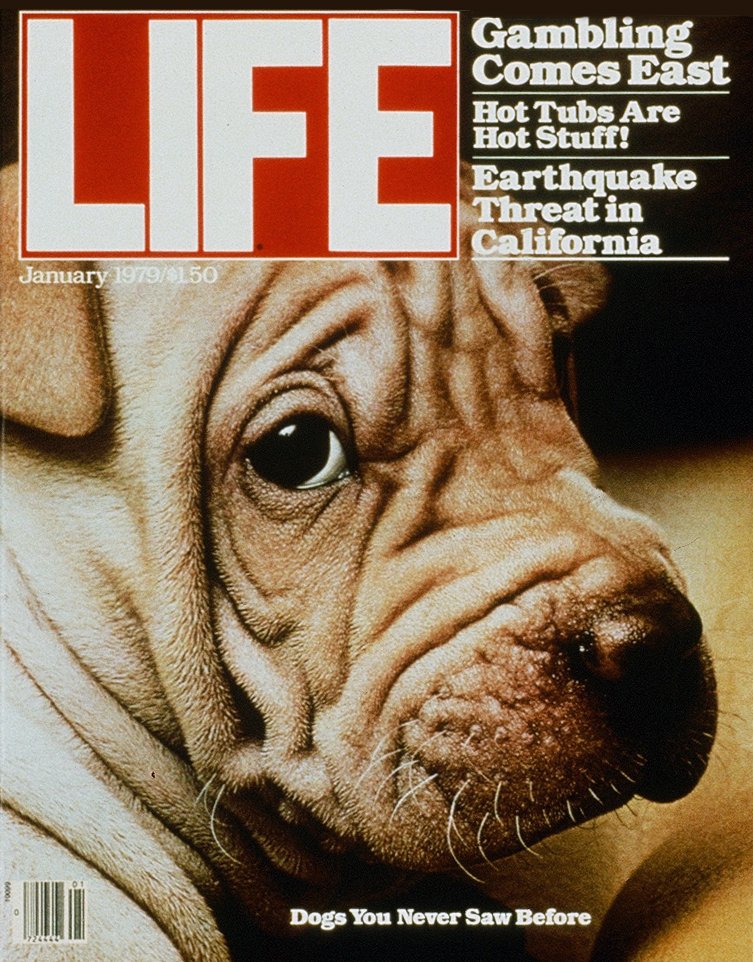

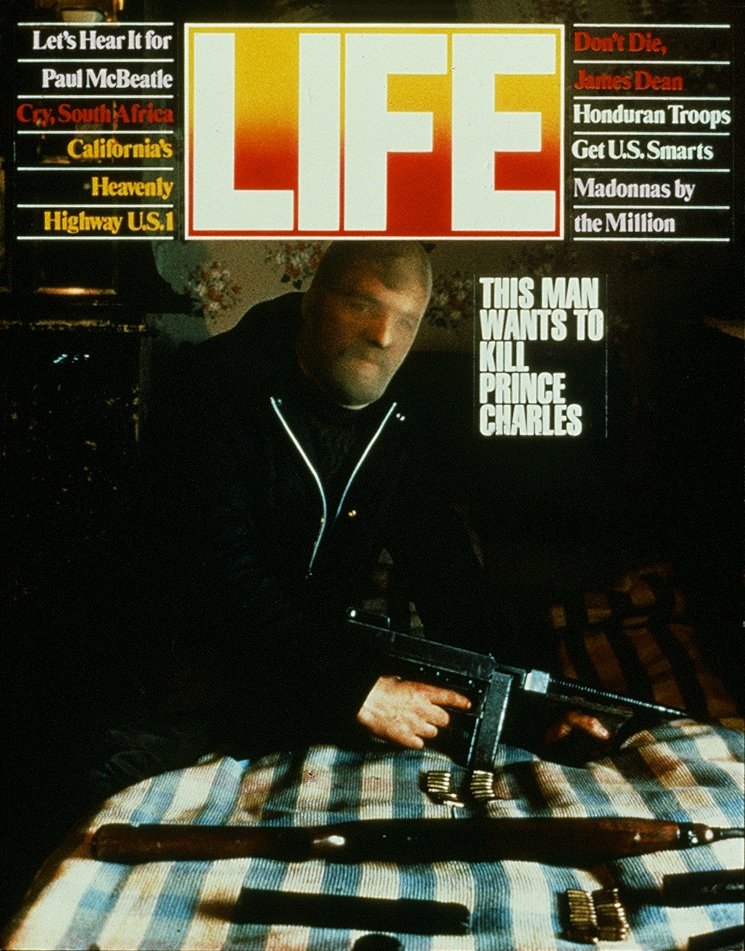

It’s a Wonderful LIFE

A conversation with designer Bob Ciano (LIFE, Esquire, Wired, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY MAGCULTURE

Today’s guest, Bob Ciano, is probably best known as the designer who guided the venerable LIFE magazine into its second chapter, shifting, after five decades as a weekly, to a monthly. But in an era where editors and art directors did not enjoy the downright chummy partnerships we have now, he’s known for a lot more.

