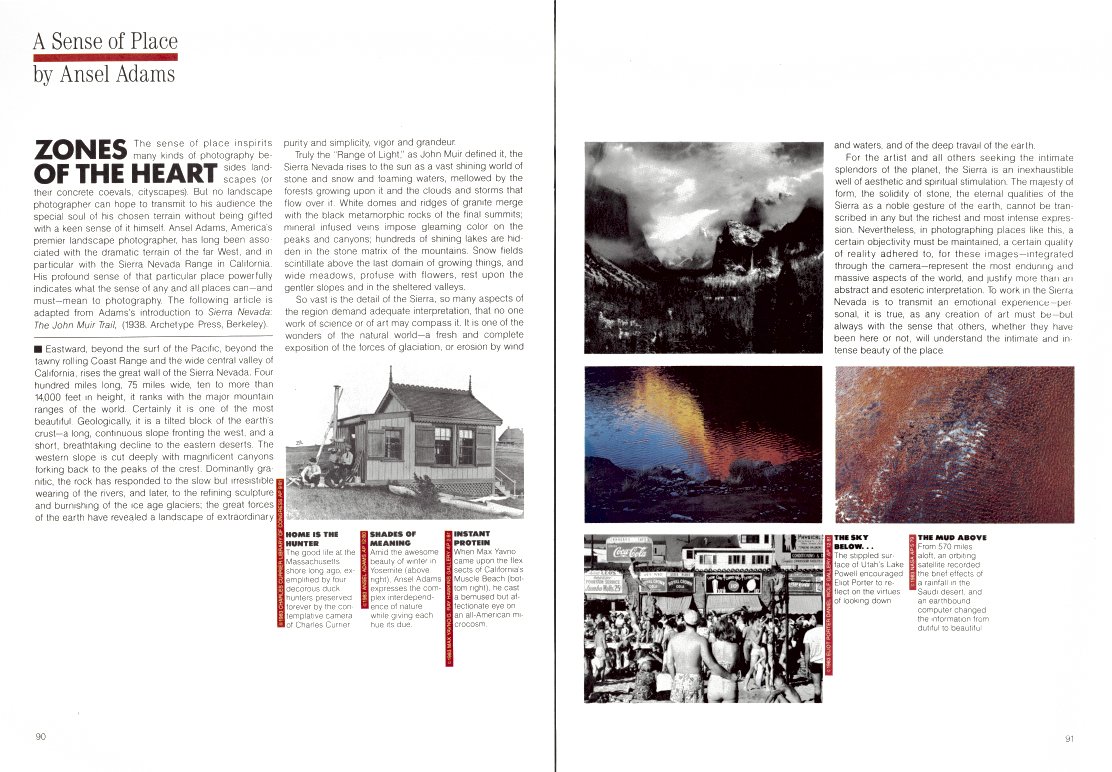

The Arkansas Traveler

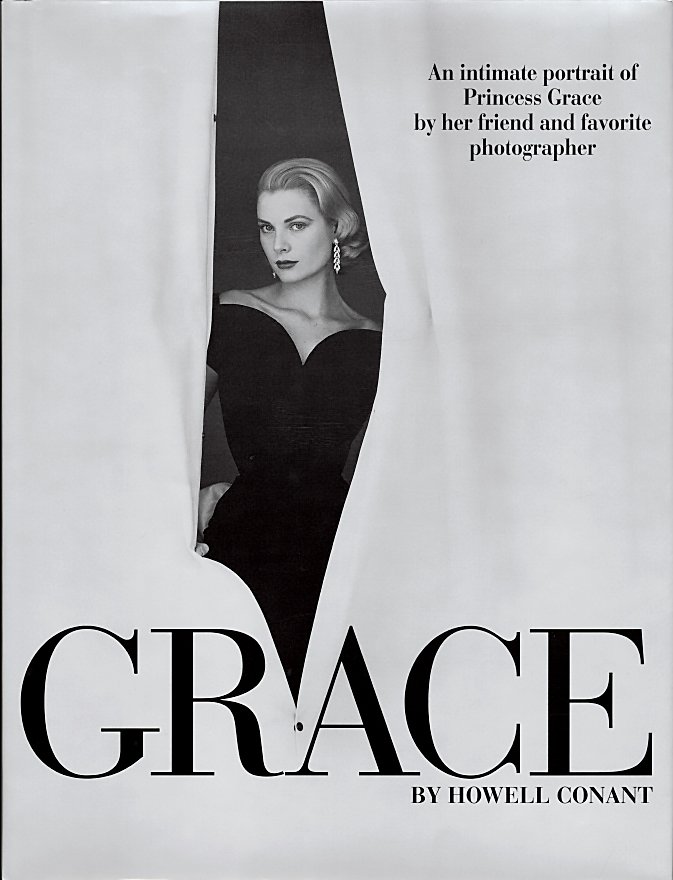

An outsider in an insider’s game, Will Hopkins left a hardscrabble life in 1960s Arkansas to travel the world and became one of magazine publishing’s great design practitioners.

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH THE SUPPORT OF MAGCULTURE

Photograph by Barbara Bordnick

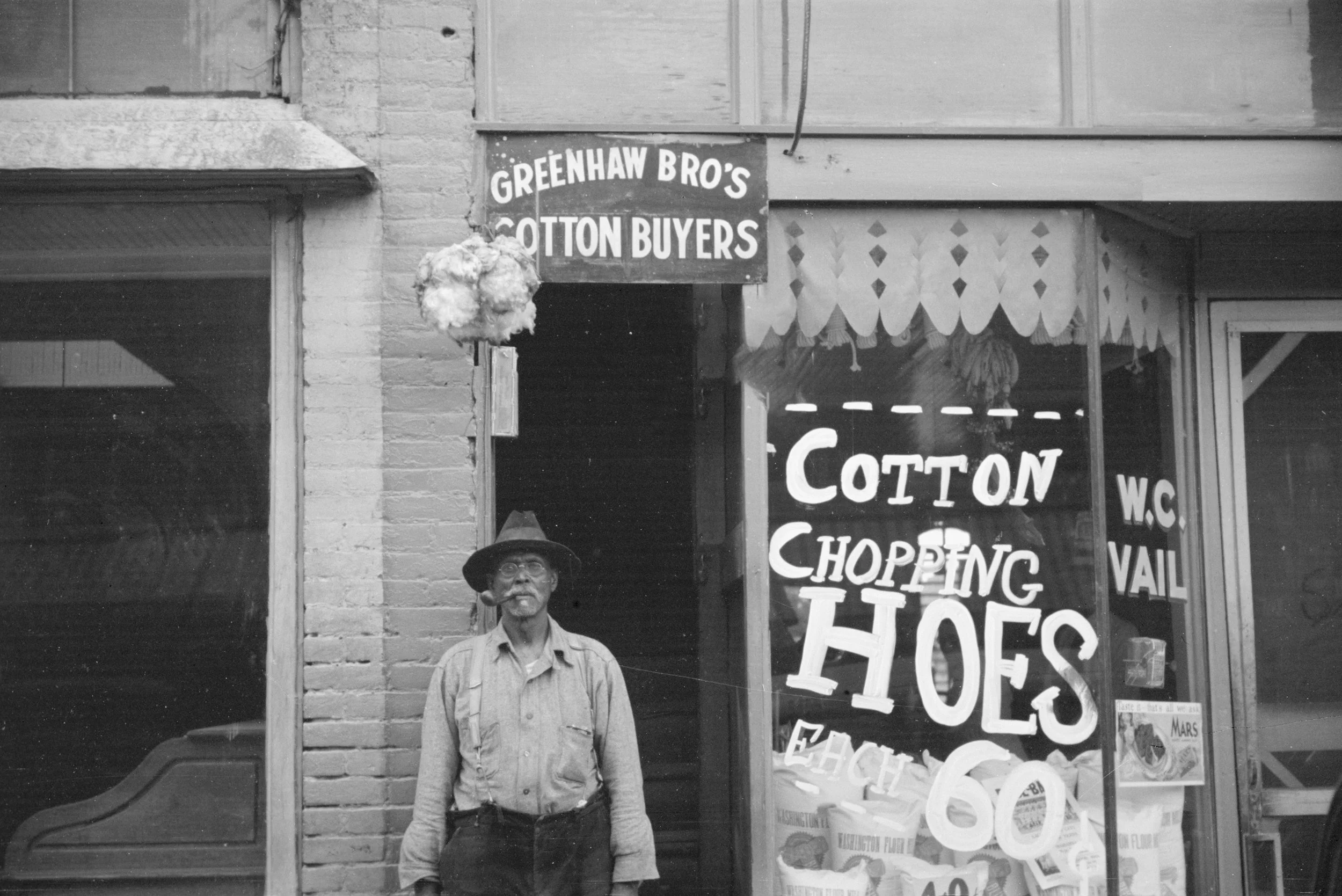

If Marianna, Arkansas looks like the kind of place that Walker Evans would’ve photographed, that’s because it is. And it was in that cotton belt town in 1936 that William Paschal Hopkins came to be.

Born to Charles, a cotton merchant, and Martha, a housewife, young Will Hopkins was on a path to follow his father into the cotton business. But thanks to the intervention of a distant aunt, a fashion illustrator in New York City, Hopkins’ parents were persuaded into shipping their creatively-inclined boy off to the celebrated Cranbrook Academy of Art in Detroit.

Hopkins became the “Arkansas Traveler.” After school, he took a job at Chess Records in Chicago, designing for the likes of Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, and Bo Diddley. But soon the road was calling again.

“One Sunday afternoon, I’m walking down the street in Chicago. I said to this friend of mine, ‘You know, I’m gonna go to Germany.’”

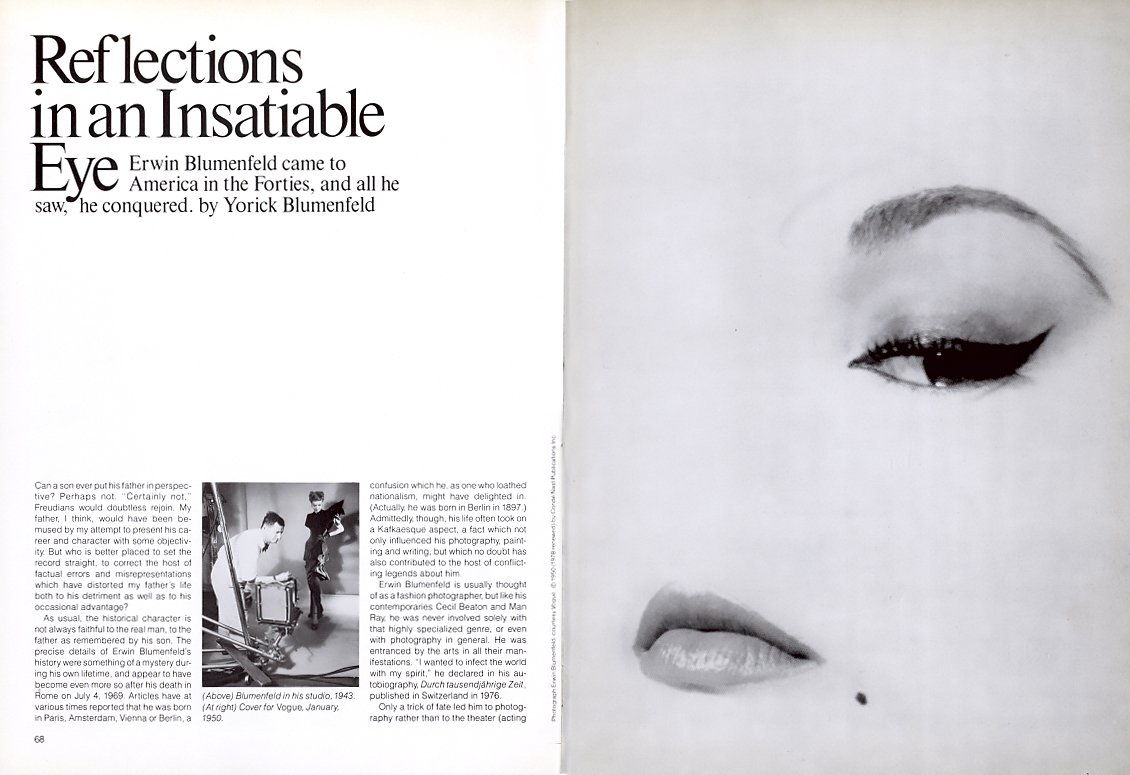

Through a friend, Hopkins had discovered Willy Fleckhaus, one of the most innovative, creative, and influential graphic designers in postwar Germany. He knew he had to go.

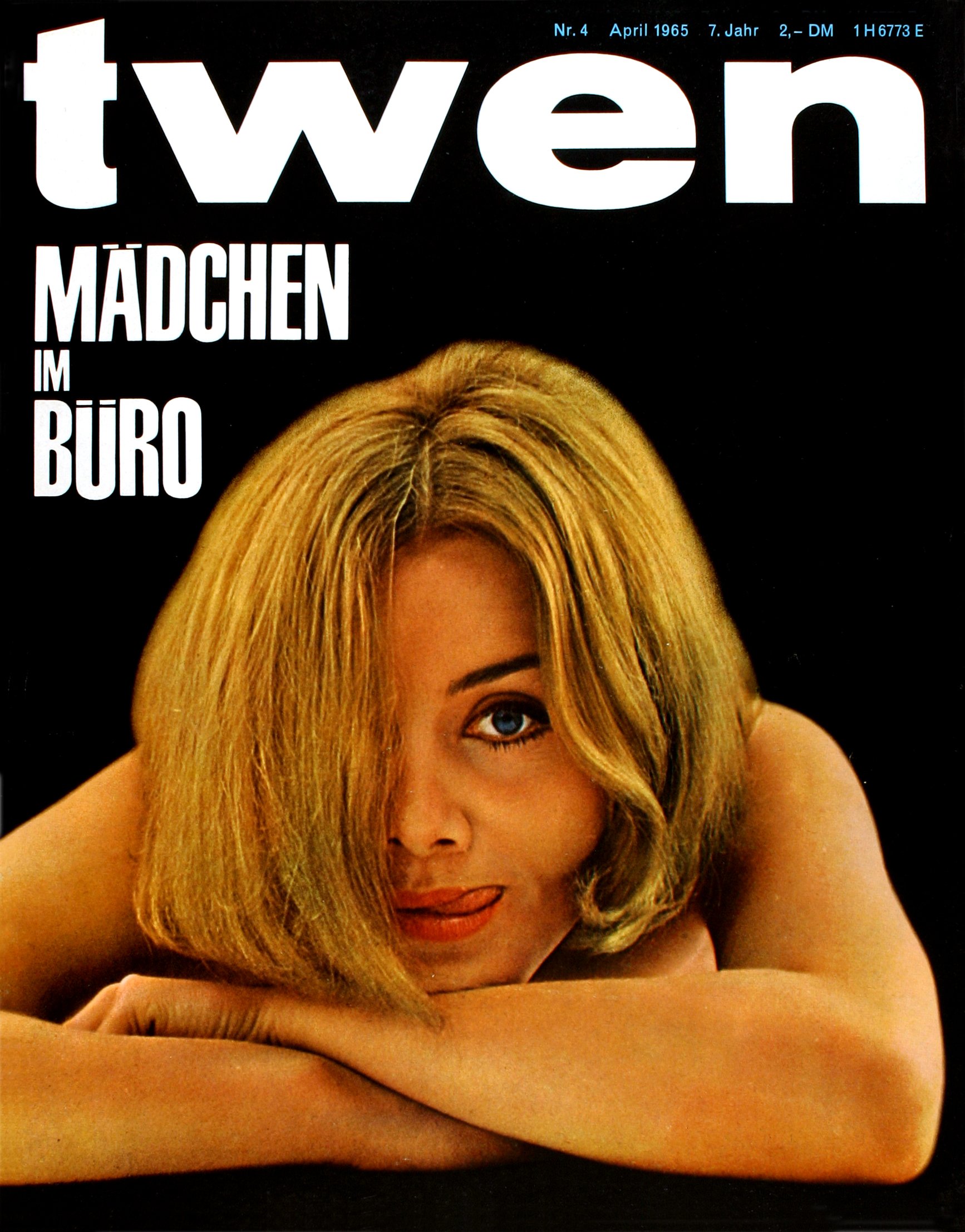

Through his revolutionary work at the magazine Twen, Fleckhaus taught Hopkins everything about the business, including the “12-Part Grid,” his layout innovation that transformed the way magazines were designed.

