Everything Old Is New Again

A conversation with Bustle Digital Group chief content officer Emma Rosenbloom

A conversation with Bustle chief content officer Emma Rosenblum

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT LANE PRESS

Emma Rosenblum is a best-selling author and is about to release a new novel. But that’s not why she’s here.

As the chief content officer at Bustle Digital Group, overseeing content and strategy for titles like Bustle, Elite Daily, and Nylon, she has witnessed some, if not all, of the massive shifts and changes in the media business. The ups and downs and highs and lows, as it were.

Emma’s media past includes stints at New York magazine, where she began her career, Glamour, Bloomberg Businessweek, Bloomberg Pursuits, where she served as editorial director, and Elle, where she was executive editor.

Meaning she’s a good person to talk to about the state of media today, a world where the change never stops. And she also has an insider’s opinion about the legacy big publishers and the advantages that BDG, as a digital-first operation, might have over them.

And did we mention she’s an author? Her first novel, Bad Summer People, was a national bestseller and her second novel, Very Bad Company, will be released in the coming weeks.

BDG published its first print edition of Nylon in April.

“We are as efficient as possible in an industry that is notorious for inefficiencies, and we’re lean and we’re scrappy. That has allowed us to survive and create great stuff in this era where it’s harder to break through as traffic continues to decline for every site.”

Arjun Basu: Tell us about your journey to this point. Your CV is long and it’s been through all sorts of things, and we won’t even get into your writing career just yet. So how did you get to where you are now,

Emma Rosenbloom: I have been in media my whole career. And now I am 96 years old. So that’s a long time. No, I’m not 96, middle age, young middle age. And I started right out of college. I got an internship at New York magazine. And this was in 2003, right at the time when Adam Moss took over New York and revitalized the magazine there.

And I was there for about eight years, which was just the greatest time to be at any magazine at any point in history. The crew there was just all geniuses. And all I did was learn and absorb and figure out how to become an editor and a writer and also how to marry stories with visuals because Jody Quon was the photo director there and still is. And is a genius also.

So that was a very good base to go into media. And it led me to go after that to Glamour. I went to Condé Nast for a couple of years. I wanted to try out women’s magazines. And that was a fun experience, moving to a monthly. It was a high time at Condé. And after that I went to Bloomberg to BusinessWeek magazine.

I wanted to go back to weeklies. I felt like I was craving harder features. I spent five years there, and then I decided to go back to women’s magazines, to Elle magazine at Hearst. And I was there for two years with the editor, who’s still the editor now, Nina Garcia. I was the executive editor.

And then I was recruited to Bustle Digital Group, five years ago at this point, to run at that time it was, I think, four sites we had. At a certain point it ballooned up to about 12, maybe three years ago, and now we’re back to a healthy, eight-and-a-half-slash-nine brands.

And I’m the chief content officer here, so I run our editorial team, our fashion team, our beauty teams, our operations for the editorial side. And I’m part of our C-suite. So I'm working with our executives across the board on company strategy and with our revenue side to figure out how to make money doing what we do. So that’s how I’ve landed right here.

Arjun Basu: So I’m going to ask you about your job, as it is now. How does that work in terms of editorial and content policy, are the different media brands silos, what’s shared is it a front-end/back-end kind of thing? What’s a typical day like for you—and I know there probably isn’t a typical day?

Emma Rosenbloom: There isn’t a typical day, which is why I like my job, but we have come to, I think, a very efficient division of workload amongst our teams. Each brand does have its own editorial team, in terms of the actual editors that are creating the content that go up on the site every day. And they work with freelancers and writers to figure all of that out. And each site obviously is different in terms of the amount of stuff that they’re putting up every single day.

Then our creative team and our fashion team and beauty are hubbed. So each of those teams has people that work across a number of sites. So that’s creating original artwork for stories on our sites, doing all the photo shoots for stories on our sites, and the fashion that goes with the photo shoots.

And so we are as efficient as possible in an industry that is just notorious for inefficiencies, and we’re lean and we’re scrappy. And I think that has allowed us to survive and create great stuff in this era where budgets are decreasing and it’s harder to break through on the internet as traffic just continues to decline digitally for every single site.

Arjun Basu: Yeah, so BDG is one of those groupings, those media companies that feels like it has been at the center of a lot of changes, like if you wanted a case study for media in the aughts and now in the teens and the twenties, BDG would be a great case study. All the highs and the lows of the changes that have been going on. So is it like being in the center of a maelstrom, or because you're in an executive position, do you shield your teams from, or as much as you can from that reality?

Emma Rosenbloom: You do as much as you can. It’s impossible just because our industry changes so fast now. When I started and before that there were probably 20 years of growth and stability in media. And since then, in the past 10 years, it’s just been all over the place.

I like working at a company like BDG. I like change. I like when stuff is up and down. I like the excitement of it. That’s why I got into media. I didn’t want to be a lawyer. I didn’t want to just do the same thing every single day. So to me, the challenges that we face and how we do pivot and how do we continue to survive is part of the excitement of my job.

The company is now 10 years old. I joined five years into the company’s life. The initial strategy of the company was scale—women’s, lifestyle, digital, journalism—but scale, grow traffic. And they were very successful at that. They figured out how to do it. They figured out search.

It was a different time on the internet at that point. But our CEO, Brian Goldberg, what I have always liked working with Brian is for a number of reasons, but also because he does have vision of where things are going. And even if they’re not always a hundred percent, he sticks to his guns.

And when I came on, he recruited me because I had a strong features background in magazines. I worked at Bloomberg for five years. I was not coming from a background where traffic was important or key. It was about telling the story. It was about, What does everything look like? Is it premium? Does it read like it’s professional? And they didn’t have that at the company. And he said, “I’m hiring you to do that.”

So it’s not going to be tomorrow. We’re going to see this slow change. He believed that the internet was going to shift so that it was going to be quality over quantity, that Google is never to be trusted, that we can’t base our business on an algorithm that we have no control over. So we have to build brands that have longevity, that we can build events around, that we could possibly do print.

And I was like, “All right. It sounds as good as anything. I don’t know, Elle’s just going to continue to decline in revenue, so I might as well try this other thing.” And that mission to me sounded like, not like I was stepping into a job where the goal was going to be to just get as many clicks as possible.

The goal was going to be to create environments that looked good and that people wanted to visit, not just on a dotcom because Brian didn’t really just believe that brands could be dotcoms. And I agree with him, and I have always agreed with him. And we’ve seen that play out and it’s actually exactly what happened.

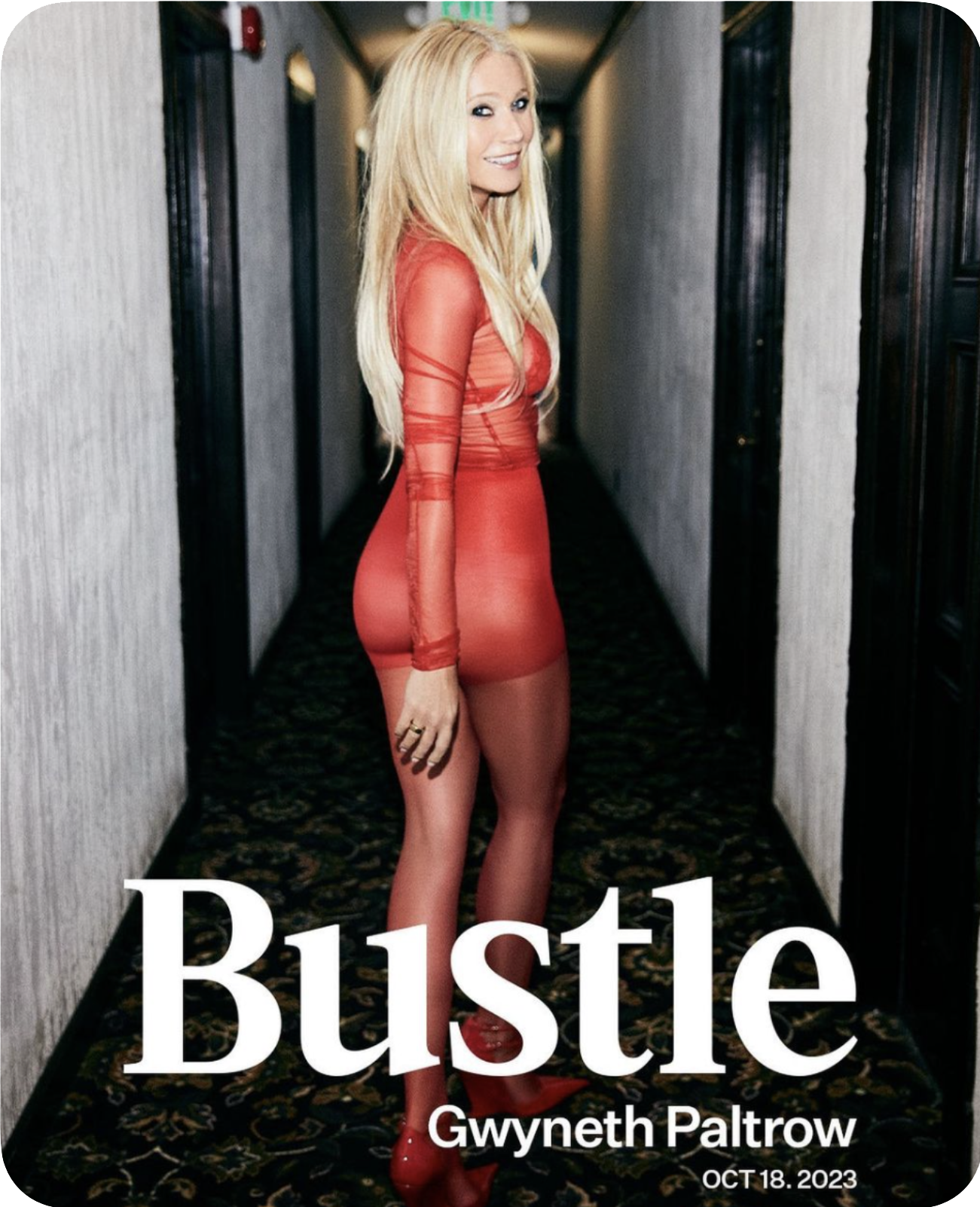

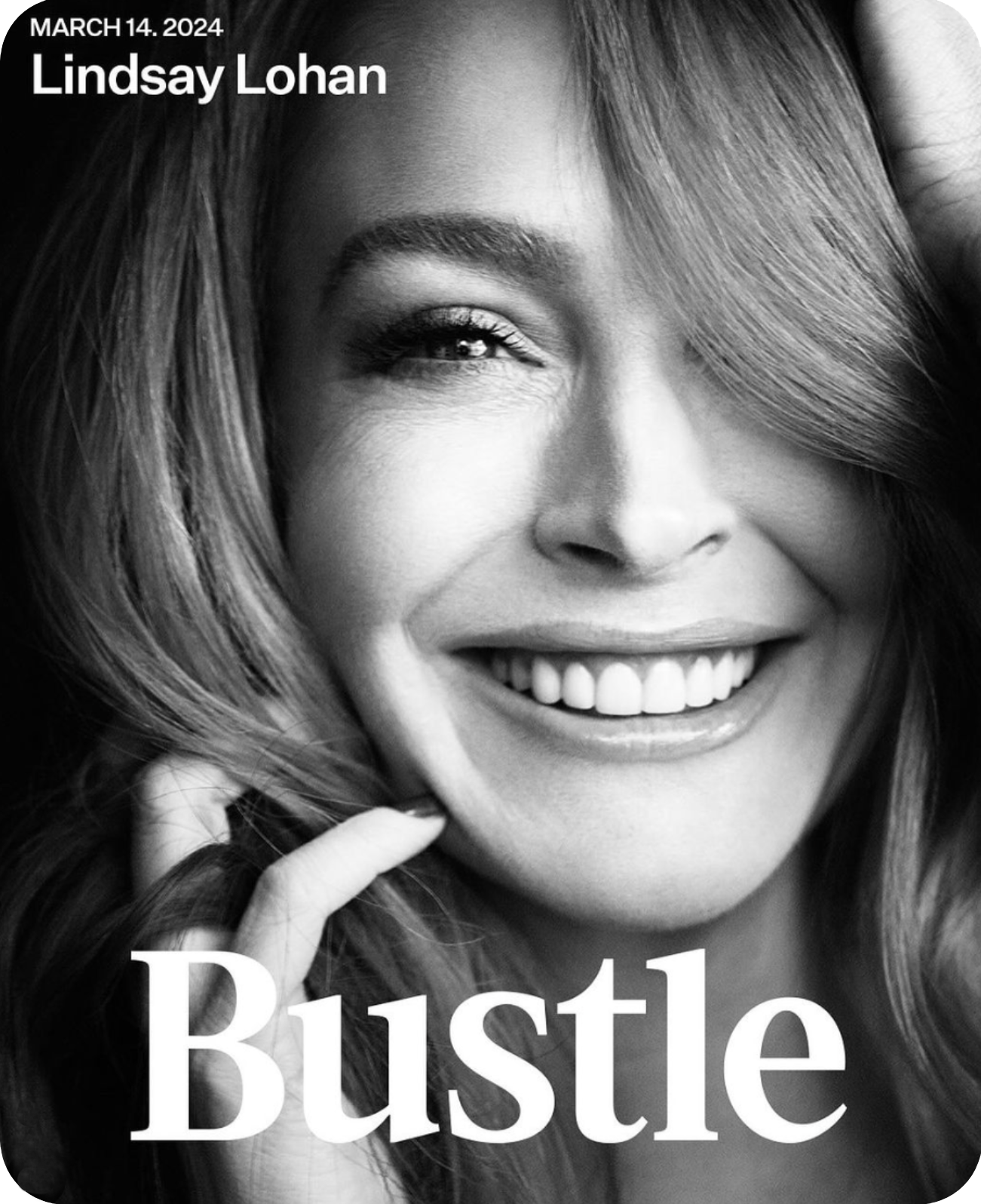

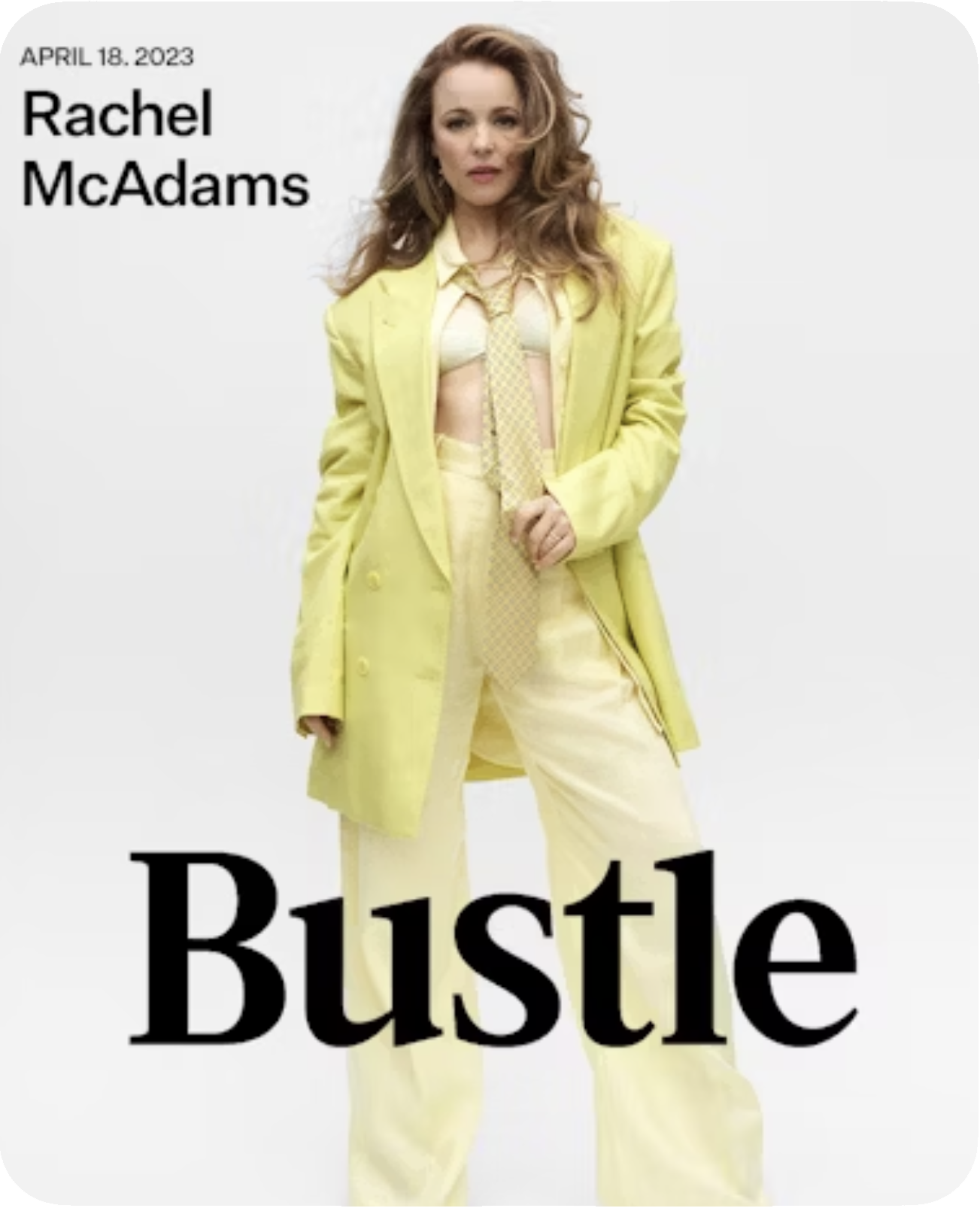

And I think early on, as a digital media company, leaning into shifting our brands more towards the legacy model of actual strong brands that people like, and return to, and see A-list celebrities in photo shoots that can’t be replicated elsewhere. There’s only a few companies now in the ecosphere that, first of all, survived.

