The London Independent

First, there was the Slow Movement, which begat Slow Media, which begat Kinfolk, the Bible of Slow Living. And now, maybe, British designer Alex Hunting has begat Slow Design. Read on. (Slowly).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH THE SUPPORT OF THE SOCIETY OF PUBLICATION DESIGNERS

For the past ten or so years, indie magazines have been booming. As digital media platforms relentlessly chase clicks and smartphones paralyze our focus, a host of fresh print publications are taking a slower and more measured approach.

Guided by the tenets of the “slow media” movement, this new breed of publishers focuses on correcting the pace of media creation and consumption in the digital age. They advocate for alternative ways of making and using media that are more intentional, longer lasting, better written and designed, more ethical—all delivered in a tactile, bespoke package.

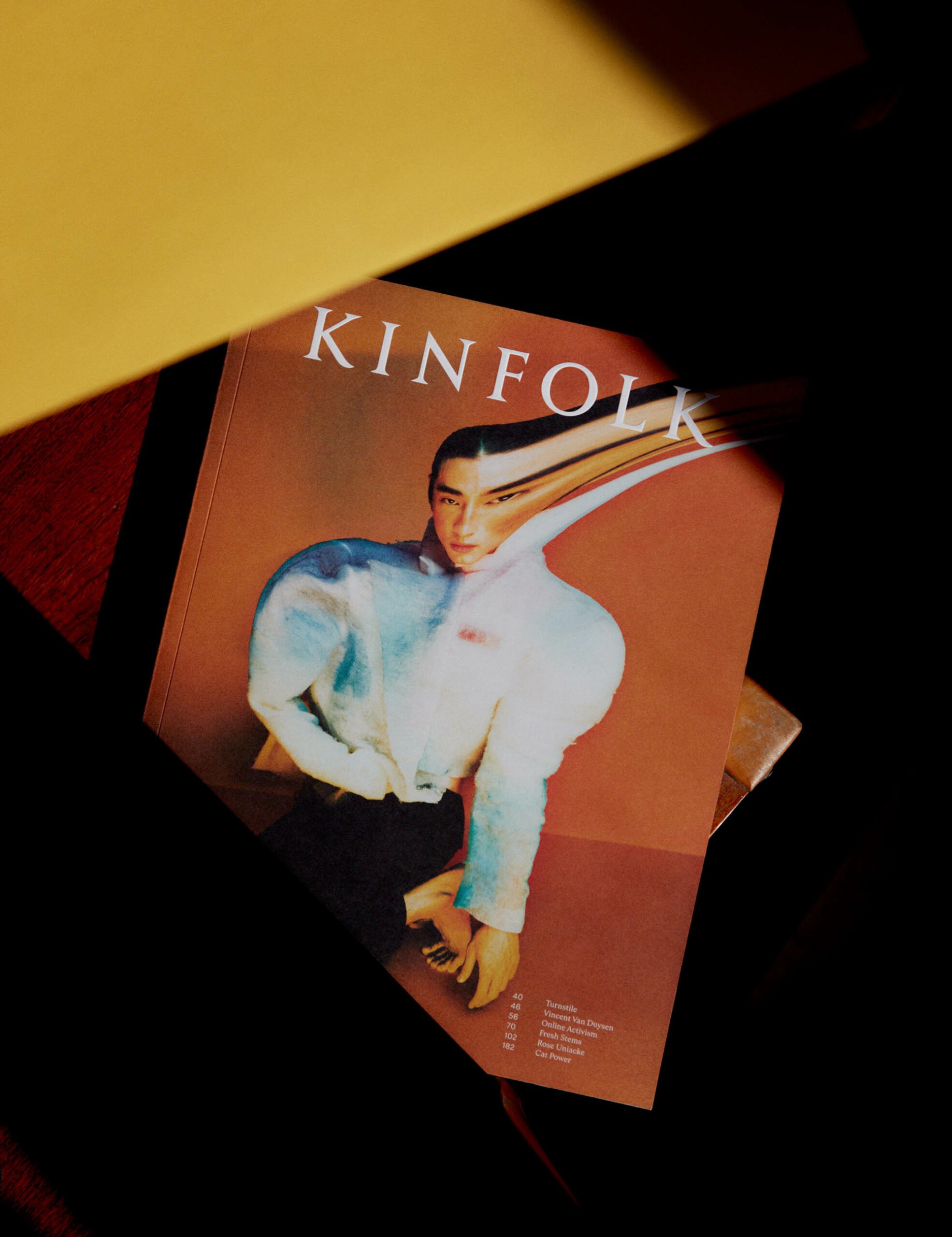

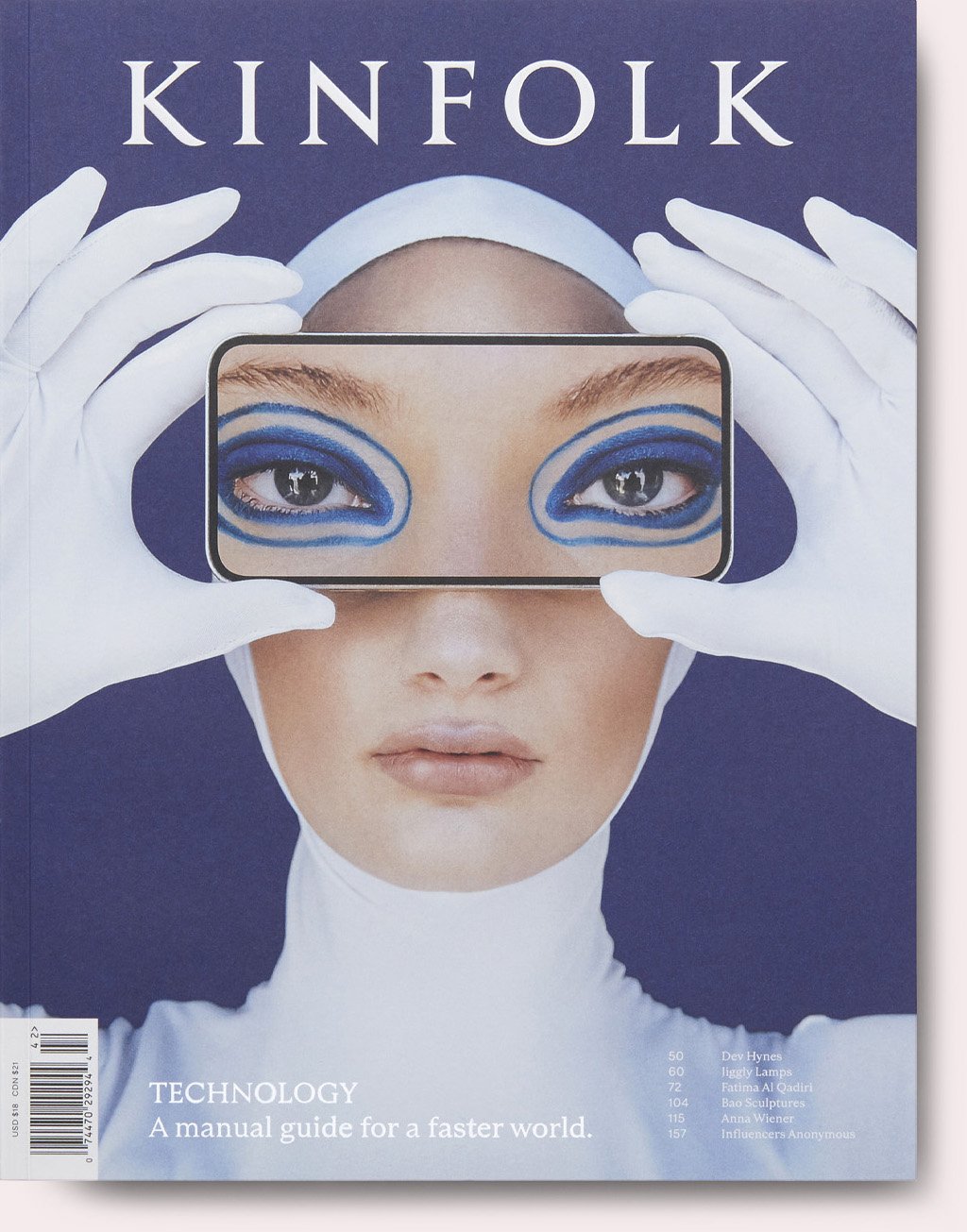

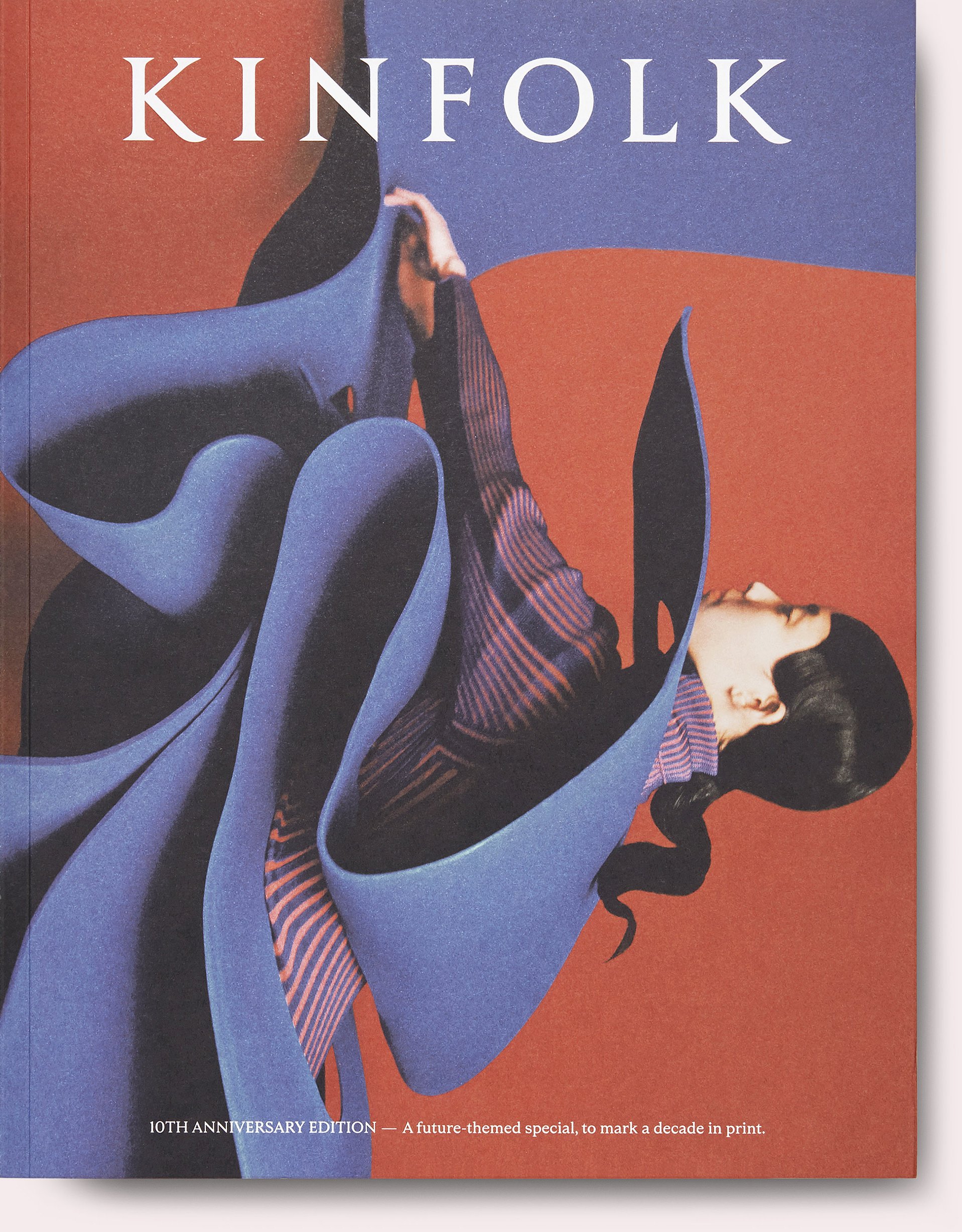

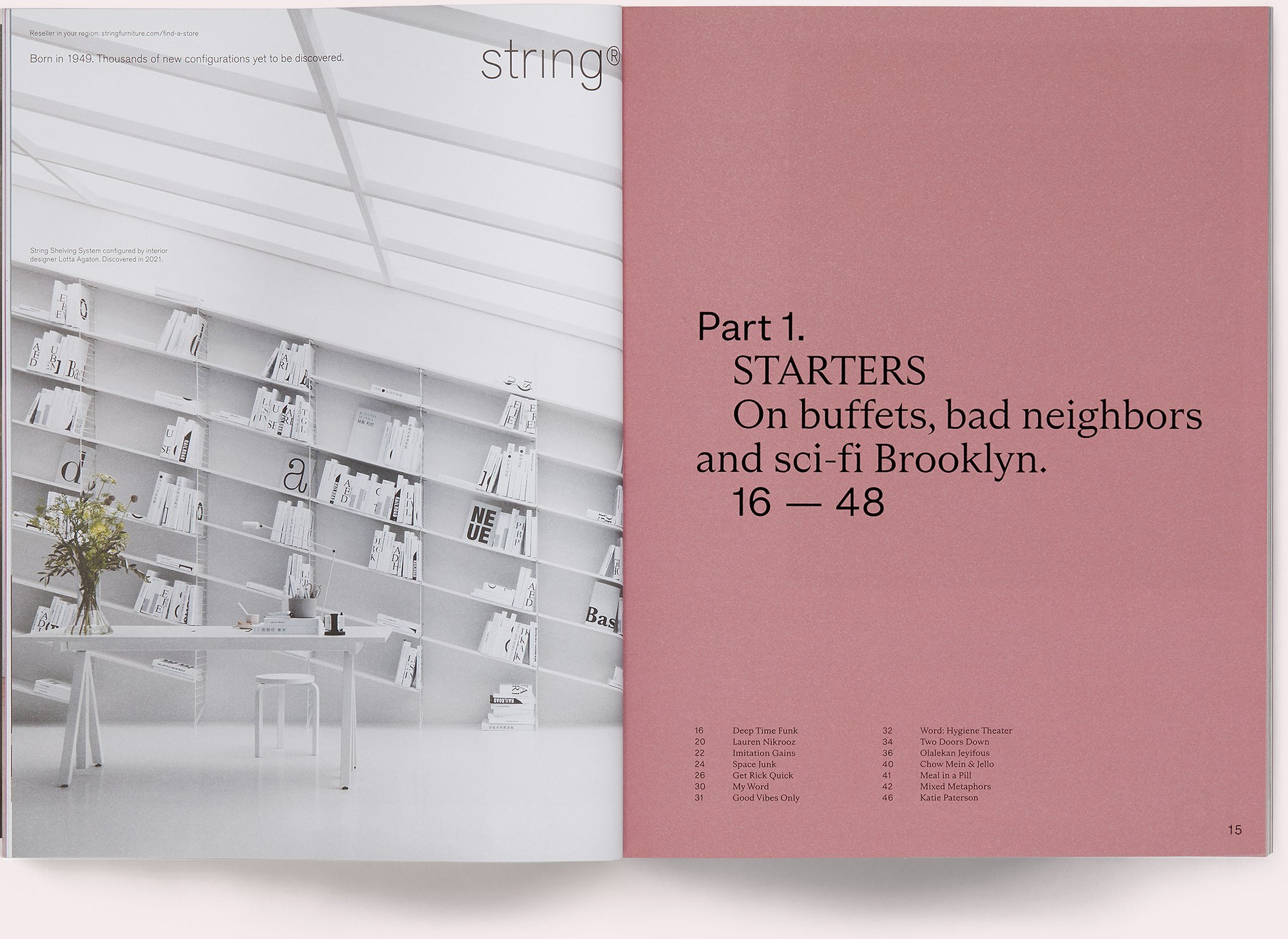

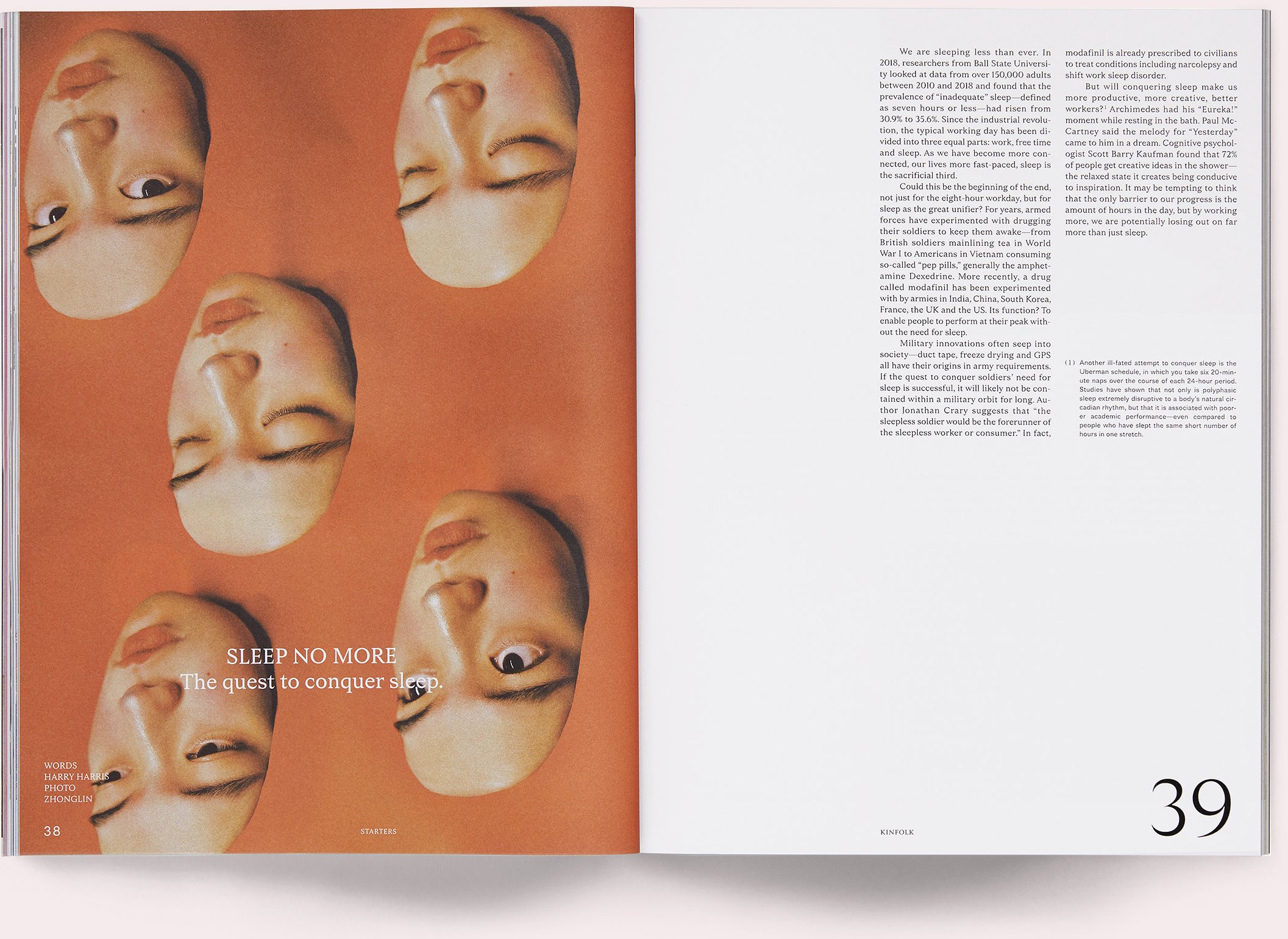

In this episode, you’re going to encounter magazine brands you’ve never heard of: Avaunt, Flaneur, Mondial, Monocle, and Port—and, one of the great success stories of the indie boom, Kinfolk. Born in Portland, Oregon, in the early 20-teens with the tagline, “A Guide for Small Gatherings,” the magazine was often referred to, dismissively, as “Martha Stewart for millennials.”

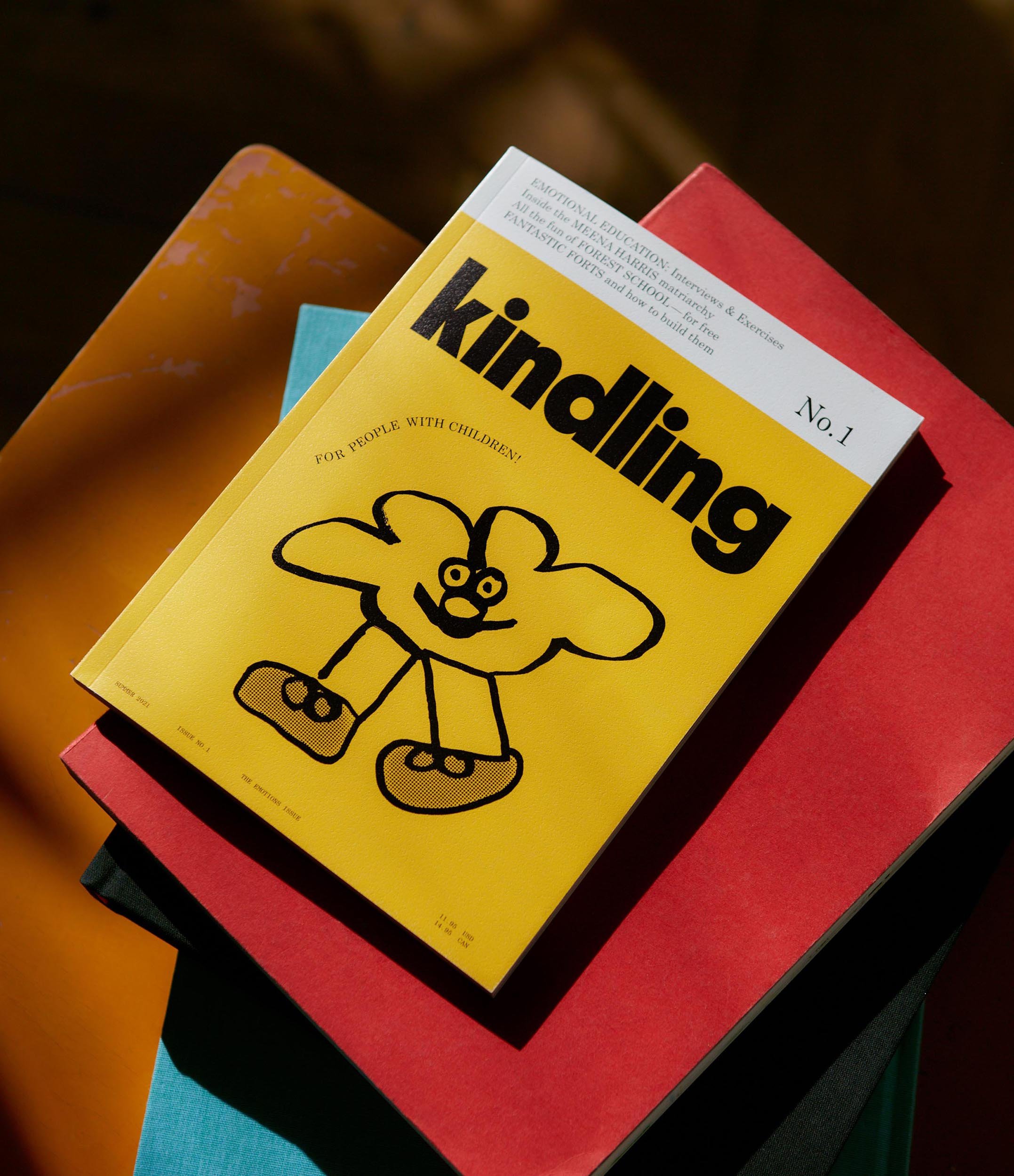

But, in recent years, Kinfolk, like its millennial stans, has grown up. The mag moved its offices to Copenhagen. They created a clothing brand, licensed local editions in South Korea, China, Japan, and Russia, published a series of coffee table books, and, in the ultimate act of adulting, launched a magazine for “people with kids.”

But one of the best moves they made was hiring today’s guest, the incredibly talented British designer, Alex Hunting.

