No Visions of Loveliness

A conversation with Linda Wells (Editor: Allure, Air Mail Look, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT MOUNTAIN GAZETTE, COMMERCIAL TYPE, AND LANE PRESS

Ed: You’ve loved our collaborations with The Spread—their Ep21 interview with former Cosmo editor-in-chief Joanna Coles remains one of our most-downloaded shows. Now, Rachel Baker and Maggie Bullock are back again, this time with the queen of the beauty magazines—Allure founding editor Linda Wells.

You can find The Spread every week on Substack, where Rachel and Maggie round up juicy gossip—from The New York Times to The Drift, and everywhere in between—big ideas, and deeply personal examinations of women’s lives to create their idea of the perfect “women’s magazine.”

Picture it: It’s 1991. You’re sitting at your desk at The New York Times, when you get a call from the office of Condé Nast’s Alexander Liberman. Alex wants to meet you for lunch at La Grenouille to discuss an opportunity: Si Newhouse has decided to launch the first-ever beauty magazine, and he thinks you’re just the woman to make it happen. You’re 31 years old. The canvas is blank. The budget is endless.

What’s your move, Linda Wells?

For the women’s magazine editors of today, struggling to keep the lights on by juggling Instagram, TikTok, marketing events, digital content, and whatever remains of their print product, this is a tale so far-fetched it feels like the stuff of an early aughts rom-com. But millennial editors’ wildest ideas about the “Town Car Era” of magazine-making were just another day at the office for Linda Wells.

Linda led Allure for 25 years, becoming a front-row fixture at Fashion Week—while also pioneering the cottage industry of backstage beauty coverage—and enlisting writers like Arthur Miller, Isabel Allende, Betty Friedan, and John Updike to write about … beauty.

In 2018, she pivoted, restyling herself as a beauty entrepreneur, launching with Revlon a makeup range she called Flesh. Now she’s back in the land of editorial, having a bunch of fun at the helm of the beauty vertical of Graydon Carter’s Air Mail, commissioning articles on everything from psychedelics to orgasm coaches.

We knew Linda Wells would be delightful, and yet she exceeded our expectations. We know you’ll love her too.

Allure’s premiere issue, March 1991

“I don’t like to change clothes. If I put on something in the morning, that’s what I’m wearing to dinner.”

Maggie Bullock: You wanna do this? Should we do this? We’re doing it.

Linda Wells: I’m ready.

Maggie Bullock: Great! So Linda as we record this, people are flying home from Europe for Fashion Week and they’re all seeing their children for the first time in weeks and unpacking. And I wonder—where are you with that? Do you still do any of the circuit? Is it a relief not to do the circuit? Tell us where you sit.

Linda Wells: I don’t do the circuit anymore. Every once in a while we’ll get an invitation and it’s ha, you don’t have to have me there. I loved it when I did it, but it was really exhausting and I know, “Boo-hoo, you’re going to all the fashion shows. What a terrible hardship that is.”

But it’s a lot. I always think about it. If you really love ice cream and then someone says you have to have it every single meal and you can’t stop having it until midnight, but then you’ve got to wake up at five the next morning and have more. It’s a lot of sweet goodness stuffed into a very short period of time—with high heels on.

And I think that was the other piece of it that was a killer was you had to get dressed every day. And that really intimidated me. I hated packing for it. It would just send me into such a tailspin. And then just the whole pressure of looking good and being photographed. It’s not who I am.

I like being behind the scenes. And so it just felt like a lot of public activity and not a lot of time to think. I always brought a book. And then of course, when books became obsolete, I brought a Kindle or an iPad or whatever. And I would read while everybody else was chit-chatting. Chit-chat before the show is exhausting because it was 45 minutes of chit-chatting.

Maggie Bullock: With the same people that you just saw the last one.

Linda Wells: I was like the rude person reading a book, but it just was a way for me to escape.

Maggie Bullock: Yeah. That is so interesting to me because I definitely perceived you as someone of like unshakable confidence who could sit in front of all those cameras and dress for all that. Honestly, the idea that caused you any kind of agita is like a genuine surprise to me.

Linda Wells: Yeah. Oh no, absolutely. And it was always like, you’re not thin enough. You’re not young enough. Even when you are young enough, you’re not young enough. You’re not thin enough. And I never personalized like the models.

The models part of it to me was like, they were a different species up there. People would always say isn’t it depressing to look at models all day? And I’m like, “No. I don’t think I’m like them. They’re just—there’s no relationship.” But it was just that expectation, I think, and the expectation of all these fashion editors.

And they really do dress the part and they think they come to the job at the very beginning as people who really like to wear clothes, and try on clothes, and change their clothes. I don’t like to change clothes. If I put on something in the morning, that’s what I’m wearing to dinner.

Maggie Bullock: I don’t want to take us too far off track, but my personal theory has always been that people who grew up to be fashion editors are often people who had a really easy relationship with clothes. Like they didn’t feel conflicted and terrible about themselves when they tried on new clothes. Because they’re thin, and beautiful, mostly, and whatever. They fit that ideal. I know I’m really vastly oversimplifying and many uncountable hours have probably been spent in the therapy chairs of fashion editors. But I did always think, Yeah, it’s a little bit easier for you to love clothes in an uncomplicated way. That’s the way that it seemed to me.

Rachel Baker: What’s the beauty equivalent? What’s in people’s heads who become beauty editors?

Linda Wells: I think that’s become a prerequisite in a way of being a beauty editor. It didn’t used to be because beauty editors were really much more behind the scenes. You’d go to events, but the events weren’t public events. They were meeting with a brand or learning about a new product or going to a launch, but it wasn’t really that outward facing. And so now, if you’re a beauty editor with any value at all, you’ve got a great big Instagram account, and you post, get-ready-with-me and you put on your technique and you show everything and it’s like I’m not that person either.

You can do a winged eye in the back of an Uber, and that’s not me. So I think that there’s that kind of expectation of a certain amount of personal skill that’s not about being the editor, or being a writer, or being any of those things. It’s about makeup skills and hair skills.

Rachel Baker: Performance.

Linda Wells: Yeah. And that was not what the job used to be. So it’s a lot harder, I think, for beauty editors today.

Maggie Bullock: Or it’s just a totally different skill set, right?

Linda Wells: That’s true.