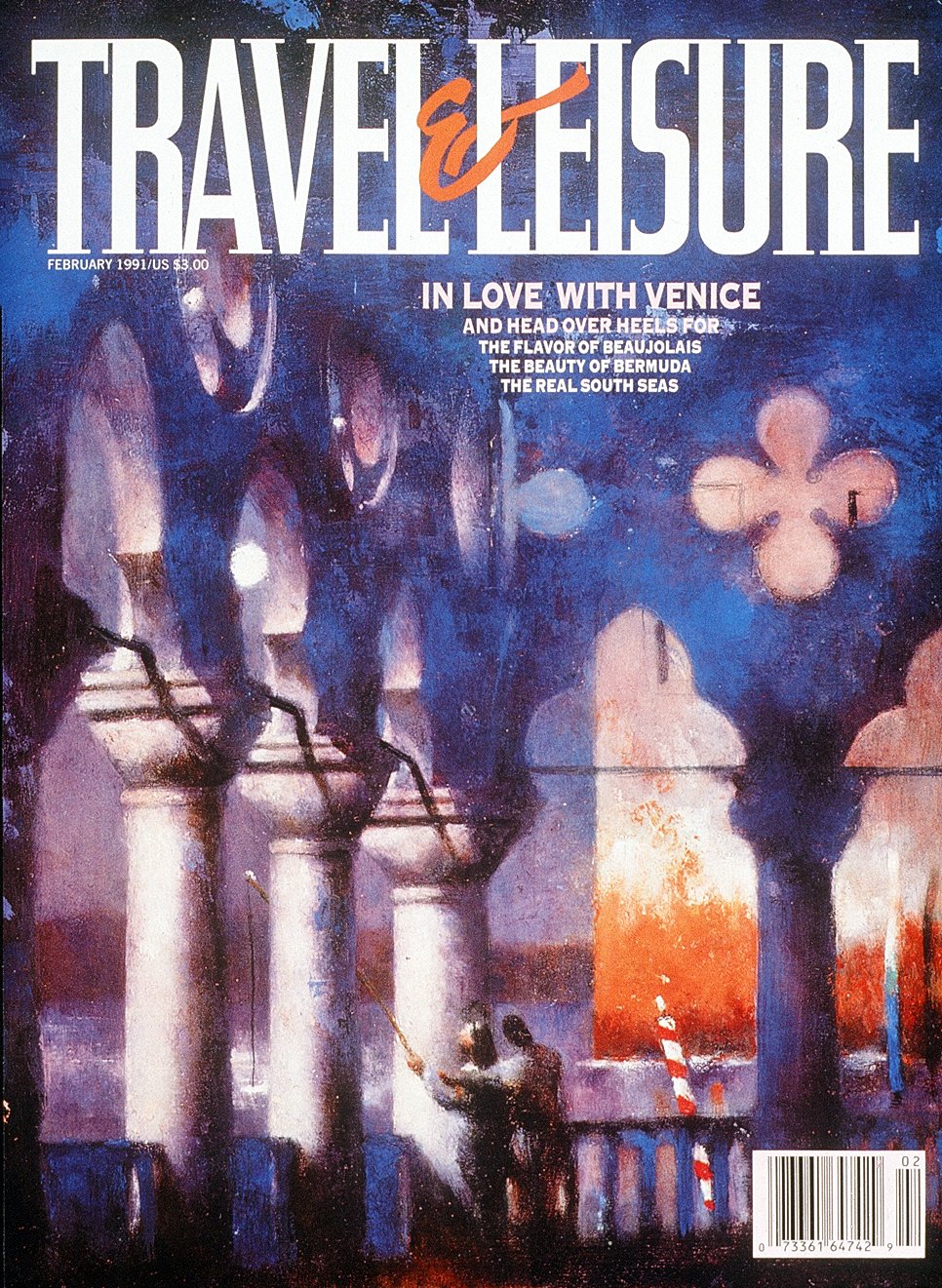

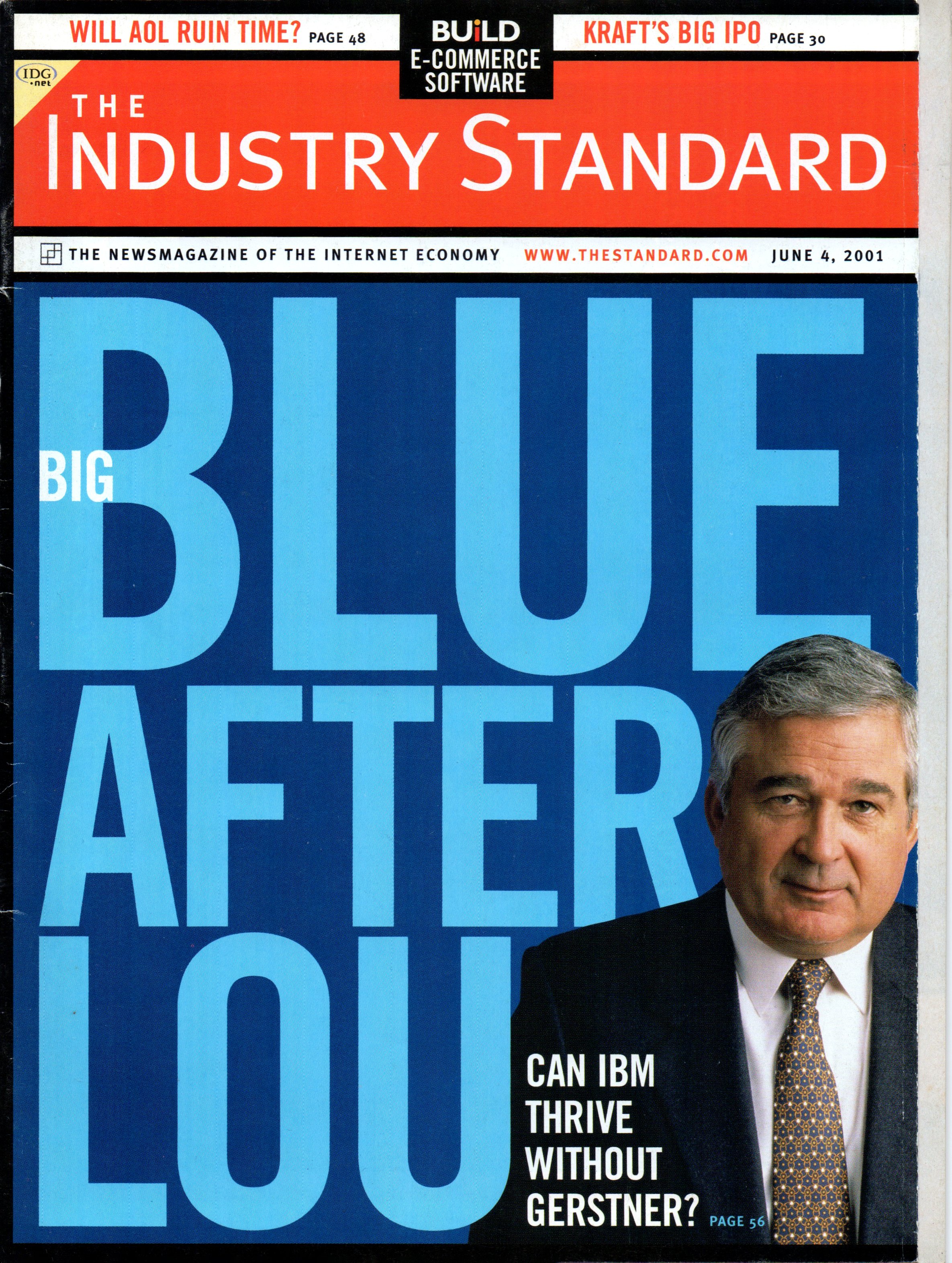

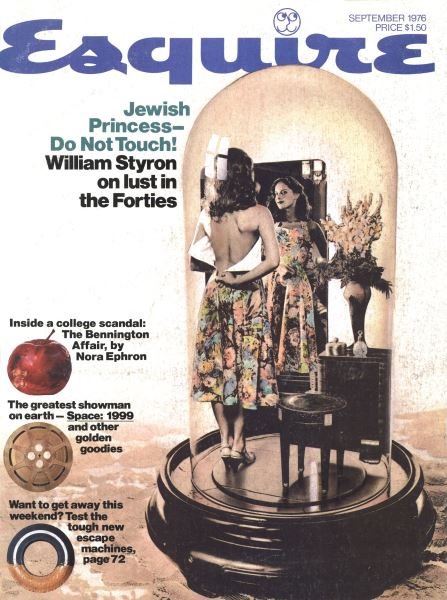

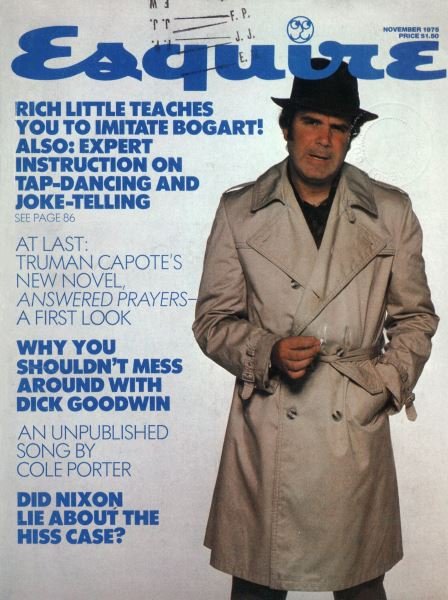

In his career, which continues to this day, Ciano has punched his time card at all of these places: The Metropolitan Opera, Redbook, Opera News, Esquire, The New York Times, LIFE, Travel & Leisure, Wells, Rich & Greene Advertising, The New York Times (again), Encyclopedia Britannica, The Industry Standard, Forbes ASAP, Wired, St Mary’s College, Cal Arts, as well as his current Bay-area studio, Ciano Designs.

And in the middle of all that, he had an entire side career as a renowned album cover designer.

Talented and successful—and, by all accounts, extraordinarily kind—Ciano did not leave all of these jobs voluntarily. As he says in our interview, “firing art directors was a sport in those days.” Ciano himself has lost more jobs than most people have had.

In preparation for this episode, Ciano shared an fascinating artifact from his archive. It’s a note from LIFE editor-in-chief Richard Stolley’s monthly column, where Stolley is taking the opportunity to sing the praises of his unsung art department. This is what he wrote:

Next to my office on the 31st floor of the Time & Life Building is the layout room. It is dominated by a 19-foot counter set three and a half feet off the floor so you don't get a crick in your back bending over color transparencies. All the ingredients of the stories in every issue come together in the layout room. First, departmental editors, reporters and picture editors gather there, and we begin to put slides and pictures in a logical sequence. About that time, I turn to somebody and ask, “Will you please get Ciano?”

Moments later, Bob Ciano, LIFE’s art director, strolls in. Bob wears a beard and jeans, a kind of uniform of the day among art directors; in every other way, he is unique and one of the best in the magazine business. It is his job to take all the elements and ideas that other staff members have brought to a story and transform them into vibrant, intelligent layouts. The task is not unlike turning a kitchenful of ingredients into a feast. (It is no accident that Ciano is a great cook.)

Ciano has been in charge of our art department since LIFE became a monthly in 1978, having previously worked at Esquire and The New York Times. He decides which of his associates will design an article or does it himself. The arson story in this issue is his. “Fires are hot and colorful,” Ciano explains, “but because of the conditions, this story had to be shot in black and white.” Ciano decided that a symbolic point could be made by literally setting the opening photograph on fire. He put a match to it, and the blazing print was re-photographed in our lab. “If we can make a reader feel heat coming off that page, then we’ve done something he’ll remember.”

Though LIFE designers have won [hundreds of] awards, they toil in anonymity, getting no bylines on the articles they play a major role in shaping. Their reward, as Ciano puts it, “is to move readers, to touch their emotions. We’ll use whatever graphic tools we can.”

Ciano left LIFE—by his own decision—after an 8-year stint. Why? Because there’s something worse than getting fired, and that’s getting bored. It happens.

Our editor-at-large Steven Heller caught up with Ciano recently. Their lively conversation covers the magazine business the way it was, the way it is, and the way it will be.

Steven Heller: I just want to start by paying homage to my good friend and one-time mentor, Bob Ciano. His name was one of those few that I kept track of as a young wannabe designer or art director, not knowing what either of those really entailed. But I go back as far as Redbook.

And I forget when we actually met, but I do remember when you came to The New York Times to work with Lou Silverstein on the “C Sections,” which sounds slightly obscene, but that’s what we used to call them: the “C Sections.” And you did The Living Section. I don’t remember whether it was called Living or not, but there was a big fish on the front page.

Bob Ciano: A fish. And the face of Pavarotti.

Steven Heller: Yes. It was very unique. And the fact that you were coming over to our neck of the woods to newspaperland was a big thrill. Do you remember why you were recruited?

Bob Ciano: I wasn’t recruited. Well, I had talked to Lou before I was at Esquire, and I got fired. Art directors got fired a lot in those days.

Steven Heller: It was a sport.

Bob Ciano: It was a sport. And I called him the day after I got fired and said, “I need a job.” And he said, “Come on over.” So I got fired on a Wednesday and I was at The New York Times the following Monday. It was pretty amazing.

Steven Heller: Well, before we get into what you were doing at Esquire prior to that, I just want to say that it was because of you that my career existed. I was doing the Op-Ed page at the time, and they put me on the Book Review for a short period of time. And you were slated to take over the Book Review. You may or may not remember.

Ciano moved to The New York Times to work with Lou Silverstein on the “C” Sections. “I got fired [by Esquire] on a Wednesday and I was at The New York Times the following Monday. It was pretty amazing.”

Bob Ciano: I don’t remember that. Wow.

Steven Heller: You were slated to take over the Book Review and I was to go back to the evil devils in Op-Ed land, and I kind of came into your office and cried, probably alligator tears, but basically you said, “You want to do the Book Review? I’ll pull out.”

Bob Ciano: Oh my, I don’t remember that.

Steven Heller: That was one of the most generous things ever done for me, and probably in our whole crazy little industry of print design magazines and newspapers.

Bob Ciano: Well, I’m glad I did that.

Steven Heller: And then, I guess, a year later you took over Life.

Bob Ciano: Yeah. It was very hard to leave the times. I enjoyed working with Lou and those new sections were very exciting for me. I don’t know if you remember, but in The Living Section we actually had a comic strip.

Steven Heller: Yeah. It was Rick Meyerowitz and Tony Hendra.

Bob Ciano: Yeah. And all the characters were food. And every week they would deliver the comic strip and Abe would get it and he would call me within minutes and say, “This isn’t funny.” And then he would hang up.

And he pulled the plug when the food kidnapped Craig Claiborne and started sending ransom notes to The New York Times editor, saying, “If you don’t stop the recipes, we’re going to kill Craig.” That was the end.

Steven Heller: Did it run?

Bob Ciano: It ran for several months. And then when they did that, he pulled it.

Steven Heller: But did that particular comic strip run or was that pulled?

Bob Ciano: I don’t remember. I doubt it. The other thing we did, which I always felt good about, was there was a weekly article by John Leonard. And I connected him to Guy Billout. And Guy did the illustration every week. And it was just a nice little thing to have every week to anchor on. But I had a lot of fun. And I had a lot of fun with the Sports Monday. And the front page.

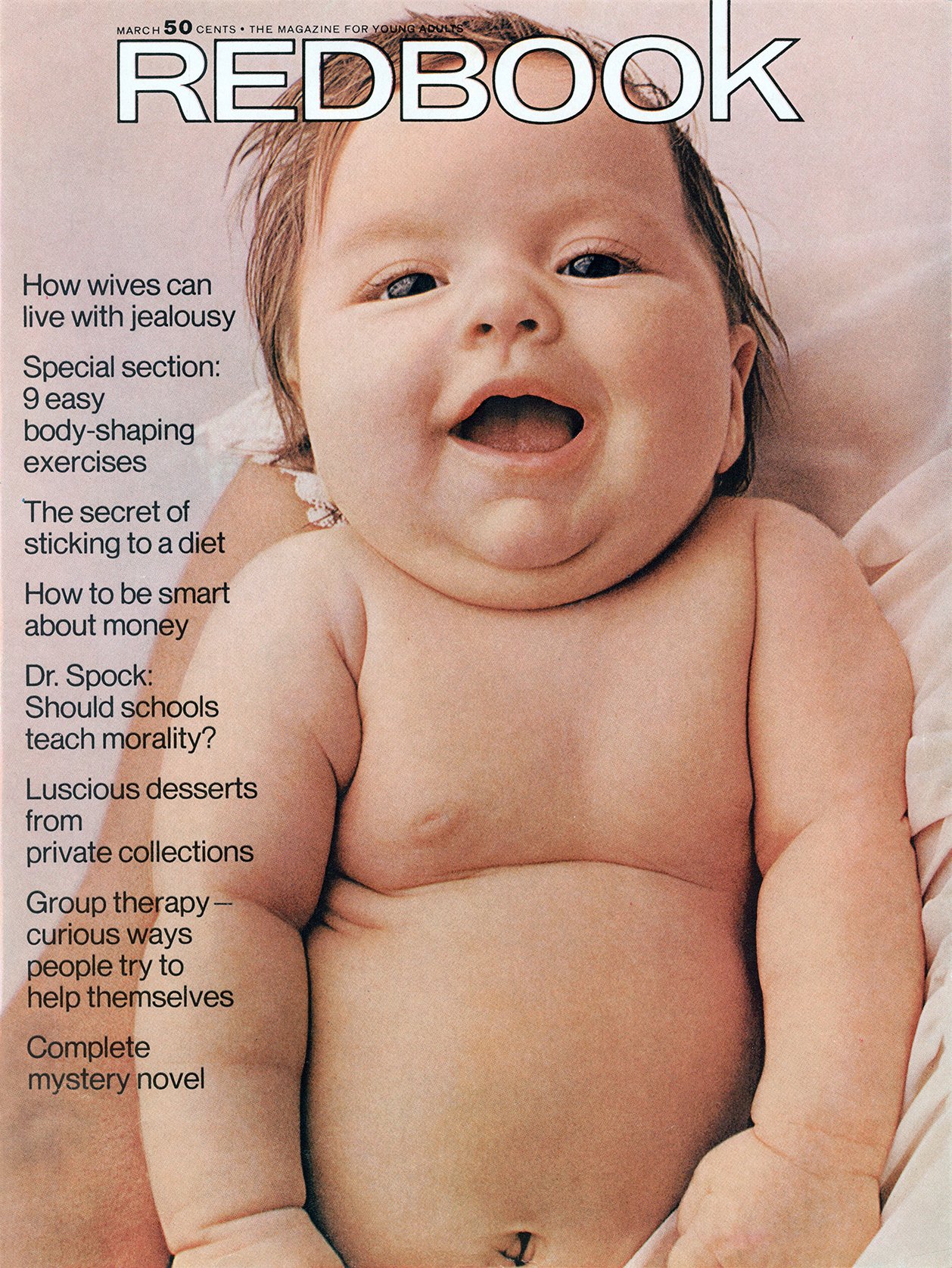

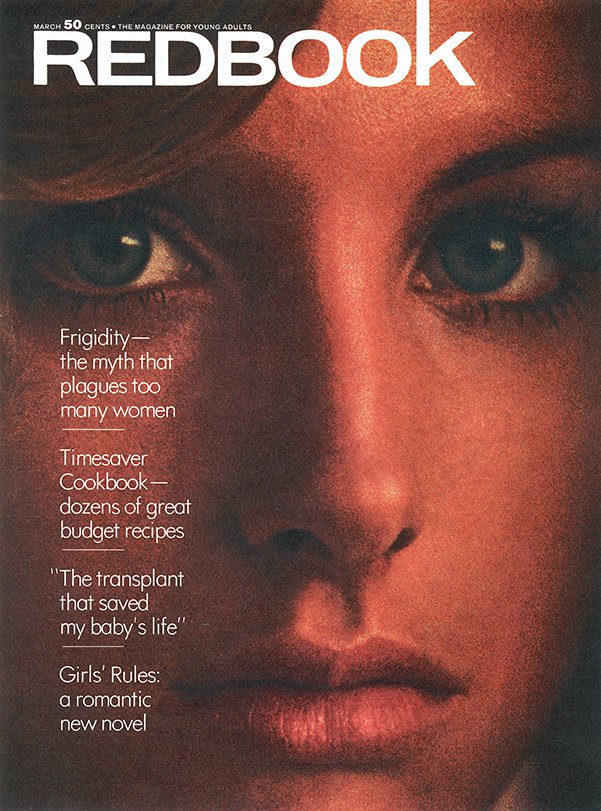

Steven Heller: It was very special having you there, particularly having seen the work you did in Redbook, believe it or not, because Brad Holland was in Redbook and I think …

Bob Ciano: … and I know if he mentioned it to you, but I bought him a bed.