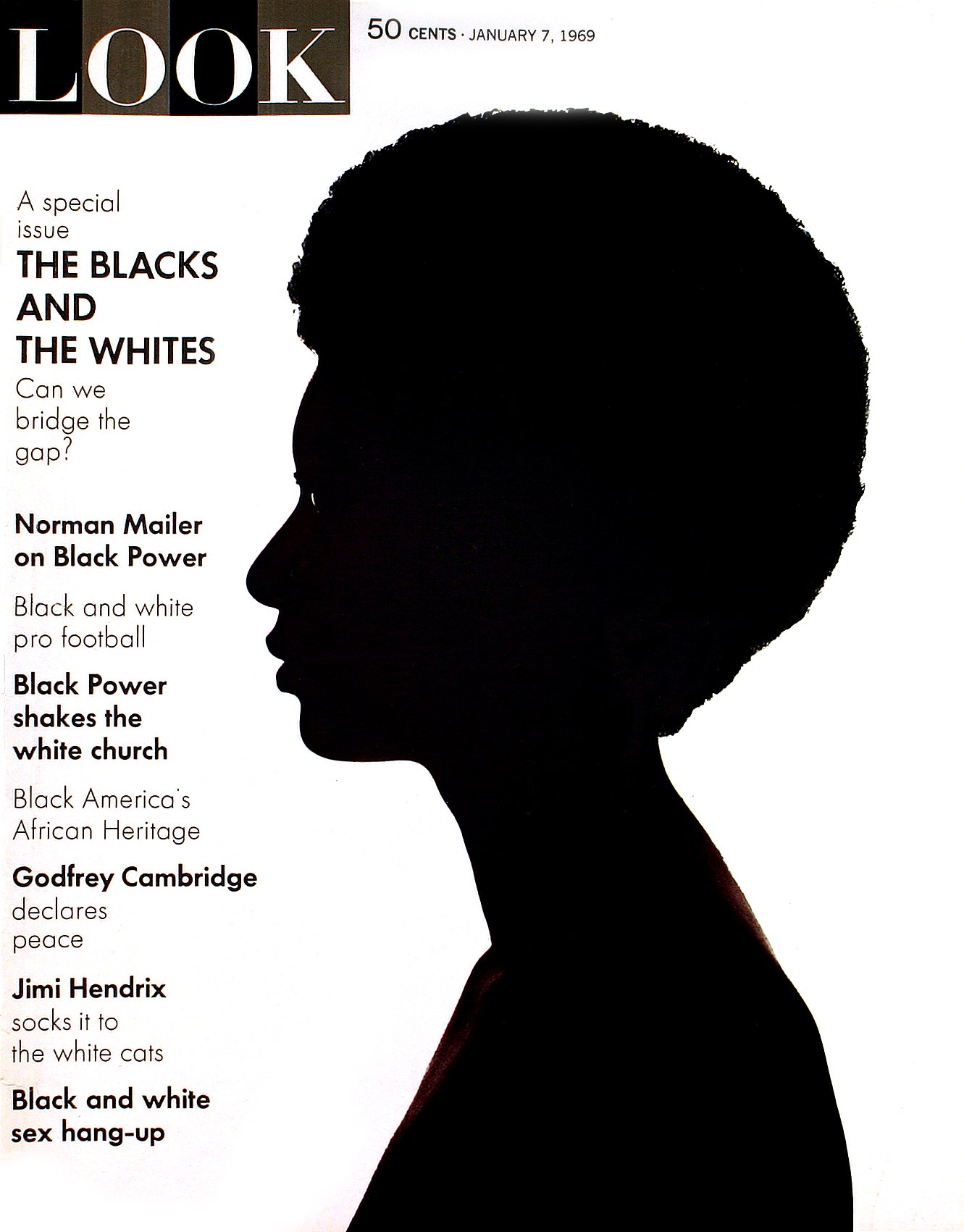

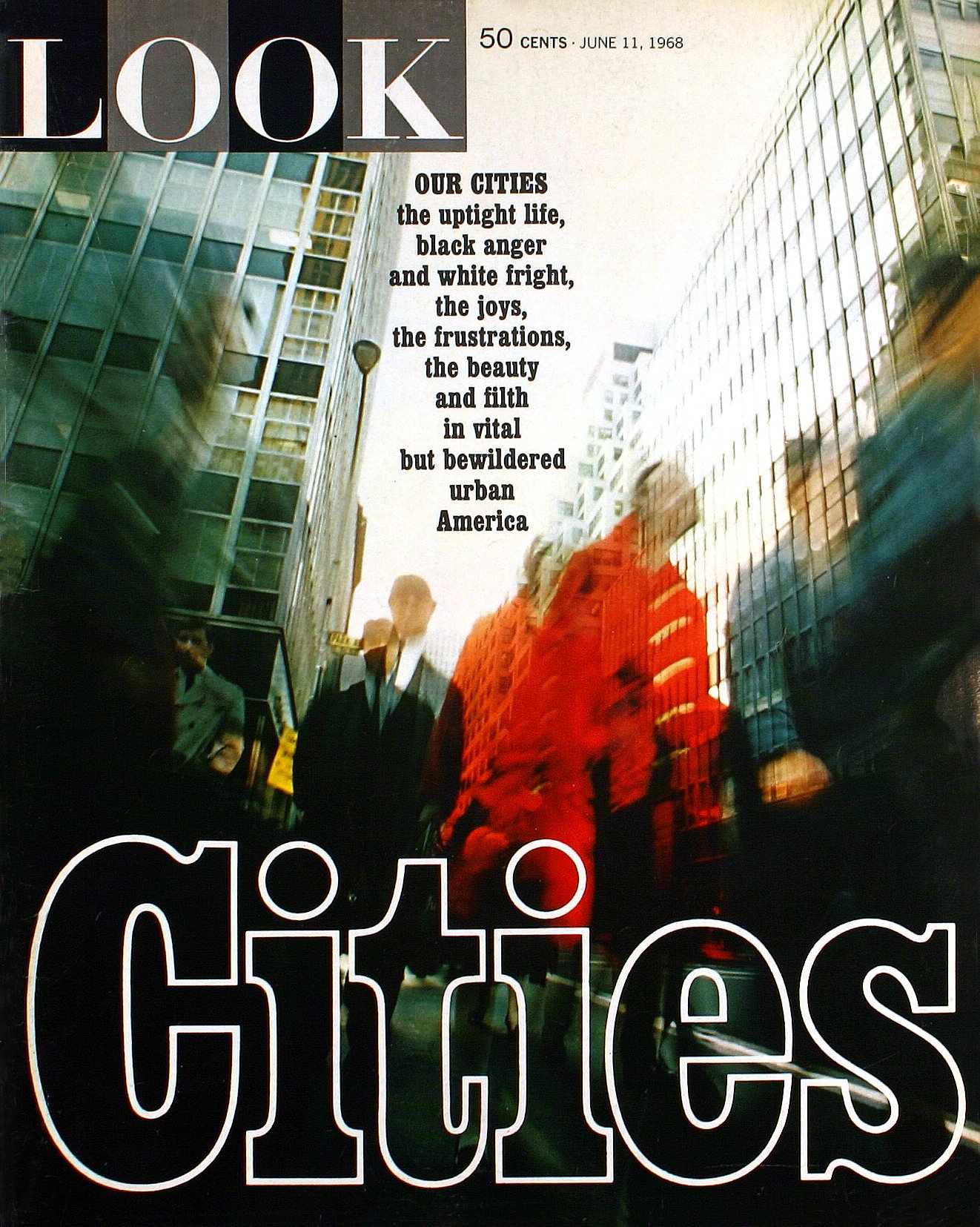

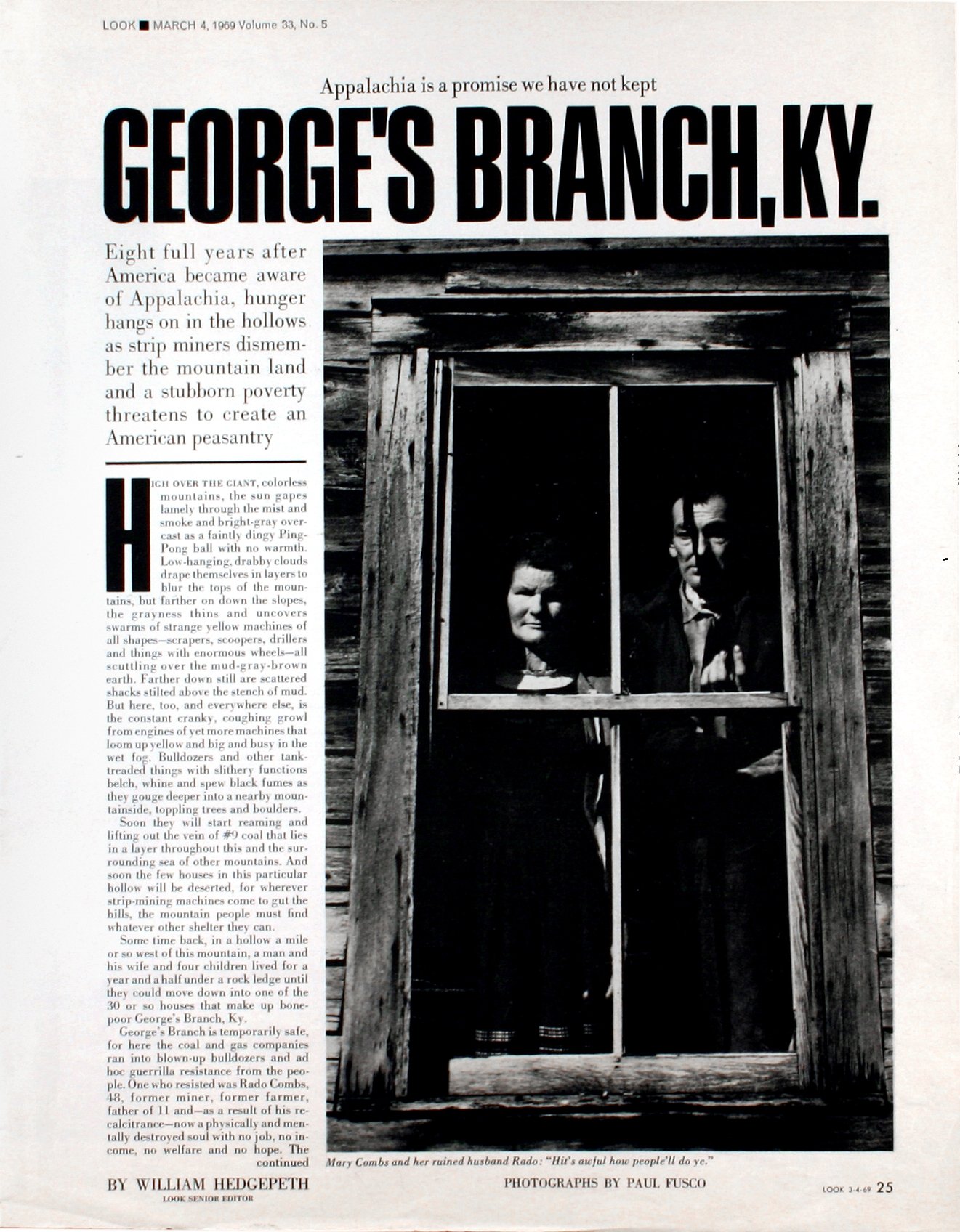

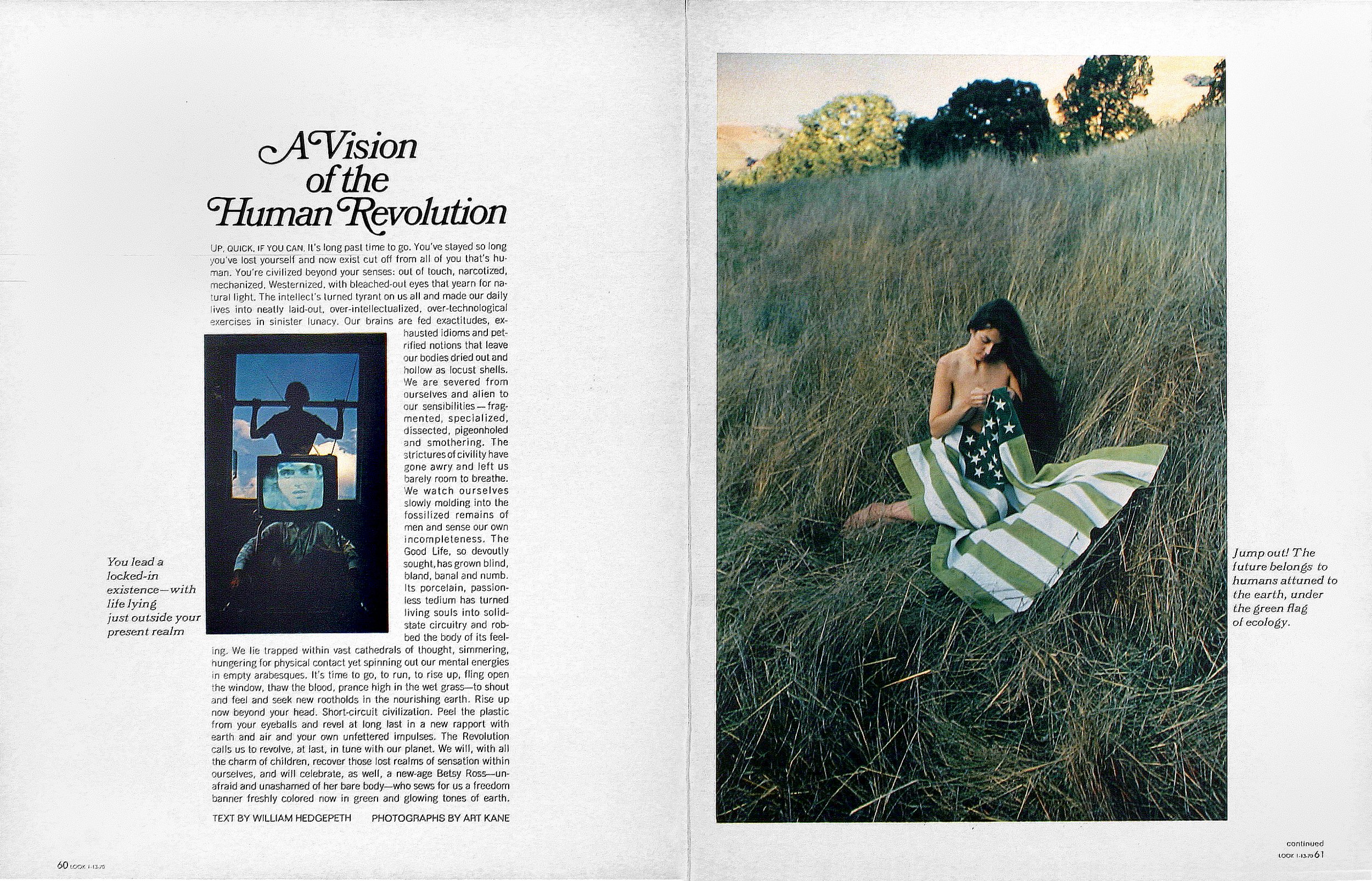

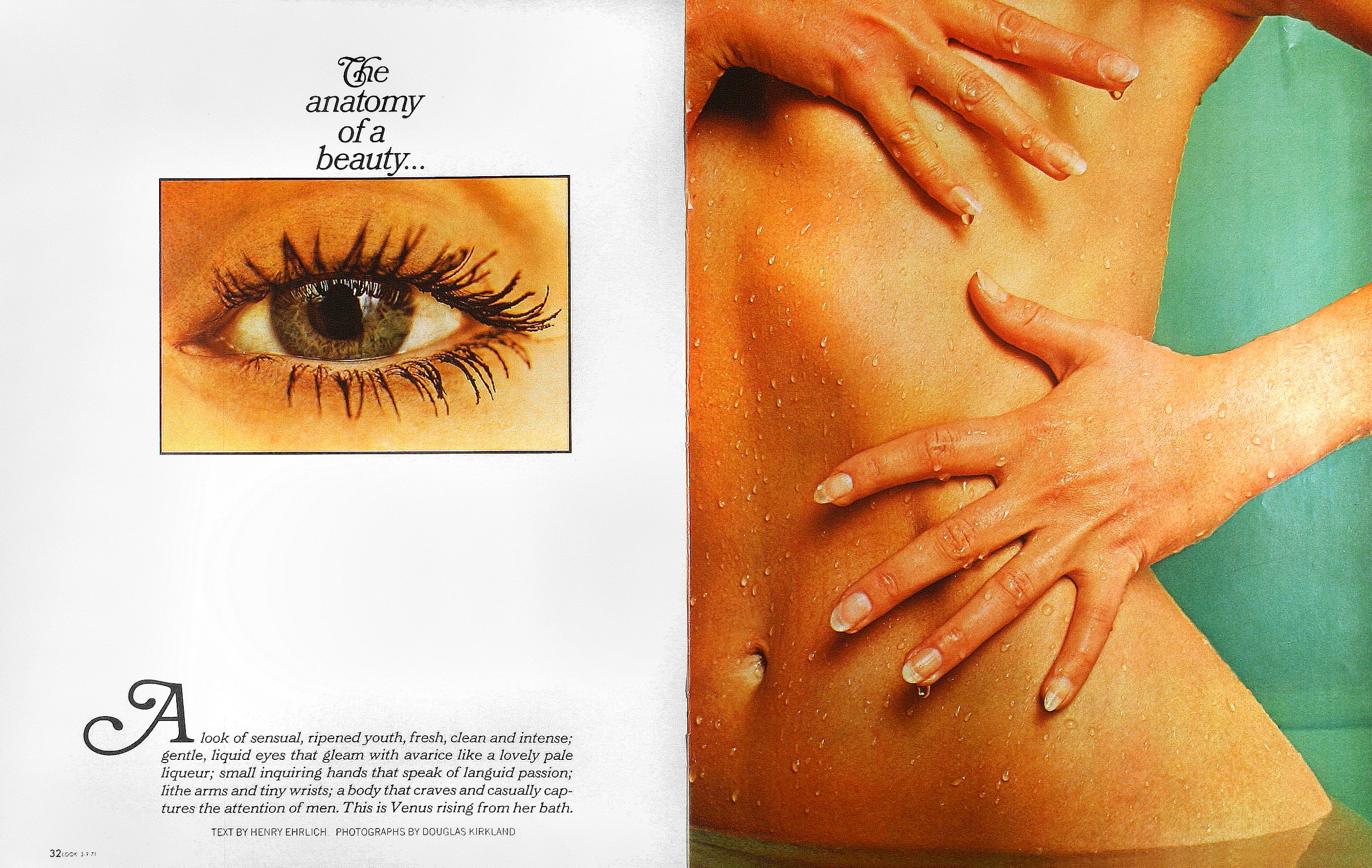

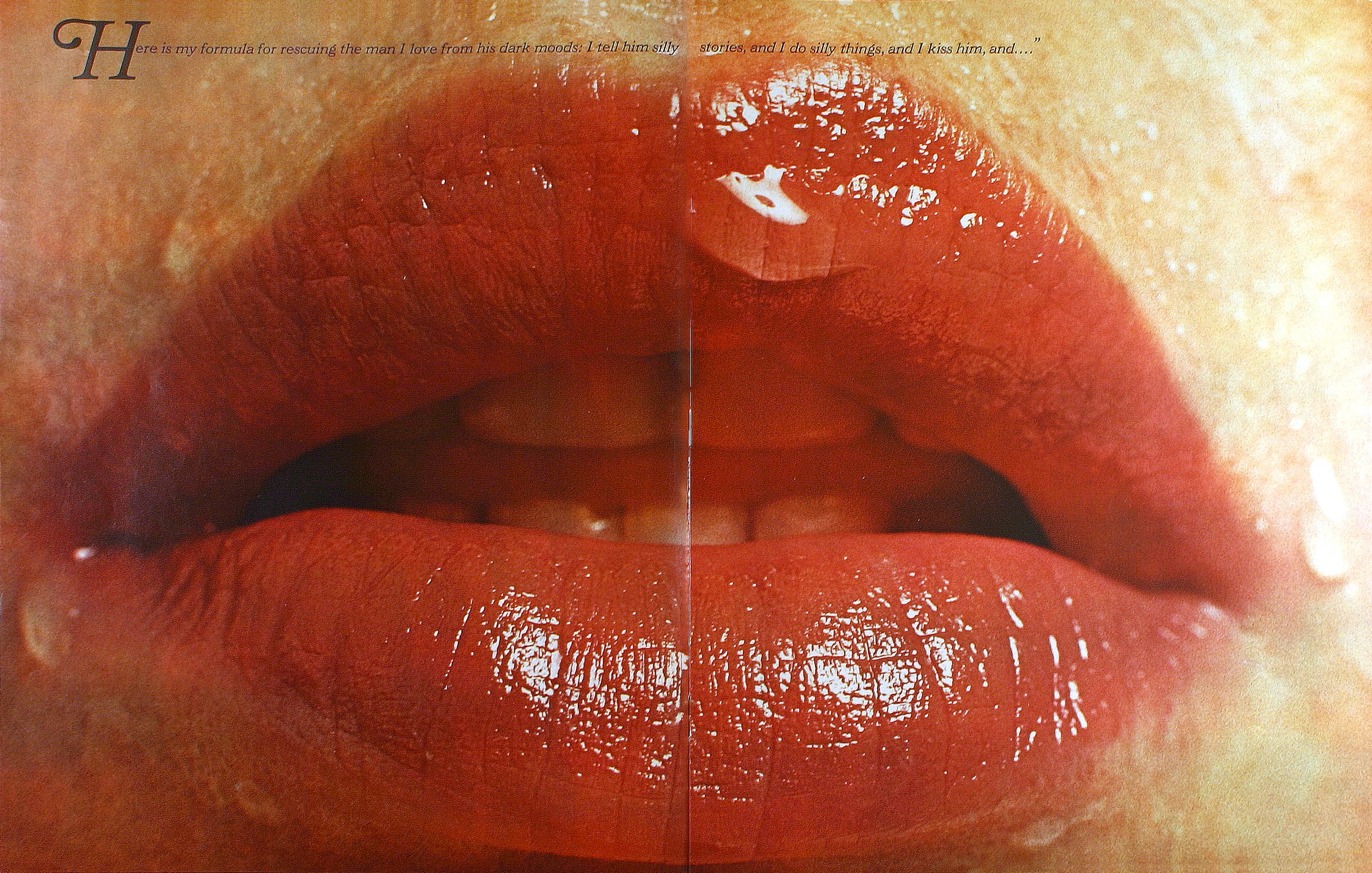

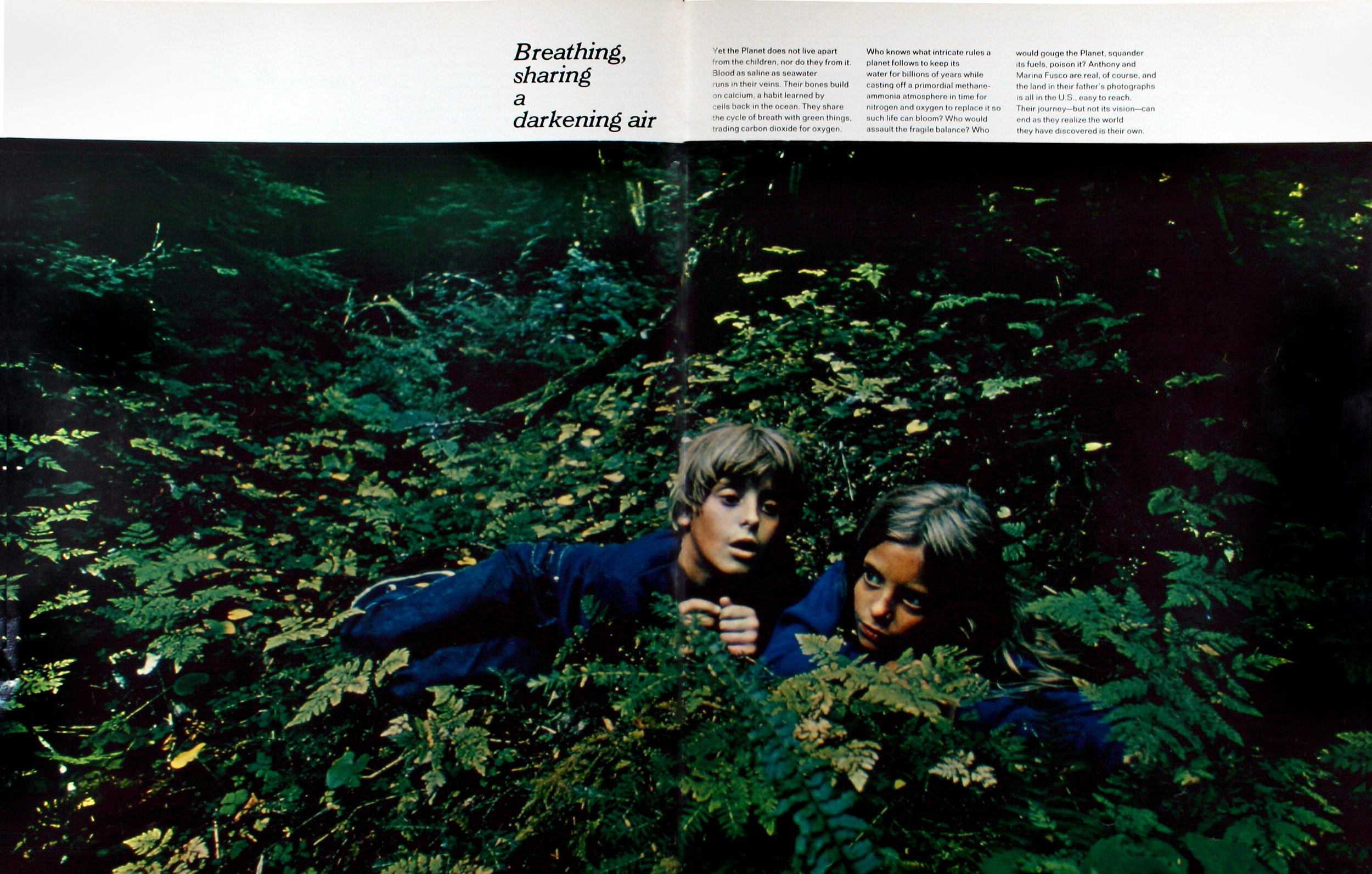

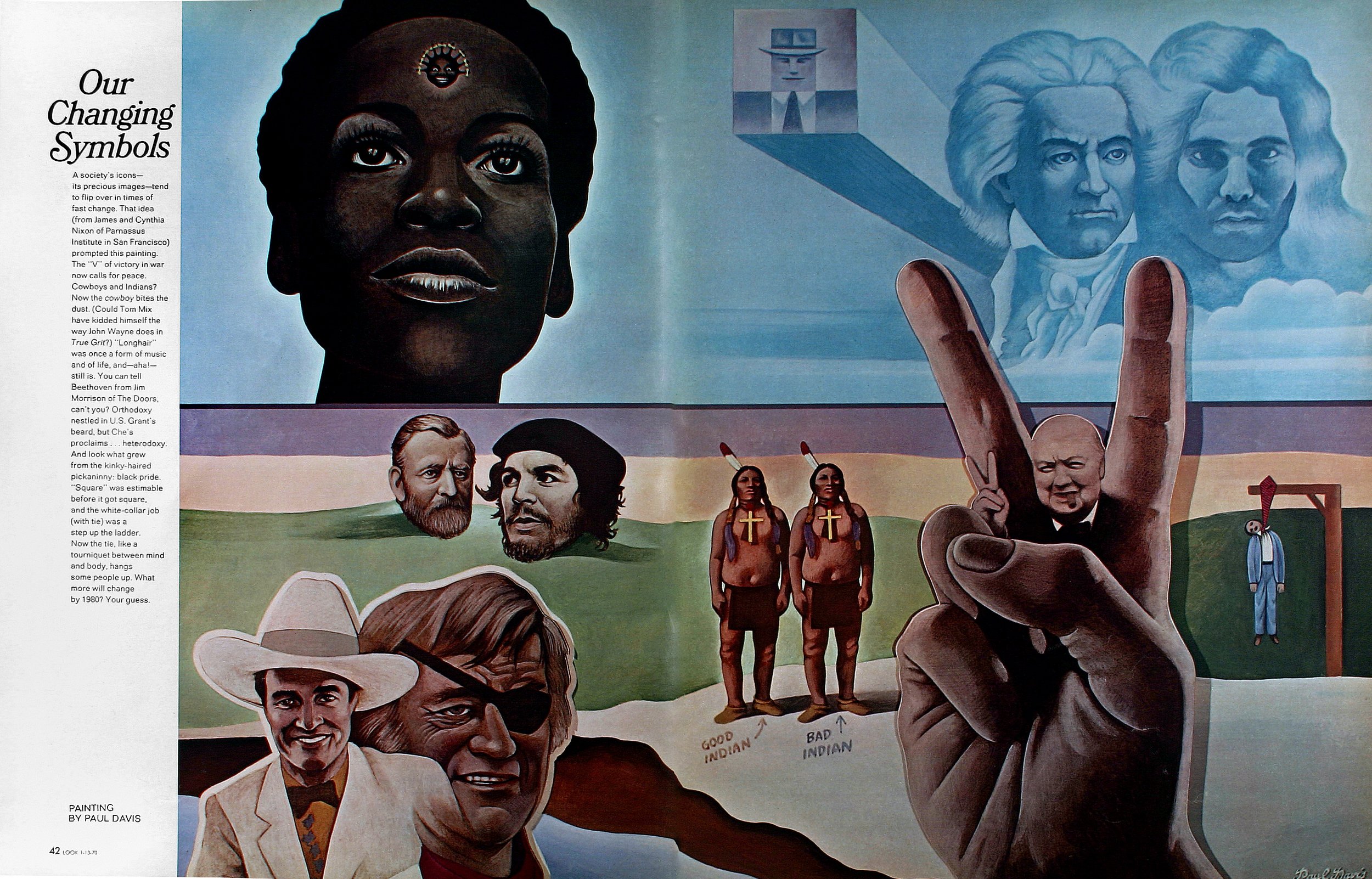

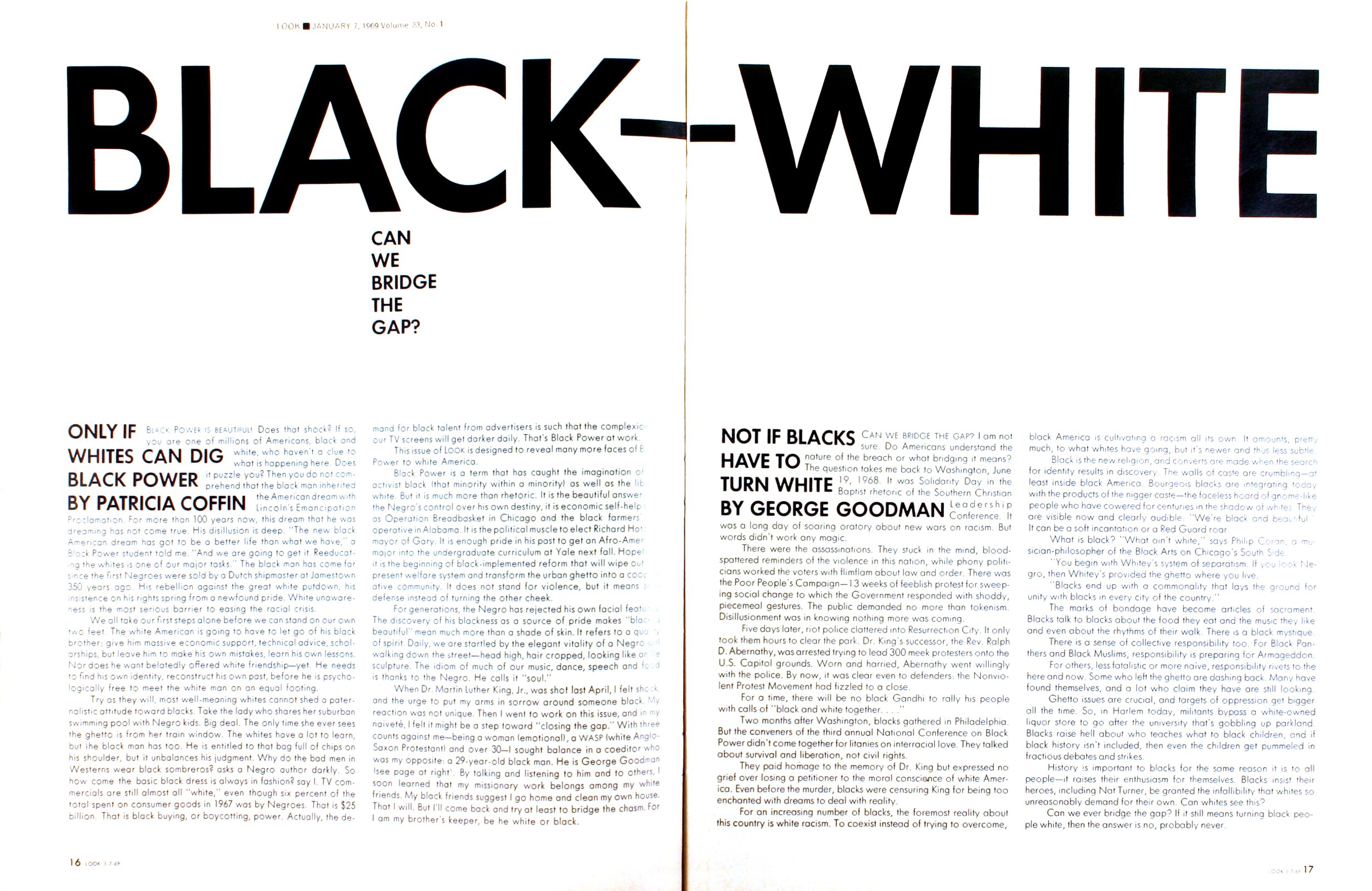

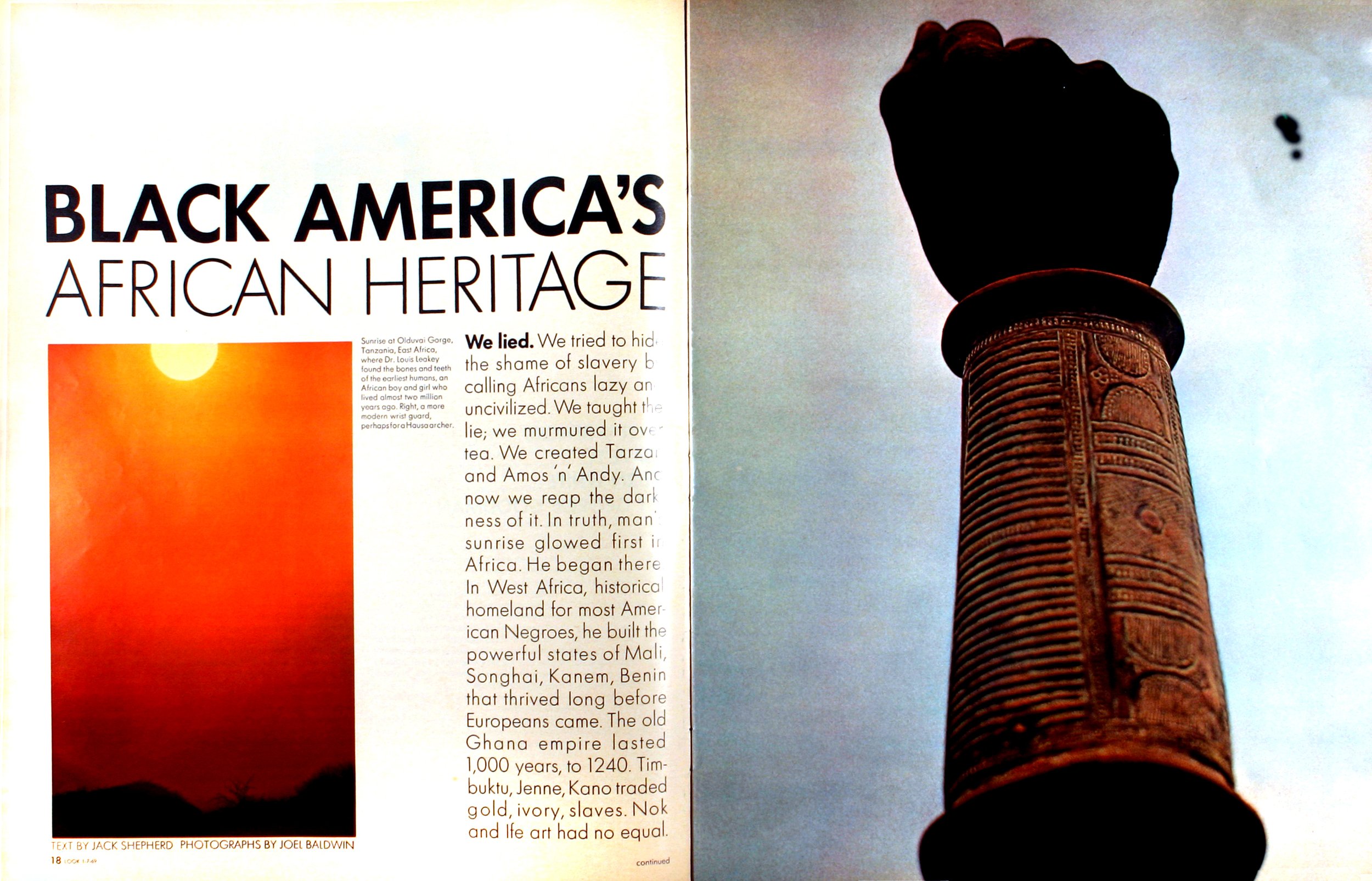

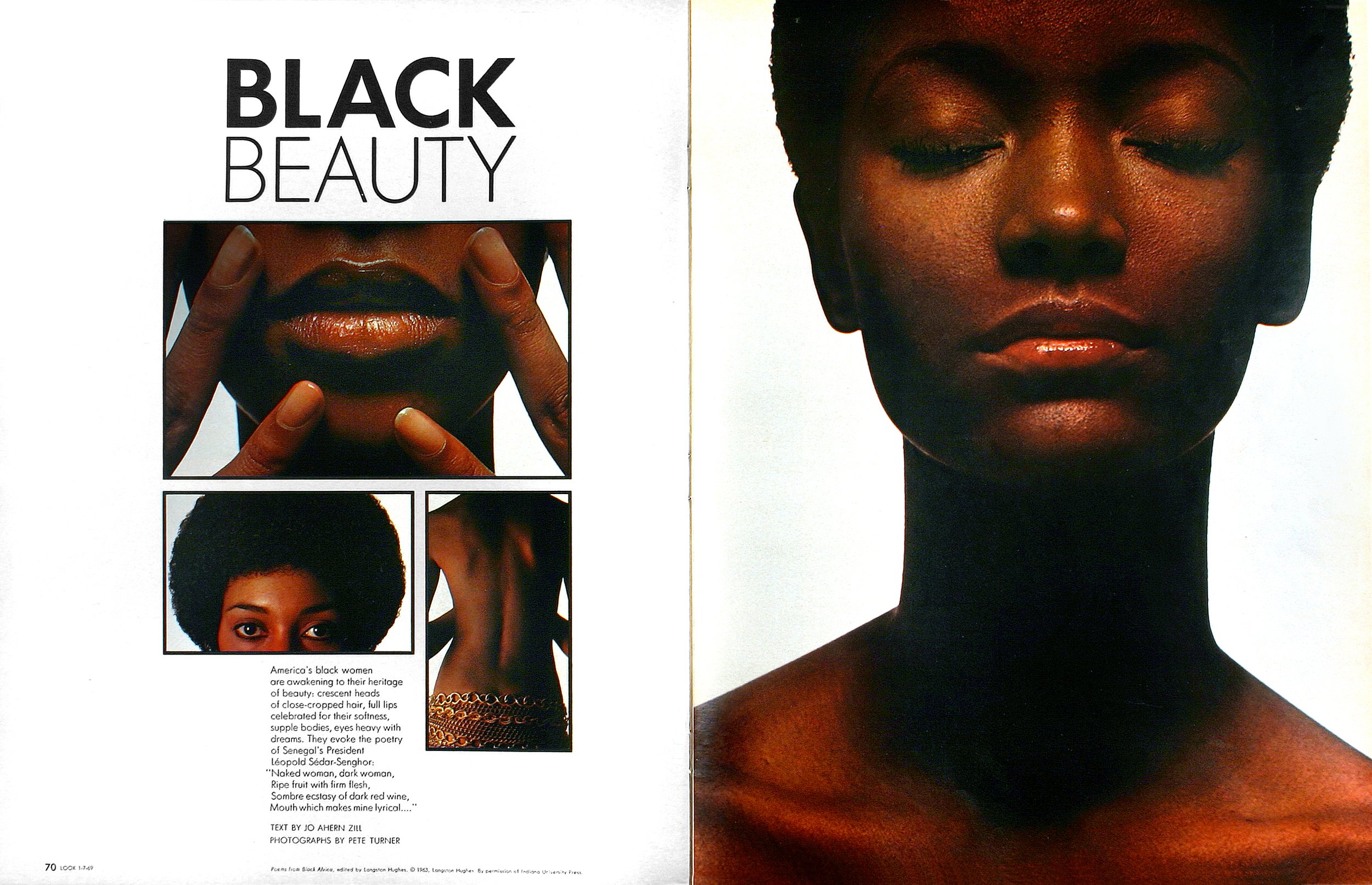

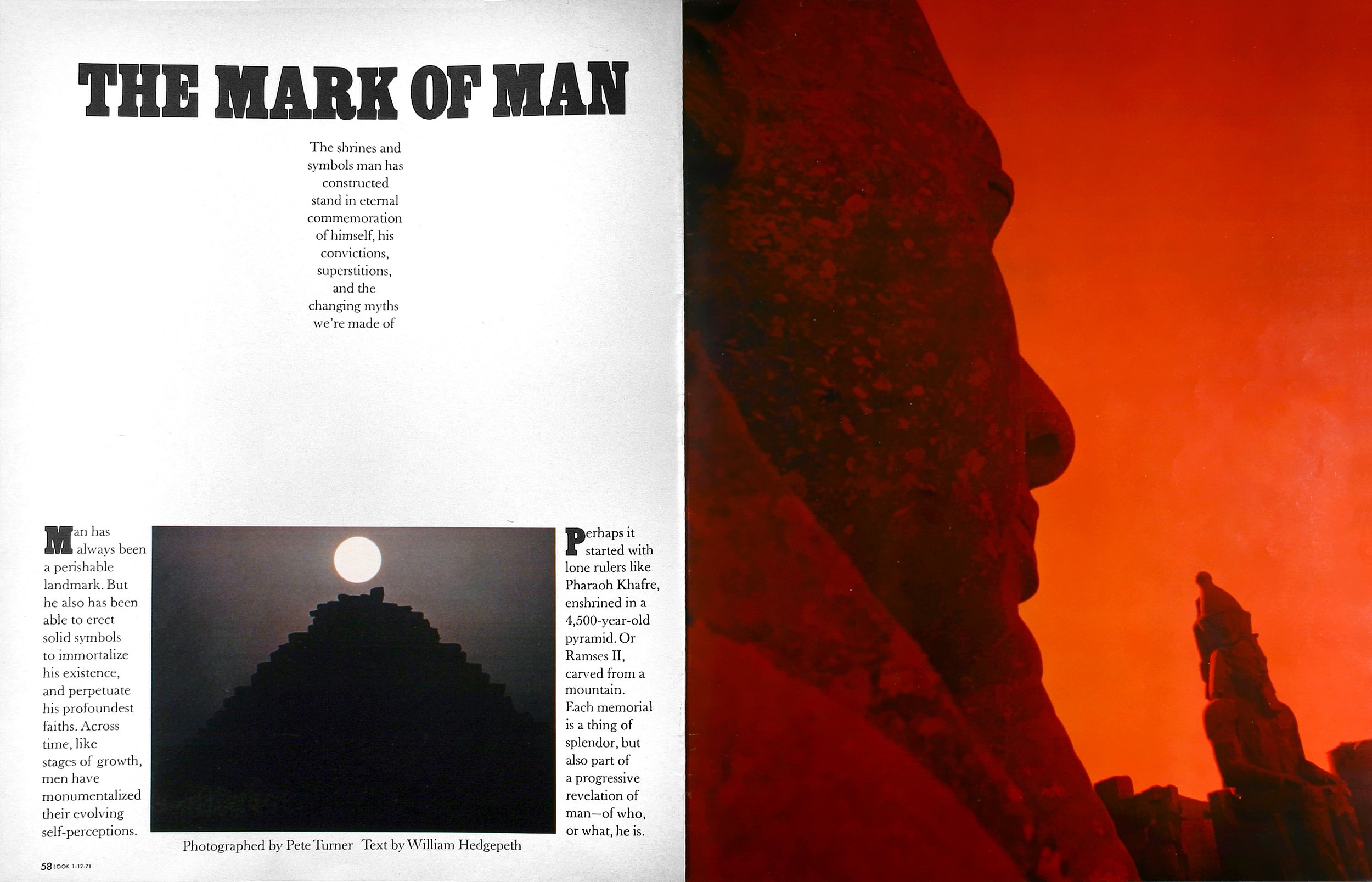

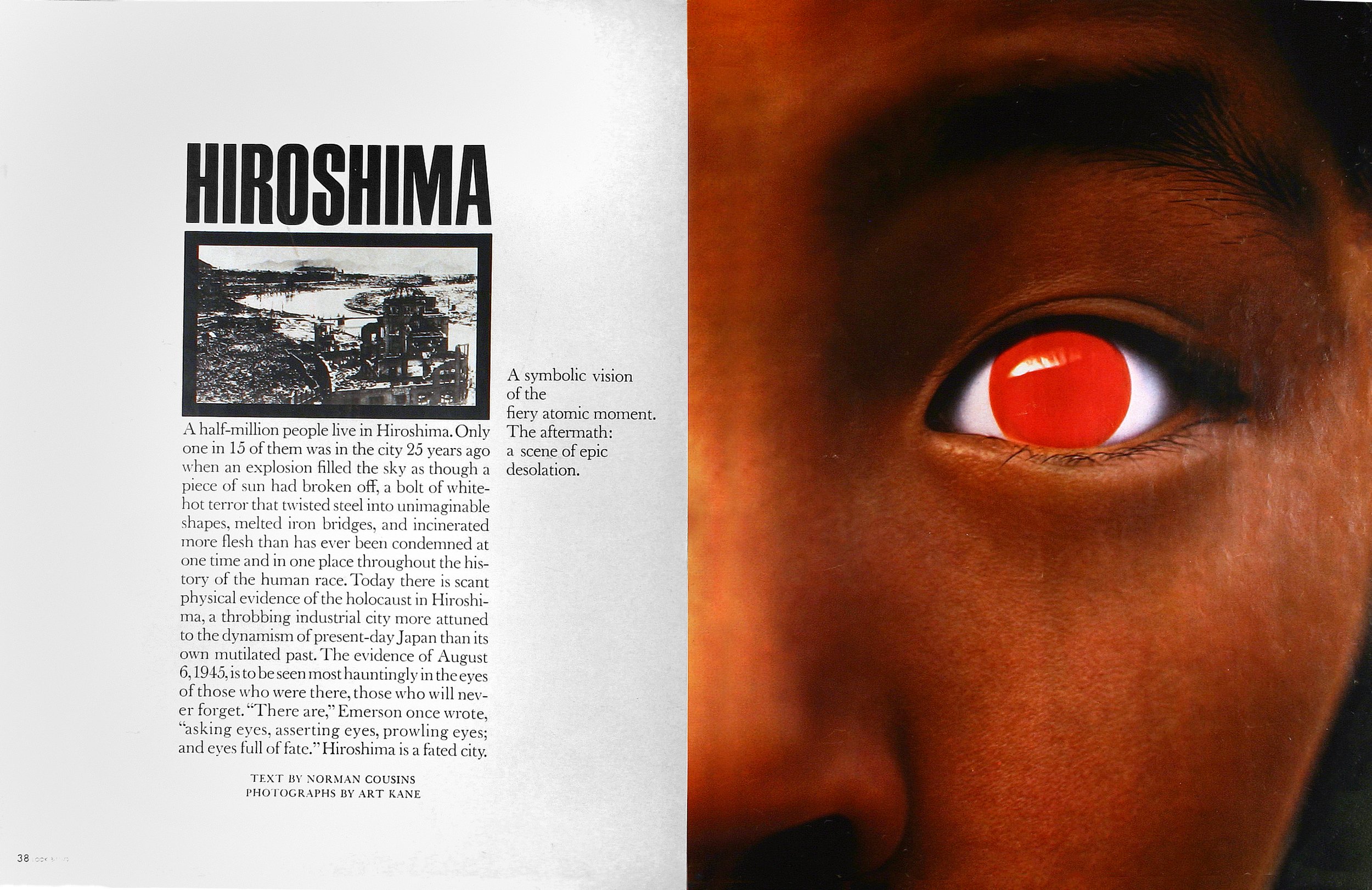

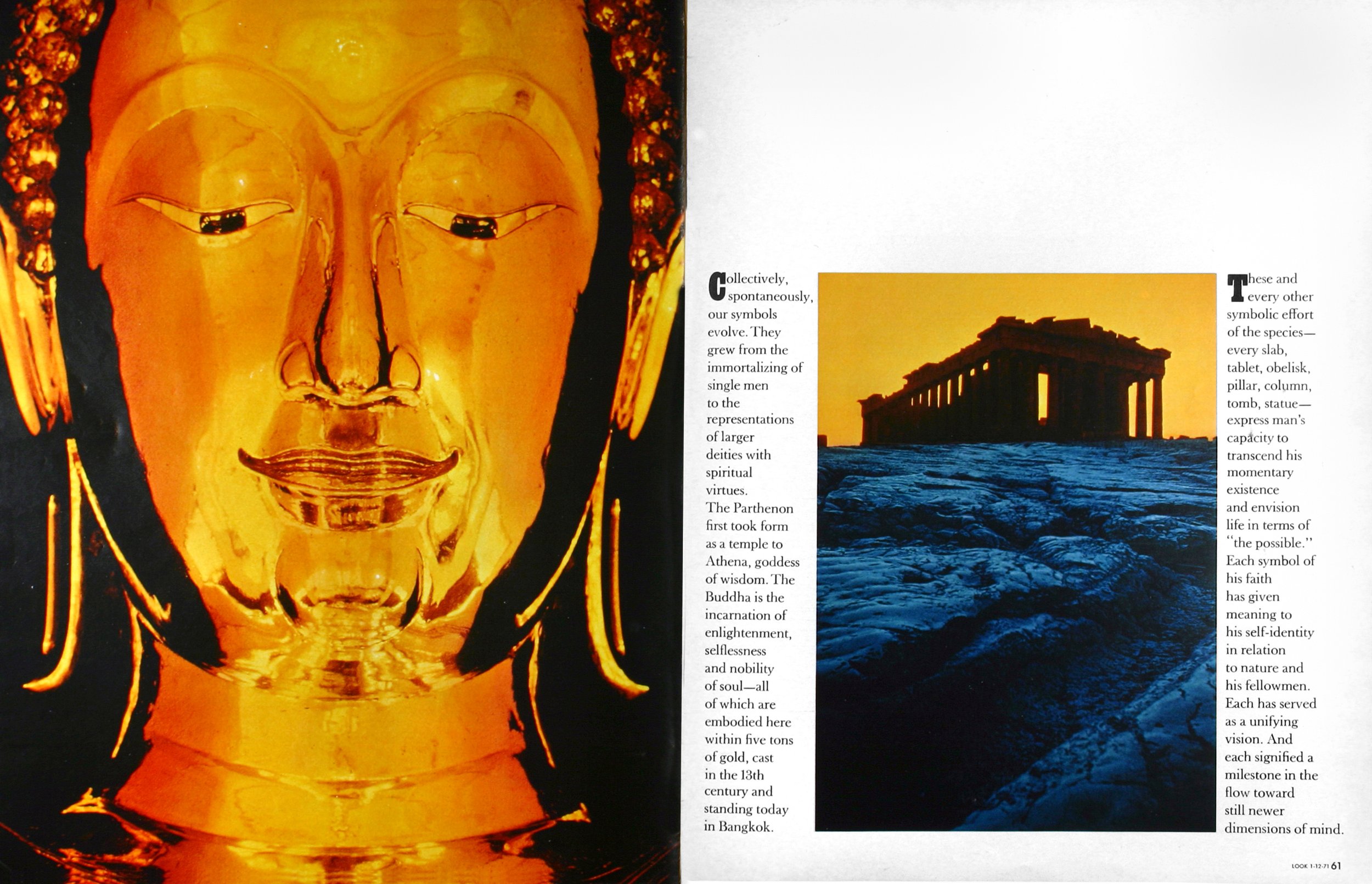

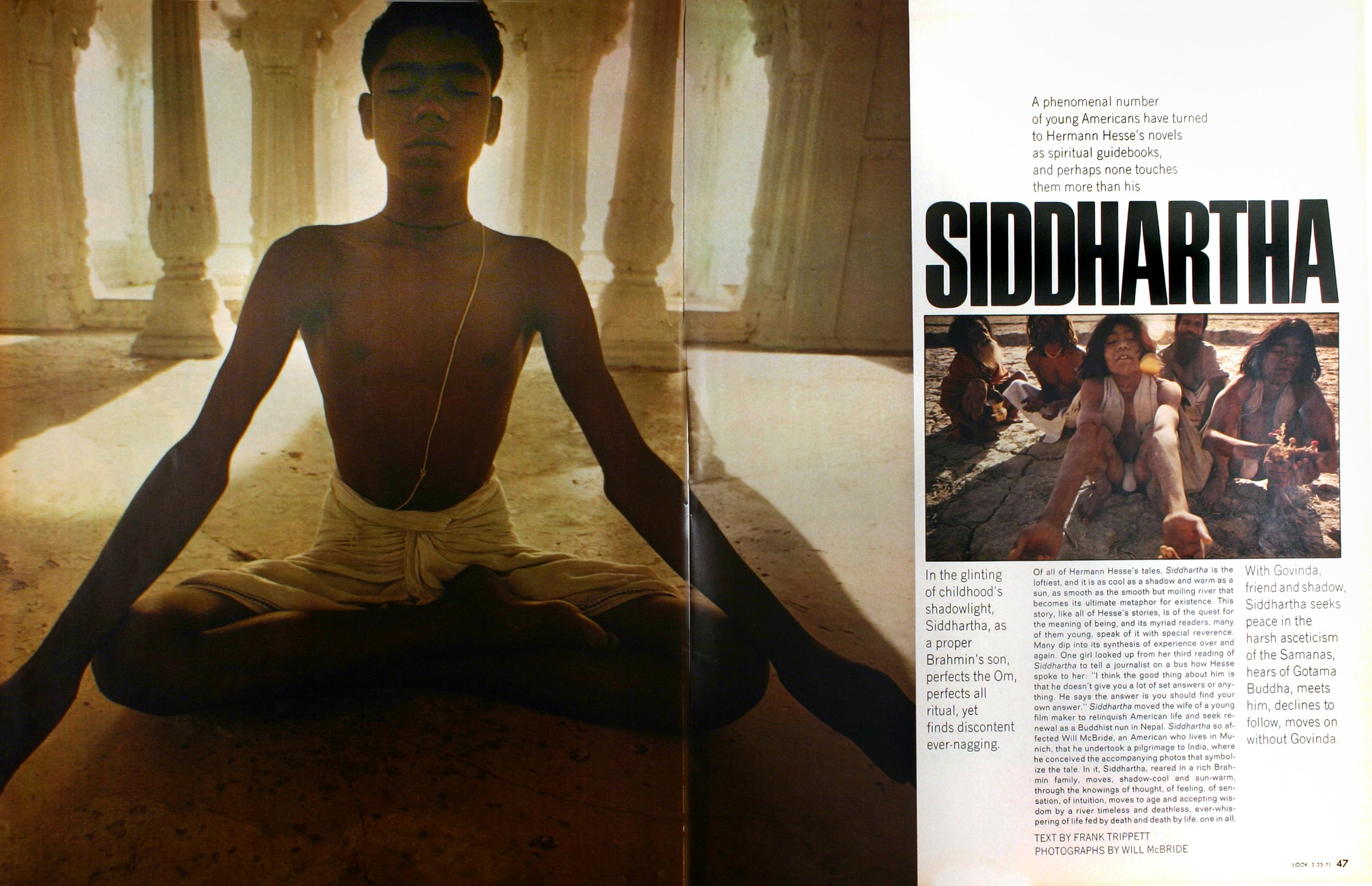

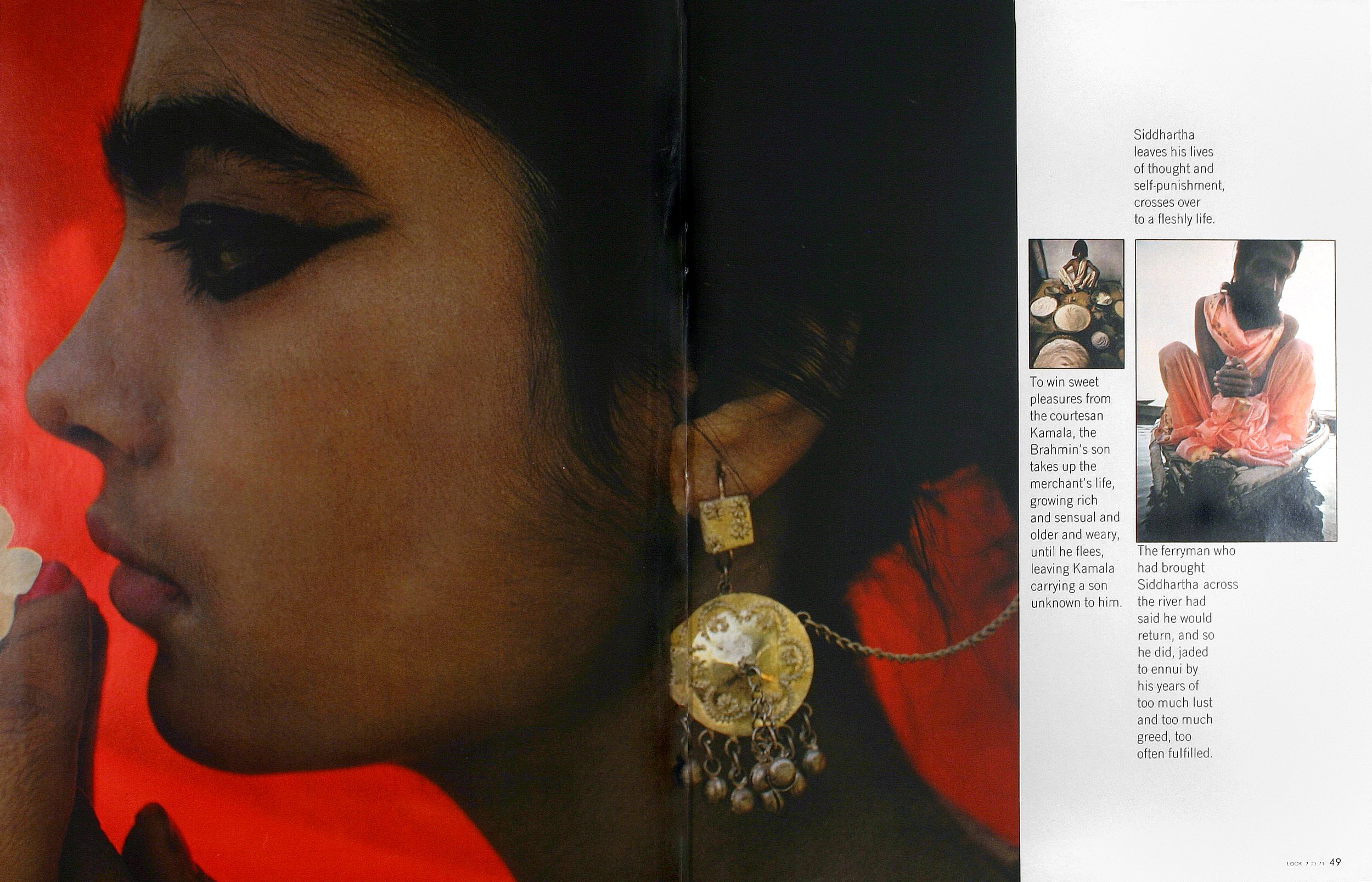

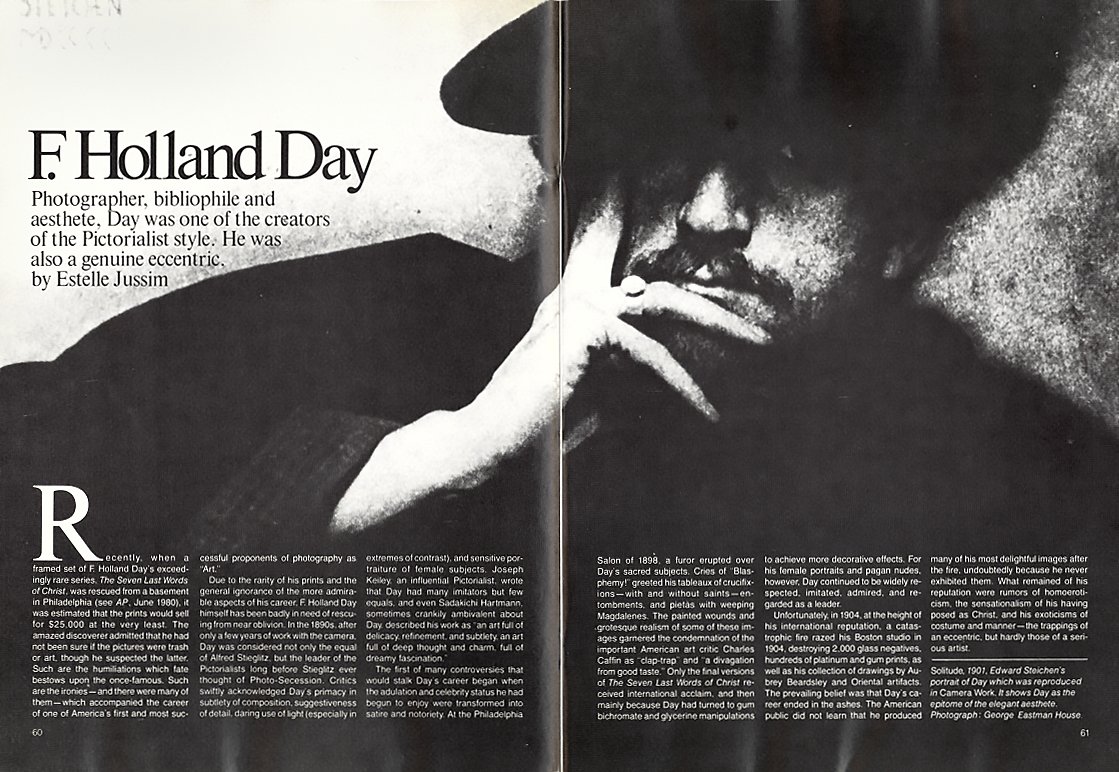

After three years in Munich, Hopkins moved to New York to take the helm at Look magazine. Look enjoyed a spirited rivalry with the more conservative Life magazine, and published hard-hitting stories on civil rights, racism, gay marriage, and the environment. It featured the more cutting-edge design of the two, which Hopkins credits to his implementation of Fleckhaus’s grid system.

After Look closed in 1971 (followed by Life in 1972), Hopkins would go on to open his own studio where he continues to run a thriving design business, Hopkins/Baumann, in Minneapolis.

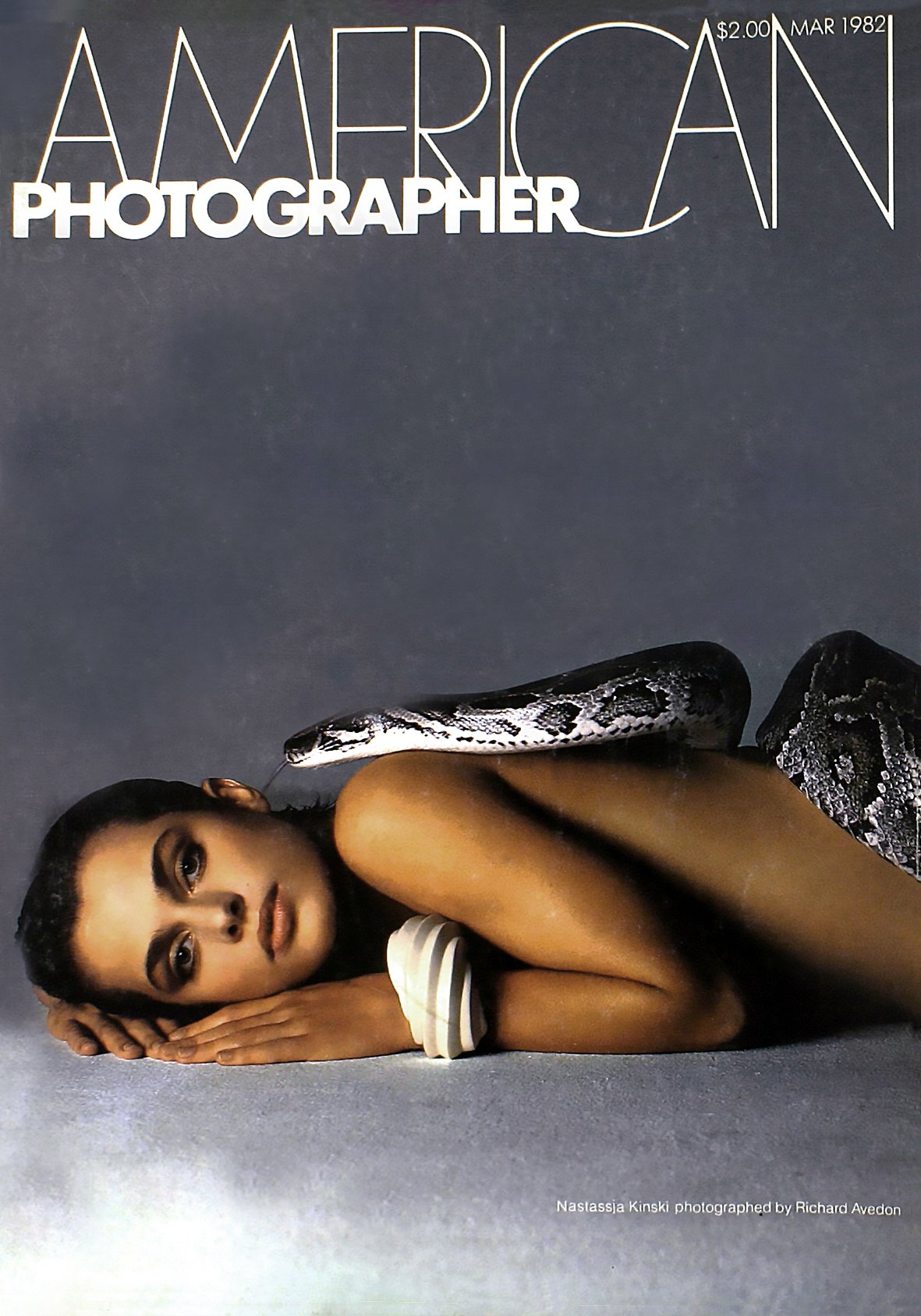

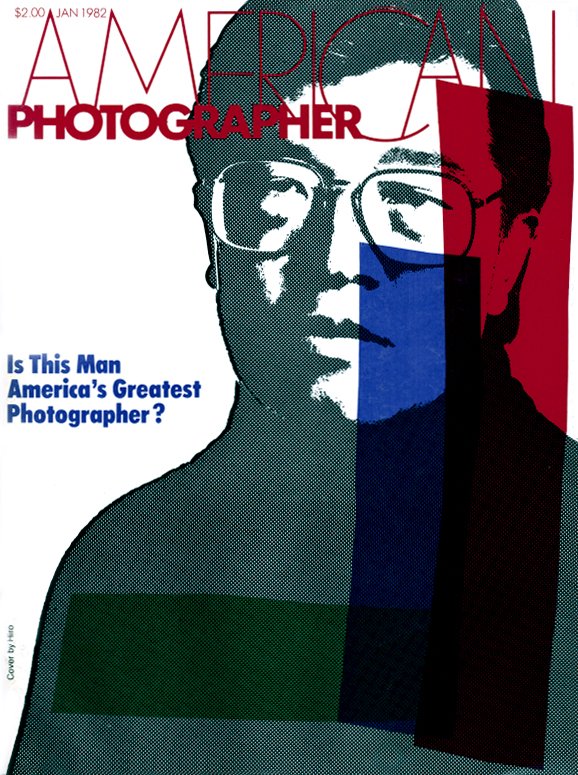

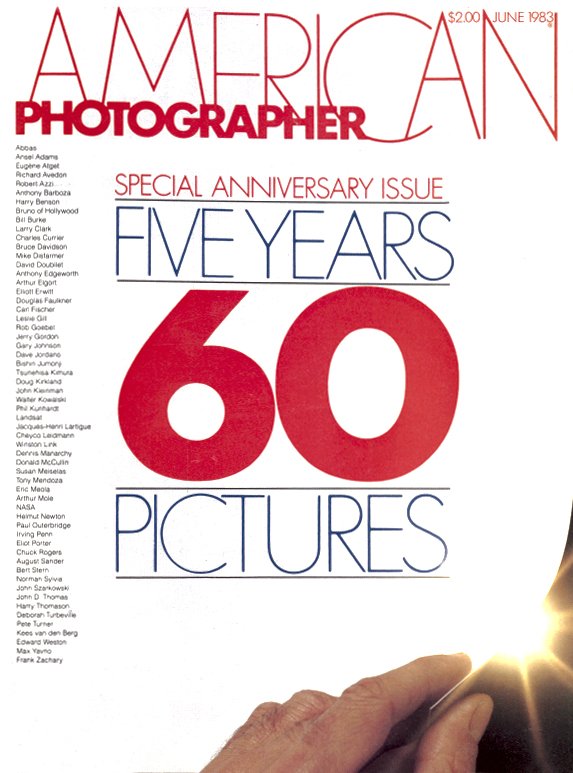

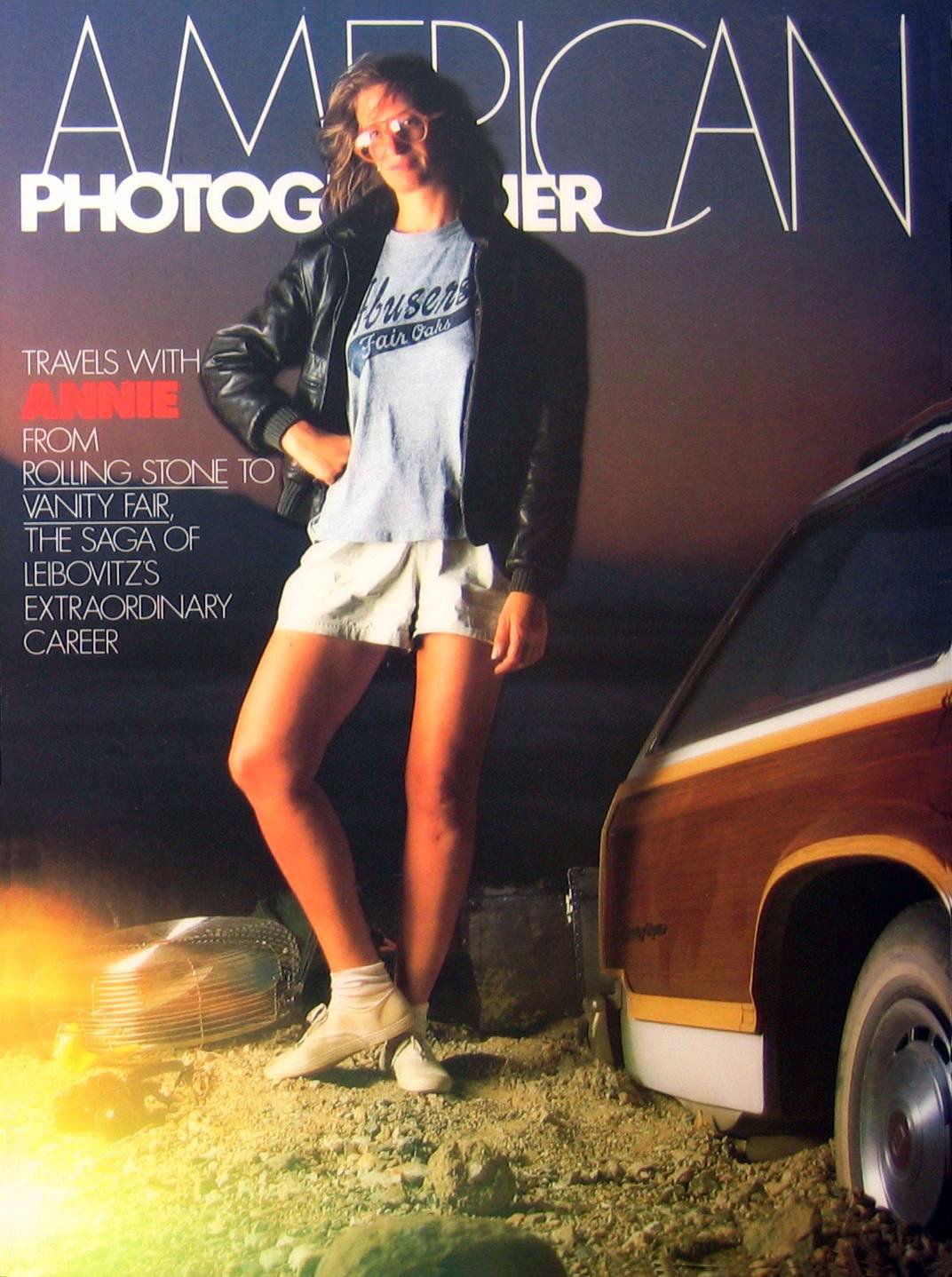

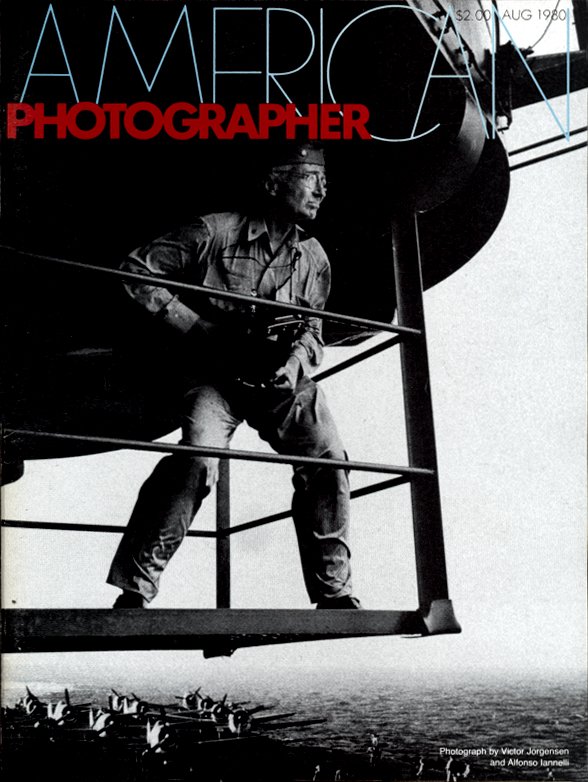

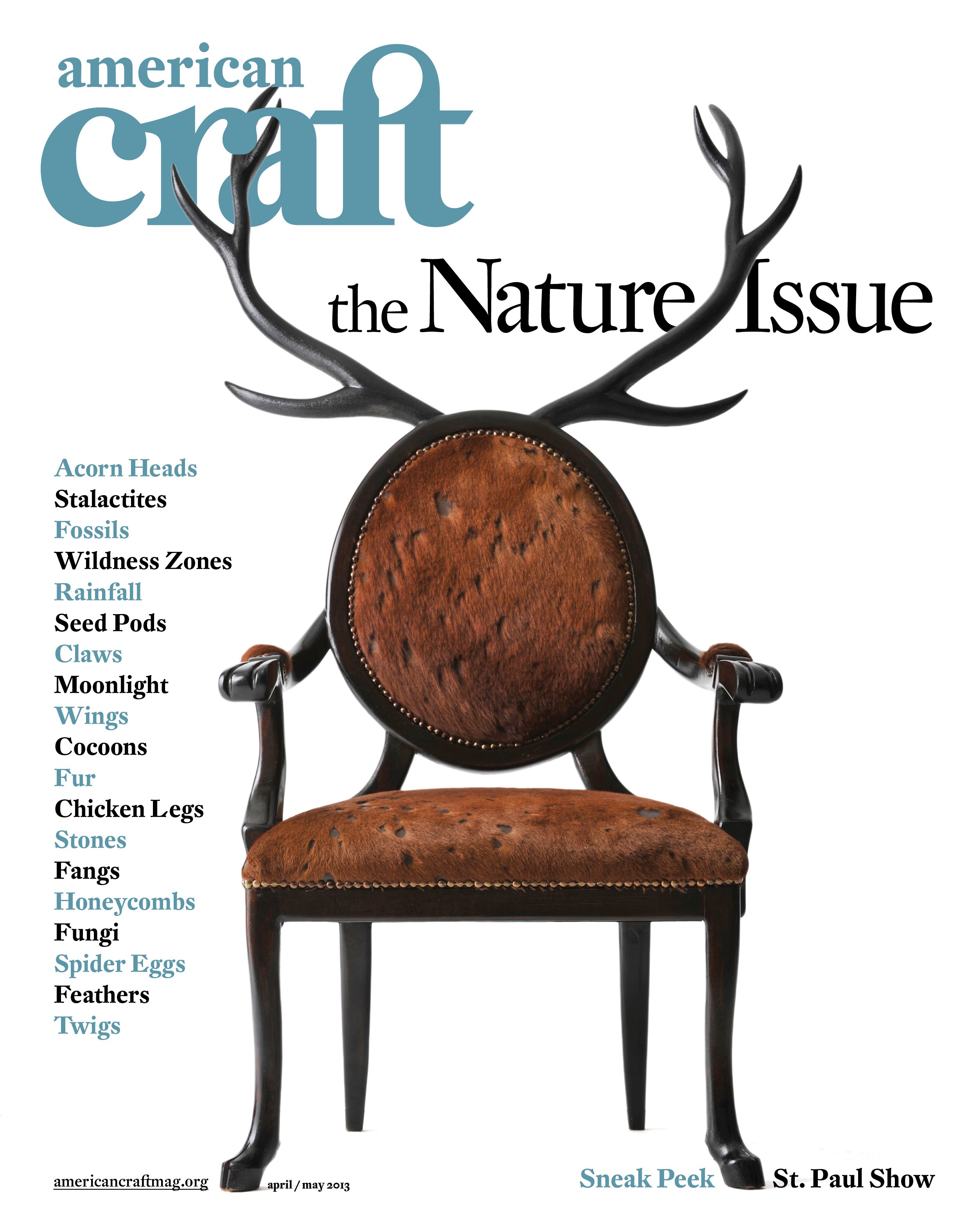

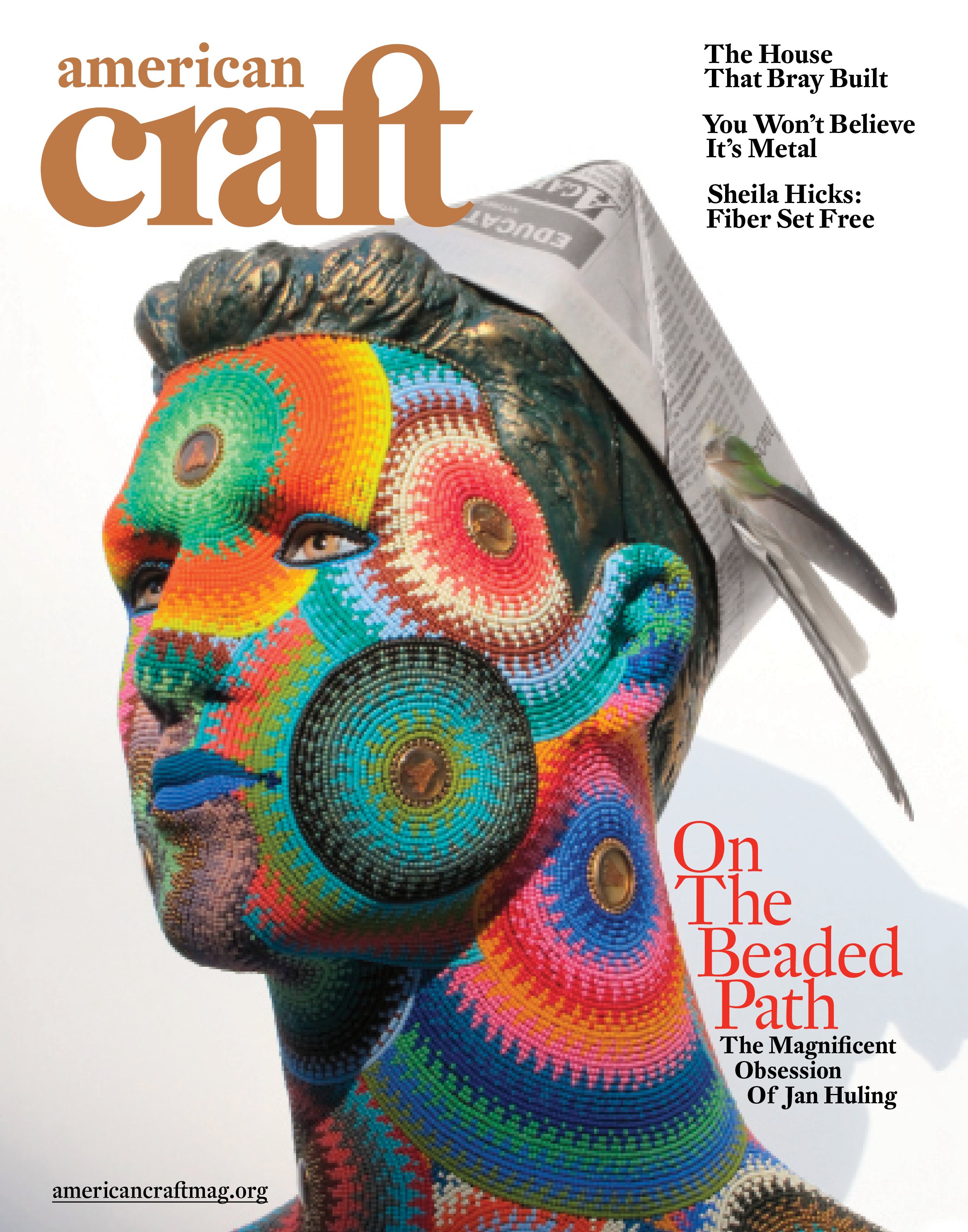

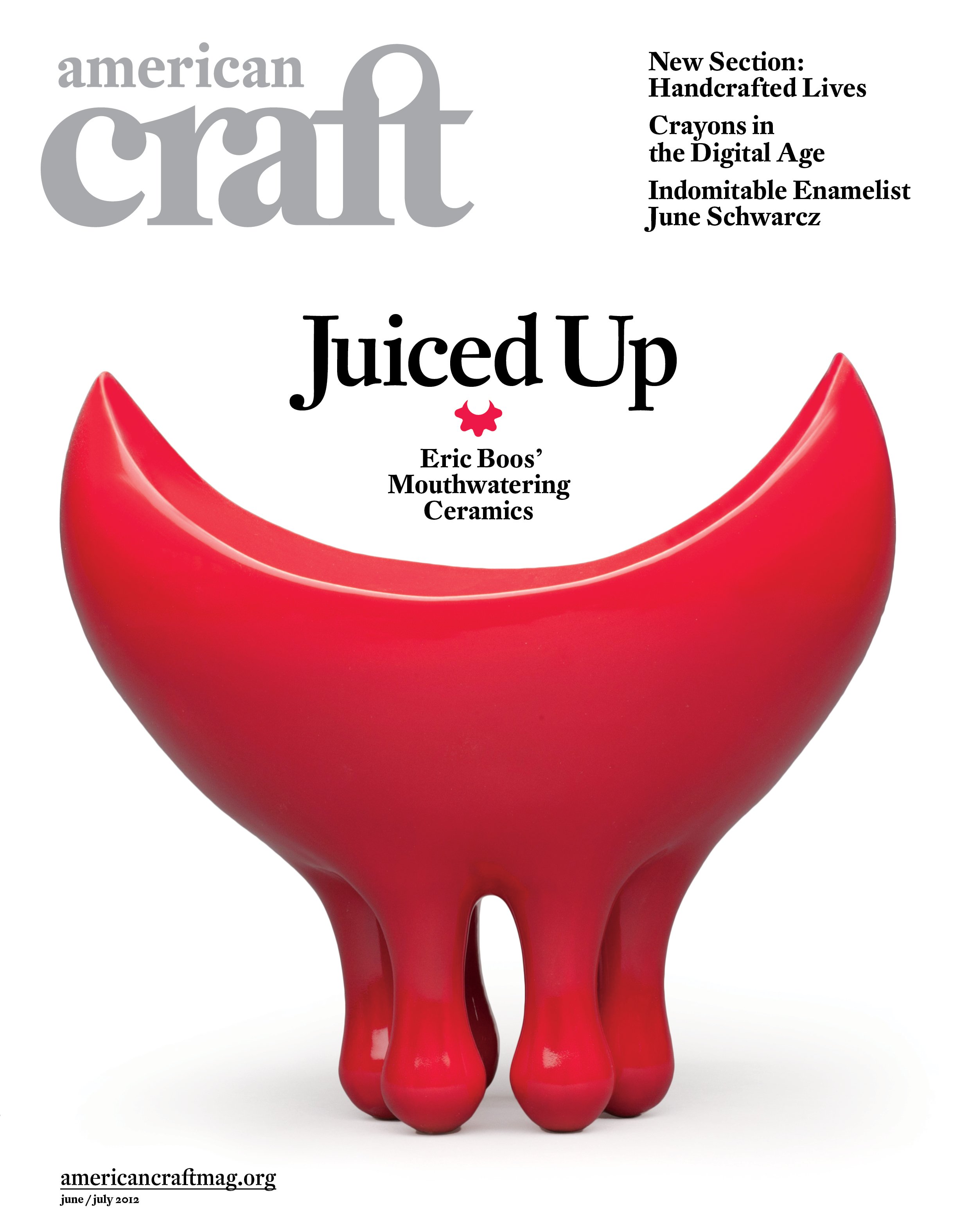

After a non-stop, 65-year career in magazine publishing, Hopkins’ memory is rich, but not quite what it used to be. But thanks to his partner in work and in life, Mary K Baumann, who helped to fill in the gaps, we learned why Hopkins seemed to attract magazines with “American” in the title (American Photographer, American Health, American Craft), how to drive a Volkswagen from Chicago to Germany, and about the good old days when art directors got wined and dined by French publishers.

Hopkins (right) with his partner in business and life, designer Mary K Baumann. Photograph by Barbara Bordnick

“And then [Fleckhaus] realized that I’m not going away. So he says, ‘What are we going to do with you?’ And I said, ‘Listen, I come from Arkansas. And when we’ve got something to do, we do it. I had to get over here because I wanted to work for you. I’m here and I’m ready to work.’”

George Gendron: I want to start where we all start: at your birthplace. If somebody looked at your career, you know, you’re over in Munich, you’re working on Twen with Willy [Fleckhaus], you’re the art director of Look Magazine, during the heyday of those big magazines, Look and Life. You go on to redesign every magazine imaginable here in the US—you do L’Express in France. People would think you grew up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, you had very affluent parents who were art dealers and socialites, and you just slid right into this world, man. But we’ve heard a rumor that you were born and raised in Arkansas. Could that be true?

Will Hopkins: That was the truth.

George Gendron: Tell us a little bit about where you were born.

Will Hopkins: I was born in Marianna. I was born in the hospital in Memphis because my parents believed in that kind of thing. But I was raised in Marianna, Arkansas. And it was, what did I say?

Mary K Baumann: Six thousand people.

Will Hopkins: Yeah.

Mary K Baumann: Five thousand were black and one thousand were white.

Will Hopkins: Yeah.

George Gendron: And how many art directors were there in town?

Will Hopkins: There were none. There was an art director—you know, a 17 year old or something—who did the high school yearbook.

Greenhaw Brothers Cotton Buyers, Marianna, Arkansas, ca. 1936 (Library of Congress)

George Gendron: But he was not necessarily a role model of yours. So when you were 12, what did you want to be?

Will Hopkins: You know, I didn’t get into anything. I mean, I did do, I did, some painting and some stuff like that and so on, but not a lot. I went to the University of Arkansas, which was the only place I could get in, you know, because I had such poor grades. I went there for a few years and I was not doing well because I was really going to all of the stuff in the art department and I didn’t take any other courses, hardly.

And my parents talked to my aunt who was in Connecticut—she was an illustrator in New York, a fashion illustrator—and said, “What can we do with this kid?” You know. And she said she had friends who were at Cranbrook Academy of Art outside of Detroit. And so that sounded—that wasn’t too bad for my parents.

George Gendron: Did you know what Cranbrook was then?

Will Hopkins: No. And my parents didn’t want me to go to Gotham. There’s no way they were gonna let me loose in New York. But I could go to Detroit because a lot of people from Marianna, or in Arkansas went to Detroit, because they worked in the car business and the factories.

“I knew that I didn’t want to be a cotton buyer, and I didn’t want to just hang out [in Arkansas], so this idea of going to Cranbrook was really interesting. I had no idea what I was getting into. But I went and I had a great time.”

So, anyway, I went to Cranbrook. I went up there and I stayed for two years. I mean, I could do some, some sort of illustration or something in the art school at the University of Arkansas. But there was really not much to do there. I mean, there were a few teachers, but there wasn’t a lot going on.

But I really knew that I didn’t want to be a cotton buyer, and I didn’t want to just hang out there, and so this idea of going to Cranbrook was really interesting and I had no idea what I was getting into. But I went and I had a great time.

George Gendron: Well, you must have because it couldn’t have been that much later, that suddenly you show up at Willy Fleckhaus’s studio in Munich, Germany.

Will Hopkins: Yeah. Well, after I left Cranbrook, I went to Chicago. And I had a friend who was an A&R man at Chess Records. And I started doing some album covers and stuff like that, and other odds and ends around there that they needed done.

And I did that till they fired him. And the Chess brothers asked me to come in and have a meeting with them. And they said, “We’d like for you to do some more stuff here.” And I said, “Well, yeah, but you fired my friend.” And I said, "I don’t like that” or something.

And so they said, “Well, okay. All right.” And they said, “Goodbye.” And I said goodbye to them.