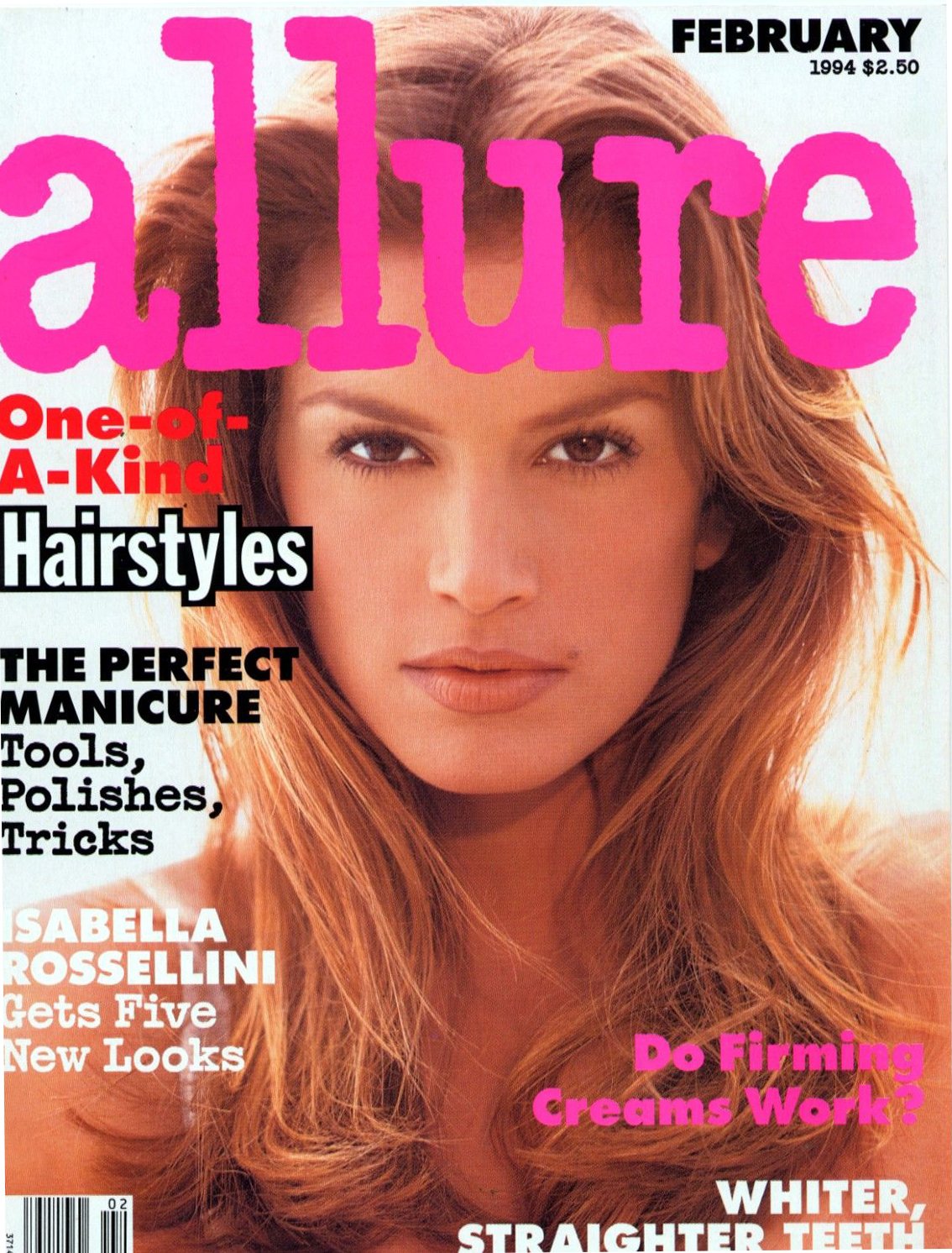

Allure launched at the height of the “Supermodel Era.” Among its early cover models: Linda Evangelista, Cindy Crawford, Bridget Hall, and Kate Moss.

“Allure was deliberately aggressive and deliberately not pretty. I was going to say ‘ugly.’ It wasn’t ugly, but it wasn’t trying to be pretty. We didn’t want to be pretty.”

Maggie Bullock: So, actually, going in the way back machine how did little Linda Wells, at Trinity college. Do I have that right?

Linda Wells: You do.

Maggie Bullock: Would she have ever envisioned this kind of future, this kind of career um, you know? Reading up on her books and writing her papers.

Linda Wells: Right, that's all I cared about. No, really, when I graduated, I didn’t have a career plan. I didn’t have a job, which is unthinkable for people who are graduating from college now. They’ve got their whole strategy. They’ve had all their internships. I wasn’t that person. I didn’t really even know, or think about, life that way. And no one in my family was from this world. They were all finance people.

So I graduated and I was really at a loss of what I was going to do. Because what I wanted to do was go to graduate school. My father was like, “Sorry, no.” And I went to New York and interviewed with everybody: graphic design firms, ad agencies, book publishing, and then magazine.

I interviewed at Hearst and I interviewed at Condé Nast. And got the job at Condé Nast as a—they had this program called Rover—the Rover program—and it was for the most green beginners ever who knew nothing and they would put you in different jobs where there was an opening.

So let’s say, the assistant to the assistant to the shoe editor was sick. Then they’d stick you there for a couple of days until the assistant to the assistant got better. And what you would do is take shoes down to the messenger room, or you’d Xerox shoes, or you’d mark up shoes and put them away. It was like being at an Amazon warehouse—but a really nice one.

Maggie Bullock: But you did eventually land more full time in the beauty department at Vogue. Is that right?

Linda Wells: I did. Yeah. I got a full time job in the beauty department as an assistant there. So that was my step up.

Maggie Bullock: That was actually my first real job too, in the beauty department of Vogue under Sarah Brown, actually.

Linda Wells: Oh, wow! It was a very different place when I was there. It was a Grace Mirabella world and Anna Wintour was there as the creative director, about a year into when I was there.

Maggie Bullock: So tell us about Grace Mirabella. Were you so low on the totem pole that you didn’t really interact?

Linda Wells: I didn’t really interact with her much. When I decided to leave and got this job at The New York Times I was packing up my boxes and she came in and said, “Kiddo, don’t leave!” And I thought, You don’t know my name, do you?

“There was the assumption that you had to live, and breathe, and act as if you were the Vogue reader and the Vogue editor all rolled into one.”

Maggie Bullock: Were you a natural fit as a Vogue girl? Did that shape you in some way, that experience? Obviously it’s a larger than life, like cultural idea now to be a Vogue person, but what was your experience like?

Linda Wells: I did feel a little bit like I fell off the turnip truck because I was born in New York, but I spent four years of high school in St. Louis. And so I felt like I had a bit of a midwestern in me. And so I think that was at odds a bit with what the atmosphere was. And then, everyone was really well dressed and they wanted to look like they belonged there.

So there was that part of it that felt at odds. And then the funny thing about this, and I don’t know whether you experienced this Maggie, but being an editor at Vogue—and even just at the lowest level, an assistant at Vogue—there was the assumption that you had to live, and breathe, and act as if you were the Vogue reader and the Vogue editor all rolled into one. So you became, or I became, the biggest snob ever about little tiny things. I’m making no money, I can’t afford a taxi. I have an attitude about where the best vacation is—Is Capri better than the Amalfi Coast? Who am I?

Maggie Bullock: It is a really weird psychology. Also, you’re living in a shoebox, you’re eating ramen.

Linda Wells: I ate ramen. If I wasn’t living on hors d’oeuvres. I’d go to events and have lots of hors d’oeuvres. And then you would be a snob about, I don’t know, where you got a facial or what cream you would use. And you weren’t going to go to the drugstore to buy something. It would be so de classé.