Steven Heller: You bought him a bed?

Bob Ciano: I asked him to do something for Redbook and he did. And he was telling me when he delivered it that he didn’t have a bed to sleep on. He was in some small hotel or something. He had just come to New York, and he didn’t have enough money, so I doubled a fee so he could go buy a bed.

Steven Heller: I never knew that.

Bob Ciano: Yeah. That always I always felt that was one of my contributions to our business “Get Brad a Bed.”

Ciano’s 6-week-old daughter Melissa once graced the cover of Redbook.

Steven Heller: Well, I don’t want to go on gushing for the whole hour that we’re doing this, but I will, because your reputation in those days was as one of the nicest art directors, as well as one of the most creative art directors in New York.

Bob Ciano: Well, thank you.

Steven Heller: And part of that was your love of illustration, your keen eye for photography, and your aptitude with typography, which was a very important element in those days. And you could make it all work.

Bob Ciano: It still is.

Steven Heller: It still is, but some people forget that.

Bob Ciano: Especially students.

Steven Heller: So how did you get into the business of art direction?

Bob Ciano: By default, by total default. I went to Pratt Institute and I got thrown out. I was studying architecture. I had Mrs. [Sybil] Moholy-Nagy as a teacher. And in those days we would get eight-week problems, build a model, and have drawings. And the teachers would walk through the room. You had to have your drawing table horizontal, and they would look at your work. And if she didn’t like your work—she had a cane—she would smash it. She would’ve just gone WHACK! No comment.

But I wanted to be a baseball player. I really thought I was going to make it as a pitcher. I was on a sandlot team and the catcher was Joe Torre. But the bigger thing was that, when I was 13 and we moved into a new apartment, the family moving out were the Koufaxes. And I was going to have the same bedroom as Sandy. And I thought that was fate, that I was going to be a pitcher.

And, as we all know, it didn’t happen, but I missed so many classes that I got thrown out of school. And I had to get a job at BBDO doing pasteups. And I went from there to Columbia Records as a designer. And the art director I reported to was Reid Miles.

Steven Heller: Really?

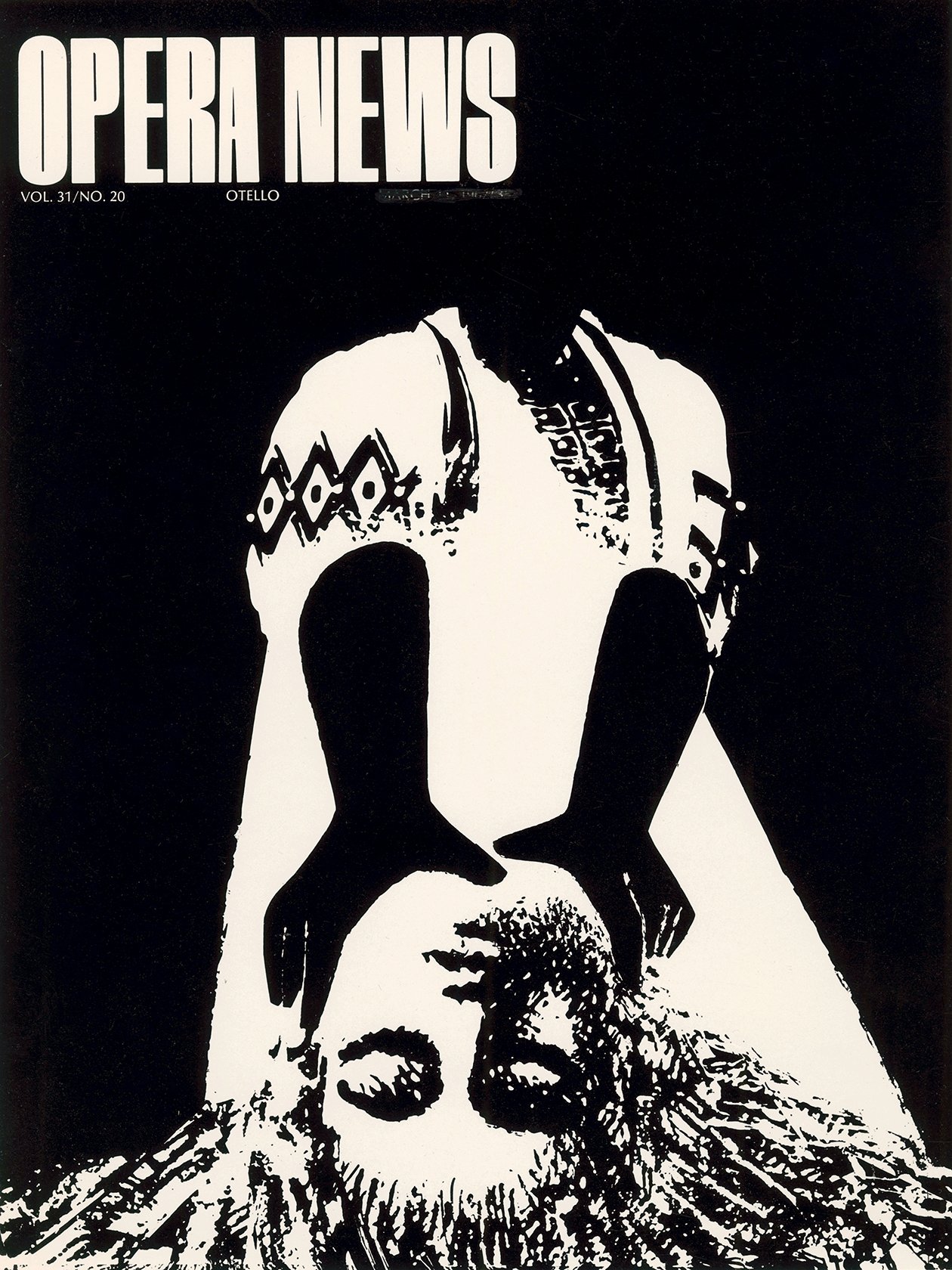

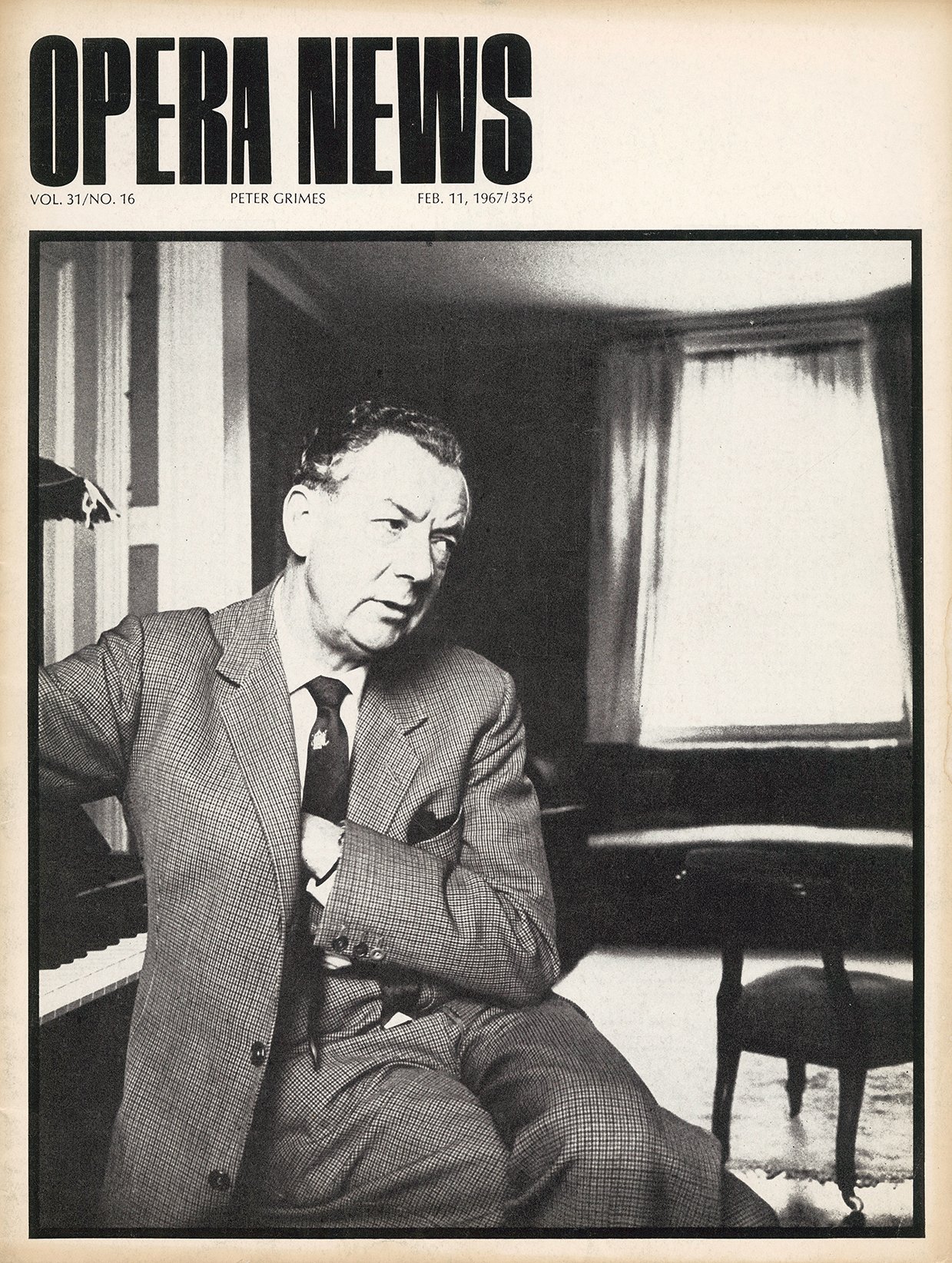

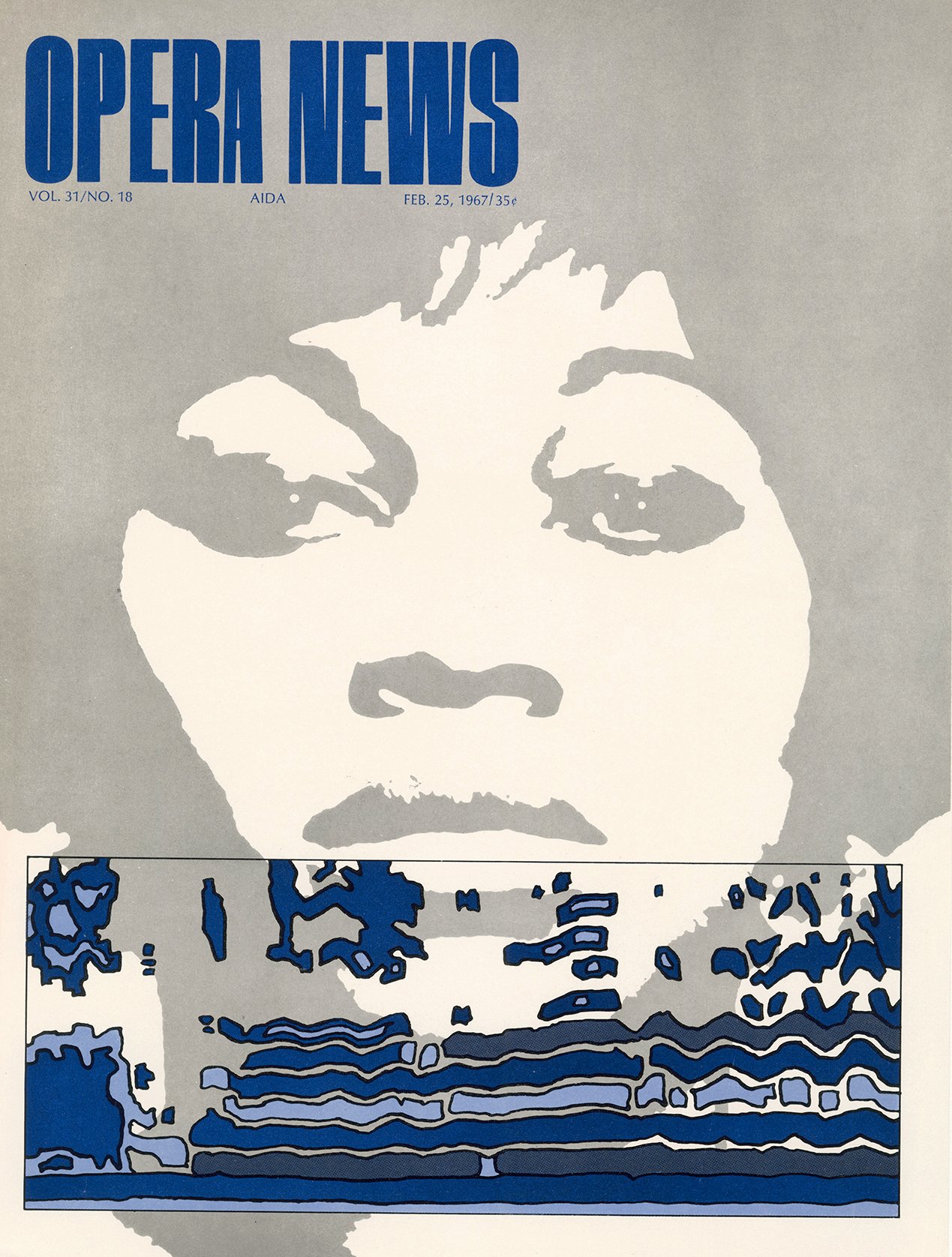

Bob Ciano: Yeah. Reid Miles and Bob Cato were the art directors. John Berg was the assistant. And I worked there a few years, and saw an ad for Opera News. And I went for an interview. I didn’t know how to do a magazine. I faked my way into the job and they hired me, the editor hired me.

