Part of the Story

A conversation with former magazine designer (Outside), editor (O, The Oprah Magazine), writer (Esquire, others) and best-selling author Susan Casey. Interview by George Gendron

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT COMMERCIAL TYPE AND FREEPORT PRESS.

Susan Casey has won National Magazine Awards for editing, writing, and design—a feat that may well be unprecedented in the industry’s history.

In her native Canada, they call people like this “Wayne Gretzky.”

She has worked—under various titles—for the following magazines: The Globe & Mail, Outside, Time, Esquire, eCompany, Business 2.0, Sports Illustrated Women, National Geographic, Fortune, and O, The Oprah Magazine. She also worked for the iconic 1990s fashion brand Esprit.

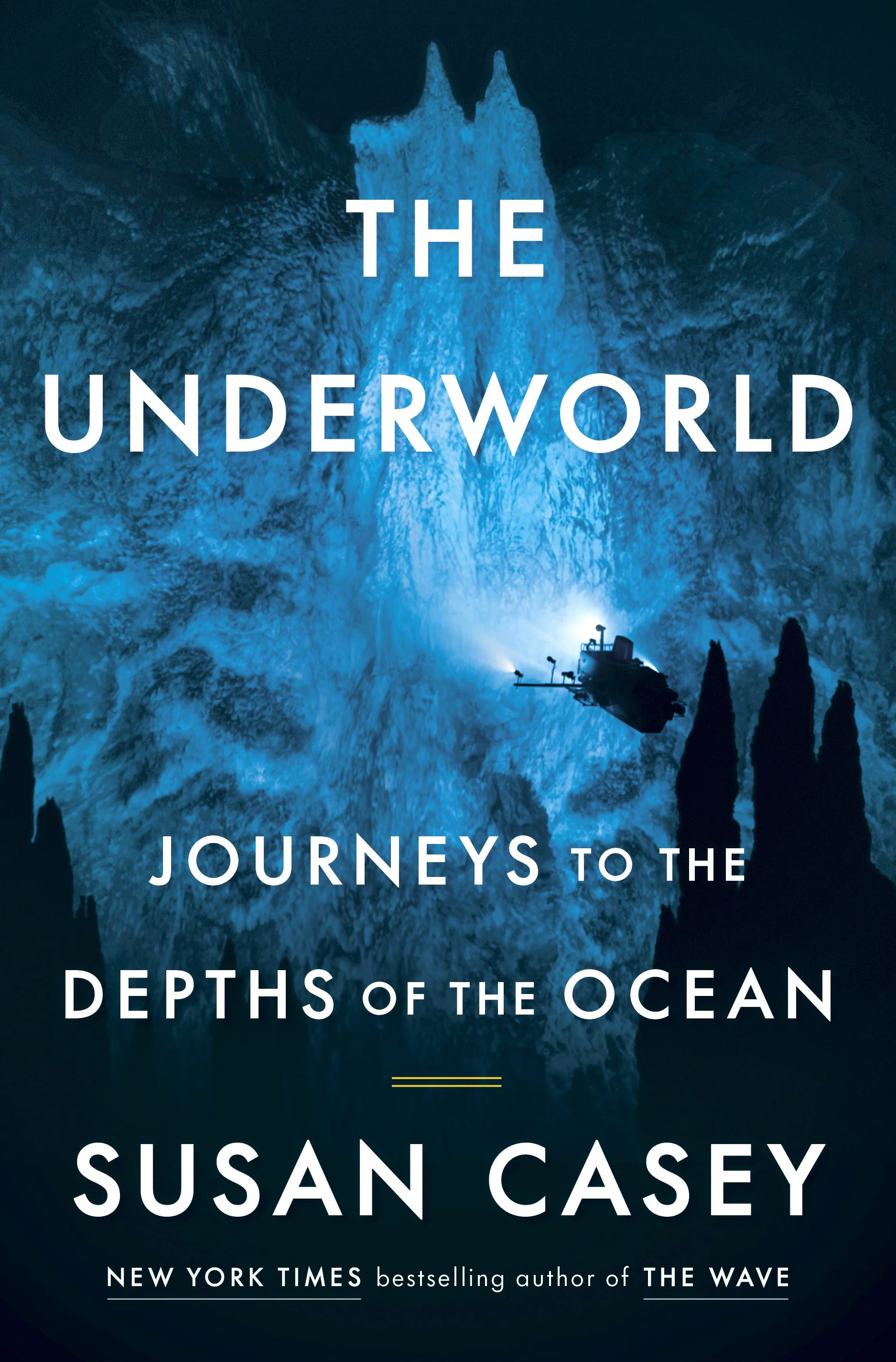

These days—literally on any given day—you’re likely to find Casey in the water, where she spent much of her childhood, later with the swim team at the University of Arizona, and, as an adult, as the author of four immersive books—all best sellers—about the ocean: The Wave: In Pursuit of the Rogues, Freaks, and Giants of the Ocean, The Devil’s Teeth: A True Story of Obsession and Survival Among America’s Great White Sharks, Voices in the Ocean: A Journey Into the Wild and Haunting World of Dolphins, and her most recent, The Underworld: Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean.

A self-proclaimed “outspoken designer” early in her career, she refused to accept the career path limits others imposed and instead laid the groundwork for a rich creative life.

“I really believe that people want to read stories, but as we get further and further into this fragmented attention age, the bar just keeps getting higher and higher.”

George Gendron: I happen to be talking to a former colleague of yours, Dan Okrent. He said one of the most flattering things ever written about him was the acknowledgements in your first book when you were talking about all the people at Time Inc. And he said, “Make sure you ask her what exactly did I do to help her out.” He told me an interesting story. Hans Teensma had just left New England Monthly, and Dan somehow had been admiring you from afar when you were up in Toronto. And he connected with you. And he said you came down and met him and you went back home and he thought for sure that you had taken the job. And then you came back down to North Hampton, you and your dad and hung around and then you were back home, then you called him and said, “Nah.” He harbors no ill will. And he blames it all on your dad.

Susan Casey: Well, my dad was a guy that you could not pay to do anything he didn’t want to. He was the only person who told me not to take the job at O. And I didn’t, I said no, but everybody else was like, “You’re insane.”

And I was like, “I really want to write this book. I’ve got a contract.”

And my dad said, “What are you going to do? Are you going to bet on yourself, or are you going to fold here?” And he just said, “Oprah schmoprah.”

And I was like, “Yeah, Oprah schmoprah.” So I turned that one down too.

George Gendron: I was doing a bit of research and I came across the most interesting quote from something you had written, and here it’s verbatim:

While I was watching for the side effects of the jolt of testosterone, a nice thick brow bone perhaps, or some new facial hair. The flip side of tribulus terrestris snuck up and delivered a jolt of its own. This stuff makes you wicked horny.

