Pourovers, Patrón, and Print

In Marfa, Texas, you can (maybe) glimpse a future for independent media.

In Marfa, Texas, you can (maybe) glimpse a future for independent media. By Sasha von Oldershausen/The New York Times

The Sentinel’s HQ in Marfa, Texas.

Editor’s note: We’ve been big fans of The Big Bend Sentinel since we stumbled upon it a few years ago. It’s just another reason to visit Marfa, Texas. Oh, also, their operation might be the future of media, too.

When Landrie Moore was looking for a venue for her destination wedding, she knew she wanted a space that really reflected life in this small, remote desert town.

Her guests would be coming from as far as Ecuador and England, and Ms. Moore, 35, who works for a boutique hotel firm, hoped to provide a memorable and authentic experience for those travelers. When you visit a new place, she said in a phone interview, “you want to feel like a local.”

Which is why she decided to get married mere feet from the office of The Big Bend Sentinel, the region’s oldest newspaper (where I worked as a reporter in 2014 and 2015).

Ms. Moore’s wedding, in June, was the first of five held last year in the Sentinel, a cafe and cocktail bar in the newspaper’s newly renovated office building. The space is perhaps the most visible sign that The Big Bend Sentinel is under new ownership: Maisie Crow and Max Kabat, who moved to Marfa from New York City in 2016, took over last year from Robert and Rosario Halpern, the paper’s publishers of 25 years.

“We kind of saw us in a way,” Mr. Halpern said of the couple.

“Buy a newspaper?” Mr. Kabat, 37, recalled thinking when the Halperns first approached him and Ms. Crow about a potential sale. “What are we, idiots?” Their background is in consulting and documentary filmmaking. (The New York Times is a producer of a forthcoming film by Ms. Crow.)

Since 2004, nearly 20 percent of local papers in the United States have folded or merged, according to a 2018 study by the Hussman School of Media and Journalism at the University of North Carolina. In many cases, publishers have been replaced by a narrow network of large investment groups that have acquired hundreds of failing newspapers.

But Marfa is no ordinary town, and its newsweekly has been a pillar of the community for nearly a century—long before Marfa became cool. The Big Bend Sentinel’s pages are pasted up with major issues of the day (the death of Antonin Scalia, the Supreme Court justice, on a nearby luxury ranch, for example, and the possibility of a border wall just 60 miles away) alongside valedictorian announcements, photo spreads of homecoming events and advance coverage of the town’s many festivals.

Before Mr. Kabat and Ms. Crow (who is originally from Corpus Christi, Texas) took over, the paper ran solely on ad sales and subscriptions. “It was able to sustain itself on a shoestring, but we wanted to expand the potential,” Ms. Crow, 38, said. They hoped to bring locals closer, physically, to the institution covering their hometown.

Max Kabat and Maisie Crow, publishers of The Big Bend Sentinel.

“Buy a newspaper? What are we, idiots?”

So they bought the building previously occupied by Padre’s, a dive bar that went out of business in 2016, and before that, a funeral home, and began renovations.

“We had to sage the whole place,” said Callie Jenschke, whom the couple hired to handle interior design.

—

Continue reading at The New York Times.

ORIGINALLY POSTED ON 25 FEBRUARY 2020 ©THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY

Back to Entry/Points

Chapter 05: Dick Move

The one where I made you ask.

The one where I made you ask.

ILLUSTRATION BY JASON SCHNEIDER

Editor’s note: In the late 2000s, John Korpics was the creative director at Fortune. He lived with his wife and kids way the hell up in Westchester County. Given his long commute, and being the industrious type, he decided to put that dreadful time to use. This column is what he came up with.

I’d like to apologize to all the folks who got on the train at White Plains this morning. I pulled a classic dick move.

I was sitting in a two-seater and I was sort of half asleep and leaning over into the other seat, eyes closed, when the doors at White Plains opened. Instead of sitting up straight and making the seat readily available, I just kept my eyes closed and stayed in position.

Truly a dick move.

It pains me to admit that my commute does sometimes bring out the worst in me, but there it is. I’ll never pretend I’m something I’m not.

Now, if someone taps me on the shoulder and asks me to make a little room, I absolutely do it, no hesitation. But every once in a while—and it’s really not very often—I just sit there and make you ask.

I know it’s hard, and I know the average person will take a look at me and decide it’s not worth it and move on to the next seat, but if they screw up some courage and take what is rightfully theirs, well then they earned the seat and my respect at the same time.

If you’re ever on the train and you see some a-hole with his eyes closed enjoying more than his share of a two seater, do the right thing: Take what’s yours. On the train, and in life.

Have a good weekend everyone.

ORIGINALLY POSTED ON FRIDAY, 16 OCTOBER 2009 © JOHN KORPICS

John Korpics is VP/Executive Creative Director at Harvard Business Review. He has served as the design lead at Entertainment Weekly, Esquire, ESPN, Fortune, InStyle, and many other major newsstand magazines. His current commute is much effing easier.

Jason Schneider is a beloved Toronto-based editorial illustrator.

Back to Entry Points

“Can’t Let It Show, Can We?”

Author Terry McDonell made a deal with fellow Hearst editor—and best friend—Liz Tilberis: “She would help me with Esquire’s fashion and I would help her with ‘getting on in America.’”

Author Terry McDonell made a deal with fellow Hearst editor—and best friend—Liz Tilberis (Harper’s Bazaar): “She would help me with Esquire’s fashion and I would help her with ‘getting on in America.’” On the 25th anniversary of her passing, McDonell shares this excerpt from his book, The Accidental Life.

In the spring of 1992, Liz Tilberis came to visit me in the Hamptons, in Wainscott, where I had a place. It was Easter weekend and that Sunday we went to a lawn party at Jann Wenner’s house. It was to be relaxed, but with an elaborate egg hunt for the children, and Jann’s guest list included a range of people from the media, show business, and publishing. Turning into the long driveway, Liz joked that she was nervous, that this was going to be her first important party since moving to America from London and she wouldn’t know anyone.

I told her she didn’t look nervous.

“Of course not,” she said. “Can’t let it show, can we?”

I said most of the guests already knew about her, knew she had come to New York to rejuvenate Harper’s Bazaar.

“Do not abandon me,” she said, widening her green eyes, a look I came to know as a kind of ironic kabuki. She wasn’t nervous at all. She was going to work that party.

I remember watching her, vivid with her shining white hair, from across the lawn. Driving home, she told me she had received six invitations for weekends over the summer.

“Imagine,” she said. “They were all very nice, but they don’t know me at all.”

• • •

Our pact was that she would help me with Esquire’s fashion and I would help her with “getting on in America.” We joked about it as she got on fine on her own, not just staffing her magazine and settling her sons in private school but becoming a Knicks fan. Her “field study” took her to gardens and museums, but also to Q-Zar, a laser-tag arena in New Jersey, for a “jolly riot.” Within less than a year, she and her husband, Andrew, had slept in the Lincoln Bedroom as guests of the Clintons. “My team,” she called Andrew and the boys, but it wasn’t sappy. What worried her, she said, was being too English: “Mustn’t ever use that word jolly.”

The premiere issue of the Tilberis era of Bazaar

For my fashion education, we traveled together to Milan, flying overnight from JFK to Malpensa, eating caviar and drinking vodka. On that flight I learned that she had refused to be confirmed at her all-girls boarding school (“I didn’t believe in God”) and had been expelled from art school for entertaining a man in her room. I also learned that she had almost moved to New York five years earlier to head Ralph Lauren’s design team. She had decided to stay in London when, two days after she’d given notice, Anna Wintour, who was then the editor in chief, told her that she was moving to New York—to become the editor of House & Garden (ten months later, she would be running American Vogue). Liz could have British Vogue if she wanted it.

Of course, topping British Vogue had been another jolly riot. Bruce Weber’s first Vogue cover shoot was for Liz—a laughing model wearing minimal makeup. “Pure Liz,” her colleagues said. And it became an even better story when the proofs came back touched up with lipstick red because the printers were sure there had been a mistake. “They actually made it better,” Liz said. When she persuaded the Princess of Wales to pose for a British Vogue cover, the image was clean and simple—the look Diana made her own from then on. “It just made sense for her as a modern princess,” Liz said. “And I’m a little like Machiavelli.”

Our first day in Milan was to end with a benefit in the courtyard of an old castle that had been tented with an enormous tarp against the forecast showers. It began to rain hard in the afternoon, and by evening the waiters were poking up at huge puddles on the sagging canvas with long poles. Sting was on the program and waved to Liz as we entered. She looked from the candle-set tables to the dripping canvas and announced that we were going immediately to Bice.

We couldn’t find our car and started walking toward the restaurant in the downpour, getting soaked. Within a block, a limo driver—not ours—pulled over. He knew Liz and liked her, and thought she might want a ride.

“Fashion,” she said, climbing in, “is about long black cars when you need them.” The driver told us the tent had collapsed.

Walking into Bice, we saw Valentino and his inner circle at the large round table in the back corner—like a tableau I had seen before but couldn’t place. The women, all in red gowns, were exquisite, the men handsome in black suits, but their frowns gave the scene a starkness. Valentino made a slight nod in our direction, and when we walked over he asked if the collapsed tent would reflect badly on the fashion houses. (Armani and Versace, both based in Milan, and Valentino, from Rome, had organized the event.)

“Not on those from Rome,” Liz told him, and she went around the table complimenting everyone on how chic they looked. “Totally Valentino,” she said, and when the great designer smiled slightly the mood changed and we were invited to join them for dinner.

“I wish we could have shot that table just exactly as it was when we walked in,” Liz told me as we left Bice after midnight. “The cold power of it, like those Bronzinos of the Medici.”

Early the next morning, we began a round of appointments at designer showrooms. All went more or less the same way: Liz explaining to me (so the designer could hear) how brilliant the new line was, and then whispering to the designer what a formidable editor I was. We had a simple lunch in the backyard of the Armani palazzo with Giorgio and his top aide at the time, Gabriella Forte, while his Persian cat, Hannibal, hunted through the garden. Giorgio, too, was concerned about the collapsed tent, but he and Liz talked mostly about the distinctive cuts he was showing that season, and the importance of fine tailoring.

“Fashion is about long black cars when you need them.”

Our week in Milan paid off in many new advertising pages for Esquire, but when it was over Liz thanked me for helping her get through it. Her advice was to bring presents the next time I visited, something personal that this or that designer could relate to, perhaps a cat toy for Hannibal.

I thought hard about this and, since Armani was the most important advertiser for Esquire, I asked Gay Talese to sign a copy of his new book, Unto the Sons, to Giorgio. Esquire had excerpted Gay’s history of his family’s immigration to America from Italy. The book’s most intimate passages were about Gay’s father, who was a tailor. I had the book with me when I saw Armani the following spring at the men’s shows in Milan. Without Liz beside me, there would be no lunch, but we had coffee in his office. Giorgio opened the book, saw that it was signed, passed it over his shoulder to an assistant without reading the inscription, and asked me about Liz. When was she coming next to Milan?

