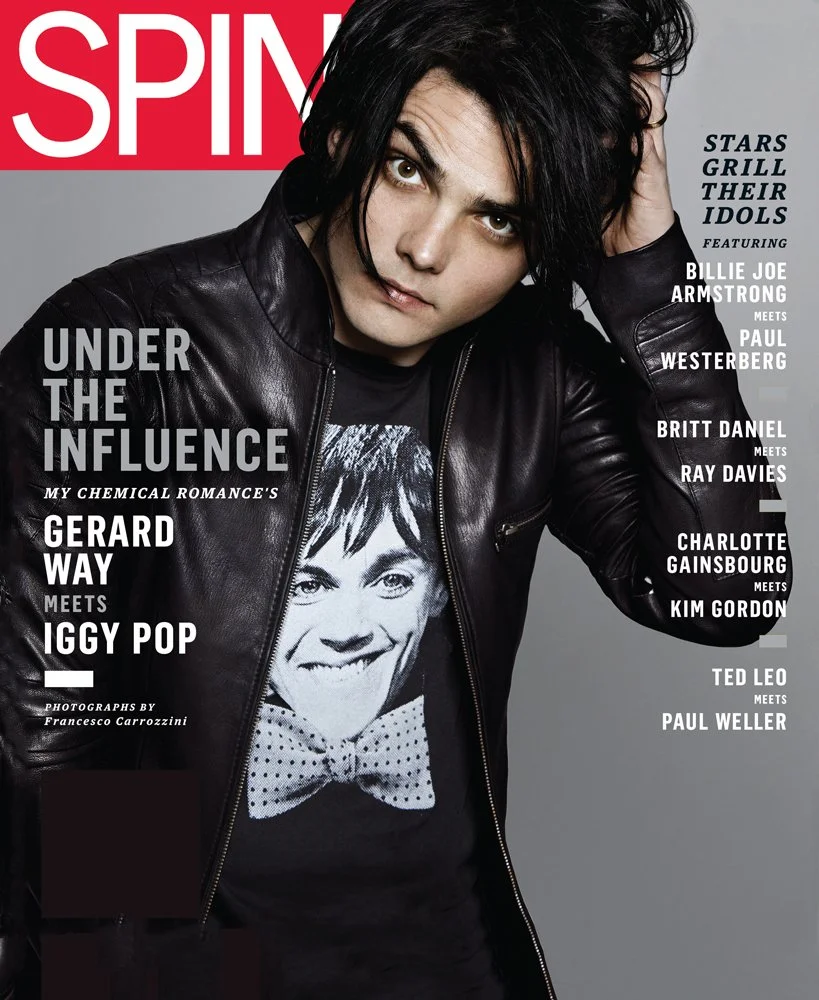

The OG Spin (1985-1990)

“Spin was a completely different look for magazines.”

Sean Plottner: Yeah now it’s, you can read it online a month before there’s ever even a print version of something, maybe.

Bob Guccione Jr: We’re keeping it separate. The print is separate from the online, except for two months later we reproduce some of the articles online.

Sean Plottner: I’d love to do a little comparison. You’re a unique editor guest on this podcast in that you are a founder of a magazine back in the eighties and now it is back. And I’d love to do a little comparison of then and now. But before we do that let’s go back to the eighties—I hope you remember them. The New York Times recently declared 1984 as a, I think they call it “the year pop stardom got supersized.” They blamed synthesizers, and MTV, and Madonna, Springsteen, et cetera, et cetera. It was 1985 when you launched Spin. And I was just wondering if you could take us back to those days. Tell us briefly how Spin came to pass.

Bob Guccione Jr: Let me take you back first in those days. There was mainstream music. Rolling Stone covered it, the regular press covered it, Newsweek covered it. There was MTV out there, not quite as edgy as people think, because it was really covering Rod Stewart and the major musicians, as well as the occasional Patty Smyth. And it was actually covering anybody who they thought would tune in. So it wasn’t quite as edgy as you’d think.

But there was this second music, this new wave. In fact, part of it was called new wave. Part of it we dubbed “underground” which eventually became thought of as “indie,” independent music. So it was an indie world that we covered. And it was music that was so good and so different and innovative and new, as to be uncommercial, first of all, that most radio stations didn’t play it.

I was living then in Manhattan, and I would drive up the east side of Manhattan to get to New Jersey rather than the west side, because I could tune into a Long Island radio station and get this new music. And at that time, taking you back to ’84, when we first started the magazine, and ’85 when we launched it, my friends and I would give each other cassettes and say, “Here’s a group I heard.” Or, “Here’s a compilation of stuff I’m listening to.”

And it was almost covert how we would swap music, like the earliest days of the internet, when people would send each other links. I was getting ready to go for dinner as I put my leather jacket on to go out—I only ever wore leather jackets—as I put this on to go out, the radio was playing “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” by Cyndi Lauper. And in that second, I said, “Everyone just wants to have fun.”

And this magazine literally appeared before my eyes—just visions of pages laid out, many of which I actually copied very faithfully in the real first issue. I had seen the type, the picture, where it went, the white space, the whole new look. Spin was a completely different look for magazines. In fact, many people made fun of it and said how amateurish it looks, but it was really based on white space—having lots of it to allow the pictures to breathe and have the type be itself a component of design.

And this magazine just came to me, all the sections came to me. And I went, “Oh my God, wow, this can take on Rolling Stone.” Then that vision collapsed, everything disappeared, a jacket was now on me, I was walking out the door, I said, “That’s a nice idea, but I can’t do that.”

“Six weeks later, and I remember this moment as if it was this morning. I was never an early riser—I’m still not an early riser—but then I was a very late riser. Ten in the morning would be when I got up. And at 6 in the morning I sat bolt upright, like you see in movies when people are possessed. I sat bolt upright, and I went, “Oh this isn’t even a question, this is a vocation.”

And I got up at that moment, I went to my dining table. I took out a pad of paper, and I just drew the whole magazine. And by 10:30 that morning, I went and had some breakfast somewhere, walked over to the offices of Penthouse, and said, “Can I get an office anywhere?”

Obviously my dad owned Penthouse, so I wasn’t just walking in off the street. And everybody said, “No, we don’t have any offices, we need the office space.”

I went to my dad and said, “Do you mind if I work at night at Penthouse when everybody’s gone home? I want to create this magazine.”

He said, “Yeah, of course. Go ahead.”

So I worked at night. And in the morning the art department came in and helped me with all my layouts to turn them into poster boards, layout boards. So that was the beginning. It was literally first of all, an inspiration, and secondly, just this sense, No, this is what I have to do. This is necessary.

And it concentrated on that world of music that my friends and I were listening to and younger people listening to. And it was always meant to be a magazine that would be at the mouth of the river where the water comes flying out of the rocks. I wanted that energy, that kinetic, fantastic energy.

Gucciones Jr. & Sr. were estranged for 18 years after a falling out over Spin’s independence from Penthouse.

Sean Plottner: Are you saying the Penthouse art team helped you with some of the design?

Bob Guccione Jr: No, no, no. It would have probably been more polished had they done so. I did all the designing in pencil and pens and markers and drew up pictures and sized them. We had in those days what was called a photostat machine, where you would take an image and you’d put it in the machine, it would then give you whatever dimensions you wanted. A xerox, a glossy xerox. It was on better paper that you would then take that and put it on a board and paste it up.

But I had a problem. I wasn’t skillful enough to get these images out of the photostat machine in the positive. So I would leave all my sizing and dimension of my images on a stack. And one of the assistant art directors in the morning would run them through the machine. And I’d come back in the evening and they’d all be positive. And then I could finish my layouts.

I’ll tell you a great story about the logo. So the logo was quite iconic for a while. It was just this black and white logo. One night I had drawn the logo. And it was meant to be black letters on a variety of colored backgrounds: red, green, yellow, white. And I was excited about the way it looked.

So I said, Let me try to work this stat machine out that’s been bedeviling me all these weeks. Let me see if I can’t actually get it right tonight. And I thought, I’ll put it through, I’ll get the negative and I’ll try to make a positive out of it. But when it came out of the machine in the negative, it was the white letters on the black box. And I went, that’s it. That’s the logo right there.

It’s fun telling these stories before computers and the fantastic tools at our fingertips today. I still use what we call a pica ruler. I designed Spin with it. I still have it and I still use it when I work on my other projects now.

Sean Plottner: Sure. Sure. Sometimes accidents are good. To what do you attribute this vision that you had for the look of the magazine. Where does that come from?

Bob Guccione Jr: I’ve no idea. I am a believing, and less of a practicing, Catholic but certainly a believer. So I would say it came from God. Why God bothers with rock and roll magazines, I do not know. But I guess he thought I was about ready to piss my entire life away lazily because I’m a very lazy person. So I think maybe God said, “Oh, give this guy something to do.”

Sean Plottner: Spin launched with financial backing from your father. Yeah. And at the time, it wasn’t Yankees/Red Sox, but you were clearly a competitor with Rolling Stone. How did you view Rolling Stone at launch?