Susan Casey: I wrote that?

George Gendron: You wrote that. “This stuff makes you wicked horny. I don’t know if my muscle mass has increased, but I’m having too much fun to care.”

Susan Casey: I was young. What can I say?

George Gendron: Give us some context for this. Where did this appear? What were you doing?

Susan Casey: In Esquire. I’m sorry to say that probably a lot of people read that. I had a column called “The Overstimulated Girl.” It was the result of me being in my early thirties, but still competing in sports and specifically swimming, in open water races, where I was again, swimming against people who are younger, wanting to keep an edge and looking around like, “What can I take?”

And so David Granger and I, we’d constantly be comparing notes about this stuff. We were friends and he was like, “You should write about this for Esquire.” So the deal with “The Overstimulated Girl” was that every month I would try a new performance enhancing drug, but there were two caveats: it had to be legal, and it had to be good for you.

Because I mean at the end of the day, my goal was not to like mess myself up, it was to enhance. I was kind of an early biohacker I guess. So I started that column. And tribulus terrestris is a precursor to testosterone—these days everybody just takes testosterone—but it works. It’s an herb and it works.

George Gendron: You were kind of ahead of the curve here. I mean, it wasn’t as if professional athletes weren’t doing it. But these days you go out and half the time I find when I’m having coffee or drinks with friends, all we talk about are supplements. You know, it’s kind of accepted in a way it hadn’t been back then. And so this idea that you were just going to take a supplement, do it for 30 days, and then write about it was—it was pretty cool. Were you ever concerned about the medical consequences?

Susan Casey: Well, I was looking into that, you know. That was part of the, “it has to be good for you.” I mean, I still was in the sports world, so I had access to trainers and coaches and things like that. And you know, I’ve always been interested in this. But I was the guinea pig. If it felt bad in my body, I would stop taking it. And I would write either I stopped because I didn’t like it or I stopped because I didn’t think it was doing anything, or it was bothering me somehow.

There was no shortage of stuff, but some of it was pretty funny. Like around that time there was an Olympics. And I think it was the Japanese marathoners—female Japanese marathoners—who were doing amazingly well. And people were like, “What are you guys doing in your training?”

And they were like, “We’re taking this larva from giant hornets” or something.

And I was like, “I want some of that hornet larvae.”

And so that’s the kind of thing I was doing. It was an editorial project as well, for me, just investigating. Sometimes I look back on that and I think, you know, that was really a career path I could have taken, I think at that time I could have really gone down that path.

And I remember having a conversation with my agent, who at the time was Sloane Harris, who’s just an amazing literary agent. I said, “I think maybe I should write a book about this—these supplements and these ways that you can perform better in your life.”

And he was like, “Nah, nah.”

He worked at ICM and Binky Urban, who was one of his partners there, had a hip problem. And I was like, “Take MSM. Do not take glucosamine and chondroitin, just take straight MSM.” It’s what they give to racehorses when they have leg problems.

So Binky took the MSM and it fixed her hip instantly—which if it works for you, it works very fast. And she was like, “What else should I take?”

And I remember being on the phone with her, just going through a list and I just thought, you know, I think maybe there’s something here.

George Gendron: Have you ever looked back and regretted that you didn’t do the book and pursue a career as a science writer? Well, you have, in a way.

Susan Casey: I’ve always been really interested in science because that’s where so many good stories are. And I do think it was something that I could have done and didn’t do. And I’m not sure why Sloane was so opposed to it, but he was really helping me decide what to do. And he was very good at that. He steered me to The Wave.

George Gendron: That was two decades ago, but still, have you got any recommendations?

Susan Casey: I’ve got lots.

George Gendron: You know, like for thinning hair?

Susan Casey: I’ve got lots. I’ve got lots. Okay. For thinning hair—there’s something that blocks testosterone for thinning hair and it’s, I can’t remember the name of it. It’s a prescription drug. It’s pretty harmless. I’m sorry, I can’t remember the name.

George Gendron: It’s okay. I’m taking notes here.

Susan Casey: If you take testosterone, you’re going to work at counter purposes for hair loss. Here’s the other thing though, George, I think most men don’t realize how good they look bald. Men look great bald. I’m married to a bald guy.

George Gendron: So listening to the introduction to our conversation—as I imagine it—and thinking about your accomplishments: designer, editor, magazine writer, book author, open water swimmer. I have to ask, and you started to touch on this a little bit, what was it about your family, about your youth, about growing up that set you up to succeed at such an extraordinary level on so many different fronts?

Susan Casey: Well, you know, I grew up in Canada, in Toronto, in a family of athletes. My dad was a hockey player. His brother was a NHL hockey player, and my cousins were among the crazy Canucks, the downhill ski racers.

We were a ski racing family and a hockey family, and I was particularly interested in the water for reasons I can’t tell you. I just always was. And just sort of went one day to my parents and said, “I want to be a competitive swimmer.”

And they were like, “Okay.”

George Gendron: Wait, how old were you?

Susan Casey: Ten. And keep in mind that at the time I kind of knew how to swim, not very much. I don’t know where this came from. I just announced I wanted to do it. As it turned out, there was a good swim team near where I grew up in the suburb of Toronto. And that’s how it began.

It was really formative for me. But the message I got was, “Of course you want to do sports. Go ahead, we’ll support you.”

George Gendron: What did your brothers do? What sports did they play?

Susan Casey: I have two younger brothers. One of them was a football player and he ended up playing all the way through college. They also played hockey and baseball and just about everything. But football kind of shook down. My other brother was a ski racer.

I never had the message at any point in my life—or in my career—where something was off limits for me because I was a girl. I was never taught that. I was never taught to believe that. I never did believe it.

You know, the thing is, being Canadian, you’re never overly self-confident. I always say there’s no such thing as an arrogant Canadian. I mean, you grew up next to this elephant next to you, the United States, and nobody in Canada thinks they’re the main show in town ever. It’s never like, “I’m sure I’m going to be successful at this.” It’s like just, “I’m willing to try.”

George Gendron: This is reminding me of the conversation we had with Graydon Carter. I said to him, having just read his book, I was surprised about how open he was about anxiety. And he said, “Well, I’m Canadian.” And yet he went on to talk about how he felt it was a source of real competitive advantage in a variety of different ways.

Susan Casey: I do too. I think that particularly for young career people, like as I was—I went to school in the States on a swimming scholarship at the University of Arizona, but I soon found myself back in Toronto, in my bedroom where I grew up, wondering what I was going to do because my student visa was over when I graduated.

