A Crime of Attitude

A conversation with editor and author Tina Brown (Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, Tatler, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT MOUNTAIN GAZETTE AND COMMERCIAL TYPE

As George Bernard Shaw once said, “England and America are two countries separated by the same language.” Turns out it may be more than just the language.

Early in my career it became clear the British were coming. The first wave arrived when I was an editor at New York magazine: Jon Bradshaw, Anthony Hayden-Guest, Julian Allen, Nik Cohn—all colorful characters who brought with them, as author Kurt Andersen said in Episode 2, “an ability to kick people in the shins that was lacking in the United States.”

And kick they did.

A decade later, the British trickle became a surge that appeared everywhere on the mastheads of premiere American magazines. There was Anna Wintour. And Liz Tilberis. And Harry Evans. Joanna Coles. Glenda Bailey. Andrew Sullivan. Anthea Disney. James Truman. And, of course, today’s guest, Tina Brown.

And the invasion continues today, with the Brits taking over our newsrooms and boardrooms. Emma Tucker at The Wall Street Journal. Will Lewis at The Washington Post. Mark Thompson at CNN. Colin Myler at the New York Daily News.

But none of them made it bigger faster than Tina Brown. Si Newhouse never knew what hit him. Brown, having just turned 30, grabbed the wheel of Condé Nast’s flailing 1983 relaunch of Vanity Fair and proceeded to dominate the cultural conversation for the next decade.

And then? Another massive turnaround at The New Yorker. The first multimedia partnership at Talk. Nailing digital early with The Daily Beast. Then Newsweek. And, more recently, the books, the events, and the podcast.

So Tina, what exactly is it with you Brits that makes your work so extraordinary?

“Well, I think that the plurality of the British press means that there’s a lot more experimentation and less, sort of, stuffed-shirtery going on. The English press is far more eclectic in its attitude and its high/low aesthetic, essentially. There’s much less of a pompous attitude to journalism. They see it as a job. They don’t see it as a sacred calling. And I think there’s something to be said for that, you know? Because it’s a little bit more scrappy, I think, than it is here. And I think that’s served us well, actually.”

So it’s no surprise then to learn that there were early signs of future-Tina. Here we call it “good trouble.” Tina’s got another name for it. As the story goes, teenage-Tina, blessed with a “tremendous skepticism of authority,” somehow managed to get herself kicked out of not one, not two, but three—THREE!—boarding schools. Her offenses? Nothing serious. Just what the ASME Hall-of-Famer refers to as her “crimes of attitude.”

And you know, when you think about it, what is any great magazine but a crime of attitude?

—George Gendron

George Gendron: I want to start in what might seem like an improbable place, which is January 22nd, 1989, and a meeting you had with [Hearst CEO] Frank Bennack. And if I was writing a social-media post about that meeting today, the headline would be “Tina Brown’s Best Job Offer Ever. You Won’t Believe What Happened Next.” So refresh our memory about what you heard when you went up to Frank’s office that day.

Tina Brown: Well, he wanted me to be the editor of Harper’s Bazaar. He wanted me to leave Vanity Fair and come and be the editor of Harper’s Bazaar. And he sort of promised me all the treasures, as it were, of Hearst Magazines, the mighty magazine empire. And I was very tempted, actually, because I loved the idea of reinventing another magazine. You know, I’ve been at Vanity Fair since 1984 at that point.

And I’ve always loved the whole process of reinvention as opposed to being a steward. Vanity Fair was doing really well at that point. We cruised to the top of the heap. And the thought of perhaps having a chance to take another great legendary magazine, Harper’s Bazaar, which had the wonderful Carmel Snow as the editor in the thirties and forties, who was a great heroine of mine.

I thought, you know, It might be very exciting. So I was genuinely piqued. My interest was genuinely piqued, which I think is important when you have an offer. If you’re going to end up, sort of, talking to your current boss about it, you don’t do that unless you’re willing—really interested in leaving.

Otherwise, you are, frankly, just “playing” with your boss essentially, and sort of saying, “Give me a raise.” But I was actually very tempted to do it.

George Gendron: But in addition to that, he was basically offering you the top job of any magazine they had in their stable. But he was also saying any magazine you’d like to start. And you left the meeting and you said something, I guess to yourself, that I found absolutely fascinating. You said to yourself, “It felt ridiculous that I couldn’t think of anything to want.” That’s not a position that lots of journalists ever have experienced.

Tina Brown: And certainly now it wouldn’t be the case in terms of, you know, the lack of opportunities. But, listen, I was editing the best magazine, I felt, in the world. And frankly, Harper’s Bazaar is the only title in his stable I would have considered.

So I didn’t really want to edit any of the other magazines and nor did I wish to start one. And so, yeah, I guess it was, I was in a lucky moment in my career, shall we say. I mean, it was the golden moment, right? It was the equivalent of peak TV, but peak magazines. There were opportunities.

There were companies that were starting things, launching things, doing things with a decent sort of budget and a proper staff. And we did not know how lucky we were at the time. The thing about the golden era is you never know you’re in one till it stops. So now I look back and think, My God, that was Camelot!

“The first issues of Vanity Fair were absolute turkeys.”

George Gendron: I want to ask you a question that certainly is relevant to Vanity Fair, but you’ve had so many launches and turnarounds under your belt now. I’m. I’m stepping back and asking it in a broader context, and that is, when you think about assembling your team, what’s your team? What are the essential players you really feel you want with you at the beginning of a launch or the beginning of a turnaround?