Bob Guccione Jr: Very admirably, actually. And I’ve always maintained that admiration for Rolling Stone. I was a little young for it when it had its height in the sixties. And of course in the seventies I was still a young teenager and I wasn’t that interested in Rolling Stone. But as a young man in my early twenties I read it and just was profoundly moved by the quality of journalism and the outsider nature of it.

It wasn’t following the mainstream. It wasn’t safe. It wasn’t conservative. It was bold. And I thought that was great. And, of course, I came from the household where Penthouse was the epitome of all of those things: bold, courageous, superb journalism, very controversial, a lightning rod for criticism, even governmental action. Penthouse was the ultimate lightning rod in the media at the time.

So all of these helped form my own idea for Spin. And in my impression it had to have meaningful and intelligent and honest journalism. And that was key. But people think I was a music fan. Of course I was a fan of music, but I didn’t start it out of an interest in music. I started it out of interest in journalism and telling stories and knew that music was the connectivity for the generation I was talking to.

And it was my interest and it was fun and I liked fun and I wanted the magazine to be fun. And right from the beginning, it was provocative and weird and offbeat. My appreciation for Rolling Stone was always there. I think it has, as all great magazines and including Spin, its moments of ups and downs, dipped below the horizon sometimes. But it was a trailblazer.

And in a sense I viewed Spin’s competition with Rolling Stone as similar to Penthouse’s with Playboy. And ultimately Penthouse was the better magazine than Playboy and it succeeded. And I think we made Spin the better magazine than Rolling Stone during the time that we competed, that I owned it. And we succeeded, we became the number one music magazine.

Although in the beginning we were the 93rd, I think, when we launched. And certainly people laughed at me, Sean, when I said, “We’re going to compete with Rolling Stone.” They laughed and they stopped themselves. “Didn’t mean to be rude.” And I said, “No, that’s okay. I get it. I get it.”

Sean Plottner: I looked up some reviews of Spin when it first came out and the two words I see most often are ’edgy’ and ’alternative.’ Not surprising. I also took a look at just to do a cover comparison. And I was a reader of both magazines back in the eighties. I was a huge fan of Rolling Stone. Of course, they came out twice a month. Now I did a cover comparison of what they put on their cover in 1985 and compared it to what Spin did. Spin went with Madonna, Talking Heads, Sting, Annie Lennox, Pat Benatar, Keith Richards, Bruce, Bob Dylan. And it’s not so much the rock stars that Rolling Stone had on their covers. They had Hall and Oates, they had Billy Idol. They had three covers with Don Johnson that year. They had another cover with Clint Eastwood. One with David Letterman. Julian Lennon, which I think was a stretch, but we probably understand why. Madonna with Rosanna Arquette. It was quite a movie bent, and Spielberg was on the cover too. So it does seem like Spin was able to reclaim the more musical/cultural, less TV, movie, Hollywood influence in those early years.

Bob Guccione Jr: To put that in context, Rolling Stone moved to New York in the early eighties. And when I wanted to be “big media.” Jann Wenner, who I respect a lot, wanted to be one of the big media players. And he knew that Rolling Stone wasn’t going to be able to do that if it kept just being the voice of the moment in music. It had to go beyond that. It had to go beyond the ads for roach clips.

He wanted the ads for GM and luxury goods. So he made a magazine that was far more mainstream. He put Tom Cruise on the cover. That was the first, I think, of the non-music covers. And people were like, “What?” But it became very popular. It worked.

Because a new audience now adopted it and glued themselves to it. And so he started to become the big media brand he wanted to be. I always wanted to be a big media success too. And I was very happy and delighted that we did actually usurp Rolling Stone in importance and significance to the generation that was coming up.

But I never wanted to be that mainstream because it never personally interested me. And also it was well done. Don’t forget People magazine was selling like four and a half million copies a week on the newsstand. So it was done. And I never wanted to do things that were done.

Partly out of insecurity that I wouldn’t do them as well. And partly out of boredom, like, What’s the point? I want to do things that are new and innovative. And it was ironic that first year, some of those covers were iconic music legends: Keith Richards, Springsteen.

We didn’t interview Springsteen, we did seven essays about him by different writers, including Tama Janowitz and Amir Baraka. That showed the kind of thinking we had in those days. But we had him on a cover. And Sting. And they were big musicians, the ultimate musicians at the time.

But it was what was in those pages. The first issue had Madonna, who at the time was unknown, pretty much, she broke just as we were coming out with her big MTV video where she comes out like Marilyn Monroe. But really Madonna, U2, REM, Red Hot Chili Peppers were all in the first issue. All of them unknown.

So that was our beat. That was our focus. We knew where we wanted to go. I always say about Spin when we launched it, we didn’t know what we were doing, but we knew what we wanted to do. So we followed that North Star.