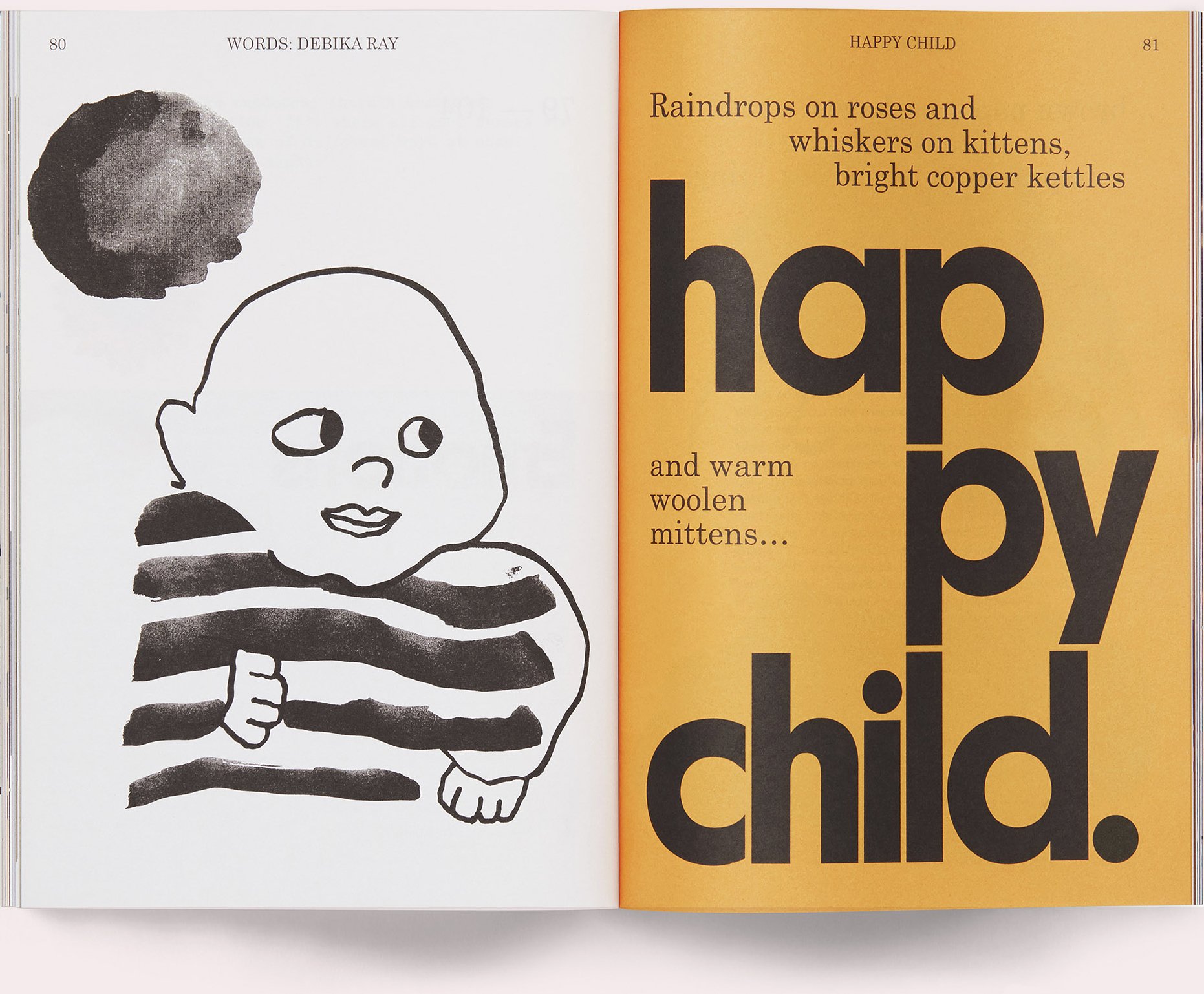

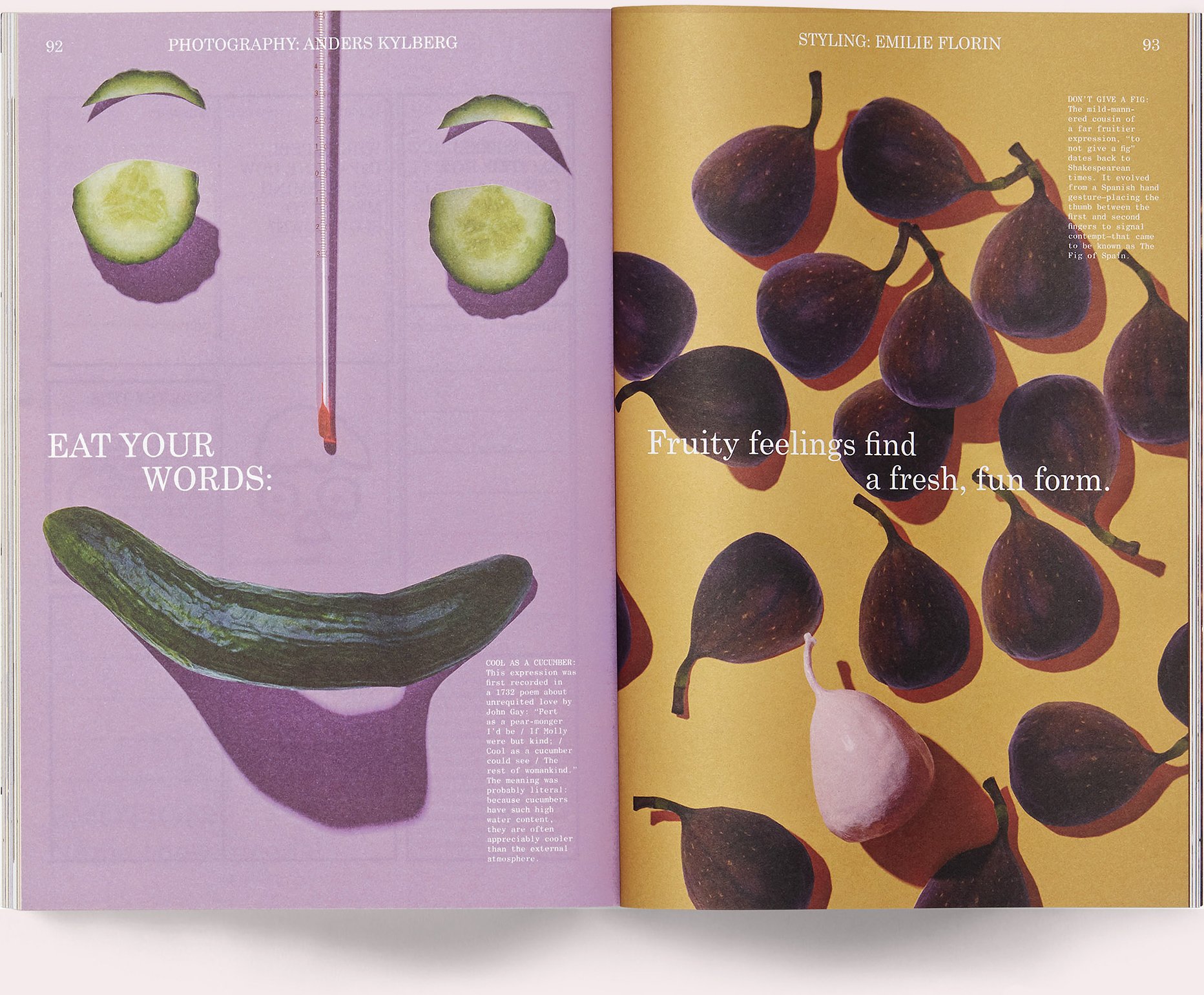

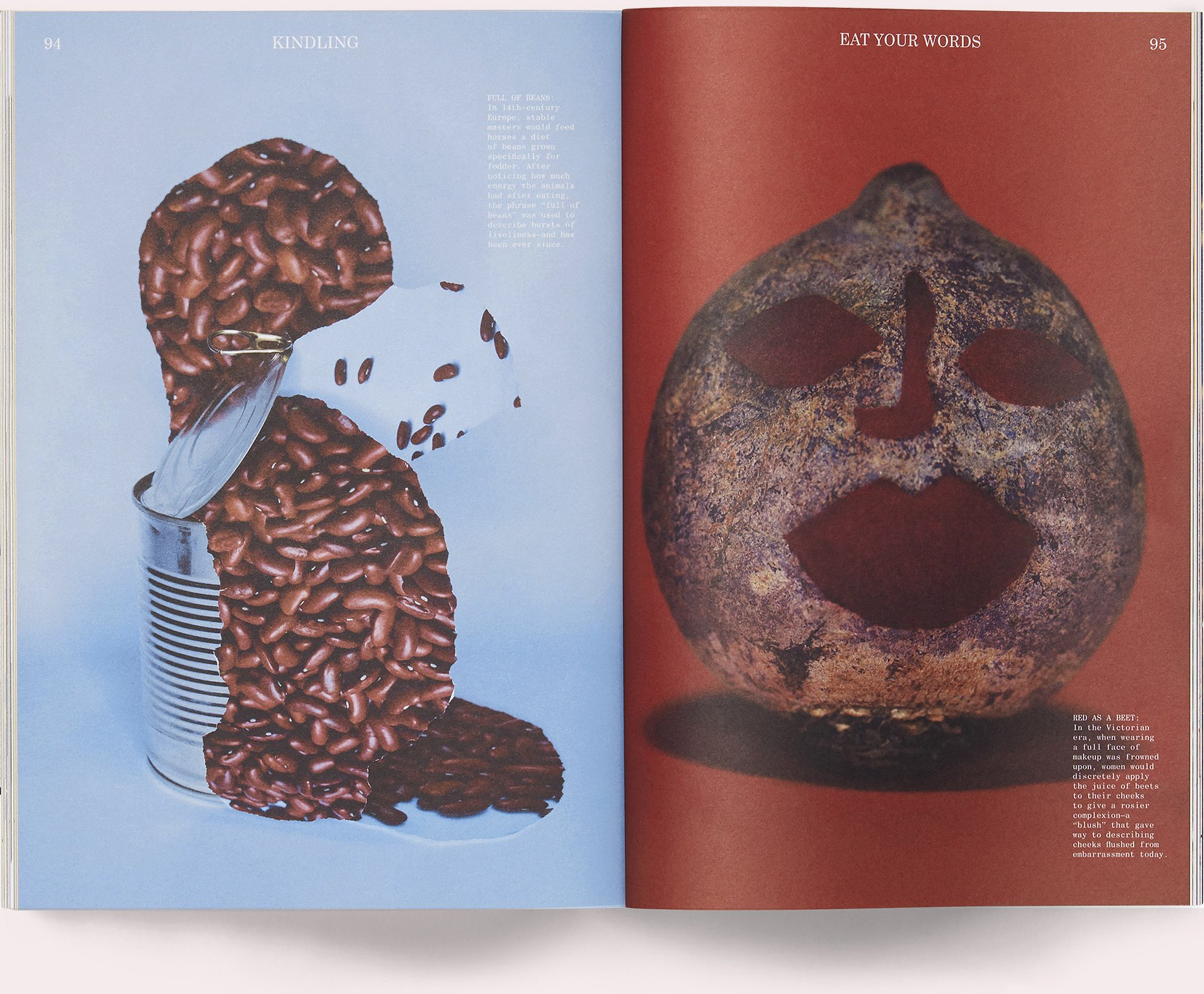

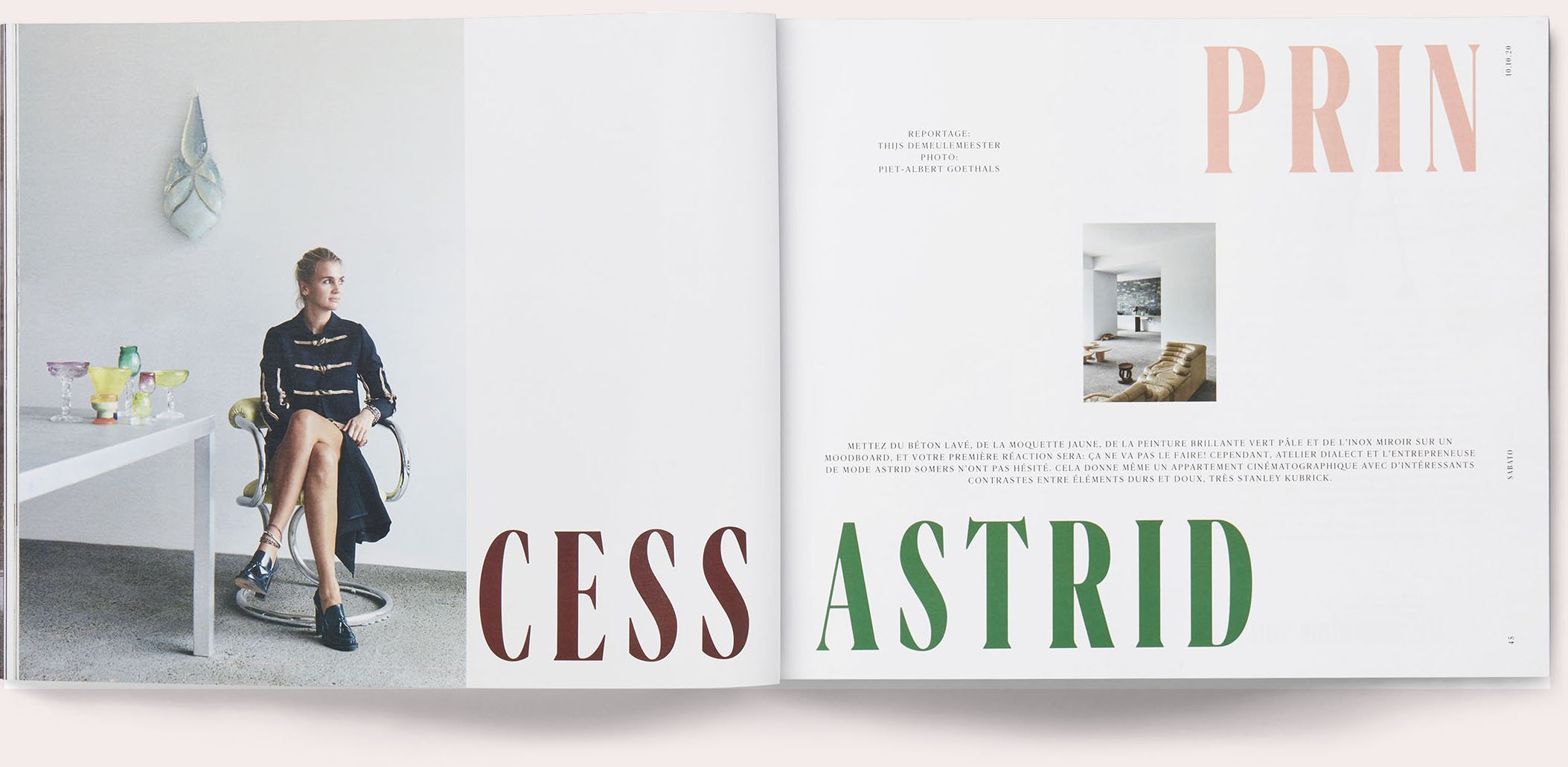

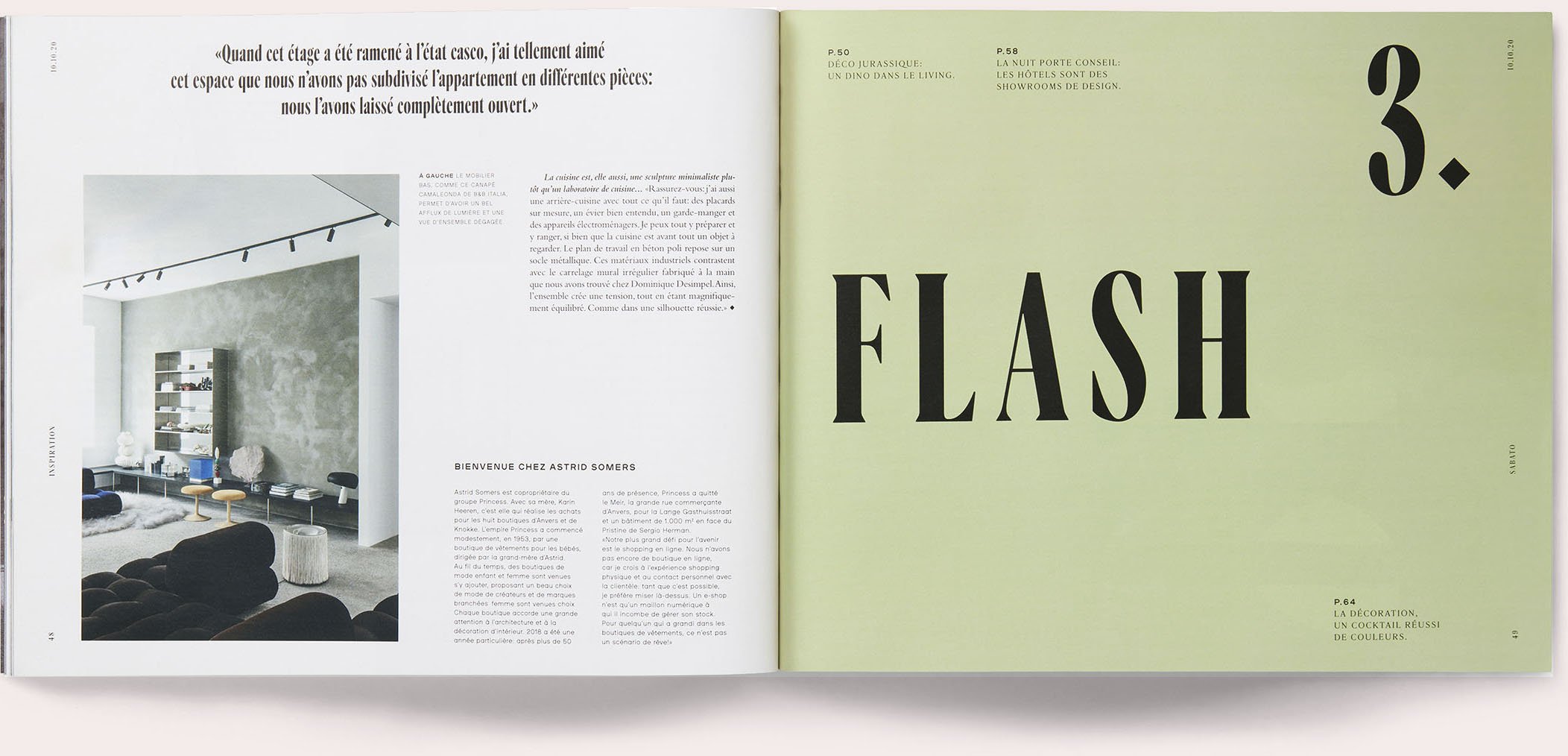

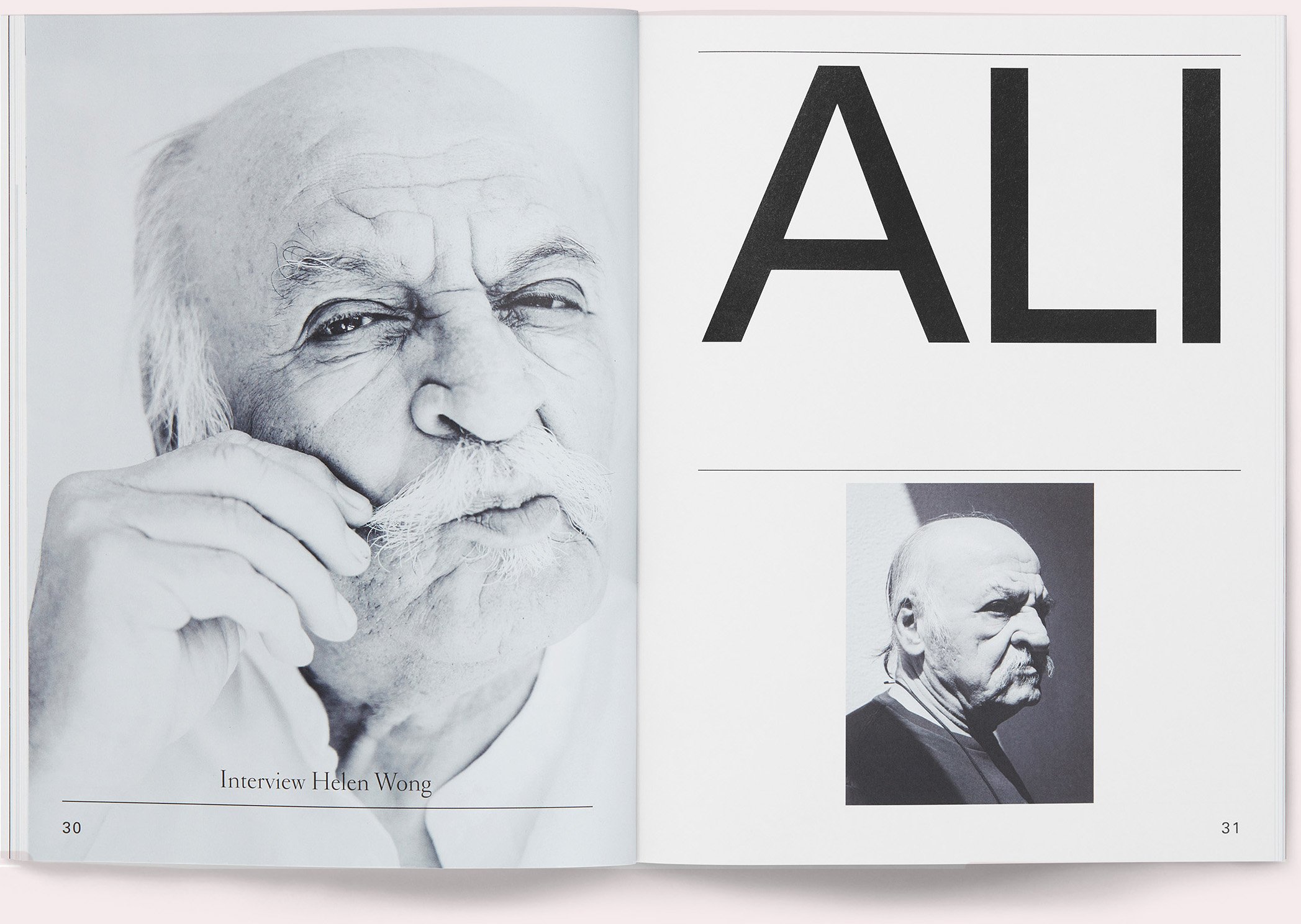

Intentional or not, Hunting is a practitioner of slow design. His instinct for space allocation and pacing eliminates those outdated, overwhelming TL;DR sections. His stunning magazine pages are subtle, spare, and expertly crafted. Perfect for indie magazines, which is good, because that’s pretty much all he does.

We’ll talk to Alex about why, at age 35, he’s so bullish on print, why his university experience didn’t go as planned, and how a pair of mentors literally changed his life.

And, if all of this bores you, well, there’s plenty of talk about houseplants.

Patrick Mitchell: Before we get into this, I have to ask, as an amateur horticulturist myself, I was reading an interview you did with Jeremy [Leslie] at magCulture, and I saw a photo of your studio from, I don’t know, five or six years ago, and there was a little jade plant on your desk and I just want to know, how’s that jade plant doing now?

Alex Hunting: Oh, I think, I think that’s toast. That’s in, uh, plant heaven somewhere. I used to try and have plants quite a bit in the studio. I used to try and liven it up a bit. But yeah, I actually went to a plant place to get maybe that one and another couple, and I just asked for what can’t die. And they still do. I’m not green fingered at all. So, yeah. That’s long gone.

Patrick Mitchell: I mean, that is the number one plant you can’t kill. But somehow you managed. When I went to work at Oprah, I had a little apartment in New York and I bought a jade plant. And it’s spawned dozens of clippings for other people, and I have the main stalk of it here, and it’s about a four foot tall tree now.

Alex Hunting: Wow. So, before we get off the plant topic, the only plant that we—my girlfriend and I—we bought a “cheese plant.” Do you know about cheese plants?

Patrick Mitchell: No.

Alex Hunting: I don’t know whether it’s the same name, but it’s sort of giant-leaved, loves loads of natural light, but doesn’t need much water.