Tina Brown: Well, I actually feel strongly that personality and temperament and sort of psychological meshing is as important as the talent pool. So I’m quite good at that, actually, I have to say.

Casting a team—it’s like casting a show. You want your manager. You want your, what I call “outside person,” who’s connected to the world of artists, talent, stories in the outside world. But then you want your “inside people,” who are going to like working diligently on people’s copy and actually handling the way things run and, really, the craft element, as it were, of the magazine. You want people with visual sense, you want people with story sense.

So it’s really about finding those individuals who, together, make the perfect team. And actually, If you could get that right it stays together a very long time. And that has certainly been true of everything that I’ve done. I mean, the team I put together at Vanity Fair literally only left five years ago. They stayed 25 years after I left.

And the same is true at The New Yorker, where the team is still there, most of them. Now new people have come in and my people have started to drop from it, but they’re all there. Most of them. I mean, Jeffrey Toobin left, but David Remnick, of course, who’s the editor, Malcolm Gladwell, who I discovered—all of these people. Adam Gopnik. You know, these wonderful writers and editors and so on. They’re all mostly still in place.

And you know, you have to refresh the team as well. And know when you have to do that, when you have to feel the team is now needing a new injection of blood. And that can sometimes be difficult because then, of course, your fresh new faces that you’ve put together have suddenly become the old guard.

So that’s always a little difficult. But I usually didn’t stay long enough to have that problem. I used to just go on and do something else.

“When I took over Tatler, it was a ridiculous little shiny sheet with a staple through it. Kind of an old debutante thing.”

George Gendron: It’s interesting listening to you talk because I’m married to Sarah Noble, who is a recruiter of high-level editorial talent in business, finance, and entrepreneurship and she’s just closing her business now. She’s been at it for 25 years. And if you ask her when these real high level searches fail, why do they fail? It’s chemistry. She paid so much attention to, not just their technical skills or checking their bio, she talks to people who have worked with them to get a sense of what it is like on a day-to-day basis, shoulder-to-shoulder.

Tina Brown: Well, a lot of people don’t do enough diving on that. They tend to kind of go by resumes and I never did. I never went with people’s CVs. It was important to me to know they’d had some experience, but you know, when I put my first team together at Tatler, my features editor was a former travel agent. But she loved traveling and had lots of ideas and was connected to the world. And I thought, This is a person who will bring in a lot of ideas. Because you have to be engaged with what’s happening.

And I always like to have somebody with me each time I would hire either a TV producer or someone who was not actually a magazine editor who would actually also be part of the team because they had the outreach skills and they also had the producing skills, if you like, to work with the writers.

Brown with her husband, Harry Evans, founding editor of Condé Nast Traveler.

Some writers have great ideas, but they’re quite ‘interior.’ And they’re not necessarily the best person to bang on the door and get the interview. Some reporters are very good at that sort of importunate story-getting. But others, really, do much better if you can put the story in front of them and they write some wonderful story, but they’re not going to be necessary for people to get the story.

George Gendron: I think that this issue you’re raising about chemistry and the importance of the team is related to something that actually goes all the way back to your childhood. And at one point you’re talking about having been kicked out of, I don’t know, three prep schools or something like that. And I think you refer to your pranks as “crimes of attitude.” And then you go on, of course, several times, particularly with regard to Tatler, talking about, “Look, you might not have money, but you have to have an attitude.” And in fact, you really need an attitude when you don’t have money. And I think that question of attitude is so linked to the chemistry of the team.

Tina Brown: Well, that’s right. You can’t really manufacture that. And it’s the same thing—by the way, I used to say, “If you haven’t got a budget, get a point of view.” But also, that’s really how I judge writing, too. It’s not only about what they’re writing, it’s Do they have a voice? Does this person speak to you from the page with a very individual voice?

And actually, I was pretty good at finding that, you know, like resonating with that. And I would usually know by about four or five paragraphs in, Does this writer have a voice or are they simply a fact-gatherer? And the fact is that you can teach a writer how to write a lead if you like. You can restructure a piece. You can help the writer to shape the piece. But you can’t tell a writer how to notice the right things. Or how to have a voice.

I particularly realized this thing about noticing the right things when I was very pleased because I got an interview with somebody on one of my royal books who’d actually been with the Queen on the day that Diana died. I thought, Bingo! I’m going to get the best eyewitness account.

This guy didn’t notice anything! I mean he wasn’t being, you know, retentive about his information. He was just a very dull guy who didn’t really notice the right things. He wasn’t acute to what the atmosphere or what people looked like that day, or sounded like, or felt like.

And actually one of the things I found during my writing for magazines like Tatler and Vanity Fair, very often photographers were very good sources. Because, actually, they noticed things. They went into a room and they were trying to get a picture. And they weren’t at all involved in the whole engagement of the information. But they were sensing the best place, what people wore, you know, the colors of the thing, the weather, what was the view outside the window. They were actually pretty well-versed. And I used to get quite a lot of very interesting information from photographers because the other thing is that people don’t think they’re listening. And of course, you know, they do.

George Gendron: And, of course, the other thing about a photographer is that the subject doesn’t pay any attention to them usually.

Tina Brown: Exactly. They can be invisible.

George Gendron: That’s a great tip for young editors these days. So, I want to fast forward now to your new job, 1984, at Vanity Fair and kind of set the stage for that job. Remind everybody, how old were you?