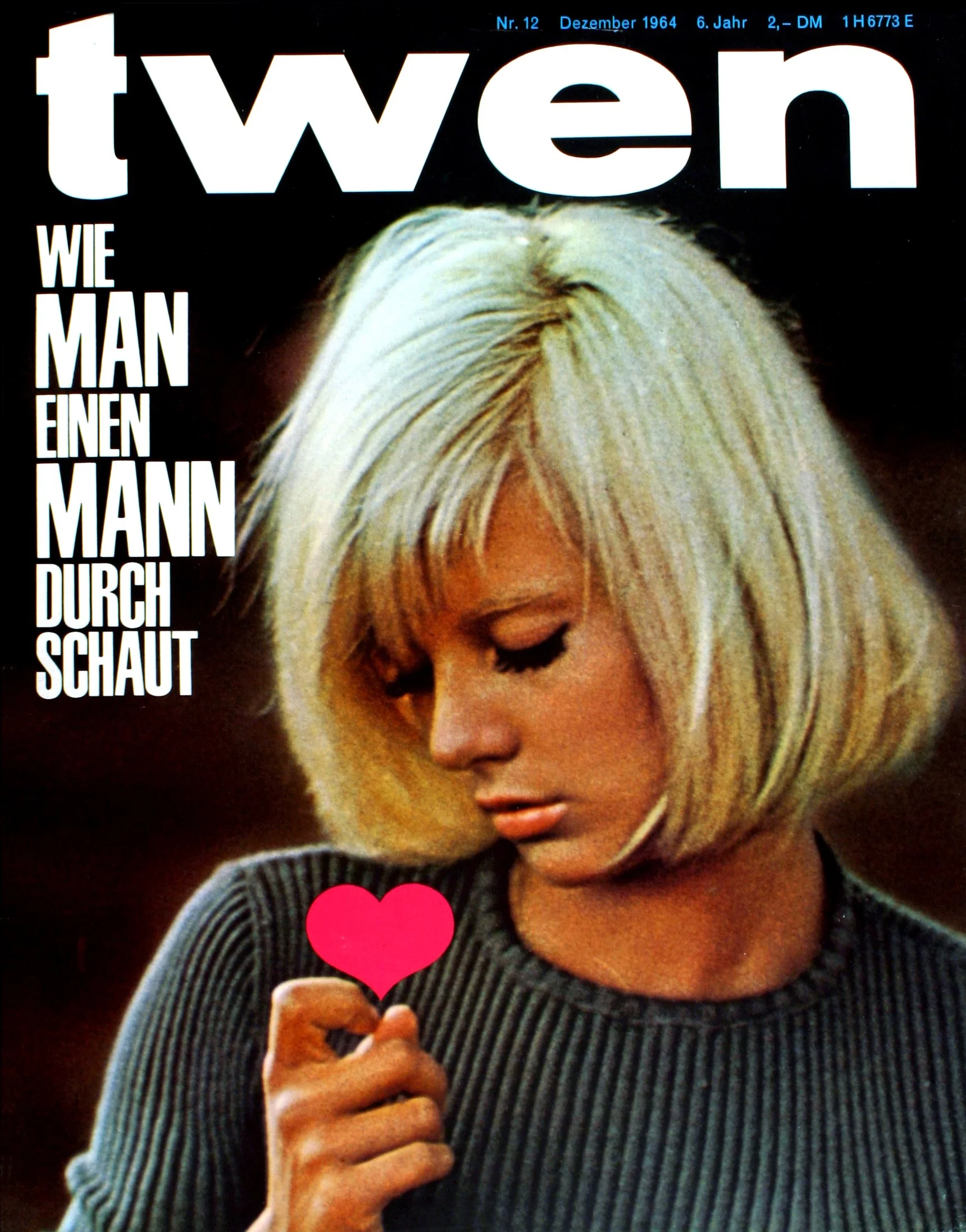

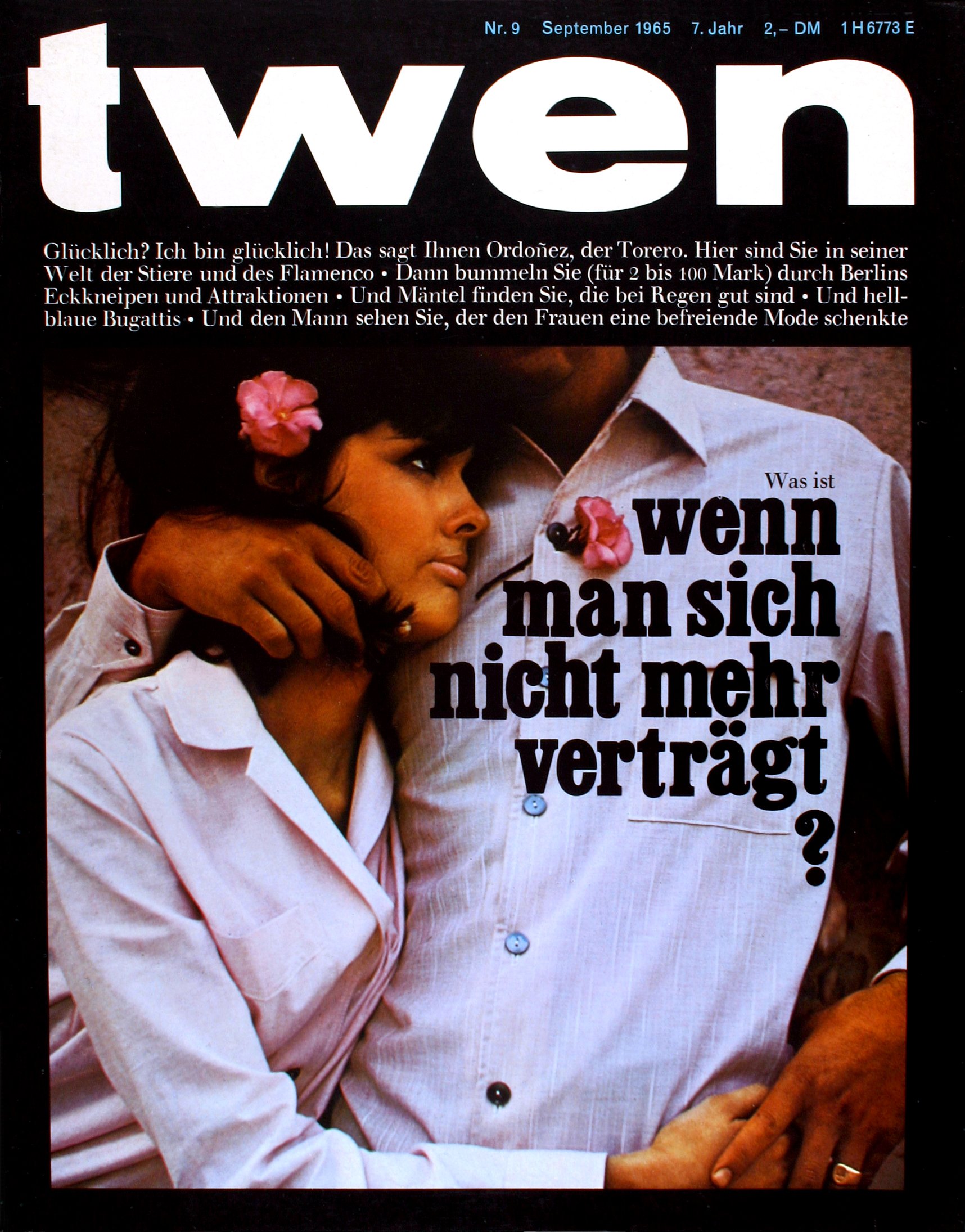

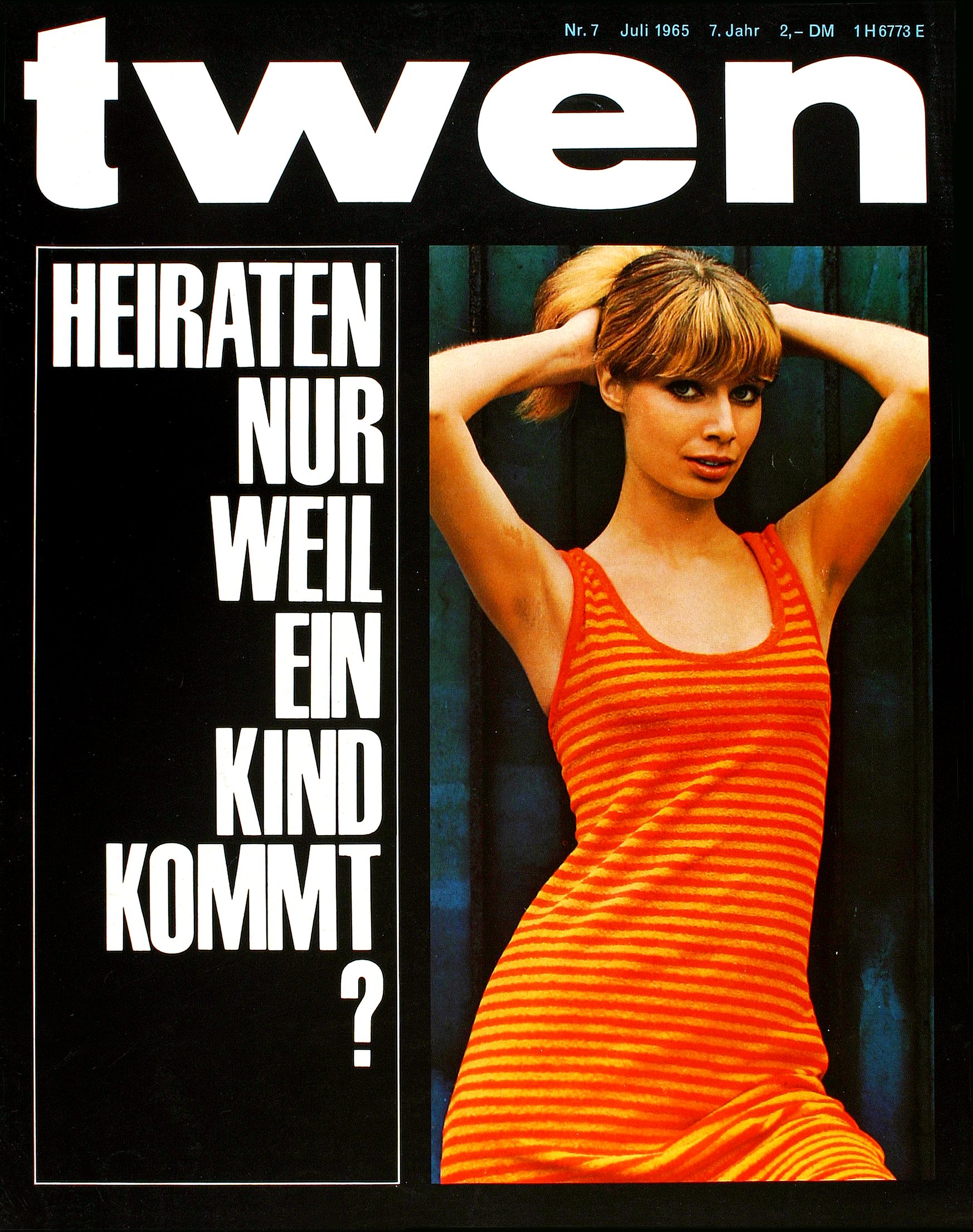

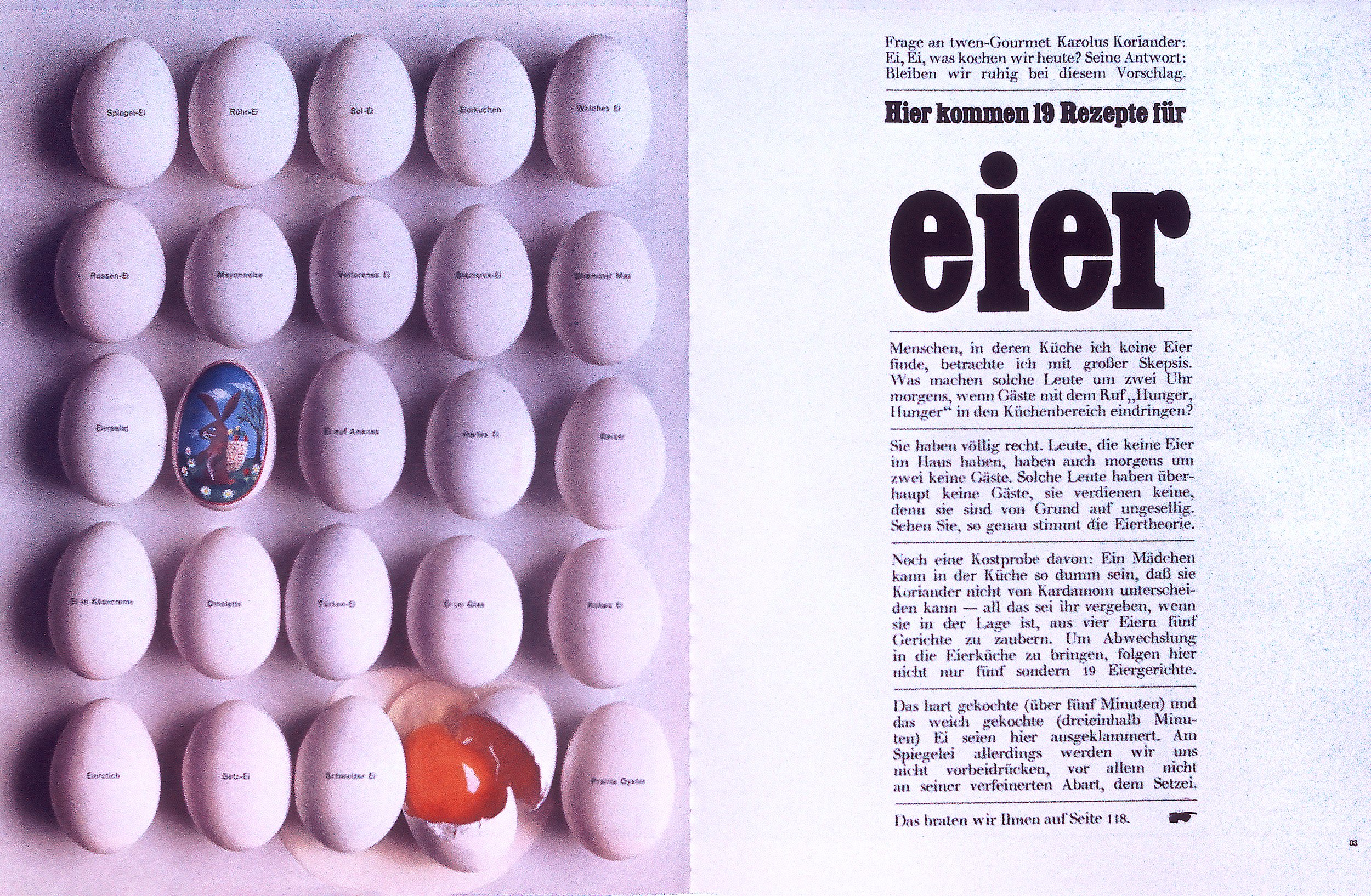

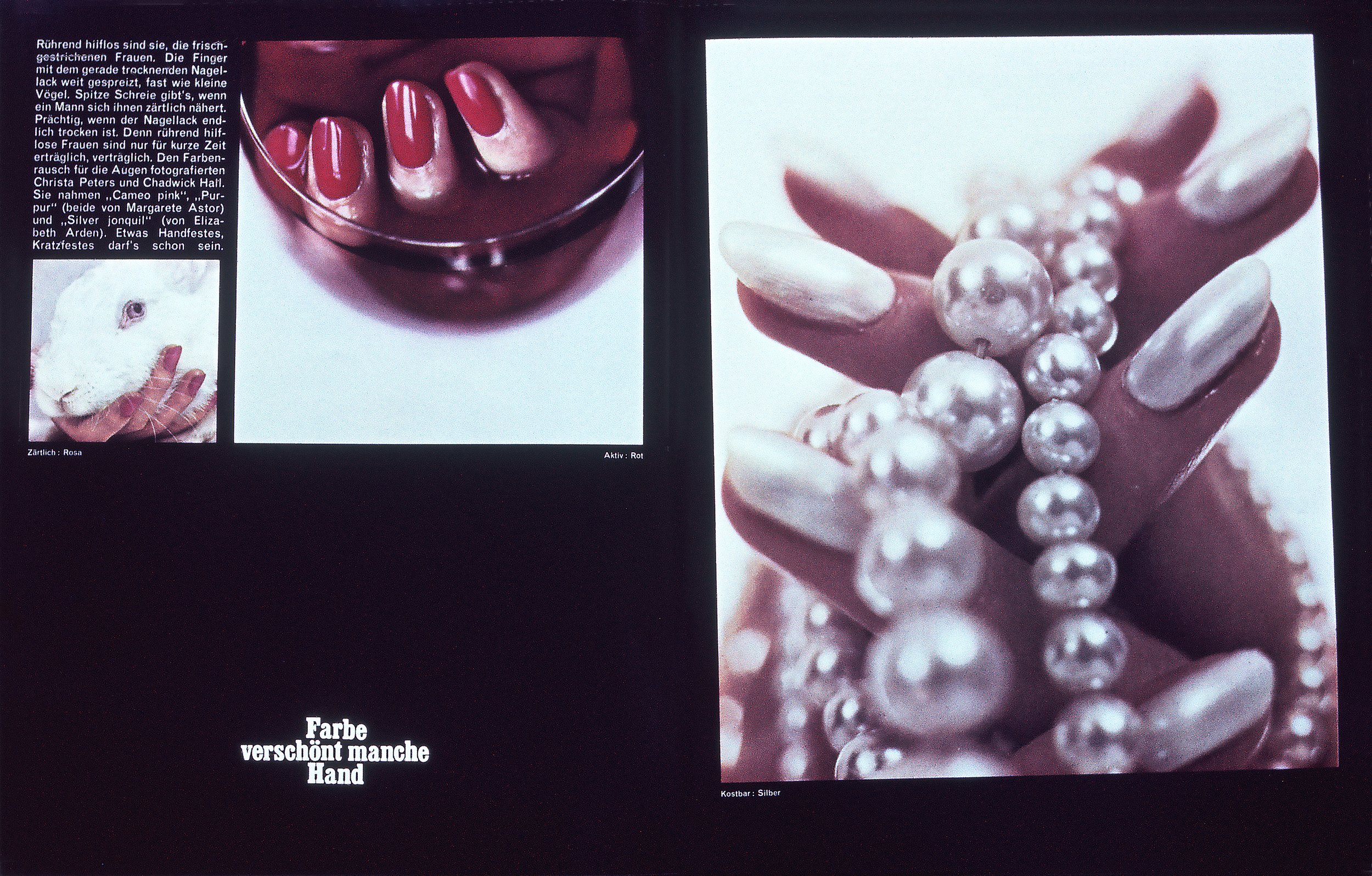

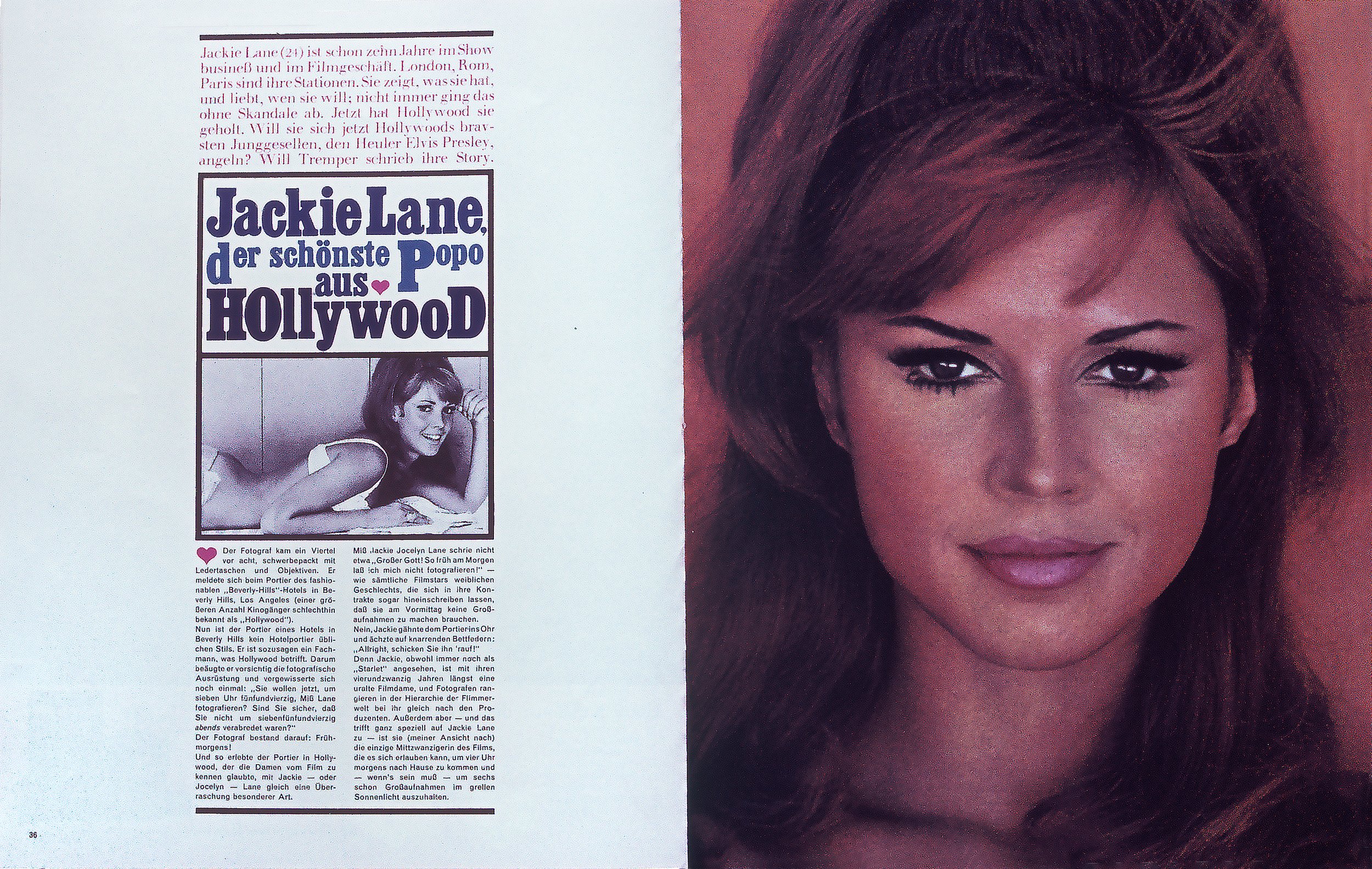

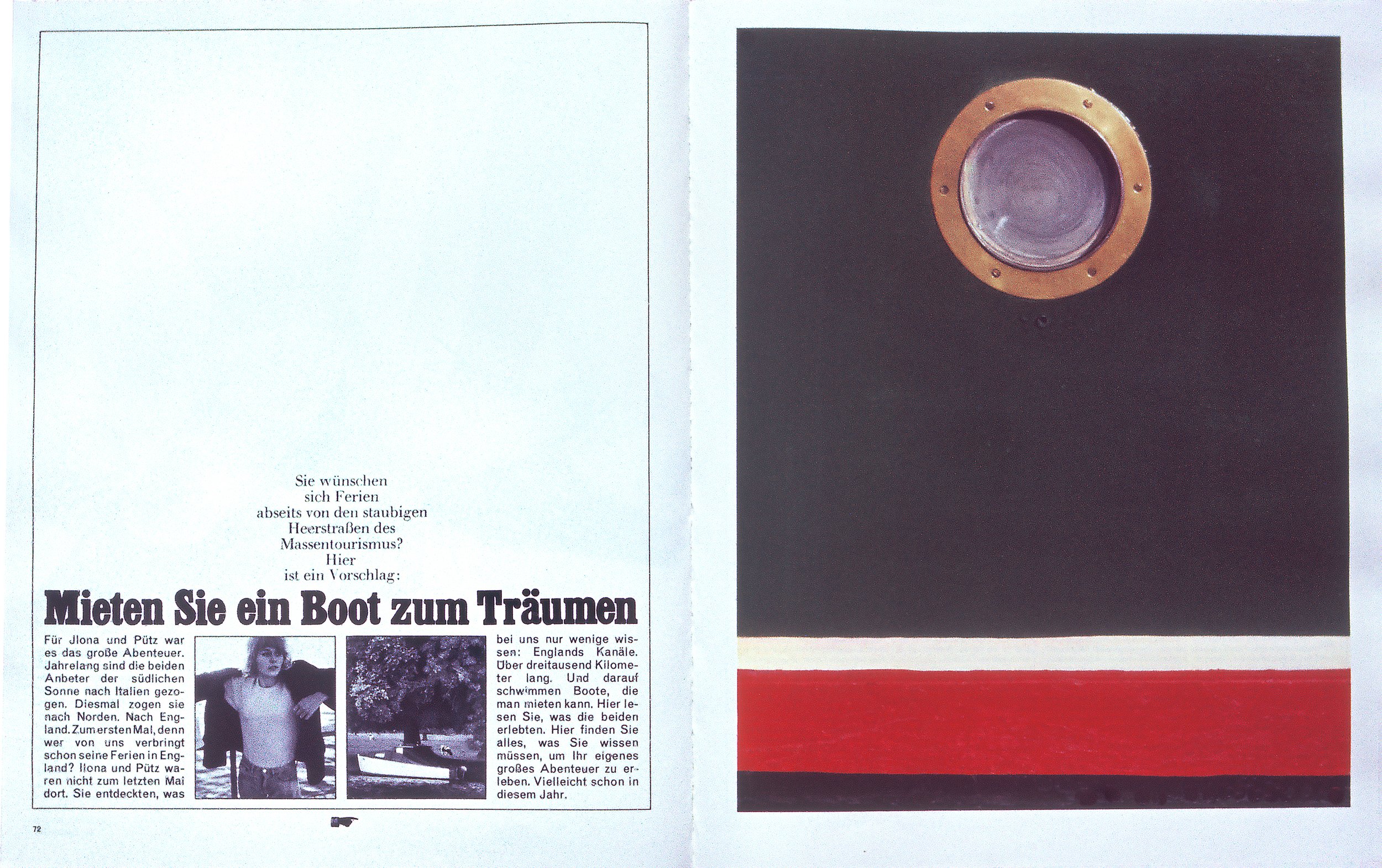

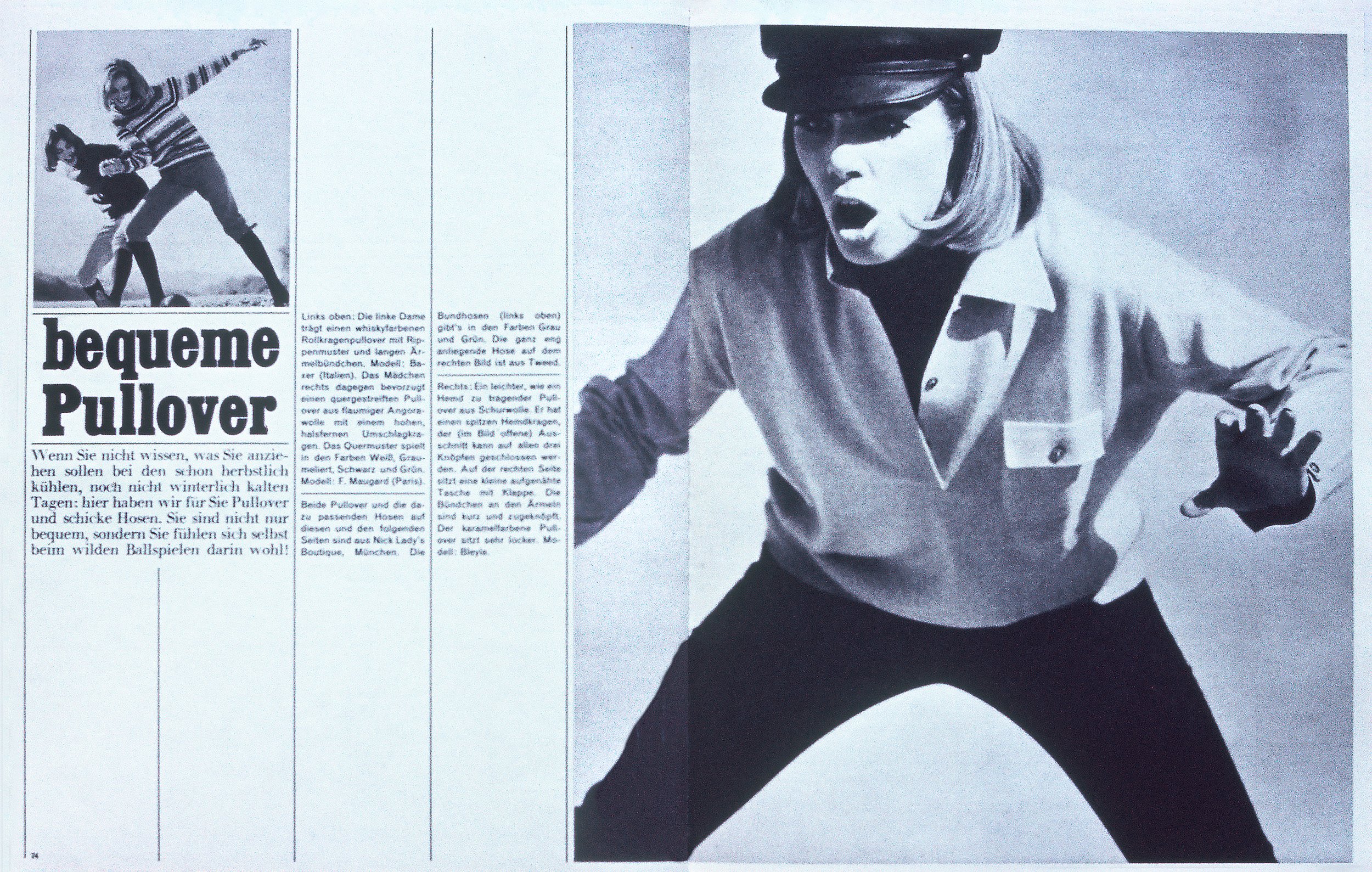

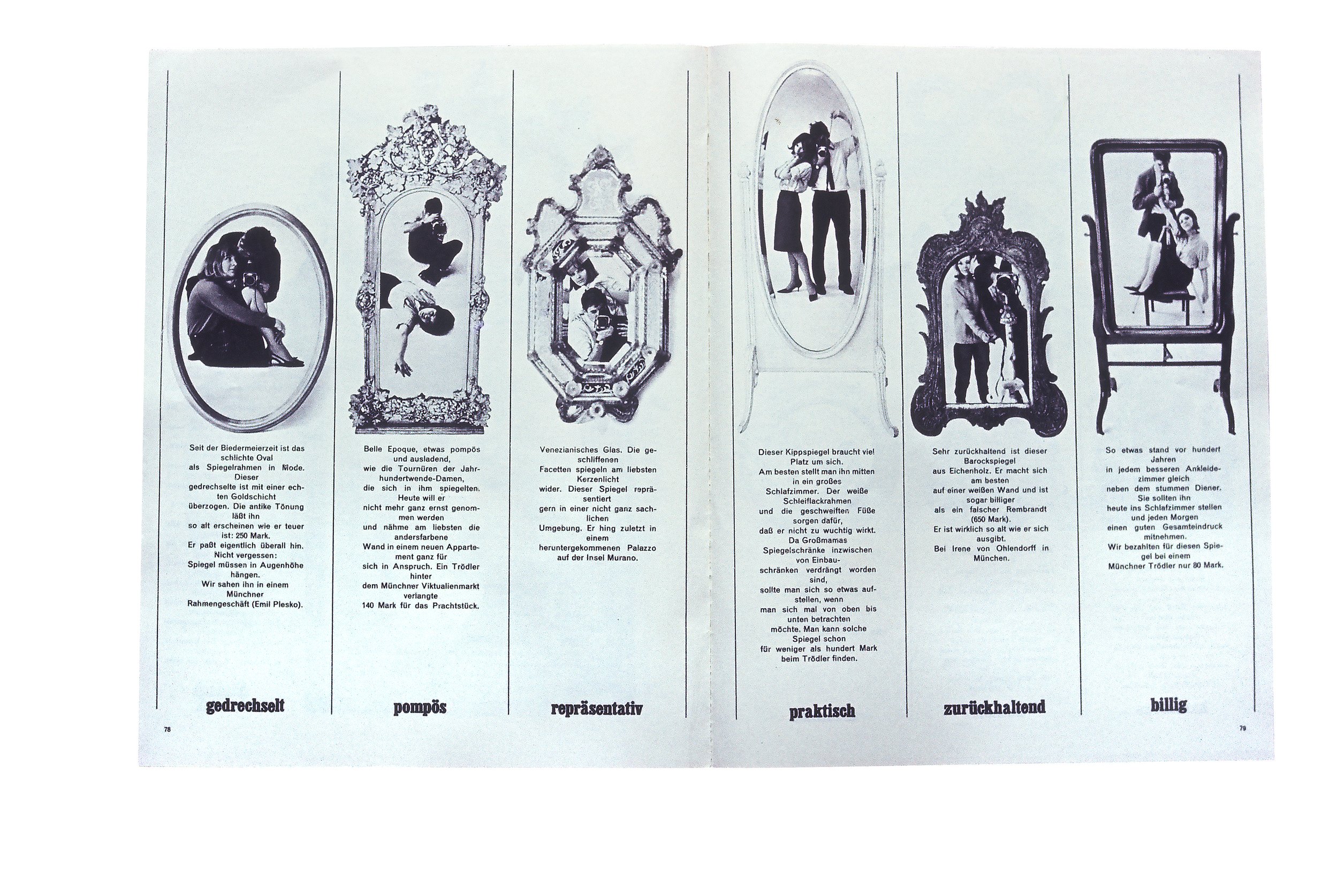

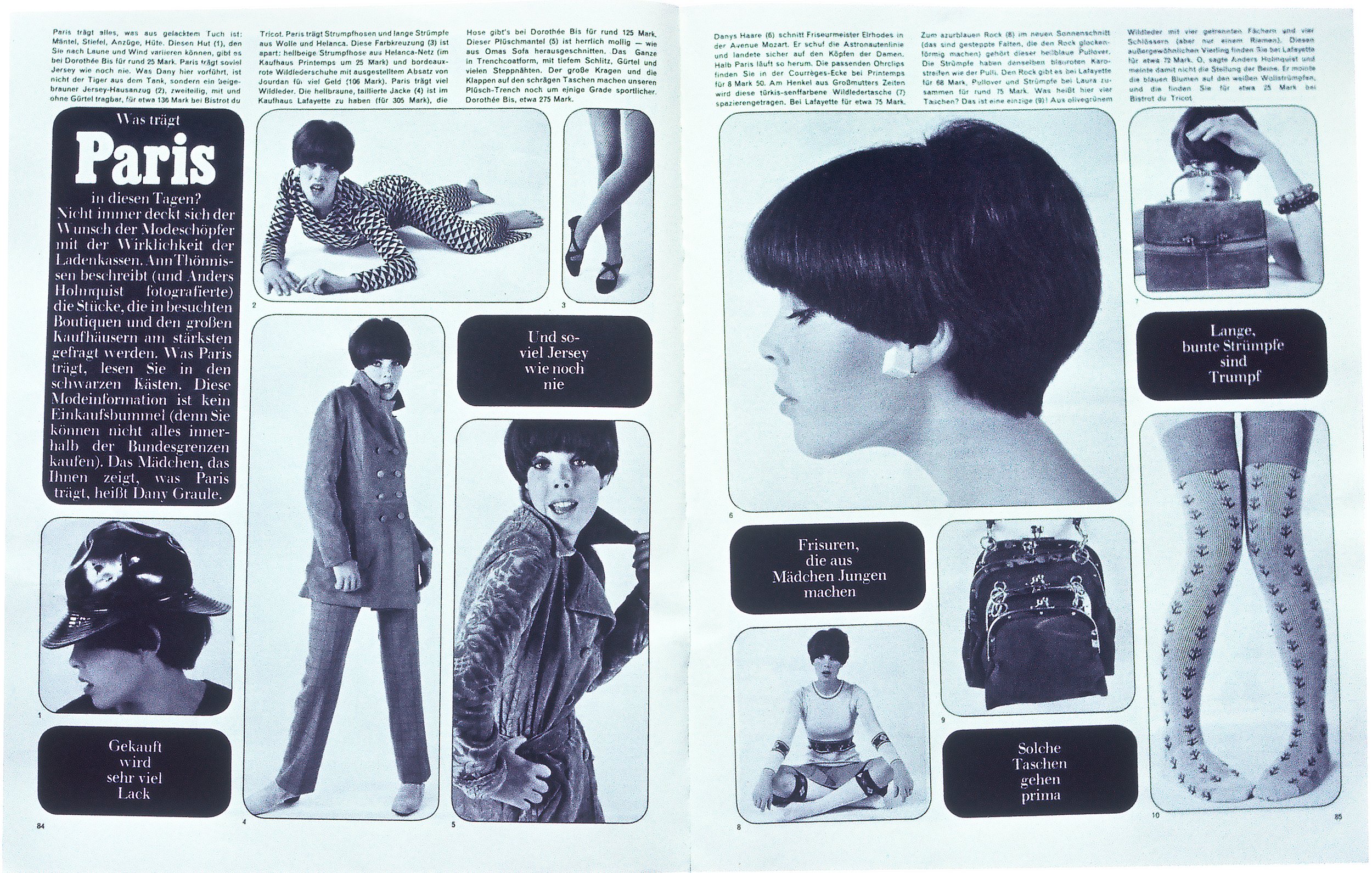

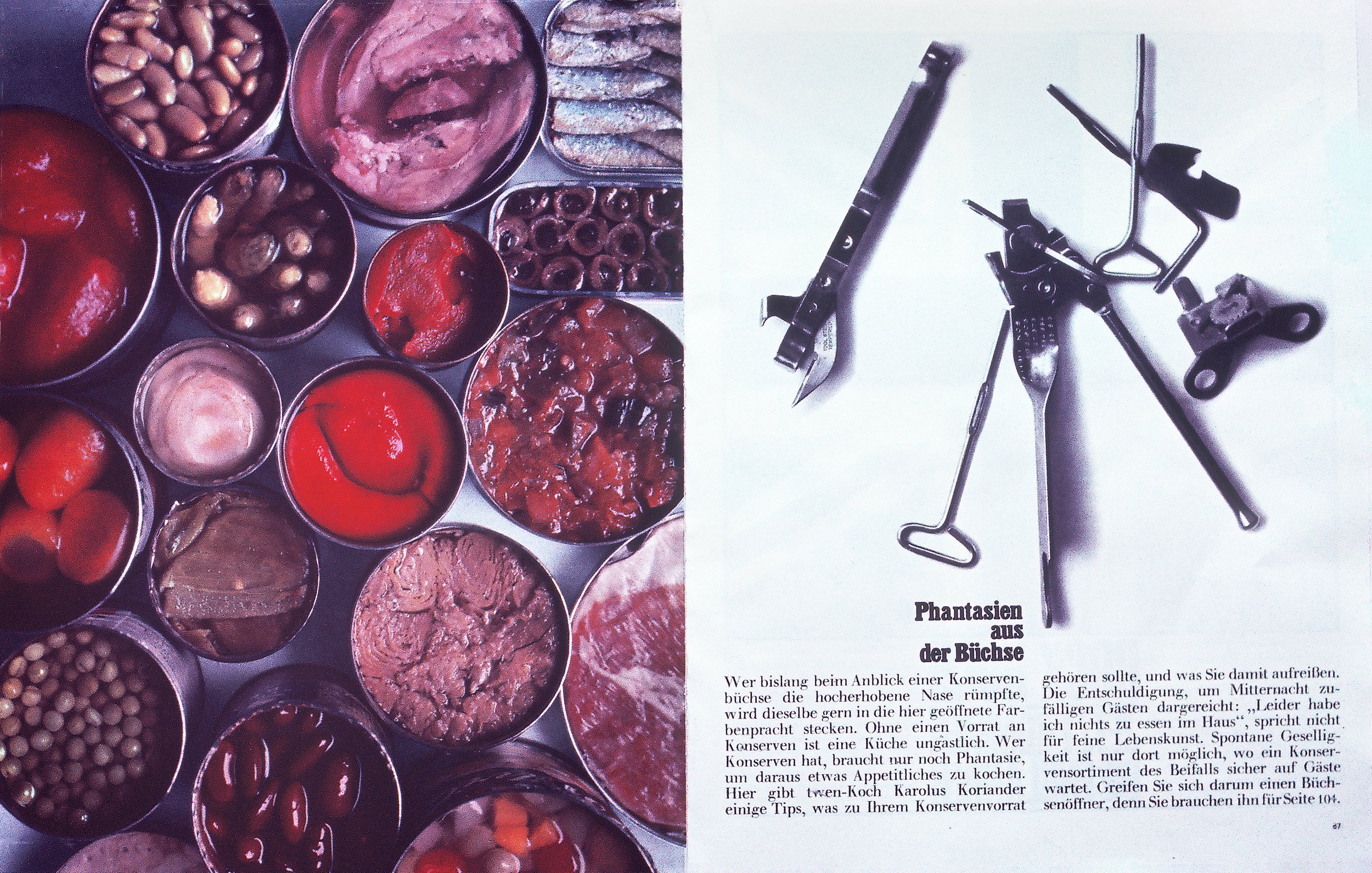

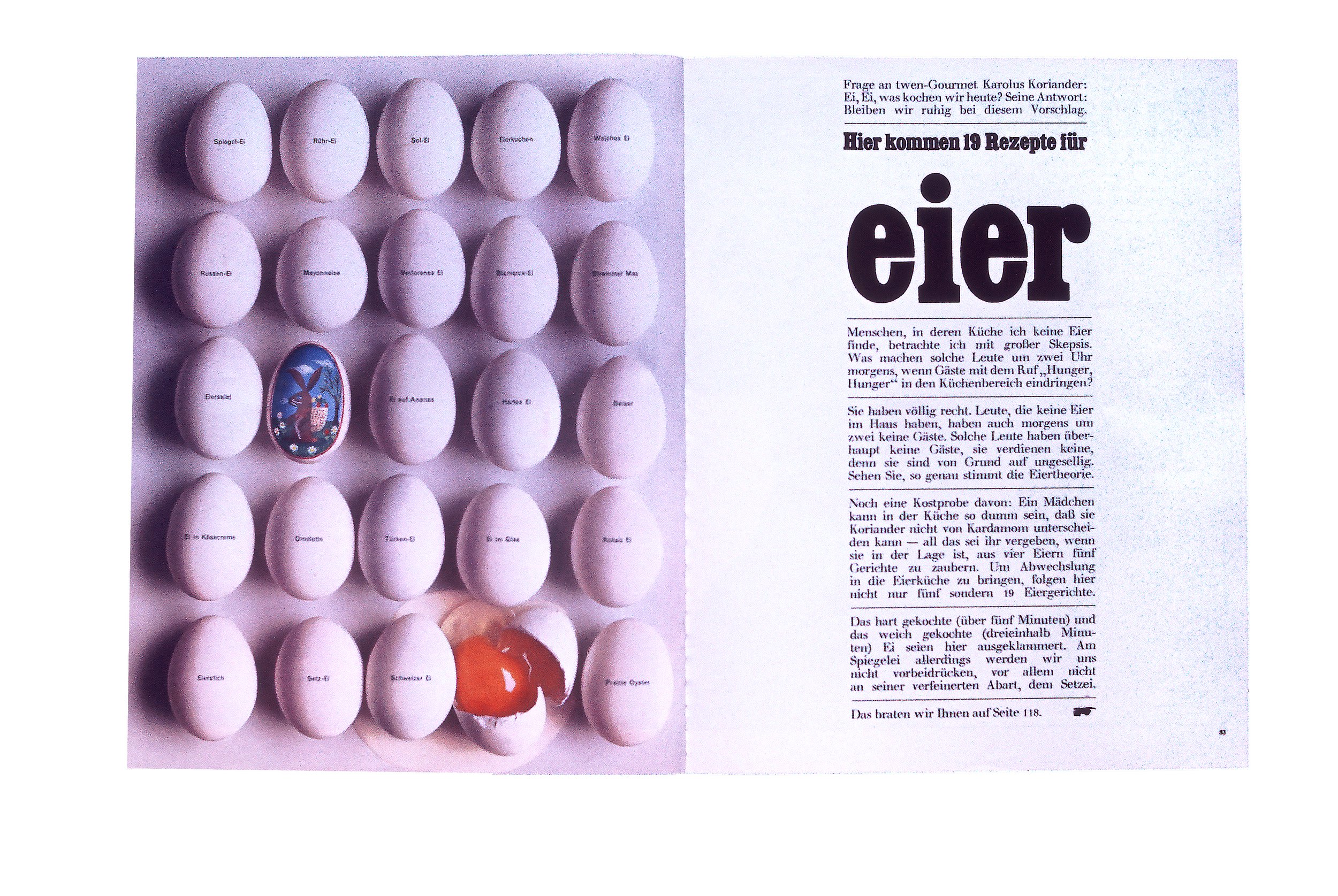

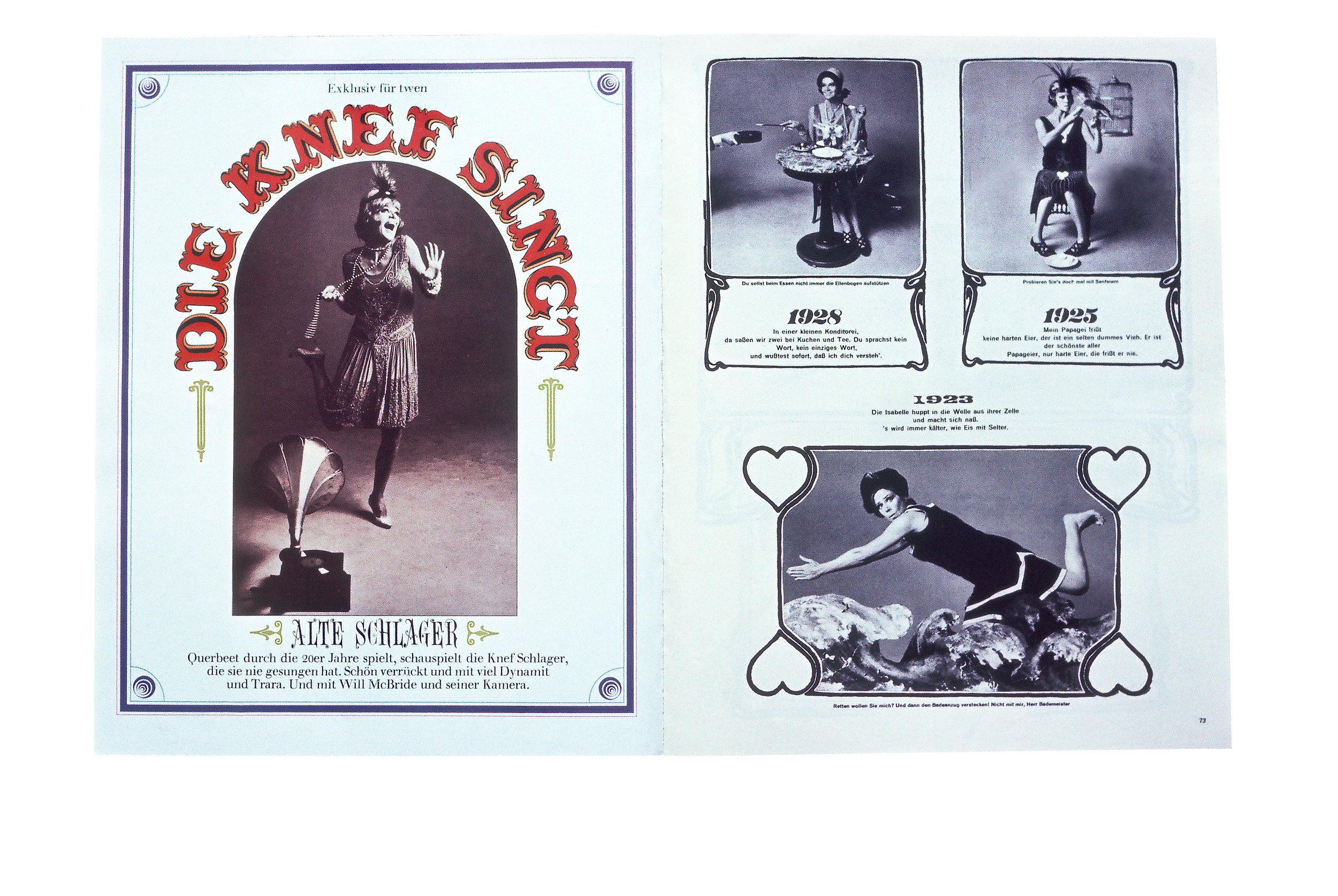

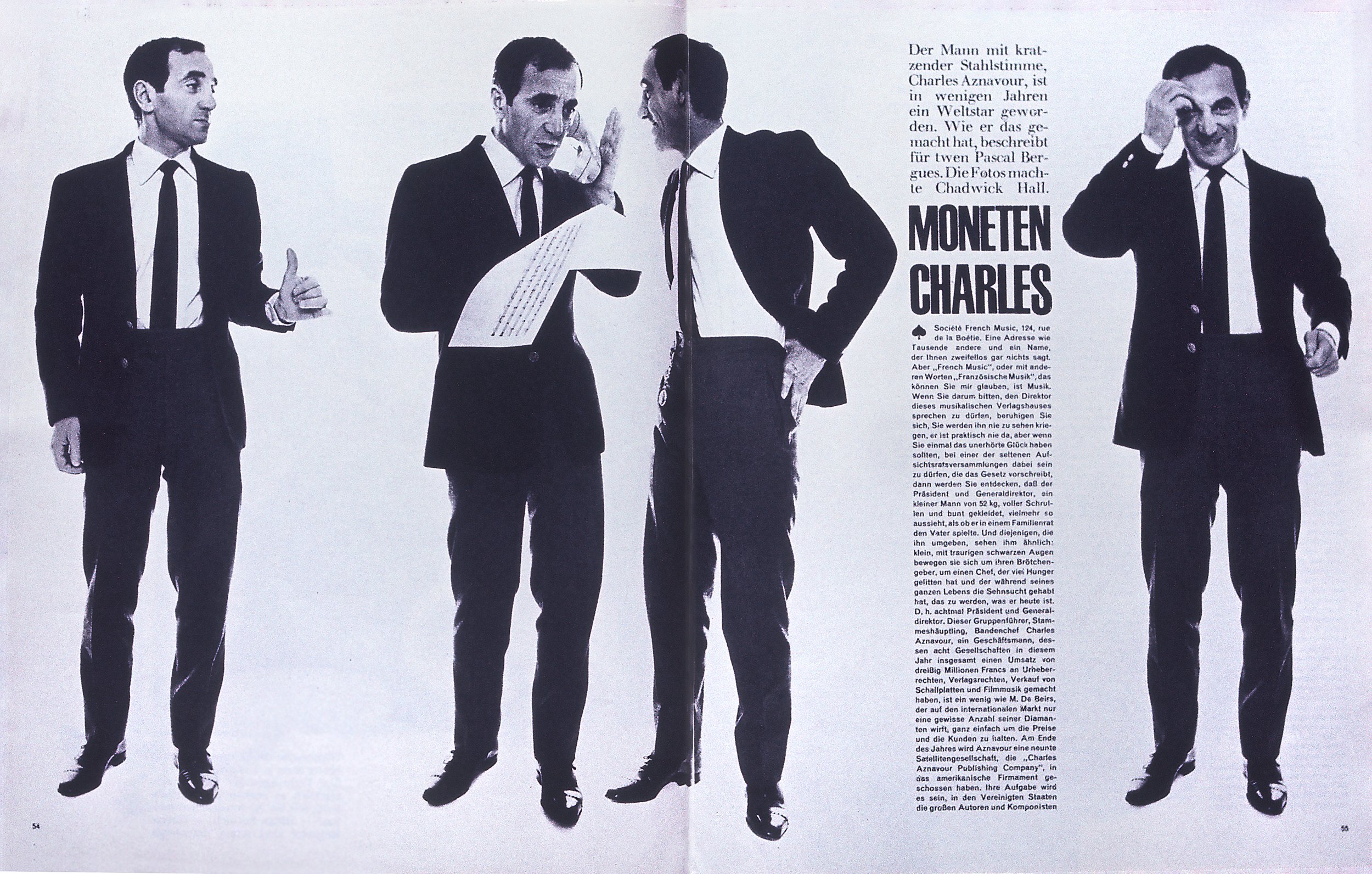

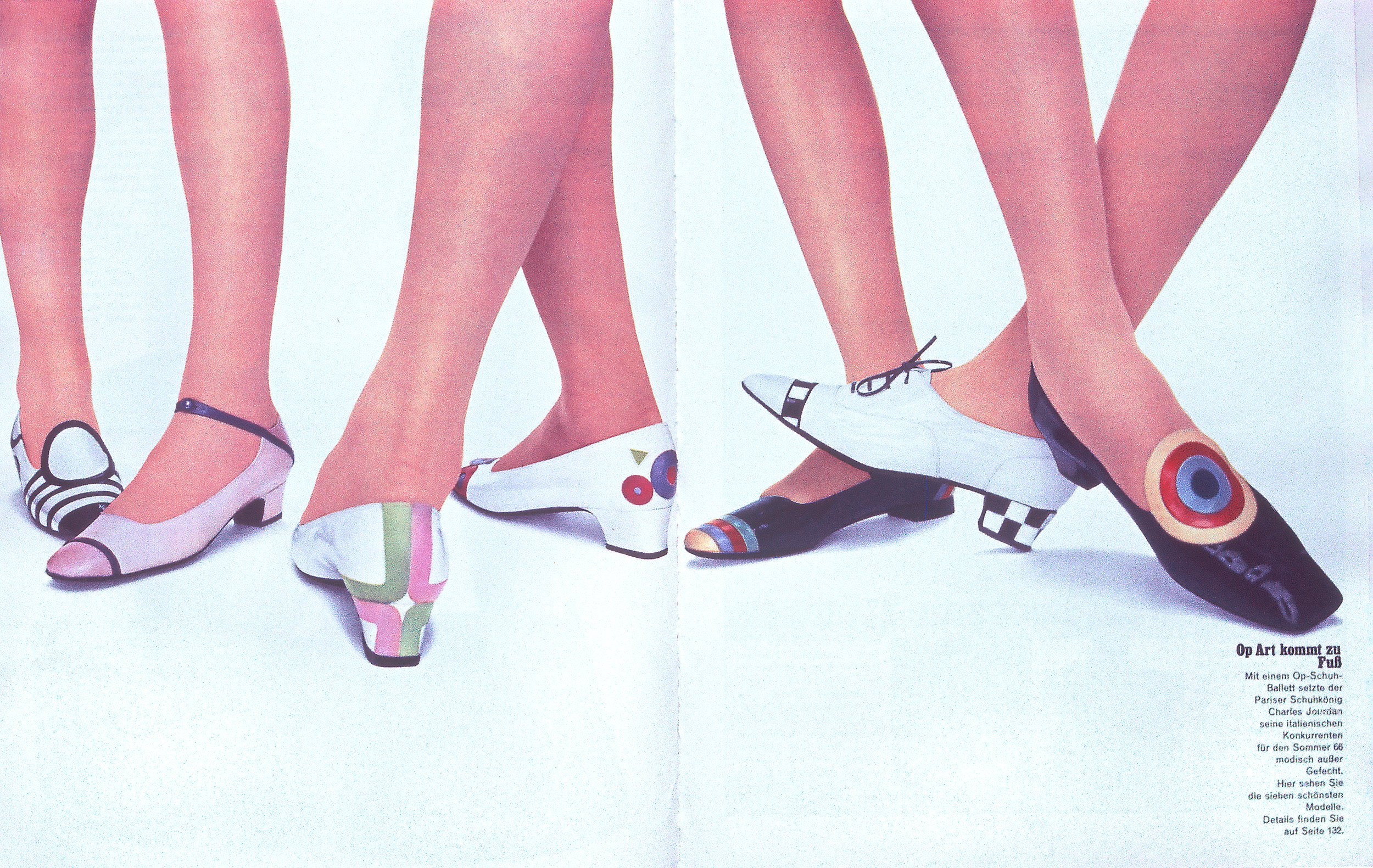

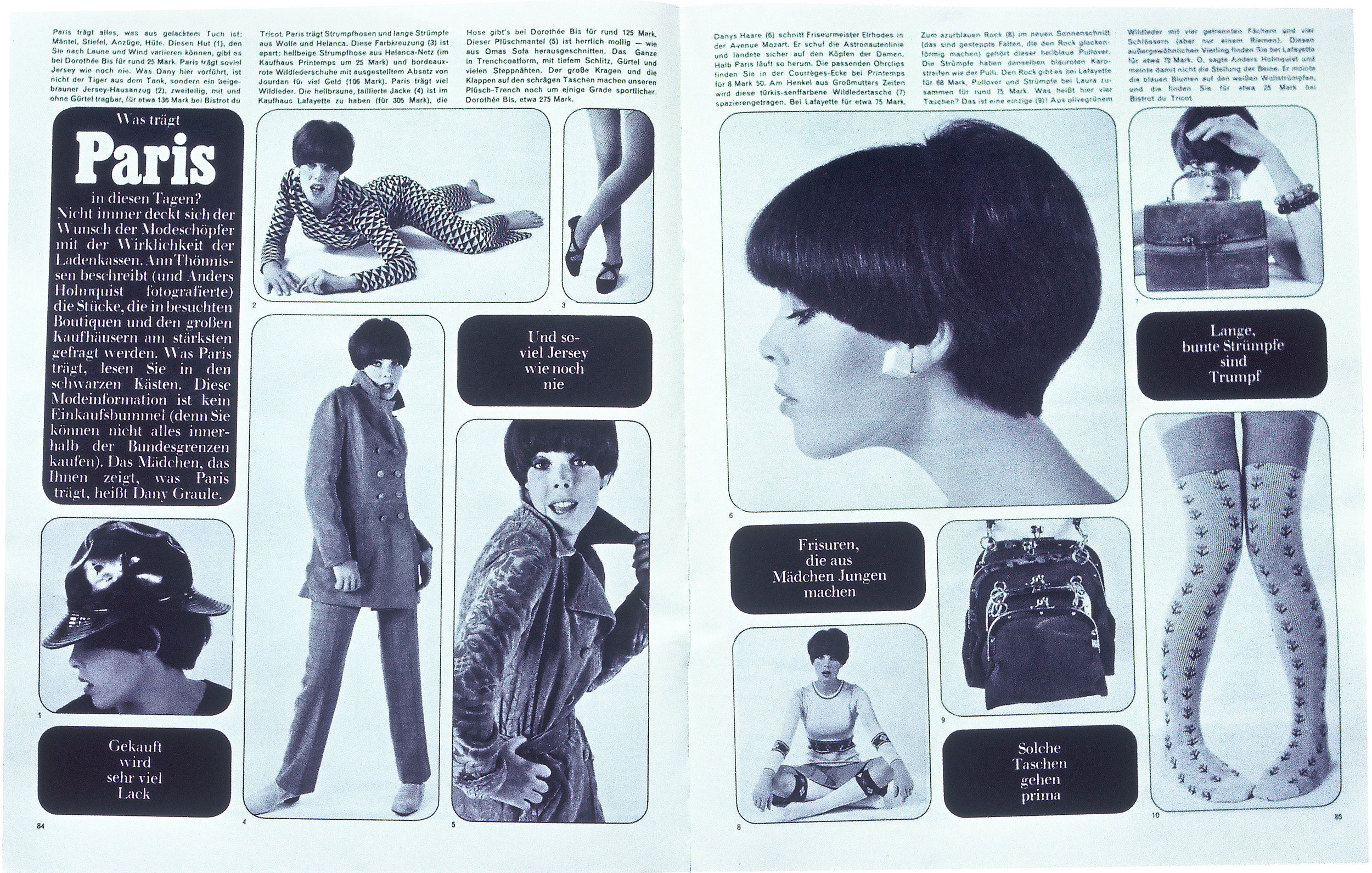

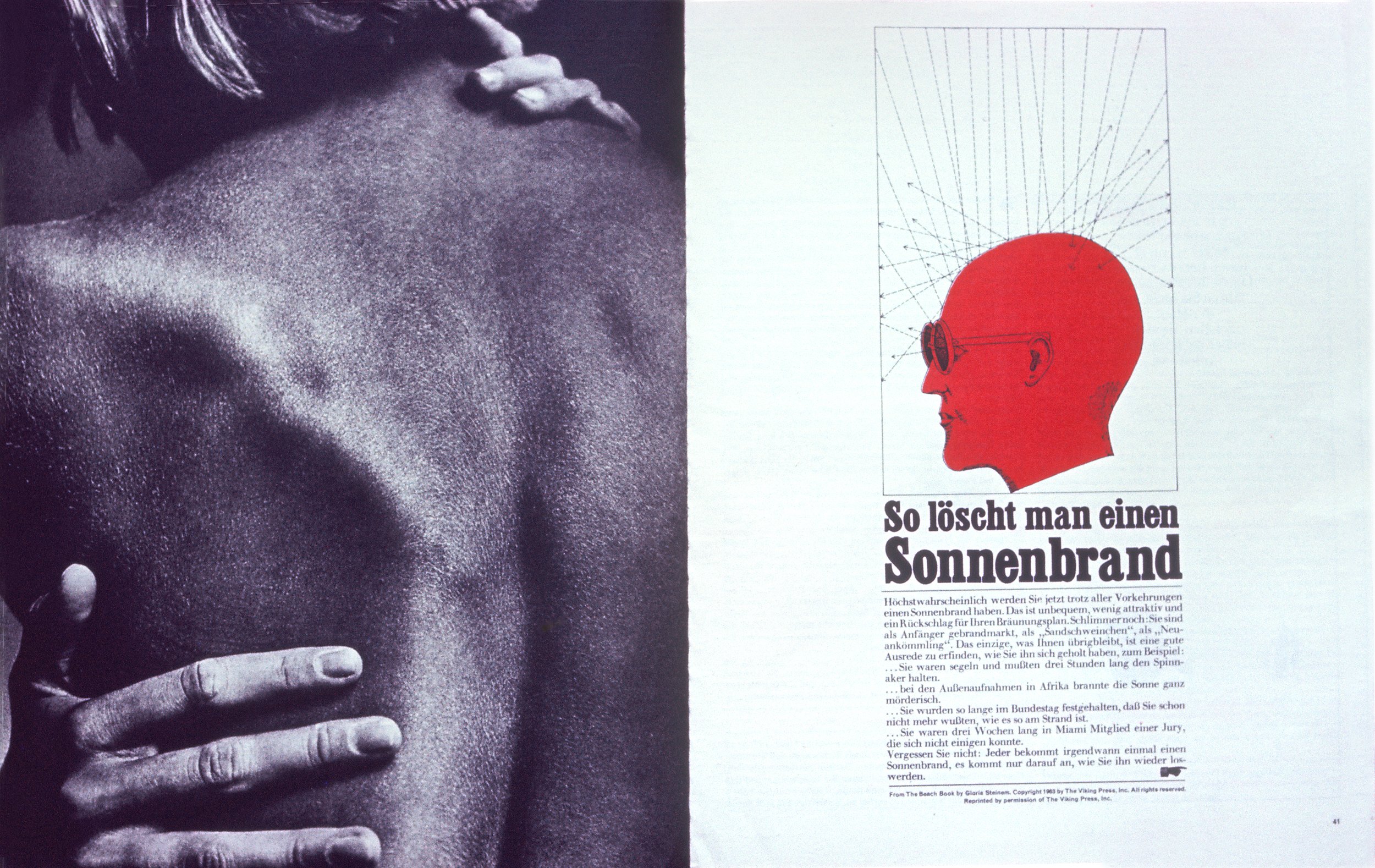

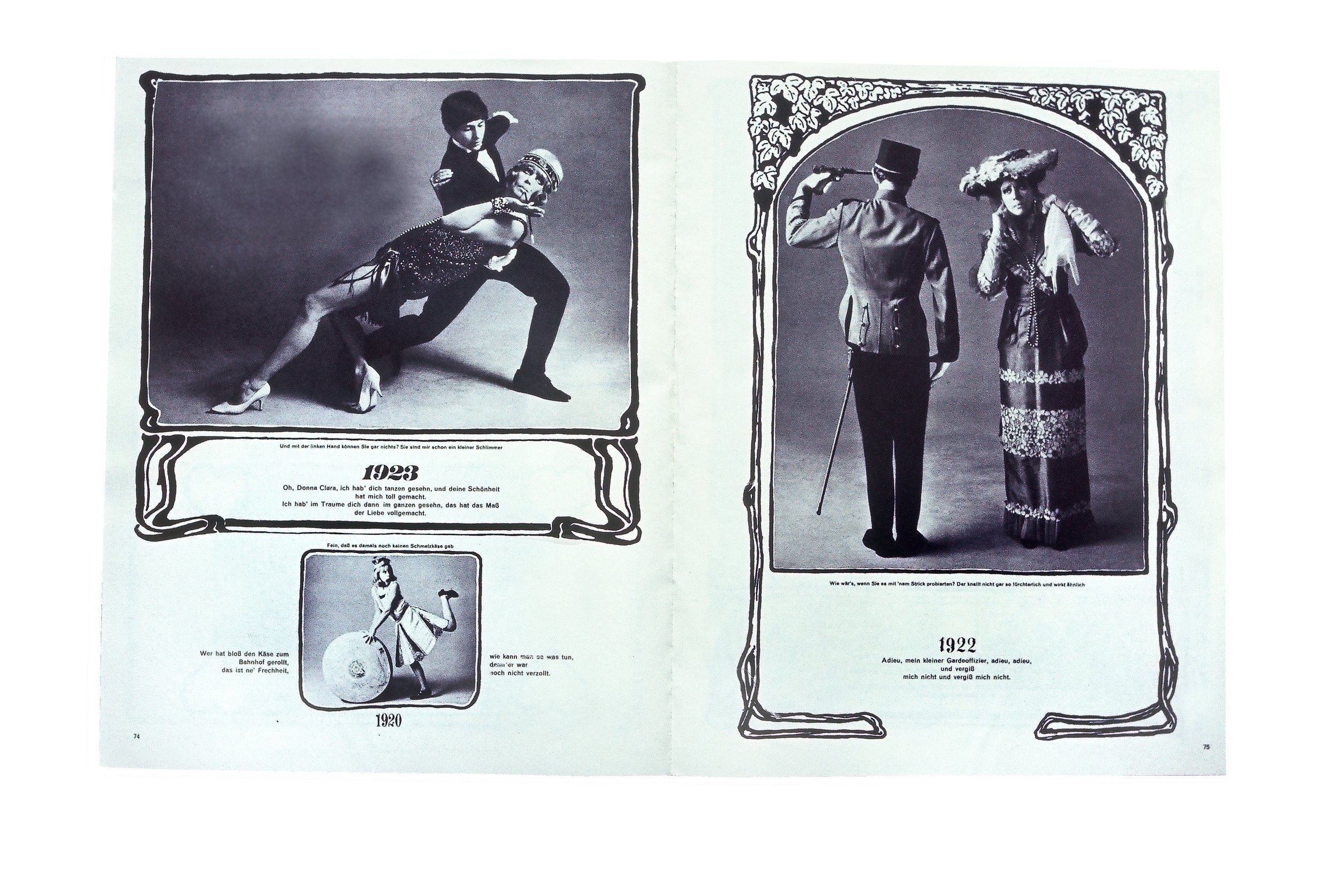

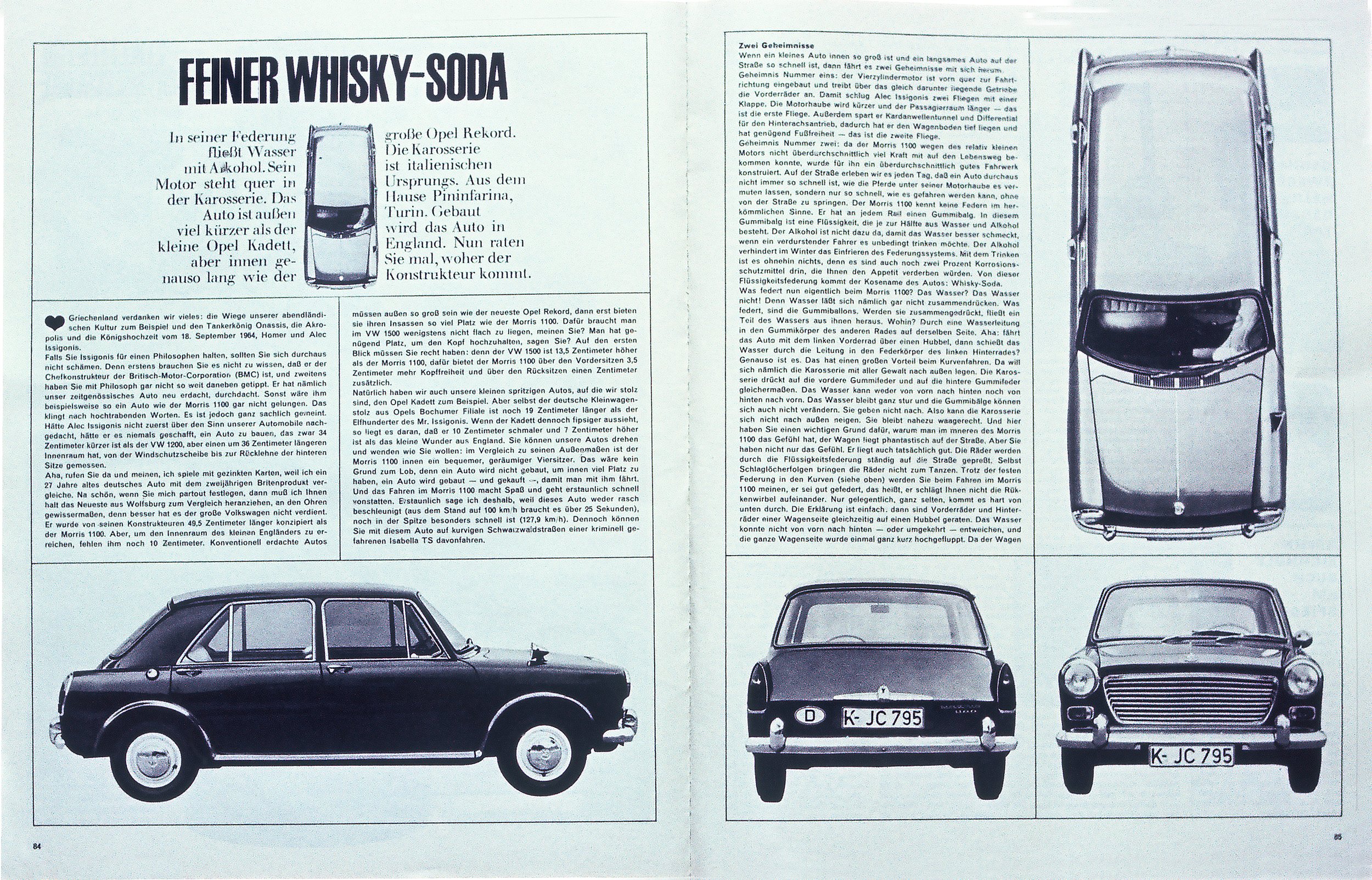

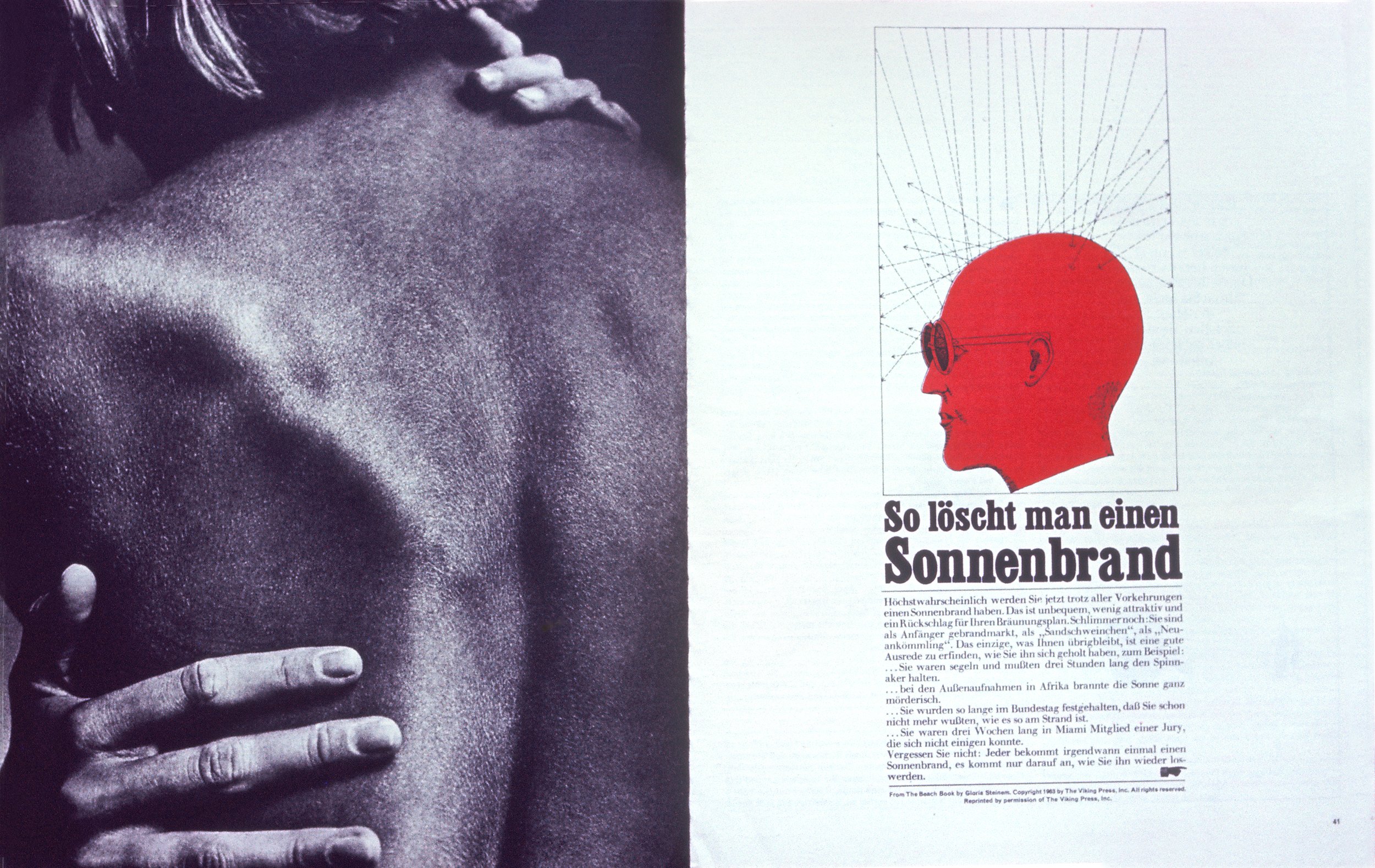

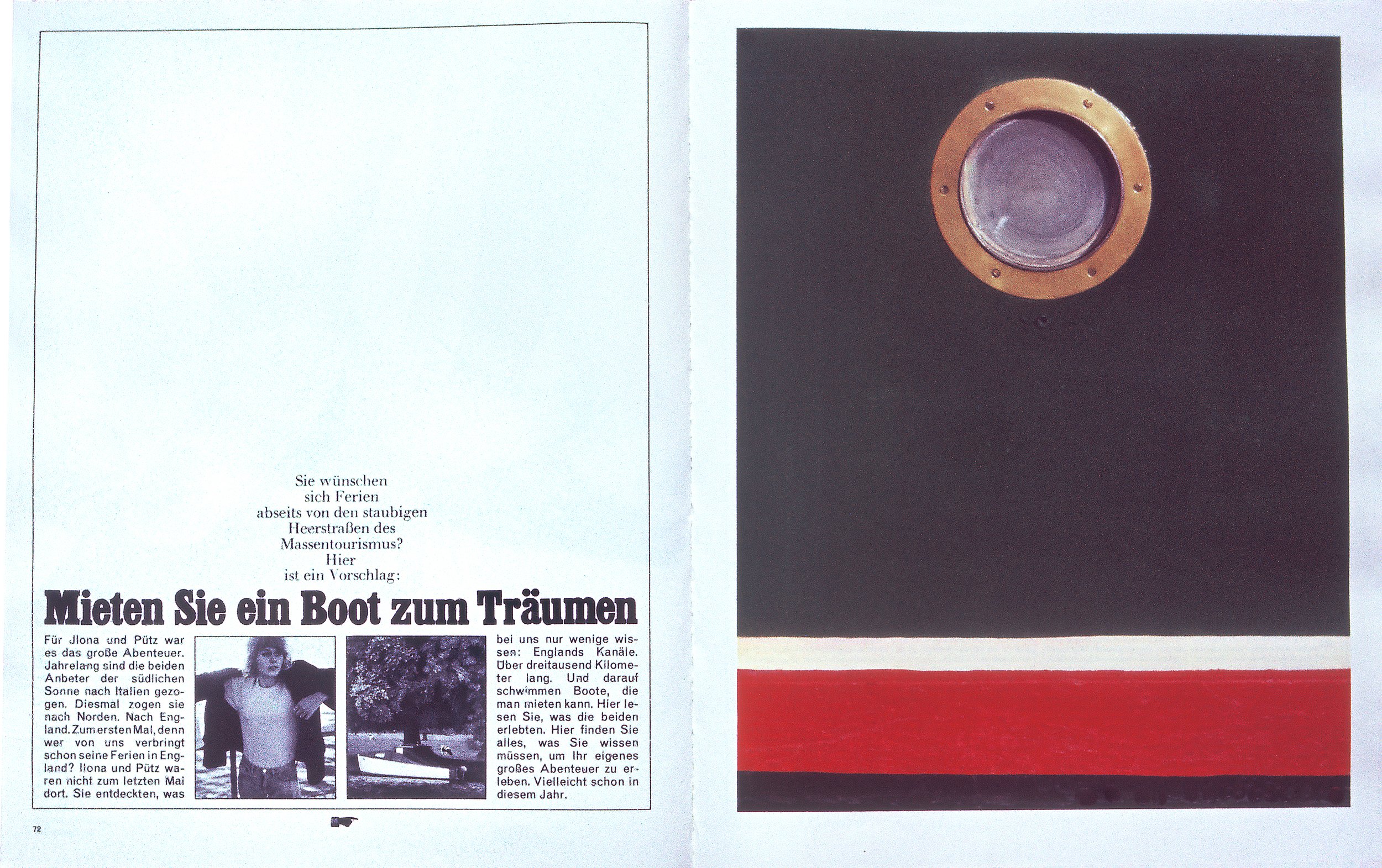

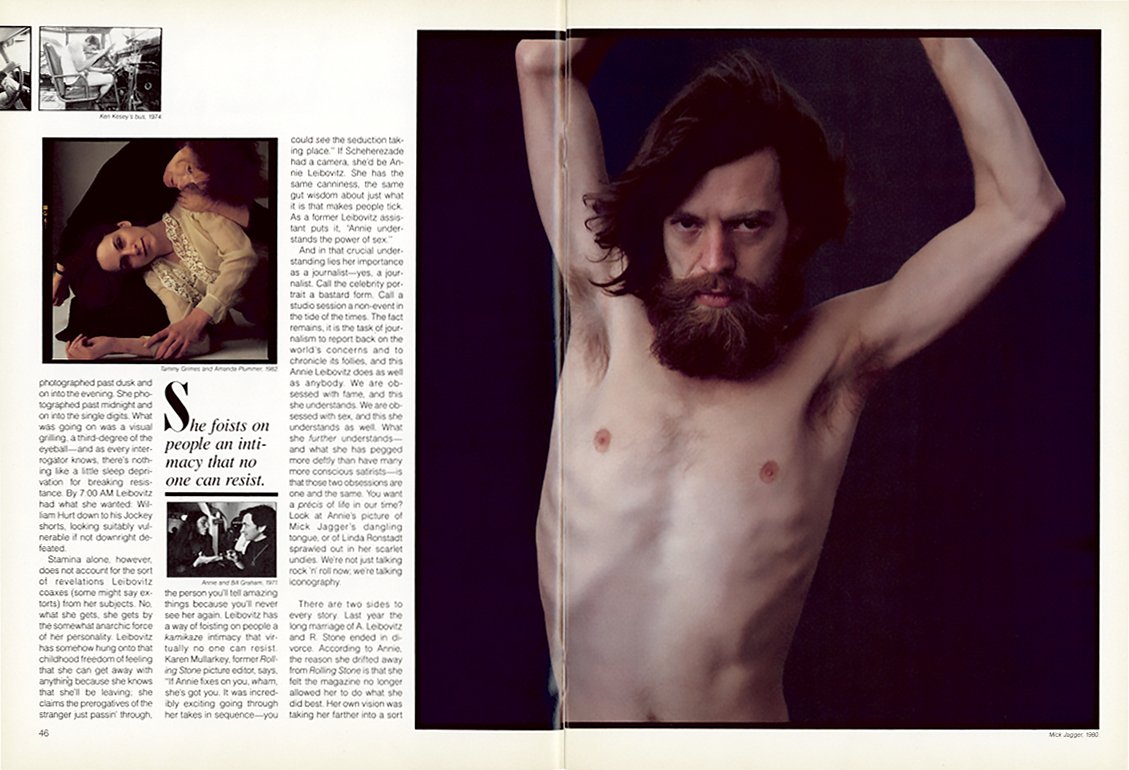

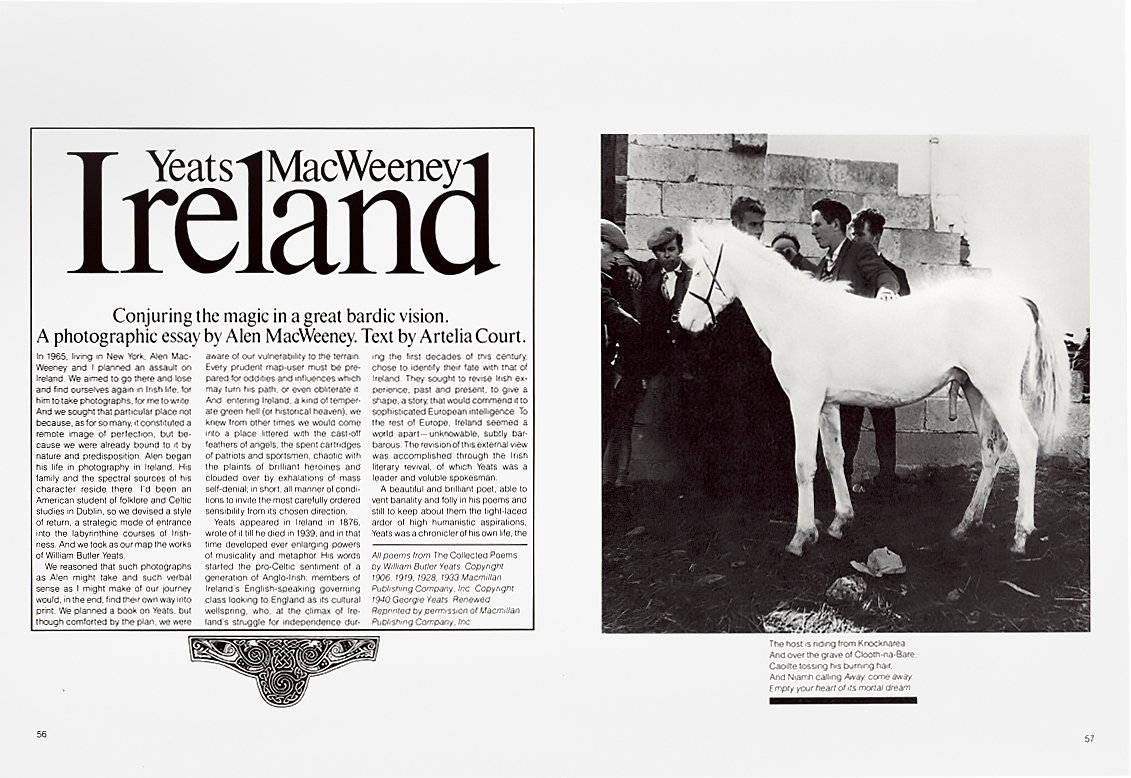

Twen Magazine, Munich, Germany, 1963–1966

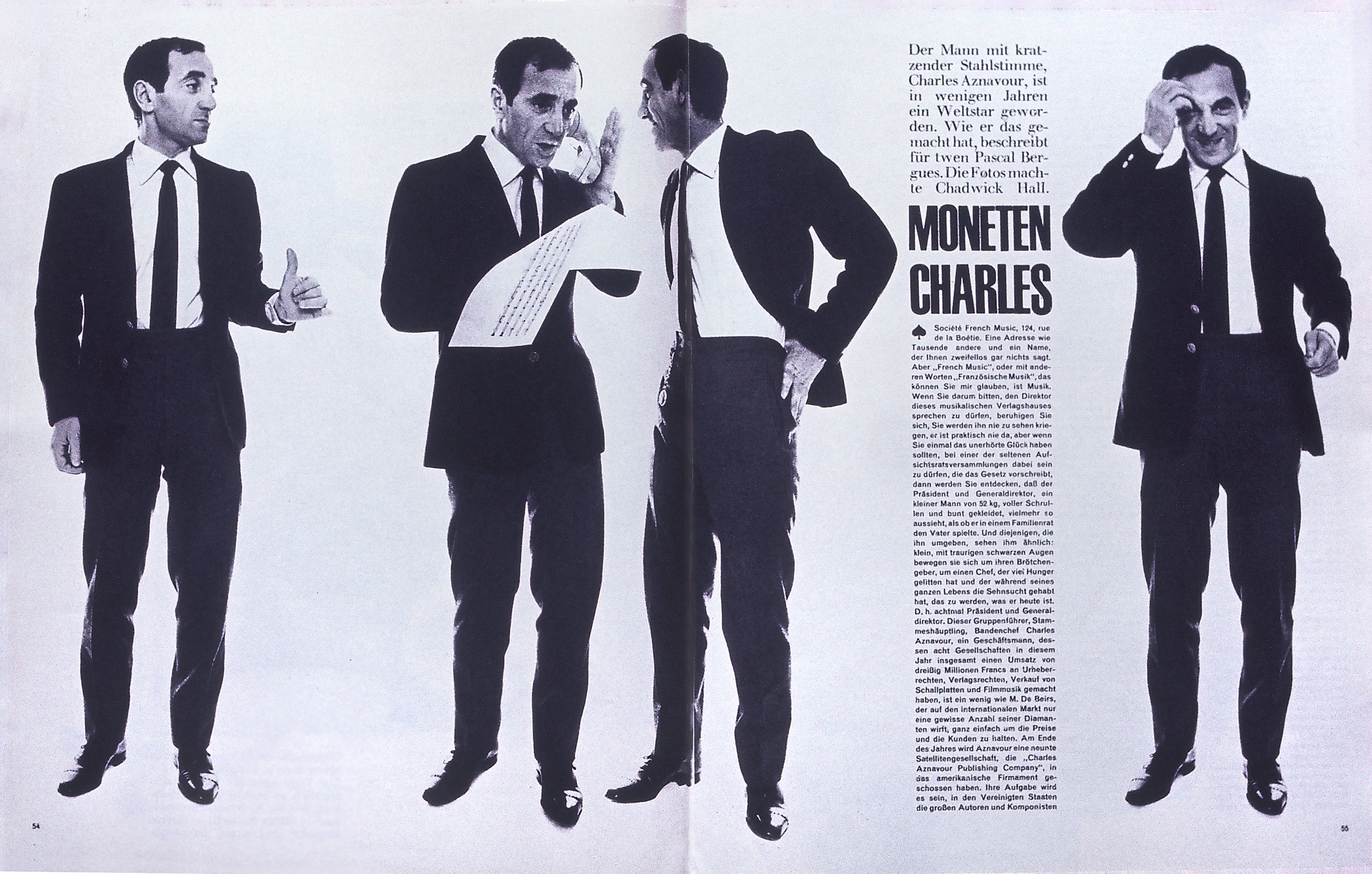

George Gendron: I’m anxious to hear about, not so much how you got to work with Willy Fleckhaus, but what was it like? I mean, you read about him today and he has kind of been rediscovered, it seems to me. At least rediscovered here, really in the US. People talk about him as one of the greats, number one. Number two, some people say, at least in Western Europe, he really created the role of art director as we know it today.

Will Hopkins: Yeah. Max Bill in Switzerland was who he copied.

George Gendron: What was the magic in that studio?

Mary K Baumann: Let me just back up for a moment. What drew Will initially to Fleckhaus, somebody had handed him a European design magazine while he was at Chicago Scene and Fleckhaus was featured in there. And Twen was featured in there. And Will said, “I gotta go work for this guy.” So...

Will Hopkins: One Sunday afternoon, I’m walking down the street in Chicago. I said to this friend of mine that I was walking with, I said, you know, “I’m gonna go to Germany.”

Mary K Baumann: Anyway, it was that influential on him. And he told his then-wife, “We’re going to Germany.” And she said, “Well, I have to finish the school year.“

Will Hopkins: She was a teacher.

Mary K Baumann: And they packed up and went to Germany. And ...take it from there, Will...

Will Hopkins: ...And we got on a freighter. And I knew the captain of the freighter through my friend in Detroit. And we hopped, skipped, and jumped.

“My parents didn’t want me to go to Gotham. There’s no way they were going to let me loose in New York. But I could go to Detroit because a lot of people from Marianna went [there] to work in the car factories.”

George Gendron: Let’s fast forward to your in the studio. That’s what I want to hear, man. Yeah. What was that like?

Will Hopkins: So I got there, to … Frankfurt?

Mary K Baumann: Cologne.

George Gendron: Munich?

Will Hopkins: No, we met him up north.

Mary K Baumann: Yeah. He arrived in Cologne and discovered that the magazine had moved. So they had gotten a Volkswagen...

Will Hopkins: We took our Volkswagen...

Mary K Baumann: ... he took the Volkswagen and got to Munich and they were camping out in a campground. And you showed up at Twen...

Will Hopkins: ...in my suit...

Mary K Baumann: ...walked up all these stairs because they didn’t have an elevator.

Will Hopkins: It was the sixth floor of the building...

Mary K Baumann: ...and said, “Here I am!” And they gave him back his portfolio, which he had sent before. And they said, “Well, uh, Fleckhaus is on vacation. Can we call you when he gets back?” And he said, “No, because I’m at the campground. I’ll just sit here and wait.” So he waited. And after several days they got into trouble and Will was very good mechanically. So they brought him into the art department.

Will Hopkins: I was sitting in the art department. Waiting.

Twen Magazine, Munich, Germany, 1963–1966

George Gendron: Yeah. But that’s a different definition, Will, of being “in” the art department. [Laughs]

Will Hopkins: So, I waited there. I knew I had to wait there. I couldn’t get out of there. Because if I did, I wouldn’t be able to get back in. So I just came every day and I sat on a sofa and then when they had a problem, I would jump in and help.

And so Fleckhaus gets there and he says, “You’re ‘the Hopkins’.” And I said, “That’s me.” And he said, “Well, I’ll see you later.” And he has a little office that was as big as two phone booths, that was off of the big room that we were working in.

And his editor comes in and he’s talking to the editor. And then he somehow realized from the editor that I am there to work for him and I’m not going to go away. And he said, oh my god. And he says, “Get that guy in here!” So now there were three of us in a space the size of the desks that we’re sitting at here. There were three of us in the room.

Willy Fleckhaus, art director of Twen.

And he says, “What are we gonna do with you?” And I said, “Listen, I come from a little area in Arkansas, and when you’ve got something to do, you do it. And I had to get over here because I wanted to work for you. And I’m here and I’m ready to work. And he said, “All right.”

George Gendron: Did he say it with that level of enthusiasm?

Will Hopkins: Something like that. And then I think he told me to go wait because he’s still talking to the editor. And Fleckhaus ran the magazine. The editor didn’t. Fleckhaus ran what it was gonna be.

So anyway, Fleckhaus comes out and he says, “Let’s go through this project and see how much we can do this afternoon.”

And he had these spreadsheets. And he would draw on that sheet or whatever, you know, sometimes just write something on it and then I would go execute it.