There’s Hearst, there’s Dotdash Meredith, there’s Condé. Those are the ones that are still alive and have brands that can attract A-list celebrities. And we’re like in there now, which is crazy to think about where Bustle started from, which was basically just let’s flood the internet with kind of junk content that we can get programmatic ad revenue.

So we’ve spent these past five years transforming the editorial piece into a semblance of what the legacy media companies have, which is quality editorial, amazing photo shoots, beautiful looking sites. And then this print piece, which we’re going to talk about, this Nylon print piece is the last piece of the puzzle that we’re adding on.

We’ve reverse engineered it. The other companies have been doing the opposite, right? They’re decreasing their print and trying to figure out how to make their digital good. We’ve made our digital good. And now we feel like we can make print. In smaller ways, but it’s not gonna put us out of business. It’s not like something that we’re going to have to then scale back.

So that’s the strategy of where we are. And again, it has been a case study for digital media over the past 10 years. It’s been really fascinating.

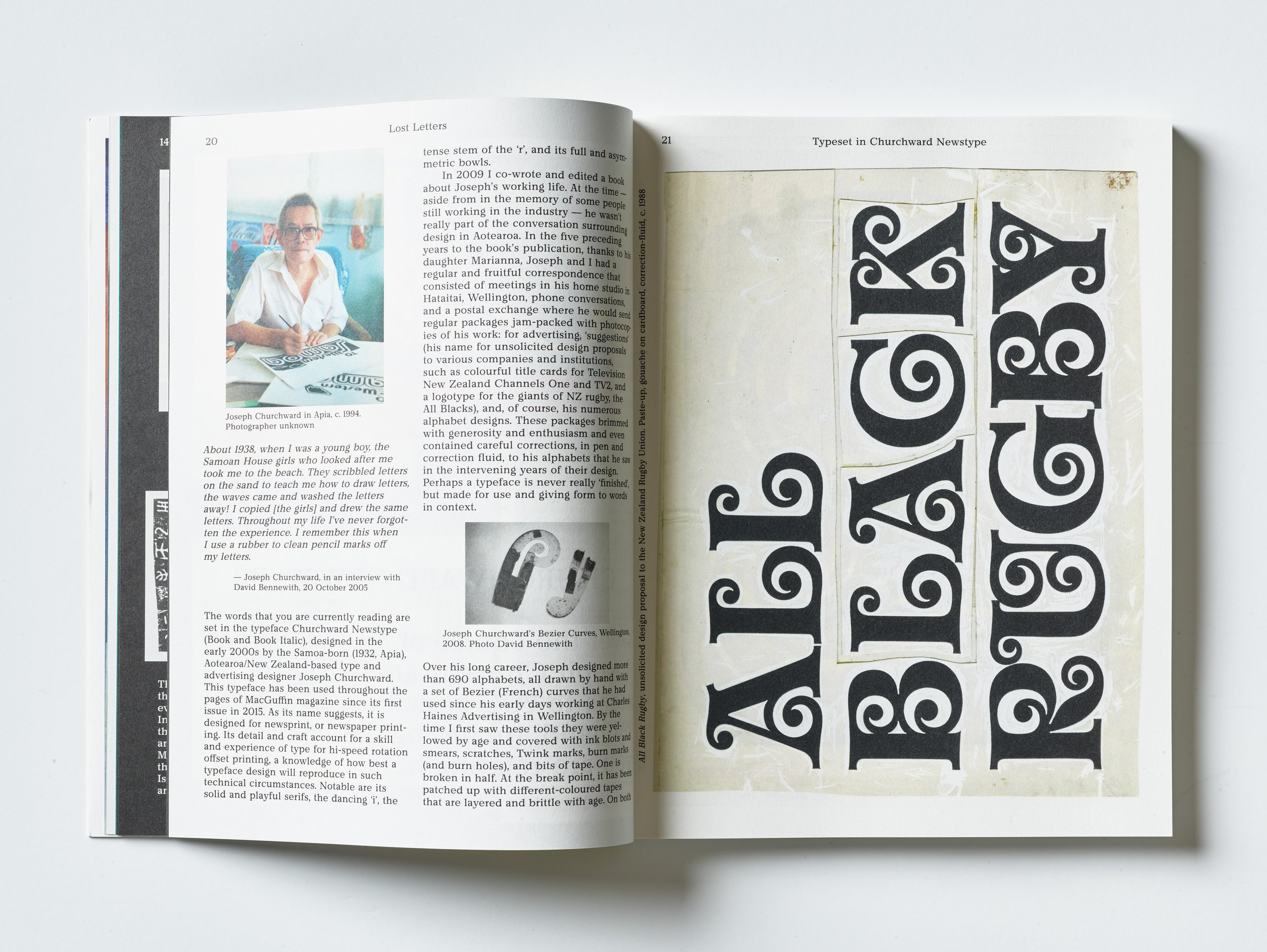

Selected pages from the new issue of Nylon.

“It’s basically elder millennials at this point who are super into Nylon, but it’s very much a product for Gen Z. It’s cool. They love this idea of being able to touch something. It’s so novel to them.”

Arjun Basu: Yeah, media in general. So, we will get to Nylon, of course, but what is the tension between quantity and quality at a company like yours?

Emma Rosenbloom: You always have to have a base layer, right? In digital media, you can’t be a magazine. We were talking about before we started recording the kind of slow pace of what making a magazine used to be where everything was labored over for hours and days, and we don’t have the luxury of doing that as a digital media brand. You have to have stories up every single day or Google will not recognize you as a site to direct traffic to. So you have to have a certain amount of content. So that is what we think of as the base layer.

We used to have a lot more stories go up every single day that would be created specifically for search traffic. So SEO stories. We’ve decreased the amount of those because obviously we weren’t getting the same return on them, but also this idea that it is literally impossible to put up 80 stories a day on a brand and have them be good. It’s impossible.

There’s not enough editors in the world who’d be able to do that. And you’d inevitably get tons of stories where you’re like, Why are there so many typos in this? Who wrote this? Like a high school student? But that’s what digital media was because there weren’t enough people to do it. The quality just tanked.

So we are very much focused on having the base layer be fine and be good and be professionally edited. And then on top of that, we build our “Moment Journalism,” where we have amazing packages by our editors, depending on the site, what they are. We have beauty awards. We have zeitgeisty essay packages on Bustle about what your life online is like as a millennial. We hire freelance writers to do reported stories—we’re not hard hitting news—but that are making news and being shared. Our goal is always to have our stories be shared.

So those are the, sort of, cherries on top that we’re also doing—not every single day. And Brian likes to tell this anecdote that in the old days, when you thought of what’s the best media company in the world, you’d say, “It’s Disney,” right? Think about how successful Disney is. And now, when people ask him, “What’s the best media company in the world?” He says, “The NFL.” Because he says the NFL has figured out that you don’t have to own every single night of the week. They are just going to own a certain amount of Sundays a year, and make those the biggest events, the best events that they can be, and make the most money that they can. And that’s it. And then you’re out.

So this idea of Moment Journalism on top of this, sort of, base layer is what we go for when we’re thinking of, Okay, Bustle is going to have 12 big stories a year. How do we get those out? How do we make them the best that we can make them? What kind of money are we spending on those?

And then leave the rest to the kind of base layer that’s going up every day. That’s the model that we go for now. And we’ve figured out that this is the way forward. But it’s taken us a while to get there. I don’t think everyone else is there. So don’t steal my secrets if you’re listening to this. That’s what we do.

Arjun Basu: Magazine people listen to this more than anyone else, so the secrets are stolen. And so in an editorial calendar, a lot of your brands also have events, obviously, and flywheels for more content and not just print, but video, and audio. Is that part of the calendar? Are those things like, We’re having this party in two months. This is what’s gonna come out of it. Put that in the calendar. Is that part of the matrix?

Emma Rosenbloom: It is. So, for example, around our big Nylon Coachella event—I do think that edit and events are very tied and it’s the content that comes out of the events that then we use to promote our events. So it’s this circle of help that we give them. I will also say that we use that to show our clients the return on their investment. We have sponsors for these events. And the more the content and the pictures from influencers on Instagram get out there the happier our clients are. We can say to them, “You invested this amount of money for an activation at Nylon Coachella event and it got 300 million impressions on Instagram because of the amount of people that were putting it up.”

And I think for them to be able to see that, it’s very gratifying. And then they know that it was money well spent. And also that feeds our sites, and we’re happy to promote all of that across all of our social channels.

So for sure it becomes a kind of content-generation event as well. So it’s hand-in-hand whenever we do them and we do them, we’re increasing the amount of events. But events are a tricky business, too. You can’t do too many of them. They’re low margin. They’re hard to produce, expensive. They take a lot of people. But you can make big money on them. That’s the path that we’re going forward with.

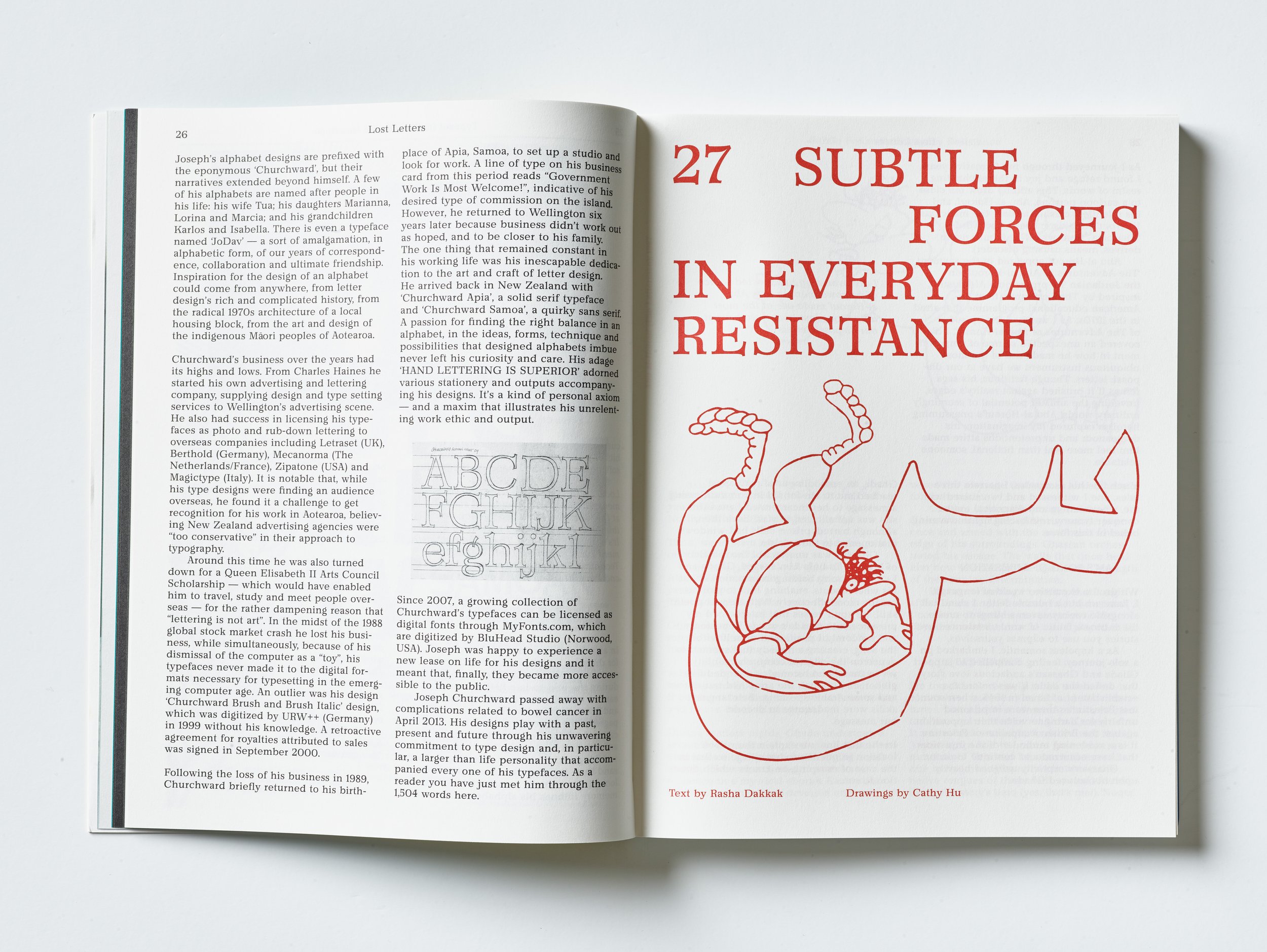

Nylon House at Coachella 2022

Arjun Basu: Okay. So Nylon’s back in print, after seven years. And the interesting thing to me in this issue is that it’s volume one, number one. I was speaking to Kat Craddock from Saveur a few weeks ago, and they just continued their number system. And I and asked her about that, and she said, “We want to emphasize continuity.” And so: 1) How did the decision come about, or why did it come about, to return to print? And 2) to start it over as a brand new thing?

Emma Rosenbloom: We had always planned on bringing Nylon back to print in some way. We’d done a few test runs of special broadsheets that were like newspaper quality where we printed our cover stories across 20 pages, plus a few other stories. And that was for Coachella last year. We had a cover with Anitta, the musician, and everyone just went crazy for it.

And we had always thought, Okay, when we have the time, the staff, and some money, we’re going to try this. We have people on our staff who’ve worked in print. I, obviously, have worked in print. I was like, “Okay, we can do it. It’s going to be a lift. But we just really wanted to.” Brian has always really wanted to. He thinks print is an important thing for the brands to begin to, even moreso, live outside of digital. We don’t like the idea that we’re fully dependent on platforms, Google, Facebook, Instagram. It’s like the idea that we could exist as a business outside of those in any way, we want to jump out. And print is one of those.

It doesn’t matter if Google changed their algorithm. We still have an issue of Nylon that Mark Jacobs can advertise in. But that said, obviously, knowing the cost of print, and the time it takes, and the care, we had to wait until we had enough people on our staff who could do it. And then also until we had some money freed up where we could do it.

And as an investment we needed to create this one, the one that we just created as a proof of concept before we knew that we’d be able to get huge investment from advertisers. And we did get a number of ad pages in this issue, which I was surprised and delighted by it. So the decision behind it was like, “Okay we have a little money, let’s do it.”