Maggie Bullock: Yes. I’m still completely broken by this. Rachel can confirm—I’m still broken in that way. So then afterwards, as you just mentioned, you left Vogue and went to The New York Times. That was a really cool job, because you were at the Times magazine, correct?

Linda Wells: I started at the paper and I was a bit of a fish out of water, to put it very mildly. And it was tough because I was brought in, I thought, to bring beauty to the pages of the, not, make them beautiful but cover the beauty industry. Not so much as a business, but as trends and things like that.

I was on what was loosely called the Living Style desk. It wasn’t the style that we know today. And so I kept pitching story ideas and they were just like, “These are not what we do at The New York Times.” And so I got panicky because I was on trial. They put you on trial for three months before they hired me. So I had to get a whole lot of bylines pulled together before I was going to be hired.

Wells’ on her boss, mentor, and friend Carrie Donovan: “She introduced me to the world of fashion.”

I agreed to do whatever they would throw at me. So I ended up covering a lot of the evening parties and getting all dressed up and taking my reporter’s notebook and an evening bag and going out to The Pierre and to ballrooms around New York and covering events. And it was hilarious, I have to say. If you want to be really popular at a party, pull out a reporter’s notebook. And it will be like—people would flock to me and tell me things they want so badly to be in the paper.

And sometimes I went around with Bill Cunningham and that was a great introduction to that world. So I was doing that and Carrie Donovan was the editor of The New York Times Magazine, the Style part of it. And she saw that I probably saw that I was floundering. And so she rescued me and brought me to the magazine and that was much more a natural fit.

And then I wrote every other week about beauty in the magazine. And then about a year in, I became the food editor, too. The food editor quit, so I got that job too. And it was really two jobs. And so I did both of those things.

Maggie Bullock: How did you know about food?

Linda Wells: I know it was random, but I’ve always been really obsessed with food and I’ve always cooked and took cooking classes. It was just a personal interest. And I think, again, I was on trial for three months. I did a proposal. I did the work for three months and they said, “Yes, you can stay.”

So it was an odd mix, but it was something that was incredibly fun. And it was a very fertile time for food because it was a time when Daniel Boulud broke out on his own and Jean-Georges Vongerichten came to the US. And there were just these superstars that we all know now, but at the time they were just breaking out on their own. So it was fun.

Rachel Baker: That is cool.

Maggie Bullock: But I’m noticing too, that you had Grace Mirabella and then Carrie Donovan. So what did you learn from Carrie Donovan?

Linda Wells: Oh my God, I learned everything from Carrie. She just was the most fantastic boss. I loved her so much. I learned that your boss could be more than just a boss. They could be an example of how to live. They could be a friend. I ended up scattering her ashes with another person who worked for her from the Pont Neuf in Paris.

We were really close. And she really rooted for me, so I felt great about that. And she took me everywhere. She introduced me to Ralph Lauren, and to Karl Lagerfeld, and to all the world of fashion, and took me to the shows, and introduced me to Calvin Klein, and all the biggies. And that was great, because there was no better introduction.

She also taught me about how to work with people and how to spare their egos. And I hope I learned that from her. To take good care of people who are creative, because it’s not easy to put yourself out there like that. And she had this way of, even if she was killing a story or killing a photo shoot, she’d bring the photographer in, have a conversation and they leave looking like they were walking on air and smiling. And she just had a way of magically seducing people.

She was really exceptional. She taught me a lot. And she was brutally honest too. So when I started Allure, she looked at that first issue and I took her out for lunch and she was just like, “Oh, this is not good.” She went through it and told me all about why.

Maggie Bullock: Did you agree with her? Was she right?

Linda Wells: She had points. The thing is, I also think, when someone gives you criticism, it’s a gift. So I wanted to pay attention to it and take it in and not become defensive. We were doing something. I don’t want to get ahead of myself about Allure, but it was deliberately aggressive and deliberately not pretty. I was going to say ugly. It wasn’t ugly, but it wasn’t trying to be pretty. We didn’t want to be pretty. So I think that was a little jarring to people who had a different expectation of what this was going to be. It took a little while.

Rachel Baker: Yeah. Just to rewind it back just a minute. You were, I don’t know, 30 when Si Newhouse called you and asked you to create a beauty magazine. From scratch. Can you tell us what that call was like?

Linda Wells: It was, first it was Alex Liberman, who was the editorial director of Condé Nast and the creative side. Si was the business side and Alex was the creative side. And Alex wanted to have lunch at Le Grenouille, and I thought, That’s a little public. I don’t know.

Because it was a place that a lot of these people went for lunch all the time and I thought, Condé has been trying to hire me back. And Anna Wintour tried to hire me back to Vogue to be a beauty editor, a beauty director. And I really loved being at the Times, so I didn’t really want to go back and do something at a place I’d already been.

So when Alex called me to have lunch, I just thought that’s what he was doing. And I just thought that would be not very thoughtful to Carrie Donovan whose relationship was really important to me. So I said, “Could we have lunch in your office or a meeting in your office as opposed to at a very public place?”

And so I went to meet with Alex and we went to Si’s office and I was like, “Oh, maybe this is about something else.” And it was a very simple conversation. And if you had ever met Si or heard about Si he was a man of very few words and very long pauses. Very long pauses. You had to try your very hardest not to fill in that pause.

Rachel Baker: Yikes.

Linda Wells: So, I went to his office, and Si said, basically, “I want to start a beauty magazine and I want you to be the editor.” And that was it. I mean, he said, “Also, I want it to be journalistic.”

And then I got on my high horse and said, “If it’s going to be journalistic, then we can’t be beholden to the advertisers.” Because Condé Nast was very advertising-friendly. And there was the fantastic example of Condé Nast Traveler, which had started a few years before us. And “Truth in Travel” was their subhead and they were going to be critical of the travel industry.

But it was different in the beauty world because beauty had never had anybody criticize anything that they did. And it was a very close relationship between advertising and editorial. And I learned at The New York Times where I was really encouraged to be tough and encouraged to be critical.

And when, when the big companies, all the big beauty companies would complain about something that I did or wrote, usually, the top editors would come and congratulate me. My bosses and Abe Rosenthal were thrilled: “Good. Go for it.” They wanted it to be tough. It was a different scenario at Condé Nast that didn’t really have that approach to these subjects and also our advertising was going to be beauty.

So unlike the travel magazine, not all of its advertising was travel advertising. A lot of it was, but not all of it. But for us, we were going to be critical of the very people who were supporting us. So that was a bit of a process to figure out how we were going to do that.

“I like being behind the scenes. I always brought a book. And I would read while everybody else was chit-chatting. Chit-chat before the shows is exhausting.”

Rachel Baker: Wow. My next question was going to be what kind of hoops did you have to jump through to ultimately get the job—but it sounds like they knew they wanted you and you pushed back on them, which is incredible. How old were you then?

Linda Wells: I think I was 31 when it started. I think I was hired in April of 1990. So yeah, I wasn’t really pushing back. Of course, I was going to take the job. I’m not crazy. It was the chance to start your own magazine with the support of Condé Nast, which is, there’s nothing in the world like that kind of financial support and also support for you as an editor. They just really stood behind their editors.