And it was the days when there was still an engraver, a typesetter, and a printer. And I invited each of those guys together to lunch and said, “I don’t know how to do a magazine. You’re going to have to help me out, or if something goes wrong, I’m going to blame you.”

And they were terrific. They taught me how to mix ink, how to set type. I was always on press checks. And we did a weekly. I had an assistant and we did between 72 and 96 pages a week for 26 weeks.

Steven Heller: And you did a hell of a lot of beautiful covers, including covers by Milton Glaser.

Bob Ciano: Milton, Stan Zagorski, Erté, the French artist. Well, what happened was I succeeded a guy named Paolo Lionni. He was Leo Lionni’s son.

Steven Heller: “Pippa.”

Bob Ciano: Pippa. And I never met him, but I found a form that he sent out to artists and it said,

“Dear—and a line—We are returning your artwork for the following reasons.” And it would say, “poor idea lack of color, wrong size blah, blah, blah.”

And there was only one made out, and all of the negative things were checked off, and it was addressed to Alexander Calder.

Who, I guess, he knew through his father. And I thought, “You know, this form is terrible, but this is a good idea.” I can ask anyone. And it was one of the most important things I learned. Don’t hesitate to ask people even if they’re well known to do something. And I paid everyone a hundred dollars for a cover. And, if they wanted, two tickets to the opera.

And nobody said “no.” I mean, [Richard] Avedon did portraits. Everyone said “yes.” Milton did several covers a year. Erté got a hundred dollars to do an original painting.

“I saw an ad for Opera News. And went for an interview. I didn’t know how to do a magazine. I faked my way into the job and the editor hired me.”

Steven Heller: How long did you stay at Opera News?

Bob Ciano: I worked one year at the old Opera House on 40th Street, and then I worked three years at Lincoln Center. And all the while what I did was, I put Opera News, I sent gift subscriptions to every magazine art director I knew of, and Bill Cadge called me and said, “Would you like to come to Redbook as my assistant?” And I did. And that was fabulous.

And we did a lot of illustration in the magazine then: John Alcorn, Milton, Bernie Fuchs, Joe Bowler. I mean, maybe seven or eight. Danny Maffia. And photographers. Like, when I was at Opera News, I started working a lot with Duane Michals and Alen MacWeeney and Tony Ray-Jones. And I commissioned Bill Brandt in London to do eight pages on the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company for a hundred dollars. And he did it.

As I said, nobody said, “No.”

Steven Heller: So just listening to you, I’m getting all sweaty and shaky. It just sounds like heaven on earth and the kind of thing that I wanted to be involved in.

Bob Ciano: Yeah, you were doing Screw. That was exciting.

Steven Heller: But that was a stepping stone. But how did you feel doing all of this? You were kicked out of school and here you were top of your profession almost.

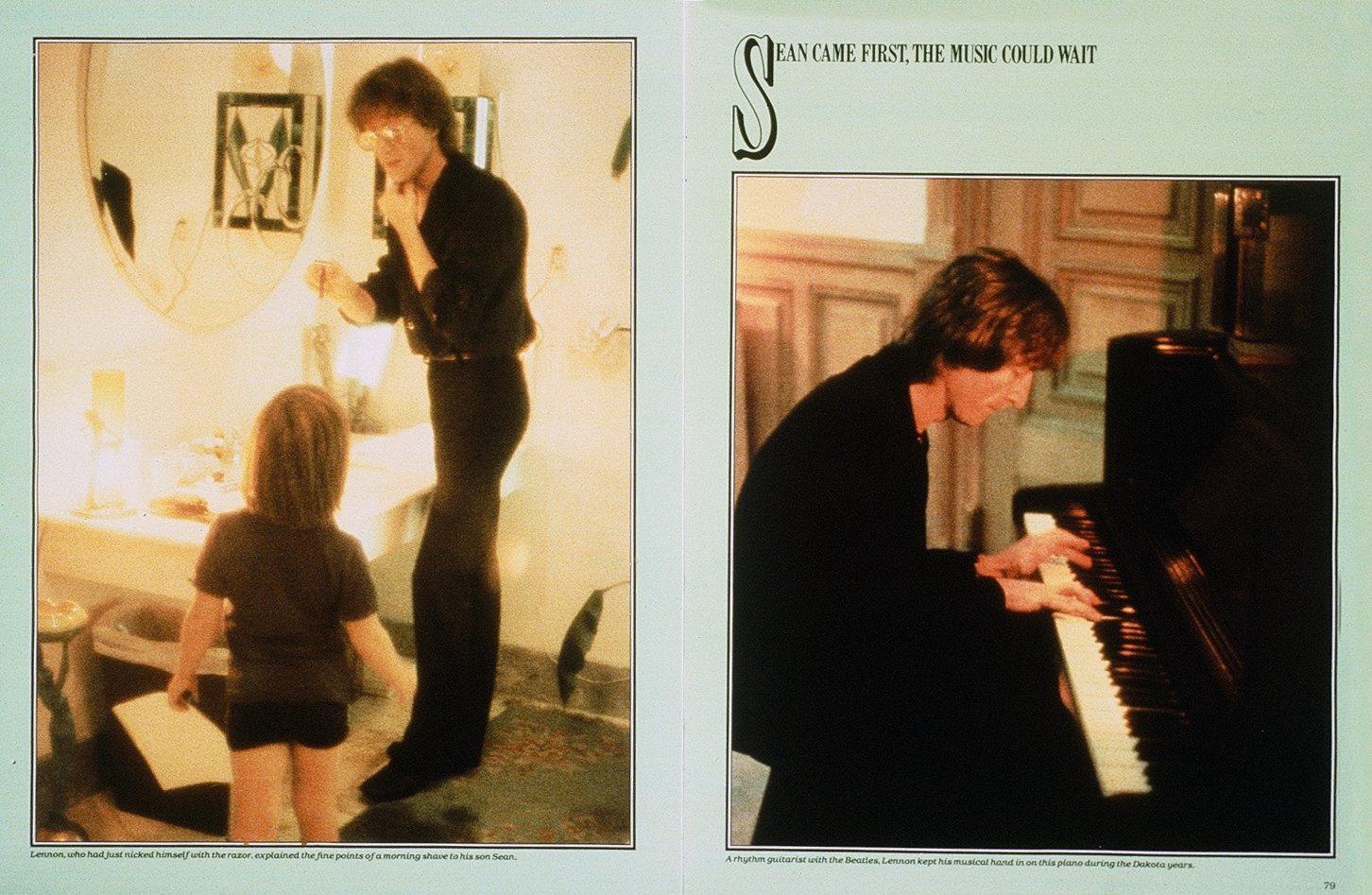

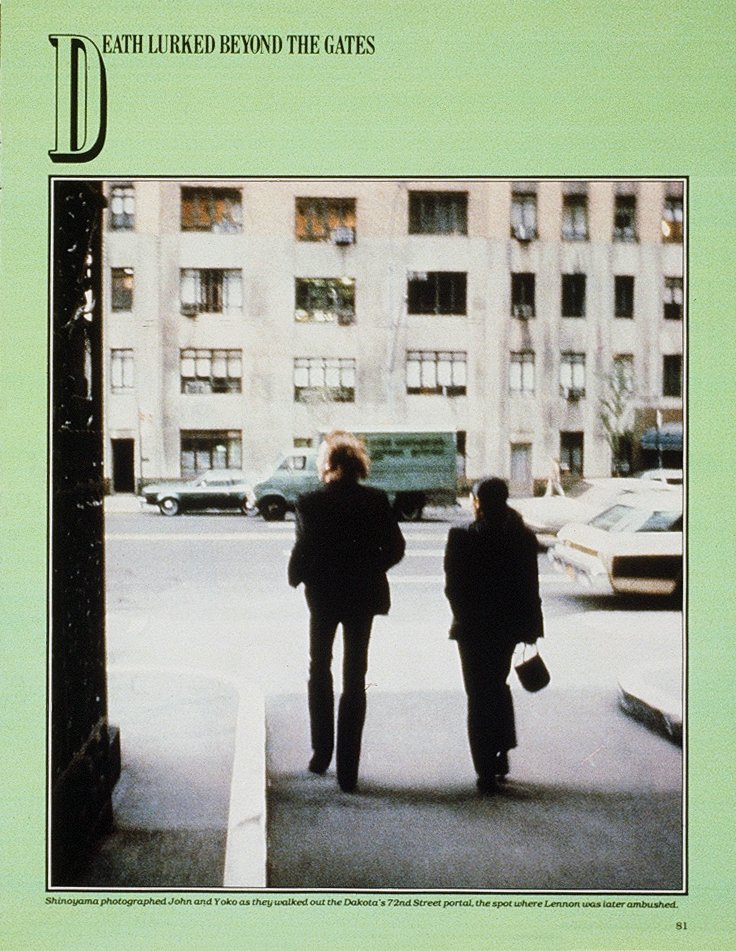

Bob Ciano: I was kicked out of school. My family was incredibly upset. My parents never knew what I did. Ever. I would explain it over and over. When I was at Life magazine, Dick Stolley, the editor, wrote an editor’s note about the art department. And it said, “We have hundreds of photographs. We don’t know what to do with them. We call Bob and his art department, and they come in, wearing their designer clothes, black shirts, and black jeans, and they take all the pictures. And a day or two later, they come back with a wonderful story. And in the process, they won X amount of awards.”

So I sent this editor’s note to my mother, thinking maybe this would impress her. Of course, she was never impressed. And after a few days, I called her and I said, “Did you get the article that they wrote about me and the art department?” She said, “Yeah, you wear jeans to work? What kind of job is that?” And I never tried to explain it again.

I just loved it. I still do. I can’t get enough of it.

Steven Heller: So one of the things that I remember of your work back then was it was so cinematic, particularly in Life magazine, which was known for its photography, but not really known for its graphic designery until you got there.

Bob Ciano: That was the way the structure of the magazine had been. And the one good thing when I got that job was I was handed a stack of resumes of designers who had worked at the old Life magazine and I decided, “I’m not hiring any of them. All I’m going to hear about is the old magazine.” And I hired people who were kind of new to magazines. Mary Kay Baumann, several other people. Carla Barr. And we just attacked it differently.

And the editor and the picture editor were very open to doing that. And I, you know, I had OD’d on Ingmar Bergman and François Truffaut. And I was very into movies.

Steven Heller: Right. And they were designers themselves.

Bob Ciano: Yeah. I remember I used to go to a place on Macdougal Street—the Folklore Center—and I went one Sunday and there was a sign on the door and it said, “Had to close. Shirley wants to see Wild Strawberries.” And I didn’t know what that was. And I found out and I went up and went to see the movie at Second Avenue and, like, 63rd or 64th Street. And I was blown away. I mean, I was not used to seeing things like this.

Steven Heller: Did you ever go to the Charles Theater on Avenue B? That’s where many of the avant-garde films and foreign films were shown.

Bob Ciano: Yeah. And there was a place on 57th Street. And there was usually, there were director there talking about the film, and before the film started they would serve espresso for free.

Steven Heller: Right. I used to go there with Ruth Ansel. So let’s jump back a second to Esquire. How did that come about?

Bob Ciano: I was at CTI Records doing covers, with Pete Turner, Alen MacWeeney, Stan Zagorski, and that had just kind of petered out. We had so many creditors after us that when we got our paychecks, we had to go to one teller at the bank and halfway waiting online, the teller would waive his or her hand and say, “No more money today.” And we’d have to wait for another check to come in to pay it. It was Creed Taylor, but he let us do anything we wanted with covers.

Steven Heller: I don’t think I’ve seen any of those covers.