I was very depressed. I wanted to be back down in Tucson, Arizona. But actually getting into the magazine business in Toronto was great because it’s a small pond. And when you’re in a small pond, you just get your hands on the wheel far more easily. There’s less at stake, so they let you do things. And I think it’s a pretty valid way to start. It was helpful to me anyway.

“We would send people off on these amazing experiences like to the top of Mount Everest. And I was like, ‘I kind of want to go to the top of Mount Everest, but in my own way.’”

George Gendron: So at the University of Arizona you majored in philosophy in French Lit. So which of those was most instrumental in helping you in your life as a designer?

Susan Casey: Well, really, I think I majored in swimming at the University of Arizona. But when I got there I was really interested in everything. I wanted to take every course. Ethical Philosophy really struck me and so did—I wanted to be an English major, but I had a bad first English class, so I switched to French. Now, being Canadian, I speak French, and so instead of taking English Literature, I ended up taking French Literature.

And then I also took a lot of art classes. I took studio art, and it turns out that there were great artists in Tucson at that time—painters particularly. And so it was a little bit of everything. And I took graphic design. I had a great graphic design teacher. But I wasn’t really thinking about a career.

I don’t know what I wanted to do. Perhaps if I had been allowed to stay in Tucson, Arizona, I would’ve gone to work for an ad agency. That was sort of the level of my thinking at that time. But, you know, I ended up back in Toronto.

And magazines kind of came to me. And then the second I started working in a magazine, I was like, “This is it. This kind of combines everything I love. It’s storytelling, it’s visual, it’s the written word.” That was that.

George Gendron: Yeah. I understand that. I think given the pressure on young people today to be really focused at an early age on what they want to do is not only really corrosive, but it also creates this misunderstanding on their part that anybody who’s been successful has been really strategic about this.

Susan Casey: I remember thinking that I wanted to be a photojournalist. And I thought a photojournalist was somebody who took pictures and then wrote the story about the pictures. Turns out the University of Arizona had this really sort of elite photography department, and you know, I got in there and they were like, “Oh, no, no, no. You will be a photography major.”

And, and then it got very technical and I was like, “No, this is not what I thought it was.”

So it was a lot of trying to figure it out. Being in sports at a really young age—and you know I was 16 when I went to university, and a young 16 because swimming really doesn’t give you a lot of social immersion. It’s your swim team and you’re looking at the bottom of the pool for five hours a day. And I just was very naive and unsure of the world. Curious, but pretty clued out, I think.

George Gendron: I’m going to get ahead of myself here, but you brought this up and so I can’t resist, which is, I grew up with a bunch of young guys who were swimmers, not at your level, but they were competitive swimmers. And they were all introverts. And by that I don’t mean they were solitary or anything, but they were just introverts. And, um, when I think about magazine editing in particular, or magazine making, God, it’s such a collaborative enterprise. How do you think about that? Are you an introvert?

Susan Casey: Totally. I think all writers are. And I always have been. I don’t know. You know, it’s a good question about swimming. I think it would be fair to say that I don’t know very many naturally extroverted swimmers. But the thing is, like a lot of people, I think I’m totally an introvert, but I can bust it out when I need to. I can be an extrovert when called for, but then I need to recover.

And that actually became a bit of a challenge later in my magazine career when part of the job, quite clearly of being an editor-in-chief, is to go out and show yourself, go to events. I never wanted to do that. I just wanted to get out of the office whenever the work would allow and go work out.

You have to be able to get up in front of people and convey what it is that you’re looking for and you know, articulate direction. With books and magazines, there’s always an element of, Well, you have to promote this to the audience that it was made for. So there is that part of it. With books in particular, I have to do a lot of public speaking now—and I love that, actually. I find it really fun. But like I said, then I want to go away and recover.

George Gendron: So I’m trying to figure out the chronology here, but at some point you do come back to the states and you land a job—it sounded like it was a good job, at least in terms of title—at Esprit. That was a really sexy company, viewed from the outside. One of the things that made it so interesting and sexy was it was part of this group of companies—Patagonia, Ben & Jerry’s—that they were introducing us to the idea of social responsibility and business. And yet you did not have a great time there.

Susan Casey: So I went there when the company was undergoing a big change. The Tompkins, who started it—Doug and Susie Tompkins—had gotten divorced and Susie had taken control of the company and she started The North Face. Doug and Yvon Chouinard from Patagonia were very close friends and, I think, real visionaries.

And Susie hired Neil Craft, who was the original creative director for Barney’s. And Neil brought in Rip Georges, an art director who I knew and admired his work. Rip hired me to come down and basically oversee the art department, which was big. It was like 10 people.

And I had just gotten a green card and I wanted to move to the States. So this seemed like a great opportunity. And I lived in Vancouver. My husband and I (at the time my husband) drove down to San Francisco and found a place to live. And almost immediately I knew that I was in trouble at Esprit.

I remember the very first day that I was in there looking through the art department—and they had won so many awards, right? Gilles Bensimon had done the photography. It was pretty well known. And so they were talking all this talk about this socially-progressive company, but when I went into the art department, like all I saw were corrugated plastic packaging and neon ink—it was a big greenwashing thing, really.

I just remember thinking, Well, if we’re really going to do this, we should get rid of all this packaging. And just people looking at me like I had three heads, like, “You just can’t do that.”

So what I would say about Esprit—I learned a couple things that were really valuable. One was that I never wanted to use any creative powers that I had, any communication abilities that I had, to sell stuff. That wasn’t for me.

I wanted to tell stories. And if there was no narrative involvement in the selling, like it wasn’t a relationship with a reader, a relationship with an audience, I did not want it. Advertising and marketing was not for me. And fashion was not for me.

I ended up in this situation again, but I learned that it was never good to have two bosses. So I had Neil on one hand, Rip on the other, and they wanted different things all the time. I don’t know, I only lasted about eight months there. I couldn’t stand much about it. But particularly I couldn’t stand the hypocrisy of the company. It ended up crashing and burning shortly thereafter.

George Gendron: Yeah, it did. Yeah. It’s interesting because too often we grow up with this understandable belief that you’re going to learn the most and grow the most in organizations that you really love and admire. And sometimes that’s just not true. Sometimes it’s kind of like you’re going down a path and you follow something and you discover it’s a dead end, it’s a cul-de-sac, and you back right out. And you’ve earned a lot. And it sounds like that was true for you at Esprit.

Susan Casey: Yeah, it really was. I remember one time we had done an ad campaign with Steven Meisel. And I remember the prints came in and they were like, unbelievable. And I remember just thinking, Oh my God, like I’m holding a Steven Meisel print! And then I remember somebody and probably Susie Tompkins or Neil Craft came over and said, “You know what? We picked the wrong model. And we’re just going to throw this in the garbage.”