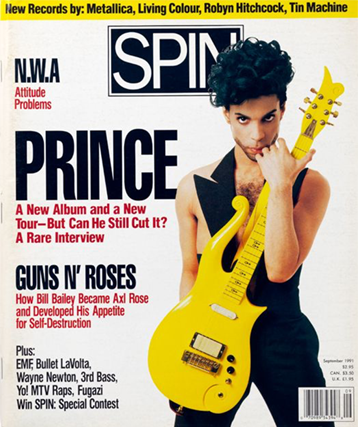

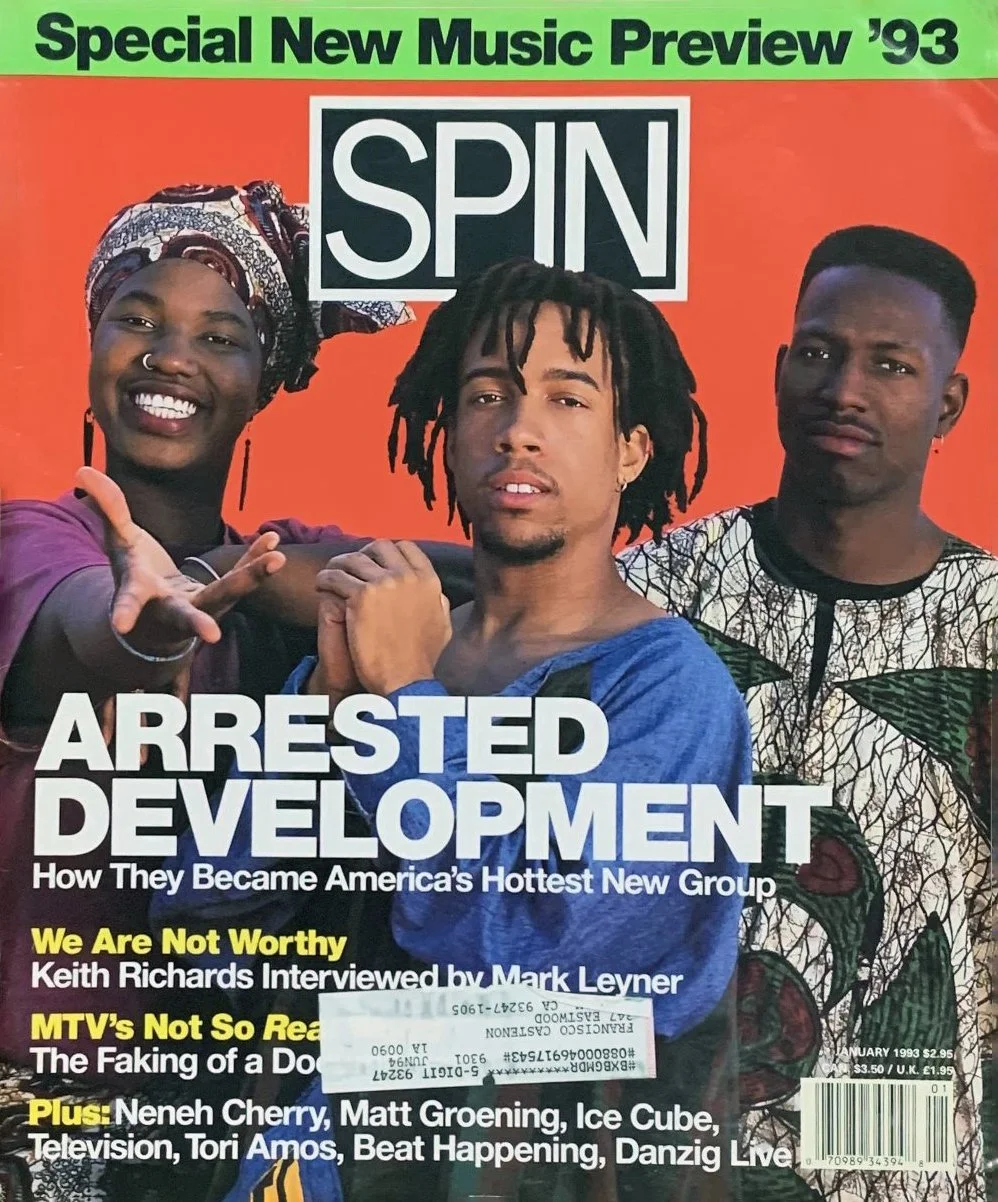

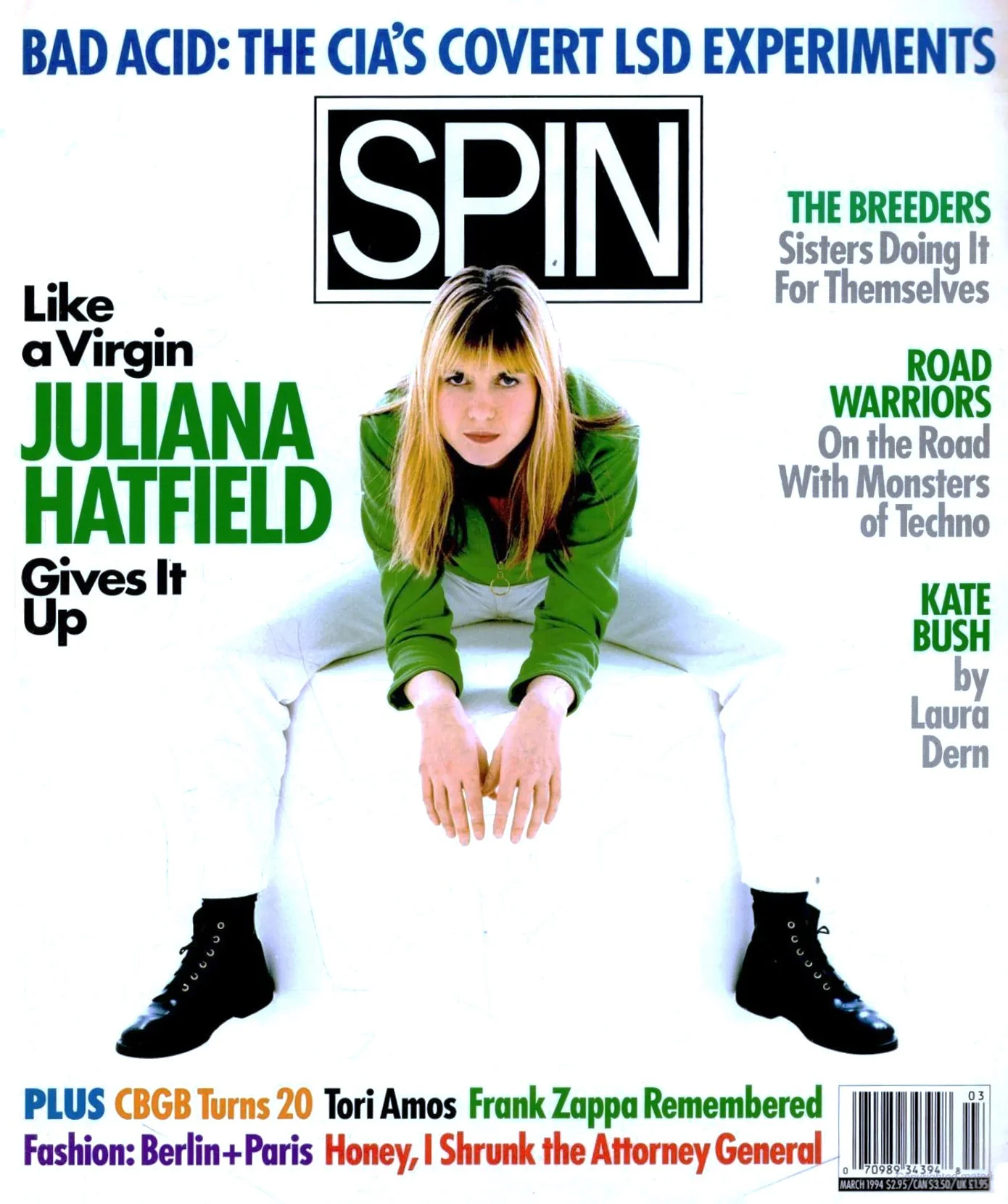

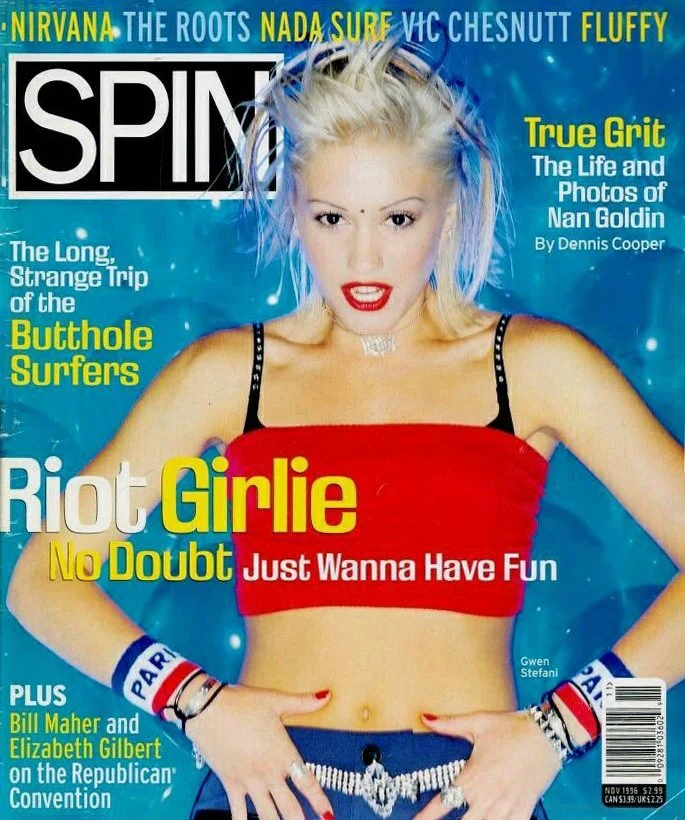

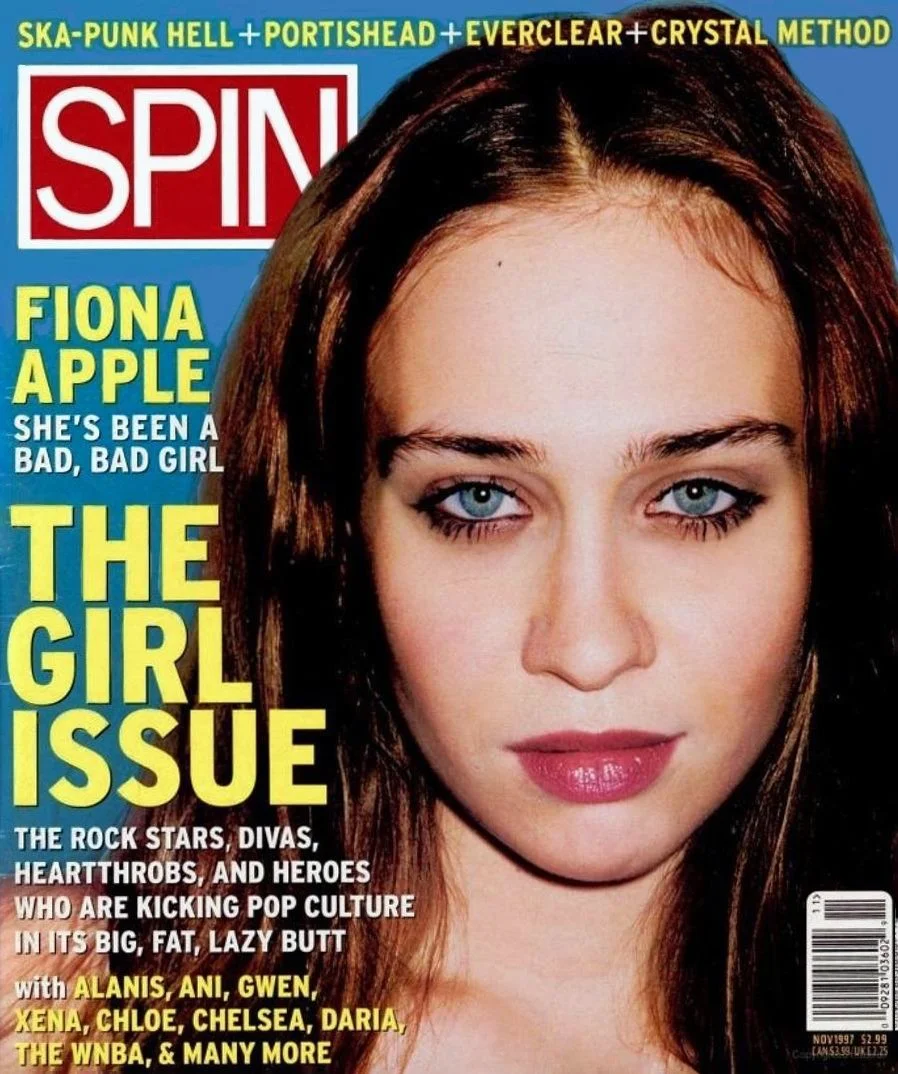

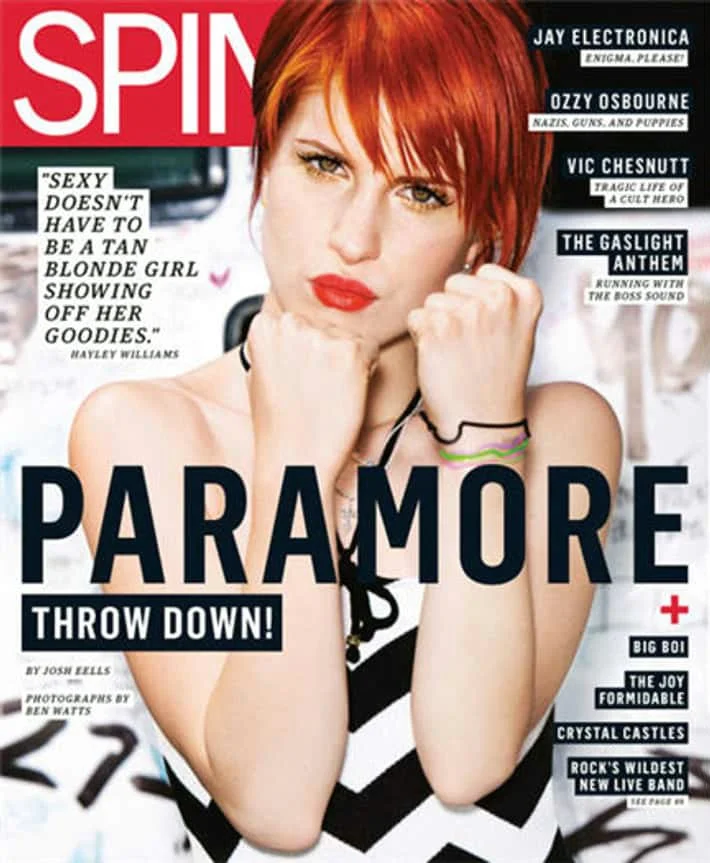

Spin in the 90s

“I think we made Spin the better magazine than Rolling Stone during the time that we competed.”

Sean Plottner: Tell some stories about your first run through with Spin. Some of your mistakes, regrets, lessons, successes. I do want to talk about Axl Rose, but let’s build up to that.

Bob Guccione Jr: Oh, sure. Let’s crest with Axl. Wow. Let me—of course, this is a book, isn’t it? You’re talking about all of the stories. I will try to answer that question and I’ll answer it this way: I’m not being faux humble when I say we didn’t know what we’re doing. I really didn’t know what I was doing.

I had worked for Penthouse in various departments from an early age on. I never went to college. I didn’t finish high school, actually. I finished, but I didn’t graduate. So I was not an educated person and I worked pretty much immediately in magazines and was a writer. And, I alluded to this earlier, very lazy.

So I was drifting through life, actually working, putting out some things, my own magazines. But Spin was the first real important magazine I worked on. We got the first issue together. Brilliant bunch of people had joined me: Glenn O’Brien, Scott Cohen, Ed Rosen, James Truman, Jessica Behrens, who was an immensely talented, brilliant young woman from England. And a bunch of other people I don’t mean to be rude and leave others out. Rudy Langlais was there and others joined in the subsequent issues. John Leland, Bart Bull, Legs McNeil came a little later on.

So we got some brilliant minds, but it turned out not one of us knew how to actually produce a magazine. So when we had the whole issue finished and literally a stack of manuscripts ready to go as I’ve said, a stack of layouts with dummy text, but pictures were in the right place, the headlines were right.

Everybody looked at everybody and said, “Well, what would we do next?” I looked at the guy who’s the managing editor and said, “You’re the managing editor, get it produced.”

He goes, “I don’t know how to do it. You gave me the title. I just wanted to be a senior editor.”

I said, “Oh,”—his name is Gregg Weatherby, shout out to Gregg—I went, “Oh I just presumed from your resume that you’d done this before.”

He said, “No, never done this before.”

So I said, “Oh we’ve got to work this out because we’re going to go on press next week.” So I called up this friend of mine, Patrice Adcroft, who to this day is my closest friend. And she was the editor of Omni at the time and Omni was a floor below us. Penthouse had bought a new building so they could accommodate all the office needs. We shared a floor with a new magazine they were doing and underneath was Omni.

So I called Patty up and said, “Patty, can you do me a favor? Can you go upstairs and talk to us for 10 minutes and just tell us literally what to do next?”

Three hours later, the woman finally walks out and says, “Okay, now you know what to do.” She looks at me and says, “You’re the land of the lost boys.”

“This magazine just came to me, all the sections came to me. And I went, ‘Oh my God, wow, this can take on Rolling Stone!’”

And I said, “That makes you Wendy.” So we called her Wendy a lot. But we didn’t know. But what we did do was write pieces and edit and find and discover and explore with passion. Honest, genuine passion. If we like something that was going in the magazine. If we heard a great story, that went in.

It’s always been about stories to me. Always about stories. Not just about someone’s got a record. We had a meeting once many years later, jumping ahead, and I was a bit pissed because nobody had any ideas. So I said, “Where are the stories? Where are the stories?”

And somebody said, “Well, Tom Petty’s got a new record coming out.”

“But that’s a record review. Where’s the story?”

“It’s Tom Petty!”

“Yeah, I get that. I know who Tom Petty is. Where’s the story?”

“It’s his first record in three years.”

And I said, “That’s not a fucking story.” I said, “I don’t care if you do a story of clowns standing on their heads in buckets of piss. I want a story.” And that was the end of the meeting.