It wasn’t so much that it was just let’s be sure that we agree what this is and what this means. So I didn’t say yes to the offer in that room that day, but I did later that very day. So I was thrilled to be there.

Rachel Baker: What was happening in the beauty world at that time that made Si and Alex be like, “We’ve got to do a beauty magazine and we need Linda to do it.”

Linda Wells: It was still a kind of quiet time in the beauty world. It was before Retin-A was approved by the FDA, and I always think of that as a watershed moment because it was the first time that a prescription medication to make you look better was approved, but with the marriage of science and beauty in a really legitimate way.

It was still really early days, but what they knew was that those beauty pages in the Condé Nast magazines, particularly Vogue, Glamour, were really successful. They had very high readership and they had built-in advertising. So I think that they saw that and saw the way that The New York Times was covering it and thought that could be good territory for Condé Nast.

Maggie Bullock: So what was your vision? Like, invent the form of a beauty magazine.

Linda Wells: At the time it was really taking my only two experiences, which is Vogue and The New York Times, and mashing them up together. So it was like the visual excellence of Vogue and journalistic excellence of the Times, and trying to see if those two things could be pushed together.

And in the end, we didn’t go with quite the visual excellence of Vogue for a number of different reasons, but the short version is that I was a little afraid of it being too pretty, and too predictable, and a little obvious. And Alex Liberman kept saying, “We don’t want any visions of loveliness.” And he kept repeating that, “No visions of loveliness.”

He wanted it not to look like one of those magazines that you found in a beauty salon. This was such a long time ago that it’s hard to remember. Beauty was a very reverential pristine, retouched, perfect concept of a very narrow definition in every way.

And beauty photographs were really quite limited, too. Most photographers shot fashion. So we’d be like, crop in. They’d crop in on the picture to make a beauty picture. But it was really the advertising world that had all the creativity and beauty and it didn’t exist in a very big way in magazines.

So it was trying to figure out how we were going to interpret beauty, and talk about it, and make it exciting. And it was a time of MTV and it was tabloids and it was a rougher time. And I think that we wanted to pick up on that kind of energy. So the layouts and the design ended up looking very much like that world.

Maggie Bullock: And then you also put a lot of energy into making it quite literary, right?

Linda Wells: I think that the assumption is that beauty is superficial and vain and hence not smart and not provocative or complicated. And to me, the reason that I found the subject interesting was because people have really conflicted opinions about the way they look, the way they present themselves to the world, the beauty standards. All these things are really fraught and it became a subject of feminism. And it became a subject of politics.

There are a lot of issues in there that I think magazines weren’t really parsing very much and dissecting. And so I wanted to be able to do that. Not just in reporting, but also to have real writers, literary writers, explore the subject. So it was fulfilling a fantasy because I love to read and I love great writers.

So I read The Country Girls by Edna O’Brien and got her to write for the first issue and put her on contract. And we had those great Condé Nast budgets. And so people would write for us. And I’d say, “Write for us!” And sometimes people would say, “I need a new couch.” So sure. Okay. If that’s what it takes, I don’t care what you’re using the money for, just write for us.

So we had Arthur Miller, we had Edwige Danticat, we had Isabel Allende, Geraldine Brooks, Betty Friedan, Diane Ackerman. I mean, it was an exceptional group of writers. David Sedaris in the really early days. Fay Weldon. And they would immediately think that we wanted them to write about something like makeup, or they didn’t feel like they belonged in the magazine, or they wanted to approach it in an obvious way.

And we would talk to them about, What does it mean to you? And what was your vision of beauty? And what was your interaction? And how did you feel about this? And they just really would dive in. And it was always the most fantastic surprise what we would get from these writers.

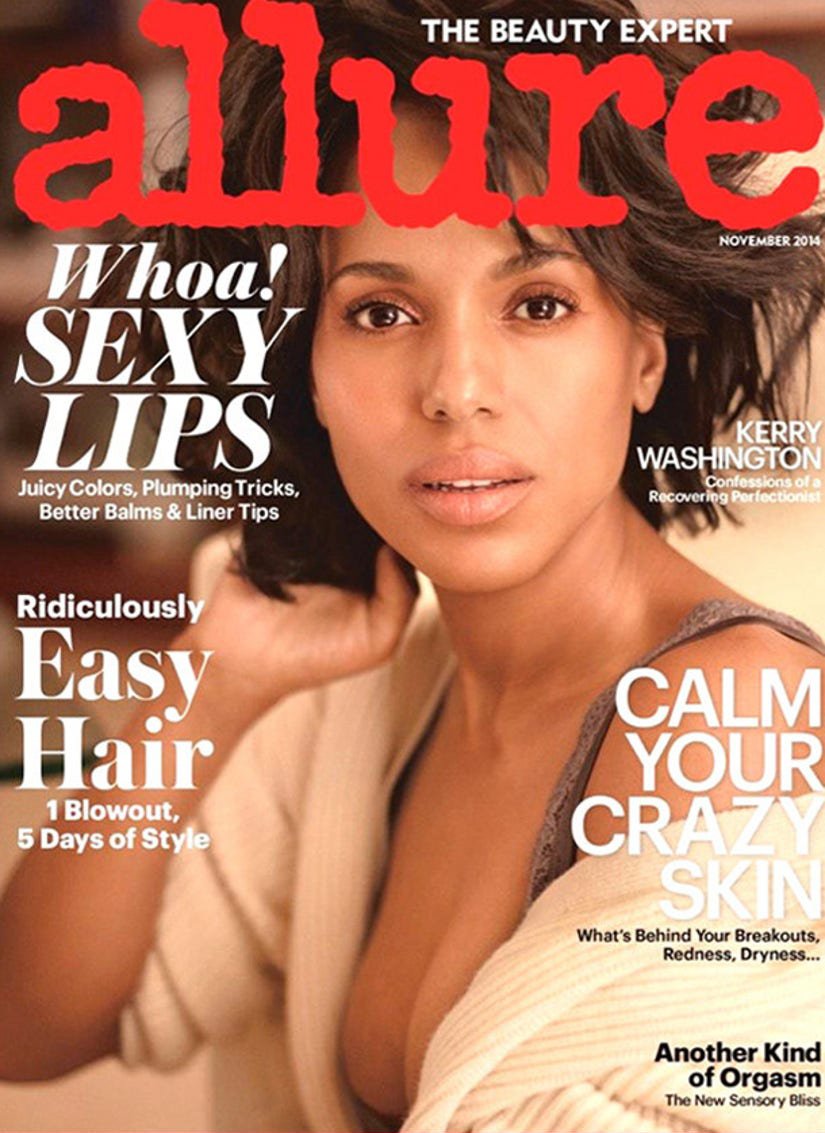

The new millennium brought a new approach to Allure’s covers: celebrities

Maggie Bullock: And tell us, how did you get Updike to write about psoriasis?

