The New York Observer

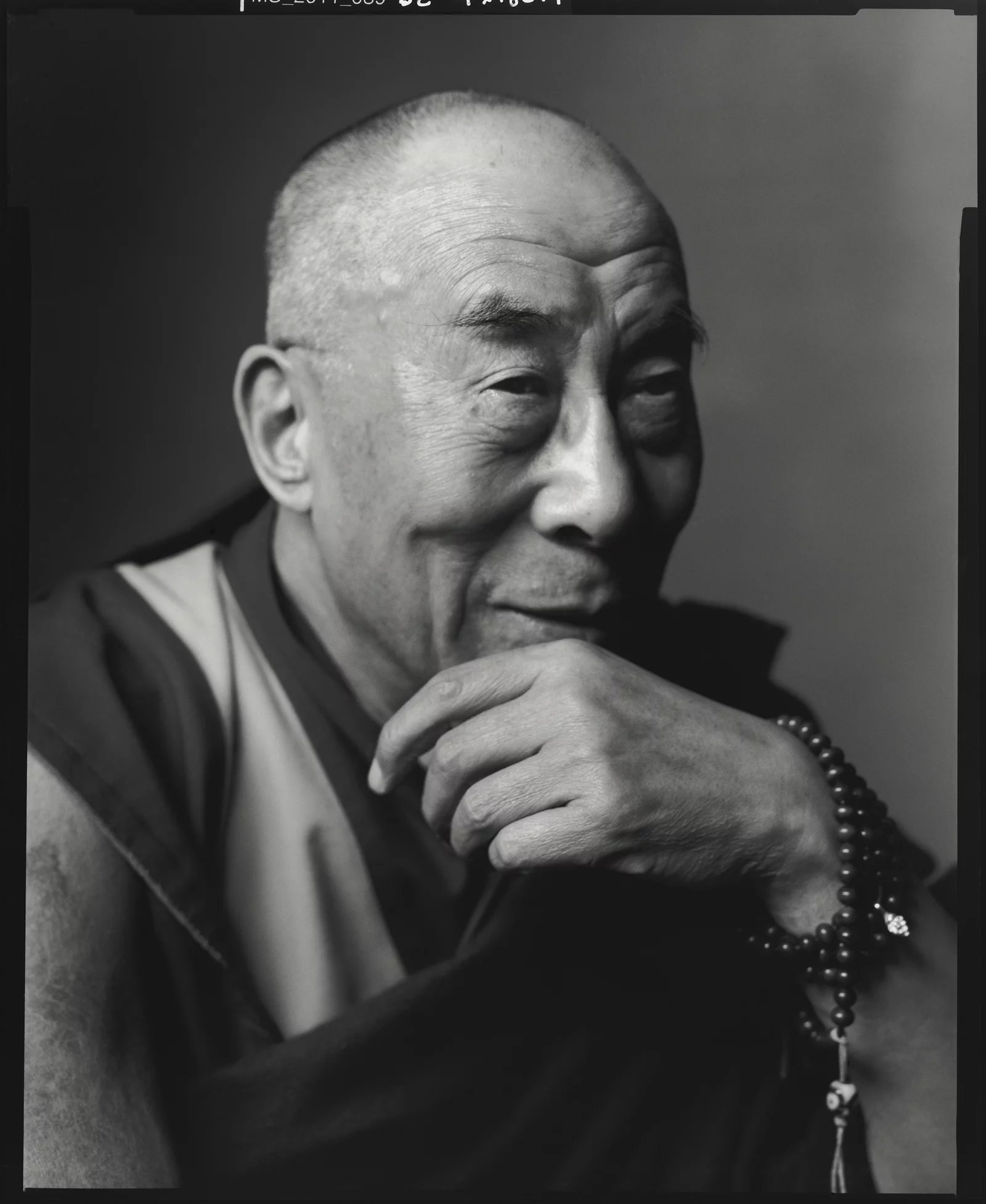

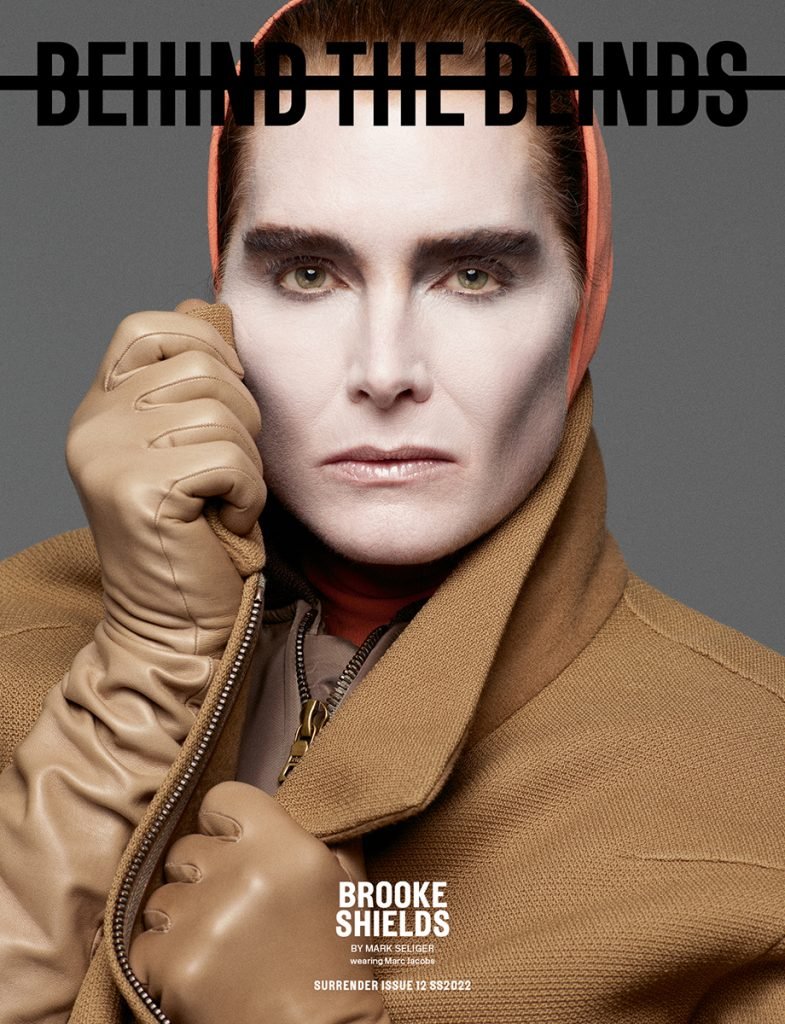

A conversation with photographer Mark Seliger (Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone, GQ more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT MOUNTAIN GAZETTE AND COMMERCIAL TYPE

“I finally went up to Graydon and I said, ‘Hey, you know, I know you like me. I know you wanted me to be here, but I can also do covers.’”