So at the end of the meeting, my assistant, a guy called Matt Hanna, who went on to run VH1, came in to me and he said, “So that’s the new standard, is it? ‘Buckets of piss’?”

I said, “Yes! BOP! It’s got to meet the BOP standard.” And for years afterwards, that was our inside the editorial staff joke. Does it meet the BOP standard? But it was that drive to make sure we didn’t let our standards down. You know, another stupid profile. Tom Petty was a great artist. It wasn’t that interesting. It’s a record review. It’s not a story.

We once did 10,000 words on a guy called Joe Ely, who was basically a failed musician out of Austin. Great musician. Country rock, perhaps a little too early before people knew what that meant, or could mean. So he failed at either rock or country. The guy used to stay on my couch in New York City when he came over with his girlfriend and we gave him 10,000 words because it was an interesting story.

Sean Plottner: Did you ever assign something, get something that you’d hoped to run, but you had to kill for some curious or unfortunate reason?

Bob Guccione Jr: Yeah, that happens a lot.

Sean Plottner: Anything memorable?

Bob Guccione Jr: Christopher Hitchens wrote for me. I had to fire him because he made stuff up and I caught it. He didn’t think we would. He was a bit arrogant. He thought Spin wouldn’t bother. But we fact checked firstly, and plus I was a well-read person. I read things in his pieces that didn’t sound right. I checked it myself and it wasn’t.

So after the second time, he wrote three pieces, two we killed. I said, “That’s it. You can’t write for me anymore.” We killed some pieces because they weren’t good enough, or we got usurped. We never killed a great investigative piece because we were always so ahead of everyone else on stories. Like Live Aid, for instance. And that’s a great story I would like to tell you about.

But one story I remember we killed was when Celia Farber asked to go to Christiania. It was, and maybe still is, a little enclave where there were no basic laws about drugs. You can do whatever you want. It’s a drug-open society. And she and Anton Corbijn—who is now famous as a movie director, but who I brought to America as a photographer actually, I made him our staff photographer—they went off to Christiania. And it was just no story. It was just boring. Every attempt to turn it into a story failed. So finally we killed it.

But it was very rare that we killed the story because it didn’t work. We often had to kill minor stories because they weren’t written well enough or, as I said with the Hitchens case, he was doing a piece on George H.W. Bush and he manufactured stuff. And I just said, “That’s it. Bye.”

Sean Plottner: Let’s move on to Axl. And the reason I love the Axl Rose/Bob Guccione story—which I’m gonna let you tell here—but it’s particularly interesting in light of editors having to deal with celebrities in all kinds of ways. We recently had Will Welch of GQ on the podcast, and he told an interesting story about essentially giving the keys to the kingdom to Beyoncé for her to execute a cover and cover story for GQ. He called it “a deeply-involved collaboration.” Tell us about Axl Rose, of Guns N’ Roses fame, who I must have heard him three or four times just this weekend, on fade-outs from the football games, going to commercials. His voice is still everywhere.

Bob Guccione Jr: I’m going to first just make a reference to what I just said about GQ being Faustian. I don’t mean that to be as disrespectful as it sounds. I don’t mean it to sound entirely disrespectful when I call it “Faustian.” Often a publication will say, “we’d rather have celebrity X.” And after a while if you give up your integrity, you give it up.

And so they put Beyoncé on the cover. She gets to write a piece that is essentially a free, multi-page advertisement in a large-circulation magazine for herself. It’s bullshit. It’s bullshit. It does no service.

And I still believe—and I will go to my grave believing—that ultimately the role of journalists and editors is an obligatory role. We are obliged to be honest with our audience. We are obliged to show warts and all. I don’t like photoshopping of covers. I never liked photo retouching of covers. I never did it.