“I saw that same copy of Unto the Sons a year later on a bookshelf in Gabriella Forte’s apartment in New York.”

• • •

“Looking for fasion material for my “Editor’s Notes” column in Esquire, I asked Liz what it was she noticed first when she met someone—expecting, I suppose, something smart about shoes or haircuts. Instead she paraphrased a line from a Katharine Hepburn film: “I notice whether the person is a man or a woman.”

Very sexy, when she said it—and direct, like her taste as an editor. She had a clear eye for the sociology of fashion that could capture (or shred) any look she saw on any runway or street. “Downtown Marie Antoinette” was the look her friend Jean Paul Gaultier was showing that year. “Blind Anchorwoman,” which she pointed out to me one day when we were walking across Central Park South, was maybe a bit of a reach but I knew what she meant. Our boss was “Black Paw” because of his fingernails. “Being wicked,” she called it and we did a lot of it. Her only insecurity as an editor was dealing with writers.

In England she had been a celebrity as a fashion editor, even appearing on the sides of double-decker buses with her oldest son in an adoption-awareness campaign; but there was a disconnect with journalists, because she was just a fashion editor. She was worried that New York would be like London, where the literary scene was closed to her. This could be problematic if she couldn’t get interesting writing (part of Vogue’s mix) into Bazaar. I said I could introduce her to writers if she was feeling pressed.

“What about you,” she said. “I wouldn’t be afraid of editing you.”

“You wouldn’t be doing the editing anyway,” I said. “What’s your idea? You have to give your writers an idea first.”

“Oh, yes, I know that,” she said. “Write fashion and rock and roll. You edited Rolling Stone, or so you say.”

“What’s the piece again?”

“Roll over, Beethoven,” she said. “Tell Balenciaga the news.”

When I finally wrote that piece for her, it was called “Not Fade Away: Mingling Destinies of Rock and Roll and Fashion.” I was all over the map—her map—when it came to which designer went with which rocker. I had the obvious: Giorgio Armani with Eric Clapton, and Calvin Klein as a Mudd Club vet. Liz explained that fifteen years previous, Richard Tyler had dressed Rod Stewart in glitter and spandex for his Blondes Have More Fun tour, and last year he had fitted himself with the Council of Fashion Designers of America’s most prestigious award as Womenswear Designer of the Year. “That has to mean something,” she said.

Voguette that she was, having begun as an unpaid intern in the late ’60s, Liz was amused by my characterizations of the period. “All that hard-rocking creative sexuality and open rebellion, come on…” Where was my nuance? She told me about Pop and Op Art overpowering textile design, and Twiggy flirting around London in little gym slips. She told me not to ignore Dr. John because his gris-gris was about voodoo accessories, and that Carnaby Street had a men’s shop named I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet; it sold used military uniforms, and she had slapped several into her “More Dash Than Cash” pages as soon as she saw them.

She insisted she was not about language (“My mind is too full of pictures, not enough room then for words”) except she was as hungry for specific details as any line editor I ever worked with.”

• • •

When she took over at Harper’s Bazaar in 1992, Elizabeth Jane Kelly Tilberis was a size 12, which she said was “practically illegal in our business.” One gossip column applied the word bovine. She laughed that off and lost weight as her Bazaar came together, dropping to a size 8. She said her “slinky” staff helped her look the part but added, with a green-eyed wink, that “fashion editors should never look better than their models.”

Liz knew every fashion trick, every cliché, but she didn’t pander. Instead of snapping at the heels of the flush and splashy Vogue, she decided to simplify. Her relaunch of Bazaar (September 1992) was quieter than expected. The cover was a very graphic Patrick Demarchelier shot of Linda Evangelista looking smart and confident with a small cover line: “Enter the Era of Elegance.” It was cool, but there was no snobby chill. Even cooler, the logo was unbalanced, an act of innovation that winked with subliminal ink. By comparison, Vogue’s grunged-up models covered with type looked sloppy. Downtown suddenly seemed almost quaint. Liz’s inside pages too were sleek and inviting, with understated glamour in the white space and more of creative director Fabien Baron’s innovative typography. It was practical, democratic fashion, elegant in its execution.

“In a little over a year, Bazaar was back as one of the world’s preeminent fashion magazines, challenging Anna Wintour’s Vogue. The paparazzi loved Liz, and she dazzled them with her bob of white hair, which looked silver in photos. She was having another jolly riot. Bazaar’s circulation climbed as she nurtured her photographers, swapped risqué stories with models, complimented stylists and charmed advertisers. With readers, she stressed building personal style with common sense. One of her “Editor’s Letter” columns celebrated the humble sweater. By then she was a size 6.

“Tilberis was a size 12, which she said was ‘practically illegal in our business.’”

“THAT DECEMBER, some 250 fashion and publishing people were invited to the brownstone in the East Eighties she and Andrew had rented from director Mike Nichols. There was a huge Christmas tree in the living room and white flowers everywhere, and the townhouse was packed with her New York friends—Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, Donna Karan, Leonard and Evelyn Lauder, Barbara Walters, Jann Wenner, people named Trump. The party was to celebrate her triumphant first year and Bazaar’s many honors, which included two National Magazine Awards. Hearst had taken out a full-page congratulatory ad in the New York Times. The columnist Billy Norwich wrote that it was the kind of soigné party he used to read about in urbane novels.

When Liz walked me to the bar, I said, “The gang’s apparently all here.”

“Someone named Jerome just whispered to me, ‘There are people in this room who should not be here,’ ” Liz said. “I don’t know what that means exactly.”

“Yes, you do,” I said, figuring it had to have been the notorious “social moth” Jerome Zipkin. “You want me to kick his ass?”

“Oh yes, please.”

She made a very short speech that night. “A magazine is only people,” she said. “It walks in the door in the morning, and out the door at night. Please let’s never forget that.”

None of us knew she had been diagnosed with stage III ovarian cancer and had a procedure scheduled for the next morning.

• • •

“When her cancer was reported in the media, she came forward with some of what she had been going through, first on the “Editor’s Letter” page: I never wanted to be a poster girl for cancer. But cancer has become part of who I am, along with my big feet and my English accent. I have greenish eyes, I was born on Sept. 7 (the same day as Queen Elizabeth), and I have ovarian cancer. So do almost 175,000 other women in the United States.

Privately she joked that she had arrived hungover for her procedure, the day after her Christmas party. For the next seven years she would balance treatments and operations with her work at Bazaar. She wore catheters under evening dresses. She escorted Princess Diana on one of her visits to New York, even though she was in chemotherapy. Diana had been one of the first people on the telephone when Liz emerged from her first major operation.

“Diana who?” said Andrew.

“Diana Windsor.”

“Sometimes Liz didn’t feel like talking to anyone, but the depression that must have come with the cancer otherwise never showed. “My cancer diet” she said of her slender figure. There were sores in her mouth and her appetite was gone. Then her mouth dried out and her fingernails splintered. Growing weaker, she would tell a story about Andrew having to get her tights on for her in the morning, and somehow make it funny.

“I never wanted to be a poster girl for cancer. But cancer has become part of who I am, along with my big feet and my English accent.”

One morning in her office, when I said something about how good her hair looked despite chemotherapy, she laughed. “It’s a wig,” she whispered. Her sons called it “Larry,” for the way Laurence Olivier looked in Henry V.

By then she was a size 4.

Her memoir was called No Time to Die. In it she wrote about the place she and Andrew had found on the bay in East Hampton:

I’d go down to the narrow strip of beach at the back of our house each morning and sit on my favorite rock with a cup of tea, often so weak that he’d have to carry me back. In what was a real family tragedy, Sophie, one of our Labradors, had recently died.

I knew that dog. That house was where Liz and Andrew had sheltered me during the summer when my marriage was ending. Too soon after, I got a call from Andrew.

“She’s gone,” he told me. “There’s nothing left to say.”

• • •

The bare stage was edged by pots of her favorite white orchids, and overhead was a large black-and-white Patrick Demarchelier photo of Liz, smiling out at the more than a thousand people filling Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall. Every important designer was there, along with top editors and Hearst executives. Si Newhouse and Anna Wintour came together. Hillary Clinton sent a statement. Bruce Weber, Trudie Styler and Calvin Klein were on the program, along with Liz’s doctor, and her brother, Grant, also a doctor. I spoke, too. I said Elizabeth Jane Kelly Tilberis was a caviar hound and a rocker. Last on the program was Dr. John. He played “My Buddy.”

Excerpted from The Accidental Life: An Editor's Notes on Writing and Writers a Rolling Stone by Terry McDonell (Knopf). First edition published August 2, 2016. Get a copy here.

Back to Entry/Points

Graydon Goes Shopping

Shoe horns, lampshades and CBD-infused elixirs are among the goods Graydon Carter is selling at a new newsstand-style shop in New York.

Shoe horns, lampshades and CBD-infused elixirs are among the goods Graydon Carter is selling at a new newsstand-style shop in New York. By Ruth La Ferla/The New York Times

Graydon Carter’s retail venture, Air Mail Newsstand, is an extension of Air Mail, the digital newsletter he started with Alessandra Stanley. (Photograph by Daniel Paik)

Call it instinct, or a second sight: Graydon Carter claims he knows a reader when he sees one. While scanning the streets of Manhattan’s West Village this week, Mr. Carter said pointedly, “In this part of the city, you’ll have many more readers than nonreaders.”

That may be why he chose a stretch of Hudson Street near Perry Street in the Village as the site of a new retail venture, Air Mail Newsstand, which is an extension of the digital newsletter, Air Mail, he started in 2019 with Alessandra Stanley.

The shop arrived in Manhattan after Air Mail opened others in London and Milan. Its merchandise, like the newsletter it is named after, is meant to appeal to an urbane crowd.

A rigorously edited selection of books and high-end glossies like The World of Interiors, Kinfolk, and Beauty Papers is supplemented by various novelties with a statusy, you-can-only-find-it-here appeal. Say, a curly brass shoehorn ($145); a palm-tree-patterned Chez Dede lampshade ($345); old-fashioned typewriter paper ($15); or an Air Mail logo baseball cap ($30) like the one Larry David wears in recent episodes of Curb Your Enthusiasm.

Is Mr. Carter, Vanity Fair’s former editor in chief, adopting a new identity as a shopkeeper? Not quite. But “there is a merchant inside everybody,” he said unflappably.

He sees retail as an inevitable adjunct to publishing, a symbiosis that has also been recognized by brands like Monocle, which had a shop in the West Village, and by Highsnobiety, a sneaker blog that evolved to include an online store and a twice-yearly publication that won the National Magazine Award for general excellence this year.