Tina Brown: Just turned 30. Actually, I was 30 in November and I took over in January. And I arrived—I had been a consultant at Vanity Fair after Tatler because Tatler was bought by Condé Nast magazines. And meanwhile in America, while I was working for Tatler in the UK, they’d started Vanity Fair in America with a massive budget. I mean, my budget at Tatler was absolutely a cheese-pairing little budget of £10,000 an issue, or something ridiculous.

And Vanity Fair in America was launching with this massive sort of fanfare. They had a huge advertising campaign, billboards, and hoardings in airports saying, “Coming soon, you know, Vanity Fair!” And unfortunately, that’s always a very bad idea, as a matter of fact, because hype can set you up immediately for a fall. It’s very hard to live up to the hype.

And the first issues of Vanity Fair were absolute turkeys. I mean, they hired [Richard Locke] the deputy editor of The New York Times Book Review to be the editor. He’d never done a magazine of this kind. He wasn’t visual. He had no sense of covers and stories. He really was a sort of literary “sub” actually, really.

And it was a massively wrong appointment. They just got it wrong. And unfortunately the poor guy, he just literally flummoxed and fell on his face. So then they were casting around in this very embarrassing situation. And they put in, as a replacement, [Leo Lerman] the features editor of Vogue, who was a 75-year-old, old school, kind of Vogue-y, friend of, you know, the Maria Callas generation.

I mean, it was just, again, a terrible appointment. They thought, “Oh, well, Leo knows the ropes. He’ll be able to do something good with the visual staff,” et cetera. But it was another disastrous appointment. And it was when they started to realize that Leo couldn’t do it either, that they asked if I would come in and sort of be the, kind of, young consultant for a while.

And I came in the summer of 1983, before I took the job, to spend six weeks at Vanity Fair and see if I could bring something to it. And I realized within about a few days, really, that he just couldn’t do it, you know. And that actually, I could. I knew what needed to be done.

But here I was, I’d been brought in as a consultant, Leo had just got the appointment. So they asked me to stay, and if I would I would stay with him. And actually, when I look back—this was, for me, it was really the audacious part, I think. I thought to myself, Well, if I stay and help Leo out, I’m going to wind up just helping Leo out. And I’m going to end up being the magazine editor with Leo in charge. And I don’t really want that.

So I said, “Thank you very much, I’m going back to the UK.” And it was a gamble, actually, because I could have just lost it. And once I got back to the UK, I sat there for a while thinking, I’ve blown it, I’ve really blown it. I’m not going to get this job and it won’t come round to me again. Leo’s going to be okay, they’ll find someone else to help him. And there’ll be five years before I hear a peep.

Brown’s first issue of Vanity Fair, April 1984 (above), and (below) in her Condé Nast office.

But, actually, it soon went down-down. And the next thing is Harry, my husband, and I were on vacation in Barbados over Christmas. And I got this call saying, “Would [you] come into New York and meet with Mr. [Si] Newhouse, the chairman of Condé Nast, and Alexander Liberman”—the great editorial director … this very cultured artist and “style czar,” if you like, who was the editorial head of Condé Nast.

And I was asked if I would come in. And, of course, I realized when they asked me to come in, they were asking me to come in on New Year’s Day. So I flew into the meeting and that was it. I never went home again. For three years, actually. Harry went back to London. He packed up the house and he did all that and said, “You know what? I’ll figure it out. I’ll figure out a landing pad.”

Which he did. He went off and taught at Duke University for a semester until he joined me in New York as president of Random House. But it was a real gamble, I have to say. And I do say when people ask me about career advice, I do tend to say yes. You know? Don’t ask yourself, is this going to work? Where am I going to live? What am I doing? You know, recognize an opportunity and then figure it out afterwards.

I saw it as a great opportunity. And I also think something that’s not working is a great opportunity for a young, hungry talent, you know. When I took over Tatler, it was a kind of ridiculous little shiny sheet, you know, with a staple through it. Kind of an old debutante, joke thing.

And yet I could see that was an opportunity. I could take this thing and turn it into a real magazine. Because the great part about it was it would be mine. So it’s much better to have something small, failing, ailing, that’s yours. And you can make an impact and you can sort of put it together and reinvent it than it is to join some big thing as a cog in the machine in some mighty title somewhere where you’re just going to be, frankly, doing the photocopying, and printing things out, and getting people’s coffee and all that.

I would never have worked in a situation like that. I wanted to get my hands on it and create something of my own, you know. Which I did.

George Gendron: Listening to you reminds me in 1975, I was a young editor at New York magazine, and I got an offer out of the blue from Boston magazine, which was in really bad shape to come up and turn it around. And the owner of Boston was infatuated with New York. I don’t think he knew anything about me. Didn’t know how old I was. So I went into Clay Felker and told him about the offer. And he looked at me quizzically and he said, “So what’s the question?”

And I said, “Well, what do you think?”

And he said, “Well, I’m going to ask you a question. How many 25-year-olds do you know who get to actually run a magazine?” And that was it.

Tina Brown: Clay understood. I mean, exactly right. I was 25 when I took over Tatler. And it was tiny, but it was mine. And Vanity Fair is the same. How many times do people get the chance to have something of their own? I’m glad to hear you did it.

George Gendron: And it’s so easy to jump to the conclusion that the number one person is responsible, right? But think about what you just said about Lerman. If you had gone in and made him look good, people would have ascribed all of that success to him.

Tina Brown: Indeed.

George Gendron: And not to this young 30-year-old Brit.