I believe if somebody has a bump on their nose, they have a bump on their nose. That’s it. So yeah, we banged heads with a lot of celebrities. We had our shares of knock down, drag out fights. The thing with Axl Rose was actually much more interesting than just disagreeing with a publicist on how somebody was going to be handled.

We received a contract in the mail. All press that were interested in doing a piece on Guns N’ Roses—we had not expressed interest at this point but they knew we would be at some point—was given this contract. The contract said Guns N’ Roses completely controlled the interview. We have to agree to every line, we have to agree to the captions under the photographs, we have to agree to the headline and the deck.

Violate any of that and you admit to, in this contract, owing us $100,000. So they have imposed a penalty that if you didn’t let them have complete control, you agreed to pay them $100,000. So one of my editors walked into my office waving this thing at me and said, “Bob, you’ve got to editorialize about this.”

And I said, “No, I’m not going to editorialize about it at all.” I said, “Run it. Print it. Print the contract.” And we put it in our upfront section. And that was it. And as the cover was being shipped about two weeks later, I said, “Add a line above the logo: ‘How to get your own Guns N’ Roses interview, page 10.’” And 10,000 people filled it out and sent it in.

And the Guns N’ Roses management representative called me up and screamed at me. He says, “We’re getting mailbags, but we don’t even know where to put them.”

I said, “That’s what you get. You wanted the contract, now you’ve got it. You’ve got 10,000 people”—whatever number it was—“10,000-something people want it. Great. You reply to them. They’re your fans.” Oh, they hated us.

Then I said to my editors—this part people don’t know—I said, “Who is this prick, this Axl Rose?” I have nothing, I have no axe to grind with him anymore, by the way. FYI, you know, people sometimes say, “Oh, you and he should fight.” But now we’re both senior citizens, we’re not going to go fight about that.

I said, “Who is this guy?” Because he’s a nasty little guy. The press reports about him had shown that he was not very nice, and that he was hitting fans who were trying to take a photograph of him—he hit some 16-year-old kid from behind in St. Louis. So I said, “Who is this guy?”

So I sent a reporter to Indiana. And he did a real gumshoe job of finding out who this guy was. We published his real name—I forget what it is [Ed: It’s William Bruce Rose, Jr.]. And we got this story about a girlfriend who basically sold all belongings to support him, to go out to Hollywood and have a shot at fame. And he got out there and dumped the girl.

So it was that one little story. And it was an expose of who this guy is. No one did that sort of thing. People just took everything on face value, Oh, here’s Guns N’ Roses. They’re big. Let’s write about them. Let’s keep on their good side. So I said, “If this was a politician, we’d want to know who he was.”

So we did that kind of report on him. And he was incensed. Then he came out with that song, “Get in the Ring,” in which he attacked not only myself, but a few other people who he had a beef with. He was like, he was like the “Mini Me” version of Donald Trump in music—he had his enemies list and he put them in this song.

And I didn’t know about that. I wasn’t listening to the record. Somebody came into my office one day and said, “Oh, you’ve got to hear this, boss.” And they played it, and I thought, “Oh, that’s genius. This is great.”

So I called up Geffen Records, who were putting him out at the time, and I said, “Hey, I just heard this invitation to get in the ring. When would you like to? I’m pretty available. When would you like to do it?” I said, “I practice full-contact karate three, four times a week. So I get in the ring three or four times a week. I’m happy to do it one more time. When would you like to?”

“Oh we can’t speak to that …” and blah, blah, blah.

I said, “Well, you put the record out so actually you can speak to it, you know?” I said, “I don’t have his number or I’d call him myself.”

So anyway, finally I said, “Look, I’ll tell you what, you sound very busy. I’ll tell the press that I accept the invitation.” And of course it became a big press thing. And then, you know, I milked that and had fun with it. And I knew that it was building up this tremendous interest in Spin. So, you know, let it go! And I, of course, really was a full-time practitioner in karate in those days. I was for many years. And I was not worried about getting the ring with him or anyone else.

I was very glad nothing came of it because what good could have come from that? It was better left as a great big publicity swirl and a great joke. And here we are, some almost 30 years later, still talking about it. But I have no malice against him. I hope he has no malice against me. He dissed me in a song, I dissed him in public. And that was the end of it.

