Rule No. 55: Be Perfectly Imperfect

In this excerpt from his new book, Fast Company designer Mike Schnaidt explains how to establish your creative voice in just three days.

Chef and author Molly Baz

A NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR

As a designer writing my first book, I leaned heavily on my experience of collaborating with magazine editors. (Okay, now I know your pain of needing more words.)

During my years at Men’s Health, we’d often conceptualize the design of our packages before assigning text—a skill that came in handy in the early stages of developing Creative Endurance. I started by prototyping the book to create a fun and digestible design. Then, I moved on to the writing.

Popular Science, where we focused entire issues on single topics, inspired my thematic approach to endurance. I expanded the theme across athletics, creative industries, and a variety of generations ranging from a nine-year-old, to a seventy-six-year-old, and those in the midst of their careers, including Molly Baz, the open and honest star of Rule No.55.

Honesty was a priority as I shaped Creative Endurance. Inspired by Esquire’s What I’ve Learned franchise, I removed my questions from many of the interviews, creating a direct connection between the subject and reader. You’ll see that approach in my interview with Russell Francis below.

With 39 interviews’ worth of material, I had a lot of great stuff on the cutting room floor. One other thing that I learned from Esquire: If text doesn’t fit into the confines of your grid structure, squeeze it outside of the margins. See how I applied these concepts in the excerpt below, and to be really inspired, pick up a copy of Creative Endurance.

Chicken Cutties. Cae Sal. Sunday Supps. Say what? We’ll get to that, but first, let’s grab a bite to eat with chef Molly Baz.

It’s been three days since she quit her writing job at the food magazine Bon Appétit, where Baz developed her approachable personality across print and video. How will she establish her creative voice?

Baz sits with a friend to strategize her next move: the launch of a newsletter. “People don’t care if the recipes are from Molly at Bon Appétit,” her friend says. “They just want you.” An empowering moment.

-

EMBRACE THE PAST

Reflect on your unique work experiences and skills. Baz’s writing and on-camera experience set her apart.

ENVISION THE FUTURE

Stay attuned to the needs of your target market. Baz bucked the trend of formality in cookbooks with a relatable approach.

You might worry about being the real You, as fear of rejection and conformity arise. Will people like you? Will you fit into your industry? Baz’s example proves the value of standing out by being imperfect.

To answer my original query: Baz’s abbreviations for chicken cutlets, Caesar salad, and Sunday supper strain the stress out of the cooking experience. These casual recipe titles sound like ones your best friend might suggest throwing together as the two of you hang out in the kitchen. “Chicken Cutty” makes the process of brining, breading, and frying a piece of poultry feel achievable, especially for a cook who fumbles his way through the kitchen (that would be me).

Baz’s creative voice carved her space in the food world. Her initial Patreon newsletter grows into a cooking club, titled The Club. Two cookbooks, Cook This Book and More in More, follow, along with a line of cookware for Crate & Barrel.

“I want people to recognize when a dish feels like me,” she says. “I don’t want it to feel like it could be anything you find on Recipes.com.” Your creative voice will help you stand out like this food personality, whose show, Hit the Kitch, sports a number of subscribers in the six-figure range on YouTube.

During our interview, I asked about her creative process. “Do you sit down and write a bunch of different recipe names before deciding on one?” I ask.

“No, that’s just how I speak,” she replies, with utmost confidence. Fair.

Q&A

THE NINE-YEAR-OLD

Dispatches from early childhood, via Camille Gerke.

Occupation: Kid

Location: Jersey City, New Jersey

Camille Gerke and I sit on the floor of her living room, and she’s drawing with colored markers. As she explains the strifes of a Thanksgiving art project gone awry at school, she remains fixated on the task at hand: a drawing of aliens and monsters. Her mind is racing. “When I’m angry, I draw because it helps me calm down,” she says, her voice matter-of-fact. Within minutes, she’s transformed a blank sheet of paper into a canvas full of dreams. I spoke with Gerke to learn how adults can resurrect their childhood imagination.

What can adults learn from kids?

-

Before you start working, take a moment to visualize your creation. Doodle! Don’t jump right onto the computer.

Mistakes are part of the creative process. Instead of fixating on what’s wrong, focus on what’s right.

Kids don’t think practically, and that works to their advantage. Think big when you’re brainstorming. You can always dial it back.

Adults worry about work. And work is boring. You need to look at it from a child’s perspective. Children’s brains are hardwired for imagination and curiosity. As soon as adults take on everyday responsibilities, they forget what their childhood was like.