Linda Wells: I know. John Updike. We really wanted John Updike to write for us. And I loved what he was writing for The New Yorker. And we had several editors over the years who interacted with these writers and had relationships with them. And generally, I would hire them from The New Yorker and they were assistant-level people and they would have this senior job and they would have a great Rolodex.

So we went through Mary Turner and she would write these letters. And it was letters. It was in the mail because John Updike wasn’t on email. And so we’d send him letters about story ideas that we’d have. And he would send us back postcards that you buy at the post office. And he would type on the little postcard. It was pre-stamped and it was almost like an index card. And he would very politely reject our ideas, but in a way that made us feel humiliated.

And we’d be like, “Oh, this is so embarrassing.” We go back and try again. And he wrote something for The New Yorker about spending the summers with all the women whose husbands went to the city to work. And while they were with their kids on the beach, because he had psoriasis and he would hang out and sunbathe while they were playing with the kids. And this became his group of friends and how he would spend his days.

And so I thought that’s a beauty story. He wrote a story about that. We just sent him that idea, and suddenly we got this envelope, and in it was the manuscript. And there was no contract and no agreement, and there it was, and of course it was perfect. And we called it “The Prodigal Sun”—S-U-N. And it was such an excitement. We were so thrilled.

Maggie Bullock: Do any of these stories live in an archive? Can you find them?

Linda Wells: I can’t find them. I don’t know why, but Allure doesn’t have an archive like that. You can search for Kim Kardashian’s hair color, but you can’t search for John Updike’s psoriasis. And I don’t know why.

Maggie Bullock: That is sad. That is really sad. A personal question—because I did start out in beauty—I just wondered how you talked about these stereotypes of beauty being a less-serious subject. I just wondered how you, on a personal level, have dealt with or played with that stereotype about what it means to be a beauty person.

Linda Wells: I guess in a way I don’t really think of myself as that. I’m not someone who gets a lot of facials or wears a lot of makeup. I don’t personalize it. And I think that’s really true of almost everything that I’ve done. It’s not personalized. And so I look at it as a fascinating subject to pull apart and explore and see what it means about us as a culture. But I don’t look at it as How can I look better? or How do I look?

I care about the way I look, but I don’t care that much about the way I look. I’m one of those people who looks in the mirror and then goes about my day. And I feel sorry for people today because everyone’s on zoom and they’re photographing themselves. And I think there’s a requirement now in the beauty world to be a beautiful person in a literal way. And that’s not fun, you know. And I’m not young and none of that bothers me in the sense of me doing my job.

Rachel Baker: So these last couple months, there’s been some chatter about the “Town Car Era” of magazines. And you landed at Condé Nast as an editor-in-chief right in the middle of that. What do you make of that image that everybody’s talking about once again?

Linda Wells: The hilarious thing is everybody was talking about it all the time. I would laugh and I’d like every profile of every editor would start and she steps out of her town car and her high heels go clickety-click across the sidewalk and I’m like, “Here we go again.” And it was a great time. It was a really fun time to be an editor, because Condé Nast took care of us. Si Newhouse believed that we should be living like our subjects. And out in the world. And so the indulgences were many.

And it was almost as if you were looked down upon if you didn’t take advantage of them, if you didn’t spend enough money. And it was like, you were not rewarded for having a tight budget. Eventually, yes, that was important. But in the first 10 or 15 years I was there, that was not the attitude at all. It was excessive.

Rachel Baker: And what were the perks—will you tell us? Did you get an interest-free mortgage?

Linda Wells: I had an interest-free mortgage. That was really great. And then eventually, you know, I had to pay it back. That was shocking—Everything isn’t free? And so yes, I had an interest free mortgage. And it was funny because when I got there, I didn’t know any of these things and I was coming from the times where you didn’t get anything. You didn’t, for the most part, you didn’t take a pen home at night.

I got there and I didn't know this until well in. I got a call from human resources and they said, “Oh, we have a car for you.” Meaning a car for me to have to drive, not a town car, which yes, I had that town car thing. So I was like, “Oh, that’s fantastic.” It was a former ad director’s car and she left. And so I got her old car and I thought, This is the greatest thing going. And then people were like, “You’re crazy. That’s someone’s old car. You should be getting a new car and you should be getting a better car because you’re an editor in chief. You don’t stick around for this Hyundai thing or whatever it was.”

I thought I’d died and gone to it. I was so happy to have a car. And I didn’t really know what was available to me, but once it was available to me, believe me, I went for it. It was trips on the Concorde, and Michael Jackson was on my flight one time, and it was rooms, plural, at The Ritz. When I had kids, I brought my kids to the fashion shows and the nanny and we all hold up at The Ritz and I had a bassinet that used to be someone else’s bassinet and then I’d keep it in storage at The Ritz and then I passed it along to another editor at another magazine. And it was just, it was extreme.

I remember one time the CEO, Steve Florio, was supposed to moderate a panel discussion in Detroit at Chrysler. And at the last minute he decided he couldn’t do it or he didn’t want to do it. And he called me begging for me to do it. And I was like, “Okay, sure, I’ll go.”

And he said, “I’ll fly you there on a private plane and I’ll get you anything you want at Prada.”

And I said, “Fine.”

And then I ended up, I was on Northwest Airlines. I’m like, Who are all these people? This is not a private plane. And then he was like not available to go with me to Prada for shopping. Now, can you imagine going with the CEO shopping at Prada? But I ended up saying, “Why don’t I do this? I’ll just go to Prada. I’ll get something and I’ll send you the receipts.”

Wells talks homemade beauty fixes with Katie Couric, c. 2014

But that was like—kind of the grandiosity of it. And I remember one time there was an advertiser who was very unhappy about what we had done published in Allure. And this happened all the time, by the way, unhappy advertisers all the time. And that’s the consequences of being a journalist in this field. So this advertiser was a part of a huge organization. A very big beauty company, one of the largest. And he decided he was angry.

We wrote a story: Does hair dye cause cancer? And we did all this research and the research said that it did not, that it was clear. And so it was a lot of just apocryphal rumors and things like that. He was so angry that we even asked the question. He said to me, “I’m going to destroy you and your magazine.” He called me to tell me that.

So he tried to get all of the beauty companies in the US to band together and to boycott Allure. No advertising. No editorial coverage. He was gonna put a stop to us. And this culminated in a meeting that he decided to have like December 23rd—maybe it was the 24th. And my whole family went down to the Caribbean on vacation with my little kids, and my husband, and the nanny. And I was in New York meeting with angry advertisers.

The CEO, Steve, felt so terrible about it that he sent me down to Antigua on a private plane. I had a much better experience. I was like, I did my work and I got to Antigua without any problems. It was fantastic. And they didn’t pull the advertising. And it turned out that the advertiser was retiring on January 1st. And so this was going to be his last act. But as I walked him to the elevator after we had this meeting, he gave me a kiss on two cheeks and, “Happy holidays!” And I was like, “What are you talking about? You went after me!”

Maggie Bullock: And tried to get the whole industry to go after you, too.

Linda Wells: Yeah, that was cute.

Rachel Baker: Kiss, kiss.