“In a magazine you can’t just sell ideas,” Mr. Carter, 74, said. “If you recommend a book you want to help the reader find that book. If you’re writing about a TV show, you tell the reader where it’s streaming.”

The Air Mail Newsstand was designed by Basil Walter, an architect who worked with Mr. Carter to develop the Waverly Inn. (Photograph by Justin M. Weiner)

Air Mail Newsstand, which is inside a 1905 rowhouse, has honey-oak floors, brass finishings, and a mirrored bar that serves oddly tangy coffee. Magazines are displayed at the front of the shop and a rotating selection of books is at the rear. At the moment, 100 titles are gathered under the heading, “Female Authors, Past and Present,” a highbrow grouping including works by Jane Smiley, Zadie Smith, Hilary Mantel, and Daphne du Maurier.

The shop was designed by Basil Walter, an architect who worked with Mr. Carter to develop the Waverly Inn, his restaurant in the West Village, and spaces where Mr. Carter hosted parties as the editor of Vanity Fair.

Like the canniest of merchants, Mr. Carter is himself a well-informed and unabashedly zealous shopper. Air Mail Newsstand’s selection of CBD-infused elixirs, lapel pins, and other goods—like many of the items featured by the newsletter’s e-commerce arm, Air Supply—is “based on things we’ve tried out and like,” he said.

Mr. Carter, while seated at a table at the rear of the shop on Tuesday, pulled out an object as flat and trim as a credit card. “This is an amazing tape recorder,” he said with the candid delight of a boy discovering his first Erector Set. The device, which costs $159, is sold at Air Mail Newsstand and, Mr. Carter explained, can connect to a smartphone.

He acknowledged that it seemed counterintuitive for a digital publication to open a newsstand-style shop—especially as both print magazines and traditional newsstands have been on the decline. But Mr. Carter is undaunted. “We love print, obviously,” he said.

Air Mail has occasionally published print versions of the newsletter and an annual or biannual print product is no pipe dream. “We’ll do print at some point,” Mr. Carter said.

“But we only have so many hours in a day, and I’m retired—well not really retired,” he conceded with a touch of faux regret. “I should be playing golf right now.”

ORIGINALLY POSTED ON 19 APRIL 2024 © THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY

Back to Entry/Points

Chapter 04: The Talker

The one with the Chappaqua Squawker

The one with the Chappaqua Squawker

ILLUSTRATION BY JASON SCHNEIDER

Editor’s note: In the late 2000s, John Korpics was the creative director at Fortune. He lived with his wife and kids way the hell up in Westchester County. Given his long commute, and being the industrious type, he decided to put that dreadful time to use. This column is what he came up with.

“Did you ask your father?”

“What did he say?”

“So I guess the economy’s getting better.”

“Why do you need to do that?”

“Did you finish your homework?”

“What should we do for dinner?”

“Again?”

Blah blah blah blah.

• • •

As I’m riding home on the 6:52 Peaker, selfishly enjoying the first quiet and peaceful minutes of my endless day, these are the truncated conversations that I hear coming from the woman in the seat across from me. I wait. Patiently.

I’m sure she’ll make this a quick call and hang up because this is a peak train full of hardcore commuters. No rookies.

And we know the rules and they are as follows: Have your ticket ready when the conductor comes around, keep your station bought bevy on the floor, not the seat in case it spills, and—unless you need to convey immediate information that will save American lives—stay off the effing phone.

You most certainly do not ramble on with your daughter about dinner, homework, and sleep plans. That’s why nerd geniuses like Bill Gates invented Texting Lady.

WTF.

In cases like this, I have a few options. I can ask her politely to keep her voice down and try to keep the conversation short, which is exactly what Mr. Rogers would do because he was a very calm and patient man and he truly loved humanity.

But you see, I got about 5 hours of sleep last night, and I’ve been at a stressful job all day, and I’m sitting under these interrogation-strength fluorescent lights, so the Mr. Rogers in me is not going to show up.

The second option is to stare. Fix a concrete hard gaze on her that lets her know exactly what I think about the fact that she’s sucking up all of my relaxation time with her inane conversation. So I try the stare. And, well, she just stares back.

Go ahead lady.

Another option, which I can only use if I get lucky, is that I wait until she gives the person on the other end of the conversation her cell number. “I might lose you. Just in case I do, my number is blah blah blah blah blah blah blah” and you write that precious number down—r-e-a-l-l-y carefully so you make sure you have it correct—and when you get home you sign her up for automatic phone messages from the home shopping network. “Please alert me by phone when you have a sale of any Wizard of Oz figurines. God bless.”

Unfortunately, I have no such luck tonight. The digits are not forthcoming, and so finally I resort to my last option (and my new favorite). I pull out my iPhone, take her picture, and blog about her.

Served.

Remember people, the train is a community, and if you aren’t a good neighbor, well, chances are someone’s going to leave a flaming bag of dog shit on your step.

Oh wait, she’s getting off. Chappaqua. Figures.

ORIGINALLY POSTED ON THURSDAY, 15 OCTOBER 2009 © JOHN KORPICS

John Korpics is VP/Executive Creative Director at Harvard Business Review. He has served as the design lead at Entertainment Weekly, Esquire, ESPN, Fortune, InStyle, and many other major newsstand magazines. His current commute is much effing easier.

Jason Schneider is a beloved Toronto-based editorial illustrator.

Back to Entry Points

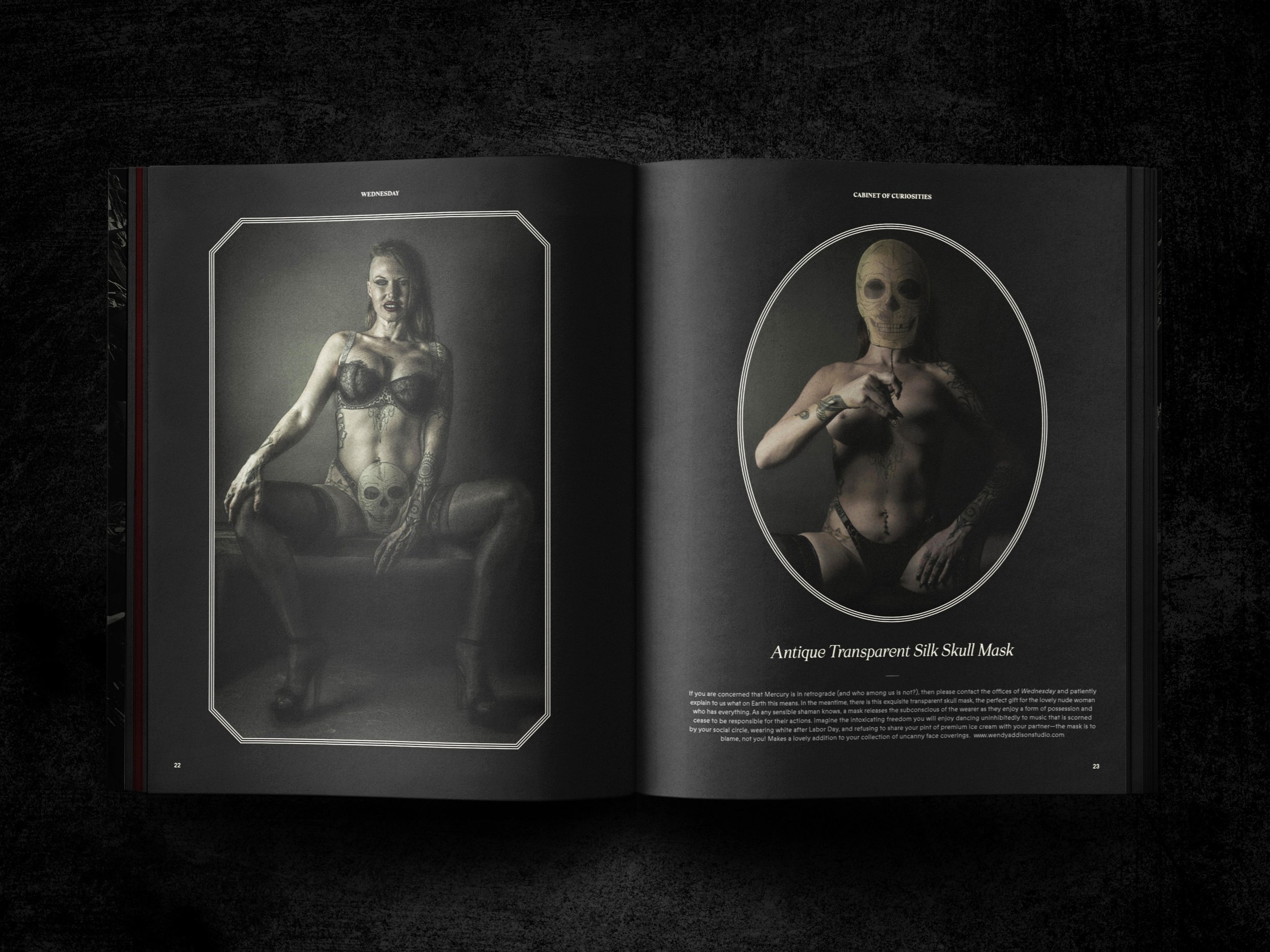

The Dark Art of Magazining

Wednesday is a new magazine they call “The Bible of Dark Culture.”