I remember the shoot cost $250,000. And I think it was 1990, maybe. And I just remember thinking, Seriously?! You’re going to throw away these Steven Meisel prints? And thinking, you could never say that you are good at your job if you’re throwing away a $250,000 photo shoot. If you don’t like the model, why didn’t you decide that before you hired him?

I remember her taking scissors to a Yohji Yamamoto sweater and saying, “You know, what we need to have is this sweater, but sleeveless.” And just watching the sleeves come off this beautiful—anyway, it just went on like that. The fashion world was not for me.

George Gendron: So you go from Esprit to Outside magazine. How did that come about?

Susan Casey: I always loved Outside magazine as a reader. I knew they were in Chicago and I always thought that Outside magazine was just top-notch on writing and content and stories. Like there’s so many famous, memorable stories from Outside. But I always thought the design lagged. I particularly noticed that when I read one of their anthologies—best of first 10 years or something—and I enjoyed reading it as a hardcover book more than I enjoyed reading the actual magazine.

I’ve always felt like art direction and editorial, they’re not separate, right? Like, readers don’t look at this and think, Oh, I really like that typeface. They think, I want to read this. Or not. So for whatever reason, I wasn’t loving the experience of reading Outside magazine as a magazine.

And when I heard that they were moving from Chicago to Santa Fe, I reached out to them. I wasn’t, again, a usual suspect or an obvious name for that job. But eventually they contacted me. And Santa Fe was super interesting to me because I loved living in the Southwest and I would be excited to go back there. So I ended up meeting with Mark Bryant, the editor. They hired me and I moved to Santa Fe when the magazine moved to Santa Fe. So that would’ve been like 1994.

I remember something that really had a big impact on me was after I ended up working for The Globe and Mail, which was Canada’s national newspaper—like The New York Times of Canada. And they had a number of magazines. But we were in this newspaper environment.

I went to a conference, a newspaper designers’ conference. And I remember going to this seminar where they had presented the results of a study where people wore devices on their foreheads. And then they measured how their eyes tracked when they looked at various layouts. And they learned some things about what gets people’s attention and where you should put things.

And it was basically about visual hierarchy. And that ended up informing absolutely everything I ever did—putting words and images on a page—and understanding the hierarchy that gets a reader into the page. And there was a moment in time, maybe some people will remember and lots won’t, but there was this moment in time where there were typographers winning a lot of awards and they were like, David Carson I’m thinking of who was a friend of mine actually.

But I thought they worked as pieces of art, but they had nothing to do with readability. And that was not my jam at all. I wanted to try to figure out a way that words and images could end up so that the whole was more than the sum of the parts. That you don’t look at it and think, What a cool piece of artwork. It was like, I want to read this story.

George Gendron: Your period at Outside magazine was really formative in so many ways. Can you recreate the story of the event that led up eventually to the book Into Thin Air? You were there then at that time.

Susan Casey: Yeah. In fact, that came out of an editorial meeting. I’ll start a little before that. Working at Outside Magazine from 94 to 1999. I always tell people it was like being on the original cast of Saturday Night Live. It was John Krakauer. It was Mike Paterniti. Hampton Sides, Sarah Corbett. I mean, it just went on and on. Kevin Fedarko, Alex Heard, Annie Proulx, David Quammen. I could go on.

So that, for me, was absolutely an incredible opportunity to be around amazing storytellers. And as I said, the magazine was really a pretty tabula rasa for design, so I redesigned it a bunch. But the other thing was, it was a magazine makers’ staff. I was a creative director, but I was very outspoken. I pitched stories.

We used to—John Thaman was on our staff and he was a particularly gifted headline writer. And we used to really play around like, how long can we make the headline? Can we make the first stands of Hiawatha into a headline?

And so that was fun. It was really a collaborative environment. And I remember one time—Everest was obviously a big part of our beat—seeing a bunch of photos of just a bunch of garbage at the top of Mount Everest and finding out, not being a mountaineer, but learning about it, working at Outside, that there would be a kind of a city that would spring up each climbing season.

And I remember thinking. What do you mean? There’s a whole city that springs up and then it just, should there be a city at the base of Mount Everest? And then it was like, “Okay, what’s that like?” So the story that I pitched actually in an editorial meeting was, “Let’s send a writer to this city.”

There’s probably all kinds of stuff going on there—there’s probably like all kinds of human drama going on in this little city—and spend a month in this city and see what goes on. Because this is not something that I really knew about. And I remember Mark picking up that idea and saying, “Let’s send John Krakauer—John was a really gifted climber, very experienced. And he was on a book tour for Into the Wild, which was a book that he had written about, a really amazing book about Christopher McCandless in Alaska.

So Mark called John and John said, “Well look, if I’m going to go to Everest, I want to climb it.”

So that ended up pushing the story back a year because we had to go out and figure out how we were going to get $70,000 to buy a permit for John to go climb Everest. And if John had gone up the year that we proposed originally, everybody summited on a beautiful sunlit day and came back down and everybody, it was all fine. But of course, that’s not what happened the following year when he went up.

So we knew he was there. He was on a really good team. We obviously knew that John could handle himself as a climber. He had climbed first ascents of many things, but never in what they call the death zone above 20,000 feet. And so I remember this very clearly because it was shocking that we were having a barbecue at Hampton Sides’ house and everybody was there. And we heard, we found out pre-internet days, right, that people were dead. Nobody knew where John was.

And so there were about 24 hours in there where we didn’t know whether John was okay, whether he was alive or dead. And then when the story started coming out, it was just like. “Oh my God!” So that’s how Into Thin Air happened.

And then John wrote a story, 17,000 words. This is around the time when you’re starting to hear “People don’t want to read. People don’t read stories in magazines.” It’s like, “Yes, they do.” It’s just that the bar is pretty high. And anyway, that 17,000 word story was read by a lot of people.

And there was another really formative moment in there because I just remember after that, John was shaken by that experience, affected as you, I think deeply. But he immediately turned to writing the book. And I remember walking into Mark’s office one morning and John had sent the manuscript and it was in a box. And here’s this box of, I don’t know, 400 pages. And I just remember opening it and looking at the cover page, and thinking like, that’s somebody’s soul in a box. And that moment really struck me: Uh, I really want to write books.

George Gendron: Wow. So that really wasn't an epiphany. Those don’t occur very often in people’s lives.

Susan Casey: Just holding the manuscript, the fruit of this incredible experience and this unbelievable wrenching work that went into it, it really hit me. It was like, this is something really worthwhile.