And also that it’s the 25th anniversary of the first Nylon. It was also the 25th anniversary of Coachella. And so we felt like that was thematically a nice tie-in so we could have it at our event, which we did.

And then to start it over at issue one, volume one is just because the magazine, physically, is so different it didn’t quite make sense to just continue. And also there was a pretty long break—seven years. It’s under new leadership. That said, if you flip through it, there’s a lot of nods to the old Nylon.

“Hearst, Dotdash Meredith, Condé. Those are the ones that are still alive and have brands that can attract A-list celebrities. And we’re in there now.”

Arjun Basu: I was going to say that it feels like Nylon, like that I had maybe been away from a magazine for seven years and then I picked it up again. I looked at it. I was like, “Oh, yeah, that’s Nylon.” It’s still very downtown. It still feels like Nylon just seven years later with the regular evolution that a media might take.

Emma Rosenbloom: That’s a very nice compliment. And that’s the nicest thing someone could say about it because that’s exactly what we were going for. We obviously did all of our research in terms of going through all the old Nylons. We picked and we picked some franchises that they used to do. We used some of the language that they used in terms of naming sections. We also used old covers in certain areas in the magazine and just felt like there were enough winks and nods to the old product.

It’s a new audience though, too. Like we definitely wanted to have a nostalgia of—it’s basically elder millennials at this point who are super into Nylon, but it’s very much a product for Gen Z. It’s cool. They love this idea of being able to touch something. It’s so novel to them in that they’ve never had that before.

But it’s definitely geared towards that. Not to age myself, but we have this Coachella portfolio in this magazine, which turned out amazing. I had not heard of one these people. I was like, “Who are all these people?” Obviously I know Gwen Stefani. At least I know our cover star, but that’s what we’re going for. We want people who are cutting edge and cool. And that’s what Nylon always was. So that’s what we’ve tried to do.

The oldies like me will be like, “Who?” But I think we did successfully figure out the kind of talent to feature, and also the ways of shooting them that felt modern. Because the photography in this magazine to me also feels very modern. And if you look at the old magazines, it feels very of its time, in a cool way. But if you put those pictures in a magazine now, it would look like a black and white photo from the 1950s appearing, and that was the strategy—just nodding to the past, but looking towards the future.

Arjun Basu: I was looking through your Instagram and you have that photo of you and the editors looking at the pages on the wall. I was just overcome with such nostalgia at that point. I still love that moment where the art director would come and just start putting pages up. It just looked like, that’s where it happens. That’s the magic where you see if you have a book or not.

Emma Rosenbloom: Totally. And you know what, when we first put up the wall, I was like, “This is a failure. This is like the least coherent magazine I’ve ever seen in my life.” So we made a lot of changes. Our creative director, Karen Hibbert, worked at Condé for a long time, and I thought she would be upset when I was like, “Oh shit, we have to redo all this stuff.” But she was like, “No, you’re right. We’ve got to go back to the drawing board.” Because the sections weren’t working together. It just wasn’t right yet.

But that’s the fun of making a magazine. It’s like an art project married with words. And that’s what we all learned when we were young. And it’s what we love doing.And I had so much fun doing that. And I also had nostalgia standing at the wall and thinking, “Oh man, it was so good back in the old days. We just got to stand here with our arms crossed and….”

Arjun Basu: Exactly! Random pointing … and we called it a “book” for a reason. It had to cohere.

Emma Rosenbloom: Totally.

Arjun Basu: So you’re doing two a year. Is that the plan?

Emma Rosenbloom:This year we’re doing two. We shall see about next year. Brian’s dream is to go up to four. I don’t think we would go beyond that. It doesn’t make financial sense. So we’ll see about advertiser interests. We already have a lot for the second issue. And we knew that was going to happen because as soon as you have a physical product to give to people they want in. But it’s an expensive endeavor. And my hope is always that we don’t overcommit ourselves.

I’m also looking at the budgets and looking at the revenue that we’re taking in. And you need to be sober and not be like, “Magazines! Weee!” Because I also know how much it costs to do a cover shoot, and I know how much it costs to print it, and to hire freelancers—because we don’t actually have a real staff. All those things cost money and I don’t want us to get to a point where we have to scale back.

I would rather just be, like, really humming and having an amazing two times a year product than get ourselves into trouble with four. Though Brian’s never been one to hold back. So we’ll see what happens next year.

Arjun Basu: Speaking of Brian, I read an interview where he’s talking about the pivot to luxury, as a way to accommodate, or maybe even circumvent, media changes. And certainly luxury and beauty is a sector that knows how to spend properly and has never eschewed print. I think they understand—luxury and fashion and beauty—understand the sensual nature of a magazine. And it is a luxurious thing. The cover of Nylon is proof of that. The thought that went into the paper—we talked before we started recording about the low quality of so much of the paper that you get in a magazine store. But then you have those magazines that are coming out two, four times a year. They’re creating objects now, luxury objects. Print is luxurious, and that doesn’t mean it’s inaccessible.

Emma Rosenbloom: I completely agree. And obviously that correlates to the actual advertisers in the magazines we have. Our fashion and beauty business is really strongest for print. And that’s where we think we’ll get all of the traction.

And this idea that print is more of a collectible and it’s something that people will keep around rather than just chuck for the next month, which is what it used to be. I also like to think about and talk about—particularly coming from women’s magazines—how we used to sit around in pitch meetings and think about, Okay, how do we best tell women how to live their lives? What advice can we give? What service packages can we do?

Because that’s where people got advice. It was magazines. And that is obviously not where people get advice from now. They get advice from TikTok. And it’s often wrong, but they get it there anyway. And so completely transitioning away from service in a magazine is freeing, honestly, for someone from my background, where you can be like, “I don’t have to tell anyone anything. I just have to do really beautiful, huge pictures with high-quality profiles. Or stories that are deep dives.” And that’s kind of it.

You don’t need that kind of “bitty” front-of-book. It’s funny, actually, when we started to design the magazine—this was part of the design problem—where when I was conceiving of the front of book, I was like, Okay, service, front-of-book, bitty. It’s like a phantom limb that comes back to you and you’re like, “I know how to do a front-of-book. I edited one for eight years.”

And then we did it in this bigger format. We had a slightly different front of book. And it looked horrible because this is a big, pretty magazine. And when you try to do like bitty infographics, like, it looks not right. And so we were, like, “Nope. Goodbye. Scratch that.”

And so that was an interesting exercise in the magazines of 2024 versus the magazines of 15 years ago, 20 years ago, and how different they are. So it was a learning experience for me as well, even as someone who’d been doing it for so long, which was great.

Arjun Basu: So that’s interesting, because I was going to ask about, beyond the obvious reasons, how social—and especially the influencer economy—has changed everything. But change at a magazine must have been one of the realizations when you were creating the print of Nylon, for example. There’s a whole group of people who are doing exactly what a front-of-book, or even a back-of-book would do on a regular basis. Why try?

Emma Rosenbloom: And you know what, don’t try because the reader’s not gonna connect with that. They don’t need that. We used to do these, how do you do day-to-night dressing? That’s not something that you need to do in a magazine anymore. We do have trend pages, but they’re very visual. They’re not explaining anything. They’re not telling you how to get dressed. It’s just runway pictures because it’s a nice way to break up the big pictures. But, yes, it was a very interesting new way of thinking about what print means. And like anything, it’s changed, but in a way that’s cool, I think. And in a way that can make the magazine look even more beautiful and also more attractive to advertisers.

“It is literally impossible to put up 80 stories a day [per] brand and have them be good. It’s impossible. There’s not enough editors in the world who’d be able to do that.”

Arjun Basu: And your target audience is not the target audience it was even seven years ago.

Emma Rosenbloom: No. Not at all.

Arjun Basu: They’ve just grown up in a completely different reality.

Emma Rosenbloom: They have not even ever bought a magazine. They don’t have any magazine subscriptions. You get a copy of Vanity Fair and you’re like, “Why?” Okay. These are the people that are again thinking about it as a product that they can hold up on Instagram and take a picture with and be like, “Look what I got!”

In a way it reminds me of how people think about books now and how they can be a way to disconnect, first of all, from their digital lives. And it’s also a status symbolizer where people are posting their books on Instagram because they’re like, “I’m not just about Instagram. I also read books.” And I think magazines can be in that same world. And that’s how we’re seeing people interacting with them.

I don’t know if people are reading it. They’re definitely posting it. So that’s good, right? I think they’re flipping through.

Arjun Basu: Absolutely. That’s the currency now. That gets to my next question, which is about the future of media. It’s a big question, but someone like you or someone within BDG seems like a good person to think about that and answer it because you probably have answered it—or at least thought about it. So what do you think is down the road?

Emma Rosenbloom: It’s definitely a question we think about every day when we are having our executive meetings and looking at our revenue and thinking about ways to continue as a company and be profitable. I see the trend away from scale. I don’t think we’re ever going back there. I think that’s done.

I see a world where we will continue to shed some brands across the bigger legacy companies until they’re smaller, those companies. I don’t think the world that can continue to support all the brands that exist.I still see that like that there’s going to be attrition there. And I think the biggies will survive.

And I think the biggies will survive in a way that we hope our biggies survive, which is this mix of digital, and print, and events. And I think it’s going to be a smaller industry going forward, but it can still be super-profitable for the companies that can make it profitable.

People will always need—I hate the word content—but they need it. And also we still seem to provide a space for regular people to connect with things that they can’t get into, people they can’t meet, celebrities that they’re never going to see in real life. There is still no other conduit. We thought, and you know what, I probably was guilty of this too, that Instagram was going to replace media for celebrities. They have their own Instagrams. Why do they need a magazine? Guess what? They all still want to be in magazines.

And this is 10 years later. This is not just, like, yesterday. Beyonce has 300 million followers on Instagram. She was just on the cover of W magazine. We own W. They still need us. So that’s not going away. And that is super valuable and will continue to be. There seems to just be this symbiotic relationship between culture, and exclusivity, and media. And I think that’s how we’re going to continue to make money.

Our events, it’s the same thing. Only a certain number of people can go to these events, even though they’re broadcast all over Instagram. You can’t go to our Coachella event unless you’re invited to our Coachella event. You can’t really put a price on that. And I think that’s the way forward.

And that’s why a brand like Vogue will always exist. That’s why GQ will probably continue to exist. I don’t know about Hearst, but there are a couple of brands there that will continue to exist. And the rest might just go by the wayside. Now, granted, they might find their like sort of niche way forward dependent on the company, but that’s how I see it going. And that’s why I think we should double down on our brands that we can monetize in that way.

Arjun Basu: We talked about books. I really thought that everyone would have an e-reader and would be reading eBooks. We wouldn’t be carrying books anymore. And that’s totally not the case. E-readers have plateaued. Audiobooks are coming up, but people still want books. They carry them. And again, they’re objects, they’re things. But they’re just things that people have that have meaning. And I think print is still special. I think we’re going to see brands that abandoned the platform come back like you’ve done with Nylon. So what about the other Nylon brands then?

Emma Rosenbloom: Oh, you mean the Nylon France and Nylon Japan? Our international brands? Nylon Guys? We only own the US Nylon. It’s licensed out internationally. We have a relationship with them, obviously. And we share content occasionally. I think it would be great if we actually had a collaboration, particularly with Nylon France. They have real brand equity, and France is obviously where all the luxury advertisers are, and they know and love Nylon there.

We, possibly, will bring back Nylon Guys. We own the IP, we own the Instagram channel. With all of those there’s potential there. We already have it as a franchise on digital, we’re going to shoot a specific Nylon Guys feature for the next issue because I just love it. I think that it’d be so fun to have its own little space. So that’s what’s happening there.

Nylon Japan is quite a success. We did a little shoot with them, we shot a Japanese band and we worked with them on that for this issue. It’ll be interesting to see how we can collaborate more with them, particularly now as we’re in print. And I would like to continue doing so. It wasn’t top priority before this, but now we have the actual impetus to be like, “Alright, guys let’s do this together.” So we’ll see.

“Beyoncé has 300 million followers on Instagram! She was just on the cover of W magazine. Celebrities still need us.”

Arjun Basu: So beyond chief content officer, which sounds like a very big job. You have two other jobs: You’re a mother and you’re also a novelist. And you have a book coming out. And when I was in magazines—I’m also a writer—I got this question all the time: When do you write? And I hated that question. So I’m going to ask you.

Emma Rosenbloom: Yes, my second book is coming out next month. I have a third book that I’m currently writing. And the answer is for the third book, I’m not. I don’t have that much time. I’m behind because this job has been very busy lately, which is great, but also it’s not allowing me time to do my side gig as a novelist.

When I started writing my first book, it was the height of work-from-home, pandemic-y time. And I found that being just on Zooms all day long was really draining, and I hated it. And I felt like I wasn’t doing anything creative and I’d just be exhausted after the day and felt just like I’d accomplished nothing.

I started in between Zoom meetings with those 15 minute-odd breaks that I would have, just seeing if I could write fiction. I didn’t think I had the bandwidth to write a nonfiction book because that’s actual work, and fiction is just making stuff up. And after a chapter, I was like, “Huh, I’ll just keep going.”

And I just kept going. And I’m a pretty fast writer. I was trained at New York magazine, you just had to bang stuff out. And I think sometimes people who are writing fiction get too wrapped up in going back and trying to change stuff before they plow forward. And I had very much been taught to just get the draft done and then you can send it to an editor and then you can make it better.

And that was exactly how I always had done stuff. So it wasn’t hard for me. I was, like, “Alright, if I have to get to 83,000 words, I’ll get to 83,000 words.” It was just like over a course of a few months. And then, not really thinking that anything would come of it, but being like maybe I can make 50 bucks on the side or something who knows?

And then it sold. And it did well. And now I have this other book coming out. So it’s been a delightful surprise in my career and a twist that I didn’t necessarily think would happen. But it’s super fun and it uses a very different side of my brain, which I like.

Arjun Basu: That’s what I was going to ask you about, because when I was editing. I found I was using the same side of my brain, but when I was more in the executive planning, strategy roles, I found that I could write more because I wasn’t using the same part. I wasn’t mentally exhausted in the same way as I was when I was editing.

Emma Rosenbloom: It’s totally true, yeah. My job is managerial. I’m just making decisions and telling people what to do, basically. I remember I had this funny conversation with Joanna Coles, who was the chief content officer at Hearst, where she said, “You think that your job’s going to be harder as you go up.” She was like, “It’s actually much easier. You just tell them what to do.”

Arjun Basu: That’s the secret.

Emma Rosenbloom: It’s not real work. To me as a writer and as an editor, the real work is always sitting down with a blank page and you’re like, “Oh God, help me. Here we go.” But my job is not like that. It’s just people asking me questions and me saying, “Yay. Nay.” I don’t know. It’s a little bit more complicated than that, but in a nutshell what it is.

So, yes, this writing is a completely different thing. And it’s hard in certain ways, like, I don’t know what to do with a plot. That’s not my main skill. But I can write characters because I had always written profiles. And I can write dialogue. And I know what a kicker is. Once you start writing fiction, it’s all just like the end of a chapter, it’s like a kicker. And there’s beginning and middle and end.

And you know that from your training as a magazine person, but it’s so different. And so I’m able to do both for now. We’ll see what happens with my third book. I’m at a little bit of an impasse. I hope my editor doesn’t listen to this.

Arjun Basu: We’ll be sure to send them the link. So we always end these things with three magazines or media that you’re really enjoying right now.