How would you describe your childhood right now?

Good. I have a cat, and I get to walk him. Not many people get to walk their cat.

Do you get any ideas from your cat?

Yes. I recently made a book called The World of Blue (her cat’s name). Blue wakes up. Cleans his bedroom. Then he sits on Camille’s face and meows until she’s up.

What do you want to be when you grow up?

A zookeeper so I could work with Bengal tigers. I’d also love to make my own TV show. It would be about a high school girl that also fights bad guys by shooting lasers out of her hands. She works for the government, but is trying to keep it a secret. I’d also really love to be an illustrator for a book.

What would stop you from being an illustrator?

If someone ripped up all my drawings. That’s it.

How long does it take you to finish a drawing?

Three minutes. I visualize it in my head first, so I have a better idea of what I want to draw. Right now I’m in a phase where I don’t like to color my drawings, so I can do them quicker. I like to hum while I draw. It helps me focus. (Takes out a drawing.) This is about a girl named Alexa. One night a UFO crashes in their backyard. This is Number Twelve. She’s from another planet called Bop.

How do you start a drawing?

Usually, I have thoughts about the character in my brain. I start with the head shape, add the hair, the eyes, and the nose. If I draw a speech bubble next to them, then I add another character. Otherwise they’d be talking to themself, and that’s just weird.

What are you drawing in school right now?

Thanksgiving is soon, so we’re making turkeys. It started out really easy because I saw a male turkey, called a Tom, in Pennsylvania, and I put it in my memory box. But then, while I was painting the turkey, I made a huge mistake and totally messed it up. I was using too much water, and the paint smudged. I was so angry! I was fixated on this feather clump. My teacher comforted me and said, “The more you worry, the harder it’s going to be for you to finish. You’ll focus on the things that are wrong with it, instead of the things that are right with it.”

That’s great advice. Did it help you?

Yes! I started by improving what was wrong with the turkey. I focused on getting rid of each imperfection before moving on to the next. It’s just an artist’s instinct.

Are there any other classes you like?

Writing is fun, and I could do it for hours. But, I spend a lot of time drawing, so I don’t write. Also, writing makes my hand really sore.

What else are you drawing in school?

I recently entered a contest to make a drawing for the school yearbook. I didn’t make any sketches. I drew it in fifteen minutes, and I thought about the diversity of my friends when I drew all of the characters.

What worries you?

Grades. They toy with a child’s emotions. You could change a child’s perspective of school by giving them too much homework. I’m also worried about getting older. I don’t want to lose my creativity.

Do you have any final words of advice for adults on how to be more creative?

If you don’t like your job, then quit it, and do something fun.

Rule No. 56: Make an Impact

Use Your Creative Superpowers for Good

“What’s next when you’re only two decades into your career?”

You’ve leapt over the distractions, rolled under the barrage of revisions, and skipped from job to job. The wall that stands before you is a tough one to climb: your midlife crisis. How will you overcome this obstacle?

As a young designer, I had big aspirations of breaking into the publishing industry. I drafted my checklist and chipped away, literally working at every single place I dreamed of. Entertainment Weekly, check. Esquire, check. Popular Science, check. Men’s Health, double-check. Fast Company, check.

But now, just like Sara Lieberman, my measure of success has evolved. What’s next when you’re only two decades into your career? And to make matters worse, the publishing industry is, well, not exactly thriving as it once was. If this were a movie, cut to the scene where I’m running as the ground is collapsing behind me and magazines are falling into the pit. There aren’t many left. So…where to next? Midlife crisis: Activated.

The power-up to overcome my midlife crisis was discovered a few blocks away from me in Jersey City.

The deadline was looming for this manuscript. Running on fumes, I took my work to a local coffee shop. Cliché, I know, but I wanted to have the full writerly experience, as this was my first book. Among the sound of coffee beans buzzing and frothing milk gurgling, a gravelly voice emerged. It was an older gentleman, sharing writing advice with a young barista on break.

“Can I read you a poem I once wrote?” he asks, seizing a teachable moment. The poem was about his time during the Vietnam era, aboard a steam-propelled ship. A powerful piece. Both the barista and I felt the weight of the words.

“Damn, that was good,” I say, as an icebreaker. His name was Russell Francis.

Interviewing a stranger for this book was a bucket-list item of mine, so I mustered the courage to ask Francis to be a part of this project. His wisdom would be perfect. The next day, we have a great conversation, and it becomes clear to me: That interview will be the end of the book.