Wednesday is a new magazine they call “The Bible of Dark Culture.” By Steven Heller

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE DAILY HELLER / PRINT MAGAZINE

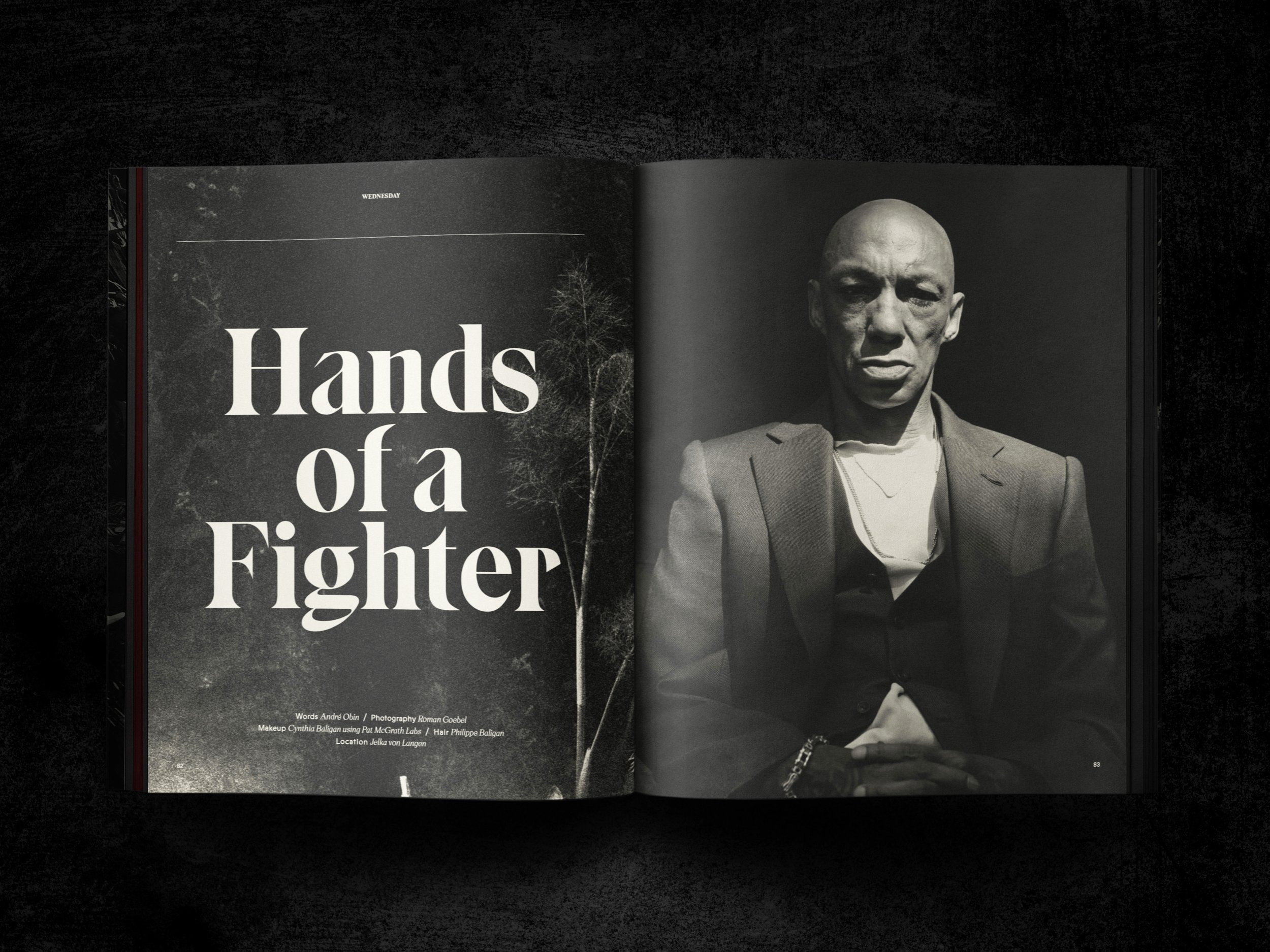

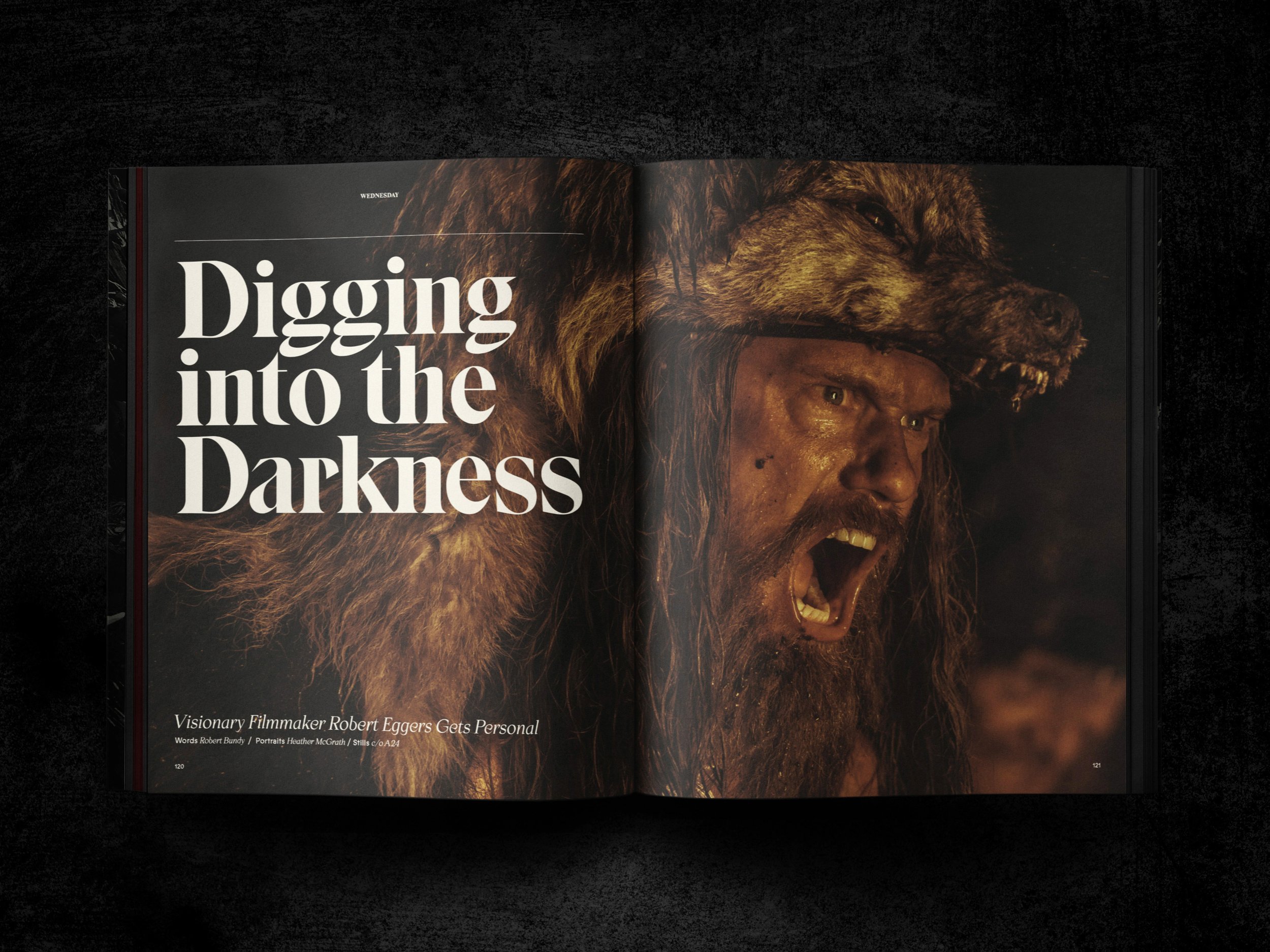

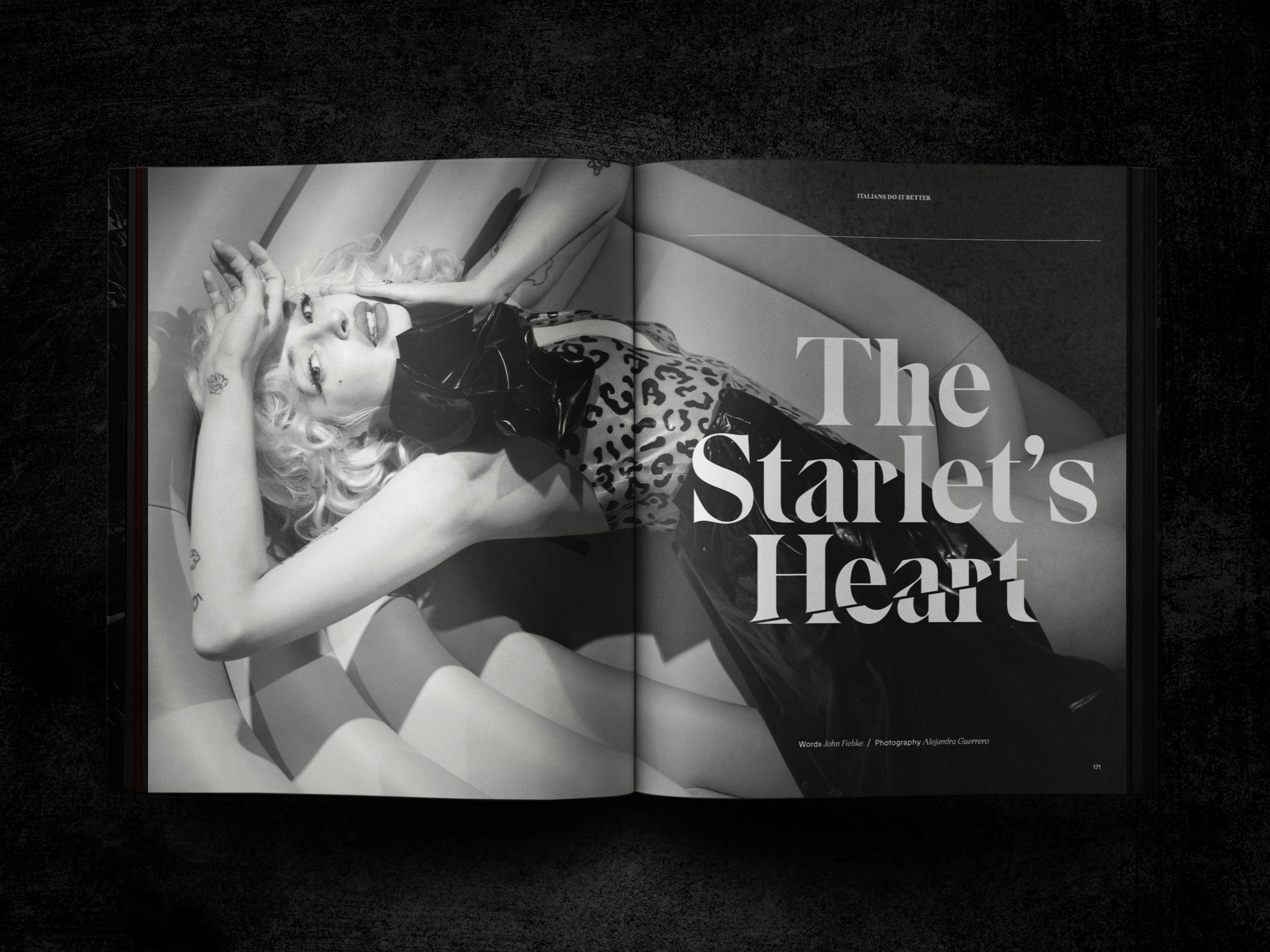

What is “Dark Culture”? When you see this new magazine, you’ll understand. It is a journal of that which “has been with us ever since we first learned to make fire.” An experiment in publishing, Wednesday is a storehouse of art and words, thick with content. Holding it is an experience. I asked editor-in-chief and creative director Kevin Grady to tell me about this new magazine in an age when print is supposed to be dead.

• • •

Steven Heller: Wednesday is quite an impressive magazine in its heft, design, and editorial content. I’m curious about the name and subtitle. What does Wednesday refer to? And why is this mag “Pertaining to Dark Culture”?