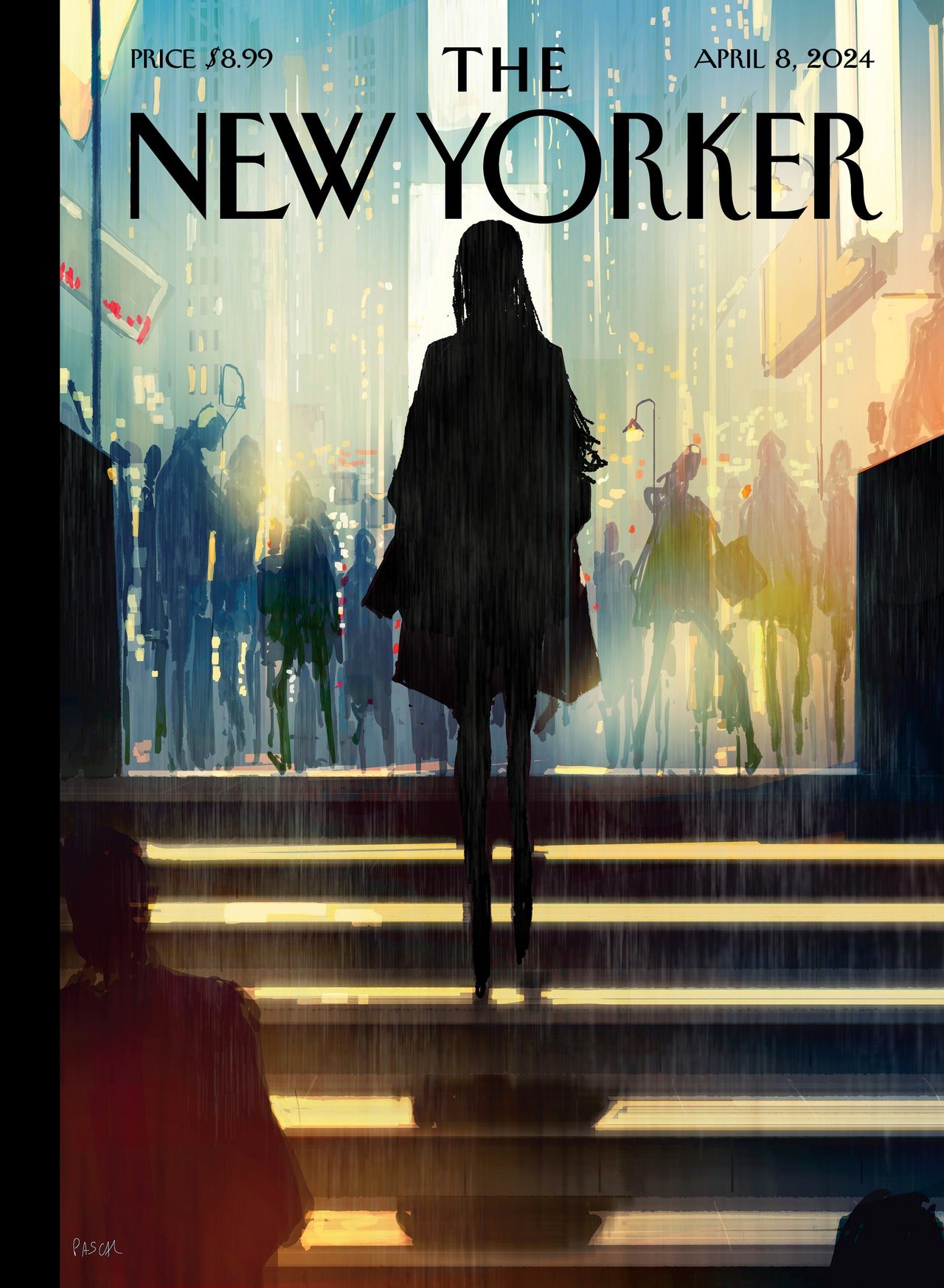

Emma Rosenbloom: Okay. I’m always going to say The New Yorker, which is just such a boring answer, but it is the one place where at least when I dive into any article, it is always better than I think it’s going to be. I think it’s going to be boring. And then I end up reading it and learning so much and then boring my husband to death on a car ride where I’m like “I read this article in The New Yorker, let me tell you all about it.” And two hours later, he’s like, “Can you stop telling me facts from this article from The New Yorker?”

It is so well-done, and well-edited, and well-written, and will continue to be, hopefully forever, because at least we have to have one place in our industry where it’s just the shining star of quality writing, and editing, and storytelling. And also so much unexpected humor in that magazine. It’s not boring. So that’s number one.

I always, on my way back from dropping my kids off, I listen to Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend, because the world is a very dark place and I am over The Daily and I can’t listen to it anymore. And that used to be my routine. And then I was like, “I can’t.” So I’ve switched over to Conan and he makes me laugh. And I look like a lunatic, probably, on the Upper East Side.

And then let’s see an unexpected one for number three that I’m always looking at. This is also so boring. This is another thing that is not actual media, but The New York Times Cooking app is so effing genius. And I am so jealous of it as a digital person. Like we don’t have products in that way necessarily. We don’t have standalone apps or anything. But they cracked a code, it’s like a drug-addiction for me, The New York Times Cooking app. And it’s not just the recipes, it’s the storytelling with the recipes. Everything is thought of in such a smart way. So good job, New York Times, on the Cooking app because I open it more than I open Instagram.

Emma Rosenblum: Three Things

For more information, visit BDG online.