The day before the manuscript was due, I’m rushing to edit this last-minute interview, and amidst the pangs of uncertainty over the whole project, Francis calls me. Crap. Is he going to back out? I worry. “Son, you’ve got some balls for asking a stranger to be in your book,” he says. “But what you’re doing is really special. Creatives need inspiration to keep working.”

I made an impact on him, and in return, he made an impact on me. This feeling unlocked an extra gear to drive faster and harder on this book, because I could clearly see the purpose of my craft as a writer. I broke through the wall of my midlife crisis, and I discovered the impact I want to continue to make.

Everyone you’ve met in this book aspires to make an impact.

There was Molly Baz, who was making cooking more accessible. Jay Osgerby, who was designing objects with a purpose. Dean Karnazes, who was inspiring others to run. Anthony Giglio, who was challenging people’s perceptions of wine. And Caroline Gleich, who was breaking down gender barriers in the outdoors.

Reader, now it’s your turn. What kind of impact do you want to make? Is it in your culture? Your environment? It can be local, global, or hey, even in outer space. But once you discover your impact, you’ll unlock your Creative Endurance.

MY GROWTH PLAN

“Don’t Tell Me I Can’t Do Something.”

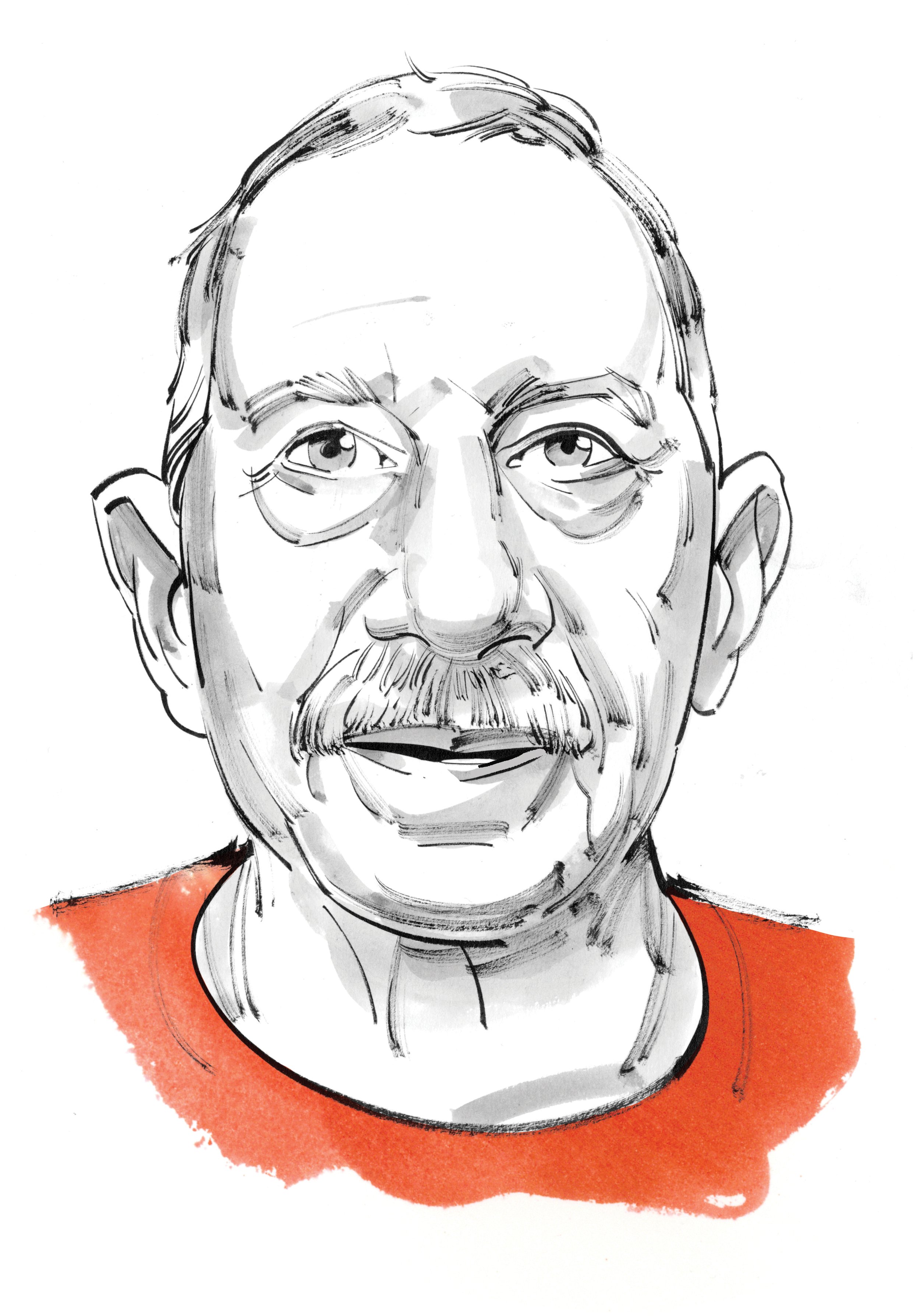

Russell Francis discovered his creativity later in life, and at 76 years old, won’t let go of it.