George Gendron: What’s interesting about that story is if you go back to the genesis of what you were talking about, you were behaving or thinking about or contributing as much as an editor as you were as a designer,

Susan Casey: Right? I’ve always been a designer with a lot of opinions about words, because to me, the design and the words, like I said, really have to support each other. So I would refuse to design a story without a headline, for instance. I would refuse to do anything without the words. How I did it would be dependent on those words. And also as a typographer, my grail was, How can we present this in a more beautiful, more readable way?

George Gendron: When you and I were talking a couple of weeks ago before you made a quick trip out to the Great Barrier Reef, you used the phrase about your time at Outside magazine: “That’s when I started to teach myself how to be an editor.”

Susan Casey: Yeah, I mean these are great editors. And we had big, you know, 11 x 17 pages that would come along and they would have the edits on them. So I would be looking at the edits and studying the edits. I did that for a long time.

George Gendron: So the designer who has always thought of herself as an editor/designer, or designer/editor, is now actually teaching herself how to edit, but with the goal maybe of wanting to write books. Was it that explicit at that point: “I want to write books”?

Susan Casey: I’ve always been a writer. I think you know if you are. But I never thought I could make a living as a writer, and I really did have to make a living. And I loved designing, so I was learning as I was making a living and designing that I was definitely evolving away from designing because I was getting frustrated. I wanted to be part of the story as well.

We would send people off on these amazing experiences like sending John to the top of Mount Everest. And I was like, you know, “I kind of want to go to the top of Mount Everest, but in my own way.” It was more aquatic, what I wanted to do. And so I don’t know if it was that straightforward.

I know this very well now, especially for nonfiction, in order to write a book, you need to have a story that’s worthy of a book. I wasn’t in that position, but that came shortly thereafter when I did find a story that was worthy of a book. I was trying to become better as a writer and as an editor.

George Gendron: Yeah, that makes sense to me. Now, around this time you’ve been at Outside magazine, I guess five years. And on the one hand you’re experienced, on the other hand, you’re still young. And you get what I can only describe as a dream job offer from Norm Pearlstein. I mean, can you describe what you—the first time somebody reads this, they’re going to do a double take.

Susan Casey: It’s really strange. It’s still strange to me. We had had a lot of success with Outside in the magazine world. We had won a lot of awards. We were starting to be known for the quality of the magazines we were putting out, both the literary quality and just the magazine making of it.

I was starting to think about moving on but I didn’t know where to, and I had met up with John Huey on I think it was ASME judging. I was really struck by John’s irreverence. I’ve always had a deeply irreverent streak myself. I remember we just spent the whole time just howling with laughter. And I remember thinking he had just gone to Fortune. I was like, That would be an interesting magazine to work on.

And around that time, I forget what prompted this, but I ended up meeting Norm. And Norm had brought John in to do Fortune. They were both from the Wall Street Journal. And so Norm offered me a chance to come to Time Inc. as an editor at large. And at the time it was 1999.

It was Henry Mueller who is a former editor of Time Magazine, and Dan Okrent who’s one of the all-time great editors, and me. And I was, as I told you before, like in a very different place in my career. I think they brought me in there because they wanted me to work on art direction, but I was also given a mandate that I could do other things. And I did.

George Gendron: Meaning what?

Susan Casey: I wrote a column for the first magazine that I worked on for them, which was a spinoff of Fortune called eCompany. eCompany was based in San Francisco. Probably nobody remembers it now, but it was at that time when there were 300, 400-page magazines coming out about the internet. So we had so many pages that they were like, “How are we going to fill these pages?”

“Susan, you want to write a column about industrial design?”

And I was like, “Sure.” I had a lot to say about that.

It was the early days of Apple but also other companies. Starbucks. Design made a big difference to these companies and it was starting to become part of what it looked like a progressive company and a successful progressive company in this visual age was going to have to take this into account.

So I started writing a column called “Object Oriented.” It was about corporate design and not just in the real world, but digitally as well. And as it turned out my editor on that column was Tim Carvell—The most brilliant editor and writer I’ve ever met. And Tim is now the showrunner for John Oliver. He used to be the head writer for The Daily Show with John Stewart.

So Tim was my first editor. And Tim taught me a lot. That was my introduction to writing and sometimes I would write a four or 5,000-word column because we just needed to fill those pages.

George Gendron: Yeah, those were the days. Oh my God.

Susan Casey: Yeah. It seems surreal to talk about it now. I remember so many things from that era. Like we rented out Pac Bell Stadium in San Francisco for our launch party. And it was just this big glistening bubble about to just pop. We were right there at the very moment it popped and a little late to that party.

“The deal with ‘The Overstimulated Girl’ (Casey’s Esquire column) was that every month I would try a new performance-enhancing drug, but there were two caveats: it had to be legal, and it had to be good for you.”

George Gendron: But, but every time he turned around, there was another magazine. And they didn’t look like traditional startups. They would come out and they’d be 280 pages.

Susan Casey: Yeah, no, eCompany was a big fat magazine for a couple years. And then it was folded into Business 2.0. And then I think both of them—I forget what happened to Business 2.0—went on for a while longer, but I feel bad. It really was fun.

George Gendron: Yeah. So you ended up staying at Time until 2008?

Susan Casey: Yeah. It was almost 10 years. I did a number of things. I think one of the reasons I’ve never been a big stay-er at jobs. I tend to get really restless. But they kept moving me onto more and more interesting projects. And I loved my bosses, so I really enjoyed working at Time Inc.

George Gendron: Yeah. Including you, uh, you launched, you were part of the team that launched, Sports Illustrated for Women.

Susan Casey: I didn’t work on the launch of that. I worked on the relaunch of that and that was my first time being an editor in chief. And it came about because AOL bought Time Warner. And Norm said to me, “I think we better put you on a magazine because I don’t know, these editors at large—that looks like an item that might get swiped off the budget here.”

We were still in shock. I was like, “Surely we bought them. Really? They bought us? What does that mean, exactly?”

And so Sports Illustrated Women had spun off from Sports Illustrated. And it was a little bit offensive to me as a female athlete who never thought of herself as a “female athlete.” Like it was just, I’m an athlete, okay? But all the women who worked on Sports Illustrated proper had basically put out a test issue of this magazine and Norm had asked me to critique it. And I took it apart pretty savagely.

And one of the reasons was because when I was at Outside, I was really noticing that our readership had become 50/50. There were more and more women coming to Outside. And I think that was because there were more and more women actively involved in various sports.

But actively involved in sports does not mean that we are just going to cover the WNBA and women’s soccer. It means skiing. It means mountaineering. It means everything. So I was really wanting to take Sports Illustrated for Women and turn it into something that I thought had a more commercial chance, which was really a female version of Outside.