More from Magazeum

Back to the Interviews

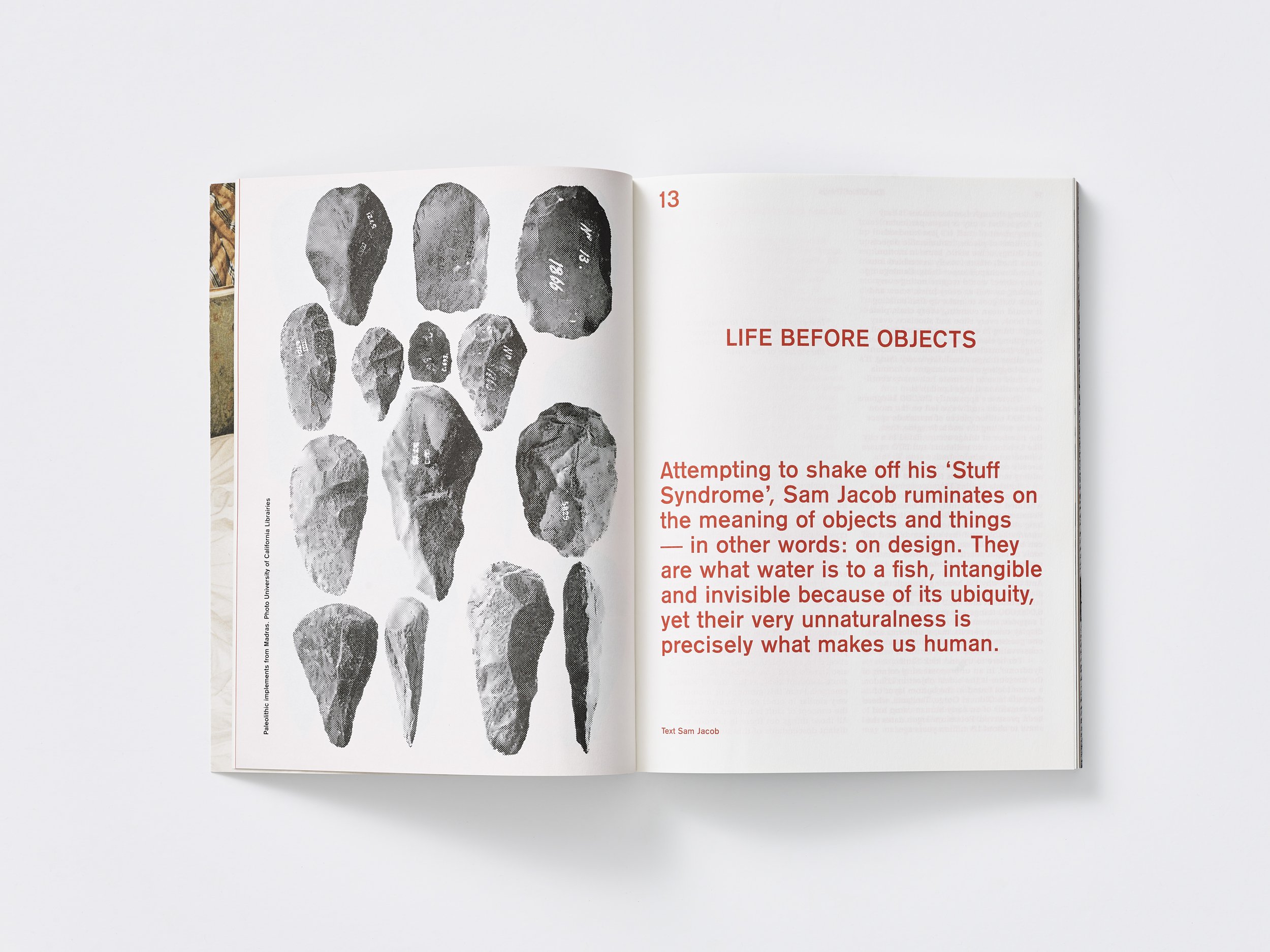

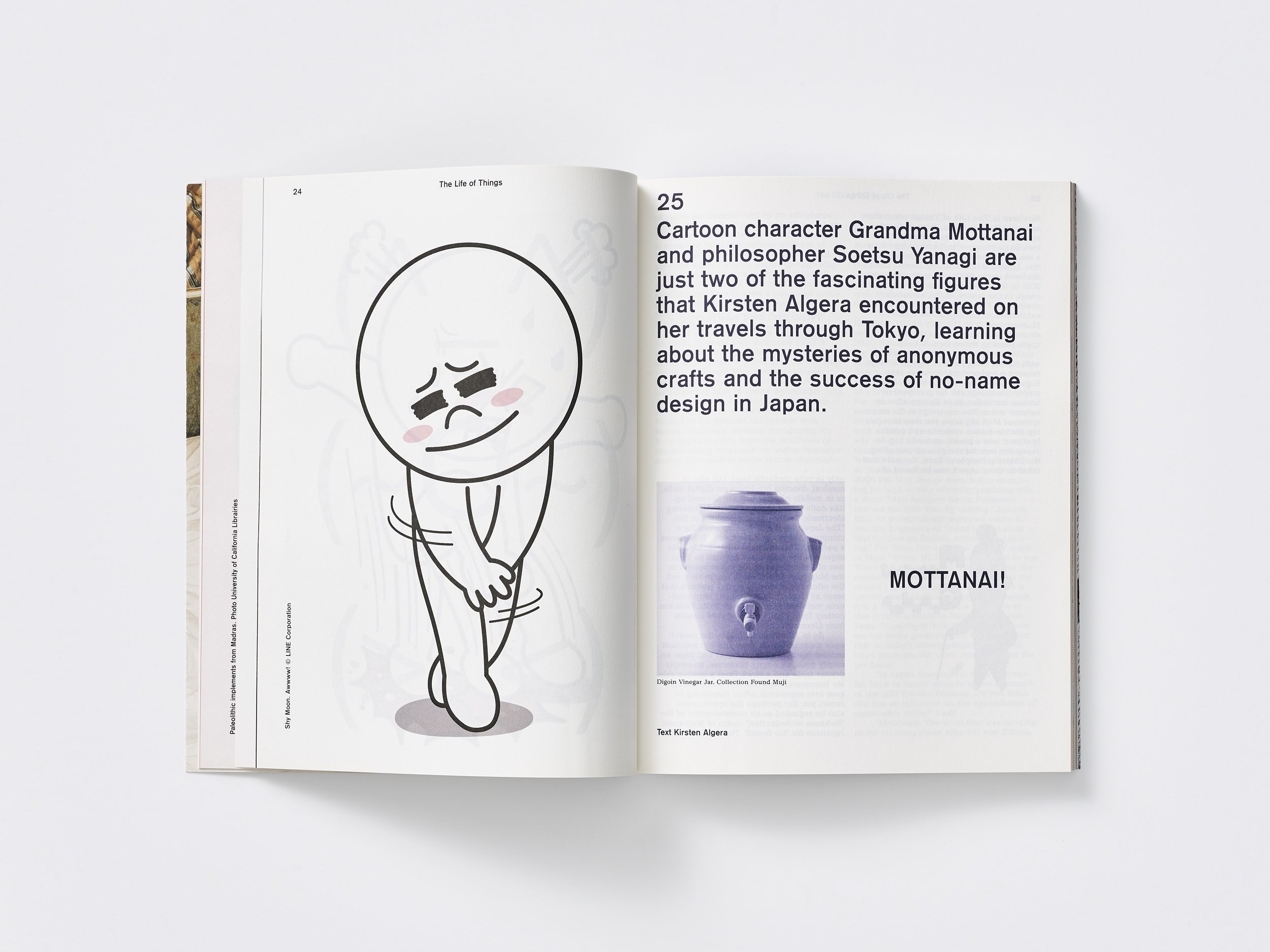

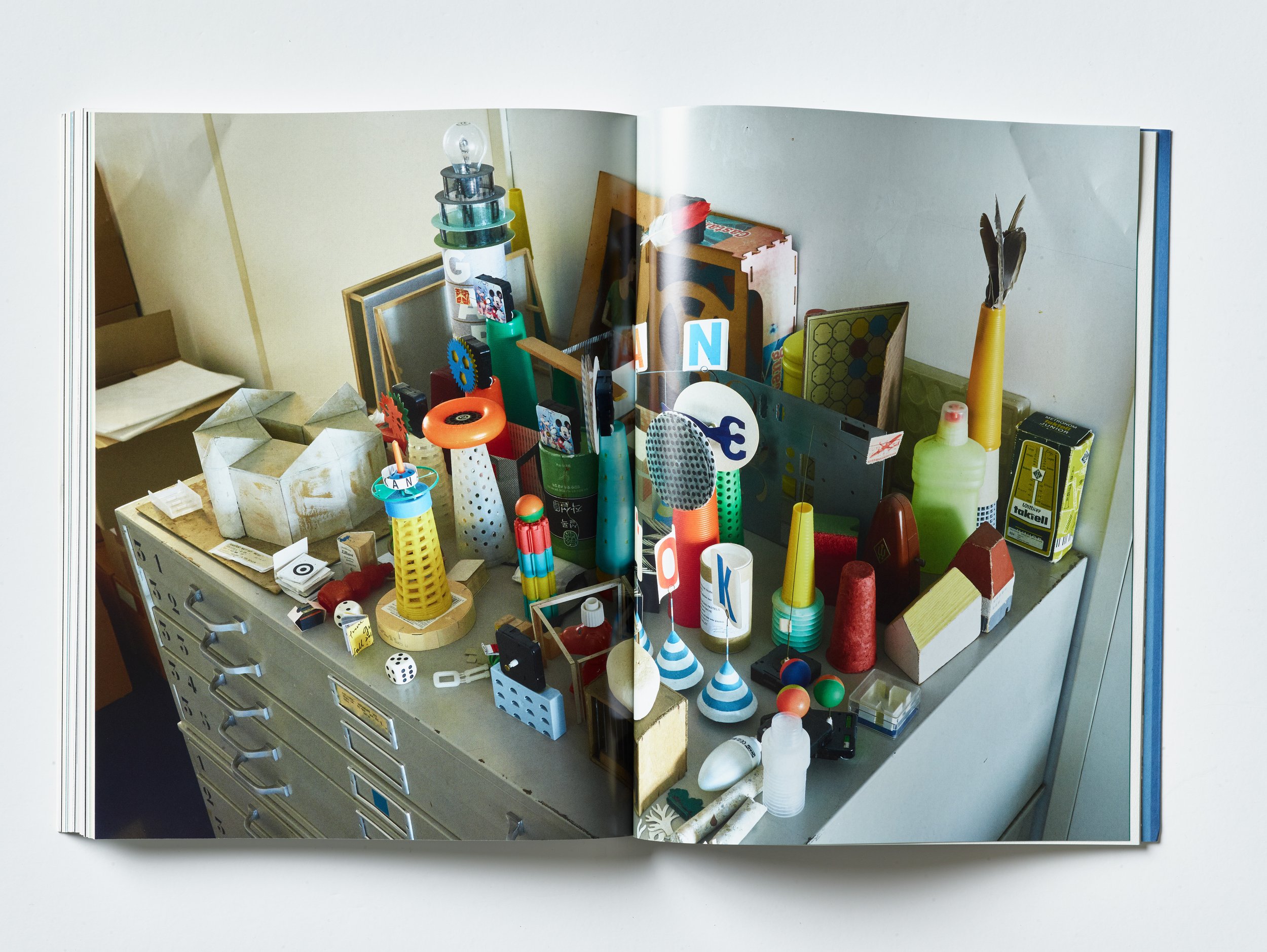

The Extraordinary Life of Things

A conversation with MacGuffin founders Kirsten Algera and Ernst van der Hoeven

A conversation with MacGuffin founders Kirsten Algera and Ernst van der Hoeven

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT LANE PRESS

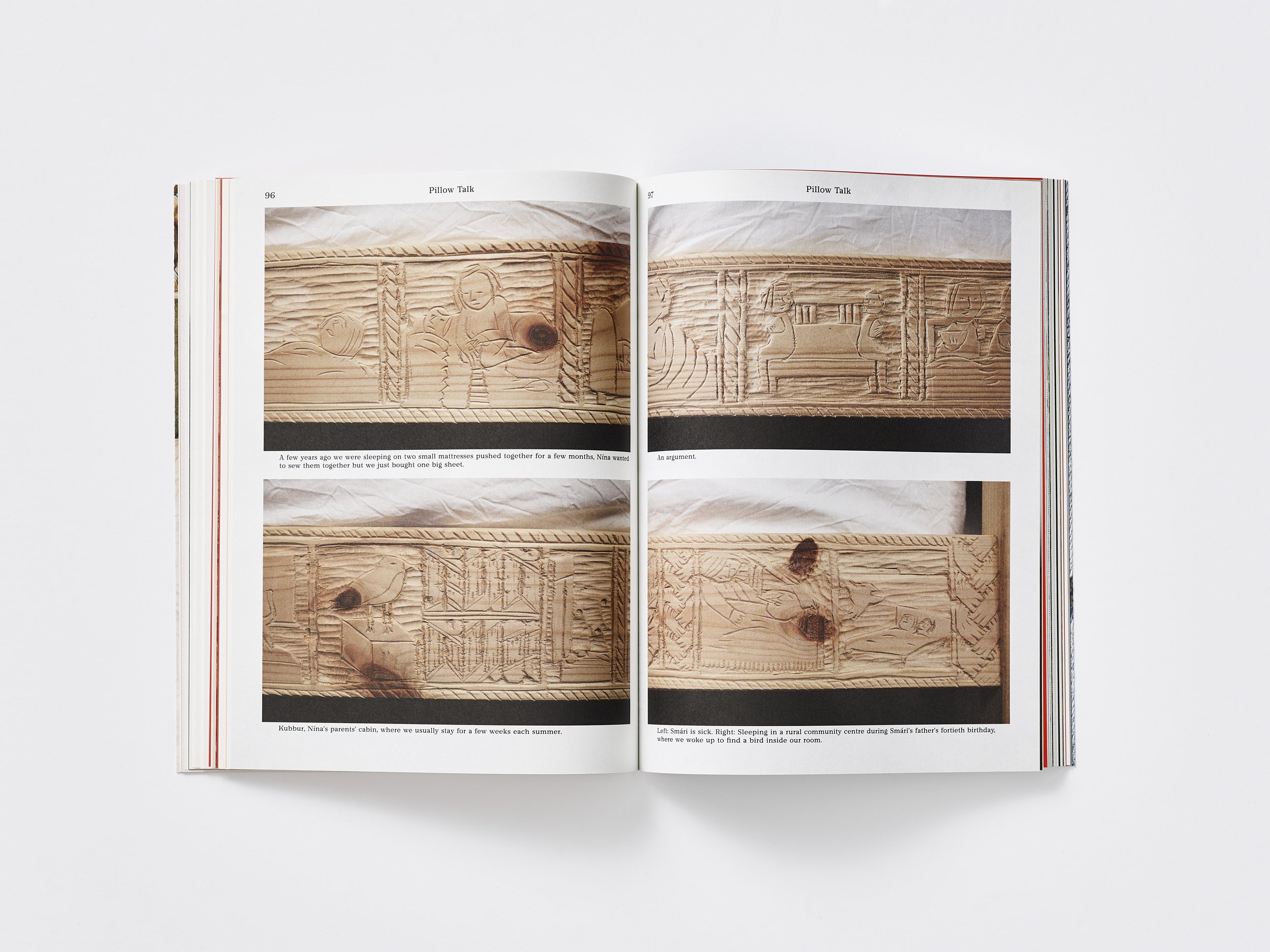

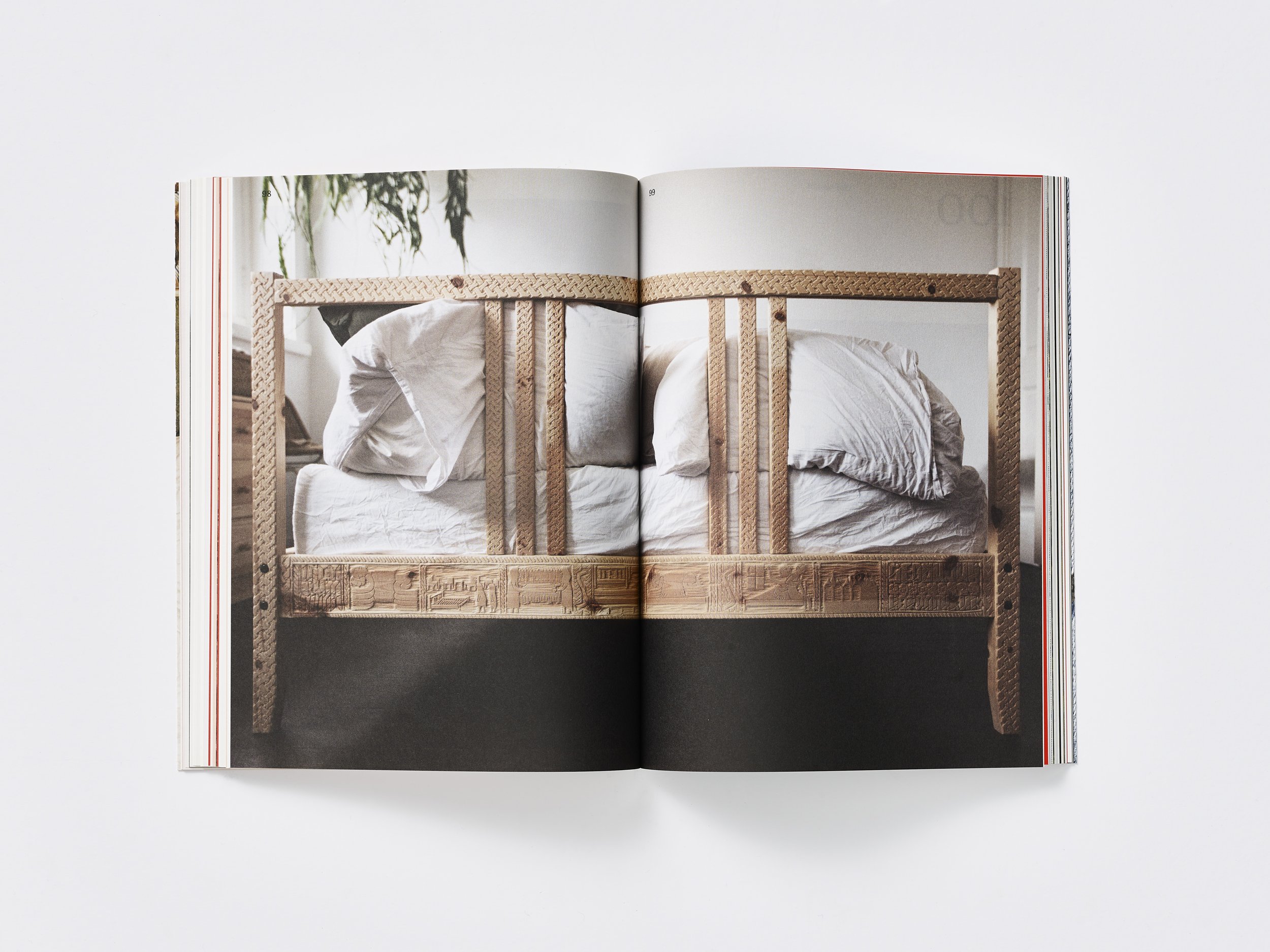

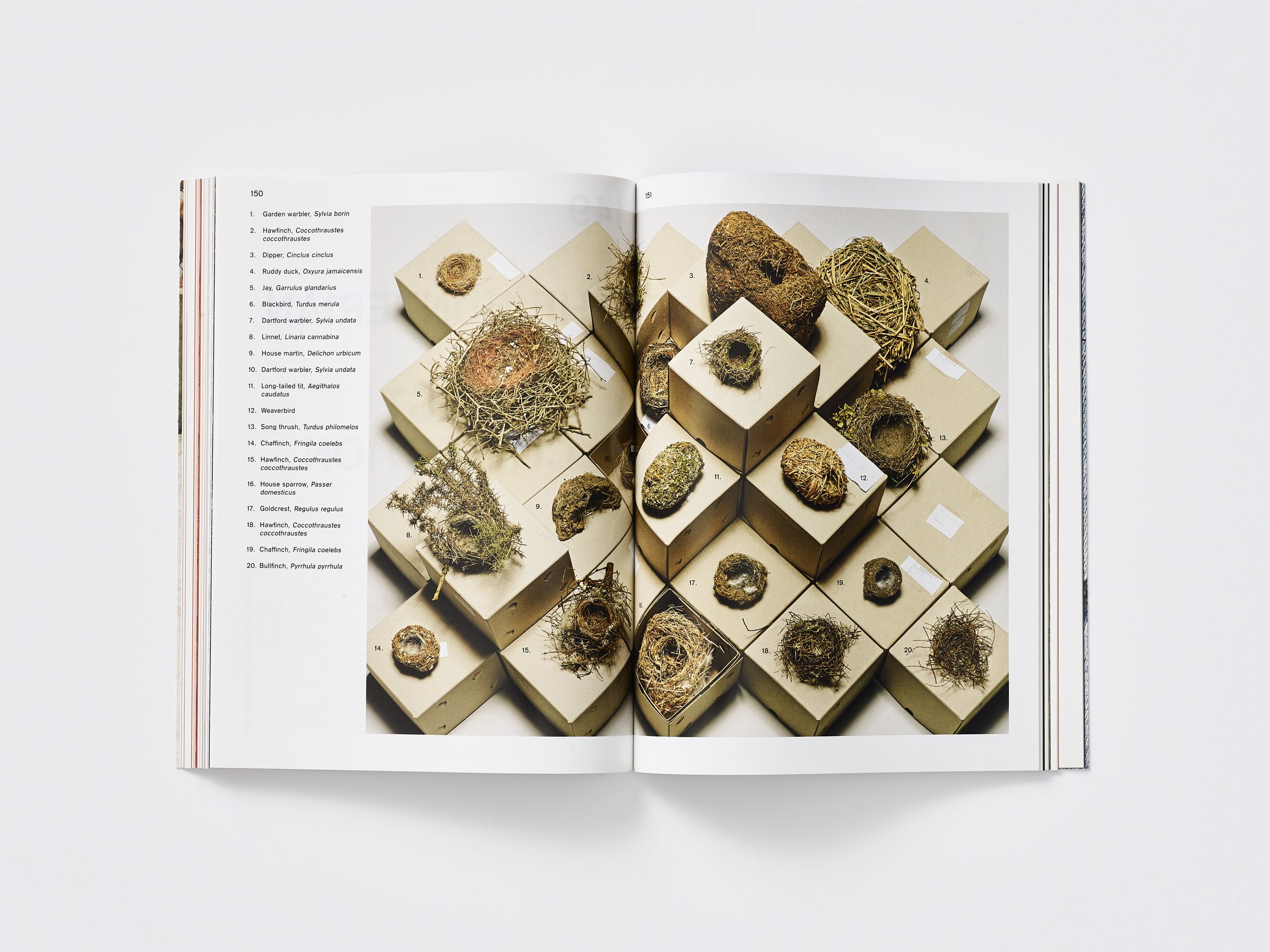

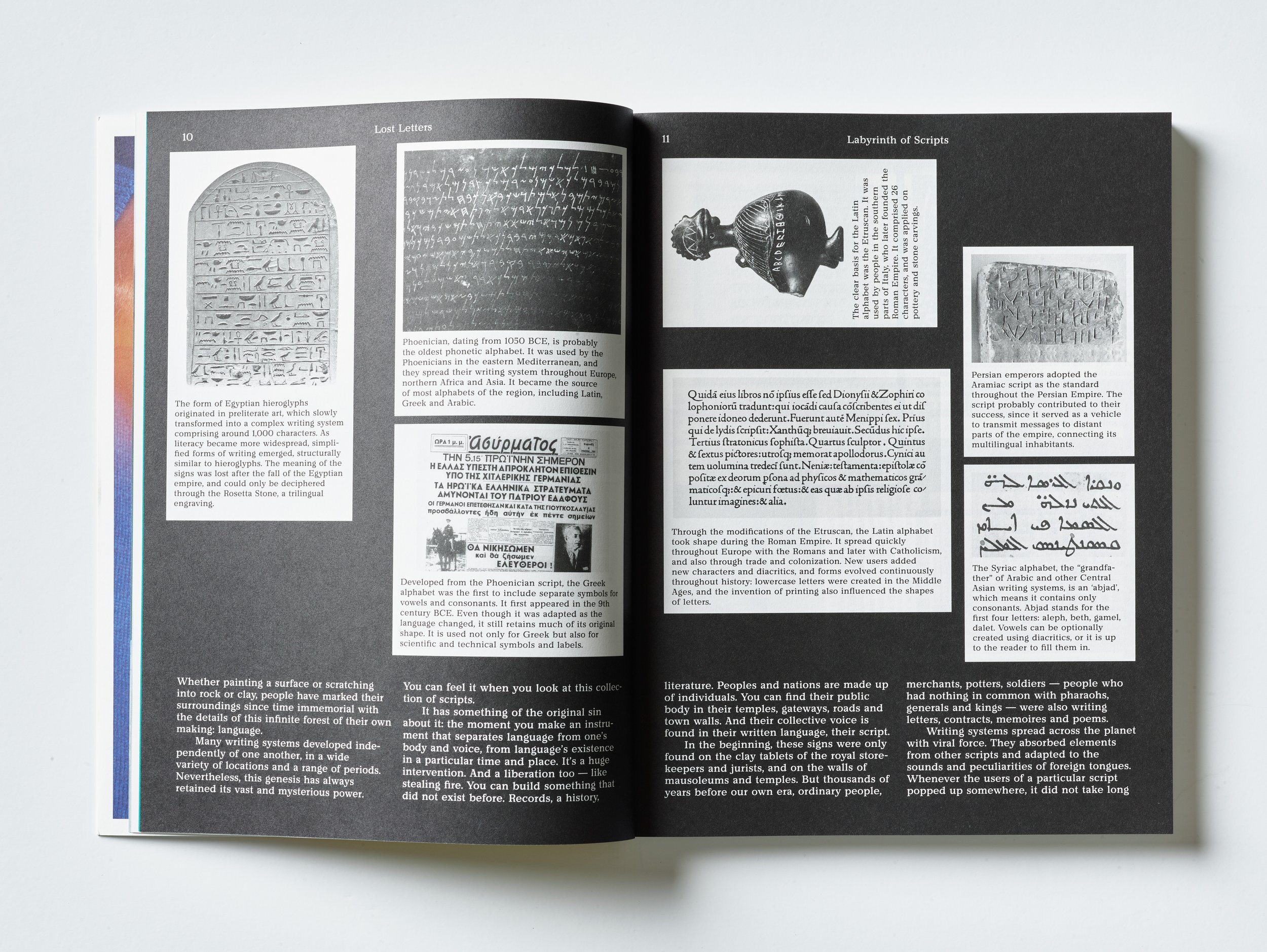

The Bed. The Window. The Rope. The Sink. The Cabinet. The Ball. The Trousers. The Desk. The Rug. The Bottle. The Chain. The Log. The Letter. These aren’t random words thrown together. Nor am I reading a list of things I need to buy—though stop for a moment and admire the poetry and cadence of the list. No, those words are the themes of every issue of MacGuffin.