• • •

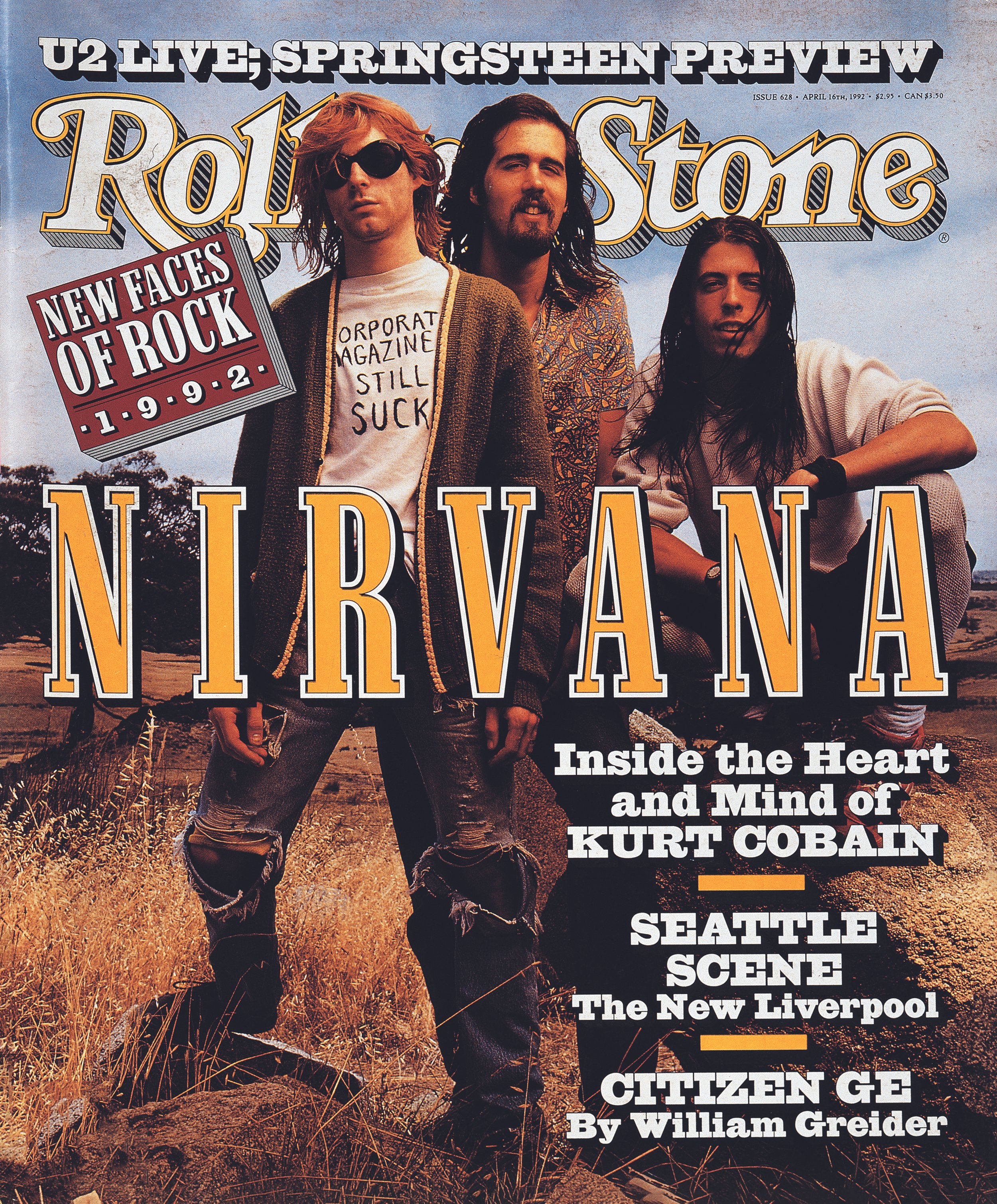

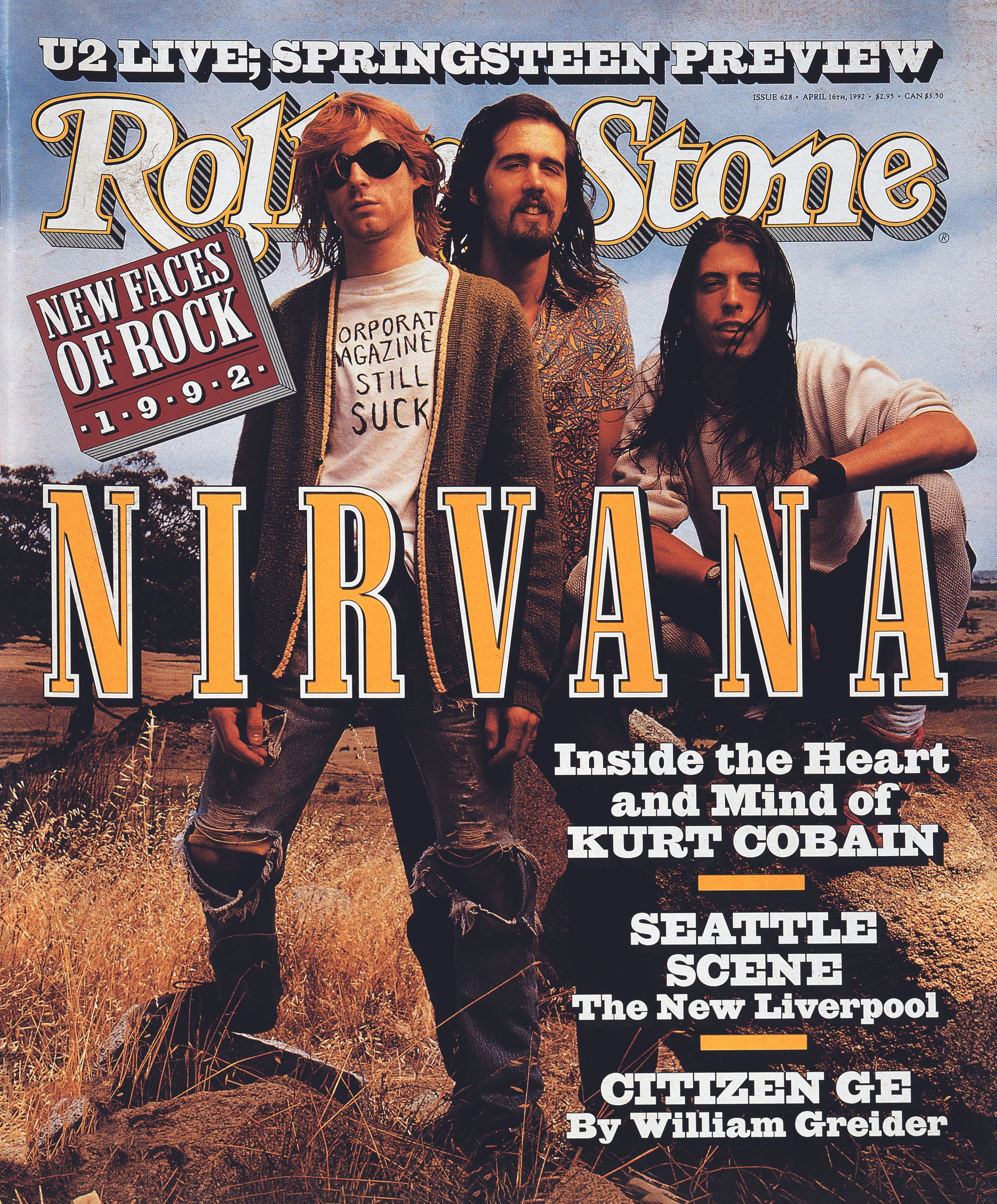

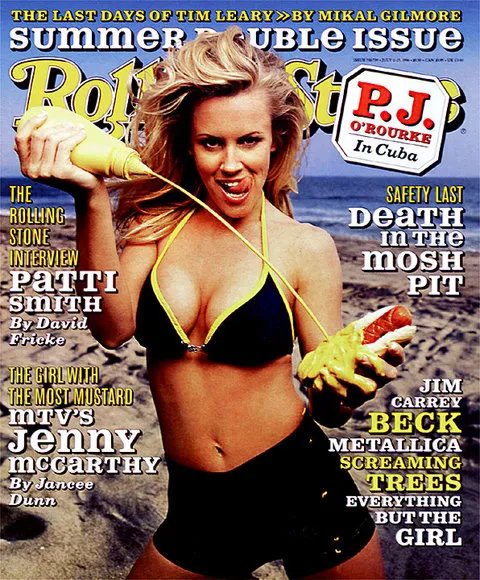

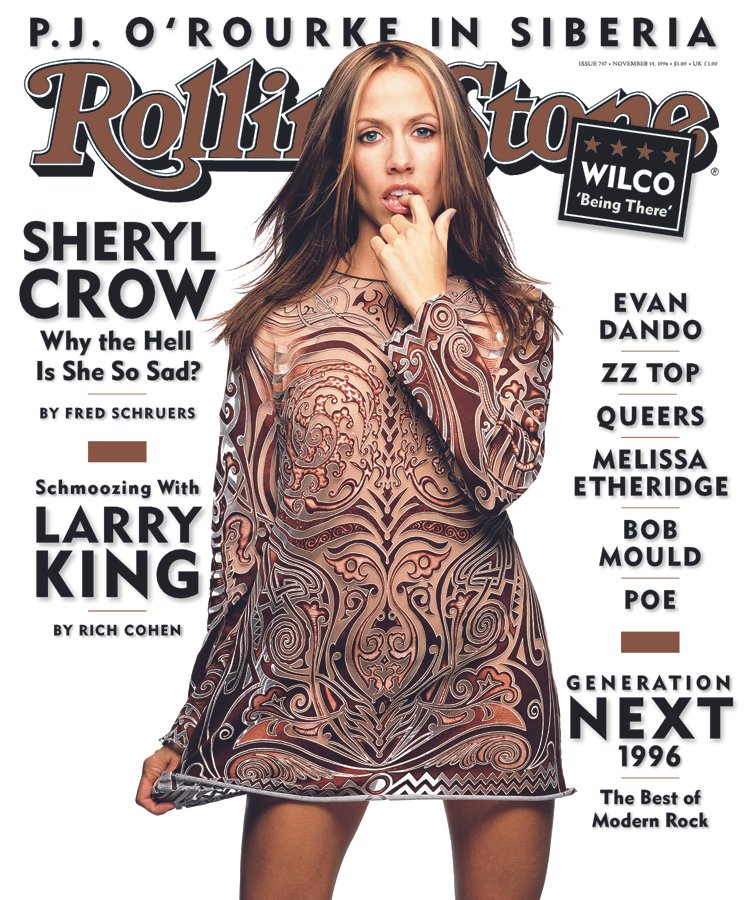

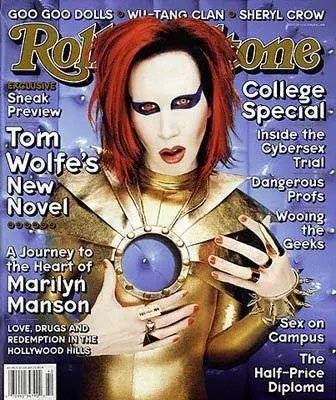

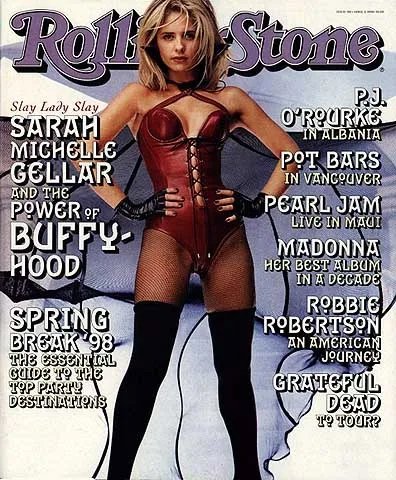

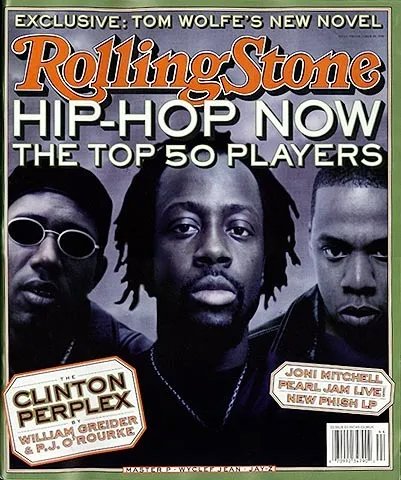

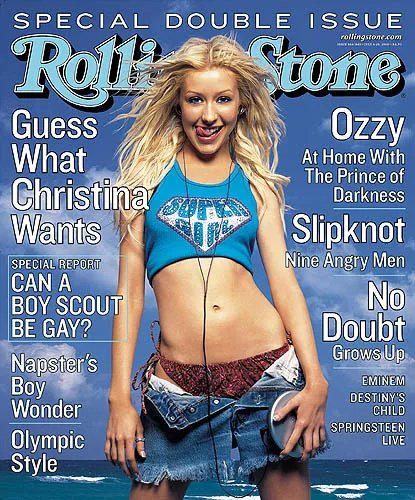

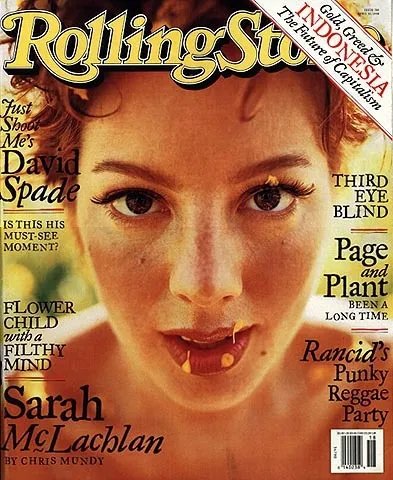

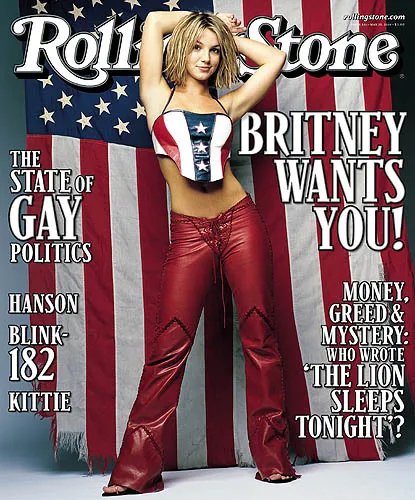

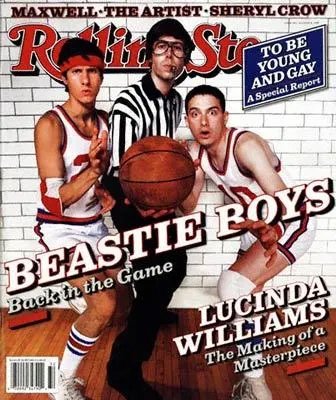

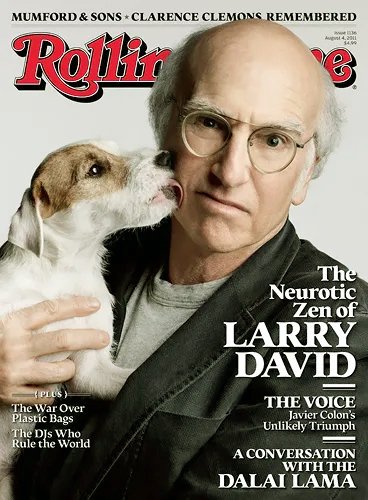

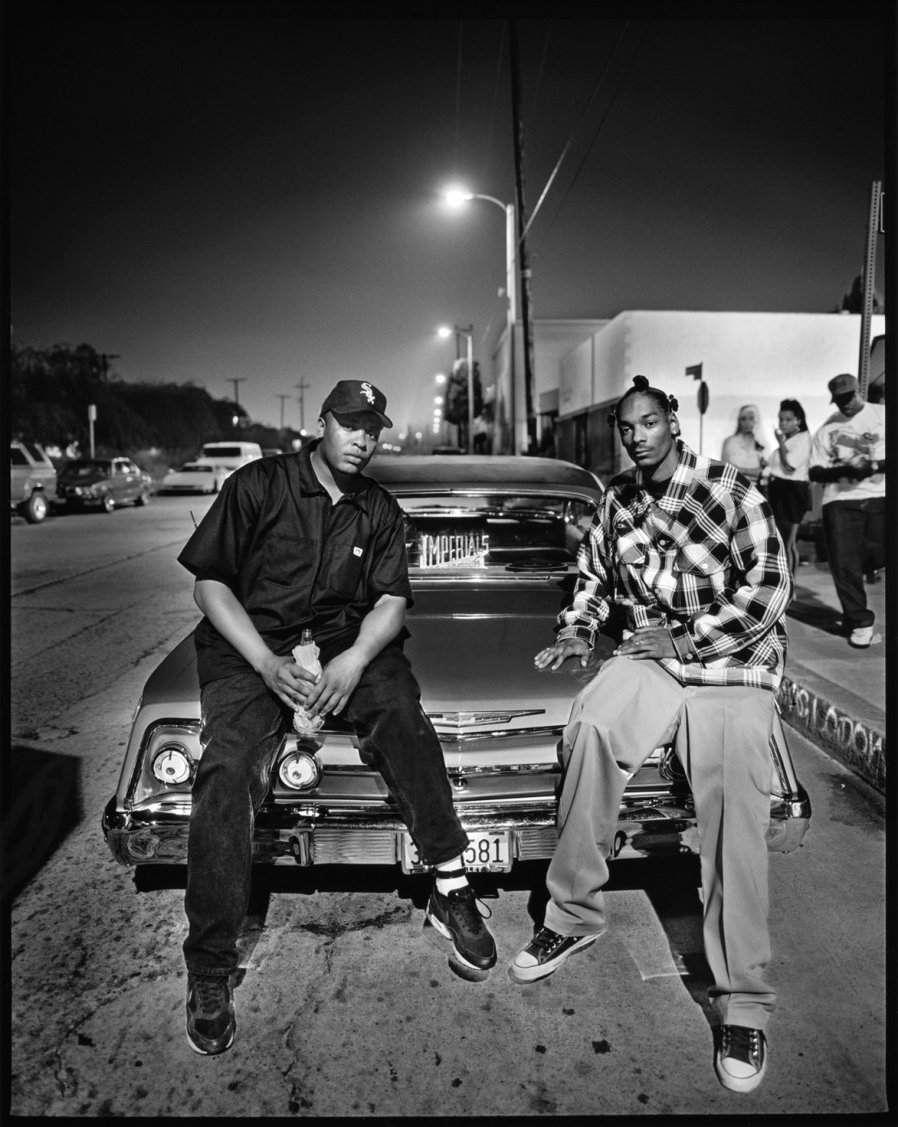

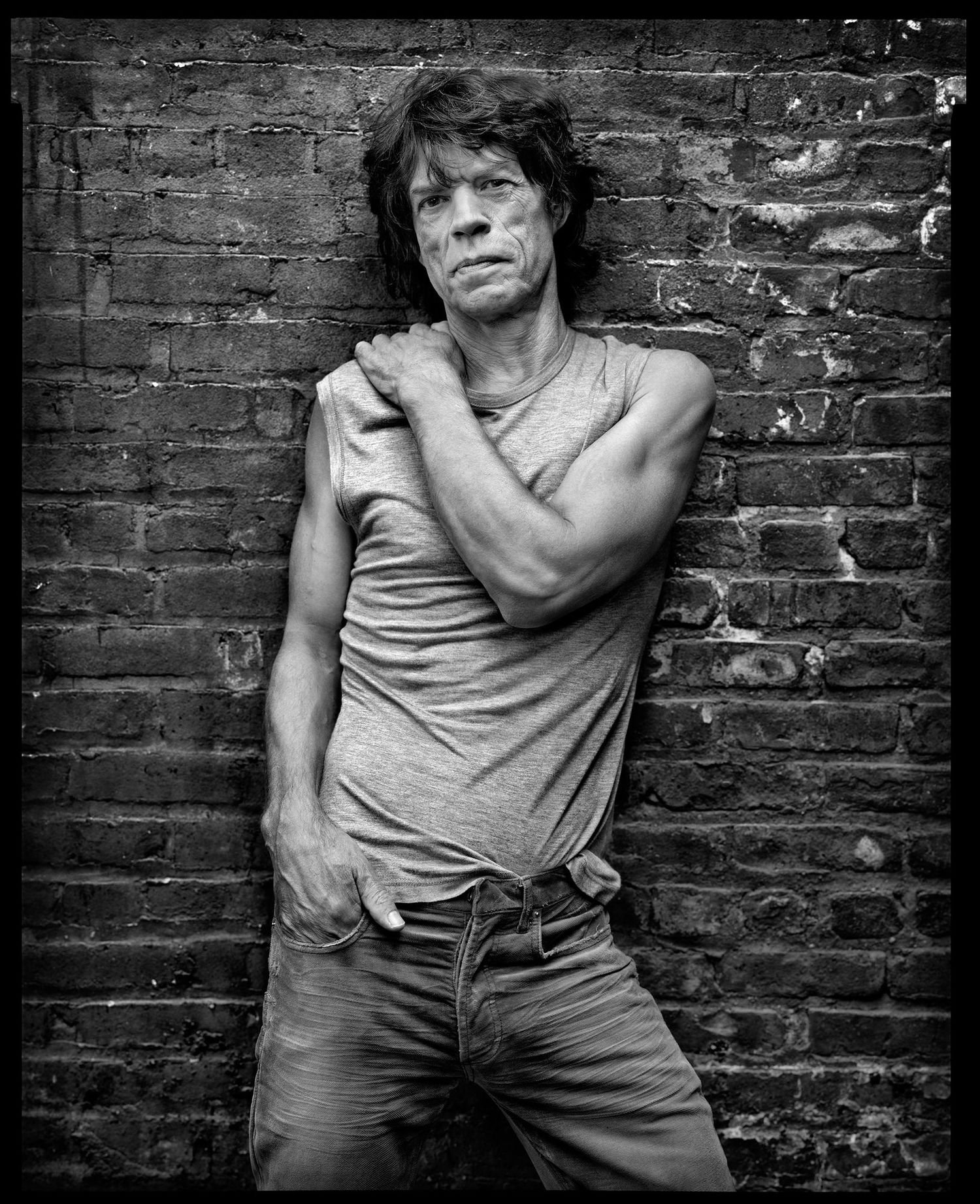

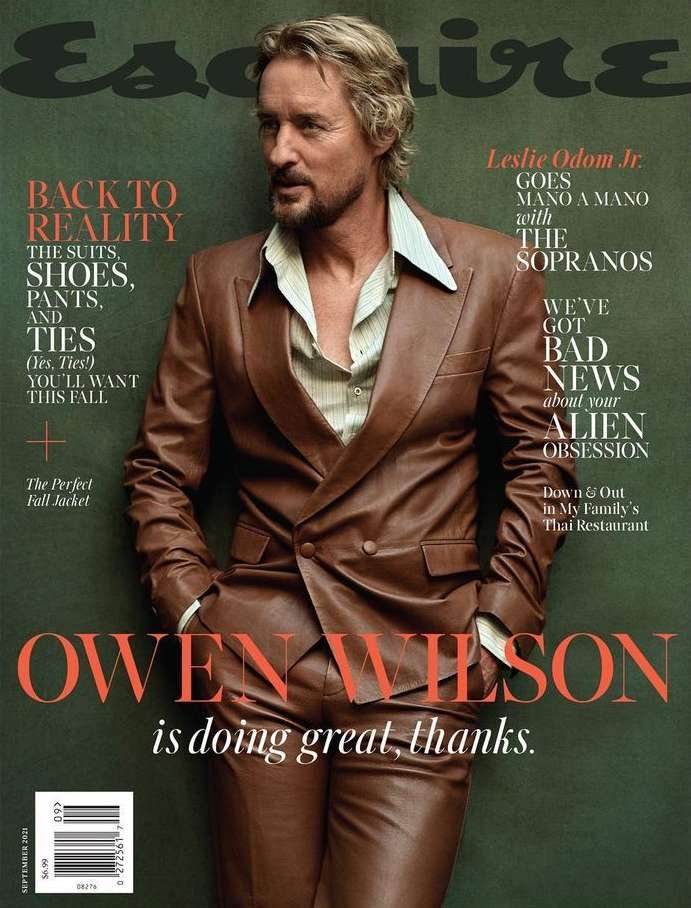

That’s today’s guest, Mark Seliger. He’s the same Mark Seliger who, at the moment of this exchange with Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter, had already shot over 180 covers for Rolling Stone, where he was the chief photographer from 1992-2002.

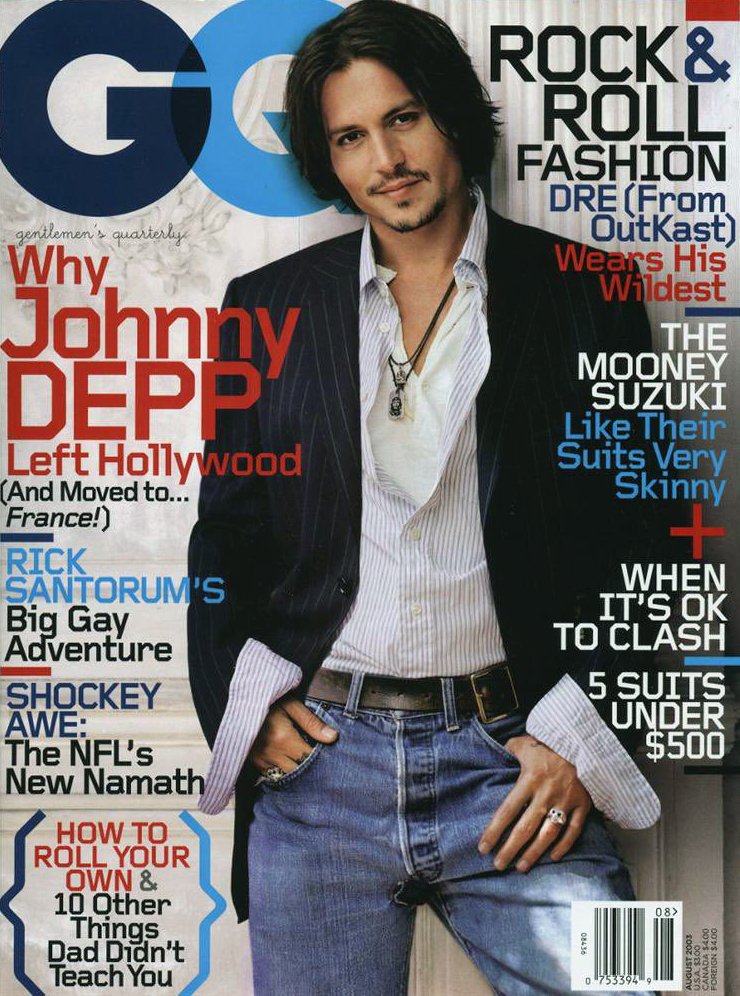

Seliger had been heavily recruited by GQ and Vanity Fair to move to Condé Nast. But, as he learned, the days of being Fred Woodward’s go-to image maker were over. Once again, he was the new guy. And he saw an opportunity to reinvent himself.

Fortunately, reinvention is Seliger’s middle name. (Well, it’s really Alan, but you get what we mean). For example:

Seliger grew up in rural Texas, but decides to go big and moves to New York City to get into the magazine business. Reinvention #1.

He gets early work at business magazines like Manhattan, Inc. In short time his portraiture lands him a few plum assignments at Rolling Stone. Reinvention #2.

Unforgettable shoots and an immediate connection with Woodward lands him the title of chief photographer, and he picks right up where the legendary Annie Leibovitz leaves off. Reinvention #3.

His exposure at Rolling Stone leads Seliger (along with his pal Woodward) to directing music videos for A-listers like Lenny Kravitz and Courtney Love, and Gap commercials with LL Cool J and Missy Elliott. Reinvention #4.

When Covid hits, and publishing effectively shuts down, he pivots to documentary photography and produces an epic portfolio of an empty and still New York City that becomes the book, The City That Finally Sleeps. Reinvention #5.

And somewhere in the middle of all of this, Reinvention #6: Seliger starts writing songs in his free time, and then forms the band Rusty Truck. And at the moment Seliger is reminding Graydon Carter that he knows his way around a cover shoot, Rusty Truck releases its first album, Luck’s Changing Lanes, which is produced by Lenny Kravitz, Gillian Welch, Willie Nelson, Dave Rawlings, Sheryl Crow, T-Bone Burnett, and Bob Dylan.

That’s a lot. A whole lot. But for Seliger, it’s all of a piece. Photography, music, work, life. He says it’s all about following your curiosity. Observing. Not just looking but seeing. “For me,” he explains, “it’s all about storytelling—the storytelling in photography translated well into the storytelling of songwriting. And that exploration leads you to do something that you’d never done before.”

That’s the story of his life.

George Gendron: Before we even begin, I need to clarify something. Are we talking to Mark Seliger, the photographer who happens to have a fabulous country music band [Rusty Truck], or are we talking to Mark Seliger, the musician who happens to pick up a camera now and then?

Mark Seliger: Yeah. Well, You are talking to—kind of a way I describe my photography is that my photography is my wife and my music is my mistress. And music has always been a nice, big element to the way that I think about my work. It gives me inspiration. And then, probably around 1999, I decided that I was going to start working on songwriting. And I took those elements of what I gained from the visual world and put them into songwriting.

George Gendron: Do they enhance and complement each other in some way?

Mark Seliger: A hundred percent. I think my moments of playing with other musicians and being on stage, it’s like going to therapy for a month. And I always say when you’re up there playing with musicians, it’s really like a moment where everything else falls behind for a second. Your other life is just like the backseat for a minute.