But they grow! We put it in our hallway when we bought our flat a few years ago. And it’s in the communal hallway because it’s got a big skylight, and it’s taken over the entire thing to the point where the residents are just complaining. But it’s the only plant that we’ve never had die.

So I just can’t bear for us to get rid of it. And it’s a monster. An absolute monster. That’s the only…

Patrick Mitchell: …That’s your first child.

Alex Hunting: Yeah, exactly.

Patrick Mitchell: All right, so you’re 35 years old. You’ve got your own studio in a major world design center, and you’re doing world-class work. Can we agree that you’re an unqualified success?

Alex Hunting: That’s a really horrible first question! [laughs]

Patrick Mitchell: Think about what you thought about back in school. What did you think you’d be doing by age 35?

Alex Hunting: Oh. Well, when I was in art college, there’s no way I would’ve thought I would’ve—I was a disaster at college.

But no, I am really happy with a lot of the work. I mean, you’re always insecure about everything. I’m constantly having a sort of crisis about whether I’m doing enough of the good enough quality work or whether I should be trying to do bigger work or growing the studio, or keeping the studio smaller or, blah, blah, blah. Back and forth all the time.

But if I take a step back, yeah, I’m very, very happy. I’ve been very lucky with the projects that we’ve had over the years, and they all lead to one another. A huge amount of it is luck. But yeah I’m pretty happy, in general.

Patrick Mitchell: You went to the University of Arts London, is that right?

Alex Hunting: That’s right. London College of Communication.

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. It’s considered the number two art and design school in the world. And just for those listening at home, number one is Royal College of Art, also in London. UAL is two, Parsons is number three, RISD is four, and MIT is five. Can you talk about what led you to the university coming out of high school? What were you thinking about pursuing and how did you get into such a prestigious place?

Alex Hunting: Yeah, sure. So, I guess at school I—it’s probably quite common with a lot of people that end up doing graphic design—I, personally, I couldn’t have told you what graphic design was. I wanted to be an artist, you know, I wanted to be a fine artist. I was into painting.

I thought I was really good. And I did my foundation course at Chelsea Art College, which is, again, part of University of the Arts. University of the Arts is made up of three or four colleges like [Central] Saint Martins, London College of Communication, London College of Fashion, and Chelsea.

So I did my foundation at Chelsea, which is quite renowned as a fine arts college. And it’s amazing how life is a coincidence, because I asked my fine art teacher at high school, “I want to be an artist, where should I go?”

And he was an amazing guy, brilliant teacher, but bless him. I think he just basically told me his college that he had gone to, which was not necessarily the best place. So I could have easily ended up somewhere else. But there was a really good painter in the year above me, who was going to Chelsea. And he was basically saying to me, “You’ve got to go to University of the Arts or Slade or somewhere like that.”

So I went there. I applied and, luckily, I got into the foundation course. And then I just realized pretty much the moment I got there that there was no way that I was cut out to be an artist. I was surrounded by brilliant people that were actually amazing artists. And all I wanted to do, I guess, was sort of boring, traditional painting, which is what I’d been doing. I don’t know what it’s like in America, but high school, you start learning how to, I don’t know, you’re doing acrylics and then you’re doing oil painting or you’re doing whatever and you are life drawing, learning that stuff.

And then I got to Chelsea and it was proper fine art. And the teachers were saying to me, “Turn it upside down and rip it up.” And that sort of thing. So I was a bit lost really. And I didn’t do a huge amount of work as a result. And then I got towards the end—and at the end of your foundation you’ve got to apply somewhere. You’ve got to decide what to do.

“I certainly didn’t think I’d be setting up my own business. I certainly didn’t think I was going to run a studio or anything like that. It wouldn’t remotely cross my mind.”

And there was no way that I was going to do fine art. And I suddenly started panicking about thinking, “Oh, am I actually going to get a job with anything?” And so I just got recommended by the teachers, “Well, you should think about graphic design.”

And the course at LCC had a pathway, which was graphic design/illustration. And that sounded like a good compromise for me, because it’s a bit arty, but also a bit designy. So I went on to that. But again, I was pretty terrible at college.

I sort of floated around for a couple of years, and I didn’t achieve a huge amount and that sort of thing. And then it all turned around because I did a year in industry. I was really lucky that my college offered a “year out” between your second year and your final year.

And I really did it because I just wanted to go abroad. Because you can do internships anywhere. And I really wanted to spend the summer abroad somewhere. And I wasn’t achieving much at college and panicking a bit. And I basically did a year of internships right bang in the middle of my degree. And it just totally changed everything for me really. Like, I suddenly got what graphic design was, suddenly understood what I should be doing, understood what I liked, and it just changed everything really.

Patrick Mitchell: Did you go abroad for these internships?

Alex Hunting: I did. The whole plan was to be able to go abroad. So I had one lined up that I wanted to do because I was desperate to go to Barcelona for the summer. But I did a couple in London. I did one at a studio called This Is Real Art, which is run by an amazing designer, Paul Belford.

And I mean, I basically was just phoning up. I went to an interview and, I mean, my portfolio is just—looking back on it, it’s just amazing—it was just appalling the quality of stuff. And I just kept basically phoning up and eventually he just relented and let me come in.

And I had an amazing senior designer, a guy called Sam, who I was seated next to, who just basically held my hand for three months, and gave me a bit of confidence, and told me what I should be doing. And then my next one was with Jeremy Leslie, who I think you must know quite well through the magazine world, right?

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah.

Alex Hunting: Yeah. So Jeremy used to do a magazine design conference called Colophon, which was in Luxembourg, which was just, like, a massive indie magazine festival. And they were doing a book to celebrate the festival called We Make Magazines. And it was basically a massive book about all of the independent magazines that you could think of.

And I wasn’t really into editorial design, particularly. I wasn’t into anything. But I quite liked book design. And basically the internship was just to help design this book. And it was me and a guy called Lars [Laemmerzahl], who was at my college as well, who were helping design it. And it just completely opened my eyes to this amazing, incredible world of independent mags. Bonkers, absolutely bonkers, sort of stuff.

So it was a real eye-opener. And from then forward, I was just really motivated. It pushed me a lot in that direction, actually, towards editorial design. So I owe basically a huge amount to that year in industry. But in terms of the college education in general, I think, because I was a bit lost, I didn’t have the best experience.

But I think it might be different in the States, but arts education here is not in a particularly great state, actually. I think a lot of the people that I have, that come and intern or come as juniors in college, the amount of money they have to pay now. And you don’t even get a space of your own at college. You don’t even have a desk or something, which I think was the one thing at art college you probably used to have, right? You used to pay your money and have a little bit where you could go in and work.

So I didn’t necessarily have the best time at college, but being in London was amazing. And I think it’s the people that you meet and the opportunities I think you get, are so much more important in a way. Or they were more important to me than all of the teaching and that sort of thing.

Patrick Mitchell: I remember when Jeremy was doing that event. I was always desperate to go, but it never worked out. But that’s the kind of thing that can really focus you on what you want to do with your life. And it sounds like such an intense weekend in such a specialized area really may have been the education you needed to guide you to where you are now.

Alex Hunting: Yeah, for sure. And I think the passion that you were seeing from all of these different people doing insanely different subject matter, but all storytelling, or image makers, all that sort of stuff, like incredibly diverse subjects, and all brought together for one sort of party, basically, over the weekend. It was amazing. Absolutely amazing.

So yeah, I owe Jeremy a lot for that. It was really, really eye-opening and it really focused me so much to the point where, as I say, I hadn’t been achieving much, hadn’t been doing very well in my degree, all that sort of stuff. But I came back into the final year and I just got it really. I finally understood graphic design, I’d learned a lot from people in the industry, I knew what I wanted to do more, the sort of studios that I was looking at, all that sort of thing.

So yeah, it was all really from there. So it was very lucky that I wanted to go to Barcelona for the summer.

Patrick Mitchell: In your college, did you get any education at all on the entrepreneurial aspect of launching your own career? Did they teach you any of the skills to run your own business?

Alex Hunting: I probably didn’t go to it, to be honest with you. I’m sure that they do those things. There are probably those electives. There are probably those talks and those things. But I just was disillusioned with the whole thing. I was having a good time, but, you know, I wasn’t … yeah. So I’m sure they do. I’m sure they do.

But I wasn’t really thinking about that, you know, I certainly didn’t think I’d be setting up my own business. I certainly didn’t think I was going to run a studio or anything like that. It wouldn’t remotely cross my mind.

I’d enjoyed interning so much that I just thought, “Oh, you know, when I leave, I’ll just go and try and get a job somewhere and work there forever. It’ll be the best, best time. It’ll be a lovely time.”

Patrick Mitchell: I think most people would agree it takes balls to go out on your own, to get space, to get clients, and all that. Did you grow up in a family with entrepreneurs?

Alex Hunting: My dad has run his own business pretty much his entire career. And I think you do get a little bit of that. I mean you see the bad stuff as well, I guess. You see times when you are flush and times when you are not, and that sort of thing.

So I think there’s a good work ethic from seeing that, being around that. Which I think I have always had—obviously apart from being at college—but once you’re focused on your own thing...

Patrick Mitchell: Was he passionate about what he did?

Alex Hunting: Yeah. He always says to me that he fell into what he did because he was a little bit lost. He’s a surveyor, he runs a chartered surveying business. But he really enjoys his job because he’s out and about, and he’s meeting new people, and he’s built a business. He’s very social, employs lots of people, and he’s a good boss.

So, yeah, I think he definitely enjoys it. I don’t think it’s a passion in the way, I mean, I always forget, and I think it’s amazing how lucky—whenever I think it’s awful, when work is hard—we are just like the very, very minority of people that are really passionate, that their, kind of, their hobby is almost their job. And that is a huge privilege to have.

Patrick Mitchell: There’s a lot of talented designers, but there’s not a lot of designers who have whatever that missing trait is that allows them to have the confidence to just open their own place. And I’ve met some amazing people who have just failed miserably, as our business falls apart around us, who have been forced to go out and try to start their own business and they just can’t function outside of a corporate structure. But you did. And look at what you’ve done with yourself.

So let me ask you, I know you worked a couple places before you launched your studio, but when you did, what were the challenges? Did you open your door with clients already in hand or did you have to start hitting the pavement looking for work?

Alex Hunting: I was doing some freelance-y sort of bits and pieces. I think like everyone, you start freelancing, and then get to a point where it sort of naturally becomes like a business, and you need help on projects. So it becomes a business.

But what did I start with? So I was really lucky that I was doing some freelance work for The International New York Times, the Opinion section, before it was the International Herald Tribune, and then it became The International New York Times, and they were looking for a London-based freelance part-time art director.

And that was amazing as an opportunity because it was only part-time. But I had some regular—do you know what I mean—kind of income, while I could do other projects. And obviously when you’re starting out, your fees are so low for the projects that you want to do because you’re in that constant struggle of wanting to do great work to try and attract more work, but you know that great work you’re getting just pays so poorly.

So I was lucky in that sense that I had a bit of that buffer. And that gave me a bit of space to be able to start the business really. But I do think that editorial design is actually quite good, it’s like a good part of graphic design, in a way, to start a small business. Because, by its very nature, it’s regular work. So if you get a magazine contract—whether that’s quarterly or monthly, biannual, all that—when you get those coming in you can plan. You know that you’ve got x amount of work lined up.

And obviously it depends how many of those contracts you’ve got, but as opposed to if you are just going out and trying to get, say, branding projects or that sort of thing, it’s not necessarily as easy. So I’ve always thought editorial design is quite good like that.