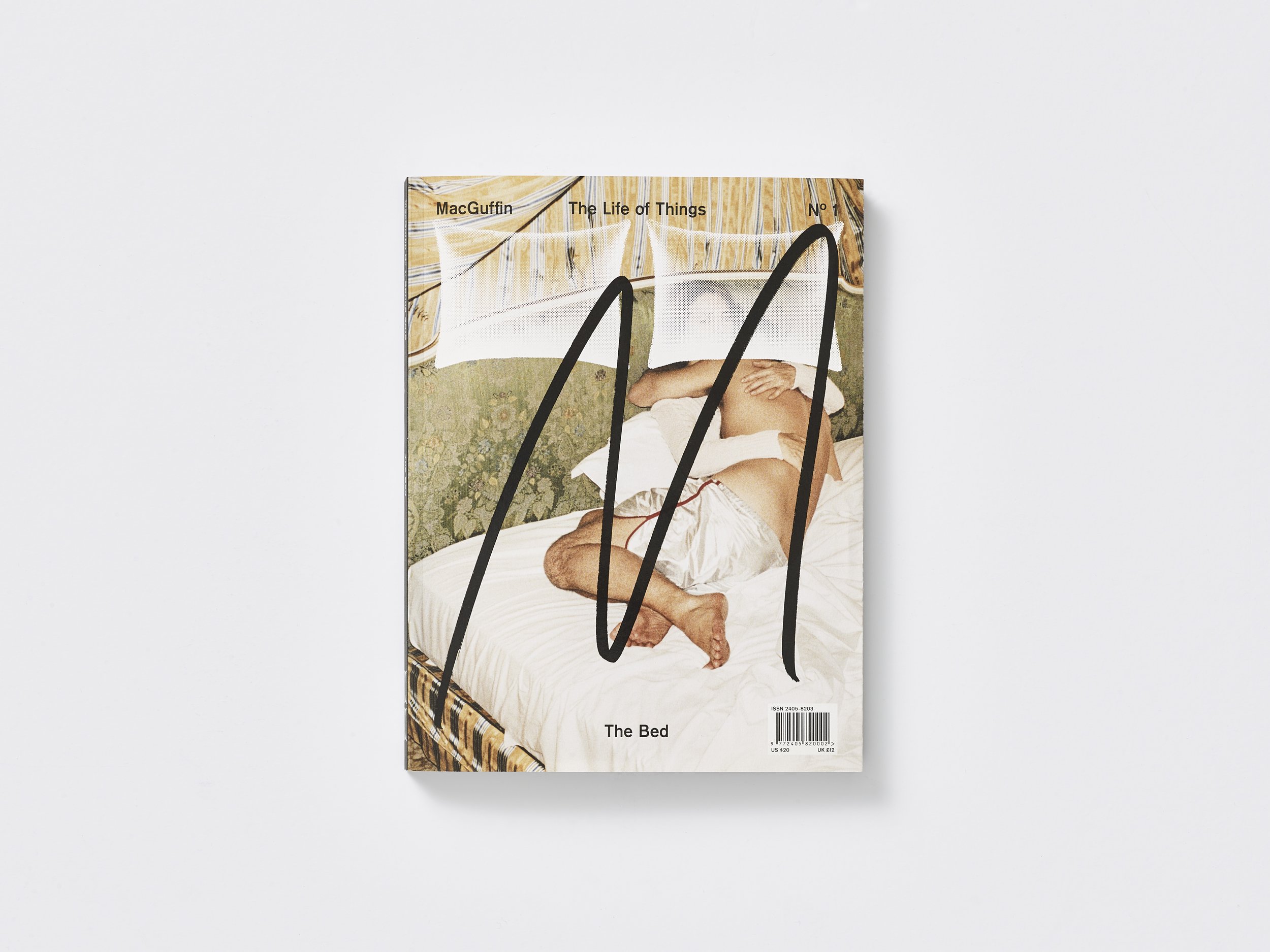

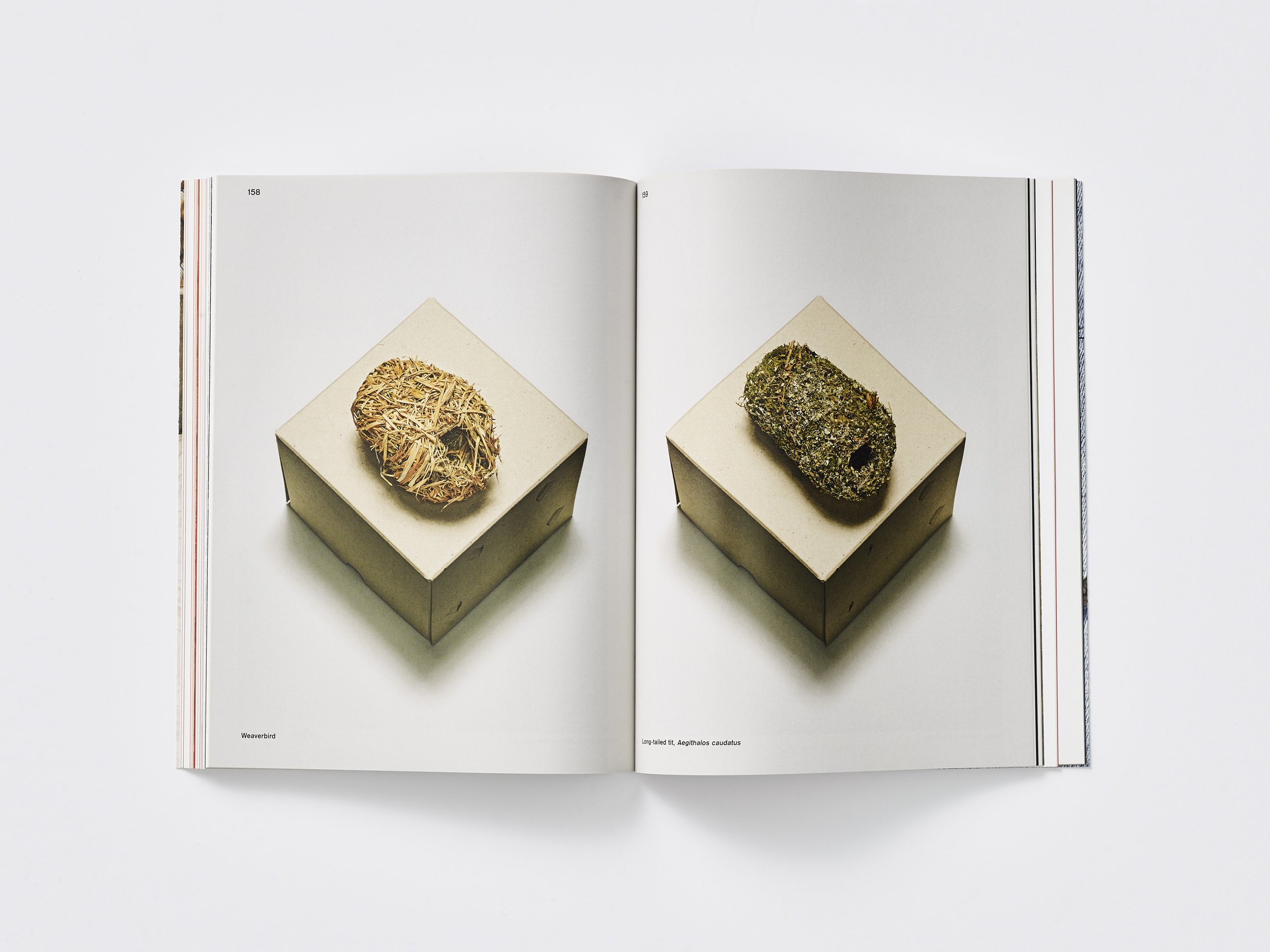

MacGuffin bills itself as a design and crafts magazine about the life of ordinary things. And in that simple descriptor, you can discover an entire world. Founded in 2015 by Kirsten Algera and Ernst van der Hoeven, two Dutch art historians and designers, each biannual issue of MacGuffin is based around a single object or word, and then explores that thing in its entirety in quite surprising, and inspiring, ways.

MacGuffin doesn’t ask much of its global audience but reading it and experiencing it, might change the way you look at the world. The magazine came about because Ernst and Kirsten both felt that the discourse around design had become disconnected from the concerns of most of the world’s people.

In some ways, they have created a magazine that rejects the modern to appreciate what already exists. But don’t mistake the magazine or their ambition for nostalgia: MacGuffin is a thoroughly modern project and an ambitious one: oversized, heavy and thick.

Both Ernst and Kirsten acknowledge they are creating an object about objects. A collectible. A collection. They do this with an openness to the world and a thoughtfulness that is admirable. Because the world of MacGuffin is the world all of us live in.

Arjun Basu: A lot of people that I’ve spoken to have already mentioned MacGuffin. There’s two magazines that they bring up—and we’ll get back to why they mention both of these—but it’s either you or Apartamento, and it really is across the board. If I kept a running tab of who got mentioned more, right now maybe Apartamento’s in the lead, but MacGuffin is a close second. So I’ll start with you, Kirsten. Tell us about your journey to this point, to the creation of the magazine.

Kirsten Algera: Okay. That’s a long story. I’ll try to keep it short. I think it started when we met, Ernst and I, because we both worked for a department that was called the Dienst Aesthetische Vormgeving, which is the Department of Aesthetic Design.

And it was a government institution for post and telephone companies. So lots of different things, stamps and telephone cards and post offices and all sorts of other design that this department guided in a way.

And it was a very special department because it not only it guarantees quality in, in the design of things, but also it was a nursery you could say for graphic design and for spatial design and for product design. So it was a special place. And I came there and Ernst, I think you were already gone by then.

So it was very, very short that we met each other, but we kept in contact. And after I think like 10 years or 12 years, I had a very bad accident. I fell out of a window in my home here in Amsterdam and I was in hospital for a long time and did a lot of revalidation. And it was a sort of point in my life where I was confronted with what I could and could not do and had to decide what to do.

So I started doing freelance jobs and doing a PhD in graphic design. And then I met Ernst again, and he asked me to work for him on the research of a project that he did. It was a project, it was an art installation in a park in The Netherlands and it consisted of a sort of cascade of textiles of cloth, indigo, hemp. Woven cloth.

And Ernst wanted to make it in the north of Vietnam, where there was this sort of refugee community of women that needed a job because they were abducted to China in their youth. And they came back and they were expelled from their communities.

And the only way that you could go there was by motorcycle. So we had long rides and then, afterwards, long evenings to discuss all kinds of things. And one of the things that we discussed was design because we both worked in the design world and we were very much uninspired by it, you could say, because it was about commercial success and innovation and star designers. And we were not really into that.

And when we talked to the women there in the north of Vietnam. We realized that the design world that we were working in was so one-dimensional. And in the talks with the women that we encountered there it was really, for us, it was surprising to hear: A completely different view on what design and crafts are in a human life. And Ernst, maybe you remember that you told me once that one of these women came to you after the textile was made, no?

Ernst van der Hoeven: Yeah, there was a whole fuss about how this woven cloth would have been sewn together. Of course I had the idea it would be beautiful, because it was 88 different grades of indigo. And I thought it would be nice if it would be gradient, but they could not understand why that was so important. Because for them, it was just a big cloth, like for maybe a fan or whatever. The whole concept of art, and the whole concept of a park, they could not understand that. I had, of course, brought with me some sketches, but they looked at me very bluntly and said, “We do it our way.”

We could not communicate because I don’t speak Vietnamese. But in the end what I did, I just went with them on the field and there we assembled the cloth together with the women, and that helped—by just doing. The good thing is that Kirsten and I both realized that the whole idea of art or design was not in their minds, but 88 percent of the whole project was done by them, anonymously.

So we thought, Why isn’t there a platform that is there for all the people that make beautiful things and are not heard? Or all the things that are already there and have a second life? Or other things that are having a history because of their use?

Arjun Basu: So was that the impetus for the thing? That there was just this basic thing missing in the world, which was that celebration—as opposed to the celebration of the new, and the shiny, and avant garde stuff, or just “high design,” and that the world was missing a celebration of what these women celebrated?

Kirsten Algera: Yeah, I think so. I think that we really felt the need to stretch the whole definition of design to make it a lot more broader than all these iconic and these new things. So it’s beyond the new that what we wanted. And also I think we wanted to tell the stories that these objects set in motion.

So one of the first things that we had, actually, was the title of the magazine, MacGuffin. Because we saw that an object has a life—it’s not just something that is made, or just something that is sold. It tells us a story, and you can look at the world through the eyes of this object. And that was our starting point.

Arjun Basu: You’re both art historians. How much of that influences the way MacGuffin actually turned out?

Ernst van der Hoeven: We both started maybe as art historians, but we’ve done a lot of things. And after my study of art history, I went into city development and urbanism. And after that I did a master’s in landscaping. And in between I did a lot of art-related projects. So I always had the problem that I was a generalist and then, at a certain moment I was designing gardens and parks and then curating exhibitions.

So people always ask me, “What are you doing? What is your discipline?” I always had difficulties deciding in which discipline I wanted to be. And the moment we started the magazine, this all fell together. Because you use all the knowledge that you have on the different fields. And I think that is something that I really enjoy now that I can say, “I’m an editor of a magazine.” And all the disciplines that I’ve worked in feel like something that I can use.

Arjun Basu: There’s two words that are parallel to each other, but that really do mean different things, except I think you guys just destroy it. And that’s, ‘editor’ as you just said, but ‘curator’ as well. And I think in an odd way, you have really just combined those two words in a way that is, I think, amazingly unique. You said you’re an editor, but do you consider yourself, what you’re doing, curation?

Ernst van der Hoeven: I’m very happy with this question, because it’s exactly what we do: We curate a magazine. And for us, it’s as we make this magazine, it could easily also be an exhibition. So we work on it as curators. And that’s also the reason why we’ve been asked to make various exhibitions for design museums or institutions, or together with students for their presentations.

Arjun Basu: Kirsten, how do you feel about those words?

Kirsten Algera: I think it’s very good that you mention it because we always try to make a portable exhibition, in a way. That’s what we say. So for the magazine, it’s really important that there’s a mix of visual essays, and text, and all these layers that form the magazine together. And I think, yeah, we’re curators, maybe even more curators than we are editors.

But I also think that in a lot of places, because everything in the design and art world has become so hybrid, a lot of people are curating these days. I’m teaching graphic designers and I always tell them. “You’re curators too—curating your portfolio, curating the work that you make.”

Arjun Basu: That, I think, goes into the decision process for the selection of the word for each issue. The way each word is—they’re all objects, sure—but the words themselves feel stretched, and the definitions are very elastic and almost poetic. The way you tackled The Sink, for example, and it led you to the underground. It’s very elastic, very open. Every issue functions as a kind of metaphor. So how do you come up with the word?

Kirsten Algera: Actually it’s quite easy for us to find the new theme. People always ask us, “Do you have a bucket list? How long is it? Is it difficult? How do you decide?” And most of the time it’s quite spontaneous. And of course it’s also in a dialogue between us two, but there are also some things that we take into account, for example: What did we do before?

So the first one was a piece of furniture, The Bed. Then came a building element, The Window. Then we did The Rope, a material. And then we did The Sink—sort of a world in between. So there’s a rhythm in that, I think. And then it, of course, has to be an interesting theme and also a theme that allows us to go in different disciplines and different fields.

And also, an object that we are motivated to describe because it’s interesting. And because if you look through its eyes, you can see lots of interesting things. That’s really important to us. And most of the time it starts with a quite concrete start. For The Sink, we read the novel by Italo Calvino.

Arjun Basu: Invisible Cities.

Kirsten Algera: Yeah. It was about Armilla, a city of pipes, and sewers, and hoses. And that got us thinking about the sink, like this world in between the sewer and the kitchen. So, many times there’s some sort of starting point. And it can be a novel, but it also can be a work that we saw, or a situation, or whatever. So the next issue will be The Wall, which is not a coincidence since we’re living in a world where walls are the talk of the day, of course. And also very important. It’s urgent.