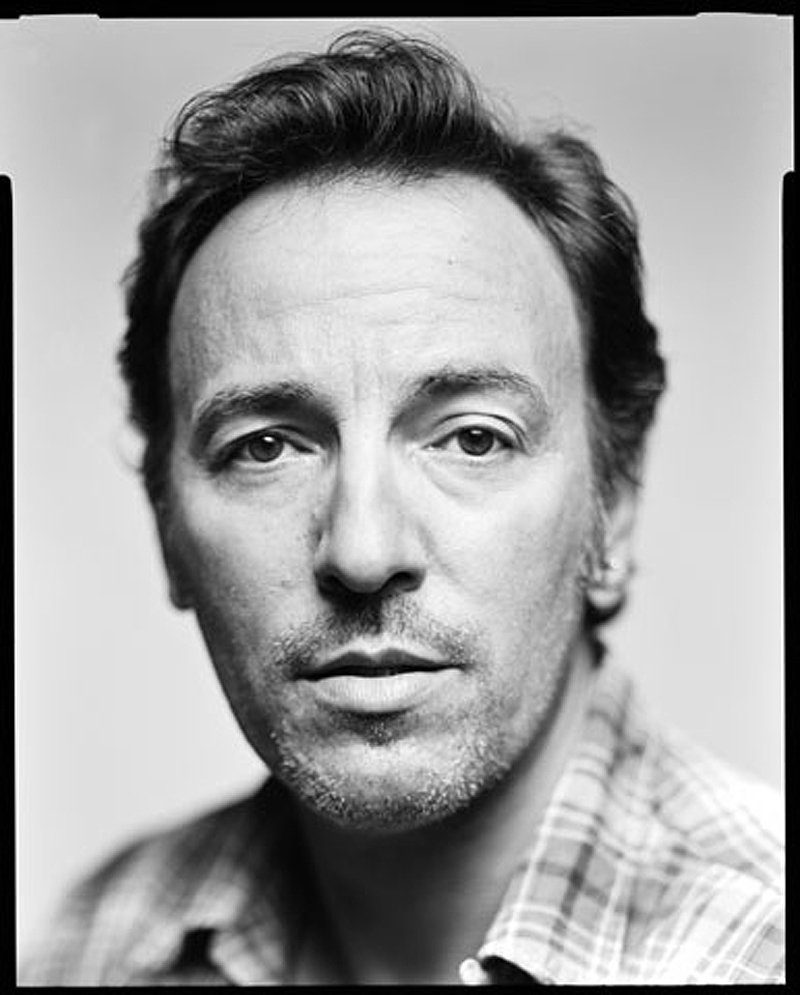

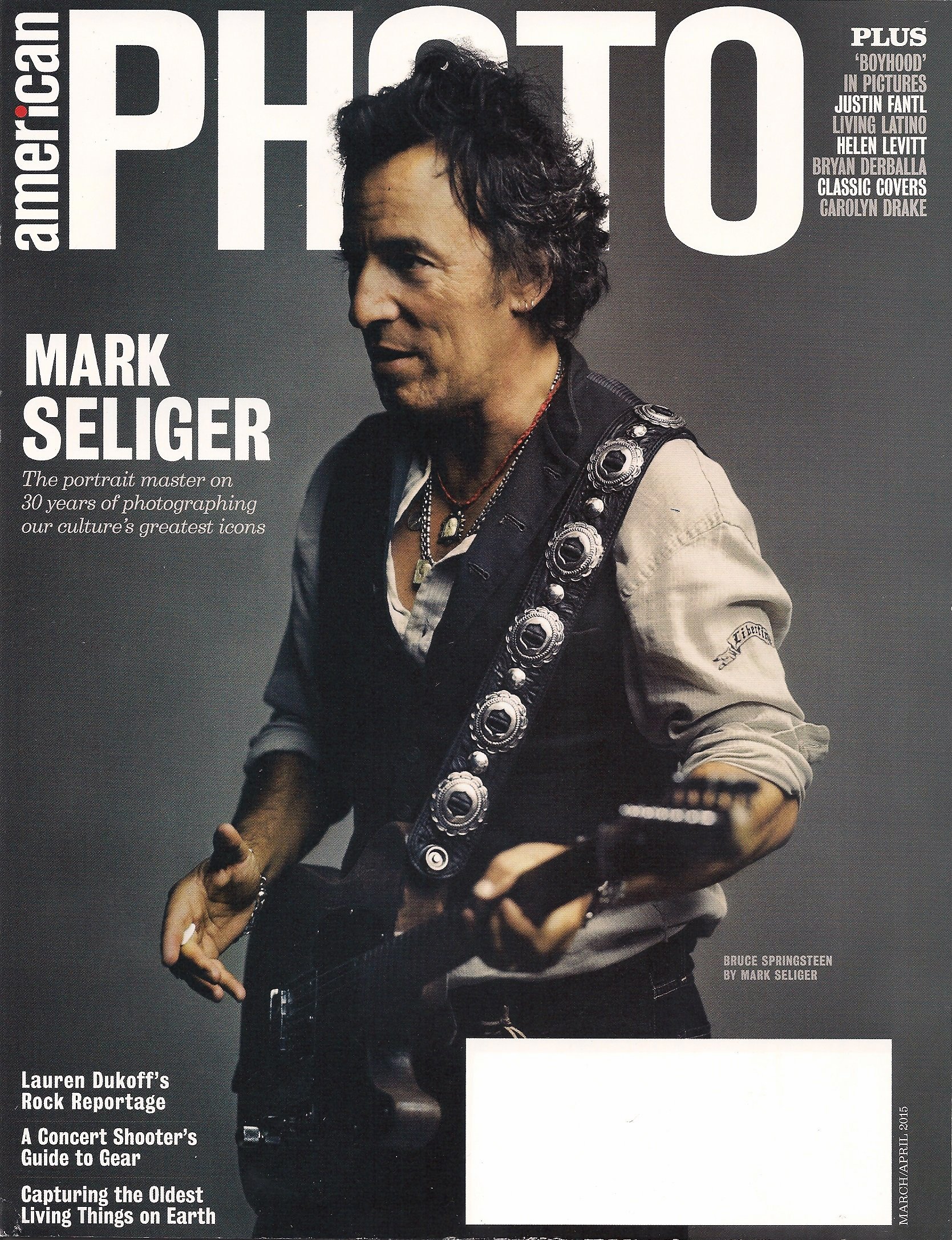

But then what it does is both things inform me of each other. The songwriting informs me of imagery and the imagery informs me of songwriting. So, like I said before, it’s like music is a very playful experience. That’s why they call it ‘playing.’ And that’s a quote from Bruce Springsteen.

And photography is a much more interior kind of process for me. One where I rely on the expertise of other people when we’re in the process, but largely rely on myself when I’m deciding on how to make pictures.

George Gendron: It seems to me, given the kind of music and the kind of photography that you do, that one is a kind of solo practice and one is much more collaborative. Is that true?

Mark Seliger: Yeah, both of them definitely have an immense amount of collaboration, but what really comes across with photography is that it’s very reliant on me coming up with the idea and the ability to organize what that idea is before I bring anybody else in.

It’s very similar in songwriting too. It’s like when you have an idea for a song, in order to be able to go from one line to verses and then choruses, you really have to sit and think about it and put it together. And then once you do determine what that song is going to be, then the band can come in and make it much better.

And the same way with photography, too. I’m certainly not hesitant at all to just going out and taking pictures without any support. And some of those images are some of my favorites. But when I’m working on a project where I need the support, everything is curated around who would be the best support for the project in order to be able to make it come to life. And the comfort of playing with the same musicians over the years has given me a lot of security in just going out there and performing.

George Gendron: I want to take this moment to rewind here for a second and go back to 1984, before either Mark the Musician or Mark the Photographer. And you make the trip 1500 miles—and thousands of light years—from Houston to New York City. And you land in what I’ve heard you refer to and what we at Print Is Dead refer to as the “Golden Age of Magazines,” right? The 80s—I don’t think there was anything like it. Can you, in your own words, describe the magazine as you saw it when you landed in New York City back in 1984? What were the titles that everybody wanted to work for, everybody wanted to shoot for? Who were the creative directors, art directors, editors everybody wanted to work with? Who were the photographers you wanted to be when you grew up?

Mark Seliger: Wow, that’s an expansive question!

George Gendron: No, I don’t want to turn the whole podcast into this, but I’m anxious to hear what seems most memorable to you. What struck you about the state of the magazine world then?

Mark Seliger: The interesting thing about the magazine world is that, It wasn’t really until I got to New York and started to spend time at newsstands and magazine stores and bookstores that I really got the breadth of what was out there.

And it really ranged for me. At that time I loved Interview. I loved Rolling Stone. Vanity Fair was definitely reinvigorated at that point and very picture-oriented. And there was a lot of friendly competition in the way that people thought about making images.

So I moved into the editorial world, I got to know the photographers that were working for those magazines. I got to know who they were. Very respectful. My personal background was really more from studying the history of photography, so more current-day photographers I wasn’t really that aware of.

So once I started to study magazines and editorial, I got to know a lot of new talent and became friends with a lot of people too. Some of my peers at that time were people like Karen Kuehn. There was Chip Simons, who’s also a buddy of mine. There were the big legendary guys that were obviously kind of a grade ahead of me.

That was Albert Watson, Herb Ritts, and Annie Leibovitz. And then there was the grade higher than that was, like, the Avedons, and the Penns, and Mary Ellen Mark, and people that—they’d had a long life in photography, but still were producing some of their best work.

“Music has always been a nice, big element to the way that I think about my work. It gives me inspiration.”

George Gendron: Was this intimidating, exhilarating, or both?

Mark Seliger: It was very exhilarating, I think. Intimidating? No, because I wasn’t there yet. I didn’t even consider being a part of the club. But I was just thrilled to be able to see that there was such an affinity for photography and for good photography.

Once I started to work with some of the publications and some of the books, I got an opportunity to see my work next to some of my heroes and some of the people that I really respected. And so that was very challenging. I would use that as an area of how I could grow. What could I do? What were the ideas that were coming out of editorial? Who’s doing what? And that was important.

George Gendron: When you think back about that very first portfolio of yours—I think at one point you said you had two of them that you were trotting around town, dropping off. What was in it? Can you describe the contents of your first portfolio?

Mark Seliger: It was really very simple. It was portraits I had done some in school and then portraits I had done outside of school. My brother lived in Crown Heights and I had spent six months there when I first got to New York. And that was in Brooklyn. And we lived in a Hasidic community and a couple of the portraits were some of the friends of my brother.

I had gone to Wyoming for a friend’s wedding and taken a day and a half and just drove around to different ranches and photographed a couple of great-looking cowboys.And that was in the portfolio. And then I had done some kind of experimental color work that I had in there just You know, to represent my take on editorial.

So that was more, that was really more for magazines and less for assisting. And people liked it. They liked them. They liked the variety. They liked the black-and-white. They liked the soulfulness of that. And they also liked the color. And I do believe that my entrée into the magazine world was really because I did color pretty well. And that was what a lot of magazines were looking for.

George Gendron: Yeah. I’m curious what, when you think back, when you get a bunch of journalists, photographers together over drinks, invariably people start reminiscing about “My big break.” What was your big break?

Mark Seliger: That’s pretty easy. I was working for a business magazine, Manhattan, Inc. And Manhattan, Inc. was really new on the newsstand. It was taking, obviously, the world of business, and using photography to create something that felt very visual.

You would work with business owners or CEOs and you would make very artful photographs and portraits of these people. So I was lucky enough to get in there. A wonderful editor by the name of Jane Clark brought me in. And I would say probably the biggest assignment that I did for them was a story on Nathan’s Famous Hot Dogs.

And it was in Coney Island. And I spent a couple of days there redoing it and carving it and making sure that it was like the best story I possibly could do. They were super-willing to let me come there and spend days and nights over there taking pictures. And being in those pages definitely gave me a lot of attention in order to be able to work for a magazine like Rolling Stone.

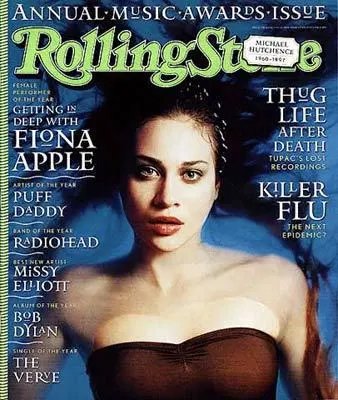

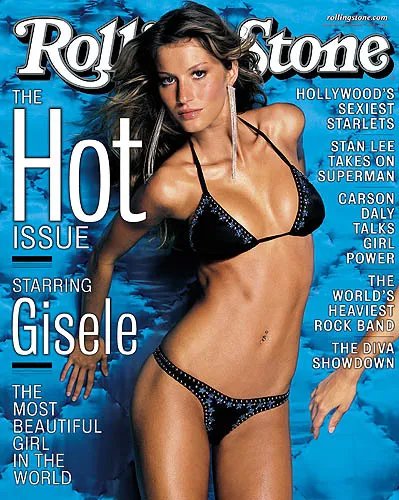

I’d sent in my portfolio to Rolling Stone probably three or four times, with notes to Laurie Kratochvil. And I think right after that story came out, I got my first assignment from Rolling Stone, which was their “Hot Issue” and it was the Hot College, which was NYU film school.

And that was one of my most expensive endeavors ever because I had borrowed a friend’s car, went out to the location, which was downtown Manhattan. And I was packing up after the shoot and it had been very icy a couple days before—it was still icy. And I left the front door open as I was packing up the back of the car. And as I went back over to grab my last case, a city bus came and knocked the door off. And so I had to buy my friend a new door for his Celica.