Tina Brown: Exactly. I wasn’t having any of that. But it’s a gamble because, as you say, he could have been a giant success with somebody else to help him. So yes.

Well, Clay Felker was a very good friend of mine. And he was a great magazine maker. Oh my God! I regret that I never was able to work for him. The timing was never such that I would be able to work for Clay, but I would have loved to do so because I think he was one of the great magazine visionaries of all time.

George Gendron: Can you, in a sentence or two, put your finger on what you thought it was that was the driver of Clay’s brilliance?

Tina Brown: He had this fantastic sense of story and this wild curiosity. You’d have dinner with Clay and you’d start talking and he would immediately start driving down to, like, what was interesting, what—you know, he was just this omnivorous, devourer of the world. And he was able to then turn what he’d heard into a story idea.

And he really believed, as I do, that people in magazines have to be engaged with the world they’re covering. And he used to walk through those offices, apparently at New York magazine. And he would say to people at the lunch hour, “Why are you here?”

Because he thought people should be out—like attending a panel, or going to a talk, or seeing a movie, or you know, something to bring back, like a golden retriever, to the pages of the magazine. And I believe that’s what an editor does.

Now, there are different kinds of editors. There are the impresario editors, like Clay and, frankly, like I am, or there are editors who stay behind a shut door and they edit copy. But personally, I think a magazine editor has to be an impresario because you’re putting together all of these elements. And so it’s not just about what’s on a page. It’s also the visuals, the cover, the packaging, the mix—all of those things take a much more entrepreneurial attitude to the form of magazines.

George Gendron: I’ll tell you a funny story about Clay in this context. In 1975, just before I left and we had acquired The Village Voice. John Simon, the theater critic, was on vacation, so I got Gary Giddins to review a play. And we ended up writing a scathing review of a play called Dr. Jazz, which was in preview, but was supposed to open up the following night. And the play didn’t open. And I had already committed to publishing it. So a scathing review comes out of a play that hasn’t formally opened yet.

And I walk in on Tuesday morning and the whole newsroom gets really quiet and they’re all looking at me. And Clay’s just standing in the corner. And so Gary and I are there. And we’re two kids. And so we walk in and—it was a who’s who of Broadway—and they were there to protest. And Clay had said to Gary and me, “Don’t say a word.” And we walk in and he goes, “I told you, look at how young they are! They’re babies! Okay, you can leave now.”

So they left, we left. I went back to the newsroom, Gary went back to The Voice, the Theatre Alliance crew left. And that afternoon Clay came over, and he leaned over my desk and he said, “Did you think you were going to be fired?”

And I said, “Well, I called my wife to warn her.”

He said, “I have one message for you: Aren’t magazines amazing?”

“I was editing the best magazine, I felt, in the world.”

Tina Brown: Oh, I love it. Yeah, he really had a great time. It was most fun. You know, one of his greatest friends and writers is this wonderful man, Edward J. Epstein, who just died.

George Gendron: He was extraordinary.

Tina Brown: Yeah. I mean It was a great era.

George Gendron: I don’t think people really appreciated Epstein.

Tina Brown: No, I did. I thought he was an amazing journalist. Incredible. He also shared Clay’s great, avid devouring of the world, and the scene. He was a great friend of the British tycoon, Jimmy Goldsmith. He used to fly around in his jet and Ed would go with him and touch down in Paris and Mexico. And always the observer, and never caught up in it, but always the one who could see and learn. And I mean, he was just, he just loved it. And he would then regale the world with what he saw.