Maggie Bullock: So cute. You launched in 1990, right?

Linda Wells: 1991 was the first one. And I started working there in 1990, yeah.

Maggie Bullock: So you were right where you needed to be when this whole era of the celebrity really took off. The idea of celebrities on the cover of the magazine instead of the models. What was the turning point or the point at which you were like, “Whoa, we’ve entered a new phase.” Does that stand out in your mind?

Linda Wells: Yeah, yeah. It was because we were very much wedded to the model and I came around when the supermodel was hitting its peak. And so that was really exciting. It was like that moment where Gianni Versace was alive and had all the girls on the runway at one time. And the power of that whole group.

And there was nothing better than if you get Linda [Evangelista] on a cover and Cindy [Crawford] and Christy [Turlington] and Naomi [Campbell]. It was that really great moment of beauty and models and larger than life characters. And while that was happening, the actors were really downplaying beauty and wearing converse high tops, big dresses, and no hair and makeup.

It wasn’t a time of really glam squads and things that happen now. So then InStyle came along and really made celebrity their identity. And they were having huge success in it. And you just felt the balance shift. And I think it was partly that the designers became uninterested in the supermodels in the same way because they felt the supermodels were getting too much attention.

And they ended up getting all those Eastern European models, who were very anonymous and looked all alike. And so the personalities disappeared from the runways and from fashion and celebrities became the big personalities.

And they started claiming fashion and beauty as something they wanted to participate in. And that meant they would get contracts with fashion brands. And so it shifted in a big way. The whole business shifted to a more celebrity driven business.

And I remember, I think our first celebrity cover was Sharon Stone. And that was funny because we were shooting her—I think the first cover was shot by Herb Ritts, so that was a different shoot. But we shot her previously and we had borrowed, for the shoot, a gown from John Galliano. And it was like one-of-a-kind, embroidered silk. It was an incredible dress. And she was about to get in the dress—she was in a hotel room and we were shooting her—and she said, “You know my rule, don’t you? I wear it. I keep it.”

And the stylist on the shoot called me up in a panic. “Sharon Stone says that if she wears the dress, she’s going to keep the dress.”

And I’m like, “That’s not our dress to give her.”

So I think she’s going to be shot in the hotel robe. And that’s what we did. We shot her in the hotel robe. And she looked great. But that was the assumption on the part of the celebrity that, “I will get all the jewels and I will get all the things.”

“I got on my high horse and said, ‘If it’s going to be journalistic, then we can’t be beholden to the advertisers.’”

Maggie Bullock: Sharon Stone loves a declaration. She’s like, “It will be such. You will now give this to me.” But also on the other hand, nobody wears a robe better. Your backup plan was good.

Linda Wells: The downside of the celebrity was the celebrity profile. There’s only so much you can say after a while when everyone’s covering the same people. There’s just not that much more to bring to it. And one of the things that we started doing, and it started out as an accident, but we found all these pictures, I think first with Helen Hunt. We found all these pictures of her as a child actor and all through her days, we brought them to the interview and she looked at them and she commented on them.

And that became our point of difference. And it was a moment of unrehearsed reaction. And it was a reaction to the way they looked, which is what we cared about at Allure. What they were wearing, and what their hair was, and their eyebrows. And there was always a comment. And the comments were funny. And so that was just an element of humanity that didn’t exist in a lot of the profiles. I think that GQ would get a great profile, but for the most part it was very much standard phoned-in, kind of predictable.

Maggie Bullock: I loved those things. I still love that technique. It’s such a smart way to crack them open.

Linda Wells: Yes. And it was always surprising to me when they wouldn’t expect it and a few would get angry when we’d bring the pictures out and, “I’m not doing this.”

And I’m like, “We do this in every issue. Who’s not telling you? Someone’s got to prep you.”

But it was really fun. And one of our best profiles was when Judith Newman went out to interview Britney Spears. And we’d photographed her first, which usually didn’t happen. We usually got the story first and then the photograph.

So we’d photographed her first, and so we were stuck. We had to run this thing. And every time they were supposed to meet, Brittany would cancel. And Brittany would cancel. And Brittany would cancel. And Judith was there. And then she spent another day. And she spent another day. And she lives in New York.

She called me and I was like, “Can you stay a couple more days?”

And she said, “Can you pay for my divorce?”

So I said to her, “Write the story, ‘Frank Sinatra Has a Cold.’” It’s the story about celebrity for the celebrity who doesn’t show up. The sort of empty-vessel that celebrity actually is. And she wrote such a good piece.

Maggie Bullock: This feels like a bumpy pivot because we’re talking about the highs, but can you tell us about the day when you got fired from Allure after so many years there? What was that like?

Linda Wells: Actually, the funny thing was, it was surprising. Working for Condé Nast, what should never surprise you is that you will someday be fired. People were fired all the time. Magazines closed. I remember people saying, “I was abruptly fired.” And I thought, What other way do they do it?

And I know how the famous Grace Mirabella was fired—she found out when she was watching Liz Smith on TV. Some gossip report on local TV. It’s never pretty and it’s never easy, but I didn’t expect it. And then again, of course it seemed like it was time. I probably should have left before, but I didn’t want to. I really liked it.

And so I remember going back to my office. And It was handled very strangely because they said they were going to announce the new editor at a certain time. And it was like, I would say, it was in a half an hour. I was like, “Oh. Not very much time.”

And you know, “Yes, you can stay and you can move up to the floor with all the executives. And you can be on that floor and you can do whatever.”

And I thought, Oh God, I don’t want to do that.

Wells talks beauty trends at New York Fashion Week, c. 2011

But I wasn’t really thinking because it was such an out of body experience. So I went back to my office, I saw Paul Cavaco, who is the creative director, and my work husband, and who I adored so much. And I was like, “I was just fired.”

He’s like, “What?”

So I said, “We have to get everybody in the conference room immediately.” And I went and told them. But I had no time to think about what I was going to say and how to prepare. And I was still in shock. And people were crying and it was terrible. I felt like I was abandoning them. And I’m sure that they knew that this meant that it wasn’t going to be so great for them either.

And this had followed a lot of budget cuts, and before I was fired, I was asked to fire certain people who were paid a lot. And I thought, They’re doing a good job. I don’t really feel like I want to fire them. And I’m sure they thought She’s not going to be the right person to do these cuts. But I’m glad I didn’t fire them.

Can you imagine if I fired them and then I was fired? And then it was like, “Why don’t I ruin people’s lives who I felt were really great people.” So I was spared that. And then I went back to my office and I thought, Oh, I’ve got this full inbox. And then I was like, Wait a second, that’s not my problem anymore. And so I just walked out of the office and I never went back.

And I didn’t go to the 78th floor. Or whatever floor it was. I just thought it was strange. If I’m going to go, I’m not going to hang around and pretend I have a job or act as if I’m a puppet up here. I don’t want to do that. So I just left. And that was that.

Maggie Bullock: I heard you talk about this once and you said that everybody else is crying, but you did not cry. Is that true?

Linda Wells: Yeah.

Maggie Bullock: Are you just not a crier?