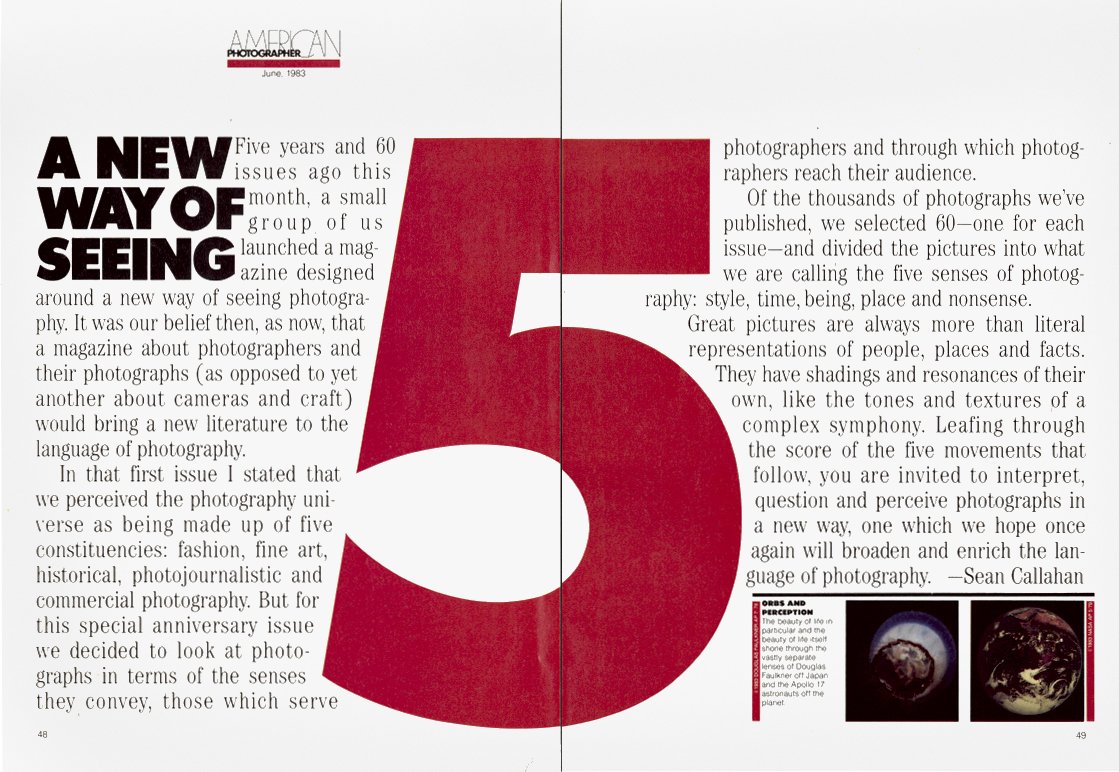

Mary K Baumann: And that little sheet was the 12-part-grid.

George Gendron: That was it. A little, tiny thing.

Will Hopkins: Yeah. Right. Yeah. I’ve got them around here. We can put one up on the screen if you want.

Mary K Baumann: Anyway. The beauty of the 12-part grid is that it provided a standard throughout the publication. And so you could have two columns at six units. You could have three columns at four units. And then you could mix it all up. And it was a way to build scale and contrast within the publication.

“One Sunday afternoon, I’m walking down the street in Chicago. I said to this friend of mine, ‘You know [what]? I’m gonna go to Germany.‘”

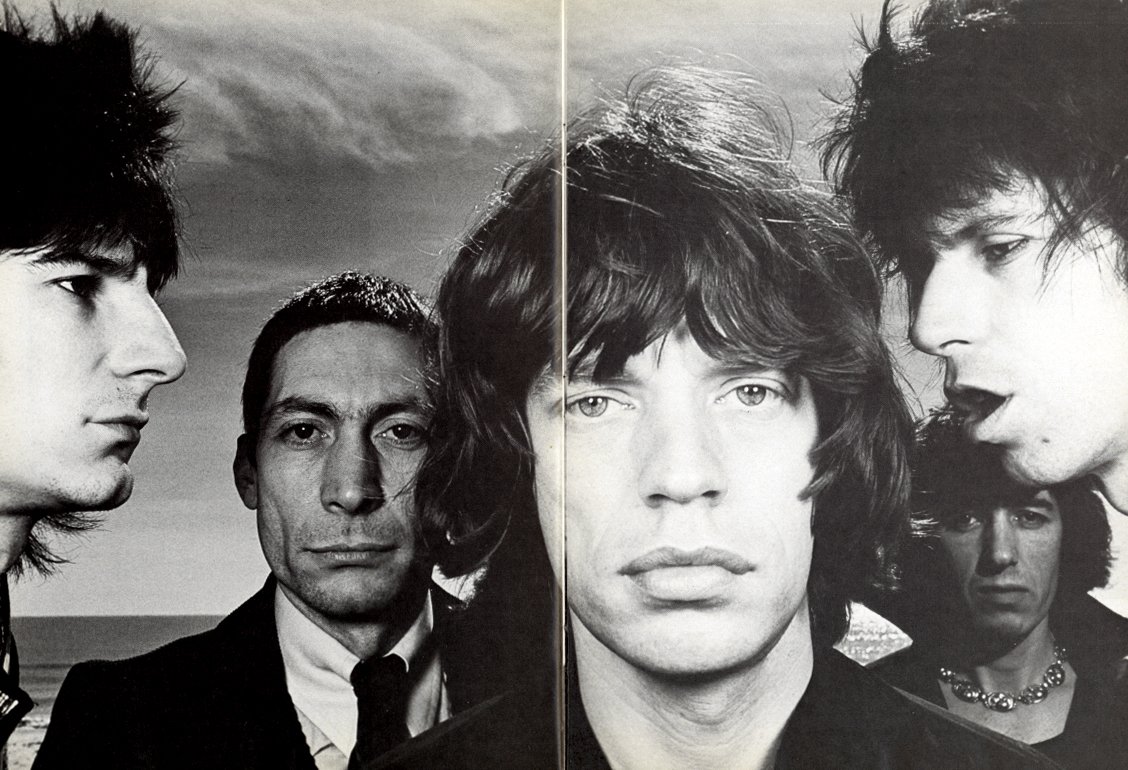

George Gendron: I was just about to say, when you look at pages, for example, from Twen in those days, it feels as if it were executed last month. You worked with these very large and very horizontal images that broke up the verticality of the grid that was just breathtaking.

Mary K Baumann: The other thing about that grid is because of those 12 parts, it was a way to build—well you would say white space, but it was really breathing room—within the publication so that you could focus on the content. It was a way to get your eye to focus more clearly on the content.

George Gendron: So that 12-part grid almost suggests a kind of Germanic engineering approach to design in a certain kind of way. And I’m curious whether people were enamored of that in the same way they became enamored in this country with the engineering of Mercedes and Audi and BMW. Has that ever occurred to you?

Will Hopkins: I’ve never bumped into people who had any idea about it. When I tell people or show people, when we deal with some publication that we work with and we sit down and we say, “Now this is how we put a page together.” We show these little pieces of, you know, sketches, little pages and we start talking about, you know, how you can look at this and how you can work with it.

Mary K Baumann: One of the things about the grid—you know, you started out with a blank page and it’s like you’re working in a vacuum. But the underlying grid was a way for you to easily organize content, pictures, words, and so on.

Will Hopkins: Mm-hmm. Yep.

Mary K Baumann: And that was a real key to it, is like you weren’t reinventing the wheel every day. And it was a way to create a certain consistency throughout the publication, so it looked like you were in the same place.

I’ll get back to Fleckhaus, but I met Will, he was a visiting lecturer at the University of Minnesota. Look had just folded and he walked in and I was like, “Oh, this is magic. He’s this art director from Look Magazine.” And this was in the journalism school, and he walks in with a three piece suit, pocket watch and a sheepskin coat thrown over his shoulder. He was like a celebrity walking into our classroom. Anyway, he showed us this 12-part grid, and we were producing a magazine and we just got it like that. It was just amazing and suddenly everything made sense.

Will Hopkins: At least for her. [Laughs]

Mary K Baumann: At least for me.

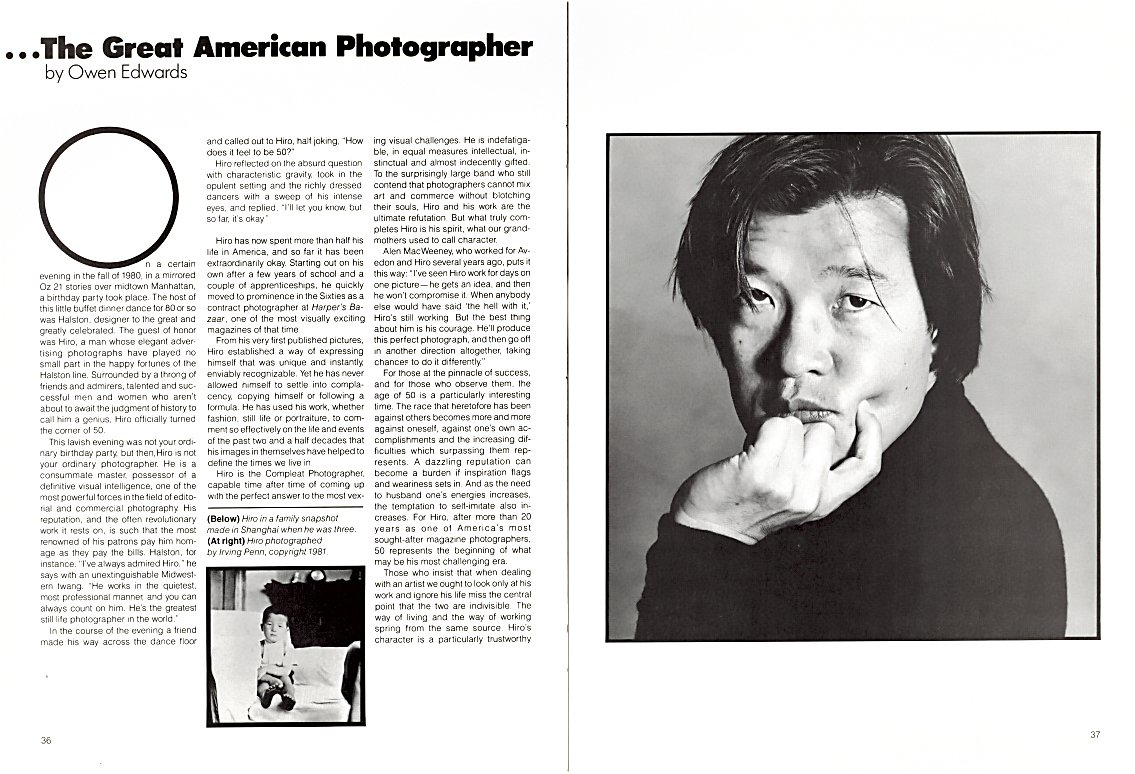

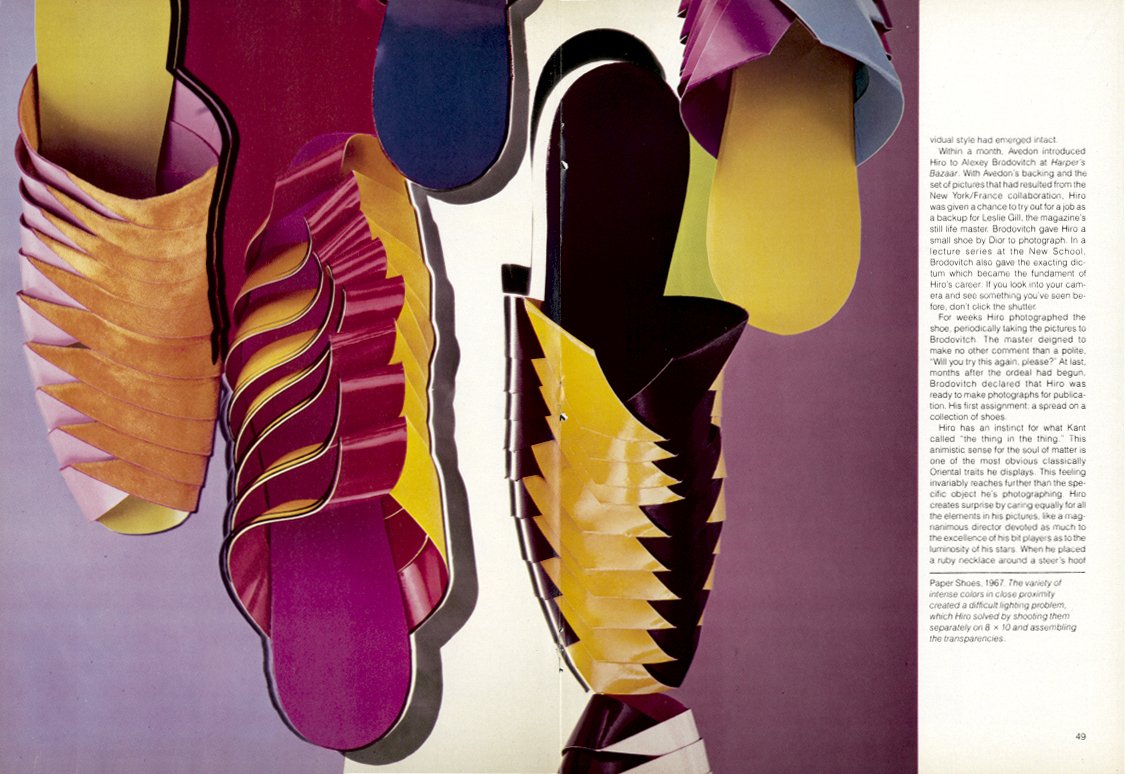

One of the things that Will has told me about working for Fleckhaus, that was truly amazing working there, because of the way Twen looked, it was a showcase for photographers.

So photographers from all over the world were walking into the Twen offices from the US, and England, and Italy, and all over. So he got this tremendous education in photography from some of the greatest photographers around. The other thing that was very interesting about his time, I think one of the reasons Fleckhaus liked him being there, is that he had—this was after World War II—he had an American under his thumb. He had his little American. So any visitor that came into the office, he would bring by and introduce him to Will...

Will Hopkins: ...or he would call me to come into the office or, you know, something like that, just so that he could—I remember once he had like about four East Germans in there—and he says, “Hopkins!” And they sort of shook, and I came in and he said he wants a Coke or something. I mean, he didn’t have anything for me to do, he just wanted them to see me.

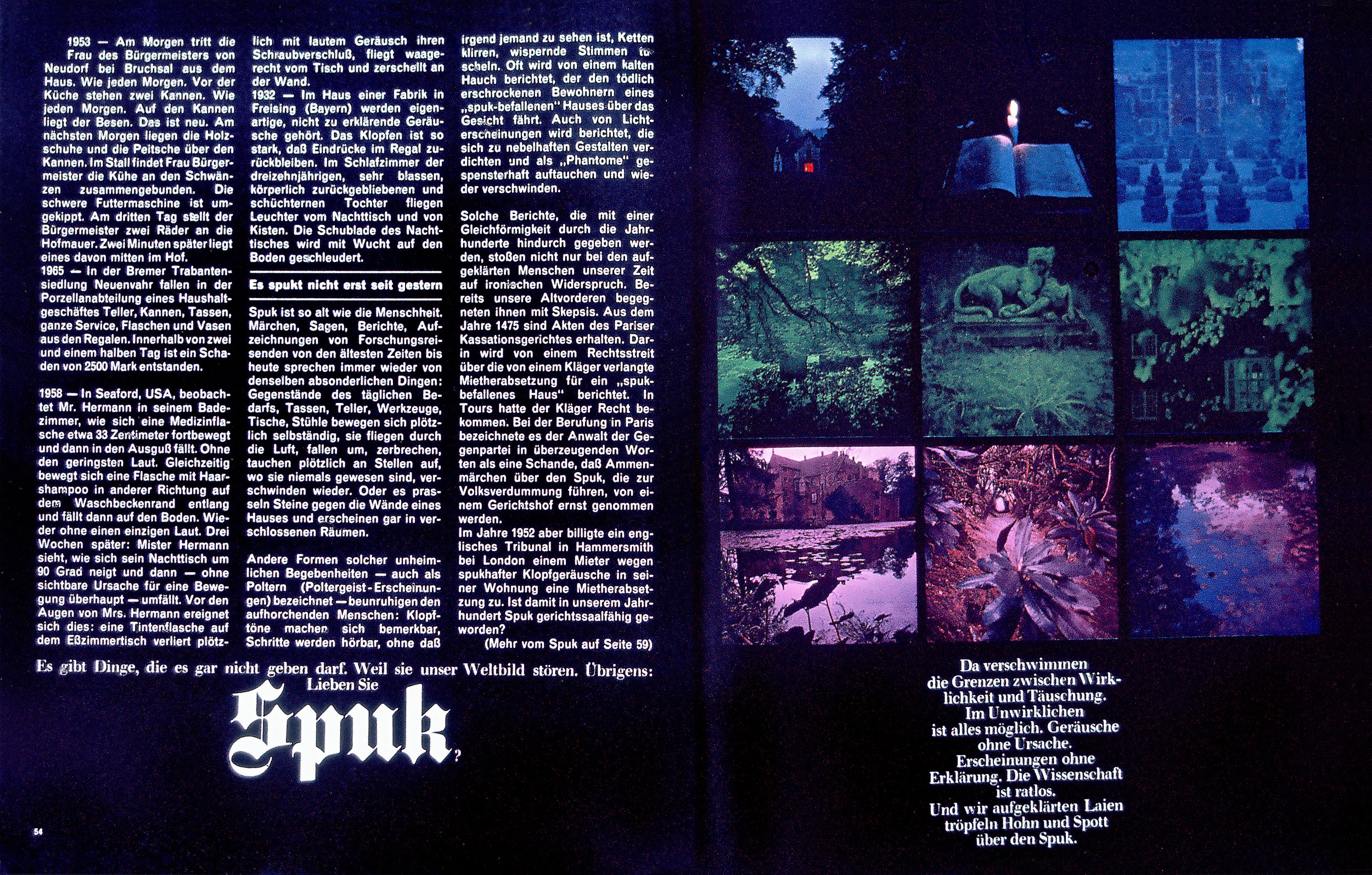

The 12-Part Grid, developed by Willy Fleckhaus in Germany, and imported to the US by Hopkins.

George Gendron: Were you establishing his democratic cred?

Will Hopkins: Well, yeah. It was just that he had “an American,” you know. And you look at these guys from the other side, they didn’t know what to do. They were astonished that an American was there working for him. They were astonished that there would be an American in that office.

George Gendron: Did they list you on the masthead as, “The American: Will Hopkins”?

Will Hopkins: They didn’t list me on anything.

George Gendron: But, you do manage to leverage the work that you had done there and you come back and you’re now on the staff. You’re an art director at Look Magazine, right? It’s 1967.

Will Hopkins: Yep.

George Gendron: Were they using the 12-part grid there or did you eventually use it?

Will Hopkins: No, no. I did.

George Gendron: So you used it when you became the art director?

Will Hopkins: I came there and I started doing layouts, and I just used the grid. And I got Neil Shakery, and Don Mennel, and Renee Schumacher. And they grabbed onto it when they came to work there, and I said, “This is how I do this.” And they said, “You got it.” They got it. Just like that. The other people who had been working there before never paid a lot of attention to it and didn’t know how to use it.