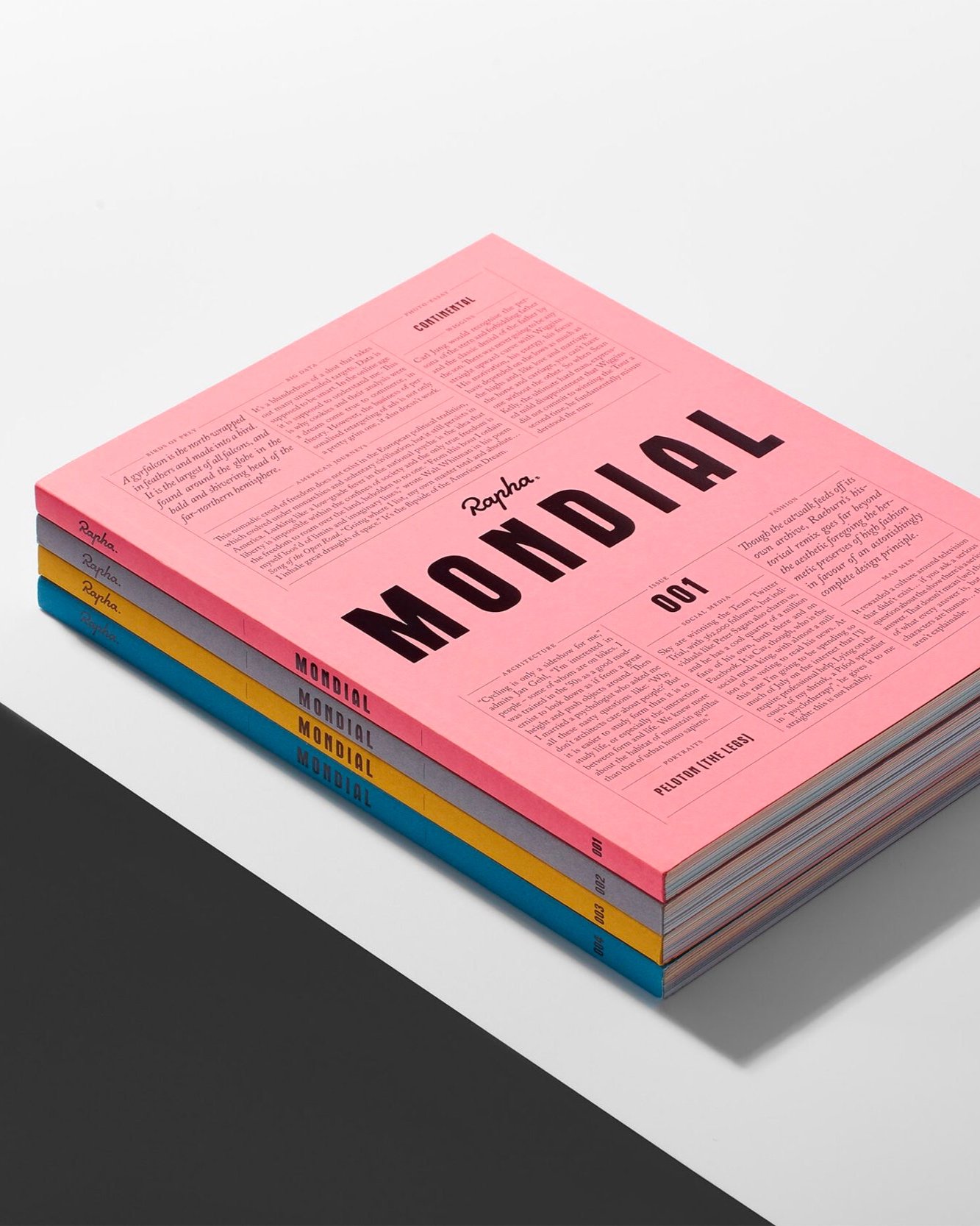

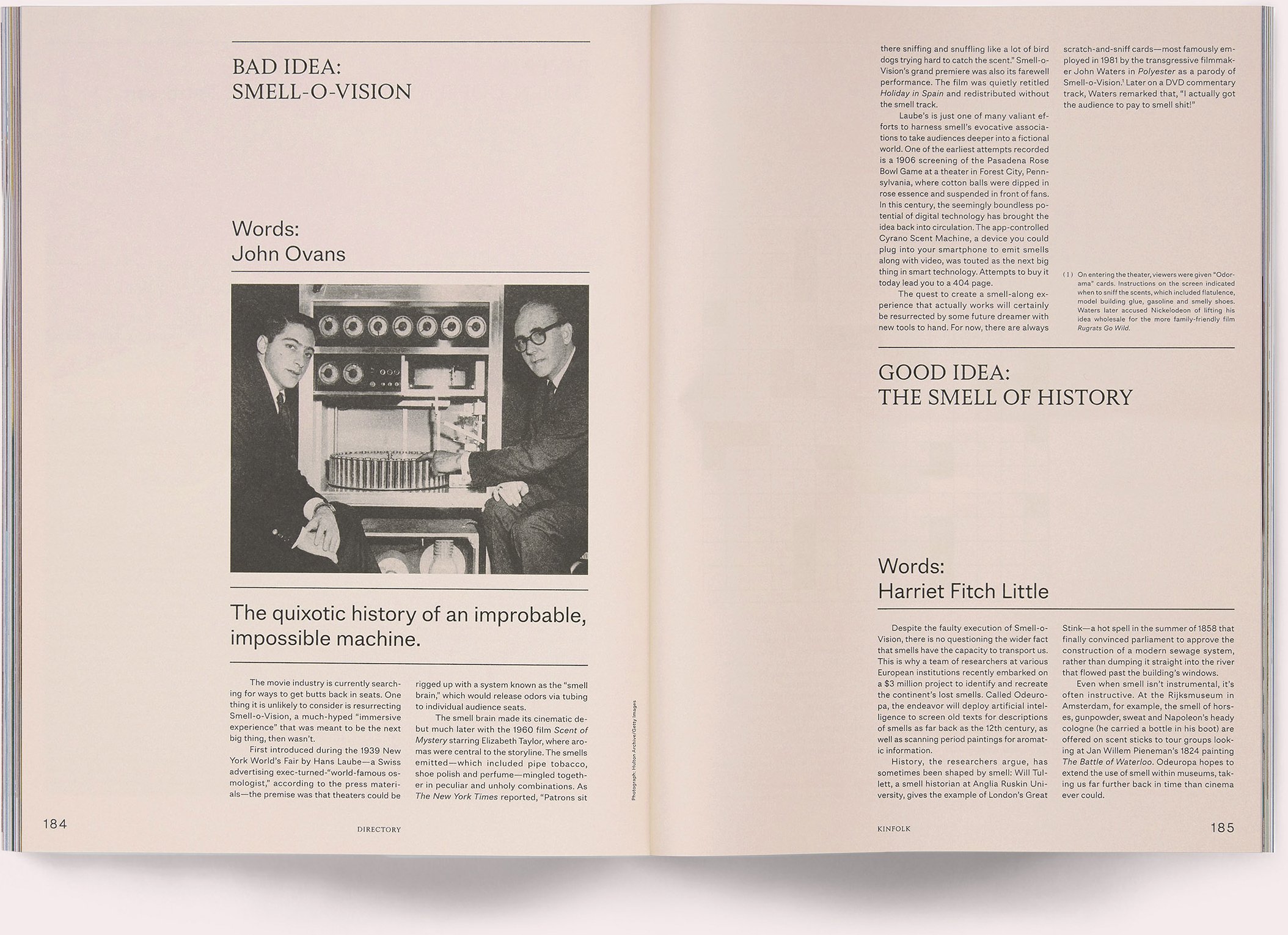

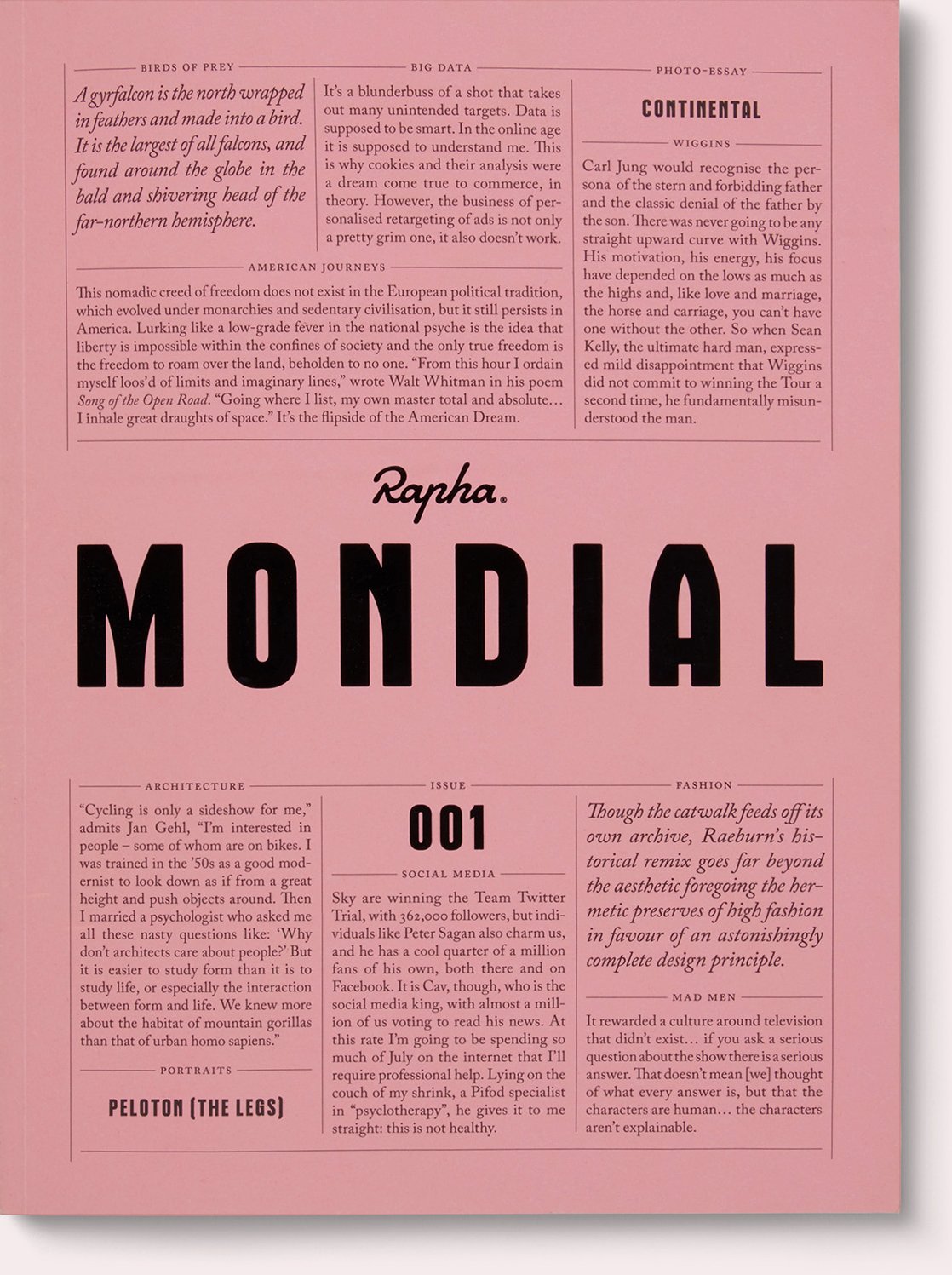

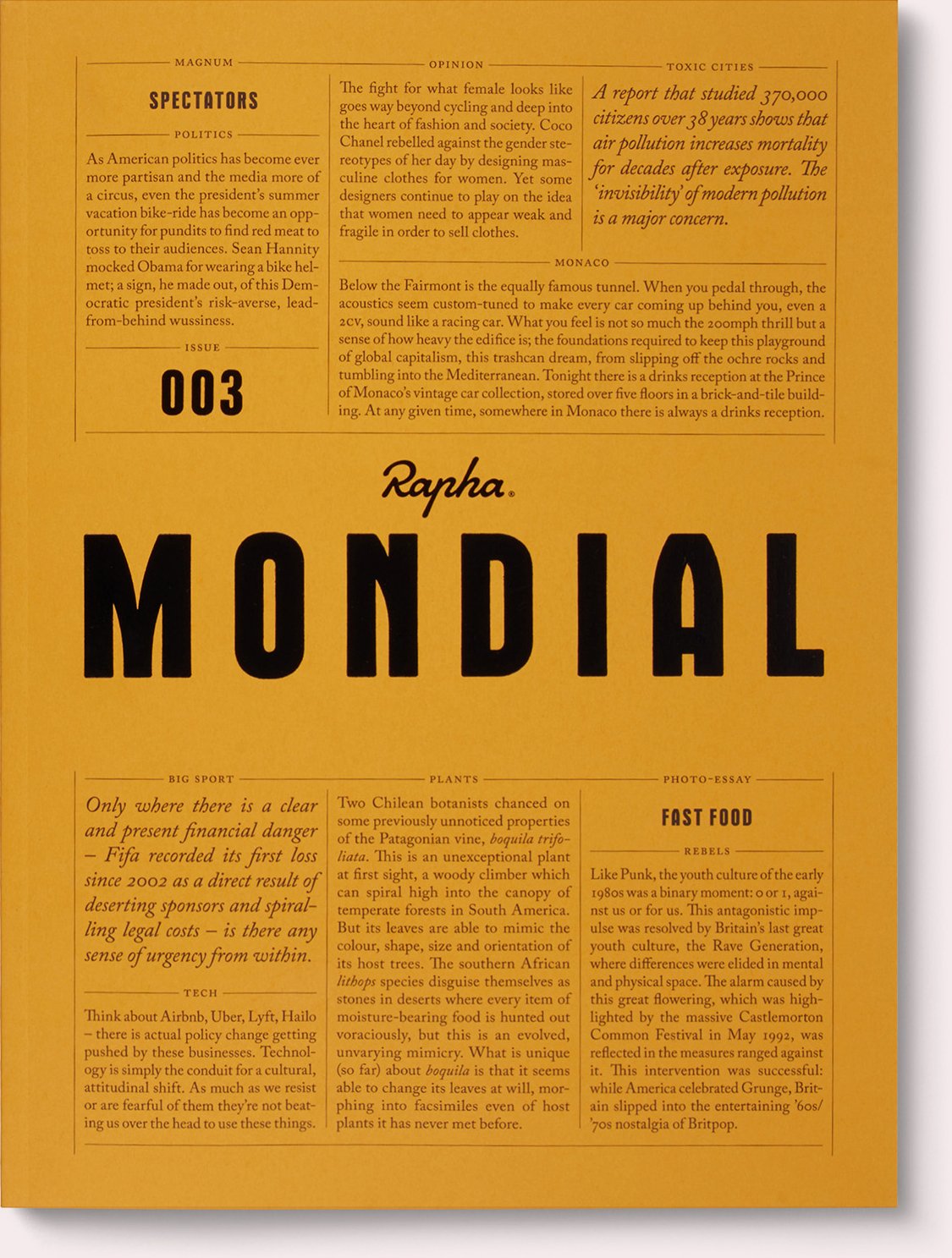

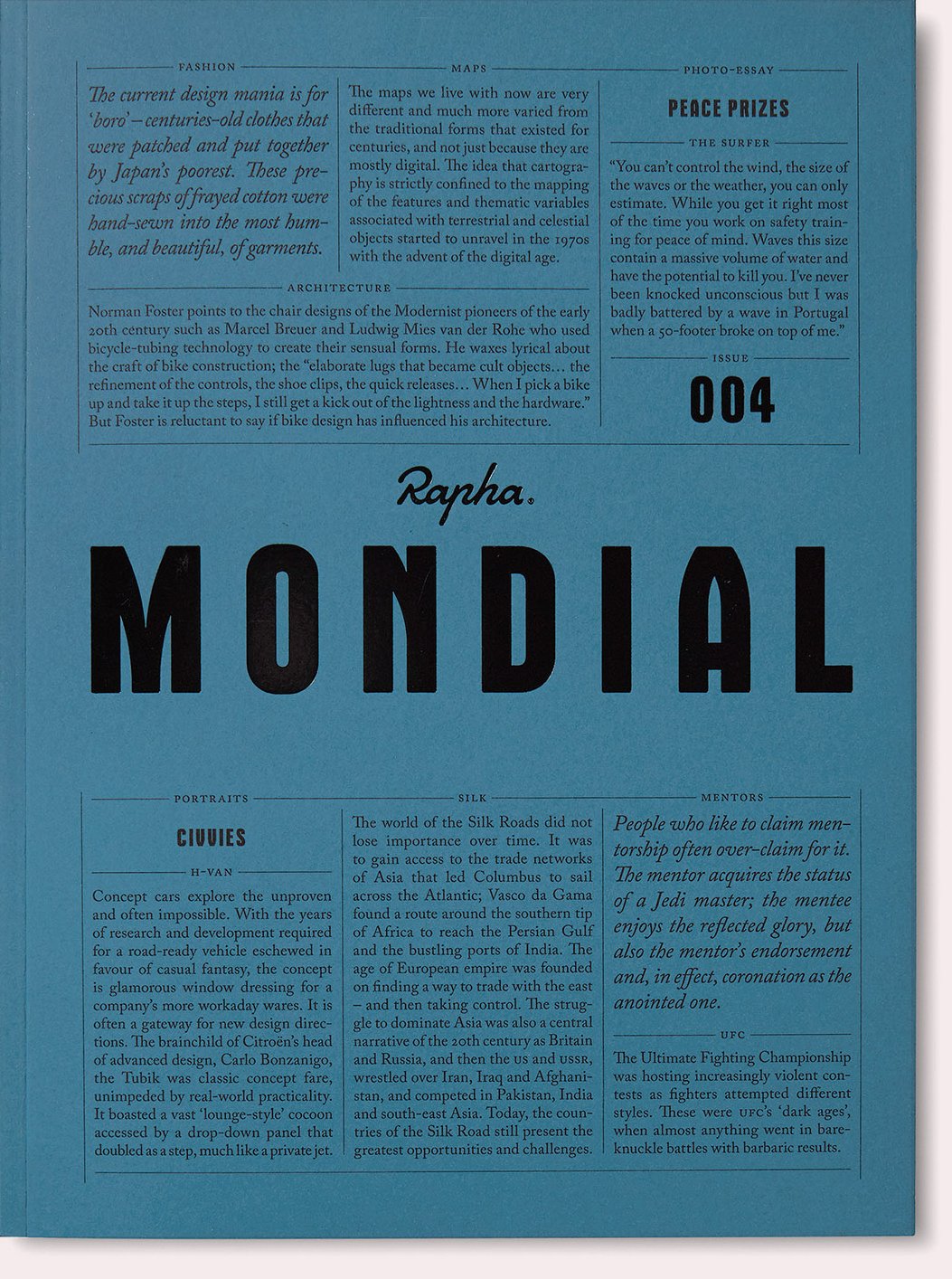

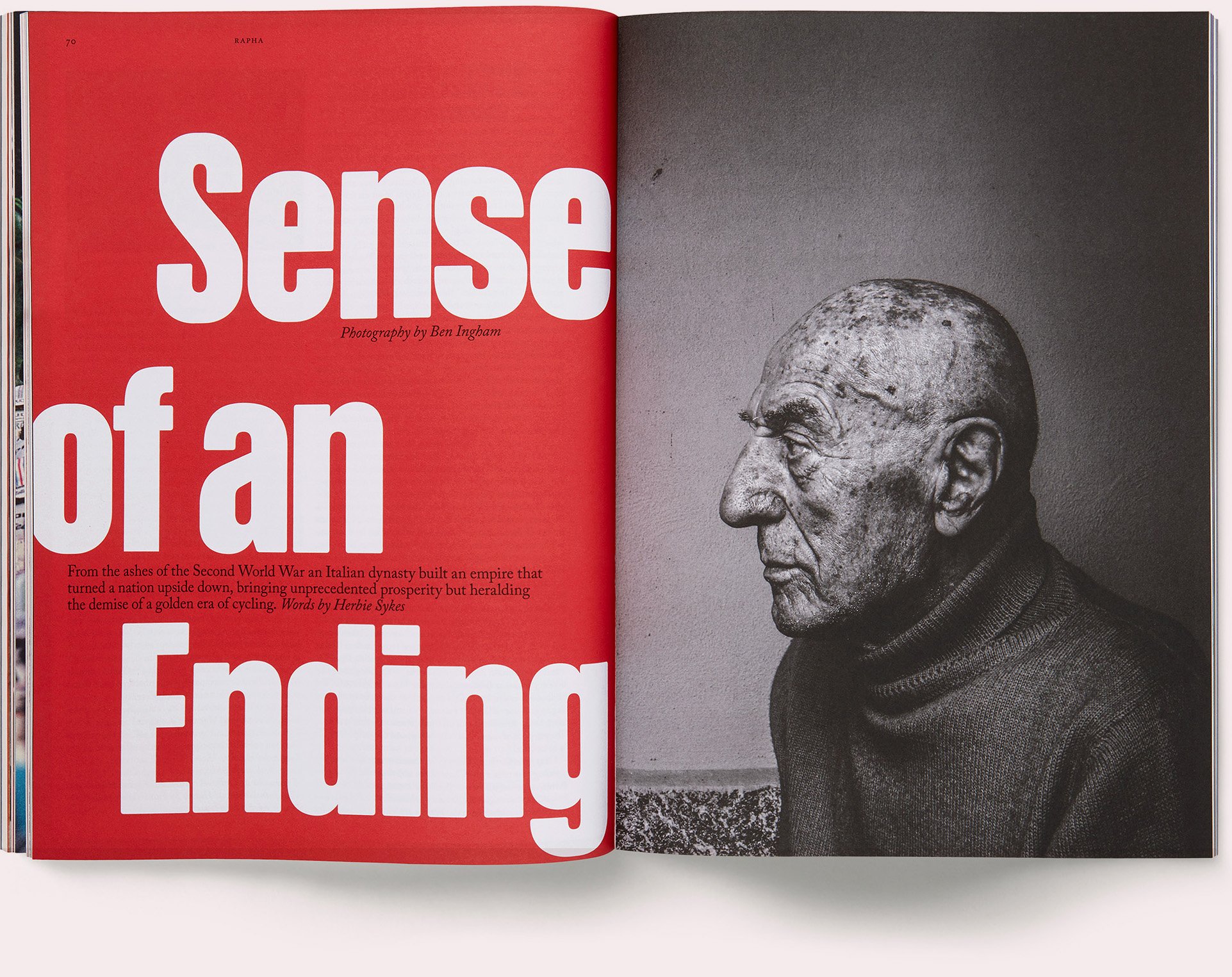

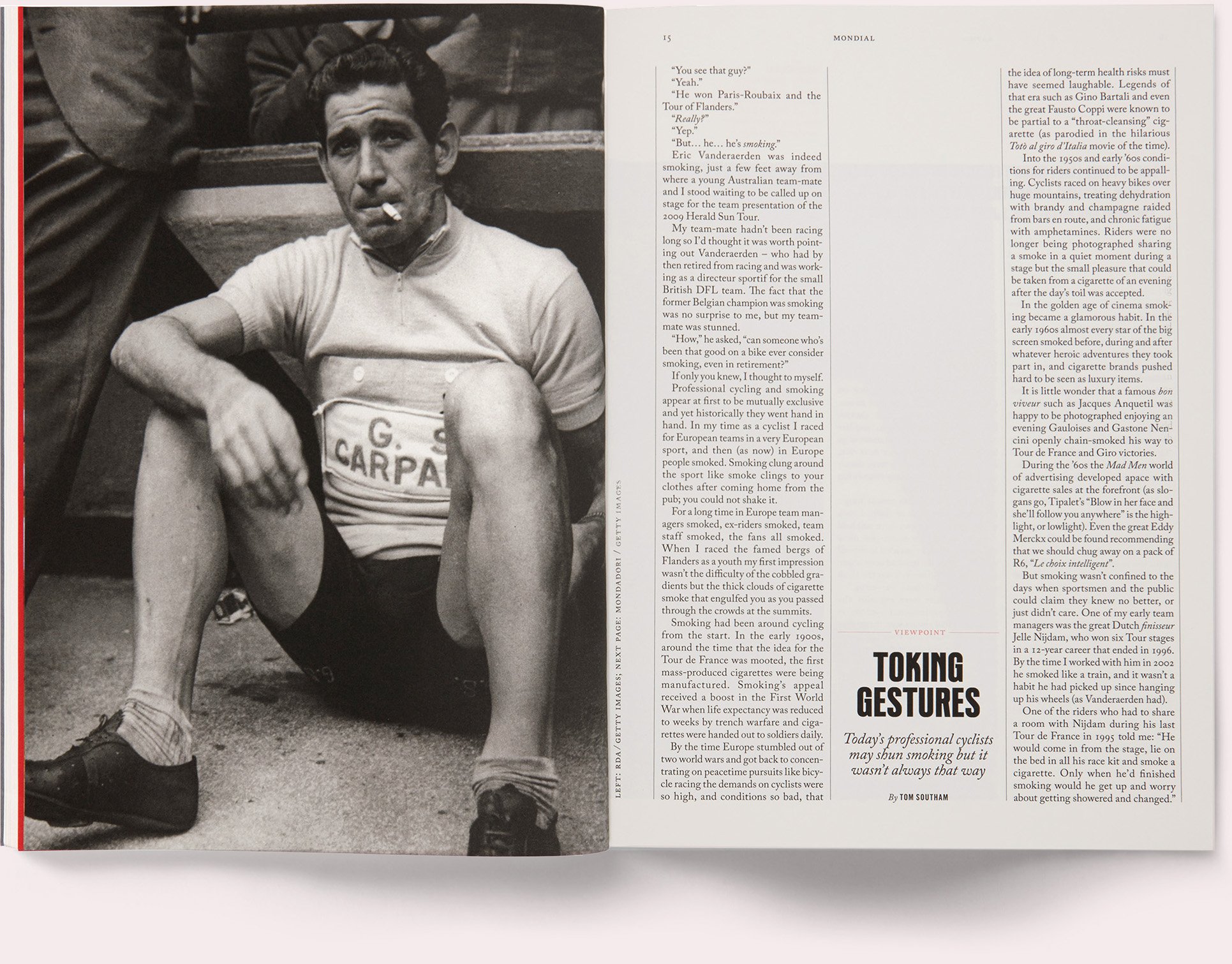

And I was quite lucky that, relatively early on, I started freelancing. I was working with Matt Willey on a magazine called Avaunt. And then after that, the first big, great project that my studio took on was Rapha’s magazine Mondial. And then quite soon after that we started doing Kinfolk.

And those were biannual or quarterly magazines. And so even that as a start, you just know that there’s X Amount of money coming in and off the back of that, it all grew from there. And you’re going out and getting clients from there.

“We are just like the very, very minority of people that are really passionate, that their hobby is almost their job. And that is a huge privilege to have.”

Patrick Mitchell: When I look at your work, which is really just stunning, I find it fascinating that someone with your talent has somehow avoided working for the big brand name magazines. Have you ever been approached by the big publishers?

Alex Hunting: Yeah, I have. I have actually. But not in the UK, though. Only in the US, once. Well, it’s happened twice. But it’s your terrible, terrible visa system that you have. So basically, if you get offered one of these jobs, you have to get an O-1 Visa, which means you are really good in your field and you are allowed to come over to the States.

But if you have a girlfriend, or a wife, or anything like that, your partner is not allowed to work under that visa. So, my girlfriend, who’s got a very successful career of her own—they’re not really decisions that you can just make on your own, sadly.

But, it never happened. I’m not sure how well I would do. I don’t mean that I’d get bored, but I do l really like working on lots of different things.

Patrick Mitchell: So if Condé Nast or Hearst called you tomorrow— with a great offer and no visa problems—with a job in the States. Would that be tempting?

Alex Hunting: What’s the title? What’s the Condé Nast title?

Patrick Mitchell: Vanity Fair.

Alex Hunting: Oooooh. Yeah. I mean, yeah. Vanity Fair or Wired or something like that—I’d be very, obviously, it’d be hugely, it’d be ridiculously flattering. And it would never happen. But I’d definitely have to think about it. No, I was obsessed with the idea of working in New York. And I love New York. And every time I go there I just always think, “God, I’d love to live here and work here.”

Patrick Mitchell: You mentioned Matt Willey, who people know from The New York Times Magazine, and who had some great success there, he’s now a partner at Pentagram in New York. What would you do if Pentagram called you tomorrow—again, no visa issues—with an invitation to join them as a partner? In London or New York.

Alex Hunting: Yeah, of course. I always think [Pentagram’s] such a designer’s thing. It’s the most flattering thing you could be asked to do in our industry, isn’t it? Because of the history, and all the partners that have gone before.

I also love the idea that it’s just all those individual teams. I love it. That you build your own little pod. And I kind of love, I mean, I don’t know what it’s like on the inside, but I like the idea that it’s quite dog-eat-dog. Like, you’ve got to hold up your end of the bargain. When you’re sitting around the, like, end of year meeting or whatever, and it’s “Michael Beirut’s brought in MasterCard!” or something. And you’re like, “Oh shit!”

Patrick Mitchell: Well, that is the thing, from what I understand, what separates the people who make it there from those who don’t, is that ability to not only bring in business, but handle the pressure of being responsible for bringing in business. In addition to doing great work.

Alex Hunting: Yeah, yeah. No, I bet. The whole business, it’s a whole other equation, isn’t it? And it’s the size of those brands, isn’t it? Because, you can run a very successful small agency where you are super hands-on and handle everything. But then when you start dealing with those huge clients—I can’t imagine what that’s like. The pressure. The insane pressure.

But yes, I would, obviously. That would be amazing. Amazing. I remember reading Vince Frost’s book. I don’t know if you read it, but he was, like, the youngest-ever Pentagon partner. But I remember he, pretty much, didn't like it that much and he much preferred running his own thing.

I’m sure there’s lots of people that go into it who run their own thing, who realize that they probably preferred it, but you just can’t say “no” to it, can you? That’s the thing.

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah it’s really an interesting thought. Note that we’re two people who, to this point [laughs], haven’t had the invitation to go work at Pentagram yet. However, that said, I would say from your output, and I know from my job satisfaction, I don’t need big, giant brands to make me proud of my work or feel successful. I’m just doing, as you look like you’re doing, a lot of work that just makes you very happy.

Alex Hunting: For sure, for sure. I guess you’re still your own boss there though, aren’t you? Which is the one thing that you hold onto, right? Like you’re still, you are your own boss, even if you’re at Pentagram.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, but then you have the collective air conditioning bill, and the lighting bill, and the plumbing bill, and the employee payroll, and all that stuff.

Alex Hunting: Yeah, true, true, true.

Patrick Mitchell: All right, let me shift gears a little bit. You talked about Matt Willey and Jeremy Leslie, two noted, important magazine designers and thinkers and makers. Along those lines, when I was at Fast Company, we used to talk about the value of having mentors. We used to call it your “personal board of directors.” Who’s on your board? Who do you turn to for advice?

Alex Hunting: I speak a lot with a pal of mine, Charlie [Hocking], who I went to college with. He’s a brilliant designer. He was a design director or motion director for Design Studio. Do you know Design Studio? Like the big London branding agency. But anyway, at college he was always just a brilliant designer. We are super good friends. And I’ve always really, really trusted his opinion. He doesn’t work in editorial design, but he’s just got really impeccable taste. So I speak to Charlie a lot about stuff.