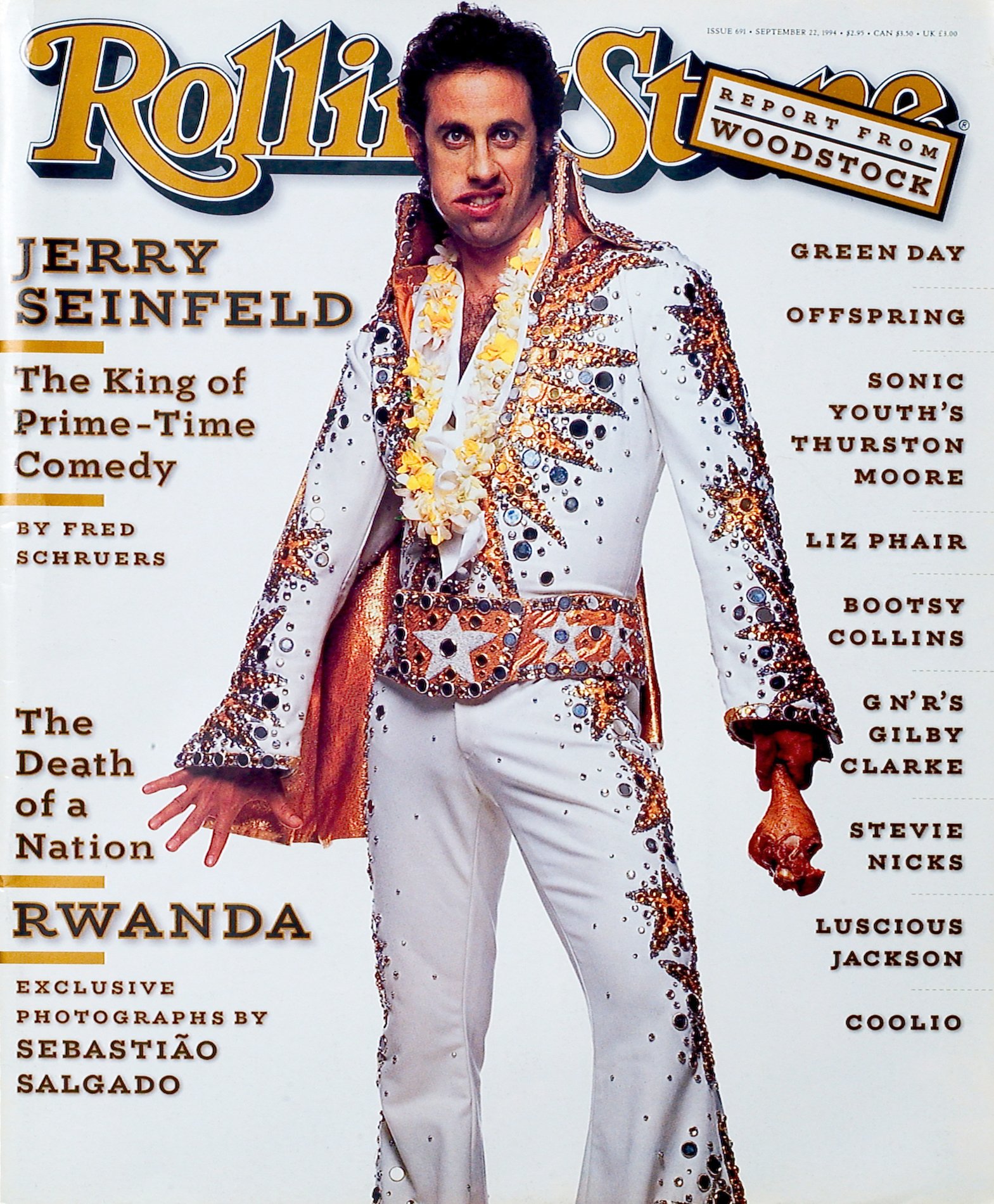

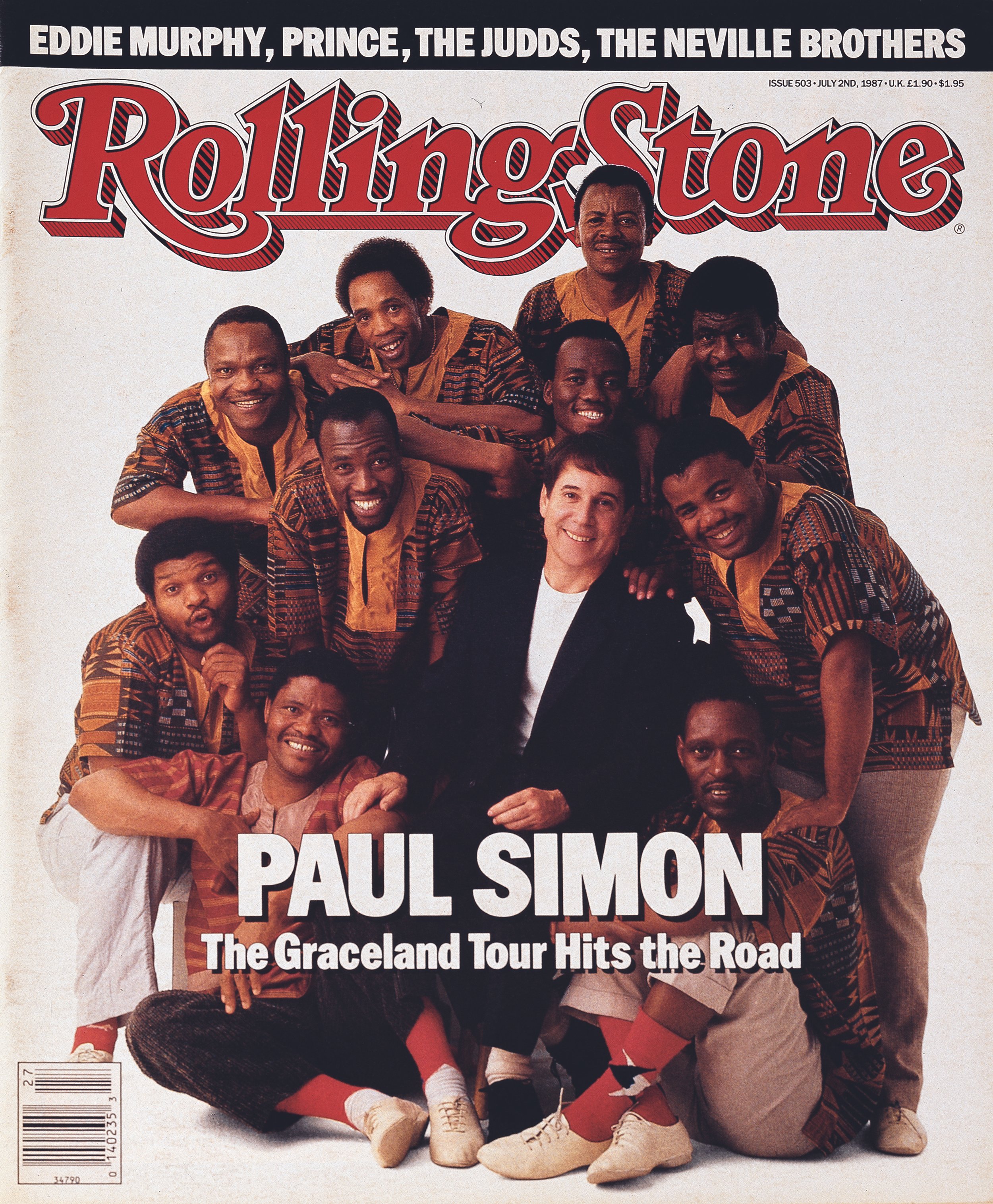

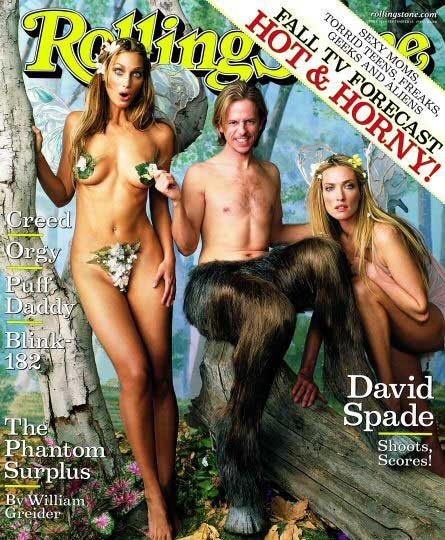

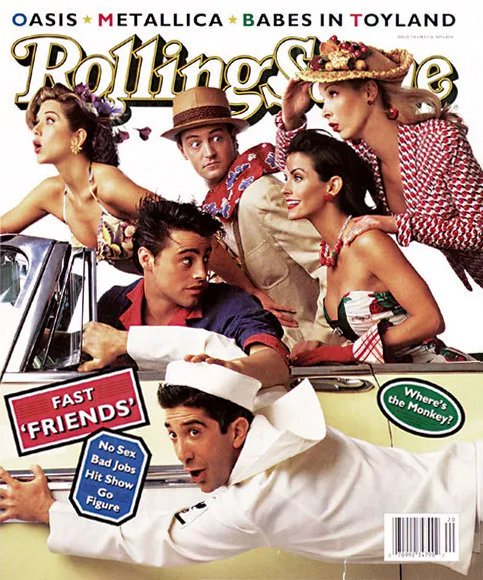

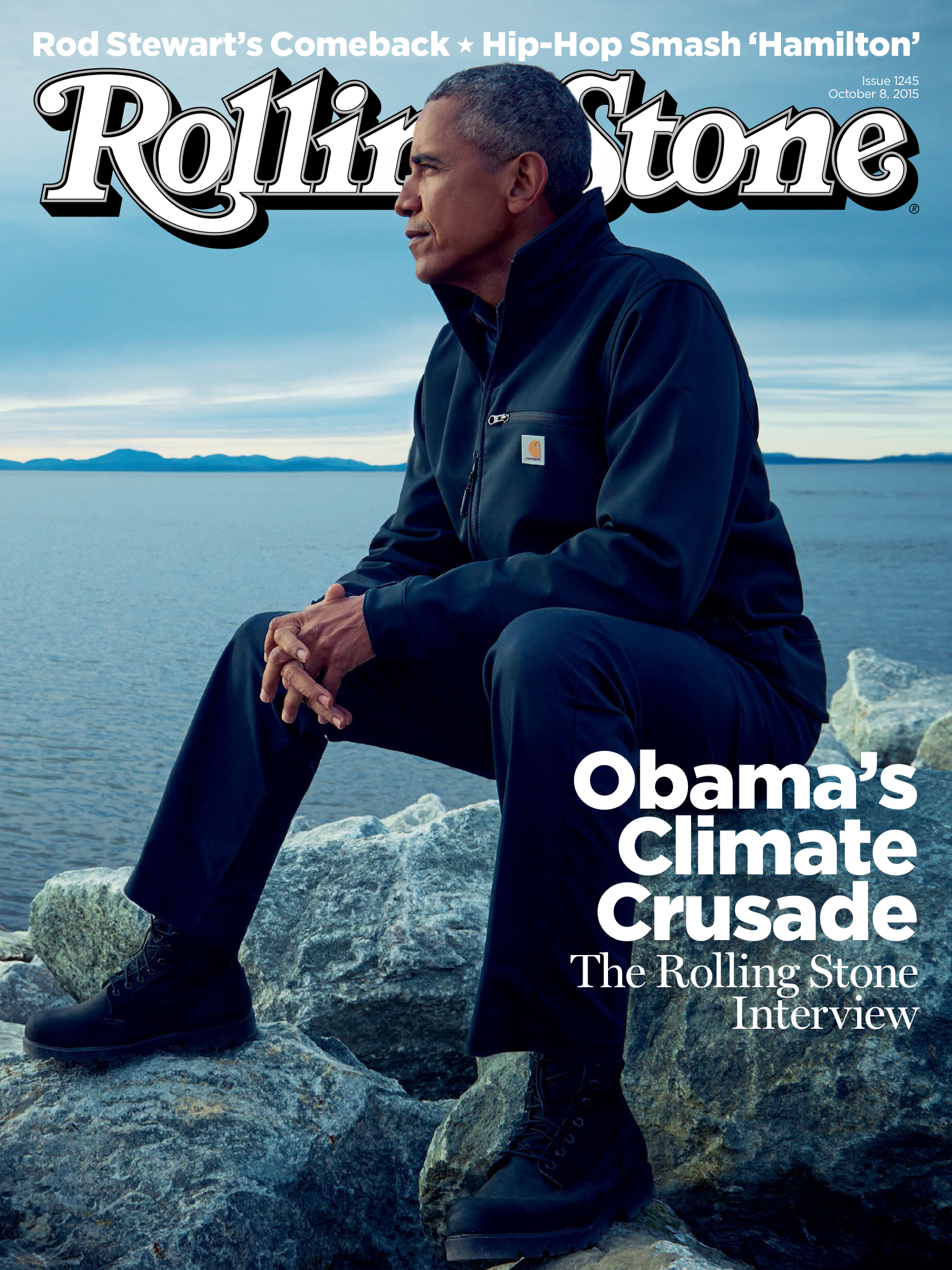

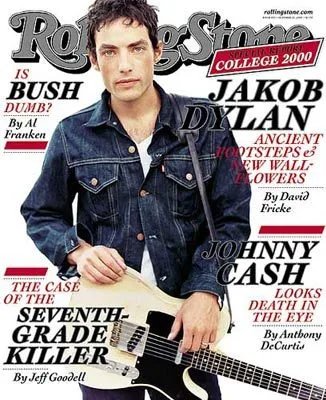

But it was amazing. And after that I started to get some pretty interesting assignments for Rolling Stone. And then about six months later, I got my first cover, which was Paul Simon and Ladysmith Black Mambazo. And that was a thrill. For me that was like, “Okay, if I never get a chance to do another cover again, I’m just thrilled that I got to do one Rolling Stone cover.” And over the years—I think I’ve officially finished my work at Rolling Stone—but I have 180-something covers under my belt.

George Gendron: We were just talking to Jan Wenner recently and Jann said to tell you it’s 188.

Mark Seliger: Oh, wow. That’s fantastic. Okay. There you go.

George Gendron: Yeah. It had to be fact-checked by Jann Wenner.

Mark Seliger: Yeah. And that was the wonderful thing about working for Rolling Stone is that Jann really took a great personal interest, and giving me that trust, and letting me run with ideas, but also being very supportive of the journey.

And that was a different time, too. That was very true of Rolling Stone. And then, obviously, when I went over to Vanity Fair and I worked under Graydon Carter, it was the same kind of an experience. Different method, but definitely somebody who was very hands on and loved the process of working with writers and with designers and with photographers and artists.

George Gendron: What an extraordinary opportunity to work in an environment and a culture created by two of the magazine legends, Jann and Graydon.

Mark Seliger: Yeah. And I think what was unique is that being—for me at Rolling Stone—even though I was their staff photographer, I was still ‘outside’ of the office. But in the interior of the office fighting for those images and fighting for the layouts, you had the great Fred Woodward, you had Laurie Kratochvil, you had Jodi Peckman, Jim Franco, and Fred’s teams. And I would hear about these battles of having a great image that they wanted to run on a cover. And then perhaps Jann had a different idea about what he liked.

George Gendron: When I was talking to Jann recently about you and about the fact we were doing the podcast, he spoke wistfully about what he called the triumvirate. And in his mind, the triumvirate was you, Fred, and Jodi. And when I say ‘wistfully,’ he was like, “Yeah, you know, since Annie was there in the early days, she and I were collaborators, but I really wasn’t a part of that.” And you could tell, maybe, he really wished he were.

But it raises a question where you talk frequently about what you call ‘the concept.’ That a good photograph, a good shoot starts with the concept, the idea, the preparation, the research, and so on. Describe the kind of relationship you had with Fred, and Jodi, and Laurie. What kind of collaboration was it? Was it largely expected that you would come into them with at least an initial concept for a shoot? Would they call you and would they already have an idea for the concept or is it all of the above depending upon the situation?

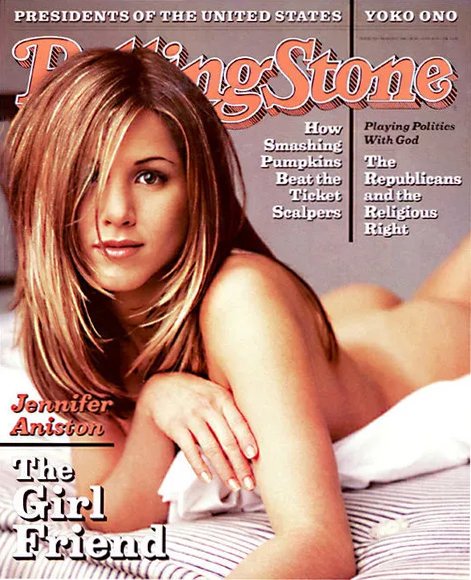

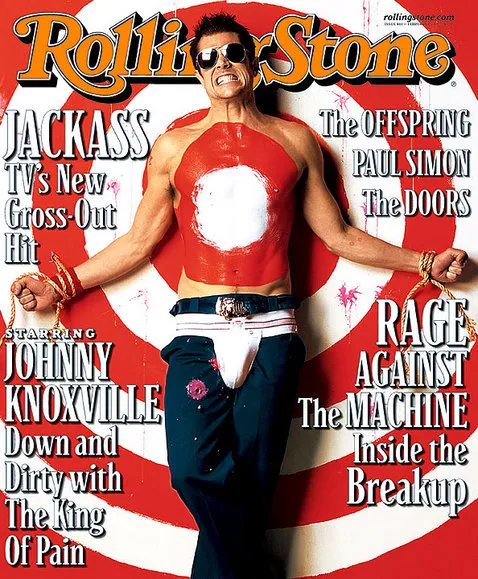

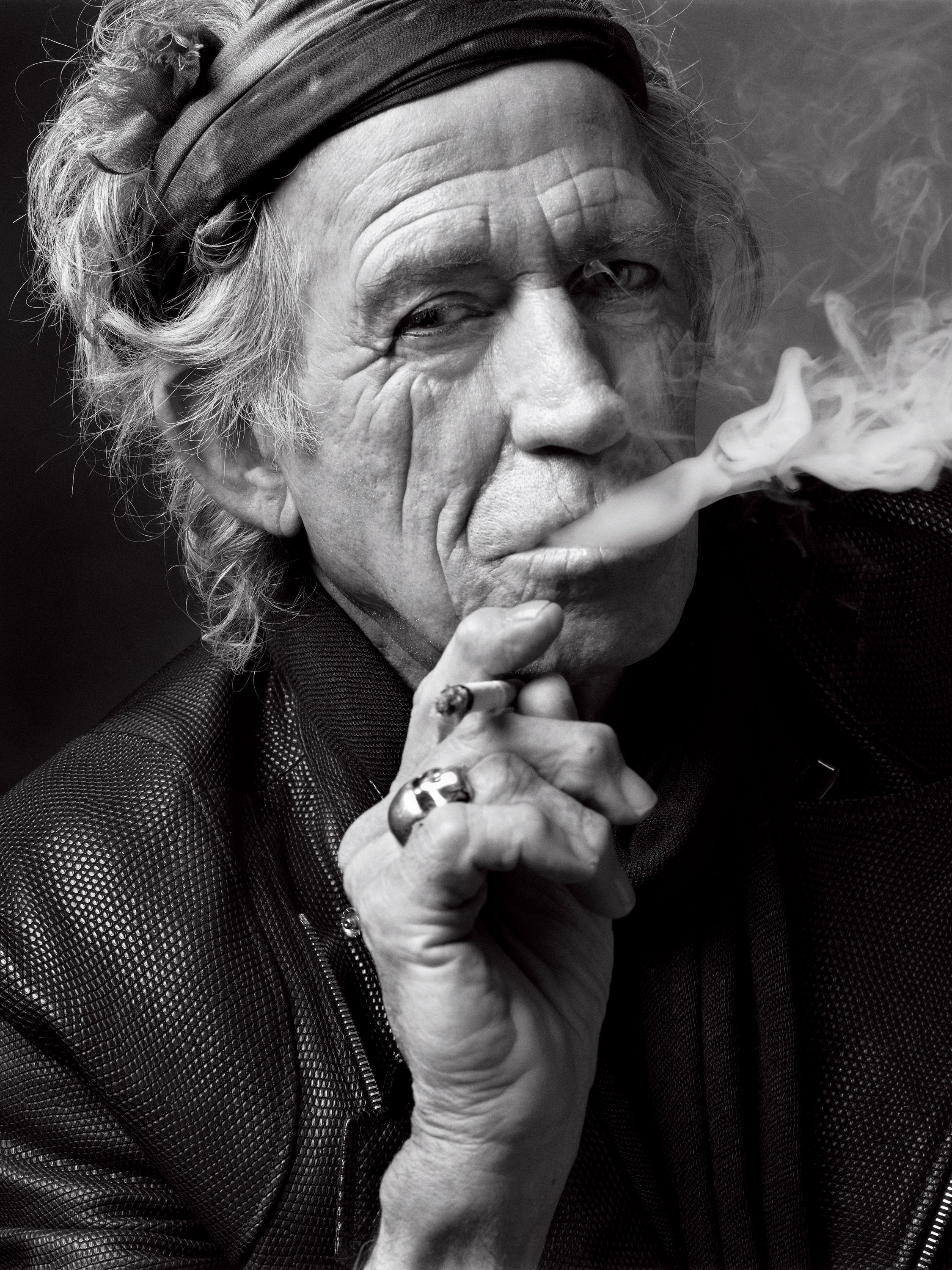

Mark Seliger: I would say probably, if I described the typical protocol, it would be that I would get the assignment from Jodi or Laurie. And if it was a cover, we take the cover subject and I would do as much research as I possibly could before my initial meeting with him if we had the time to actually work on a really specific concept, which we usually did.

So I would just—I’d sit at the library and do research and listen to music at home and look at lyrics or I’d study films of whoever I was photographing and then I would make two lists. One list would be everything that came to mind when I thought about the actor or the project. And then the other one would be a list that was antithetical to who they were or what they were doing.

And I would take all those ideas and I would just start to cross them out until I came up with four or five solid ideas. And sometimes I would cross out everything except for a couple on one column. Then I would go to the magazine and I would meet with Fred and Jodi. Or Fred and Laurie. Or just Fred. And I would run all the ideas by them, and we would settle on one or two. And then I would start to piece together what those drawings would feel like, and I would sketch them out for my own benefit. And then go to work.

George Gendron: I’m not sure I understood column two, the antitheticals that came to mind. Give me an example, even if it’s one you just make up.

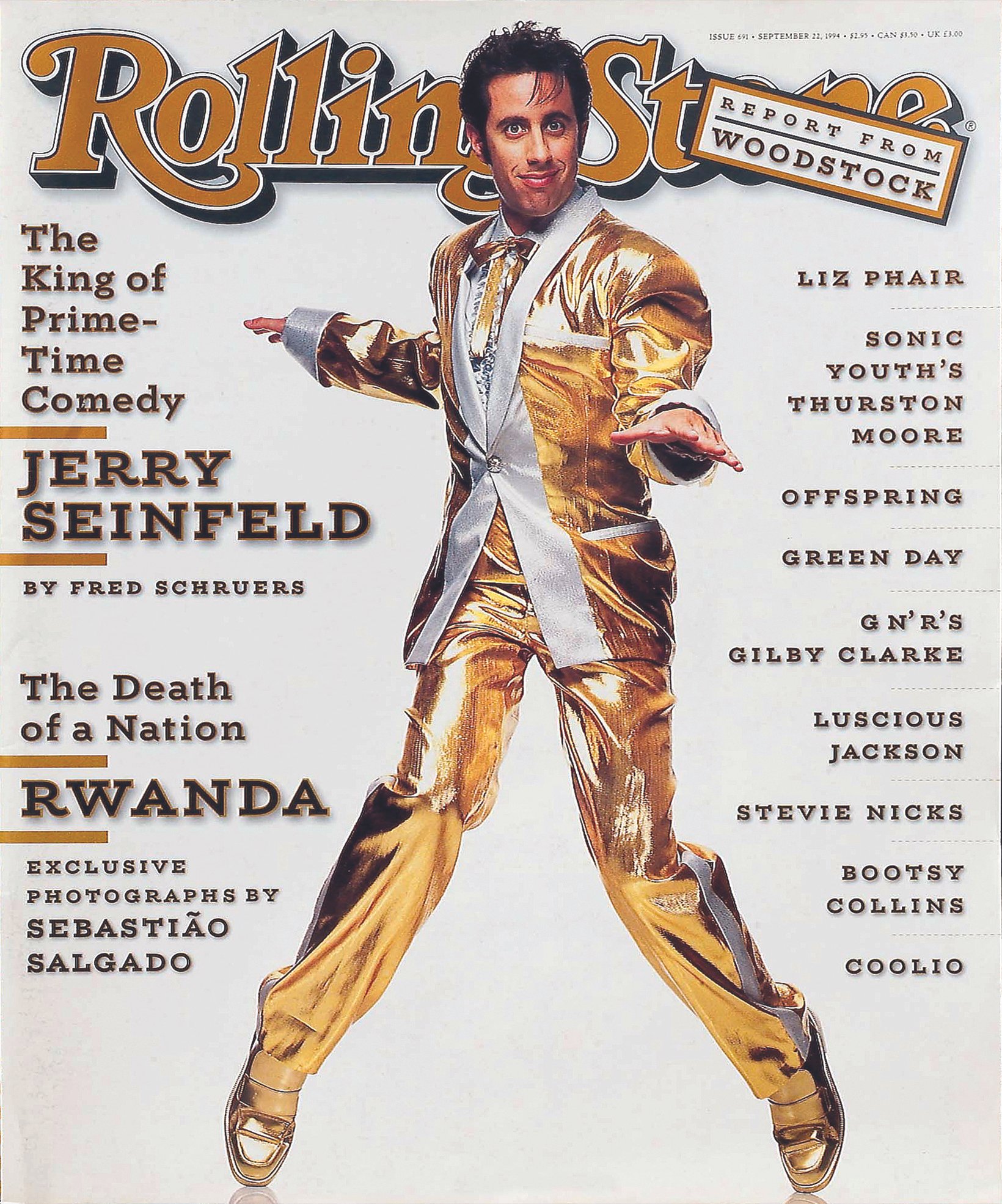

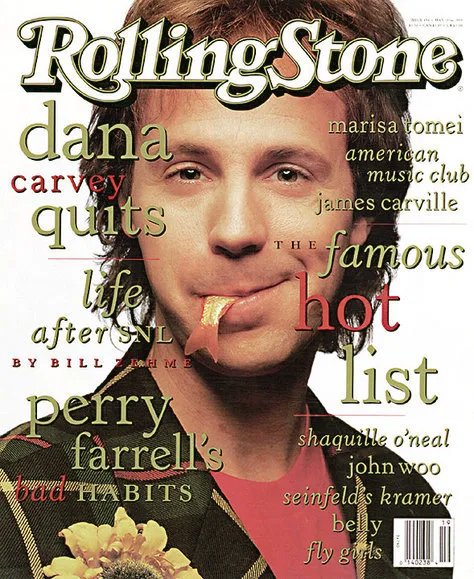

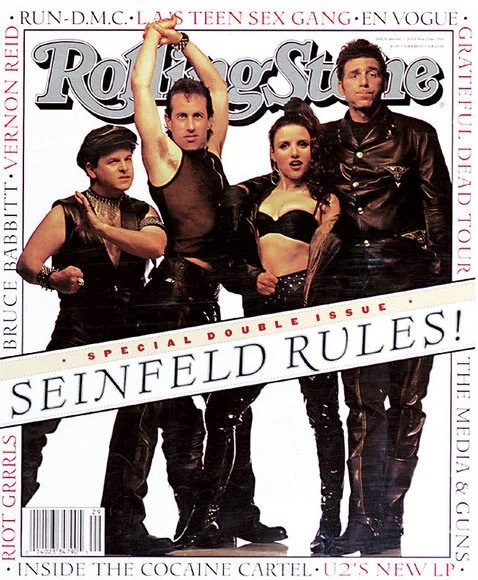

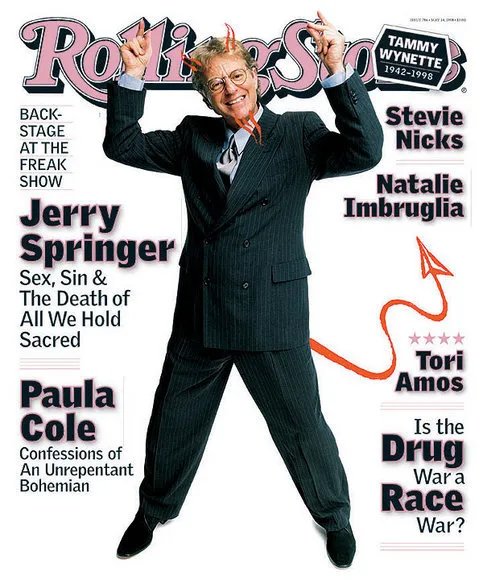

Mark Seliger: Oh. Jerry Seinfeld as Elvis Presley. I have no idea what that means, but I came up with this idea. Fred really liked it. And he said, “What if we did a double cover and we had the young Elvis and the old Elvis?” And that became a double issue.