Kevin Grady: The name Wednesday references a verse from an English nursery rhyme from 1838 called “Monday’s Child,” which says, “Wednesday’s child is full of woe.” This reference was also the inspiration for Charles Addams’ Wednesday character in his Addams Family cartoons. We felt the name was an appropriate and evocative title for the project.

The magazine itself was created to explore darkness as a catalyst for creativity in music, art, film, fashion, literature and beyond. Darkness is having a moment in our pop cultural landscape, extending well beyond Goth. Perhaps it’s because we’re living in such dire times, but from fashion to [a quote] from artist Gerhard Richter that says “art is the highest form of hope,” a sentiment we really agree with, we see the artistic expressions documented in Wednesday as inherently positive, a sort of light in the night.

Steven Heller: The reference to Edward Gorey in the founder’s letter suggests a sense of lugubrious satire. Is this the intent of the magazine, to make the dark side a little lighter?

Kevin Grady: Absolutely—it’s like taking lemons and making lemonade. There’s a bit of gallows humor in the mix: When things seem bleak or hopeless, sometimes all you can do is laugh. It’s empowering in a way.

Steven Heller: Why publish a magazine, even a fairly exotic thematic one, at this time in the digital age?

Kevin Grady: Digital expressions continue to underwhelm me on the whole—I crave tangible expressions of creativity. I think lots of people can relate to that, hence the renewed popularity of vinyl, for example. And as we reference Wednesday as “The Bible of Dark Culture,” we wanted the book itself to be hefty, like an actual bible. The texture and blind embossing on the cover also invite a more sensual interaction with the magazine than you’d have if it were all digital.

ISteven Heller: am not sure how to categorize Wednesday. What do you say? Is it fashion-literary-art? Is it cult? Where does it sit on the magazine rack?

Kevin Grady: We see it as what you might expect if Edgar Allan Poe was brought back to life and guest-edited an issue of Kinfolk. In a way, it’s a lifestyle magazine, like many others that focus primarily on art, music and fashion, only through a dark lens. It’s also being distributed by Gingko Press as a book, so it’s not actually appearing in a magazine rack setting in most instances.

“We see the artistic expressions documented in Wednesday as inherently positive, a sort of light in the night.”

Steven Heller: What is your mandate as editor-in-chief, and how does that translate to your contributors?

Kevin Grady: Wednesday follows two previous publications that I founded, GUM (with Colin Metcalf) and Lemon. My intention now is quite similar to what it was then—to create compelling experiences in print. When I open up most magazines, I’m usually disappointed. Many follow conventions that are quite predictable.

With Lemon, we were able to collaborate with such icons as David Bowie and Daft Punk, based largely on the uniqueness of our approach and our expression. They sensed we were making Lemon purely for the love of it, a true passion project. Wednesday’s contributors are motivated by the same or similar aspirations.

I would like Wednesday to become a brand. In addition to the annual book, my collaborators and I would like to create products—scented candles, fragrances, apparel, perhaps our own absinthe—all building on the theme. Potentially it could expand into music as well.

Steven Heller: Who comprises your ideal audience?

Kevin Grady: I’ve joked that Wednesday is a magazine for mortals. Which is a pretty broad audience! But it’s true, we all have to grapple with our finite nature, and this is at the core of so much of Wednesday’s content. People who identity with Goth culture certainly have been quick to appreciate Wednesday, but the interest extends beyond that initial core. Almost everyone loves a good ghost story, regardless of demographics.

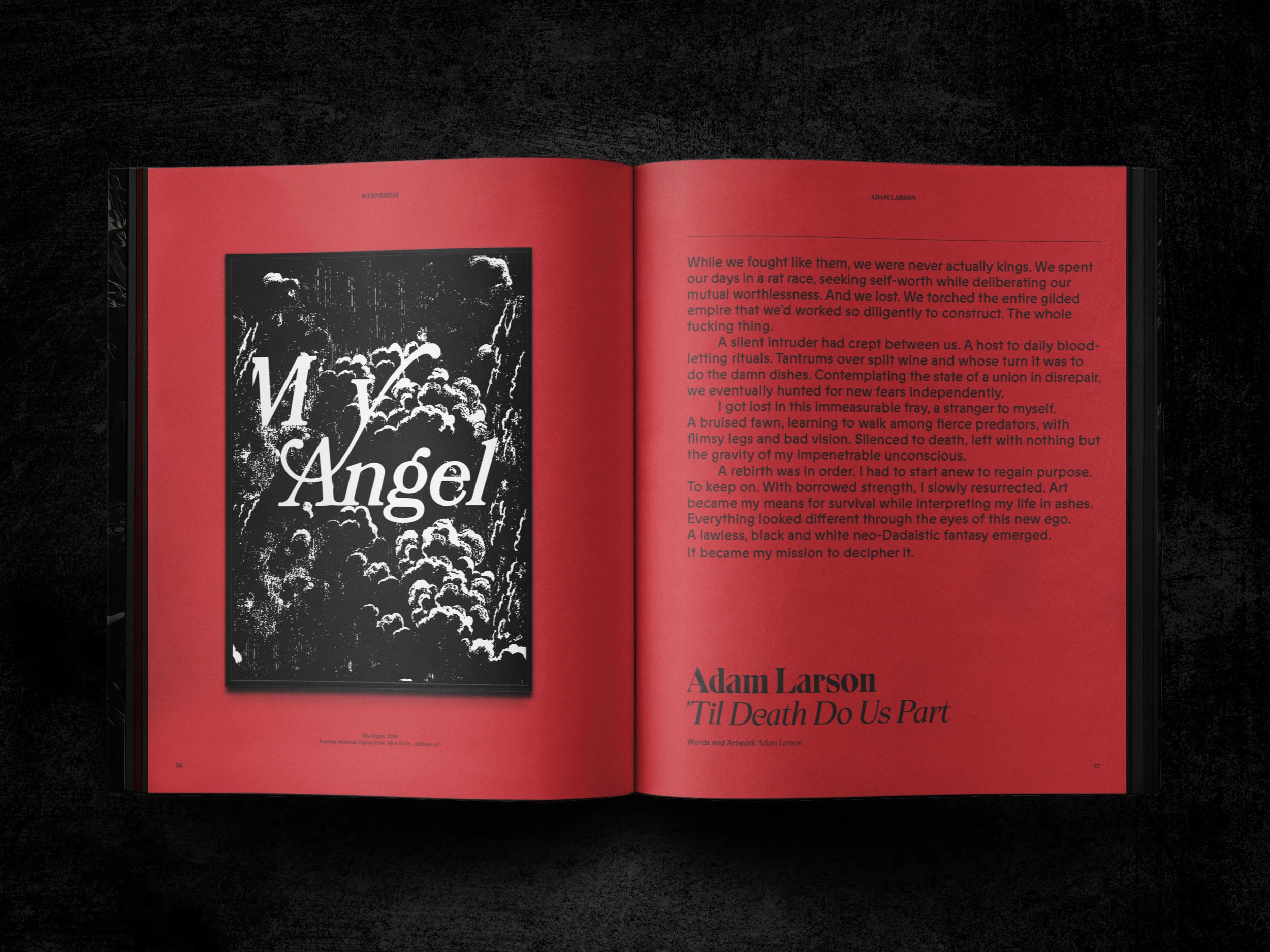

Most of our writers are quite mature as well, so there’s a lot of life experience packed in our pages. One story, by head writer Robert Bundy, is particularly poignant and involves grappling with the dementia and death of a loved one. Another feature, by Wednesday creative director Adam Larson, presents art he made following a painful breakup. People of all backgrounds can relate to topics like this.

Steven Heller: You call this “The New Bible of Dark Culture.” I admit I am not familiar with any of the contributors or the work included, other than Aubrey Beardsley, who represents an older dark culture, and Richard Brautigan. Where do you draw your content from?

Kevin Grady: There is a very broad subculture to draw inspiration from. It perhaps starts with musical luminaries such as The Cure, Joy Division and Depeche Mode and extends into the work of contemporary fashion designers like Rick Owens and Jun Takahashi. There’s a renaissance of original, intelligent horror films like A24’s Hereditary and Midsommar, and no end of fine artists who delve into morbid content. Inspiration can be found almost everywhere.

Steven Heller: How do you plan to keep an ambitious and presumably costly work such as this sustainable?

Kevin Grady: By not quitting our day jobs! We’re prepared to grow this organically over time, as an extension of the creative work we do professionally. So there’s less of a “make or break” aspect to it than there would be if we were trying to make a living from it. That’s pretty liberating. There’s still a lot we need to figure out, but it helps that we’re an annual as opposed to a monthly publication.

—

©2024 PRINT MAGAZINE

Steven Heller has written for PRINT since the 1980s. He is co-chair of SVA MFA Designer as Entrepreneur. The author, co-author and editor of over 200 books on design and popular culture, Heller is also the recipient of the Smithsonian Institution National Design Award for “Design Mind,” the AIGA Medal for Lifetime Achievement and other honors. He was a senior art director at The New York Times for 33 years and a writer of obituaries and book review columnist for the newspaper, as well. His memoir, Growing Up Underground (Princeton Architectural Press) was published in 2022. Some of his recent essays are collected in For the Love of Design (Allworth Press). He is also an editor-at-large and cohost of the Print Is Dead (Long Live Print) podcast. His interviews include designer Bob Ciano (Ep24) and illustrator Brad Holland (Ep05).

Back to Entry/Points

Chapter 03: The Sunny Side

The one where I fly too close to the sun.

The one where I fly too close to the sun.

ILLUSTRATION BY JASON SCHNEIDER

Editor’s note: In the late 2000s, John Korpics was the creative director at Fortune. He lived with his wife and kids way the hell up in Westchester County. Given his long commute, and being the industrious type, he decided to put that dreadful time to use. This column is what he came up with.

The 8:05 Peaker heading into the city. Sitting on the Sunny Side.

At certain times of the morning one side of the train gets blasted with sunlight. Usually, only a rookie sits on the sunny side because it’s very hard to read or see a laptop screen or sleep with the sun blasting in the window, especially when it’s intermittently blocked by trees and buildings creating a strobe effect, which I’ve heard can cause a stroke or a seizure in some cases.

That would be a bad way to start the day. But today I’m rolling in my new Maui Jim™ prescription sunglasses, and life is good.

I designed a business card for my optometrist friend, Dr. George Amatuzzi. I did it for free, because I’ve been going in to see him for about 12 years now and I just couldn’t stand looking at his effing ugly business cards anymore. They were printed on a thin gray stock—really, who chooses gray stock?—and designed from some sort of standard template that a printer gives you to choose from.

So I took one of his cards, went home and designed him a new one, took it back in and asked him to please accept this gift on behalf of all the people in the world with 20/20 vision who couldn’t stand looking at his effing ugly business cards anymore. He said ‘thanks’ and told me to pick out some sunglasses, which I did.