I’m good mates with a guy called Kuchar Swara. He was the art director of Port—he founded Port with Matt Willey. And he’s the creative director of The Telegraph now, which is one of our national newspapers. He’s an amazing editorial designer. I speak a lot with him. And then I run a lot of stuff past my girlfriend who, again, not a designer, but she’s a set designer.

I do think it’s super important to do that stuff, particularly because I do run my own thing and because I’ve been doing my own studio for quite a long time now. I did work for a couple of places, but it was only for a few years really. So it is important to get outside of that, I think. To not think that you know it all, or ...

Patrick Mitchell: ... have to have all the answers...

Alex Hunting: … Yeah. Yeah, definitely. I’ve got a few mates that—I’m sure it’s the same in the States—there’s a little London, sort of a bit of an editorial design scene. Like we go to Type Tuesdays, Eye magazine does a lot of talks, and there’s a lot of things we go to. And I’ve gotten to know quite a few people there.

So there’s a lot of magazine people that I chat to about things. I do think it’s important. And the mentor thing was massive for me. As I said, you know, I owe Jeremy a huge amount for pointing me in that direction. Matt as well. I learned so much from Matt. I didn’t even work with him for very long at all. I interned with his old studio, Studio 8, just after I’d graduated. And Matt was only there briefly because he was working at Frost. He was doing a kind of, not sabbatical, but Vince had asked him if he wanted to be a creative director there for a bit. So he was only in the studio for a little bit. But we worked on a magazine called You Can Now, which was the magazine that the first studio I worked for published. And Matt did the initial design and then I did a couple of the subsequent issues. So I worked with him on it.

And you just learn so much from seeing someone like that up close. Just how they do layout, after layout, after layout, after layout, to get to something that’s great. And particularly people that have got a lot of time and patience for you, which Matt always did.

So yeah, I owe him a hell of a lot. I think it’s really important, the mentor thing.

“There’s a huge amount of dross in the independent magazine world as well, right? There’s some total crap out there.”

Patrick Mitchell: Who’s on your team at your studio? Are you a solo act?

Alex Hunting: At the moment there’s only me and two others. But they’re pretty much always freelance—not freelance, but it’s normally like three-month or six-month contracts.

Because we don’t only do—obviously, I know we’re mainly talking about magazines—but I do a fair bit of branding and digital design as well. So it depends on which projects are in and whether there’s, like, a web developer working on something for a couple of months, or it’s a branding designer, or a motion designer. That sort of stuff.

I’d say the most people I’ve ever had was probably five at one point. But sometimes it’s me between freelancers and sometimes it’s me on my own for a bit. So it sort of goes up and down really. I’ve constantly been struggling with that: what constitutes success?

When I first founded the business, I set out to think to myself, “If I don’t have 20 people working on projects in the next few years, this isn’t a successful business.” And, I’ve very much fallen away from that idea now.

But it’s constantly thinking about, “Are we doing the right work? Do we want to grow the studio? Does that mean we’re doing better work? Or does that just mean we’re doing more work?” I don’t know. I think it’s a bit of a struggle really. But I think everyone probably goes through that. What type of work to do to fund staff, and whether you need a bigger space, and all that stuff.

Patrick Mitchell: I don’t want to get too nitty gritty, but I do want to ask, say a new magazine comes in. What’s your process for producing—so it’s a brand new design that doesn’t exist. You’ve got to create a redesign and launch an issue. Can you touch on the bullet-point process that you go through to get a new magazine up and running?

Alex Hunting: Initially it’s all type. It’s like type research, basically. Sometimes when something comes in, you can just see it in your head. You think, “Oh, it should be like that." And you think of references and all that sort of thing. I try not to look online a huge amount. I’ve got loads and loads of old archived mags from the sixties, seventies, eighties, nineties— all sorts of mags.

But the process, I guess, of tight pairings is the thing that I think about, which I guess everyone does. What’s going to give it character, what’s going to give it his identity? What are those elements?

Patrick Mitchell: I’m thinking more in terms of working with the clients. Do you find that your portfolio helps you fly through the presentation process a little more easily than it might in a design studio? Do your relationships come in where you have an understanding that you’re not going to have to go through round after round after round, and show option after option after option of look and feel?

Does it go that way? Or does it go more organically and more fluidly?

Alex Hunting: Most of the time clients that approach us, they approach us because of something that we’ve done. And so you can pretty much gauge, pretty confidently, where something should be in its visual direction.

We definitely do get stuff rejected. I tend to not show multiple routes. But sometimes if I’m not sure or if there’s a couple of things that we are working on that think is working well, then we will. I used to be way more precious about when stuff got rejected.

Patrick Mitchell: Because you’re a millennial?

Alex Hunting: Yeah, probably, yeah. I’d just, I’d have a bit of a tantrum or whatever to myself and think, “This is ridiculous.” But you know, the reality is that I’ve totally grown to realize that, ultimately, you almost always end up with something that’s better. Or, like, I find it because I challenge myself so much more after that’s happened.

And also the client, a lot of the time, most of the time, they are right because they know what they’re trying, they know the magazine might look cool to you, but it might not be the appropriate thing. So I’ve become much less precious about that sort of thing.

And I think it does end up leading to good work. Plus you can also leave all those excellent little ideas in a drawer and come back to them for something else.

Patrick Mitchell: Do you find yourself getting involved in editorial conceptualization in terms of like, creating new departments, or branding departments, naming things? Do you do all of that stuff too?