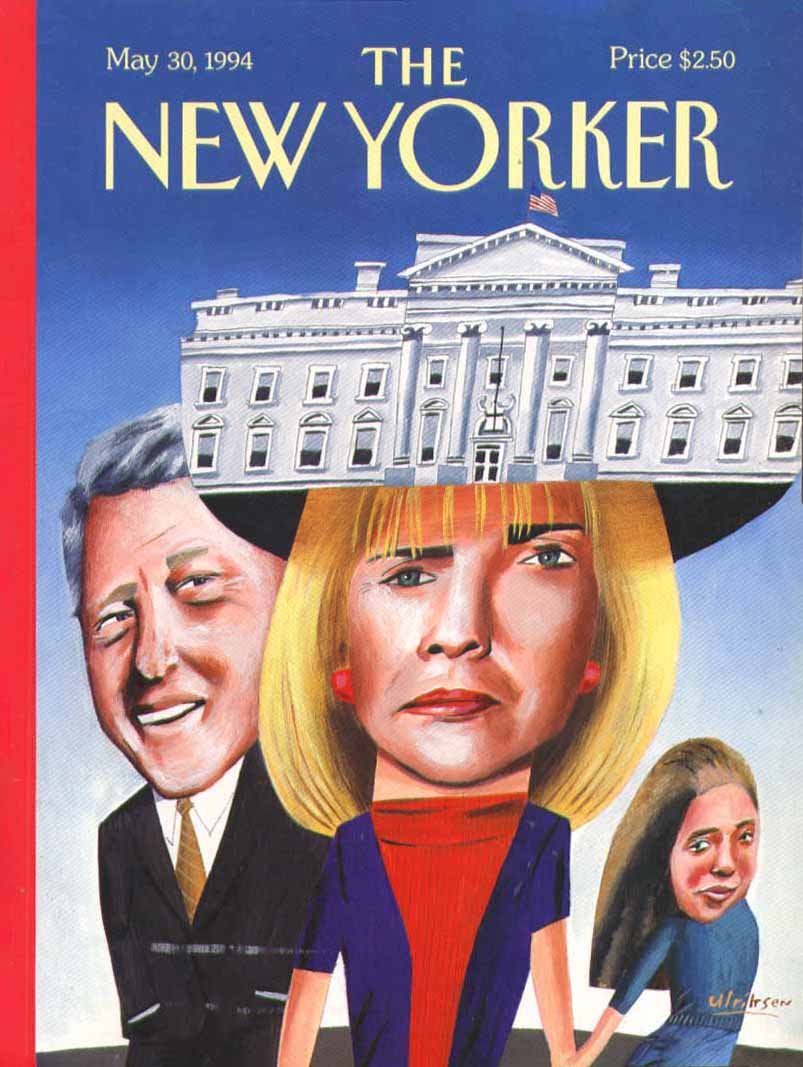

George Gendron: Now I’m going to fast forward to you moving to The New Yorker, which I know took a lot of people by surprise. And yet, in your book The Vanity Fair Diaries, going all the way back to 1987 you wrote, “The New Yorker needs a fresh layout, cover lines, more vibrant cover illustrations, blurbs introducing the stories, the introduction of photography, shorter pieces to vary the length and tone, and a contents page.” And that paragraph ends with a very emphatic and enigmatic, “Hmm.” So was that you already anticipating a move?

Tina Brown: Well, I think it was me realizing that I knew exactly what it needed. And once I’ve identified that, I have a vision, then the next stage is like, “Well, how can I implement it?” You know, I didn’t actually want to move to it when I first was offered it, as you see in the Diaries. It took me a year or two to want to because I had young kids. And also I loved Vanity Fair.

And you know, Si Newhouse put in Bob Gottlieb in between. But I gradually came to see that actually I did understand exactly what The New Yorker needed. And it was a great and wonderful literary challenge as well as being just an editing challenge to think that I could save this crown jewel of the empire, as it were.

Because it really was—the New Yorker was dying when I took it over. It was, as Tom Wolfe once brilliantly put it, “easier to praise than to read.” I mean, people would say, “Oh yes. I have The New Yorker.” “Of course I read The New Yorker.” But they weren’t reading The New Yorker.

And it was gradually losing all of its advertisers. And it was a very aging demographic. It was a dying brand. And it had about 600,000 readers. But, as you know, there’s 600,000 readers who are gradually getting old and peeling off. And they weren’t the people the advertisers wanted to reach.

So if I hadn’t come in then at that moment, it really was on its last legs. It was quite close to folding. It was a very exciting moment to be able to come in and save it. You know, I love that mission, which is very high-adrenaline.

George Gendron: In a recent conversation with David Remnick, he pointed out that he thinks that people, even really savvy media people, dramatically underestimated the nature of the turnaround. And pointed out that The New Yorker had really been in trouble, gradually, since the late sixties. This was not recent.

Tina Brown: Well, it takes a long time for a great title like that to die. And it was like 10 years in the dying, as it were. Maybe more. But it was very exciting to turn it around. My goal was to keep the best of it and bring in new, exciting blood. And I think that’s really important in a turnaround. I mean, I often see new people coming into organizations, they make big dramatic statements about “I’m going to do this, I’m going to do that.” And they diss, essentially, the thing that they’ve taken over and said “we’re going to make this so different.”

And I really didn’t do that, actually. I thought that it was very important to respect the legacy of what was there. I mean, let’s face it, there was John Updike. There was Roger Angell. There was Lillian Ross. There were some amazing people there.

So my goal was to keep those people, and I did, and sort of thin out—there was a kind of underbelly of quite mediocre people, quite honestly. I used to define them as people who thought that they were good because they were there, as to being there because they were good. Which is different.

It’s like, “Oh yes, I write for The New Yorker.” But actually they’re pretty mediocre. And there were a lot of them. A lot. And they’d started to gather in greater and greater numbers. So what I had to do, frankly, was to take out that layer. Keep the great people like Updike, and Angell, and the late, great Brendan Gill. And bring in people who I thought, in their own way, were good or even better, such as Anthony Lane, and Remnick, and Jane Mayer, and Ken Auletta. These are all the new people that came in and they were every bit as good and sometimes better than some of the people who’ve been there before. So that was, really, the challenge.