Occupation: Poet, Painter

Location: Jersey City, New Jersey

Three years, nine months, and twenty-seven days later, when I returned from war, I was not the same person.

The Vietnam War started as I graduated high school in Jersey City. I chose to go into the United States Navy. I wanted to make my father proud.

I was the main propulsion engineer on an aircraft carrier. I worked in the boiler room, and the engine was in there. Steam propulsion. Very hot.

We were in Asia, and in the distance, we saw the USS Liberty coming toward us. Smoke was pouring out of it, so obviously something was wrong. We had to prepare for an attack. I figured a world war was happening.

I went down into the hole. They locked the door behind me, and I had to do my job. Monitor the gauges on the wall. I’m down there, looking at a nuclear device that is damn near going to blow up and destroy everything around me. I had three seconds to shut the entire engine room down, or we’d be done. I was in alert mode.

-

Sometimes a compliment from a stranger can push you forward.

Discipline is required for long-term creativity.

It’s never too late to explore your creative potential.

This was the event that triggered my PTSD. I was emotionally shattered, but my art was buried deep within.

Eventually, after the war ended, I was 100 percent disabled. I could no longer work. I didn’t want to accept that I was disabled. Don’t tell me I can’t do something.

All of a sudden, I started to write.

I showed some writing to a friend of mine, Pete. “That’s good shit,” he says.

“If you say so,” I tell him. I am not educated. High school education. I wanted to go to college, but went into the navy instead. Pete’s a bright guy, and I trust him.

I was working on a painting. On wood. I brought it outside in front of my house, listening to whatever this creative voice inside of me is. The school day for the children was over, and a few kids walk by. They say, “Hey, Mister, that’s really nice.”

I showed that piece to Pete too. He says “You’re gonna have to do something with this.”

I went to the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Art to show the artistic director my work. She asks me, “How do you paint?” I didn’t know how to answer. I thought you just wore a beret or something. I said to her, “I put the canvas on the floor. I get on my hands and knees, and I fight with it. It makes me crazy.” She says, “You’re an artist. That’s what artists do.”

After looking at my paintings, she says, “You are now a matriculated student in the school.”

That was the first time I felt like a man that was given something very important.

In 1994, I went to the decommissioning ceremony for the ship I was on during the Vietnam era. I’m standing between two guys, and I take a poem out of my pocket. I read it. The guy next to me says, “I had to read that poem in college. I always wanted to meet the writer. Do you know who he is?” I tell him, “Yeah. It’s me.”

This was my poem, “More Steam.” It came from the heart. I wrote it in one shot, about that ship I was on, and sent it to the National Library of Poetry. I couldn’t wrap my head around the fact that this guy read my poem.

If I could pursue another creative activity, I would act. I can live the emotions of other characters through what I was denied. I would play Steve McQueen’s character in The Sand Pebbles.

Without my military training, I would not have the discipline to continue to paint, write, and see my creativity unfold.

I’m seventy-six years old. At this point, I need to stay alert. Breath to breath. Moment to moment. I need to be fully available to everything that’s happening in my day. Creativity is a gift.

Mike Schnaidt is a designer, educator, and writer based in Jersey City, New Jersey. His first book, Creative Endurance, offers practical tips to help creatives overcome their biggest challenges. As Fast Company’s creative director, he leads a team of art directors and photo editors who create visual content for the brand. Schnaidt has designed a variety of publications covering pop culture, fashion, food, and science, and has won awards from the Society of Publication Designers, Advertising Age, and Art Directors Club. He holds a Master of Science in Communication Design from Pratt Institute and teaches graphic design at Kean University.

Excerpted with permission from Creative Endurance: 56 Rules for Overcoming Obstacles and Achieving Your Goals (Rockport Publishers, an imprint of The Quarto Group, 2024) by Mike Schnaidt. All illustrations by Kagan McCleod. Creative Endurance is available wherever fine books are sold. Learn more at quarto.com.