Linda Wells: I’m not much of a crier. Although, if you get me on a TV show with a good song I could fall apart really easily. No, I am a bit of a stoic and I think that it seems as if I have no emotions maybe, but I’m very placid on the outside and then inside I’m thinking about things, but no I didn’t cry.

There was a moment where I just felt terrible for everybody. But I didn’t cry for myself. And I don’t think I really ever cried for myself about that. It was bad, but I did really feel as if that chapter was over. And it was time for me to move on. And it was time for me not to feel bitter about it.

There were a lot of people who were fired and were really angry about it for a long time. And I just didn’t want it to ruin the previous 25 years, which were great. And I was really proud of what we accomplished. And so I just thought, I’m not going to let that one day color my attitude about the previous 25 years. It was the end.

Maggie Bullock: I’m just curious where you were in the arc of your generation of editors being fired or replaced had that turnover really started to happen already? And also, Rachel and I wondered if you are on a text chain with a bunch of them. Like, you know, did you console each other? You all went through this very unique experience, but you all went through it.

Linda Wells: I feel like I was probably the first of the editors to go. And I remember Graydon Carter was really fantastic and took me out and we had lunch and he’s just, “If you’re going, it’s just a matter of time before everybody goes.” And he was very brilliant in the way that he executed his own departure and it was so well done.

And I think that people who saw the writing on the wall left before they were pushed out. But I think for Allure it was tough because I felt that they just took a line in the salary and they just fired everybody over that line. I remember being on a text And seeing one person was gone and then, I was getting texts like, “Oh, they just fired X and they just fired this.”

“I learned that I’m not meant for the corporate world whatsoever. And even though people are like, ‘Condé Nast is so corporate.’ Oh no. No, it’s not corporate. That’s corporate.”

Rachel Baker: This is a little bit of a gear shift, but there’s been such a revolution over the past decade in terms of inclusivity, vis-a-vis beauty types, skin color, and body ideals. Thinking back to Allure’s heyday, how much of that was part of the conversation in making your magazine?

Linda Wells: It wasn’t a huge part of making the magazine. We included a variety of people, but it wasn’t a conversation, a daily conversation. And it’s regrettable. I look back on it and I think, That wasn’t good. And I think that we fell into the same concept of what beauty was. And it was a narrow definition of what beauty was.

And, there were incidents like, we did a shoot once where we had all these models lined up at a sink and they were wearing, like, what’s now thought of as skims, but they were not skims at the time. But it looked like that kind of beige underwear, all lined up at a sink and there was a dermatologist there and it was some kind of concept.

And one of the models was significantly heavier than the others. And I got it back from the retoucher and her body was made to look like all the others. And the head of production came in to me and she said, “I’m really upset about this.”

I’m like, “What was it?”

And she showed her to me. I’m like, “What happened to this model?”

And the photographer had gone and done it on his own and directed this. And I was like, “Oh my God.” But that sort of showed me how it was just rote. And how at every level, this is what was just commonly done. And it could be done because of the ease of retouching. There were just incidents like that, that were visible issues.

But it was a different time. And I don’t even think it’s fair to even defend it. It was just then. And if you look back, I think about the number of cover lines I had of “Lose 10 Pounds.” It was like I was fully delivering diet culture, beauty culture once a month, like clockwork. And that’s not good.

Maggie Bullock: We’re also guilty. The number of cover lines I’ve written trying to rephrase weight loss stories. They’re countless. And the number of weight loss personal test drives I have done and written.

Linda Wells: I have a human guinea pig for all of them. And I have a tough time forgetting that because it’s so part of my life from when I was a teenager. And I’m always thinking, I’ve got to lose weight. Or, I wish if I could just be a little bit thinner, my life would be perfect. But it’s just like you get on the scale and they can make or break your day. And I know better. But it’s just in your blood cells. I don’t know what it is.

Maggie Bullock: Yeah. It’s really hard to shake. So one thing that kind of bowls Rachel and I over, amongst many, in your story is that it felt like pretty quickly after you left Allure, you were reinventing yourself. You became Revlon’s chief creative officer. And then a couple of years later, you launched your own beauty brand, Flesh Beauty. This is a podcast called Print Is Dead and we’re very much focused on that side of things. Obviously, now you’re back on the editorial side. What’s your, kind of, post-mortem on switching to the other team for a while? And did you like being over there? Or did you long to be back in editorial land?

Linda Wells: It was such a great experience in terms of just learning something completely different. Something I thought I knew but knew from the outside and didn’t know anything about from the inside. And in some ways I wish I’d done it 20 years earlier so that I had that perspective because it was fascinating. It’s just, it’s a different orientation, a different world.

I learned that I’m not meant for the corporate world whatsoever. And even though people are like, “Condé Nast is so corporate.” Oh no. No, it’s not corporate. That’s corporate. There’s factories and there’s supply chain—and the number of hours I spent in meetings about supply chain.

And I don’t know why I was there, but there I was, sitting there trying to stay awake, and also Googling acronyms under the table because I didn’t know what I was talking about. But it was really interesting. And I was working for a CEO who came from Colgate and he went to Unilever, Fabian Garcia. He was fantastic.

He wanted to have a better relationship with Ulta and he saw what was happening with all the indie brands in beauty and thought, Is there a way for us to create a brand internally that mimics the Indie brand format, which is quick-to-market, no red tape, no deliberating, get it out fast, and really trust your gut.

“Condé Nast took care of us. Si Newhouse believed that we should be living like our subjects. And out in the world. And so the indulgences were many.”

So I raised my hand to do that. So it wasn’t really my line. But I hired a makeup artist, I hired a designer and I went with the makeup artist to Italy, and we created the formulas, and I created the concept, and we created the names, and named all the products, and made the identity, and worked with our social media person to create an identity on Instagram.

And it was so insanely fun. And that was a success in terms of what was asked of me. The challenge was that at Revlon, they didn’t work this way. They weren’t in the prestige business. And it’s a different business that requires a different kind of service in the store that you have to pay for.

It requires marketing, merchandising—all these things that it just isn’t You set it up and then the people come. It isn’t—it’s a new brand. So It was really doomed from the beginning, honestly. We had too many products. We didn’t have a DTC presence. Everything that indie brands are doing, Glossier, or you name it, was not the way we were doing it.

We came out with something like 160 SKUs right off the bat, which is an insane amount of stuff. But what I cared about was the quality of the products, and the way they looked, and the way they sounded, and their personality. And I love them, and I still have them, and I still use them. I love those products. And they were great.

Rachel Baker: And I love the name too. We love Flesh.

Linda Wells: So outrageous. And we named one lip gloss Moist and people were just losing their minds about it. And we just had so much fun. It was so much fun.

Rachel Baker: So tell us about Air Mail. You launched the beauty vertical Air Mail Look last year. What was the mandate from Graydon there?