George Gendron: So column two is almost more random ideas, right? What’s the connection between Elvis and Jerry? There is none, but who knows where that might lead.

Mark Seliger: Well, you know, And if you think of Jerry being a comedian, somebody, Who’s like this, this nebbish-y and, like nothing ever really happens on Seinfeld. It’s just like one little idea that kind of keeps going on and on. And Elvis was this iconic rock star. And, Jerry’s a rock star, too. And that’s why he could pull it off so well. The concept of the show, Seinfeld, was like that little bit of polarity to what you think Elvis was.

George Gendron: No, I get it. I get it. I think of Jerry and I think of Manhattan. I think of Elvis and I think of Memphis.

Mark Seliger: Yeah. And that was the way that I worked on a lot of fronts. Even with music, I would try to relate to what I was hearing in the music. A line in the music. How it made me feel just intrinsically. And then I would write down everything that came from that. And Column B might be something that was just stream-of-consciousness. It may not even relate necessarily to the music. Didn’t mean that it was going to be a gag, but it was just something that was very different.

It might be—if you think of Neil Young on the desert floor, it might be Neil Young in the back of a limousine. Or something. There was always the ability to take something and flip it on its head that I liked about the concept. And then there were all the other aspects to the concept that had to be really brought to fruition, which was where were these people going to be? How much time did we have? What was reality and what was fantasy? And then we would start to carve that back a little bit.

I had this thought about Tom Petty on a camel in Joshua Tree. And I met with him and I told him about my idea and he was like, “I like that.”

He goes, “I rode a camel once in Egypt.”

And I was like, “Oh, I guess this is going to work out.” However, he didn’t realize how far it was to get to Twentynine Palms.

But it was too late, because we were already an hour-and-a-half into the drive before he realized it was going to be another hour-and-a-half. And we got to Joshua Tree and the camel was there, and he suited up, and then we caught an incredible photograph of him at sunset. And it was fantastic.

George Gendron: That’s probably the only time a camel ever set foot in Joshua Tree.

Mark Seliger: That’s probably true. Yeah.

George Gendron: You never know down there. It might not have been the last time people thought they saw a camel.

Mark Seliger: Yeah, right? Yeah. There’s a lot of things people probably saw at Joshua Tree that really weren’t there, that were nice mirages. But the power of coming to an assignment with an idea was really my approach to the way that I worked at the very beginning. And always the way that I’ve worked since.

And it doesn’t mean that idea needs to be overly-clever or highly-produced. It can be something just very simple and very reductive. And that’s also a concept.

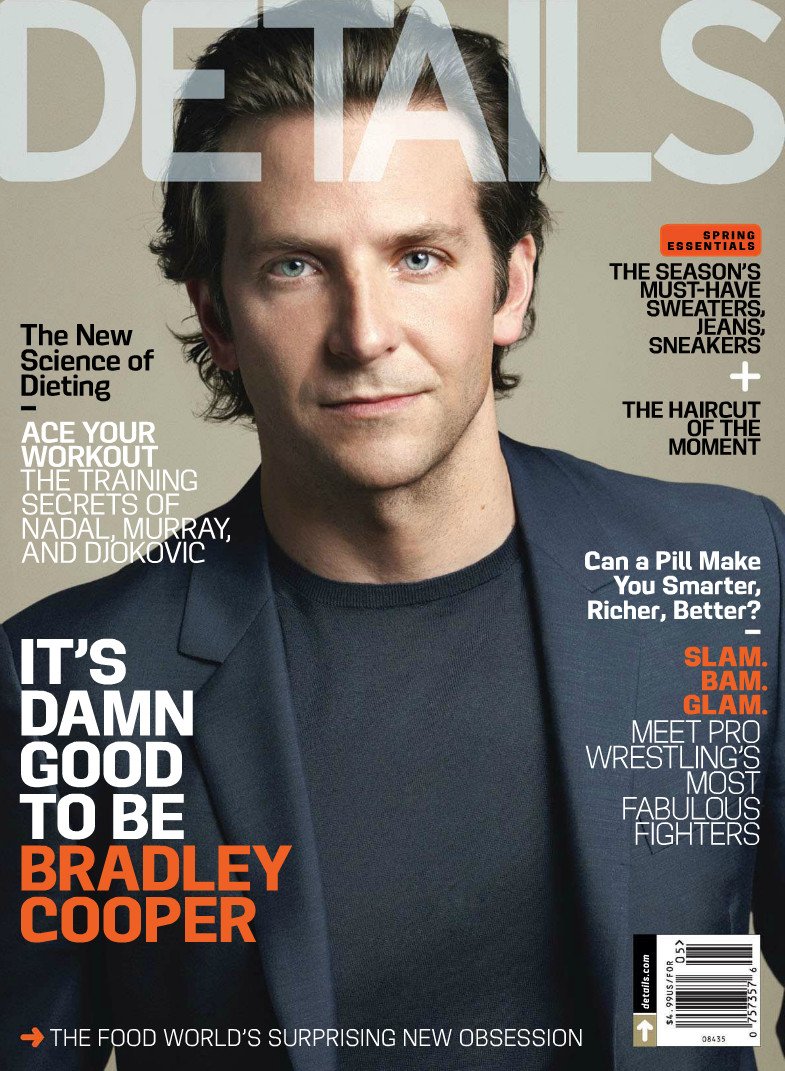

George Gendron: When you think about covers that you’ve done that required pretty elaborate staging versus covers that you’ve done that are really stripped-down portraiture, do they have a different psychic effect on you in terms of how you feel about them?

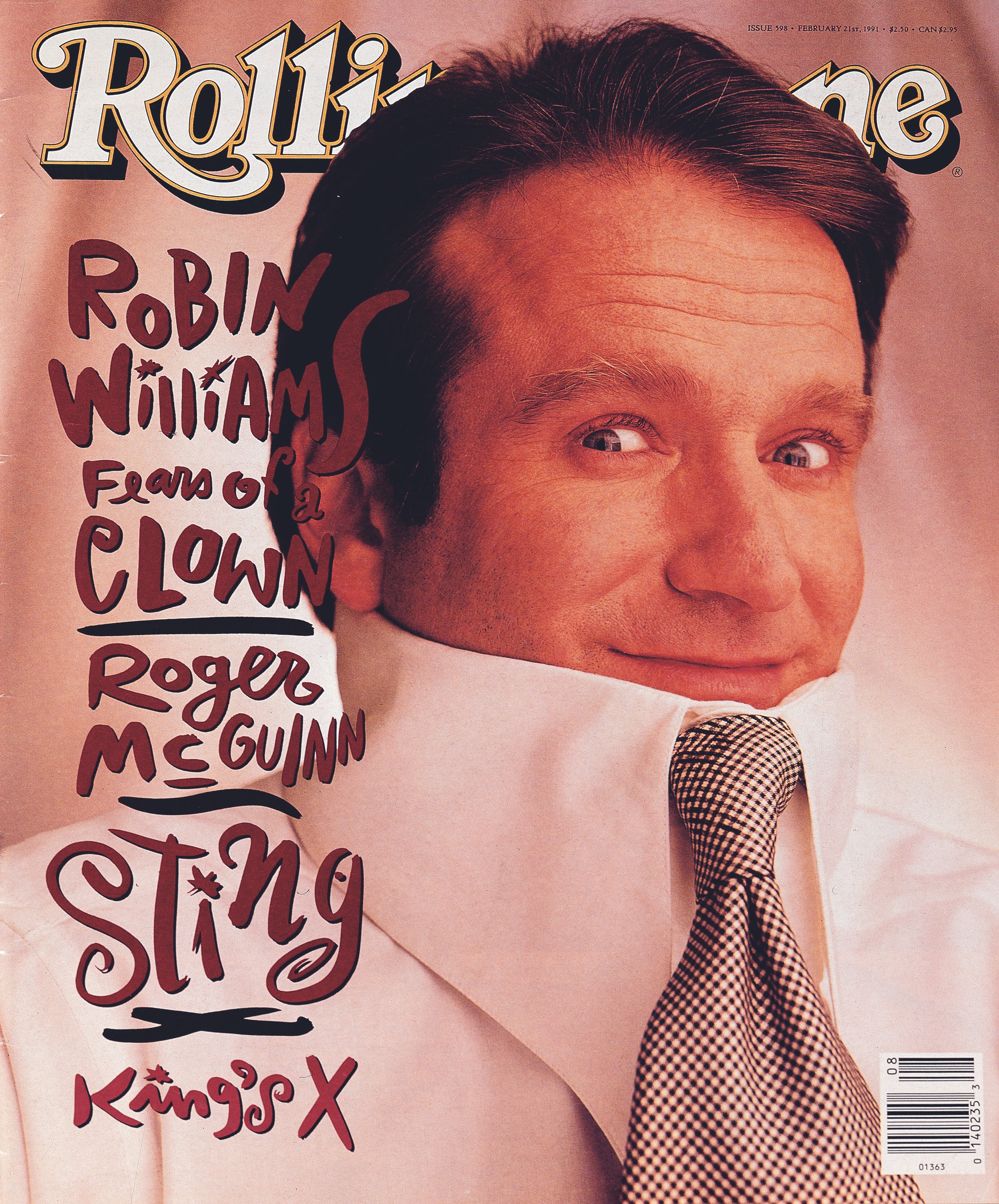

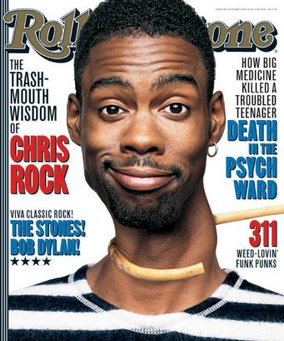

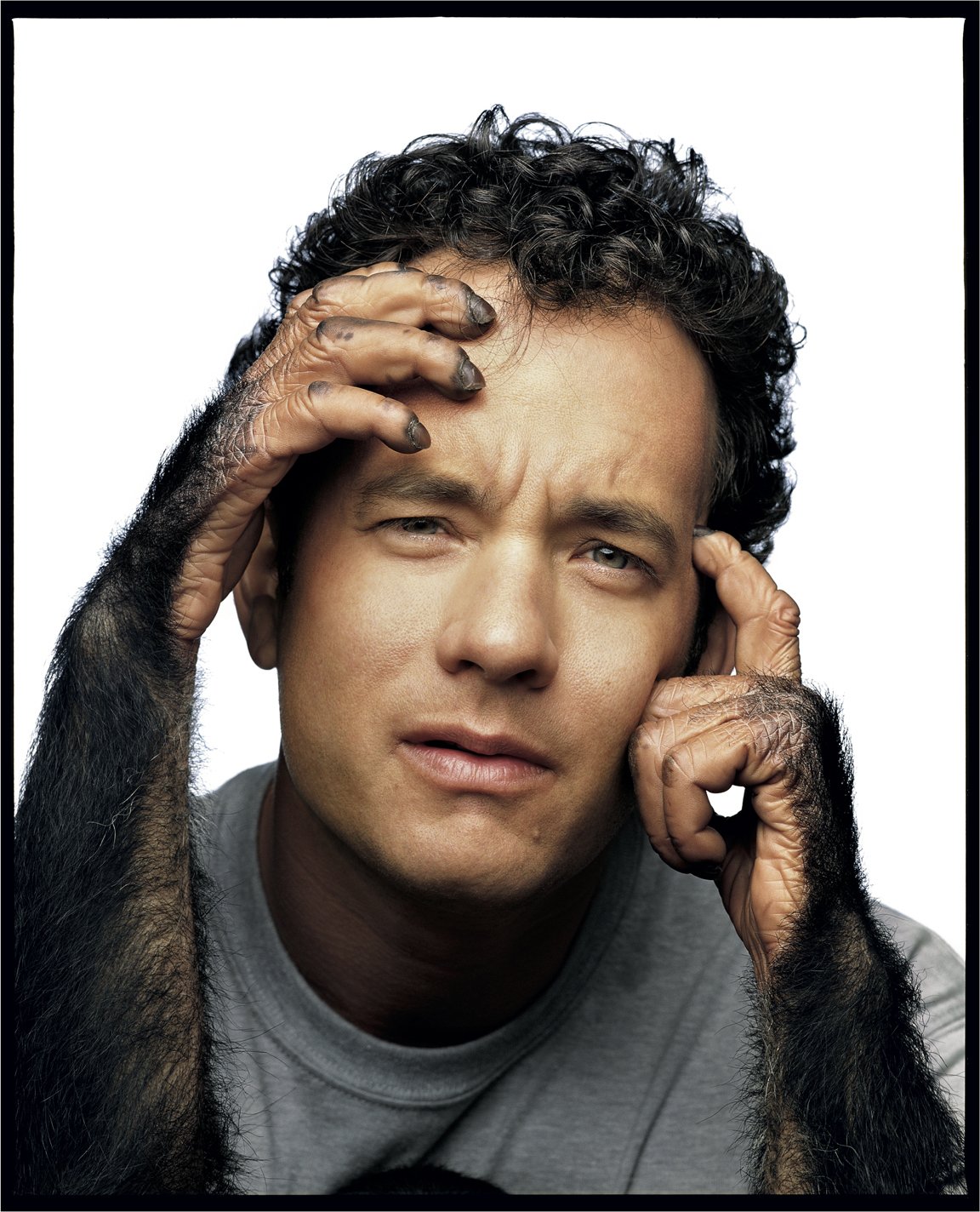

Mark Seliger: No, not at all. In fact, I think a lot of the times that we would work with actors and comedians was that there was a very simple wink to the image. So there was that one little twist. Because you’re dealing with coverlines and design. And they didn’t want a lot of production. They wanted things to be very simple.

That was always challenging. But I remember one of the first comedians I ever photographed was Robin Williams. And I got Robert Molnar, the very talented, amazing stylist, to build an oversized collar that basically hid Robin Williams’ mouth. But it was almost like a clown collar.

And when I did that photograph I actually faxed over a Polaroid to Fred—that was the good old fax days—during the shoot. And he saw it, and he was like, “Genius! This is great!” And that was really liberating for me that I could take something so simple and yet have an impact. Not only from the standpoint of being an interesting, intriguing image, but also that there was a spin of comedy involved in it.