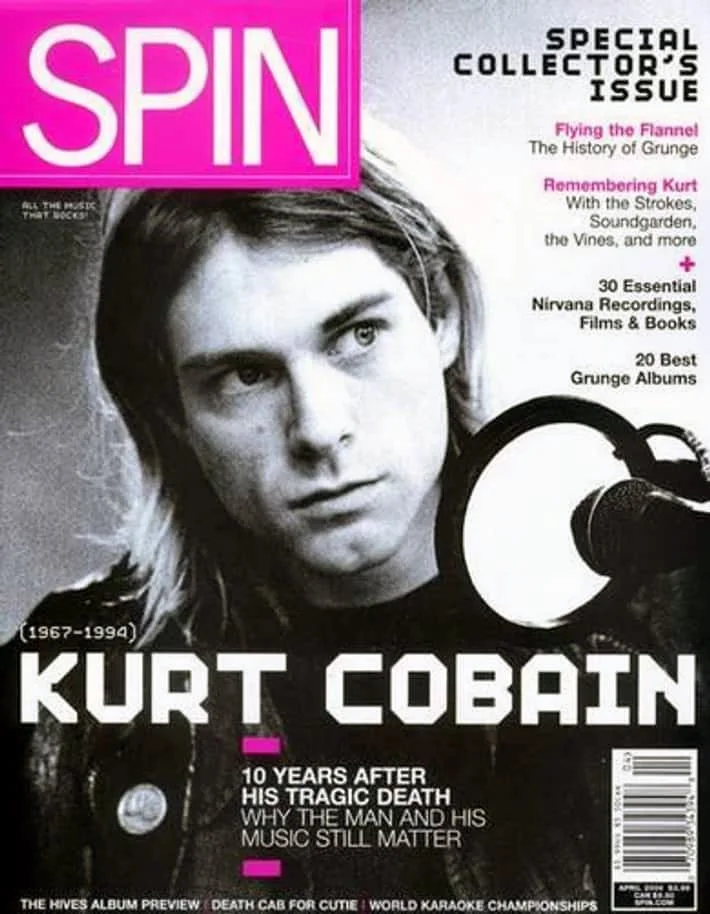

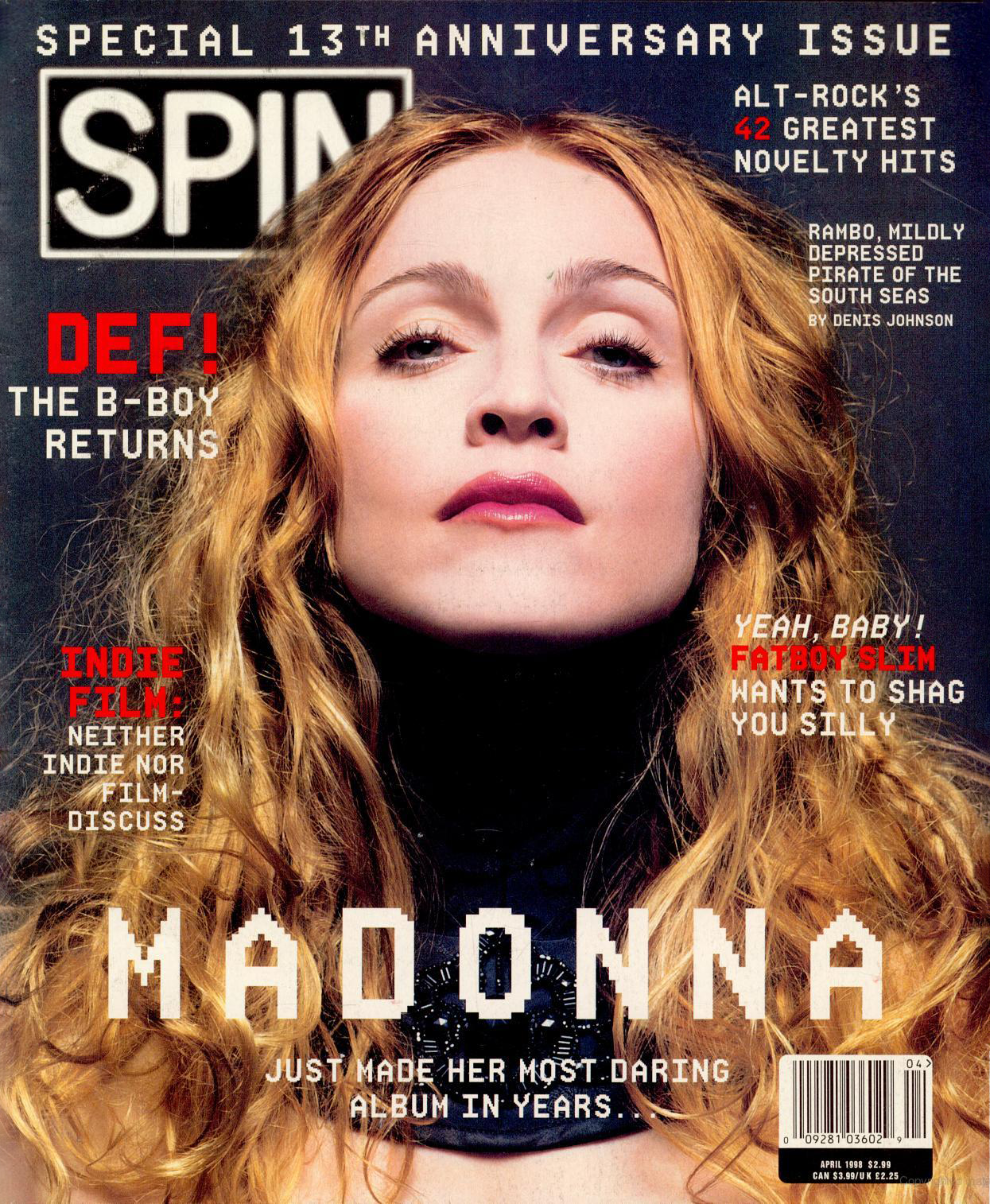

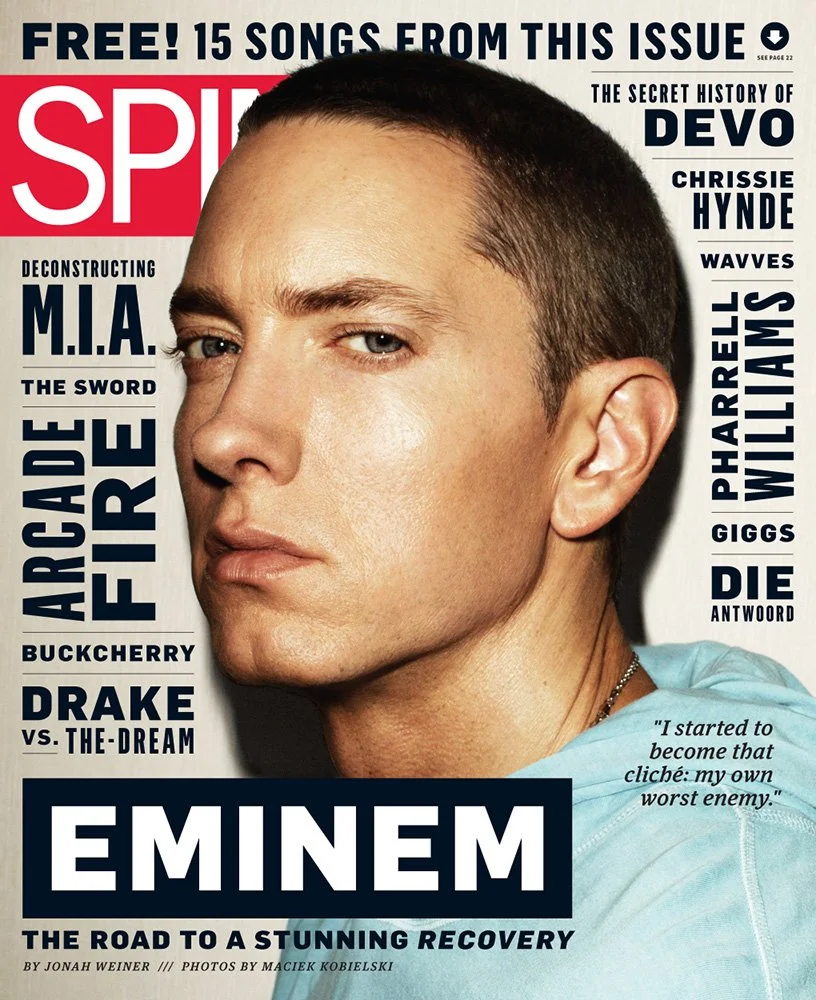

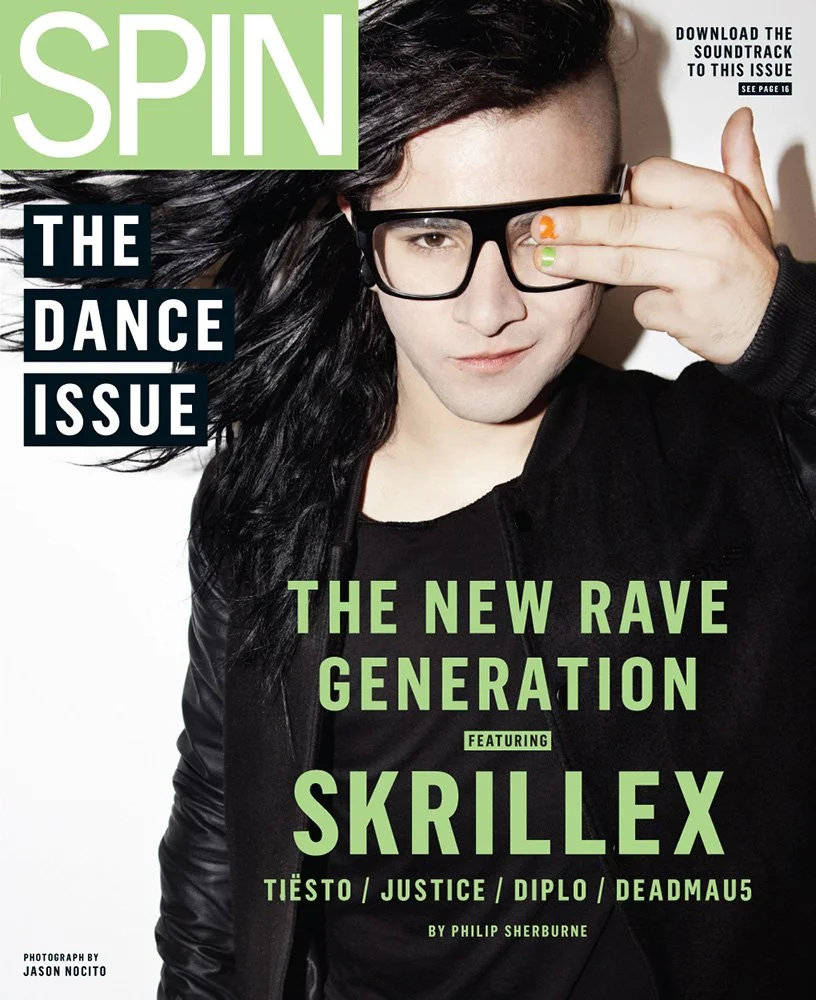

Spin in the 2010s

Sean Plottner: Yes. You are mentioned by name in the song “Get in the Ring.” Good for you!

Bob Guccione Jr: I hope there’s something else I’m remembered for ultimately.

Sean Plottner: You know, we’d be remiss to not talk about your father, Bob Guccione, and his influence on you. He was a prominent magazine publisher in his own right. What was it like growing up as the son of the founder of Penthouse?

Bob Guccione Jr: It was a bit anticlimactic—or my answer is going to be a bit anticlimactic. First of all, I didn’t even really know what that meant. And in 1965, when my father launched Penthouse in London, my mother left him. She’d had enough. He was not a faithful man. And she saw the writing on the wall when he was starting a magazine, where he was taking pictures of beautiful nude women all the time, that this wasn’t going to become a better situation.

So she took us kids to a suburb of London. My dad continued to live in London. And in 1969, he brought the magazine to America. In 1971 we moved, as a family, to America so the family could be close. We were not living together, but we got to see our father and he got to see us.

Really, when you’re in the eye of that storm, and I remember being in high school, at 15-16, and people would find out that I was his son—and Penthouse was a lot in the press—and they would think, Oh, that’s interesting, he’s interesting. And I had no idea what I was talking about. No idea at all.

And my father was very smart. He never let any of us ever go to a photoshoot. We never saw a nude woman. Unless we picked up the magazine. He didn’t want us involved in that world. He knew that we were too young and impressionable. And, by the way, horny. He wanted us out of it. He kept us out of it. My brothers and I were kept out of it. My sister, it was not an issue for her, but it would have been for us.

But I grew up away from him. All my conscious years—I was nine when they left each other, my parents—and I was very close, I was the closest to him. Partly, I think, because I was his namesake. And I had the same interests, even as a young teenager and a young man, especially.

And I always looked up to him tremendously, loved him greatly. I did not have much expectation of a sort of father who was going to go play ball with me. I once got him out to Hyde Park in London to kick a soccer ball with me. He kicked it once and said, “That’s it.”

He literally kicked it to me and I picked it up and kicked it back, and he said, “No, we’re going in now.” So he played ball with me once. One time. I didn’t have expectations of him that he couldn’t meet. And I think that was a great success in our relationship.

We also had a famous falling out. Penthouse wanted to collapse Spin into it. And I said, “No, you’re a partner, but I’m not going to yield on that one. You would have no respect for me if I did. I’d have no respect for myself if I did.” And so we separated. And for 18 years we didn’t talk, which was sad. But during that period there was never a day I didn’t love him. But I made the decision from day one I wasn’t going to let the fact that I wasn’t speaking to my dad run my life. It was my life.