Linda Wells: He brought me in to write about beauty and wellness for Air Mail, and he is the greatest boss. He and Alessandra Stanley are the greatest bosses because they just let you do what you do. And sometimes I feel like my mission was, can I scandalize Graydon with this, but he’s pretty un-scandalizable, if that’s a word. That was going along well. And I think the stories are really well-received. And I think that was a big thing. And again, there’s a built-in advertising interest in the subject. And he saw that this subject is just exploding.

And so we started having conversations about what that would look like and how it would be. And he came up with the name, Air Mail Look. And then he, very generously, had me work with a deputy editor from Air Mail, Ashley Baker, who is my partner in crime and so much fun. And we talked every day and we just came up with a lineup and off we went.

And I have the art director and the creative director from “Big” Air Mail. We call it Big Air Mail because we’re little. And then we have a photo editor who I knew from the Vanity Fair days, Susan White. So we have this incredible talent and no one’s full time on Air Mail Look, but we put our heart into it. It’s enormously fun. We just laugh about, Should we do this story? And we’ve got these outrageous stories.

Rachel Baker: You can really feel that as a reader. Even skimming the headlines this morning just to refresh my memory, I was like, “Oh, that’s hilarious.” What’s your favorite story you’ve worked on recently?

Linda Wells: The story about the orgasm coach. There was nothing better. I don’t know if you saw that one, but it was so hilarious. So a friend of mine, Lisa Eisner, was telling me, “There’s this guy in LA and he teaches women how to have orgasms.”

I’m like, “Say no more.”

We have this fantastic editor who’s working with us, Lauren Bans, who was at GQ, and she’s a TV writer. And so...

Rachel Baker: The Spread loves Lauren.

Linda Wells: Oh God, she’s so good. I love her so much. So she was available to us because of the writer’s strike. So we brought her in to be an editor and she knew a writer in LA who was willing to do it, another TV writer. And so this woman went off and had a session with a man called “The O Man.”

He was a physical trainer. He became an orgasm coach. And she paid $800. It was a low price because it was like a holiday discount. And she had two hours of orgasms. I don’t know how many there were, but I would say probably safely 40. Maybe that’s an exaggeration, but it was certainly over 20. She was exhausted.

But it was hilarious. My phone went crazy the morning it happened and I was getting texts from men who lead entertainment divisions of giant companies, and they’re like, “Whoa! This should be a TV series.”

Rachel Baker: Yeah, it should.

Linda Wells: I talked to one person in that world about it, so I’m hoping so. Yeah.

“Designers lost interest in supermodels because they were getting too much attention. So celebrities started claiming fashion and beauty as something they wanted to participate in. The whole business shifted. ”

Rachel Baker: Fingers crossed. So you invented Allure in your early thirties. You created beauty publishing. And then you worked on the corporate side. If you had all the funding in the world, what would you create?

Linda Wells: I do feel like I should create a skincare line. I even have a name. I have a concept. I know. But the market is so oversaturated. I feel like what needs to happen in skin care is something that just doesn’t happen often enough, and that is the marriage of science with sexiness. There is no sexy science. And there should be.

We should have products that perform really well and in a legitimate way and that are fun and well packaged, and fun to name and look at and put on your counter and that you look forward to using. But they should also deliver on the performance.

And it’s very separate in the beauty world. It’s either it’s clinical, and it looks clinical, and it sounds clinical or else it’s frivolous, and indulgent, and luxurious, but it really doesn’t do anything. And so I would love to do a mashup of those things. But I don’t know. I think that to do it, I just think there’s so much in the industry right now.

And then we had this influx of celebrity lines. And I get it. I know that in order to get attention, you need a celebrity behind your brand. And in order to get attention, you need an influencer behind your brand. And that was one of the negatives about Flesh was we didn’t have that. It wasn’t an influencer brand, and it wasn’t a celebrity brand.

And so it’s hard to get brand recognition and awareness without that. But right now, a lot of these celebrity brands are dying and a lot of the influencer brands are dying. So I think that there needs to be a bit of a shakeout and then maybe I’ll do it. Who knows?

Rachel Baker: So you just solved skincare. Can you solve magazines? If you were in charge of Condé Nast now what would you do? Or can magazines be saved?

Linda Wells: I think that they can be. But I think that they can’t be in the model that—I’m not saying anything that’s so ingenious—the business model is beyond broken. And there’s no point in trying to force magazines into the current business model, which I think the surviving magazines are still trying to do and they’re trying to be all things to all people. Or a lot of things to all people.

And I think when you look at some of the really exciting creative magazines, like The Gentlewoman, or Homme Girls, or Beauty Papers, or Self Service. They’re really specific. They drill right into their subject. They’re not all disparate, they’re very focused, and they feel precious. They’re expensive, and they’re on really good paper, and they don’t come out every month.

So I feel like in a dream, it would be having a lot of little magazines that speak to a smaller consumer. And then maybe have more to it than just the magazine. You look at Homme Girls and they have clothes. Or you look at Self Service and they have exhibitions. Is there another something they could do?

Air Mail has these newsstands, and they’re opening another newsstand in March, and what does a journalism brand selling products look like? And can that be done? And it’s breaking the old habits of selling a lot and having a lot of advertisers. Get one advertiser. The Air Mail model of having a single advertiser per issue is really attractive.

It’s a very luxurious experience. The advertisers are the absolute highest luxury. And it looks good for Air Mail and it looks good for the advertiser. It’s a really happy marriage. And so that to me is like a really good solution. And doing fast on digital, but keeping—it’s like slow food—making the slow part of it be the magazine, and the contemplative part of it, and the more artistic part of it, or creative. There’s probably no money to be made there, though.

Wells interviewing hairstylist Orlando Pita backstage at a 2002 Celine runway show in Paris. Photo by Franz Walderdorff

Rachel Baker: I think you just articulated the future of Spread Media. Are you ready, Maggie?

Maggie Bullock: Let’s sidebar about this later. In the meantime, I have a very important question. So actually, our final question for you is I bet or we bet that people ask you beauty questions all the time. So what is the one that you get the most?

Linda Wells: The one about the neck. Everybody asked me, and that’s probably my age too, but really the question I get more than anything else is: I want to get my eyes done. What should I do about my neck? Nora Ephron hit it when she said, “I feel bad about my neck.” That’s every woman who’s ever been on a Zoom call. Unless you’re under 35.

So I think that’s the thing I get. And I have one friend who is in the film industry who texts me once a year and says, “Who should I get to do my eyes?” And I have to go back to my file and look at who I sent her last time. “You should go to this guy.” And we just repeat it. It’s like Groundhog Day every year.

So it’s all about plastic surgery. It’s about injections. It’s about lasers. I went to a dinner party on Friday night of extraordinarily accomplished women. And that’s what they want to talk about. And I was talking to Anna Deavere Smith at this party, to drop a name, but she was like, “Why isn’t there a Kennedy Honors for beauty?

I’m like, “Yeah. Pitch me that.”

Wells’ current project: Air Mail Look, a collaboration with Air Mail founder and former Vanity Fair editor-in-chief, Graydon Carter

You can find Linda Wells at AirMail Look and on Instagram @lindawellsny. And don’t miss out on the best reads of the week every week at The Spread on Substack.

More episodes from The Spread