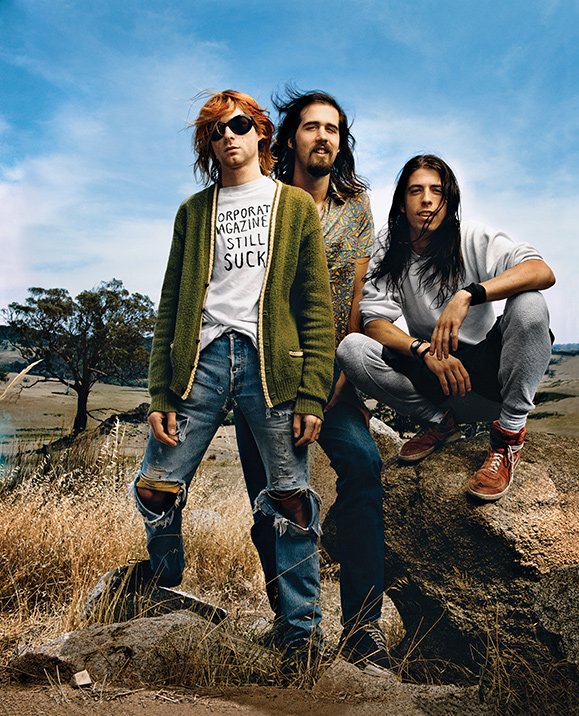

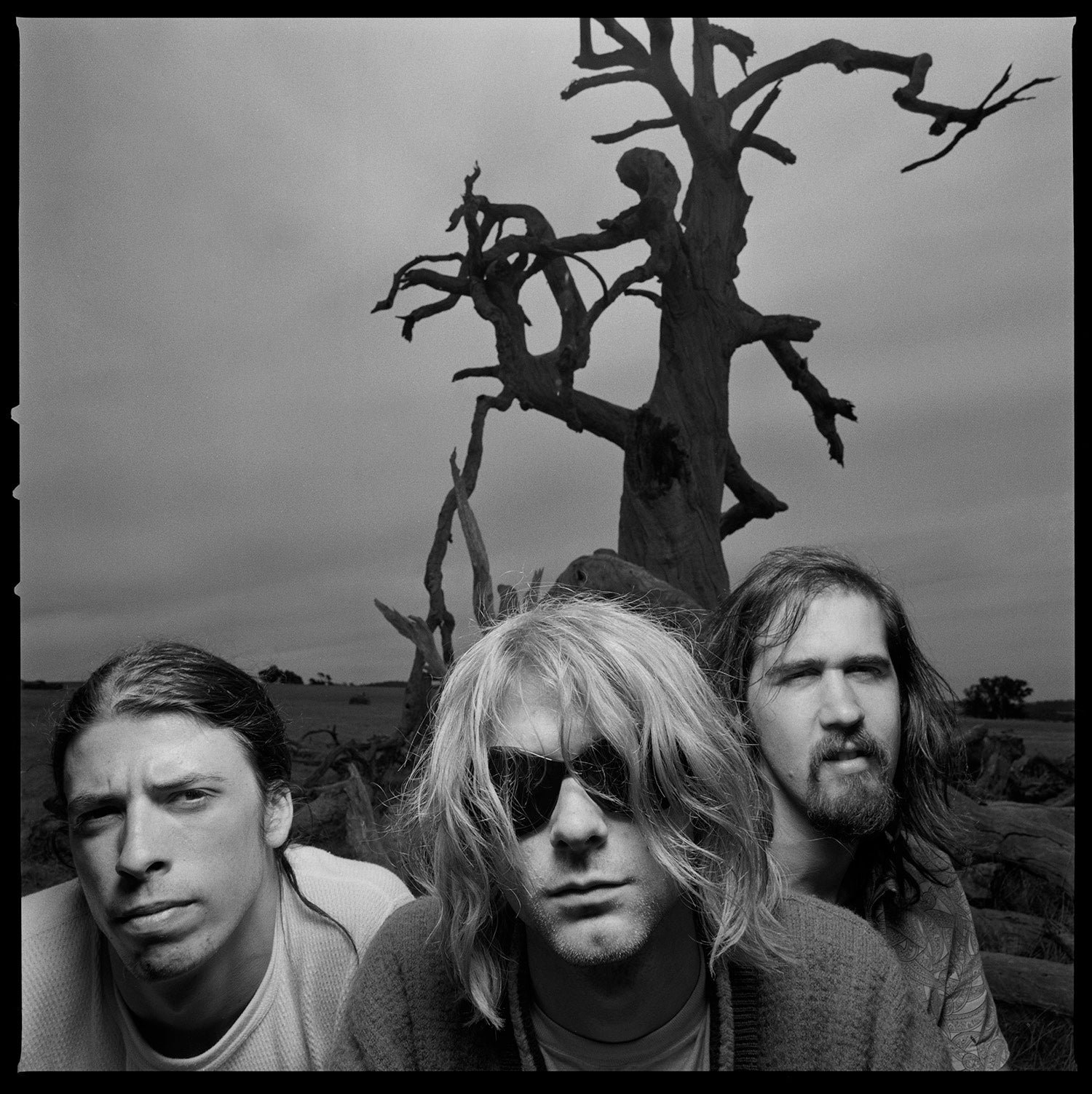

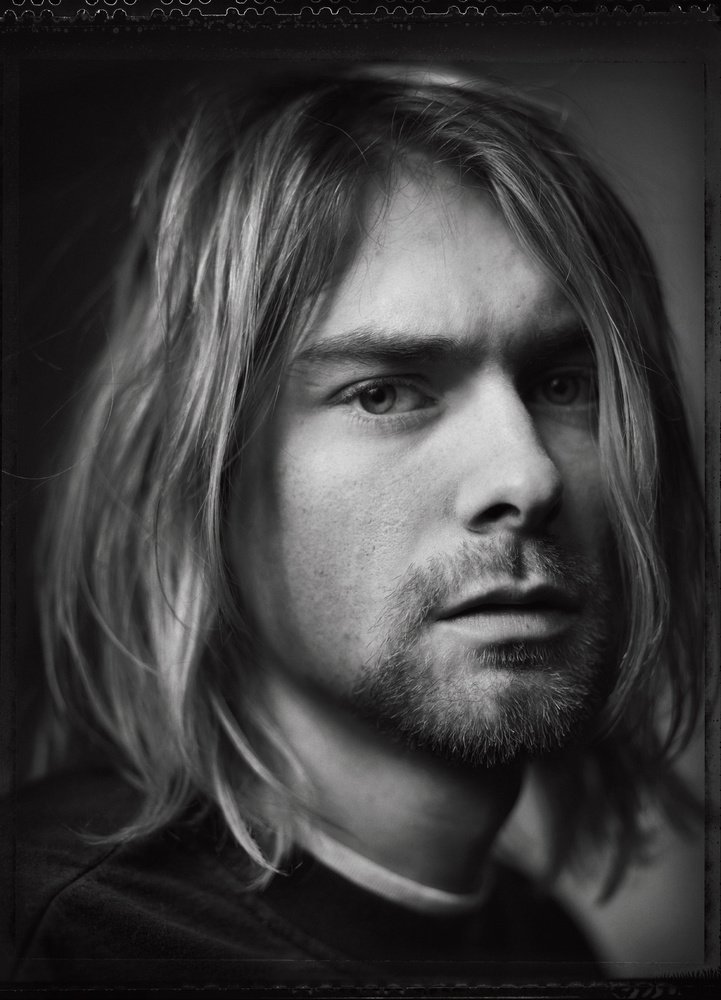

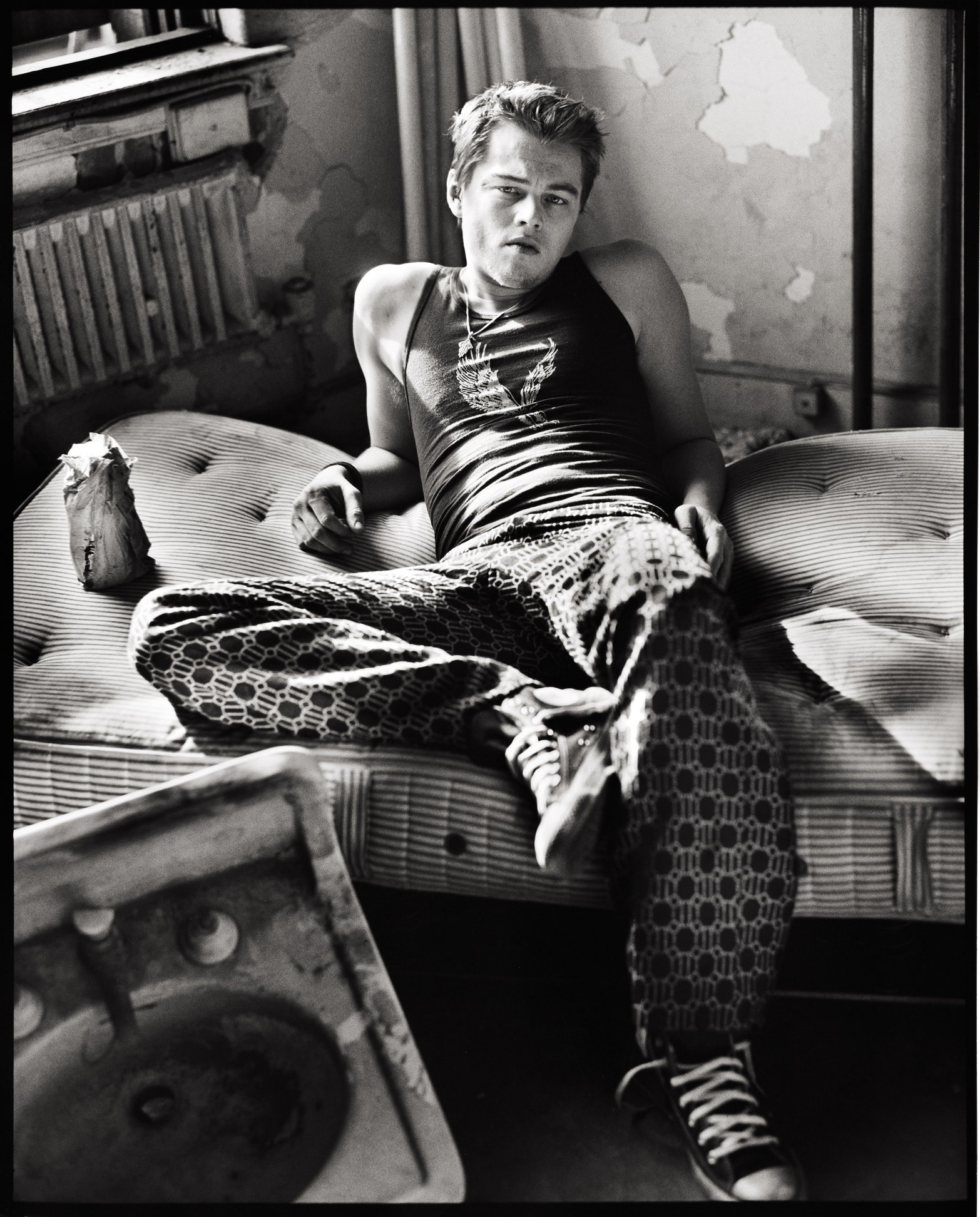

Kurt Cobain and Nirvana were Seliger muses.

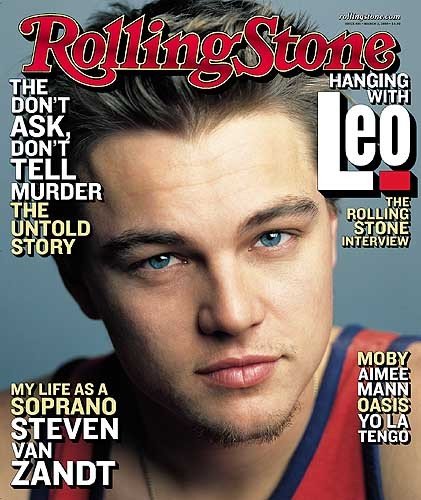

George Gendron: When you were shooting for a cover did you have an acetate that you could lay over the Polaroid to actually help you envision?

Mark Seliger: Of course. That was the sign of real success when you were carrying around a Rolling Stone acetate or a Vanity Fair acetate. That was the business card you wanted to have. And that would really change the course of the shoot with a subject. You take that Polaroid and you slap an acetate on it. The subject would see that and they would go, “Man, is that the shot?”

And I’d go, “I have no idea. But we got this far. And if the Polaroid is this good then I bet you we can probably get there.”

George Gendron: Were you ever backed into a corner where somebody on the spot said to you, “Promise me, that’s the cover, man”?

Mark Seliger: And I probably lied many times if they did. But I usually would take a Polaroid and I would already start to shoot. I wouldn’t necessarily show a Polaroid before I’d already shot the images and then the Polaroid would be pulled a couple of minutes after we started the shoot. But yeah, any way I could encourage my subject—and that was certainly one of them—to entice them into where we were heading, throwing that acetate on a Polaroid was a great success. I do remember some Polaroids being better than the film for sure.

When I did the last portrait of Kurt Cobain, I did it on a 4 x 5 Polaroid, which was called Type 55, so you got to keep the Polaroid negative and the Polaroid and seemingly everything was good with him. And during that Polaroid there was like this really introspective, quiet moment that we didn’t really get with the balance of the film.

And when I got back to New York—I literally carried in a water bucket this Polaroid negative on the plane, through the airport, and back to my house—I washed it, hung it up, contacted it, and I was like, “Wow! I wonder if the film is going to be this good.” And that was the shot.

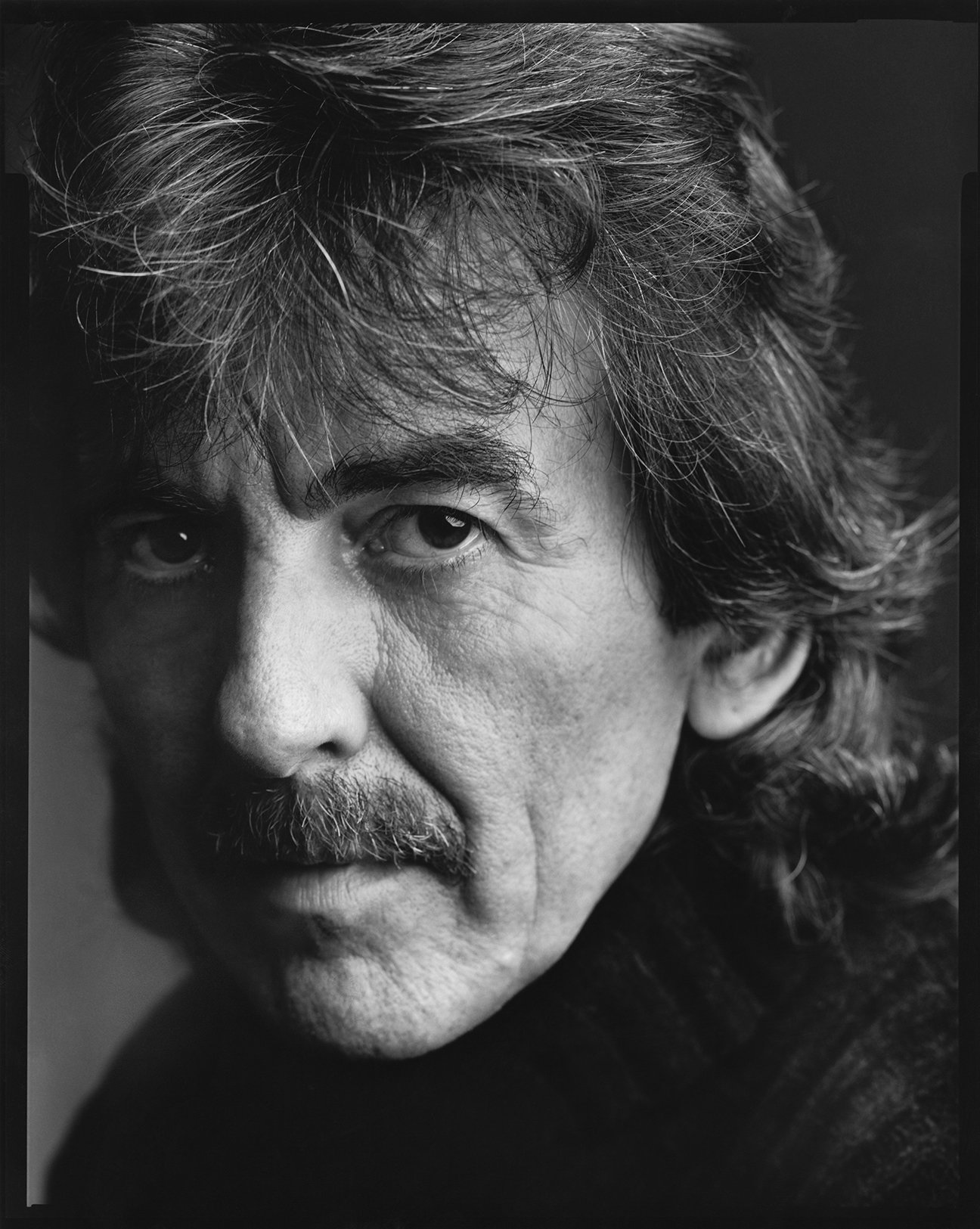

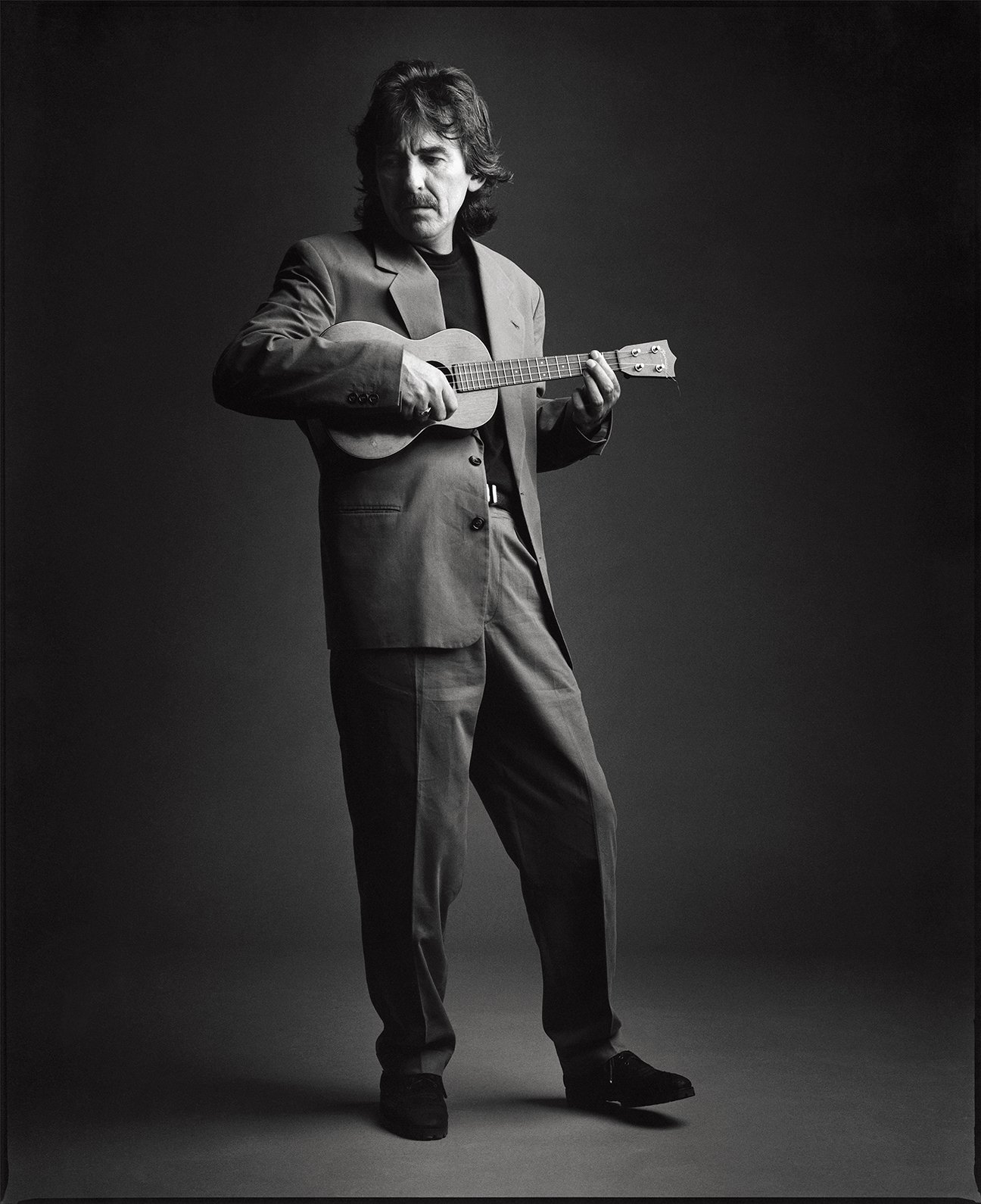

George Gendron: If people who are listening to this aren’t aware of it, you have a site called Crosseyed Arts. And you have some black-and-whites on there that—I don’t think ever made it into a magazine, but they were part of a magazine shoot. And, God, some of them are priceless. And alongside each one of those you have a great anecdote. I’m thinking of George Harrison.

Mark Seliger: Oh my gosh! That one involved Jann Wenner, too. Right?

George Gendron: You want to tell that story? About George?