At the end of my life, God gives me a ticket and says, “This is your invoice, pal, for one life.” It doesn’t say you can defray it to somebody else. In the end we reconciled beautifully, six or so years before he died. I was with him when he died, and our love was intense and renewed and I sensed we had never been broken.

Sean Plottner: Wow. I assume he taught you a lot?

Bob Guccione Jr: Oh, absolutely. My greatest influence of all time. My second would have been Patty Adcroft, who I mentioned earlier. But no, my dad was a great influence. But he was a great influence with a single sentence. I remember once I was struggling with an article—actually I wrote it for Penthouse—about two New York City cops who had solved a rape case. And I said, “I just can’t get it down to under 6,000 words.”

And he looked at me, he said, “It’s not a problem if there’s 6,000 good words.”

And do you know, I keep that with me to this day. That was 1984. I was writing for Penthouse before I started Spin. And he was like that. He could tell you things. He said to me once, “Art is not a competition.” Because I felt I wasn’t doing good work.

He goes, “Art is not a competition, you do your own work.”

“Art is not a competition”—four words, fantastic advice. He gave me great advice as a human being. I said to him once I felt insecure about something. He says, “We’re all insecure.” He says, “It’s the measure of the man how we deal with insecurity.” Again, lifelong advice, lifelong pillar that has held me up in many instances.