Arjun Basu: So the MacGuffin experience includes your Projects, which you mentioned. The curations you do, the art exhibits, and then you have a podcast about the pawn shop in Amsterdam, which is fascinating in-and-of-itself. It just seems so perfect for what MacGuffin is that you would do a podcast based on a pawn shop in Amsterdam. It just feels right. What else do you think might be coming to enhance the MacGuffin world?

Kirsten Algera: I think the podcasts will be a series of podcasts. So we’re working right now on one that is based on The Log. It will be about trees, of course. And the next one will be about The Letter. So we’re working on that.

And, like you say, I think it’s the perfect medium for things we want to do because it gives us the chance to also incorporate sound, and sound design, and telling stories in a different way. So that’s really interesting to us.

The other thing we were thinking of, but we’re a super small team so we don’t know yet if we can manage that, is to make a website that shows our research. Because before we produce the magazine, we do months and months of research, so do the contributors, and you never see anything of that. And sometimes objects or subjects just don’t make it into the magazine.

So that’s something that we want to show on a website, all this research. And also we think that it can be interesting for other people to use it, and annotate it in a way, or do something with it. And the other thing that we would love to do is make a sort of digital newsletter that gives a more actual relation to what is in the magazine.

So all the interesting events, and movies, and websites, and stuff that is related to what we discussed in the magazine, but we can’t show because when it’s printed, it’s finished, of course. But those two things, I think we can only do that if our team grows a little bit. And we’re not sure if that’s going to happen.

Ernst van der Hoeven: Something we are experimenting with a little bit is how we could develop also as a publishing house. During the period when we were working we found a very interesting lecture of an Italian professor working in Milano. And he had published it in Italian, and we translated that in English into a small booklet called The Poetics of the Oriental Rug. And that became quite successful because by translating it, it opened a whole new audience.

The professor is long dead, but the words he pronounced are still very valuable, and still accessible, by the booklets that we made. So in every issue there’s so much new content that, in our opinion, needs a bigger audience. If we had more time, if we were a bigger team, we would really like to establish a small publishing house and I’m working a little bit more on books as well.

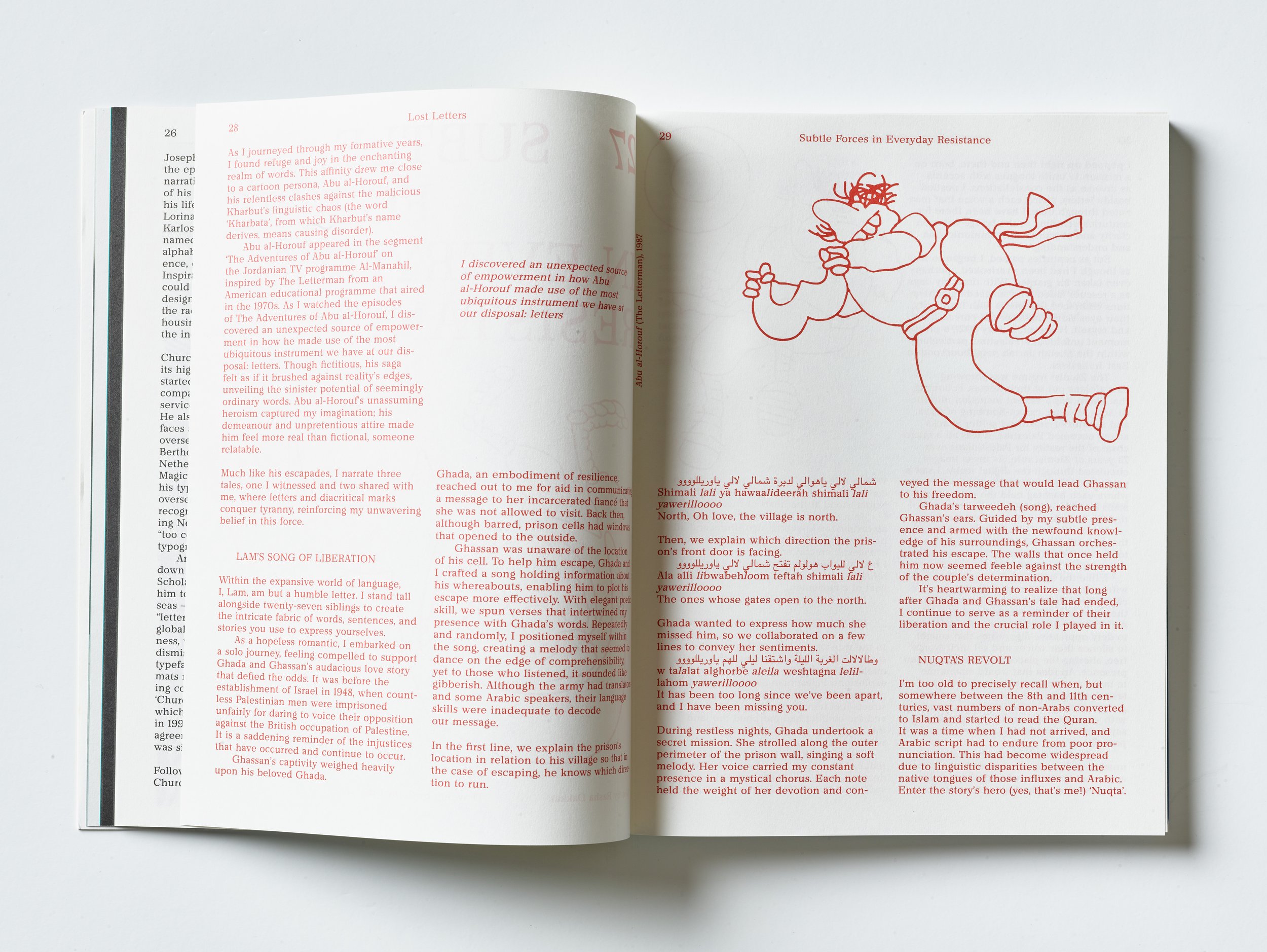

The premiere issue of MacGuffin

Arjun Basu: So many magazines, when they talk about how they expand their ecosystem of media, it seems obvious. But they all follow the same path. Just given the very nature of MacGuffin and “the life of things” as a tagline, it feels infinite what you could actually do with that brand.

Kirsten Algera: That’s true. You could say that it is a way of looking at the world. And you can do that in many places, in all the media that you want. Right now we’re already doing a lot of workshops, so I think it’s working well as a sort of education model in a lot of art schools, at least in design schools.

But we also make exhibitions. And for us, it’s interesting to work in other media because we try, for example, in exhibitions to look at them as if it were a magazine. So, What is an exhibition that has the magazine as a model? And How can a magazine be an exhibition? Or How can an education model be a magazine? So we’re experimenting with that as well. And it’s interesting to us.

Ernst van der Hoeven: Yeah, I’m just thinking about the counter-cultural aspect of the magazine that we make. And that’s something that we also like to focus on when we make exhibitions: the untold stories and maybe the forgotten things that, in the beginning, might not be so interesting, but when we dig deeper, we find very intriguing material. We always like to feature the untold, and the not-so-obvious part of the story. I think there we also see a similarity in how we work.

Arjun Basu: MacGuffin feels very international, but in a very Dutch way. I love Holland, I have many friends from there. And one of my favorite things in the world is vla, which always makes Dutch people laugh.

Ernst van der Hoeven: We never eat vla.

Arjun Basu: Yeah. They always that about poutine where I come from. But from the beginning, it’s felt like a very international project. That the audience is the world, and not people in Amsterdam. How intentional is that—and who is the audience?

Ernst van der Hoeven: That’s not intentional. Not at all. When we started the magazine, this is a question that we have been asked by many people, with whom we’ve pitched the whole idea of making a magazine where we take one object as a departure. And a lot of people thought we were insane. This is not going to work! And Who is going to read this? And we were not so obsessed with our readership. We thought, We have a story to tell.

And we also thought the time was right for an antidote for ‘design’ as a word with a huge ‘D.’ That was something that we were very aware of, and also very confident about. That’s nothing that we were insecure about. So the whole audience was not something that we weren’t worried about too much.

Later on, when we started to monitor Instagram, who was actually reading us, we were amazed by the fact that a lot of young people, from 23–31, are the main readers of our magazine. So we were happily surprised that we make a magazine for a younger generation than the generation we belong to ourselves.

Arjun Basu: That speaks to the design of it too, because it really is an object in and of itself. It’s a big, heavy thing. It’s very tactile. I’ve always said, “Print needs to be printy-er.” It needs to exploit that idea that it’s a sensual object, it’s not a screen. And you guys really do that. It’s this thing that you want to hold.

Ernst van der Hoeven: That’s so good that you mentioned that because we really hope that people understand that we see MacGuffin also as an object itself. And the way we make it’s also very crafty and the choices of the paper, the font, everything plays a part in that.

And when we started the magazine we thought, If you have to sacrifice so many trees, make something that stays, that keeps its value as a compendium or as a series of books, even. Because you can call it a magazine, but a lot of people also collect it as a series of, maybe, books. And that makes sense.

Kirsten Algera: Yeah. And I think the surprising and interesting thing, as well, is that when we started, we thought we would make a magazine for the design world, for people who are interested in design or in art. But I think the audience and the readership is much broader now. And that also started with interest from the magazine world, which is a world in itself, you could say.

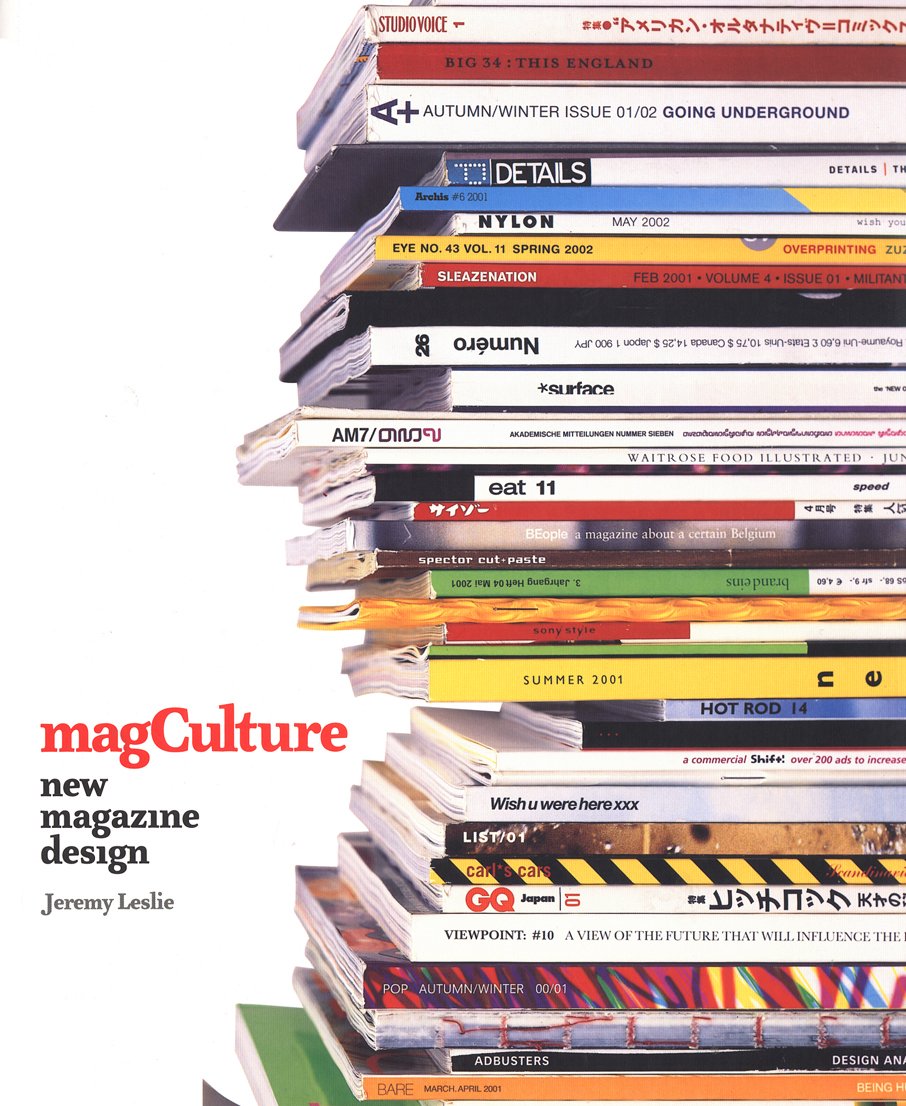

So you talked to Jeremy Leslie last time, and he’s one of those people who are part of this very intense, and very connected, and interesting magazine world. And we didn’t realize that when we started, that that would be part of the readership, as well.

But to come back to your question, from the start we thought We have to be as international as possible. Not only as a business model, but because this is interesting for everybody. And also because we want design to come out of that Euro-centric or Western-oriented bubble and also look at other places and other objects.

Ernst van der Hoeven: I’m just curious to hear from you what you find so typically Dutch about it. Because a lot of people think that we are made in London. They don’t even recognize that we are Dutch. And we’re not against being Dutch.

The most recent issue of MacGuffin on “The Letter”

Arjun Basu: No, you shouldn’t be against being Dutch. But I think there's a curiosity that Dutch people have about the world. And the way they look at it. They are very international. I find Dutch people are very curious about things. And Dutch design, on top of that, the world lost some great looking money when you adopted the euro. Dutch money was the most beautiful money in Europe. Any money that has a Piet Mondrian painting on one of its sides is okay by me. It’s fantastic. And just the design sensibility that happens in Holland. It definitely felt more European. I think an American MacGuffin would obviously be a very different publication. But when you start to think about it, you go, No, this is Dutch. That’s just me. But I just find it a very Dutch thing.

Kirsten Algera: Yeah, I can imagine that. There used to be a very strong Dutch graphic design. And design tradition, of course. That’s the reason that we worked for this Department of Aesthetic Design, that was called, by the way, in the corridors of the organization, the Department of Aesthetic Delay, because they delayed everything by looking carefully at the design.

But that was over in the beginning of this century. And a lot of the subsidies that were very common 10 years ago are gone. So, in that sense, The Netherlands is no longer a country that really pumps a lot of money into design or graphic design. It’s more like the rest of the countries, probably.

Arjun Basu: That’s a shame. I’ll ask each of you this question—I ask this to everyone. Kirsten, what are three magazines or media that you’re consuming right now that really impact you and are meaningful?

Kirsten Algera: That’s a really difficult question because there’s a lot, of course. Maybe the first I can mention is the book I’m reading right now, because we’re researching The Wall, as I said, and I’m reading a book that is called The Wall by Marlen Haushofer. She’s an Austrian writer. She wrote it in 1963.

And it’s a beautiful book, a very strange science fiction book, about a middle-aged woman who wakes up in the morning and finds that everyone has vanished. So it’s very post-apocalyptic in a way, but it’s also really beautifully written. And it took years and years before it got known, this book, because there wasn’t a lot of attention for Austrian female writers. But now there is. So that’s the sort of inspiration, in quite a dystopian way, I have to say.

As for magazines, I really like magazines with a very clean, and maybe not too huge of an editorial concept. Revue Faire is a French magazine that I like very much. It’s about graphic design and it always has one theme that can be one essay or one photo series.

They also started a magazine right now that’s called 12 Photos. It consists of 12 photos, like it says, that can be folded out into posters. And they are the graphic designers that I like most. So they’re very special. The third one…has to be three?

Arjun Basu: That’s what I ask, so yes. It has to be three.

Kirsten Algera: Maybe not so much a current magazine, but more of an inspiration is Nest. Do you know this magazine: a “quarterly of materials”? I think it was really important to us when we started because it showed this other design world that we were interested in—not the iconic design world, but everyday life. It was anti-materialistic, in a way, interiors—so prison cells, and igloos, and strange collectors.

And it was beautifully made, as well. For us that was something that we looked at from the start, although I think we’re a completely different magazine. But the attention to everyday life environments, and how people relate to that, was pretty important to us.

Arjun Basu: Ernst, your turn.