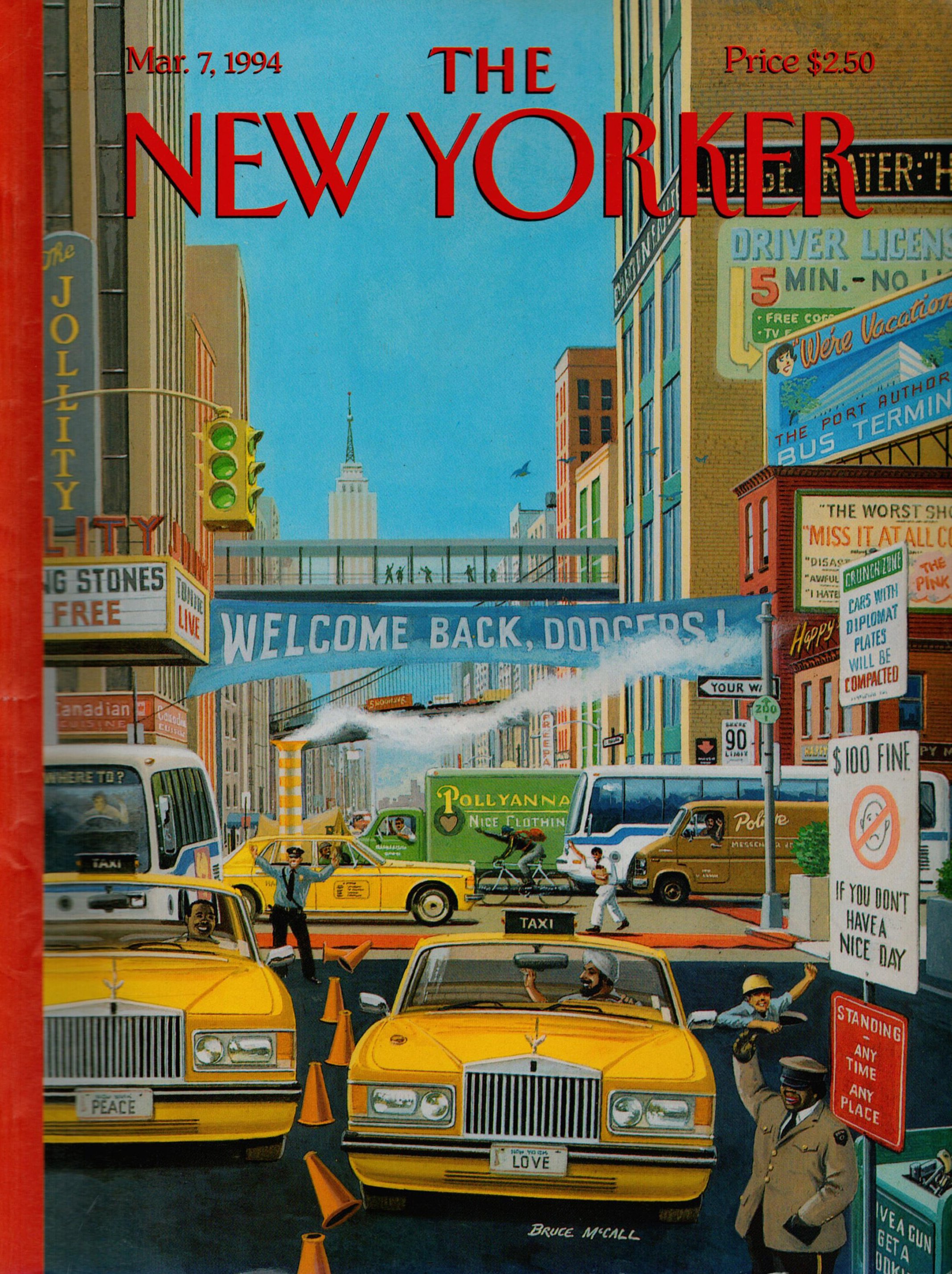

And then visually—it hadn’t been visually interesting since the days of Harold Ross in the twenties and thirties. What I discovered when I went back to look at the very first issues was how different the early New Yorker was to the, sort of, late period New Yorker. It was much more visually vibrant. They had people like Peter Arno and Charles Addams, and they would use those brilliant cartoonists full page. Those cartoons were full page! And the covers—they had an iconoclasm to them.

So, that’s what I really decided I had to do is to find a who le new race of cartoonists out there and illustrators and bring back that whole sense of visual irreverence to the magazine. And I replaced the quite, frankly, stale cartoon editor with a new cartoon editor, Bob Mankoff, who only just recently retired. A wonderfully, hysterically funny character. And brought in François Mouly, who’s still there, actually, to be the Illustrations and covers editor. So I replaced the whole visual team, essentially.

“He sort of promised me all the treasures, as it were, of Hearst Magazines.”

George Gendron: It’s very interesting, having read your Diaries, to compare the early days, your early days, at Vanity Fair huddled in a room with Charles Churchward and Ruth Ansel and literally reinventing the magazine. And I’m talking about in an unbelievably granular level of detail, where you’re not just reinventing what a contents page is for the first time, but you’re also talking about small photos, and margins, a really elegant black rule here. But I mean, from the ground up.

Tina Brown: Well, I think it’s all terribly important. I mean, I think captions, for instance, are incredibly important. Headlines, captions, blurbs. They’re the things that give a magazine voice. I always felt that you had to be able to throw a magazine on the floor and have it fall open and know what that magazine’s title was.

And you knew that from the layout, from the headlines, style, from the pull quotes. All those things I really drilled down on every pullout quote in that magazine was chosen by me. Because I felt that I was giving the flavor that I wanted to give of that particular article. And I knew how to pull in the reader from those things. And they’re small accumulating details that make up a very compelling page. But it’s gone. It’s an art form that’s over.

George Gendron: Okay, but we can reminisce for a minute here, right?

Tina Brown: Yes. It was an art form. There’s no doubt about it.

George Gendron: Yeah, it was. It was. I love the story about you rummaging around as you get ready for the April issue of Vanity Fair, the first issue of yours, and finding an Annie Leibovitz portfolio of up-and-coming comedians in the art department.

Tina Brown: And I fell in love with it. I said, “Hey … ‘April Fool’s’!” I wrote the headline. And there was, like, Pee Wee Herman, and Whoopi Goldberg in the bath—if you remember that wonderful picture of Whoopi Goldberg in that white milk bath. I mean, these were iconic pictures when you look at them, and there they were lurking in a drawer.

George Gendron: I suppose you didn’t find any of those when you were rummaging around The New Yorker.