And here I am, sitting on the sunny side in my Maui Jim™ prescription sunglasses, which I thought were cool when I picked them out, but now I’m not so sure. I’m starting to think they look a little doofy.

As you can see, I’m also wearing a summer-weight suit jacket—even though it was 40 degrees this morning—and a button-down collar with no tie, which is actually a fashion mistake. But do I look like I give a damn? Nope. Not today.

Life is good.

ORIGINALLY POSTED ON WEDNESDAY, 14 OCTOBER 2009 © JOHN KORPICS

John Korpics is VP/Executive Creative Director at Harvard Business Review. He has served as the design lead at Entertainment Weekly, Esquire, ESPN, Fortune, InStyle, and many other major newsstand magazines. His current commute is much effing easier.

Jason Schneider is a beloved Toronto-based editorial illustrator.

Back to Entry Points

Rule No. 55: Be Perfectly Imperfect

In this excerpt from his new book, Fast Company designer Mike Schnaidt explains how to establish your creative voice in just three days.

In this excerpt from his new book, Fast Company designer Mike Schnaidt explains how to establish your creative voice in just three days.

Chef and author Molly Baz

A NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR

As a designer writing my first book, I leaned heavily on my experience of collaborating with magazine editors. (Okay, now I know your pain of needing more words.)

During my years at Men’s Health, we’d often conceptualize the design of our packages before assigning text—a skill that came in handy in the early stages of developing Creative Endurance. I started by prototyping the book to create a fun and digestible design. Then, I moved on to the writing.

Popular Science, where we focused entire issues on single topics, inspired my thematic approach to endurance. I expanded the theme across athletics, creative industries, and a variety of generations ranging from a nine-year-old, to a seventy-six-year-old, and those in the midst of their careers, including Molly Baz, the open and honest star of Rule No.55.

Honesty was a priority as I shaped Creative Endurance. Inspired by Esquire’s What I’ve Learned franchise, I removed my questions from many of the interviews, creating a direct connection between the subject and reader. You’ll see that approach in my interview with Russell Francis below.

With 39 interviews’ worth of material, I had a lot of great stuff on the cutting room floor. One other thing that I learned from Esquire: If text doesn’t fit into the confines of your grid structure, squeeze it outside of the margins. See how I applied these concepts in the excerpt below, and to be really inspired, pick up a copy of Creative Endurance.

Chicken Cutties. Cae Sal. Sunday Supps. Say what? We’ll get to that, but first, let’s grab a bite to eat with chef Molly Baz.

It’s been three days since she quit her writing job at the food magazine Bon Appétit, where Baz developed her approachable personality across print and video. How will she establish her creative voice?

Baz sits with a friend to strategize her next move: the launch of a newsletter. “People don’t care if the recipes are from Molly at Bon Appétit,” her friend says. “They just want you.” An empowering moment.

-

EMBRACE THE PAST

Reflect on your unique work experiences and skills. Baz’s writing and on-camera experience set her apart.

ENVISION THE FUTURE

Stay attuned to the needs of your target market. Baz bucked the trend of formality in cookbooks with a relatable approach.

You might worry about being the real You, as fear of rejection and conformity arise. Will people like you? Will you fit into your industry? Baz’s example proves the value of standing out by being imperfect.

To answer my original query: Baz’s abbreviations for chicken cutlets, Caesar salad, and Sunday supper strain the stress out of the cooking experience. These casual recipe titles sound like ones your best friend might suggest throwing together as the two of you hang out in the kitchen. “Chicken Cutty” makes the process of brining, breading, and frying a piece of poultry feel achievable, especially for a cook who fumbles his way through the kitchen (that would be me).

Baz’s creative voice carved her space in the food world. Her initial Patreon newsletter grows into a cooking club, titled The Club. Two cookbooks, Cook This Book and More in More, follow, along with a line of cookware for Crate & Barrel.

“I want people to recognize when a dish feels like me,” she says. “I don’t want it to feel like it could be anything you find on Recipes.com.” Your creative voice will help you stand out like this food personality, whose show, Hit the Kitch, sports a number of subscribers in the six-figure range on YouTube.

During our interview, I asked about her creative process. “Do you sit down and write a bunch of different recipe names before deciding on one?” I ask.

“No, that’s just how I speak,” she replies, with utmost confidence. Fair.

Q&A

THE NINE-YEAR-OLD

Dispatches from early childhood, via Camille Gerke.

Occupation: Kid

Location: Jersey City, New Jersey

Camille Gerke and I sit on the floor of her living room, and she’s drawing with colored markers. As she explains the strifes of a Thanksgiving art project gone awry at school, she remains fixated on the task at hand: a drawing of aliens and monsters. Her mind is racing. “When I’m angry, I draw because it helps me calm down,” she says, her voice matter-of-fact. Within minutes, she’s transformed a blank sheet of paper into a canvas full of dreams. I spoke with Gerke to learn how adults can resurrect their childhood imagination.

What can adults learn from kids?

-

Before you start working, take a moment to visualize your creation. Doodle! Don’t jump right onto the computer.

Mistakes are part of the creative process. Instead of fixating on what’s wrong, focus on what’s right.

Kids don’t think practically, and that works to their advantage. Think big when you’re brainstorming. You can always dial it back.

Adults worry about work. And work is boring. You need to look at it from a child’s perspective. Children’s brains are hardwired for imagination and curiosity. As soon as adults take on everyday responsibilities, they forget what their childhood was like.

How would you describe your childhood right now?

Good. I have a cat, and I get to walk him. Not many people get to walk their cat.

Do you get any ideas from your cat?

Yes. I recently made a book called The World of Blue (her cat’s name). Blue wakes up. Cleans his bedroom. Then he sits on Camille’s face and meows until she’s up.

What do you want to be when you grow up?

A zookeeper so I could work with Bengal tigers. I’d also love to make my own TV show. It would be about a high school girl that also fights bad guys by shooting lasers out of her hands. She works for the government, but is trying to keep it a secret. I’d also really love to be an illustrator for a book.

What would stop you from being an illustrator?

If someone ripped up all my drawings. That’s it.

How long does it take you to finish a drawing?

Three minutes. I visualize it in my head first, so I have a better idea of what I want to draw. Right now I’m in a phase where I don’t like to color my drawings, so I can do them quicker. I like to hum while I draw. It helps me focus. (Takes out a drawing.) This is about a girl named Alexa. One night a UFO crashes in their backyard. This is Number Twelve. She’s from another planet called Bop.

How do you start a drawing?

Usually, I have thoughts about the character in my brain. I start with the head shape, add the hair, the eyes, and the nose. If I draw a speech bubble next to them, then I add another character. Otherwise they’d be talking to themself, and that’s just weird.

What are you drawing in school right now?

Thanksgiving is soon, so we’re making turkeys. It started out really easy because I saw a male turkey, called a Tom, in Pennsylvania, and I put it in my memory box. But then, while I was painting the turkey, I made a huge mistake and totally messed it up. I was using too much water, and the paint smudged. I was so angry! I was fixated on this feather clump. My teacher comforted me and said, “The more you worry, the harder it’s going to be for you to finish. You’ll focus on the things that are wrong with it, instead of the things that are right with it.”

That’s great advice. Did it help you?

Yes! I started by improving what was wrong with the turkey. I focused on getting rid of each imperfection before moving on to the next. It’s just an artist’s instinct.

Are there any other classes you like?

Writing is fun, and I could do it for hours. But, I spend a lot of time drawing, so I don’t write. Also, writing makes my hand really sore.

What else are you drawing in school?

I recently entered a contest to make a drawing for the school yearbook. I didn’t make any sketches. I drew it in fifteen minutes, and I thought about the diversity of my friends when I drew all of the characters.

What worries you?

Grades. They toy with a child’s emotions. You could change a child’s perspective of school by giving them too much homework. I’m also worried about getting older. I don’t want to lose my creativity.

Do you have any final words of advice for adults on how to be more creative?

If you don’t like your job, then quit it, and do something fun.

Rule No. 56: Make an Impact

Use Your Creative Superpowers for Good

“What’s next when you’re only two decades into your career?”

You’ve leapt over the distractions, rolled under the barrage of revisions, and skipped from job to job. The wall that stands before you is a tough one to climb: your midlife crisis. How will you overcome this obstacle?

As a young designer, I had big aspirations of breaking into the publishing industry. I drafted my checklist and chipped away, literally working at every single place I dreamed of. Entertainment Weekly, check. Esquire, check. Popular Science, check. Men’s Health, double-check. Fast Company, check.

But now, just like Sara Lieberman, my measure of success has evolved. What’s next when you’re only two decades into your career? And to make matters worse, the publishing industry is, well, not exactly thriving as it once was. If this were a movie, cut to the scene where I’m running as the ground is collapsing behind me and magazines are falling into the pit. There aren’t many left. So…where to next? Midlife crisis: Activated.

The power-up to overcome my midlife crisis was discovered a few blocks away from me in Jersey City.

The deadline was looming for this manuscript. Running on fumes, I took my work to a local coffee shop. Cliché, I know, but I wanted to have the full writerly experience, as this was my first book. Among the sound of coffee beans buzzing and frothing milk gurgling, a gravelly voice emerged. It was an older gentleman, sharing writing advice with a young barista on break.

“Can I read you a poem I once wrote?” he asks, seizing a teachable moment. The poem was about his time during the Vietnam era, aboard a steam-propelled ship. A powerful piece. Both the barista and I felt the weight of the words.

“Damn, that was good,” I say, as an icebreaker. His name was Russell Francis.

Interviewing a stranger for this book was a bucket-list item of mine, so I mustered the courage to ask Francis to be a part of this project. His wisdom would be perfect. The next day, we have a great conversation, and it becomes clear to me: That interview will be the end of the book.

The day before the manuscript was due, I’m rushing to edit this last-minute interview, and amidst the pangs of uncertainty over the whole project, Francis calls me. Crap. Is he going to back out? I worry. “Son, you’ve got some balls for asking a stranger to be in your book,” he says. “But what you’re doing is really special. Creatives need inspiration to keep working.”

I made an impact on him, and in return, he made an impact on me. This feeling unlocked an extra gear to drive faster and harder on this book, because I could clearly see the purpose of my craft as a writer. I broke through the wall of my midlife crisis, and I discovered the impact I want to continue to make.

Everyone you’ve met in this book aspires to make an impact.

There was Molly Baz, who was making cooking more accessible. Jay Osgerby, who was designing objects with a purpose. Dean Karnazes, who was inspiring others to run. Anthony Giglio, who was challenging people’s perceptions of wine. And Caroline Gleich, who was breaking down gender barriers in the outdoors.