So I wrote a proposal for that. I knew that what they were doing wouldn’t work because there just weren’t enough women who cared that much about women’s softball. If you really care about baseball, you’re probably watching men’s baseball too. So it didn’t slice and dice that neatly in my opinion. So they let me try it.

And I did it for about two years and we had fun. I wouldn’t say it was super successful, but it wasn’t unsuccessful either. But it was never going to be one of those big circulation magazines that Time Inc. wanted. Eventually it got shut down, but I ended up staying and becoming the development editor for the company. So then my next remit was like, Let’s launch something that could be really big.

George Gendron: What was that?

Susan Casey: Well, it never happened, but for a couple years I was like, “Okay, so AOL bought us, what can we do with that?” And I remember Isolde Motley, my boss, her daughter was at Harvard, and we were like, “Look at this thing called the Facebook. That’s really, that could be really something now.”

One of the things I had always really wanted was to take a women’s magazine and shake it up, really make it more ambitious in a literary sense and in a magazine thinking sense and less of what we thought of as a traditional women’s service magazine. And so I was trying to work on that format, but at the same time, I also wanted to do something really big so they couldn’t shut it down.

So I came up with the idea with Isolde helping me with a magazine called Love. And it was basically a magazine about finding relationships. And it was aimed at young women and it was very irreverent and it was going to have this digital component that we wanted to have AOL work on with us.

And then the merger condiment would make sense, right? Like there was something here that we could do. But we were early. I could not get myself through the corporate wringer on this. Like, I remember going down to Dulles and talking to AOL people and they didn’t care about these magazine people.

I couldn’t get all the wheels in the track, but we tested it, we spent quite a bit of money developing it. We tested it against Cosmo and it tested really well. It was going to have all these different online components where you could match with people. And this is in 2003. So it was early.

George Gendron: Oh, wow.

Susan Casey: But you know, I ran into this problem that I would later re-encounter, which was that the editorial side of the company was incredibly good, but the executive talent pool was less visionary. And I remember being very frustrated by the lack of executive direction for Time Inc.

George Gendron: Yeah. I’ve heard that from other people as well.

Susan Casey: You know, Every time they would reshuffle their decks, there would be new jobs, new titles and all this. But nobody had a vision for how to get into this digital world. There were some editors that were really on that, like Terry McDonell, who was one of my big mentors, and doing things but the company itself was really like just running around chasing its tail.

I mean, it was a bad deal, right? It was famously bad. It will go down in history as one of the worst things ever, right? It was awful. But there was this thing that you could just barely grasp the outlines of. And that’s what I was trying to do was figure out, What is that?

There is something we can do. There’s something—here’s the word—’synergistic’ we can do here. But it was just, I don’t know if I didn’t have the corporate chops to be able to get everybody aligned or whatever. It was just impossible to actually get it done—for me anyway.

George Gendron: You took time off for one of your books, didn’t you? Around 2007, 2008, 2009?

Susan Casey: Yeah. Actually it was after SI Women shut down. I had been pursuing a story—Walter Isaacson had asked me if I wanted to write for Time, and I said, “Absolutely.” This is when I was an editor at large.

And he said, “What do you want to write?”

And I had found this story as I was leaving outside. I had mono—my last days in Santa Fe had mononucleosis. And we lived in a remote area and I had a satellite dish. So when I had mono, I was like sleeping all bizarre hours. And I remember getting up in the middle of the night and turning on the satellite dish and getting the British BBC feed and seeing this documentary about these great white sharks. And I just couldn’t believe what I was seeing.

And I didn’t know where it was, but I figured it was in the southern hemisphere because I had never seen any geography like this. And I couldn’t figure out: What are all these great white sharks doing in this place? And there were these two guys in a row boat with all these sharks around them. And I just was staring at it.

And it was David Attenborough and then I found out that the place was actually within San Francisco City limits and it was called the Farallon Islands. And I had lived in San Francisco for several years at Esprit, and then when I was working on eCompany. And I never knew about the Farallon Islands. And this was my job at Outside, was to know about these crazy wild places with great white sharks. Are you kidding? American great white sharks?

So Walter was like, “What do you want to write about?”

And I was like, “I want to go to these islands.” And so this is again, kind of pre-internet, just beginning. And the Time research department is like, “Okay, let’s find out about these islands.” And we couldn’t find anything.

We found some scientific papers about seals, and that was it. And I then discovered that you can’t even get a permit to go to this place. Like even National Geographic couldn’t. But the BBC had done this documentary there, so Time reached out and got me a permit. It’s through the US Fish and Wildlife Service to be there for five hours.

And because this is back in the day when we had money, I chartered a boat from San Francisco and went out to the Farallon Islands with my assistant. And it is a crazy boat ride. Just an insane boat ride. You’re going over the San Francisco Bar and the Potato Patch and there’s the Farallon Islands.

And the reason they look so bizarre is because they’re on a different tectonic plate. The San Andreas fault runs right through San Francisco, along the ocean there, and it’s actually the edge of the Pacific plate. They just looked like what they are, which is what 18th century sailors used to call them The Devil’s Teeth.

So I ended up meeting the scientists, didn’t see a shark, and they were like, “Okay, we’re really disappointed.” I was going to write, I don’t know, a 600-word magazine piece for “American Place,” which is the back page of Time. And I didn’t see any sharks. So one of the scientists I think said, “Look, we can’t get you a permit, but we are in charge of the internship program, so if you come back next year, you can stay for two weeks.”

And I was like, “I’ll be back.”

So I went back the next year as an intern for this shark project and it was really mostly about bird research that was happening on this island and became friends with the scientists and had stayed in touch with them. And as I found out more and more about this place, the story just kept growing and growing, growing.

And here now is a story that is a book. So I realized it went from a tiny magazine story to maybe a bigger magazine story to, “Oh no, this is a book.” And Time Inc.—Isolde Motley and Norm Pearlstein and John Huey said, “Of course you could write this book. Go ahead, write it. You can take time off if you need.”

And I did.

George Gendron: Yeah. Yeah, it was extraordinary.

So you ended up writing The Wave in 2001, The Devil’s Teeth, 2006, Voices In the Ocean, 2016, The Underworld, which I just read. In fact, I sent you an email—and I don’t mean to flatter you just because we’re having this conversation—I said it was one of the best nonfiction books I’ve ever read. I also felt that way about Devil’s Teeth. I just reread it. And it’s gripping in a way, like a detective story almost. I can’t describe it.

Susan Casey: Well actually, so The Wave was my second book, so that was 2010. So Devil’s Teeth was my first book. And here’s the thing about Devil’s Teeth. I had a really good editor, Jennifer Barth. She’s just brilliant. And I was still going from that position of we have to get people to read it by making it impossible to put down. Just like in a magazine story and how you’re using typography and what your first paragraph is. I really believe that people want to read stories, but as we get further and further into this fragmented attention age, the bar just keeps getting higher and higher.