Tina Brown: No, I didn’t. But I was able to go out and find a whole lot of new illustrators like Edward Sorel, who was a great illustrator. Art Spiegelman, Barry Blitt, Bruce McCall. These were all wonderful people that I brought into The New Yorker and they really enlivened the look and brought color to the pages, too.

And then I actually brought into The New Yorker, the very first photographer as a staff photographer. And that was Richard Avedon. I thought, I want to open the windows of the magazine. I want to bring in photography. But I want it to be in keeping with the pristine Caslon typeface of The New Yorker and make it feel really matched to the words and to the seriousness.

And I felt the only photographer I knew that really could do that and in a way that would be absolutely perfect would be Avedon. And he was. For several years, he was the only photographer that ever worked with us. And you know, the idea was to put in two or three, maximum, Avedon shots in that great, clean, strong black and white style of his, and they just made the pages sing.

Brown’s first issue of The New Yorker, with an illustration by Ed Sorel, October, 1992.

“I am omnivorous when it comes to ideas and engagement, politics, foreign affairs, culture.”

George Gendron: It was very interesting listening to David Remnick talk about how, without the work that you had done, he never, ever would have been able to do what he’s done with The New Yorker.

Tina Brown: Oh, that’s generous of him. David is a massive talent, so he would have got there. I would say that, certainly, I did have to “break the china” to make it what it became. And he’s done a wonderful job ever since.

George Gendron: What’s the one thing, when you look back on your time at The New Yorker, you would do over? The Easter Bunny on a cross cover?

Tina Brown: Yeah, I wasn’t thrilled with that when I look back. Mostly because it actually appeared the week that I was getting the National Magazine Award, you know, for general excellence. And so, there was all this uproar going on about this cover just at the moment when I actually should have been sitting there basking and having a very good week.

So yeah, I probably wouldn’t do that again. But I wanted to stand behind Art Spiegelman, you know. Because Art Spiegelman is such an amazing talent. He’s very iconoclastic. And he’s very dangerous, essentially, in what he wants to do. And I was always standing behind him. And I felt if this is what he really wanted to do, I would take a deep breath and have him do it. But probably I wouldn’t do that again.

George Gendron: One of the things that I find really interesting in your writing are the comparisons that you make between England and the US. And I want to start in particular with the comparison that you make about British journalists and American journalists, which might help explain the massive exodus of journalists out of the UK here into the US, where It seems as if everybody I’m familiar with, anyway, has had extraordinary success. What is it about you Brits and the sensibility, seriously, that you bring here, that publishing sensibility that works so well?

Tina Brown: Well, I think that the plurality of the British press means that there’s a lot more experimentation and less, sort of, stuffed-shirtery going on amongst, what I call the “quality press.” The English press is far more eclectic in its attitude and its high/low aesthetic, essentially.

You know, a famous name, like, I don’t know, John le Carré or someone, would not be at all dismayed by writing for a tabloid, you know, if the money was good. It remains, in England, a sort of informal profession, where people do not feel that they’re part of the sort of highbrow press, and therefore they wouldn’t be caught dead in a tabloid or something. That’s not true in the UK press.

There’s a lot more crossover between high/low, tabloids and broadsheets, little magazines, as we call them, which is like the New Statesman kind of magazine, or The New Republic kind of magazine here, as it would have been. Those things are far more informal and light in terms of aesthetic and the fact that different people can work for them. And there’s much less of a pompous attitude, quite honestly to journalism.

So I think, at its worst, British journalism can be really salacious, et cetera. But there’s also a lot of talent, and enjoyment of words, and irreverence that goes into putting out some of the most tabloid newspapers.

I mean, the headlines, picture cropping, picture editing, picture choice, for instance, in the British tabloids is superbly good most of the time. And there’s just nothing like it in the United States, actually. I can’t think of a newspaper—I mean, newspapers are dead anyway, frankly, but I mean, before they died, I used to be amazed at how dull many of them look, quite frankly, compared to the British press. And indeed the European press.

I love the French and German magazines of the past, that probably they’re in bad shape now, but things like Stern magazine in Germany or Paris Match in France, these were more racy in their outlook. And I think that’s probably why British editors cross over here and they make an impact on us because they’re splashier, essentially, and much more irreverent. And I think it plays well for modern tastes.

George Gendron: You know, when you’re talking about journalism as an industry in the UK, using the example of John le Carré being willing to write for a tabloid, that also reminds me of British actors. Same exact thing. I’m amazed to find some of the most amazing talent and they’re doing TV series for the BBC and mystery shows.

Tina Brown: It’s true.

George Gendron: They’re extraordinary.

Tina Brown: They are. They see it as a job. They don’t see it as a sacred calling. And I think there’s something to be said for that, you know? Because it’s a little bit more scrappy, I think, than it is here. And I think that’s served us well, actually. And yeah, there’s a second diaspora going on now, you know.

A Brit has just taken over CNN, Mark Thompson, who came from the BBC and took over The New York Times. There is Will Lewis, who came out of The Telegraph, and some of Murdoch’s stuff, The Wall Street Journal, he’s now taken over at The Washington Post. So a second influx is coming our way. And Emma Tucker has taken over from The London Sunday Times has taken over The Wall Street Journal. So yes, another horde has arrived since my day.

George Gendron: Well, it made for good spectator sport, right? So, I want to ask you about the the moments in your Diaries when you talk about the house that you and Harry had in Quogue, on Long Island, and your whole tone—the tone, the pace, the rhythm of your prose slows down. Can you talk about that a little bit? Do you still have that house?