Alex Hunting: Yeah, in terms of formats and that sort of thing. It totally depends on the magazine. If we are doing something from scratch we’re often creating packages around how we can best show this sort of imagery, and this would go well with this sort of shorter storytelling, or this section’s like bitty-er stuff, or all that sort of thing.

If it’s a magazine from scratch, we tend to do a bit of that. Not lots of it. But a lot of the clients that we have are normally really great and they’re often asking—they want to be, they’re really design conscious, a lot of them. They want the design to be as good as it can. They want the design to help inform, how some of those editorial, how a lot of those formats are going to be. So yeah, we do do a bit of it. I’d like to do more of that.

• • •

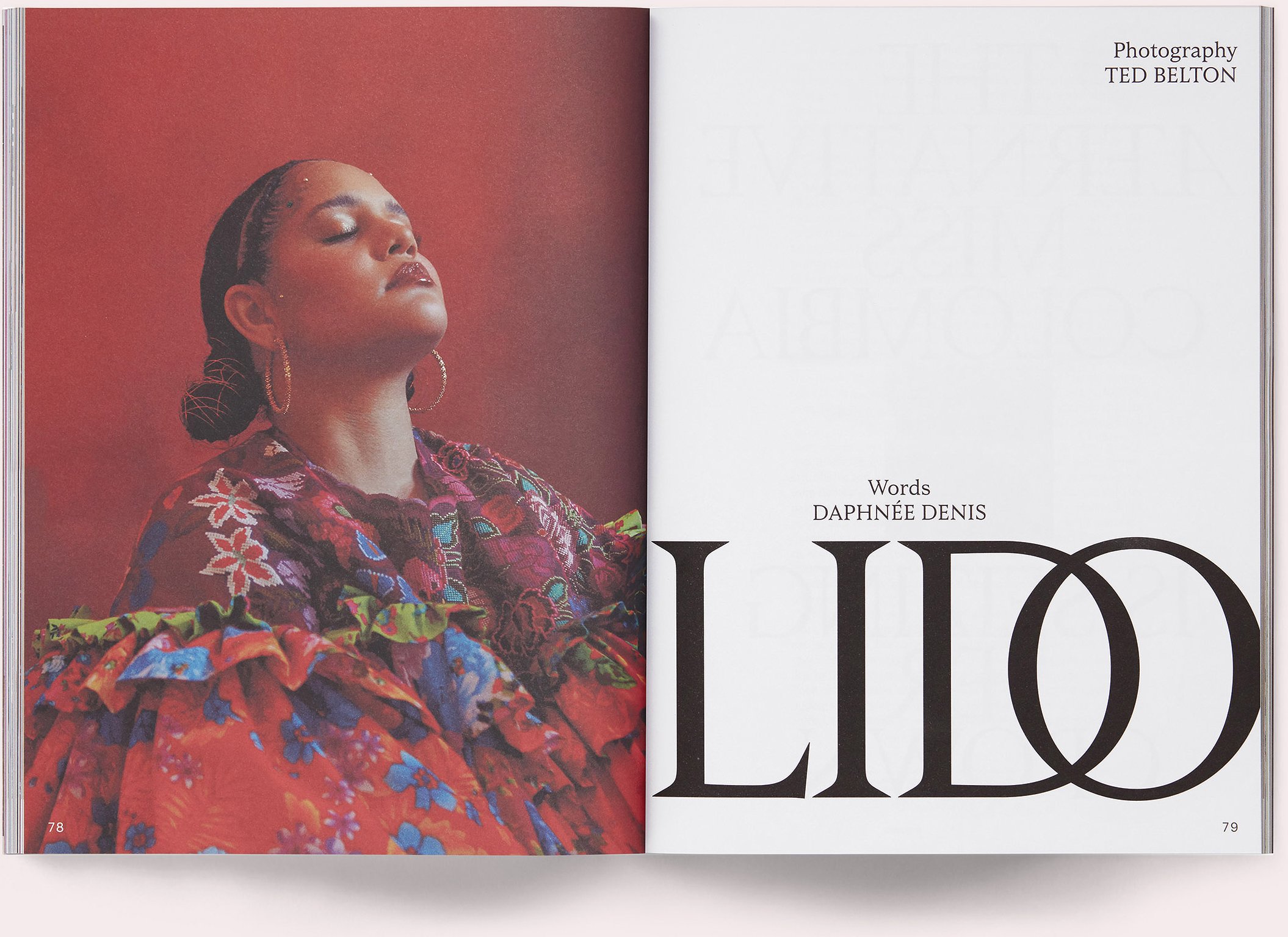

Patrick Mitchell: We’re going to shift a little bit now. I want to talk about Kinfolk. You’ve done a lot of work with the people at Kinfolk. How did that relationship begin?

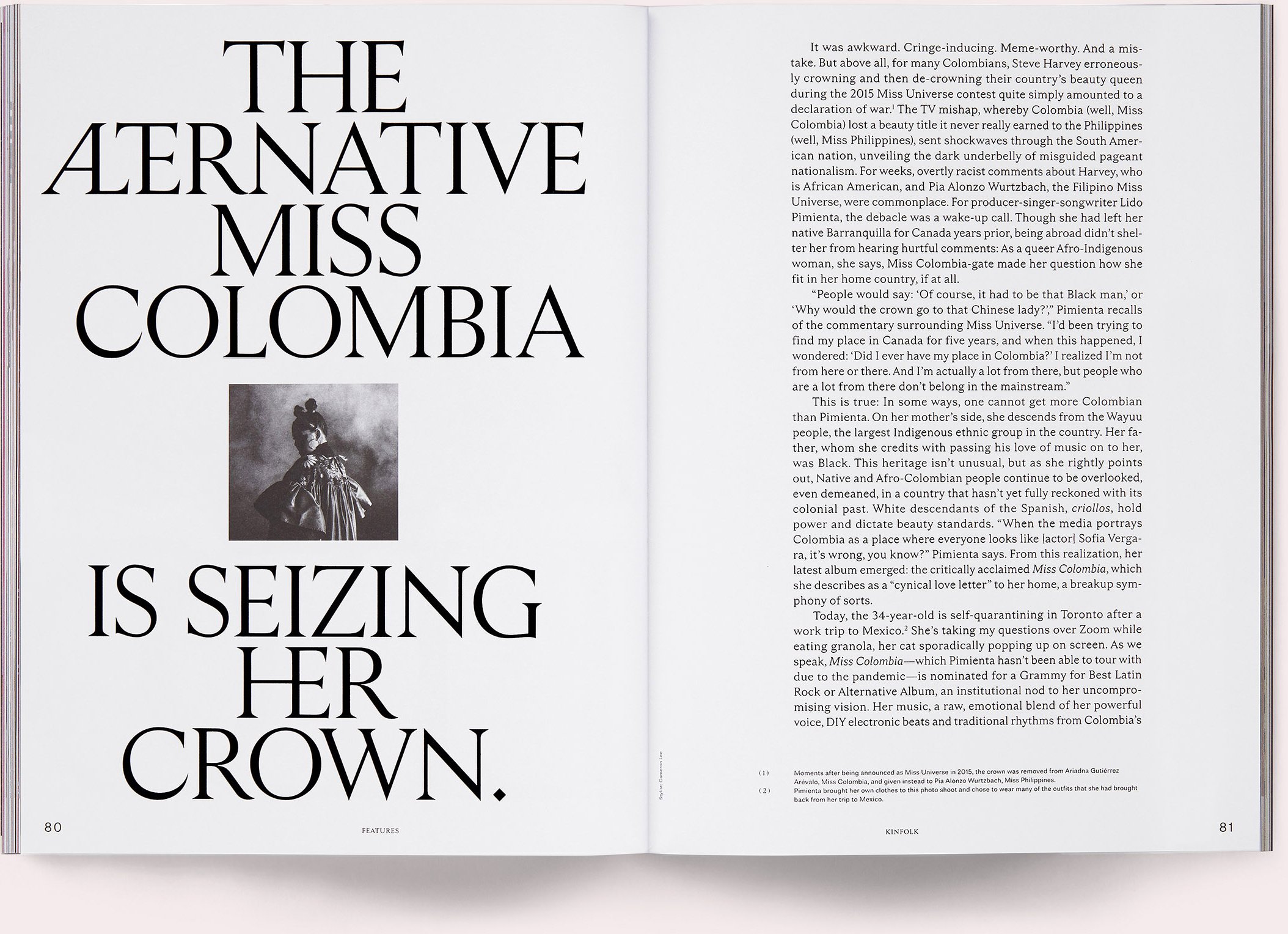

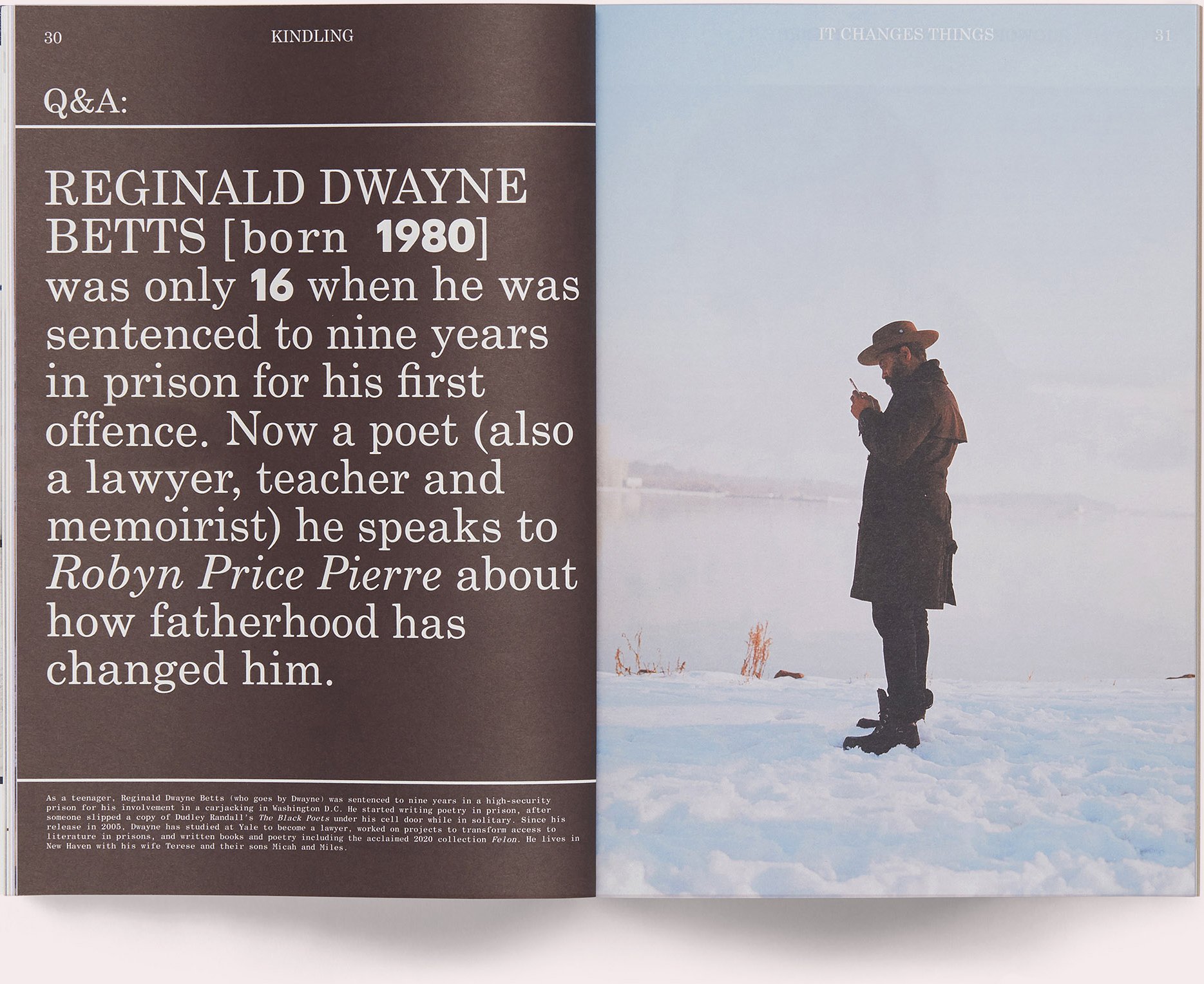

Alex Hunting: I got approached by Nathan Williams, who’s the founder. He got in touch with me in—I think it was 2016. Something like that. And he didn’t actually get in touch with me about Kinfolk. He’s the founder of Kinfolk. Kinfolk was initially based in Portland, and it was a massive US success story in the indie world.

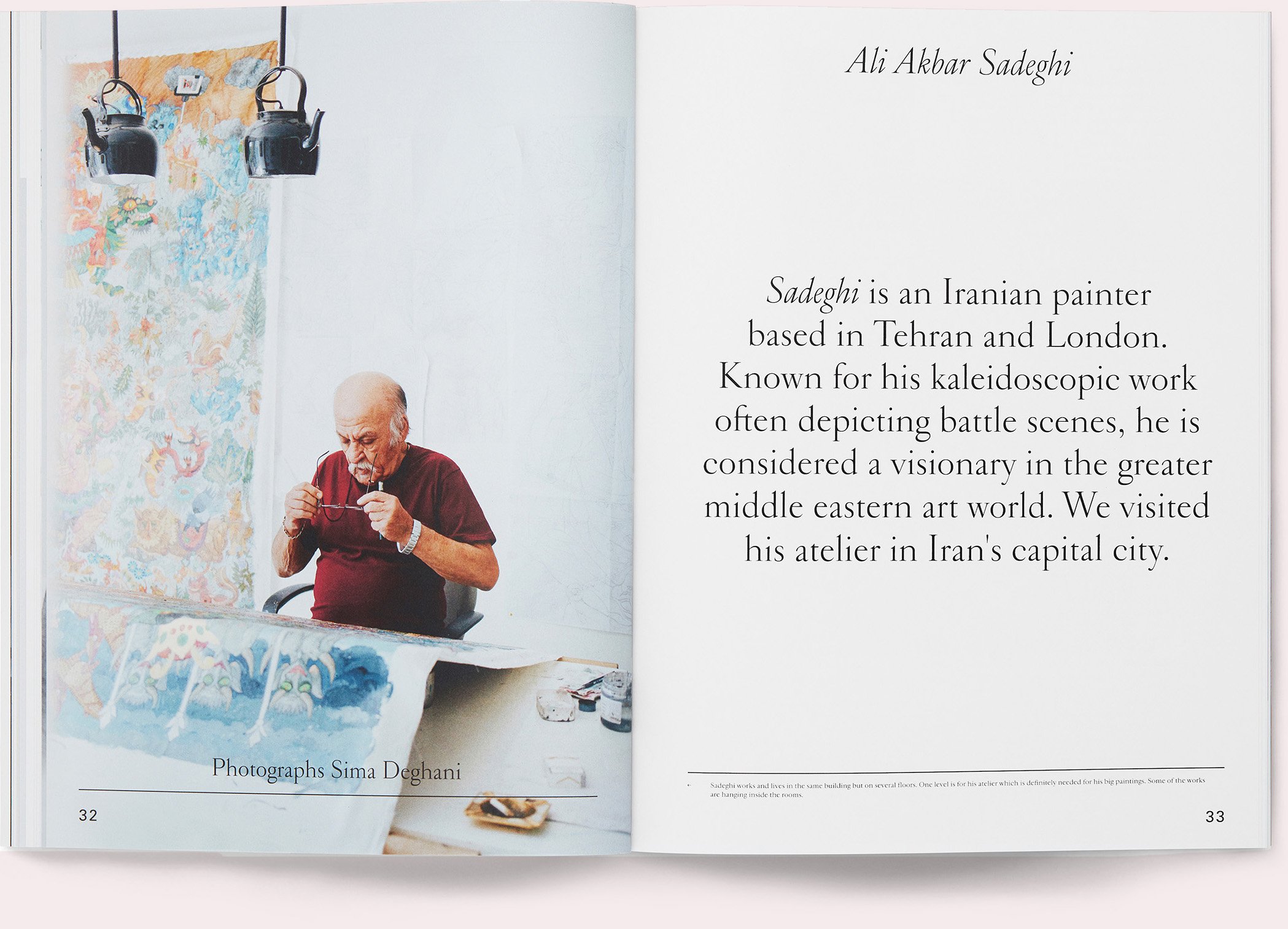

And they moved their headquarters to Copenhagen, Denmark. And it was a kind of slight repositioning of the magazine and the company around being a bit more for an international design audience—as opposed to necessarily just like a West coast, slow-living kind of vibe.