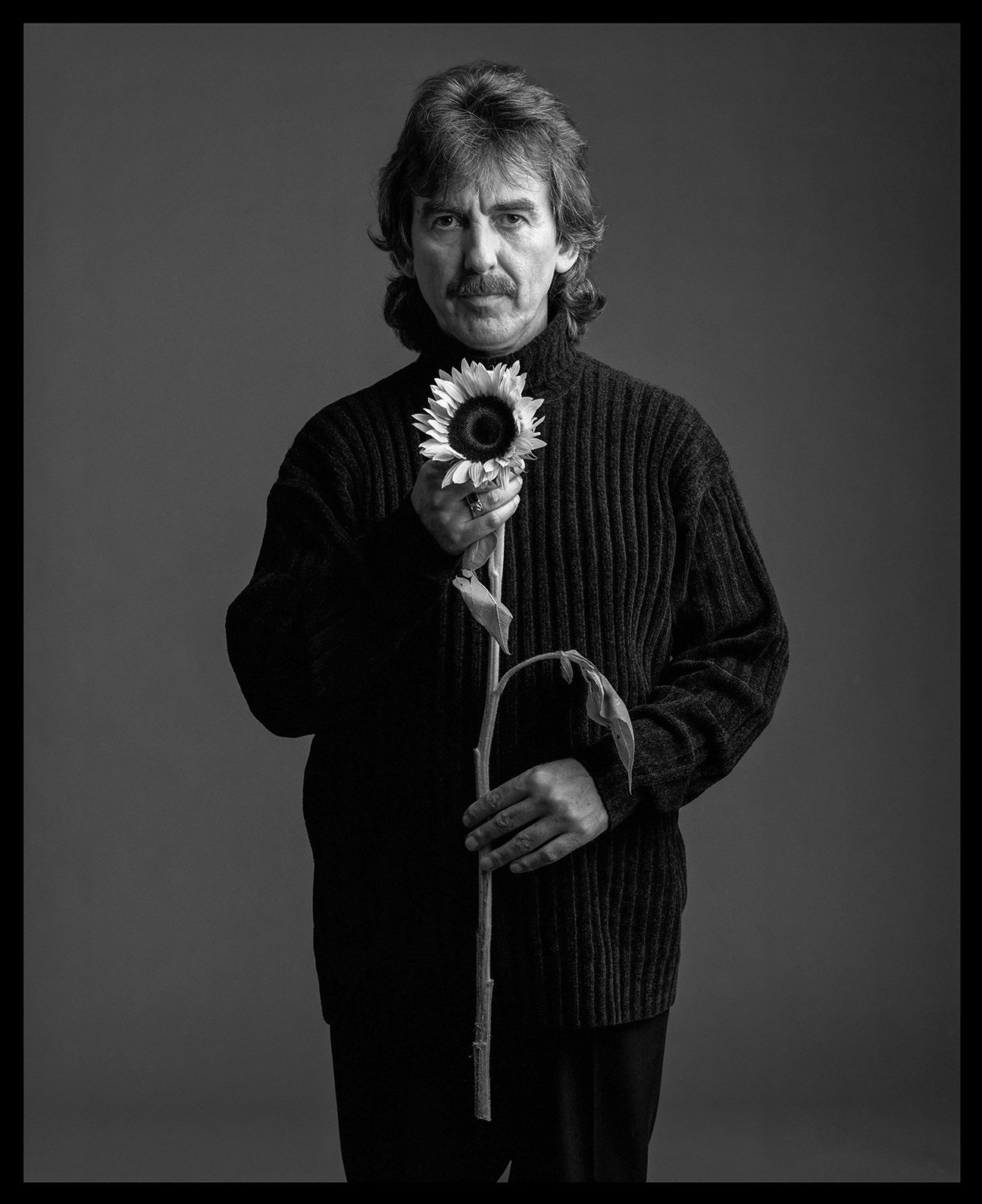

Mark Seliger: That was a real big ‘pinch me’ moment for me. That was during the 25th Anniversary portfolio for Rolling Stone. And I was given this portfolio along—there were, I think, five other photographers that were included. And they were all top names like Kurt Markus, and Herb Ritts, and Albert Watson, and Bruce Weber. And I was included in this portfolio.

And one of the biggest moments for me was that I got to photograph a Beatle. I got to photograph George Harrison. He was very reluctant to do the shoot, but they talked him into it. And he was mad at Jann for a review of Dark Horse in, like, 1973. And that’s why he didn’t want to do it.

But I kind of went into the shoot knowing that George was going to be a little cantankerous and angry at Rolling Stone, so I would have to soften him up a little bit. About a week before, I had been working with Tom Petty, and I knew that they were, obviously, friends. And I asked Tom what I could do in order to soften things up with George.

And he said, “Hey, you know what? George loves a ukulele. If you bring a couple ukuleles.” He says, “Oh, he’s got ’em in the back of his car. But if you could bring a couple ukuleles, you would win him over for sure.” So I went out and found a bunch of ukuleles. I went to a boutique-y music store in LA and I found a Martin that was really beautiful. But it was a rental, right?

It was probably a $2,500–3,500 ukulele. So I got them to rent it to me. I went over to the shoot. While we were shooting, George noticed that there were like four or five ukuleles that were sitting out on a table where the styling was. And he said, “Oh, wow, these are really beautiful.”

And I said, “Yeah, I rented them. I just thought it’d be great if we had one.” We did a picture with one. And—this is exactly why I signed up to do this job—he takes one of the ukuleles, I think it was the Martin, and he performed for our crew for about 20 minutes. And he sang all these beautiful Hawaiian ballads.

Literally everybody had a tear in their eye. We took a nice group picture. And as we were wrapping up, I saw him walking out the front door. And I walked up to him and he said, “Hey Mark, this was really great.” And he said, “We’ll meet someday again on the Avenue.” And I said, “That ukulele that you’ve got, the Martin, is a rental. And unfortunately, I can’t part with it.”

And he goes, “Oh, that’s all right. Just bill Jann Wenner.”

George Gendron: And did you?

Mark Seliger: And I had to bill Jann Wenner! I don’t know if he still remembers that, but that actually really did happen. But it was pretty—that one still hurts.

George Gendron: On the heels of these incredible stories you’re telling, and this body of work that you’ve produced, I’ve got to ask you a question, and I’m sorry if this is embarrassing, but did you really, when you were just starting out, did you really throw up before every time you went out to do a big shoot?

Mark Seliger: I think it was more like I felt like throwing up. I think the actual action of puking didn’t happen. I just was that nervous every time I did. I still get nervous every time I do a shoot. It still builds up in me and I have to find a way to keep myself medicated. Not medicated, meditative, I should say.

George Gendron: Boy, I can’t identify with that on so many fronts. But that kind of anxiety, I think, is healthy in terms of leading to a great performance, isn’t it?

Mark Seliger: Yeah, no, I always have to sit by myself before a shoot and all my notes, make my checklist, make sure that I cover everything that I need to do. I mean, yesterday we had a shoot and I had seven or eight different setups that I wanted to do in a couple of hours. And in order to make sure that I covered everything, I drew everything out and just checked things off as we were going along. But I had to sit for a good half an hour just making sure that I had prepared everything properly before my subject got there.

George Gendron: Frankly, I do this. I did this before we got on the podcast today. I teach at Dartmouth. I do it before every class. I can’t imagine not doing it. I feel like it gets me to a point where I feel by the time the event—whatever it happens to be, a class, an interview, a podcast, whatever it is, speech—by the time it starts, it has built a kind of confidence in me that, yeah, that I’m ready. And I can actually enjoy it too. That’s the other thing.

Mark Seliger: Yeah. Once I’m in motion, which I’m, I think I’m a pretty physical type of photographer, so I move around a lot. I’m very specific about direction. Once I’m in that, everything else goes away and I’m fine. I just go for it. And then I’m good at reading people. I know when they’re ready to move on.

I know when things have arcked, and that arc is now going into more or less the finale or zoning back a little bit. But however long that session is, I’m completely engaged in it until the very end. And then it’s over. But you really do feel that arc. And I think the buildup to just starting, you have to psych yourself into it in order to be able to be ready to go.

George Gendron: I don’t know if this is true or not or accurate or not, but since we’re talking about a certain kind of performance anxiety, I think I heard someone say once that that’s when you started writing songs. That it was a kind of anxiety you had about something. You were at Rolling Stone. You had been there for a long time. Maybe it was—was it boredom? I don’t know whether it was anxiety. But there was something you felt you needed to do something else at the same time and you started writing music. Does this ring true for you?

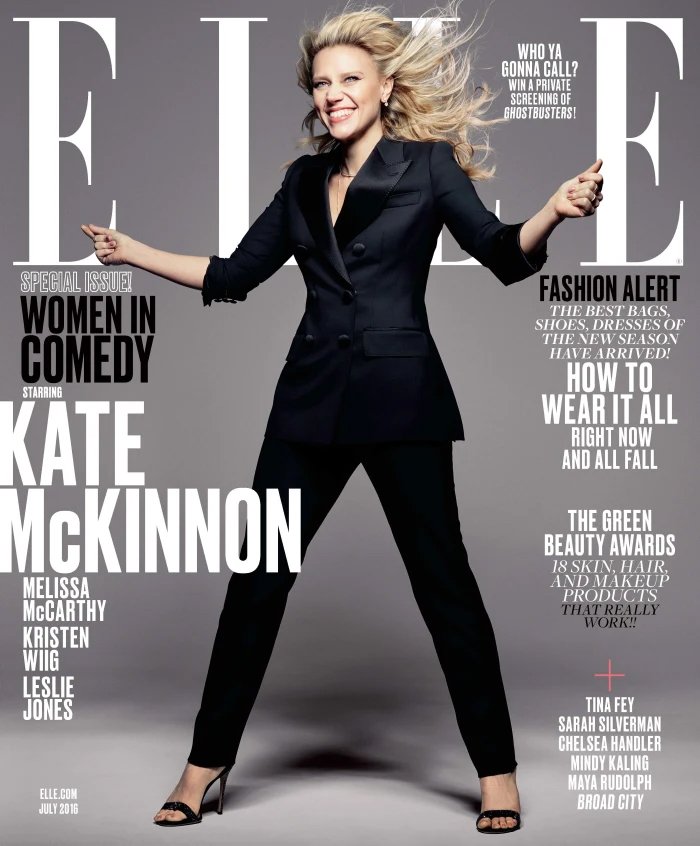

Mark Seliger: Yeah, this is how it happened is that, it had come to the end of the road with Rolling Stone. It was time to move on and I didn’t necessarily want to do it then, but I also felt the magazine was changing and I needed to spread my wings a little differently.

But there was that period, as I was trying to make that decision of how I was going to do that, that was melancholy for me. And it was also emotional. And that led to feeling like I could sit down and I could write how I was feeling. And that actually led to songwriting.

I did it in a poetic way. I had been playing guitar badly for years, but I was very interested in the idea of doing something a little different for myself that would give me another outlet while I was making this transition. And so I started writing. I went out on Avenue C—there were a couple of bars that did open mic. And I would go out on a Sunday evening with my guitar. And I’d go and I’d wait in line and I would try out one of these songs I was working on.

And shockingly enough, I really enjoyed it. And it was something that I kept on doing. And then one song led to another, and pretty soon I had three or four songs. And I started playing with the band and I just found such a sense of enjoyment.

And I remember Fred and I having a talk years before, where he stressed to me—we were talking about multiple art forms—and he says, “There’s nothing that says that you can’t do more than one thing in your lifetime, and do it well.” And it was really even before I started to write. And I just, I love that about him.

I reminded him—I think we were working on our third record and I was telling him about working on this record. And I said, “You’re the one who gave me the idea to start all this anyway by telling me that it was good to have other art forms that you enjoyed.”

And the evolution of my work has never been one where it’s been one direction. In fact, I think personal style has always been a tough peg for me. I don’t know if I really understand that. I know what makes sense to me per-project. And the technical aspect of that is like a paintbrush. So I’m not quite sure what it’s going to be.

If you go into a New York deli and they give you a menu that has over 10 pages of different things to order—some days you feel like a burrito and some days you feel like a lox, bagel, and cream cheese.

I don’t know where it’s going to go until I’ve figured out what the idea is. And it’s the same with music. I don’t really know where it’s going to go until I get in there and start to figure out what something sounds like.

George Gendron: I remember you talking at one point about, I guess, a kind of tension that exists for young artists, young craftsmen. And that is the tension between on the one hand, you’ve actually explained that you studied the photography of magazines that you wanted to shoot for. Perfectly understandable, really smart strategically. On the other hand, you at one point got feedback on your first portfolio, someone saying, “Well, I really don’t see a distinguished personal style here.” How do you manage that tension? “I want to be a Rolling Stone photographer.” And that connotes a whole lot of stuff, but then there’s also Mark Seliger, what he wants to do. Is that a tension or is that not a tension for you?

Mark Seliger: Pretty much when I would get an assignment, it was almost like it was a one-off, right? Like I just knew that I had to perform as best as I possibly could. And I wasn’t even thinking about what tomorrow was going to be.

And so when this editor who told me that, you know, wrote a little note when I dropped my portfolio off said, “Hey, thanks for dropping your work off. But, even though the portraits are very serviceable, I don’t really see any personal style here. Best of luck.”

Hey, that was okay. That was a hard one to get. The next day I got a job. What that taught me was that you had to have pretty thick skin in this business because it was going to be, definitely, an opinion from one day to the next. And the best critique was going to come from yourself. And you were going to be your own best judge of how your work was moving forward.

And I was really hard on myself. I would typically, after a shoot, I would write down everything that I forgot to do or everything that I could have done better. And then I would reread that and then I would try not to look at it again and hopefully that it would become rote in the next session that I was about to do.

That was how self-critical I was on every approach. And I learned that the competition that I faced with other photographers was really—it just wasn't useful. I was competing against myself more or less. And that’s really where I would take it.

So that tension, unfortunately, was self-inflicted. And I had to learn how to not beat myself up so badly. And the way that I would do that is I would just do better and better work. And then once I started to take chances, and sometimes you fall straight on your face, I’d just get up and dust myself off and work hard at trying to get a better experience on the next one. You’ve got to move on. And that’s the great thing about photography is that it doesn’t last for much longer than just the session. And then you’re onto the next thing.

“That was the sign of real success—when you were carrying around a Rolling Stone or Vanity Fair acetate.”

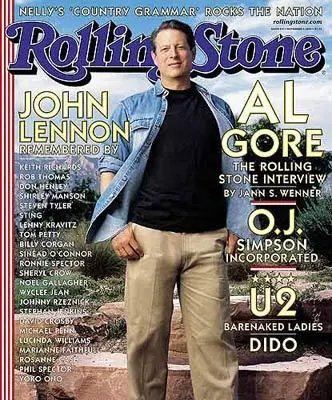

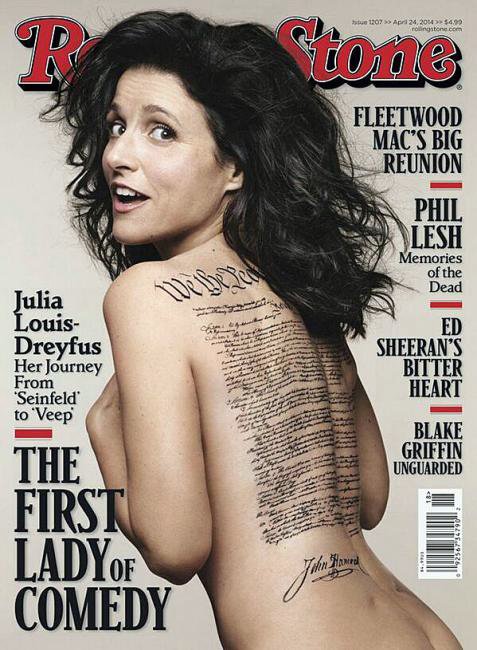

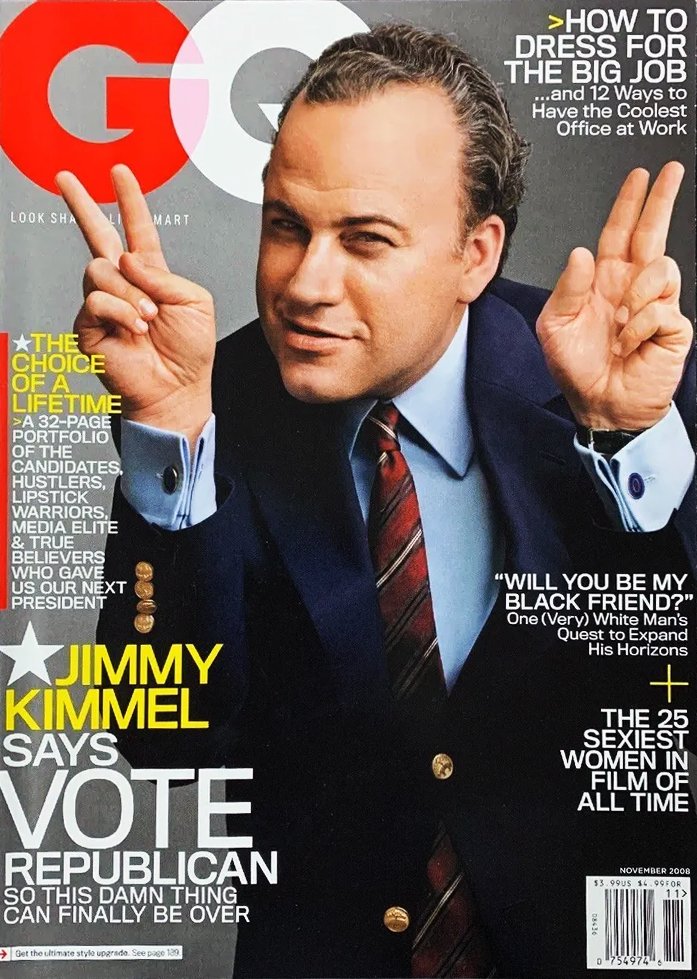

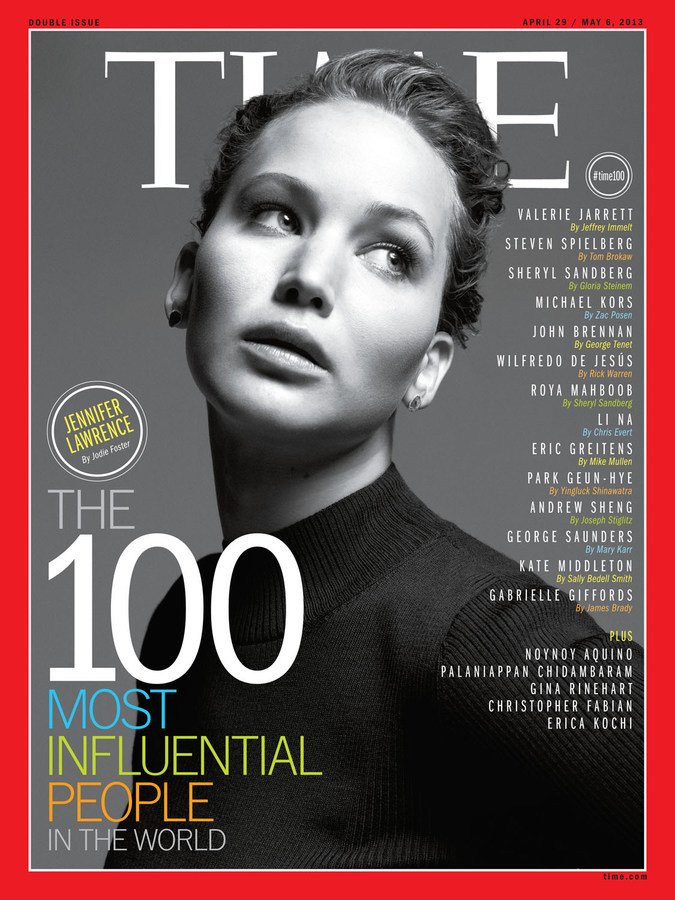

George Gendron: So in 2002 you moved to Condé, where I think your original deal was really focused on Vanity Fair. How would you compare the two cultures—or can you compare the two cultures?