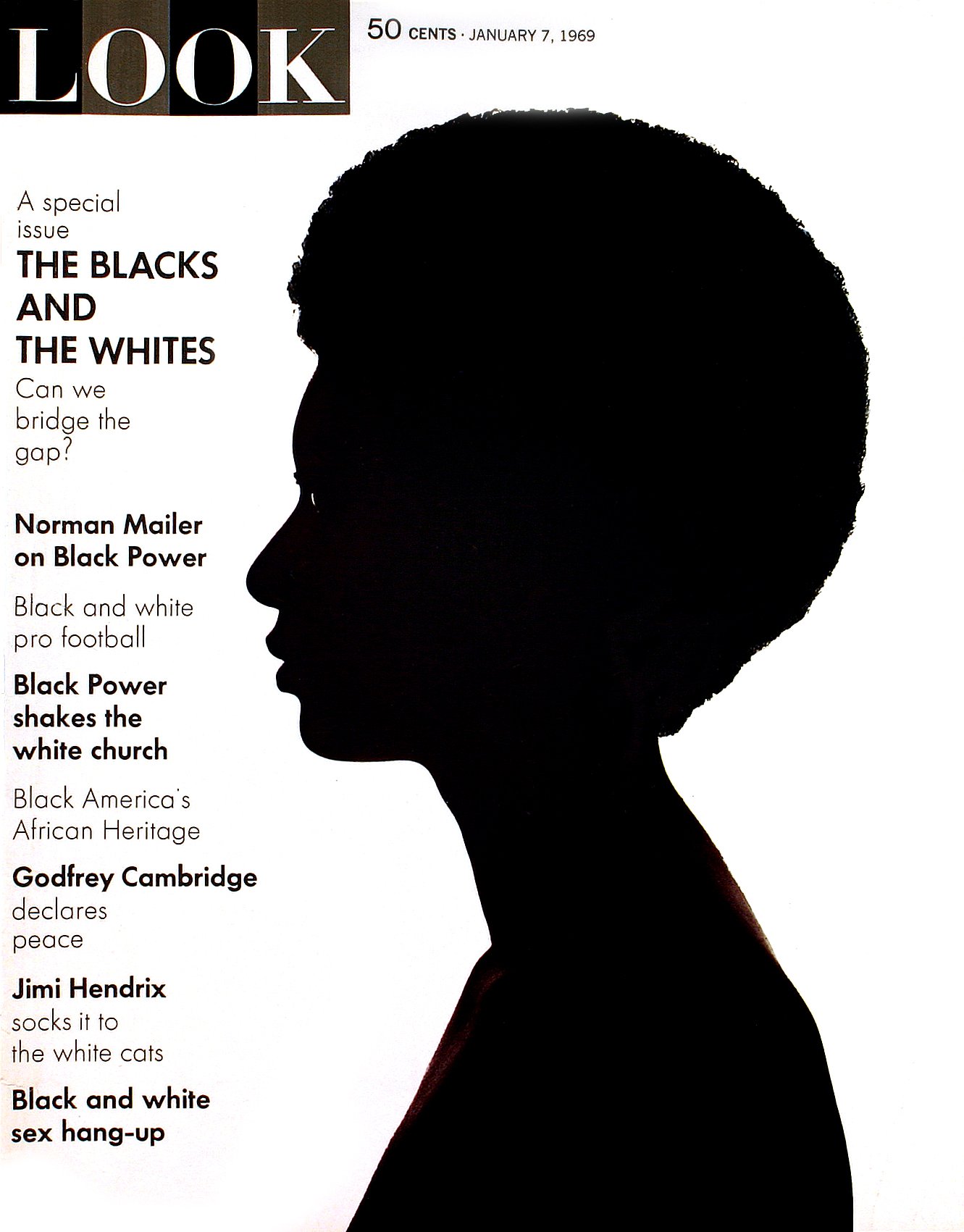

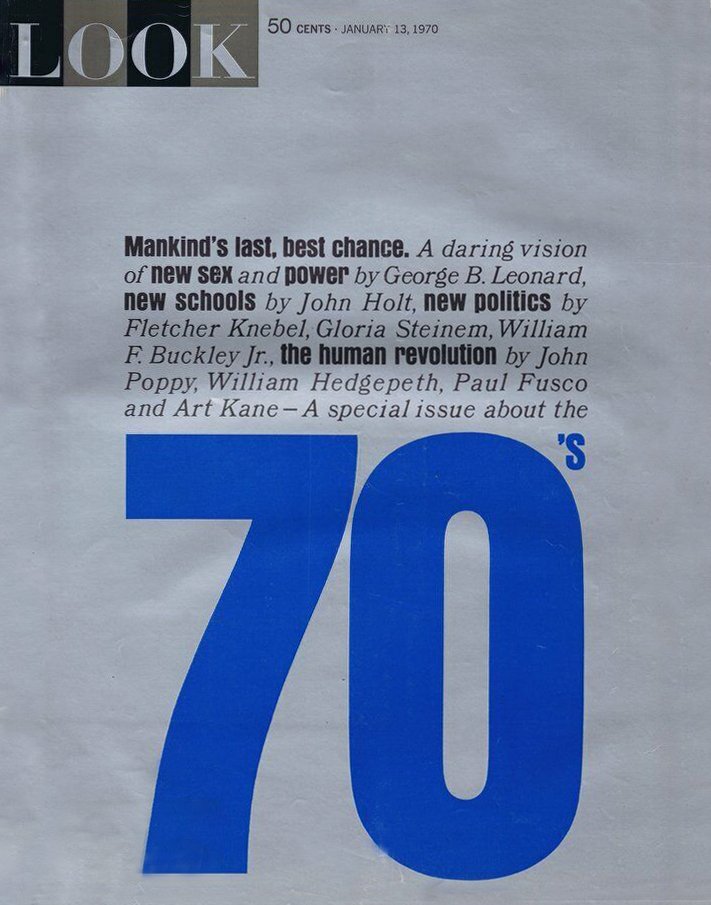

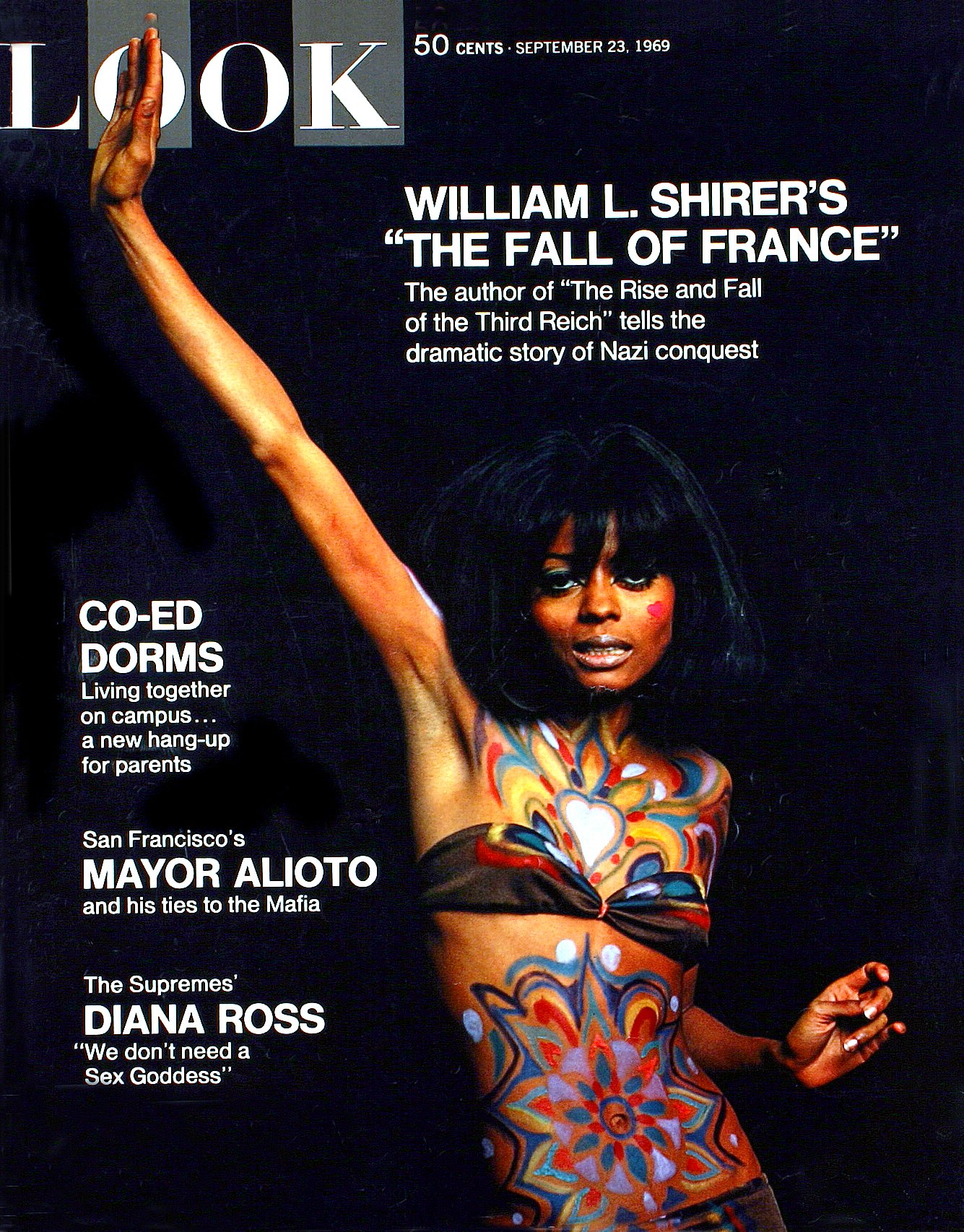

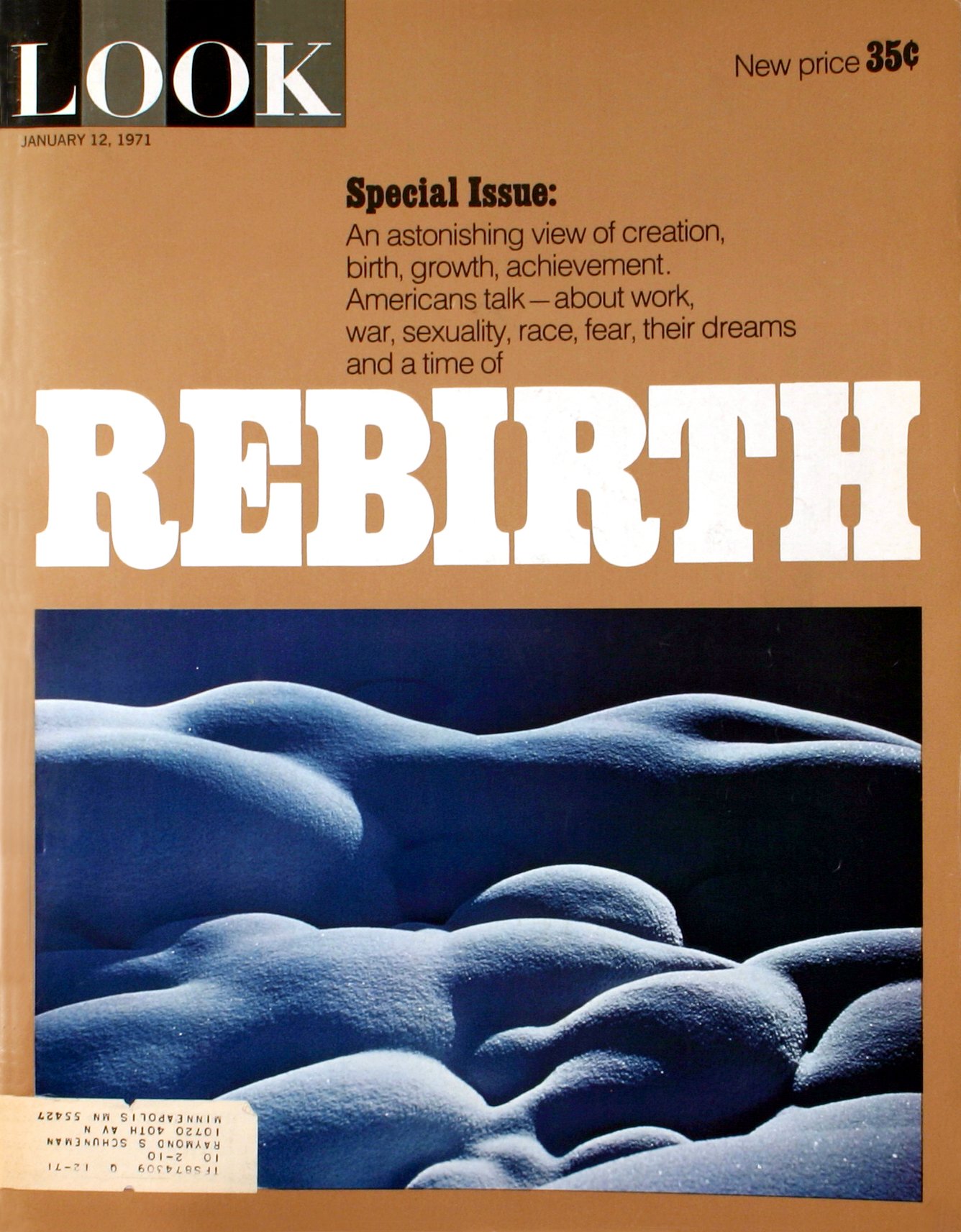

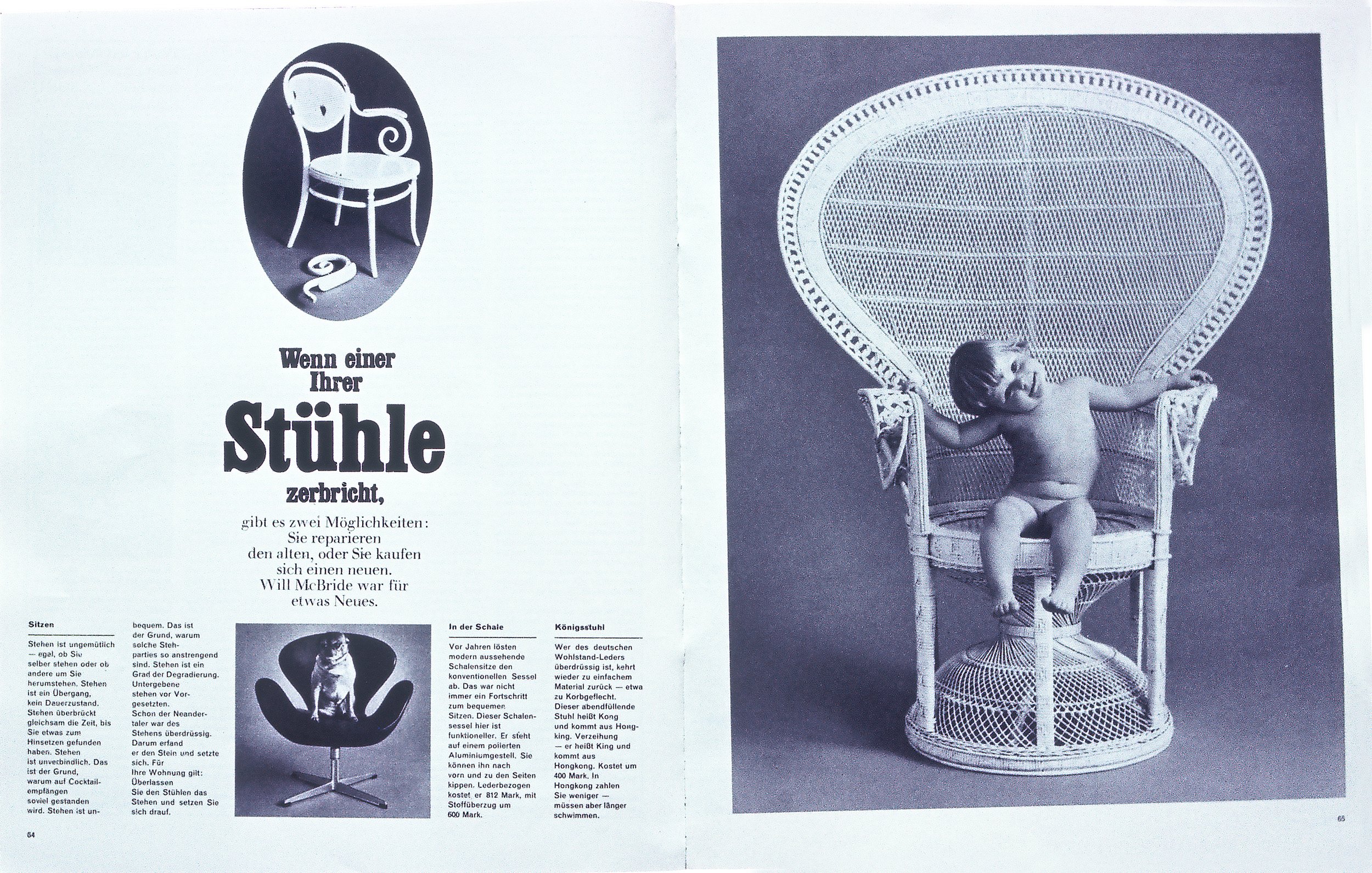

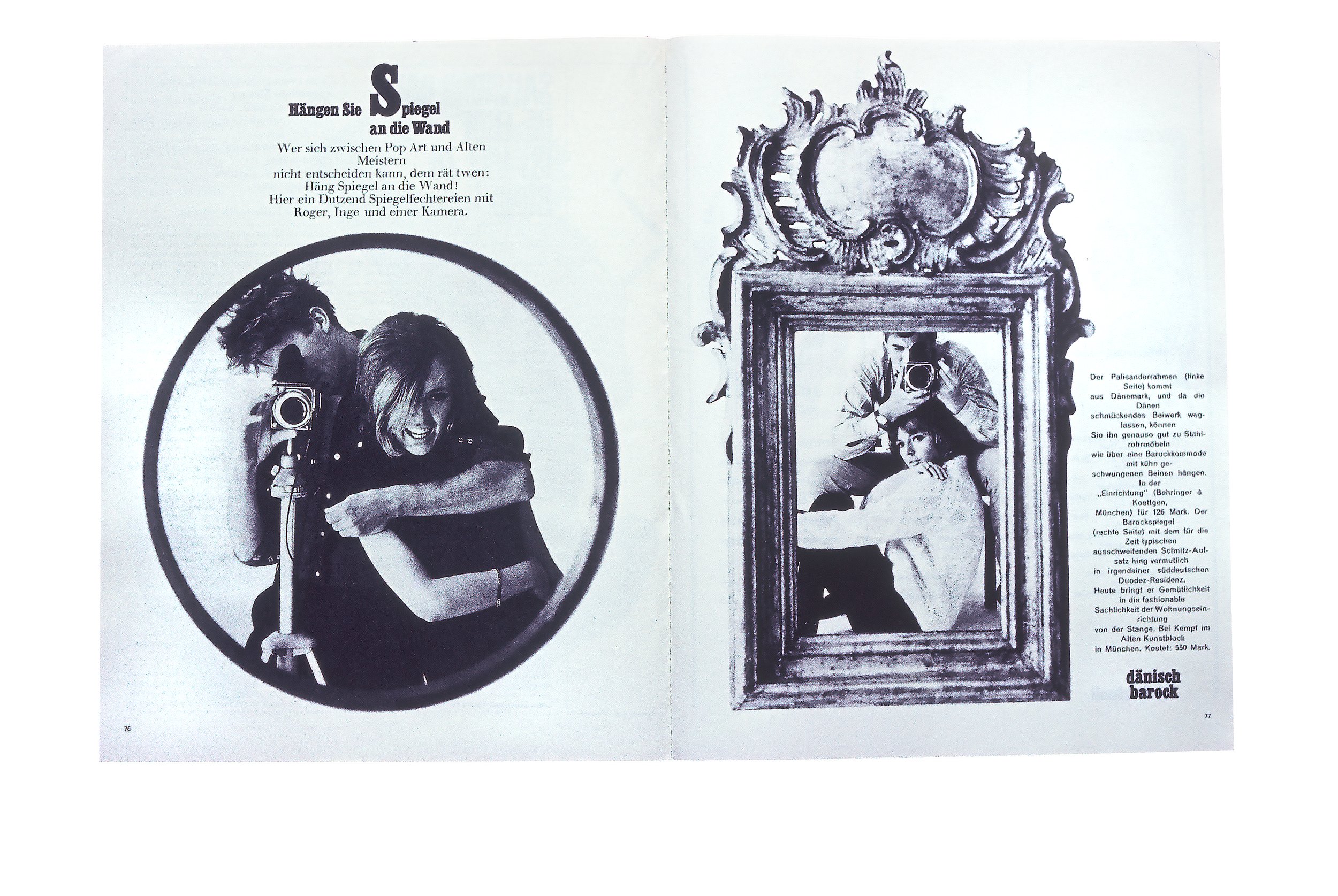

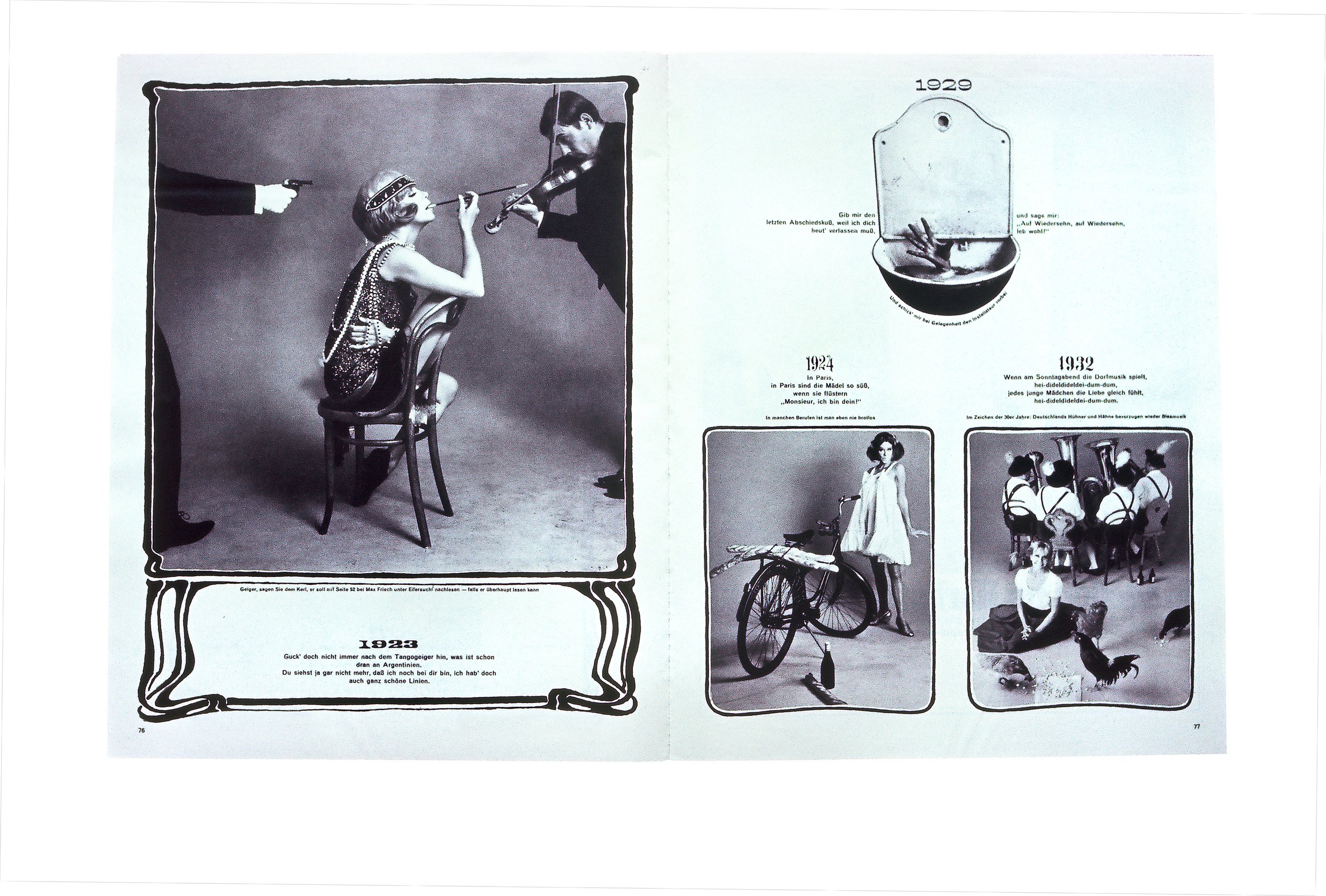

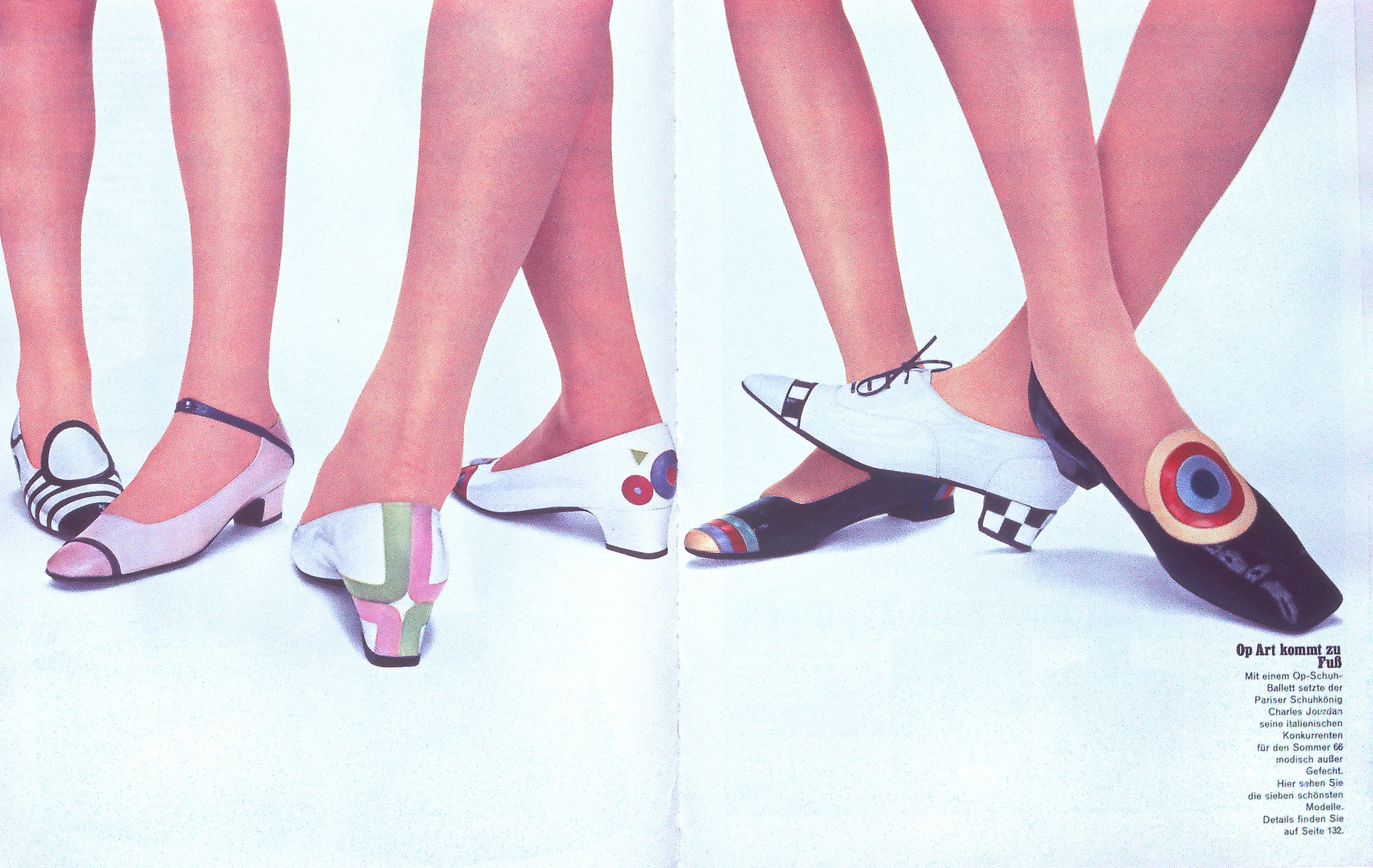

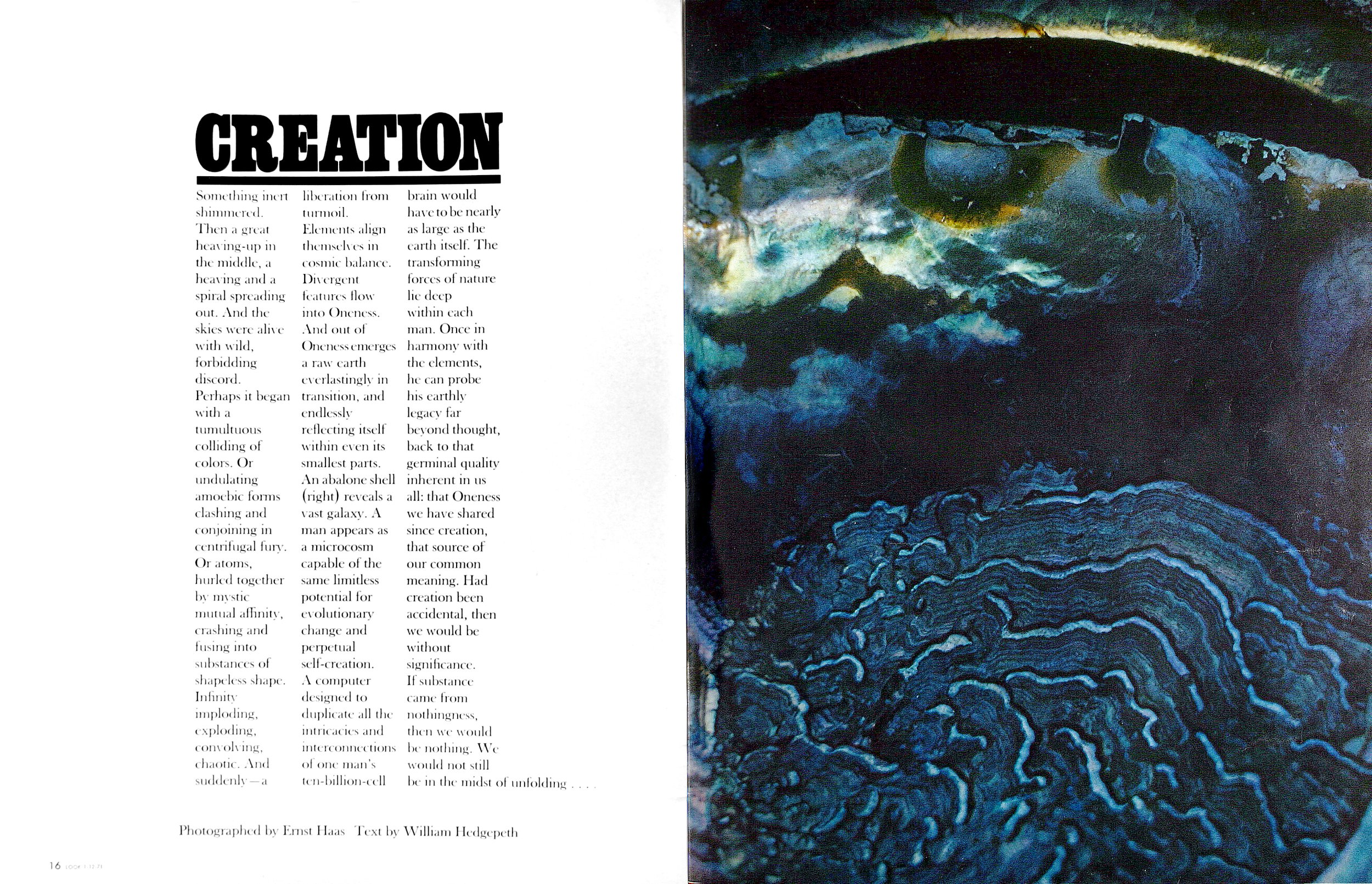

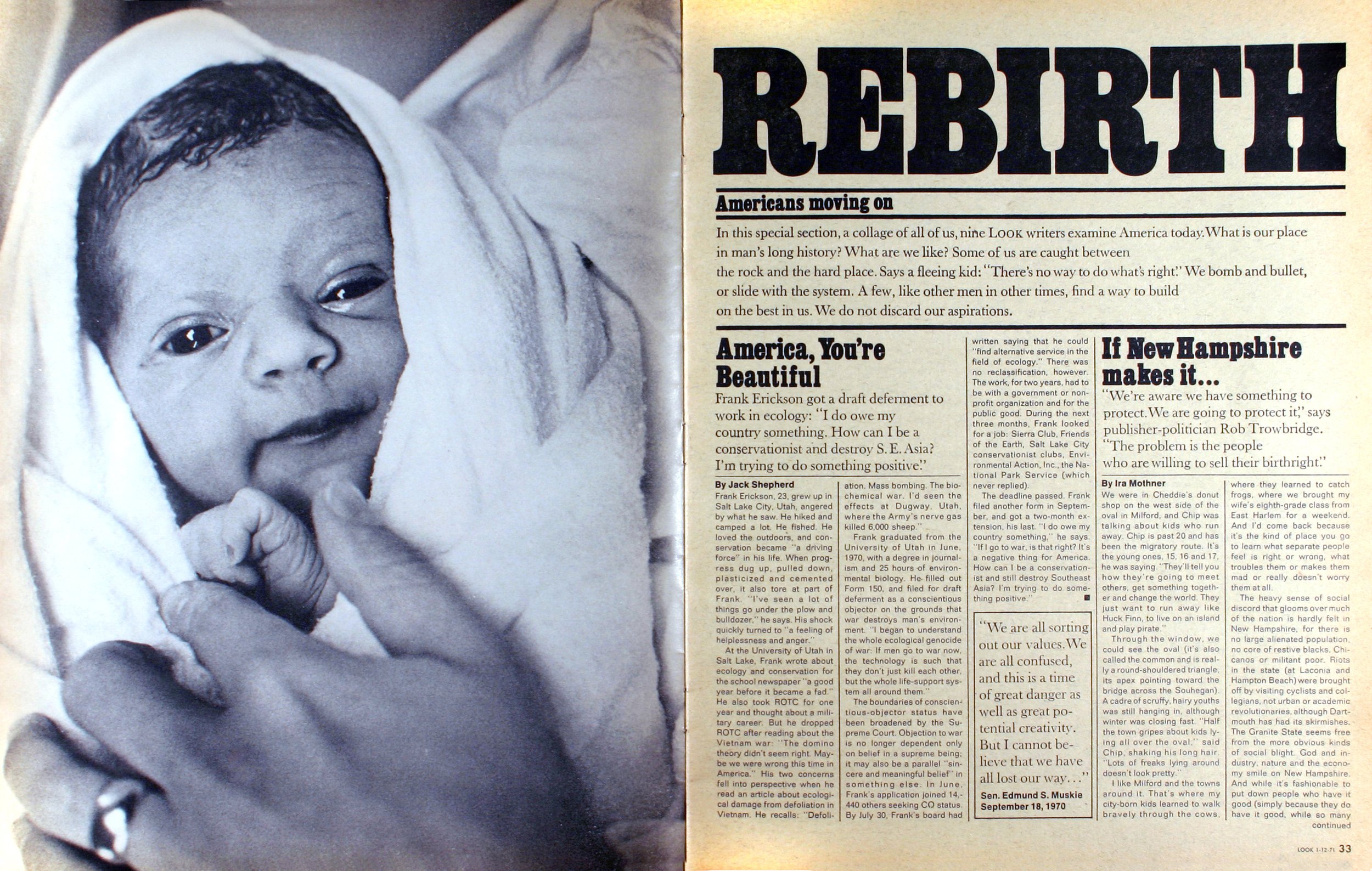

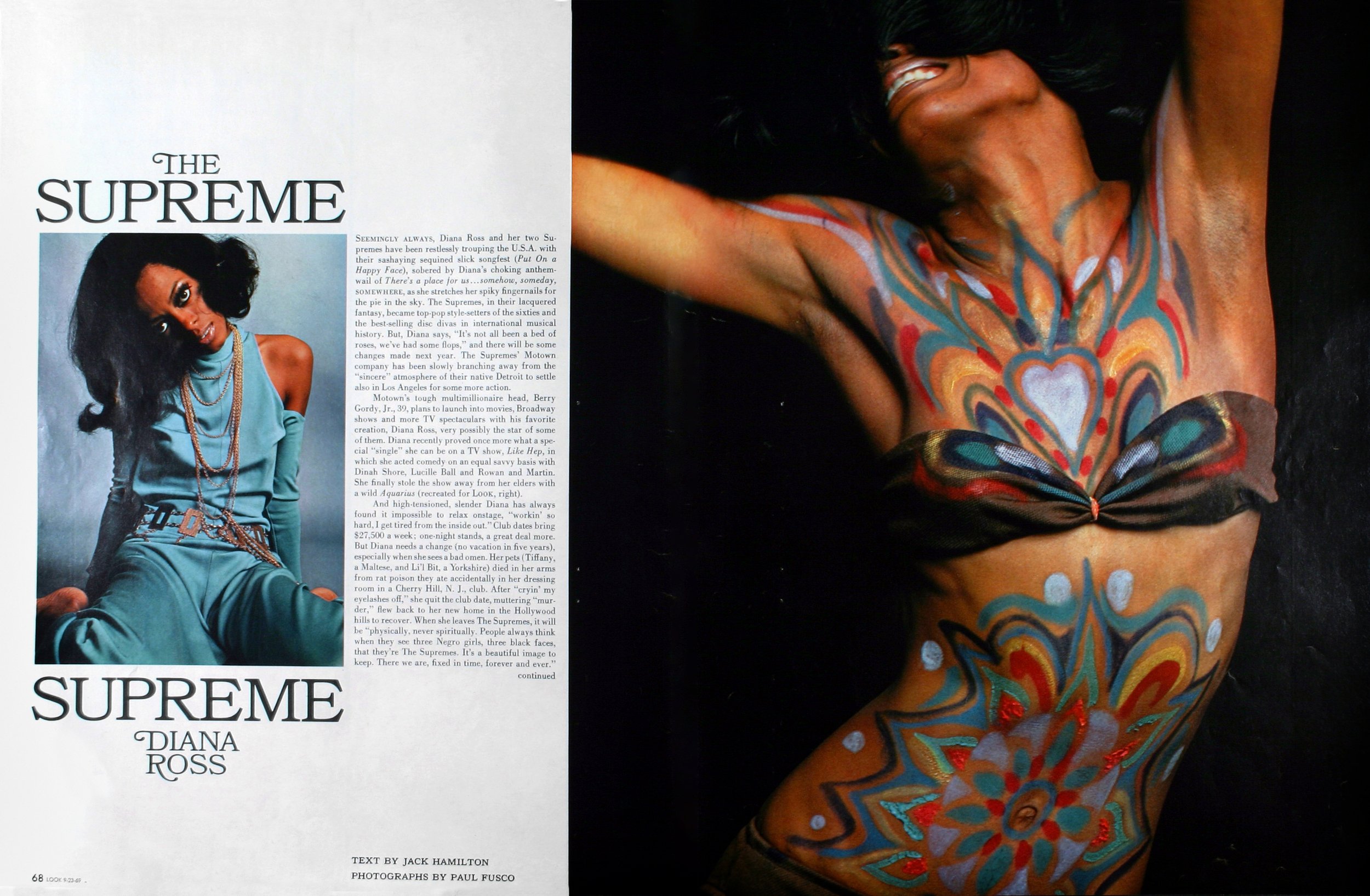

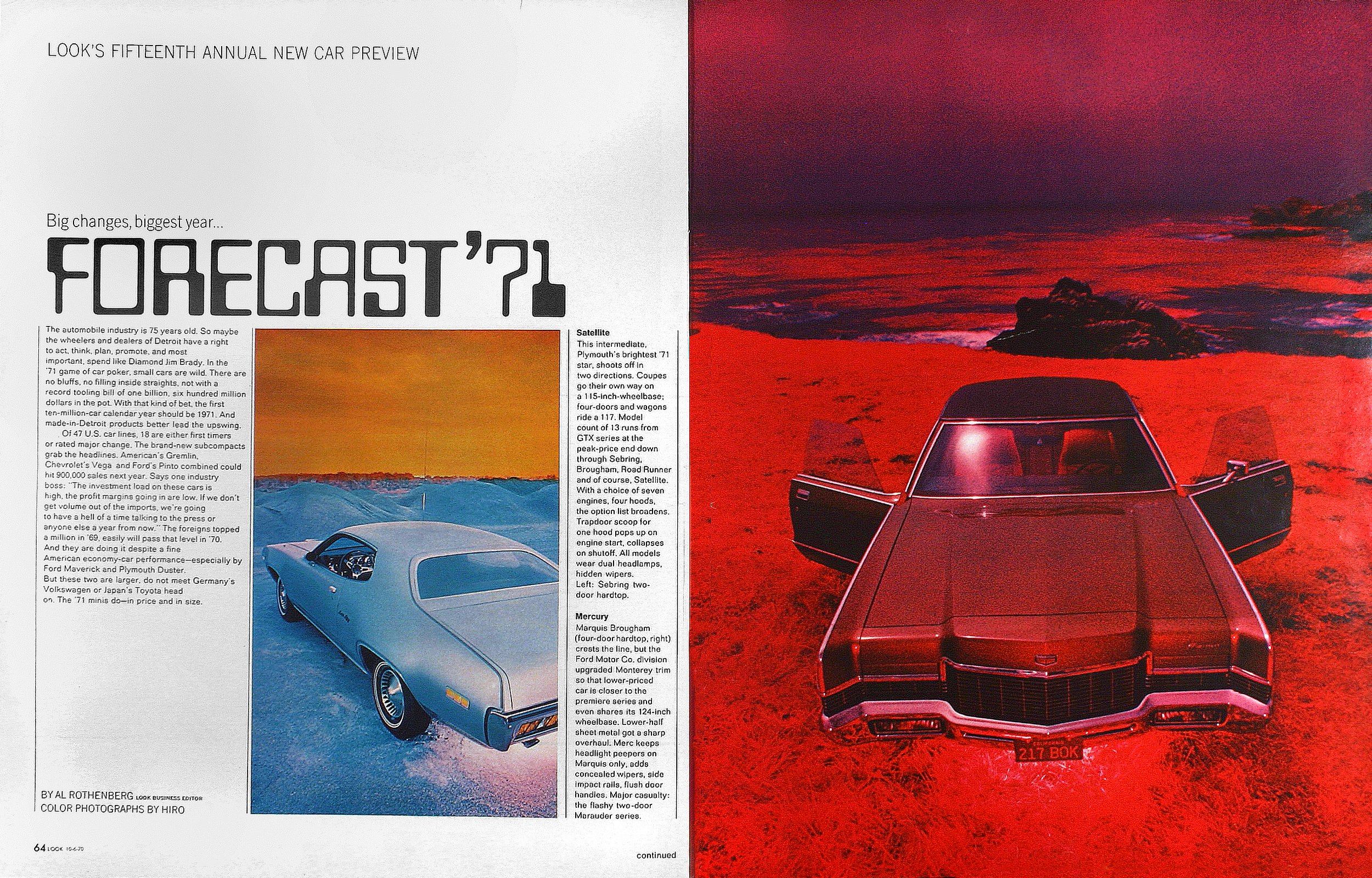

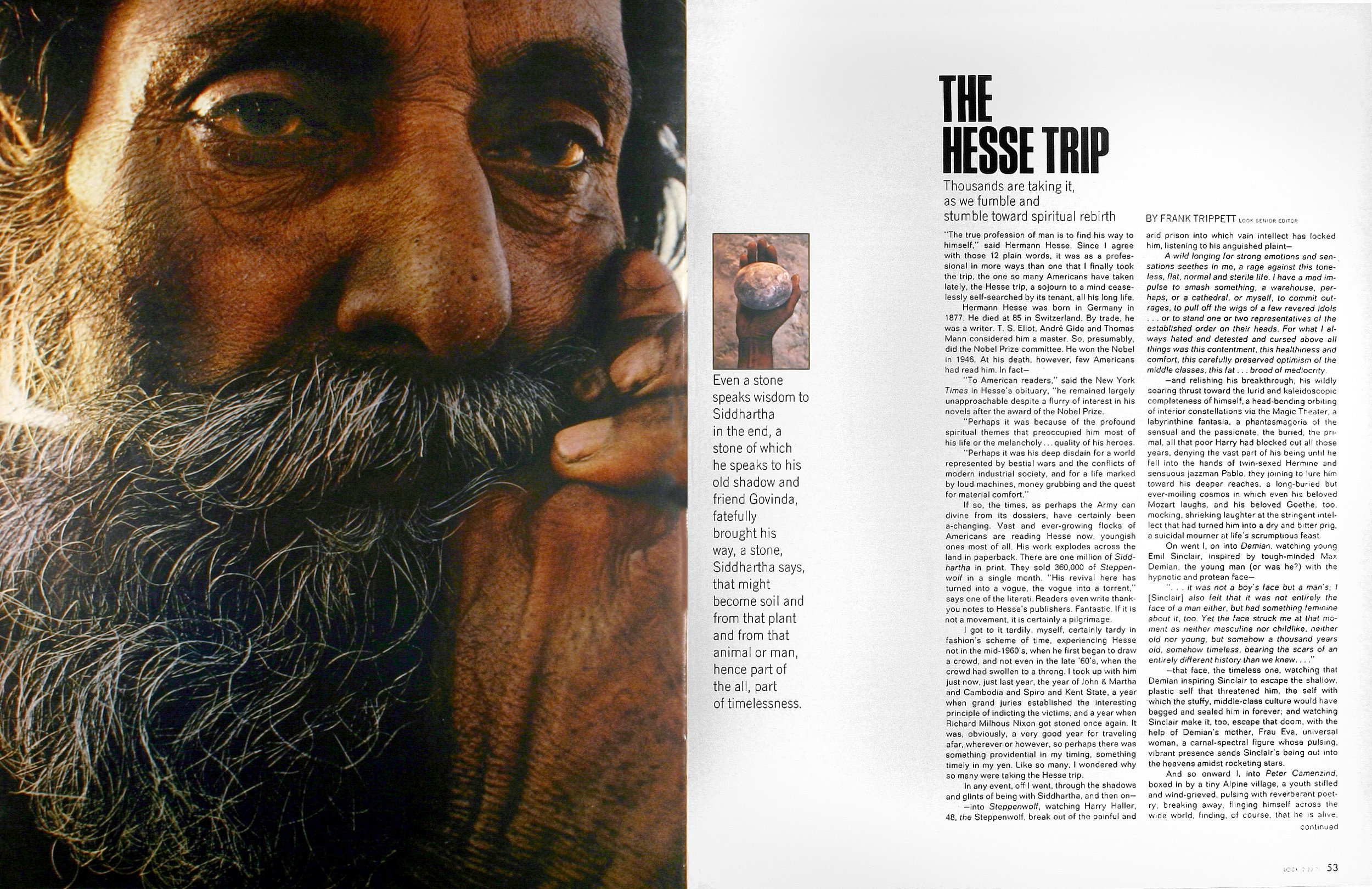

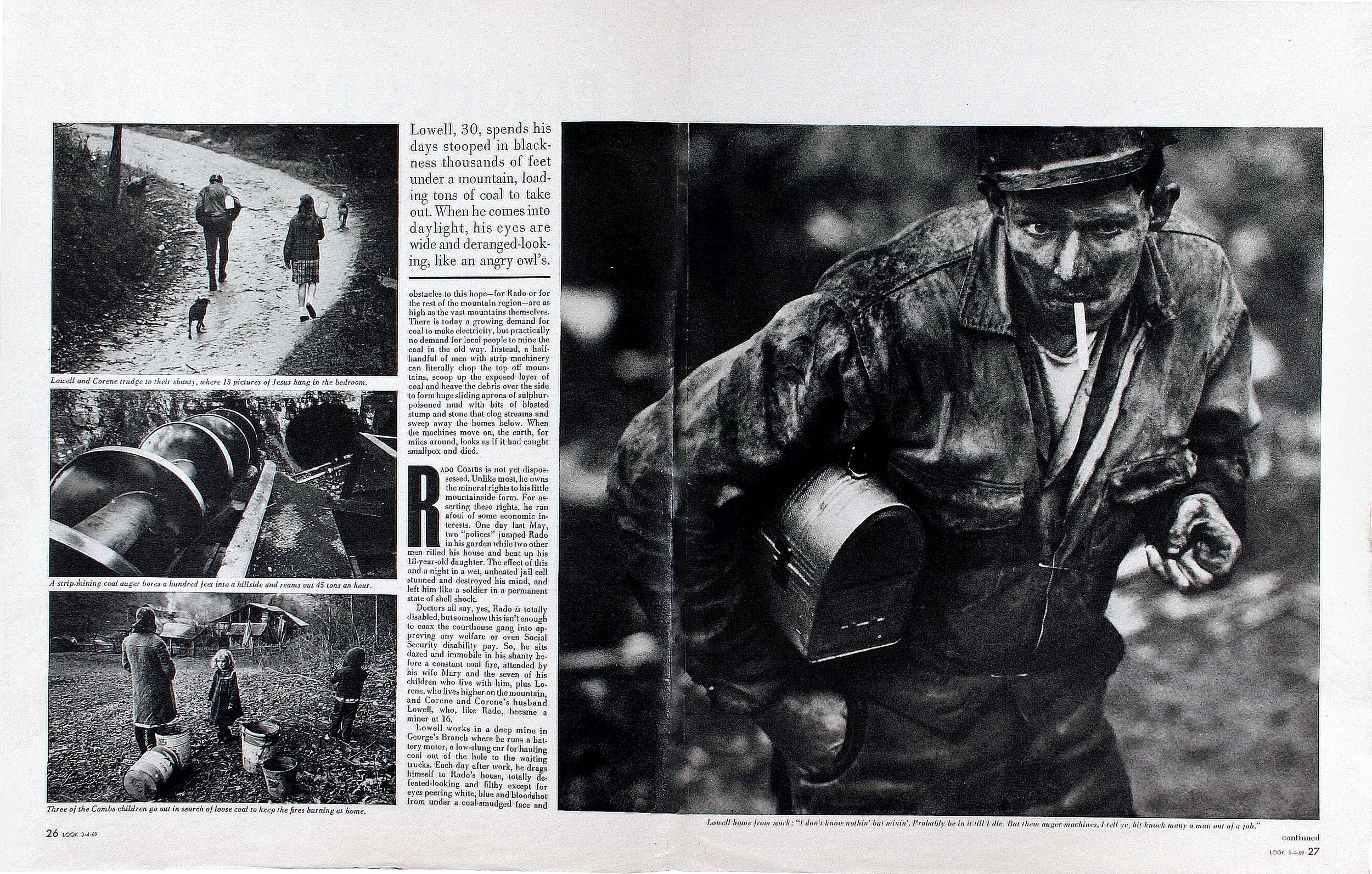

Look Magazine, New York, 1967–1971

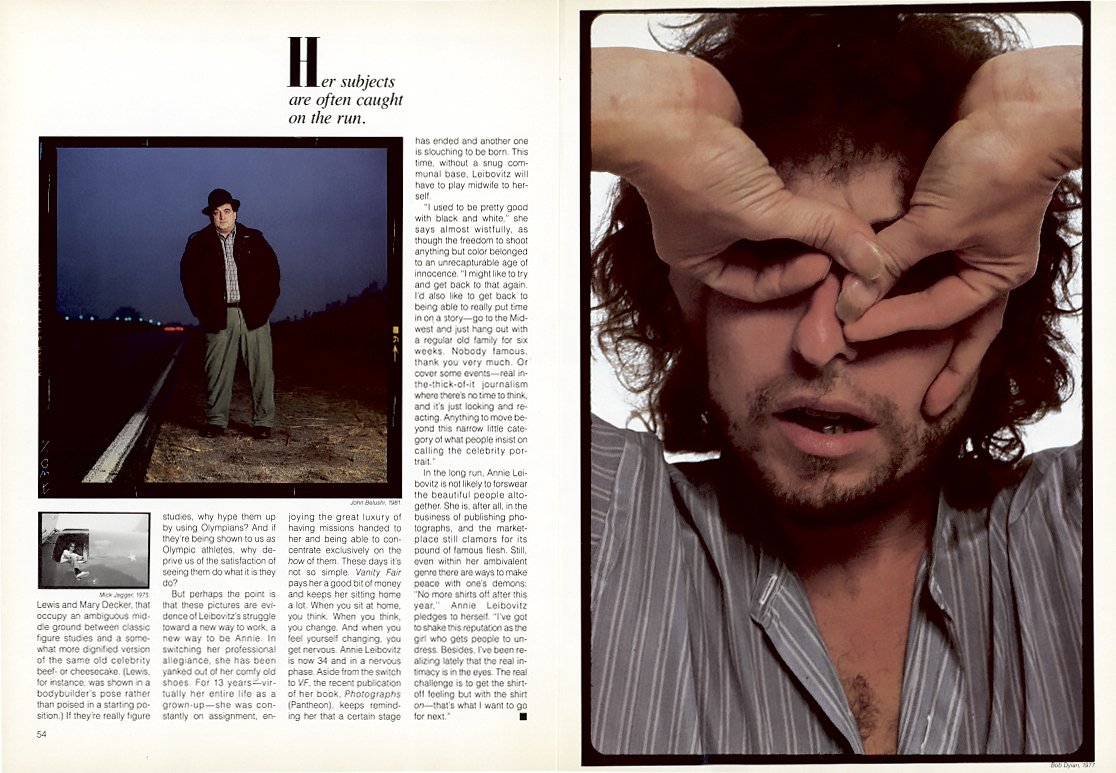

George Gendron: So this is ’67 is during the heyday of Look and Life magazines.

Will Hopkins: Mm-hmm. Yeah.

George Gendron: And I’m curious because Life was probably twice your size in terms of circulation, I want to guess. It was larger. And I’m really curious, how do you guys...

Will Hopkins: I don’t know if it was that.

Mary K Baumann: Look was biweekly and Life was weekly, but I, that wouldn’t affect the circulation. Life was definitely bigger than Look.