Bob Ciano: Oh! I’ll send you some. I still get contacts from people who want prints of the covers. We used to print extra covers and sell them for a dollar. And so I heard about the Esquire job. The editor was Don Erickson. And he hired me. I was a little surprised, but …

Steven Heller: … And who had preceded you at Esquire?

Bob Ciano: Richard Weigand. And the art department hated me. I ended up having to replace everyone.

Steven Heller: Really? Why did they hate you?

Bob Ciano: They really liked Richard, and they thought somehow I was involved in getting him fired. I only met Richard once. He was a lovely man. Who knows? But you know, as in those days, then 12 months later, I got fired. So...

Steven Heller: … And was it with Don Erickson still as editor?

Bob Ciano: No. I’m trying to think of the guy who fired me. I probably blocked it out.

Steven Heller: But was it one of those firings where a new editor comes in and “mows the lawn”?

Bob Ciano: Yes, pretty much. But it was like musical chairs. The new editor would come in, fire the art director. They’d get a new art director. The new art director was Michael Gross, who was also then at the Lampoon. And the magazine wouldn’t do any better. Then the editor would get fired. The new editor would come in, fire the art director. They never asked the art director who was there to redesign the magazine.

But I must admit I kind of enjoyed the year I was at Esquire. I mean, Nora Ephron was one of the editors. Gordon Lish. It was very heady for me to have these incredible writers and to be involved with them.

“Abe Rosenthal came up to the art department and said, ‘You’re leaving? Don’t you ever come back to The New York Times again.’ He was so pissed at me.”

Steven Heller: That was the generation that preceded us and was kind of such an honor to be with those people.

Bob Ciano: Yeah. It was exciting.

Steven Heller: I’ll tell you a quick story. I wanted to get out of Screw, and I interviewed at Esquire with Richard Weigand. Don Erickson was the editor, so I interviewed with him too. And the two of them spent an hour convincing me not to come over to Esquire. It would’ve been a low-level job in any case, but they said, “You have much more promise elsewhere.” But they didn’t promise where that would be. So from Esquire, you came to The New York Times, almost immediately.

Bob Ciano: Yeah. And in those days it was relatively easy to move around. So I remember I got fired on a Wednesday and I called Lou Silverstein on Thursday, and I started the following Monday, working with Lou.

Steven Heller: And how did you know Lou?

Bob Ciano: I had talked to him about working at the Times before that, but then the Esquire job came up, and that was to be the art director. So I took that job. But I loved working with Lou. I mean, he was crazy, but I was...

Steven Heller: … He was a great man. But he brought you in a very special capacity. I mean, you were there when he was revolutionizing the paper. So he wanted a co-revolutionist.

Bob Ciano: But I would walk into his office with a sketch and before I even showed it to him, he would reach for his tracing pad, like whatever I did, and slip it under the first page and start to change it.

And when we had pages to show Abe Rosenthal, we would get on the elevator to go down to the third floor where the editors were. And Lou would still be leaning on the elevator wall, making changes. And I am sure you remember these big graphite pencils and his fingers were always black and all that.

But I found him wonderful to work with. Frustrating at times, but wonderful. And he kind of let me do what I wanted to do and, you know, would make comments and changes that were always right.

Steven Heller: So you always felt that there was respect for the print art director?

Bob Ciano: Oh, yeah. Yeah. We also put together, I don’t know if you remember, there was an afternoon paper.

Steven Heller: Yeah. “PM Paper.” Or whatever it was called.

Bob Ciano: Yeah. And it had The New York Times and a really tiny logo, but in big words, it said “Monday,” “Tuesday,“ and it was just like the day of the week.

Steven Heller: And you had a special office upstairs? Secret office, as I recall.

Bob Ciano: Yeah. We used to hide. And we would, when we finished the section—I forgot about that—we would leave everything. We wouldn’t take anything with us. We would leave T-squares, drawing tables, like we had gone out for coffee and just not come back. And then the next section we worked on, we would commandeer another attic space somewhere in the building.

Steven Heller: Lou was good at hijacking real estate.

Bob Ciano: He was terrific. And when he would explain the designs to the editors, Abe and Artie Gelb and that crew, he would be like a Talmudic scholar. I mean, he would talk in these beautiful—you, you would have to agree with him. But, yeah, I loved working with him.

Steven Heller: So you worked at the Times for about a year?

Bob Ciano: About a year and a half, almost two. We did all the sections, the only one that was done when I got there was the Friday Weekend section.

Steven Heller: Well, that was a radical section at the time.

Bob Ciano: Yeah. Oh yeah. And that kind of set the stage for things.

Steven Heller: That’s when Artie Gelb wanted people like Red Grooms to do the front pages.

Bob Ciano: Yeah. Yeah. I’m trying to think of who was there. Eric Seidman was the art director.

Steven Heller: Right. He did Week in Review review. And Travel.

Bob Ciano: And “some guy” did the book review. I don’t remember him.

Steven Heller: Bob Nelson?

Bob Ciano: No. You!

Steven Heller: Oh, that me.

Bob Ciano: That me. Yeah. But it was a backbreaking thing because with the new sections we would be there late, especially when they debuted. And I remember that we weren’t allowed to pick photographs. The picture editors would pick a picture or two. And during one of the closings for one of the new sections, there were just terrible photographs on the page.

And I said to Lou, “Look at that. We’ve got to change that picture.” And I started to go over to the picture editor and he grabbed my arm and he said, “Are you going to be here tomorrow night to do this? And the next night? And the next night?”

I said, “No.”

He said, “Then don’t do it. Only if you want to take it over should you do it.”

And he was right. He was right.

“We used to have a minimum of 28 editorial spreads in a row in the middle of the magazine. And if we got one spread less, we would start complaining.”

Steven Heller: Well, remember those were the days we couldn’t touch type.

Bob Ciano: Right. You had to look and peer over somebody’s shoulder.

Steven Heller: You had to look at it upside down even. But I remember the day that you announced that you were leaving and it was a heartbreaking day. We didn’t share an office, but your cubby office was next to mine. You could probably hear me singing Beatles songs. But I thought, “This guy is too important to have one of these cubby offices.”

Bob Ciano: Yeah. It never occurred to me. No. It was so much fun. But Abe Rosenthal came up at one point to the art department and said to me, “You’re leaving? Don’t you ever try to come back to The New York Times again.” He was so pissed at me.

Steven Heller: Yeah. He took things personally.

Bob Ciano: Very personally. But I had taken a job to be art director of Forbes, and I don’t remember who the art director was, but somebody who had some medical problem, some eye issue, and Malcolm Forbes hired me, but said, “You can’t start right away because we have to transition out because of the art director’s medical problem.”

But I took the job and I was going to start in a month or two, and then the editor of Life magazine, Phil Kunhardt called me and said, “Would you be interested in interviewing?” And I went over after work one night. And I brought my tray of slides, my carousel. He never looked at the work at all. And he was one of these people who interviewed you by not saying anything and causing you to talk your head off.

So we sat there and stared at each other because I had a friend who was working—this was at the startup of the new monthly Life an editor named Byron Dobell.

Steven Heller: Byron used to be at New York.

Bob Ciano: Right. And he said to me, “Now, when you get interviewed, Phil is not going to say anything and you’re going to blab. So don’t blab. And make him talk.” So I tried to make him talk. And neither one of us talked.

And after about 20 minutes I said, “Do you want to ask me anything?” And he said “No. I think not.” I said, “Do you want to look at my work?” He said, “No, that’s not necessary.” And I thought, “This is a waste of time.” And as I’m leaving, he says, “Oh, one thing. Is there anyone else you could suggest for this job?” And I was so taken aback, I said, “What about Will Hopkins? Or...” I named a whole bunch of people. And he said, “Oh, I’ve seen them. I’ve seen them all.” And I went home and I thought, “What a waste.”

And 10 o’clock the next morning he called me and said, “Would you like to come and work at Life magazine?” And I, to this day, can’t tell you why he picked me. But when I got there, he gave me a folder with almost 150 resumes from people who wanted to be the art director. And most of them had worked at one point for the old weekly Life.

And I decided on the spot I would not hire someone who had worked for the old magazine because I was afraid all I would hear about was, “We used to do it this way, we used to do it that way.” And I hired people that had never worked at a magazine.

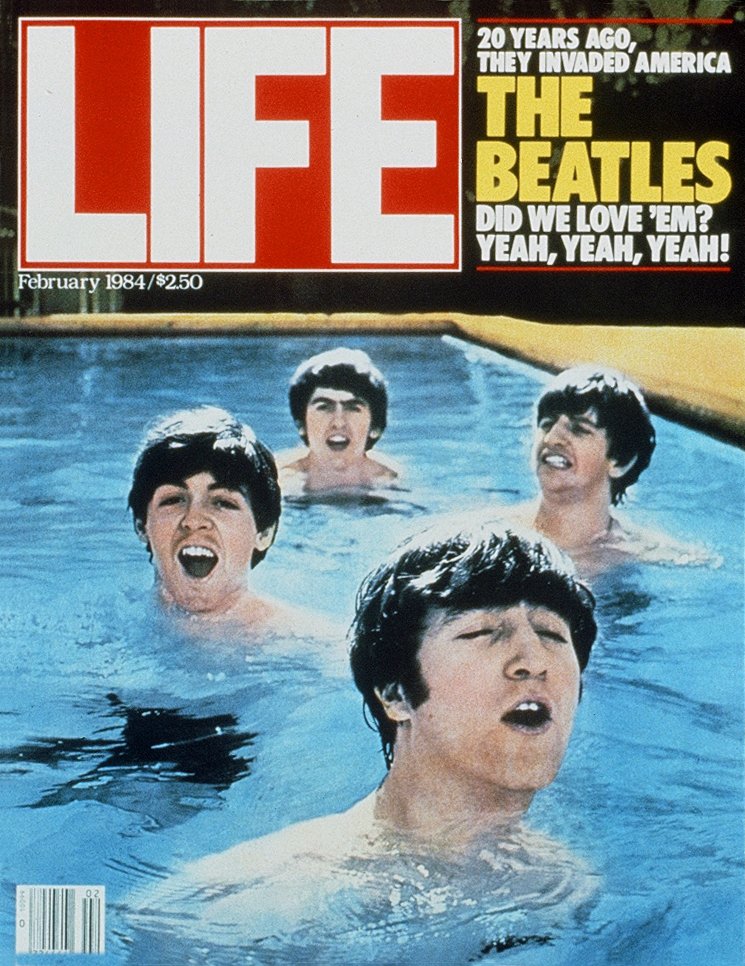

Steven Heller: How long was it before the weekly turned into a monthly?

Bob Ciano: It was several years. They did one or two special issues a year, usually on a single subject. And they did that to also keep the name, to keep the copyright. So it was about six or seven years. So then it came back as a monthly.

Steven Heller: And then how long was it a monthly?

Bob Ciano: Well, I was there until ’87 or ’88. And then it continued on for a while longer. I started in ’78. So I was there about eight or nine years.

Steven Heller: I remember when you did take over, there was a lot of anticipation to see how it would change, if it would change, what would change. I mean, by the time it folded, it was a full-color magazine. It wasn’t the old Life at all. But it still used type that looked like it came from the same Linotype machine.

Bob Ciano: Yeah. We tried to keep a connection.

Steven Heller: But you made it clean. It was clearly a new magazine with an old title.