Reader, now it’s your turn. What kind of impact do you want to make? Is it in your culture? Your environment? It can be local, global, or hey, even in outer space. But once you discover your impact, you’ll unlock your Creative Endurance.

MY GROWTH PLAN

“Don’t Tell Me I Can’t Do Something.”

Russell Francis discovered his creativity later in life, and at 76 years old, won’t let go of it.

Occupation: Poet, Painter

Location: Jersey City, New Jersey

Three years, nine months, and twenty-seven days later, when I returned from war, I was not the same person.

The Vietnam War started as I graduated high school in Jersey City. I chose to go into the United States Navy. I wanted to make my father proud.

I was the main propulsion engineer on an aircraft carrier. I worked in the boiler room, and the engine was in there. Steam propulsion. Very hot.

We were in Asia, and in the distance, we saw the USS Liberty coming toward us. Smoke was pouring out of it, so obviously something was wrong. We had to prepare for an attack. I figured a world war was happening.

I went down into the hole. They locked the door behind me, and I had to do my job. Monitor the gauges on the wall. I’m down there, looking at a nuclear device that is damn near going to blow up and destroy everything around me. I had three seconds to shut the entire engine room down, or we’d be done. I was in alert mode.

-

Sometimes a compliment from a stranger can push you forward.

Discipline is required for long-term creativity.

It’s never too late to explore your creative potential.

This was the event that triggered my PTSD. I was emotionally shattered, but my art was buried deep within.

Eventually, after the war ended, I was 100 percent disabled. I could no longer work. I didn’t want to accept that I was disabled. Don’t tell me I can’t do something.

All of a sudden, I started to write.

I showed some writing to a friend of mine, Pete. “That’s good shit,” he says.

“If you say so,” I tell him. I am not educated. High school education. I wanted to go to college, but went into the navy instead. Pete’s a bright guy, and I trust him.

I was working on a painting. On wood. I brought it outside in front of my house, listening to whatever this creative voice inside of me is. The school day for the children was over, and a few kids walk by. They say, “Hey, Mister, that’s really nice.”

I showed that piece to Pete too. He says “You’re gonna have to do something with this.”

I went to the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Art to show the artistic director my work. She asks me, “How do you paint?” I didn’t know how to answer. I thought you just wore a beret or something. I said to her, “I put the canvas on the floor. I get on my hands and knees, and I fight with it. It makes me crazy.” She says, “You’re an artist. That’s what artists do.”

After looking at my paintings, she says, “You are now a matriculated student in the school.”

That was the first time I felt like a man that was given something very important.

In 1994, I went to the decommissioning ceremony for the ship I was on during the Vietnam era. I’m standing between two guys, and I take a poem out of my pocket. I read it. The guy next to me says, “I had to read that poem in college. I always wanted to meet the writer. Do you know who he is?” I tell him, “Yeah. It’s me.”

This was my poem, “More Steam.” It came from the heart. I wrote it in one shot, about that ship I was on, and sent it to the National Library of Poetry. I couldn’t wrap my head around the fact that this guy read my poem.

If I could pursue another creative activity, I would act. I can live the emotions of other characters through what I was denied. I would play Steve McQueen’s character in The Sand Pebbles.

Without my military training, I would not have the discipline to continue to paint, write, and see my creativity unfold.

I’m seventy-six years old. At this point, I need to stay alert. Breath to breath. Moment to moment. I need to be fully available to everything that’s happening in my day. Creativity is a gift.

Mike Schnaidt is a designer, educator, and writer based in Jersey City, New Jersey. His first book, Creative Endurance, offers practical tips to help creatives overcome their biggest challenges. As Fast Company’s creative director, he leads a team of art directors and photo editors who create visual content for the brand. Schnaidt has designed a variety of publications covering pop culture, fashion, food, and science, and has won awards from the Society of Publication Designers, Advertising Age, and Art Directors Club. He holds a Master of Science in Communication Design from Pratt Institute and teaches graphic design at Kean University.

Excerpted with permission from Creative Endurance: 56 Rules for Overcoming Obstacles and Achieving Your Goals (Rockport Publishers, an imprint of The Quarto Group, 2024) by Mike Schnaidt. All illustrations by Kagan McCleod. Creative Endurance is available wherever fine books are sold. Learn more at quarto.com.

Back to Entry/Points

How to Create a Great Magazine Out of Thin Air

Fifty years ago, Texas Monthly was little more than an idea dreamt up by a local lawyer with minimal experience in journalism. Then it was an actual thing. How did that happen?

Fifty years ago, Texas Monthly was little more than an idea dreamt up by a local lawyer with minimal experience in journalism. Then it was an actual thing. How did that happen? By William Broyles

Founder, Michael R. Levy (left) and founding editor-in-chief William Broyles in the Texas Monthly office around 1974.

Editor’s note: This article was part of Texas Monthly’s special fiftieth-anniversary issue.

It would not be the last time a writer pointed a loaded gun in my face during Texas Monthly’s first year.

In the fall of 1972, Gary Cartwright and I were making the rounds in Dallas. Gary was a journalist with a national reputation who had agreed to write a story for the first issue of a new magazine started by some young nobodies with no experience. I was the rookie editor, the nobody of nobodies. Gary was a real catch for us. If he were to write for our first issue, it would give us credibility, of which we had zero. But before Gary started writing, he wanted to put me to the test.

Texas Monthly’s premiere issue, February 1973

He took me to meet his crusty old editor at the Dallas Times Herald, who thought I was one of their copy boys. Then came the Dallas nightlife challenge. We started at the Colony Club, one of the classier joints on what remained of Dallas’s notorious Strip. I had a few drinks. Gary had more than a few, plus other substances, some of them legal. We met exotic dancers at various bars. They all knew Gary, as did the bartenders. Come midnight, Gary was just hitting his stride. He was in Hunter Thompson’s league as far as partying went. I was not.

Back then our per diem was $5 for food and $8 for a room. Gary, who was used to Sports Illustrated expense accounts, was not impressed. He’d arranged for us to stay in the apartment of his friend Pete Gent, so I went back there while Gary soldiered on into the Dallas night. Gent had played for the Dallas Cowboys and would soon publish a best-selling novel about life in the NFL. Like Gary, he was a substance tester, boundary pusher, and norm exploder. He was supposed to be out of town.

It was a restless night. Gent’s apartment was in the Love Field flight path. Two years earlier I’d been patrolling the jungles of Vietnam. Every two minutes or so, as I lay on Gent’s couch, a plane would come screaming into a landing. To me, each one sounded like enemy artillery fire. I had to fight the urge to yell “Incoming!” and throw myself onto the floor. I had just gotten to sleep when all the lights came on. A loaded gun was inches from my face. A very large human, under the influence of something far stronger than alcohol, was holding it.

Pete Gent.

“Who the f— are you?” he asked.

Gent thumbed the hammer back, his finger closing around the trigger. Gary was standing in the doorway. Without taking my gaze off Gent’s pinballing eyes, I spoke to Gary.

“Please. Tell him who I am.”

“You know this asshole?” Gent asked Gary.

Gary looked at me, then shook his head.

“I’ve never seen him before in my life.”

That memory comes to me while I’m reading through a bound volume of the first year of Texas Monthly. Dan Goodgame, the current editor in chief, has loaned me an office on the seventeenth floor of an elegant tower on Congress Avenue. Texas Monthly occupies the entire floor. That 1973 year was a half century ago, and we were all so young and felt like we could do anything. In those days each issue was a tightrope walk with no net. Each was a minor miracle. At some point years later, the miraculous became the normal, momentum built, the improvised became an institution, the guerrilla operation became an army. It’s all beyond what I could have imagined fifty years ago.

Trying to find the bathroom, I get lost, then lost again trying to find the kitchen, then lost again trying to get back to my temporary office. Along the way I walk down a hallway lined with the magazine’s nearly six hundred covers, arranged chronologically and mounted behind glass. I pass a state-of-the-art recording studio, where an audio team is producing a podcast episode. Texas Monthly isn’t just a magazine anymore. It’s a diversified media company with a strong online presence supported by a highly committed new owner, Randa Duncan Williams.

—

Continue reading at texasmonthly.com

ORIGINALLY POSTED IN FEBRUARY 2023 ©TEXAS MONTHLY

Back to Entry/Points

Chapter 02: Commuting Is No Yoke

a/k/a “The 7:25” Peaker

The one where I get all touchy-feely against my will—a/k/a life on the 7:25 “Peaker”

ILLUSTRATION BY JASON SCHNEIDER

Editor’s note: In the late 2000s, John Korpics was the creative director at Fortune. He lived with his wife and kids way the hell up in Westchester County. Given his long commute, and being the industrious type, he decided to put that dreadful time to use. This column is what he came up with.

First, I would like to welcome my 5 new followers. You represent the best that mankind has to offer and I thank you.

Today I wanted to talk about the 7:25am “Peaker,” which is the morning express peak train into the city. This is the train of choice or people who need to be at work by 9am and want as few stops as possible. Type A people. Type A-holes. I tend to take the next train, the 7:35, which is a local train and a little less intense. But today it’s the 7:25.

Look long and hard at this photo. And now imagine starting every day of your life just like this. Packed to the rivets, industrial strength fluorescent lights, and hundreds of people who dream in the form of a powerpoint presentation. This is why they always have those ads for Aruba on the walls at the end of the train car. “Honey, I’m not sure why, but I think we should take a trip to the islands.”

This is a silent train, which is to say that nobody talks—either on a phone or to another passenger. If someone tries to talk to you, which actually happened to me this morning, you know right away that they’re a rookie, a new commuter, and you briefly think to yourself, “Isn’t that odd. He’s talking to me. Huh.”

And then your coffee starts to wake you up a little more and the look on your face shifts to a look that now says, “Sorry. I don’t mean to cut you off in the middle of that story about your recent relocation, but it’s 7:25 am, and I’m just not the person you wish I was. Goodnight.”

I’m not proud of that. It just is. You’re either tired or hung over or reading or sleeping, but the one thing you are not doing is making conversation.

The other drag about the 7:25 is that it’s full, which means there are no empty seats, which means that someone has to sit “bitch.” (Someone has to sit in the middle seat in a three seat row). In order to do this, you have to gently nudge the person in the outside seat awake, ask to step over them, and then sit down in the middle, which then wakes up the person in the window seat.

If you successfully navigate that obstacle course, then consider this: Of the three average Americans now sitting in these three seats, what do you think the odds are that one of them is morbidly obese?

Turns out they’re pretty good actually. And finally, if the gods are truly against you today, one of the three people that you’re now rubbing arms and thighs with will decide to eat his egg and cheese breakfast out of a Tupperware container.

Jackpot. Picture complete.

Which makes sitting bitch one of the worst experiences you can have on a commute, because the only thing worse than talking to someone at 7:25 in the morning is touching them and smelling their eggs.

That’s it for today. Look at the picture. Look hard. Tomorrow I’m catching the 7:35.