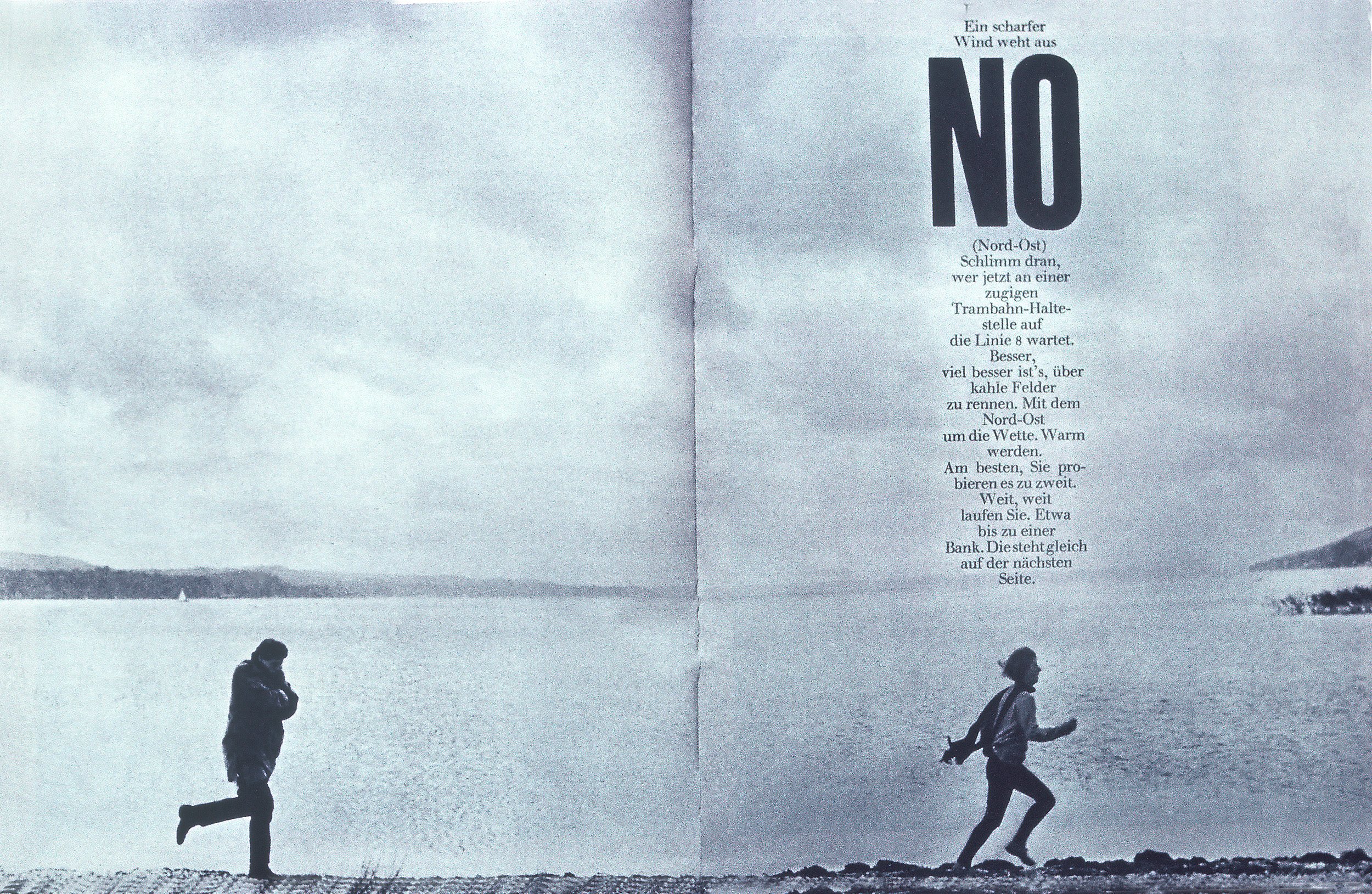

George Gendron: I guess my question is how did you and your colleagues at Look think about, if you did at all, differentiating yourself from Life Magazine across town?

Will Hopkins: I don’t think we really paid a lot of attention to it.

Mary K Baumann: After Will was at Look, I was at Life Magazine. And having been around those guys at Life, they thought of themselves much more as a news magazine. Not the monthly Life, but the weekly Life. They considered themselves the news and pictures. Whereas Look was a little more trend-oriented.

George Gendron: And a little more feature-oriented I would think.

Mary K Baumann: They both did features, but Look was definitely more feature-oriented, more trend-oriented.

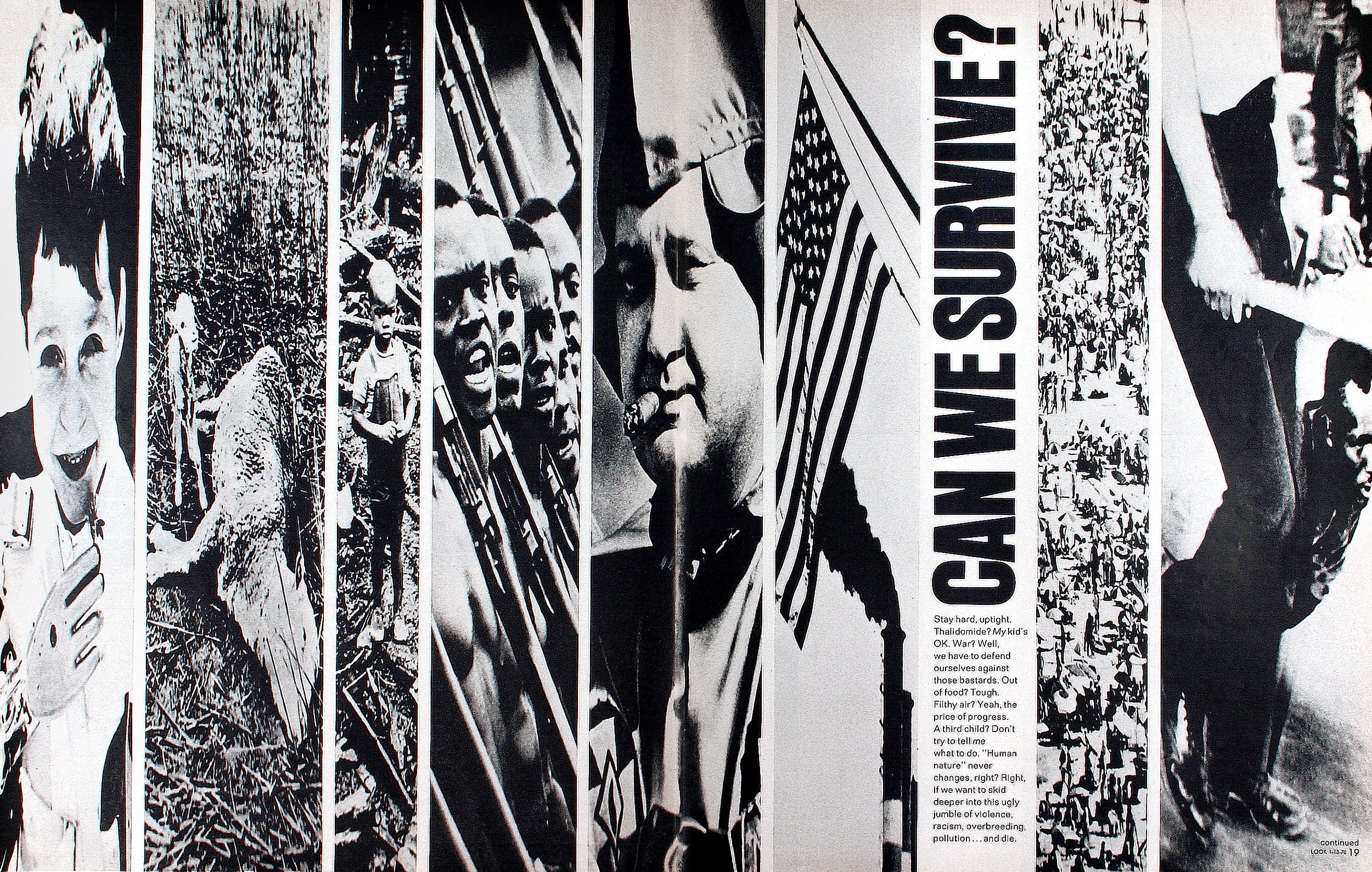

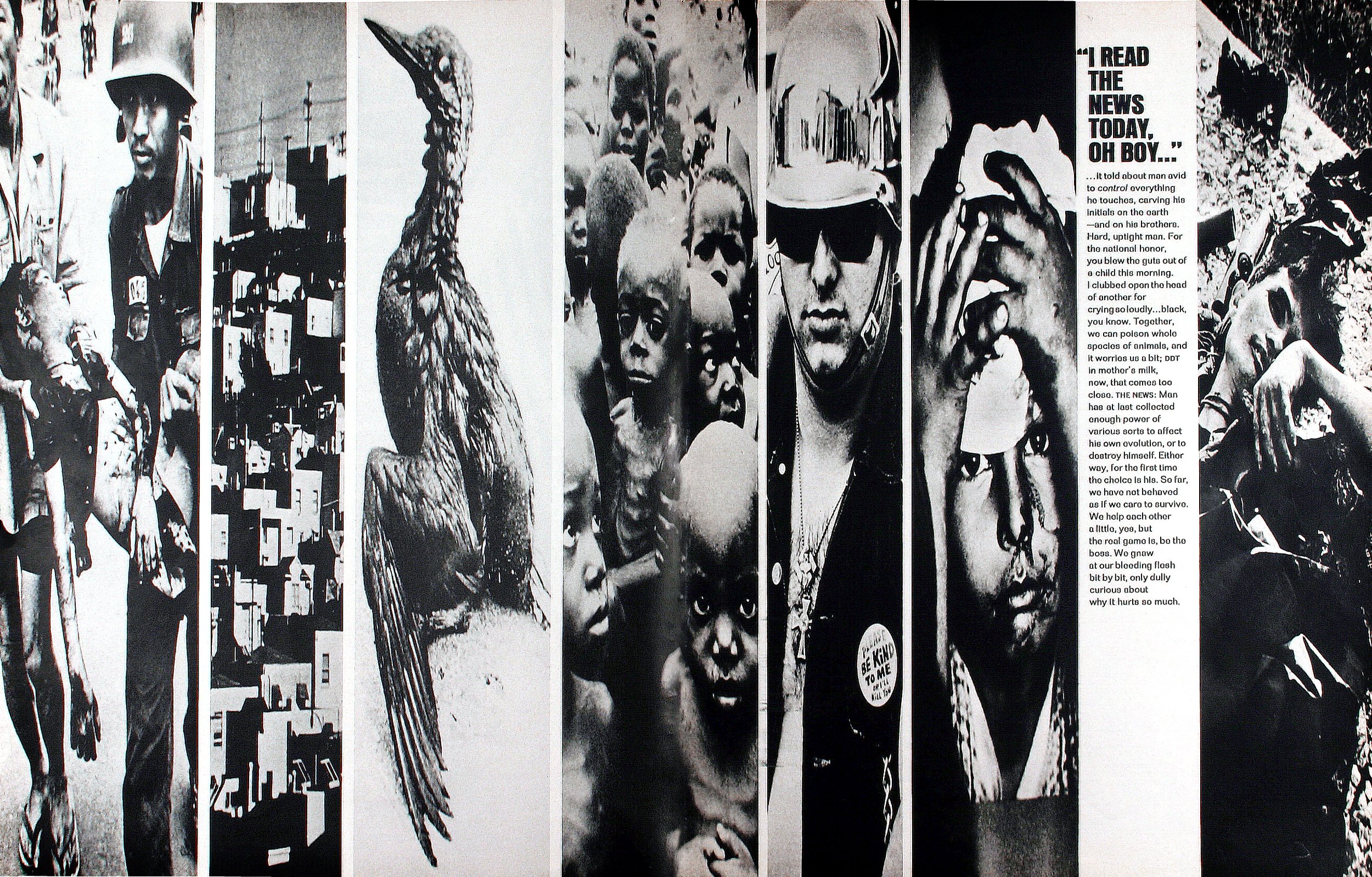

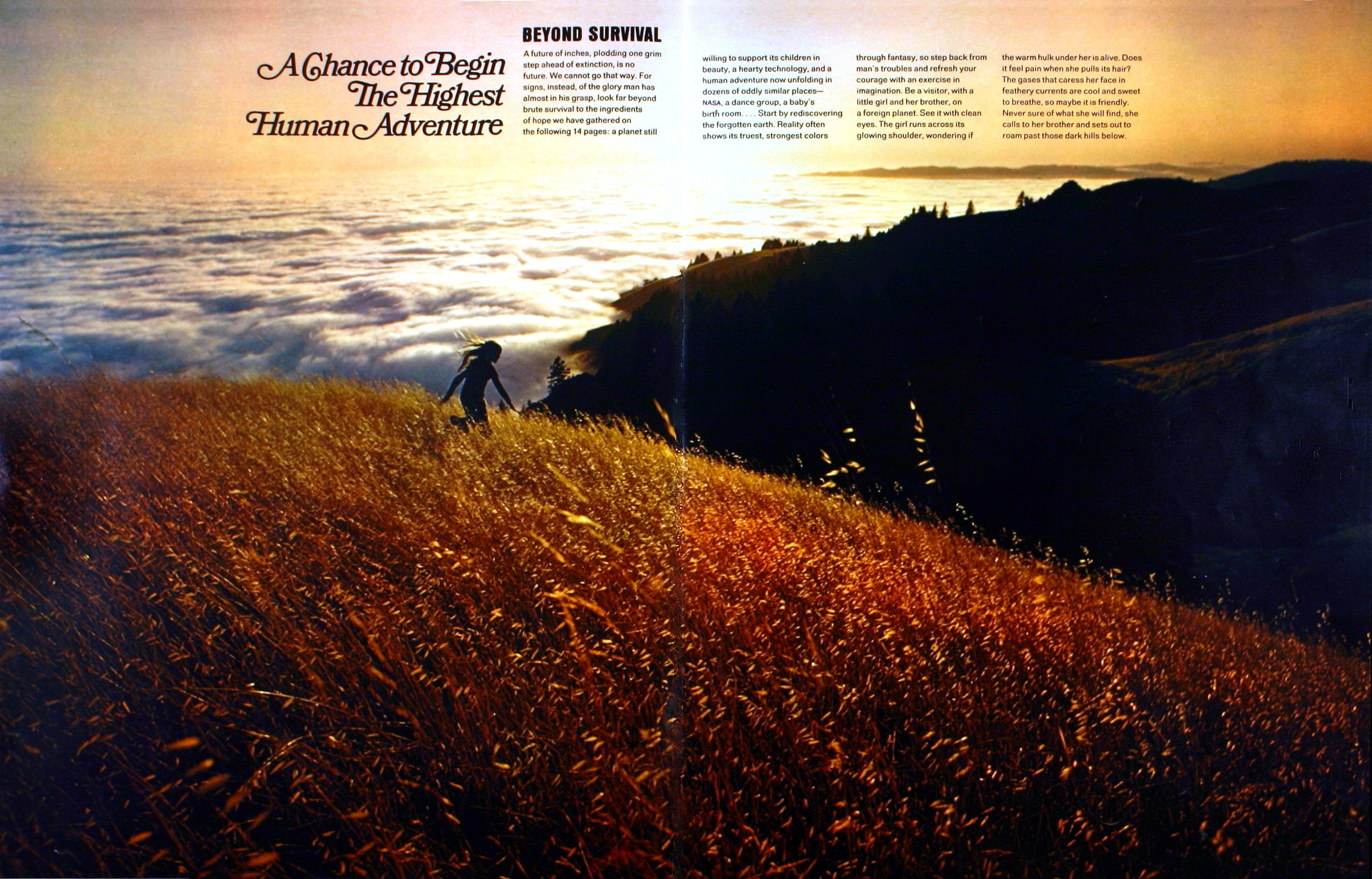

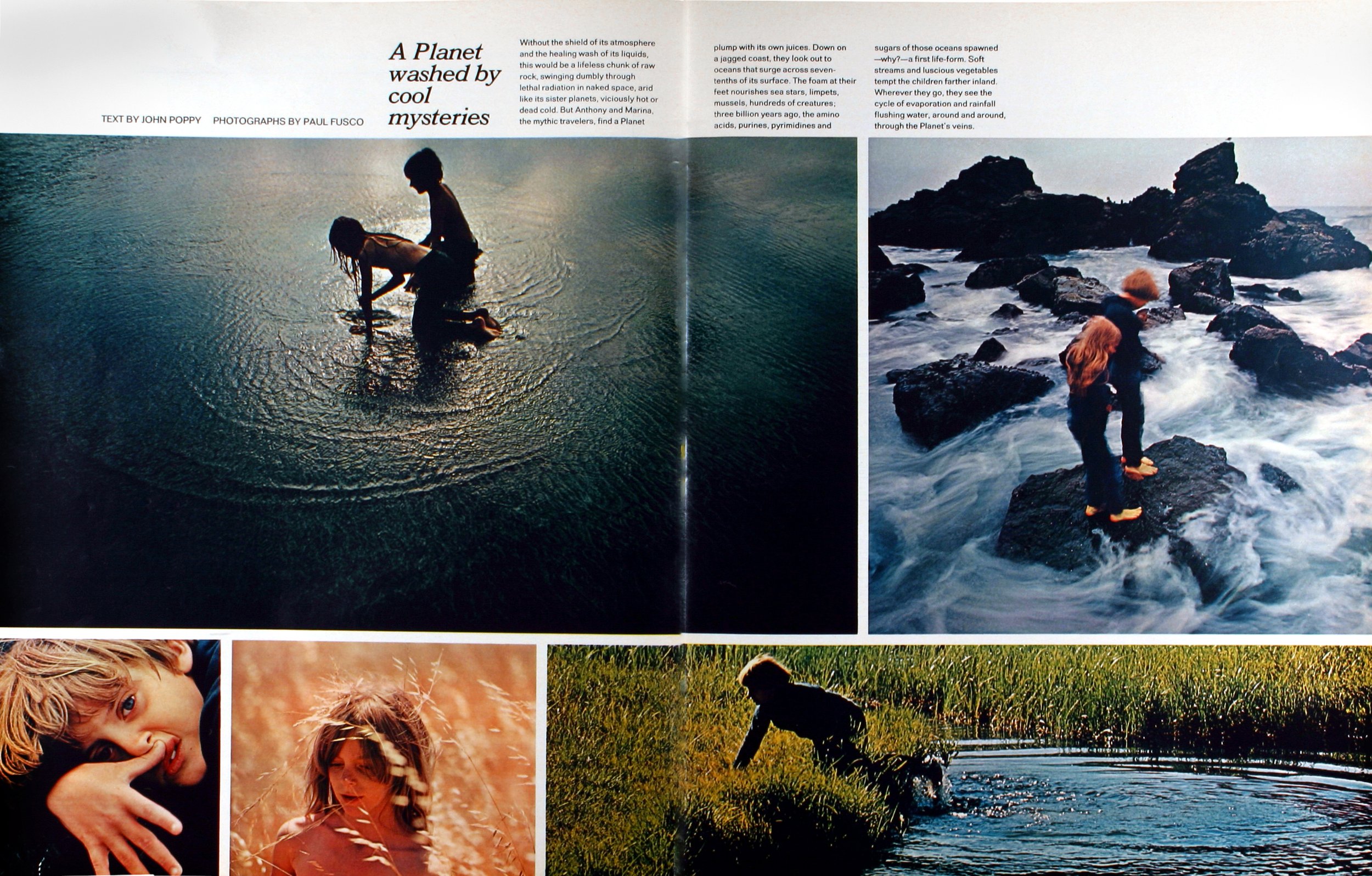

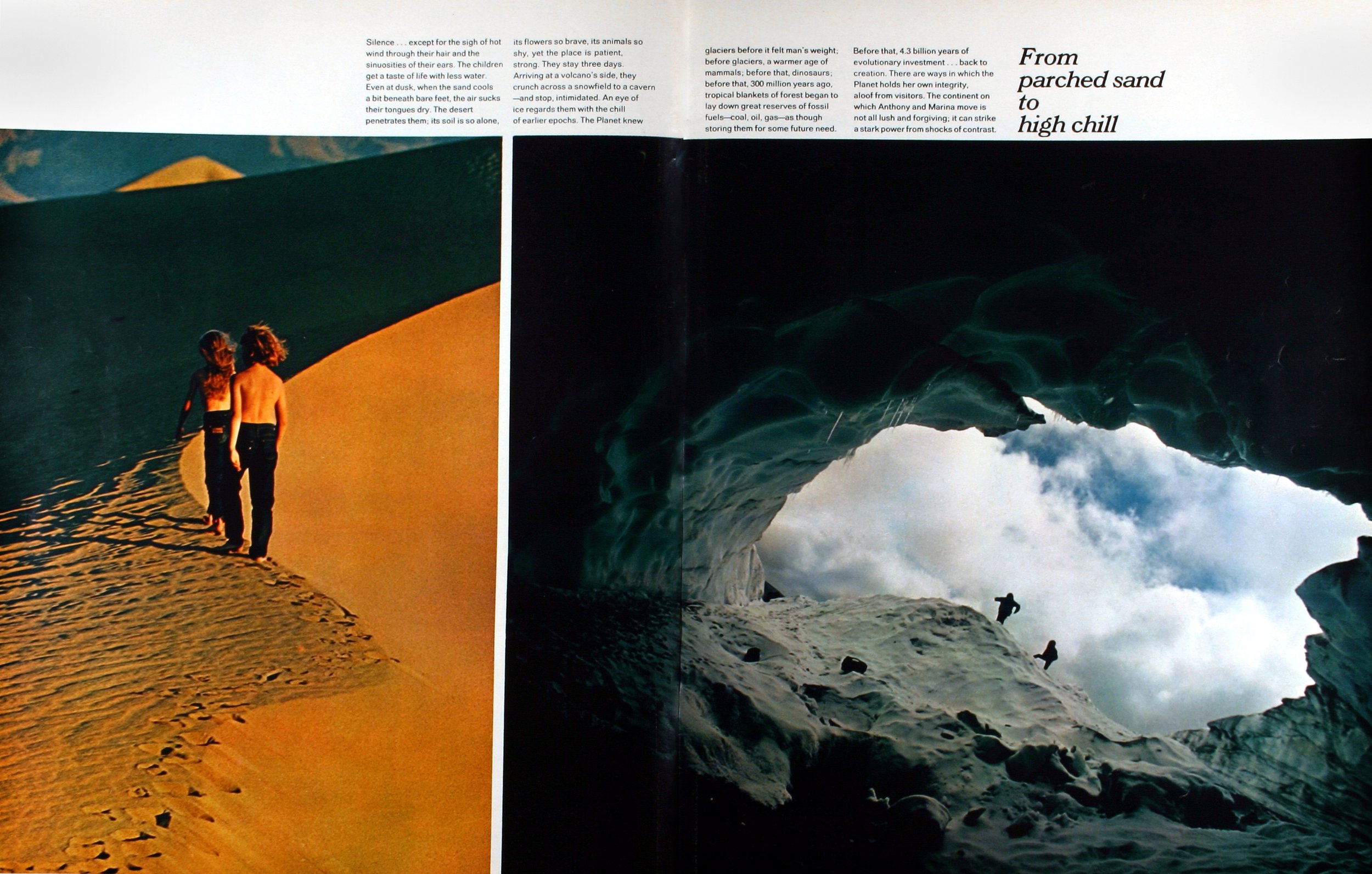

George Gendron: I can’t help but think back to a special issue that you guys did in, it must have been January of 1970, and the issue was “The ’70s” and you were looking forward…

Will Hopkins: Yeah.

George Gendron: …to the decade. And you did a piece that, to this day, I think is stunning. And I forget what you called it, but it was really the first major piece that I can think of about climate change.

Will Hopkins: Mm-hmm.

Look Magazine, Interior Pages

George Gendron: And now, keep in mind, this is, like, two years before the Club of Rome had even published their “The Limits to Growth,” which put climate change and sustainability on the map. So you guys were way ahead of the curve, but, not only that, you decided not to publish the clichéd photos of environmental degradation. You want to talk about the art direction on that particular story? I think Paul Fusco did the photography?

Will Hopkins: Right. Yeah. He did most of the photos. George Leonard was the editor on that issue. And, he would come to New York and he would set up his office in this hotel room about a block from the office.

George Gendron: Okay, I’m liking this guy already.

Will Hopkins: And then we would go there and on things like that issue, we would get down—I mean, uh, I worked hand-in-glove with Fusco—and we were laying out all these pages and we were doing them on these little grid sheets. And then I would put them in my pocket and go back to the office and then start handing them out.

George Gendron: Someday I really gotta see what you have in terms of memorabilia for these so-called “little grid sheets.”

Mary K Baumann: One of the things that I think was key about both Twen and Look, was Willy Fleckhaus was an extremely strong art director and almost acted as the editor. At Look, Alan Hurlburt was equally as strong. And he was the art director who hired Will. And so he had these two great, strong art directors who were extremely editorially involved in the magazine. They weren’t just doing pretty pages. And I think they were very important for his career as mentors.

George Gendron: And you started a trend that continued through the decades during the heyday of magazines, which I came to really resent. And that was that you art directors ruled the goddamn place. You were, you were art directors editors in chief!

Will Hopkins: Well, I don’t think it was quite that.

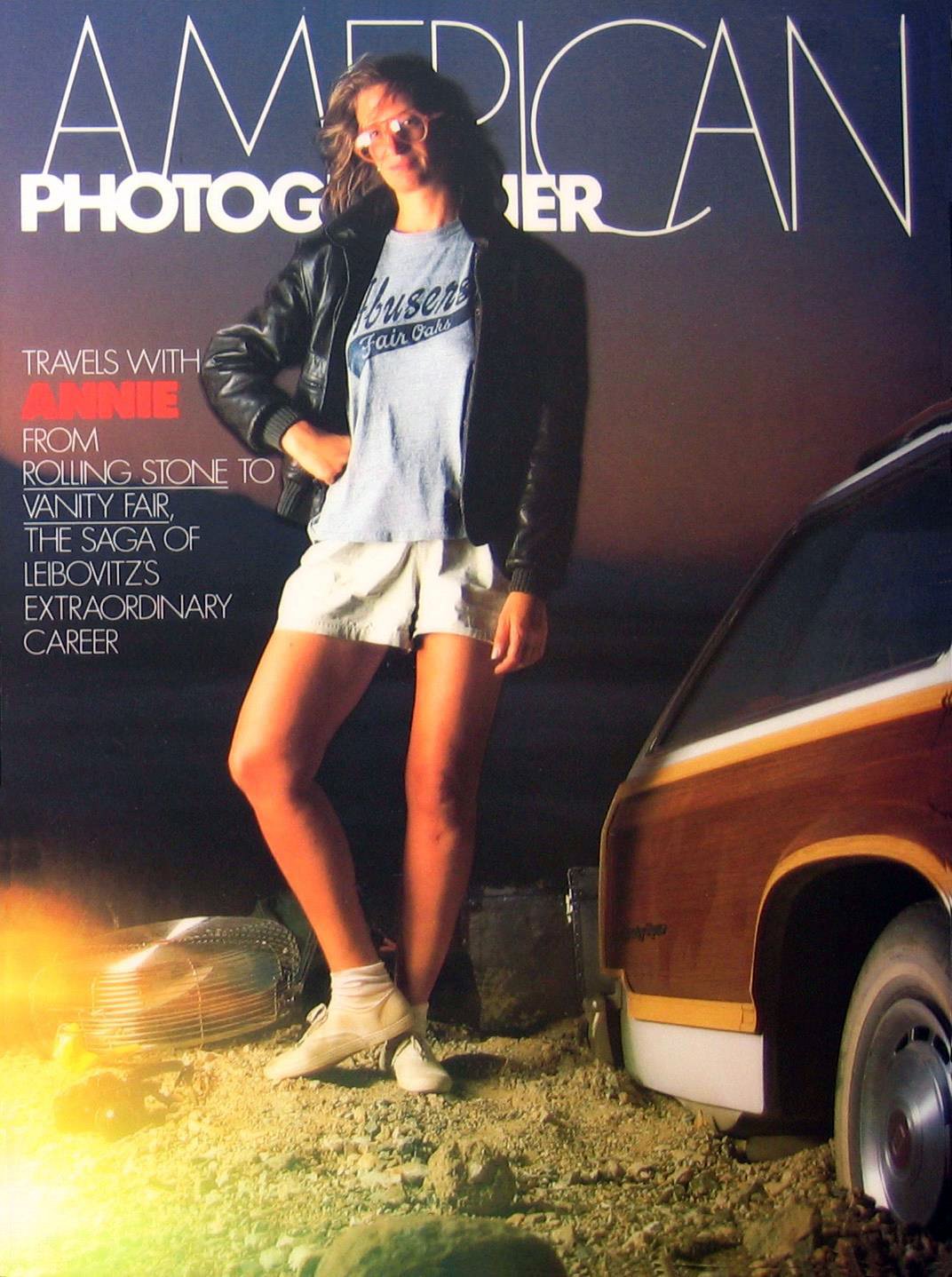

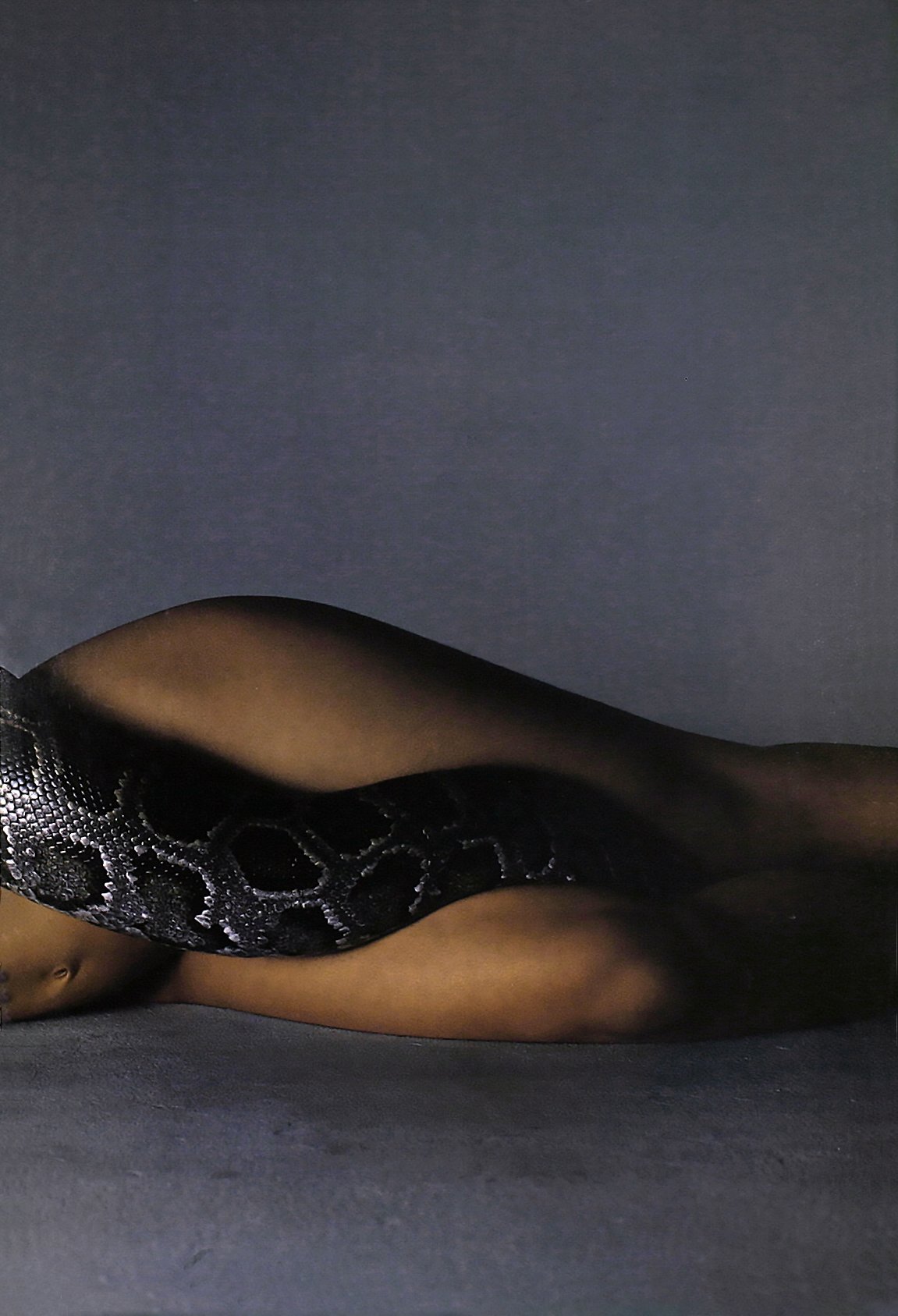

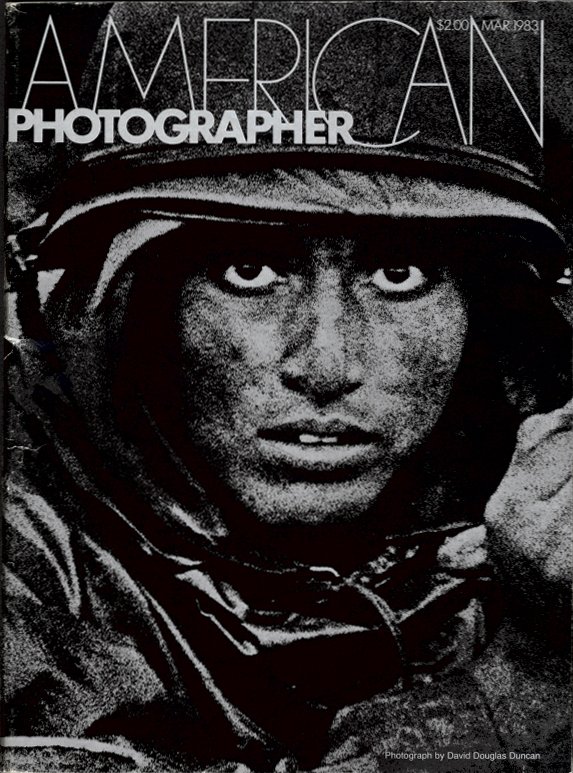

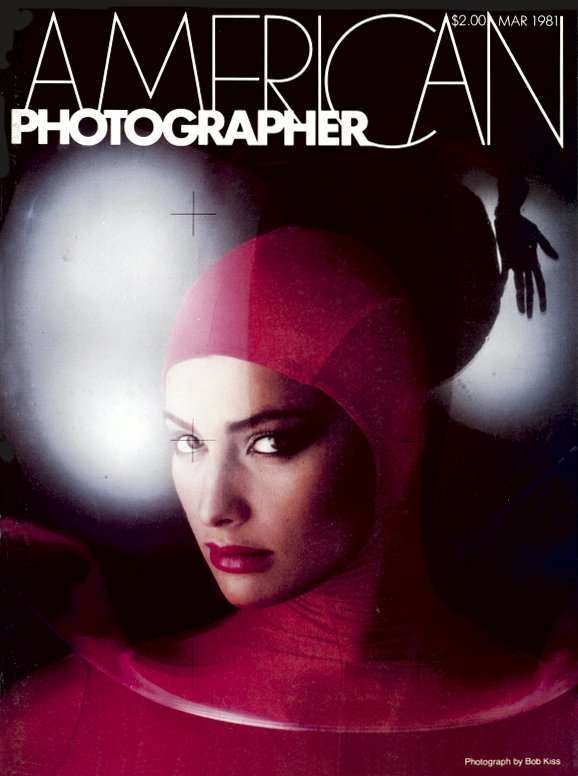

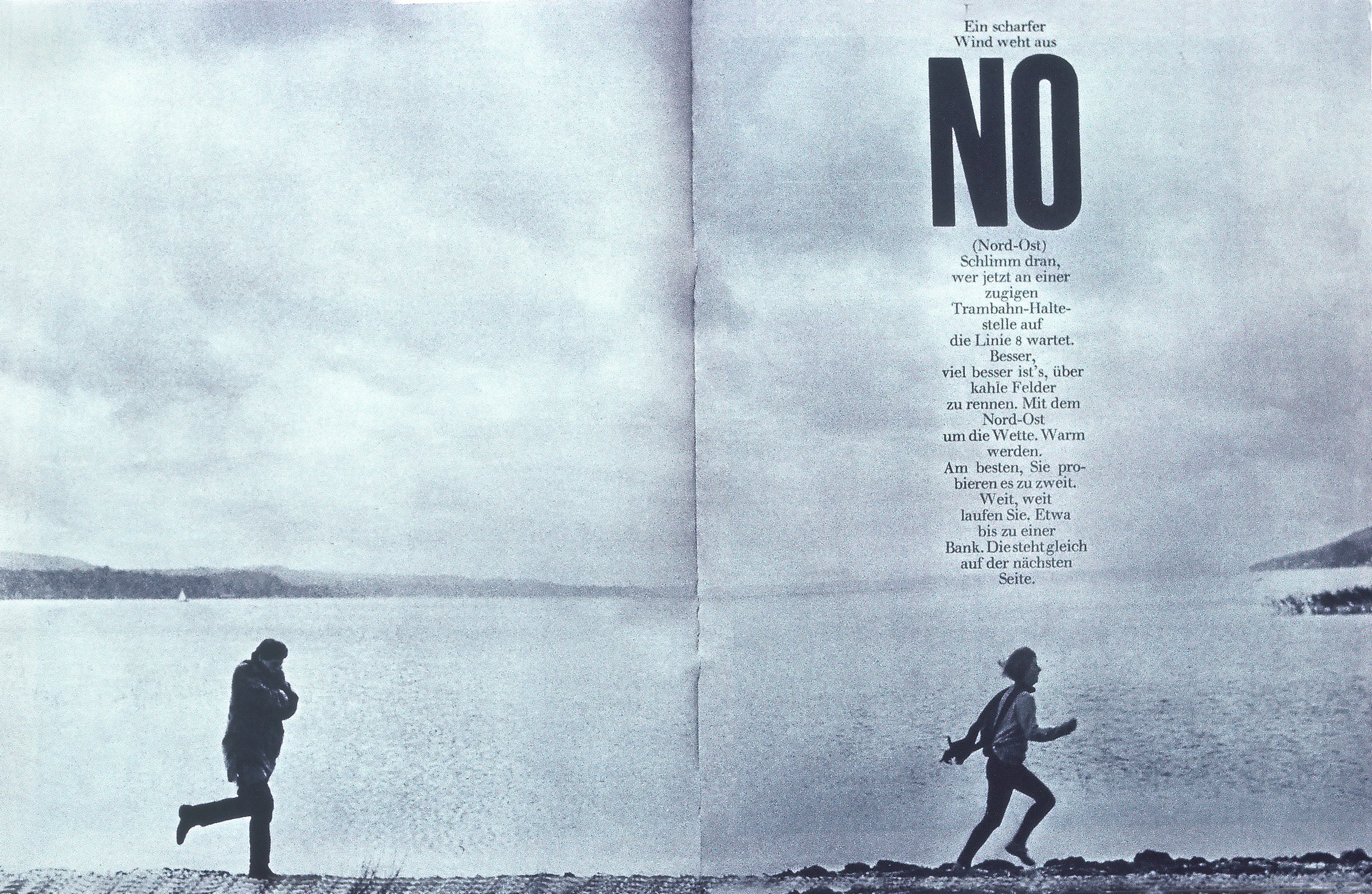

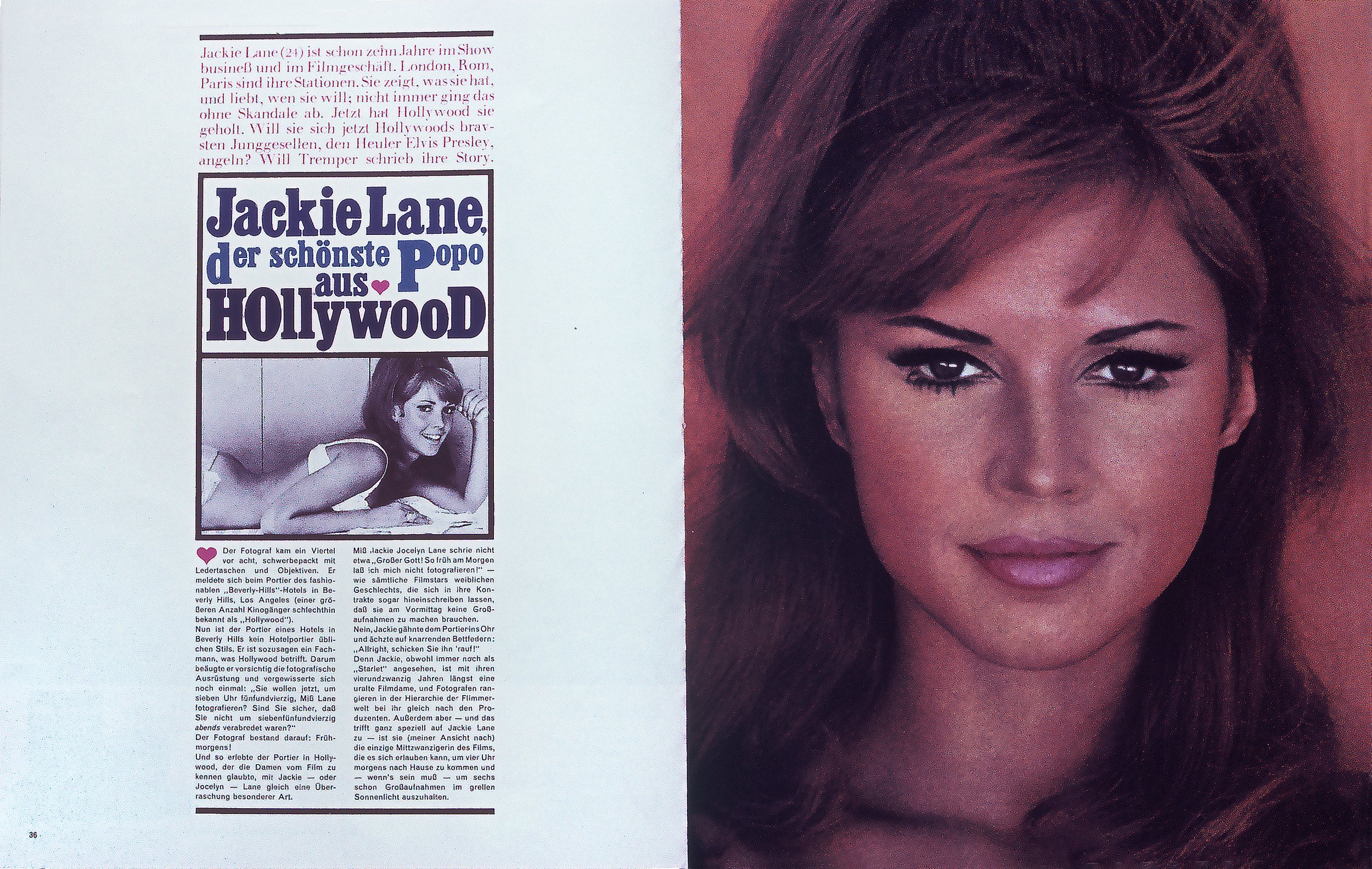

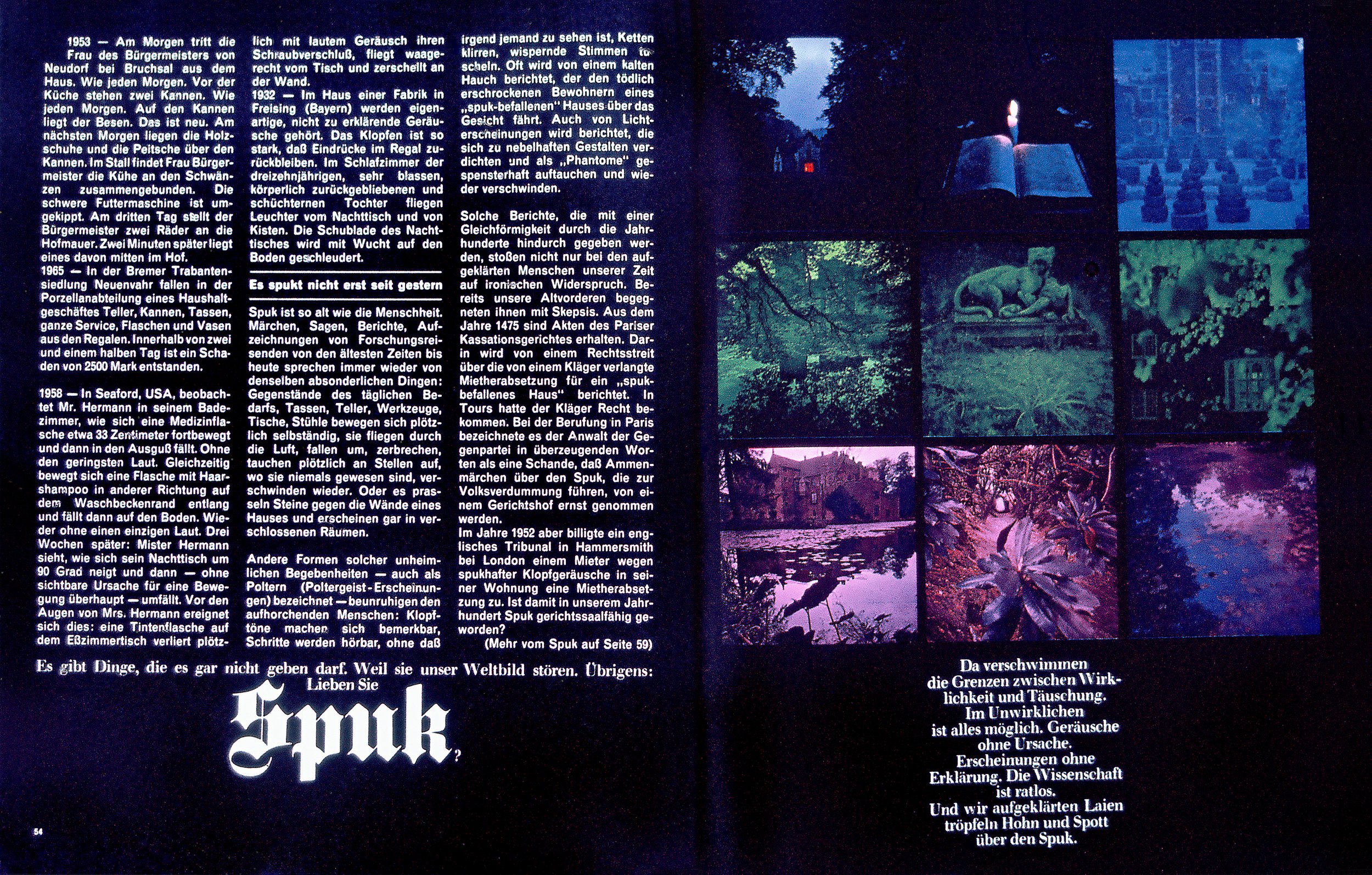

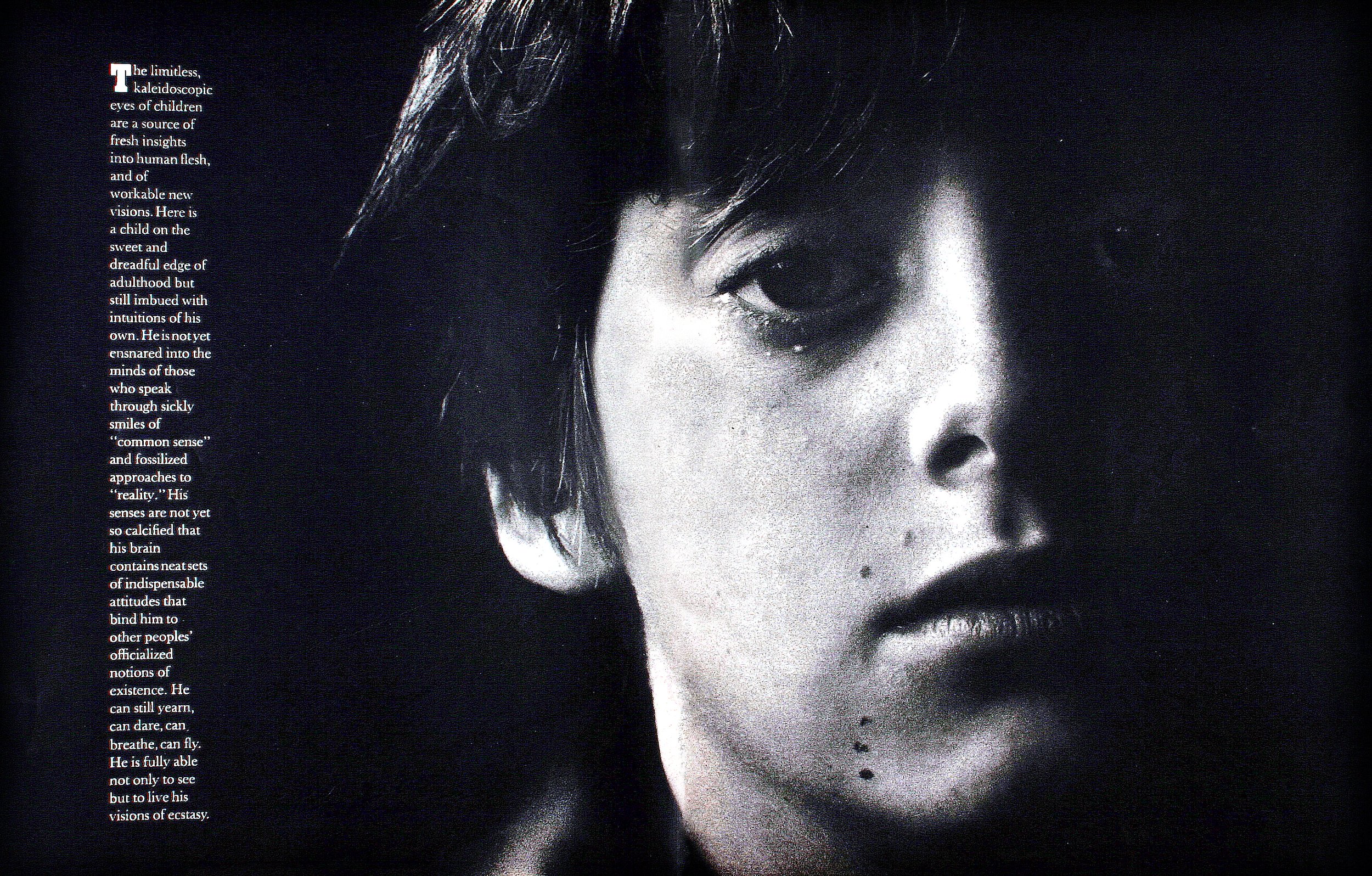

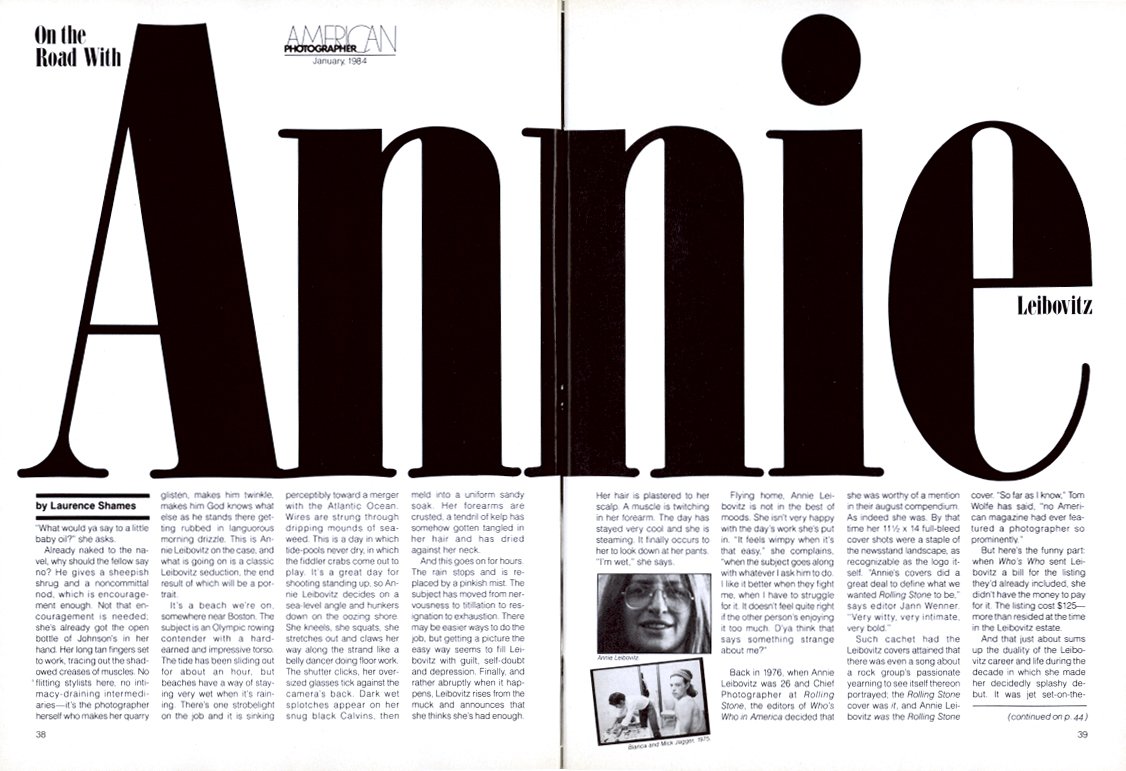

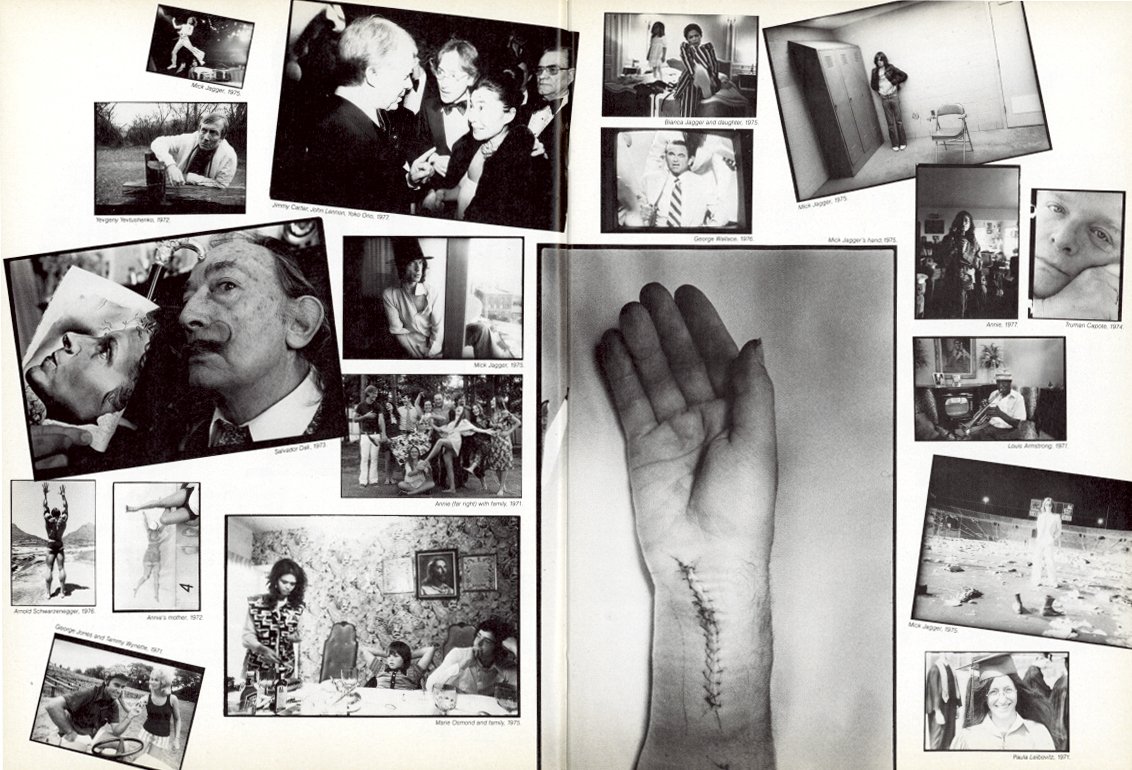

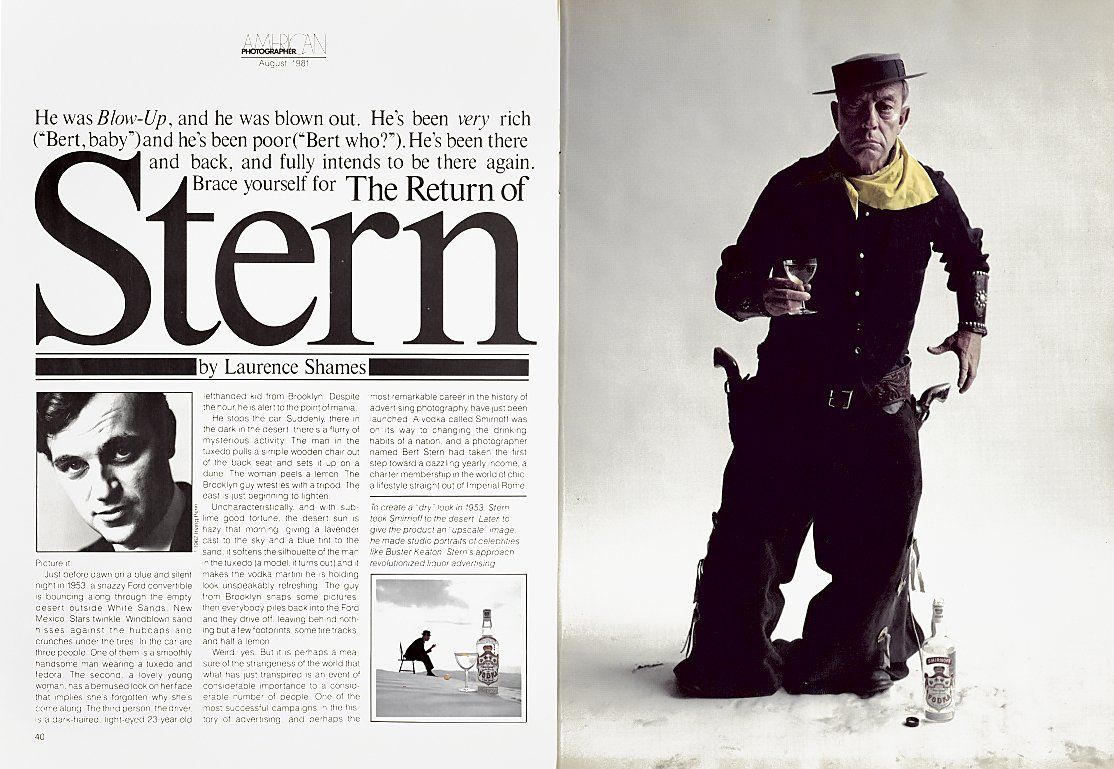

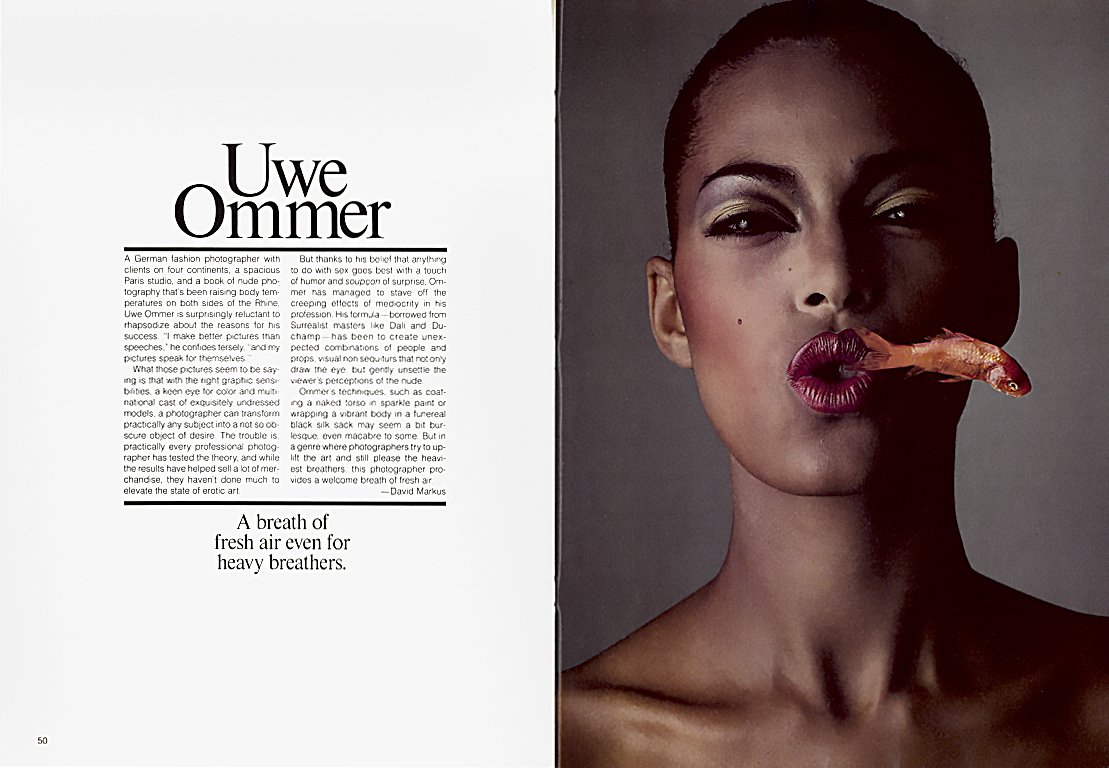

American Photographer, New York, 1978-1985

George Gendron: No, I know, I know. But, having come from the other side of the newsroom, I just have to point that out.