And so I was always cognizant of that. And I think for me, the biggest challenge with nonfiction narrative writing is structure. Because you never want to drop the thread of that narrative because you don’t have a safety net under you. Someone’s going to click onto TikTok if you lose their attention and any other of the million things they could be doing with that particular fraction of their attention.

Structuring is really hard. To me that’s the hardest part. You see some of the really great narrative nonfiction writing. That’s when you really want to start looking at, Okay, how are they telling this story? There’s a million ways you can tell a story. You make a choice.

I’ve always been of the mind that if you don’t have the right lead, the rest of it—it’s like building on a faulty foundation. For me, at least I can’t go on until I have the lead that I feel like it’s right. And part of it’s instinctual, I think, because like I said, you can do it any number of different ways, but you know it when you have that firm foundation.

George Gendron: Yeah, I forget who it was, it might have been Joan Didion who said, “I can’t write without having a headline, number one. And number two, I need to know how the story starts and I need to have a sense of how it ends.” And that makes perfect sense. Of course, it’s a lot easier to talk about than it is to do it.

Susan Casey: Yeah. And only in the Devil’s Teeth have I had a natural narrative. So it was, okay, I show up at this island and the book ends—you know how it ends. So that’s a chronological narrative more or less. The only book that I’ve had that the rest of it has been, okay, how are we going to knit this narrative together in a way that makes sense? Who are the characters? Who are the main characters? It almost feels like braiding with tweezers sometimes.

George Gendron: Well, you do it really masterfully. Are you able to talk about what comes next in terms of book projects or is it way too premature?

Susan Casey: I always have a hard time after I’ve written a book, and The Underworld took seven or eight years. And I really went into the trough at that time. I have several ideas that I’m pursuing. And I’m waiting for one of them to gel. I’m going to keep writing about the ocean. It’s my thing.

I’m starting to get a pretty good knowledge base about it, and it helps. It's the thing I find most fascinating, so that’s what I’m going to write about. But you know, there’s a difference between a story and a topic. I’ve got a few topics. I don’t have, yet, a story. And either I’m going to have to make a story or I’m going to find a story.

George Gendron: Yeah. Boy, that’s such a crucial distinction too. I think you either learn that really early on in whatever way it’s taught to you or you discover it. Or you just don’t. I mean, there’s so many writers who I think never really get it.

Susan Casey: You know, sometimes I find myself being jealous of people who take a topic and write a book about it. I have never been able to do that. It’s so diabolically hard to write a book that I never really want it to go out the door unless I think it has a shot of finding a readership. I would die inside if I felt like—it’s like having a kid, right? It’s like I want to give them the best possible shot in life. I want to make sure they get a good education. Once they’re made, sure that they’ve got the best possible chance. And that’s how I feel about my books.

George Gendron: I want to return to something that we talked about earlier on. You worked in magazines for roughly 20 years, and you’ve been out of that game for about 10 years now. Do you miss magazine making at all?

Susan Casey: Oh, totally. I love magazines and I love particularly when you get the team. My experience at Outside is sort of the height of that. But everywhere I went, it was really my goal to create a team where the whole would be more than the sum of the parts. And that you really can’t get on your own.

Going out on O was really great because O was in many ways my favorite job. And it was also a different kind of problem. It’s this big commercial magazine with big circulation and it’s channeling Oprah’s voice as opposed to coming up with a unique voice for a magazine. But at the same time, I wasn’t really sure how it could get any better.

I didn’t see that happening. I could see resources, from 2000 to when I left around 2014, every year it was a cutting thing, right? It was cutting people. It was cutting budgets. I got tired of that. And I could also see that there was going to be a diminishing return situation.

But I knew that I could write books with the team that I have for that. I have an amazing editor at Doubleday, Bill Thomas. And I could continue to do that. I believed that if I had any juice left, that I would put it towards trying to connect people to the ocean. But yes, I miss magazines.

George Gendron: So let’s go back to Oprah. You and I talked about it earlier. It sounds like it may have been one of the few times that you ended up really totally ignoring your father’s advice, right?

Susan Casey: They offered me the job twice. The first time I turned it down. And it was not because I didn’t want to do it, I really did. And I loved Amy Gross, who was the editor who went out. She was the one who actually kind of recruited me. I thought she did an amazing job. I thought the magazine was really well done.

But I had signed a contract for The Wave and I had done none of the reporting and I was planning to move to Hawaii. It was a serious contract. I had a responsibility. I met Oprah. Oprah offered me the job on the spot. And I loved her.

I wasn’t a big watcher of the show. I wasn’t that familiar, but I knew what she stood for and we connected and I really wanted to do it. And then I went back to New York and I was like, “I just agreed to do two things and I can only do one of them.” I went and spoke to Kathy Black and I said, “I really want to do this, but I need six months.”

And I had also agreed to cover the 2008 Beijing Olympics for Sports Illustrated, and I was in charge of covering Michael Phelps. So I didn’t want to not do that either. And also I was the only one who had credentials and had access to Phelps and I couldn’t let SI down. So I said, “Give me six months and I’ll be here.”

And they were like, “No, sorry, you’ve got to come now.”

And I was like, “Okay, then no.”

That was when everybody thought I was really nuts. And you know, David Granger, my buddy, he was like, "these jobs don’t come along very often."

And everybody was like, “You said no to Oprah?”

And I was like, “Well, I didn’t want to.”

So then I went off to Hawaii and there was the great financial crash, right? And I was like, “Why didn’t I take that job again?”

But then, I did report The Wave and I was writing it. The other thing that happened was my father died very suddenly. And so I think if I had gone to that job, it was a big blow to me personally and I couldn’t have just functioned. I didn’t function. It wouldn’t have worked out.

But about six months later, Ellen Levine called me from Hearst and said, “They hired somebody, it’s not working out. Would you consider coming now?”

And I was like, “Now is good.”

So I did. You know, I’d never thought I would get a second bite at that. And I did. And I was very grateful.

George Gendron: When you and I were talking before, prior to this conversation, you talked about the effect of your father’s death. It sounded like it was absolutely devastating.

Susan Casey: Totally. He was my main supporter and he was my role model too. He was just a great guy. I just missed him. And he was very fit and nobody expected it. He was only 71. He had a heart attack, unexpectedly. Very unexpectedly.

George Gendron: Yeah. Sorry to hear that. That’s always hard to deal with, the death of a parent. But especially when it comes completely out of the blue and there’s no preparation for it whatsoever.