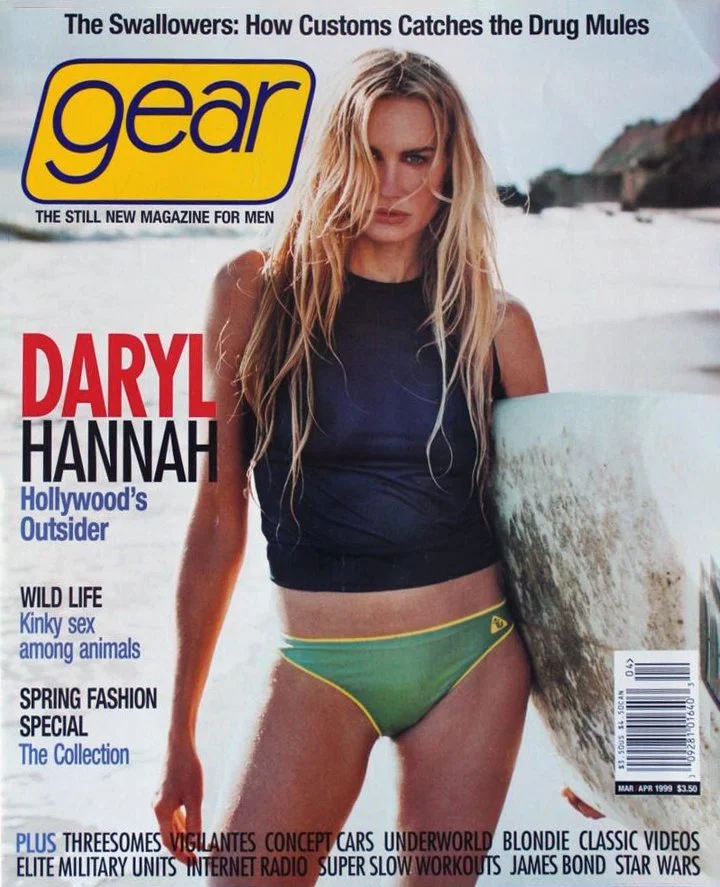

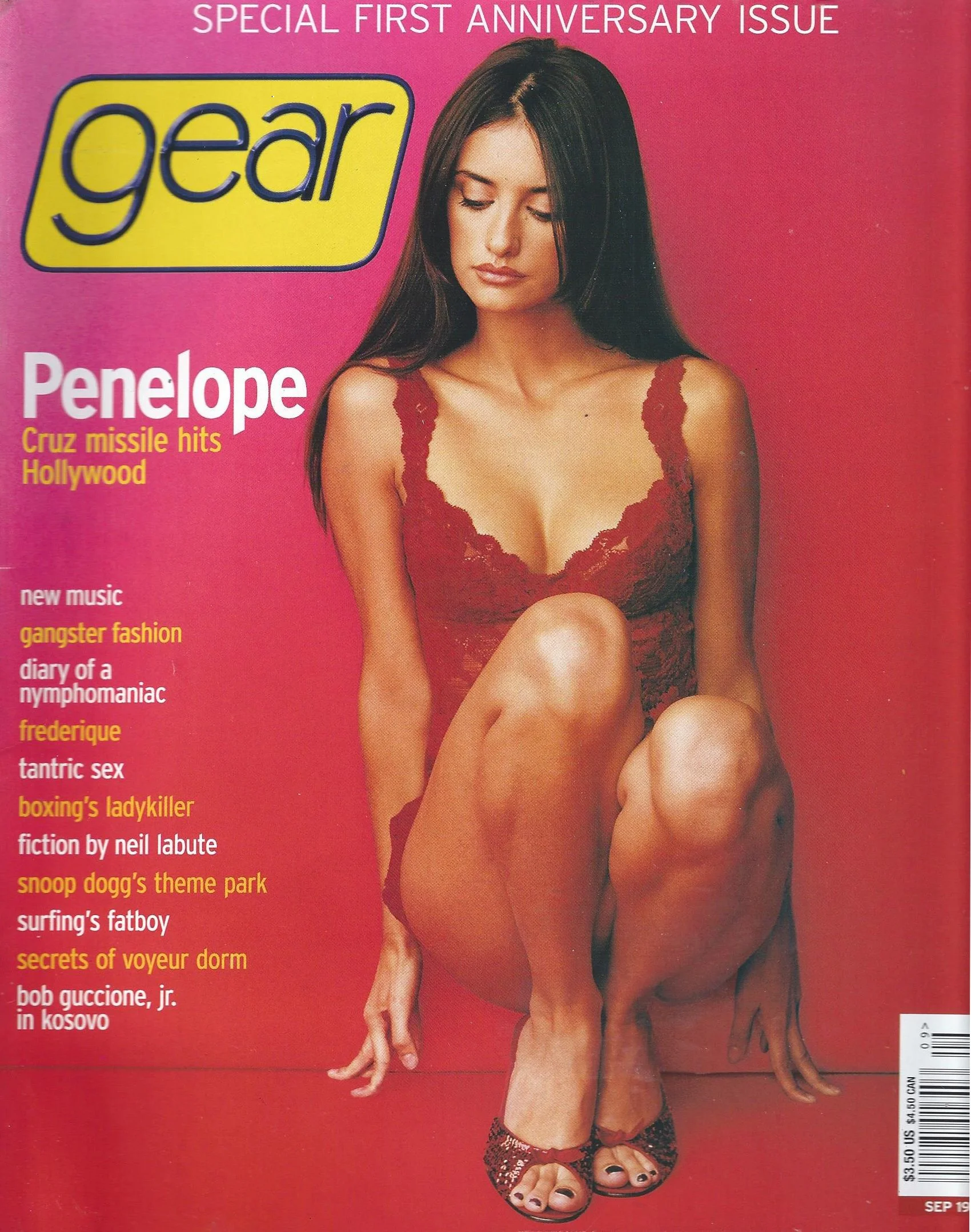

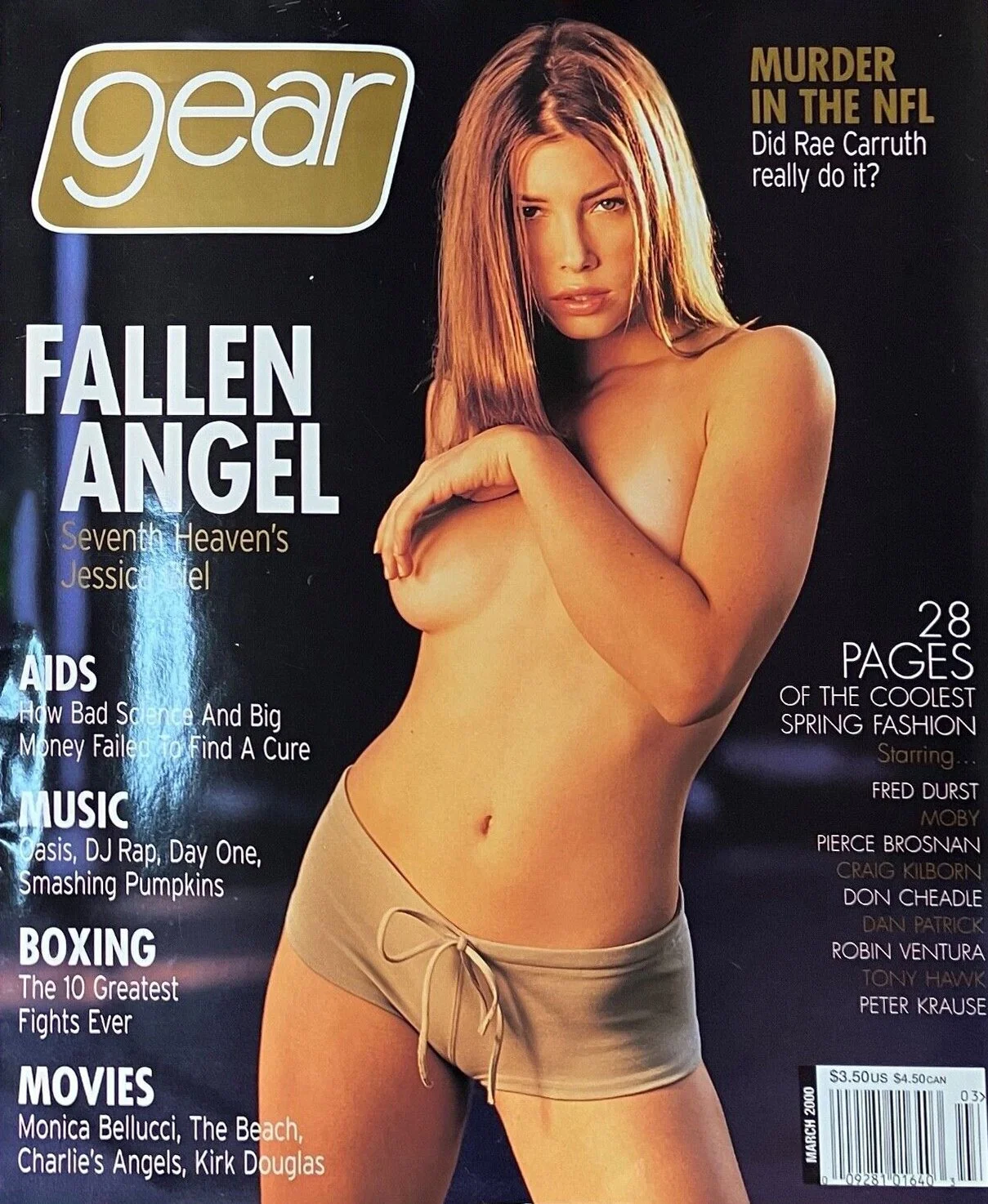

Gear, Guccione Jr.’s take on the “lad mag” ran from 1998–2003

Sean Plottner: Your ignorance of Penthouse early on reminds me of Bruce Springsteen. He recently told Howard Stern that—talking about raising his kids—one day his son came home from school and said, “Hey dad, what’s the ‘Tenth Avenue Freeze Out?’” Because he had no knowledge of what his father was doing up until that time.

Bob Guccione Jr: Yeah, that’s interesting. We project onto people like Springsteen’s kids what we think we’d be like. But my dad, his thing was to cook pasta for his family. That’s what we knew him as. And we knew other things, and after a while we got older, and we read other things. We saw him on television on many talk shows in America. And that was—it was almost an abstraction to that.

Sean Plottner: Well, and he certainly had his own style. He certainly didn’t wear pajamas all day.

Bob Guccione Jr: No, he had his own style. And I’ll tell you something else he taught me, most important of all. The most important thing—he never actually articulated it, but he led by example. I remember once he got a Brandeis award as Publisher of the Year, and I was there. I was about 16 years old. And he gave this speech about the importance of free speech. And it makes me emotional to this day.

And I thought, That’s it! You have to have the courage to stand up for this. It’s not an abstraction. Even though I was only a kid, I thought like this. It’s not an abstraction. It’s not just an ideal. It’s actually a fight. And it taught me to fight. It just taught me to fight.

And we fought PMRC (Parents Music Resource Center). We fought against rock censorship. I was the only guy in the media who would debate Tipper Gore and Susan Baker. Not because I was the best—I may have become very good at it—but I was the only one who would respond. By the time they exhausted the list of every other known music editor, they got to me because it was 1985, Spin was very young and small.

And I said, “Yeah, I’ll debate Jimmy Swaggart. Sure, whatever.” And I did. I debated him on Crossfire. And nobody else would touch it. But I knew it was important. I knew you had to fight early: “The thin edge of the wedge,” before it took a hold. And he also taught me the infinite value and essence, and essentiality of courage. You had to have the courage of your convictions. You couldn’t talk the talk, you had to walk the walk. You had to fight.

We broke the Live Aid story. We broke that story about Live Aid failing and that the money went to buy weapons, not food. In 1986, we broke that story. Every single record advertiser, which made up 90 percent of our advertising revenues—therefore it was crucial—pulled out of the next issue. They said we had salaciously impugned Bob Geldof and Live Aid and we were wrong.

And that day I called a meeting with my staff and they came into my office, a small, little office, some were just in the doorway and I said, “We can either put our tail between our legs and say, ‘We’re sorry, we’re wrong, and please forgive us.’ Or we can say, ‘We believe we’re right and we will fight to the end.’” And everybody in the room went, “Yeah, let’s fight to the end!”

And I said, “Well, I was going to do that anyway. I just wanted to make sure you were on board.” And I said something—and I’ll never forget this because it’s always also guided my life—“I’d rather fail for the right reason than succeed for the wrong reason.”

And that was instilled in me by watching my father fight for what he believed in. But also it was important and instinctual in me. And we had to do that a few times with some unpopular articles. But we were proven right in the end.

The other time we did it was with our AIDS column. We were the only music or entertainment magazine—in fact the only mainstream magazine in America—that had an AIDS column every month in 1987, through to 1997 when I sold it. So I’m very proud of the fact that we stood our ground. And secondly, I’m very proud of the fact we were proven right. That matters.

Sean Plottner: You’ve proven to have the courage to speak your mind over the years. You do speak your mind. And I think that’s terrific. You come across as ‘up.’ Very cheerful. You’re a “cheery bloke,” we might say.

Bob Guccione Jr: You might!

Sean Plottner: And yet you tell me that your girlfriend has dubbed you “the day ruiner.” And my guess is because you speak your mind.

Bob Guccione Jr: That’s one part of three. She was asked by the owner of Spin to write down job descriptions of everybody at Spin, because she’s the executive editor of Spin. And she wrote down: “Bob: day-ruiner, destroyer of dreams, makes people cry.” And it’s the best job description I’ve ever had—the only job description probably.

And it’s a joke, but she meant that I don’t give publicists what they want. I’m going to call “bullshit” on bullshit. And that’s true. And her nickname for me, since we’re being honest, is “asshole.” So I like “cheery bloke.” I like cheery bloke a lot better. I’m going to tell her—

Sean Plottner: But does she have to witness you dancing around the living room to the sounds of “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” every once in a while. Or do you not go there anymore?

Bob Guccione Jr: Never. We don’t go anywhere dancing. Let me tell you, I personally do not dance because I will lose friends and girlfriends forever. I used to dance, as we all did when we were out clubbing. But no, there’s no more dancing left in my legs.

Sean Plottner: Have you ever gotten the chance to tell Cindy Lauper that story?

Bob Guccione Jr: I did. I was on a TV show with her in the early nineties, backstage. It was, like, a local one. In Cleveland or somewhere. The Cleveland afternoon TV show. I do love Cleveland. It’s a great music town.

Sean Plottner: Yeah, it is.

Bob Guccione Jr: And I went there many times. And there’s a great radio station there, but I forget the name of it, damn it.

Sean Plottner: WMMS.

Bob Guccione Jr: That’s it! I was there many times.

Sean Plottner: Kid Leo.

Bob Guccione Jr: Yep. And so we’re on this afternoon show and she was there and I said, “Oh my God, Cindy Lauper! I’m Bob Guccione Jr. from Spin magazine.”

She goes, “Oh, I know Spin. How come I’m not on the cover?”

I said, “Well, you should be because you inspired it.”

Sean Plottner: That’s terrific.

Bob Guccione Jr: And she laughed and said, “Well, put me on the cover.” But we never did.

Sean Plottner: Bob, none of us are getting any younger. I think you’re approaching 70. What do you think your legacy will be? Or what would you like your legacy to be?

Bob Guccione Jr: I want to say that I’m very saddened by the dilapidation of the standards of journalism and the lack of simple—not even deep—courage in journalism and reporting today, outside of the obvious great reporting done on politics by the usual suspects: The Times, NBC News, and so on.

I am sorry that people think it’s more important to have a good relationship with a big pop star than it is to write something interesting for the readers. I’ve always, throughout my career, maintained that we work only for the readers. We don’t work for advertisers or distributors. We don’t even work for our investors.

All of those people have agreed to work with us. We don’t work for them. We do work for the reader and it is our obligation—this is both romantic and actually, I think, tactical—to provide them with honesty. And to not give up our integrity ever.

So I don’t know where in the end I’ll wind up when they put me in my box. Will I have been a great success? Will I be rich? I have been rich. I have been poor. I’m not rich now. But where will I be? I don’t know. But I hope—I hope—that I’ve never, ever compromised what I believe to be right and fair. And if I leave that record on the planet, that’s a good record to leave.

More from Print Is Dead (Long Live Print!)