Mary K Baumann: I think that you as an editor are very visually aware, George. But you know, it is interesting. I mean, I’ve worked for really good editors and some really lousy editors. And the lousy editors cannot really see how to pace a story visually or put it together conceptually. Whereas I think art directors, well, many art directors have that ability to, almost like a movie director, direct how a publication unfolds.

George Gendron: You know, the reason I guess I focus on this is that my first job was at New York magazine. And when we moved from 32nd Street to 41st Street, the art department, the design department was adjacent to the newsroom. So my four-square desks were a couple of feet from people like Walter Bernard. And Milton [Glaser] was constantly there from Push Pin and I took it for granted that magazines were run by these teams—these editorial and design partners. Boy, was I wrong about that! I thought that was the norm.

So I’m curious about the social side of your magazine life during your period at Look. Who were your friends? Who were your buddies? Who would you go out and have a beer with?

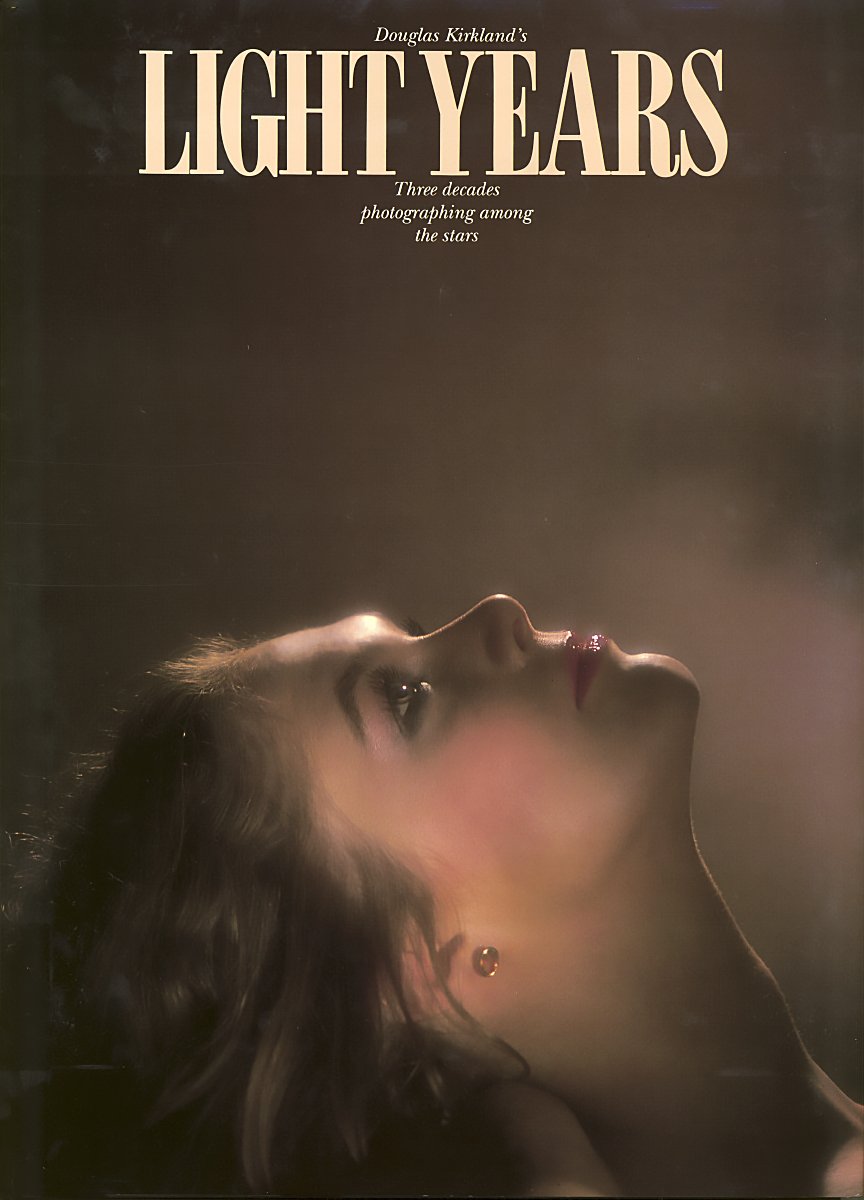

Will Hopkins: Well, my friends were mostly the West Coast guys. George Leonard, and John Poppy, and Paul Fusco moved out there, and, you know, Doug Kirkland was out there.

George Gendron: Did you guys have a big office out there? Or, what are you talking about? A bureau? What was it?

Will Hopkins: It’s more like a bureau. But they really hung out in Mill Valley. So every time I went out there I went to Mill Valley. I didn’t spend a lot of time in the city.

George Gendron: Yeah. I suspect you went out there often.

Will Hopkins: Yeah. As often as I could. I really liked them. I had a great time with them. And I learned a lot from them.

George Gendron: Were you still at Look when it folded?

Will Hopkins: Yeah. Mm-hmm.

George Gendron: What was the last day at Look for you? What was that like, Will?

Will Hopkins: Well, for quite a few weeks I would come to town from Connecticut and I had to go do something and I didn’t have any place to go. And I would go to Look. And I would go up and the offices were empty and my office was empty, basically, but I could go in my office and I could call on the phone, things like that.

American Photographer, Interior Pages

George Gendron: Were you looking for a job? What were you doing?

Will Hopkins: I was just … I was trying to find out what to do.

Mary K Baumann: One of the things that Will has told me is that on the last day, everybody was trying to get people jobs. So there were a lot of phone calls being made. Everybody was concerned about that. And you said that you were on the phone trying to get people jobs. Douglas Kirkland told me that he came in and he immediately got his images out of there.

Will Hopkins: Yeah.

Mary K Baumann: He took his images because they were donating the photography to the Library of Congress. For example, all of Paul Fusco’s images went to the Library of Congress and once they were in the Library of Congress, it was like hell to get them back out. But Douglas had all his images, so that was just a very interesting aside.

George Gendron: Yeah, That is really interesting. So back then having possession of the actual images was 99% of the IP battle, right?

Mary K Baumann: Exactly. So, I mean, Paul Fusco later—or was it Jimmy Karales?

Will Hopkins: Yeah...

Mary K Baumann: ... who did a lot of the very important civil rights images. He could only get ten of his images out at a time in order to make prints of his negatives. Which was difficult.

George Gendron: The reason I’m so interested in this is because when I was at New York, of course that was, you could argue a spinoff, right, of the magazine. The Sunday magazine for the Herald Trib. And when former Herald Trib people talked about the last day of the Tribune, it sounded like people talking about the death of a family member. I mean it was really, really traumatic for people.

In his memoirs, Jann Wenner talks about the last days at Rolling Stone and going into an office that had been his office for 30 years. And little by little, the place is literally, physically being dismantled. So I wonder whether anybody at that time had the sense that as Look closed, Life closed, this was the beginning of the end of an era, in a way.

Will Hopkins: Yeah. I’m sure it was.

Mary K Baumann: The other interesting thing is I came to know the Look people much later. But it was very much like a family. And they would always gather around stories and writers would work with the art director to lay out the story so you knew what was going on in the story. So there was a level of collaboration that was very key. The other thing is that Look had a room where they put all the layouts up on the wall, and the story was not considered for the magazine until it was laid out.

“They took me to the South [of France] and dined me and wined me, and I had a great time. But I don’t know how much I made from that.”

George Gendron: It makes sense the minute you describe it, right? For a magazine that was as visual...

Mary K Baumann: And when I was at the monthly Life we had closings on Monday and we would often be doing stories on Monday that would close that day.

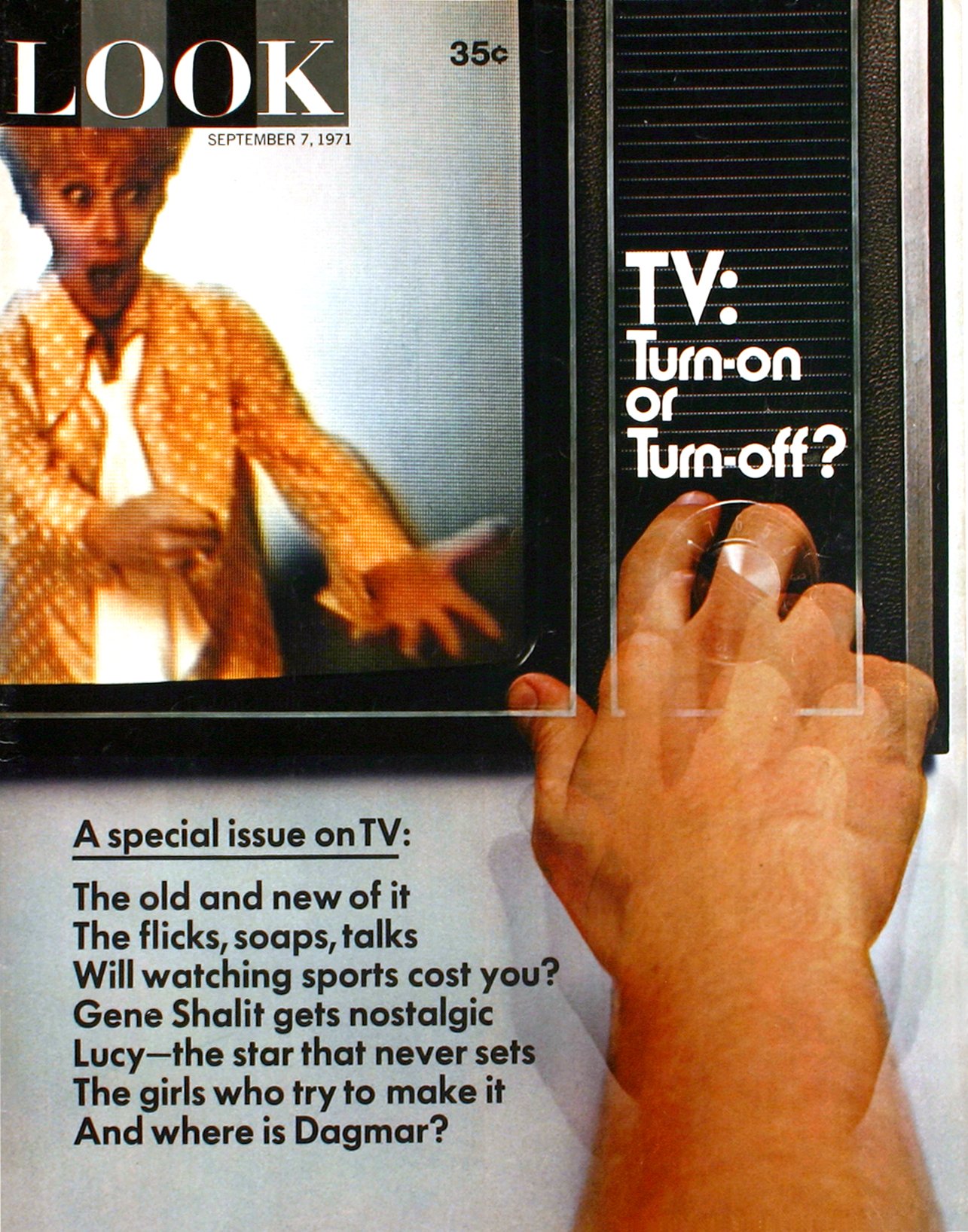

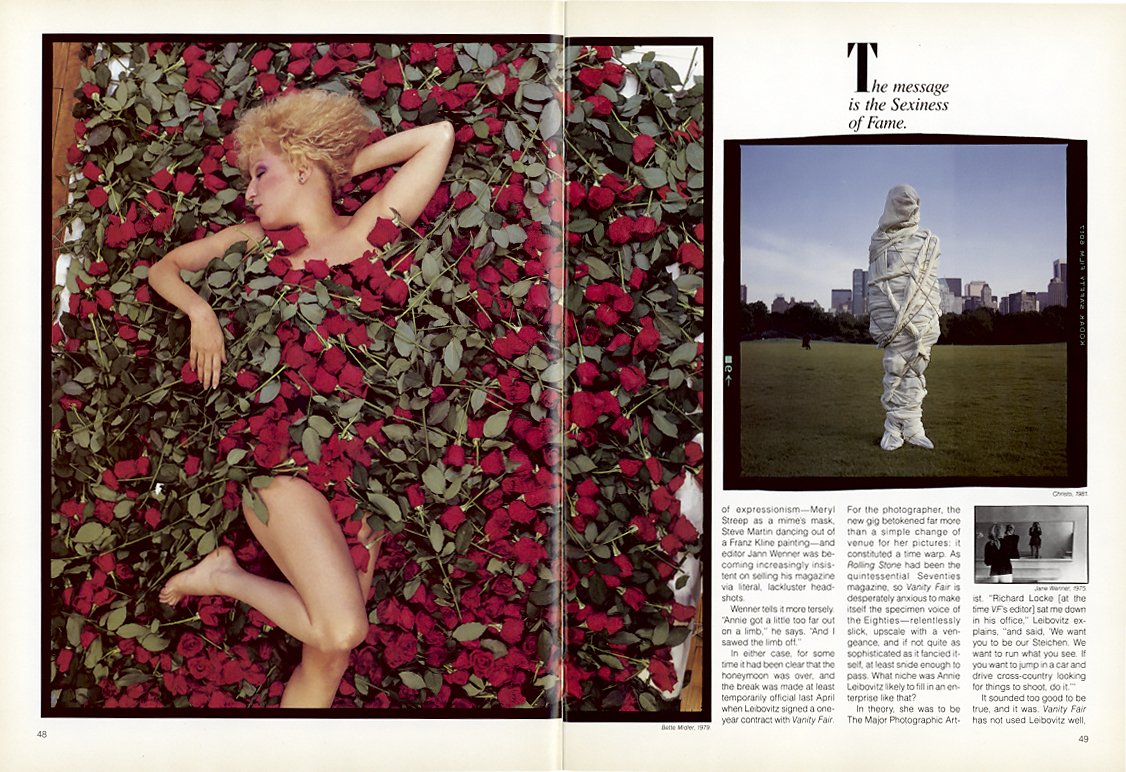

George Gendron: That’s extraordinary. Well, talking about how visual that magazine was, I have to talk about a magazine that was just so important and influential, and that’s American Photographer, where you were not just the art director or design director, you were a co-founder. And I’m curious about how that came to be.

Will Hopkins: Well, Sean Callahan asked me...

George Gendron: Sean had been an editor at Look?

Will Hopkins: No. At Life. At Life...

George Gendron: Oh, at Life. That’s right...

Will Hopkins: … And he was like a junior editor at Life. And he had a friend, Alan Bennett, and they got together to form this magazine. And they asked me to be part of it. And I jumped in. And it was, for a while, quite fun.

George Gendron: Presumably you had your own studio at this time, right?

Will Hopkins: Basically, yeah.