Ernst van der Hoeven: I would start with The Whole Earth Catalog, a counterculture magazine and product catalog at the same time, made by Stuart Brand between 1968–1972, and also occasionally thereafter. It appeared several times a year, so not really regular. And why I like it so much, I think, is mostly because of this editorial focus on self-sufficiency, ecology, alternative education, do-it-yourself, holism, and especially I liked the slogan they featured: “Access to tools.” Something we within MacGuffin also, in a way, do.

And what was very inspirational for us is that you make something that gives access to a lot of people, almost like a paperback Google version. And it was also beautifully-made. And very generous in the sense that it gave all the product information that you could get with very nice tutorials without the possibility to buy it there.

They gave all the information to the vendors, so you could buy it if you wanted to. But this was not a sales document or device. I found that a very beautiful and generous magazine. And you could always scroll through it and find new things—information about machines, and seeds, and tools, and all kinds of stuff. Very rich.

A totally different magazine that I like because it’s very cheerful and gay is Butt magazine, made by Jop van Bennekom and Gert Jonkers. Very Dutch. It was a small, very quite intimate magazine that existed from 2012–2021, and then they took a break, I think, for 10 years.

And quite recently they are back, basically because the Italian brand, Bottega Veneta likes to help re-entering these niche magazines. And they do it with a very clever way that also their advertisement is themed in a way that everybody understands. It’s a very sweet magazine and it was a beautiful platform for queer people and their friends to speak straightforward about their lives, ideas, work, and sex life. So it’s just quite open, and I really loved that.

A third one … well, yeah, there’s a quite young magazine that is made by Lou-Lou van Staaveren. She’s one of the editors who also works for us as a photographer. That’s a nice thing—if you work with young people you really see their development and you can follow that and we could foster that a little bit.

They are making a magazine about gardening. And being an avid gardener myself, I really love that idea. And what they’re doing are very nice, themed, small editions on compost making, or a certain flower, or a certain phenomenon in nature. It’s a quarterly and it is made with a lot of love, and it is something that I really love to get. And I really read it because there’s a lot of knowledge that you’d like to know as a gardener.

Kirsten Algera: Yeah, and it’s also very special, I think, that it joins art, design, and gardening, so it shows all these relationships that are really interesting, I think. Pleasant Place.

Arjun Basu: “Pleasant place” is a way that I think we could describe the world you’ve created with MacGuffin. Thank you both for taking the time to talk to us.

Kirsten Algera: Thank you very much.

Ernst van der Hoeven: Three Things

Kirsten Algera: Three Things

For more information, visit MacGuffin’s website.

More from Magazeum

Back to the Interviews

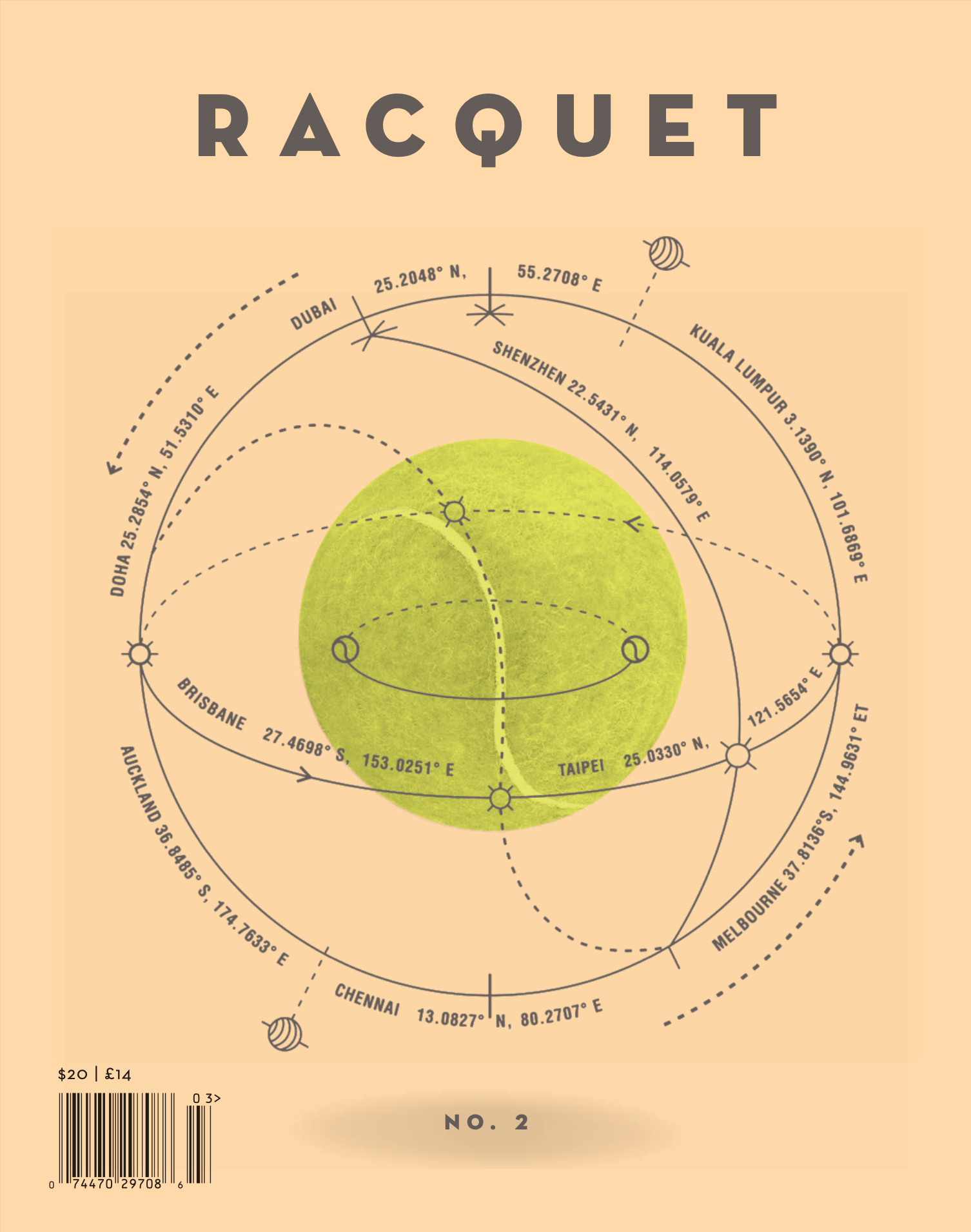

String Theory

A conversation with Racquet editor-in-chief and cofounder, Caitlin Thompson

A conversation with Racquet editor-in-chief and cofounder, Caitlin Thompson

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT LANE PRESS

Media, and most every brand in general, talks a lot about building and nurturing a community. Tribes, even. Finding one, inserting yourself into it, and then making your message an integral part of it. And what activity creates a more loyal community, than sports? If there is the ultimate niche audience, sports is it. It goes without saying that every sport has fans. And some lend themselves to something beyond fandom; they are lifestyles.

And few magazines have built up a brand around a single sport and its audience and their lifestyle as much as Racquet.

Launched with a Kickstarter campaign in 2016 by Caitlin Thompson, Racquet is a presence at major tennis events and has inserted itself into the lifestyle of tennis fans and players alike. The path has been rocky at times, but Thompson is clear about her aim to provide a “premium experience at a premium price,” as she told the Nieman Lab in an interview in 2017.

Like any other media, Racquet will live and die based on a business plan, and it is quite possible that Racquet magazine is just a small part of a larger creative media agency, all centered around a global community. And while she is not loath to smash some volleys in the direction of the tennis establishment, she is doing this while also trying to recenter the entire community and become its new beating heart.

Caitlin Thompson has much in common with the world’s top tennis players: passion, drive, ambition—and a willingness to make … a racket.

Arjun Basu: Caitlin, you were a tennis player.

Caitlin Thompson: Yes.

Arjun Basu: And you went to school on a tennis scholarship, right?

Caitlin Thompson: That’s right.

Arjun Basu: And then you got into journalism and a lot of political journalism. And then you had this Kickstarter. So how did you get to that moment? What was your journey to that moment? What niche were you filling? What was missing in your consumption of media that you saw an opportunity for something like Racquet?

Caitlin Thompson: Tennis was something I grew up with. And for me, my connection to the game came through my grandmother. It was a way to connect with another person. Probably the person I loved the most in my world.

My parents were classical musicians. They were itinerant. They would go on tour for extended periods every summer with the symphony. At the time it was the Montréal Symphony when I was working growing up. Later, it was the Atlanta Symphony and they would be on tour for a couple of weeks at a time, in Asia, Europe, wherever.

And when I was really young, I started basically getting shipped off to go stay with my grandmother who had taken up the sport of tennis as a retiree. She was a nurse who had done a lot of sort of blue collar jobs. Not from a lot of money, but she’d taken up recreational tennis in the tennis boom of the seventies and eighties. And on public tennis courts, she had taught herself how to play and it became her whole world.

And for me to get sent to her house in Phoenix, Arizona meant that I was part of her world, which meant that I was going to play tennis with her every morning, whether I knew how to play or not. And she would fill up a giant jug of Arizona tap water, bring her Marlboro 100s, and go out at 5 am, as people in their 60s and 70s do, and just play tennis balls. I can picture that scene. It was incredible—chain link fence, bringing our own hopper, balls that would get dusty. And just, this was like my magical time with this lady who is so funny and cool. And she wasn’t the world’s greatest tennis player.

She didn’t have the world’s greatest game. We didn’t even keep score. And a lot of people—growing up as I did in the competitive tennis space later on I started competing in tennis and got to be pretty good at it—but their origins and their dreams were always tied to professional glory and winning Wimbledon and being ranked number one, this or that.

And for me, that stuff was interesting enough, but really the goal was always just to recapture this joy that I had as a little kid playing a game with my grandma. And so after competing in the sport up through college, which paid for my college. It’s not entirely clear to me that I would have been able to afford to go to any college I wanted to, so this was certainly a very big windfall for me personally to have college paid for, especially one that offered a degree in something that I knew I wanted to study.

The Missouri School of Journalism was on my radar and I wasn’t good enough to get recruited by everybody; schools weren’t falling over themselves to have me play on their tennis teams. So I tried to make a pragmatic choice to say I’ve already had one career that has done me well, and I’ve probably summited, or at least gotten to my ceiling.

But now, knowing that I had excelled in English and yearbook classes—I even started a newspaper on my block when I was 11 years old, reporting on my neighbors. I think the news bug and the storytelling bug was in me very early.

Arjun Basu: Wait a second! Reporting on your neighbors?

Caitlin Thompson: Yeah. I got into some trouble as well because one of my neighbors was an amateur arsonist and I wrote about it and his parents were not thrilled.

And that’s also when I learned about libel laws. So, an education at an early age. I didn’t do too many editions of the paper. I don’t think the neighbors really loved it, but I would go door to door selling it for a quarter. I knew I wanted to tell stories and I grew up reading the Esquire of David Granger’s era and loving long form journalism, loving storytelling, loving the idea that magazines could really set an agenda, and wanting to set an agenda.

And I studied magazine journalism at the University of Missouri, I got to work on the, I don’t want to call it a student magazine, because at Missouri—the Missouri method, as they call it, is that if you’re a broadcast student, you work at the local NBC affiliate; if you’re a newspaper, you work at the local newspaper that is in competition with the other media outlets; if you’re working in the magazine sequence, you work for either the alternative weekly or the magazine that covers international affairs. And I did both because—and it’s not like you’re working for the college newspaper or the college magazine. They have those too.

But the journalism students were really encouraged and mandated to work for publications that had a real life audience of adults and it’s you know, it’s immersion really, and it was an immersive education. That was great. However, one of the things that was not great about that education is that immediately upon graduating, the internet had begun decimating a lot of magazines and newspapers, whether or not those magazines or newspapers were aware of it yet, and newsrooms even at that time in the early 2000s were already… . You know, the era of the golden age of the bar cart and the expense accounts and the black cars and all that stuff was certainly ending if it hadn’t already ended.

And so for me, getting into digital media was the only real option if I wanted to have a job that paid me; I couldn’t afford being an editorial assistant for $14,000. I don’t come from a family with a trust fund, but also getting real experience to be able to do stuff in the digital space was just pragmatically where I could report.

And so I worked overseas for a little bit. I worked in China for a magazine for about 18 months. And then I came back to the States and worked at the Washington Post. And at the NewsHour, which is a program on PBS, still somehow going, still somehow a program on PBS, it felt dated and dusty even at the time.

And then I got hired to come work at Time magazine up in New York, but all in the sort of niche of political reporting. Somehow I just fell into politics as my default subject matter of expertise. And I didn’t love it. I wasn’t a political, economies major or anything like that. It just seemed like that was where important stories could be told.

But I had, after my third presidential election, somewhat of a realization that we are covering politics like sports. But what I really want to do is talk about politics for their own sake, how to make the world better, issues, things that matter to people, not who’s winning the news cycle. I found that very cynical. I found it very pointless. And I think we’re seeing what the effects of two decades really of that style of coverage has wrought us, which is, you turn politics into entertainment, you get entertainers.

And I thought actually conversely, in some weird way, going into sports would allow me personally to talk about or commission writers or reporters or illustrators or whoever to grapple with issues that I care deeply about but in the guise of something that’s fun and global and interesting which is this sport that I grew up loving that was actually on the right side of history and ahead of its time and bringing together a lot of disparate conversations and reaching a lot of far flung places and it was handbuilt because nobody else was doing anything like it in the space. And so that’s a long-winded way of saying all of this felt like it organically led one to the next.

Arjun Basu: Obviously you never lost your love of the game and you were still playing. Was there any media that you were consuming at the time about tennis? Where did you go for stories or what were you reading?

Caitlin Thompson: It’s a good question. And it assumes that I didn’t lose my love of the game. I in fact did lose my love for the game for a couple of years. My last match at the Big 12 conference championships was—I did not finish. My team lost before my match had a chance to complete. And I remember leaving my rackets, my bags and my shoes.

And keep in mind, this is before the climactic scene of Ritchie, “The Baumer,” Tenenbaum, in The Royal Tenenbaums. I was like, I really did that. I just was done. And I didn’t pick up the racket again for many years because I was completely over it and treating tennis like a job. But obviously I still followed the sport and I still cared about some of the storylines and it was weird because a lot of the sport changed in my time as a competitor and as a young professional.

And it atrophied, the conversation around tennis. That began for me with this public tennis court, tennis in culture, in movies as a symbol. I grew up watching Trading Places and Who’s Harry Crumb?, and famous Italian Fellini films where tennis was just kind of part of it.

It was just as much about drinking your water out of a tennis ball can as it was a country club, which I had never belonged to. And the tennis space, even though the nineties and early two thousands gave us some amazing athletes, obviously Agassi, Chang, Becker, Courier, Sampras, the Williams sisters towards the end of the nineties, Capriati, et cetera.

Arjun Basu: Steffi Graf.

Caitlin Thompson: Yeah. Steffi Graf. I had a poster of her on my wall.

“I grew up reading Esquire and loving long-form journalism, storytelling, and the idea that magazines could really set an agenda.”

Arjun Basu: Never would I have thought in those days that Steffi Graf and Andre Agassi would be, not just get married, but would be a very successful couple. But anyway that’s not what we’re here to talk about.

Caitlin Thompson: We could have a whole separate discussion about our speculation about the marriage of Steffi Graf and Andre Agassi because I agree with you. Never, listen, you don’t know, it takes all kinds, everybody’s got their person, but yeah, like I really saw that despite the fact that tennis was really producing a lot of very interesting stars the world around tennis kind of shrunk to only be about those stars.

Tennis stopped being this societally interesting vehicle for social change. It stopped being this place that it didn’t take a private club membership or a ton of money to access, When people talk about tennis being a country club sport, like that’s so unfamiliar to me that I am forced to reckon with the fact that’s how a lot of the sport was perceived during a lot of my lifetime.

And that was never my reality. And these sorts of examples kept cropping up in the tennis infrastructure. The tennis world has shrunk the pie, but the people getting a slice of that pie, the Nikes and the IMGs, and a few of the Grand Slams have gotten so rich off of it. They’re not incentivized to actually really grow the sport or make it bigger.