And they were going to start a new magazine, alongside Kinfolk, which was going to be an interiors magazine. And Nathan had seen what I’d done with the Rapha magazine, which is funny because it’s not particularly interiors-y, but he’d obviously liked something in the design. And he asked me to come over to Denmark and meet him and have a chat about it.

And so I started working on the concept for this new magazine. And um, loved it. It was really great. I really got into the process. Anyway, I remember we were quite deep into it and he just sent me an email one day saying, “Yeah, we’re not going to do it. We’re not going to do it, but would you be interested in redesigning Kinfolk?”

So, yeah, obviously, I jumped at the chance to do it. And it’s actually a shame that the [first] mag didn’t happen because it’s one of those ones which I was so happy with the design, you know, the initial mag we were working on. And actually, redesigning Kinfolk was a much more difficult challenge, because of the baggage that comes with it basically.

So it started there. And I did the initial redesign in 2016, and then redesigned it again beginning of last year maybe, or just a bit before. And yeah, it’s been amazing. I guess it’s been six years, really. And they’re just the loveliest team. Amazing editor. Just a whole amazing team. The kindest, nicest people. I mean, actually out of every magazine I’ve been involved in, anywhere, it’s the most organized, slickest operation I’ve ever experienced. So yeah, it’s great.

Patrick Mitchell: Nathan is no longer with Kinfolk, right?

Alex Hunting: No, no. He left a couple of years ago.

Patrick Mitchell: And so who owns it now?

Alex Hunting: It’s part owned by a Korean investor. It has Korean investors. I mean, Kinfolk is massive in Asia. So we still do a licensed Korean edition, Japanese edition, and we have a concept space in Seoul, South Korea. It’s got a massive audience there.

Patrick Mitchell: Is the editorial team still in Copenhagen?

Alex Hunting: Yeah. It’s exactly the same in terms of the mag. All based out there. Although increasingly British, actually. The editor-in-chief [John Clifford Burns] is British, the editor is British [Harriet Fitch Little], and I’m British. The art director, Christian [Møller Andersen], he’s Danish. And there’s an in-house art director as well, Staffan [Sundström], who’s Finnish. So there is a “Scandi” element to it. But there’s a lot of Brits involved.

Patrick Mitchell: I think about Kinfolk as one of your “name brand” clients and, I guess it is a name brand. But it’s a sign of the times that it’s a global brand with a circulation of, what, 80,000? Yet it is by far—and I say by far—one of the great success stories to come out of the indie mag boom of the early 2000s. And you’ve worked for a few of these.

Can you talk a little bit about your perspective on indie magazines? Jeremy [Leslie] has this amazing little shop [magCulture] in London where he focuses on shining the light on the best of the indie magazines—in the world of print publishing, indie magazines really are one of the positive lights. Most of the news coming out of our business is bad, but exciting things, good design, things like that, are happening with indie mags. Is that something that is going to continue to grow?

Alex Hunting: Yeah. I always find it amazing that I often get people—I had someone the other day apply for an internship and they were studying architecture, but they just really love the idea of working in magazines, and can they come and intern. I was thinking, “Don’t be a fool! Continue with the architecture!” But it’s amazing. I’m still of that generation of pre-mobile. Pre-digital as well. Just, just about. So magazines were a big thing for me growing up, because they were—I mean, I think they still are—they’re culturally significant things, right?

It’s where you get your subcultures, like skateboarding magazines, music magazines, all that sort of stuff. And I think they’re still massively important in terms of defining that sort of—I mean, nothing’s really taken that place.

You obviously have digital websites, blogs, and social accounts that are massive, that basically operate as magazines. They are magazines. But it’s amazing the kind of cache that they still have, the printed stuff. There’s a huge amount of dross in the independent magazine world as well, right? There’s some total crap out there.

But it’s the luxurious element of it—the fact that some of them might only exist for one or two issues and disappear. In a way that’s what makes a lot of it exciting, right? Because basically people do what they want and sometimes they get picked up and lots of people read them, and a lot of the time people don’t.

But they still have a sort of a purpose, don’t they? And I guess most of that was a reaction against the fact that the newsstands—just that whole world has just been falling apart.

“I think that the most interesting space—and I’m slightly biased about it because I had such a great experience working on the Rapha magazine—but I think that “brand” magazines can be one of the more exciting spaces for the industry.”

Patrick Mitchell: They tend to spend a lot of money on paper and printing. And it’s funny, because when you walk into a newsstand that has a lot of indie magazines, you would think that design is going to be a really big part of it. And I’ve tried to figure out what’s really happening there, because you open them up, and the design suddenly isn’t that great. There’s a lot of white space. It’s very precious. It’s small titles and centered text. They look like books. They’ve got nice photography. But there’s no “editorial design” once you get past the cover.

And I don’t know if Monocle is considered an indie mag. I guess it’s not from a “big” magazine publisher. But I tend to think of Kinfolk and Monocle as two success stories of magazines that started in non-traditional ways. And also, ironically, both supported by Asian partners. Nikkei owns part of Monocle, and as you said, a Korean company owns a big chunk of Kinfolk. Or all of Kinfolk.

Alex Hunting: I totally agree with the design thing. I think a lot of it is because, in all those indie mags, there’s so many editors. They’ve always been a space for writers, right? You know, the literary-type sector. There’s a whole creative space of people desperate to start magazines that aren’t designers as well. I’m always amazed by that.

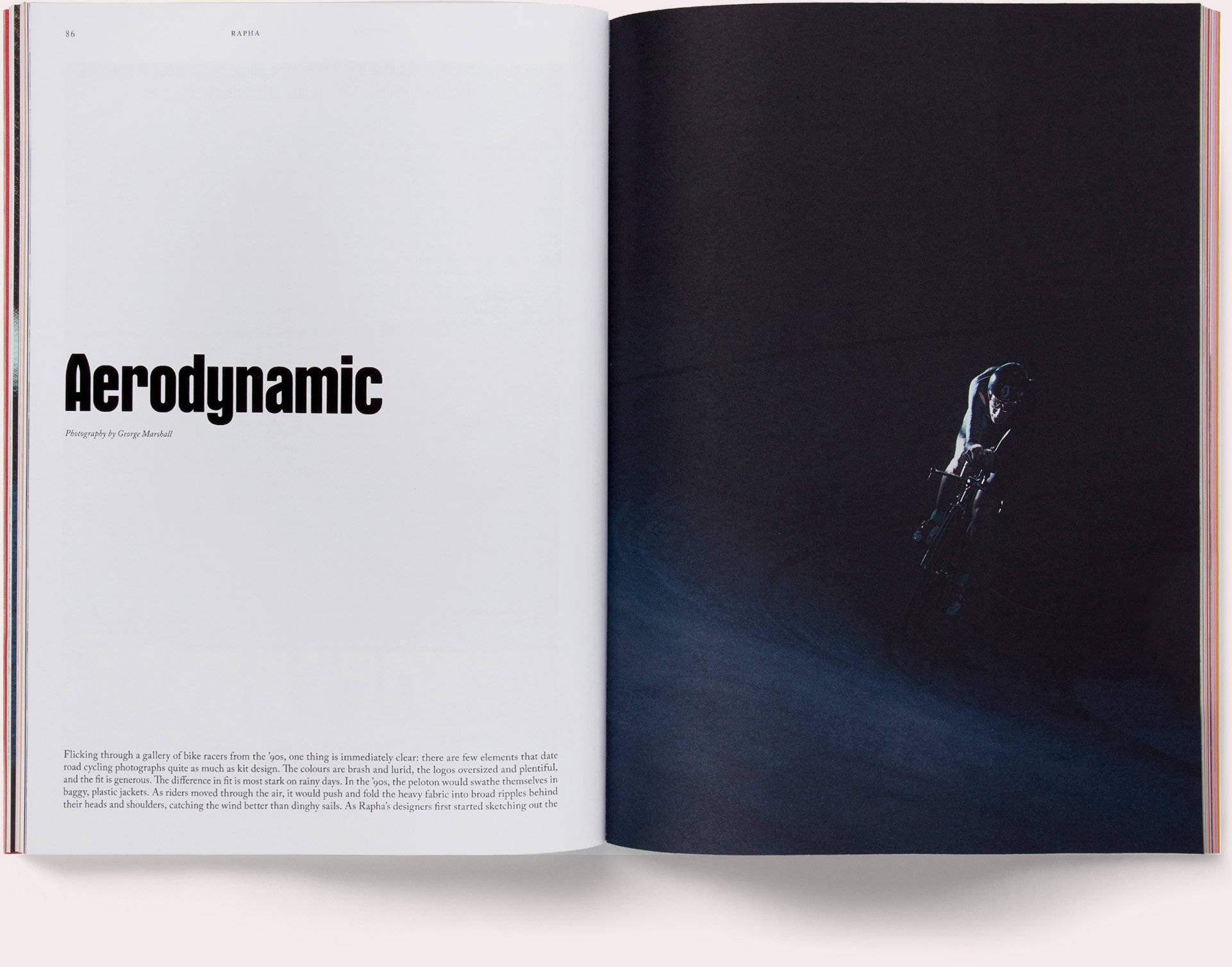

Obviously there’s loads of magazines which, kind of, they’re just put together by people, so some of the content might actually be great, but it’s not guided by a designer. I think that the most interesting space—and I’m slightly biased about it because I had such a great experience working on the Rapha magazine—but I personally think that “brand” magazines can be one of the much more potentially exciting spaces for the industry.

I really believe that because I think that the right brand, with the right kind of storytelling can often make so much sense. Because so much of the problem with newsstand magazines is like, this advertiser, that advertiser, this person’s got to be on the cover, all this sort of stuff. And so much of that stuff goes out the window with the brand magazines, because it’s essentially just a marketing expense for the company. They can spend quite a lot of money on it.

But if the brand’s great, and the brand’s got good values, and it’s got amazing editors, and amazing designers, I think lots of brands can see the value in it. And it shows you, it still 100% has that—it’s often the high point of a brand’s editorial output, isn’t it? It still is that physical thing. So I think that’s a relatively exciting space still.

Because there’s often with, if it’s like a particular kind of brand—so obviously with Rapha, the magazine’s a cycling magazine, but it had a brilliant editor, had an amazing in-house art director, Jack Saunders, who’s just an incredible creative mind to work around.

And the storytelling around cycling was so exciting—the sort of stories you would never see in a traditional cycling magazine. But brought to life with amazing attention to detail in terms of the production, the photography, all this sort of stuff, because the vision of the company is great.

And there’s plenty of brands out there where you could see that could be an amazing thing, you know?

Patrick Mitchell: And they wouldn’t have the pressure, like if Hearst launches a magazine, well, that means it’s got to come out monthly, and it’s got to get a certain number of readers, and a certain number of advertisers, and become a business. Rapha can decide to do a magazine, because it’s a great format for a certain thing, and do six issues and call it a day. And it’s a success.

Alex Hunting: Exactly. Exactly. So yeah, I love the indie mag scene. And I think it’s brilliant. And I guess that’s why I’m still doing what I’m doing, really. As I say, it’s from going to that independent magazine festival all those years ago. So yeah, I love it.

And I’m still amazed. I keep thinking it’s going to die down really. But it’s just constant, isn’t it? New titles, new titles, new titles. I think it will die down because printing has just gone completely insane. The cost of printing. It’s just, it’s next level now.

But then, I guess digitally, there’s always ways around it. I’m sure people will find a way to keep publishing stuff.

Patrick Mitchell: Has your relationship with Kinfolk led to more work?

Alex Hunting: Yeah, definitely. Definitely. I mean, people have approached me just because of working on that title. It’s also led to some really nice—I’ve got a few Danish lifestyle-y clients. Furniture or homeware, that sort of stuff. Stuff that’s in that world in that Copenhagen little bubble. So yeah, it’s definitely led to stuff.

And we’ve also done another mag with Kinfolk as well. I’ve worked on a couple of the books and all sorts of stuff like that. It’s been a really fruitful relationship.

Patrick Mitchell: So you get a lot of work from word-of-mouth. Do you do actual biz development to get new work? Or do you not need to do that?

Alex Hunting: Yeah, I’ve definitely done it over the years. I think the hit rate has got to be under 5%, or something. I used to do these really big send outs where I’d send a fresh issue of every best thing that we’d done to the marketing director or the so and so of loads of particularly niche companies we really wanted to work for.

I think once it worked. I think. And I try to get in front of people. Like I do try to meet people. But I’d say the vast majority is word-of-mouth. Or not necessarily word-of-mouth, it’s just, you do a project, someone sees it, they like it, they want something like that.

They get in touch. So I do a bit. It’s probably 20% new business, I guess, 80% word-of-mouth. But often that means the work dries up.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, I can relate. It’s almost impossible to be an effective business development person as the person who also has to do all the work that you get.

Alex Hunting: That’s definitely the job that I need, really, that I do need to hire. Much more kind of a project management/new business type of job. I’ve been thinking about that for so long. It’s such a key part of the business.

My dad used to always say that. He said, “You should always be spending 25% of your time, at least, on generating new business.”

Patrick Mitchell: And what percentage do you spend?

Alex Hunting: Definitely not that! Definitely not. Two percent, three percent.

Patrick Mitchell: So you’ve accomplished a lot at the tender age of 35. And you’re so busy, I imagine it’s going to be tough to answer this question, but how are you thinking about the, say, the near future in terms of you, your business, your life, all of that stuff? Just keep plugging or do you have wider goals?

Alex Hunting: Yeah, I don’t know. I was saying to you earlier, I’ve just had a son. Well, he’s 18 months now. So that’s been quite a preoccupation where I’ve been keeping my head above water in general. Just working, keeping the business going, trying to do good work, and trying to spend time with him a bit, and all that sort of stuff.

So, I think, for the near future, it’s just carry on as is, really. For a bit. And I always always say this, but I would like to grow it a bit. I would like to grow the studio a bit in terms of—I’ve had some great designers in recently and there've been some really great relationships with some of them. And I’ve not been able to offer them a job at the end of their freelance contracts. And I’ve wanted to, and that sort of thing. I’ve let quite a bit of talent actually fall away, which has always been quite gutting. So I’d like to be in a position, do you know what I mean, to have a bit more of that.

But apart from that, no, just try and do as much good work as possible. Really. That’s it.

Patrick Mitchell: All right, we call this The Million-, or Billion-Dollar Question. I guess it depends on how big your ambitions are. But let’s say Jeff Bezos called you today and said, “Alex, I’m going to give you a blank check. The only stipulation is you have to use it to create and launch a print magazine. Money is no object.” What would you make?

Alex Hunting: Oh. Um. Cricket Magazine? No, I was thinking about that. I would love there to be a decent cricket magazine, but the imagery would just always be too, too, too rubbish. I’m a big cricket fan, so that would be good. But it’s just, it’s not a very, it’s not a very image-based, image-led thing. I think, do you know, I thought about it. I have actually thought about magazines a lot because I’ve always wanted to start my own magazine. So there’s been a few ideas I’ve had over the years. But I think the magazines that I—besides kind of current affairs, or news, or that sort of thing—the magazines that I really enjoy are the ones that are very meta, or, like, macro, how they, like, zoom in on something.

Do you know the magazine Flaneur? Do you know that magazine? It focuses on one street somewhere in the world. And all of the content, the stories, are based around this one street. And the team goes and lives there. And I just think it’s amazing, the richness that comes out of it. And I loved Colors for that sort of thing as well.

So I’ve often thought what would be cool would be a magazine that each issue’s dedicated to a 24-hour period, basically, at any point in [history]. And Jeff Bezos could fund the best writers, the best photographers, and the best artists to find stories and bring them to life, of any 24 hour period. Basically, like, any period.

But you wouldn’t pick a famous year. It’d be like, I don’t know, 2000, I don’t know, 2004. Sort of ... June 3rd, 2004. Random. I love the idea that you could find those incredible stories from any random time. But you’d need quite a lot of budget, I reckon. Quite a bit of research resources.

For more on Alex Hunting, visit his website or follow him on Instagram @alexhunting1