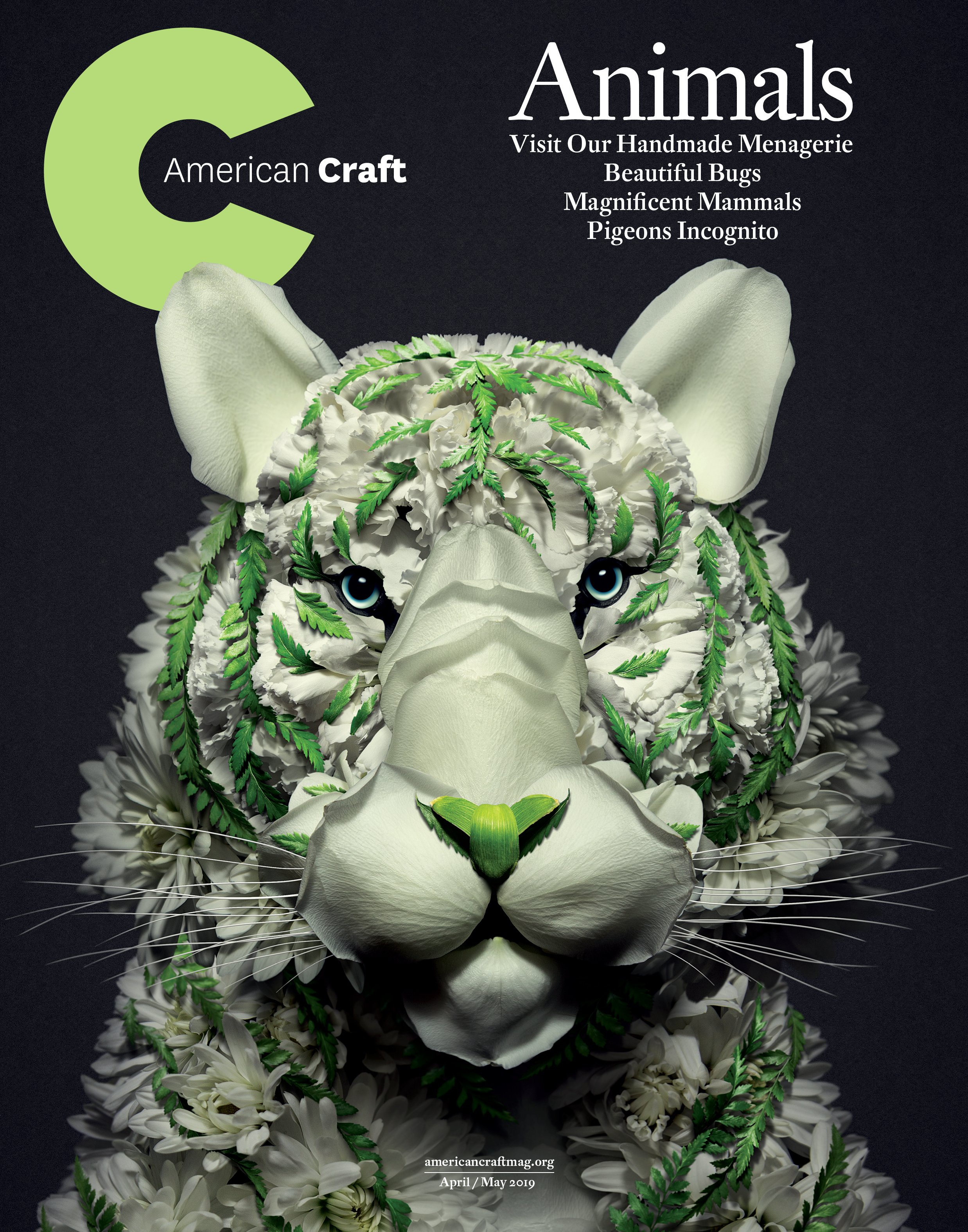

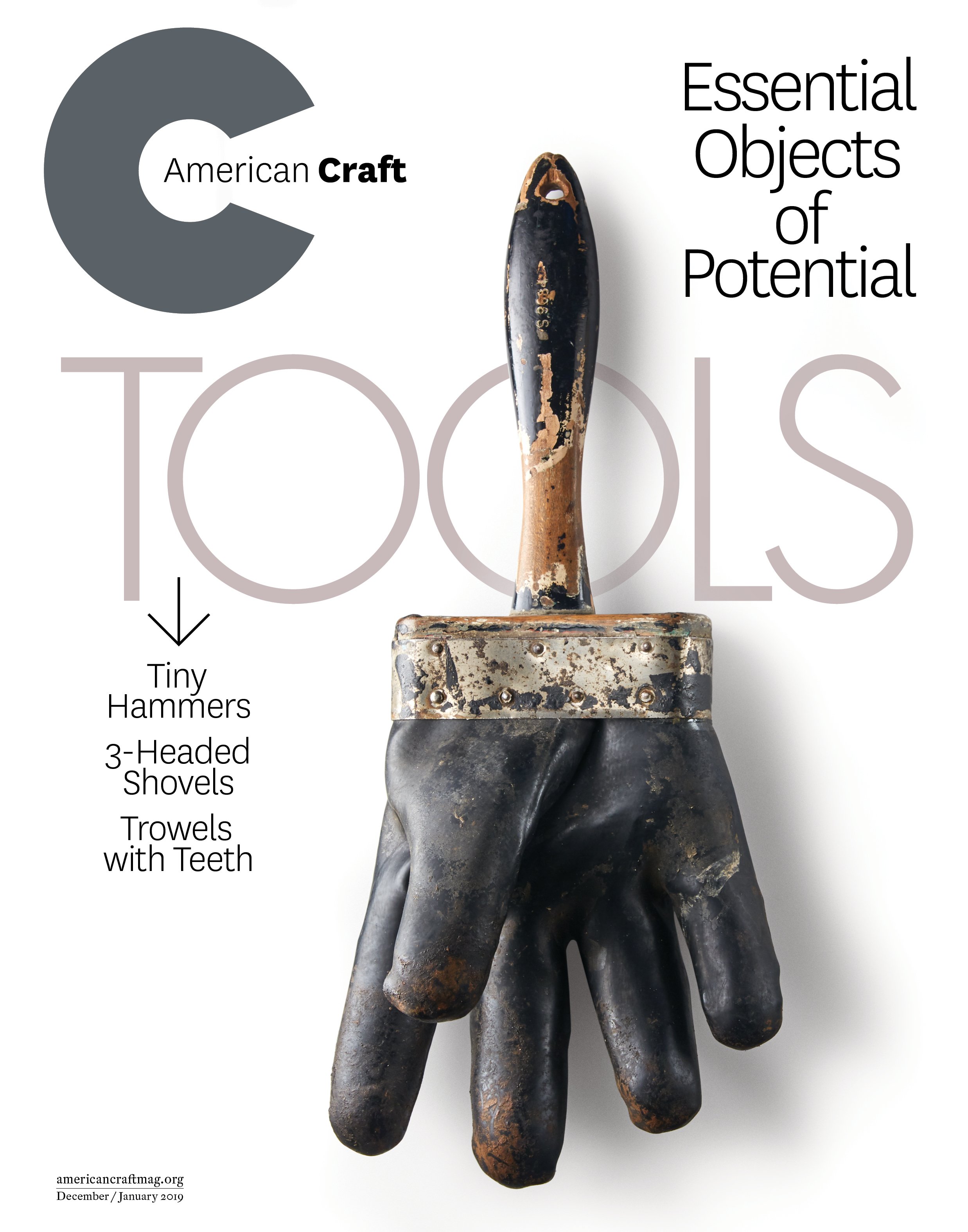

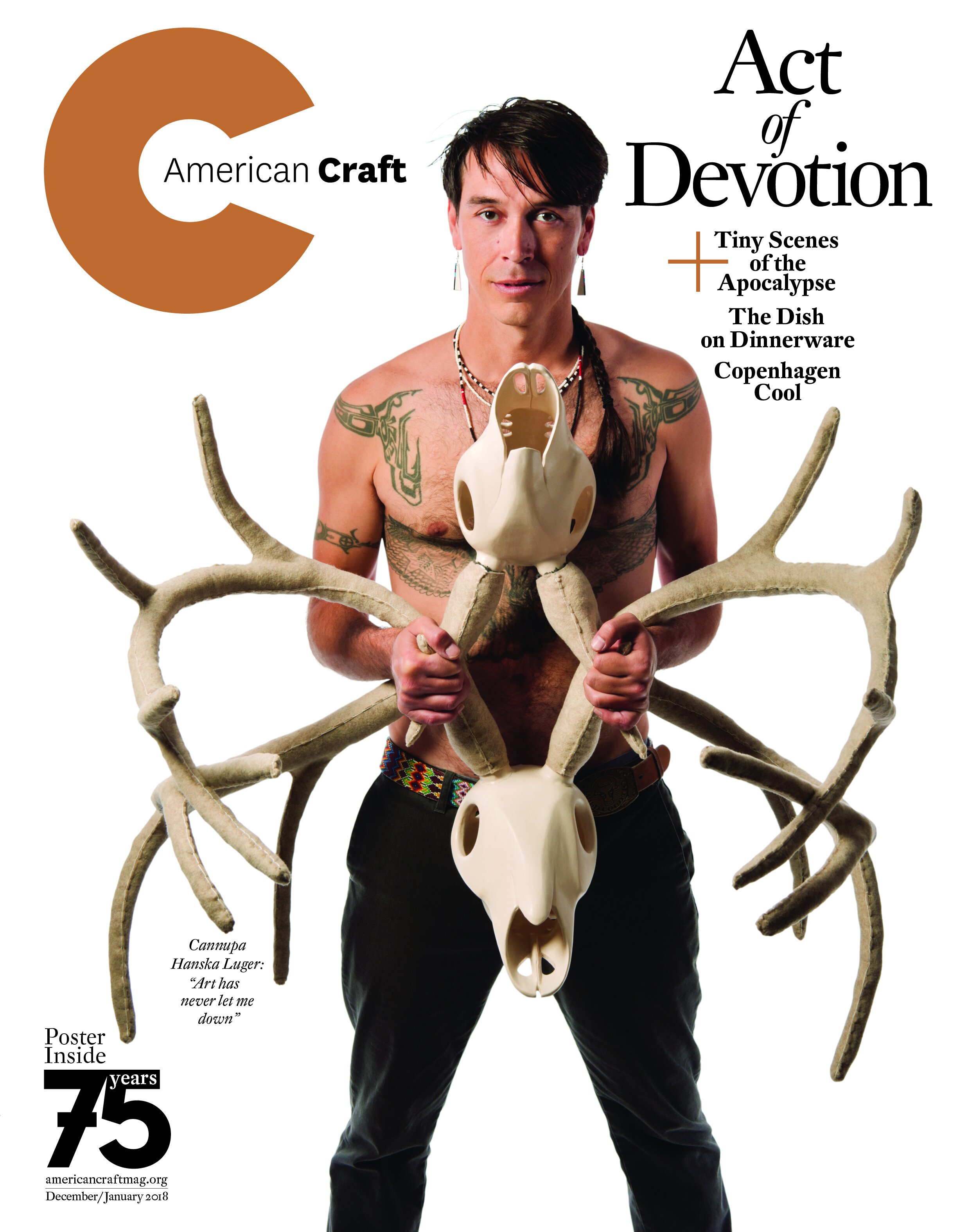

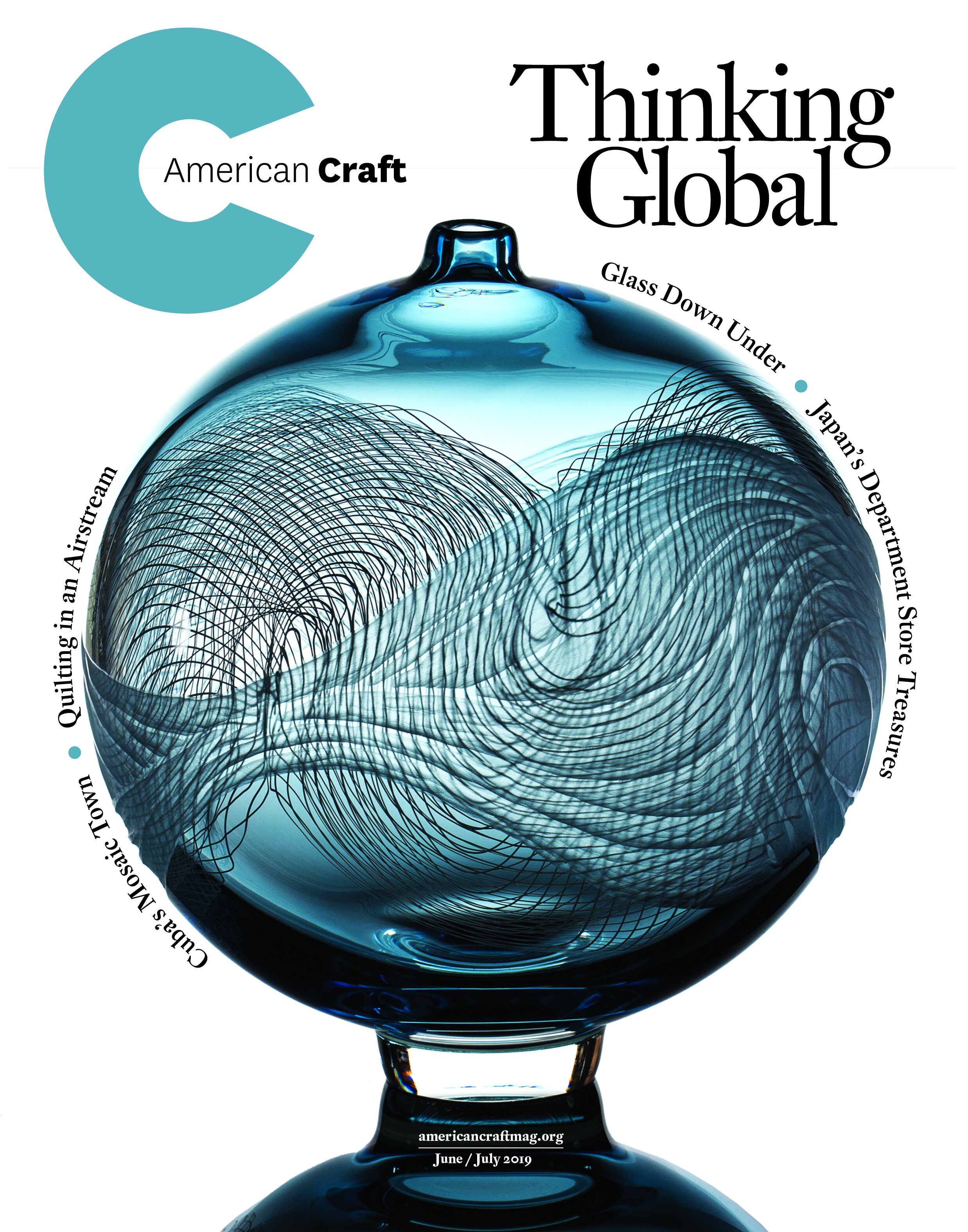

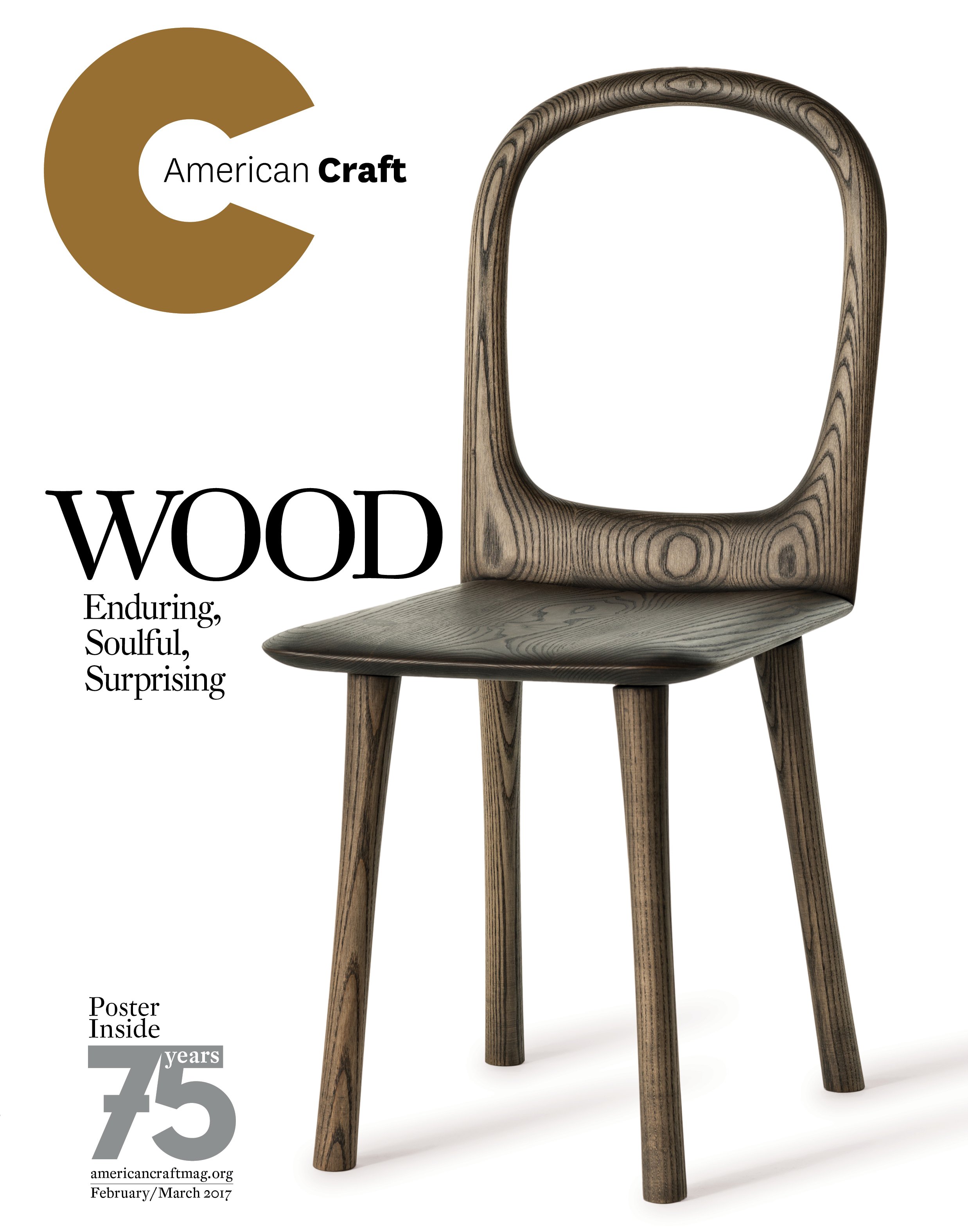

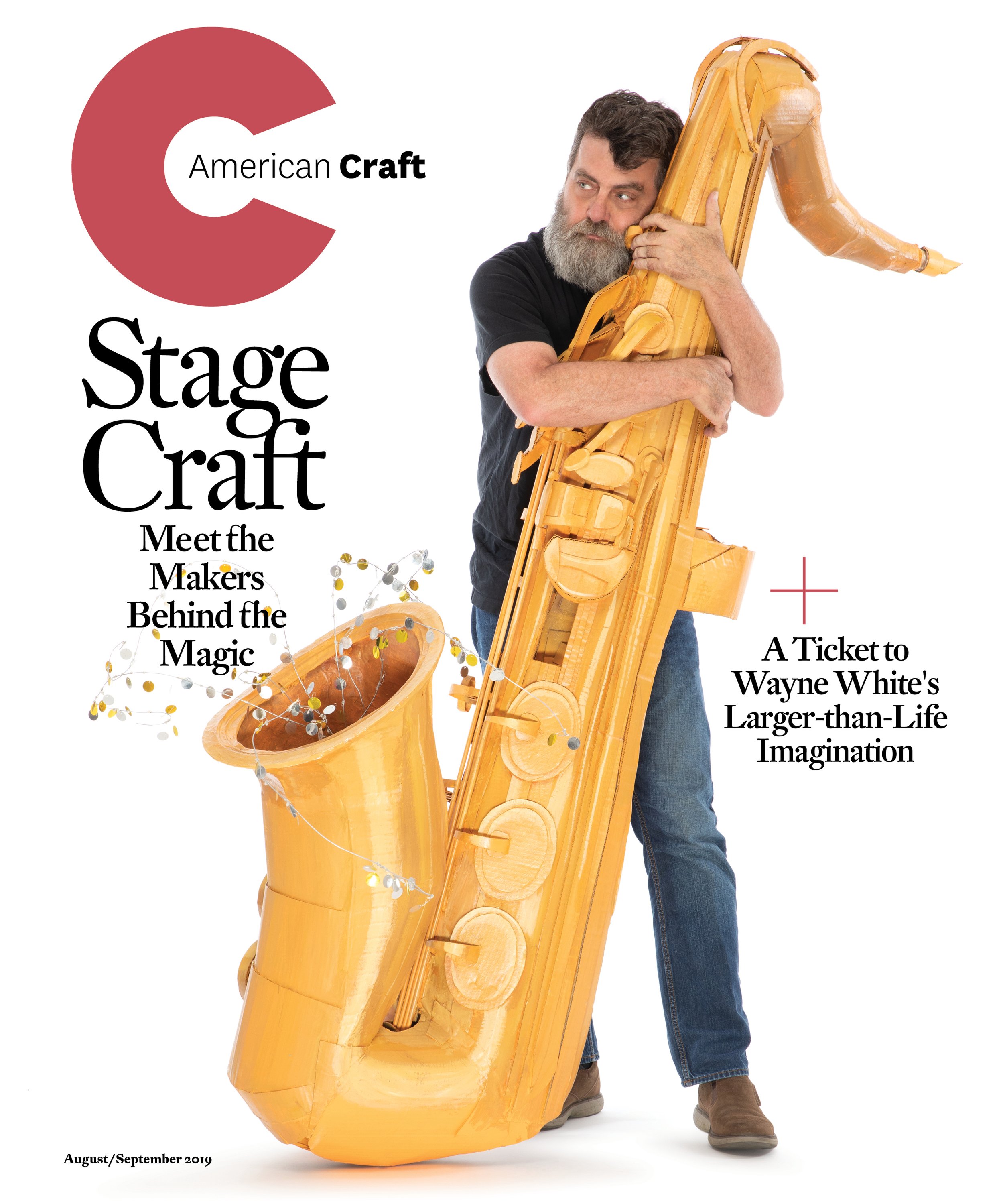

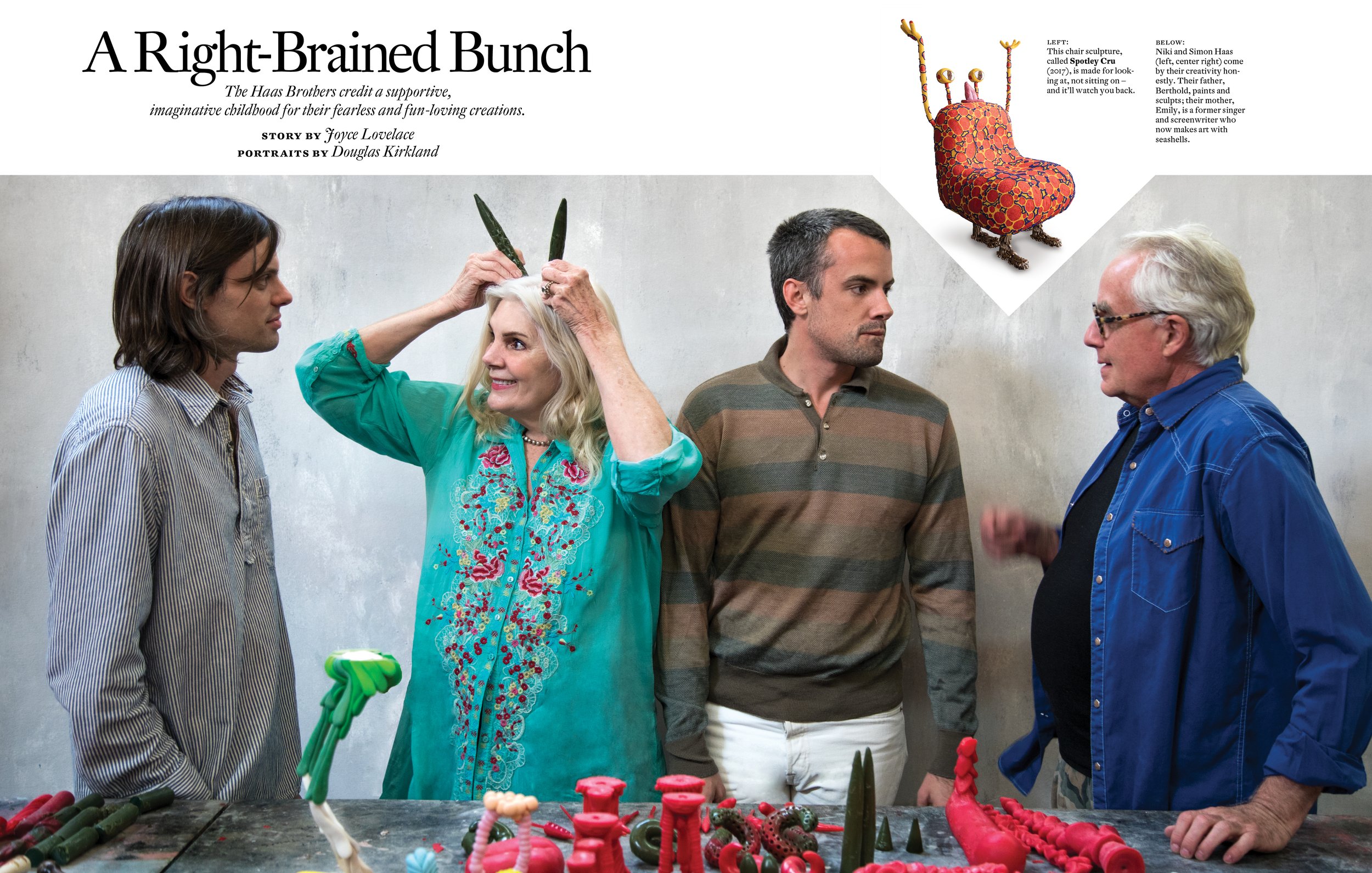

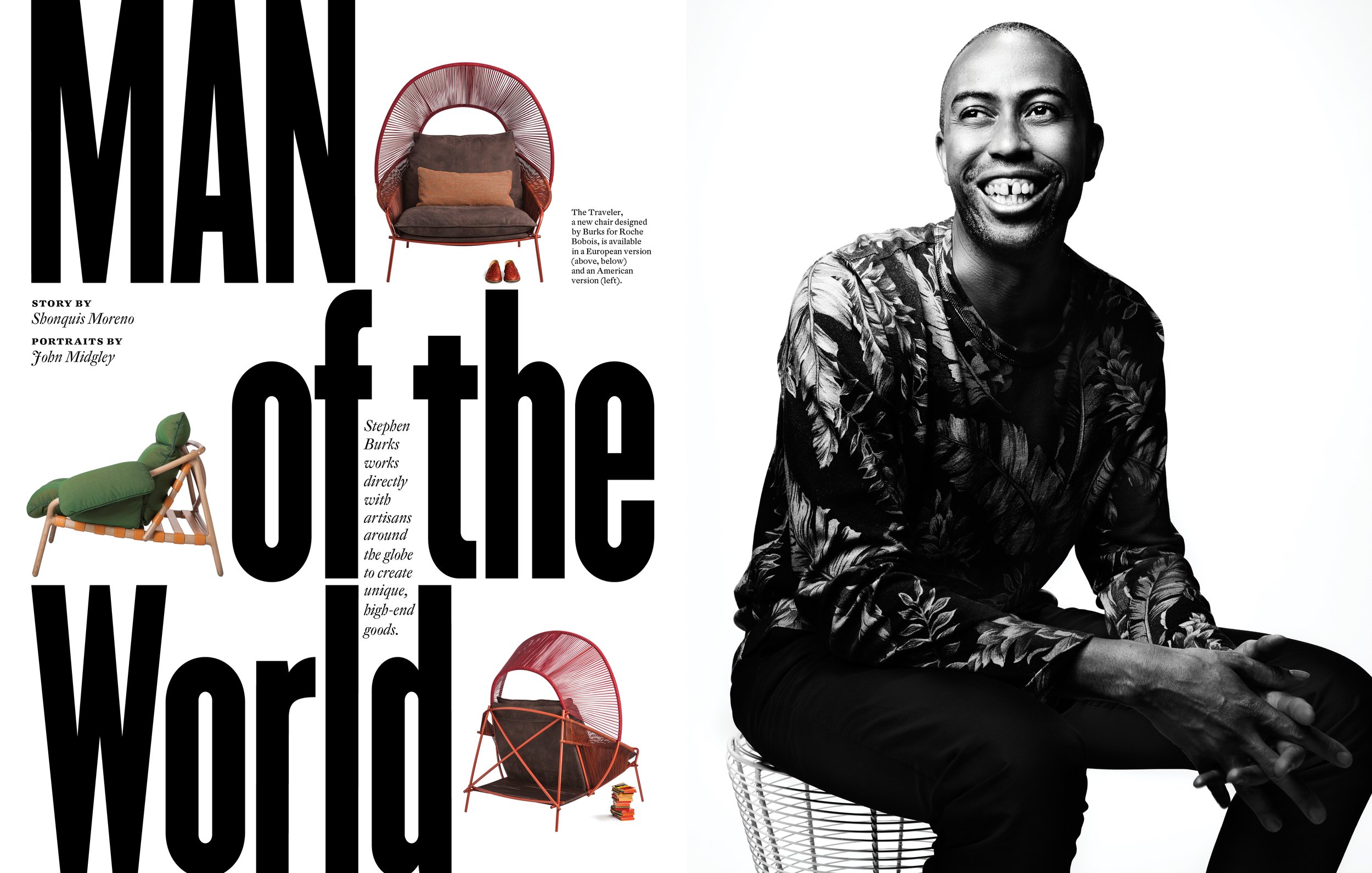

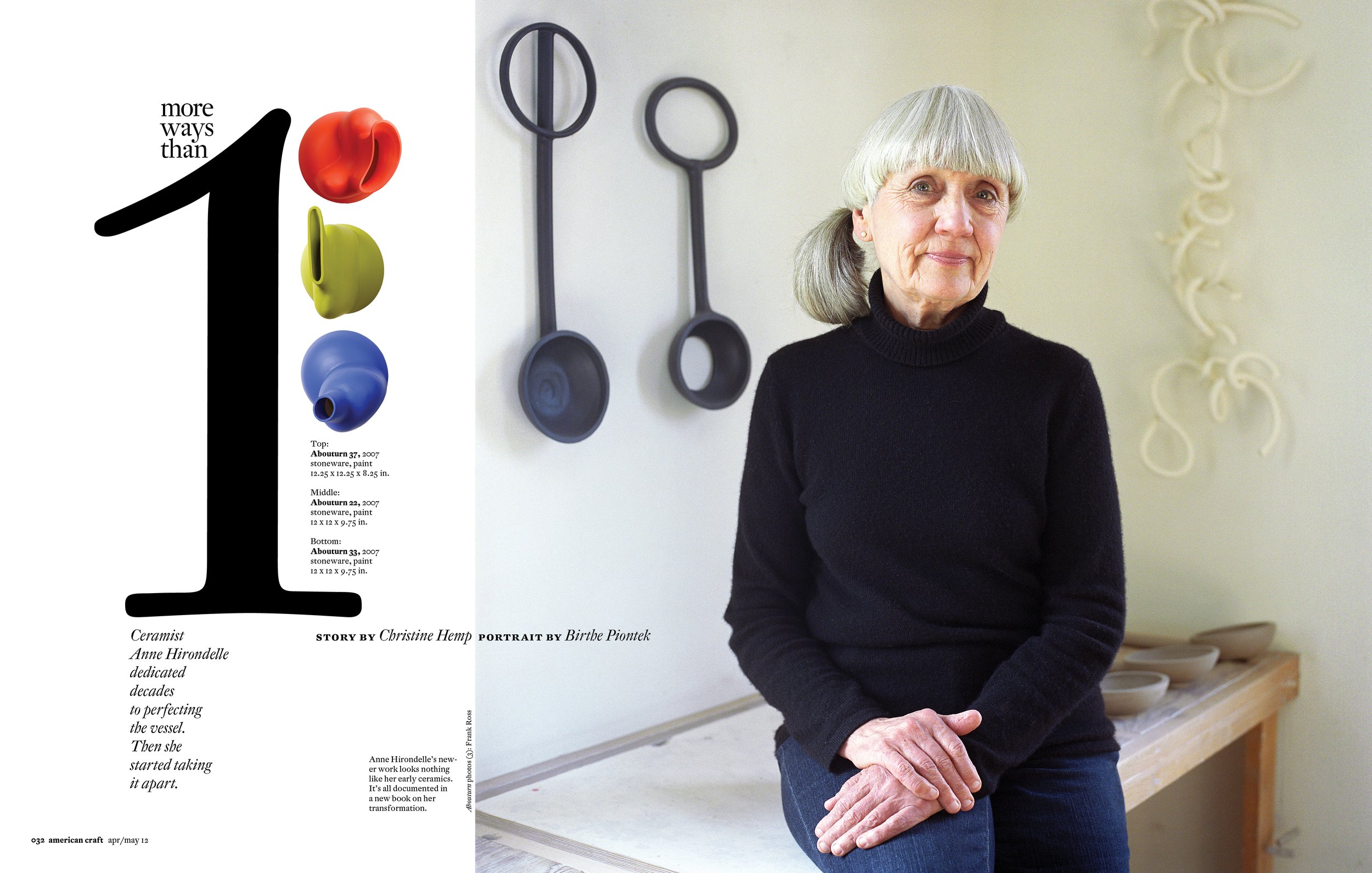

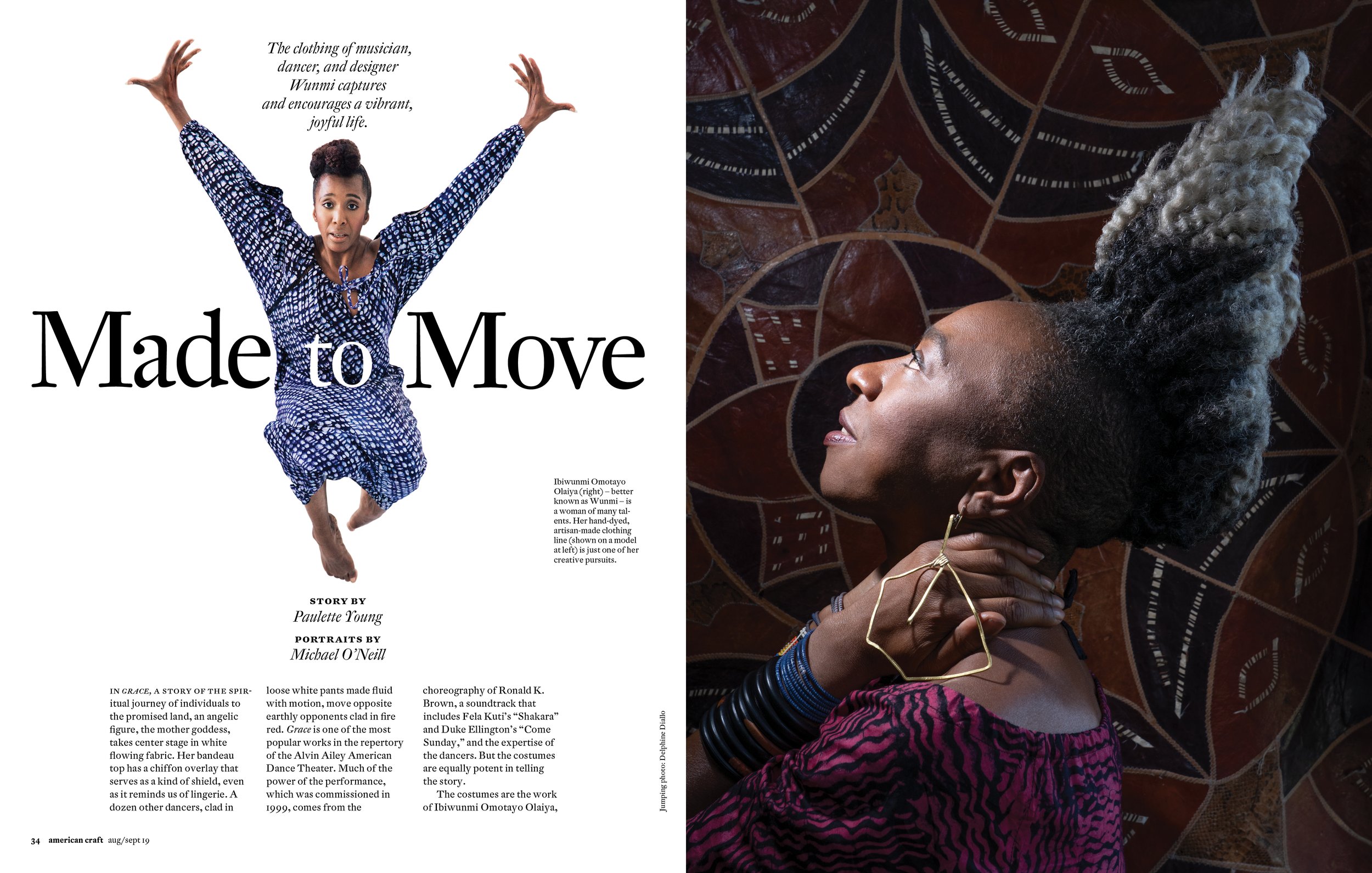

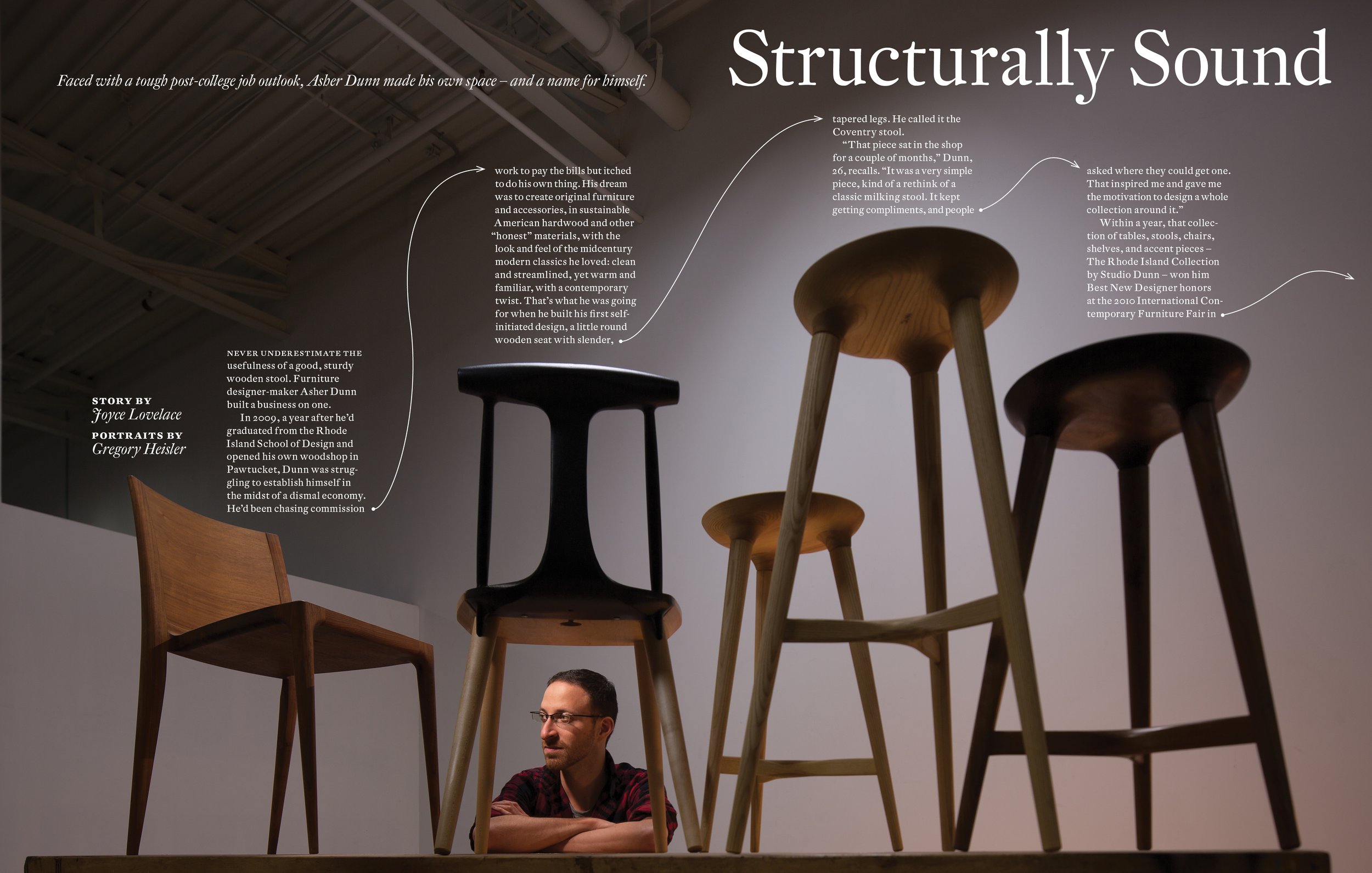

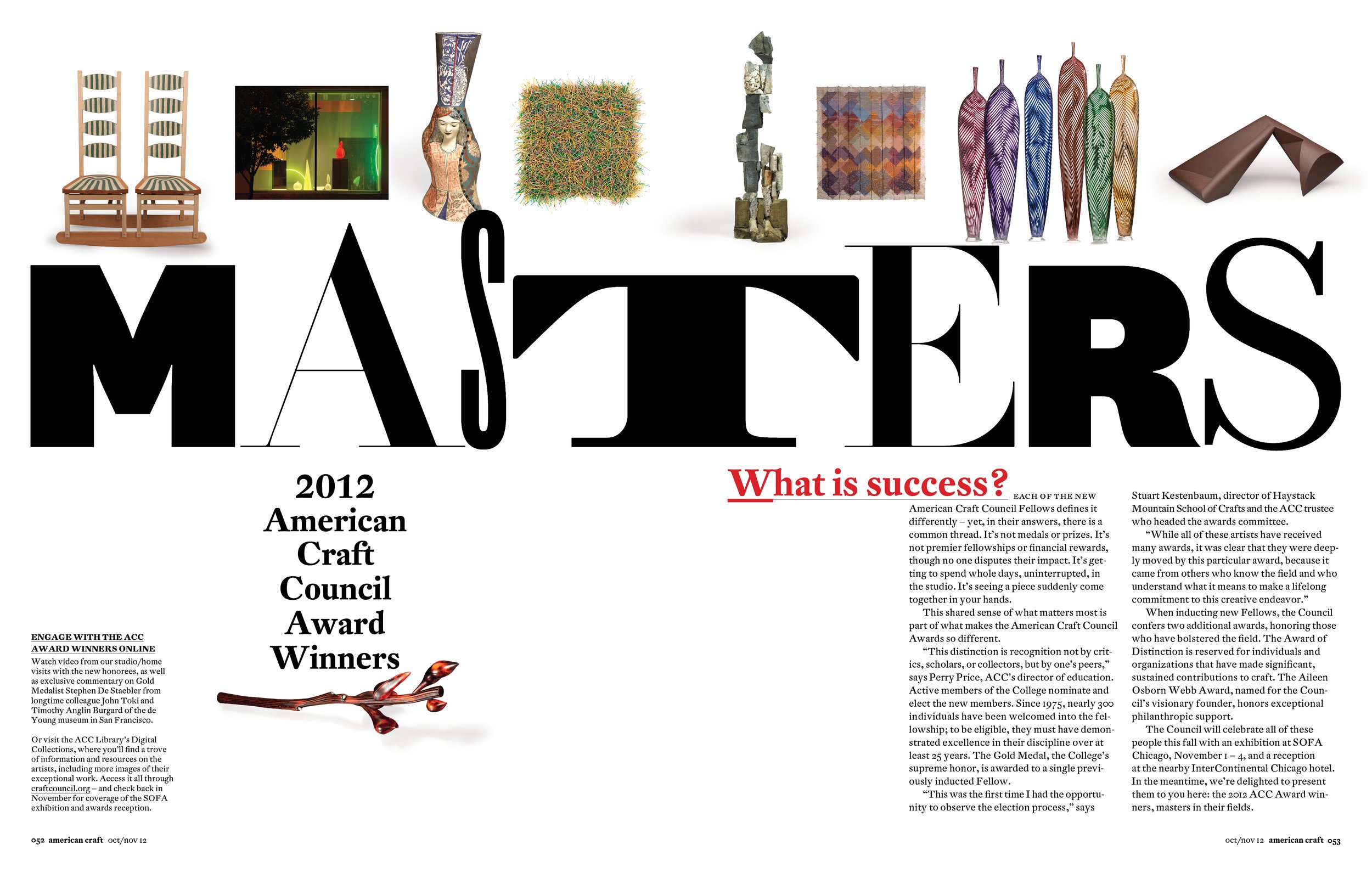

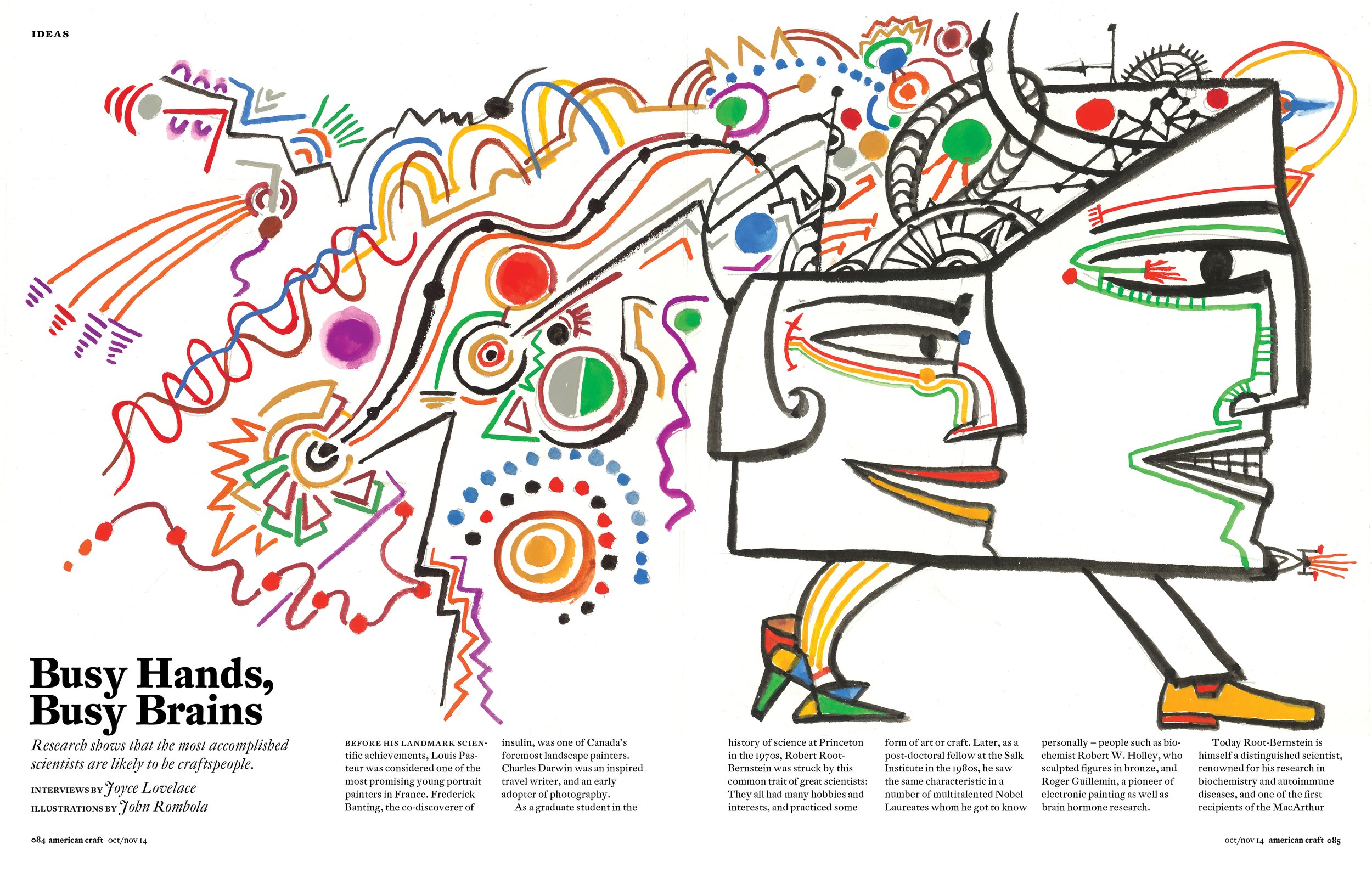

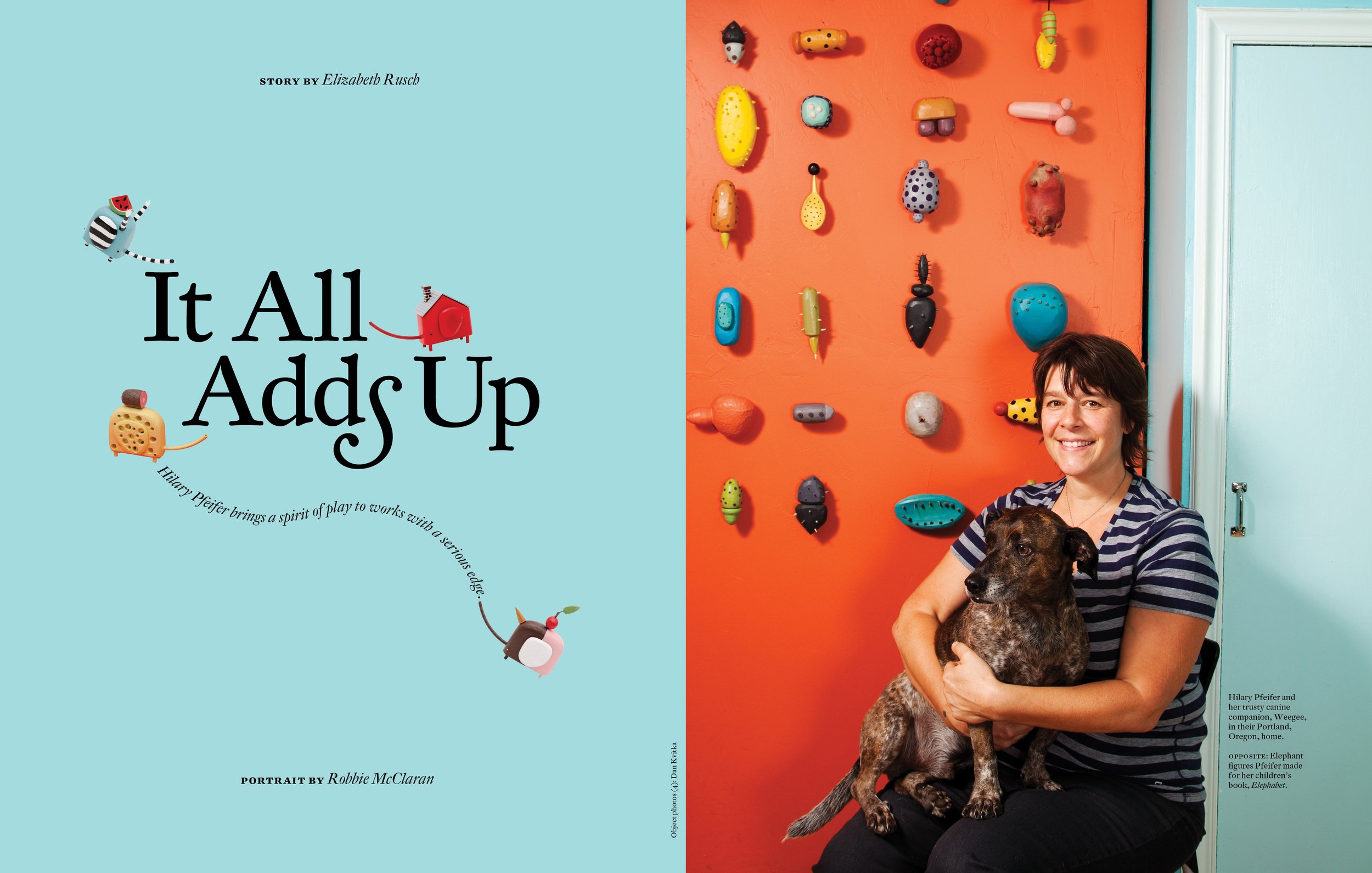

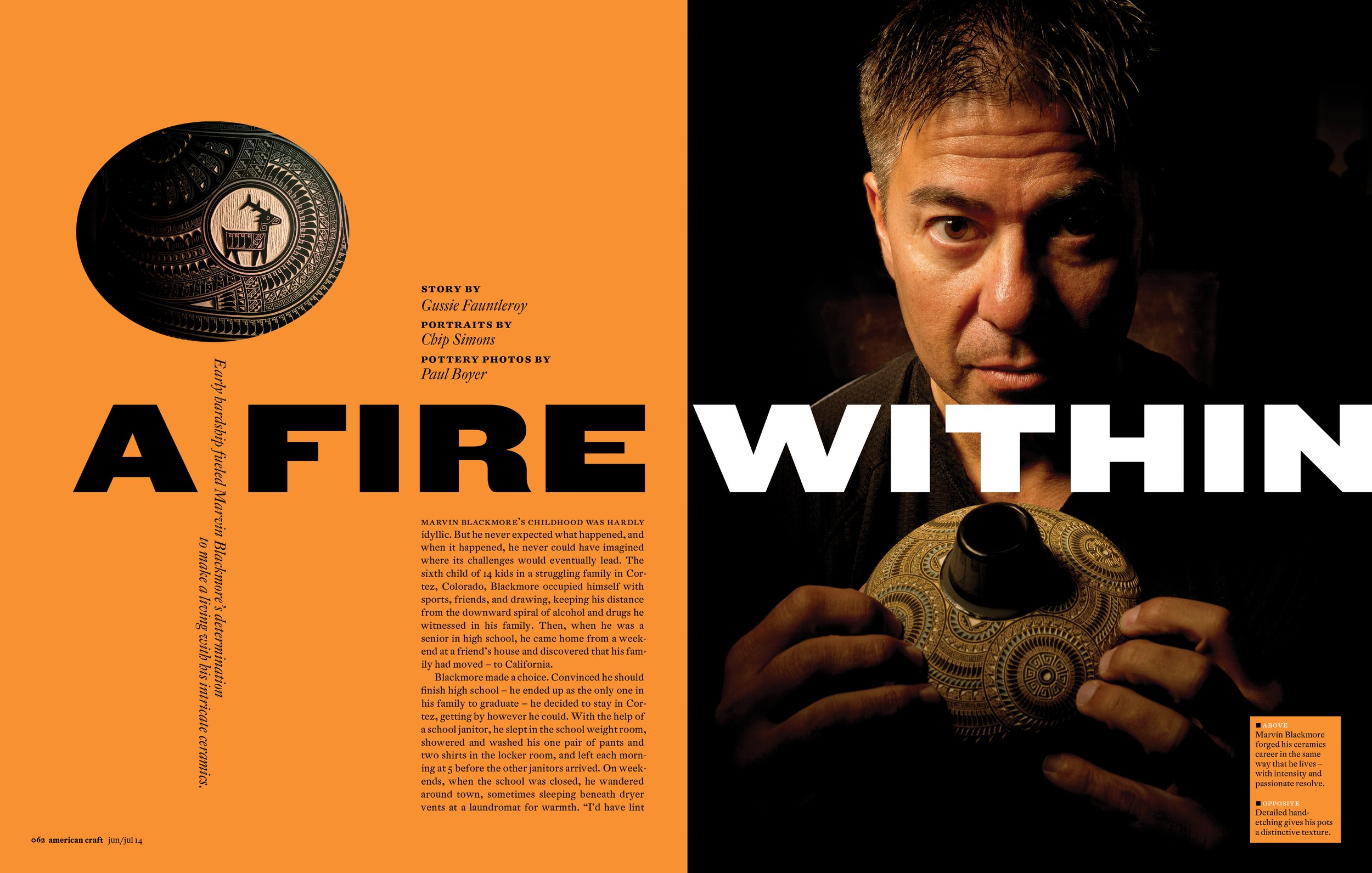

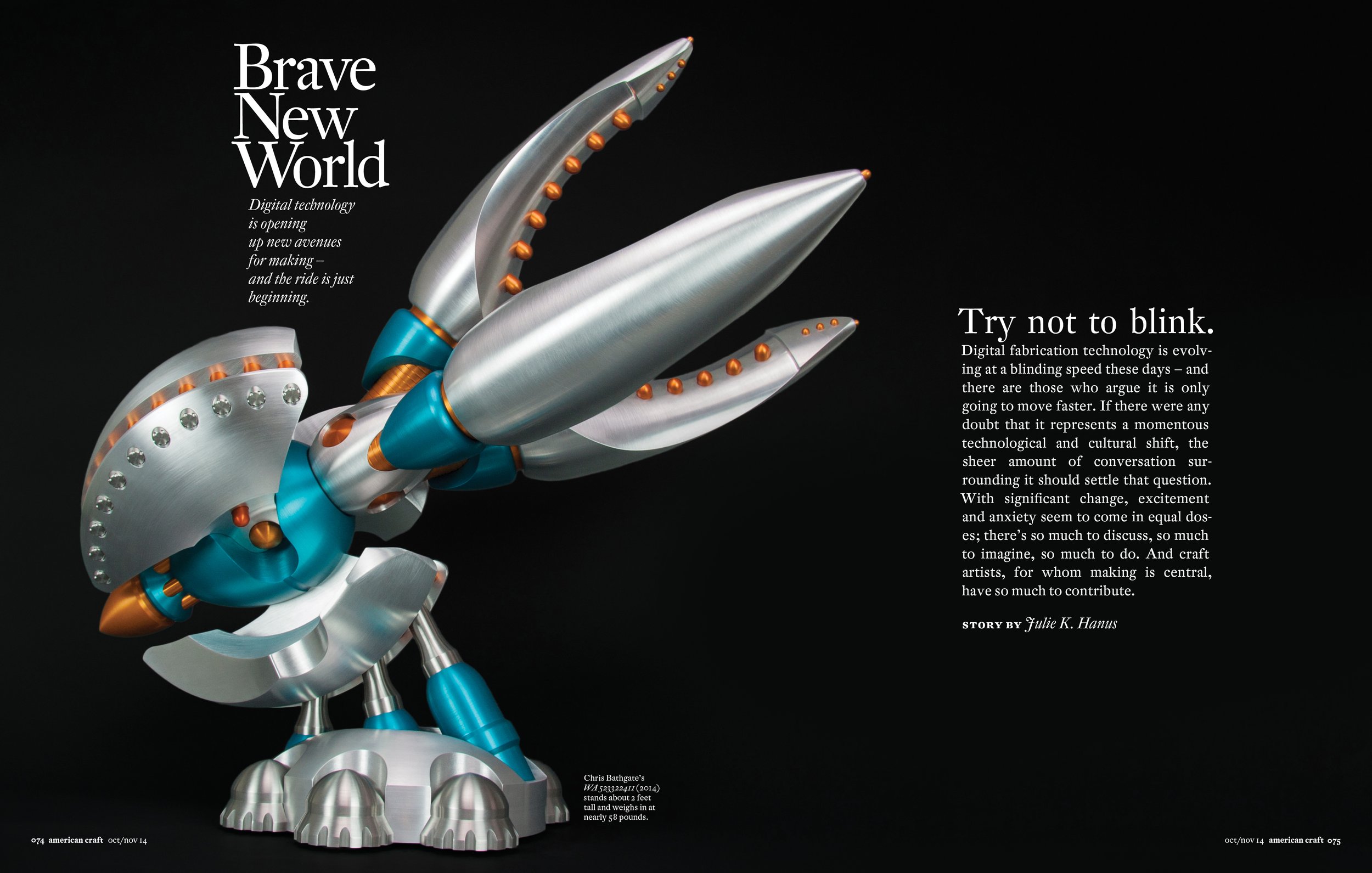

American Craft, Minneapolis, 2013-2019

George Gendron: So I’m curious, when they described American Photographer to you, before there was anything to look at, how did they describe the magazine? What was the concept?

Mary K Baumann: You know at that point in time the photography magazines were all gear-oriented and this was much more focused on the image—the image, and the art of the image, and the philosophy of the image, and the concept of the image. It explored the act more of doing the photography from a mental state of mind versus just the equipment.

George Gendron: And just featured exquisite photography. The reason I asked was that some of us thought of this kind of as a reincarnation in a way of Look magazine, but about photography for photographers.

Mary K Baumann: I think that’s a pretty good description. The beauty of the magazine, I mean it was a real entrepreneurial effort. And it was started with very little money. My recollection is that Alan Bennett somehow got the money through Alan Patrikof and it was, like, $250,000, which is just unheard of. I don’t know how they did it, but he was turning that money over constantly.

Will Hopkins: Weekly!

Mary K Baumann: Alan Bennett was just brilliant at keeping it all together. But the other thing is, because it was a showcase, they didn’t have to pay for images. The photographers wanted to be in the publication. So you didn’t have that overhead of photography...

Will Hopkins: ...because we were doing stories about them.

George Gendron: It’s interesting though, when you talk about $250,000, I was trying to start my own magazine back then and it was a regional magazine, so I suppose you could argue that it shouldn’t have been quite as expensive as American Photographer, but the people warned me—including Alan Patrikof, who I pitched and had several conversations with about my concept—the problem with starting with too little capital was you would invest your time and energy and your capital and the premier issue and then you’d be out hustling for more money and the subsequent issues would suffer.

That is a miracle that you guys were launched on something like $250,000 and were able to sustain that level of excellence. That makes some sense to me because I was following both that and American Health at the same time.

Will Hopkins: ...Haha! T George [Harris]!

Mary K Baumann: We used to joke that Will could only do magazines with American in the title...

Hopkins in his studio at 14th Street and 5th Ave, in Manhattan. The American Health offices were downstairs. Photograph by Michael Robert Soluri

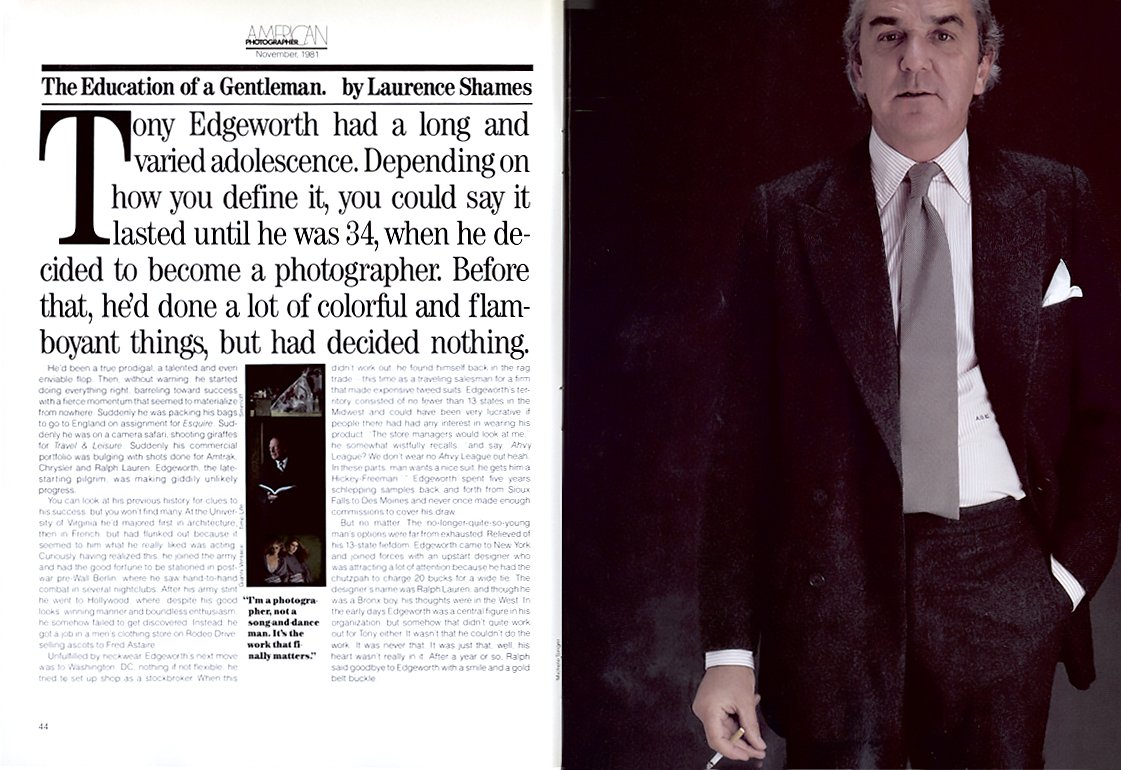

George Gendron: Well, you were doing that, but you were also doing redesigns of Forbes, Sports Afield, Architectural Digest. I think you did L’Express in France. Do you mind if I ask, I’m just really curious for all of the designers who were out there right now, what did you guys charge for redesign back then? Just ballpark.

Will Hopkins: Oh, well, I don’t know. It wasn’t a lot.

George Gendron: Well, it’s, it still isn’t a lot. [Laughs]

Will Hopkins: I mean, it wasn’t. I don’t have any idea of what it was. But they took me to France and dined me and wined me and took me to the South [of France] and all that kind of thing. And I had a great time. I don’t know how much I made from that.

George Gendron: Yeah, that’s the French. I was trying to acquire—this is after that time period, but when I was running Inc.—a magazine called L’Entreprise, which was Inc. in France, and the same thing—they wined and dined me. I couldn’t believe it. And they would take you sailing and they would, they reminded me of the Japanese. It was kind of like, “Well, we have to get to know you before we can even consider doing business with you.” And then at the end they refused to sell it to me.

But I look back, that is one of the most enjoyable courtships I ever had professionally. So here you are, you are the quintessential New York designer, and then you leave.

Will Hopkins: Mm-hmm.

George Gendron: You leave New York and you go to Minneapolis. Did your bride, or future bride, have anything to do with that?

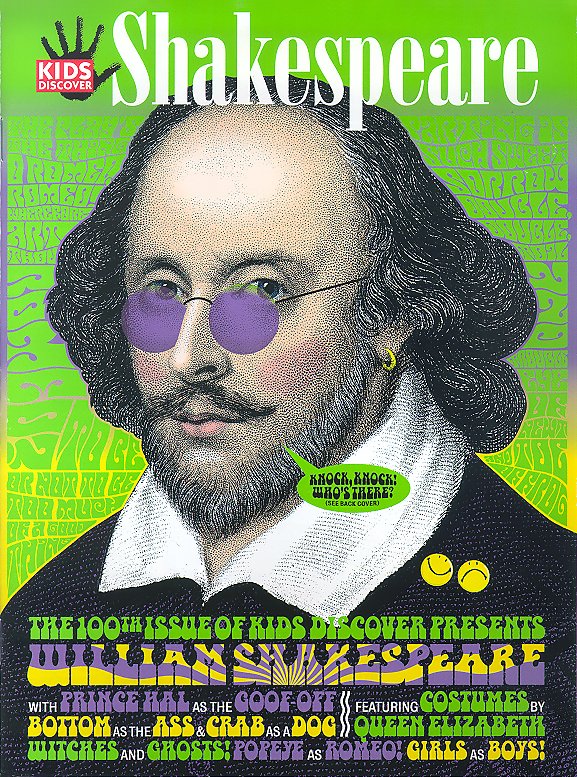

Mary K Baumann: We were married at that time and we were partners in our firm, Hopkins/Baumann. And we were doing, on a regular basis, a children’s magazine called Kids Discover. And we were trying to do a number of book projects. This was after 9/11. And I’m originally from Minnesota. And we said, “You know, we’ve got to think about getting out of New York. It’s getting too expensive and we can really work anywhere. So we found this great loft on the Mississippi River, on the northside of Minneapolis, and bought it and moved out here and have not regretted it since.

George Gendron: Is that the place that Patrick and I saw when we were out there with you?

Mary K Baumann: Yeah.

George Gendron: That place was spectacular.

Will Hopkins: Yeah. We love it.

Mary K Baumann: So we can live and work here—and hopefully die here. And, I mean, the interesting thing about being—and you probably not being in New York—when we were in New York, all of our friends were in publishing in some way, shape, or form.

Here our friends are architects, doctors, teachers, photographers, and other people too. But it’s a much more, I guess, realistic way of living. It’s not so much focused on just one industry.

George Gendron: Yeah, I understand that. Well, even here in Boston, I have to say, it can lead to a kind of professional “bubble” that you’re in, in terms of, you know, your friends are other editors and designers, illustrators, photographers, and so on. And, I don’t know, I have to say, selfishly, I’ve always found those people to be extraordinarily interesting to hang around with.

But I’m curious when you guys, well, I guess since you announced to your friends and colleagues that you were leaving, and this is post-9/11, that probably didn’t come as quite the shock because there were a lot of people who were thinking about whether they wanted to stay in New York at that point.

Mary K Baumann: We thought that people would say, “Are you out of your mind?” But they didn’t. They said, “Minneapolis? Oh, that’s a good idea.” Coincidentally, we were living in a building on the west side called The Apthorp which is one of the great west side buildings. And it had been sold and they were going to turn it into condominiums.

And we were in a rent-stabilized apartment and, I think, paying $1,700 a month for 2000 square feet. And they were going to sell our apartment for $4.5 million. We said, “They’re gonna try and get us the hell out of here.” So that was another motivating factor to move.

George Gendron: So we’ve talked about a small town in Arkansas, we’ve talked about Munich, we’ve talked about New York, Chicago, Minneapolis. I’m curious whether either or both of you feel that location kind of has an impact on people who are creating print products.

Will Hopkins: Oh, I think it does.

Mary K Baumann: I don’t know so much anymore. I mean, it certainly has expanded. I don’t think it’s as New York-centric as it used to be. However, I mean certainly the talent in New York is... oh, I don’t even know if that’s true anymore.

We did this magazine called American Craft, which was a bimonthly. And we had people working all over the place. We had great photographers in every city that we needed. So I think you can really do it. I don’t know if there’s the business acumen outside of New York for publications.

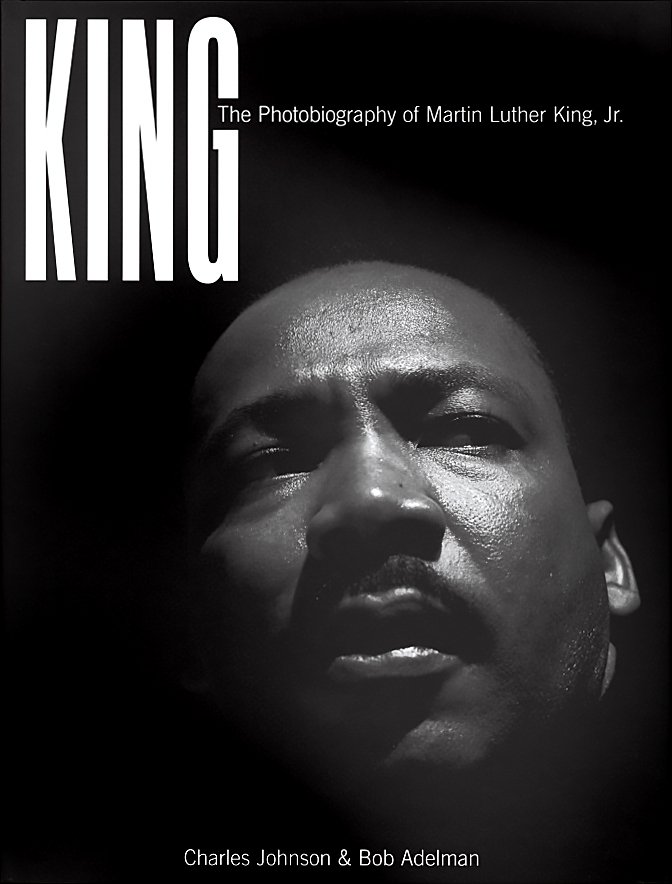

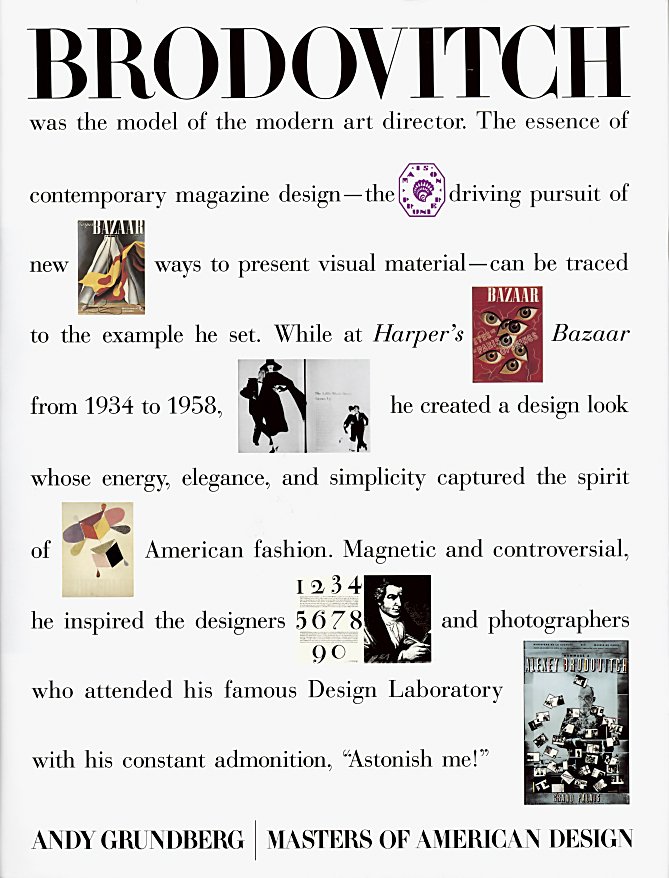

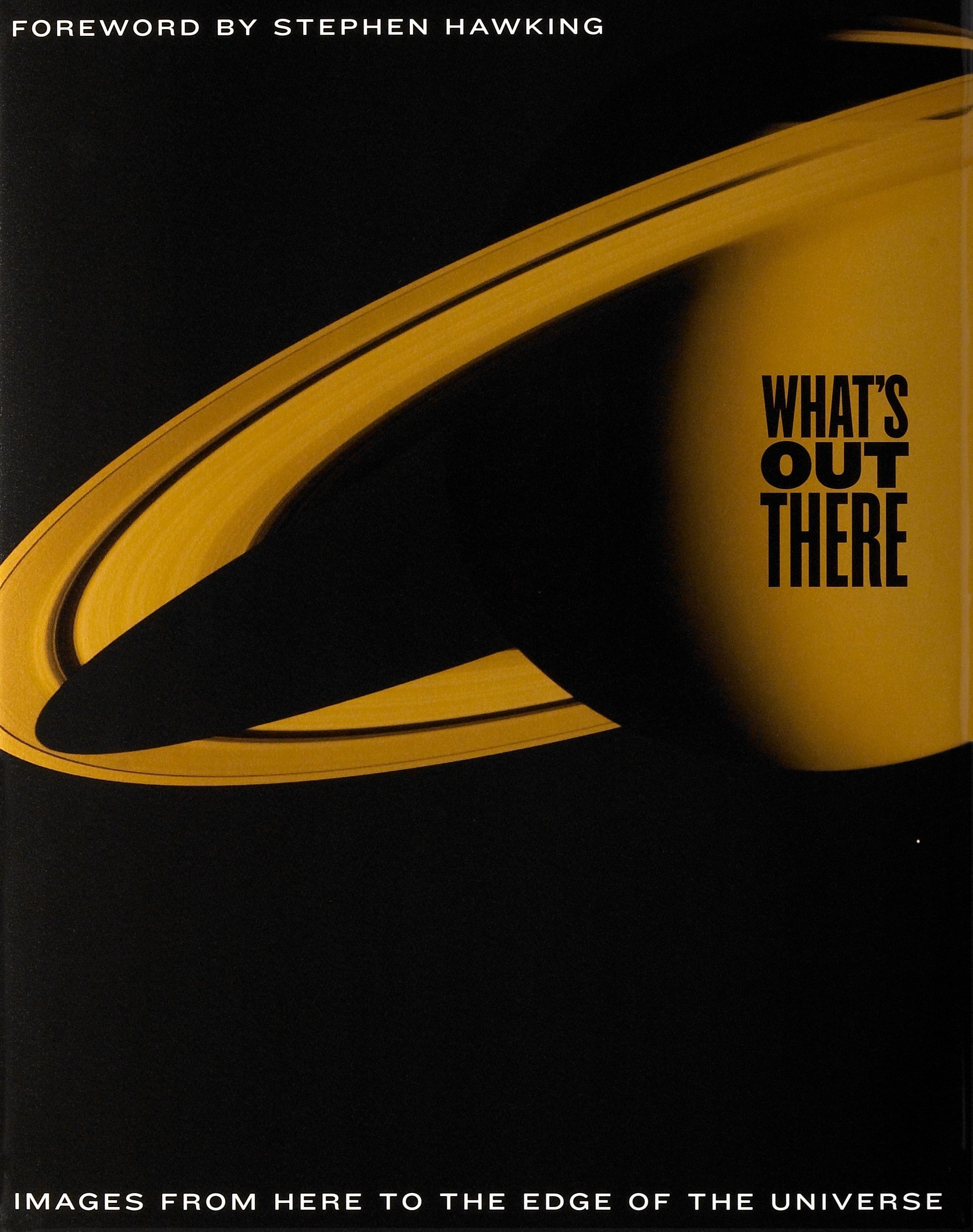

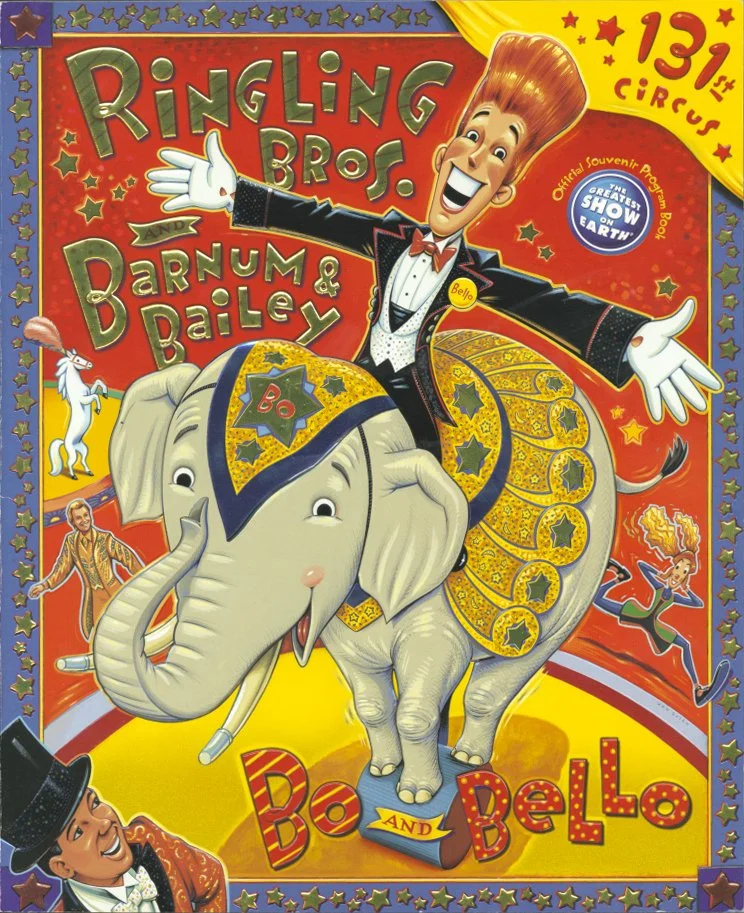

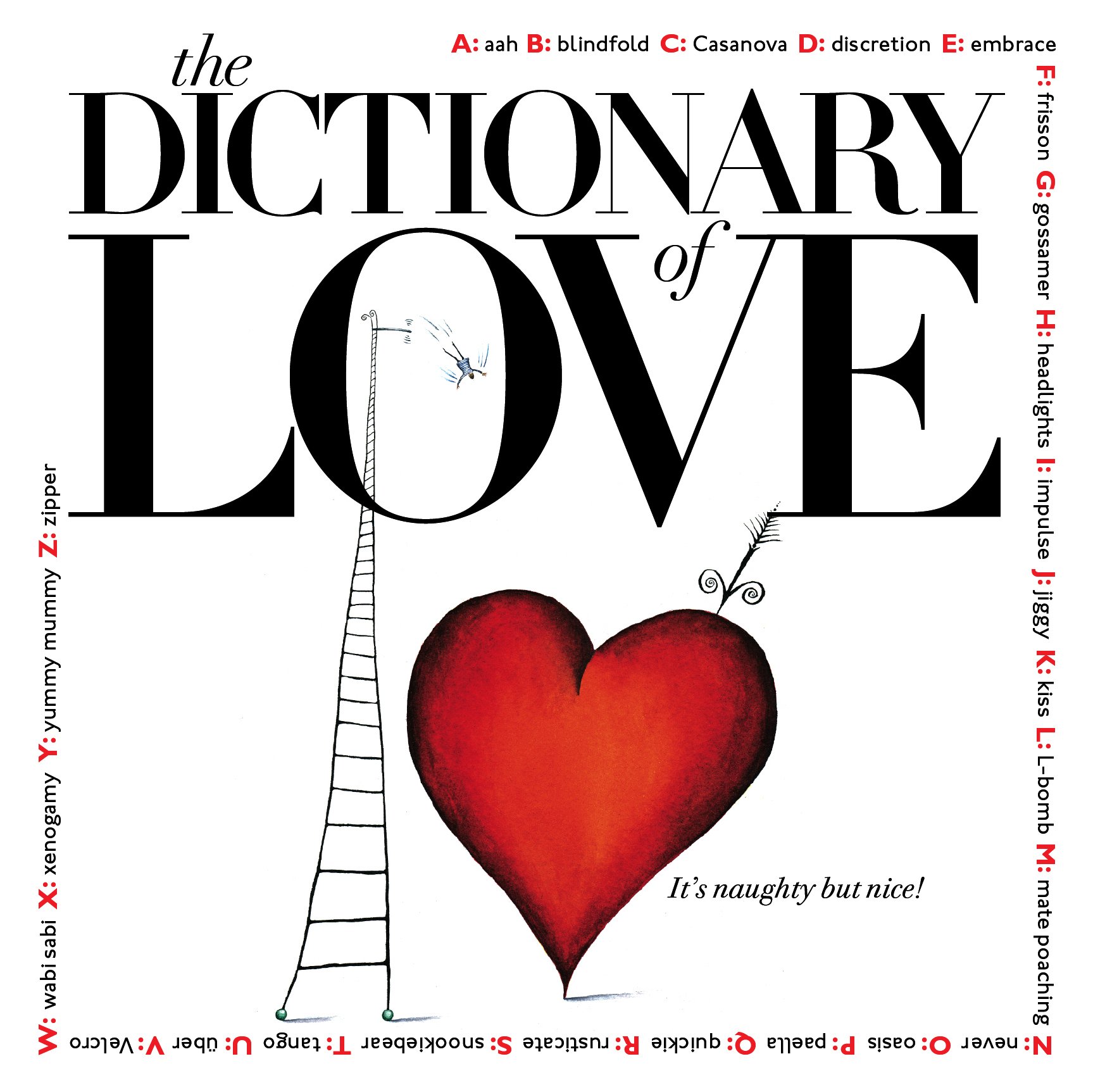

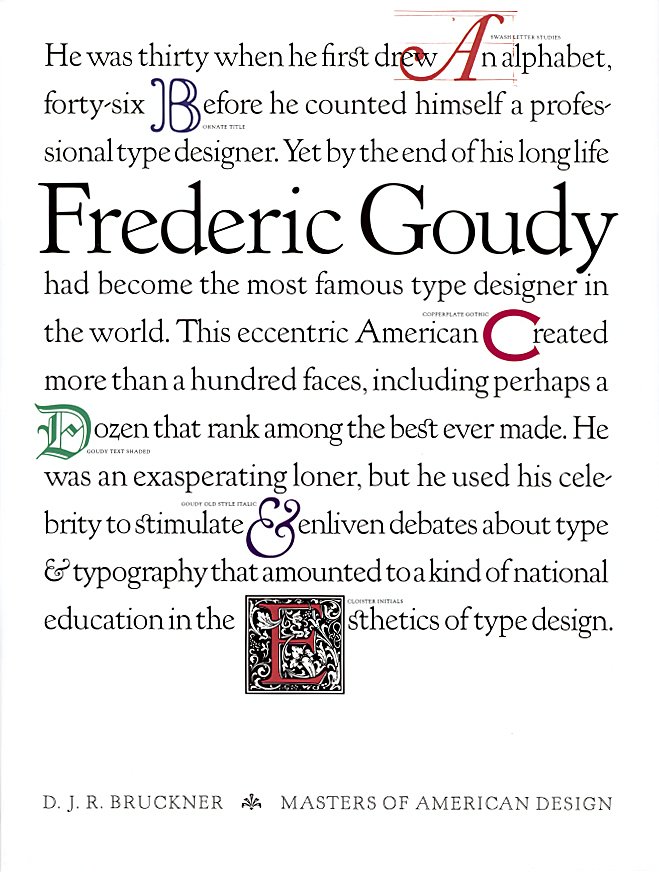

Books & Miscellaneous Works

George Gendron: No, that’s interesting. I hadn’t thought about it quite from that perspective. We were talking recently with Dorothy Kalins about Metropolitan Home, and she was talking about how interesting it is to take a look at a magazine like Inc., that was very much influenced by its founder, Bernie Goldhirsh, who was a graduate of MIT and was really enamored of innovation and entrepreneurship. And Fast Company was very influenced by the fact that its founders had worked at the Harvard Business Review. Wired, out in San Francisco, impacted obviously by the fact that you had the birth of the PC out there and kind of the concentration of technologists.

And so I’m not sure you could have launched Inc., or Wired, or Fast Company in New York given the unbelievable influence of Wall Street. It’s just something we think about sometimes. It’s that connection between where you are and where you work and the publication that you...

Mary K Baumann: I do think that the East Coast does dominate the news cycle.

George Gendron: Yeah. That’s interesting. Will, I’m curious, going all the way back to where we started this conversation in a small town in Arkansas, did that play a role in your career in any way? Was that an advantage for you? And I asked that because we were talking to Kurt Anderson about Spy magazine and Kurt made the comment, you know, it’s ironic when you think about Spy and how urbane a magazine it was in many respects. Kurt comes from Nebraska and Graydon Carter comes from Canada. And so we got into a conversation about how their naïvete about New York was actually a source of competitive advantage. They weren’t part of that crowd. They didn’t want to be a part of that crowd.

Will Hopkins: Yeah. I could see that.

Mary K Baumann: Knowing Will, and being from Minnesota, when I moved to New York, I felt it was an advantage not being from New York, because I was humbler. I wasn’t as arrogant. I was curious. And I think Will has that same quality. People liked you.

George Gendron: You’re pointing out something that’s true, which is, if you grew up in New York or around New York, a lack of humility and arrogance were considered to be sources of competitive advantage.

Will Hopkins: Right? Exactly. Exactly. Yeah.

Mary K Baumann: You know, people would always tell us that we were approachable. We would see people and we were kind to people and we were good with our employees and all those sorts of things. Which, I think, maybe not coming from New York, it was definitely true in both of our cases.

George Gendron: Yeah, I can see that. The first time I ever actually met you face to face was when Patrick and I were out doing a presentation for your event, and you know, by the time we got on the plane to come back, I felt like I had known you my whole life. As I do now!

Mary K Baumann: Right. Exactly!

Will Hopkins and his partner in life and work, Mary K Baumann, continue to do client work from their loft overlooking the Mississippi River in downtown Minneapolis. For more information, visit their website.