ORIGINALLY POSTED ON TUESDAY, 13 OCTOBER 2009 © JOHN KORPICS

John Korpics is VP/Executive Creative Director at Harvard Business Review. He has served as the design lead at Entertainment Weekly, Esquire, ESPN, Fortune, InStyle, and many other major newsstand magazines. His current commute is much effing easier.

Jason Schneider is a beloved Toronto-based editorial illustrator.

Back to Entry Points

The Last Days of Time Inc.

An oral history of how the pre-eminent media organization of the 20th century ended up on the scrap heap.

An oral history of how the pre-eminent media organization of the 20th century ended up on the scrap heap. By Sridhar Pappu and Jay Stowe/The New York Times

Editor’s note: To accompany our John Huey interview, we wanted to share this exquisite oral history of Time Inc., as reported by The New York Times.

It was once an empire. Now it is being sold for parts.

Time Inc. began, in 1922, with a simple but revolutionary idea hatched by Henry R. Luce and Briton Hadden. The two men, graduates of Yale University, were rookie reporters at The Baltimore News when they drew up a prospectus for something called a “news magazine.” After raising $86,000, Mr. Hadden and Mr. Luce quit their jobs. On March 3, 1923, they published the first issue of Time: The Weekly News-Magazine.

In 1929, the year of Mr. Hadden’s sudden death, Mr. Luce started Fortune. In 1936, he bought a small-circulation humor publication, Life, and transformed it into a wide-ranging, large-format weekly. Later came Sports Illustrated, Money, People and InStyle. By 1989, with more than 100 publications in its fold, as well as significant holdings in television and radio, Time Inc. was rich enough to shell out $14.9 billion for 51 percent of Warner Communications, thus forming Time Warner.

The flush times went on for a while. But then, starting about a decade ago, the company began a slow decline that, in 2018, resulted in the Meredith Corporation, a Des Moines, Iowa, media company heavy on lifestyle monthlies like Better Homes and Gardens, completing its purchase of the once-grand Time Inc. in a deal that valued the company at $2.8 billion. The new owner wasted no time in prying the Time Inc. logo from the facade of its Lower Manhattan offices and announcing that it would seek buyers for Time, Fortune, Sports Illustrated, and Money. The deadline for first-round bids was May 11.

We reached out to more than two dozen editors and writers who worked at Time Inc., asking them to reflect on the heyday of this former epicenter of power and influence, as well as its decline. These interviews have been condensed and edited.

—

Continue reading at nytimes.com

ORIGINALLY POSTED ON 21 MAY 2018 © THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY

Back to Entry/Points

Less Than Words

In his 2018 TED talk, illustrator Christoph Niemann lets his pictures do the talking.

In his 2018 TED talk, illustrator Christoph Niemann lets his pictures do the talking.

Without realizing it, we’re fluent in the language of pictures, says illustrator Christoph Niemann. In a charming talk packed with witty, whimsical drawings, Niemann takes us on a hilarious visual tour that shows how artists tap into our emotions and minds—all without words.

Back to Entry/Points

Outdoor Voices

Media is broken. Mountain Gazette is here to fix it.

Media is broken. Mountain Gazette is here to fix it.

Editor’s Note: Mountain Gazette has been on our radar for a while now. We kinda think that if magazines were made like this twenty years ago, the business might be in a different place. Great writing, inspired imagery, a bodacious trim size, and expensive. (And worth every penny!). Here’s what founder/editor Mike Rogge has to say about it.

—

My name is Mike Rogge. My work as a journalist and film producer began at Ski The East then continued at Powder Magazine, ESPN, Vice Sports, and The Ski Journal. After that I went into writing, directing, and, later, shooting and producing short films that appeared across the world from the Brooklyn Museum to PBS and the Banff Mountain International Film Fest Festival.

My company, Verb Cabin, purchased Mountain Gazette in January 2020 in an effort to bring back the beloved title. I love nostalgia and the history of mountain culture. I also love a good f*cking challenge. Through it all I’ve learned just as much from failure as I have from wins.

Media, especially outdoor media, is broken. The old advertising model is dead, the new way of delivering content is too reliant on affiliate sales, click-bait, and pay-to-play gear reviews. Social media, and the internet at large, is sort of trash.

Nobody writes stories about the joy of going outside. Nobody is interested in tales about how people live, work, and play outside. Nobody, that is, except for those of us working here at Mountain Gazette. Through print, Mountain Gazette aims to deliver stories straight from the hearts of mountain town people to your inbox, feed, and mailbox. And you know, it’s working.

We sold out of our first revival issue in six weeks. We’ve sold out of every issue since then. We’re great at making magazines, if I may be so bold to say so, because of the collective people it takes to make each issue entirely unique.

Together, with a mighty staff made up of old friends and new, and an incredible group of subscribers, I am focused on unearthing the classic Mountain Gazette issues and celebrating the heritage of the original outdoor magazine.

Mountain Gazette’s been home to some of the world’s greatest writers and craftiest photographers, but until now those stories and photos were buried in ski bum garages and dusty, old antique shops.

You can follow our progress on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook. You can drop me a line anytime.

Most importantly, with the return of Mountain Gazette, I want you to know this isn’t my magazine. It’s yours.

Visit Mountain Gazette’s website to learn more.

Back to Entry/Points

Chapter 01: The One Where I Explain Myself

Welcome to the first post on my effing commute.

ILLUSTRATION BY JASON SCHNEIDER

Editor’s note: In the late 2000s, John Korpics was the creative director at Fortune. He lived with his wife and kids way the hell up in Westchester County. Given his long commute, and being the industrious type, he decided to put that dreadful time to use. This column is the result.

Welcome to the first post on my effing commute.

Every weekday of my life I spend three and a half hours of my day (mostly on a train) going between my job in Manhattan and my house in Westchester County, NY. The life of a long distance commuter (which is an actual term that has a specific definition that I believe I meet) is a soul sucking, Kafkaesque existence that I would wish on no man or woman. But it is my life and I’ve learned to accept it. I’ve also decided to use my time to share my living hell with as many people as are interested.

You’re welcome.

So tonight it’s 8:15 pm and I’m on an “Off Peaker,” which is a train that doesn’t run within the designated peak rush hour times, which is to say I’m on a late train going home, which usually means it’s full of drunks and shopping trophy wives yacking on their cell phones.

Today, though, is Columbus Day, which is kind of a holiday (no mail, no school), but not really (Wall Street and my job: open), which means it’s a light volume day on the rails.

So besides having to pee but not wanting to use the train bathrooms (there’s like ten blogs worth of writing to be done later on train bathrooms), I’m enjoying the ride with my feet up and plenty of “spread out room.”

It's a good ride.

As you can see, I’m wearing a tie today, which means at some point this morning when I was getting dressed, I thought I might need to look like I was in charge today, which I am usually (in charge). But I don’t always want to dress the part.

If this blog was called “My Effing Living Room,” there would never be a picture of me in a tie. There would more likely be a picture of me in some sort of Hanes underwear product and a t-shirt that I got for free and then cut the sleeves off of. That’s just how I roll.

Thanks for reading. See you next time.

ORIGINALLY POSTED ON MONDAY, 12 OCTOBER 2009 © JOHN KORPICS

John Korpics is VP/Executive Creative Director at Harvard Business Review. He has served as the design lead at Entertainment Weekly, Esquire, ESPN, Fortune, InStyle, and many other major newsstand magazines. His current commute is much effing easier.

Jason Schneider is a beloved Toronto-based editorial illustrator.

Back to Entry Points

Banana Republic’s One-Hit Wonder

A travel writer looks back at a magazine that dreamed big. (And went nowhere).

A travel writer looks back at a magazine that dreamed big—and went nowhere. By Neal Moore

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE WEBSITE ABANDONED REPUBLIC (APRIL 2021)

—

I picked up my first copy of Trips magazine at a “safari & travel” Banana Republic store of yesteryear. I was a kid, it was the late 1980s, and I can say—as oddball as this might sound—that I’ve spun the globe with it ever since. Its mantra of what travel can (and should) look and feel and taste like, open-mindedness-wise, sense-of-curiosity-wise, and being-alive-wise—“to get as deep inside a culture as constraints of language and understanding will allow”—has helped form my take, my very own spin on this world.

There was only ever one issue produced—so the Spring 1988 edition serves as both the debut and finale edition. I’ve lost my original copy a long time back and have since given away many more, so I try to snag one every chance I get (thanks eBay).

I like to think of Trips as a bible of adventure, a relic of expedition, and an unadulterated view into the “safari & travel” vision of Mel & Patricia Ziegler, founders of the long-abandoned original Banana Republic.

Banana Republic founders Patricia and Mel Ziegler

The Zieglers, both retired journalists with the San Francisco Chronicle, hired their friends, established ink-slingers, to write the magazine’s copy. It was clearly a labor of love.

Flip the pages, and the articles will transport you in search of the soul of Hawaii with National Geographic journalist Marguerite Del Giudice; hurl you into Apartheid-era South Africa with Rolling Stone, The Village Voice, and Esquire writer Mark Jacobson; bike alongside His Majesty, the King of Tonga with screenwriter, actor and novelist Charlie Haas; and ride to the back of beyond of Australia with photographs by Hakan Ludwigsson and text by Newsweek’s Tony Clifton.

The magazine was likely the first to introduce The Thorn Tree Forum into print, an idea picked up and popularized by Lonely Planet eight years later in 1996.

“It was, effectively, Kenya’s first postal system,” explains the Zieglers, referring to an old thorn tree in the courtyard of the New Stanley Hotel in Nairobi where travelers used to pin their urgent, cryptic messages.

“We borrowed the name for this column. Items will be culled from letters, news clippings, documents, anything concise and interesting that crosses our desk. Travelers’ tales, tips, observations, complaints, and cultural artifacts are welcome.”

The Zieglers hired Roger Black to design Trips.

To get the oddball rolling, first-hand travel tips from veteran travelers were offered—from “How to turn a golf ball into a drain plug for overseas bathtub,” to “Create a travel journal as you go: Mail postcards to yourself!”

I love them all—the sketches, the travelogues, the photos, the irony, the off-the-beaten-track discoveries. One of my favorite travel tales, penned by Sports Illustrated writer Gary Smith, whisks the reader onto a Portugal-bound train chockablock with banana and fish smugglers.

I’ve hiked with Trips across Tigray, Ethiopia, adventured with it into the dusty dorps of the Klein and Groot Karoo of Southern Africa, listened to the call to prayer with it in Islamic West Luxor, and I’ve gotten lost with it the back alleys of Bangkok, Hong Kong and Taipei—all places I’ve called home.

These days, I find myself canoeing with this tried and trusty and true companion across America, most days carefully stowed away in my dry bags, and on days like today, taken out to peruse and inspire.