Tina Brown: Well, I still have a house in Quogue, but not that one, which got thoroughly damaged by Hurricane Sandy. You know, it’s my place. It’s my happy place. It really always was. I like to live life at a frantic pace in the week, and then I completely contract out at the weekend and I do slow down. And Quogue always represented that spiritual home where I could get out there, light the fire in winter, or walk on the beach and just completely turn into a different rhythm, which would be more contemplative, more meditative.

It’s where I did my writing. It’s where Harry did his writing and where I could be with my children. And it was just, you know, another way of life. And without it, I would honestly have totally incinerated, because I could not live at that pace and work at that pace without being able to then go into this other zone. And I’ve always lived like that and I still do, actually.

Even though Harry’s no longer with me, I still always go out to Quogue whenever I can. I mean, really, every weekend unless I can’t for any reason. And I do the same thing. I’m on my own now, but you know, I read, I walk, I think, I relax, and then I’m very rejuvenated for Monday morning.

George Gendron: OK, two questions wrap up now. One is—you have to ask this—anyone who reads The Vanity Fair Diaries has a vivid sense of the Tina Brown of the eighties, and I’m assuming the nineties and on. What’s the Tina Brown of today like?

Tina Brown: I still live at a frantic pace. I’m—two things—I’m actually doing at the moment. I wrote my book [The Palace Papers: Inside the House of Windsor—the Truth and the Turmoil], obviously, on the royals last year, which did very well. And that was my total obsession for a year and a half.

I’m now guest curator at the Aspen Ideas Festival, which means it’s 25 panels a day for seven days. So it’s a bit like putting out a massive magazine with, you know, endless features in it, which is sort of enormous fun. And I also started an investigative journalism summit in London, in my husband’s name and legacy, called Truth Tellers: The Harry Evans Investigative Journalism Summit. I launched it last May. I raised the money. I convened about 60 incredible journalists from all over the world.

So I’m still just as engaged with journalism, but I’m using live platforms to, essentially, be my magazine replacements. I find that the convening of panels, discussions, interviews, and so on. I mean, it’s not as much of a gratification as the page, but it’s as near as I can get to the sort of mix, and excitement, and intellectual combinations of people and so on that were very similar to a magazine. In fact, doing the Aspen Ideas Festival is really like doing The New Yorker, but on steroids for seven days. And I’m enjoying that at the moment.

So I haven’t slowed down and I haven’t really stopped bringing my own creativity to a mix of ideas. I am omnivorous when it comes to ideas and engagement, politics, foreign affairs, you know, culture. I’m a news junkie. I’m an entertainment junkie. I’m, you know, I’m just as engaged essentially as I always was, really, by putting out magazines.

Shortly after its merger with The Daily Beast, where Brown was founding editor, Newsweek ended its print edition.

“Everything online—it’s just an uncalibrated list of stories. It’s just a boring list of stories and down you scroll.”

George Gendron: Well, we’re thrilled to hear that. Now to close, we have to ask you—and I don’t know whether we tipped you off to this or not—but we end most of our podcasts, or many of them, with what we call The Billion-Dollar Question. And, in your case, the question is this: Imagine that it’s 2005-ish and Laurene Powell Jobs wants to give you and Harry a billion dollars, with one caveat—you have to launch something in print. She loves what you have done in print. What would the two of you have made?

Tina Brown: I think we’d have done a newspaper magazine together. We always wanted to do that. It’s something that had the feel of a newspaper, but was actually a magazine. And I still think that could be enormously exciting. However, I don’t think anybody reads print now.

And until we have a module on our computer where you could just hit print and out comes a completely bound—which may happen. I mean, it’s not at all a non-possibility in today’s tech world. Technically, it can happen.

And maybe that will be the answer to revive some print, because I have to say that what is boring about reading everything online—and it is boring—it’s just an uncalibrated list of stories. There’s no sense of hierarchy—of any kind. You can’t splash a headline. You can’t splash a picture and say, “This is the important thing today.” Or you can’t create an energy of “pay attention to this.” It’s just a boring list of stories and down you scroll.

And yes, you can blow up the picture if you want and look at the pictures and so on. It doesn’t have anything like the glory of a double page spread by Annie Leibovitz. It just doesn’t. It never has and it never will. But, like everybody else, I read everything on my phone. So I can’t pretend that I’m sitting here reading a pile of print magazines because I’m not. I’m reading everything on my phone.

George Gendron: But you do sound excited about the potential for this. By the way, did it have a name or do you not want to go public with that just in case?

Tina Brown: We never gave it a name, but we used to talk about it sometimes at breakfast. You know, I think, if you could print it, maybe instantaneously, maybe people would. Who knows. But I suspect it’s gone. And it’s all about the digital. But the only thing I will say is that, you know, people tire of things. And sometimes people—they’d call it retro perhaps—but our kids who never saw magazines and grew up reading everything on phones, they might find print exciting and exotic to try to create it this way. But right now it just feels like it’s gone.

Talk, launched in 1998, was a partnership formed by Brown, Harvey Weinstein (Miramax), and Ron Galotti (a former Condé Nast publisher) to make books, a magazine, television programs, and films.

For more on Tina Brown, subscribe to her podcast, TBD with Tina Brown, where she talks with actors, politicians, journalists, and the newsmakers of tomorrow. Her 2022 book, The Palace Papers: Inside the House of Windsor—The Truth and the Turmoil, or our favorite, 2018’s The Vanity Fair Diaries are available wherever books are sold.

Related Stories