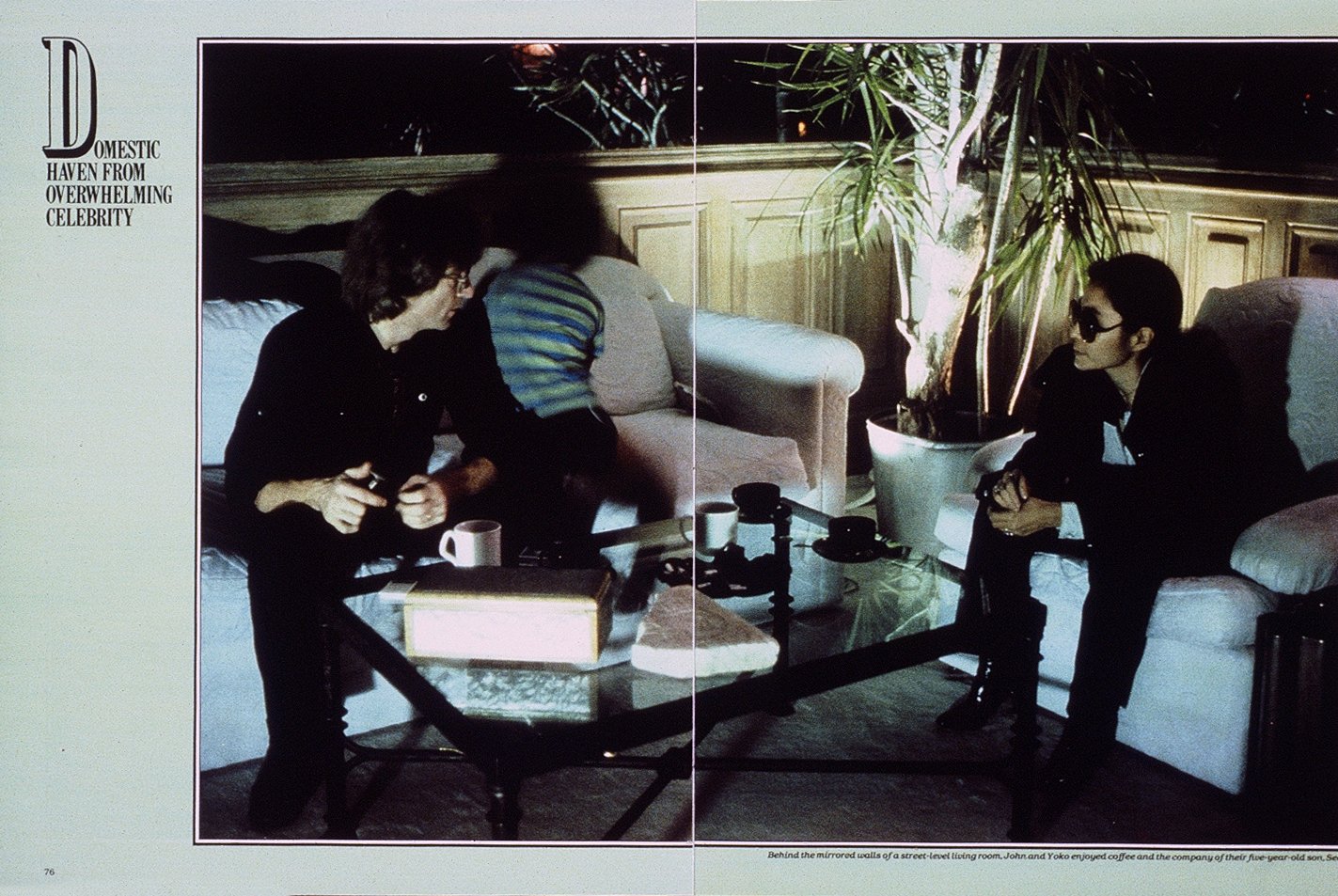

Bob Ciano: When I think about the magazine, we used to have a minimum of 28 editorial spreads in a row in the middle of the magazine. And if we got one spread less, we would start complaining. So it was really a wonderful thing to work on.

And I could call anyone anywhere and say, “We want to do a story.” And they knew the magazine. I didn’t have to explain it. And I remember the editor, Phil Kunhardt, said to the staff, “Come up with a picture story idea that you’ve never seen.”

And I wanted to do the Emperor of Japan at home. How naïve! We never did it. You have to go through the Imperial Household Agency. And every time we would approach them, they would ask us to do something else: send magazines, have an editor talk to them, blah, blah, blah. And I was saying to a friend who’s Japanese, I was saying to her, “I don’t know how to get through to them.”

And I remember we were having lunch and she slammed her chopsticks down and she said, “Are you stupid? They’re saying, ’no!’ They’re not going to let you go into the Imperial household and take pictures of the emperor.” And I said, “Well, why don’t they just say no?” And she said, “Oh, you’re even more stupid than I thought! They want you to go away.”

Steven Heller: This was Hirohito?

Bob Ciano: Yeah.

Steven Heller: So what were some of the joys of your editorial ideas? What are the ones that you remember most fondly?

Bob Ciano: At Life? Or in general?

Steven Heller: At Life.

Bob Ciano: Oh. We did a story on cocaine that I loved—and stories were like five or six spreads minimum. And a lot of famous people. I remember we did five actresses. Reid Miles did the shoot out in Hollywood. We’d done one with Joan Collins portraying famous women in history and she and Reid just didn’t get along and she was always screaming at him and threatening to leave and so on.

And then we did a lot of kind of gritty street stuff, which I really enjoyed, on news stories or aftermath of the news. There are just too many to specifically remember.

Steven Heller: A segue question is, among the magazines you worked for, you hired lots of designers, you worked with a lot of people, and many of them became designers in their own right. Can you talk about a few of those people that came through your “School of Ciano”?

Bob Ciano: Well, I always thought that people should stay, like, three or four years and then they should leave. I didn’t fire them, but I thought, “If I’m doing my job right, they should want my job.” And since I wasn’t going to give them my job, they should find other places. So, Mary Kay Baumann was one of the best hires. She went on to do Geo. And then she and Will Hopkins married and they did American Photographer, and then they did American Craft magazine, which I thought was fabulous.

Carla Barr went on to do Connoisseur. Charles Pates went to a catalog company [Garnet Hill] and redid all their stuff. He started a music site. It’s called PatesTapes, that’s still around and is fabulous if you don’t know it. He used to give out mix tapes to everybody, and this transitioned to an online equivalent of mix tapes. So there are maybe a hundred or 200 subjects, and it’s free. It’s fabulous. And those are the people that come to mind.

Steven Heller: I want to take this time just to make two little anecdotes about you. One you may not remember at all, but over the last 15 years I’ve been doing a lot of work on Ladislav Sutnar. And there’s a story I always tell, and hope it’s not apocryphal, that you were in the Art Director’s Club when it was on Madison Avenue in the Look building. And you were sitting around, out in the vestibule or something, and there was some dejected old man sitting near you—I may have over dramatized the old man bit—but you were talking to him very politely and interestedly and he was saying how he used to be rather big in the organization and it turned out to be Sutnar.

Bob Ciano: That’s a true story. I thought he was a really nice guy and when I looked at his work I thought it was fabulous. I thought he did really groundbreaking stuff. You know, I’ve learned now that people avoid old men,and I’ve gotten into that category of being avoided. So, I think I first felt sorry for him and then realized this is a very talented, wonderful designer. And I loved hearing what he had done and his stories.

Steven Heller: The other tale I want to tell is, I forget whether I was ill or just plain depressed, but you brought me, speaking of Japan, a bonsai tree. And I think it was an oak. The first one died, as you might remember, and you had to come over with your medical bag and act as a tree surgeon to this little miniature guy. And that stayed alive for a few months. And then I didn’t have the heart to tell you it passed on.

Bob Ciano: Oh, I still grow them.

Steven Heller: And also when my son was born, you sent us a care package of Bob Ciano’s jams and spaghetti or meatballs, which, for those who never received them, are beautifully-packaged and hand-calligraphed labels.

Bob Ciano: Well, I still do that. So, you’re on the jam list.