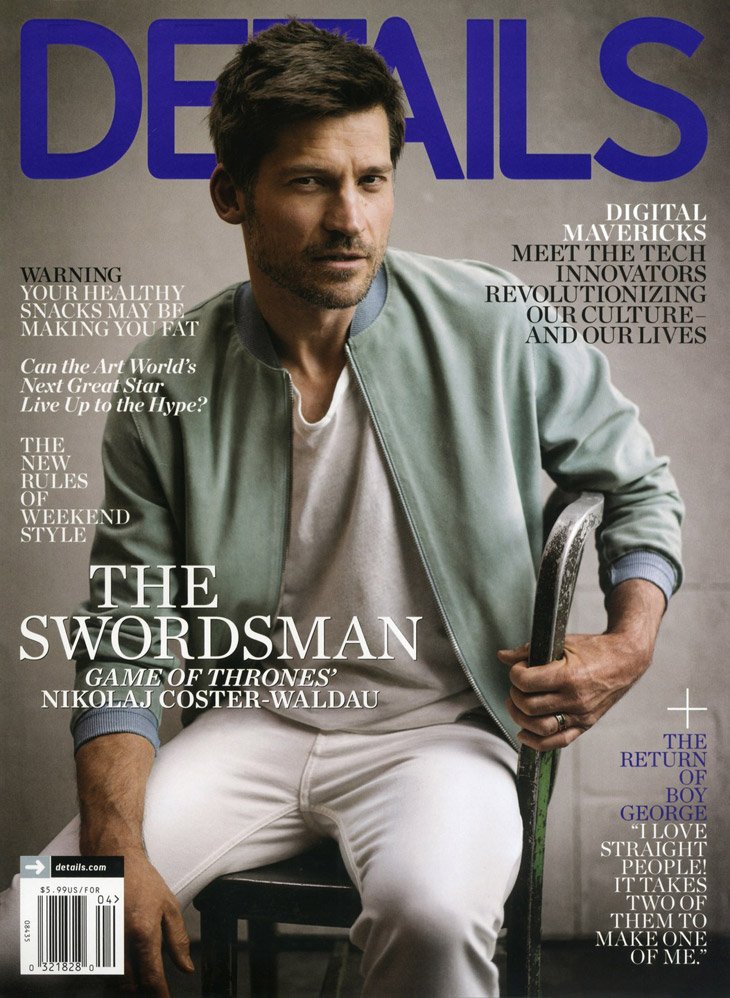

Mark Seliger: Art Cooper from GQ approached me first and told me that he really wanted to see if I could move over. I was still at Rolling Stone but I definitely felt like the end was near. And Jann was looking to change things up, too. And Art Cooper came to me, the legendary editor at GQ—25 years—and I was excited about what he was telling me. And then it just came up that Graydon also wanted to talk to me.

And so it was like here were these two huge magazines with Condé Nast, and they wanted me to come over. And I had a meeting with James Truman and we figured out that we were going to try to move this thing forward. But it was a bigger roster of people.

But the difference was it wasn’t a singular performance, even though Rolling Stone had other photographers, I was their primary photographer. Vanity Fair had their photographers, right? And I was just a part of that roster. GQ, they were looking to shake things up, but they also had a lot of editors involved, so I wasn’t necessarily the first choice for everything as well.

I had to really be willing to start over again. And by starting over, I really mean that exactly. They tested me out. And I don’t think I did a cover for Vanity Fair until I think it was almost my second year there. And I finally went up to Graydon and I said, “Hey, you know, I know you like me. I know you wanted me to be here, but I can also do covers.”

And he was like, “Oh, okay. I gotcha.”

George Gendron: This is a man speaking who’s done 188 of them for Rolling Stone!

Mark Seliger: Because I really, I loved the idea. But I didn’t want to take away from any of the other photographers. I just love the idea that the magazine—I read it. I studied it. I liked everything about it. I liked [Design Director] David Harris, the way that he designed. I liked [Photography Director] Susan White, the way that she interacted with photographers. They were just a great new family.

But I definitely had to build up their attention and that took time. And their trust. And that took time. And I’m still working with them, and I still enjoy working with them. And there’s so many great moments through that transition that really taught me about how to start over again, which I really appreciated. The idea of the ‘newness,’ yet the familiarity of great design and great craft.

George Gendron: It’s something that I think we all experienced in the magazine industry in one form or another. And now, of course, it’s just a fact of life for everybody. No matter what industry you’re in, what career you have, it’s people constantly having to reinvent themselves. And that does require a certain amount of perseverance and grit, persistence and patience. All at the same time, I think.

Mark Seliger: Yeah, but I really don’t think that—that should never scare anybody because, in my opinion, that curiosity is what keeps you on your toes, just in your own self evaluation. We just tried not to do the same picture over again twice. We try to keep it evolving,

George Gendron: Mark, if I were to go back and I haven’t done this, but if I were to go back and do a word search of all of the conversations we’ve had with all of these legends in the magazine industry, the one word that surfaces over and over again is ‘curiosity.’ And I’m really curious. I’m curious. I’m yeah, there you go. I’m asked by students all the time. Are you born with that? Is that kind of a gene you’re born with? Can you cultivate that? How do you, as you get older and more confident in your career, how do you nurture it and keep it alive?

Mark Seliger: I think it really depends on how aware you are artistically. And I use the terminology of ‘observation.’ It’s big with me as a photographer and as an artistic person, I’m always observing something. I’m always seeing something.

I’m using it, whether I’m putting it in the filing cabinet for ideas or whether I’m using it for my next project. I just like observing. I like taking references of things that I notice and using them in the way that I think in the way that I create. And so I think that curiosity really equals observation.

And then also just exploring where you do something that you’d never done before. And I like firsts. I think that was the whole idea behind starting to write songs is that to me again, it was a new first. And it wasn’t that far away from what I thought about in terms of storytelling. Which is very big for me. The storytelling in photography translated well into the storytelling of songwriting. And so I could really—I could understand that. And that’s where that came about.

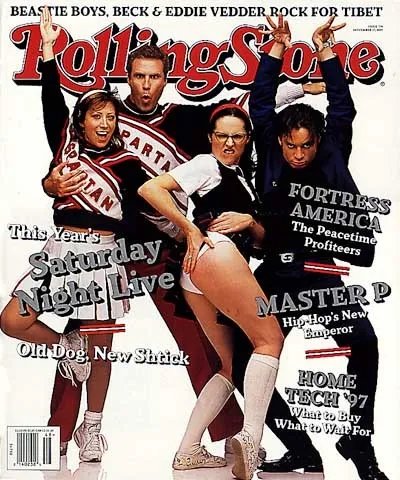

George Gendron: This reminds me of your relationship with Fred Woodward. So one way to look at your profile would be to say, “Mark Seliger was at Rolling Stone from such and such a date to such and such a date.” But within that, you and Fred also started not only collaborating on photography, but you were codirecting music videos.

Mark Seliger: Yeah. We became buddies pretty quickly. And it was really like the three amigos with Matt Mahurin, Fred, and myself. And we would go and we would have dinners together and we would pontificate on what we loved, and who we were, and where we saw things going. Dreaming, I would call it, right? We were dreaming.

And I got lucky. I found myself really entrenched in the music world, which led me to being asked to see if I would do music videos. And the first one was with Shinehead. And I just, I don’t know, I just loved the creativity that Fred and I were doing at the magazine. I said, “Hey, would you be interested in collaborating on a music video?”

And we decided to join forces. And then that led to working with Paula Cole. We did a Courtney Love/Hole video, “Violet,” which got a lot of play. And then we went on to do a big season of commercials for The Gap with LL Cool J, and Missy Elliott, and Dave Navarro, Junior Brown, Aerosmith—all these really incredible moments together. So we were moonlighting quite a bit on these other projects.

And Fred designed pretty much every book except for one or two of mine. So we were also working that on the side. And it was just a very collaborative time. And we still collaborate. We still work on projects together. But I found that two heads were better than one when doing the music videos. Even though there were moments when Fred couldn’t do them because of his workload and I would just do them on my own.

But I remember one of the highlights for us is that we got to do a Lenny Kravitz video called “I Belong to You.” And we did it in the Bahamas, and I had just rekindled a relationship working with Lenny on his record, 5, and I just loved the song and I pushed to wanting to do this.

And so he went to the Bahamas and Fred and I created this—I think it’s probably one of the best things that we’ve ever done together. And it was just the best time in the world. It was so far from anything that you would think of as, like, going to work. It was just absolutely magical.

That was really the joy of spending time together, I think, was feeding off each other creatively. We’d watch countless movies together in order to get inspiration. We would make notes. He would write—Fred’s an incredibly talented writer on top of it. And he would basically write all the notes up. And there would be pages and pages of things that we wanted to get to that there was no way we were going to be able to complete.

George Gendron: You talk about Fred and designing books, that brings us to your projects, your independent projects, your books. I’m really curious, do you have a favorite—because I do—almost everybody who knows your work has one that they just can’t stop talking about. Do you have a personal favorite of the projects that you’ve done on your own?

Mark Seliger: First of all, George, that’s very nice to hear. I don’t personally know what people think of the books. I don’t really ask that, but it’s great to know that people do. They are records and indexes for me of times when I was involved in a project.

I’m very connected to my very first book, When They Came to Take My Father: Voices of the Holocaust. Growing up in Houston, Texas, I was from a reformed Jewish family. We were taught about the Holocaust. And then when I had an opportunity—the very first opportunity I had, to make a book was with Arcade Books under Little, Brown and it was a book on survivors stories, survivors of the Holocaust, with a writer by the name of Leora Kahn, a researcher. And then she helped put it together, essentially.

Fred designed that book. It wasn’t printed well the first time, and that was very disappointing. And I learned my lesson about how you have to be on press. But that book really holds a special place for me because it was my first book, and it was something that I felt had a real sense of importance to it.

And once I did that book, and I cemented those stories, the way I took pictures for magazines changed. I became much more reductive in the way that I did portraiture. And that’s really special to me. And I think all those books, in a way, have a little special moment for me. What’s your favorite, George?

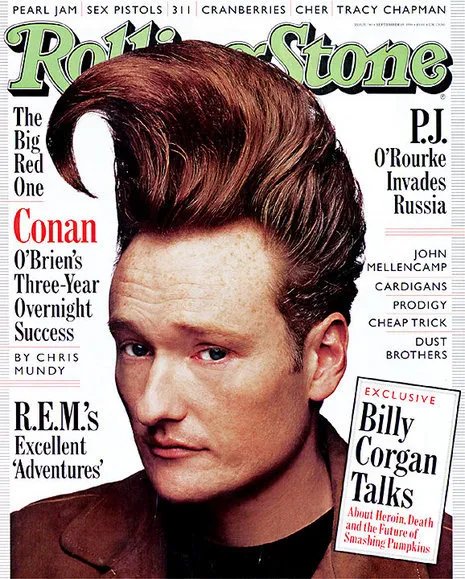

An image from Seliger’s “Covid book,” The City That Finally Sleeps

“Hey, the cops are coming! You guys need to get out of here!”

George Gendron: My favorite, having been born in Brooklyn, and gone to college in New York, worked at New York magazine, was The City that Finally Sleeps. And I’m not even sure I can articulate exactly why I’m going to say what I’m about to say, but one of the photos in there is of Waverly Place, and every time I look at it, it gives me the chills. It’s just, it’s gorgeous. And it allows you to see the city in a way that you rarely do. I remember sometimes at New York, if we were working really late on a late close or something like that, you’d go out and the streets wouldn’t be totally deserted, but the crowds would have gone. And there’s something about the city when it’s not mobbed that’s just, it’s magnificent. And it allows you to enjoy the spaces in a way that you can’t during the day. And I just found that book to be extraordinary.

Mark Seliger: I’m so glad you referenced that too. And I, it was something that, that really happened to me during that time is that, it was this very impulsive moment where everything just went away. And there was this incredible fear that there was this thing, this evil thing, that was lurking in our world. And yet the city was blossoming in the height of Spring.

And I live in the Village. My studio is in the Village and here I was walking through, or driving through, the Village with not a soul on the street and a few cars parked outside, but there was this canopy of cherry blossoms that were illuminated by the streetlights. And the streets never looked more alive. And not because there was anybody on them. It was just that the city was breathing almost like in repair or in a sense of rest.

And to me, that’s what gave me the idea to go out and really start to document a resting New York, a place that was in need of a rest. And every day we would go out and my assistant, Davis McCutcheon, was very thoughtful about wanting to come out and do it with me.

And we just would find a different landscape every day. And we would find the opportune time to shoot it. And it really became like this mission to document New York. I had no idea it was going to be a book, but it just felt like it was something that I needed to do.

George Gendron: I could talk to you about that book forever. I won’t because we’re running out of time. But you have that one photo of the 7 Train with most of the Silver Cup sign in the background. My grandmother commuted on that from the time she was 20 until the time she died at 75—55 years going back and forth between Manhattan and Queens. And, again, those photos are just extraordinary. And your stories about making the photos—they’re just fabulous.

Mark Seliger: I’ve gotten close to being arrested a couple of times in New York, but that was definitely one moment where I really felt like I was going to be in the clinker. My assistant didn’t trust attaching a little portable strobe on a piece of metal near the 7 Train, so I went ahead and did it myself. I jumped over a gate and locked it down and we got three frames before a guy came running over and saying, “Hey, the cops are coming! You guys need to get out of here!”

And I went over and grabbed my strobe and we hightailed it over to a taxi that we found and jumped in there and got away. It was a close call. And I had a very angry engineer when he got popped with a flash while he was driving into the station. They were not happy.

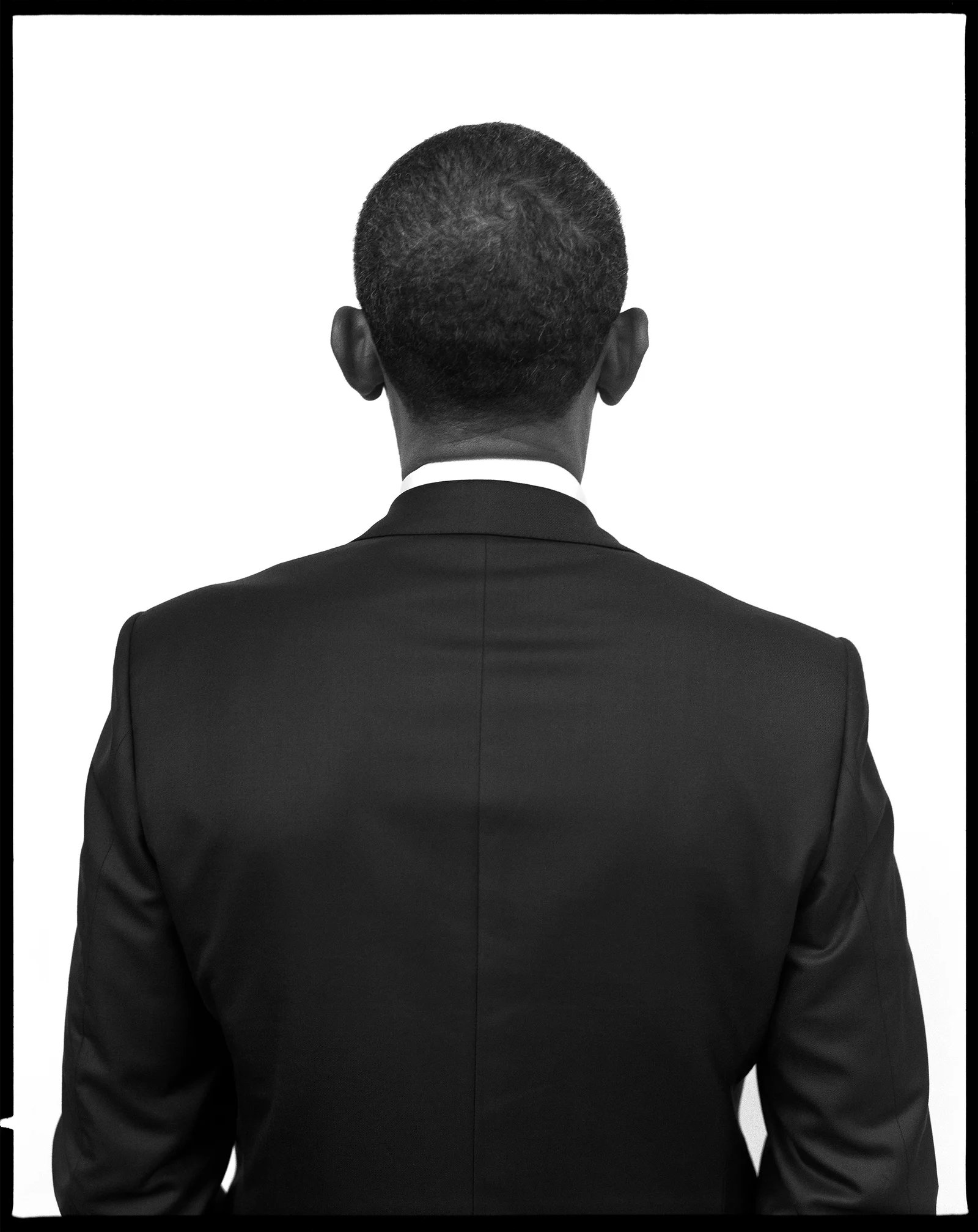

George Gendron: In wrapping up, I want to ask you something, and it’s going to sound like I’m flattering you and maybe I am, but there is a legitimate question at the end of this. Do you ever stop to think that you have led many lives that most people just dream about. You shot for Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair, photographer of the stars, got that one. Check. Musician with your own band. Check. Publisher of your own books. Check. Hang out and are friends with other celebrities. Check. Photographed a president. Or two or three. Check. Have your own studio in lower Manhattan. Check. Directed music videos featuring stars like Natalie Merchant, Lenny Kravitz. Check. Featured in the podcast, Print is Dead (Long Live Print!). Check. What have you not done yet?

Mark Seliger: That’s the biggest one, for sure.

George Gendron: What have you not done? What’s left?

Mark Seliger: Yeah, no. I am very excited about the next—I call it chapter three for me—which is continuing on the path that has been set up for me, but also the things I really want to explore. I’ll move forward on that level.

But it’s definitely wonderful to be able to actually take some time—over COVID was a great time for me to step back and look at the archive and go, “Wow I’ve had some pretty incredible experiences!” And that’s when we set up the archive you’re talking about which was—we call it “B sides”—and we went back into the archive and we looked at the imagery that, essentially, was never really viewed because after you finish with your edit, you just put everything back into the closet...

George Gendron: ...and you’re onto the next assignment, yeah.

Mark Seliger: Yeah. So that was really refreshing to be able to do that. But I am a very grateful human being and I look forward to the next year for sure.

George Gendron: When you invite the Print Is Dead team over for dinner, what art are we going to find on the walls in your home? And when we come over, what should we bring?

Mark Seliger: Okay first of all, probably a really cold bottle of rosé, if you come in the summertime. Which is fun. And then you’ll find on the walls beautiful, old family photographs that I have from pictures I’ve taken of my dad and my mom. And then pictures that I’ve acquired through the family archive.

And then you’ll see one of the first photographs I ever bought and made sense to me was an Arnold Newman picture of Stravinsky. So my great mentor in college was James Newberry and he really helped us to understand the history of photography. And when he introduced me to Arnold Newman, that was really one of the first light bulbs going off.

And that picture of Stravinsky where he’s got his hand on his head, but he’s mimicking the shape of the piano lid. Then, obviously, the top of the piano mimics the musical note. And just the composition of it was so beautiful that I was like, “Wow. There is a lot to be learned.” And I have a couple of those pieces up in my apartment that keep reminding me of why I wanted to become a photographer.

Mark Seliger’s website is currently under construction but you can reach him here, and be sure to check out Crosseyed Arts.

Related Stories