Susan Casey: Yeah. And he was just so excited about The Wave. And he never got to read it. He was always there. He was always there.

George Gendron: Was there—I don’t mean this to sound trite and I hope it doesn’t, but did you learn anything from how you were able to deal with that grief and that sense of loss?

Susan Casey: I certainly did. I had a therapist at the time who said, “Well, you know, this is a tragedy, but now you’re going to be able to have a deeper well of compassion. Welcome to being human, okay? You are now officially human. And you are going to be able to be there in a way that you wouldn’t have been before for other people that are going through grief.”

And that is exactly how it has been. I have a sense of humility. It’s the most humbling thing in the world. And talk about a wave—grief is like a tsunami. And so I feel very present for people who are enduring that, we all will. And also I learned to be even more fearless, I think.

Because when your worst nightmare happens—for me it was my worst nightmare losing my father—you’re not scared of anything anymore. And you can survive it. And you will be stronger. And I’ve heard it said that grief can make you softer or harder. I think for me it made me softer, but it also made me stronger.

George Gendron: That’s very moving. Let’s step back for a second and see if we can put some of this in a different kind of perspective. We all know what an EGOT is, right? Someone who has won an Emmy, a Grammy, and Oscar, a Tony Award—the four major performing arts awards in the United States. Only 21 people in the world have ever done that. In the magazine world, we have our National Magazine Awards—I guess our version of the Academy Awards. There’s only one person I know who has received the award for General Excellence, Design Excellence, and Writing Excellence. We need an acronym for that. Got any ideas, as the only person who’s ever pulled that off?

Susan Casey: Maybe it’s a hat trick. Let’s go back to the Canadian hockey metaphor.

George Gendron: That's what I was thinking about, given your dad. So let’s close with this. Pat and I were talking about a friend and colleague we have who constantly talks about something that’s kind of in the air and in the water these days which is the importance of focus. You know, if you really want to achieve any kind of mastery, focus, focus, focus, 10,000 hours of practice, blah, blah, blah. On and on and on. Just think for a second, Susan, what you might have accomplished if you had just learned to focus in your life.

Susan Casey: You constantly have to work on this now because I think our brains are plastic and we’re being taught not to focus. But let me tell you something: swimming for five hours a day and staring at a black line on the bottom of the pool does teach you how to focus.

George Gendron: I can’t even imagine that. I can’t even—and I love the water, I love swimming. I can’t even imagine that.

Susan Casey: It’s not boring. That’s the thing that people don’t understand. In swimming, you’re always monitoring everything all the time. Michael Phelps said to me, “I've never gotten my head position right.” Just before he won eight golds in Beijing.

And that’s how you always are in the water. It’s like you’re always, what about my hand angle? How do I feel? What about my hips? Like you, you’re just always thinking about it. It’s never a zoning out sort of thing. It’s always just complete presence. And I’ve noticed over time that the more present you are, the easier things are.

George Gendron: Does that account for your success at open water swimming? Which was interesting. You once said that as a competitive swimmer—younger—you weren’t quite extraordinary in terms of the caliber of your performance. You had made the team blah, blah, blah. And then you said, “Well, when I was in my thirties, I discovered open water swimming and I kind of was relaxed and performing at a certain level wasn’t that important to me. And I got better.”

Susan Casey: I was in the room of the great swimmers, but I wasn’t going to make the Olympics. But I was around. But they don’t train swimmers the way they used to because they’ve learned it’s too much training. And what I was really prepared for in the end was to swim a 10-mile race. And I didn’t realize that until I started doing it.

George Gendron: Do you still hold some kind of a record? Somebody said you hold some kind of a record for open water swimming where you swam from island-to-island in Hawaii.

Susan Casey: I’ve done that a bunch of times. I think there was a record, I don’t know if it stands. It might. I had a few records that were around for a while, but records never last forever.

George Gendron: No, no. I realize that. Well forget the records, but the ordeal or the challenge—or you would probably say the opportunity—is to swim from Island A to Island B, Island B to Island C. Is that basically it?

Susan Casey: Yeah. It was to swim from Lanai to Maui, which is a race they have every year. I’ve done it a bunch of times. And one year it just turned out that it was particularly good conditions. I mean, that is part of it, right? It was like we had no wind, we had no waves. So the times were very fast. I forget what year that was.

George Gendron: That’s extraordinary. Swimming from island to island.

Susan Casey: Yeah. The last time I did that race, I ended up—at the end—swimming next to Peter Thiel, who was also an open-water swimmer. Pretty good, too.

George Gendron: Okay. We won’t go there. We’ve avoided politics completely.

Susan Casey: He seems normal enough in the water. But I guess not so much out of the water.

George Gendron: Here’s the last question I want to ask you. And I don’t mean to get into politics, but how can I not ask you this? Especially given what you’ve talked about in terms of kind of the, the four really major, major books, bestselling books about the ocean and the theme of conservation runs through all of them. Are you hopeful now about the future of the environment—in this day and age, right now, today?

Susan Casey: Yeah. It’s a really interesting moment to ask me that because as you said, I just got back from the Great Barrier Reef. And you know, the nine tipping points, environmental tipping points, three of which are in the ocean, one of which is corals, was basically announced by the group that does this—I think it’s in Norway—that we’ve passed the tipping point for corals.

So in other words, there doesn’t seem to be much hope for a future with corals. What I was doing over there was hanging out with scientists that are trying to work on this, and there are some things they’re doing, like they’re selectively breeding more heat tolerant corals and things like that. But at the end of the day, unless we do something about fossil fuel emissions and excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, corals will not survive.

And when you see the beauty of the Great Barrier Reef, it is mind blowing. So right now I’m not feeling particularly hopeful because I know what that tipping point is and how unlikely it is that we are going to even be able to stop at this point, at two degrees. That’s too much for corals to survive. And to live in a world without them is just unthinkable, really.

So at the same time, I have this pessimistic—you know, I can see the trajectory. I also met all these people that are just doing everything. So there is this very pessimistic path right in front of us. But the ocean is really resilient. All of nature is resilient. And if we can stop adding, we could actually, we could fix this. The window’s closing. Already, the ocean’s going to be very different, even if we stop today.

But we could really turn this around. Will we? That’s the question. And you know, every scientist I interviewed over in Australia was like, I could make them cry very easily in an interview, but they also were very determined, and these are brilliant people doing everything. And you could see it happening in Australia. Even the government is like, “Oh fuck, we can’t lose corals.”

This is a different story in the US right now. This sort of mad dash towards burning as much fossil fuel as possible. I just wonder, do these people have children? And they just obviously must not know what this means. We have a window, but it’s closing.

More from Print Is Dead (Long Live Print!)