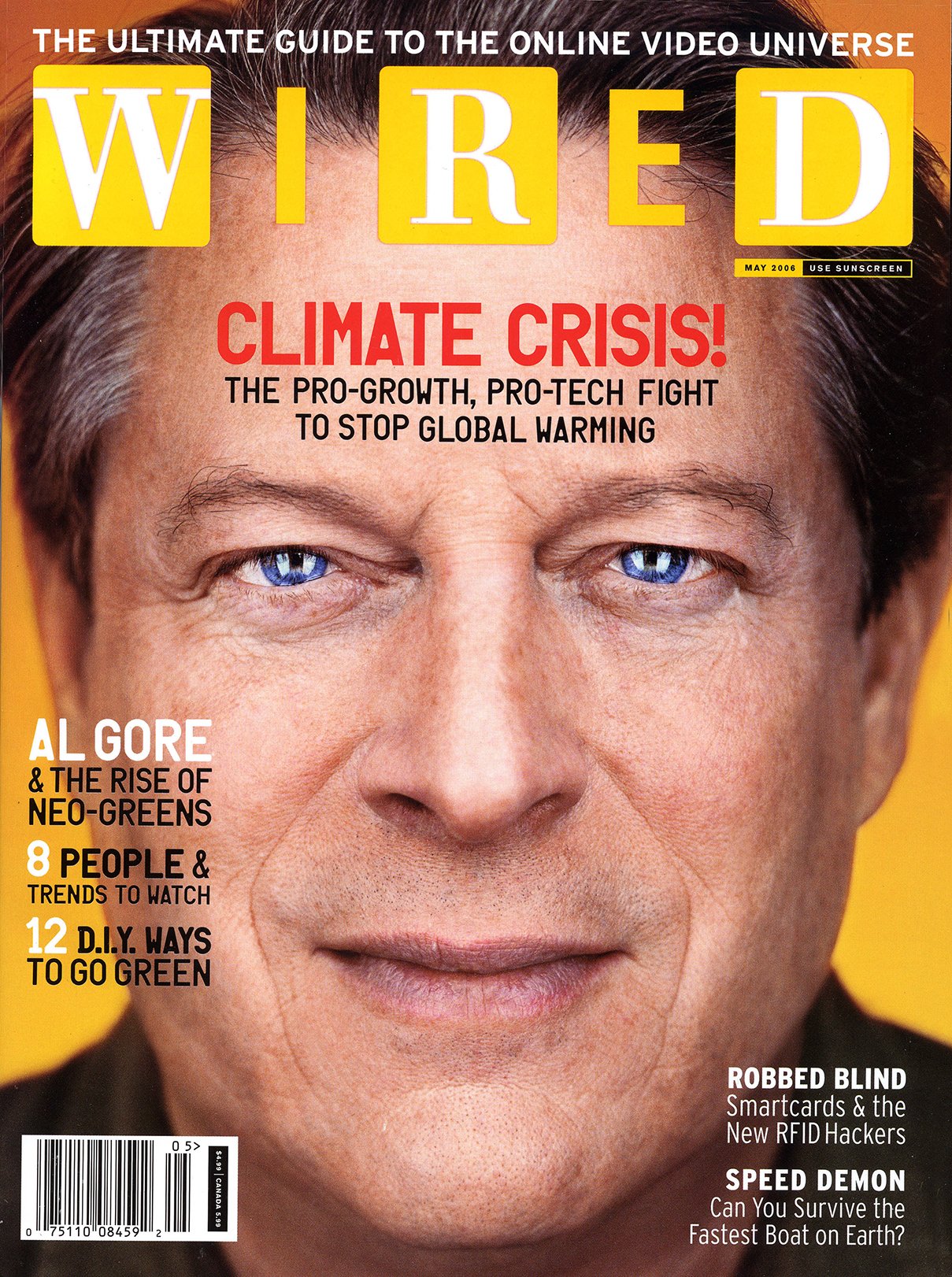

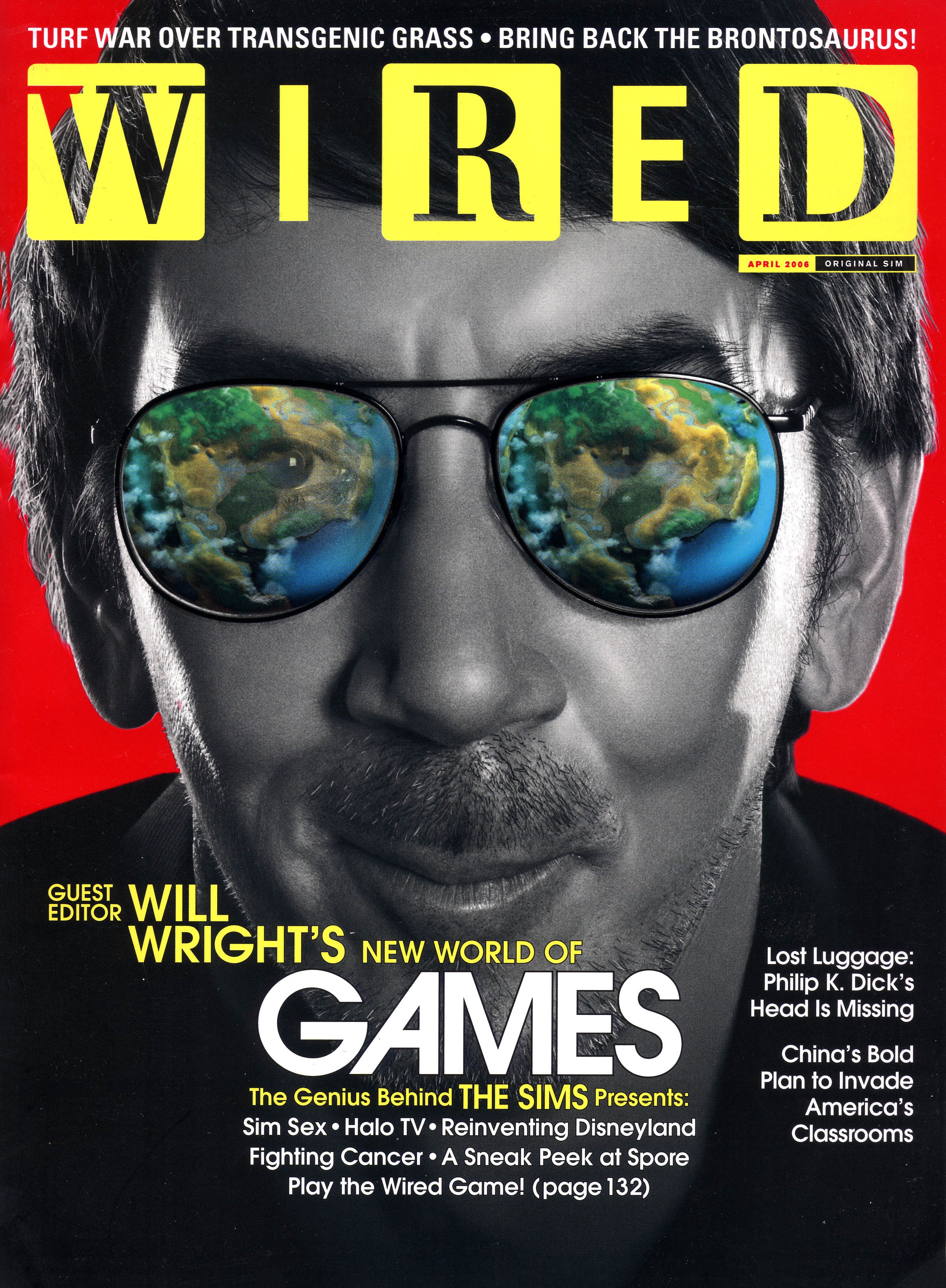

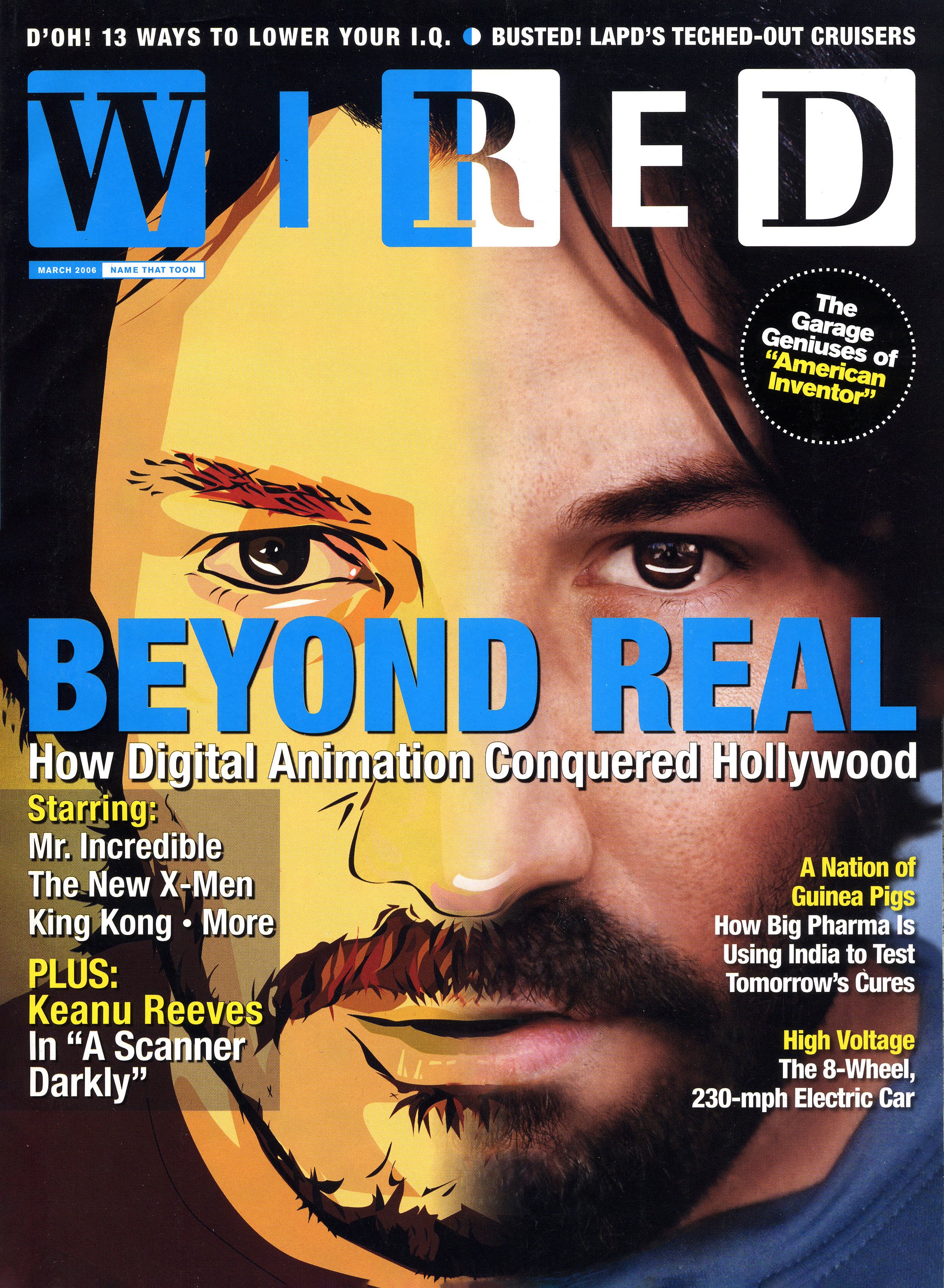

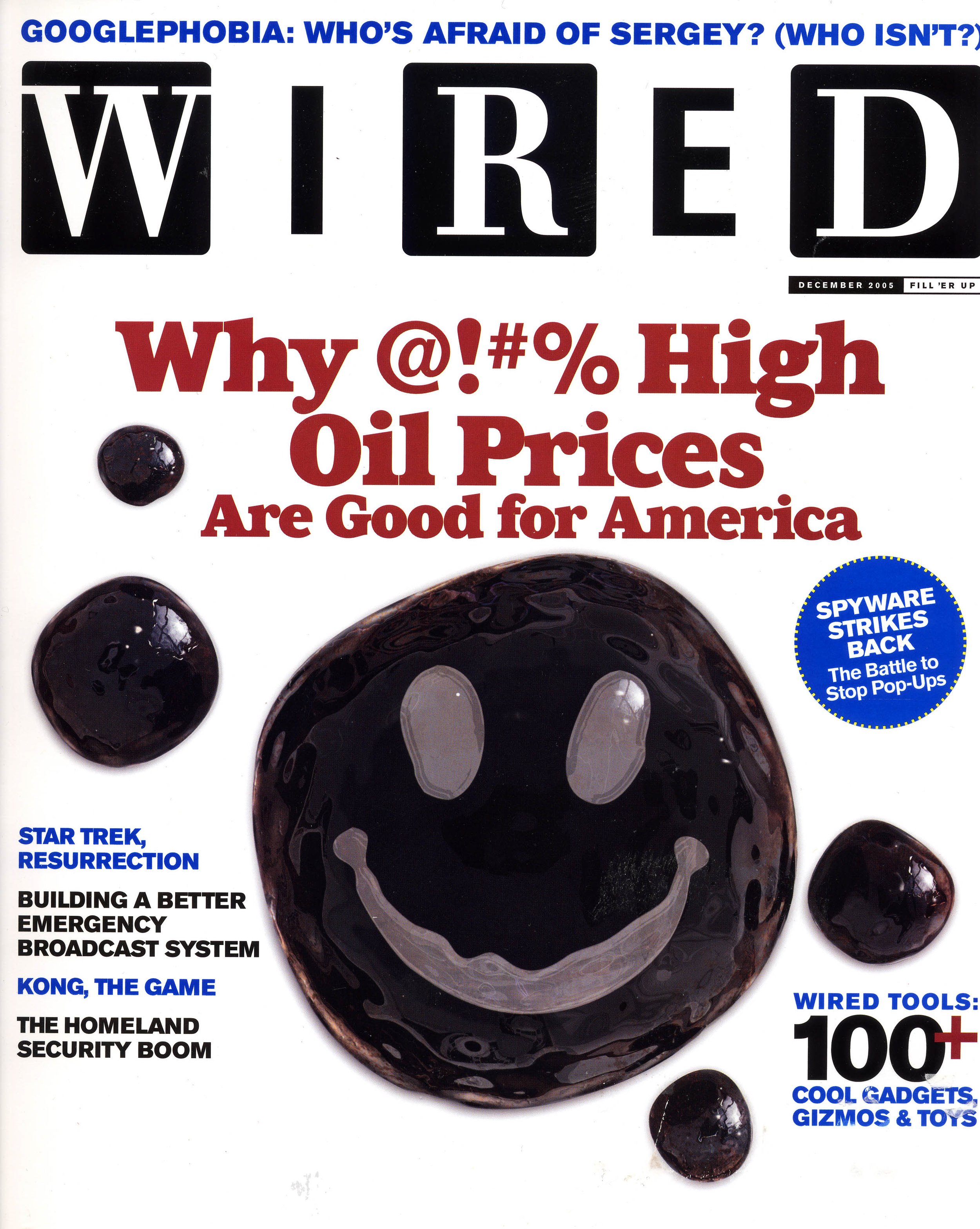

Steven Heller: So, back to magazines, I didn’t realize that you had become creative director of Wired in 2005. How did that come about?

Bob Ciano: When I came to California, it was for Encyclopedia Britannica. I had moved to Chicago. And in Chicago we were opening something called Britannica School. We were going to do online learning and they decided that the office should not be in Chicago, where the book division was, and it ended up being San Francisco.

So I came here and about a year into it, we all got fired. There were 50 of us. The whole office got fired. And I got a job at The Industry Standard, a weekly magazine. And the first year I was there, we had 8,000 pages of advertising. So many pages that we had to start a second magazine because we couldn’t bind all the ads into the weekly.

Steven Heller: What year was that?

Bob Ciano: 2003 or 2004. Most of the ads ended up not being paid for because they were startups that went out of business. So, from there, I was doing Forbes ASAP, designing that, and somebody I worked with at The Industry Standard was working at Wired and the art director announced he was leaving, like, within two weeks.

And Jeremy LaCroix, a designer at Wired, recommended me to be the art director. And they hired me. I was supposed to stay a month or two while they did a search. I was not going to be considered for being the art director because I was too old, I was told.

Steven Heller: Was this before it went to Condé Nast?

Bob Ciano: No, it was Condé Nast, but they were here in San Francisco. The two months ended up being a year there. And I had a great time. I loved being there. I loved the magazine. And a year later they hired somebody and I moved on.

Steven Heller: Did you see any irony in “Mr. Print” working on a print magazine called Wired?

Bob Ciano: Yeah. I did. But I didn’t let it get in the way.

Steven Heller: So what happens after Wired? You’re in San Francisco, the next I hear of you is that you’re teaching.

Bob Ciano: Well, you know, I started teaching at SVA when I was still in New York in the sixties, late seventies. I was teaching a class with Ed Lee. He was a designer at Columbia Records with me. And we co-taught a class. And then I taught at NYU and I taught, oh, a lot of places—I’ve always been teaching. Always.

Steven Heller: Always magazine design?

Bob Ciano: No. I did classes on typography. I did classes on just thinking. It didn’t have to be magazines. It could be how do you come up with good ideas.

So after being at Wired, I went to work at St. Mary’s College as their creative director, and that was doing their magazine—they really wanted to upgrade their magazine. I did all the campus signage. I did the letters going out to donors to raise money. I did uniforms for the basketball team. And that was fun. I enjoyed that. But, after a while, I get antsy and I want to try something else.

Steven Heller: You’ve been antsy a lot in your life.

Bob Ciano: Yeah. I once made a list and it’s, like, about 22 or 23 places that I’ve worked as an art director. I must admit it was easier to move years ago, when I lived in New York. You know, people were switching off all the time. Things seem much more static now, and as I’ve gotten older, you know, I don’t get calls from people looking for art directors. So I’ve morphed to just being, not just, but being a teacher and doing freelance. But, strangely enough, freelance has been very busy.

Steven Heller: Very busy. Since Covid or before Covid?

Bob Ciano: Before Covid. So currently I’ve got two books going. I’ve been doing music videos, and magazine redesigns.

Steven Heller: All out of your Ciano Designs studio?

Bob Ciano: Yeah, this room. All out of this room. Before Covid I had two people in the dining room working, but now we do it long distance.

Steven Heller: Going back to teaching, I face this getting into my dotage, that the students tend to know a lot more than I do, in terms of popular culture, in terms of technology, and the quality, at least on the surface, of what comes out of their machines is so far superior to what I used to do when I’d mark up tracing paper pads like Lou Silverstein did. How do you cope or adjust to this kind of newness? In the face of growing older?

Bob Ciano: I push back against it. I make them sketch on paper. They think I’m, you know, ancient. But I’m more interested in their process than I am in their finished work. So I spend a lot more time making them do thumbnail sketches, pushing their ideas to past where they want to go.

And I’m always preaching that it’s better to start way out, in an uncomfortable place. You can always bring your design back. But it’s very hard to start conservatively and then push it out. So I make them sketch a lot and we talk about the idea more than the finished art. And they’re all working on their tablets. And I think it’s restrictive.

I had a student last semester who was doing a book and she had the type set and I asked her what size the type was and she said the text is all 24 point. And I said, “What is 24 point? How big is that?” And she said, “It’s 24 point.”

And I realized she didn’t know what a point was. And she didn’t really know the size because she was looking at it on the screen. So it kind of led me to do several classes on what’s a ‘point’? What’s a ‘pica’? Why are we still using this nomenclature? That you can use type as a visual element, a design element. It can be the only design element. Don’t just, like, throw in some type.

And the students tend to resort to, “I’ll do hand lettering.” Because they don’t want to deal with points, and picas, and Bodoni, or whatever. So I kind of force them to do that. And I also teach them calligraphy. You know, how to take a pen and—I just, sadly, saw in the paper a few weeks ago that David Lance Goines died.

Steven Heller: Yeah. He was 77.

Bob Ciano: … And we were scheduled to go to his print shop. Every semester I took a group to his shop. But I think it’s important for the students to explore and it’s too easy in Procreate to get the same old answers over and over. And it’s just not good enough.

Steven Heller: Do you see that as the rule? Because I see as, certainly as an exception to the rule, that students are interested in hot type, hot metal, letterpress, silk screen—things that we were—that they are interested in.

Bob Ciano: I’m not seeing that here. I’m not. I mean, I introduce it in the class, because I teach a class on typography and design for illustrators. And, at the beginning they’re not interested. But by the end I hope they are. And one of the nice things, and I don’t know if you’ve come across this, I’ll get an email from a student who I had, maybe, five years ago, who’ll say, “It’s now sinking in. The stuff you told me is now making sense. It didn’t make sense when I was a student.” And that’s always gratifying.

Steven Heller: You always get one out of every 20 that will do that.

Bob Ciano: That’s a pretty good ratio.

Steven Heller: That’s a pretty good ratio.

Bob Ciano: I still try to push illustration. You know, I have no problem with photography, but I don’t think illustrators are being used enough. And I think they bring something to the table that photography doesn’t particularly do.

Steven Heller: How do you feel that the students have changed in the last 10 or 15 years?

Bob Ciano: I don’t know if they’ve changed as much as I’ve changed. Or maybe they’ve changed and I’ve stayed still. They seem too quick to settle on an answer. And the exploration part doesn’t seem as emphasized as much as I think it should be. They’re very interested in the surface of what things look like, but there’s no surprise or depth. They’re very adept at polishing things, but I don’t think they spend enough time thinking about things.

So I play opera for them. I introduce things that they’re not familiar with. I show them work of illustrators that they’ve never heard of because they’re from 30 years ago. So I’ll show them the work of Guy Billout and they don’t know who he is. How could that be? So I make each student do five minutes on somebody whose work they like.

And last semester one student did five minutes on Mœbius, which was a surprise. So we talked about Mœbius and then we talked about Tin-Tin. And then I showed them Guy Billout’s work and they loved it. And I said, “Would you like to meet him?” And we did a Zoom with him for two hours. The one good thing about, the only good thing about—for two years we were doing Zoom classes only—was that I was able to get people from all over the world to talk to my class. Every week I had somebody dialing in from somewhere—people they wouldn’t see. So from Italy, from Japan, from South America, it was great.

Steven Heller: So I want to end with two questions. I’m working on a piece based on the old Fisk advertisement, “Time to Re-Tire.” Do you remember that little boy holding a tire around his nightgown? And of course it’s related to me and others like me who are wondering if designers ever retire or just fade away like old soldiers. What do you think about that?

Bob Ciano: I think we’re old soldiers. What would I do? I don’t play golf. You know, this is too much fun. As long as I feel like I can do things. I don’t apply for jobs anymore because once they see my resume, they know I’m too old. But as I said there’s turned out to be a lot of freelance out there. And as long as I feel like I can still do the work, I’m going to die in my chair.

I have this video interview with Saul Bass that somebody did. You may have seen it. But at the end of the interview the interviewer says, “Are you going to retire Saul?”

And he said, “Are you crazy? I’m having too much fun. Why would I stop working?”

And I feel the same. As long as I feel like I can do it, I’m going to do it.

Steven Heller: That’s great. So the last question I have: Is print dead?

Bob Ciano: No. It’s just different. I think things are morphing all the time. And I don’t know if print has to be print in a traditional way anymore. I think one could do a magazine in all different forms. And that’s the exciting part. I try to avoid telling my students, “This is the way we used to do it.” Nobody cares. How best to do it now with the tools we have now.

Steven Heller: And we could call it anything we want.

Bob Ciano: Exactly. Magazines, or books, have come in many forms over centuries. They’re not going away. They’re always changing. Is there going to be a Life magazine again? No. Do we need one? Probably not. But there are ways to tell stories and there are ways to present information that can be special and can be memorable. And we just have to find those ways. And be willing to try things.

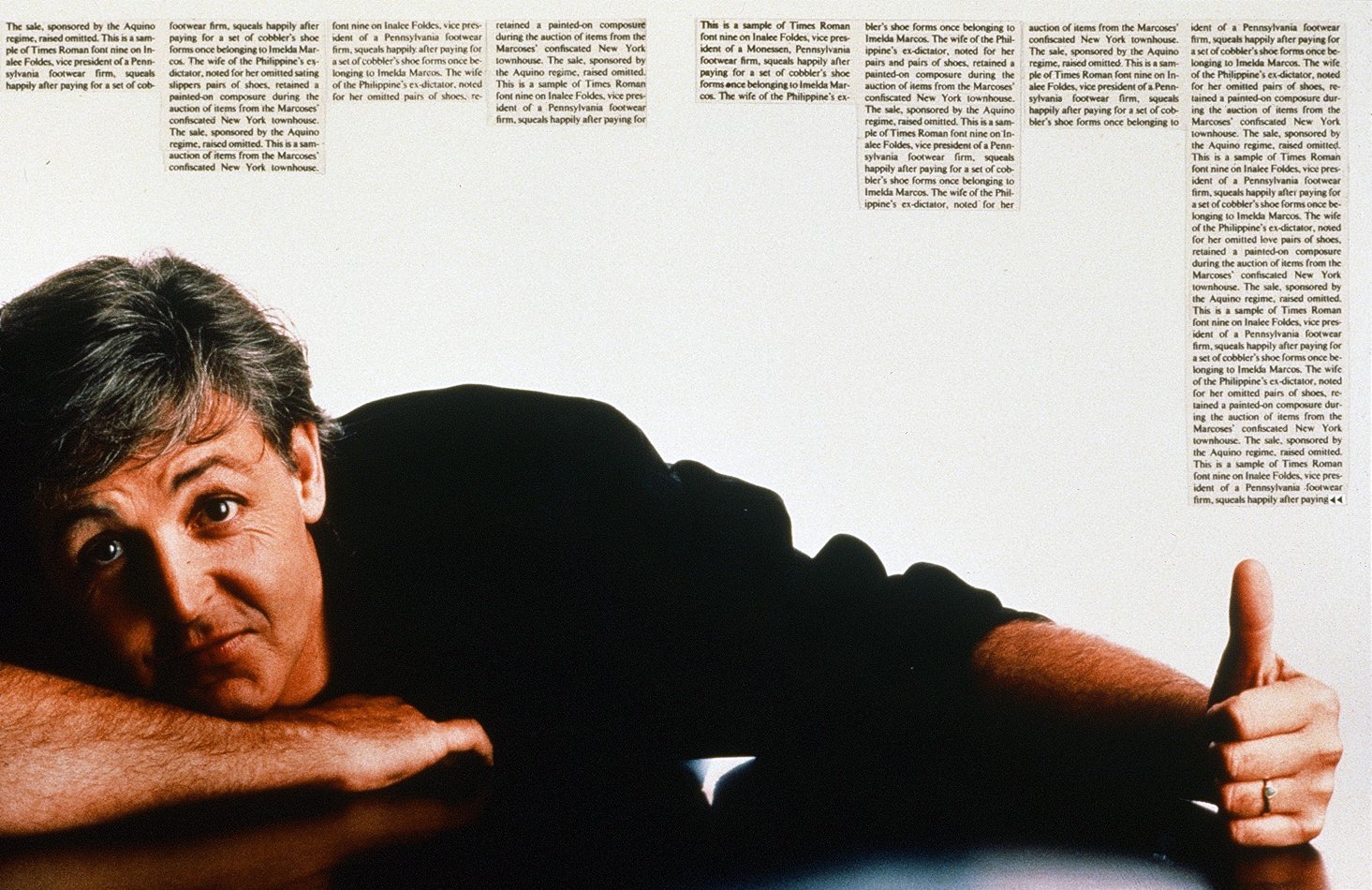

In between his magazine gigs, Ciano did stints designing album covers for Columbia and CTI Records.

For more information on Bob Ciano, or to beg for a jar of his homemade spaghetti sauce, start here. In addition to running his studio, Ciano teaches in the Illustration Department at California College of the Arts.

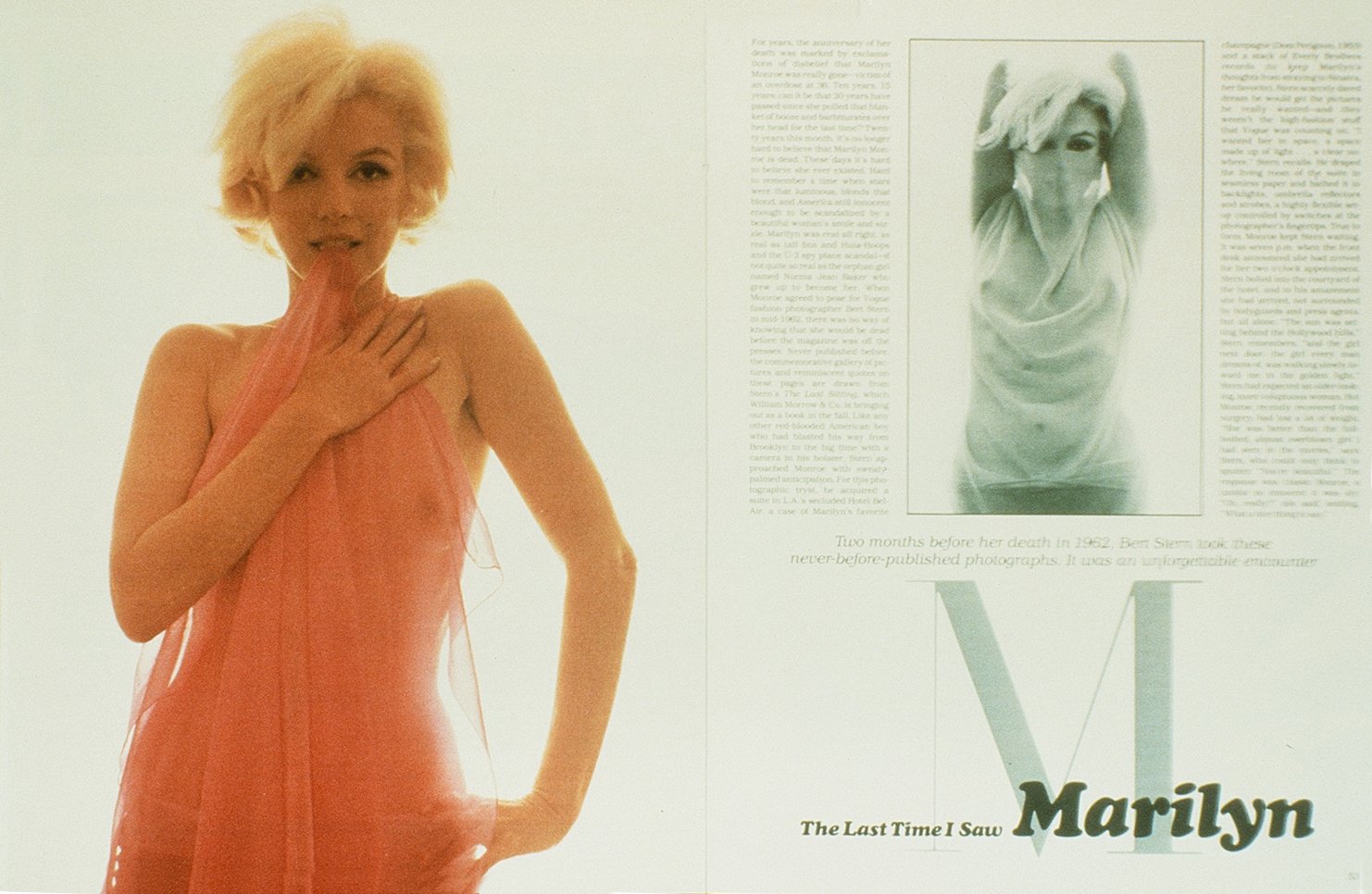

More Like This